As the 1940s began, Abilene, Texas, stood at a crossroads. Founded just sixty years earlier as a railroad town, it had grown steadily but was still deeply marked by the recent struggles of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. The decline in farm prices during the 1920s and 1930s had slowed the city’s economic growth. Droughts had plagued the region, forcing some Abilene families to become migratory workers seeking opportunities elsewhere as early as 1936. Despite these hardships, the spirit of the city, often promoted by optimistic boosters as the “Future Great City of West Texas”, remained. Civic leaders had already taken steps to secure the city’s future, such as excavating vital water sources like Lake Fort Phantom Hill, completed in 1937. In 1940, Abilene’s population was 26,612. This West Texas community, shaped by agriculture and the railway lines that connected it to the nation, was about to experience a decade of unprecedented change. Across the Atlantic, war had erupted in Europe in September 1939, prompting the United States government to begin a massive expansion of its military forces as a precaution. This national mobilization would soon reach Abilene, transforming it in ways few could have imagined. Abilene’s pre-war experience with economic difficulty likely fueled a community desire for the stability and opportunity that large federal projects could bring, aligning with the city’s long-standing proactive approach to growth.

The Look and Feel of Wartime Abilene

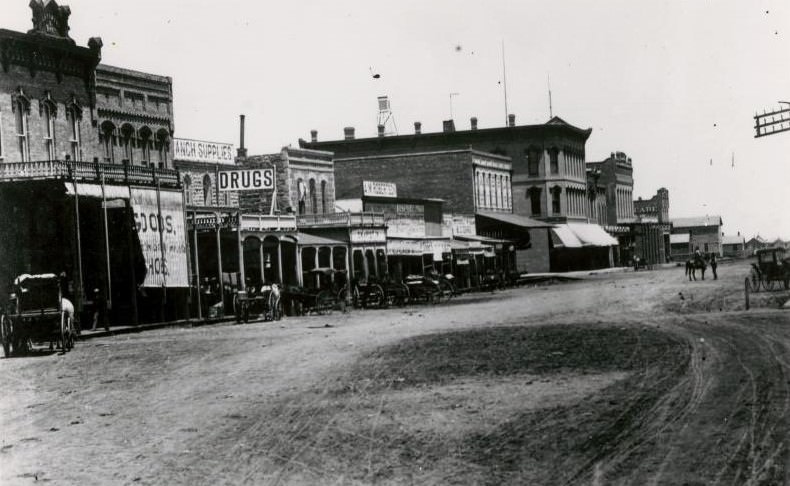

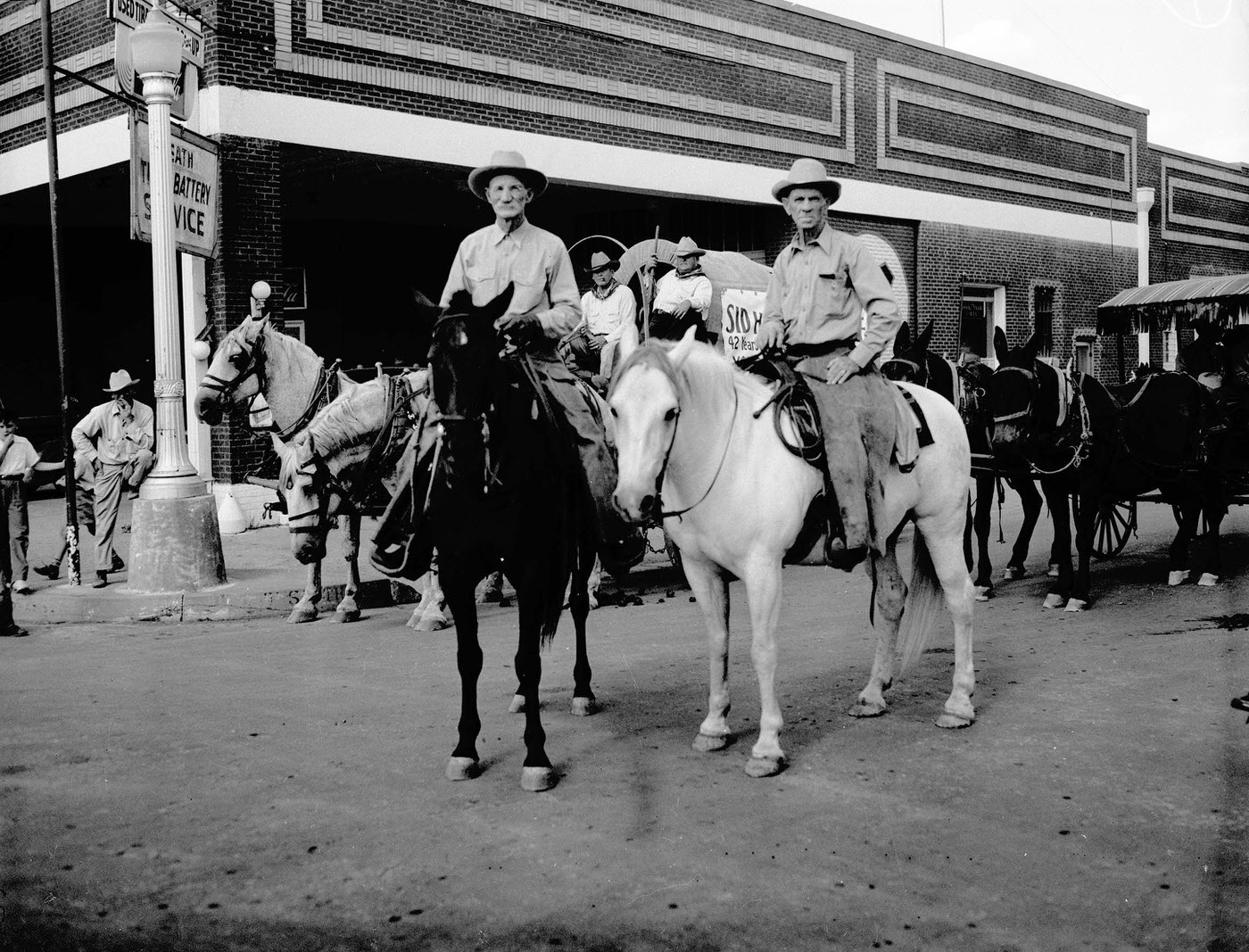

Downtown Abilene during the 1940s presented a scene of heightened activity and energy. Streets like Pine and Cypress, the city’s commercial heart, bustled with increased traffic, including early model cars and pedestrians. The sidewalks were filled with shoppers, local residents, and the ubiquitous sight of soldiers in uniform exploring the town.

