The story of Abilene, Texas, begins not with gradual settlement, but with a strategic decision tied to the westward march of the railroad. In 1880, the Texas and Pacific (T&P) Railway extended its tracks across the state. Taylor County had been officially organized just two years prior, in 1878, with the small settlement of Buffalo Gap serving as its designated county seat. However, the path of the railroad held the power to reshape the county’s future.

A group of determined local ranchers and businessmen saw an opportunity. Claiborne W. Merchant, John Merchant, John N. Simpson, John T. Berry, and S. L. Chalk met with H. C. Whithers, the T&P’s track and townsite locator. They successfully persuaded the railroad company to alter its planned route. Instead of passing through Buffalo Gap, the tracks would run through the northern part of Taylor County, crossing land owned by these very men. This decision was not merely about convenience; it was a calculated move. By securing the railroad’s path through their property, these landowners positioned themselves to benefit directly from the commerce and growth the T&P would inevitably bring, deliberately diverting development away from the established county seat. Abilene’s creation, therefore, was not a matter of chance; it resulted directly from the actions of local landowners who saw the railroad as a tool to shift the county’s economic and administrative center for their benefit.

Naming and Planning the Town

With the route secured, a site for the new town was selected between Cedar and Big Elm creeks, just east of Catclaw Creek. Claiborne W. Merchant proposed the name “Abilene”. The name was borrowed from Abilene, Kansas, a well-known cattle town that had served as the endpoint of the famous Chisholm Trail. This choice likely served as a form of marketing, aiming to evoke images of prosperity and connection to the cattle trade, even though Abilene, Texas, would quickly develop a more diverse agricultural and commercial base. It was an aspirational name, projecting confidence in the new town’s future.

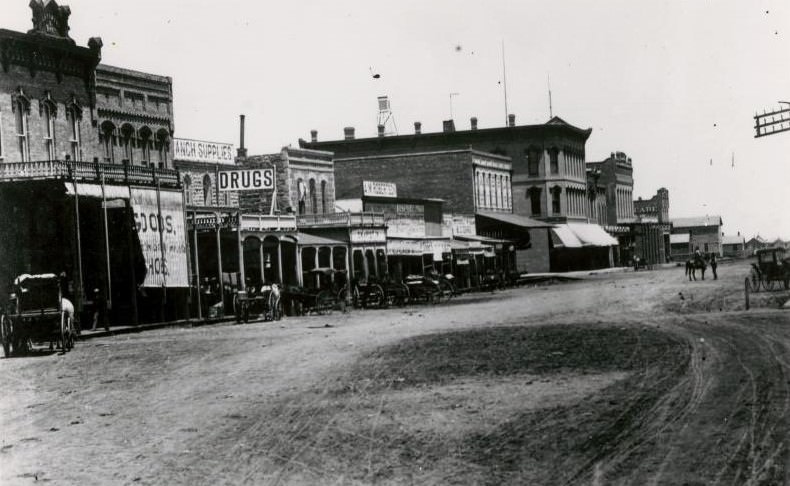

The Texas and Pacific tracks reached the designated spot around January 13-15, 1881. Railroad officials, including J. Stoddard Johnston and H.C. Whithers, formally laid out the townsite. They established a grid system: streets running east and west received numerical designations, while those running north and south were given the names of trees, such as Pine, Cypress, and Oak. The T&P Railway actively promoted its creation, billing Abilene as the “Future Great City of West Texas”.

The Birth of Abilene: The Lot Auction

Anticipation for the new town ran high. Even before the land was officially offered for sale, several hundred people, possibly as many as 800 according to one Dallas newspaper, had already gathered and set up camp at the site. In this nascent tent community, the foundations of civic life began to form, with early businesses and even a Presbyterian church established before the town technically existed.

The formal beginning of Abilene occurred on March 15, 1881, when the auction of town lots commenced. The sale was a success. Over the course of two days, eager buyers purchased 317 lots, generating $51,360 for the organizers. Among the very first purchasers was Charles Gilbert, who secured a lot for his newspaper, the ‘Abilene Standard Reporter’, making it one of the town’s founding businesses. With the conclusion of the auction, the tent city on the prairie was officially born as Abilene, Texas.

