The 1920s brought big changes to America, and St. Louis, Missouri, was an important city during this time. The city was full of people, busy factories, and many kinds of jobs. Social rules and culture were also changing. St. Louis in the 1920s was a lively place, growing fast and adjusting to a new, modern way of life.

As the 1920s began, St. Louis was a major American metropolis, grappling with the opportunities and challenges of urban life. Its population, physical layout, and the diverse peoples who called it home set the stage for the decade to come.

Population and Urban Scale

In 1920, St. Louis ranked as the sixth largest city in the United States, boasting a population of 772,897. This substantial number of residents lived within a dense urban environment, with a population density of 11,684 people per square mile—a figure twice that of modern St. Louis, painting a picture of a city teeming with life and activity.

Throughout the decade, the city’s population continued to climb, reaching 821,960 by 1929. This represented a 6.3 percent increase over the decade. Despite this absolute growth, St. Louis’s national ranking slipped from the sixth to the seventh-largest city. This relative slowing of growth compared to some other American urban centers hinted at shifting national development trends that were beginning to influence the city’s trajectory, even as it experienced a period of general prosperity. The peak growth phases for St. Louis appeared to be in the preceding decades, and this subtle shift indicated emerging undercurrents that would become more pronounced in later years.

The city’s population in 1920 was predominantly white, accounting for 90.9 percent of its residents. A significant portion of this white population, 14.7 percent, was foreign-born, underscoring St. Louis’s role as a destination for immigrants.

The African American community in St. Louis was substantial and growing. In 1920, nearly 70,000 African American citizens resided in the city, constituting 9 percent of the total population and making St. Louis the eighth-largest African American urban center in the nation. This community had seen rapid growth in the years leading up to the 1920s, fueled by the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South seeking economic opportunities and an escape from harsher Jim Crow laws, as well as by an influx of refugees fleeing the violence of the 1917 East St. Louis race riot.

St. Louis was a mosaic of European immigrant groups. Germans had a long and established presence, forming distinct neighborhoods like Bremen (later Hyde Park) and maintaining a robust ethnic culture with German-language schools and societies. Irish immigrants, arriving in large numbers since the mid-19th century, had also carved out their own communities, notably in the “Kerry Patch” on the near north side and around the Cheltenham area, working in industries like clay mining and brewing.

Italian immigrants, whose major influx began in the 1890s, were heavily concentrated in “The Hill” neighborhood. This area, initially a mining camp for the local clay deposits, grew significantly in the first two decades of the 20th century into a cohesive and self-supporting Italian enclave. Eastern European immigrants, including Poles, Russians, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, and Romanians, also established communities. Many settled in tenement housing on the near south side, working in nearby foundries and factories, or in areas like those around Cass Avenue. For instance, by 1920, the Sheridan and Thomas corridors near Cass Avenue were predominantly populated by Yiddish-speaking Russian and Romanian Jewish immigrants.

St. Louis Economy in the 1920s

The 1920s were a period of significant economic activity and transformation for St. Louis. While some traditional industries faced profound challenges, others flourished, and new sectors emerged, painting a complex picture of the city’s financial and industrial life.

Before 1920, St. Louis was renowned as one of America’s foremost brewing centers. Companies like Anheuser-Busch and the Lemp Brewery were industrial giants, with Anheuser-Busch recognized as the world’s largest brewery by 1904. The city’s identity and economy were deeply intertwined with its beer production.

The implementation of National Prohibition in January 1920 brought this era to an abrupt halt, forcing all legal brewing activities to cease. The city’s breweries had to adapt or face closure. Anheuser-Busch, under the leadership of August A. Busch Sr., managed to survive by diversifying its production. The company shifted to manufacturing a non-alcoholic cereal beverage called Bevo, along with other products like baker’s yeast, ice cream, soft drinks, and corn syrup. This diversification allowed them to keep a significant portion of their workforce employed.

Other breweries had different fates. The William J. Lemp Brewing Company, another titan of St. Louis brewing, struggled to make its near-beer product, “Cerva,” profitable. The immense Lemp brewery complex, once valued at $7 million, ceased operations and was sold in 1922 for a mere $588,500 to the International Shoe Company, marking a dramatic end to a brewing dynasty. Falstaff Brewing Corporation, which had acquired the Lemp’s “Falstaff” brand name earlier, also survived Prohibition by producing near beer, soft drinks, and cured hams. Smaller breweries like Hyde Park Brewery went into a hiatus, reopening only after Prohibition’s repeal. The Griesedieck Brothers Brewery also closed during Prohibition, using the time to update their facility before re-entering the market in 1933. The impact of Prohibition on St. Louis was profound, dismantling a cornerstone of its economy and forcing a painful restructuring for those companies that managed to endure.

While brewing faced a crisis, St. Louis thrived as a national leader in shoe manufacturing throughout the early twentieth century. By 1929, the city’s factories produced an astounding 87 million pairs of shoes annually, and Washington Avenue was recognized globally as a center for the shoe trade.

Two giants dominated the St. Louis shoe industry: the International Shoe Company (ISC), which for many decades was the world’s largest shoe manufacturer, and the Brown Shoe Company. In 1920, Brown Shoe Company operated five factories in St. Louis alone. The industry provided employment for thousands, though working conditions were often challenging, leading to unionization efforts and strikes in the early 1900s. These labor disputes prompted some companies, including Brown Shoe, to begin establishing factories in smaller towns outside the city to access different labor pools. The 1920s also brought market challenges. A sudden shift in women’s fashion toward shorter hemlines made high-topped boots, a staple product, less popular, leading to an overstock and a financial crisis for Brown Shoe Company in 1920, from which it eventually recovered.

