Cleveland entered the 20th century as a city brimming with energy and undergoing rapid change. In the decades before 1900, it had already grown into an important American industrial center. The new century saw this growth accelerate. In 1900, the city was home to 381,768 people. Just ten years later, by 1910, this number had jumped to 560,663. This increase of nearly 47% in a single decade showed Cleveland’s powerful attraction for people seeking new lives and jobs. Beyond its growing population, Cleveland was also a center for new ideas. In 1900, it ranked eighth among all U.S. cities in the number of patents given to its residents, a testament to its spirit of invention and progress. The sheer speed of this population boom created both exciting opportunities and significant challenges for the city, affecting everything from housing to city services.

A City of Newcomers: The “New Immigration”

A primary driver of Cleveland’s remarkable growth was the wave of “new immigration.” During the 1900s, large numbers of people from Southern and Eastern European countries made the journey to America, with many choosing Cleveland as their destination. Among the prominent groups arriving were Italians, various peoples from the Austro-Hungarian Empire—including Slovenes and Slovaks, who formed particularly large communities in Cleveland—and Russians. Many of the Russian immigrants were Jewish families escaping persecution in their homeland.

While these newer groups were arriving, older immigrant communities also continued to expand. People of German descent, for example, were the largest foreign-born group in Cleveland in 1900, numbering over 40,000. The Polish community, smaller in earlier years, grew and established more of its own institutions. Syrian-Lebanese immigrants also arrived in increasing numbers, many having come from farming villages near Beirut and Damascus. They adapted their skills to find work in the urban environment.

These diverse groups of newcomers often settled in specific neighborhoods. This allowed them to live near others who spoke their language, shared their customs, and could offer support as they navigated life in a new country and sought jobs in Cleveland’s many factories and businesses. For instance, the Haymarket District and parts of the near West Side became early homes for many Syrian-Lebanese families. This gathering of people from so many different backgrounds turned Cleveland into a truly multicultural city. This rich diversity also meant that the city and its institutions had to find ways to serve a population speaking many languages and holding varied traditions, highlighting the importance of organizations like settlement houses and ethnic churches.

Expanding Boundaries and Reordering Streets

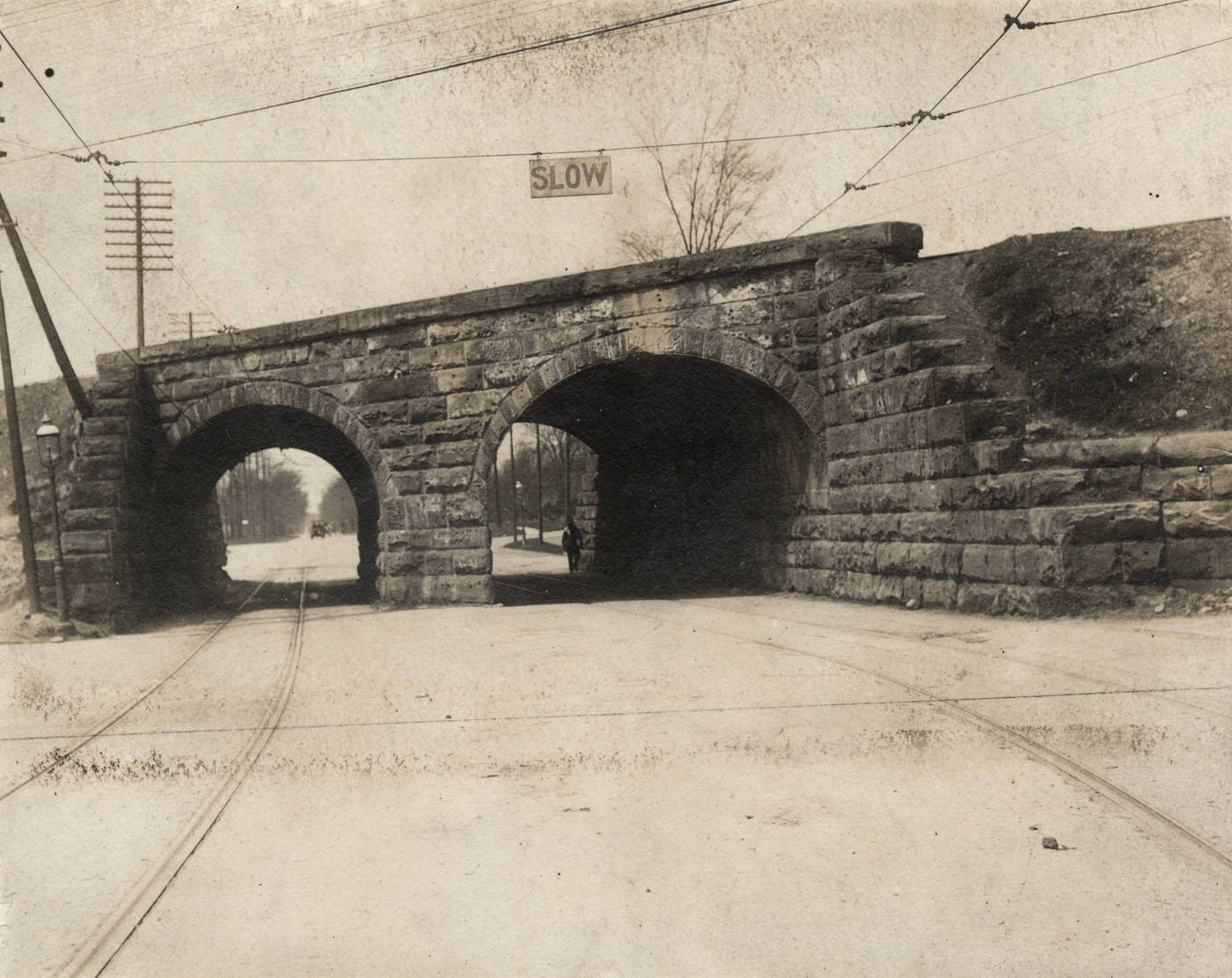

As more people poured into Cleveland, the city itself grew larger, annexing nearby communities. The village of Corlett became part of Cleveland in 1909. Just a few years earlier, in 1905, South Brooklyn was annexed, and its existing electric light plant became part of Cleveland’s city services. Collinwood would be annexed in 1910.

Each of these annexed areas had its own system for naming and numbering streets. As Cleveland absorbed them, it ended up with a confusing mix of street names and addresses, making it difficult to find one’s way around. To solve this problem and create a more organized city, Cleveland undertook a massive project in 1906 to rename many streets and renumber all addresses according to a unified plan. This was a huge but essential step for a rapidly modernizing urban center. These administrative changes were vital for forging a single, functional city out of many distinct parts, reflecting a deliberate effort to manage Cleveland’s explosive growth systematically.

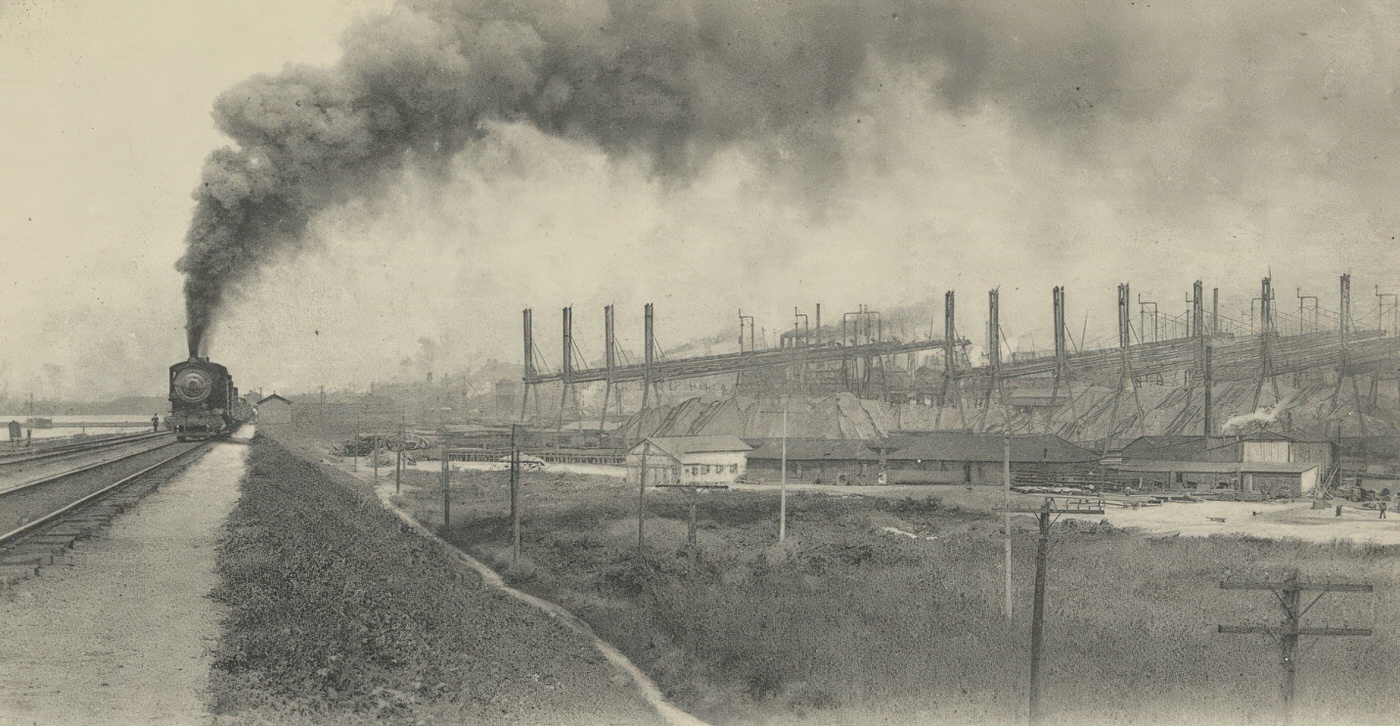

Cleveland’s Industrial Might: A National Powerhouse

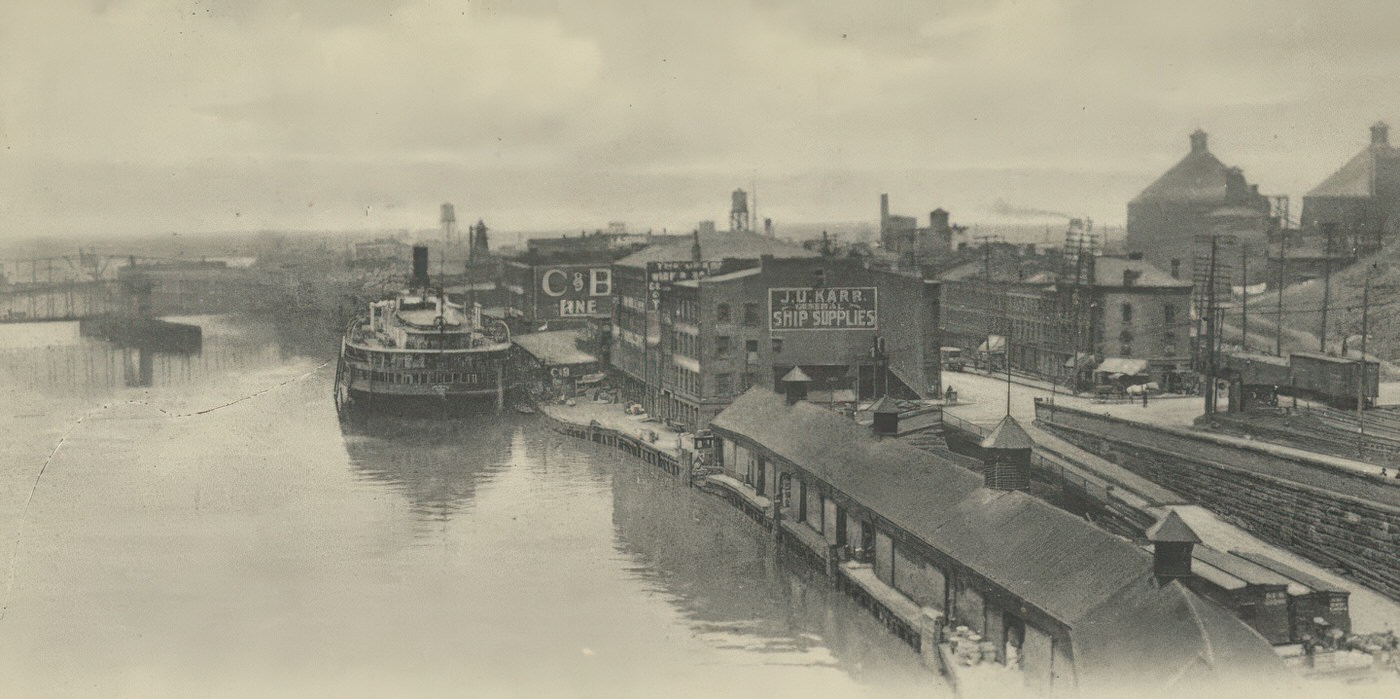

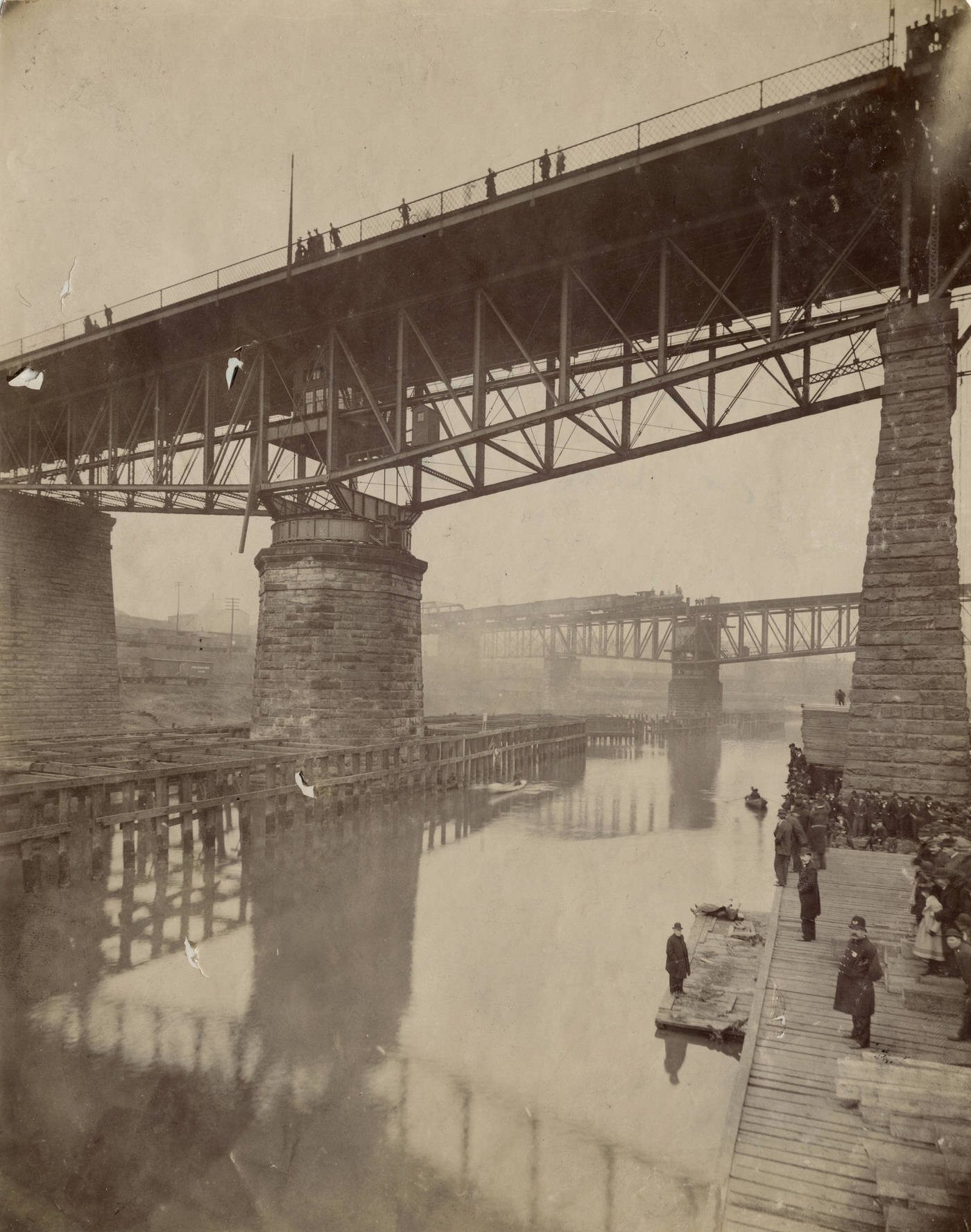

At the dawn of the 20th century, Cleveland stood as one of America’s industrial giants. Its prime location on the southern shore of Lake Erie, coupled with an extensive network of railroads and waterways, provided unparalleled access to crucial raw materials like iron ore and coal. This strategic position also made it easier to ship finished products to markets across the country.

