At the turn of the 20th century, St. Louis stood as a significant urban center in the United States. In 1900, it held the distinction of being America’s fourth largest city, with a bustling population of 575,238 people. This large number of residents underscored its national importance as the new century began. The city did not stop growing; by 1910, the population had swelled to 687,029. This steady increase brought both opportunities and significant challenges as St. Louis worked to accommodate its expanding populace. The early years of the 1900s marked a high point in St. Louis’s national standing, a period when it stepped onto the world stage by hosting major international events.

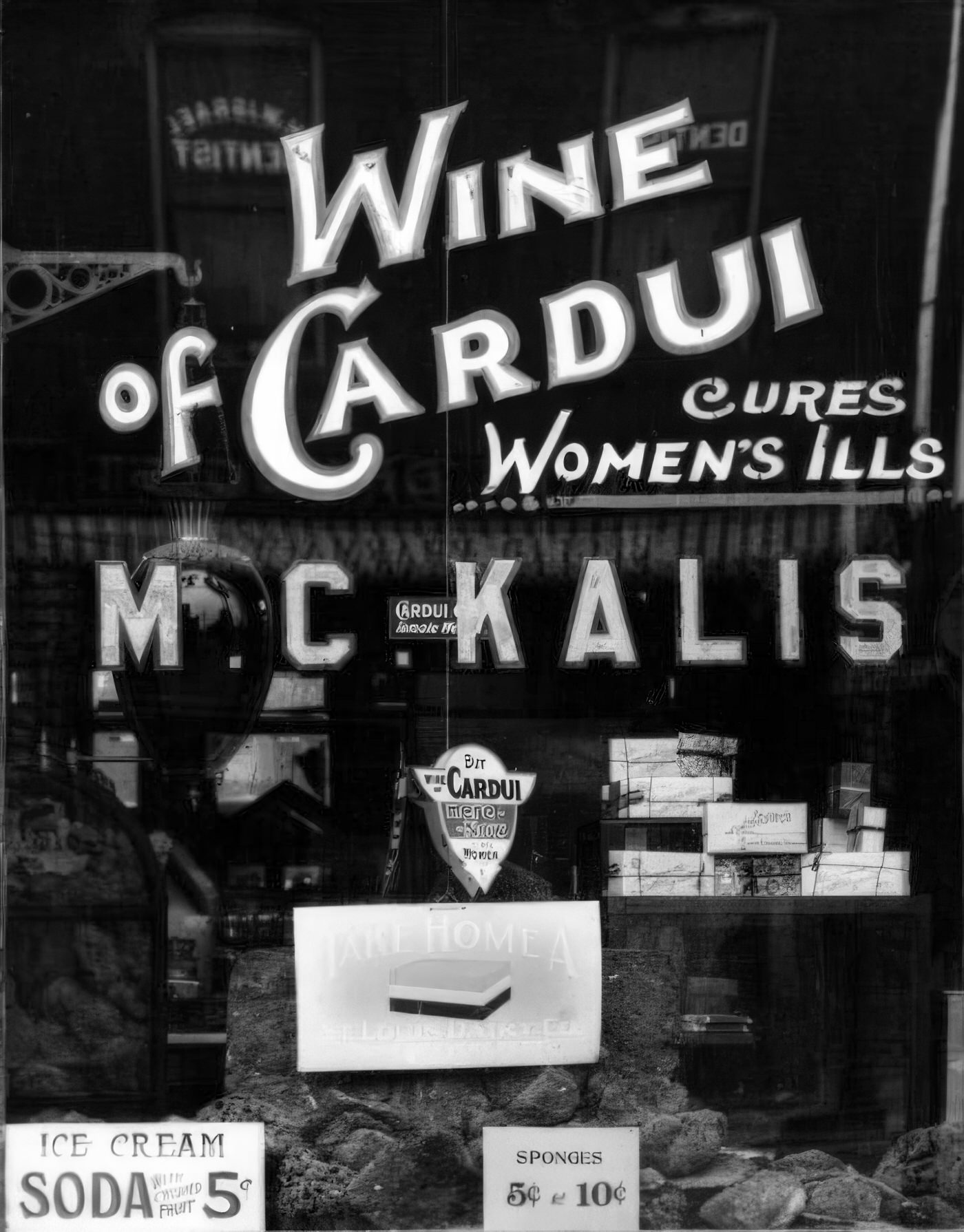

The substantial growth in population during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was fueled by St. Louis’s position as a major destination for both immigrants arriving from other countries and Americans moving from other parts of the nation. The city’s thriving industries, such as brewing, shoe manufacturing, and other forms of production, offered jobs that attracted many hopeful new arrivals. This rapid urbanization, while creating a vibrant and economically active environment, also placed immense strain on the city’s existing resources. The need for housing, sanitation, and transportation grew daily, creating a dynamic tension between civic pride, as seen in grand projects like the World’s Fair, and the urgent need for social and infrastructural reforms. This situation in St. Louis mirrored what was happening in many American cities during this era of industrial strength, large-scale immigration, and swift urban growth, presenting a complex set of issues for the city to address.

The Diverse People of St. Louis

St. Louis at the beginning of the 1900s was a city built by waves of immigrants. Its population was a rich mix of different ethnic communities. Earlier arrivals, primarily Irish and German immigrants, had already established themselves in the city. They were joined in the early 20th century by new groups coming from Southern and Eastern European countries, adding to the city’s cultural fabric and creating what one observer called a “bewildering Babel of voices”.

These diverse groups often settled in distinct ethnic neighborhoods. “Kerry Patch” became known as a center for Irish residents. Italian immigrants, many arriving to work in the clay mines, largely established themselves in an area that would later be famously known as “The Hill”. The German community was substantial and had a strong presence in various industries, particularly brewing.

African Americans also formed a significant and growing part of the city’s population, though their lives were heavily shaped by segregation. In 1900, St. Louis City was home to 35,289 African Americans, making up 6.1% of the total population. They were often concentrated in specific residential areas due to discriminatory practices, with “Clabber Alley” mentioned as one such neighborhood. The city’s long-standing role as a “gateway to the west” continued to attract people from various backgrounds seeking new lives and opportunities, contributing to its diverse and evolving demographic makeup.

Education in a Changing City

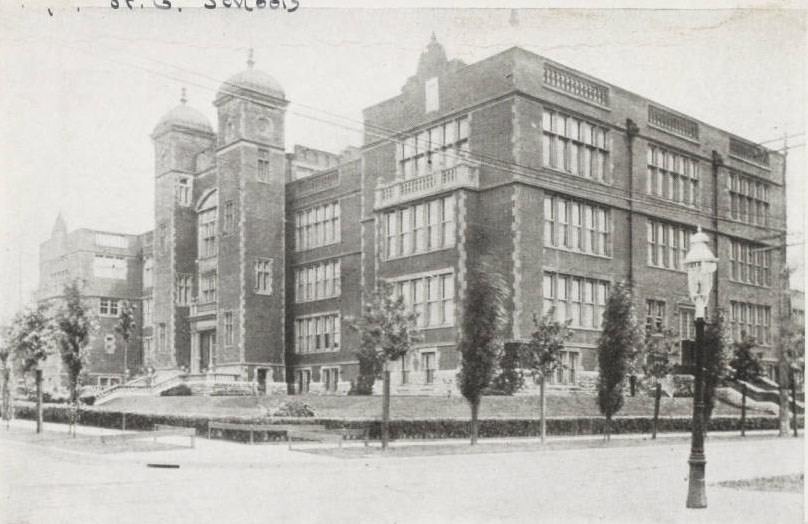

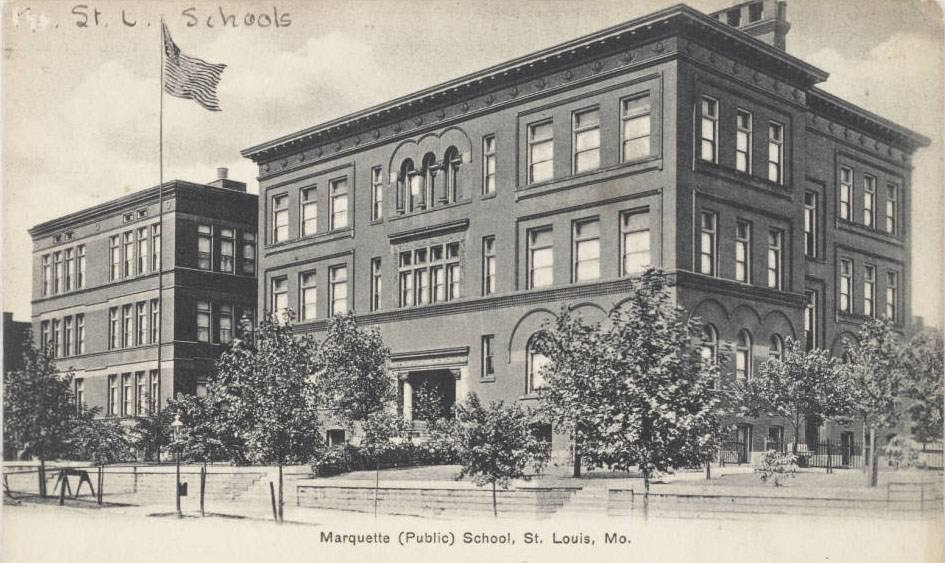

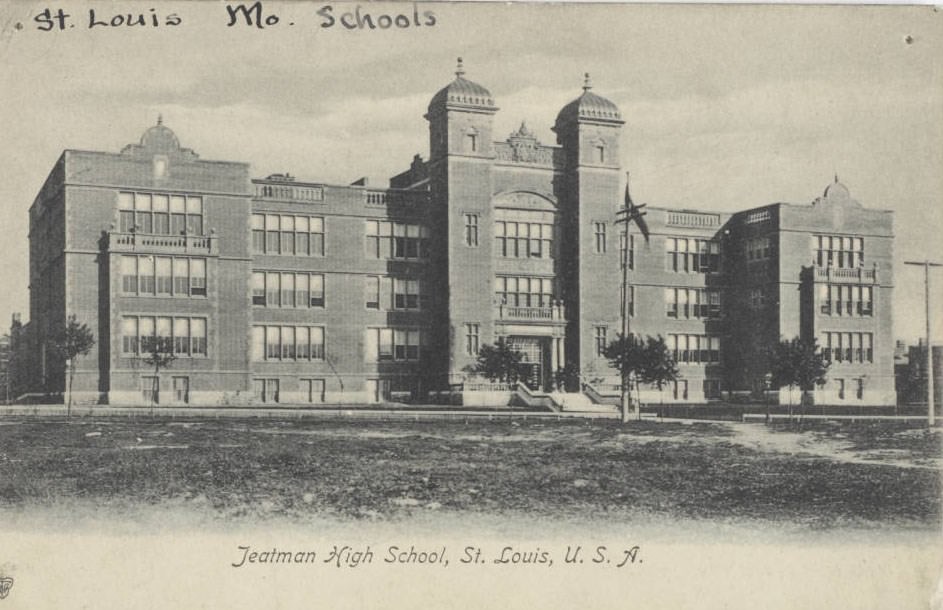

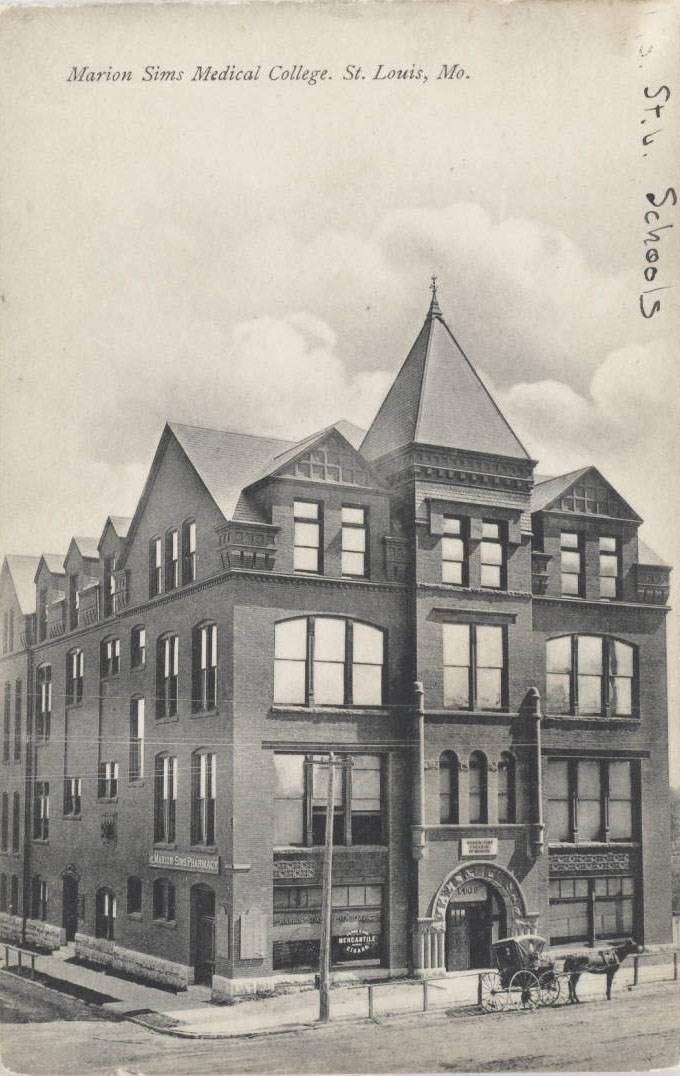

The St. Louis public school system experienced notable changes at the beginning of the 20th century. A key figure in this transformation was William B. Ittner, who served as the Commissioner of School Buildings from 1897 and continued as an architectural consultant for the schools into the 1910s. Ittner was responsible for the design of approximately fifty schools in St. Louis. He introduced innovative “open floor plans,” which featured long hallways with classrooms arranged on either side. This design aimed to maximize natural light and ventilation in each room, improving the learning environment. Architecturally, Ittner’s schools often drew from Tudor Revival or Georgian styles. The William Clark School, designed in 1906, stands as an example of his influential work.

The education of African American children remained a critical issue. Sumner High School, recognized as the first high school for African Americans west of the Mississippi River, had been operating in older, often inadequate, surplus school buildings. Due to persistent pressure from parents advocating for better facilities, a new building for Sumner High School was finally constructed in 1911. This development highlighted the ongoing struggle for equitable educational resources within a segregated system.

In higher education, Washington University, founded in 1853, was a well-established institution. A major development occurred in 1905 when the university relocated its main campus to a new site northwest of Forest Park. Construction of the first buildings on this new, more spacious campus had begun in 1900, allowing for future expansion and the development of new academic facilities.