Prominent buildings defined the skyline and served as focal points. The 16-story Hotel Wooten, opened in 1930, stood as West Texas’s first modern skyscraper and enjoyed full occupancy during the Camp Barkeley years, catering to visitors and military personnel. Next door, the Paramount Theatre, also opened in 1930, offered grand movie-going experiences in its Spanish/Moorish-inspired atmospheric interior, a popular destination for soldiers and civilians alike. The Texas & Pacific Railway Depot, built in 1910, remained a vital hub, handling the constant movement of troops and supplies, with the nearby 1936 WPA overpass helping to manage traffic flow.

Long-standing businesses like the Abilene Reporter-News and restaurants such as the Dixie Pig, El Fenix, and Farolito were part of the downtown fabric. Along major routes like South 1st Street (part of the Bankhead Highway), early tourist courts and motels catered to travelers, a sign of growing automobile use. While significant new civic construction paused during the war, the existing buildings from the 1920s and 1930s formed the backdrop for the intense activity. News and entertainment flowed through KRBC radio, which had begun broadcasting in 1936. The atmosphere was one of purpose, patriotism, and the constant motion generated by a city deeply involved in the national war effort.

An Army Comes to Town: The Rise of Camp Barkeley (1940-1941)

The Army’s need for vast training grounds, particularly in climates suitable for year-round activity like Central Texas, presented an opportunity. Abilene’s citizens seized it, raising funds in 1940 to acquire land southwest of the city specifically to attract a military base. This local initiative proved successful, and the government leased the land for development. Construction on the new camp began in December 1940 and proceeded at a remarkable pace, finishing just seven months later in July 1941. Architect-engineers Freese and Nichols completed the initial facilities for 20,000 men within 90 days, earning praise for speed and cost-efficiency. The installation was named Camp Barkeley, honoring World War I hero David B. Barkley, though a clerical error permanently misspelled his name on official records.

