At the beginning of the 1860s, Cleveland was rapidly transforming. The city was experiencing a remarkable surge in population and laying the groundwork for its future as an industrial powerhouse.

Building a City: Public Works, Infrastructure, and Governance

The rapid growth of Cleveland in the 1860s necessitated significant efforts in municipal governance and the development of public infrastructure to support its expanding population and economy.

Governance: Several individuals served as mayor of Cleveland during the 1860s. These included George B. Senter (whose terms were 1859-1860 and again in 1864), Edward S. Flint (1861-1862), Irvine U. Masters (1863-1864), Herman M. Chapin (1865-1866), and Stephen Buhrer (1867-1870). The framework for city government had been influenced by the Ohio General Assembly’s General Municipal Corporation Act of 1852. This act standardized governmental structures for municipalities across the state, establishing administrative boards to oversee various city services and making more official positions elected rather than appointed. A further development in local governance occurred with Ohio’s Metropolitan Police Act of 1866, which created a Board of Police Commissioners responsible for overseeing and funding police operations.

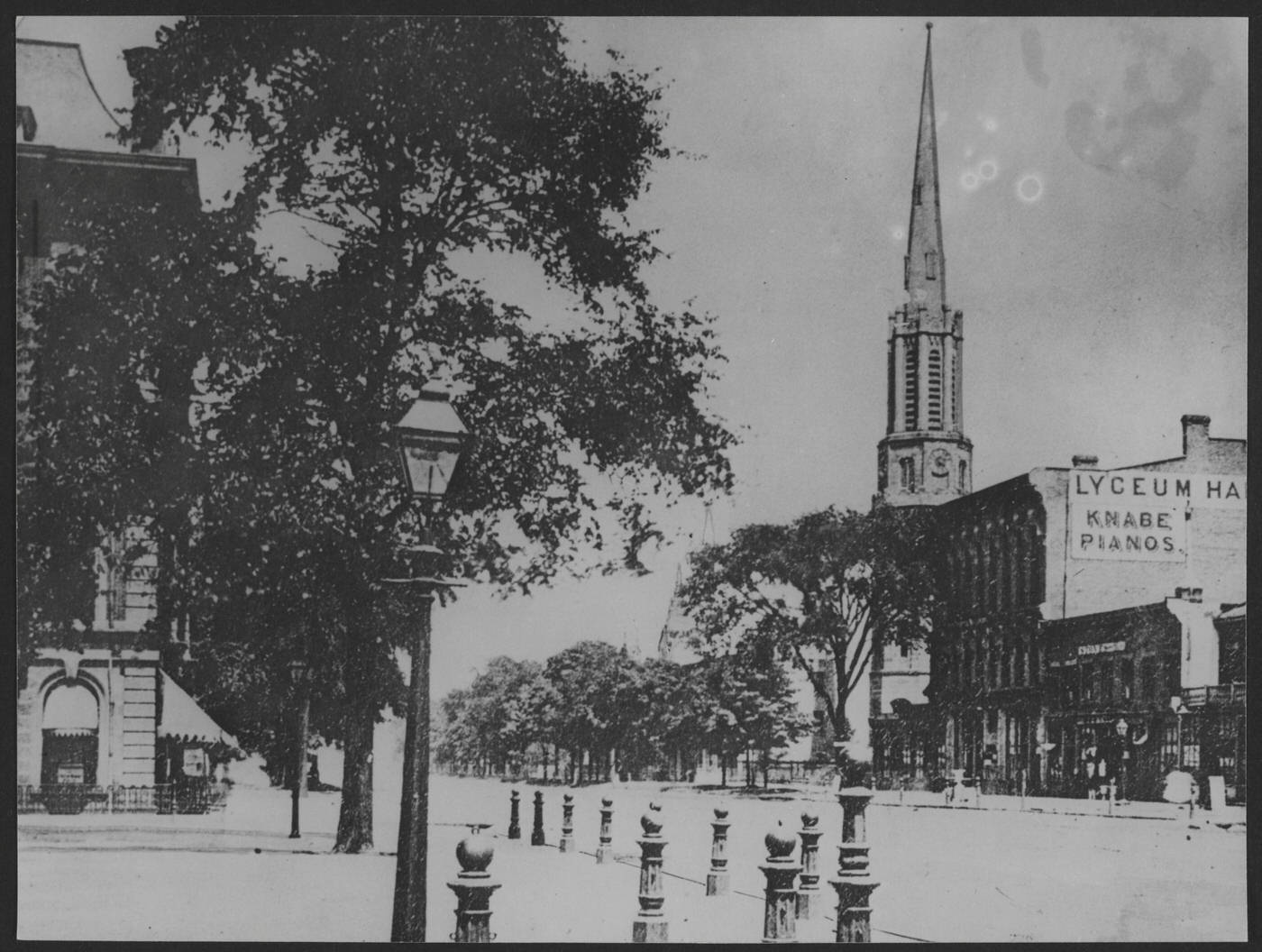

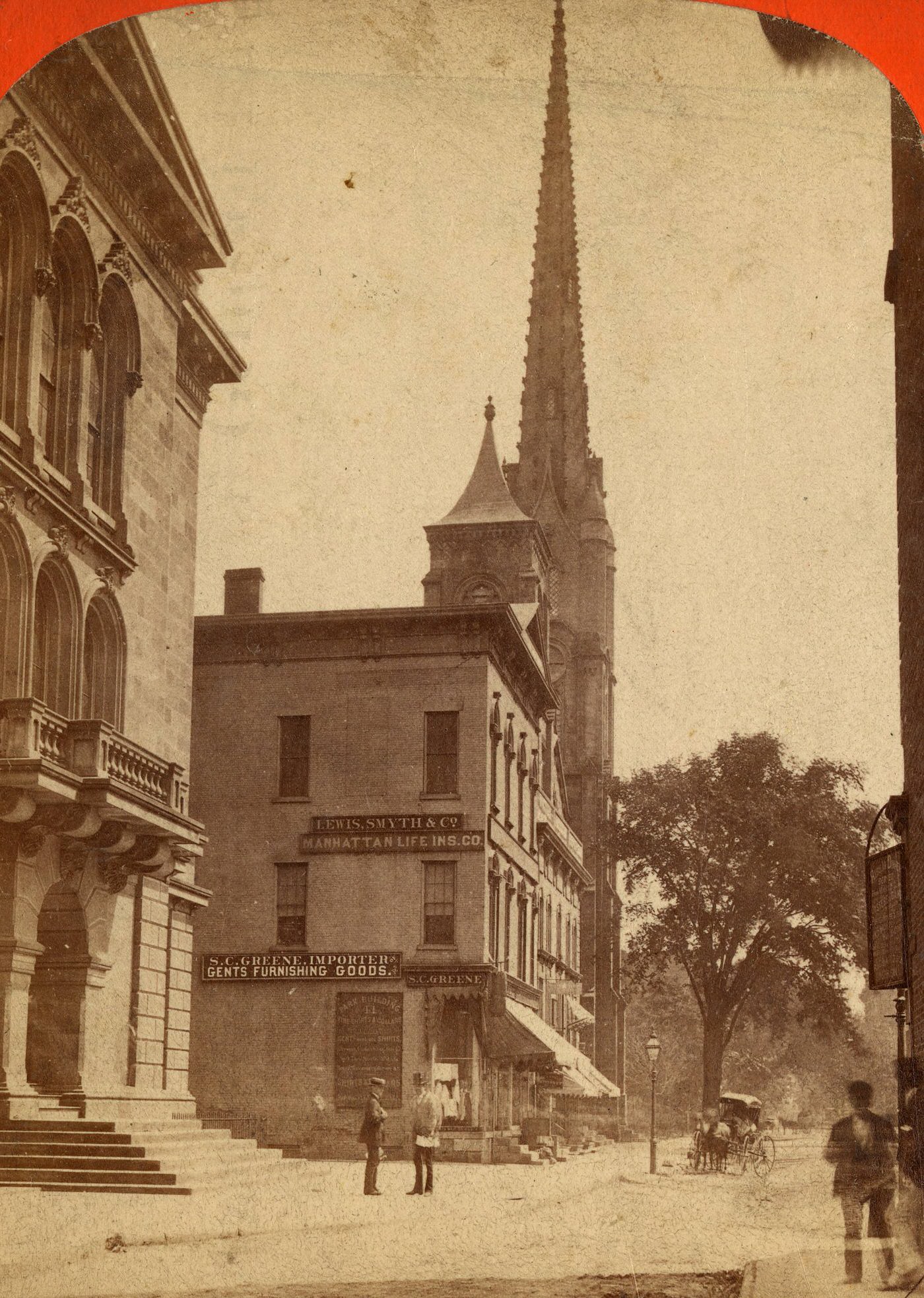

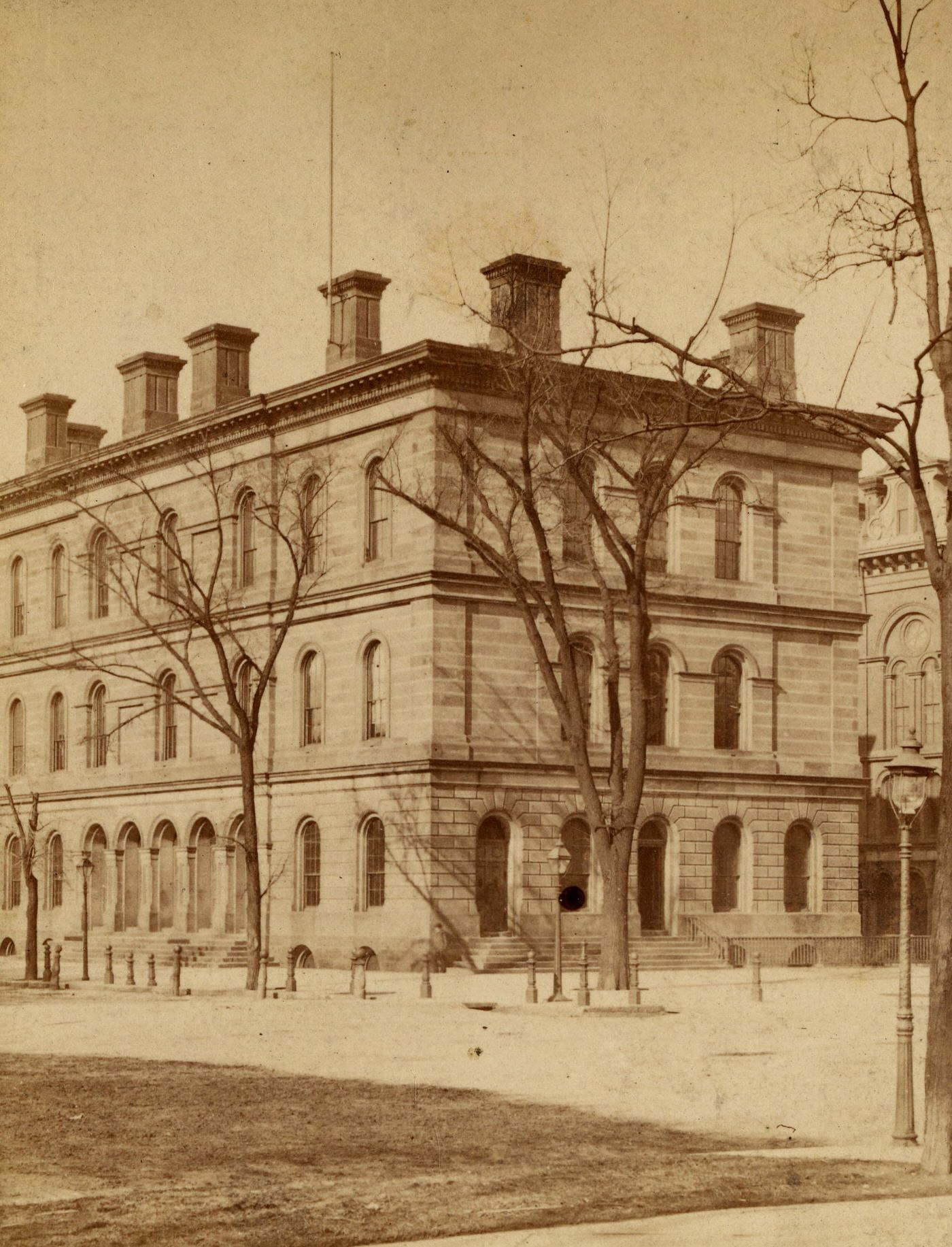

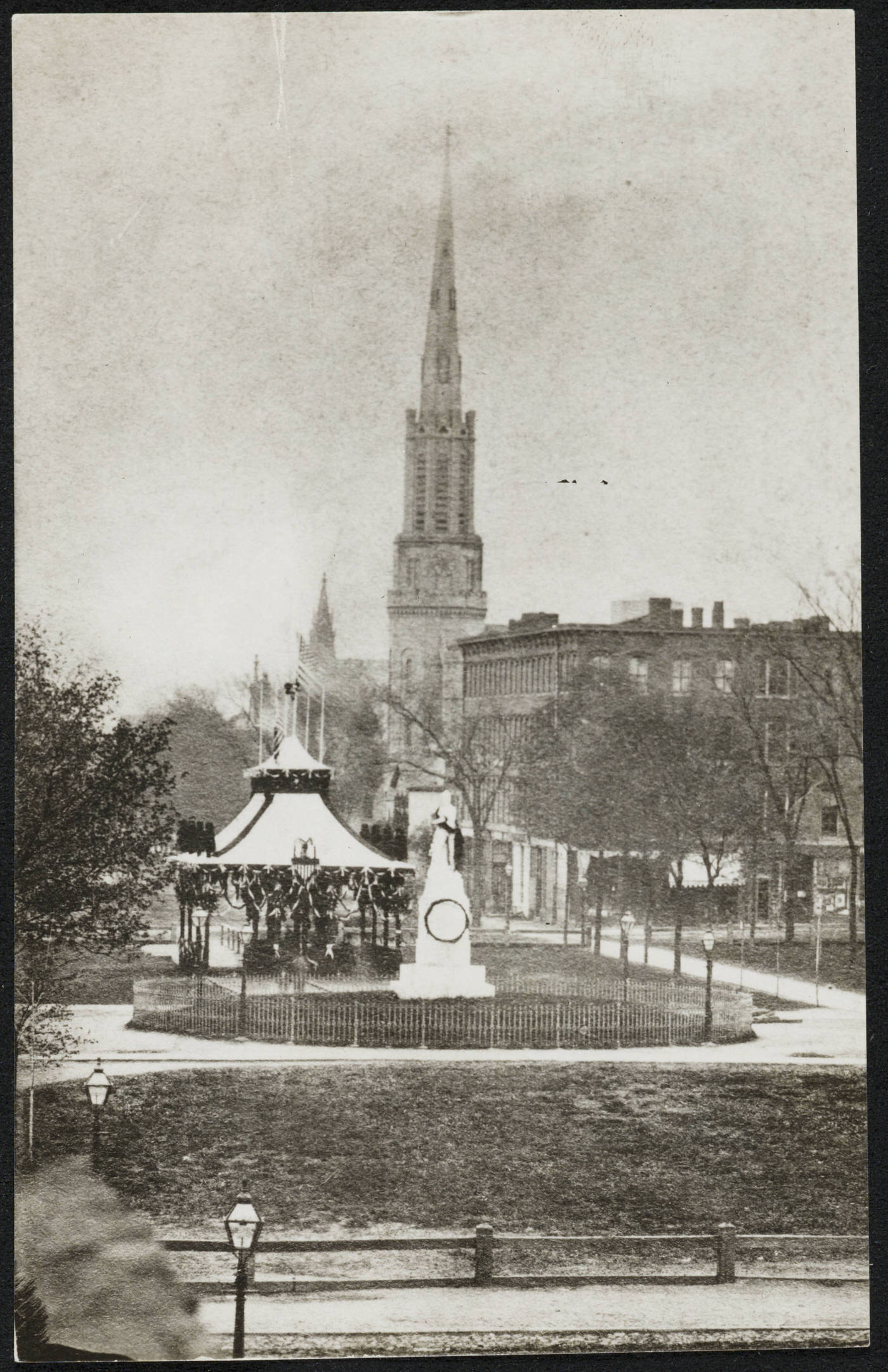

Public Buildings: A key public building project of the decade was the construction of the third Cuyahoga County Courthouse. This new courthouse opened in 1860, prominently situated on the north side of Public Square, on Rockwell Avenue. Built of dressed stone, the three-story structure cost $152,500 and was designed to house various county offices, including those of the auditor, probate judge, recorder, and treasurer, as well as courtrooms and jury rooms. Interestingly, while plans were made and a design competition was held in 1869 for a lavish new Cleveland City Hall, envisioned in the French Second Empire style, this building was ultimately not constructed. Cleveland would not have its own permanent, dedicated city hall building until 1916, occupying leased commercial spaces in the interim.