Forging an Economy on the Plains (1880s)

The Texas and Pacific Railway was more than just a transportation link for early Abilene; it was the town’s very reason for existence and the primary engine of its initial economy. Its arrival in 1881 connected the isolated West Texas region to national markets, opening up possibilities for trade and attracting the settlers needed to build a community. The railroad dictated Abilene’s location and shaped its early trajectory, demonstrating the immense power of transportation infrastructure in settling the American West.

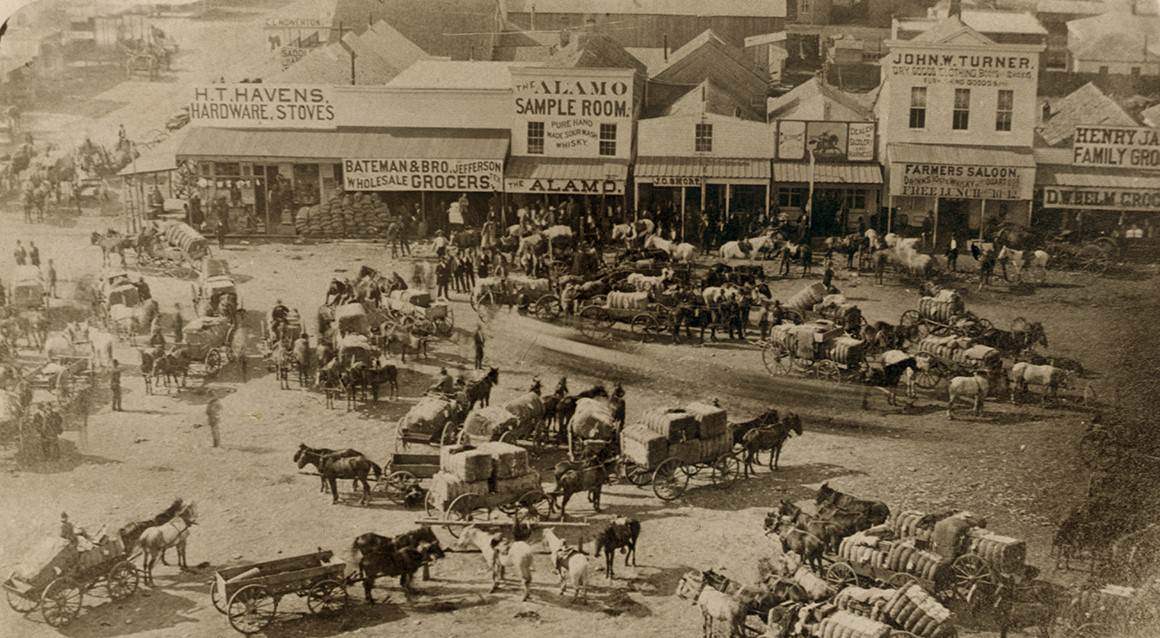

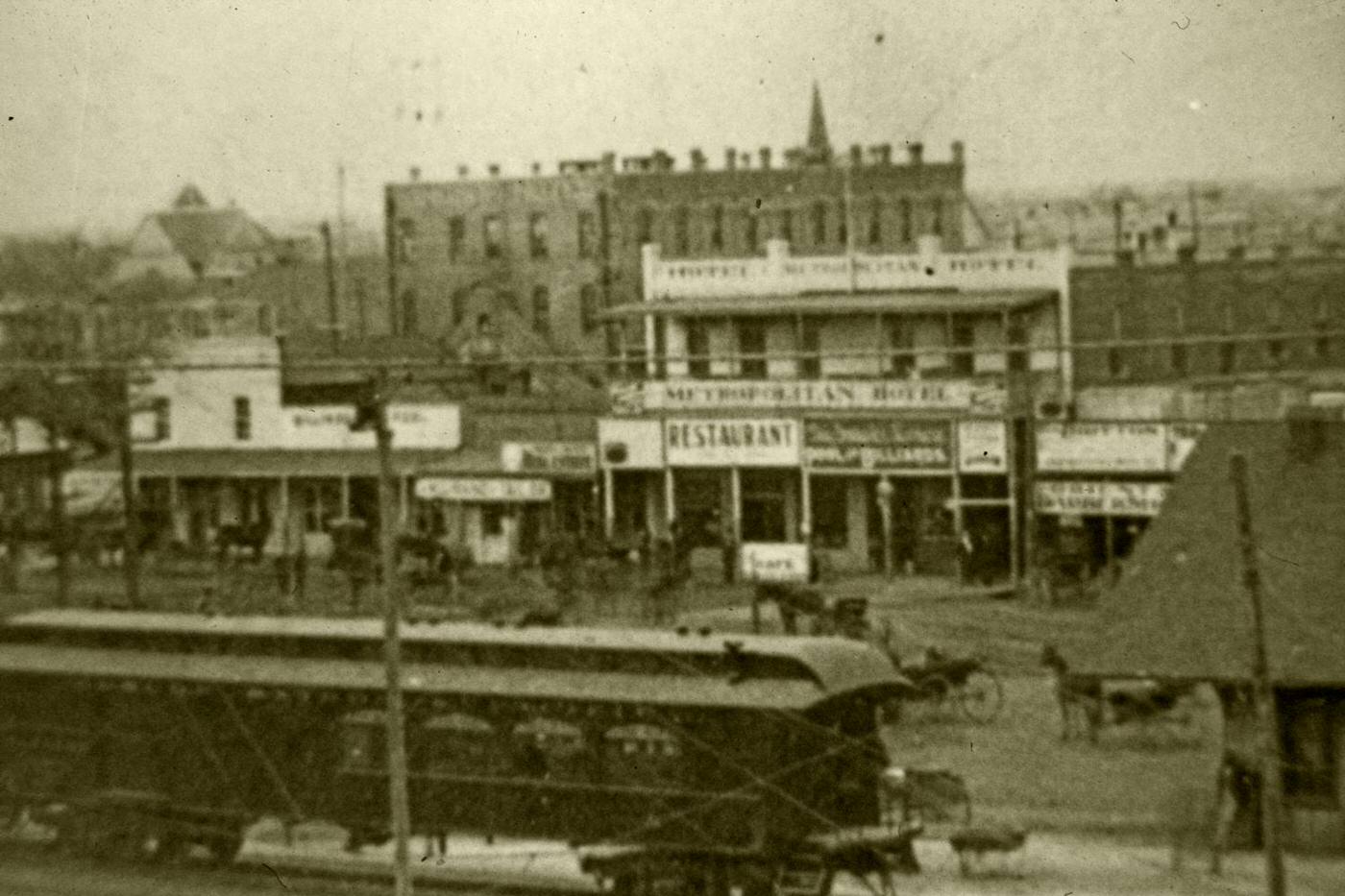

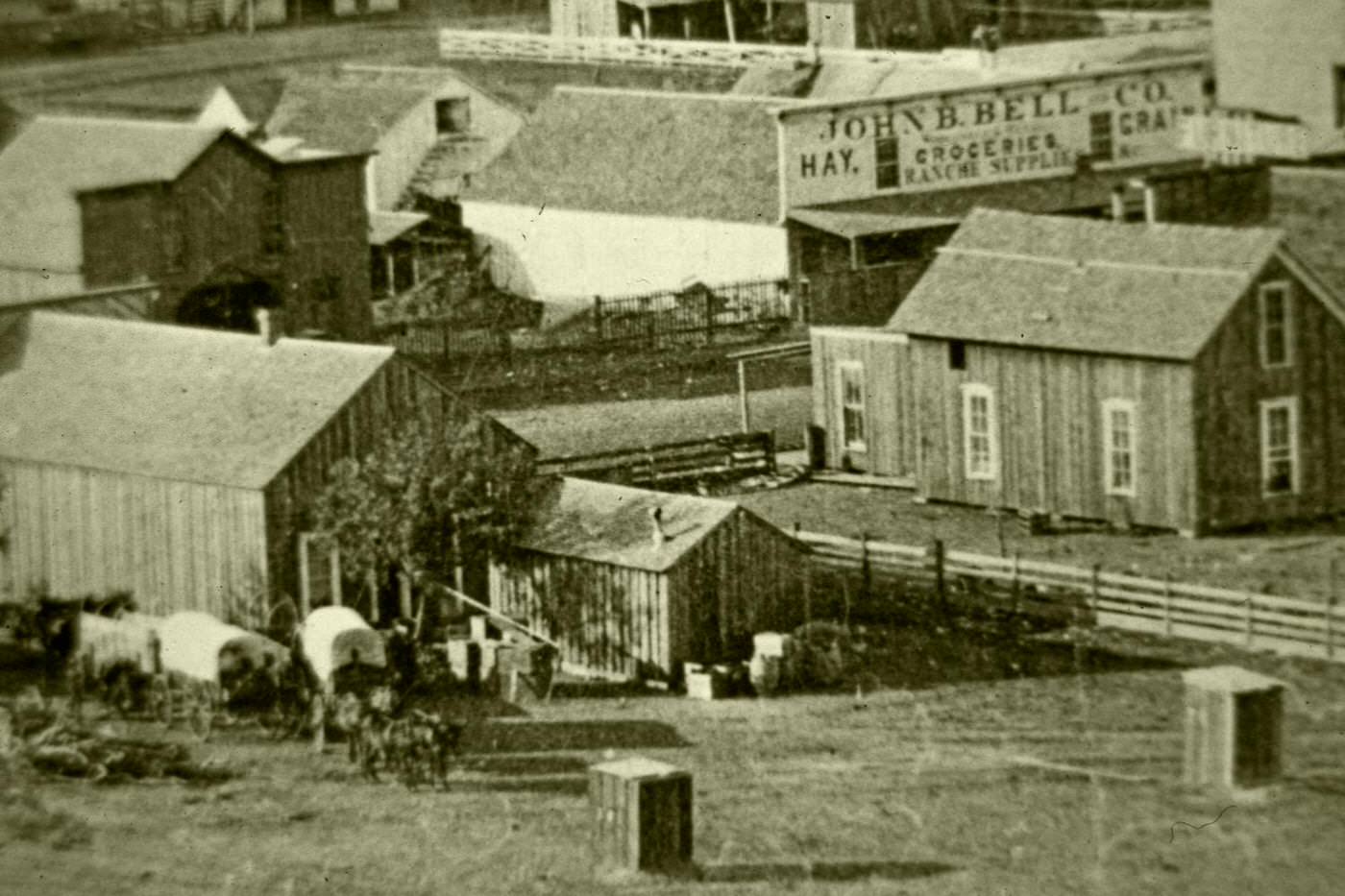

Reflecting the background of its founders and its Kansas namesake, Abilene initially served as a stock shipping point for cattlemen. The railroad infrastructure developed rapidly to support the growing town. The first T&P depot, established in 1881, was simply a repurposed railroad car located near Pine Street. This makeshift arrangement was quickly superseded in 1882 by a more substantial, two-story