Growth in Other Manufacturing Sectors

Beyond brewing and shoes, St. Louis’s manufacturing sector was diverse and saw growth in several key areas during the 1920s:

Electrical Goods: The city was a significant center for the production of electrical motors, fans, and other apparatus. Century Electric Company, Wagner Electric Corporation, and Emerson Electric were the “big three” electrical manufacturers based in St. Louis. Century Electric, known for its innovation in electric motors for both household appliances and industrial use, underwent considerable expansion in the 1920s. The company made plans for and began construction of a dedicated foundry complex at Spring and Forest Park to consolidate its casting operations; this facility poured its first heat on April 30, 1930, becoming one of the largest job-shop operations in the Midwest.

Chemicals: The chemical industry also saw advancement. Monsanto Chemical Works, founded in St. Louis in 1901 by John Francis Queeny, expanded its product lines in the 1920s to include basic industrial chemicals like sulfuric acid. In 1928, Edgar Monsanto Queeny, John’s son, took over leadership of the company. Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, another established St. Louis firm, continued its growth under the leadership of Edward Mallinckrodt, Sr. (until his death in 1928) and his son, Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr. A significant development for Mallinckrodt in the 1920s was the 1922 introduction of analytical reagent chemicals for sale, which they had initially developed for their internal use.

Automotive Industry: St. Louis played an early role in the burgeoning American automotive industry, serving as a center for automobile manufacturing, sales, and service. While many small, independent auto manufacturers had existed, the 1920s saw a consolidation trend favoring larger companies with mass production capabilities. Nevertheless, local brands like the Gardner Motor Car Company, founded by Russell Gardner (previously of the Banner Buggy Company), produced automobiles in St. Louis from 1920 until 1931, making over 40,000 vehicles. Ford Motor Company and General Motors also operated assembly plants in the St. Louis region, recognizing its strategic location and skilled labor force. The area around Locust Street became known as St. Louis’s “Automobile Row,” lined with dealerships showcasing the latest models.

Food Processing (Non-Brewing): The food processing industry, apart from brewing, remained a vital part of the St. Louis economy. Ralston Purina Company, founded by William H. Danforth, was a major producer of animal feeds and breakfast cereals. In 1920, Donald Danforth, William’s son, joined the firm and was instrumental in establishing a 337-acre research farm in Gray Summit in 1926 to scientifically formulate feeds. That same year, Purina Dog Chow was launched. The Pet Milk Company, originally the Helvetia Milk Condensing Company, moved its headquarters to St. Louis in 1921 and officially adopted the Pet Milk name in 1923. During the 1920s, Pet Milk expanded its offerings to include fresh dairy products like ice cream and butter, growing its service area from its Tennessee plant throughout the Southeast. Switzer’s Licorice Company, a long-standing St. Louis confectioner known for its real licorice extract, continued its operations through the decade.

The diverse manufacturing base, with growth in sectors like electrical goods, chemicals, and automotive parts, helped St. Louis navigate the economic shift caused by Prohibition. This period marked a transition towards a more modern industrial profile, less singularly dependent on its 19th-century brewing fame.

