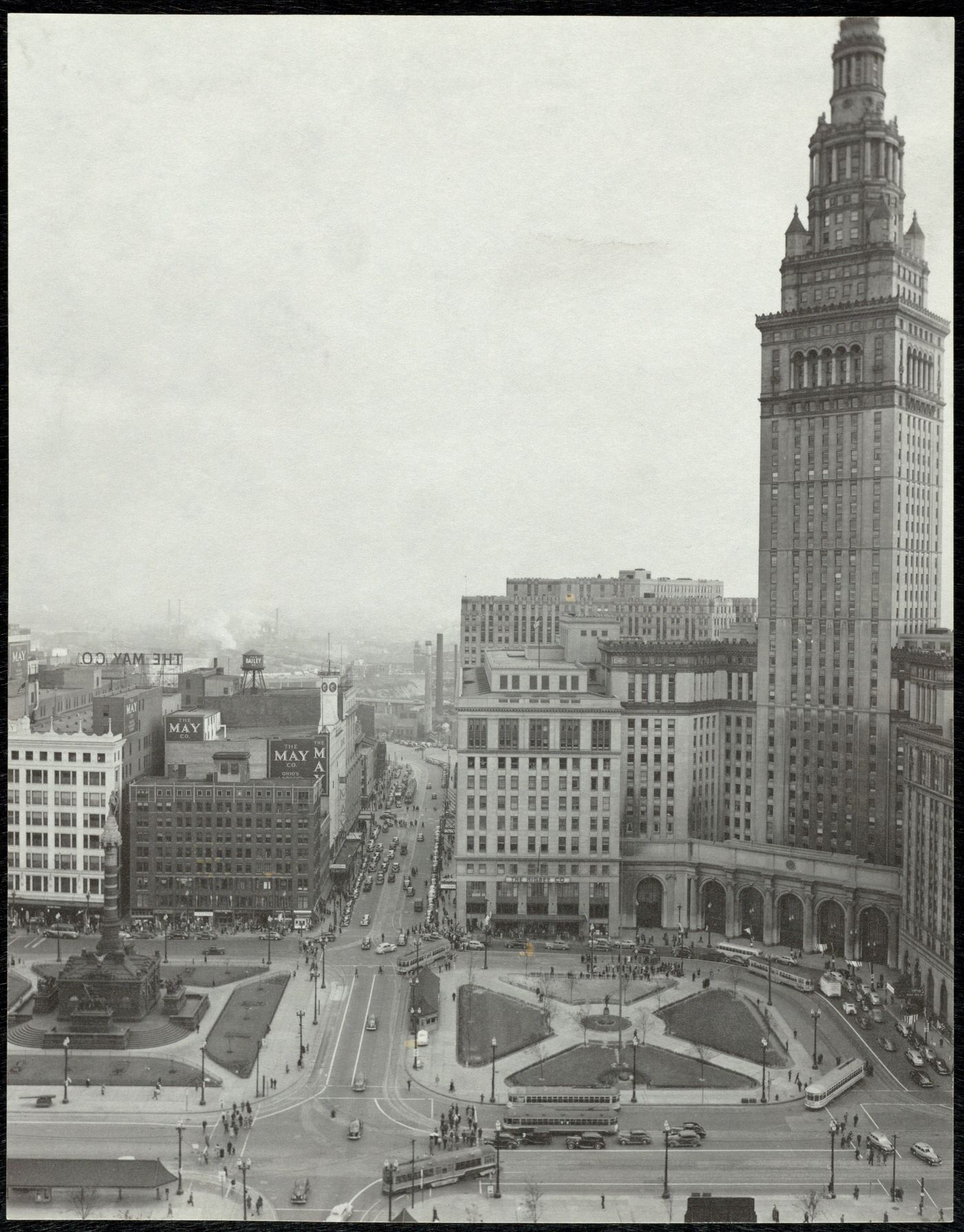

As the 1940s began, Cleveland stood as a significant American city. In 1940, its population was recorded at 878,336. This figure positioned Cleveland as the sixth-largest city in the United States at the time. This population number showed a slight decrease from the 1930 census, which counted 900,429 residents. The decade of the 1920s had seen Cleveland grow by 13%, surpassing 800,000 people by 1920 and reaching its peak population in 1930. The 1930s, however, brought the first slowdown in this growth, with the 1940 census revealing a 2.5% decline.

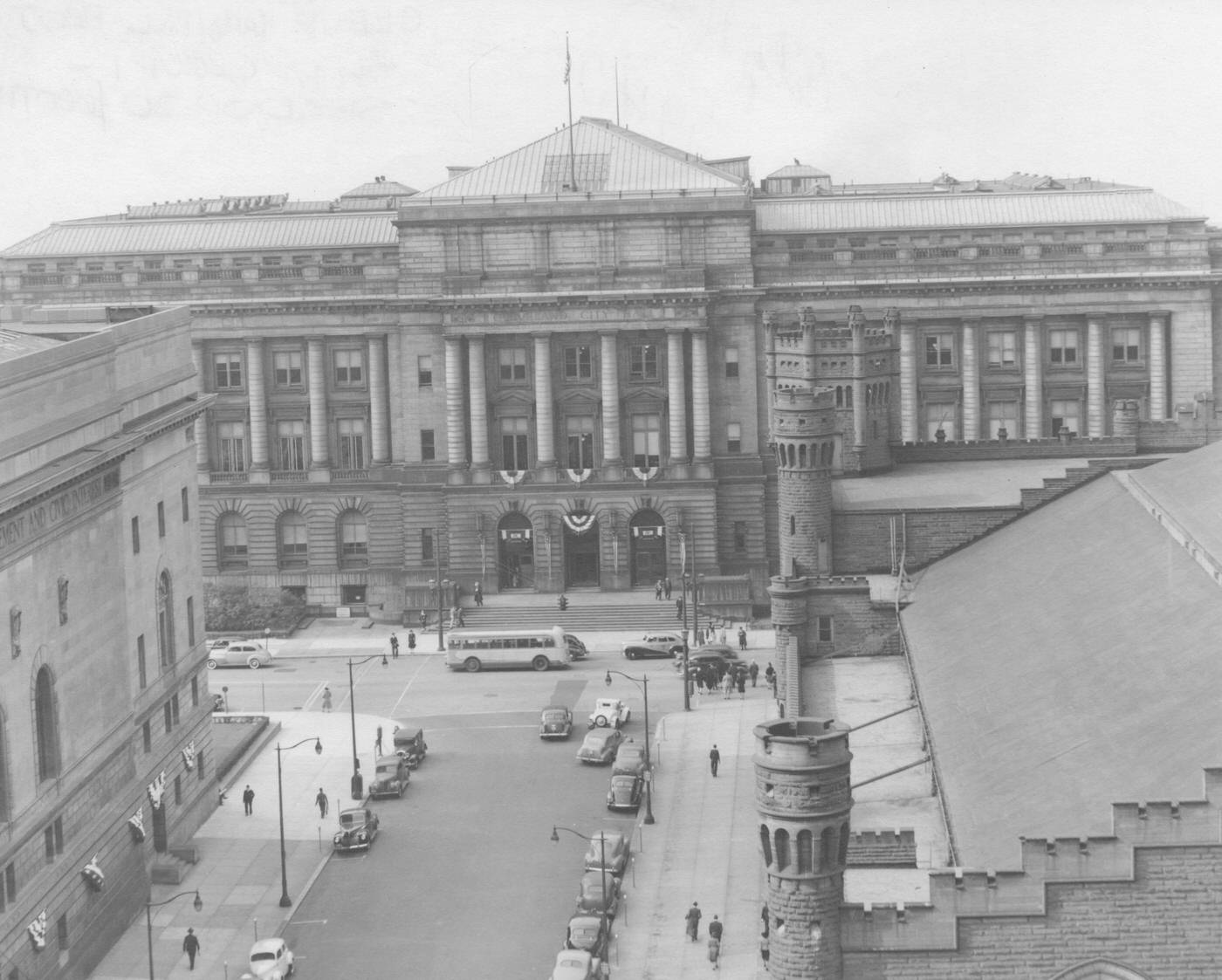

Cleveland’s population had grown steadily for decades. However, the 1940 census revealed a slight decrease, the first in a century. This change reflected the harsh realities of the Great Depression. The economic despair of the 1930s had caused widespread unemployment and hardship, likely leading families to leave Cleveland in search of opportunities or resulting in fewer new residents arriving. Despite this small dip in numbers, Cleveland maintained its status as a major urban center, a powerhouse of industry with a substantial workforce ready for the industrial demands the impending war would bring. The city’s consistent high ranking among U.S. cities (5th largest in 1920, 6th in 1930 and 1940) made it a natural focal point for federal initiatives. Its established industrial infrastructure and large, skilled labor pool were invaluable assets, first for New Deal recovery programs and then, critically, for the massive mobilization required by World War II.

Tragedy Strikes: The East Ohio Gas Company Explosion of 1944

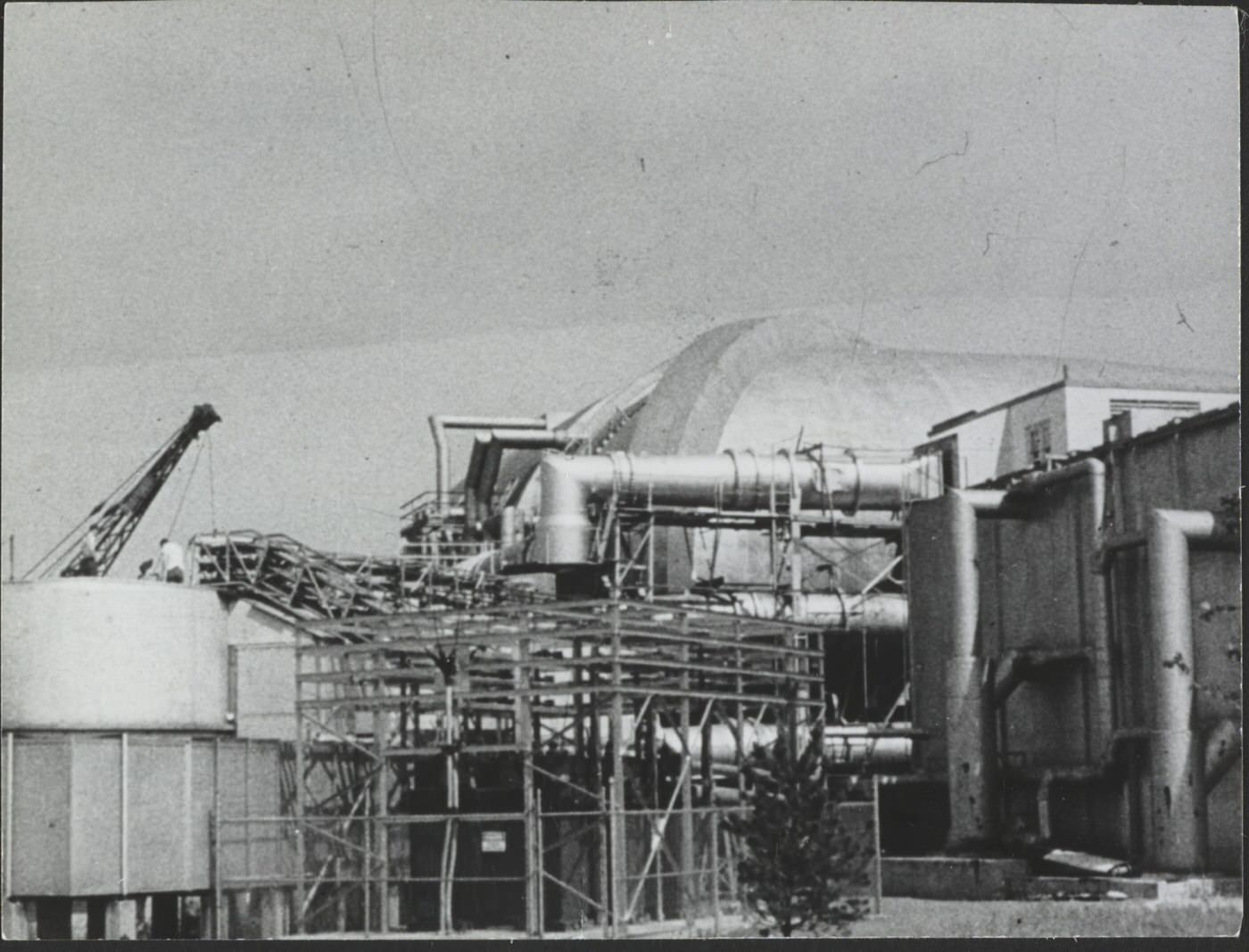

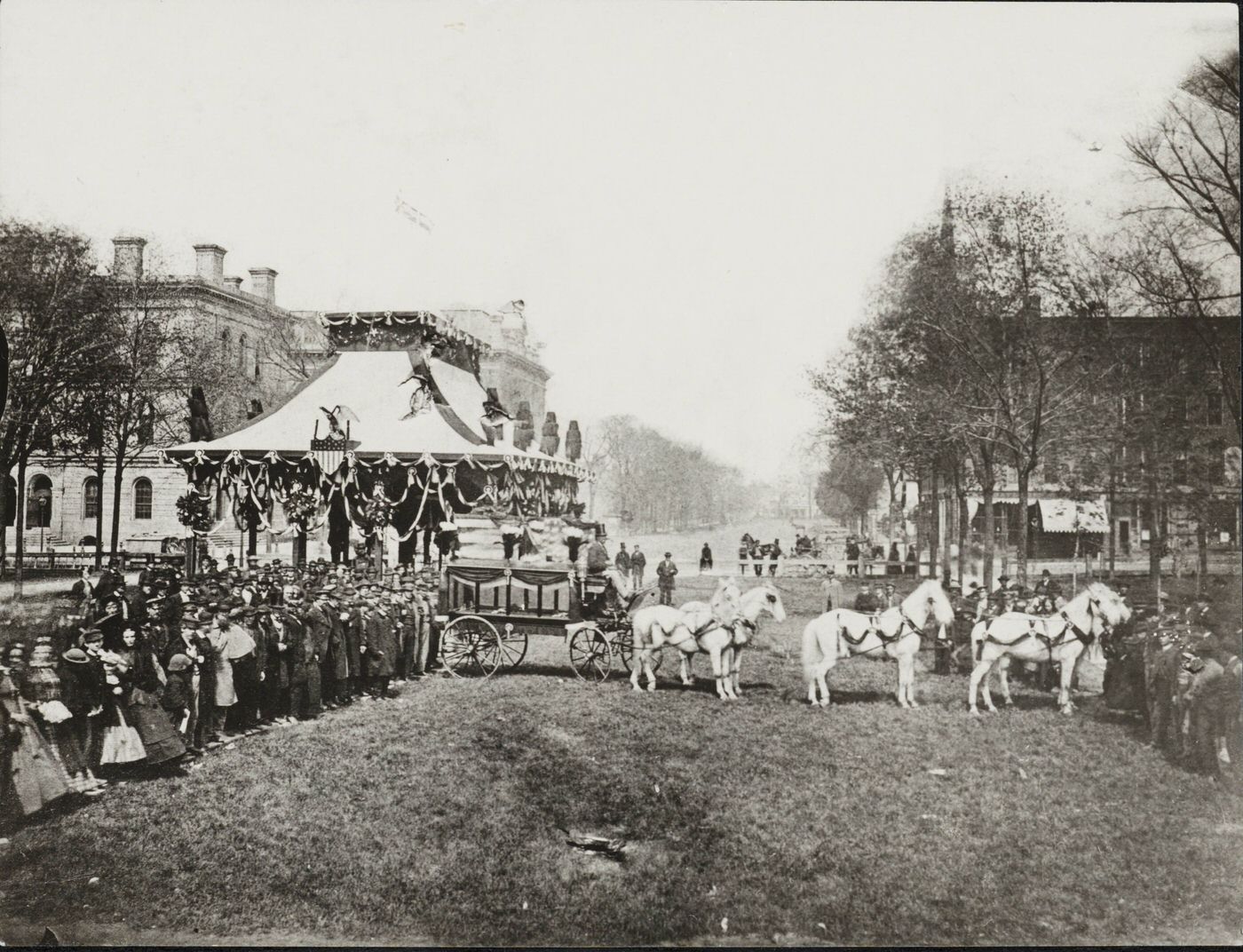

On Friday, October 20, 1944, Cleveland experienced a devastating home front disaster when a liquefied natural gas storage tank at the East Ohio Gas Company exploded, followed by a second tank. The explosion and ensuing fire engulfed homes and businesses in a tidal wave of fire across more than one square mile of Cleveland’s east side, an area bordered by St. Clair Avenue NE, E. 55th Street, E. 67th Street, and the Memorial Shoreway. The initial tank, built in 1942 to provide reserve gas for local war industries, began leaking white vapor around 2:30 P.M. The gas mixed with air and became combustible, exploding at 2:40 P.M..

The fire spread through 20 blocks, destroying 79 homes, 2 factories, 217 cars, 7 trailers, and 1 tractor. Vaporizing gas flowed into underground sewers, causing further explosions that ripped up pavement and damaged utilities. The death toll reached 130, with hundreds more injured. The immediate area was evacuated, and refugees were sheltered at Willson Jr. High School, where the Red Cross assisted approximately 680 homeless victims. The disaster severely tested the city’s Civilian Defense preparations. Occurring in the midst of a global war, this industrial accident was exceptionally traumatic, blurring the lines between distant battlefield dangers and immediate home front hazards. The fact that one of the storage tanks involved was built to support war industries underscored the inherent risks associated with rapid industrial expansion for wartime production. In the aftermath, the analysis of the fire’s cause led to the development of new and safer methods for the low-temperature storage of natural gas.

Lingering Shadows of the Depression: Economic Realities and Final New Deal Efforts

The early 1940s in Cleveland were still marked by the economic hardship of the Great Depression. In January 1931, the city faced a severe unemployment crisis, with 99,233 people out of work and an additional 25,400 either laid off or on part-time schedules, meaning roughly half of Cleveland’s population was directly affected by joblessness. By 1933, the unemployment rate in Cleveland hovered between 30% and 70%.

