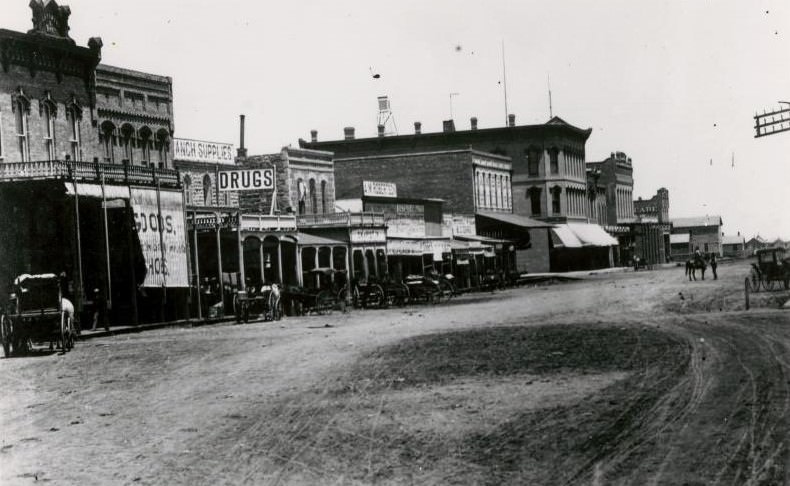

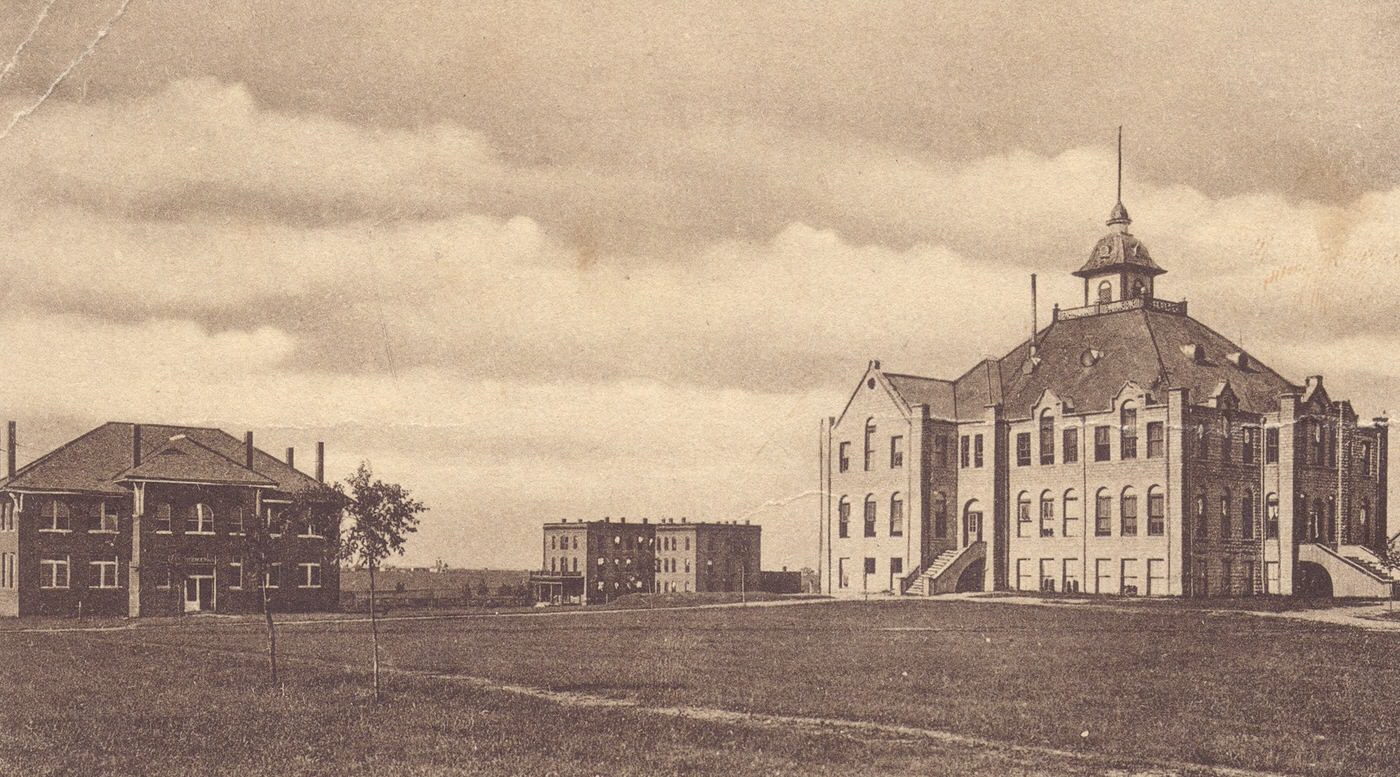

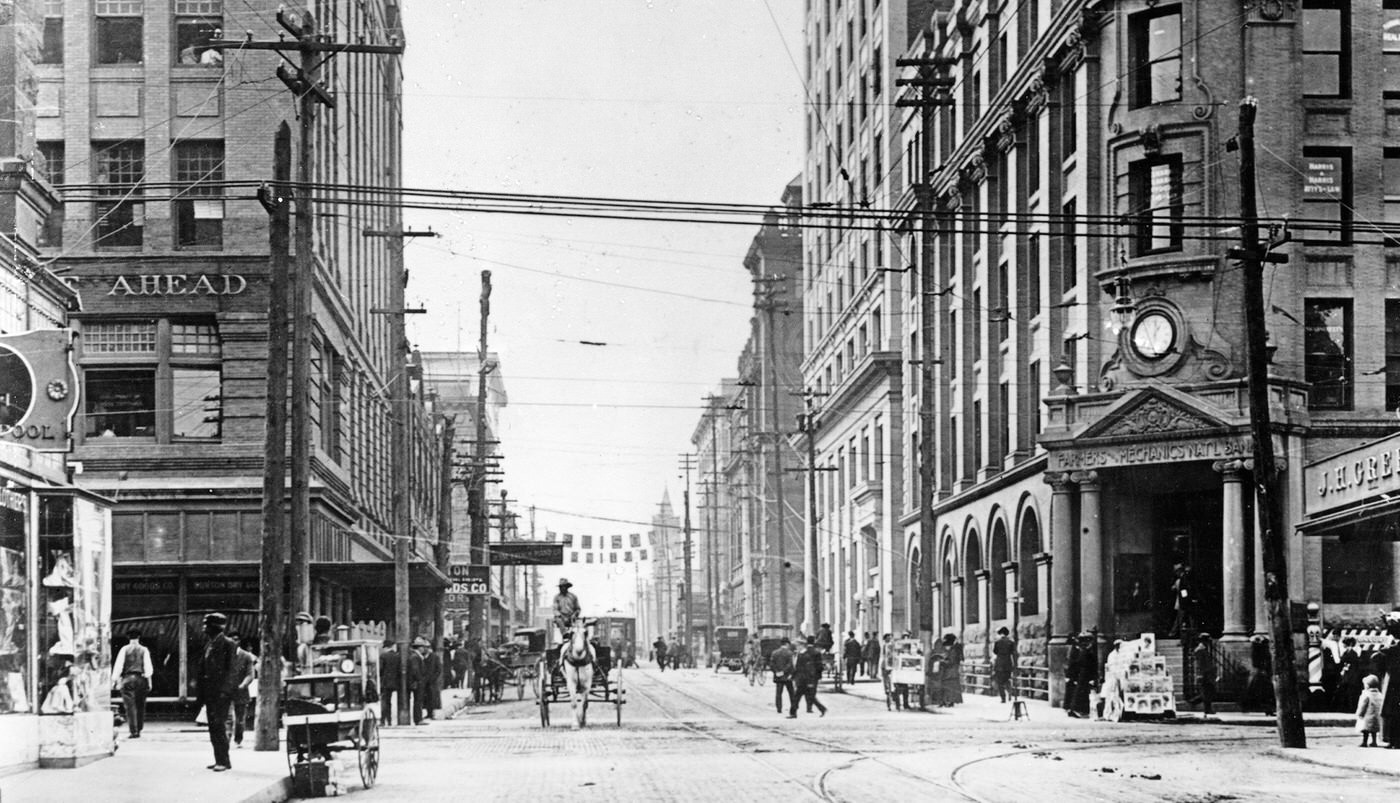

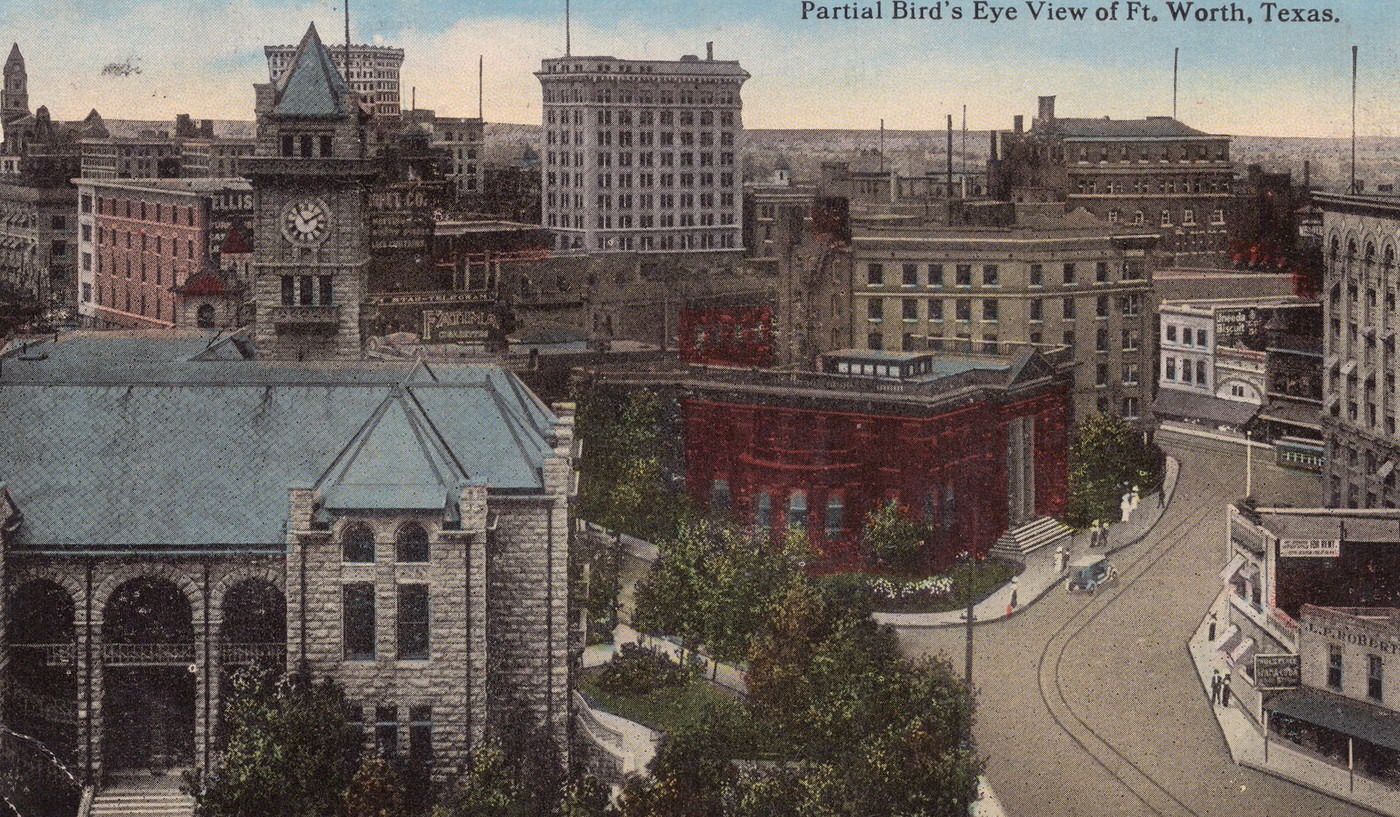

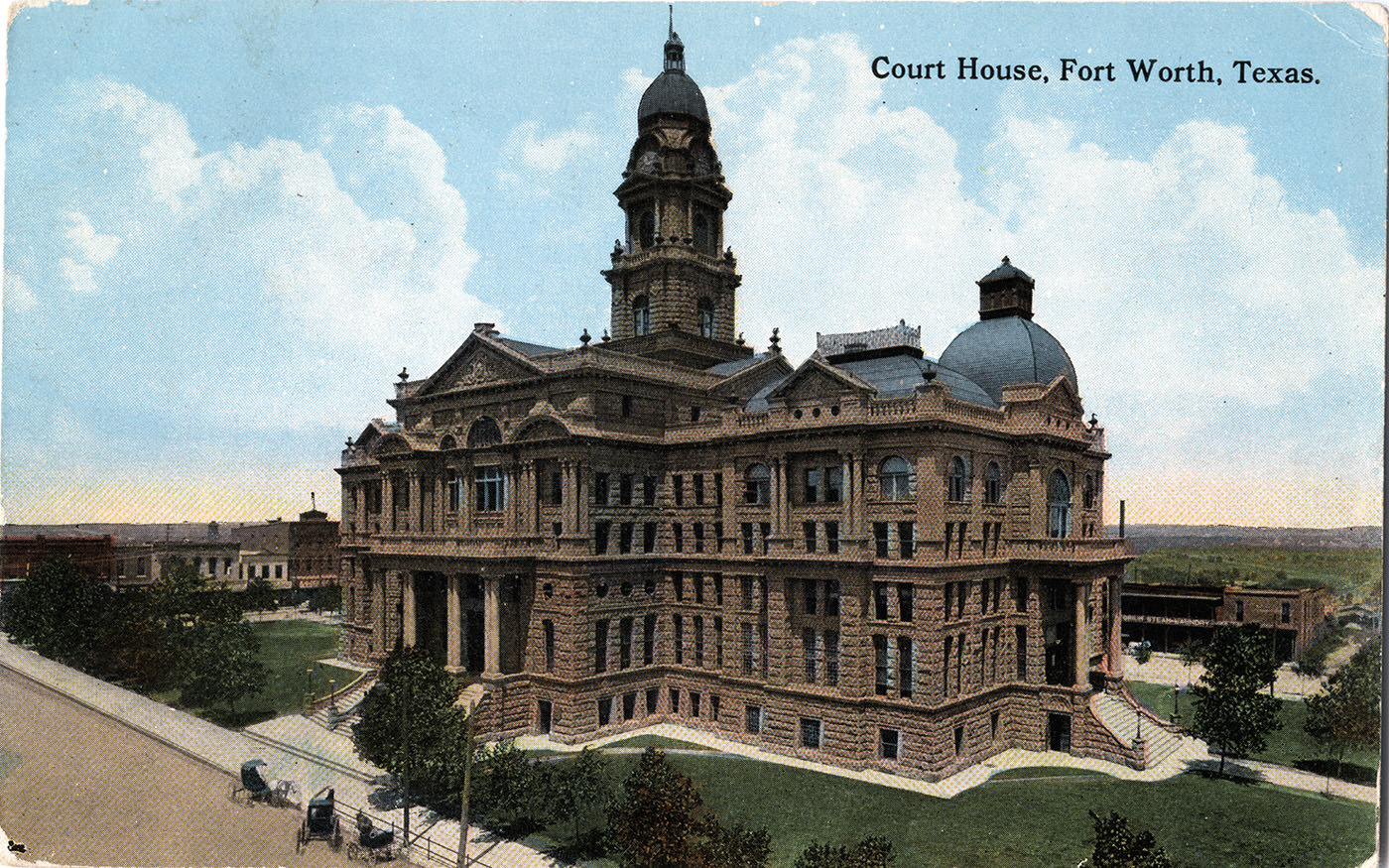

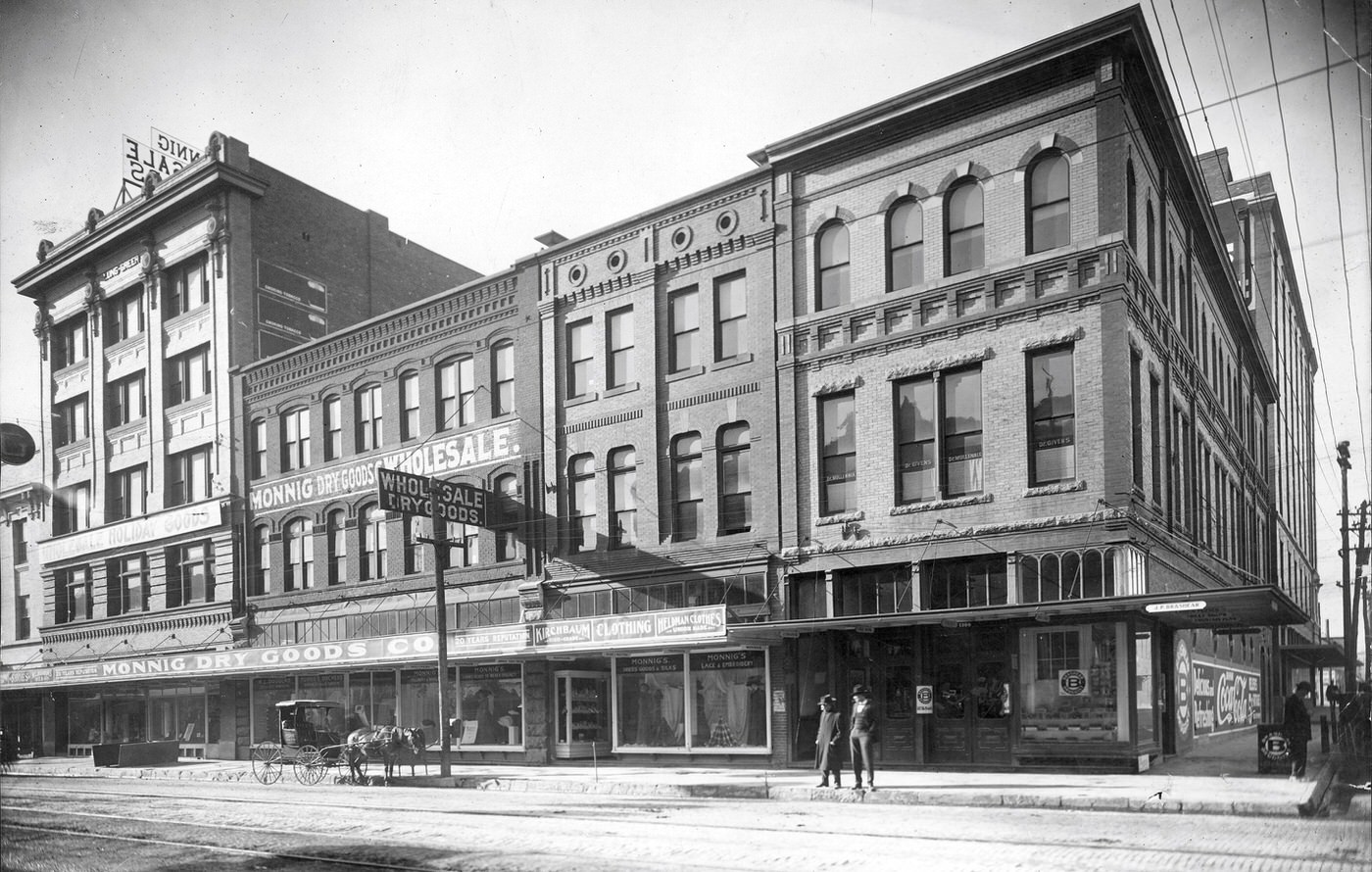

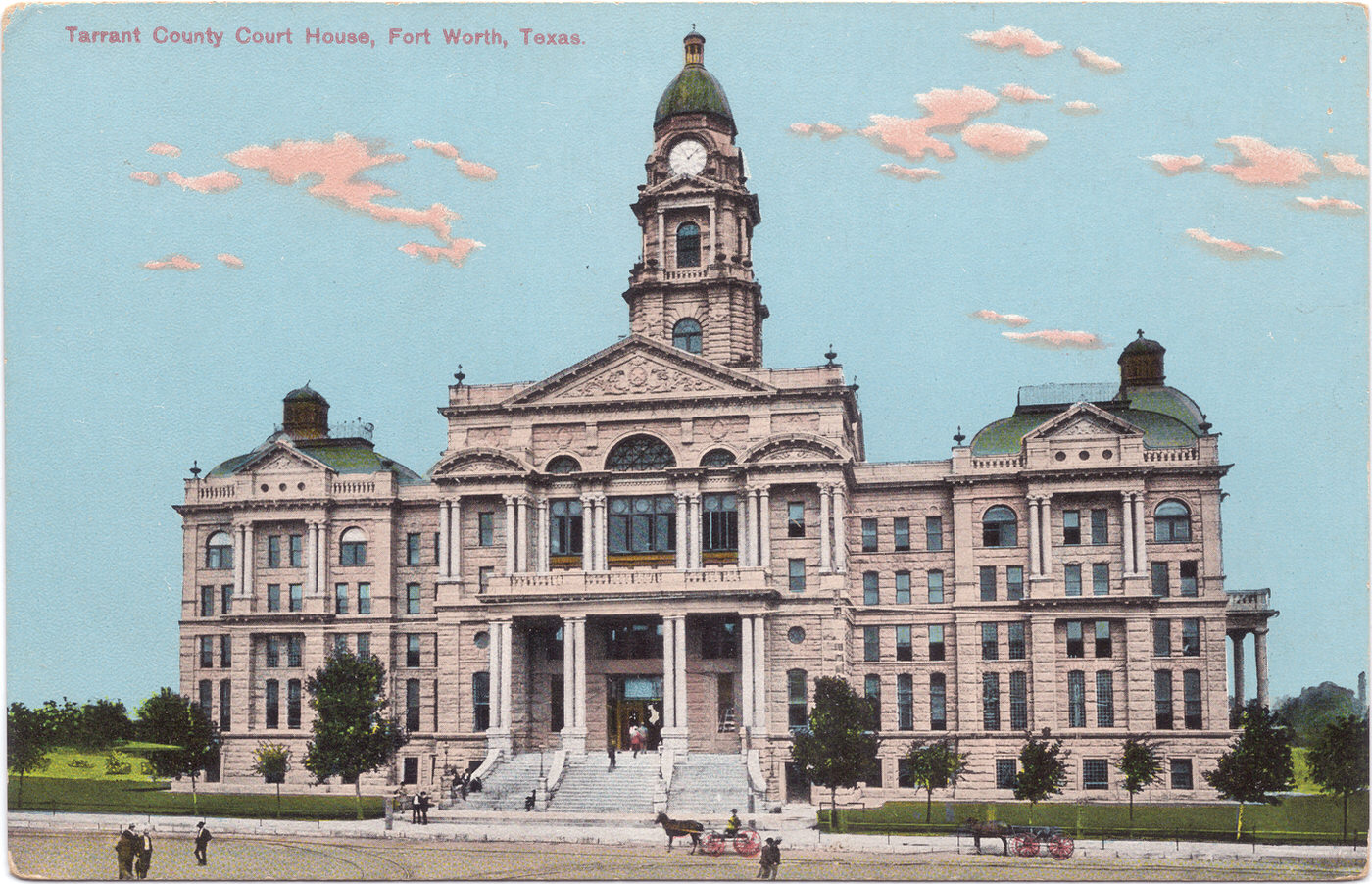

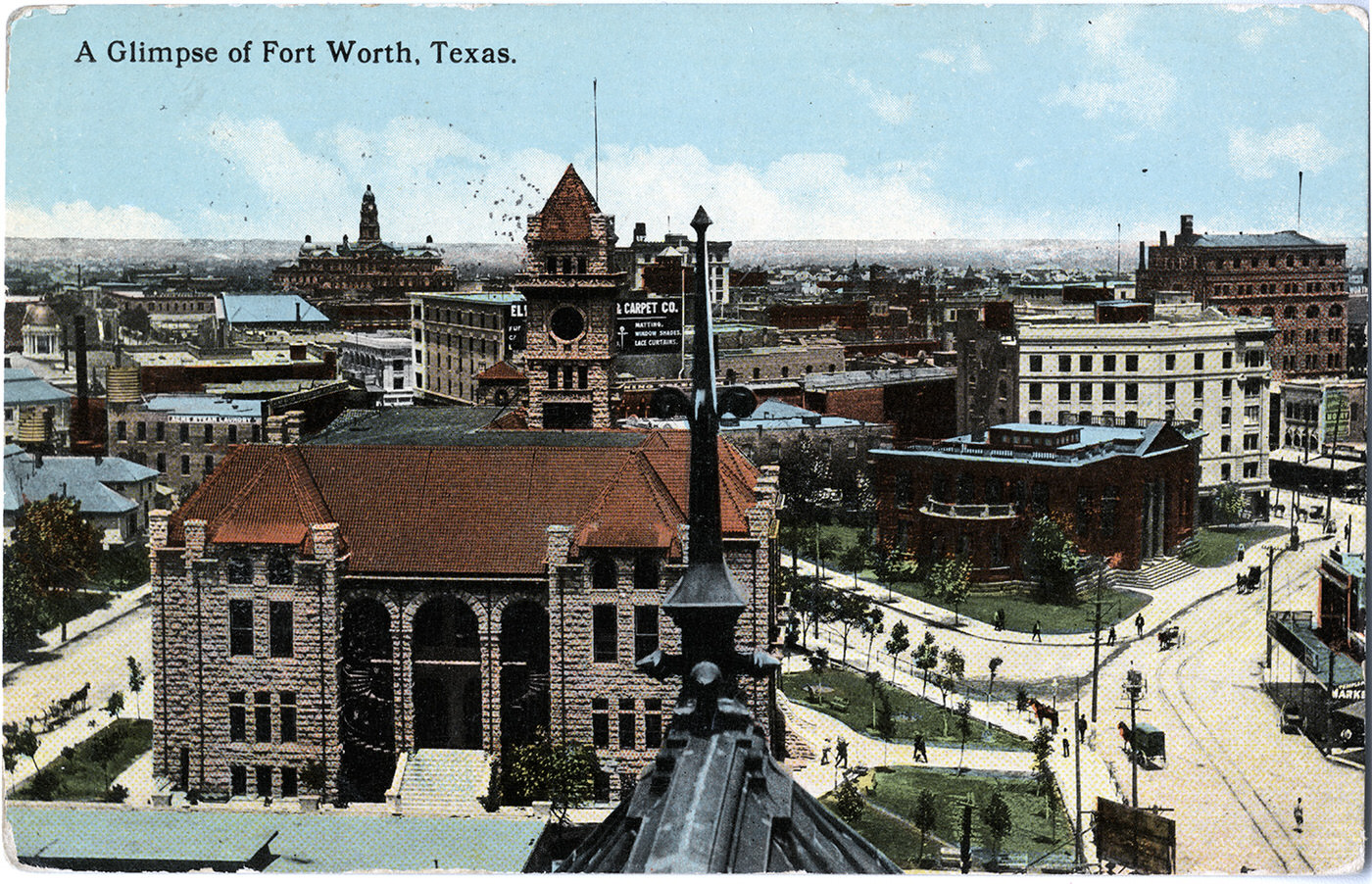

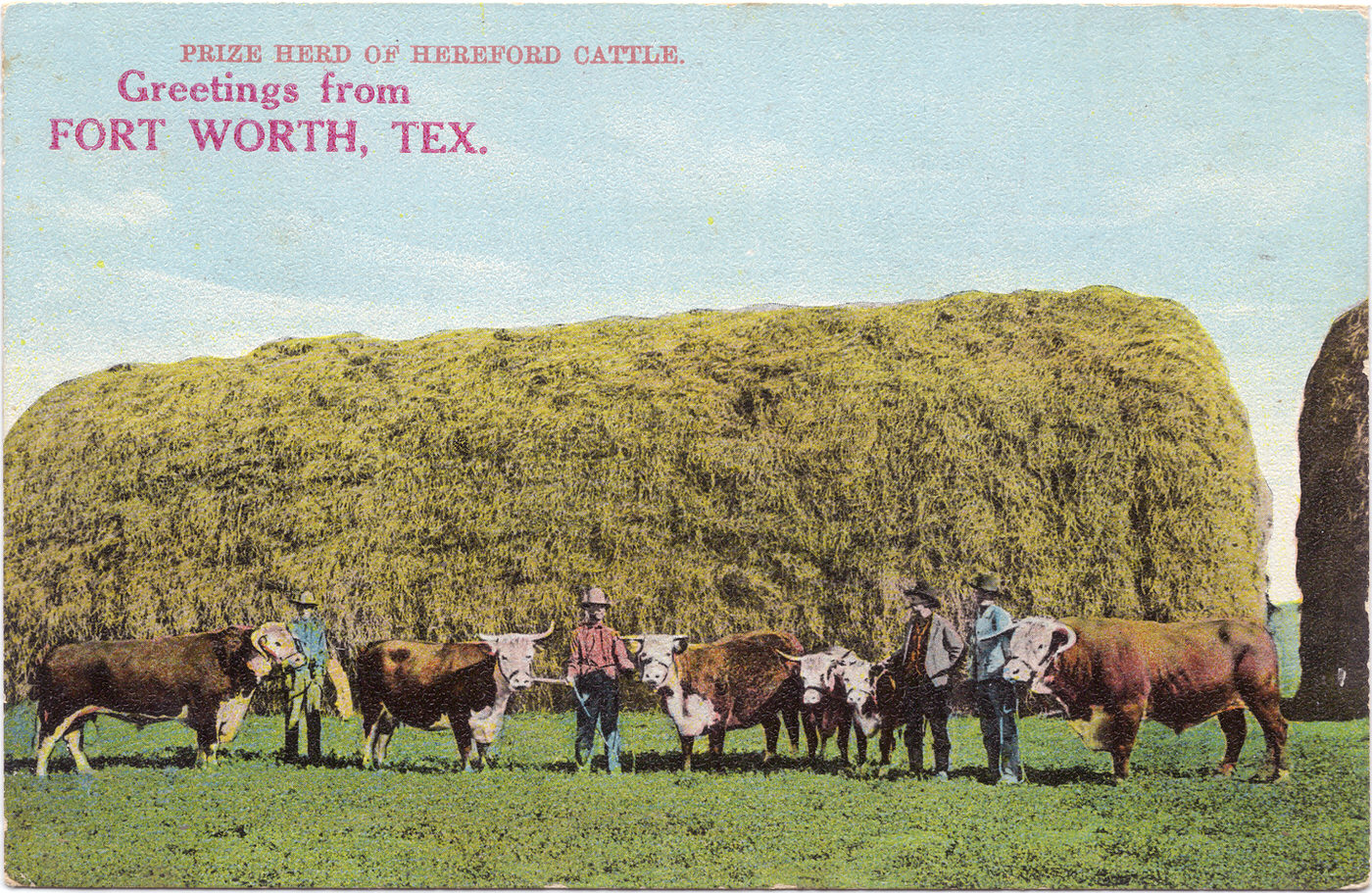

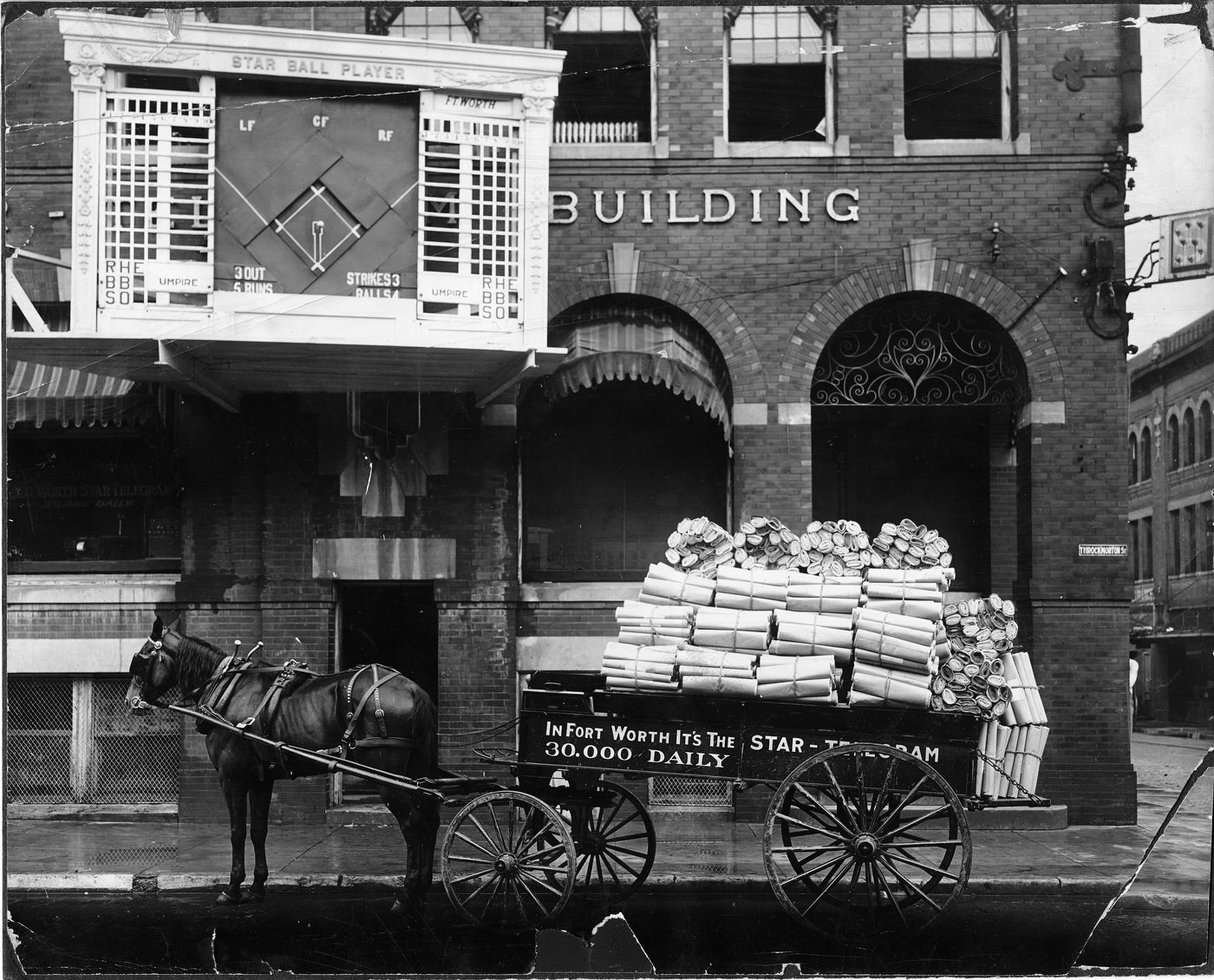

In the 1910s, Fort Worth, Texas, was a city growing fast, full of energy and big dreams. Its population had reached an impressive 73,312, a figure made even more remarkable by the fact that it represented a staggering 175 percent increase from just ten years prior, when only 26,688 residents called it home. This explosive growth wasn’t accidental; it was the direct result of a calculated pivot towards industrialization, building upon the city’s hard-won identity as “Cowtown”

