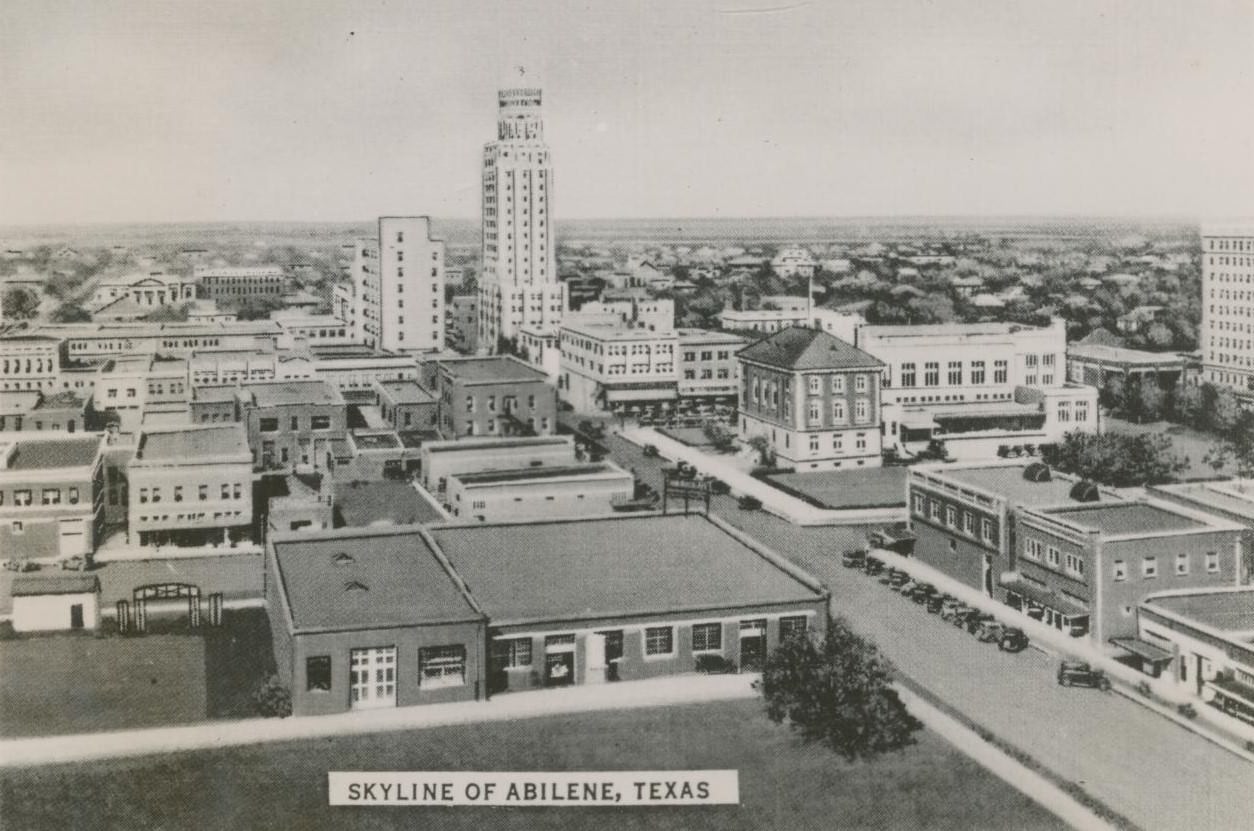

Abilene, Texas, stood at a crossroads as the 1950s began. The city had recently benefited from the economic activity generated by Camp Barkeley during World War II. This large army training camp brought an influx of soldiers and federal money, significantly boosting the local economy. However, the camp’s closure after the war created uncertainty about Abilene’s economic future. Fortunately, the post-war national economic boom helped, and many returning veterans chose to settle in Abilene, starting businesses that contributed to stability. In 1950, the city’s population was recorded at 45,570, establishing it as a key agricultural center and railroad hub in West Texas.

Dyess Air Force Base Takes Flight

The economic void left by Camp Barkeley’s closure spurred Abilene’s leaders into action. Following the outbreak of the Korean War, civic leaders, organized through the Abilene Chamber of Commerce’s Military Affairs Committee (MAC), saw an opportunity. Remembering the prosperity Barkeley had brought, they launched a determined campaign to secure a permanent military installation. Figures like Oliver Howard, W.P. Wright Sr., and influential politicians Senator Lyndon B. Johnson and Congressman Omar Burleson championed Abilene’s cause in Washington D.C. and the Pentagon.