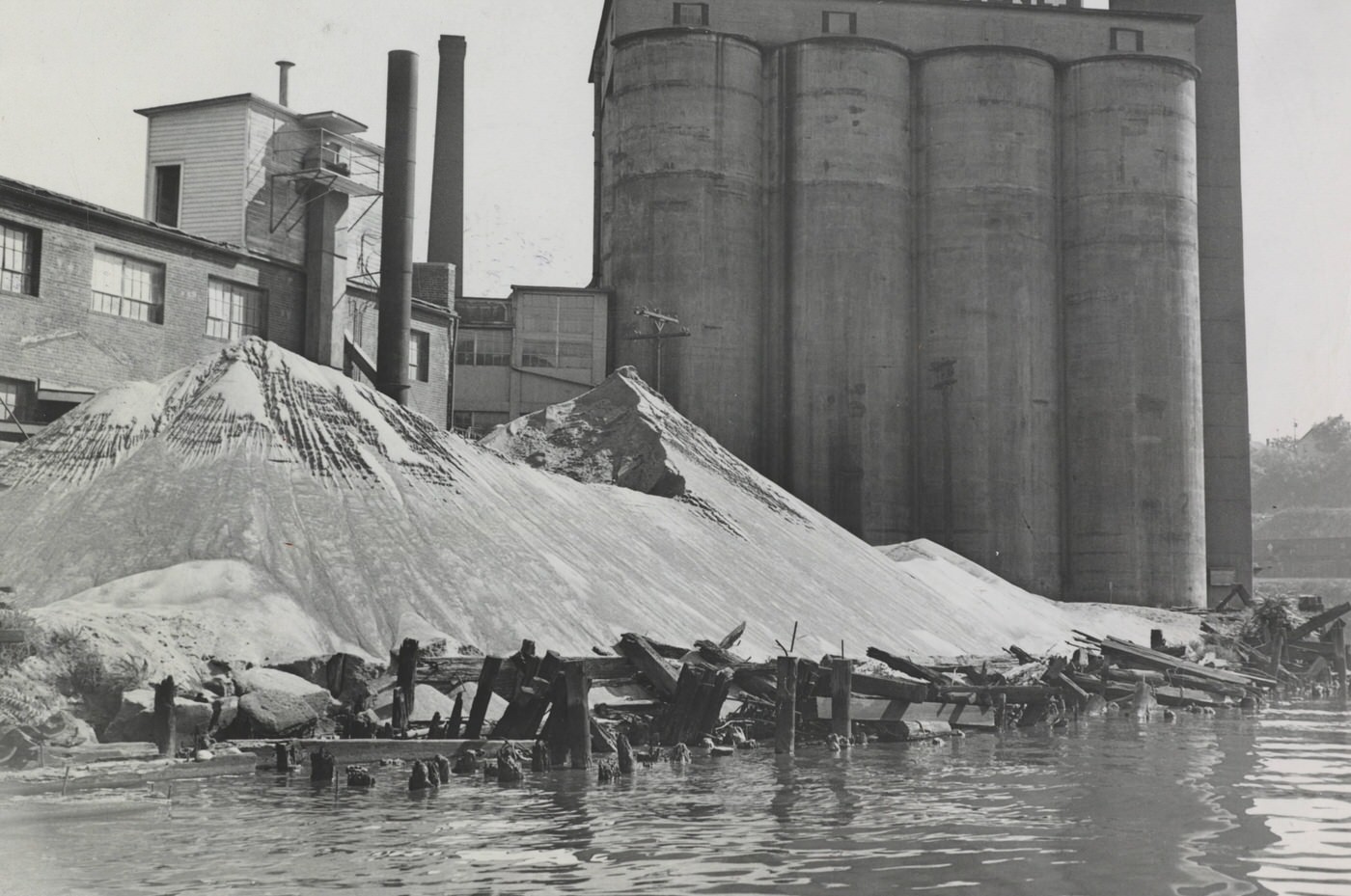

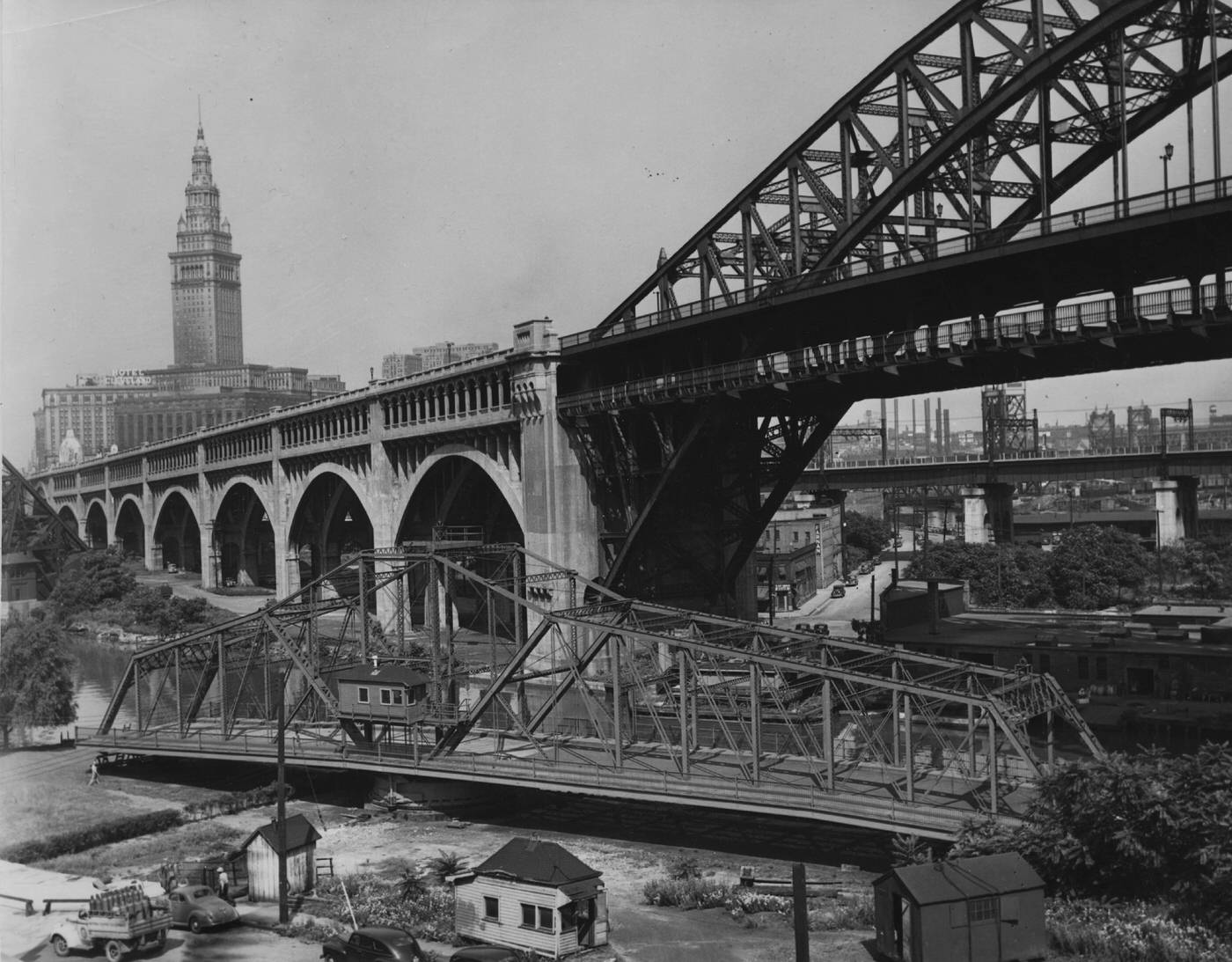

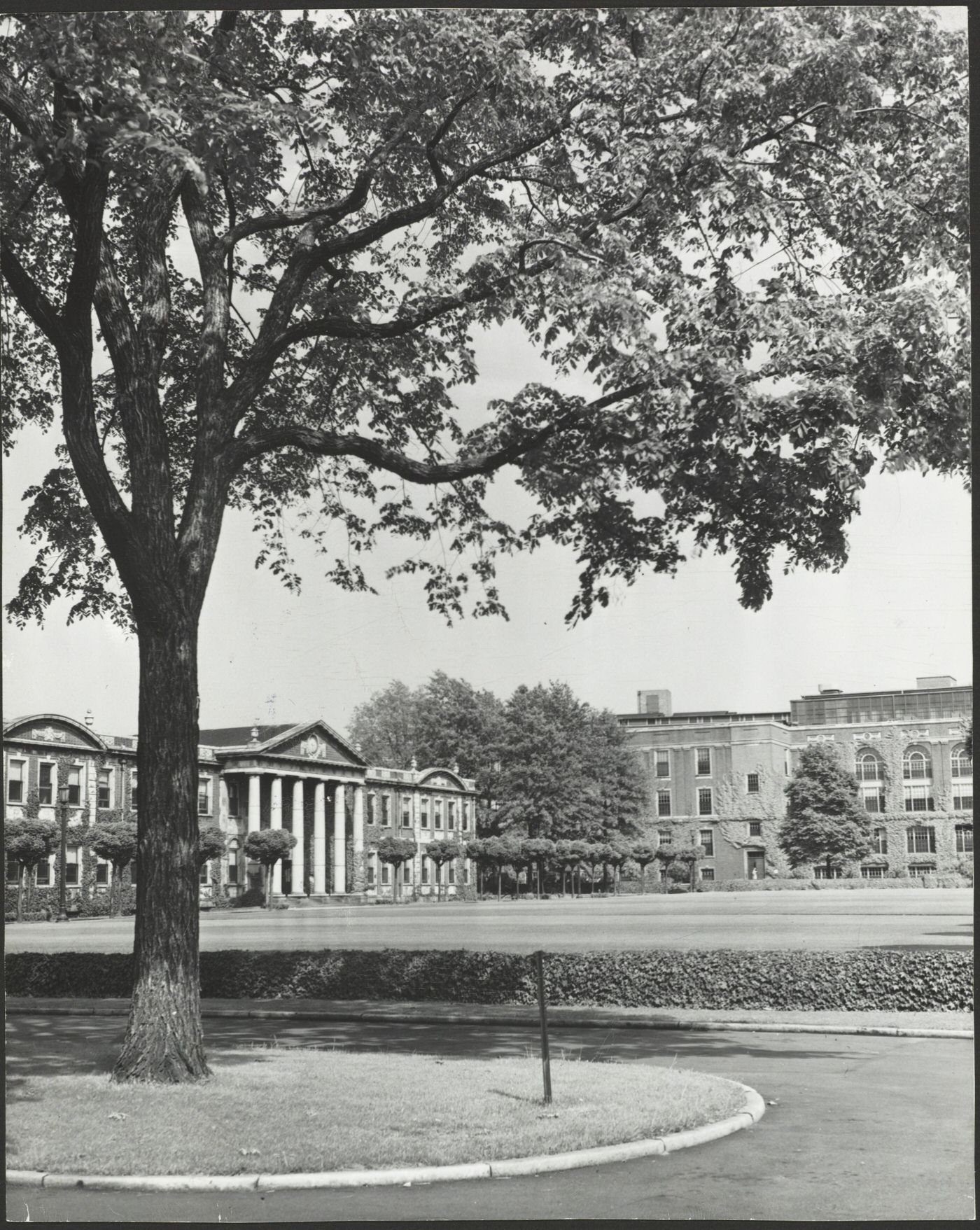

Federal New Deal programs, particularly the Works Progress Administration (WPA), remained active in providing a crucial safety net. The WPA provided jobs through various public works projects. These included upgrading airports and streets, developing the Metropolitan parks system, enhancing the city zoo, creating cultural gardens, and constructing public housing for the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA). A major WPA achievement was the construction of the first segment of the Memorial Shoreway. WPA employment in Cuyahoga County fluctuated, reaching a peak of 78,000 in October 1938. As businesses began to recover and recall workers, these numbers declined, and the WPA program officially ended by March 1942, as the demands of the war effort absorbed the available workforce. The sustained, large-scale WPA operations well into the early 1940s underscore the depth and persistence of the Depression’s impact on the city. The private sector had not sufficiently recovered to provide adequate employment until the war mobilization began in earnest.

Public housing projects such as Cedar-Central, Outhwaite Homes, and Lakeview Terrace, funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA) and started in the mid-1930s, were completed and providing much-needed low-cost housing. The WPA’s focus on infrastructure, while primarily aimed at job creation, inadvertently improved Cleveland’s capacity to handle the subsequent wartime boom. Enhanced transportation networks, recreational spaces, and additional housing stock provided a somewhat better foundation for the massive industrial expansion and population shifts that World War II would bring.

Public Safety and Reform: The End of the Eliot Ness Era

Eliot Ness, known for his earlier efforts against organized crime in Chicago, served as Cleveland’s Safety Director from December 1935 until his resignation on April 30, 1942. His tenure was marked by significant efforts to combat crime and corruption. He modernized the police and fire departments, leading to a reported 25% drop in total crimes and an 80% drop in juvenile crime during his first eighteen months, with arrests and convictions increasing by about 20%. Ness introduced more rigorous, scientific training for police recruits, revised civil service examinations, and mandated character investigations. He also oversaw the centralization and intensive utilization of police communication systems, including two-way radio and teletype.

Traffic safety was a major focus for Ness. His revised traffic control system is credited with cutting auto accident deaths in half, earning Cleveland the American Legion’s National Safety Award in 1939. Beyond law enforcement, Ness initiated social programs, founding Cleveland Boys Town and establishing a Welfare Department within the police department to assist officers’ families in need. These reforms were a local embodiment of broader Progressive Era ideals aimed at making city governance more efficient and less prone to corruption.

The notorious Cleveland Torso Murderer, active between 1935 and 1938, posed a significant challenge during Ness’s time. Most victims were dismembered and decapitated transients found in or near the Kingsbury Run area. Ness ordered the shantytowns in Kingsbury Run, where many victims were found, to be burned down. While this action coincided with the end of the murders, the killer was never officially identified. This grim episode highlighted the limitations of even a determined reformer when faced with exceptionally heinous crimes involving marginalized victims in a city grappling with social distress. In 1940, Ness began working part-time for the Federal Social Protection Program, and his increasing absences from Cleveland drew criticism. He left his post as Safety Director in April 1942 to become the National Director for that federal program.

