The 1890s marked a period of dynamic growth and significant change for St. Louis, Missouri. As the Gilded Age reached its zenith, the city, already a major American urban center, expanded its population, diversified its industries, and undertook ambitious urban development projects. This decade witnessed St. Louis grappling with the opportunities and challenges of rapid industrialization and urbanization, laying the groundwork for its entry into the 20th century.

A City of Swelling Numbers and Diverse Peoples

St. Louis experienced a notable increase in its population during the 1890s. The number of residents grew from 451,770 in 1890 to 575,238 by 1900. This expansion solidified its standing, making it the nation’s fourth-largest city by the close of the decade. A pivotal event, the “Great Divorce” of 1876, had earlier separated St. Louis City from St. Louis County, establishing fixed city boundaries and tripling its land area to 61 square miles. This provided the necessary space for the growth observed throughout the 1890s. While these boundaries offered immediate room for development, the decision to fix them in an era of widespread urban growth across the nation set the stage for future limitations as metropolitan areas continued to spread beyond such defined lines.

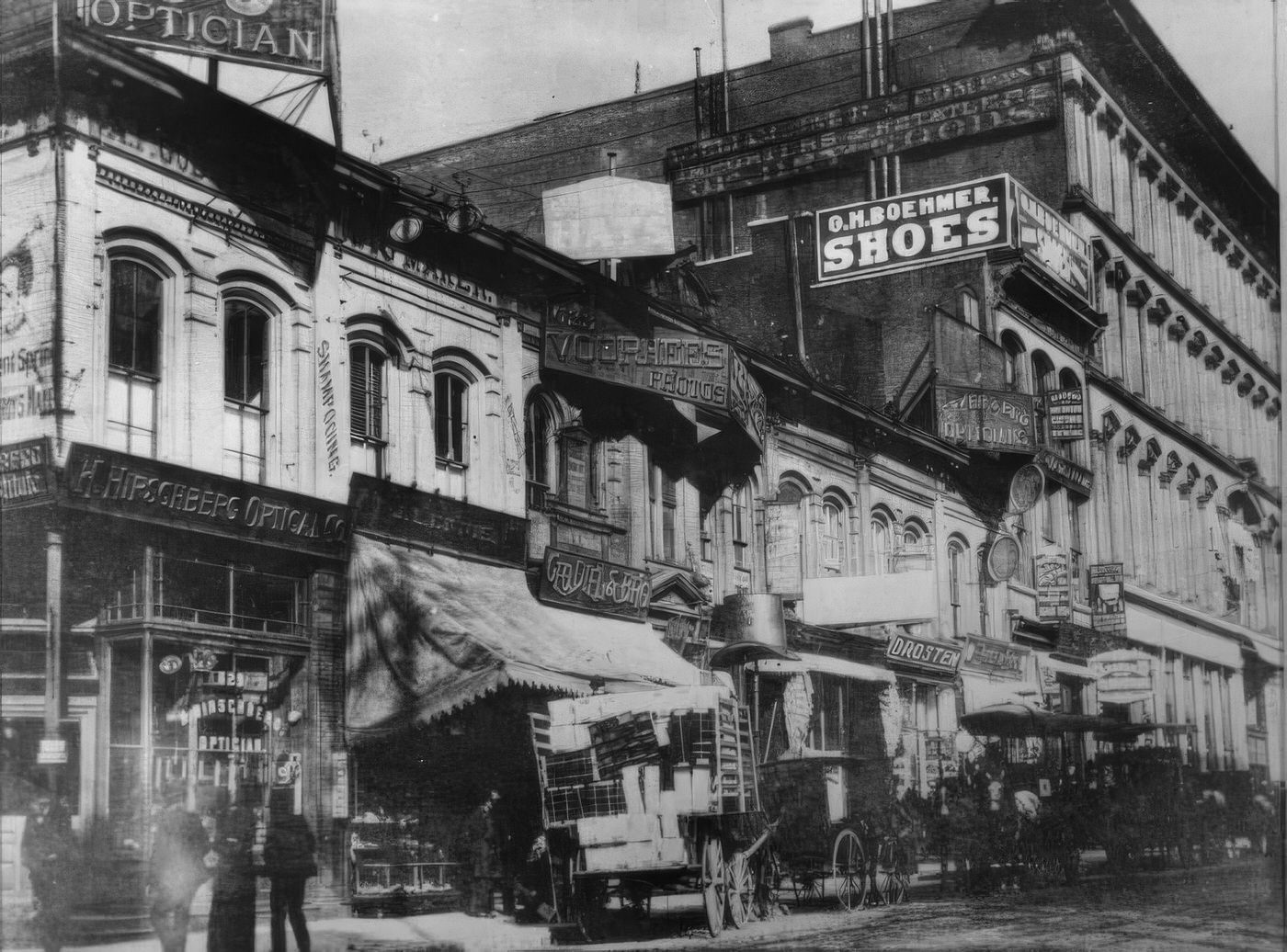

German immigrants and their descendants remained a substantial and influential ethnic group in St. Louis during the 1890s. They significantly shaped the city’s cultural, business, and social fabric. Neighborhoods such as Hyde Park, which was previously the town of Bremen, and various areas on the near south side, maintained a distinctly German character. German-run businesses, particularly breweries, were prominent. Social and cultural institutions like the Turnvereins (gymnastic and social clubs) played a vital role in the community. These organizations, with the Nord St. Louis Turnverein and its large gymnasium being a notable example, not only promoted physical fitness but also advocated for causes such as the inclusion of physical education in public schools. German-language newspapers, including the Westliche Post, once edited by prominent figures like Carl Schurz and later Emil Preetorius, and the Anzeiger des Westens, continued to serve the large German-speaking population, providing news and maintaining cultural connections.

The Irish also constituted a major and established immigrant group in St. Louis. By the 1890s, distinct Irish enclaves and community institutions were well-rooted. Neighborhoods like “Kerry Patch,” located on the near north side, and “Dogtown” in the Cheltenham area near Forest Park, were widely recognized as Irish strongholds. Central to the Irish community’s life were their Catholic parishes. St. Bridget of Erin Church served the Kerry Patch area, while St. James the Greater was a focal point for Dogtown residents. Numerous other Catholic churches with Irish congregations, founded in earlier decades, continued to minister to their communities throughout the 1890s. Having overcome significant hardships and discrimination in earlier periods, the Irish community in St. Louis had, by the 1890s, built strong neighborhood and religious foundations that provided a sense of identity and mutual support.

The African American population of St. Louis increased during the 1890s, a trend fueled in part by ongoing migration from the Southern states following the Reconstruction era. St. Louis often served as a transit point or a new home for African Americans seeking opportunities and refuge from the Jim Crow South, including some of the “Exodusters” of the late 1870s and 1880s. By 1880, African Americans made up 6.36% of the city’s total population, and this demographic continued to grow through the 1890s.

Neighborhoods like “The Ville,” originally known as Elleardsville, became increasingly significant centers for the St. Louis African American community. Kinloch, another important Black community located in St. Louis County, also began its development during this decade. Within these communities, institutions formed the backbone of social and cultural life. Churches such as Antioch Baptist Church and St. James AME Church in The Ville were vital. St. Paul’s AME Church, which had erected its first dedicated building in 1872, relocated to a new site in 1890, reflecting the community’s growth and changing needs.

Educational advancement was a priority. Sumner High School, established in 1875 as the first high school for African Americans west of the Mississippi River, continued to be a cornerstone of Black education in the city. In The Ville, Simmons Elementary School opened its doors in 1898. Furthermore, Stowe Teachers College, which would later become Harris-Stowe State University, traces its origins to this period, beginning as a normal school department of Sumner High in 1890. Despite these advancements and the active building of community institutions, African Americans in St. Louis faced pervasive discrimination and the hardening lines of segregation in nearly all aspects of life. The proactive establishment of their own churches and schools was a testament to the community’s resilience and determination to create spaces for advancement and cultural preservation in the face of systemic obstacles.

The 1890s saw the continued arrival and establishment of newer immigrant groups, adding further complexity to St. Louis’s diverse population. A significant influx of Italian immigrants, which began in the 1880s, persisted through the 1890s. Many were drawn by employment opportunities in the clay mines located in southwest St. Louis, leading to the formation of the prominent Italian neighborhood known as “The Hill”. This area rapidly developed into a self-sufficient community with its own shops, churches, and social organizations, such as the “Big Club,” where residents gathered. A smaller Italian settlement, “Little Italy,” also emerged in northern St. Louis.

Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, including a significant number of Jewish people, also arrived in large numbers during this period. They often found work in the city’s expanding factories and established distinct ethnic enclaves. The character of St. Louis’s Jewish community, previously dominated by German Jews, was profoundly altered by the arrival of these Eastern European Jews. Established synagogues such as B’nai El, Shaare Emeth, and United Hebrew, along with the more recently formed Temple Israel (1886) and various Orthodox congregations, served this growing and diversifying Jewish population. Newspapers like The Jewish Voice, which began publication in 1888, provided a crucial communication link within the community. Among other Eastern European groups, Czech (Bohemian) immigrants had been settling in St. Louis since the mid-19th century, primarily in the “Bohemian Hill” area, now part of Soulard. They had established institutions like St. John Nepomuk Parish and secular organizations such as the Cesko-Slovansky Podporujici Spolek (C.S.P.S.), which constructed the Czech National Hall in 1890.

Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, including a significant number of Jewish people, also arrived in large numbers during this period. They often found work in the city’s expanding factories and established distinct ethnic enclaves. The character of St. Louis’s Jewish community, previously dominated by German Jews, was profoundly altered by the arrival of these Eastern European Jews. Established synagogues such as B’nai El, Shaare Emeth, and United Hebrew, along with the more recently formed Temple Israel (1886) and various Orthodox congregations, served this growing and diversifying Jewish population. Newspapers like The Jewish Voice, which began publication in 1888, provided a crucial communication link within the community. Among other Eastern European groups, Czech (Bohemian) immigrants had been settling in St. Louis since the mid-19th century, primarily in the “Bohemian Hill” area, now part of Soulard. They had established institutions like St. John Nepomuk Parish and secular organizations such as the Cesko-Slovansky Podporujici Spolek (C.S.P.S.), which constructed the Czech National Hall in 1890.

