As the 1980s dawned, Fort Worth stood as one of Texas’s five largest cities, a position earned through decades of growth following World War II. This expansion was driven by key industries like national defense and aviation, alongside a growing manufacturing sector and the development of major highways. The city’s population had surged in the post-war years, nearly doubling between 1946 and 1960. While the pace slowed slightly in the 1970s, Fort Worth entered the new decade as a significant urban center, attracting workers to its robust job market.

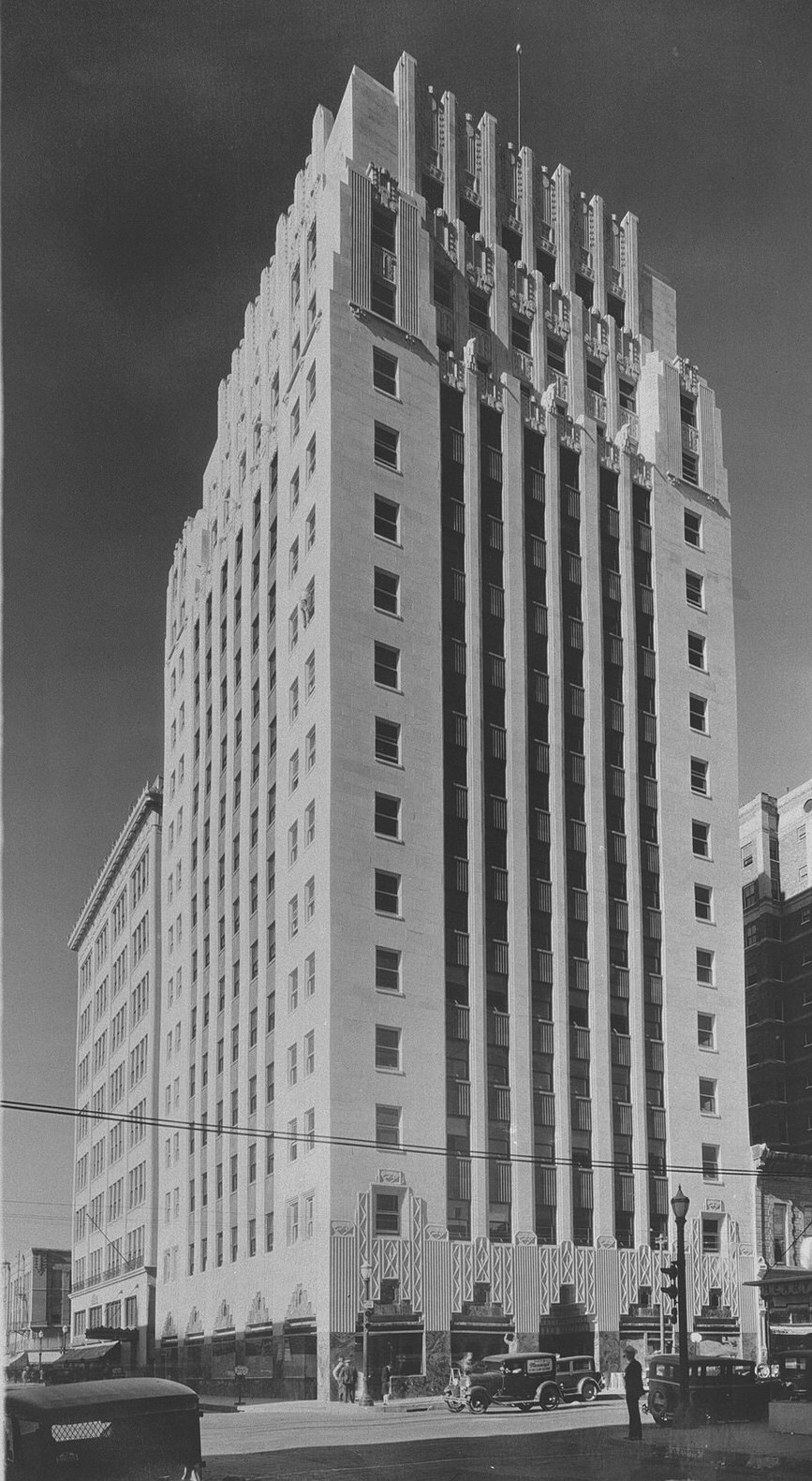

The economic foundation seemed solid. Defense and aviation industries, long established, served as anchors. Manufacturing had diversified considerably; the number of plants grew from 601 in 1948 to 937 by 1963, employing over 94,000 people by 1971. Even as the old meatpacking giants Armour and Swift closed their doors in the 60s and 70s, other industries filled the gap. The oil industry also maintained a strong presence, with companies like Western Company of North America and Texas Refinery Corporation having offices downtown, benefiting from the high oil prices of the 1970s. Major employers like General Dynamics and Bell Helicopter were pillars of the local economy, providing thousands of jobs.

However, beneath the surface, changes were underway. Decades of suburban growth, fueled by new highways, had transformed surrounding farmlands into housing tracts and strip malls. This outward migration, common across America, began to affect the downtown core, which faced challenges from vacant buildings and a decline in activity. While the city had expanded its physical footprint through annexation, covering 100 square miles by 1949 and continuing to grow , the central business district was showing signs of needing revitalization. Fort Worth entered the 80s with apparent economic strength, but its reliance on industries like oil and defense, coupled with the early effects of suburban drain, set the stage for a decade of significant challenges and transformations.

Riding the Economic Rollercoaster

The early 1980s saw Texas riding high on an oil boom. Prices peaked around $40 per barrel in 1983, fueling investment and a sense of prosperity across the state, including Fort Worth. Money flowed freely, financing drilling operations, real estate development, and lavish spending. But the boom was short-lived.

By the mid-1980s, a combination of factors – including global oil surpluses, reduced demand due to energy conservation efforts, and shifting OPEC policies – caused oil prices to collapse dramatically. Prices plummeted to as low as $9 per barrel between 1985 and 1986. This triggered a severe recession across Texas, hitting the state hard even as the rest of the U.S. economy began to recover. Banks called in loans made during the boom years, leading to widespread financial distress. The state government eventually created the Economic Stabilization Fund, or “Rainy Day Fund,” largely in response to this energy price slump.

Fort Worth felt the impact acutely. The energy company owned by Eddie Chiles, a prominent Fort Worth oilman and owner of the Texas Rangers baseball team, declared bankruptcy. The downturn rippled through the local economy, affecting banking and real estate. Statewide, hundreds of thousands of jobs were lost, particularly in oil production and construction. This difficult period pushed Texas, and Fort Worth within it, to accelerate economic diversification, shifting employment towards the service sector, including professional, scientific, and technical fields.

Despite the oil bust’s severity, Fort Worth’s economy had other pillars. The defense and aviation industries remained critically important throughout the decade. General Dynamics, building the vital F-16 fighter jet, and Bell Helicopter Textron, a major helicopter manufacturer, were significant employers. In the late 1970s and early 80s, General Dynamics employed close to 14,000 people, while Bell employed around 8,700. These companies pumped millions into the local economy through payrolls and subcontracts with local businesses. While not entirely immune to fluctuations, particularly cuts in defense spending that also occurred during the 80s , this large aerospace presence provided a crucial buffer against the worst effects of the oil crash, distinguishing Fort Worth from cities solely dependent on energy. The decade’s economic hardship underscored the need for a broader economic base, a process already underway but accelerated by the oil bust.

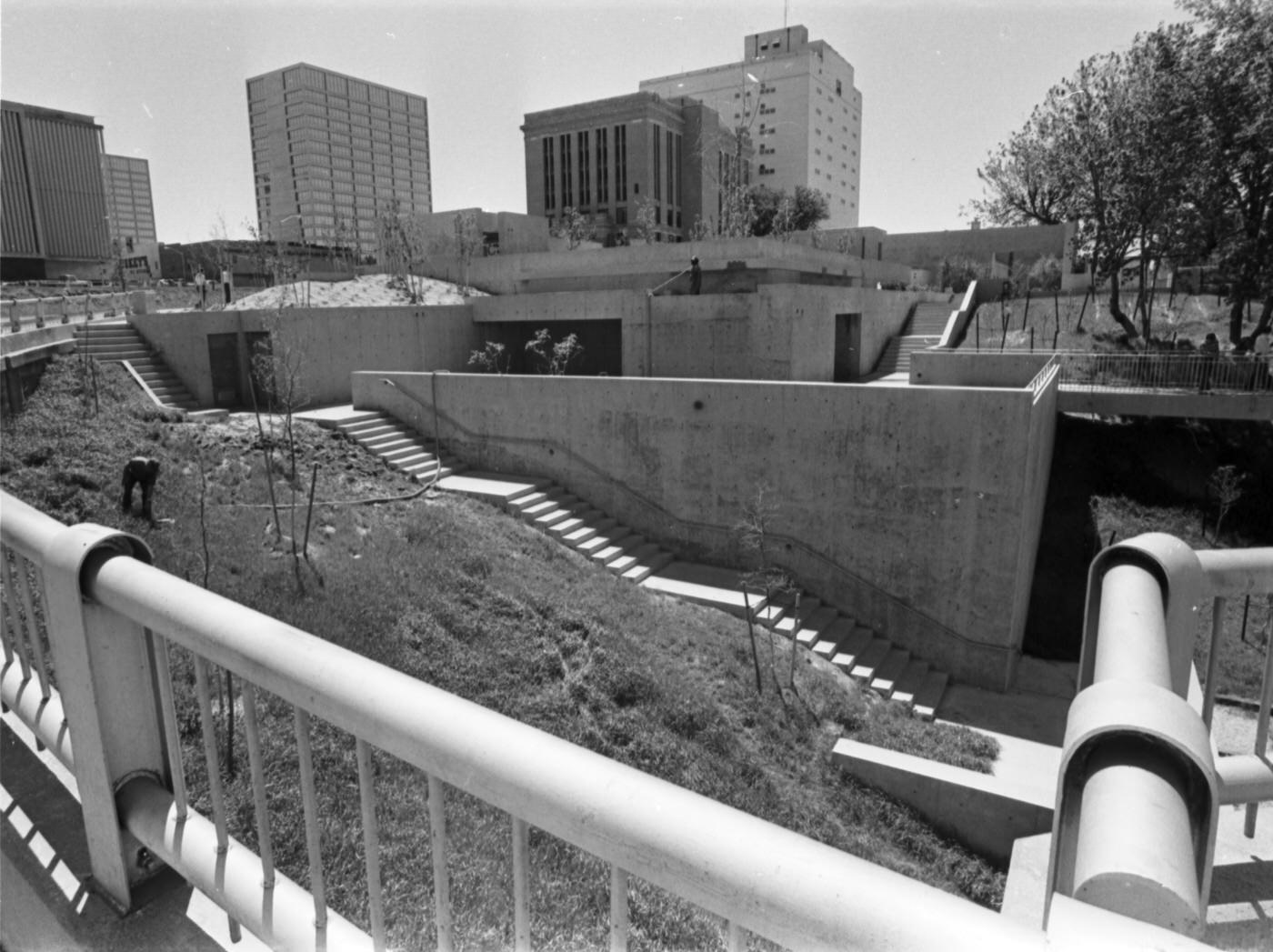

Remaking Downtown: Sundance Square Takes Shape

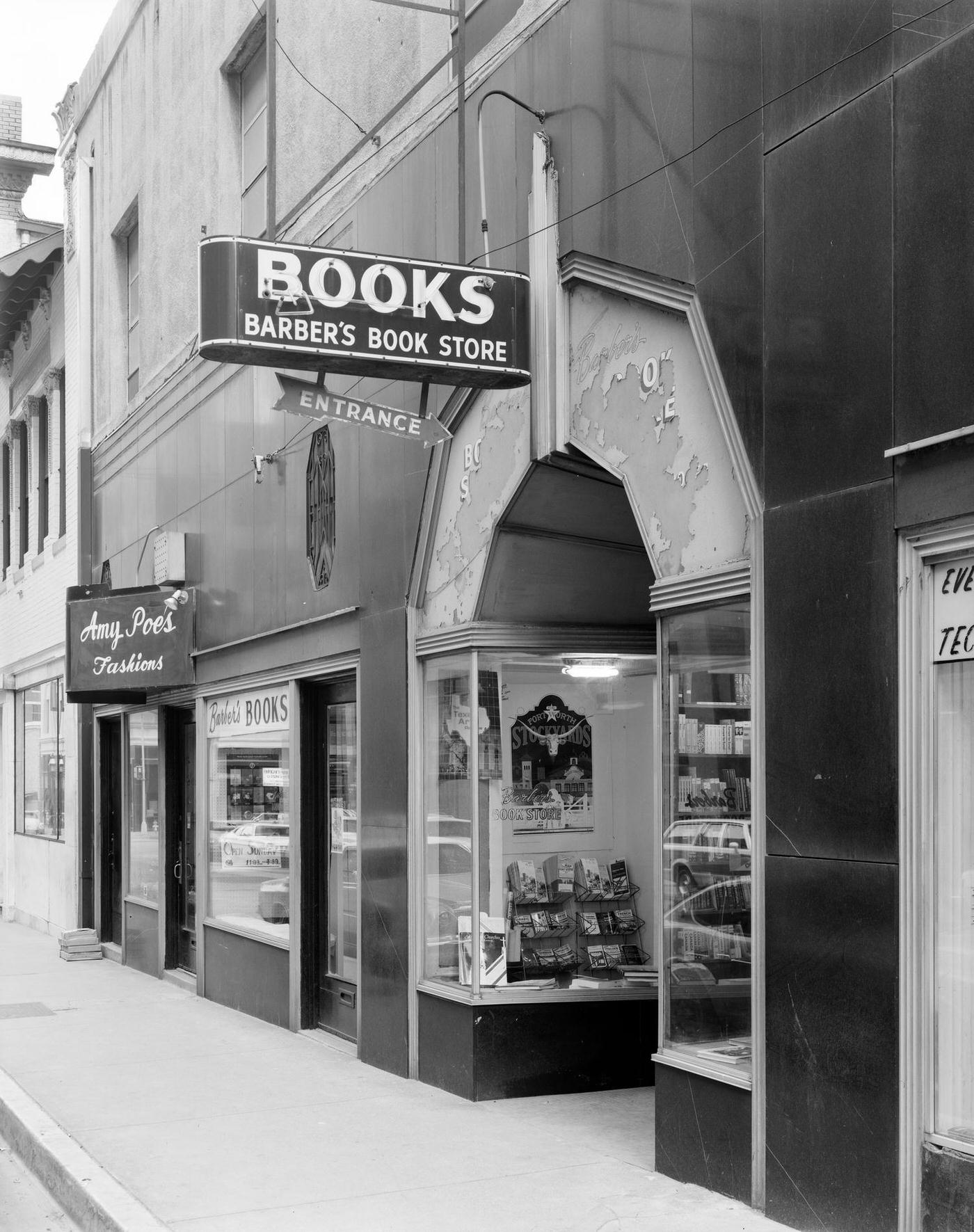

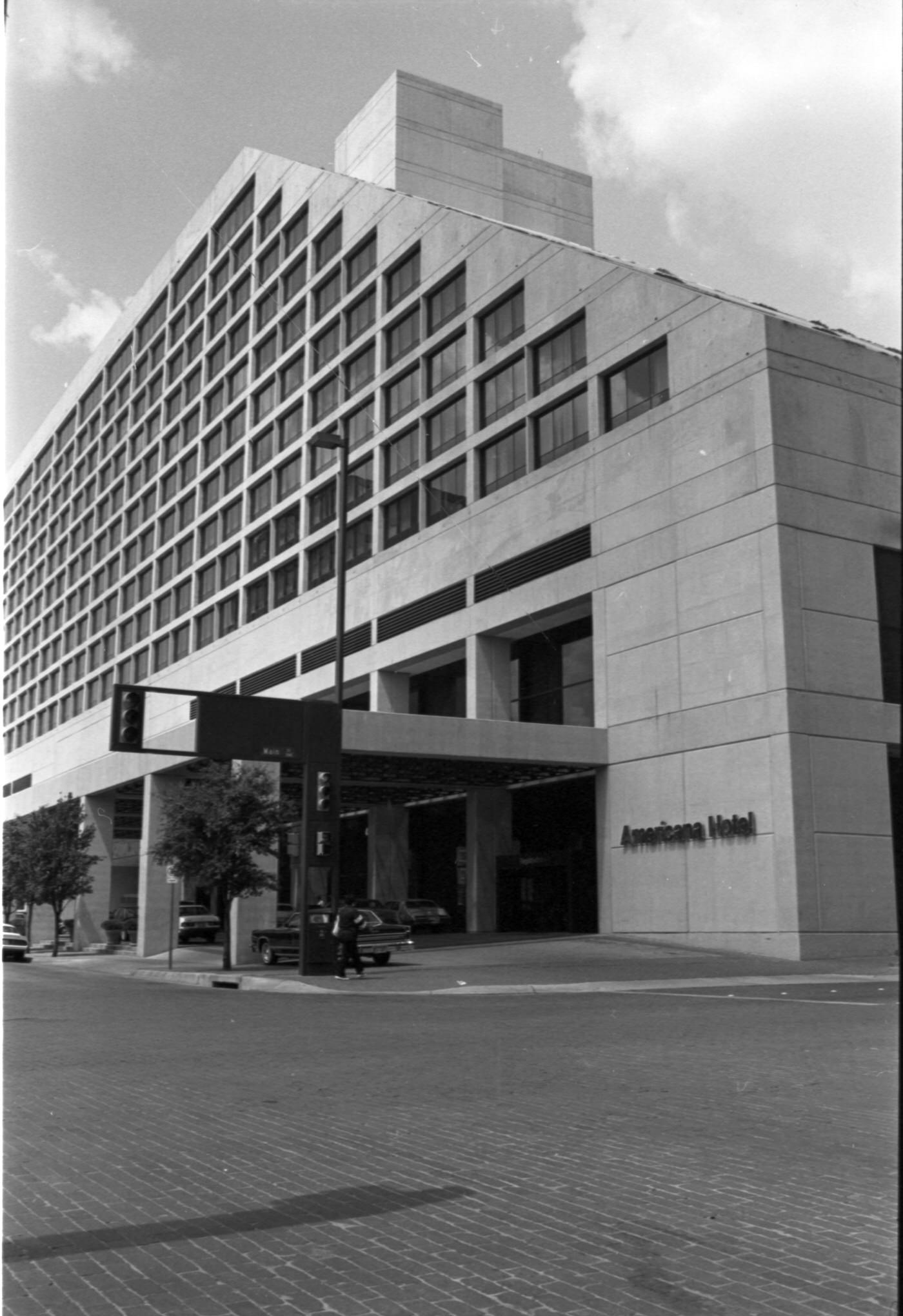

While the suburbs thrived, downtown Fort Worth faced difficulties in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The outward migration of residents and retail had left parts of the central business district feeling empty, particularly after business hours. Entire city blocks had been cleared for redevelopment projects that never happened, leaving behind vast surface parking lots. Large parking garages, sometimes spanning streets and connected by sky-bridges, along with an indoor mall that cut off parts of downtown, further fragmented the urban fabric and discouraged walking. The area lacked the continuous activity and pedestrian-friendly atmosphere found in more vibrant city centers.