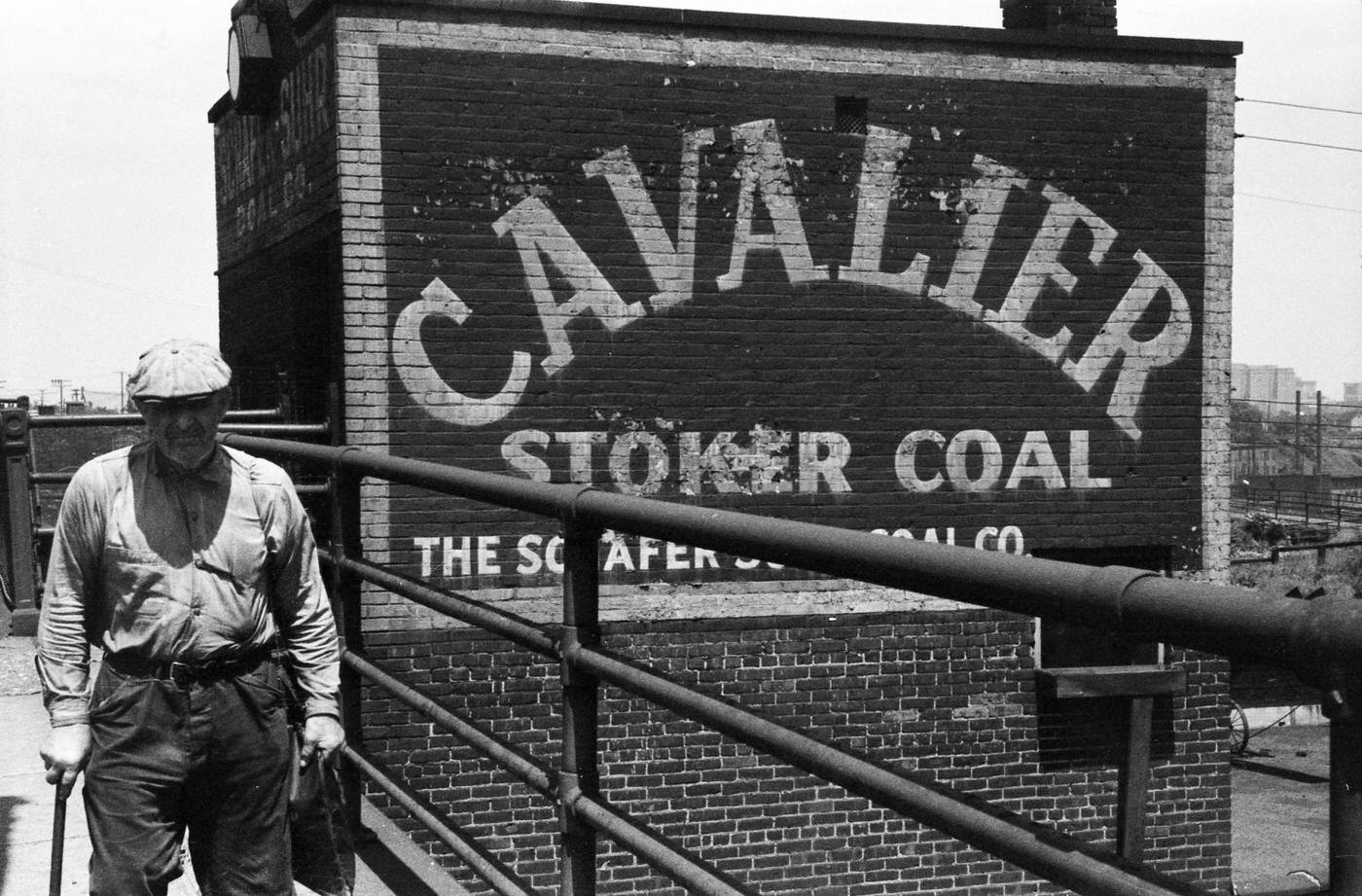

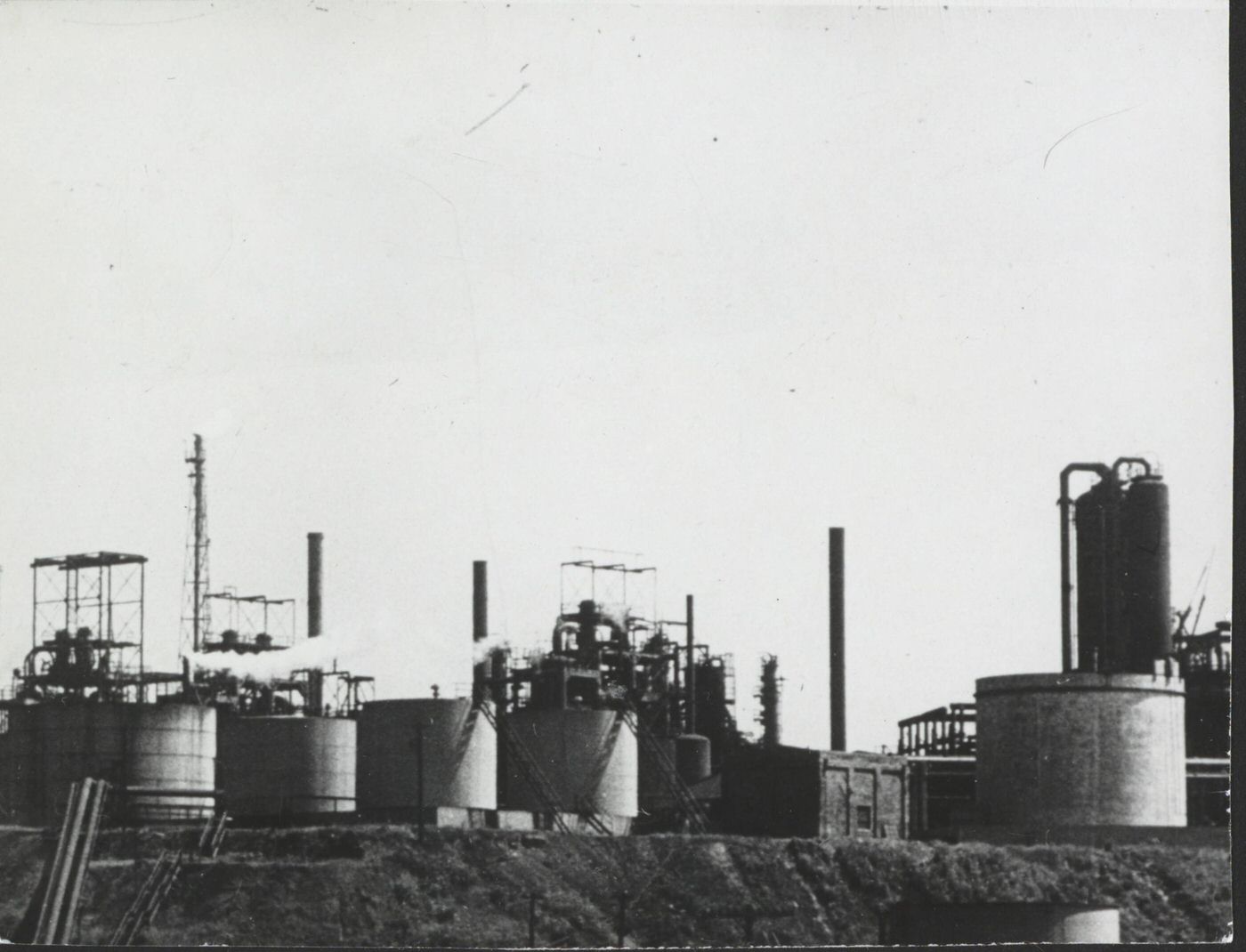

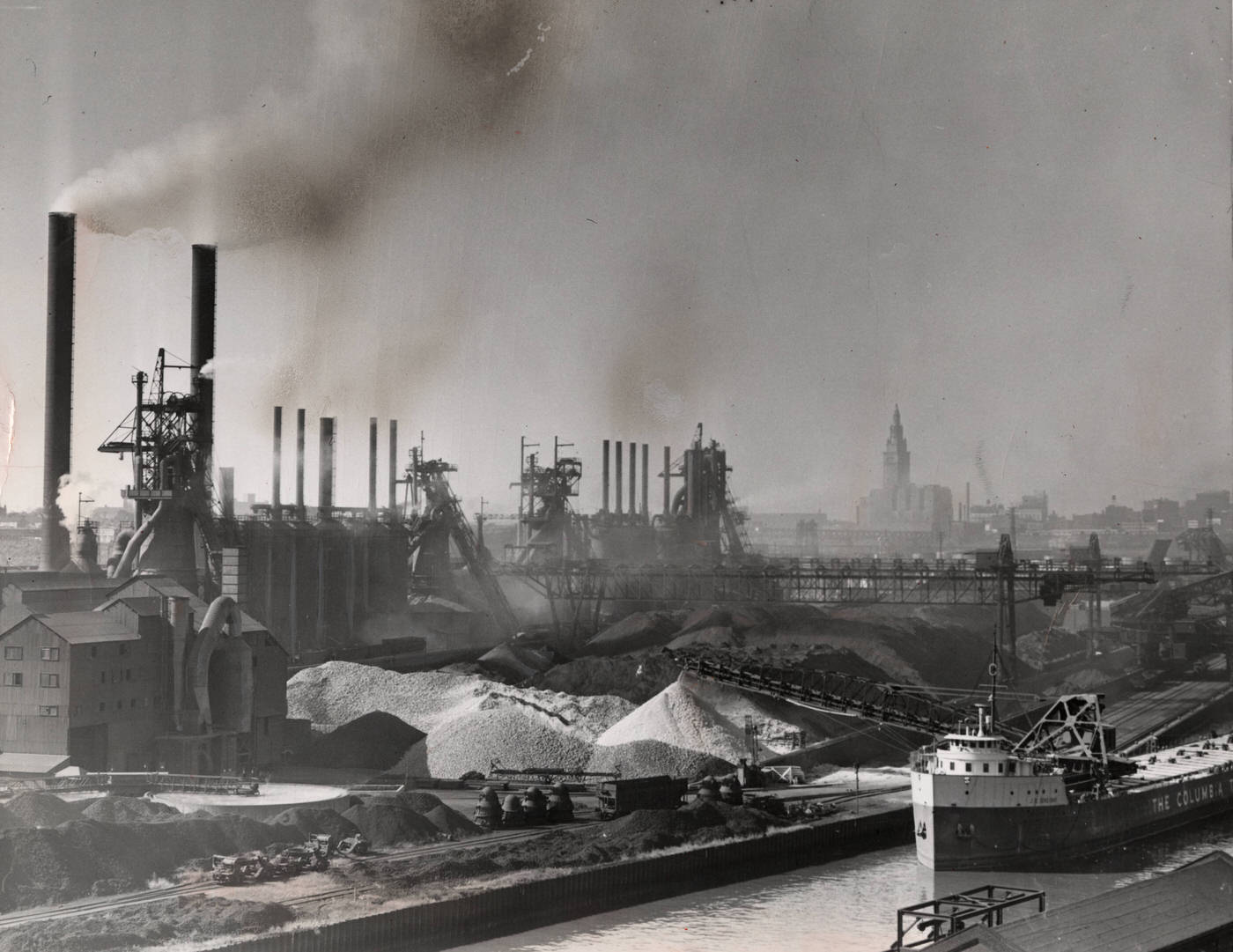

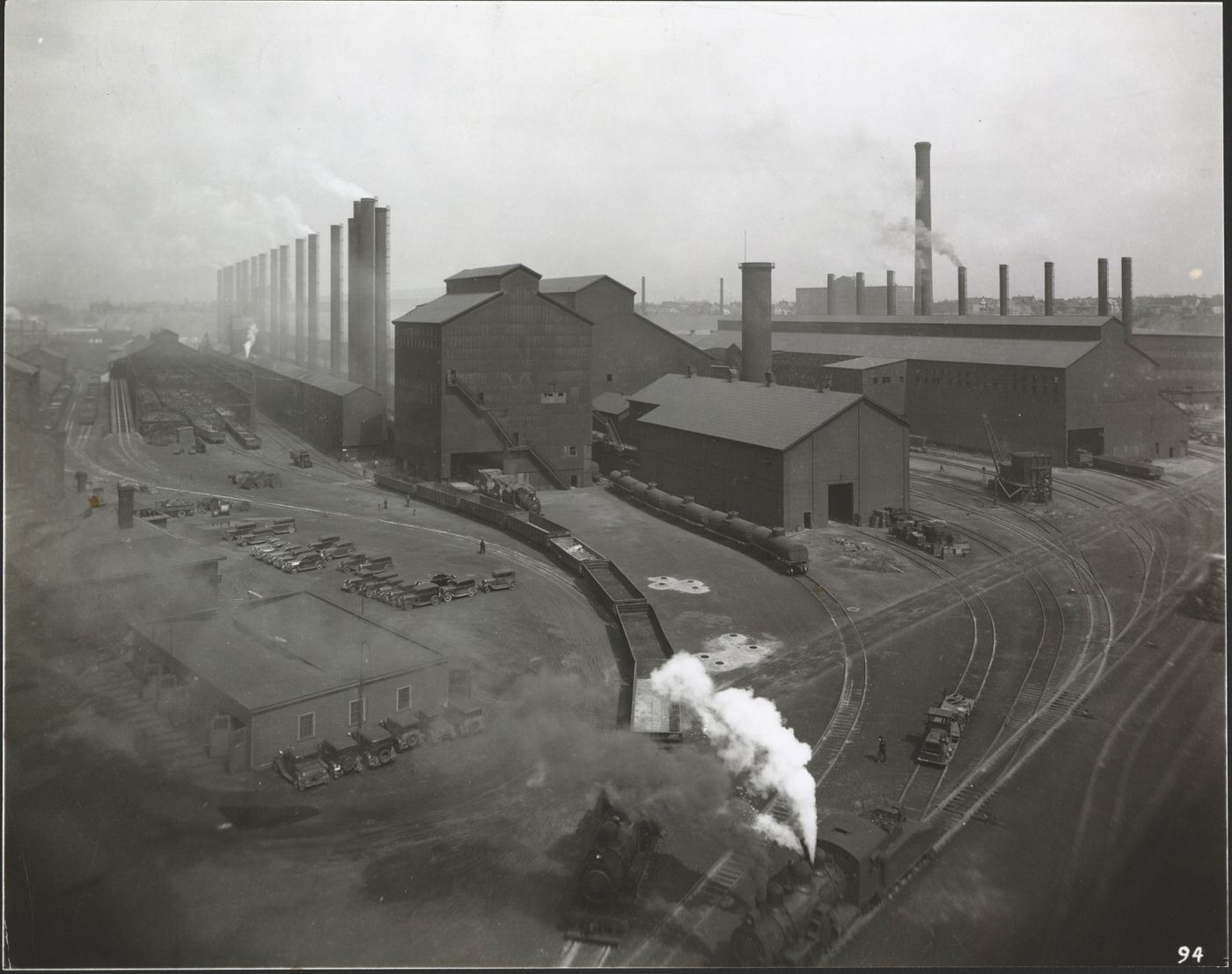

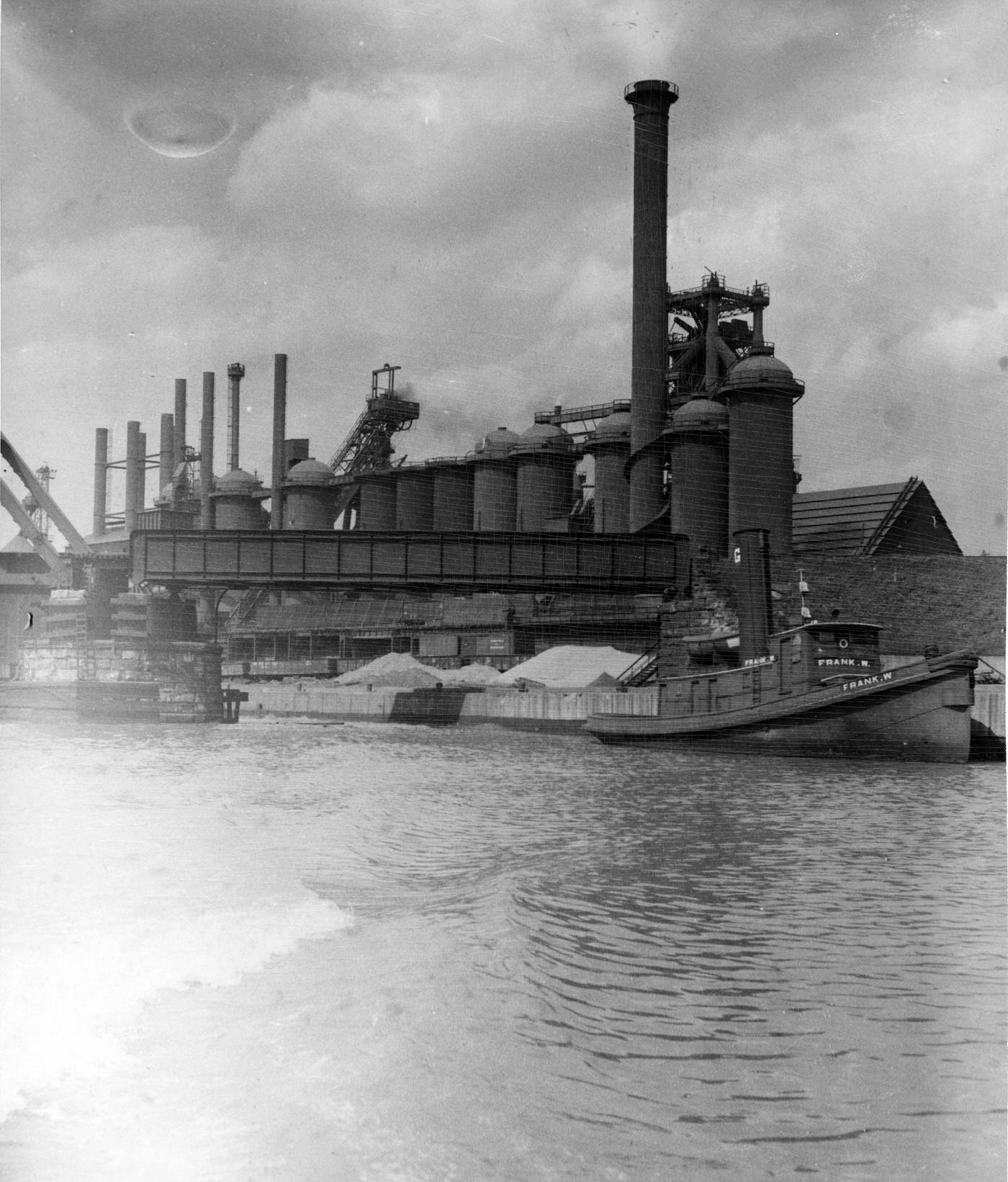

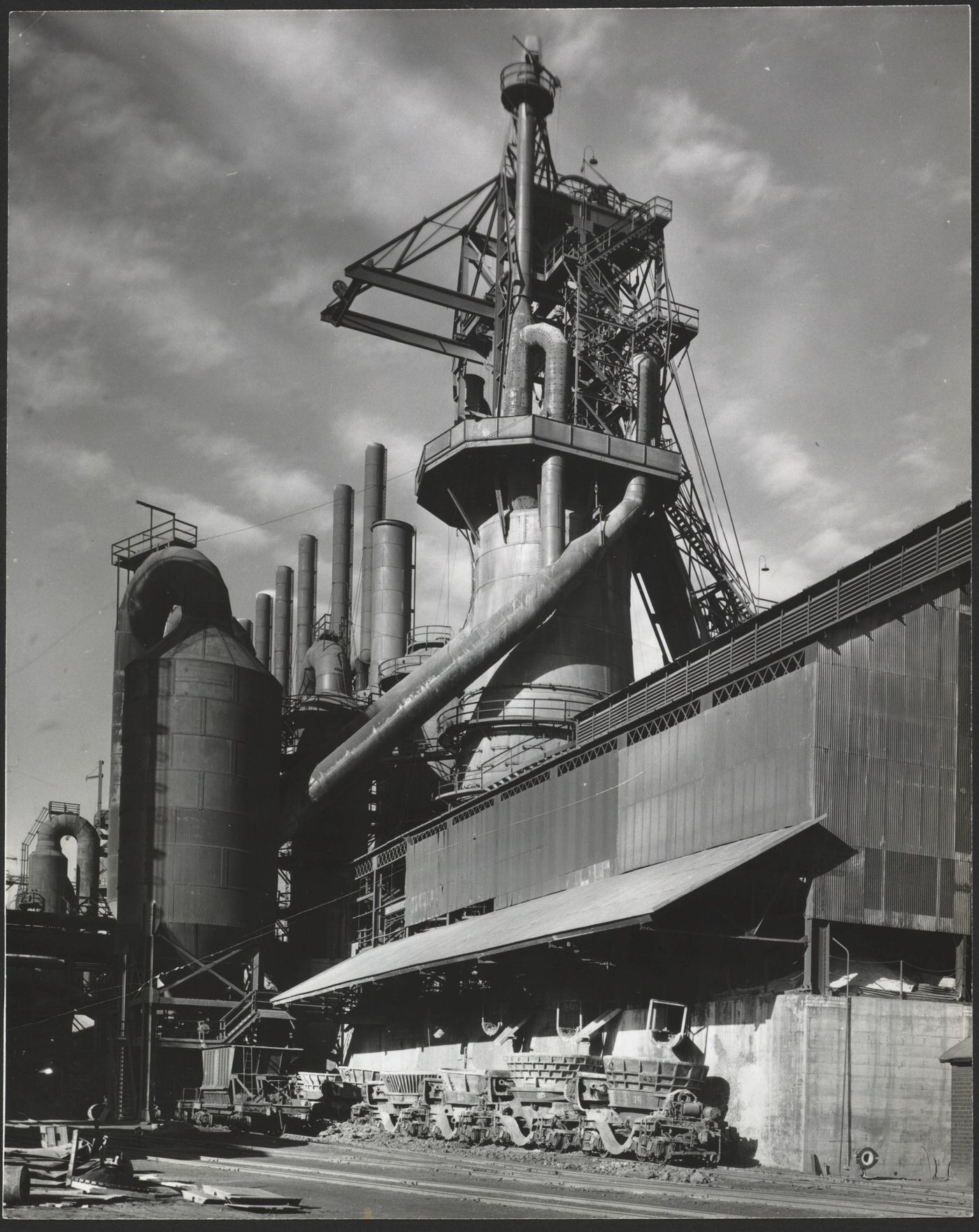

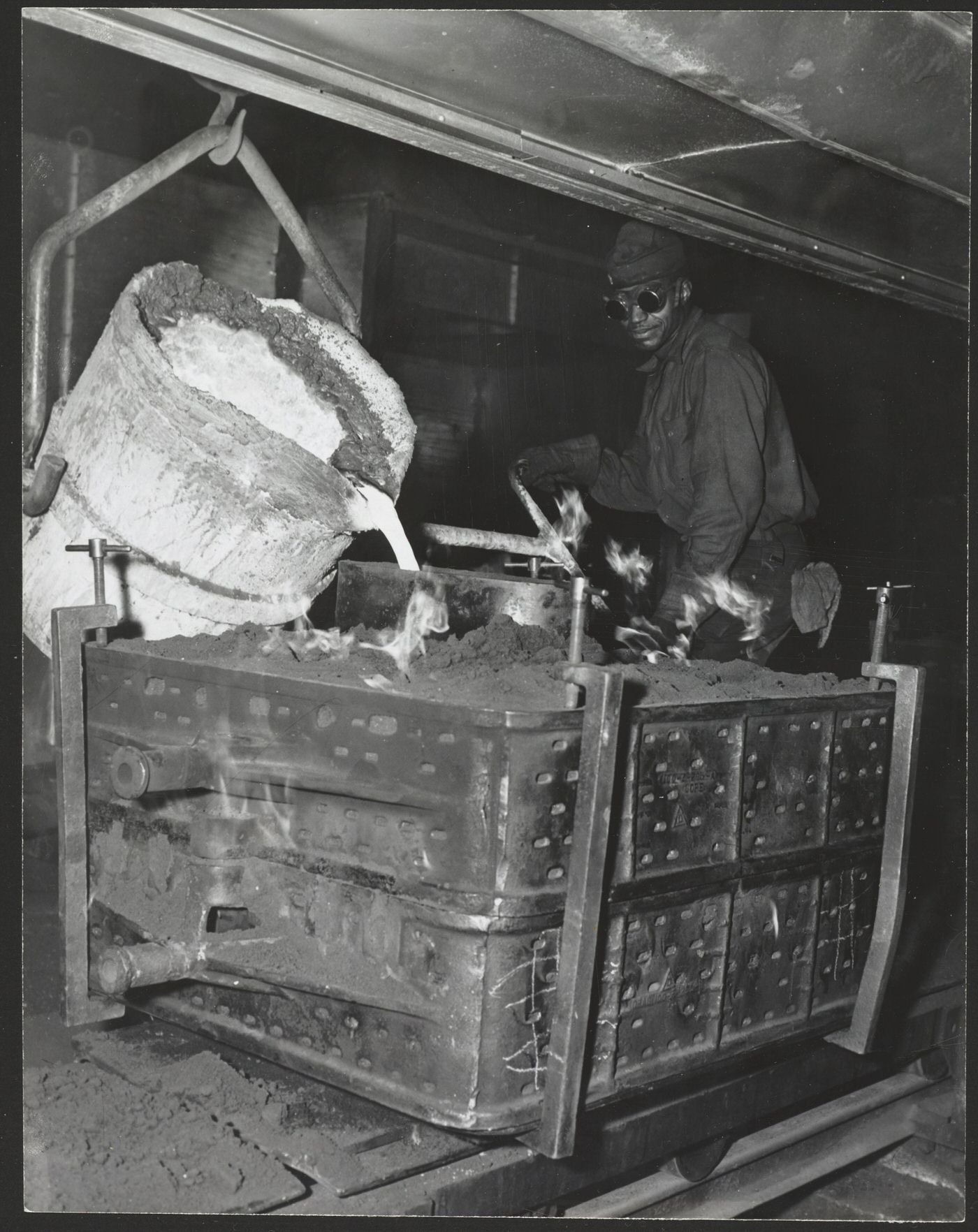

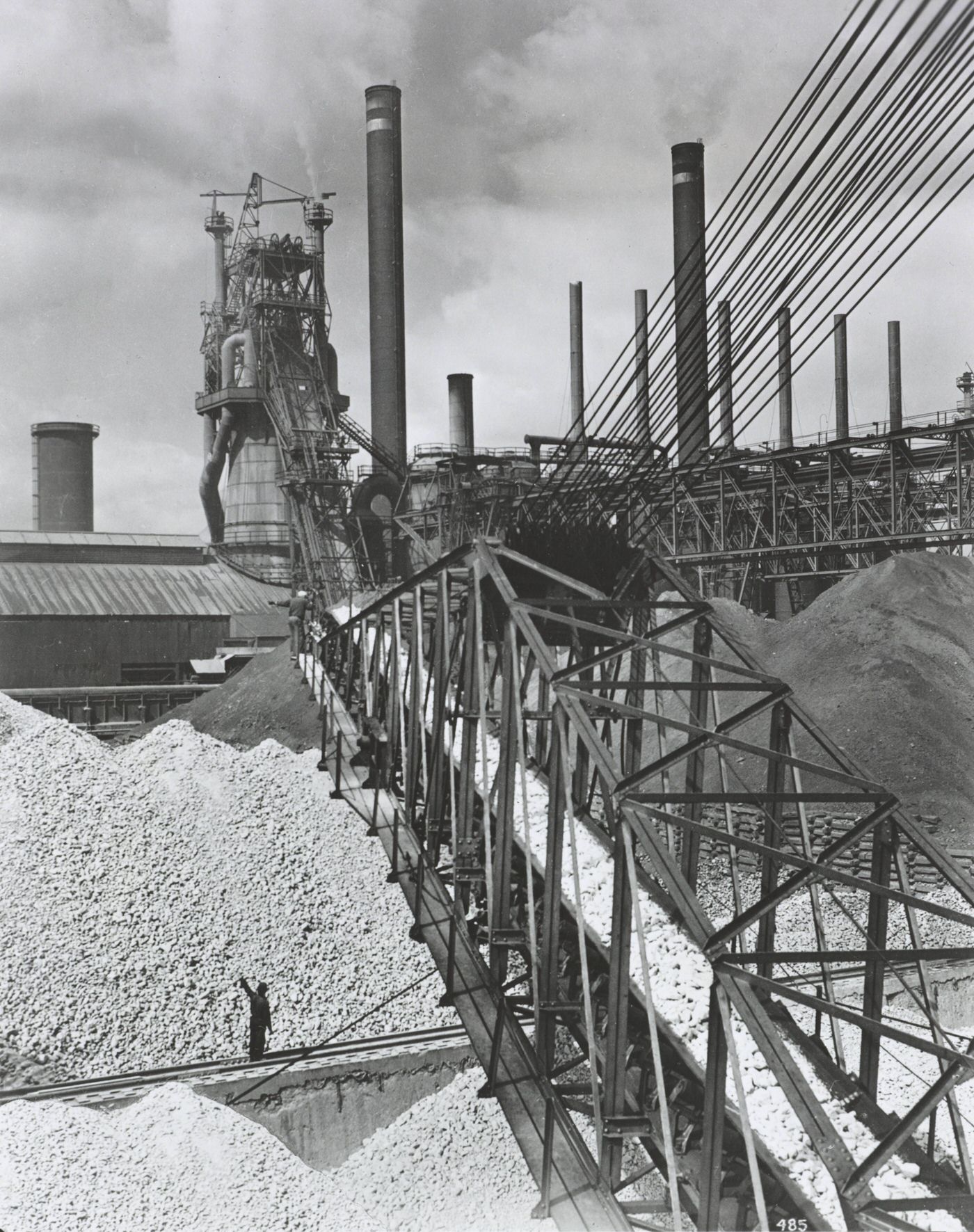

The War Machine: Cleveland’s Industrial Might

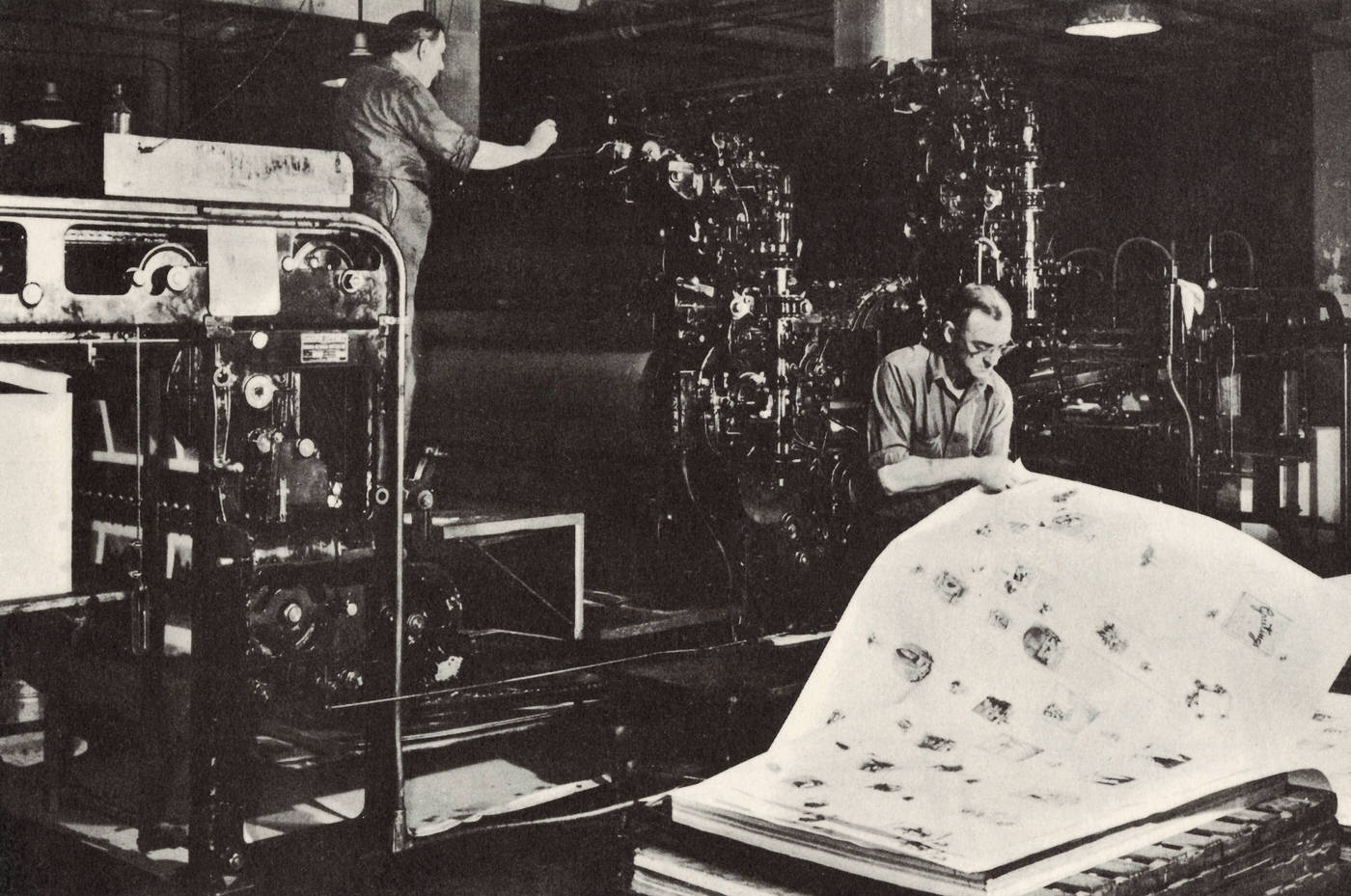

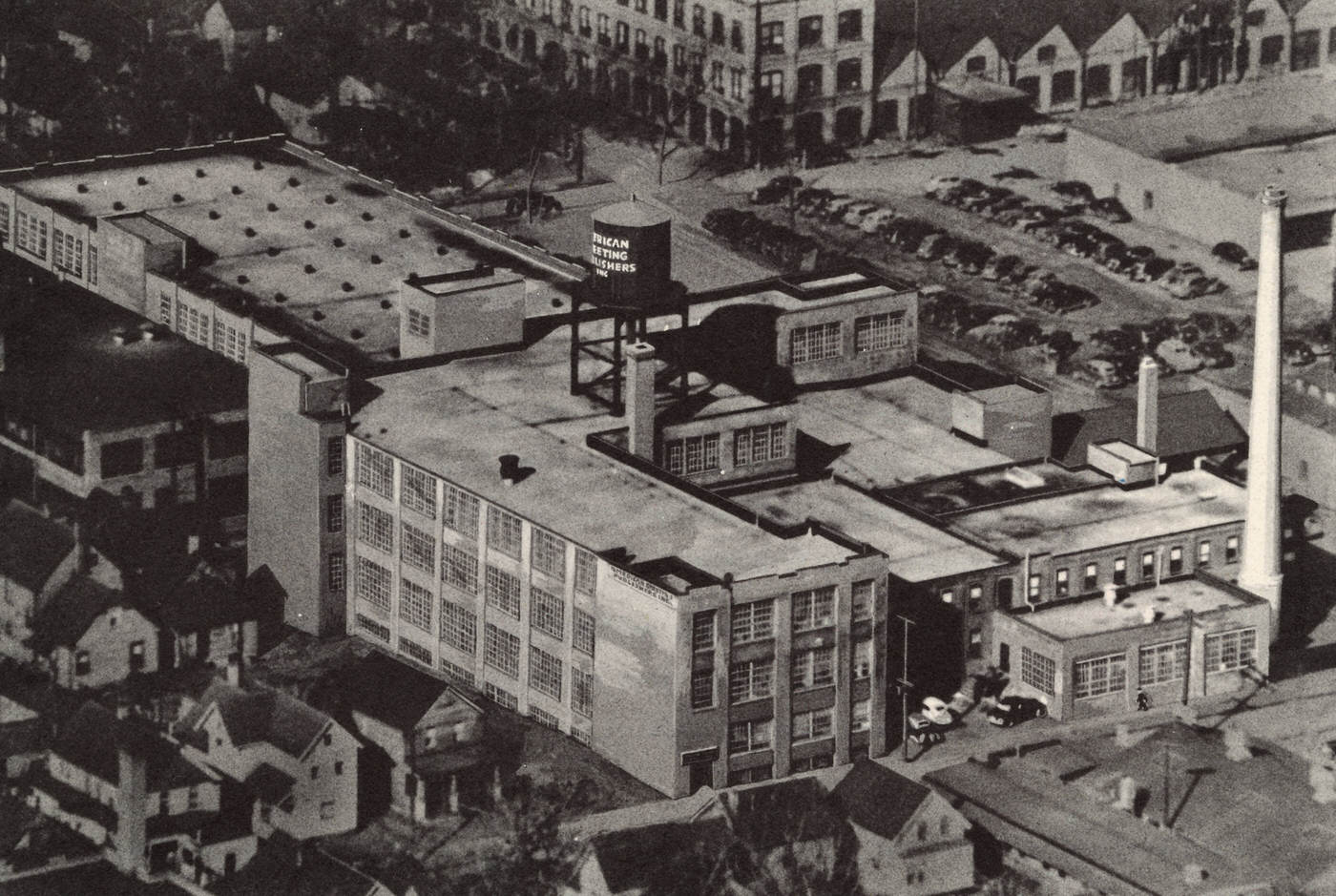

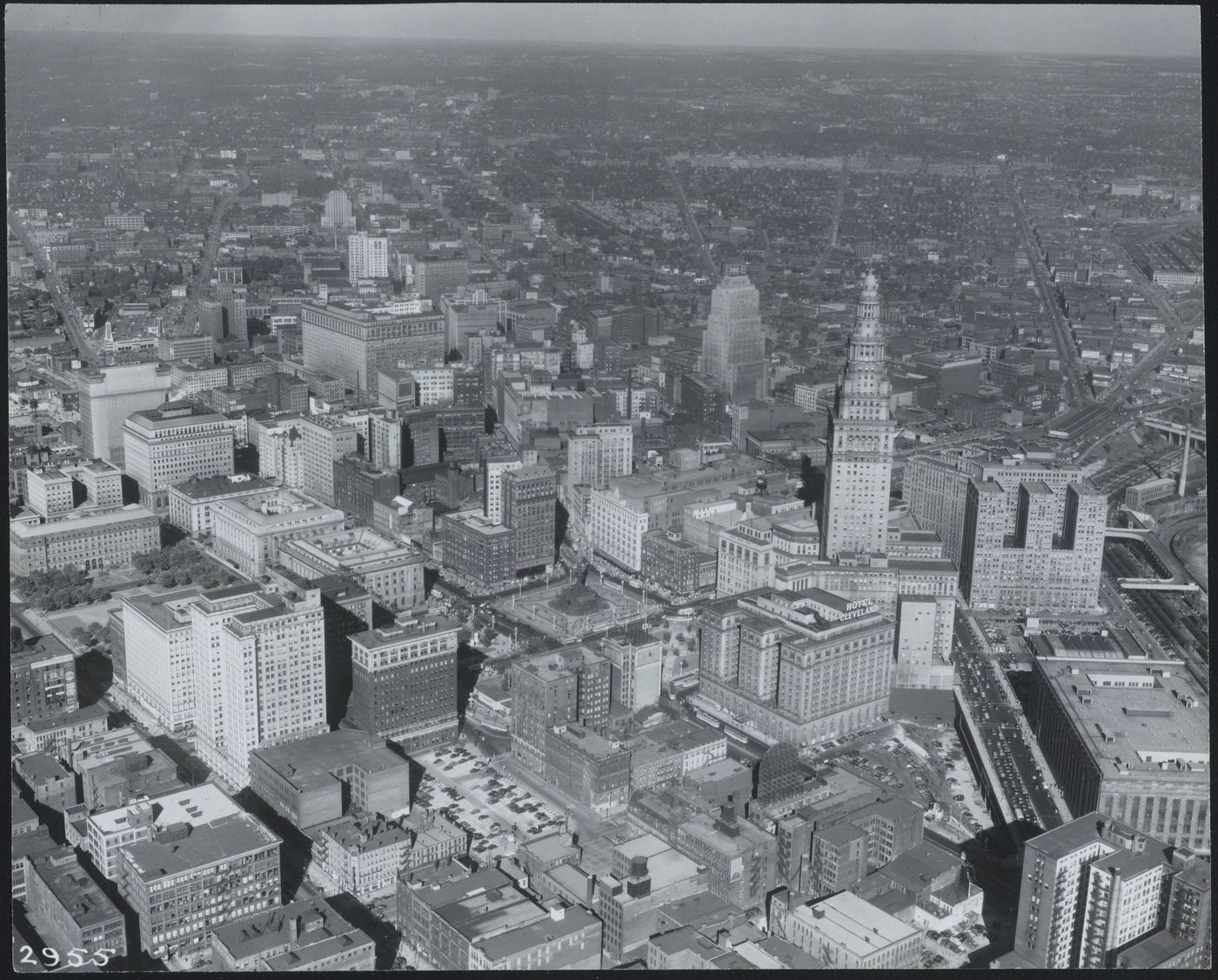

Cleveland’s well-established and diverse industrial base, with strengths in steel, machine tools, automotive components, and electrical machinery, was ideally suited for rapid conversion to war production as the United States entered World War II. The city’s manufacturing sector experienced explosive growth. By September 1944, overall employment in Cleveland was 34% higher than in 1940. Specifically, manufacturing employment surged from 191,000 to 340,000 during this period. Cleveland’s factory employment index reached an impressive 179.7 (with 1939 as the baseline of 100), significantly outpacing the national average of 156.3. This pre-war industrial diversification was a key strategic asset, allowing for a flexible and resilient response to diverse military needs, unlike cities heavily reliant on a single industry.

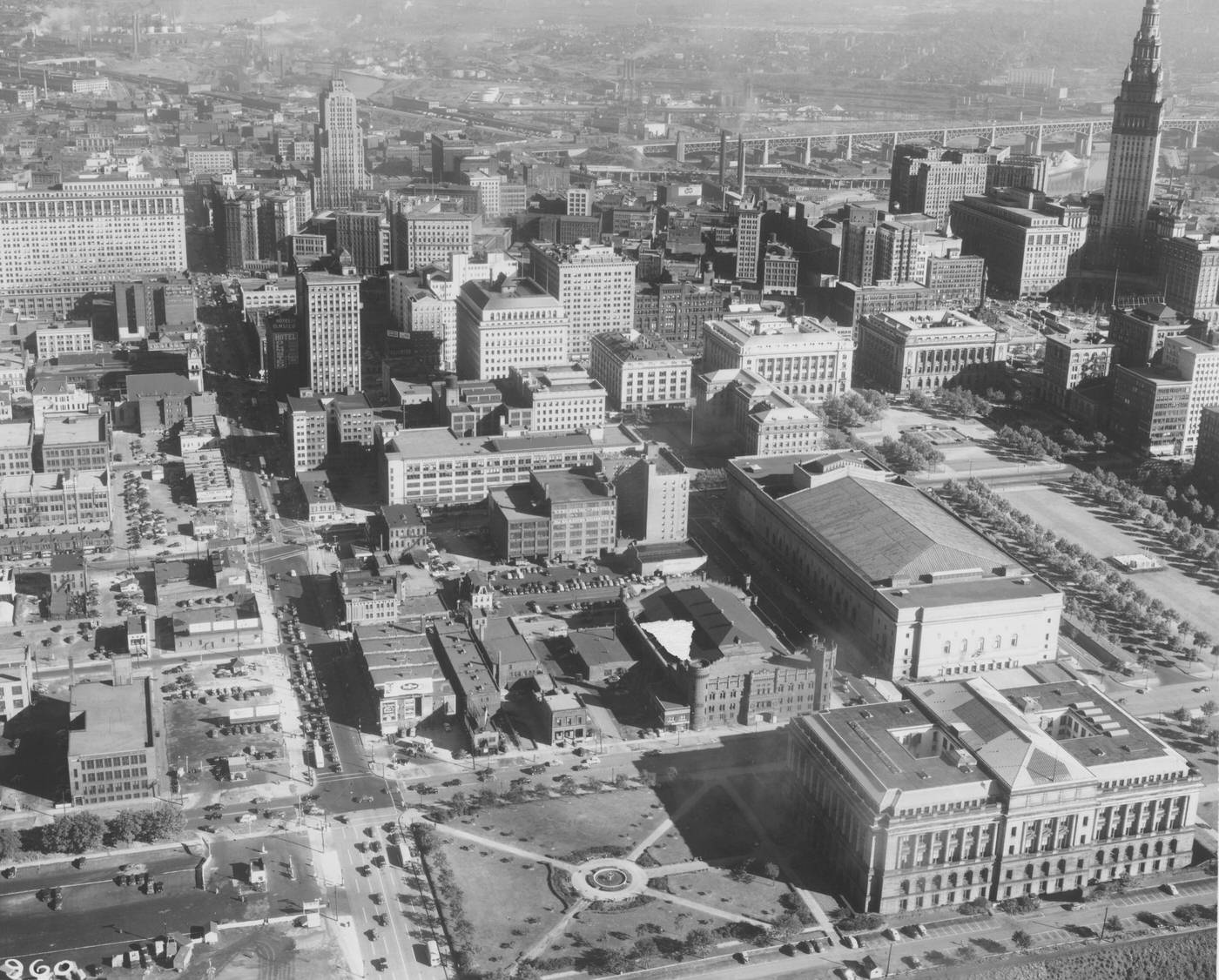