A Powerhouse of Industry

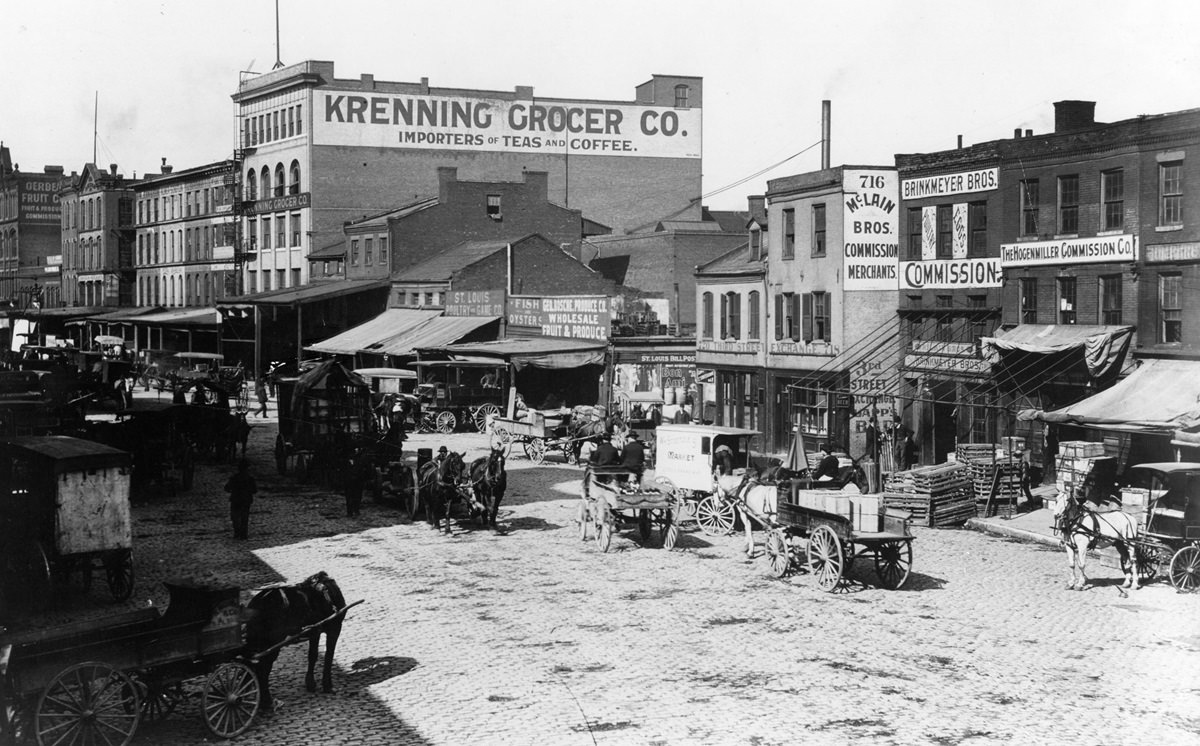

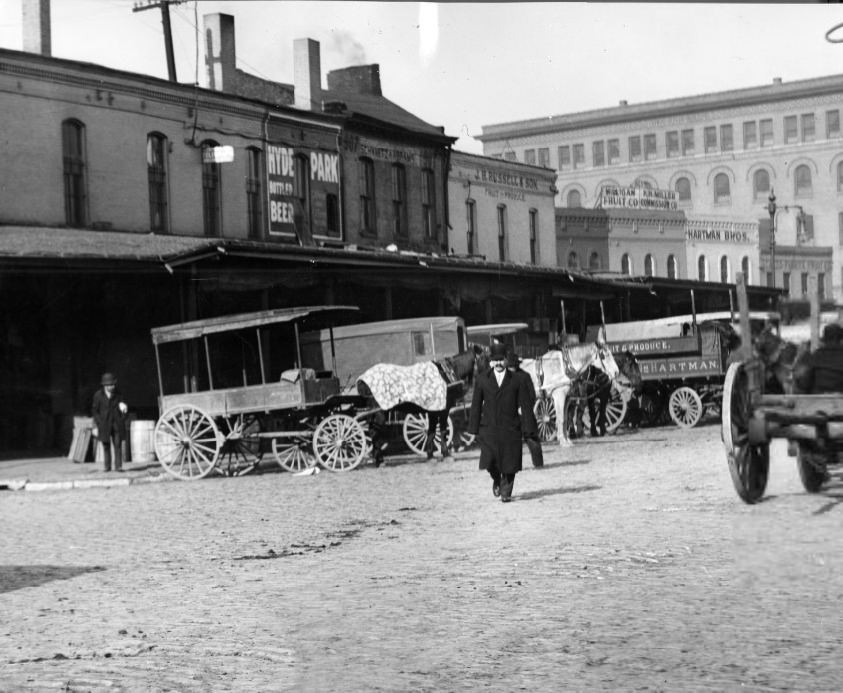

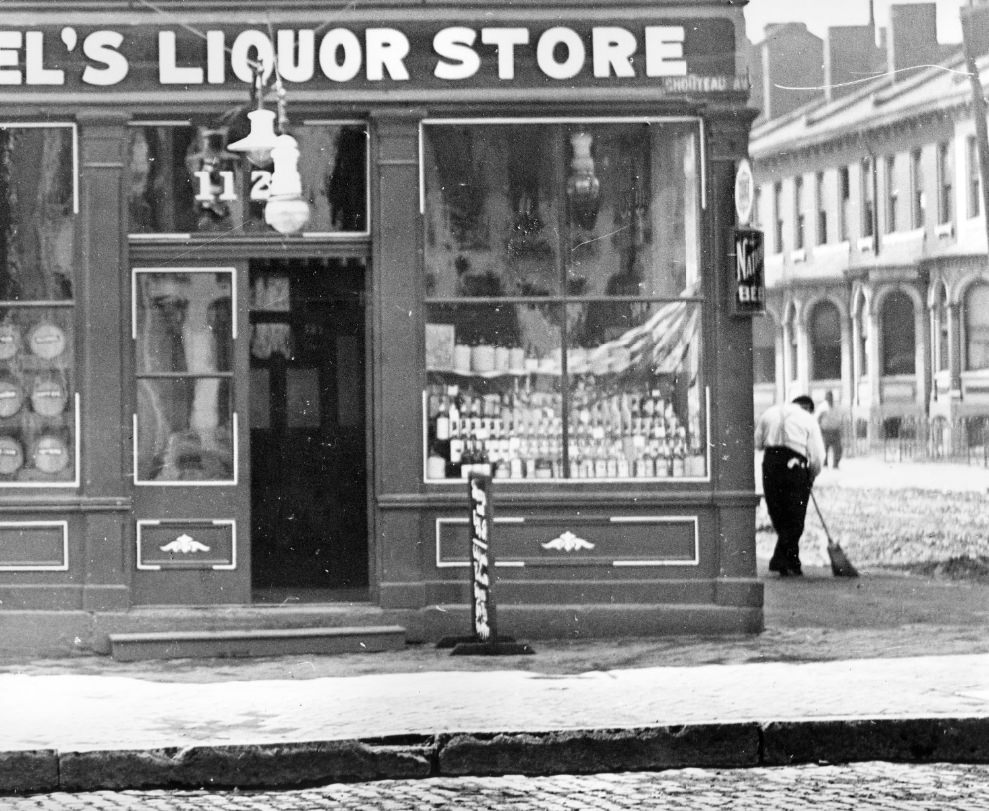

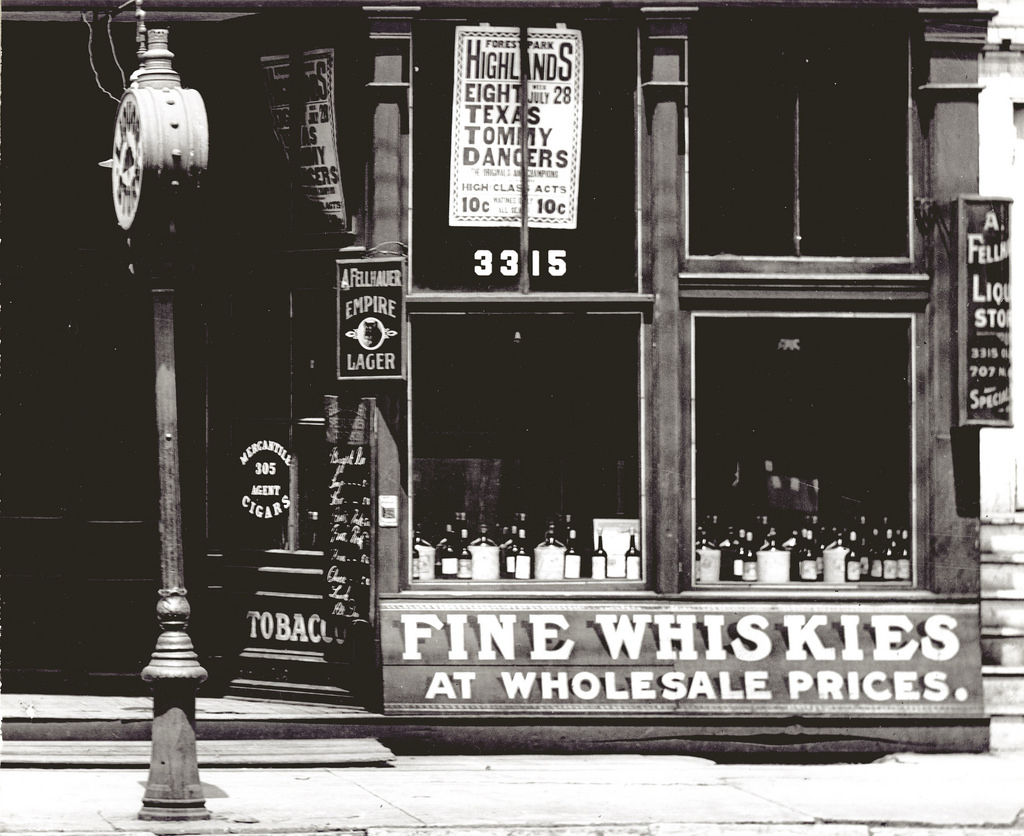

St. Louis in the early 1900s was a formidable manufacturing center. Several key industries drove its economy. Brewing was a major enterprise, with companies like Anheuser-Busch already having deep roots and a significant presence in the city. Shoe manufacturing was another cornerstone of the local economy; St. Louis was one of the nation’s largest shoe manufacturing cities.

Other important industrial sectors included the production of textiles, various types of machinery, and tobacco products. The city saw the construction of new industrial facilities during this time. For instance, the American Brake Company built its office complex in 1901, and the Hall and Brown Woodworking Company constructed a millwork building in 1910. Guth Lighting also established a new facility in 1912.

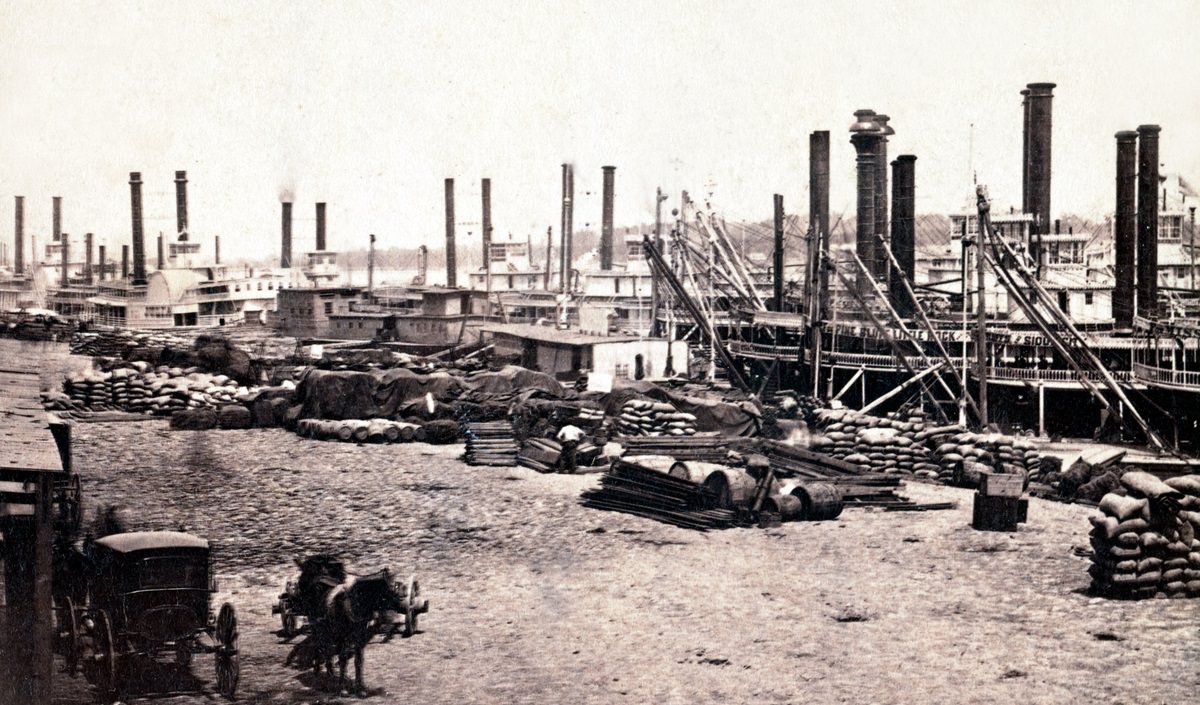

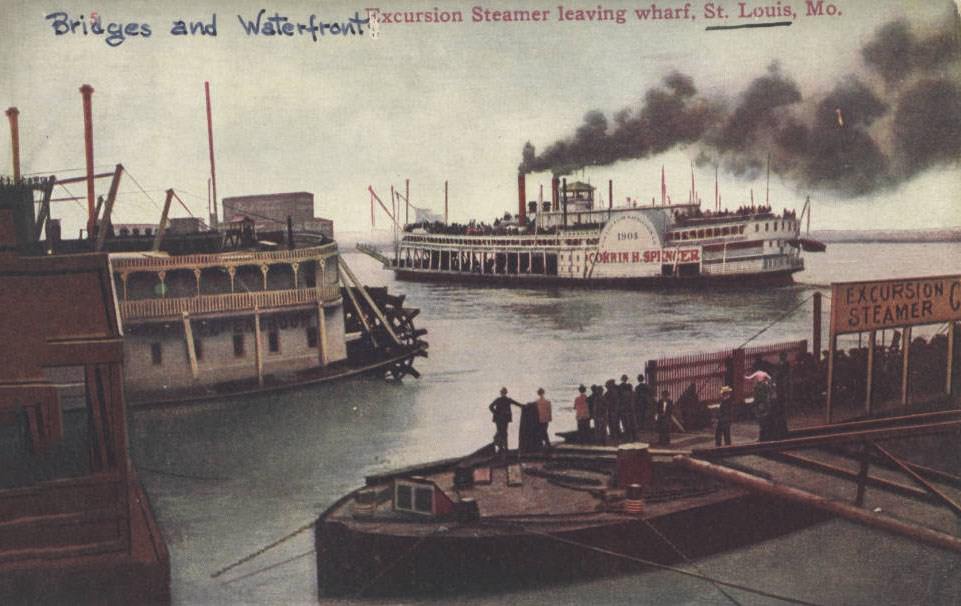

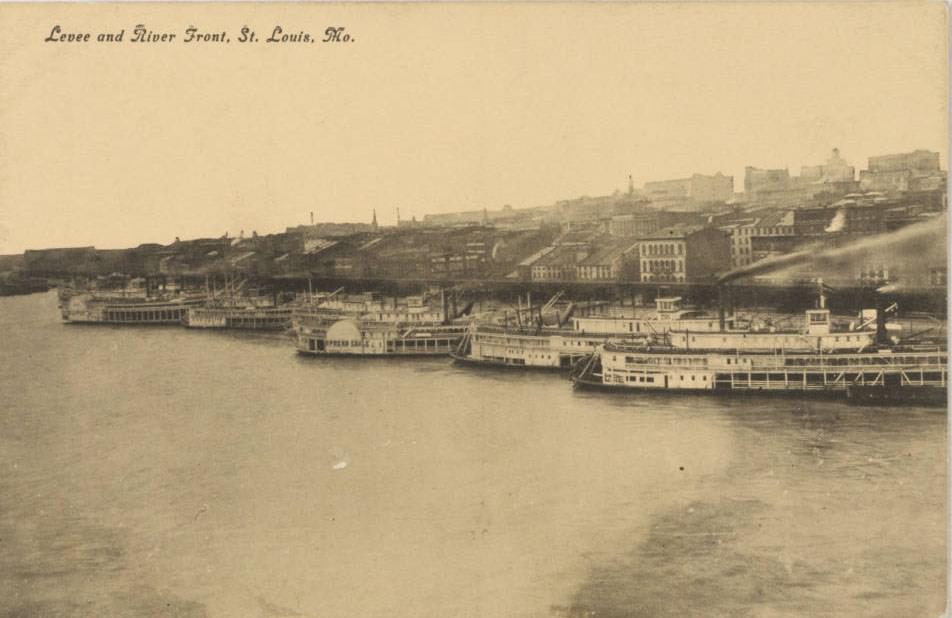

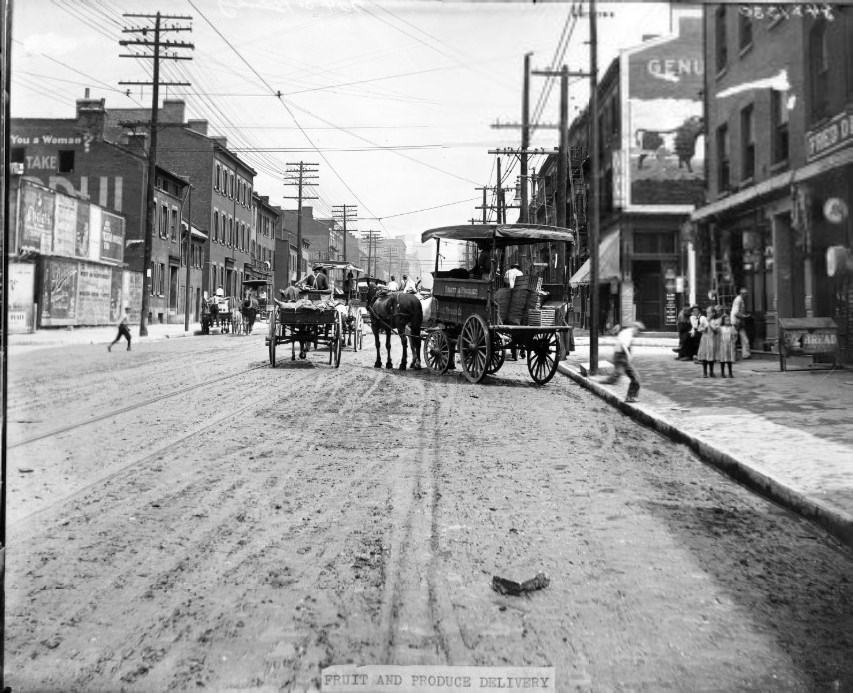

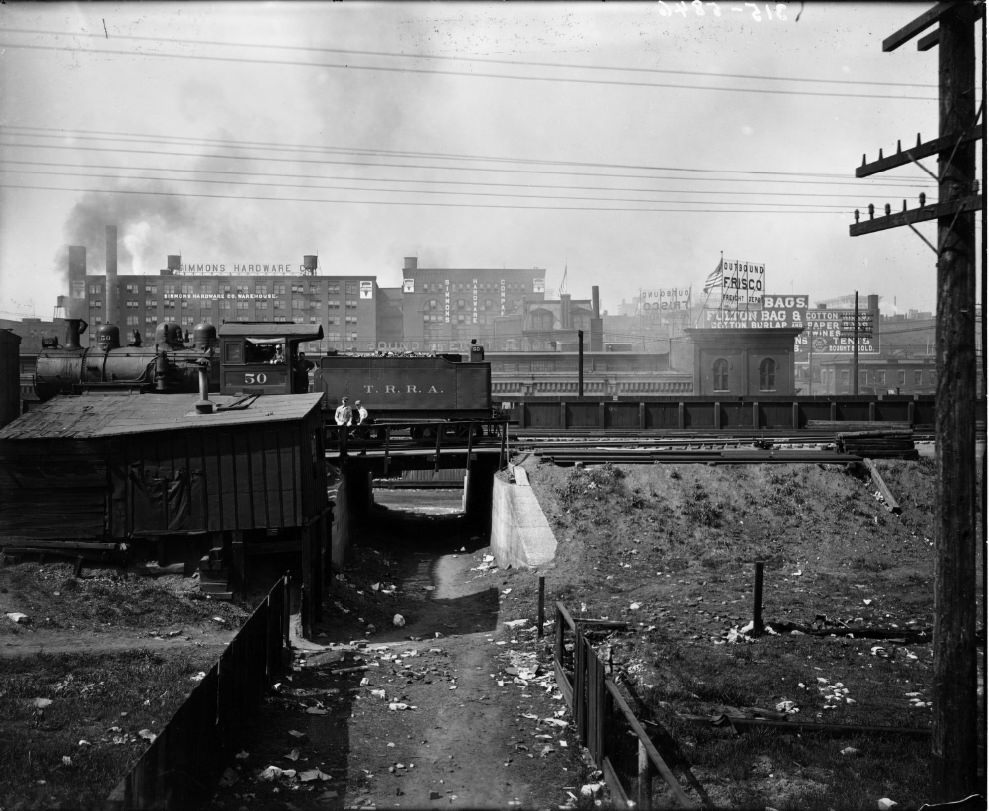

The city’s strategic geographical position on the Mississippi River, coupled with its development as a major railroad hub, was crucial for this industrial growth. These transportation advantages provided factories with ready access to essential raw materials, such as timber, coal, and iron ore from surrounding regions, and also allowed them to ship their finished goods to markets across the country. The workforce that powered these booming industries was significantly composed of the many immigrants who came to St. Louis seeking employment.

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World’s Fair)