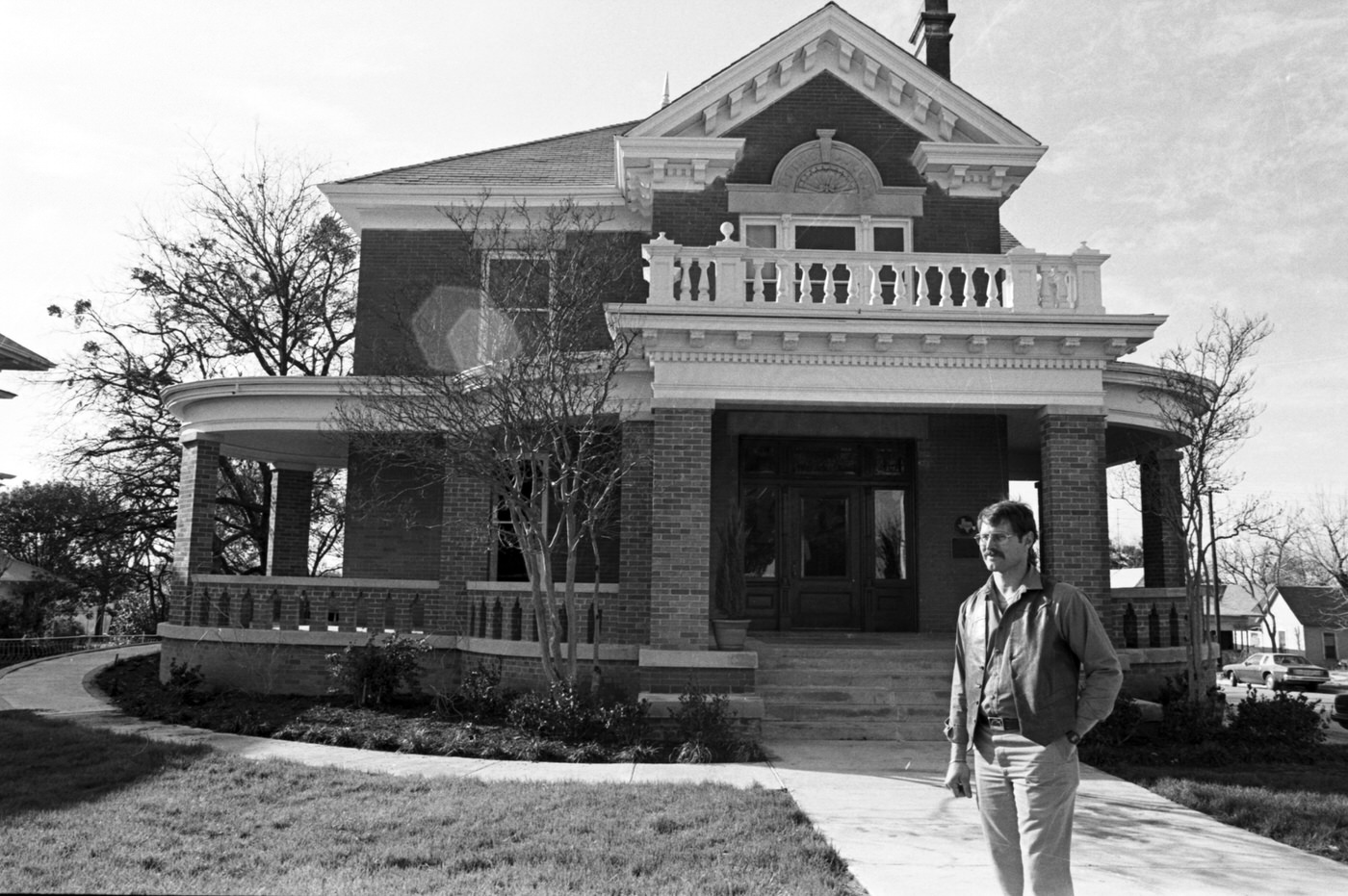

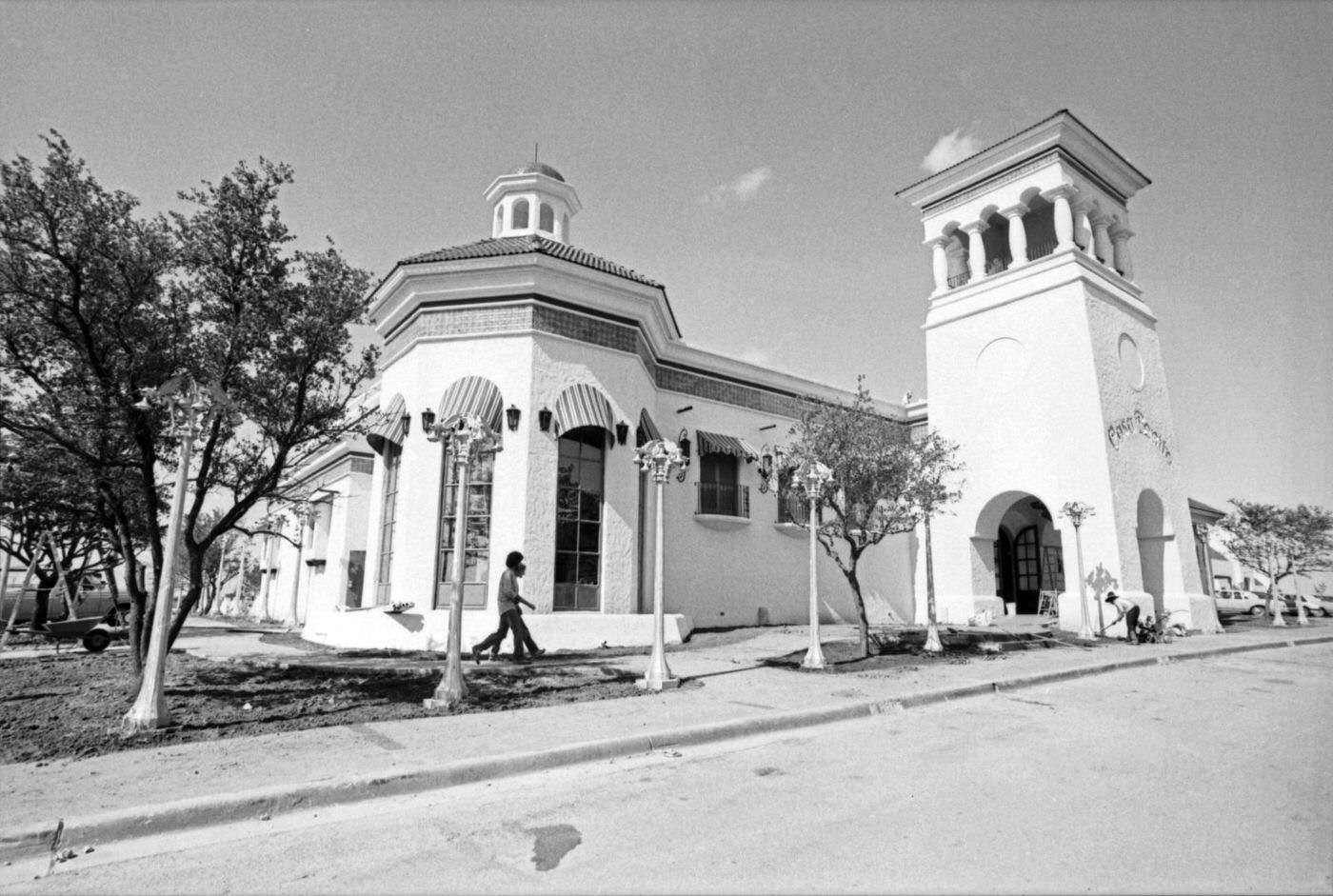

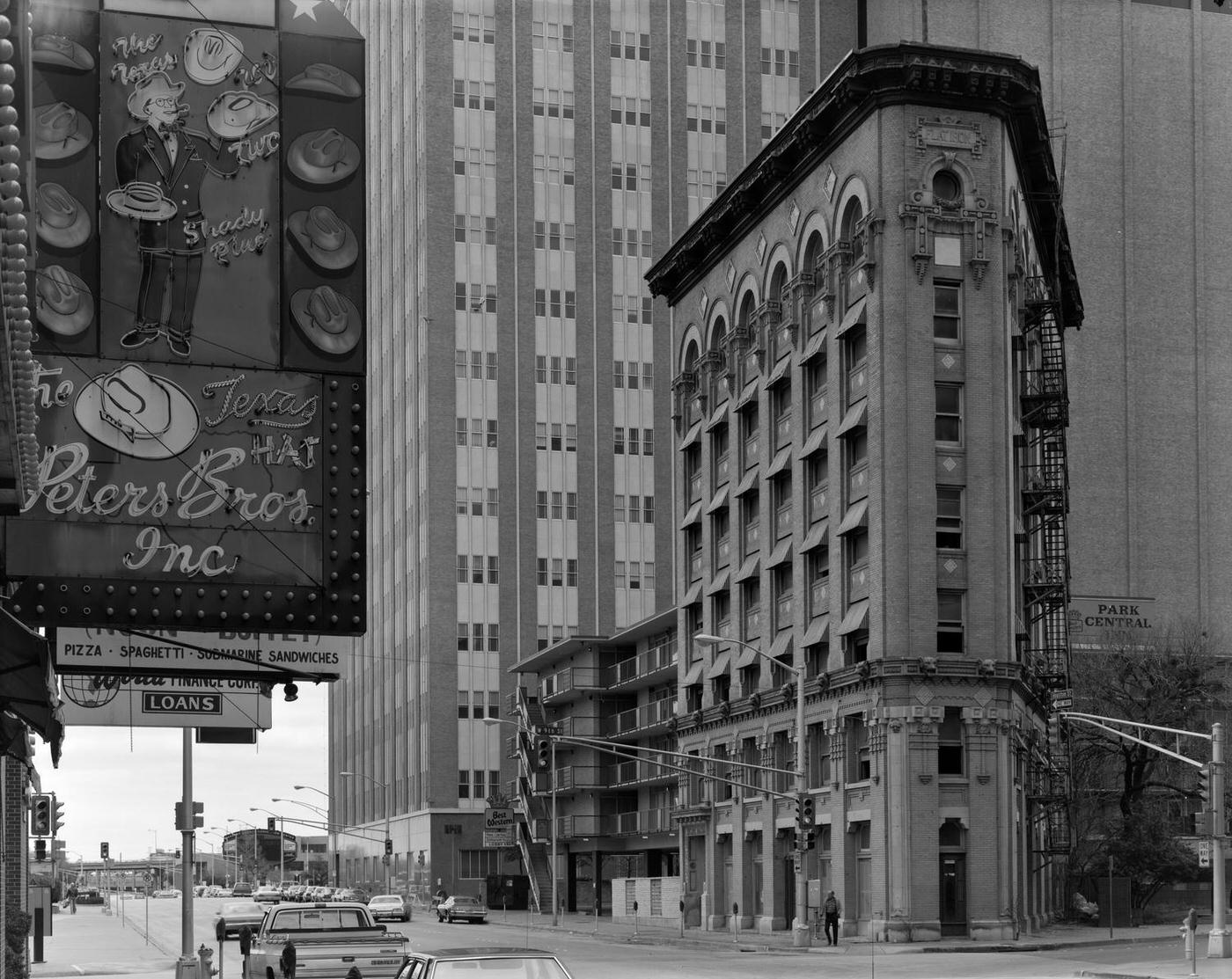

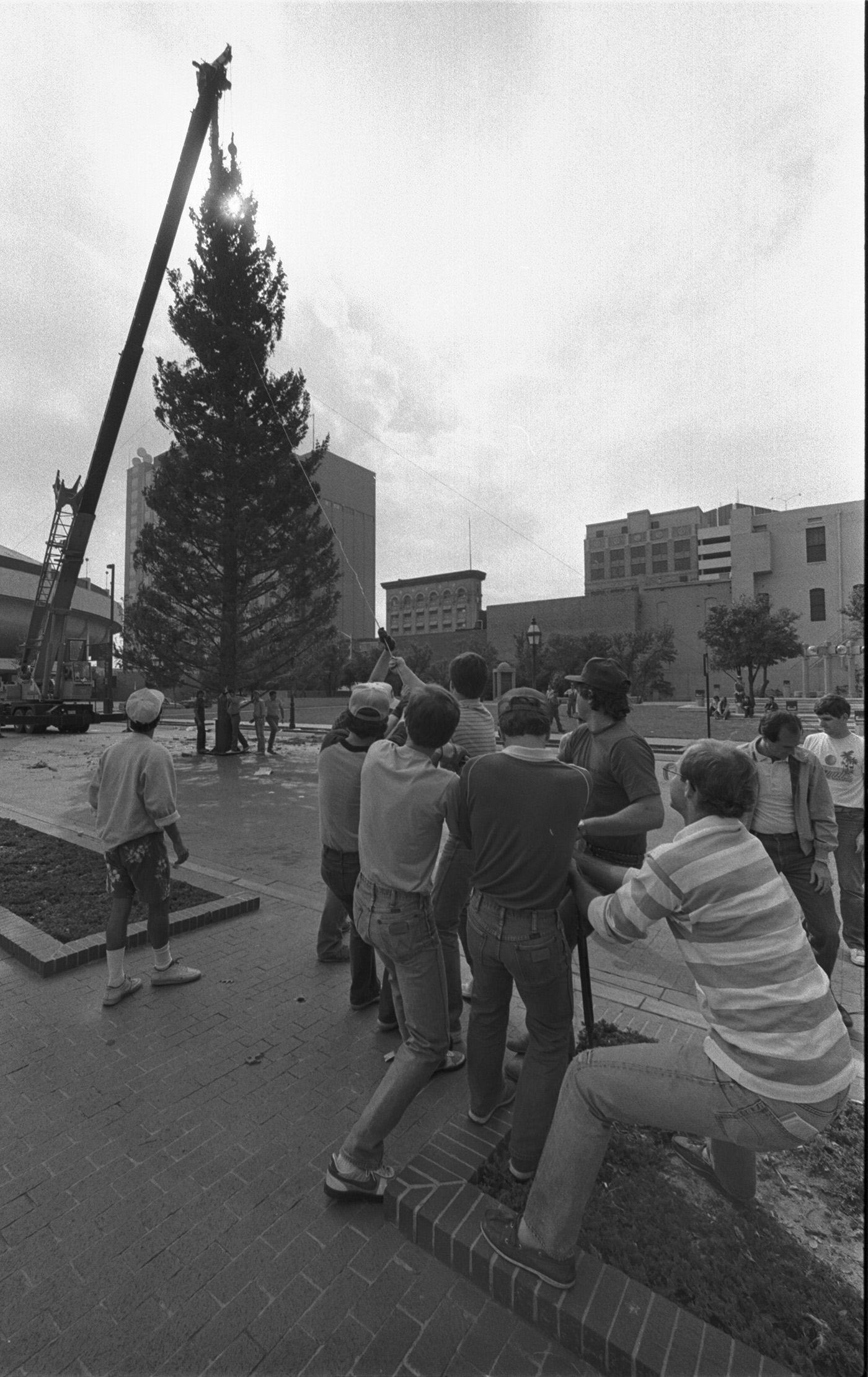

Witnessing this decline, billionaire oil heir Sid Bass embarked on an ambitious revitalization project in the early 1980s: Sundance Square. Inspired by the lively, integrated urban environments of cities like New York, the vision was to create a cohesive, walkable district where historic buildings and new construction housed a mix of shops, restaurants, offices, entertainment venues, and eventually, residences. The name itself, chosen during the 80s, evoked Fort Worth’s Western heritage by referencing the Sundance Kid, an outlaw who, along with Butch Cassidy, frequented the city in earlier times.