The federal government coordinated much of this massive effort. The Cleveland Ordnance District Office, located in the Terminal Tower, managed contracts with 800 defense plants throughout northern Ohio. The intensity of industrial activity and the need for labor management were underscored by the regional office of the War Labor Board in Cleveland; operating from the Union Commerce Building, it became the third-busiest in the nation, handling approximately 400 cases per week. The immense pressure and scale of wartime production also likely accelerated technological and managerial innovations within Cleveland’s industries, fostering rapid advancements to meet urgent demands for efficiency and high output.

Several Cleveland companies made pivotal contributions to the war effort, manufacturing a wide array of essential military hardware and components. This focus on complex, high-precision items demonstrated the city’s sophisticated engineering capabilities and highly skilled labor force.

Key Cleveland Wartime Industrial Contributors

| Company Name | Key WWII Products | Noted Employment Figures (Peak/Approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| Thompson Products (TRW) | Aircraft engine valves, other aircraft components | 16,000-21,000 (TAPCO plant) |

| Jack & Heintz (JAHCO) | Airplane starters, autopilot devices | 8,700 |

| Parker Appliance Co. (Parker Hannifin) | Aircraft valves, fluid connectors, hydraulic systems | 5,000 |

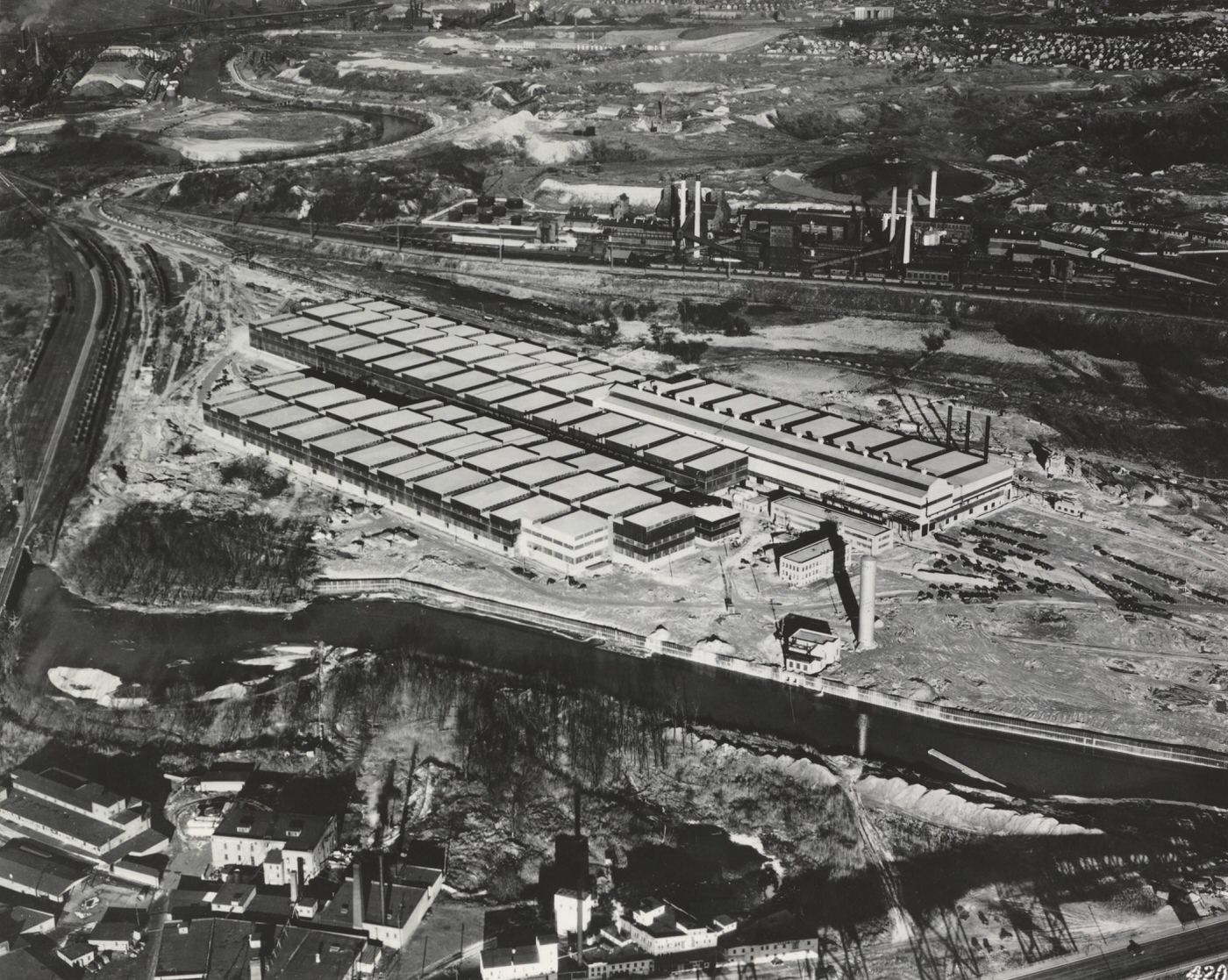

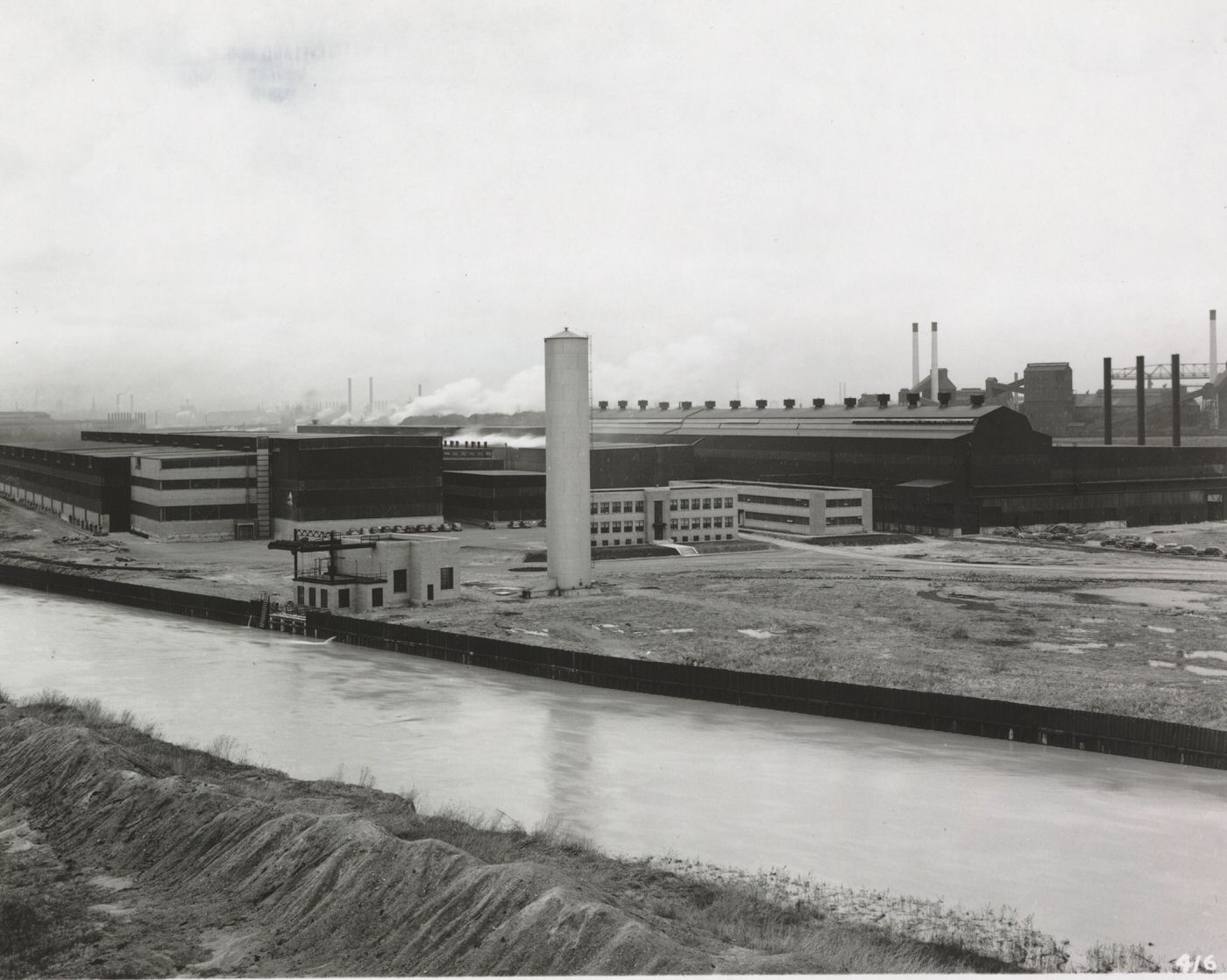

| Cleveland Bomber Plant (Fisher Body) | B-29 engine nacelles | 14,000 |

| Auto-Ordnance Co. | Design for Thompson submachine guns | 1000+ |

| Cleveland Twist Drill | Production excellence (general) | 1000+ |

| H.K. Ferguson Co. | Construction of Oak Ridge thermal diffusion plant | 1000+ |

