The 1920s was a decade of dramatic change and growth for Cleveland, Ohio. The city was rapidly transforming, becoming a major player on the national stage, bustling with new industries, diverse cultures, and ambitious construction projects that reshaped its very skyline.

Population Surge and National Prominence

At the dawn of the 1920s, Cleveland stood as a significant American metropolis. Decades of industrial growth and waves of migration had swelled its numbers. By 1920, the city’s population reached 796,841, officially making it the fifth-largest city in the United States. Some counts from the time even placed the population slightly higher, at over 800,000. This figure underscored Cleveland’s established importance in the nation’s urban hierarchy.

A key characteristic of this burgeoning population was its diversity. In 1920, an impressive 30% of Cleveland’s residents were foreign-born. This substantial immigrant population was drawn by the promise of employment in the city’s booming factories and contributed significantly to its cultural and economic life. The city was a powerful magnet for those seeking new opportunities, leading to a rich, and at times complex, social fabric woven from many different backgrounds.

Throughout the decade, Cleveland’s population continued its upward trajectory. By the time of the 1930 census, the number of residents had surpassed 900,000. This represented an increase of more than 100,000 people in just ten years, a growth rate of 13%. Such sustained expansion reinforced Cleveland’s status as a dynamic and growing urban center.

However, this period also marked a subtle but important demographic shift. While a 13% growth rate was substantial, it was, in fact, an all-time low for Cleveland up to that point. It was the first time in the city’s history that its rate of population growth had actually decreased. This slowdown, occurring even before the Great Depression took its full toll, hinted at underlying changes. Factors such as maturing industrial sectors, evolving migration patterns, or the early beginnings of movement towards outlying areas were starting to influence the city’s demographic trends, setting the stage for future shifts.

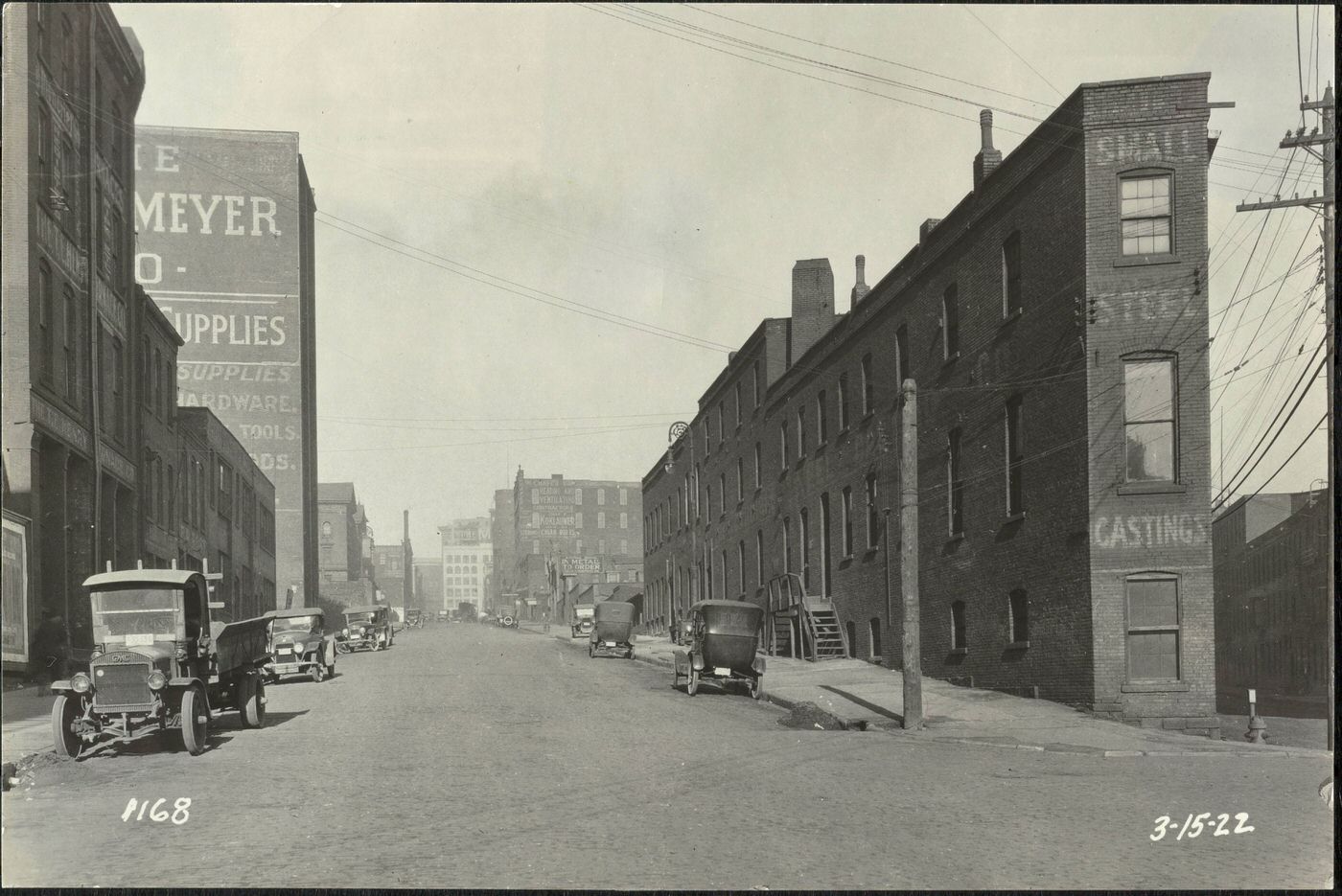

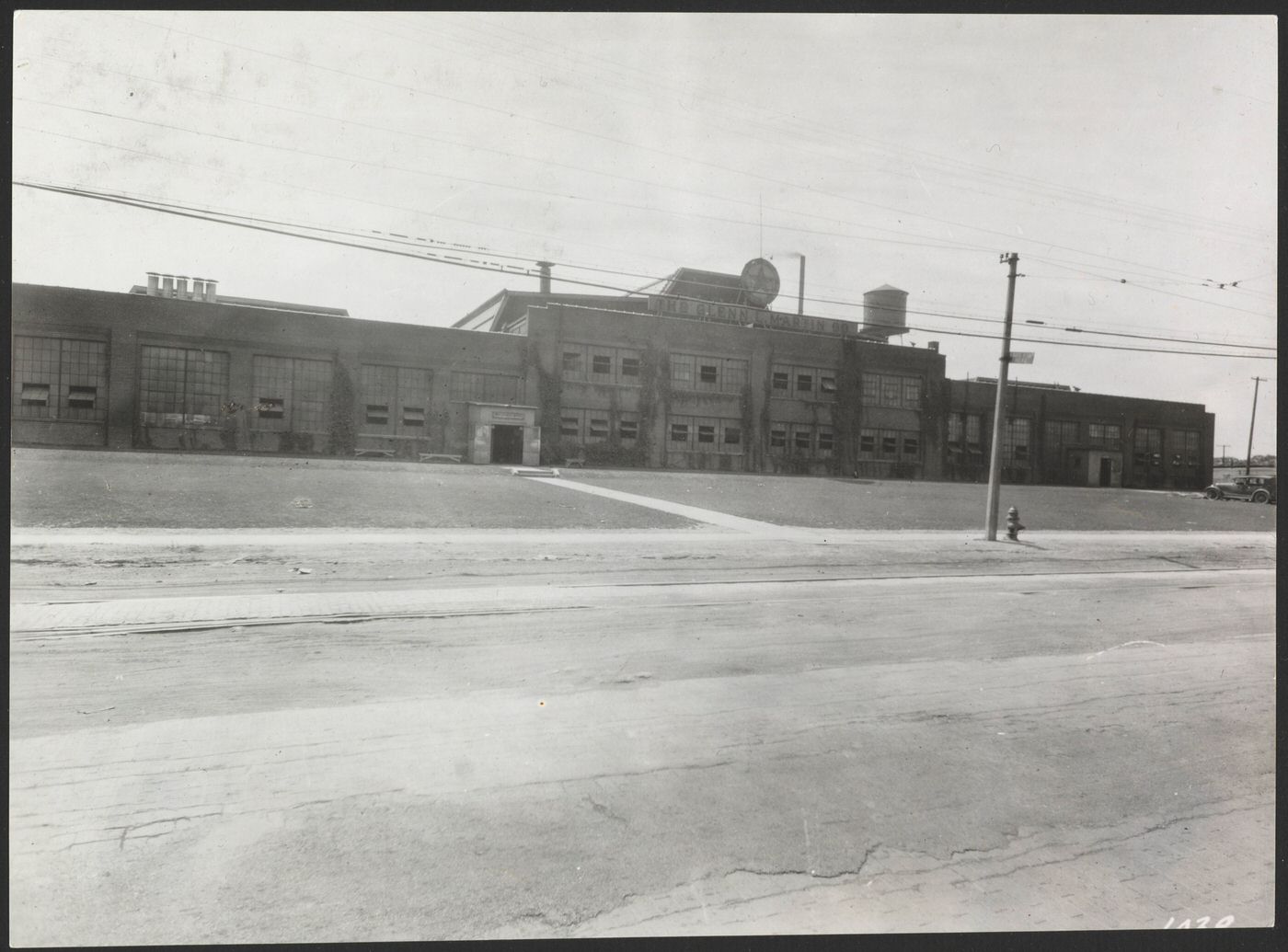

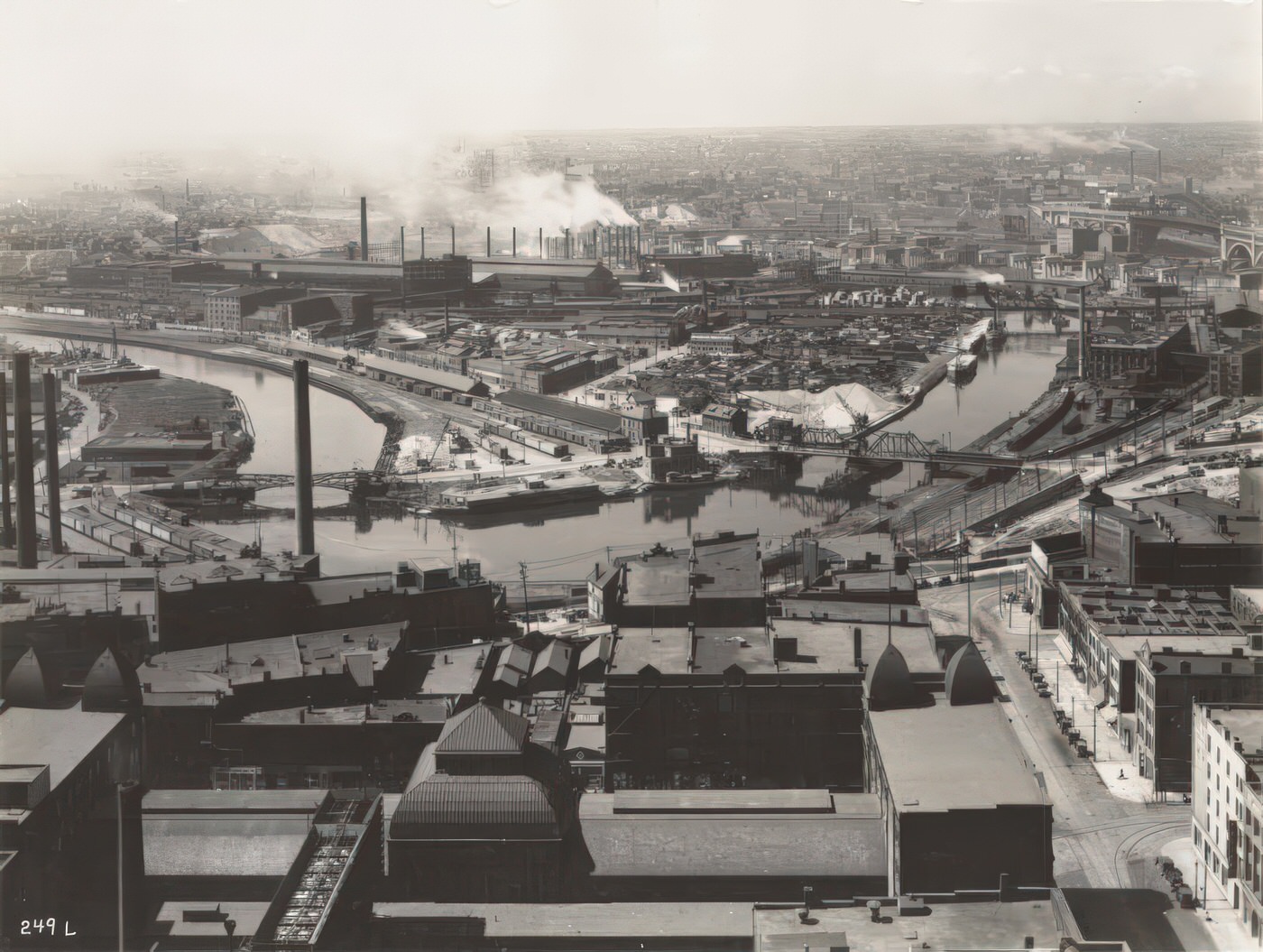

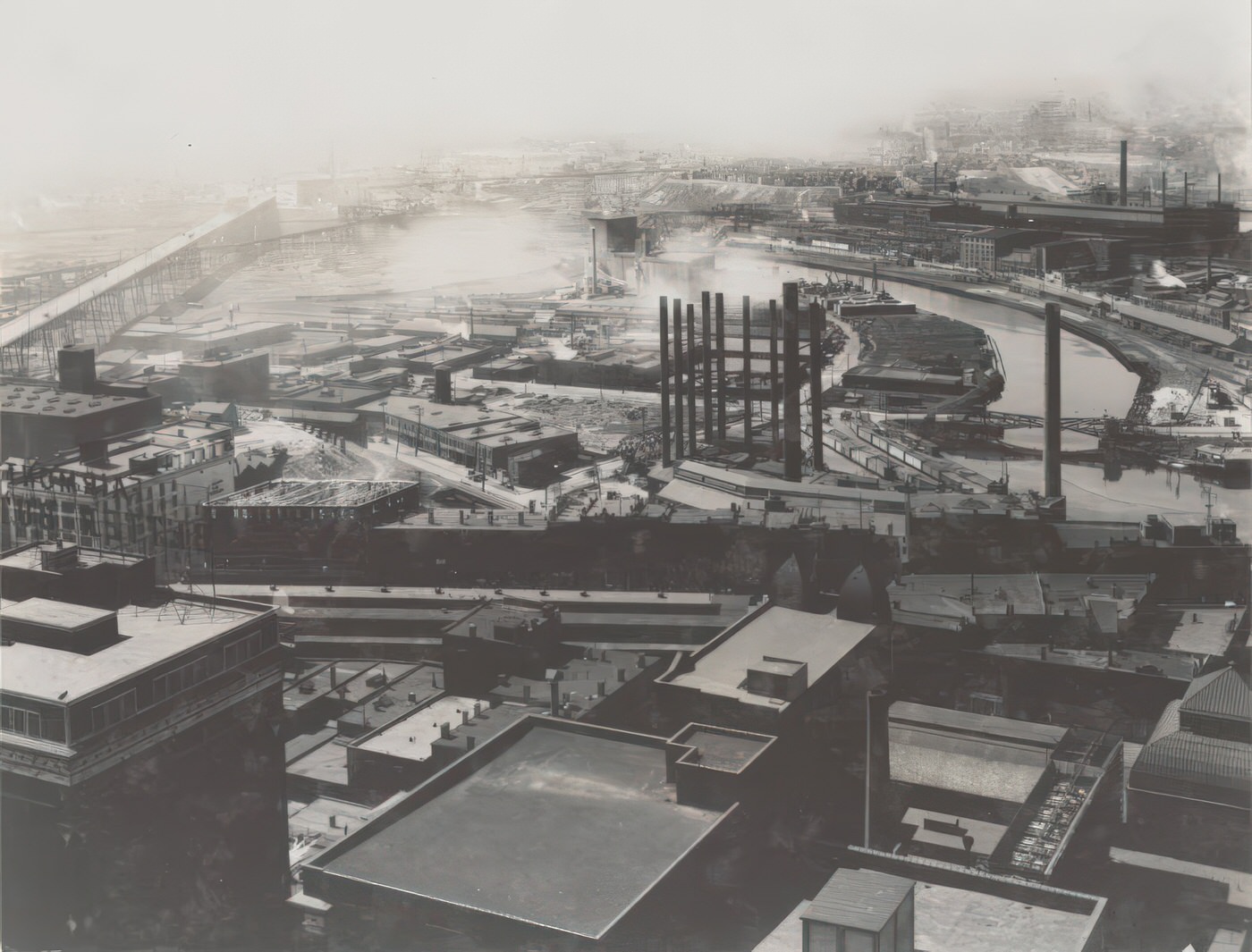

Cleveland’s Industrial Might

Cleveland’s economic power in the 1920s was rooted in a diverse and robust industrial base. The city was a specialist in several key sectors that were driving American innovation. By 1920, its leading industries were automobiles, machine tools, iron and steel, and electrical machinery. This industrial strength was built on a dynamic relationship between these sectors; for example, the burgeoning automotive industry created substantial demand for locally produced machine tools, steel, and electrical components, fostering an interconnected and thriving economic ecosystem. The city was also a significant center for chemical products, such as paints and varnishes.

Cleveland played a prominent role in what are known as “second-industrial-revolution industries,” which included electric light and power, petroleum refining, and chemicals, alongside automobiles and steel. This placed the city at the forefront of technological advancement. For instance, General Electric (GE) maintained important manufacturing and research-and-development facilities in Cleveland, having acquired the pioneering Brush Electric Company in 1892. GE continued as a major producer of electrical appliances and lighting systems through the 1920s. Another example of industrial prowess was the Gabriel Company, a major supplier of shock absorbers to the automotive industry. The Warner & Swasey Company was a leader in machine tools, while firms like Dravo Wellman and Babcock & Wilcox were prominent in industrial equipment manufacturing.

Beyond heavy industry, Cleveland’s garment industry reached its peak during the 1920s. At this time, the city ranked close to New York as one of the nation’s foremost centers for the production of ready-to-wear clothing. This highlighted another significant facet of Cleveland’s manufacturing landscape.