The iron and steel industry formed the backbone of Cleveland’s economy. By 1900, Cuyahoga County, where Cleveland is located, was the fifth-largest producer of iron and steel in the nation, with an output of 968,801 tons. A major development occurred in 1901 with the formation of the U.S. Steel Corporation. This massive company absorbed the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company’s facilities (which had earlier become part of the American Steel and Wire Company). U.S. Steel continued to invest heavily in its Cleveland operations, constructing new wire and strip mills between 1907 and 1908. Alongside such large consolidations, new independent companies also emerged. For example, the Corrigan-McKinney Steel Co. began building blast furnaces in 1909, signaling the continued vitality and growth of the local steel sector. Efficiency in the steel-making process was dramatically improved by innovations like the Hulett automatic ore unloader. Invented in 1899 by Cleveland’s own George Hulett, this machine greatly reduced the time and labor needed to unload iron ore from lake freighters at the city’s docks.

Oil refining was another industry with deep roots in Cleveland, largely due to John D. Rockefeller, who founded the Standard Oil Company in the city in 1870. Although the Standard Oil Trust had faced legal challenges in Ohio in 1892, leading to its national reorganization in 1899 and eventual federal dissolution in 1911, the company’s extensive refining operations and economic influence remained significant in Cleveland during the 1900s. Standard Oil was renowned for its operational efficiency and its ability to turn byproducts into valuable commodities. By 1909, Standard Oil employed 60,000 people nationally. The dynamic interplay between massive corporations like U.S. Steel and emerging independent firms, all benefiting from technological advancements and Cleveland’s geographical advantages, defined the city’s industrial character in this era.

The Dawn of the Automobile Age in Cleveland

Cleveland was a cradle of the American automobile industry in the early 1900s. This new industry grew with astonishing speed. By 1909, auto manufacturing was the city’s third-largest industrial sector, with 32 factories employing over 7,000 workers. The value of automobiles produced in Cleveland that year reached nearly $21 million. This was a remarkable achievement for an industry that was hardly present in census figures just a decade earlier.

Several local companies and visionary individuals spearheaded this automotive boom:

The Winton Motor Carriage Co., founded by Scottish immigrant Alexander Winton, was a true pioneer. Winton is credited with selling one of the first American-made gasoline-powered cars in 1898. His company was known for innovations such as making the steering wheel standard equipment around 1900 (instead of a tiller), producing some of the earliest commercial trucks in 1898, and offering an optional compressed-air self-starter by 1908.

The Baker Motor Vehicle Co., established by Walter Baker, specialized in electric cars. Baker showcased his first electric vehicle in 1900. These cars were quiet, easy to operate, and became popular as “urban ladies’ cars”.

The White Sewing Machine Co., a well-established Cleveland firm, ventured into automobiles under the leadership of Rollin H. White, son of the company’s founder. Initially, White focused on steam-powered cars, which were known for their quality and dependability. A key innovation was Rollin White’s patented flash-steam boiler in 1900, which allowed steam cars to start much more quickly than earlier models. The company produced 193 steam cars in 1901 and by 1906, its annual output reached 1,500 cars, with the company claiming at the time to be the largest automobile manufacturer in the world. In 1906, the automobile division became a separate entity, the White Motor Co., and around 1909 began to transition towards gasoline engines and the production of trucks, a field where it would become a major force.

Other Cleveland companies like the Peerless Motor Car Company and the F.B. Stearns Company catered to the high-end market, producing large, powerful, and luxurious automobiles.

Cleveland’s early strength in the automotive sector was built on a diverse technological foundation, with companies successfully producing gasoline, electric, and steam-powered vehicles. This period of intense innovation and rapid growth established the city as a key player, even as the mass-production methods pioneered by Henry Ford in Detroit began to reshape the industry’s future.

The National Pastime: Cleveland Naps Baseball

Professional baseball held a special place in the hearts of Clevelanders during the 1900s. The city’s American League team was known as the Cleveland Naps, a name adopted in 1903 in honor of their star player, Nap Lajoie. The Naps had their share of memorable moments and star players duing this decade.

Elmer Flick, a native of nearby Bedford, Ohio, captured the American League batting title in 1905 with an impressive.308 average. One of the most celebrated events in Cleveland baseball history occurred on October 2, 1908, when Naps pitcher Addie Joss threw a perfect game against the Chicago White Sox at League Park. This remarkable feat, achieved with only 74 pitches, was a highlight in a tense pennant race and remains one of baseball’s legendary performances. Adding to the team’s star power, the iconic pitcher Cy Young returned to Cleveland to play for the Naps in 1909, winning 19 games that season. These achievements and the presence of such talented players ensured that professional baseball was a significant and exciting part of Cleveland’s public life, fostering local pride and passionate fans.

Educating Cleveland: Schools and Universities

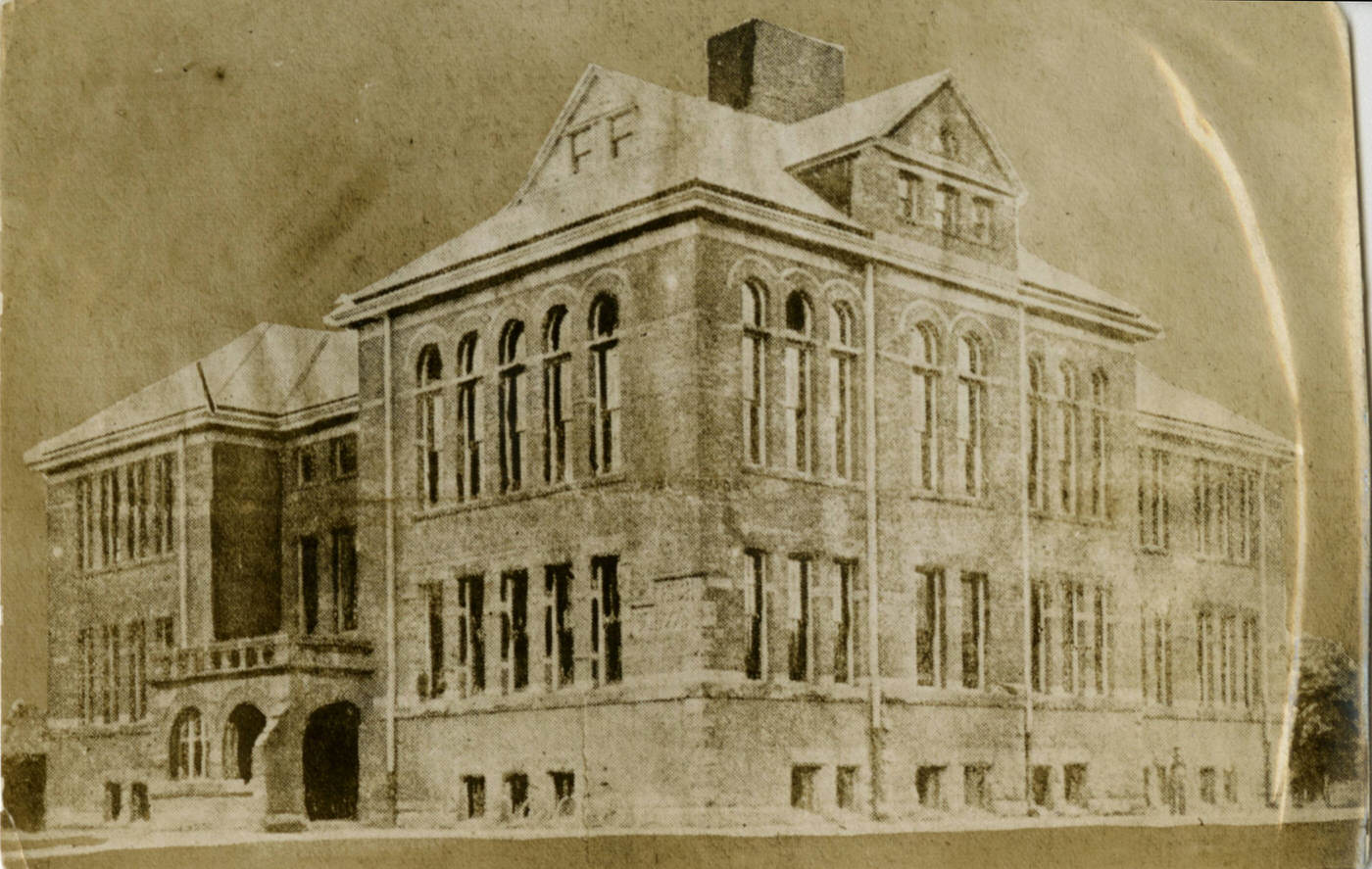

The Cleveland Public Schools (CPS) system saw significant expansion and innovation during the 1900s, particularly under the leadership of Superintendent William H. Elson, who was appointed in 1905. Reflecting Progressive Era ideals, the school system broadened its role beyond basic academics. Playgrounds and summer school programs were opened in 1903, and the first medical dispensary in a public school was established at Murray Hill School in 1908.

A key development was the creation of specialized high schools to meet the diverse needs of students and the demands of an industrial economy. A technical high school opened in 1908, followed by a commercial high school in 1909. An industrial school for children who were not academically inclined and had typically dropped out after 7th or 8th grade also opened in 1909. This school offered a curriculum split between academic work and practical training in industrial skills, home economics, and physical education. Kindergartens, providing early childhood education, had been introduced into the system in 1896.

Recognizing the needs of Cleveland’s large immigrant population, evening schools increasingly focused on teaching English and civics, helping newcomers prepare for naturalization exams. Public libraries also played a role in serving immigrant communities. The Cleveland Public Library’s Broadway Branch, for example, opened in 1906 with funding from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. It specifically catered to the local Czech and Polish communities by offering books in their native languages and providing citizenship classes.

Higher education institutions in the city also continued their development. Western Reserve University (WRU) added notable buildings to its campus, including Harkness Chapel (dedicated in 1902, though construction may have started earlier) and Haydn Hall (1902). Case School of Applied Science inaugurated its second president, Charles S. Howe, in 1904 and expanded its facilities with the Rockefeller Mining and Metallurgy building (1905) and the Rockefeller Physics building (1906). The area where these institutions were located, University Circle, even derived its name from the streetcar turn-around on Euclid Avenue that served the campuses. These developments underscored the growing importance of specialized and vocational training, as well as higher learning, in a city increasingly defined by industry and technology.

Shipbuilding on the Great Lakes

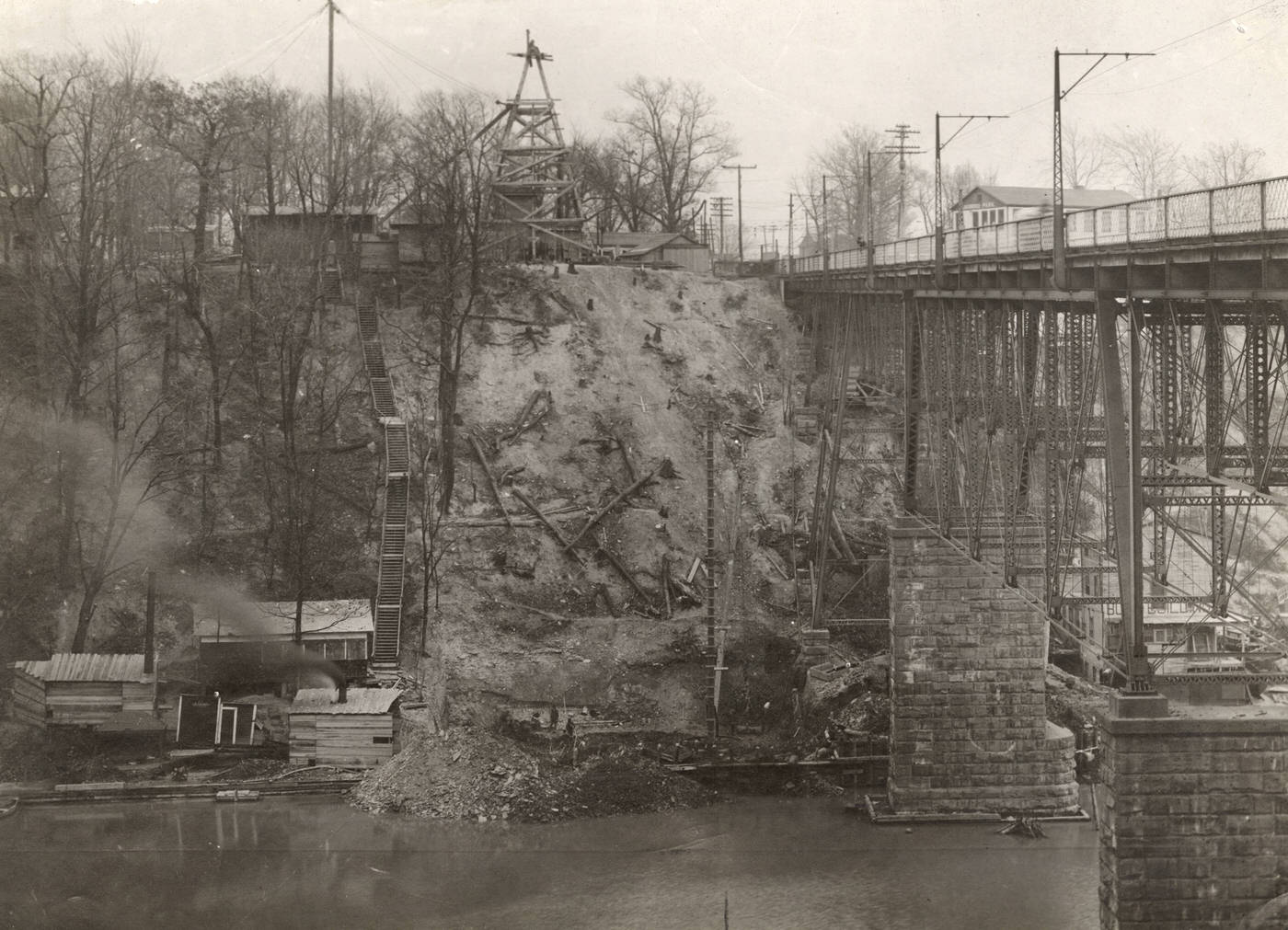

The shipbuilding industry was another vital part of Cleveland’s industrial landscape. In 1900, a major consolidation occurred with the formation of the American Ship Building Company, which brought together several firms, including the existing Cleveland Shipbuilding Company. This new entity became the leading shipbuilder on the Great Lakes.