Thompson Products, through its TAPCO (Thompson Aircraft Products Company) plant in Euclid, was a crucial manufacturer of aircraft engine components, notably cylinder valves, employing over 16,000 workers at its peak. Jack & Heintz (JAHCO), formed in 1940, rapidly expanded to produce airplane starters and autopilot devices. Its workforce grew from about 50 to over 8,700 by 1944, including several thousand women, and the company became known for high worker morale due to exceptional benefits despite long hours. The Parker Appliance Company became the U.S. Air Force’s primary supplier of vital valves and fluid connectors, employing 5,000 Cleveland residents by 1943 and setting standards for military aircraft components.

The Cleveland Bomber Plant, operated by Fisher Body, produced an astounding 13,772 engine nacelles for the B-29 Superfortress bomber. These were highly complex components, and the plant’s output accounted for 87% of all B-29 nacelles required for the 3,970 such bombers built during the war. This facility alone employed 14,000 workers. Other significant contributions included the Auto-Ordnance Co.’s development of the design for Thompson submachine guns, Cleveland Twist Drill’s recognition with the first Army-Navy Star Award for production excellence, and H.K. Ferguson Co.’s rapid construction of the Oak Ridge thermal diffusion plant. The city’s steel mills also operated at full capacity to meet the relentless demand for raw materials. The rapid scaling of companies like Jack & Heintz and the massive employment figures at plants like TAPCO illustrate the immense mobilization of labor, which had profound social and infrastructural implications for Cleveland.

Daily Life Under Wartime Conditions

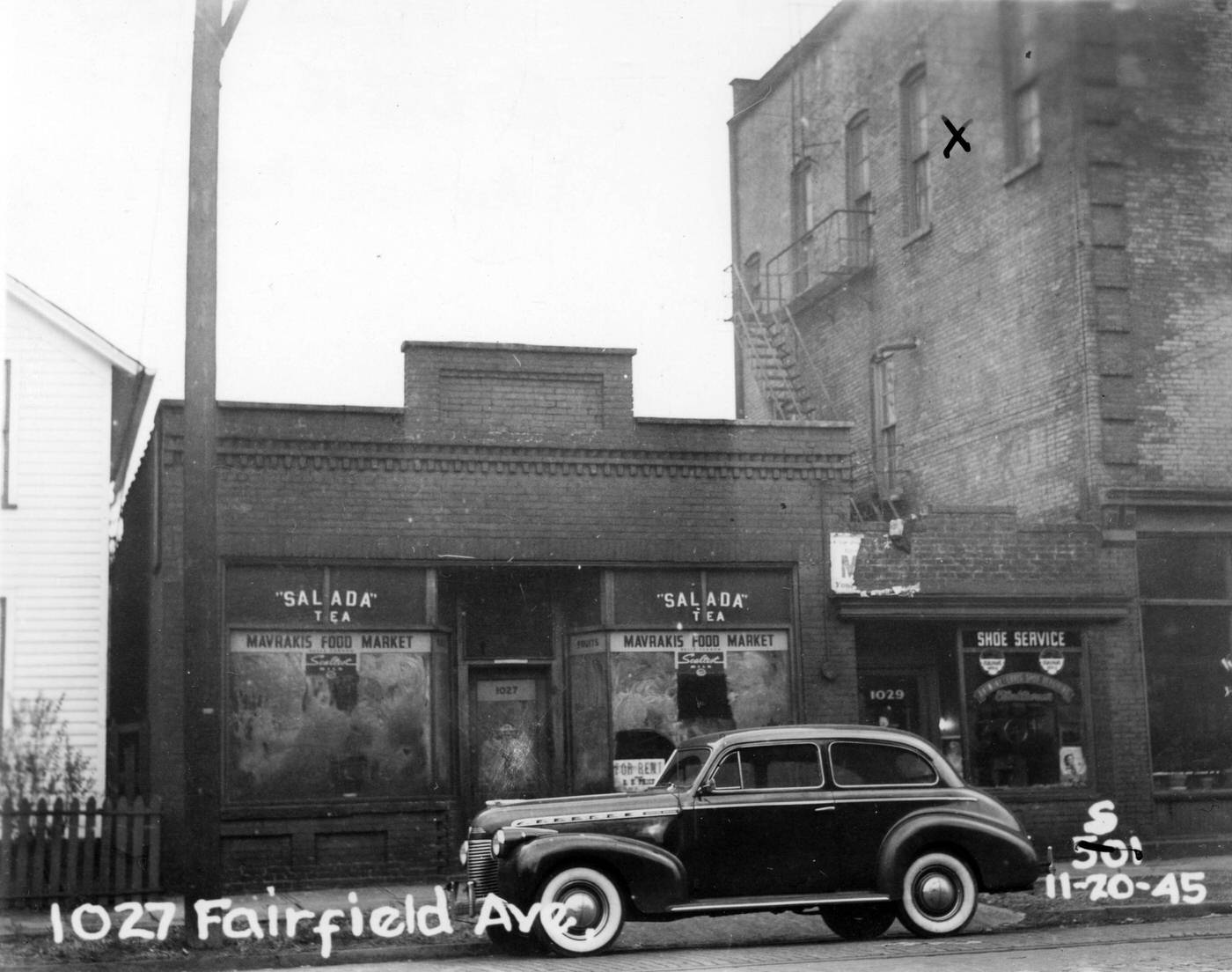

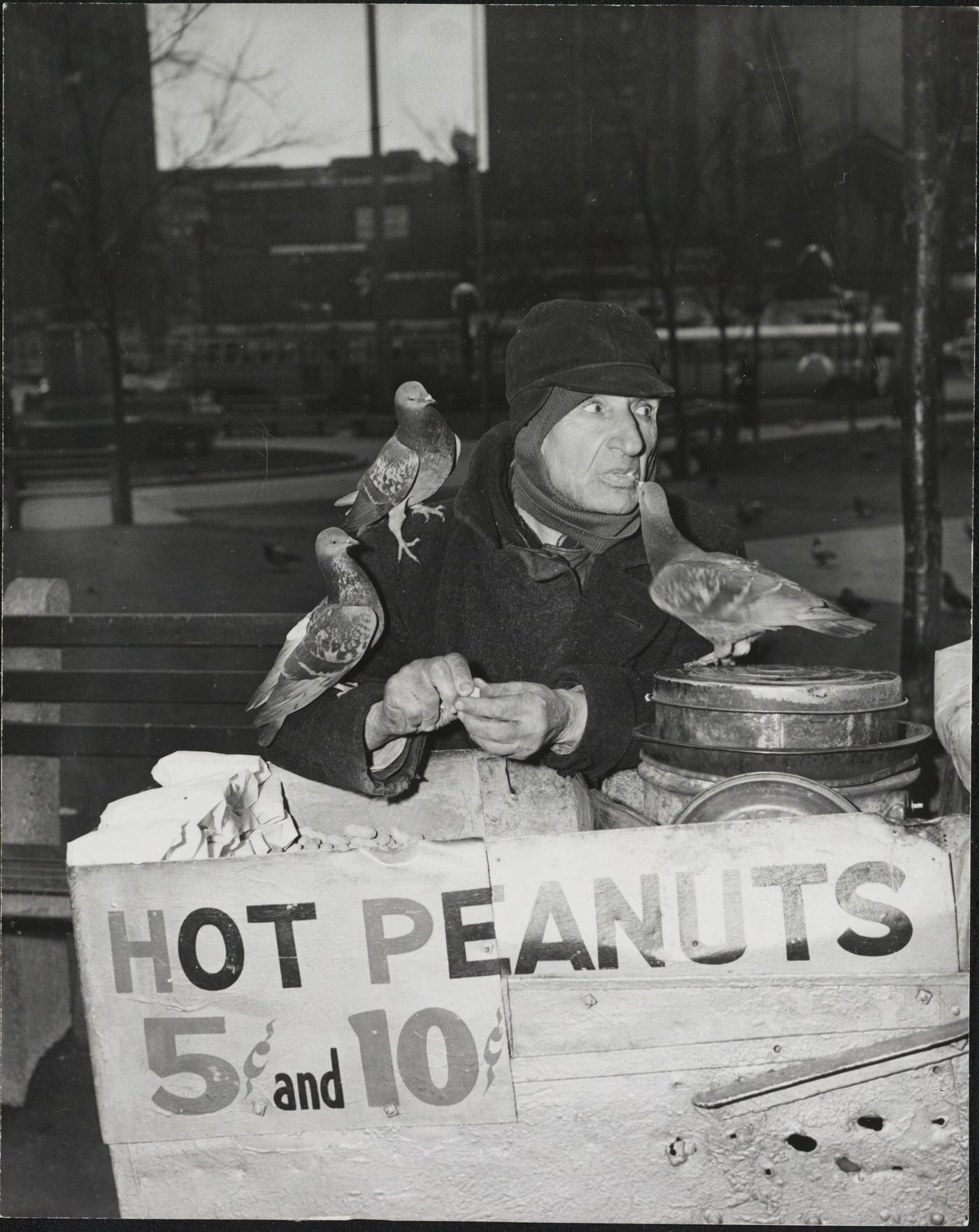

The war effort permeated every aspect of daily life for Clevelanders. Rationing of scarce commodities such as sugar, meat, and gasoline was managed by 29 local War Price & Rationing Boards, which issued permits to civilians. This system fundamentally altered shopping habits and household management.

Cleveland residents actively participated in war bond drives, contributing significantly to financing the war. By the eighth and final war loan drive, Cuyahoga County residents had purchased a total of $2.5 billion worth of bonds. The “Block Plan,” a neighborhood-level strategy for organizing bond drives, blood drives, and scrap collection, originated in Cleveland, showcasing a high degree of civic organization and community engagement. This grassroots approach demonstrated a population actively participating beyond mere compliance with federal mandates.

Victory Gardens became a common sight, actively promoted to supplement the food supply, with a special emphasis at events like the 1942 Home & Flower Show. Citizens also diligently collected scrap metal and other materials essential for war production. These activities fostered a sense of collective effort and shared sacrifice, reshaping daily routines and even the physical landscape of the city with the proliferation of home gardens.

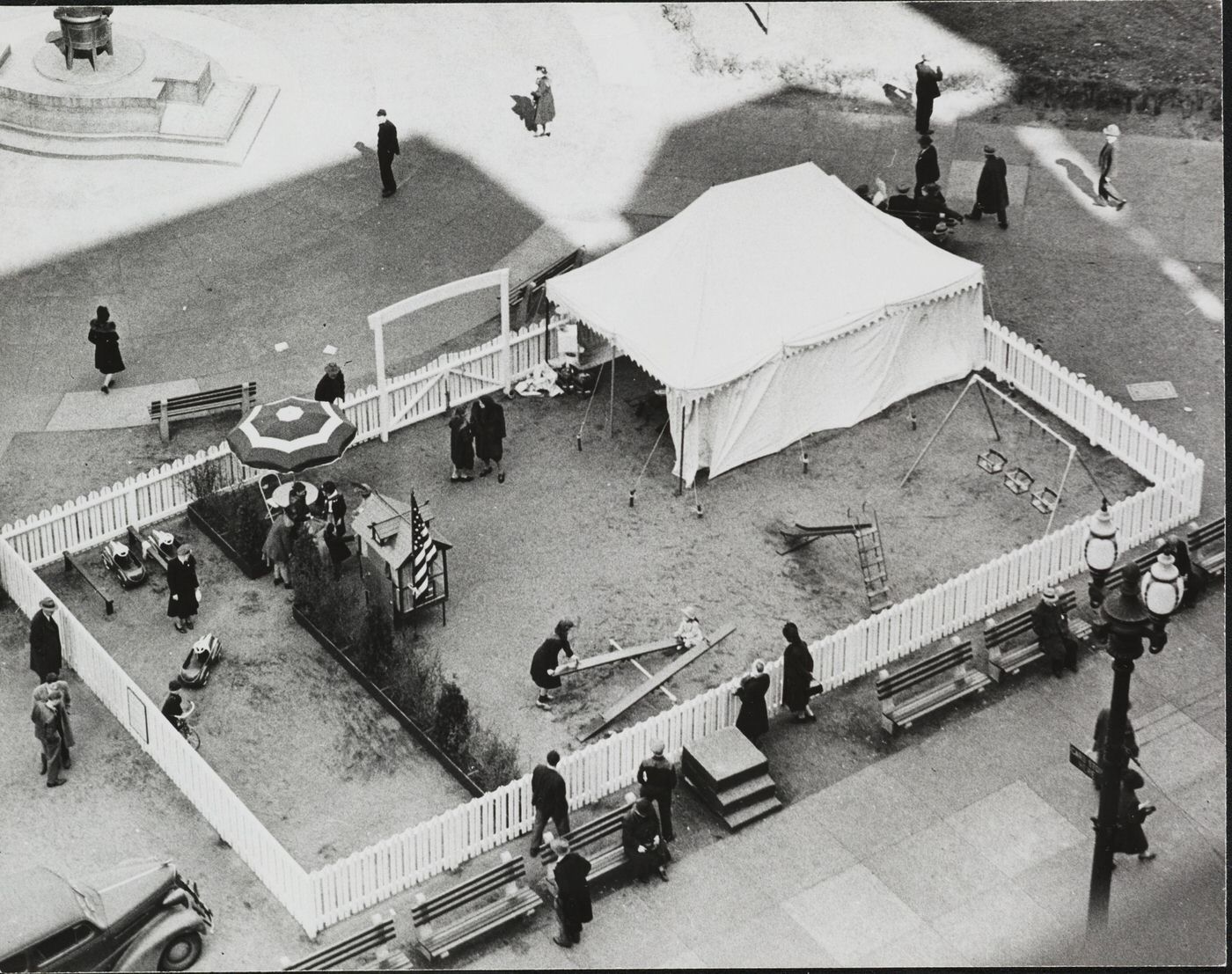

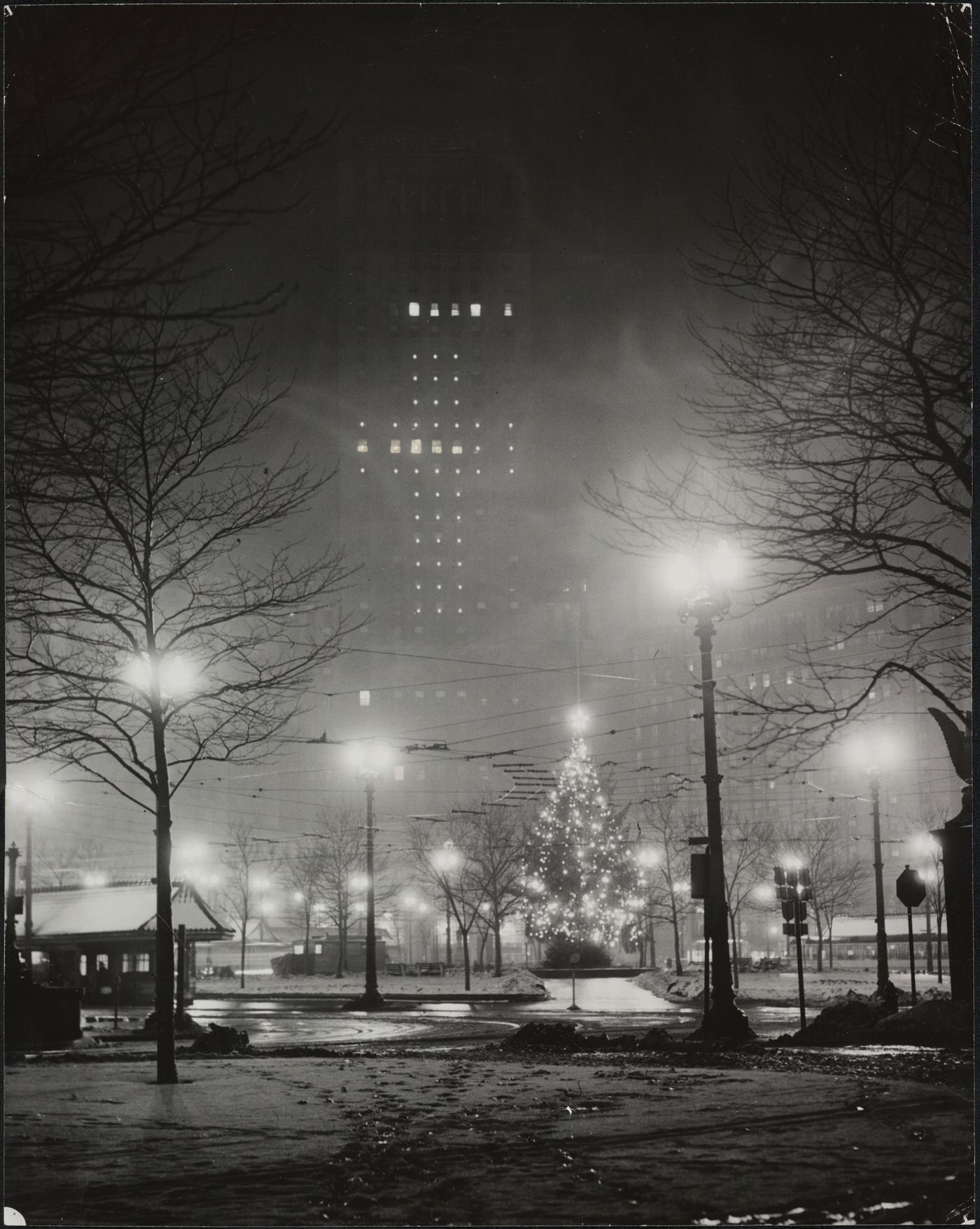

Preparedness for potential threats was a visible part of wartime Cleveland. Under Civilian Defense Director William A. Stinchcomb, lighting “blackouts” were rehearsed by the summer of 1942. Air raid drills were common, with schools actively participating and teaching techniques like “Duck and cover”. These measures, even if the direct threat to Cleveland was low, served as constant reminders of the ongoing war and fostered a sense of shared vulnerability and collective responsibility for safety.