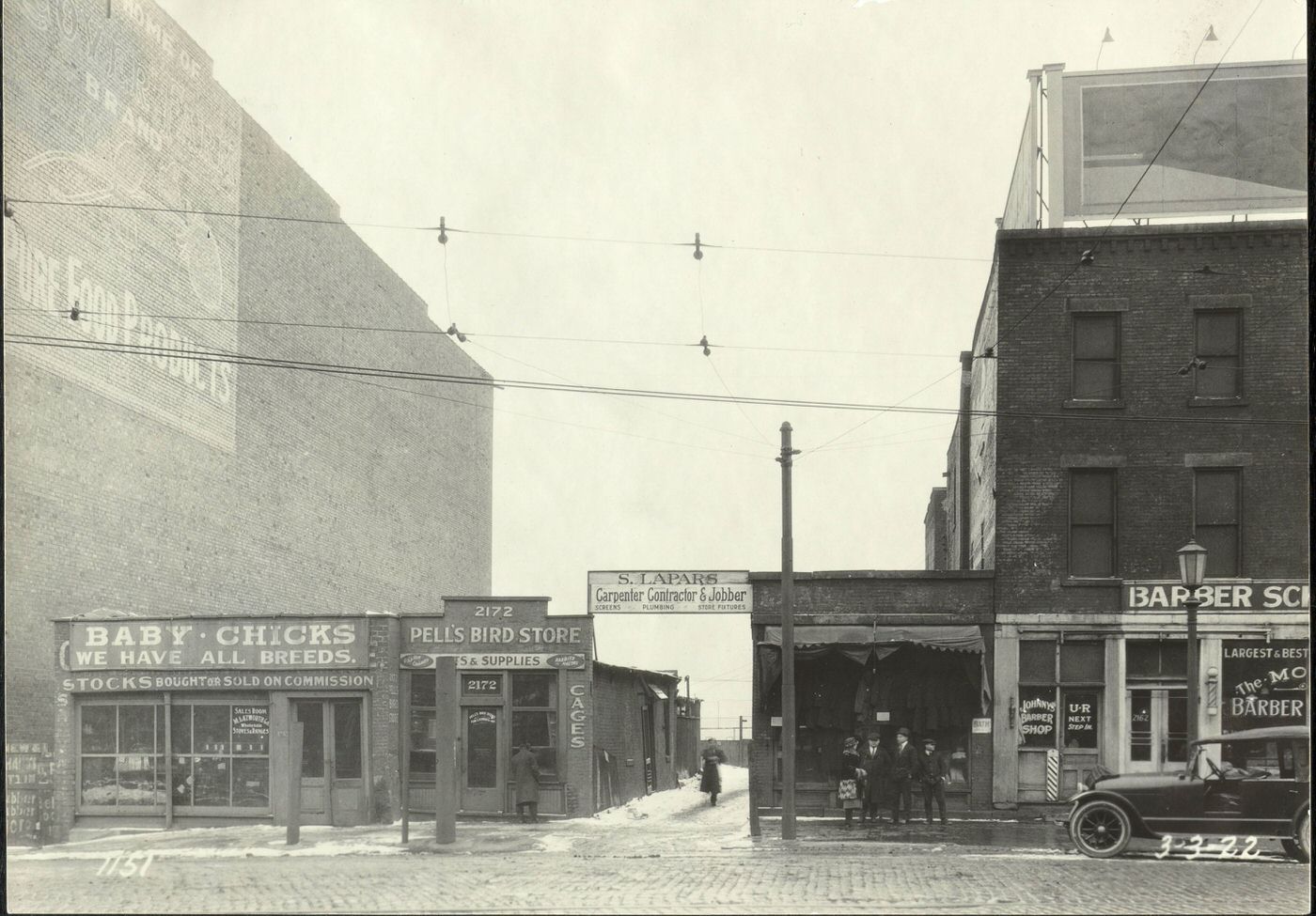

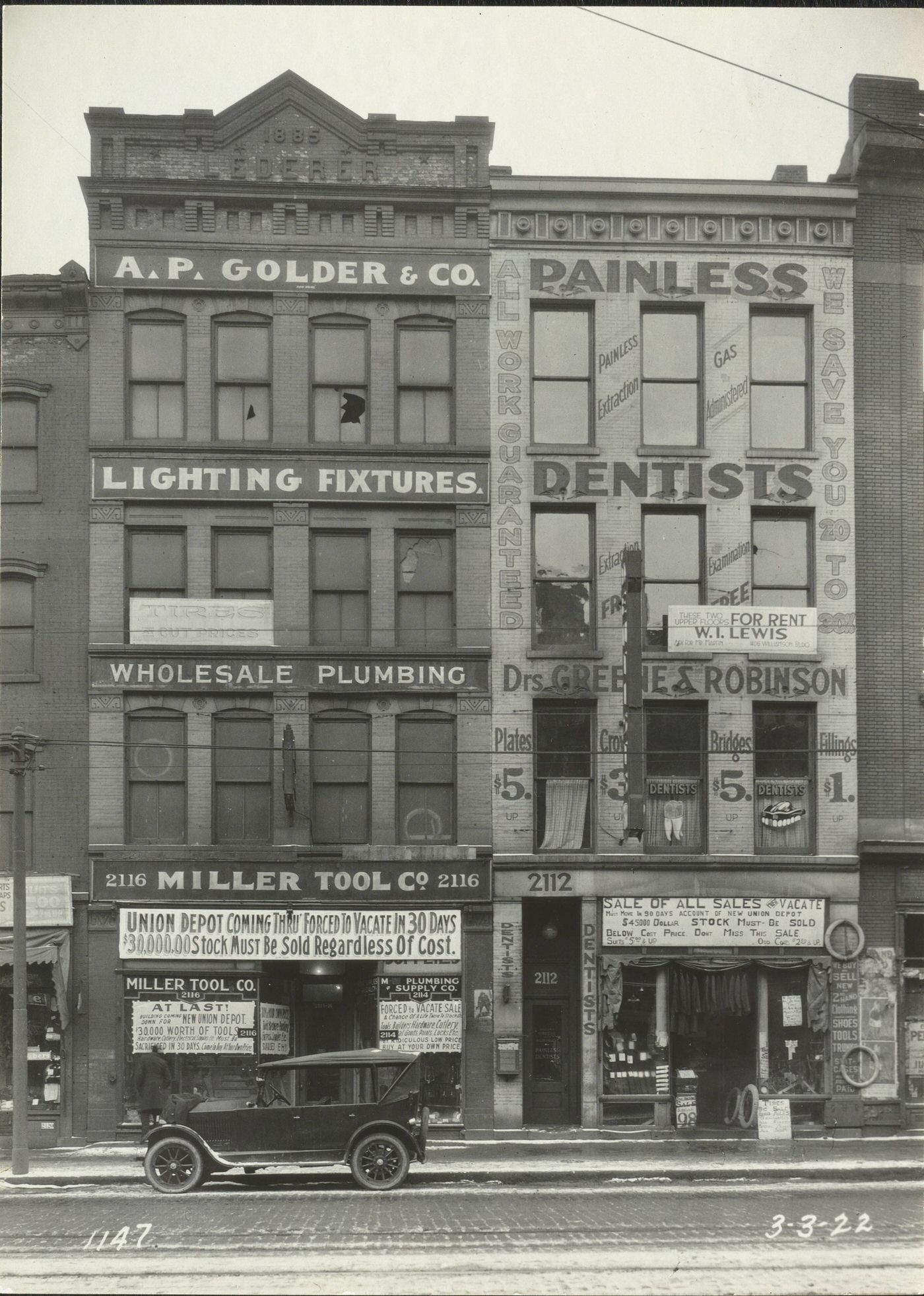

The Bustling Retail Scene

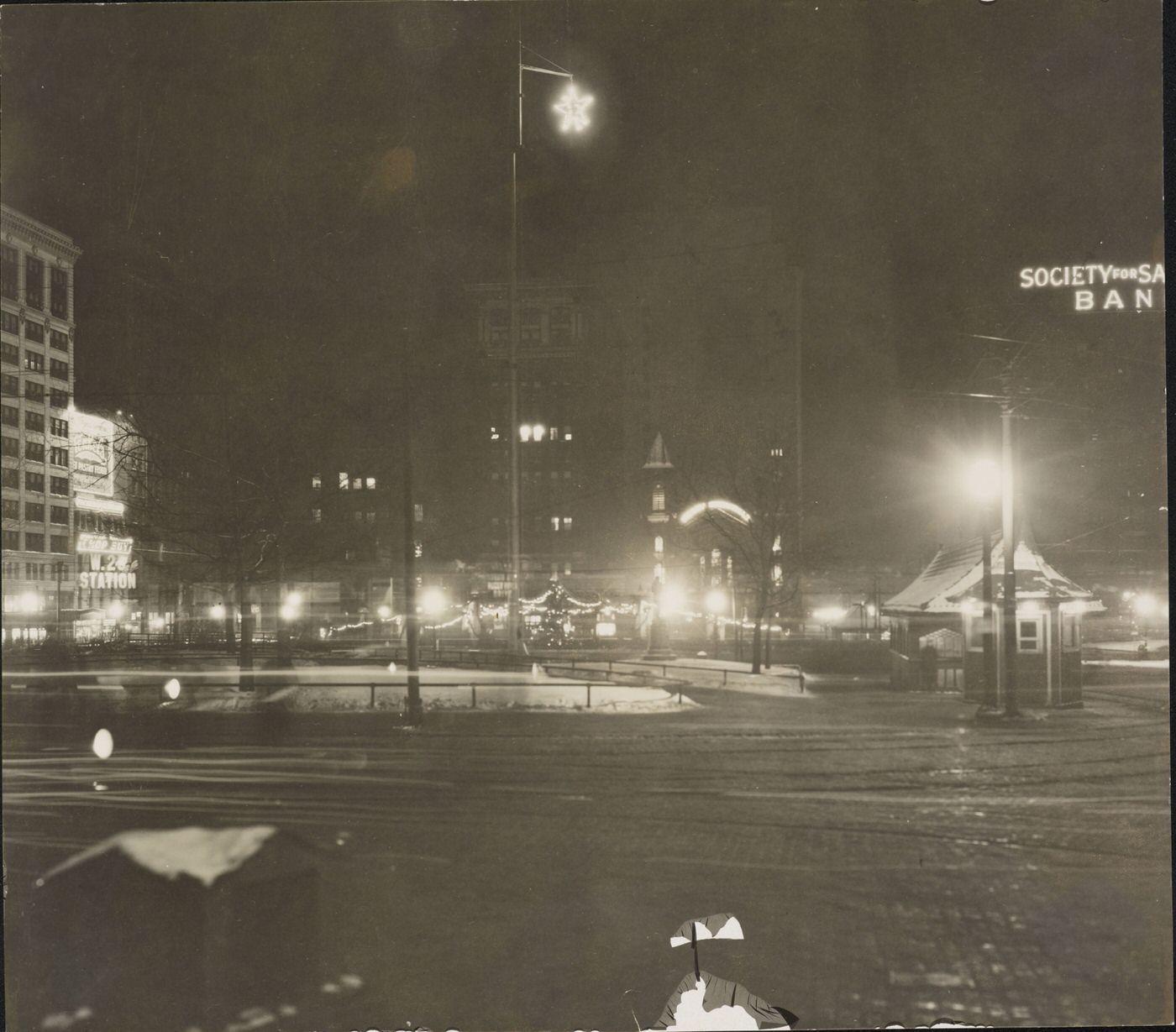

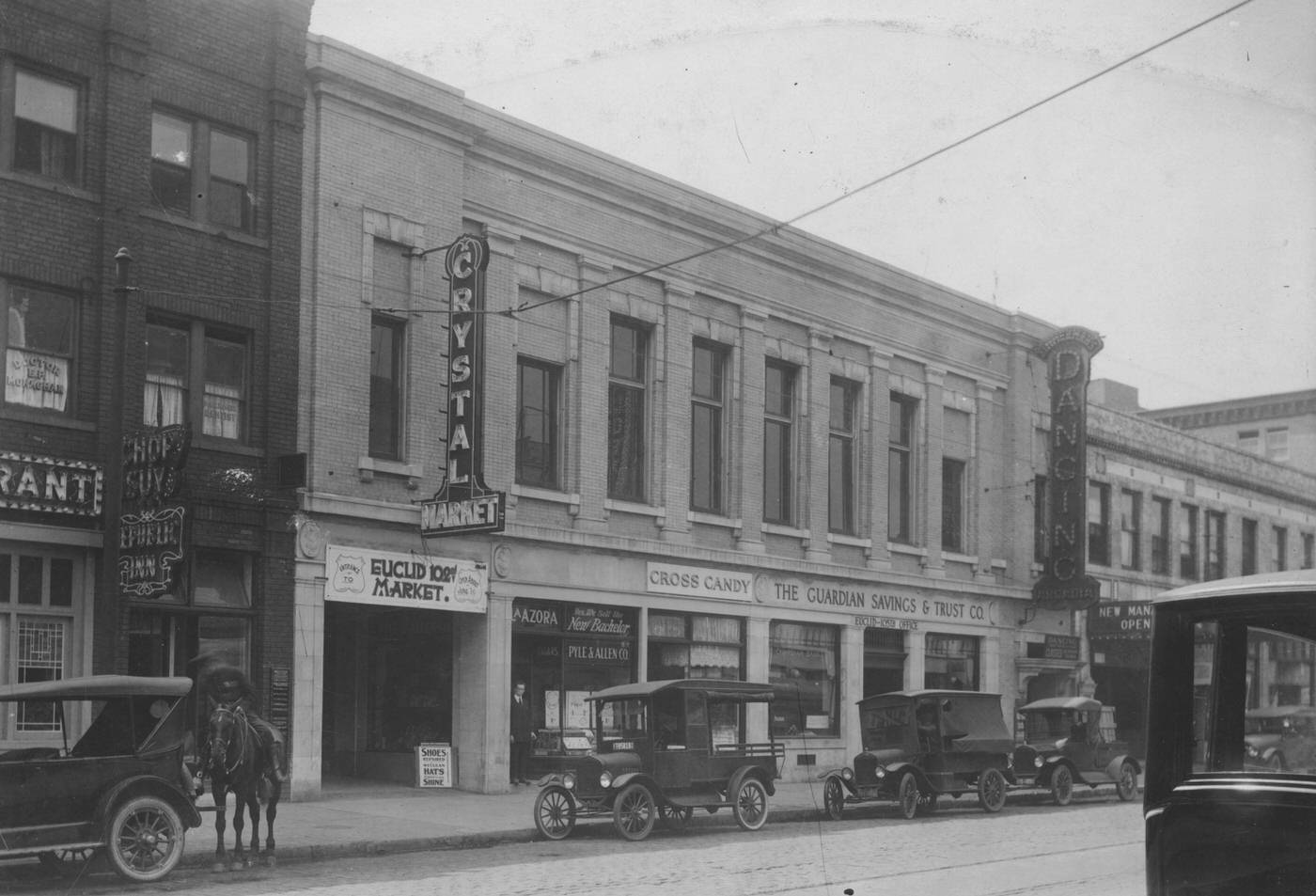

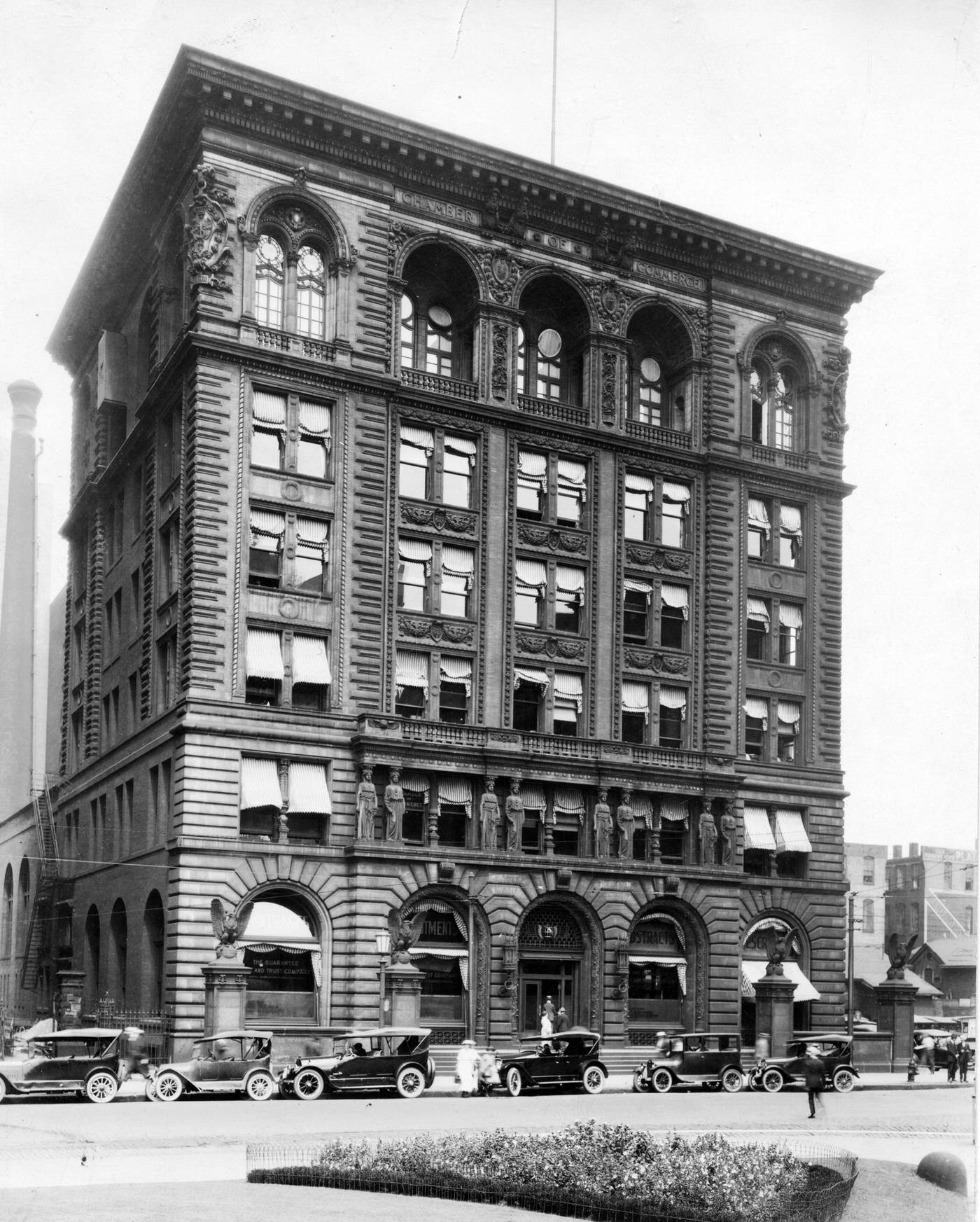

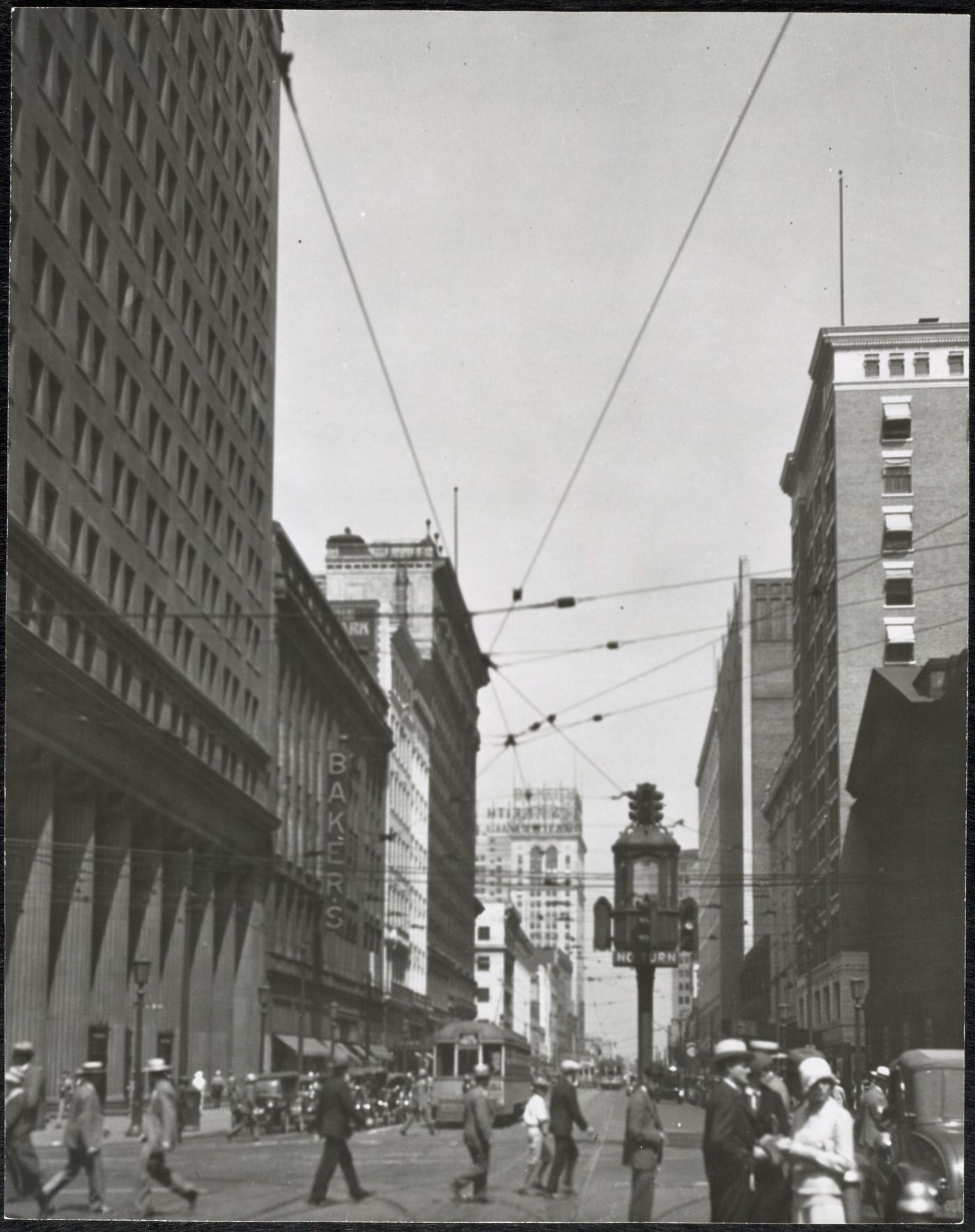

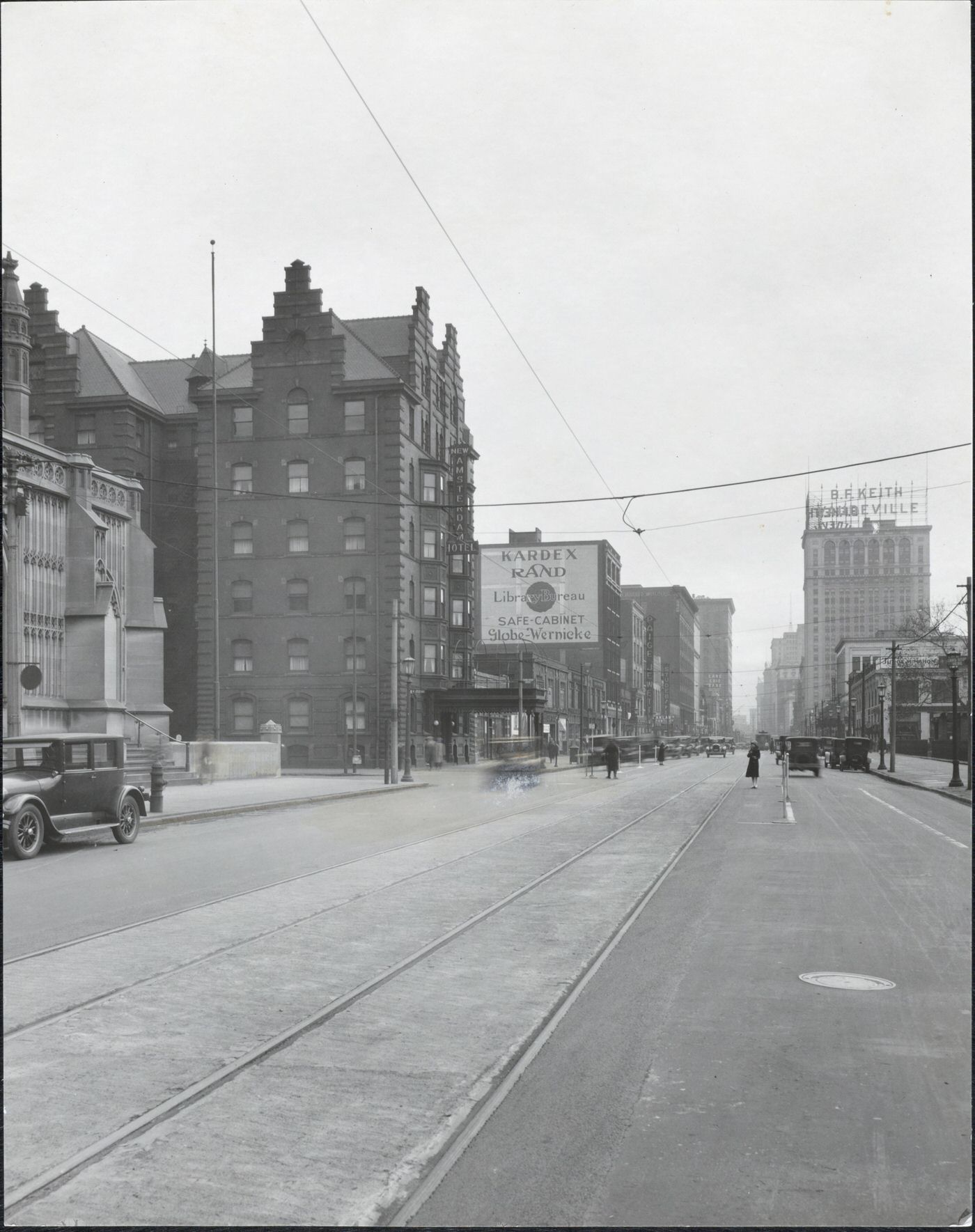

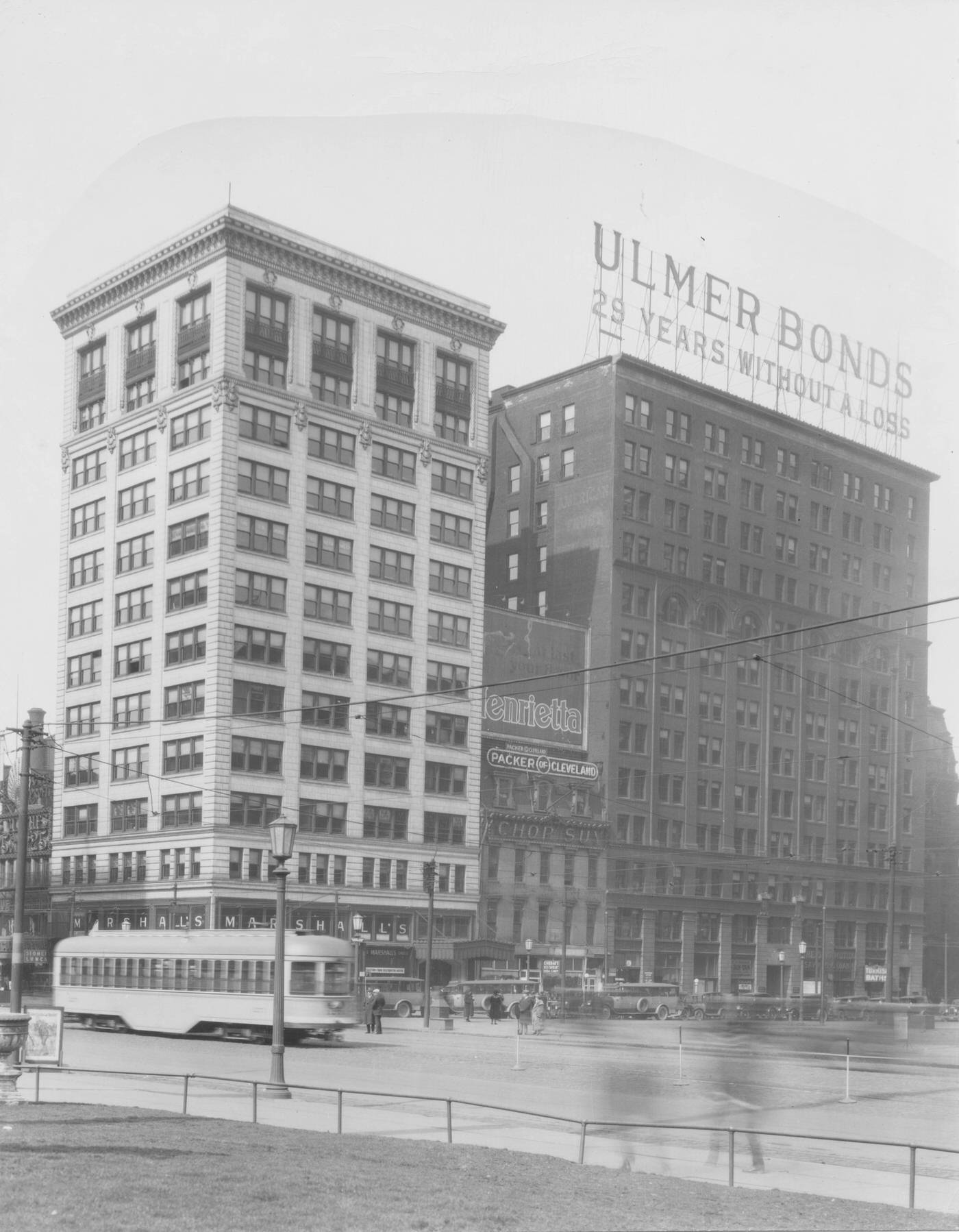

The 1920s ushered in a “golden age” for retail in Downtown Cleveland. The city’s main shopping district, centered on Euclid Avenue, was often favorably compared to New York City’s famous Fifth Avenue, signifying its status as a fashionable and vibrant commercial hub.

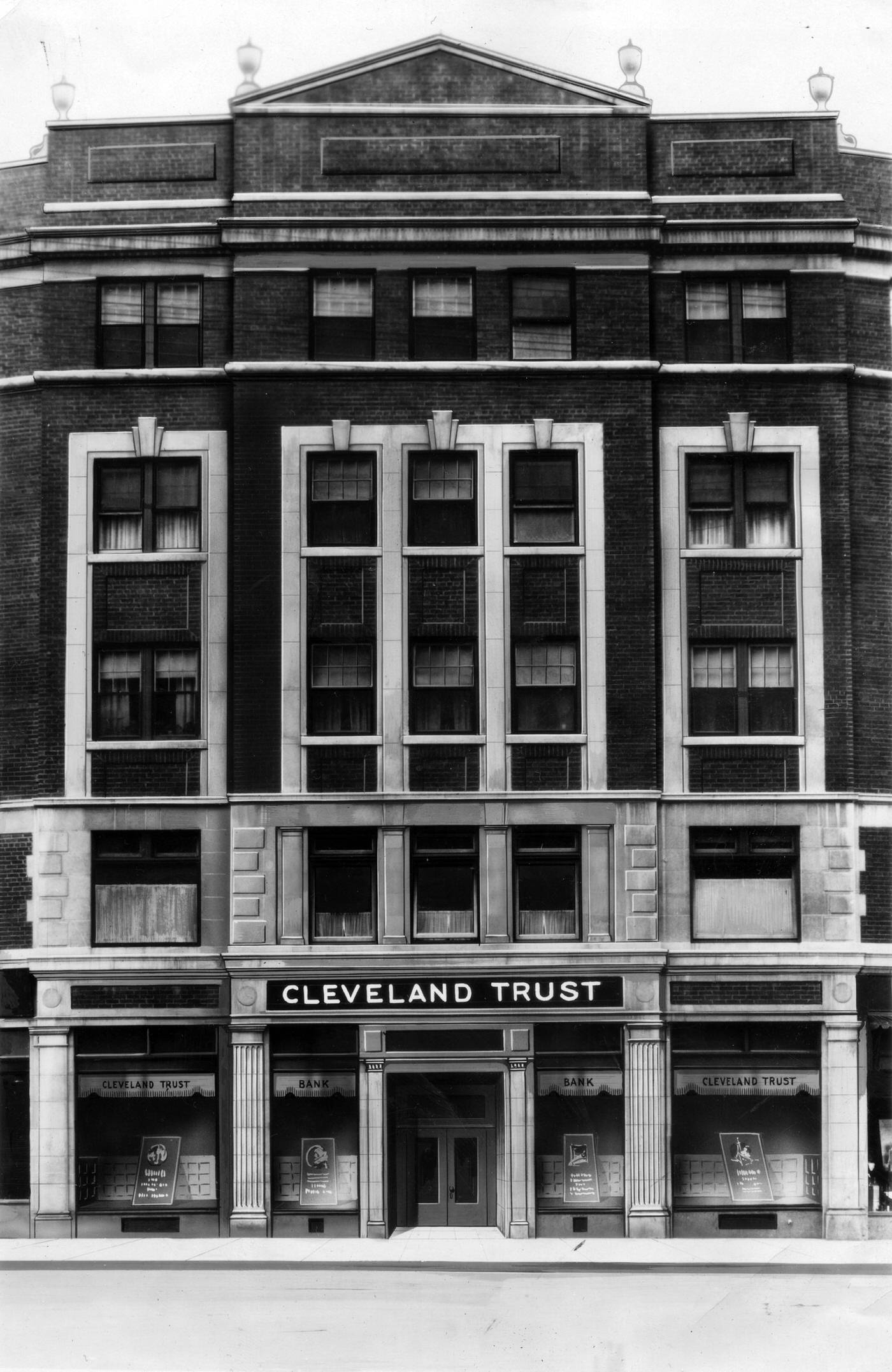

Dominating this scene were several major department stores, which had already established themselves as downtown landmarks by building grand, palatial structures between 1900 and 1915. Stores such as Higbee’s, Bailey’s, The May Company, Taylor’s, Halle’s, and Sterling Lindner Davis offered an extensive variety of goods and primarily catered to middle- and upper-class shoppers.

The retail landscape was also evolving with the rise of chain stores, which became a significant force in Cleveland during the 1920s. National chains like the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co. (A&P), Grand Union (both grocery stores), S.S. Kresge, and F.W. Woolworth (variety stores) expanded their presence. They were joined by successful local chains, including Kroger and Fisher Bros. in the grocery sector, and Marshall Drug Co., Standard Drug Co., and Weinberger Drug Stores in the pharmaceutical retail market. The impact of this trend was substantial; by 1929, chain stores were responsible for 35% of all retail sales in Cleveland.

This decade also saw strategic shifts by major retailers. Sears, Roebuck & Co., facing a decline in its traditional mail-order business, adapted by building two large physical department stores in Cleveland in 1928, one on each side of the city. Bailey’s department store also began to look beyond the downtown core, opening a branch in the Euclid-East 105th Street shopping center in 1929, followed by another in Lakewood in 1930. These moves by major retailers signaled the early stages of a shift in retail patterns, hinting at the future growth of suburban shopping areas and a gradual decentralization of commerce from the traditional city center.

Work, Wages, and Labor Relations

For many working people in Cleveland, the 1920s brought a measure of prosperity. Real wages for workers in Ohio saw an increase during the decade, rising from an annual average of $672 in 1920 to $834 in 1929. This economic improvement was felt by a segment of the workforce.

However, this prosperity was not shared equally. African American workers, many of whom were recent migrants to the city and often lacked the specific skills or education sought by some industries, faced significant discrimination from both employers and labor unions. These barriers often confined them to the expanding residential areas on Cleveland’s east side, which faced overcrowding and deteriorating conditions. Despite these challenges, some Black residents did achieve the milestone of homeownership in neighborhoods like Mt. Pleasant and Glenville during this era. The economic disparity created an undercurrent of inequality beneath the surface of the “Roaring Twenties.”

For organized labor, the 1920s were a challenging period. The focus shifted towards maintaining existing union memberships rather than organizing new workers. Efforts to unionize major industries like steel had faced setbacks, and employer groups such as the American Plan Association actively promoted the “open shop” (non-unionized workplaces), sometimes resorting to the use of strikebreakers and labor spies to counter union activities.