Throughout the 1900-1909 decade, the Cleveland shipyards of the American Ship Building Co. were busy launching vessels essential for Great Lakes commerce. Notable ships built during this period included the SS Milwaukee in 1902 (originally the Manistique-Marquette & Northern No. 1, a lake freighter), the SS Anna C. Minch in 1903, and the SS Milwaukee Clipper in 1904 (originally named the Juniata and built for the Anchor Line).

Cleveland’s prominence as a shipbuilding center was directly tied to its other major industries, especially iron and steel. The city’s strategic location on Lake Erie made it a natural hub for building the vessels needed to transport raw materials like iron ore and coal to its furnaces and factories, and to carry finished products to other markets. This created an interconnected industrial ecosystem where shipbuilding supported and benefited from the city’s overall manufacturing strength.

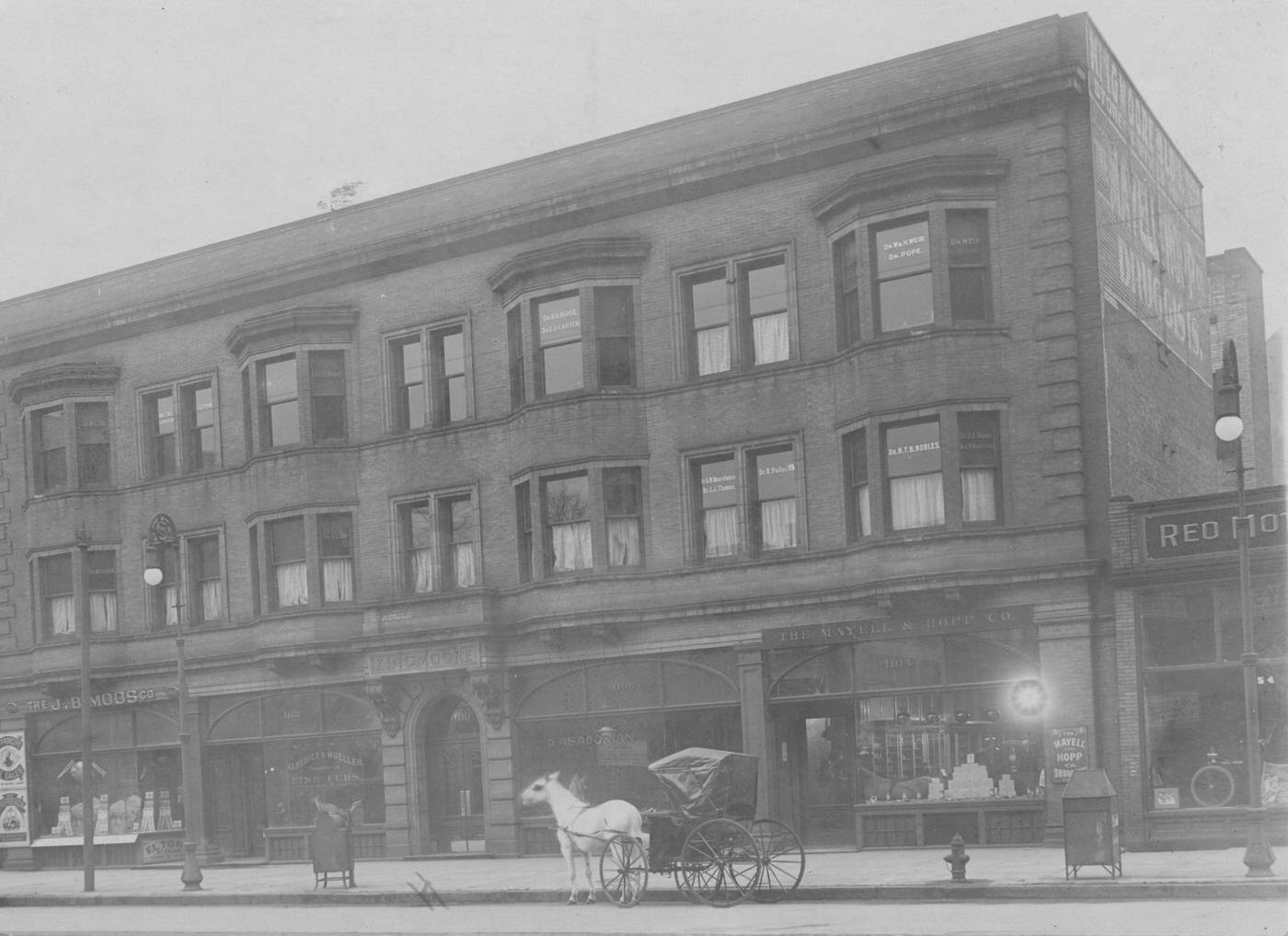

The Garment Industry: A Major Employer of Immigrants

Cleveland was a nationally recognized leader in the production of ready-to-wear clothing, particularly men’s garments and women’s suits and cloaks. By 1910, this industry employed approximately 10,000 people, making up about 7% of Cleveland’s entire workforce. A significant aspect of Cleveland’s garment sector was that around 80% of these workers were employed in large, relatively modern and well-equipped factories. This contrasted with cities like New York, where smaller, often more cramped, “sweatshop” conditions were more common.

The Garment Industry: A Major Employer of Immigrants

Cleveland was a nationally recognized leader in the production of ready-to-wear clothing, particularly men’s garments and women’s suits and cloaks. By 1910, this industry employed approximately 10,000 people, making up about 7% of Cleveland’s entire workforce. A significant aspect of Cleveland’s garment sector was that around 80% of these workers were employed in large, relatively modern and well-equipped factories. This contrasted with cities like New York, where smaller, often more cramped, “sweatshop” conditions were more common.

Several large firms dominated the Cleveland garment scene in the 1900s:

The L. N. Gross Co., founded in 1900, specialized in producing women’s shirtwaists (blouses) and was an early adopter of the specialized division of labor in its manufacturing processes, which increased efficiency.

The Joseph & Feiss Co. was a leading manufacturer of men’s clothing. Around 1900, the company moved into a substantial new plant on West 53rd Street to accommodate its growing operations.

H. Black & Co. was a major producer of women’s suits and cloaks.

Printz-Biederman Co., established in 1893, also specialized in women’s suits and coats.

The Richman Bros. Co. focused on men’s suits and coats.

Supplying many of these manufacturers with fabric was the Cleveland Worsted Mills.

The workforce in Cleveland’s garment factories was remarkably diverse, reflecting the city’s status as a major destination for immigrants. Jewish immigrants played a prominent role, alongside large numbers of Czech, Polish, German, and Italian workers. To tap into this labor pool, many garment factories were strategically located within or near these ethnic neighborhoods. This industry provided essential employment, especially for newly arrived immigrants and women, and its evolution towards larger factory settings marked a shift in industrial organization.

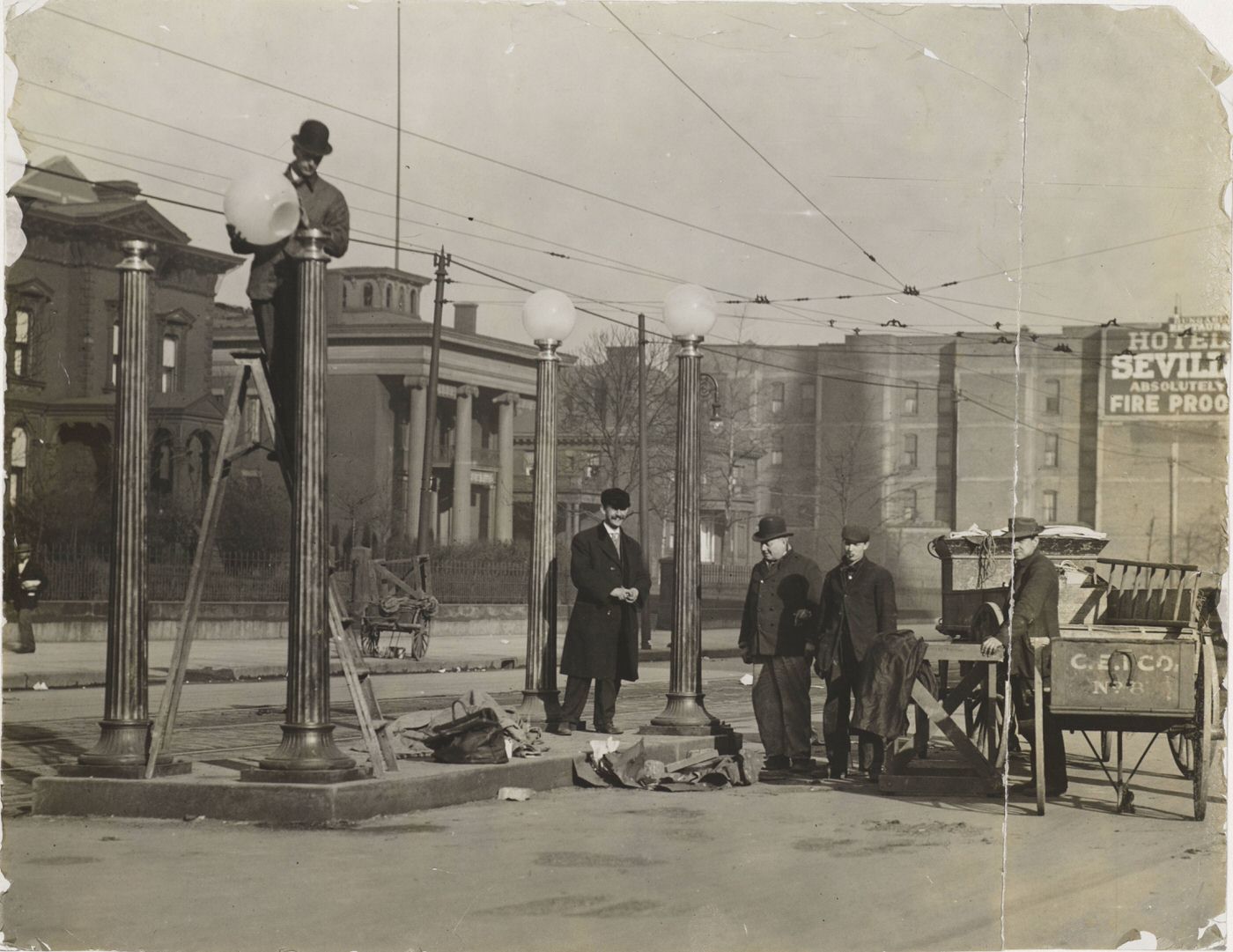

The Electrical Boom

Cleveland was at the forefront of the rapidly expanding electrical industries in the early 20th century. By the end of the 1900-1909 decade, the city was a national leader in the production of electrical goods such as carbons (used in arc lighting), lamps, and electrical hoisting apparatus. It had already established itself as the leading producer of electric automobiles by 1900.

Key to this growth was the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. (CEI), formed in 1892. CEI was instrumental in expanding power generation and distribution throughout the city and surrounding areas. The company’s customer base grew dramatically from about 1,400 at the turn of the century, fueling both industrial and residential electrification.

Another important local company was the Lincoln Electric Co., founded in 1896 by John C. Lincoln, who had gained experience working with electrical pioneer Charles F. Brush. Lincoln Electric initially produced electric motors and became a pioneer in the development of arc-welding equipment, a technology crucial for many manufacturing processes.

The availability of electricity also spurred the growth of industries manufacturing electrical home appliances. By the time of World War I, Cleveland was a significant producer of items like coffee percolators, vacuum cleaners, and washing machines. The city’s leadership in diverse electrical applications, from heavy industrial equipment to household conveniences, underscored its role in this technological revolution that was transforming both factories and homes.