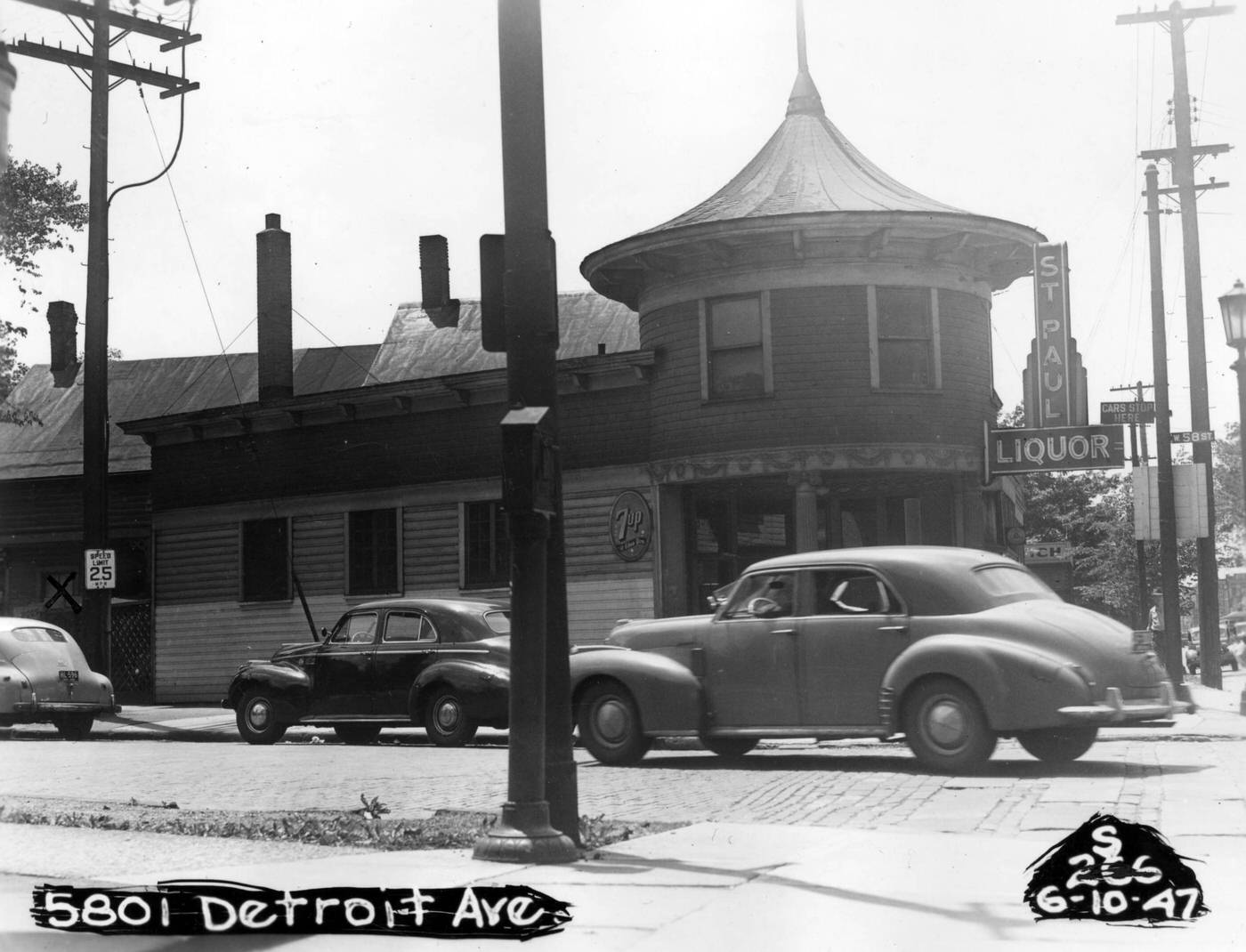

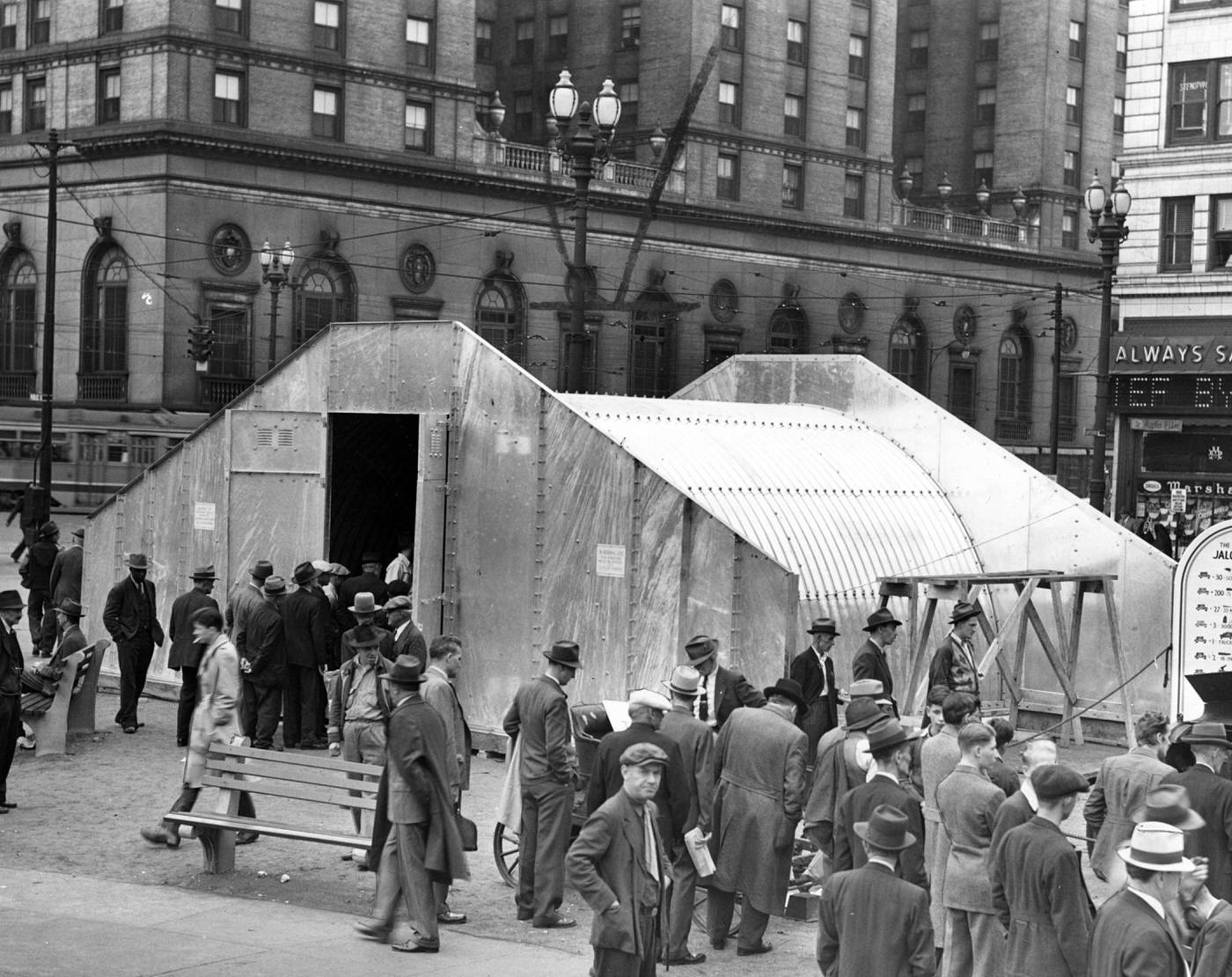

Community mobilization extended to supporting the troops and the war effort through various organizations. The War Services Center, a temporary structure built on Public Square with donated materials and labor, housed recruiting offices, war bond and stamp sellers, and crucial support agencies like the USO, Red Cross, and War Housing Service. The local branch of the Stage Door Canteen, located in Playhouse Square, offered hospitality and entertainment to servicemen passing through or stationed nearby. These centralized hubs demonstrated an organized community response to manage the social and logistical needs arising from wartime mobilization, providing both practical support and morale boosters.

The Second Great Migration: Newcomers Shape the City

World War II acted as a powerful catalyst for the Second Great Migration, drawing significant numbers of people to industrial centers like Cleveland. Waves of Southern Blacks and Appalachian whites moved to the city seeking employment in the booming war industries. Cleveland’s Black population experienced substantial growth during this period, increasing by 75% during the 1940s alone, from 85,000 in 1940 to significantly more by the decade’s end, on its way to 251,000 by 1960. This demographic surge meant that by the early 1960s, African Americans constituted over 30% of the city’s population.

This rapid influx of new residents placed immense strain on Cleveland’s existing infrastructure, particularly housing, schools, and social services, which were already affected by Depression-era underinvestment and wartime restrictions. While fueling the war economy, this population boom simultaneously intensified existing urban problems and created new challenges related to resource allocation and social integration. The arrival of new groups also interacted with Cleveland’s established European ethnic enclaves, leading to complex inter- and intra-group dynamics as communities competed for resources and space, or sometimes formed new alliances.

Women and African Americans in the War Effort and Workforce

The urgent need for labor during World War II created unprecedented opportunities for women and African Americans in Cleveland’s workforce. Nationally, women comprised about 30% of Ohio’s wartime workforce. Locally, companies like Jack & Heintz employed several thousand women in their plants. The Cleveland Transit System also began hiring women as conductors in large numbers, with 223 female employees by 1943. This large-scale entry of women into industrial roles, often those previously held by men, provided them with new skills and economic independence, contributing to evolving gender roles in the post-war era, even if many were displaced from these jobs when men returned.

African Americans also found new job opportunities due to wartime demand and the more egalitarian labor practices of some unions like the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). More than one million African Americans served in the U.S. armed forces during WWII, though they faced segregation and discrimination even while in uniform. A stark example of this contradiction occurred in Cleveland in May 1943, when Private R.J. Wood, an African American Marine, was arrested for impersonating a Marine simply because local police were unaware that Black Marines existed. This wartime paradox, contributing significantly to the war effort while being denied full rights at home, fueled greater determination within the Black community to fight for civil rights in the post-war period.

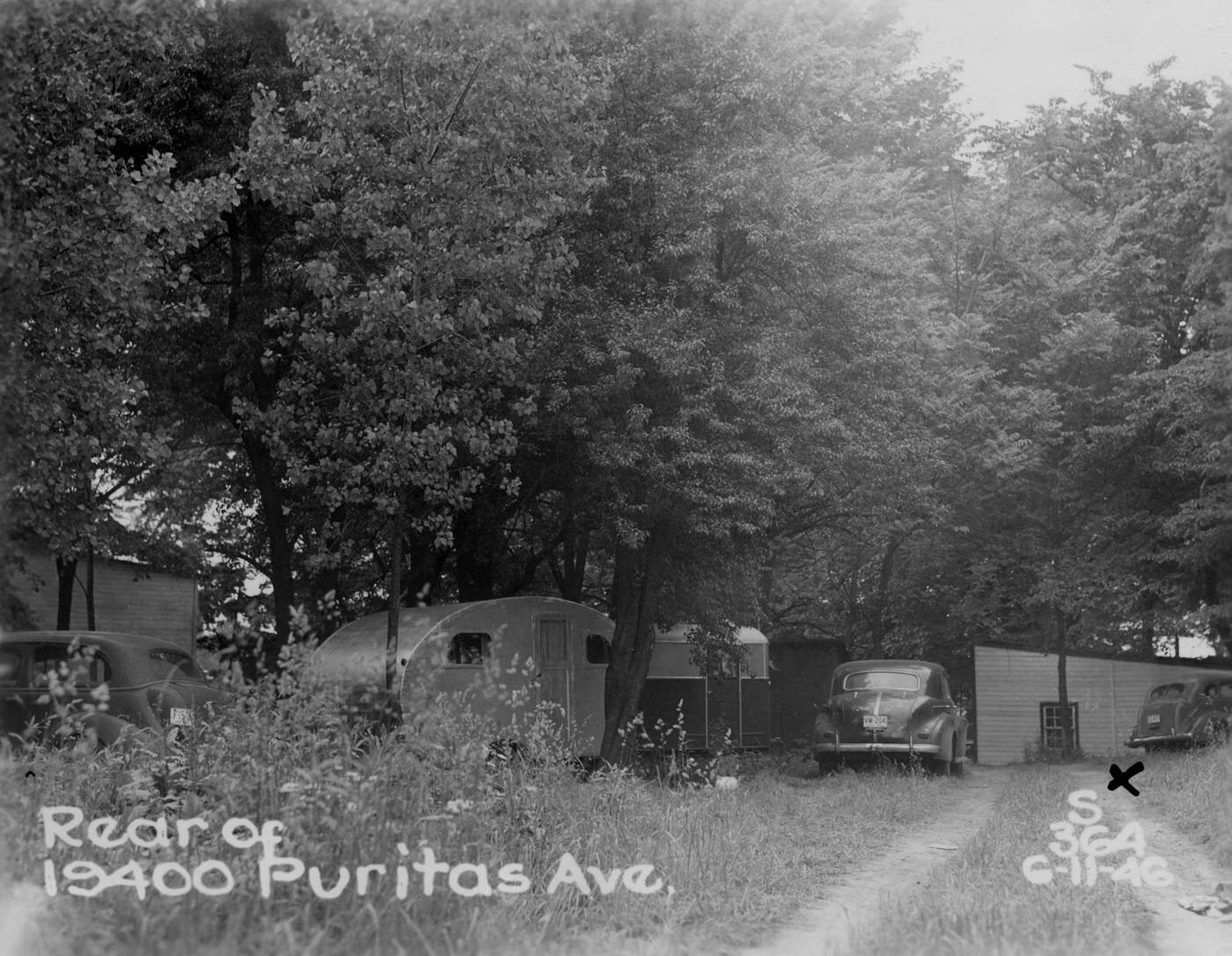

Housing Challenges and Racial Tensions: Crowded Neighborhoods and Discrimination

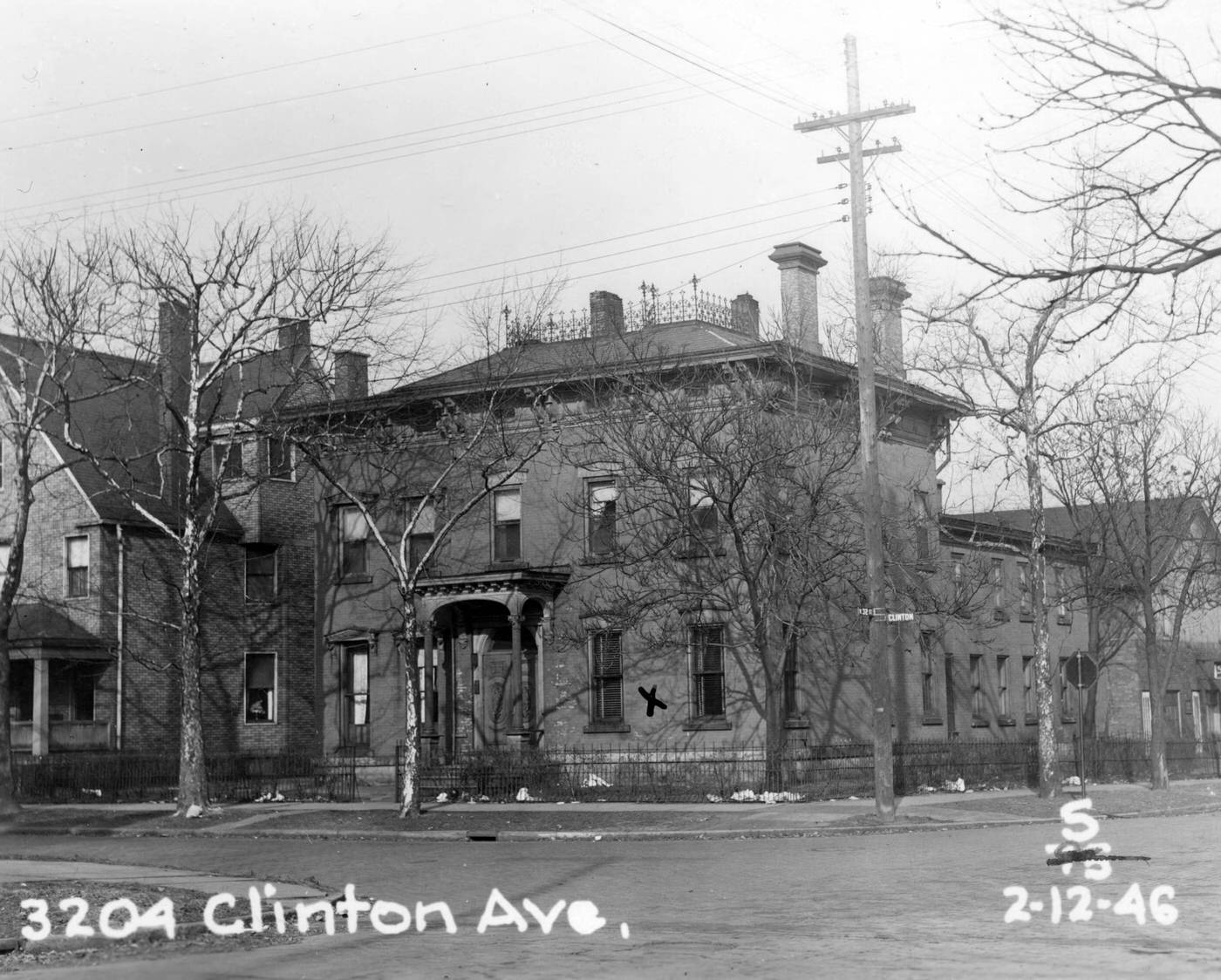

Cleveland faced a severe housing shortage throughout the 1940s. The city’s housing vacancy rate was a mere 3% in 1940 and plummeted to an astonishing 0.5% by March 1943, a result of wartime building restrictions and the massive influx of defense workers. This crisis disproportionately affected African Americans. They were largely confined to the already crowded Cedar-Central neighborhood, which expanded into Hough and Glenville as the Black population grew. This expansion, however, did not translate into better or more integrated housing. Landlords in areas transitioning to Black occupancy often subdivided existing structures into smaller, less adequate units and sharply increased rents.

Discriminatory practices such as “blockbusting” by real estate agents and the use of racially restrictive covenants in property deeds actively maintained segregation and limited housing options for Black families. Public housing projects, intended to alleviate housing shortages, often reinforced segregation. Outhwaite Homes, for example, was built specifically for African American residents, while Lakeview Terrace and Cedar-Central were initially designated for white-only occupancy. Carver Park Apartments, completed around 1940, was also constructed for Black occupancy. This official sanctioning of segregation in public housing legitimized and reinforced private discriminatory practices, creating systemic barriers to fair housing. The combination of the housing shortage and segregation created not just a physical crisis but also significant social stress and likely contributed to health disparities within these densely populated Black neighborhoods. Racial tensions sometimes flared, as seen in conflicts over access to public parks like Woodland Hills Park and Forest Hills Park in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The struggle for equitable treatment was also evident in professional spheres, as exemplified by African American attorney Chester K. Gillespie, who faced significant racial discrimination when attempting to rent office space in downtown Cleveland in 1945.

Community Voices: The NAACP and the Future Outlook League

In the face of discrimination, Cleveland’s African American community organized and advocated for their rights. The Cleveland branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), established in 1912, was a prominent force. During the 1940s, the branch grew significantly, and by 1945, it had a full-time executive secretary and 10,000 members, making it the sixth-largest NAACP branch in the nation. The NAACP actively challenged exclusionary policies in public facilities, housing, employment, and education through legal action and negotiation.

The Future Outlook League (FOL), founded in 1935 by John O. Holly, employed more direct-action tactics, including pickets and economic boycotts under the compelling slogan, “Don’t buy where you can’t work”. The FOL aimed to pressure white-owned businesses in Black neighborhoods to hire Black employees. While its activities lessened during World War II due to increased job opportunities, the FOL rebounded with campaigns in the post-war years. The growth and activism of these organizations during the 1940s signaled an increasingly assertive African American community, laying the groundwork for future civil rights struggles by employing diverse strategies, from legal challenges to economic pressure.