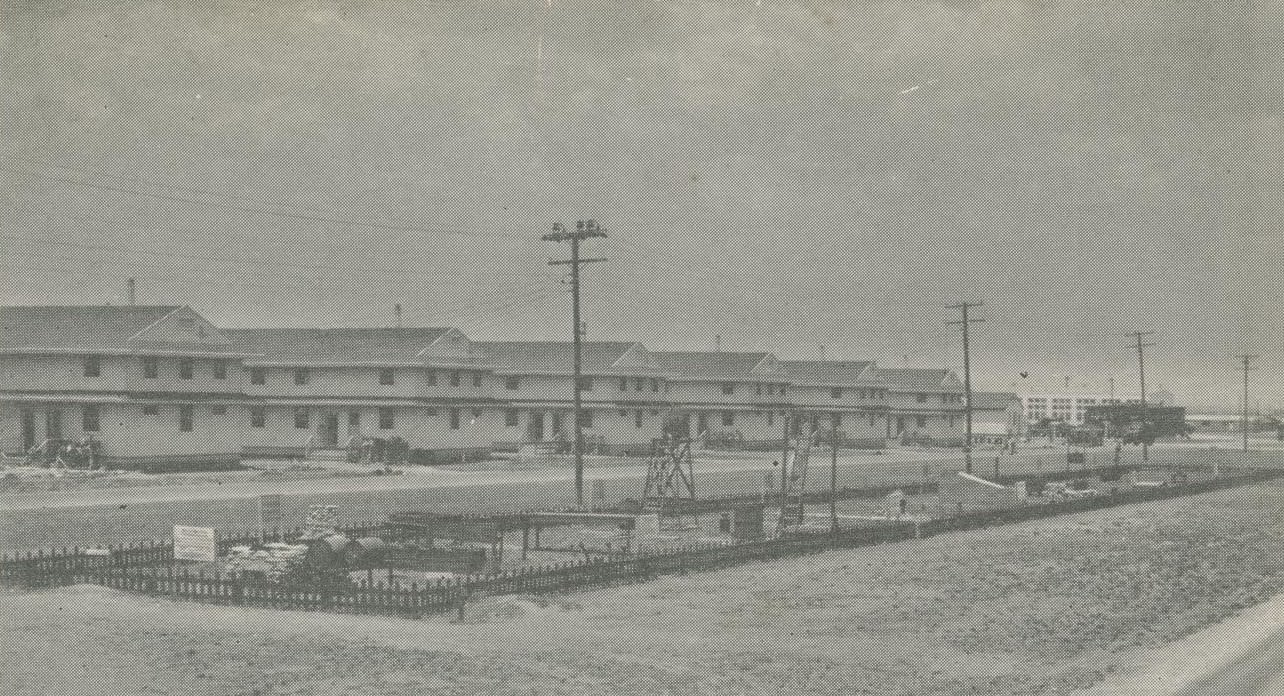

The community’s commitment was powerfully demonstrated when residents raised nearly $1 million—a very large sum at the time, equivalent to over $10.8 million in 2024 dollars—to purchase 3,500 acres of land. This land was added to the 1,500 acres of the former Tye Army Airfield and gifted to the Air Force. This significant local investment, born from the desire for economic security after Barkeley’s closure, was instrumental in convincing federal officials of Abilene’s suitability and dedication.

Their efforts succeeded in July 1952 when Congress approved $32 million for the construction of a new air base. Groundbreaking took place in September 1953. Reflecting a desire for permanence, a stipulation required all base buildings to be permanent structures, built with distinctive red brick in a Texas ranch style. The base officially opened as Abilene Air Force Base on April 15, 1956, a highlight of the city’s Diamond Jubilee celebration.

On December 1, 1956, the base was renamed Dyess Air Force Base, honoring Lt. Col. William E. Dyess, a Texas native and World War II hero. Its first operational unit, the 341st Bombardment Wing of the Strategic Air Command (SAC), had already activated on September 1, 1955, equipped with the B-47 Stratojet bomber. The 96th Bomb Wing followed on September 8, 1957, initially flying B-47s before transitioning to the B-52 bomber, supported by KC-97 and later KC-135 Stratotanker refueling aircraft.

The establishment and operation of Dyess AFB provided a tremendous economic stimulus, quickly becoming the city’s largest employer. This, combined with oil discoveries, triggered explosive population growth.