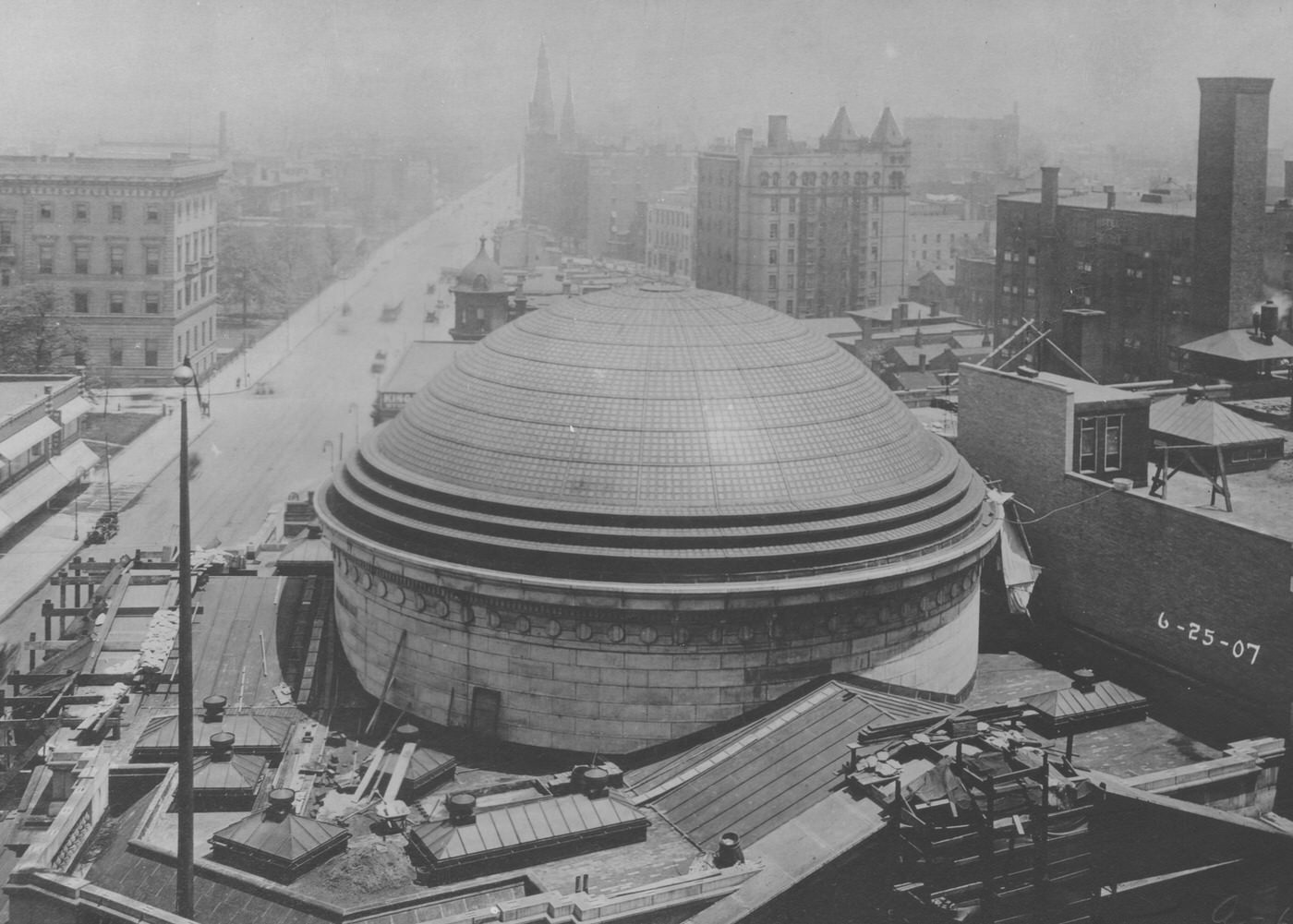

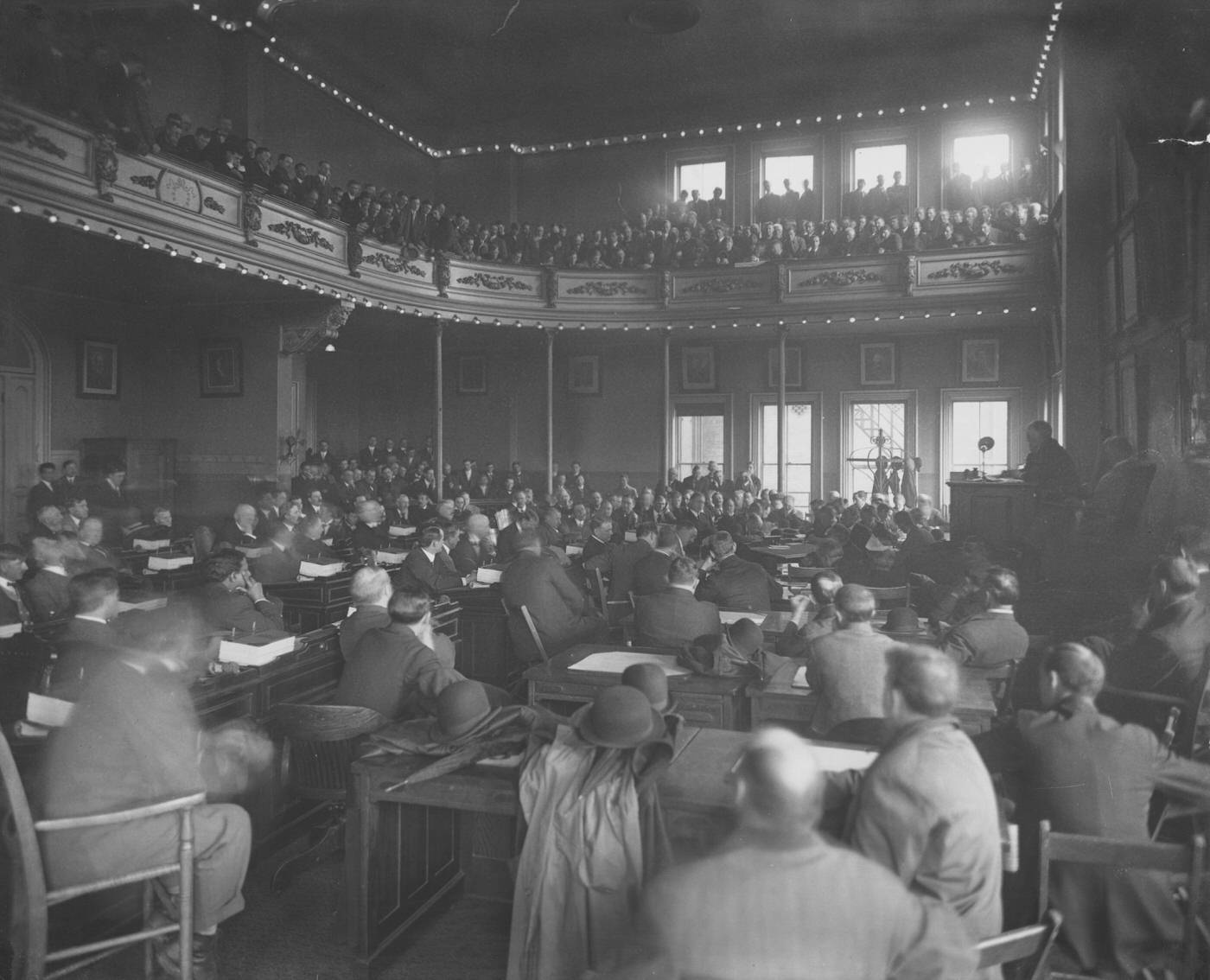

The 1909 Industrial Exposition

To celebrate and promote its diverse industrial capabilities, Cleveland’s business leaders organized a grand Industrial Exposition in 1909. This was the first time the city’s wide array of manufactured goods, from steel and automobiles to garments and electrical equipment, was showcased to a broad public audience on such a large scale. The exposition was a clear statement of Cleveland’s confidence in its industrial prowess and its ambition to be recognized as a leading manufacturing center in the United States. It represented a conscious effort to build civic pride around the city’s remarkable industrial achievements.

Life in the Bustling City: Neighborhoods, Work, and Daily Routines

Life for many working Clevelanders in the 1900s was defined by long hours and modest pay, despite the city’s industrial prosperity. In the garment industry, for example, workers often faced low wages and extended workdays with few benefits. However, conditions in Cleveland’s larger garment factories were generally considered somewhat better than in the smaller, more crowded sweatshops found in cities like New York. For unskilled immigrant laborers, such as those from Hungary, a typical workday in the late 1890s and early 1900s could be 10 to 12 hours long, for weekly earnings between $8 and $12. Safety was a major concern in heavy industries like mining and steel production, where standards were often minimal, leading to frequent accidents.

Precise wage data for Cleveland during this specific decade is somewhat scattered. National averages from 1905 show that men in manufacturing jobs earned about $11.16 per week, while women in similar roles earned significantly less, around $6.17 per week. More specific union wage scales for Cleveland for the years 1907 to 1909 were published in U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics bulletins, but these require detailed review for individual occupations. A general overview from 1900 provides some context: bartenders might earn around $425 annually, electricians $1,550, while domestic servants earned about $144 per year, though this often-included room and board. The stark difference between the city’s industrial output and the daily realities for its workforce highlighted the need for labor organization and reform.

The Rise of Labor: Unions and Strikes

The early 1900s were a period of significant labor activity in Cleveland. By 1900, the city was home to 100 different labor unions, with 62 of them affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), 14 with the Knights of Labor, and 24 operating independently. This demonstrates a substantial level of organization among workers. However, the growth of unions faced challenges, slowing after 1904 due to opposition from employers, unfavorable court decisions, and the continuous influx of new immigrants who could fill jobs.

A key development for garment workers was the formation of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) in New York City in 1900, an organization that would soon have a presence in Cleveland. Cleveland saw its share of labor disputes. One notable success was the 1905 Cigar Makers’ Strike, where the union reportedly won all of its demands. There was also an unsuccessful strike by garment workers against the Prinz-Biederman company in 1908; the lingering dissatisfaction from this dispute contributed to the larger garment workers’ strike that occurred in 1911. The Cleveland Federation of Labor (CFL), which was the local precursor to the AFL-CIO and had been chartered in 1887, continued to be an active force in the city’s labor scene. This era was characterized by a persistent struggle for better wages, shorter hours, and improved working conditions, with unions achieving some victories while also encountering considerable resistance.

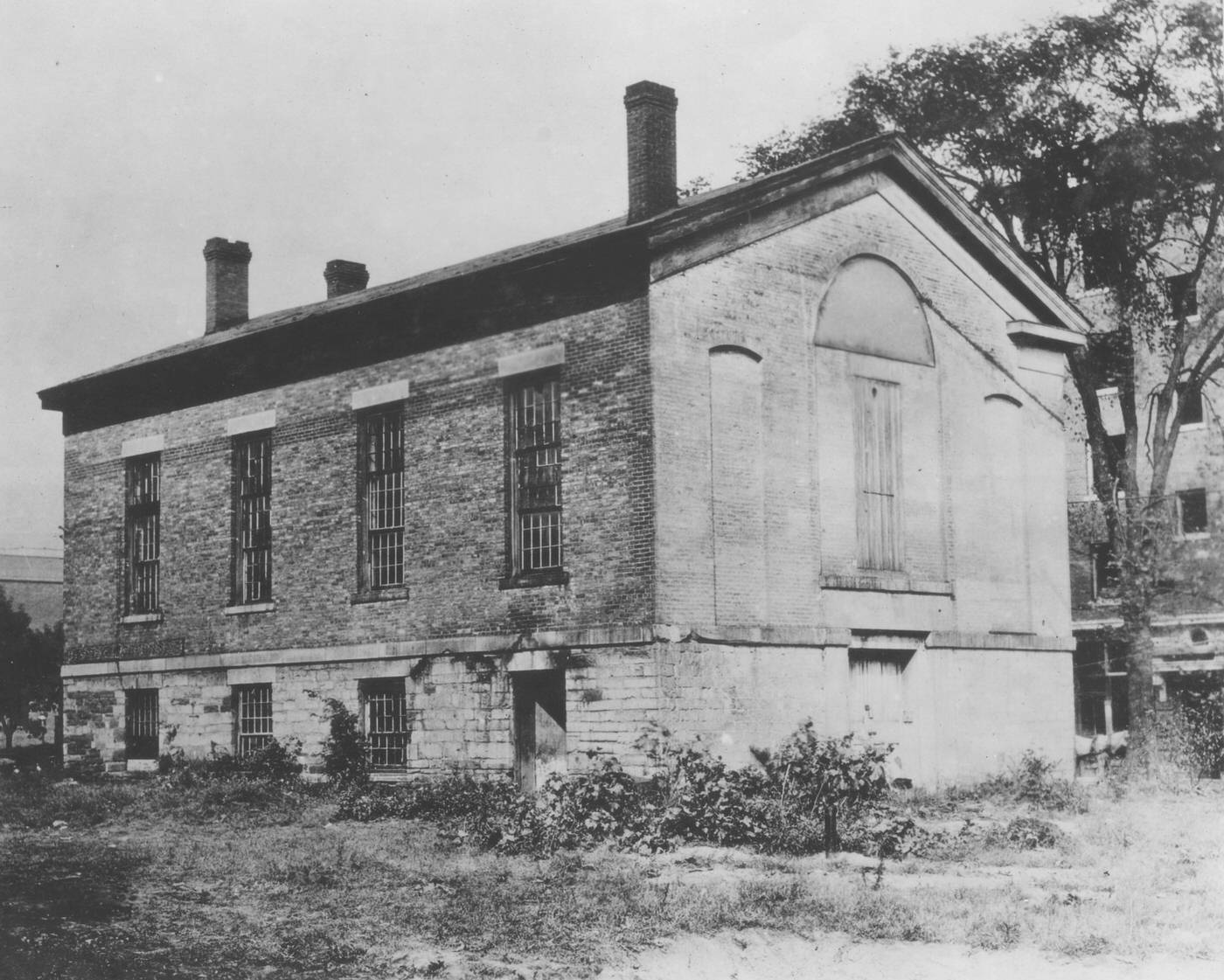

Finding a Home: Housing the Masses

The rapid increase in Cleveland’s population, largely due to immigration, placed enormous strain on the city’s housing supply. This often led to overcrowded and inadequate living conditions for many working-class and immigrant families. During this period, Mayor Tom L. Johnson’s administration, despite its progressive reforms in other areas, reportedly paid little direct attention to solving these housing problems.

Typical housing for working-class families often consisted of wood-frame buildings, sometimes with two separate dwellings built on a single city lot. As the population grew, these neighborhoods became increasingly dense. By 1890, the average Cleveland dwelling housed nearly six people. Immigrant neighborhoods, such as the Haymarket district or areas near the industries along the Cuyahoga River flats, often faced particularly challenging conditions with overcrowding and basic sanitation issues. The Village of West Cleveland, for instance, had developed in the late 19th century partly as an attempt by working-class immigrants to find better living conditions away from the grime and noise of heavily industrialized areas like the “Triangle” district.

In response to these pressing social needs, settlement houses emerged as vital community resources. Institutions like Hiram House, which initially served Jewish immigrants and later Italian and African American communities; Alta House, focusing on Italians in Little Italy; and Goodrich House, assisting South Slavic groups, played a crucial role. These organizations offered a range of services, including adult education classes, kindergartens for children, vocational training to help people acquire job skills, visiting nurses to address health concerns, and health inspections. They also worked to help immigrant families adapt to their new urban environment and American society. This created a stark contrast within the city: the opulent mansions of Millionaires’ Row on Euclid Avenue stood in sharp opposition to the often difficult living situations in many working-class and immigrant neighborhoods. Settlement houses were a key response to these disparities, attempting to provide support and opportunities.

Daily Sustenance: Feeding the City

Access to food was a daily concern for Cleveland’s growing population. Public markets were essential. The Central Market and the Sheriff Street Market, which had opened in 1891, served as important sources of fresh produce, meats, and other goods. The existing Pearl Street Market, a precursor to the famous West Side Market, was reportedly in poor condition by the mid-1890s. This situation spurred plans for a new, grand market facility. Under Mayor Tom L. Johnson, construction of the West Side Market began in 1908, a major civic investment designed to serve the city’s needs for decades to come.

For many working-class and immigrant families, food procurement often involved growing vegetables in small yard plots, if available, and purchasing staples from the public markets. Many single immigrant men lived in boarding houses where meals were provided as part of their lodging.

Food preservation was crucial in an era before widespread refrigeration. Common household techniques included drying meats and fruits; salt-curing meats; smoking meats to extend their usability; pickling various vegetables, fruits, and sometimes meats in brine or vinegar; making fruit preserves, jams, and jellies with sugar; and using ice houses. These ice houses stored large blocks of ice harvested in winter, which could then be used throughout the warmer months to keep perishable items like milk and meat from spoiling. A look at a typical family food budget from 1890, which provides context for the early 1900s, shows significant portions of income were spent on essentials like flour and cornmeal, pork products, other meats, vegetables, and potatoes. The combination of public markets and home preservation techniques was vital for ensuring families had enough to eat.