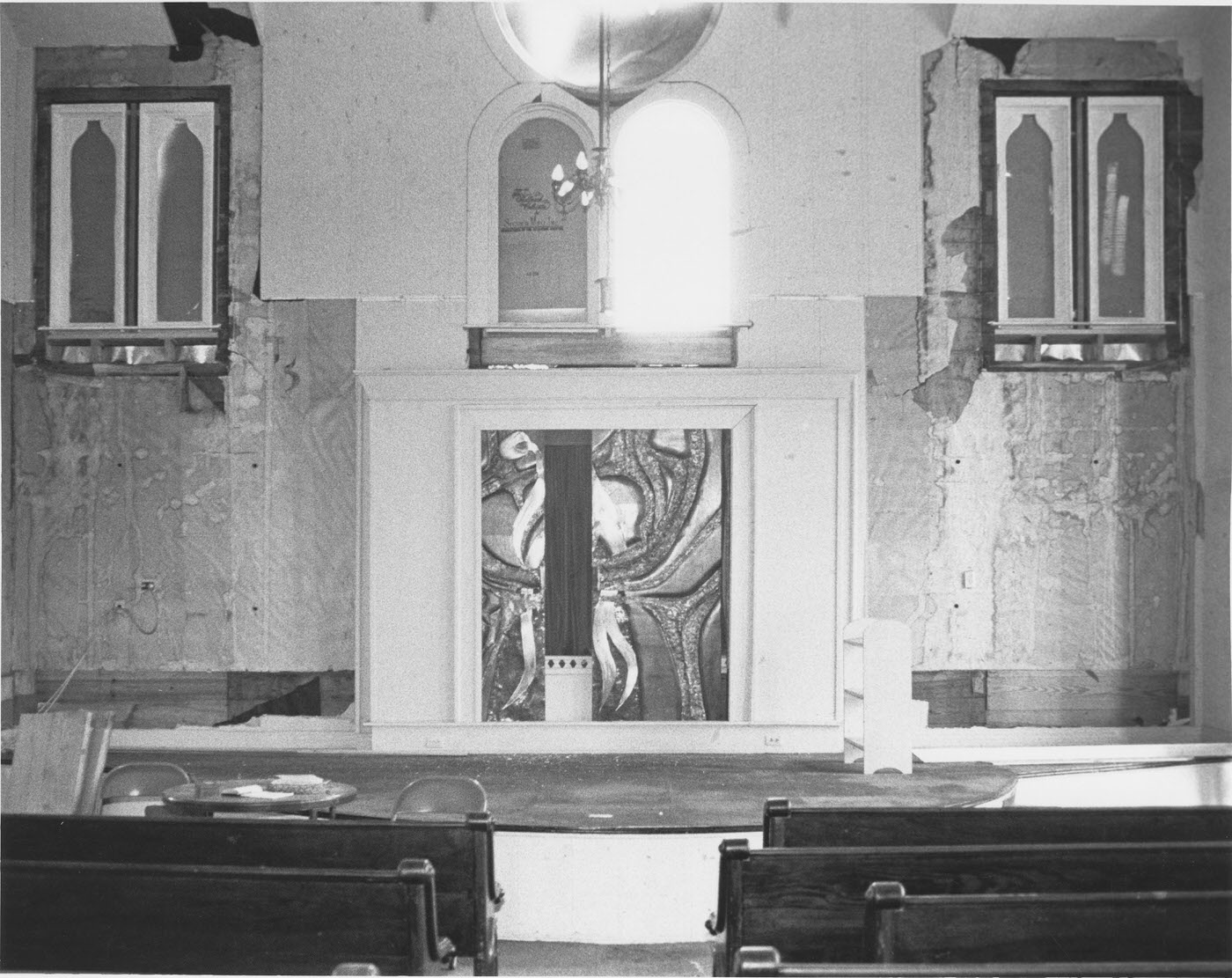

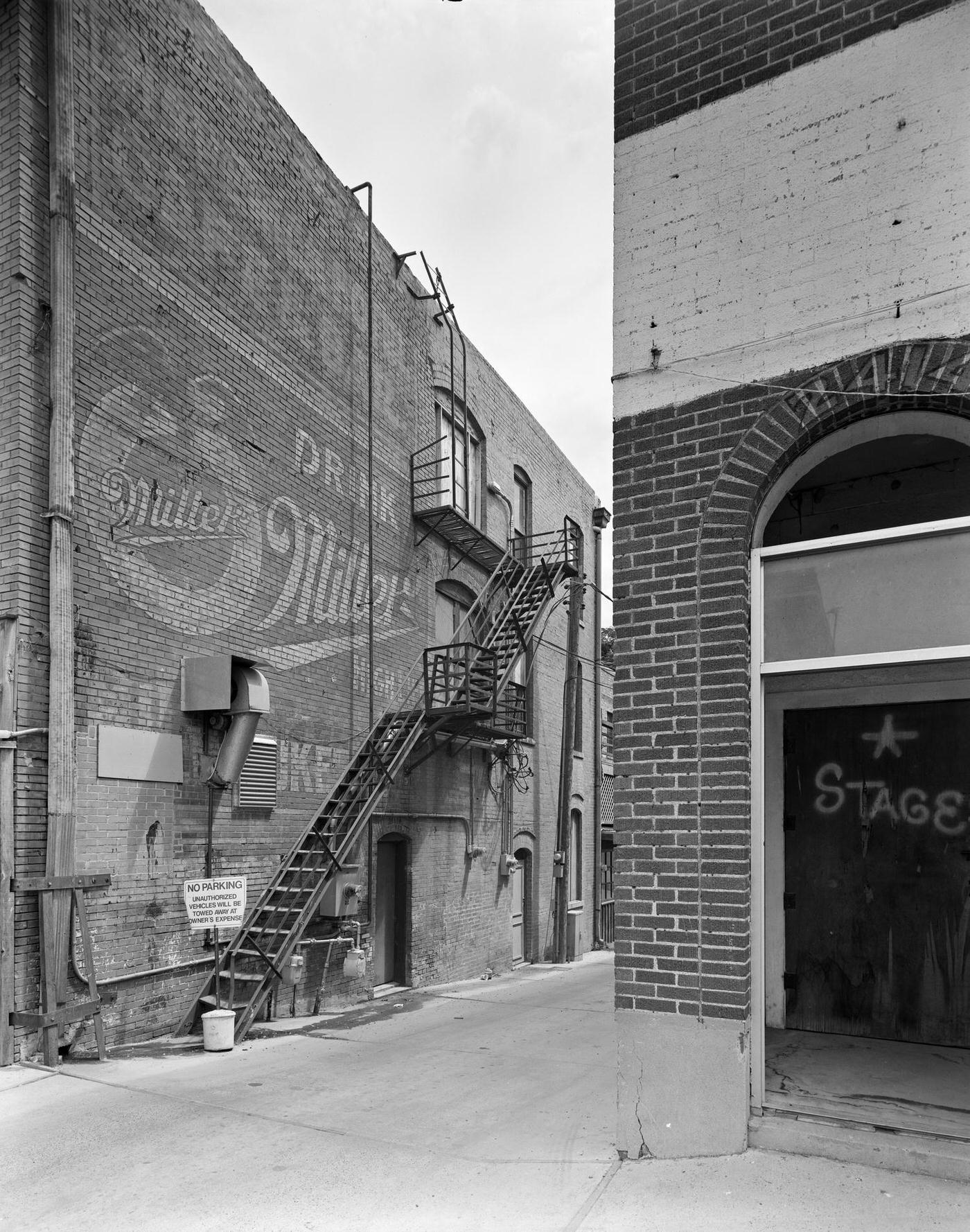

Development began even as the oil bust loomed. The Bass family financed the construction of the impressive twin City Center office towers: the 33-story Wells Fargo Tower (originally City Center Tower II) completed in 1982, and the 38-story D.R. Horton Tower (originally City Center Tower I) finished in 1984. Simultaneously, efforts focused on restoring historic structures. In 1980 and 1981, Sundance undertook the renovation of its first two buildings, Blocks 41 and 42 on Houston Street, which today house businesses like Razzoo’s Cajun Cafe, Riscky’s Barbeque, and Haltom’s Jewelers. Architects Thomas E. Woodward, known for his work with historic buildings, and later David M. Schwarz, were brought in to help shape the design and master plan. Adding an early cultural spark, the unique Caravan of Dreams performing arts center opened its doors at 312 Houston Street in 1983.

This large-scale private investment found a crucial ally in the city government, led by Mayor Bob Bolen, who took office in 1982. Recognizing the importance of public support, the city established a Public Improvement District (PID) in 1986. This PID provided funding for essential services that enhanced the area’s appeal, such as increased security, cleaning and maintenance, free parking programs, and public events like the Main St. Arts Festival. The development of Sundance Square in the 1980s was a bold, long-term commitment to downtown’s future, initiated during uncertain economic times, and made possible through a combination of significant private capital from the Bass family and vital support from the city.

The Sounds and Styles of 80s Fort Worth

The cultural pulse of 1980s Fort Worth beat strongly in its music venues and was reflected in the fashions seen on its streets. Two major, yet very different, music destinations defined the decade.

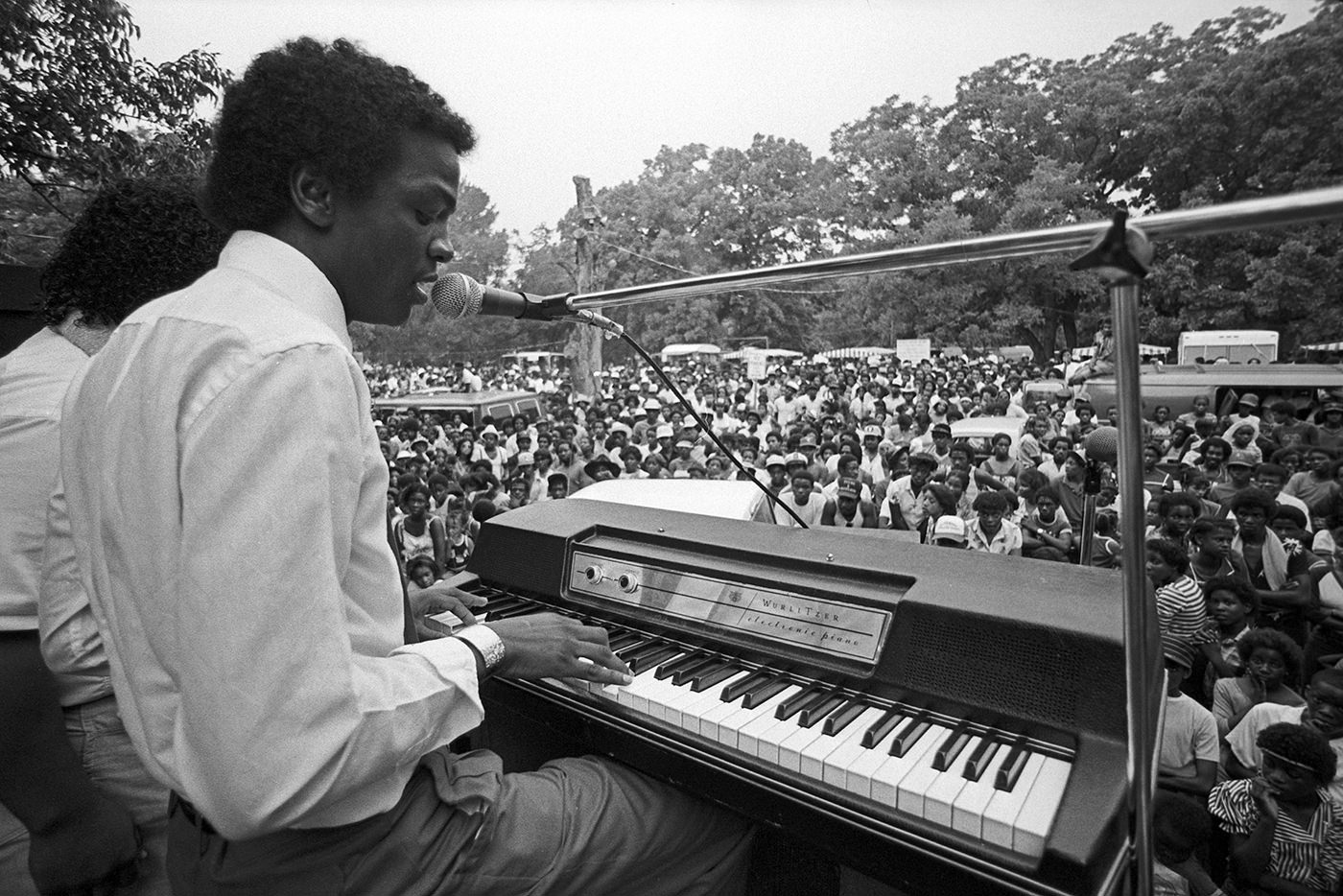

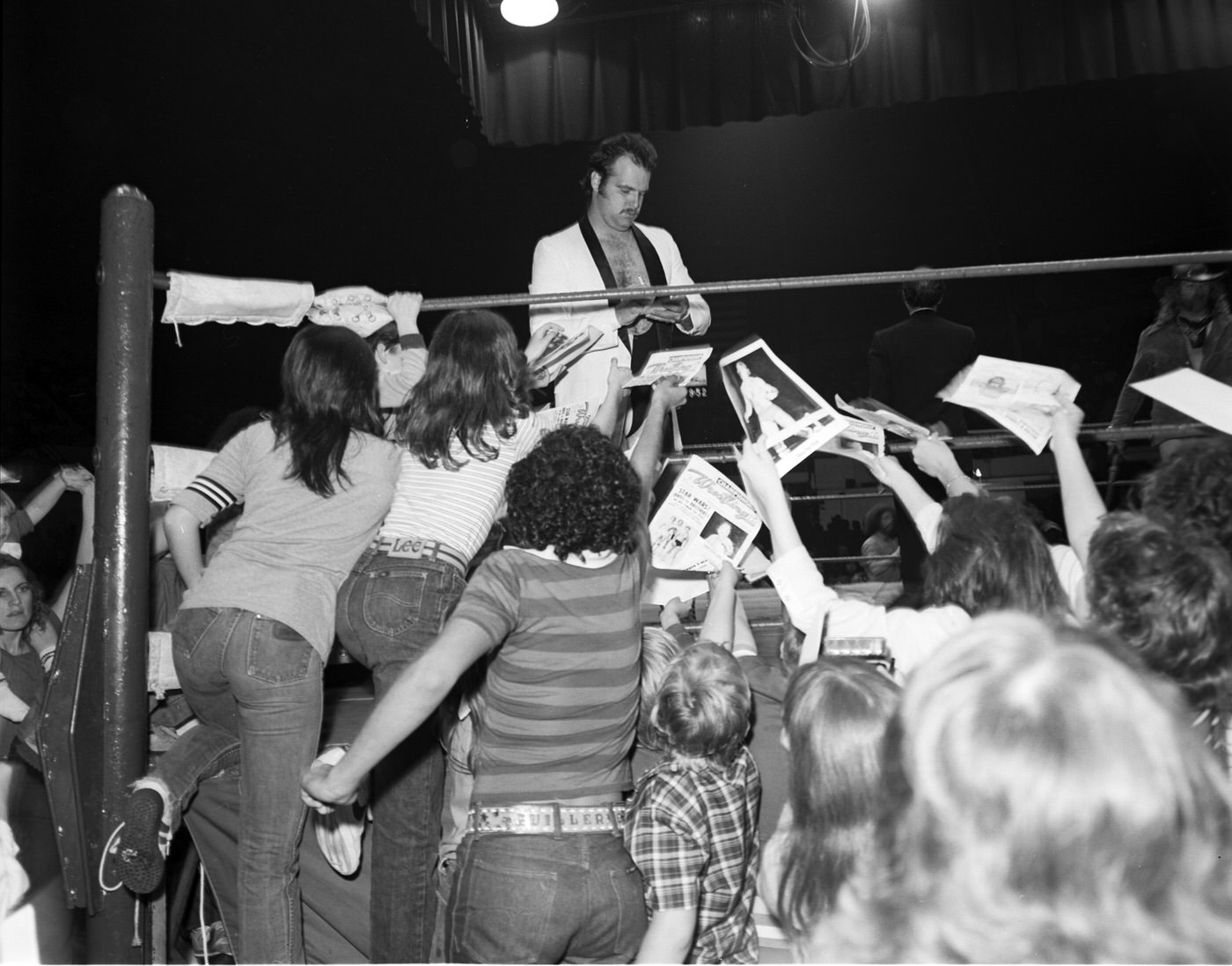

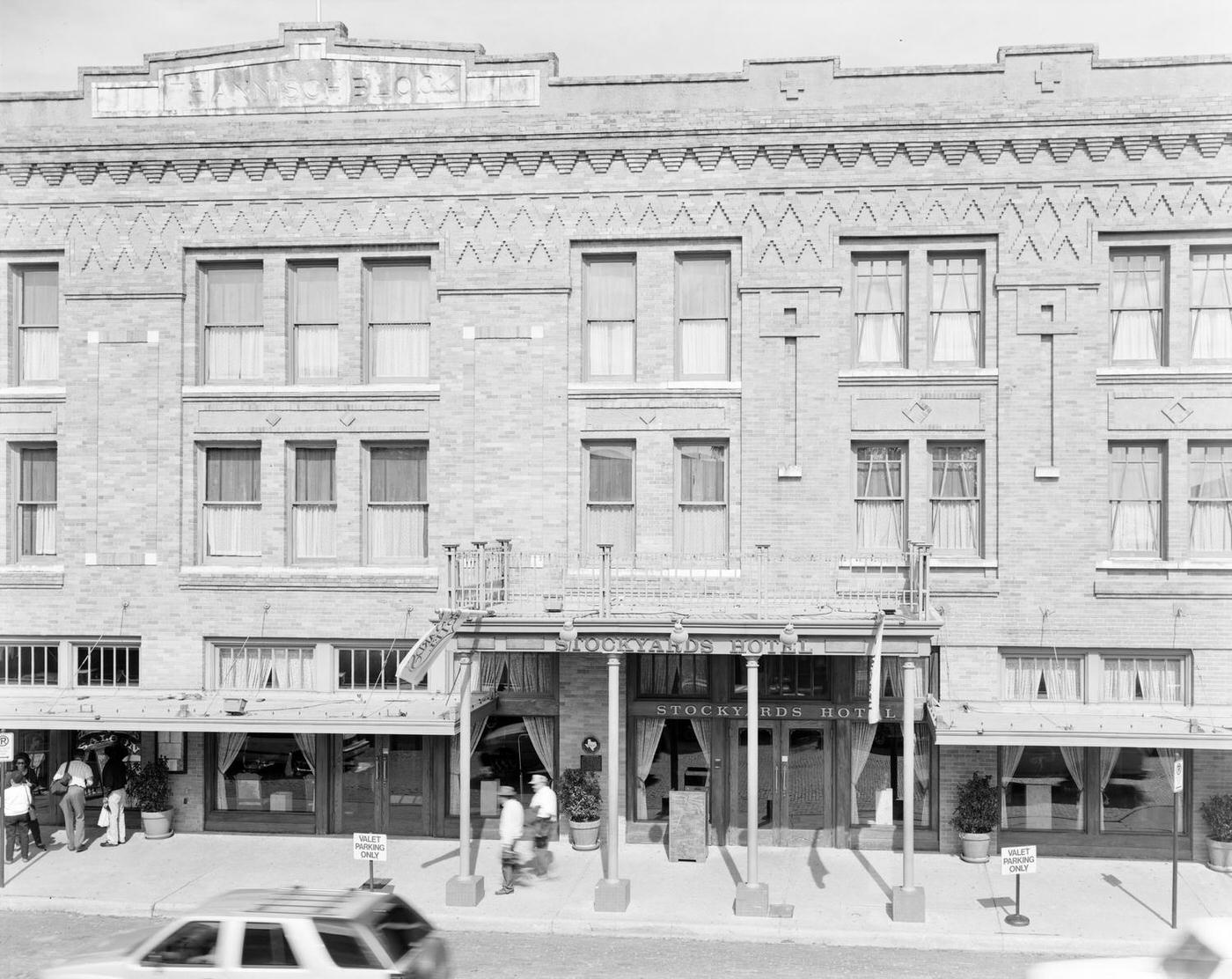

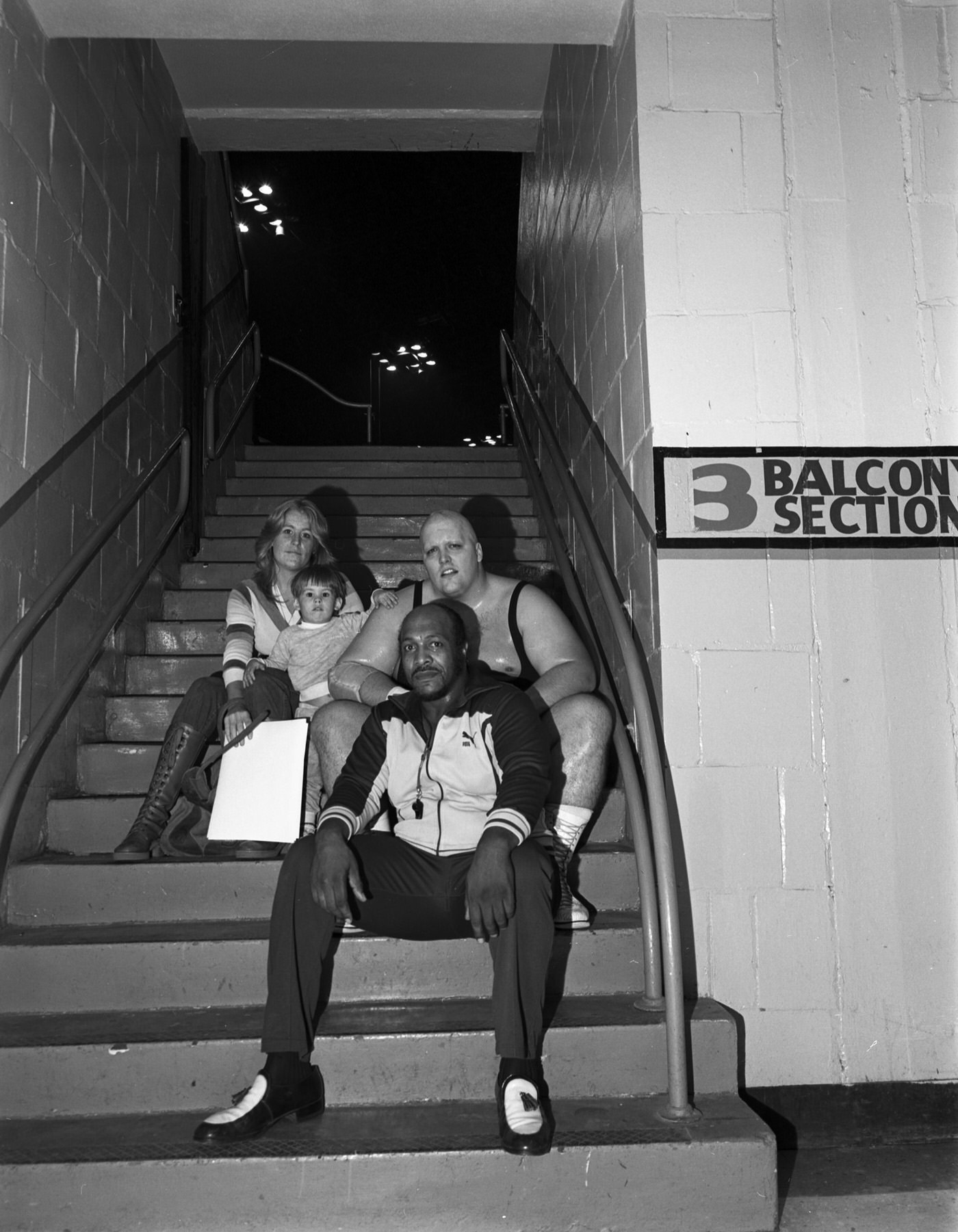

Billy Bob’s Texas threw open its massive doors in the historic Stockyards on April 1, 1981. Capitalizing on the “Urban Cowboy” movie craze sweeping the nation, it billed itself as the “World’s Largest Honky-Tonk”. Housed in a former cattle barn turned department store, the 100,000-square-foot venue could hold 6,000 people and offered live bull riding, dancing, games, and bars alongside its main stage. It was an instant hit, drawing huge crowds and hosting country music royalty like Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Larry Gatlin, and Marty Robbins in its first week. It also became a launching pad for future stars like George Strait and Rick Treviño. Even rock bands like ZZ Top and The Beach Boys played its stage. The club became a major tourist draw but faced financial troubles later in the decade as country music’s popularity waned, leading to bankruptcy and a temporary closure in January 1988 before reopening under new ownership.

