The decade of the 1910s was a period of profound transformation for Cleveland, Ohio. The city throbbed with industrial energy, its population swelled by waves of newcomers, and its physical and social landscapes were reshaped by technological advancements, civic ambitions, and global events.

The city was experiencing explosive growth. Its population climbed from 381,768 in 1900 to 560,663 by 1910, making it the sixth-largest city in the United States. This rapid expansion continued, with the city’s population reaching 796,841 by 1920. By that year, Cleveland was home to over 800,000 people, a testament to its magnetic pull as an industrial center brimming with opportunities.

This era, particularly from 1870 up to 1914, was defined by the “new immigration,” a massive influx of people from Southern and Eastern Europe. However, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 acted as a stark dividing line. The conflict largely halted the stream of European immigrants. Simultaneously, the war effort created an immense demand for labor in Cleveland’s factories, a demand that began to be met by a new wave of migration: African Americans moving north from the Southern states in what would become known as the Great Migration. The 1910s, therefore, were not a period of uniform demographic trends. The early years saw the continuation of established European immigration, while the latter half of the decade witnessed a fundamental shift towards internal migration, driven by the war. This change began to reshape the city’s ethnic and racial makeup, setting the stage for new social dynamics in the years to come.

To accommodate this burgeoning population and expanding industry, Cleveland’s physical footprint also grew. The city annexed the village of Corlett in 1909 and Collinwood in 1910. Between 1912 and 1915, portions of Shaker Village were also incorporated into Cleveland. This expansion brought existing communities and their infrastructures—or lack thereof—under Cleveland’s governance. The rapid growth and amalgamation of different areas necessitated civic reorganization. For instance, a significant re-standardization of street names and addresses occurred in 1906 to manage the confusion arising from multiple systems in previously independent villages, a process that remained relevant as new territories were added in the 1910s.

Waves of Newcomers: Major European Immigrant Groups

Cleveland in the 1910s was a city of immigrants, each group contributing to its vibrant, complex character and establishing institutions that were vital for preserving their heritage and navigating life in a new land. These ethnic-specific churches, fraternal organizations, newspapers, and social clubs provided more than just familiarity; they offered essential social safety nets, economic support through insurance and loans, avenues for language retention, platforms for political mobilization, and, fundamentally, a sense of belonging in a bustling, often overwhelming, urban environment. These institutions were not merely social outlets but multi-functional organizations that facilitated both cultural preservation and practical adaptation to American life, acting as both a buffer against hardship and a bridge to new opportunities.

Hungarians: Hungarian immigration to Cleveland reached its peak around 1910, and by 1920, the city was home to 43,134 Hungarian immigrants. They primarily settled on the city’s southeast side, concentrated around Madison Avenue (now East 79th Street) and Woodland Avenue, in areas with streets like Bismarck, Rawlings, and Holton. A smaller Hungarian community also formed on the west side, near the Lorain Avenue and Abbey Avenue marketplace. Many Hungarians found work in the demanding environment of steel mills and foundries, such as Eberhardt Manufacturing, National Malleable Steel Castings, and Ohio Foundry. Some, like Theodore Kundtz who founded Kundtz Manufacturing Company, became significant employers themselves, with Kundtz employing around 2,500 workers by 1900. Community life was rich, with self-help and sick benefit societies like the Gróf Batthány Lajos Society (formed in 1886) providing crucial support. Cultural organizations flourished, including the First Hungarian Dramatic Society (1891) and the Cleveland Hungarian Self-Culture Society (1902), which began offering English classes in 1903. Numerous churches served the community; Cleveland was the site of the first Hungarian Roman Catholic, Reformed, and Greek Catholic churches in North America, all established in the 1890s. The First Hungarian Lutheran Church, established in 1906, later operated an orphans’ home. The influential Hungarian-language newspaper, Szabadság (Liberty), founded in 1891, became a daily publication in 1906.

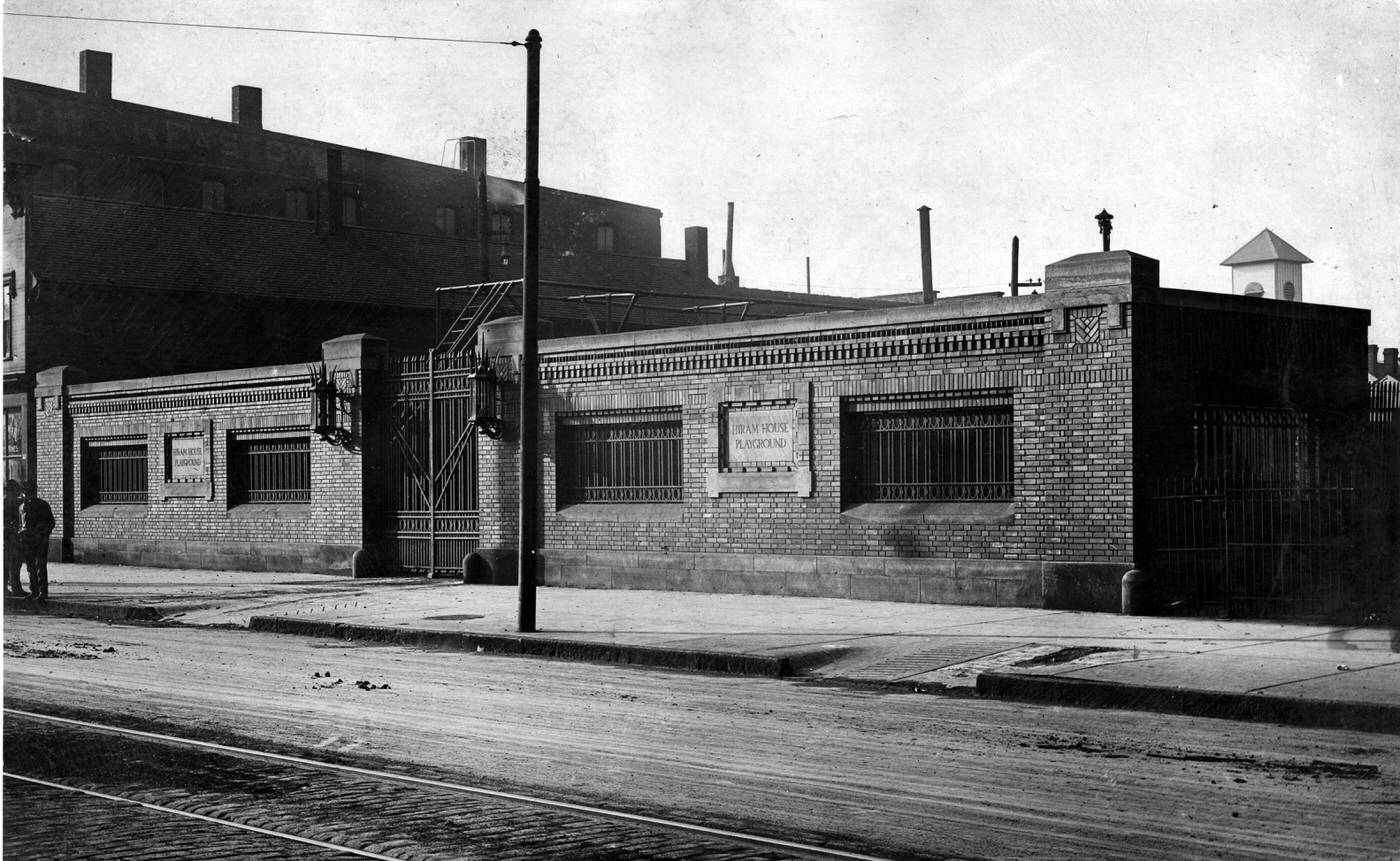

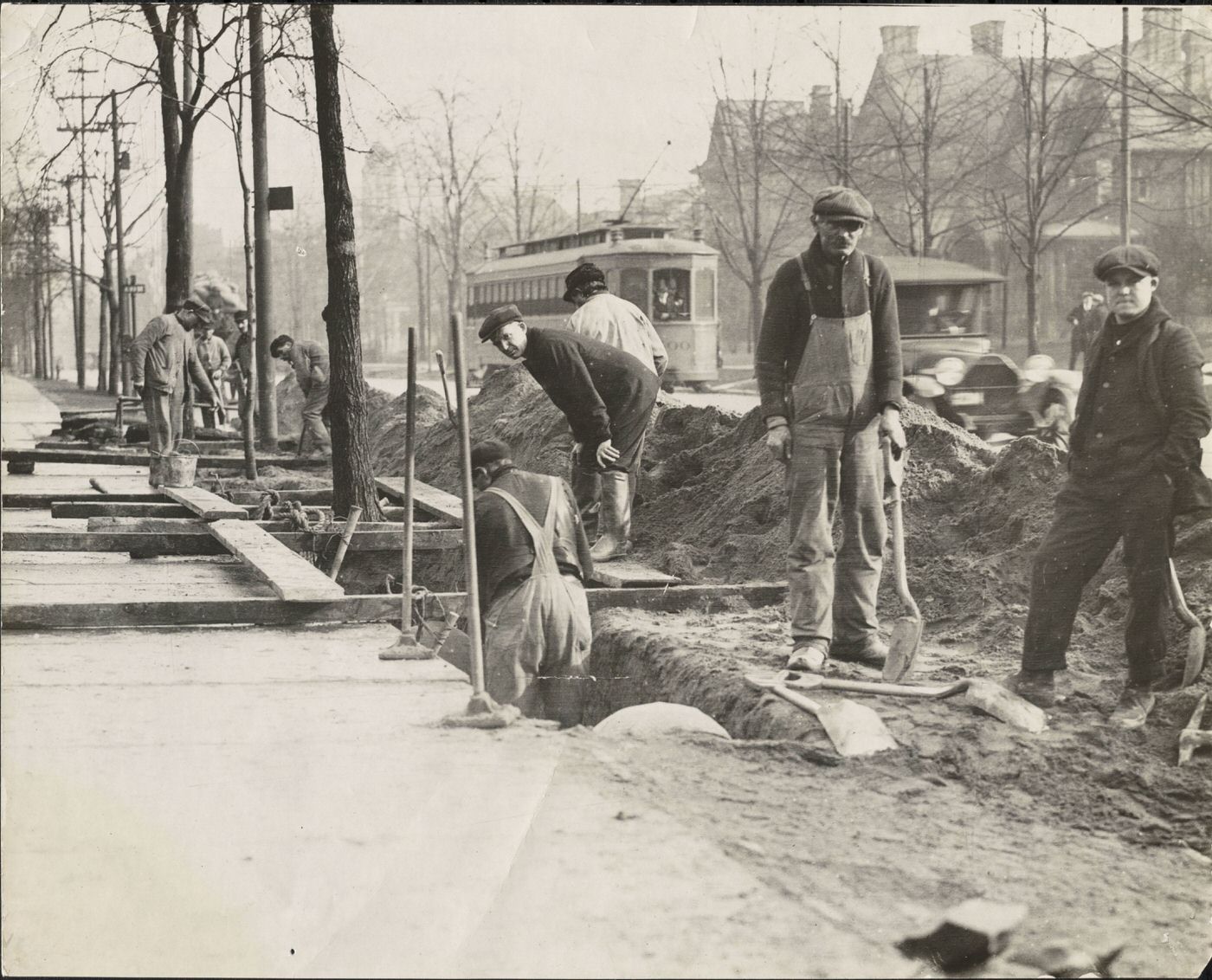

Italians: By 1910, Cleveland’s Little Italy neighborhood, centered around Mayfield and Murray Hill Roads, had a population of approximately 10,000. Another significant Italian settlement, known as “Big Italy,” located along Woodland and Orange Avenues, housed 4,429 Italians in the same year. Italian immigrants often worked on public infrastructure projects such as bridges, sewers, and streetcar tracks. Others found employment in tailoring, monument work, gardening, and were prominent in the city’s fruit industry. They established “Hometown societies” like the Ripalimosani Social Union, which provided a connection to their specific places of origin, and founded churches such as St. Anthony’s and Holy Rosary. The Hiram House settlement house began to engage more with the Italian residents of Big Italy in the 1910s, particularly after hiring an Italian-speaking worker. The Italian-language newspaper, La Voce Del Popolo Italiano (The Voice of the Italian People), adopted its permanent name in 1910. Initially, it leaned Republican in domestic politics and later, in the context of European events, expressed support for Mussolini before condemning his government during World War II.

Poles: The Polish population in Cleveland saw its most significant growth between 1900 and 1914, reaching 35,024 by 1920. Major Polish settlements included Warszawa (later part of Slavic Village) around St. Stanislaus Church, Poznan near East 79th Street and Superior Avenue, and Kantowo in the Tremont area. Smaller enclaves existed near Otis Steel works (Josephatowo) and Grasselli Chemical Co. (Barbarowo). Polish immigrants were a substantial part of the workforce in the city’s steel mills, particularly at the Cleveland Rolling Mills (which became American Steel & Wire). By 1919, Poles constituted over half of this major plant’s workforce. They also found employment at companies like the Kaynee Blouse Co., Cleveland Worsted Mills, and Grabler Manufacturing Co.. Roman Catholic churches, such as St. Stanislaus (the mother parish), Sacred Heart of Jesus, and St. Hyacinth, were central to community life. Fraternal insurance organizations like the Polish Roman Catholic Union and the Polish National Alliance were highly influential, offering both financial security and cultural cohesion. The Polish National Alliance, for example, built meeting halls that housed significant collections of Polish literature. Recognizing the need for women’s organizations, the Association of Polish Women in the U.S. was established in 1911. The community was served by Polish-language newspapers, including Narodowiec (1909-1914) and Wiadomosci Codzienne (which began publishing in 1914).

Czechs (Bohemians): Cleveland was a global center for Czech immigrants. By 1910, the city had the fourth-largest Czech population worldwide, with approximately 40,000 residents. The period from 1900 to 1914 marked the greatest influx of Czechs to the area. “Little Bohemia,” a vibrant Czech enclave, was located in the Broadway area, stretching from East 37th Street to Union Avenue. Czech immigrants worked in a variety of trades, including as tailors, shoemakers, and masons, and in factories. Some, like Frank J. Vlchek, who founded the Vlchek Tool Company, became successful industrialists. The community’s social and cultural life was rich, with the Bohemian National Hall, dedicated in 1897, serving as a meeting place for over 40 different lodges, societies, and clubs. Czechs established numerous churches and freethinker halls, the latter reflecting a segment of the community that was secular or atheist. They also founded savings and loan societies. Newspapers like the socialist Americke Delnicke Listy (American Workman’s News), which began in 1909, and the daily Svet (World), starting in 1911, kept the community informed. The Czech community in Cleveland played a pivotal role in the movement for Czechoslovak independence, notably through their involvement in the Cleveland Agreement of 1915.

Slovaks: In the early 1900s, Cleveland was reputed to have the largest Slovak population of any city in the world, with an estimated 35,000 Slovaks residing there by 1918. Their initial settlements were near East 9th Street and the Cuyahoga River, later expanding to Buckeye Road, the Newburgh area (near American Steel & Wire), and Lakewood’s “Birdtown” neighborhood (close to National Carbon Co.). Churches were foundational to Slovak community life, including St. Ladislas Catholic parish (founded 1889) and Holy Trinity Lutheran (the first Slovak Lutheran congregation in Ohio, organized 1892). The Dr. Martin Luther Evangelical Lutheran Church (Slovak) was established in 1910. National fraternal-benefit societies with headquarters in Cleveland, such as the First Catholic Slovak Union (founded 1890) and the First Catholic Slovak Ladies Union (founded 1892), provided crucial insurance and social support. The Slovak League of America, an important national organization, was formed in Cleveland in 1907. Newspapers like Jednota (Union), established in 1891, and Hlas (Voice), published from 1907 to 1947, served the Slovak community. Cleveland Slovaks were also key participants in the 1915 Cleveland Agreement, advocating for a unified Czechoslovak state.

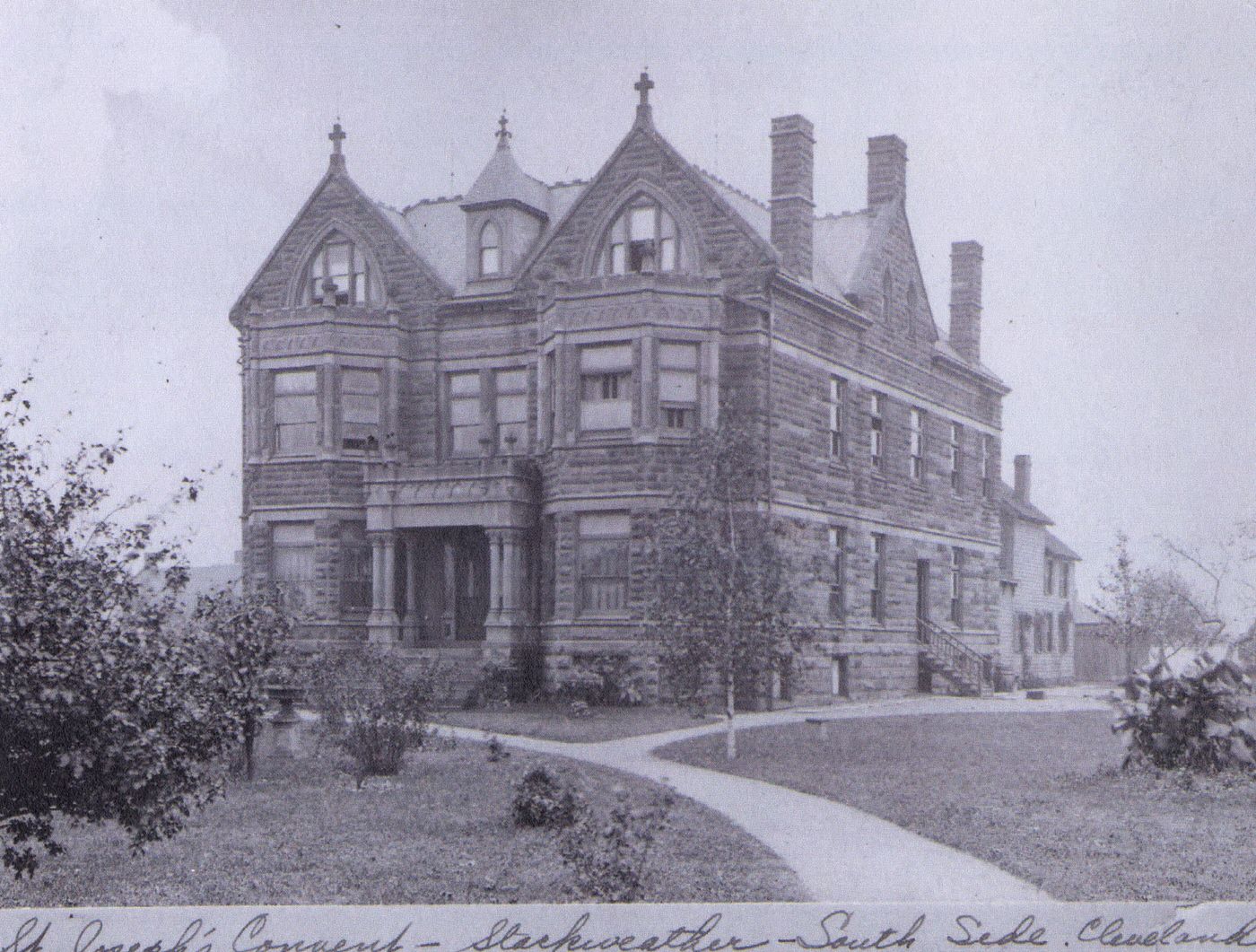

Slovenes: Cleveland’s Slovene population reached 14,332 in 1910, making it the third-largest Slovene city globally at the time. The period of heaviest immigration was between 1890 and 1914. They settled primarily in the Newburgh area, along St. Clair Avenue (between East 30th and East 79th Streets), and in the Collinwood and Euclid neighborhoods. Community development included the establishment of national parishes like St. Vitus (1893), St. Lawrence (1901), and St. Mary (1906), along with mutual insurance societies, numerous singing and drama clubs, and Slovene-language newspapers such as Ameriska Domovina (American Homeland, early 1900s) and later Enakopravnost (Equality, from 1918, reflecting earlier liberal sentiments). A significant development was the effort to build National Homes as social and cultural centers, which began in 1903 and saw the first dedications in 1919.

Syrian-Lebanese: The immigration of Syrian-Lebanese individuals to Cleveland peaked around 1910. Early settlers often began as itinerant peddlers. They established communities in the Haymarket District (Woodland, Orange, Carnegie Avenues) and on the near West Side, including Ohio City and West 14th Street. Their occupations evolved from unskilled labor in steel mills, automotive factories, and construction (roads, sewers, carpentry) to owning small businesses such as grocery stores, fruit stands in the West Side and Central Markets, and restaurants. Community life was characterized by strong family bonds and social gatherings, often involving sharing news from Arabic-language newspapers published in New York.

