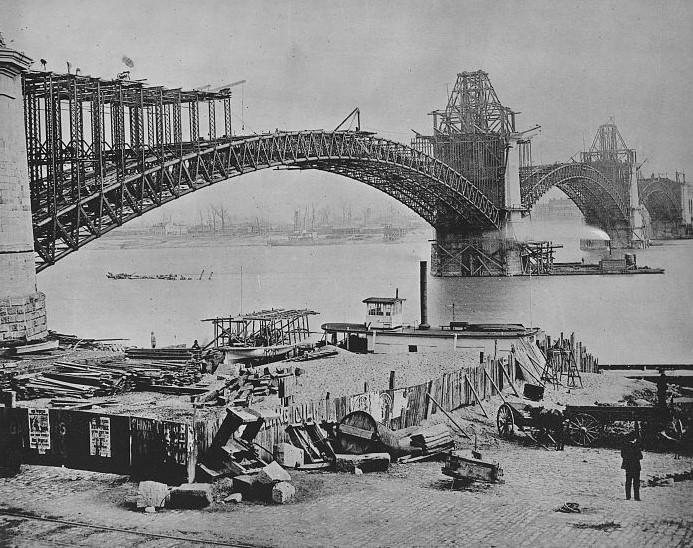

St. Louis entered the 1880s as a city undergoing significant transformation. The 1870s had set the stage for growth with events like the completion of the Eads Bridge in 1874 and the “Great Divorce” from St. Louis County in 1876. These changes, combined with national trends of industrialization and immigration characteristic of the Gilded Age, positioned St. Louis for a dynamic period of development in its economy, infrastructure, and social fabric. The city was a bustling hub, drawing people and commerce. Like many urban centers of the era, it faced both the opportunities and challenges that came with rapid expansion. The 1880s for St. Louis represent a critical juncture where the groundwork laid in the 1870s began to manifest in tangible urban growth and economic shifts, all within the broader, often turbulent, context of America’s Gilded Age. This decade was not just about recovery from earlier national events, but about actively building a modern industrial city. The Eads Bridge, designed to connect railroads across the Mississippi, fundamentally altered trade patterns away from sole reliance on river transport, and the 1880s were the first full decade to experience its economic effects. The “Great Divorce” tripled the city’s land area, setting new boundaries and responsibilities for governance and development that would unfold throughout the decade. As a major city, St. Louis was deeply enmeshed in the Gilded Age trends of industrial boom, technological innovation, and increased immigration. This confluence of local structural changes and national trends implies that the 1880s were a period where St. Louis was actively shaping its modern identity.

The Faces of a Growing City: People and Communities

The population of St. Louis surged throughout the 19th century, and the 1880s continued this trend, bringing with it a diverse array of people who would shape the city’s character. This growth placed considerable demand on housing, employment, and public services, creating a dynamic and sometimes strained social environment.

The decade began with a population of 350,518 in 1880. This figure represented a 12.9% increase from the 310,864 residents recorded in 1870. By the end of the decade, in 1890, the city’s population had further expanded to 451,770, marking an additional 28.8% growth. This robust population growth, even if at a slightly moderated percentage compared to the immediate post-Civil War boom of 93% from 1860 to 1870, signifies St. Louis’s sustained appeal as an urban center. A net gain of over 100,000 people in the 1880s was a large influx for any city and necessitated significant adjustments in all aspects of urban life. This demographic pressure was a key driver for industrial expansion, urban development, and social changes.

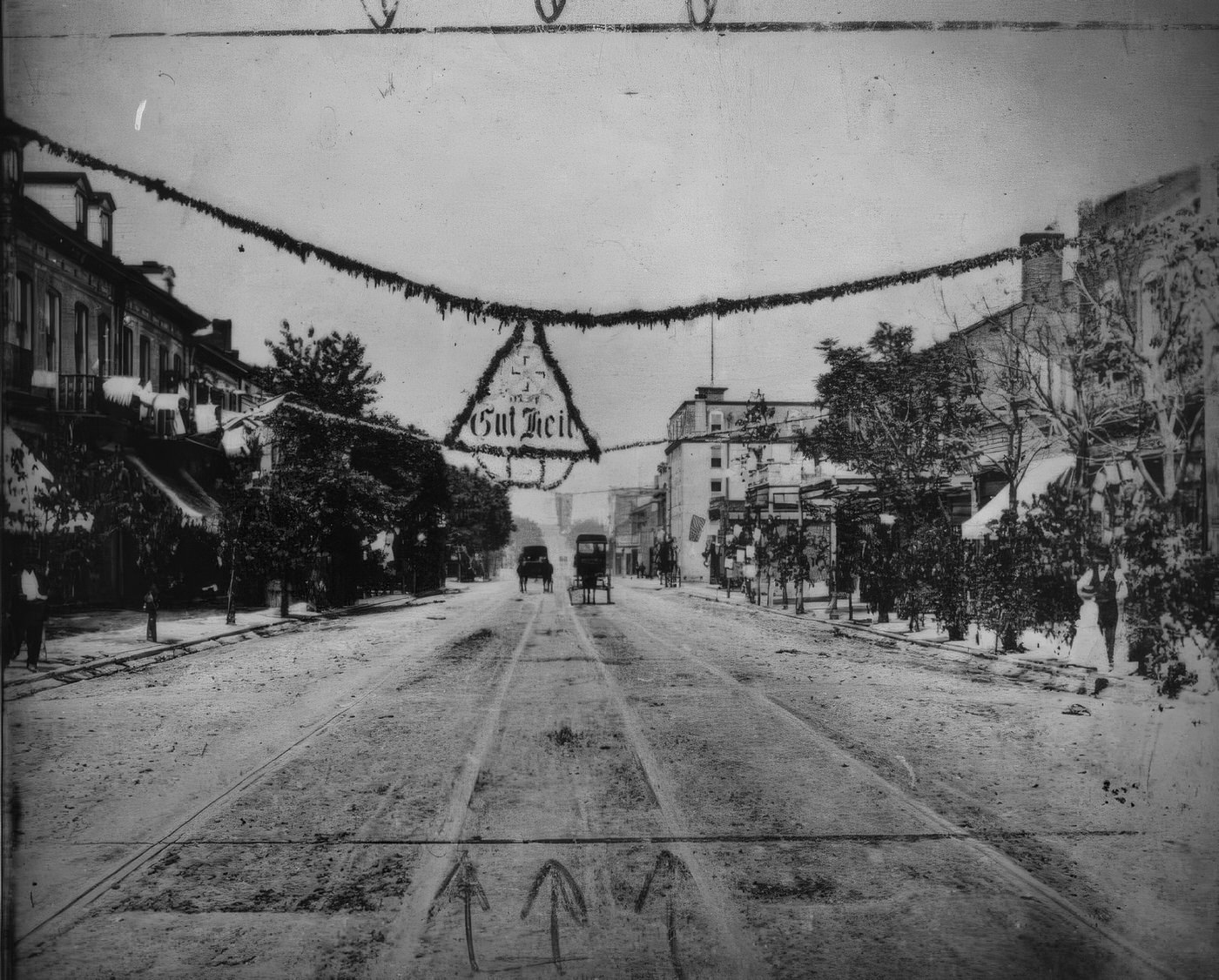

Established immigrant groups, primarily Germans and Irish, formed a significant portion of the populace. By 1880, Germans represented over half of St. Louisans claiming an ethnic identity, and their influence was evident, with 46% of public school children being of German heritage. They established strong communities with their own churches, vibrant social clubs known as Turnvereins (gymnastic societies emphasizing physical fitness and cultural activities), and influential German-language newspapers like the Westliche Post. Neighborhoods on the south side, such as Soulard and Benton Park, and north side areas like Bremen (Hyde Park), were heavily German. The Irish community, having arrived in large numbers before and after the Civil War, was also substantial. Many initially faced hardship but became integrated into the city’s workforce and established neighborhoods like “the Patch” in Carondelet. The deep roots and organized nature of these communities provided both stability and complexity to St. Louis’s social fabric, influencing local politics, labor movements, and social customs.

The 1880s also marked an increase in immigration from southern and eastern Europe. Italians began to arrive in greater numbers, laying the groundwork for “The Hill” neighborhood. Czech immigrants, also known as Bohemians, settled in areas like LaSalle Park, establishing institutions such as St. John Nepomuk Chapel. These newer immigrants often found employment in the city’s expanding factories and construction trades, sometimes living in crowded tenements on the near south side. The Chinese community, though smaller, continued to grow around its “Hop Alley” commercial and residential center. The influx of these new groups added further layers to St. Louis’s multicultural identity and supplied crucial labor for its industries.

The African American population in St. Louis increased to 6.36% of the total by 1880, partly due to migrations like the Exoduster movement of 1879, as individuals sought opportunities away from the post-Reconstruction South. This community actively built its own institutions. Churches such as St. Paul’s AME, which constructed its building in 1872, Quinn Chapel AME, St. James AME, First Baptist, and Central Baptist were central to community life, often serving as centers for organization and relief. Education was a priority, with Sumner High School (established 1875) being the first high school for African Americans west of the Mississippi, and Elleardsville Colored School No. 8 (in what became The Ville) having African American teachers by 1877. The Ville neighborhood was emerging as an important residential and cultural center. However, this period also saw the hardening of racial segregation, with Jim Crow laws beginning to take root. This duality shaped the urban experience for African Americans, fostering internal strength while facing external limitations.

