The 1950s were a time of big changes for St. Louis, Missouri. The city reached its highest number of people and then started to see a shift. Families began moving, new neighborhoods grew, and the very look of St. Louis started to transform. This decade set the stage for the St. Louis we know today, with moments of exciting growth and new challenges.

People on the Move: City, Suburbs, and New Homes

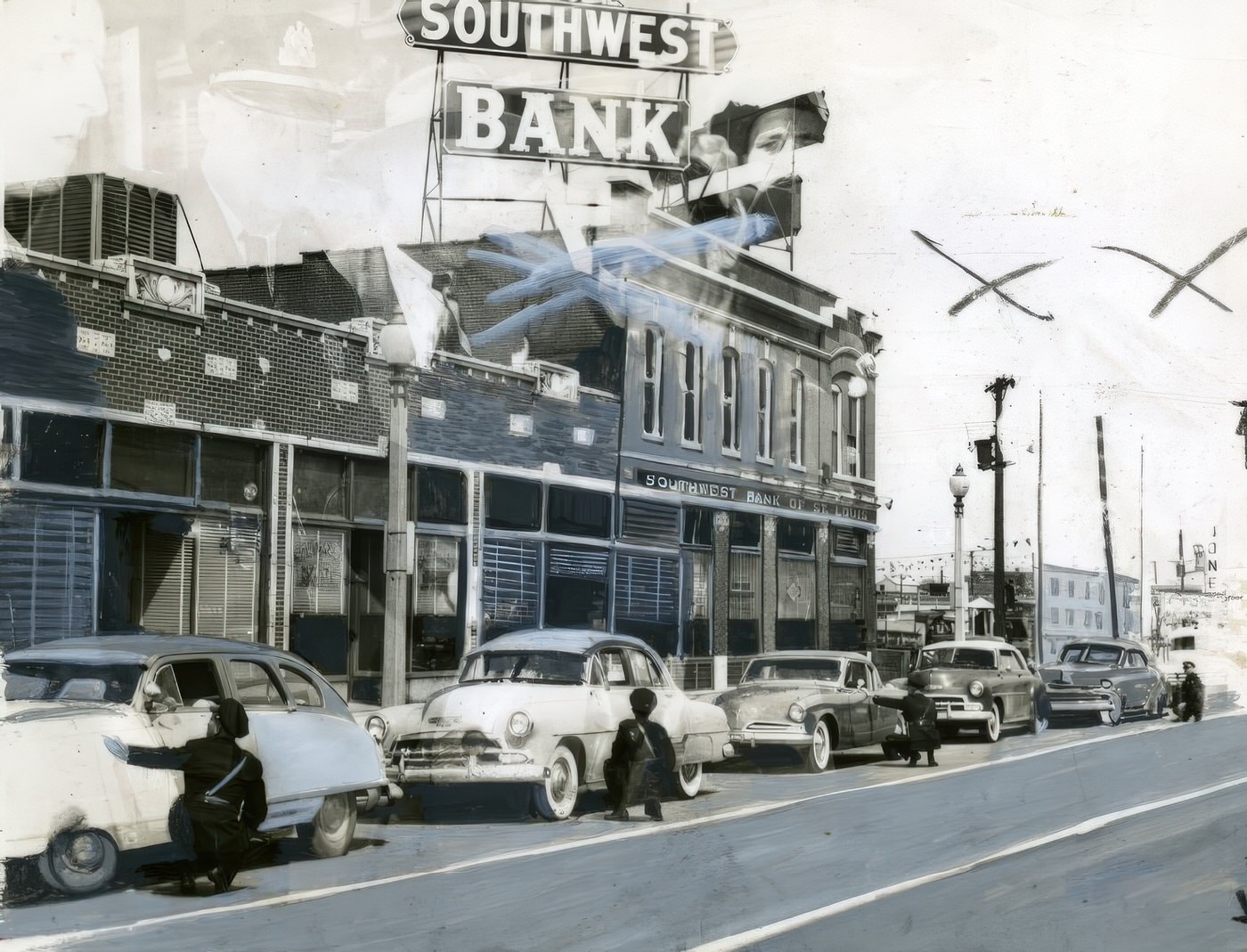

In 1950, the City of St. Louis had more people than ever before, with 856,796 residents. St. Louis County also grew, from 406,349 people in 1950 to 703,532 by 1960. This was a time when many families, especially white families, began moving from the city to the growing suburbs. This movement, sometimes called “white flight,” was driven by several things. People wanted new homes with more space, and government programs like FHA and VA mortgage programs made it easier to buy them in the suburbs. The construction of new highways also made it easier to live further from the city center and still commute for work.

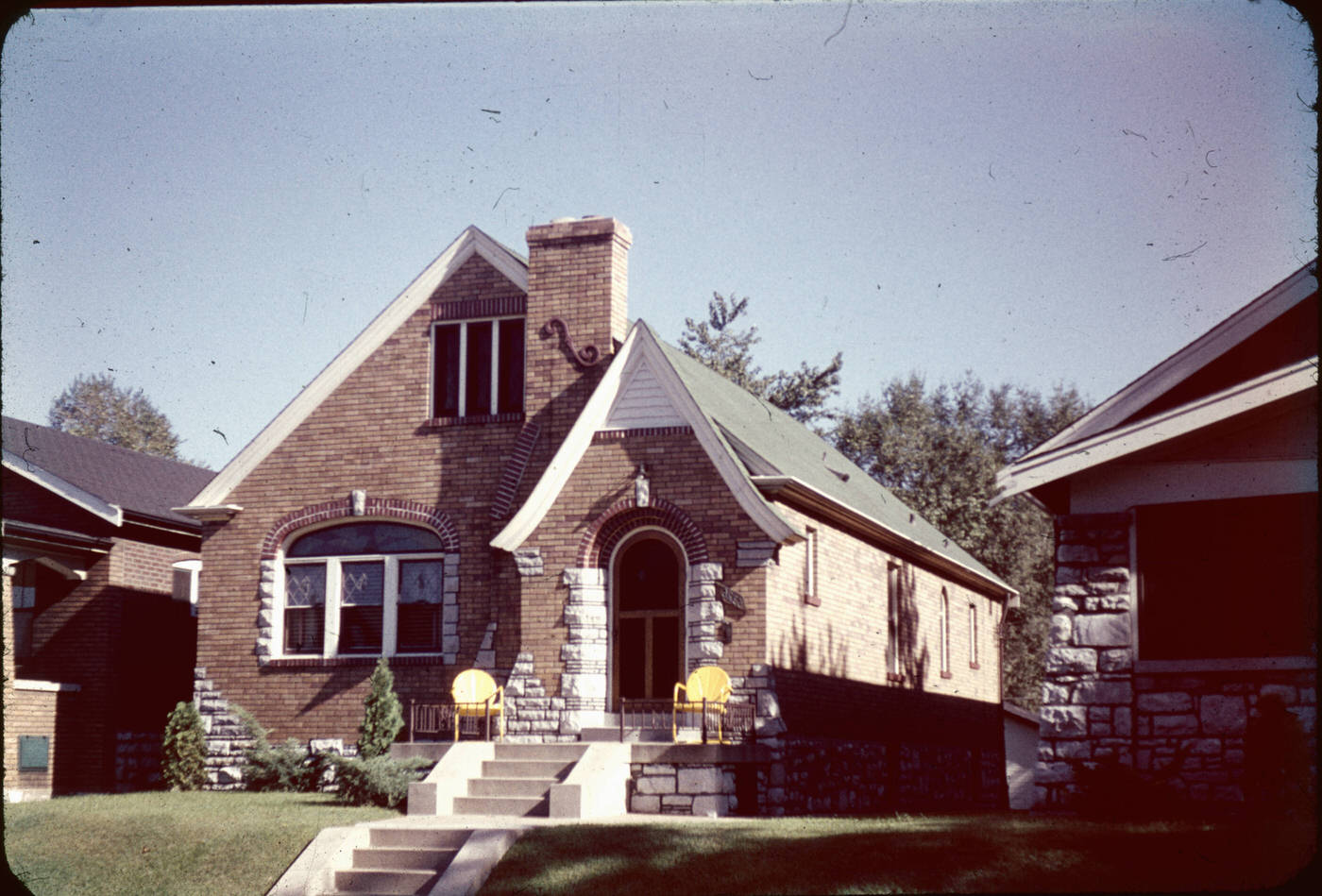

Many of these new suburban homes were built quickly to meet the demand. Some neighborhoods saw the arrival of unique, factory-made houses called Lustron homes. These all-steel, porcelain-enameled houses were advertised as modern and easy to care for. The first Lustron home in the St. Louis area arrived in Webster Groves in January 1949. Modern Housing Corporation was the local dealer for Lustron homes, and about 24 of them can still be found in areas like Brentwood on Litzinger Road. These homes, costing around $7,000, came with built-in fixtures and were seen as a solution to the post-World War II housing shortage.

The shift to the suburbs wasn’t just about new houses. It also reflected deeper social and economic currents. Racial segregation played a significant role. Restrictive covenants had historically limited where African American families could live, and as the African American population in the city grew (from 109,000 in 1940 to 154,000 or 18% of the city’s population by 1950), some white residents chose to move to the suburbs. This movement had long-term consequences for both the city and the county, changing the makeup of neighborhoods and the resources available to them. The city’s fixed boundaries, set in 1876, meant it couldn’t easily expand its tax base as people moved out, leading to financial challenges down the road.

Reshaping the City: Urban Renewal and Housing Projects

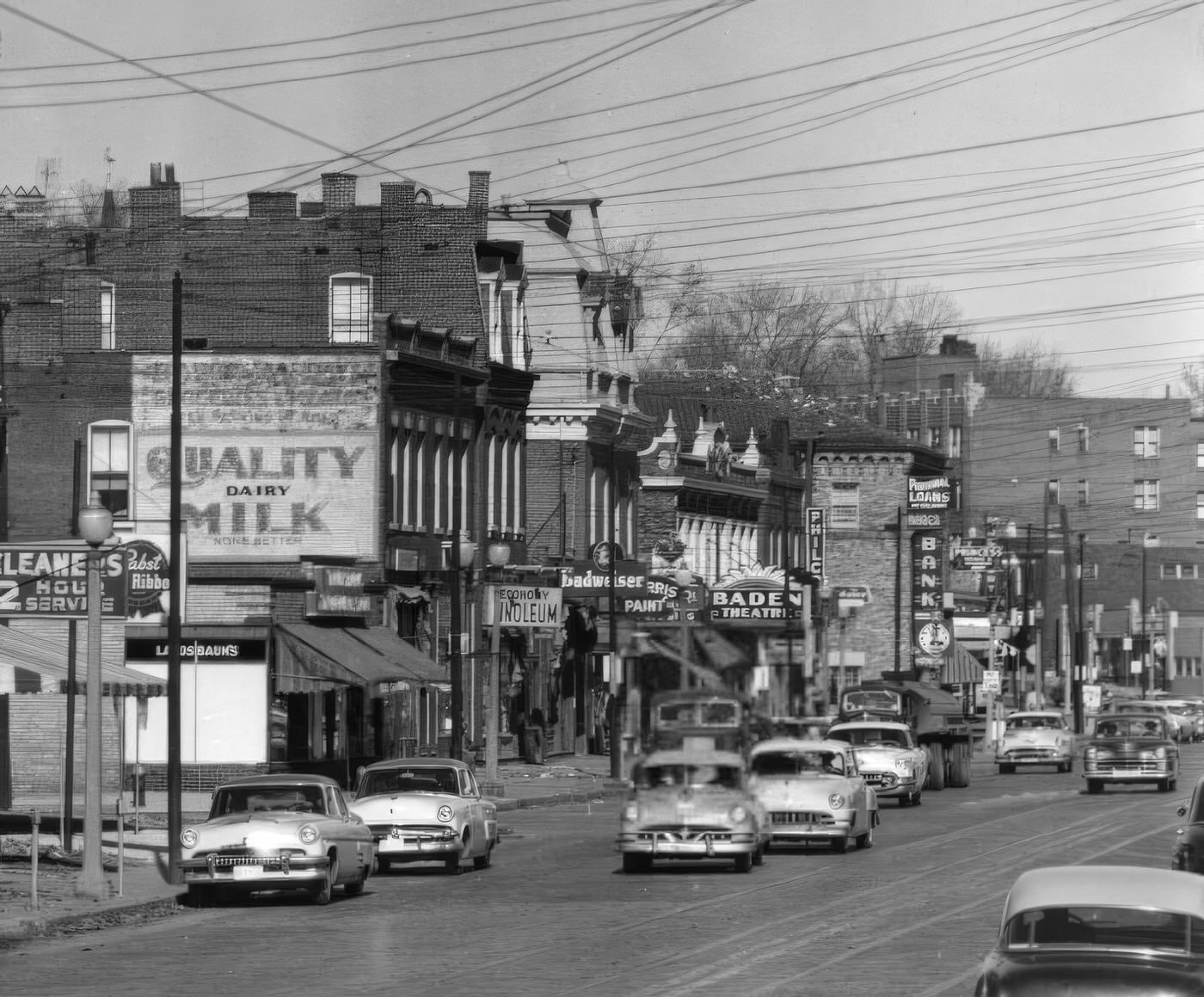

While suburbs grew, the City of St. Louis faced challenges with its existing housing. Much of the city’s housing was old, with many buildings dating back to the 19th century. A 1947 survey found that 33,000 homes didn’t even have private toilets. These conditions, combined with overcrowding, led city leaders to look for solutions.

