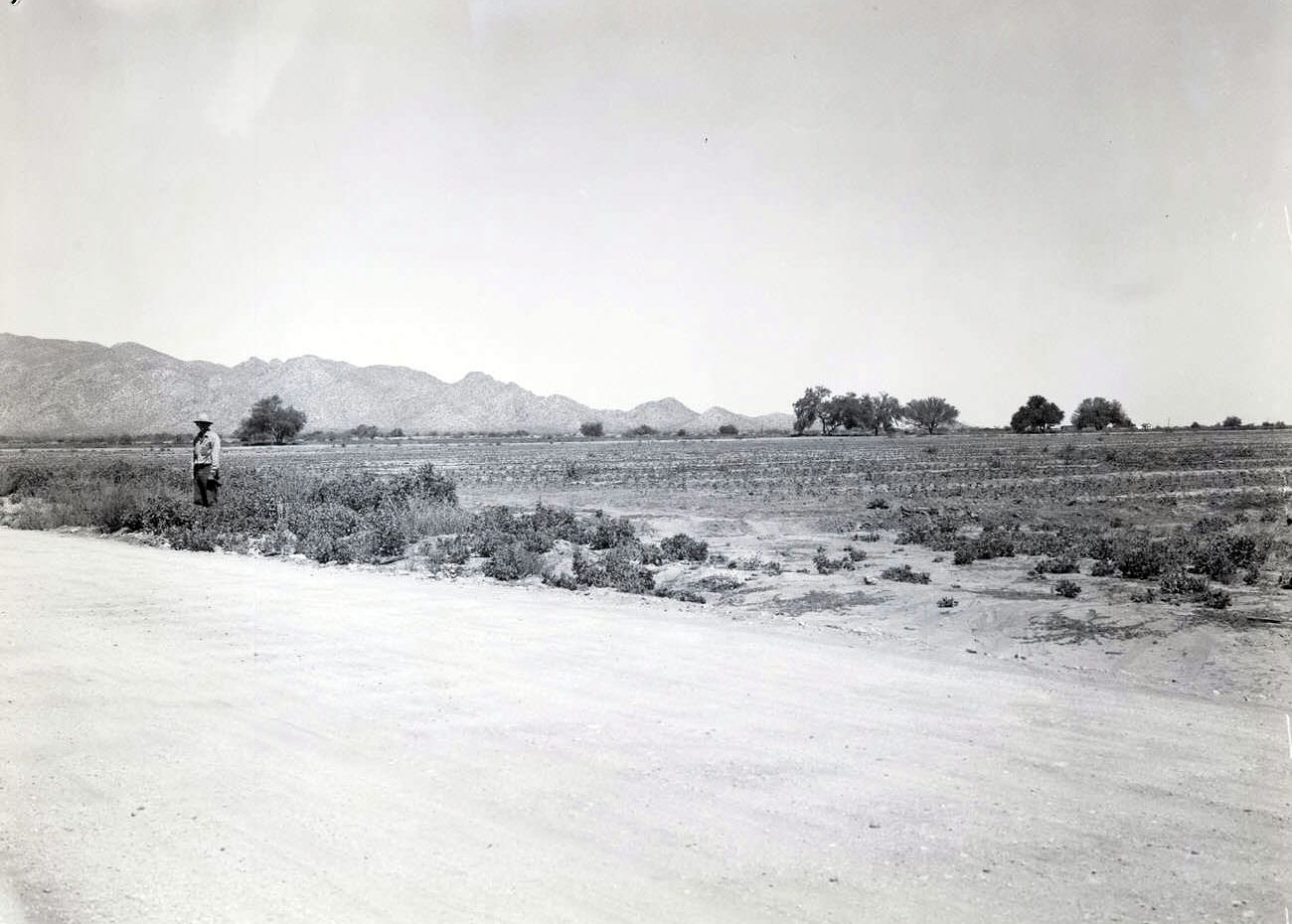

The 1940s marked a period of profound change for Phoenix, Arizona. At the dawn of the decade, it was a city deeply rooted in agriculture, its growth steady and aligned with national trends. The New Deal’s programs had provided a significant economic boost, helping Phoenix recover from the Great Depression and laying some groundwork for future development. However, the city’s character was still largely that of a regional commercial hub for the surrounding irrigated farmlands, a “garden city” reliant on the “5Cs”: copper, cattle, climate, cotton, and citrus. The Salt River Project and its network of canals, many following ancient Hohokam pathways, were the lifeblood, transforming desert into productive fields. While tourism was a growing sector, with resorts like the Arizona Biltmore and Camelback Inn attracting winter visitors, and small-scale manufacturing of items like ice and early air coolers (mostly swamp coolers) existed, agriculture was the undisputed king. This reliance on water made its careful management essential for any prosperity. As the 1940s unfolded, particularly with the advent of World War II, Phoenix stood on the cusp of a transformation that would reshape its economy, population, and very identity.

The Eve of Transformation: Phoenix at 1940’s Dawn

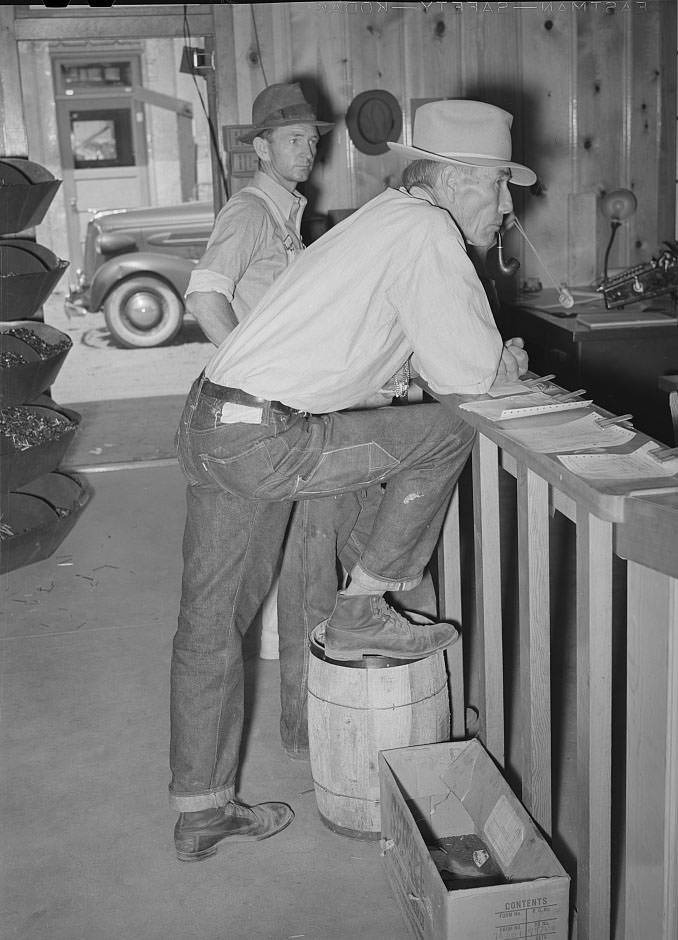

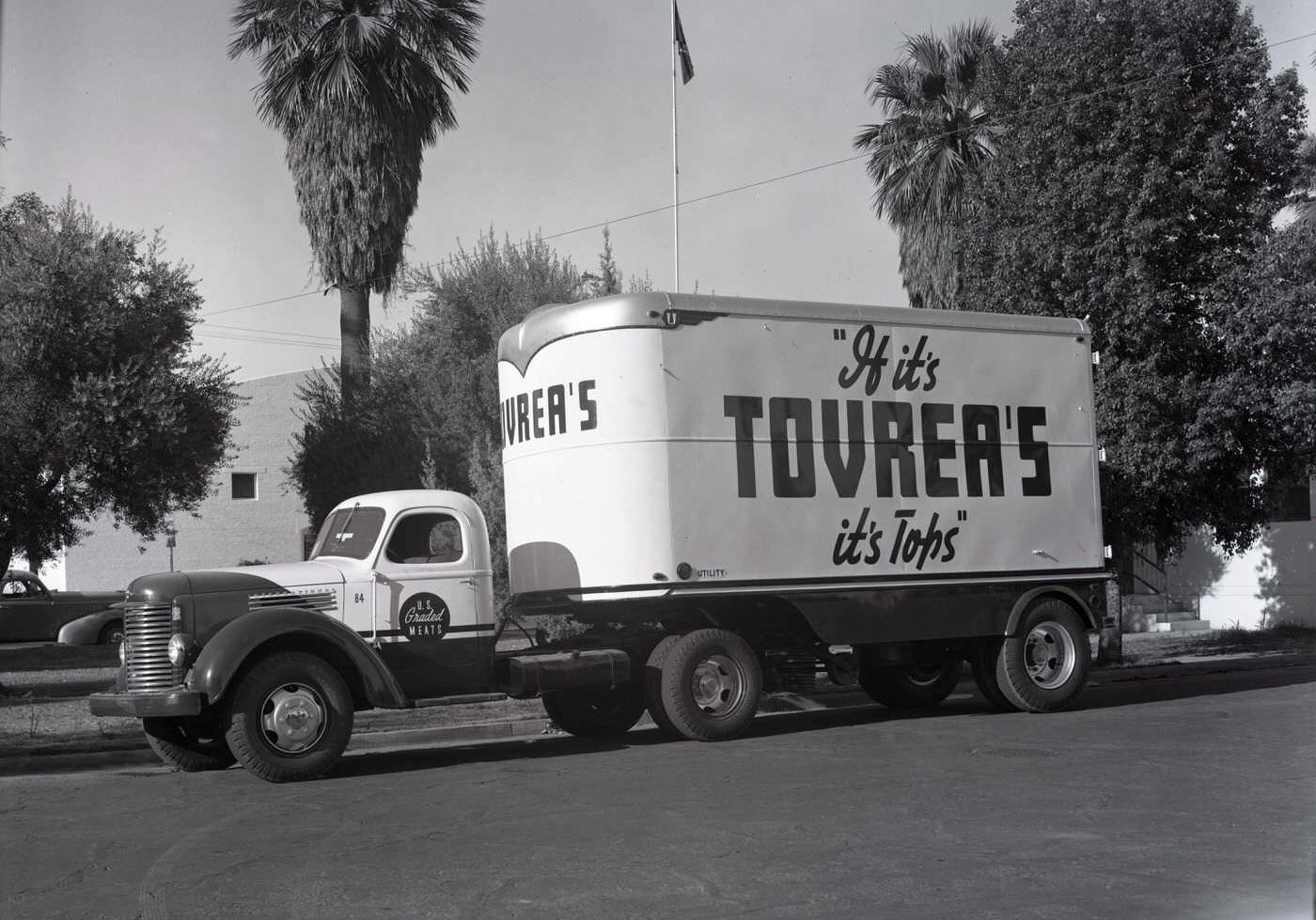

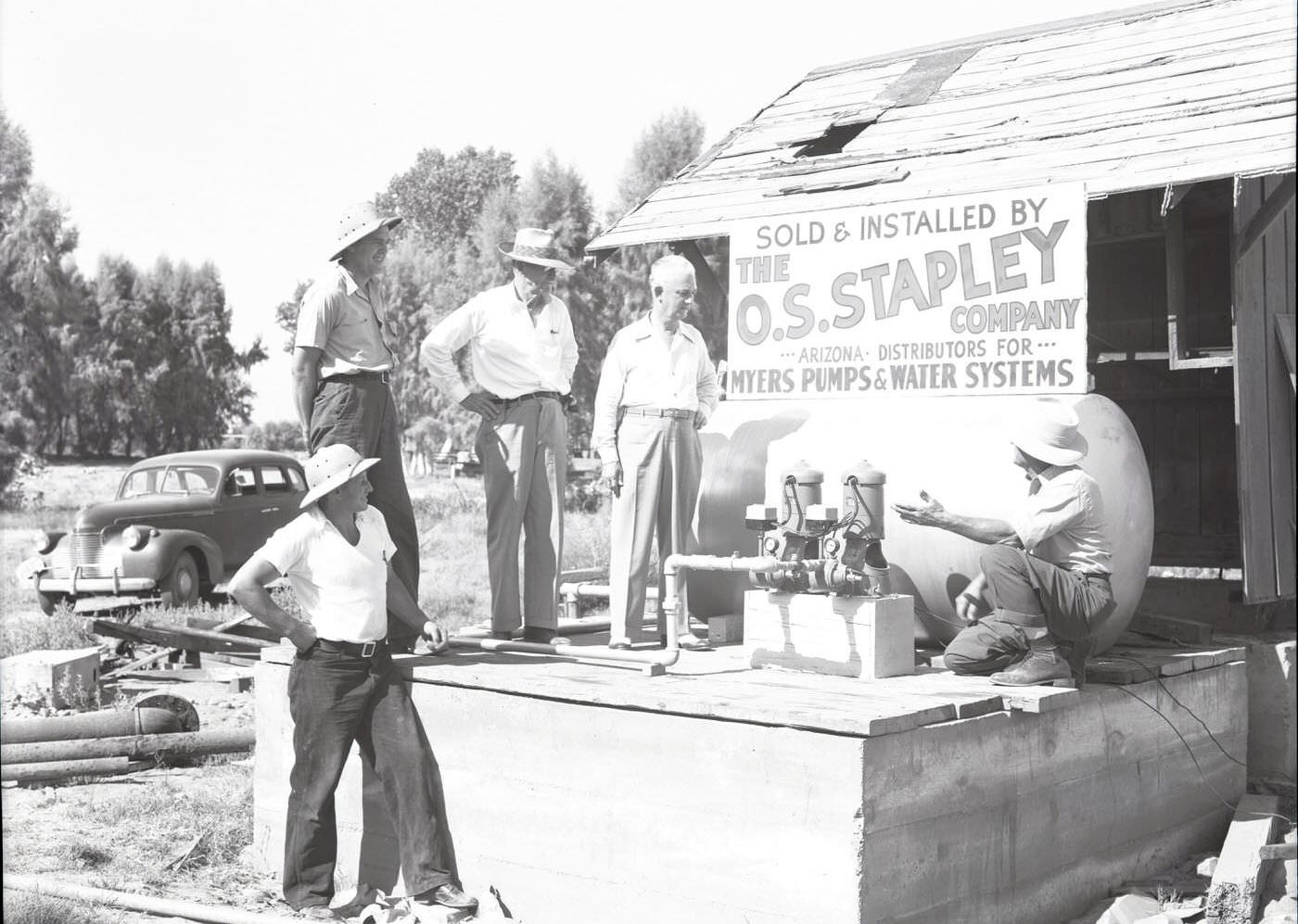

In 1940, Phoenix was home to 65,414 people, its city limits encompassing roughly 9.6 to 15 square miles. This population represented a 36% increase from the previous decade, a testament to the recovery spurred by New Deal initiatives. The city’s economy, while showing early signs of diversification, was overwhelmingly agricultural. The Salt River Valley, with Phoenix at its center, was a major producer of citrus fruits like oranges and grapefruit, as well as cotton, alfalfa, cantaloupes, dates, and various grains. In 1939, crops were valued at nearly $16 million, with livestock and beef products adding another $3 million. The Tovrea feedlots and slaughterhouses were significant operations.