wooden structure. This new depot housed passenger waiting rooms, railroad offices, a dining facility, and even hotel rooms on the second floor, becoming a central hub of activity.

While cattlemen played a key role in Abilene’s founding, agriculture rapidly emerged as the cornerstone of the local economy. In 1880, just before Abilene’s creation, Taylor County’s economy was dominated by ranching, with over 30,000 cattle reported. However, even then, farmers were beginning to experiment with crops suited to the West Texas climate, cultivating small amounts of wheat, corn, peaches, and cotton.

The citizens of the new town actively worked to foster an agricultural identity. In 1884, Charles Edwin Gilbert, editor of the Abilene Reporter, spearheaded the organization of the city’s first fair. Held in an upstairs room, the fair showcased local produce like corn, millet, oats, wheat, and the increasingly important cotton crop. Gilbert believed such displays would demonstrate the area’s farming potential and attract families seeking agricultural opportunities. This fair marked a deliberate community effort to diversify beyond ranching and railroad services.

This promotional effort continued with a “District Fair” in 1888, involving surrounding counties, followed by another successful fair in 1889. The 1889 fair was particularly significant, helping to establish Abilene as a regional hub, counteracting the negative image caused by droughts in 1885-86, and proving the area’s viability as a farming region, which encouraged further migration. By the end of the decade, in 1890, Taylor County boasted 587 farms and ranches. While cattle remained important, substantial acreage was now dedicated to crops like oats (6,000 acres), corn (4,000 acres), wheat (3,000 acres), and cotton (4,000 acres), indicating a decisive shift towards diversified agriculture.

Alongside the railroad and farms, a variety of businesses sprang up to serve the growing population during the 1880s. As previously noted, the Abilene Reporter newspaper was present from the very beginning in 1881. Its publisher, Charles Gilbert, added Abilene Printing in 1882, establishing two enduring local enterprises.