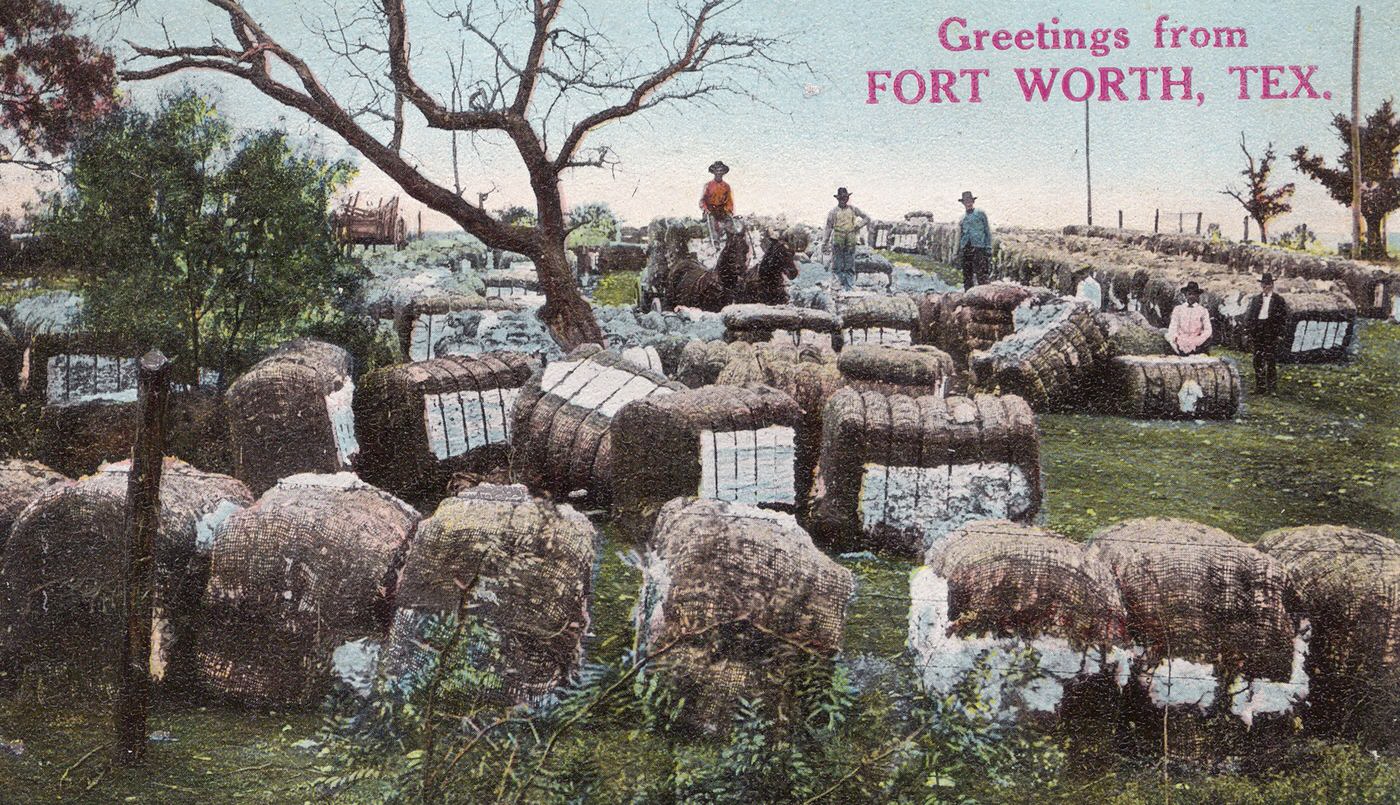

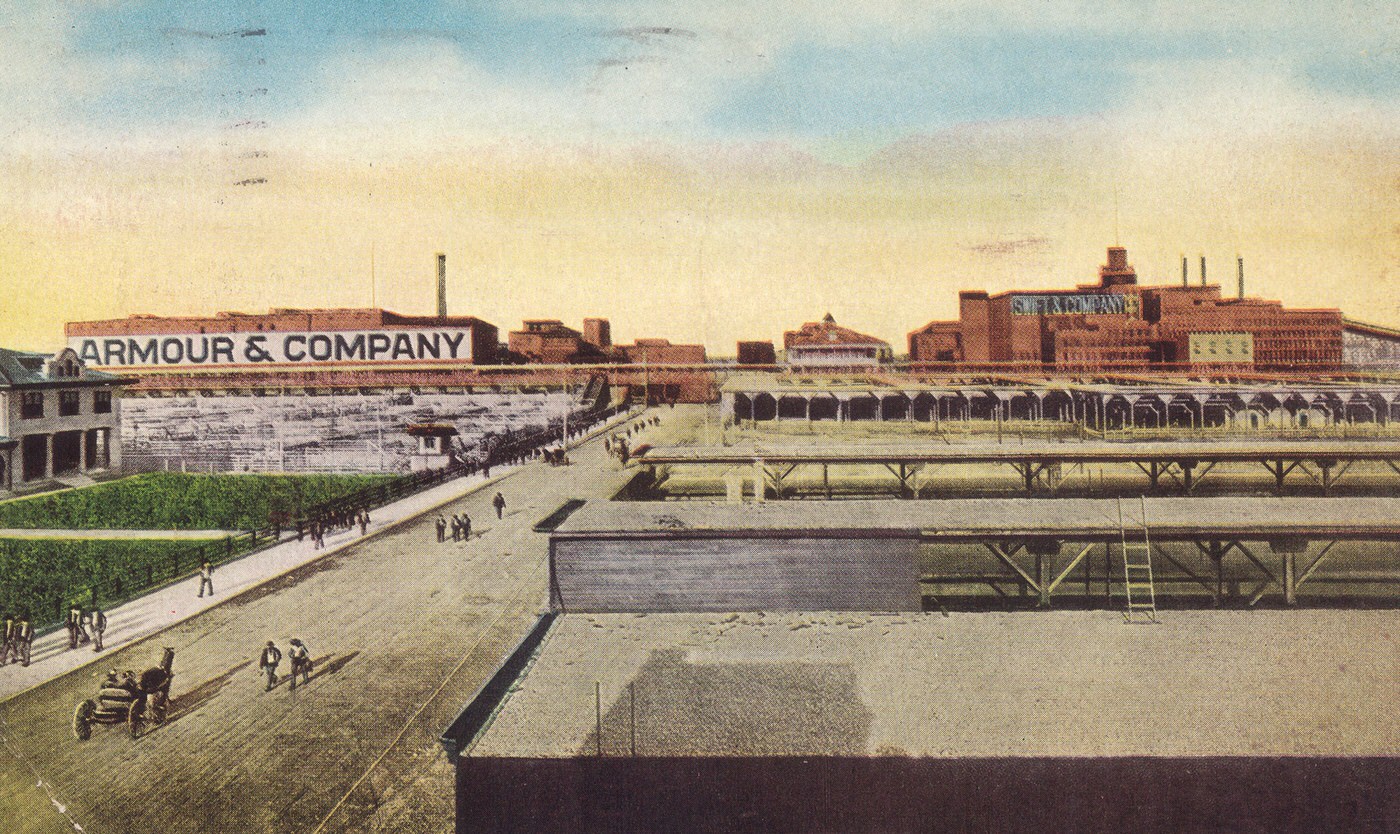

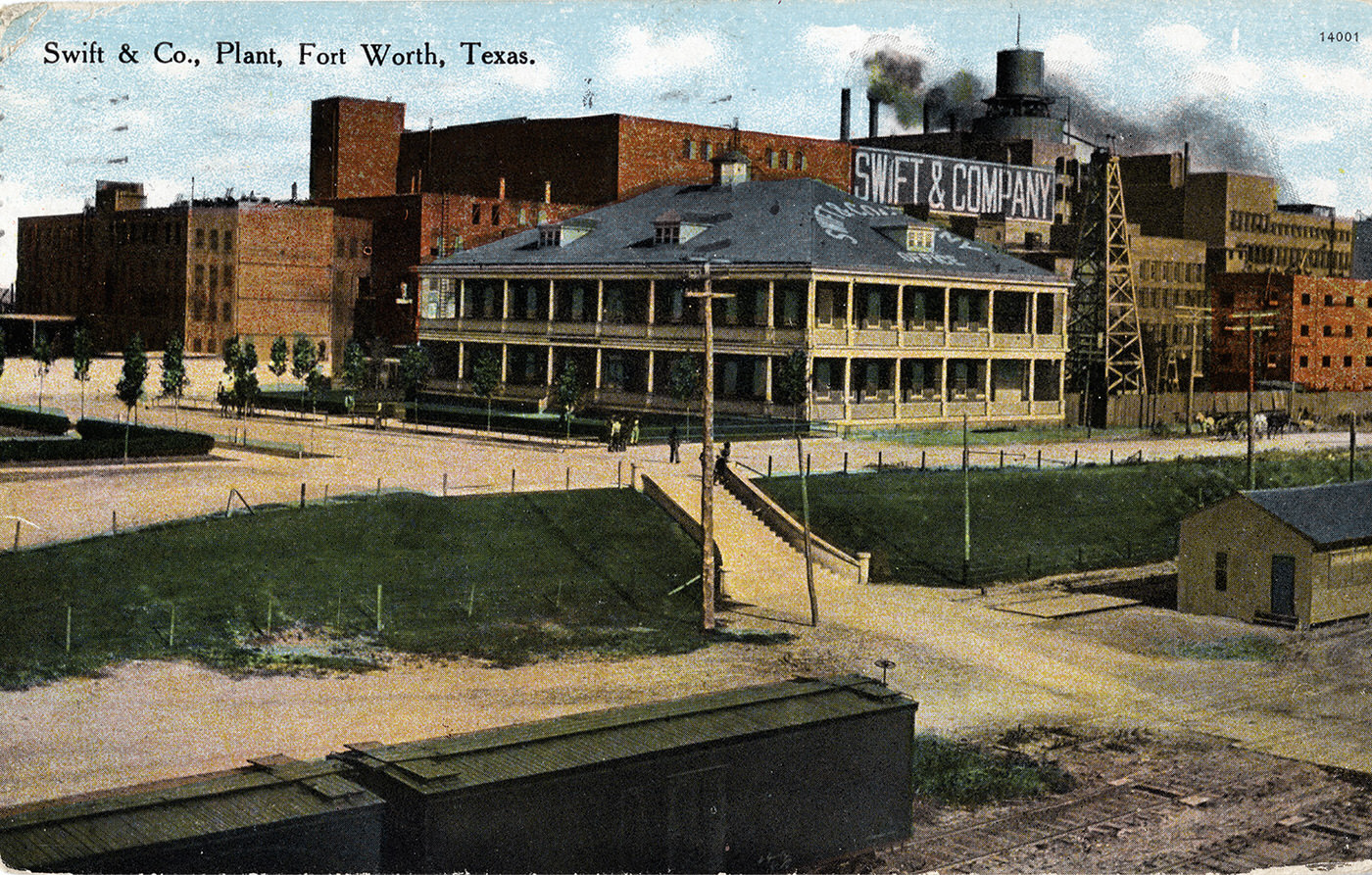

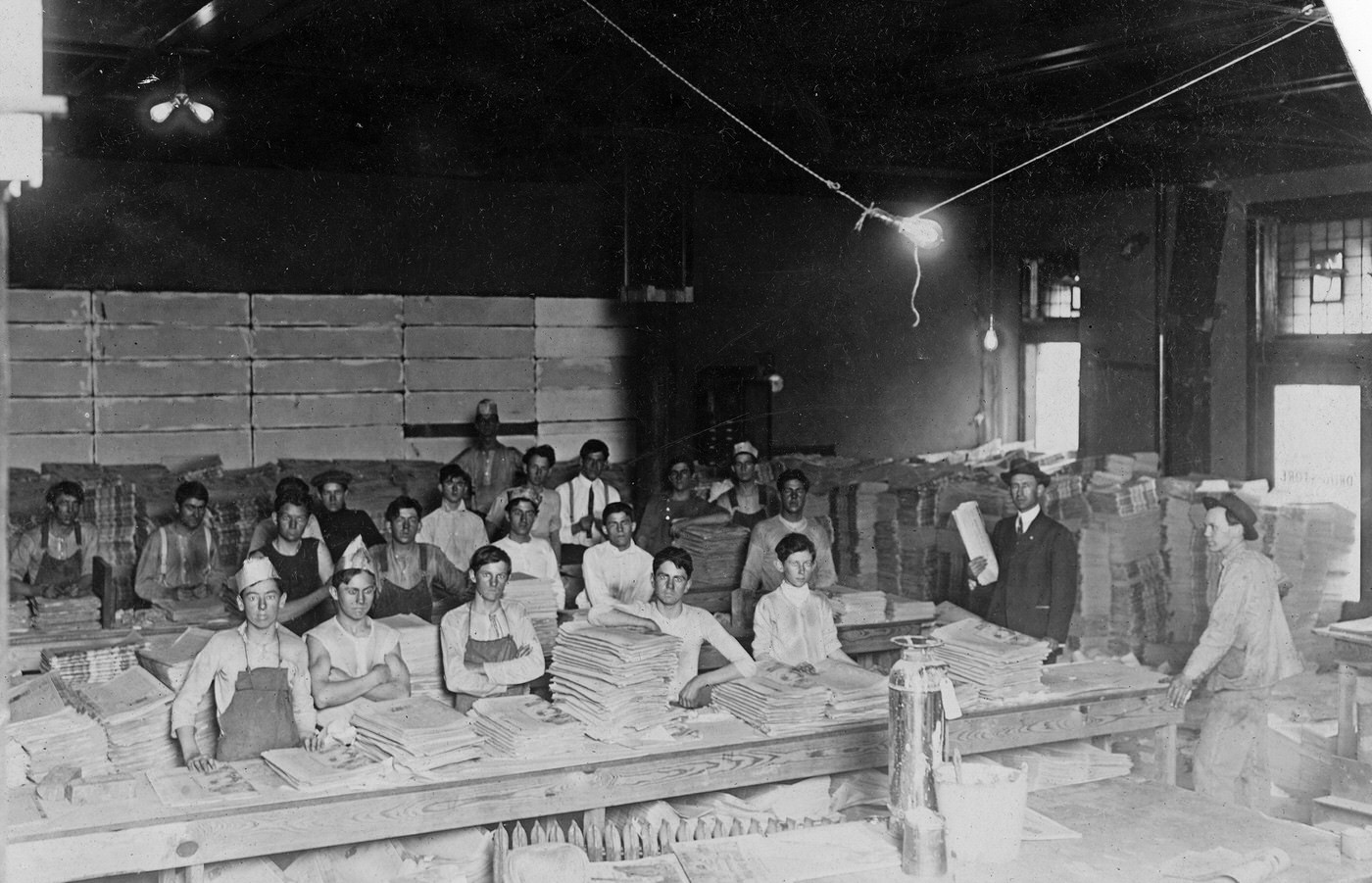

The city’s roots lay deep in the cattle trade. For decades, it served as the last major stop for rest and supplies for drovers pushing millions of longhorns north along the legendary Chisholm Trail. But by 1910, the open range cattle drives were largely a memory, replaced by a more modern, industrial engine: the massive meatpacking plants. Lured by civic leaders and advantageous conditions, the giants of the industry, Armour & Company and Swift & Company, had established sprawling facilities just north of the Trinity River in 1902, opening officially in 1903-1904. These plants, alongside the ever-expanding Fort Worth Stockyards , were the primary drivers of Fort Worth’s meteoric rise, employing thousands and attracting waves of migrants seeking opportunity. Fort Worth wasn’t merely growing; it was actively being engineered into a major industrial hub, leveraging its geographical position in cattle country and its increasingly robust infrastructure.

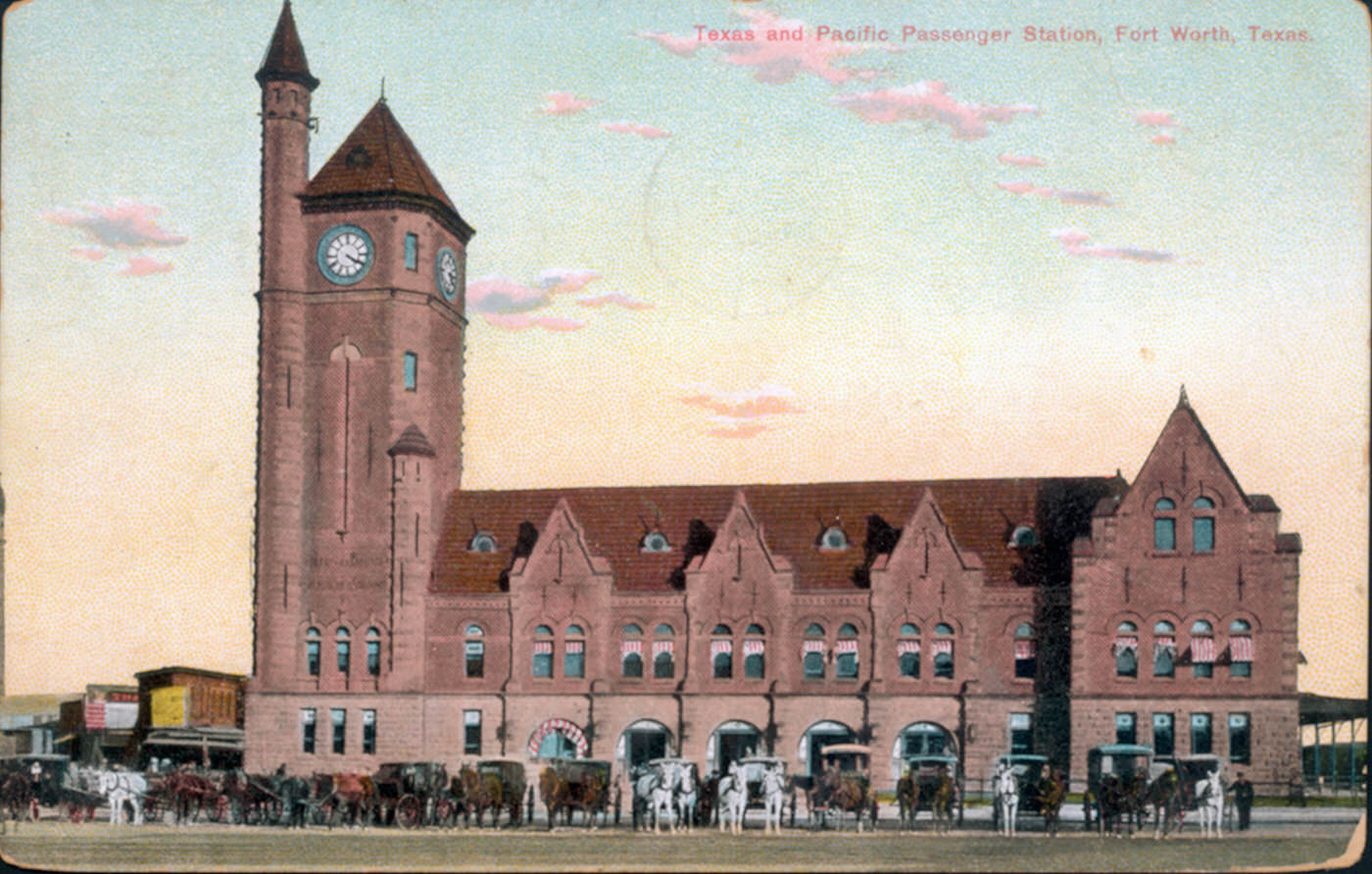

Underpinning this industrial might was Fort Worth’s status as a critical railroad nexus for the Southwest. By 1910, an impressive network of steel arteries converged on the city. The Texas and Pacific Railway (T&P), whose arrival in 1876 had famously rescued the town from economic stagnation, was now joined by Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MKT or “Katy”), the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF), the Fort Worth & Denver City (FW&DC), and the Fort Worth & Rio Grande. This intricate web of rails was the lifeblood of the meatpacking industry, efficiently transporting livestock into the Stockyards and shipping processed meat products out to the nation, while simultaneously fueling commerce across the region. Fort Worth entered the 1910s not just as a city shaped by its past, but as one aggressively forging a new industrial future.

A City Exploding: Population Growth (1910-1920)

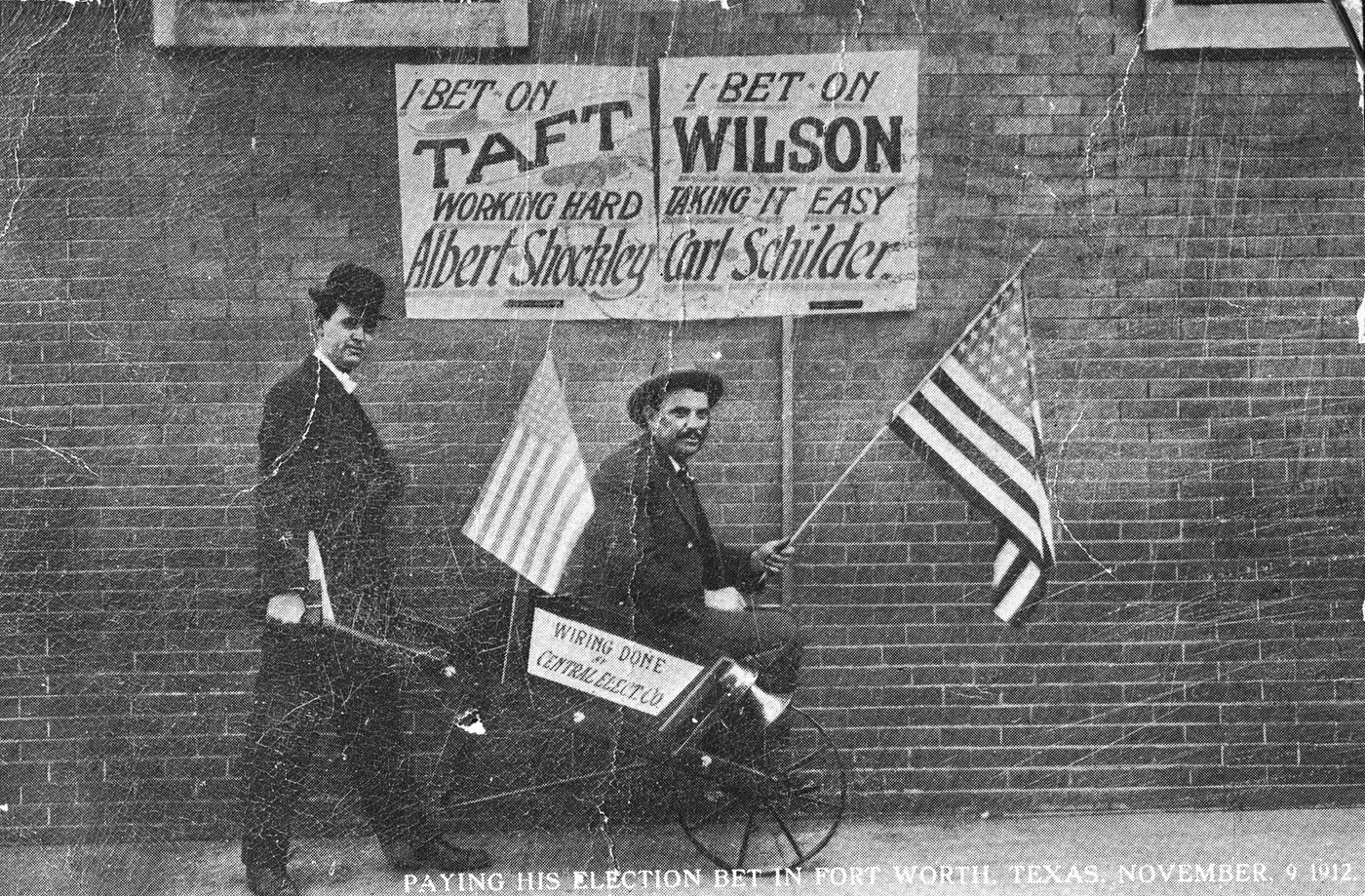

The dramatic population surge that characterized the first decade of the 20th century continued, albeit at a slightly less frantic pace, into the 1910s. Having entered the decade with 73,312 residents, Fort Worth counted 106,482 people by the 1920 census. This represented a robust 45% increase over the ten-year period, cementing Fort Worth’s position as a major Texas city.

This continued growth was fueled by a confluence of factors. The established industries, particularly the ever-expanding meatpacking plants and the railroads that served them, remained powerful magnets for jobseekers. Added to this were the powerful new stimuli emerging later in the decade: the massive military mobilization for World War I beginning in 1917, which brought tens of thousands of soldiers and support personnel, and the nascent effects of the West Texas oil boom, also starting around 1917.

A significant new stream of migration during this decade originated south of the border. The Mexican Revolution, which erupted in 1910, displaced thousands of people seeking refuge from the violence and instability. While Fort Worth had seen a small number of Spanish-surnamed residents in previous decades, likely connected to railroad work or the earlier cattle trade , the revolution marked the beginning of a substantial Hispanic community. Fleeing persecution and economic disruption, many Mexican nationals and Tejanos moved north. By 1920, Fort Worth was home to an estimated 3,785 ethnic Mexicans , who established early neighborhoods, or barrios, often near the railroad lines and industrial areas, known by names like La Corte, “Little Mexico,” and El TP (likely near the Texas & Pacific rail yards). Alongside this international migration, Fort Worth continued to attract people from other parts of the United States, particularly from the rural South, drawn by the promise of industrial jobs and urban opportunity.

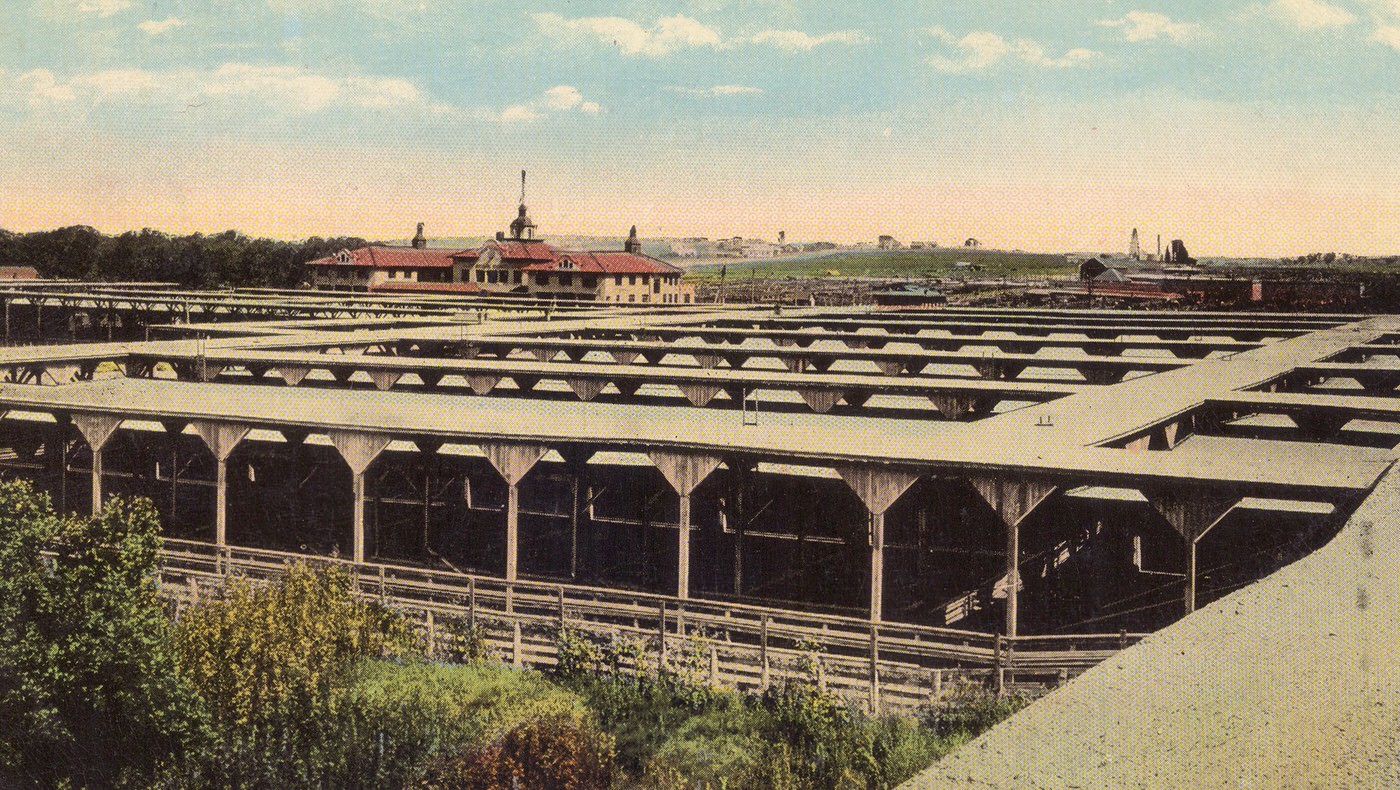

The Wall Street of the West: Stockyards and Meatpacking Thrive

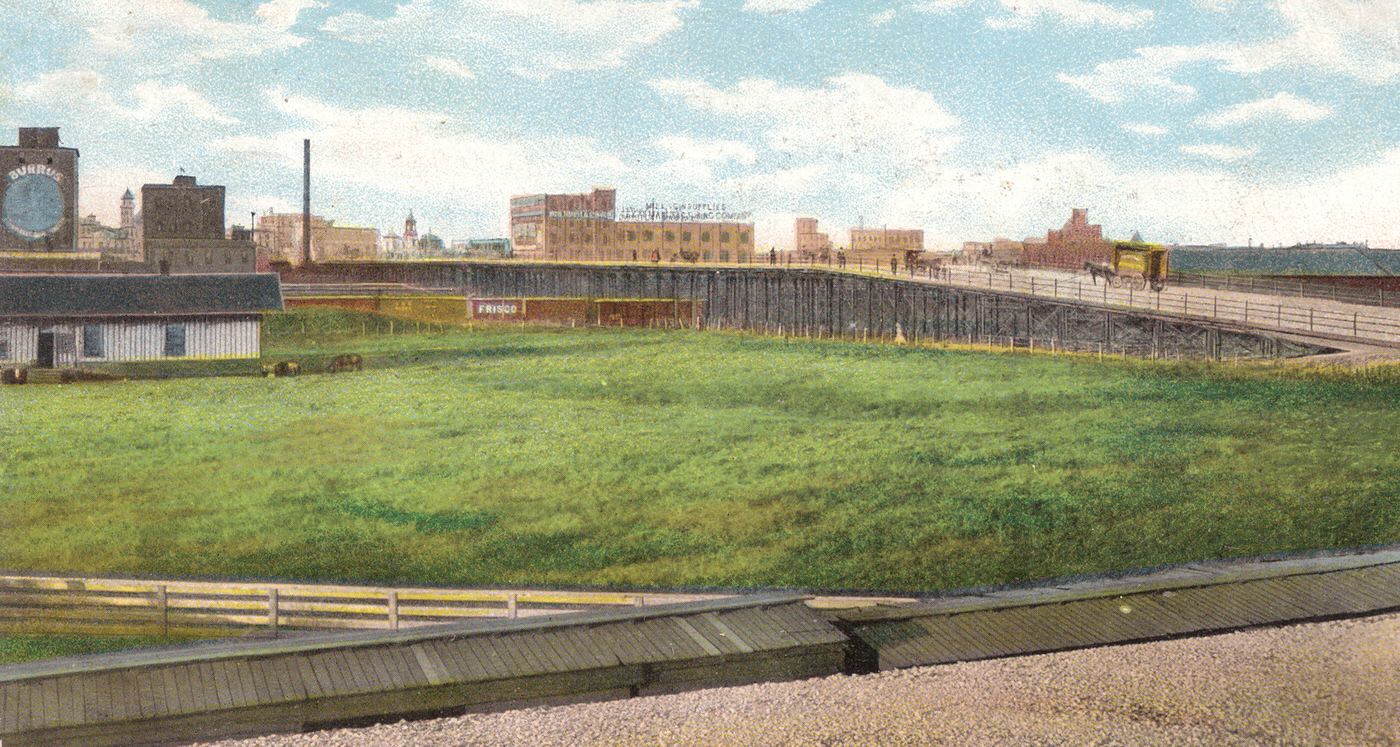

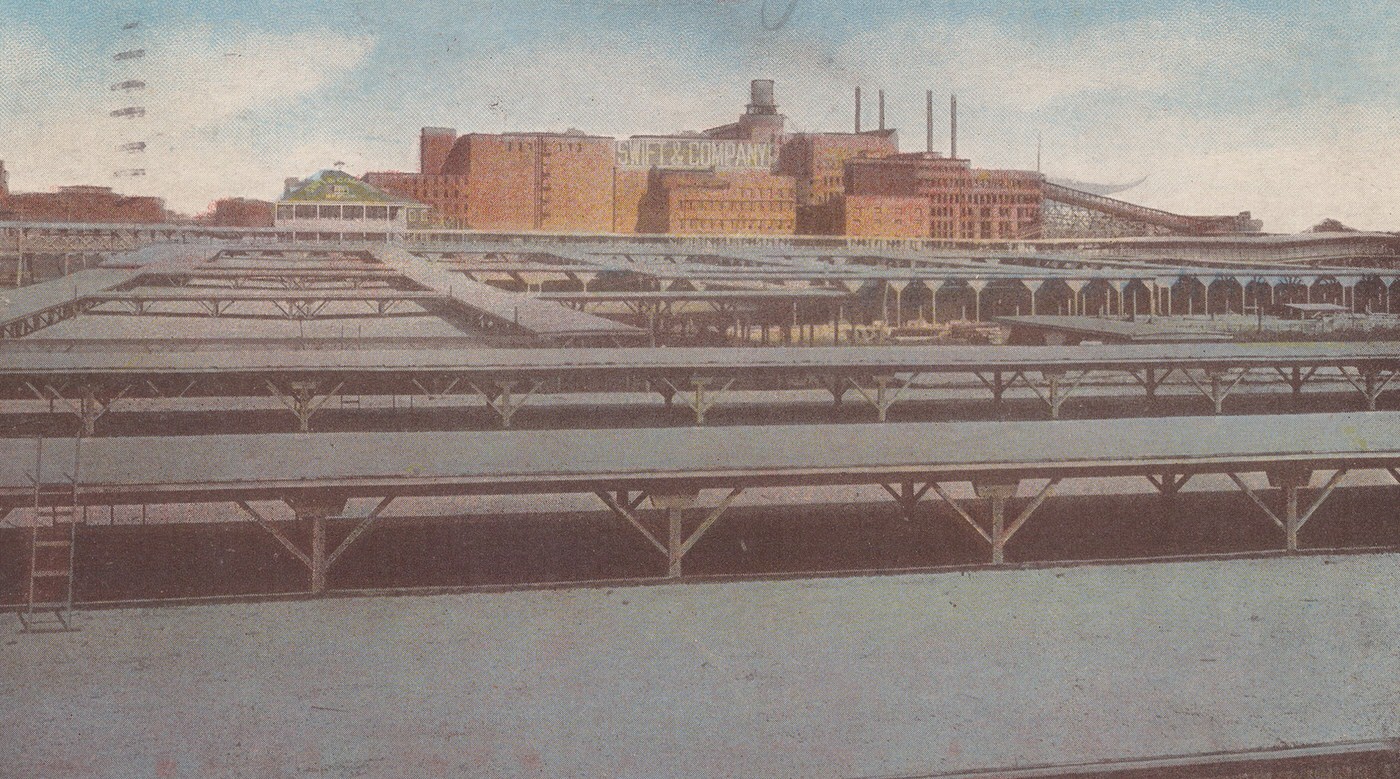

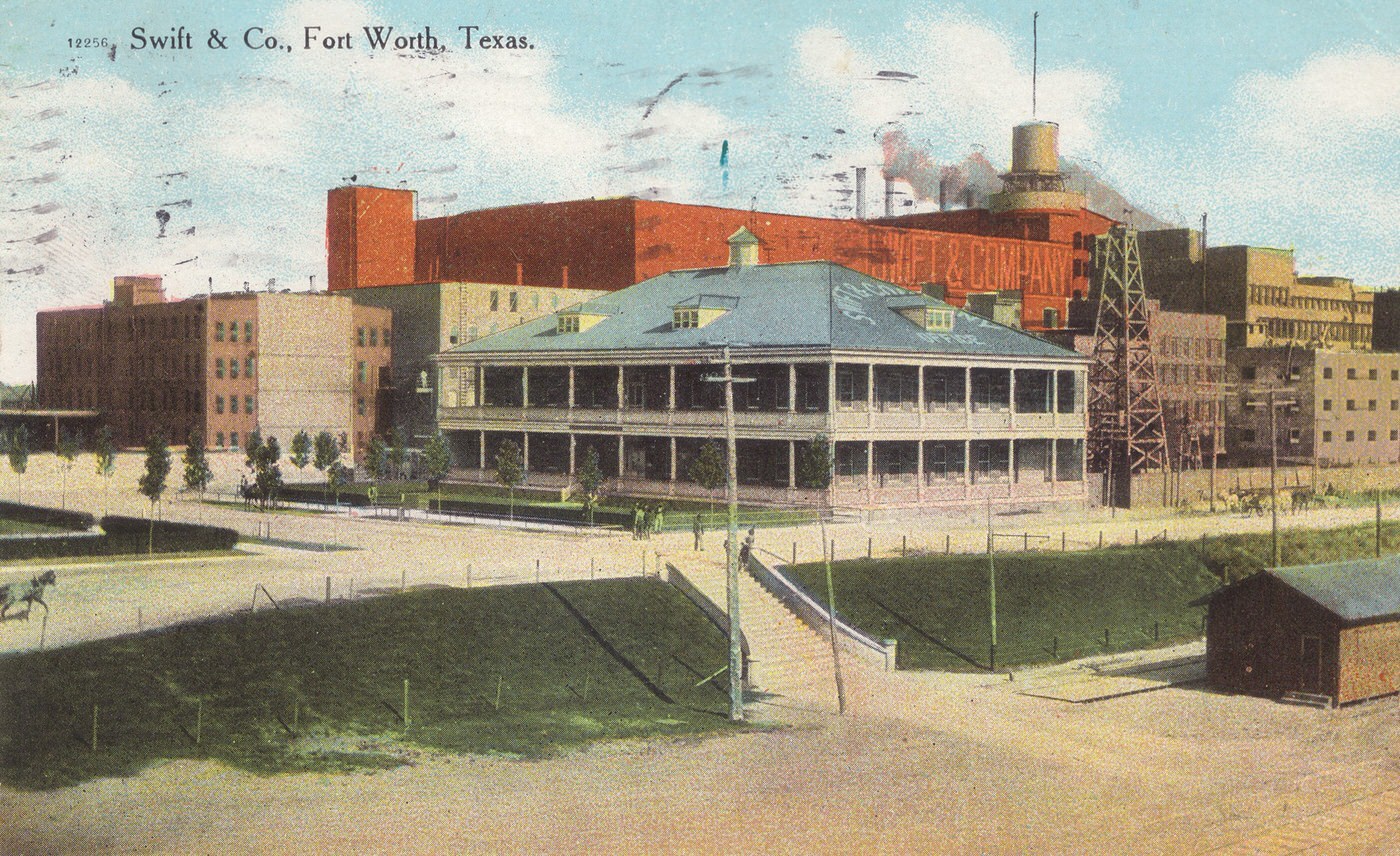

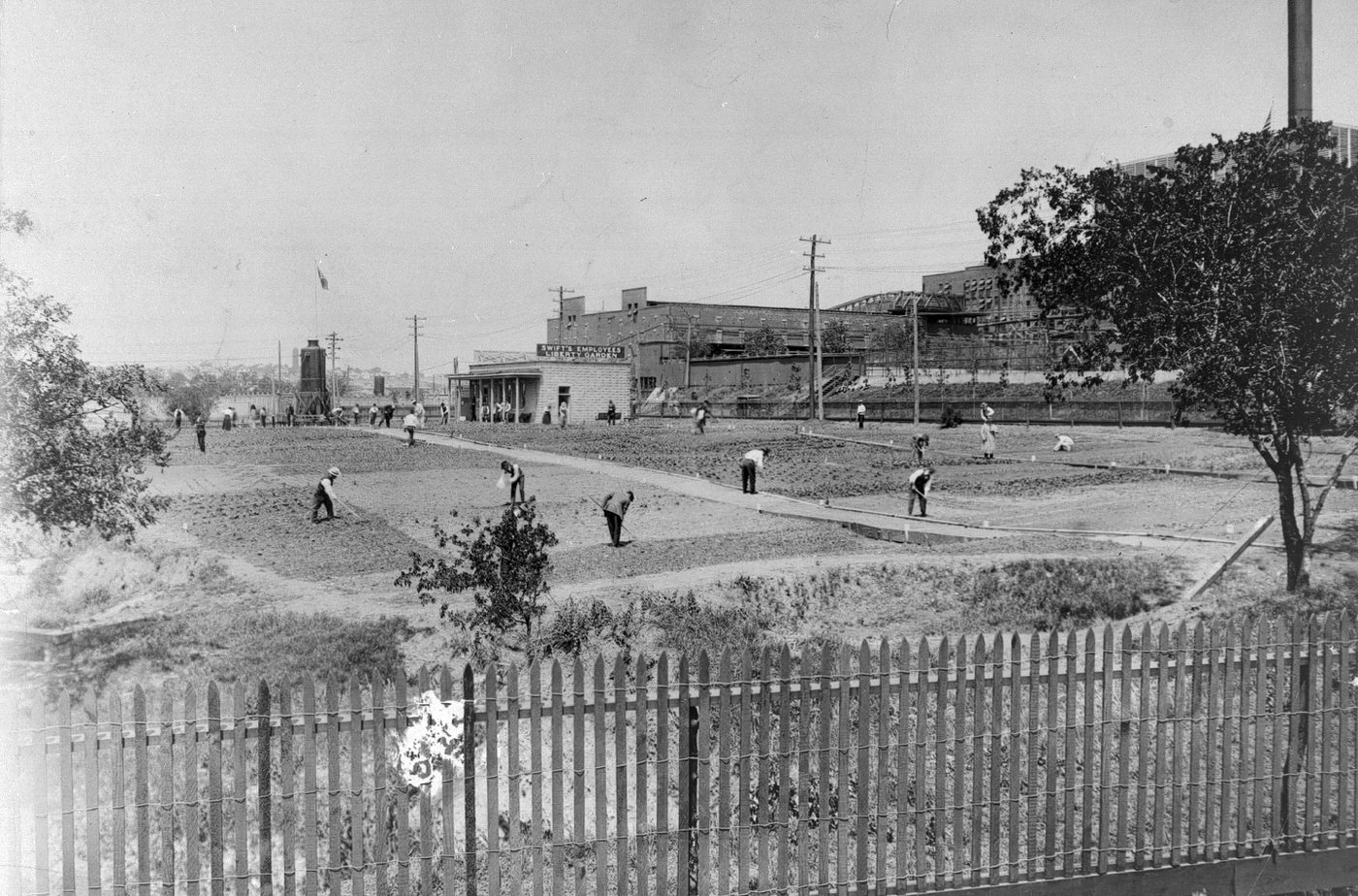

The decade of the 1910s saw the Fort Worth Stockyards and the adjacent meatpacking plants consolidate their dominance, earning the district the moniker “The Wall Street of the West”. Armour and Swift, the titans whose arrival had ignited the previous decade’s boom, continued to expand their massive operations. Swift & Company, for instance, undertook a major enlargement in 1908-09 that nearly doubled its plant capacity, enabling it to process an astounding 5,000 hogs daily, alongside vast numbers of cattle, sheep, and poultry by 1909.

