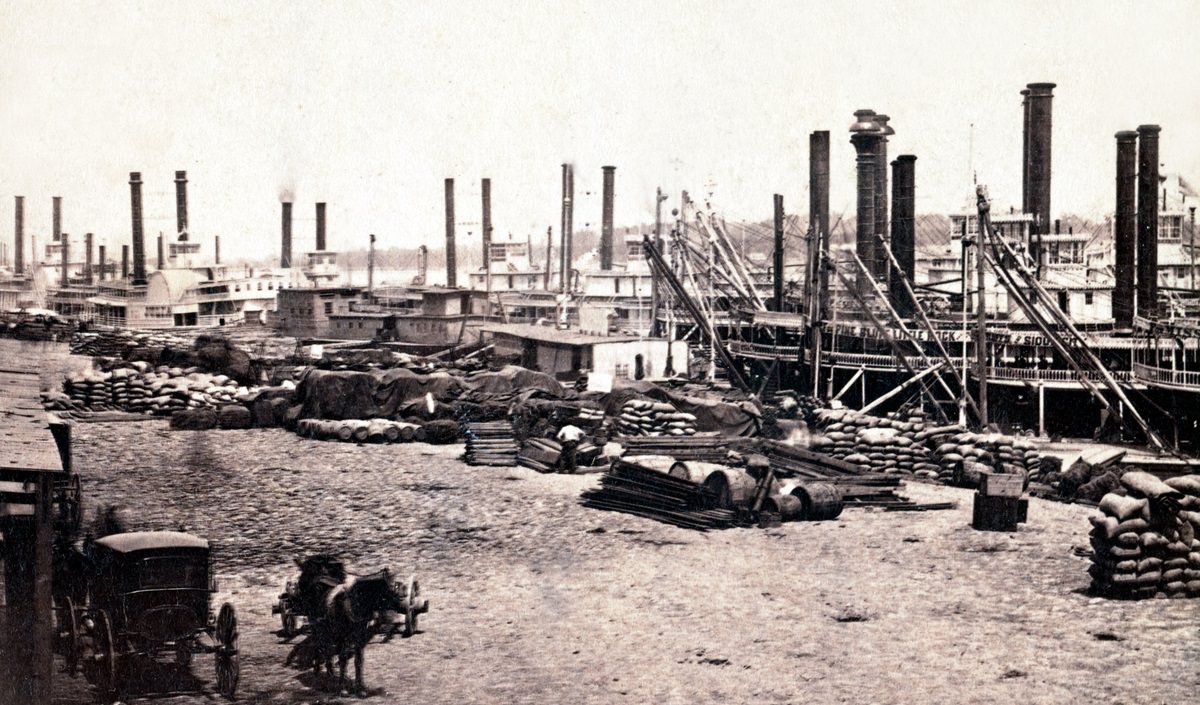

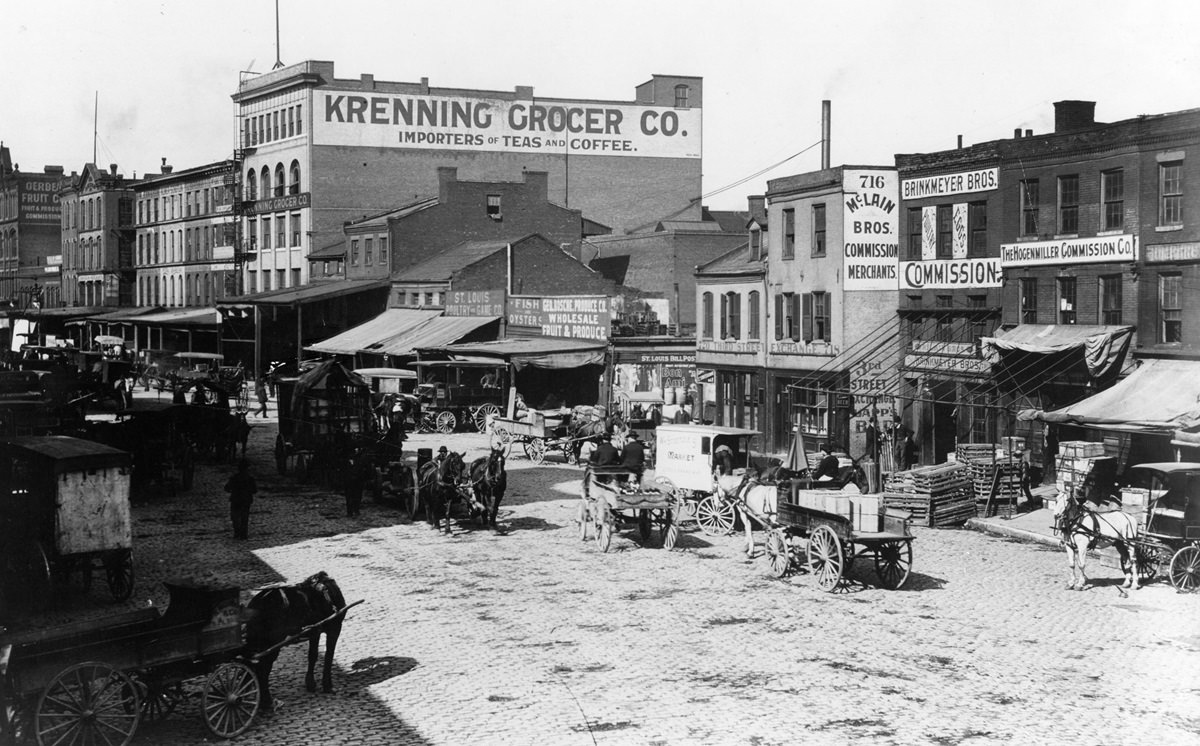

The 1970s were a time of big changes for St. Louis, Missouri. The city was dealing with many of the same problems that other older American cities faced, often called the “urban crisis”. Factories that had once provided many jobs were closing or moving away, a process known as deindustrialization. This meant fewer jobs and less money for the city. As businesses left, the city’s downtown area, once a busy hub, became quieter. St. Louis struggled with a shrinking amount of money from taxes, and some parts of the city began to show signs of decay, with rising crime and poverty. Across the Mississippi River, East St. Louis faced even tougher times. Between 1960 and 1970, it lost almost 70 percent of its businesses, leading to very high unemployment and poverty. Even with these difficulties, a group of St. Louis business leaders called Civic Progress believed the city could bounce back. They focused on efforts to renew downtown, building on projects started in the late 1960s.

