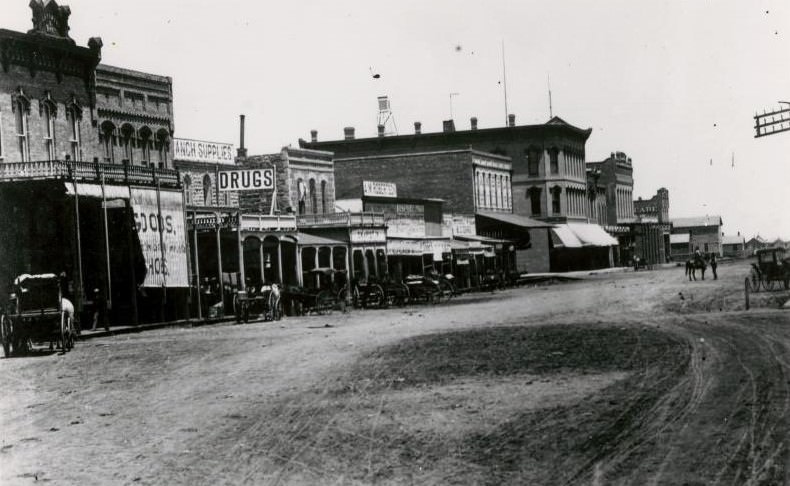

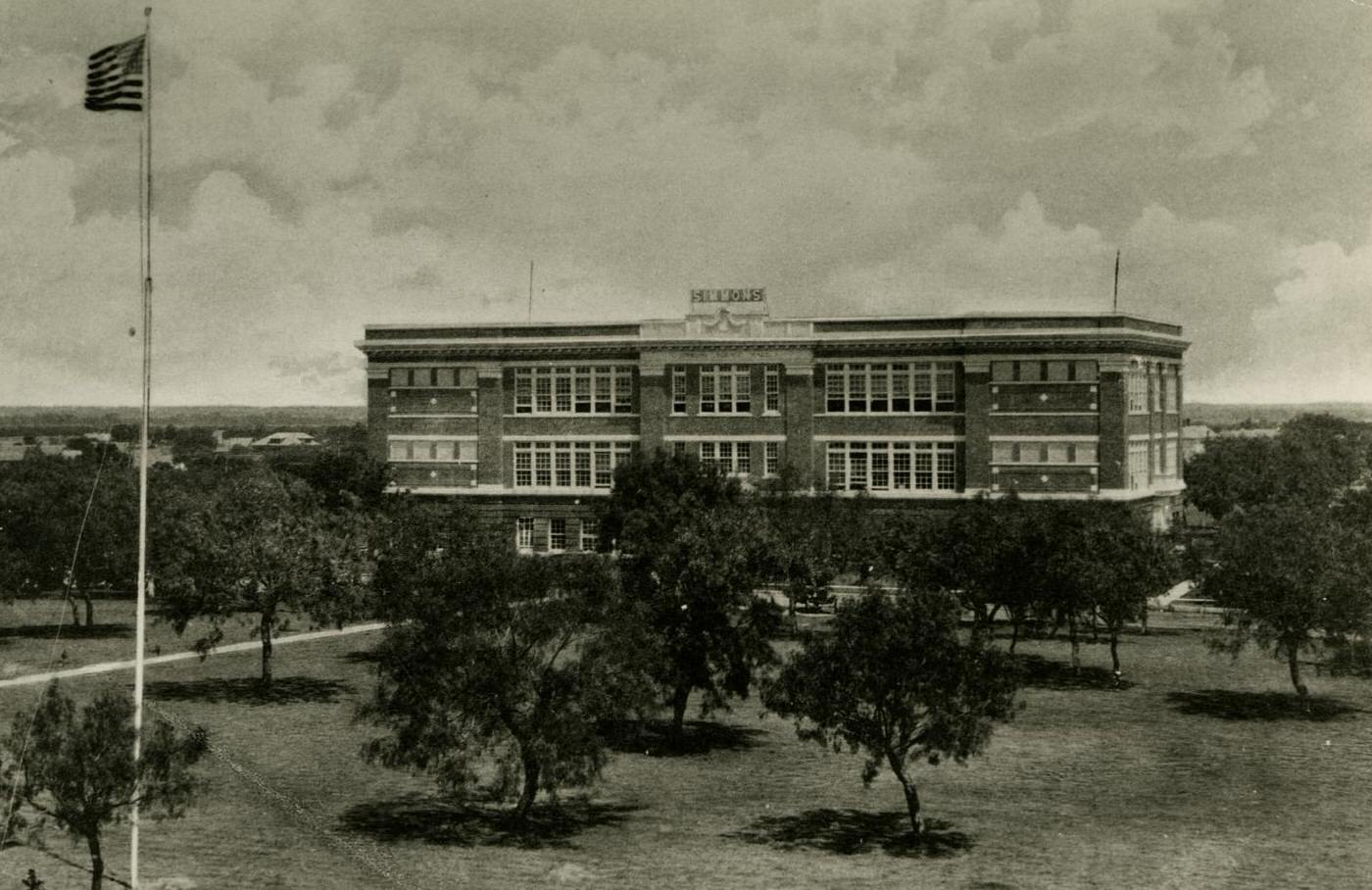

Abilene entered the 1930s on the momentum of significant growth. Its population had surged from 10,274 in 1920 to 23,175 by 1930, establishing itself as a burgeoning regional center for trade and benefiting from earlier oil discoveries. Railroad promoters had previously dubbed it “The Future Great City of West Texas”. Yet, this decade would test the city’s resilience as it confronted the twin crises sweeping the nation: the economic devastation of the Great Depression and the environmental catastrophe of the Dust Bowl. These forces reshaped daily life, the economy, and the very landscape of Abilene and Taylor County.

The Grip of the Depression

The nationwide stock market crash of October 1929 initially seemed distant to many Texans, who placed faith in the state’s agricultural and oil-based economy. However, the ensuing economic collapse rippled outward, inevitably reaching Abilene. The city’s growth, already hampered by severe droughts in previous decades, slowed significantly as farm prices, a cornerstone of the local economy, continued their decline through the 1920s and into the 1930s. This heavy reliance on agriculture made Abilene particularly susceptible to the downturn.

Farmers across the region faced dire circumstances. The price for staple crops like cotton plummeted, sometimes to as low as five or six cents per pound. This made it nearly impossible for farmers to cover their debts on land mortgages and increasingly necessary farm machinery. Farm foreclosures became alarmingly common across the plains. In response to these pressures, Abilene leaders urged local farmers to diversify their crops, hoping to shield the community from the volatility of single-crop prices and unpredictable weather.