Street Improvements and Utilities: The 1860s saw continued improvements to Cleveland’s urban infrastructure. As previously noted, horsecar service, a new form of public transportation, was inaugurated in 1860, facilitating movement within the growing city. Efforts to improve sanitation included the construction of the city’s first sewer in 1858. The provision of street lighting also advanced. Gas lighting, supplied by companies such as the Cleveland Gas Light & Coke Co. (which had been organized in 1846), progressively replaced the older, smoky oil lamps on city streets. By 1850, around 50 gaslights illuminated key thoroughfares like Superior Street and River Street. This expansion continued into the 1860s, and the west side of Cleveland began to receive gas lighting around 1867, through the services of the Peoples Gas Light Co..

Bridges: Connecting the east and west sides of Cleveland, divided by the Cuyahoga River, was an ongoing necessity that required the construction and maintenance of bridges. While specific details of major new bridge constructions exclusively within the 1860s are not extensively documented in the provided materials, it is clear that existing structures, like the Columbus Street Bridge (first erected around 1836), were vital. The Seneca Street bridge, another important crossing, had collapsed in 1857, necessitating its replacement in the subsequent period. The development of these public works and infrastructure projects was essential for the functioning and continued growth of Cleveland as it transformed into a major urban center.

The Crucible of War: Cleveland and the Civil Conflict

The 1860s were dominated by the American Civil War, a conflict that profoundly shaped Cleveland’s development, its economy, and the lives of its citizens.

Answering the Call: Public Sentiment, Recruitment, and Local Support

When the Civil War erupted in April 1861, Clevelanders who supported the war, from both the Democratic and Republican parties, came together to form the Union party. This local coalition was dedicated to supporting President Abraham Lincoln and the Union war effort. Public sentiment regarding the war and the issue of slavery was, however, varied. Many settlers from Connecticut had brought anti-slavery ideals to the Western Reserve region of Ohio, but individual views often aligned with political party affiliations.

The city’s newspapers reflected these differing opinions. The Cleveland Leader and the Cleveland Herald and Gazette, both Republican papers, tended to blame southern actions for events like John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859. In contrast, the Democratic Plain Dealer attributed blame to Brown himself and to abolitionist Republicans. While Lincoln won a 58% majority in Cleveland in the 1860 presidential election, this victory did not necessarily indicate widespread, fervent abolitionist sentiment or a universal desire to halt the expansion of slavery.