A notable example of labor-management relations could be seen at the Joseph & Feiss Company, a major garment manufacturer. It remained a non-union shop throughout the 1910s and 1920s, a time when many competitors in other cities were becoming unionized. This was largely attributed to the progressive policies implemented by Richard Feiss, the factory manager from 1909 until 1925. He introduced measures such as ergonomically designed workspaces, company-sponsored employee programs, medical services, and, notably, a five-day work week in 1917—several years before Henry Ford famously did so in his factories. However, these progressive programs were deemed too expensive by other company leaders, and Richard Feiss was forced out of the company in 1925.

Despite the general economic growth, there was a “growing feeling of insecurity in life and property” among Clevelanders. The city experienced high rates of murder, property crime, and automobile theft. The Cleveland police division faced significant criticism and calls for reform due to issues such as outdated precinct boundaries, corruption within its ranks, poor detective work, low officer morale, officers drinking on the job, and instances of police brutality. This difficult environment for law enforcement was compounded by the challenges of enforcing Prohibition.

Key Cleveland Industries and Businesses of the 1920s

| Industry Sector | Prominent Cleveland Companies/Examples | Significance in the 1920s |

|---|---|---|

| Automotive | Jordan Motor Car Company, White Motor Company, various parts suppliers | Leading industry by 1920, drove demand for steel, machine tools, electrical parts |

| Machine Tools | Warner & Swasey | Essential for manufacturing, supported automotive and other industries |

| Iron & Steel | U.S. Steel (American Steel & Wire Div.) | Foundational industry, supplied raw materials for manufacturing and construction |

| Electrical Machinery | General Electric (Nela Park), Lincoln Electric | Growth in electrical appliances, lighting, and industrial motors |

| Garment Industry | Joseph & Feiss, Printz-Biederman | Peaked in the 1920s, Cleveland was a national leader in ready-to-wear clothing |

| Chemicals | Grasselli Chemical Co. | Production of paints, varnishes, and industrial chemicals |

| Retail Department Stores | Higbee’s, Halle Bros. Co., May Company | Dominated downtown shopping, offered wide variety of goods |

| Retail Chain Stores | A&P, Kroger, Marshall Drug Co. | Became a major part of local retailing, offering competitive pricing |

The Jazz Age and Entertainment Erupts

Cleveland fully embraced the vibrant spirit of the Jazz Age in the 1920s. Jazz music surged in popularity, transforming the city’s soundscape. Dance halls such as the Golden Slipper, later known as the Trianon Ballroom, and numerous speakeasies became lively centers for jazz sessions. These venues hosted both talented local musicians and nationally renowned figures. Icons like Paul Whiteman and Bix Beiderbecke made Cleveland a regular and important stop on their tours, and future bandleaders Artie Shaw, Guy Lombardo, and Woody Herman were active in the local scene during this period. However, access to these cultural experiences often reflected the era’s social divisions; jazz sessions were frequently segregated, with different times allotted for white and Black musicians and audiences. This practice highlighted a significant contradiction of the era: a period of groundbreaking artistic innovation coexisting with entrenched discriminatory practices.

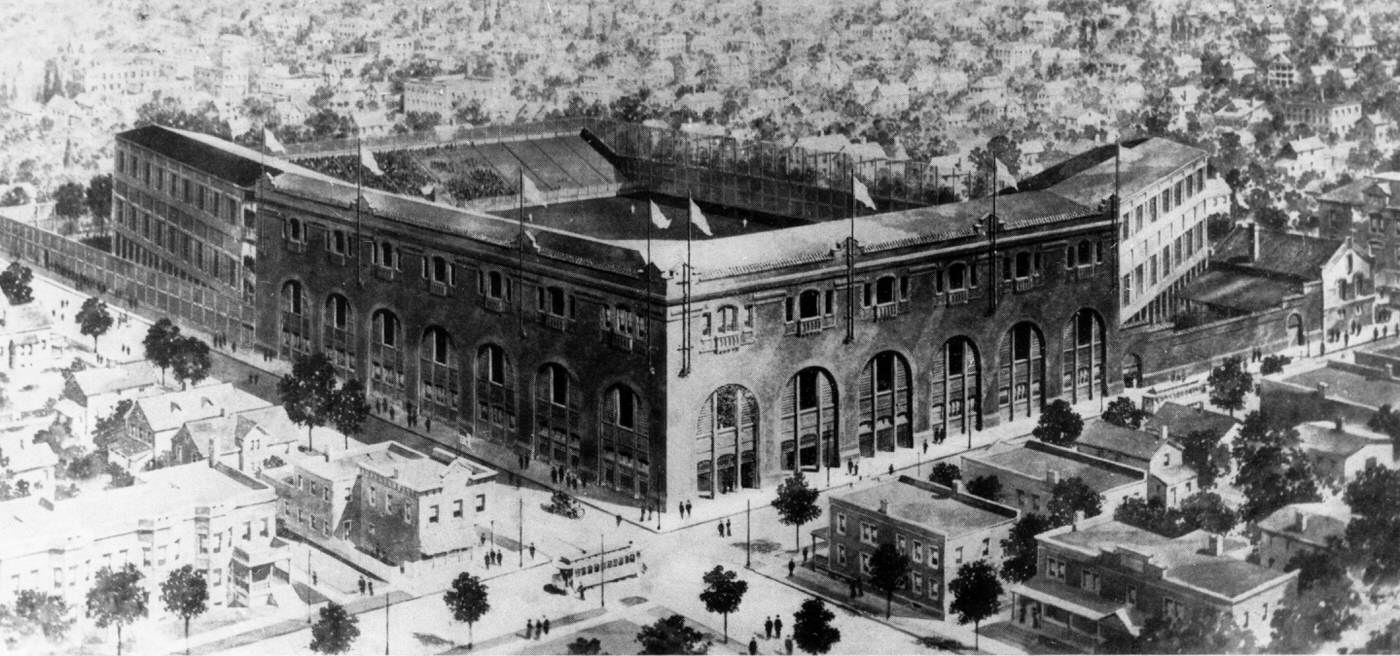

The city’s entertainment offerings expanded dramatically with the establishment of Playhouse Square in 1921. This district rapidly became a premier destination for theatergoers. In a remarkably short span of 19 months, between February 1921 and November 1922, five grand theaters opened their doors: the Allen Theatre, the Ohio Theatre (later Mimi Ohio Theatre), the State Theatre (later KeyBank State Theatre), the Palace Theatre (later Connor Palace), and the Hanna Theatre. These opulent venues, designed in lavish architectural styles such as Italian Renaissance and European Baroque, presented a mix of silent movies, legitimate stage plays, and vaudeville shows. Patrons often dined at nearby establishments, such as Monaco’s Continental Restaurant located in the Hanna Building, making an evening at the theater a complete social event.