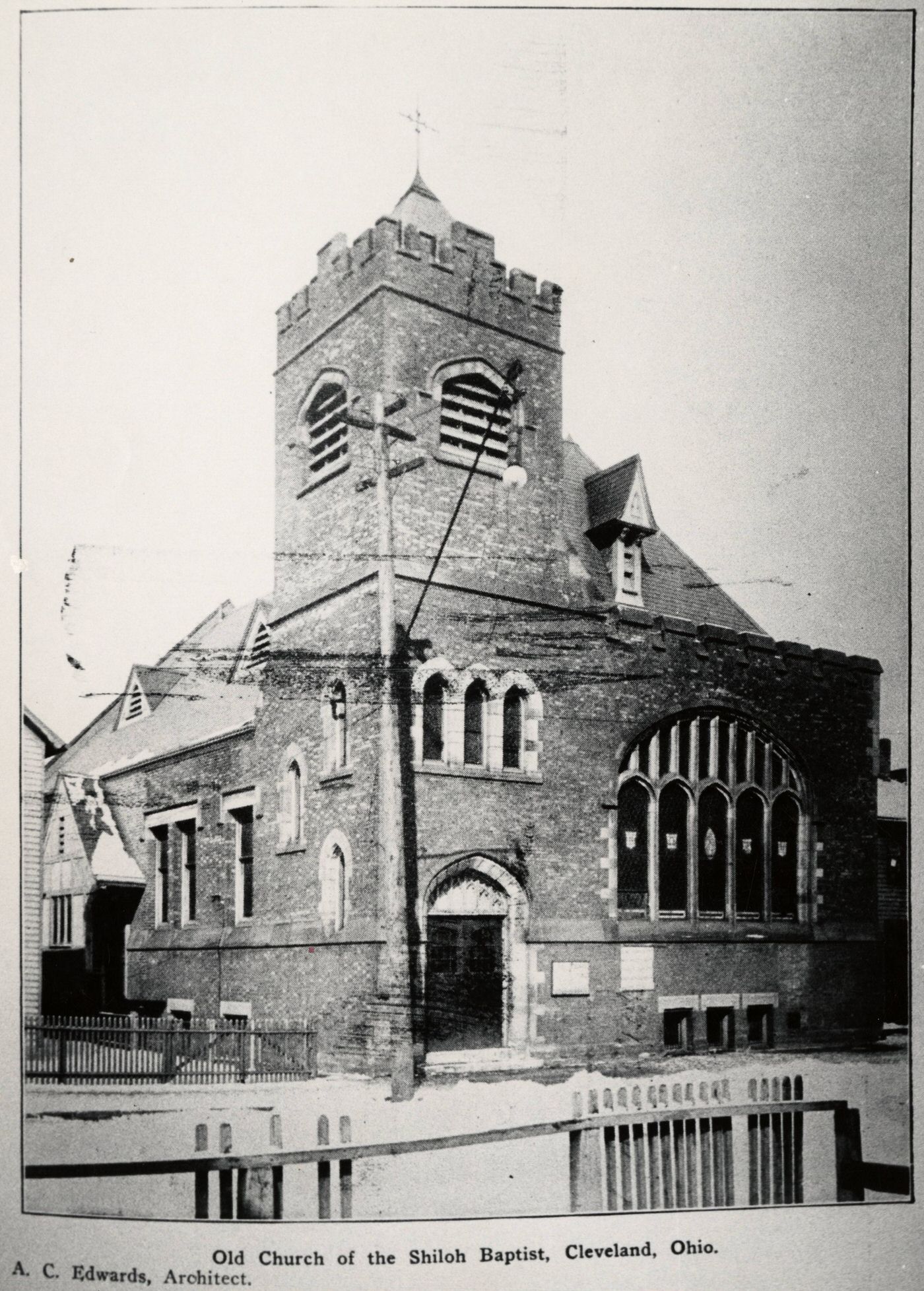

African Americans: The 1910s marked a pivotal era for Cleveland’s African American community, as the Great Migration began to draw thousands from the rural South to Northern industrial centers. Driven by the promise of economic opportunity, particularly as World War I created labor shortages and simultaneously curtailed European immigration, Cleveland’s Black population surged by an astounding 308%, growing from 8,448 in 1910 to 34,451 by 1920.

Most of these newcomers settled in the Central Avenue district, an area that became increasingly concentrated with African American residents. This influx, however, occurred within a context of rising racial discrimination. While Cleveland had a history of better race relations compared to some other Northern cities in the 19th century, the 1910s saw a hardening of racial lines. By 1910, only about 10% of Black men in Cleveland worked in skilled trades, with a large number employed in service jobs.

Housing became a significant challenge. Discriminatory practices such as restrictive covenants in property deeds (which by 1914 often explicitly barred sales to “colored people, Jews, and foreigners generally”) and biased zoning policies pushed African Americans into specific, often overcrowded, neighborhoods. These areas, frequently characterized as slums, suffered from decaying housing stock as families were often forced to sublet to make ends meet. This period laid the groundwork for long-term patterns of residential segregation in the city.

Major Immigrant Groups and Primary Settlement Areas (Early 20th Century)

| Hungarians | SE side (E.79th/Woodland), West side (Lorain/Abbey) |

| Italians | Little Italy (Mayfield/Murray Hill), Big Italy (Woodland/Orange), Collinwood |

| Poles | Warszawa/Slavic Village (E.65th/Fleet), Poznan (E.79th/Superior), Kantowo (Tremont) |

| Czechs | “Little Bohemia” (Broadway, E.37th-Union Ave.) |

| Slovaks | E.9th St., Buckeye Rd., Lakewood (“Birdtown”) |

| Slovenes | Newburgh, St. Clair Ave. (E.30th-E.79th), Collinwood/Euclid |

| Syrian-Lebanese | Haymarket District, Near West Side (Ohio City) |

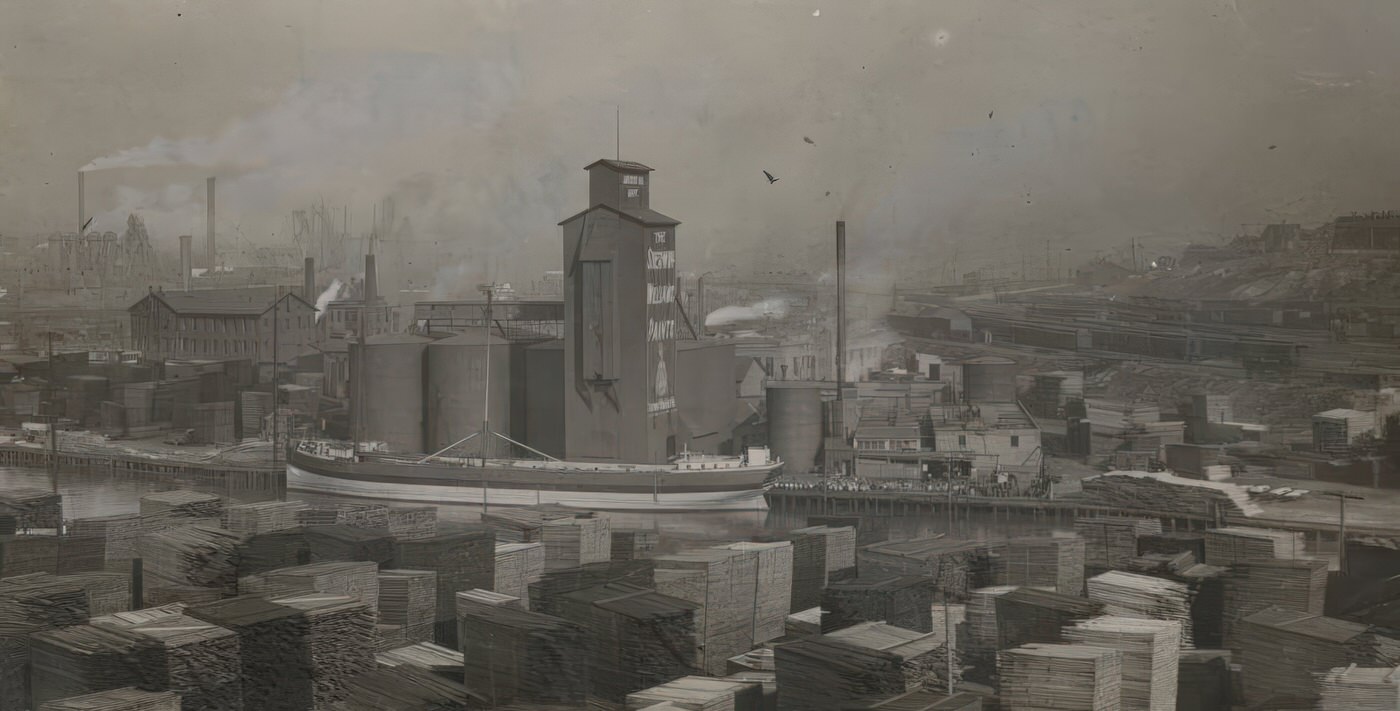

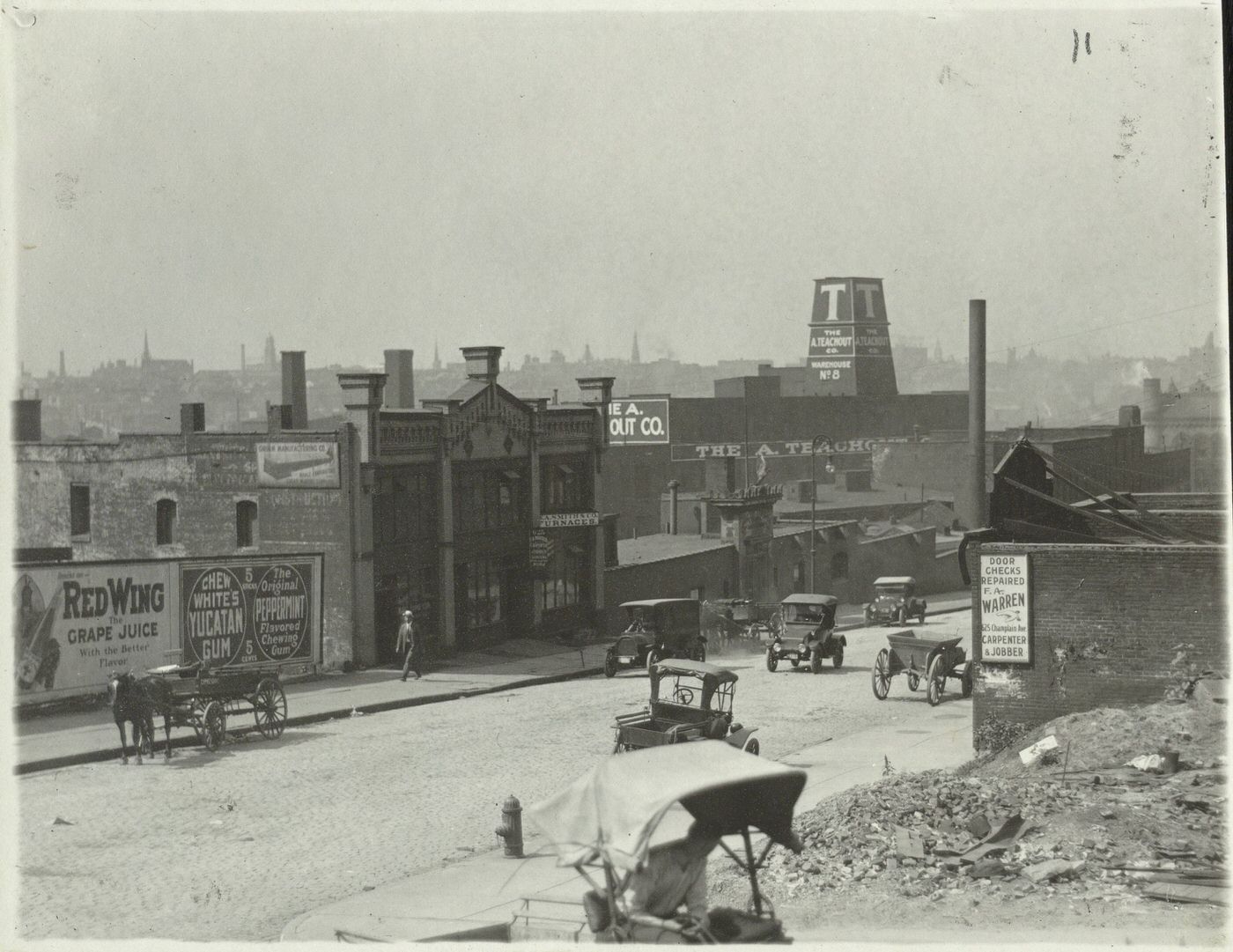

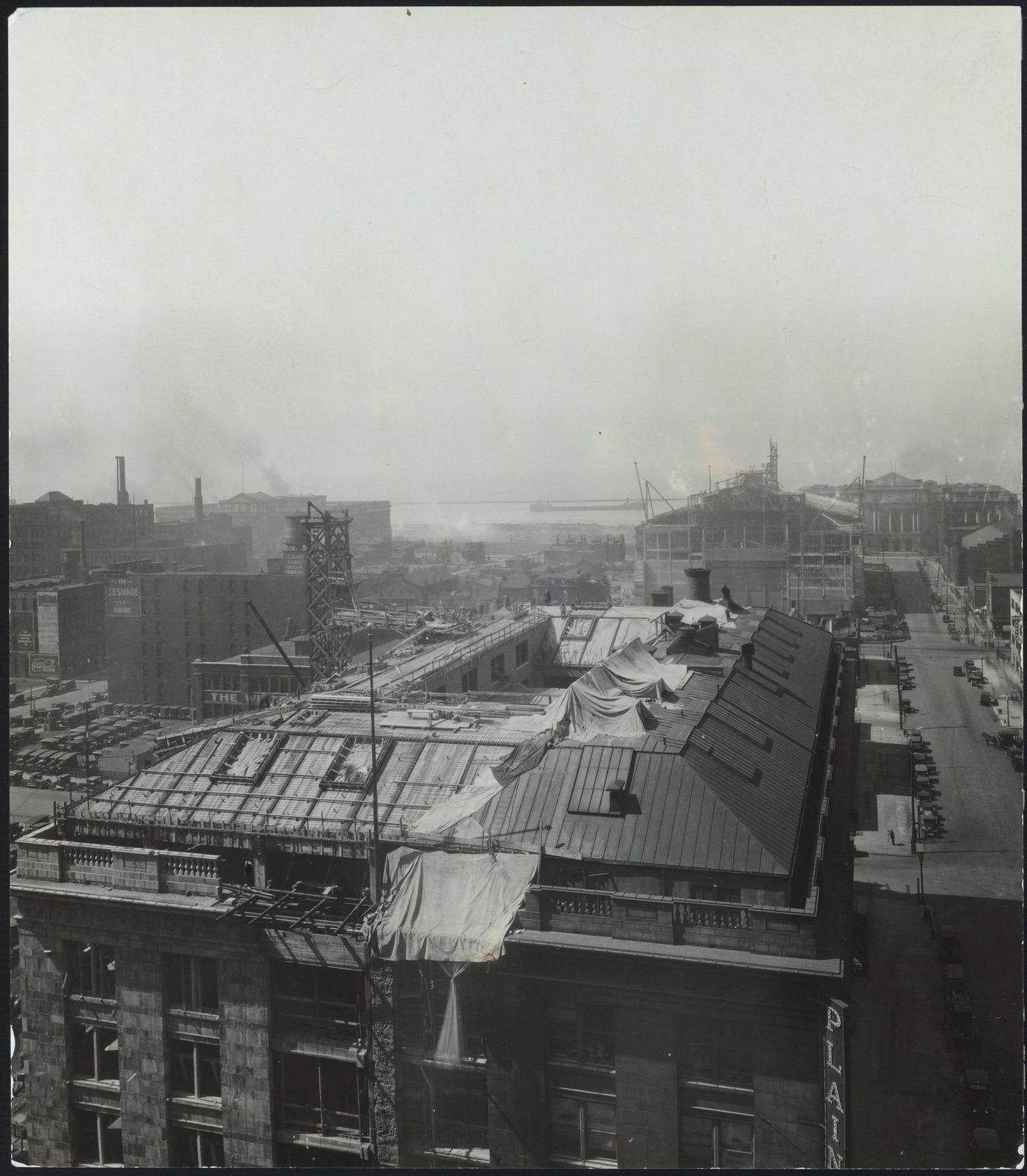

Cleveland in the 1910s was an industrial titan, its economy driven by a powerful and interconnected set of industries. The city’s strategic location on Lake Erie, at the confluence of rail and water transport, made it an ideal hub for manufacturing. This industrial prowess was not based on isolated sectors but on a dynamic ecosystem where the growth of one industry often fueled others. For example, the booming steel production directly supplied the burgeoning automotive and shipbuilding sectors, while the expanding electrical industry provided power to factories and manufactured essential components. This synergy created a robust, if sometimes volatile, economic engine.

Engines of Growth: Dominant Industries

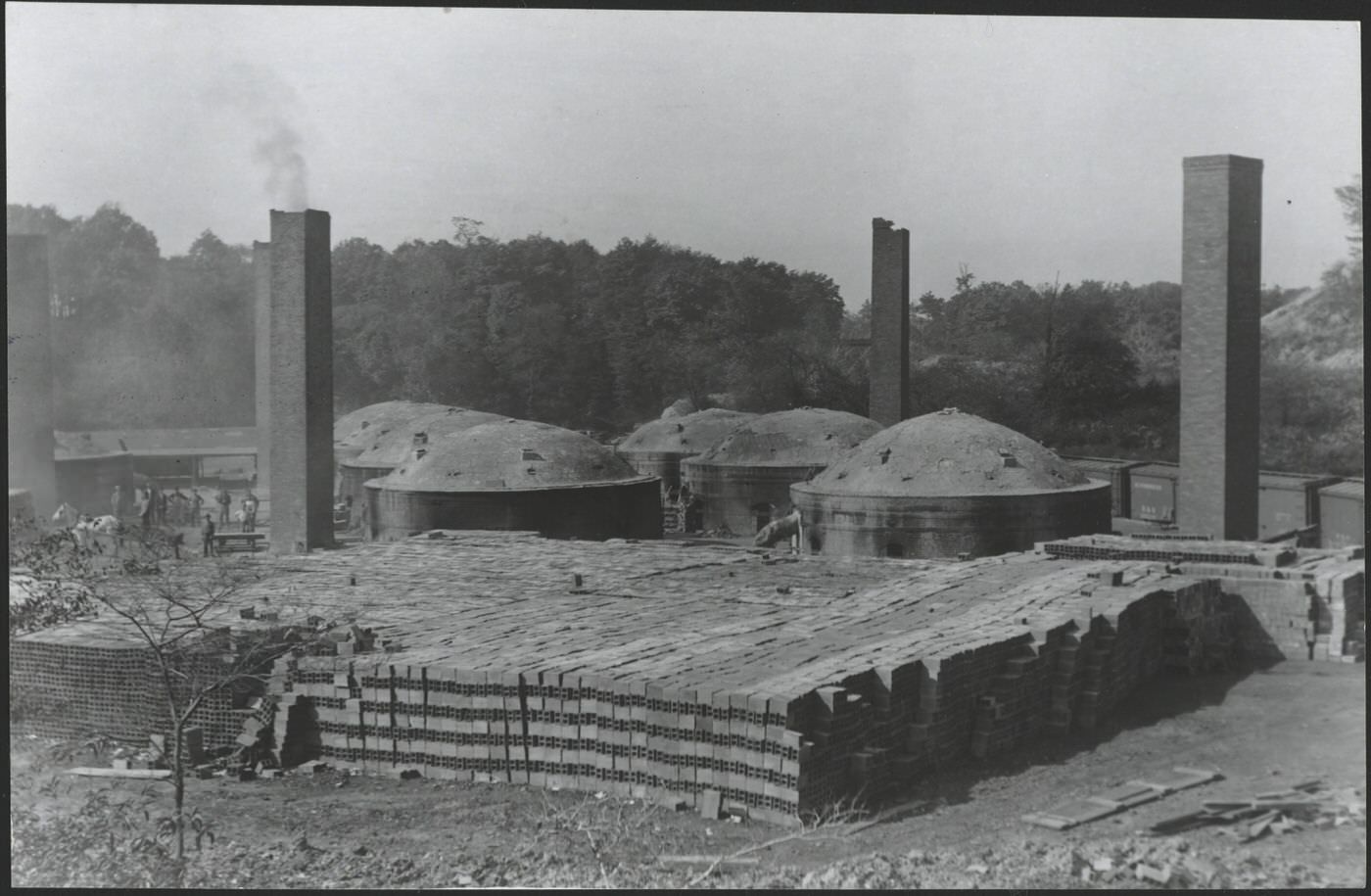

Steel: The iron and steel industry remained a cornerstone of Cleveland’s economy, though it ranked second in terms of output value by 1910. The early 20th century saw significant consolidation and expansion. U.S. Steel Corporation, formed in 1901, had absorbed the Cleveland Rolling Mill Company and expanded its Cleveland facilities, the Cuyahoga Works, in 1907-1908 with new wire and strip mills. Independent producers also grew; Corrigan-McKinney Steel Co. began constructing blast furnaces in 1909, laying the foundation for a major independent steelmaker. Otis Steel also expanded, notably with its new Riverside Works in 1912. Technological advancements were also key, with companies like the Steel Improvement Company, founded in 1913, focusing on enhancing steel properties through new thermal processes.