One of the most noticeable changes in St. Louis during the 1970s was its population. Many people were leaving the city. In that decade alone, St. Louis City lost 169,000 residents. This was a 27 percent drop from the number of people living there in 1970. The city’s population went from 622,236 in 1970 down to 453,085 by 1980. This was part of a long-term trend. In 1950, St. Louis had over 850,000 people. By 2010, it had lost 63 percent of that peak number.

Several things caused the population drop in St. Louis during the 70s. Families were having fewer children, so the average number of people in a household went down from 3.1 in 1950 to 2.2 in 2010. Also, new highways were built through city neighborhoods, and some areas were cleared for new development projects, like the Mill Creek Valley renewal, which removed homes. While the city was losing people, the areas around it, St. Louis County, were growing. The county’s population went from 951,353 in 1970 to 973,896 in 1980. A key shift during this time was that African American families began moving to the suburbs in larger numbers in the early 1970s. The Black population in St. Louis County grew from 4.8 percent (45,700 people) in 1970 to 11.25 percent (109,686 people) in 1980. In St. Louis City, the actual number of Black residents fell because so many people were leaving the city overall. However, because more white residents left the city, the percentage of Black residents in the city increased from 40.9 percent in 1970 to 45.5 percent in 1980. Despite these shifts, St. Louis remained a very segregated city, with clear dividing lines between Black and white neighborhoods. This movement of people and the loss of industry created a tough cycle for the city, where fewer people and businesses meant less money for city services, which in turn made the city a harder place to live for those who remained.

