During the 1940s, Fort Worth played an important role in America’s efforts during World War II. The city became a center for aircraft production after the government built the Fort Worth Army Airfield, later known as Carswell Air Force Base. Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, which later became part of Lockheed, opened a plant near the airfield. Thousands of workers built B-24 Liberator bombers, which were used heavily in the war.

Fort Worth’s economy in the 1940s was a dynamic mix of old and new, with traditional industries reaching unprecedented peaks even as modern manufacturing surged forward, driven largely by the demands of World War II. Texas itself was largely agricultural, a sparsely populated state compared to eastern hubs, where many residents lacked cars or even radios. Yet, the decade would bring dramatic change, fueled by global conflict and industrial might, reshaping Fort Worth’s economy, skyline, and daily life. While the familiar sights and sounds of the Stockyards remained, new forces were rapidly taking hold.

Economic Engines: Cowtown Meets the War Machine

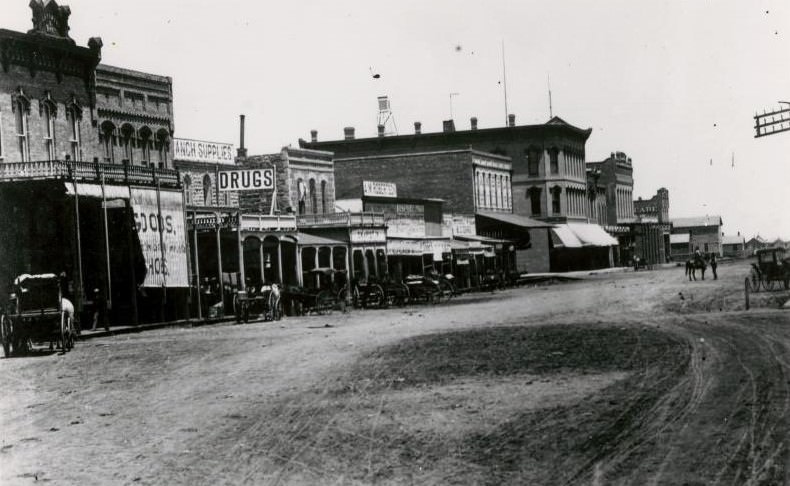

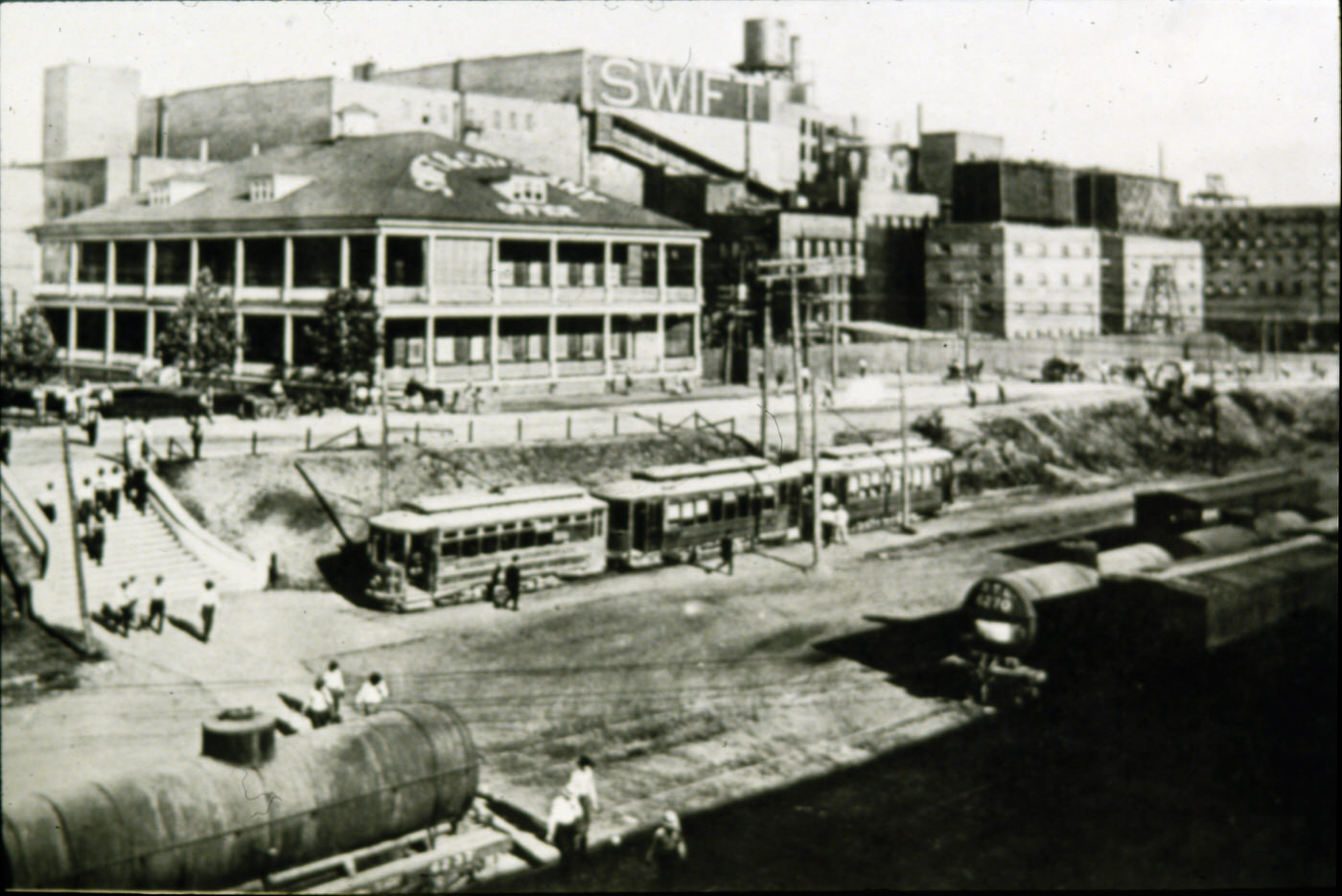

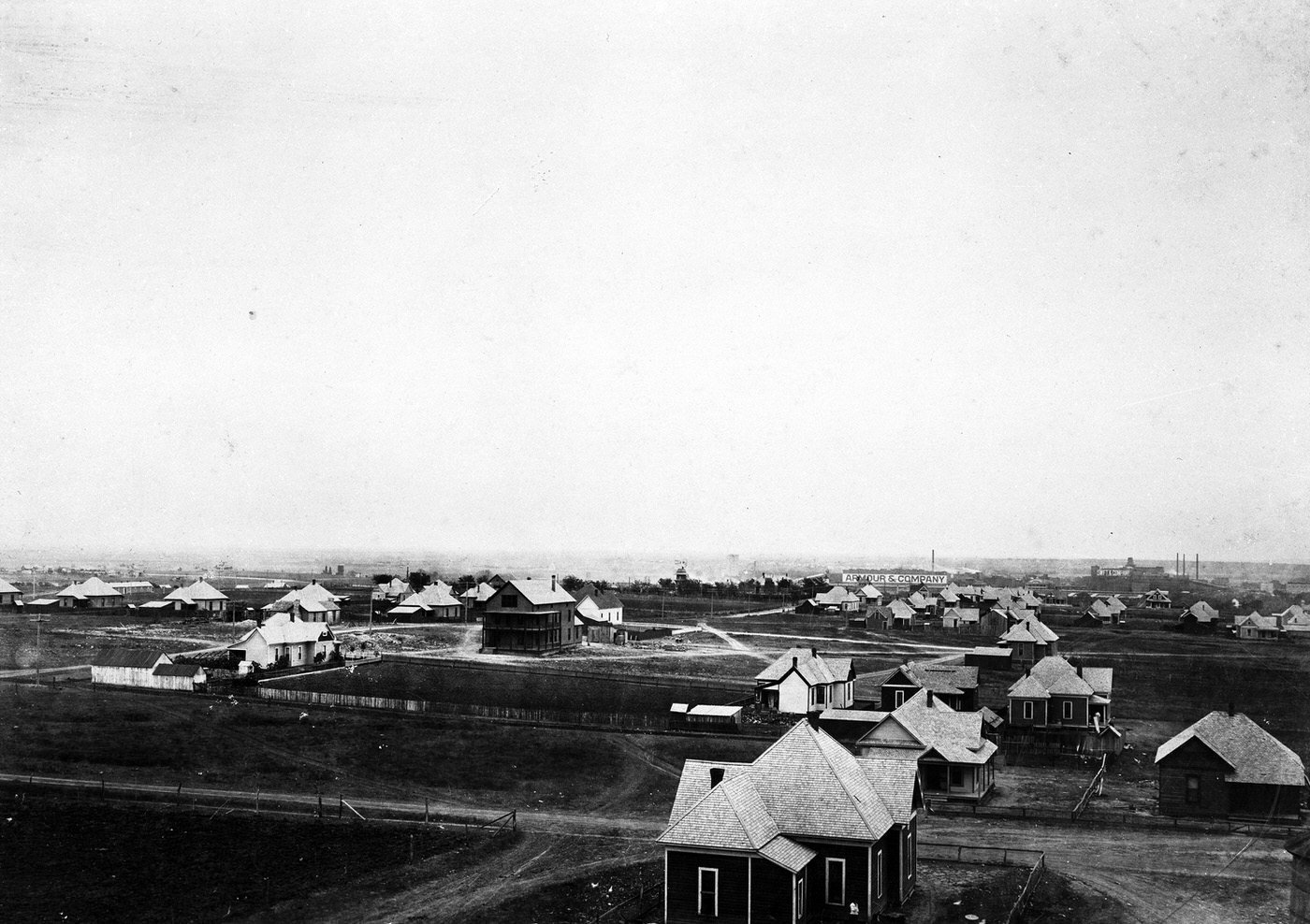

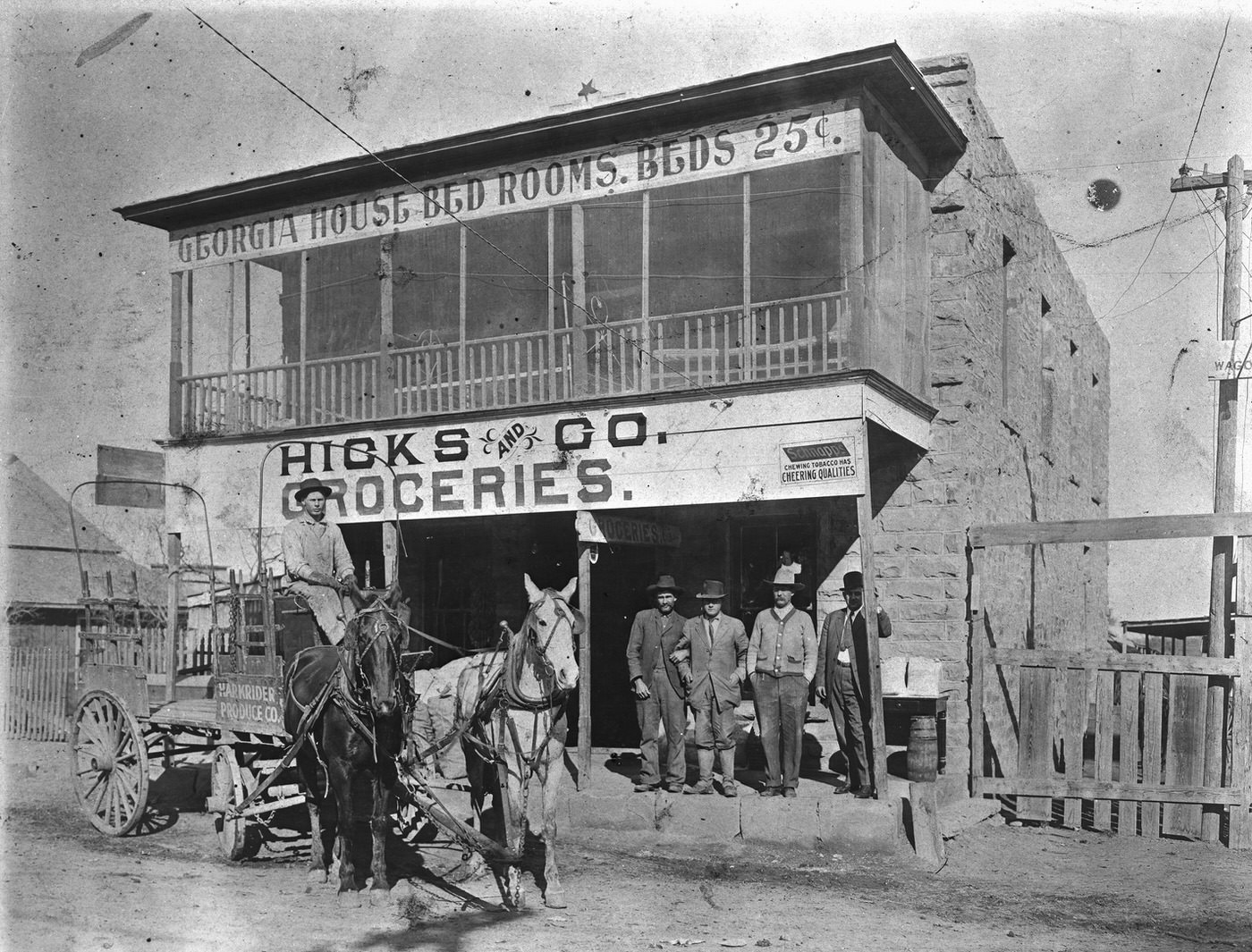

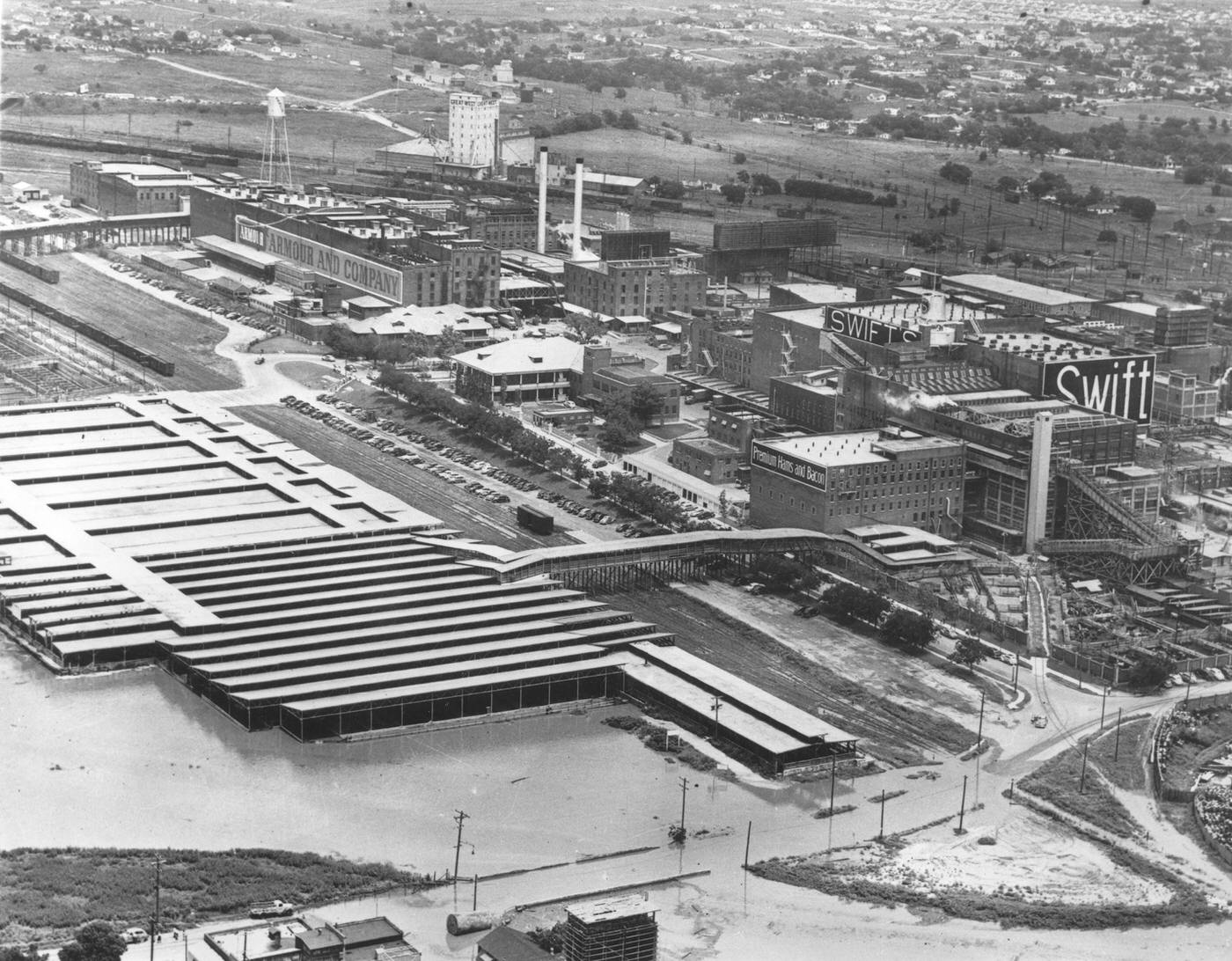

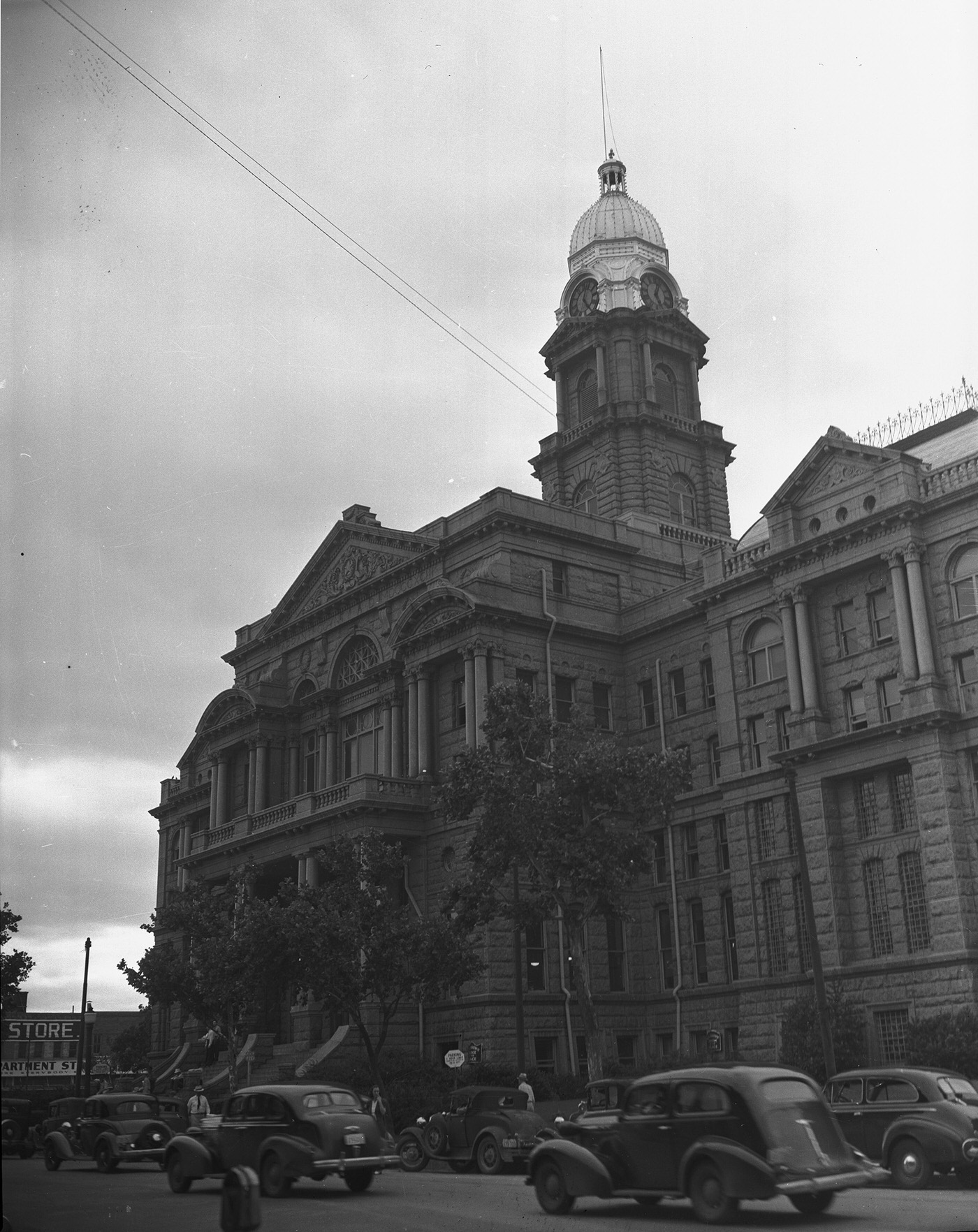

The Fort Worth Stockyards, the heart of “Cowtown,” continued to be a dominant force. The sprawling complex north of the Trinity River was a hive of activity, centered around the buying, selling, and processing of cattle, calves, hogs, sheep, and even horses and mules. The impressive Spanish-style Livestock Exchange Building, known as the “Wall Street of the West,” housed the numerous commission companies, telegraph offices, and railroad agents facilitating this massive trade.

World War II created an immense demand for meat, pushing the Stockyards to record levels. Fort Worth solidified its position as the nation’s largest sheep market, handling around two million head annually. The absolute peak of activity occurred in 1944, when the total number of animals processed surpassed 5.25 million – a record that would stand as the highest in the market’s history. During these peak years, forty-eight different commission