Automotive: The 1910s marked Cleveland’s ascent as a major player in the nascent automotive industry. By 1909, automobile manufacturing was the city’s third-largest industry, boasting 32 factories, employing over 7,000 workers, and producing nearly $21 million worth of vehicles and parts. Pioneering companies like the Winton Motor Carriage Co. continued to innovate, having introduced the steering wheel as standard and an optional self-starter by 1908. Baker Motor Vehicle Co. was known for its electric cars, while the White Motor Co., a leading steam car manufacturer (producing 1,500 cars annually by 1906), transitioned to gasoline engines between 1909 and 1911 and increasingly focused on truck production. The decade saw the introduction of new Cleveland-made automobiles like the Chandler (1913) and the Jordan (1916). Crucially, Cleveland became the second-largest center for automotive parts manufacturing in the U.S. during the 1910s. Companies like Thompson Products (later TRW), which began making engine valves for Winton in 1904, exemplified this critical sub-sector. The symbiotic relationship with the steel industry was evident, as 70% of Cleveland-made steel was destined for automotive manufacturing by the 1920s.

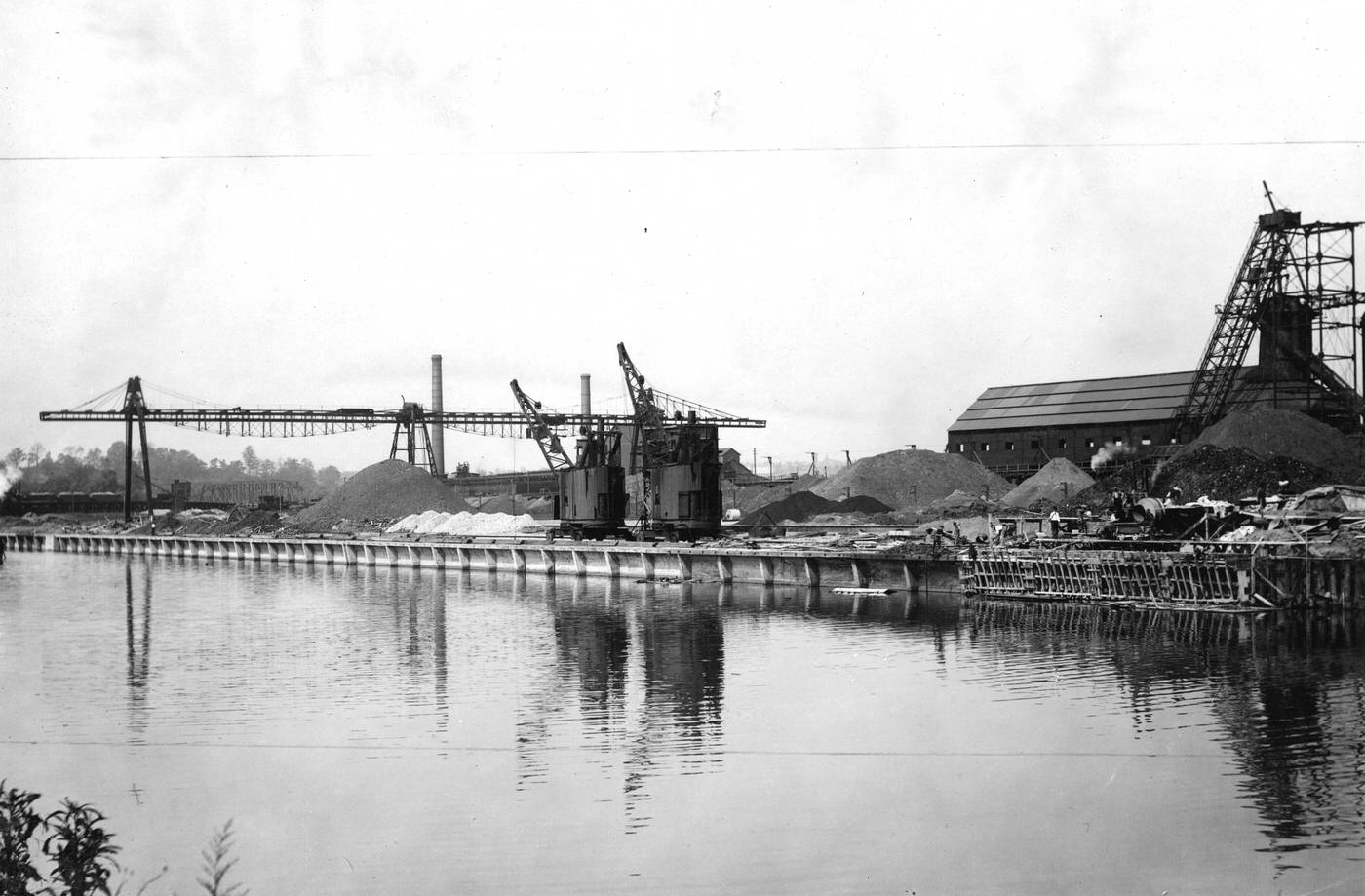

Shipbuilding: The American Ship Building Company, formed in 1900 through the consolidation of several firms including the Cleveland Ship Building Co., Ship Owner’s Dry Dock Co., and Globe Iron Works, was a dominant force on the Great Lakes. The company prospered in the early 1900s, driven by the steel industry’s increasing demand for new ore carriers. Notable ships built in its Cleveland yards during this era included the SS Milwaukee (launched 1902), the SS Anna C. Minch (1903), and the SS Milwaukee Clipper (originally the Juniata, built in 1904 for the Anchor Line).

Garment Industry: Cleveland was a nationally significant center for garment production, an industry that was a major employer in the 1910s. By 1910, approximately 10,000 apparel workers were employed in the city, with a notable 80% working in large, well-equipped factories, a contrast to the smaller sweatshops more common in New York City at the time. Key companies included the L.N. Gross Co., founded in 1900 and specializing in women’s shirtwaists; H. Black & Co., a major manufacturer of women’s suits and cloaks; the Joseph & Feiss Co., a leading producer of men’s clothing; and the Printz-Biederman Co., founded in 1893, which specialized in women’s suits and coats. The industry was initially concentrated in the Flats and later shifted to the Warehouse District, eventually spreading to the east side along Superior Avenue.

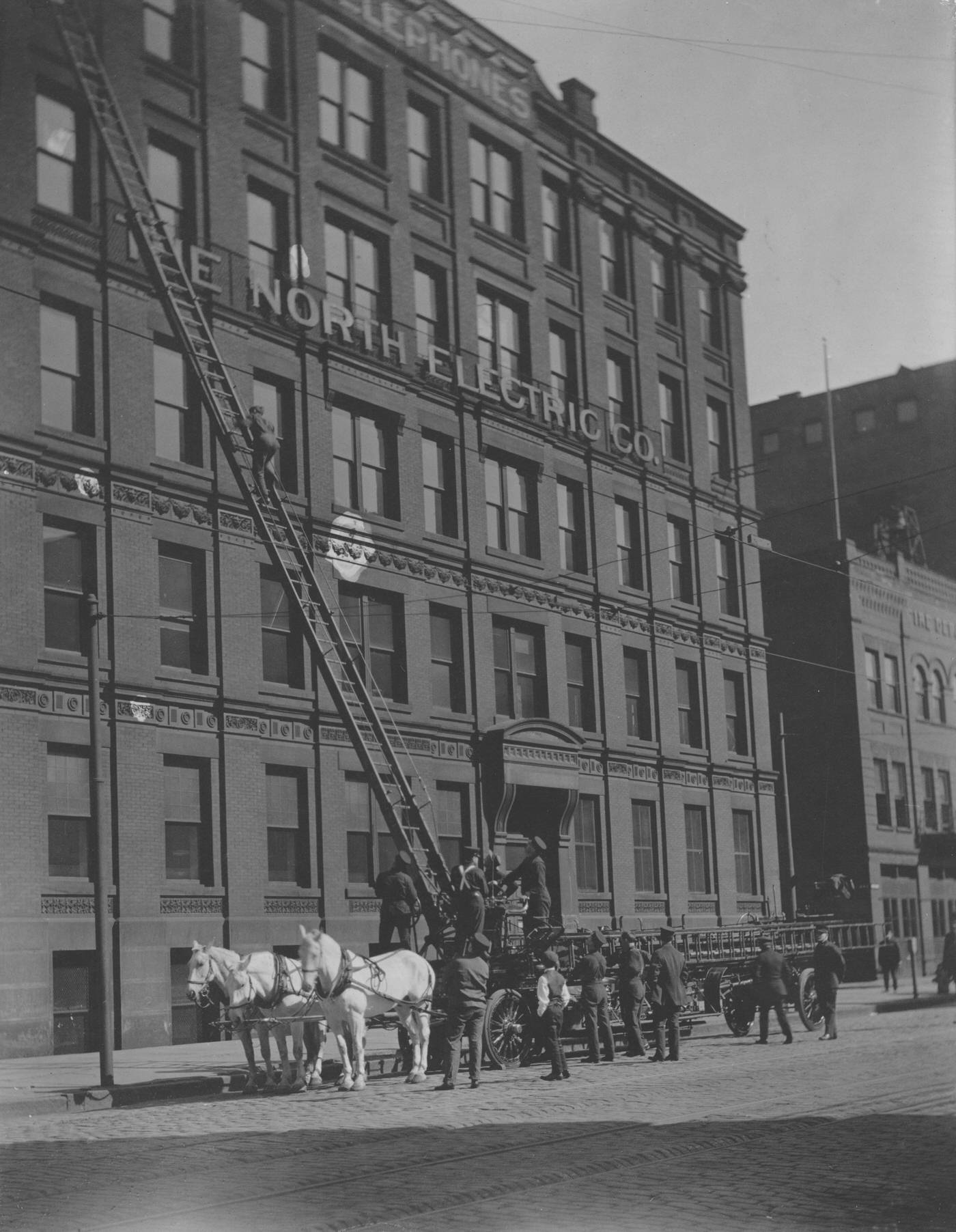

Electrical Industry: The city’s electrical industry was also booming. The Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. (CEI), formed in 1892, continued to expand its power generation and distribution capabilities. By 1909, Cleveland held a leading national position in the production of electrical carbons, lamps, and electrical hoisting apparatus. The Electrical League of Northern Ohio was established in 1909 to promote the industry and its standards. Innovations continued, with companies like the Elwell Parker Electric Co., organized in 1893, developing electric industrial trucks in 1906.

Standard Oil: Following the Ohio Supreme Court’s 1892 ruling that forced the dissolution of the Standard Oil Trust in Ohio, and the subsequent 1899 reorganization of Standard Oil (New Jersey) as a national holding company, the operations in Cleveland continued. However, the landscape changed dramatically with the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1911 order to disband the Standard Oil (New Jersey) holding company. This resulted in Standard Oil of Ohio becoming an independent entity. At that point, it primarily controlled marketing operations within Ohio and owned an aging refinery in Cleveland, but it lacked its own crude oil reserves and pipelines, a significant challenge for its future. Globally, in 1909, the larger Standard Oil entity employed 60,000 people, indicating the massive scale of its operations before the final breakup.

Key Cleveland Industries and Representative Companies in the 1910s

| Industry | Representative Companies |

|---|---|

| Steel | U.S. Steel (Cuyahoga Works), Corrigan-McKinney Steel, Otis Steel |

| Automotive | Winton, Baker, White, Chandler, Jordan (parts: Thompson Products) |

| Shipbuilding | American Ship Building Company |

| Garment | Joseph & Feiss, H. Black & Co., Printz-Biederman, L.N. Gross Co. |

| Electrical | Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. (CEI), Lincoln Electric |

| Oil Refining | Standard Oil of Ohio |

Life on the Line: Working Conditions and Wages

Despite Cleveland’s industrial prosperity, life for the working class was often characterized by arduous conditions and modest pay. Factory work typically involved long hours, often ten to twelve per day, in environments that were frequently unsafe and could lead to serious accidents. The drive for efficiency often meant tasks were highly specialized, leading to repetitive and monotonous labor for many employees. For immigrant workers, such as the Hungarians, jobs in steel mills and foundries were described as “back-breaking and dangerous,” with industrial accidents being a common occurrence.

In the garment industry, while Cleveland’s factories were generally larger and better equipped than the notorious sweatshops of New York City, workers still faced low wages and long hours with minimal benefits. By 1910, about 80% of Cleveland’s approximately 10,000 apparel workers were employed in these larger establishments. Some of the larger garment companies, like Joseph & Feiss and Printz-Biederman, influenced by “Taylorism” or “Scientific Management” and the threat of unionization, did begin to provide increased amenities for their workers. These included cleaner and better-run cafeterias, clinics, libraries, and even nurseries, alongside recreational activities and classes in English and homemaking skills. These measures aimed to improve productivity and reduce employee turnover, but also served as a paternalistic counter to union organizing efforts.

Specific wage data for Cleveland during the 1910s is somewhat fragmented in the available records, but some figures provide a glimpse. Nationally, in 1905, male manufacturing workers averaged $11.16 per week, while women earned significantly less at $6.17 per week. Anecdotal accounts from Cleveland’s garment industry in the early 1910s suggest a cutter might earn $15 per week during the busy season but only $6 or $7 during slow periods. A new cutter might start working for free for several weeks before earning $4, eventually rising to $8 per week. In 1904-1905, Cleveland plumbers reportedly earned $4 per day. National wage indexes for the furniture industry in 1910 show male assemblers and cabinetmakers earning around $0.228 per hour for a 58-hour week (totaling $13.22), while male hand carvers earned about $0.313 per hour for a 56.1-hour week (totaling $17.36). In the boot and shoe industry nationally in 1910, average hourly earnings for selected occupations were 31.4 cents, translating to an average full-time weekly earning of $17.11; for all occupations in those establishments, the averages were 24.3 cents per hour and $13.26 per week. The general lack of a robust social safety net meant that illness, injury, or periods of unemployment could quickly plunge working-class families into severe hardship. This precarious existence, despite the city’s overall economic boom, underscored the daily struggle for survival and basic dignity for a large segment of Cleveland’s population and provided fertile ground for the labor movement.

Voices of Labor: Strikes and Union Activity

The challenging working conditions and economic insecurity faced by many Cleveland workers fueled efforts to organize and demand better treatment. By 1900, Cleveland was home to 100 labor unions, with 62 affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), 14 with the Knights of Labor, and 24 independent unions. However, the path of labor organization was fraught with difficulty. After 1904, union growth in Cleveland slowed due to a combination of factors including hostile court decisions, the continuous influx of new immigrant labor (which could sometimes be used to break strikes), and heightened opposition from employers.

One of the most significant labor disputes of the era in Cleveland was the Garment Workers’ Strike of 1911. Beginning on June 6, between 4,000 and 6,000 workers, primarily members of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), walked off their jobs. Their demands included a 50-hour work week, an end to charges for the use of machines and materials, and a closed shop agreement on subcontracting. The strike, which lasted four months, was marked by considerable unrest and violence. Strikers picketed and reportedly stoned the Printz-Biederman factory. While local newspapers initially showed some support for the strikers, this sentiment shifted as the violence continued. There were allegations that the manufacturers themselves encouraged or instigated some of the violence to discredit the strikers; one picket committee member later admitted to being paid by the Cloak Manufacturers’ Association for such actions. Employers effectively countered the strike by contracting work out to non-union shops in smaller Ohio communities and by continuing their operations in the New York market. The ILGWU, facing mounting financial pressures from supporting the strikers, was ultimately forced to call off the strike in October 1911 without achieving any of the workers’ demands. The strike was a costly defeat for the unions, amounting to over $300,000, and it hampered their ability to organize Cleveland’s garment workers for several years. This local struggle was part of a wider wave of militancy among garment workers in major cities like New York and Chicago around this time.

Beyond the 1911 garment strike, other labor actions occurred. A successful cigar makers’ strike took place in Cleveland in November 1905, where the union reportedly won all its demands. An earlier, unsuccessful strike against the Prinz-Biederman company in 1908 had already demonstrated the growing frustration among garment workers. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a more radical labor organization, also had a presence in Ohio during this period. Despite these efforts and the existence of numerous unions, organized labor in Cleveland faced an uphill battle against powerful employers, an often unsympathetic legal system, and challenging economic conditions. Victories were hard-won and often difficult to sustain, illustrating the significant power imbalance that characterized industrial relations in the early 20th century.

As Cleveland’s population and industries expanded, so too did its physical boundaries and the complexity of its urban fabric. The 1910s were a critical period for shaping the modern city, with developments in land annexation, housing, transportation, civic architecture, public markets, parks, and essential services.

Expanding Borders: Annexations and City Growth

To manage its rapid growth, Cleveland continued to annex surrounding communities. Following the annexation of Corlett in 1909, the city incorporated the village of Collinwood in 1910. Between 1912 and 1915, Cleveland also annexed portions of Shaker Village, specifically areas designated GG and MM. These annexations were crucial for expanding the city’s tax base and extending municipal services to newly developing areas. The process of integrating these new territories often presented administrative challenges. For instance, a major effort to standardize street names and address numbering across the city had been undertaken in 1906 due to the confusion caused by differing systems in previously annexed villages. This need for standardization remained pertinent as Cleveland continued to absorb more communities in the 1910s.

Shelter for a Growing Populace: Housing Conditions and Early Suburban Growth

The rapid influx of workers between 1900 and 1920, when Cleveland’s population doubled, placed immense strain on the city’s housing stock, leading to inadequate and often harsh living conditions for many. Working-class neighborhoods frequently consisted of densely packed wood-frame houses, sometimes two to a lot, leading to overcrowding. Immigrant families often resided in boarding houses where even beds were shared in shifts due to the sheer number of occupants. Areas like the Haymarket district became known as the city’s first slums , and the industrial Flats, with its swampy and unhealthy environment, were largely given over to factories rather than residences.

Despite these pressing issues, housing reform received limited attention from city administrations, including that of reform mayor Tom L. Johnson. While a Chamber of Commerce investigation in 1917 highlighted the urgent need for remedies to poor living conditions, concrete actions were slow to materialize.

Concurrently with the strain in inner-city areas, the 1910s witnessed the accelerated development of suburbs. Improved transportation, particularly the expansion of electric streetcar lines, made areas like Cleveland Heights more accessible and appealing to those seeking to escape the grime and congestion of the industrial city. This period saw a rapid appearance of large-scale residential developments, often situated near streetcar routes. The character of suburban housing also began to diversify, moving beyond large mansions to include more modest bungalows and other housing types, catering to a broader segment of the middle class. This dual reality—increasing pressure on inner-city housing alongside the growth of suburban alternatives for those with the means—marked an intensification of socioeconomic and, increasingly, racial segregation in housing patterns, a trend that would shape the metropolitan area for decades to come.