Beyond mainstream entertainment, Cleveland’s avant-garde scene also made its mark. The Bal-Masque balls, hosted by the Kokoon Arts Club, were known for their risqué and unconventional nature, often causing a stir and scandalizing some segments of the city’s society.

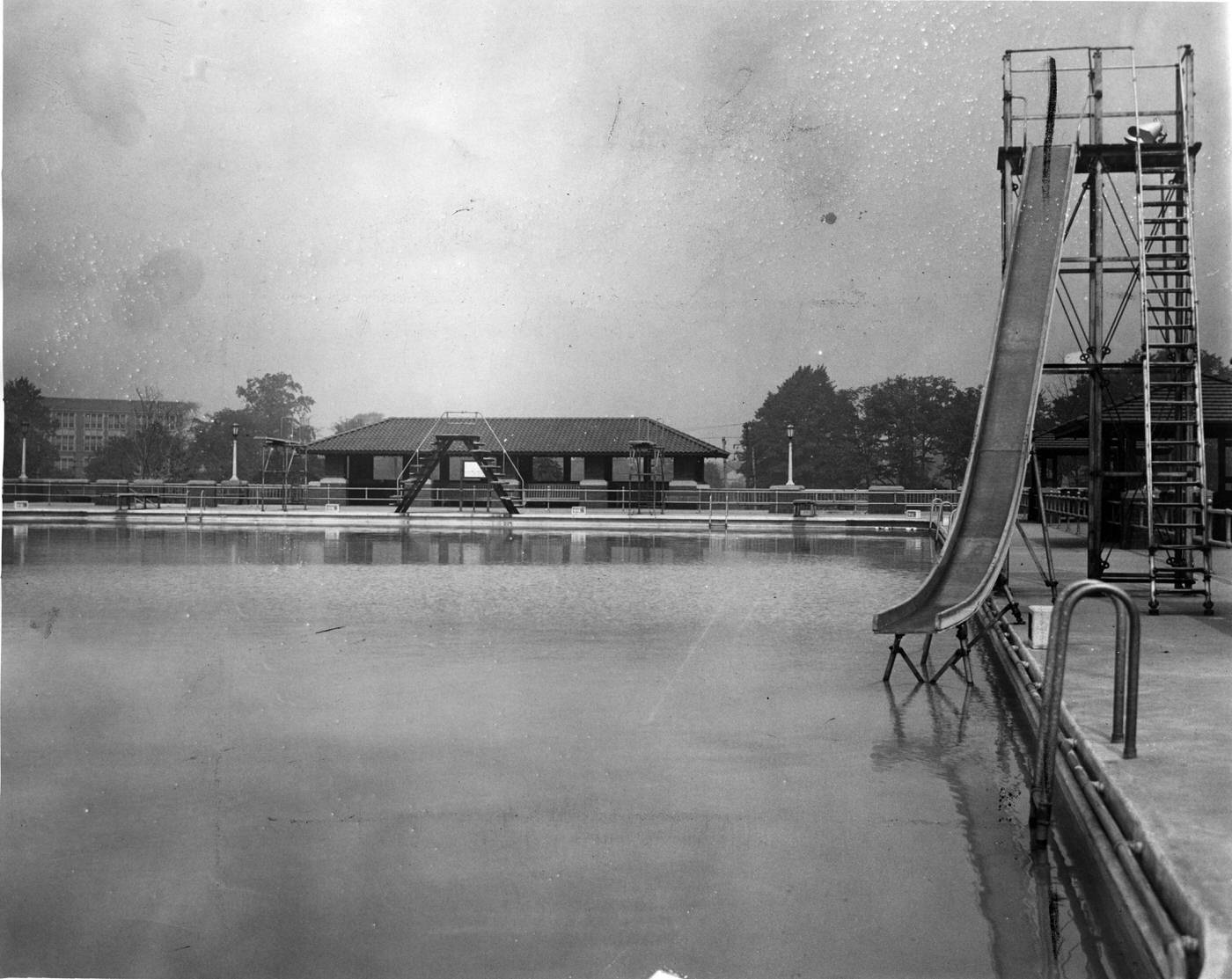

For everyday leisure and recreation, Euclid Beach Park stood as a major attraction. This popular amusement park offered a wide array of diversions, including a massive dance pavilion where popular dances of the 1920s like the foxtrot and two-step were enjoyed. The park also featured a scenic pier, and thrilling roller coasters such as the Racing Coaster, which had opened in 1913, and the even more exciting Thriller, which debuted in 1924. Another ride, the Witching Waves, was part of the park’s offerings in the 1920s before it was later replaced. The proliferation of these varied entertainment options—from grand theaters to amusement parks—points to the rise of mass entertainment and a growing leisure culture accessible to a wider range of Clevelanders than ever before.

Cultural Institutions and the Arts Flourish

The 1920s was a period of significant growth for Cleveland’s cultural and artistic institutions, reflecting the city’s ambition and civic pride as it solidified its national standing. The Cleveland Institute of Music, a key educational institution for aspiring musicians, was founded in 1920. In the same year, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History was established, adding to the city’s scientific and cultural resources. These joined the Cleveland Museum of Art, which had opened its doors in 1916 and continued to be an important cultural landmark.

The Cleveland Orchestra, which had debuted in 1918 under the leadership of conductor Nikolai Sokoloff and manager Adella Prentiss Hughes, rapidly built a strong base of local support throughout the 1920s. The orchestra performed regularly at prominent city venues including Gray’s Armory, the Masonic Auditorium, and the Public Auditorium. Its reputation grew beyond Cleveland as it began touring, with performances in other Ohio cities, along the East Coast, and even internationally in Canada and Cuba. The orchestra reached new audiences through its first radio broadcast in 1922 and released its first commercial recording—a shortened version of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture—in 1924. Education was a core component of the Orchestra’s mission; its Saturday instrument school, initiated in 1920 in cooperation with the Cleveland Board of Education, taught music lessons to children, and by 1929, nearly 3,000 students were enrolled. The commitment to a permanent home for the orchestra was solidified in 1928 when John and Elisabeth Severance pledged $1 million for the construction of Severance Hall. The development of such world-class institutions was an act of civic identity-building for a metropolis aiming to be recognized not just for its industrial might but also for its cultural achievements.

Karamu House, founded in 1915 as the Playhouse Settlement by Oberlin College graduates Russell and Rowena Jelliffe, was another vital cultural institution. Its mission was to promote interracial activities and cooperation through the arts, providing social services and activities for Cleveland’s growing African American population. In 1922, its theater troupe, originally the Dumas Dramatic Club, was renamed The Gilpin Players in honor of the noted African American actor Charles Gilpin. The Playhouse Settlement itself was renamed Karamu Theater in 1927, and the entire settlement eventually adopted the name Karamu House. During the 1920s, Karamu House became a significant venue for African American theater, producing works by influential playwrights. Notably, the legendary Harlem Renaissance poet and writer Langston Hughes launched his career at Karamu during this decade.

Fashion, Social Norms, and Daily Life

The 1920s brought transformative changes to social norms, particularly for women, and these shifts were mirrored in fashion. Empowered by gaining the right to vote with the passage of the 19th Amendment, many women began to cast off the restrictive social customs and clothing of previous eras, including corsets. A new ideal of the “young modern woman” emerged, characterized by more revealing fashions, the embrace of colorful and exotic jewelry, and the use of cosmetics. Accessories related to cigarette smoking also became symbols of this liberated lifestyle.

Cleveland’s department stores played a role in bringing these new styles to local consumers. Establishments like Rosenblum’s offered a wide array of clothing, including the latest women’s dresses, suits, and popular fur coats made from materials like raccoon and muskrat. Men’s fashion included suits and overcoats, and tailoring services were widely available. Fashionable Clevelanders kept pace with international trends. Prominent social figures like Phyllis Peckham were noted in newspapers for wearing imported “robe-de-style” dresses and other chic attire to events at Playhouse Square. Local boutiques, such as Quinn-Maahs—operated by Katherine Quinn and Gertrude Maahs, both former dress buyers for Halle Brothers—catered to this demand by traveling to Paris to scout and purchase the newest French fashions for their Cleveland clientele. These boutiques also created house-made garments inspired by, and sometimes directly copying, Parisian couture designs.

Daily life in 1920s Cleveland varied across social classes. For many working-class families, leisure time often involved seeking relief from the challenges of urban life through affordable entertainment. Popular options included visits to amusement parks like Euclid Beach, watching shows at nickelodeons (the precursors to modern movie theaters), and attending baseball games. In contrast, the city’s wealthy elite typically preferred more refined pastimes, such as attending classical music concerts, visiting fine art collections, and participating in exclusive social gatherings. Middle-class neighborhoods saw expansion during this period, particularly on the city’s West Side, as more families could afford modest homes.

An interesting, though temporary, aspect of Cleveland’s connection to national media occurred when Time Magazine was published in the city from 1925 to 1927. The move was an effort to improve the magazine’s delivery times to the West Coast. Co-founder Henry Luce and his family settled into Cleveland Heights during this period. His partner, Britton Hadden, however, found Cleveland less stimulating. Despite differing opinions on the city, Time’s circulation saw a significant increase during its Cleveland years, climbing from 70,000 to 111,000. The magazine’s distinctive red cover border was also acquired at the Penton Press in Cleveland.

Sporting Life

The decade began on a high note for Cleveland sports fans. In 1920, the Cleveland Indians won the World Series, a major achievement for the city. That championship season was marked by both triumph and tragedy, as it was also the year that beloved Indians player Ray Chapman tragically died after being hit by a pitch.

Throughout the 1920s, the Cleveland Indians experienced a range of fortunes in the American League. Following their championship, they finished a strong second in 1921 with a record of 94 wins and 60 losses. They achieved another second-place finish in 1926, with 88 wins and 66 losses. In other years during the decade, their performance varied, with finishes ranging from third to seventh place in the league. Key players from the early part of the decade included the legendary Tris Speaker, who also managed the team, pitcher Stan Coveleski, and infielder Joe Sewell. Towards the end of the 1920s, new stars like Earl Averill and Lew Fonseca were prominent figures for the team.

Beyond baseball, Cleveland also became a center for another exciting new sport: air racing. The first of many National Air Races was held in Cleveland in 1929. This event drew significant attention and featured famous aviators, including Amelia Earhart, who flew to the city from Santa Monica, California, to participate in the Women’s Air Derby. These events showcased Cleveland’s growing role in the burgeoning field of aviation.

Cleveland’s Cultural Bloom in the 1920s

| Institution/Venue Type | Specific Examples (Name) | Key Developments in 1920s |

| Music Education | Cleveland Institute of Music | Founded in 1920. |

| Symphony Orchestra | Cleveland Orchestra | First radio broadcast (1922), first recording (1924), tours, Saturday instrument school popular, pledge for Severance Hall (1928). |

| Theater District | Playhouse Square | Established 1921; Allen, Ohio, State, Palace, Hanna theaters opened (1921-1922) presenting movies, vaudeville, plays. |

| African American Arts | Karamu House (Playhouse Settlement/Karamu Theater) | Gilpin Players formed (1922), renamed Karamu Theater (1927), produced works by Langston Hughes and others. |

| Museum | Cleveland Museum of Natural History | Established in 1920. |

| Jazz Venues | Golden Slipper (Trianon Ballroom), various speakeasies | Hosted local and national jazz acts; sessions often segregated. |

| Amusement Park | Euclid Beach Park | Popular dance pavilion (foxtrot, two-step), pier, roller coasters like “Thriller” (1924). |

The Reign of Prohibition and a Thirsty City

The 1920s in Cleveland were lived under the shadow of Prohibition. Ohio enacted state-level prohibition in May 1919, which was soon followed by national Prohibition with the passage of the Volstead Act in January 1920. From the outset, Prohibition was deeply unpopular in Cleveland and its enforcement was lax. Despite the law, liquor remained readily available throughout the city.

The scale of illegal alcohol activity was vast. By 1923, it was estimated that around 30,000 Clevelanders were actively involved in selling liquor. Approximately 10,000 illegal stills were thought to be operating, and an estimated 100,000 residents were violating the law by producing alcohol in their own homes. Speakeasies, hidden bars where alcohol was sold illegally, became common fixtures. A particularly large concentration of these establishments could be found in the area between Carnegie and Lexington Avenues, from East 55th Street to East 79th Street.

Bootlegging—the illegal manufacture, transport, and sale of alcohol—was rampant. A significant source of illicit liquor was Canada, with smugglers transporting alcohol across Lake Erie into Cleveland. In winter, when the lake froze, cars were reportedly used for this smuggling. The notorious bootlegger Johnny Joyce was a prominent figure in Cleveland’s underworld and even maintained an office in the city’s famed Arcade building. This widespread disregard for the law demonstrated a societal rejection of Prohibition and created a fertile ground for criminal enterprises.

Americanization, Inter-Group Relations, and Racial Tensions

The dominant Anglo-American Protestant society in Cleveland engaged in efforts to “Americanize” the large immigrant population. These initiatives were carried out through public schools, settlement houses like Hiram House, and various religious missions. By 1926, there were 19 Protestant missions specifically catering to different ethnic groups in the city.

Interestingly, these Americanization efforts, which initially aimed at assimilation, had a somewhat paradoxical outcome. By 1920, they had brought many Anglo-Americans into closer contact with diverse ethnic cultures. This interaction, in turn, fostered a growing awareness and, in some circles, a celebration of ethnic diversity. This led to movements promoting cultural pluralism and the preservation of ethnic folk cultures, exemplified by the establishment of the Cleveland Cultural Garden Federation and the dedication of the first ethnic garden (the Hebrew Garden) in 1926. This represented a shift from straightforward assimilation efforts towards a more complex negotiation of identity in a multi-ethnic city.

However, life in this mosaic of peoples was not without friction. Tensions sometimes arose between different ethnic groups, often rooted in Old World political or cultural antagonisms. For instance, historical animosities between Poles and Ukrainians from Galicia resurfaced in Cleveland, leading to Ukrainians choosing not to live in Polish neighborhoods. Similarly, plans by the Magyar (Hungarian) community to erect a statue of Louis Kossuth in a prominent public space faced opposition from Slovaks who viewed Kossuth unfavorably. Internal conflicts also occurred within religious denominations, particularly the Catholic Church, over the extent to which ethnic customs and languages should be accommodated and ethnic priests appointed.

While relations between Anglo-Americans and white ethnic groups gradually evolved towards a degree of mutual recognition, race relations between Black and white Clevelanders took a different, more troubling path, worsening considerably during the early 20th century. The Great Migration, which saw Cleveland’s Black population increase by over 300% between 1910 and 1920, led to a severe housing crisis for African American newcomers. Prejudice and discrimination against Black people were deeper and more pervasive than anti-ethnic sentiment, severely affecting their economic, housing, and educational opportunities.

Housing discrimination, through “whites only” policies and restrictive covenants in deeds, increasingly confined Black residents to the expanding Central Avenue ghetto. This area faced overcrowding and deteriorating conditions. Segregation also became more pronounced in public life. Many restaurants overcharged Black patrons or refused them service altogether. Theaters often excluded Black people or relegated them to separate balcony seating. Popular amusement parks like Euclid Beach Park were generally for whites only. This pattern of racial segregation was a more imposed and restrictive process than the often voluntary self-segregation of ethnic neighborhoods, fundamentally shaping urban geography and limiting opportunities for African Americans. Even public schools were affected; the growth of the ghetto created some de facto segregated schools, and a policy allowing white students to transfer out of predominantly Black schools exacerbated this. In the 1920s, school administrators frequently altered the curricula in ghetto schools, shifting the focus from liberal arts to manual training.

In response to these mounting challenges, a “New Negroes” leadership began to emerge in Cleveland during the 1920s and 1930s. This movement advocated for racial pride and solidarity while actively working for equal rights, largely through organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Organized Crime and Law Enforcement Struggles

The immense profits to be made from illegal alcohol directly fueled the rise and sophistication of organized crime in Cleveland. Gangs like the Mayfield Road Mob, so named because its members often met in the Little Italy section of Mayfield Road, evolved into powerful local crime syndicates during the 1920s through their control of bootlegging and illegal gambling operations. Under leaders such as Joseph Lonardo, the Mayfield Road Mob formed partnerships with other criminal groups, notably the Jewish-Cleveland Syndicate, which included figures like Moe Dalitz. These criminal organizations often employed intimidation and violence to protect their territories and operations. This era effectively transformed small-time gangs into wealthy and influential enterprises, capable of corrupting officials and impacting the city’s safety.

The rise in organized crime contributed to a “growing feeling of insecurity in life and property” among Clevelanders, who were confronted with high rates of murder, property crime, and stolen cars. This climate of lawlessness was exacerbated by significant problems within the Cleveland police division. The department faced calls for reform due to issues such as outdated precinct boundaries, corruption (including bribery of officers), poor detective work, low morale among officers, on-the-job drinking, and instances of police brutality. Federal “dry agents” tasked with enforcing Prohibition in Cleveland also faced challenges; they were often targets of bribery, faced retaliation from criminal elements, or, in some cases, even became involved in bootlegging themselves. The pervasiveness of police corruption and inefficiency likely undermined public trust in law enforcement and other institutions. In a stark illustration of these challenges, J. Edgar Hoover, then Acting Director of the Bureau of Investigation (the predecessor to the FBI), ordered the closure of the Cleveland Division in 1924. This decision was made due to violations of Prohibition laws by the Special Agent in Charge and a lack of adequate facilities for the Bureau’s operations in the city.

Social Unrest and Disasters

Cleveland entered the 1920s still processing the impact of recent social upheavals and tragedies, which contributed to the decade’s complex atmosphere. The May Day Riots of 1919 had deeply shaken the city. These violent clashes involved Socialists, led by figures like Charles Ruthenberg, members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and trade unionists. They were protesting the jailing of Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs and American intervention in the Russian Civil War. The demonstrators clashed with a group of self-styled “patriots,” police, and even military troops, resulting in two deaths, numerous injuries, and 124 arrests, including Ruthenberg. The Socialist Party’s headquarters were ransacked by a mob. The aftermath saw a surge of nativist xenophobia in media coverage, with foreign-born participants being labeled “foreign agitators” and calls for their deportation. This sentiment foreshadowed the restrictive national immigration acts of 1921 and 1924. Although the intensity of the First Red Scare gradually receded as the 1920s progressed, the memory of this violent tumult lingered.