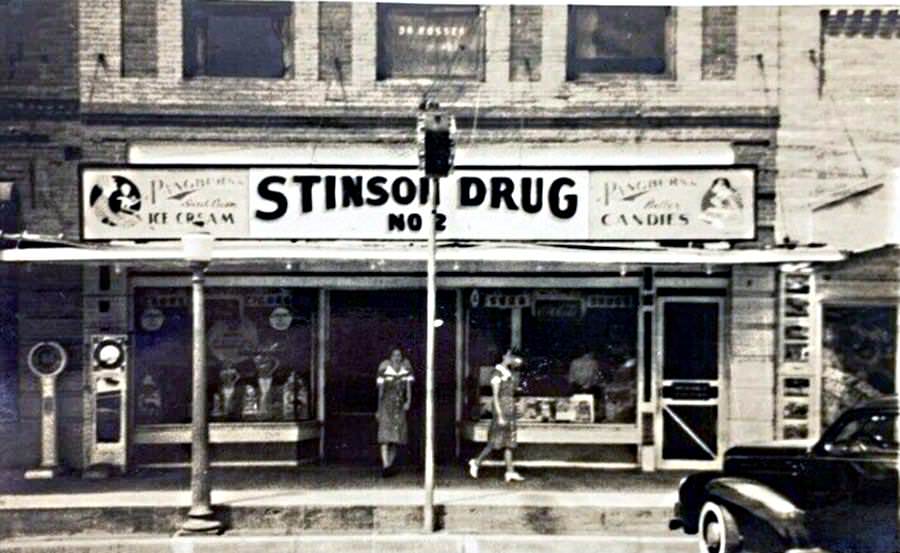

Businesses also felt the strain. While specific data on Abilene business closures is limited, the statewide picture included numerous bank failures and widespread economic hardship. Institutions like the Farmers and Merchants National Bank, a predecessor of today’s First Financial Bankshares, managed to endure these challenging times, demonstrating resilience. The vital oil industry, which had spurred growth in the 1920s, suffered statewide from overproduction and drastically falling prices, impacting Abilene’s independent oil operators.

Unemployment soared nationally, reaching nearly 25 percent by 1933. Texas experienced fierce competition for the few available jobs. This widespread joblessness pushed many families into poverty. The economic desperation led some Abilene residents and others from the drought-stricken region to leave their homes, becoming migratory workers following crop harvests, often heading towards California.