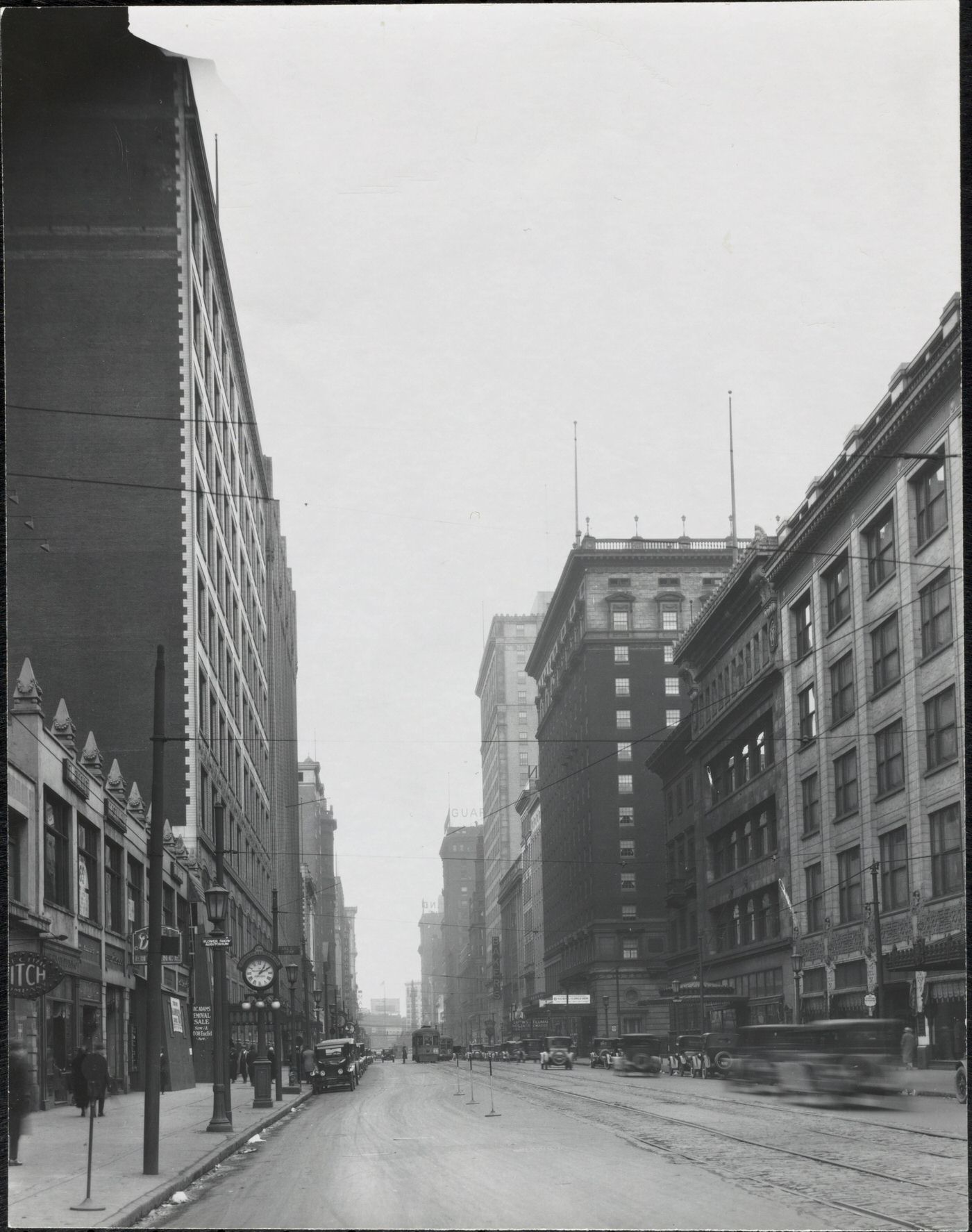

On the Move: Electric Streetcars, Interurban Lines, and the Dawn of the Automobile Age

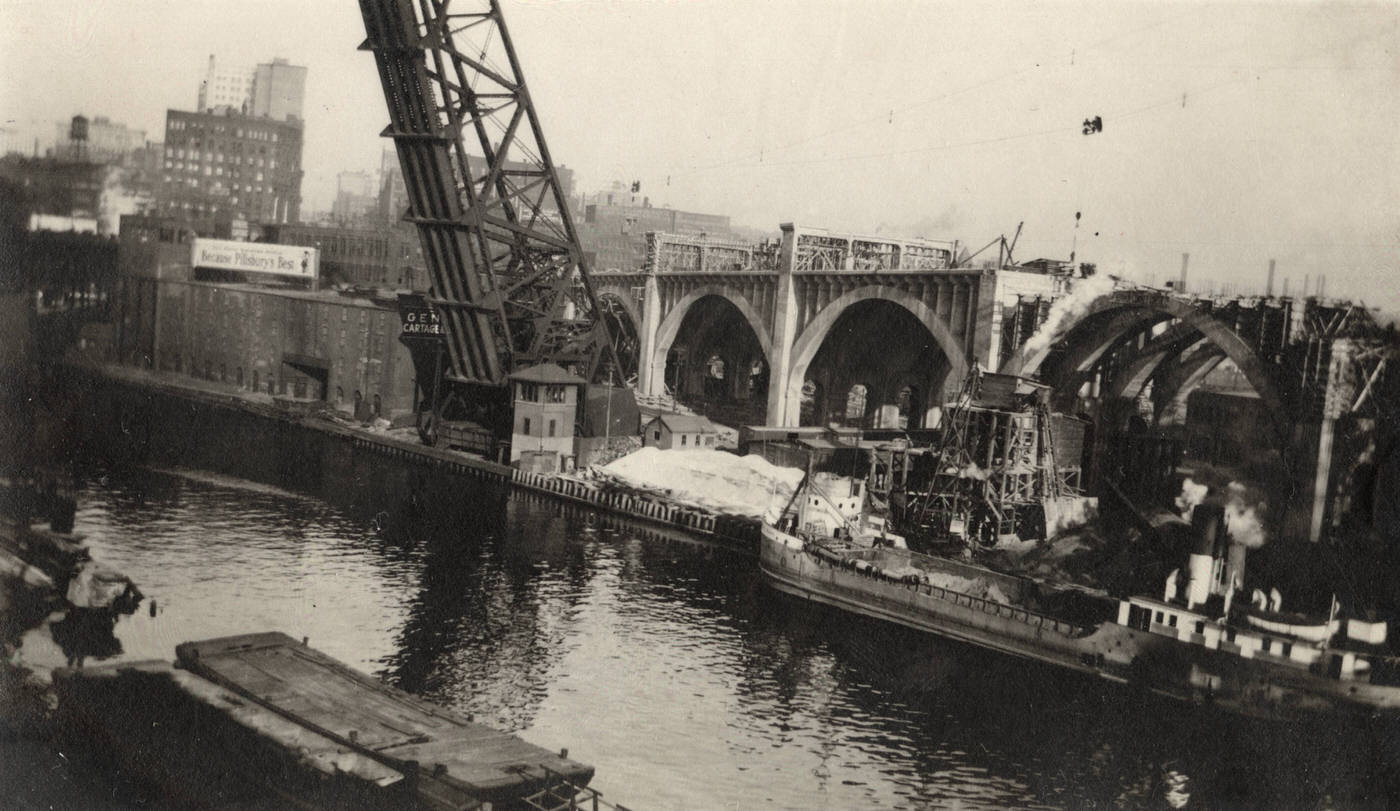

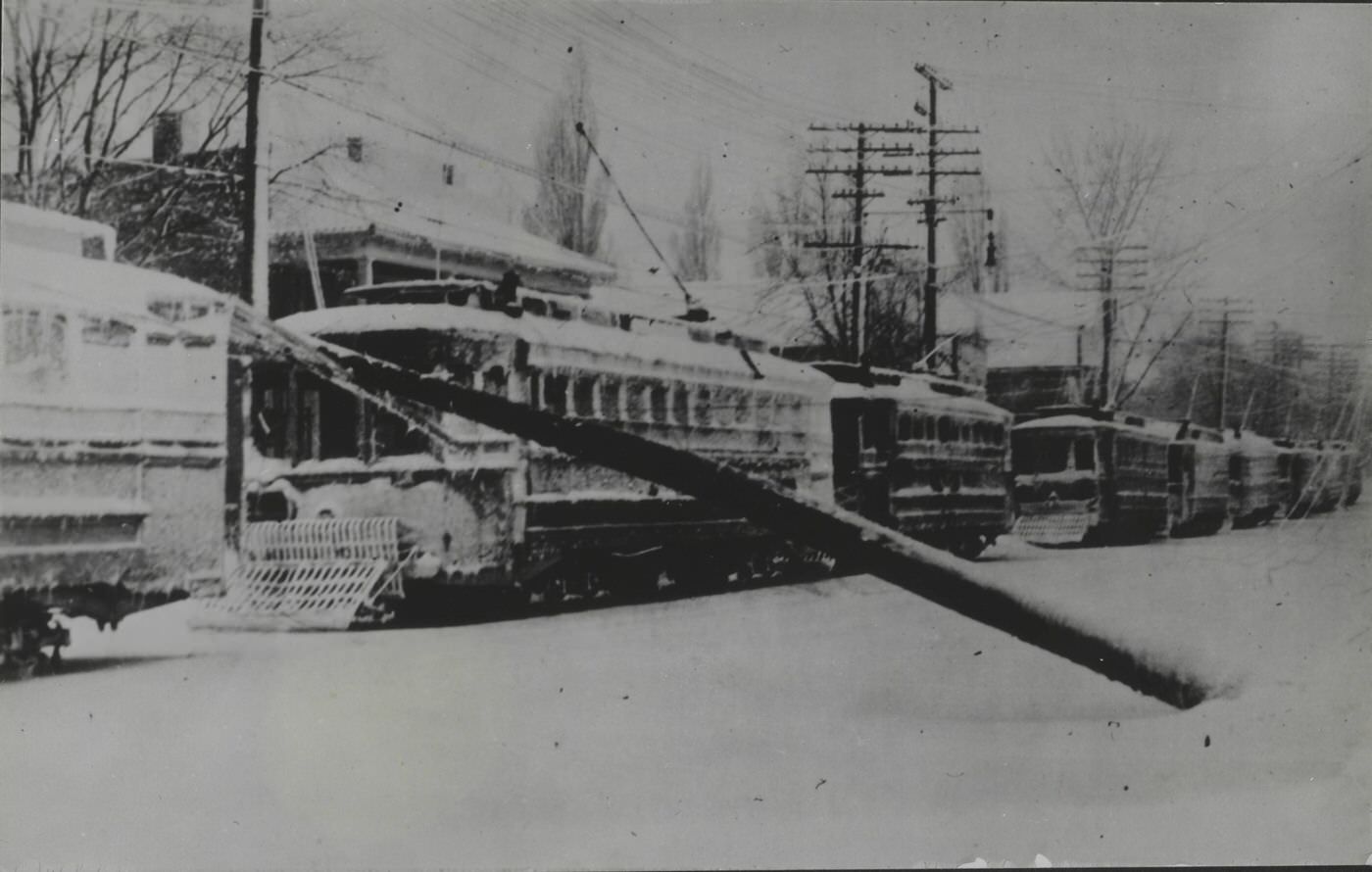

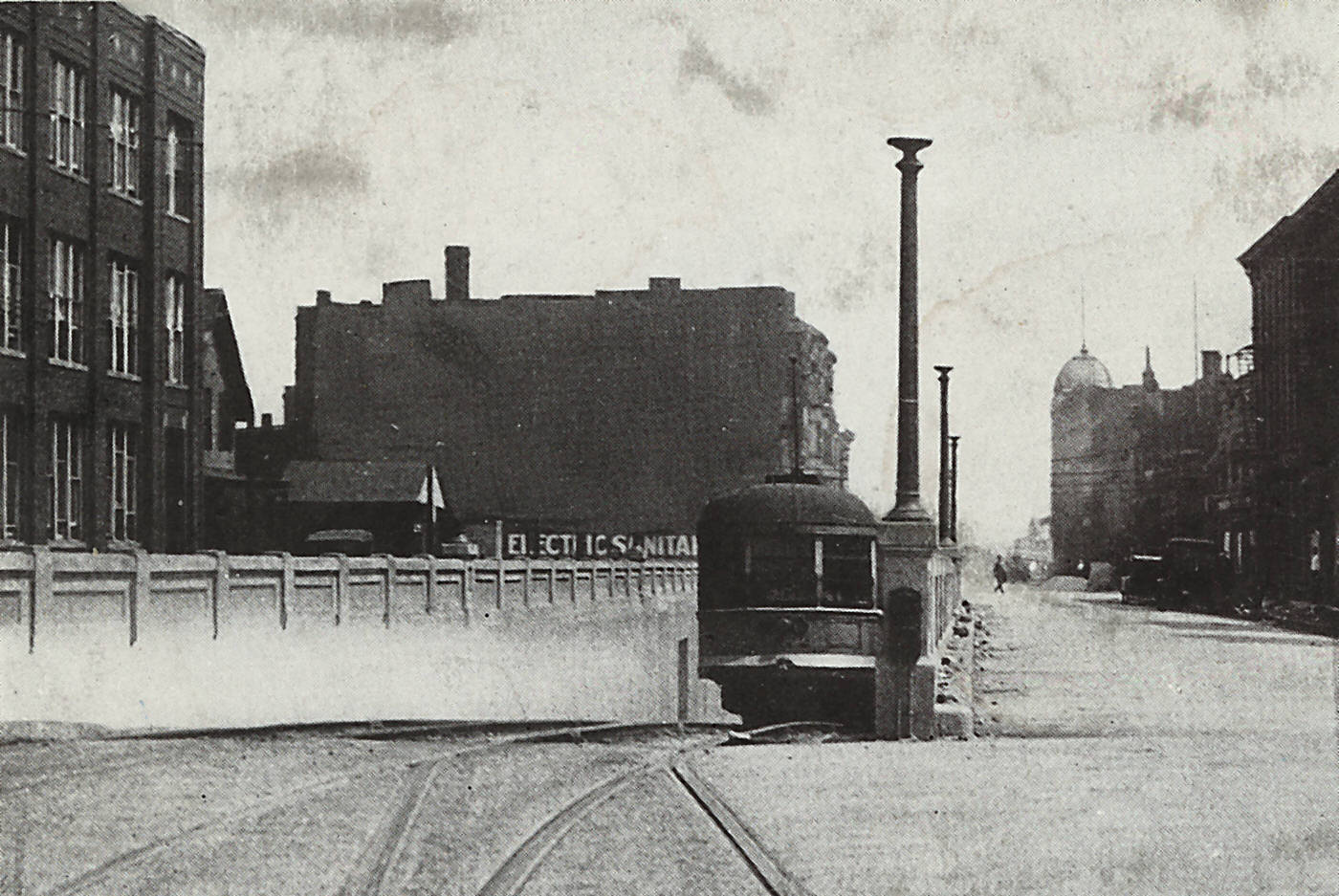

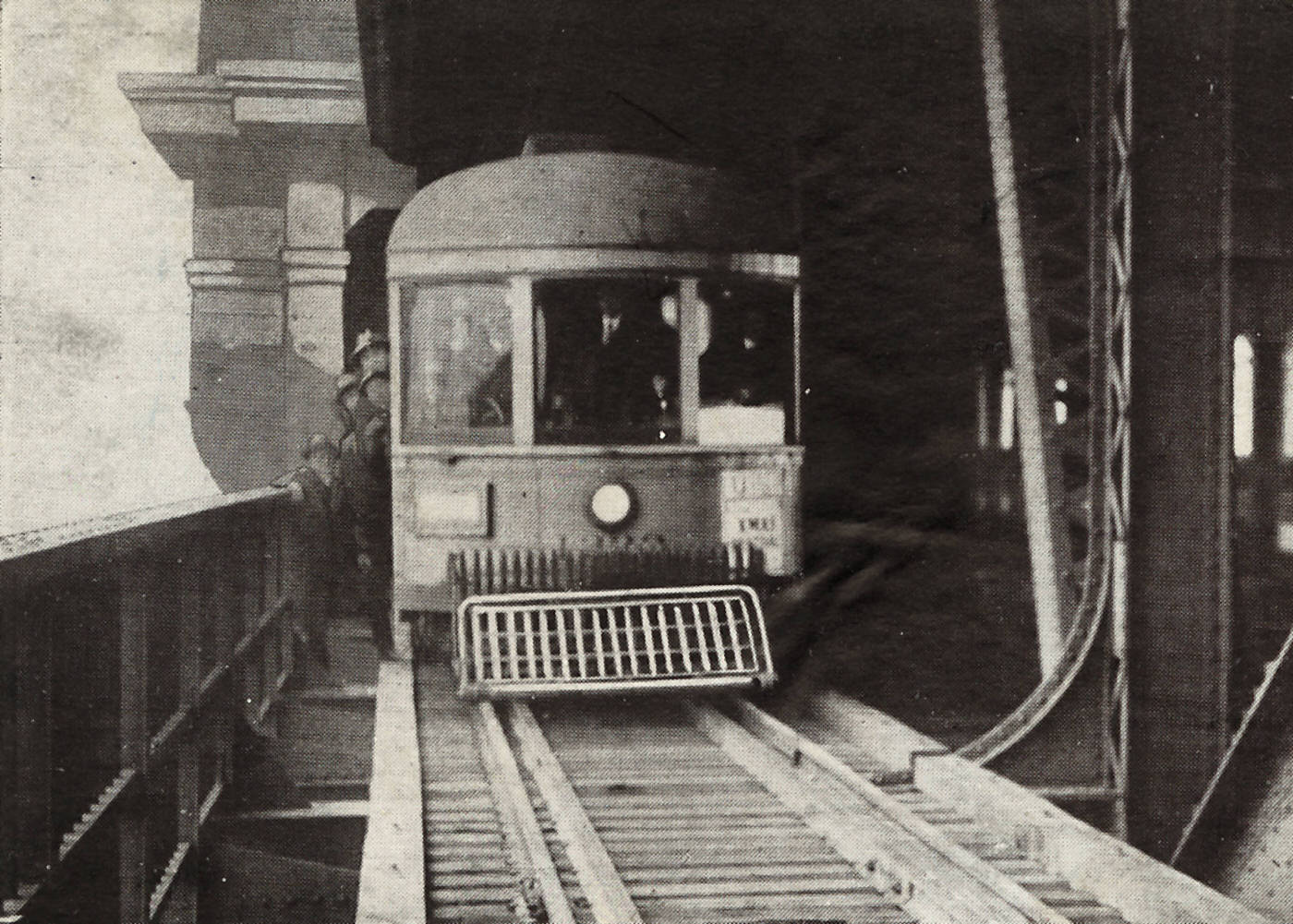

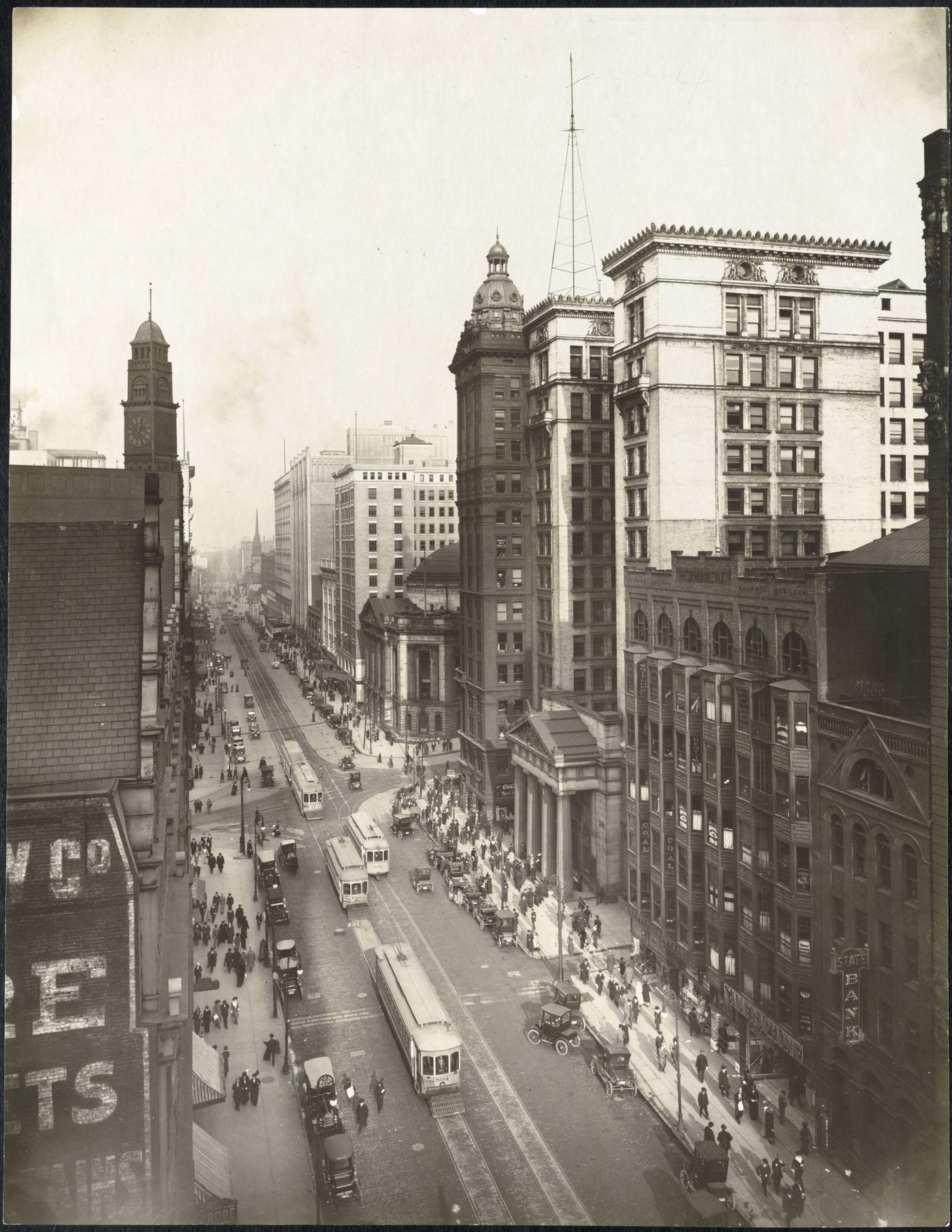

Transportation in Cleveland during the 1910s was a dynamic mix of established electric streetcar networks, extensive interurban railways at their peak, and the rapidly emerging automobile. Electric streetcars were the primary mode of urban transit. A significant development was the Tayler Franchise of 1910, which consolidated Cleveland’s competing streetcar lines under the single management of the Cleveland Railway Company. This franchise aimed to provide service at cost while ensuring a 6% return for investors and allowing for public oversight. Peter Witt, serving as the city’s railroad commissioner, introduced operational improvements like the “skip-stop” system to speed up service and designed the “Pete Witt Car,” a new streetcar model with more efficient passenger flow.