companies, along with numerous speculators and traders, operated within the yards. Ownership also consolidated during this time; by 1944, United Stockyards Corporation had purchased all the stock of the Fort Worth Stock Yards Company, dissolving the original entity but continuing operations under the established name. Sometime during the 1940s, the name began to be commonly written as one word: Stockyards.

This wartime boom represented the zenith for the Stockyards’ volume. Even as millions of animals passed through the pens, the seeds of change were being sown. The rise of paved roads and the trucking industry after the war would eventually offer greater flexibility and lower costs than railroads, leading to a decentralization of the livestock market. While this shift occurred primarily post-war, the infrastructure enabling it was developing during the 1940s. The record numbers of 1944 masked an underlying transition, as another industry was simultaneously experiencing explosive growth and fundamentally altering Fort Worth’s economic landscape.

Aviation Takes Flight: The Bomber Plant

Before the war, Texas was known for pilot training but lacked significant aircraft manufacturing. Recognizing the coming need for military aircraft as war loomed in Europe and America emerged from the Great Depression, the U.S. War Department decided in 1940 that expanding existing facilities wasn’t enough; new defense plants were required. The Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce campaigned aggressively and successfully persuaded Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation (Convair) to build a major facility in the city.

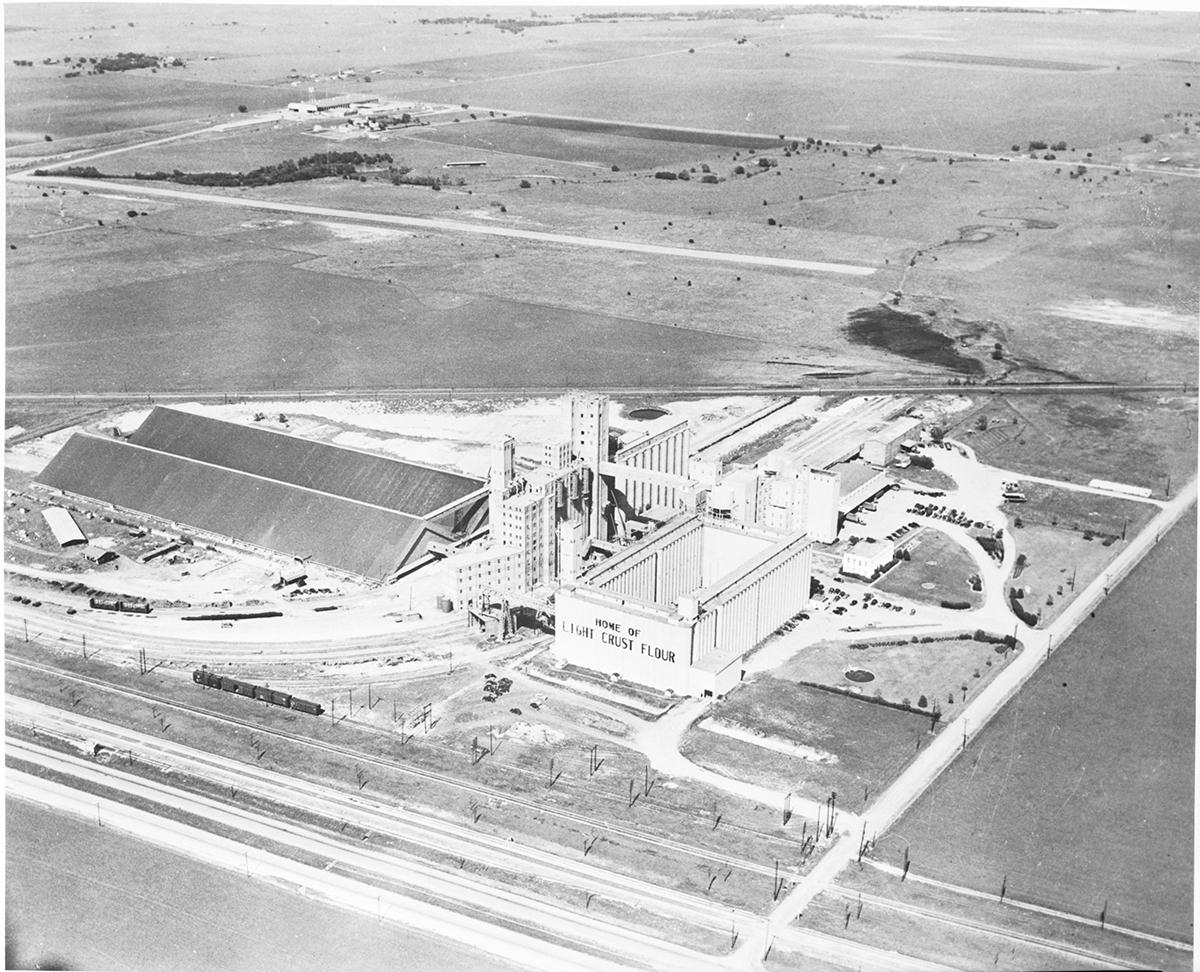

Groundbreaking for Convair Plant No. 4 took place on April 18, 1941. Built by the Austin Company of Cleveland, Ohio, the massive, mile-long factory was constructed with remarkable speed. Less than a year later, on April 17, 1942, the first B-24 Liberator heavy bomber rolled off the assembly line – 100 days ahead of schedule. This plant became a critical production center, manufacturing more than 3,000 B-24 bombers during the war. It also modified B-24 airframes to create C-87 Liberator Express cargo planes and, later in the war, produced a limited run of the new B-32 Dominator heavy bombers.