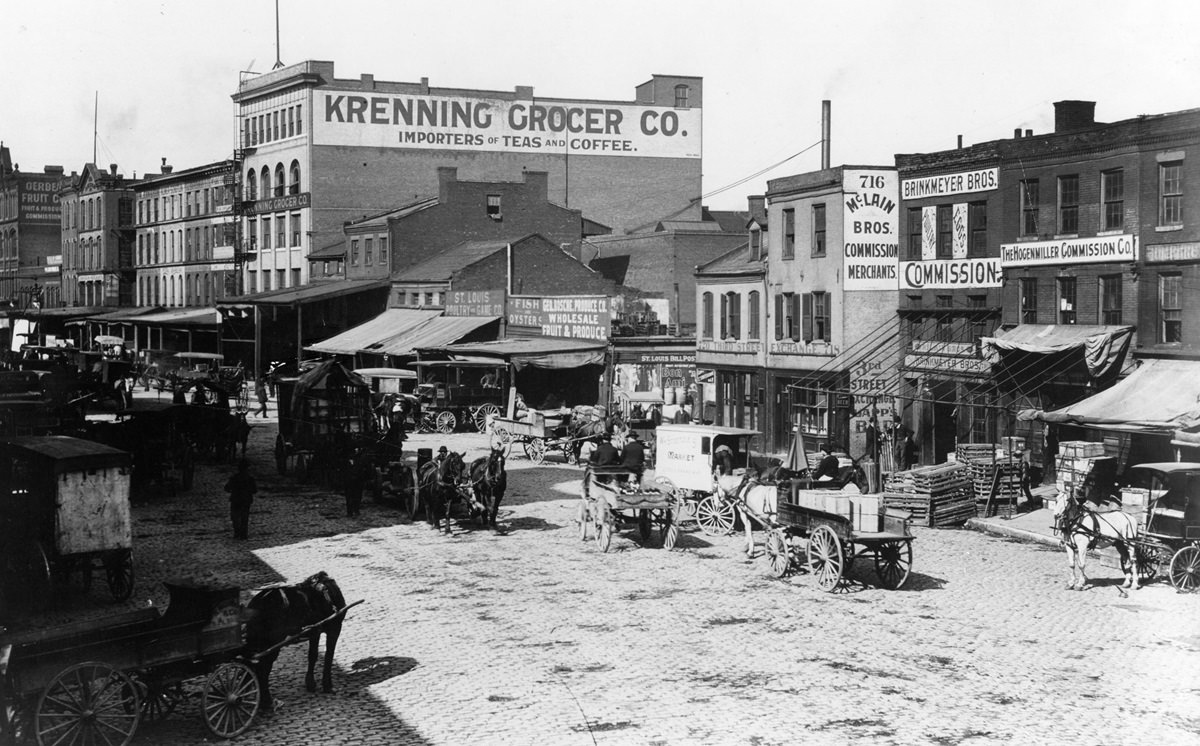

Commerce and Trade

St. Louis’s geographical position on the Mississippi River and its history as a gateway to the west continued to define its commercial character in the 1920s.

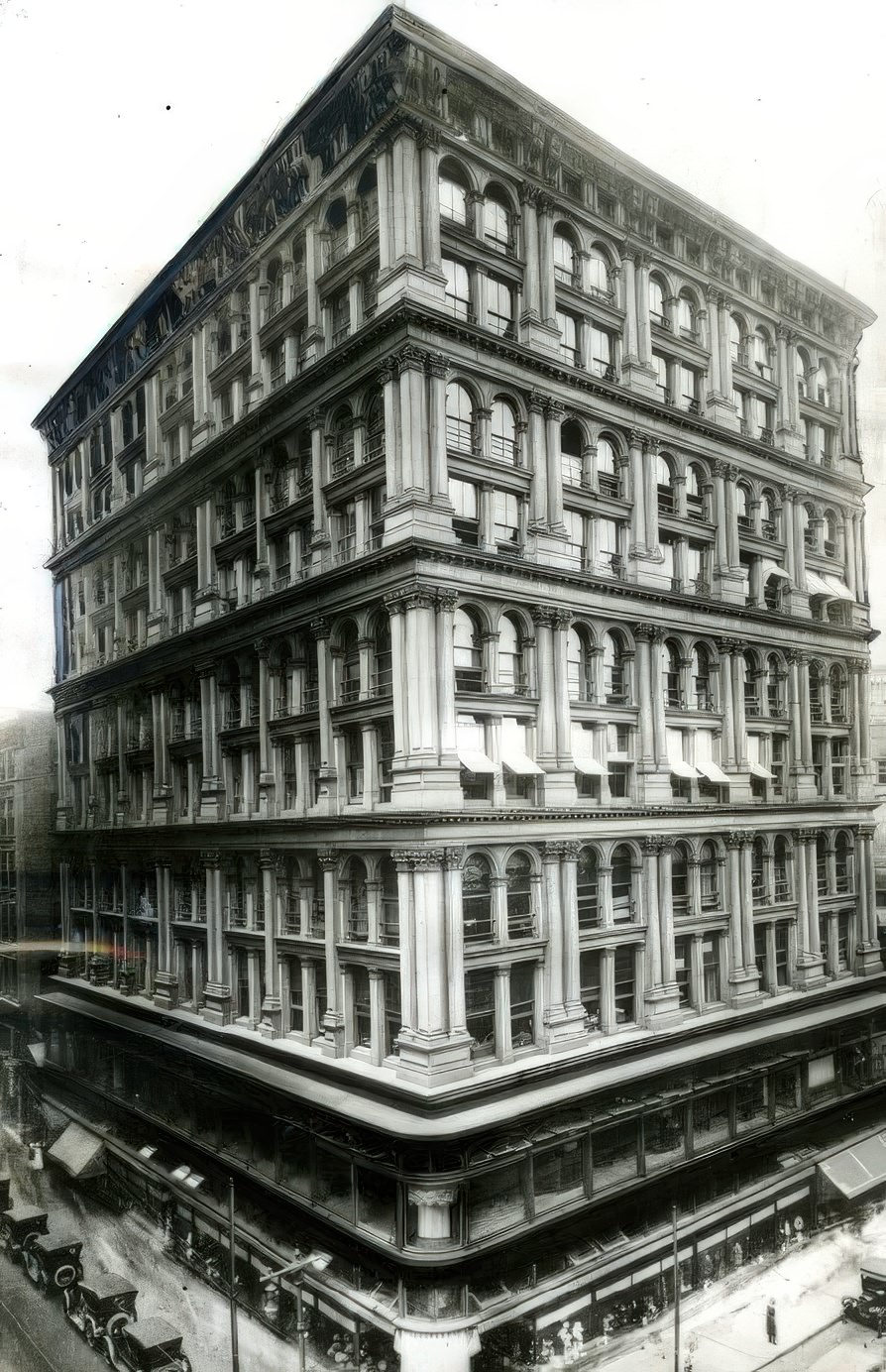

Wholesale and Retail Hub: The city remained a significant center for wholesale trade. According to the 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica, 35 lines of industry in the St. Louis district conducted business valued at $1,582,957,145 in 1920. Prominent wholesale sectors included dry goods ($240 million), carpets and linoleums ($240 million), boots and shoes ($175 million), groceries ($175 million), railway supplies ($210 million), and hardware ($115 million). These figures underscore the city’s role in distributing a wide array of goods. Department stores like Famous-Barr, Stix, Baer & Fuller, and Scruggs-Vandervoort-Barney were major players in the downtown retail scene, though specific operational details for the 1910s and 1920s are limited in the provided materials.