Connecting Cleveland to its surrounding region was a comprehensive network of electric interurban railways. By 1910, six separate interurban systems radiated from the city, including the Northern Ohio Traction & Light Co., the Cleveland, Painesville & Eastern Railroad, and the Cleveland, Southwestern & Columbus Railway. These lines provided frequent and relatively inexpensive service to cities like Akron, Canton, Painesville, and Toledo, as well as numerous smaller towns, facilitating commerce, commuting, and leisure travel. Interurbans played a crucial role in integrating Cleveland with its hinterland and spurred real estate development along their routes.

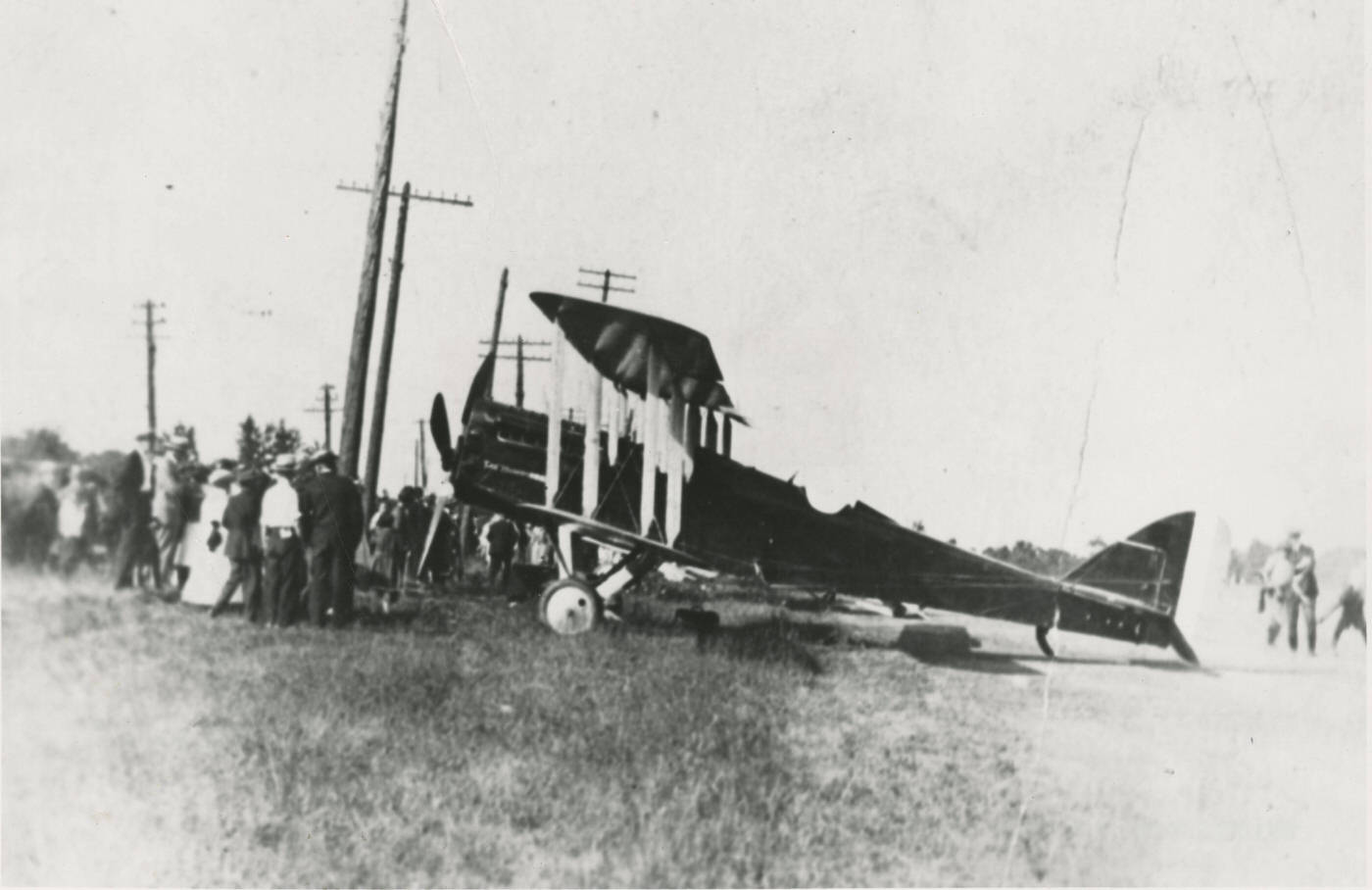

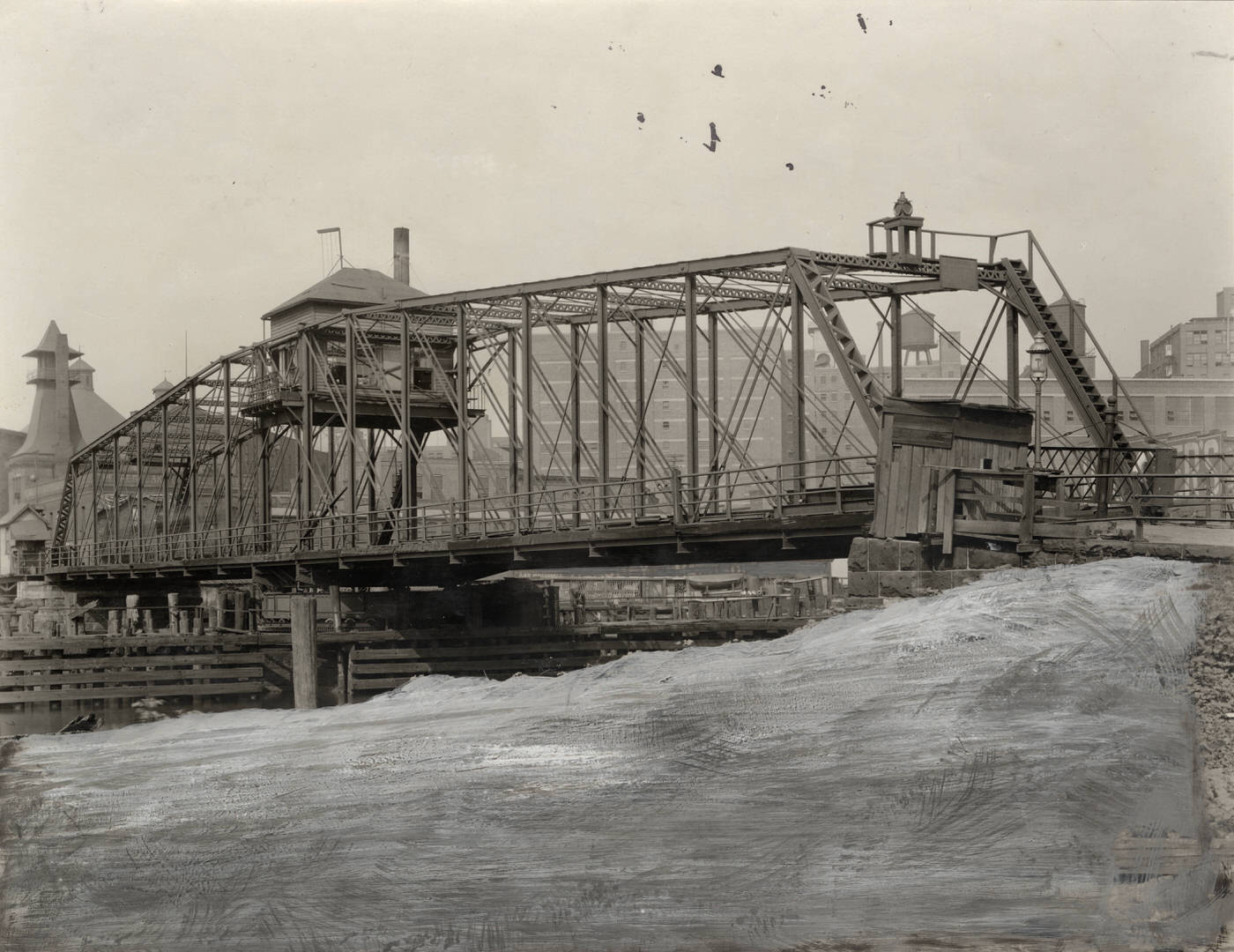

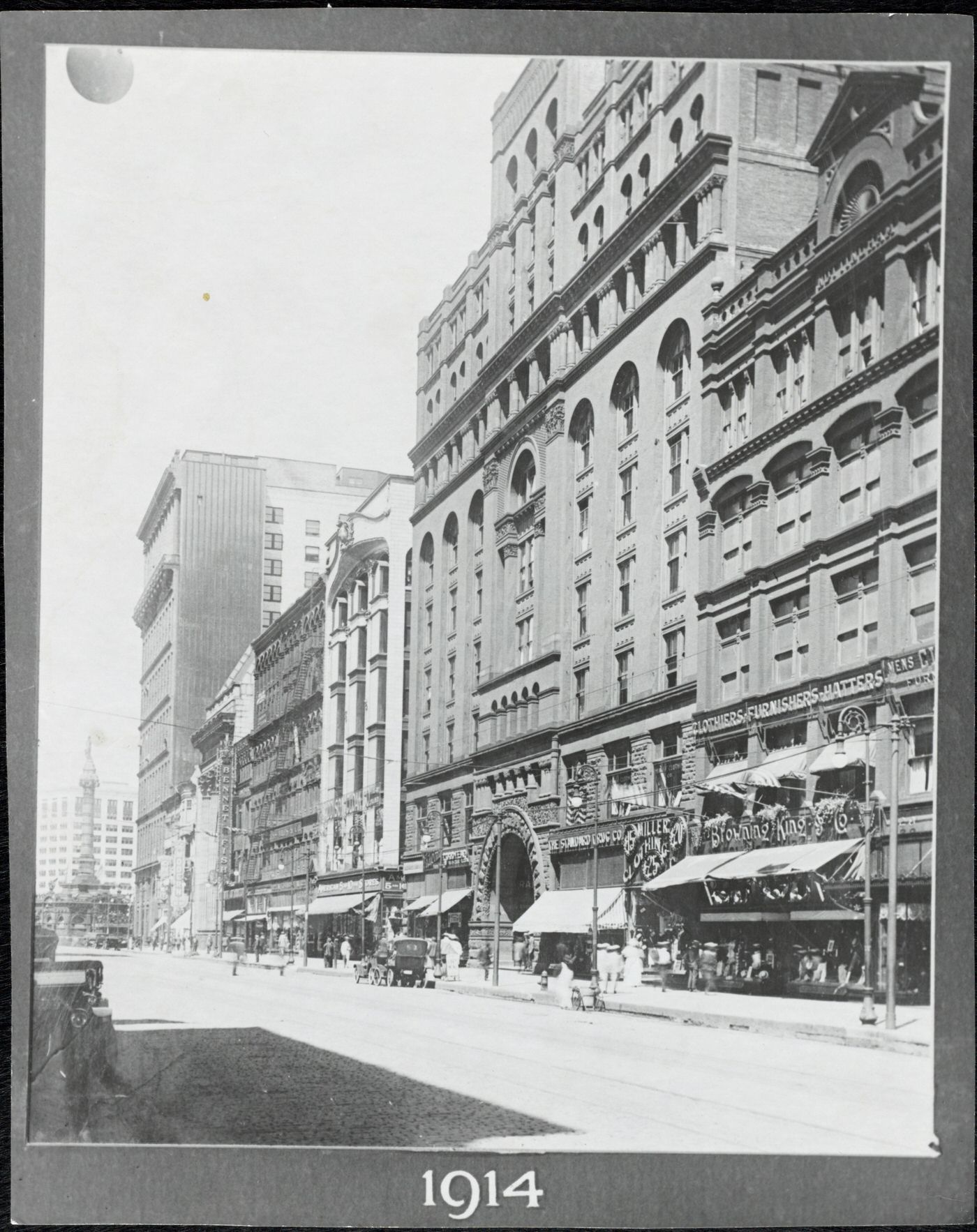

The 1910s also heralded the true dawn of the automobile age in Cleveland. Per capita car ownership was soaring. Cuyahoga County saw automobile registrations jump from 61,000 in 1916 to 211,000 just ten years later, indicating the rapid adoption of this new technology. Henry Ford recognized Cleveland’s market potential by opening a Model T assembly plant in the city in 1914. The increasing presence of automobiles began to reshape the urban landscape and create new challenges. Chester Avenue, for instance, became known as “Automobile Row” due to the concentration of car-related businesses. The rise in traffic led to the installation of the first electric traffic light in the United States at the intersection of East 105th Street and Euclid Avenue in 1914. While public transit remained dominant for mass movement, the growing number of private automobiles signaled a shift in personal mobility and began to place new demands on street infrastructure, such as the need for better paving and wider arterial roads. This transitional period saw these varied transportation systems coexisting, each influencing the city’s development and the daily lives of its residents.

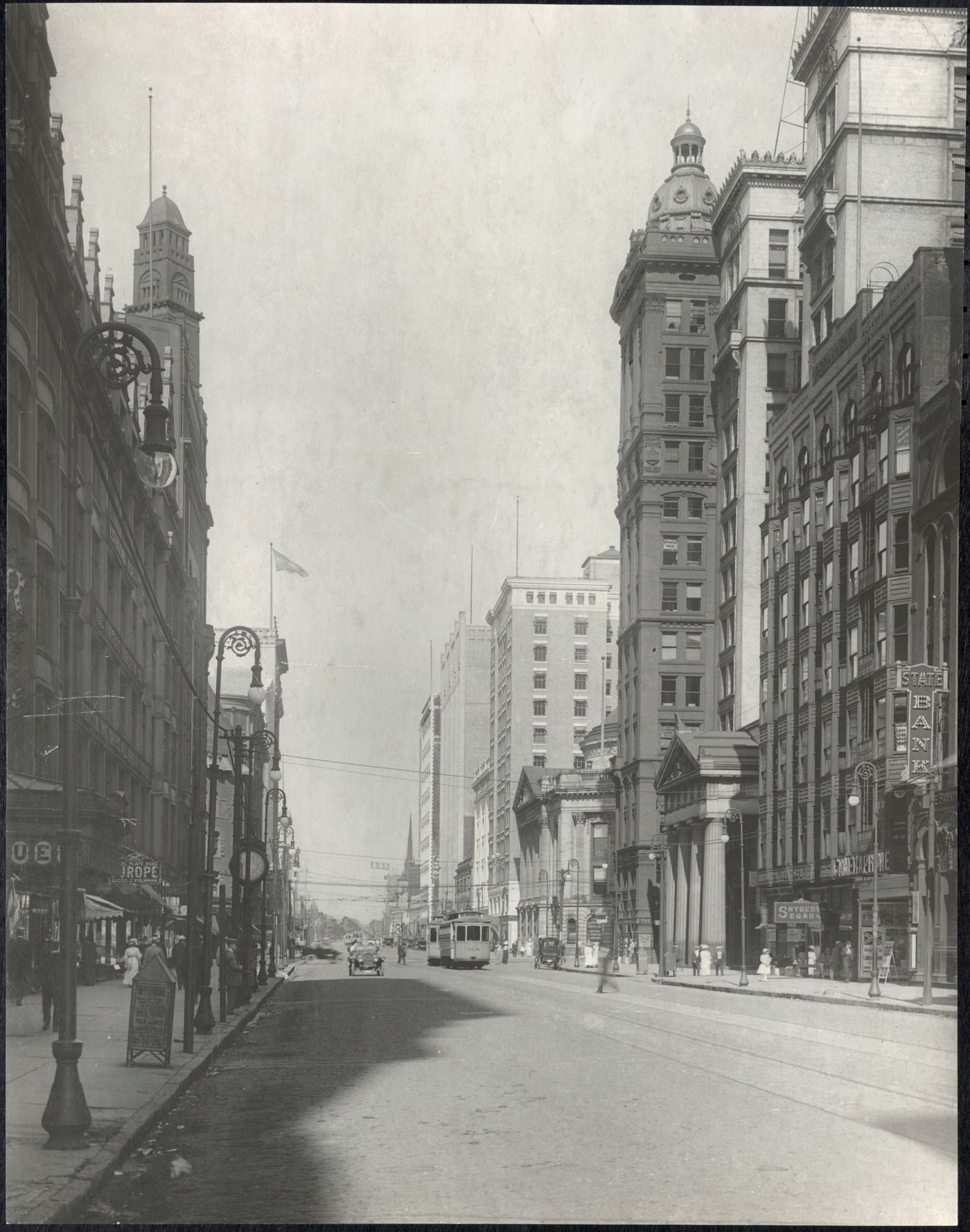

Grand Designs: The Group Plan and Civic Architecture

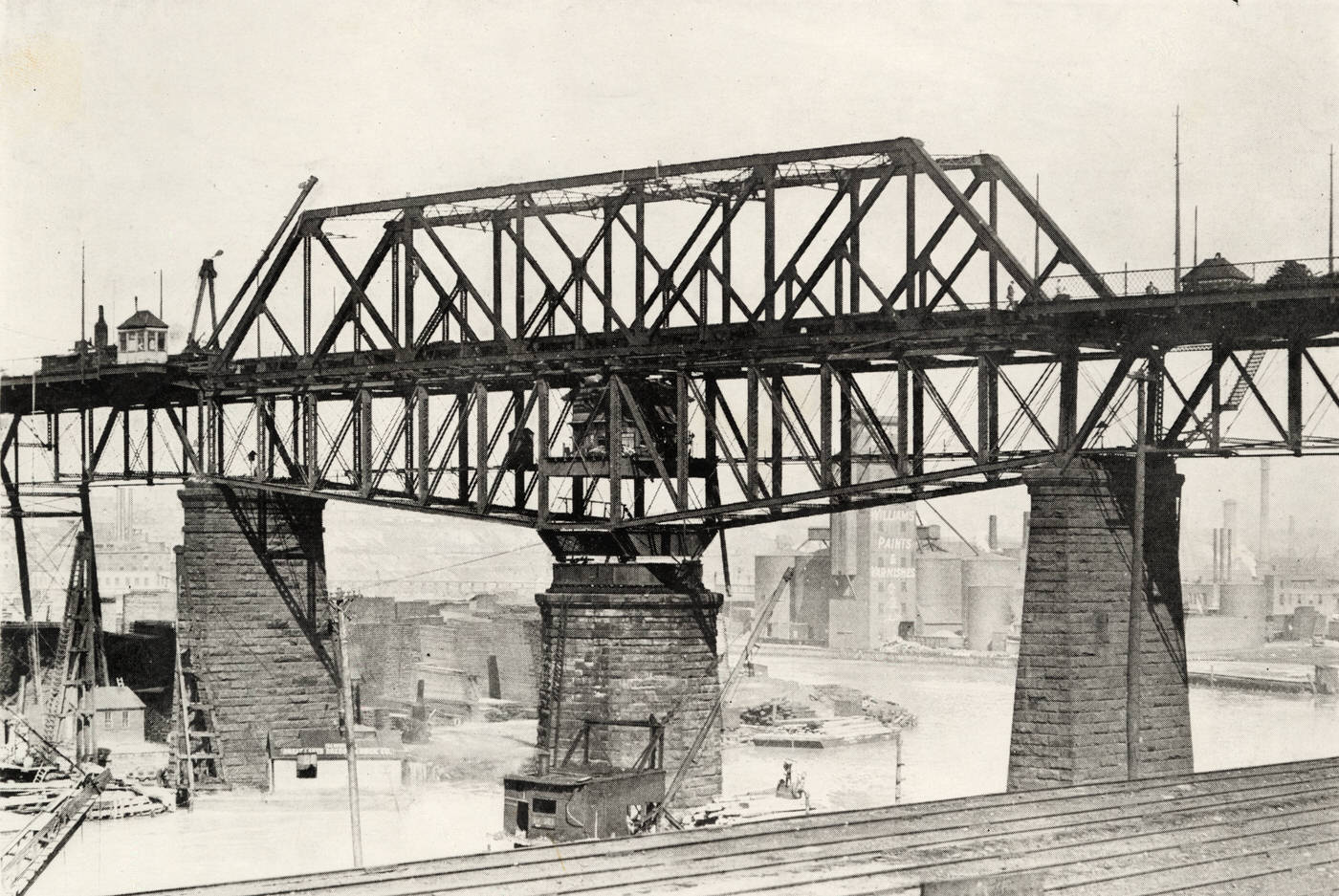

The 1910s saw the materialization of Cleveland’s grand civic vision with the construction of key buildings from the Group Plan of 1903. This ambitious urban planning initiative, deeply influenced by the City Beautiful movement and the Beaux-Arts architectural style, aimed to create a monumental and orderly civic center. Designed by a commission of nationally renowned architects—Daniel Burnham, Arnold W. Brunner, and John M. Carrère—the plan called for a series of impressive public buildings arranged around a spacious central Mall.