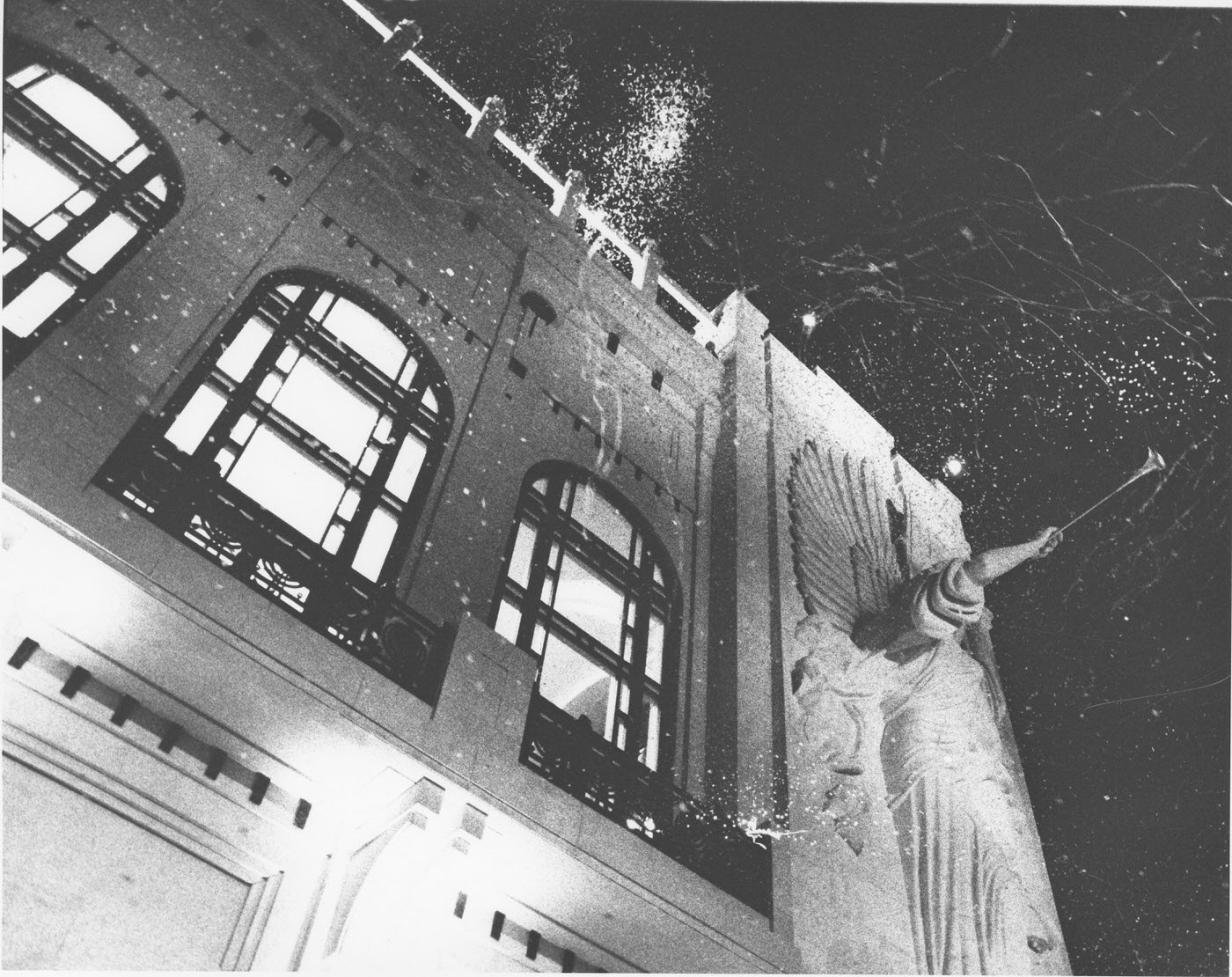

In stark contrast stood Caravan of Dreams, which opened downtown in September 1983. Located at 312 Houston Street within the burgeoning Sundance Square area, Caravan was an adventurous, multi-arts center dedicated to new forms of music, theater, dance, poetry, and film. Financed by Ed Bass and artistically directed by Kathelin Hoffman, it featured a live music club, a recording studio, a theater, dance studios, and even a rooftop cactus garden with a geodesic dome. Its opening weekend featured Fort Worth native and avant-garde jazz legend Ornette Coleman. The venue hosted experimental jazz artists like Sun Ra and Cecil Taylor, blues musicians, and spoken word performers like William S. Burroughs. It even had its own record label, releasing albums and films. Caravan of Dreams offered a sophisticated, experimental counterpoint to the mainstream country scene thriving just a few miles north.

Fashion in 80s Fort Worth was a blend of national trends and Texas traditions. Everyday wear for many included jeans – often tight-fitting, tapered, or acid-washed, sometimes with zippers at the ankles – paired with T-shirts (band tees, retro designs, or oversized styles with rolled sleeves), sweatshirts, and polo shirts, reflecting the era’s popular preppy look. Big, teased hair held high with hairspray was a defining look for women, along with bold accessories like large earrings and plastic bangles. Neon colors were popular, as were leg warmers. Western wear remained a constant influence. Pearl snap shirts, cowboy boots, denim jackets, and sometimes elements like fringe, leather, or concho belts were integrated into daily style, reflecting Fort Worth’s “Cowtown” identity. The “prairie look,” featuring calico prints and ruffled blouses, also saw a resurgence early in the decade. Television shows like Dallas, filmed nearby, also influenced styles, popularizing looks with large shoulder pads and voluminous silhouettes. Fort Worth’s 80s culture showcased this duality: embracing the boot-scootin’ energy of Billy Bob’s while also supporting the boundary-pushing art at Caravan of Dreams, all while residents mixed national fashion fads with enduring Western flair.

Where Fort Worth Hung Out: Malls, Arcades, and Skating

For leisure and socializing, especially for younger residents, the 1980s in Fort Worth revolved around several key types of places: shopping malls, video arcades, and roller skating rinks.

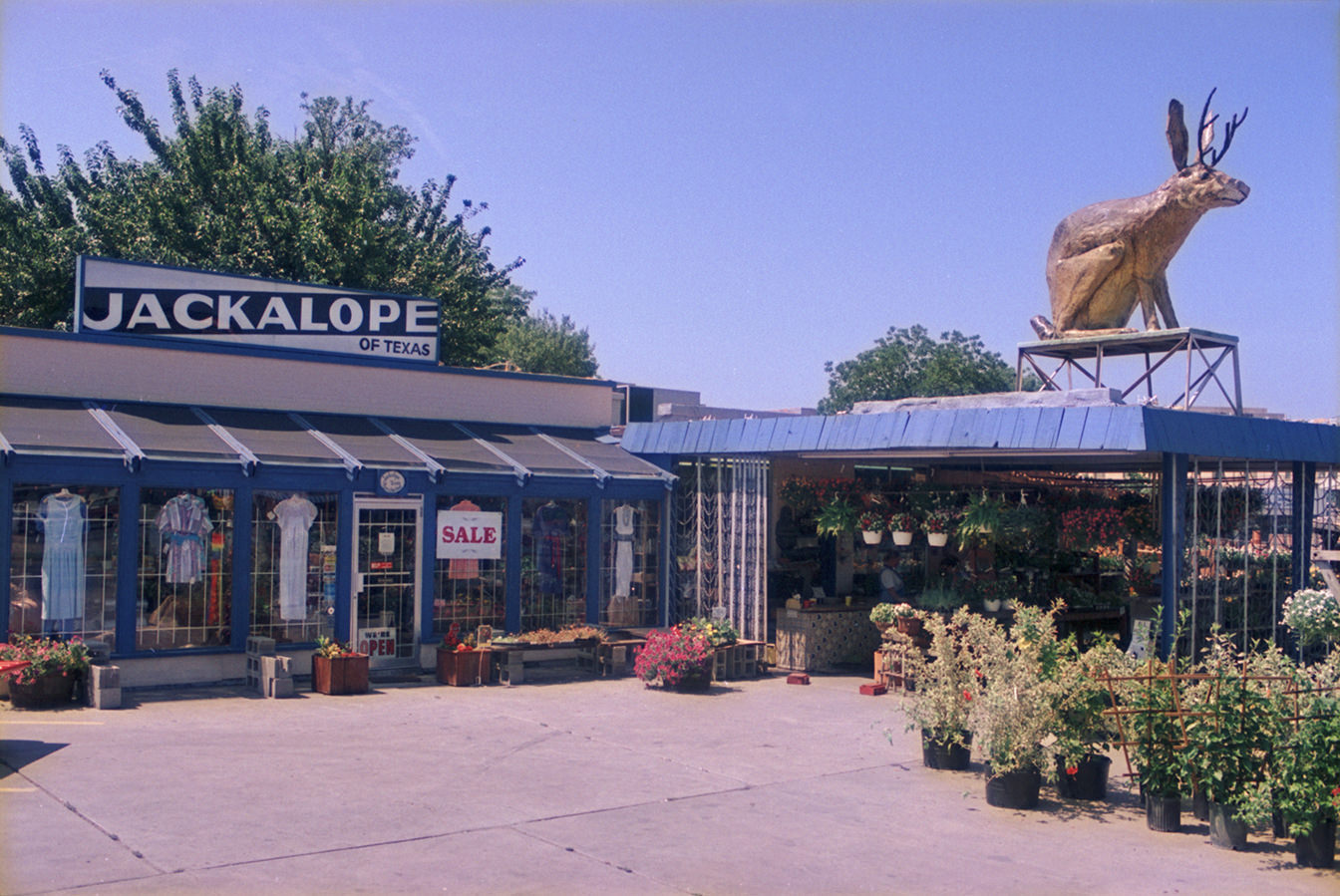

Malls were more than just places to shop; they were destinations. Ridgmar Mall, located on the west side off Interstate 30 and Green Oaks Road, had opened in 1976 and remained a major hub throughout the 80s. Its original anchor stores were Dillard’s, JCPenney, and the upscale Neiman Marcus, with Sears joining in 1977. Hulen Mall, in the southwest part of the city, was another popular enclosed mall, drawing shoppers from a wide area and featuring the typical mix of department stores and smaller shops found in suburban malls of the era. Downtown, the Tandy Center offered a different mall experience, notable for including an ice skating rink and a large arcade that even featured a carousel, making it a significant entertainment draw, particularly in the early part of the decade.

Video arcades exploded in popularity during the 1980s, and Fort Worth was no exception. These noisy, dimly lit spaces filled with games like Pac-Man, Donkey Kong, and Space Invaders were magnets for teenagers and young adults. Large arcades were found within malls like the Tandy Center , and undoubtedly within Ridgmar and Hulen as well. Arcades also existed as standalone businesses or were common features inside roller skating rinks and movie theaters.

Roller skating rinks provided another popular form of entertainment and social gathering. Places like Skate World in Watauga, just north of Fort Worth, featured large wooden floors, disco balls casting spinning lights, and powerful sound systems blasting the pop, rock, and disco hits of the day – artists like Duran Duran, Michael Jackson, and The Fixx were common staples. Rinks often had specific skate sessions, like “ladies only” or the anticipated “couples only” skate. While some older rinks like Rollerland, located near Southwest High School, closed down in the early 80s, others continued to thrive or even opened new, like the retro-themed Interskate in Lewisville, built in 1982. Forest Park Roller Rink offered a unique experience with its ability to roll up tarp walls, creating an open-air feel during warmer months. These hangouts – the bustling malls, the glowing arcades, and the energetic skating rinks – were central to the social lives and leisure time of many Fort Worth residents during the 1980s.

Landmarks in the Limelight: Stockyards and Culture

The 1980s marked a period of transition and definition for two of Fort Worth’s most iconic areas: the historic Stockyards and the esteemed Cultural District.