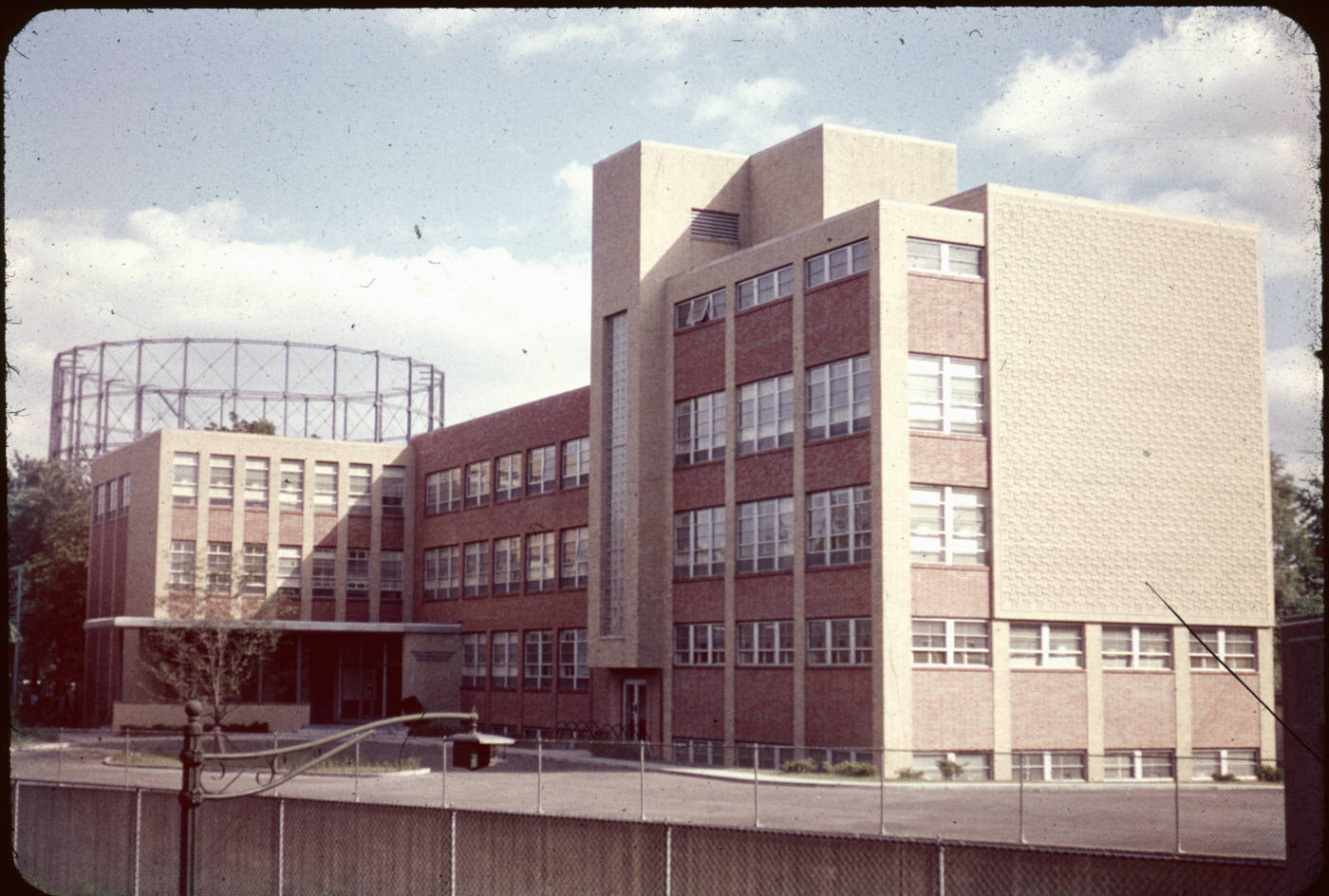

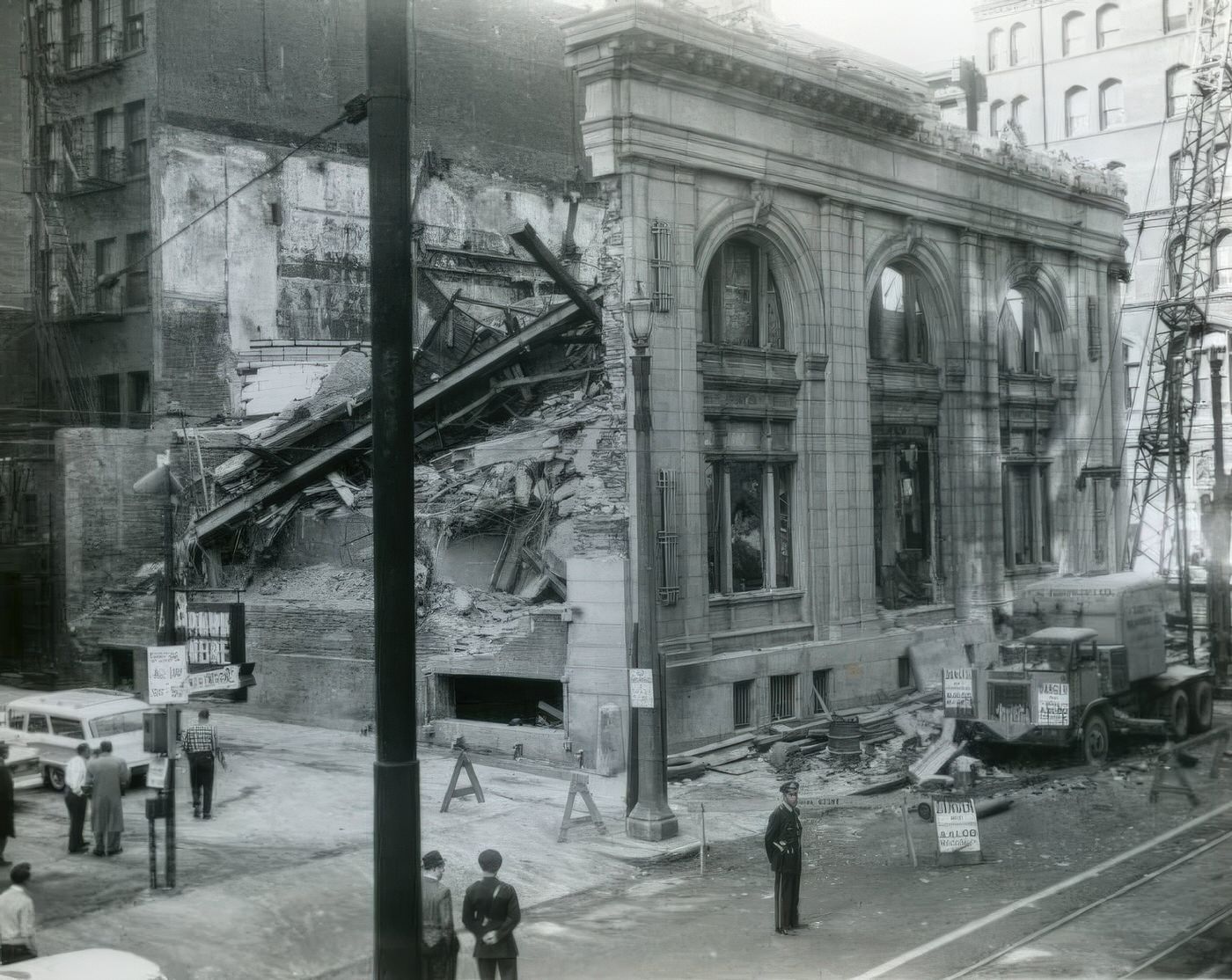

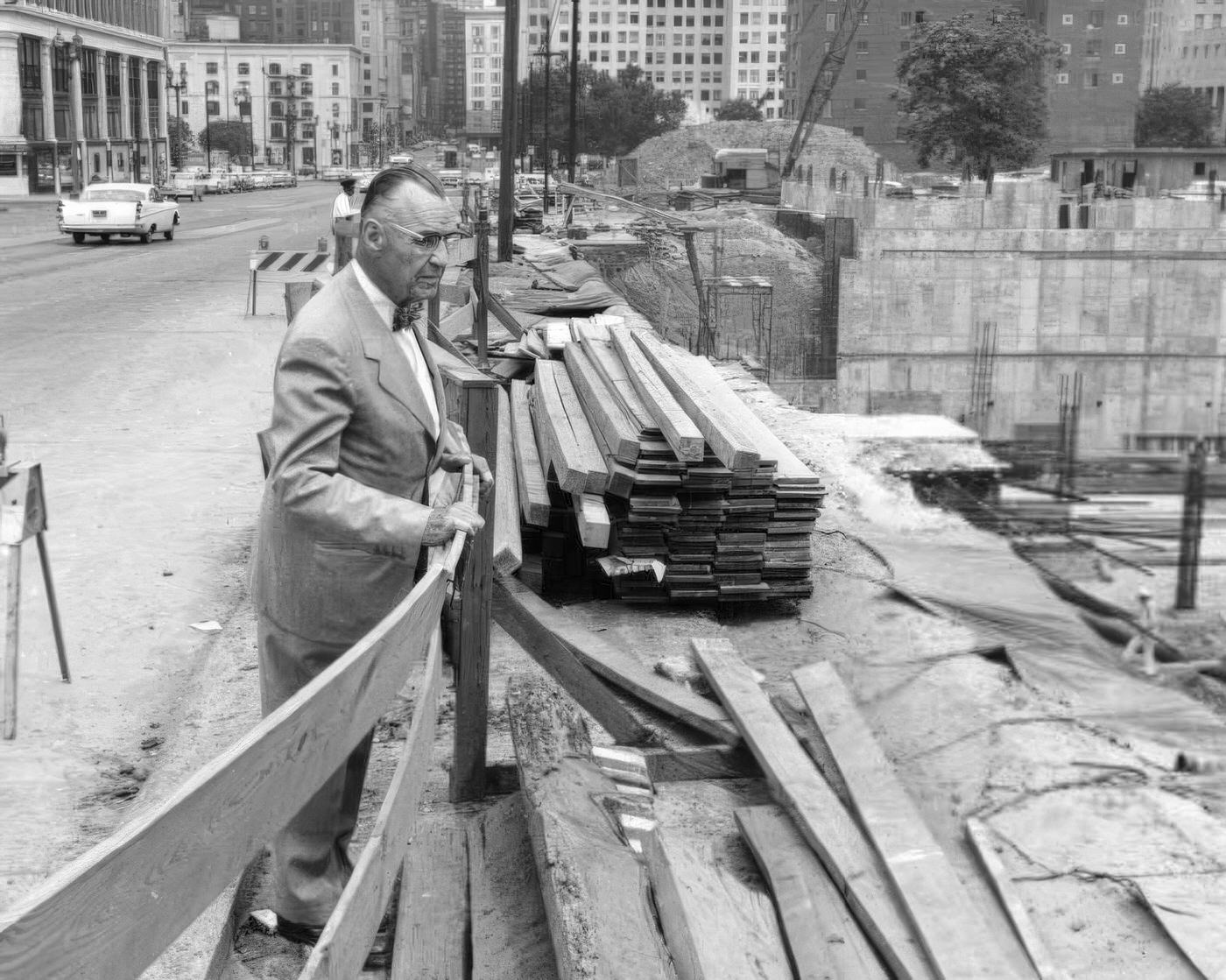

One major approach was “urban renewal.” This often meant tearing down older neighborhoods deemed “slums” and replacing them with new developments, including public housing projects and new infrastructure. Mayor Joseph Darst, who served from 1949 to 1953, was a strong supporter of these efforts. Under his leadership, projects like the John Cochran Gardens apartments were completed in 1953. Cochran Gardens, designed by the same firm as the later Pruitt-Igoe, was initially seen as more successful and featured bold massing and rhythmic balconies that provided a sense of human scale.

The most famous, and ultimately infamous, of these projects was Pruitt-Igoe. First occupied in 1954, it consisted of 33 eleven-story buildings. Initially, some residents were pleased, describing their new apartments as a “poor man’s penthouse”. For many, it was an improvement over the crowded and unsanitary conditions they had lived in before, offering indoor plumbing and electric lights. Chester Deanes, who moved into Pruitt-Igoe with his family in 1956, recalled his mother and siblings having their own rooms for the first time. Early residents often formed strong community bonds, with children playing in the breezeways and neighbors helping each other.

However, problems at Pruitt-Igoe began to surface relatively quickly. By 1958, issues like elevator breakdowns, vandalism (often by transients), and poor ventilation were becoming evident. Maintenance suffered as rental income couldn’t cover costs, especially as vacancy rates began to rise due to the deteriorating conditions and concerns about crime.