Economy and Industry

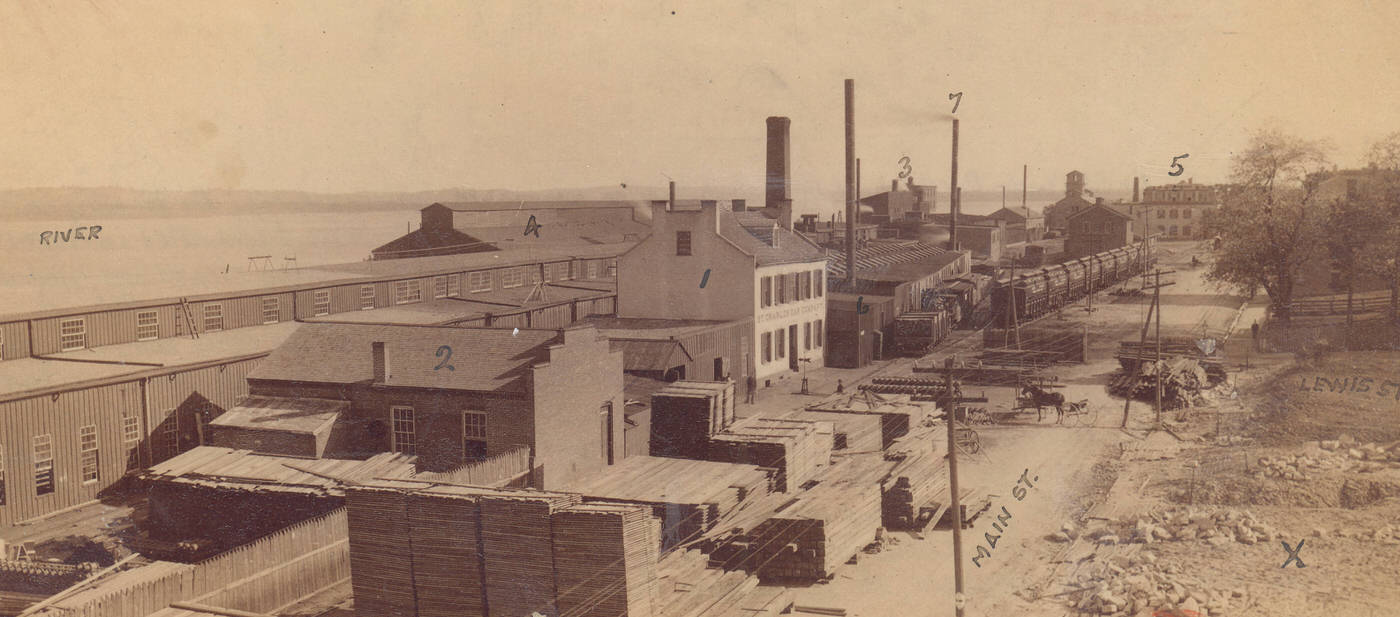

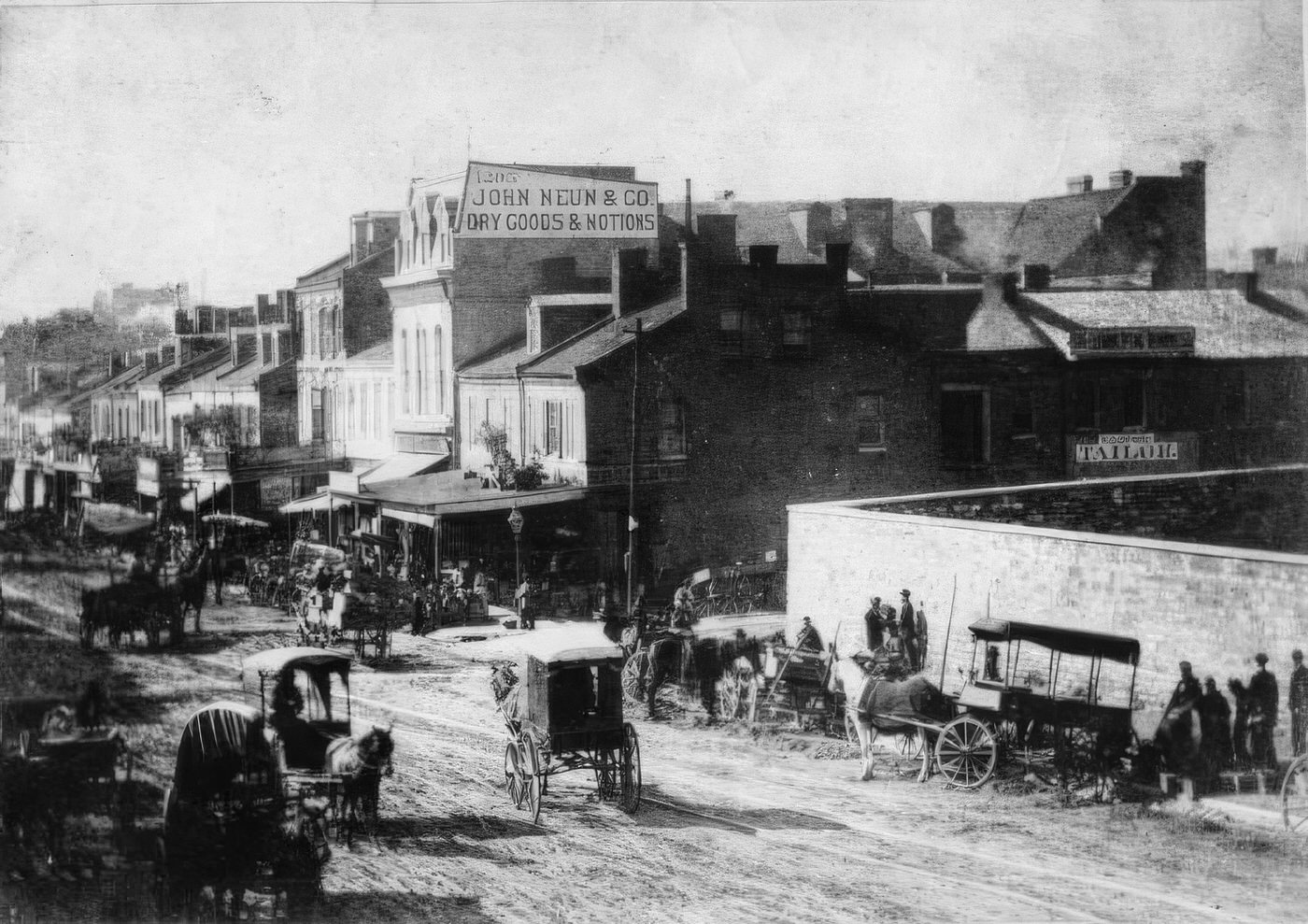

St. Louis in the 1880s was a powerhouse of industrial activity, its growth fueled by diverse manufacturing sectors and an evolving transportation network. The city’s manufacturing output value was recorded at $104,383,587 in 1880 for the city proper, with the broader St. Louis Industrial Area reaching $139,519,484. These figures underscore St. Louis’s mature status as a manufacturing center at the decade’s outset, poised to capitalize on the Gilded Age’s industrial expansion. This established base, with existing factories, transport links, and a growing labor pool from immigration, attracted further investment.

Brewing was a flagship industry. Giants like Anheuser-Busch and Lemp dominated the scene. Adolphus Busch of Anheuser-Busch was an innovator, using refrigerated railroad cars and pasteurization to distribute beer nationally, making Budweiser a leading brand. St. Louis was the third-largest beer producer in the country after the Civil War. Attached beer gardens, such as Joseph Schnaider’s, became popular social and entertainment venues, serving thousands daily with food, drink, music, and theater.

Tobacco processing was another area where St. Louis excelled, particularly in plug chewing tobacco. Liggett & Myers, incorporated in 1873, had become the world’s largest manufacturer of plug chewing tobacco by 1885. The Drummond Tobacco Company was also a major player, with many industry leaders hailing from nearby tobacco-growing regions. Flour milling remained a significant sector, even as Minneapolis began to emerge as a national leader. The E.O. Stanard Milling Company was a prominent local firm.

The meatpacking industry saw East St. Louis, Illinois, develop as an important stockyard and processing center with the establishment of the National Stock Yards in 1873, closely linked economically to St. Louis. By 1880, meatpacking was a massive employer in St. Clair County, Illinois. Innovations like the refrigerated railway car, pioneered by figures such as Gustavus Swift, transformed the industry nationally, allowing for wider distribution of fresh meat.