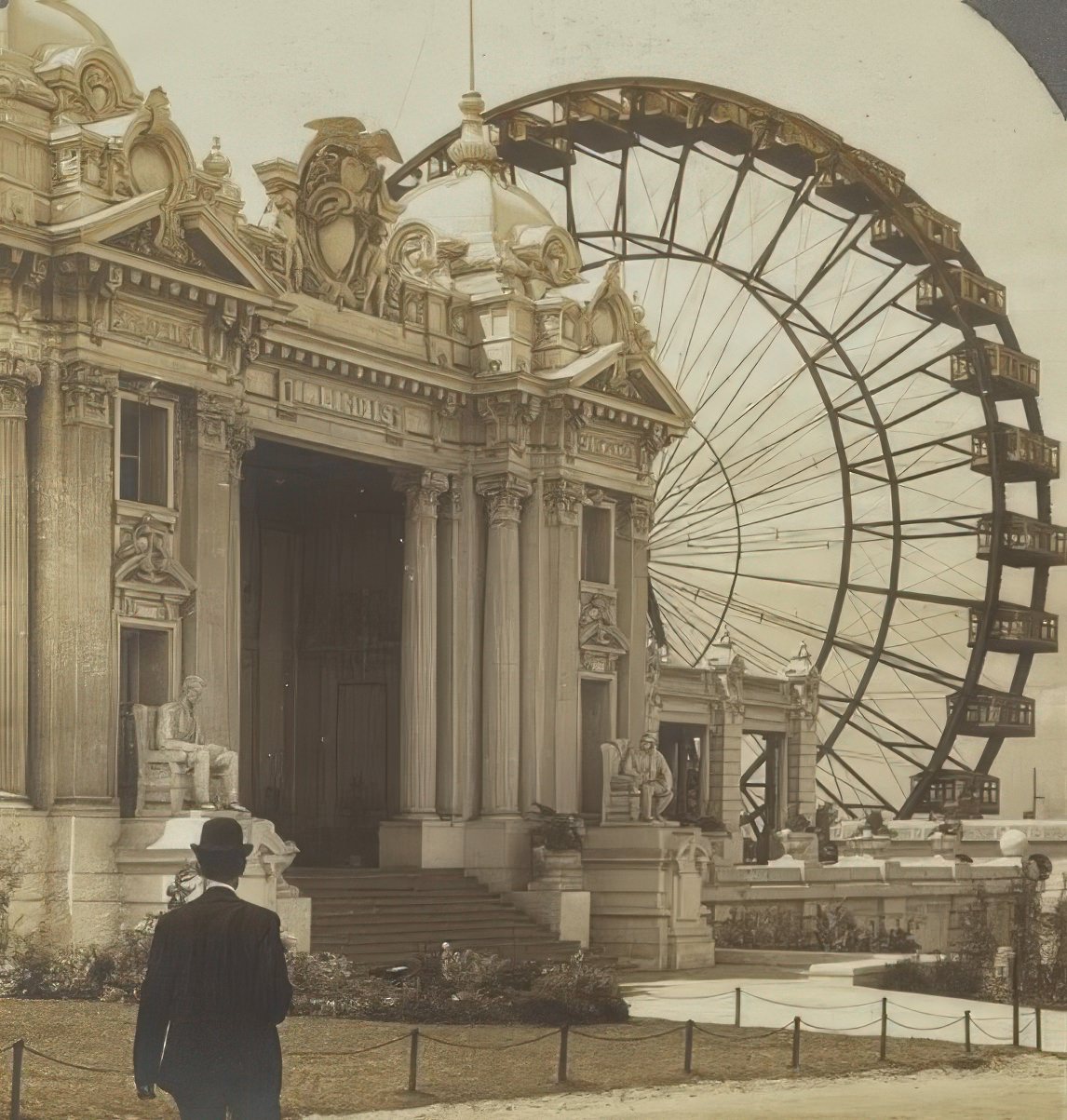

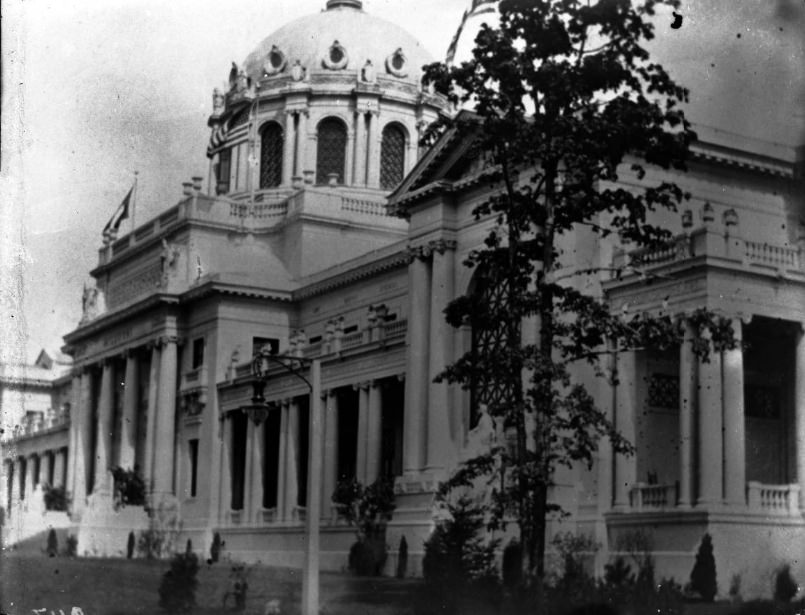

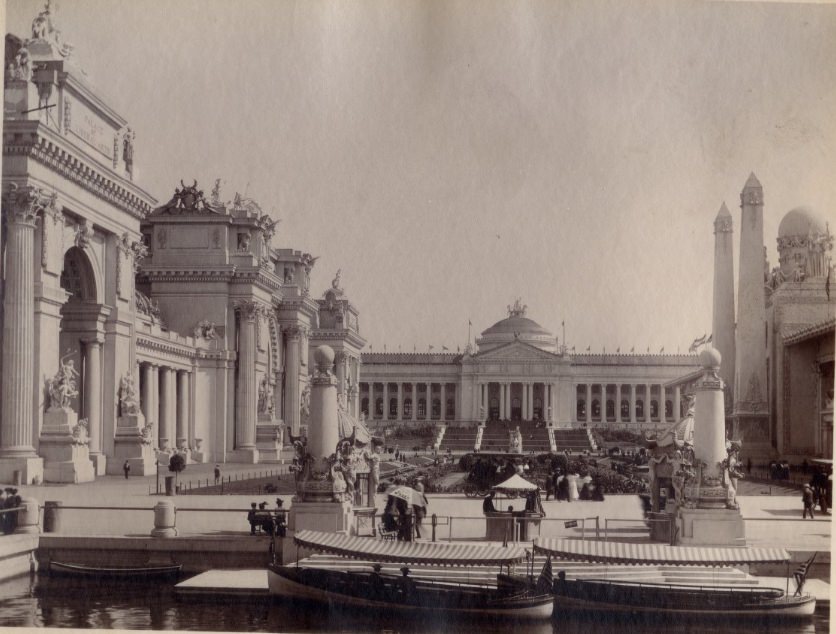

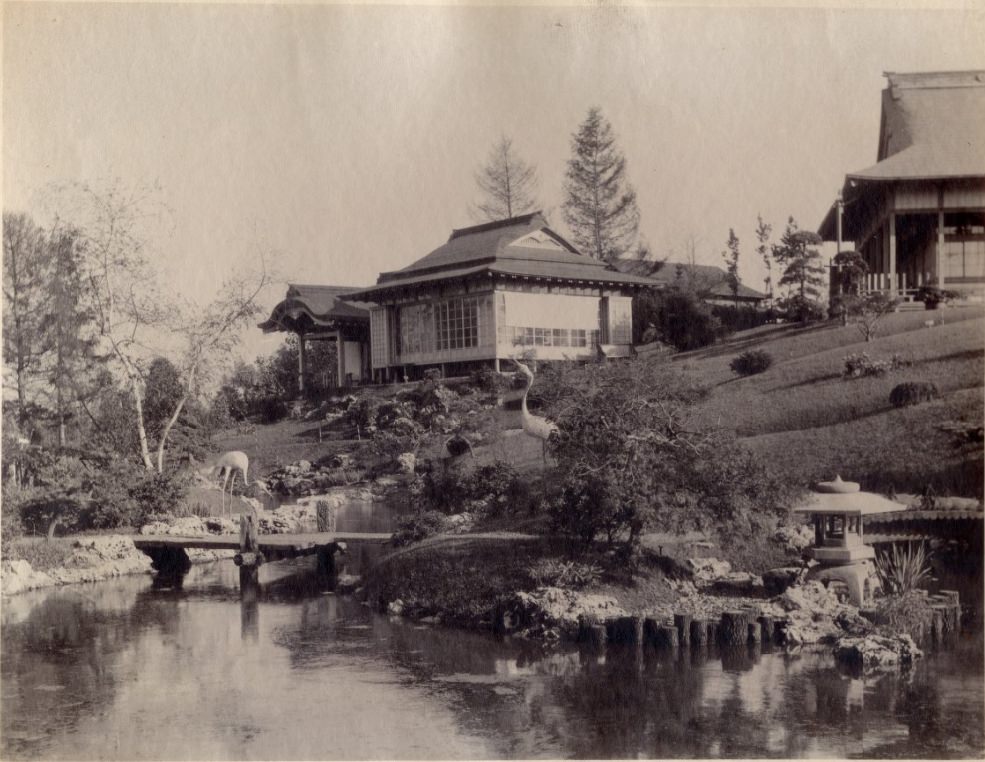

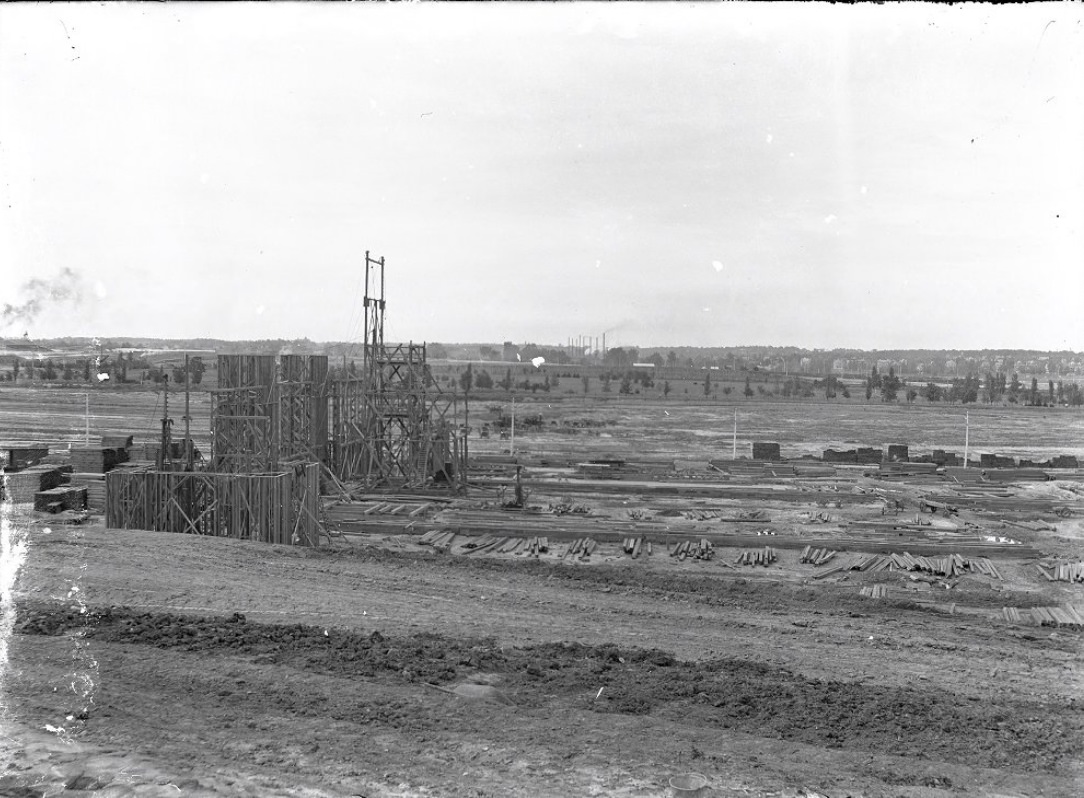

The year 1904 was a landmark for St. Louis, as it hosted the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, more widely known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. This massive event transformed a 1,200-acre section of Forest Park into a global showcase. The fair, built at a cost of twenty million dollars, was designed to promote St. Louis on an international stage and to celebrate American modernity, showcasing advancements in technology, commerce, science, and the arts. Over its seven-month duration, it attracted at least 19 million visitors from around the world.

The fairgrounds were dominated by approximately 1,500 grand buildings, most of which were temporary structures. These were constructed primarily from “staff,” a mixture of plaster and fiber, which allowed for elaborate designs in the prevailing Beaux-Arts architectural style. Isaac Taylor served as the director of works, overseeing a site plan that followed Beaux-Arts principles of axial planning, with avenues and lagoons radiating around the central Grand Cascades at Festival Hall.

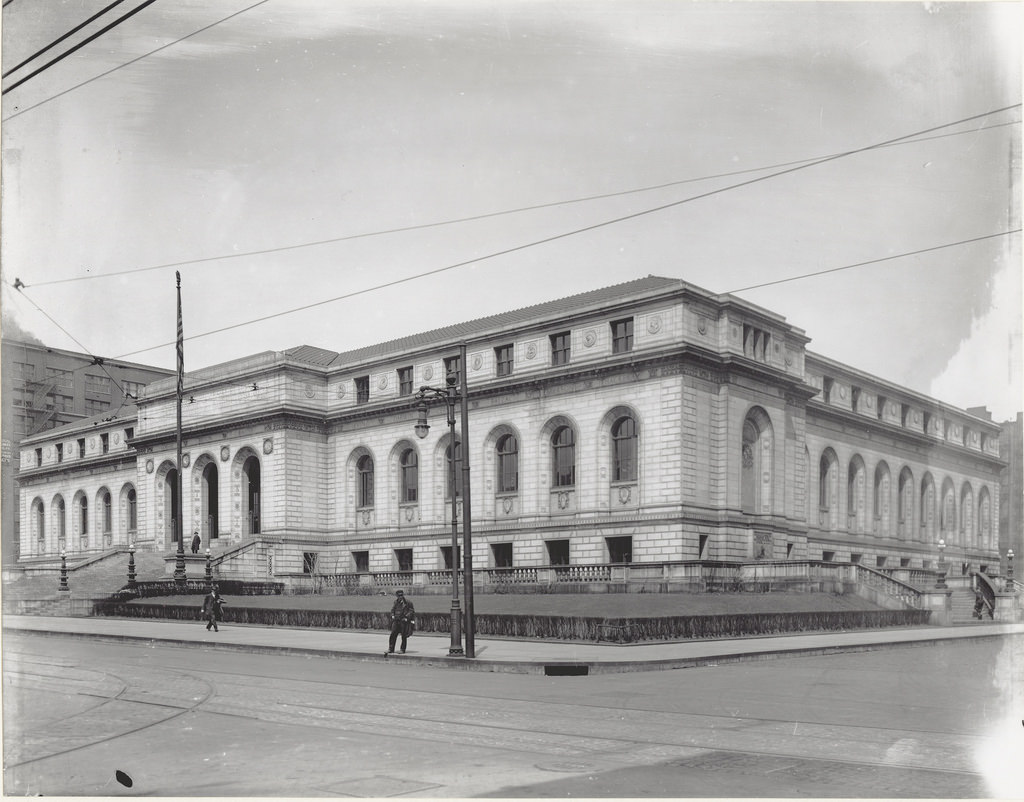

While most structures were temporary, a few were built to last. The most notable of these was the Palace of Fine Arts, designed by architect Cass Gilbert. This building, the most expensive constructed for the Fair, later became the permanent home of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

Exhibits at the Fair were diverse and impressive. Art from around the globe was displayed, including works by American painter Winslow Homer and Japanese ceramics. Technological marvels, such as demonstrations of electricity, new forms of transportation, and the X-ray machine, captivated audiences. Agricultural products from various states and countries were also a major feature. A significant development at this fair was the inclusion of decorative arts, such as furniture, textiles, and pottery, which were exhibited as fine art for the first time at an international exposition.

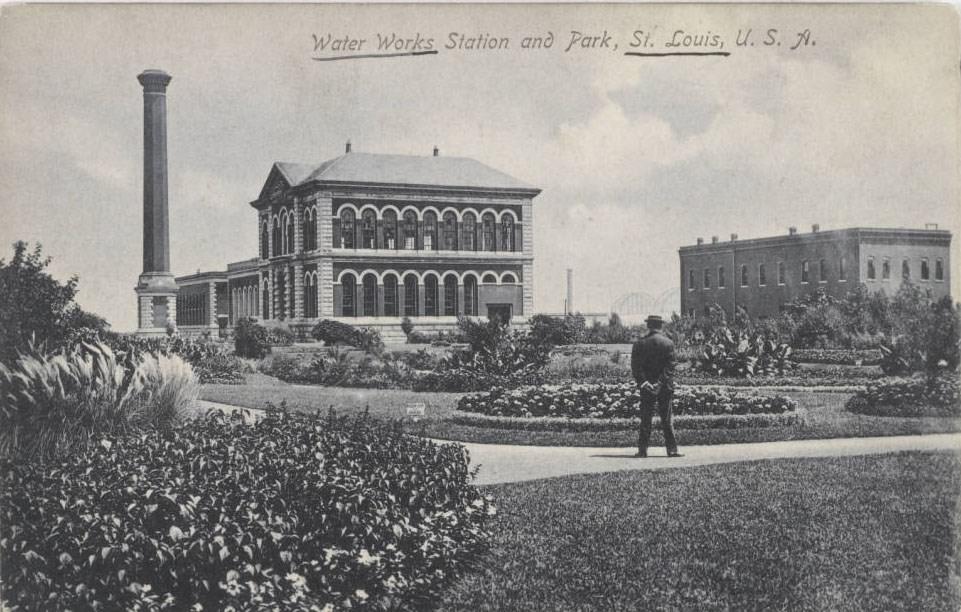

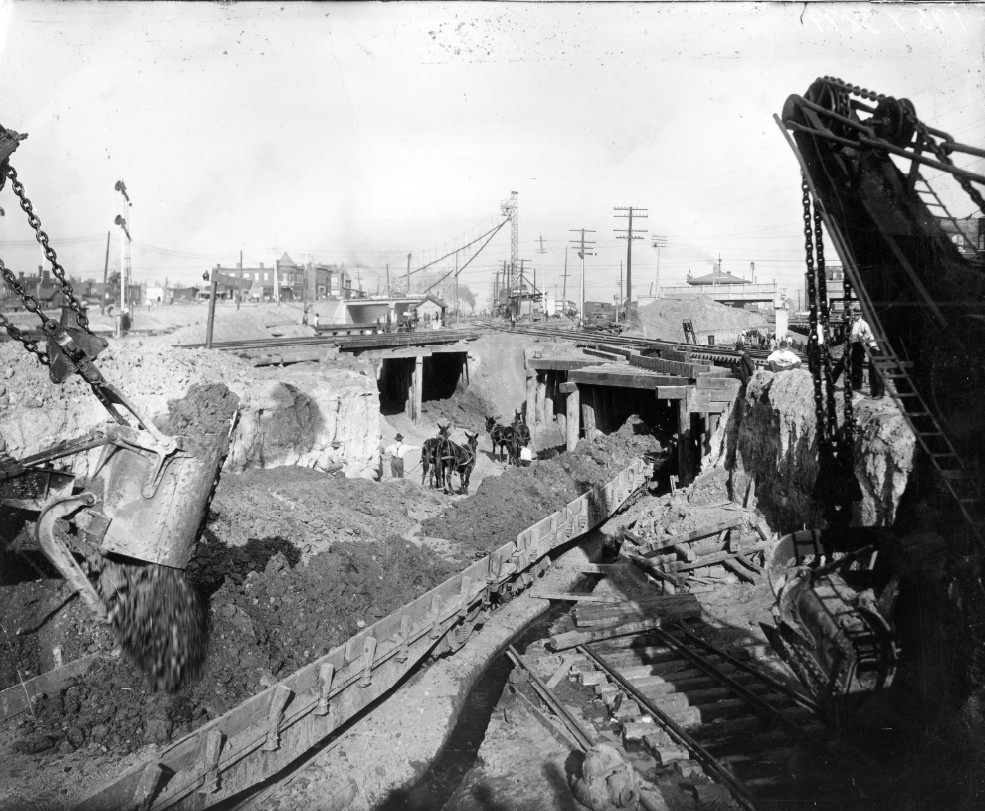

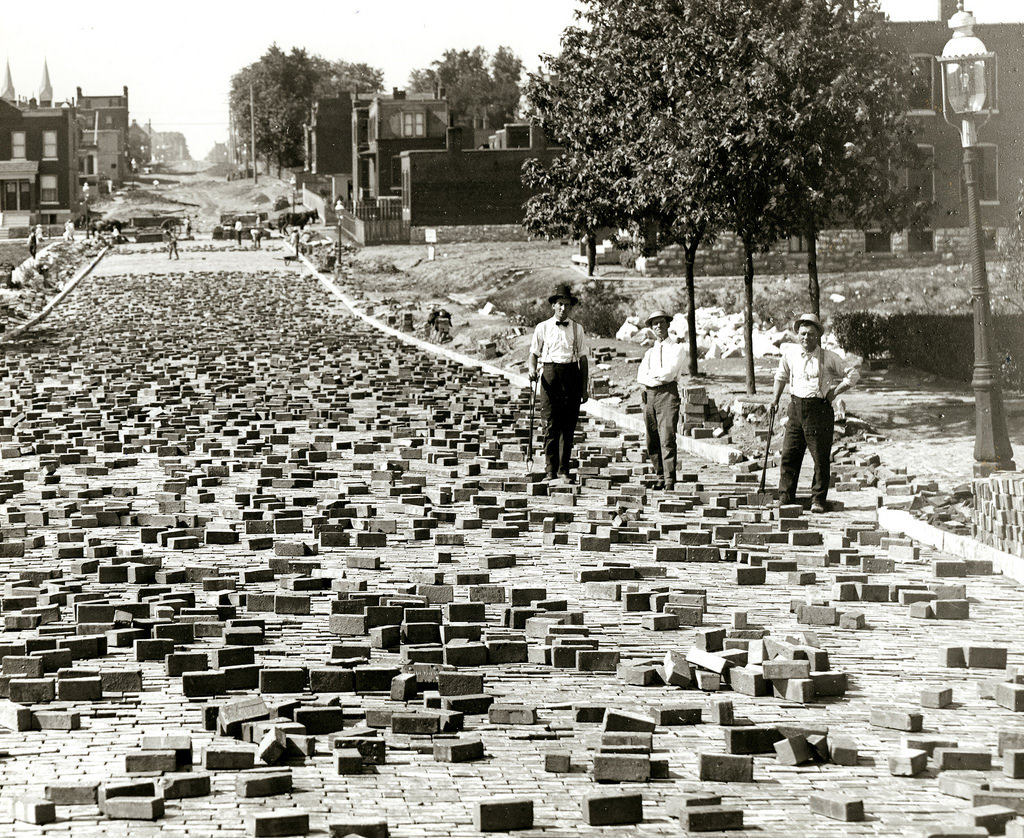

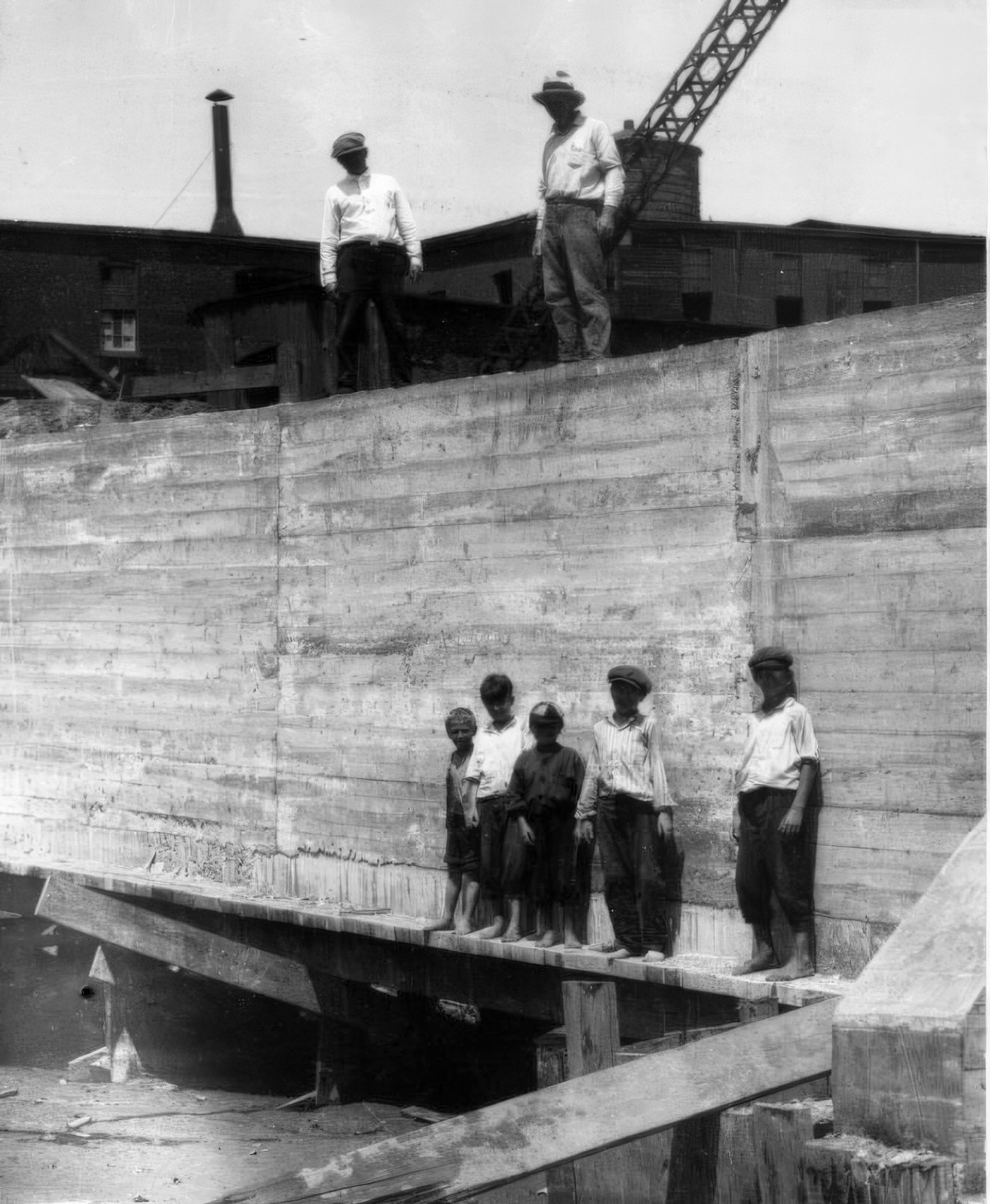

The Fair spurred significant infrastructure improvements for St. Louis. Transportation systems were upgraded, and the city’s water systems saw improvements. Within Forest Park itself, major landscaping work was undertaken, including the rerouting of the River Des Peres, to accommodate the fairgrounds. An army of 10,000 laborers was employed to transform the park from a largely undeveloped area into the spectacular setting for the Exposition. The Fair, therefore, was a complex event: a celebration of progress and innovation that simultaneously perpetuated and reinforced colonial attitudes and racial hierarchies through its human exhibits, offering a critical look at the societal values of the era.