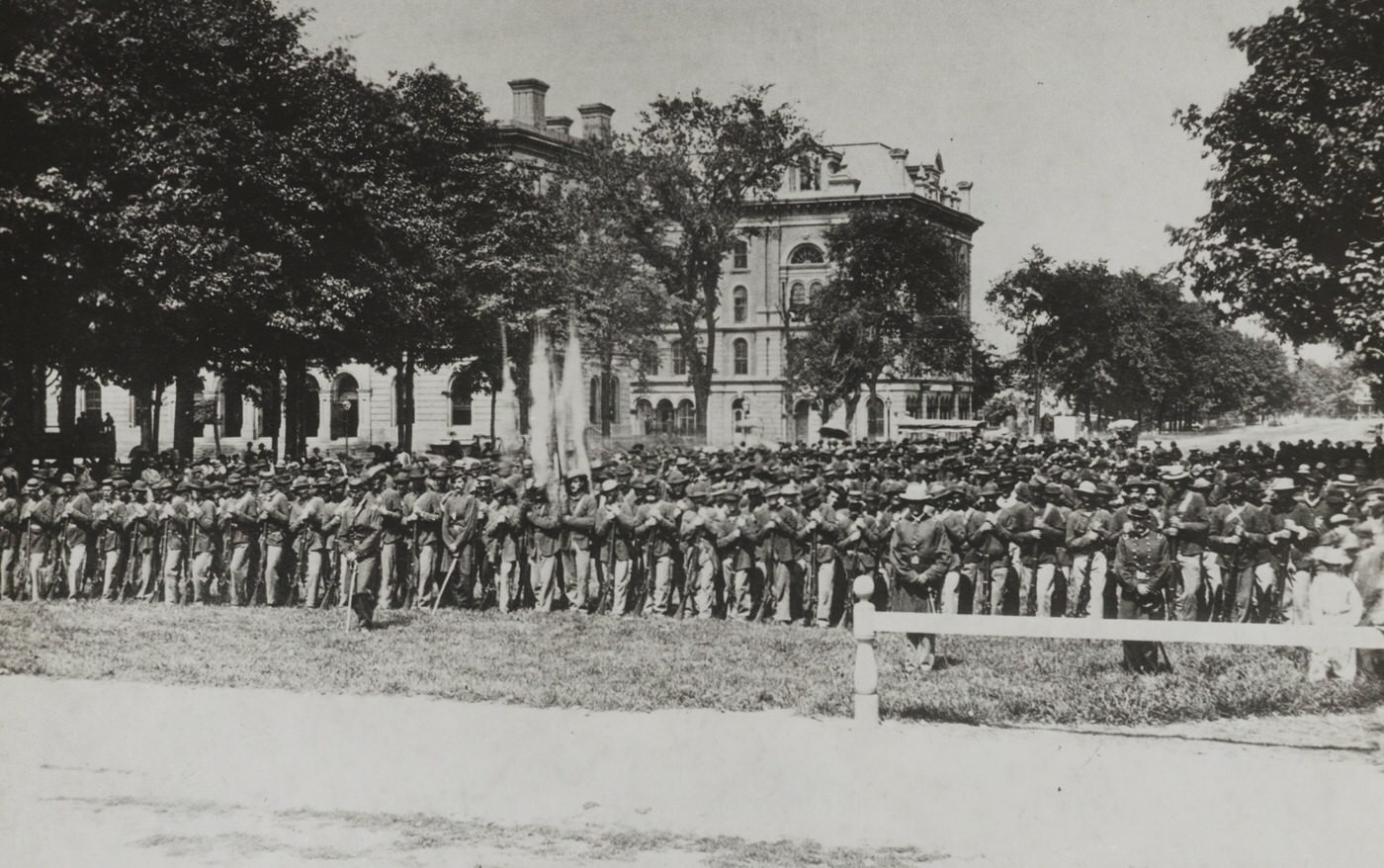

Despite any underlying political differences, Cuyahoga County contributed significantly to the Union Army. Approximately 10,000 recruits from the county served in the military. Ohio, as a state, played a major role, raising nearly 320,000 soldiers. This was the third-highest number of soldiers from any state and the highest number per capita in the Union. Notably, this figure included 5,092 free black men from Ohio who enlisted to fight for the Union.

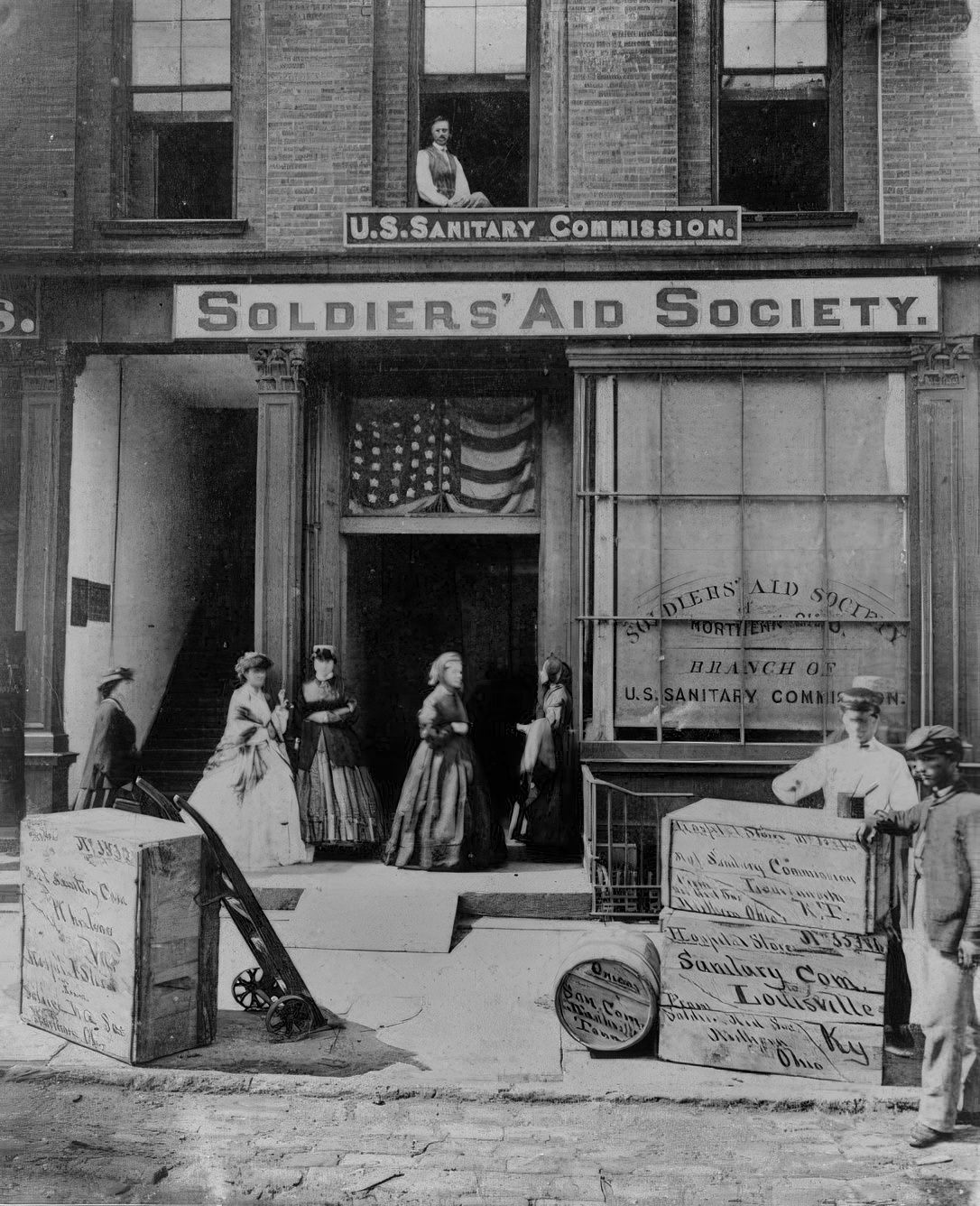

Local government and citizens actively bolstered recruitment efforts. The city of Cleveland, Cuyahoga County, and individual city wards offered financial incentives, known as enlistment bonuses or bounties, to encourage men to join the army. Beyond financial support, wards and townships organized drives to collect essential supplies like food, clothing, and fuel for the families of soldiers. A vital civilian organization was the Soldiers’ Aid Society of Northern Ohio, established in 1861. This society made enormous contributions, providing over $982,000 worth of various supplies to soldiers. They organized fundraising events, such as the Northern Ohio Sanitary Fair in 1864, and in 1863, opened a Soldiers’ Home near the Union Depot to provide food, shelter, and care for soldiers who were on leave or had been discharged. This widespread community involvement demonstrated a strong commitment to the soldiers and the Union cause, even as debates about the war’s ultimate aims continued.

The Home Front Transformed: Camp Cleveland and the U.S. General Hospital

The realities of the Civil War became a tangible part of daily life in Cleveland with the establishment of major military facilities within the city. Camp Cleveland, founded in 1862 in an area now part of the Tremont neighborhood, was the only significant Civil War camp in the vicinity to remain operational throughout the entire conflict. Strategically located on 35.5 acres, the camp benefited from an elevated, flat terrain, access to clean water, and was primarily composed of wooden buildings rather than tents, offering more permanent structures. Its location provided easy access to different parts of the city. Over the course of the war, more than 15,000 soldiers passed through Camp Cleveland, whether for enlistment, training, recovery from illness or wounds, or eventual discharge from service.

Life for new recruits at Camp Cleveland involved a swift transformation. Upon arrival, they exchanged their civilian clothes for the Union Army uniform: trousers of blue wool, dark blue frock coats, and the distinctive dark-blue caps known as “kepis”. Soldiers were housed in barracks, typically 20 feet wide and 60 feet long, with each building accommodating 32 men and equipped with a stove for heating. Sleeping arrangements were basic, consisting of un-planed wooden bunks, with straw serving as mattresses and knapsacks often used as pillows. Meals were brought directly into the barracks and distributed to each man. During their leisure time, soldiers could receive visitors, write letters home, attend religious services, enjoy picnics, listen to music, or venture into Cleveland. “Base-ball” games were also a popular pastime on the parade grounds.

To care for the sick and wounded, the U.S. General Hospital Cleveland (USGHC) was constructed near Camp Cleveland. This extensive 3.76-acre medical complex treated more than 3,000 soldiers during the war. The majority of deaths at the hospital were not from battle injuries but from diseases prevalent at the time, such as malaria, typhoid fever, and measles. The hospital even had a reading room for convalescing soldiers, though it came with strict rules, including a prohibition against spitting on the floor. The presence of these military installations also provided an economic stimulus to the local area, creating employment for carpenters, washerwomen, cooks, and physicians. Camp Cleveland and the USGHC brought the war home to Cleveland, reshaping parts of the city and deeply involving the community in the national struggle.

Industry in Wartime: Factories, Production, and Economic Shifts

The Civil War years triggered an economic boom in Cleveland, dramatically speeding up its change from a town focused on commerce to a city driven by manufacturing. Starting in September 1861, government contracts for war supplies led to a significant upswing in business activity.

Several key industries in Cleveland experienced remarkable growth. Iron production was crucial to the war effort, and the number of incorporated iron companies in the city expanded from three to twelve during the war years. Firms like Otis & Co. played a vital role by supplying railroad iron and axles for gun carriages. A major technological step forward occurred when the Cleveland Rolling Mill Co. in the nearby Newburgh area reorganized in 1864 and, in 1868, installed Bessemer converters for steel production, one of the first such installations in the western United States.

Shipbuilding also flourished. In 1863, Cleveland shipyards built 22% of all ships constructed for use on the Great Lakes. By 1865, this impressive figure had doubled to 44%. This boom was supported by local companies, such as the Cuyahoga Steam Furnace Co., which manufactured iron ship fittings and engine components.

The garment industry saw similar prosperity. The firm of Davis, Peixotto & Co. produced thousands of military uniforms for Union soldiers. A notable development was the establishment of the German Woolen Factory in 1862, which became the first company in Cleveland to manufacture wool cloth.

The war years were also profitable for entrepreneurs like John D. Rockefeller. His partnership with Maurice B. Clark in a consignment firm, which dealt in agricultural products like grain and meat, saw its profits soar from $4,000 in 1860 to $17,000 by the end of 1861, largely due to sales to the government. In 1863, Rockefeller took his first steps into the burgeoning oil refining business. By 1865, Cleveland was home to 30 oil refineries, indicating the rapid growth of this new industry.