Their influence extended far beyond the packinghouse gates. Demonstrating a deep integration into the local and regional economy, Armour and Swift became joint owners in several key ventures, including the Fort Worth Belt Railway Company (essential for moving livestock and products), the Stockyards National Bank of North Fort Worth, the Fort Worth Cattle Loan Company (financing the ranchers), and the Reporter Publishing Company, which produced the influential The Live Stock Report. This intricate web of ownership highlighted the immense economic power wielded by the packers, shaping not just the livestock market but also transportation and finance in the region.

The sheer economic weight and desire for operational autonomy of this industrial complex led to a unique political development. In February 1911, the area encompassing the Stockyards and packing plants incorporated as a separate municipality: Niles City. Named after Louville V. Niles, a Boston investor instrumental in bringing Armour and Swift to Fort Worth, this enclave was designed to shield the valuable industrial properties—estimated to be worth between $12 million and $30 million within its half-square-mile boundary—from Fort Worth’s taxation and regulations. Governed initially by a mayor, marshal, and five aldermen, and boasting a population of just 508, Niles City functioned as the “richest little city in the world”. This arrangement underscored a clear tension between the powerful, self-contained industry and the growing metropolis of Fort Worth, which viewed the enclave as both an asset and a challenge to its own expansion and revenue base. Although Niles City successfully resisted annexation for most of the decade, Fort Worth eventually prevailed through state legislative maneuvers, absorbing the industrial heartland in 1923.

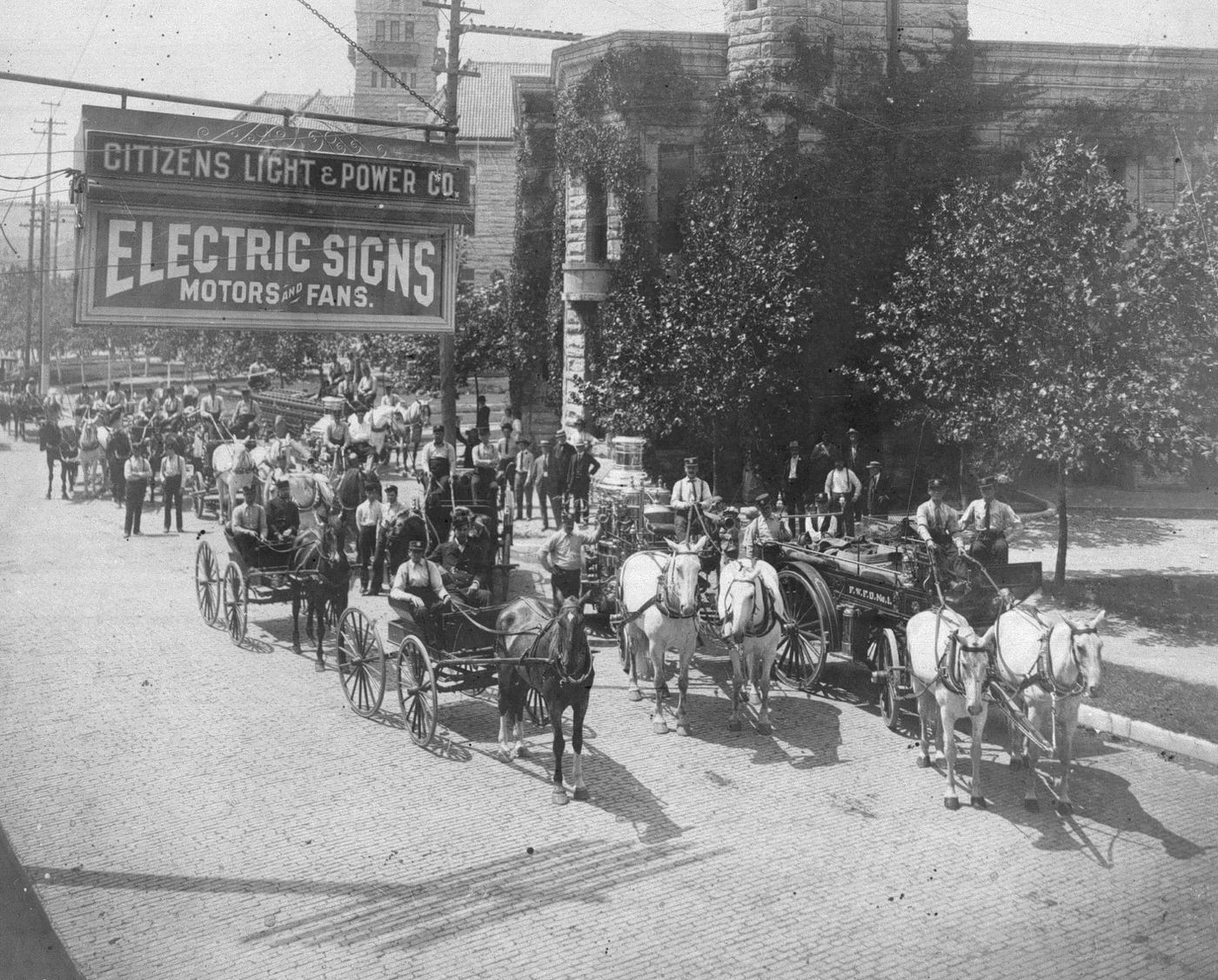

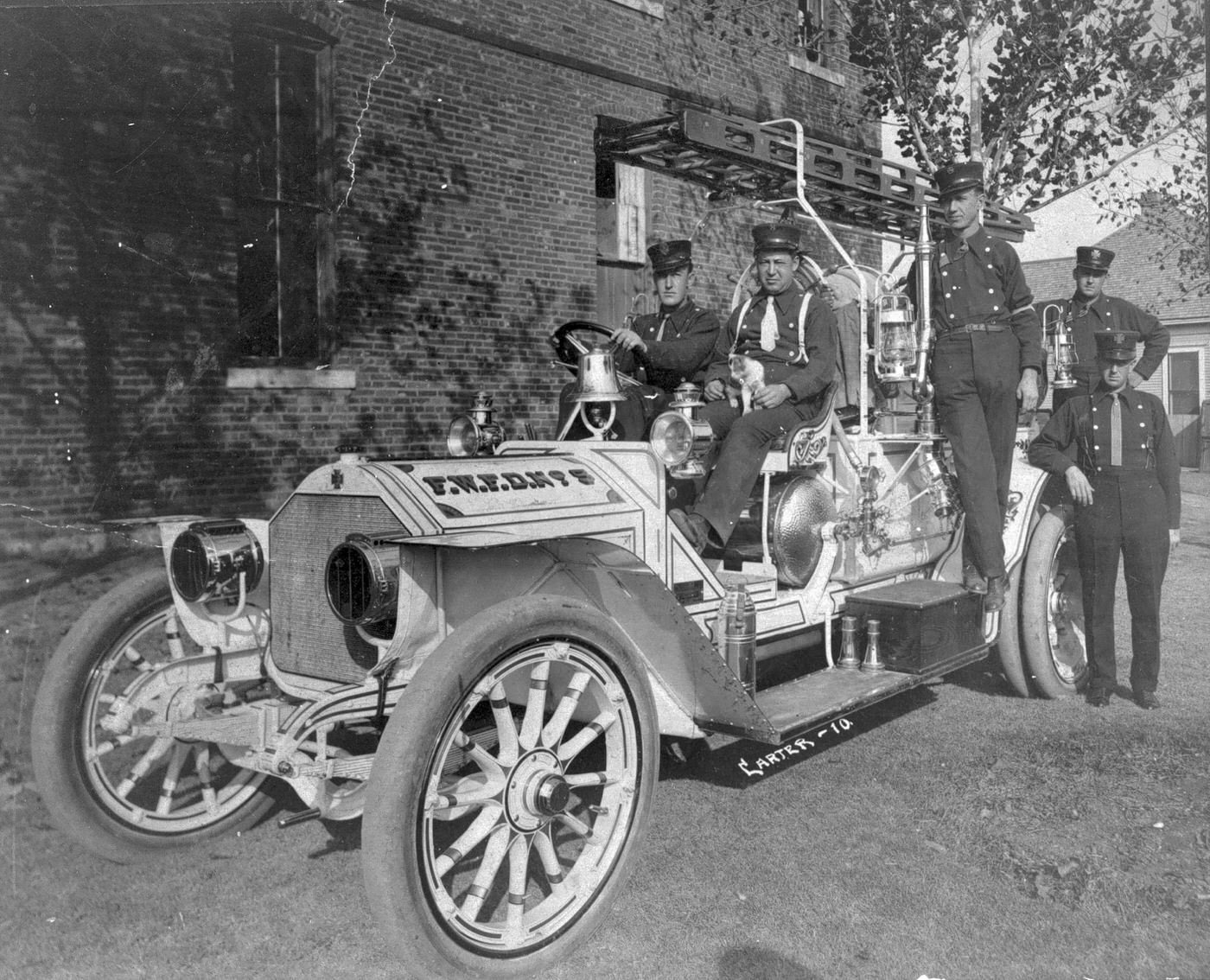

The Stockyards Company itself continued to invest strategically. Following a devastating fire in March 1911 that destroyed the original wooden horse and mule barns , the company embarked on a major construction project. Completed in March 1912 at a cost of $300,000, the new Horse and Mule Barns were state-of-the-art, fireproof structures built of distinctive red brick and concrete-encased steel and iron, designed by Klipstein & Rathmann Architects. This wasn’t merely replacing lost facilities; it was a calculated move to mitigate future risk and capture a burgeoning market. With a capacity for 5,000 animals, these barns positioned Fort Worth perfectly to capitalize on the immense demand for cavalry and draft animals spurred by World War I. Soon, Fort Worth became the largest horse and mule market not just in the United States, but in the world, supplying Allied governments during the conflict.

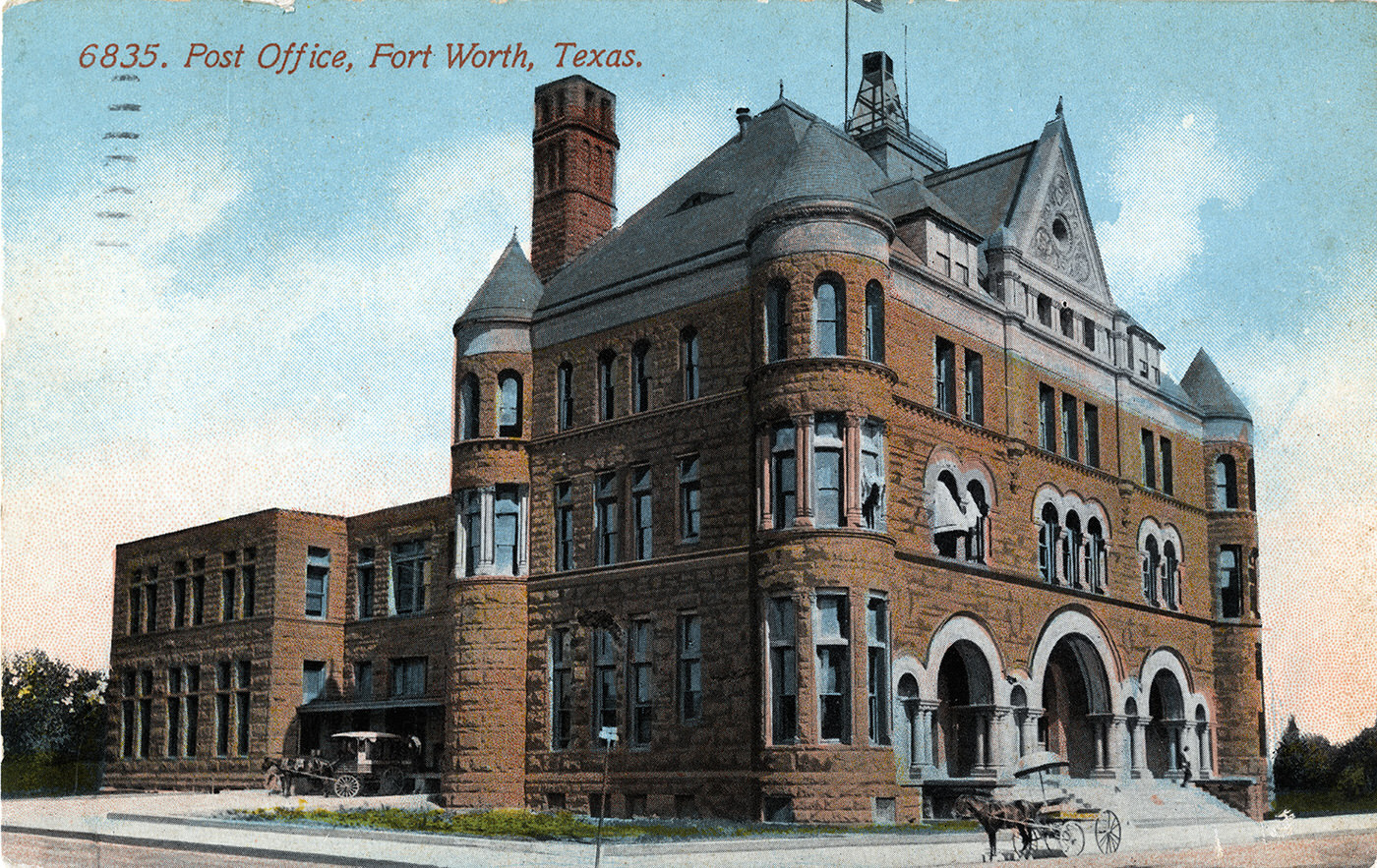

Laying the Foundation: Building a Modern Infrastructure

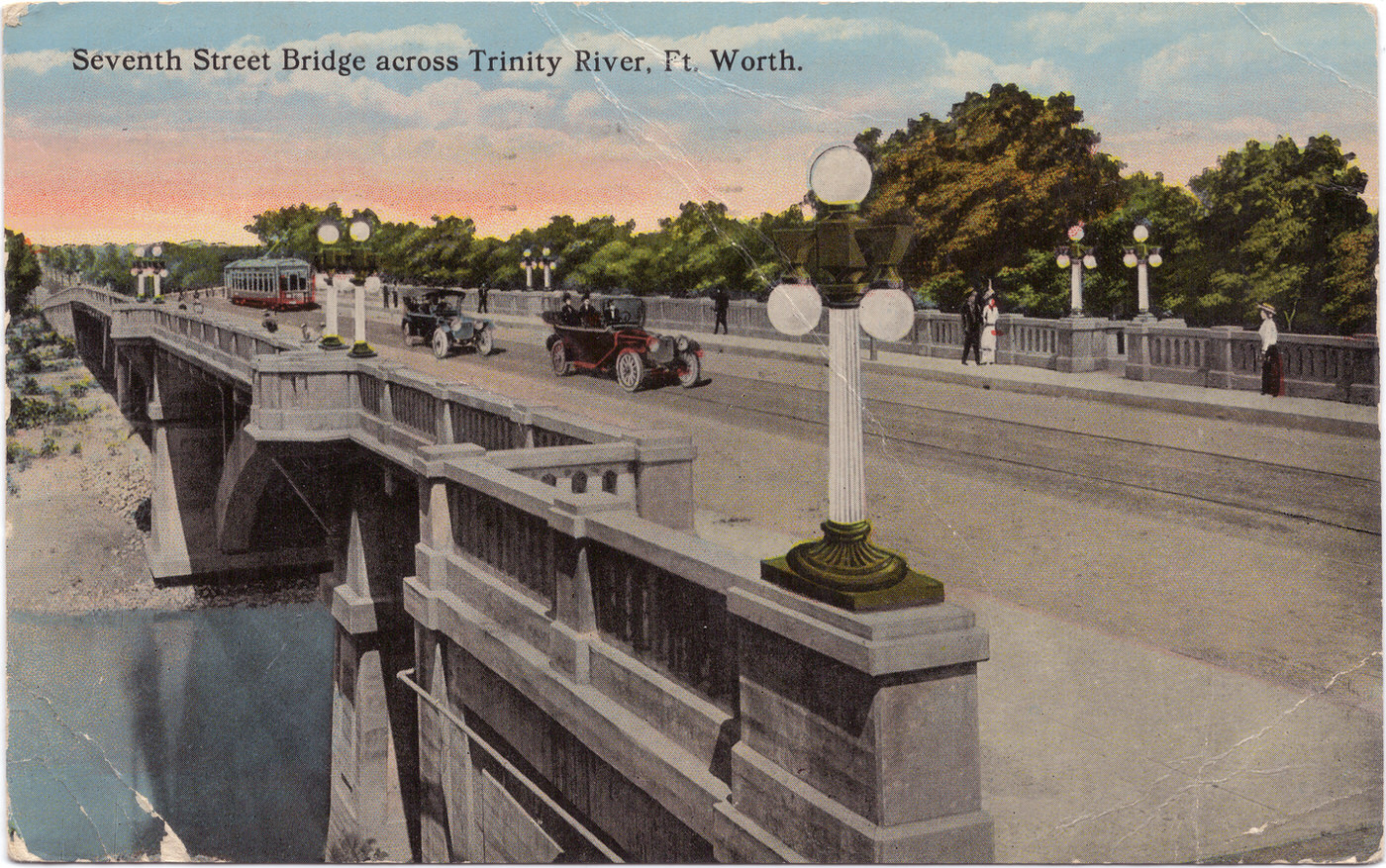

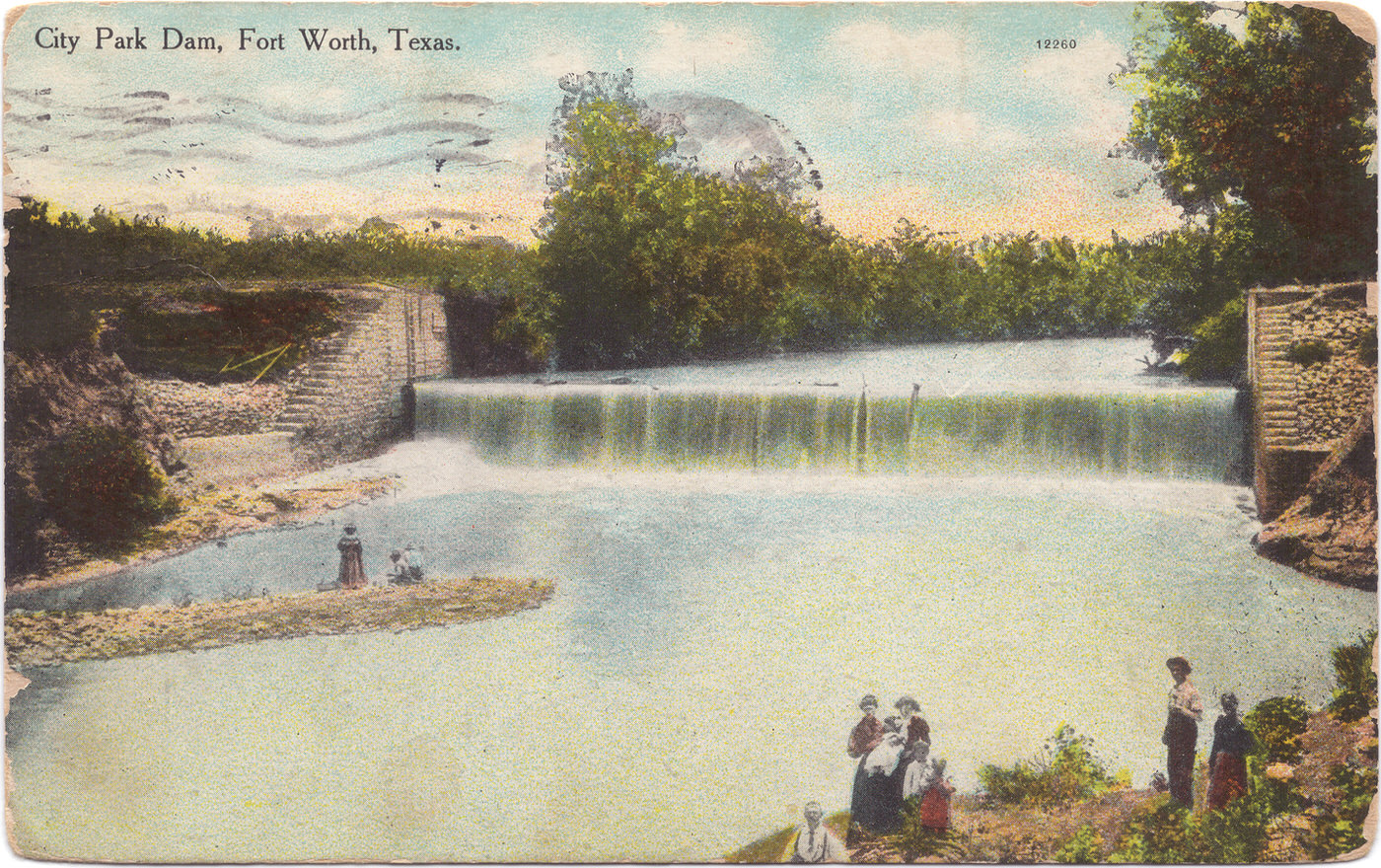

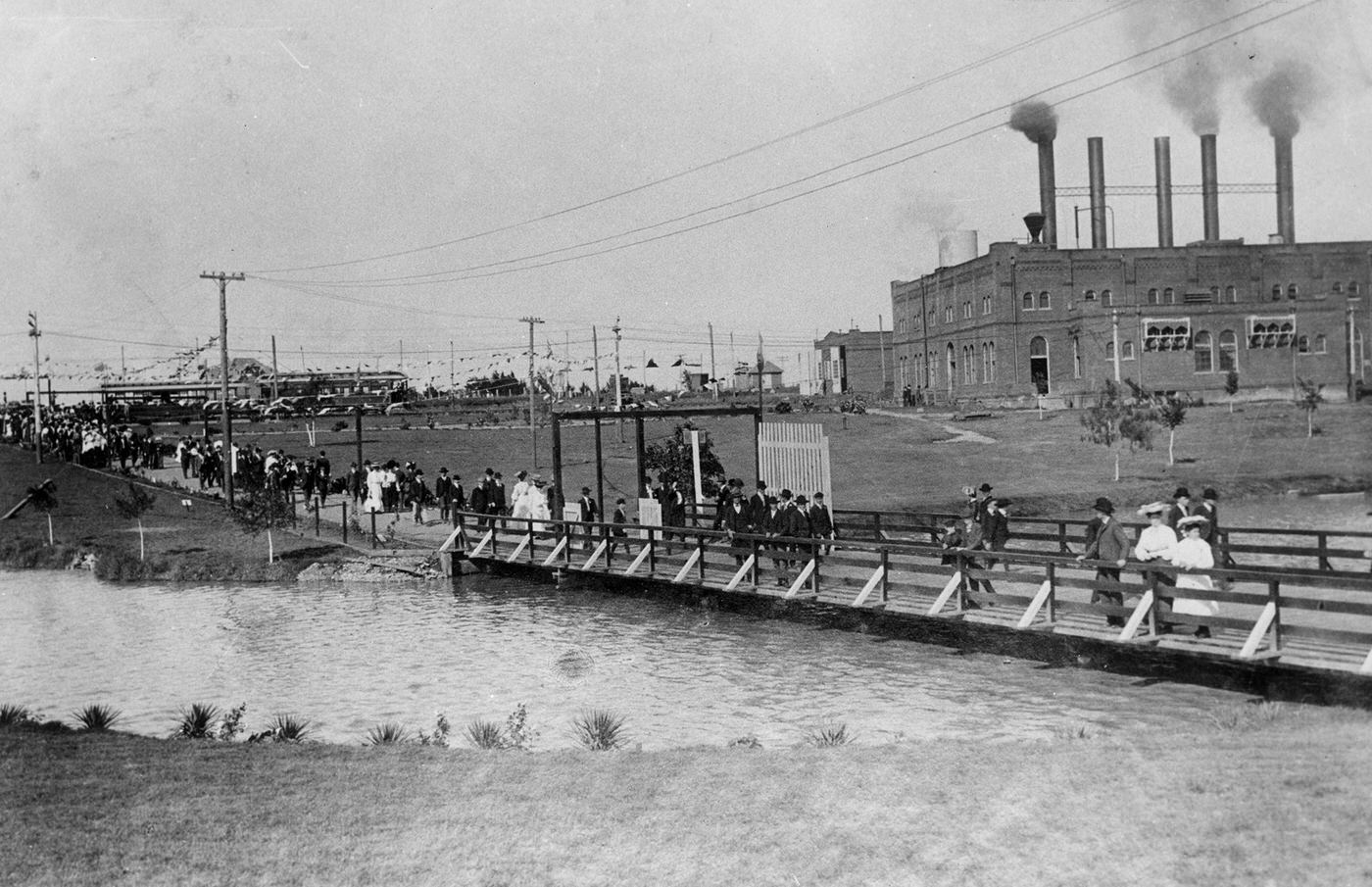

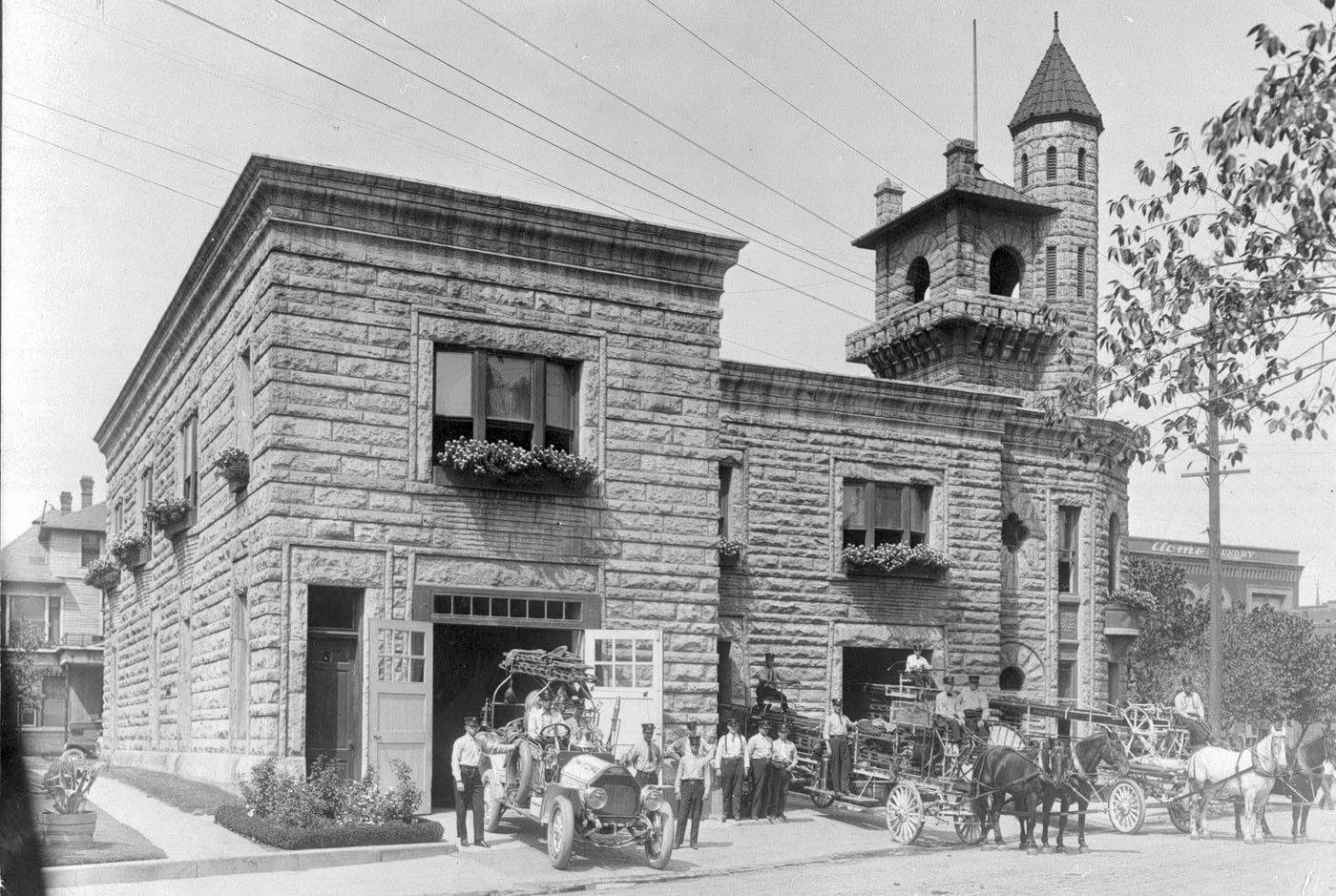

The relentless growth of the early 20th century placed immense strain on Fort Worth’s existing infrastructure. The 1910s became a crucial decade for building the systems necessary to support a modern industrial city, particularly in securing a reliable water supply and improving transportation networks. The city’s earlier reliance on shallow wells, springs, and the often-unreliable Trinity River was no longer sustainable.

Responding to this crisis, Fort Worth embarked on an ambitious project: the creation of Lake Worth. Following recommendations from engineers like John B. Hawley (who would later found the prominent engineering firm Freese and Nichols), construction began in November 1911. The dam, an impressive structure for its time, was completed in October 1914 at a cost of $1.6 million. When it first filled later that year, Lake Worth was the largest man-made lake in Texas and a significant engineering achievement.

Running parallel to the lake’s construction was the development of the city’s first water treatment facility, the Holly Water Treatment Plant. Named after the Holly Manufacturing Company of New York, which supplied the original pumping engines for the earlier Holly Pump Station built in 1892 , the new filtration plant began partial operation on January 31, 1912. Initially, it treated water drawn directly from the Clear Fork of the Trinity River. This phased approach allowed the city to improve water quality while the larger Lake Worth reservoir and its crucial 6.5-mile pipeline were still under construction. The pipeline finally connected the lake to the Holly Plant in May 1916, and the plant achieved full operational status, utilizing the vast new water source, in 1918. Together, Lake Worth and the Holly Plant represented a monumental investment, securing the water supply essential for the city’s continued expansion and public health.