The plant’s impact on Fort Worth was immediate and immense. Peak wartime employment reached 32,000 people, with some estimates up to 38,000 workers, drawing individuals from Fort Worth and surrounding towns like Cleburne, Decatur, and Denton. This surge of industrial activity and employment quickly established aviation as Fort Worth’s largest industry during the 1940s, surpassing even the record-setting Stockyards in economic weight. The sheer scale and speed of the Bomber Plant’s development underscored the massive national mobilization for war and irrevocably added a modern industrial dimension to Fort Worth’s identity, establishing it as a vital center for national defense that would shape its economy for decades.

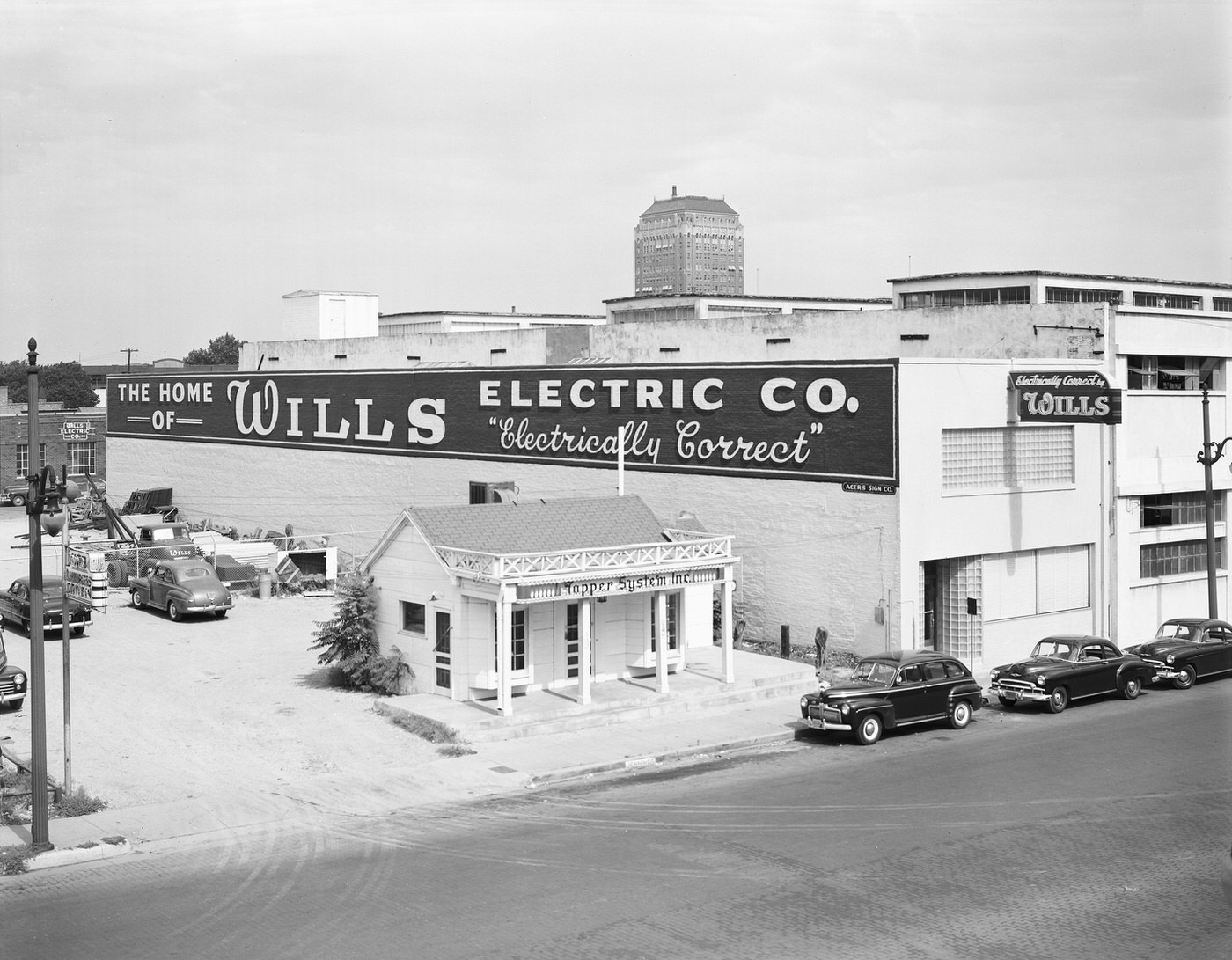

The Oil Industry

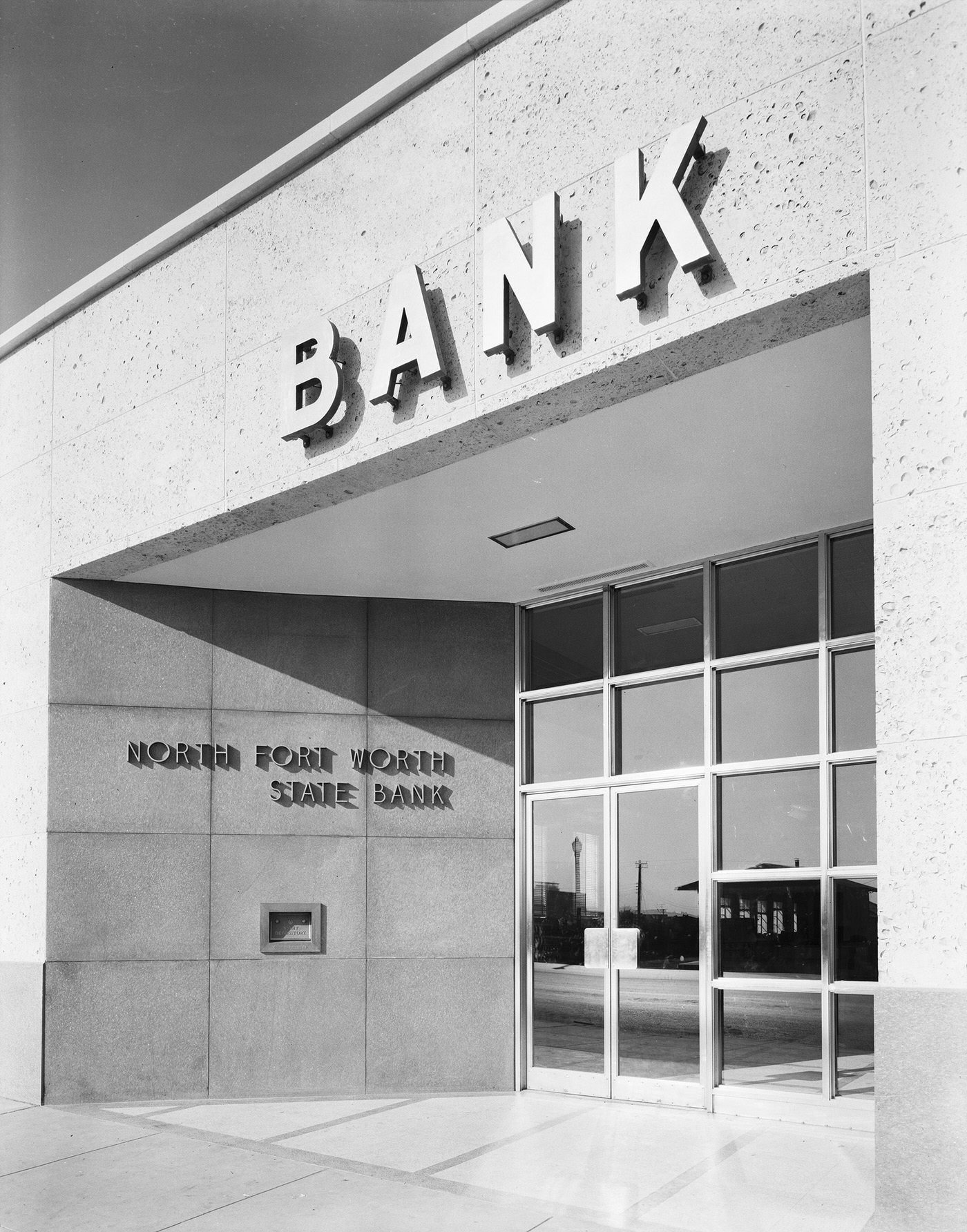

Fort Worth had been an administrative and refining center for the oil industry since the booms of the 1920s. While the 1940s didn’t see the kind of explosive growth experienced by aviation, the oil and gas sector remained a steady and significant part of the city’s economy. Major oil companies maintained offices in Fort Worth, and though the East Texas oil field’s dominance faded, the rise of West Texas and the Permian Basin kept the industry active locally.

One tangible sign of this continued presence was the operation of oil refineries. In 1941, Premier Oil Refining Company of Texas purchased the refinery previously operated by Transcontinental Oil and then Ohio Oil Company. Premier continued to operate this Fort Worth facility, one of seven refineries in the city around 1930, throughout the war years and until 1956. The original Transcontinental refinery, built in the 1920s, had processed 15,000 barrels of crude oil daily. Other related businesses thrived as well. The Fort Worth Machinery and Supply Company manufactured the well-regarded “Fort Worth Spudder,” a portable drilling machine popular across oil fields through the 1940s and 1950s. Additionally, the Texas Refinery Corporation kept its offices downtown. While the major growth spurt was in defense, the established oil industry provided crucial economic stability and diversification during the decade, contributing to the overall wartime prosperity.

The War’s Shadow: Fort Worth on the Home Front

World War II reshaped Fort Worth not just economically, but socially and physically, bringing military installations, rationing, and community-wide efforts to support the troops overseas.

The massive Convair Bomber Plant required an adjacent airfield. Initially designated Tarrant Field, construction began alongside the plant in 1941. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army’s plans shifted, and the airfield’s role expanded. In July 1942, Tarrant Field Airdrome was officially assigned to the Army Air Forces Flying Training Command.

The base quickly became one of the first schools dedicated to transitioning pilots and crews to the B-24 Liberator bombers being built next door. Over 4,000 students received B-24 training here. The training mission evolved with the factory’s output, later shifting to the B-32 Dominator and then, in 1945, to the B-29 Superfortress. This close link between production and training created a powerful military-industrial hub on the west side of Fort Worth.

The facility was officially named Fort Worth Army Air Field (FWAAF) in May 1943. The constant arrival and departure of trainees, instructors, and support staff brought thousands of military personnel into the city throughout the war years, adding to the bustling atmosphere and demand for local services and entertainment. In March 1946, the base was assigned to the newly formed Strategic Air Command (SAC), cementing its strategic importance in the post-war era. In January 1948, it was briefly renamed Griffiss Air Force Base, then quickly renamed again as Carswell Air Force Base in honor of Major Horace S. Carswell, Jr., a Fort Worth native, B-24 pilot, and Medal of Honor recipient.

The War’s Shadow: Fort Worth on the Home Front

World War II reshaped Fort Worth not just economically, but socially and physically, bringing military installations, rationing, and community-wide efforts to support the troops overseas.

The massive Convair Bomber Plant required an adjacent airfield. Initially designated Tarrant Field, construction began alongside the plant in 1941. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army’s plans shifted, and the airfield’s role expanded. In July 1942, Tarrant Field Airdrome was officially assigned to the Army Air Forces Flying Training Command.

The base quickly became one of the first schools dedicated to transitioning pilots and crews to the B-24 Liberator bombers being built next door. Over 4,000 students received B-24 training here. The training mission evolved with the factory’s output, later shifting to the B-32 Dominator and then, in 1945, to the B-29 Superfortress. This close link between production and training created a powerful military-industrial hub on the west side of Fort Worth.

The facility was officially named Fort Worth Army Air Field (FWAAF) in May 1943. The constant arrival and departure of trainees, instructors, and support staff brought thousands of military personnel into the city throughout the war years, adding to the bustling atmosphere and demand for local services and entertainment. In March 1946, the base was assigned to the newly formed Strategic Air Command (SAC), cementing its strategic importance in the post-war era. In January 1948, it was briefly renamed Griffiss Air Force Base, then quickly renamed again as Carswell Air Force Base in honor of Major Horace S. Carswell, Jr., a Fort Worth native, B-24 pilot, and Medal of Honor recipient.

The war effort consumed vast quantities of materials, leading to shortages on the home front. To ensure fair distribution and control inflation, the federal government, through the Office of Price Administration (OPA), implemented a strict rationing system in 1942. Fort Worth residents, like all Americans, received ration books filled with coupons or stamps. Purchasing essential goods required paying both the monetary cost and the correct number of ration stamps.