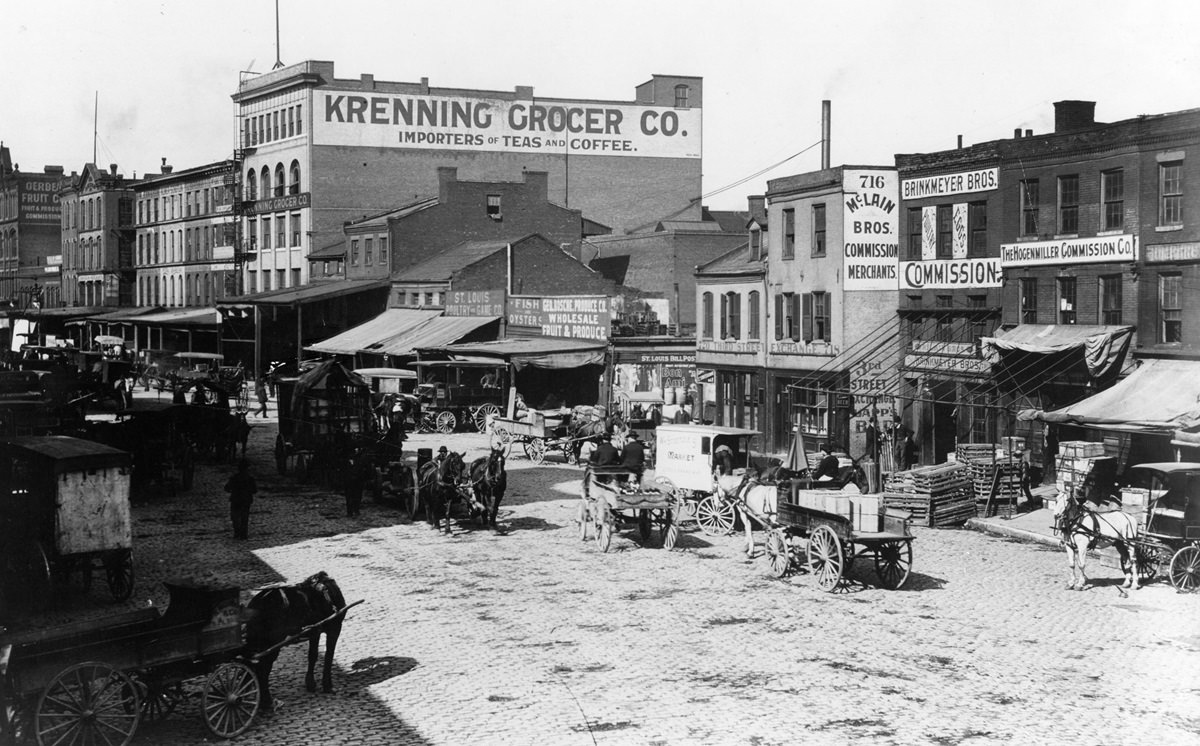

Shoe manufacturing was a rapidly growing industry. The Hamilton-Brown Shoe Company, for example, built a factory in 1888 and aimed for world leadership in boots and shoes. The Lasters’ Protective Union, organized in 1880, signaled an active workforce in this sector. The garment industry, centered on Washington Avenue, also expanded, driven by the mail-order business. Firms like N & J Friedman’s employed hundreds in producing ready-made clothing. The iron and steel industry continued to thrive, producing a wide range of goods. St. Louis also led in producing lead paint pigments and was a major coffee distribution point, with substantial operations in groceries and lumber. The city’s diverse industrial base provided resilience, and innovations like refrigerated transport were key to accessing national markets.