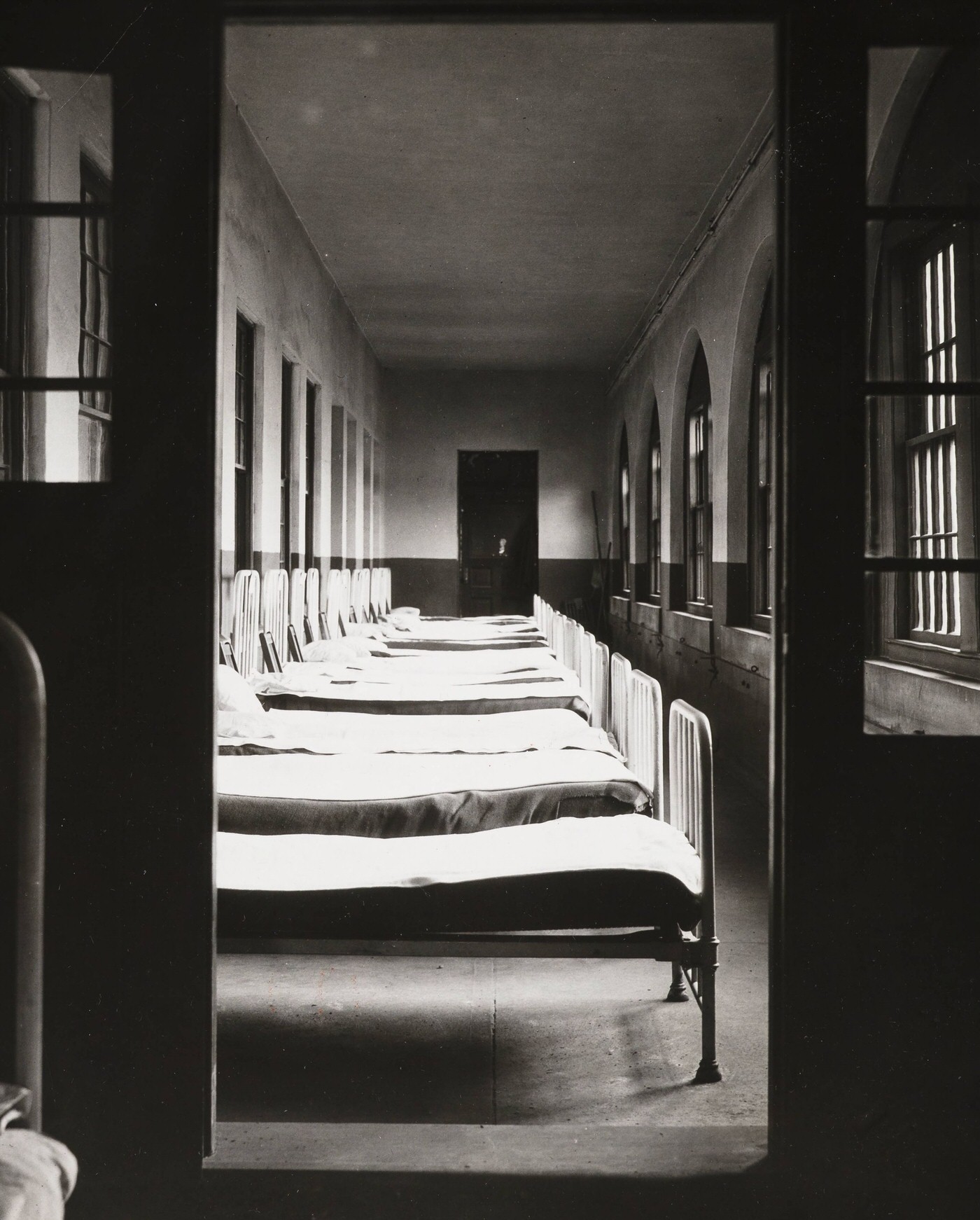

The city was also impacted by the devastating Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919, with some experts suggesting a possible fourth wave occurring in 1920. This global health crisis had claimed at least 4,400 lives in Cleveland alone, leaving a profound mark on the community and shaping public health awareness and approaches in the years that followed.

Towards the end of the decade, on May 15, 1929, Cleveland experienced another major tragedy: the Cleveland Clinic Disaster. A fire, believed to have originated from nitro-cellulose X-ray film ignited by an exposed heat source (an unguarded 100-watt light bulb), rapidly released smoke and poisonous gases, primarily phosgene, through the main clinic building. The disaster resulted in the deaths of 123 people, including 80 visitors and patients and 43 clinic employees. Ninety-two others were injured. Among the deceased was Dr. John Phillips, one of the founders of the Cleveland Clinic and head of its Medical Department. Although an investigation later absolved Clinic officials of legal responsibility for the fire, the event had significant consequences. It spurred the development of new national safety standards for the storage and labeling of hazardous materials, especially nitro-cellulose film. Locally, the investigating commission recommended that Cleveland’s police and fire departments be supplied with gas masks and that a municipal ambulance service be established to improve emergency response.

Governance and Political Landscape

Cleveland’s municipal government underwent a significant structural change in the 1920s. From 1924 to 1931, the city operated under a City Manager plan, which replaced the traditional Mayor/Council form of government. This change was part of a broader Progressive Era movement that sought to bring more efficiency and less partisan politics to municipal administration. William R. Hopkins served as City Manager for a significant portion of this period, from 1924 to 1929. However, the hope of limiting the role of political parties was not fully realized. The established Republican and Democratic parties adapted to the new system, with Republican party leader Maurice Maschke and his Democratic counterpart Burr Gongower reportedly reaching an agreement to split city patronage positions between them.

The city’s national political profile was highlighted in 1924 when Cleveland hosted the Republican National Convention. This event brought politicians, media, and attention from across the country to Cleveland.

The city’s political representation also began to more closely reflect its diverse population. Individuals of Southern and Eastern European immigrant backgrounds, along with African Americans, started to win an increasing number of seats on the city council. By 1927, for example, three African American councilmen were elected, indicating their growing influence within the local Republican party organization. This trend showed an evolving political landscape where previously underrepresented groups were gaining a greater voice in civic affairs.

Major Cleveland Development Milestones of the 1920s

| Project/Initiative | Key Dates/Completion | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Union Terminal/Terminal Tower | Site Demolition 1922; Excavation 1924; Tower Steelwork 1926; Tower Completed 1927; Formal Opening 1930 | Reshaped downtown skyline, major transportation hub, symbolized modernity |

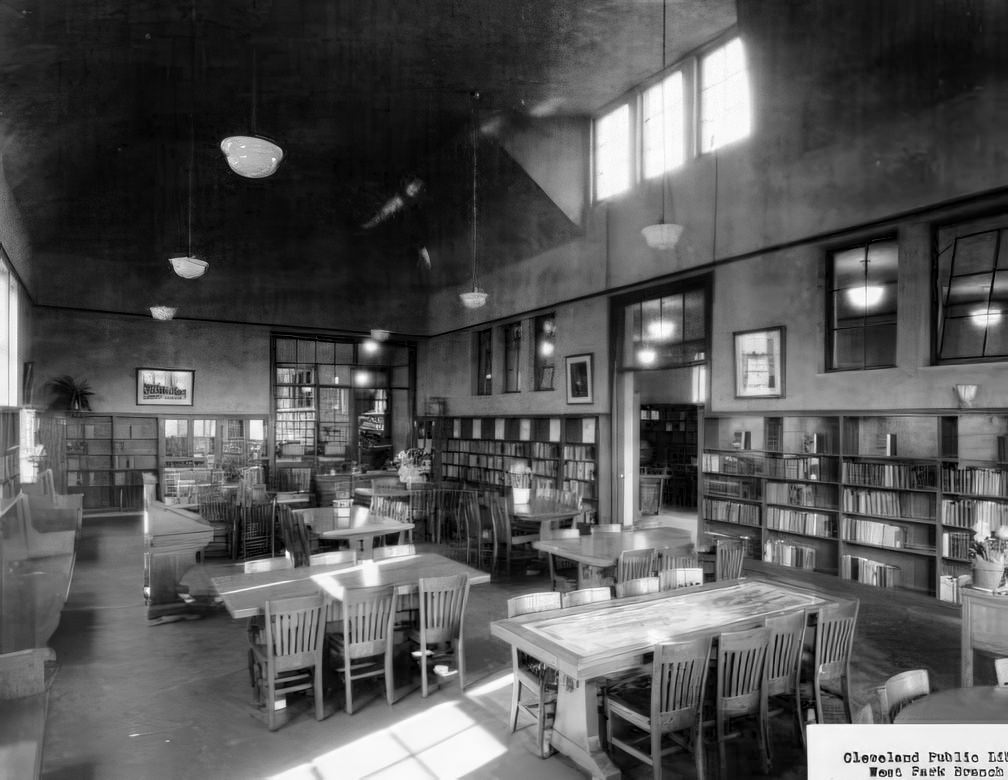

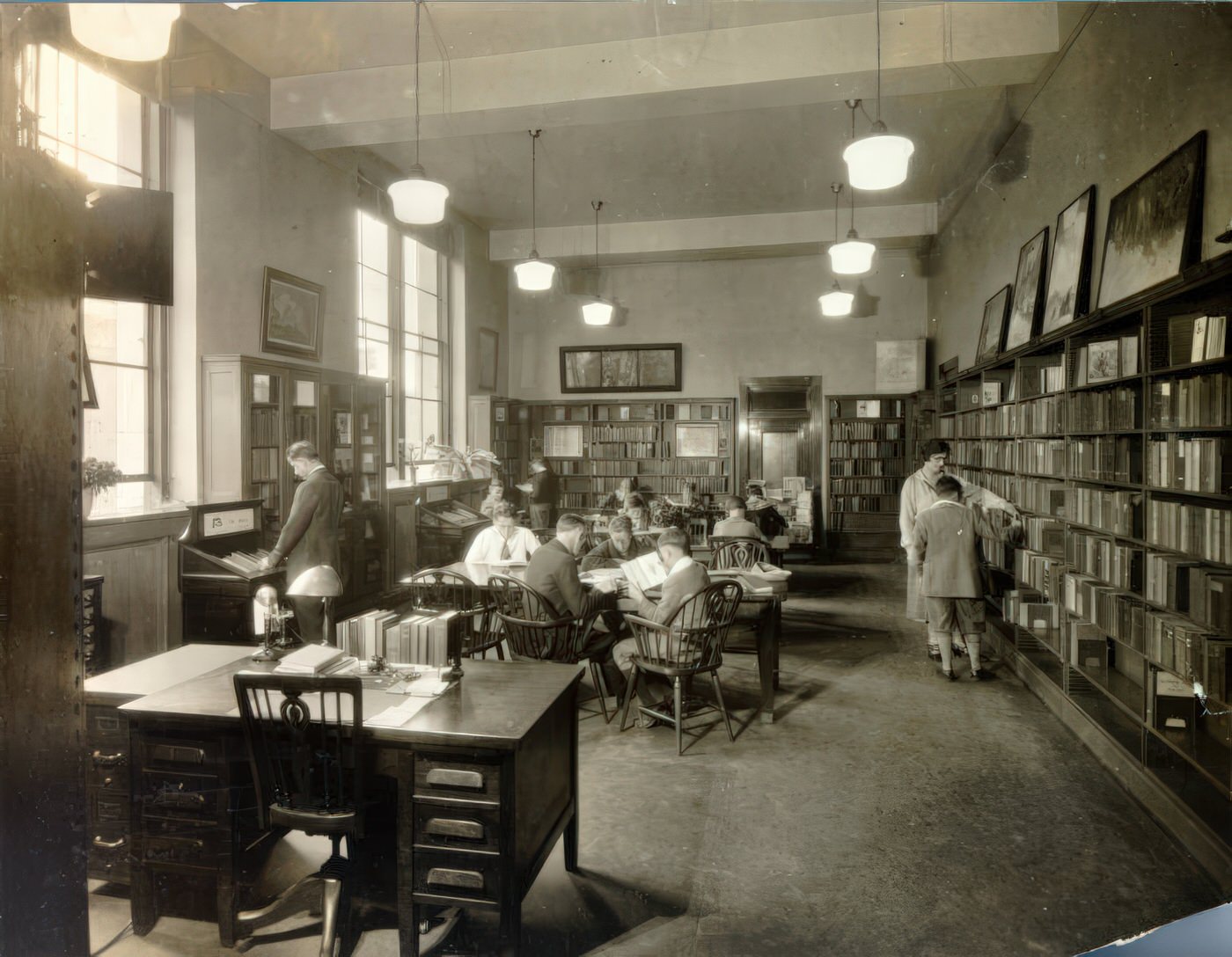

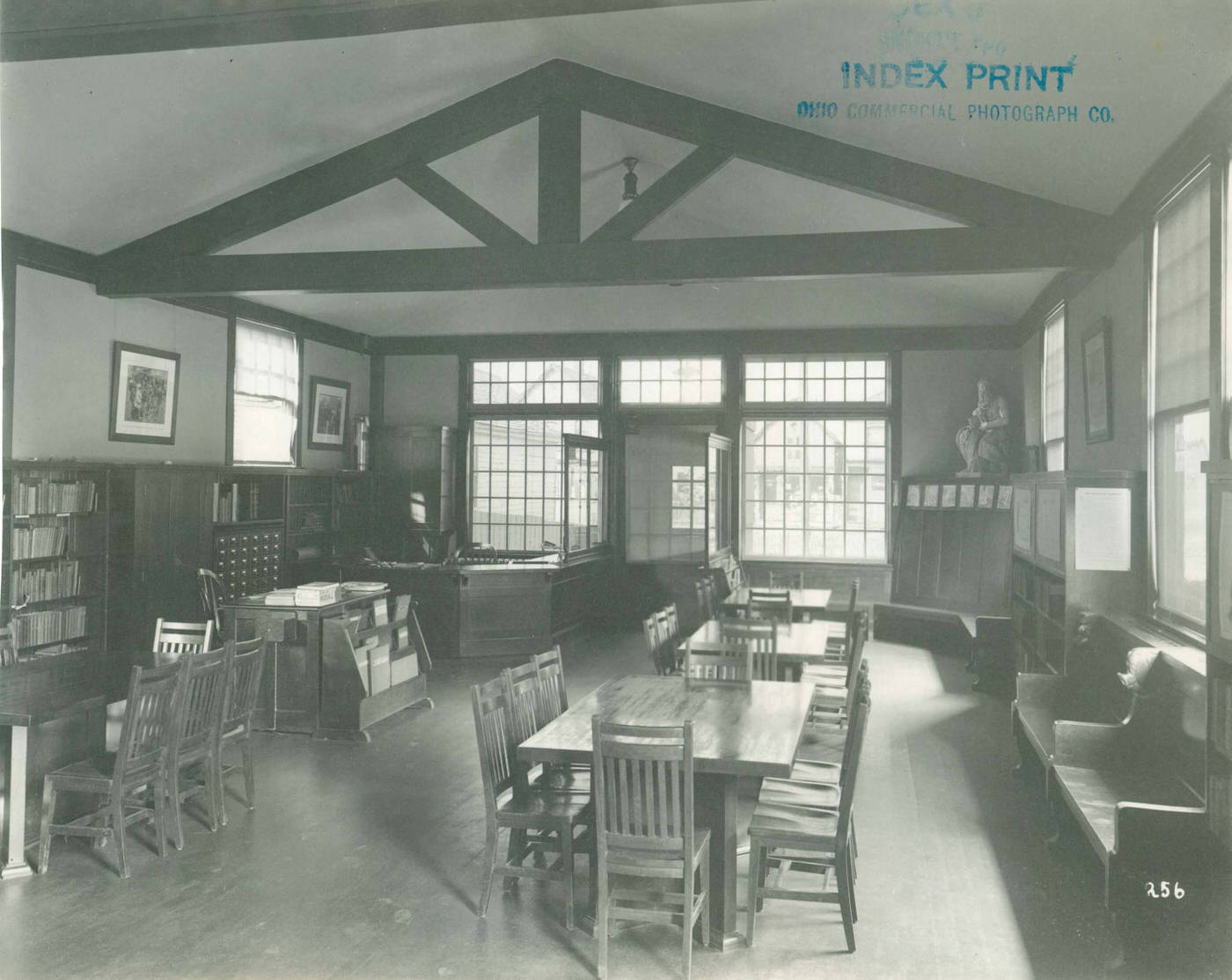

| Public Library Building (Group Plan) | Opened 1925 | Major civic and educational resource, part of the Group Plan |

| Cleveland Airport (Hopkins) | Opened 1925 | Positioned Cleveland at the forefront of aviation |

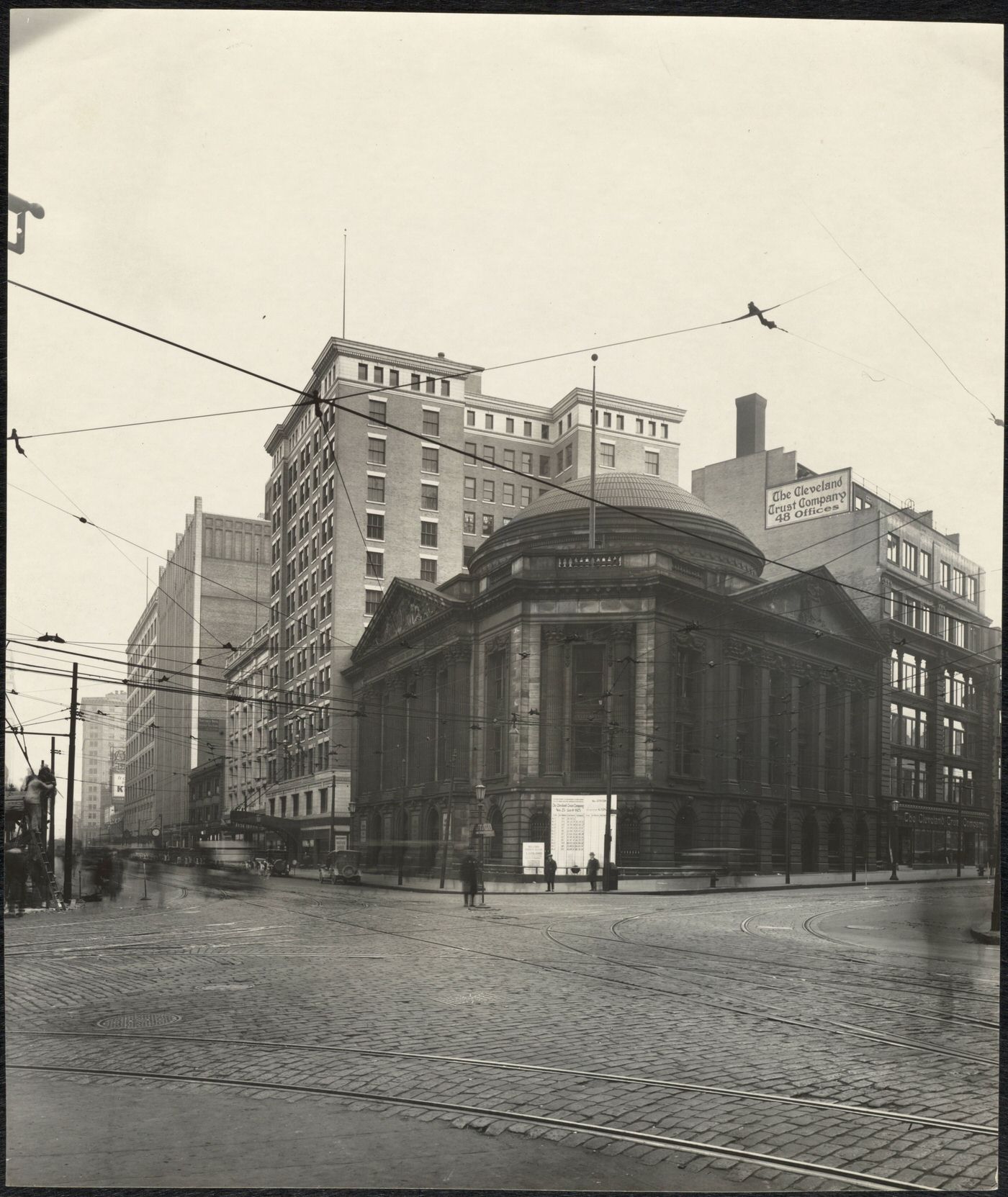

| Federal Reserve Bank Building | Completed 1923 | Reinforced Cleveland’s role as a financial center |

| Public Auditorium (Group Plan) | Opened 1922 | Major venue for conventions and public gatherings, part of Group Plan |

| Board of Education Bldg. (Group Plan) | Completed 1930 | Centralized educational administration, part of Group Plan |

| Shaker Heights Development | Ongoing in 1920s; Rapid Transit service began 1920 | Pioneering garden city suburb with integrated light rail, driven by Van Sweringens |

| City Zoning Ordinance | Adopted 1929 | Formalized land use regulation in the city |

| Baldwin Filtration Plant & Reservoir | Completed 1925 | Ensured filtered and chlorinated water for the city, improving public health |

| Kirtland Pumping Station Expansion | Completed 1927 | Further improved city water supply quality and capacity |

| Wastewater Treatment Plants | Westerly (1922), Easterly (1925), Southerly (1927) | Advanced public sanitation and environmental protection |

| City Manager Plan of Government | Implemented 1924-1931 | Experiment in municipal governance structure |