The Enduring Fur Trade: The fur trade, an industry foundational to St. Louis’s early economy, maintained its importance. By the 1920s, St. Louis was recognized as the largest primary fur market in the world, with sales reaching $27,200,000 in 1920. Local dealers handled pelts from as far as Alaska and northern Canada.

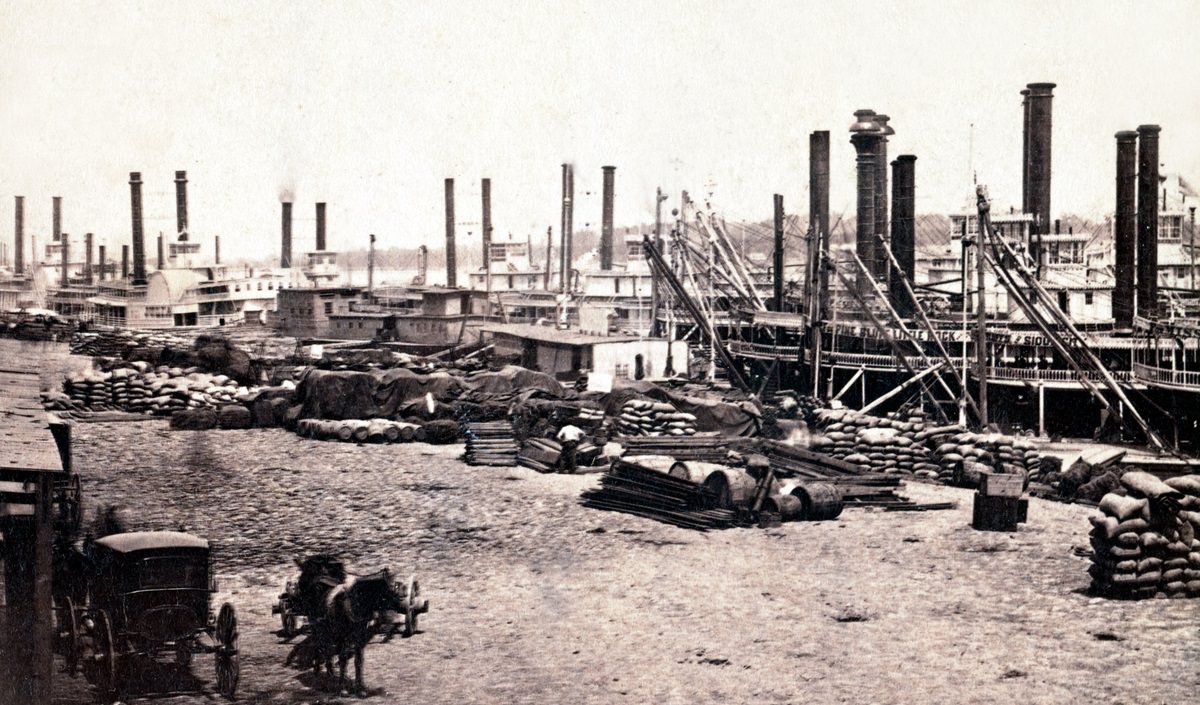

River Traffic and Transportation: Although railroads had largely supplanted steamboats as the primary mode of long-distance transport, the Mississippi River still played a role in St. Louis commerce. In 1920, the port handled 166,140 tons of outbound freight and 177,925 tons of inbound freight by water. During the 1920s, there were active promotions by farmers, shippers, and businessmen for developing a deeper river channel to help lower railroad freight rates, indicating a continued interest in leveraging the river for commercial advantage.

Banking Institutions: The city was a significant banking center. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, established in 1914, was fully operational, playing its role in the nation’s new central banking system. In 1920, the combined assets of St. Louis banks and trust companies totaled $637,615,811, and bank clearings were $8,294,027,135, a substantial increase from 1910. The First National Bank in St. Louis was formed in 1919 through the consolidation of three existing banks (St. Louis Union National Bank, Mechanics-American National Bank, and Third National Bank), creating an institution with resources of $155,953,137. It further consolidated with Liberty Central Trust Co. in 1929. Mercantile Trust Company, established in 1899, was a prominent financial institution. By 1909, it employed over 200 people and had a significant surplus. It continued to be a major player in the 1920s, involved in financing local businesses and even international loans, such as a $33 million refunding loan for Bolivia in 1929 arranged by Stifel, Nicolaus Investment Company, with which Mercantile had connections. Boatmen’s Bank, another long-standing institution, became Boatmen’s National Bank of St. Louis in 1926.

Labor and Employment

The 1920s saw evolving labor dynamics in St. Louis, reflecting national trends of industrial growth and worker organization.

General Trends and Wages: Nationally, employment in manufacturing, service, clerical, and sales occupations grew. In St. Louis, industries like shoe manufacturing, electrical goods, and automotive production provided numerous jobs. Wages for unionized trades in St. Louis saw increases. For example, a 1921 Bureau of Labor Statistics report indicated that nationally, weekly wage rates in 1920 were 28 percent higher than in 1919 and 98 percent higher than in 1910 across various trades. Specific data for St. Louis from 1913-1920 showed hourly wage increases for selected trades. The 1920s continued this upward trend for many, though specific St. Louis employment numbers by sector for the entire decade are not fully detailed in the provided materials. However, the general prosperity of the Roaring Twenties suggests a relatively strong employment landscape in the city’s diverse industries until the latter part of the decade.