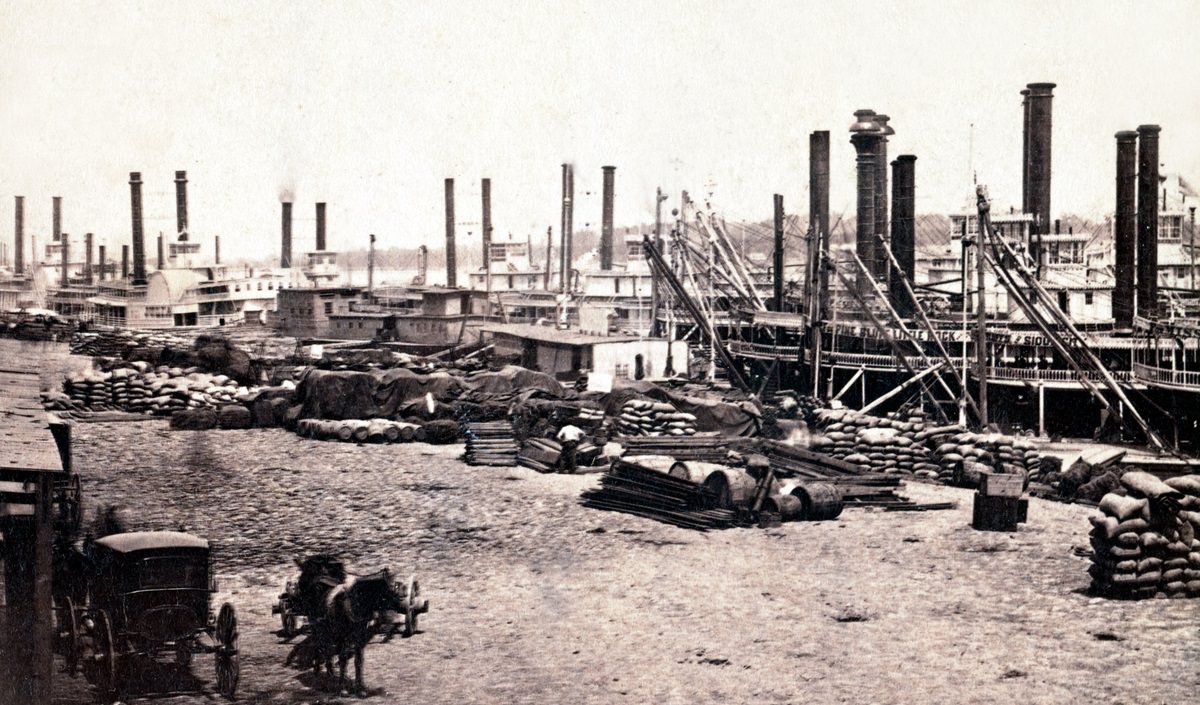

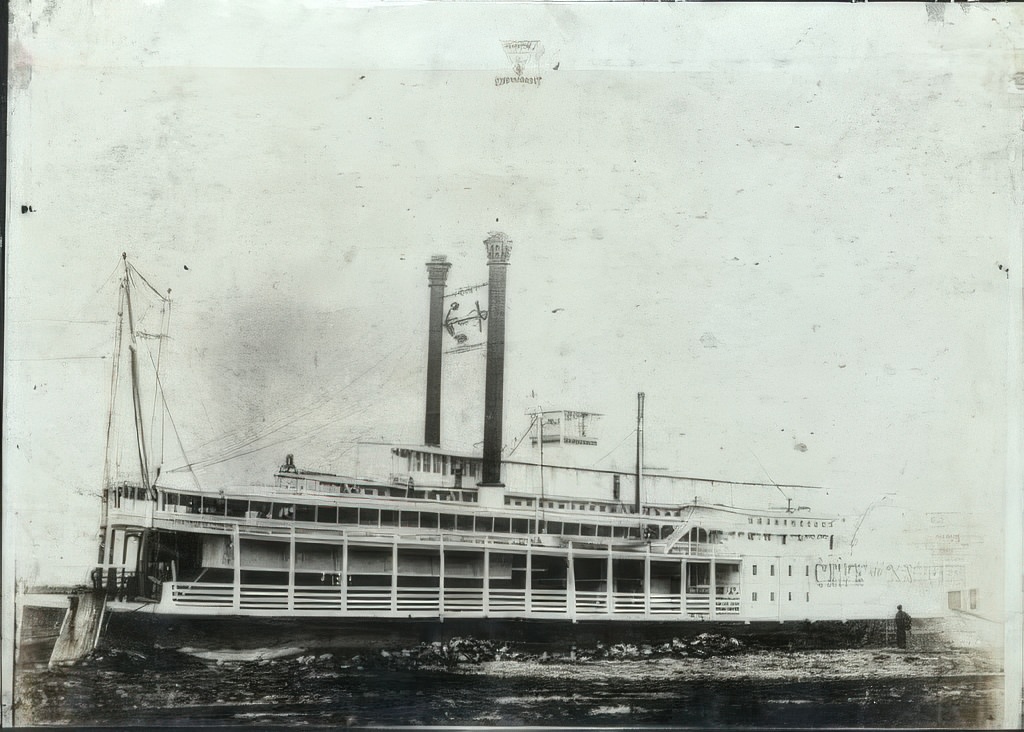

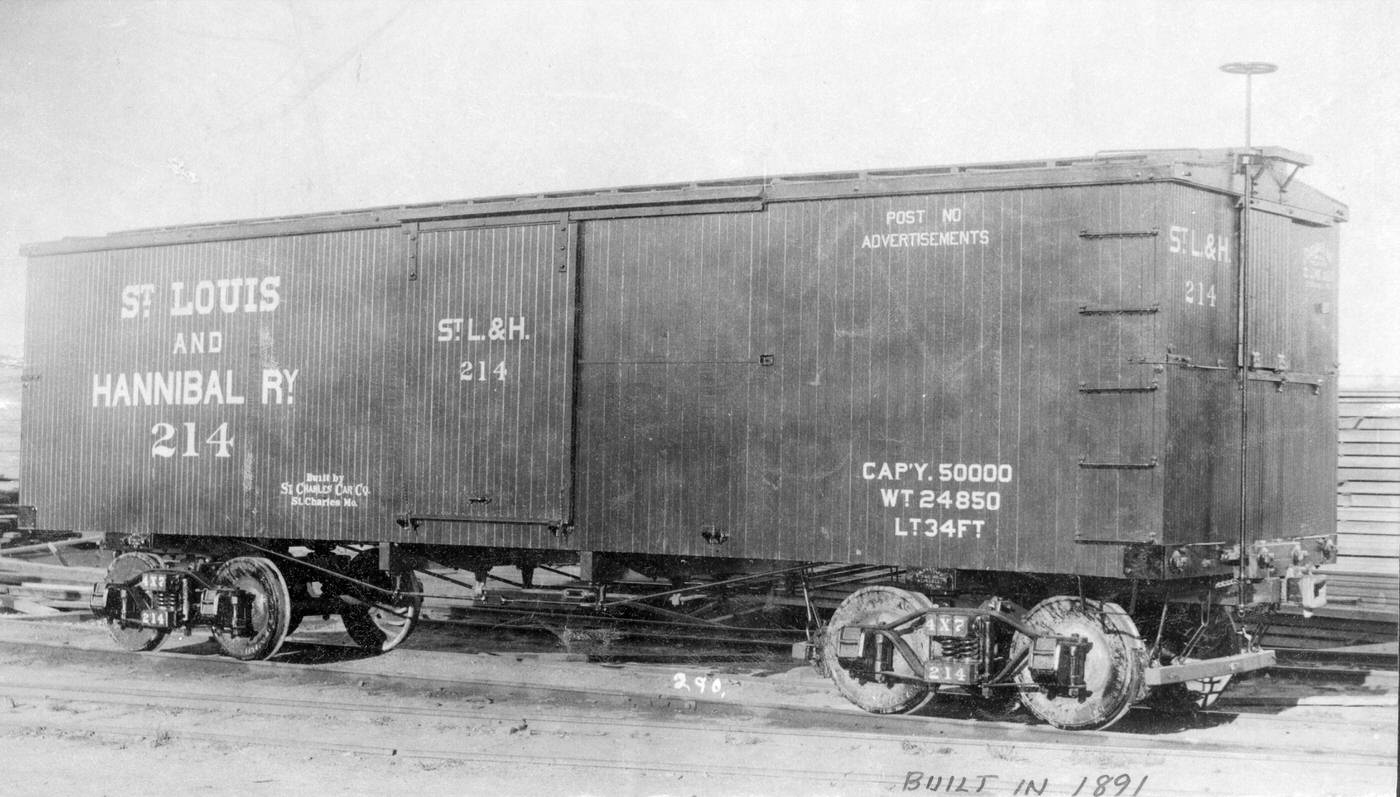

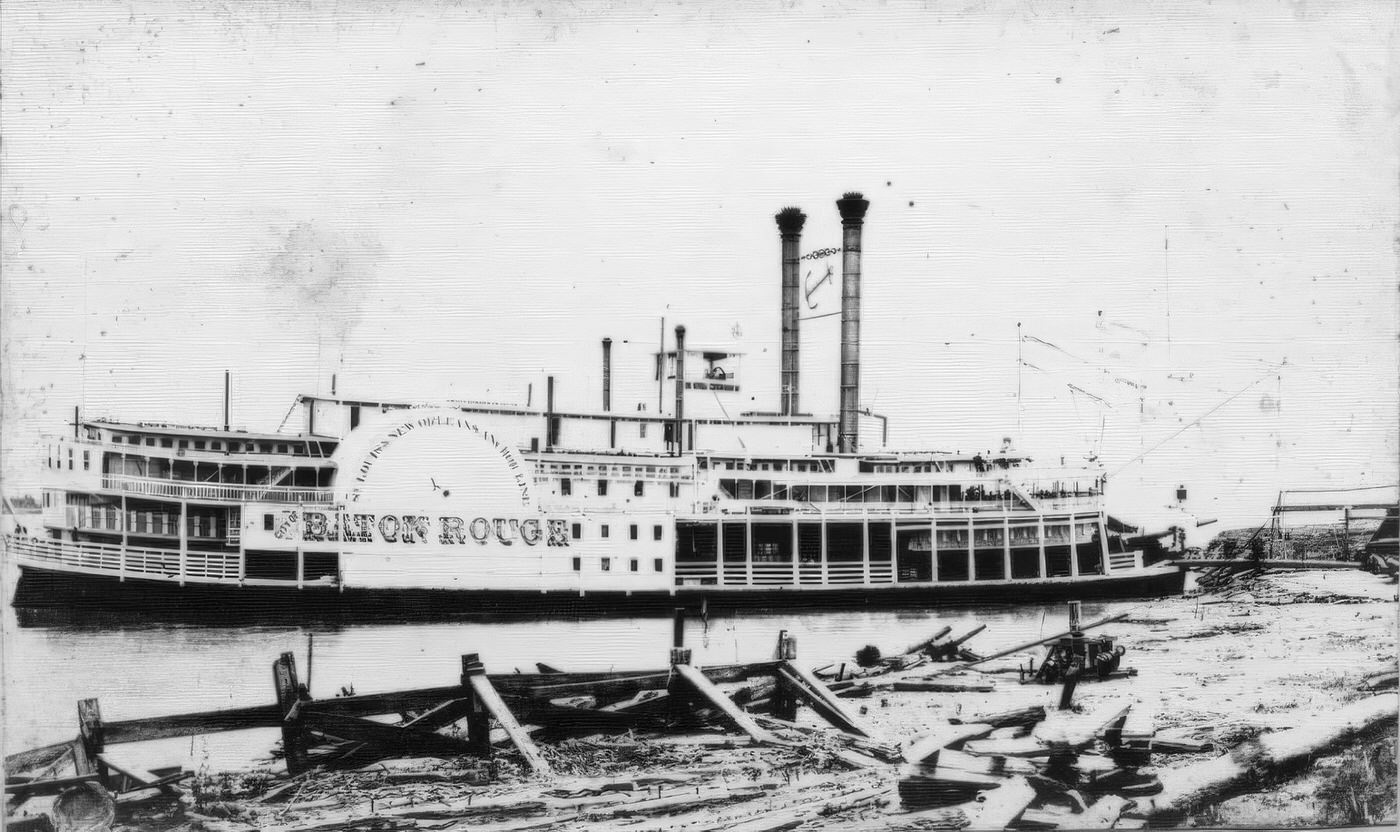

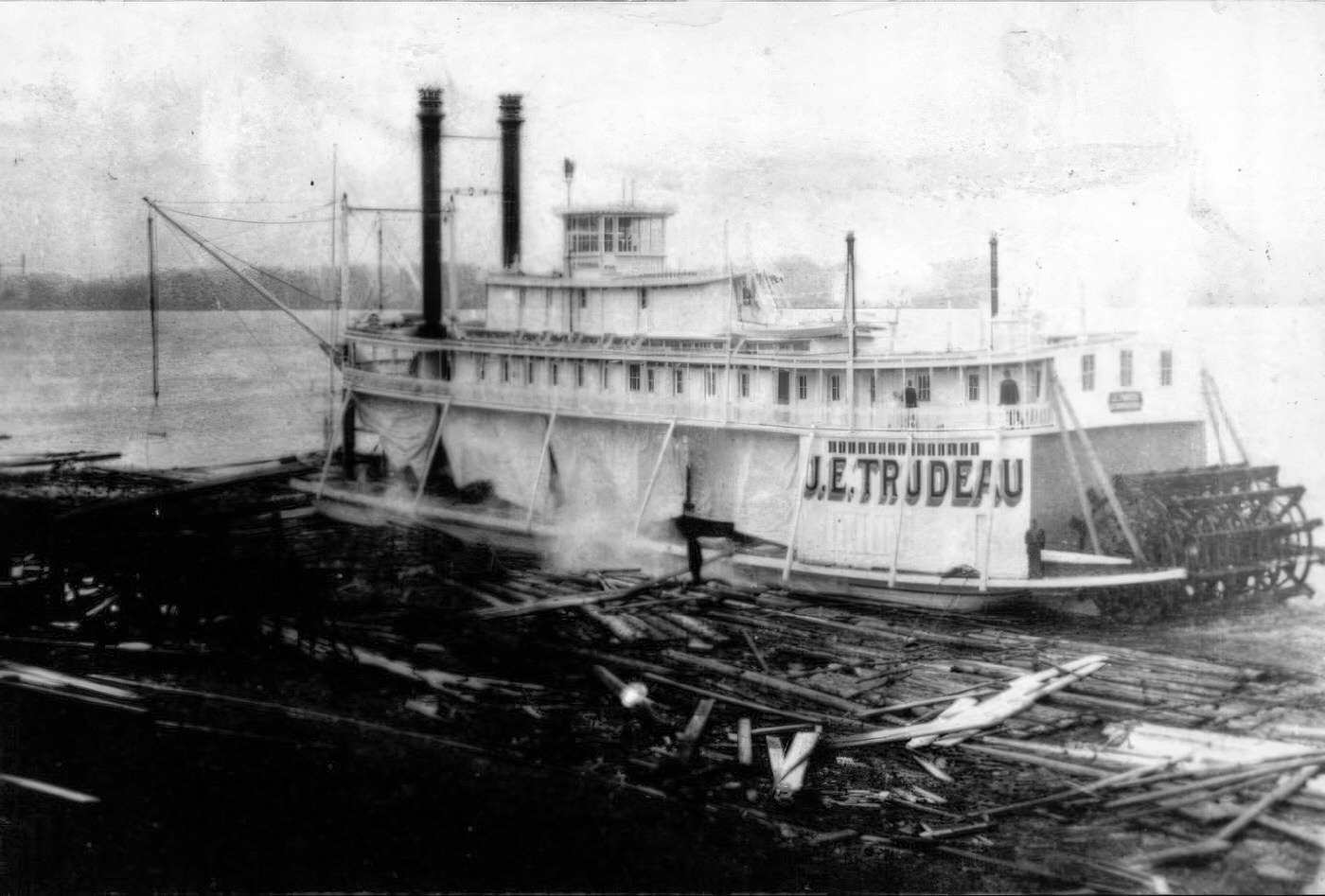

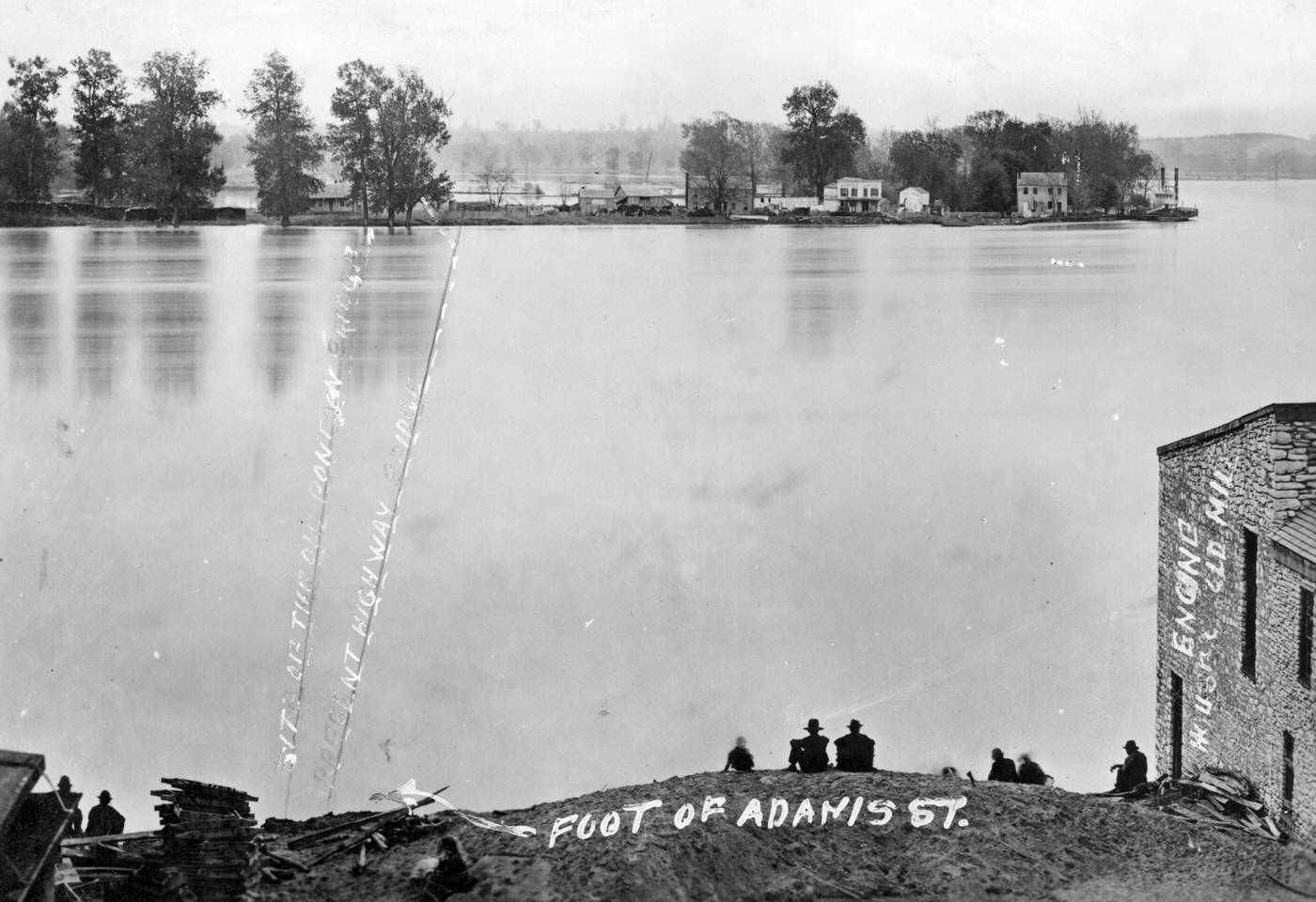

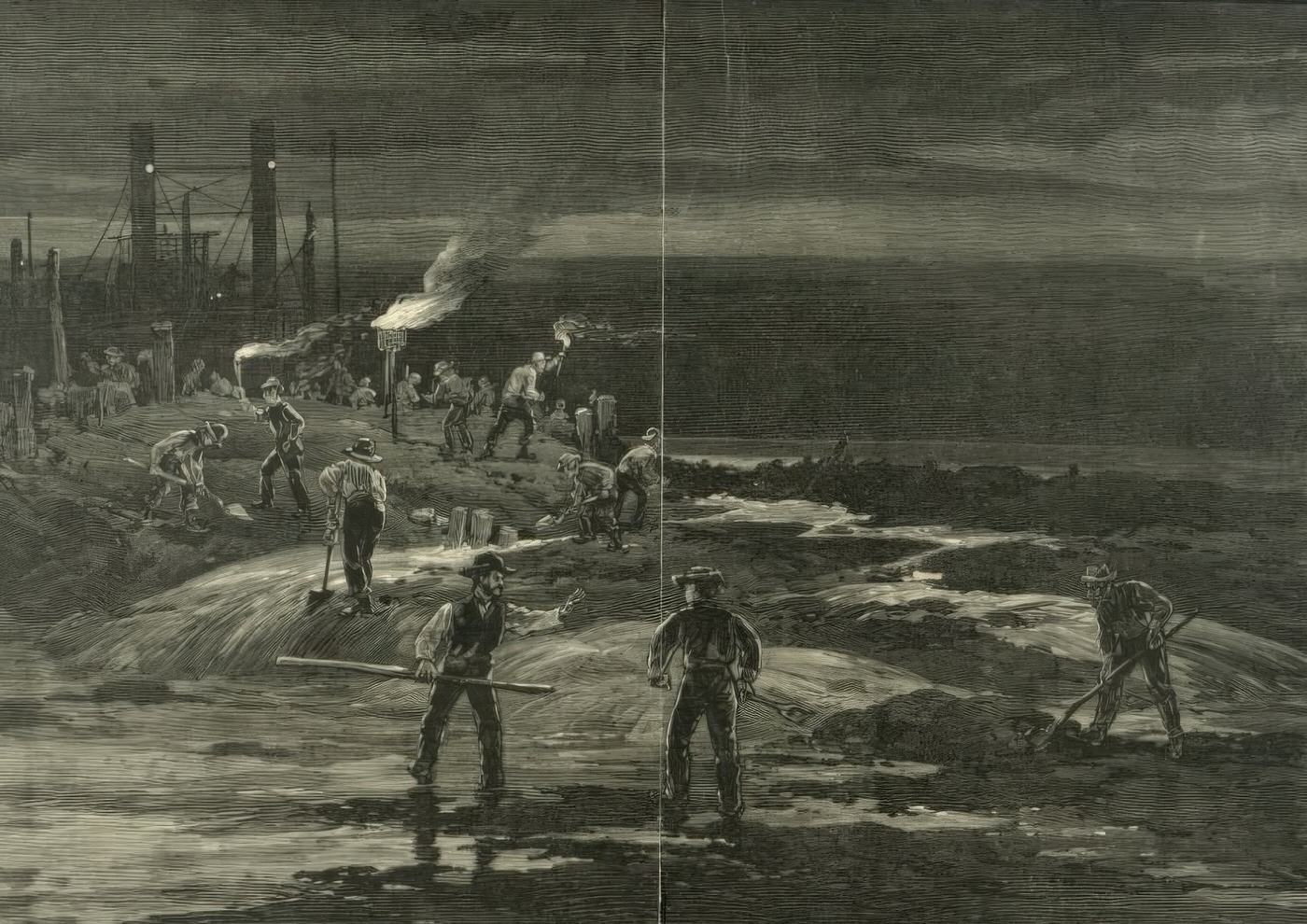

The Eads Bridge, completed in 1874, was pivotal for integrating St. Louis into the national rail network. Although it faced initial financial difficulties , by the 1880s, especially after Jay Gould’s Missouri Pacific Railroad obtained a lease in 1881, its role as a vital rail link was solidified. Railroads increasingly dominated transportation, leading to the decline of steamboat commerce by the 1880s. Cotton, for instance, largely transitioned to a rail commodity. Despite this shift, St. Louis remained a significant inland port, with the Mississippi River facilitating year-round navigation for remaining river traffic. The city served as a commercial gateway between the West, the South, and various points along the major rivers.

Shaping the Urban Landscape: Growth and Infrastructure

The 1880s were a decade of significant physical development for St. Louis, as the city adapted to its growing population and industrial might. The administrative and geographical restructuring from the “Great Divorce” of 1876 directly shaped this urban development. The separation from St. Louis County tripled the city’s land area to 61 square miles, incorporating areas like Forest Park, O’Fallon Park, and Carondelet Park. This expansion provided crucial space for residential, commercial, and industrial growth and included foresight in securing major parklands for the burgeoning city.

The provision of essential services struggled to keep pace with this growth. The city’s water supply relied on the Bissells Point Plant (opened 1871) and the Grand Avenue Water Tower (built 1870). To meet increasing demand, construction began on the Bissell Water Tower in 1885, completed in 1887, and a low-service pumping station was established at Chain of Rocks the same year. Despite these additions, high demand and upstream pollution remained persistent challenges. Sanitation and sewer systems were also under pressure. St. Louis had been developing a combined system since the 1850s due to earlier cholera outbreaks. While major sewer network construction is noted for the 1890s, the Board of Health and Board of Public Improvements were active throughout the 1880s managing waste and addressing public health concerns like yellow fever.

Street lighting in the 1880s saw the dawn of a new era. While gas lighting from companies like Laclede Gaslight was common, electricity began to make its mark. Tony Faust’s Restaurant and the St. Louis city library were electrically lit as early as 1878. The Turner Building (1880) and Beers Hotel (1881) were among the first large commercial structures to be wired. Pope’s Theater was electrified in 1884, and the St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall, completed the same year, was one of the first buildings in the country with electric lights. This piecemeal adoption of electric lighting in prominent buildings showed a city embracing technological advancement.