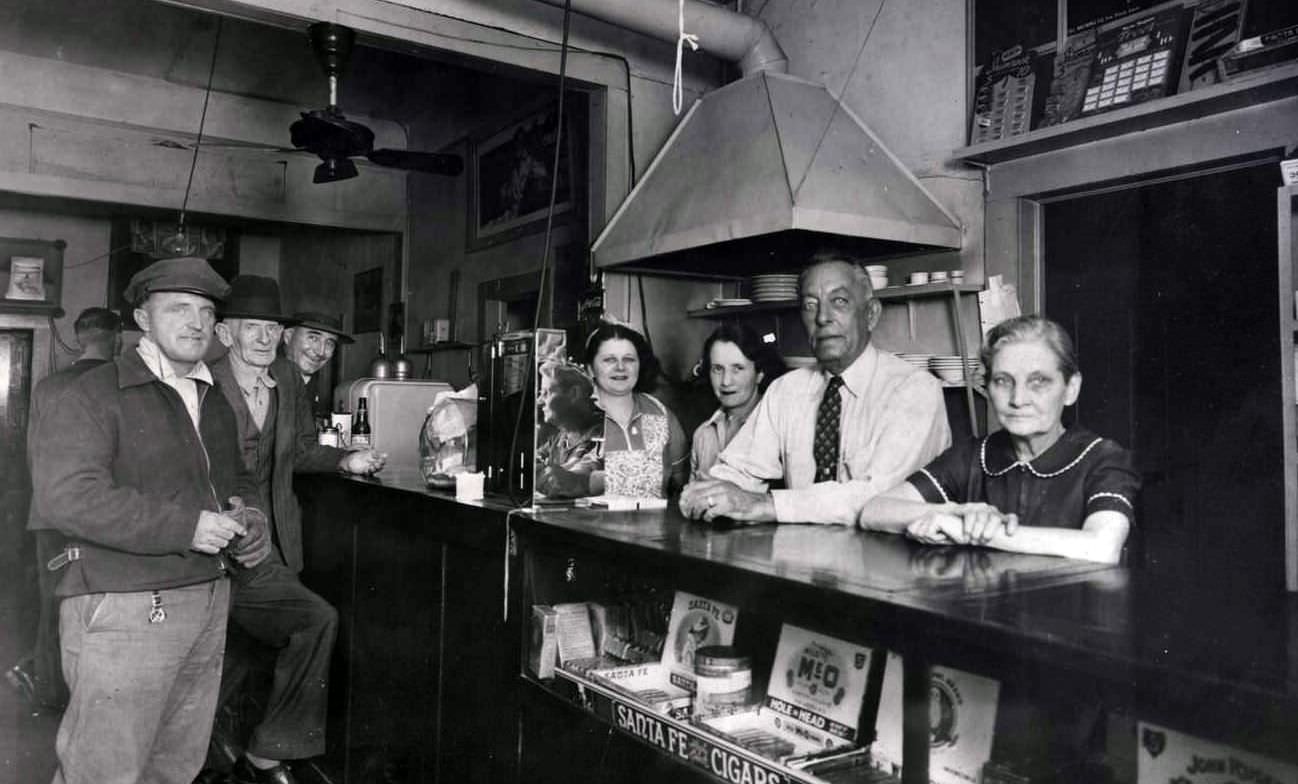

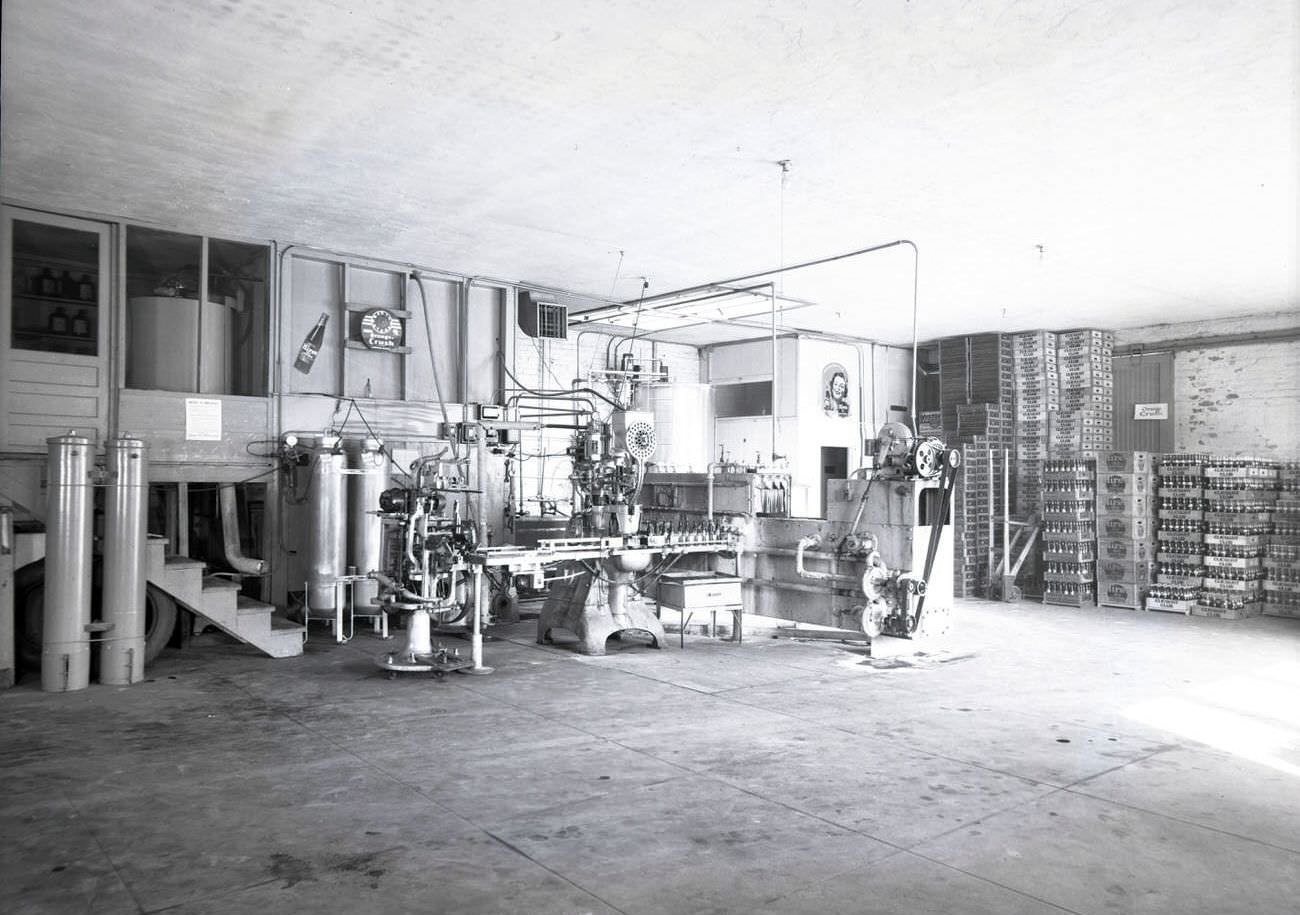

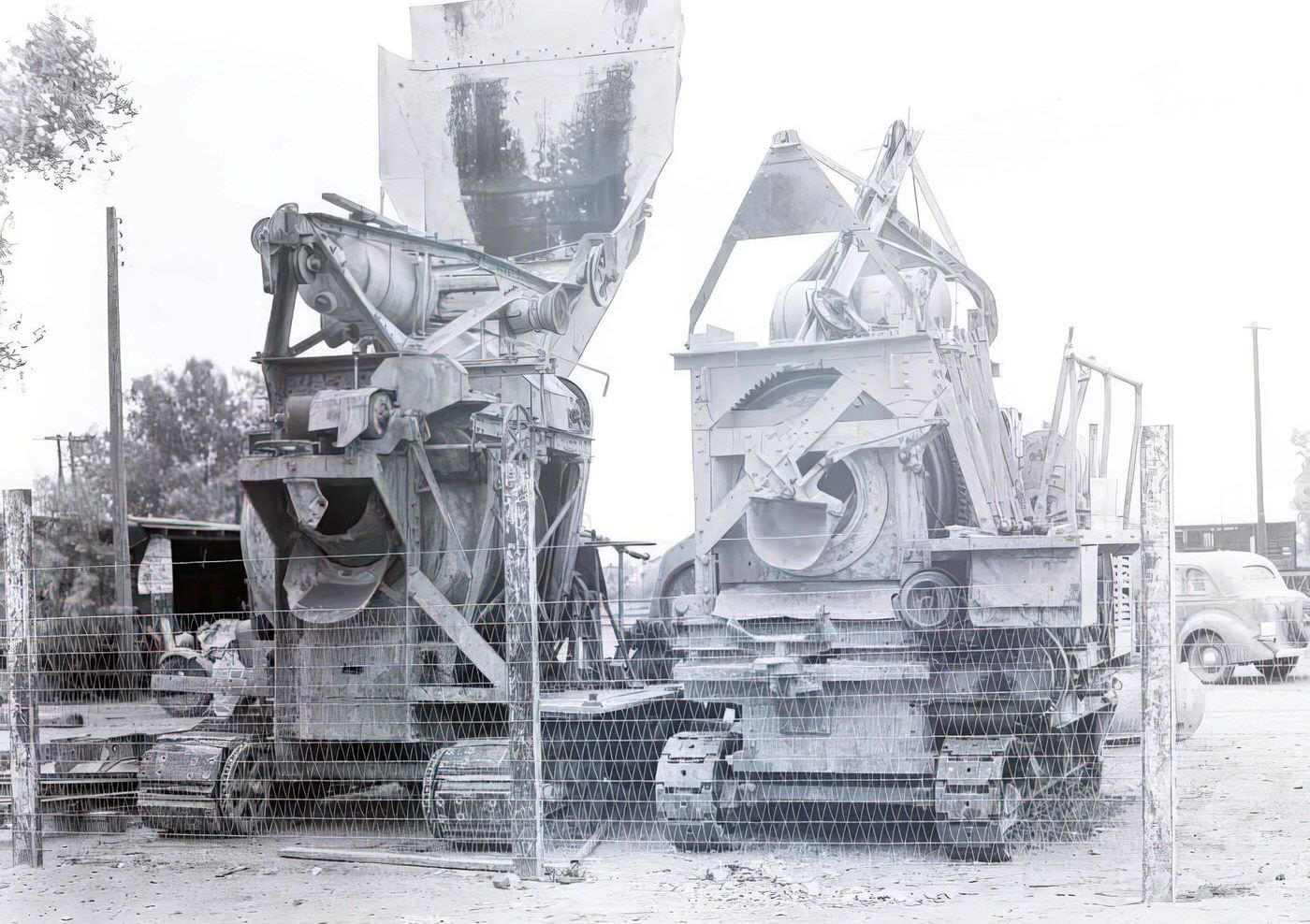

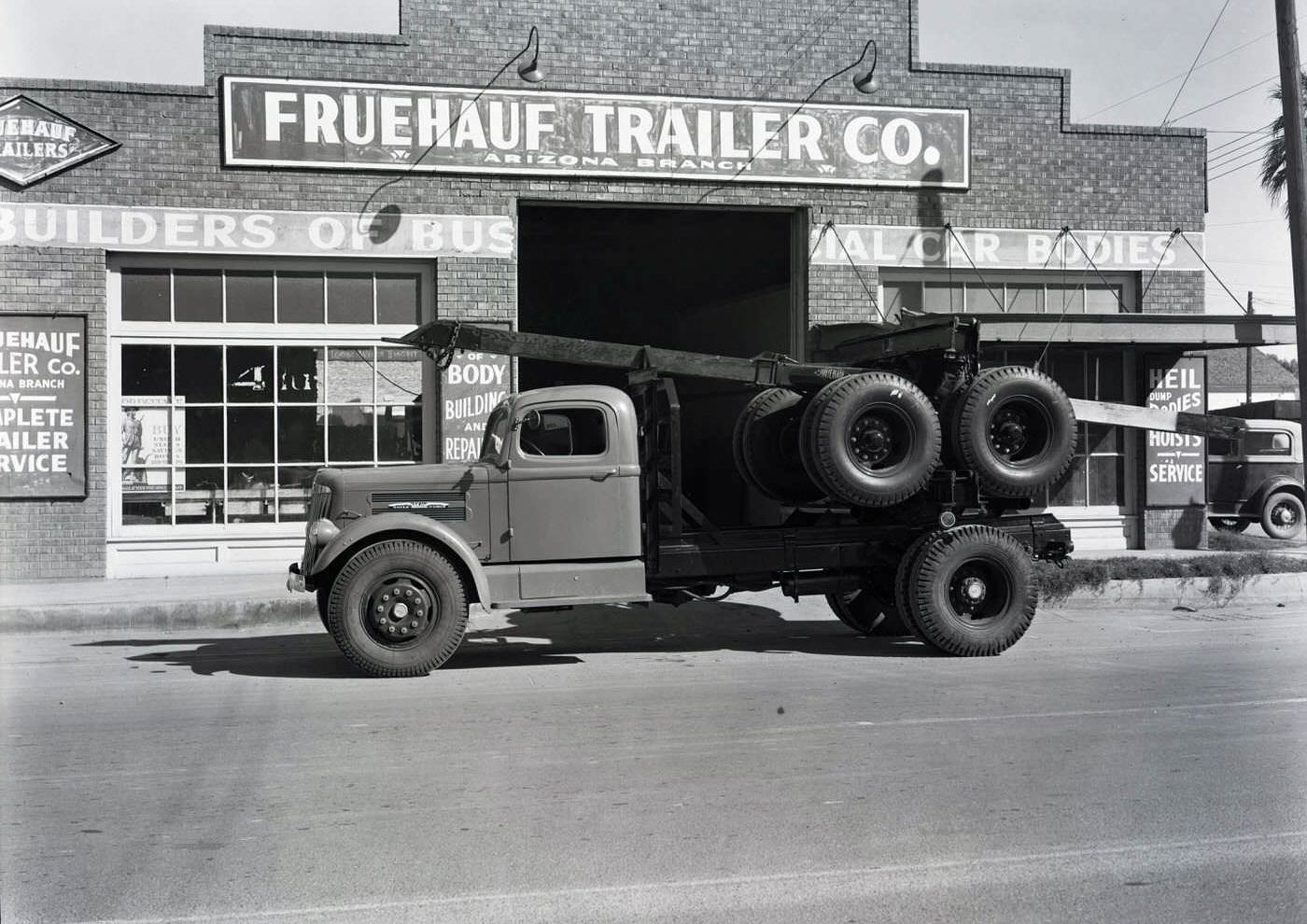

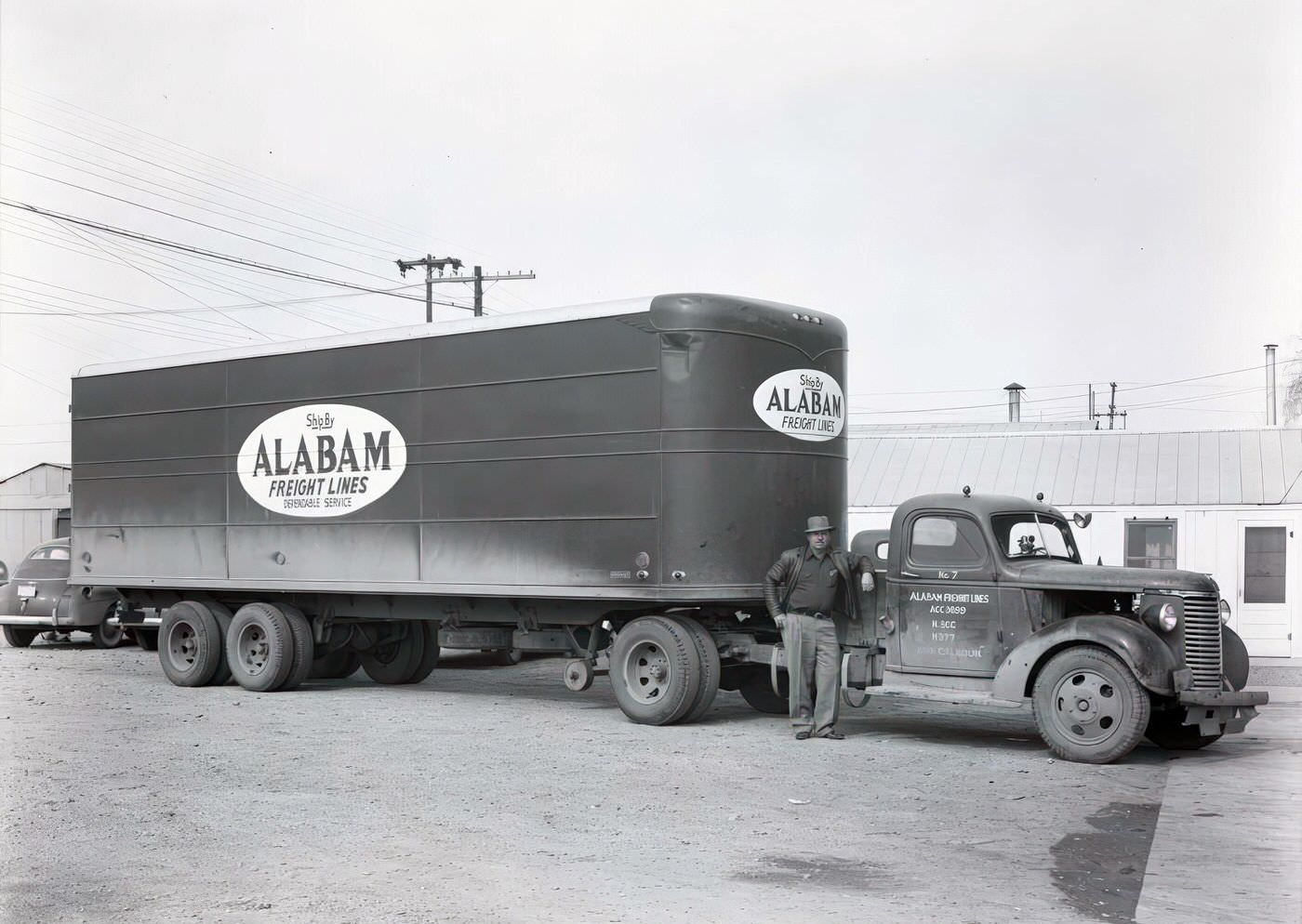

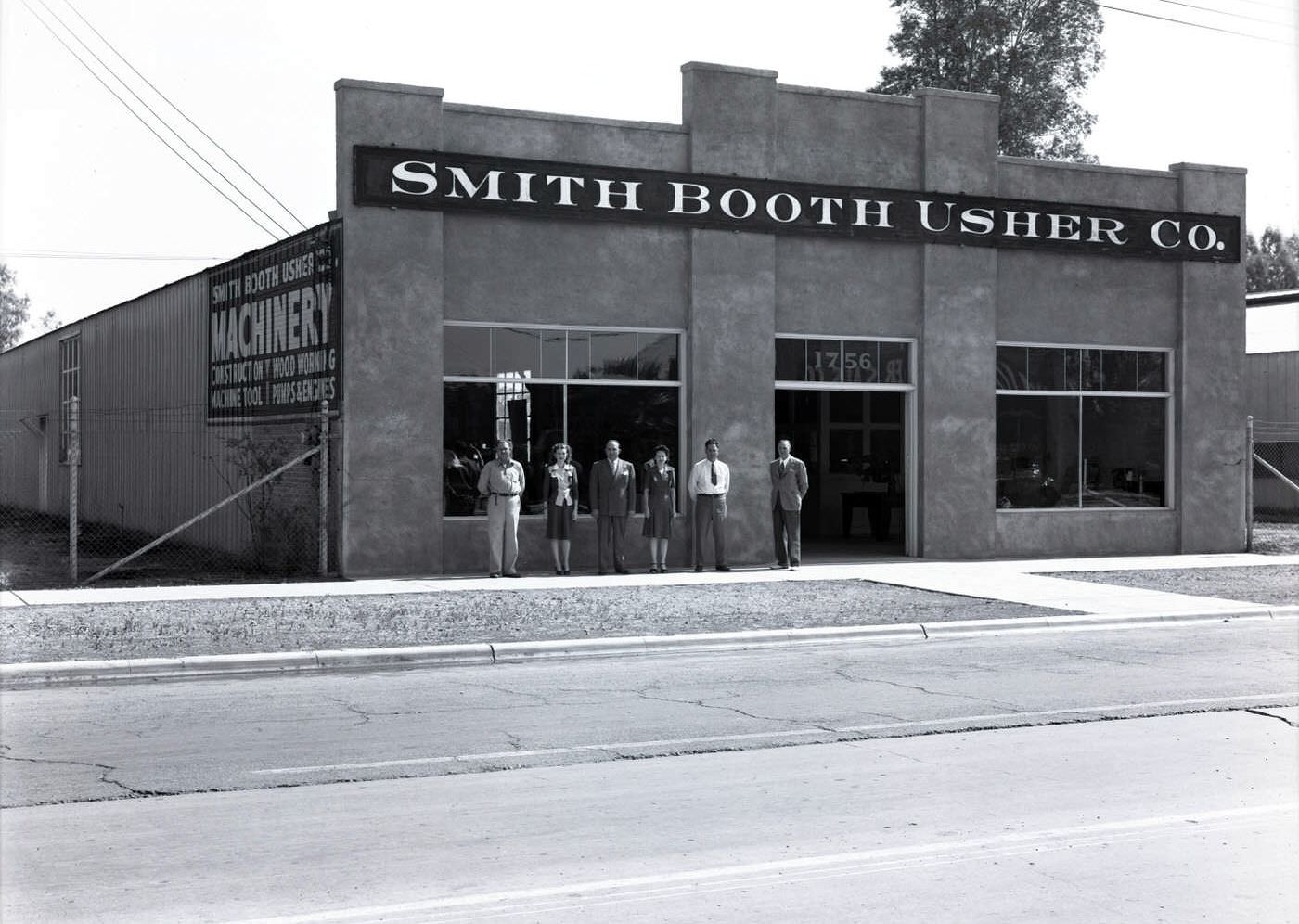

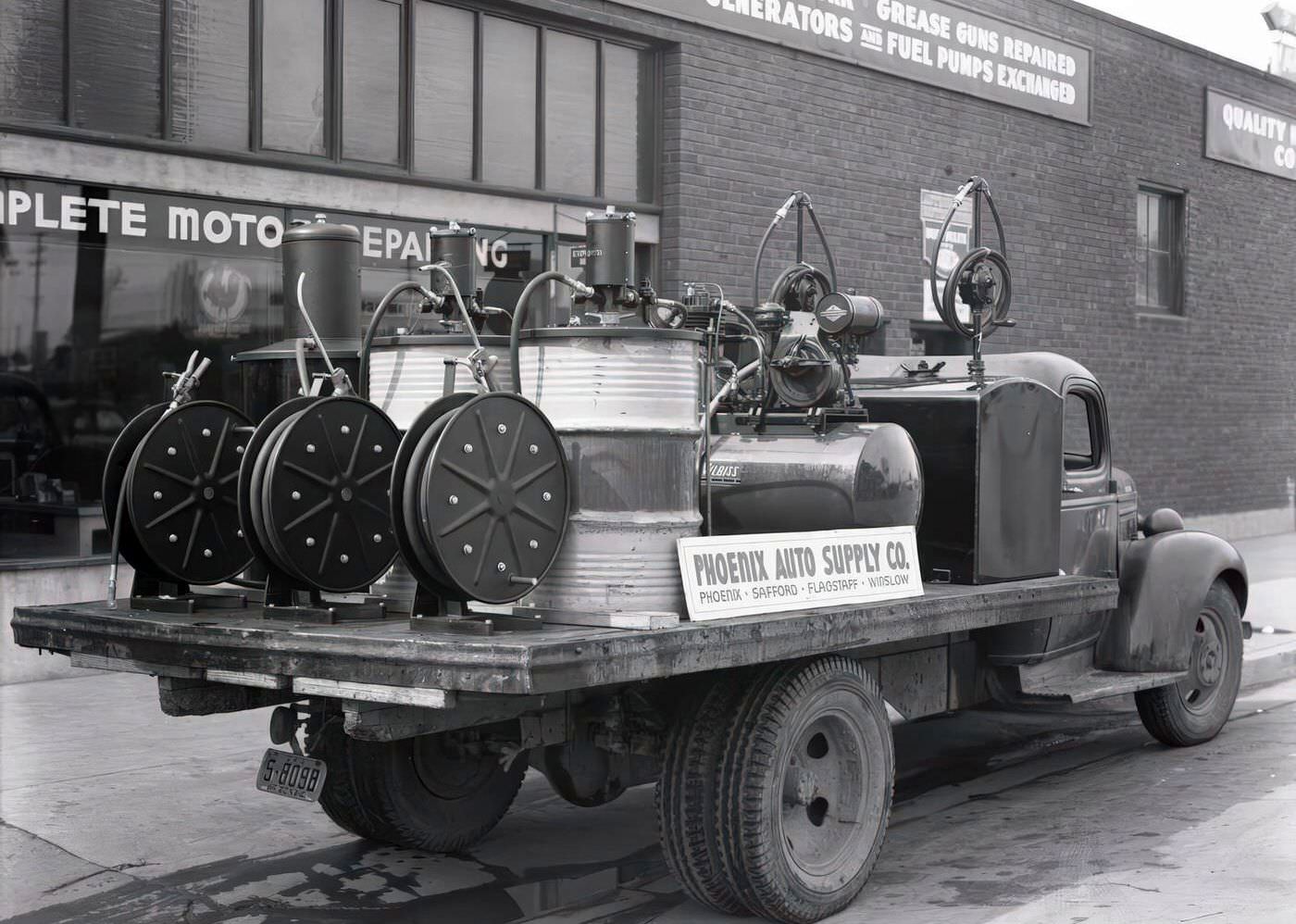

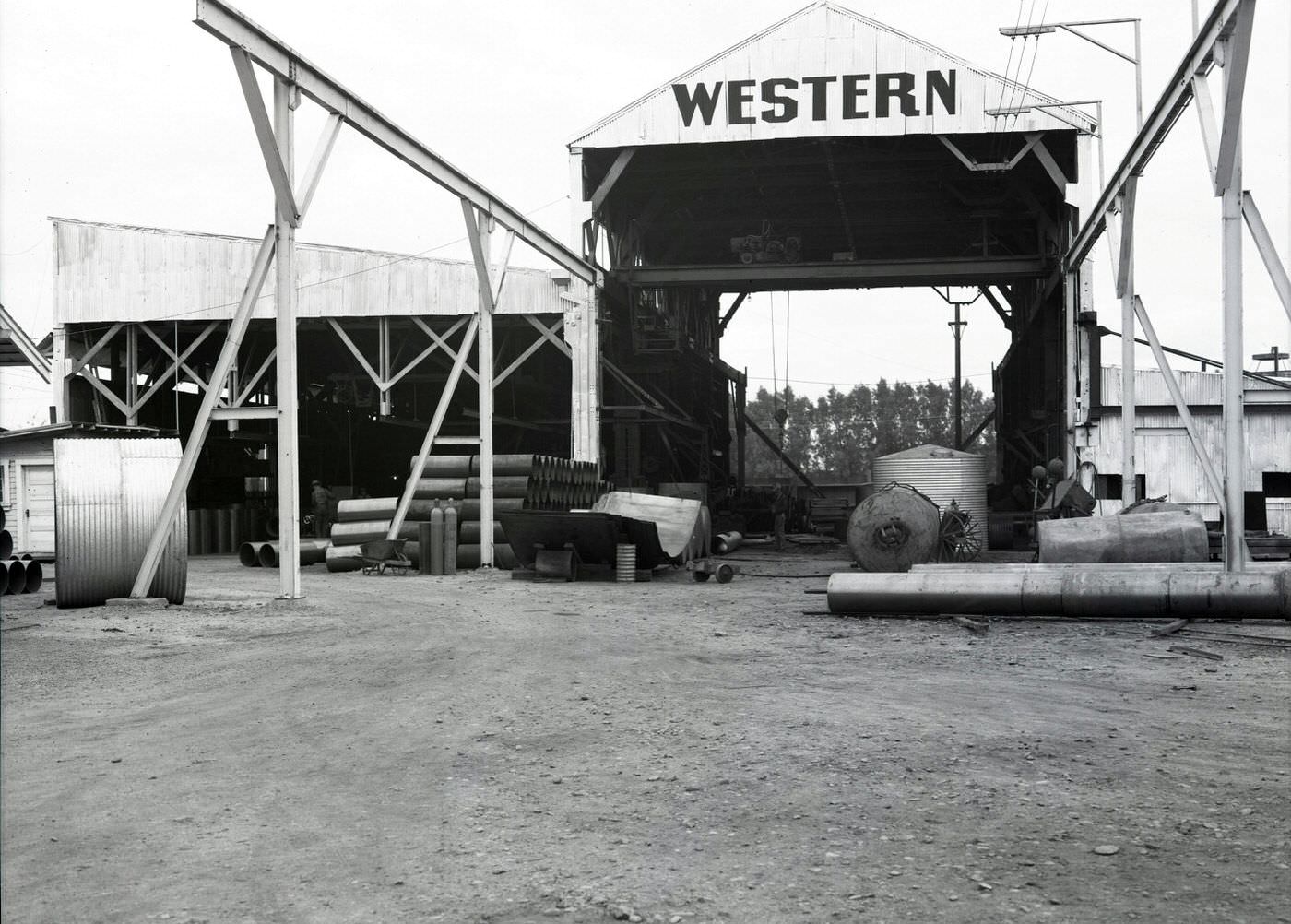

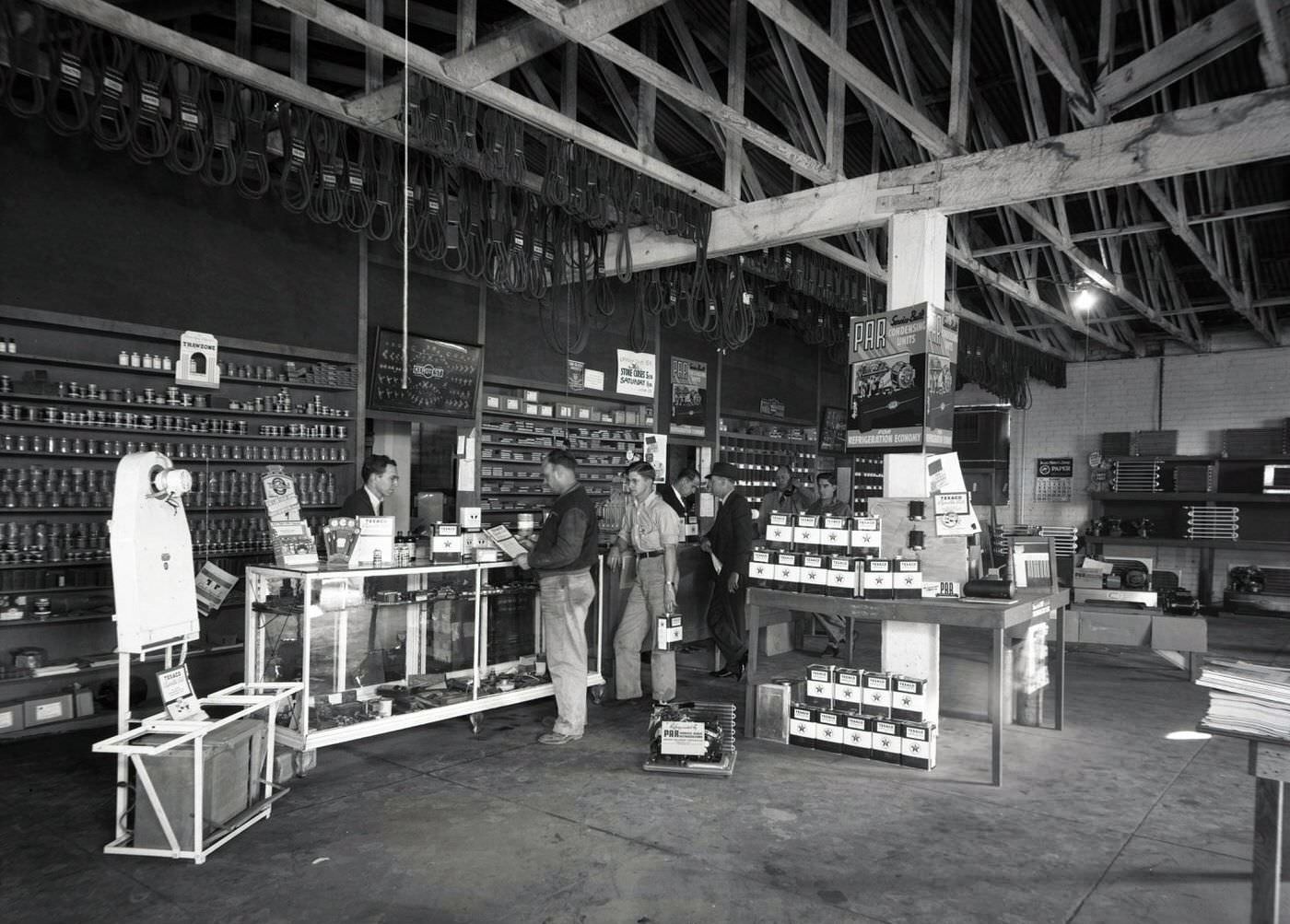

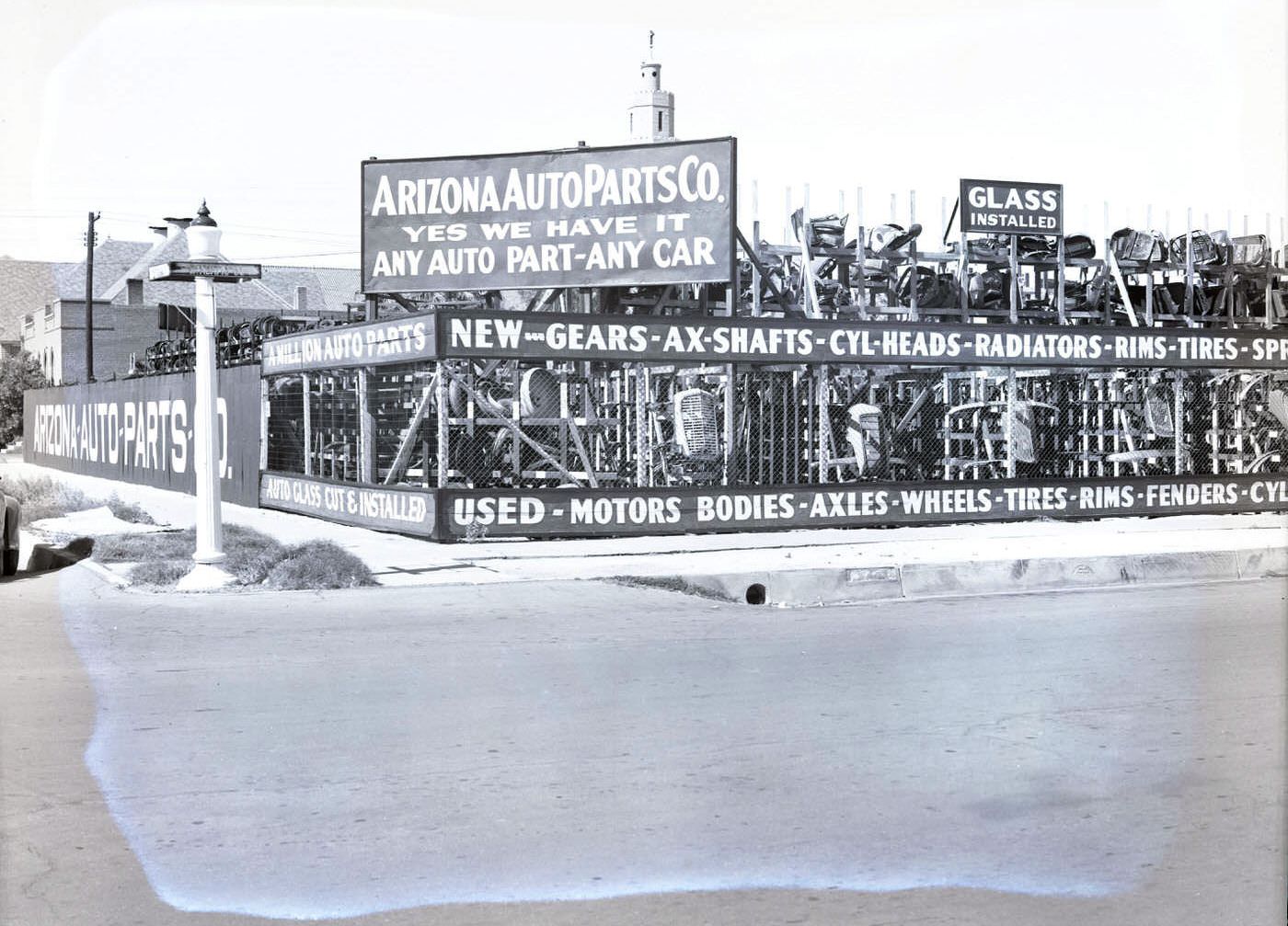

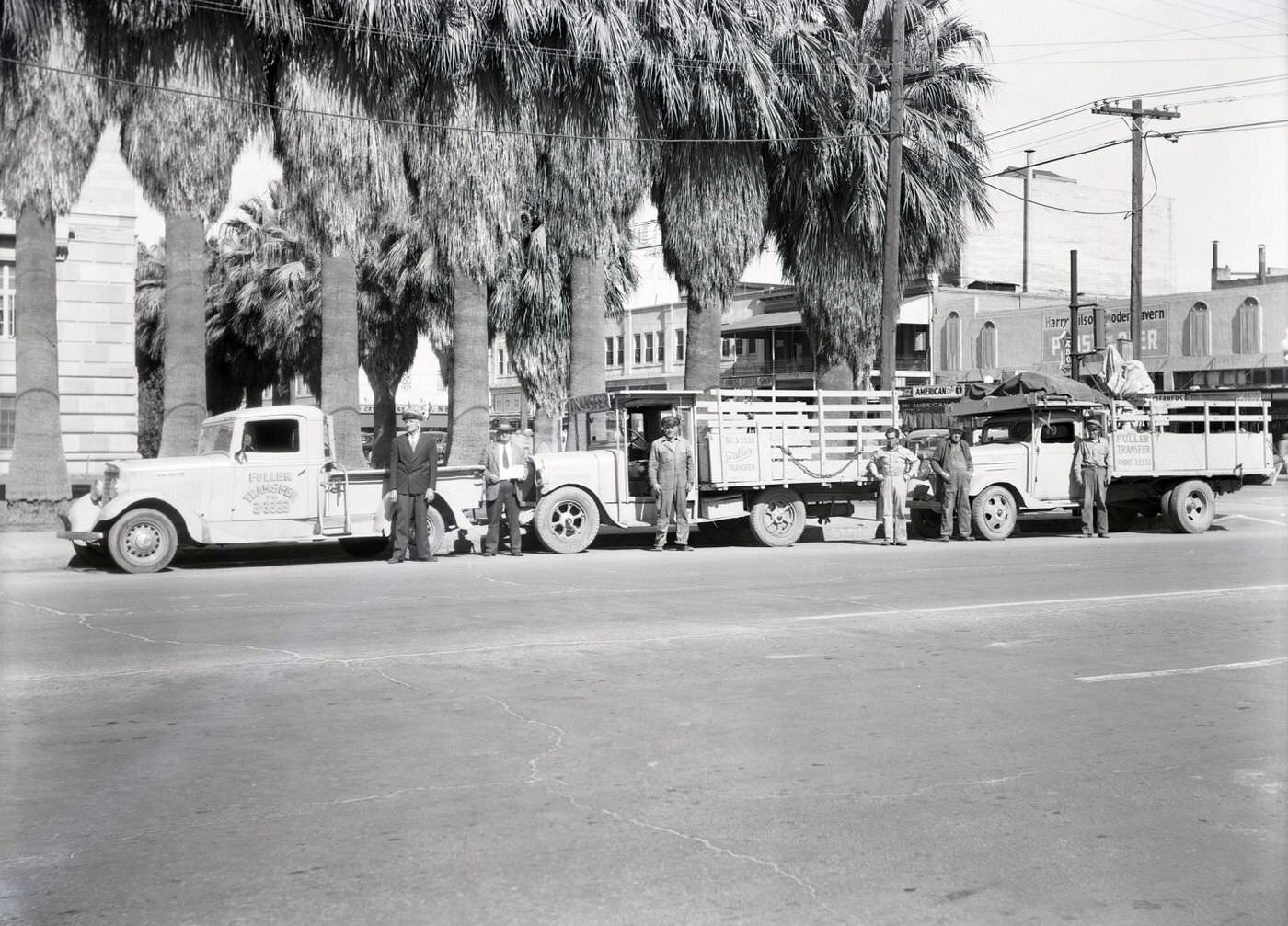

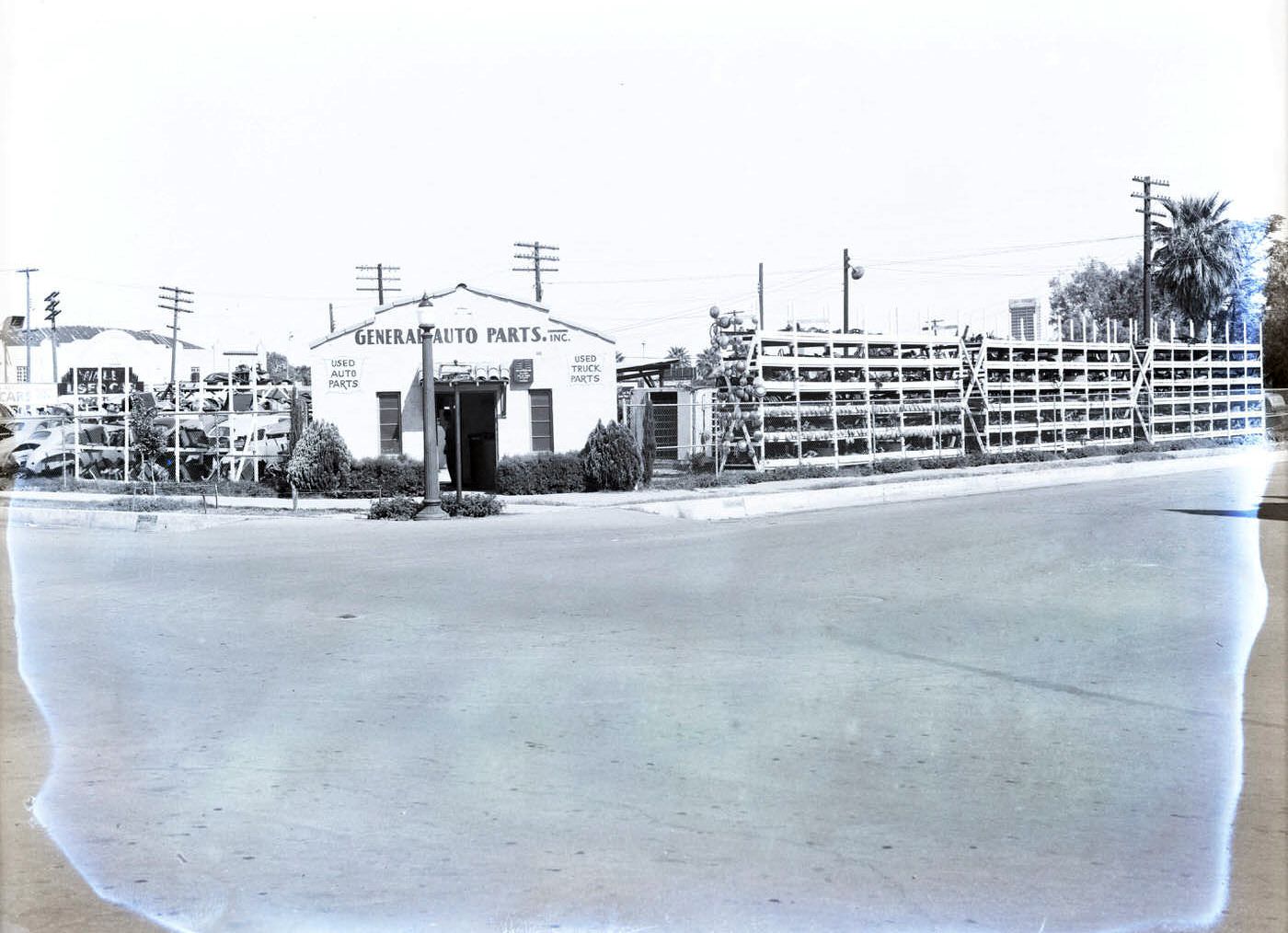

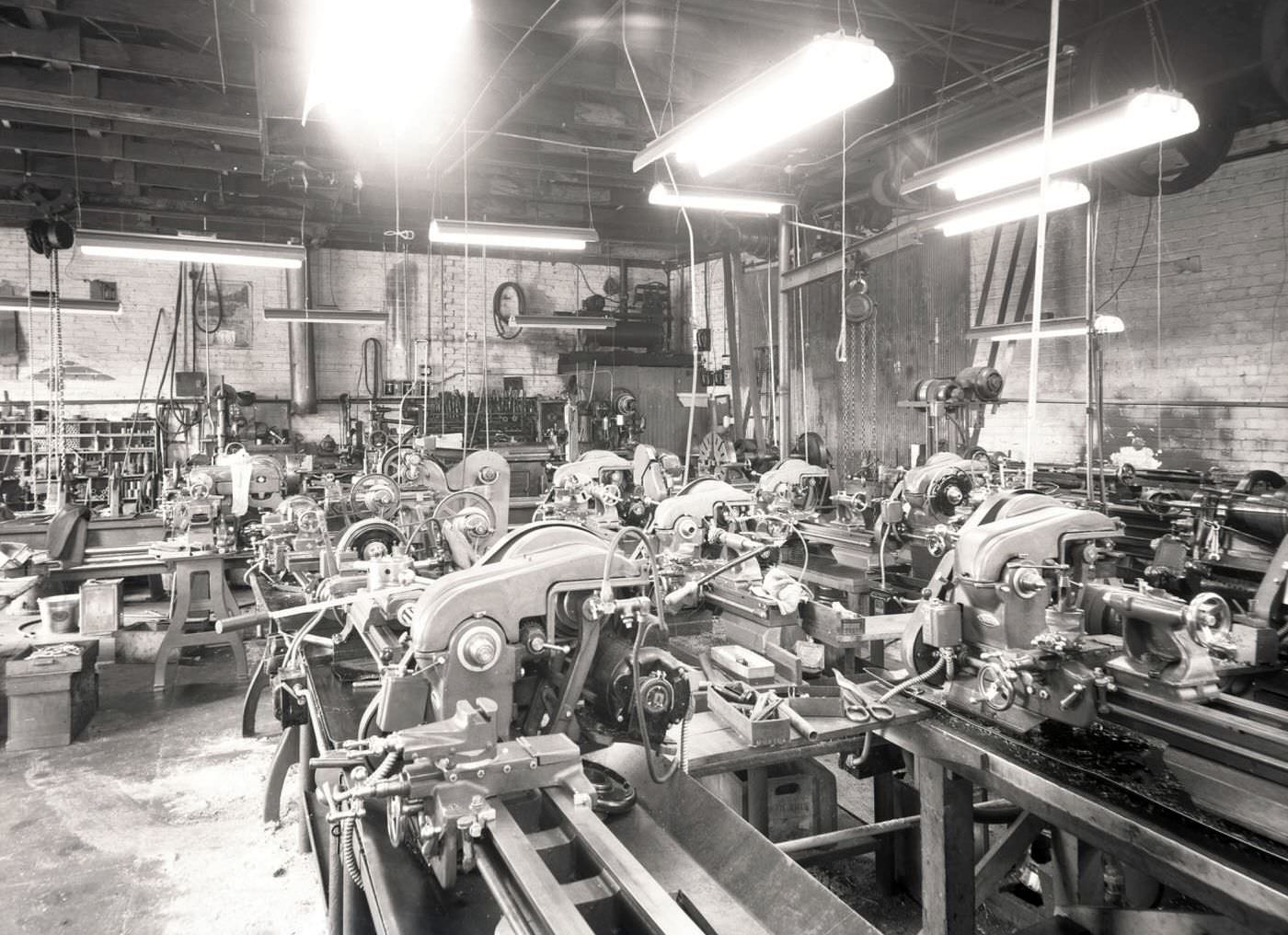

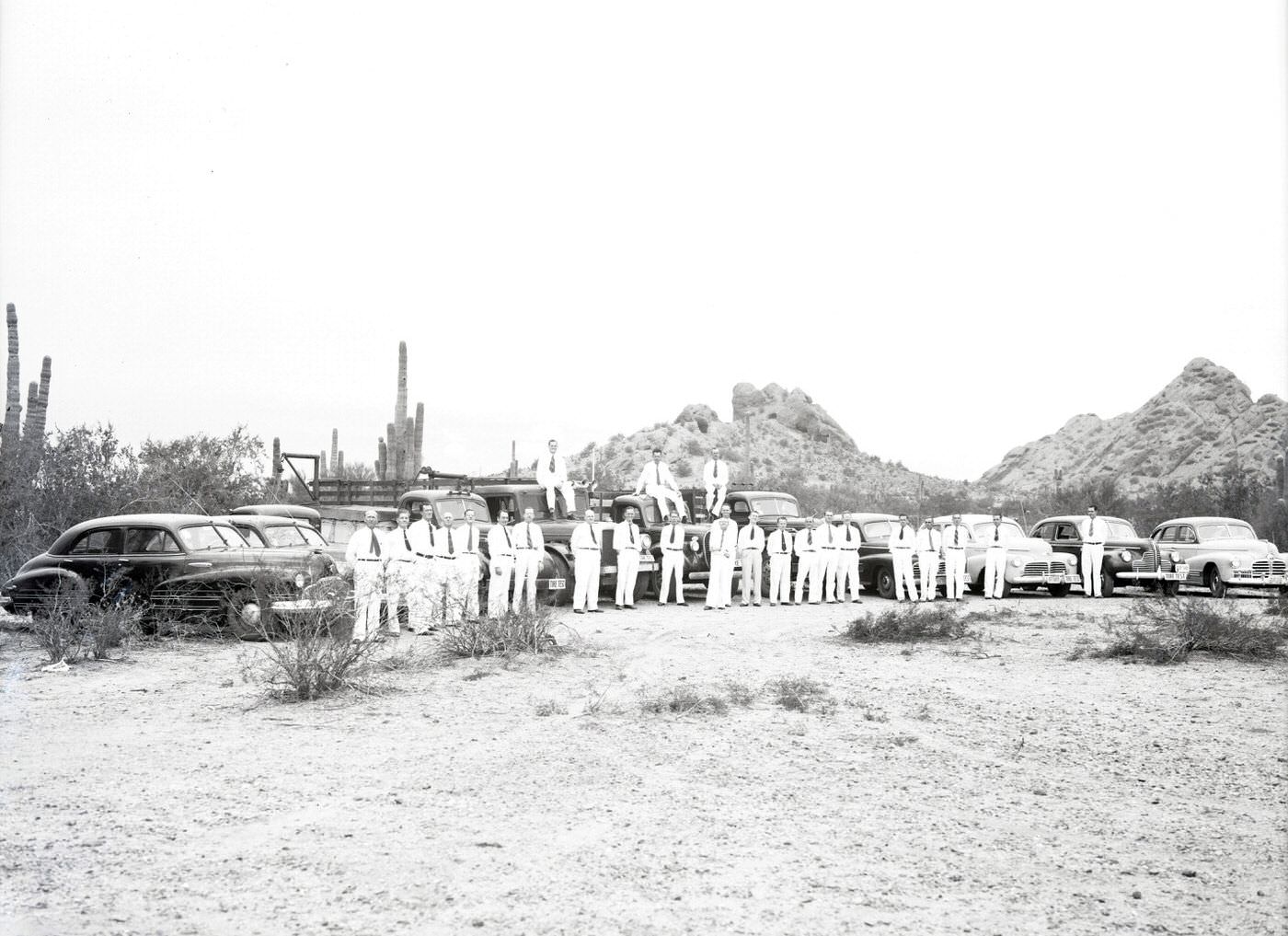

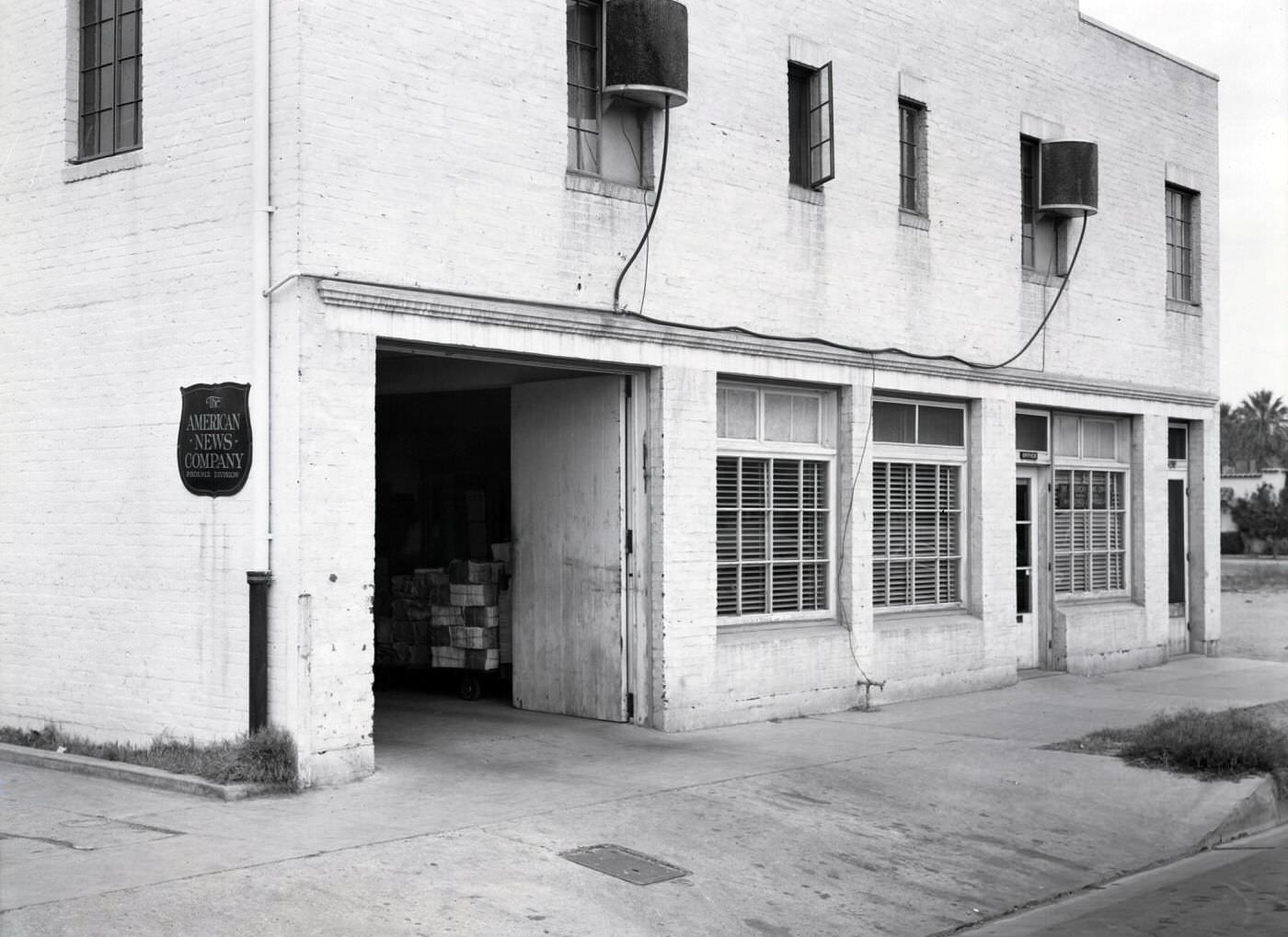

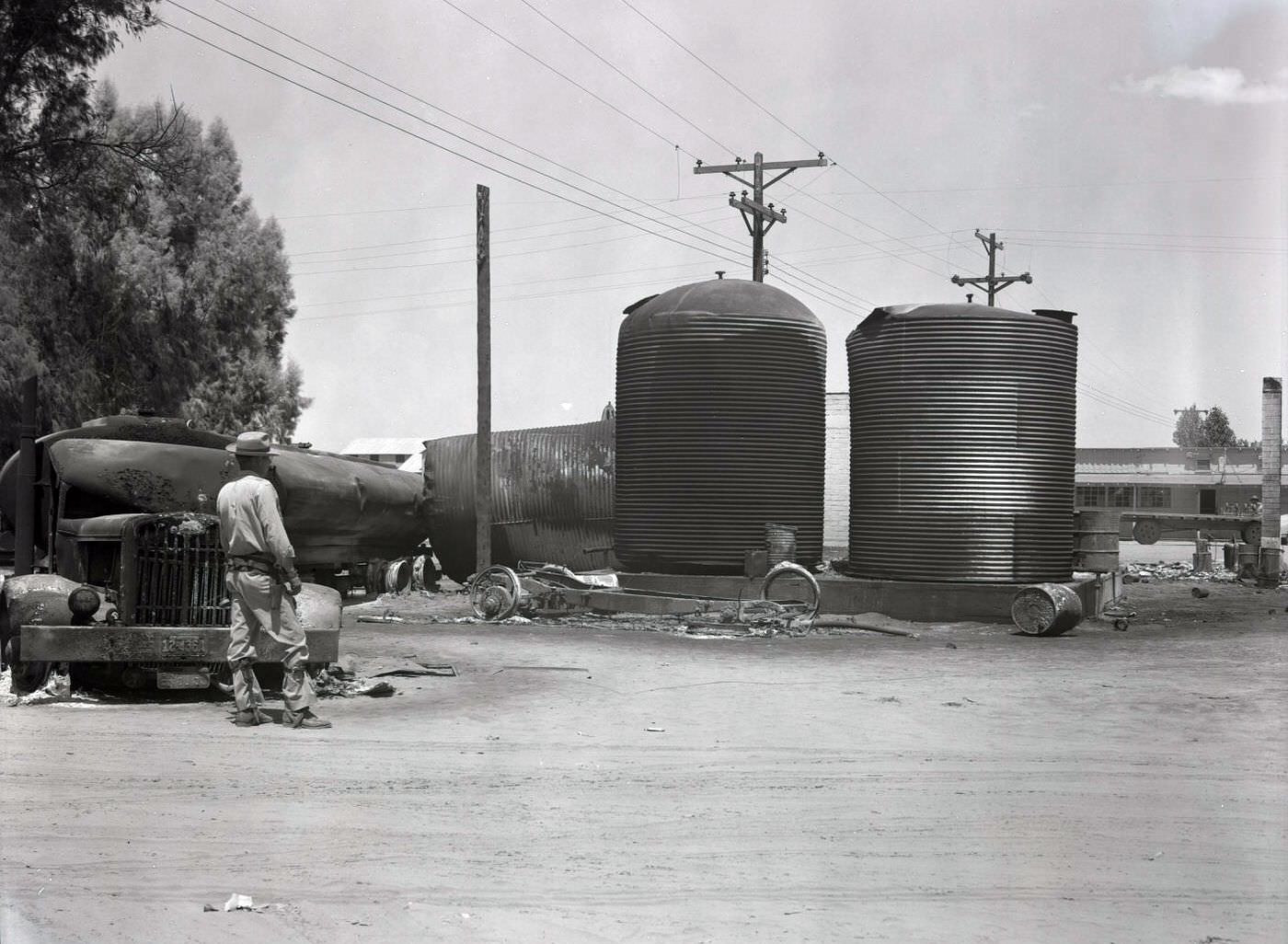

This agricultural output made Phoenix an important wholesale center, with 194 such establishments supported by national railroad connections. Local manufacturing was modest, including enterprises like Arizona Flour Mills, Holsum Bakery, and, notably, 30 small firms making air conditioning units, primarily evaporative “swamp coolers,” employing about 200 people. Ice production was also a key local industry, vital for homes, businesses, and the refrigerated railcars transporting produce.

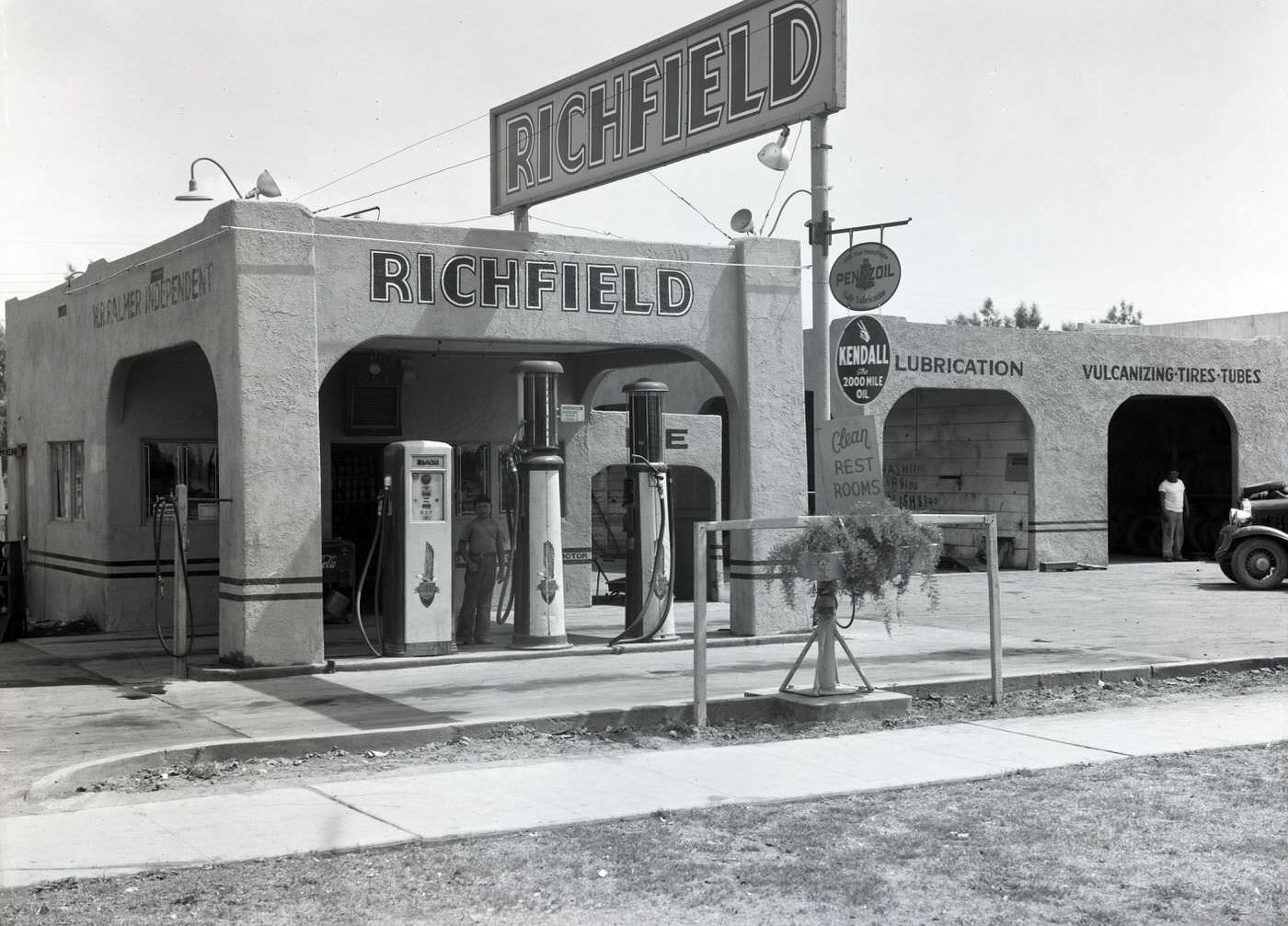

Daily life was supported by a growing infrastructure. There were 11,852 residential and 8,721 business telephones managed by Mountain States Telephone Co.. Three radio stations broadcast to the populace. Transportation within the city relied on the Phoenix Street Railway’s electric streetcars, while Sky Harbor Airport, served by three airlines, connected Phoenix to the nation. Nearly 46,000 cars were registered in Maricopa County, signaling the growing importance of personal vehicles. The first streamliner train arrived at Union Station in 1940.

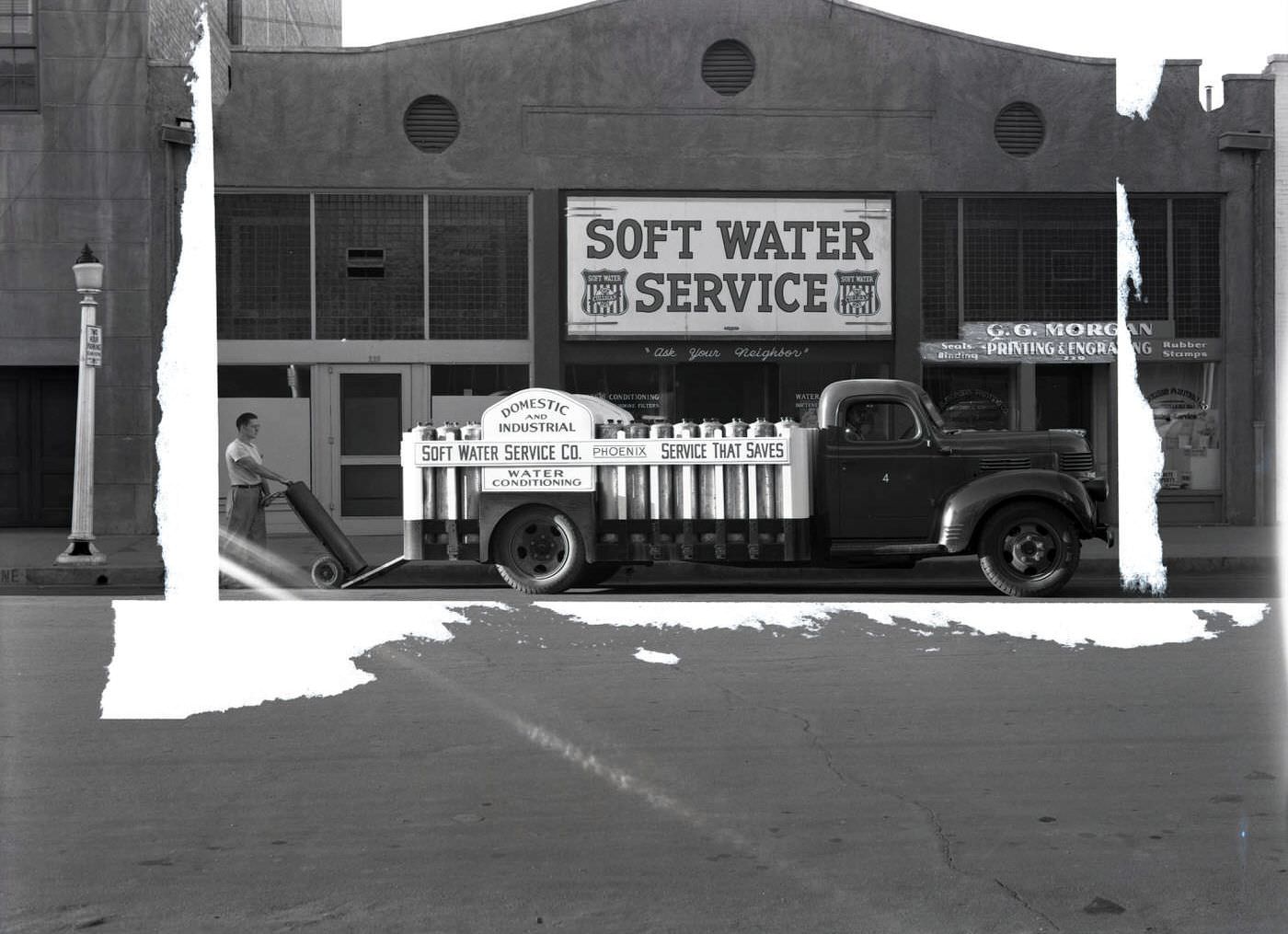

The city’s water supply, managed by the Salt River Project (SRP) and drawn from the Verde River and reservoirs like Roosevelt Dam, was fundamental to its existence in the arid desert. This intricate system of canals and water management not only supported the dominant agricultural sector but also made urban life possible, a critical factor as Phoenix approached a decade of unprecedented wartime and post-war expansion. The ability to harness and distribute water was the foundational element upon which all other development rested. While agriculture was the primary focus, the presence of a tourist industry and small manufacturing ventures hinted at a potential for economic breadth that would soon be realized.

Military Aviation’s Dominance

Arizona’s clear desert skies and abundant open land made it an ideal location for military aviation training, a fact that became critically important in the 1940s. Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the federal government recognized this strategic advantage and began establishing and expanding airfields for training military pilots. This foresight transformed the Phoenix area into a major hub for Army Air Corps training.

At the forefront of this effort was Luke Field. In 1940, the U.S. Army selected a site near Phoenix, and the city leased 1,440 acres to the government for $1 a year, effective March 1941. Construction, undertaken by the Del E. Webb Construction Company, began swiftly. The base was named Luke Field, inheriting the name from a facility in Hawaii that was transferred to the Navy. Lieutenant Colonel Ennis C. Whitehead was its first commander, and future Arizona senator Barry Goldwater served as director of ground training the following year.