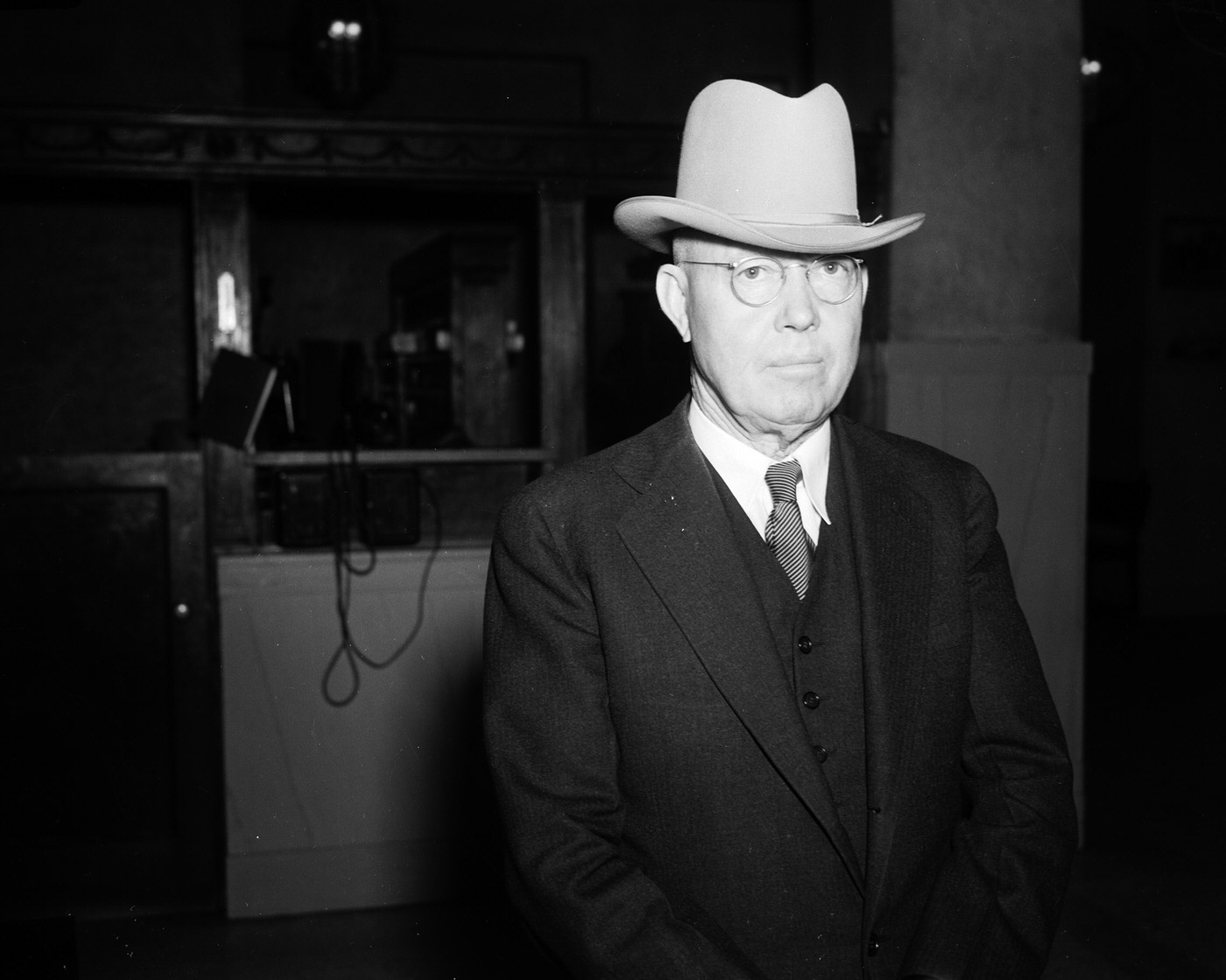

Despite this pervasive economic gloom, remarkable local investment still occurred. Abilene businessman Horace O. Wooten financed the construction of two major downtown landmarks: the 16-story Hotel Wooten and the adjacent Paramount Theatre. Both opened their doors in 1930, right as the Depression was taking hold. These ambitious projects, undertaken amidst national financial collapse, provided much-needed construction work and signaled a persistent local belief in Abilene’s future, even as hard times began.

Under Dusty Skies

Compounding the economic misery was a severe environmental crisis. The 1930s brought a devastating, prolonged drought to the southern Great Plains. Abilene, situated in a region with naturally low rainfall, felt the effects acutely. High temperatures and lack of moisture parched the land.

This drought, combined with years of agricultural practices ill-suited to the plains environment, set the stage for the Dust Bowl. Decades of intensive farming, particularly the “great plow-up” of native grasslands to plant vast acreages of wheat and cotton, had removed the natural vegetation that anchored the topsoil. When the rains stopped and the winds howled, the exposed, dry soil became airborne.

The consequences for agriculture were catastrophic. Wind erosion stripped away fertile topsoil, burying fields, fences, and equipment. Crops were destroyed season after season. Livestock suffered immensely; cattle sometimes died after consuming dust-covered grass, forming mud balls in their stomachs. Ranchers faced the grim choice of watching their herds starve or selling them at drastically reduced prices.

The human toll was also heavy. Pervasive dust infiltrated homes despite efforts to seal windows and doors, coating everything in grit. Engines were damaged. Respiratory ailments, often termed “dust pneumonia,” became a serious health concern, particularly for the young and elderly. The relentless dust, heat, and hardship created immense psychological stress.