Several of these landmark structures were completed during this decade, transforming the face of downtown Cleveland:

The Federal Building (now the Howard M. Metzenbaum U.S. Courthouse) was the first of the Group Plan buildings to be completed, opening in 1910. It originally housed a post office, customs house, and courthouse. Its exterior is adorned with statues representing Jurisprudence and Commerce, sculpted by Daniel Chester French, who also created the statue for the Lincoln Memorial.

The Cuyahoga County Courthouse, a near-twin to City Hall in its classical design, was finished in 1911. Its exterior features statues of great lawgivers from history, including Moses and Thomas Jefferson.

Cleveland City Hall was completed in 1916. Its grand design, including a massive mayor’s office with rich wood detailing and a three-story, oak-paneled City Council chamber, reflected Cleveland’s status as the nation’s sixth-largest city at the time.

While other components of the Group Plan, such as the Cleveland Public Library and the Public Auditorium, were completed in the 1920s, the progress made in the 1910s firmly established the Mall’s framework. The original vision for a Union Terminal at the north end of the Mall, along Lake Erie, was ultimately abandoned, with the city’s main rail terminal later developed at Public Square under the Van Sweringen plan. In 1911, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., son of the famed landscape architect, joined the Group Plan Commission to contribute to the planning of the Mall itself. The construction of these monumental buildings during the 1910s was a powerful statement of Cleveland’s civic pride, its economic strength, and its aspirations to be a leading American metropolis with a beautiful and dignified public heart.

The World Stage Comes to Cleveland: The Impact of World War I

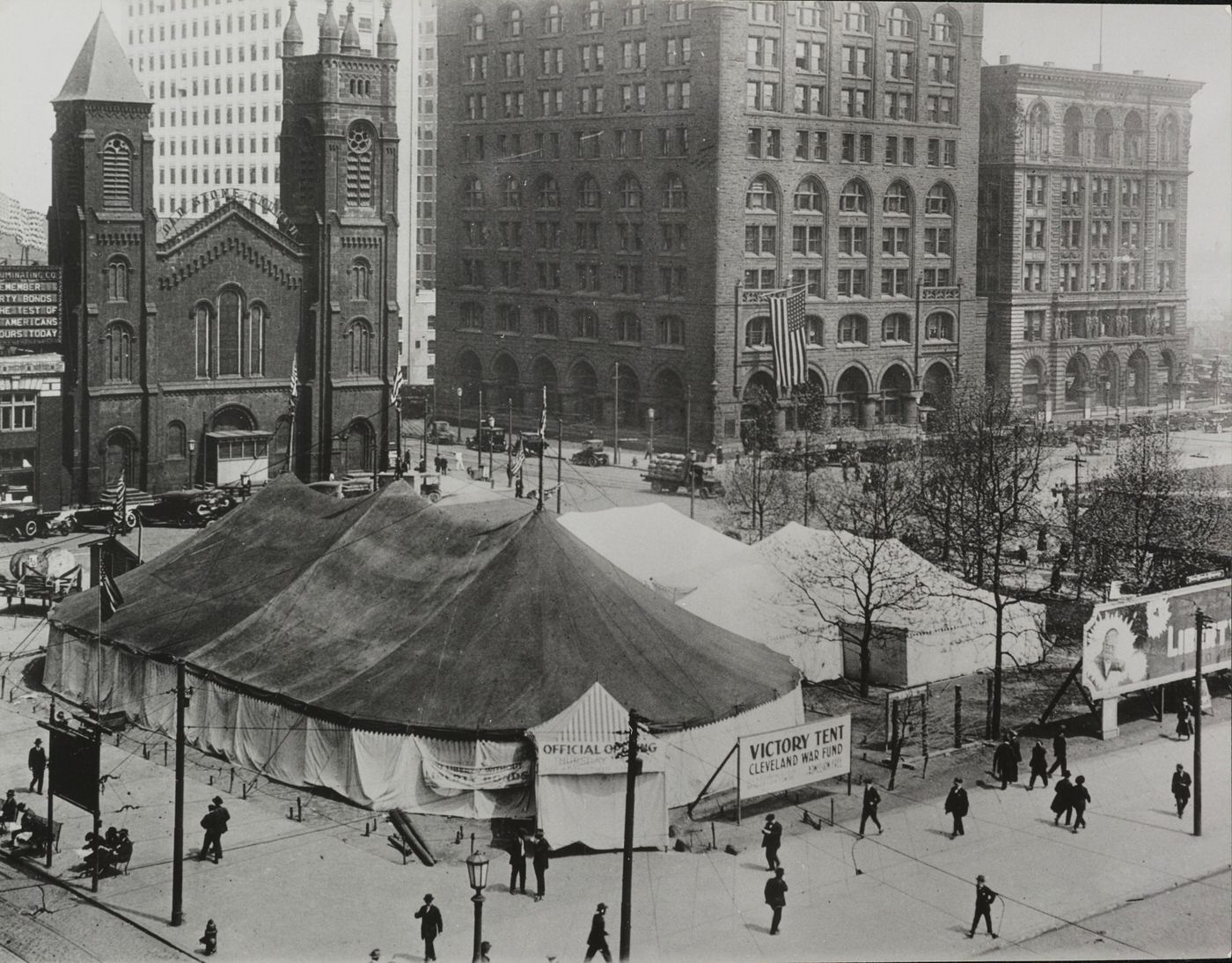

The outbreak of World War I in Europe in 1914, and the eventual entry of the United States in 1917, had a profound and multifaceted impact on Cleveland. During the years of U.S. neutrality (1914-1917), Cleveland’s industries experienced an economic boom, fulfilling massive contracts for war materials for the Allied powers. Factories churned out uniforms, weapons, trucks (the White Motor Company alone produced 18,000 for the U.S. and its allies), and chemicals for explosives. By the autumn of 1918, it was estimated that Cleveland had produced $750 million worth of munitions since the war began.

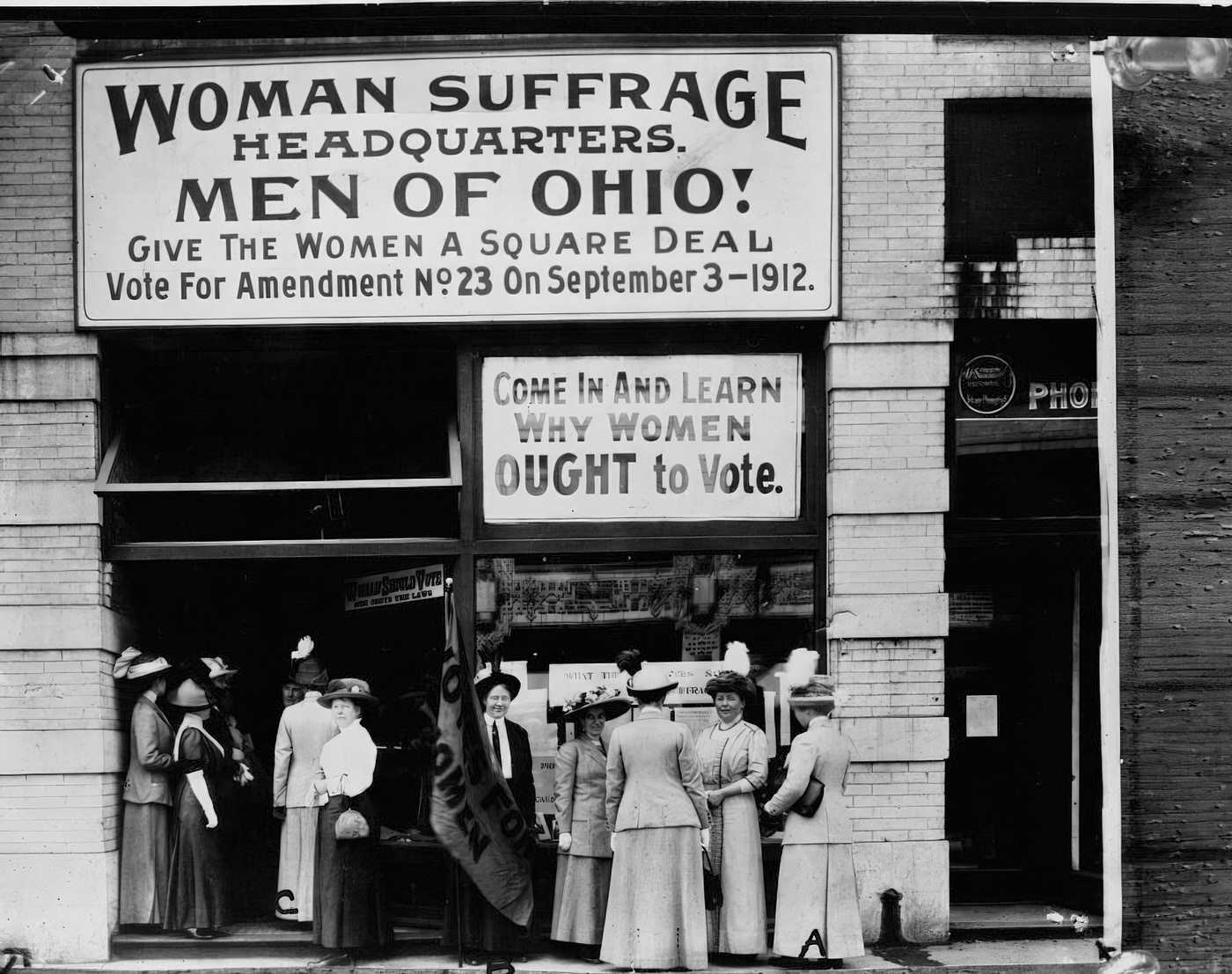

This industrial surge created significant labor shortages. With European immigration effectively cut off by the war, employers turned to new sources of labor. The most significant of these was the African American population of the South, leading to a 308% increase in Cleveland’s Black population between 1910 and 1920. Women also entered the workforce in greater numbers and in new roles; for example, the Cleveland Public Schools dropped a rule forcing female teachers to resign upon marriage, and women began working as streetcar “conductorettes”.

Civic life in Cleveland was thoroughly mobilized for the war effort. Mayor Harry L. Davis appointed a Mayor’s Advisory War Committee to coordinate local activities. This committee oversaw initiatives such as “war gardens” (community and home gardens to increase food production), the “Four Minute Men” speakers’ bureau (which delivered short patriotic speeches), and local efforts for the Treasury Department’s Liberty Loan drives. Clevelanders responded enthusiastically, oversubscribing the first two Liberty Loan campaigns by $70 million. Food conservation programs, like “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays,” promoted nationally by the U.S. Food Administration under Herbert Hoover, were likely adopted by Cleveland families to ensure adequate supplies for troops and allies. The war also brought significant social tensions. While patriotism was widespread, an Americanization Board was established by the Mayor’s Advisory Committee, and free English and civics classes were offered in numerous locations, reflecting an effort to assimilate the city’s large immigrant population. However, intense pressure was placed on ethnic communities, particularly the city’s 132,000 residents of German extraction and its Hungarian population, many of whom had initially hoped for U.S. neutrality. The German language was dropped from the curriculum of public elementary schools, and the German American Savings Bank changed its name to the American Savings Bank to appear less provocative. Anti-war sentiment, voiced by radical political groups including some Socialists, was met with suppression. Socialist leader Eugene Debs was arrested in Cleveland in 1918 for a speech criticizing the war and was subsequently imprisoned. World War I thus acted as a powerful catalyst, accelerating economic production and permanently altering Cleveland’s demographic landscape, while also testing the city’s social cohesion.

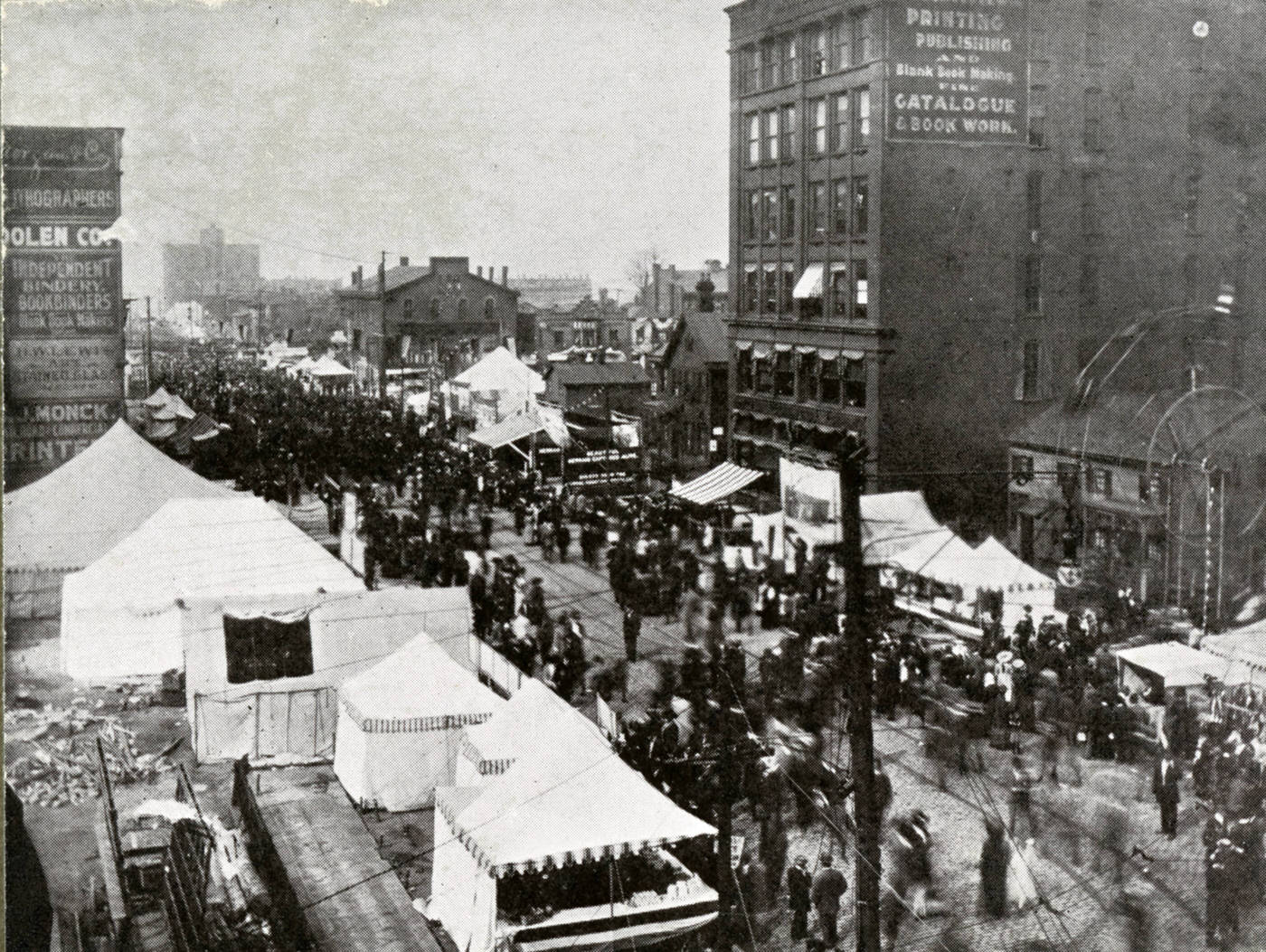

Feeding the City: The West Side Market and Food Distribution

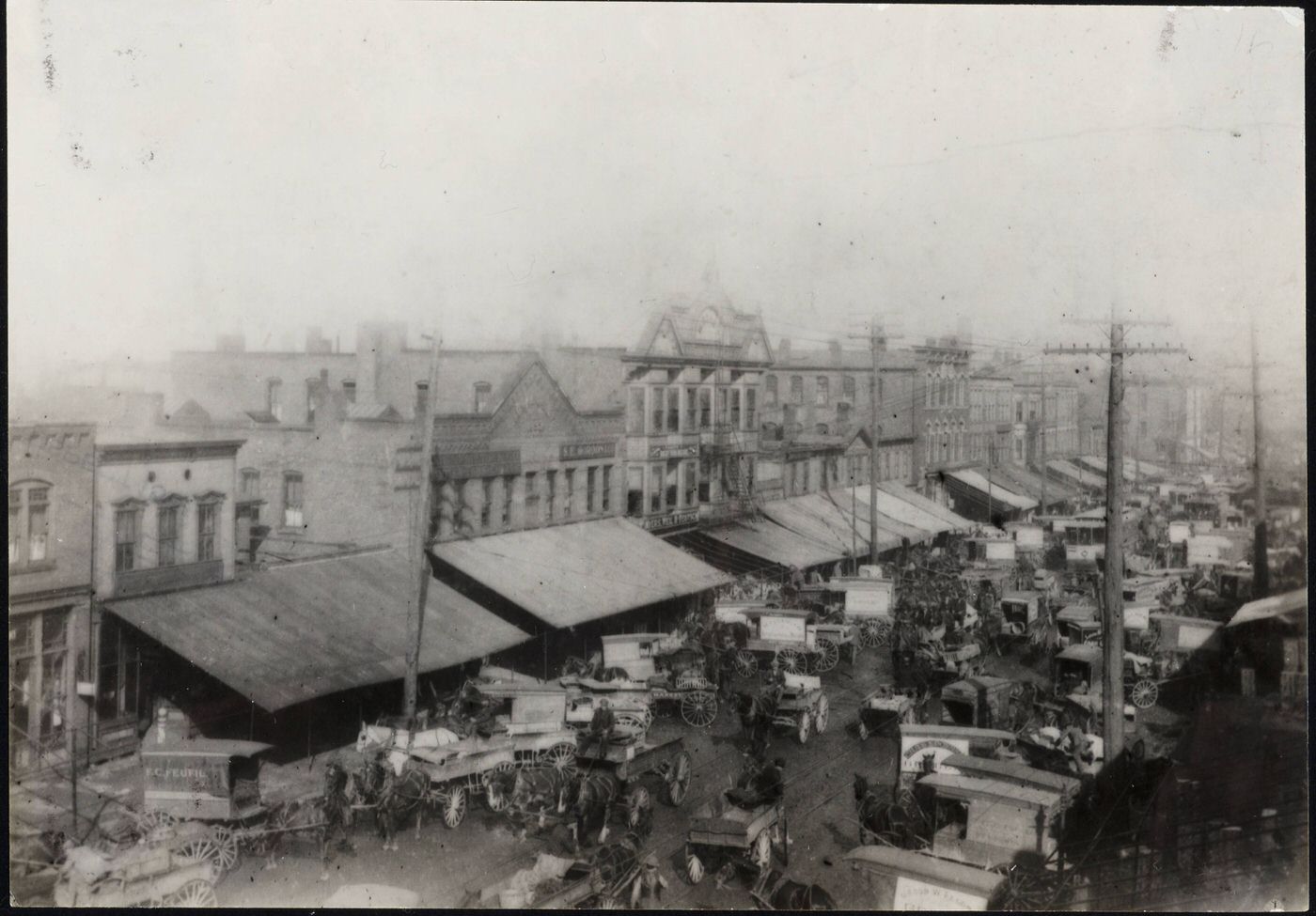

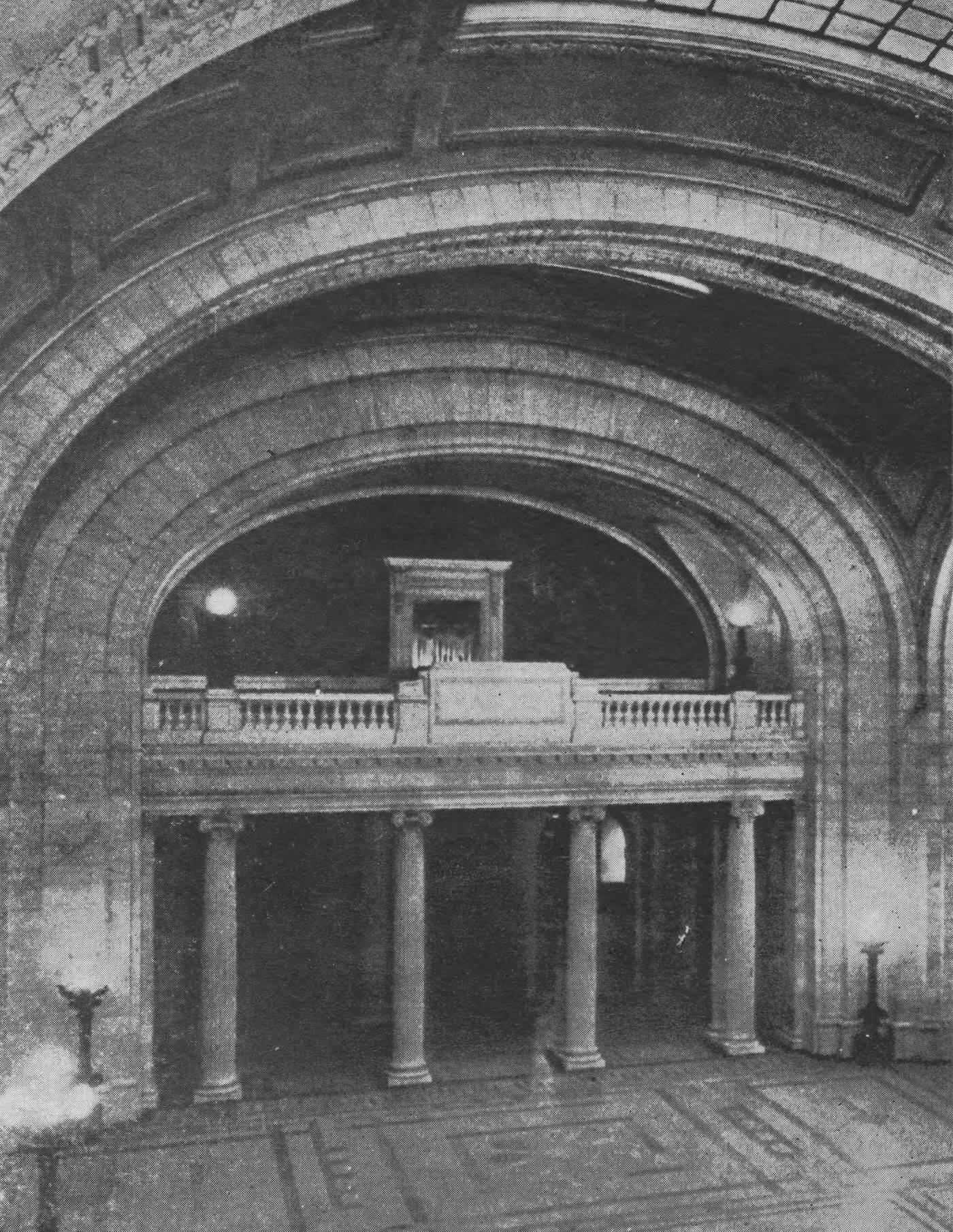

A cornerstone of Cleveland’s food distribution system, the West Side Market, opened its doors on November 2, 1912. Championed by former Mayor Tom L. Johnson and designed by the prominent local architectural firm of W. Dominick Benes and Benjamin Hubbell, the market was a significant civic project. Construction began in 1908, with the cornerstone laid in 1910. The market was conceived to replace the aging Pearl Street Market and to serve the city’s rapidly growing and diverse immigrant population.