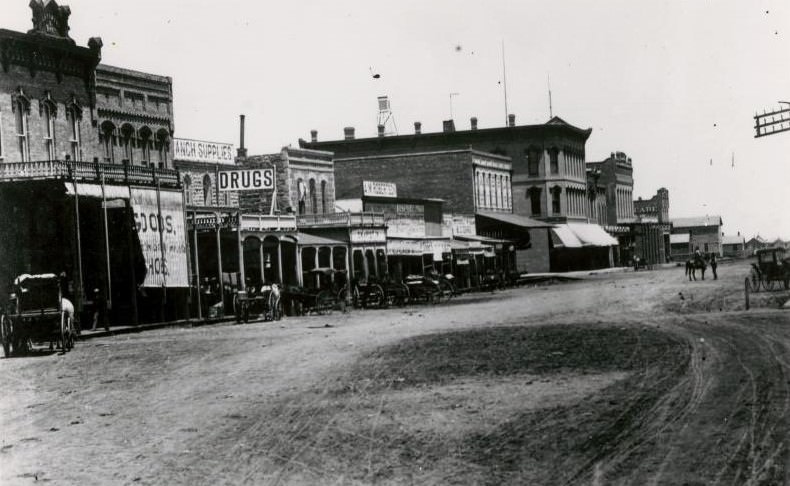

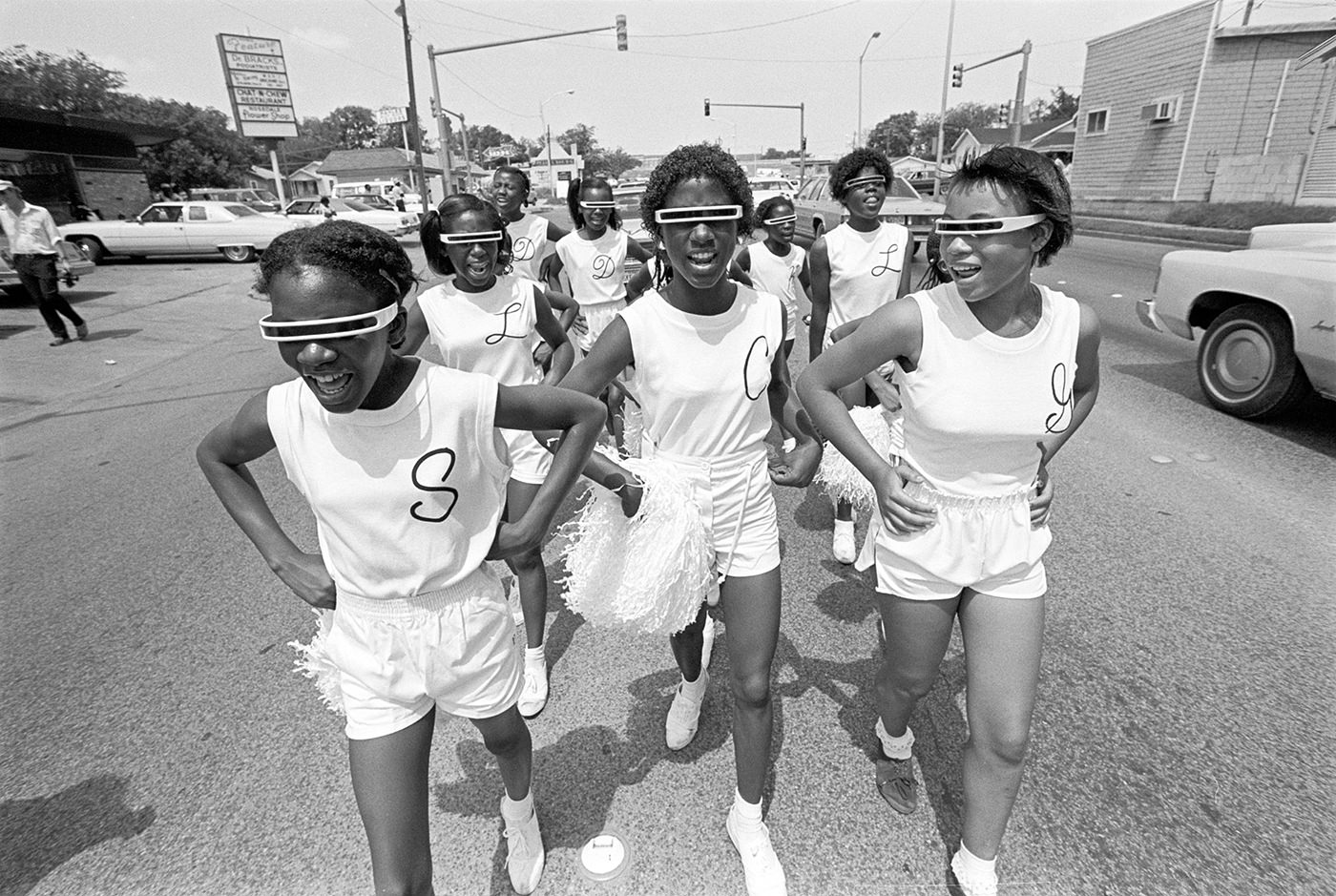

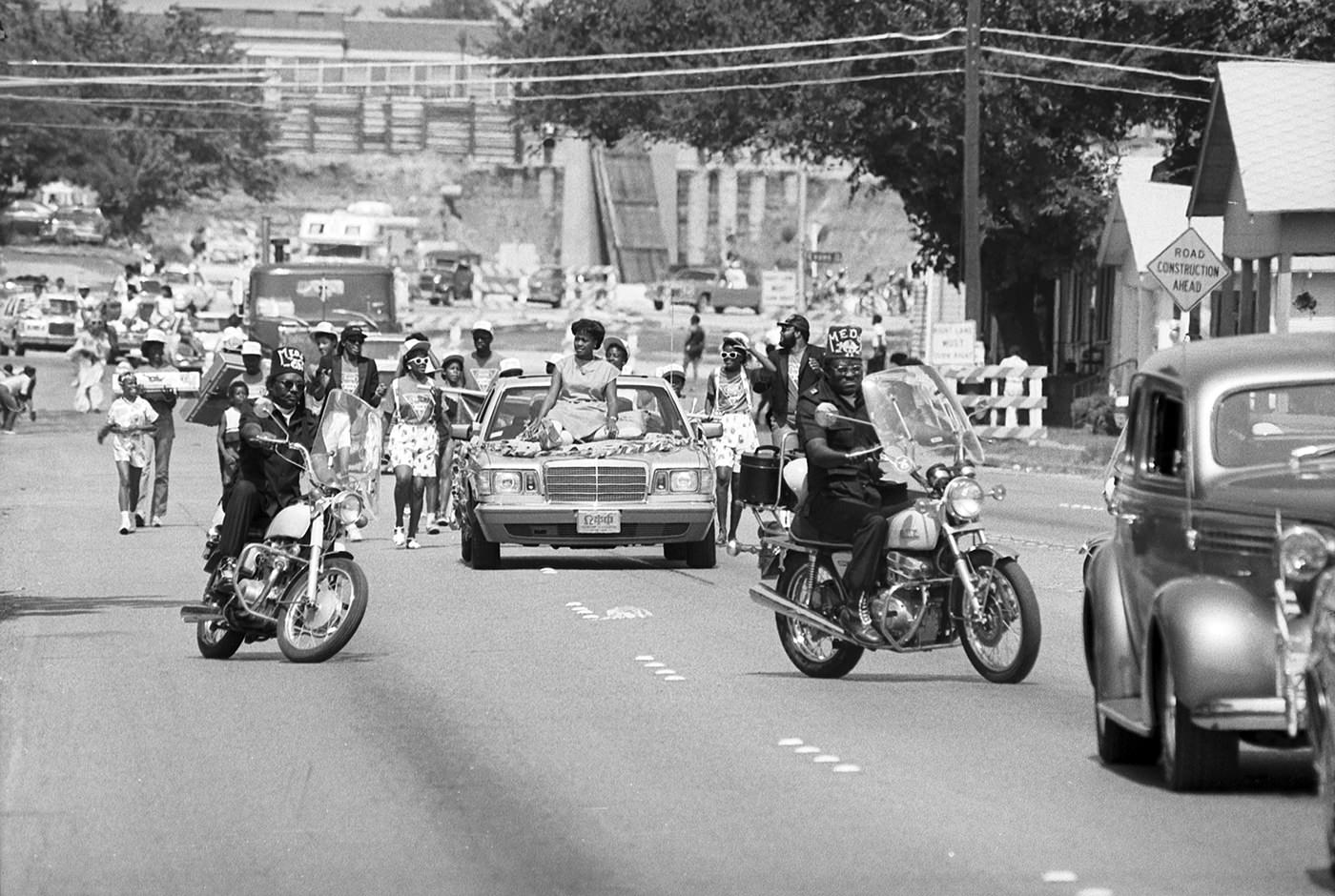

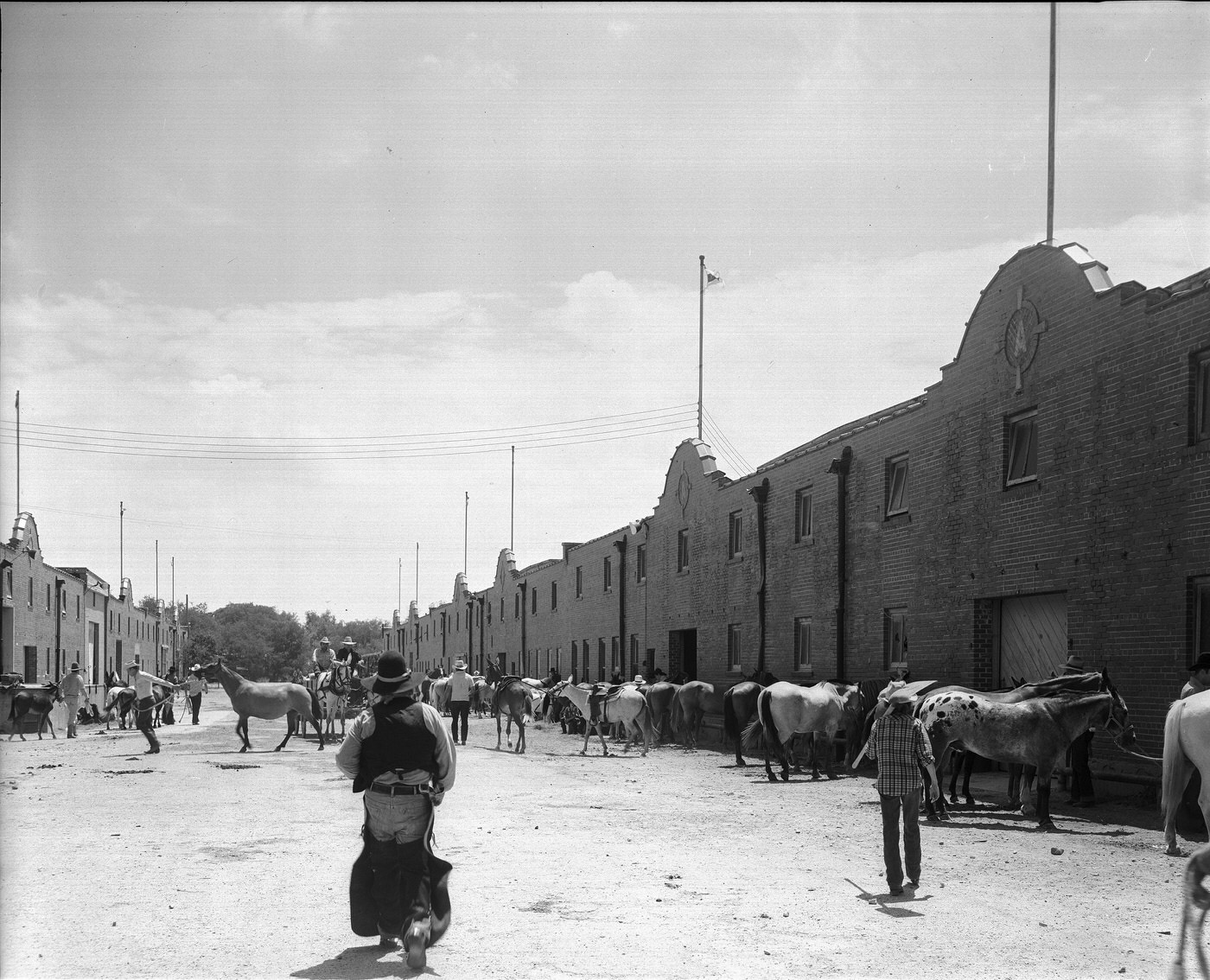

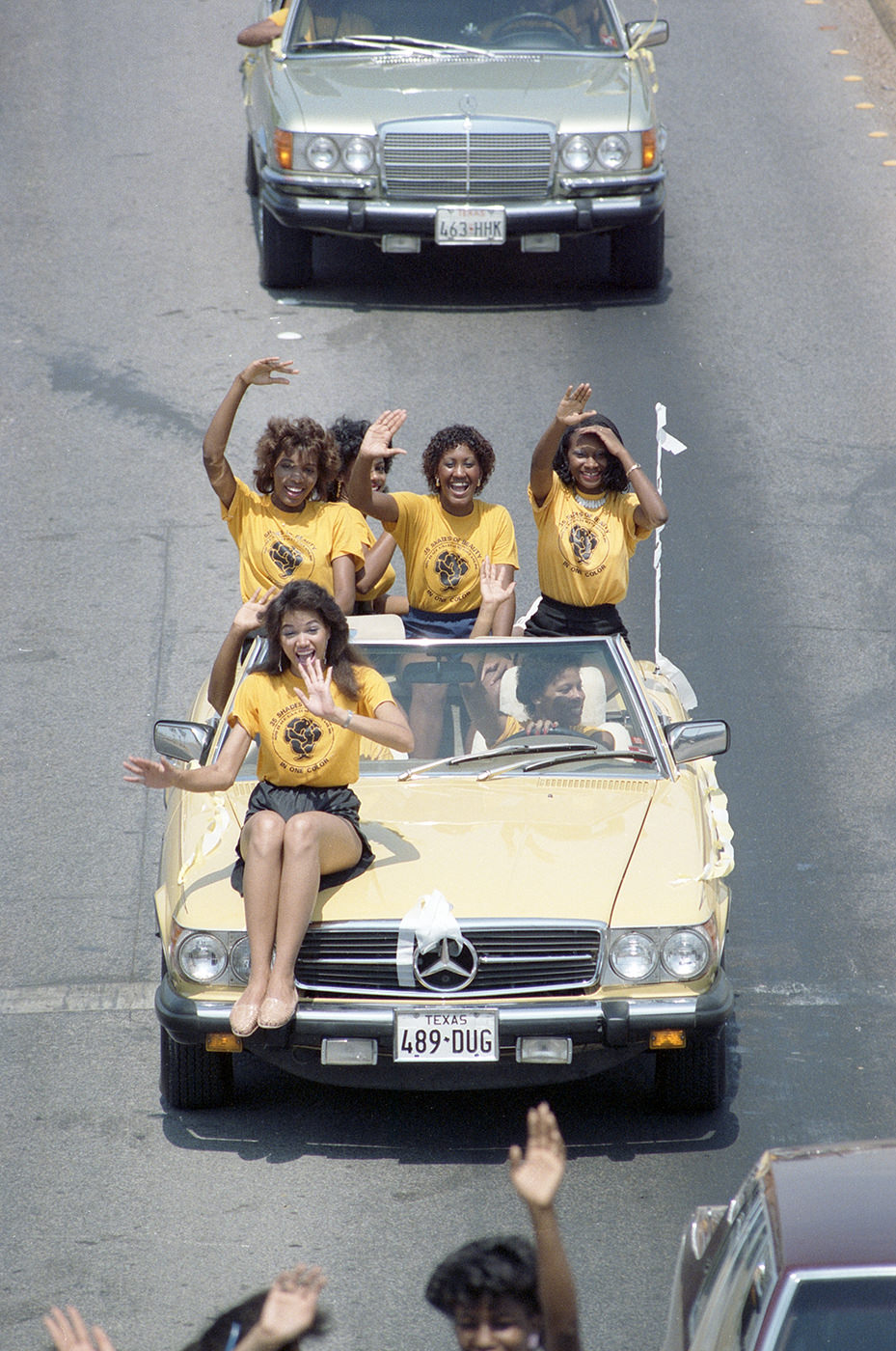

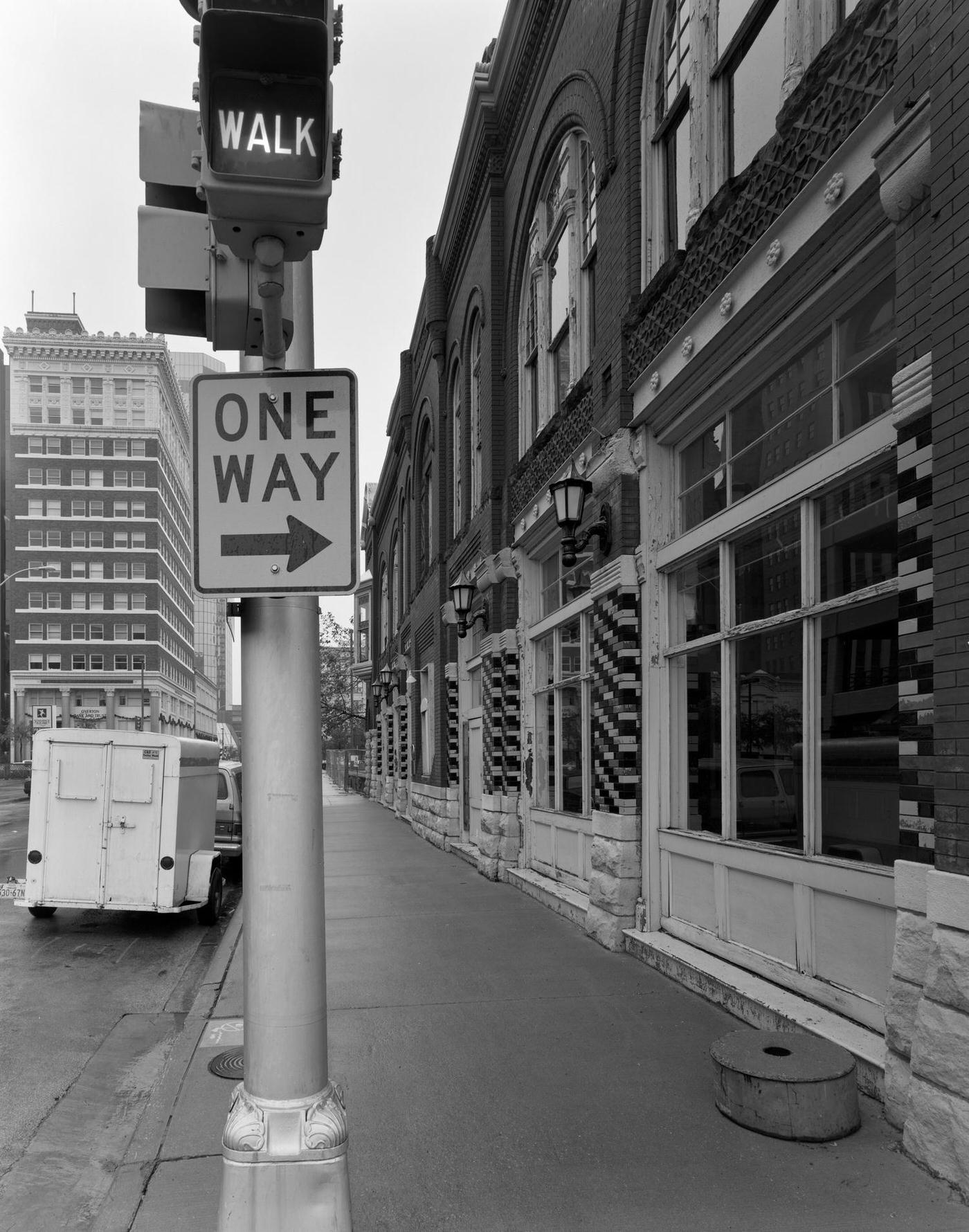

The Fort Worth Stockyards, once the heart of the region’s cattle industry, saw its original economic purpose continue to fade during the decade. The rise of decentralized livestock auctions and the efficiency of truck transport had diminished the need for massive central stockyards since World War II. The last of the giant meatpacking plants, Armour and Swift, had already closed in 1962 and 1971, respectively. By 1986, livestock sales through the Stockyards reached an all-time low, handling only a small fraction of the millions of animals processed in its peak years. However, as the cattle business declined, a new focus emerged: preservation and tourism. Efforts spearheaded by the North Fort Worth Historical Society, founded in 1976 by Charlie and Sue McCafferty, led to the Stockyards being designated a National Historic District. This paved the way for preserving the area’s unique architecture and heritage. In the 1980s, the historic Livestock Exchange Building, once dubbed “The Wall Street of the West,” found new life housing a museum dedicated to Stockyards history, opening in 1989. The area began actively cultivating its “Cowtown” image to attract visitors, leveraging its history with attractions like the twice-daily cattle drive, which became a signature event. While its days as a working stockyard were largely over, the 1980s saw the Stockyards begin its transformation into the major heritage tourism destination it is today.

Meanwhile, just a few miles south, Fort Worth’s Cultural District solidified its reputation as a center for world-class art. The Kimbell Art Museum, housed in Louis Kahn’s architectural masterpiece opened in 1972, continued its mission of acquiring art of “definitive excellence”. The 1980s, under director Edmund “Ted” Pillsbury, were a period of significant growth for the collection. The museum acquired major European masterpieces by artists like Caravaggio, La Tour, Velázquez, David, Monet, Cézanne, Picasso, and Matisse, alongside important works of ancient Egyptian, Asian, African, and Pre-Columbian art. The Kimbell also began organizing prestigious international loan exhibitions, starting in 1982, enhancing its global standing.