Daily Life in Abilene (1950s)

Life in 1950s Abilene reflected a community navigating tradition and rapid modernization. Daily routines revolved around work in the expanding economic sectors – Dyess AFB, oil fields, agriculture, and growing service industries – alongside family life, school, and church activities. However, the pervasive drought cast a long shadow. Dust storms frequently disrupted life, forcing residents indoors to battle the penetrating grit by sealing windows and doors with wet rags. Water conservation became a necessity, with restrictions likely in place and reliance on periodic water deliveries in some areas.

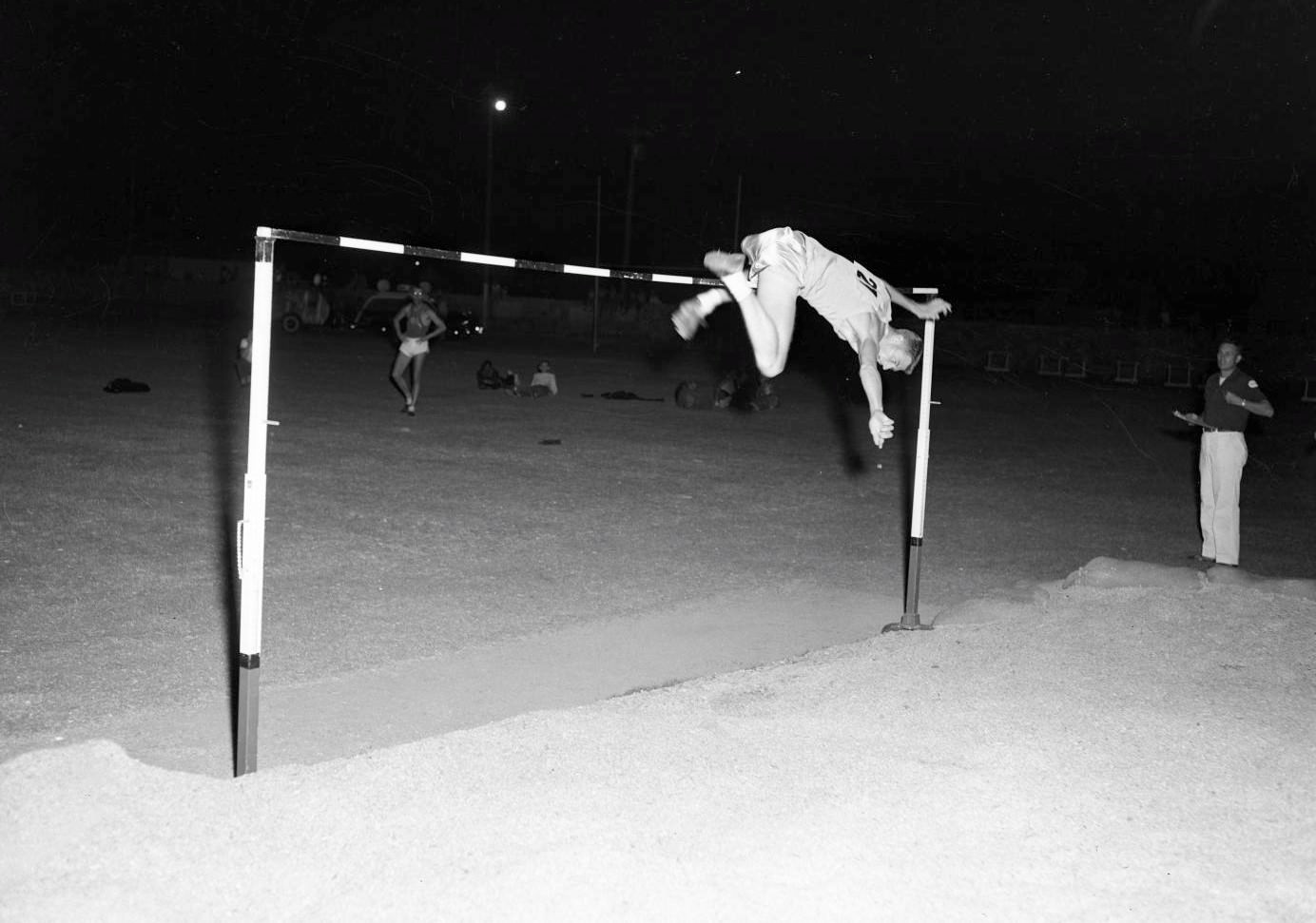

Entertainment options blended the old and the new. Drive-in theaters like Eplen’s Drivateria were popular spots for dates and socializing. The grand Paramount Theatre, opened in 1930, remained a central movie palace. Radio station KRBC had been broadcasting since the 1930s, providing news and entertainment. Television was emerging nationally, but widespread local access likely developed later, as the first full-power Abilene stations signed on after the 1950s. A major source of community pride and excitement was high school football. The Abilene High School Eagles achieved legendary status with a 49-game winning streak and three consecutive state championships (1954-1956), uniting the town. The Abilene Blue Sox offered semi-pro baseball until 1957. Casual social activities included “cruise night” and window shopping downtown at stores like Minter’s.

Community life saw cultural growth. The Abilene Philharmonic Orchestra held its first concert in 1950. Various performing arts groups, including little theaters, ballet companies, a civic chorus, community band, and an opera association, were active. Groups like the Abilene Astronomical Society held meetings. The West Texas Fair and Rodeo continued as a regional event. Churches remained central to social and community life. Baptists, Churches of Christ, and Methodists were the largest denominations, but Presbyterians, Lutherans, Episcopalians, and Catholics also had congregations. New church buildings, like the striking First Baptist Church (1954), rose during the decade. Temple Mizpah served the Jewish community, particularly active with servicemen from the base. Throughout the 1950s, Abilene remained legally “dry,” prohibiting the sale of alcohol.