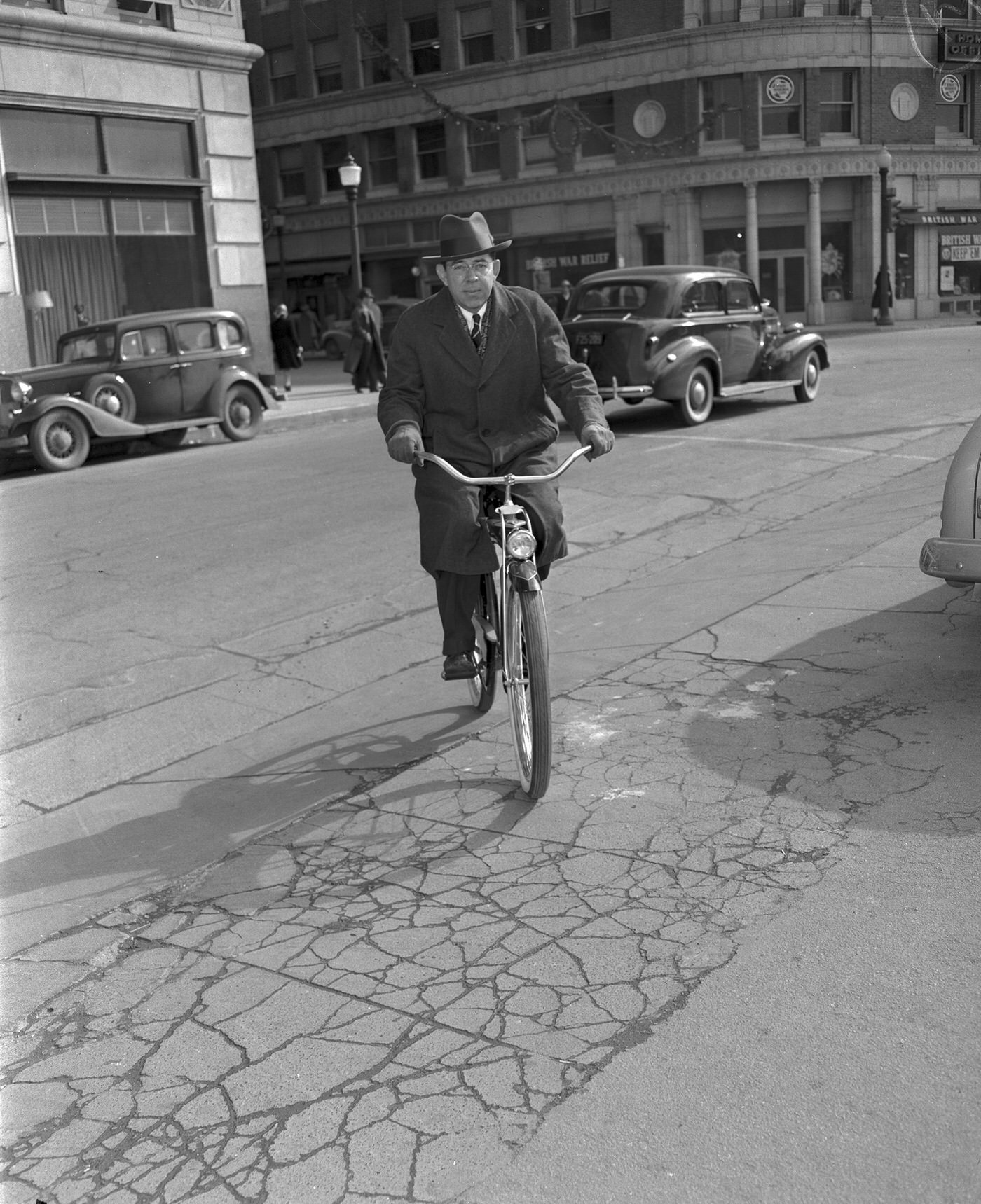

The list of rationed items was extensive and impacted daily life profoundly. Tires were the first item rationed (January 1942), followed quickly by automobiles. Gasoline was tightly controlled, with motorists needing specific cards and windshield stickers limiting purchases, often to just three gallons per week, drastically curtailing driving. Food staples like sugar (the first food rationed in May 1942 and the last item to remain under rationing until 1947), coffee, meat, cheese, butter, lard, margarine, canned goods, and dried fruits all required stamps. Other necessities like shoes, clothing (especially anything made with silk or nylon), fuel oil for heating, and even typewriters and bicycles were added to the ration list. Some consumer goods, such as new cars, refrigerators, and many metal toys, simply disappeared from stores as factories converted entirely to military production.

This system forced widespread adaptation. Families learned to make do, utilizing recipes that stretched or substituted rationed ingredients. People carpooled, rode bicycles more often, and mended clothing instead of buying new. Rationing fundamentally altered consumption habits and fostered resourcefulness throughout Fort Worth households.

Beyond individual adjustments, Fort Worth communities actively participated in collective efforts to support the war. War Bond drives were ubiquitous, heavily promoted through payroll deductions and campaigns urging citizens to invest “at least 10% of every paycheck”. Children collected savings stamps to trade for bonds, and rallies, sometimes featuring celebrities, encouraged purchases. Texas collectively raised over $3 billion through these drives.

The “Salvage for Victory” campaign mobilized citizens to recycle essential materials. Scrap metal drives became increasingly common, with communities, schools, and churches gathering tons of metal (Texas collected 1.5 million tons total), rubber, paper, and even kitchen fats.

Victory Gardens sprouted across the city – in backyards, school grounds, and community plots. Encouraged by the government to supplement the food supply and reduce the strain on commercial agriculture and transportation, home gardening became a widespread activity. It’s estimated that half of all American households grew a Victory Garden, and in Texas, these gardens produced a significant portion (around 40%) of the vegetables consumed during the war. These shared activities – buying bonds, collecting scrap, tending gardens – created tangible connections between the home front and the war effort, fostering a powerful sense of community spirit and shared purpose in Fort Worth.

Daily Life in Wartime Fort Worth

The massive influx of workers for the Convair plant and other industries, combined with military personnel, put significant pressure on Fort Worth’s housing stock. To address the acute shortage near the Bomber Plant, the government constructed Liberator Village in the White Settlement area. This large complex consisted of 1500 prefabricated dwelling units, ranging from barracks-style buildings to small houses, providing essential accommodation within walking distance of the plant for thousands of workers. Descriptions of living conditions vary, but the village served its purpose until it was closed in 1955.

Public housing initiatives from the late 1930s also came to fruition. Butler Place, a 250-unit project designed by prominent local architects like Wiley G. Clarkson and Wyatt C. Hedrick, opened in 1940 east of downtown specifically for Black families. Built on land cleared of dwellings deemed substandard, it offered units with modest rents (around $15.50-$16.75 monthly) and fostered a strong community, known for events like outdoor movie nights. In 1946, 32 additional units were built at Butler Place to house Black veterans and their families. Its counterpart, the 252-unit Ripley Arnold project for White families, was also completed during this period. The creation of these segregated housing projects reflected the prevailing racial policies of the era, embedding separation into the city’s development.

Established neighborhoods saw varied fortunes. Ryan Place, known for its stately homes on Elizabeth Boulevard, had suffered during the Great Depression, with construction halting. While it began a slow recovery after the war, the 1940s were likely a period of relative quiet for the neighborhood. Similarly, the historic Fairmount district, with its turn-of-the-century homes, was still a viable neighborhood but began a period of decline after the war as residents moved towards newer suburbs. Areas like Arlington Heights, developed around the WPA-funded high school built in the late 1930s, were established residential zones. Small incorporated towns like Westover Hills, established in 1939, functioned as early suburbs, reaching a population of 260 by the late 1940s. The decade thus saw contrasts: rapid, government-led housing construction driven by immediate needs alongside older neighborhoods experiencing slower transitions.

Fort Worth’s high schools were centers of student life and community identity. R. L. Paschal High School, the city’s oldest, carried a rich history and strong traditions. Under Principal O.D. Wyatt (who took over in 1940), the school initiated its homecoming game tradition and operated under an honor system without tardy bells. Paschal excelled in sports, winning state basketball championships in 1945 and 1949. Arlington Heights High School, housed in its impressive 1936 WPA building on a hilltop, maintained a famous rivalry with Paschal, considered the oldest in Texas. This rivalry often involved spirited (and sometimes paint-fueled) pranks between the student bodies. I. M. Terrell High School served the city’s Black students, located near the Butler Place housing project. Student activities included school newspapers, clubs like Paschal’s Outdoor Club, and intense focus on athletics, reflecting both typical teenage life and the social structures of 1940s Fort Worth.