Public transportation was revolutionized by the evolution of streetcar lines. These were essential for connecting downtown to developing neighborhoods like Benton Park. A major milestone was the introduction of electrically operated streetcars in 1887, signaling a shift from older horse-drawn or steam-powered systems. This innovation promised faster, more efficient urban travel and directly enabled further suburbanization within the city’s expanded limits.

The city’s architecture in the 1880s reflected its prosperity and aspirations. The Victorian era’s influence was prominent. The Old Post Office, completed in 1884, stands as a prime example of the Second Empire style, characterized by its mansard roof and elaborate detailing. Towards the end of the decade, the Richardsonian Romanesque style gained popularity for public buildings like police and fire stations, such as Fire House No. 26 (built 1887), conveying a sense of strength and authority. The St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall, a massive structure completed in 1884, was another significant architectural statement of the era. These large-scale projects demonstrated a city investing in its future and projecting an image of importance.

Life in 1880s St. Louis: Culture, Education, and Society

Daily life in 1880s St. Louis varied greatly across its social strata, reflecting the broader inequalities of the Gilded Age. The wealthy and emerging middle class enjoyed new comforts and technologies, while many in the working class and newly arrived immigrant communities faced difficult living conditions. Upper-class families resided in opulent homes, often in newer, fashionable areas or private streets, increasingly equipped with electricity and telephones. Middle-class Victorian homes frequently featured a piano, a symbol of modest prosperity. In contrast, many working-class individuals and recent immigrants lived in crowded tenements, particularly on the near south side, where sanitation could be poor. Records from the Female Hospital (formerly the Social Evil Hospital) during this period paint a stark picture of the health struggles faced by poor women, including servants, prostitutes, laundresses, and factory girls, who contended with illness, addiction, and hardship.

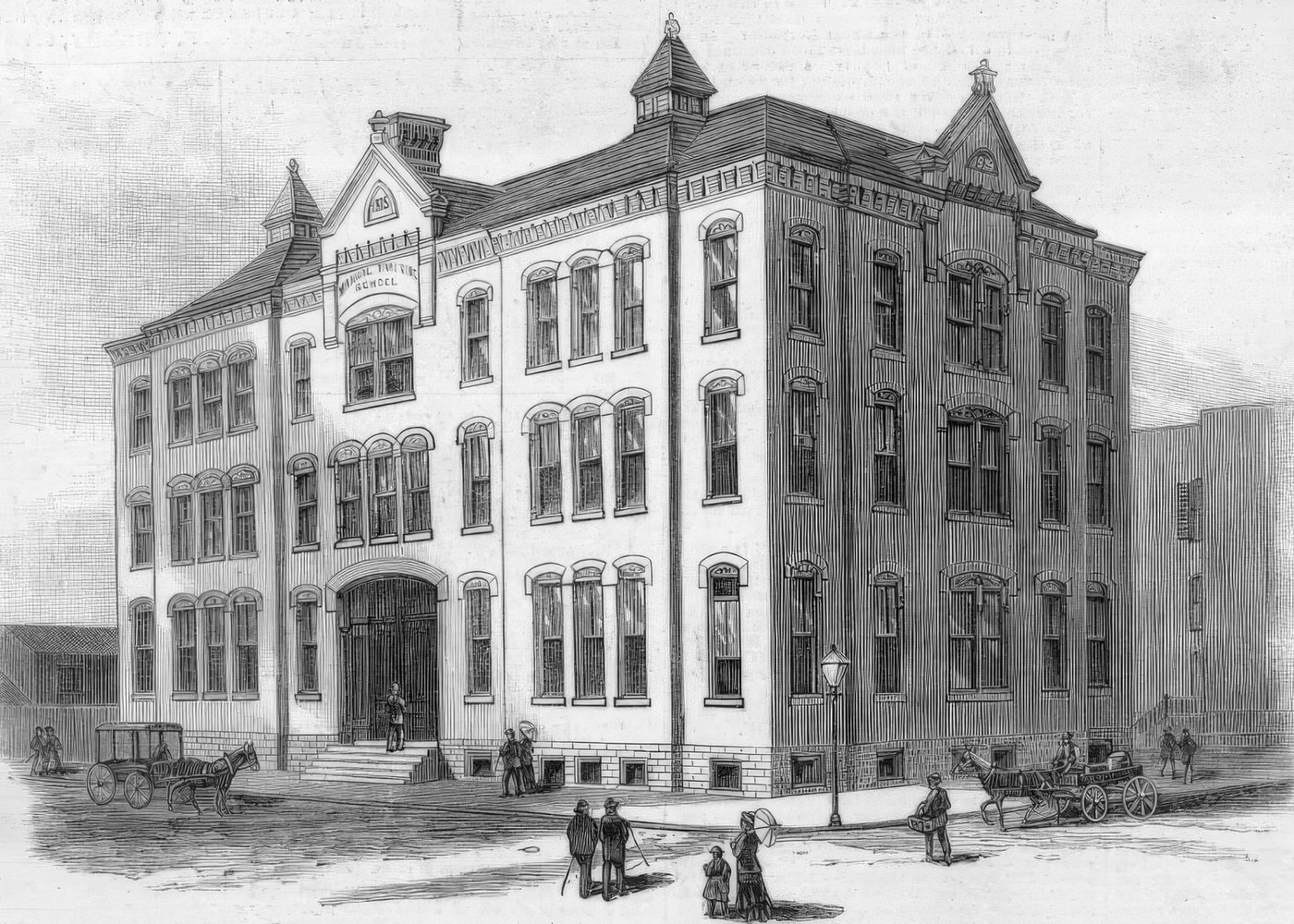

St. Louis was a significant center for educational development. The public school system, shaped by leaders like William Torrey Harris (superintendent until 1880), was highly regarded. By 1881, a substantial portion of public school students, 20,000, were of German heritage, highlighting immigrant participation in education. The city was a pioneer in the free public kindergarten movement, largely due to the efforts of Susan Blow starting in 1873. By the early 1880s, this system was well-established and expanding, serving as a model for other cities; in 1886, St. Louis was training over 4,000 children in its kindergartens. Higher education institutions also flourished. Washington University strengthened ties with preparatory schools, introduced new degrees, and saw increased female enrollment; its law school graduated its first known African American recipient, Walter Moran Farmer, in 1889. Saint Louis University began construction of DuBourg Hall in 1888 on its new Midtown campus and started building the new St. Francis Xavier College Church in 1884. Concordia Seminary erected a large Gothic structure in 1883 with a library, dormitories, and gymnasium. Eden Theological Seminary relocated to the outskirts of St. Louis (Wellston) in 1883 to better serve the urbanizing region.

Public health remained a constant concern. The St. Louis Board of Health, established after an earlier cholera epidemic, worked to enforce sanitary regulations. Yellow fever cases, often arriving with individuals from other cities, prompted quarantine measures and improvements at the Quarantine Hospital. The Female Hospital provided care for the city’s poor and marginalized women. These efforts reflected a growing awareness, influenced by national public health movements, of the importance of sanitation in combating disease.