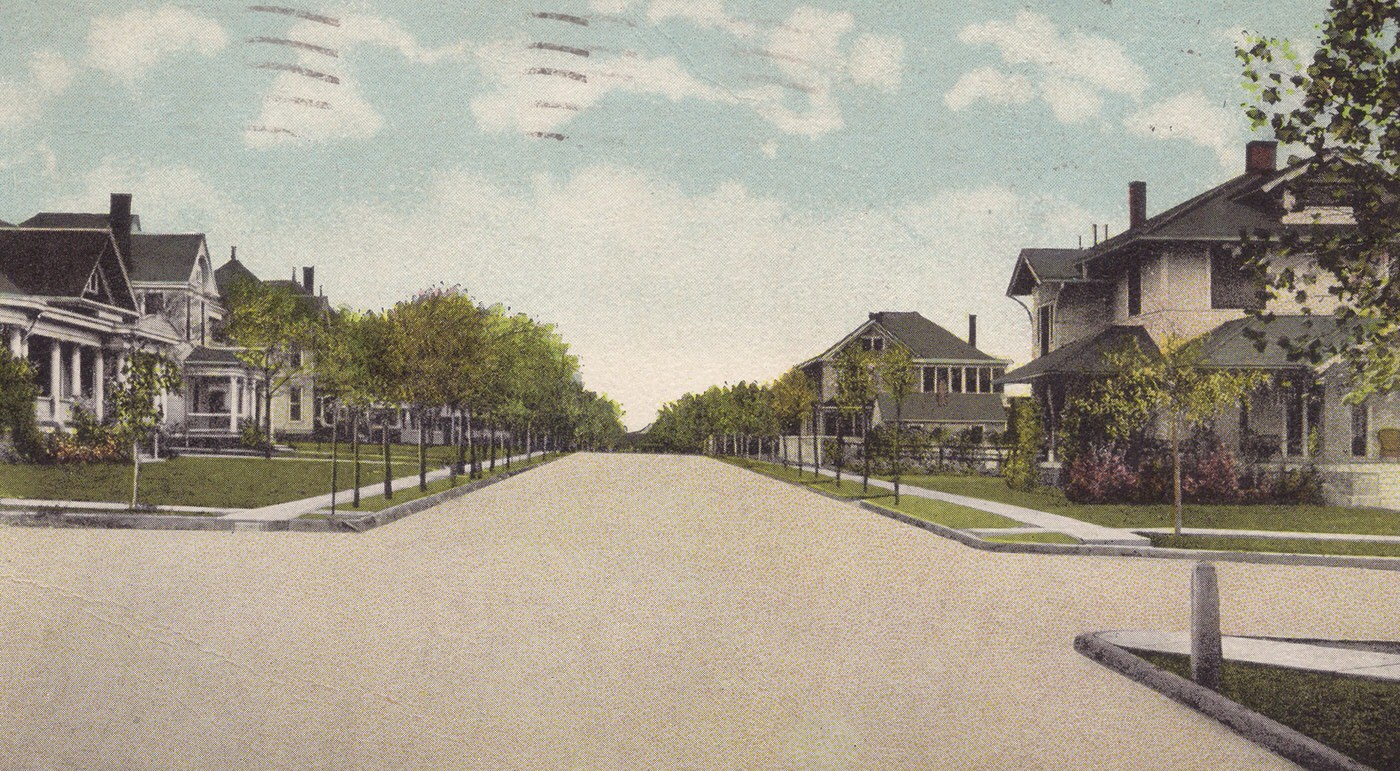

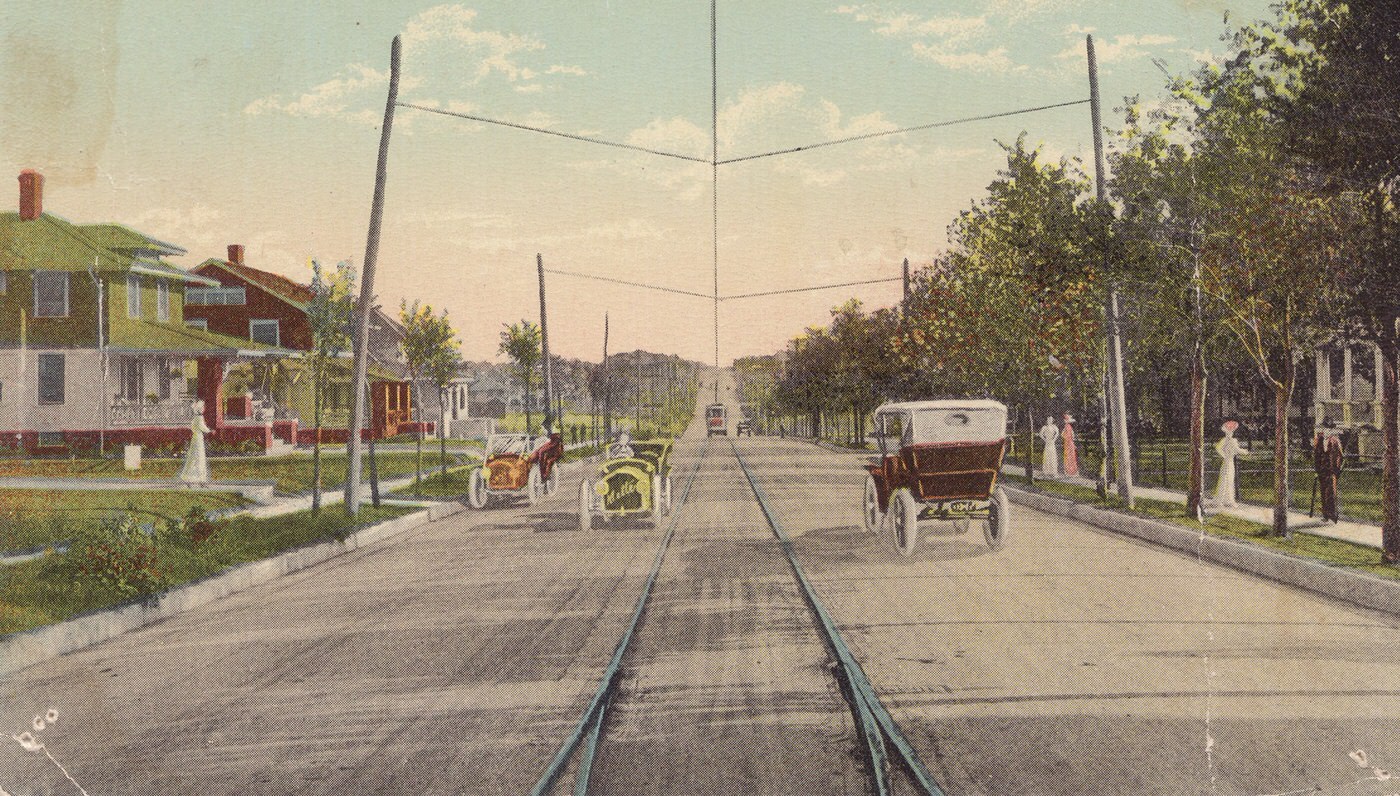

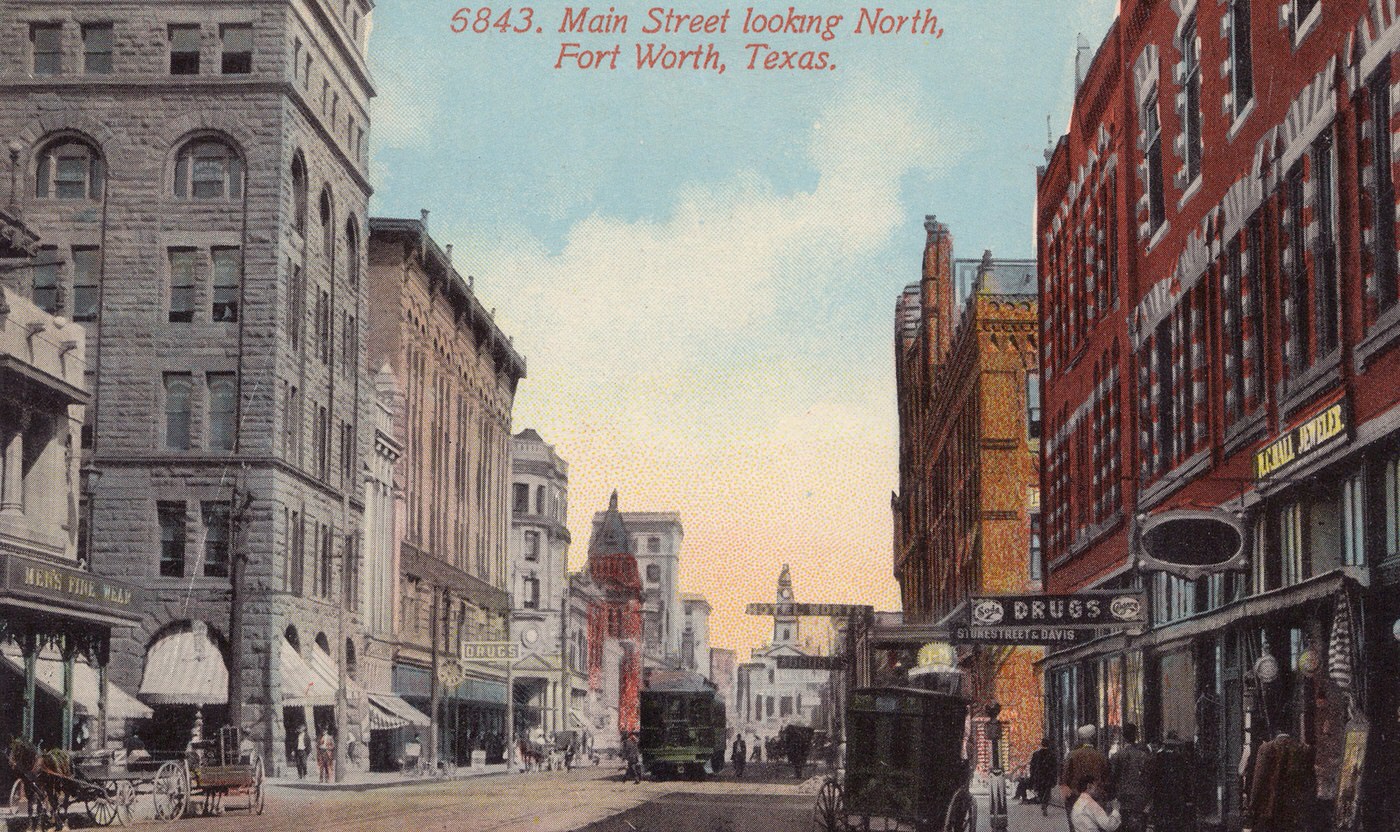

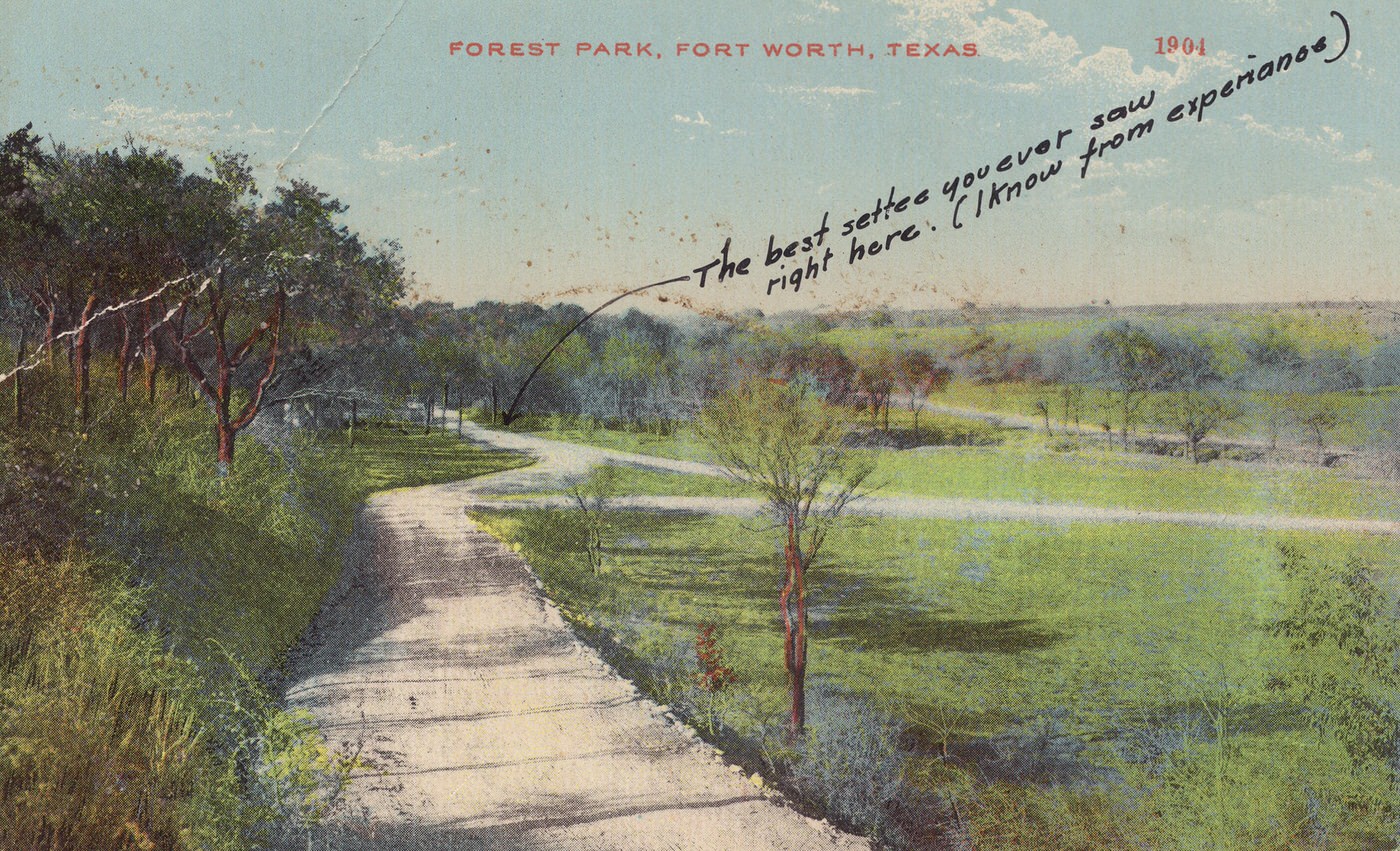

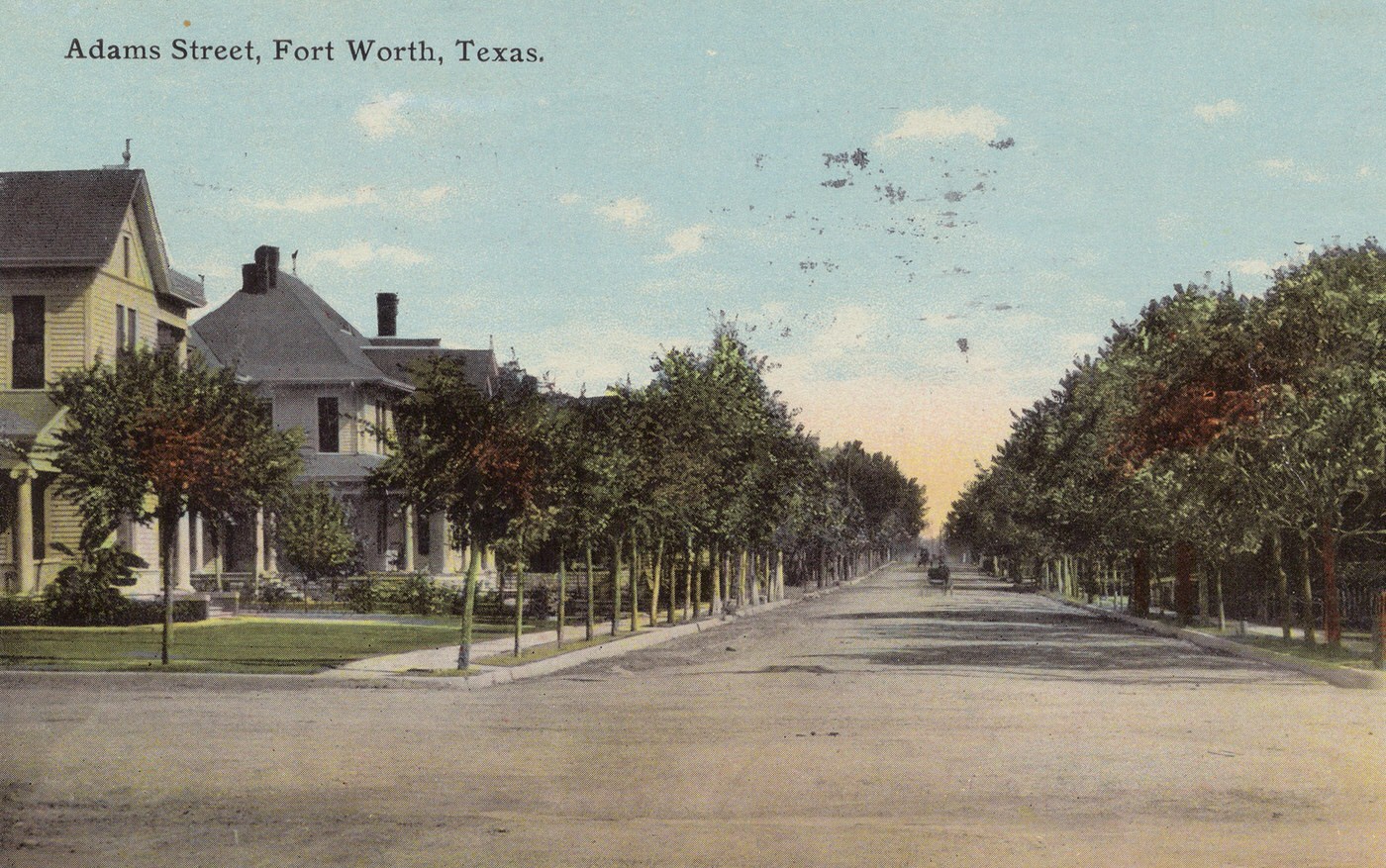

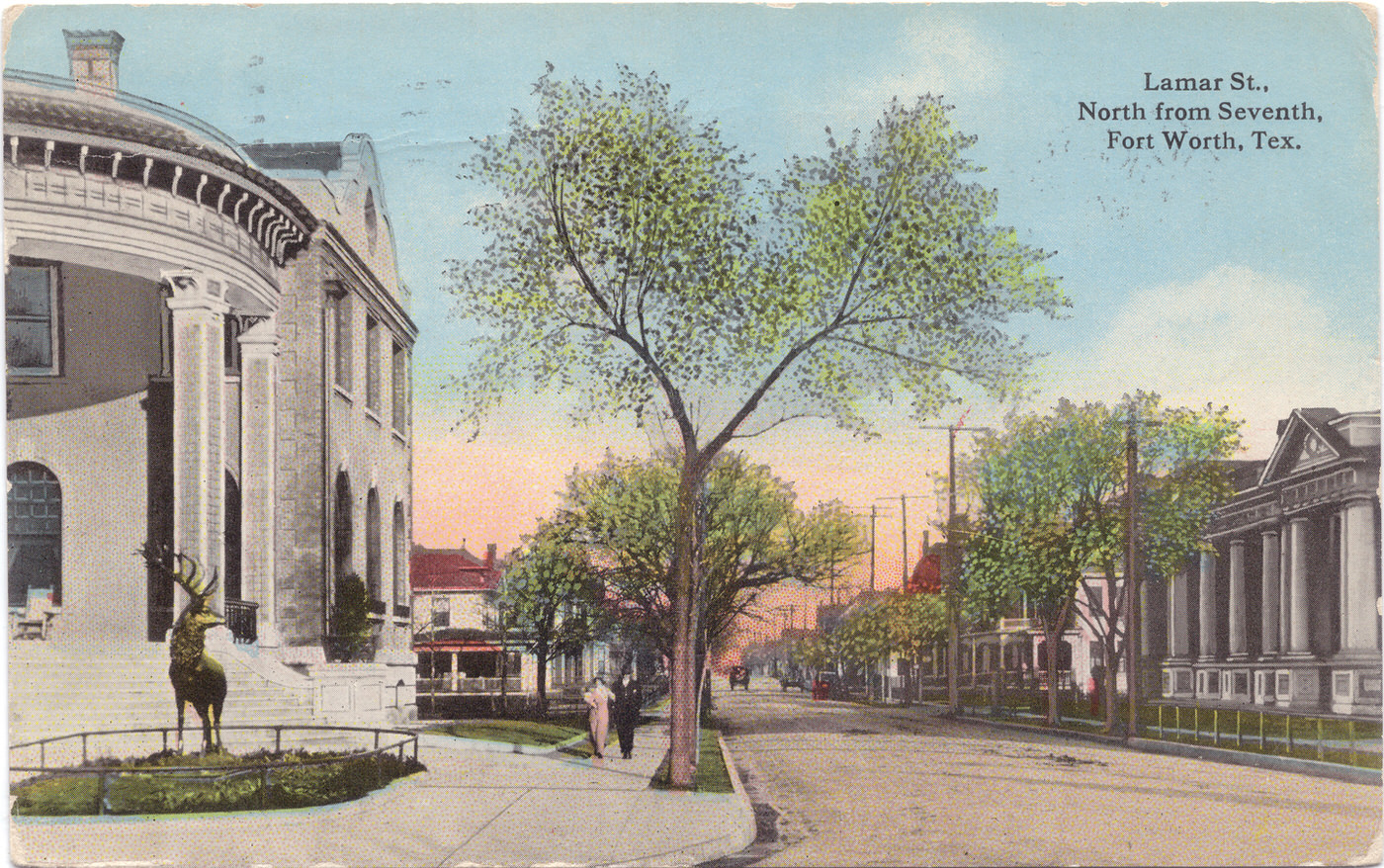

Transportation infrastructure also saw significant upgrades. While early street paving efforts had begun in the late 1890s, often using durable Thurber bricks on main thoroughfares like Main Street , the 1910s saw continued focus on improving connectivity. A major project was the development of what would become Camp Bowie Boulevard. Overseen by noted landscape architect George E. Kessler and constructed between 1918 and 1919, this nine-mile street cut through the growing Arlington Heights neighborhood west of downtown. Initially named Arlington Heights Boulevard and consisting of narrow asphalt strips flanking streetcar tracks, it was renamed in 1919 to honor the massive WWI training camp it traversed. The project also included the planting of over 700 trees, an early city beautification effort.

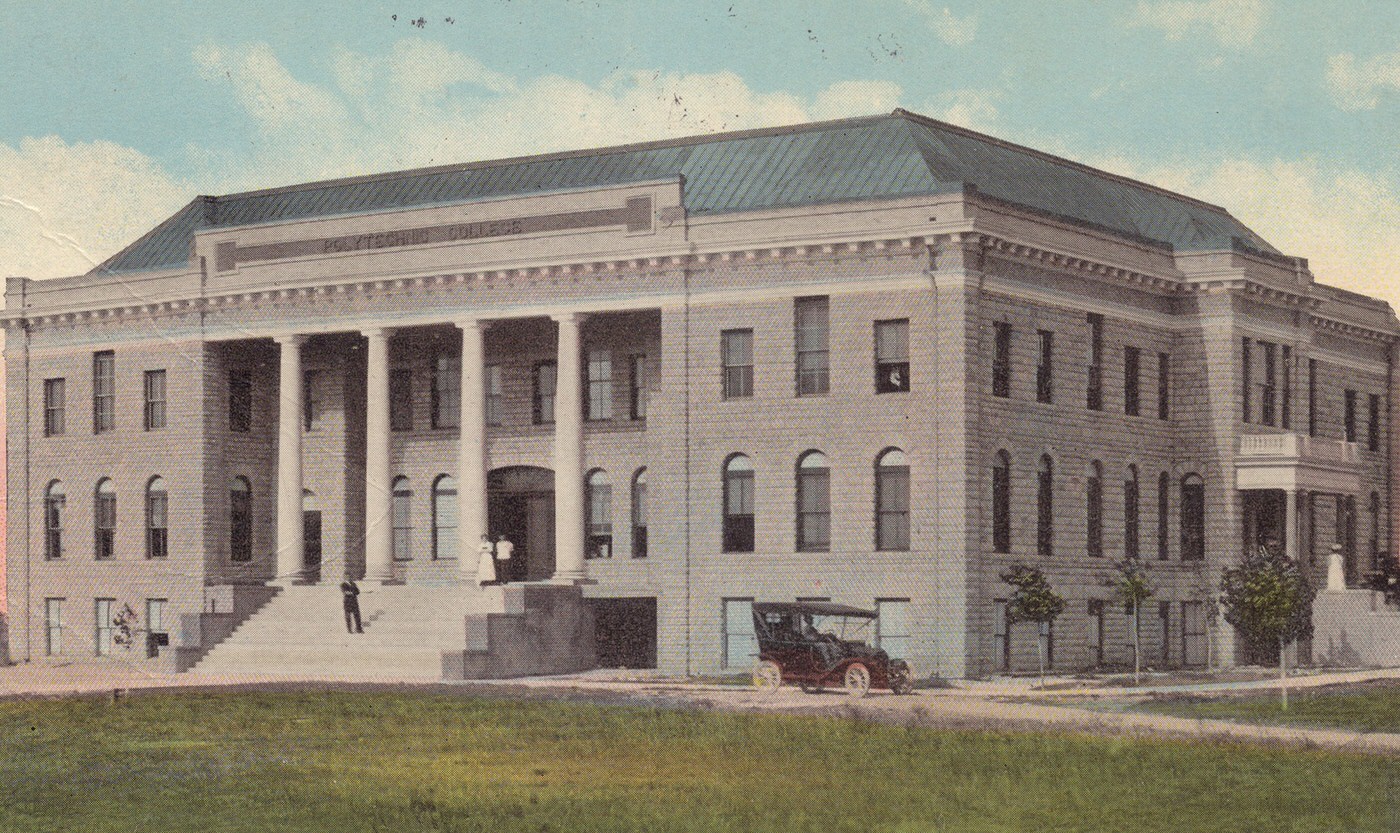

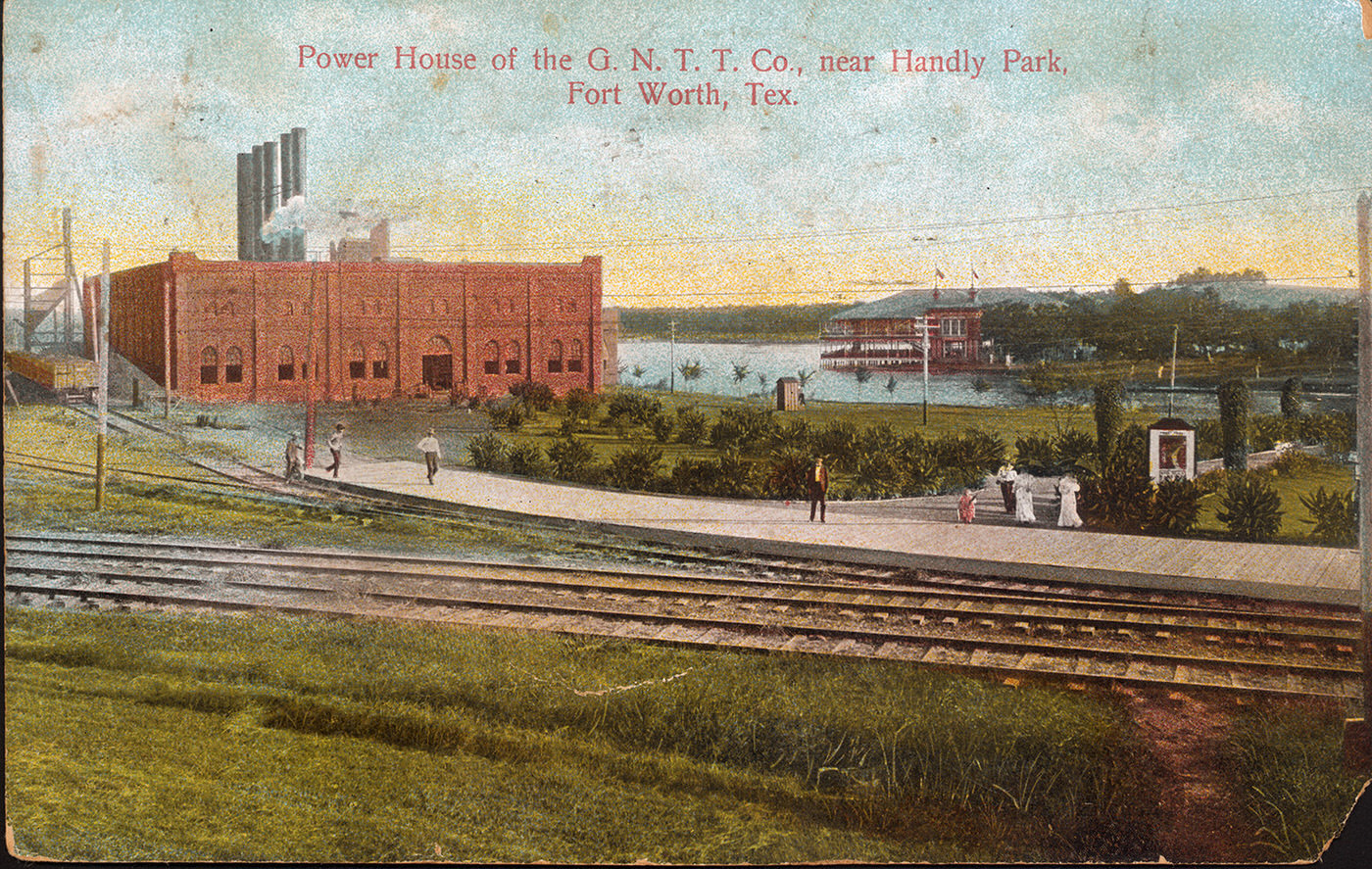

Connecting the expanding city was the electric streetcar system, operated during this decade by the Northern Texas Traction Company (NTTC), which had taken over in 1905. Streetcars were vital for commuting and facilitated the growth of suburbs like Arlington Heights and Polytechnic by linking them to the downtown core and industrial areas. The NTTC also continued to operate the popular Interurban line, established in 1902, providing hourly passenger service between Fort Worth and Dallas. These infrastructure projects – water, paving, transit – were not isolated events but rather interconnected responses, essential for managing the pressures and realizing the potential of Fort Worth’s dramatic early 20th-century growth.

The Great War Transforms Fort Worth (1917-1919)

The entry of the United States into World War I in April 1917 unleashed forces that would profoundly and rapidly reshape Fort Worth. Already booming from the meatpacking industry, the city was about to become a major military center, layering a massive defense complex onto its existing economic base and accelerating its development in unprecedented ways.

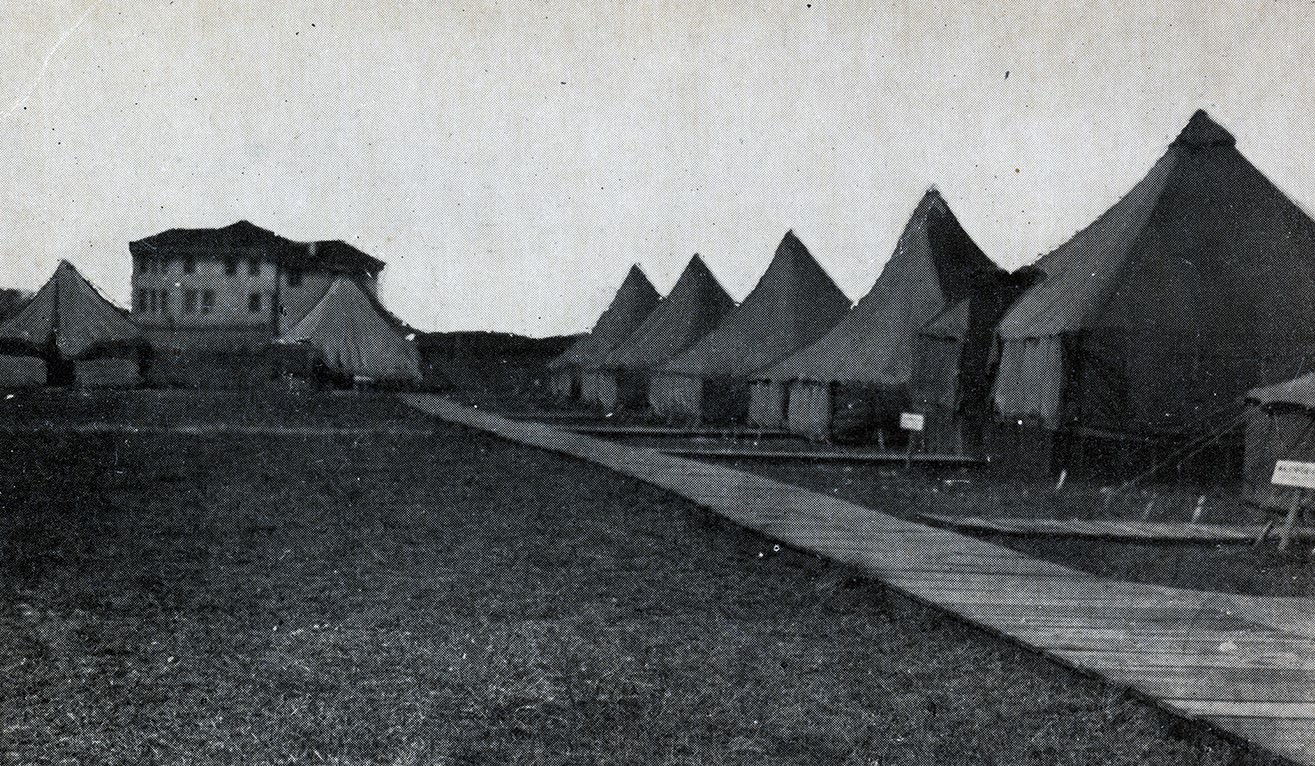

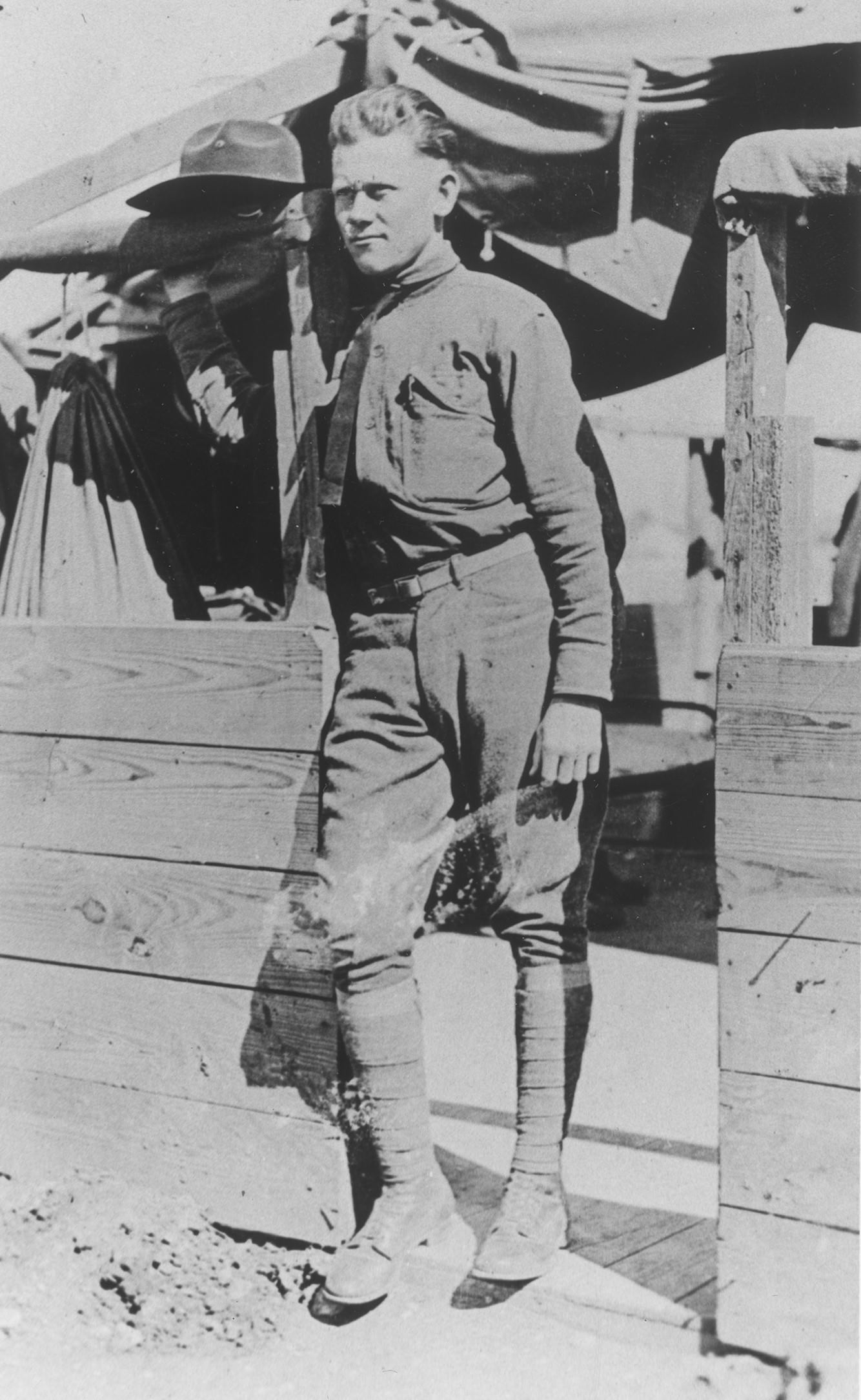

In the summer of 1917, construction began on Camp Bowie, a vast training facility established on over 1,400 to nearly 2,200 acres of leased land in the Arlington Heights area west of downtown. Built at a cost of over $3 million, the camp sprang up with remarkable speed, involving over 5,000 workers erecting more than 1,500 buildings. Named for the Alamo hero Jim Bowie, Camp Bowie’s primary mission was to train the 36th Infantry Division, composed of National Guard units from Texas and Oklahoma. Before the camp closed in August 1919, over 100,000 soldiers, including some 3,000 African American troops, passed through its gates for training before heading to the European theater. After the armistice, the camp served as a crucial demobilization center, processing soldiers back into civilian life.

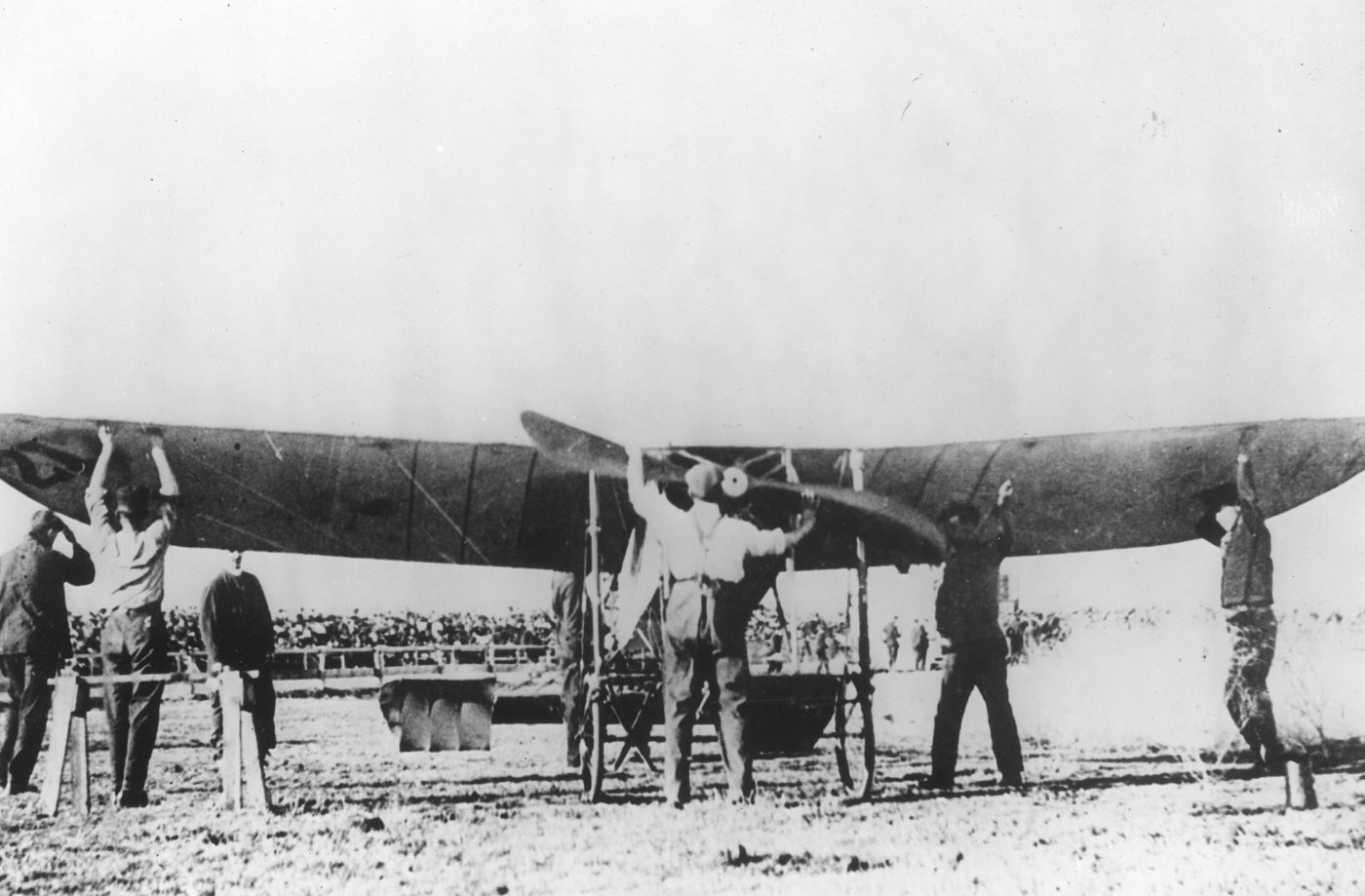

Simultaneously, Fort Worth became a significant hub for military aviation. Attracted by the region’s mild climate, which allowed for year-round flight training, the Canadian Royal Flying Corps (RFC) arranged with the U.S. government to establish training facilities in the area in 1917. Three major airfields, collectively known as the Taliaferro Fields, were rapidly constructed: Field 1 at Hicks, Field 2 in Benbrook, and Field 3 in Everman. This massive construction effort employed around 7,000 workers. After the U.S. entered the war, the Army Air Service took over the fields, renaming Field 2 as Carruthers Field and Field 3 as Barron Field. These facilities became vital training grounds for both Canadian and American pilots, laying the groundwork for Fort Worth’s future as a center for aviation and defense – a legacy seeded in the urgency of wartime mobilization.

The sheer scale of this military buildup delivered an intense economic jolt to Fort Worth. The influx of tens of thousands of soldiers and construction workers created a boom for local businesses, from retailers and restaurants to service providers. The massive military payroll, estimated at $1.675 million per month, significantly boosted the local economy, contributing to a $10 million increase in bank deposits in 1917 alone. The war also solidified the Stockyards’ position as the world’s largest horse and mule market, supplying crucial animals for the Allied war effort.

The End of an Era: Hell’s Half Acre Fades

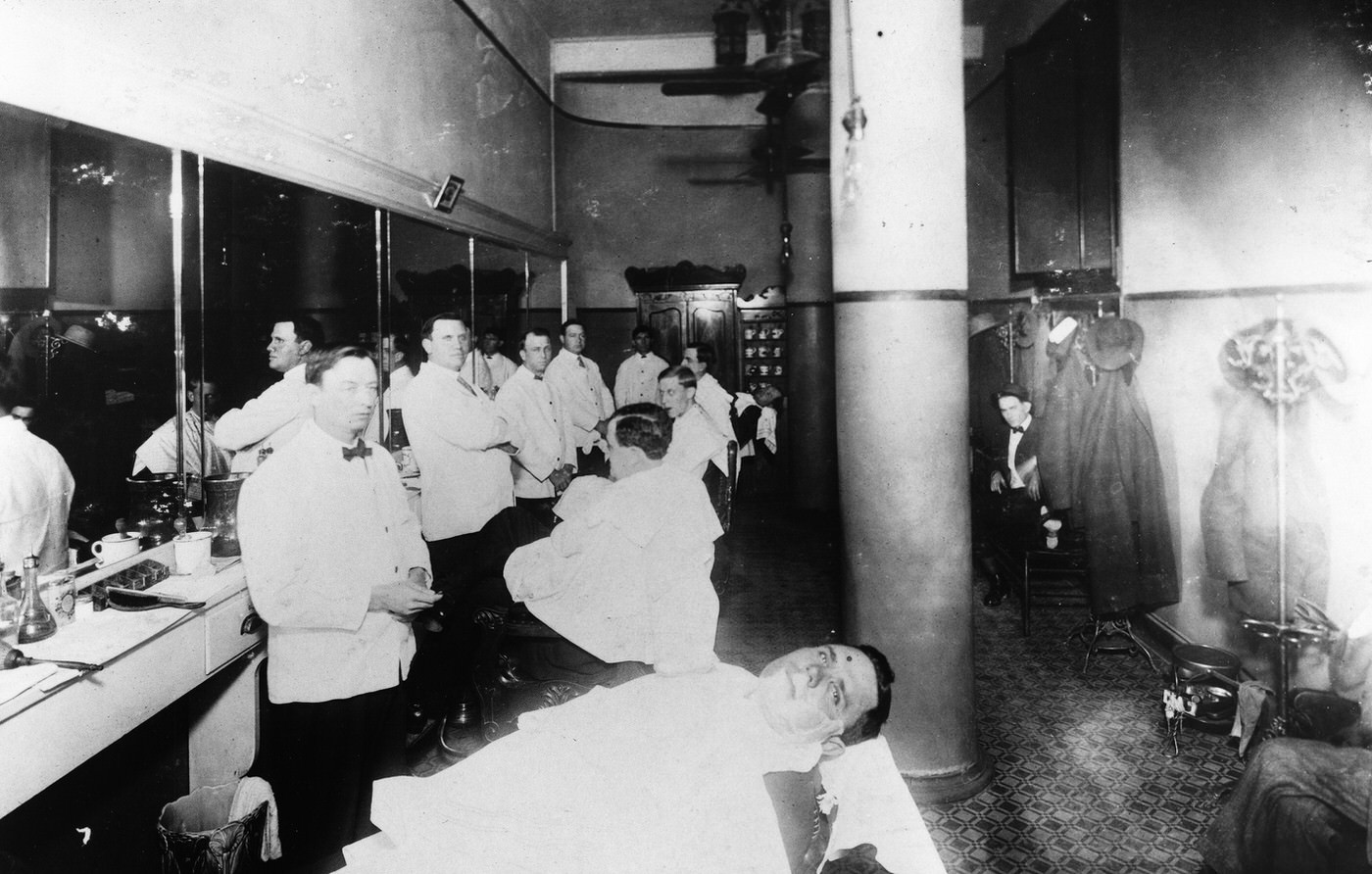

For decades, Hell’s Half Acre had been Fort Worth’s notorious alter ego – a sprawling district of saloons, gambling dens, dance halls, and brothels south of the courthouse that catered to cowboys, railroad workers, and travelers. While its heyday was arguably in the late 19th century, the Acre, often called the “Bloody Third Ward,” lingered into the 1910s, its reputation for vice and violence diminished but not extinguished.