Building Blocks: Infrastructure and Growth

The dramatic population surge Abilene experienced in the 1950s demanded significant infrastructure development. The near-doubling of residents between 1950 and 1960, fueled by Dyess AFB and oil discoveries, necessitated rapid expansion in housing, roads, and public facilities.

New housing subdivisions emerged to accommodate the influx of families, characteristic of the post-war suburban boom across America. Neighborhoods featuring the popular ranch-style homes of the era, such as River Oaks, Brookhollow, and Tanglewood, saw development primarily during the 1950s and 1960s. Older areas like Original Town North likely saw infill and changes as well. This construction boom provided homes for the growing workforce connected to the air base and related industries. However, given the era’s segregation practices, this new suburban growth primarily benefited the white population, likely reinforcing existing patterns of residential separation.

Road networks required upgrades to handle increased traffic. Texas invested heavily in roads post-WWII, utilizing federal aid and state funds, including the Colson-Briscoe Act of 1949 which supported farm-to-market road improvements. Abilene voters demonstrated local commitment by passing the first of many street improvement bond packages in 1950. City ordinances from that year detail specific projects, authorizing $153,000 in bonds and targeting streets like South 5th, 7th, 8th, and Oak Street for paving and upgrades. While the Interstate system was still in the future, these 1950s efforts laid the groundwork for a more modern street system capable of supporting the expanding city. The historic Bankhead Highway (South 1st Street) also saw the construction of motels catering to increased automobile travel.