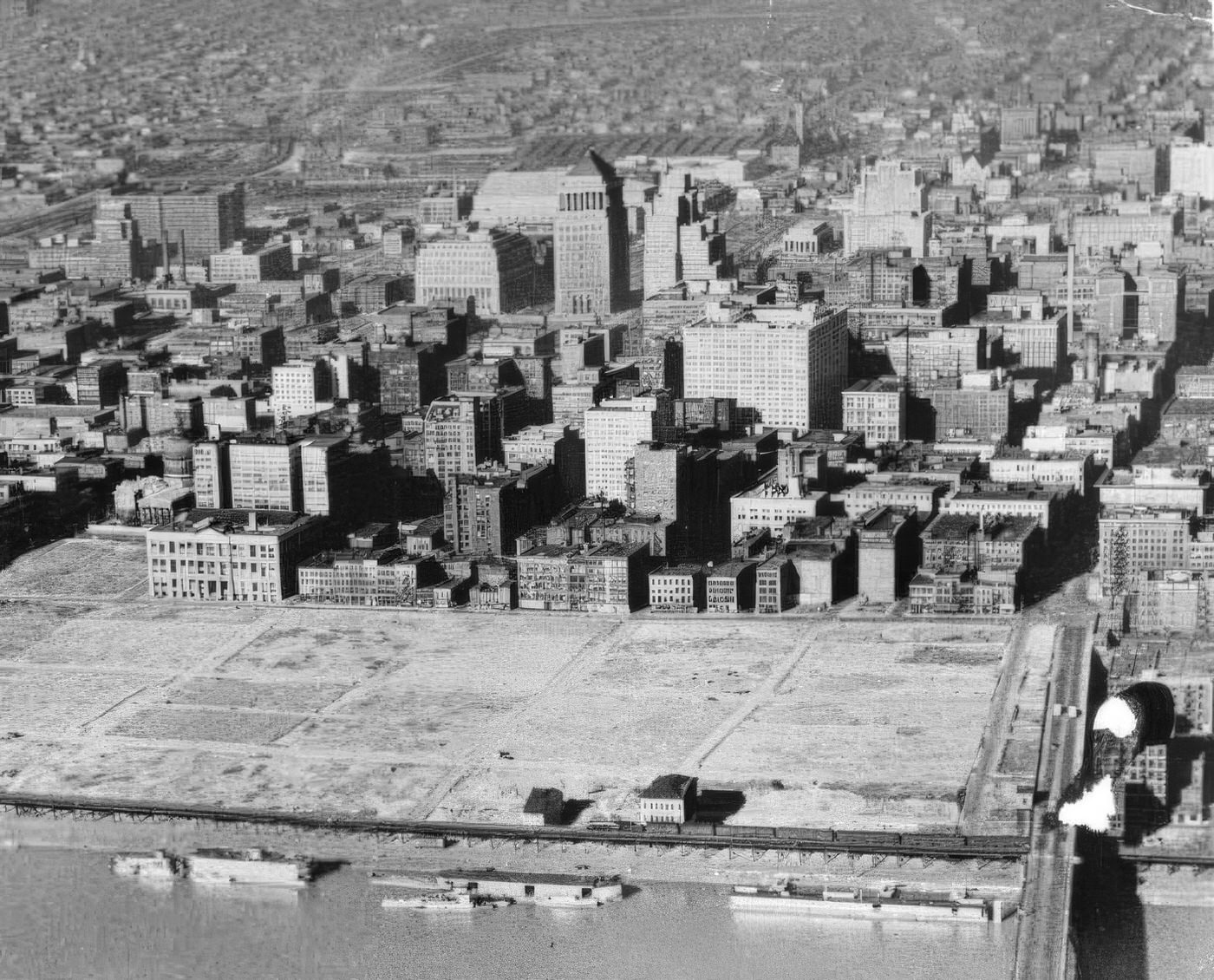

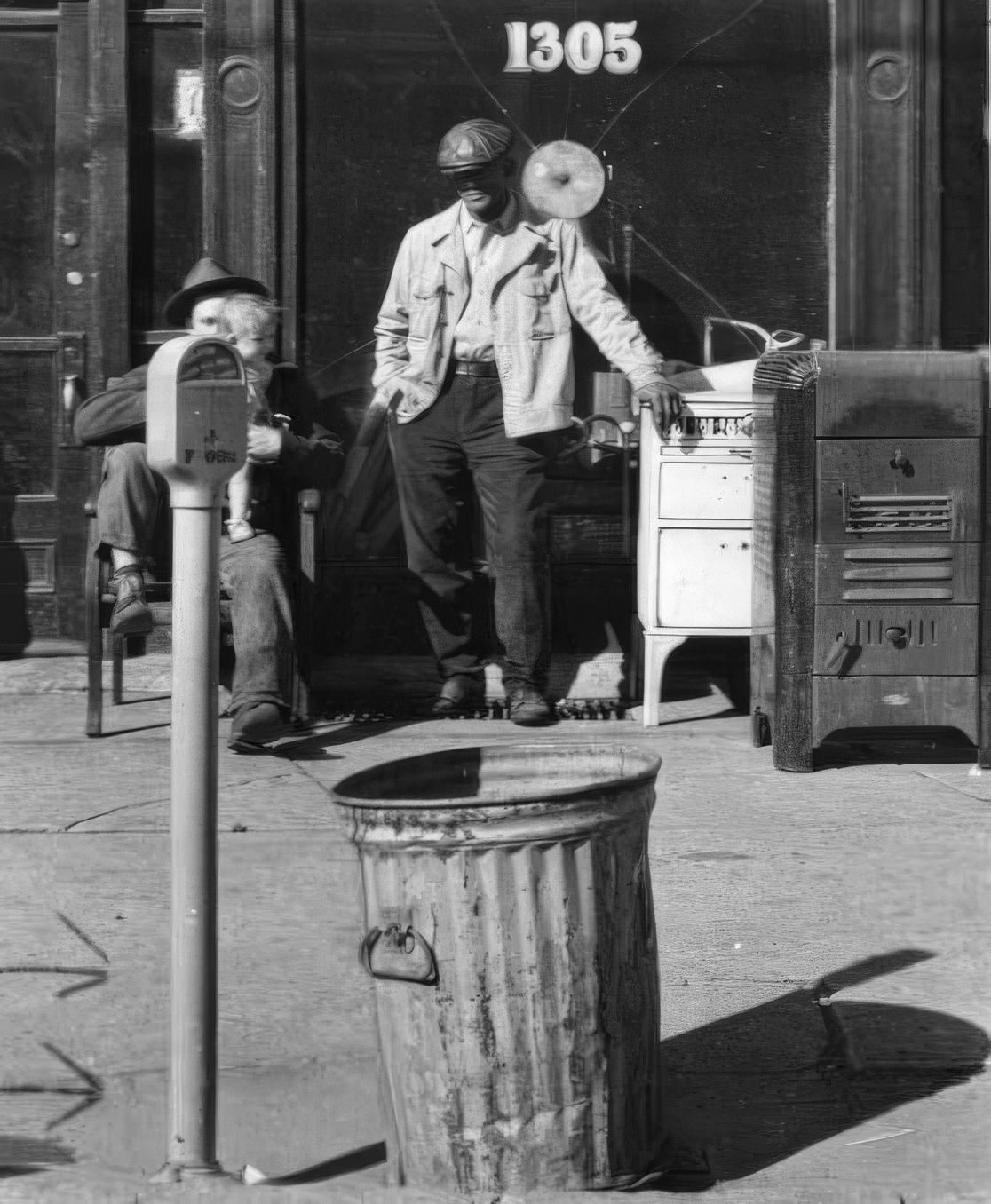

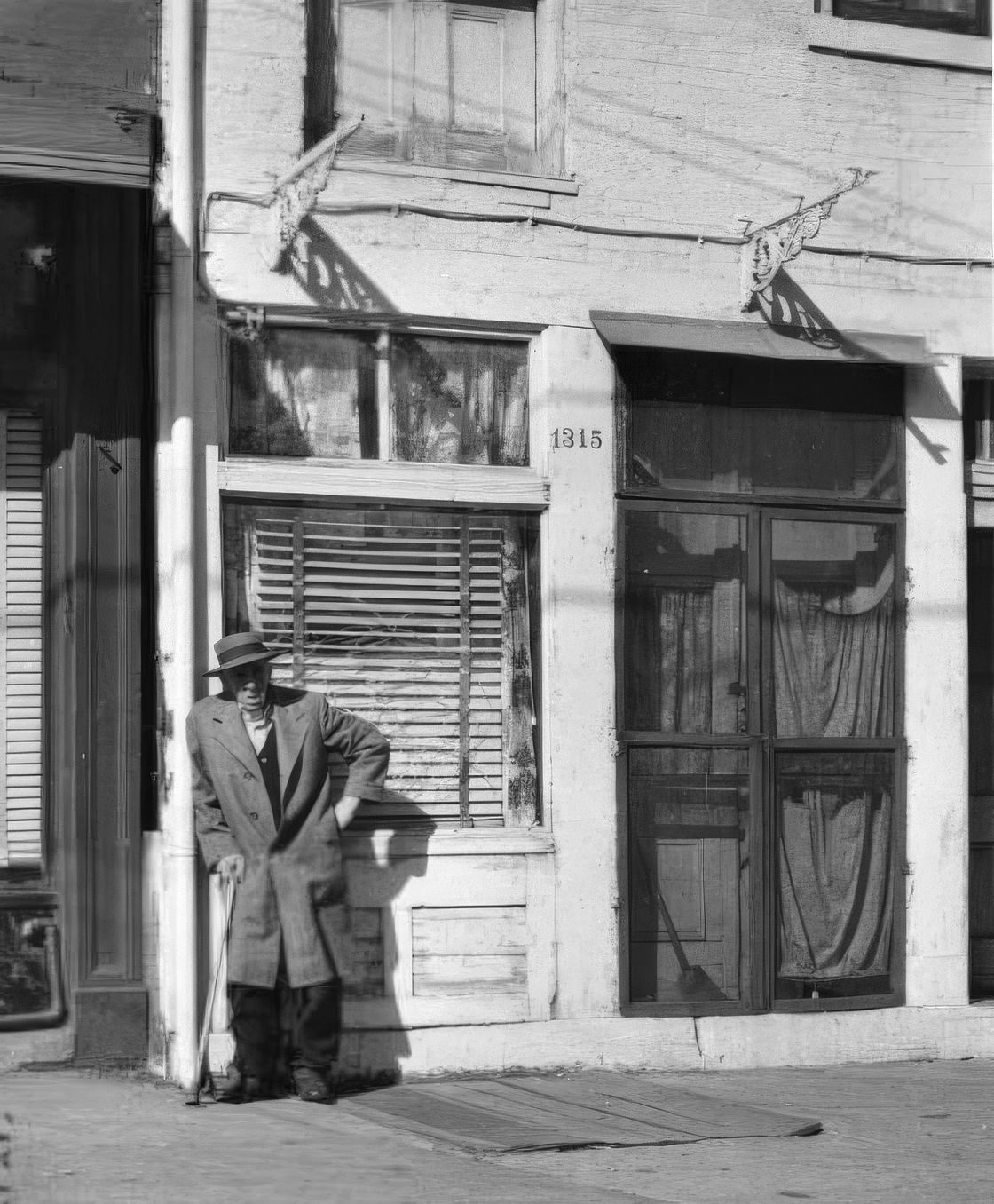

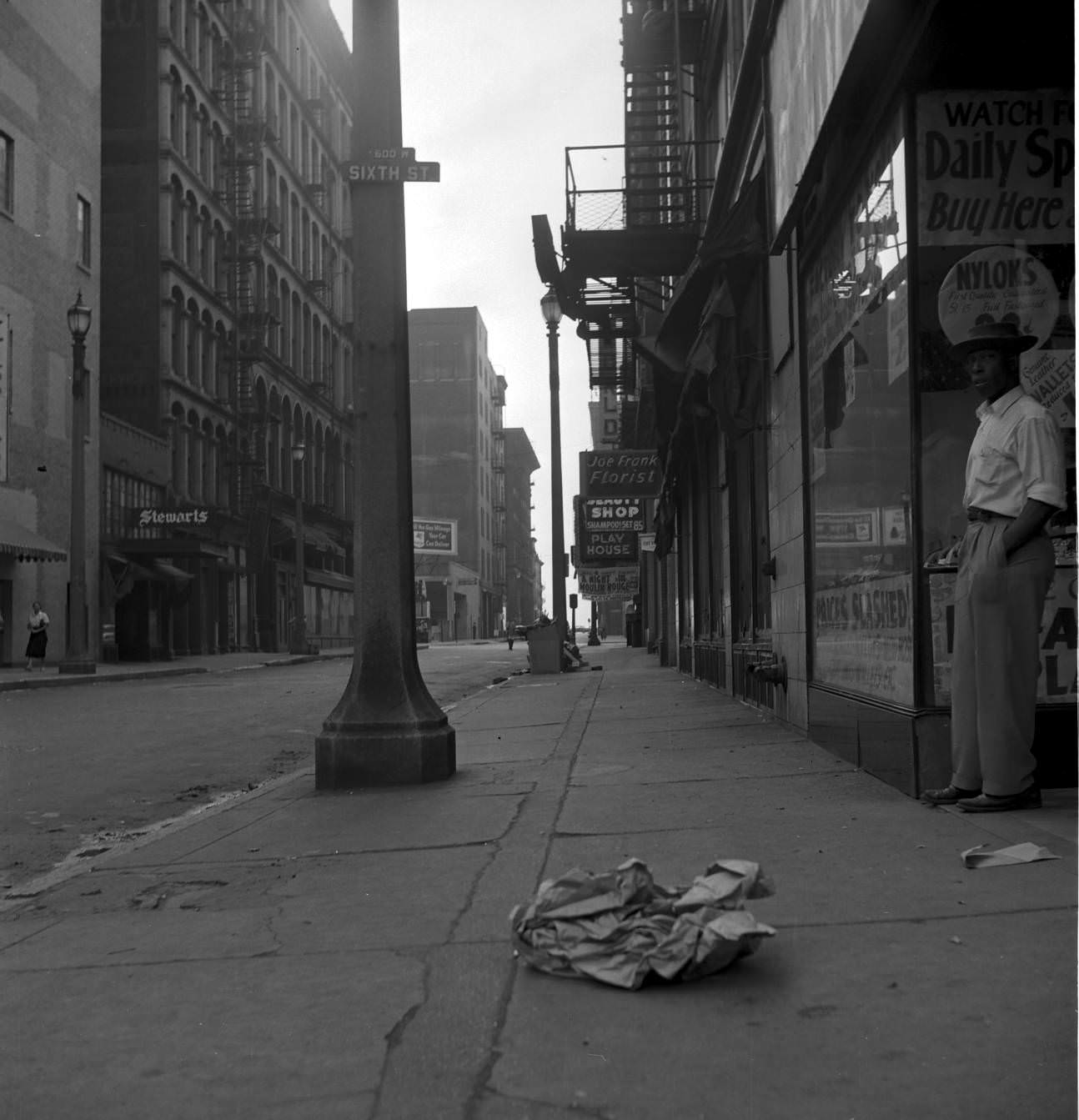

Another major urban renewal project was the clearance of the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood. This historic African American community, home to around 20,000 people and hundreds of businesses and churches, was labeled a “slum”. Demolition began in February 1959, displacing its many residents. While some areas were indeed in disrepair due to overcrowding and neglect by absentee landlords, many former residents remembered Mill Creek as a vibrant, close-knit community. Displaced families often moved to public housing projects like Pruitt-Igoe or to other neighborhoods to the northwest of Mill Creek, which sometimes led to overcrowding in schools in those areas. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch often described Mill Creek Valley in terms of blight, though some articles acknowledged the community’s vibrancy. The displacement from Mill Creek Valley had a profound and lasting impact on the city’s Black community, disrupting social networks and scattering residents.

These urban renewal projects were part of a broader national trend, often funded by federal programs like the Housing Act of 1949. While intended to improve living conditions and revitalize city centers, they often had complex and sometimes detrimental consequences for the existing communities, particularly minority communities. The decisions made during this era significantly shaped the city’s layout and social geography for decades to come.

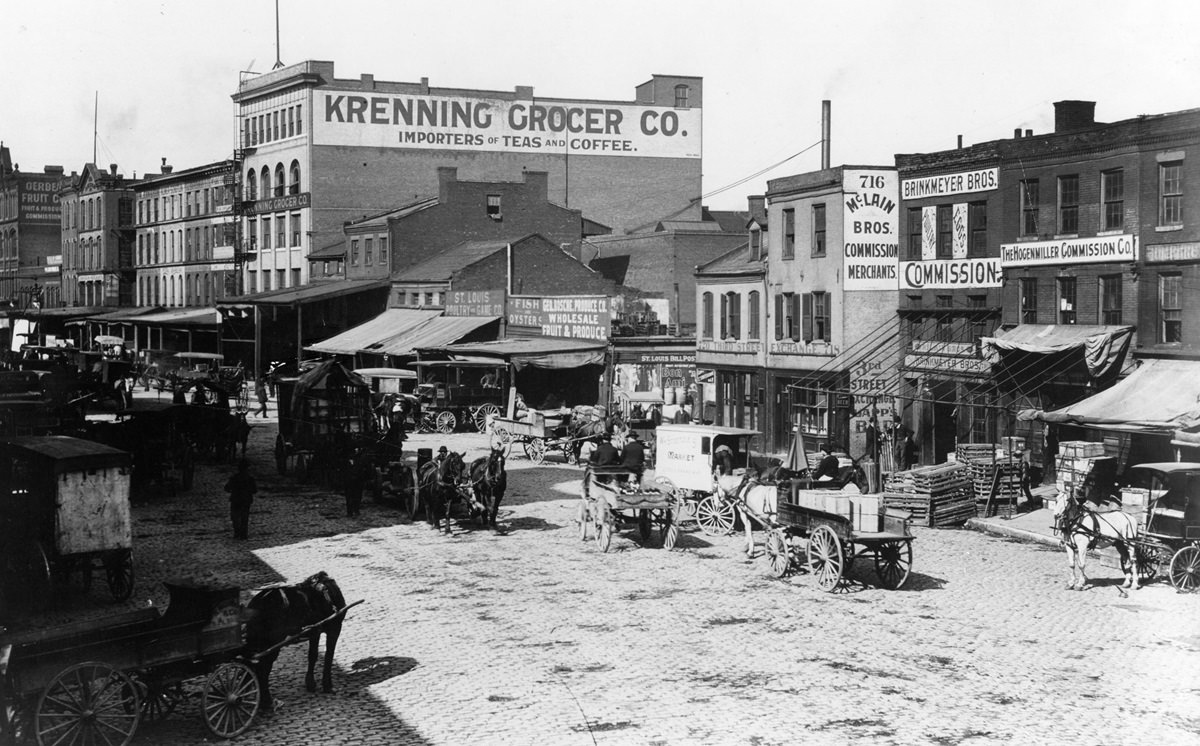

The City’s Work: Industries and Labor

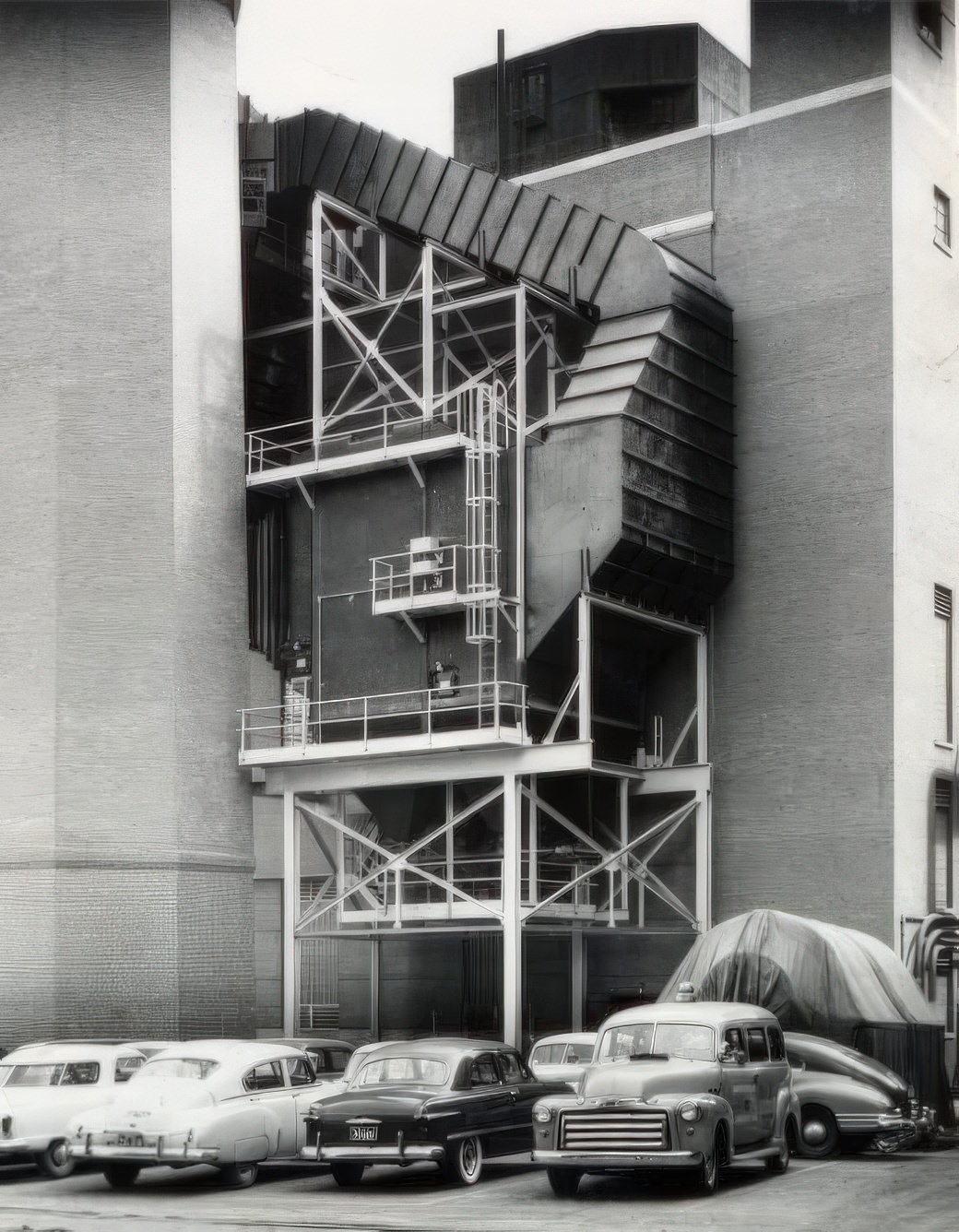

The 1950s saw St. Louis’s economy continue to rely on its established industries, though shifts were occurring. Manufacturing employment nationally began a long-term decline around this time, although it peaked in May 1953 before seeing post-war recessions and recoveries.

The automotive industry had a strong presence. While St. Louis was an early center for automobile manufacture, sales, and service, the post-war era saw the dominance of the “Big Three” (Ford, Chrysler, General Motors) nationally. The St. Louis Car Company, a historic local manufacturer of streetcars and railcars, continued operations, though its focus had shifted somewhat from automobiles.

The aviation industry, which had boomed during World War II, continued to be important. Companies like McDonnell Aircraft were significant employers.