The market building itself was an impressive structure, featuring a distinctive 137-foot clock tower and a grand interior hall with a 44-foot high Guastavino tile vaulted ceiling. Initially, it housed 109 indoor stands where vendors sold a wide array of products, including meats, dairy items, bread, groceries, and various ethnic specialty foods, reflecting the city’s multicultural makeup. Fresh produce was originally sold from curb stands outside the main market house, with dedicated outdoor produce aisles added a few years later to better accommodate these vendors.

The opening of the West Side Market represented a major step in modernizing Cleveland’s food supply system. It provided a large, organized, and more sanitary venue for the sale of perishable goods, crucial for feeding an expanding urban populace. Beyond the West Side Market, the city’s food supply in the 1910s relied on a network of market gardening, often undertaken by European immigrant families, and an increasingly centralized milk distribution system where middlemen in the city handled sales from dairy farmers. By 1909, Cuyahoga County was a leading potato producer in Ohio. Wholesale grocers also played a vital role, distributing non-perishable items like dried, canned, and bottled goods throughout the city. The West Side Market quickly became, and remains, an important social and economic hub, a place where the city’s diverse cultures met and mingled.

Public Spaces: Parks and Recreation

Cleveland’s approach to public parks evolved during the 1910s, reflecting both the City Beautiful ideals of grand civic spaces and the Progressive Era emphasis on active recreation and neighborhood amenities. Efforts initiated in the previous decade by Mayor Tom L. Johnson (1901-1909) continued to influence park use; “Keep Off the Grass” signs were a thing of the past, and city parks increasingly featured playgrounds, athletic fields, basketball and tennis courts, and public bathhouses. Skating rinks were popular in larger parks like Brookside and Rockefeller, and park shelters in Edgewater and Woodland Hills had been converted into municipal dancing pavilions, promoting active community use.

Established parks like Wade Park (now Wade Oval), Gordon Park, and Edgewater Park remained vital recreational areas for the city’s residents. The area around Wade Park, in particular, saw significant cultural development with the establishment of the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1916. The renowned Olmsted Brothers architectural firm was engaged to design the Fine Arts Garden surrounding the museum, enhancing the park’s Beaux-Arts character.

A landmark development in the 1910s was the formation of the Cleveland Metropolitan Park District in 1917. This was the realization of a vision championed by engineer William Stinchcomb since 1905, who foresaw the need for an “Emerald Necklace” – an outer chain of parks and parkways encircling the rapidly growing metropolitan area. Early land acquisitions for this system began in the late 1910s, laying the foundation for one of the nation’s premier regional park systems. This multi-faceted approach to public green space—combining aesthetically pleasing civic parks, neighborhood recreational facilities, and large-scale conservation efforts—demonstrated a growing understanding of the importance of open space and recreation for the well-being of an industrial city’s diverse population.

Essential Services: Sanitation, Water Supply, Street Paving, and Public Lighting

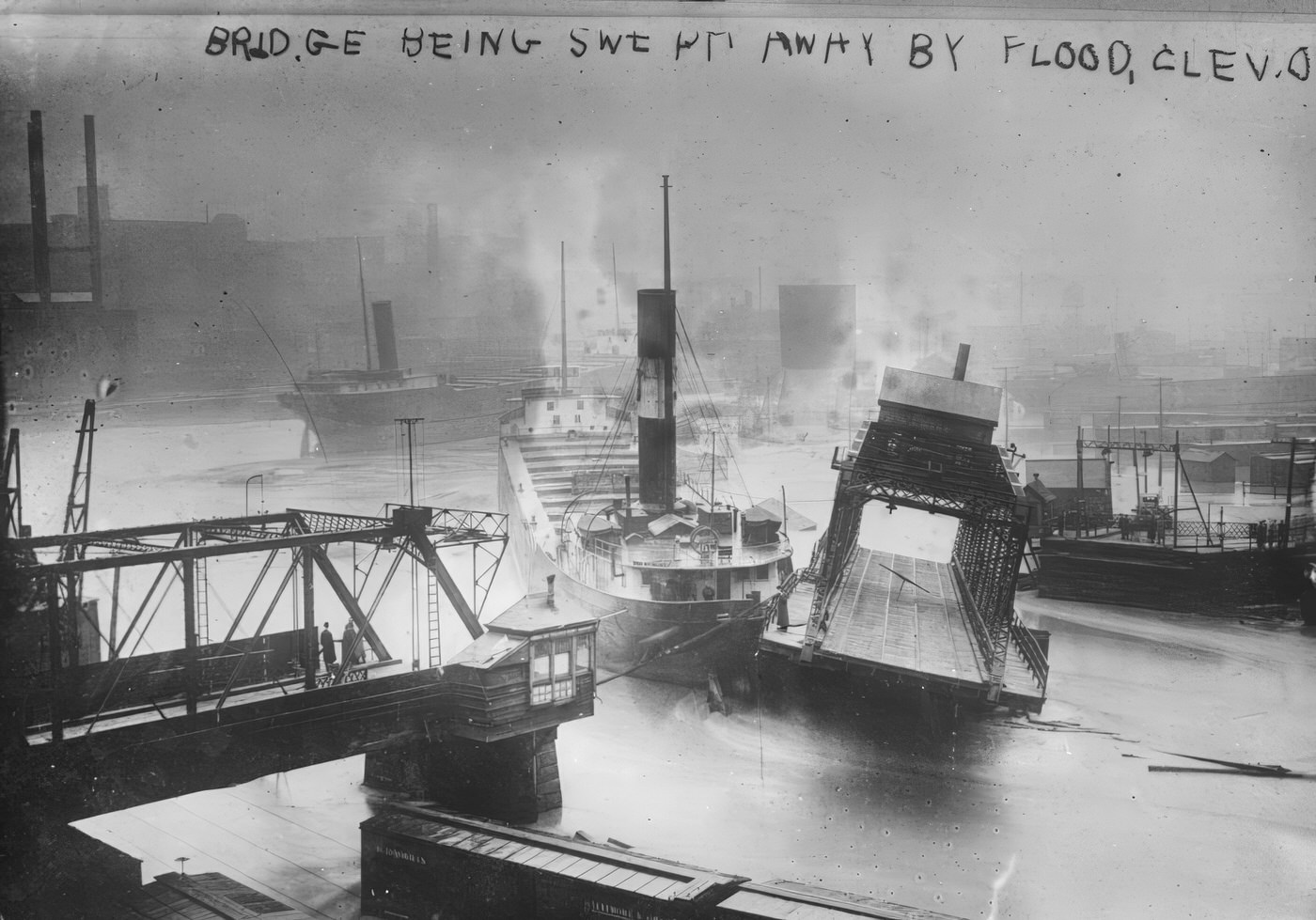

Providing essential services for a rapidly expanding city like Cleveland was an immense and ongoing challenge in the 1910s. Significant strides were made in improving the water supply. Following studies and recommendations, the city began chlorinating its water in 1911, and partial filtration was introduced in 1917. These measures led to noticeable decreases in water-borne diseases like typhoid fever. The Kirtland Pumping Station, built in 1904, and its associated intake tunnel, were critical components of this system. However, the dangers involved in constructing such infrastructure were starkly highlighted by the final and tragic Waterworks Tunnel Disaster on July 24, 1916, when an explosion killed 11 workers and 10 rescuers. Garrett Morgan, an African American inventor, famously used his safety hood to rescue two men and recover four bodies.

Sanitation, particularly sewage disposal, remained a major concern. As late as 1914, fifty separate sewer lines were still discharging raw sewage directly into the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie. Progress towards a solution began in 1911 when the city was authorized to operate an experimental sewage-treatment plant. The positive results from these experiments led to the construction of major treatment plants (Westerly, Easterly, and Southerly) in the 1920s.

Street cleaning and paving also saw improvements. A Bureau of Street Cleaning was established in 1913, and in 1916, responsibility for solid waste collection was transferred to the Department of Public Service. The increasing volume of traffic, especially automobiles, created strong demand for better-paved and wider arterial streets throughout the 1910s.

Public lighting continued to expand. The city acquired existing electric light plants through the annexation of South Brooklyn in 1905 and Collinwood in 1910. Under Mayor Newton D. Baker, a new municipal light plant was constructed, opening in 1914, reflecting a commitment to public ownership of utilities. The Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company (CEI) also played a major role in expanding both electric and district steam heating services. The Electrical League of Northern Ohio, formed in 1909, worked to promote the burgeoning electrical industry. Despite these advancements, the development of comprehensive public health infrastructure often lagged behind the city’s rapid growth and industrial pollution, a common struggle for industrial cities of that era.

The 1910s were a decade of dynamic civic engagement, cultural evolution, and significant challenges for Cleveland. The city grappled with modernizing its governance, addressing pressing social needs, expanding educational opportunities, and navigating the profound impacts of global conflict.

Governing the Metropolis: Mayor Newton D. Baker and the Home Rule Charter

A key figure in Cleveland’s governance during this period was Mayor Newton D. Baker, who served from 1912 to 1916. Baker was a prominent advocate for municipal Home Rule, a movement aimed at giving cities greater autonomy from state legislative control. He played a crucial role in drafting the 1912 Ohio constitutional amendment that granted municipalities this right. Subsequently, he was influential in selecting the commission that wrote Cleveland’s first Home Rule Charter and campaigned for its passage in 1913.

Approved by voters and implemented on January 1, 1914, the Home Rule Charter marked a significant step in modernizing Cleveland’s government. Modeled after the earlier Federal Plan, it maintained a mayor-council form of government but introduced several reforms. The city council was reduced from 32 to 26 members, elected by wards. The charter distinctly separated executive and legislative powers, granting the mayor authority to appoint department heads without needing council approval. Elections for mayor and council became nonpartisan. Importantly, the charter incorporated Progressive Era tools of direct democracy: initiative, referendum, and recall, designed to give citizens more control over their government. During his tenure, Mayor Baker also oversaw the construction of a new municipal light plant, which opened in 1914, reflecting the city’s move towards public ownership of utilities. The adoption of Home Rule was a recognition that a large, complex industrial city like Cleveland required more direct control over its own affairs to effectively address its unique challenges.

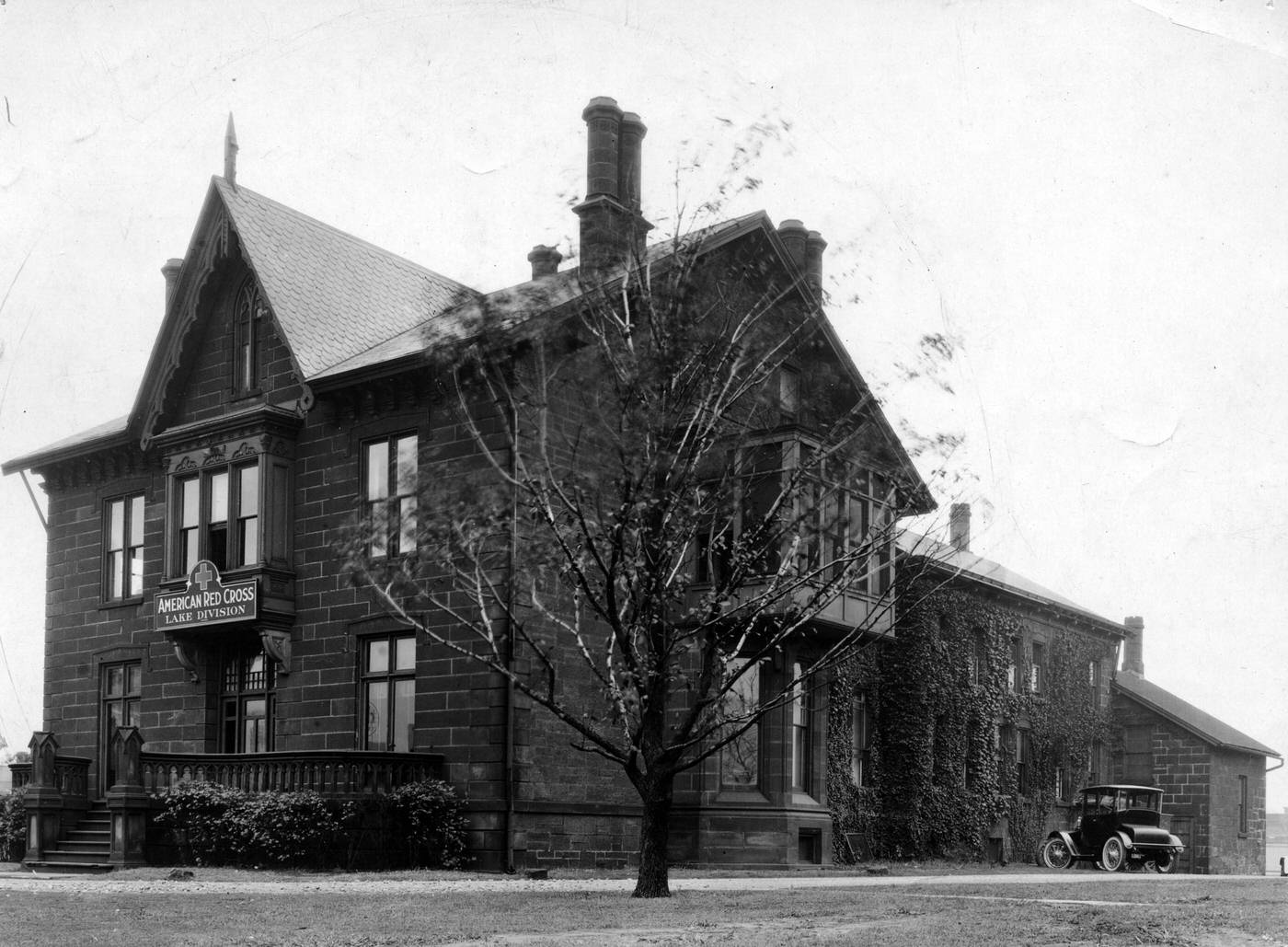

Community Support: Philanthropy and Settlement Houses

The immense social needs of Cleveland’s rapidly growing and diverse population spurred significant developments in organized social welfare. The 1910s saw a shift towards more coordinated and professionalized philanthropic efforts. A landmark achievement was the founding of the Federation for Charity & Philanthropy on January 7, 1913. Created under the aegis of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, this nonprofit, citizen-led federation aimed to better coordinate the fundraising and service delivery of the city’s numerous, often independent, charities. In 1917, this body merged with the Cleveland Welfare Council (which had advised the city’s welfare department) to become the Welfare Federation of Cleveland. This move signaled a trend towards centralized, efficient, and somewhat less overtly religious approaches to philanthropy, designed to address widespread urban problems more systematically.

At the grassroots level, settlement houses continued to provide vital services in immigrant and working-class neighborhoods. Prominent among these were Hiram House (established 1896), which initially served Jewish immigrants and later expanded its outreach to Italian and then African American communities; Alta House (established 1900), which focused on the Italian residents of Little Italy; and Goodrich House (established 1897, later Goodrich-Gannett Neighborhood Center), which served South Slavic groups along St. Clair Avenue. These institutions offered a range of programs addressing Progressive Era concerns: education (adult classes in English and civics, kindergartens, vocational training), health (visiting-nurse networks, health inspections and clinics), and efforts to improve living conditions (advocacy for housing codes). They also played a crucial role in helping newcomers assimilate into American society. For example, Hiram House specifically began to work more closely with Italian residents in the 1910s after hiring an Italian-speaking staff member. These settlement houses were often staffed by native-born, Protestant, middle- or upper-middle-class reformers, working with predominantly Catholic or Jewish working-class immigrant clients, creating a unique dynamic in the American settlement movement.

The National Pastime: The Cleveland Naps (to become the Indians in 1915)

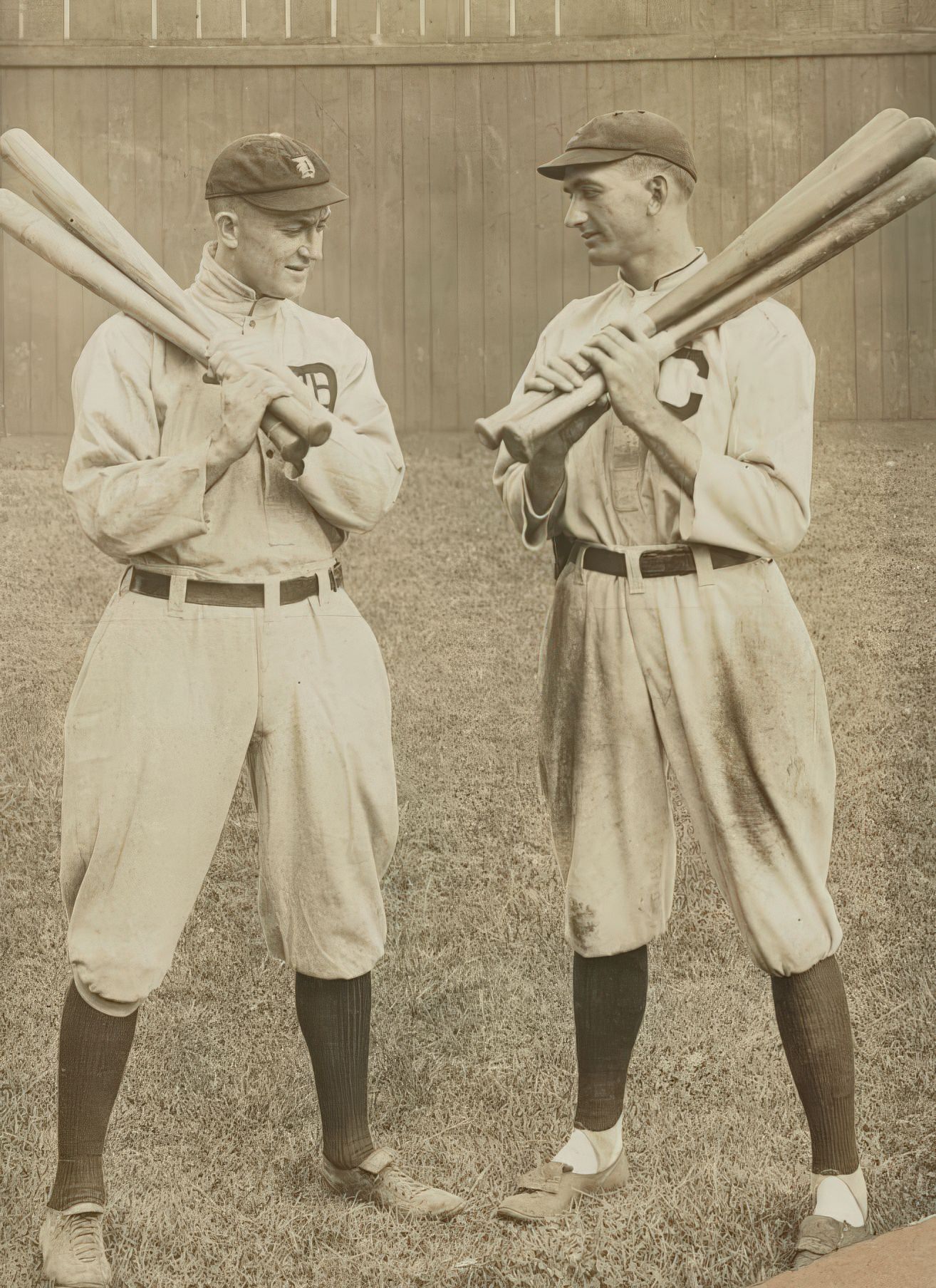

Cleveland’s professional baseball team underwent significant changes during the 1910s. The team, a charter member of the American League (founded 1901), was known as the Cleveland Naps from 1903 through 1911 in honor of their star player-manager Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie. From 1912 to 1914, the team was officially named the Molly McGuires, though many fans and sportswriters popularly continued to call them the Naps. A major identity shift occurred in 1915 when Lajoie was traded. Club owner Charles Somers solicited suggestions from sportswriters for a new name, and “Indians” was chosen. This name was a reference to Louis “Chief” Sockalexis, a Native American outfielder who had played for the old National League Cleveland Spiders in the 1890s.