Beyond newspapers and saloons, essential services and retail establishments quickly appeared. These included livery stables for horses, doctors’ offices, pharmacies, and hotels like the one within the 1882 T&P Depot. General stores offered crucial supplies. After the White Elephant Saloon closed, its building was leased to W.M. Wigley, who operated a dry goods and furniture store there. Other merchants arriving in the late 1880s included George McDaniel, who established a hardware, grocery, and dry goods business after arriving in 1889. The Wooten family, who would later build a significant wholesale grocery empire, were already present in the area before Abilene’s founding. This initial mix of businesses—providing information, social venues, transportation support, basic goods, and healthcare—met the immediate demands of the frontier settlement. As the town grew and stabilized, more organized efforts to foster economic development emerged. In 1888, the Progressive Committee was formed specifically to attract new businesses to Abilene, renaming itself the Board of Trade in 1890.

People and Community in Early Abilene (1880s)

Abilene experienced dramatic population growth in its first decade. Taylor County, sparsely populated with only 917 residents in 1880, saw a surge of settlement following the railroad’s arrival. Several hundred people were already at the townsite when the lots were auctioned in March 1881. By the end of the decade, the 1890 census recorded 3,194 people living within the city limits of Abilene, while the total population of Taylor County had jumped to 6,957. This rapid influx of residents confirmed Abilene’s success in establishing itself as a new regional center.

The population was largely composed of Anglo-Saxon Protestants, typical for West Texas settlements of the era. However, a significant Black community also formed part of early Abilene. Evidence of their presence and organization includes the establishment of Mount Zion Baptist Church in 1885 and Macedonia Baptist Church in 1890. Furthermore, Black parents took the initiative to found a separate school for their children around 1890, highlighting both the community’s commitment to education and the segregated reality of the time.

Religious institutions were foundational to the new community, with settlers establishing churches almost immediately upon arrival. The very first congregation, a Presbyterian church, was organized even before the official town lot sale in March 1881. On December 17, 1881, just months after the auction, the First Baptist Church of Abilene was founded with seventeen charter members, an effort aided by visiting Baptist superintendent O.C. Pope. Sacred Heart Catholic Church also traces its origins back to 1880. Nearby, the Lytle Gap Potosi Methodist Church had been serving settlers since 1879.

While Baptists, Methodists, and members of the Church of Christ formed the largest religious groups, Abilene’s early religious landscape also included Presbyterians, Catholics, Lutherans, Episcopalians, and Disciples of Christ. The swift establishment of such a variety of denominations demonstrates the central role religion played in the lives of the settlers and their desire to recreate familiar social and spiritual structures on the Texas frontier. These churches were not afterthoughts but integral components of Abilene’s identity from its inception.

Formal education was another early priority for Abilene’s founders and residents, signaling a commitment to building a stable, family-oriented community. A public school was already in operation by January 1883, when the city incorporated. Progress was rapid; the first class graduated from Abilene High School in 1888. As mentioned, the Black community also prioritized education, organizing its own school by 1890. Higher education also began to take shape in the vicinity, with Buffalo Gap College founded nearby in 1885. Although officially established just outside the decade in 1891, Hardin-Simmons University began as Abilene Baptist College, rooted in the growing Baptist community of the 1880s. This quick development of educational infrastructure, from elementary grades through high school and laying the groundwork for colleges, shows a community investing in its future beyond immediate frontier necessities.

Daily Existence on the Texas Frontier

The first dwellings in Abilene were part of the “tent city” that sprang up before the official lot auction. However, permanent housing construction began rapidly once the town was established in 1881. The arrival of the railroad made milled lumber more readily available, facilitating a shift away from the earlier log construction typical of the region, such as the Knight-Sayles Cabin (built 1875, now preserved in Buffalo Gap Historic Village).

An example of early lumber construction is the Tom Hill House. Originally built in Abilene in 1882 by the first Marshall of Buffalo Gap, it was expanded in 1885 and is considered the first lumber-built house and oldest remaining residence from that era in Taylor County (it too was later moved to the historic village). Another early home, the Fulwiler House, was constructed on Elm Street in 1884. By the end of the decade, more substantial homes like the Hattie and Henry Sayles Sr. House on Sayles Boulevard (built 1889) were appearing. This progression from temporary tents to log cabins (in the surrounding area) to increasingly common lumber-frame houses reflects the quick stabilization and development of the town during the 1880s.