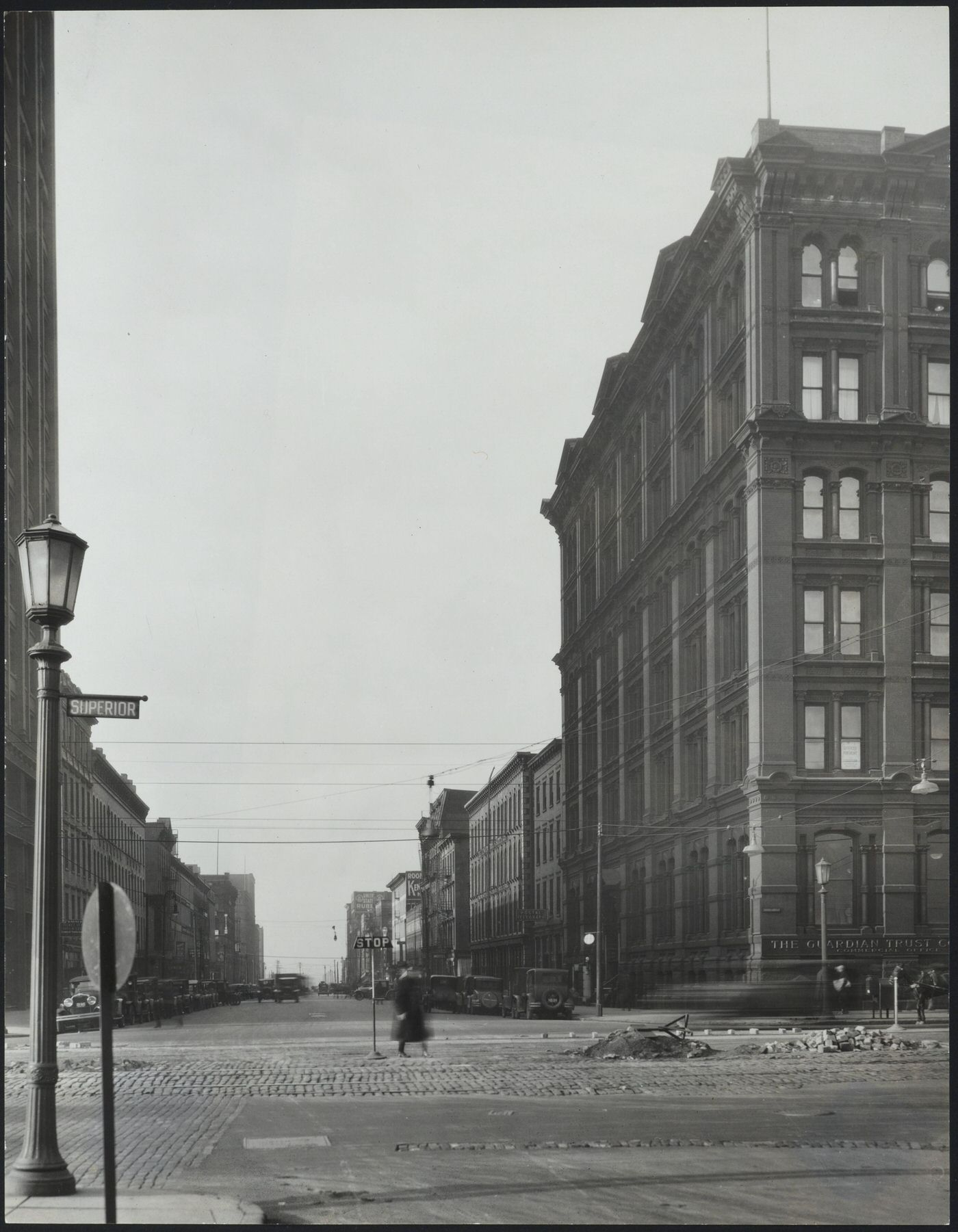

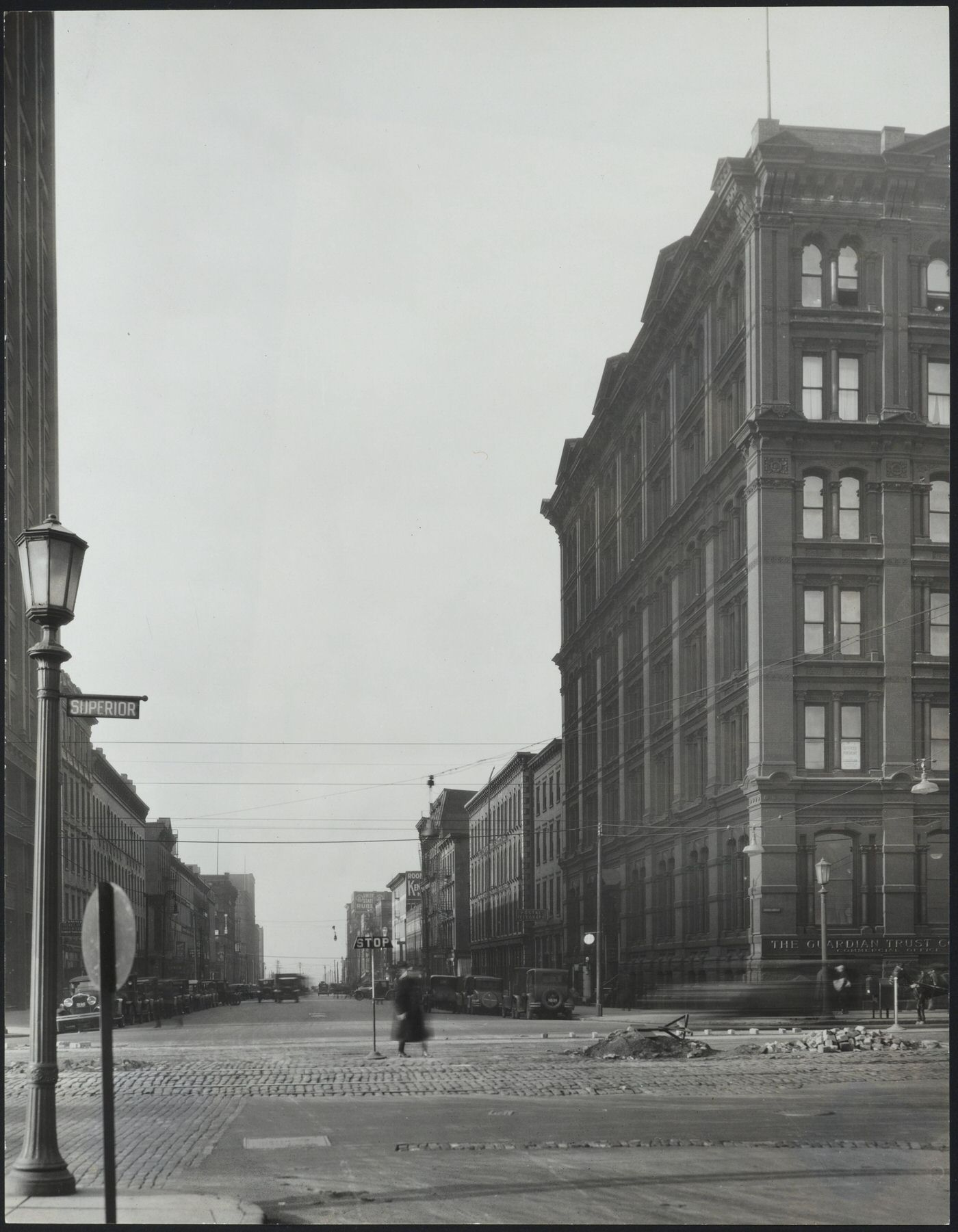

Transportation and Utilities

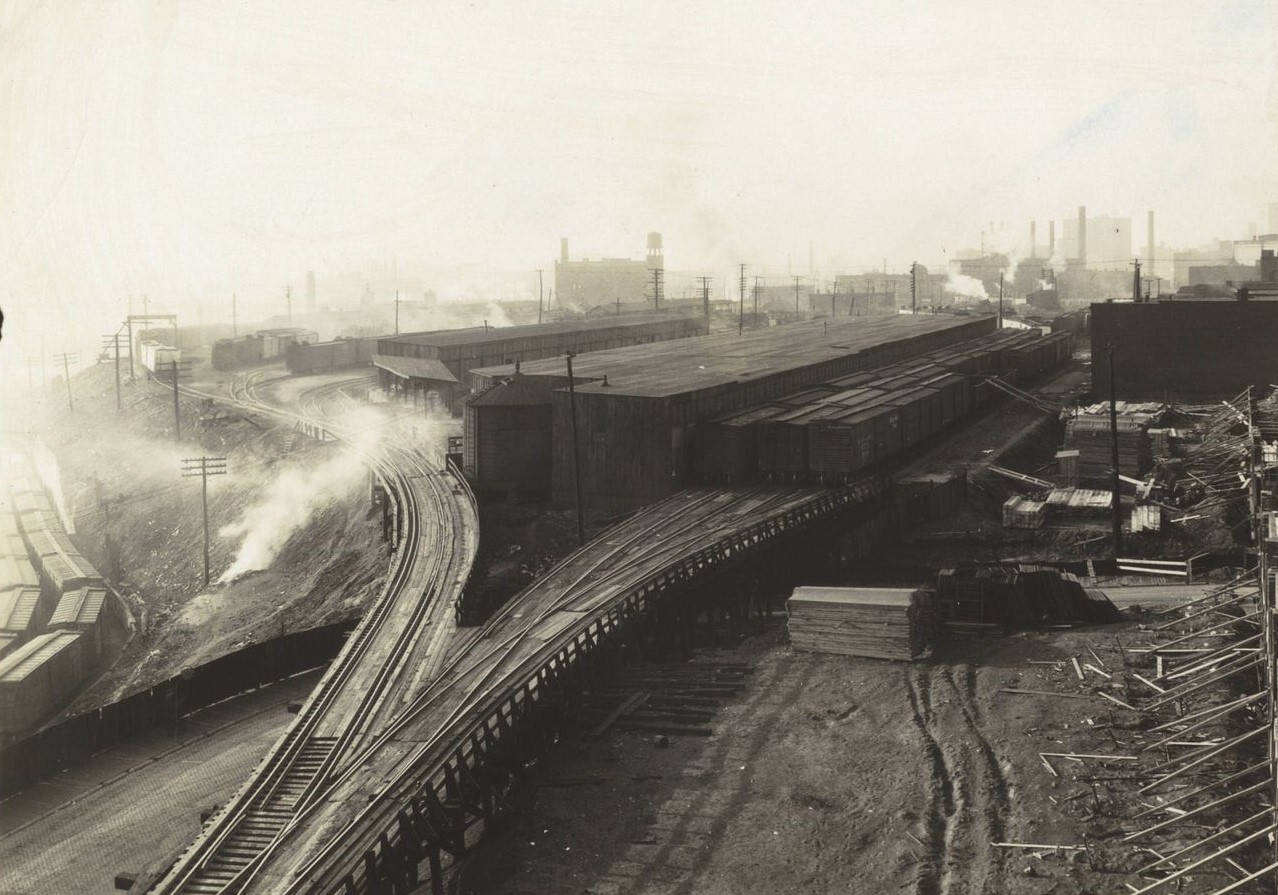

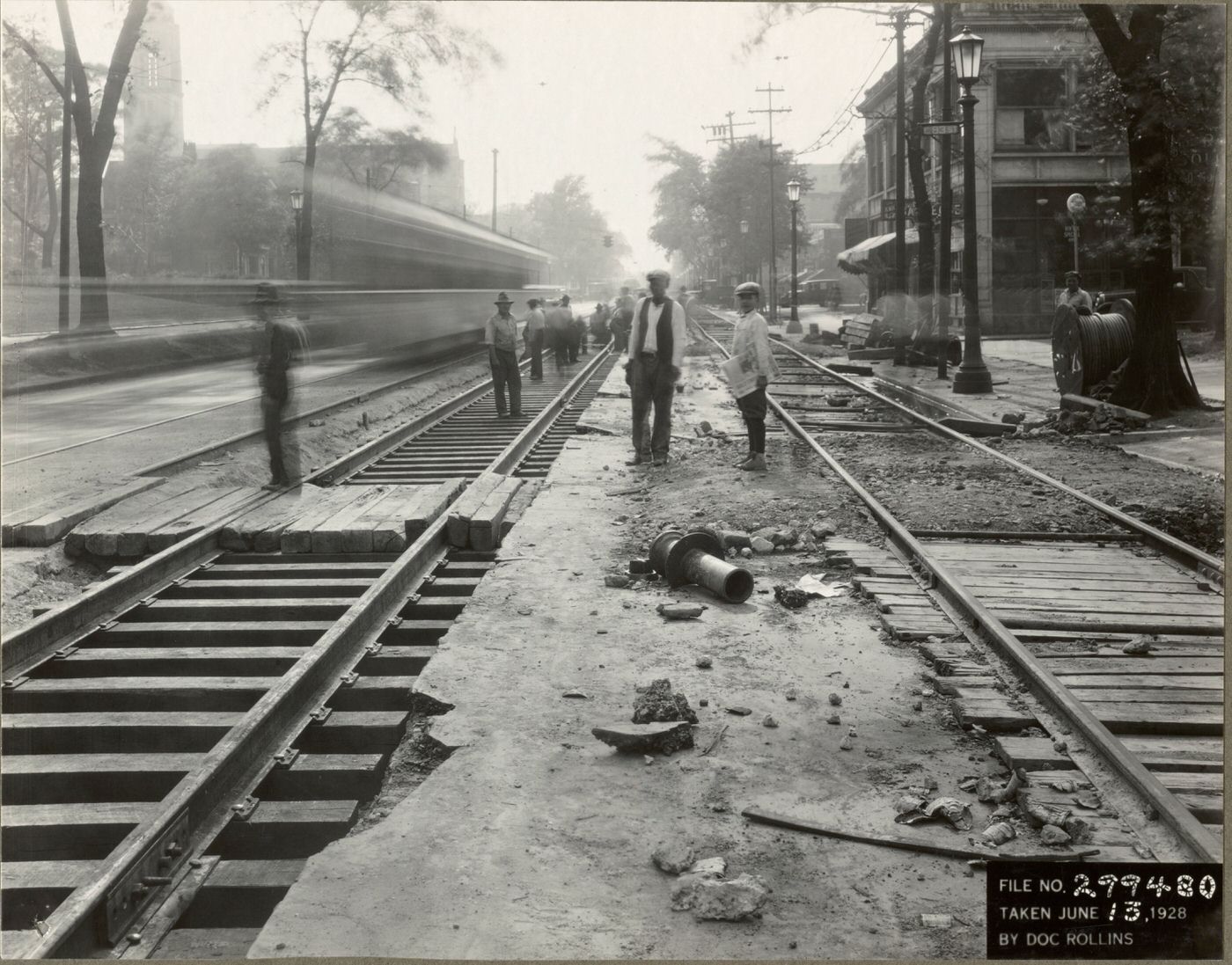

The way Clevelanders moved about their city and region was undergoing a significant transition in the 1920s. The once extensive electric interurban railway system, which connected Cleveland to surrounding towns and cities, faced a steep decline due to the rapidly growing popularity and affordability of automobiles and buses. Several interurban lines ceased operations during this decade, including the Cleveland, Youngstown & Eastern in 1925, and the Cleveland, Painesville & Eastern in 1926. Some of the more robust lines, such as the Northern Ohio Traction & Light Co. (NOT&L) and the Cleveland, Southwestern & Columbus Railway (CSW&C), attempted to adapt by investing in new, more attractive passenger cars, some purchased from the Cleveland-based G. C. Kuhlman Car Company.

Within the city, the Cleveland Railway Company operated the local streetcar system, which remained a vital part of daily life and commutes for many residents. “Peter Witt” style streetcars were a common sight on Cleveland’s streets. These cars, designed by former Cleveland Railway commissioner Peter Witt, featured a distinctive layout with front entrances and center exits, intended to improve passenger flow and reduce loading times at stops. In the 1920s, the Cleveland Interurban Railroad (which became the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit) also leased and later purchased some of these Cleveland center-entrance streetcars for its services.

Public health and sanitation saw major advancements through improvements to the city’s water system. The Baldwin Filtration Plant and its associated reservoir were completed in 1925, and a significant expansion and modernization of the Kirtland pumping station was finished in 1927. These projects ensured that Cleveland had a supply of wholly filtered and chlorinated water. The impact on public health was profound, as diseases caused by impure water, which had previously been a serious concern, virtually disappeared. By 1920, the system of water mains delivering this improved water had already grown to a total length of 985 miles, and it continued to expand to meet the needs of the growing city.

Progress was also made in wastewater treatment. The Westerly wastewater treatment plant began operations in 1922, followed by the Easterly plant in 1925, and the Southerly plant in 1927. These facilities represented crucial steps in managing the city’s sanitation and protecting public health and the environment. The combination of these new transportation options, communication methods like radio, new forms of city governance, and new tools for shaping urban space like zoning, all signaled that Cleveland in the 1920s was at a pivotal moment, laying the foundations for the modern American city of the 20th century.