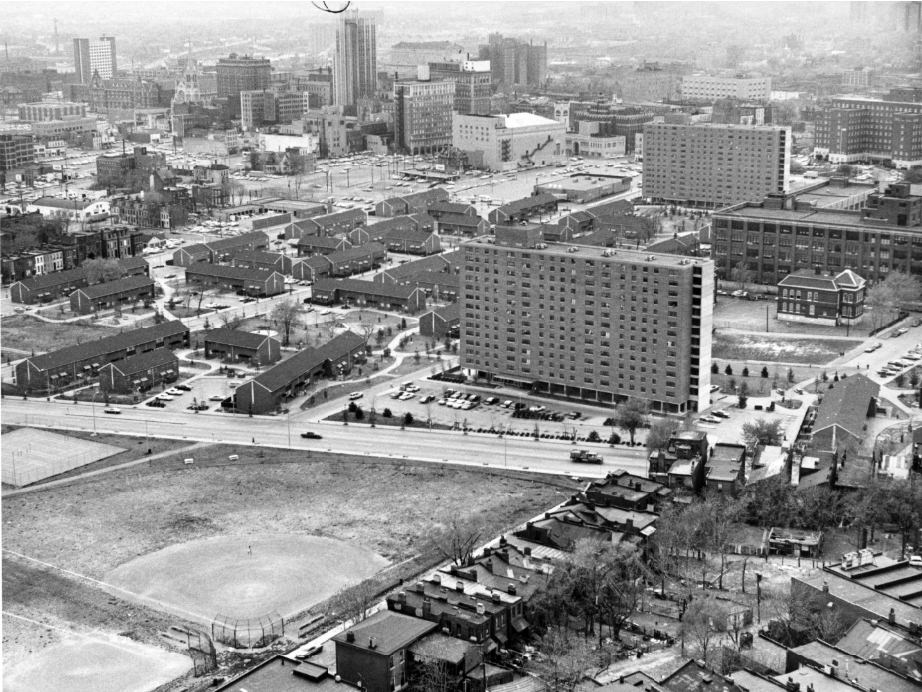

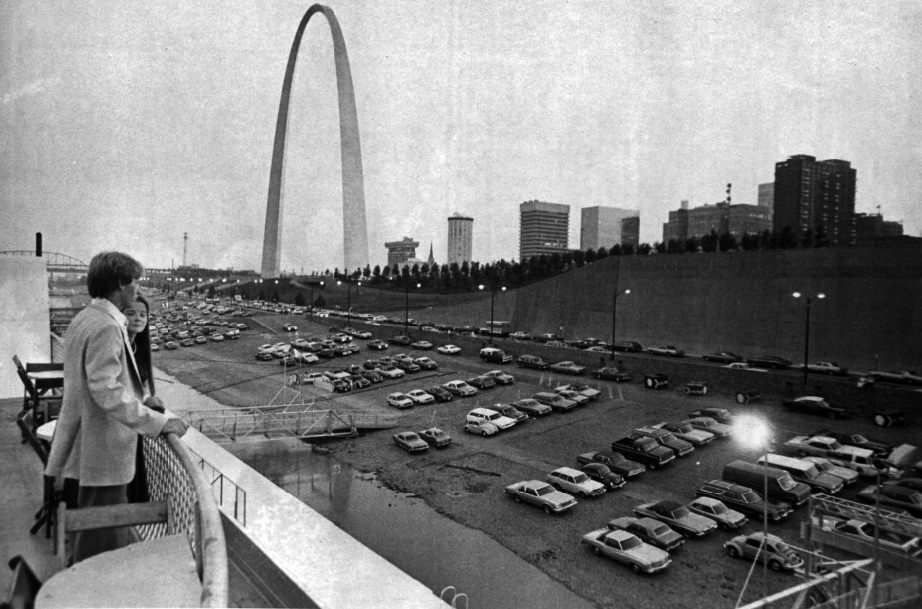

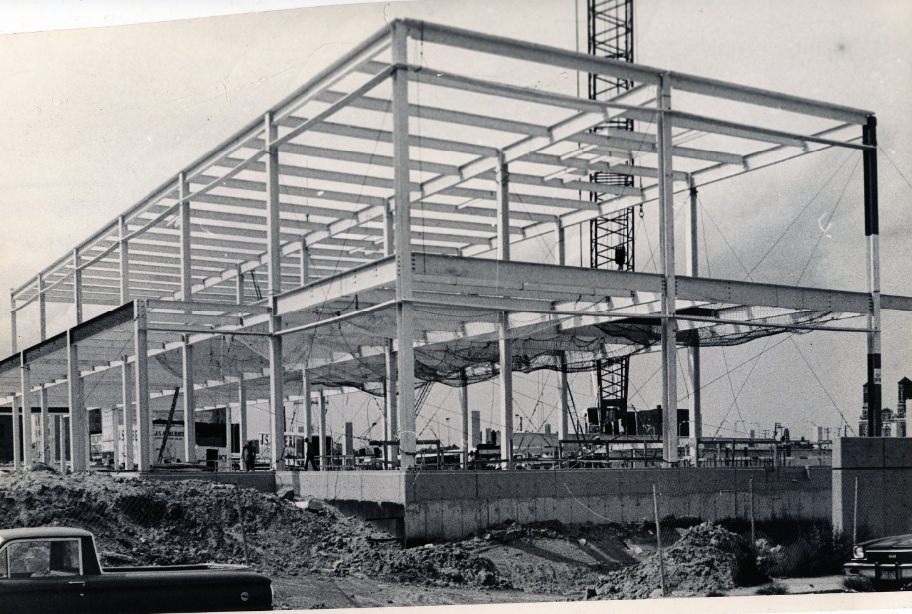

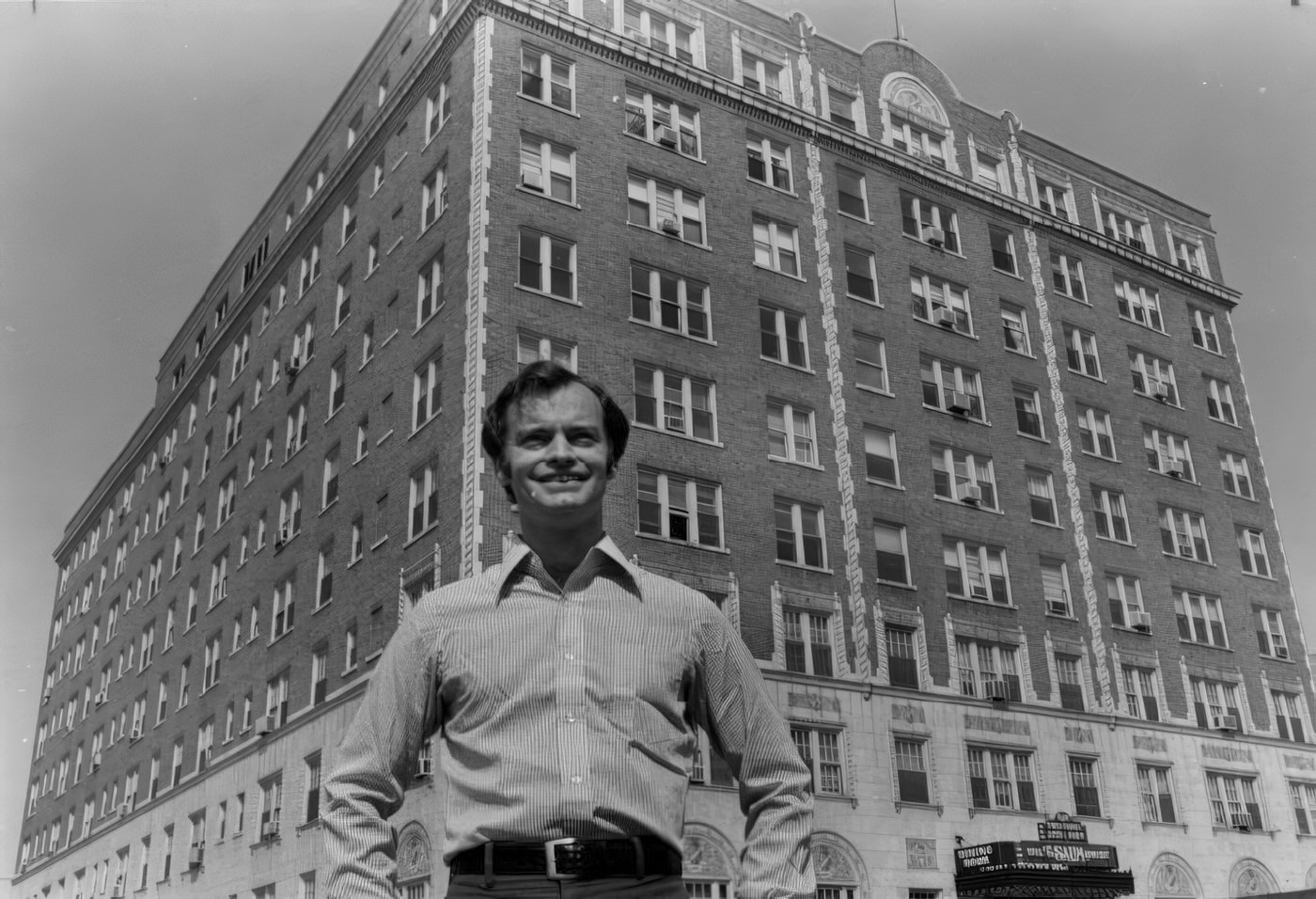

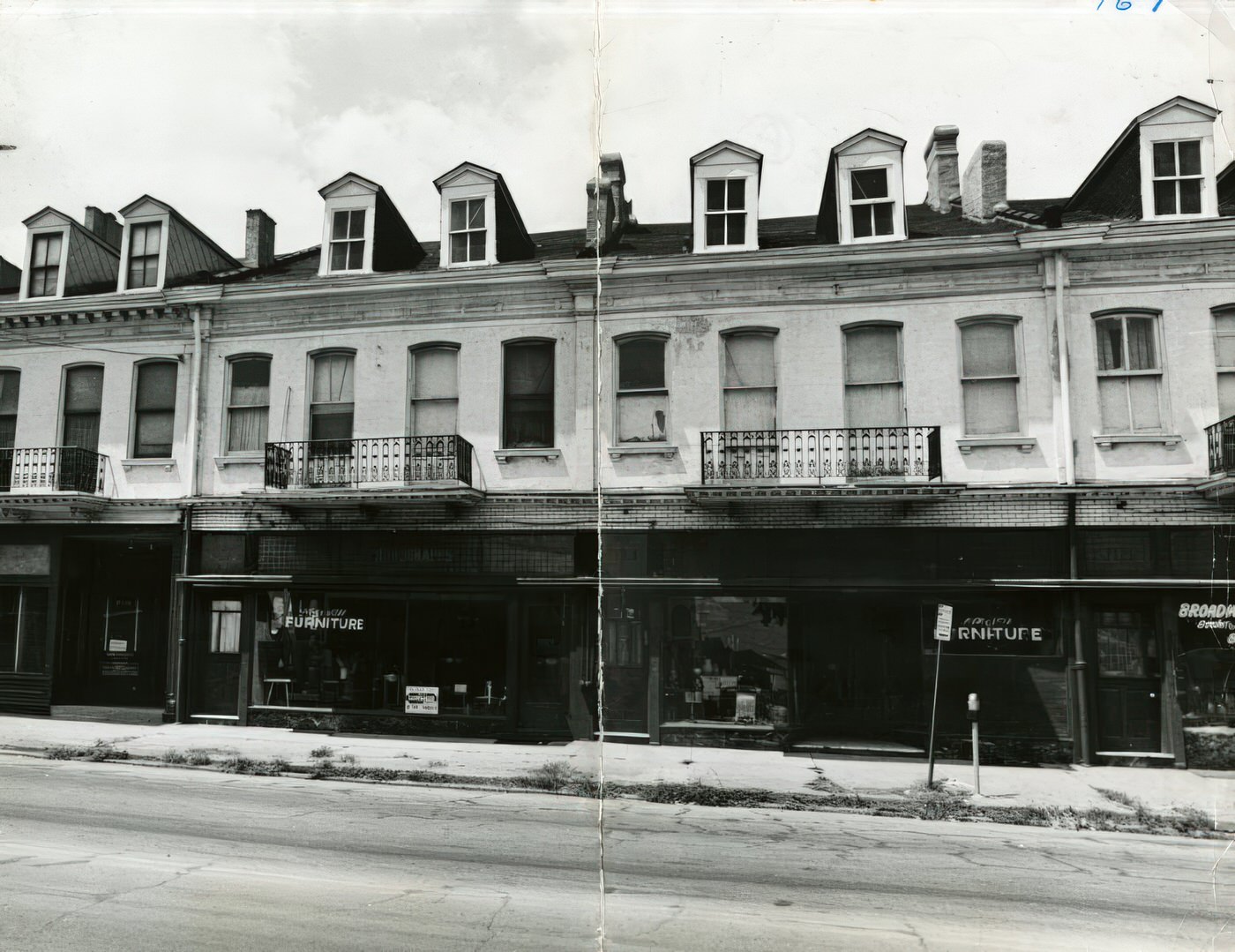

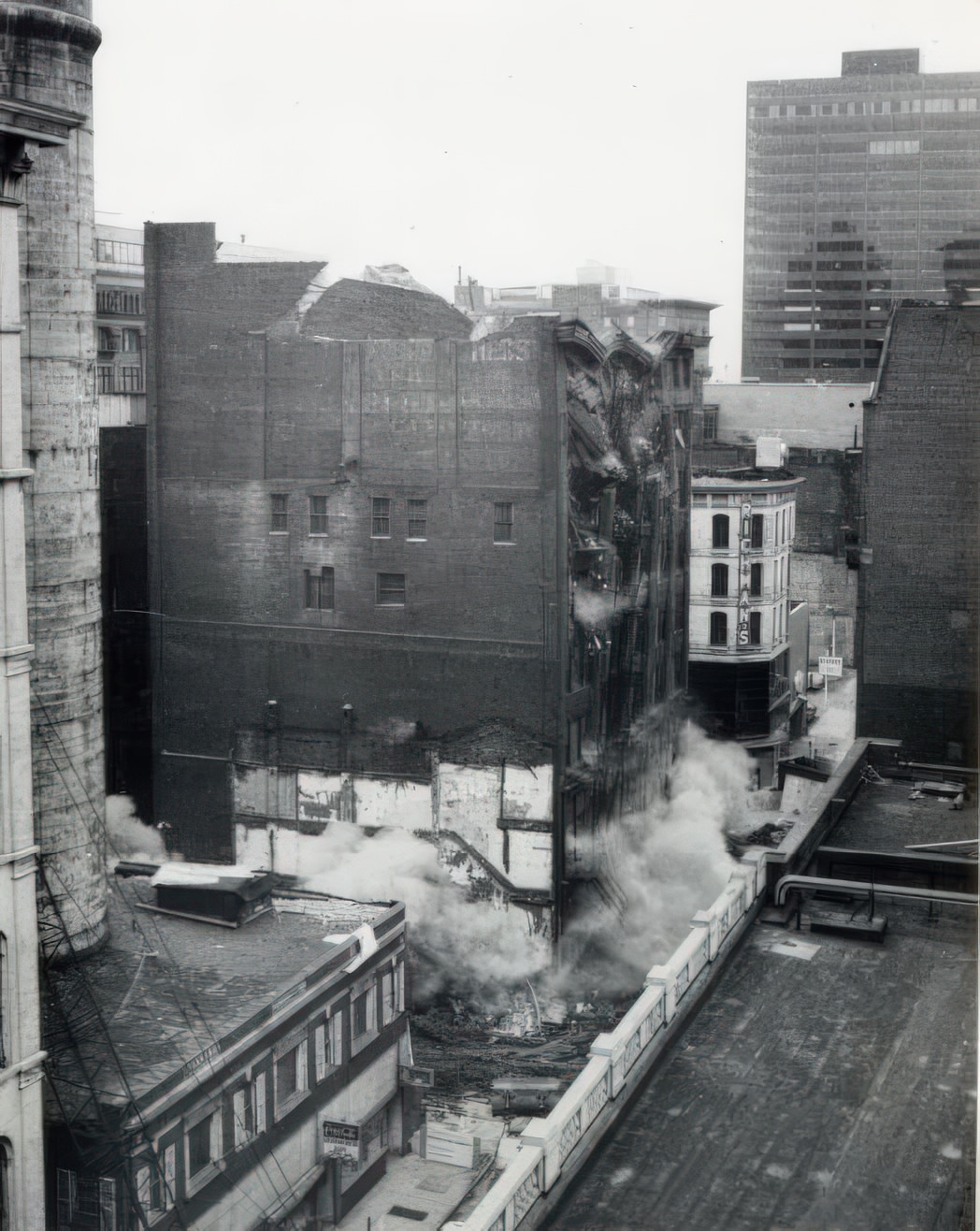

The city’s buildings and neighborhoods also saw big changes. The Pruitt-Igoe public housing complex, which was already having serious problems by the mid-1960s, got much worse. By 1970, more than two-thirds of its 33 high-rise buildings were empty. There was a lot of damage, and it was not a safe place to live. The city began to tear down Pruitt-Igoe in 1972, with the first buildings coming down in a televised implosion on March 16. The demolition continued until 1976. Pruitt-Igoe became a famous example of failed city planning and public housing ideas. The dramatic failure of Pruitt-Igoe led city planners to think differently about how to improve neighborhoods. Instead of huge projects, they started to focus on smaller, neighborhood-based efforts. This new approach was helped by the Community Development Act of 1974, a federal law that gave cities money for these kinds of local projects. Even as many parts of the city struggled, there was some new building downtown. The Cervantes Convention Center was finished in 1978. This was part of a longer period of downtown construction that had started with the building of the Gateway Arch in 1965 and Busch Stadium II in 1966. There was also a growing interest in saving historic neighborhoods. Helped by government tax programs, areas like the Central West End, Soulard, and Lafayette Square saw efforts to fix up old buildings and attract new residents and businesses during the 1970s and early 1980s. For example, the Soulard neighborhood organized to become a historic district to encourage this kind of renewal. These efforts showed a change in thinking, valuing the city’s existing character while trying to address its deep-seated problems.