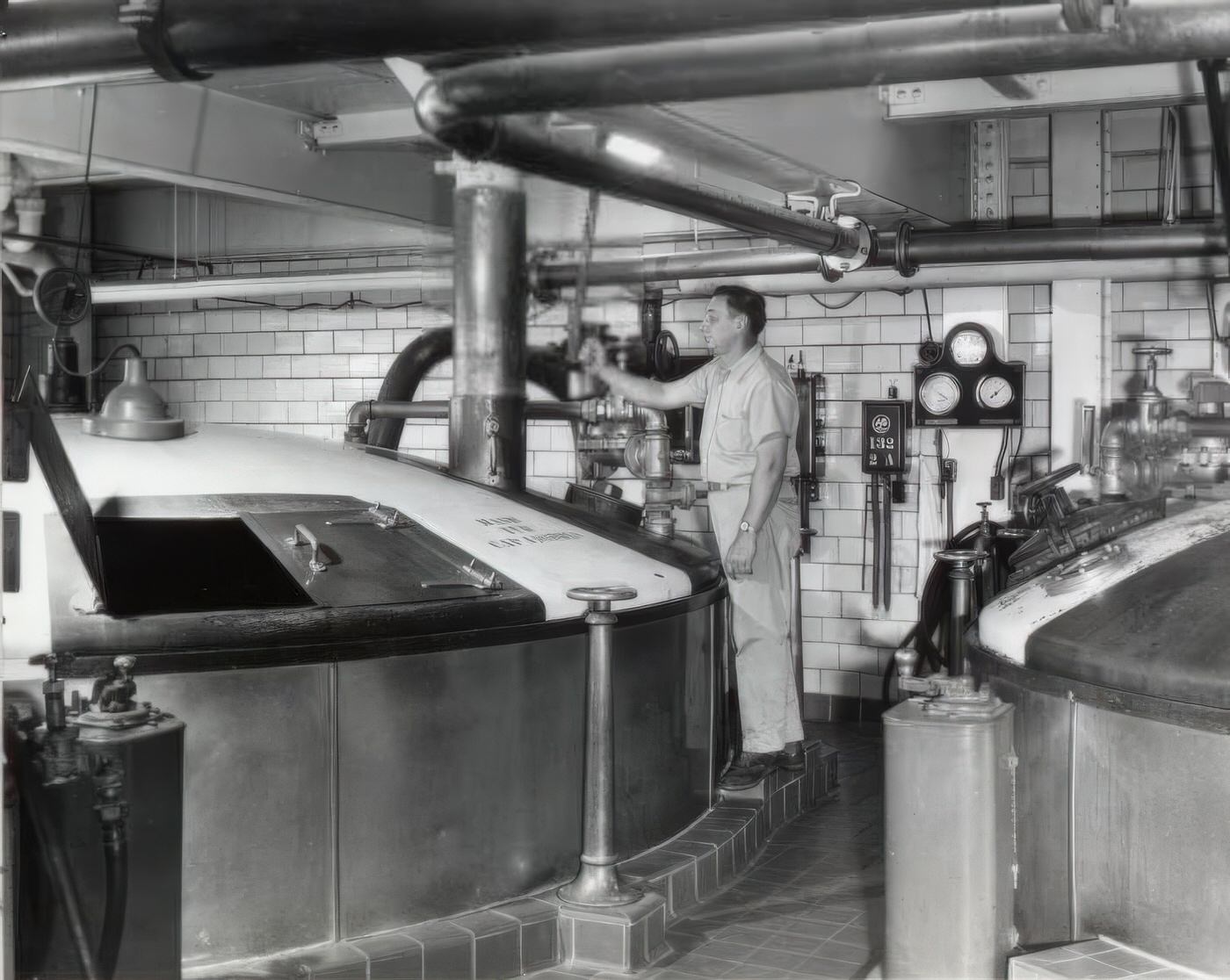

Brewing remained a cornerstone of the St. Louis economy. Anheuser-Busch and Falstaff were the two major players by the mid-1950s. Anheuser-Busch expanded by building new regional plants, while Falstaff acquired existing breweries. Griesedieck Brothers, another local brewery, saw success in the early 1950s, even sponsoring Cardinals broadcasts, but faced intense competition, particularly after Anheuser-Busch introduced Busch Bavarian beer and engaged in a price war in 1954. This competition led to Griesedieck Brothers’ sales declining, and they eventually sold to Falstaff in 1957.

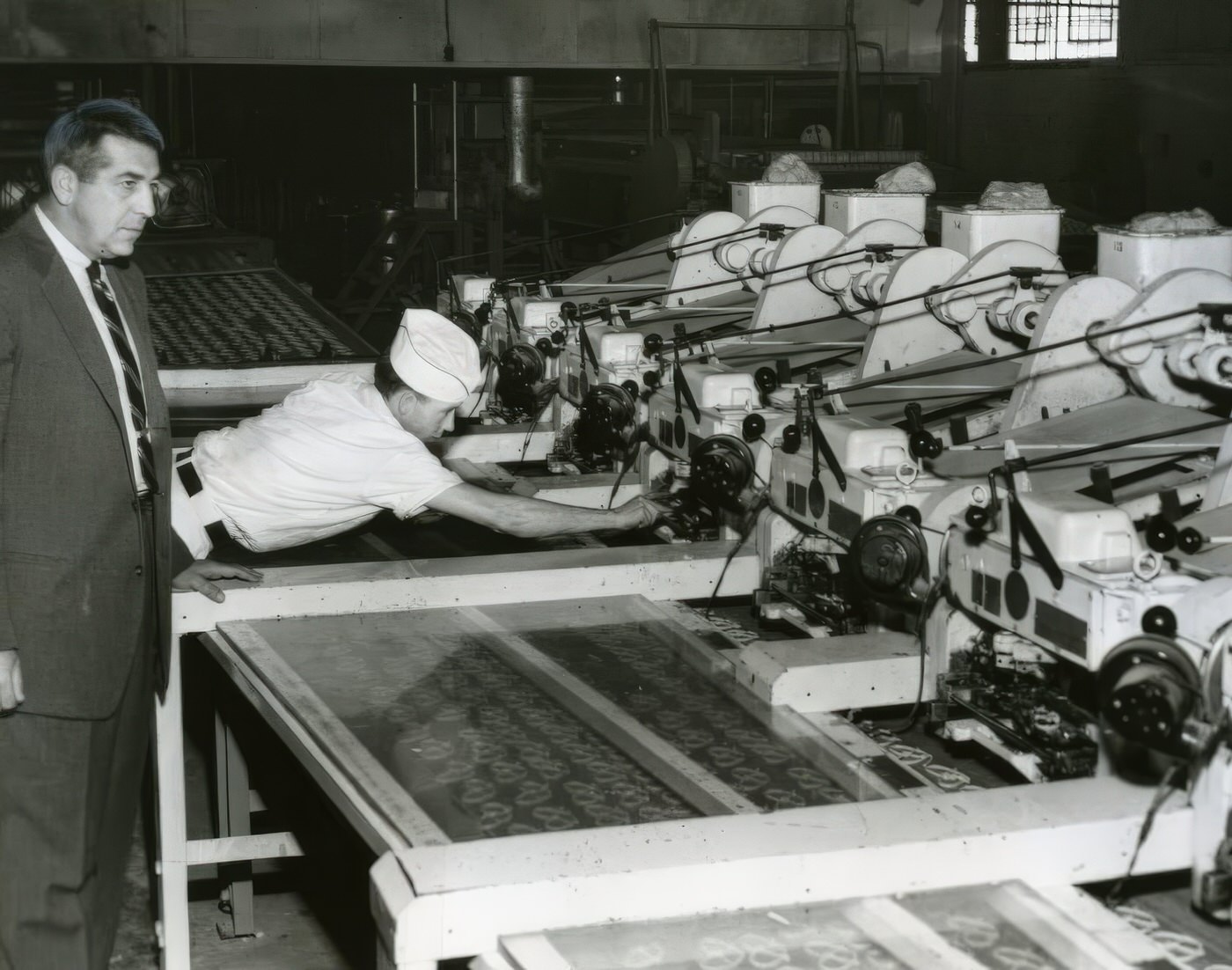

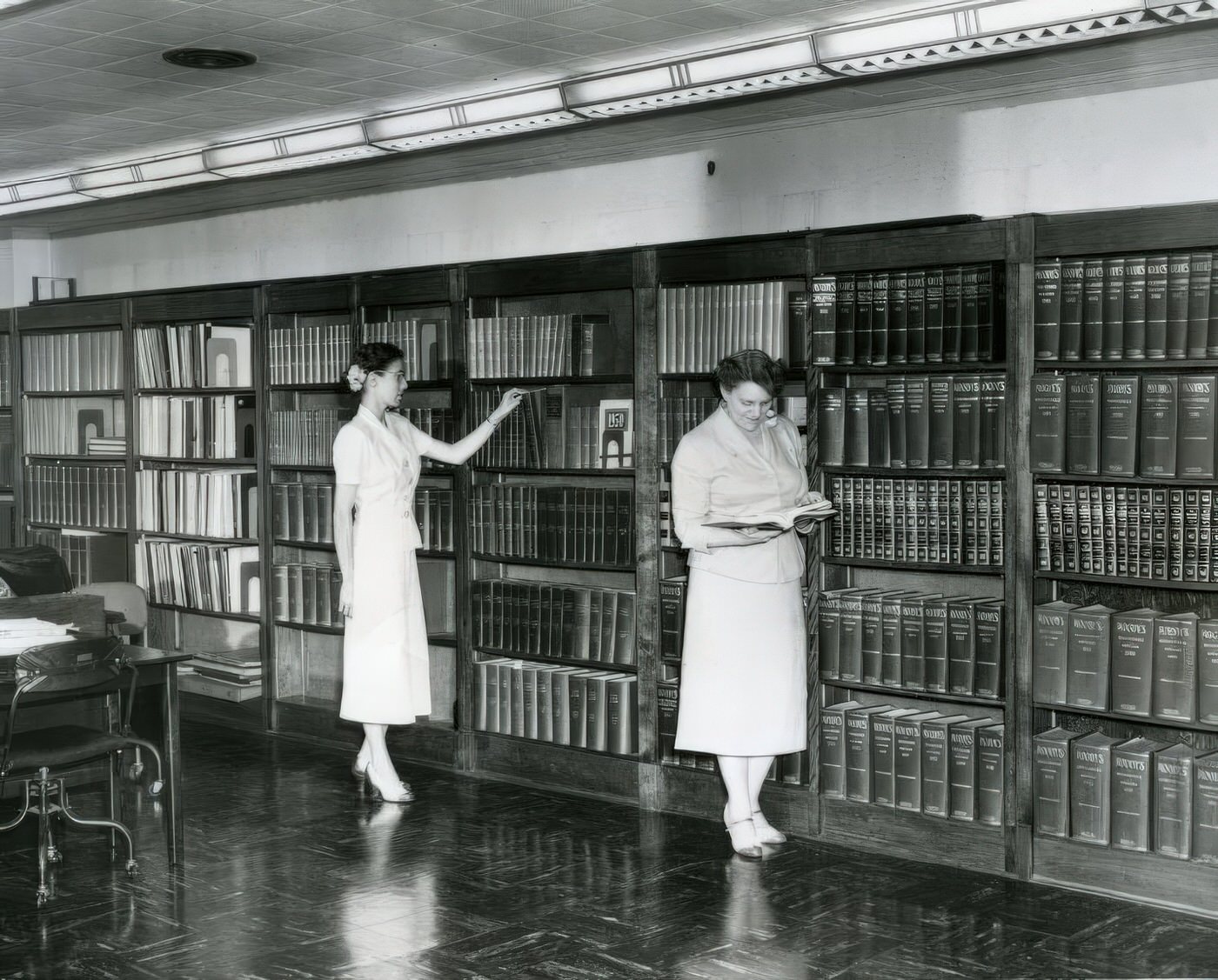

The shoe industry, historically a major employer with companies like International Shoe Company and Brown Shoe Company, had a large workforce. In 1950, International Shoe Company employed around 35,000 people and had a capacity of 70 million pairs annually. However, the decade also saw the beginning of shifts, with International Shoe closing its Chester, Illinois, plant in 1958 and increasingly focusing on retail.

The garment industry, centered on Washington Avenue, was a significant employer, especially for women. St. Louis was known for “junior” dresses. In the mid-1950s, the number of clothing manufacturers in St. Louis had tripled compared to earlier periods, and sales volumes were high. Models wore the latest gowns at shows in department stores like Sonnenfeld’s.

The electrical manufacturing industry was also prominent, with companies like Wagner Electric in Wellston employing up to 6,000 workers at its peak in the mid-1950s. Emerson Electric and Century Electric were other key players in this sector. Wagner Electric hit an employment high of 8,000 in 1953.

Nationally, the post-war period saw significant labor activity, including major strikes in 1945-1946. While specific details of large-scale strikes in St. Louis during the 1950s are not abundant in the provided materials, a labor strike did shut down the Saint Louis Zoo for several days in February 1959 over unspecified issues, with zoo managers having to feed the animals. Nationally, the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 had placed new restrictions on unions. The Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded 4,843 work stoppages nationally in 1950, with issues like health, insurance, and pension plans being prominent in negotiations.

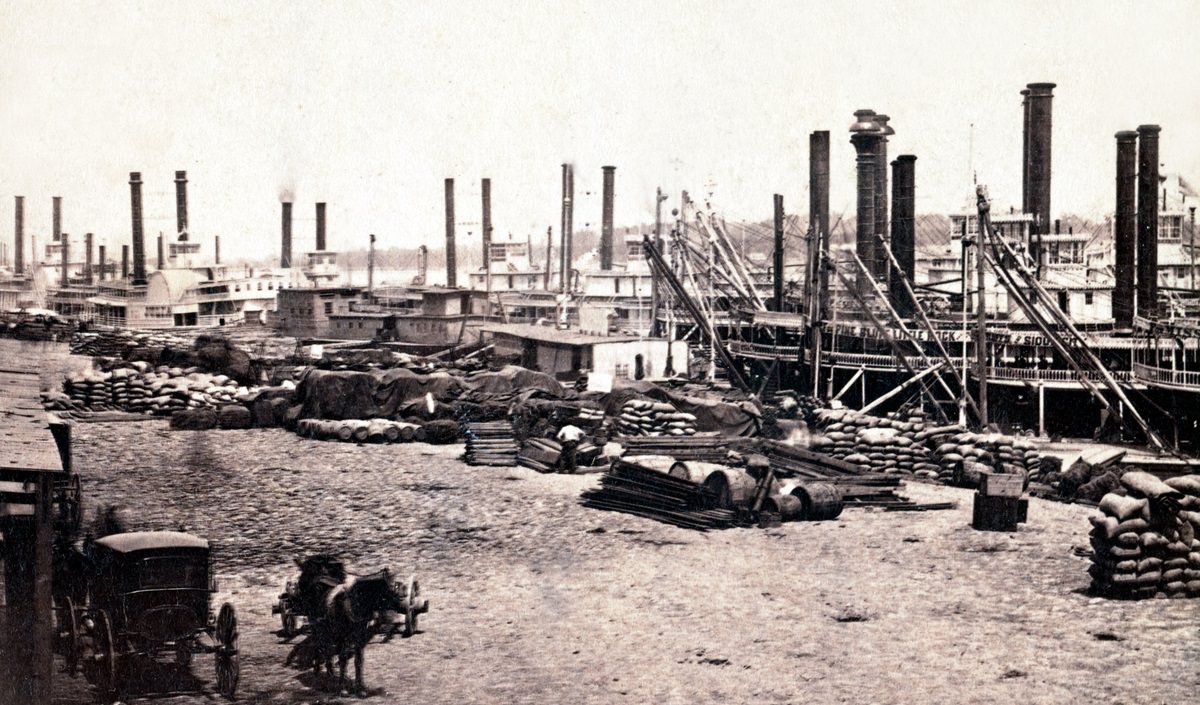

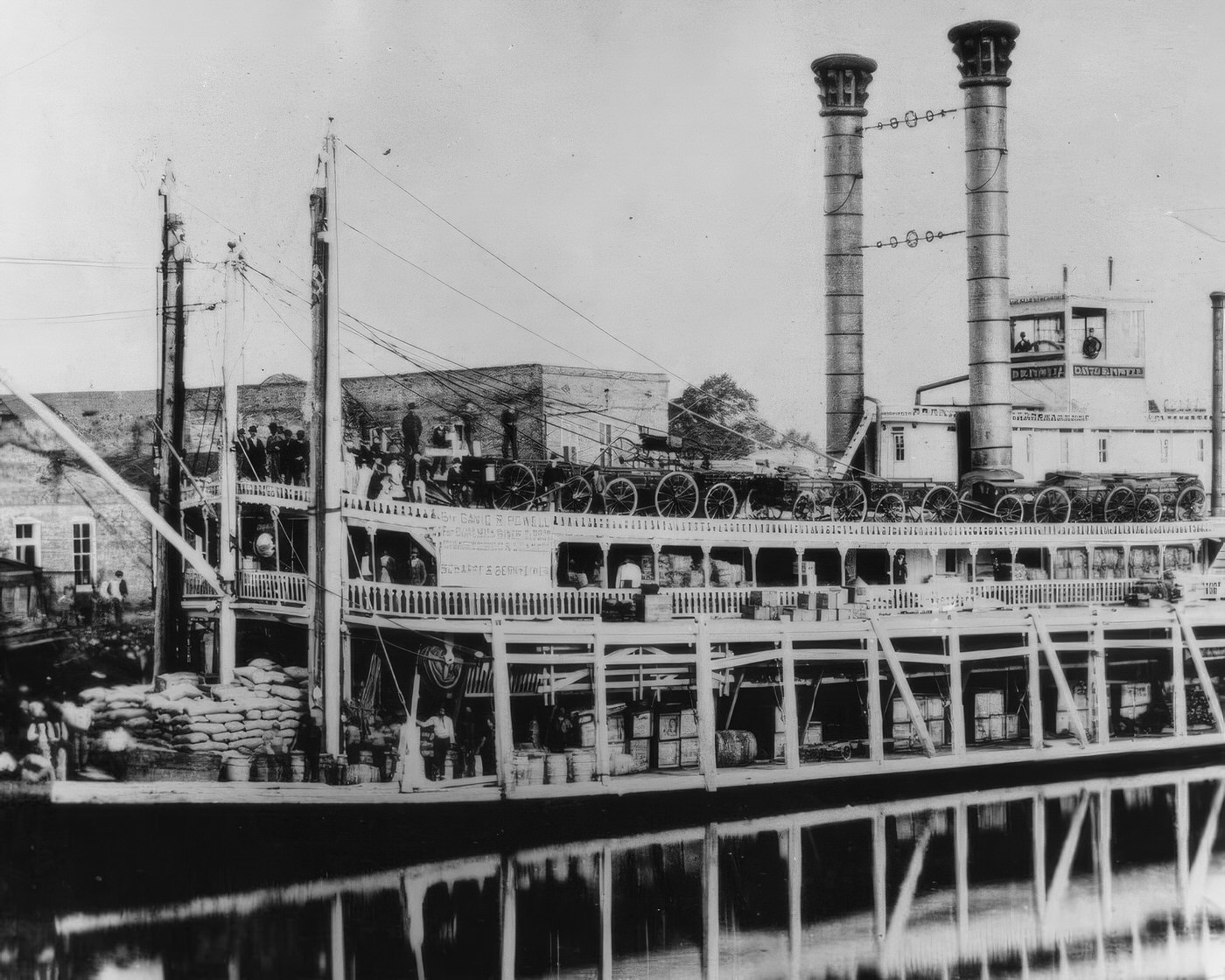

Traffic on the Mississippi River port steadily increased after the completion of the lock and dam system, with tonnage growing rapidly through the 1970s. Traffic volume increased by a factor of 8 between 1950 and 1980.