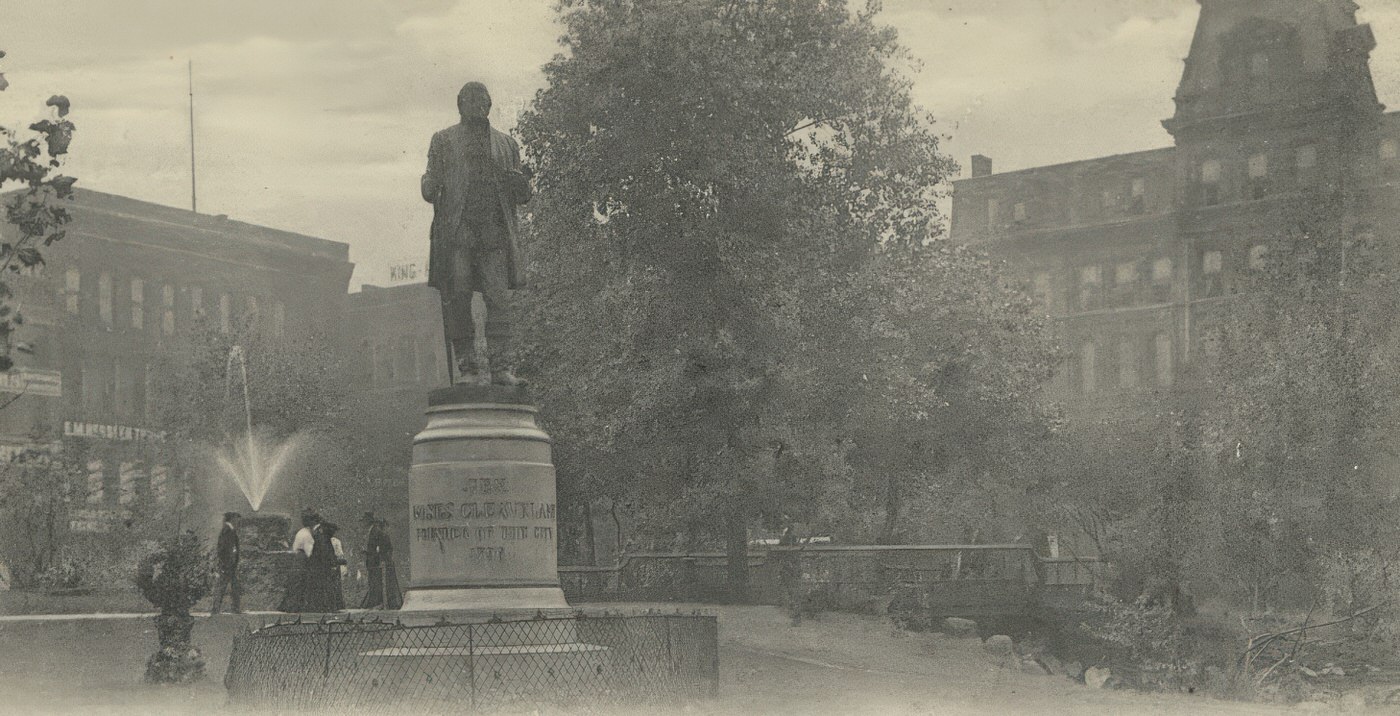

The Progressive Era and Mayor Tom L. Johnson (1901-1909)

The years from 1901 to 1909 in Cleveland were significantly shaped by the leadership of Mayor Tom L. Johnson, a prominent figure of the Progressive Era. Johnson’s administration was guided by the principles of “Home rule; three cent fare; and just taxation”. He championed reforms aimed at increasing municipal control over transit lines, with the goal of making streetcar fares more affordable for the average citizen. His push for a “three cent fare” was a direct challenge to the powerful private streetcar companies. Johnson also focused on creating a fairer tax system, believing that existing assessments disproportionately burdened working people while favoring the wealthy. He established a tax school to help revise these assessments.

Beyond transit and taxation, Johnson’s administration worked to improve city services. This included initiatives for better street paving and lighting, enhanced hospital care, and the establishment of public bathhouses in poorer neighborhoods to improve sanitation and hygiene. He also abolished license fees for peddlers, a measure intended to help small entrepreneurs and the poor. Johnson was a proponent of public ownership of utilities, believing essential services should be run for public benefit rather than private profit.

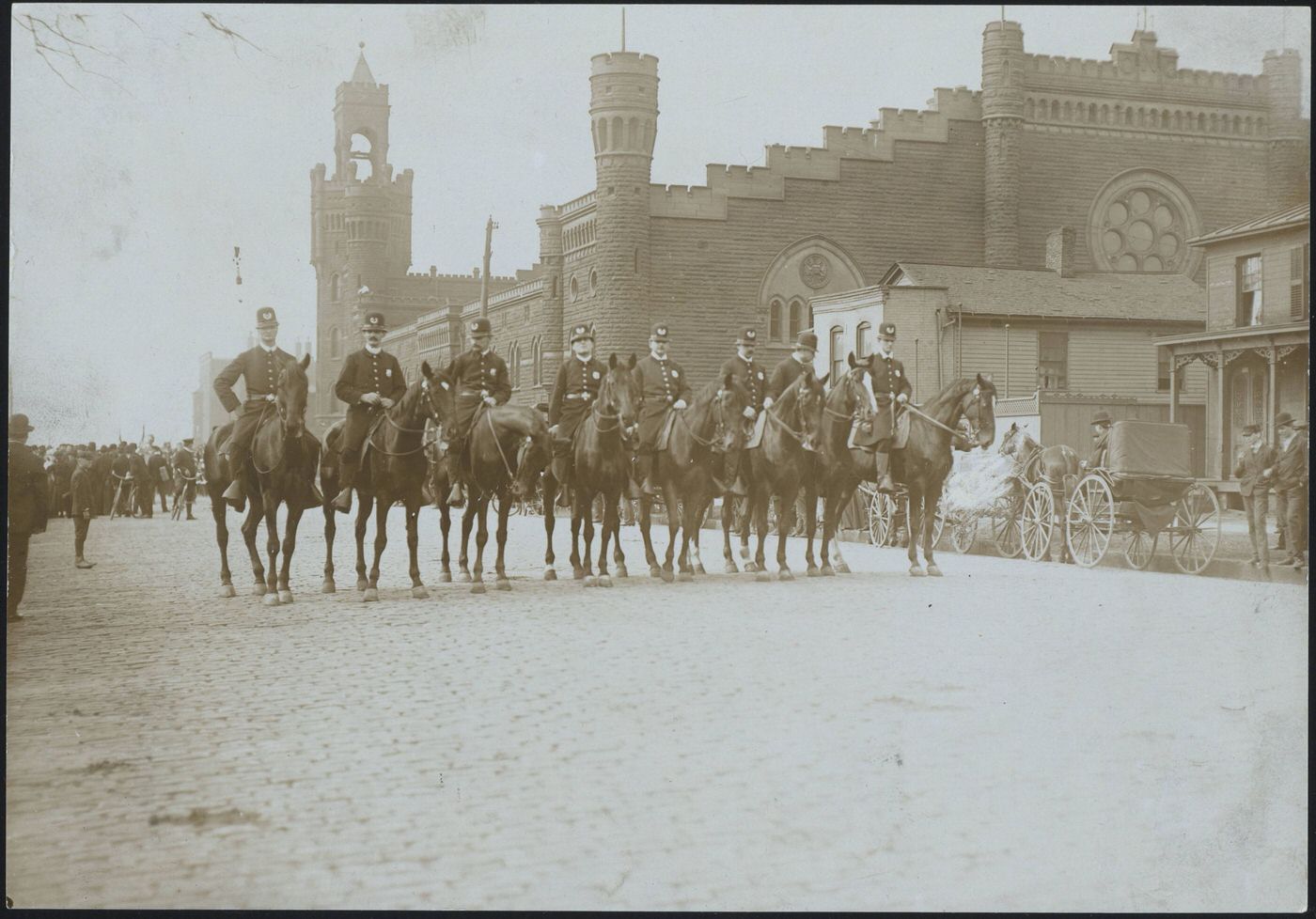

The structure of Cleveland’s city government itself was in transition during this period. The “Federal Plan” of government had been declared unconstitutional in 1902, so the city operated under a new municipal code during Johnson’s mayoralty. Key city departments managing the city’s affairs included the Law Department (formally organized in 1903), a Board of Public Safety (created in 1904 to oversee police and fire services), a Department of Public Service (responsible for streets, engineering, and public properties), and a developing focus on public health and welfare, which would later be formalized into a dedicated department. Mayor Johnson’s time in office represented a concerted effort to make city government more responsive to the needs of its citizens and to address the social and economic challenges brought by rapid industrialization and urban growth, reflecting the core ideals of the national Progressive movement.