The overall economic impact was immense. The Cleveland Board of Trade reported in 1865 that the total value of products manufactured locally reached $39,000,000. This was a striking increase from the $6,973,937 reported for all of Cuyahoga County in 1860. The Civil War, therefore, acted as a powerful catalyst, not only providing the materials needed for the conflict but also fundamentally reshaping Cleveland’s economy and laying the foundation for its future as an industrial giant.

Cleveland’s Wartime Industrial Contributions (1861-1865)

| Industry/Product | Key Companies/Examples | Contribution to War Effort/Growth |

|---|---|---|

| Iron & Steel | Otis & Co., Cleveland Rolling Mill | Supplied railroad iron, gun carriages, axles; adopted Bessemer steel process |

| Shipbuilding | Various Cleveland shipyards | Constructed 22% (1863) to 44% (1865) of Great Lakes ships; supported by local parts manufacturing |

| Garments | Davis, Peixotto & Co., German Woolen Factory | Produced military uniforms; first local wool cloth manufacturing |

| Oil Refining | Early ventures including John D. Rockefeller’s | Growth to 30 refineries by 1865; kerosene for lighting, lubricants |

| Agricultural Produce | Clark & Rockefeller (consignment) | Supplied grain, meat for government use; significant profit increase |

Forging Connections: Railroad Expansion and Port Activities

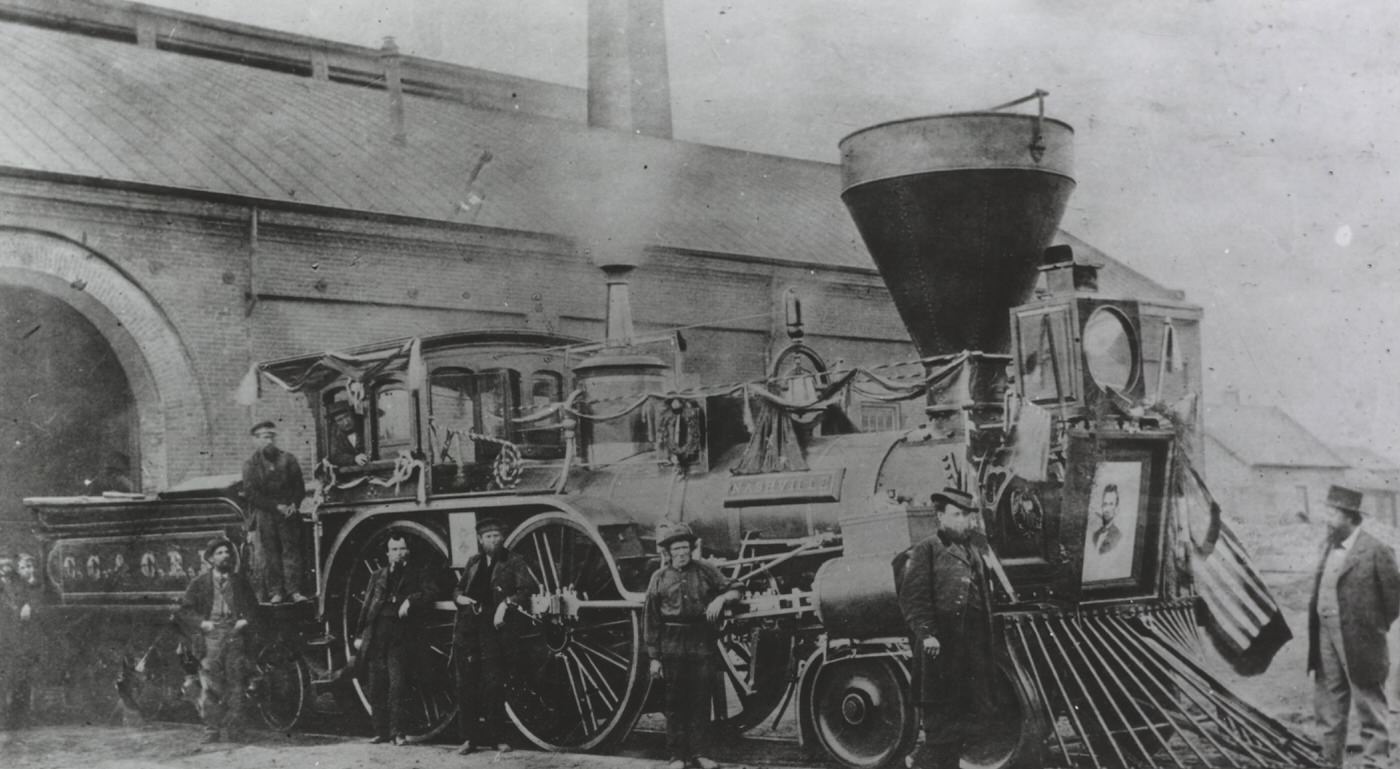

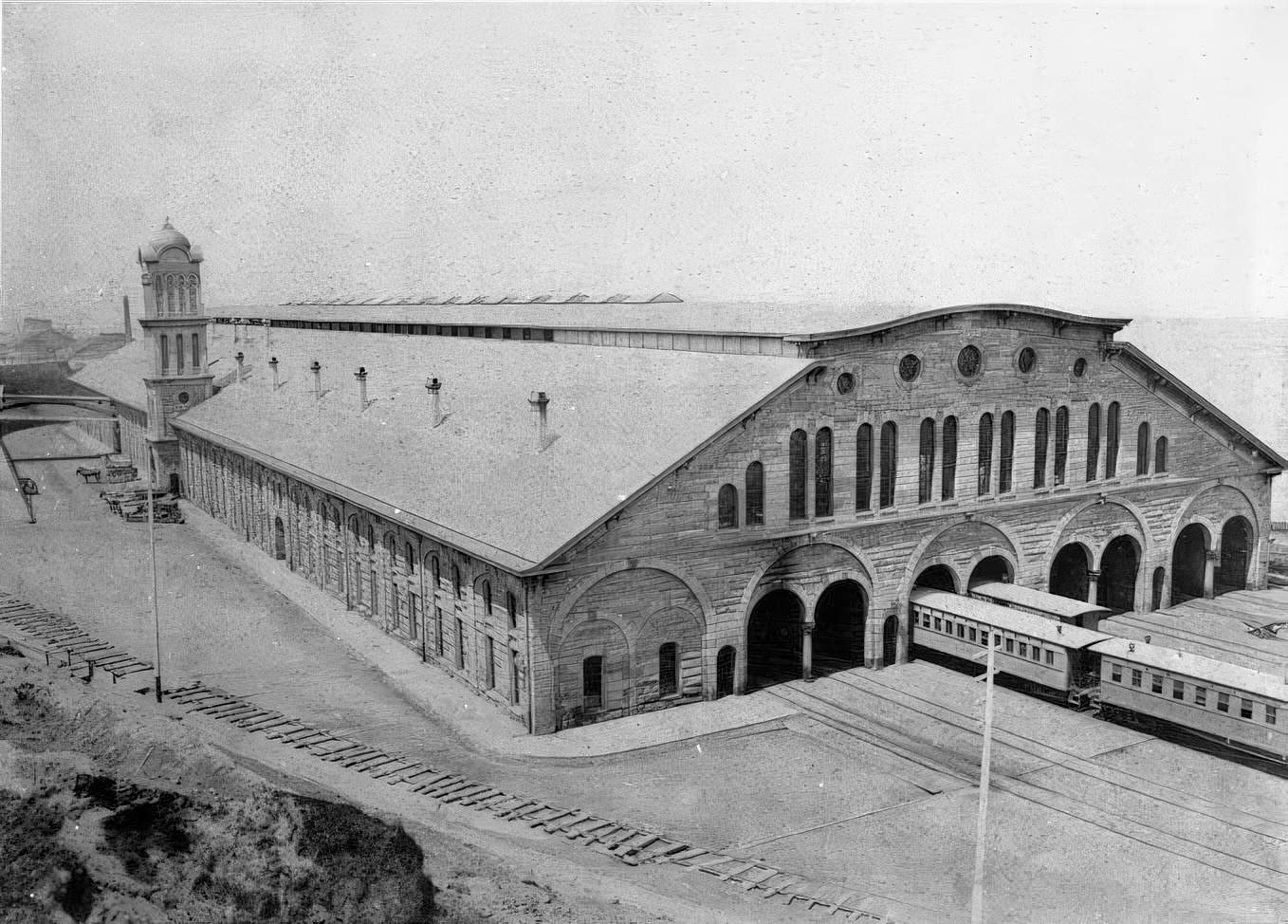

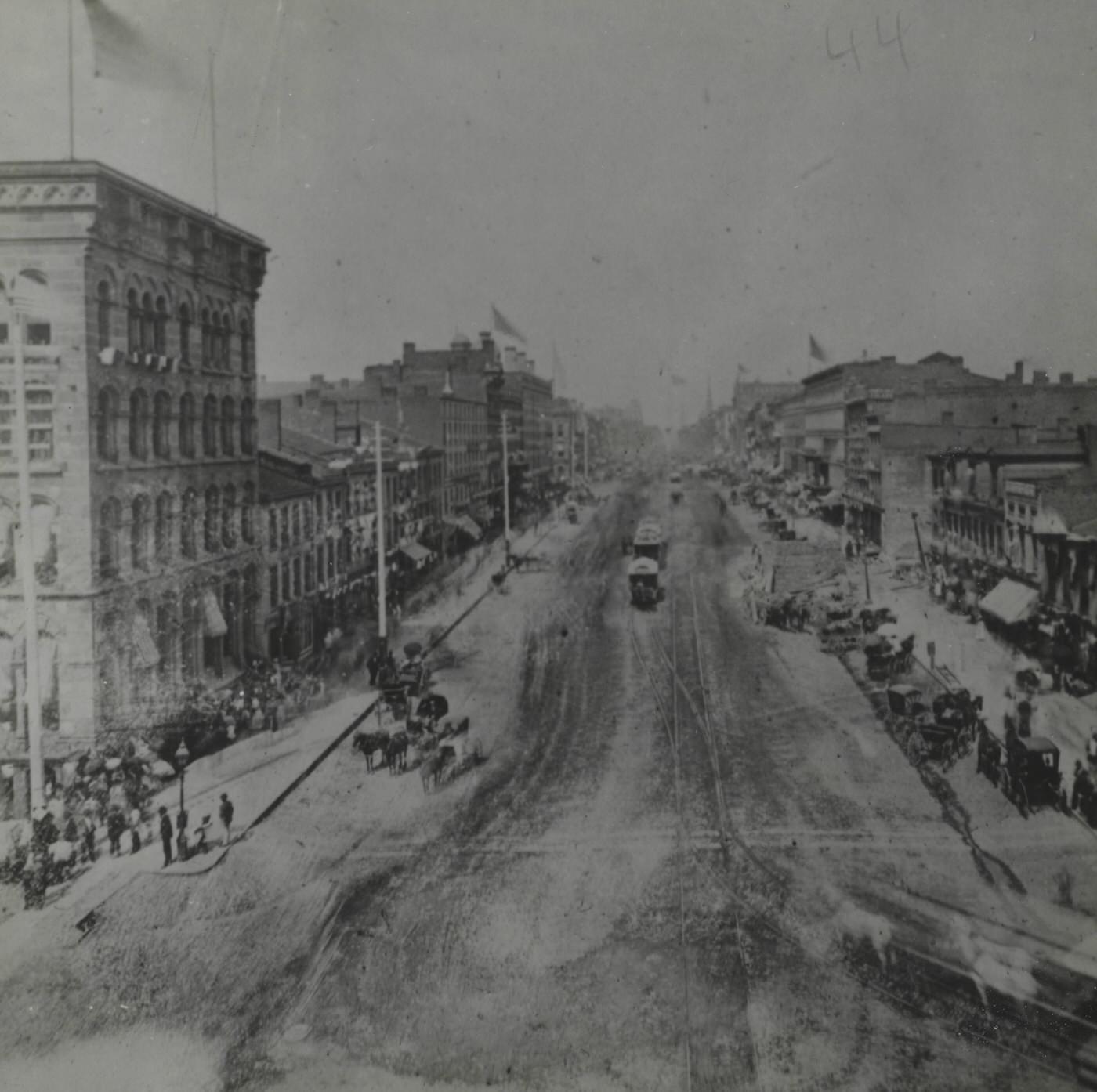

Cleveland’s role as a critical transportation hub was significantly strengthened during the 1860s. By 1870, six different railroad lines converged on the Cleveland waterfront, connecting the city to various points inland. A major milestone was the arrival of the first through train service from New York City in 1863, greatly improving connectivity to the East Coast. Railroads were rapidly becoming the dominant mode for transporting both goods and people, surpassing the canals that had previously been so vital. The Civil War itself underscored the strategic importance of railroads for moving troops and vast quantities of materials, which further accelerated this shift away from canal-based transportation. Recognizing their growing importance, Cleveland developed railroad repair shops during the 1860s to service the increasing rail traffic.

Simultaneously, Cleveland’s maritime activities on Lake Erie boomed. The discovery and exploitation of rich iron ore deposits in the upper Great Lakes region (Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota) during the 1860s transformed Cleveland into a central “hub” for the Great Lakes maritime industry. This was a significant shift, as cities like Buffalo and Chicago had previously dominated lake trade, largely due to their extensive grain shipping interests. The volume of iron ore flowing into Cleveland was substantial; during 1864-1865, over half of all the ore mined around Lake Superior was shipped to the city’s docks.

The Cuyahoga River was the heart of this bustling port activity. Its banks were lined with shipyards, docks, and a growing number of industries, including oil refineries and steel mills, which relied on the river for transportation and water. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, shipyards located on the west side of the river were highly productive, turning out hundreds of vessels of various types. A notable innovation occurred in 1869 when the Cleveland shipbuilding firm of Peck & Masters launched the R.J. Hackett. This vessel was the first ship specifically designed for the efficient transport of iron ore, marking an important development in Great Lakes shipping.

However, this intense industrial and shipping activity came at an environmental price. The Cuyahoga River became heavily polluted with industrial waste and sewage. By 1881, the river was described by Mayor Rensselaer R. Herrick as “an open sewer through the center of the city”. The pollution was so severe that the first recorded fire on the Cuyahoga River occurred in 1868, a grim indicator of the environmental impact of rapid industrialization.