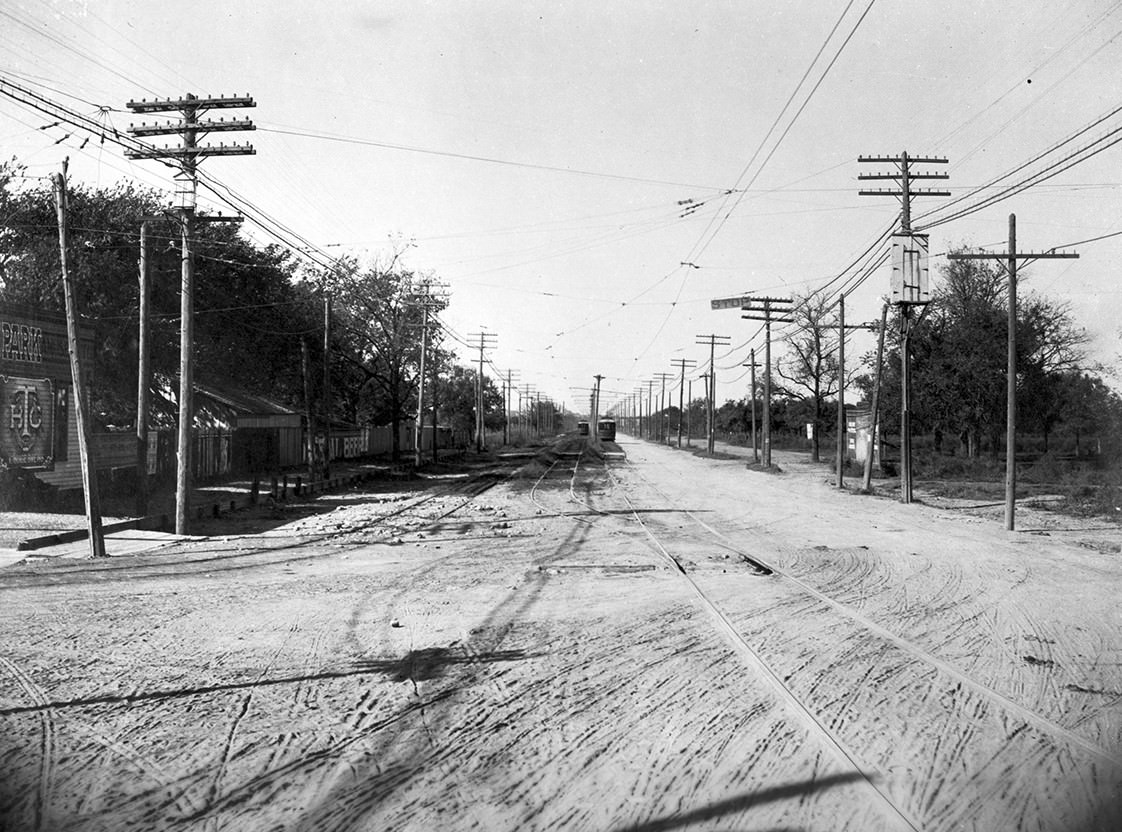

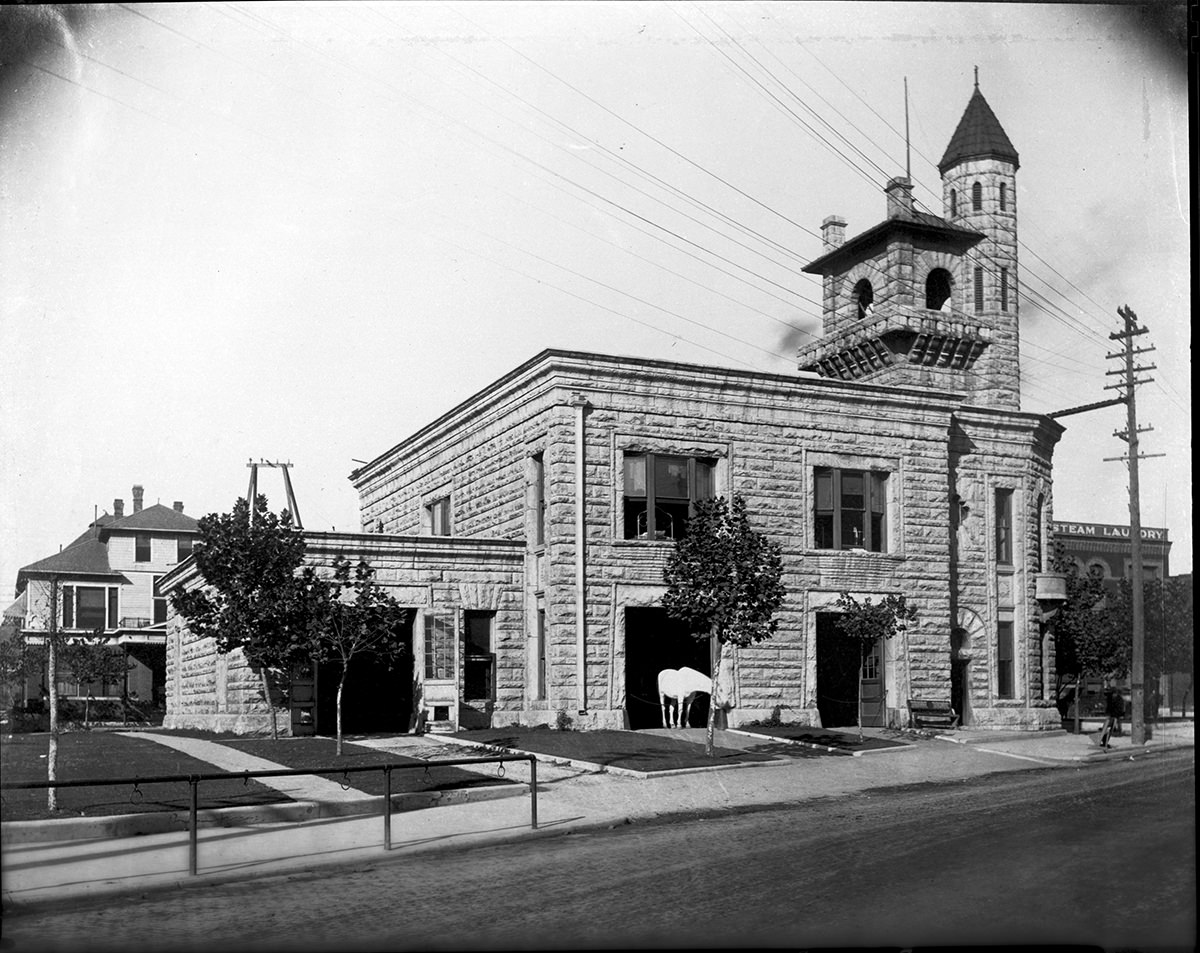

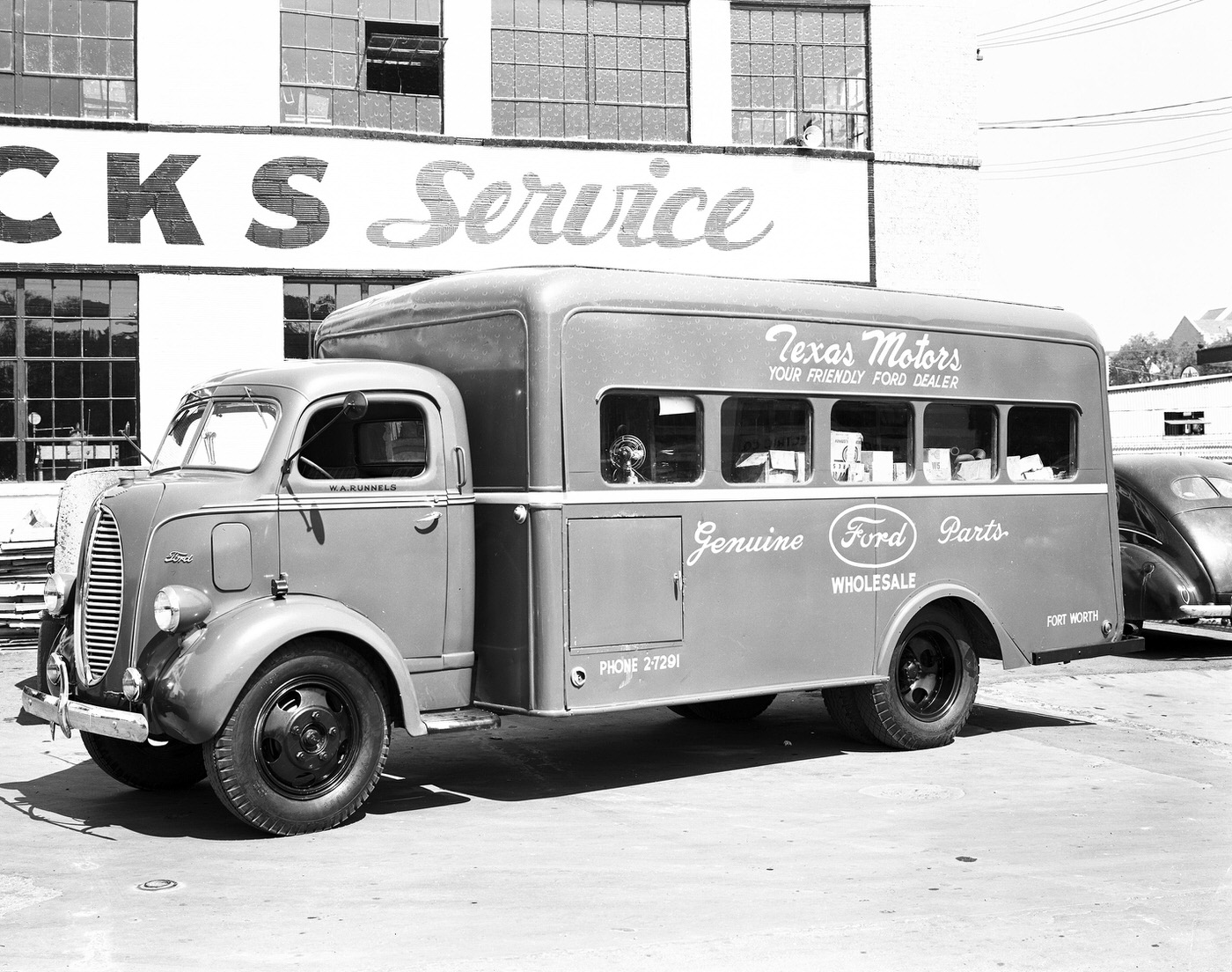

By the 1940s, the era of electric streetcars in Fort Worth had essentially ended. The Northern Texas Traction Company ceased operations around 1939, and the last interurban lines connecting Fort Worth to Dallas and other cities had stopped running earlier in the 1930s. While private automobiles were present, gasoline and tire rationing severely limited their use for many residents during the war years. Consequently, buses operated by the Fort Worth Transit Company became the primary mode of public transportation for many. Buses provided crucial service, connecting workers to major employment centers like the Convair plant and enabling students and shoppers to reach downtown destinations.