Luke Field quickly became the largest fighter training base in the Army Air Forces during World War II. It earned the nickname “Home of the Fighter Pilot,” graduating more than 12,000 fighter pilots from advanced and operational courses. Some records indicate over 17,000 pilots trained there in total. Pilots received approximately 10 weeks of instruction, initially flying out of Sky Harbor Airport until Luke’s runways were ready. Training aircraft included the AT-6 Texan, P-40 Warhawk, P-51 Mustang, and P-38 Lightning. Ground school was comprehensive, covering navigation, flight planning, radio equipment, maintenance, and weather. The scale of operations was immense; by February 7, 1944, pilots at Luke Field had logged one million hours of flying time. However, with the war’s end, the number of pilots trained dropped to 299 in 1946, and the base was temporarily deactivated on November 30, 1946, before being reactivated for the Korean War.

Another key installation was Williams Field. During World War II, it was under the command of the 89th Army Air Force Base Unit and focused on specialized twin-engine and four-engine training. Thousands of future P-38 Lightning pilots trained there on aircraft like the Beech AT-10 Wichita, Cessna AT-17 Bobcat, and the more demanding Curtiss-Wright AT-9. Later, the RP-322 training version of the P-38 arrived, and the field also offered single-engine advanced courses on the AT-6 Texan, transitioning pilots to twin-engine aircraft and preparing some for photo-reconnaissance and night fighter roles. By late 1944, Williams Field began training pilots on Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. The Army Air Forces also trained Chinese Air Force pilots at Williams Field, Luke Field, and nearby Thunderbird Field.

Falcon Field, located in Mesa, played a unique international role. Beginning in June 1941, six months before Pearl Harbor, Falcon Field was established specifically to train British Royal Air Force (RAF) cadets, an audacious experiment where a Hollywood corporation hired civilian pilots to teach British cadets using U.S. Army airplanes. Over 2,000 RAF cadets trained at Falcon Field during the war, accumulating over 300,000 hours in the air and flying a distance of forty-five million miles. This joint effort filled an immense need for trained RAF pilots who would later fly missions over Europe. A few cadets from other Allied nations also trained there.

These airfields, along with numerous auxiliary fields scattered throughout the region, underscored Phoenix’s critical contribution to the Allied victory and fundamentally altered the local landscape and economy.

Phoenix’s Pre-War and Wartime Economy

Phoenix’s economy at the start of the 1940s was firmly anchored by the “5Cs”: copper, cattle, climate (tourism), cotton, and citrus. Agriculture was paramount, with vast acreages dedicated to crops like Pima cotton and alfalfa, alongside extensive citrus groves. The climate also nurtured a burgeoning tourism industry, attracting visitors to its resorts. Copper mining in Arizona, though not centered in Phoenix itself, contributed to the state’s overall economic activity and was supported by Phoenix-based commerce.