The Underside of Progress: Challenges and Reforms

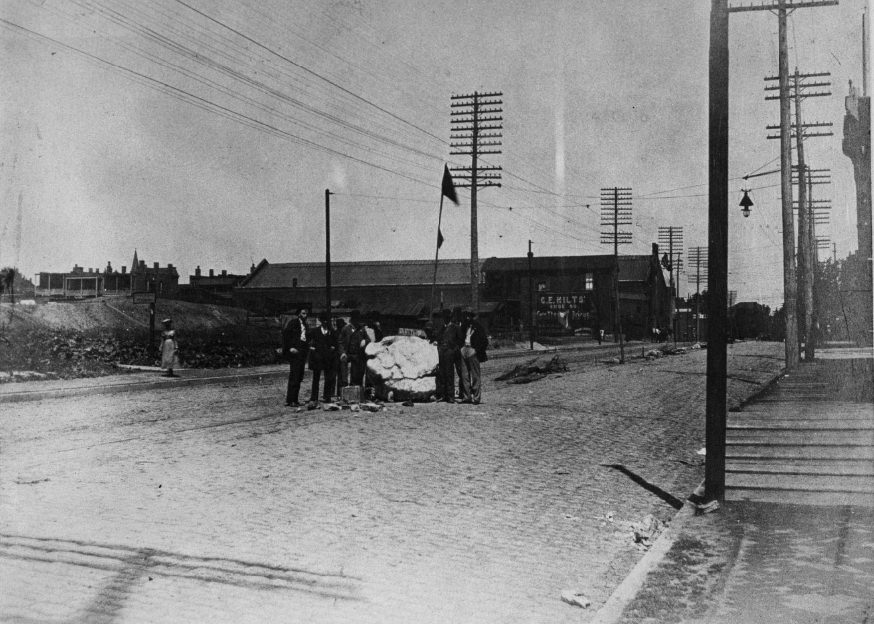

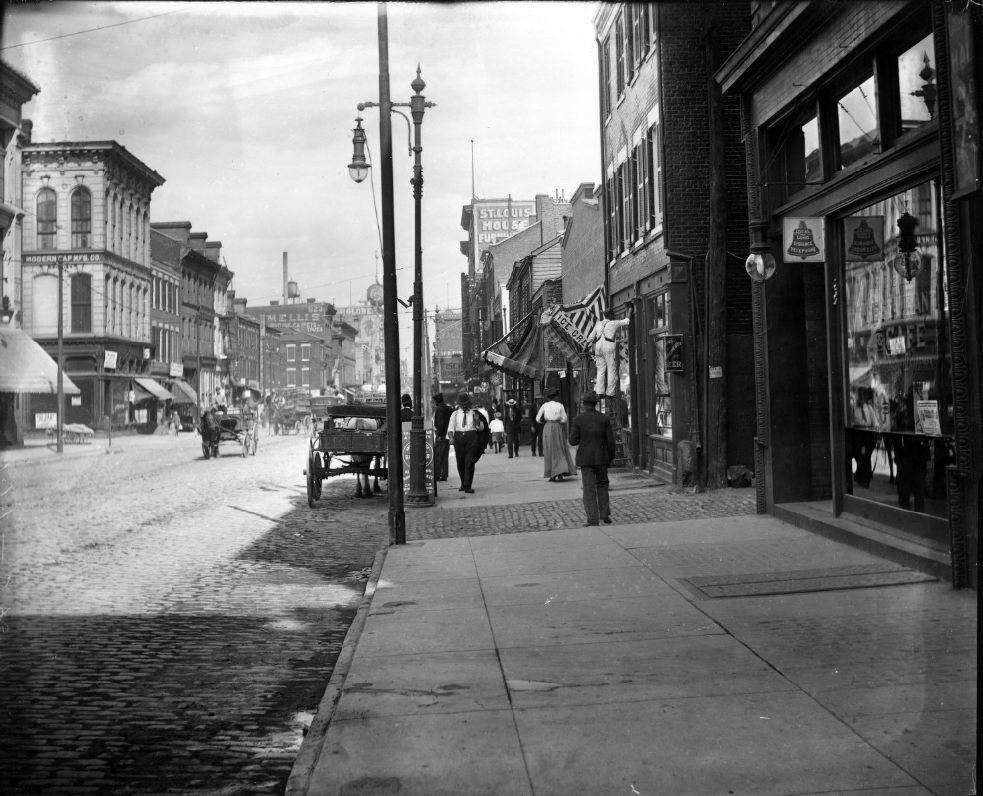

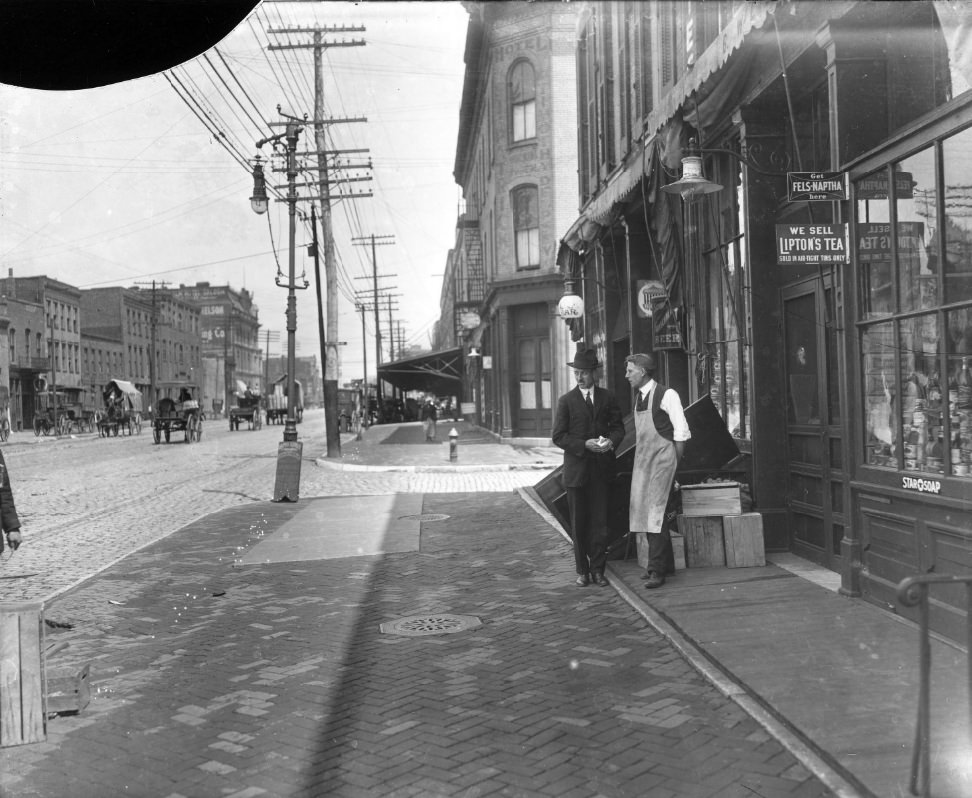

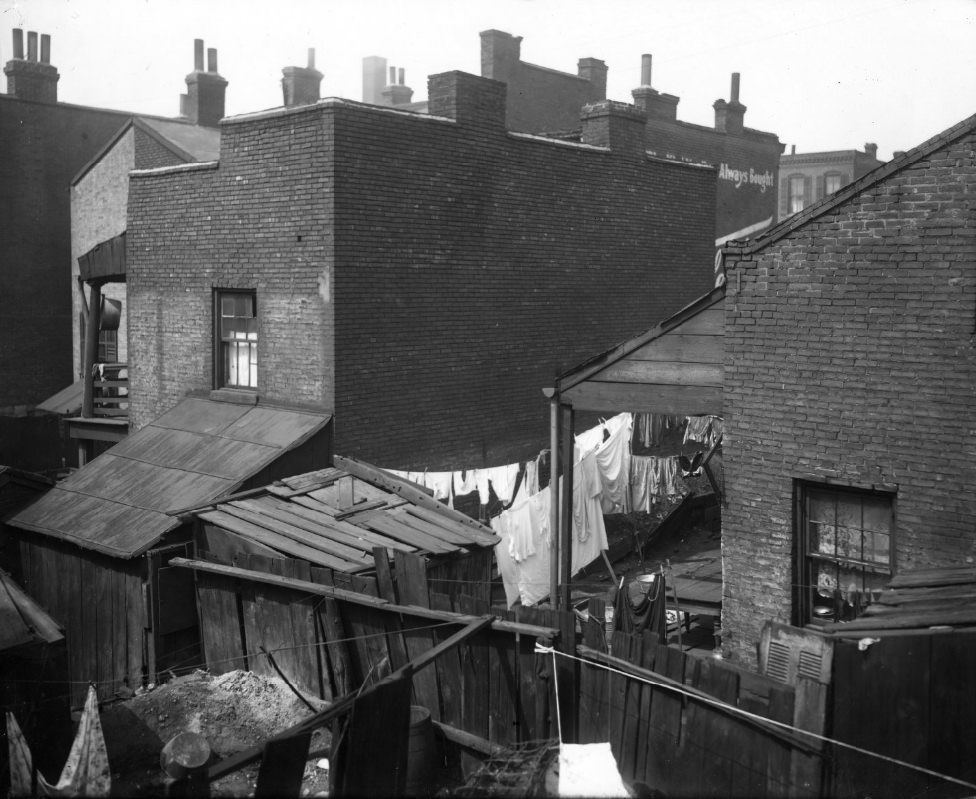

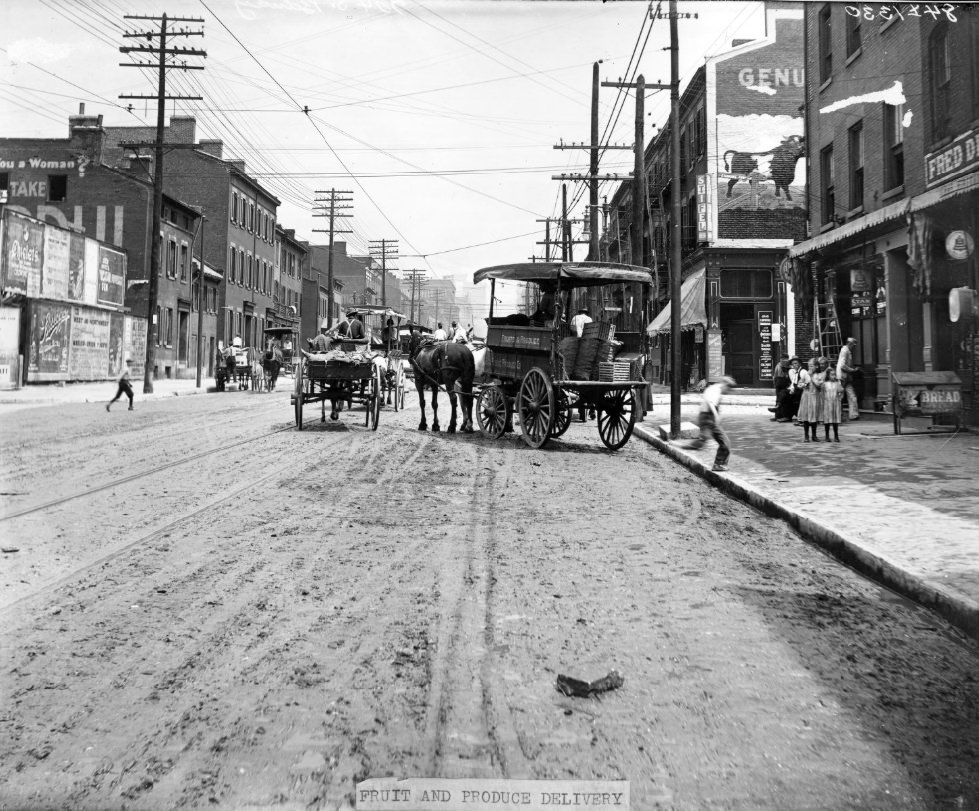

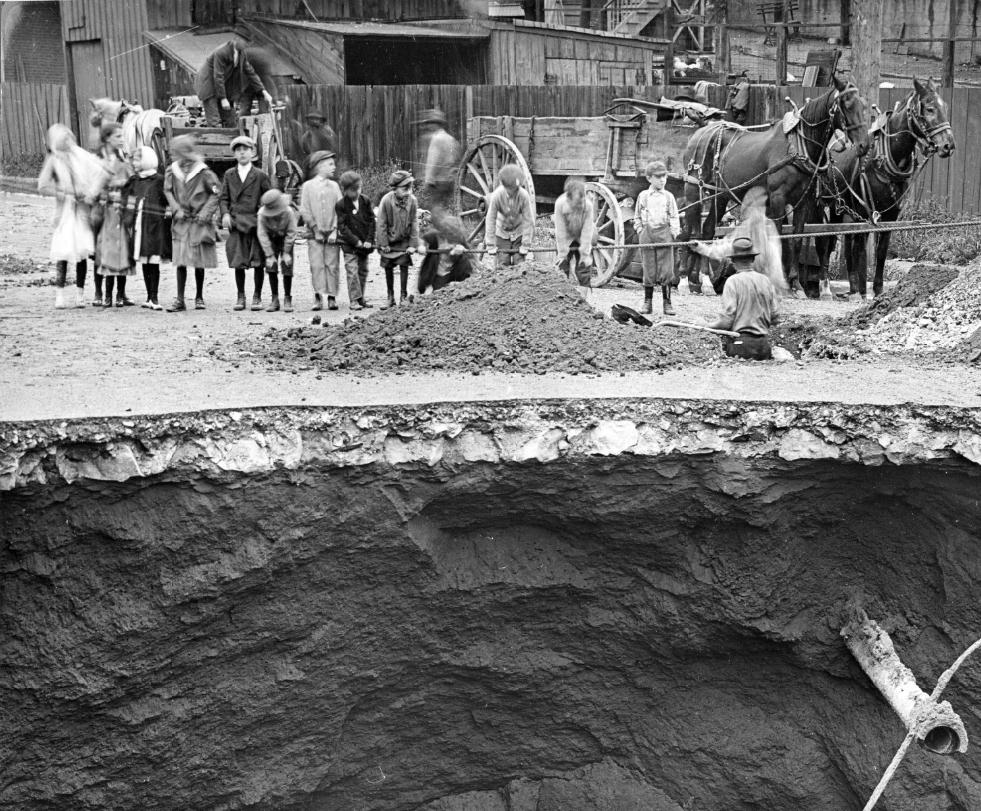

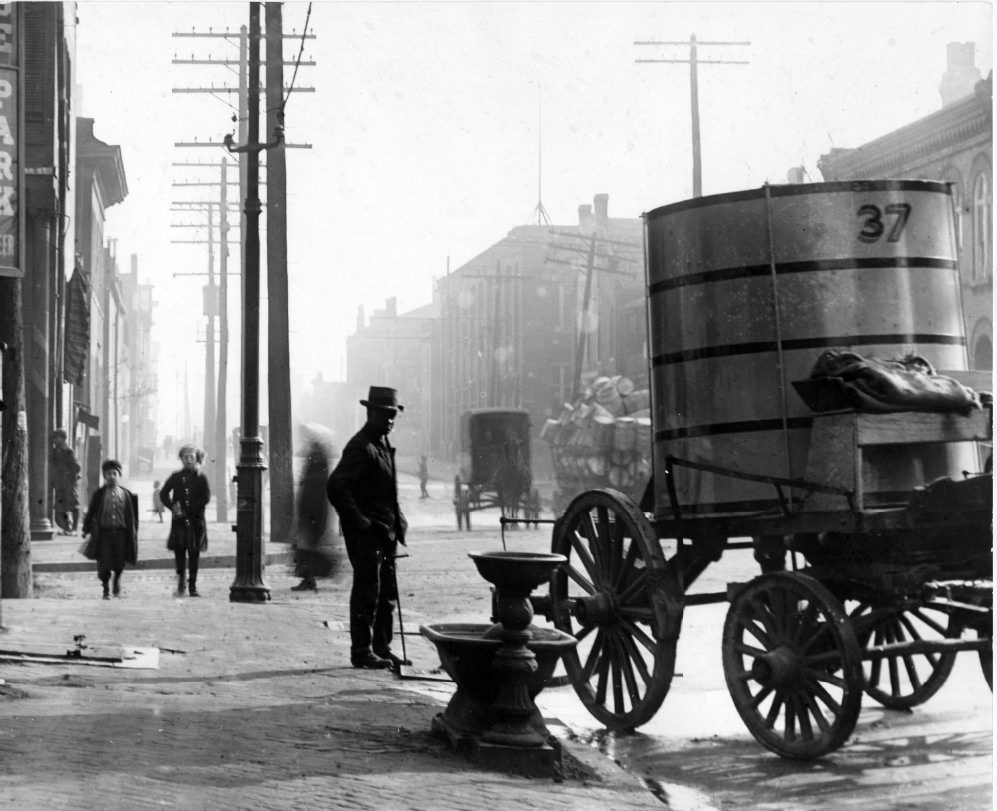

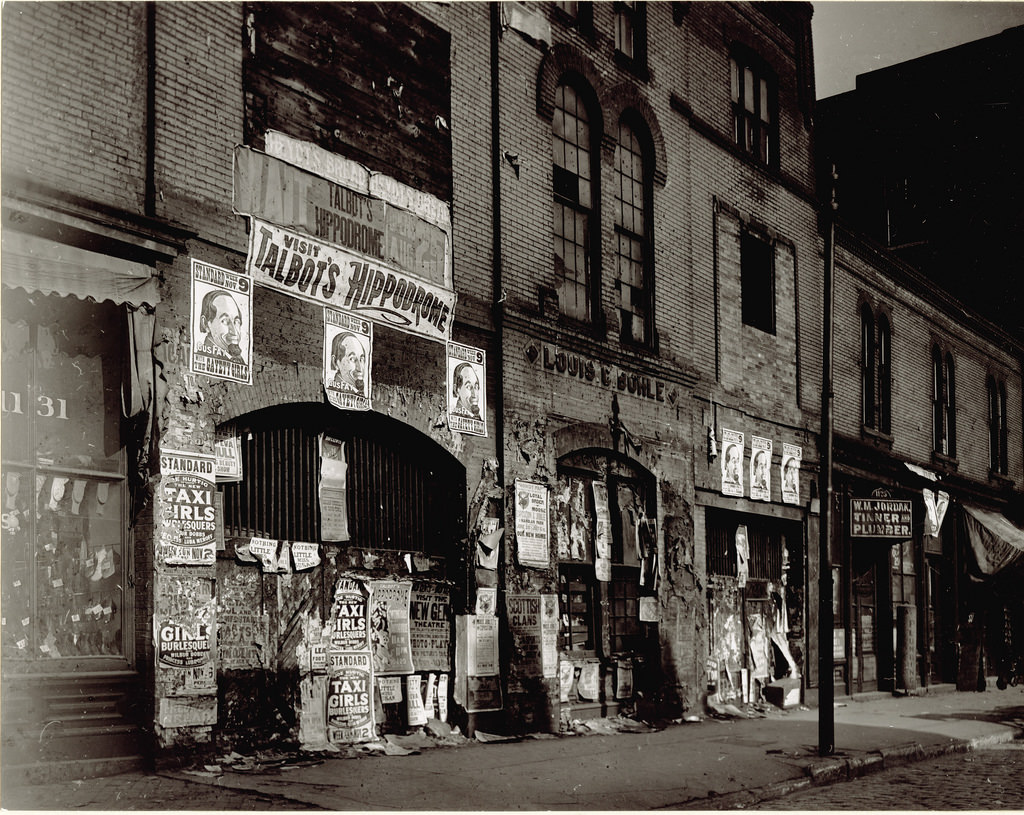

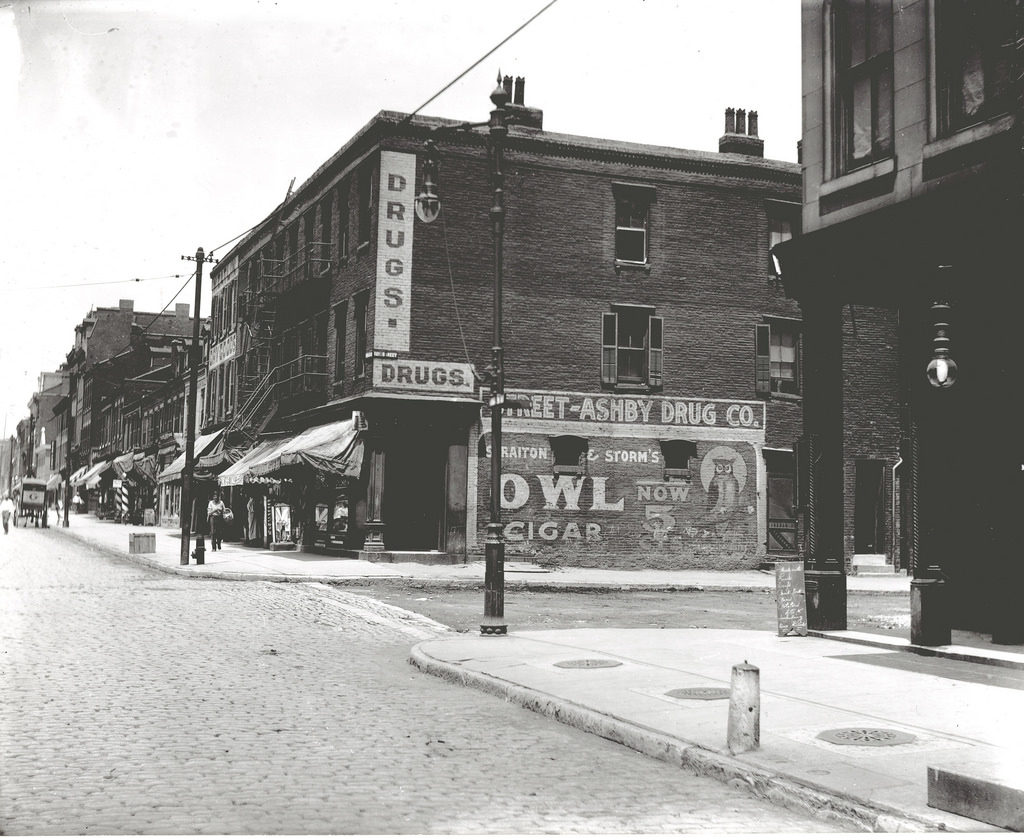

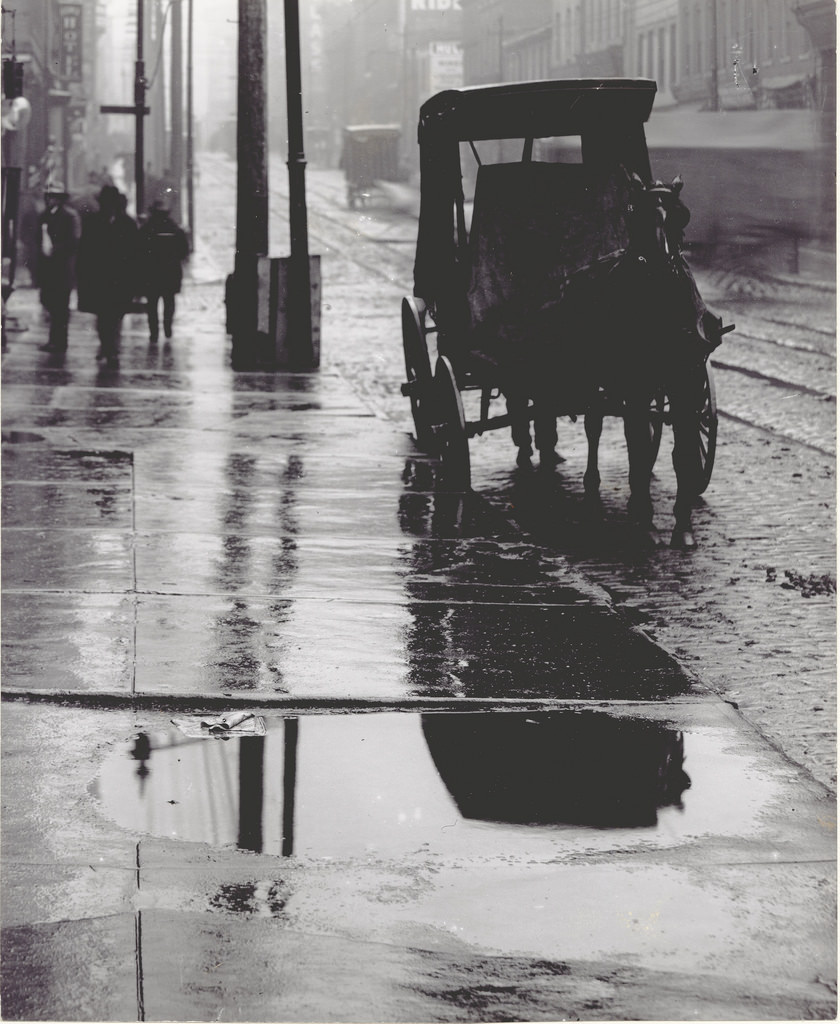

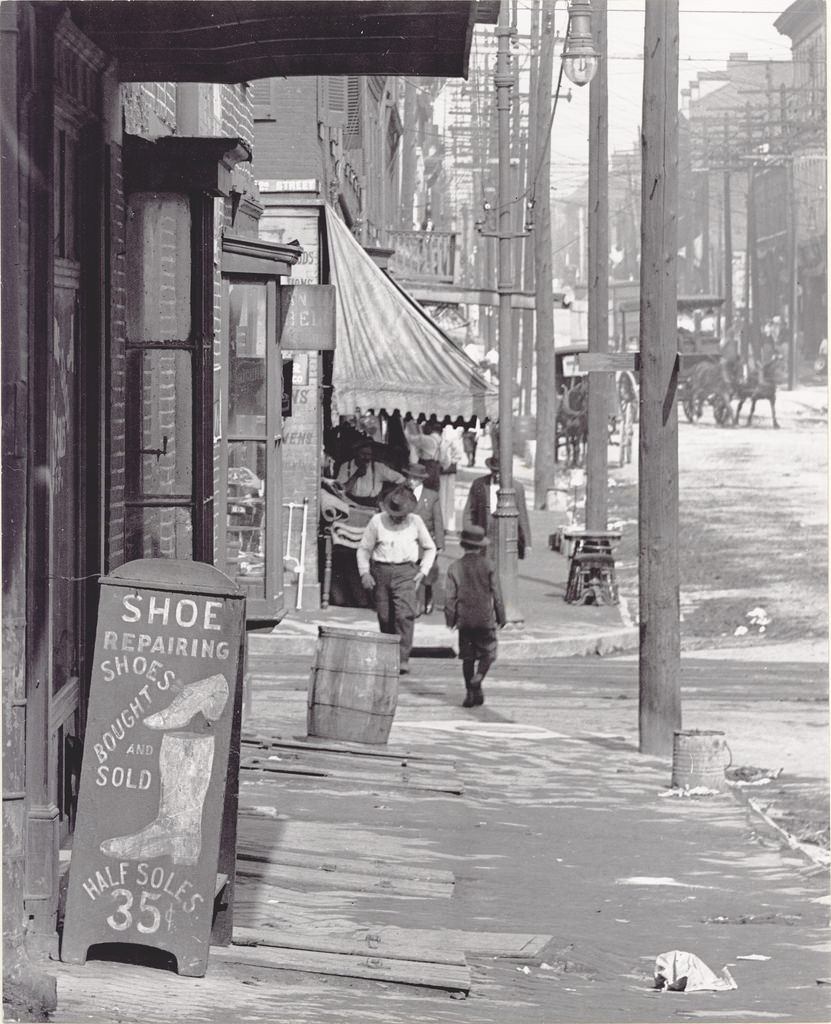

Despite its status as a growing industrial power, St. Louis at the turn of the 20th century faced severe public health and sanitation challenges. The city was widely known for its “filth”. Public spaces were often littered with garbage, and the city’s poorly paved streets would transform into impassable mud pits whenever it rained.

Air quality was a major concern. The widespread burning of cheap, soft coal, sourced from nearby Illinois coal fields, blanketed the city in a thick, “filthy smoke.” This pollution darkened the daytime sky, filled residents’ lungs, and contributed to respiratory illnesses. The city’s water supply was equally infamous. Drawn directly from the Mississippi River, the water that flowed from city taps was often a “filthy dark brown,” heavily contaminated with sand, sediment, and, alarmingly, sewage from cities upstream, including Chicago. These dire environmental conditions directly contributed to the rampant spread of fatal diseases throughout the city.

The very industries that fueled St. Louis’s economic prosperity were paradoxically major contributors to this environmental degradation. Coal-powered factories poured smoke into the air, and the dense urban population, living without adequate sanitation infrastructure like comprehensive garbage collection or a clean water supply, exacerbated these problems. The Mississippi River, a vital artery for commerce and industry, also served as a convenient dumping ground for waste, further polluting the city’s primary water source. This situation, common in many industrializing cities of the era, created a powerful impetus for public health reforms and significant investments in urban infrastructure, such as improved water treatment and sanitation systems, which were critical for the city’s future. Preparations for the 1904 World’s Fair, for instance, included efforts to improve the city’s water supply.

Social Stratification and Racial Segregation

St. Louis society in the early 1900s was sharply divided along lines of class and race. Racial segregation was a deeply ingrained and pervasive feature of city life. African Americans, who constituted 6.1% of the city’s population in 1900 and saw their numbers grow to 9% by 1920, were largely confined to specific, often overcrowded and underserved, residential areas like “Clabber Alley”.

Jim Crow practices, which enforced racial separation, were present in St. Louis, although some observers noted they were “more uneven” in their application compared to cities in the Deep South. For example, African Americans were barred from white-owned hotels and restaurants, yet they might be permitted to use the same elevators as whites in department stores or attend theaters in designated segregated sections.