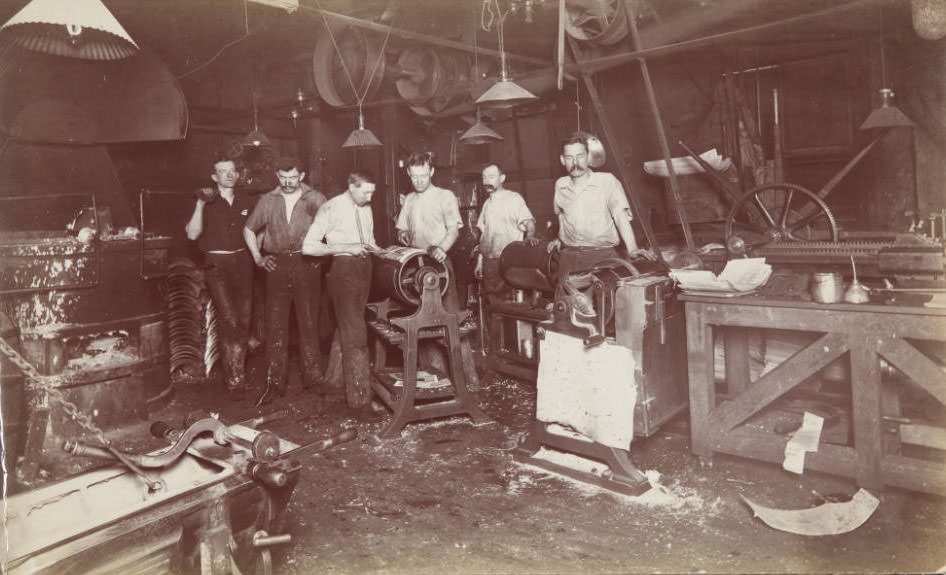

An Industrial Giant: Powering the Gilded Age

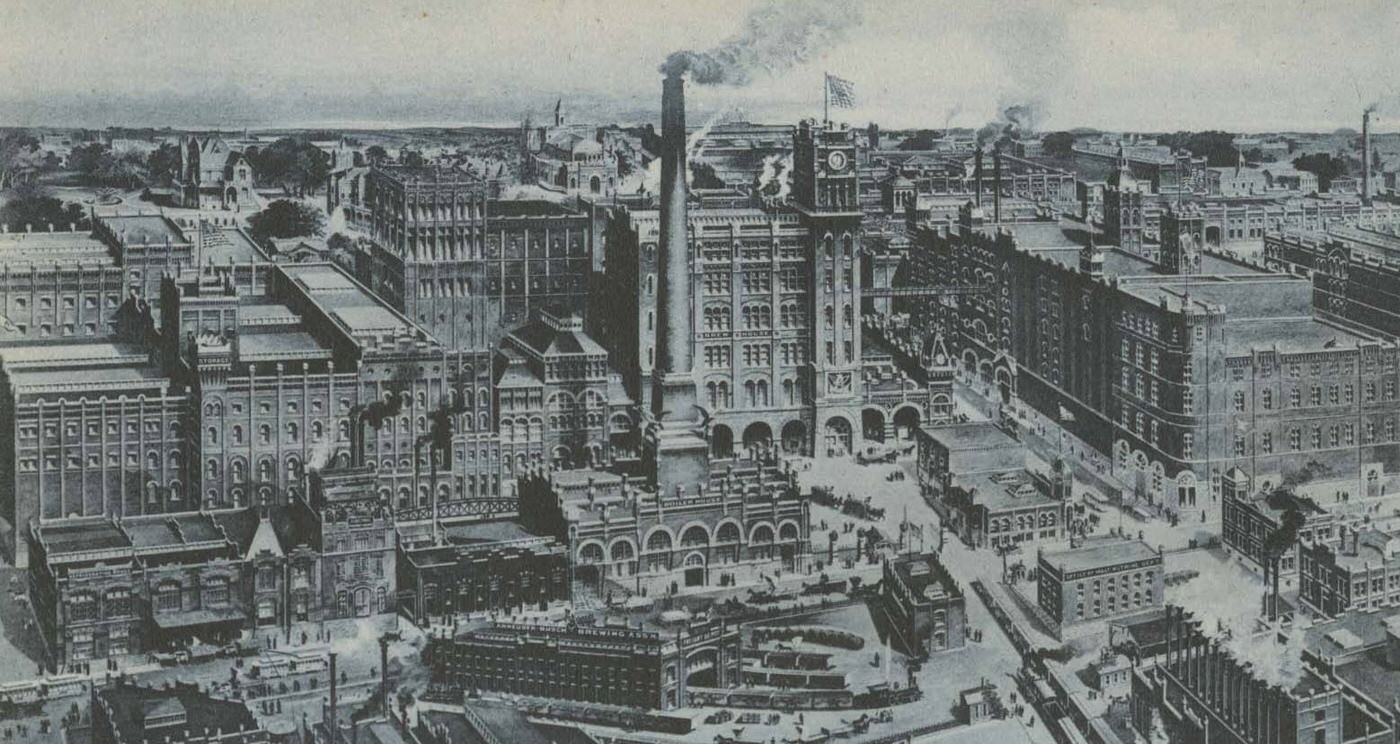

St. Louis in the 1890s stood as a formidable industrial center, its economy driven by a diverse array of manufacturing sectors. The city was a national leader in brewing, with giants like Anheuser-Busch, under the leadership of Adolphus Busch, and the Lemp Brewing Company, headed by William Lemp Sr. and Jr., at the forefront. Anheuser-Busch, in particular, achieved national prominence by the late 1890s, becoming the country’s highest-selling brewery through innovations such as refrigerated railroad cars and pioneering pasteurization techniques, which allowed for widespread distribution of its products like Budweiser. Adolphus Busch was also a significant civic figure, known for his philanthropy. The Lemp Brewery was another massive operation, credited as the first brewery to establish coast-to-coast distribution.

Shoe manufacturing was another cornerstone of the St. Louis economy, with the city emerging as one of the largest production centers in the United States. Companies such as the Hamilton-Brown Shoe Company, which saw its sales double between 1890 and 1900, and the Peters Shoe Company, established in 1892 and later a part of the International Shoe Company, were major employers and contributors to the city’s industrial output.

The tobacco processing industry also thrived, with St. Louis being a leading producer, especially of plug chewing tobacco. Prominent firms included Liggett & Myers and the Drummond Tobacco Company, the latter being acquired by the American Tobacco Company in 1898.

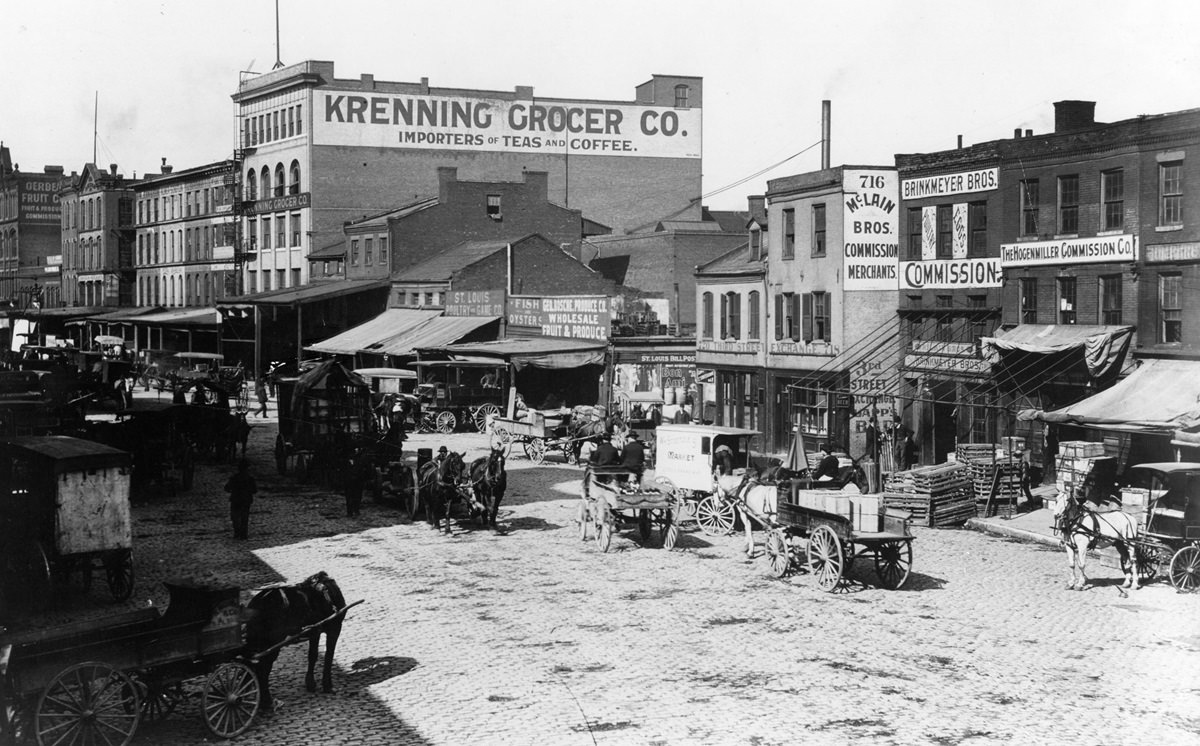

Flour milling had historically been a major strength for St. Louis, and while it lost its top national ranking to Minneapolis in 1890, it remained a significant industry. Companies like E.O. Stanard Milling were notable contributors to this sector. The clothing manufacturing industry saw expansion, particularly along Washington Avenue, which became a recognized garment district, partly fueled by the growth of mail-order retail businesses. Meatpacking, though perhaps past its absolute peak in national ranking, continued to be a substantial industry in the city and the adjacent National Stock Yards in National City, Illinois, which drew its workforce from St. Louis. This wide range of manufacturing activities, from consumer goods to processed agricultural products, underscored St. Louis’s critical role in the national economy of the Gilded Age. This diversity offered a degree of economic resilience, although specific sectors remained vulnerable to national economic shifts and competition.

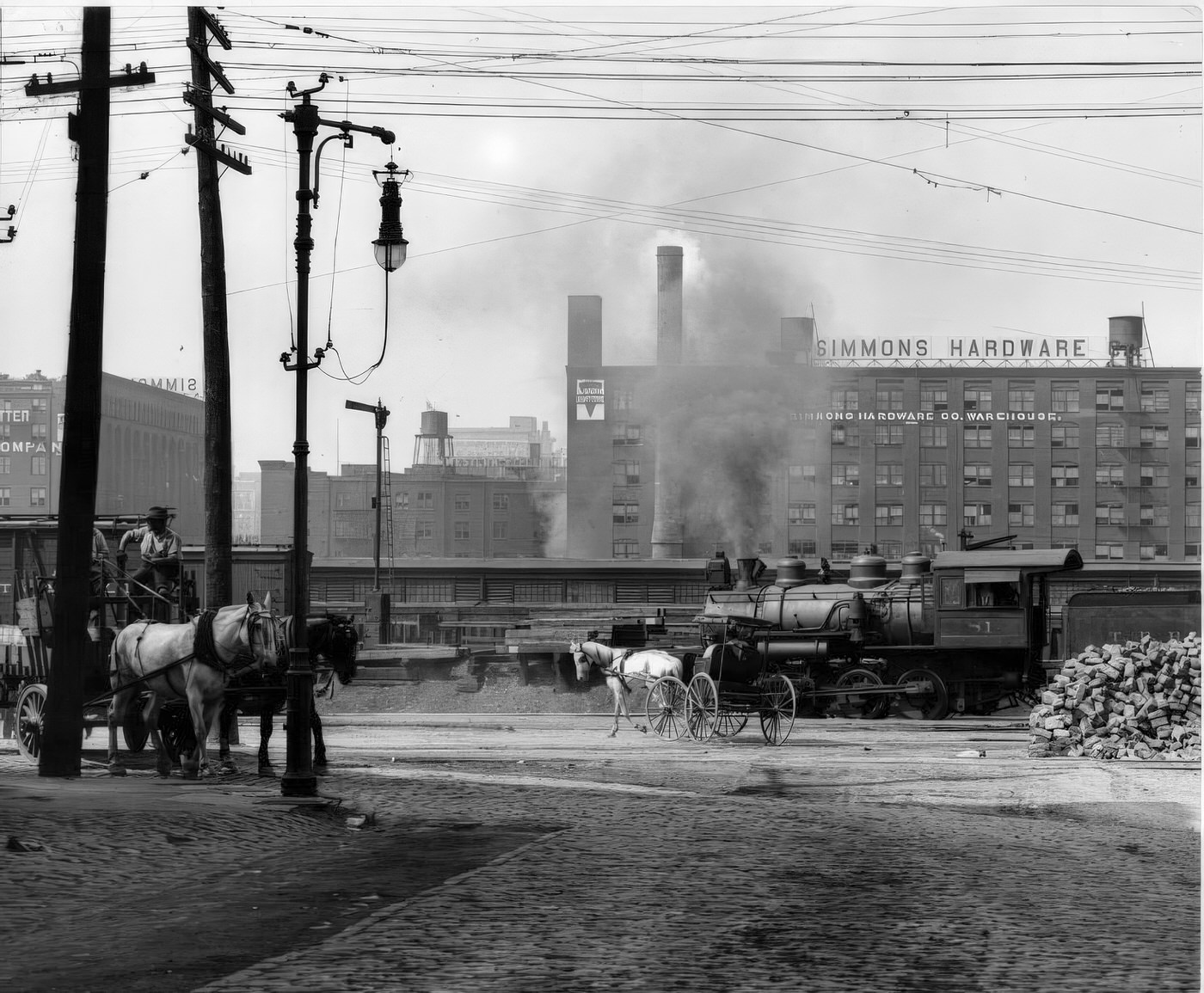

The commercial vitality of St. Louis in the 1890s was inextricably linked to its transportation infrastructure, with railroads increasingly becoming the dominant force. The city served as a crucial nexus for rail lines connecting the agricultural and raw material-producing regions of the Southwest with the industrial and consumer markets of the East. This era saw the culmination of efforts to solidify St. Louis’s position as a major rail hub.