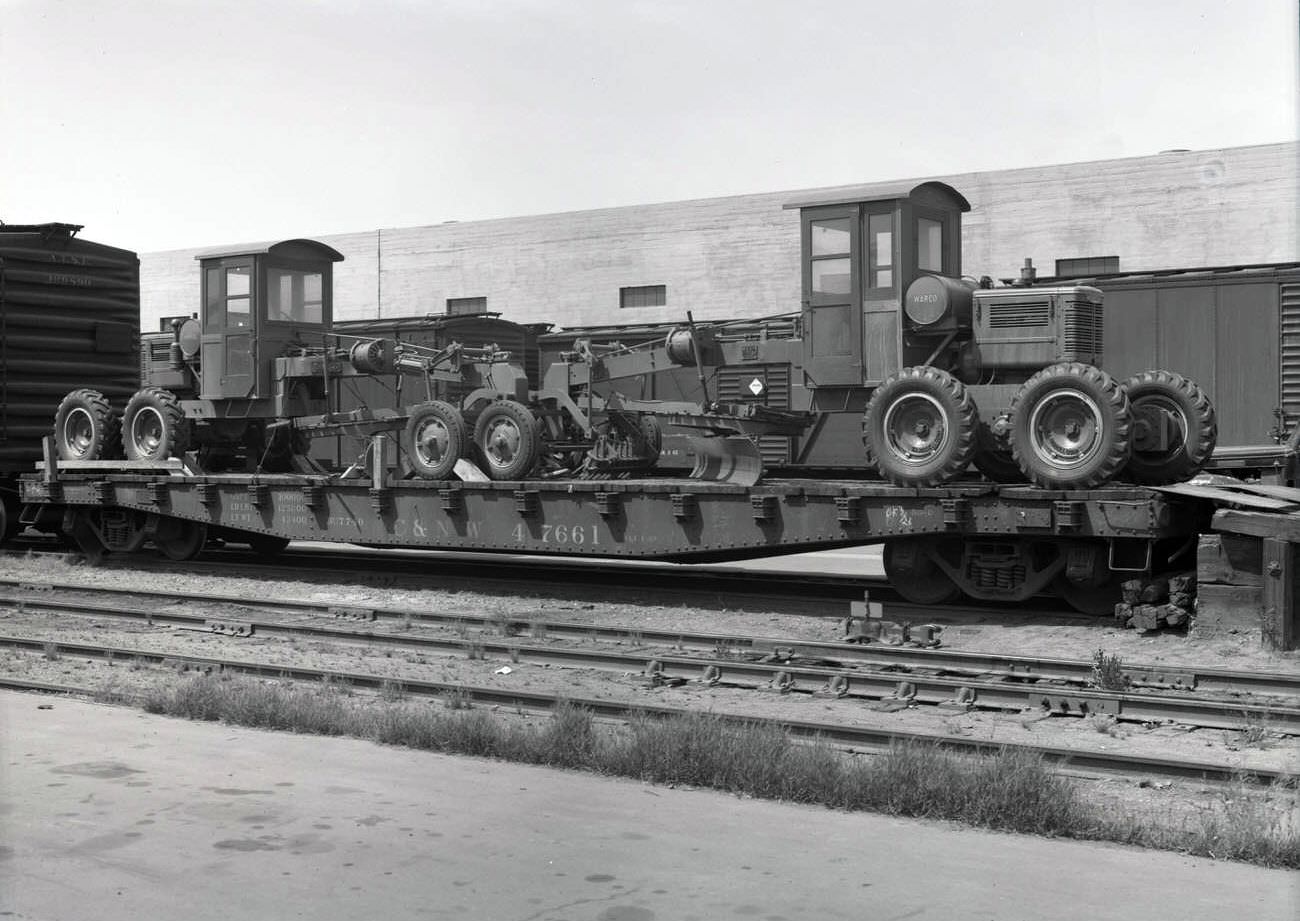

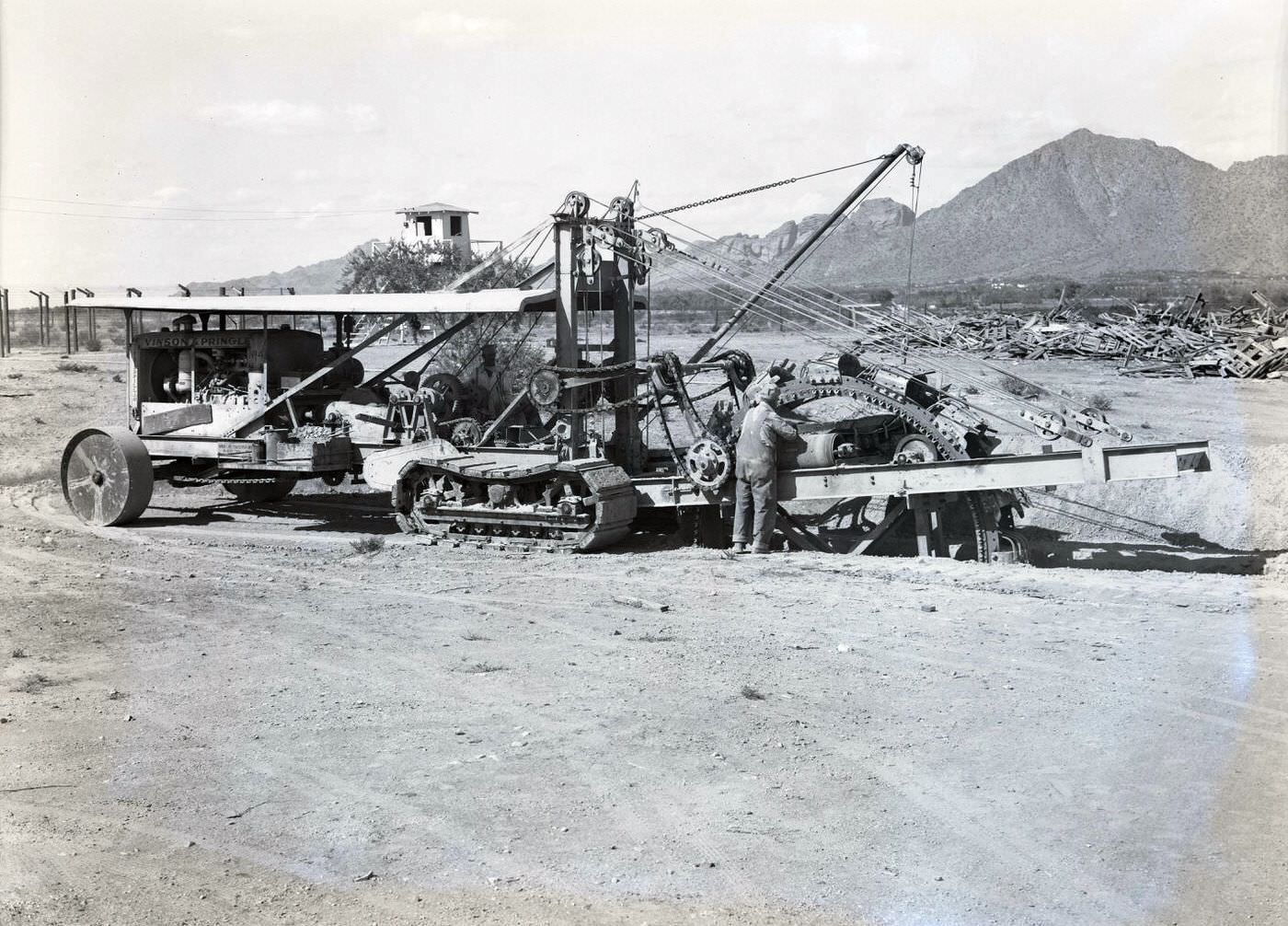

The onset of World War II dramatically amplified these existing economic strengths and introduced new dimensions. The demand for agricultural products surged. Cotton, in particular, became a critical war material, used for tires, airplane fabric, and munitions. This wartime demand revitalized the cotton industry, which had faced downturns previously. The Salt River Valley’s farms became vital contributors to the national food supply. Similarly, copper mining experienced a resurgence due to the war’s insatiable need for the metal. The Phelps Dodge company, a major copper producer, collaborated with the Salt River Project to build Horseshoe Dam on the Verde River to secure water for its operations, a project also benefiting local water storage.

Beyond bolstering traditional industries, the federal government’s wartime investments acted as a powerful economic catalyst. The establishment and expansion of military bases brought a massive influx of federal money and personnel. Fort Huachuca, near Phoenix, received $6 million for expansion in early 1941. This military spending had ripple effects, stimulating local businesses and creating jobs. Arizona’s gross income from manufacturing skyrocketed from $17 million in 1940 to $85 million by 1945, a clear indication of the war’s economic impact.

A significant development during the war was the emergence of defense-related manufacturing. In 1942, AiResearch established its Phoenix Division to produce vital aircraft components like cabin pressurization units, oil coolers, and intercoolers for bombers such as the B-17 and B-25, and later, cooling turbines for early jet aircraft like the P-80. Goodyear Aerospace also established a facility at what became Naval Air Facility Litchfield Park, building aircraft flight decks and testing aircraft. These industries not only contributed directly to the war effort but also laid the foundation for Phoenix’s future as a manufacturing and aerospace center. The arrival of Motorola in 1948 (some sources say 1949), establishing a research and development lab, marked the very beginning of the high-tech industry in Arizona, a pivotal moment that would profoundly shape the region’s economic landscape in the decades to come. This shift signaled that Phoenix’s economy was beginning to diversify beyond its agricultural and resource-based origins, driven by wartime necessities and strategic federal investments.

POW Camps and Home Front Efforts

While Phoenix skies buzzed with training aircraft, life on the ground was also profoundly shaped by World War II. The community actively participated in home front efforts, and the area became host to thousands of enemy prisoners of war.

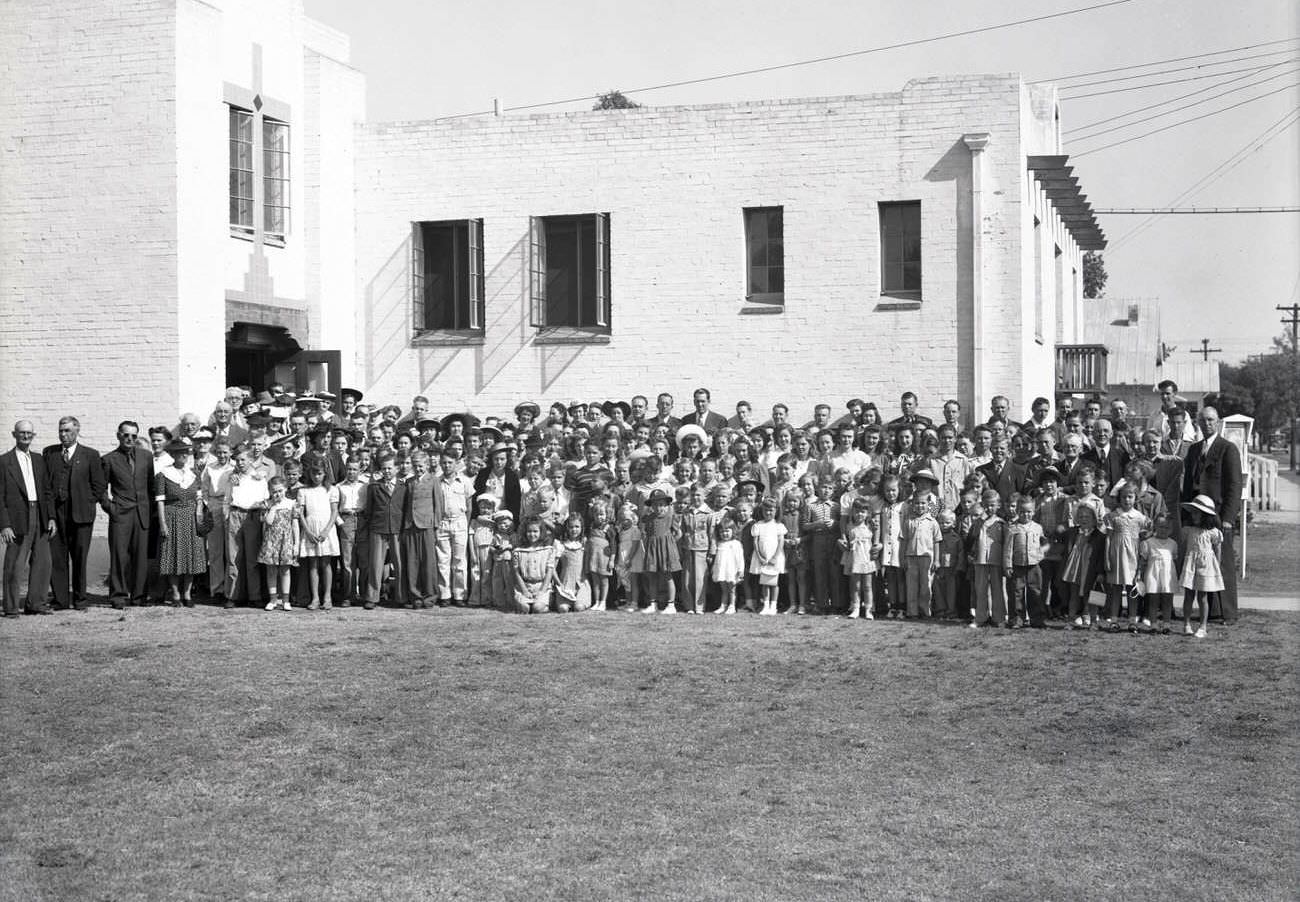

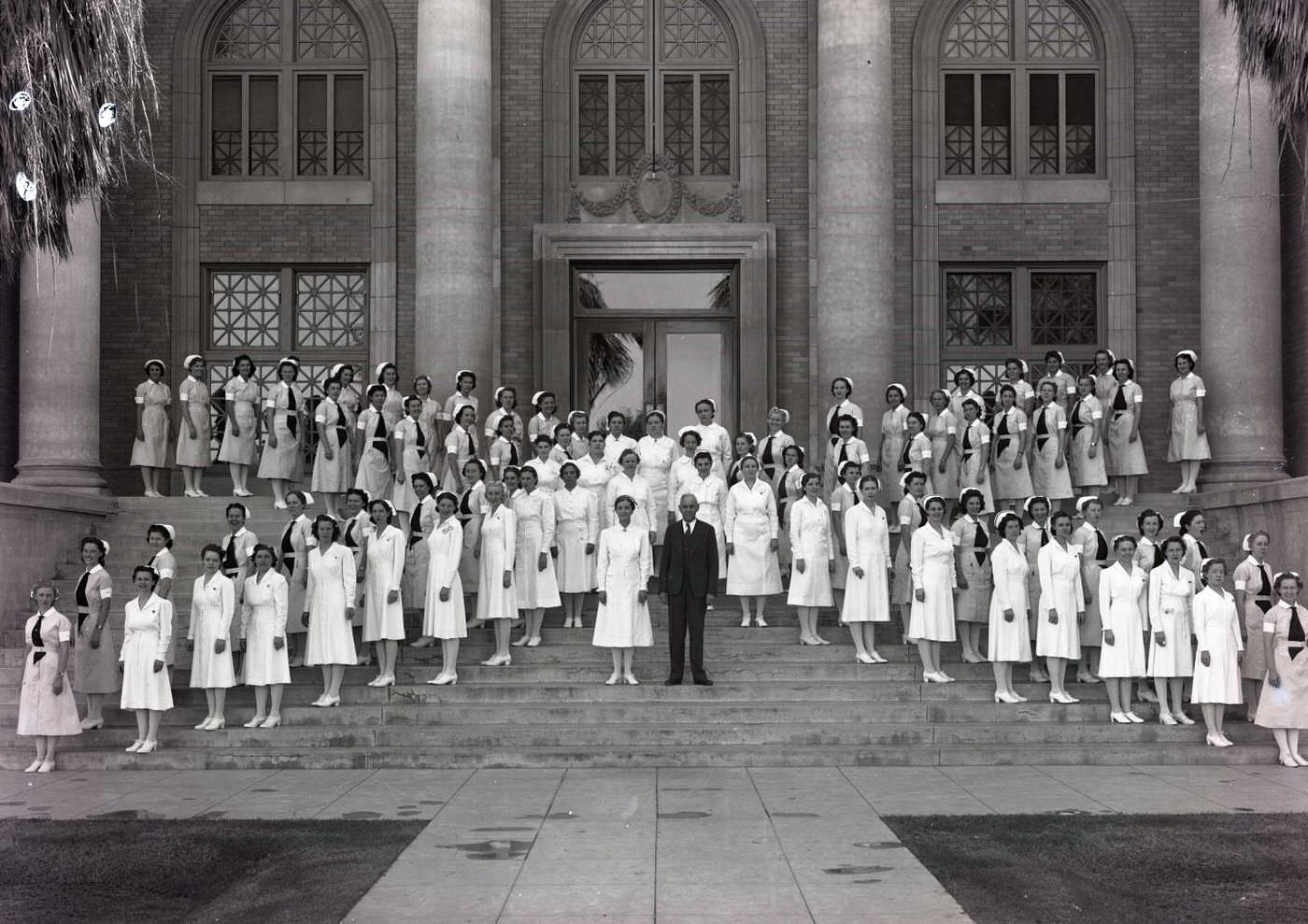

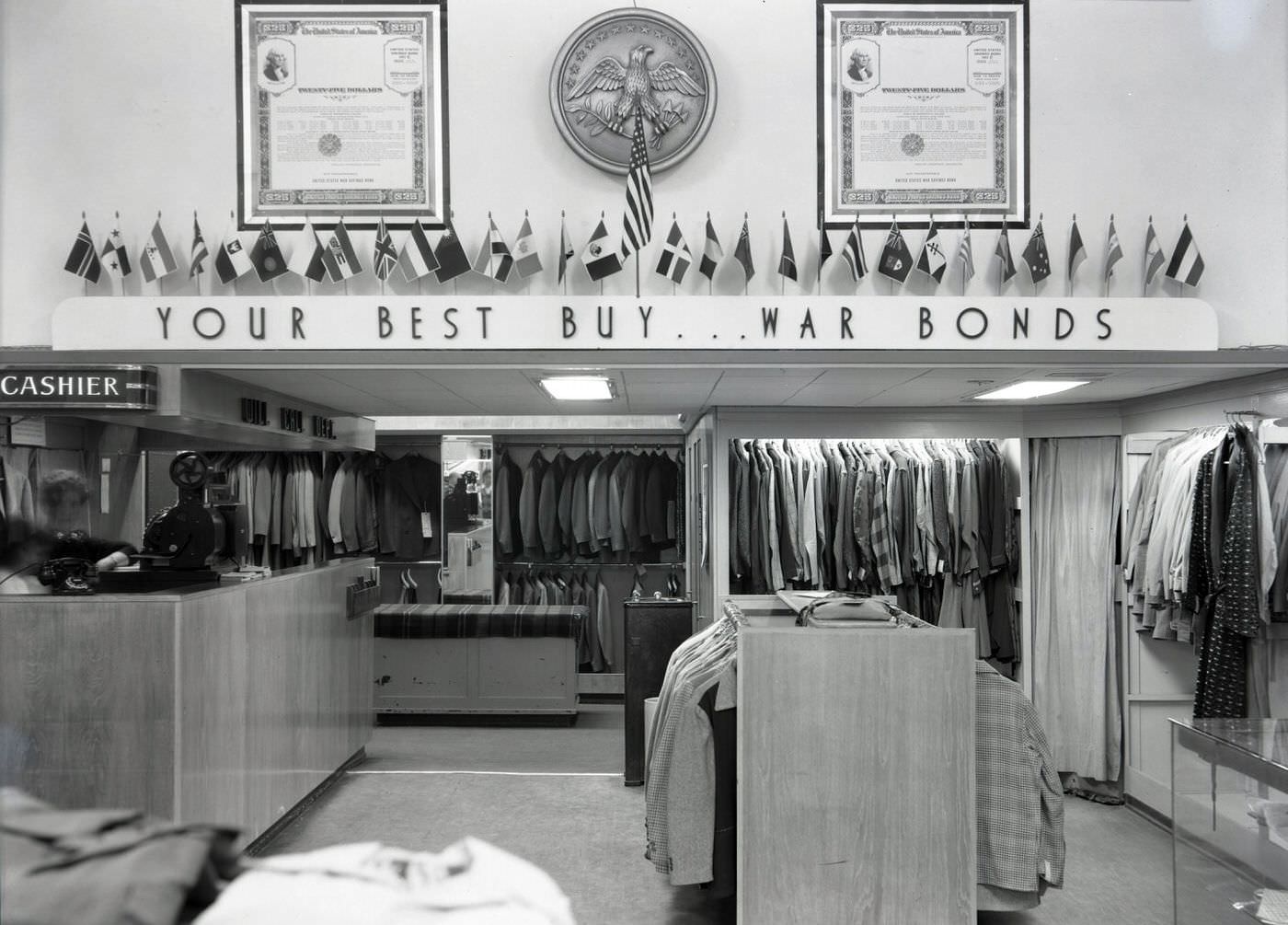

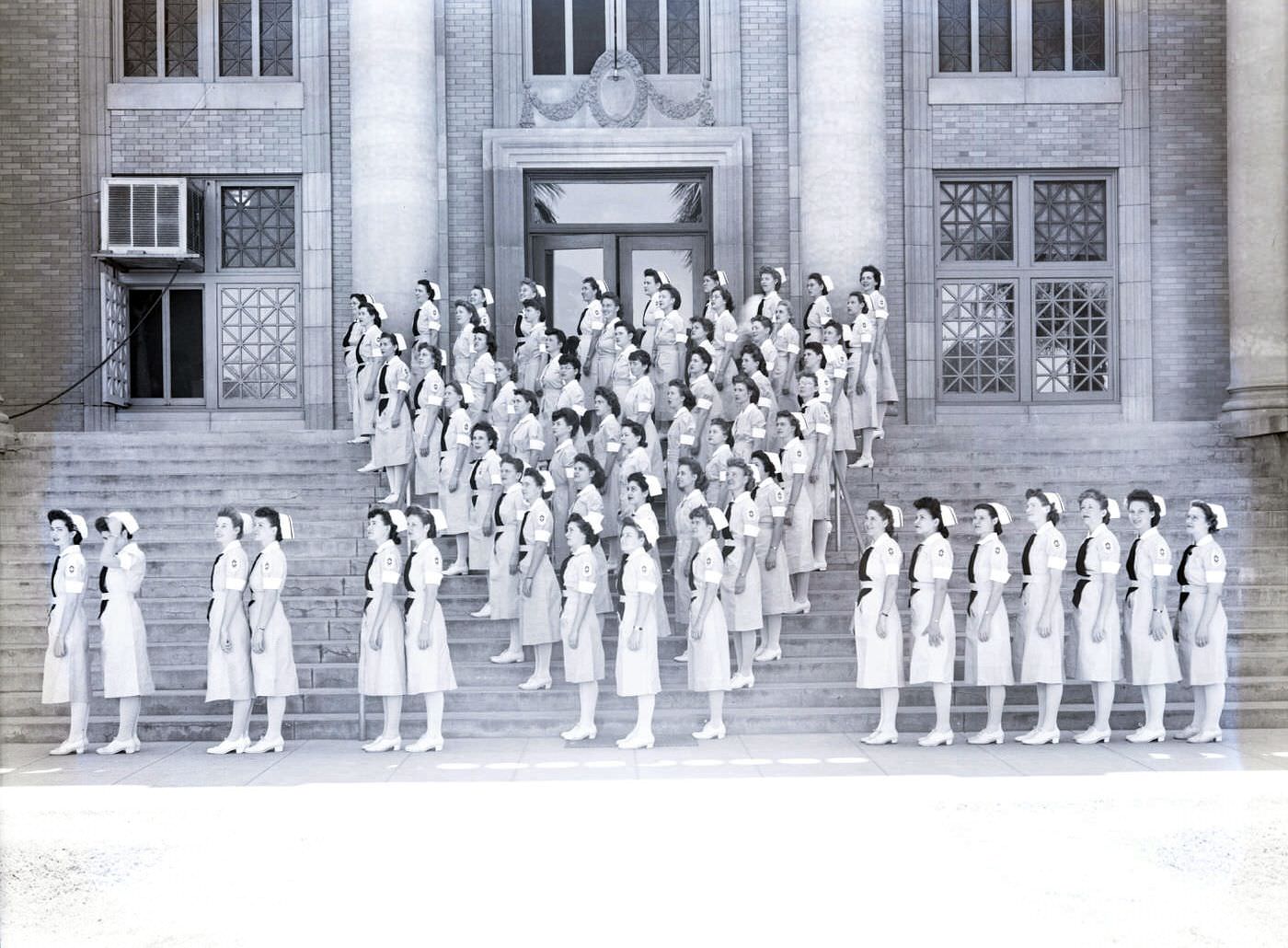

Residents of Phoenix, including its significant Mexican American community, engaged deeply in supporting the war. Activities such as rationing of food and materials became a part of daily life. People planted “victory gardens” in empty industrial lots and other available spaces, growing vegetables like lettuce, cabbage, and beets to supplement food supplies. War bond drives were common, with newspapers like El Sol even selling bonds at their offices. Women enlisted in various branches of the service, including the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAACs), WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), and the Army Nurses Corps. The Hispanic community organized dances, dinners, and lectures to show support for Latin American soldiers stationed near Phoenix. Newspapers carried announcements for selective service registration and honored local soldiers. Families displayed banners with blue stars, each star symbolizing a loved one serving in the armed forces, a poignant reminder of the personal stakes of the conflict.

Arizona’s vast, relatively isolated lands also made it a suitable location for Prisoner of War (POW) camps. One of the two main camps in Arizona was Camp Papago Park, located in eastern Phoenix. Originally built during World War I, it housed nearly 1,500 German and Italian POWs during World War II, many of whom were U-boat crew members. Conditions at Camp Papago Park were reportedly better than those in Axis POW camps; inmates were not required to work, though many chose to, earning 80 cents an hour in scrip for labor in cotton fields or fruit orchards. The camp had a theater for movies and a choir.

Despite these conditions, the desire for freedom led to escape attempts. The most famous was the “Great Papago Escape” in December 1944, when 25 POWs, including Kapitänleutnant Hans-Werner Kraus, tunneled out. They had dug a 176-foot tunnel through the hard clay, which softened when wet. While the escape itself was successful, the harsh desert terrain and vast distances proved too challenging for most, and many returned to the camp within weeks. Some escapees had even planned to raft down the Salt and Gila Rivers to Mexico, unaware that the rivers were often dry. The camp also witnessed tragedy, such as the murder of POW Werner Max Herschel Drechsler, who had reportedly shared German secrets with U.S. authorities, leading to the execution of seven men implicated in his death.

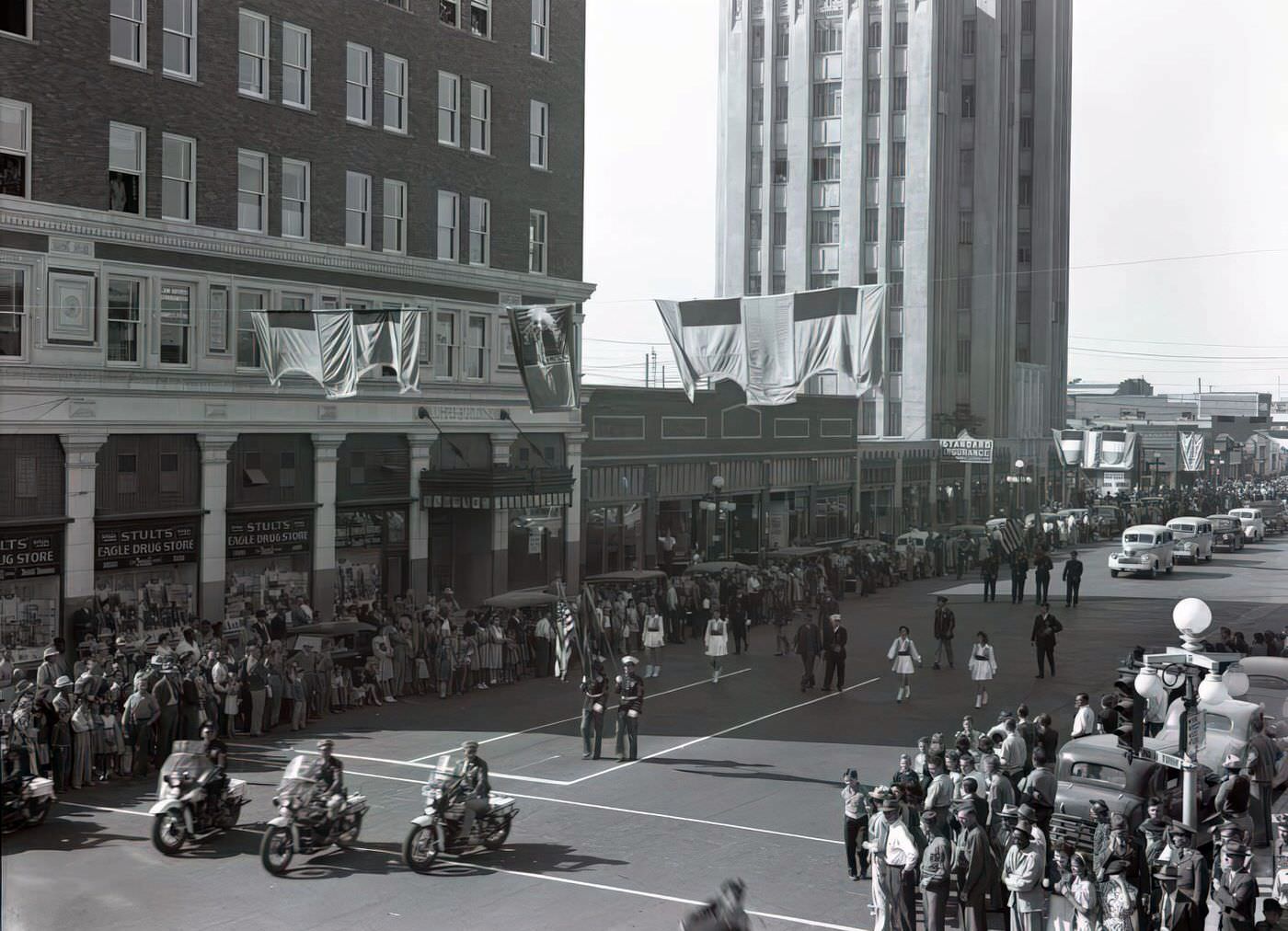

The personal stories from this era reflect both sacrifice and resilience. Silvestre Herrera, a Mexican immigrant who had worked on local farms, joined the U.S. Army despite not being a citizen, feeling it was his duty. He was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery by President Truman in 1945 and received a hero’s welcome in Phoenix, including a parade and a day named in his honor by Governor Sidney P. Osborn. In a display of community generosity, Phoenix residents raised $15,000 in 1946 to build a new home for the Herrera family. These individual and collective actions demonstrate the profound ways the war touched the lives of Phoenicians.