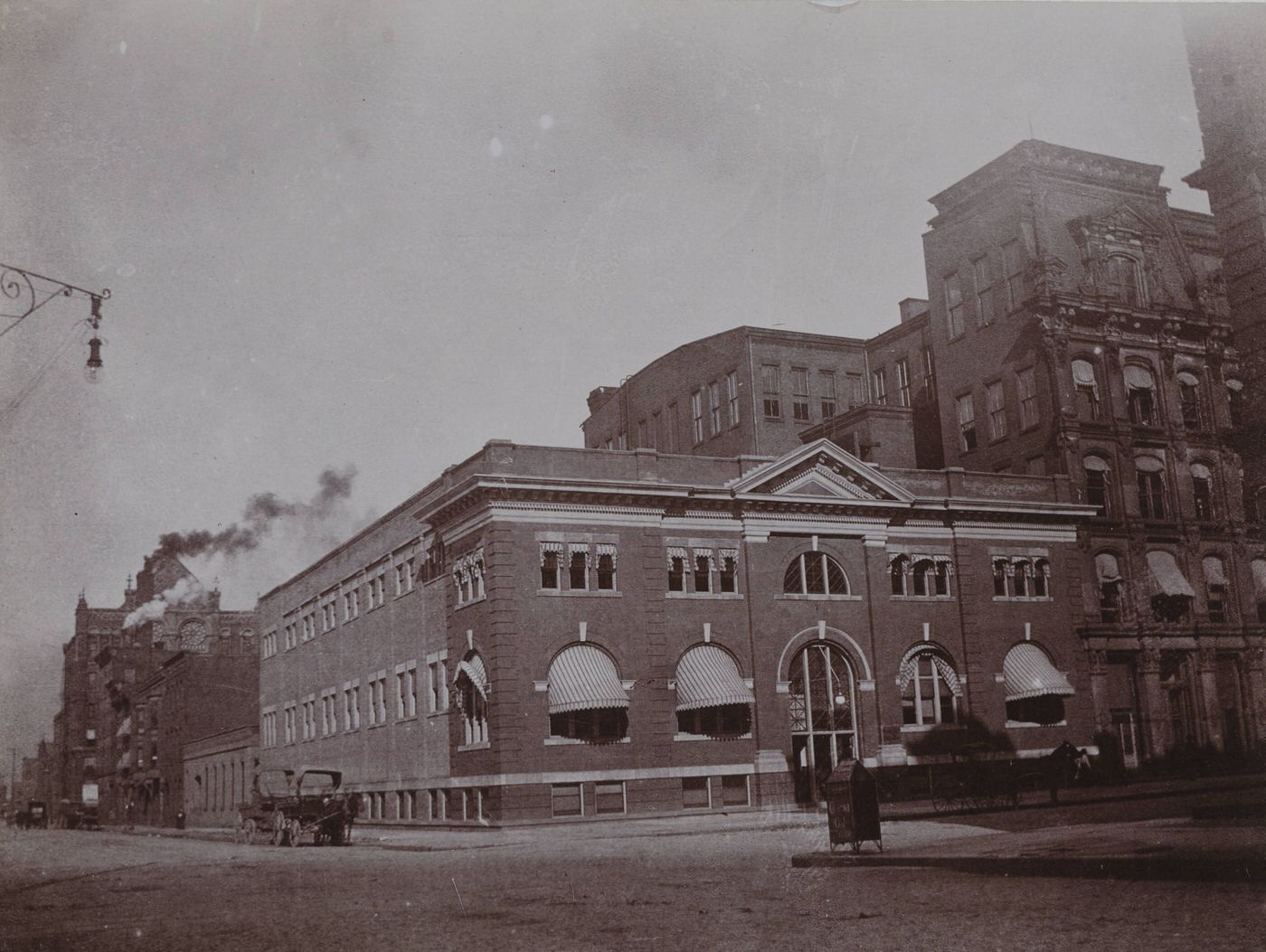

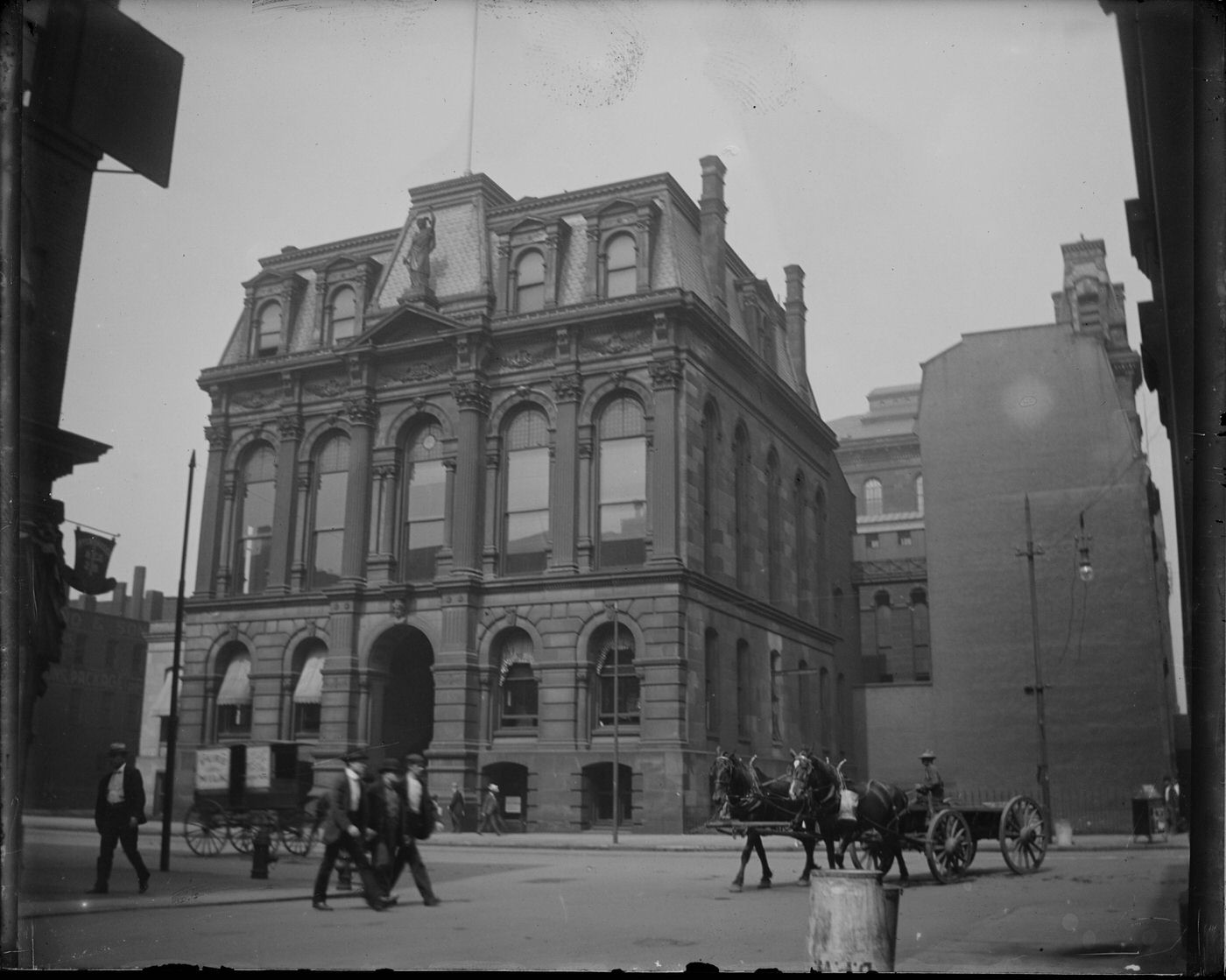

A Grand Vision: The Group Plan of 1903

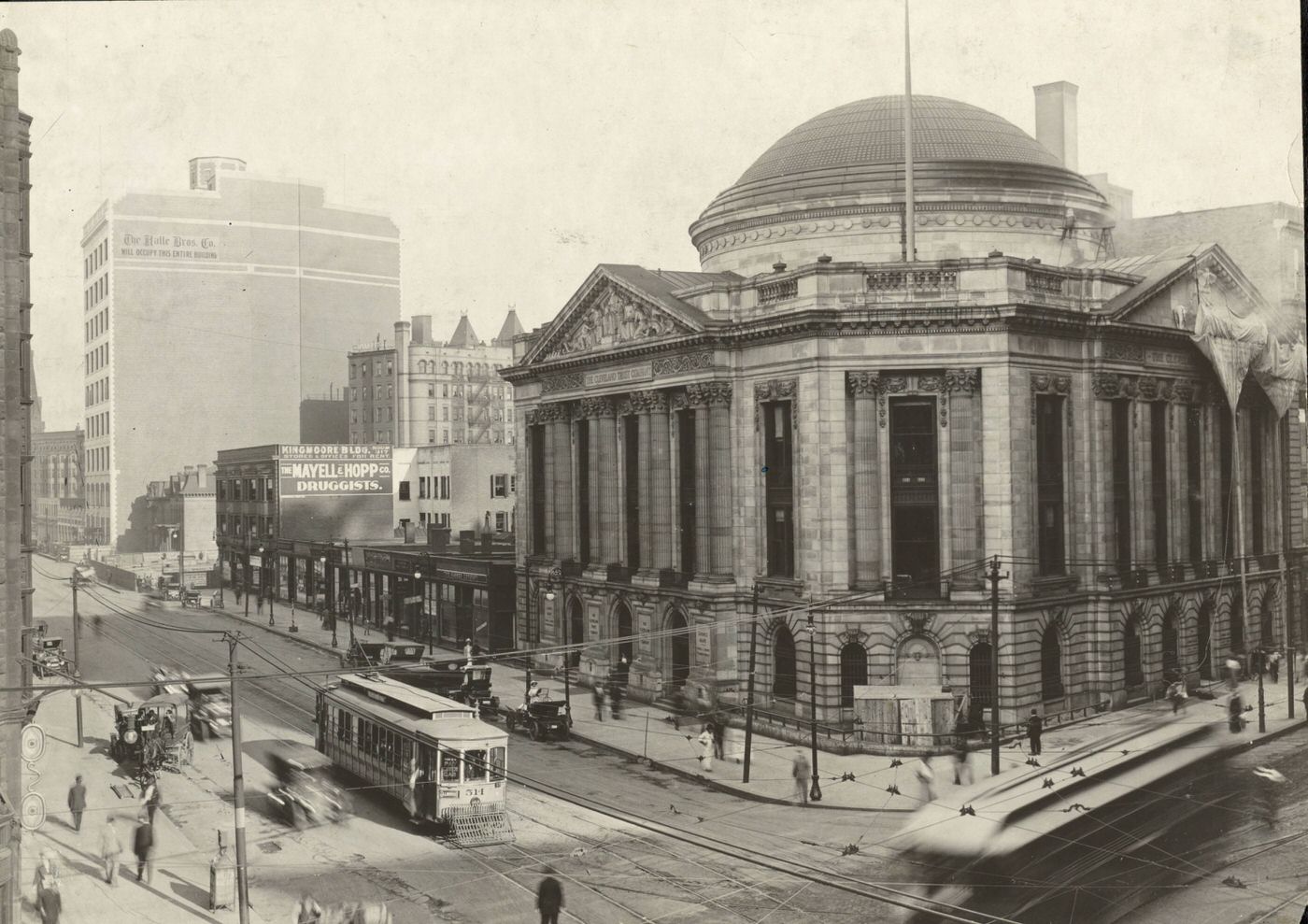

In 1903, Cleveland embarked on an ambitious urban planning project known as the Group Plan. This visionary scheme was inspired by the City Beautiful movement, a national trend that sought to improve the appearance and functionality of American cities, and by the grandeur of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The plan was developed by a commission of renowned architects: Daniel Burnham, Arnold W. Brunner, and John M. Carrère.

Their vision was to create a monumental civic center composed of impressive public buildings, all designed in the Beaux-Arts architectural style, harmoniously arranged around a large, open green space called the Mall. This was a bold statement of Cleveland’s civic pride and its aspirations as a major American city. The Group Plan aimed to bring order, dignity, and aesthetic beauty to the urban core, countering the often-chaotic development that accompanied rapid industrial growth.

During the 1900-1909 decade, the design work for several of these key public buildings was underway, and early construction phases began, although many were completed in the following decade. Among these were the Federal Building (which would become the Howard Metzenbaum U.S. Courthouse, completed in 1910) and the Cuyahoga County Courthouse (completed in 1911). Cleveland City Hall, another integral part of the plan, would follow, opening in 1916.

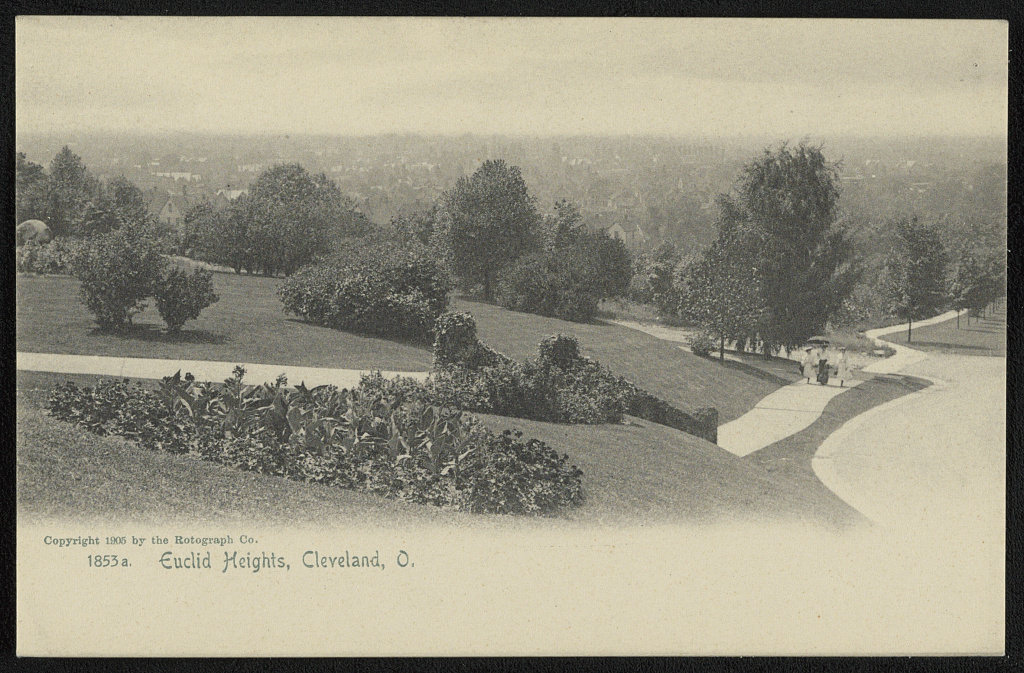

Breathing Spaces: Parks and Recreation

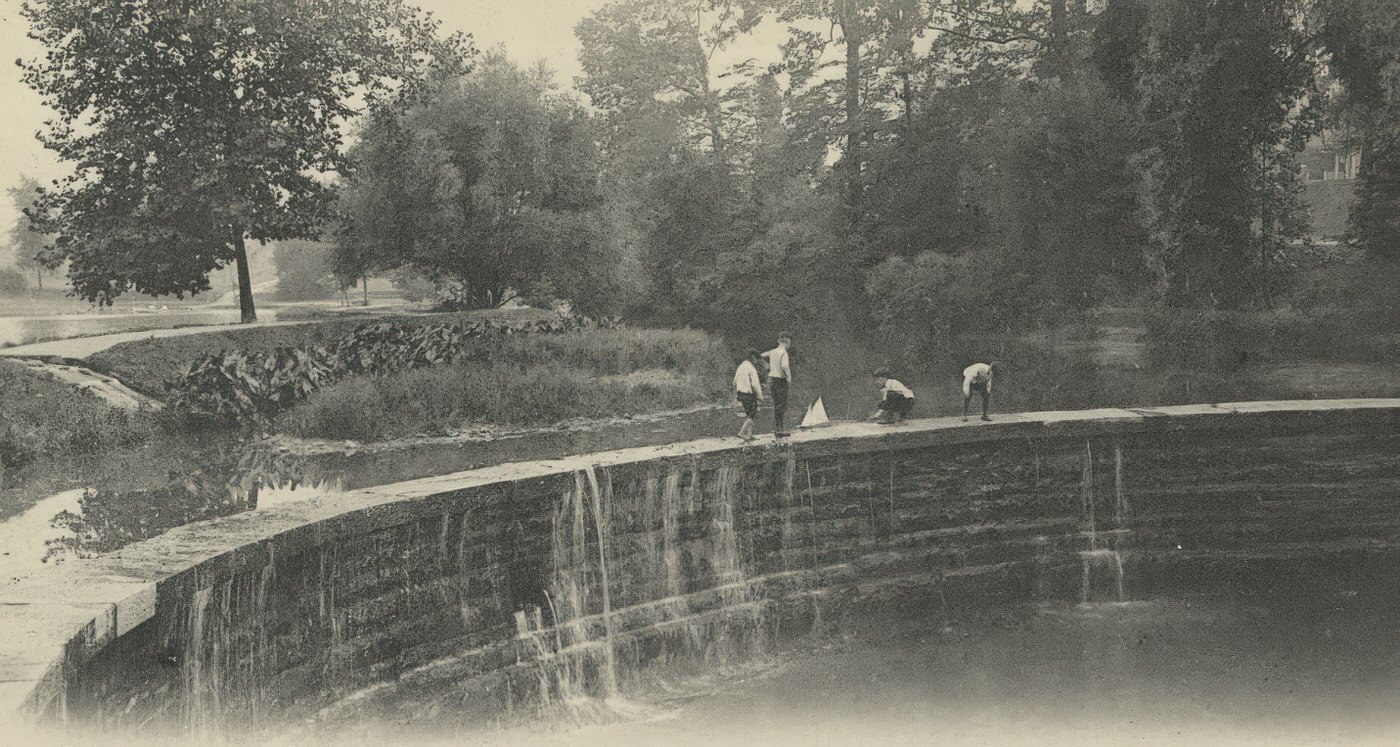

Under Mayor Tom L. Johnson, Cleveland’s approach to its public parks underwent a significant transformation, guided by the idea of “bringing the parks to the people”. One of the first symbolic changes was the removal of “Keep Off the Grass” signs, signaling a shift from parks as purely ornamental “pleasure grounds” to spaces for active public use and recreation.