The desire to formalize and legally enforce residential segregation was evident. During the World War I era, St. Louis was among the cities that explored racial zoning laws. A specific racial zoning ordinance was proposed in St. Louis in 1916, though it ultimately faced legal challenges and was struck down, following a Supreme Court ruling against a similar law in Louisville. Early city zoning efforts around 1918 explicitly linked the concept of “blight” with areas “occupied by colored people,” revealing the discriminatory attitudes embedded in urban planning ideologies of the time.

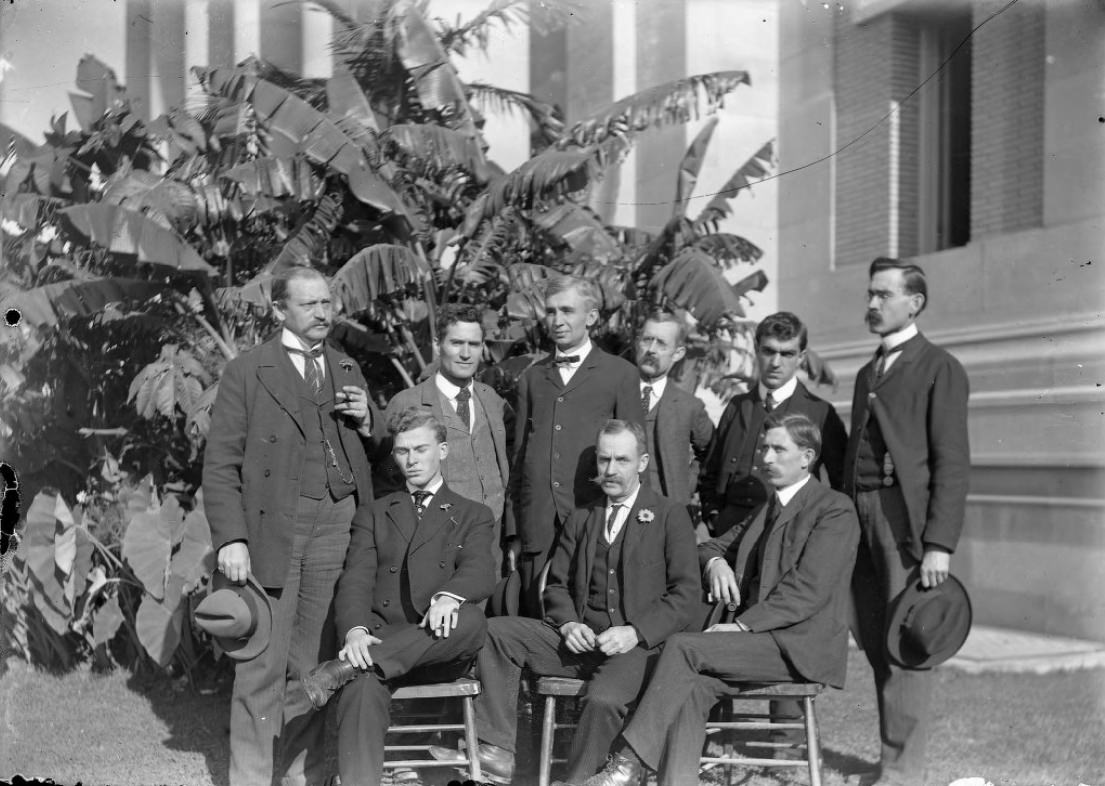

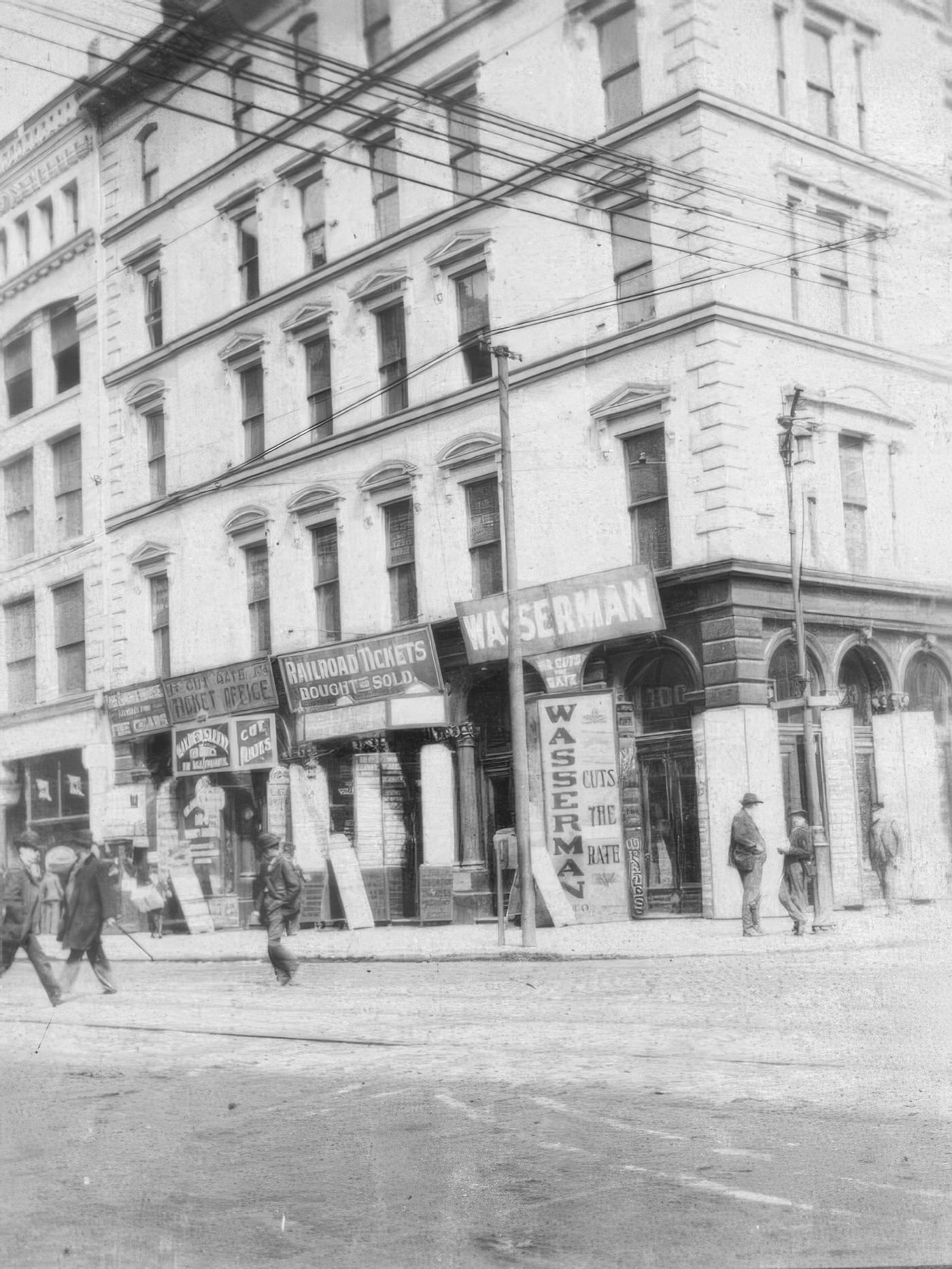

Civic Life and Governance: Corruption and Reform

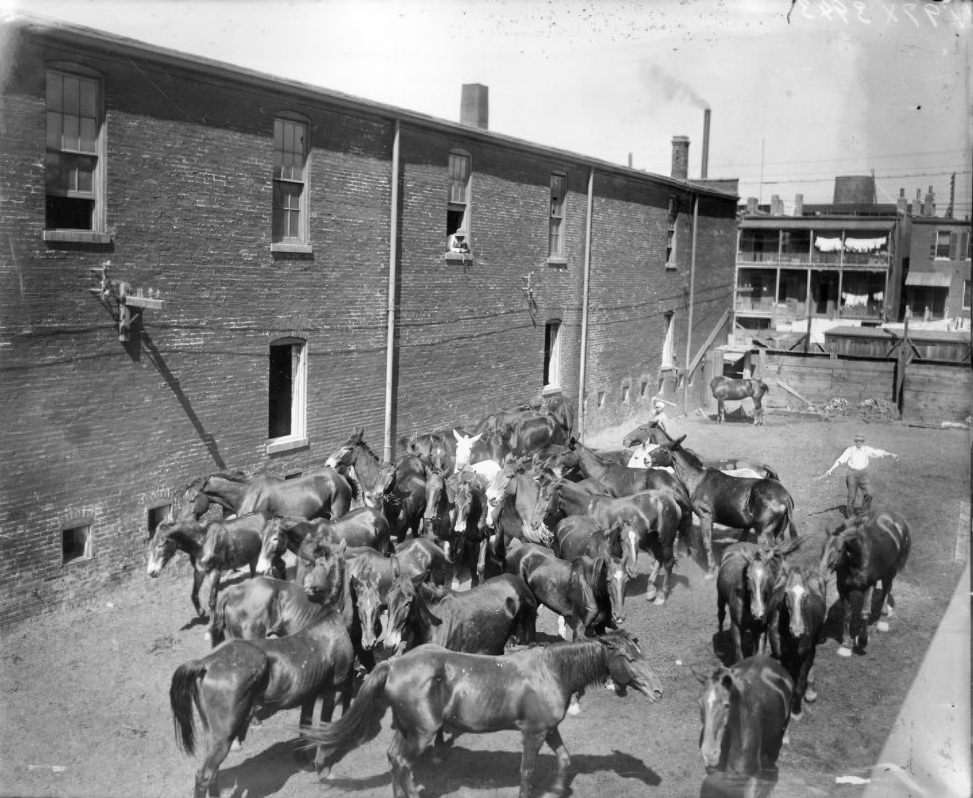

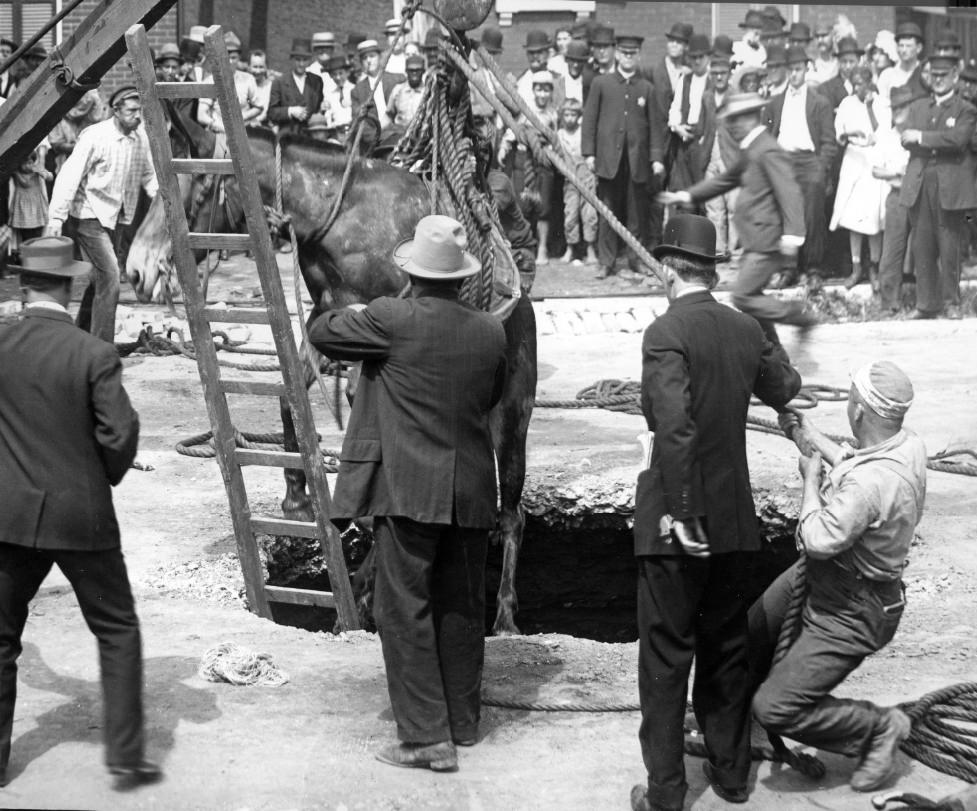

The political landscape of St. Louis at the turn of the century was often characterized by widespread corruption. “Colonel” Edward Butler, a powerful Irish political boss, became a prominent symbol of this era’s political dealings. Butler, a former blacksmith, built his influence initially through a monopoly on the lucrative business of horseshoeing St. Louis’s extensive streetcar lines. His power grew through “the Combine,” his political organization, which engaged in various forms of electoral manipulation, including intimidating voters, stuffing ballot boxes, and bribing officials to control the city’s elective government.

However, the early 1900s also marked the rise of the Progressive Era, a national movement aimed at addressing the social, economic, and political problems stemming from rapid industrialization, immigration, and urbanization. In St. Louis, this movement manifested in significant efforts to reform city governance and improve the quality of urban life.

A key figure in the local reform movement was Joseph Folk, a lawyer who gained public attention and acclaim for his vigorous prosecution of political corruption, most notably targeting Boss Butler himself. Folk’s campaign against bribery and his efforts to restore integrity to representative government, while sometimes facing legal setbacks, resonated strongly with a public weary of corruption. Adding to the pressure for reform was the work of muckraking journalists. Writers like Lincoln Steffens, in his famous articles on “Tweed Days in St. Louis,” exposed the depth of the city’s political malfeasance to a national audience, further fueling the demands for change. The high levels of corruption thus directly spurred the local reform movement, creating a dynamic where the excesses of the political machine provided the very impetus for civic awakening and the push for cleaner, more responsive government. This struggle between entrenched corrupt systems and emerging reformist ideals was a defining feature of St. Louis in the early 1900s, shaping its political path for decades.