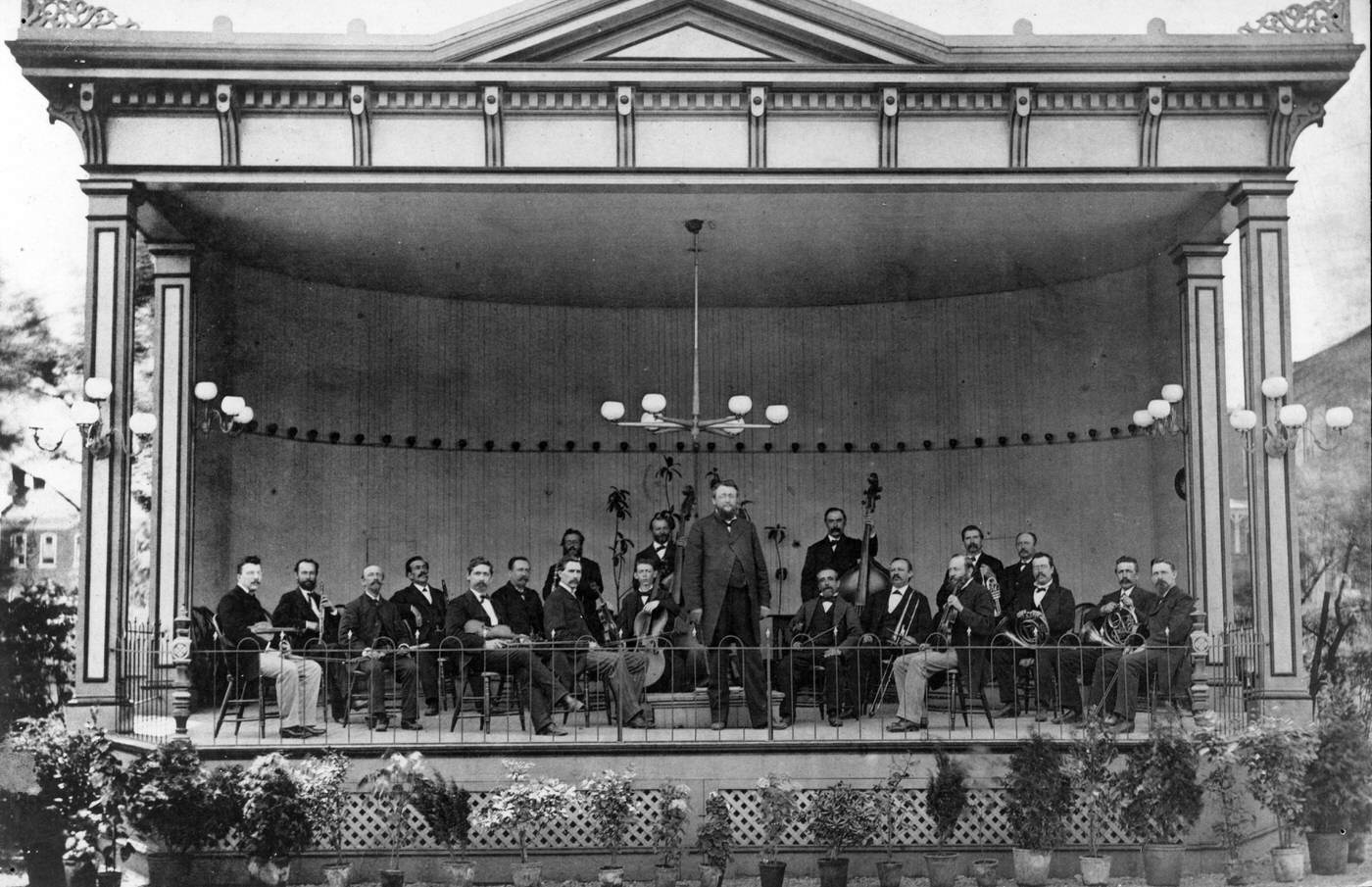

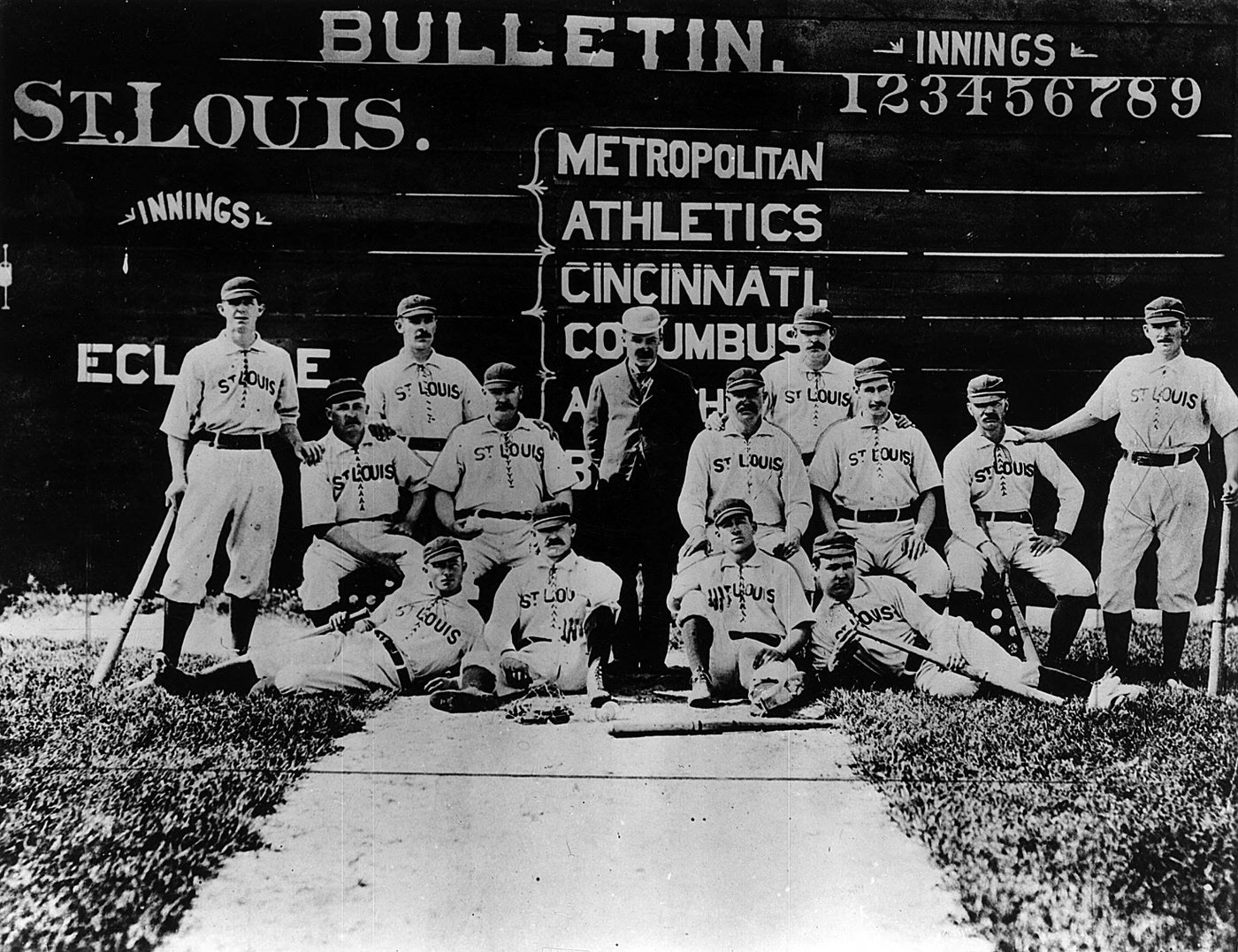

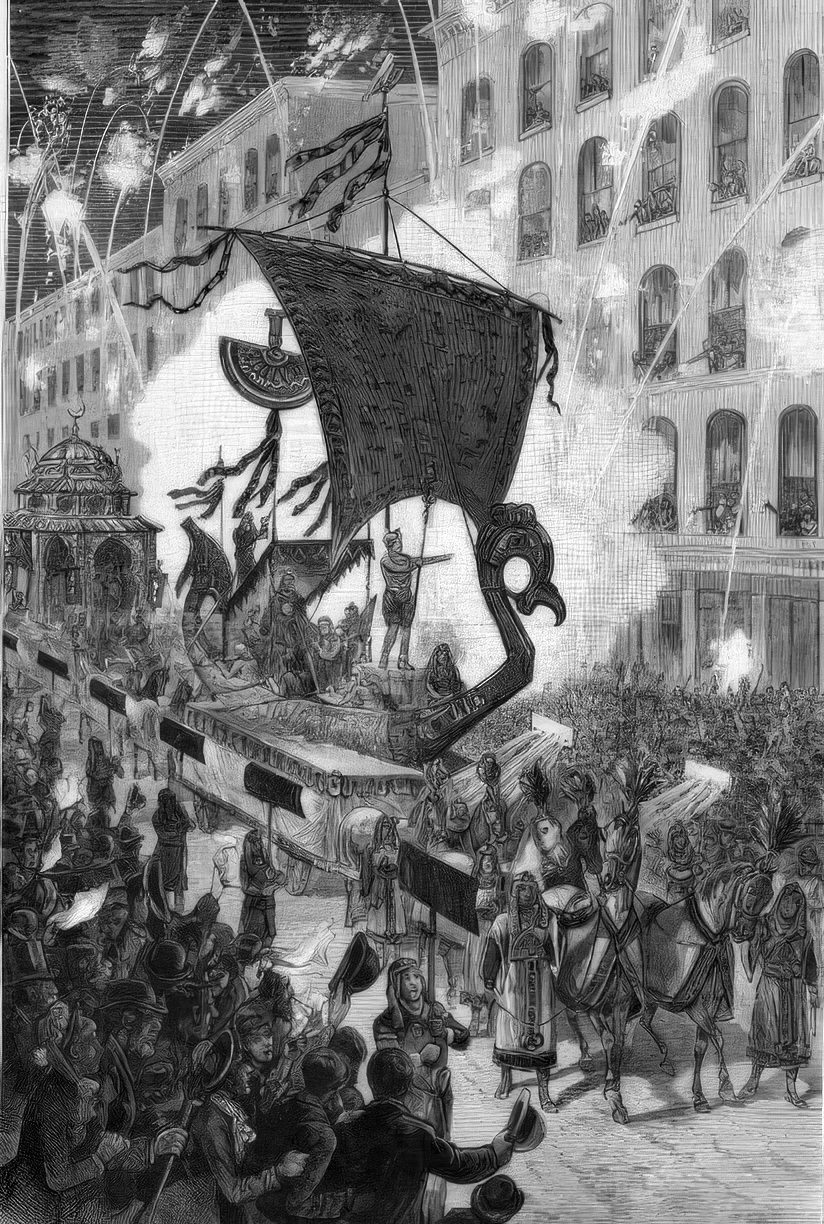

The leisure and entertainment scene in 1880s St. Louis was diverse and vibrant. Theaters like Pope’s Theater (the first in the city to be fully electrified in 1884), the People’s Theater, the New Olympic Theater, the Standard Theatre, and the Grand Opera House offered a wide range of performances, from Shakespearean drama and opera buffa to comedy and melodrama. The St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall, completed in 1884, housed a large music hall that was home to the St. Louis Symphony. German cultural influence was strong, with Turnvereins serving as popular social and athletic clubs, often featuring impressive facilities. Beer gardens, such as Schnaider’s and Uhrig’s Cave, were major gathering spots, offering food, drink, and live entertainment to large crowds. Professional baseball, with the St. Louis Brown Stockings (later the Cardinals) led by impresario Chris Von der Ahe, gained immense popularity, becoming a significant part of the city’s identity. Public parks like Forest Park and Tower Grove Park provided spaces for recreation for the broader populace.