The Economic Engine: Industry, Work, and Challenges

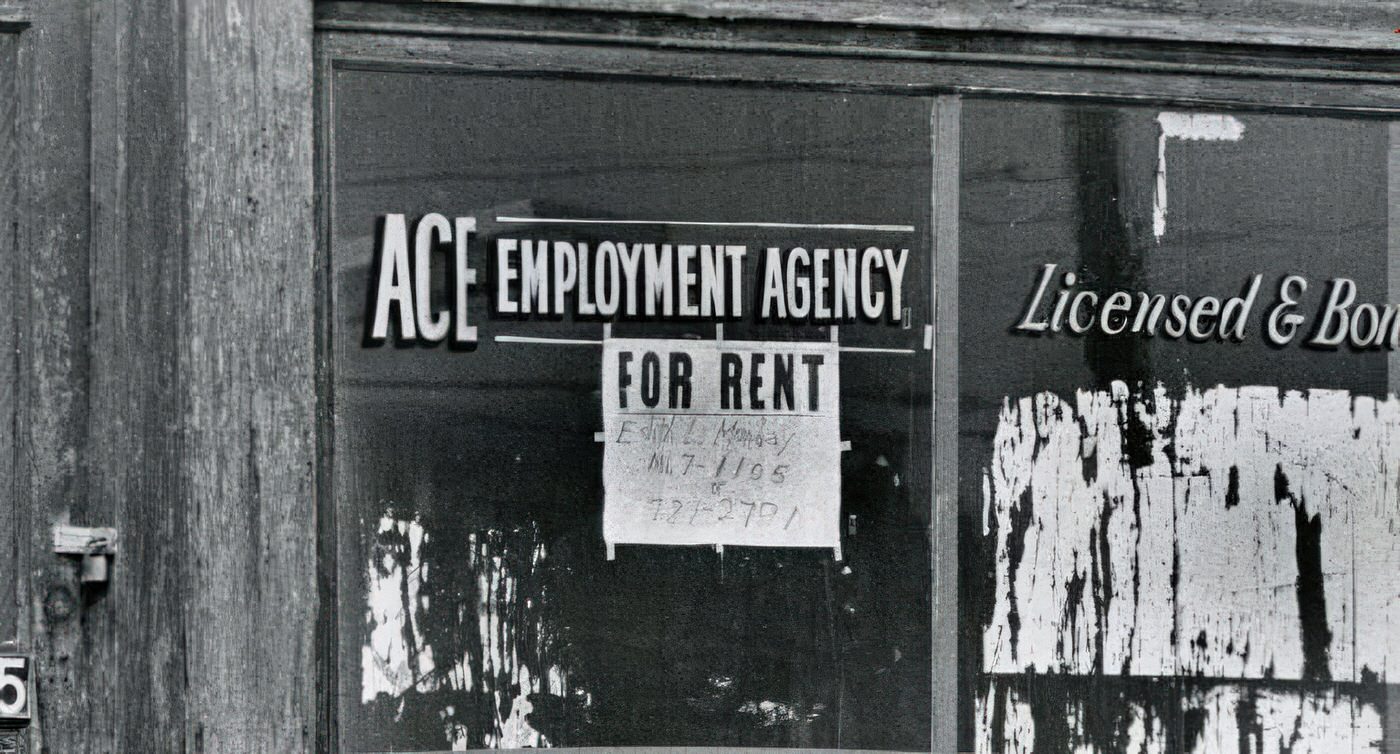

The 1970s brought significant economic shifts to St. Louis, as the city’s traditional manufacturing base faced serious headwinds. Nationally, manufacturing employment experienced two recessions in the early part of the decade, losing 1.5 million and then 2 million jobs, with a recovery in between. While there was an expansion from July 1975 through June 1979 where manufacturing added 3 million jobs nationally, the long-term trend for cities like St. Louis was challenging. By 1970, about a quarter of Americans worked in manufacturing, but this number was declining as the U.S. economy moved more towards service industries. St. Louis, an older industrial city, was particularly affected by this deindustrialization. Many factories and commercial businesses left the city, reducing the tax base and job opportunities.

The automotive industry, a major employer, was hit hard. In 1979, St. Louis area auto plants (Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors) employed around 27,900 workers on average. At that time, these plants were mostly making large cars, pickup trucks, and vans—vehicles with V-8 engines. When gasoline prices soared due to the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, demand for these larger vehicles dropped sharply. This had a severe impact on local production and employment. Chrysler’s Fenton plants, for example, were part of this landscape, though specific production numbers for the 1970s are not detailed in the provided information, the general trend was one of difficulty for plants producing larger vehicles. The Ford Hazelwood plant, which opened in 1948 and had produced various Mercury models and later the Aerostar minivan, also felt these pressures. While its closure was announced much later, the 1970s laid the groundwork for the challenges it would face. General Motors had a large presence with its St. Louis Assembly plant on Natural Bridge Road, which produced Chevrolet Caprice and Impala passenger cars alongside the Corvette. Corvette production hit a St. Louis record of 53,000 in 1979, after reaching 30,000 in 1969. However, the Caprice/Impala assembly line at this plant was closed on August 1, 1980, signaling a shift in GM’s St. Louis operations. Overall, the auto industry in St. Louis lost about two-thirds of its workers between its peak in 1979 and 1982.

In contrast to the struggles in some traditional manufacturing sectors, the aerospace industry remained a point of strength for St. Louis. McDonnell Douglas, a major aerospace manufacturer and defense contractor formed by a merger in 1967, was a key player. During the 1970s, the company began producing the F-15 Eagle fighter jet for the U.S. Air Force (starting in 1972) and the F/A-18 Hornet for the U.S. Navy (starting in 1978) at its Lambert Field facilities. These advanced military aircraft programs provided stable, high-skill employment and solidified St. Louis’s role as a critical center for aerospace manufacturing. This created a sort of split in the city’s manufacturing experience: while older industries tied to consumer goods like large cars faced decline and job losses, the high-tech defense aerospace sector offered a degree of stability and growth. This difference likely led to varying economic fortunes for different parts of the St. Louis workforce.