Despite these environmental concerns, the economic benefits of this enhanced connectivity were undeniable. The Cleveland Board of Trade reported a dramatic surge in the value of locally produced products. From an estimated $7 million in 1860, the value jumped to $39 million by 1865. This increase was a direct result of expanded manufacturing and trade, all facilitated by the growing railroad network and the busy port on Lake Erie. The 1860s thus cemented Cleveland’s position as a vital transportation and industrial center, though it also began to reveal the serious environmental challenges that would accompany such rapid growth.

Population and Early Layout

In 1860, the official count for Cleveland’s population was 43,417 people. Cuyahoga County, the larger area where Cleveland is situated, was home to 178,033 residents. This number represented a dramatic increase from just ten years earlier. Between 1850 and 1860, Cleveland’s population had more than doubled, growing from around 17,000 to over 44,000 inhabitants. This rapid expansion was largely driven by new economic opportunities and a steady stream of immigrants, making Cleveland one of the nation’s more attractive urban centers by the start of the decade. The city prided itself on offering modern conveniences of the era, such as reliable transportation options, developing public utilities, and essential emergency services, including police and firefighting forces.

Despite this growth and its burgeoning reputation, Cleveland’s physical development had been somewhat unplanned in its early years. The swampy conditions near the shores of Lake Erie meant that initial settlement patterns were often haphazard, with many early arrivals choosing to build on higher, drier ground further from the lake. Even Public Square, a ten-acre piece of land set aside as the city’s only dedicated parkland, found itself increasingly hemmed in by new construction as the city expanded. The city’s educational infrastructure was also evolving; by 1860, the school system had been consolidated, with a superintendent overseeing operations and high schools established on both the east and west sides of the Cuyahoga River. This rapid influx of people and the quick pace of development created a dynamic environment but also placed considerable strain on existing resources and urban planning, a challenge that would persist throughout the 1860s.

Daily Existence in 1860s Cleveland

Life in Cleveland during the 1860s varied greatly depending on one’s social standing and occupation. The city was a place of contrasts, from grand avenues to crowded working-class neighborhoods.

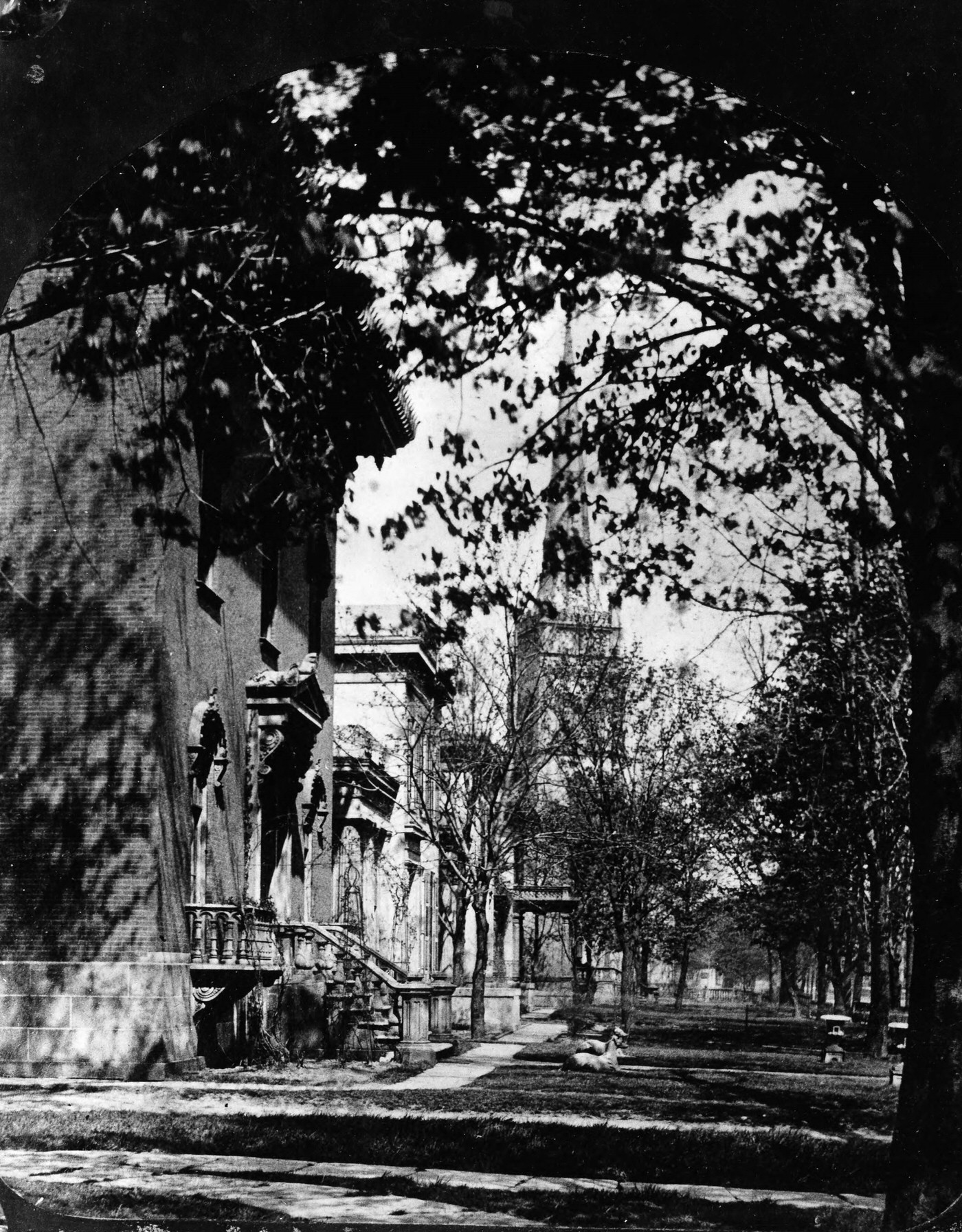

The types of homes Clevelanders lived in during the 1860s clearly reflected the city’s growing social and economic divisions. The most affluent residents often built large, impressive houses in the newly emerging suburban areas, made accessible by the horsecar lines. Euclid Avenue, particularly the stretch between what is now East 12th Street and East 40th Street, became known as the preferred address for the city’s elite. This thoroughfare was lined with stately Victorian mansions, showcasing the wealth of their owners. Examples of such grand homes from the Civil War era included the Italianate-style residence of John D. Rockefeller, built in 1866, and the Anson Stager house, constructed in 1863.

In striking contrast, and often in close physical proximity to these opulent homes, were the dwellings of the working class. Typical working-class housing consisted of wood-frame buildings, usually one-and-a-half or two stories tall. These structures were often built two to a standard city lot, with their gabled ends facing the street, creating rows of similar houses. As Cleveland’s population density increased throughout the decade, these homes naturally became more crowded.