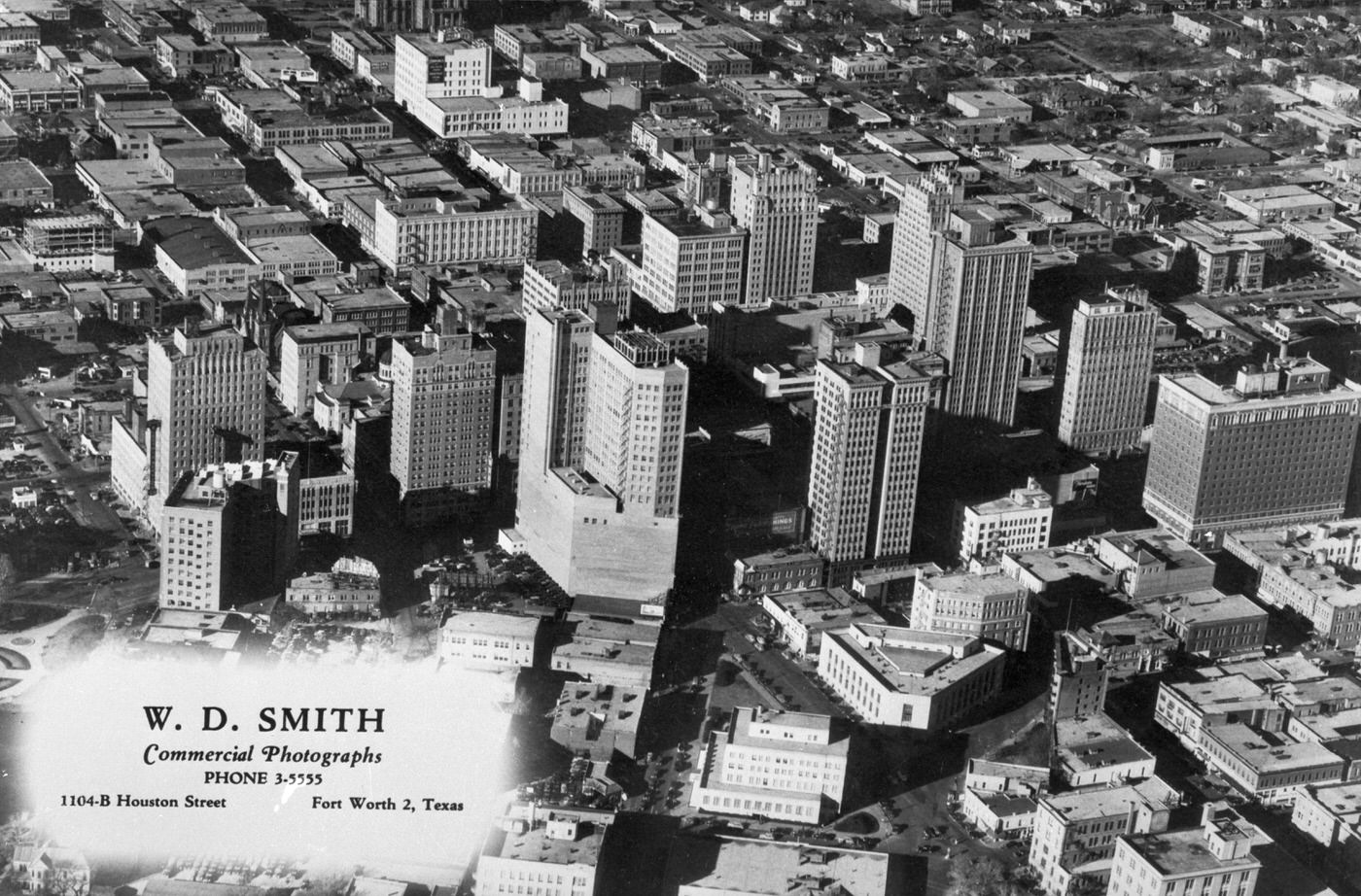

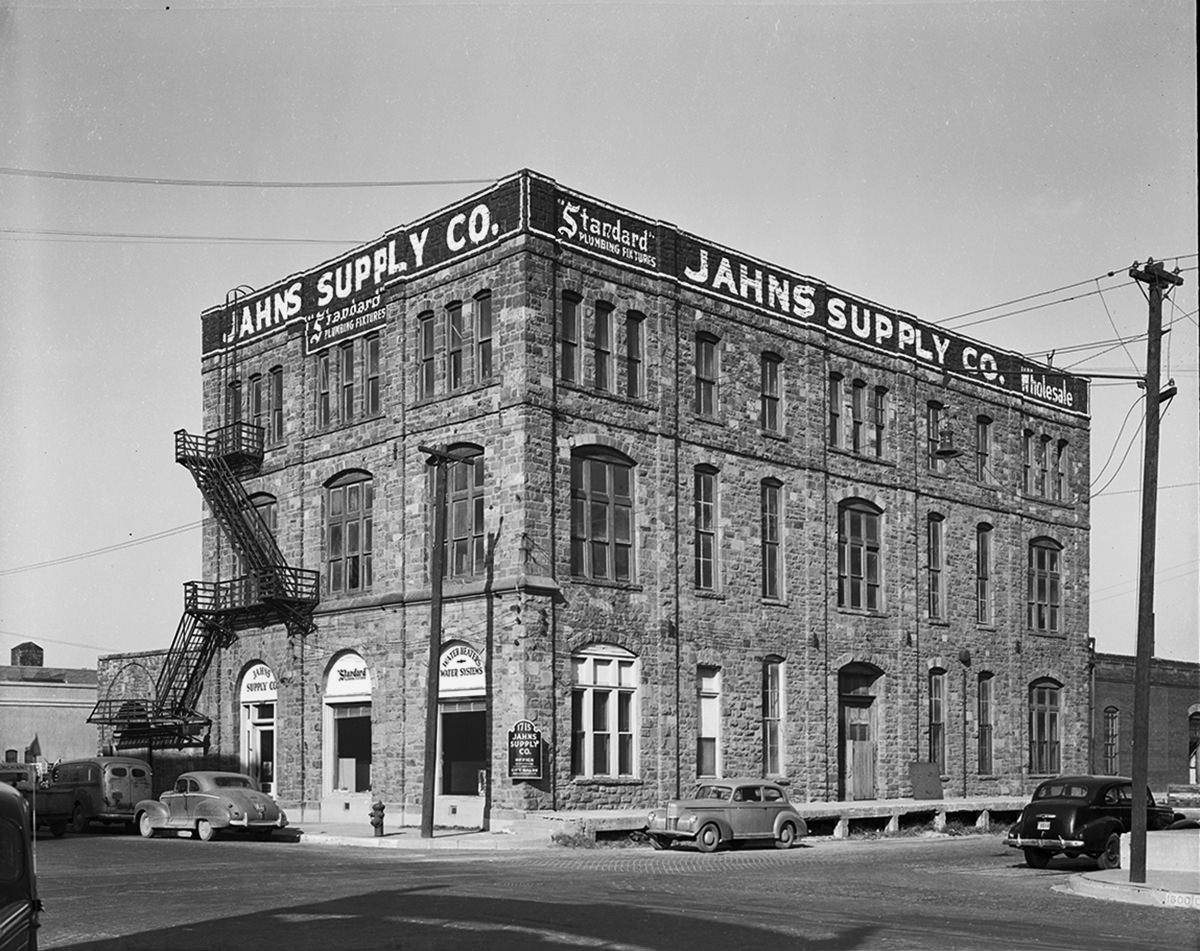

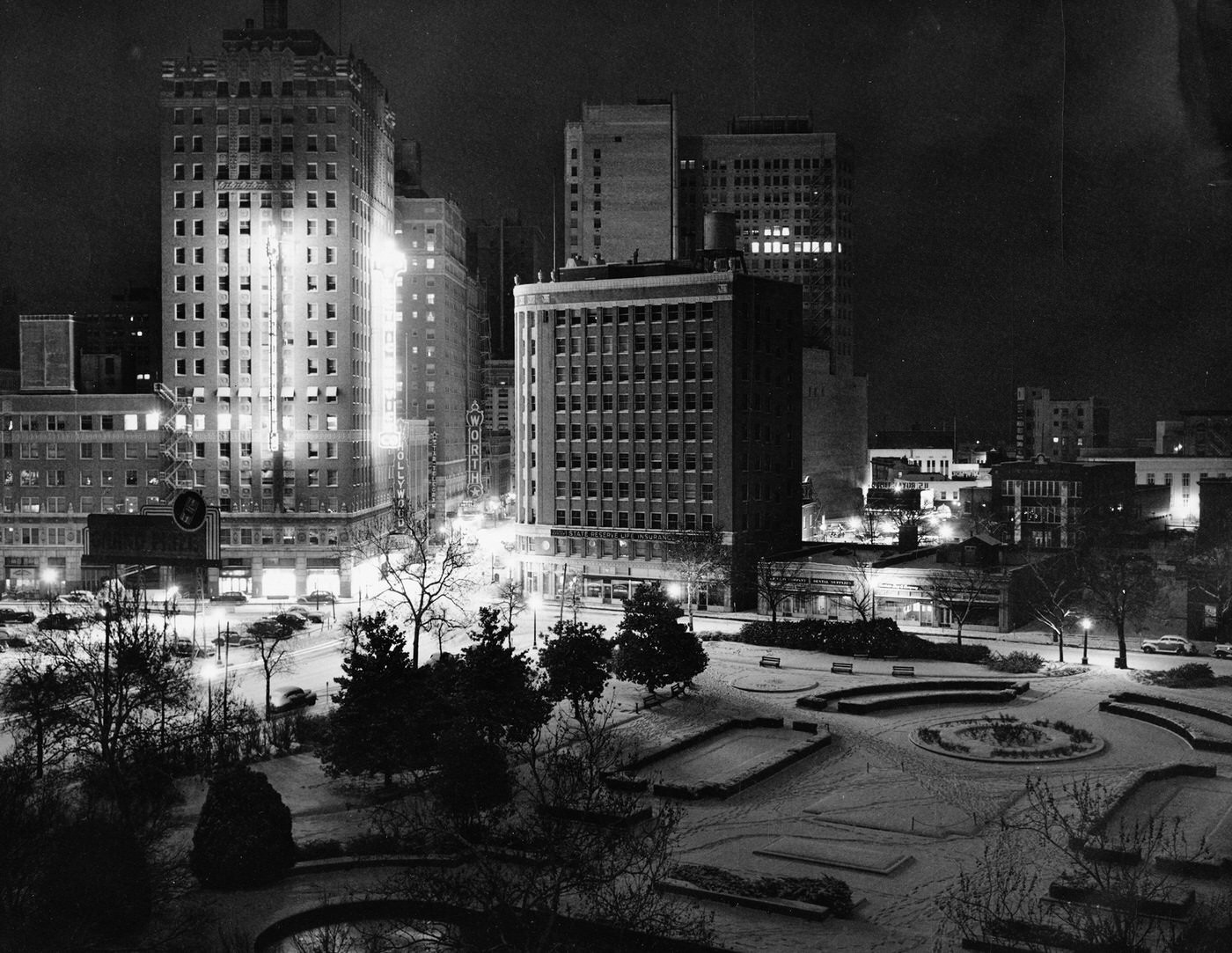

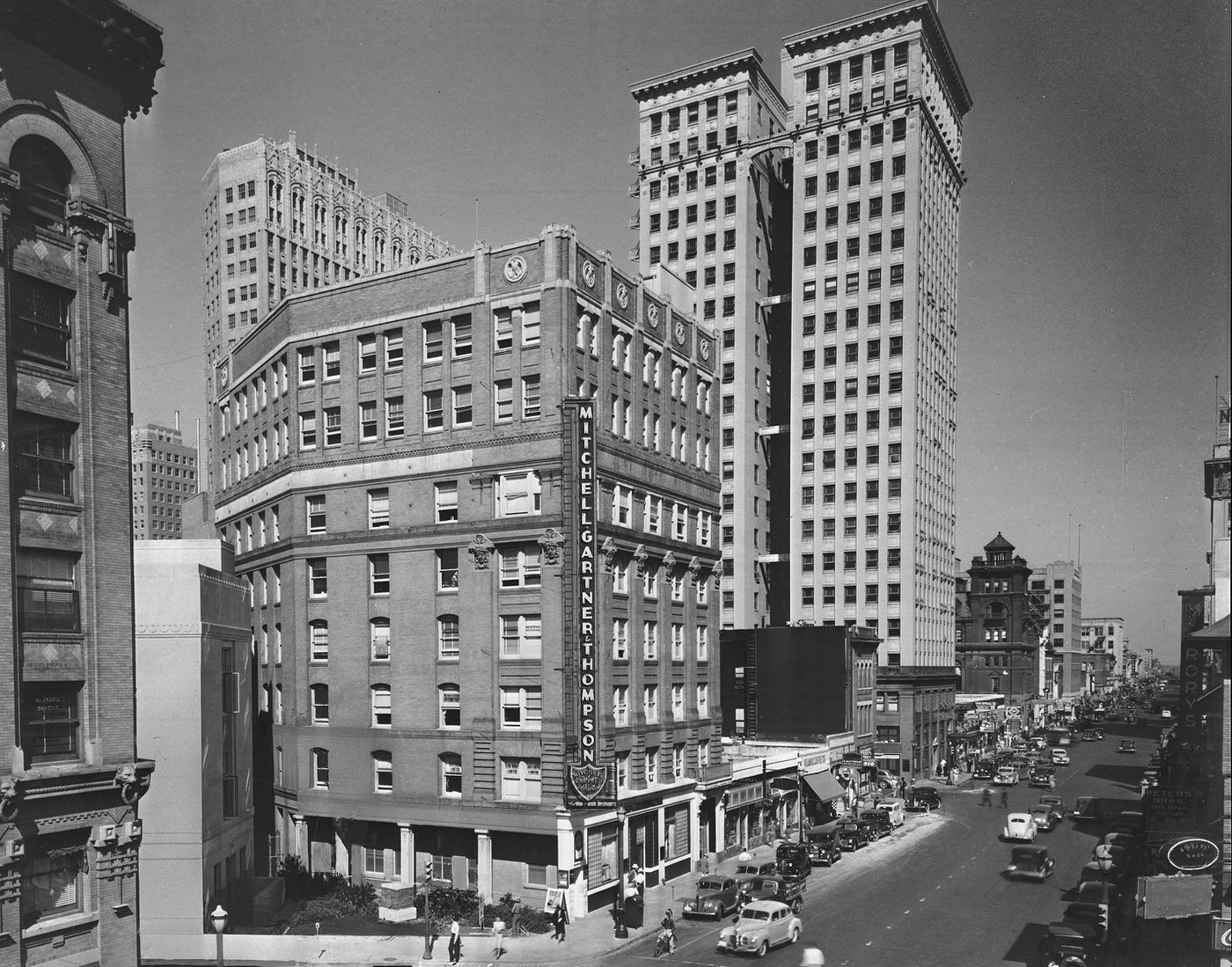

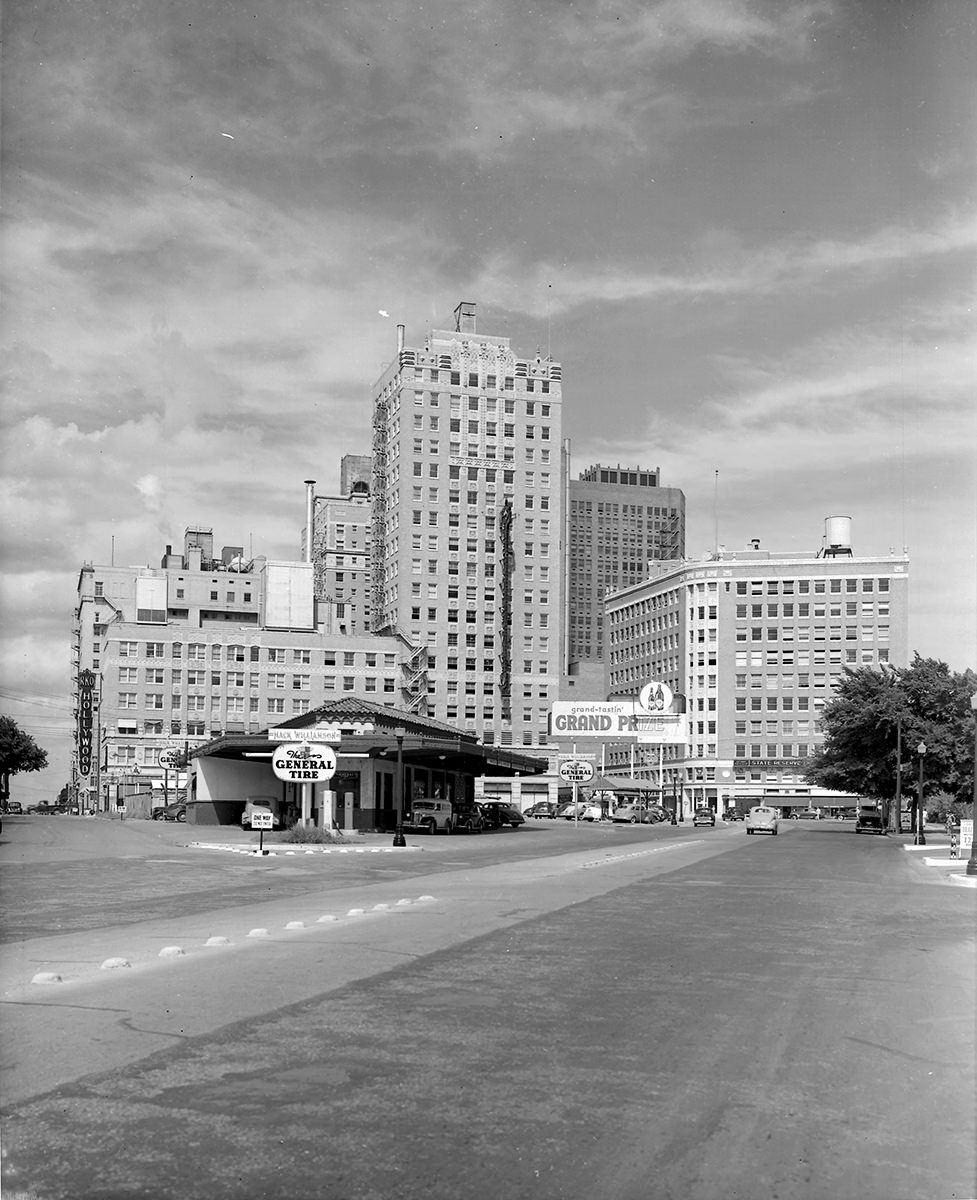

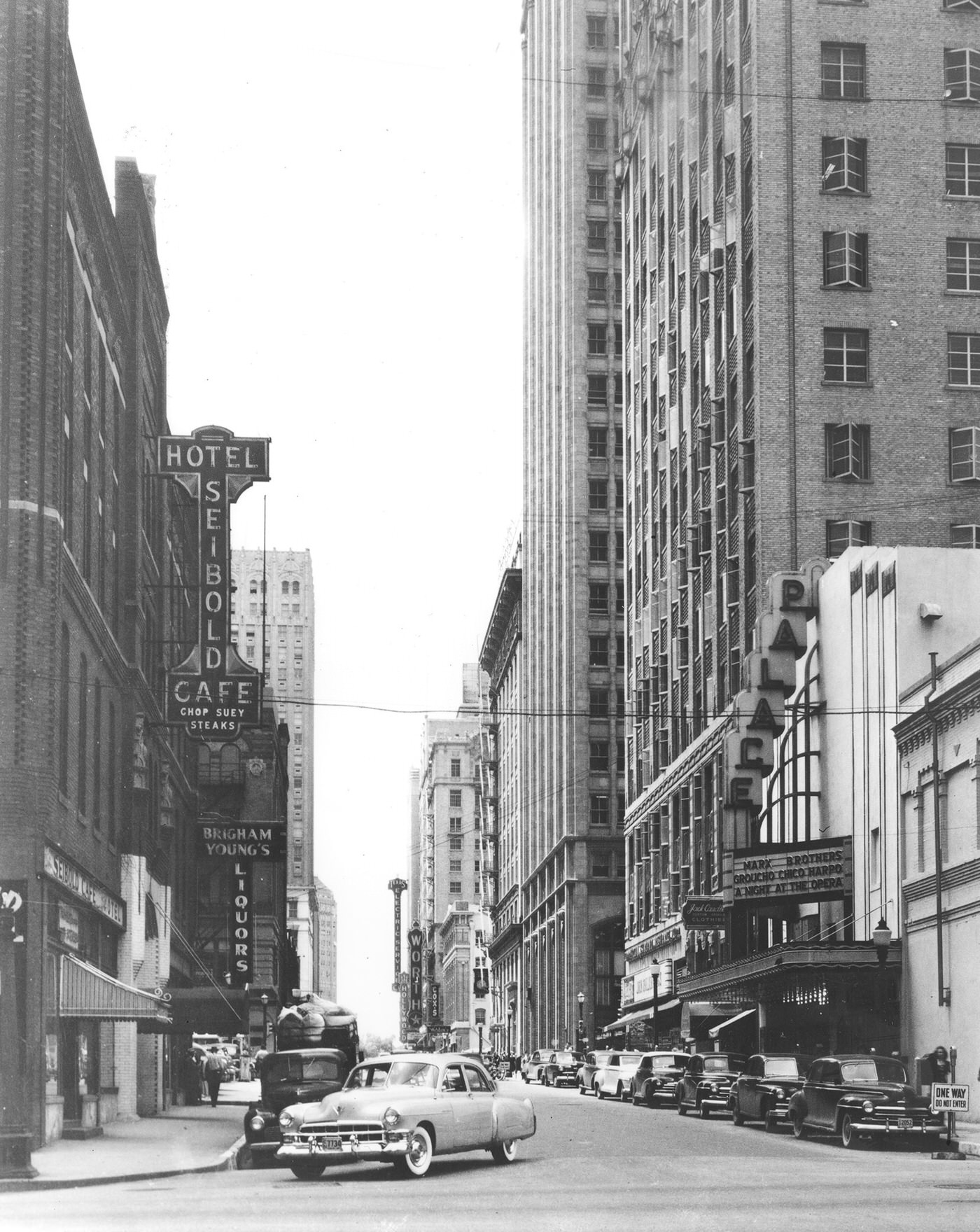

Despite the war and rationing, downtown Fort Worth remained the city’s vibrant commercial heart. Large department stores anchored the retail scene. Leonard Brothers, located at 200 Houston Street, was a dominant force, known for its wide range of products, low prices, and heavy advertising. They expanded significantly during the decade, adding furniture, appliances, and even a separate farm store. Their 1948 expansion across First Street, connected by a tunnel, famously introduced Fort Worth’s first escalator, drawing huge crowds. Stripling’s, located in the historic Powell Block at Main and Weatherford, was another major destination. Shoppers also frequented Monnig’s and The Fair department stores, along with numerous other businesses like Haltom’s Jewelers, Washer Bros. clothing, Wilson Furniture, the Famous Cafe, and Thompson’s Book Store, making downtown the undisputed center for shopping, banking, and services before the post-war rise of suburban malls.

Culture and Entertainment: Western Rhythms and City Lights