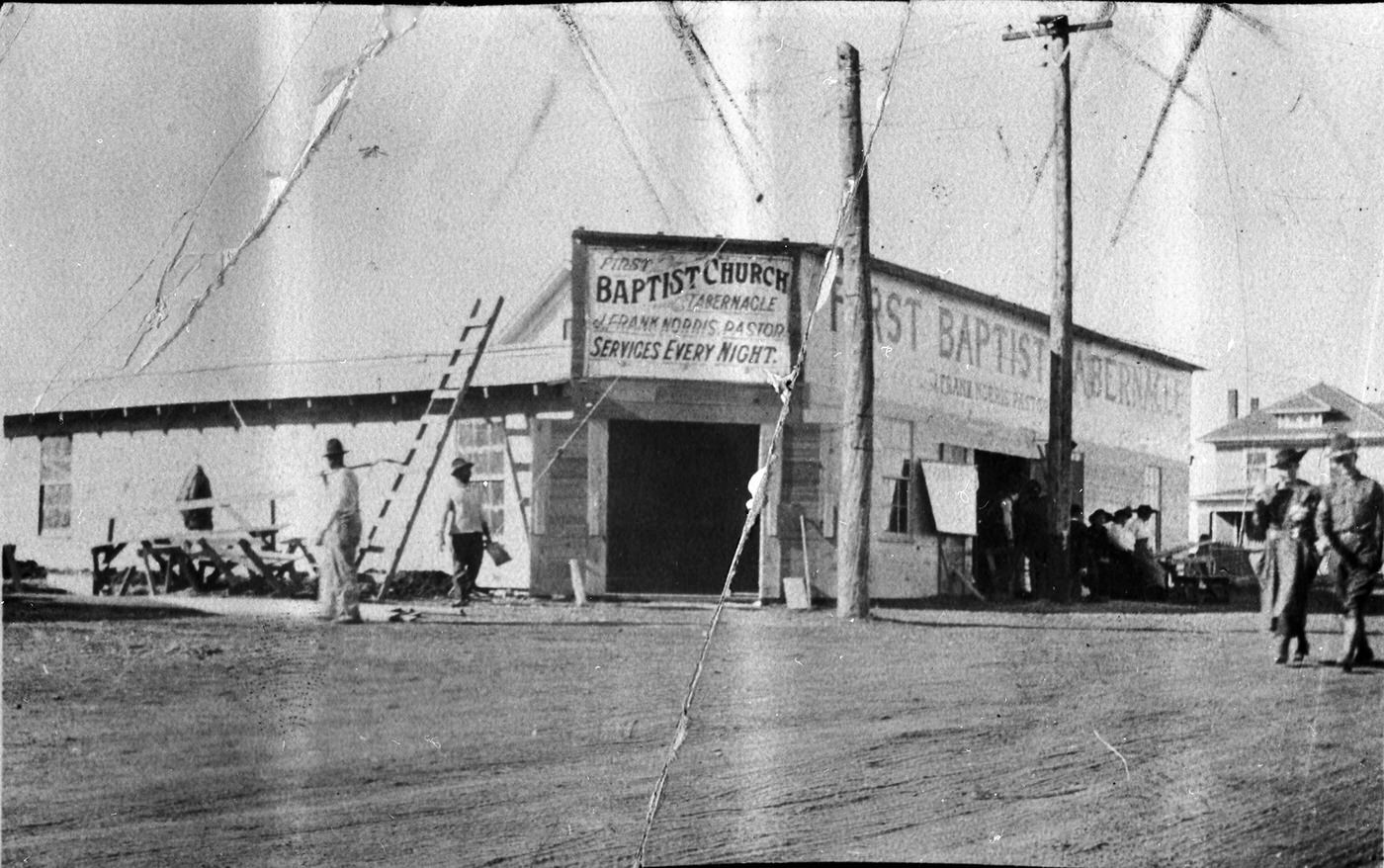

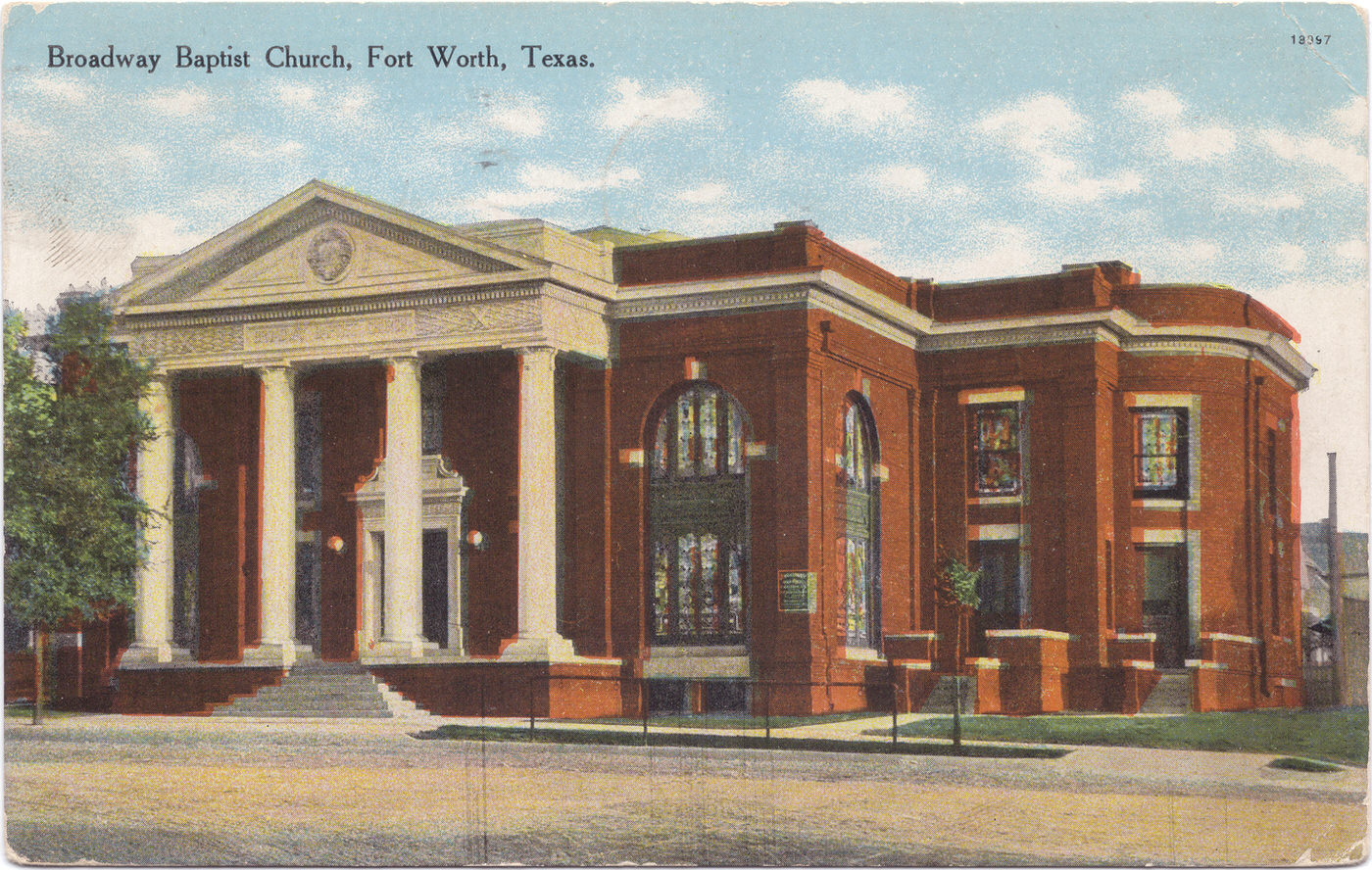

Throughout the early part of the decade, pressure mounted from reformers energized by the national Progressive movement. Figures like the fiery Baptist preacher J. Frank Norris, who arrived in 1909 and began crusading against the district around 1911, intensified local efforts to clean up the city. However, previous reform campaigns and crackdowns, like the one in 1889 following excessive violence, had proven temporary. The Acre represented a significant, albeit illicit, source of revenue and excitement that city officials and some business interests were often reluctant to fully suppress.

The arrival of Camp Bowie in 1917 proved to be the catalyst for the Acre’s final demise. The federal government had a strict policy prohibiting vice districts within close proximity to military training camps, fearing the effects on troop morale, health, and discipline. This external pressure, combined with a new city administration seemingly more inclined towards reform , led to a decisive crackdown beginning around 1917-1918.

Unlike previous efforts, this was a concerted campaign involving both city police and U.S. military authorities. They employed forceful tactics, including raids on saloons and brothels, mass arrests of prostitutes and proprietors, and potentially even the demolition of some offending structures. The sustained pressure proved effective. By 1919, the visible manifestations of Hell’s Half Acre – the open saloons, the blatant prostitution, the rowdy dance halls – were largely gone. While vice undoubtedly continued in less conspicuous forms, dispersed throughout the city, the era of the geographically defined, openly tolerated red-light district was over. Around 1920, Fort Worth officials could declare their downtown “morally clean,” marking the end of a defining, if notorious, chapter in the city’s history. The closure wasn’t simply a victory for local moral reformers; it was a direct consequence of federal intervention during wartime, demonstrating how national priorities could override local economic interests and long-standing tolerance for vice.