The brewing industry also saw significant changes. Anheuser-Busch, headquartered in St. Louis, continued to be a dominant force nationally, having become the country’s sales leader in 1957. Their St. Louis brewery was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1967. However, Falstaff Brewing Company, another historic St. Louis brewery that was ranked fourth in the U.S. in 1966, faced difficulties. Falstaff’s strategy of acquiring and refitting older regional breweries proved financially challenging. In 1975, Falstaff was sold, and on November 4, 1977, its St. Louis plant on Gravios Avenue was closed. This left Anheuser-Busch as the only major brewery operating in the city, highlighting a trend of consolidation within the industry.

The economic shifts of the 1970s, including national recessions and the energy crises, made St. Louis particularly vulnerable. The city’s reliance on manufacturing, especially industries like auto production that were sensitive to fuel prices and consumer demand, meant that national downturns had a strong local impact. The overall trend of deindustrialization and the rise of service-based economies in the U.S. presented ongoing challenges for St. Louis as it tried to adapt and compete with rapidly growing “Sunbelt” cities. Unemployment rates in the St. Louis metropolitan area reflected these struggles, though precise year-by-year figures for the entire decade are not consistently available in the provided materials. National data shows recessions in the early 1970s impacting manufacturing employment , and by 1979, while the national unemployment rate was 5.8%, local areas experienced wide variations. East St. Louis, for instance, suffered from extremely high unemployment, potentially reaching 43%. These figures underscore the economic hardship faced by many in the region during this period of transition.

Life in the Gateway City: Culture, Leisure, and Daily Rhythms

Despite economic challenges, St. Louis in the 1970s maintained a lively cultural scene, with diverse music, evolving fashion trends, and popular leisure spots providing a backdrop to daily life. The city’s soundscape was rich, blending soul, blues, jazz, rock, and the newer rhythms of disco. Oliver Sain was a central figure in the soul and R&B scene, known as a bandleader, musician, and producer who ran Archway Studios from 1965 to 2003. His studio became a recording hub for artists like Fontella Bass, Bobby McClure, Ike & Tina Turner, Little Milton, and Albert King. Michael McDonald and Angela Winbush, both with St. Louis connections, also began their impactful careers during this decade.

The jazz scene continued to evolve. The Black Artists Group (BAG), formed in the late 1960s and active into the early 1970s, was a vital force in avant-garde jazz. BAG members such as Hamiet Bluiett, Lester Bowie, Julius Hemphill, and Oliver Lake gained recognition both locally and in New York City’s loft jazz movement. The Human Arts Ensemble, featuring musicians like Charles Bobo Shaw and Joseph Bowie, also made recordings in the early part of the decade. While some older jazz clubs had closed, Willie Akins maintained a well-known weekly performance at Spruill’s. Rock and roll pioneer Chuck Berry, a St. Louis native, continued to perform, and local rock bands like Alice & Omar, Faustus, and Mama’s Pride drew crowds. Blueberry Hill, which opened in the Delmar Loop in 1972, became an important hangout and music venue. Across the river in Edwardsville, Illinois, The Granary served as a major rock club from 1971 for about ten years, known for its multi-level space and energetic atmosphere. These venues and artists ensured that live music remained a vibrant part of St. Louis culture, offering escapes and entertainment even as the city navigated economic difficulties.

Fashion in the 1970s was a bold mix of styles, and St. Louisans would have followed these national and international trends. The decade became known as the “Polyester Decade” due to the widespread use of synthetic fabrics. Early 1970s fashion carried over some late 1960s hippie influences, with an emphasis on handmade-looking details like patchwork, crochet, and embroidery. Prairie dresses, often midi-length with ruffles and floral patterns, were popular. As the decade progressed, disco music brought flashy party wear into vogue, with materials like Ultrasuede, popularized by designer Halston, gaining prominence. Bell-bottom pants and platform shoes were common for both men and women. The leisure suit became a defining, though later often parodied, look for men. Towards the end of the decade, punk fashion began to make its mark, and athletic wear started to be worn as everyday clothing. These changing styles reflected the broader cultural shifts of the era.

Leisure time in St. Louis offered a variety of options. Forest Park remained a key destination, home to the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Saint Louis Zoo, and The Muny outdoor musical theatre, providing accessible cultural and recreational activities. For thrill-seekers, Six Flags St. Louis (originally Six Flags Over Mid-America) opened in Eureka in 1971. Popular early rides included The Log Flume, the River King Mine Train, and the wooden roller coaster, the Screamin’ Eagle, which opened in 1976. Drive-in theaters were still popular hangouts for teenagers and families, with venues like the I-44 Drive-in, the Holiday, and the Airway Twin showing double features. The iconic Gateway Arch, completed in 1965, stood as a major city landmark and tourist attraction. Laclede’s Landing offered a collection of restaurants and nightclubs along the riverfront , and the historic Fox Theatre hosted Broadway shows and concerts. The Missouri Botanical Garden also provided a beautiful escape within the city.

For sports fans, the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team, a significant part of the city’s identity, played through a decade of mixed results. After their successes in the 1960s, the Cardinals did not win any championships in the 1970s, finishing the decade with an overall record of 800 wins and 813 losses. Key players from the 1960s like Bob Gibson and Lou Brock continued into the early part of the decade, but the 1970s were largely a period of transition for the team. Despite not reaching the World Series, the Cardinals provided regular entertainment and a focal point for community pride. The blend of enduring institutions, new attractions, and evolving cultural trends showed that even as St. Louis faced significant urban challenges, its residents found ways to enjoy life and connect with broader American popular culture.

Currents of Change: Activism, Politics, and Social Movements

The 1970s in St. Louis were a period of intense social and political activity, as residents and groups pushed for change on many fronts. Long-standing issues of racial inequality, particularly in education, came to a head, while new movements around labor rights, feminism, LGBTQ+ equality, and environmental protection gained momentum. City leadership, meanwhile, navigated these currents while grappling with the profound economic and demographic shifts affecting St. Louis.