The 1904 Olympic Games

In addition to the World’s Fair, St. Louis also hosted the 1904 Olympic Games, officially known as the Games of the III Olympiad. These were the first Olympic Games ever held in North America. The decision to host the Olympics in St. Louis was somewhat contentious; the Games had initially been awarded to Chicago. However, the organizers of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition threatened to stage their own international sports tournament, which would have competed directly with the Olympics. As a result, then-US President Theodore Roosevelt decided that St. Louis should host both events.

The Olympic competitions were spread out over a long period, from July 1 to November 23, and were largely overshadowed by the immense scale and popularity of the World’s Fair. Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a key figure in the modern Olympic movement, criticized this arrangement, arguing that the Games became a mere “sideshow”.

International participation in the 1904 Olympics was quite limited. Only 12 nations sent athletes, and the total number of competitors was 651 (comprising 645 men and only 6 women). The United States had by far the largest contingent, with 523 athletes, and consequently dominated the medal count, winning 238 medals. The significant cost and difficulty of traveling to St. Louis in 1904 deterred many international athletes from participating.

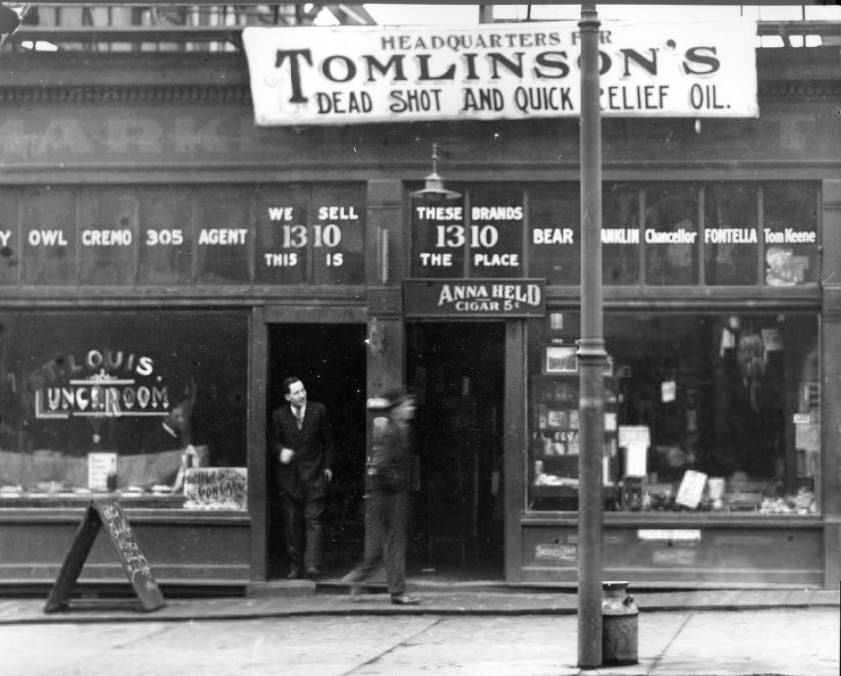

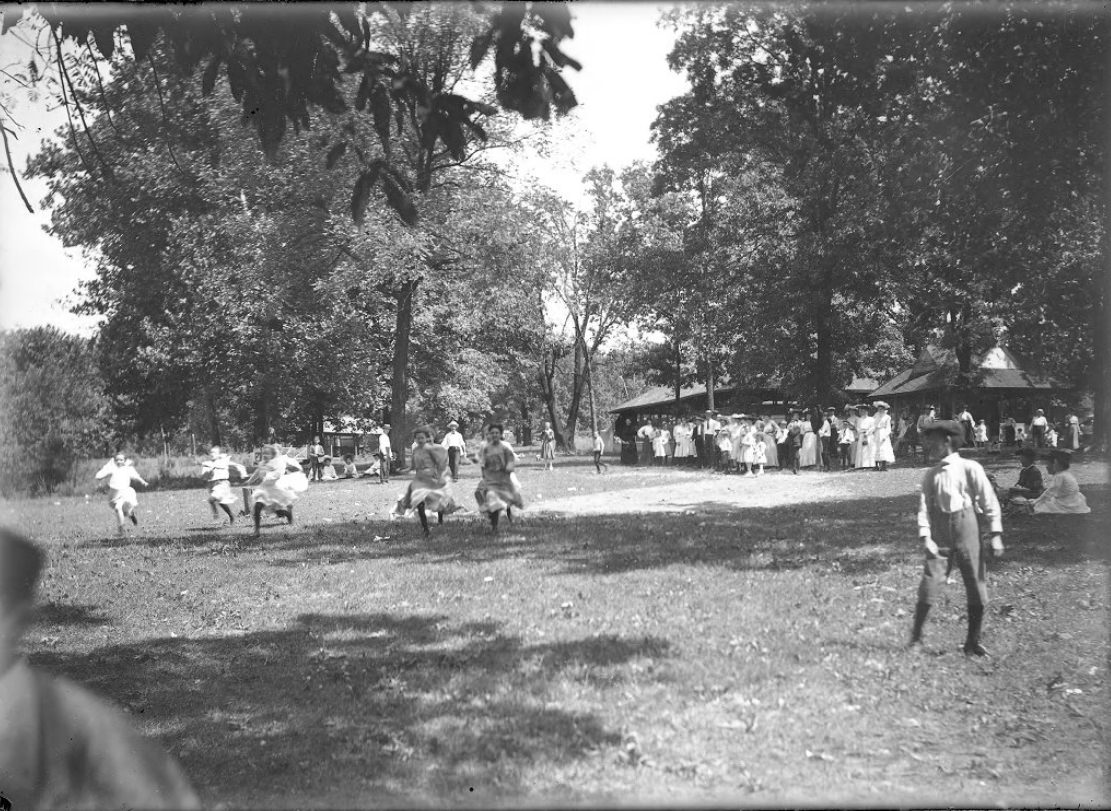

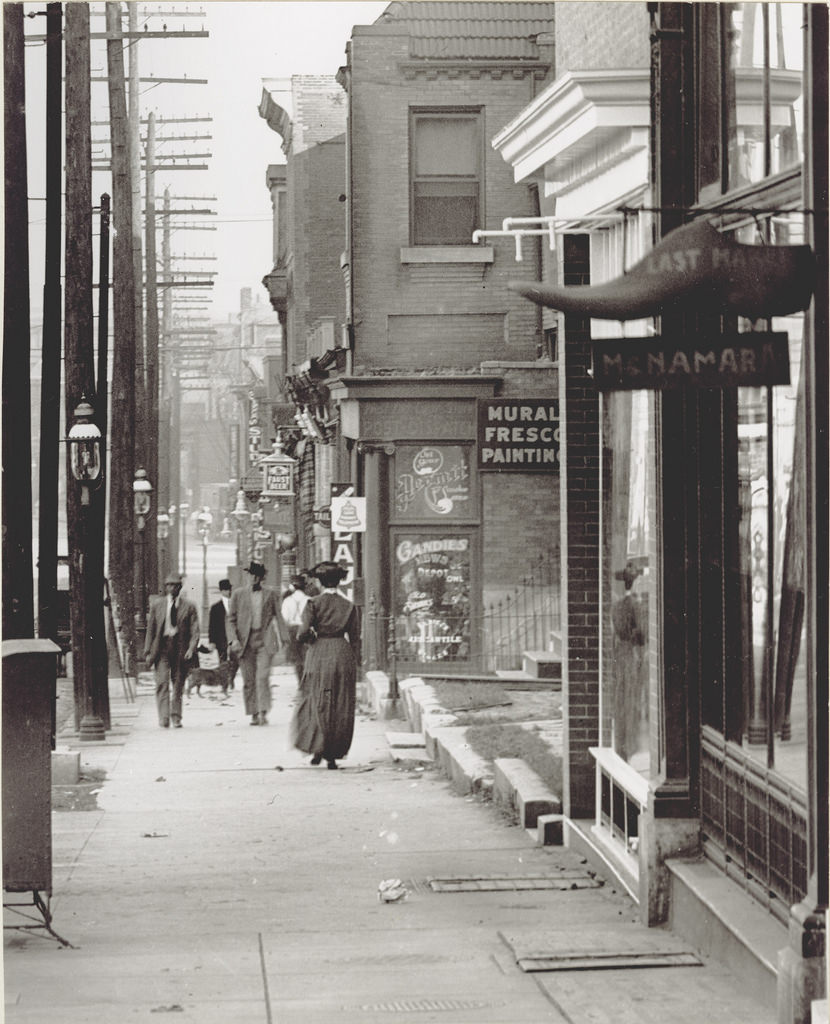

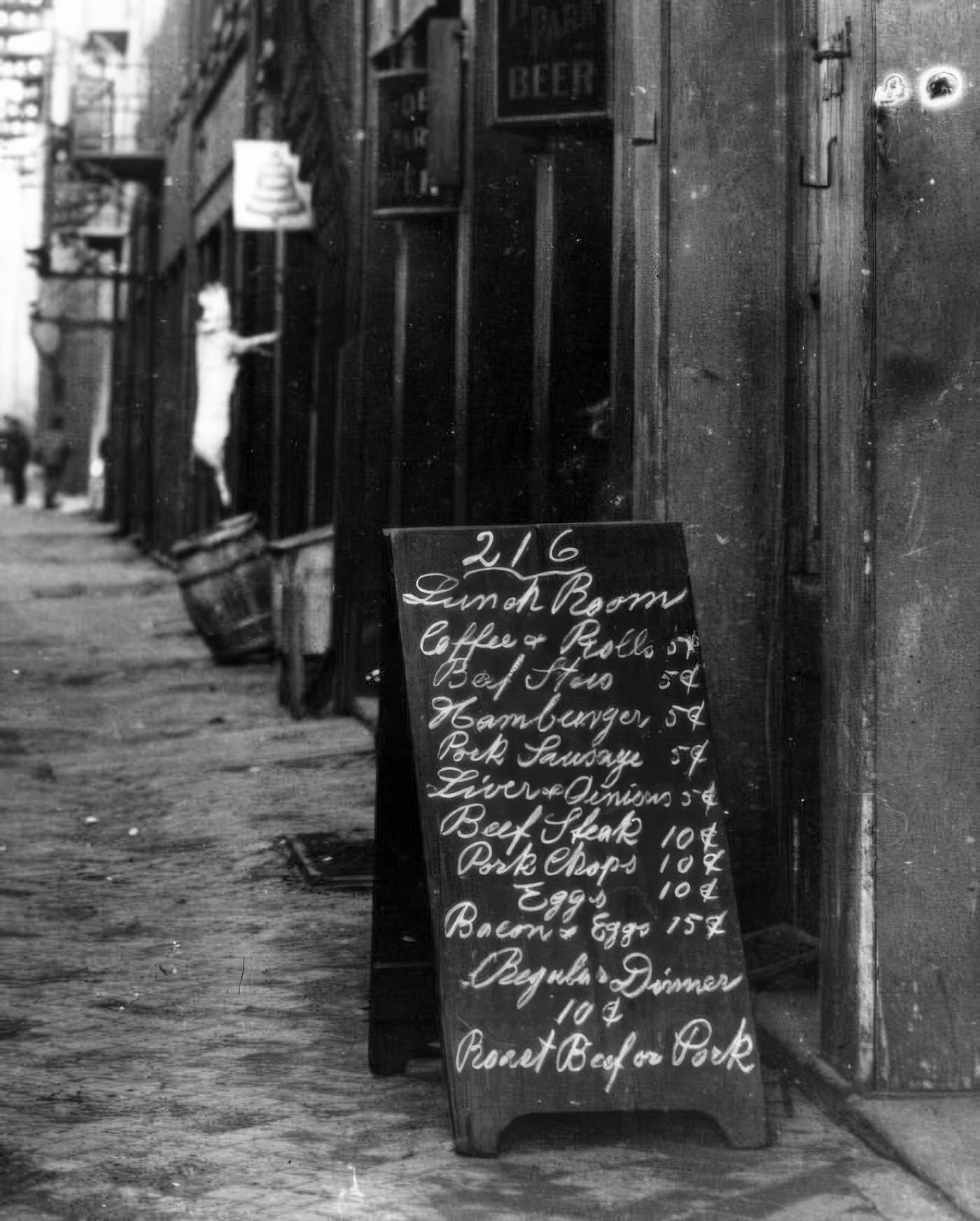

Daily Life in a Growing City

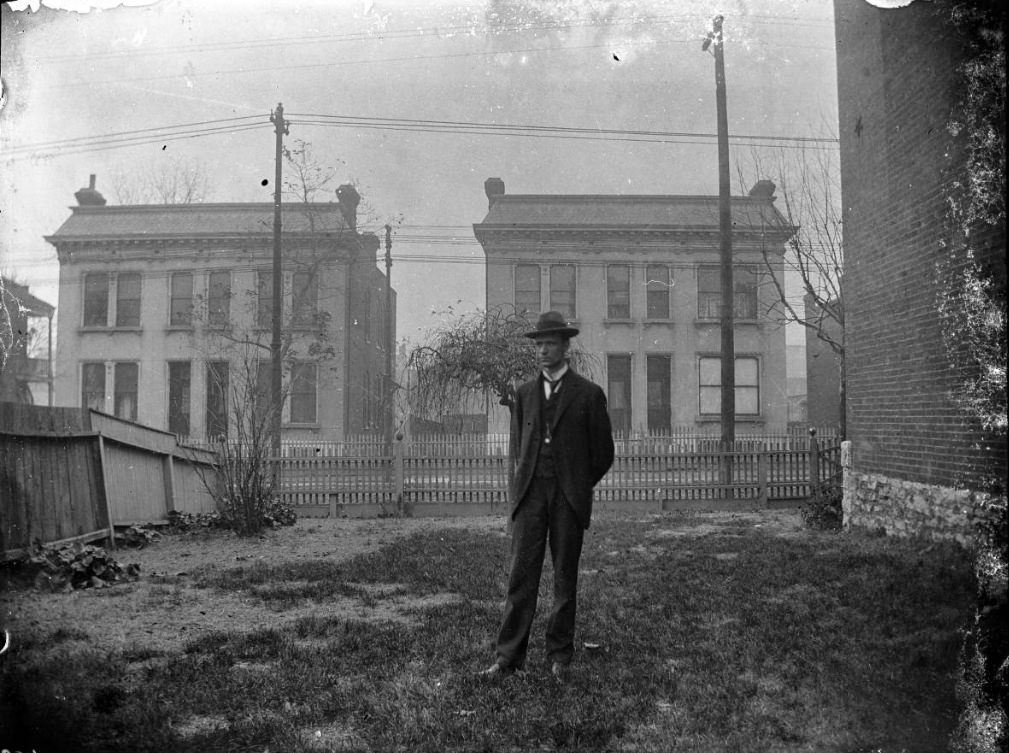

Life in St. Louis in the early 1900s was characterized by clearly defined neighborhoods, often shaped by ethnicity and economic status. Irish immigrants were concentrated in an area known as “Kerry Patch,” while many African Americans resided in a district called “Clabber Alley,” and Italian immigrants largely settled on “Dago Hill”. These names, while reflecting distinct communities, sometimes also carried the weight of prevailing prejudices.

Housing conditions varied dramatically across the city. In the poorer ethnic enclaves and African American neighborhoods, overcrowding and tenement slums were common. In working-class areas like Soulard, which by the early 20th century was home to a large number of Eastern European immigrants and nicknamed “Bohemian Hill,” common housing types included brick four-family flats, alley houses, and the distinctive St. Louis “flounder” house. Flounder houses were narrow, two or two-and-a-half-story structures, often built in dense arrangements to maximize land use.

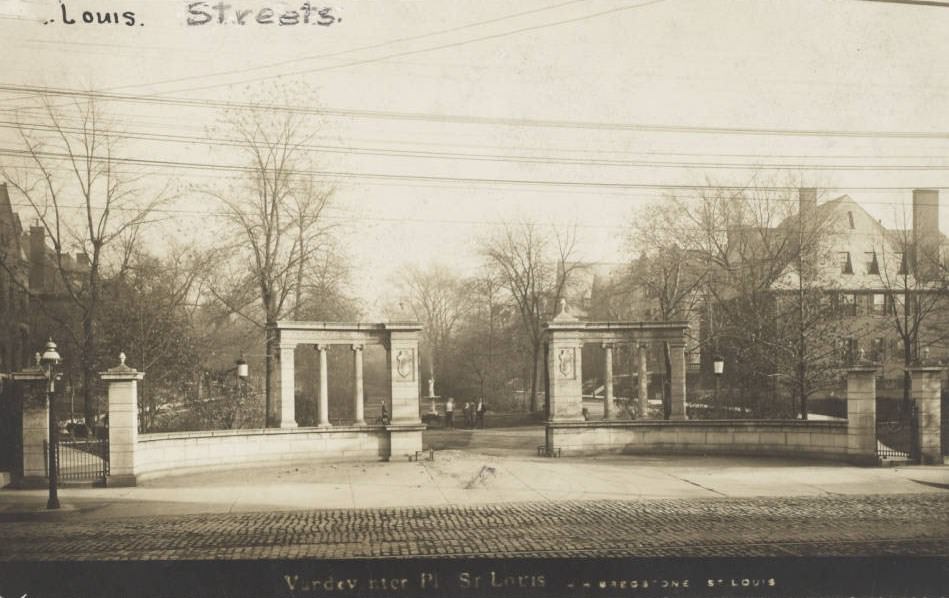

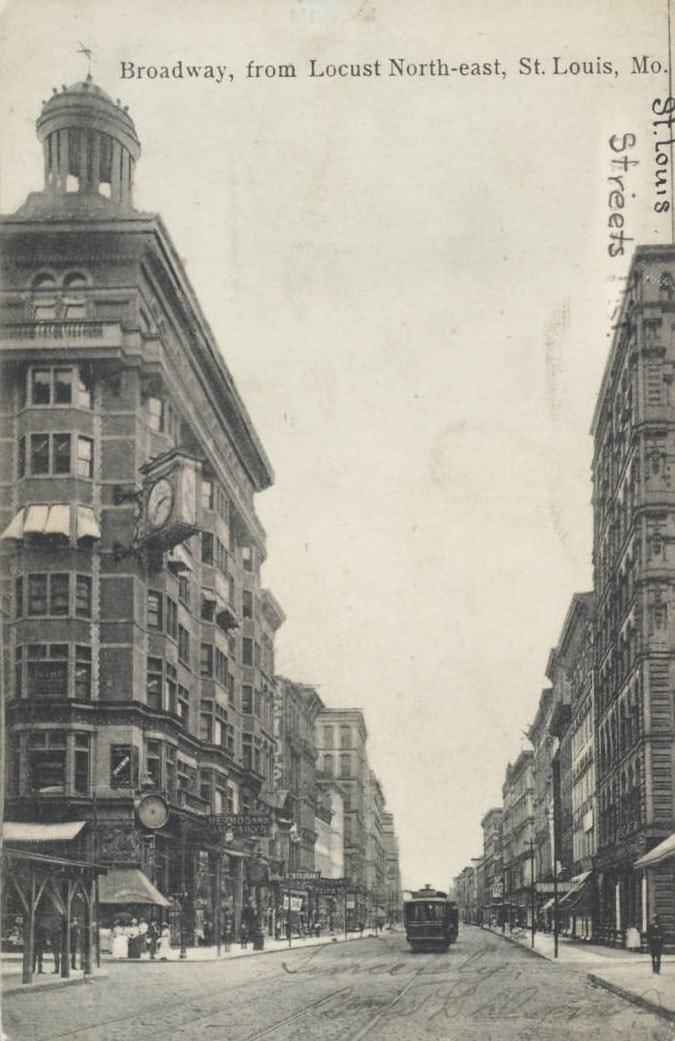

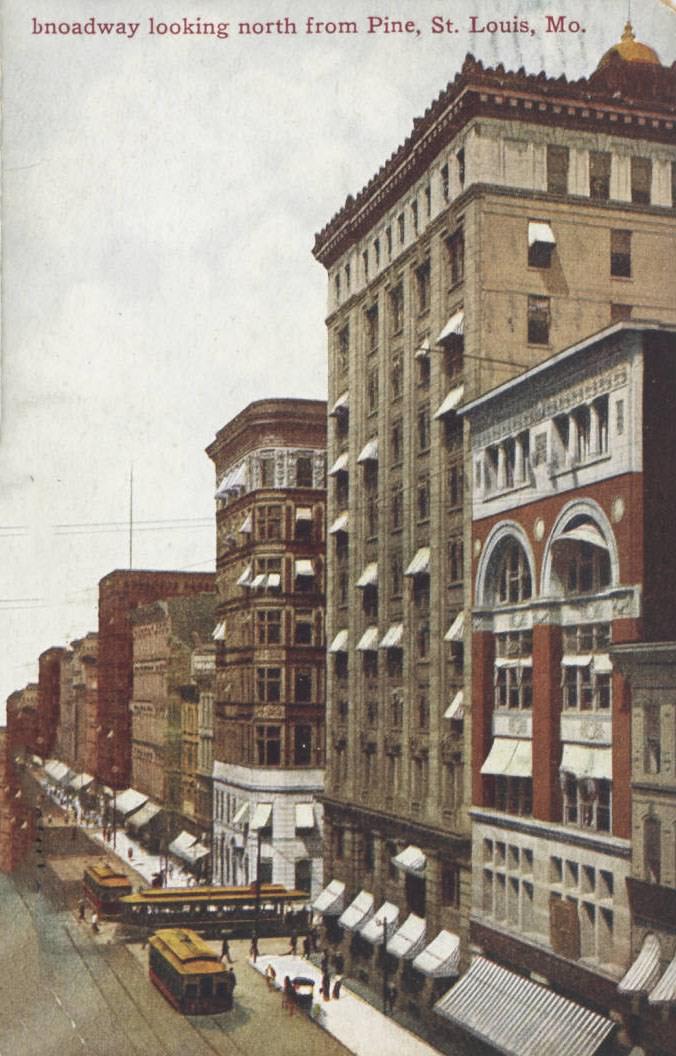

In contrast, wealthier St. Louisans were increasingly moving westward, away from the crowded city center. This migration led to the development of more spacious residential areas, sometimes organized as “private streets” designed to create exclusive, controlled environments. The Central West End, for example, was emerging as a fashionable and affluent neighborhood, conveniently located near the expansive Forest Park. The growth of streetcar lines facilitated this suburban expansion, allowing middle-class families to also move to newer developments with different housing styles, such as row houses, two-family flats, “triple-deckers,” duplexes, and walk-up apartment buildings. The city’s housing landscape, therefore, was a clear map of its social and economic divisions, shaped by income, ethnicity, race, and the transformative power of new transportation like the streetcar. These early 20th-century residential patterns established a foundation for the city’s future urban development and social geography.