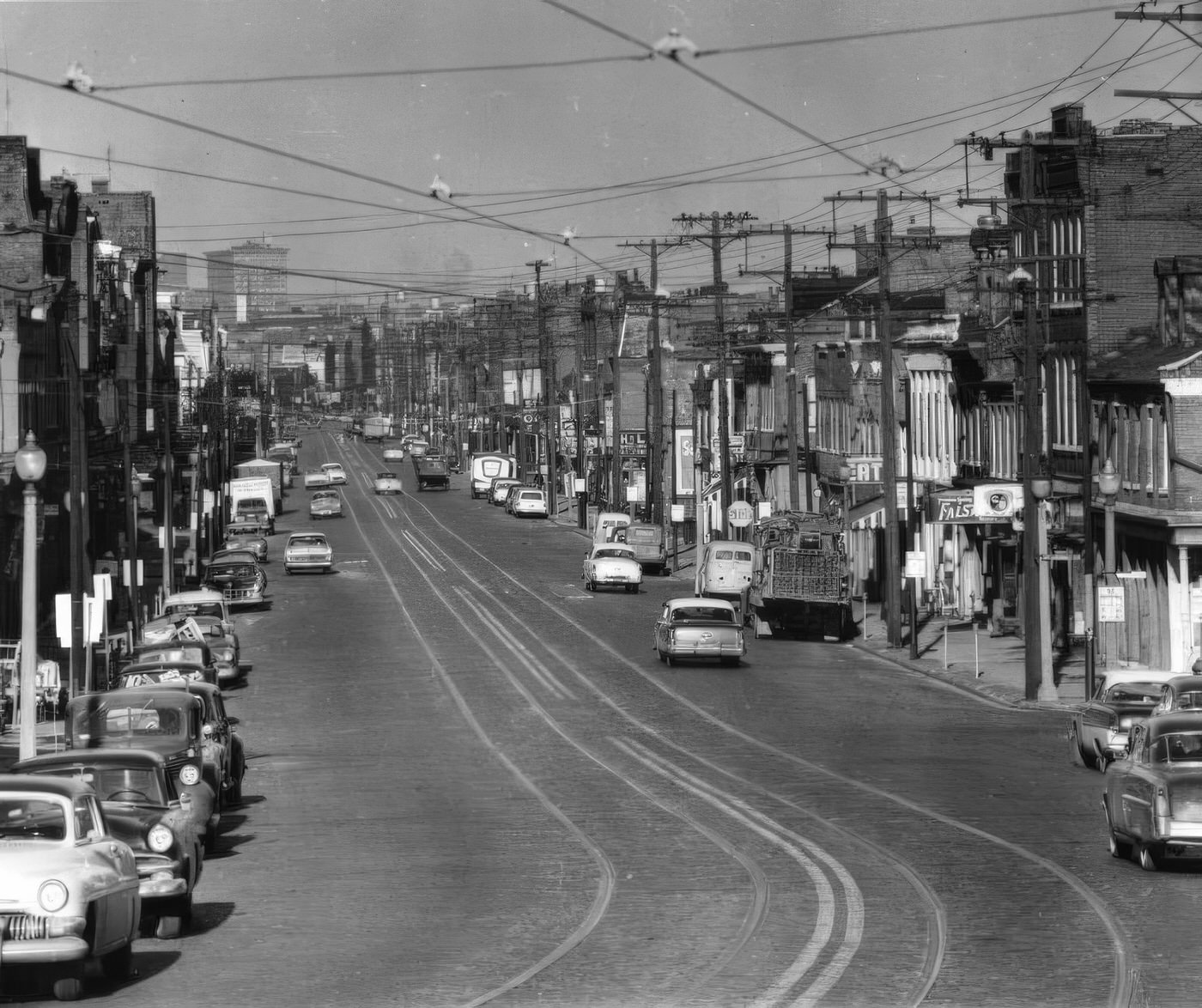

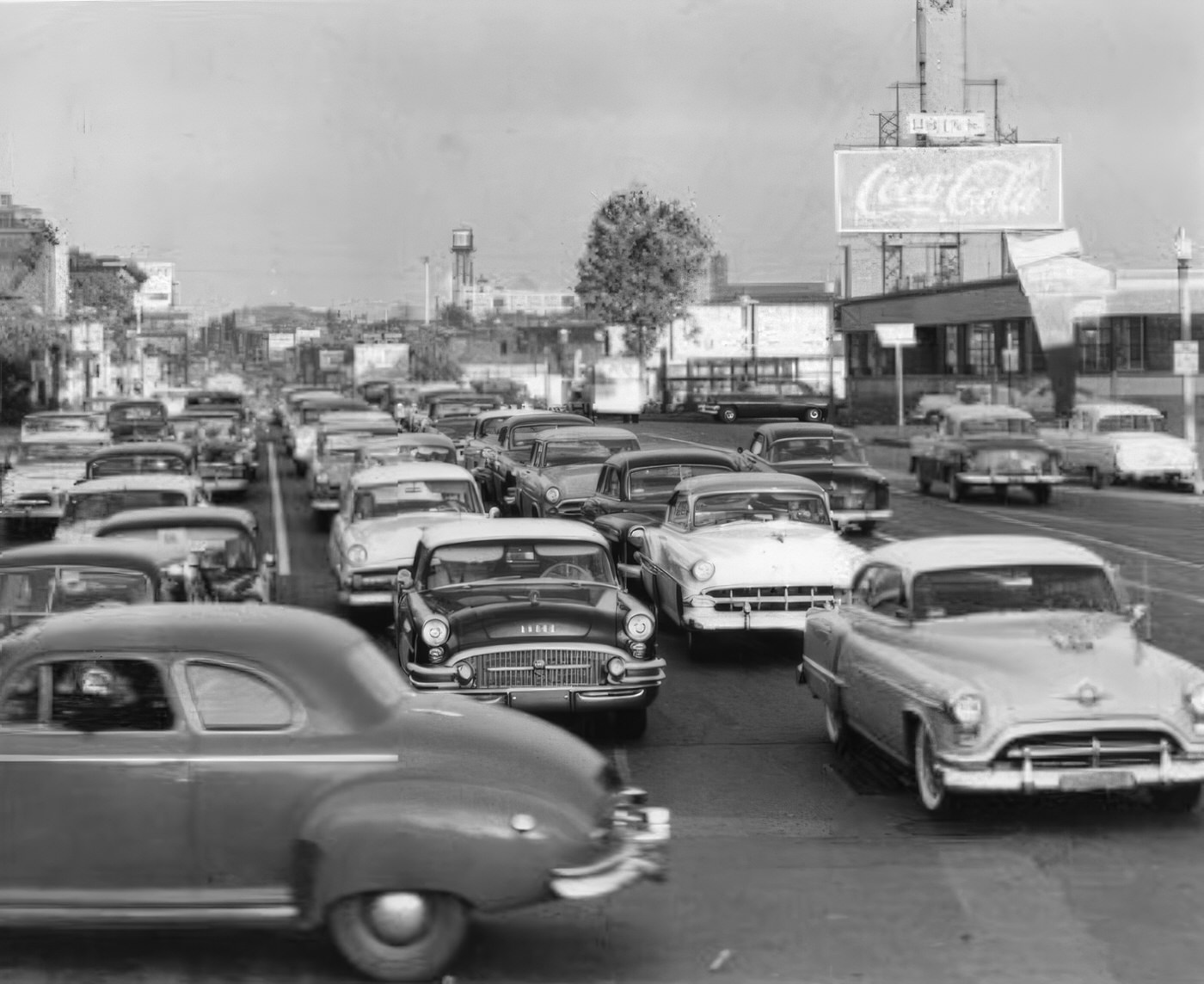

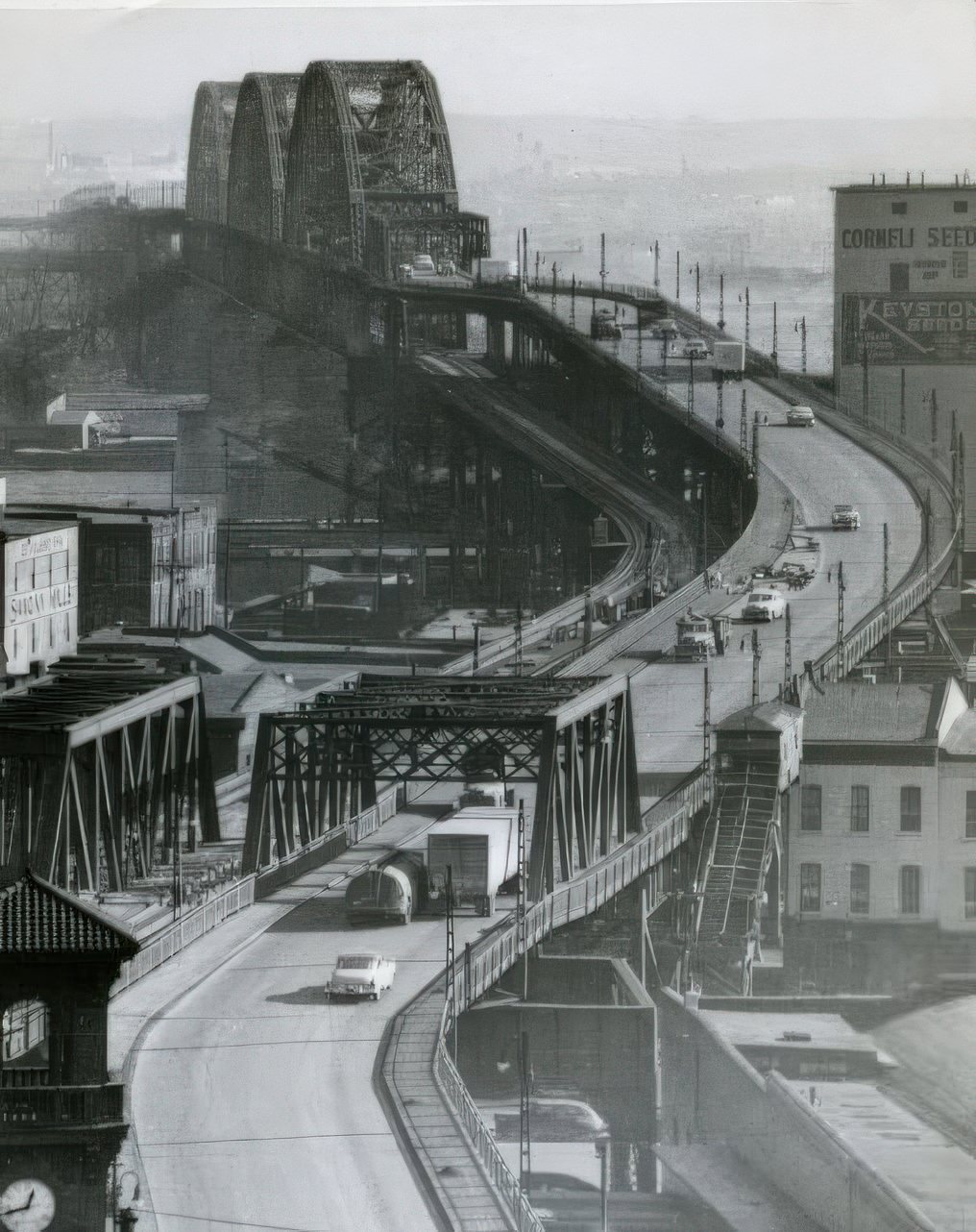

Building the Future: Highways and the Arch

The 1950s marked the beginning of a massive transformation of St. Louis’s transportation infrastructure with the advent of the Interstate Highway System. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 provided significant federal funding for these projects. Plans for expressways like the Daniel Boone Expressway (US 40), Mark Twain Expressway (I-70), and Ozark Expressway (I-44) were developed and construction began. The Daniel Boone Expressway, parts of which dated back to the 1930s and 1940s, was extended eastward in 1959 to connect with the Red Feather Highway. The Mark Twain Expressway’s route through St. Louis’s North Side was a subject of planning, proposals, and protests between 1950 and 1956, influenced by politics and race.

These highways were intended to relieve traffic congestion and connect the city to the growing suburbs. However, their construction often had a severe impact on existing neighborhoods, particularly low-income and African American communities. Vast swaths of housing were demolished, displacing residents and physically dividing communities. This process, often referred to as “slum clearance,” was part of the broader urban renewal strategy of the era but contributed to the very urban decline and segregation it aimed to solve.