Union Activity and Strikes: St. Louis had a history of active labor organization. The Central Trades and Labor Union of St. Louis and Vicinity supported a hotel and restaurant employees’ strike in 1920. While the 1920s nationally saw a decline in major strike activity compared to the immediate post-WWI years, unions like the International Typographical Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America were active, sometimes accepting wage cuts to maintain union representation in a challenging environment for organized labor. The broader context of the 1920s was one where businesses often resisted unionization, and the open shop movement gained traction. Specific major strikes in St. Louis during the 1920s are not extensively detailed in the provided information, but the existing union presence suggests ongoing efforts to advocate for workers’ rights and conditions.

Urban Development and Infrastructure

The 1920s saw St. Louis continue to adapt its physical form and infrastructure to the demands of a growing population and new technologies, particularly the automobile.

Streetcars: The electric streetcar system, operated by United Railways which reorganized into the St. Louis Public Service Company in the late 1920s (1927), remained the primary mode of mass transit. In the 1920s, the company built around 300 Peter Witt style streetcars. Fare structures evolved; for instance, in 1926, United Railways raised fares from 7 to 8 cents, or two rides for 15 cents. A route numbering system was instituted in 1928 to replace line names, though this was reportedly not popular with native St. Louisans.

Automobiles: Car ownership surged nationally in the 1920s, from 8 million in 1920 to an estimated 23 million by 1930. This trend was reflected in St. Louis, leading to increased traffic congestion downtown. The city was an early advocate for paved thoroughfares. The 1920s saw continued efforts to improve roads to accommodate automobiles, with a focus on surfacing and rebuilding. The “good roads” movement spurred these improvements.

Union Station: St. Louis Union Station, which opened in 1894, remained the largest American railroad terminal in the 1920s. It served as a hub for 22 railroads, the most of any single terminal in the world, handling a massive volume of passenger traffic.

River Traffic: As noted previously, river commerce continued, though it was secondary to rail. The city’s riverfront saw activity related to the shipping of goods.

Aviation: The 1920s marked the dawn of more significant aviation activity. Charles Lindbergh’s historic 1927 transatlantic flight in the “Spirit of St. Louis,” funded by St. Louis businessmen, brought international attention to the city’s connection with aviation. Lambert Field (later Lambert-St. Louis International Airport) was established in the 1920s, named after Albert Bond Lambert, an early aviation enthusiast

River des Peres Sewer Project: This massive civil engineering project, aimed at transforming the polluted River Des Peres into an enclosed sewer and drainage system, saw significant progress in the 1920s. Following a devastating flood in 1915, and under the direction of engineer W.W. Horner starting in 1916, plans developed as early as 1910 were implemented. After a bond issue passed in 1923, formal construction began on January 19, 1924, with Mayor Kiel initiating the digging. The project, completed between 1924 and 1931, involved constructing a 13-mile system of tunnels, pipelines, and canals, including large-diameter (32-foot) reinforced concrete pipes. This project was crucial for public health, separating sewage from surface water and mitigating flooding.

Road Paving: The rise of the automobile necessitated extensive road improvements. While specific statistics for St. Louis in the 1920s are not detailed, the national “good roads” movement was in full swing, and Missouri was actively developing its highway system. By the mid-1920s, there was a recognized need to improve the appearance of Missouri highways, leading to roadside beautification efforts. A major bond issue in 1923 included funds for widening key downtown streets like Tucker, Market, and Olive, a project completed by the late 1930s.

Utilities: The expansion of electrical utility networks nationally was a hallmark of the 1920s, leading to new consumer appliances and better lighting. In St. Louis, Union Electric Light and Power Company (now Ameren) and Laclede Gas Light Company were the primary providers of electricity and gas, respectively. The St. Louis Water Works continued to operate, with Intake Tower No. 2 having been constructed in 1913. Southwestern Bell provided telephone service. The expansion of these utilities was essential for both residential and industrial growth.

The Progressive Era’s emphasis on reform and civic improvement had a lasting impact on St. Louis’s urban planning in the 1920s. The St. Louis City Plan Commission, established in 1911, continued its work under the direction of renowned city planner Harland Bartholomew, who was brought to St. Louis in 1916.

A key achievement was the 1918 zoning plan, which St. Louis was among the first major American cities to adopt. This ordinance aimed to isolate industrial uses from residential areas, shaping the city’s development patterns throughout the 1920s and beyond by dictating land use. Efforts continued to enhance housing quality, beautify downtown and city parks, and improve public transportation and recreation. The 1923 bond issue, strongly supported by Mayor Henry Kiel, provided significant funding for many of these civic improvements, including the creation of Aloe and Memorial Plazas and the initial land clearance for what would become the Gateway Arch National Park.

Public Health

Public health remained a significant concern in St. Louis during the 1920s, with ongoing efforts to combat disease and improve sanitation. The city’s Health Department continued its work, though specific activities from the 1920s are not detailed in the provided snippets. The earlier establishment of standardized health surveys (nationally in 1921, with Hagerstown, Maryland, as a starting point) indicates a growing focus on quantitative public health measures. Smoke pollution from burning soft coal was a persistent problem, leading to the passage of a Smoke Ordinance in 1937 under Mayor Dickmann, but the issue was already recognized in the 1920s, with studies in 1926 showing St. Louis had extremely high soot deposits.