The World of Work

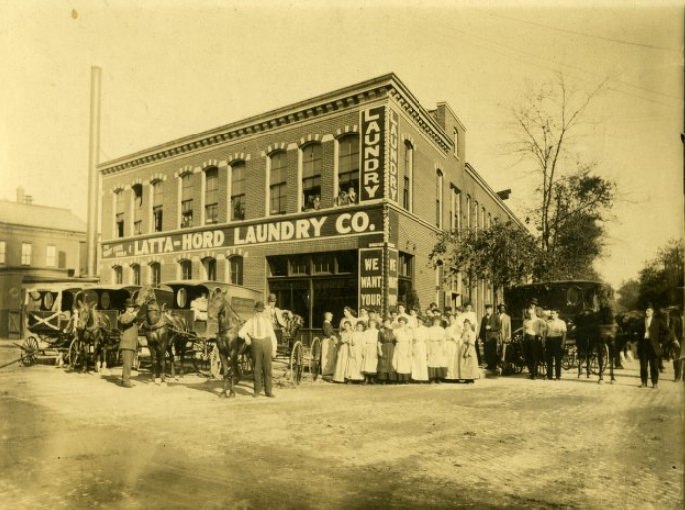

For a large portion of St. Louisans, daily life revolved around long and arduous work, often in the city’s numerous factories and industrial plants. Key industries such as brewing, shoe manufacturing, textiles, and machinery provided a vast number of jobs, drawing people to the city.

The early 1900s was an era before widespread labor protections, and child labor was a grim reality. Children were employed in various sectors, sometimes even in dangerous occupations like mining. Working conditions for adults were also frequently challenging, leading to labor disputes and a growing movement for workers’ rights. Many workers, including African American women nutpickers in the food-processing industry, actively fought for better pay, safer conditions, and the right to form and join unions.

African American workers faced particularly severe employment discrimination. They were often confined to the lowest-paying and most menial jobs and systematically excluded from skilled trades and other better-paying opportunities. Despite these barriers, African Americans in St. Louis actively contested this exclusion and fought for economic justice and fair employment.