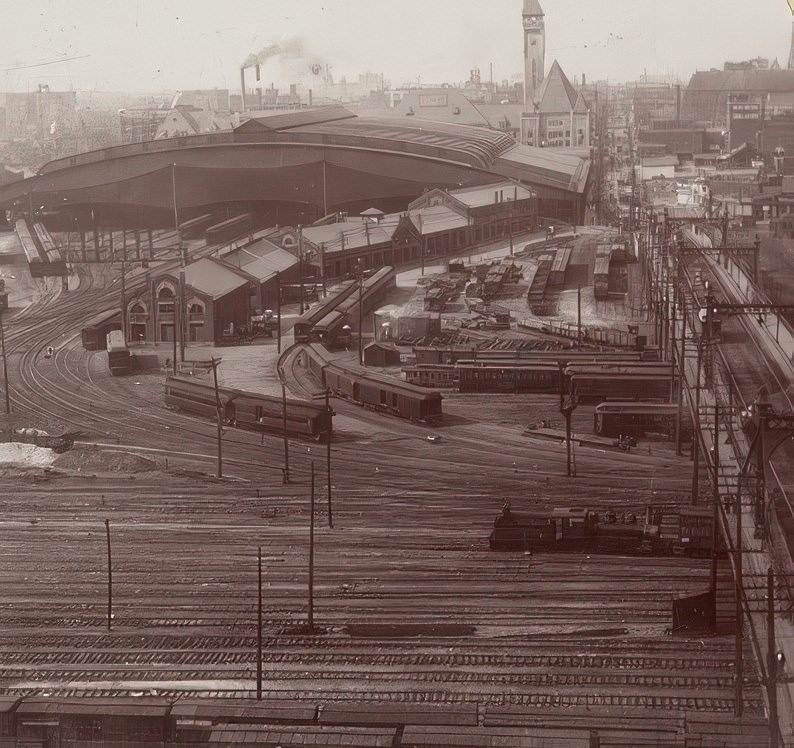

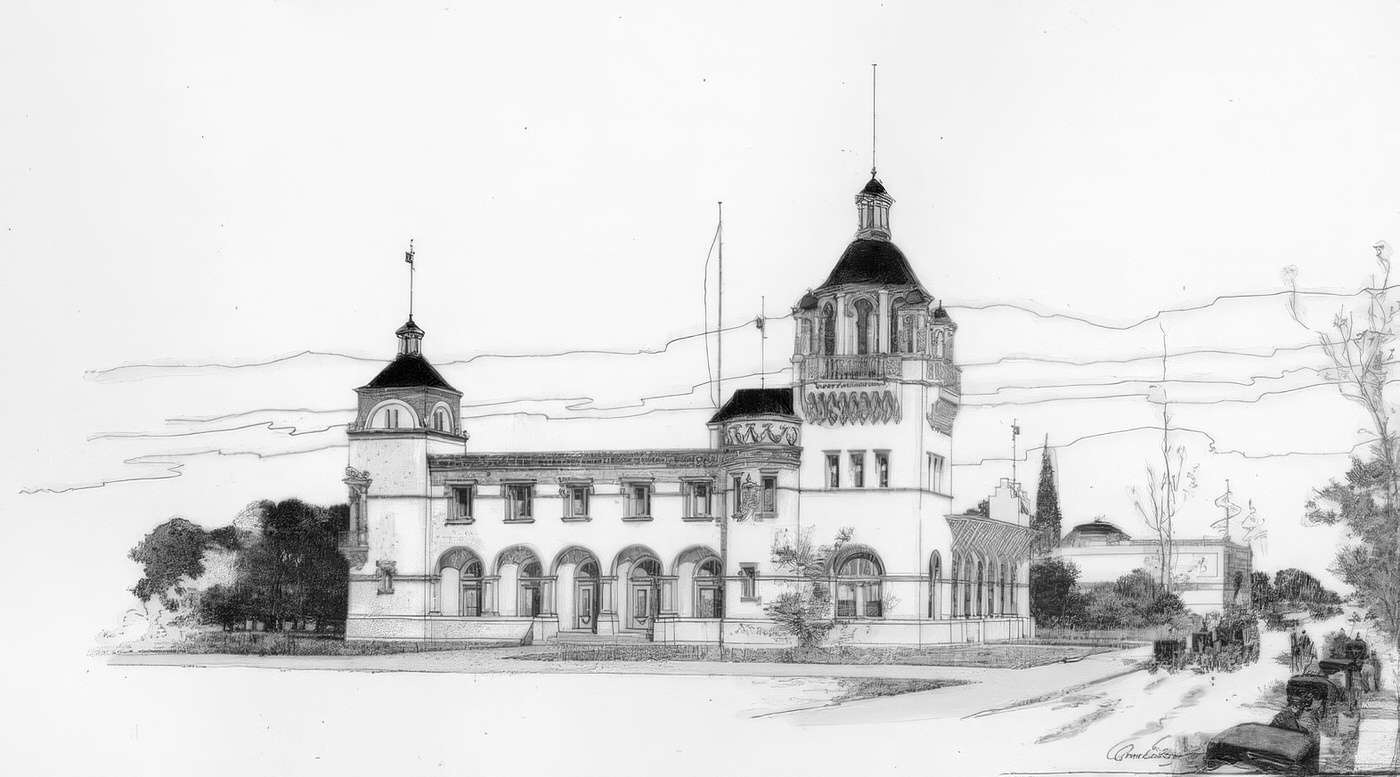

The most symbolic achievement of this focus on rail was the opening of St. Louis Union Station in 1894. Designed by Theodore Link, this grand terminal was, at the time of its inauguration, the largest and busiest railroad station in the world. Its opulent Grand Hall and extensive track system capable of handling trains from numerous railroad companies consolidated rail passenger service and stood as a testament to the city’s commercial importance.

Complementing Union Station was the development of Cupples Station, a massive complex of eighteen warehouses constructed primarily between 1893 and 1914 by Robert S. Brookings and Samuel Cupples. Strategically located near Union Station and with direct rail spurs, Cupples Station revolutionized freight handling in the city. It allowed for the efficient transfer of goods between different rail lines and to and from the city’s businesses, functioning as a central distribution point for the vast quantities of manufactured goods and raw materials that flowed through St. Louis.