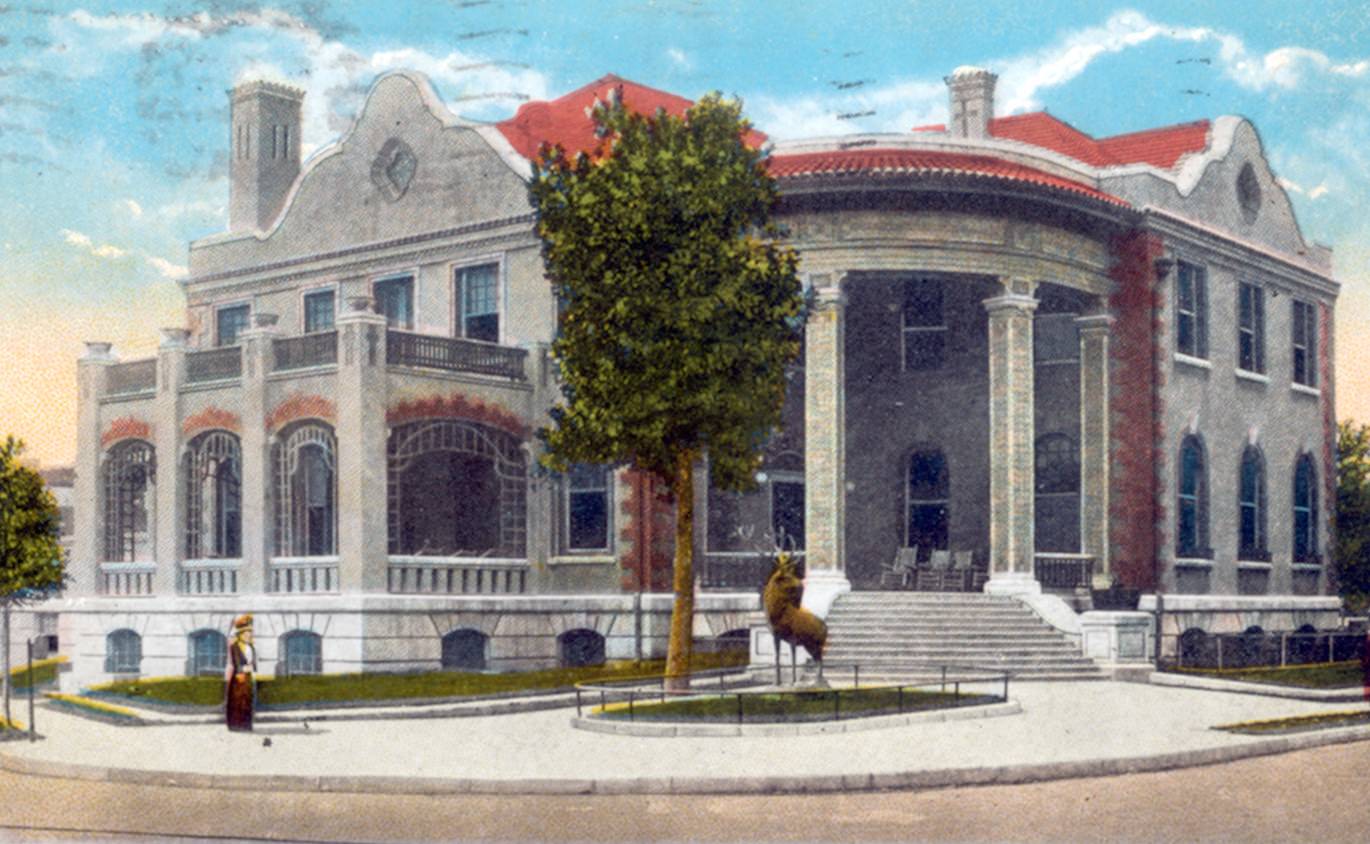

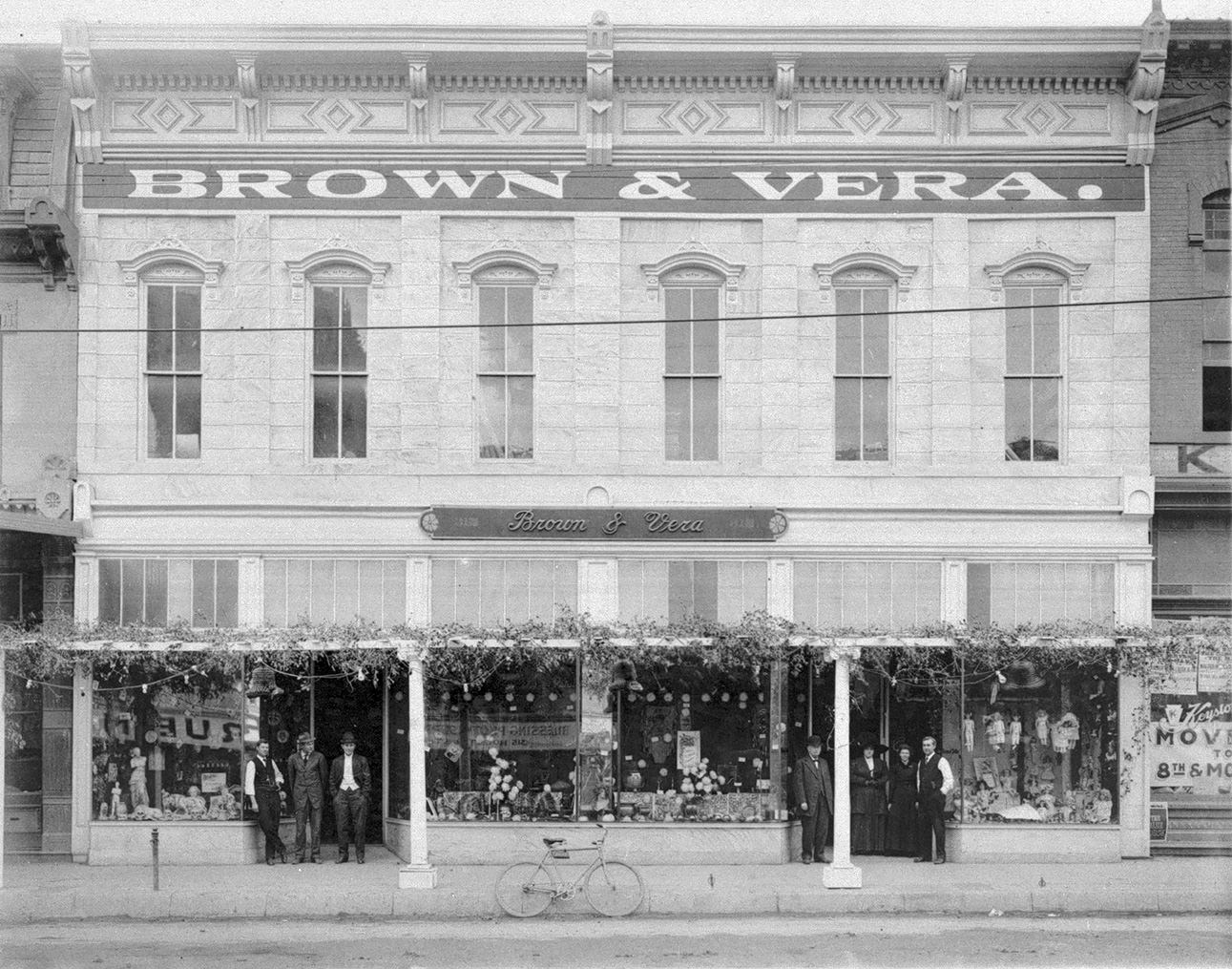

Civic Pride and City Life

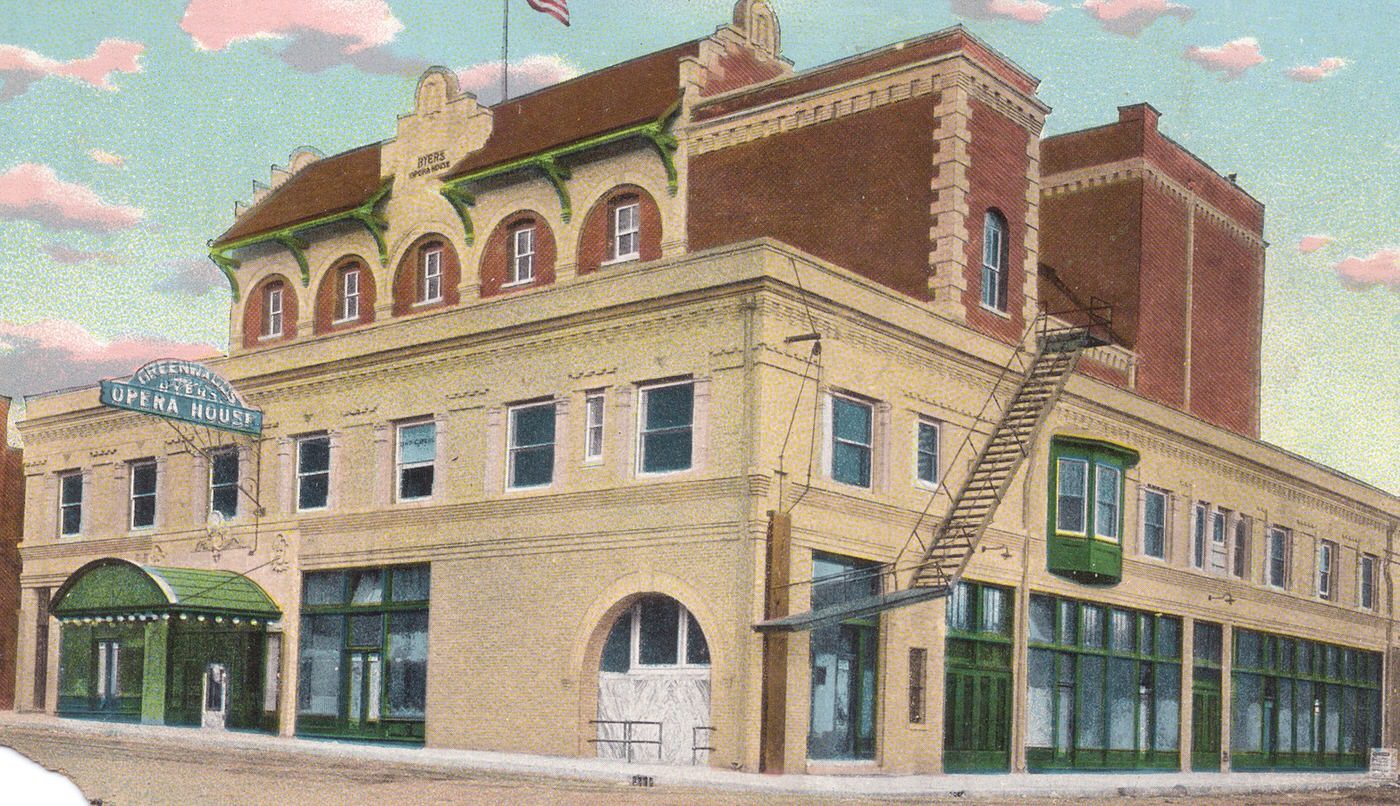

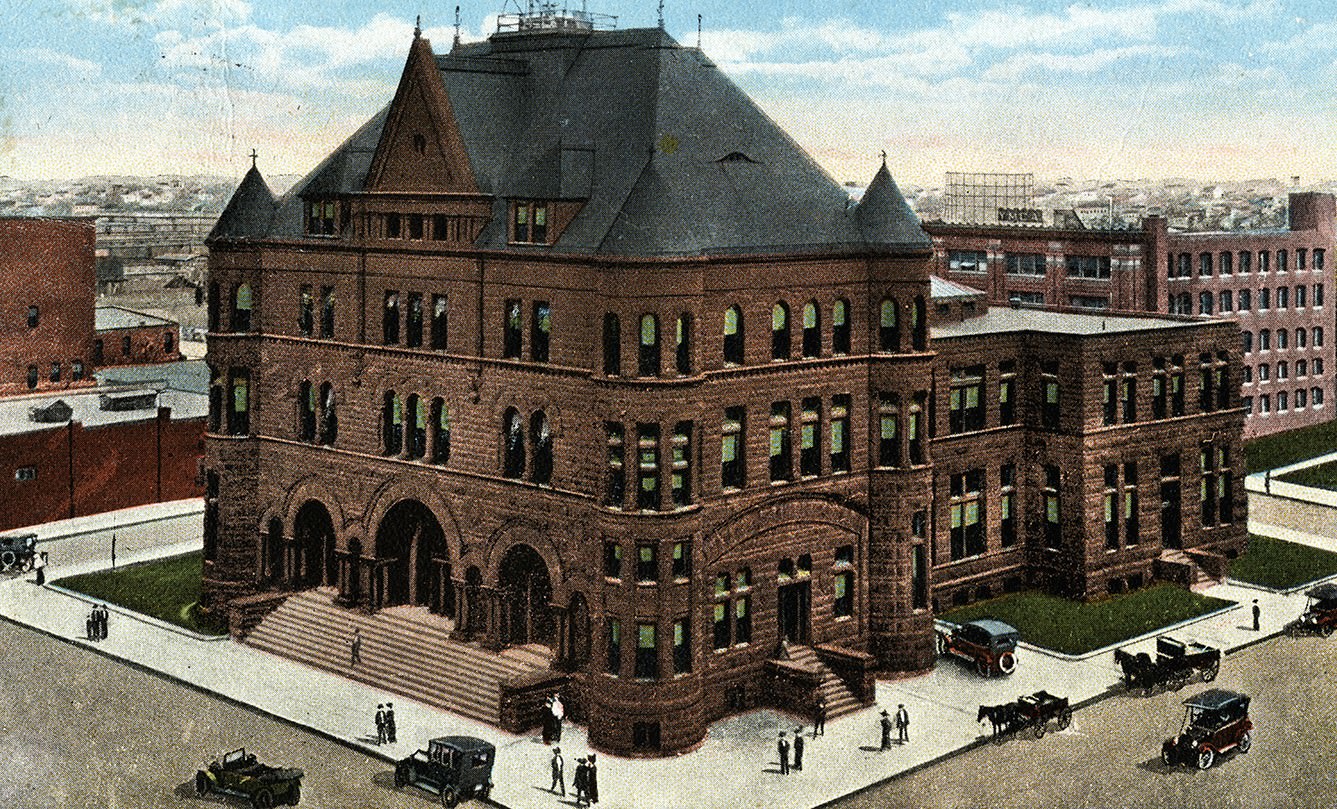

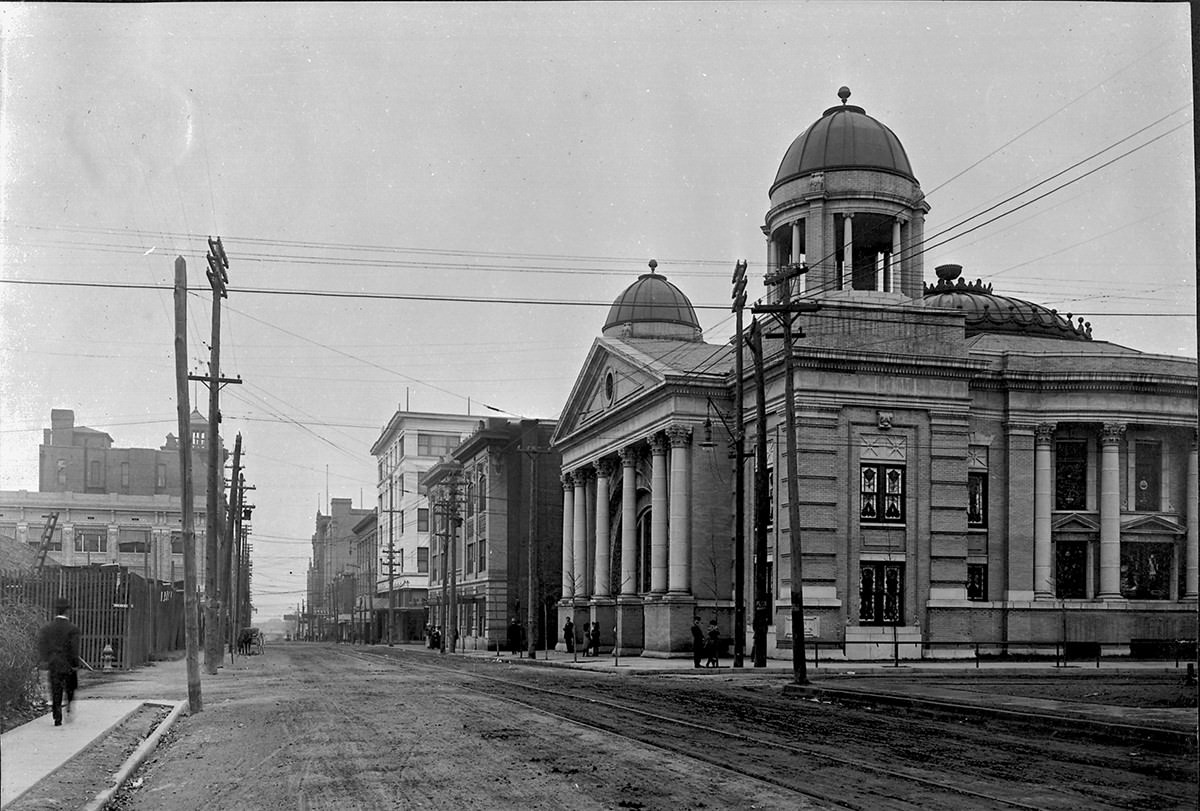

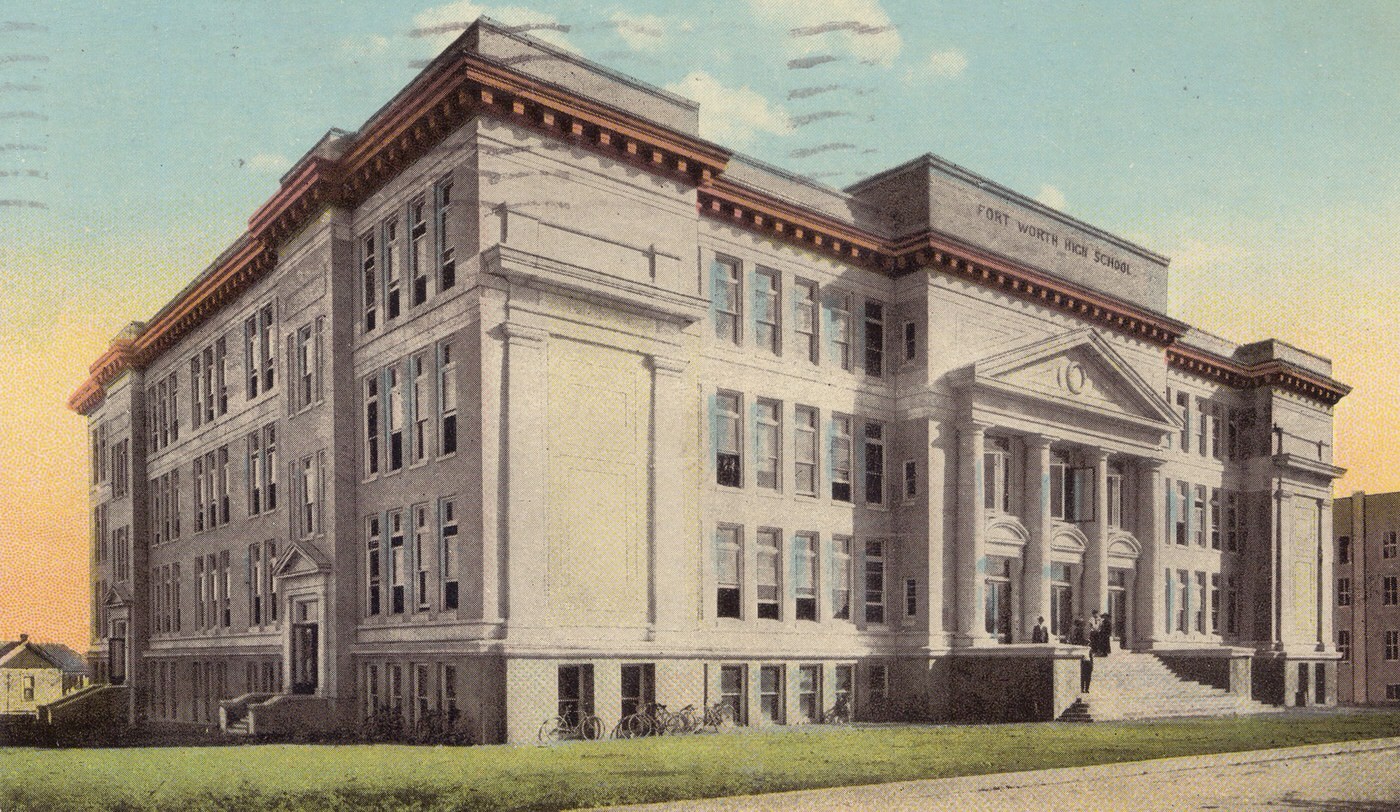

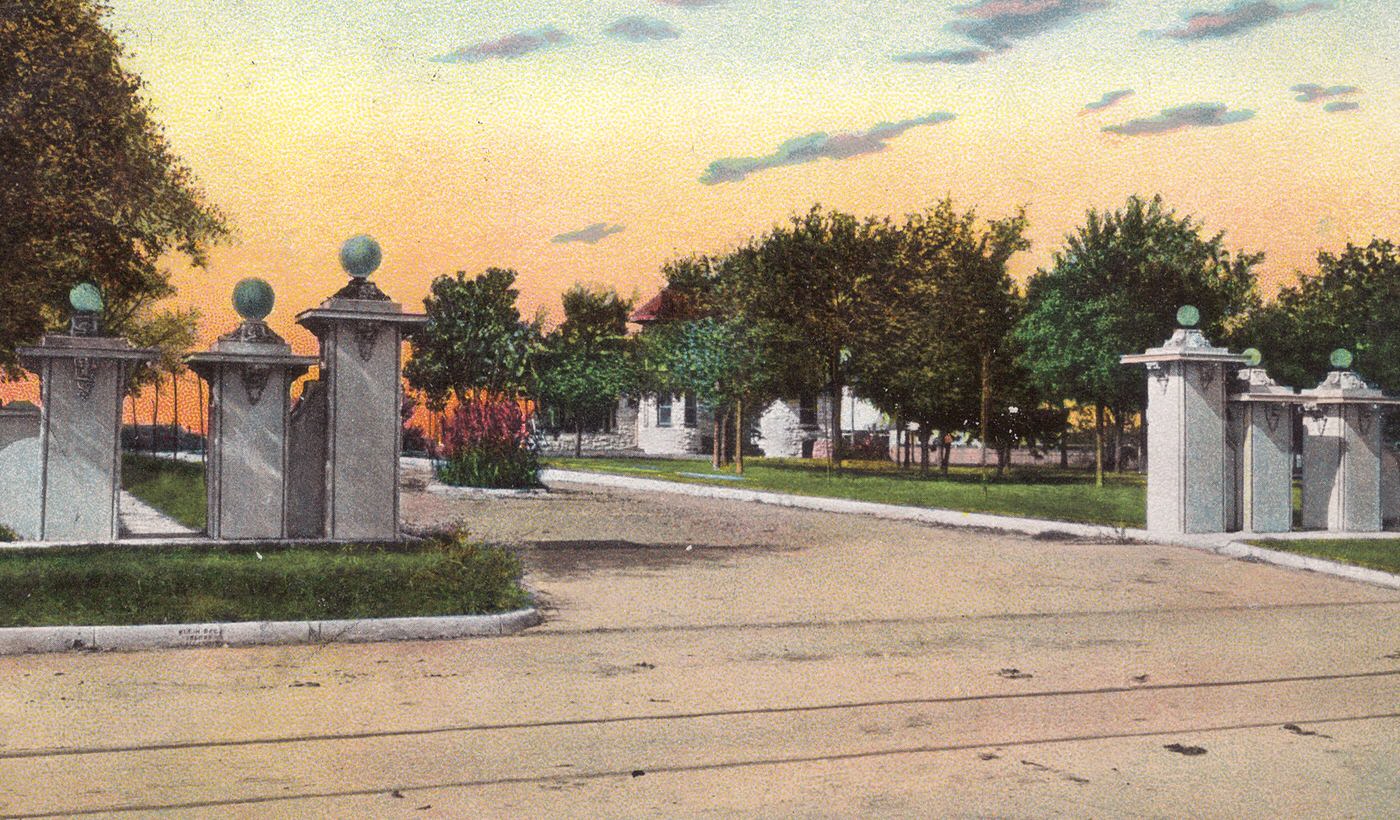

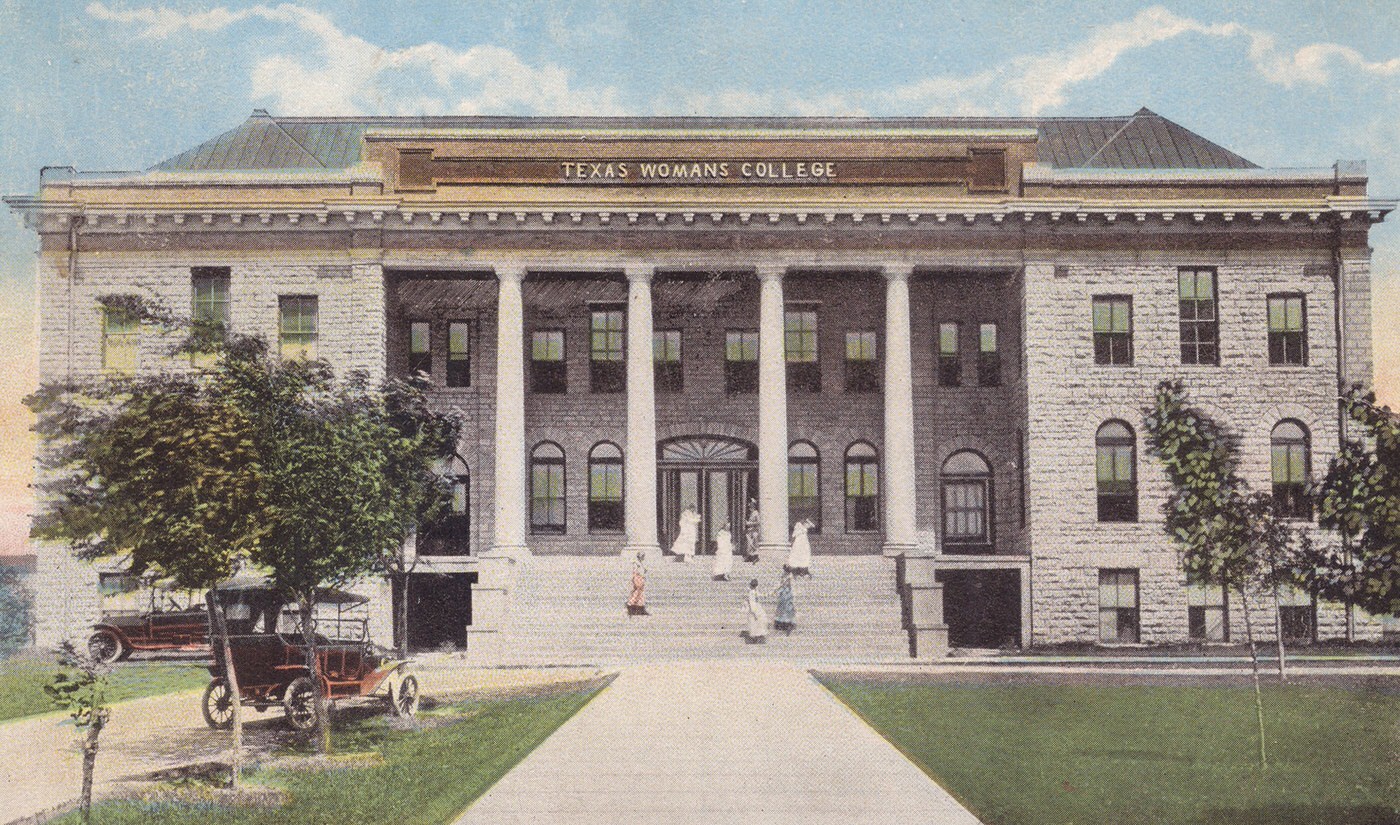

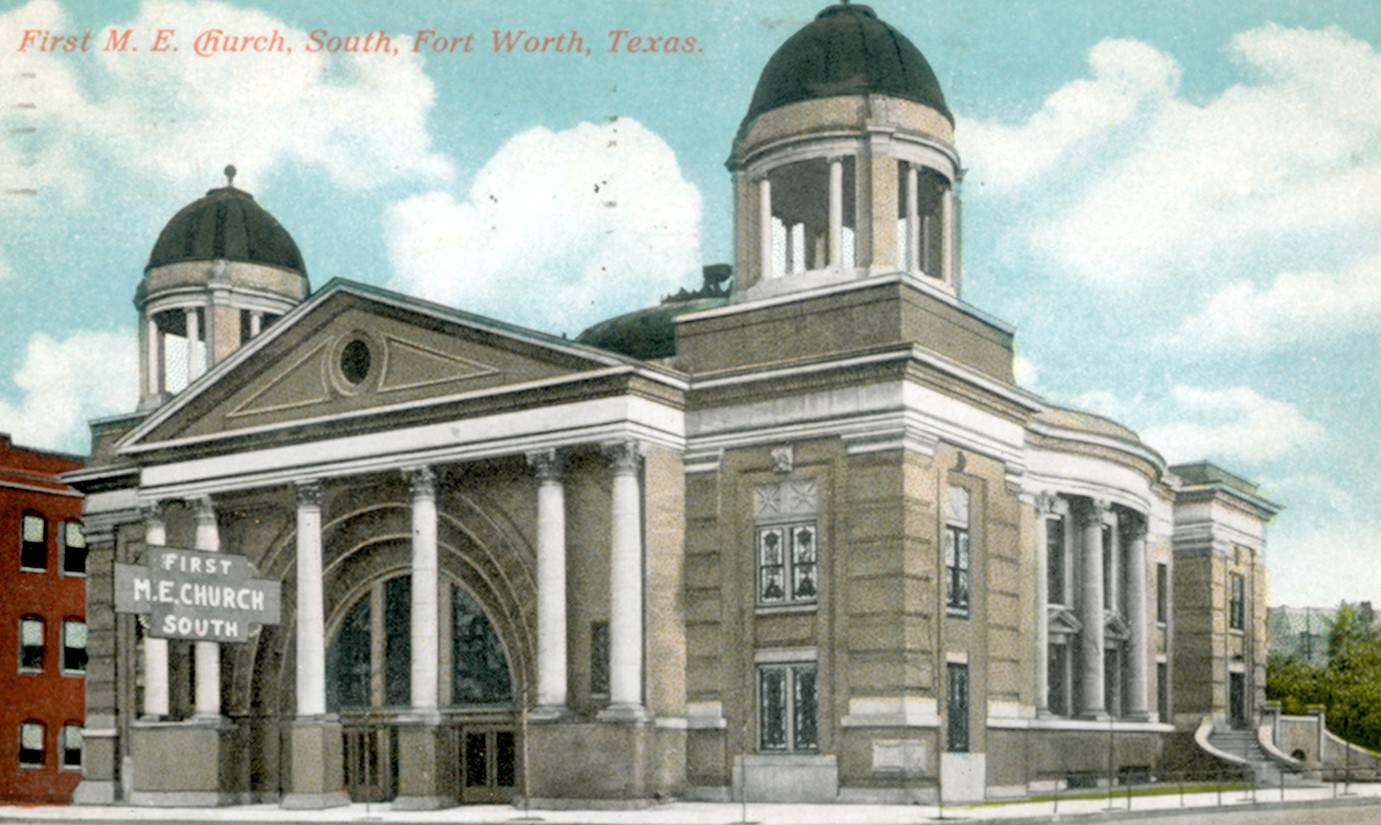

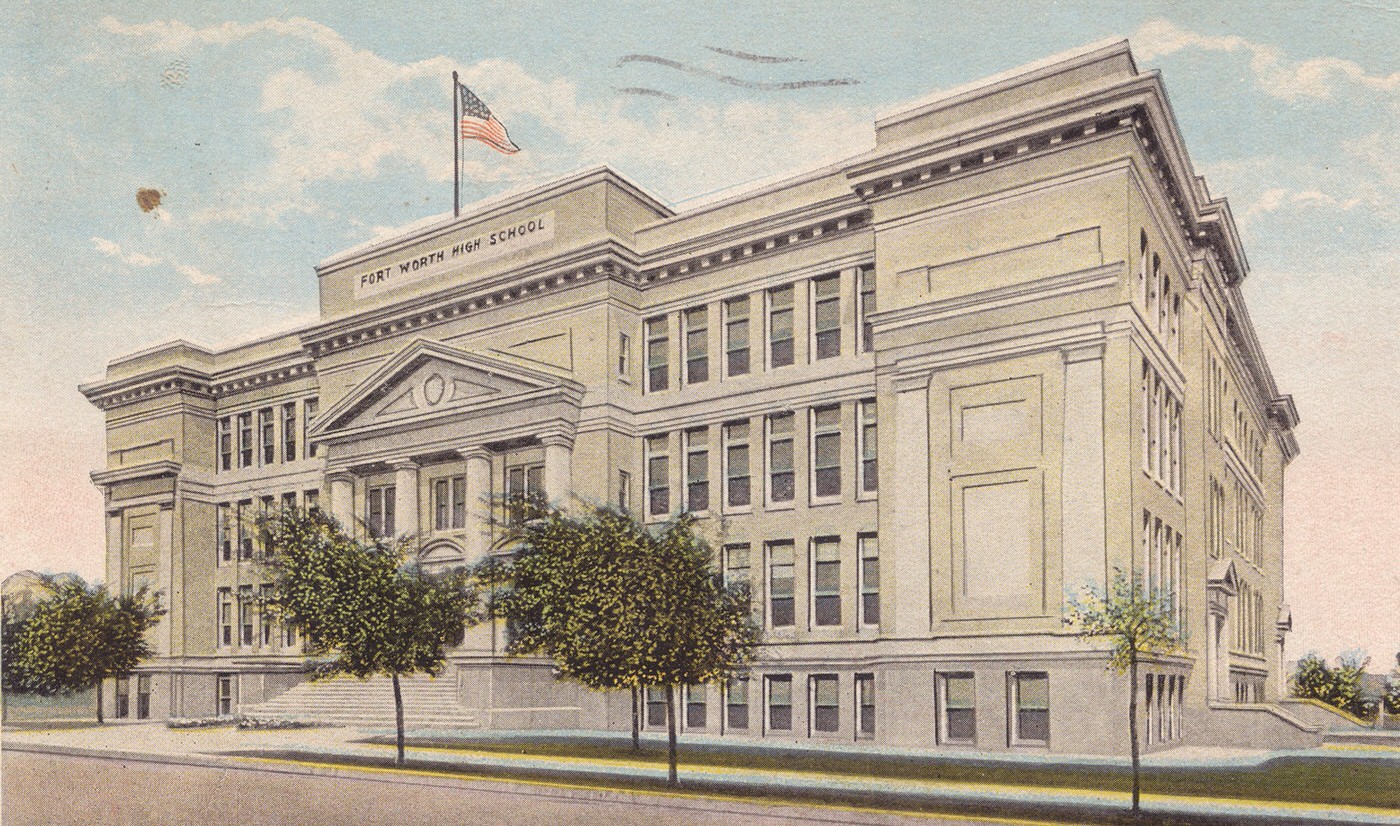

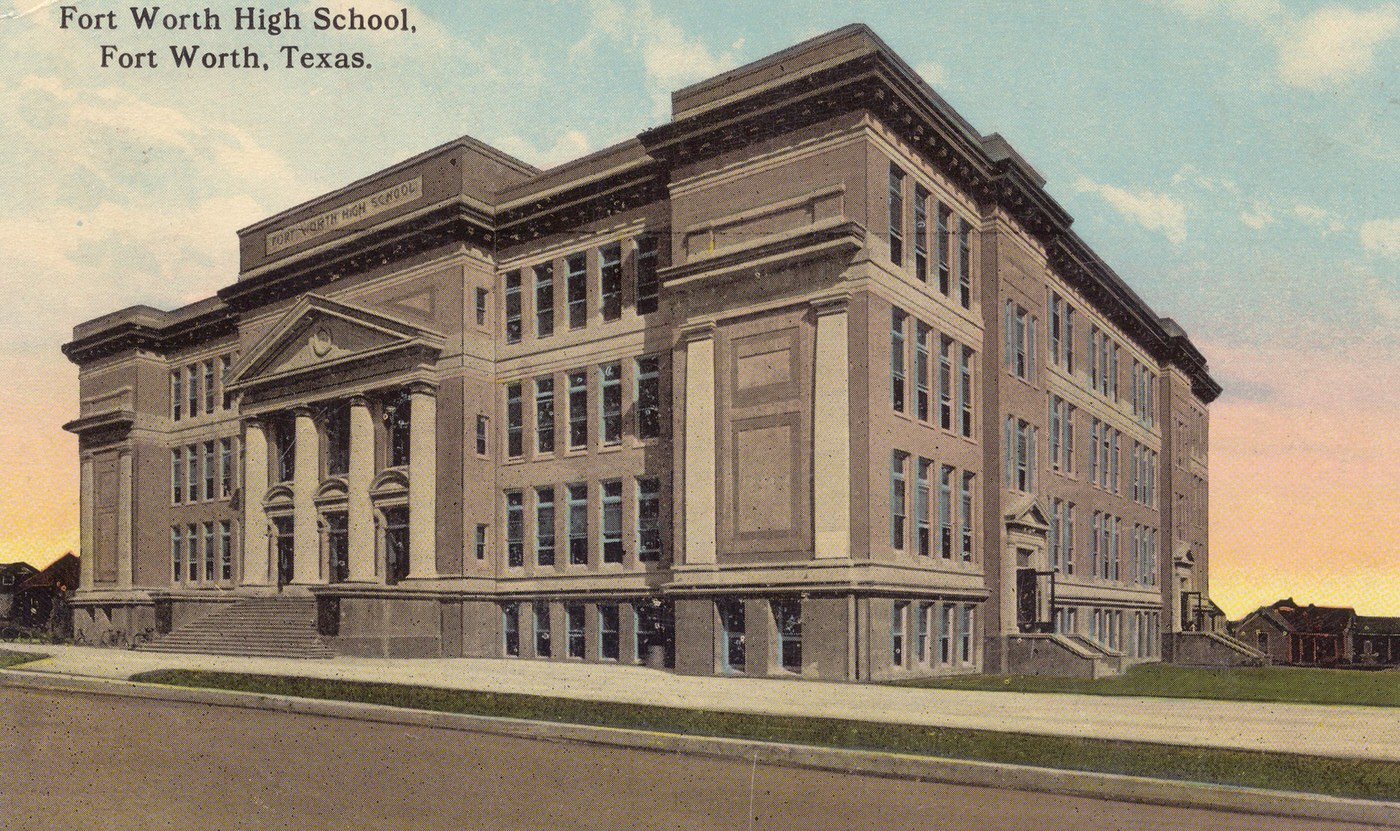

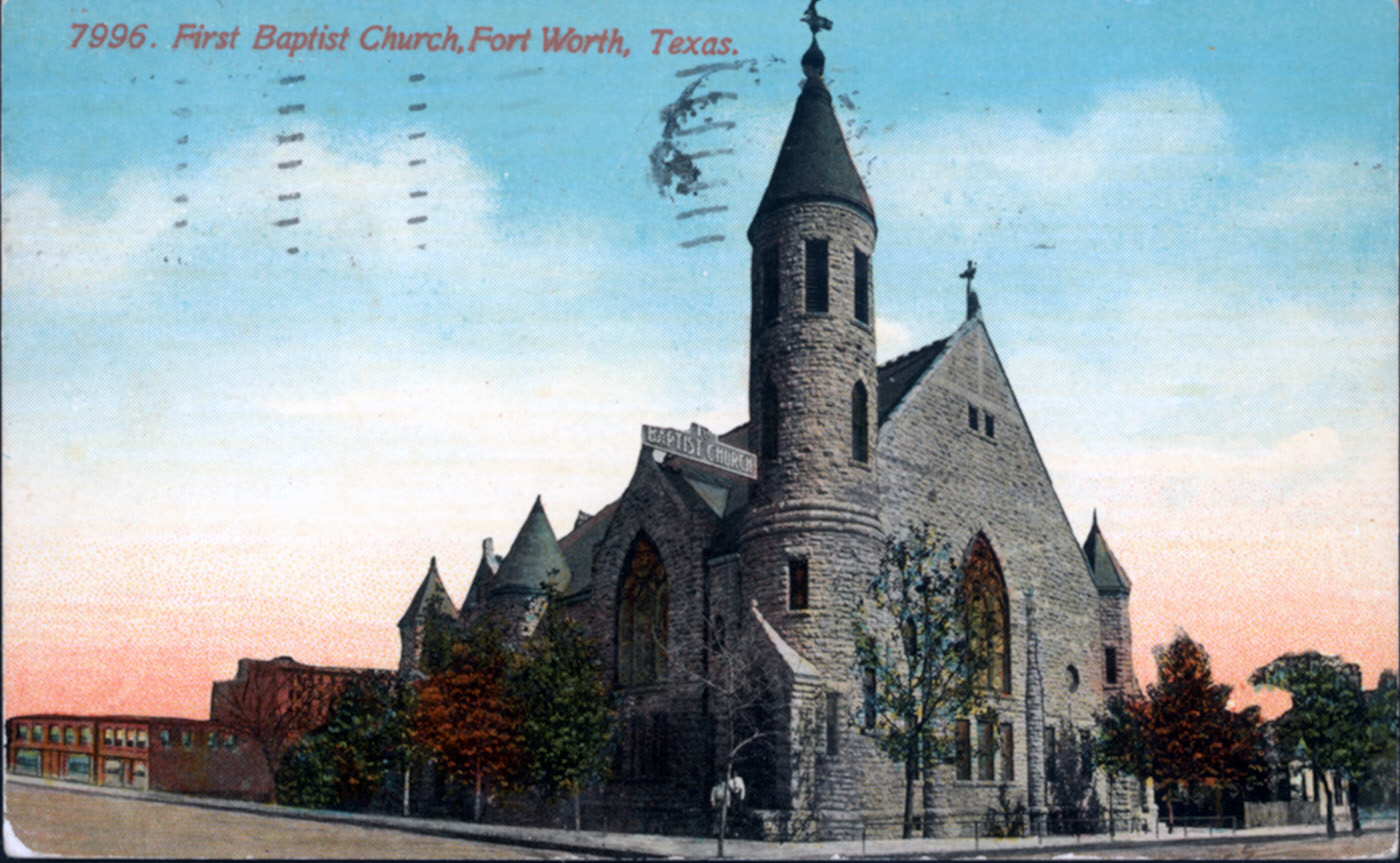

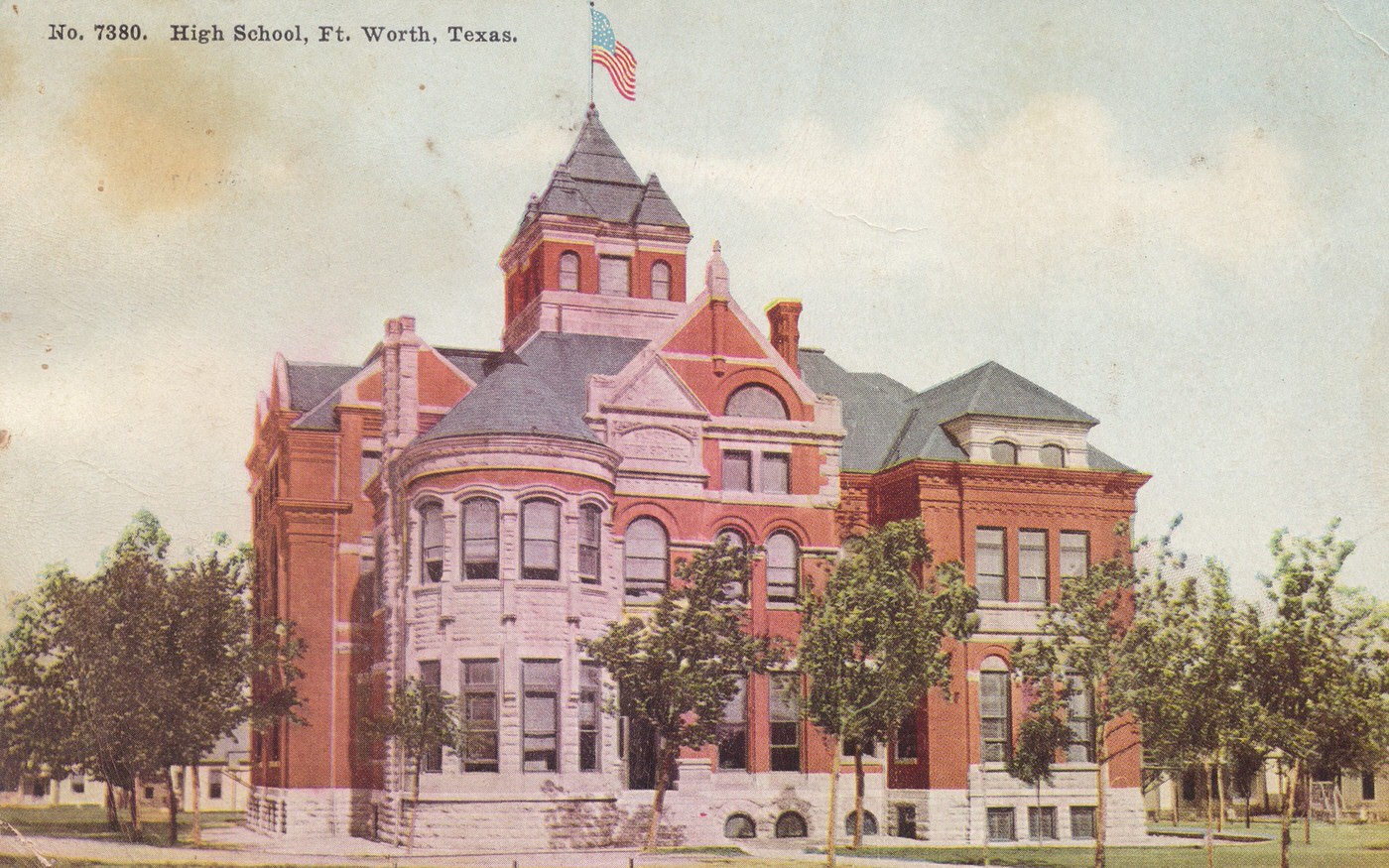

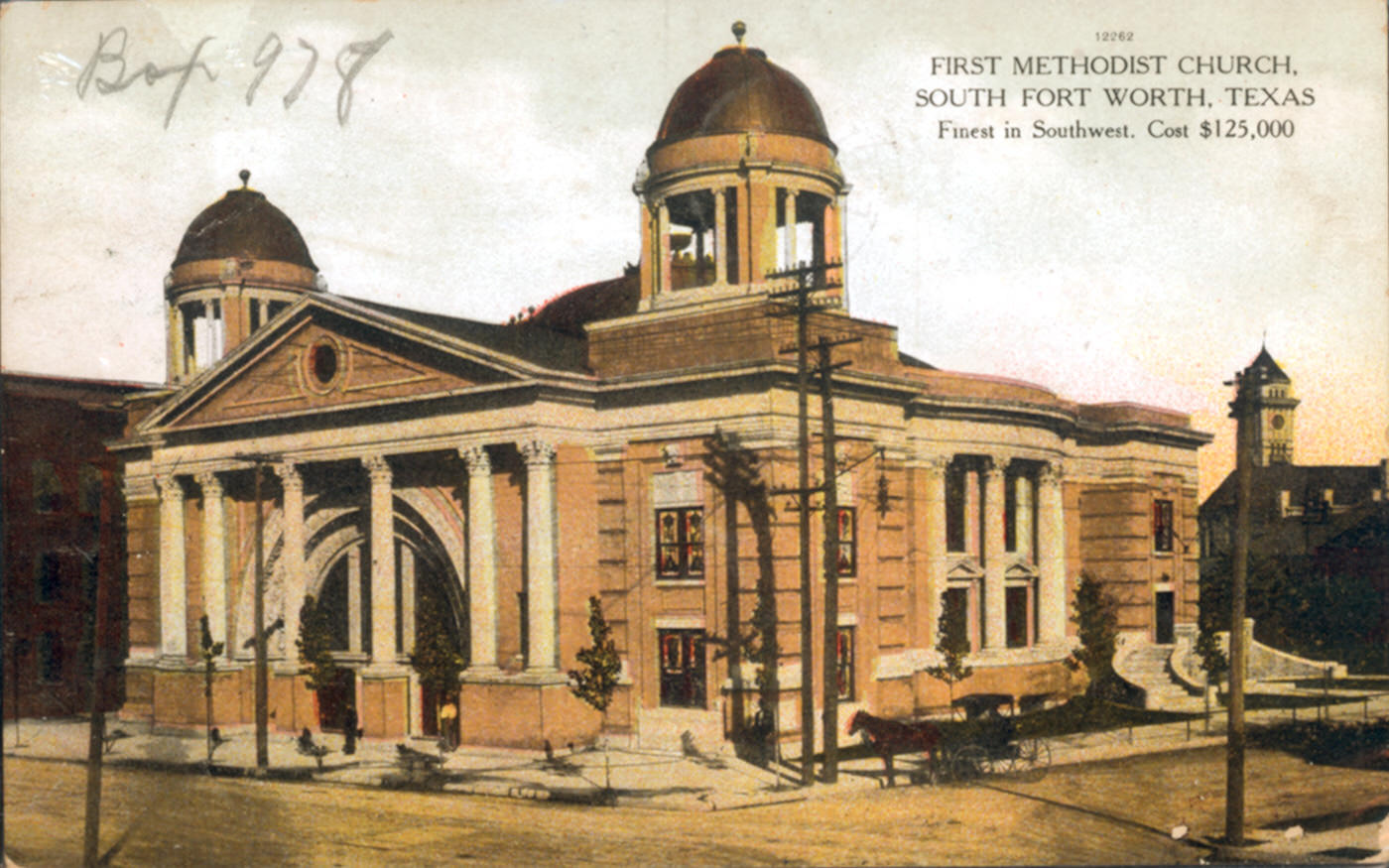

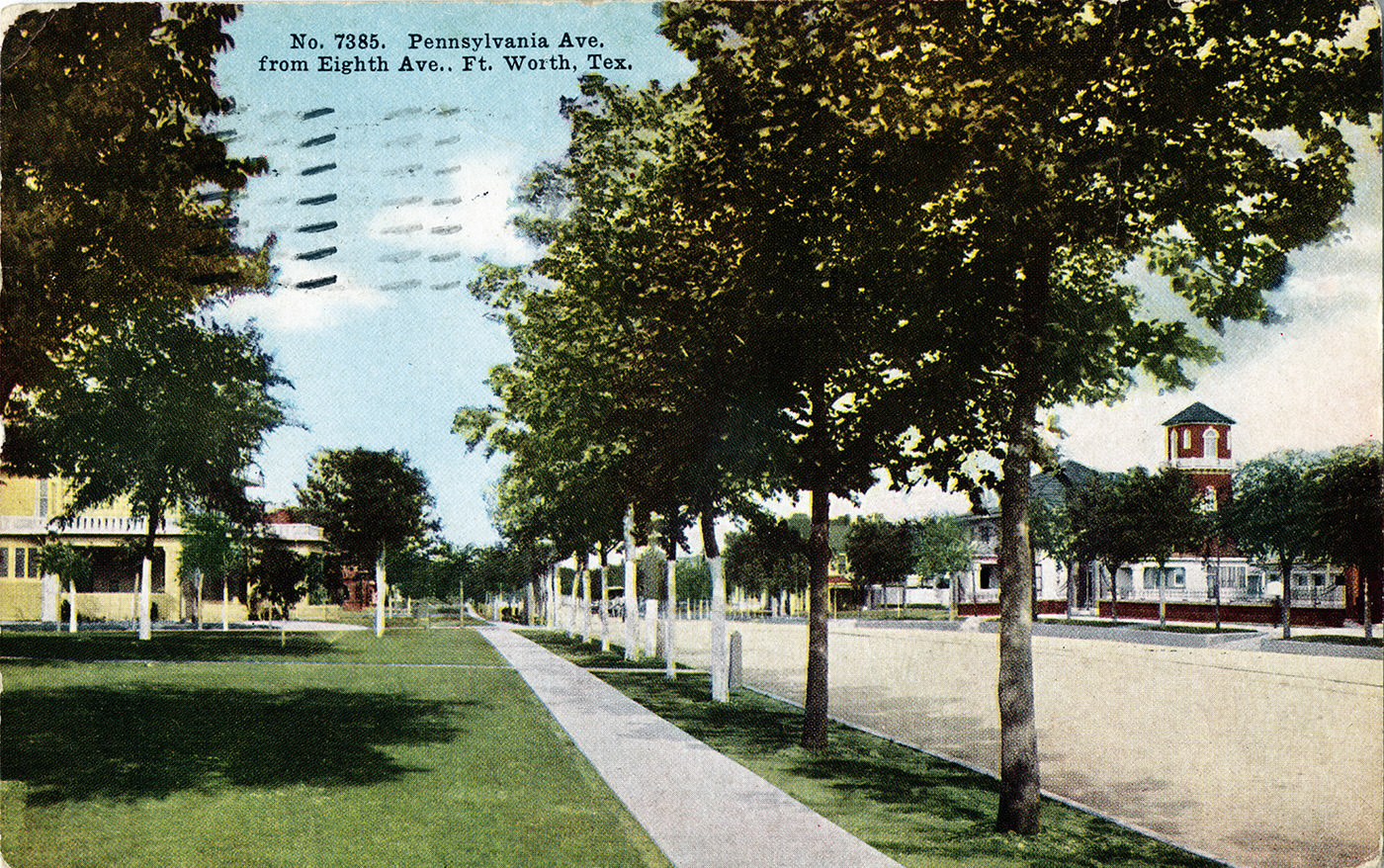

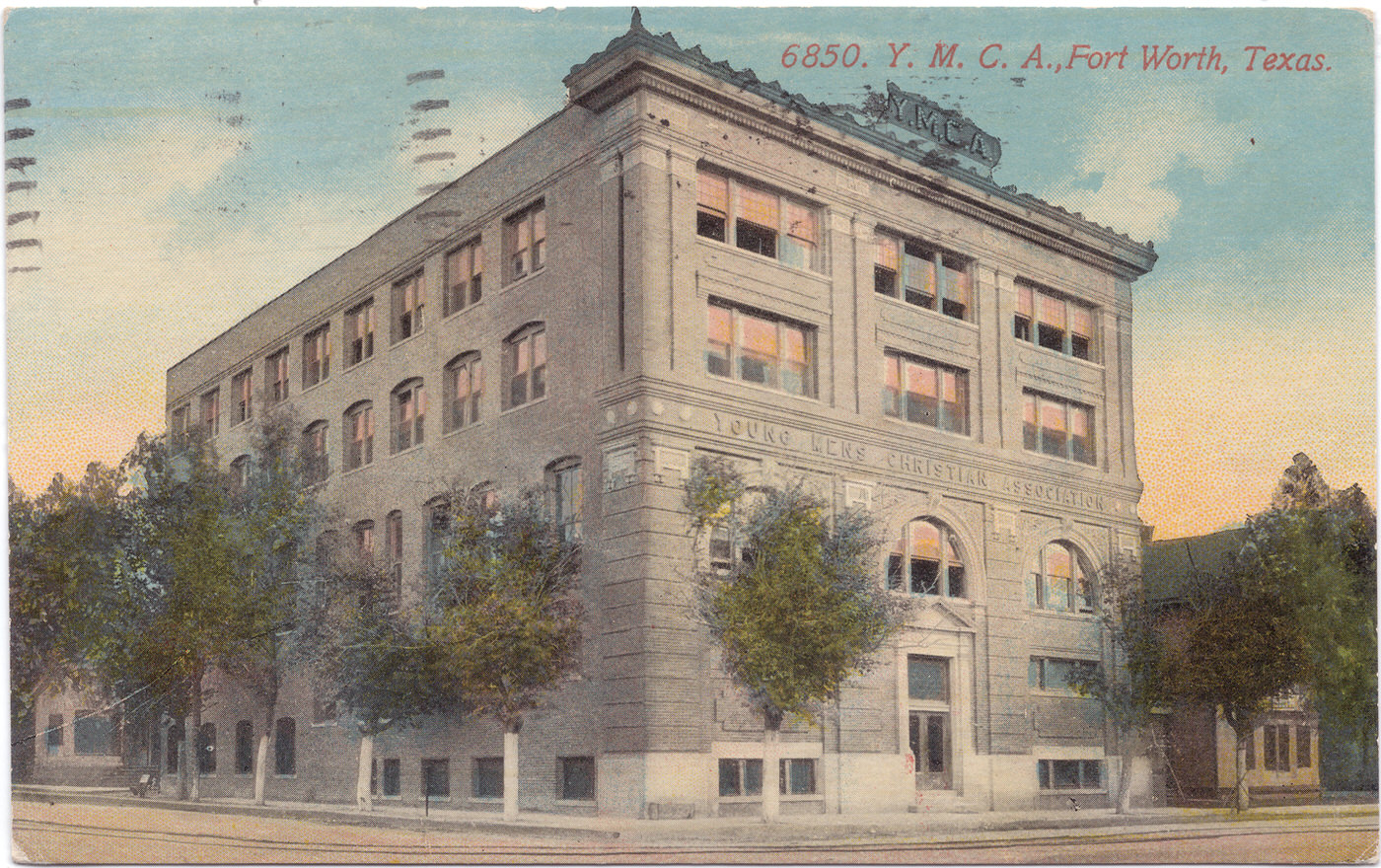

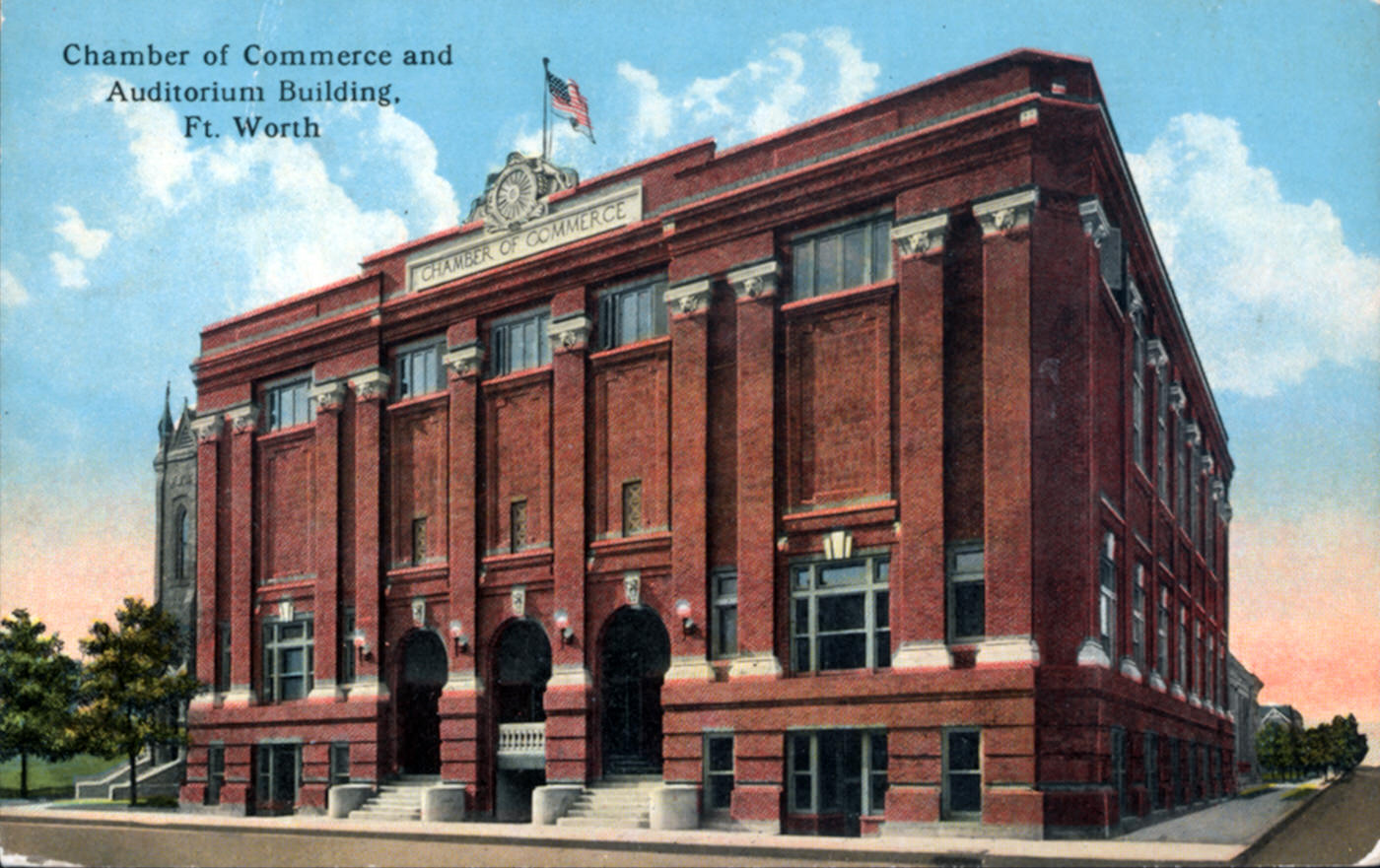

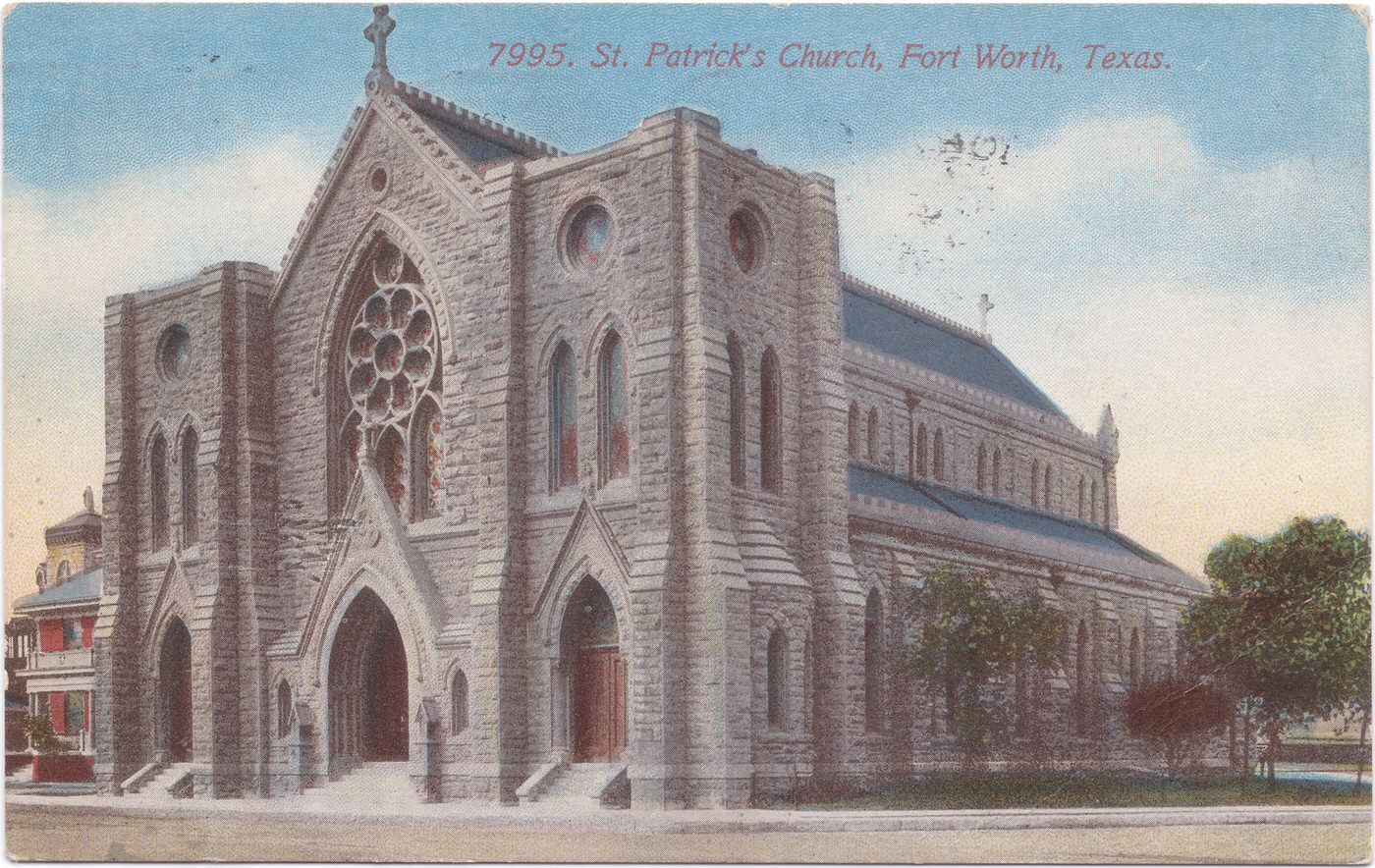