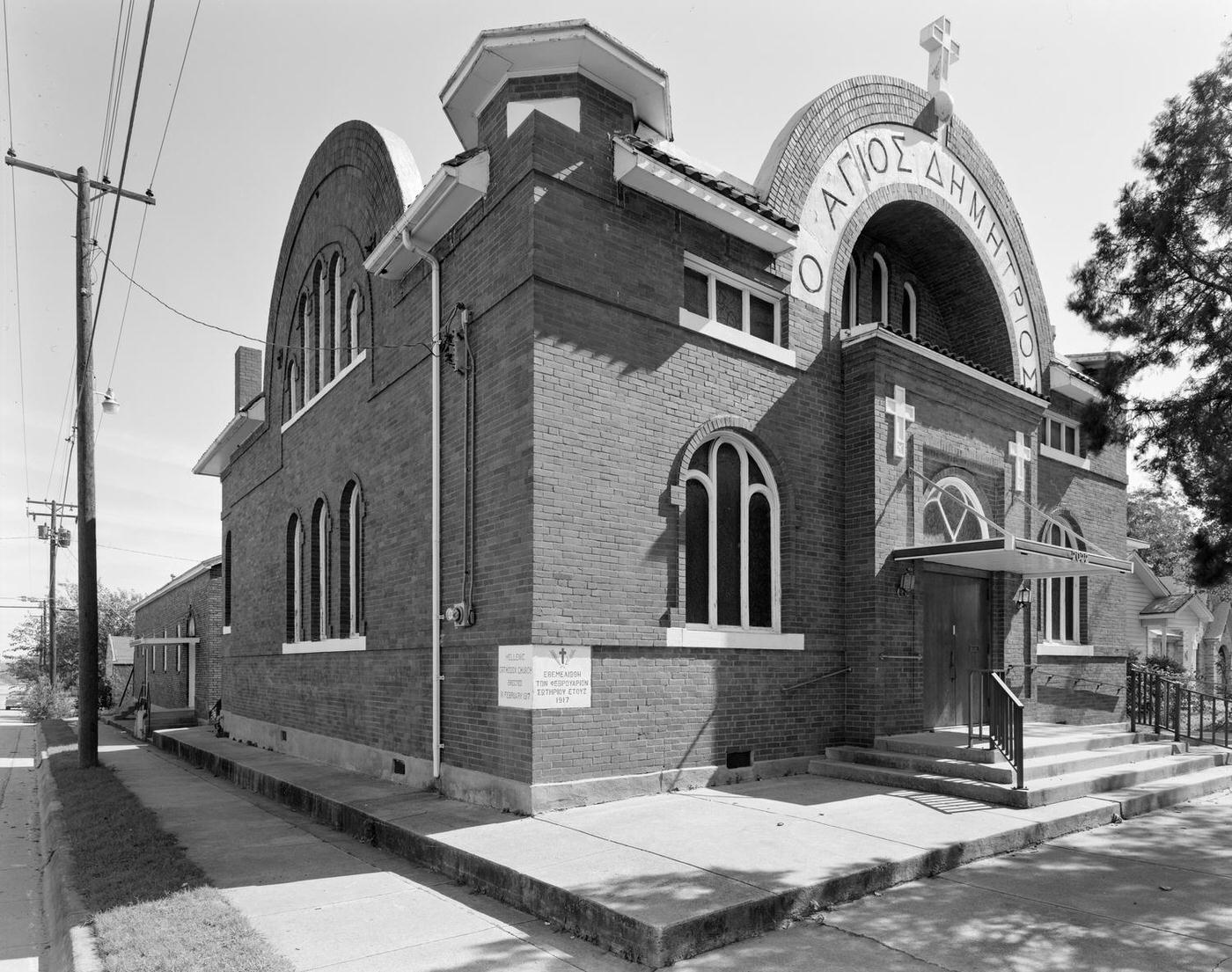

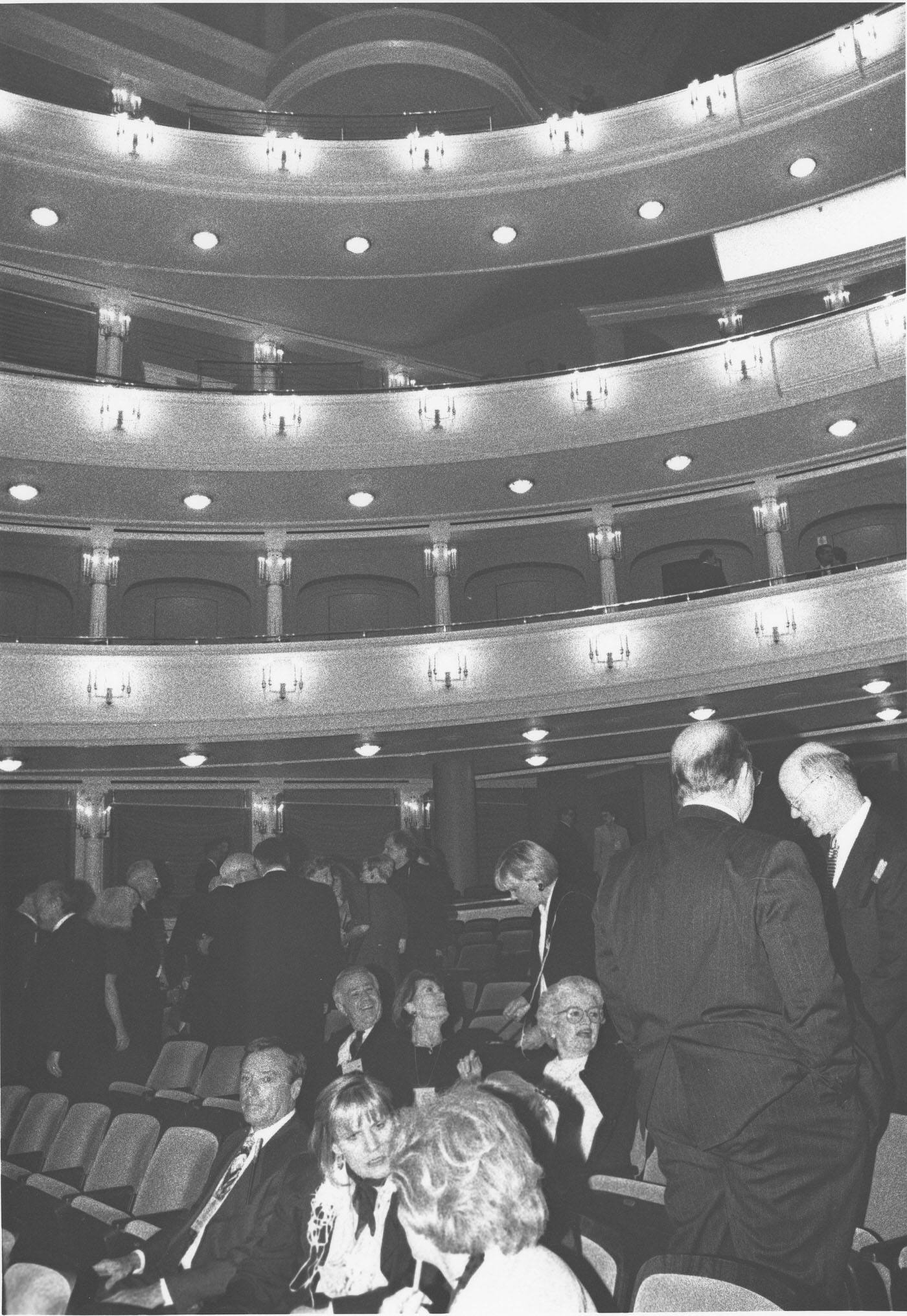

Nearby, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, founded based on Amon G. Carter Sr.’s collection of Western art by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, continued to evolve. Having officially dropped “of Western Art” from its name in 1977, the museum in the 1980s broadened its focus significantly. While maintaining its core strength in art of the American West, the Carter expanded its collection to include masterworks of American painting, sculpture, and works on paper from the 19th and early 20th centuries, featuring artists like Thomas Cole, William Merritt Chase, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Stuart Davis. Its photography collection also grew substantially, becoming one of the nation’s most important repositories of American photography. The museum’s library served as a major research center for American art and history. Together with other institutions like the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History and the Casa Mañana theatre complex , the Cultural District offered residents and visitors access to high-caliber artistic and educational experiences. The 1980s saw Fort Worth actively investing in both sides of its identity: preserving the Western history of the Stockyards through tourism while simultaneously elevating its status as a sophisticated center for fine art in the Cultural District.

Daily Rhythms: Neighborhoods, Schools, Restaurants

Everyday life in 1980s Fort Worth reflected the patterns of many American cities during that time, encompassing suburban routines, evolving urban neighborhoods, a school system undergoing significant change, and a mix of familiar chain restaurants and local dining spots.

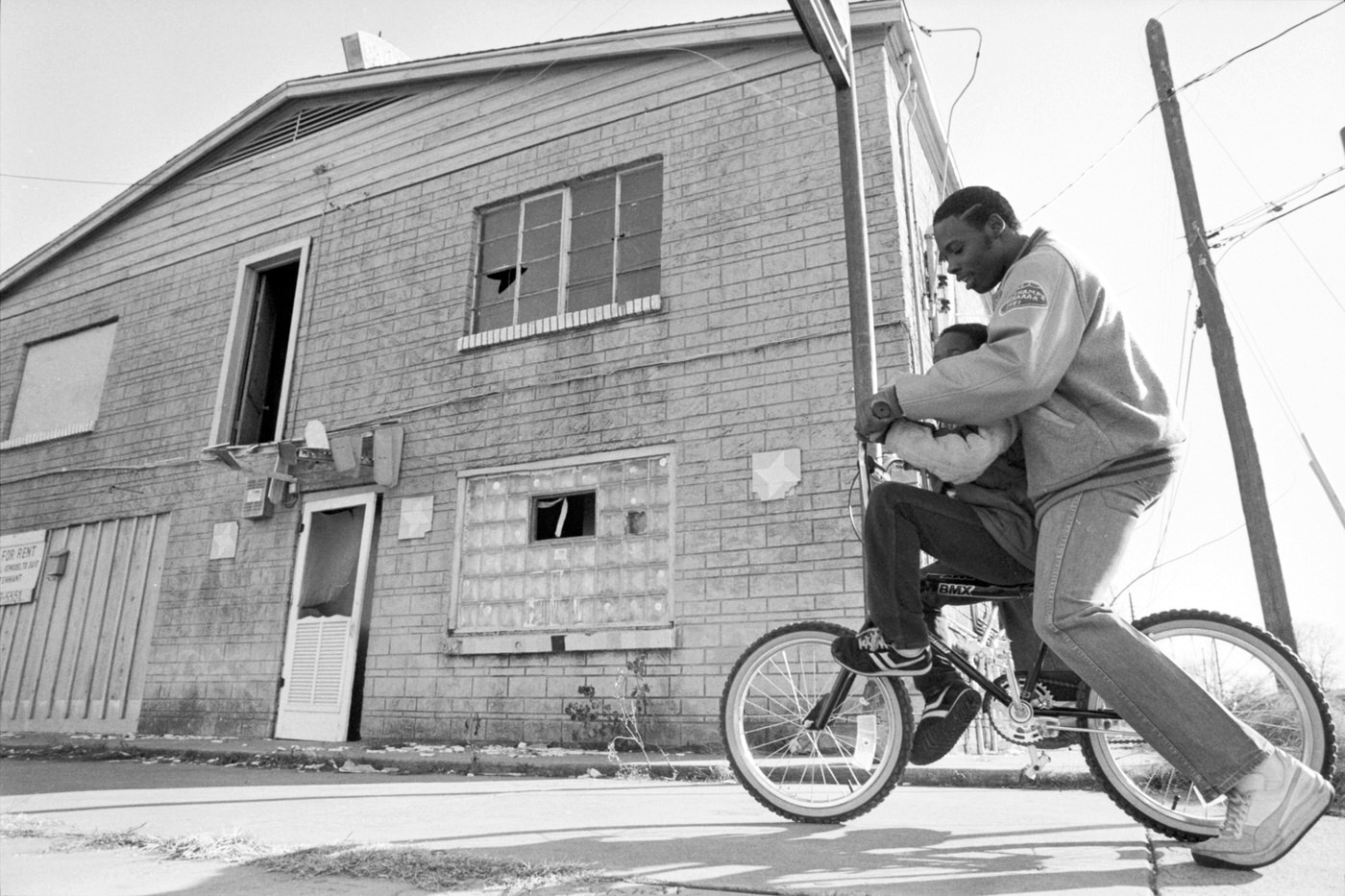

For many families, especially those with children, life centered around the suburbs. Areas like North Richland Hills offered spacious single-family homes and access to well-regarded public schools. However, this lifestyle often meant a reliance on cars for commuting, shopping, and accessing entertainment or cultural venues, which were frequently located back towards the city center or in other suburban hubs. While suburban growth was the dominant trend, some older neighborhoods closer to the city core began showing early signs of reinvestment. In the Near Southside district, Magnolia Village saw pioneering businesses start renovating historic turn-of-the-century buildings during the 1980s, laying the groundwork for future revitalization. Many inner-city areas, however, still contended with aging housing stock resulting from decades of outward migration.