St. Louis had a growing network of hospitals. Barnes Hospital, which opened in 1914 in affiliation with Washington University School of Medicine, was a modern general hospital. St. Louis Children’s Hospital also had an affiliation with Washington University’s reorganized medical school. City Hospital No. 2 (later Homer G. Phillips Hospital), acquired during Mayor Kiel’s administration (1913-1925), served the African American community. The city passed a bond issue in 1922 that allocated over $1 million for the creation of a hospital for indigent African Americans.

Education

The educational landscape in St. Louis during the 1920s was marked by continued development and the persistent reality of racial segregation.

St. Louis public schools operated under a segregated system, a practice upheld by Missouri law (Lehew v. Brummell, 1890) until the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. While one source suggests that Missouri provided comparably funded schools for Black and white students with the same curriculum and textbooks organized by biracial committees, other accounts indicate significant funding disparities, with “white” schools receiving up to three times more funding than “colored” schools. African American children often had to travel long distances to attend their designated schools, passing white schools along the way.

Sumner High School, the first high school for African Americans west of the Mississippi, had moved into a new Ittner-designed building in 1911. Due to overcrowding at Sumner, Vashon High School was planned and opened on September 6, 1927, as the city’s second high school for African American students. The curriculum in public schools during the 1920s generally shifted towards a modern liberal arts approach, including English literature, history, science, math, art, music, and physical education.

Washington University in St. Louis continued its growth. The School of Architecture had been established in 1910. Washington University joined the prestigious Association of American Universities in 1923. Rebstock Hall, for the Department of Biology, was dedicated in 1927.

SLU also saw significant developments. The School of Commerce and Finance (later School of Business & Administration) was founded in 1910. The School of Nursing was founded in 1928, and the School of Social Service in 1930. Despite some early experiments with coeducation in the law school around 1908-1910, women were largely barred from many programs until later. The first women law students graduated between 1911 and 1913, but the program then excluded women again until much later. Homecoming traditions centered around football games began to formalize in the mid-1920s.

The Urban Fabric: Growth, Challenges, and Daily Life

The 1920s in St. Louis were characterized by ongoing urban development, with neighborhoods evolving, infrastructure expanding, and daily life reflecting both the opportunities and strains of a large industrial city.

The city’s housing landscape in the 1920s was a patchwork of varying conditions, heavily influenced by class, ethnicity, and race. Many working-class and immigrant families lived in densely populated areas, often in housing that lacked modern amenities. Tenement-style dwellings were common in older parts of the city, particularly on the near south side, which housed many German and Czech immigrants working in nearby industries. These areas often suffered from overcrowding and inadequate sanitation. A 1908 survey, with conditions likely persisting into the early 1920s for many, found that in the poorest St. Louis neighborhoods, only one bathtub existed for every 200 residents, and in densely packed tenements, this ratio was as low as one for every 2,479 residents. Shared, inadequate restrooms and poor ventilation contributed to the spread of diseases like tuberculosis. The term “cold water flats” was common, indicating a lack of hot running water, and heating often relied on coal, contributing to air pollution. In some immigrant neighborhoods, like the “Kerry Patch” inhabited by Irish immigrants, conditions were described as impoverished and dangerous, with dilapidated shanties.

The Hill: This south St. Louis neighborhood was firmly established as a vibrant Italian enclave by the 1920s. Italian immigrants, initially drawn by jobs in the clay mines and brick factories that had been active since the mid-19th century, created a self-supporting community with its own shops, churches (like St. Ambrose, whose current brick structure was built in 1926 after the original burned ), and social institutions. By 1910, six foundries were operational in the area. Though initially populated by male boarders, by the 1920s, families had joined, and the neighborhood was known for its meticulously maintained homes and strong community bonds.

Soulard: One of St. Louis’s oldest residential districts, Soulard continued to be a diverse working-class neighborhood. While its grand mansions were built after the Civil War, the area also contained row houses and flats inhabited by various immigrant groups, including Germans and Eastern Europeans (earning it the nickname “Bohemian Hill”). The Soulard Market, a central feature, was reconstructed in 1929 in the Italian Renaissance style after being destroyed by a tornado in 1896.

Dogtown (Clayton-Tamm, Franz Park, Hi-Point): This area, south of Forest Park, had its origins as a settlement for Irish miners working in local clay mines and brick factories. By the 1920s, the mining industry was in decline, and the neighborhood began to diversify with German Jewish, Italian, and some African American residents moving in. It was characterized by small frame or brick bungalows built from the 1920s through the 1940s, along with some two-story single and multi-family dwellings. Despite the industrial decline, Dogtown maintained a lively atmosphere with numerous small shops, confectioneries, and pubs.

The Ville: This neighborhood became a crucial center for St. Louis’s African American community. Due to restrictive covenants and segregationist policies that limited housing options for African Americans elsewhere in the city, The Ville saw its Black population surge from 8% to 86% between 1920 and 1930. It became a cradle of Black culture, home to professionals, businesses, and entertainers. Key institutions included Sumner High School (the first high school for Black students west of the Mississippi), Stowe Teachers College, Annie Malone Children’s Home, and Poro College, founded by entrepreneur Annie Malone, which became a major employer and training center for African Americans in the beauty industry.