Shelter and Streets: Housing and Urban Change

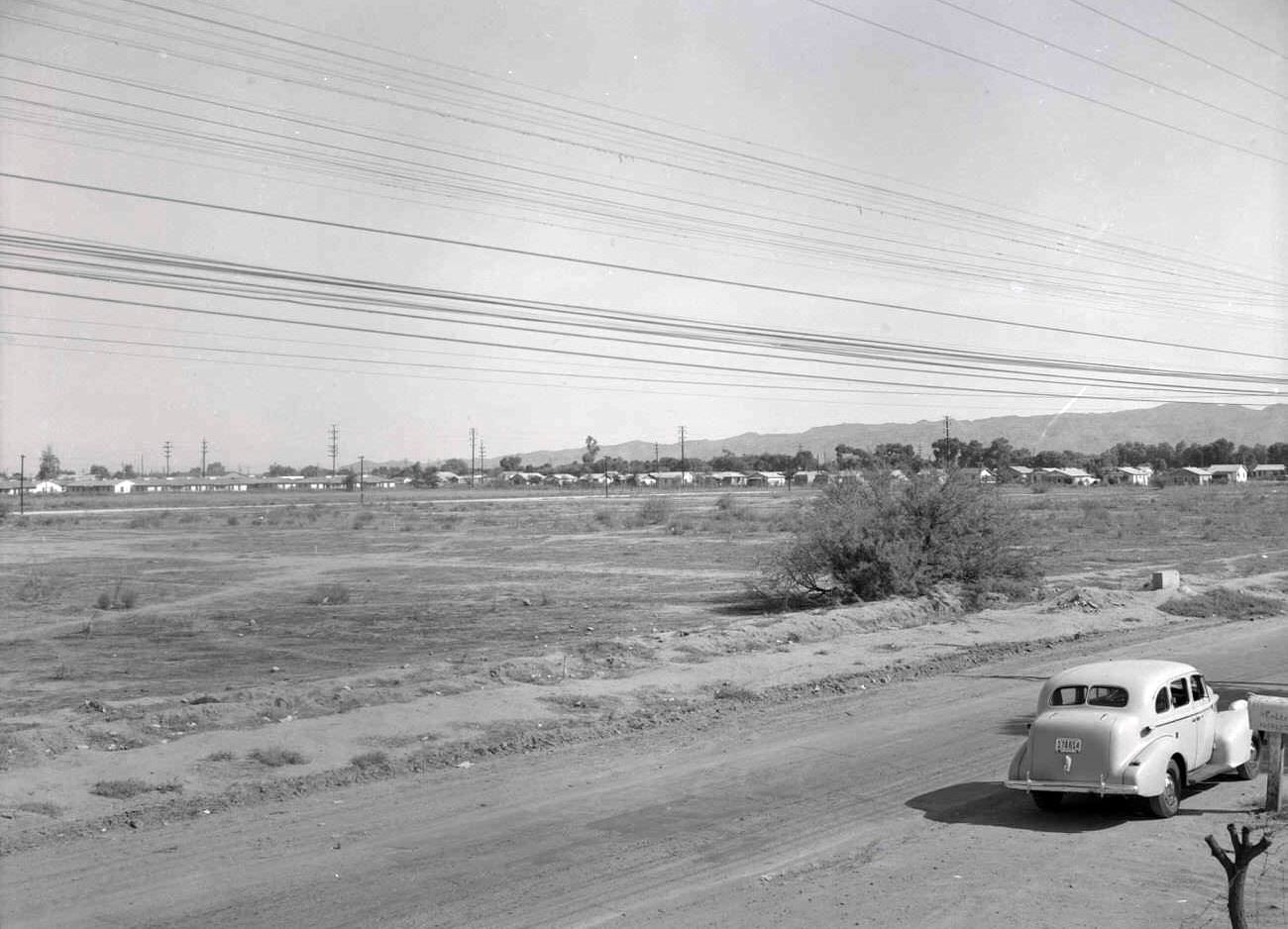

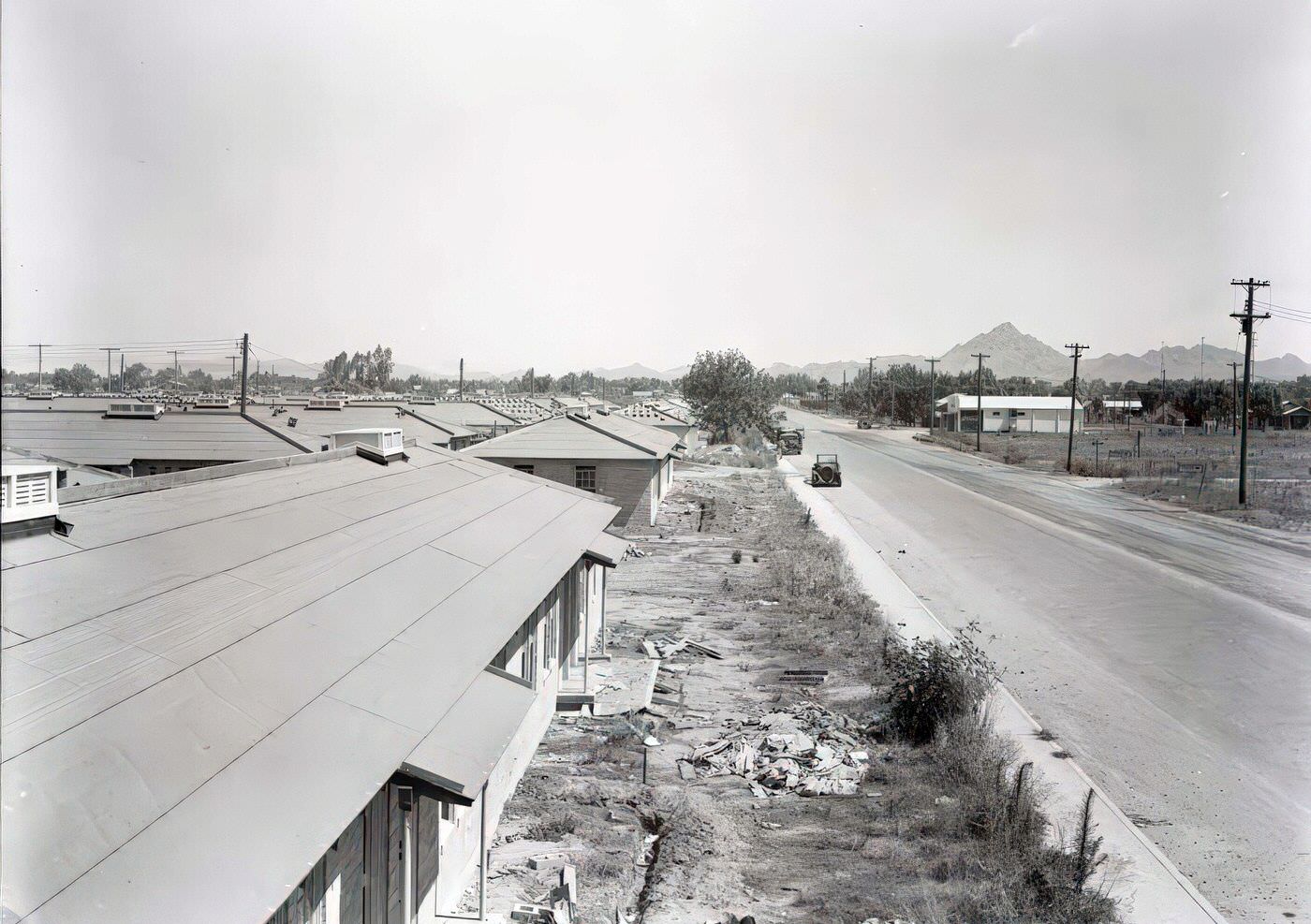

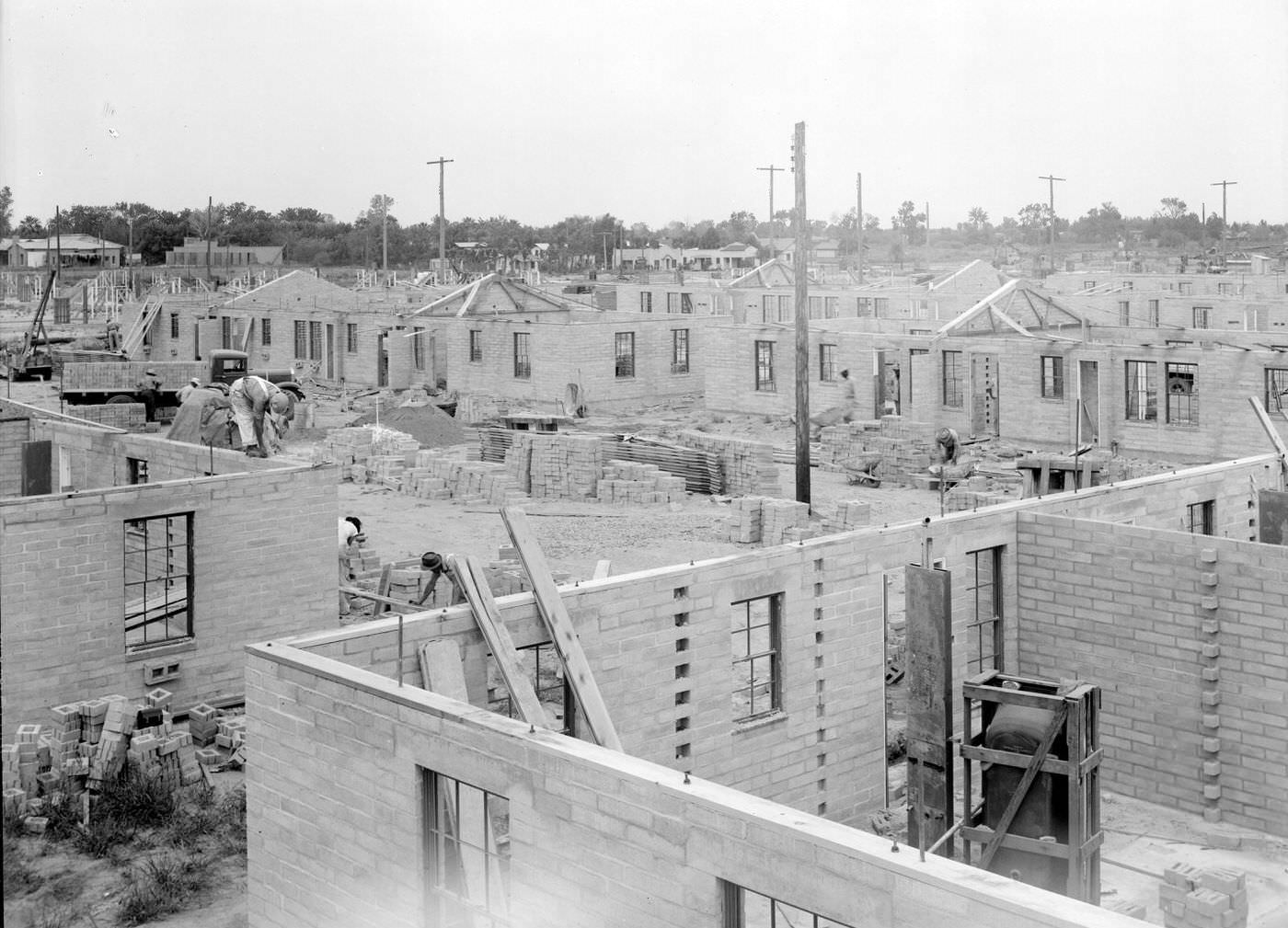

The 1940s brought a critical housing shortage to Phoenix, largely driven by the influx of defense workers and military personnel during World War II. New construction had been minimal during the Depression of the 1930s, and wartime material restrictions further limited building in the early part of the decade. As the population swelled, finding housing became increasingly difficult, and residents were often encouraged to take in boarders to alleviate the strain.

To address this crisis, several initiatives were undertaken, often with federal support. The Phoenix Housing Authority (PHA), established in 1939 under the leadership of Father Emmett McLoughlin, utilized funds from the Wagner Steagall Act of 1937 to construct public housing projects in 1941. These projects, however, were explicitly segregated: the Marcos de Niza Project was built for Mexican Americans (initially 225 homes), the Matthew Henson Project for African Americans, and the Frank Luke Project for Anglos. While these developments provided improved living conditions with amenities like electricity and heat, they also reinforced the city’s racial divisions by design. Phoenix property developers also leveraged liberal federal housing programs to build large-scale apartment housing for the growing number of defense workers and their families.

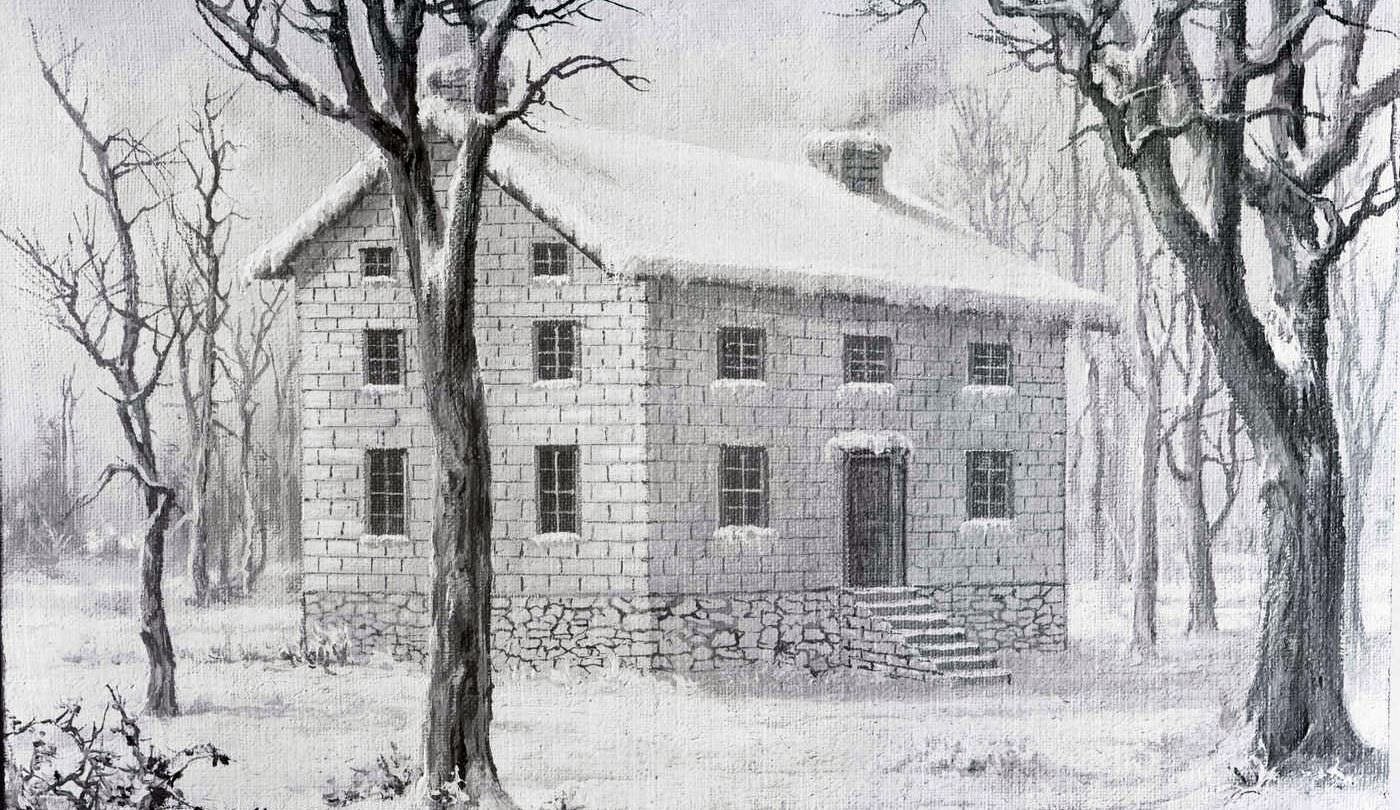

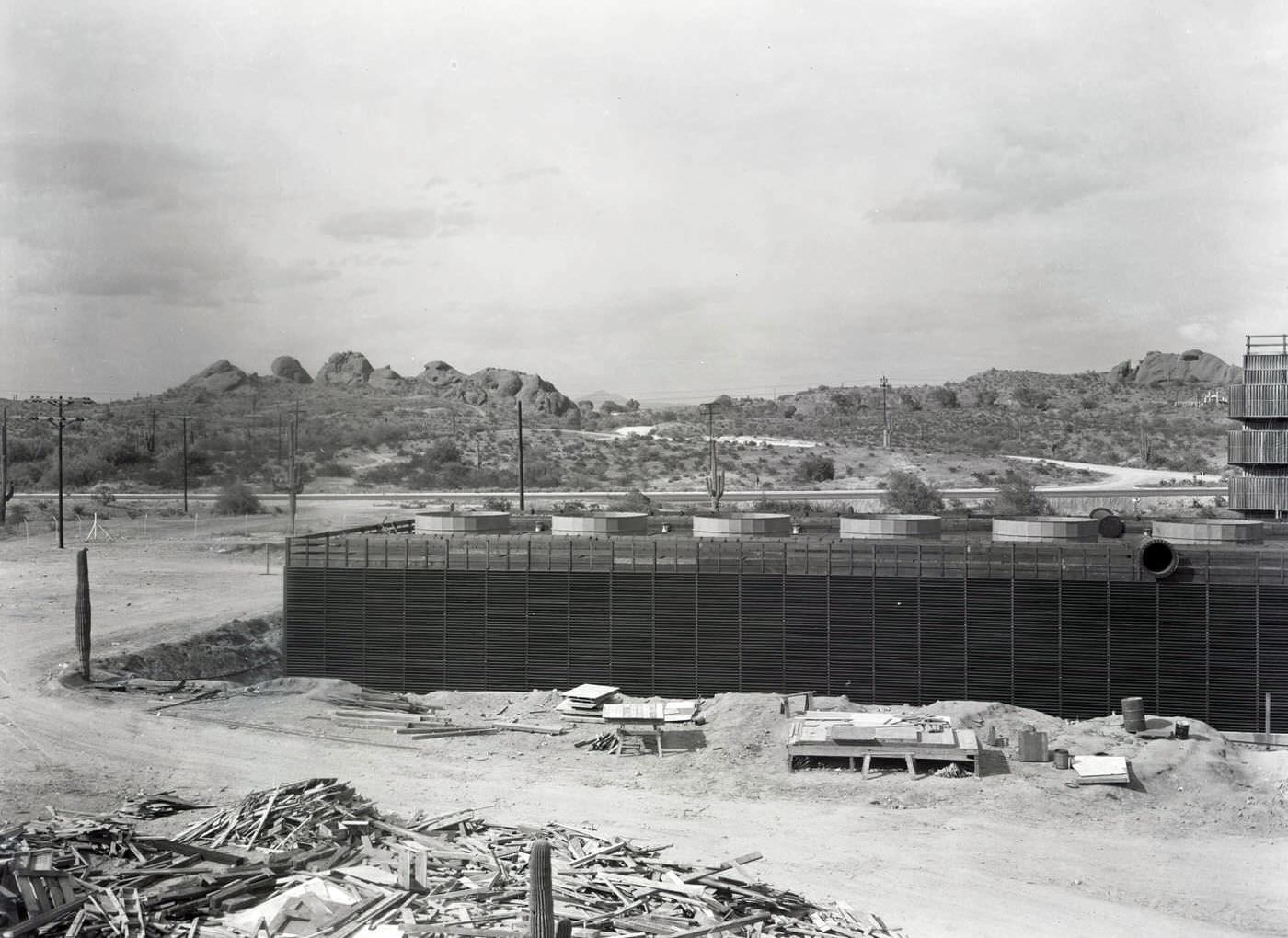

An innovative, albeit limited, approach to wartime housing emerged in Litchfield Park at the Wigwam Resort. Between 1942 and 1944, architect Wallace Neff designed and built four “Bubble Houses”. These unique monolithic dome structures were created by spraying concrete over large, inflatable Goodyear balloons, which were then deflated and removed. Intended as alternative wartime housing, they showcased an inventive use of materials and construction techniques during a period of scarcity.

A Divided City: Segregation and Social Realities

Phoenix in the 1940s was a city marked by deep-seated racial and ethnic segregation, a system that affected nearly every aspect of daily life for its minority populations. This was not merely a matter of social custom; it was often reinforced by official policies and practices, creating a multi-layered structure of exclusion.

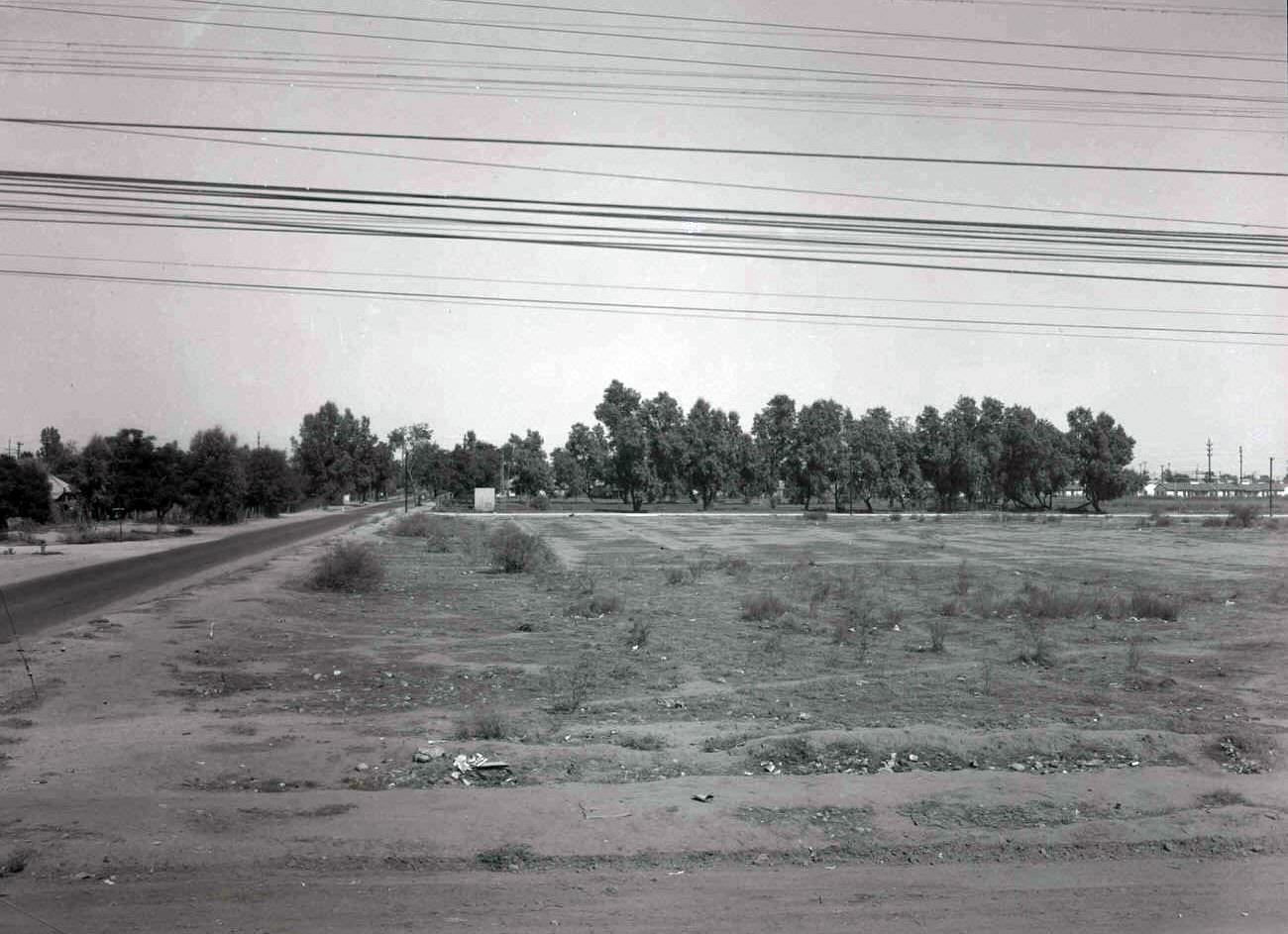

A prominent feature of this segregation was the “color line,” often identified with Van Buren Street. African American and Hispanic residents were generally prohibited from buying property or living north of this line. Federal programs like the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created national standards for property values that considered the racial profile of neighborhoods, effectively redlining areas with “detrimental races and nationalities,” which in Phoenix included African Americans and Mexican Americans. This spatial segregation concentrated minority groups south of Van Buren Street, often in areas with substandard housing and fewer city services. For instance, the El Campito neighborhood in 1947 was described as primarily mesquite trees and dirt paths, lacking paved streets or sidewalks, a condition common in many barrios until the 1950s.

Public schools were legally segregated for African Americans from 1910 to 1953. Phoenix Union High School had a separate campus, George Washington Carver High School, for its Black students. School district boundaries were sometimes adjusted to conform to the “colors of students served by schools”.

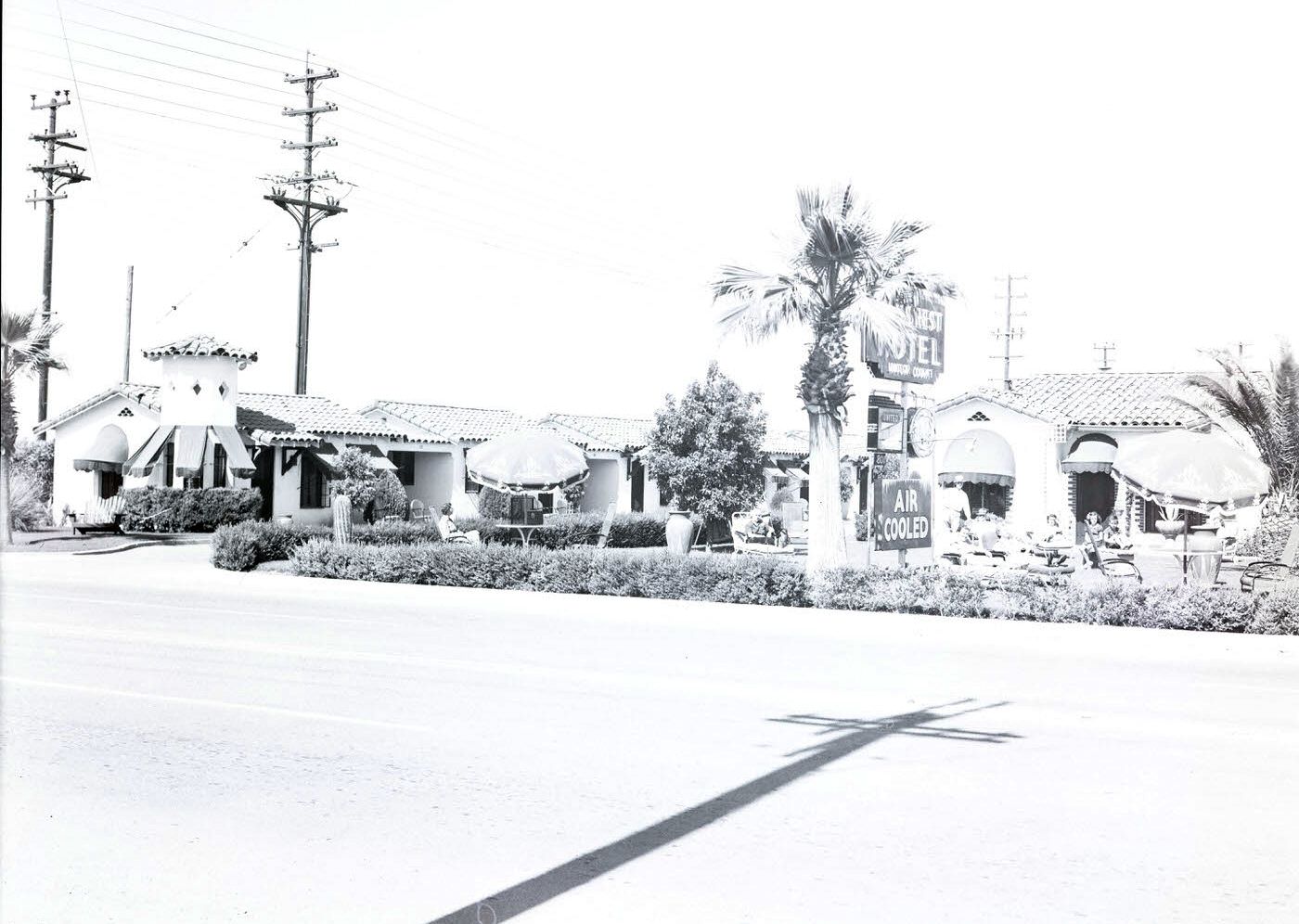

Access to public accommodations was also severely restricted. Many hotels, motels, restaurants, and theaters either refused service to Black customers or provided segregated facilities, such as requiring them to sit in theater balconies. The downtown Woolworth’s store, for example, would sell merchandise to Black patrons but did not permit them to sit at its lunch counter. To navigate these discriminatory conditions, African American travelers relied on resources like The Negro Motorist Green Book. This guide listed businesses willing to serve Black clientele, which in Phoenix were predominantly located in the Eastlake Park district, a historically African American neighborhood. Notable “Green Book” establishments included the Raymond Hotel and the Rice Hotel on East Jefferson Street, the latter having hosted famous figures such as musicians Louis Armstrong and Lionel Hampton, and baseball player Jackie Robinson.

The Mexican American community, which nearly doubled in population between 1940 and 1950 yet remained about 15% of the city’s total, also faced significant prejudice and discrimination. Signs explicitly stating “No Mexican Trade Wanted” were present in some Phoenix business establishments. Despite these hardships, the community demonstrated remarkable resilience. They maintained strong cultural traditions within their barrios and began to organize for better treatment and civil rights. After World War II, young Phoenix Hispanics, influenced by their wartime experiences, started to call for greater inclusion and equal treatment. A significant victory occurred in 1946 when the American Legion Post 41, composed of Hispanic members, successfully challenged housing segregation by advocating for the integration of a veterans’ housing development, which became the Harry Cordova Housing Project.

Native Americans faced their own form of legal discrimination. Even though President Calvin Coolidge had granted all indigenous tribal members American citizenship in 1924, they were barred from voting in Arizona elections until the Arizona Supreme Court ruling in Harrison and Austin v. Laveen in 1948. This case was brought forward by two Native American World War II veterans, highlighting the injustice faced by those who had served their country yet were denied basic democratic rights.

The pervasive nature of this segregation profoundly shaped Phoenix’s urban geography and the daily experiences of its residents. The “color line” was more than a guideline; it was a barrier that dictated access to housing, education, and economic opportunity, creating deep divisions within the city that would have lasting consequences. However, the decade also saw the emergence of resistance and activism within minority communities, laying the groundwork for future civil rights struggles.