The dual blows of economic depression and environmental disaster spurred an exodus from the plains. Families packed their belongings, often into automobiles, and left their farms in search of survival and work. Photographs and accounts specifically document “drought refugees” from the Abilene area among those migrating westward, particularly to California. This migration reflected the profound disruption caused by the Dust Bowl conditions experienced in and around Taylor County, even if it wasn’t designated as part of the absolute hardest-hit region where specific state conservation districts were initially focused. The federal government recognized the need for intervention, extending conservation efforts like the Great Plains Shelterbelt project, which involved planting millions of trees to act as windbreaks, as far south as Abilene.

New Deal Projects Shape the City

In response to the nationwide crises, President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented the New Deal, a series of federal programs designed to provide relief, promote recovery, and reform the economy. Several New Deal agencies left a lasting mark on Abilene and the surrounding area, creating jobs and building significant public works. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) played a major role. Established in 1933, the CCC employed young men and, in some cases, World War I veterans on conservation and park development projects. Abilene State Park owes its existence largely to the CCC. In 1933, the city donated land near Lake Abilene, and CCC Company 1823V, composed of WWI veterans, began work. Using local red Permian sandstone and limestone, they cleared land, built roads and culverts, and constructed key park features. After this initial phase, a reactivated, all-Black veteran unit, Company 1823CV, returned in 1935 to complete significant structures, including the distinctive red stone refectory (concession building) with its observation tower, the swimming pool, stone picnic tables still used today, pergolas, additional culverts, and a water tower. The park officially opened to the public on May 10, 1934, providing a valuable recreational resource built through relief labor. Beyond the park, CCC workers also contributed to the massive Great Plains Shelterbelt project, planting trees near Abilene to combat the wind erosion that characterized the Dust Bowl era.