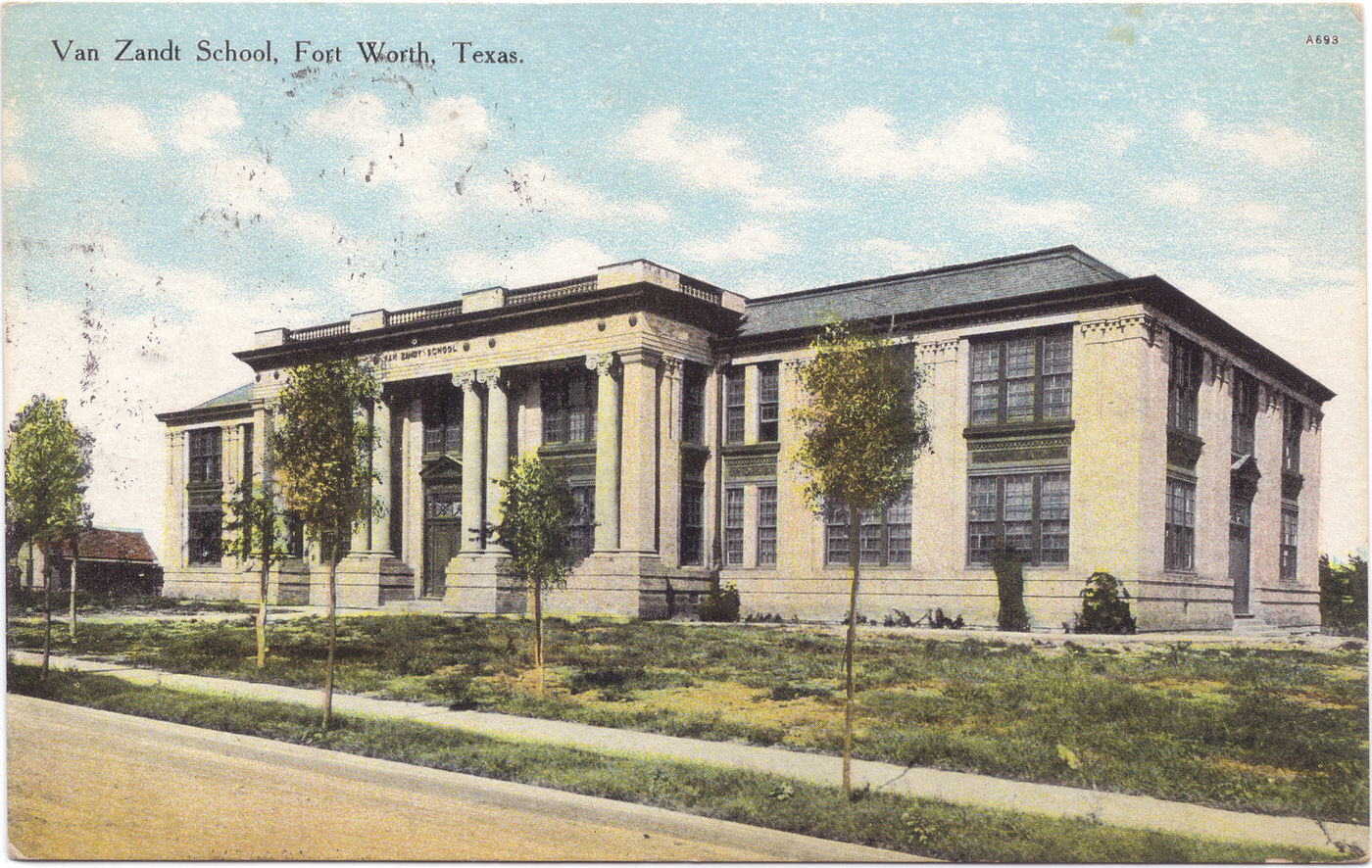

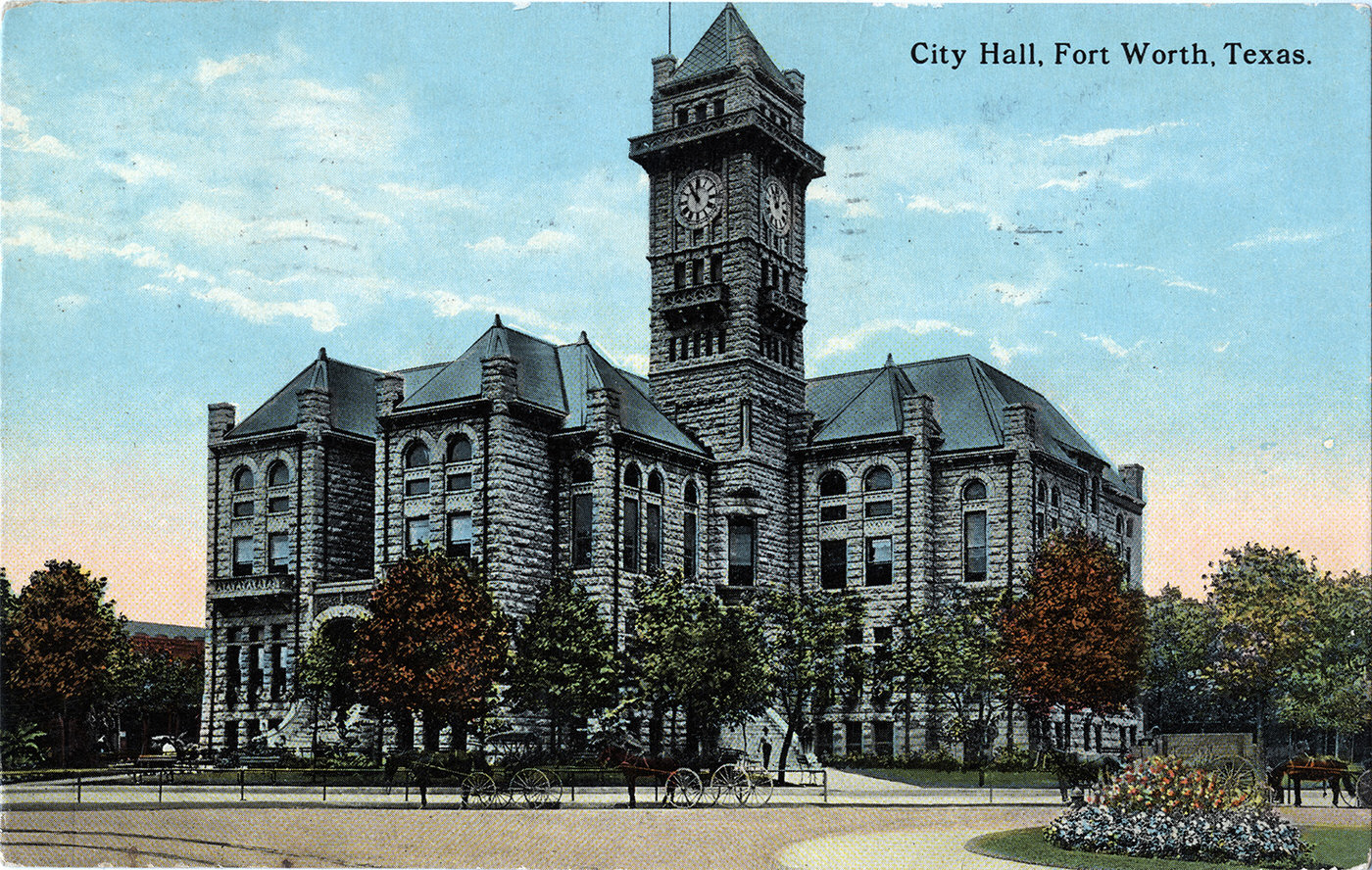

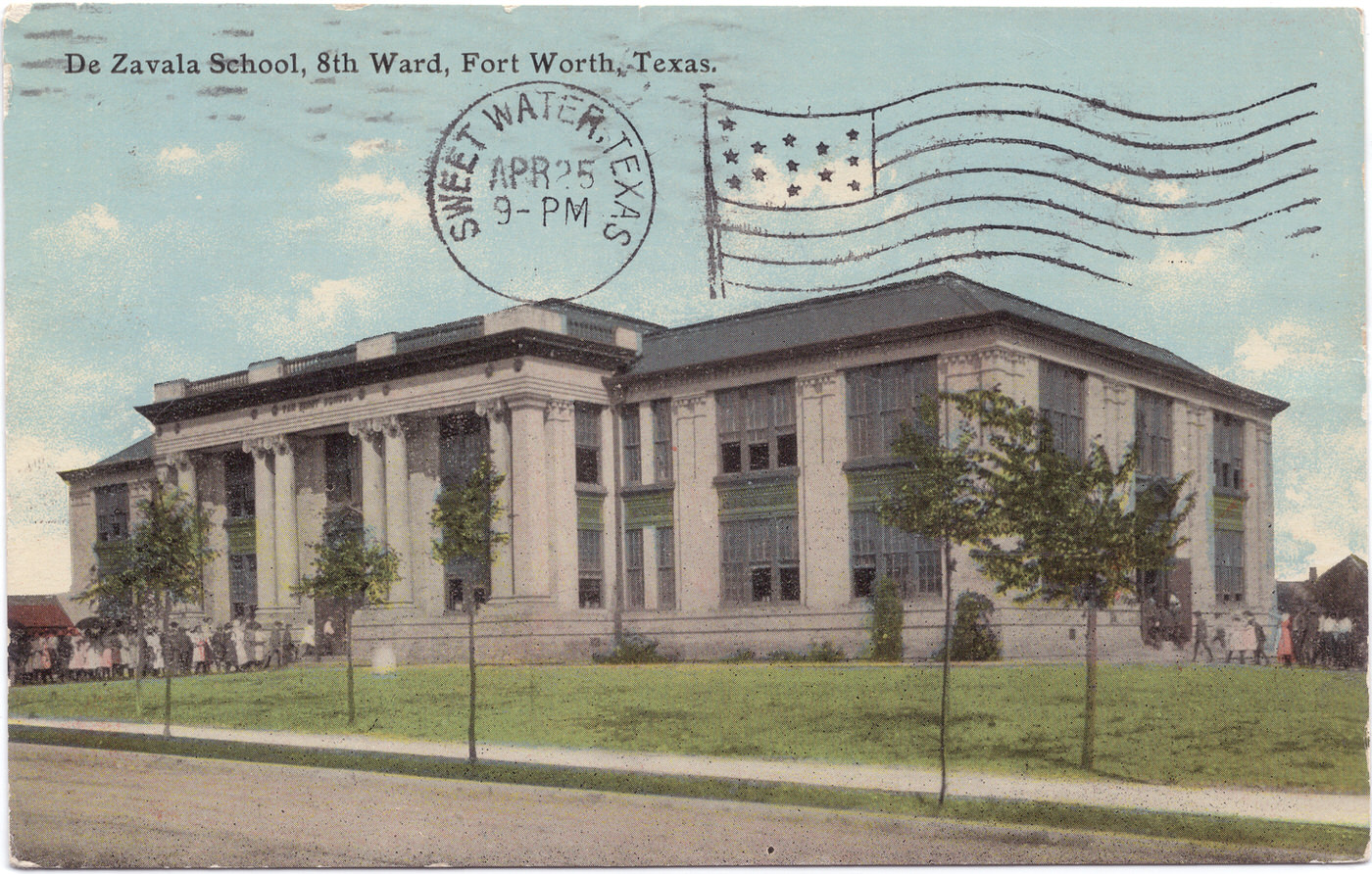

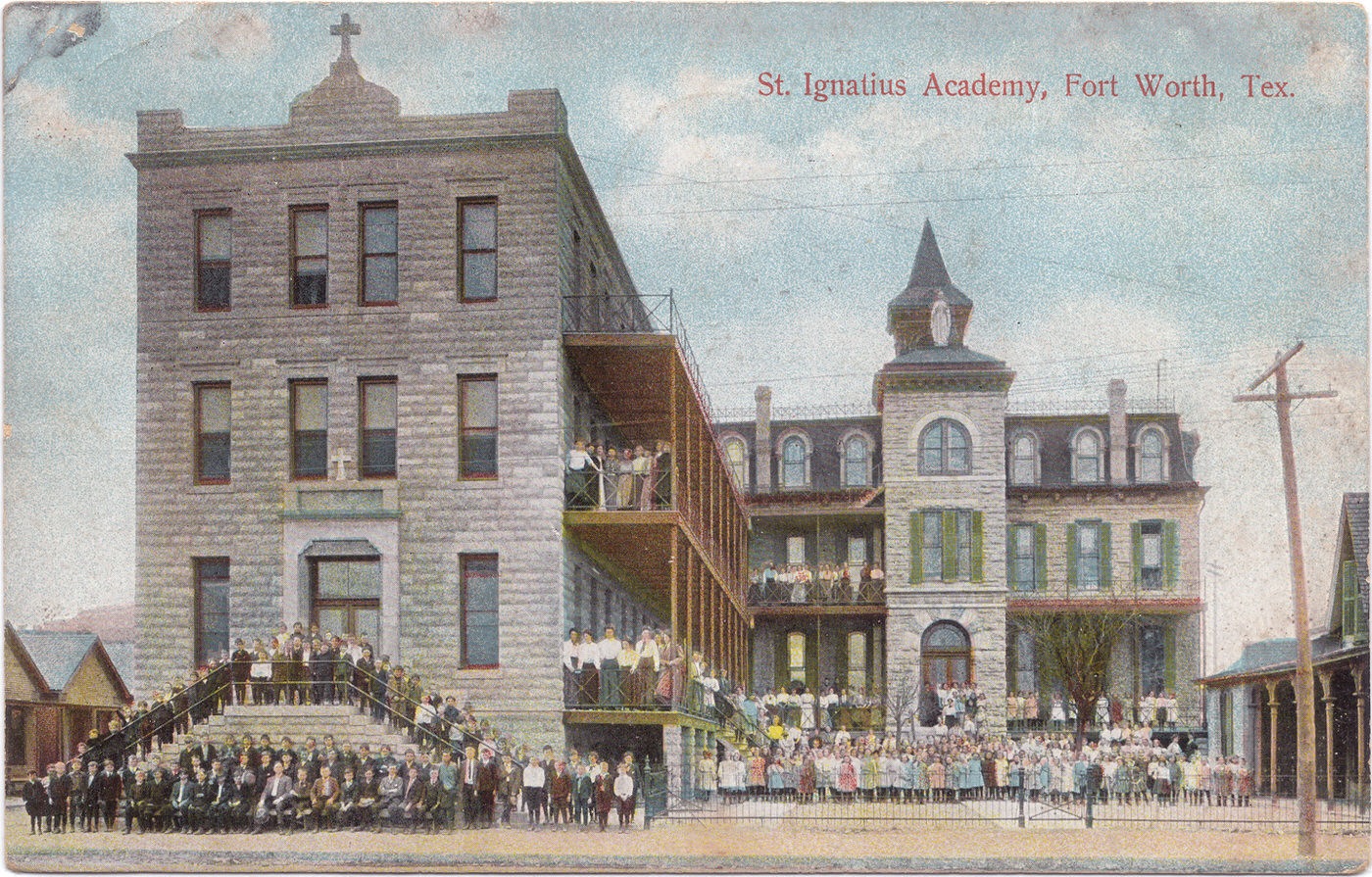

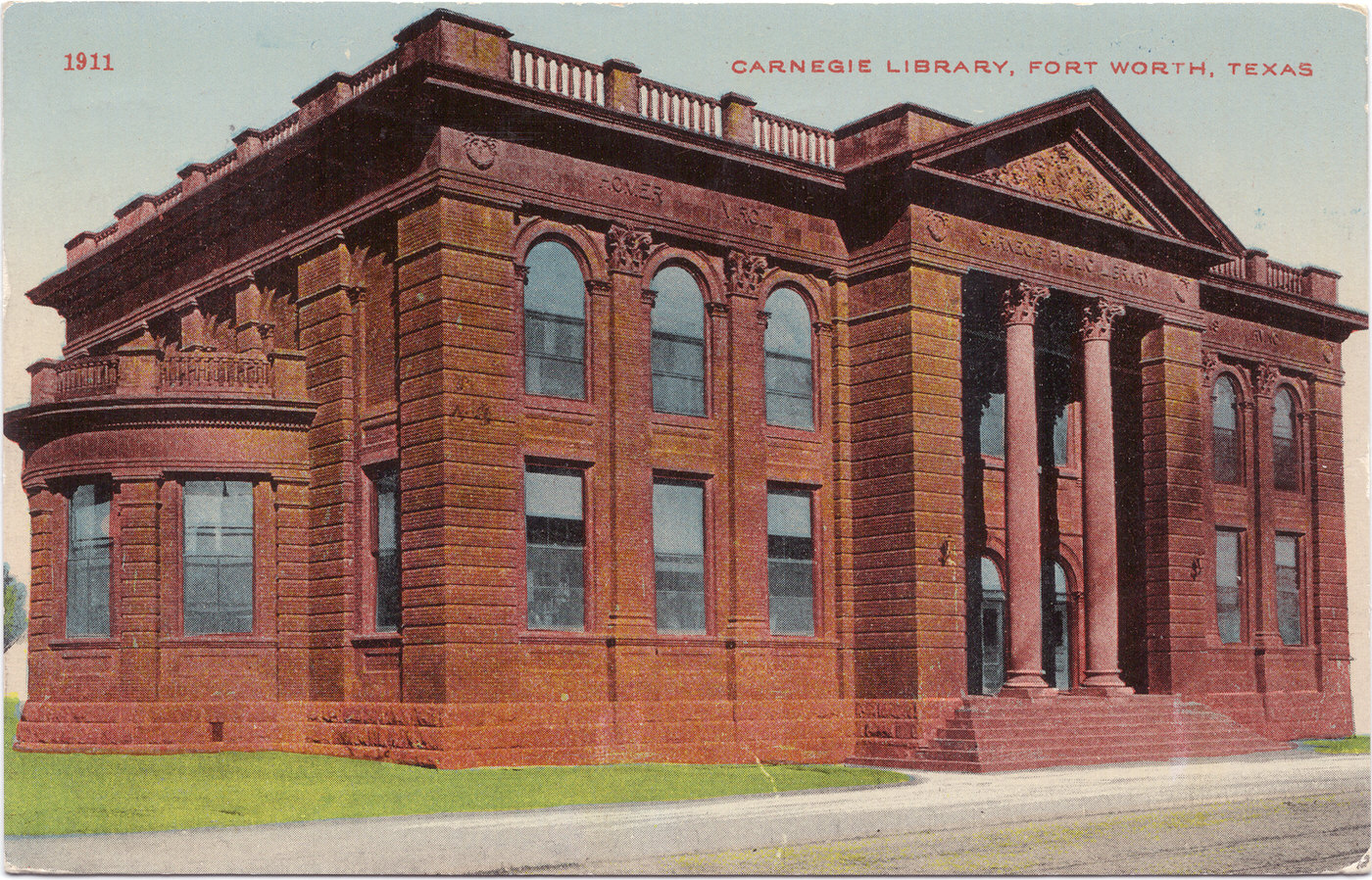

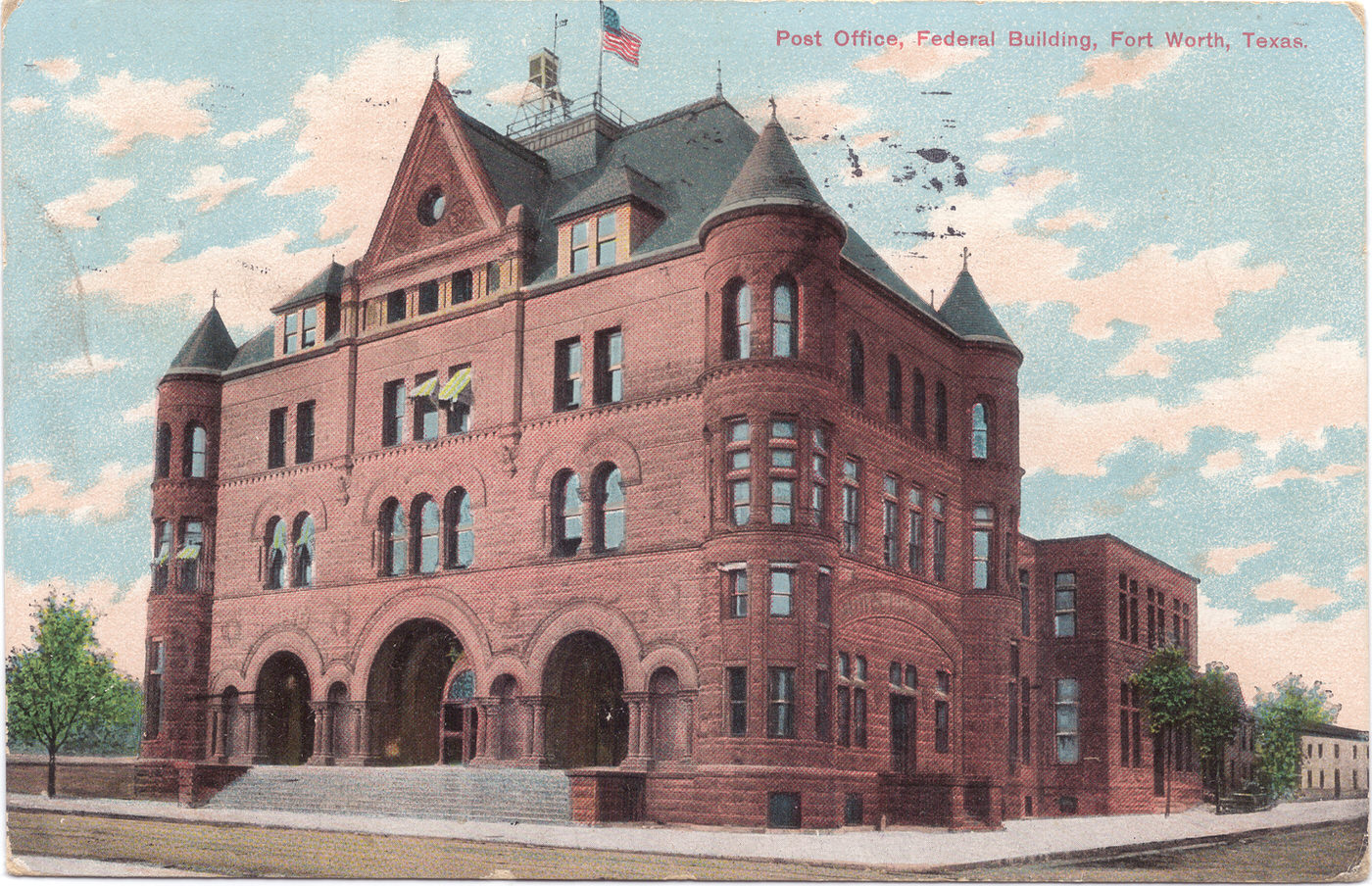

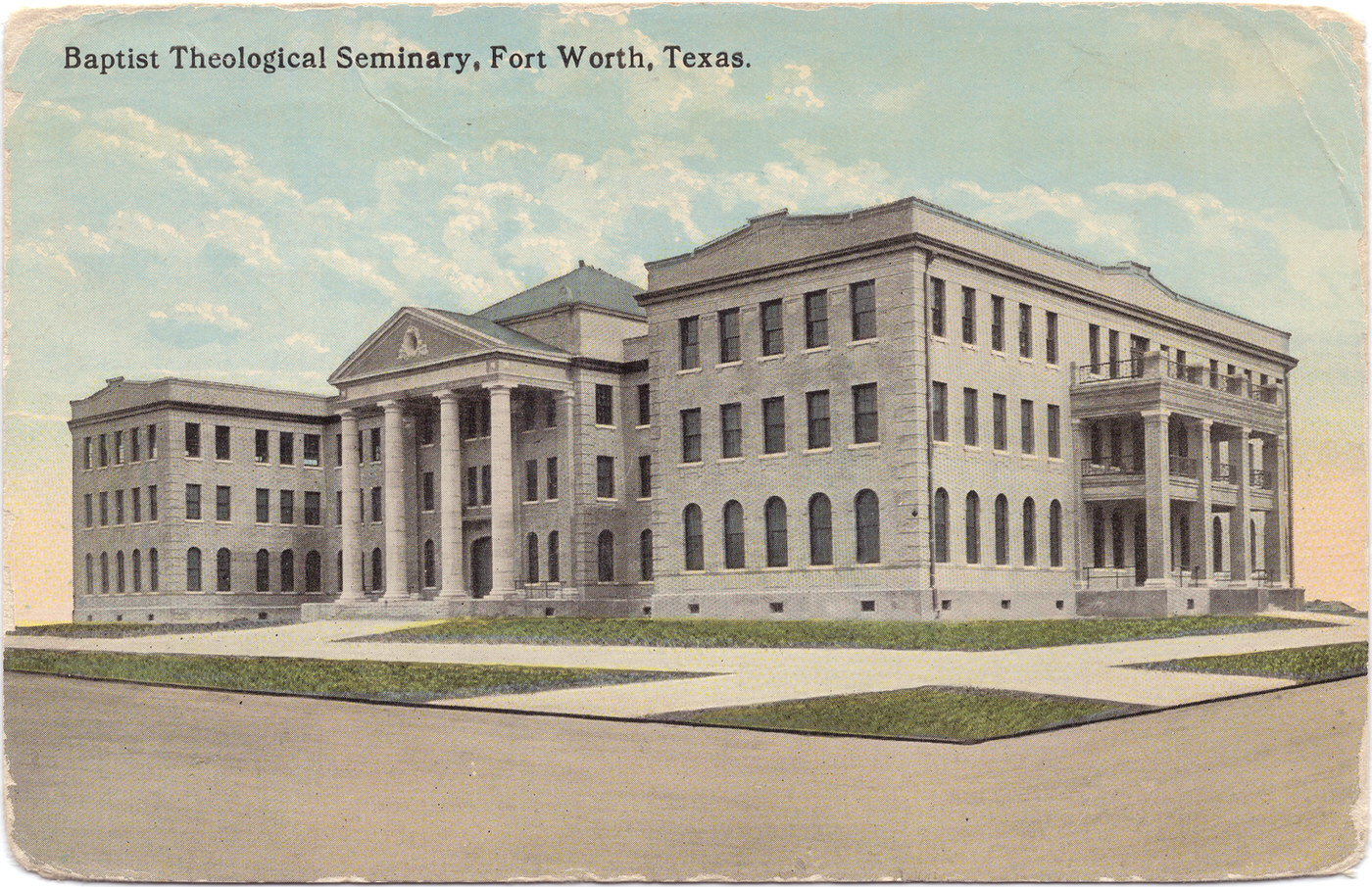

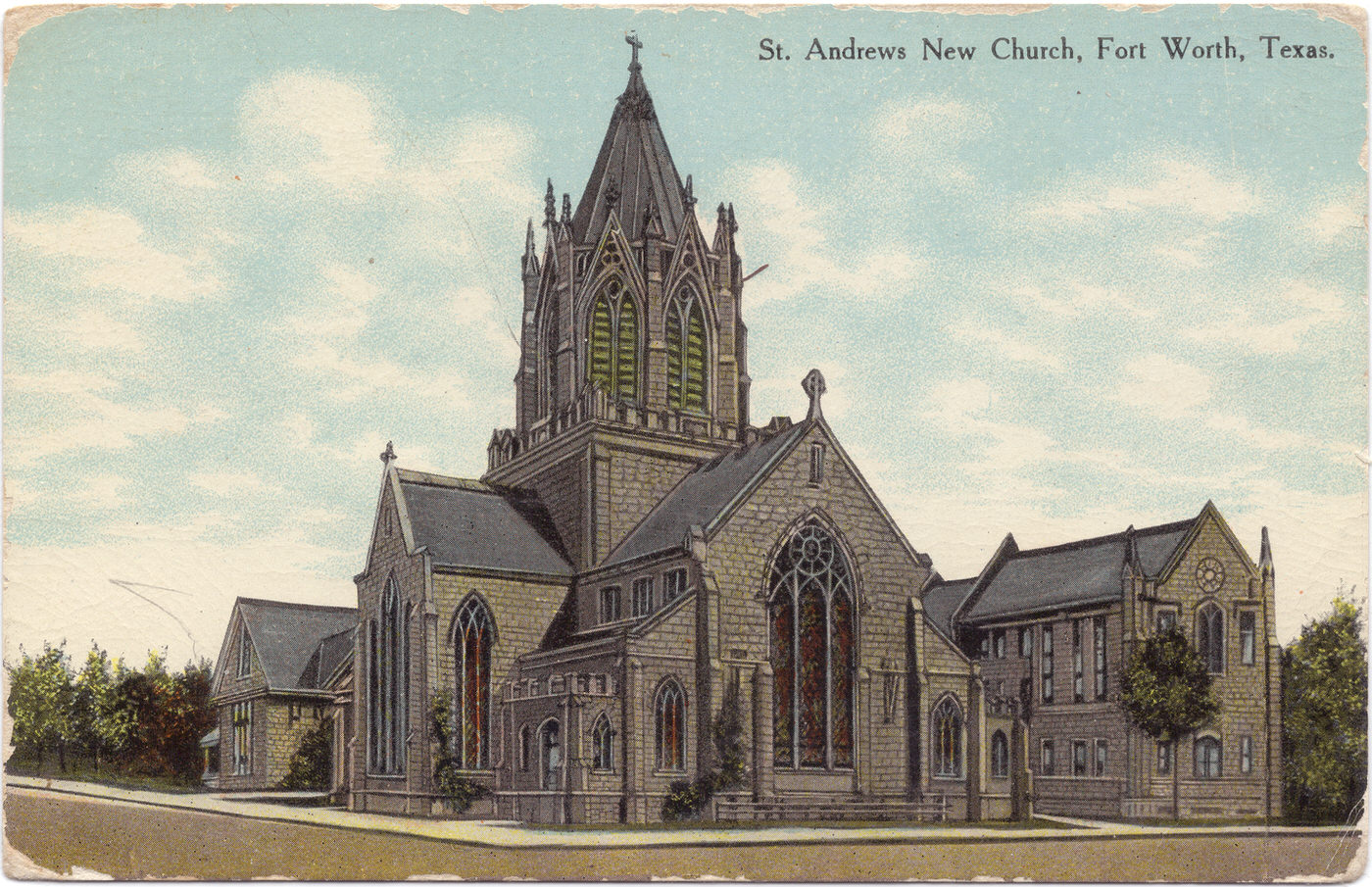

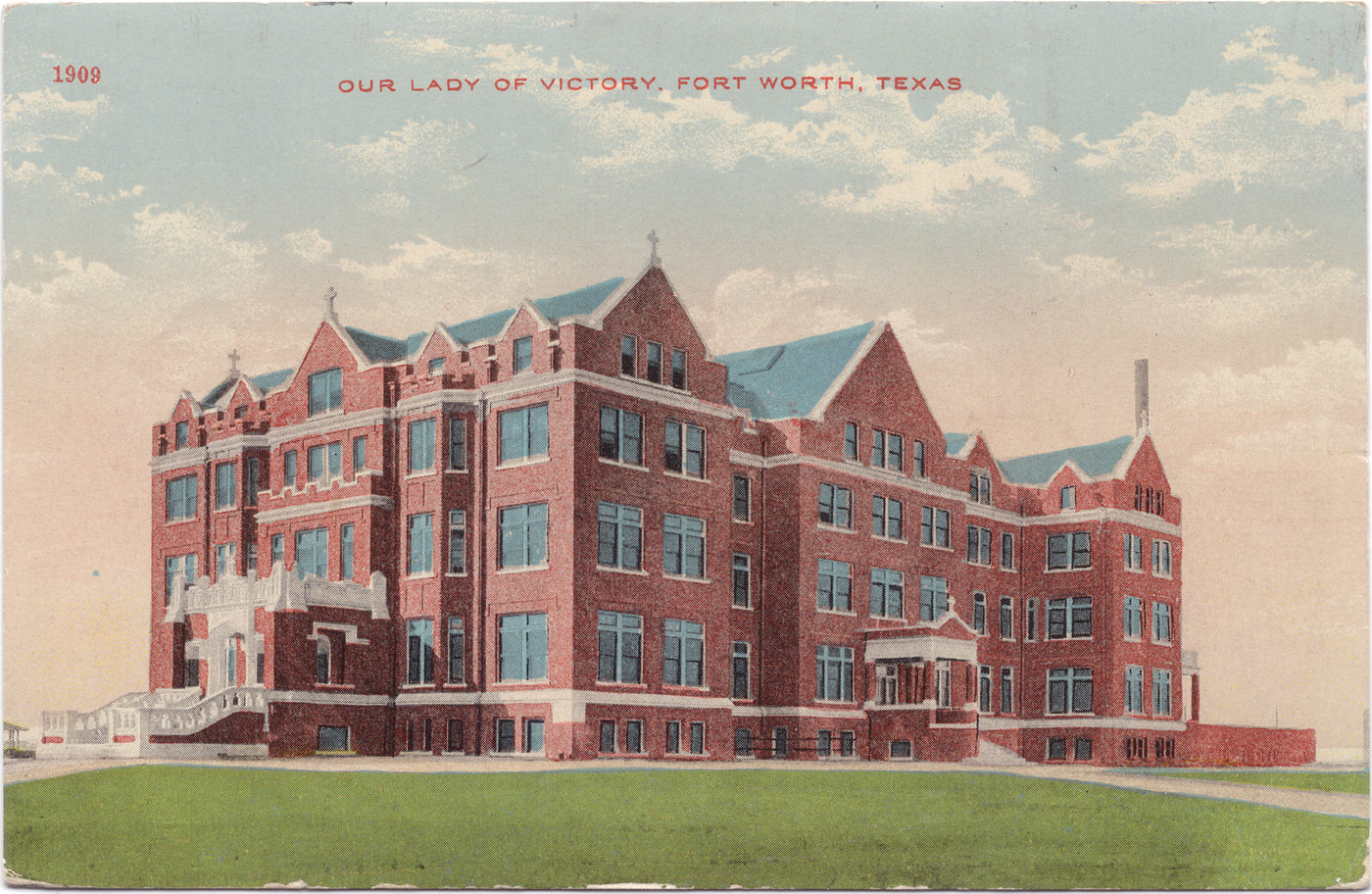

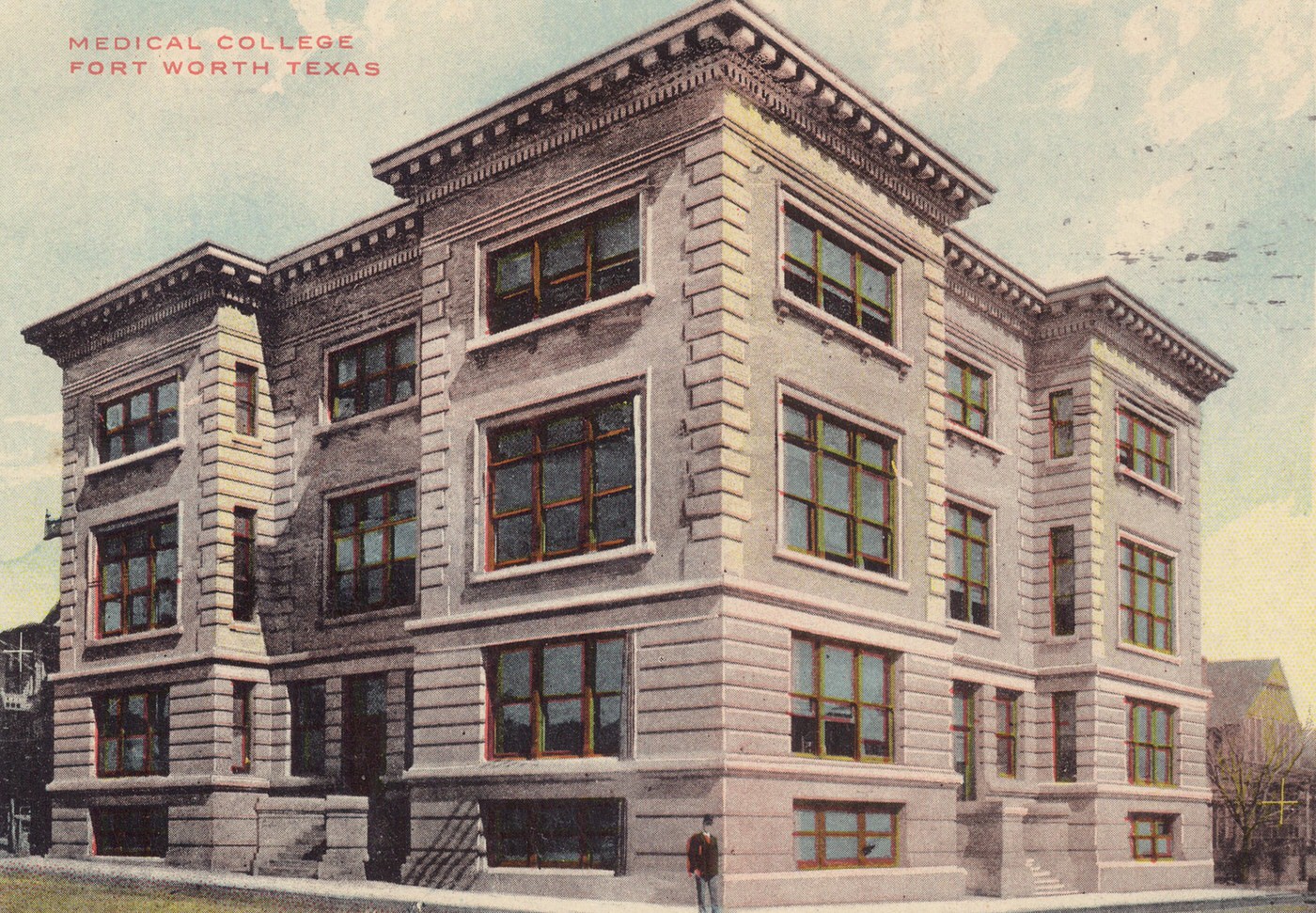

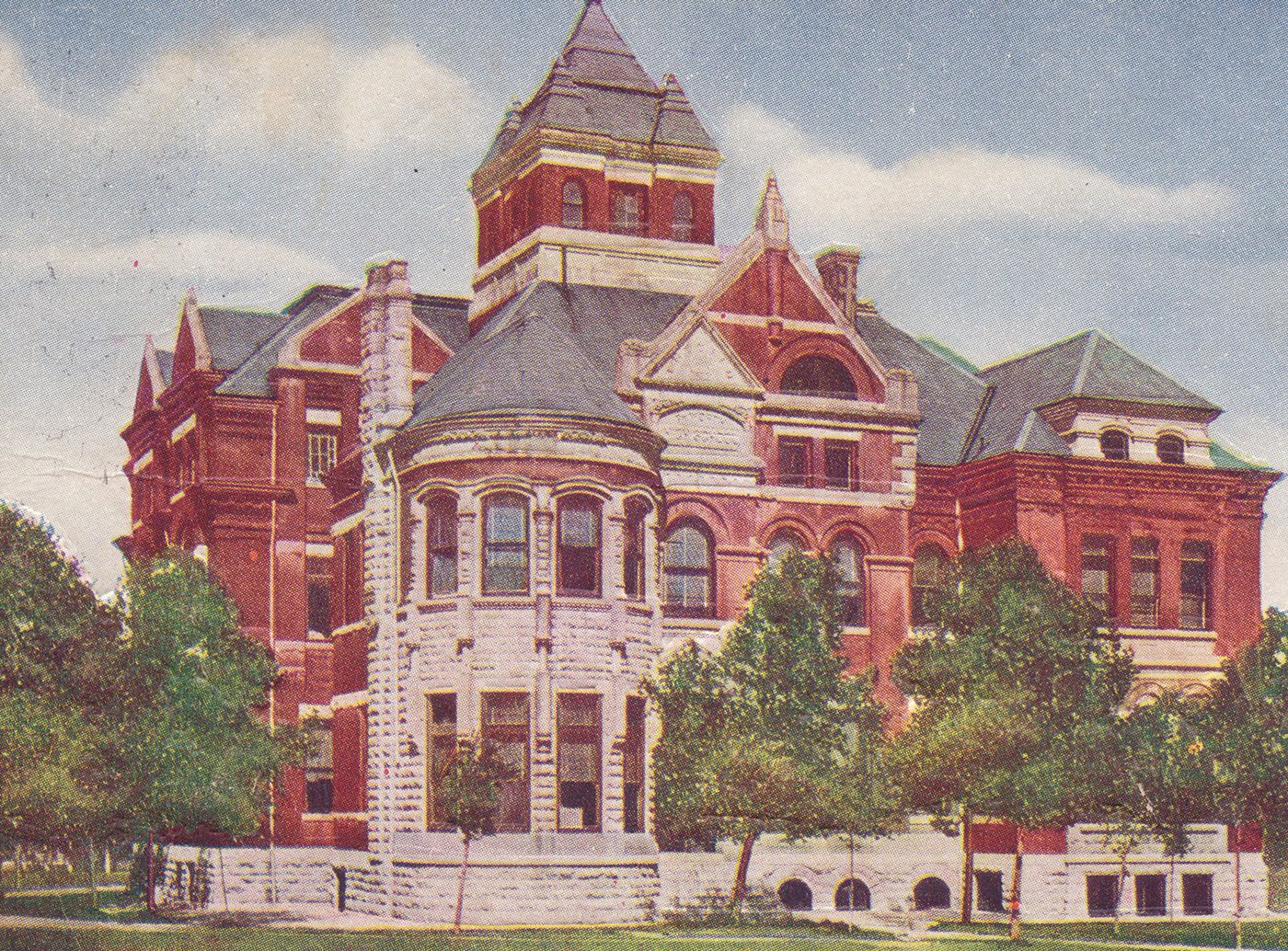

Amidst the industrial clamor and wartime fervor, the 1910s also witnessed significant developments in Fort Worth’s civic and social life, reflecting the city’s maturation beyond its frontier and Cowtown roots. Investments in education, public recreation, and established traditions showcased a growing sense of community pride and permanence.