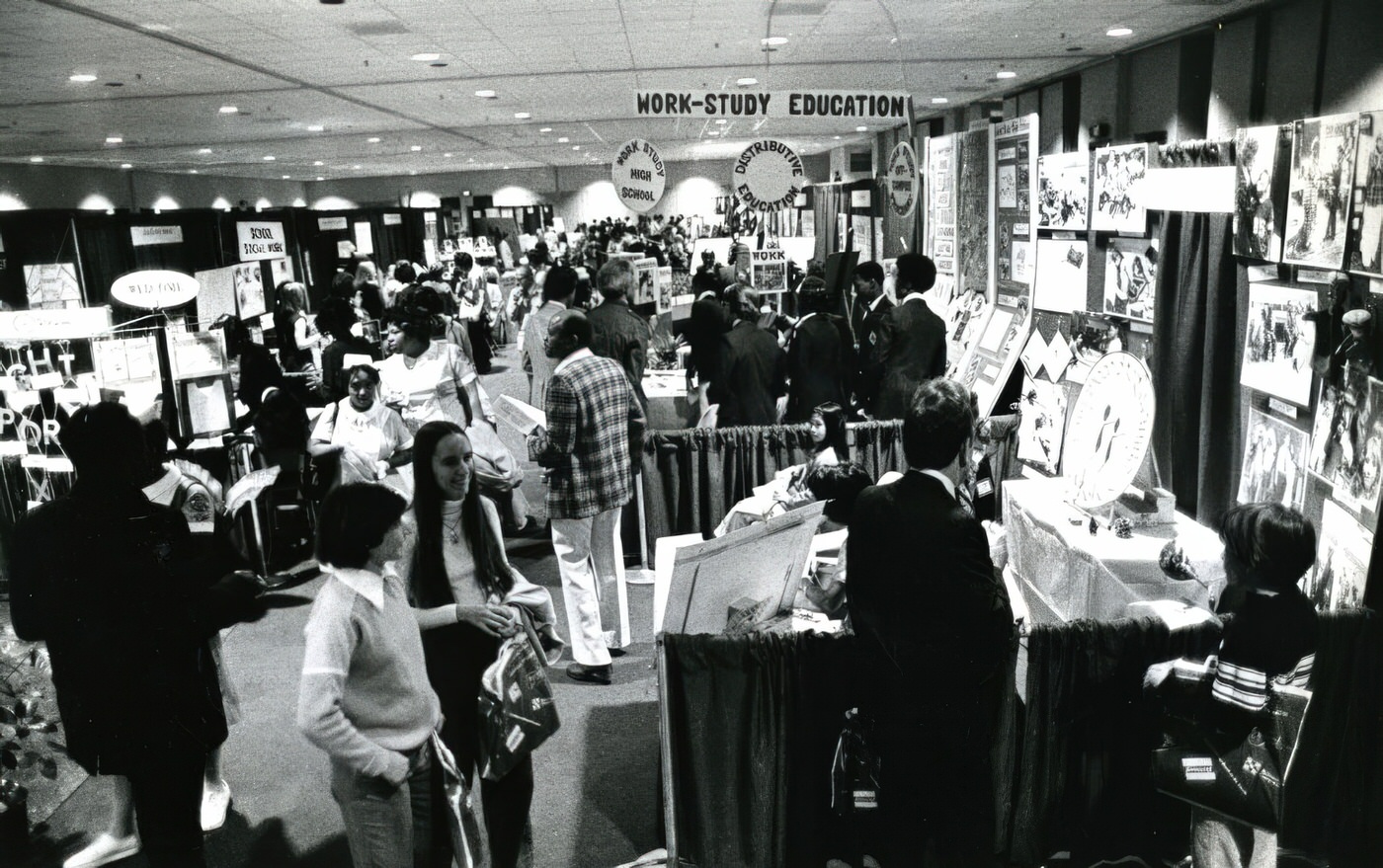

School desegregation was a dominant and often contentious issue. Despite the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling, St. Louis schools remained largely segregated, primarily due to segregated housing patterns. The state of Missouri itself was slow to formally change its constitution, only removing language that required segregated schools in 1976. In 1972, Minnie Liddell and other Black parents filed the landmark lawsuit Liddell v. Board of Education, arguing that the city’s school board and the State of Missouri were responsible for maintaining segregation. This led to a 1975 consent decree in which the St. Louis school board agreed to take steps to desegregate, including increasing the number of minority teachers and establishing magnet schools. However, the legal battles continued throughout the decade. In 1979, a federal judge initially ruled that the school board had not intentionally segregated students, but this decision was reversed in 1980 by the Court of Appeals, which found a system-wide violation and pointed to the state as the “primary constitutional wrong-doer”. The court suggested an interdistrict student exchange program with St. Louis County schools as part of the remedy. Implementing these desegregation efforts involved busing students and creating new magnet programs, but by 1978, two-thirds of Black students in the city and county still attended racially isolated schools. The struggle for equal educational opportunity was a defining feature of the decade, exposing deep-seated racial divides and the complexities of enacting meaningful change.