Civic Life and Urban Landscape

Leadership in Wartime: Mayor Frank Lausche’s Administration

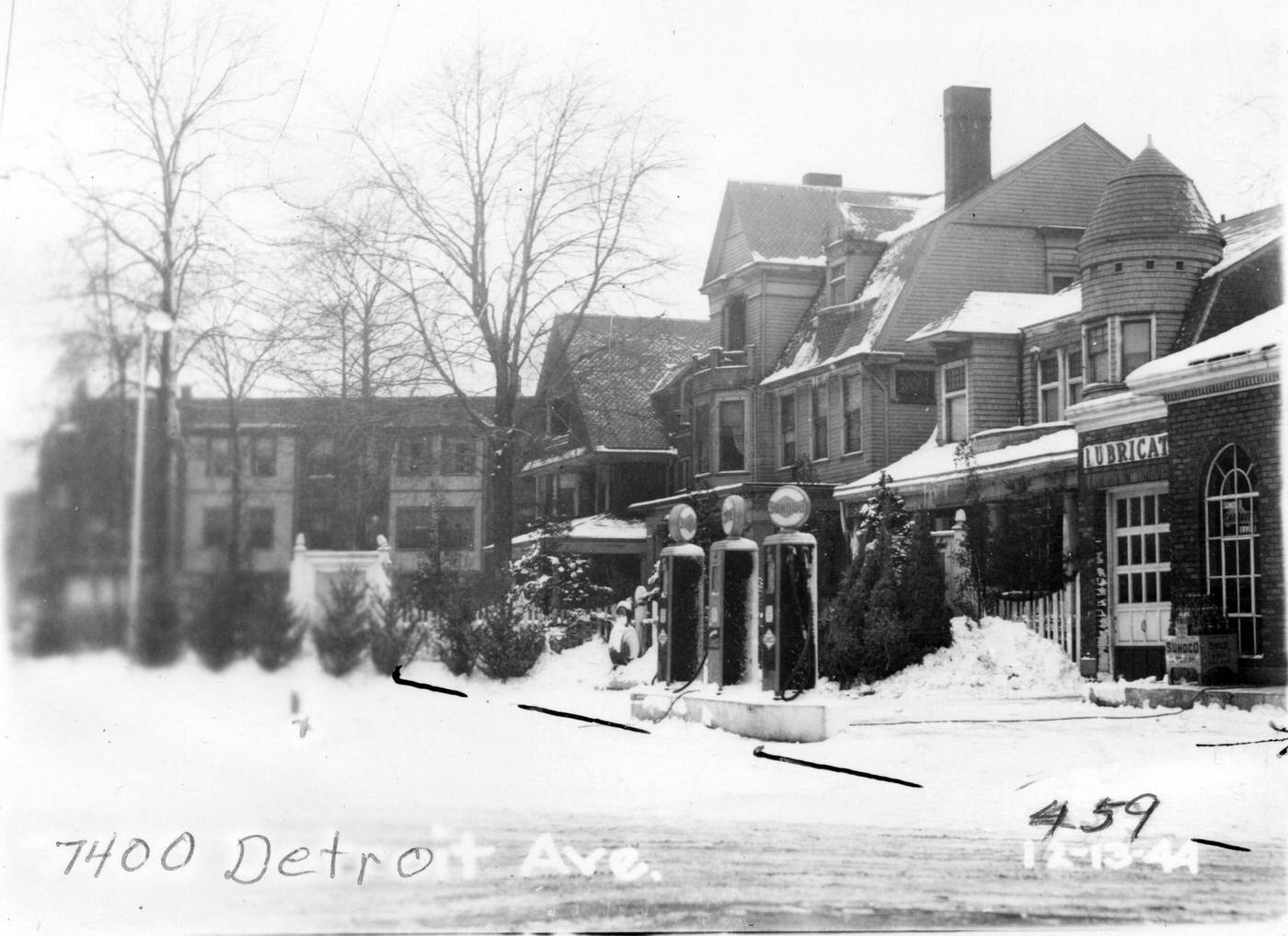

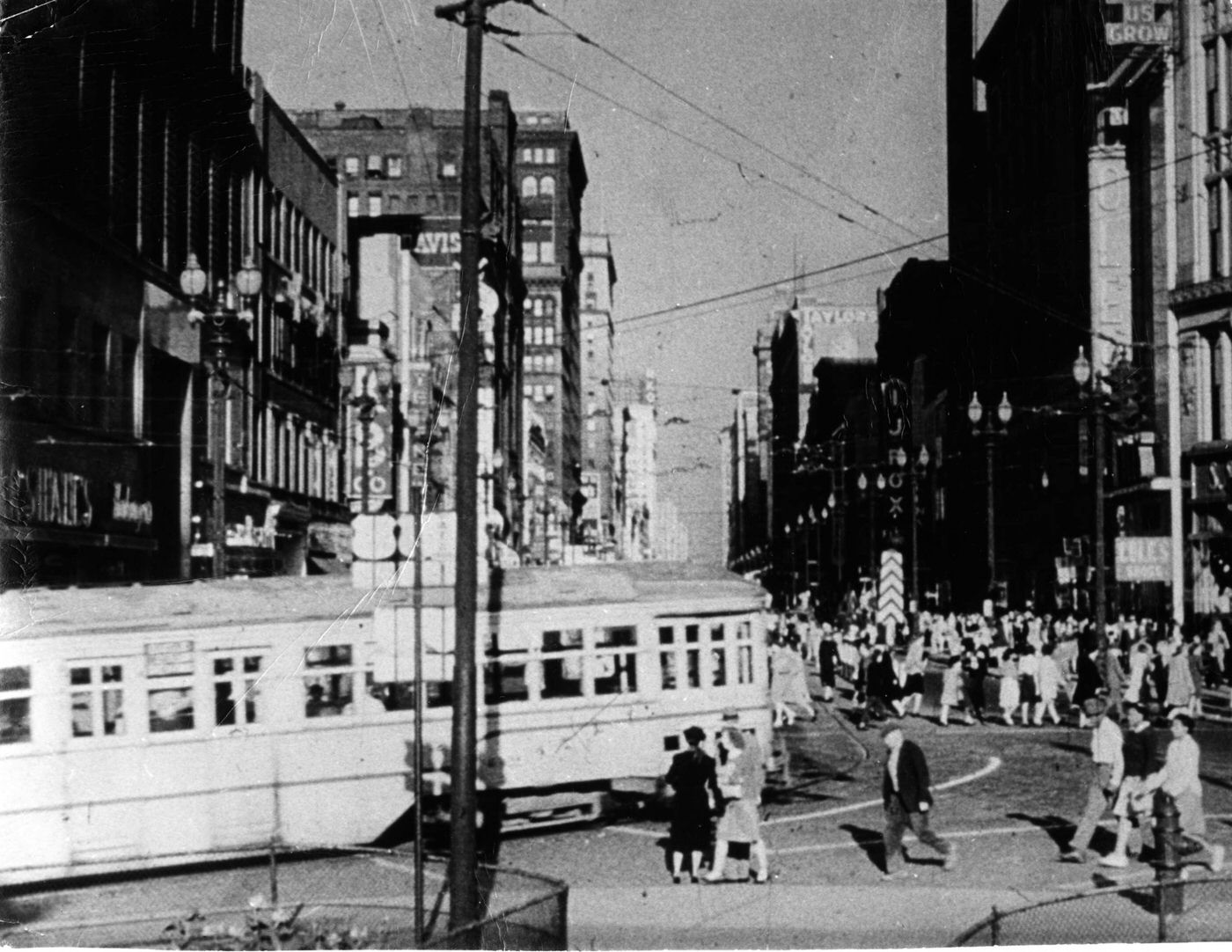

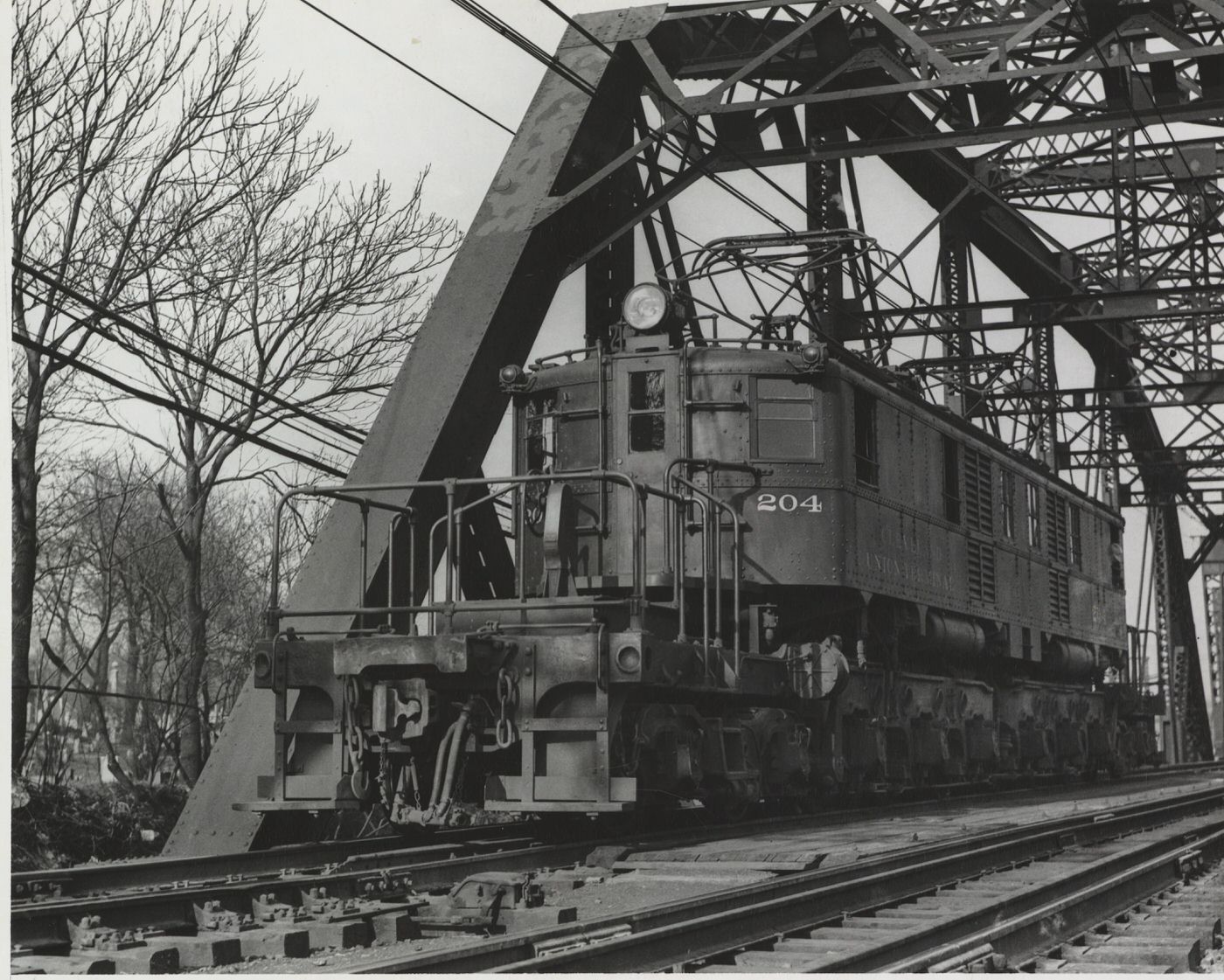

Frank J. Lausche, a son of Slovenian immigrants, was elected Mayor of Cleveland in 1941 and served two terms, guiding the city through the demanding war years. His administration was characterized by clean and frugal government. A significant achievement during his tenure was the finalization of the city’s takeover of the Cleveland Railway System, which led to the formation of the publicly owned Cleveland Transit System (CTS) in 1942. This move, occurring during a period of high demand for public transit due to war workers and gas rationing, aimed to ensure more stable and equitable service.

Demonstrating foresight, Mayor Lausche organized the Post War Planning Council in 1944, even before the war concluded. This council was tasked with coordinating future planning across crucial areas including labor, health, transportation, and significantly, racial toleration. This initiative showed an understanding that the war’s end would bring complex economic, social, and infrastructural adjustments. His War Production Committee was also credited with maintaining relative labor peace within the city during the intense production period of the war.

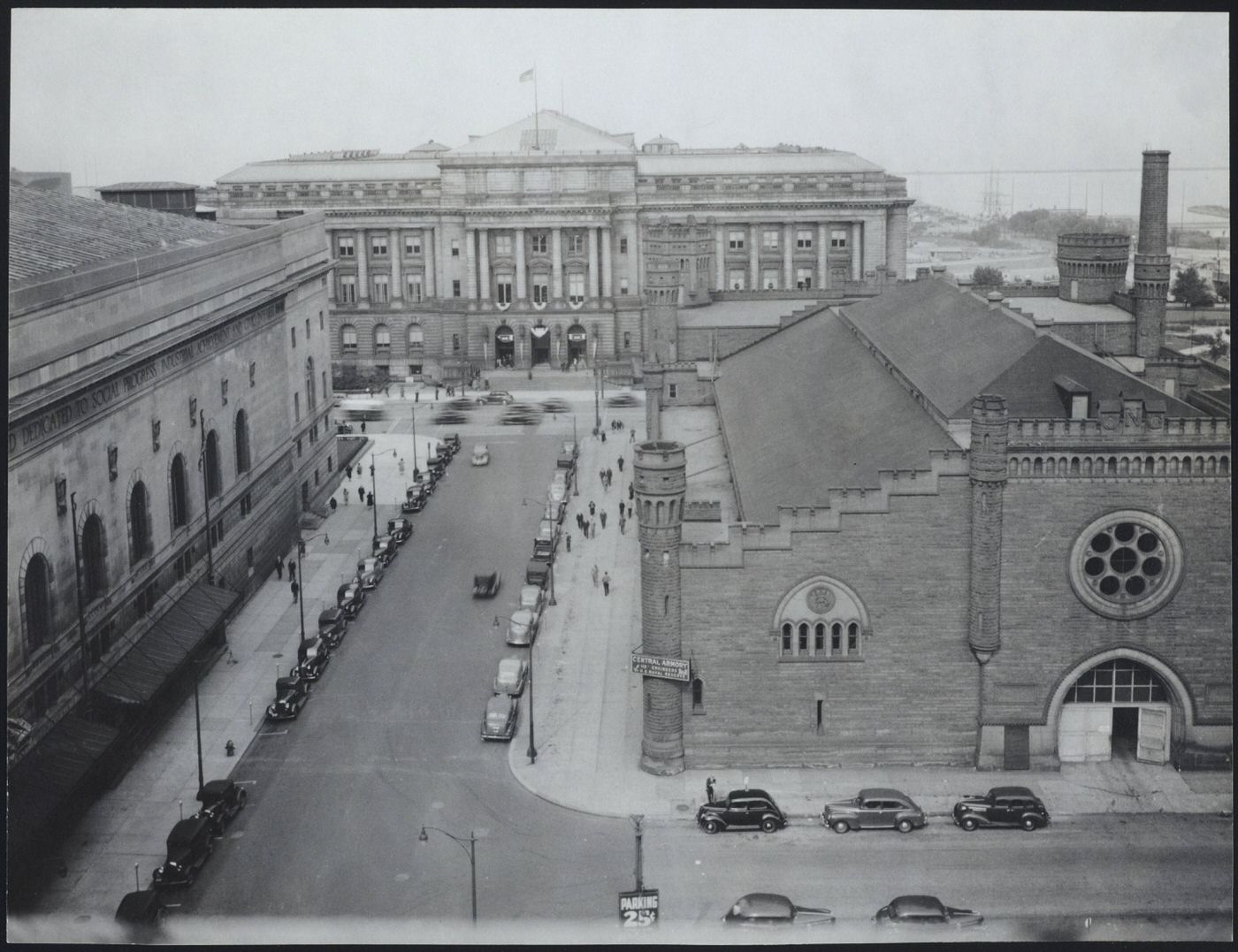

Keeping the City Moving: The Cleveland Transit System

The newly formed, city-operated Cleveland Transit System (CTS) faced immense challenges during the 1940s. Wartime conditions, including gasoline rationing and a large influx of war workers, led to a surge in demand for public transportation. This increased ridership strained an already aging streetcar infrastructure. Many older streetcars were in poor condition compared to newer buses, and 76 streetcars had been taken out of commission even before CTS took ownership.

To cope with the unprecedented demand, CTS implemented adaptive strategies, such as using bus trailers to transport factory workers. The war also brought changes to the CTS workforce, with the system hiring a significant number of women as conductors; by 1943, there were 223 female employees in these roles. Despite efforts to maintain labor peace, the pressures of wartime work led to wildcat strikes in May 1942 and April 1943. These strikes, primarily over wages and working conditions, briefly shut down the vital transit system, indicating acute underlying labor tensions even within a publicly owned essential service during a national crisis.

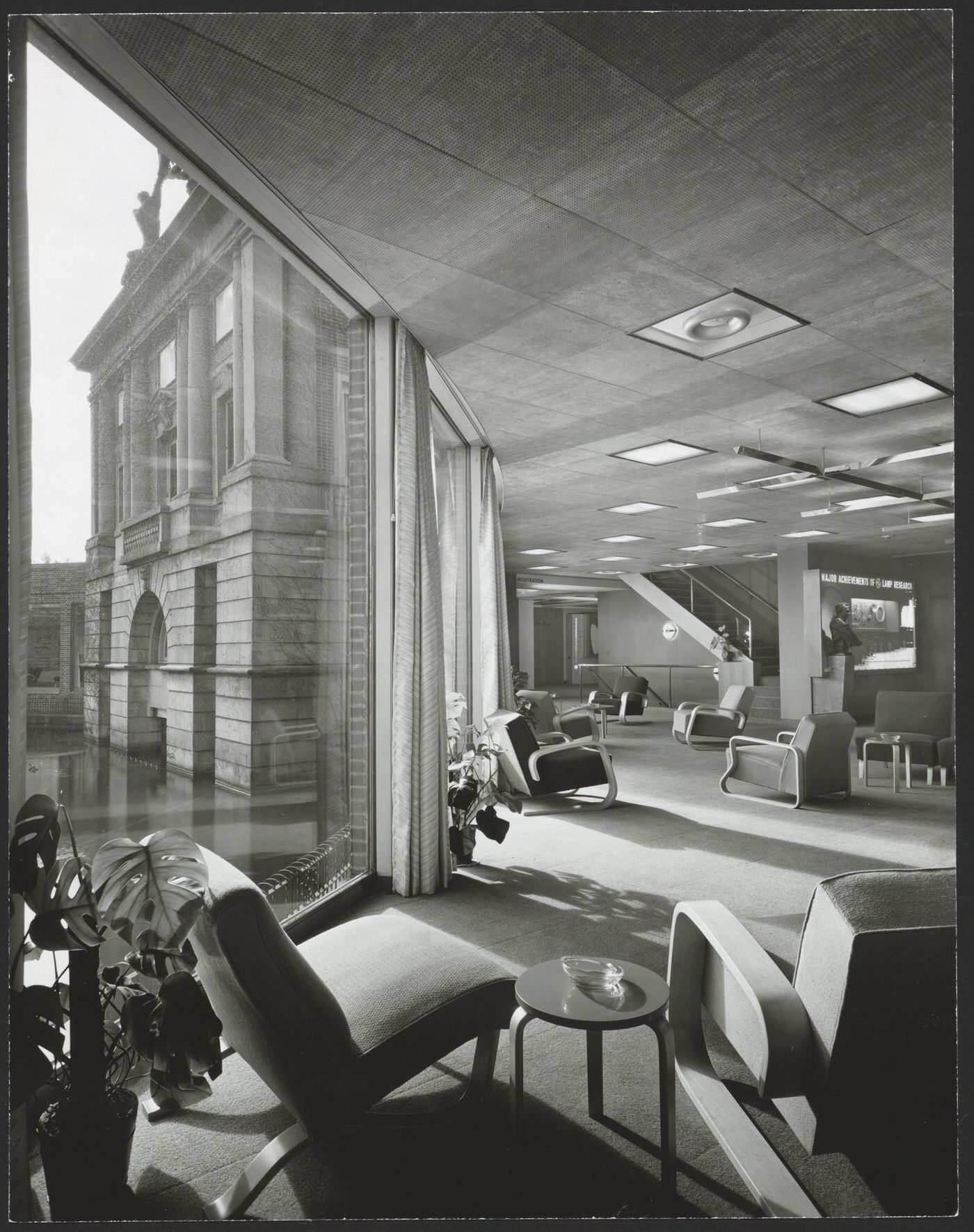

Planning for Tomorrow: Post-War Visions and Early Freeway Ideas

Even as Cleveland was fully engaged in the war effort, city leaders and planners were looking towards the future. Mayor Lausche’s Post War Planning Council, established in 1944, was a key body in this effort, tasked with addressing labor, health, transportation, and racial toleration in the post-war city. The council accurately predicted a significant suburban housing boom and warned of potential “wholesale abandonment of older areas” if the central city’s deteriorating housing stock was not rehabilitated. It also recognized the importance of monitoring interracial relations, leading to the creation of the Cleveland Community Relations Board.

Transportation planning was a major focus. The concept for the Innerbelt Freeway was conceived as early as 1940, with formal planning beginning in 1944. This freeway was designed to divert traffic around the increasingly congested downtown area and to connect the existing lakefront Shoreway with the proposed Willow Freeway. A comprehensive master plan for freeways throughout the area was developed in 1944 by city, county, and state highway departments. This ambitious plan designated downtown Cleveland as the hub of a half-wheel of expressways, parkways, and feeder roads. Key routes envisioned included the East Shoreway, the Lakeland Freeway, the Heights Freeway, the Willow Freeway, the Medina Freeway, the Berea-Airport Freeway, and the West Shoreway, along with concentric inner and outer belt freeways. The Memorial Shoreway itself had already been extended eastward to Bratenahl at East 140th Street in 1941. These extensive freeway plans, developed during the 1940s, reflected a strong belief in an automobile-centric future and laid the infrastructural groundwork that would profoundly reshape the city and facilitate the anticipated outward migration. The Post War Planning Council’s holistic approach, considering both physical infrastructure and pressing social issues, indicated an awareness of the multifaceted challenges Cleveland would face.