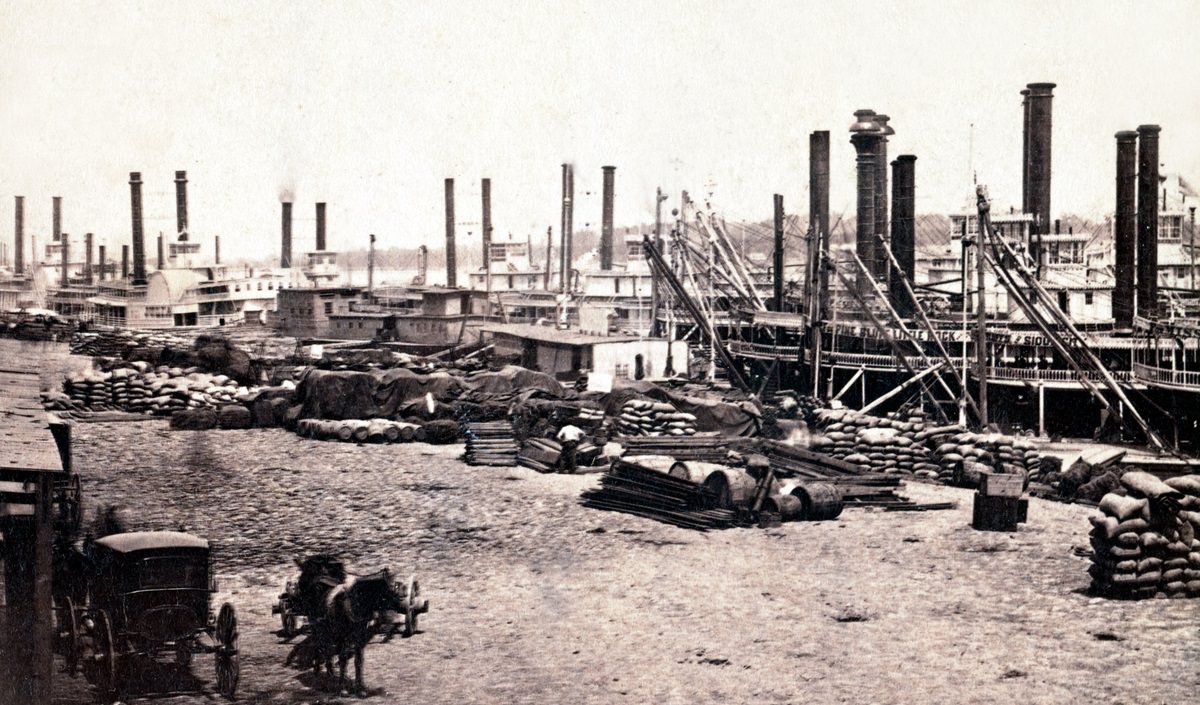

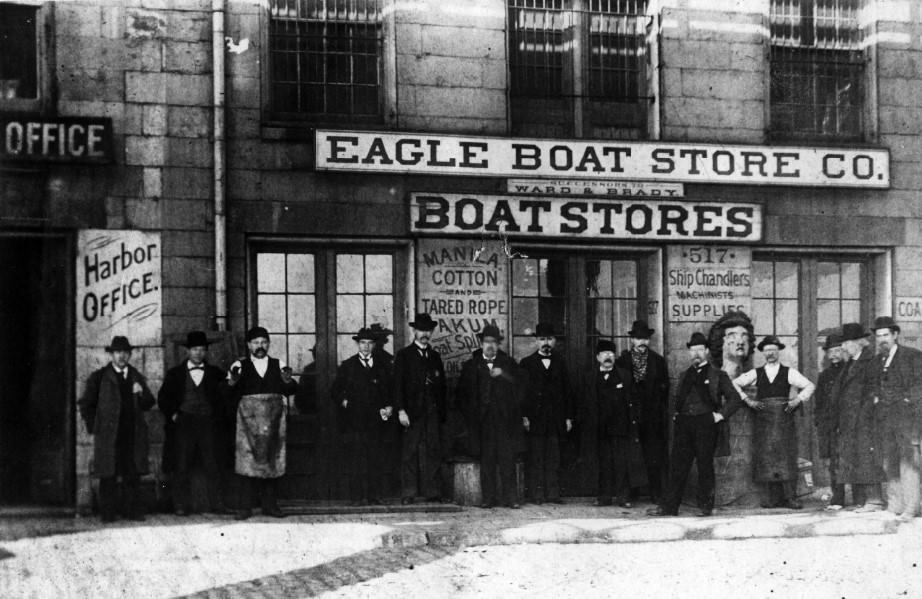

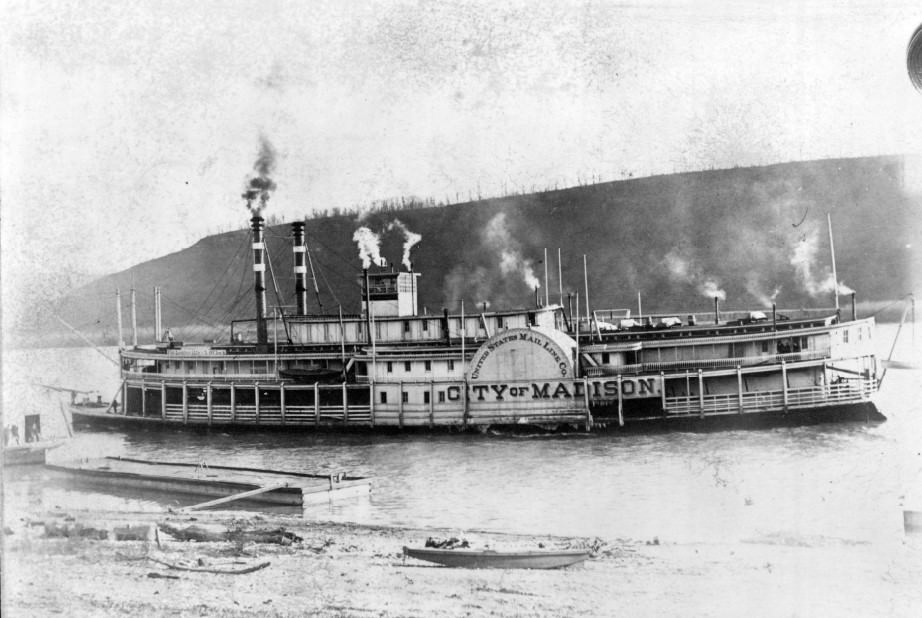

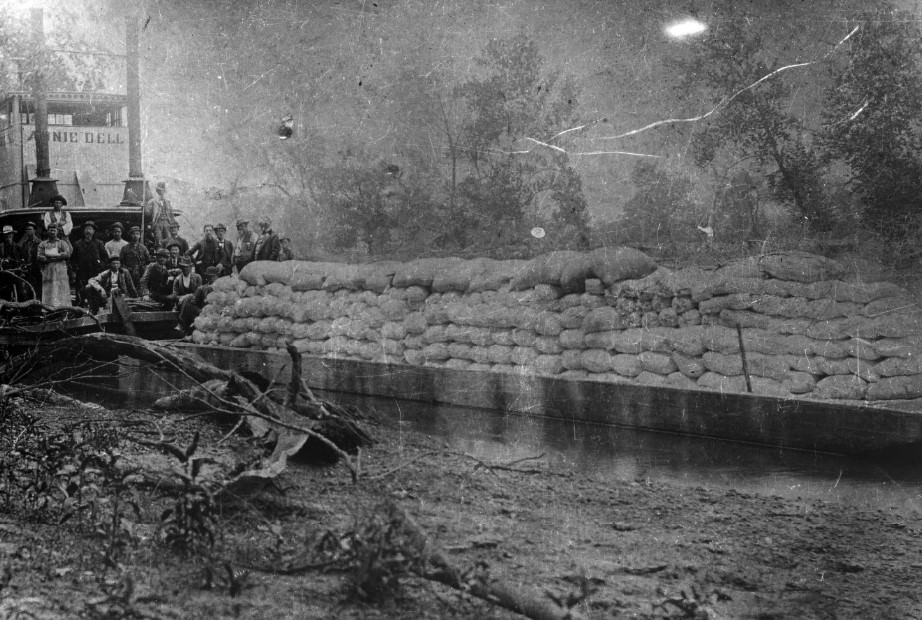

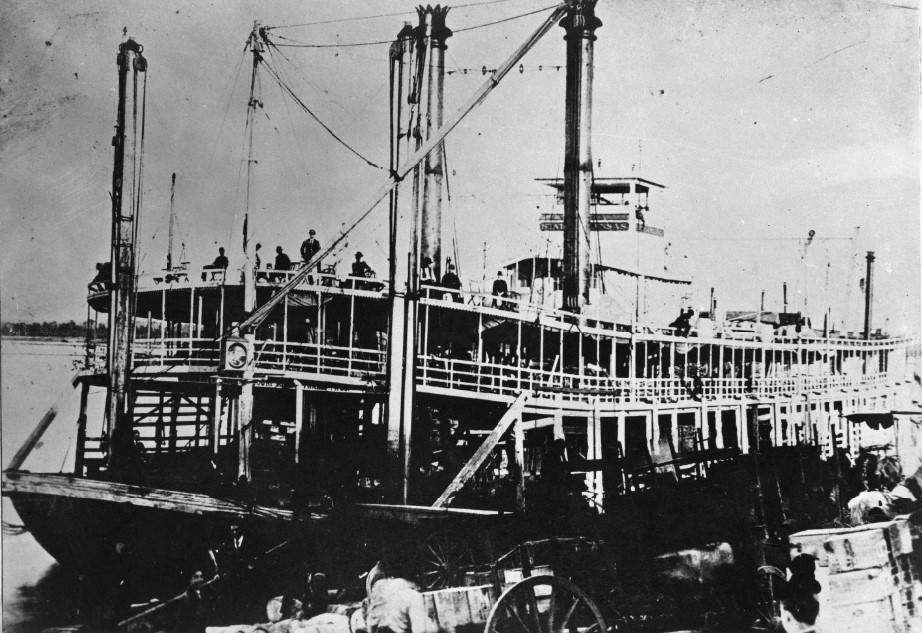

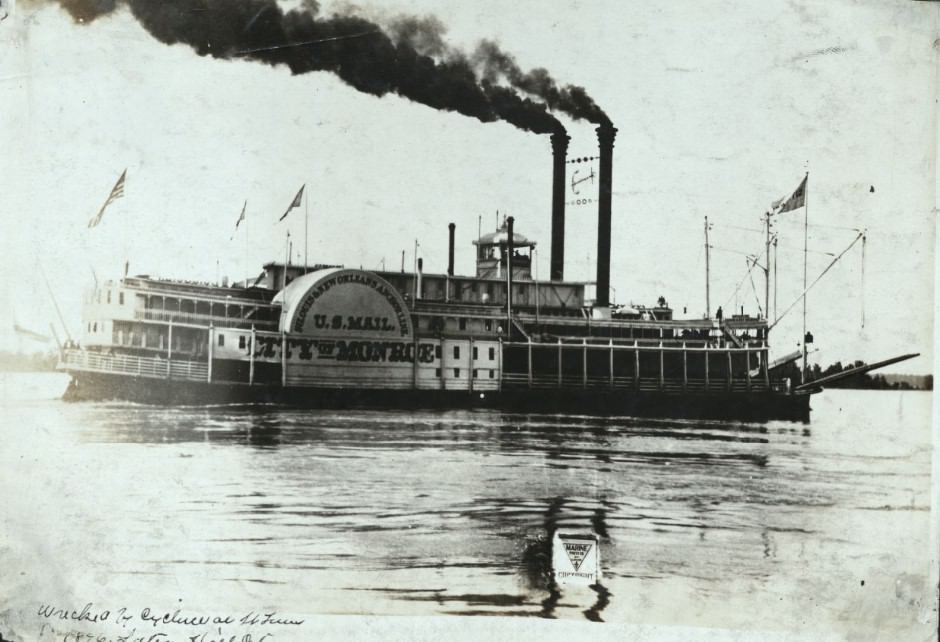

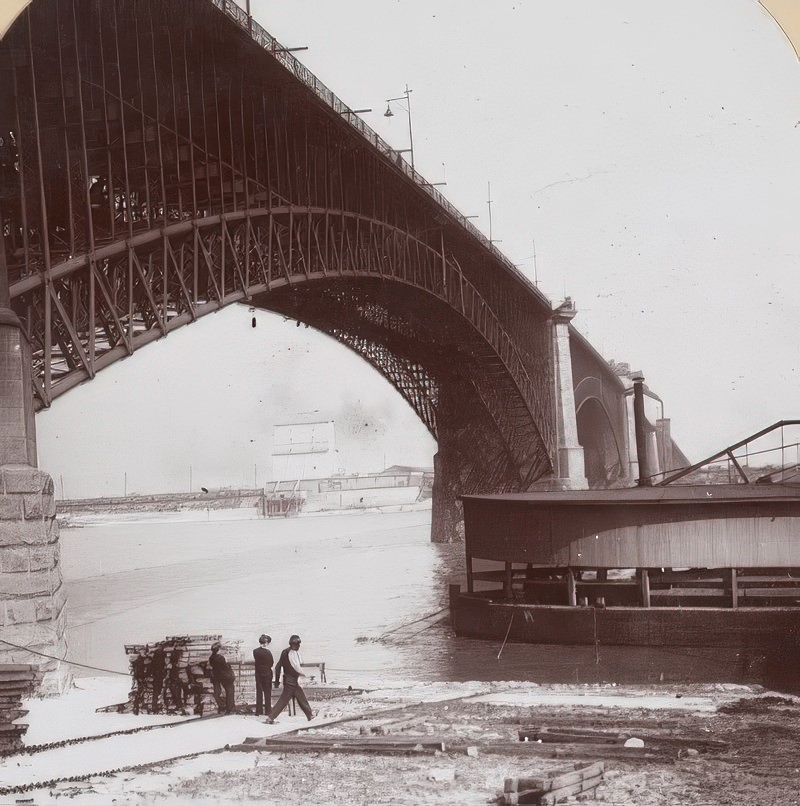

While rail ascended, river commerce, once the lifeblood of St. Louis, continued its decline in relative importance. The Eads Bridge, completed in 1874, had been a critical development, providing the first direct rail and road link across the Mississippi River at St. Louis and facilitating east-west trade. However, by the 1890s, the speed, reliability, and expanding network of railroads had largely supplanted steamboats for most forms of freight and passenger transport. The significant investments in railroad infrastructure during this decade, despite the earlier triumph of the Eads Bridge, clearly signaled a strategic adaptation to the changing transportation landscape, as St. Louis aimed to maintain and enhance its role as a central commercial hub in a nation increasingly bound by steel rails.

The Shadow of Economic Turmoil: The Panic of 1893

The decade of the 1890s was not one of uninterrupted prosperity for St. Louis. The national Panic of 1893, which began in February of that year, triggered a severe and prolonged economic depression across the United States, with profound consequences for businesses and workers. Nationally, the crisis led to the failure of over 15,000 businesses and 500 banks, and unemployment rates soared, exceeding 25% in some industrial states.

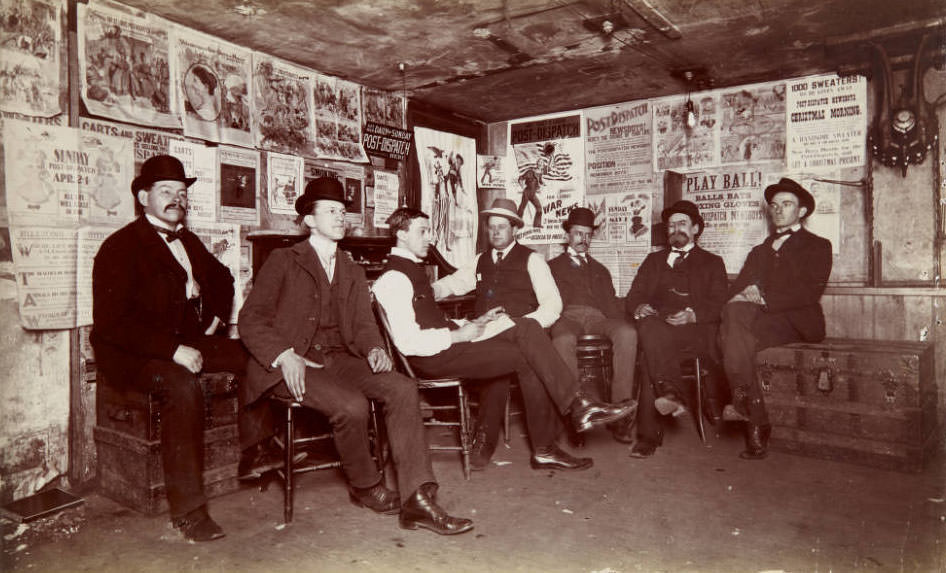

St. Louis, despite its diversified economy, was not immune to this downturn. Manufacturing growth in the city slowed considerably during the 1890s, an effect partly attributed to the depression. The critical flour milling industry, for instance, saw its production halved as the economic crisis took hold. Local newspapers, such as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, documented the economic hardship and its impact on the city’s population.

Relief efforts during this era were typically managed at the local level, often by charitable organizations and sometimes supplemented by municipal aid, but these were frequently overwhelmed by the scale of the need. The economic pressures of the Panic of 1893 undoubtedly strained the city’s resources and tested its social fabric. Such widespread economic hardship often contributed to social unrest, and the Panic likely intensified the labor movements and strikes that characterized the decade in St. Louis and across the nation.