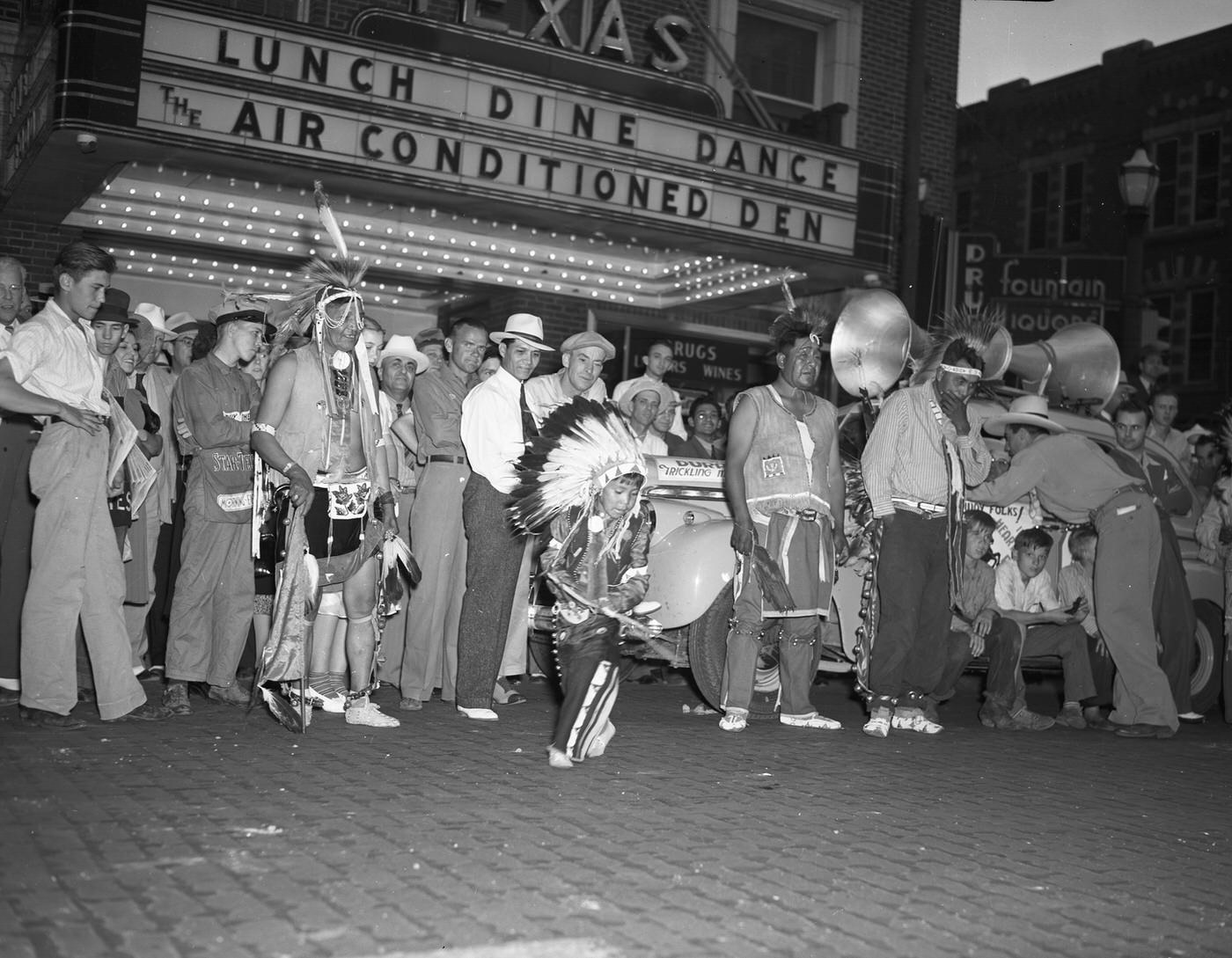

Fort Worth’s cultural scene in the 1940s offered diversions ranging from the homegrown sounds of Western Swing to the glamour of Hollywood movies and the emergence of a local modern art movement.

The unique musical blend known as Western Swing – a danceable mix of fiddle tunes, cowboy songs, jazz, blues, polka, and big band influences – had deep roots in Fort Worth. Venues like the Crystal Springs Dance Pavilion had been instrumental in the genre’s birth in the 1930s, featuring pioneers like Milton Brown and His Musical Brownies. While Brown tragically died in 1936, his former bandmate, Bob Wills, became the undisputed “King of Western Swing”. Although Wills and his Texas Playboys were based in Tulsa, Oklahoma, during their peak fame from 1934 to 1942, their music, characterized by Wills’s signature “Ah-ha!” holler, dominated radio waves and record sales throughout Texas and the Southwest during the 1940s. Wills even began making musical western films in 1940 and found immense success performing for huge crowds in California after his Army service in 1943. The infectious rhythm of Western Swing remained a defining sound for Fort Worth dance halls and social gatherings throughout the decade.