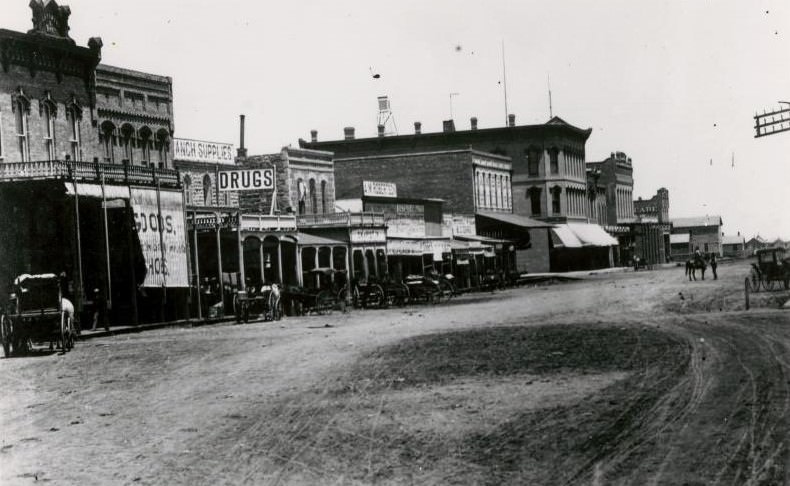

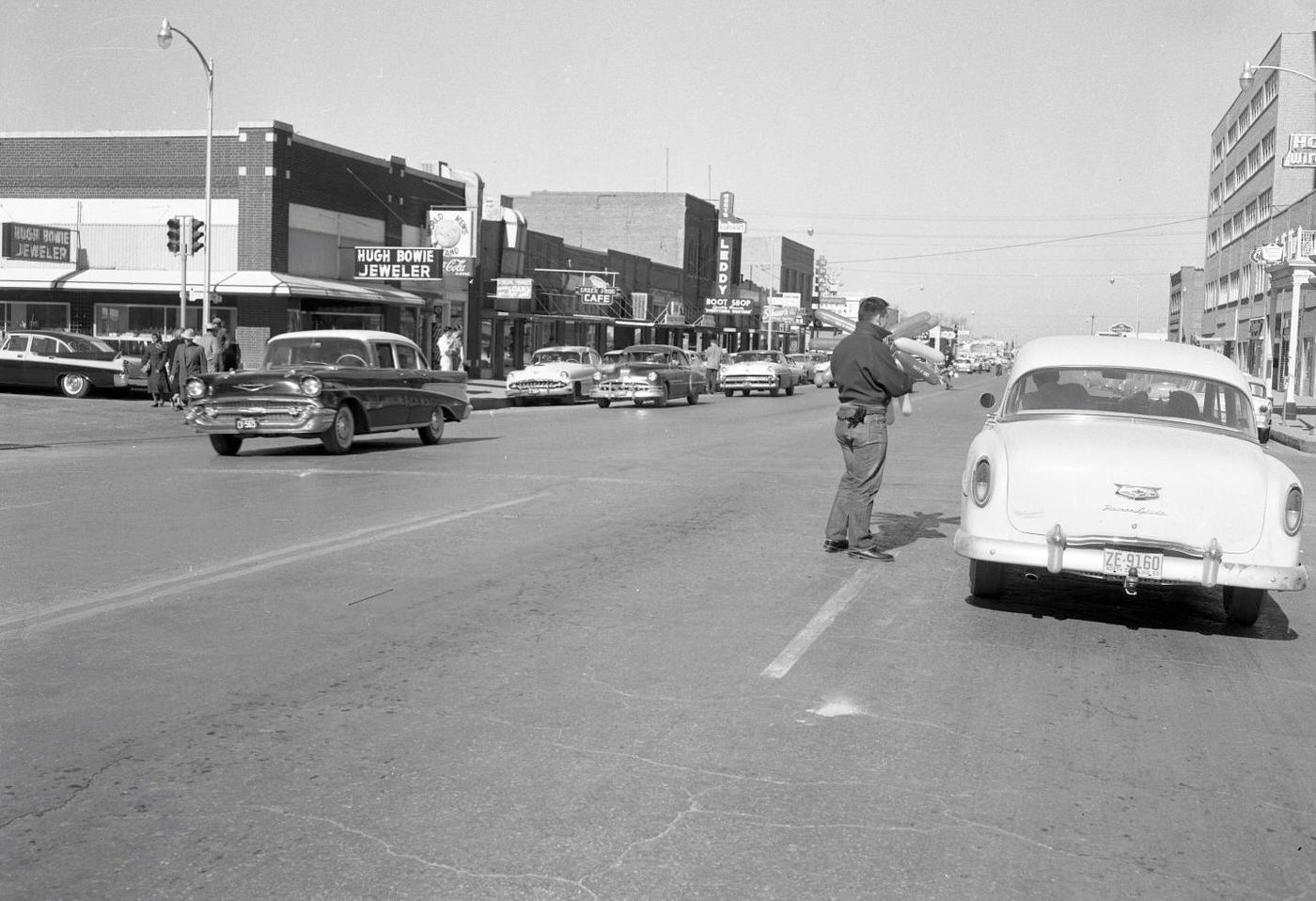

Downtown Abilene saw targeted changes during the decade, though the major shift of commerce southward was beginning. A significant public project was the replacement of the 1909 Carnegie Library; it was demolished in the 1950s, and a new, modern library facility opened on Cedar Street in 1954. The First Baptist Church completed its large new sanctuary in 1954. Some long-standing businesses like Wooten Wholesale Grocery continued operating into the 1950s before eventually closing or moving. Montgomery Ward remained in its downtown location until 1959. The Elks Lodge, which had served as a USO club during WWII, reorganized in 1955. These developments show a downtown still functioning but facing the beginnings of suburban competition, a trend accelerated by the southward residential growth and the planning for Cooper High School on the south side. The infrastructure built in the 1950s was essential for managing Abilene’s boom but also facilitated the geographic shifts that would reshape the city in subsequent decades.