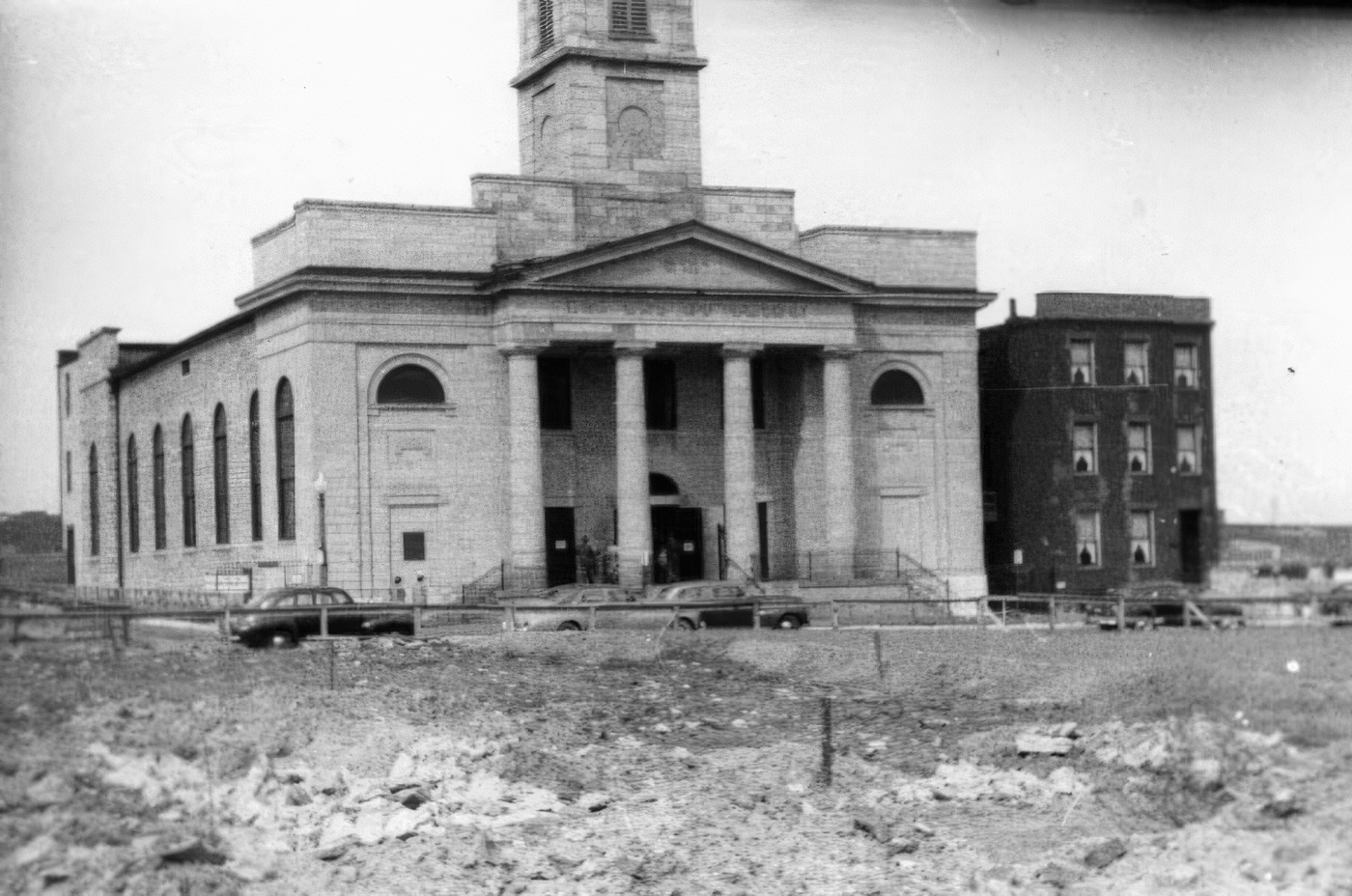

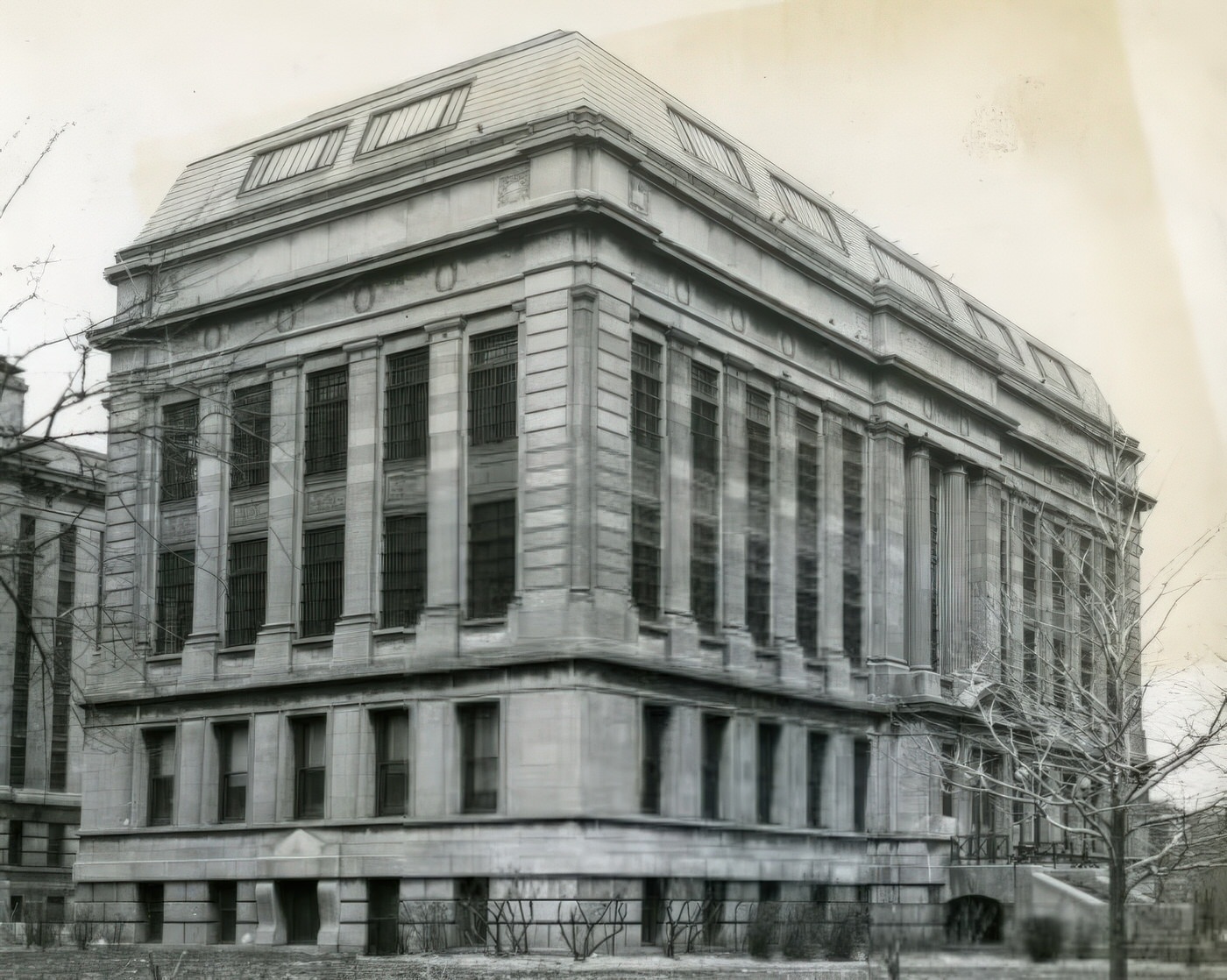

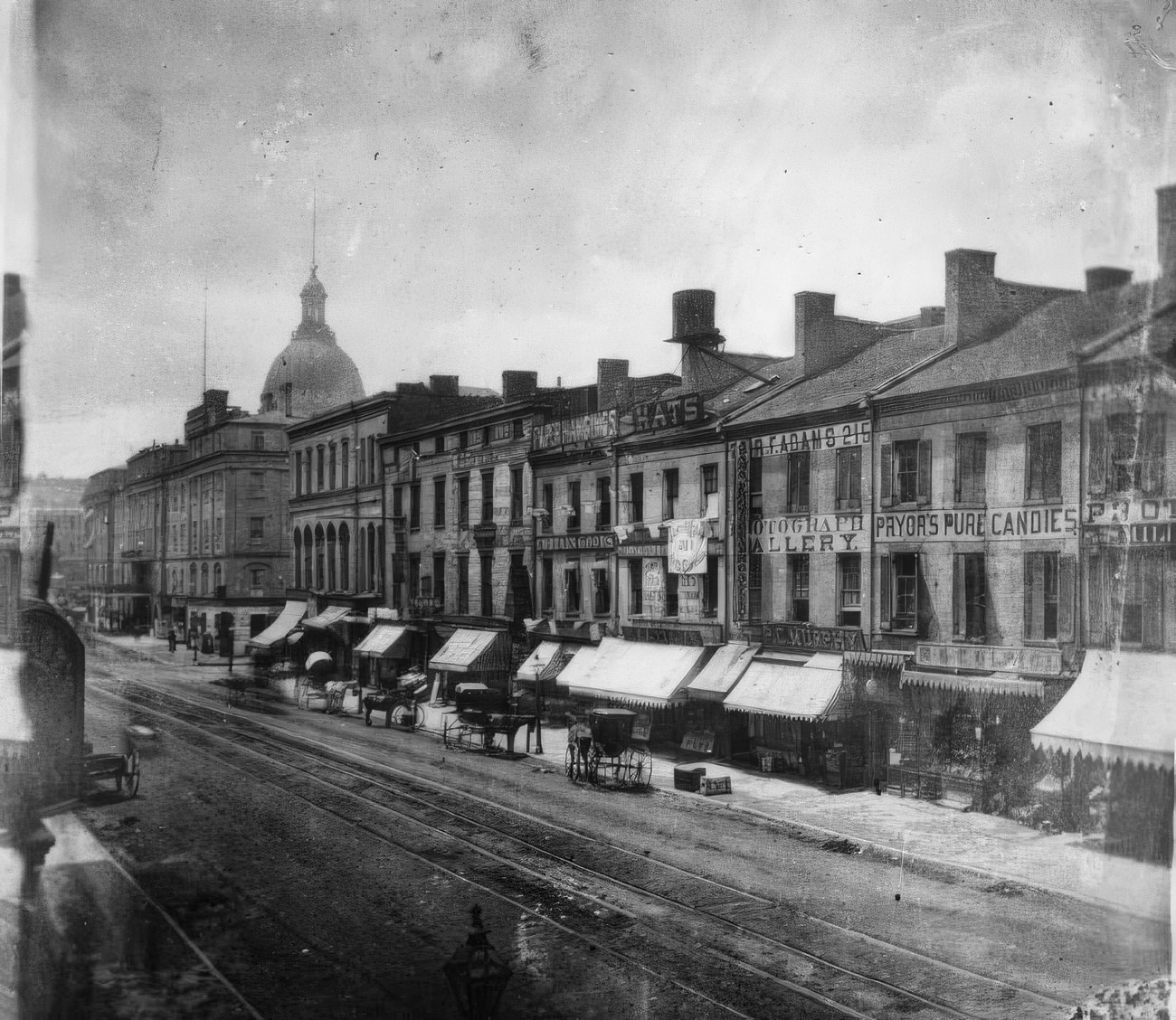

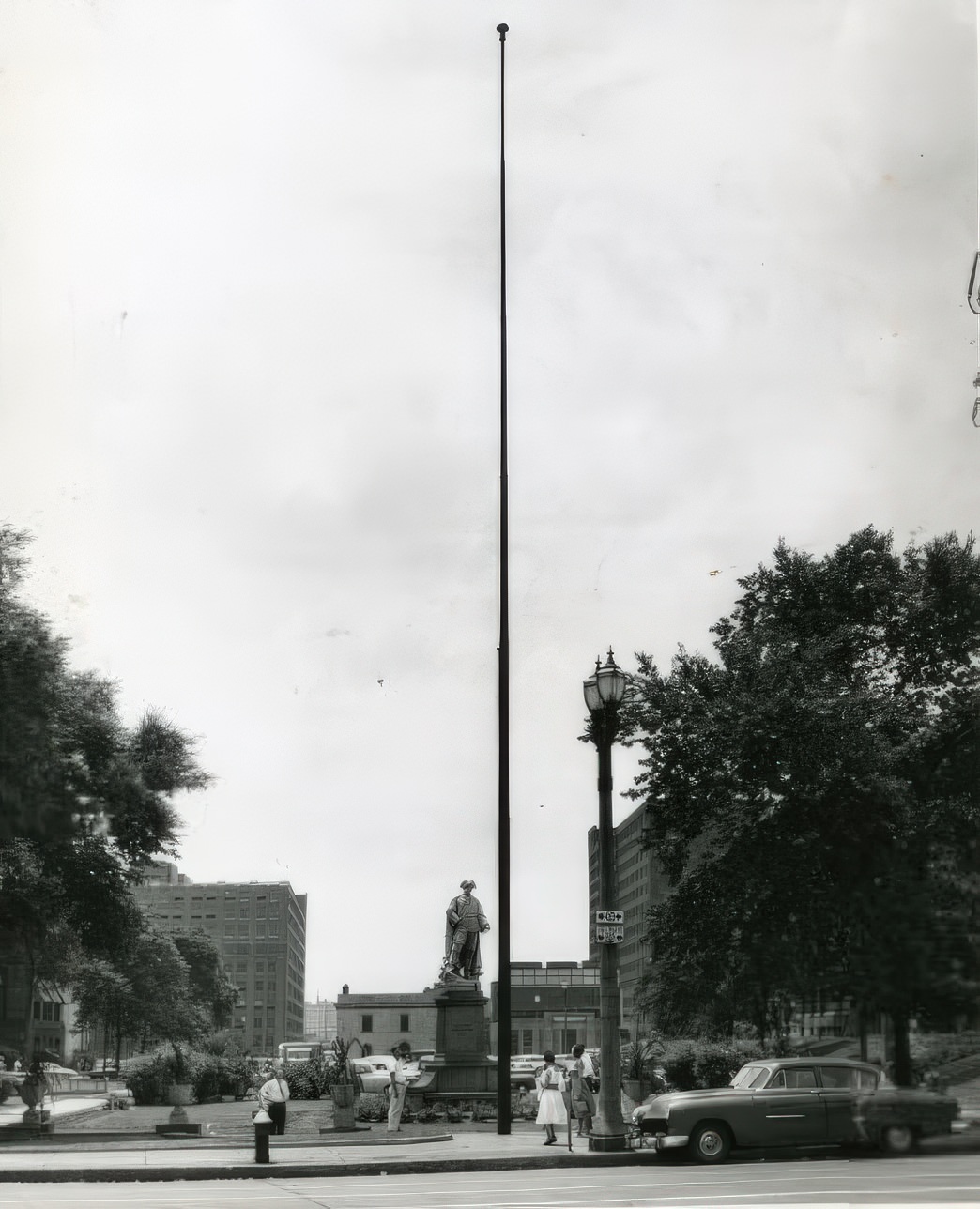

While the highways were reshaping the city, another iconic project was taking form. The idea for a riverfront memorial, which would become the Gateway Arch, originated in the 1930s. A nationwide design competition was held in 1947, and in 1948, Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen’s design for a 630-foot stainless steel arch was chosen. However, actual construction was delayed. It wasn’t until 1957 that an agreement was reached with the Terminal Railroad Association to remove the railroad trestle along the levee and for federal money to be authorized for construction. Saarinen then revisited his design, eliminating surface museums and incorporating an underground visitor center. The new plan emphasized symmetry with the Old Courthouse and featured sweeping, curved walkways mirroring the Arch’s catenary curve. Though construction of the Arch itself wouldn’t begin until the 1960s, the planning and land clearance in the 1950s laid the critical groundwork for this future landmark.

Society and Culture: Civil Rights, Entertainment, and Daily Life

The 1950s in St. Louis were a period of significant social and cultural shifts, marked by the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, changing entertainment landscapes, and evolving public services.

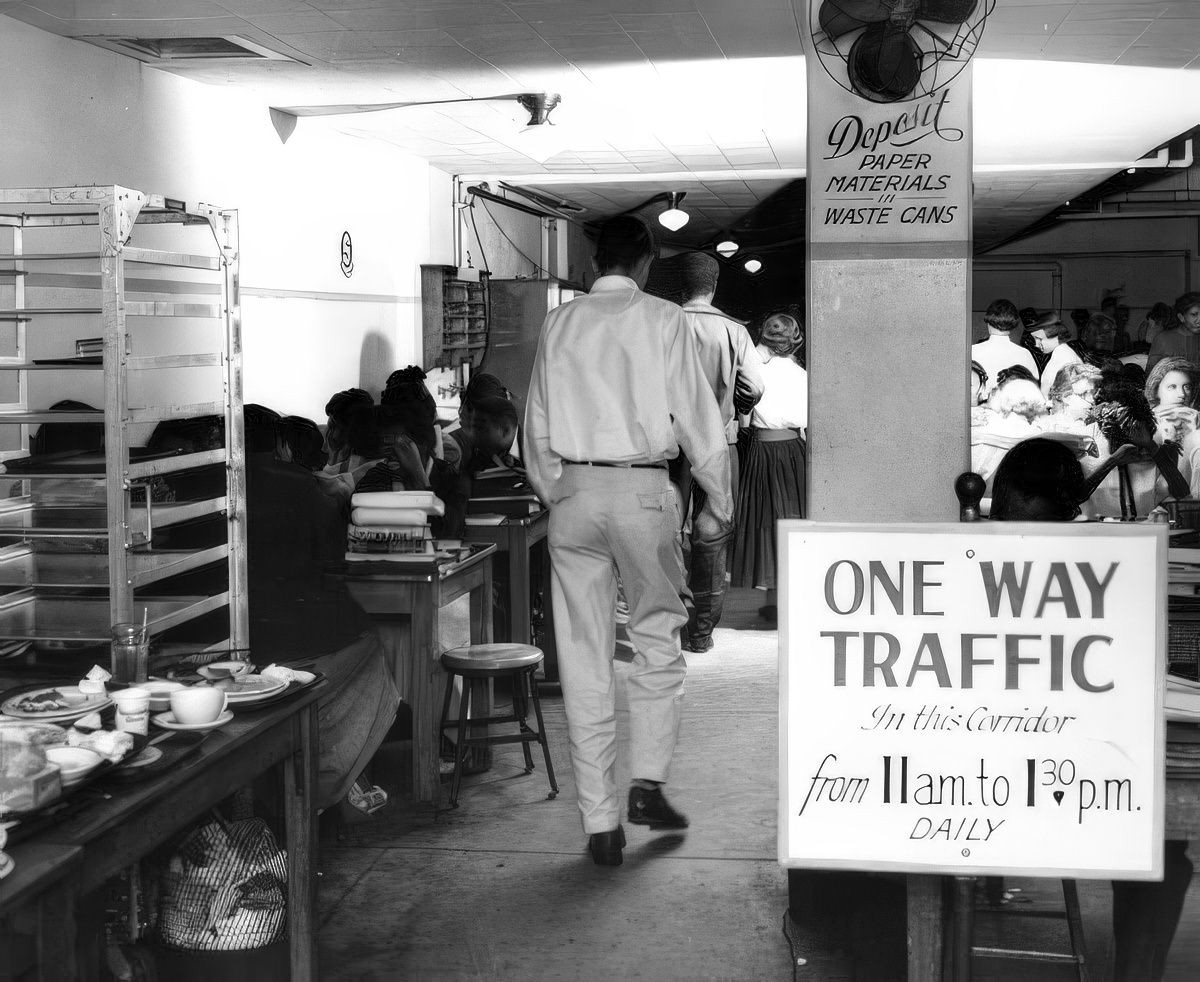

The fight for civil rights gained momentum in St. Louis during the 1950s. Segregation was deeply entrenched in many aspects of life, from housing to public accommodations. The St. Louis chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), formed in 1947, was active in challenging these norms. Starting in 1948 and continuing into the early 1950s, CORE targeted segregated lunch counters in downtown department stores like Stix, Baer & Fuller, Famous-Barr, Scruggs, Vandervoort, and Woolworth’s, using tactics like sit-ins and leaflet distribution. These campaigns, though often long and met with resistance, gradually led to changes. Stix, Baer & Fuller, for instance, finally desegregated its lunch counter in 1954 after years of CORE demonstrations. These efforts built upon earlier actions, such as the 1944 sit-ins by the all-female Citizens Civil Rights Committee led by Pearl Maddox.