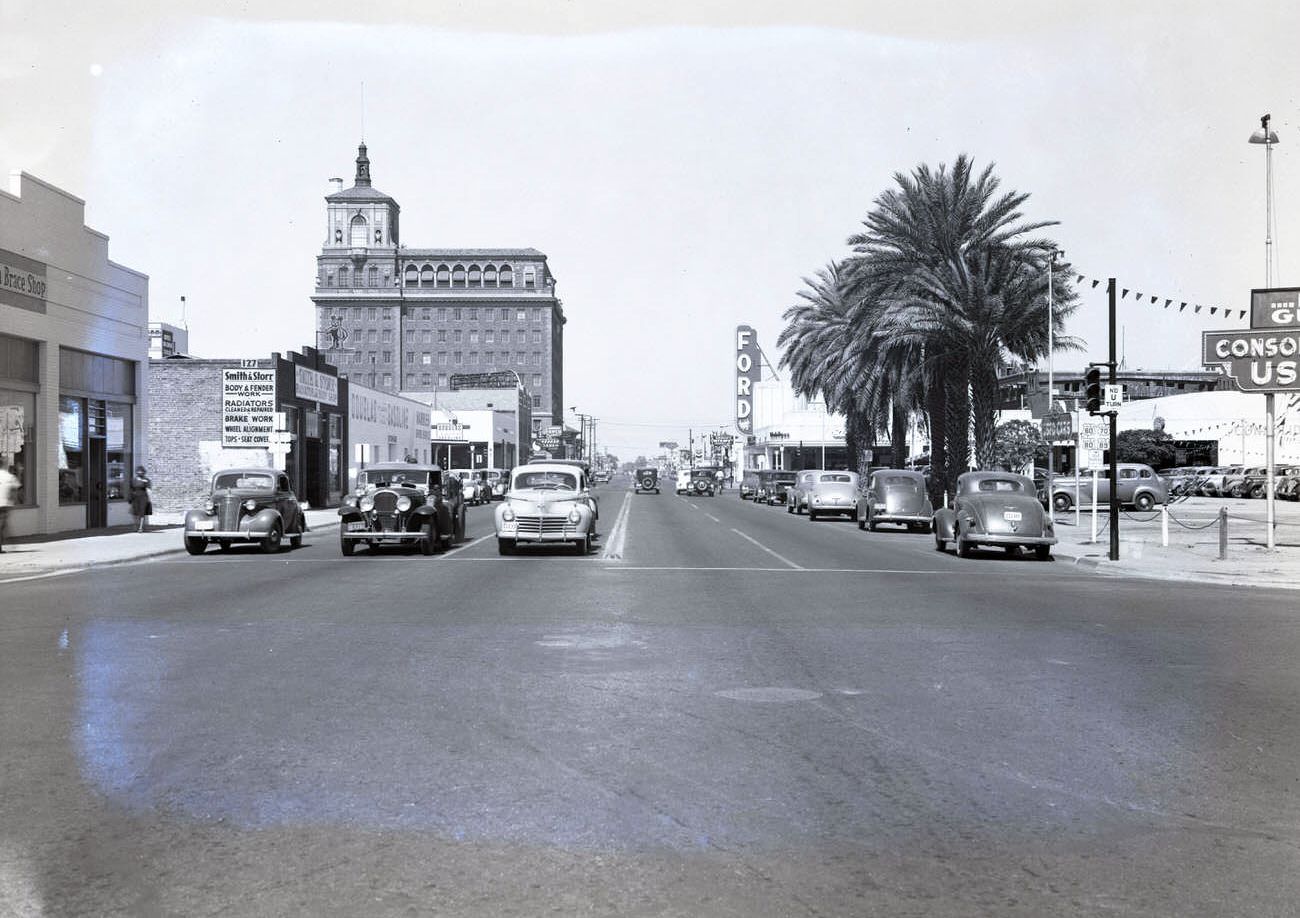

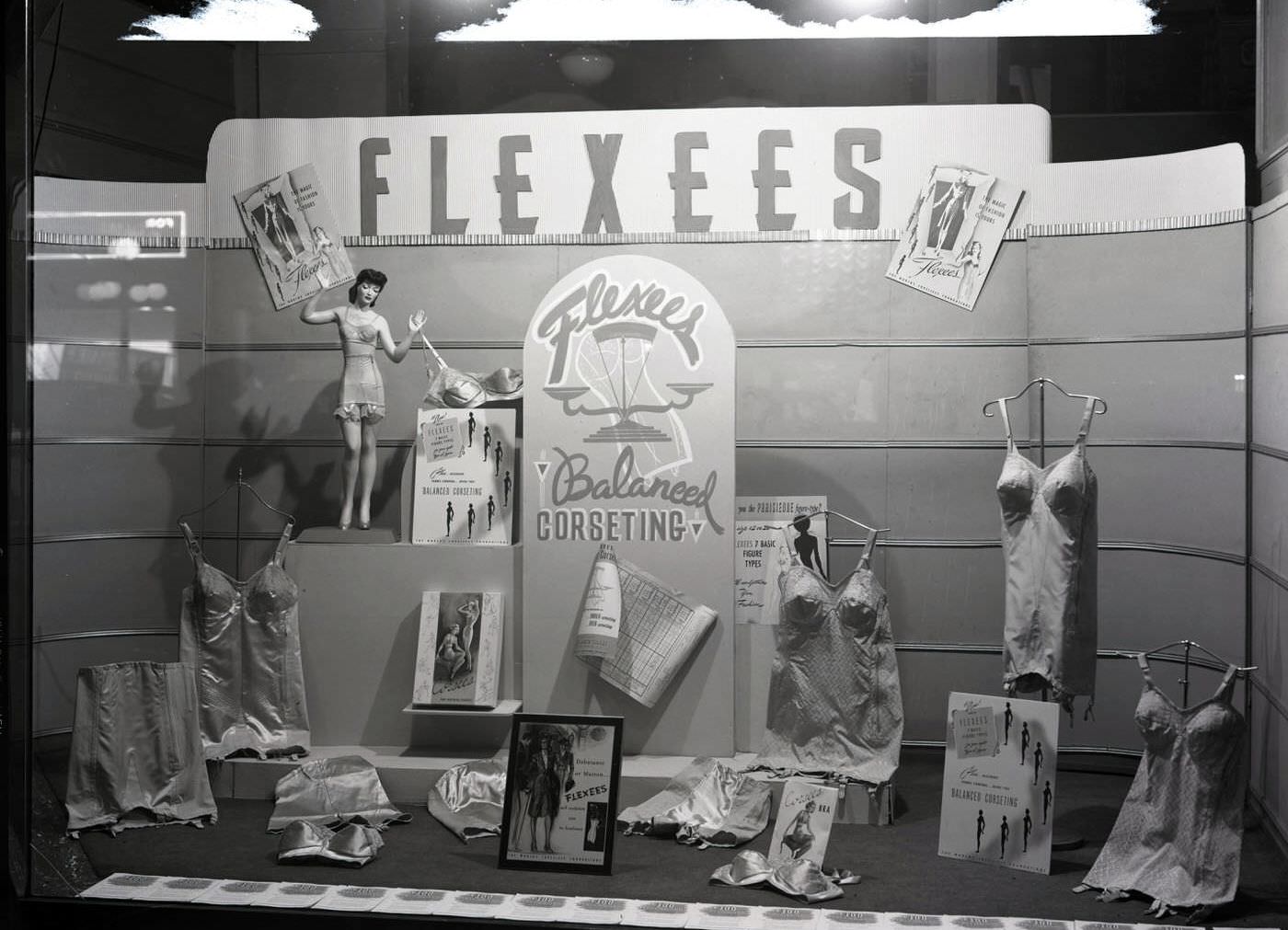

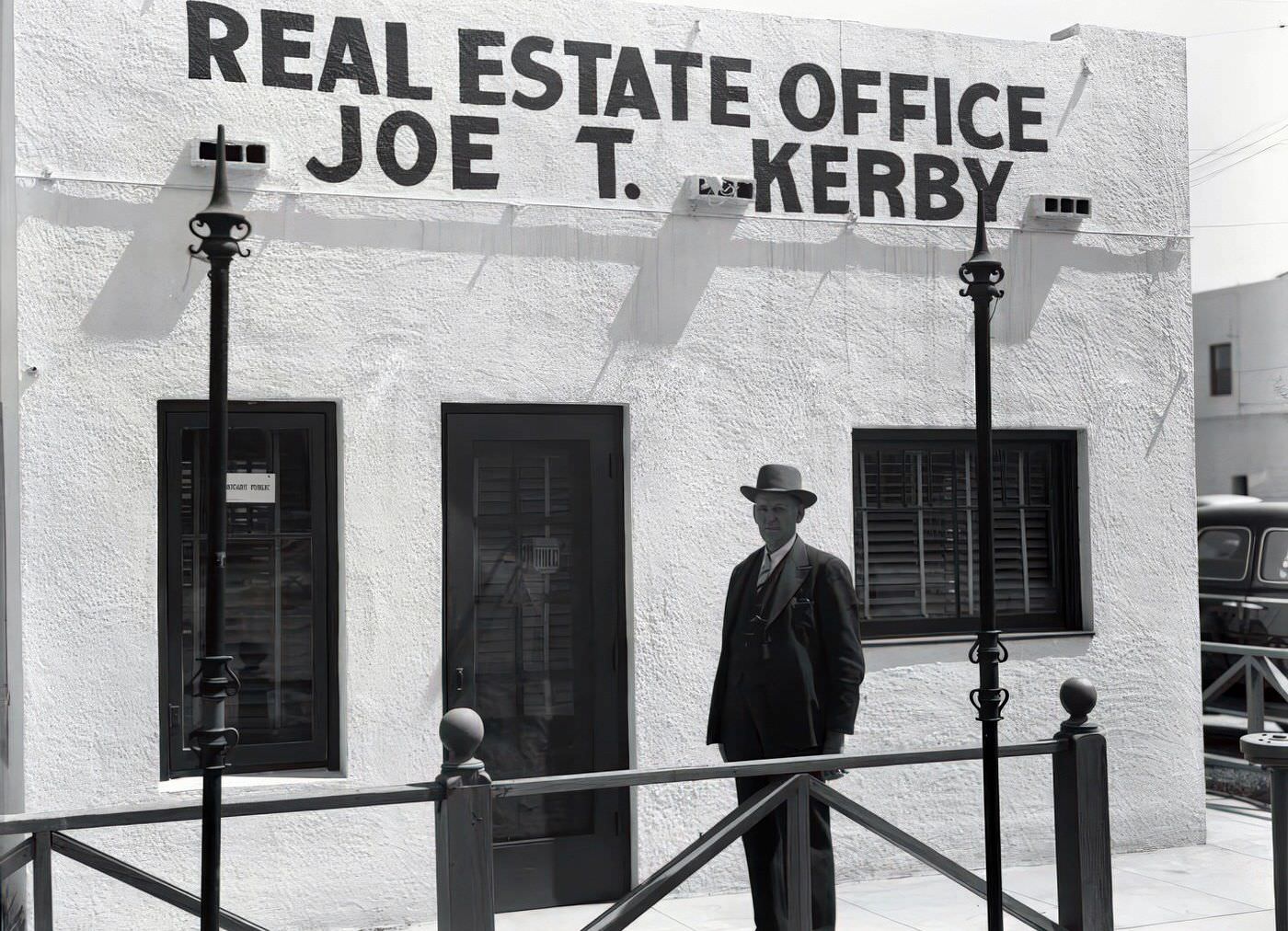

Downtown Phoenix remained the city’s vibrant commercial core throughout the 1940s. Washington Street was lined with local department stores such as Diamond’s (which was renamed from The Boston Store in 1947), Goldwater’s, and Korrick’s, alongside national chains like Sears, Montgomery Ward, and Penney’s. A shift towards modern commercial architecture began to appear late in the decade. Hanny’s Department Store, specializing in men’s fashion, opened in 1947 with a distinctive International Style facade designed by the architectural firm Lescher and Mahoney, heralding a new aesthetic for downtown businesses. This period, up to 1947, was characterized as “Mature Urban Center Development,” a time when commercial specialization and marketing approaches were undergoing significant changes. Following World War II, there was a growing tendency to disregard pre-war commercial architectural styles as Phoenix began to envision itself as a thoroughly “modern” city.

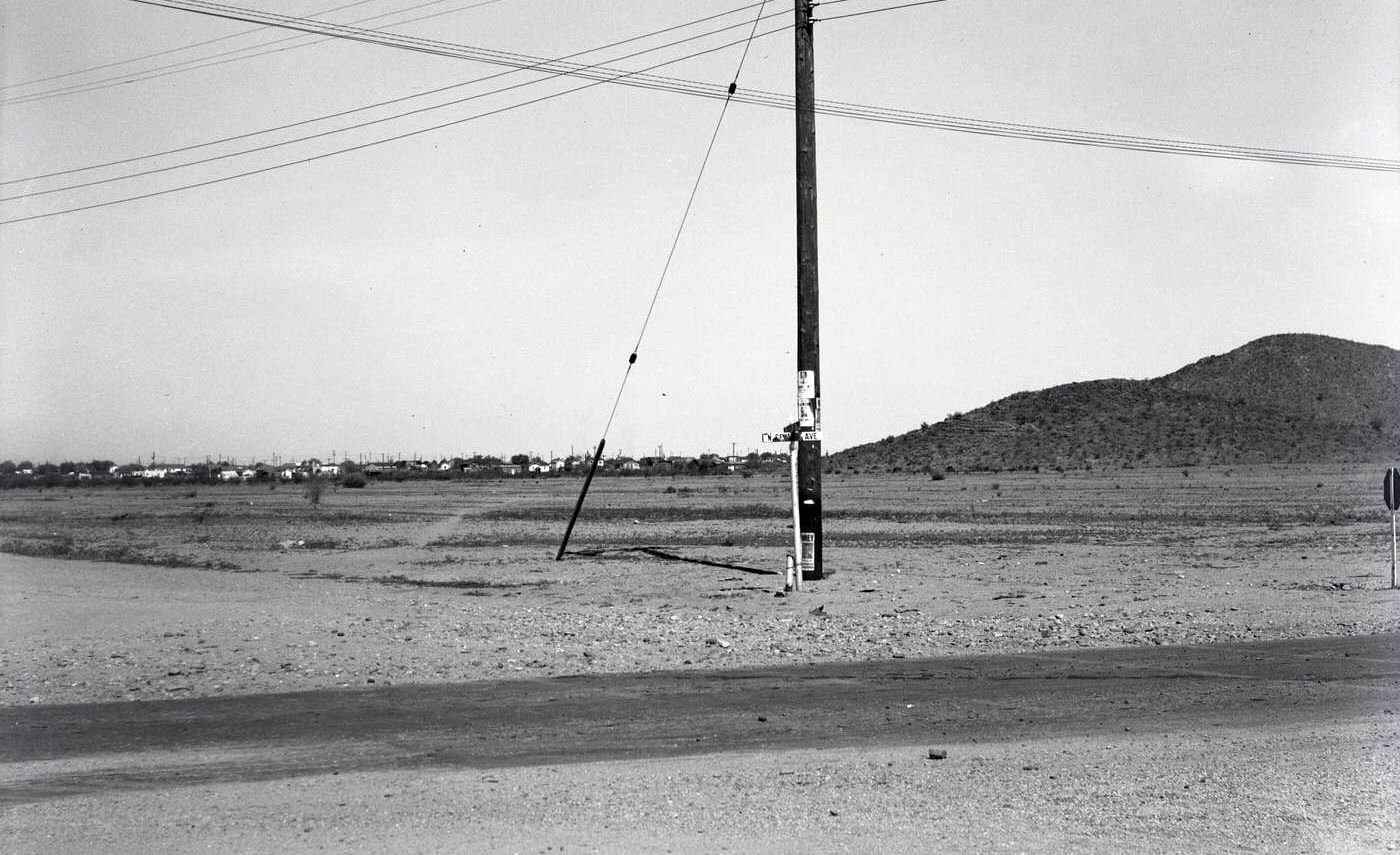

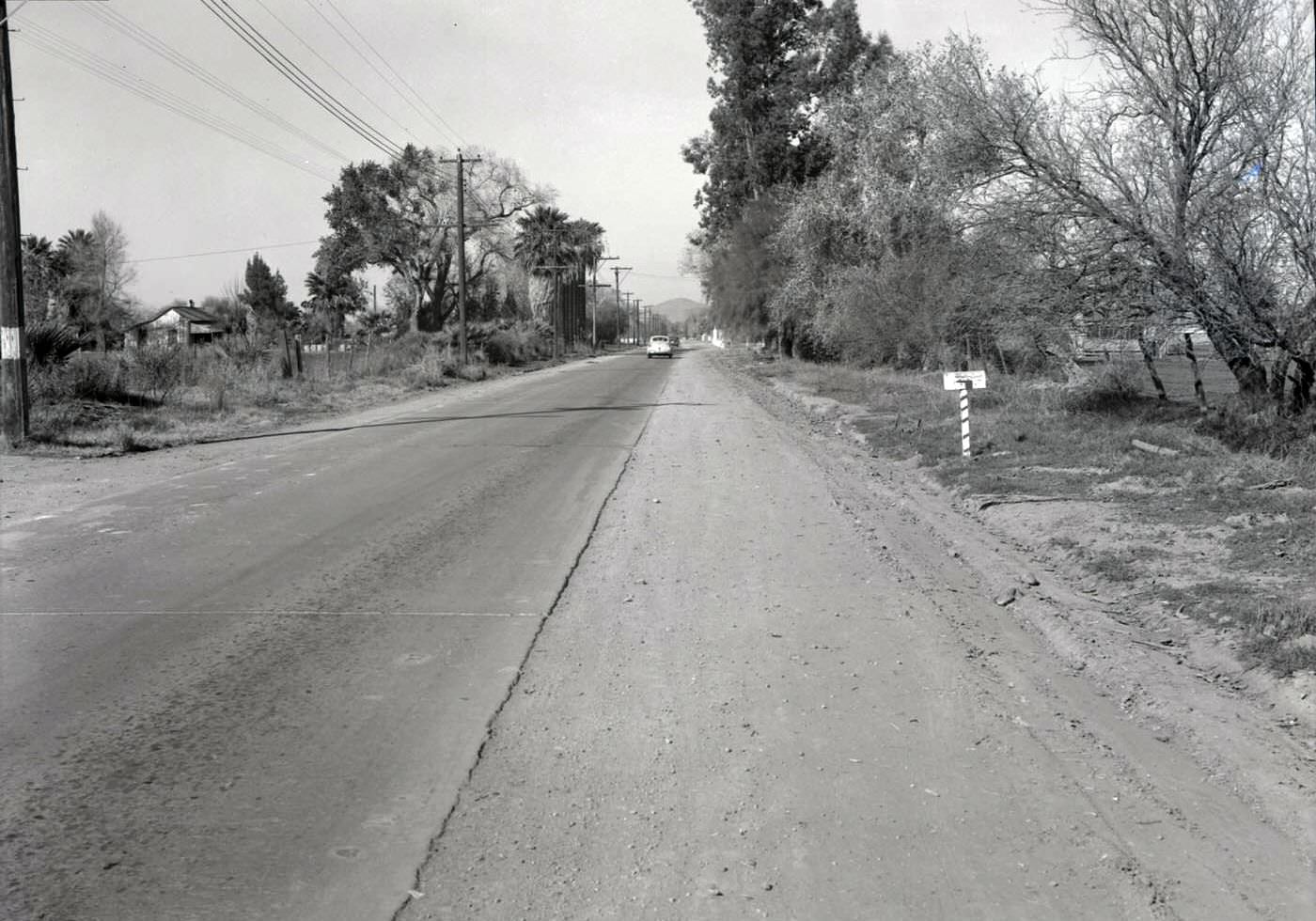

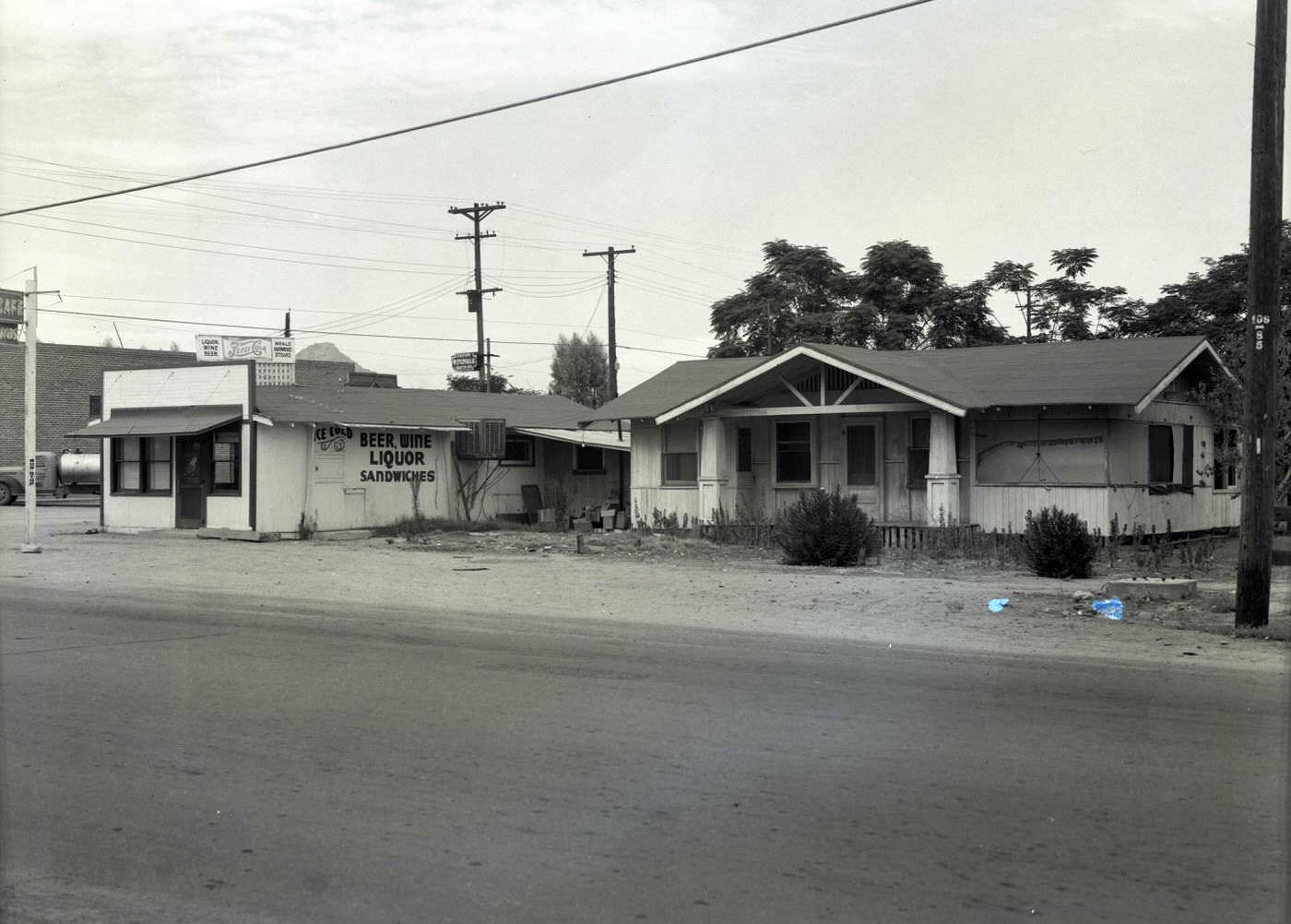

Transportation within Phoenix also underwent a fundamental transformation. The electric streetcar system, which had been a mainstay of urban transit, started its decline in the 1940s. This decline was dramatically accelerated on October 3, 1947, when a catastrophic fire at the car barn destroyed most of the streetcar fleet. Faced with the decision to rebuild the system or switch to a different mode of transport, city officials opted for buses. Streetcar service was officially abandoned in February 1948. By this time, the impact of the automobile on the city’s form was becoming increasingly evident. Commercial development began to spread along major arterial roads like Van Buren Street, 17th Avenue, Buckeye Road, and Grand Avenue, catering to the automotive public. This shift away from mass transit toward private vehicles would profoundly influence Phoenix’s future development, encouraging outward expansion and a car-dependent layout.

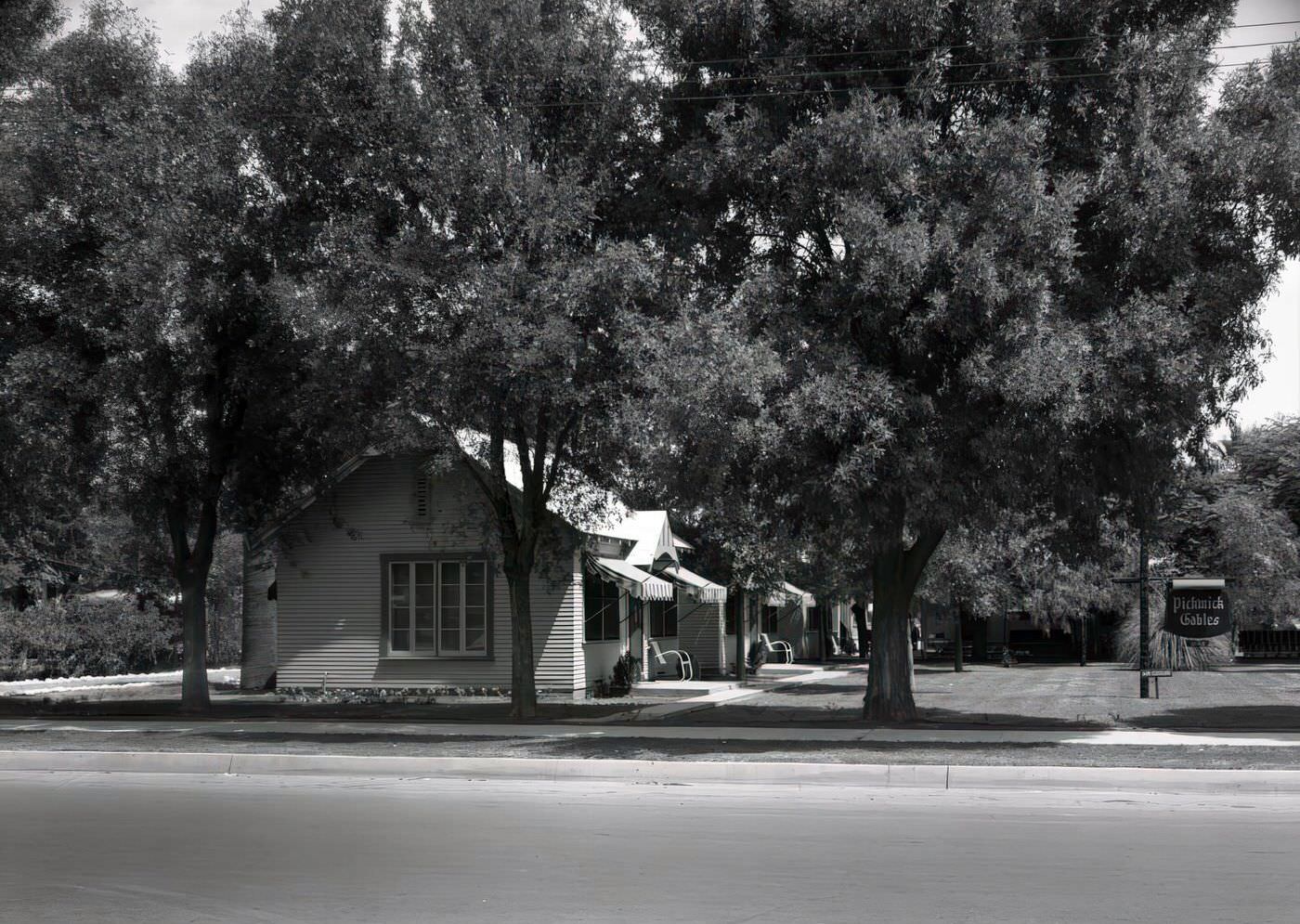

Residential growth patterns also reflected these changes. While older subdivisions such as Roosevelt, Encanto, Alvarado, and Coronado, known for their historic homes and landscaping features like palm and orange trees, remained largely intact, new developments were emerging. The establishment of Phoenix College’s new campus in 1939 spurred nearby residential construction, like the College Addition subdivision. These new areas often reflected Federal Housing Administration (FHA) guidelines, which favored features like curvilinear streets and mandated city utilities. FHA financing was extensively used for new home construction throughout the 1940s, both before and particularly after the war. Post-war, the availability of FHA and Veterans Administration (VA) loans fueled a significant building boom, filling in remaining lots in existing tracts and creating new subdivisions. Multi-family housing, especially low-density properties like duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and one-story garden courts, became a common feature of the post-war housing landscape, catering to the needs of the rapidly growing population. The federal government’s housing policies thus played a direct role in shaping the physical layout and character of Phoenix’s expanding neighborhoods.

Learning, Leisure, and Local Voices

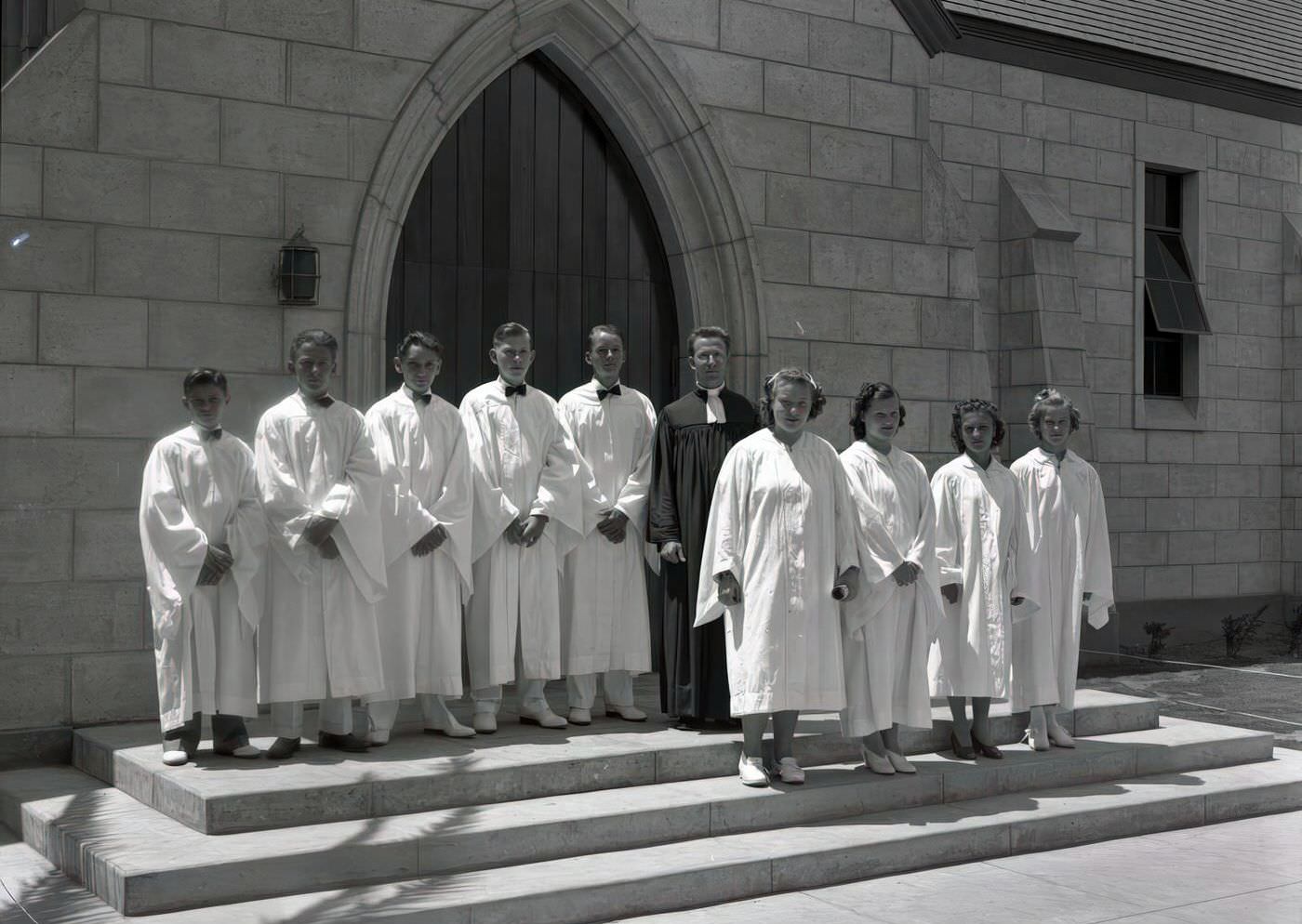

The 1940s in Phoenix saw developments in education, an array of entertainment and media options, and a growing community and cultural life, all set against the backdrop of wartime and post-war adjustments.