Urban Development and Daily Life

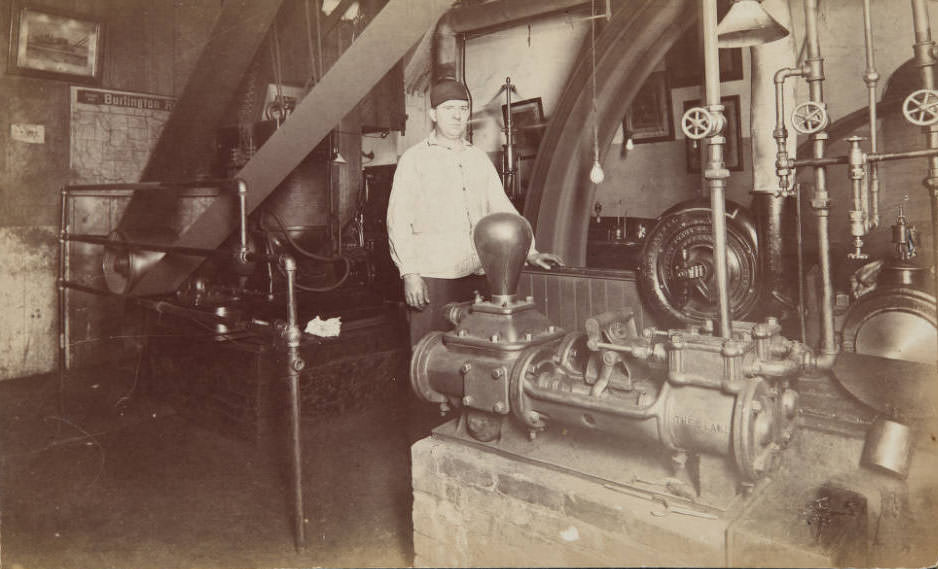

The 1890s were a transformative period for St. Louis’s urban infrastructure, with significant advancements in public services aimed at supporting its growing population and industrial base. A major focus was on improving the water supply. Work continued on the Chain of Rocks intake tower and pumping station, which had begun in the late 1880s and became operational in 1894. This new facility was designed to provide a larger and cleaner source of water from the Mississippi River, further north than the older Bissell’s Point intake. Additionally, the iconic Compton Hill Water Tower was completed in 1898, serving as a crucial component of the city’s water distribution system.

Sanitation and sewer systems remained an ongoing concern. While the massive Mill Creek Sewer had been largely completed in earlier decades, the city continued to grapple with the challenges of waste disposal in a dense urban environment. An explosion in the Mill Creek Sewer in 1892, caused by the ignition of industrial waste and sewer gases, dramatically highlighted the dangers and complexities of managing urban sanitation. Public health reports from the period would have reflected these ongoing efforts and challenges in maintaining a healthy urban environment.

Street lighting also underwent a transition. While gas lighting had long illuminated the city’s streets, electricity began to make significant inroads. The St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall, completed in 1884, was among the first major buildings in the city to feature electric lights. In 1897, a city ordinance mandated that electrical wires in the downtown business district be placed underground, a move towards both safety and aesthetics. However, the complete transition from gas to electric street lighting was a gradual process, with the last gas streetlight not being replaced until 1923.

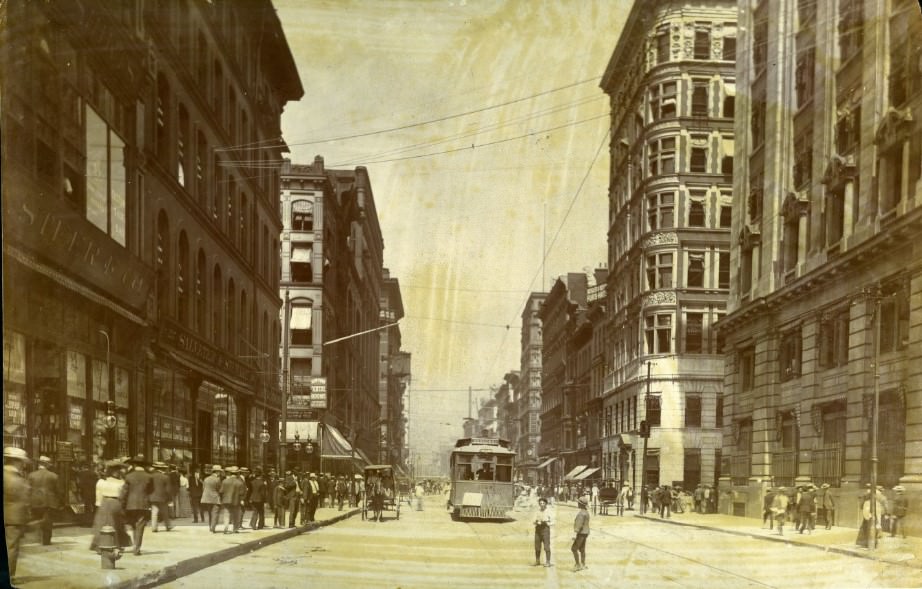

Public transportation was revolutionized by the expansion and modernization of streetcar lines, which were vital for connecting the sprawling city and facilitating suburban growth. The 1890s marked the beginning of widespread electrification of these lines, replacing horse-drawn and cable cars with faster and more efficient electric trolleys. This decade also saw significant consolidation of the numerous independent streetcar companies. The St. Louis & Suburban Railway was formed in 1890 through the merger of several lines. The Central Traction Bill of 1898 further spurred this trend by requiring franchises and allowing consolidated companies to operate on other lines’ tracks, ultimately leading to the formation of the United Railways Company. These investments in water, sanitation, and transportation infrastructure were critical for St. Louis’s development into a modern 20th-century city, though they also underscored the continuous challenges of managing public health and services in a rapidly industrializing urban landscape.

Life in the Bustling City: Classes, Cultures, and Pastimes

Daily life in St. Louis during the 1890s was a study in contrasts, characteristic of the Gilded Age with its stark disparities in wealth and living conditions. The wealthy elite resided in opulent mansions, often located in the newly developed and exclusive private places, benefiting from modern amenities like electricity and telephones. The burgeoning middle class enjoyed Victorian homes where the piano was a common fixture, indicating a degree of comfort and access to leisure. In sharp contrast, the working class, including many recent immigrants, frequently faced challenging living and working environments. They often lived in crowded tenements or densely packed neighborhoods near factories and industrial areas. However, the expansion of streetcar lines also facilitated the development of new working-class residential areas, such as Walnut Park East, offering alternatives to the most congested inner-city districts.