Public swimming pools were another battleground. In June 1949, an attempt to integrate the Fairground Park pool led to a riot as white mobs attacked African American swimmers. Although the pool was officially desegregated in 1950, attendance plummeted, and the city closed it by 1954, highlighting the intense racial animosity.

The landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954 declared state-sponsored segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The St. Louis Board of Education adopted a desegregation plan shortly thereafter, in June 1954. This plan involved redrawing school boundaries based on neighborhood demographics, aiming for the best use of facilities. An inter-racial committee of school administrators was tasked with this, using enrollment data but intentionally omitting racial identifiers from the block-level data cards. High schools were integrated in January 1955, and elementary schools in September 1955. While a 1955 report described the integration process as “smooth and almost without incident,” underlying issues of de facto segregation due to housing patterns persisted. Concerns from the Black community about potential teacher displacement and the loss of community schools were present, though not always prominently featured in official narratives.

The NAACP’s St. Louis chapter, particularly under the leadership of Ernest Calloway who became president in 1955, was very active. Membership grew significantly, and the chapter led successful campaigns for increased African American employment at taxi services, department stores, Coca-Cola, and Southwestern Bell. In 1957, the NAACP opposed a proposed city charter because it lacked civil rights provisions, and the charter was defeated. The Urban League of St. Louis also played a vital role, shifting its focus in the post-war years from domestic service jobs to opportunities in business and industry for African Americans. They advocated for community-wide programs to address substandard housing, unemployment, and inadequate health services. In 1959, a “Pruitt Committee” of The Links, Inc. worked with the Urban League to identify children’s needs at the Pruitt-Igoe complex.

Entertainment and Daily Life

The 1950s brought new forms of entertainment into St. Louis homes. Television was rapidly gaining popularity. KSD-TV (now KSDK), which debuted in 1947, offered daily local programming and NBC network shows. Popular local children’s shows like “Corky the Clown” (originally “Zippy the Clown”), played by KSD weatherman Clif St. James, began in 1954 and delighted young audiences. Radio remained a strong presence, with stations like KXOK featuring popular personalities such as Bill Addison, Ed Bonner, and Ron Elz (Johnny Rabbitt). “The Land We Live In,” a radio show recreating local historical events, continued its run on KSD into the early 1950s.

Movie palaces like the Fox Theatre, which opened in 1929, were still grand entertainment venues, though the rise of television began to impact movie attendance nationwide.

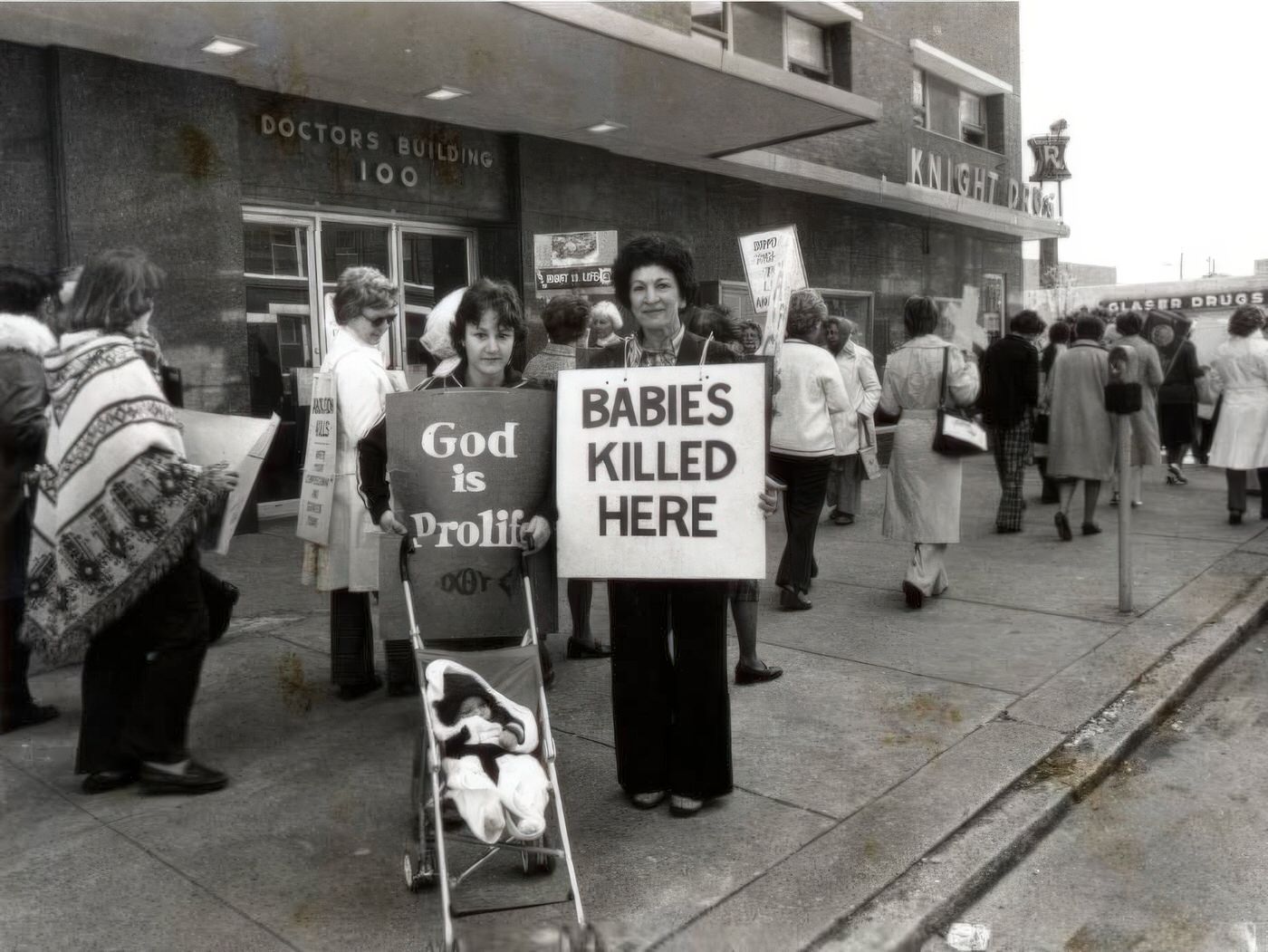

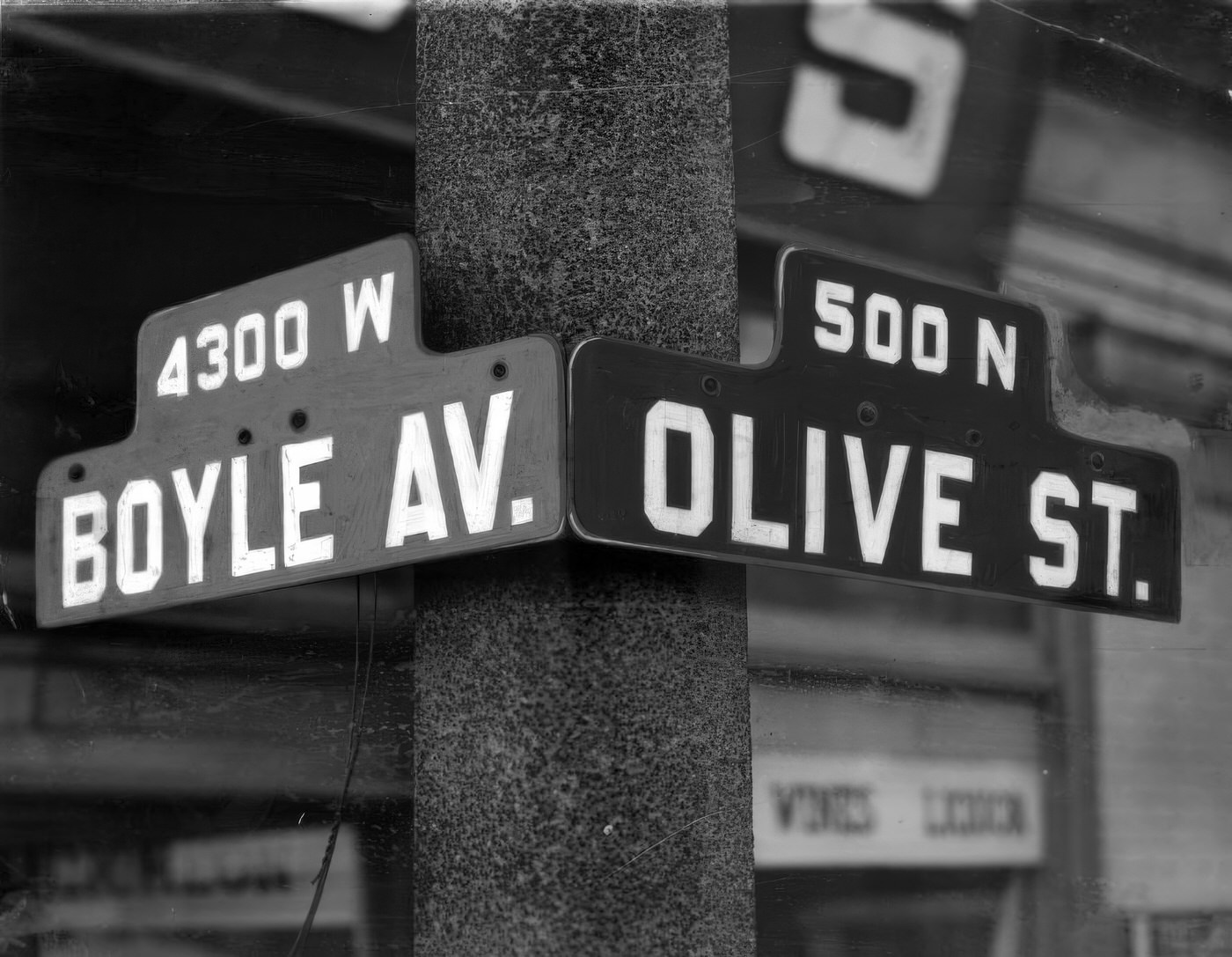

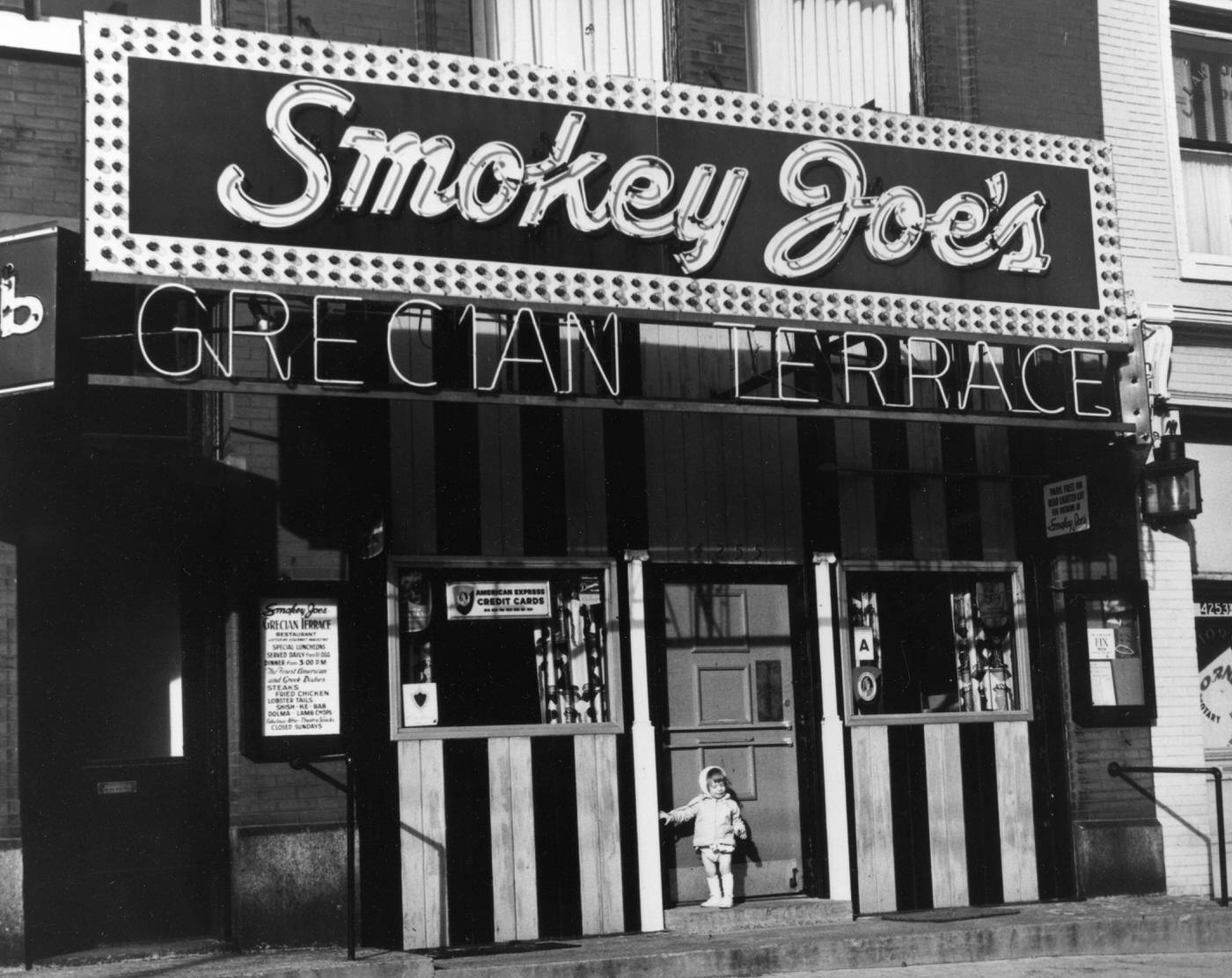

St. Louis had a vibrant music scene. The Gaslight Square entertainment district began to emerge in the late 1950s, particularly after a tornado in 1959 spurred redevelopment in the Olive and Boyle area. Early venues included Jay Landesman’s Crystal Palace cabaret and the Gaslight Bar. The area would become a hub for jazz, folk music, and comedy. Blues music also had deep roots in the city and nearby East St. Louis, with artists like Chuck Berry beginning his career in St. Louis clubs in the early 1950s, playing with Johnnie Johnson’s trio and blending blues with country influences. Miles Davis, another jazz legend with St. Louis ties, also gained prominence during this era, having started his professional career with Eddie Randall’s band in St. Louis in 1941. The Peacock Alley jazz club, originally the Glass Bar, opened in 1944 and became an important venue, hosting radio broadcasts by DJ Spider Burks. Club Riviera was another major African American nightclub, hosting top jazz and blues performers.