Culture, Sports, and Leisure in the 1940s

Sounds of the City: The Cleveland Orchestra and Popular Music

Cleveland’s musical landscape in the 1940s was rich and varied. The Cleveland Orchestra saw important leadership transitions, with Artur Rodzinski conducting until 1943, followed by Erich Leinsdorf from 1943 to 1946, and then the arrival of George Szell in 1946. Szell’s appointment marked the beginning of a transformative era for the orchestra. He made his Severance Hall debut in November 1944 to glowing reviews and quickly became known for his demanding standards, meticulous preparation, and emphasis on precision, which cultivated the orchestra’s lean, transparent sound. Under Szell, works like Beethoven’s Piano Concertos became firmly established in the orchestra’s repertoire. The 1940s, particularly the latter half, represented a crucial period of artistic ascent for this premier cultural institution.

Beyond the main orchestra, the Cleveland Women’s Orchestra, conducted by Hyman Schandler, was also active and recognized. By 1949, it was described as holding a “top place in City’s Cultural Life,” indicating a strong appreciation for diverse classical music endeavors.

Popular music also thrived. Polka music, reflecting the city’s strong Eastern European heritage, was immensely popular. Local bands like Frankie Yankovic and His Yanks gained prominence, with Yankovic signing a recording contract with Columbia Records in 1946. Radio stations frequently broadcast ethnic music, including polkas, to large audiences. The city’s jazz scene continued to be vibrant, influencing the “Swing Era” big bands of the 1930s and 1940s. Val’s in the Alley, a club on Cedar Avenue at East 86th Street, gained national fame due to the presence of the legendary pianist Art Tatum, attracting visits from jazz giants like Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald for impromptu sessions. This diverse musical environment, from prestigious concert halls to neighborhood dance halls, catered to a wide array of tastes and underscored Cleveland’s cultural vitality.

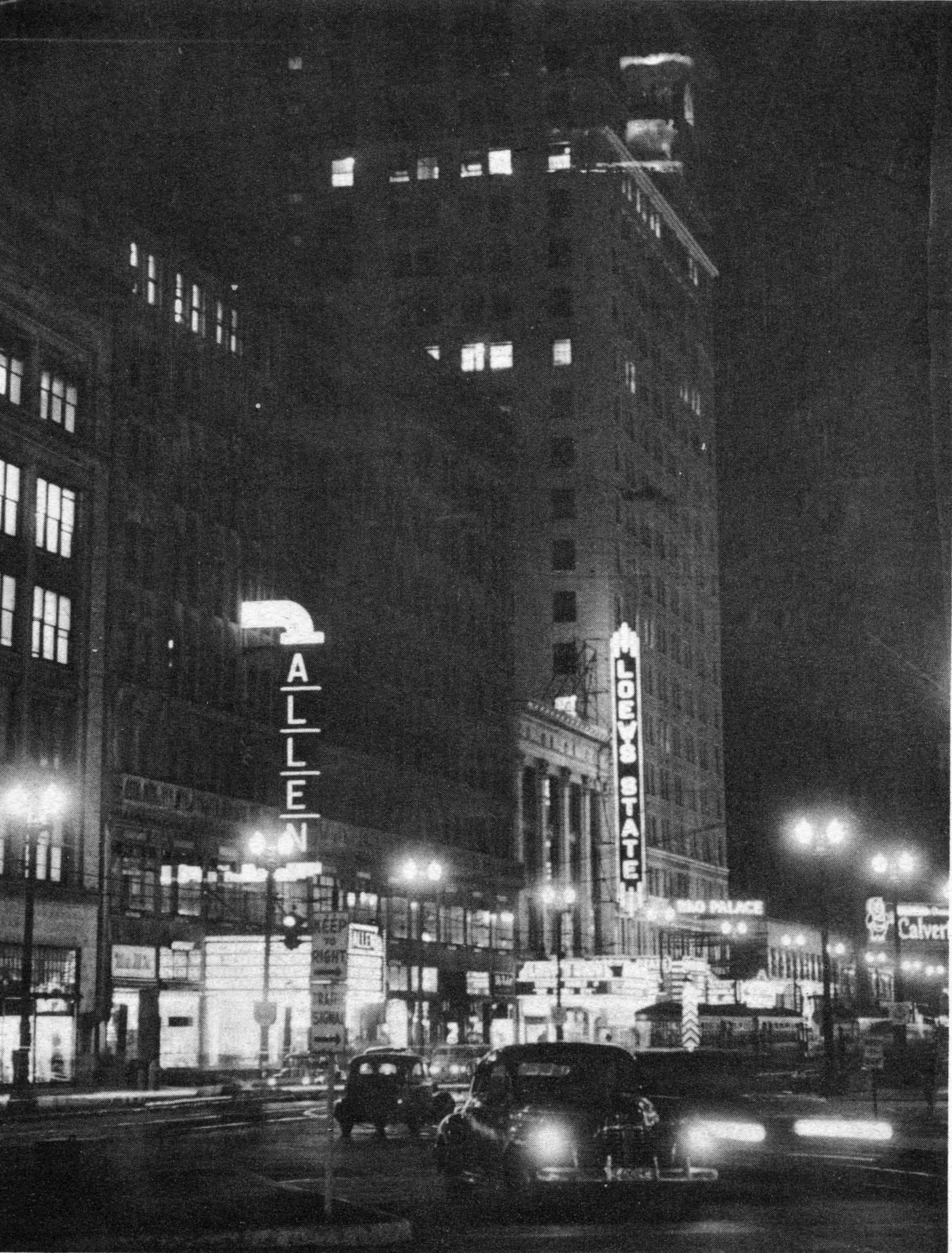

Entertainment Hubs: Playhouse Square and Local Nightspots

Playhouse Square, with its collection of grand theaters including the State, Ohio, Allen, Palace, and Hanna, continued to be a major entertainment destination through World War II. These venues offered a mix of movies, live legitimate theater, and vaudeville performances. During the war, Playhouse Square also played a role in the war effort; the USO opened a “Stage Door Canteen” there in 1943 to offer hospitality and entertainment to servicemen, and radio programs were broadcast from the Palace Theatre to promote War Bond sales. This demonstrated how cultural venues were integrated into patriotic activities and served as vital morale boosters.

However, towards the end of the 1940s, the rise of suburban theaters and the growing popularity of television began to draw audiences away from the downtown theater district, signaling a shift in entertainment patterns.

Beyond the formal theaters, Clevelanders had numerous options for nightlife and social dancing. Between the 1920s and the 1950s, over 150 dance halls were accessible in the Greater Cleveland area, not counting the many dance floors in hotels, nightclubs, and private halls. The Trianon Ballroom, for example, could accommodate up to 4,000 dancers. Clubs like Cedar Gardens, a “black and tan” establishment (meaning it welcomed both Black and white patrons and performers), gained renown in the 1930s and 1940s for its top-billed entertainment, ranging from jazz to drag shows. It was listed in the Green Book, a guide for Black travelers, from 1946 to 1955. The Harbor Inn on Elm Street also had its heyday in the 1930s and 1940s, known as a lively spot for sailors, dockworkers, and others. While general societal segregation was prevalent, these diverse nightspots, particularly integrated venues like Cedar Gardens, offered spaces where racial boundaries could be more fluid, especially in the realm of popular music and entertainment.

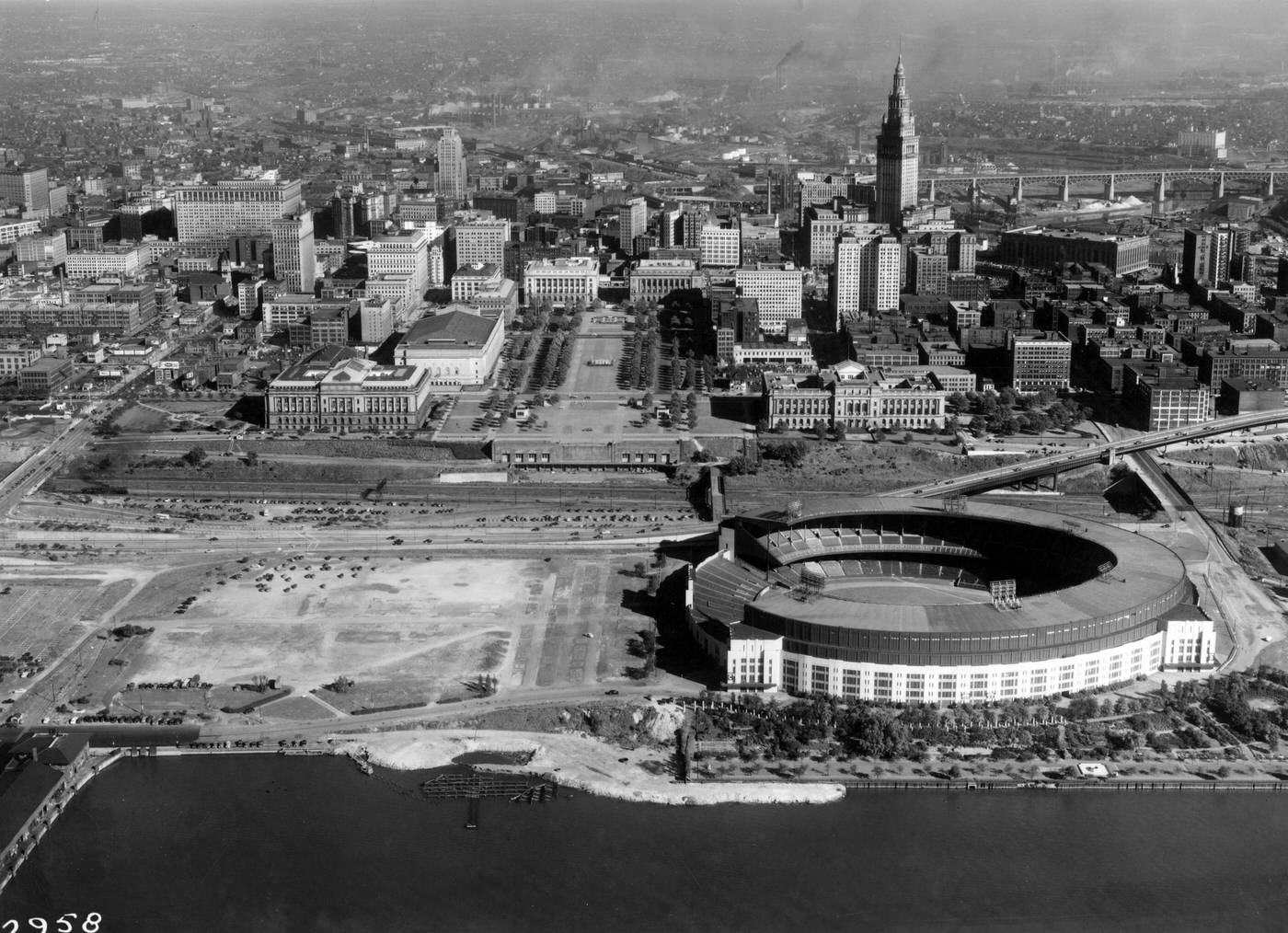

A City of Champions: The Cleveland Indians’ 1948 World Series

A major highlight for Cleveland in the post-war era was the triumph of its baseball team. The Cleveland Indians won the World Series in 1948, defeating the Boston Braves in a hard-fought six-game series. This was the team’s first championship victory since 1920 and a significant moment of civic pride.

The team was managed by Lou Boudreau, who was also a star player. The roster boasted several future Hall of Fame inductees, including Boudreau himself, Larry Doby, Bob Feller, Joe Gordon, Bob Lemon, and the legendary pitcher Satchel Paige. The World Series games played at Cleveland Stadium drew enormous crowds, with Games 4 and 5 setting new World Series single-game attendance records at the time, with 81,897 and 86,288 fans respectively. This massive turnout reflected not only the excitement of a championship run but also the post-war economic recovery and the public’s eagerness for leisure and large-scale public spectacles after years of wartime austerity.

The 1948 victory was more than just a sporting achievement. The team’s integrated roster, featuring Larry Doby, the American League’s first Black player, and Satchel Paige, made their success a powerful symbol. Occurring against a backdrop of emerging civil rights efforts and ongoing racial tensions in the city, the championship of an integrated team offered a moment of unified civic pride that, for a time, could transcend some of Cleveland’s social divisions.

Entering the Post-War World (Late 1940s)

Veterans Return: The GI Bill and Reintegration

The return of hundreds of thousands of servicemen to Cleveland after World War II brought both opportunities and significant challenges. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill of Rights, was a landmark piece of legislation designed to aid this transition. It promised extensive benefits for veterans, including financial assistance for education and vocational training, low-interest loans for purchasing homes, farms, or businesses, unemployment payments, and expanded healthcare services.

Nationally, the GI Bill had a transformative effect. Millions of veterans utilized its educational benefits, leading to a surge in college enrollment. VA-guaranteed home loans were instrumental in the post-war housing boom, accounting for about 20% of all new homes purchased in the first decade after the war. In Cleveland, various organizations mobilized to support returning veterans. The Greater Cleveland Veterans Council was formed in 1946, uniting local chapters of groups like the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), the American Legion, and Disabled American Veterans to advocate on legislation and benefits. These and other groups, such as the Jewish War Veterans, provided guidance and support services. The formation of such councils highlighted the need for coordinated local efforts to help veterans navigate bureaucracy and access their entitled benefits.

However, the promise of the GI Bill was not equally available to all. Despite its race-neutral language, Black veterans in Cleveland and across the nation faced significant systemic barriers in accessing these benefits. Jim Crow-era discrimination persisted, particularly in the South but also present in northern cities. Black veterans often encountered difficulties securing home loans due to redlining and restrictive covenants that barred them from new suburban developments. Educational opportunities were also limited by segregated institutions or informal quotas at predominantly white universities. This unequal application of the GI Bill meant that a key tool for post-war socioeconomic advancement was less accessible to Black veterans, thereby exacerbating existing racial disparities and contributing to different post-war experiences for white and Black Clevelanders.

Labor and Industry After the War: Strikes and New Agreements (1945-1949)

The immediate post-war years, from 1945 to 1949, were a period of significant labor readjustment and activity in Cleveland, as in the rest of the nation. Unions sought to consolidate gains made during the war and address new economic realities, sometimes leading to major industrial actions. The national strike wave of 1945-1946, which saw over three million U.S. workers mobilize, included a lengthy 113-day walkout at General Motors involving 320,000 UAW workers. Given GM’s significant presence in Cleveland (such as the Fisher Body plant), these national actions had local repercussions. By 1949, national strike idleness reached its second-highest point on record up to that time, with disputes often centering on wages, pensions, insurance, and other welfare benefits.

The political climate also heavily influenced local union dynamics. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which included provisions requiring union officials to sign anti-communist affidavits, had a direct impact on the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) unions in Cleveland. The Cleveland Industrial Union Council (CIUC), the local CIO affiliate, ousted leaders with alleged Communist ties to comply with the act and to prevent member unions from defecting to the rival American Federation of Labor (AFL). This culminated in the national CIO “Purge” Convention, which was notably held in Cleveland in 1949. At this convention, radical elements were expelled from the organization. This ideological cleansing, driven by Cold War anti-communism and internal union politics, reshaped the leadership and direction of industrial unions in Cleveland and nationally, and importantly, removed a major barrier to eventual cooperation and merger between the AFL and CIO. The Cleveland Federation of Labor (CFL), the local AFL body, had supported the war effort by discouraging strikes. Post-war, however, jurisdictional disputes and the CFL’s animosity toward the CIUC’s alleged Communist leanings had strained relations until the Taft-Hartley Act and the CIO purges facilitated a path towards reconciliation.

Seeds of Change: Early Suburbanization and Shifting City Dynamics

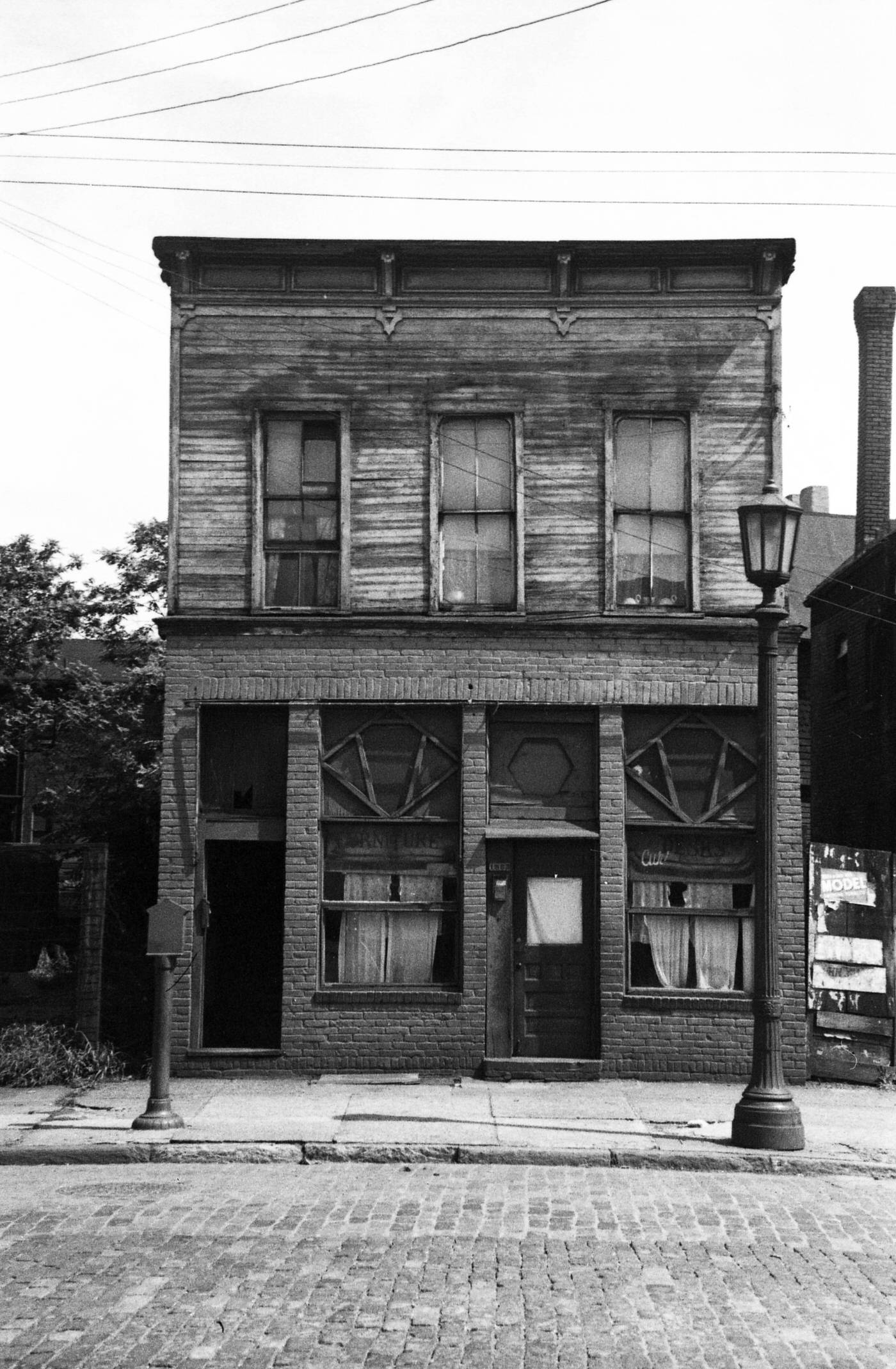

The late 1940s planted the seeds for a profound transformation in Greater Cleveland’s landscape: the rise of suburbanization. Cleveland’s Post-War Planning Council had foreseen this trend, predicting a “splurge of house-building in the suburbs” and expressing concerns about the potential for “wholesale abandonment of older areas” within the city if central city rehabilitation was not prioritized.

Several factors fueled this outward movement. Returning veterans, empowered by GI Bill mortgages, were eager to purchase single-family homes, a dream often realized in newly developing suburban tracts. By 1950, Cleveland’s proportion of the total Cuyahoga County population had already declined by nearly another 10% from its pre-war level, a clear indicator of this accelerating suburban growth.

This was not solely a residential shift. Industrial and retail decentralization, trends that had begun even before the 1940s, also gained momentum. Factories had started seeking suburban sites with cheaper land and lower taxes before 1900, and industrial corridors along areas like Brookpark Road and in Euclid continued to expand through the 1920s and into the post-war era. Similarly, retail businesses began to follow their customers outward. Sears, Roebuck & Co. had established large stores on both the east and west sides of Cleveland in the 1920s, and Shaker Square emerged as the area’s first significant suburban shopping center.

Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and Veterans Administration (VA) home loan guarantee programs were instrumental in supporting the construction of single-family homes in these new suburban areas. However, these programs often operated with, or permitted, racially restrictive covenants, effectively barring African Americans from accessing these new housing opportunities. This discriminatory practice meant that the suburban dream was largely a white phenomenon, further entrenching racial segregation across the metropolitan area. The confluence of residential migration, the movement of jobs and commerce, and discriminatory housing policies in the late 1940s signaled a fundamental restructuring of the urban-suburban dynamic, setting the stage for challenges to Cleveland’s urban core in the decades that followed.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know