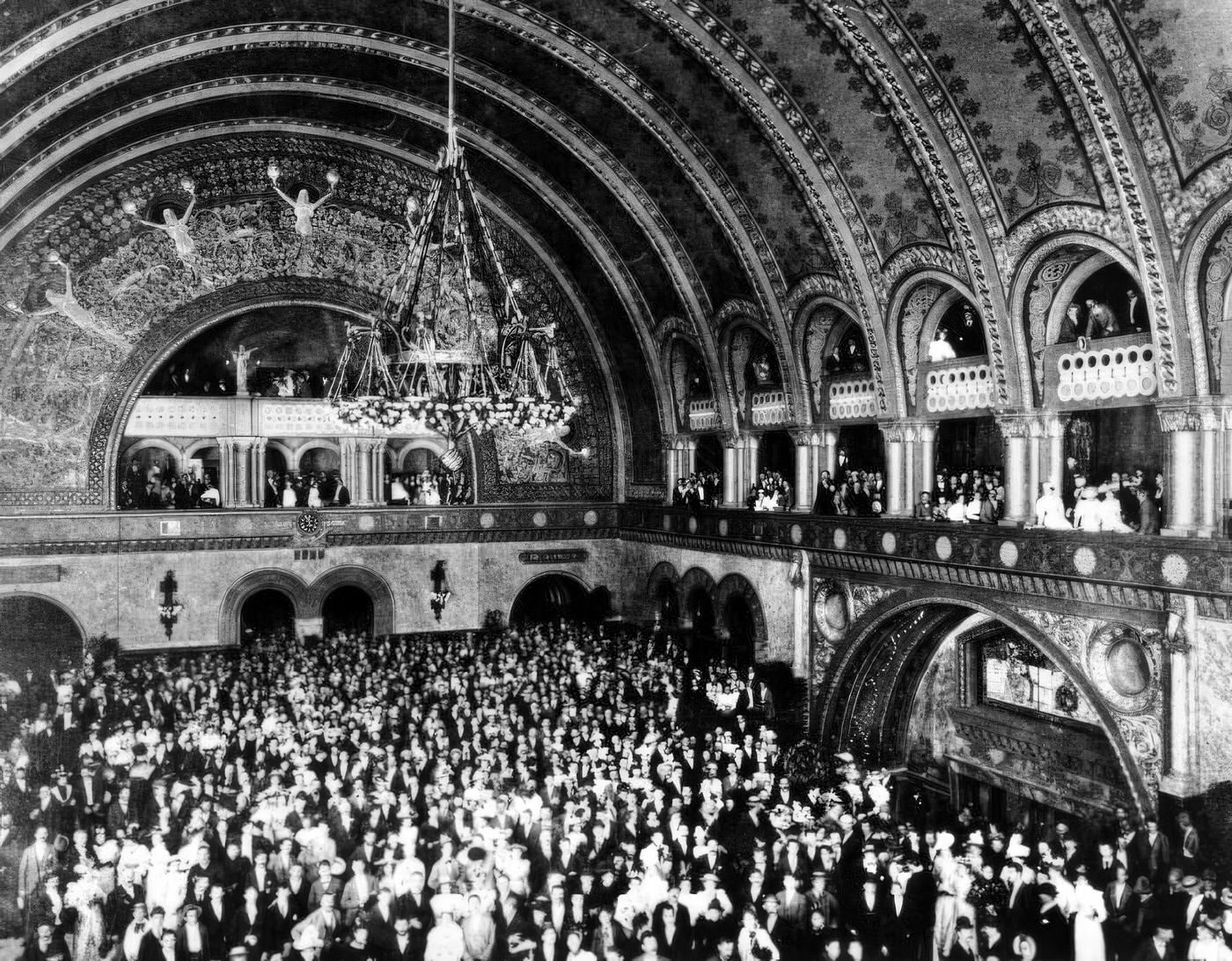

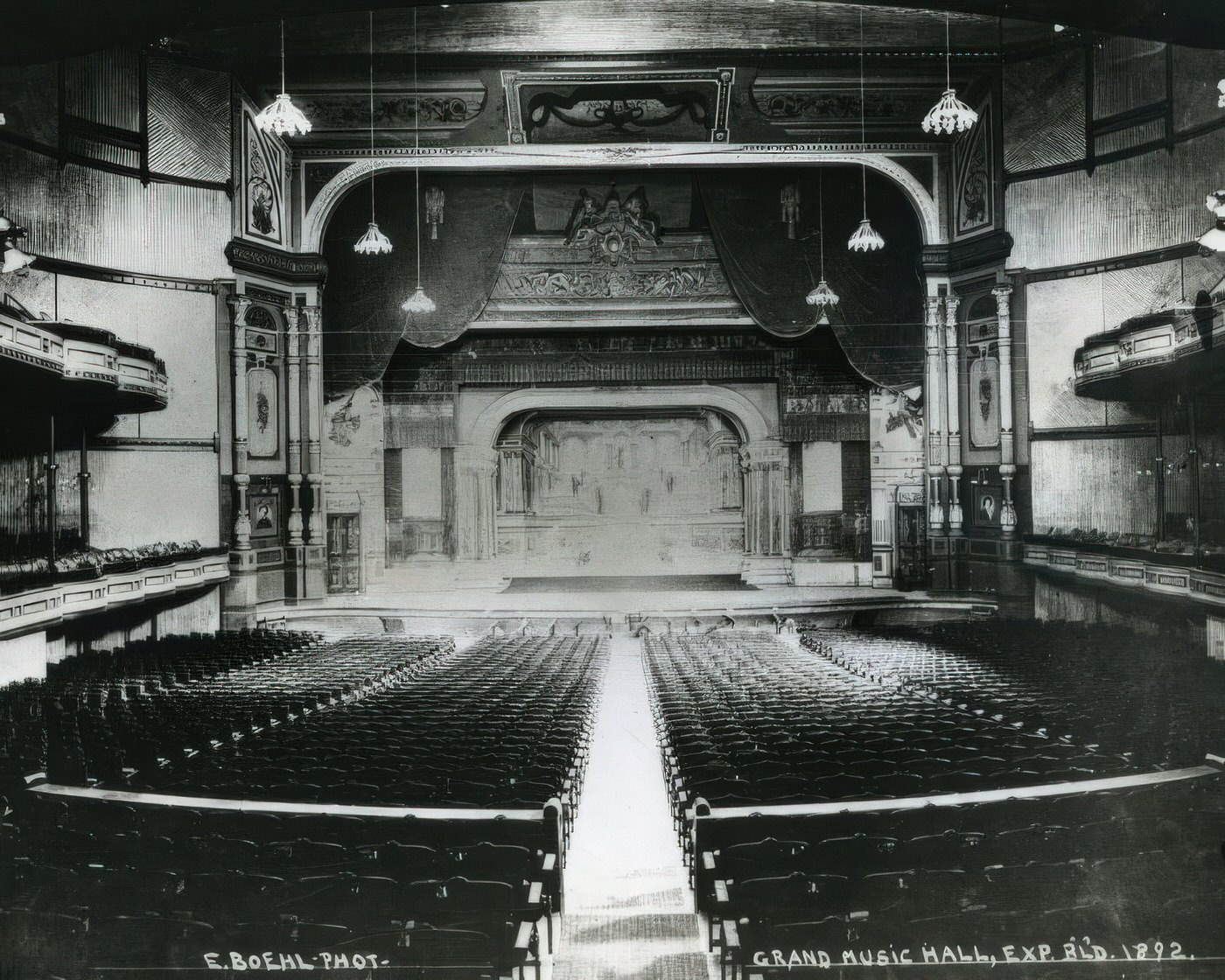

The city’s entertainment scene was vibrant and catered to a wide range of tastes. Theaters and music halls flourished. The St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall, a grand structure completed in 1884, continued to be a major venue into the 1890s, hosting concerts by the St. Louis Symphony, large conventions, and various public events. Vaudeville was a popular form of entertainment, with dedicated venues like the Casino Theater (which later became the Gayety, known for burlesque) and the Columbia Theater offering a variety of acts. The Germania Theater also opened its doors in 1892, adding to the city’s theatrical offerings.

A uniquely St. Louis contribution to American music, ragtime, blossomed in the 1890s. The Chestnut Valley district, with its saloons and brothels, became a fertile ground for this new, syncopated musical style. Scott Joplin, who would become known as the “King of Ragtime,” lived and worked in St. Louis during this period. He composed and performed in the city, and his iconic “Maple Leaf Rag” was published in 1899, catapulting both Joplin and ragtime to national fame.

Turnvereins, the German-American gymnastic and social societies, remained important cultural centers. They offered physical fitness programs, hosted choirs and theatrical performances, and maintained libraries, serving as hubs for the German community.

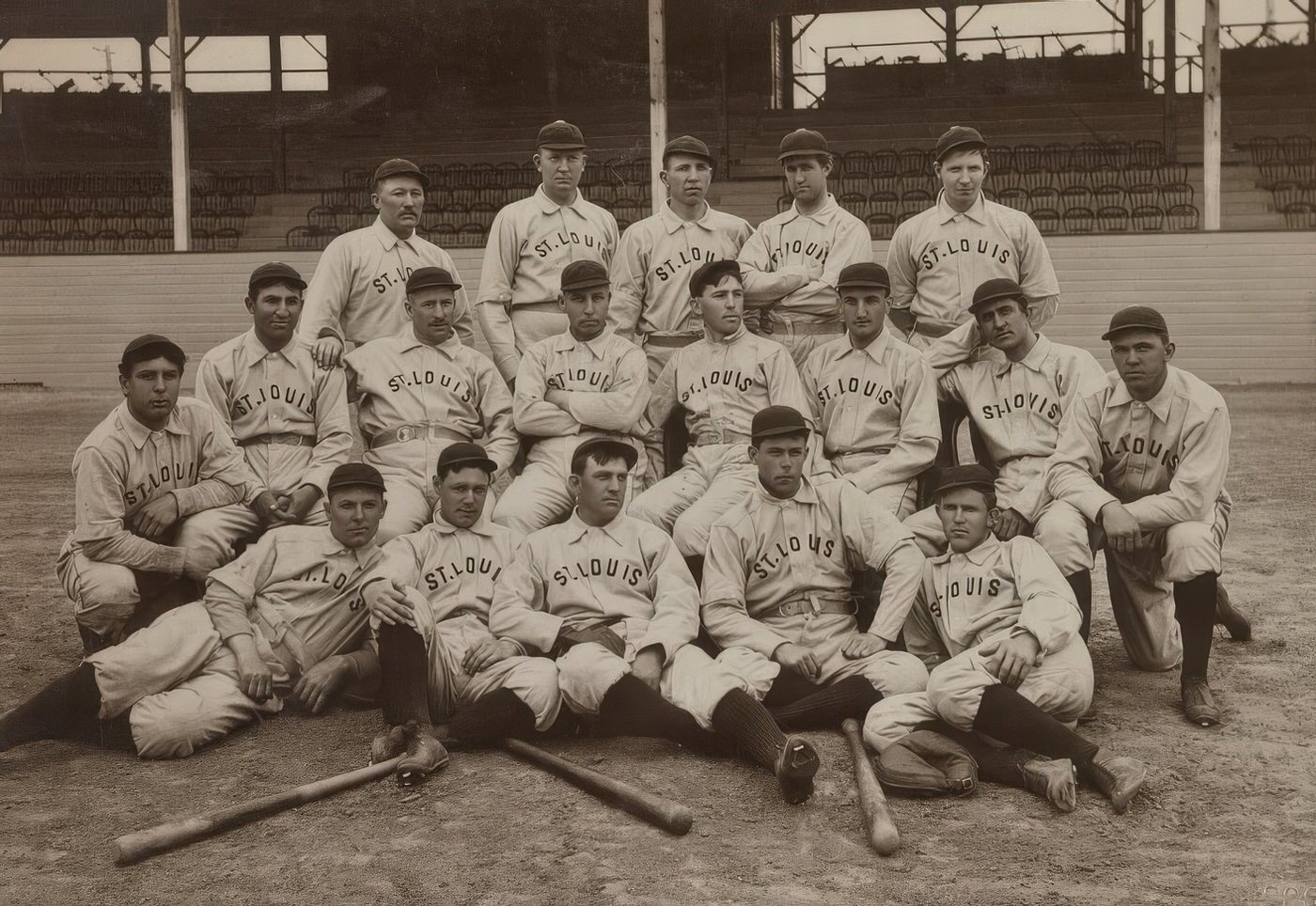

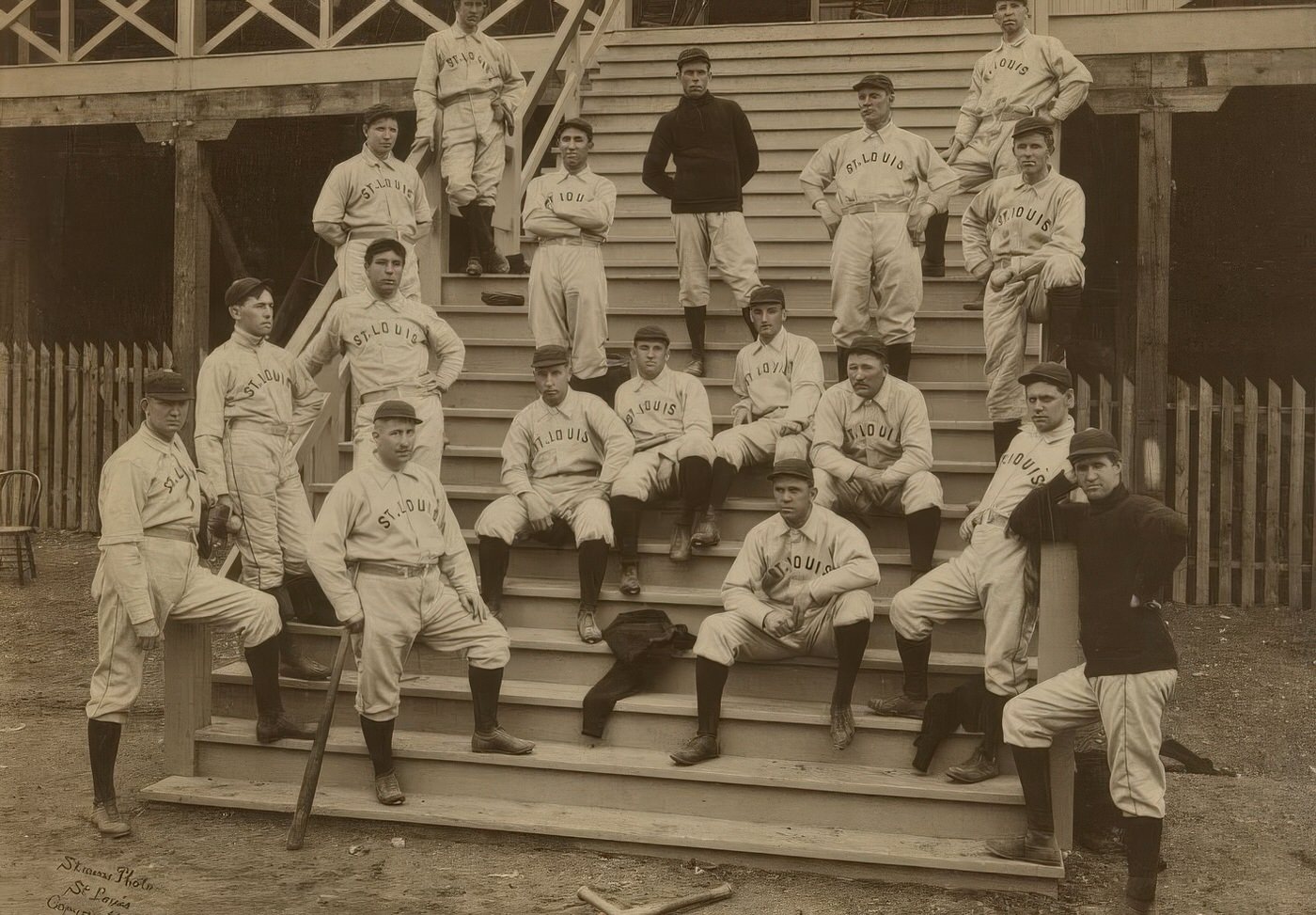

Sports, particularly baseball, captured the public’s imagination. The St. Louis Browns, owned by the colorful Chris Von der Ahe, played in the American Association in the early part of the decade before transitioning to the National League in 1892. The team, however, struggled in the more competitive National League. A disastrous fire at Sportsman’s Park in 1898 contributed to Von der Ahe’s financial ruin and the forced sale of the team. Under new ownership by Frank Robison, the team was infused with talent from the Cleveland Spiders and was unofficially dubbed the “Perfectos” in 1899, a precursor to their eventual renaming as the St. Louis Cardinals.