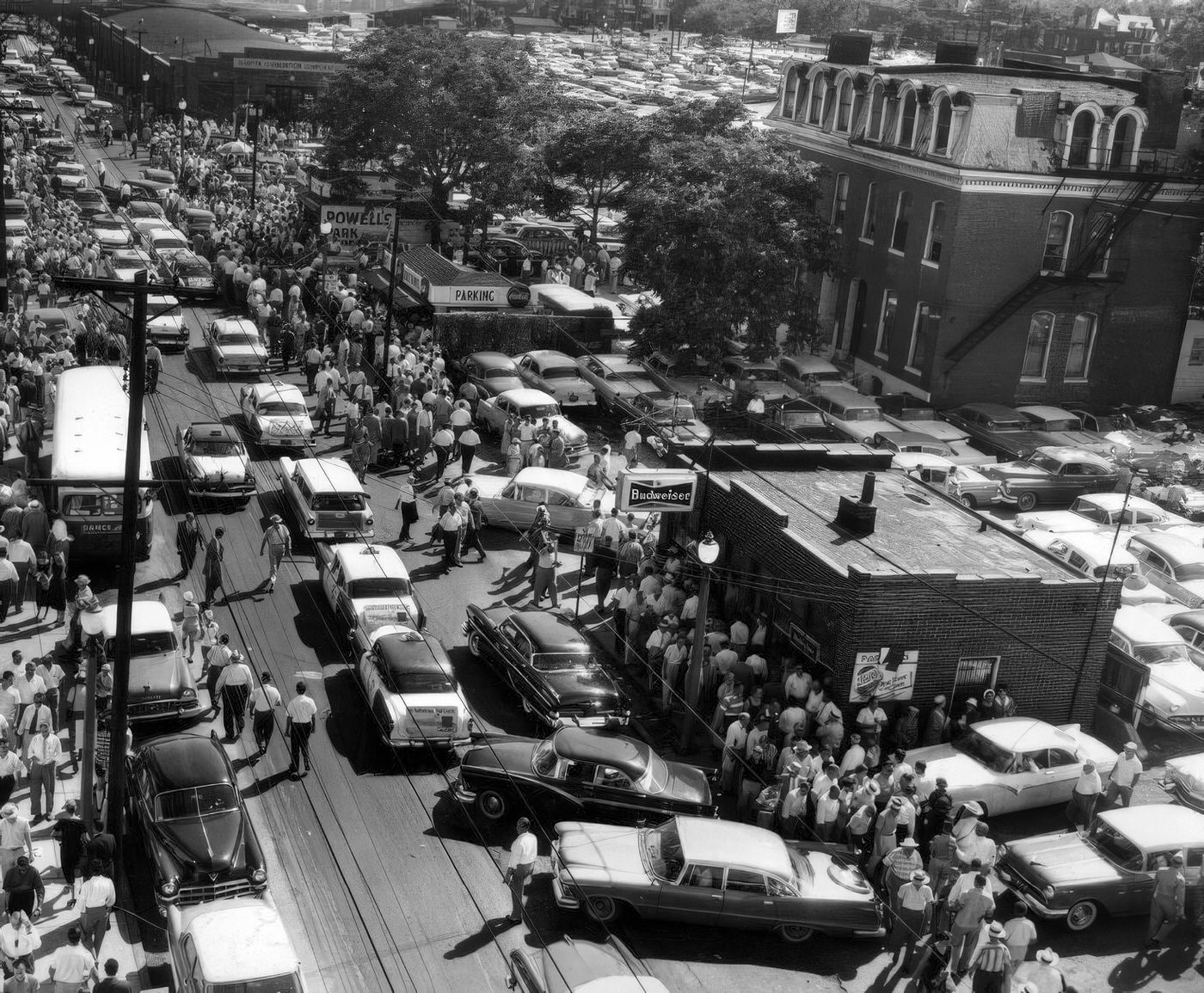

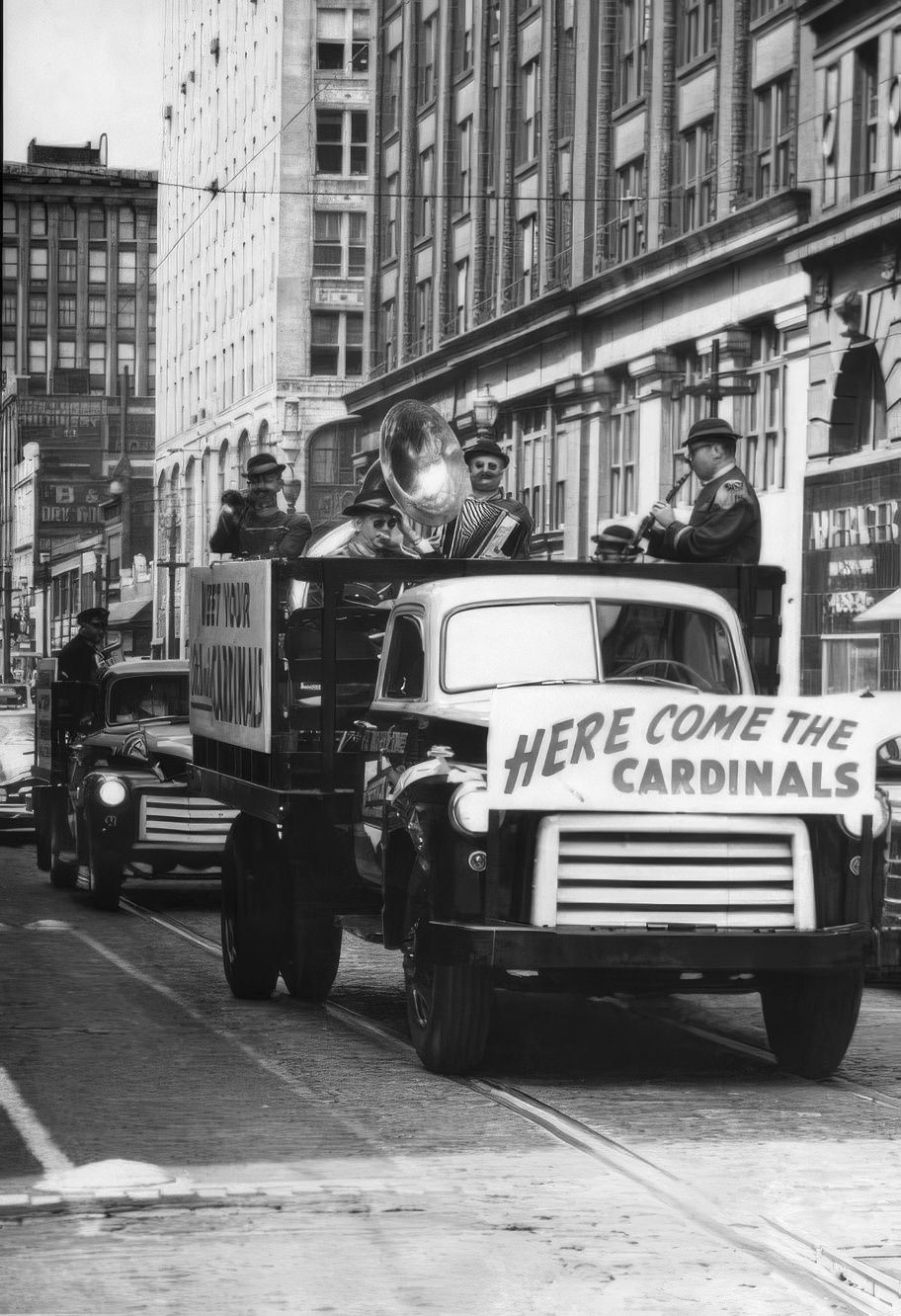

On the sports front, St. Louis celebrated a major victory when the St. Louis Hawks won the NBA championship in 1958, defeating the Boston Celtics at Kiel Auditorium. Bob Pettit scored a record 50 points in the deciding game, leading to “pandemonium on Pine Street”. The St. Louis Cardinals baseball team continued to be a major focus for sports fans. Sportsman’s Park, shared by the Cardinals and the St. Louis Browns, was purchased by Cardinals owner Anheuser-Busch in 1953 and renamed Busch Stadium (after a brief period as Budweiser Stadium). The ballpark underwent significant renovations in 1953-1954, including new wider seats and the removal of most advertising, enhancing the fan experience. The Browns departed for Baltimore after the 1953 season.

Public Health and Services

Public health was a significant concern. Polio was a feared disease, but the development of the Salk vaccine, licensed in 1955, brought immense relief. Nationwide, mass vaccination campaigns dramatically reduced polio cases by 1957. St. Louis would have participated in these efforts, likely distributing the vaccine through schools and public health clinics.

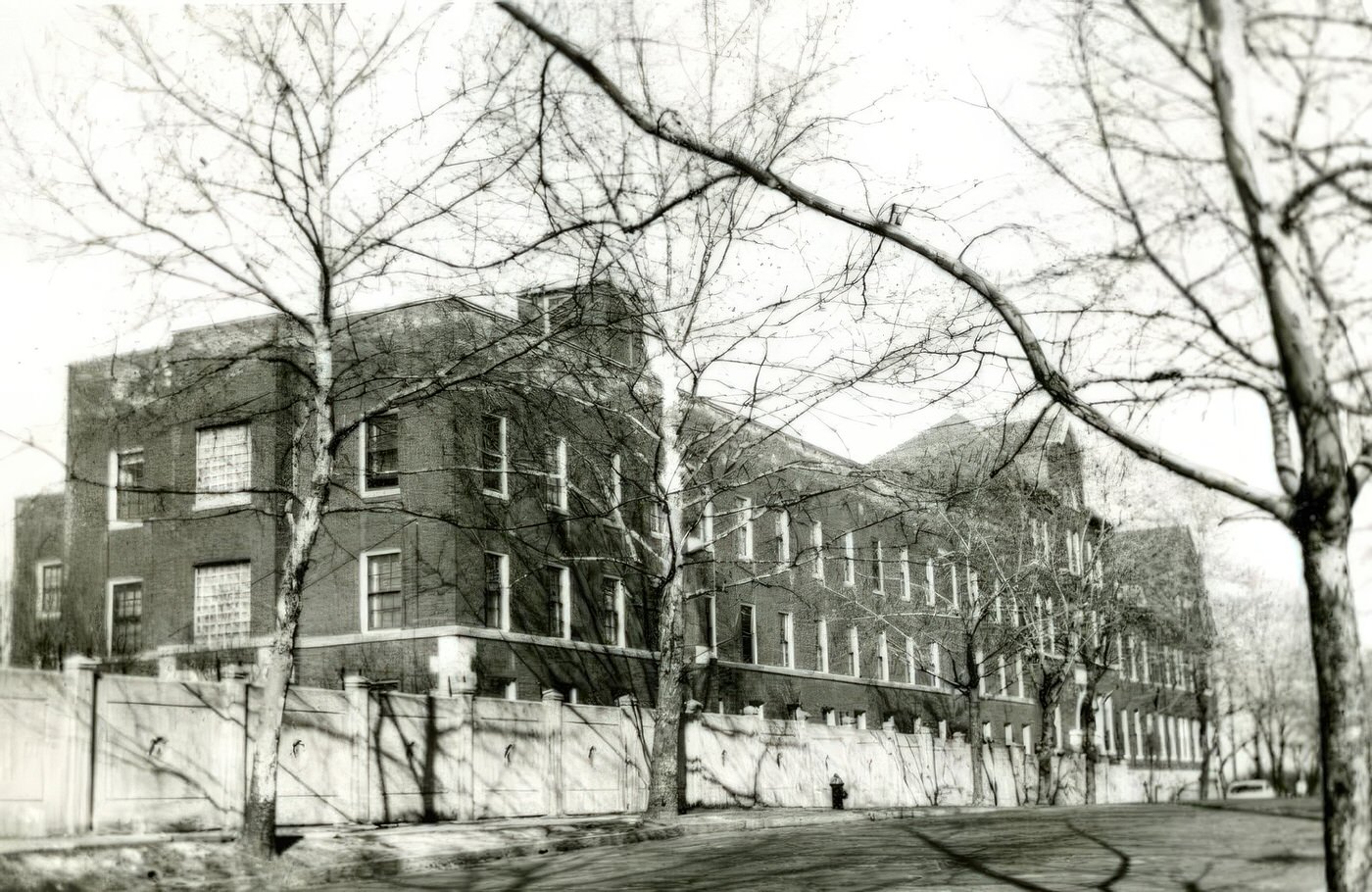

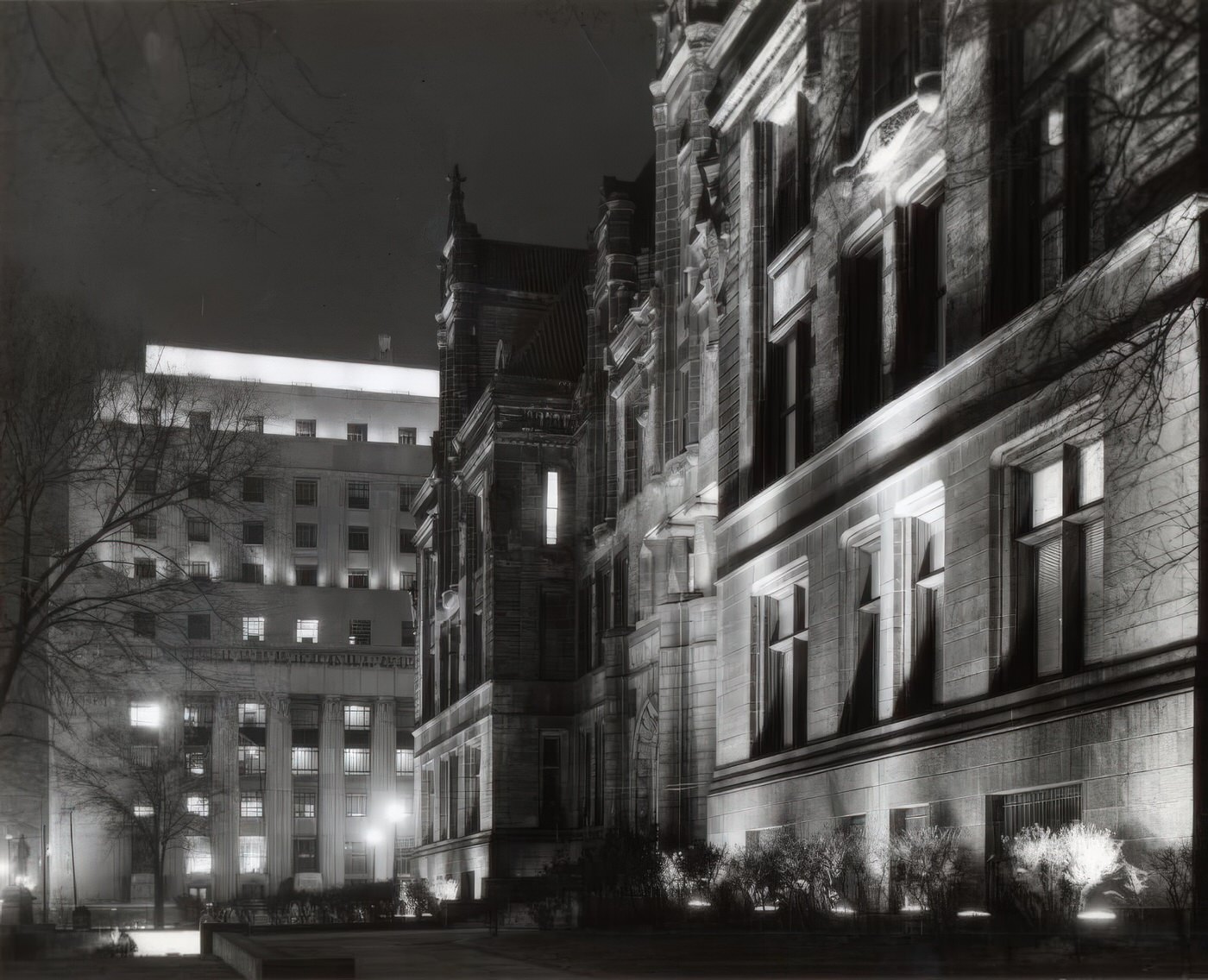

City hospitals faced considerable challenges. St. Louis City Hospital #1 (for white patients prior to 1955) suffered from underfunding, staff shortages, and deteriorating conditions, with reports of “second-class care” by 1957. Homer G. Phillips Hospital, which served the African American community, was a vital institution and a leading training center for Black doctors and nurses, making important contributions in areas like intravenous feeding and burn treatment. Despite its importance, it was consistently underfunded by the city. The 1955 desegregation order meant that city hospitals began treating patients based on geographic location rather than race, which began to change patient demographics at Homer G. Phillips. The St. Louis State Hospital (formerly City Sanitarium) housed a large and growing patient population, operating over capacity in the 1950s and functioning more as a custodial institution.

In law enforcement, the St. Louis County Police Department was officially established on July 1, 1955, reflecting the growing need for dedicated police services in the expanding suburban areas. The department aimed to be free of political influence and grew significantly in its first five years, developing policies, acquiring vehicles, and establishing patrol districts. Meanwhile, crime rates in St. Louis City were on the rise during the 1950s. Index crimes and homicides both increased, with city homicides climbing from 107 in 1958 to 129 in 1959. The FBI’s St. Louis office also handled major criminal cases, such as the Greenlease kidnapping in 1953, and maintained a focus on national security issues during the Cold War.

The city’s governance during this dynamic decade was led by Mayor Joseph Darst (1949-1953) and Mayor Raymond R. Tucker (1953-1965). Their administrations grappled with the massive shifts in population, the complexities of urban renewal, the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, and the need to adapt public services to a changing city. The decisions made and the projects initiated during the 1950s profoundly influenced the trajectory of St. Louis for the remainder of the 20th century and beyond. The outward migration of residents and businesses strained the city’s financial resources, impacting its ability to fund schools, hospitals, and other essential services.

Image Credits: The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Mercantile Library, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know