Beyond the major themes of Dyess AFB, drought, and segregation, several other developments marked Abilene in the 1950s. The city celebrated its 75th anniversary, the Diamond Jubilee, in 1956 with great fanfare. The theme “Saddles to Jets” explicitly linked Abilene’s frontier past with its modern military present, featuring a massive historical pageant, parades, and community events. The dedication of the new air base (then Abilene AFB) was a centerpiece of this celebration.

Post-War Prosperity and Problems

The 1950s ushered in an era of significant economic expansion for Abilene, driven by several converging factors. The nationwide post-World War II economic boom provided a favorable backdrop. Locally, the establishment of Dyess Air Force Base in 1956 created thousands of jobs and injected substantial federal money into the economy, becoming the city’s largest employer. Concurrently, important oil discoveries in the region during the early 1950s provided another major engine for growth.

A crucial element in Abilene’s post-war success was the role of returning veterans. Countering fears that the city might decline after Camp Barkeley’s closure, many veterans chose Abilene to start businesses, bringing entrepreneurial energy and contributing directly to the economic vitality. Programs like the G.I. Bill likely aided these efforts by providing access to education and capital.

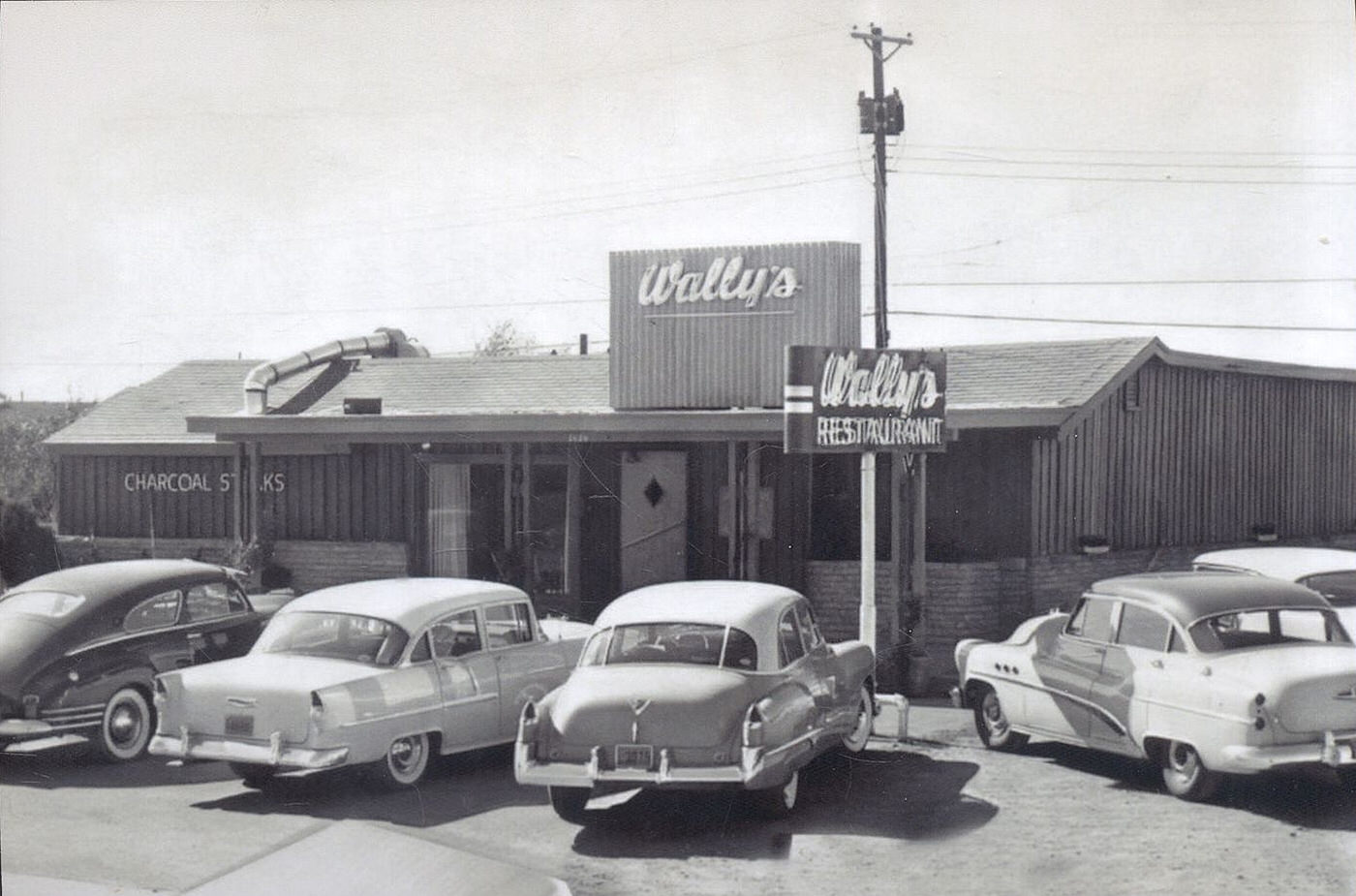

This confluence of military investment, oil wealth, returning entrepreneurs, and national prosperity led to broad-based growth. Banking deposits surged, reflecting increased financial activity. Retail, wholesale, construction, and service sectors all expanded to meet the needs of the growing population. Established businesses like H.O. Wooten Wholesale Grocery continued to operate, while new restaurants and shops emerged.