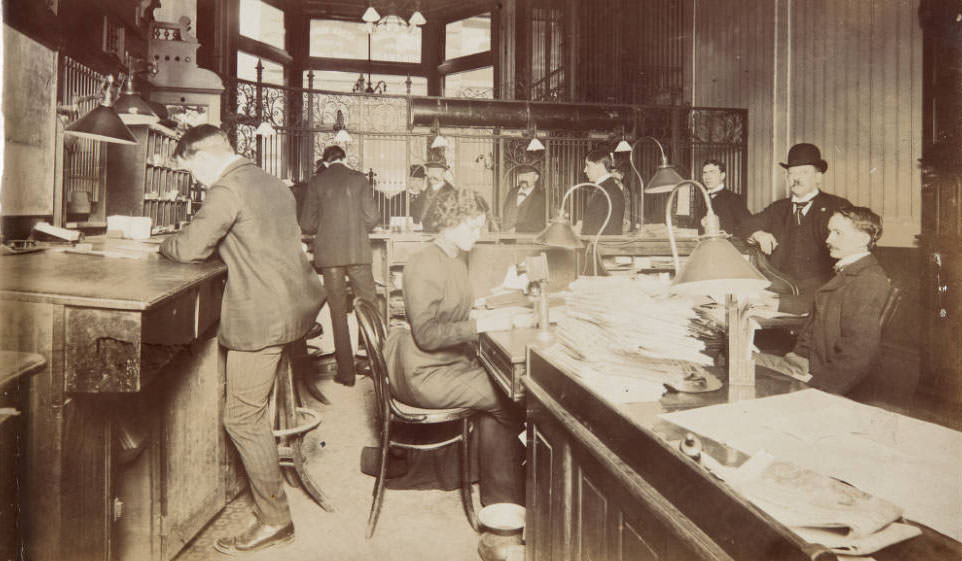

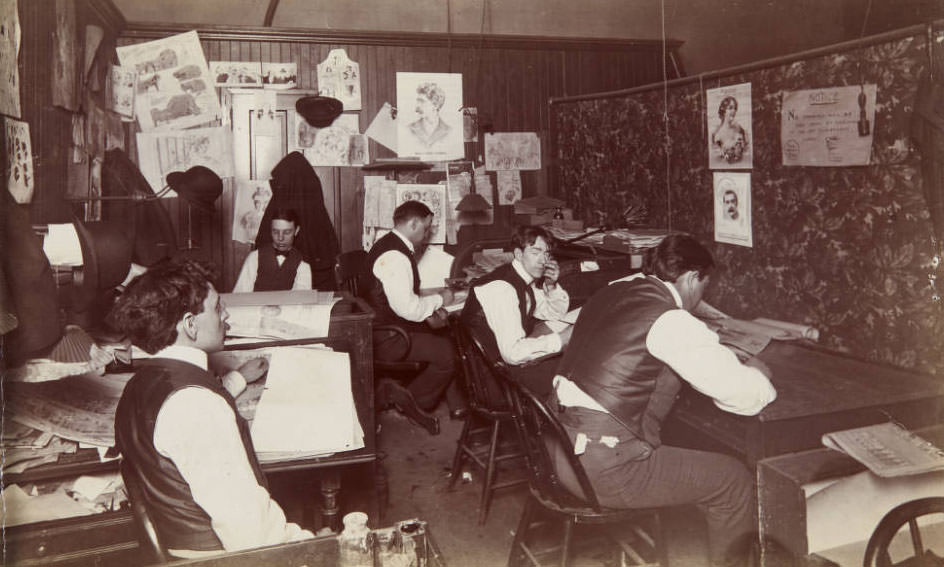

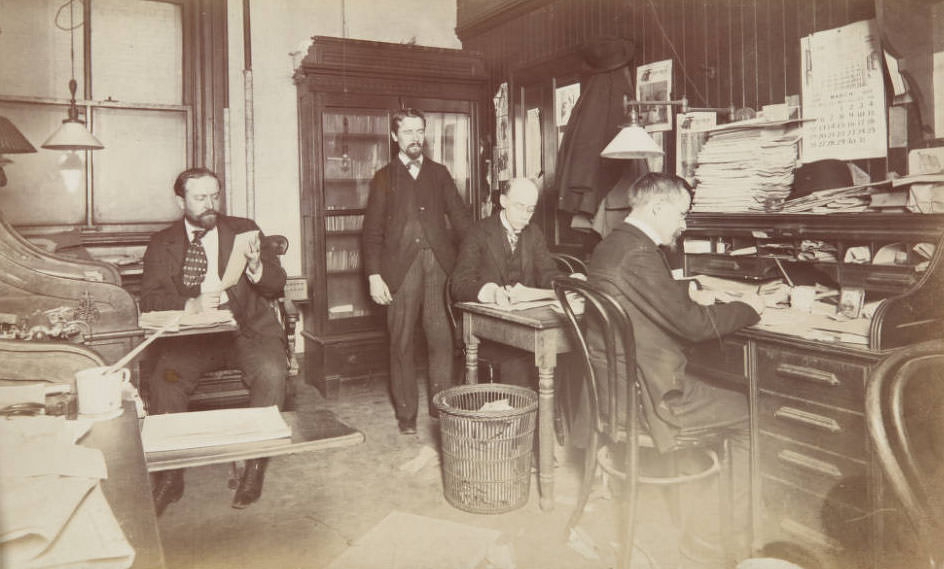

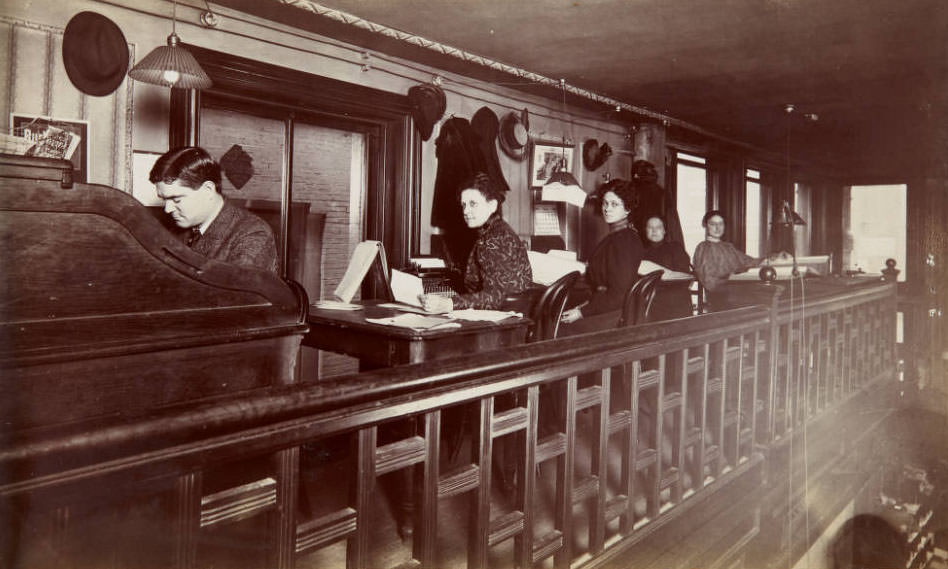

Newspapers like Joseph Pulitzer’s St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the St. Louis Globe-Democrat were powerful forces in shaping public opinion and disseminating information. They covered local events, political battles, and social issues, sometimes engaging in the sensationalist style of “yellow journalism” that characterized the era. The diverse entertainment options and the active press reflected a dynamic and evolving urban culture in St. Louis.

Architectural Ambitions: Defining the St. Louis Skyline

The 1890s witnessed a surge of ambitious construction projects that significantly shaped the architectural landscape of St. Louis, reflecting its prosperity and growing national stature. One of the most groundbreaking structures was the Wainwright Building, erected between 1890 and 1891. Designed by the renowned architect Louis Sullivan, this ten-story office building is celebrated as a pioneering example of early skyscraper architecture. Its innovative use of a steel frame and its influential aesthetic, emphasizing verticality, marked a departure in commercial building design.

Another monumental project was St. Louis Union Station, which opened its doors in 1894. Designed by Theodore Link, Union Station was an architectural marvel and, at the time of its completion, the largest and busiest railroad terminal in the world. Its grand Romanesque Revival style, featuring a magnificent gold-leafed Grand Hall, soaring barrel-vaulted ceilings, and intricate stained-glass windows, served as a majestic gateway to the city and a powerful symbol of St. Louis’s dominance as a rail hub.

The decade also saw the commencement of construction on St. Louis City Hall in 1892, a project that would extend into the next century. Designed by the architectural firm Eckel and Mann, City Hall embodies the Renaissance Revival style, drawing inspiration from the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. Its imposing presence and classical design were intended to project civic pride and authority.

In the realm of commerce and logistics, Cupples Station, constructed primarily between 1893 and 1894, represented a significant innovation. This complex of massive Romanesque style warehouses, designed by the firm of Eames and Young, was strategically located to provide direct rail access for the efficient handling and distribution of freight. It revolutionized warehousing in the city and underscored St. Louis’s role as a vital commercial entrepôt.

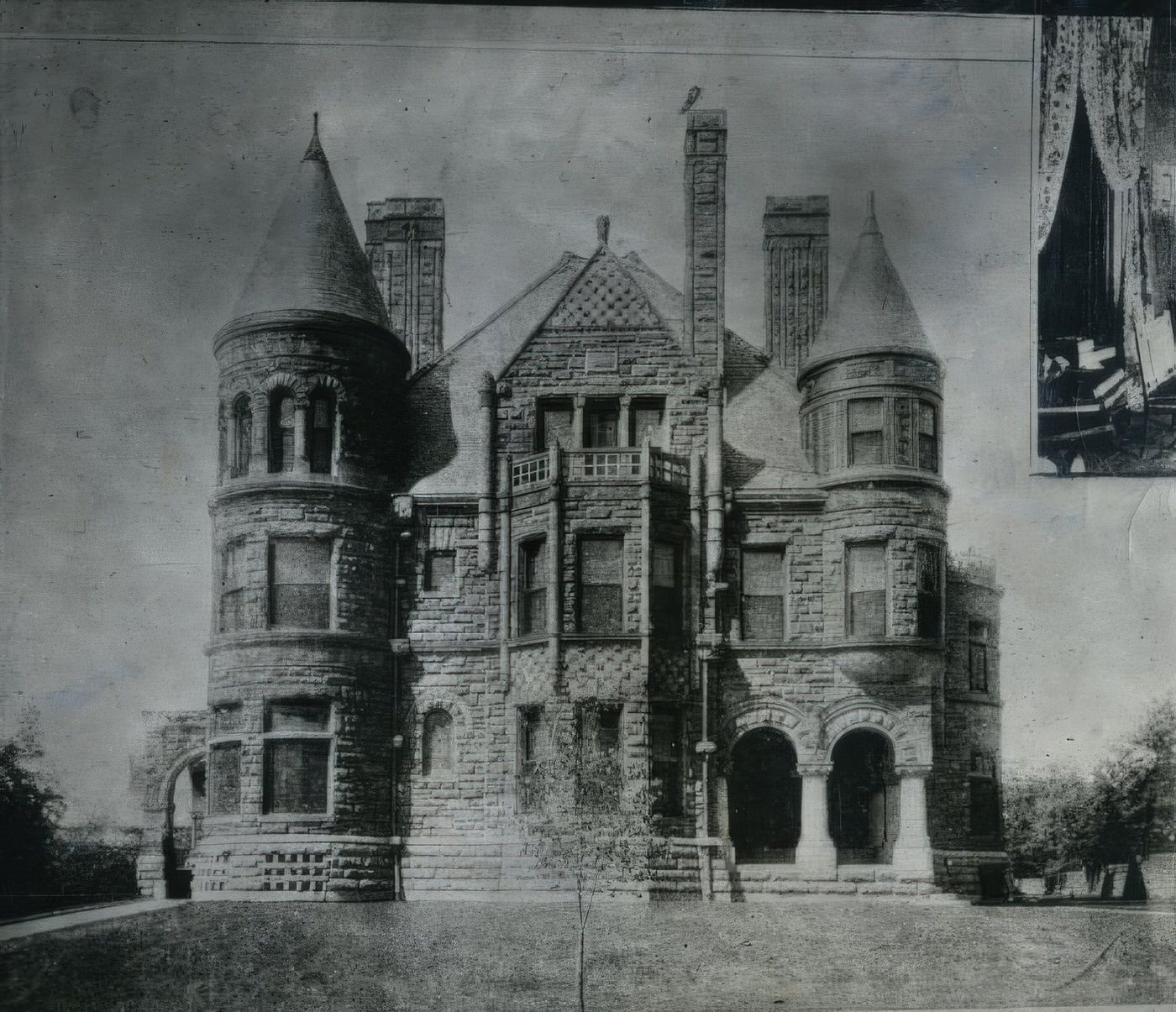

Residential architecture also saw distinctive developments with the continued expansion of private places. These exclusive, self-governing enclaves, such as Westmoreland Place, Portland Place (whose gates were designed by Theodore Link), Lewis Place, and Washington Terrace, offered secluded, high-standard living for the city’s wealthy elite, often featuring grand homes designed by prominent architects. These major architectural undertakings of the 1890s collectively showcased St. Louis’s economic vitality and its embrace of prevailing national trends in architectural design, creating enduring landmarks that defined the city’s urban character.