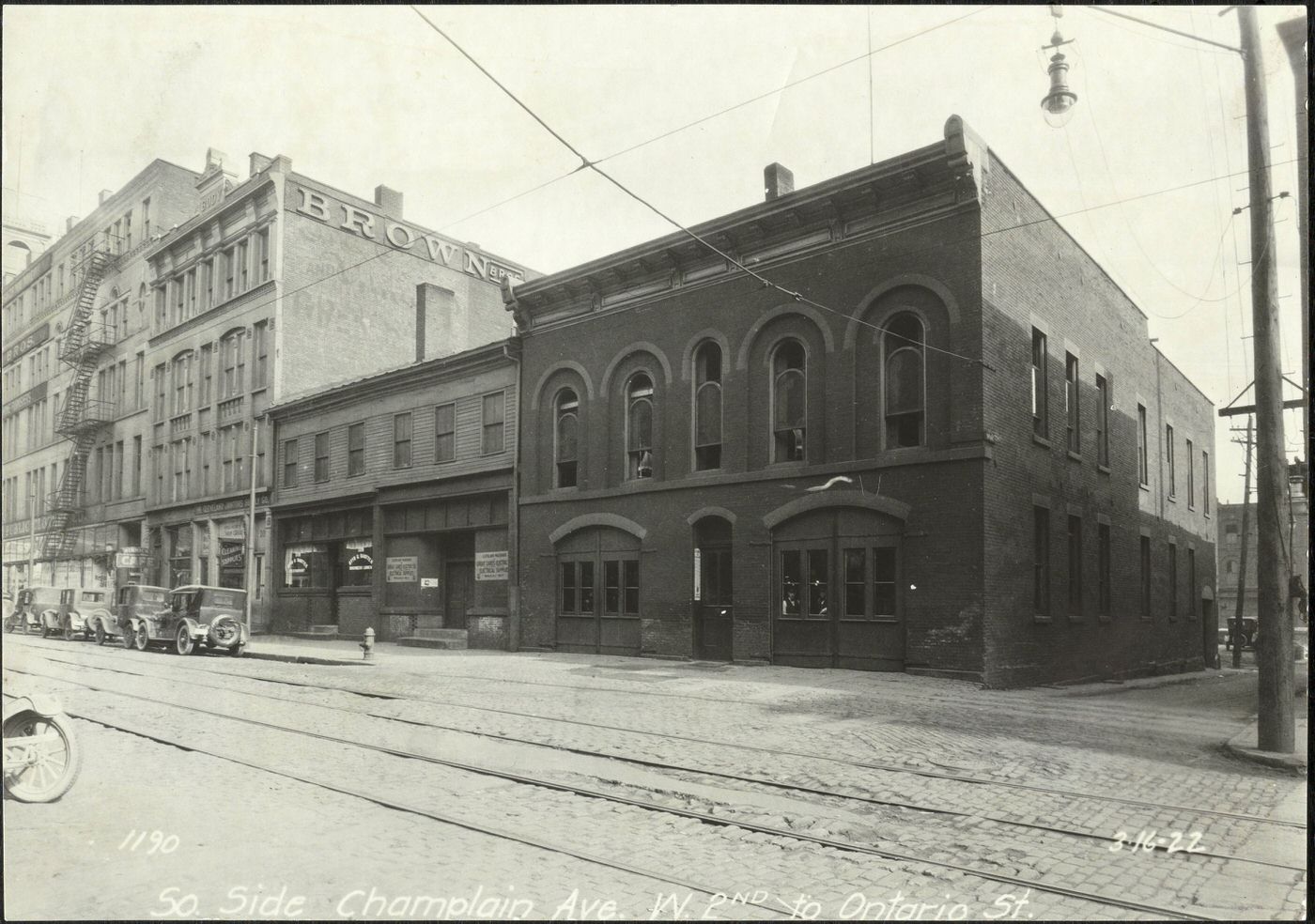

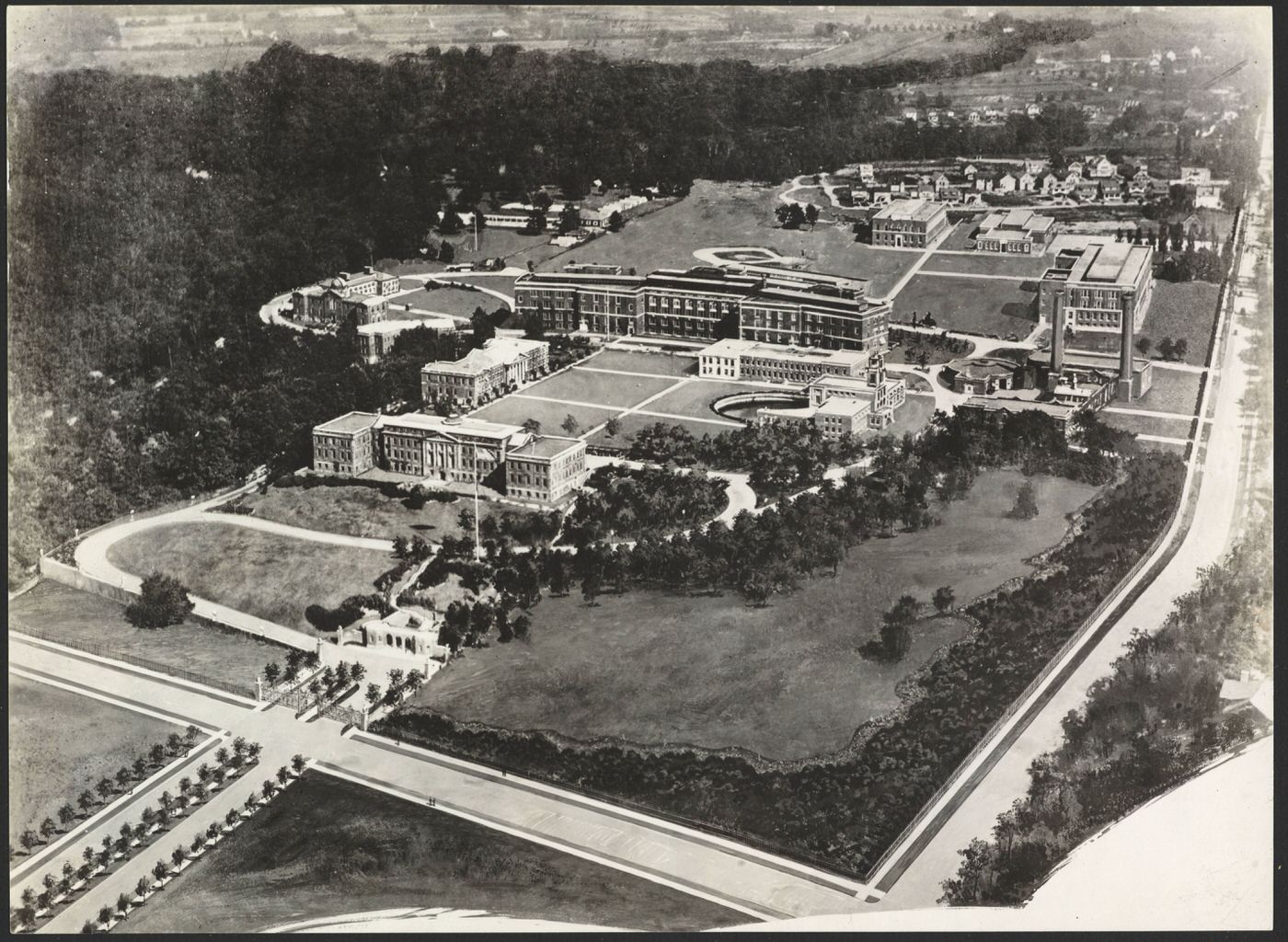

City Planning and Shaping the Urban Landscape

The 1920s saw continued efforts to consciously shape Cleveland’s urban form. The Group Plan of 1903, an early and influential “City Beautiful” initiative, guided the development of a monumental civic center around a grand mall. Several key buildings conceived under this plan were completed during the 1920s, including the Public Auditorium (1922), the Cleveland Public Library (1925), and the Board of Education Building (1930). These structures, designed in a Beaux-Arts classical style, aimed to create a dignified and harmonious public space.

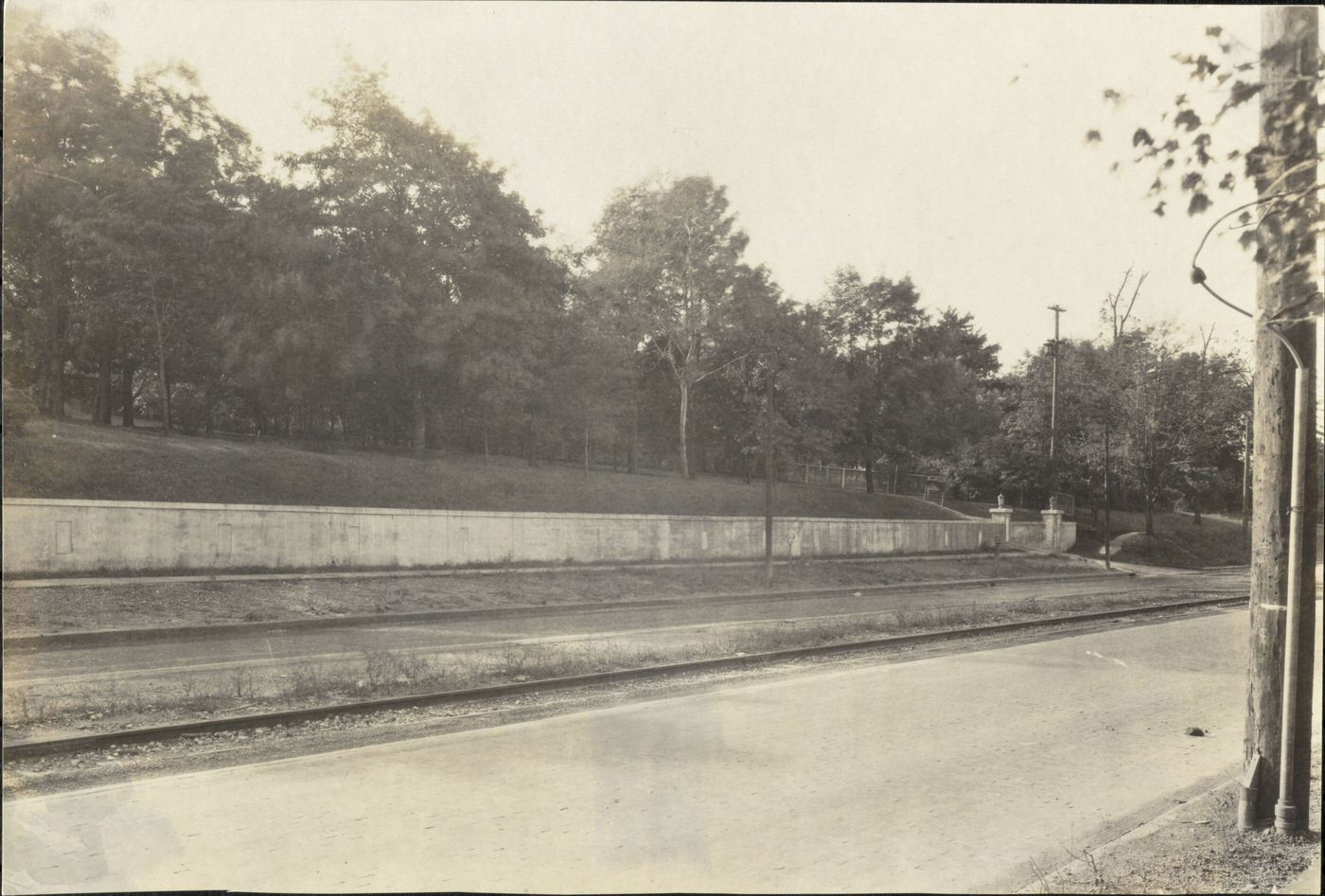

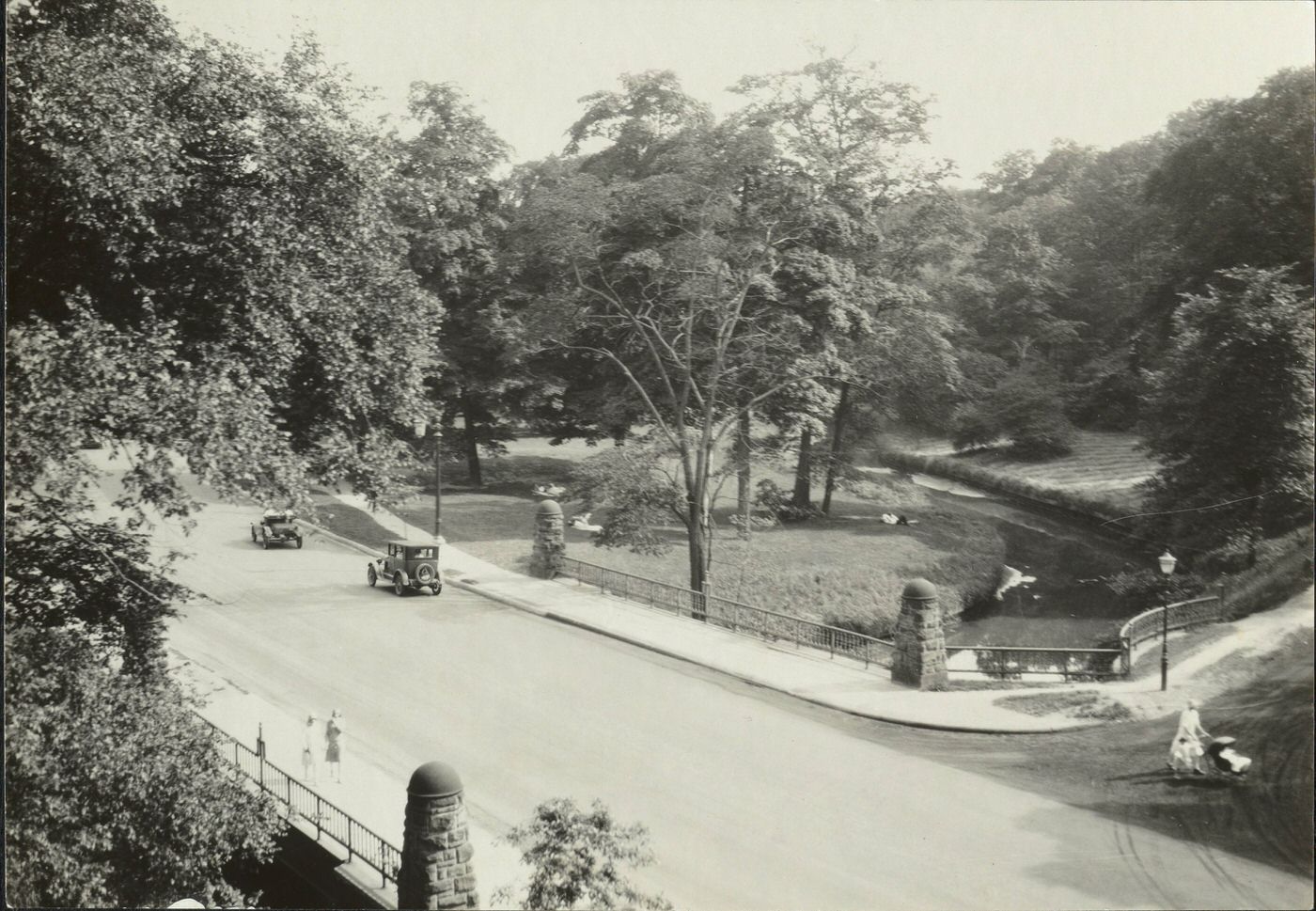

The development of the Cleveland Metropolitan Park System also progressed during this era. William A. Stinchcomb, often called the “father” of the Metroparks, was instrumental in creating this exemplary network of green spaces, providing essential areas for recreation and nature preservation for the city’s growing population.

A pioneering example of suburban planning was the development of Shaker Village (now Shaker Heights) by the entrepreneurial Van Sweringen brothers. They transformed the site of a former Shaker community into a meticulously planned garden city suburb. Their vision included strict controls on land use and architecture, neighborhoods organized around elementary schools, and commercial activity confined to designated areas like the iconic Shaker Square. A crucial element of their plan was transportation; because Shaker Village was initially remote from existing streetcar lines, the Van Sweringens undertook the ambitious project of building a light rail system, the Shaker Rapid Transit, to connect the suburb with downtown Cleveland. Service on two suburban branches of this rapid transit line began in April 1920. This endeavor even led them to purchase the Nickel Plate Railroad to secure necessary right-of-way and was a primary driver for the construction of the Cleveland Union Terminal complex, which served as the downtown terminus for their rapid transit line.

The 1920s also marked the formal beginning of land use regulation in the city itself. Cleveland adopted its first comprehensive zoning ordinance in 1929. This ordinance was based on Euclidean zoning principles, which aimed to separate incompatible land uses (e.g., industrial, commercial, residential). The adoption of zoning in Cleveland followed the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. (1926)—originating from the Cleveland suburb of Euclid—which upheld the constitutionality of zoning as a legitimate exercise of police power. Many surrounding communities, such as East Cleveland (1919), Bay Village (1920), Cleveland Heights (1921), and Lakewood (1922), had already implemented zoning ordinances earlier in the decade. While these modernization efforts aimed to bring order and improvement, some of the early interpretations of zoning also carried the potential for future urban challenges, such as encouraging single-use districts and potentially de-densifying established neighborhoods, a contrast to the mixed-use, walkable fabric of older city areas.