The diet of Abilene residents in the 1880s combined traditional frontier self-sufficiency with goods made newly accessible by the railroad. Staples common across the West included beans (especially pinto beans), beef from the plentiful local cattle, preserved pork (bacon and salt pork), sourdough biscuits made in Dutch ovens, strong coffee, cornmeal, and dried fruits.

Local resources were crucial. Settlers hunted wild game like deer, turkey, and rabbit (buffalo were rapidly declining by this time) and gathered wild berries, nuts, and other edible plants. Most families would have planted gardens to grow vegetables such as corn, potatoes, beans, tomatoes, peppers, and squash. Keeping chickens for eggs and cows for milk (and churning butter) was common practice for homesteaders. Preservation techniques were vital for surviving lean times and winters; meat was dried into jerky, cured with salt, or smoked, while fruits were dried.

The T&P Railway significantly expanded dietary options by enabling the transport of goods like flour, sugar, coffee, and canned items. It even made relative luxuries potentially available; oysters, packed and shipped inland by rail, were popular across the country during this period and might have reached Abilene tables. The presence of planned restaurants, like Charles Hatfield’s in 1882, also indicates the beginnings of commercial food service. Chili con carne, a dish strongly associated with Texas cowboys and pioneers, was gaining popularity during this time. This blend of homegrown, hunted, preserved, and commercially supplied food reflects Abilene’s position as a frontier town rapidly connecting to the wider world.

The rhythm of daily life in 1880s Abilene was largely dictated by work. For many, this involved the physically demanding labor of farming, ranching, or working for the railroad. Business owners managed their shops and services. For women, domestic chores were extensive, including cooking meals from scratch, cleaning, washing and ironing clothes, sewing and mending garments, caring for children, tending gardens, collecting eggs, milking cows, and churning butter.

Beyond work, community life offered various avenues for interaction. Church services and related activities were central for many families. Saloons provided a gathering place, particularly for men and transient workers. The newly established clubs, especially the women’s literary and Chautauqua circles, offered structured social and educational opportunities. Community bands and dramatic groups provided entertainment. Routine errands involved visiting local businesses for supplies or accessing services like the post office (opened February 1881) or the offices of doctors and pharmacists. Larger community events, such as the agricultural fairs starting in 1884, provided occasions for widespread socializing and entertainment.