Religious life was robust, with institutions serving not only as places of worship but also as vital centers for community, education, and social welfare. The Catholic Church remained the largest denomination, with a well-established network of parishes and social services. Protestant denominations were diverse and active, including Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Methodists, Lutherans (the Missouri Synod being prominent with Concordia Seminary), Unitarians, and Baptists. German Evangelical churches, with institutions like Eden Theological Seminary and Deaconess Hospital (founded 1889), played a significant role. African American churches, such as St. Paul’s AME, Quinn Chapel AME, and St. James AME, were cornerstones of their community, providing spiritual guidance and social support. The Jewish community, with synagogues like United Hebrew, B’Nai El, Shaare Emeth, and the newly formed Temple Israel (1886), was active in charitable work and religious education. New church construction and expansion, like Concordia Seminary’s new building and the commencement of the new St. Francis Xavier College Church, reflected the city’s religious vitality.

Governance, Reform, and the Public Voice

The 1880s in St. Louis were a period of political adjustment and burgeoning reform efforts, set against the backdrop of Gilded Age governance challenges. The city was led by Mayor William L. Ewing, a Republican, from 1881 to 1885, followed by Democrat David R. Francis from 1885 to 1889. These administrations operated under the new city charter established after the 1876 separation from St. Louis County, which had redefined the city’s boundaries and governmental structure. Managing the rapid urban growth and industrial expansion detailed previously were key responsibilities for city leadership.

Like many cities of the era, St. Louis contended with political corruption. Bribery, patronage, and electoral irregularities were not uncommon. However, voices for change were emerging. Joseph Pulitzer, through his dynamic newspaper, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (founded 1878), became a prominent crusader against corruption. His paper mixed sensationalism with investigative journalism, targeting tax evaders, gambling rings, insurance fraud, monopolies, and general city corruption. Pulitzer viewed his newspaper as a “vehicle for the truth,” and its aggressive stance, while creating enemies, significantly boosted its circulation and influence. He remained the owner even after acquiring the New York World in 1883. The Westliche Post, under editors like Emil Preetorius, also wielded considerable influence, particularly as the principal voice of German Republicans in the region. These newspapers were active participants in shaping public opinion and driving reform agendas.

National movements for reform also found expression in St. Louis. The push for Civil Service reform, aimed at replacing the spoils system with a merit-based system for government employment, was gaining momentum nationally. Carl Schurz, who had been an editor of the Westliche Post and served as U.S. Secretary of the Interior from 1877, was a notable proponent of such reforms.

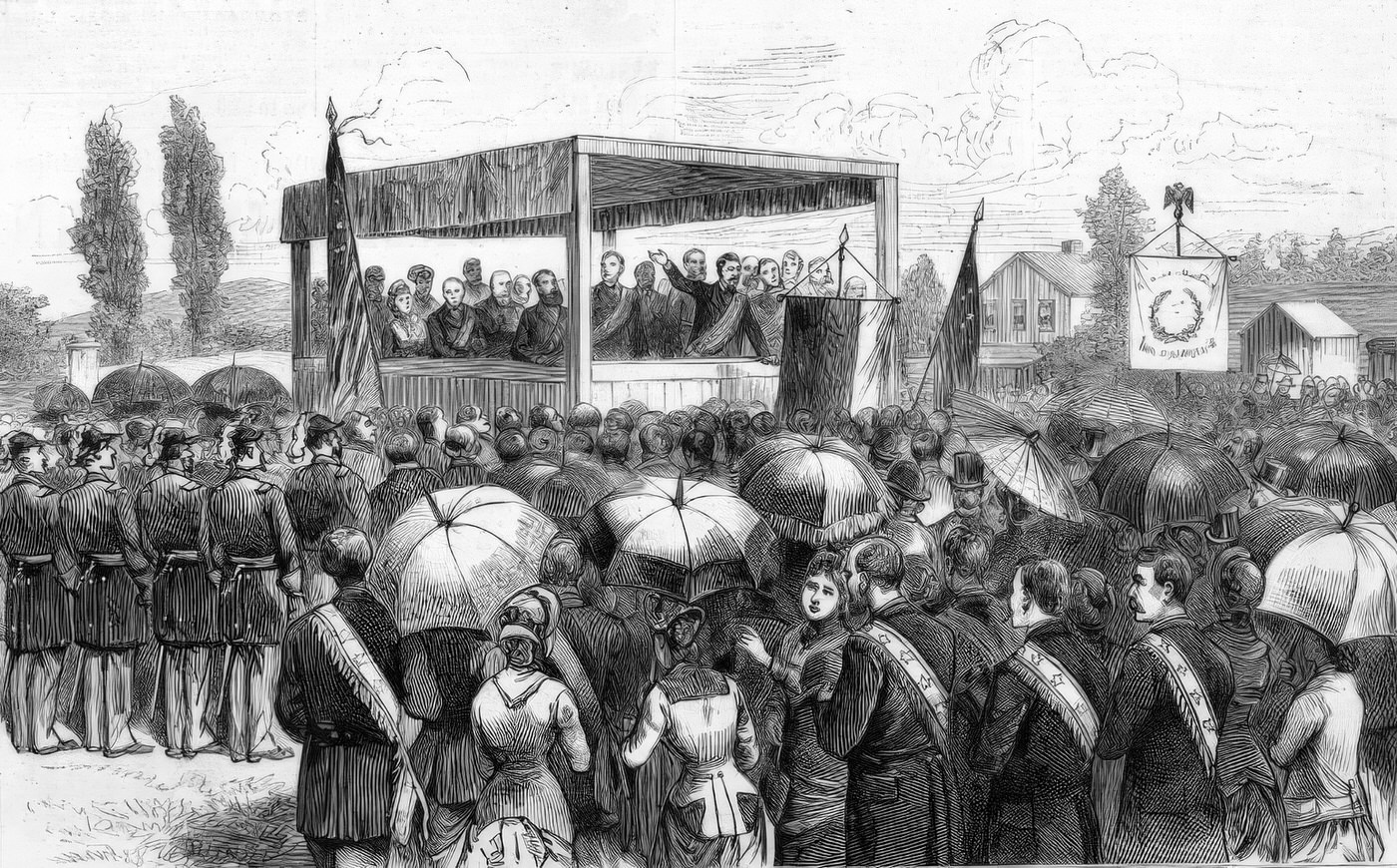

Social reform agendas were actively pursued, particularly by women. The woman suffrage movement, with deep roots in St. Louis through the Missouri Suffrage Association (founded 1867) and figures like Virginia Minor, continued its efforts. Minor’s “New Departure” strategy, arguing that the 14th Amendment already granted women the right to vote, had originated in St. Louis in 1869 and led to her landmark 1872 attempt to register, culminating in the Minor v. Happersett Supreme Court case. In 1879, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) established a Missouri branch with Minor as its president. The temperance movement was also a significant force. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), founded in 1874, grew in influence during the 1880s. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, whose “Do Everything” campaign was unveiled in 1882, the WCTU increasingly allied itself with the suffrage movement, advocating for prohibition and broader societal reforms. These movements, often intertwined, demonstrated growing civic engagement and a push for substantial social and political change, despite facing organized opposition, particularly from liquor interests.

The World of Work: Labor in an Industrializing City

The industrial boom of 1880s St. Louis brought prosperity to some, but for many workers, daily life was characterized by arduous labor and challenging conditions. Reports from the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 1880 shed light on the realities within the city’s factories and workshops. In stove foundries, for example, molders endured constant dampness from sweat with no facilities for changing clothes, leading to high rates of lung disease and rheumatism; burns from hot iron were common, and eye injuries from sparks and strain were prevalent among mounters and chippers. Machinists faced dangers from the close proximity of machinery and unhealthy dust from emery wheels. Even engineers, though their occupation was generally reported as healthy, often worked in rudimentary sheds, exposed to drafts and temperature fluctuations that could lead to rheumatic ailments. The general lack of adequate washing and changing facilities in many establishments pointed to a broader disregard for worker comfort and basic hygiene.

In response to these conditions and the broader economic pressures of the Gilded Age, the 1880s became a foundational decade for organized labor in St. Louis. The call for an eight-hour workday, championed by the American Federation of Labor in 1885, resonated strongly in the city, spurring the formation and growth of trade unions. Several significant labor organizations took root. These included the Central Labor Union, the St. Louis Trades Assembly, the Arbeiter Verband (representing German workers), and District Assembly No. 4 of the Order of the Knights of Labor. A major step towards consolidating labor power occurred in 1887 with the merger of the Central Labor Union, the St. Louis Trades Assembly, and the Arbeiter-Verband to form the St. Louis Trades and Labor Assembly. This unified body grew significantly, and by 1893, its membership reached 35,000, encompassing diverse groups such as the Women’s Trade Union, the Ladies Garment Workers Union, and the Colored Waiters Union, indicating an effort towards broader labor solidarity. Specific unions active during this period included the Harnessmakers’ Association and Typographical Union No. 8. In the burgeoning shoe industry, the Lasters’ Protective Union was organized in 1880.

This growing organization of labor led to increased activism. The St. Louis Trades and Labor Assembly lent its support to several notable strikes, including the brewery strikes of the late 1880s and the “Eight Hour” strike by the Typographical Union. The Harnessmakers’ Association reported successful strikes against wage reductions in 1879 and 1880. The Typographical Union No. 8 engaged in a strike in October 1880 against a wage cut at the St. Louis Times, which had mixed outcomes. While the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 occurred just prior to this decade, its impact, including the involvement of the Workingmen’s Party, set a precedent for large-scale labor action and influenced the climate of the 1880s. These labor struggles were often contested, with newspapers like the Westliche Post opposing the demands of radical labor during the 1877 general strike. The actions of organized labor in the 1880s, though not always immediately successful, demonstrated a growing resolve among St. Louis workers to challenge employers and fight for improved wages and conditions.

Image Credits: The State Historical Society of Missouri, Library of Congress, Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library, St. Louis Mercantile Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know