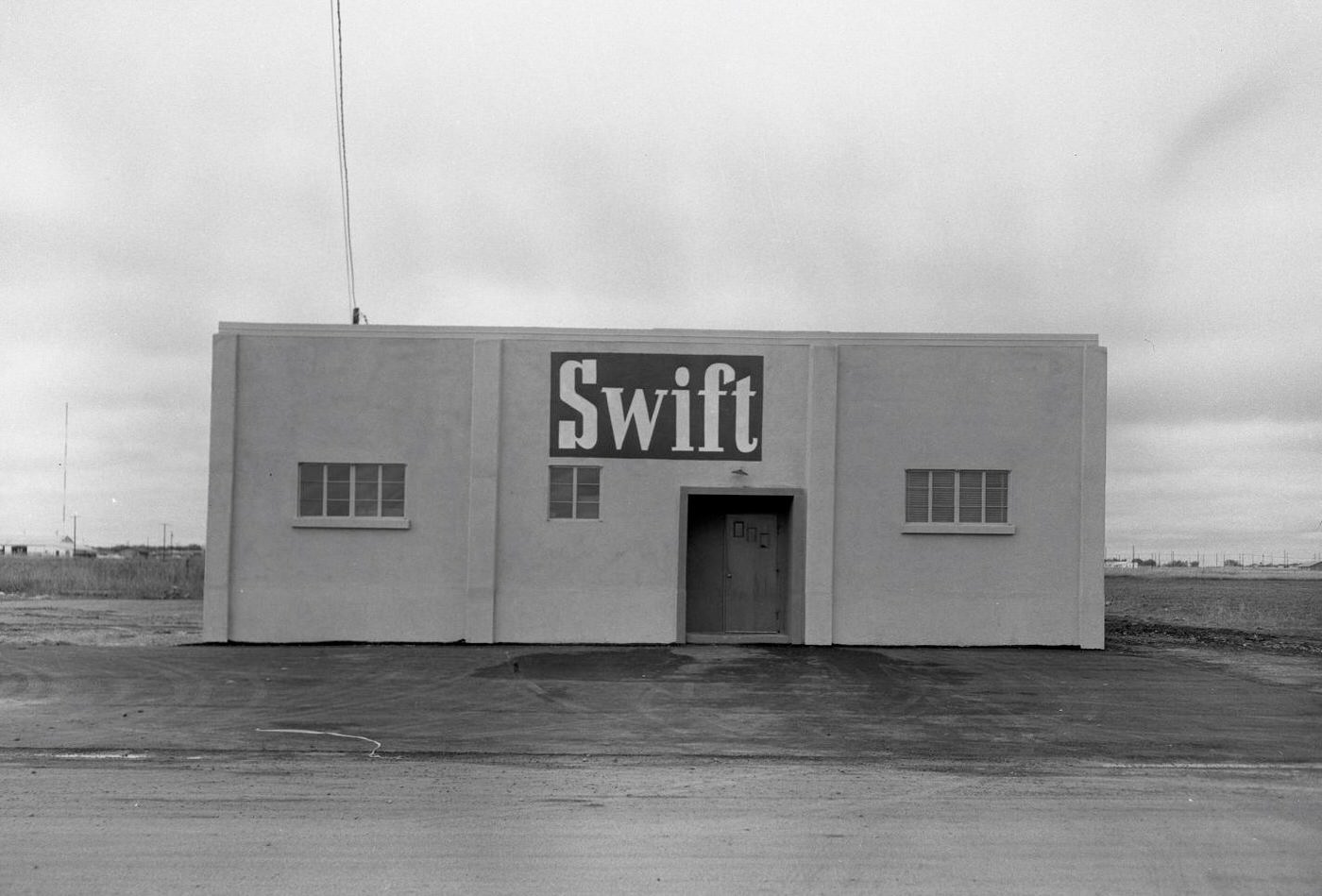

The economy also diversified beyond its traditional agricultural roots. Industries supporting the oil fields flourished. Manufacturing grew, with Taylor County hosting plants involved in meat packing, bottling, clothing, and various equipment manufacturing after the war. While agriculture remained a component, it underwent changes; cotton farming faced challenges, while livestock operations diversified to include more pigs, sheep, and poultry. The number of individual farms decreased due to consolidation and mechanization. This period marked a fundamental shift for Abilene, transforming it from a primarily agricultural and railroad town into a more complex economy driven by military, energy, and service sectors.

Under a Dusty Sky: The Decade of Drought

The 1950s brought not only growth but also profound environmental hardship to Abilene and Taylor County. A devastating drought gripped Texas from roughly 1950 through 1957, a period so severe it became the benchmark “drought of record” for the region until the 21st century. Rainfall plummeted to 30-50% below normal, and several years within this period (1951, 1954, 1956) ranked among the driest ever recorded in the state. West Texas bore the brunt of this dryness.

Agriculture, a traditional pillar of the local economy, suffered immensely. Crop yields fell drastically, sometimes by half. Many farms and ranches failed, forcing families off the land and accelerating the shift from rural to urban life. Ranchers struggled with scarce water and soaring feed prices, compelling them to sell off livestock at depressed prices. The parched land, often overgrazed, became vulnerable.

Water supplies dwindled across the state. Numerous communities imposed water restrictions, and some ran completely out of water, necessitating emergency deliveries by truck or rail. Creeks and ponds vanished. Abilene, having faced water challenges before, had constructed reservoirs like Lake Abilene, Lake Kirby, and Lake Fort Phantom Hill in previous decades. During the 1950s drought, the city took further action, building diversion dams and pumps to capture water from the Clear Fork of the Brazos River and Deadman Creek, though this led to legal battles with downstream users concerned about their own water rights.