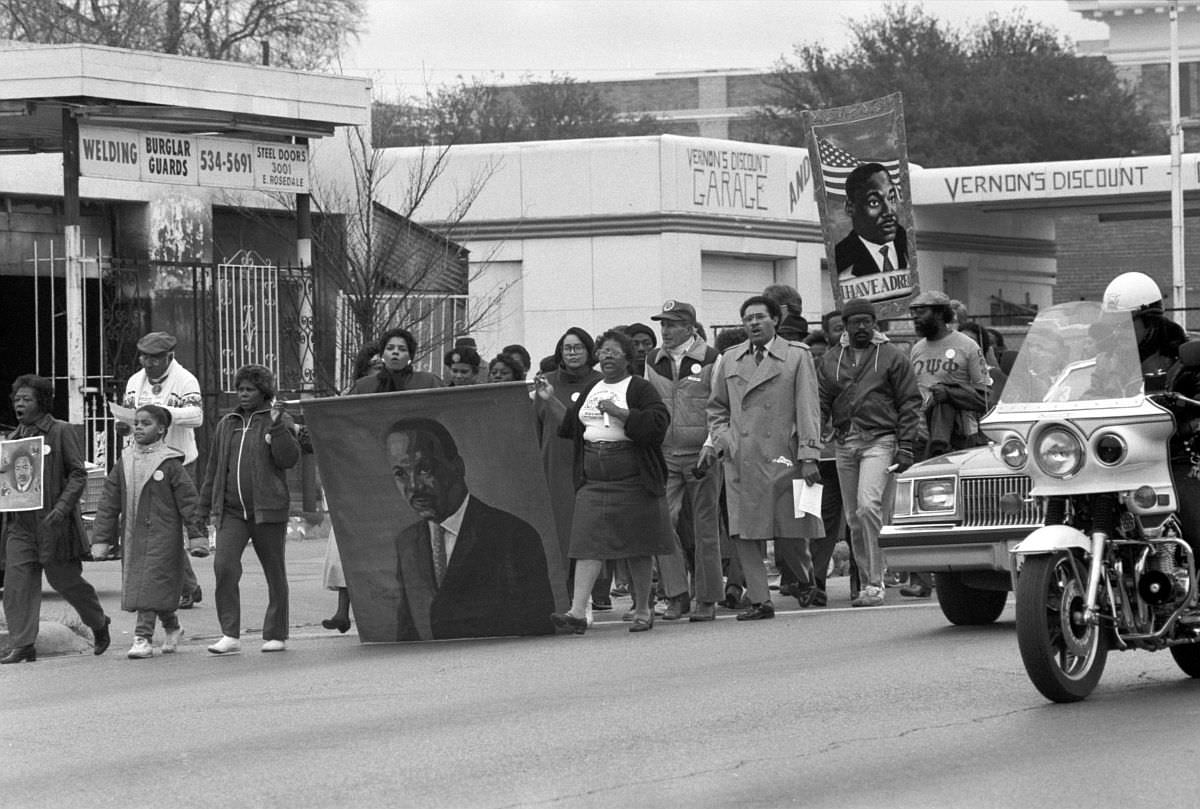

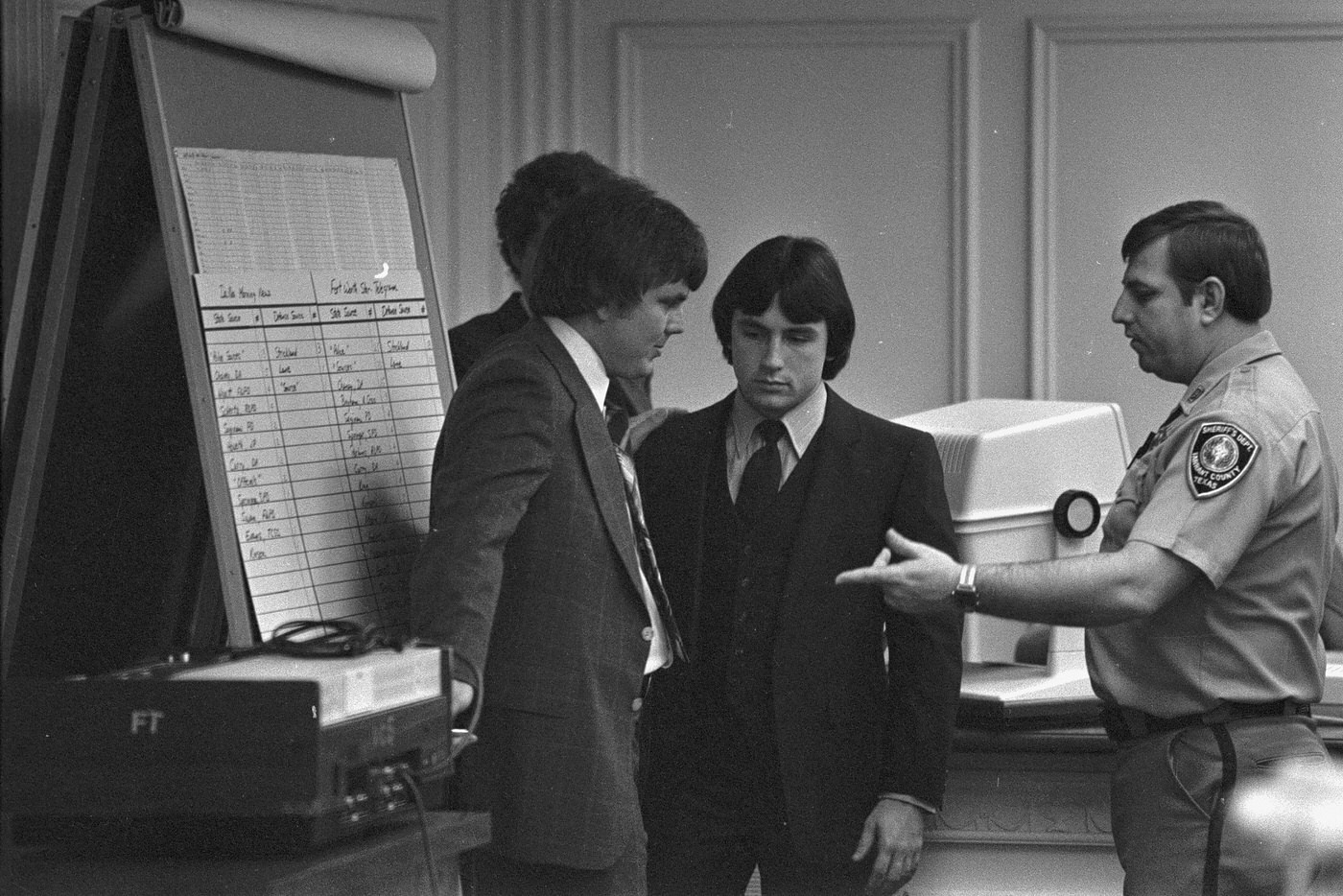

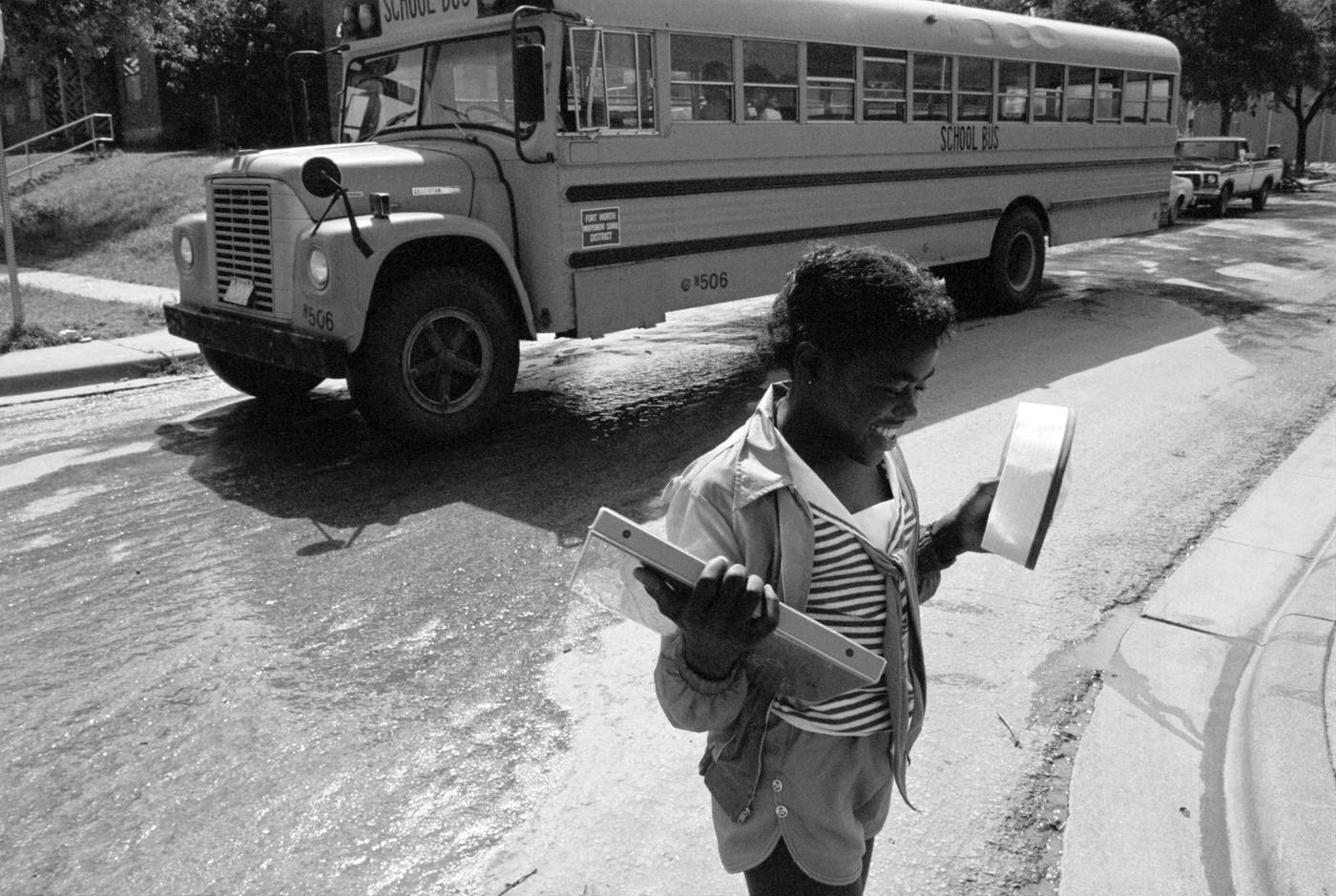

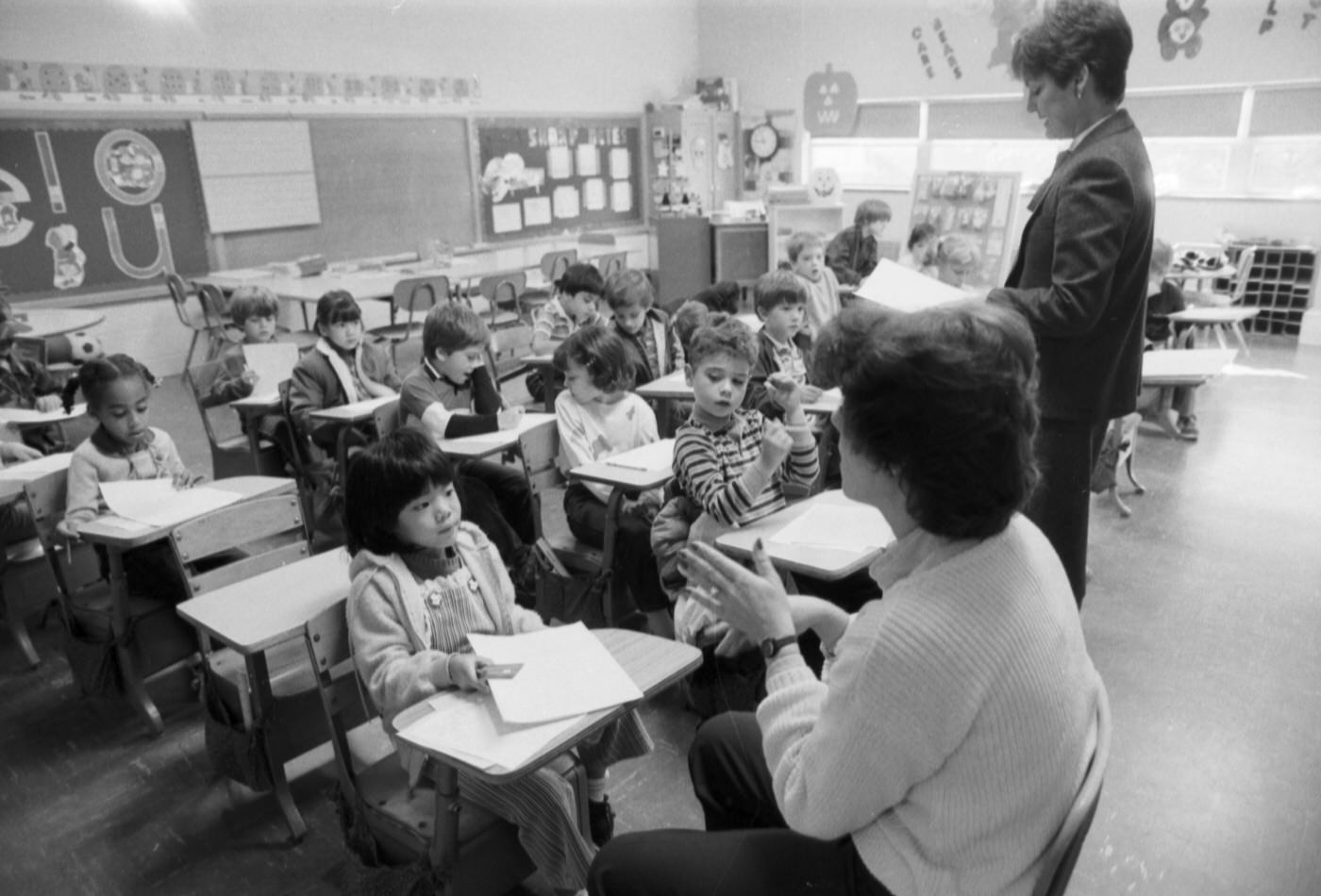

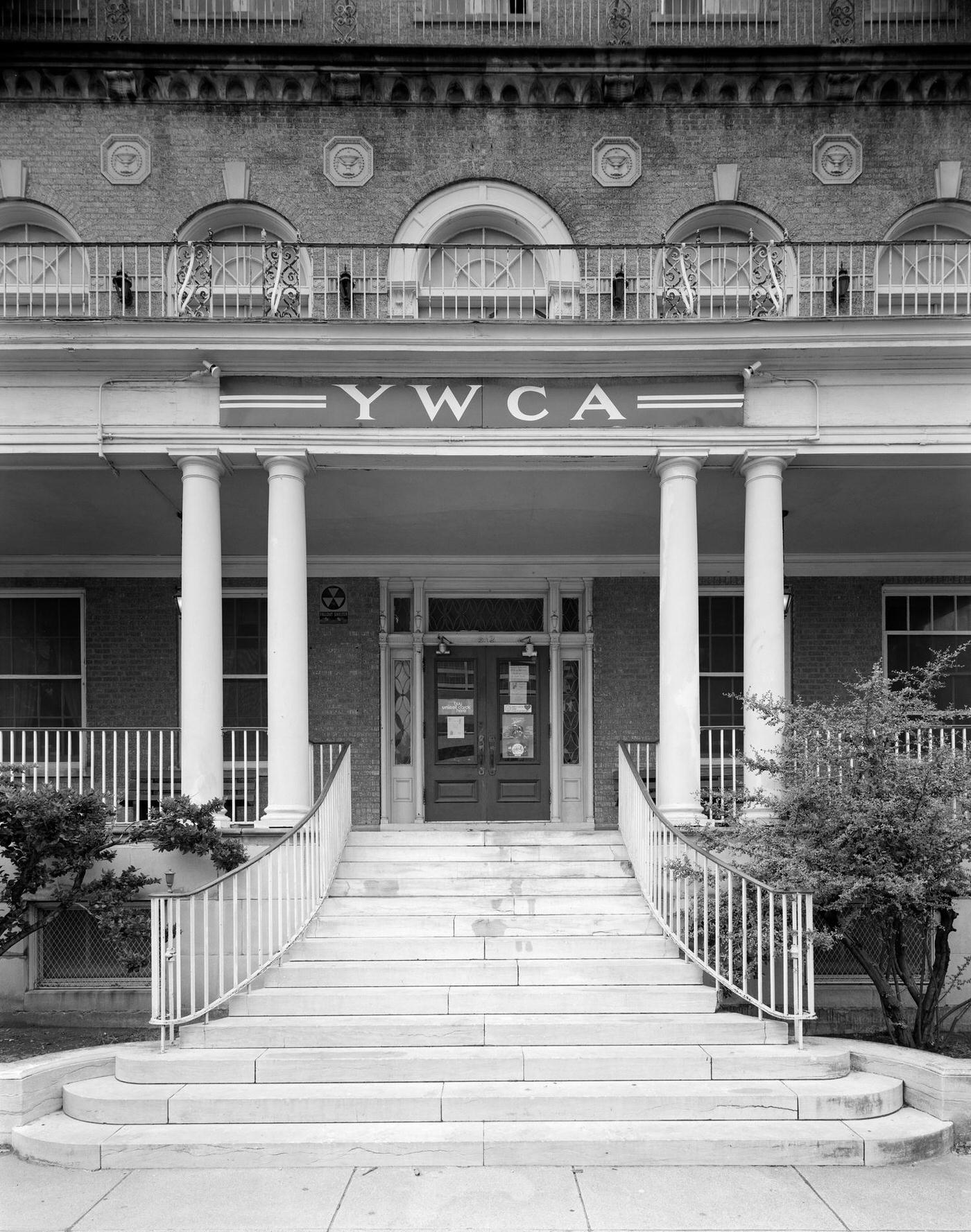

The Fort Worth Independent School District (FWISD) spent the 1980s navigating the complexities of desegregation under federal court oversight. The district had been ordered to dismantle its dual school system for Black and white students back in the early 1960s. Throughout the 60s and 70s, various plans involving busing, school pairings (clustering), and transfer policies were implemented. This process continued actively into the 1980s. In 1983, the court approved amendments to the desegregation plan, stemming from recommendations by a Citizens’ Advisory Committee. This plan aimed to balance desegregation tools with initiatives focused on “quality education” and formally recognized Mexican-American students as a distinct ethnic minority group within the district. Legal oversight persisted, with further modifications to school boundaries, funding allocations, and faculty racial balance requirements occurring in 1988. Gary Manny became president of the Fort Worth School Board that same year. By the end of the decade, in 1989, a federal court declared the FWISD had achieved unitary status in most areas (faculty/staff assignment, transportation, facilities, extracurriculars), meaning it had largely eliminated the vestiges of the former segregated system. However, the court acknowledged that some schools remained predominantly one-race due to housing patterns, a situation deemed not constitutionally problematic given the district’s efforts. The decade also saw struggles over the preservation of historic school buildings, with community efforts sometimes saving structures like the former North Fort Worth High School (J.P. Elder Annex) and Alice Carlson Elementary from demolition after closures.

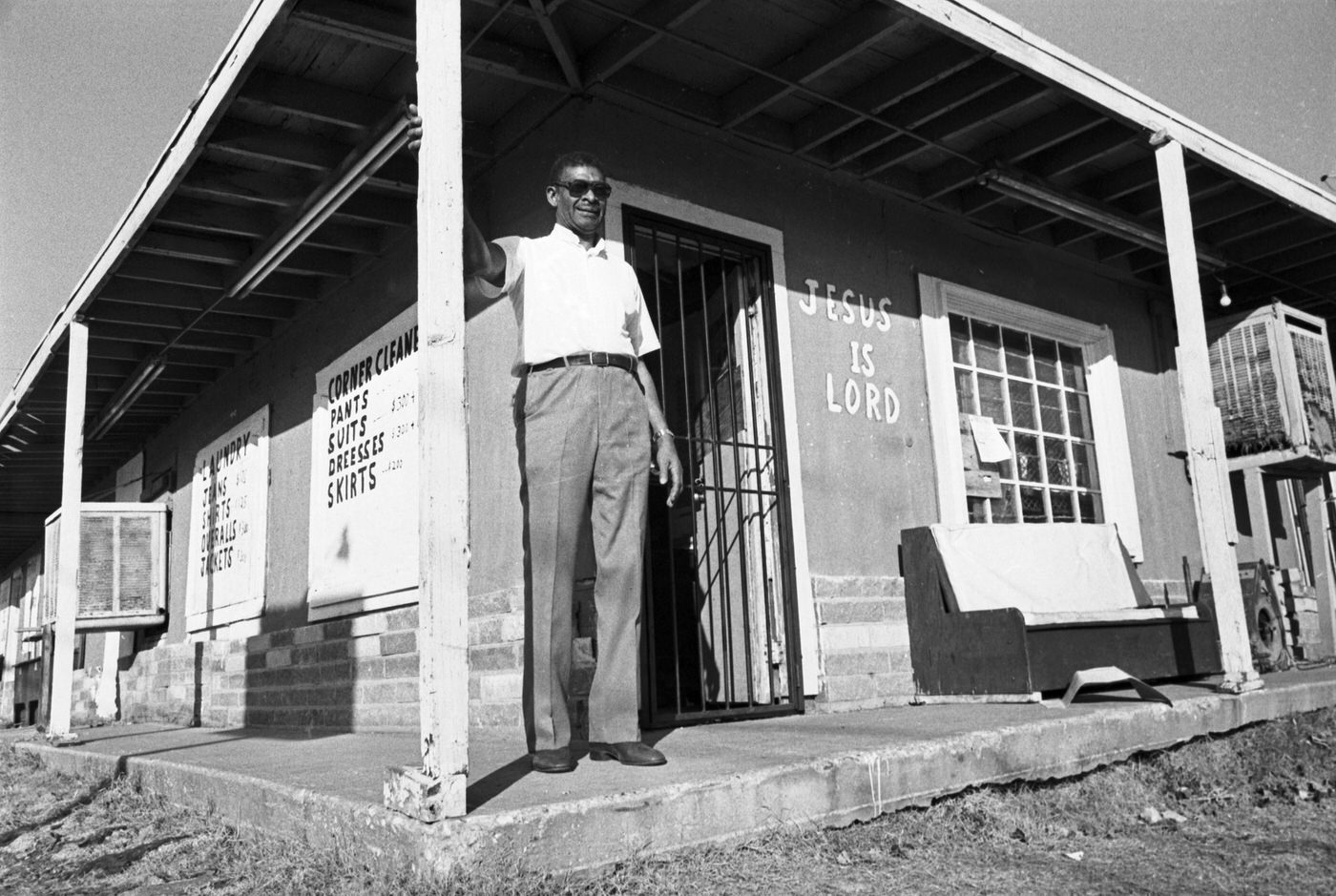

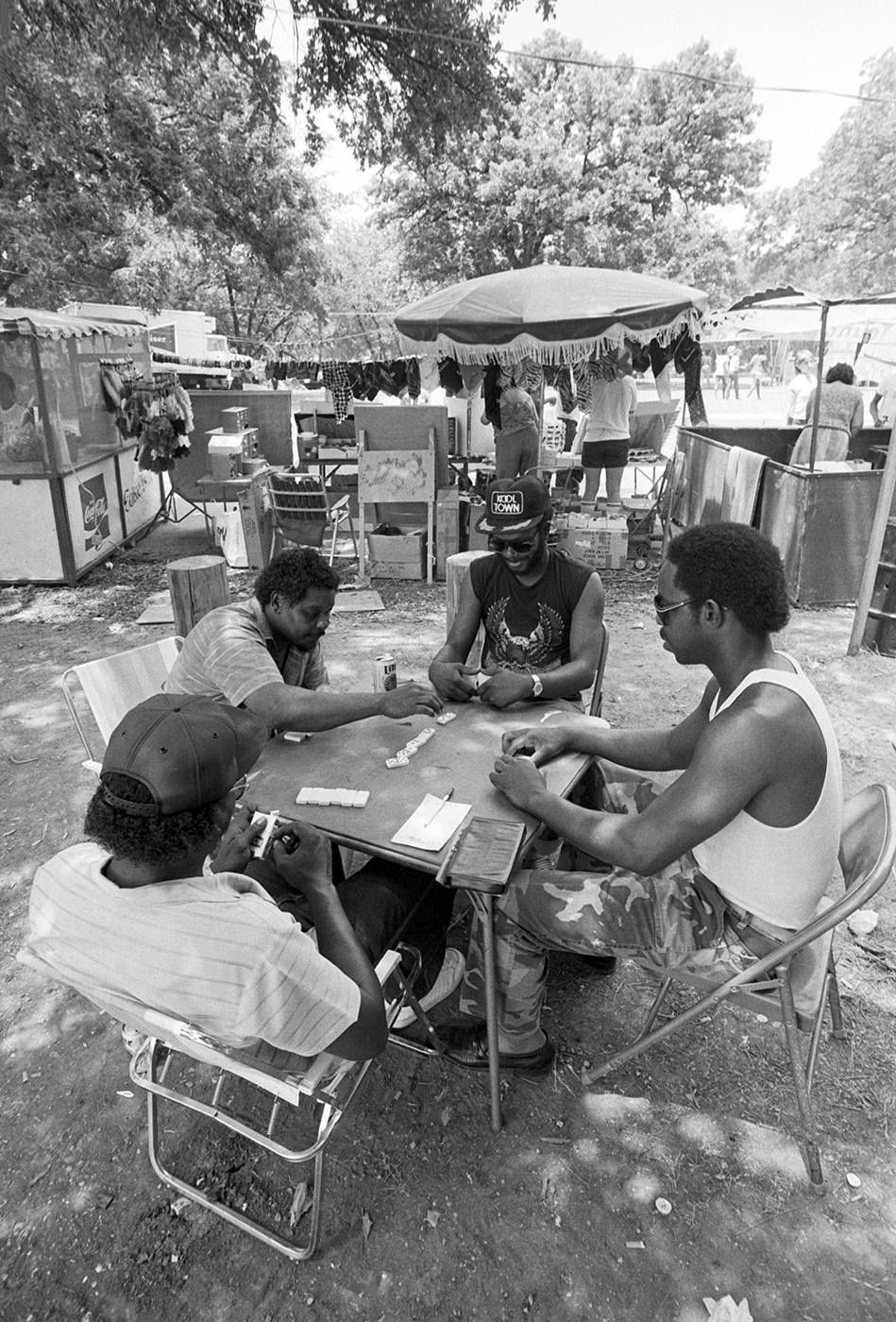

When it came to dining, Fort Worth residents had a growing number of national chain restaurants, like Chili’s and Red Lobster, offering familiar fare. Buffets were particularly popular choices for families, with establishments like Furr’s Cafeteria and the regional favorite Pancho’s Mexican Buffet drawing crowds. Alongside these chains, distinctive local eateries thrived. In the Stockyards area, Big Apple BBQ was a well-remembered spot famous for its sauce. Even after the restaurant closed, its cook, Papy Williams, continued serving the same style of barbecue from a trailer in the Stop Six neighborhood well into the 1980s. This mix of national chains and unique local spots provided the backdrop for meals and gatherings in 80s Fort Worth.