For many immigrant families and other working-class Clevelanders, housing conditions were often rudimentary. Their homes, frequently lacking basic amenities like running water or electricity, were typically located within walking distance of the factories and mills in industrial areas such as the Flats (the Cuyahoga River valley) and the Tremont neighborhood. Poverty was a common experience in these areas, and contemporary accounts often described the living conditions as dreadful. Unlike some eastern cities such as Philadelphia or Baltimore, Cleveland had very few row houses. The prevailing pattern was the individual detached house, even for modest dwellings. This was partly due to a sense of ample space for expansion in what was still considered the “new West”.

Architecturally, the Second Empire style, recognizable by its distinctive mansard roof, did make an appearance in some Cleveland homes during the 1860s, but it did not become a dominant or widespread style in the city. The overall housing landscape of 1860s Cleveland thus presented a clear picture of a society with increasing disparities in wealth and living standards, a direct consequence of its rapid industrialization and population growth.

The Expanding City: Population Surges and Annexations

The 1860s were a period of dramatic expansion for Cleveland, not just in its economy, but also in its population and physical size. Newcomers arrived in large numbers, adding to the city’s diverse character.

Cleveland’s population continued its steep upward trajectory throughout the 1860s. Starting at 43,417 residents in 1860 , the city grew to include 92,829 people by 1870. By that year, Clevelanders made up 70% of Cuyahoga County’s total population. This remarkable growth was fueled by two main streams: immigrants arriving from other countries and people moving from rural areas to the city in search of employment in its rapidly expanding industries.

To manage this influx of people and to broaden its tax base, Cleveland began to expand its geographical boundaries. This was achieved by annexing adjacent villages and townships. During the 1860s, specific land acquisitions included a portion of Brooklyn Township, a process initiated on February 16, 1864, and officially confirmed on September 6, 1864. Later in the decade, on February 28, 1867, parts of both Brooklyn and Newburgh townships were annexed, with final approval granted on August 6, 1867.

The nearby village of East Cleveland, which had formally organized in 1866 , was later absorbed by Cleveland in 1872. Newburgh, which had been a rival settlement to Cleveland in earlier years, saw its central area annexed in 1873, although some parts had been incorporated into Cleveland even before that. This process of annexation was common. Smaller communities on the city’s edge often lacked the amenities that Cleveland could offer, such as paved streets, established schools, and organized police and fire protection, making amalgamation attractive to their residents and to an expansion-minded Cleveland. The significant increase in population and the corresponding territorial growth were closely linked, as more people necessitated more land and resources. These changes consolidated Cleveland’s status as the primary urban center in the region, but also brought new administrative and social complexities.

Movement and Early Connections: Horsecar Lines and Emerging Suburbs

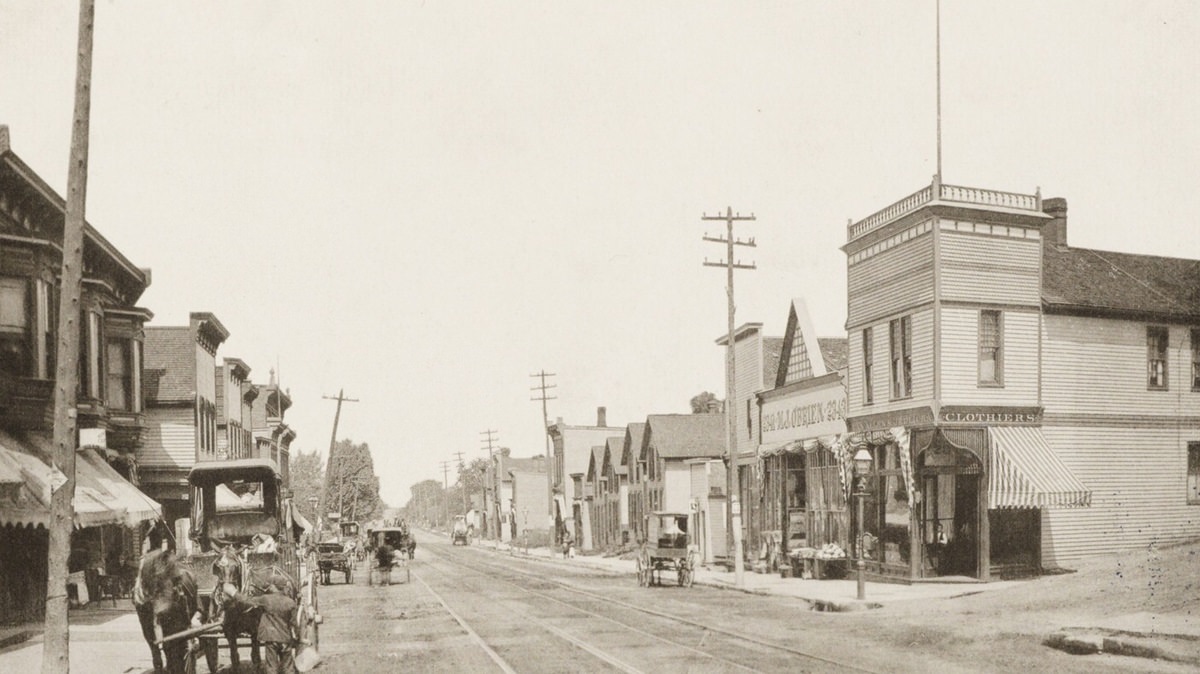

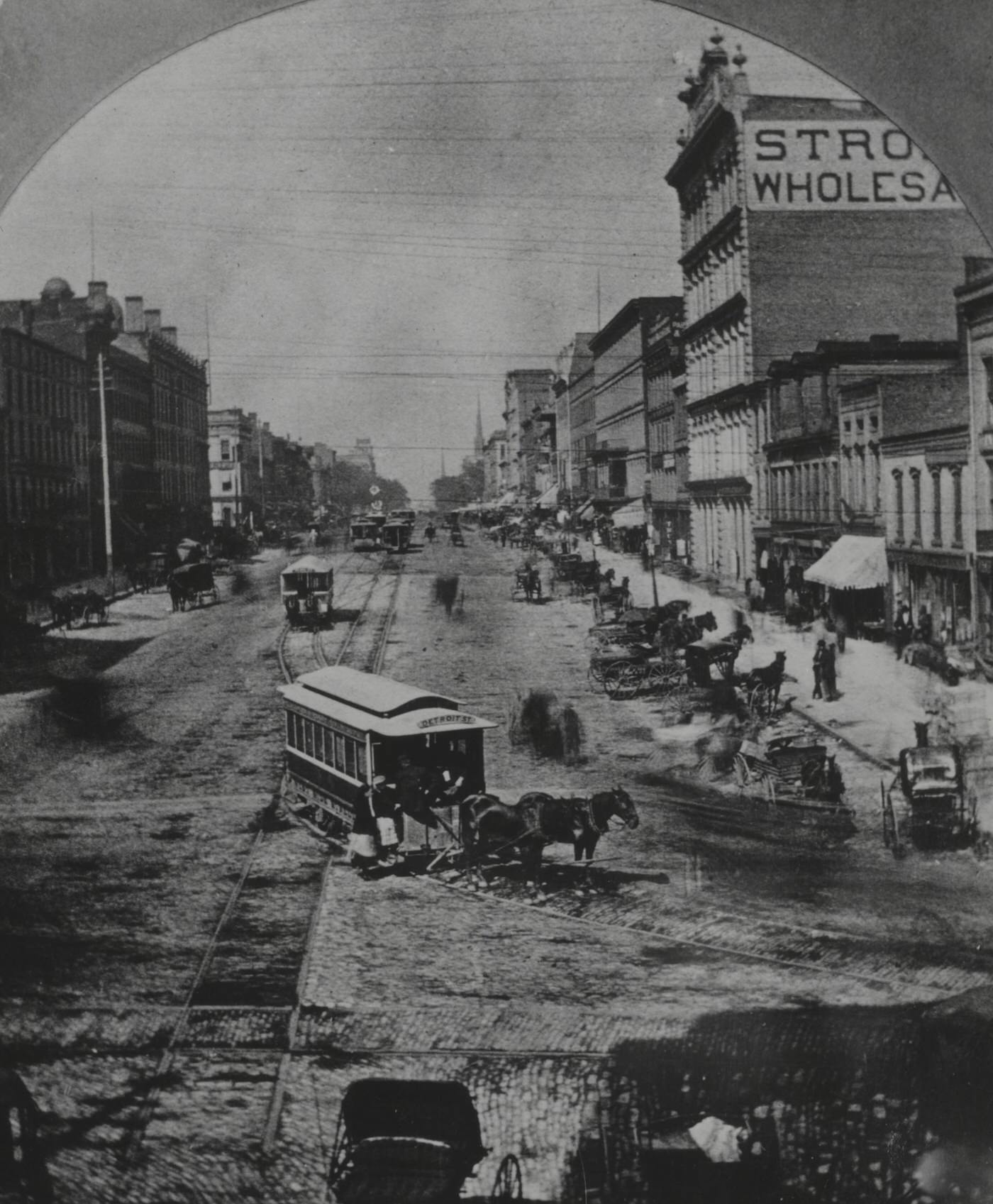

A key innovation that began to reshape Cleveland in 1860 was the introduction of horsecar service. These were essentially streetcars pulled by horses along rails laid in the streets, offering a smoother and more organized form of public transit. The East Cleveland Railway Company had commenced construction of such a line in 1859, and regular service officially started on September 5, 1860. This first line ran from Bank Street (now West 6th Street) to Willson Avenue (now East 55th Street).

Other companies soon followed. The Kinsman Street Railway Company, which operated a line on what is now Woodland Avenue, also organized in 1859. On the other side of the river, the West Side Railway Company was established in 1863, opening a route along Detroit Street the following year. This new transportation technology was not just a convenience; it actively encouraged the city’s first wave of suburban development. Wealthier residents began to build large homes on land up to three miles from the increasingly busy downtown area. These new suburban communities, such as the village of East Cleveland (established in 1866), often formed their own local governments to gain access to city-like amenities, including paved streets and police protection, which the more rural township governments could not yet provide. Further extending the reach of public transport, suburban steam lines like the Cleveland & Newburgh “Dummy” Railroad (organized in 1868) and the Rocky River Railroad (organized in 1867) connected to the ends of the horsecar lines. These steam-powered lines, sometimes with locomotives disguised as passenger cars to avoid scaring horses, carried city dwellers to rural retreats and supported the growth of these early outlying communities. The advent of the horsecar thus marked a pivotal moment, enabling Cleveland to expand outward and altering the very fabric of urban and suburban life.