Building an Iconic Skyline and Infrastructure

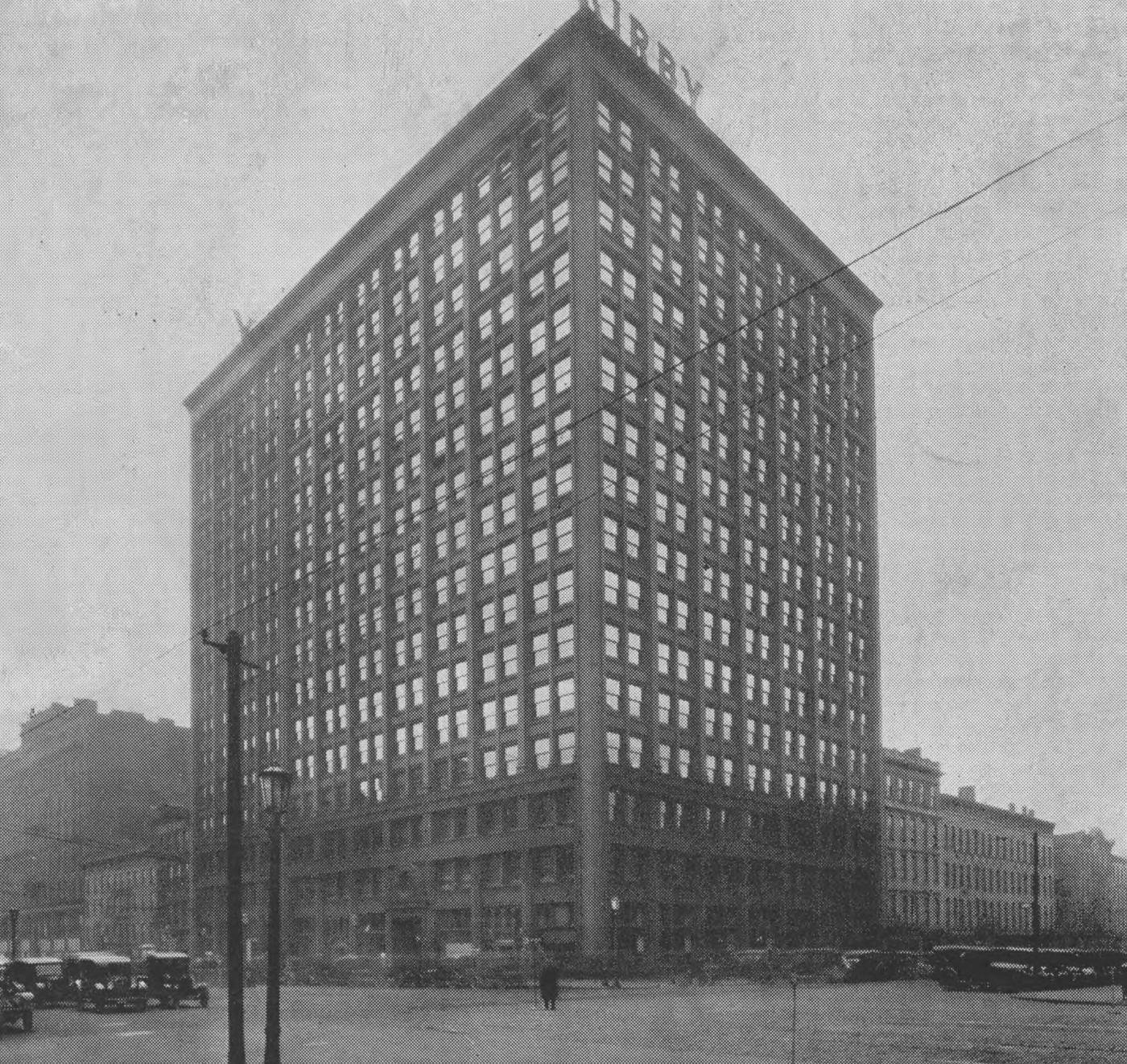

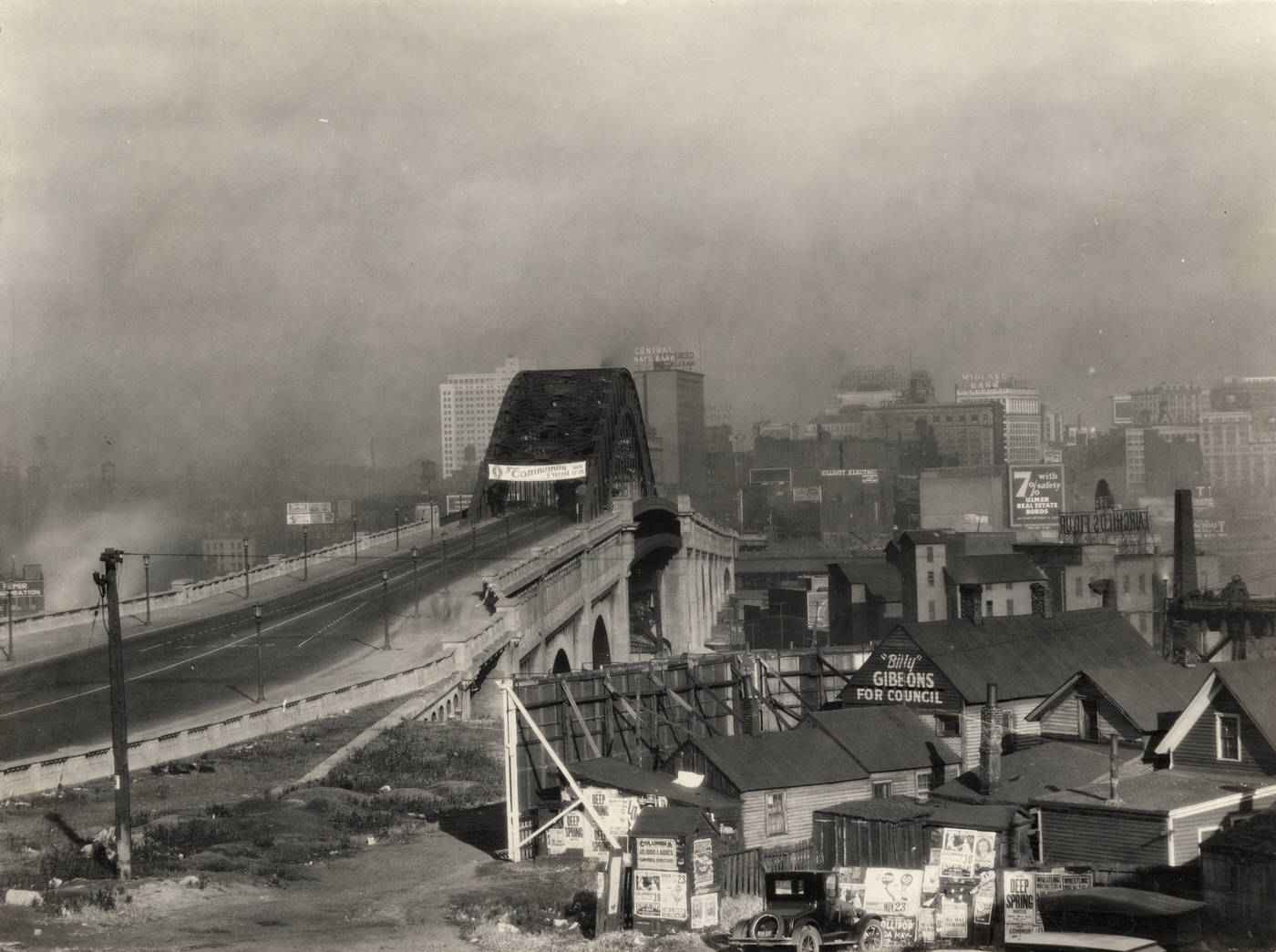

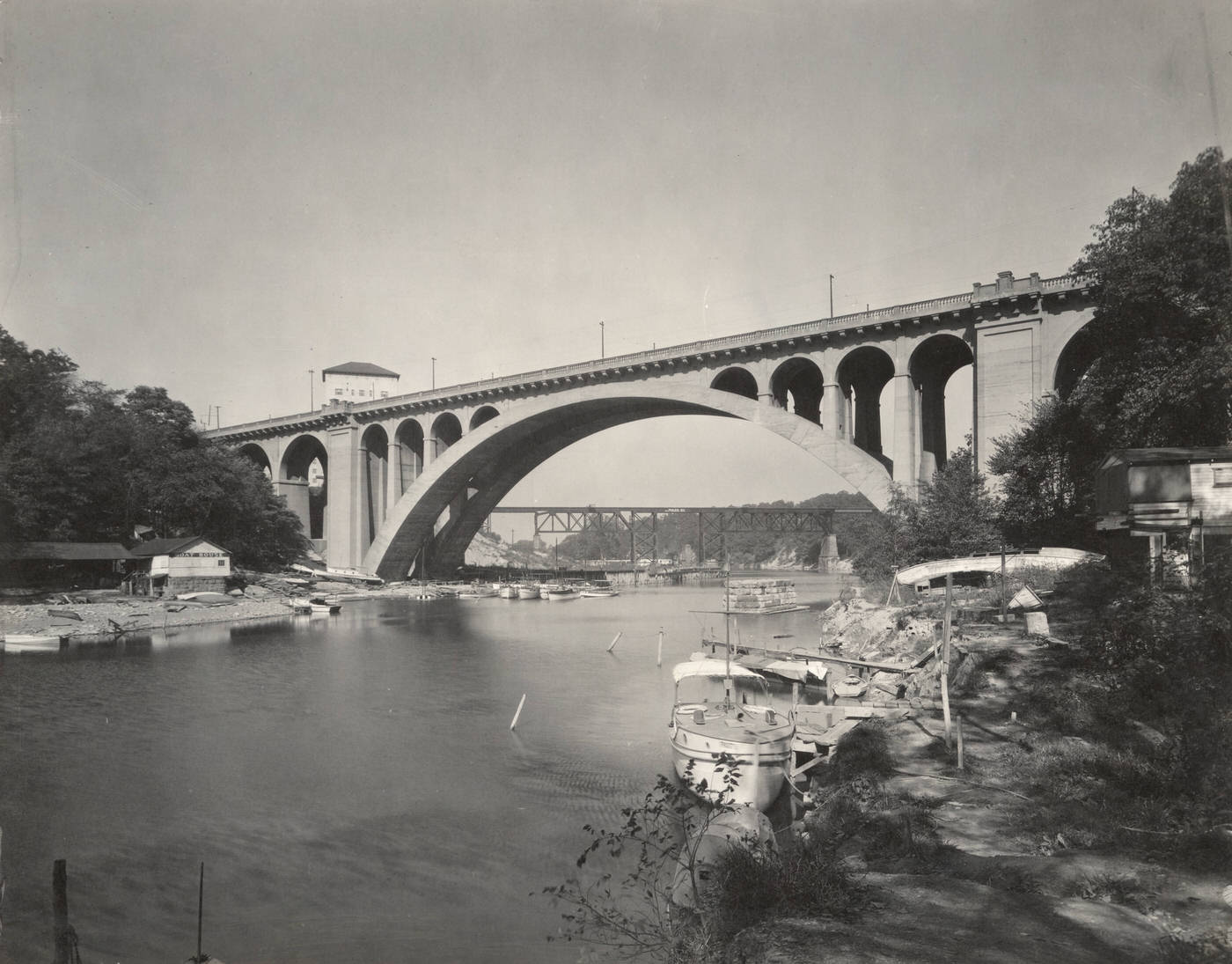

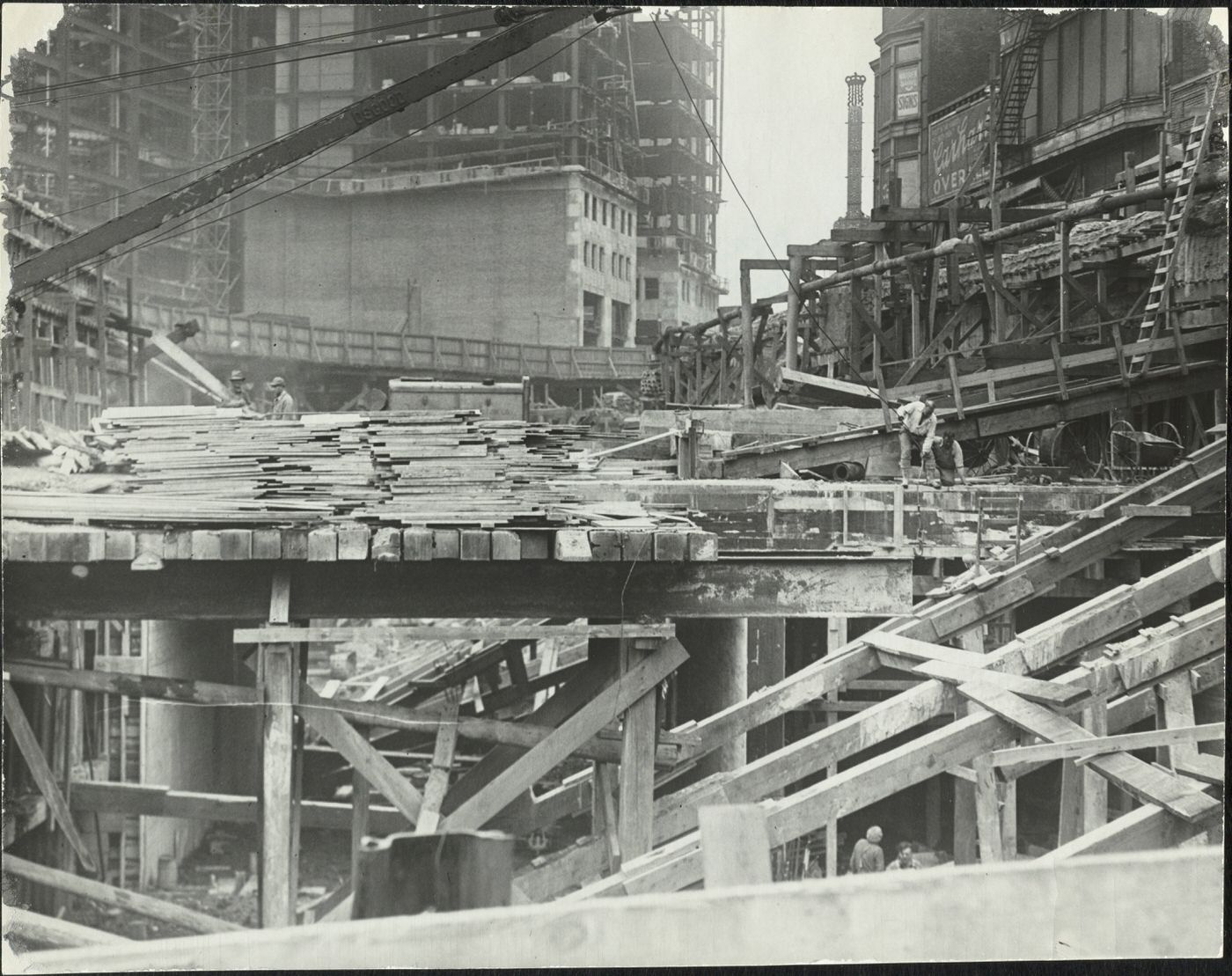

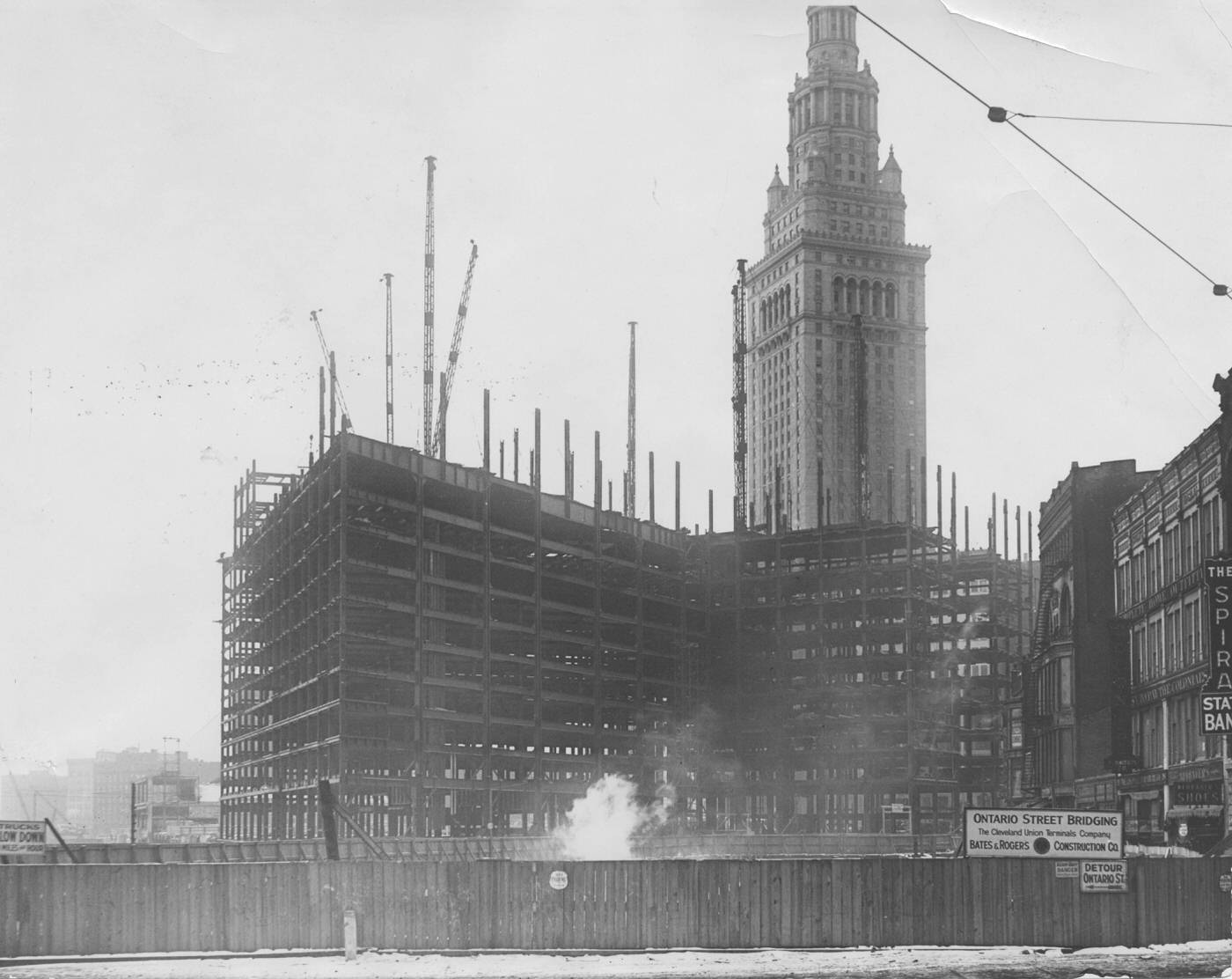

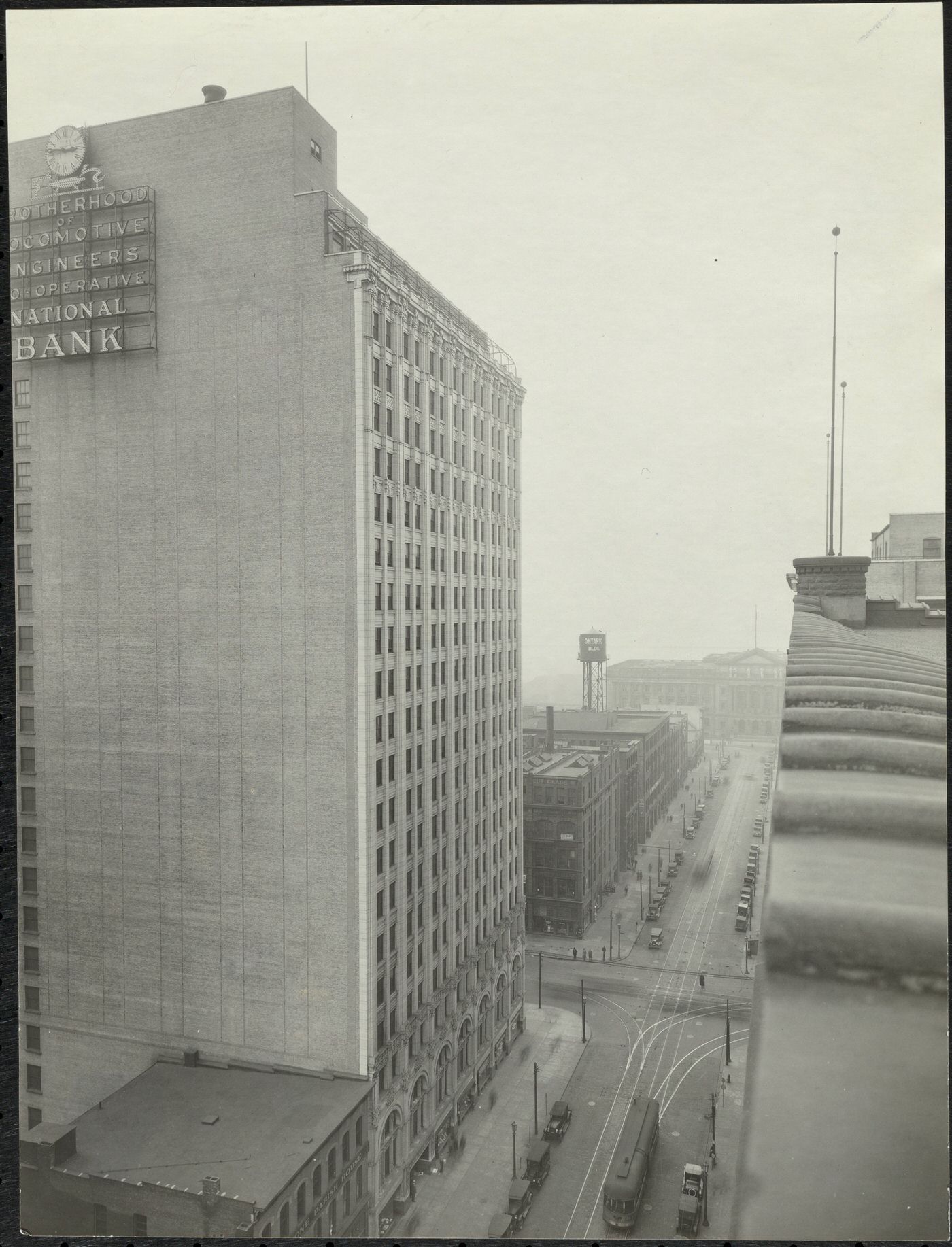

The 1920s were a period of ambitious construction in Cleveland, with projects that not only modernized the city but also created lasting landmarks. The most prominent of these was the Cleveland Union Terminal complex, centered around the Terminal Tower. This was the largest construction undertaking in the city during the decade. The vision for a new union station on Public Square, championed by the Van Sweringen brothers, was approved by voters in 1919. Demolition for the vast site began in 1922, with excavation starting in 1924. Construction of the steelwork for the tower commenced in 1926, and the 708-foot Terminal Tower was completed in 1927. Upon its completion, it was the tallest building in the world outside of New York City, a title it held until 1953. The engineering for this monumental project was unprecedented, involving foundations sunk 250 feet deep to bedrock, the demolition of over 1,000 existing buildings, and the construction of numerous bridges and viaducts for the railroad approaches. The architectural firm Graham, Anderson, Probst & White of Chicago designed the entire depot and office complex. The first train entered the new depot in October 1929, and the formal opening of the Cleveland Union Terminal group, which also included the Guildhall, Republic, and Midland buildings, took place on June 29, 1930. The complex also integrated the existing Hotel Cleveland (built in 1918) and later incorporated the new Higbee’s Department Store (opened 1931) and the U.S. Post Office (completed 1934). This massive development, driven by private entrepreneurs, reshaped Cleveland’s downtown, created a new focal point on Public Square, and symbolized the city’s modernity and ambition.

Other significant infrastructure and civic building projects also marked the decade. A new Public Library building, a key component of the earlier Group Plan, opened its doors in 1925, enhancing educational and cultural resources for Clevelanders. The Federal Reserve Bank building was completed in 1923, reinforcing Cleveland’s status as an important financial center. Recognizing the dawn of a new era in transportation, Cleveland Airport (now Cleveland Hopkins International Airport) was opened in 1925, positioning the city at the forefront of air travel. The Detroit-Superior Bridge, a vital artery connecting the east and west sides of the city over the Cuyahoga River, had its construction completed in 1918, and its impact on improving urban connectivity was strongly felt throughout the 1920s. These projects collectively represented a concerted effort to equip Cleveland with the infrastructure of a leading 20th-century city.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know