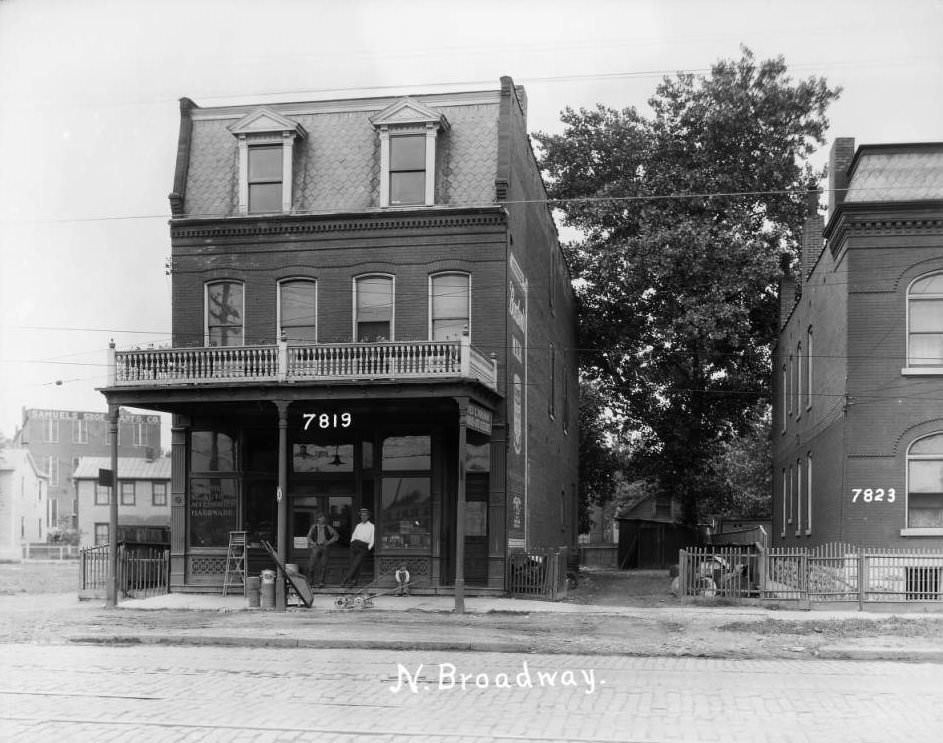

Baden: Located at the intersection of Bellefontaine Road (North Broadway) and Halls Ferry Road, Baden developed as a settlement in the early 19th century, with significant German settlement in the 1840s and 1850s, earning it the nickname “Germantown”. By the 1920s, it was an established community, though specific demographic shifts or major developments for this decade are not detailed in the provided snippets.

Streetcar Suburbs: The expansion of the electric streetcar system in the late 19th and early 20th centuries spurred the growth of “streetcar suburbs”. These neighborhoods, often characterized by multi-family flats, duplexes, and walk-up apartments, continued to develop in the 1920s, offering housing for working and middle-class families. Areas in South St. Louis are prime examples of this type of development. New residential subdivisions like High Holborn Addition (1920), Cedardale (1923), Minnikahda Vista (1925), and Sunset Gables (1929) were platted in areas like St. Louis Park (a suburb, but indicative of regional trends), reflecting the outward push of residential development. Holly Hills, envisioned in the 1920s as an opulent community, saw its grand plans tempered by the Great Depression, but development of brick bungalows continued in later decades.

Culture and Society in the Jazz Age

The 1920s, famously dubbed the “Jazz Age,” brought a new spirit of modernism and social change to St. Louis, reflected in its entertainment, social customs, arts, and literature. St. Louisans in the 1920s had a growing array of options for leisure and entertainment, though access and experience often varied by social class and race.

Forest Park Highlands: This amusement park, located near Forest Park, operated from 1896 to 1963. Originally a beer garden, it expanded to include rides like a Ferris wheel, a wooden roller coaster (the “Racer Dips” in the 1920s, later the “Comet”), dodgem cars, and a railway. The park also featured a pagoda from the 1904 World’s Fair and a Dentzel carousel installed in 1929 (though some sources say 1920). Many St. Louisans held fond memories of school picnics and rides there. However, it’s important to note that for a significant period, Forest Park Highlands only allowed white visitors.

Delmar Garden Amusement Park: Located in University City at the end of the Delmar streetcar line, this park opened around the turn of the century and remained popular until it closed in the late teens (around 1918-1919), so its presence in the 1920s was minimal if at all. It offered various entertainment venues, rides, and refreshment stands.