The team played its home games at League Park, which received a facelift before the 1910 season. The 1910 season saw the Naps finish fifth in the American League with a 71-81 record. Key players during the early part of the decade included the legendary Nap Lajoie himself, a young Shoeless Joe Jackson, and veteran pitcher Cy Young, who had returned to Cleveland in 1909 and won 19 games that year. Another star pitcher, Addie Joss, tragically died from tubercular meningitis before the 1911 season; a benefit All-Star game, a forerunner to modern All-Star games, was held in his honor in Cleveland that year.

Despite having talented players like Lajoie and Jackson, the team generally struggled throughout the 1910s, often hampered by poor pitching, and consistently finished below third place. The team reached its lowest point in 1914 and 1915, finishing in last place in both seasons. Ownership also changed hands during this period. Charles Somers, facing financial difficulties, sold the team in 1916 to a syndicate headed by Chicago railroad contractor James C. “Jack” Dunn. Under new manager Lee Fohl (who took over in 1915) and later with Tris Speaker as player-manager starting in 1919, the team began a rebuilding process. Key acquisitions towards the end of the decade, including pitchers Stan Coveleski and Jim Bagby, and center fielder Tris Speaker, laid the groundwork for the team’s future success in the 1920s. The 1910s were thus a decade of transition for Cleveland baseball, marked by the departure of a namesake star, a new team identity, and the slow assembly of a championship-caliber roster.

Learning and Advancement: Public Schools and Higher Education

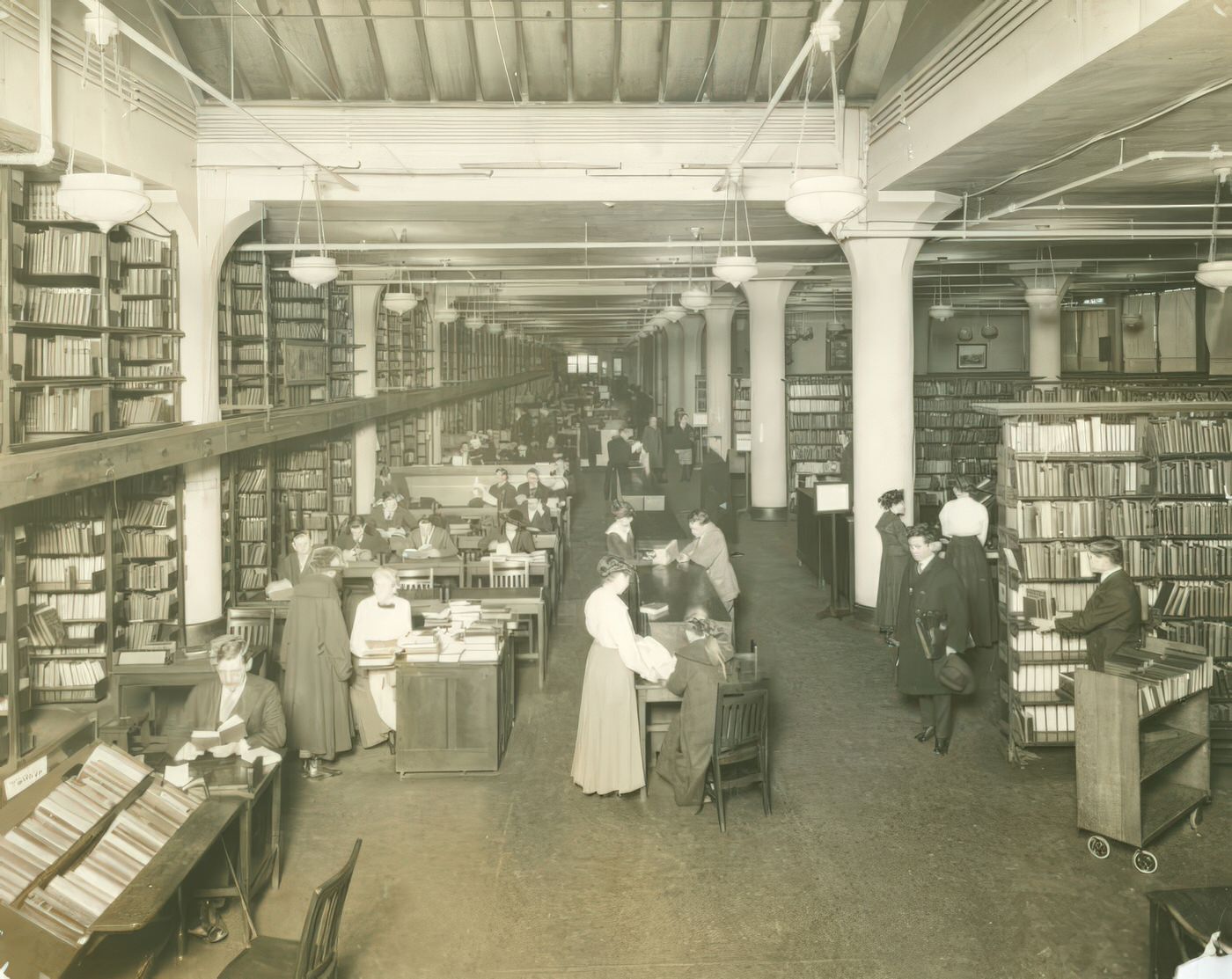

Cleveland’s educational institutions were actively adapting to the demands of an industrializing and diversifying city in the 1910s. The Cleveland Public Schools (CPS), under Superintendent William H. Elson (whose tenure ended in 1912 but whose reforms shaped the early decade), had pioneered vocational education with the opening of a technical high school in 1908 and a commercial high school in 1909. An industrial school for non-academically inclined children, offering a mix of academic and practical training, also opened in 1909 and became a model for the junior high program. Public health initiatives within schools included medical dispensaries (the first in public education at Murray Hill School in 1908) and dental inspections (starting in 1910).

However, the school system faced significant challenges, notably severe overcrowding, with the student population reaching 64,409 by 1912. The tragic Collinwood School Fire in 1908, which claimed 172 student lives, also brought scrutiny upon school safety and contracting practices. A comprehensive survey of CPS by the Cleveland Foundation in 1915 criticized inefficiencies and the failure to meet diverse student needs, noting that two-thirds of students left before the legally required age. This led to further reforms under Superintendent Frank E. Spaulding (appointed 1917), including the expansion of junior high schools, the introduction of guidance counselors and ability grouping, and an intensified focus on Americanizing immigrant children, especially as the U.S. entered World War I. The Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 provided federal funds to expand vocational education further. By 1918, the school population had swelled to 106,862, with nearly half of secondary students enrolled in commercial-technical high schools. Robinson G. Jones, who had been instrumental in organizing junior high schools under Elson, became assistant superintendent in 1917 and would later lead the district.

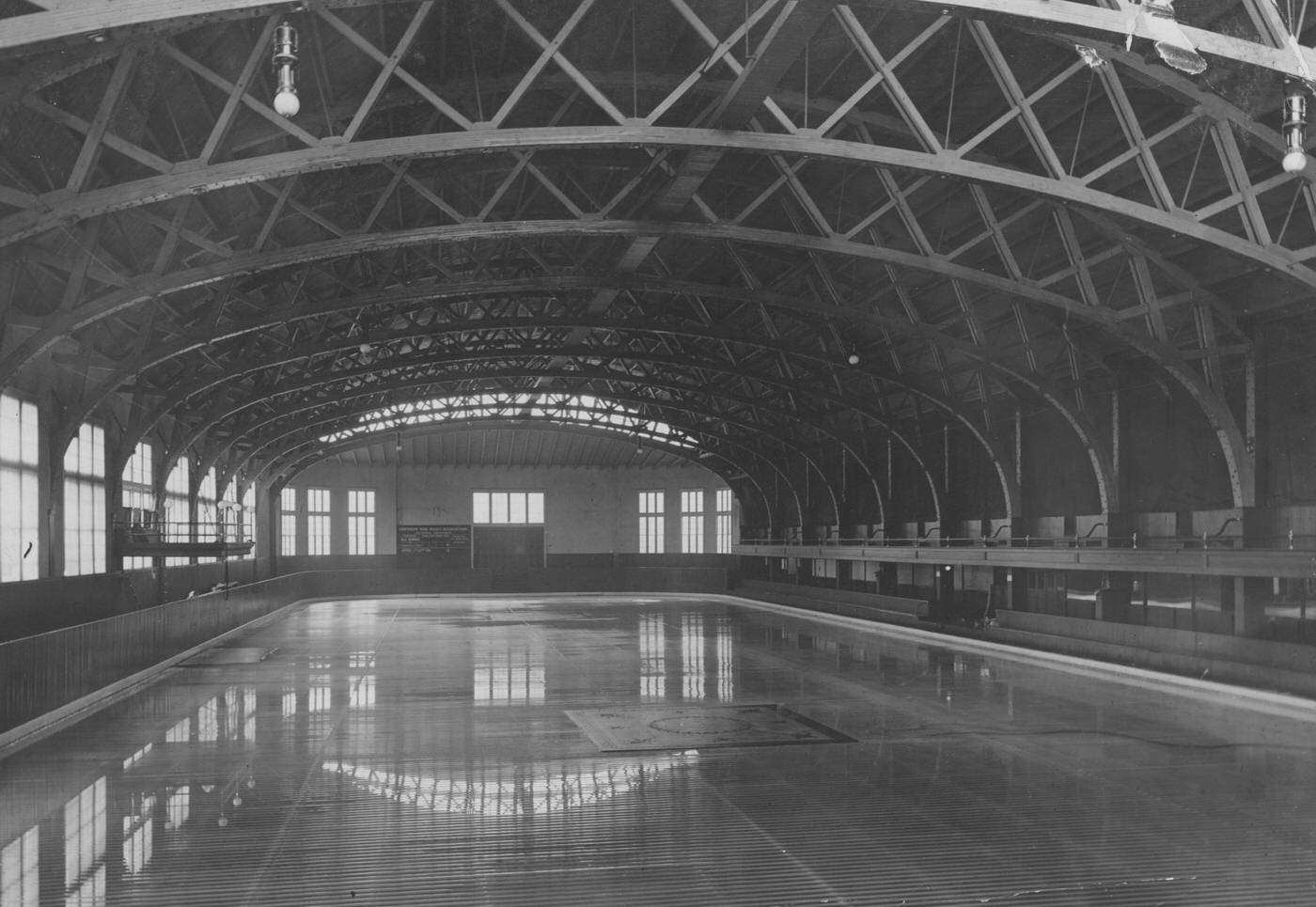

Higher education also saw growth. Western Reserve University (WRU) established its School of Applied Social Sciences in 1916 and renamed its medical department the School of Medicine in 1913. The Amasa Stone Memorial Chapel was erected in 1911. At the Case School of Applied Science, electric lights were installed in all classrooms in the Main Building in 1912, and the Case Club, its first dedicated student center (a former church), opened in 1915, providing a gymnasium, swimming pool, and social spaces. These developments reflected the increasing importance of specialized and professional education in a city driven by industry and grappling with complex social issues.

Leisure and Entertainment: Vaudeville, Early Motion Pictures, and Euclid Beach Park

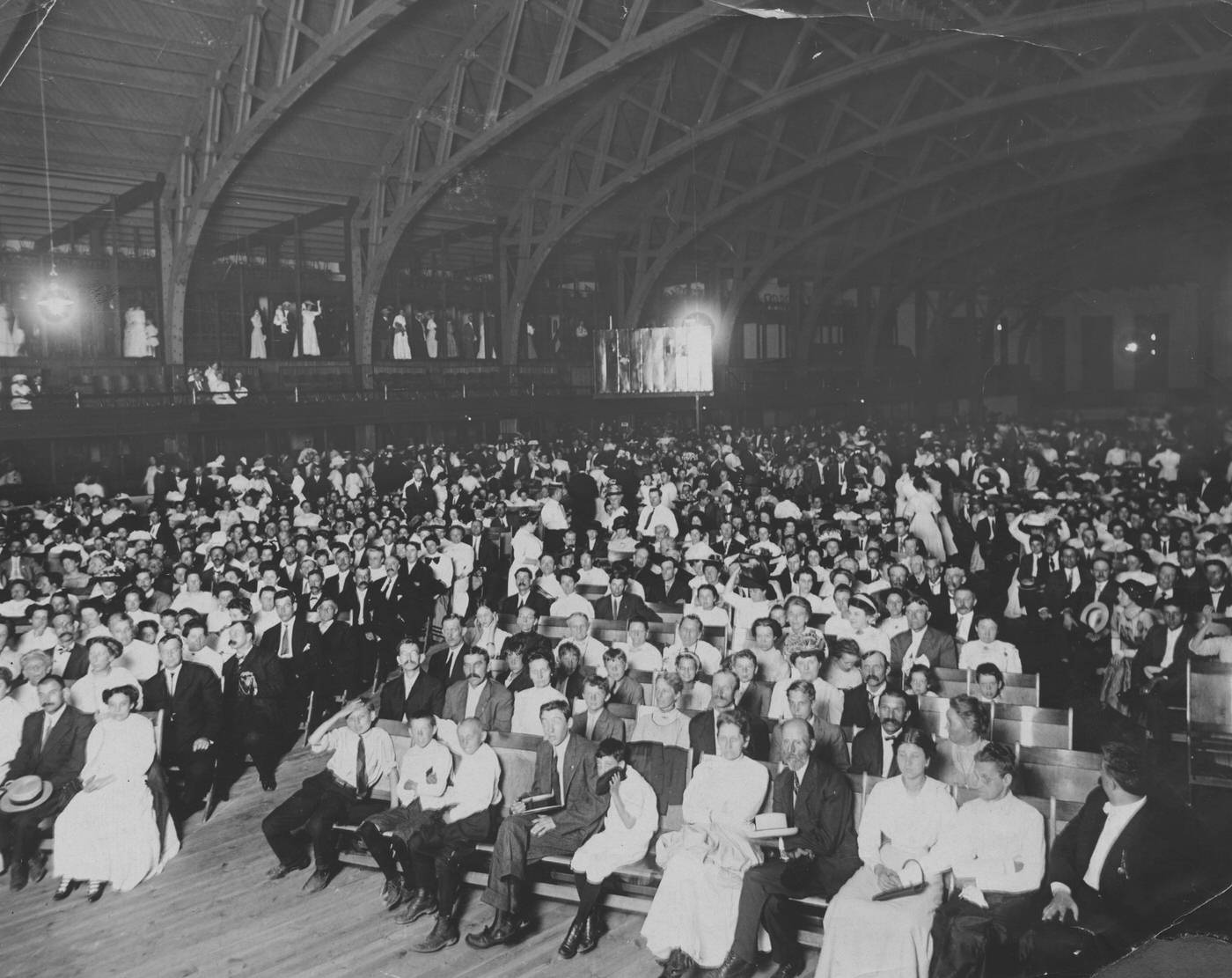

Clevelanders in the 1910s enjoyed a diversifying array of leisure and entertainment options. Vaudeville remained a dominant form of popular entertainment. The city was a key stop on the national vaudeville circuit, boasting numerous theaters. Prominent venues active in the 1910s included the grand Hippodrome (opened 1907), the Colonial Theatre, the Columbia Theatre, and the historic Euclid Avenue Opera House. Newer theaters like the Metropolitan (opened 1913, later the Agora) and the Knickerbocker (opened 1913) also featured vaudeville bills. These shows offered a “potpourri” of acts, from animal performances and acrobats to comedians like the famous Weber & Fields, musicians (John Phillip Sousa’s band played the Hippodrome in 1911), and magicians such as Houdini.

The 1910s also marked the significant rise of motion pictures, which began to challenge vaudeville’s supremacy. Cleveland’s first dedicated movie theater, the American Theater on Superior Avenue, had appeared in 1903, famously showing “The Great Train Robbery”. The Empire Theater, originally a vaudeville house opened in 1900, had been interspersing films into its programs as early as 1901. Throughout the decade, nickelodeons – small, often converted storefront theaters charging five cents for admission – flourished nationally from about 1905 to 1915, and Cleveland would have been part of this trend. Towards the end of the decade and into the next, more substantial movie theaters were built. For example, the Mall Theaters (Upper and Lower Mall), which opened in 1916, featured an innovative “double-decker” design with one auditorium above another. By 1917, Cleveland had 32 movie listings, indicating the growing popularity of this new medium.

Euclid Beach Park, under the management of the Humphrey family since 1901, continued to be a beloved destination for Clevelanders. The Humphreys focused on creating a “respectable destination,” removing the beer garden and enforcing dress codes. The park expanded its attractions during the 1910s. A new, grander carousel (Philadelphia Toboggan Company Carousel Number 19) was installed in 1910, replacing an earlier one from 1905. A major thrill ride, the Derby Racer (later renamed the Racing Coaster), designed by John A. Miller and built by Frederick Ingersoll, debuted in 1913 to much fanfare and remained a park staple until its closure in 1969. These diverse amusement options reflected a city with a growing population seeking varied forms of entertainment and escape.

Trials and Tribulations: The 1918 Influenza Pandemic and the 1916 Waterworks Tunnel Disaster

Amidst the growth and wartime fervor, Cleveland also faced significant local tragedies in the 1910s that exposed the vulnerabilities of a rapidly expanding industrial city. The most widespread of these was the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919, commonly known as the “Spanish Flu.” This particularly virulent strain of influenza reached Cleveland by September 1918. City Health Commissioner Dr. Harry Rockwood spearheaded the public health response. As cases mounted (500 by October 7), the city implemented increasingly strict measures to control the spread. Initially, voluntary closures of public gathering places were suggested, but by October 15, mandatory closure orders were issued for theaters, movie houses, dance halls, night schools, churches, and Sunday schools. Streetcar conductors were even tasked with assisting police in arresting individuals who spat on streetcar floors, a common practice then believed to contribute to disease transmission. Schools were eventually closed, and business hours were shortened, though industrial work vital to the war effort continued. The pandemic placed immense strain on healthcare facilities, necessitating the use of temporary hospitals, including the Cleveland Normal School. The epidemic began to subside in early November 1918, with restrictions lifted mid-month, although a less severe wave persisted into early 1919. The toll was devastating: over 4,400 Clevelanders died from the flu or related complications, a mortality rate higher than that of Chicago or New York City. Local businesses suffered losses estimated at $1.25 million (over $21 million in contemporary currency).

Two years earlier, on July 24, 1916, the city was shaken by the Waterworks Tunnel Disaster. During the construction of a new water intake tunnel extending miles under Lake Erie—essential for providing fresh water to the growing city—a pocket of natural gas was breached by workers. A spark ignited the gas, causing a massive explosion. The blast killed 11 tunnel workers instantly. Tragically, an additional 10 would-be rescuers also perished, overcome by the toxic gases when they entered the pressurized tunnel in attempts to save their colleagues. A notable act of heroism occurred when Garrett A. Morgan, a prominent African American inventor from Cleveland, along with his brother Frank and two other volunteers, used Morgan’s newly invented “safety hood” (a precursor to the gas mask) to descend into the gas-filled tunnel. They successfully rescued two men and recovered four bodies before officials halted further efforts. This disaster was the last and one of the deadliest in a series of accidents that plagued the construction of Cleveland’s water intake tunnels, underscoring the perilous conditions faced by laborers building the city’s vital infrastructure. These events highlighted the fragility of urban life and the high human cost associated with progress in an era of rapid industrialization and urbanization.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know