Immigrant Streams: German, Irish, and Other Communities Arrive

A substantial portion of Cleveland’s population boom in the 1860s was due to immigration from other countries. In the period leading up to and during the early part of the decade, these immigrants came predominantly from Western Europe. Among these, Germans and Irish were particularly significant groups.

Germans constituted one of Cleveland’s largest and most influential immigrant communities. They had begun arriving in considerable numbers back in the 1830s. Early German settlements were established along Lorain Street on the city’s west side and in the vicinity of Garden Street (later Central Avenue) on the east side. Although immigration slowed during the Civil War, it picked up again substantially afterward. German immigrants brought valuable skills to Cleveland; many were skilled craftsmen, brewers, and they also introduced advanced farming techniques to the area. They were active in establishing their own community institutions, including numerous German Catholic and Protestant churches, as well as German-language schools.

Irish immigrants also formed a major component of Cleveland’s population. Their numbers had swelled significantly since the late 1840s, largely as a result of the Great Famine (Potato Famine) in Ireland. Many of these arrivals hailed from County Mayo. Initially, Irish laborers found work constructing the Ohio & Erie Canal, and later, they became a vital part of the workforce in the city’s burgeoning steel mills. By 1870, the Irish population in Cleveland had reached nearly 10,000, accounting for about 10% of the city’s total inhabitants. They tended to settle in distinct neighborhoods, often on the west side, in areas that acquired names like “Irishtown Bend” (near the canal), the “Achill Patch,” and “The Angle.” The Angle was a well-known Irish enclave centered around St. Malachi Parish, which was founded in 1867. The cause of Irish independence also found support in Cleveland, with the Fenian movement having a presence in the city during the 1860s.

The 1860s also marked the beginning of a shift in immigration patterns. During this decade, new groups began to arrive, including immigrants from Italy and Eastern European countries such as Czechoslovakia and Hungary. This signaled a change that would further diversify the city’s demographic makeup in the coming years. The influx of these newcomers was noticeable enough that by 1874, Cleveland stationed police officers at its railroad stations specifically to count and offer assistance to the arriving immigrants.

These immigrant communities often formed tight-knit ethnic enclaves. New arrivals frequently lived in crowded rooming houses or clustered together in specific neighborhoods, particularly in the low-lying industrial area known as the Cuyahoga Valley, or “The Flats”. The 1860s, therefore, was a period where established immigrant groups like the Germans and Irish continued to grow and solidify their communities, while the city also began to welcome the first waves of new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. This increasing diversity was a vital source of labor for Cleveland’s industries and greatly enriched its cultural life, though it also presented challenges related to housing and social integration.

| Immigrant Group | Primary Arrival Period (relative to 1860s) | Key Settlement Areas | Common Occupations/Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germans | Established, ongoing | West Side (Lorain St.), East Side (Garden St.) | Skilled crafts (cabinetmaking, musical instruments), brewing, farming |

| Irish | Established, ongoing | West Side (Irishtown Bend, The Angle, Achill Patch) | Laborers (canal, steel mills), police force |

| Italians | Beginning in 1860s | Often in Cuyahoga Valley initially | General labor in growing industries |

| Hungarians | Beginning in 1860s | Often in Cuyahoga Valley initially | General labor in growing industries |

| Czechoslovakians | Beginning in 1860s | Often in Cuyahoga Valley initially | General labor in growing industries |

Work and Wages: Common Occupations, Pay, and Early Labor Movements

The daily work of Clevelanders in the 1860s was increasingly tied to the city’s expanding industries. Common occupations included jobs in iron and steel manufacturing, shipbuilding, the new oil refineries, garment making, flour milling, and work related to the railroads. While factories were growing, traditional craftsmen in small shops continued to produce items like farming tools and household furnishings. In 1860, for instance, records show that 374 men were employed in bar and sheet iron establishments within Cuyahoga County.

Wages for these workers were generally low, and working hours were long. Data from the 1850s indicates that an unskilled workingman might earn between $4 and $5 per week for working 60 or more hours. Women in the workforce typically earned even less. The economic boom brought by the Civil War also led to significant inflation; between 1860 and 1864, the cost of living rose by 100%, while wages only increased by about 50%. Some accounts from the 1860s describe factory boys, around 14 years old, earning $1 to $1.20 per day for piece-work, such as filling bottles. Adult men in the same factory might earn between $1.35 and $3 per day.

Nationally, working conditions in factories during this period were often harsh and unsafe. A typical workday was long, usually lasting ten to twelve hours, and the tasks were often repetitive and monotonous due to the division of labor for efficiency. While specific details for Cleveland’s factories in the 1860s are scarce, it’s known that by 1910, working conditions in Cleveland’s large garment factories, though somewhat better than in New York City’s notorious sweatshops, still involved low wages and long hours for the employees.

In response to these challenging conditions, early efforts at labor organizing continued and gained some momentum in Cleveland during the 1860s. The Typographical Union, Local 53, which is Cleveland’s oldest continuously existing trade union, received its charter in 1860 and officially reformed in 1868. Workers in other skilled trades also organized; plasterers, bricklayers, and coopers (barrel makers) formed unions in the late 1860s. The Coopers’ Union was particularly active and played a prominent role in the local labor movement, engaging in strikes in 1867 and again in 1869 to protest wage reductions or other grievances. In 1868, a broader organization called the Workingmen’s Assembly was formed, bringing together delegates from various unions and city wards. The combination of low pay, long hours, the rising cost of living, and the inherent dangers of industrial work fueled this growing labor restlessness and the strengthening of these early unions as workers sought to collectively improve their circumstances.

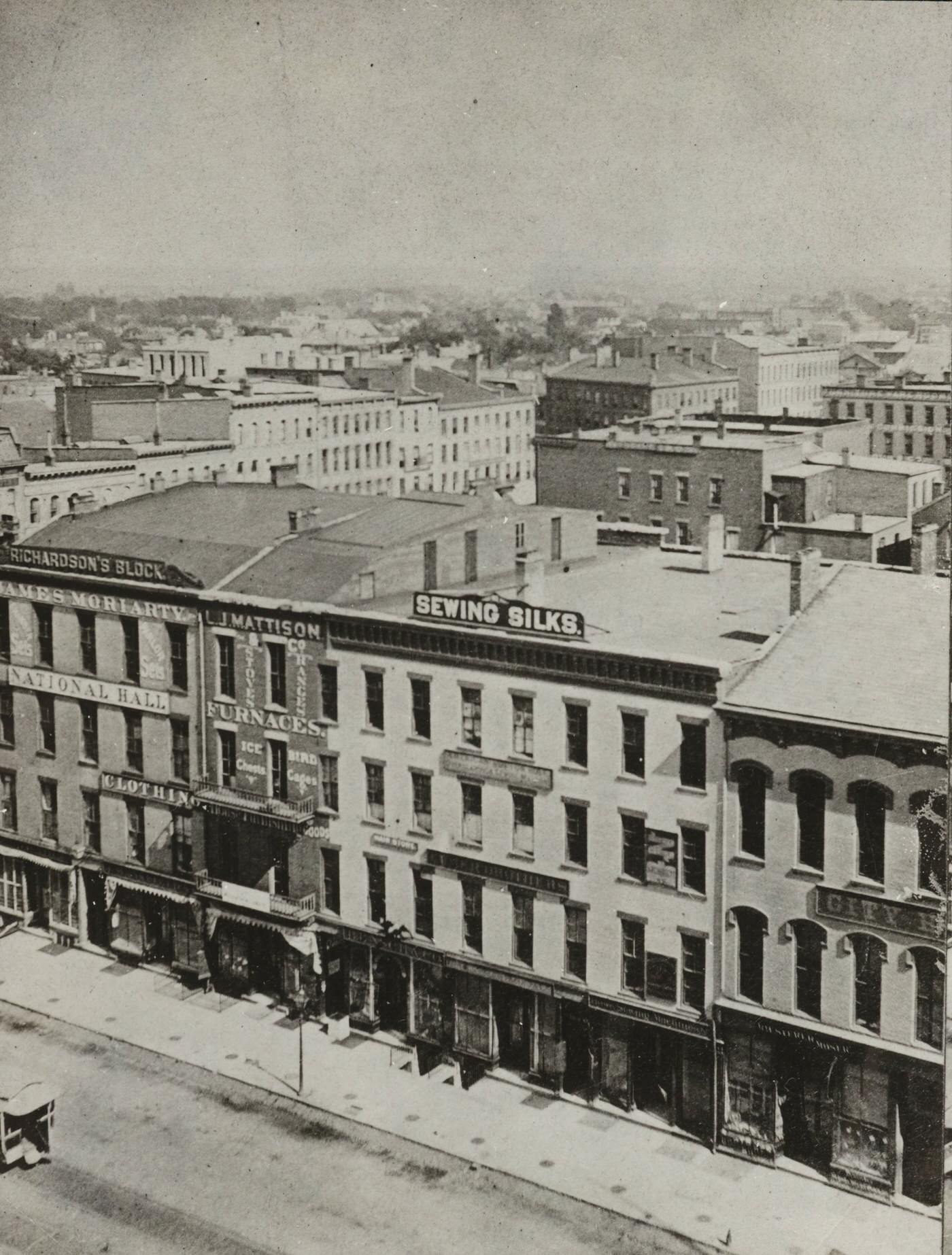

The Economic Pulse: Commerce and Early Industries

Before the 1860s, Cleveland’s economy was primarily rooted in agriculture and regional trade. It served as a commercial hub, with local craftsmen in small shops producing necessary goods like farming tools, barrels for shipping agricultural products, and household furniture. The Ohio & Erie Canal, completed decades earlier, had been instrumental in establishing Cleveland as a key transportation link, connecting Lake Erie to the Ohio River. This waterway facilitated the movement of raw materials such as wheat, corn, and coal into the city, and allowed manufactured goods to be shipped to other markets.

By the time of the U.S. manufacturing census in 1860, a shift was evident. Iron had become Cleveland’s most valuable industrial product, and items manufactured from iron were also of significant economic importance. A major player in this early iron industry was the Cuyahoga Steam Furnace Co., which produced a variety of goods including steam engines, locomotives, and stoves. Flour-and-grist milling, serving the productive farms of the Midwest, ranked as the city’s second-largest industry by value. The clothing industry also held a strong position, being the third-largest producer of goods by value in 1860. This combination of existing commercial networks, a strategic location on vital waterways, and a developing industrial base, particularly in iron, positioned Cleveland for the accelerated industrialization that the coming decade, and the Civil War, would bring.

On the Table and In the Wardrobe: Food, Markets, and Clothing Styles

Daily life for Clevelanders in the 1860s was also defined by what they ate and what they wore, reflecting both national trends and local availability.