Establishing Order: Law and Safety

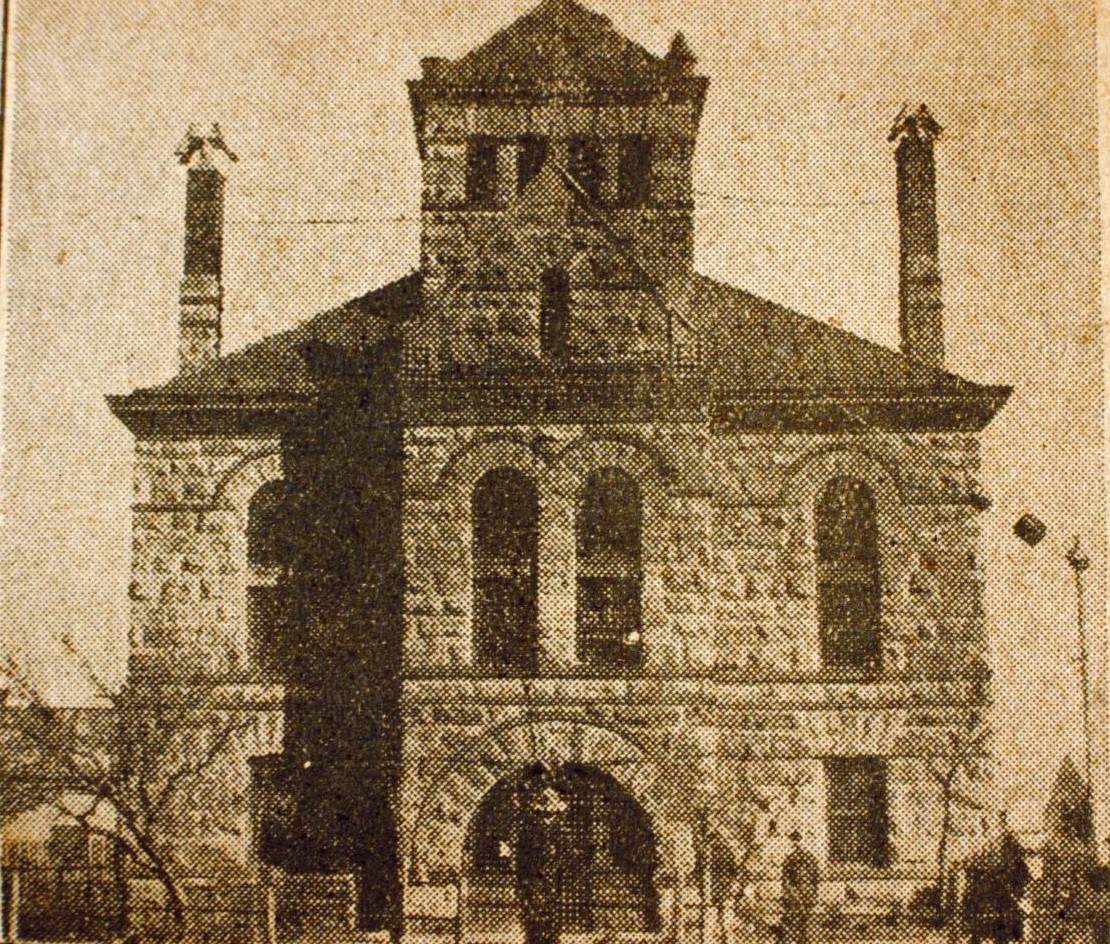

As Abilene grew, establishing formal governance and maintaining public order became crucial. The town voted to incorporate as a city on January 2, 1883, adopting a mayoral form of government. Dan B. Corley, who had also briefly served as County Judge, was elected as Abilene’s first mayor.

Later that same year, on October 23, 1883, Abilene achieved a major victory by winning the election to become the Taylor County seat, wresting the title from Buffalo Gap. This transfer of administrative power was not without conflict. Tensions ran high between supporters of the two towns, involving threats and requiring the suppression of potential armed challenges from disgruntled Buffalo Gap residents who felt bypassed and disenfranchised by the railroad and the subsequent political shift. Securing the county seat solidified Abilene’s position as the dominant center in the region. From its inception, alongside the rowdier elements, there was a conscious effort among many citizens to “tame the frontier” and create a town suitable for raising families, fostering the development of schools, churches, and civic organizations.

Despite efforts to establish order, Abilene experienced incidents typical of a rapidly growing frontier town. Its early reputation included being “rough-and-tumble” with saloon brawls. A significant early event was a major fire that swept through the business district in August 1881, highlighting the need for better safety measures.

The political rivalry over the county seat in 1883 created significant tension, nearly boiling over into armed conflict before being suppressed. Violence erupted in the “Pine Street Shootout” of 1884. This incident stemmed from a dispute over new gambling ordinances and resulted in the deaths of Deputy Sheriff Walter Collins, the man he confronted, and the mortal wounding of Collins’ brother, Frank. Broader regional conflicts also touched the area; fence-cutting disputes between ranchers and farmers adapting to new land ownership laws created tension in Taylor County during the late 1880s, nearly escalating to violence before legislative intervention. These documented incidents point less towards random lawlessness and more towards conflicts arising from specific triggers like disaster response, political struggles, regulation of vice, and resource competition common in developing communities.

The devastating fire of August 1881 served as a direct catalyst for organizing fire protection in Abilene. Initial measures were basic, relying on water wagons and buckets. Immediately following the fire, the volunteer “Bucket Brigade” was formed, led by S.H. Levell as Fire Chief.

This quickly evolved into a more structured approach. The Pioneer Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 was established, acquiring the town’s first dedicated piece of firefighting equipment—a hook and ladder wagon—though its members served without pay. Further organization occurred in March 1886 with the formation of two additional companies: the Rescue Hose Company No. 2 and the Star Hose Company No. 3. Later that year, these three volunteer units merged to create the unified Abilene Volunteer Fire Department, electing George W. Jalonick as chief. This progression shows the community’s rapid, albeit reactive, response to disaster, moving from informal efforts to an organized volunteer service with specialized equipment within five years.

Image Credits: McMurry University Library, Hardin-Simmons University Library, texashistory.unt.edu, wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know