Education and Enlightenment: Shaping Minds for a New Century

The St. Louis Public Schools system experienced continued growth and development throughout the 1890s. Student enrollment figures reflected this expansion, reaching 78,648 by the year 1899. Kindergartens, a pioneering educational initiative first successfully established as a public endeavor in the United States by Susan Blow in St. Louis in 1873, were by this decade an integral and established component of the city’s public education offerings.

High schools were also a recognized part of the educational landscape. This included Sumner High School, which held the distinction of being the first high school for African American students west of the Mississippi River, providing crucial secondary education opportunities for the Black community. The curriculum within the public schools continued to evolve, shaped by earlier reforms under superintendents like William Torrey Harris, who had advocated for a broad and rigorous educational program.

The decade also saw efforts to improve the administration and physical conditions of the schools. The Board of Education underwent a significant reorganization with the adoption of a new charter during the 1896-1897 school year. This reform aimed to address persistent issues within the school system, which often included inadequate facilities with poor lighting, insufficient sanitation, and safety concerns. The ongoing commitment to public education, from the foundational kindergartens to the expanding high schools, demonstrated a societal recognition of the importance of education for the city’s youth in an era of industrial growth and social change. The efforts to reform the Board of Education signaled a continuous drive to enhance the quality and accessibility of schooling for St. Louis children.

Institutions of Higher Learning

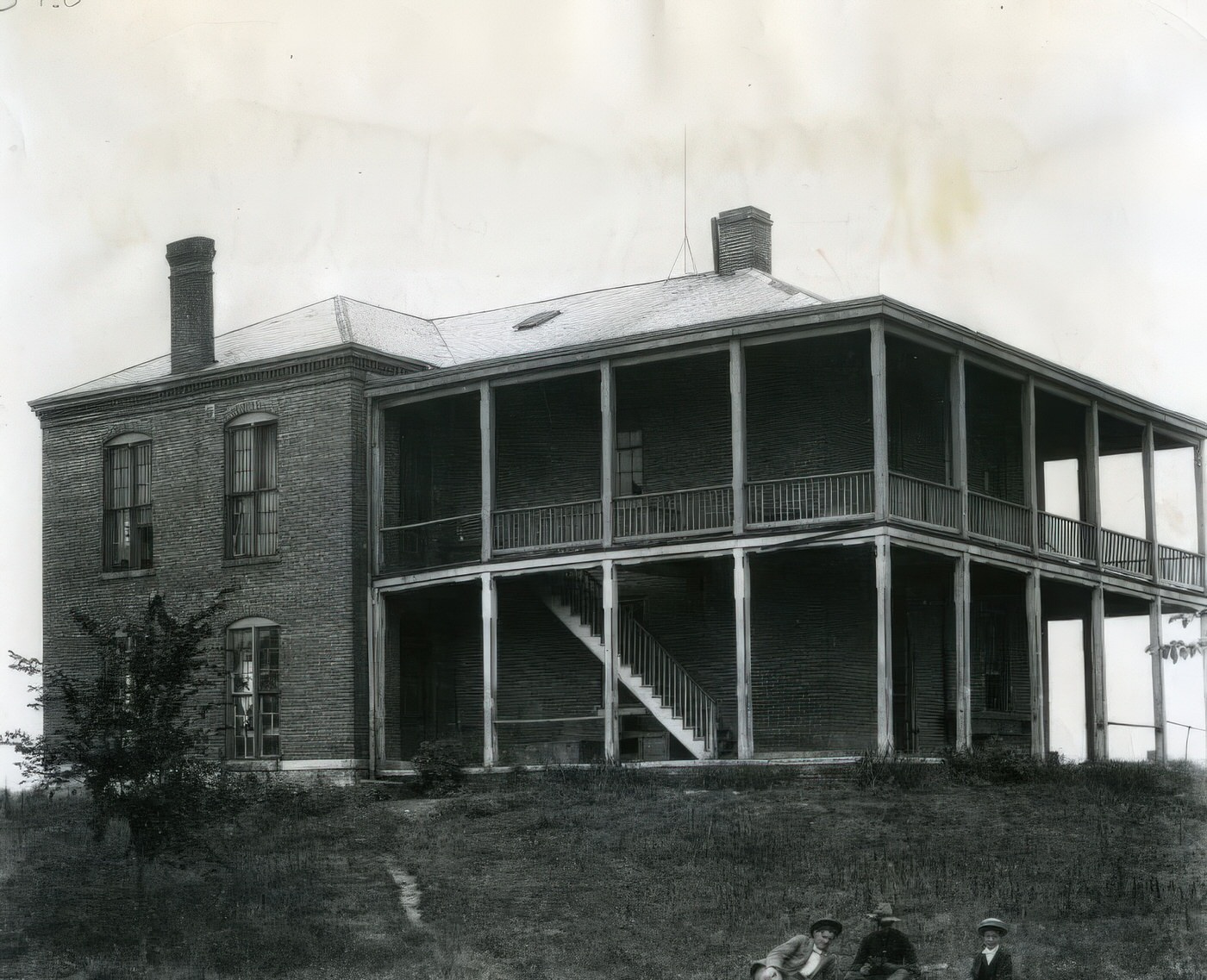

St. Louis in the 1890s was home to several institutions of higher learning that were undergoing significant development. Washington University in St. Louis, by the early part of the decade, faced financial difficulties but was revitalized under the leadership of Robert Brookings, president of its Board of Trustees. A crucial decision was made to relocate the university from its downtown location to a more spacious site. Land for the new “Hilltop” campus, west of Forest Park, was acquired, and a design competition for the new campus was held in 1899, with the firm Cope & Stewardson winning. Women played an increasingly important role in the university, becoming the main drivers of enrollment growth in the undergraduate college by the 1890s. While Walter Moran Farmer became the first known African American to receive a degree from the School of Law in 1889, by the late 1890s, African Americans were largely excluded from the student body.

Saint Louis University (SLU) had already made its move to the Grand and Lindell campus in 1889 with the opening of DuBourg Hall, which served as the university’s main building, housing classrooms, laboratories, the library, and dormitories. The 1890s saw continued development of this campus. A significant project was the construction of the new St. Francis Xavier College Church, a prominent landmark whose upper church was completed in 1898. Leadership during this decade included Reverend Joseph Grimmelsman, S.J., who served as president from 1890 to 1898, followed by Reverend James F.X. Hoeffer, S.J., from 1898 to 1900.

Concordia Seminary, a Lutheran institution, continued its mission of training pastors for the ministry. Its impressive Gothic structure on South Jefferson Avenue, which had been completed in 1883, provided facilities including a library, dormitories, and a gymnasium to accommodate its growing student population.

Eden Theological Seminary, affiliated with the German Evangelical Synod, had relocated to Wellston, on the outskirts of St. Louis, in 1883 in response to the increasing urbanization of the country. The Eden Publishing House, which would produce literature for the denomination, was established in 1895. These developments in higher education reflected St. Louis’s growth as an educational center, though access to these institutions was not always equitable for all segments of the population.

Civic Life and Its Discontents: Reform, Strife, and Calamity

The political leadership of St. Louis during the 1890s navigated a period of growth, technological change, and significant social challenges. The mayors who served during this decade were Edward A. Noonan (1889-1893), Cyrus P. Walbridge (1893-1897), and Henry Ziegenhein (1897-1901).

Mayor Cyrus P. Walbridge’s administration (1893-1897) oversaw several important civic improvements. These included the completion of the Chain of Rocks Waterworks, the implementation of regulations for garbage collection and disposal, and an ordinance requiring the removal of overhead telephone and telegraph poles in the downtown district, with wires to be placed underground. Walbridge also made history by appointing women to city boards, including the public library board and the board of charity commissioners. His tenure also saw the transition of the public school library into a free public library managed by a separate board.

Despite these advancements, St. Louis politics in the 1890s was deeply marked by corruption. Powerful political machines, such as the one associated with “Colonel” Edward Butler, a Democrat, exerted considerable influence through patronage and bribery. The “Combine,” a group of loyalists, was known for its role in manipulating city governance. The Municipal Assembly, the city’s legislative body, was frequently at the center of corruption allegations, particularly concerning the granting of valuable public franchises for utilities and services. Towards the end of the decade, reformer Joseph Folk began his notable crusade against this entrenched corruption, signaling a growing public desire for cleaner government. The governance of St. Louis in the 1890s was thus characterized by a tension between the forces of established political machines and the burgeoning movements for civic reform.

The 1890s in St. Louis, as across the nation, were a time of significant social ferment, with various movements advocating for change in response to the era’s economic and social conditions. The labor movement was particularly active, fueled by often harsh working conditions, low wages, and long hours in the city’s burgeoning industries. St. Louis had a number of established labor organizations, including the Central Trades and Labor Union, which represented workers’ interests. The economic depression following the Panic of 1893 exacerbated existing tensions between labor and capital, leading to increased strikes and protests nationally. While the direct local impact of the 1894 Pullman Strike on St. Louis is not extensively detailed in available records, its nationwide disruption of railroads, a key industry for the city, would have been felt. More locally, streetcar workers in St. Louis began organizing efforts in 1899, which culminated in a major and violent strike in 1900.

The woman suffrage movement also continued its campaign for voting rights in St. Louis and Missouri during the 1890s, building on decades of activism by figures like Virginia Minor. St. Louis hosted the Mississippi Valley Conference on suffrage in 1895, an event notable for the participation of African American representatives from the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Suffragists also actively lobbied for their cause during the Republican National Convention held in St. Louis in 1896.

The settlement house movement, which aimed to bridge the gap between social classes and provide services to the urban poor and immigrant communities, gained momentum in American cities during the 1880s and 1890s. These houses offered educational programs, childcare, healthcare, and recreational activities. St. Louis, with its large working-class and immigrant populations, saw the establishment of such institutions, contributing to efforts to address poverty and facilitate assimilation. These various reform movements, though distinct in their primary aims, were interconnected responses to the social and economic dislocations of the Gilded Age, reflecting a growing collective desire for social justice and civic betterment.

Trials by Nature and Human Endeavor

The 1890s presented St. Louis with formidable challenges, testing the city’s resilience. On May 27, 1896, a catastrophic event struck in the form of the Great Cyclone, an F4 tornado that carved a path of destruction through St. Louis and across the river into East St. Louis. The storm claimed at least 255 lives, with 137 fatalities in St. Louis alone, and injured over a thousand people. The physical devastation was immense, with more than 8,800 buildings destroyed or severely damaged. Critical infrastructure, including the eastern approach to the Eads Bridge, numerous factories such as Liggett & Myers and the Ralston Purina Mill, hospitals, and churches, lay in ruins. Entire residential areas were flattened. In the aftermath, the community demonstrated remarkable solidarity, with widespread rescue efforts and a determined spirit to rebuild the city.

Beyond this singular disaster, St. Louis, like other major industrial cities of the Gilded Age, faced persistent public health challenges. Poor sanitation, often resulting from inadequate sewer systems and waste disposal in a rapidly growing city, contributed to the spread of disease. Polluted water sources, including the Mississippi River which received sewage from cities upstream like Chicago, were a constant concern. Outbreaks of diseases such as tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and diphtheria were not uncommon. The St. Louis Health Department, or Board of Health, was tasked with the ongoing efforts of monitoring disease, attempting to enforce sanitary regulations, and improving public hygiene. Amidst these trials, the civic spirit of St. Louis also looked towards the future with ambition. Towards the end of the decade, around 1898, the initial ideas for hosting a grand international exposition to celebrate the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase began to take shape. Early planning and fundraising efforts commenced, with the city committing $5 million through bonds in 1899 for what would become the 1904 World’s Fair. The city’s ability to recover from devastating events like the 1896 tornado and simultaneously embark on the monumental task of planning a World’s Fair spoke to its underlying economic strength, the resilience of its people, and a powerful ambition for national and international recognition.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Mercantile Library, Otto E. Laroge Collection, St. Louis Public Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know