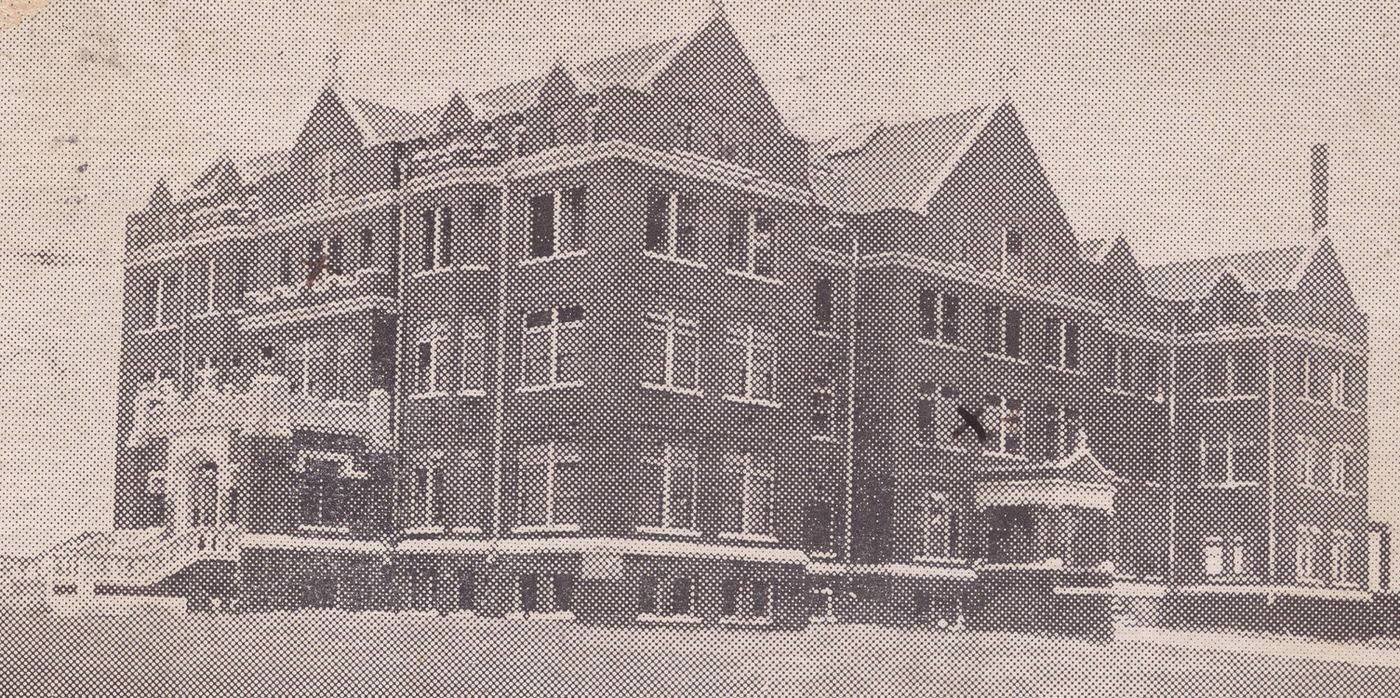

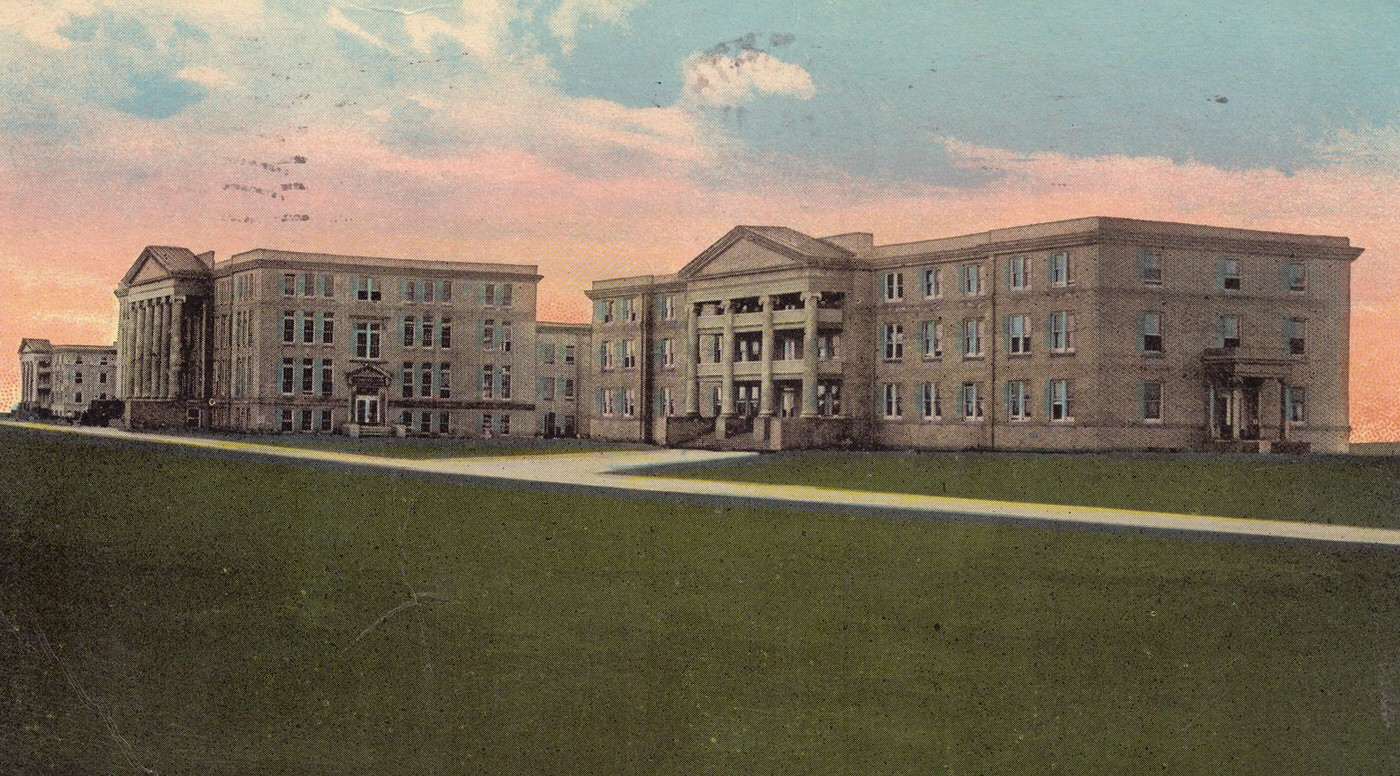

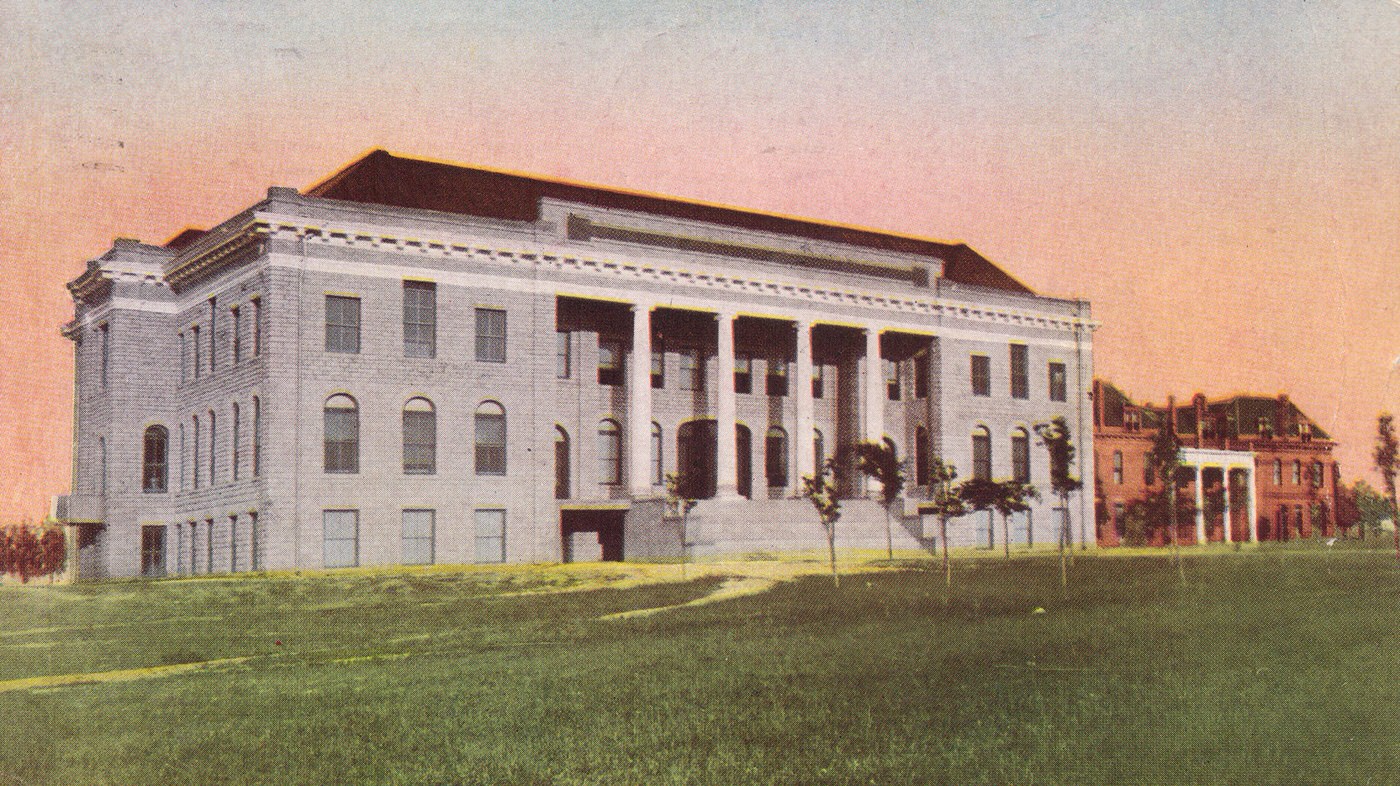

A major milestone was the completion of a grand new Fort Worth High School building in 1911. Located at 1015 S. Jennings Avenue, this impressive three-story, Classical Revival structure replaced the original high school (built 1890-91 at Hemphill and Daggett) which had tragically burned down in 1910. Designed by architects Waller & Field and built for $250,000, the new school, with its yellow brick, granite accents, and imposing columns, was a statement of the city’s commitment to public education. It was part of a larger school building program initiated in 1909, funded by a $450,000 bond issue, aimed at constructing modern, fireproof facilities to accommodate the rapidly growing student population. The establishment of a formal public school system dated back only to 1882, making the scale and quality of the 1911 high school a significant marker of progress.

Leisure and entertainment options also expanded. The creation of Lake Worth provided a new focal point for recreation. Capitalizing on this, entrepreneurs opened Casino Park on the lake’s shore in 1916. This amusement area quickly became a popular destination, featuring a boardwalk, a bathhouse for swimmers enjoying the municipal beach, amusement rides, and, most notably, the large Casino Ballroom, which could host 2,200 dancers and diners and would later attract famous big bands. Casino Park offered Fort Worth residents a modern venue for relaxation and socializing, a far cry from the rough-and-tumble diversions of Hell’s Half Acre.

The Ranger Oil Discovery’s Early Tremors (1917)

While Fort Worth was deeply enmeshed in the war effort and continuing its reign as a meatpacking capital, another force emerged late in the decade that would add yet another layer to its identity: oil. In October 1917, some 90 miles west of the city, a wildcat well on the McCleskey farm near the small town of Ranger in Eastland County erupted, revealing a massive oilfield. This discovery, quickly followed by significant strikes in nearby Breckenridge and Desdemona, triggered the West Texas oil boom.

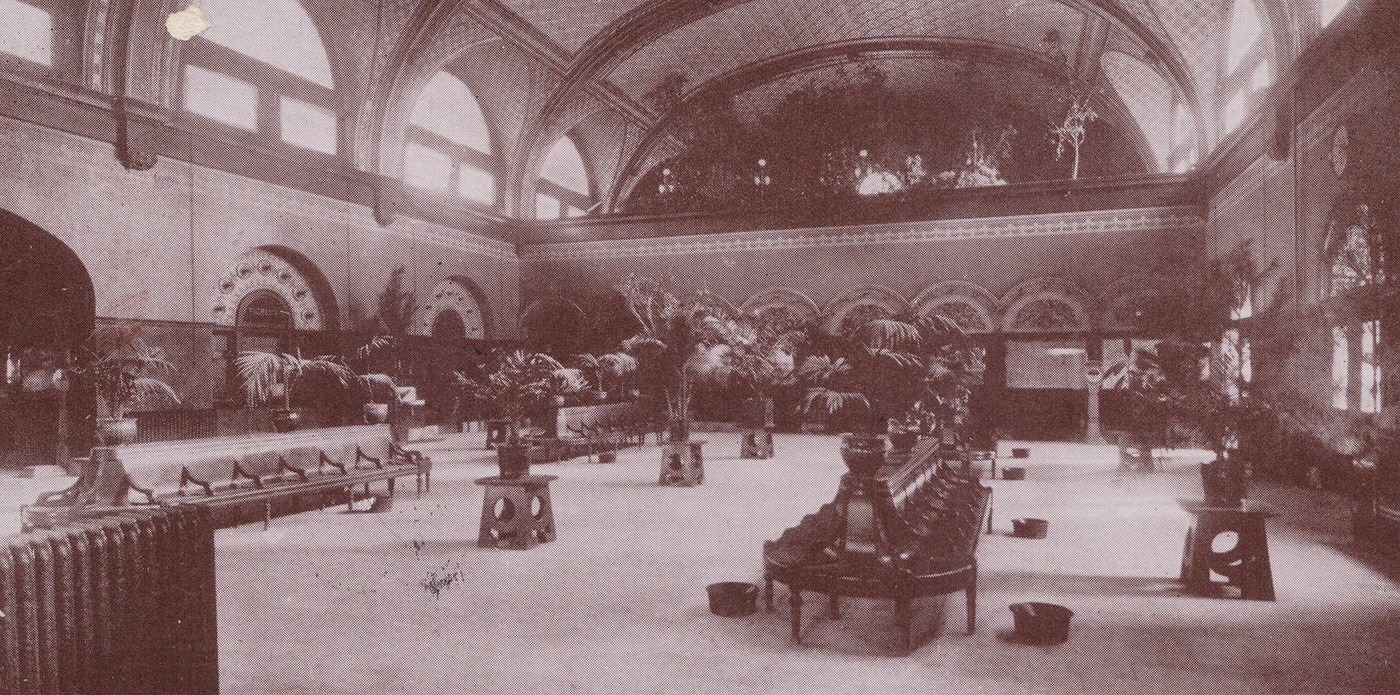

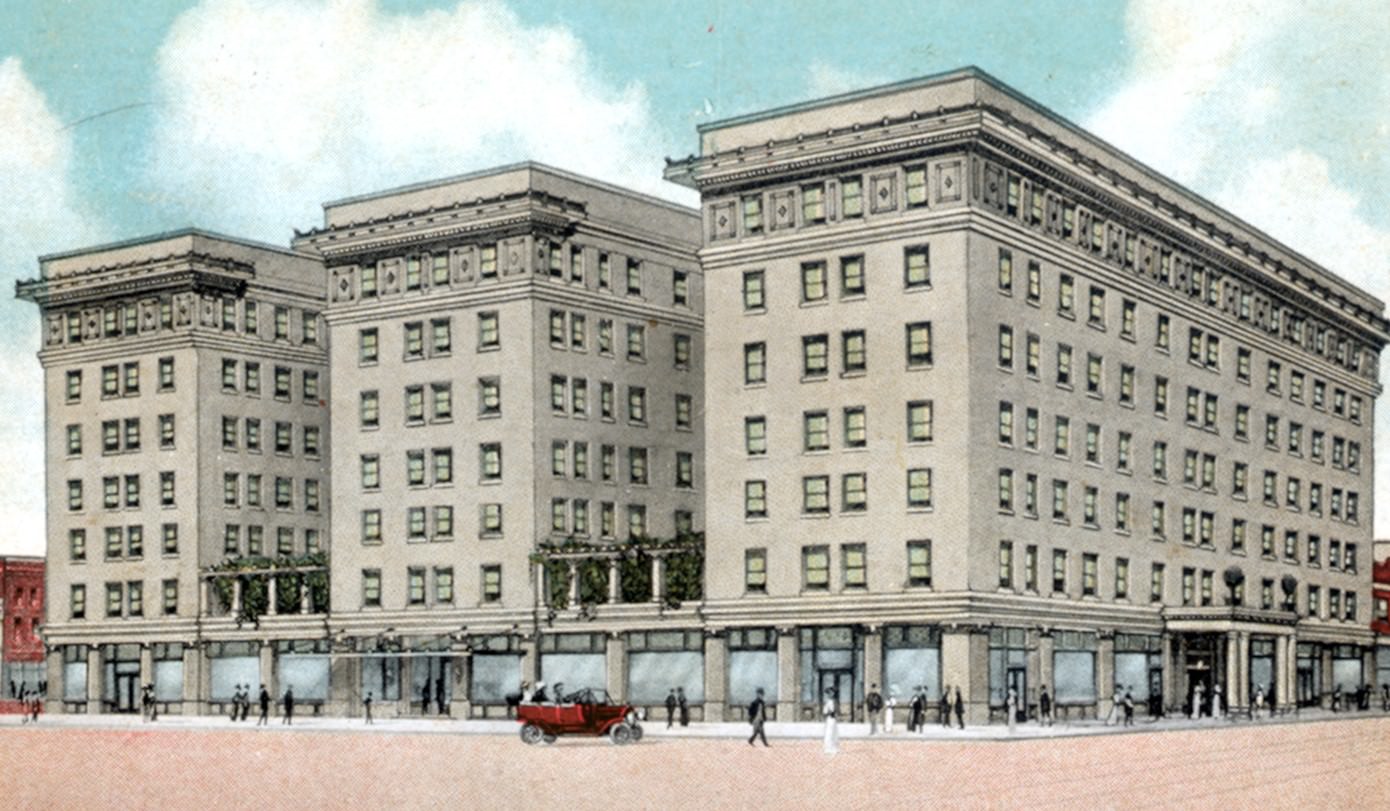

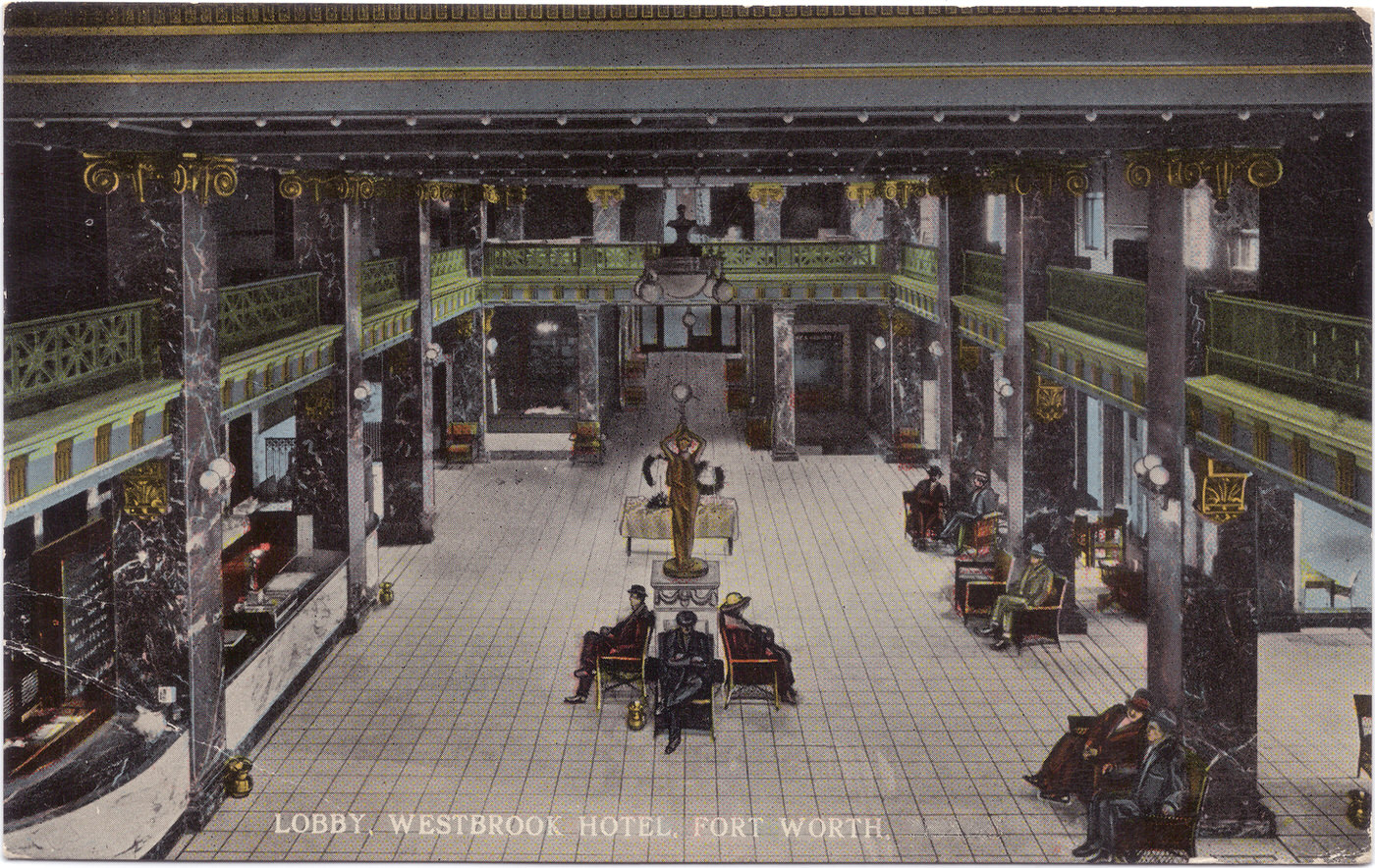

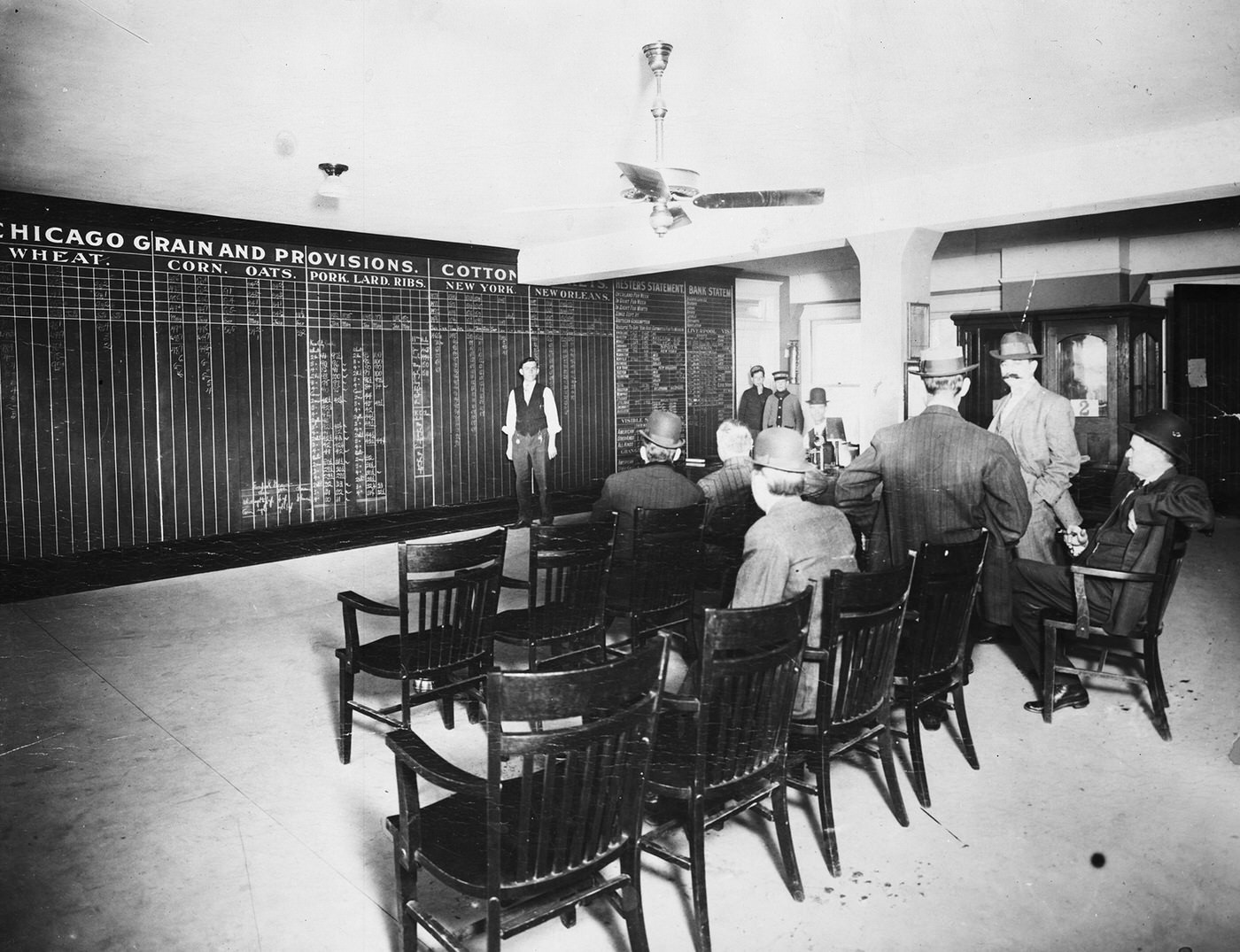

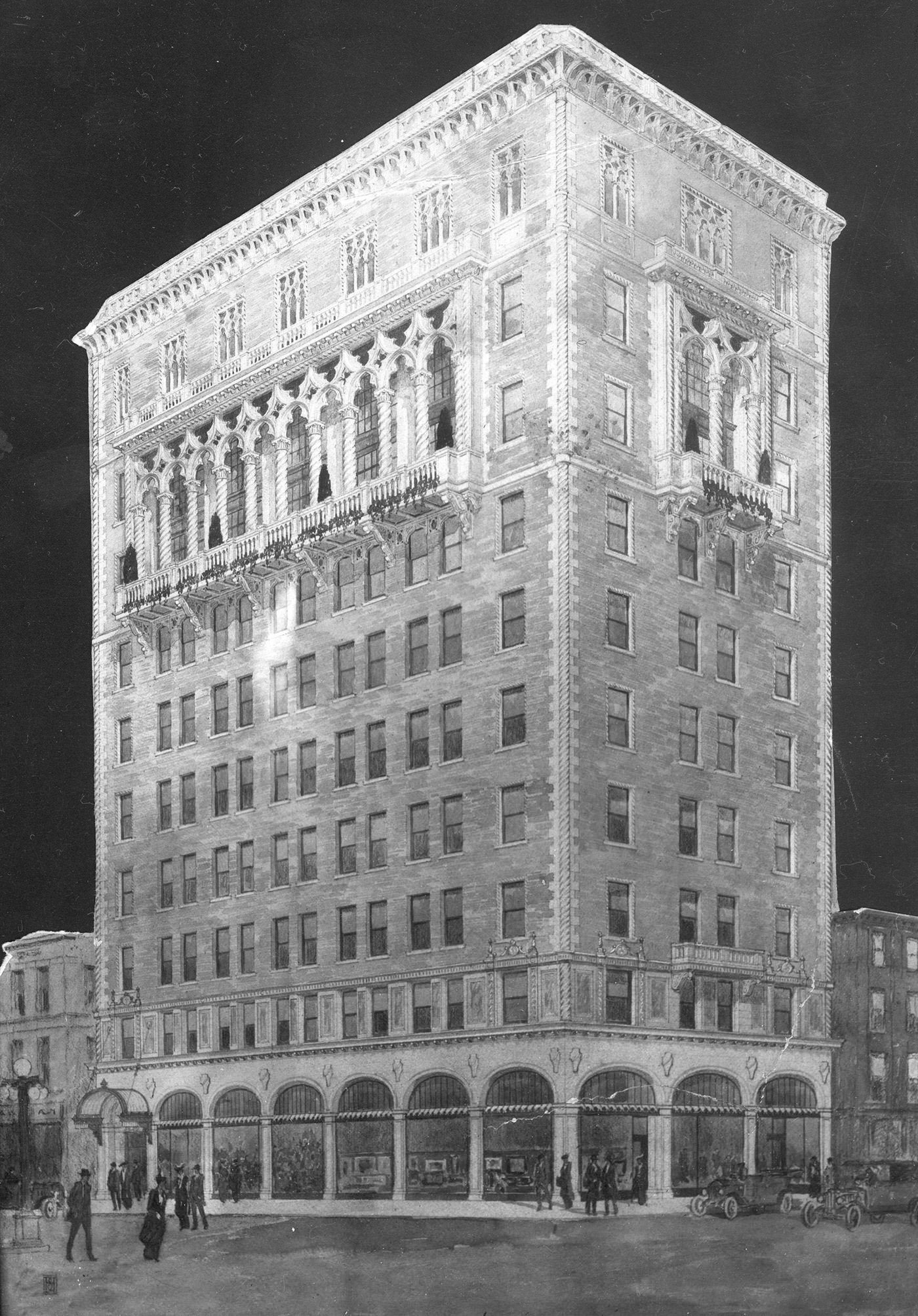

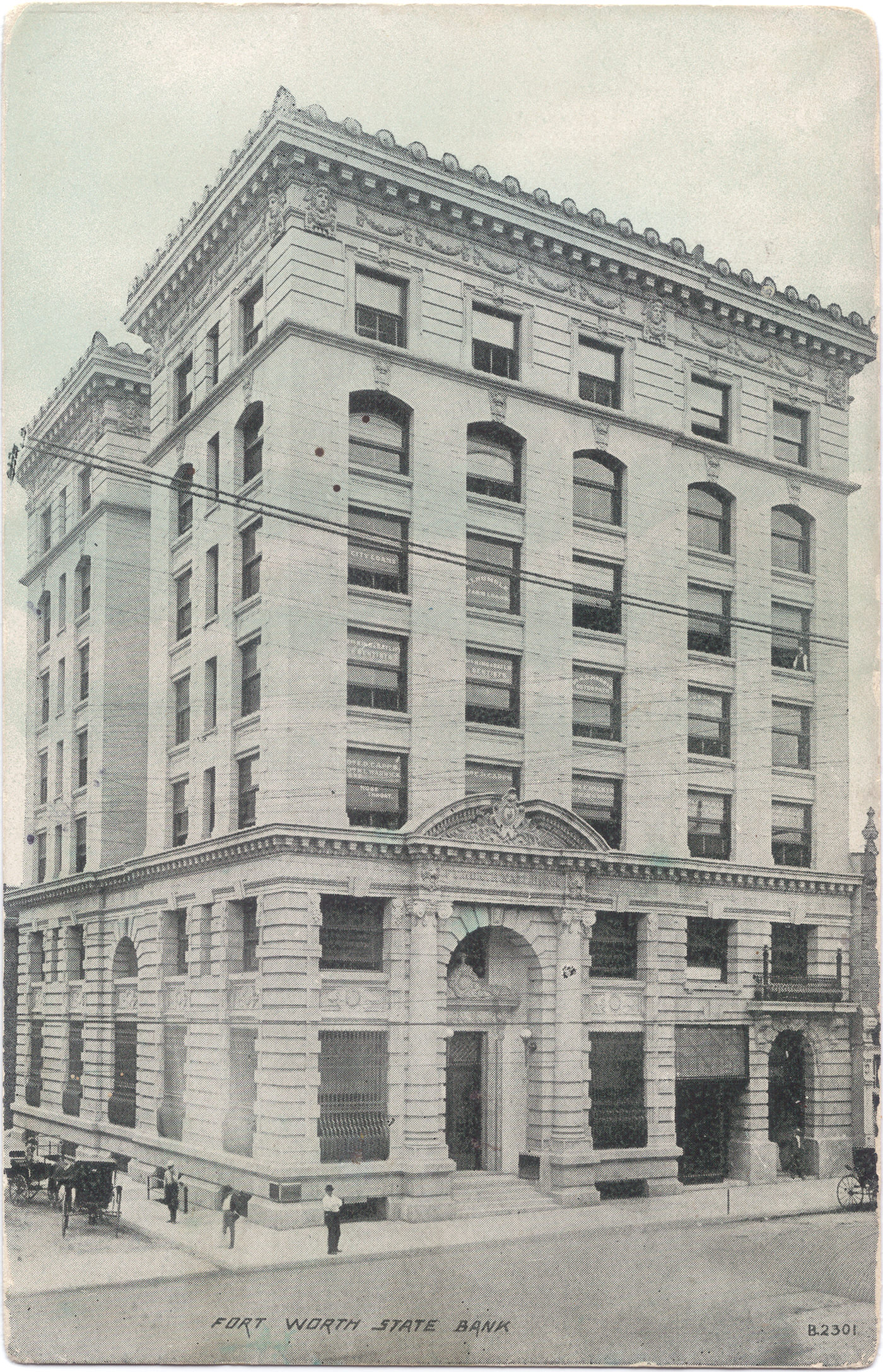

Though geographically distant, the impact on Fort Worth was immediate and electric. The city’s long-standing role as the commercial and transportation gateway to West Texas, reinforced by its extensive railroad network, positioned it perfectly to become the operational and financial hub for the burgeoning oilfields. Almost overnight, the lobbies and bars of Fort Worth hotels, like the Westbrook, buzzed with the energy of wildcatters, lease speculators, oil company executives, and financiers striking deals.

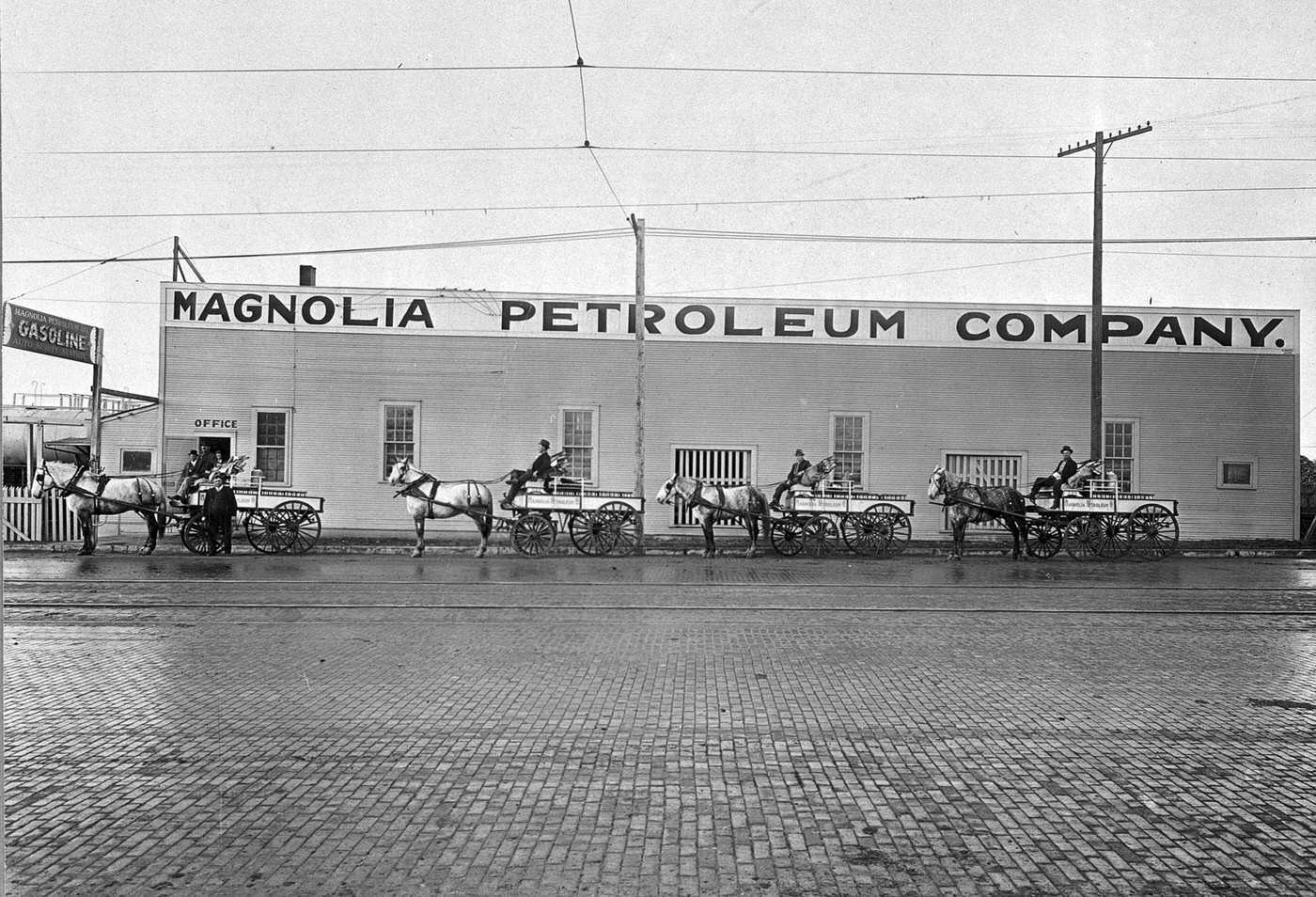

The city’s economy, already stimulated by wartime activity, received another powerful jolt. Fort Worth already possessed three oil refineries before the Ranger discovery; by the summer of 1920, five more would be built, with four others under construction, solidifying its role in processing the black gold flowing from the west. The Ranger discovery didn’t just bring business; it began to shift the city’s atmosphere and self-perception. While “Cowtown” remained a core part of its identity, the scent of oil money and the influx of a new breed of entrepreneurs began layering the identity of “Oil Town” on top. This nascent transformation, occurring simultaneously with the peak of the WWI military presence, added another powerful current to the forces reshaping Fort Worth at the close of the 1910s, setting the stage for further diversification and growth in the decades to come.

Image Credits: Jenkins Garrett Texas Postcard Collection, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Southwestern Mechanical Company Photograph Album, Texas Postcard Collection, Texas History Portal

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know