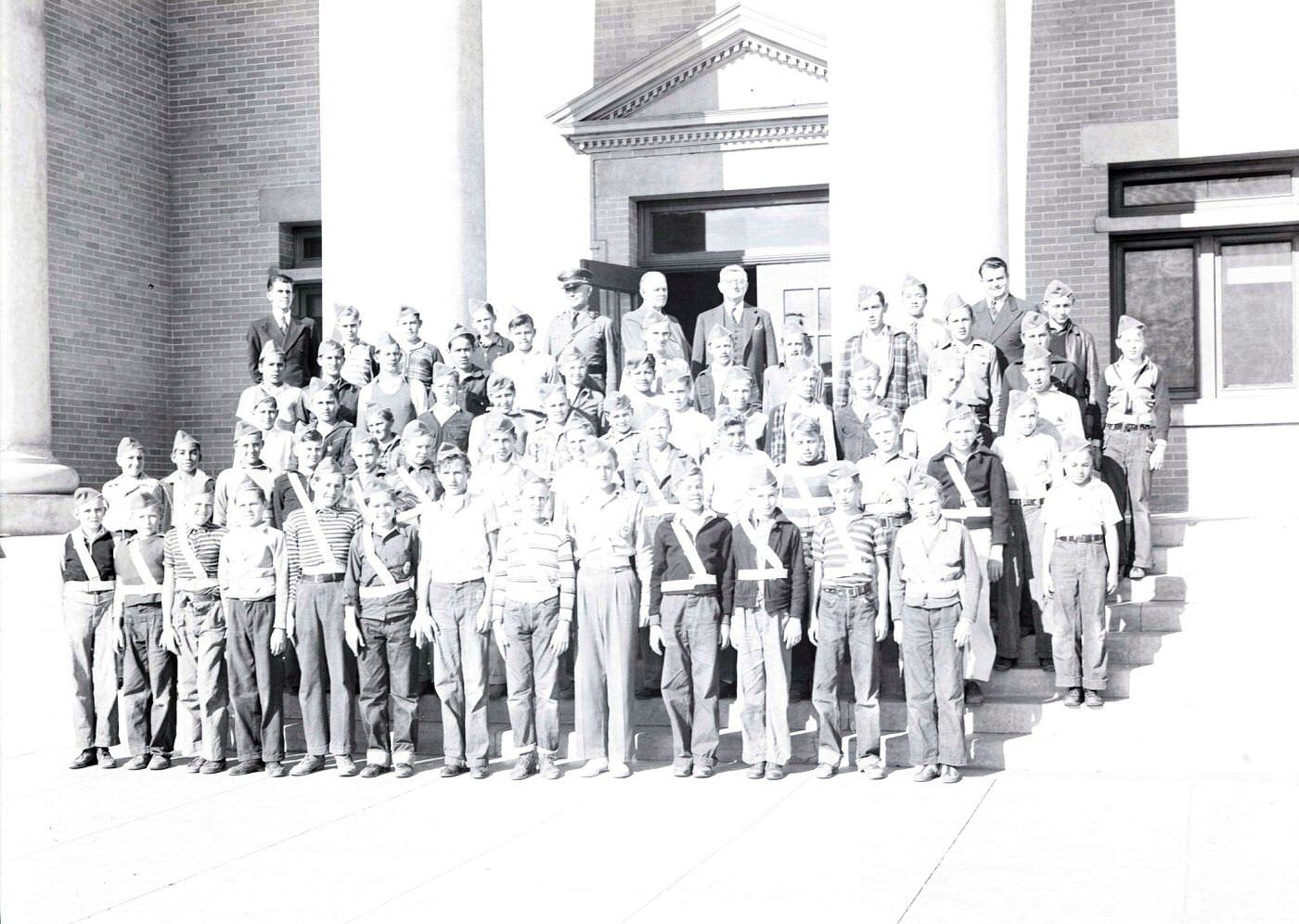

In education, Phoenix Elementary School District #1 continued with a curriculum heavily influenced by agriculture, and girls were primarily trained for homemaking roles. World War II brought significant challenges, including teacher shortages as women moved into other occupations, leading to large class sizes often exceeding 40 students. Schools operated under the “Platoon System” and incorporated wartime activities like air raid drills and victory gardens into their routines. John D. Loper, who served as superintendent from 1909 to 1944, provided a measure of stability during these turbulent years. High school students attended Phoenix Union High School, the newly built North High School (a WPA project), or the segregated George Washington Carver High School for African American students. It was during this era that cruising on Central Avenue reportedly became a popular pastime for students from different schools. At the higher education level, Phoenix Junior College (PJC) dedicated its new Thomas Road campus in January 1940. During the war, PJC offered a Civilian Pilot Training program, converting its gym into barracks for enlistees. Notably, PJC was not a segregated institution. Arizona State Teachers College (ASTC) in Tempe began offering its first graduate degree, a Master’s in Education, in 1937. In a significant step, ASTC became Arizona State College in 1945 and was authorized to grant bachelor’s degrees, broadening its educational mission. ASTC also hosted an Army Air Corps College Training Program, with flight instruction conducted at Sky Harbor Airport.