Getting Around: Highways and Public Transit

Mobility in 1980s Fort Worth was largely defined by the automobile and the expanding network of highways connecting the city and its sprawling suburbs. However, the decade also saw the formal establishment of a unified public transportation system.

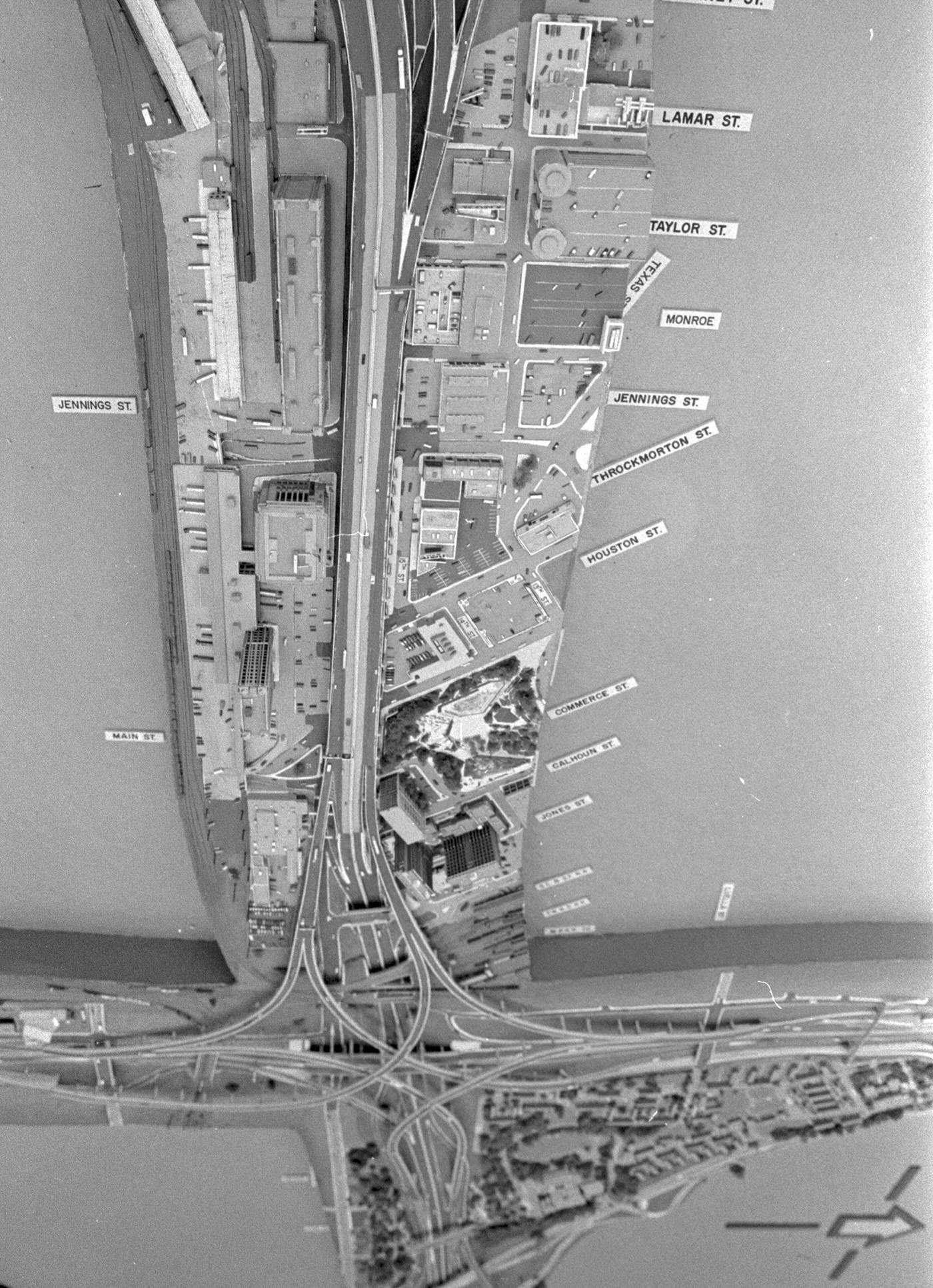

The freeway system was the backbone of transportation for most residents. Interstate 35W (I-35W), the main north-south artery, underwent significant upgrades. A major project completed in 1989 widened the stretch between downtown Fort Worth and the I-20 interchange from four or six lanes to eight lanes, reflecting the increasing traffic demands. Further south, the massive interchange connecting I-35W and I-20, originally a 1955 cloverleaf design, was being completely rebuilt, with the new interchange completed in 1991, meaning construction was likely active in the late 80s. To the north, segments of I-35W and its frontage roads were being constructed near the developing Alliance area towards the end of the decade. Interstate 30 (I-30) served as the primary east-west connector, linking Fort Worth with Dallas and points east. The section between the two cities was formerly the Dallas-Fort Worth Turnpike, with tolls removed in 1977. I-30 intersected with I-35W near downtown via an interchange built in 1958, although this junction would undergo a major reconstruction completed much later, in 2003. The heavy reliance on these freeways shaped the city’s development patterns.

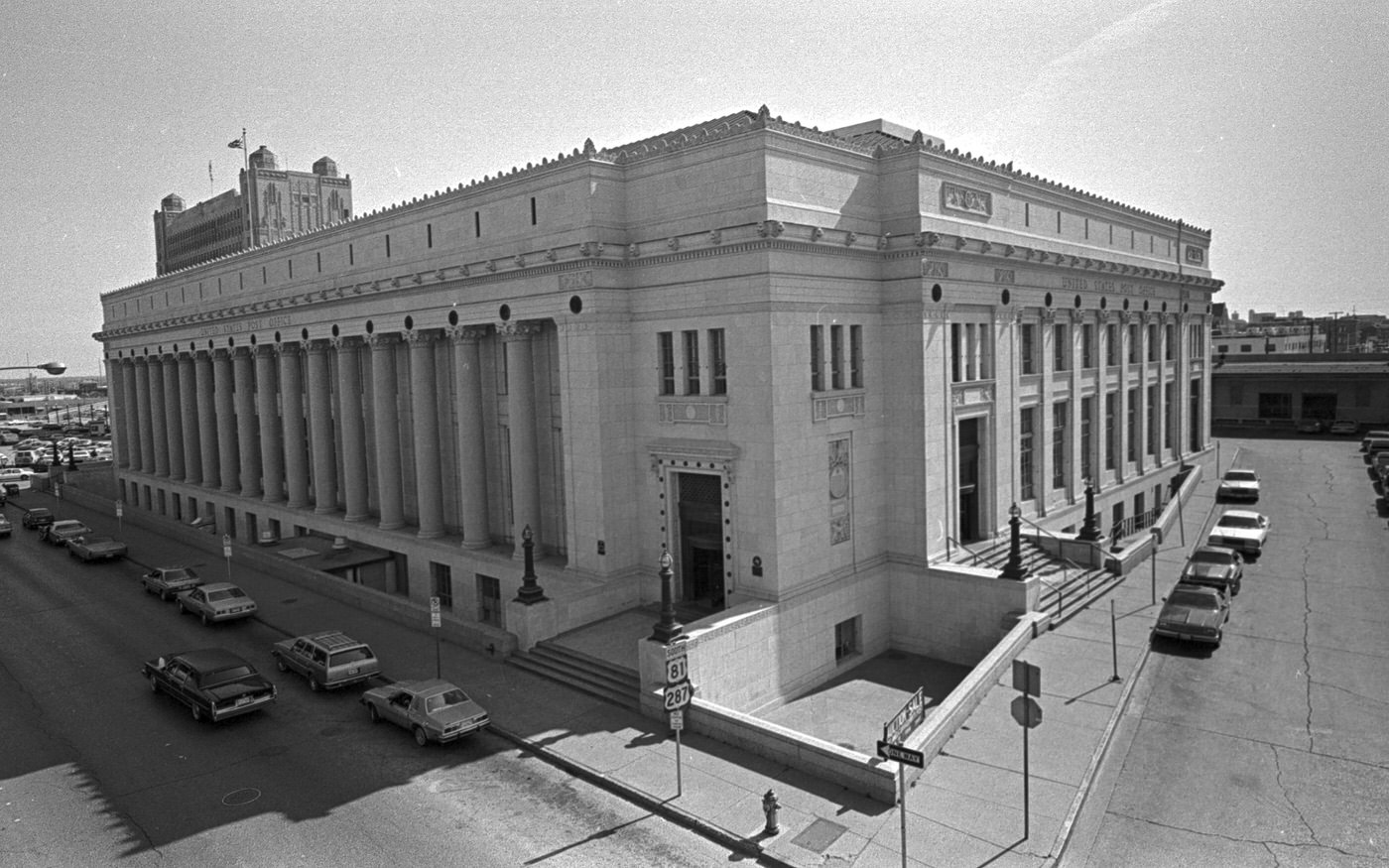

While cars dominated, efforts were made to provide public transit options. In November 1983, Fort Worth voters approved the creation of the Fort Worth Transportation Authority (FWTA), branded as “The T”. Funded by a dedicated half-cent sales tax, The T consolidated the existing city-run bus service (known as CITRAN) and SURTRAN (a shuttle service connecting Fort Worth, Dallas, and Arlington to DFW Airport) into a single agency. The T became responsible for operating the network of bus routes providing local service throughout the city and feeder connections. The agency acquired new buses during the decade to support its operations. A unique, though localized, transit element also continued to operate: the Tandy Center Subway. This short, privately owned line used repurposed electric streetcars (PCC cars) to shuttle people between the Tandy Center complex (which included offices, the mall, and a Dillard’s department store) and large parking lots situated along the Trinity River banks. Fort Worth in the 1980s was thus a city investing heavily in its highway infrastructure to accommodate growth and car culture, while simultaneously formalizing and funding a public bus system to offer an alternative mode of transportation.

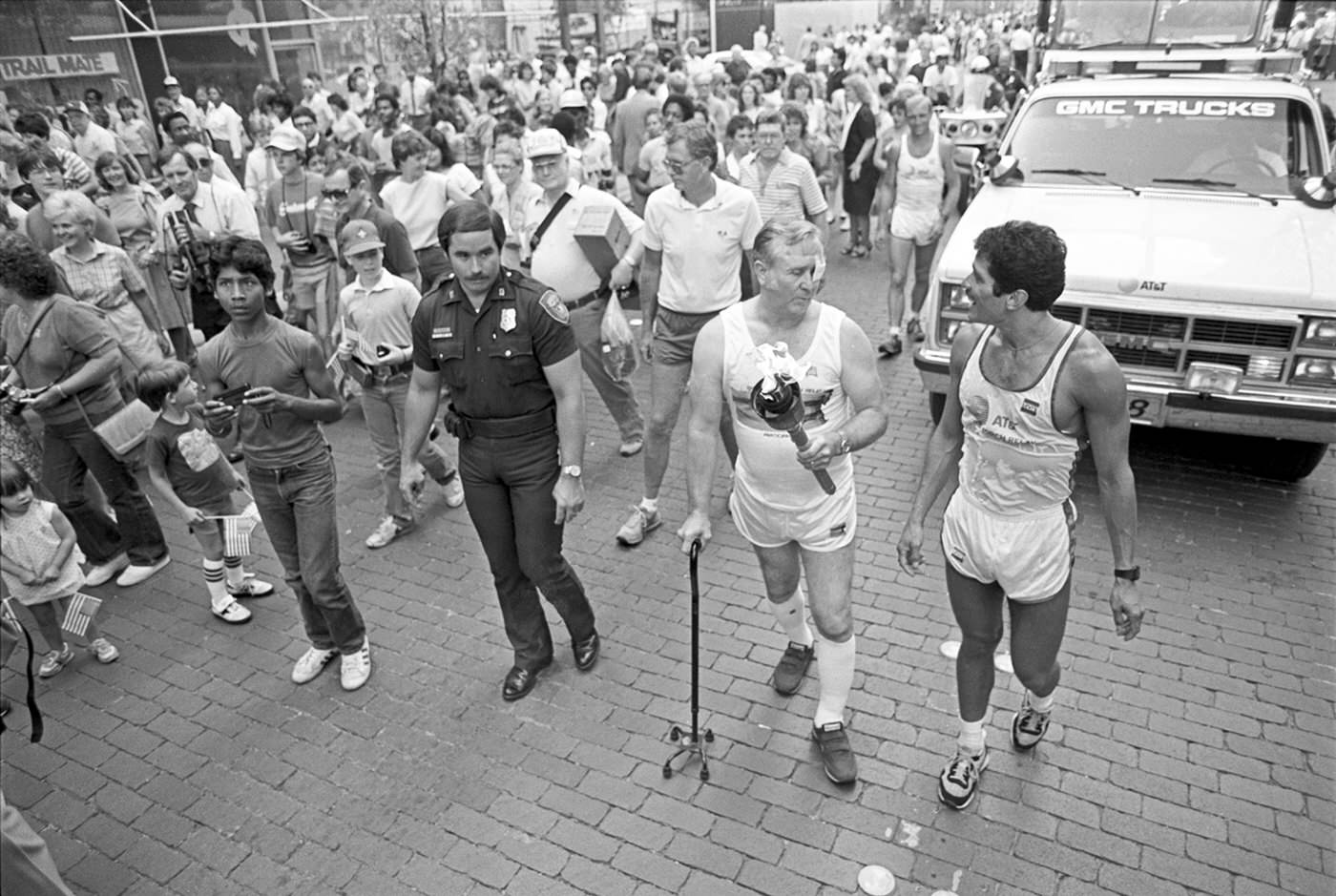

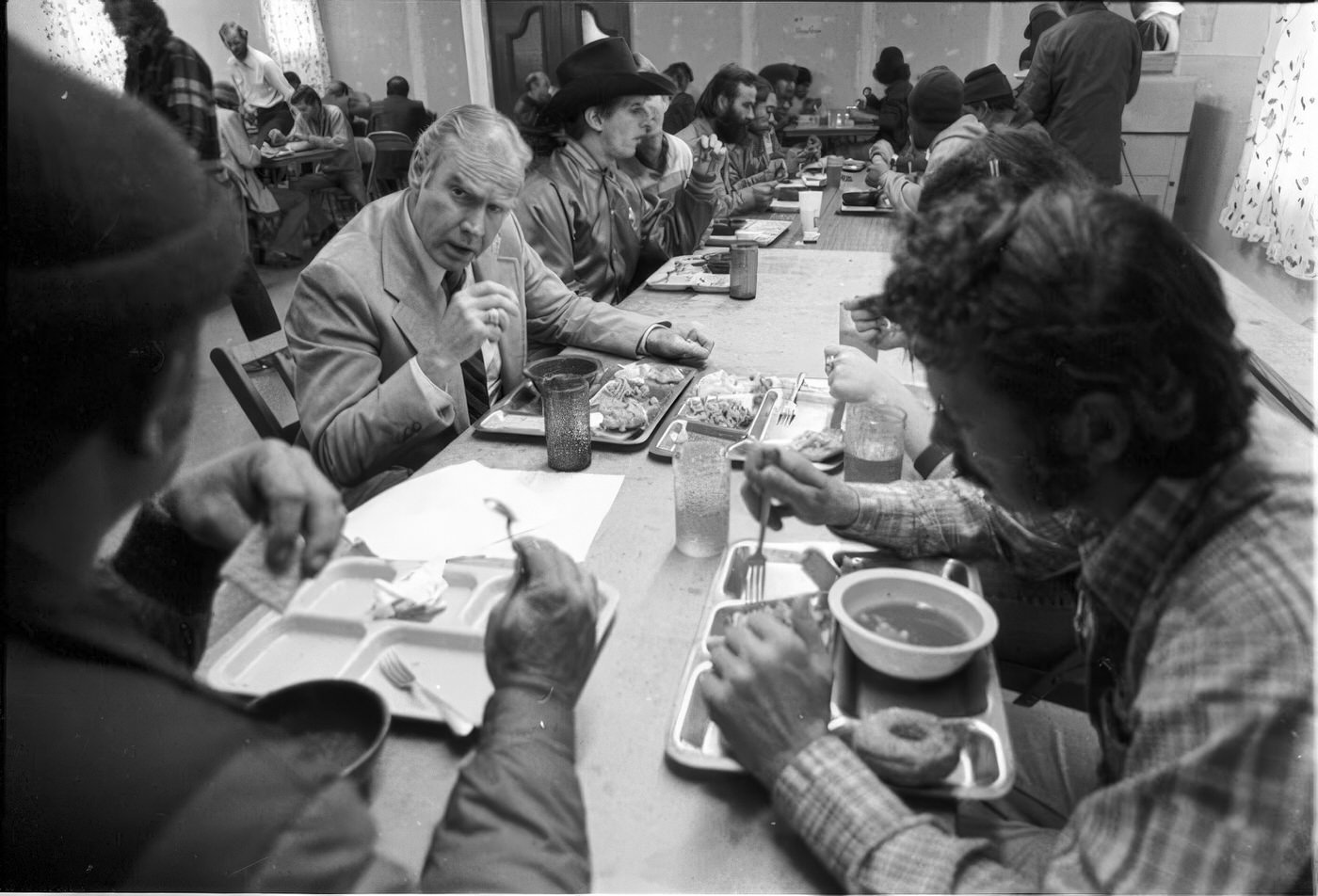

Politically, the era was largely defined by the mayoralty of Bob Bolen, who served from 1982 to 1991, becoming the city’s longest-serving mayor. A businessman who owned toy, bike, and Hallmark card shops , Bolen was known for his tireless work ethic and his ability to forge partnerships between the public and private sectors. His tenure saw the launch and advancement of several transformative projects. He was a key figure in the creation of Fort Worth Alliance Airport, the world’s first major airport designed purely for industrial and cargo purposes. This involved championing the annexation of vast tracts of land in north Tarrant County in the mid-1980s and partnering with developer Ross Perot Jr. and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Alliance Airport officially opened in 1989. Bolen also led the successful effort to convince the U.S. Treasury Department to build its first currency production facility outside of Washington D.C. in Fort Worth; the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s Western Currency Facility became a major federal presence in the city. Furthermore, Bolen was a strong supporter of downtown redevelopment, working closely with the Bass family on the Sundance Square project and helping establish the crucial downtown Public Improvement District (PID) in 1986. He also championed the creation of the Fort Worth Transportation Authority (The T) in 1983. On the international stage, Bolen established Fort Worth’s first Sister City relationships with Reggio Emilia, Italy, followed by Trier, Germany, and Nagaoka, Japan.

Image Credits: Byrd Williams Family Photography Collection, THC National Register Collection, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Basil Clemons Photograph Collection, Jan Jones Papers, UTA Libraries, Texas History Portal

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know