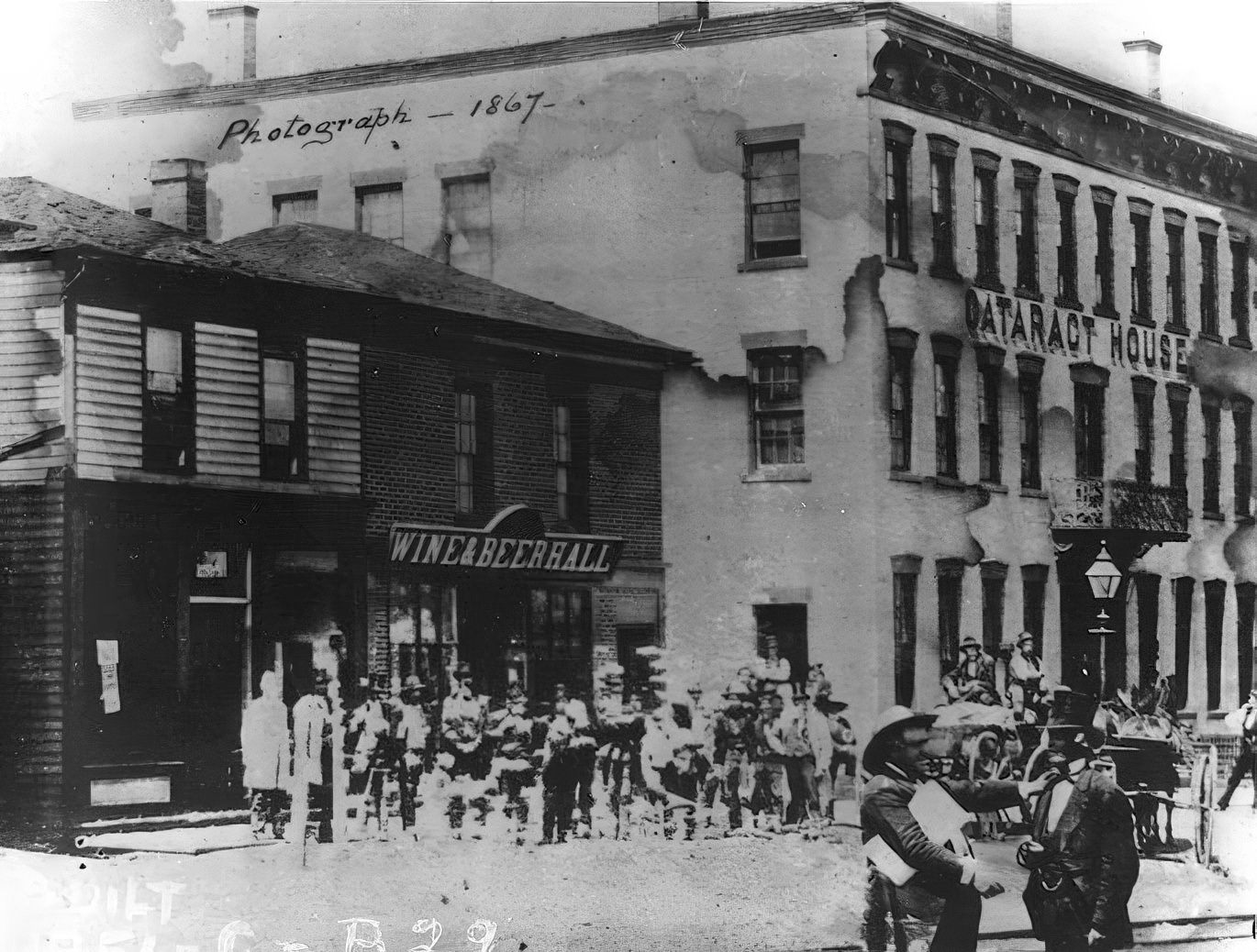

Food and Markets: Access to food was facilitated by public markets. Cleveland’s first public market had been established on Ontario Street in 1829. During the 1860s, market facilities continued to develop. A new Central Market building was completed on Ontario Street in 1867, providing a more organized space for vendors and shoppers. On the west side of the city, a wooden market house was constructed in 1868 on “Market Square,” located at the intersection of Lorain Avenue and Pearl Street (now West 25th Street).

Cuyahoga County’s agricultural output provided a variety of common food items. These included dairy products like butter, cheese, and milk, as well as orchard fruits such as cherries and peaches, grapes, and a range of vegetables, with potatoes being a significant crop. Historical records from the Ohio Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that retail prices for staples like coffee, tea, sugar, and molasses were tracked for Cleveland and other Ohio towns during the 1860s. A typical diet for working-class Americans of that era was heavily influenced by English culinary traditions and could be relatively simple or even bland, primarily seasoned with salt and only small amounts of other spices. Given the hard physical labor common at the time, diets were often high in calories, estimated around 4,000 per day, and rich in fats from butter, cream, and lard. Pork was a very common meat, as pigs were relatively easy and inexpensive to raise. Chicken and eggs were also staples. Fresh vegetables and fruits were consumed in season. To preserve food for leaner times, vegetables like potatoes, carrots, and cabbage were stored in root cellars where possible, or preserved through methods like drying, pickling, or making them into relishes and catsups.

Clothing: Women’s fashion in the 1860s was characterized by very wide skirts, which achieved their maximum circumference around 1860. These voluminous skirts were supported by an understructure known as a cage crinoline. Throughout the decade, the silhouette of these skirts subtly changed, with the fullness gradually shifting towards the back of the dress by 1868. Day dresses, often made from materials like wool or silk, were standard attire for women.

Men’s fashion during the 1860s featured high, upstanding or turnover collars, worn with neckties that had become wider than in previous decades. For business and more formal daytime occasions, men typically wore frock coats, which were often single-breasted and reached to the knee, worn over a waistcoat (vest). Trousers were full-length and frequently made from a fabric that contrasted with the coat. For informal wear, the bowler hat was gaining popularity.

Cleveland’s own garment industry was growing during this period. By 1860, the manufacture of ready-to-wear clothing was already one of the city’s leading industries. A local milestone was the German Woolen Factory, which began producing wool cloth in Cleveland in 1862. Retail establishments were also evolving. Large dry-goods stores, such as Hower & Higbee which opened its doors in 1860, began to appear. These stores utilized newspaper advertisements that often included illustrations of their goods and listed prices, a relatively new practice to attract customers. The way Clevelanders sourced their daily necessities and participated in consumer culture was thus shaped by a combination of local agricultural production, the rise of industrial manufacturing, and evolving fashion trends.

City Health and Cleanliness: Sanitation, Water, and Common Ailments

Despite its growth and claims to modern conveniences, Cleveland in the 1860s faced severe challenges regarding sanitation and public health. For many years, the disposal of waste was poorly managed. Both household garbage and industrial refuse were commonly thrown into the city’s streets, alleys, and culverts. Much of this waste ended up in the waterways, including the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie, which ironically also served as the city’s primary source of drinking water. The streets themselves were often fouled with animal waste, and in rainy weather, human waste would overflow from outhouses and cesspools.

A public water system had commenced operation in 1856, designed to supply residents with water drawn from Lake Erie. Initially, this water was supplied unfiltered. Within a few years, however, the continuous discharge of sewage and industrial filth into the Cuyahoga River and directly into Lake Erie near the water intake pipes transformed the city’s water supply into a significant health hazard. The Cuyahoga River itself became a symbol of this pollution. Heavily burdened with industrial waste and raw sewage, the river was so contaminated that the first recorded instance of it catching fire occurred in 1868.

Some efforts were made to address these issues. Private collection and disposal of solid waste began in the city’s commercial areas in 1860. The city’s first sewer line was constructed in 1858. A permanent Board of Health for Cleveland was authorized by the state legislature in 1856, and on April 10, 1866, the city council approved a set of regulations that formed the foundation of a municipal sanitary code. However, putting these measures into effective practice proved difficult. There was often public resistance to the costs associated with civic improvements, and some viewed sanitation ordinances as an unwelcome infringement on their personal rights.

The consequences of these poor sanitary conditions were evident in the health of the population. Common diseases directly linked to contaminated water, such as typhoid fever and various enteric (intestinal) illnesses, were prevalent. Cleveland had also experienced devastating cholera epidemics in the decades prior to the 1860s. Death records from the 1860s list various causes of mortality, including tetanus, “fits” (seizures), complications from “bad whiskey” (likely alcohol poisoning or contaminated alcohol), and cholera infantum, a severe diarrheal disease affecting young children. Thus, while Cleveland was an “attractive urban center” experiencing rapid growth, this progress was shadowed by serious deficiencies in basic sanitation and public health infrastructure, posing significant risks to its inhabitants.

Education and Faith: Schools, Churches, and Religious Life

Education: Cleveland’s public school system was actively developing during the 1860s. By the start of the decade, schools on both the east and west sides of the Cuyahoga River had been consolidated under the leadership of a superintendent. Andrew Freese, who served as the city’s first school superintendent, worked to implement a more structured system by grading and classifying the schools. The demand for education was growing alongside the city’s population. This was evidenced by institutions like the Brownell Street School, which enrolled an impressive 1,386 pupils in its first year of operation, 1865. By 1866, the total enrollment in Cleveland’s public schools reached 9,270 students. The educational curriculum was also evolving. While classical studies remained, there was a broader trend towards incorporating modern languages, sciences, and vocational training, although this was a gradual shift seen across the nation. To ensure quality, teachers in Cleveland were required to pass competency tests. Later in the city’s development, Louise Klein Miller would introduce a school garden program that gained national recognition for its innovative approach to education.

Churches and Religious Life: Religious institutions also expanded to serve Cleveland’s growing and increasingly diverse population. By 1865, city directories listed 50 churches. While congregations rooted in New England Protestant traditions were numerous, the religious landscape was becoming more varied. This count included 8 Catholic churches, 5 Lutheran churches, 2 Jewish synagogues, and 1 African-American church. Prominent Protestant denominations included Methodists, with congregations like the Brooklyn Methodist Episcopal Church (recognized as the oldest Methodist congregation in the Cleveland area) and the Lorain Street Church, which was founded in 1868. Baptists, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians also had established presences. German Protestant churches, such as Trinity Evangelical Lutheran (founded 1853) and St. Paul’s Evangelical Protestant Church (founded 1858), had been established prior to the 1860s, catering to the large German immigrant community. The Irish Catholic community was served by St. Malachi Catholic Parish, founded in 1867. St. John’s AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church was an important early religious institution for African Americans in Cleveland. This array of denominations and the increasing number of churches underscored the evolving cultural and spiritual fabric of the city.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know