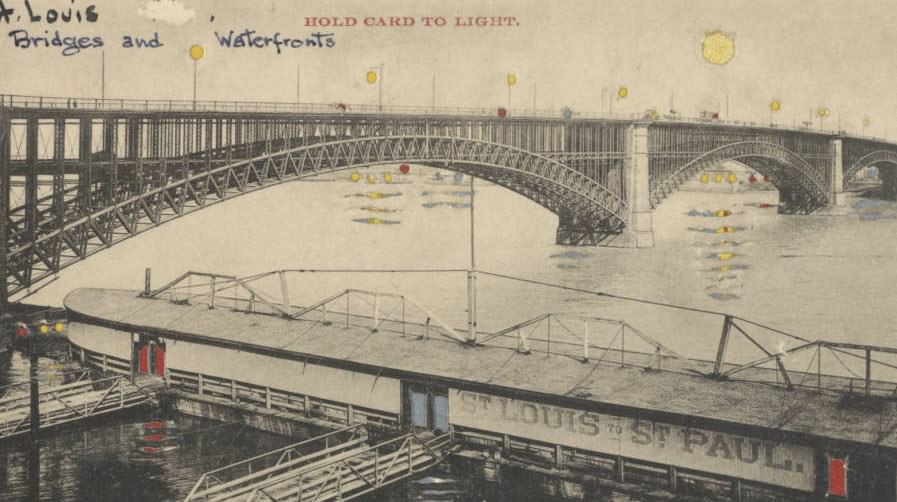

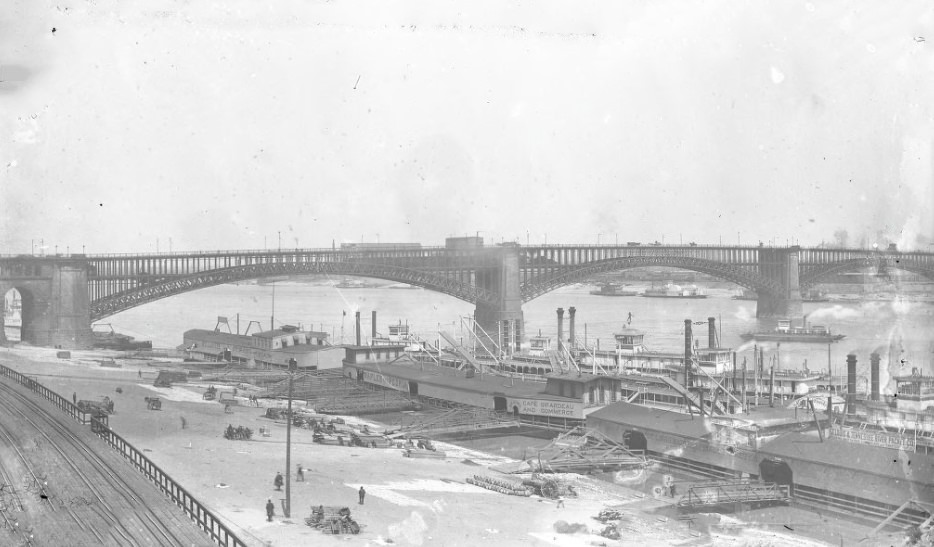

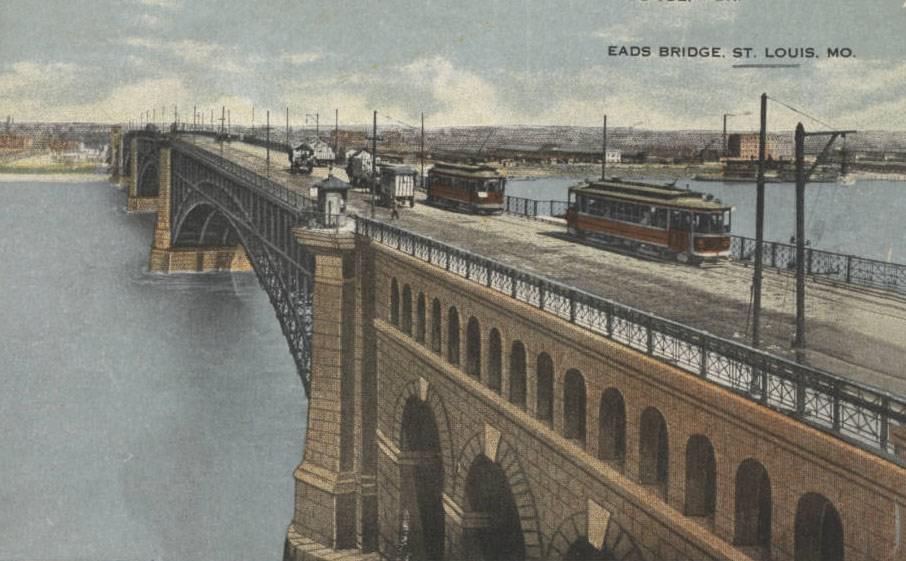

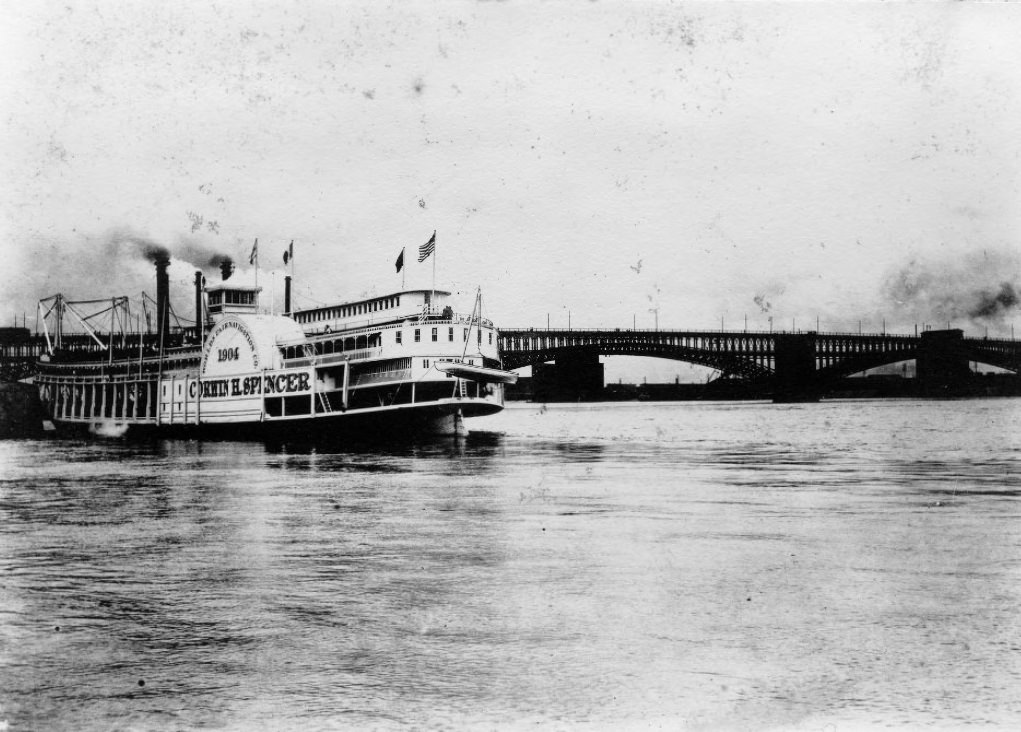

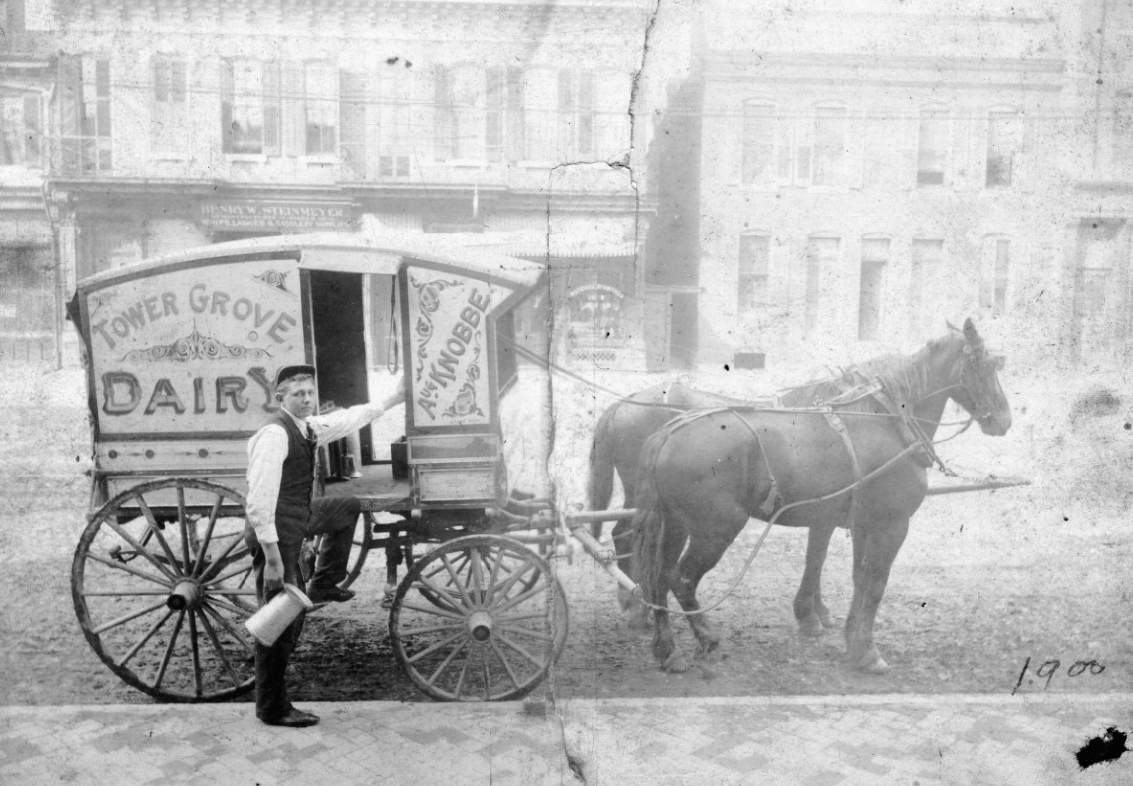

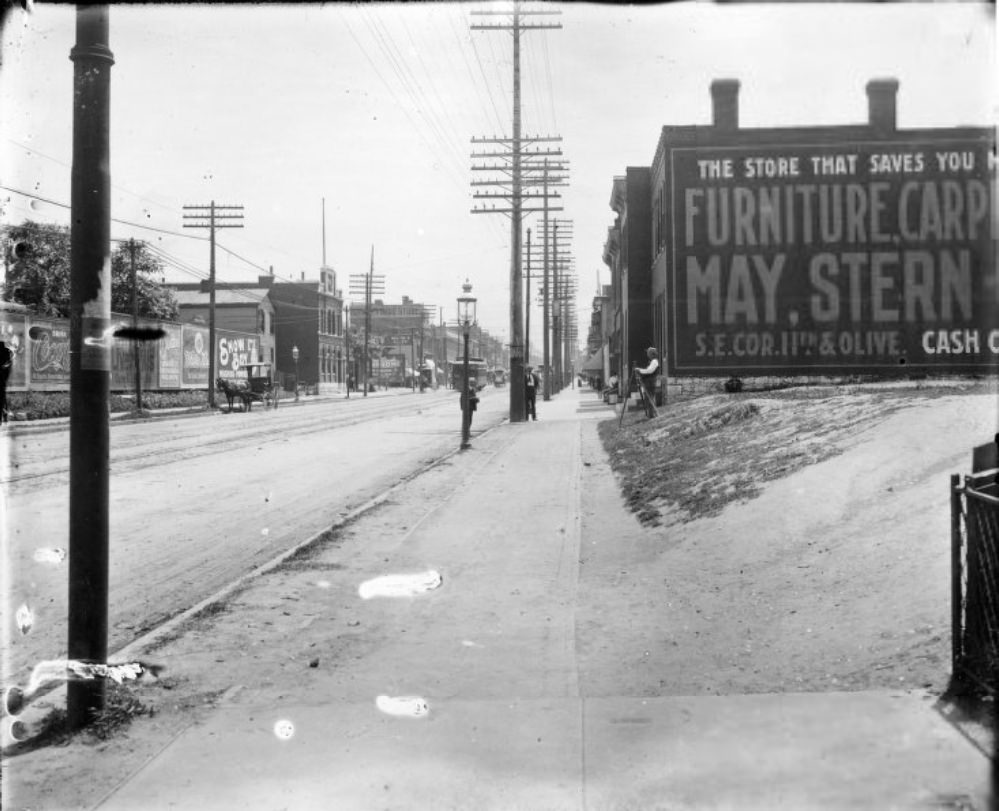

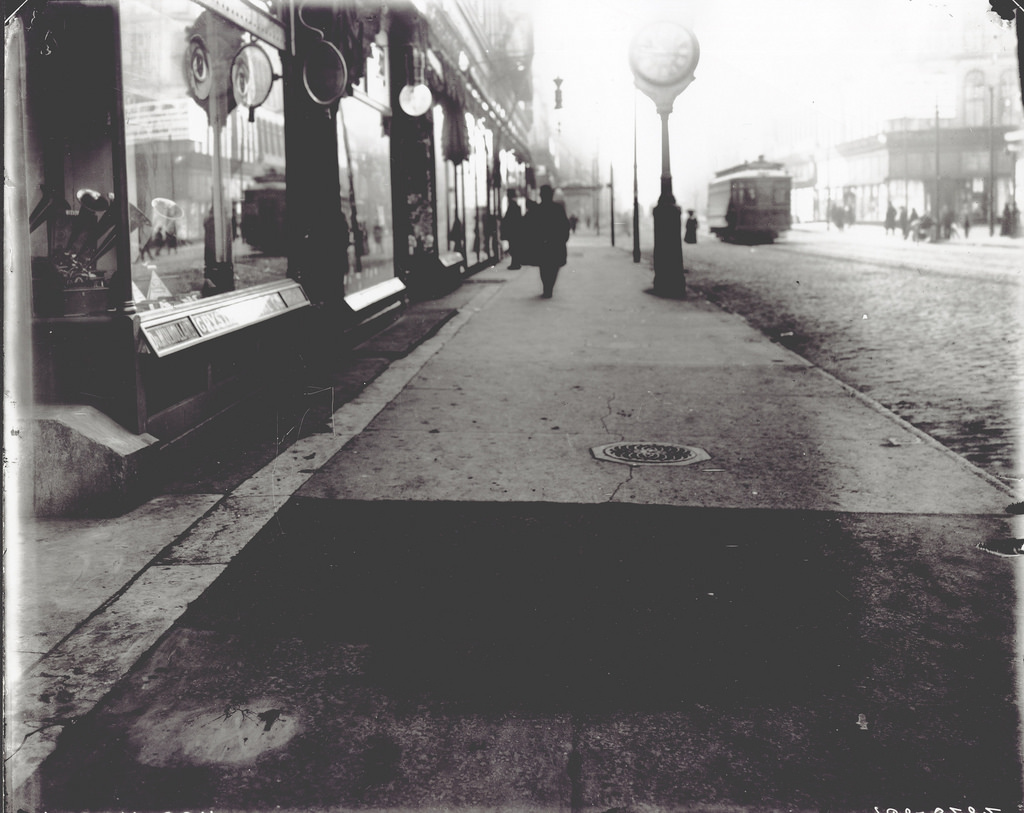

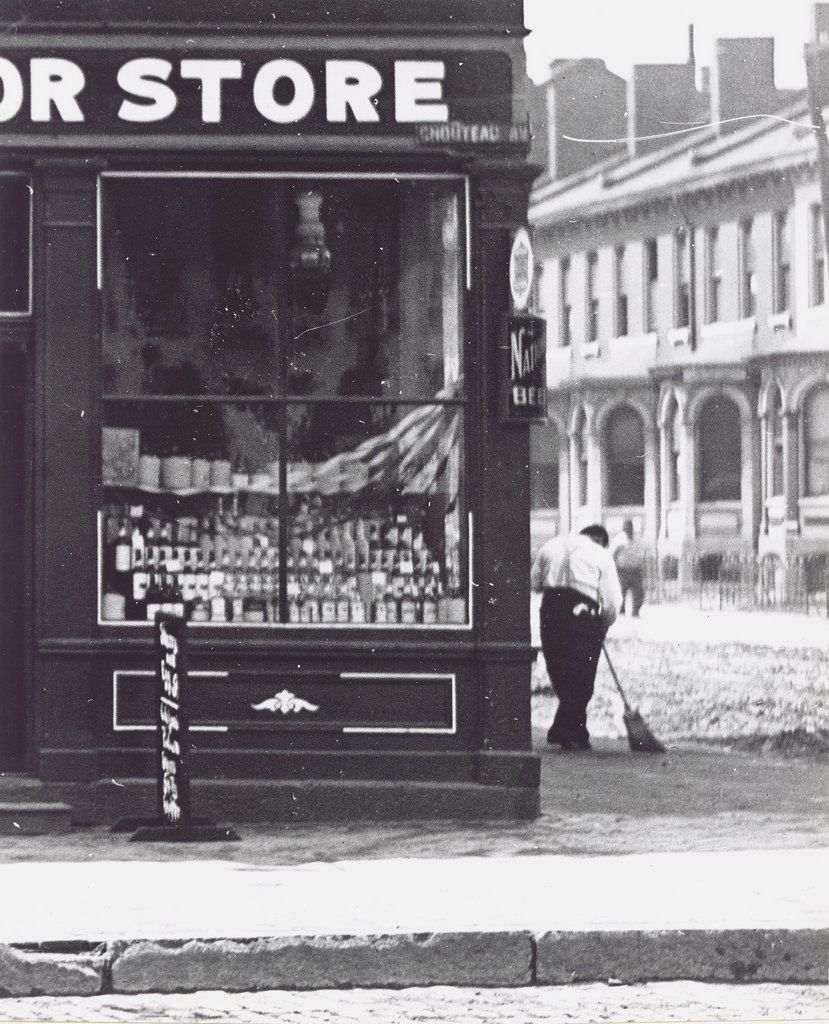

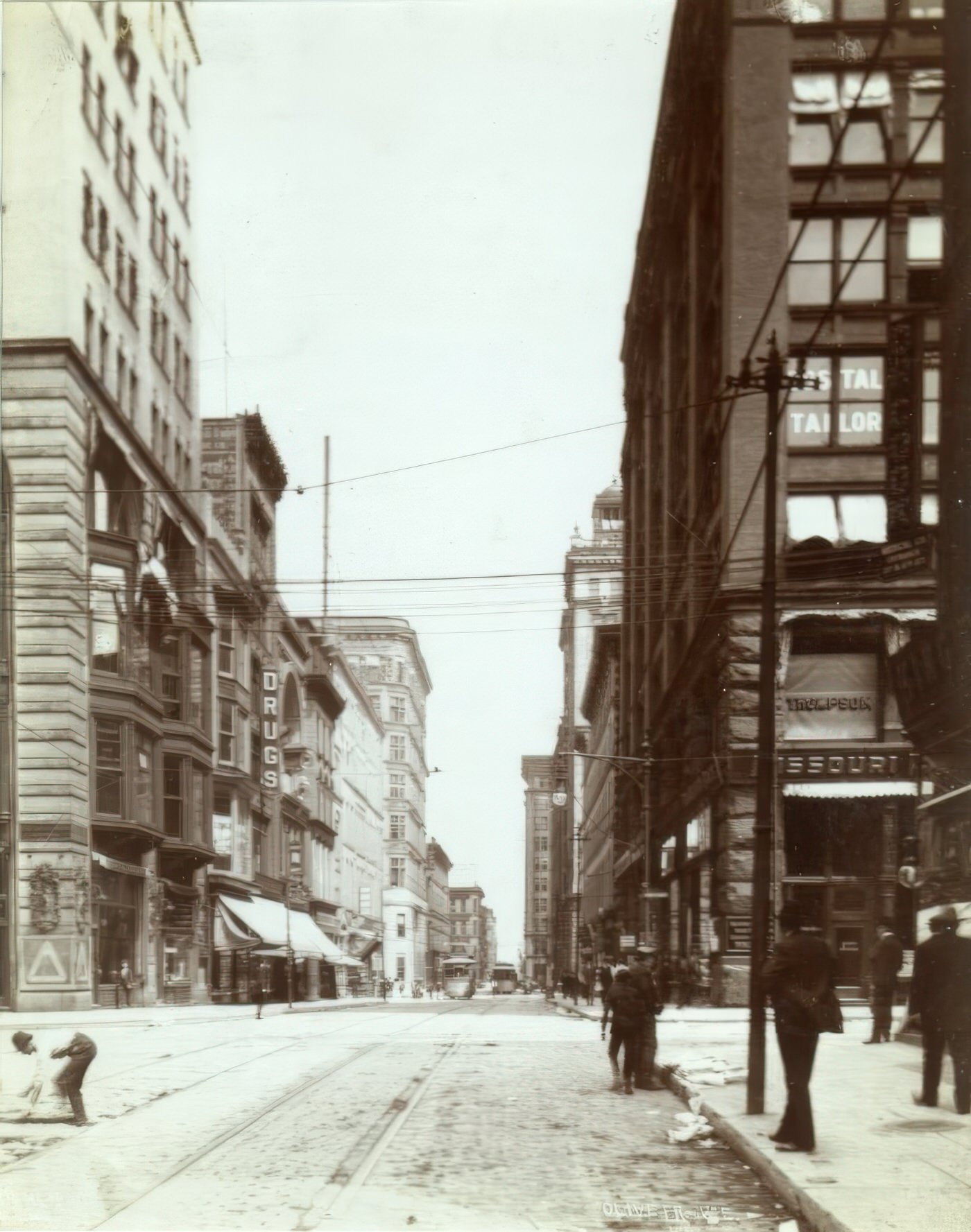

Getting Around: Transportation Transformation

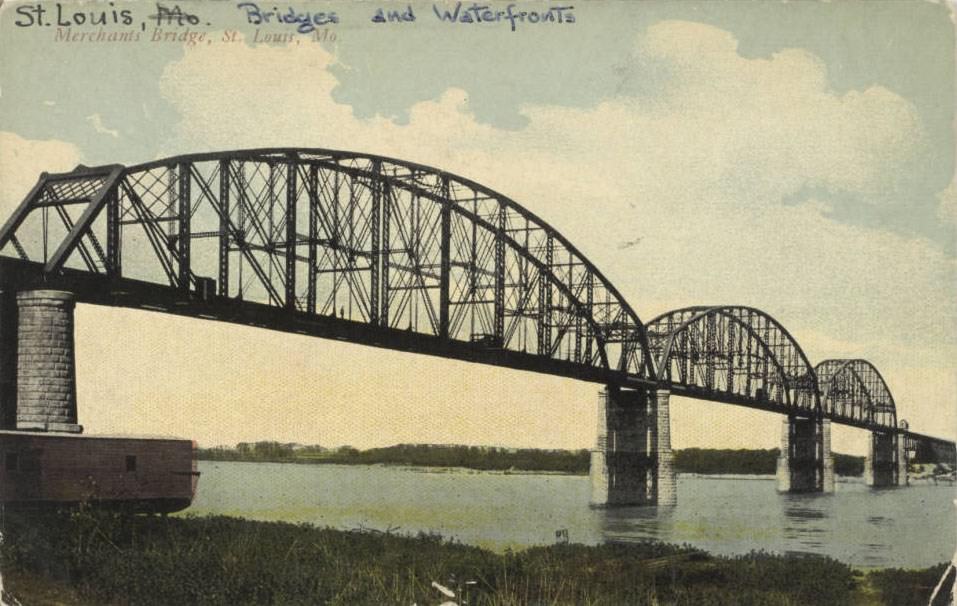

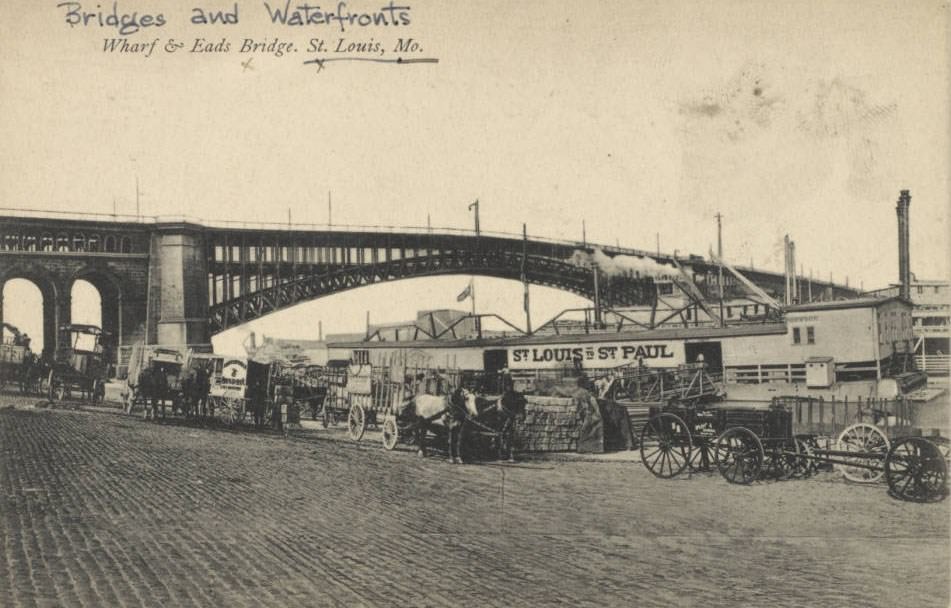

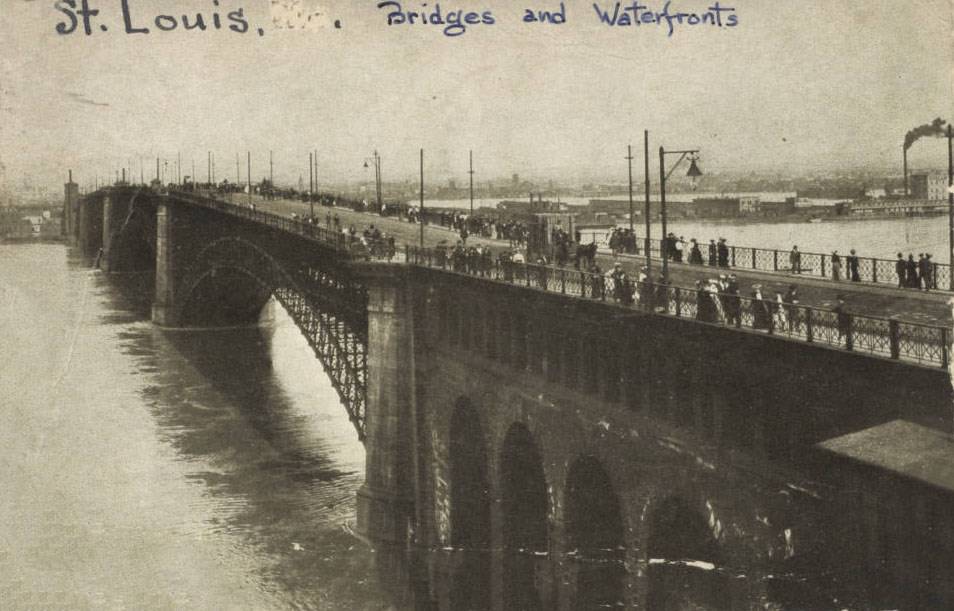

By the dawn of the 20th century, the way people and goods moved in and around St. Louis was undergoing a significant transformation. Railroads had firmly supplanted steamboats as the primary means for long-distance transportation and commerce. The Eads Bridge, an engineering marvel completed in 1874, played a vital role as a crucial link for east-west railroad traffic across the Mississippi River.

Within the city itself, electric streetcar lines were expanding rapidly. These streetcars provided an affordable and relatively efficient means of commuting for many St. Louisans, enabling easier travel between residential areas and workplaces or downtown shopping districts. The expansion of the streetcar system was a key factor in the growth of “streetcar suburbs,” as people could live further from the city center while still accessing its amenities. The importance of the streetcar system is highlighted by the fact that the city’s notorious political boss, “Colonel” Edward Butler, initially built his power base through a monopoly on horseshoeing the horses that pulled the earlier generation of streetcars.

The automobile was just beginning to make its presence felt in the early 1900s. Initially, cars were expensive novelties, primarily owned by the wealthy. However, St. Louis was an early center for automobile development and a proponent of improving road infrastructure with paved thoroughfares. As early as 1900, the city’s roads were becoming more suitable for bicycle use, which itself had demonstrated a growing public desire for individualized transportation options, paving the way for the automobile age.

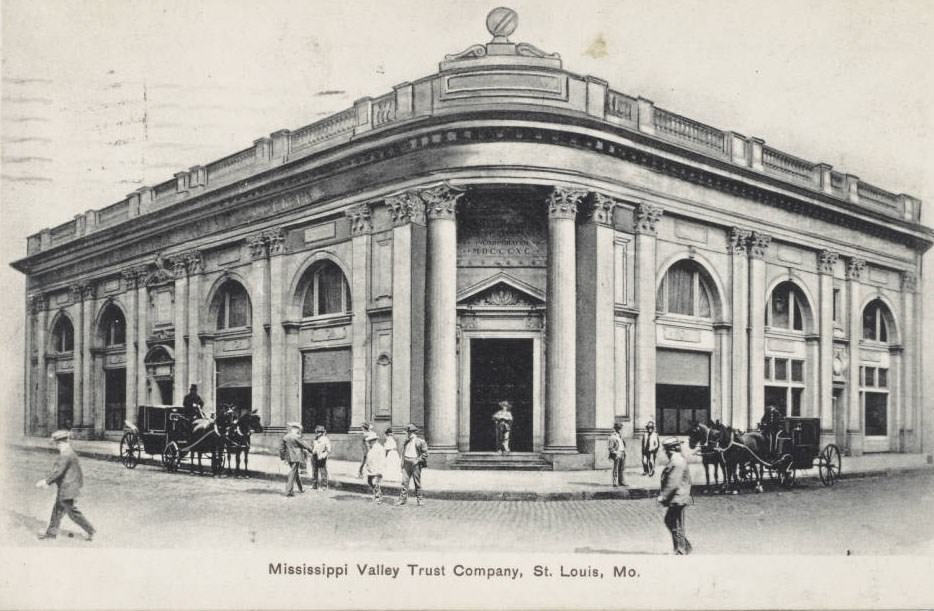

Building a Modern City: Shaping the Urban Landscape

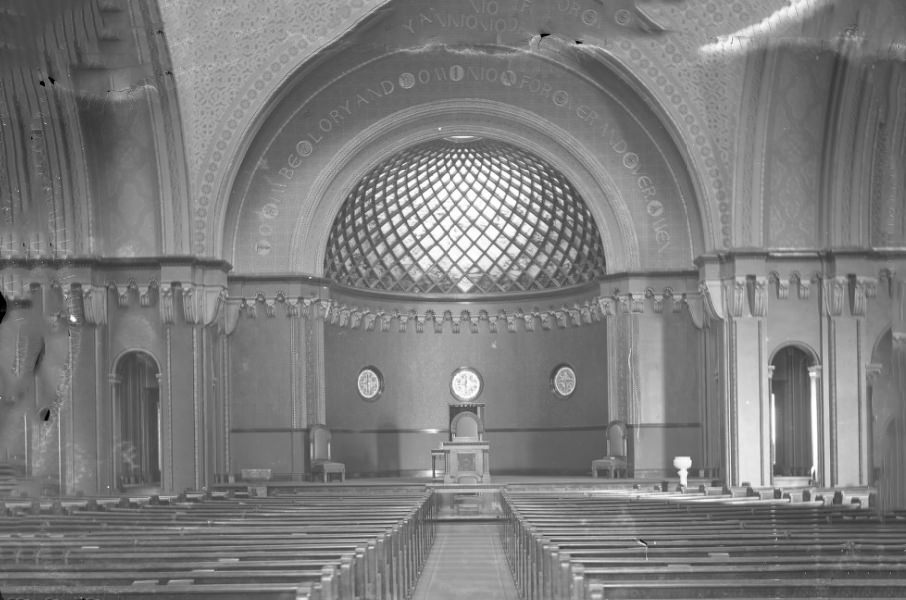

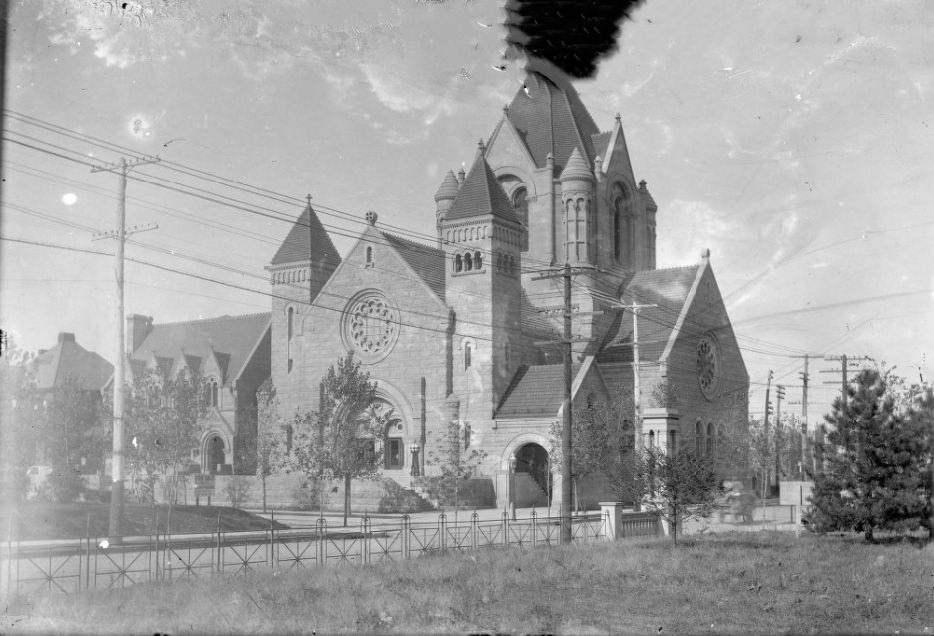

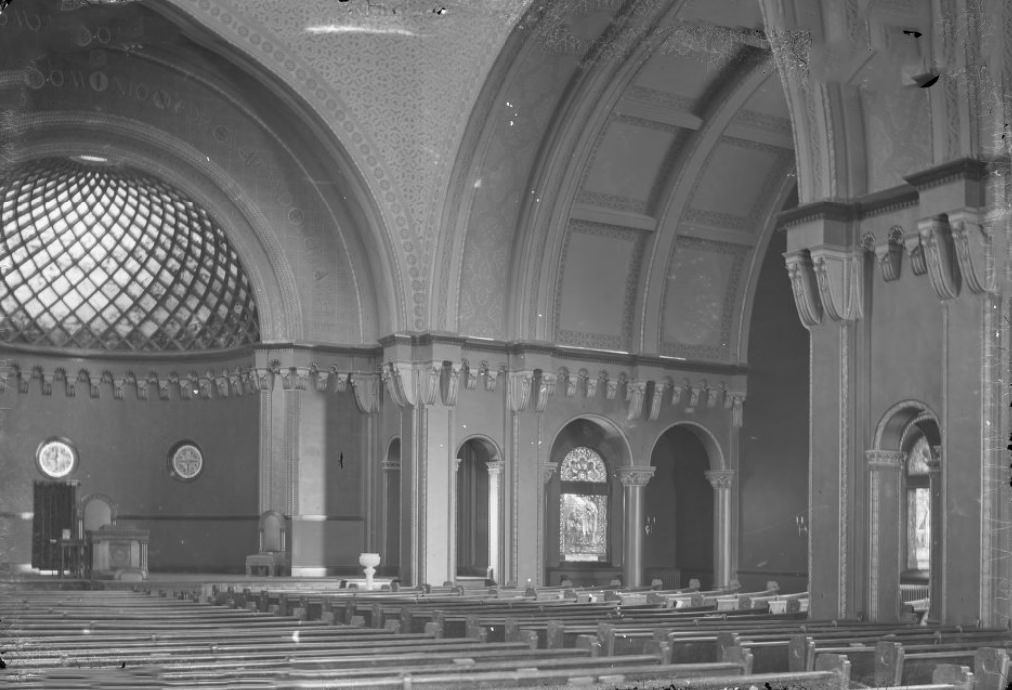

The architectural face of St. Louis was visibly changing in the early 20th century. The ornate Victorian styles that had dominated the late 19th century, such as Italianate, Second Empire, and Romanesque Revival, began to give way to new aesthetic preferences.

Among the styles gaining prominence was Beaux-Arts classicism, most grandly displayed in the temporary palaces of the 1904 World’s Fair and in permanent structures like the Saint Louis Art Museum, originally the Fair’s Palace of Fine Arts. Other styles like Arts and Crafts, Tudor Revival, and Georgian Revival also became increasingly popular for new buildings.

Industrial architecture was also evolving. While still prioritizing function, new factory and commercial buildings began to reflect changing design sensibilities. Examples from this period include:

The American Brake Company’s office building, constructed in 1901 in a Renaissance Revival style, which was later complemented by a more modern factory addition designed in 1919 by the firm Eames and Young.

The Hall and Brown Woodworking Company’s 1910 millwork building, designed by Gerhard Becker in the Romanesque Revival style, and a subsequent, more subdued Arts and Crafts style building for the same company.

The Guth Lighting facility, built in 1912, featured a reinforced concrete structure with red brick walls, showcasing a more utilitarian industrial design.

A facility for the Gast brewery, designed by Charles Mueller and constructed in 1905, presented an asymmetrical red brick appearance.

Public architecture also saw new directions. William B. Ittner’s school designs, for example, moved away from the rigid box-like schools of the past. His “open floor plans” emphasized natural light and airflow, and he employed a variety of architectural styles, often favoring Tudor Revival or Georgian elements, to create more inviting and functional educational buildings. These architectural shifts reflected St. Louis’s growth and its engagement with national design trends as it entered a new century.

Early City Planning and Civic Improvement

The challenges brought by rapid industrialization, population growth, and immigration spurred the rise of formal city planning efforts in St. Louis during the Progressive Era. The belief that urban problems could be solved through rational planning and civic action gained traction.

The Civic Improvement League, founded in 1901, was at the forefront of these efforts. Its goals were ambitious: to enhance the quality of housing, beautify downtown areas and city parks, and improve public transportation, recreational facilities, and cultural life for St. Louisans. These objectives directly addressed the negative consequences of largely unplanned 19th-century growth, such as pollution, haphazard development, and inadequate public services.

One of the most significant outcomes of these early planning initiatives was the 1918 zoning plan. This plan aimed to bring order to the urban landscape by separating industrial uses from residential areas. St. Louis was a pioneer in this regard, becoming the second major American city, after New York, to adopt such comprehensive industrial and residential zoning. The motivations behind zoning were complex. It was seen as a way to improve the quality of life for residents by reducing the impact of industrial pollution and noise on residential neighborhoods. It was also intended to protect residential property values. However, these planning efforts were not free from the social biases of the era. The concept of “blight” was sometimes explicitly linked to neighborhoods occupied by African Americans, and zoning was viewed by some as a tool to “protect” white residential areas from what they perceived as undesirable encroachments.

The emergence of the automobile also began to influence urban planning considerations in the early 20th century. City planners started to address the need for wider streets to accommodate automobile traffic, and new housing designs began to incorporate garages. These early steps in city planning marked a crucial shift towards more active municipal intervention in shaping the physical and social environment of St. Louis, setting precedents that would have lasting effects on the city’s development throughout the 20th century.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, wikimedia, St. Louis Mercantile Library, Dubach Photo Collection, Edmund Philibert Photo Collection, St. Louis Public Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know