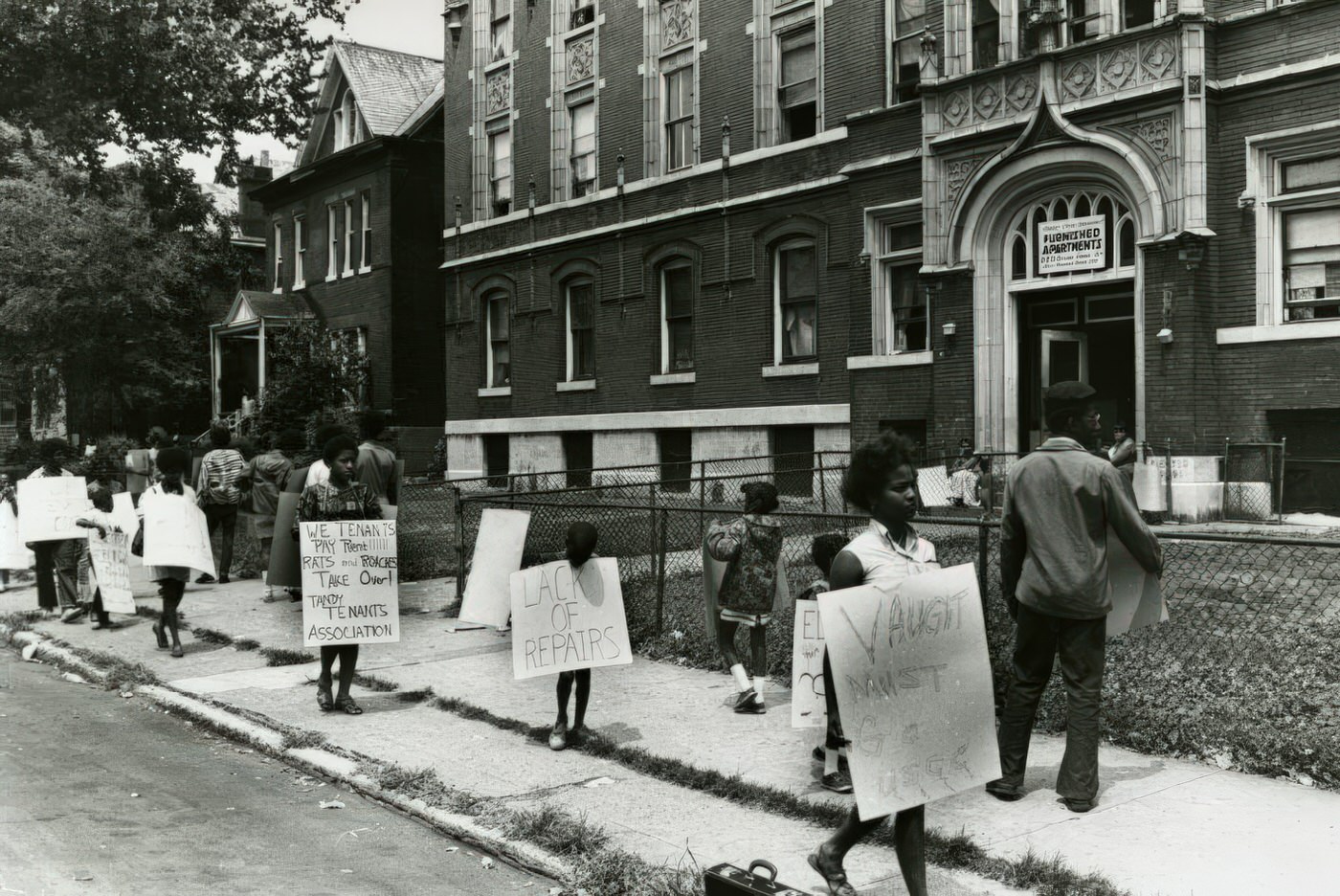

Labor activism also shaped the 1970s in St. Louis. Teachers in the St. Louis Public Schools held their first-ever strike in 1973. The strike lasted four weeks, from January 22 to February 20, with teachers demanding better pay (the typical starting salary in 1972 was $7,200), hospitalization insurance, and a formal grievance procedure. The settlement included an $800 raise paid in two installments and the requested benefits. This strike also highlighted racial dynamics within the teaching profession, as the predominantly White St. Louis Teachers’ Association and the predominantly Black St. Louis Teachers Union-Local #420 were divided during this action, though they would unite for another strike in 1979. A major political battle for labor occurred in 1978 with the campaign against Amendment 23, a proposed “Right-to-Work” law for Missouri. This amendment would have banned contracts requiring union membership or dues as a condition of employment. A broad coalition, including union members, farmers, religious leaders, civil rights groups, women’s organizations, and environmentalists, mobilized against it. Activists, including St. Louisan Jerry Tucker, argued that the law would weaken unions, lower wages, and negatively impact social services. The opposition framed the issue as a matter of fairness, economic stability for working families, and the democratic rights of workers. In November 1978, Missouri voters overwhelmingly rejected Amendment 23 by a 60-40 margin, a significant victory for the labor movement. Public transit also faced a crisis in 1973 when the Bi-State Development Agency, citing financial problems, threatened to halt all bus service. The Missouri General Assembly stepped in, passing the Transportation Sales Tax Act, which allowed St. Louis City and County to implement a half-cent sales tax to fund public transportation, thereby preventing the shutdown.

The 1970s also saw the rise and strengthening of new social movements. Feminist activism became more visible. In St. Louis, lesbian collectives like Woman’s House formed, providing crucial services such as support groups, legal aid, and libraries, though they often faced marginalization and threats of violence. One such women’s center was firebombed in 1975, an event that received little attention from mainstream media. An organization called Red Tomatoe Inc. held pop concerts primarily for women, and one of their songs, “Fight Back,” which addressed violence against women, inspired the “Take Back the Night” march movement. St. Louis held its own “Take Back the Night” march in Forest Park on June 8, 1979, drawing over 1,000 participants. Nationally, the Women’s Strike for Equality on August 26, 1970, marking the 50th anniversary of women’s suffrage, saw a march of about 100 women in St. Louis.

The environmental movement in St. Louis was particularly active and effective during the 1970s, largely spearheaded by the Missouri Coalition for the Environment (MCE), founded in 1969. MCE engaged in numerous campaigns, including a successful 1971 lawsuit concerning floodplain development near the Earth City levee. They played a key role in drafting and passing the Missouri Clean Water Act in 1972 and sponsored national conferences on recycling and endangered species. MCE also successfully litigated to prevent golf course development in Queeny Park (1975), led the campaign for the Construction Work in Progress (CWIP) law (1976) to protect ratepayers from premature charges for power plant construction, and was part of the coalition that stopped the Meramec Dam project in 1978. In 1979, MCE successfully opposed the North-South Distributor Highway (an extension of I-170) which would have destroyed thousands of homes. The Open Space Council, which helped form MCE, continued its work on river cleanups (Operation Clean Stream) and also opposed the Meramec Dam. These activist efforts often put community groups in direct conversation or conflict with city and state authorities, pushing for policy changes and greater public accountability.

Navigating this turbulent decade were two mayors. John H. Poelker (1973-1977) oversaw the creation of the Community Development Agency (CDA) to manage federal funds for neighborhood redevelopment and saw the start of construction on the new Convention Center. However, his administration faced controversy over its policy prohibiting non-therapeutic abortions in city-owned public hospitals, a policy later declared unconstitutional in the Doe v. Poelker case. Mayor James F. Conway (1977-1981) secured funding for a downtown mall and successfully lifted the city’s $25,000 salary cap for personnel. His tenure was marked by disputes with other city officials and significant controversy over the 1979 decision to consolidate hospital services at City Hospital, effectively closing Homer G. Phillips Hospital, a vital institution for the Black community in North St. Louis. This decision, along with his support for the contentious North-South Distributor Highway, fueled public opposition. Throughout the 1970s, the deeply entrenched division between St. Louis City and St. Louis County continued to complicate regional governance and problem-solving, with suburban “home rule” sentiments often clashing with the needs of the declining central city.

Image Credits: The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Mercantile Library, Library of Congress, St. Louis Public Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know