The combination of intense drought, high winds, and farming practices that left soil exposed unleashed relentless dust storms upon the region. These were not mere hazy days; residents described terrifying “black blizzards” that rivaled the infamous Dust Bowl of the 1930s. Eyewitness accounts from Abilene recall impenetrable walls of dust rolling in, blotting out the sun, and forcing people to seal their homes with wet rags against the invasive grit. Despite these efforts, fine dust coated everything indoors. Winds whipped the dust at speeds reported up to 70 mph nearby, damaging property, killing livestock, and posing health risks. Instead of rain, inches of dust collected in rain gauges.

Politically, a significant local shift occurred in 1957 when the Abilene public schools transitioned from a city-controlled system to an independent school district (AISD). This change was driven by the need for greater taxing authority to fund the massive school construction program required by the population boom. On a broader scale, the city’s political alignment likely continued its shift towards favoring Republican candidates in national elections, a trend noted for the post-war decades. The pressures of the Cold War and the Civil Rights movement were evident in local discourse, from drought-era accusations of communism directed at officials to the school board’s resistance to integration mandates.

In the business realm, local establishments like Gandy’s Big Buy, Mack Henson’s Grocery, the Dixie Pig, and Minter’s Department Store were part of the daily commercial fabric. The boot-making company Leddy Boots operated in Abilene. A key development for the city’s future occurred in 1954 with the establishment of the Dodge Jones Foundation by Ruth Legett Jones. While its major impact on downtown revitalization came later, its founding during this decade laid the groundwork for significant future philanthropy. These varied events and developments show a city actively defining itself – celebrating its heritage, restructuring its governance to meet growth challenges, engaging with national political currents, and fostering local businesses amidst the larger economic and environmental forces shaping the decade.

Image Credits: Image Credits: The Grace Museum, Hardin-Simmons University Library, Abilene Christian University Library, McMurry University Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know