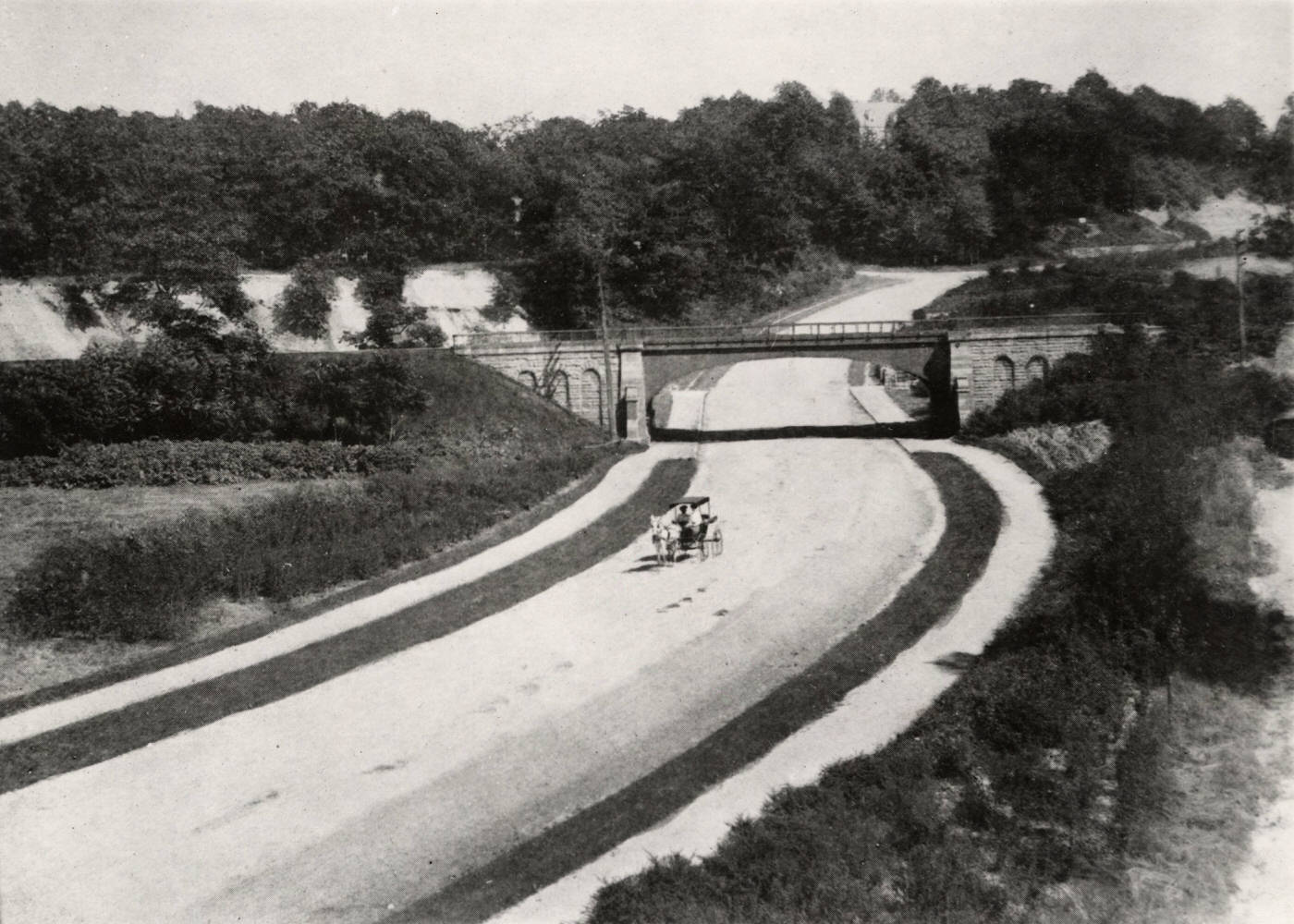

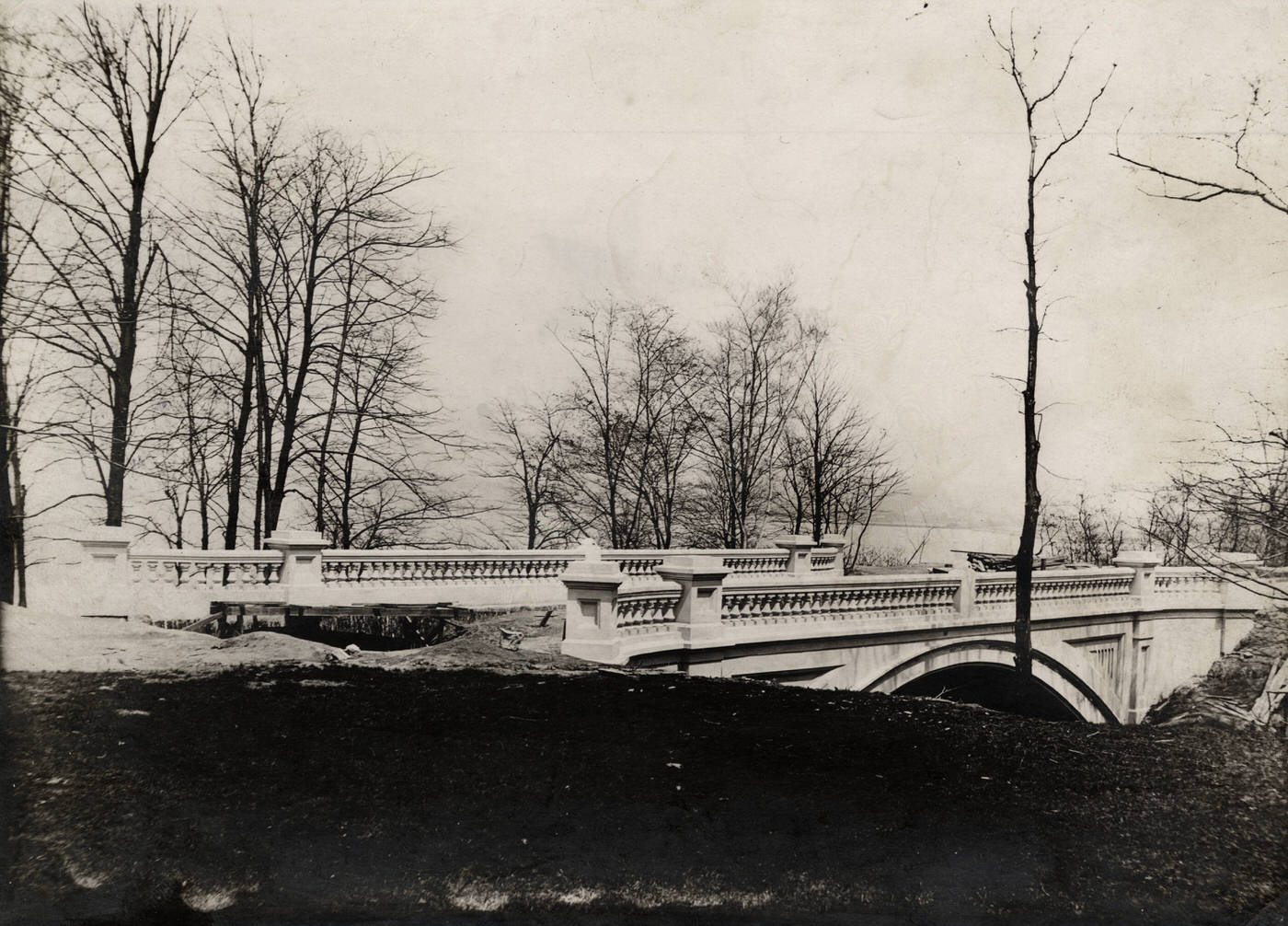

New recreational facilities were developed and expanded in major city parks such as Wade Park, Gordon Park, Brookside Park, Edgewater Park, and Woodland Hills Park. These improvements included the creation of children’s playgrounds, the construction of athletic fields, and the addition of basketball and tennis courts. Recognizing the popularity of winter activities, the city established skating rinks in all larger parks starting in 1901 and even hosted skating races at Brookside and Rockefeller parks. Park shelters at Edgewater and Woodland Hills parks were repurposed as municipal dancing pavilions, offering new social gathering spots. By 1904, eight dedicated children’s playgrounds were operating in Cleveland’s more densely populated neighborhoods, and the Division of Parks began constructing the first of five planned free public bath houses. Sunday and evening band concerts in the parks also became a popular form of public entertainment.

The ambitious boulevard system, conceived in the 1890s to connect these major parks into a cohesive network, continued to be developed during this decade. However, a persistent challenge was funding the maintenance of this expanding park and boulevard system. While bond funds could be used for land acquisition and permanent improvements, ongoing upkeep had to be covered by taxes, which often proved insufficient. As early as 1901, the parks superintendent issued warnings about the rising costs of maintaining the new park work, a concern that would continue in the years to come. This evolution in park philosophy reflected a growing understanding of the recreational and health needs of a large urban population, especially children, in an industrial city.

Fun at Euclid Beach Park

Euclid Beach Park, a beloved Cleveland amusement park, underwent a significant transformation in the 1900s. The Humphrey family took over management of the park starting with the 1901 season. Their vision was to create a respectable, family-friendly destination. To achieve this, they made notable changes, such as removing the beer garden and enforcing dress codes to ensure a wholesome atmosphere.

Under the Humphrey’s stewardship, Euclid Beach Park also introduced exciting new attractions to draw crowds. During the 1901-1909 period, these additions included a Roller Rink in 1904, the Figure Eight rollercoaster, also built in 1904, and a Scenic Railway, constructed in 1907. These improvements helped solidify Euclid Beach Park’s reputation as a premier leisure spot for Cleveland families, reflecting a broader American trend in the development of amusement parks as major entertainment venues.

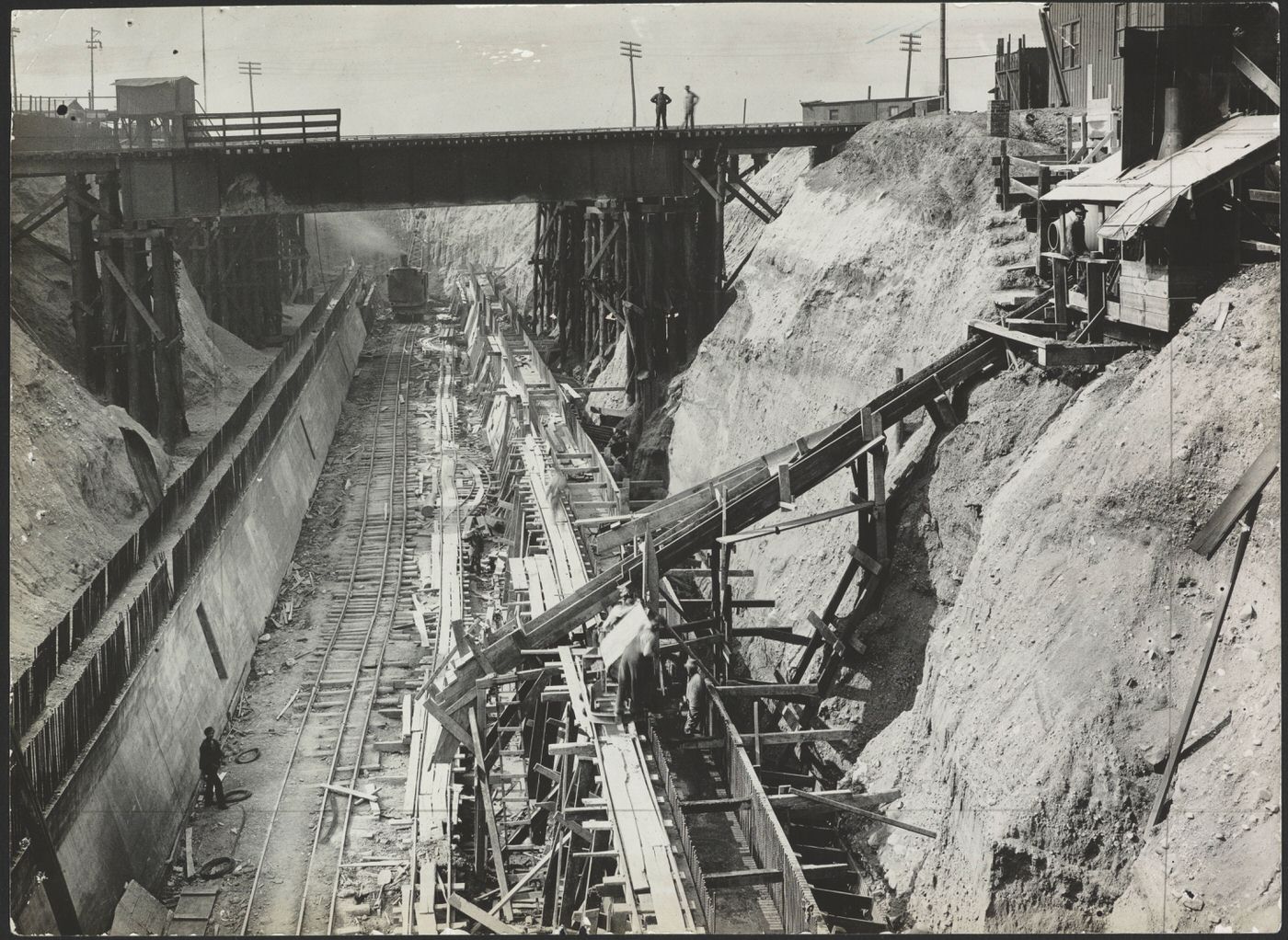

Building a Healthy City: Sanitation and Water

Cleveland in the 1900s actively grappled with the significant public health challenges that came with its rapid growth and industrial character. Efforts to improve sanitation were ongoing. Street cleaning became more regular and systematic, and by 1906, the city employed street-flushing machines to help keep thoroughfares cleaner.

The city’s water supply remained a critical concern. While a major engineering project—a new nine-foot diameter water intake tunnel extending 26,000 feet out into Lake Erie—had been started in 1896 and was completed in 1904, ensuring water purity was an ongoing battle. To address this, the city established a municipal bacteriological laboratory in 1901. This facility, headed by Professor William Travis Howard from Western Reserve University Medical School, was tasked with routinely examining water and food supplies for potential disease sources and establishing health safety standards. This marked an important shift towards a more scientific approach to public health, moving beyond earlier theories that focused primarily on “filth” as the cause of disease. However, comprehensive water filtration and chlorination, which would virtually eliminate water-borne diseases like typhoid fever, were still a few years away, being fully implemented between 1911 and 1925.

Sewage treatment was another area of focus, though major plant construction occurred later. An experimental sewage-treatment plant was authorized in 1911, leading to the completion of the Westerly, Easterly, and Southerly treatment plants in the 1920s. The 1900-1909 decade was a period of laying crucial groundwork in infrastructure and adopting scientific methods to tackle the immense public health needs of a burgeoning industrial metropolis.

Community Welfare: Charity and Social Services

The early 1900s in Cleveland witnessed a significant evolution in how the community addressed social welfare needs. While religious institutions continued their long-standing tradition of charitable work, there was a discernible shift towards more organized, professional, and coordinated approaches to philanthropy.

This trend was exemplified by the formation of the Committee on Benevolent Associations in 1900 by the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce. This committee aimed to bring more order and efficiency to the city’s many charitable efforts. This led to the establishment of the Cleveland Federation for Charity and Philanthropy in 1906. This federation sought to coordinate fundraising and the work of various social service agencies, regardless of their specific religious affiliation. A similar move towards centralized organization occurred within the Jewish community with the establishment of the Federation for Jewish Charities in 1903 (later the Jewish Community Federation).