The Work Projects Administration (WPA), another major New Deal agency, focused heavily on public construction projects, often requiring local sponsors to contribute a portion of the costs. In Abilene, the WPA undertook the construction of the Concrete Overpass along North 1st Street in 1936. This significant infrastructure project, involving elevated tracks and underpasses at Pine and Cedar streets, was designed to improve traffic flow near the busy Texas and Pacific Railway line and inject funds into the local economy during the Depression. The WPA also played a role in a critical water supply project: the construction of Lake Fort Phantom Hill, which was completed in 1937 and remains a key source of water for the city. Other WPA activities in Texas included building parks, swimming pools, highways, and public buildings, along with providing adult education and art programs. The Abilene Federal Building, constructed in 1935, also dates from this era of public works.

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was another New Deal program active in Texas, focusing on providing work and education for young people. While specific NYA projects in Abilene are not detailed in the available sources, the agency sometimes collaborated with others, such as crafting furniture for CCC-built state parks.

These New Deal initiatives provided desperately needed jobs and income during the 1930s. They also created infrastructure and amenities – Abilene State Park, Lake Fort Phantom Hill, the downtown railroad overpass – that continued to serve the community long after the Depression ended, representing a tangible and enduring legacy of this era of federal intervention.

Life Goes On: Society and Culture

Despite the profound economic and environmental stresses, the social and cultural life of Abilene continued, adapting to the times. Entertainment offered a necessary escape. The Paramount Theatre, a jewel of downtown Abilene, opened its doors on May 19, 1930. Designed by David S. Castle in the “atmospheric” style, it aimed to transport moviegoers to a Spanish/Moorish courtyard under a starlit sky, offering a grand experience during a difficult period. It quickly became a major venue for first-run films. The adjacent Hotel Wooten, also opened in 1930, served as a prominent downtown landmark and likely a center for social activity. The advent of drive-in theaters also occurred during this decade, with the first Texas drive-in opening in 1934, providing another affordable entertainment option.

Radio emerged as a key source of news and entertainment, connecting households in new ways. Abilene gained its own station when KRBC began broadcasting in 1936.

Community gatherings provided opportunities for social interaction. Abilenians enjoyed spectator sports like polo matches, horse racing, and auto racing, which took place at Fair Park during the 1930s. A series of photographs taken by Russell Lee for the Farm Security Administration in May 1939 documents one such polo match, capturing images of the game, the ponies being prepared, officials, and a diverse audience including cowboys and children enjoying the event and refreshments from a soda pop stand.

Churches played a vital role in the community’s fabric, extending beyond spiritual guidance to provide essential social services. They remained the primary providers of local charity well into the 1930s, sponsoring and funding initiatives like day-care centers, programs for the elderly and youth, civic improvement efforts, and disaster relief. Major denominations like Baptist, Church of Christ, and Methodist were prominent, alongside smaller congregations of Presbyterians, Catholics, and others. The First Baptist Church, founded in 1881, continued its ministry, as did Sacred Heart Catholic Church, established in 1880.

Families learned to “make do or do without,” stretching resources and sometimes relying on traditional practices like making their own soap. In rural areas particularly, life before widespread electricity (often brought by New Deal programs) involved laborious chores like pumping water and hand-washing clothes, tasks frequently undertaken by women. Food scarcity was a genuine concern, leading some to rely on unconventional sources like armadillos, grimly nicknamed “Hoover Hogs”. These established social structures – places of worship, entertainment venues, community events – provided crucial networks of support and normalcy, helping residents navigate the extraordinary challenges of the decade.

Image Credits: Mary Newton Maxwell, The Grace Museum, Abilene Library Consortium, McMurry University Library, Hardin-Simmons University Library,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know