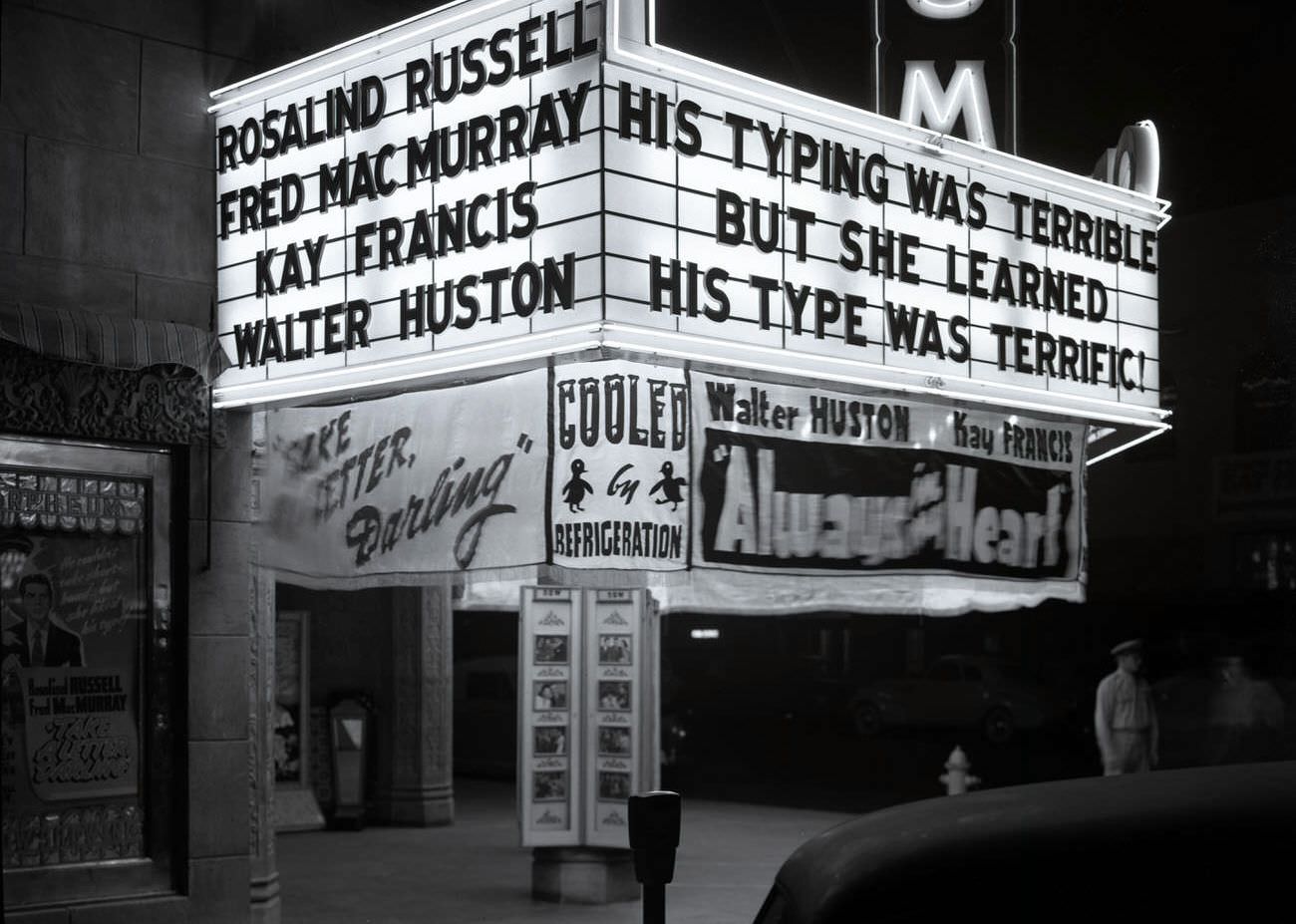

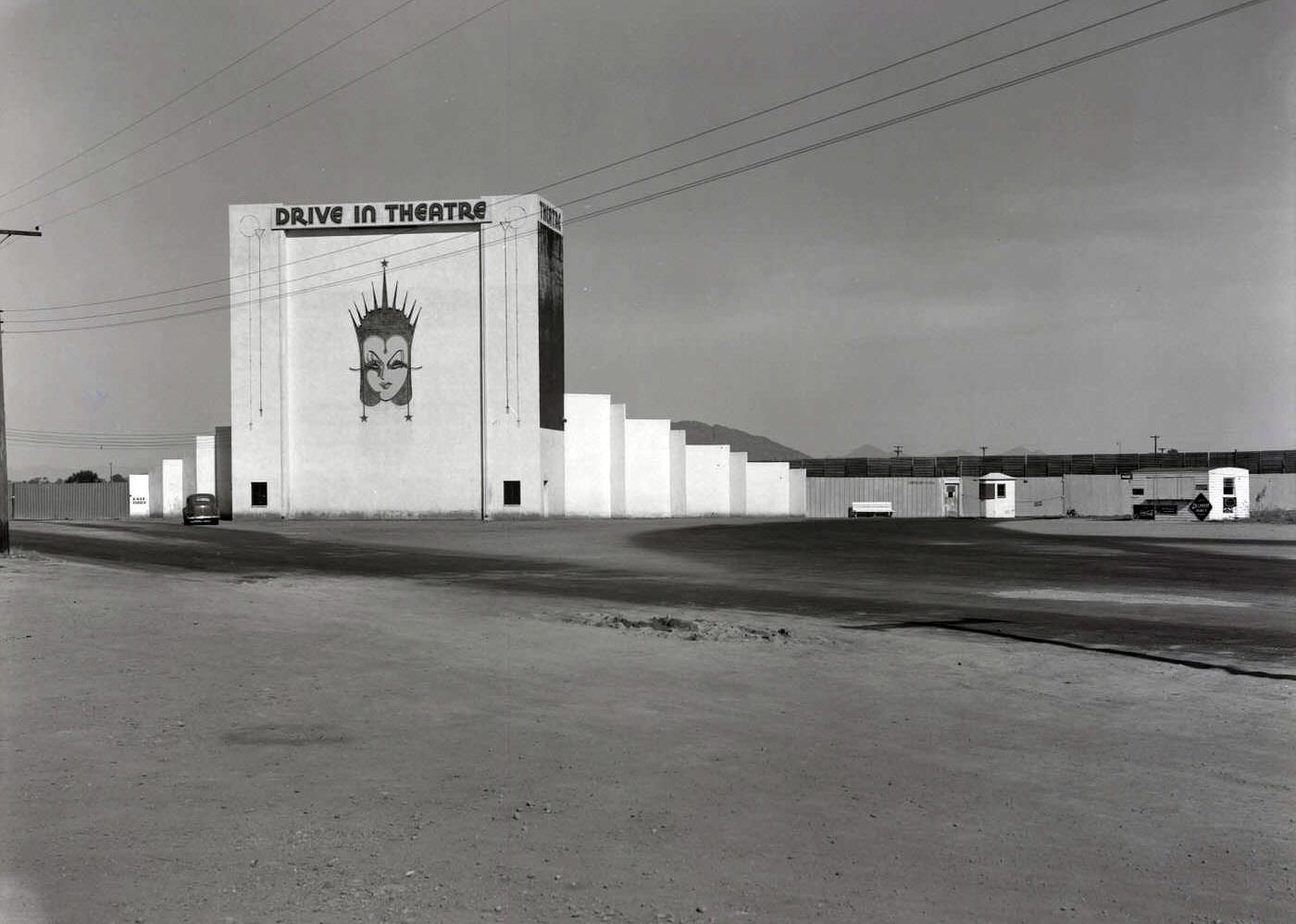

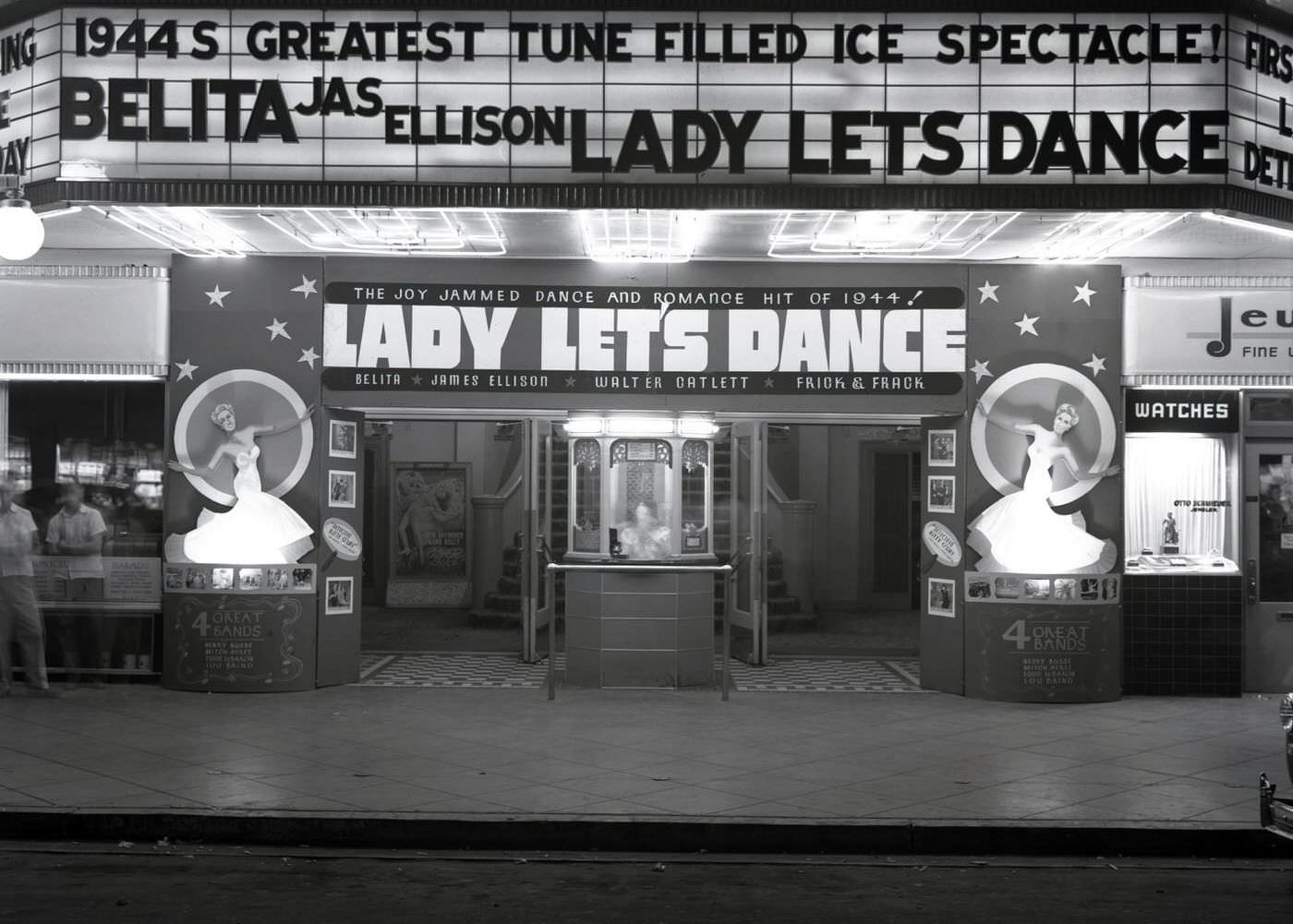

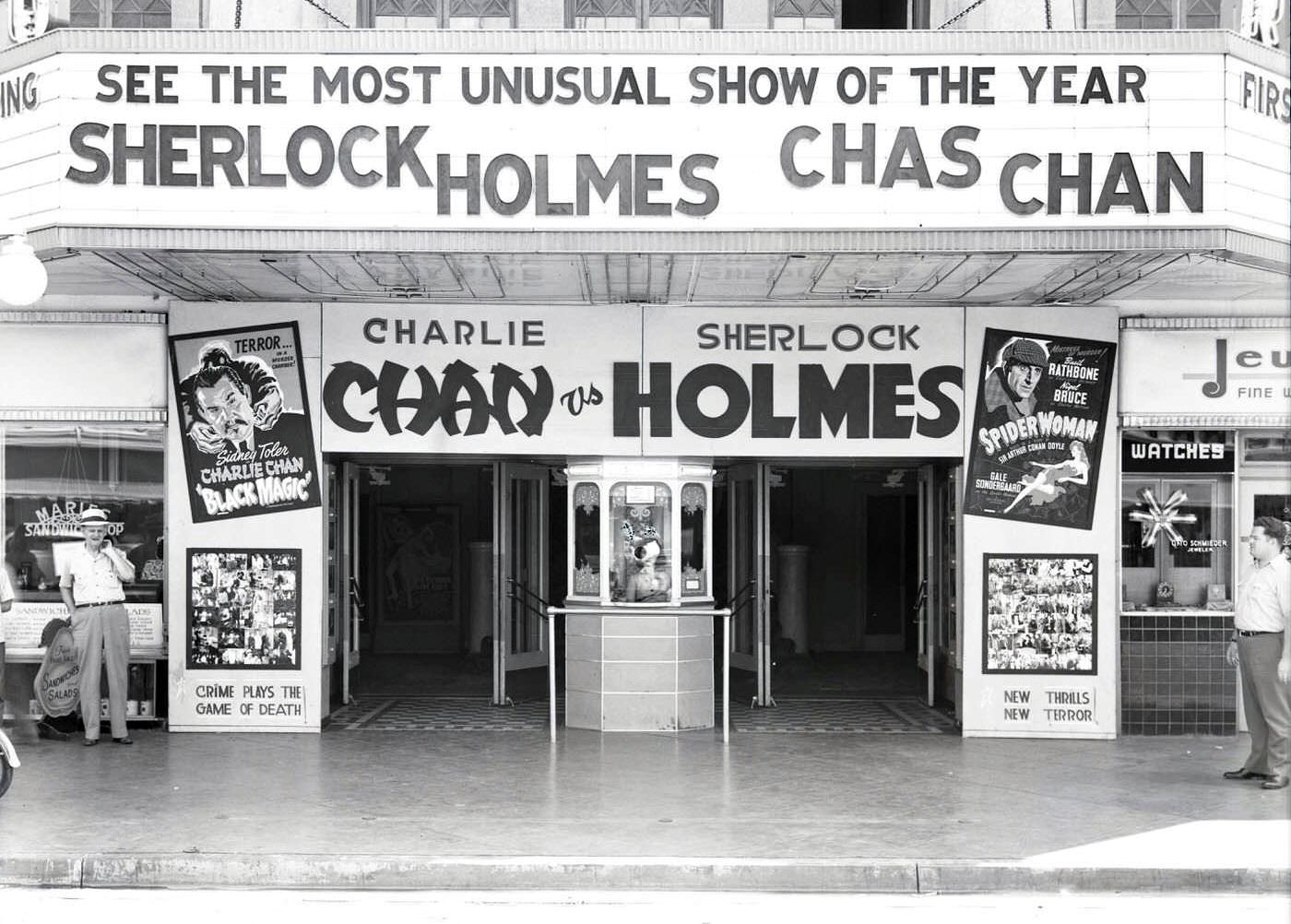

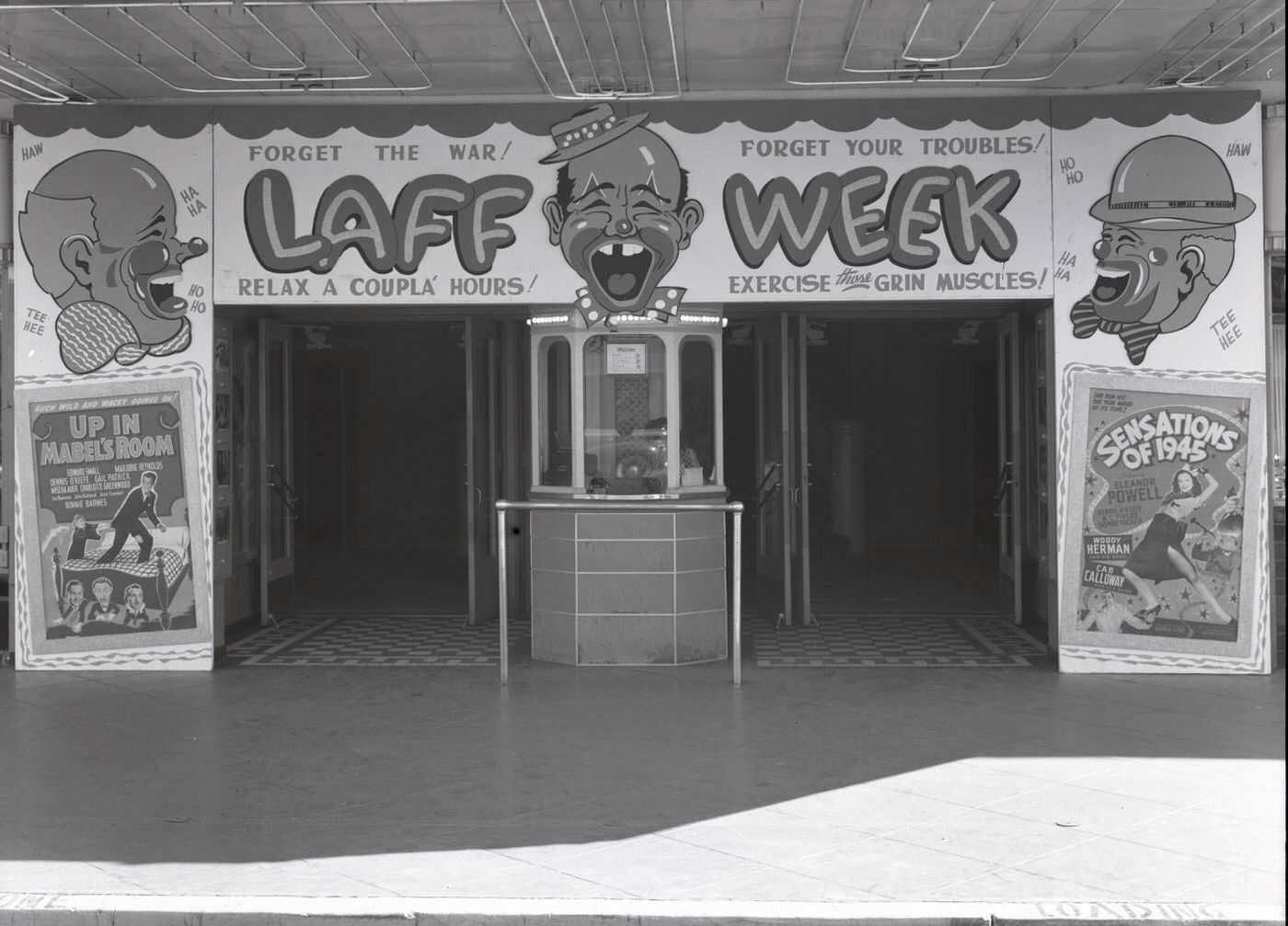

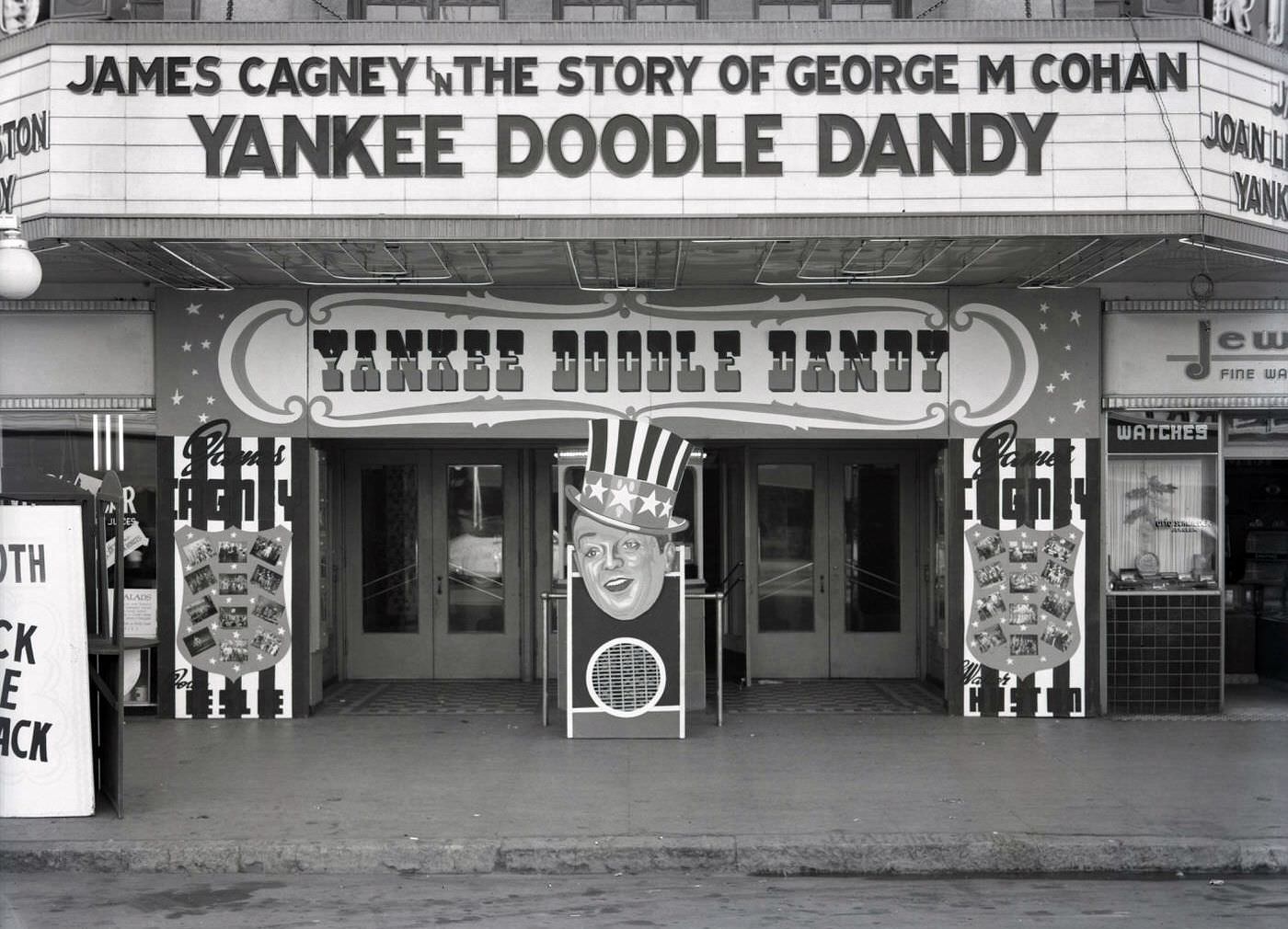

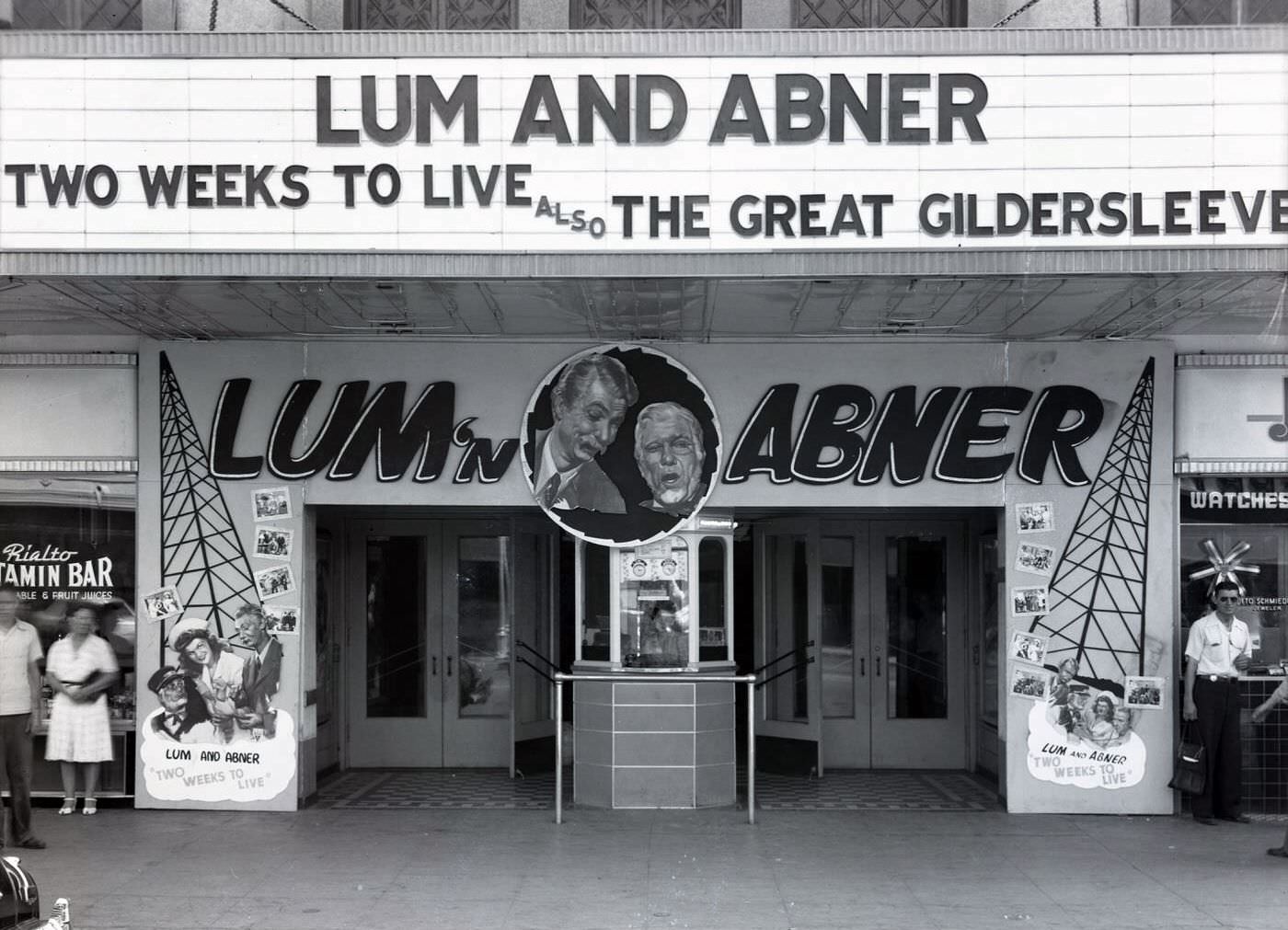

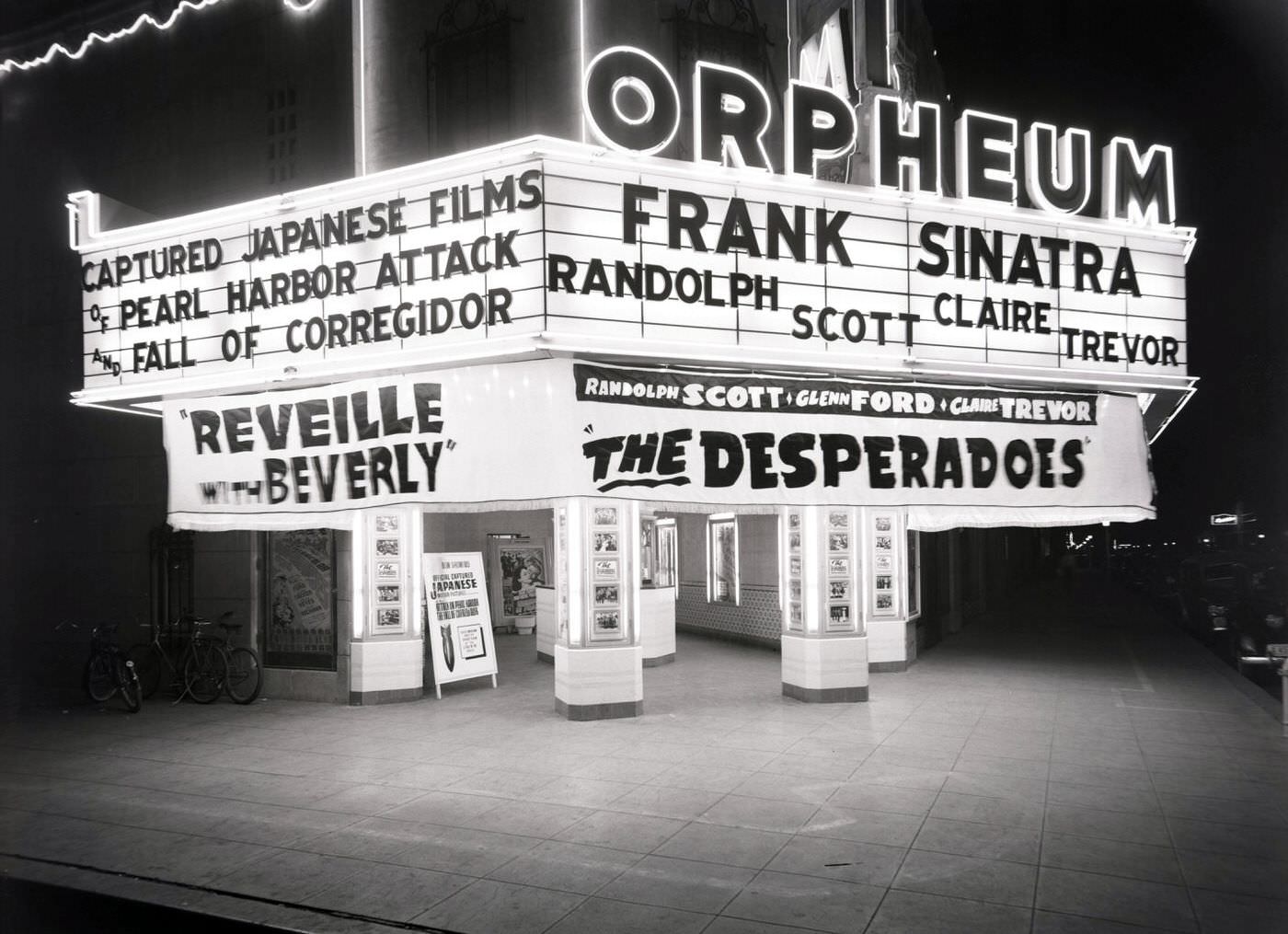

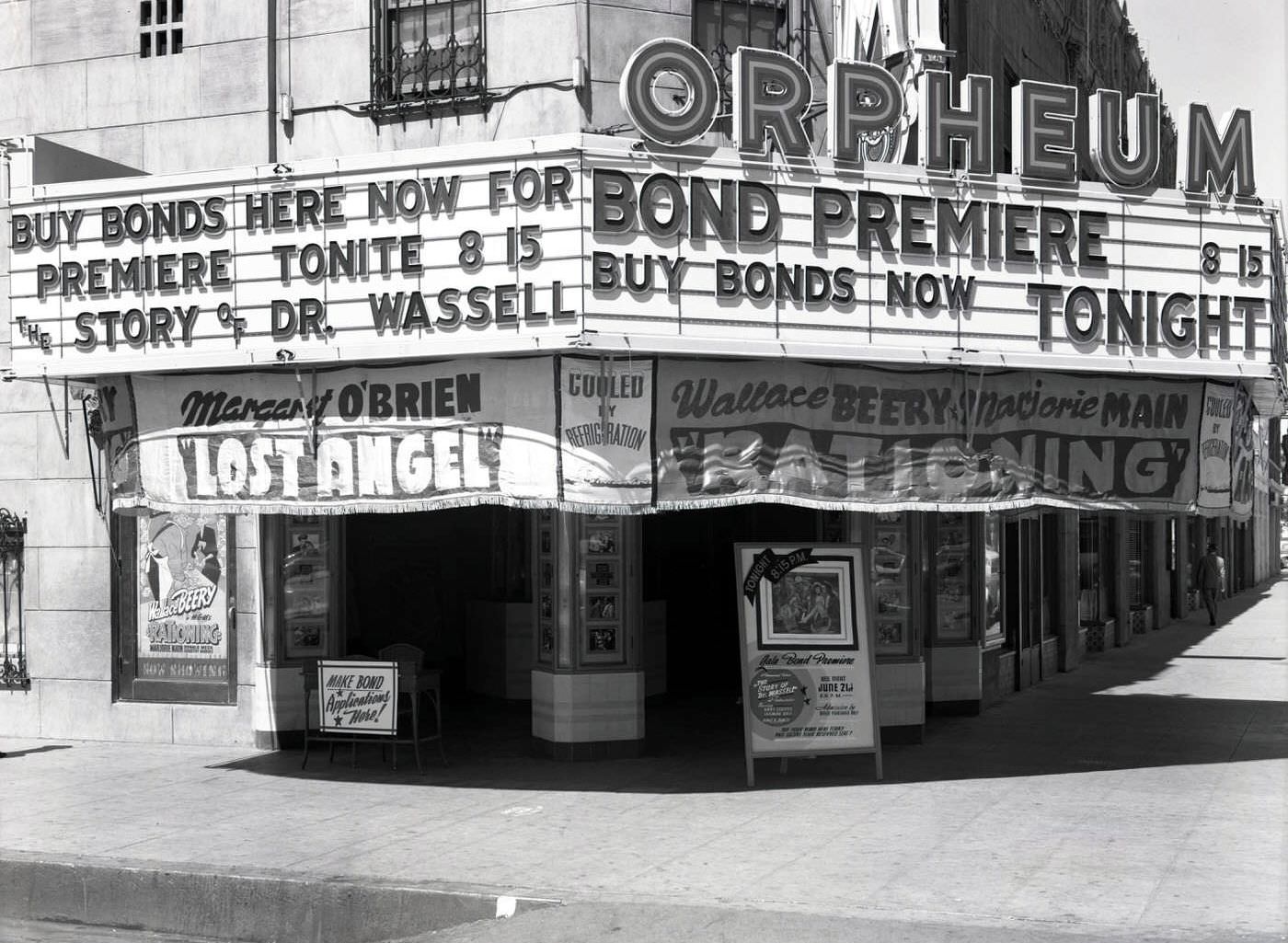

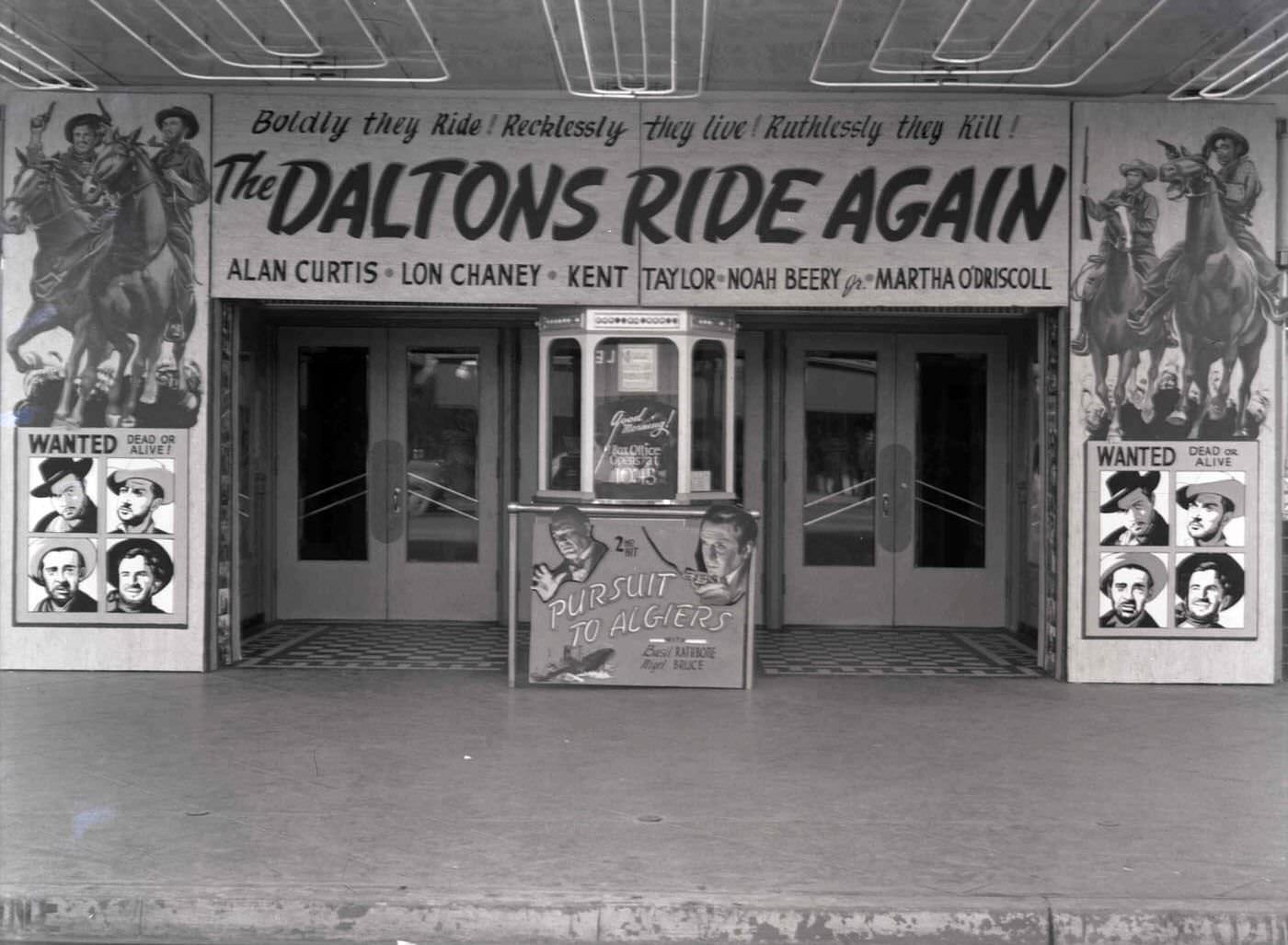

Radio was the dominant mass medium of the decade. Phoenix had three primary stations: KTAR (620 AM), affiliated with the NBC Red Network and the key station for the Arizona Broadcasting System; KOY (originally 550 AM, then 1390 AM, later 550 AM again), which was the CBS affiliate; and KPHO (initially 1200 kHz, then 1230 kHz, and 910 kHz by 1949), which became an affiliate of the Blue Network (later ABC) in 1944. These stations brought national news, popular dramas, comedies, and sports broadcasts to Phoenix listeners, alongside local programming. Towards the end of the decade, television made its debut when KPHO-TV (Channel 5) began broadcasting on December 4, 1949. Movie theaters, including downtown palaces like the Fox Theater and the Paramount (Orpheum), offered cinematic entertainment and were popular leisure destinations.

Community life was enriched by various recreational opportunities and cultural events. Encanto Park, a 222-acre oasis largely constructed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and opened in 1937, offered residents picnic areas, a lagoon for fishing and boating, a swimming pool, two golf courses, tennis courts, and an archery range. South Mountain Park, one of the nation’s largest municipal parks, featured hiking trails, roads, and lookout points like Dobbins Lookout, much of which was developed by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the 1930s and early 1940s. Mystery Castle, completed within South Mountain Park in 1945, also became an attraction. For youth, the Boys Clubs of Phoenix established its first two centers in 1946, providing activities ranging from library access and game rooms to sports and hobby clubs. Cultural institutions like the Heard Museum, the Arizona Museum, Pueblo Grande, and the Desert Botanical Garden (founded in 1938) were enhanced during this period. In the late 1940s, organizations such as the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra and the Phoenix Art Museum began to introduce programs featuring visiting artists and touring exhibits. Major local events that drew crowds included the Masque of the Yellow Moon, the Fiesta Del Sol, the Cotton Festival, and the JayCees World Championship Rodeo. A new tradition began in 1948 with the Salad Bowl, a post-season college football game accompanied by a parade on Central Avenue.

Tourism remained a vital part of Phoenix’s identity. The city was promoted as a winter resort, benefiting from its warm, sunny climate. Prominent resorts like the Arizona Biltmore, Camelback Inn, and The Wigwam in Litchfield Park catered to a mix of socialites, celebrities, dignitaries, and, during the war, military personnel. Other establishments like the Jokake Inn, Paradise Inn, and Elizabeth Arden’s Maine Chance spa also contributed to the area’s appeal as a resort destination. These institutions, adapting to wartime needs and then embracing post-war opportunities, helped lay the cultural and recreational foundations for the larger, more complex city Phoenix was rapidly becoming.

Phoenix Transformed: The Post-War Years (1945-1949)

The period immediately following World War II, from 1945 to 1949, was one of dramatic transformation for Phoenix. The wartime momentum, combined with new post-war realities, set the city on a trajectory of rapid growth and significant change.

A primary driver of this transformation was a massive population surge. Many servicemen who had trained at Arizona’s air bases or passed through the state during the war were drawn to its favorable climate and burgeoning opportunities, returning with their families to make Phoenix their home. This influx, coupled with natural increase and other migration, caused the city’s population to nearly double from 65,414 in 1940 to 106,818 by 1950. By the end of the 1940s, Phoenix had grown by 63% and its physical area had expanded to 17 square miles. This rapid demographic expansion created both immense opportunities and significant challenges for the city.

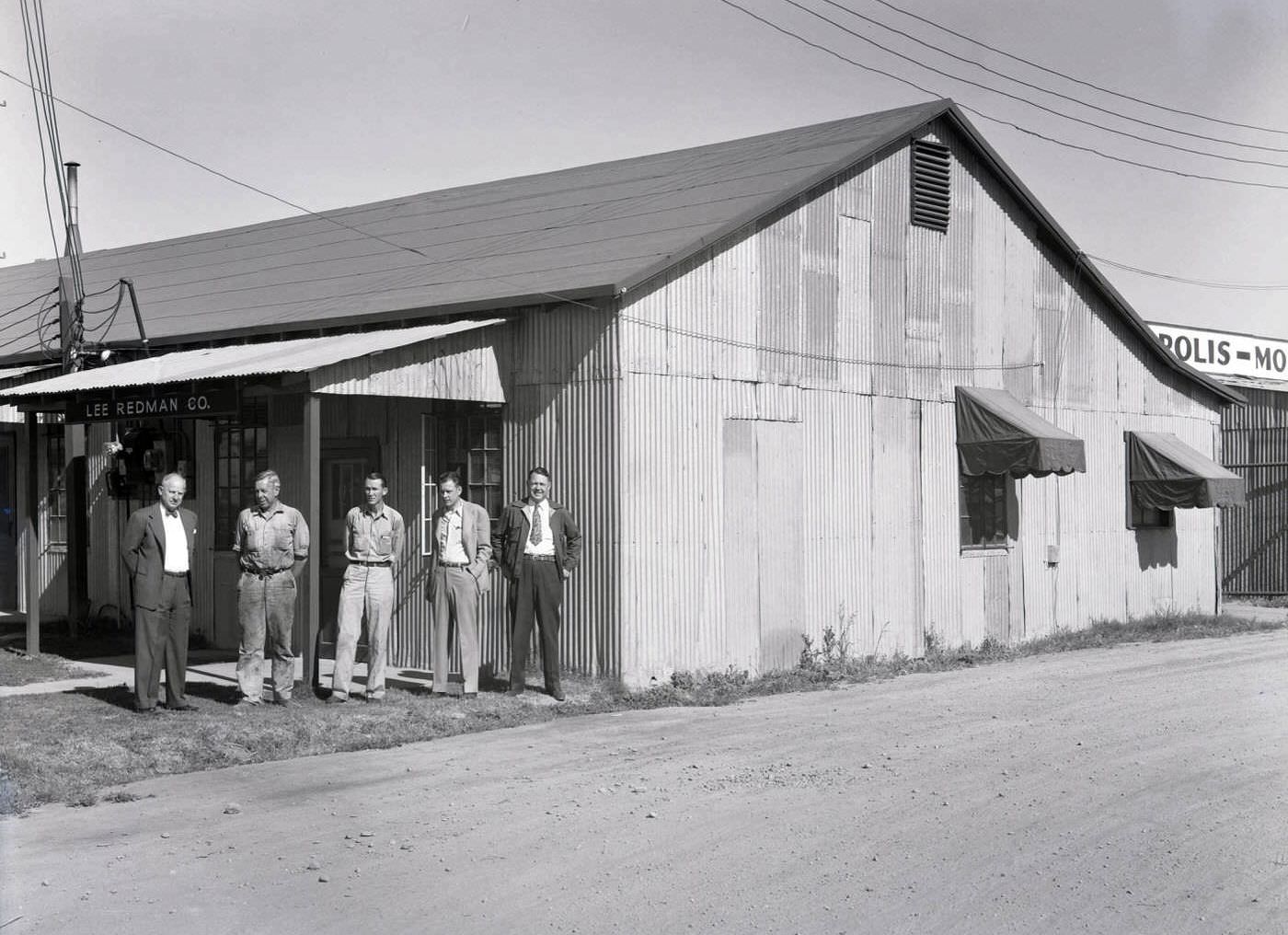

Economically, Phoenix began a pivotal shift. While the end of the war brought an initial downturn as military contracts were canceled and wartime factories closed, leading to some fears of economic hardship, city leaders actively worked to attract new industries. These efforts, supported by emerging Cold War defense spending, started to bear fruit. A landmark achievement was the arrival of Motorola, which established a research and development lab in Phoenix in 1949 (some sources state 1948). This event is widely recognized as the beginning of Arizona’s high-tech sector and signaled a conscious move towards a more diversified, modern economy. The city’s leadership began to look beyond its agricultural roots, and there was a noticeable trend of disregarding pre-war commercial architecture in favor of a more contemporary urban image.

The housing sector experienced a boom. A severe shortage immediately after the war, due to the population influx and limited wartime construction, gave way to a surge in building activity. Federal programs, particularly Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loans and, for returning servicemen, Veterans Administration (VA) loans, played a crucial role in financing new homes and subdivisions. This period saw the proliferation of single-family homes and the continued construction of multi-family housing, with an emphasis on low-density options like duplexes, triplexes, and garden apartments. A key technological development that facilitated this growth was the increasing availability of affordable home air-conditioning, making Phoenix’s intense summer heat more manageable and the city a more attractive year-round prospect for new residents.

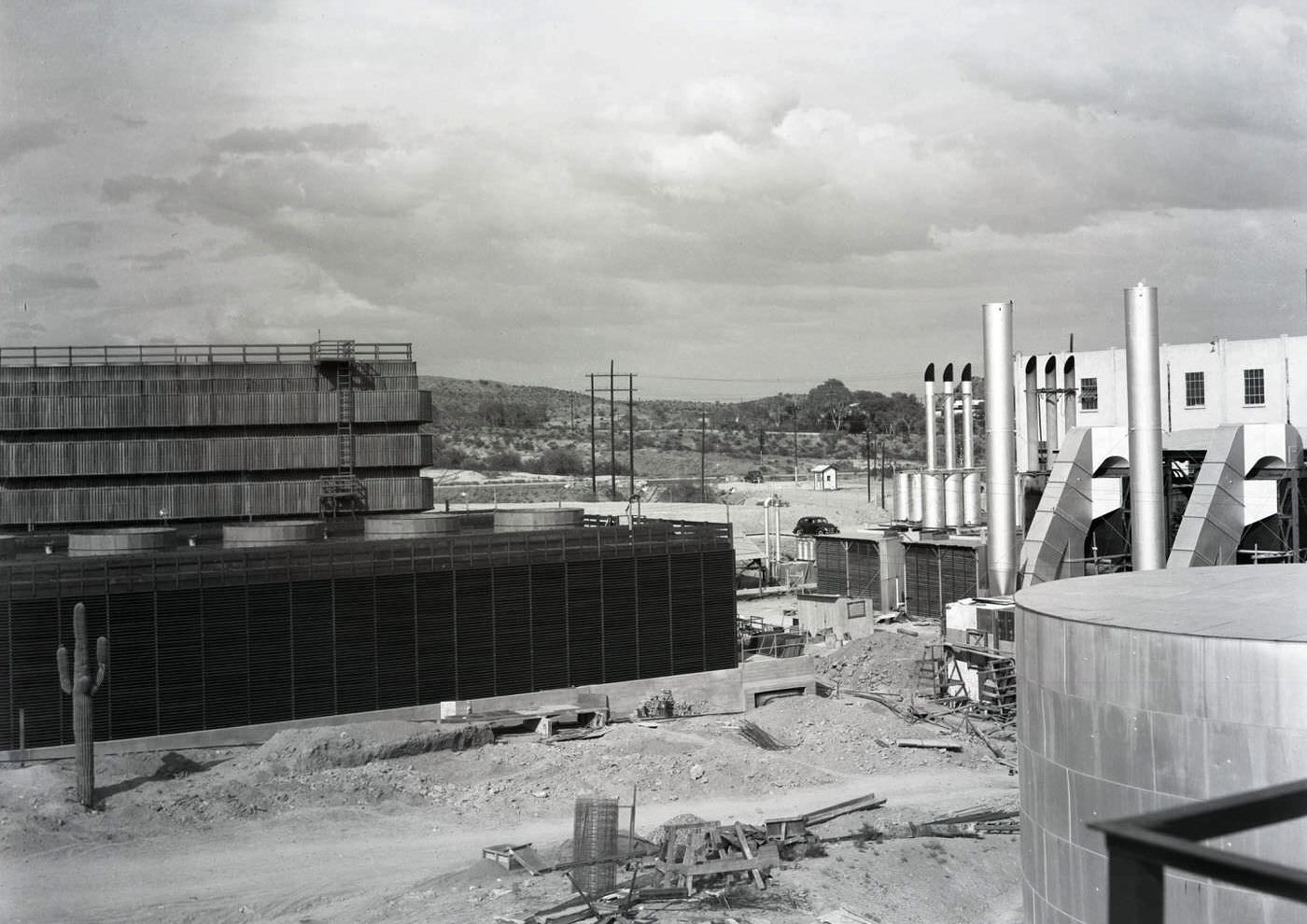

This rapid growth, however, placed considerable strain on Phoenix’s existing infrastructure. By 1946, the city faced a critical water shortage due to the combined pressures of population increase, a booming economy, and the widespread adoption of evaporative coolers. The situation became so dire that fire protection was deemed inadequate during summer months because of low water pressure. In response, city officials and voters took action. In November 1946, a $5 million bond issue was approved to fund major improvements to the water system. These improvements included upgrading the distribution network, enhancing the Verde River water intake, constructing gates at Horseshoe Dam, and building Phoenix’s first dedicated water filtration plant, the Verde Water Treatment Plant, which began delivering water in 1949.

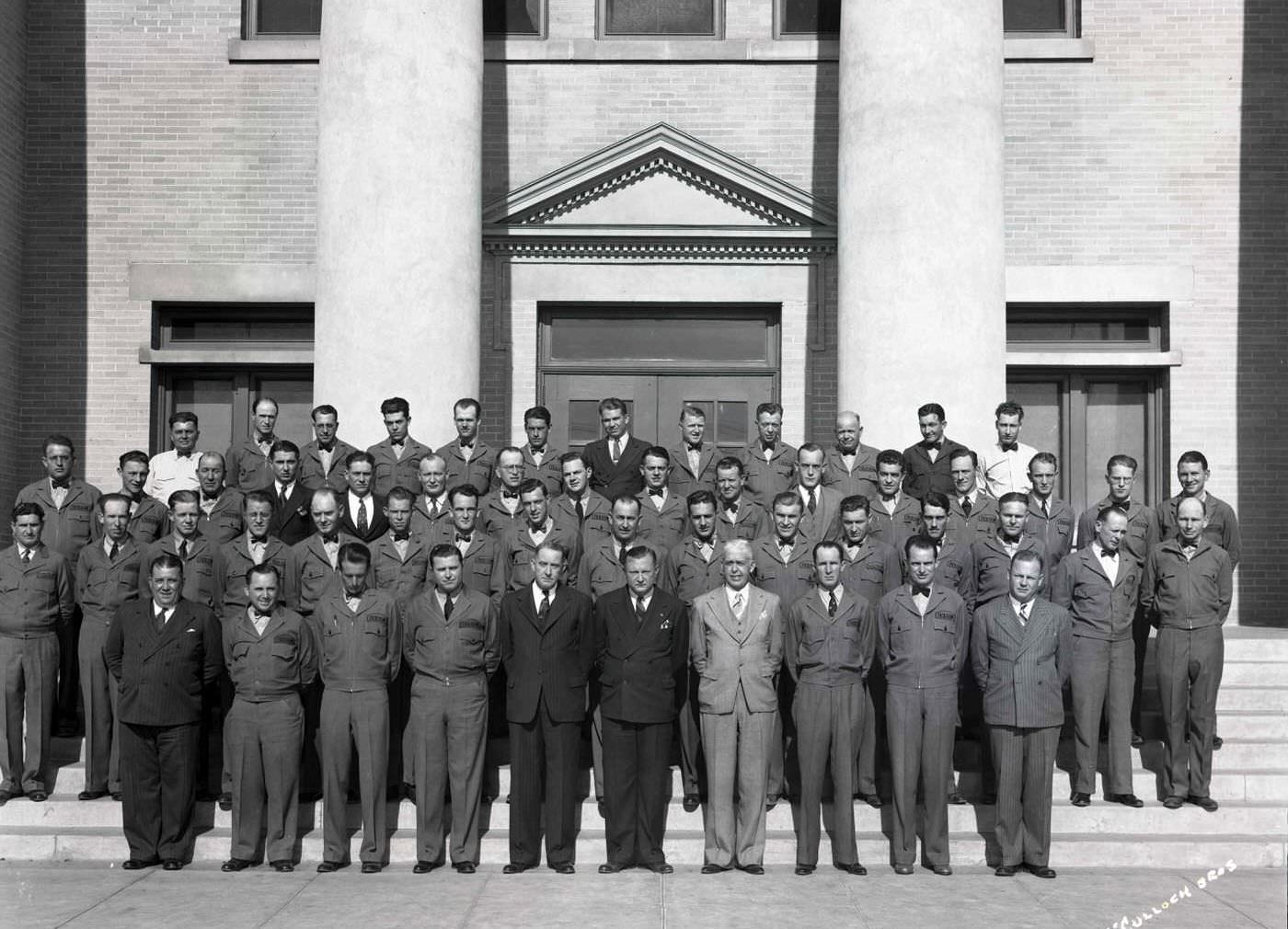

The city’s governance also underwent reform. Phoenix had operated under a council-manager system since 1914, but in the early 1940s, it was perceived by some as susceptible to corruption and political patronage. A reform movement, spearheaded by civic leaders like lawyer Frank Snell and amplified by Eugene Pulliam, who acquired the Arizona Republic and Phoenix Gazette newspapers in 1946, pushed for a more efficient and “clean” city government. This movement culminated in the rise of the Charter Government Committee, whose non-partisan candidates gained control of the city council in 1949, advocating for a stronger city manager structure and more professional administration. Annexation of surrounding areas also became a strategy for managing urban growth and expanding the city’s tax base, sometimes involving tax concessions to attract industrial development, as seen with a west side industrial area in 1949.

The late 1940s, therefore, were a period where Phoenix was actively grappling with the implications of its newfound growth. Decisions made during these years regarding economic development, housing, infrastructure, and governance laid the critical foundations for the sprawling metropolis Phoenix would become in the latter half of the 20th century.

Image Credits: McCulloch Brothers Inc. Photographs, Arizona State Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know

I like your post. If I may, with all due respect, not only are most of the images given without credit but Phoenix was never a “desert town.” It was in the middle of a natural oasis going back to the Hohokam.