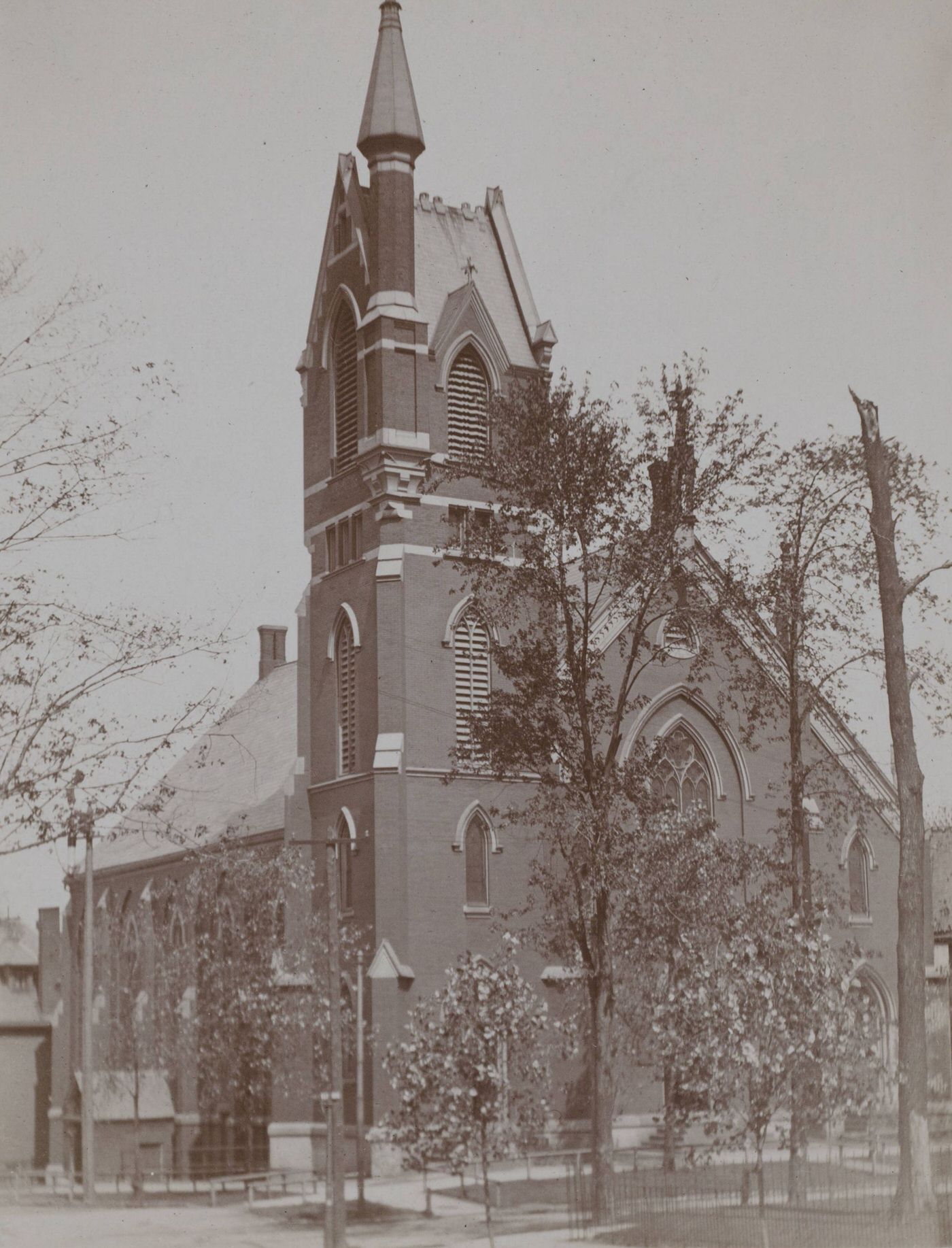

Alongside these federated movements, individual religious denominations and their congregations remained vital sources of support. Churches like St. John A.M.E. (whose new building was completed in 1908) and other African American churches provided crucial services and leadership within their communities. Lutheran churches, such as the First Hungarian Lutheran Church (established in 1906) and the Slovak SS. Peter & Paul Lutheran Church (established in 1901), catered to the spiritual and social needs of their specific immigrant groups. Catholic parishes continued to expand their schools and social welfare institutions to serve a rapidly growing Catholic population, much of it immigrant-based. Presbyterian churches were also active, supporting mission projects and settlement houses like Goodrich House, which served immigrant neighborhoods. This period marked a transition, with Cleveland developing more systematic approaches to social welfare to meet the complex needs of a large and diverse industrial city, while still relying on the foundational work of community-based and religious charities.

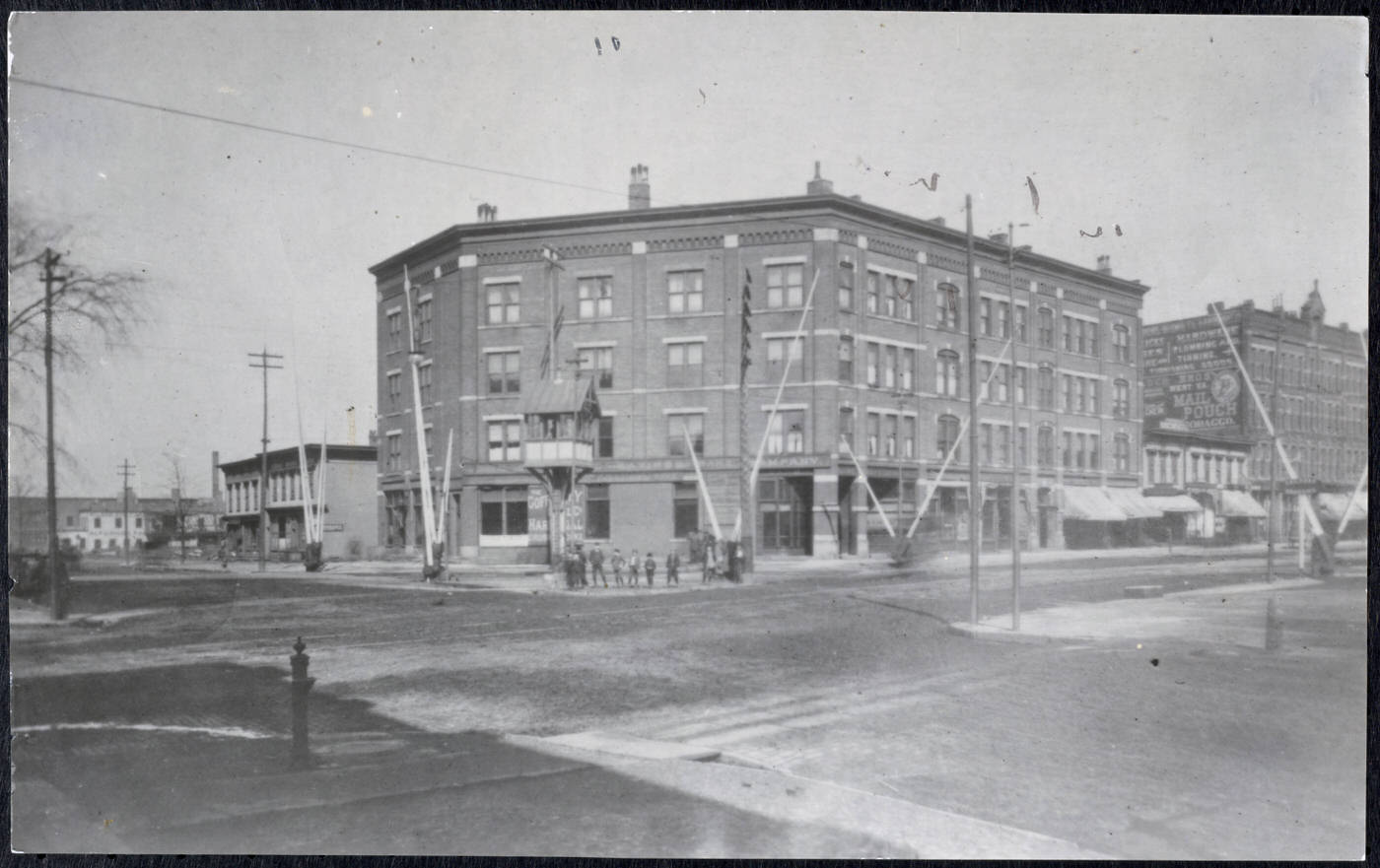

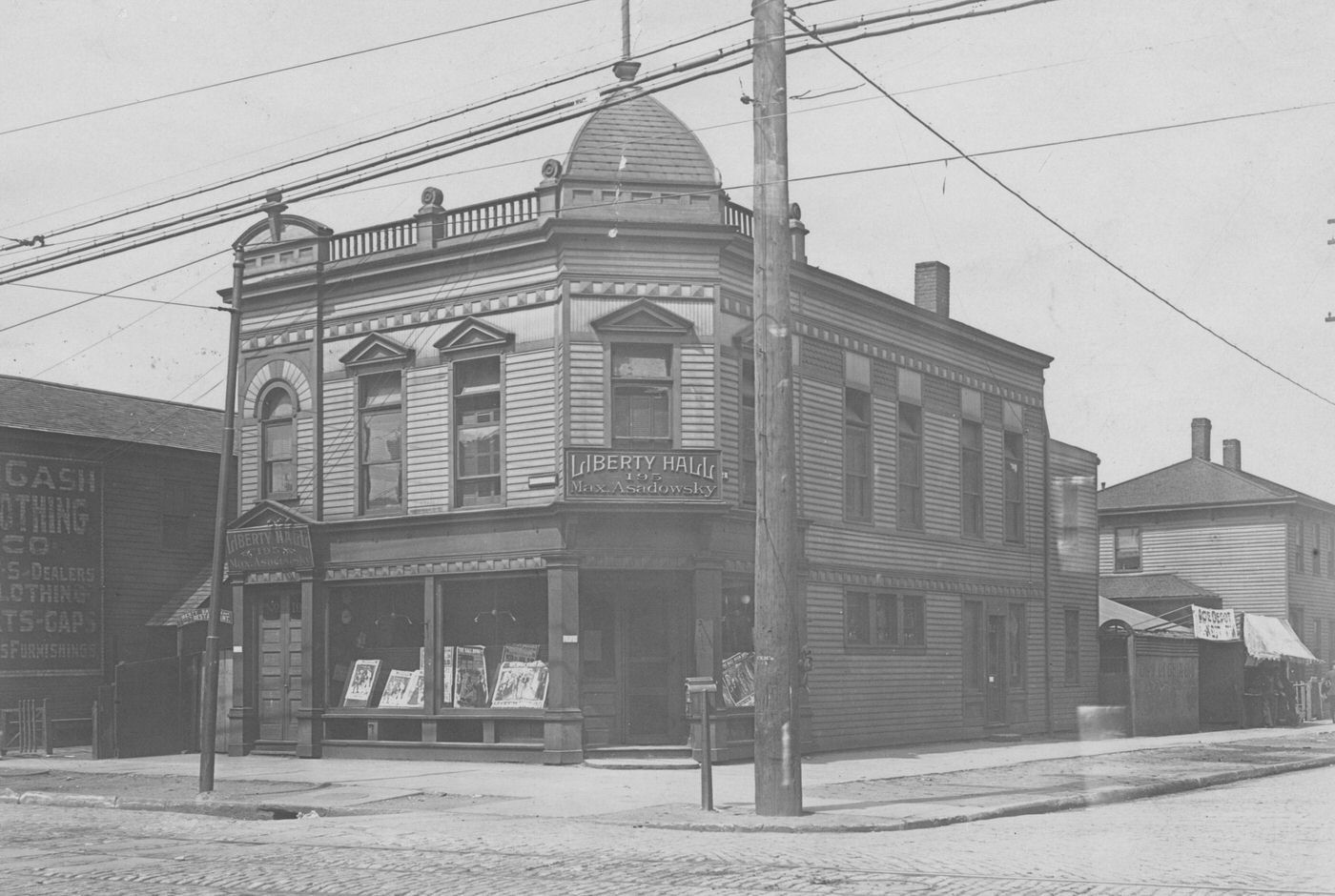

The Heyday of Vaudeville and the Dawn of Cinema

Vaudeville was the reigning form of popular entertainment in Cleveland during the 1900s, with a vibrant scene that included over 60 theaters operating between 1885 and 1930. Prominent venues at the turn of the century included the historic Euclid Avenue Opera House and the Columbia Theater. They were joined by new establishments like the Empire Theater, which opened in 1900, and the Colonial Theater in 1903. A jewel of this era was the grand Hippodrome Theater, which opened its doors in 1907 or 1908, offering a large and impressive space for performances. Vaudeville shows were true variety entertainment, featuring a mix of animal acts, skilled acrobats, comedians delivering monologues and sketches, popular musical performers, and mystifying magicians.

Alongside the established popularity of vaudeville, the exciting new technology of moving pictures began to capture the public’s imagination. Cleveland’s first theater dedicated to showing films, the American Theater, opened on Superior Avenue in 1903. One of its first features was the groundbreaking narrative film, “The Great Train Robbery”. The Empire Theater also began interspersing films into its vaudeville programs as early as 1901. These early movie houses, often called nickelodeons because of their five-cent admission price, started to appear in various locations. Among them were the Electric Theater, which opened in 1908 and was later known as the Auditorium, and the Park Theater, which began showing films in 1907. Clevelanders in the 1900s had an expanding array of leisure options, from the familiar pleasures of live vaudeville to the novel thrill of the cinema.

The Expanding Telephone Network

The telephone, once a novelty and primarily a business tool, was rapidly becoming a more common feature in Cleveland households during the 1900s. By 1905, it was estimated that approximately one in every fourteen Clevelanders had telephone service, a clear indication of its growing adoption.

This expansion was fueled in part by competition between different telephone companies. The main providers in the city were the Cuyahoga Telephone Co. and the Cleveland Telephone Co. (which was part of the Bell system). By the end of 1904, Cuyahoga Telephone served over 12,000 subscribers, while Cleveland Telephone had more than 14,000. This competition helped to drive down the cost of telephone service, making it accessible to more people.

However, this competitive environment also created a significant inconvenience for users. Because the two companies operated separate networks, a subscriber of Cuyahoga Telephone could not directly call a subscriber of Cleveland Telephone, and vice versa. Businesses, in particular, often had to subscribe to both services to ensure they could communicate with all their contacts. This issue of interoperability persisted until 1910, when the companies finally began to exchange services, allowing calls between their networks. Despite these early challenges, the telephone was fundamentally changing how Clevelanders communicated, shrinking distances and connecting people in new ways.

Moments of Crisis and Community Response

The Collinwood School Fire (March 4, 1908)

A horrific tragedy struck the region on March 4, 1908, when a fire engulfed the Lakeview Elementary School in Collinwood, at the time a village bordering Cleveland that would later be annexed. The fire, which started when an overheated steam pipe ignited wooden joists beneath a staircase, resulted in the deaths of 172 children and 2 teachers.

Investigations following the disaster revealed critical design flaws that contributed to the high death toll. While the school’s outer doors did open outward as required by law at the time, many children became trapped behind a set of inner vestibule doors that were narrower than the main exits, creating a fatal bottleneck as panic ensued. The Collinwood School Fire sent shockwaves across the nation and served as a grim catalyst for major reforms in school safety. It led to widespread inspections of school buildings and the implementation of stricter building codes and safety laws. These new regulations often mandated the use of fireproof construction materials, wider and more direct exits, and improved escape routes. In Cleveland, the public outcry and scrutiny over school safety also had political repercussions, as concerns about school contracts awarded after the fire contributed to the later electoral defeat of Superintendent William H. Elson.

Public Health Challenges: The 1902 Smallpox Epidemic

Cleveland, like many rapidly growing industrial cities of the era, faced significant public health challenges. In 1902, the city confronted a serious smallpox epidemic. To manage the outbreak, a “pest house” was constructed on the grounds of City Hospital to isolate infected patients. This facility was later repurposed in 1903 to become what was reportedly the first separate hospital in the United States dedicated to the treatment of tuberculosis, another pervasive and deadly disease of the time. Diseases like tuberculosis and high rates of infant mortality were major public health concerns, with more reliable collection of mortality statistics for Ohio beginning around 1909-1910. These recurring epidemics and chronic health issues underscored the urgent need for improved public health infrastructure and disease control measures. The city’s response, though sometimes reactive, demonstrated an evolving understanding of how to manage contagious diseases and care for those afflicted.

Nature’s Fury: The 1909 Windstorm

On April 21, 1909, Cleveland was battered by a severe windstorm, described in some accounts as a tornado. The storm carved a path of destruction through the city, causing an estimated $2 million in damages—a substantial sum at the time. Tragically, the storm claimed the lives of several people (reports vary between six and seven) and left a wide trail of damaged and destroyed buildings. Among the structures affected were 12 churches and 17 schools. The iconic twin steeples of St. Stanislaus Church were toppled by the high winds. Even City Hospital was impacted; its Middle House building was damaged so severely that it had to be demolished. In the aftermath, the city mobilized quickly to restore essential services like power and telephone lines. This natural disaster served as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of the urban environment and tested the community’s capacity for emergency response and recovery.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress, Wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know