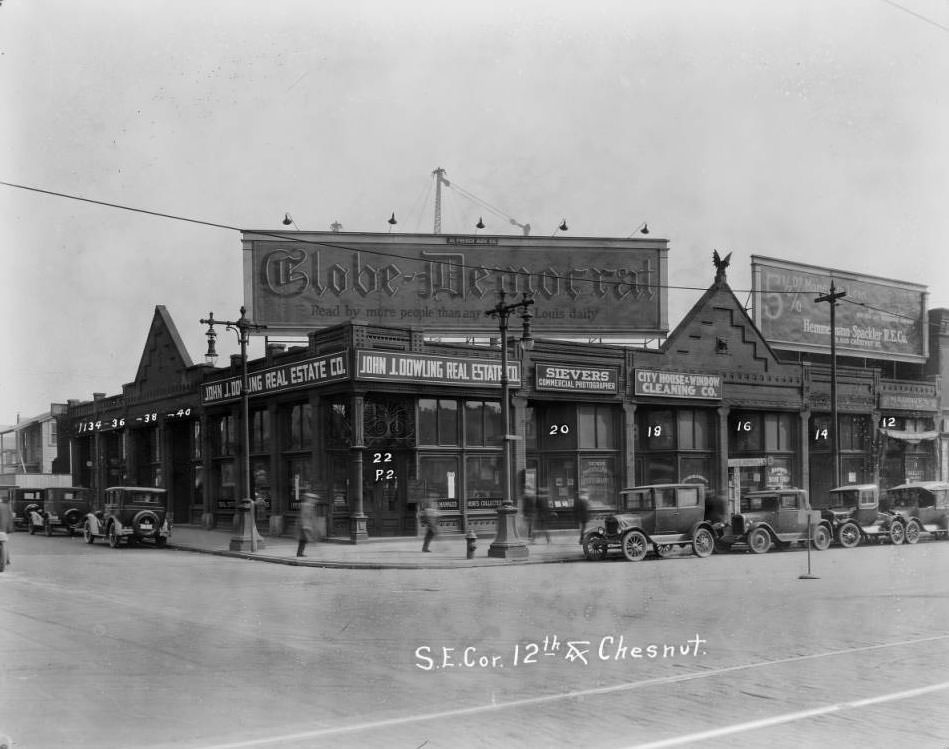

Vaudeville: Vaudeville remained a popular form of entertainment in the early 1920s. The Orpheum Theater, which opened on Labor Day in 1917 as a $500,000 Beaux-Arts style vaudeville house, was a prime venue, part of the extensive Orpheum Circuit. It featured modern amenities like advanced ventilation and lighting. Other vaudeville houses included the Garrick Theater and the Grand Theater (Grand Opera House).

Movie Palaces: The 1920s witnessed the golden age of the movie palace. These grand theaters offered an immersive experience. St. Louis saw the opening of several such establishments. The Ambassador Theatre, a lavish 3,000-seat movie palace designed by Rapp and Rapp in a Rococo style, opened on August 26, 1926, as part of a 17-story office building complex initiated by the Skouras Brothers. The Fox Theatre, another opulent movie palace with a “Siamese Byzantine” design, opened on January 31, 1929, with a seating capacity of 5,060. It was equipped for “talkies” using the Movietone process. The St. Louis Theater (now Powell Symphony Hall) also opened in 1925. By 1920, the city had 120 cinemas and 29 film exchanges, indicating a thriving cinema business even before the peak of the movie palace era.

Jazz: The 1920s was the “Jazz Age,” and St. Louis had a vibrant scene. While segregation affected venues, jazz flourished. Musicians like Bix Beiderbecke and Frank Trumbauer played at venues such as the Arcadia Ballroom. Black musicians, often excluded from larger venues by union rules, played in numerous cabarets. The city’s Black community had strong music education programs, producing many highly trained musicians.

Blues: St. Louis was an important early center for blues music, influenced by the Great Migration from the Mississippi Delta. W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues,” though composed earlier, gained immense popularity, with Bessie Smith’s famous recording (with Louis Armstrong) made in 1925.

Ragtime: Though its peak popularity was slightly earlier (1899-1917), ragtime’s influence, pioneered by figures like Scott Joplin who had lived in St. Louis, continued to be felt in the city’s musical fabric and contributed to the development of jazz.

St. Louis Symphony Orchestra: The SLSO, under conductor Rudolph Ganz (1921-1927), continued to be a pillar of the city’s cultural life. The orchestra performed a diverse repertoire, including works by contemporary composers. For instance, they performed Copland’s Piano Concerto in 1926 and Gershwin’s An American in Paris in 1928.

Arts and Literature

St. Louis in the 1920s had a dynamic arts and literary scene. The Saint Louis Art Museum, housed in the former Palace of Fine Arts from the 1904 World’s Fair, was a key institution. While specific major acquisitions or exhibitions from the 1920s are not extensively detailed, the museum continued to build its collections. The period saw the influence of Art Deco, an architectural and design movement that emerged in the 1920s, characterized by bold geometric patterns and streamlined silhouettes. Examples in St. Louis include the South Side National Bank Building (1928), the Fox Theatre (1929), and the Chase Park Plaza’s 1920s expansion. Josephine Baker, born in St. Louis, became an international vaudeville sensation and film star in the 1920s, known for her trendsetting fashion and embrace of modernity.

St. Louis was home to or had strong connections with several notable writers.

T.S. Eliot, born in St. Louis, was a leading figure of the Modernist movement. His seminal poem, “The Waste Land,” was published in 1922, profoundly shaping 20th-century poetry.

Sara Teasdale, another St. Louis poet, achieved national recognition, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1918 for Love Songs (published 1917). Her work continued to be influential in the 1920s.

Zoe Akins, a St. Louis-born playwright and author, was also active during this period, with works like Déclassée (1919) achieving Broadway success.

William Marion Reedy and his influential literary magazine, Reedy’s Mirror, had been a significant force in the St. Louis literary scene, introducing many writers, though Reedy himself passed away in 1920. His publication’s impact likely resonated into the early part of the decade.

The St. Louis Writers Guild, founded in 1920 with Sam Hellman as its first president, provided a forum for local authors. The Missouri Historical Review also featured articles on Missouri literature and authors during this time.

The 1920s in St. Louis were a decade of profound contrasts and transformations. The city buzzed with industrial energy, even as Prohibition reshaped one of its signature industries. Its population grew, becoming increasingly diverse, though marked by segregation. New forms of entertainment and social expression emerged, reflecting the spirit of the Jazz Age, while civic leaders and reformers continued to grapple with the challenges of a large, modernizing urban center.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, St. Louis Public Library, University of Missouri Digital Libraries, wikimedia, Missouri Digital Heritage, The State Historical Society of Missouri

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know