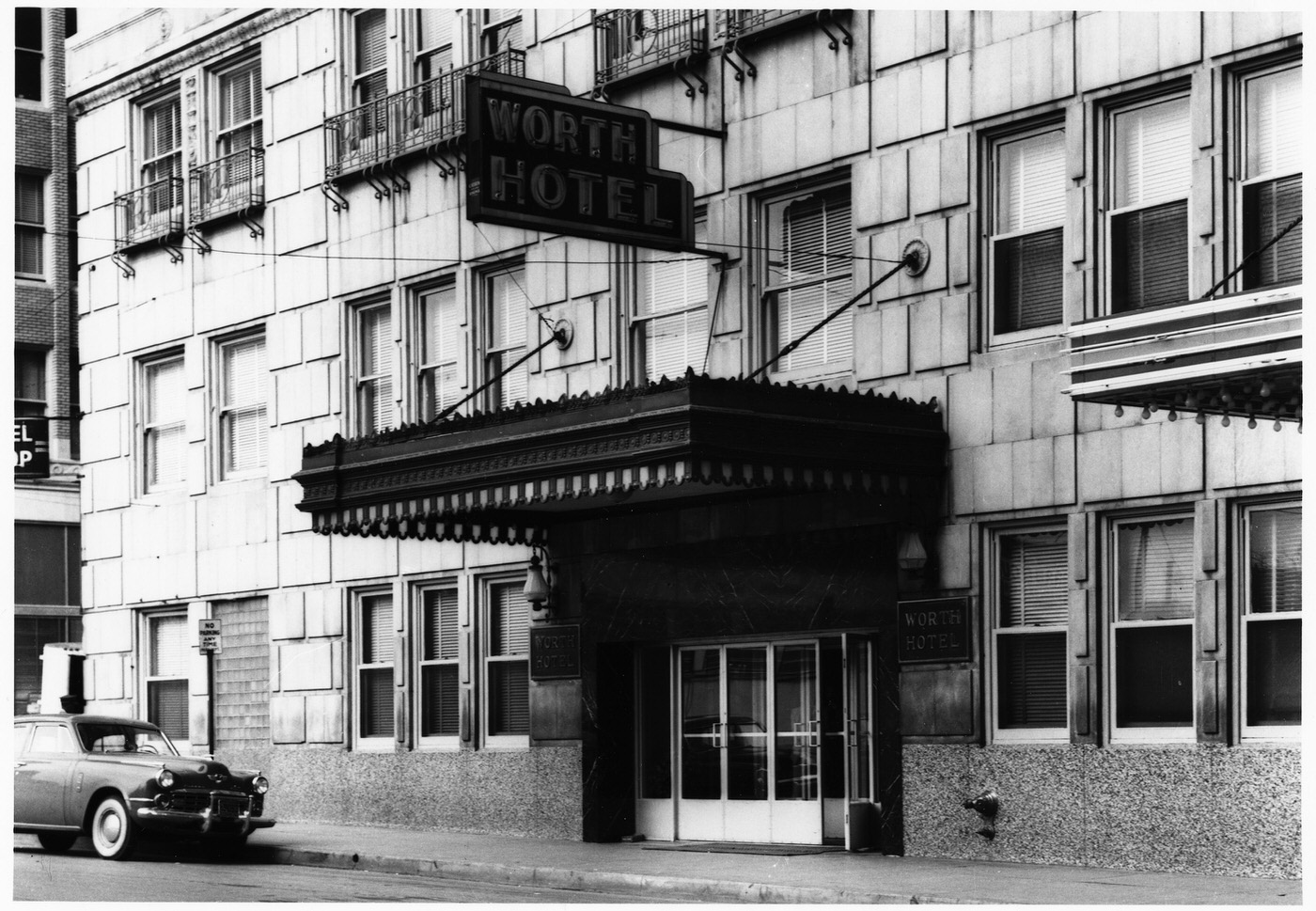

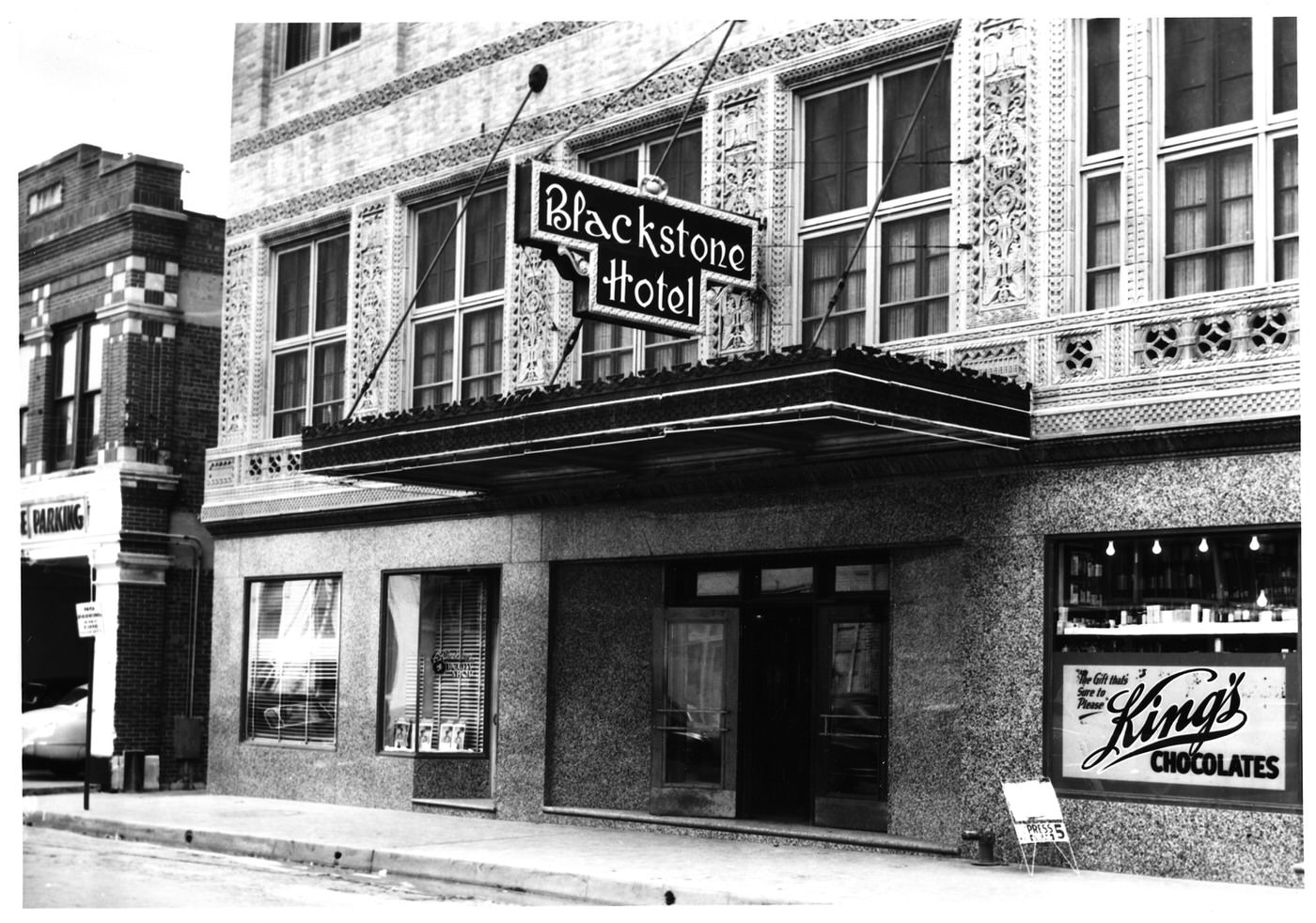

Going to the movies was a frequent and popular pastime for Fort Worth residents, offering an air-conditioned escape and a window to the world for just 10 or 25 cents. Downtown boasted several grand theaters. The Worth Theatre on West Seventh Street, operated by the Interstate Theatres chain, was a popular destination. The Hollywood Theater, an Art Deco gem designed by Wyatt C. Hedrick and opened in 1930 within the Electric Building, showed first-run features. In 1940, the Hollywood hosted the city’s first screening of “Gone With the Wind” and, together with the Worth Theatre, co-hosted the world premiere of the Gary Cooper film “The Westerner”. Other downtown options included the Palace Theatre and the Majestic Theatre, both likely part of the Interstate circuit. In the Stockyards area, the New Isis Theater, reopened in 1936, served local audiences, surviving a major flood in 1942 to continue showing films. Towards the end of the decade, the Ridglea Theater opened on Camp Bowie Boulevard in 1947.

Fort Worth offered a variety of dining options in the 1940s. Casual cafes and diners served locals and workers. Steve’s Cafe on Camp Bowie, known for ham sandwiches, operated until the late 1940s before becoming Duncan’s and later Finley’s Cafeteria. Sam Blair Cafe offered hearty meals like “Chicken In The Rough” (served without silverware) and filet mignon at affordable prices. Downtown spots included the Famous Cafe near Stripling’s, Anders Cafe (a popular pre-movie dinner spot), McCulloch Cafe (known for blue plate specials and pies), and the diner located within the T&P Station. Images from the era also capture the Canary Cafe and Jack Walton’s Barbecue. Cafeterias like the local chain Colonial Cafeteria were particularly popular with the generation that lived through the war, offering familiar fare.

Beyond movies and music, Fort Worth residents engaged in various leisure activities. A group of young, forward-thinking local artists known as the Fort Worth Circle emerged as a significant force in the city’s art scene during the 1940s. Rejecting the prevailing regionalist style, members like Bror Utter, Dickson and Flora Blanc Reeder, Veronica Helfensteller, Bill Bomar, and others explored modernism, surrealism, and abstraction, exhibiting their work locally and becoming influential figures in the arts community.

Landmarks and Developments

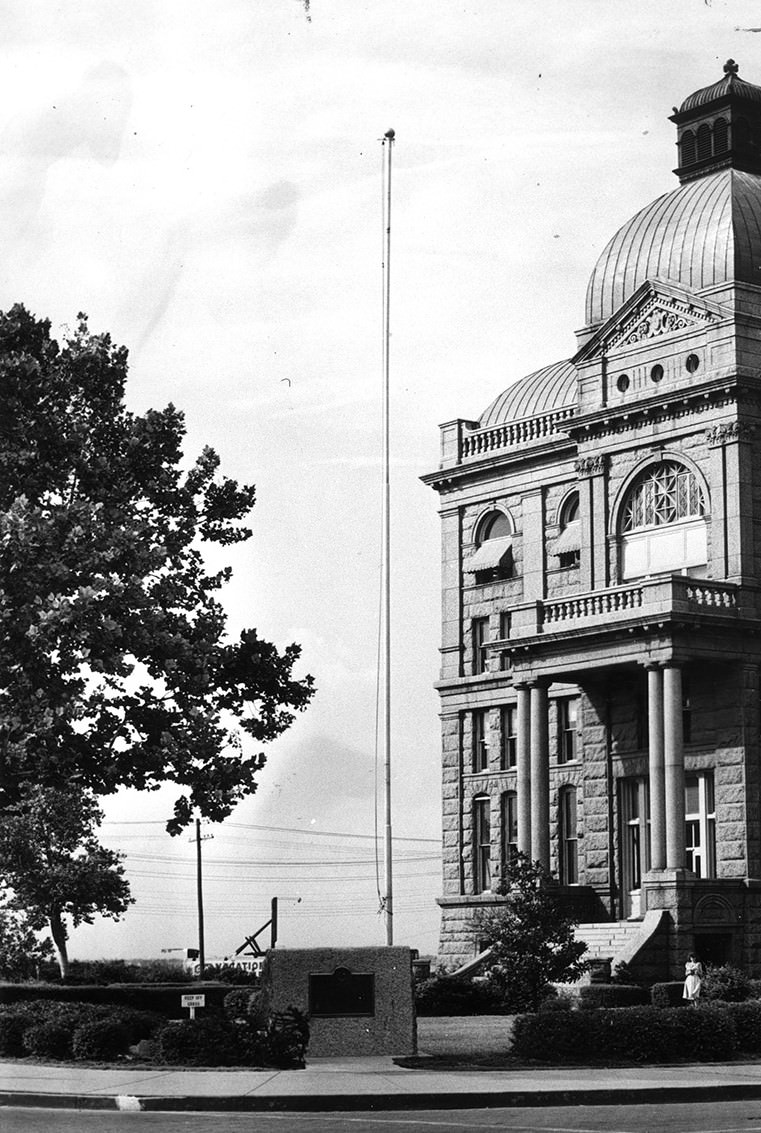

The 1940s saw Fort Worth’s landscape marked by both enduring landmarks and significant new developments, largely shaped by transportation needs and the war effort.

The Texas & Pacific Railway Terminal, opened in 1931, stood as a magnificent symbol of Fort Worth’s connection to the nation. Designed by Wyatt C. Hedrick in the striking Zigzag Moderne Art Deco style, the complex was more than just a station; it included an office tower and a large warehouse facility nearby. Its opulent main lobby, featuring marble floors, intricate metal-inlaid ceilings, and stylish nickel and brass fixtures, impressed travelers and residents alike. Throughout the 1940s, the T&P Terminal remained a vital hub, serving passengers from multiple major railroads, including the T&P itself, the CB&Q system (through its subsidiaries), Missouri Pacific, Katy, and Frisco Lines. Famous named trains like the Louisiana Eagle regularly passed through its platforms, making it a key gateway to the city and region during the peak era of American passenger rail.

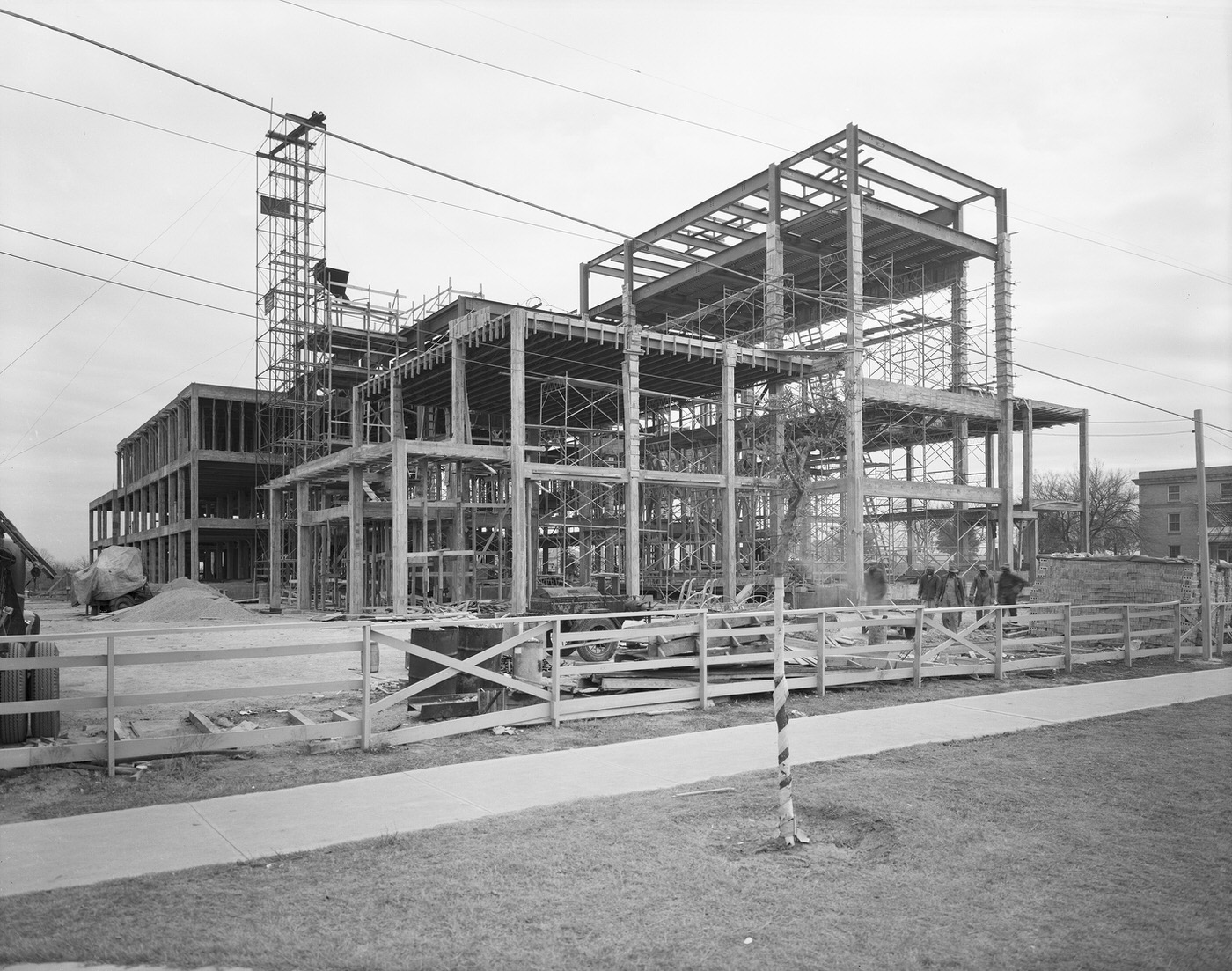

The decade’s most transformative construction projects were directly linked to the war. The mile-long Consolidated Vultee Plant No. 4 and the adjacent Fort Worth Army Air Field (later Carswell AFB) dramatically reshaped the city’s western edge and its economy. Housing projects like Liberator Village and Butler Place were built to accommodate the influx of workers and address pre-existing housing needs amplified by the war.

Existing landmarks continued to define the city. The Stockyards National Historic District, with its Livestock Exchange Building and Cowtown Coliseum, remained iconic. Downtown was characterized by significant structures like the T&P Terminal, the Electric Building housing the Hollywood Theater, and the large department store buildings of Leonard’s and Stripling’s. The Fort Worth Botanic Garden, with its established Rose Garden and Rock Springs features, offered natural beauty within the city.

Road infrastructure saw some development, though large-scale construction was largely deferred due to wartime material and labor shortages. Work focused primarily on highways deemed essential for defense under the Defense Highway Act of 1941. Improvements to existing routes like US Highway 80 (State Highway 1) continued to influence where industries chose to locate. The major push for highway expansion, including Farm-to-Market roads funded by the 1949 Colson-Briscoe Act and the planning for the interstate system, would occur in the post-war years, but the groundwork was laid during the 1940s. The war effort was undeniably the primary driver of large-scale physical changes in Fort Worth during this decade.

Image Credits: Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Basil Clemons Photograph Collection, Jan Jones Papers, Jenkins Garrett Texas Postcard Collection, UTA Libraries, Texas History Portal, Jack White Photograph Collection, wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know