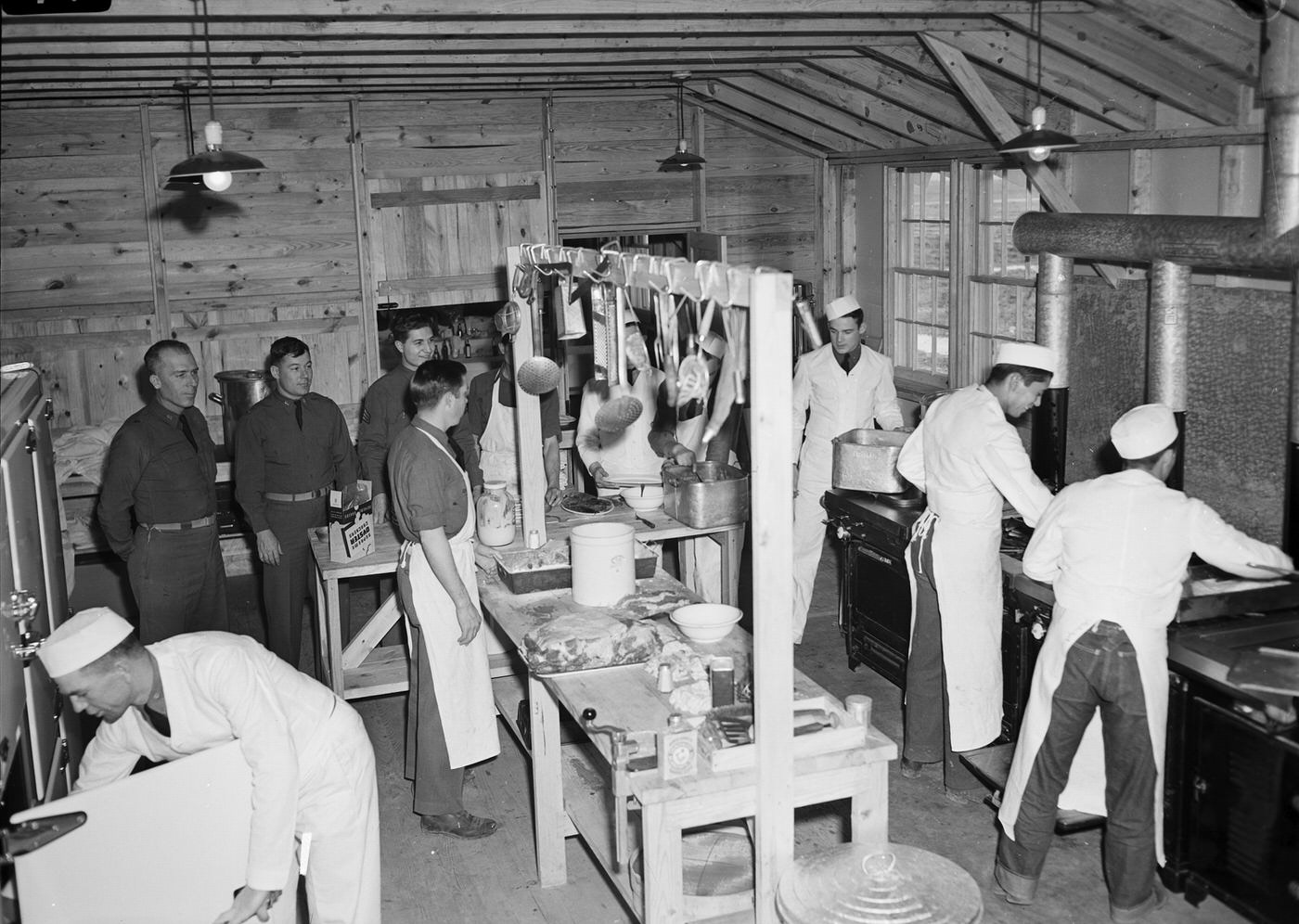

Camp Barkeley was enormous. It eventually covered between 70,000 and 77,000 acres, roughly one-ninth of Taylor County’s total land area. This included a main camp area, vast tracts for maneuvers, and combat ranges. At its peak, the camp housed between 50,000 and 60,000 personnel, effectively creating a temporary city twice the size of Abilene itself. Most soldiers lived in hutments, though some barracks were available. The camp boasted extensive facilities, including a 2,300-bed hospital, theaters, chapels, post exchanges, and even cold storage plants.

Beyond combat units, Camp Barkeley became a vital center for medical training. A Medical Replacement Training Center (MRTC) was activated in November 1941, and the Medical Administrative Corps Officer Candidate School (MAC OCS) followed in May 1942. The MAC OCS alone graduated approximately 12,500 candidates. By 1944, the medical training center housed over 37,000 personnel, including a contingent of 1,000 to 1,400 African American trainees and officer candidates. The scale and diverse functions—housing infantry, armored divisions, and a massive medical training apparatus—made Camp Barkeley a complex military city that fundamentally reshaped Abilene’s landscape and identity almost overnight.

Wings Over Abilene: Tye Army Air Field Takes Flight (1942-1946)

Complementing the massive ground force presence at Camp Barkeley, the Army Air Forces established an airfield nearby in 1942. Opened on December 18, 1942, it was first called Abilene Army Air Base, then renamed Abilene Army Airfield (AAF) in April 1943, though many locals knew it as Tye Army Air Field. Its primary mission under the Second Air Force was to train flight cadets.

Pilots learned their craft here, flying training aircraft and Republic P-47 Thunderbolts. Several reconnaissance and fighter-bomber groups cycled through the base for training, including the 77th and 69th Reconnaissance Groups and the 408th Fighter-Bomber Group. Operating as an adjunct to Camp Barkeley, the airfield added an air power dimension to the military activities centered around Abilene. This dual presence of a major Army camp and an active airfield magnified the economic and social effects on the city, bringing more personnel and diverse military functions to the area. Training operations continued until the spring of 1946, and the airfield was officially declared inactive by January 1946. The facility was sold to the City of Abilene for a symbolic dollar and served as a training site for the Texas National Guard before its eventual rebirth as Dyess Air Force Base.

Peace Returns, A Base Departs (1945 and beyond)

The end of World War II brought peace but also uncertainty for Abilene. Camp Barkeley, the engine of the city’s wartime boom, was declared surplus and officially closed in September 1945. The vast leased lands reverted to their original owners. Tye Army Air Field was also deactivated shortly thereafter. There were genuine concerns that without the massive military presence, Abilene might revert to its pre-war economic struggles, potentially becoming a “ghost town”.

However, Abilene’s civic leadership, having witnessed the profound economic benefits of the military installations, refused to let the momentum fade. The Abilene Chamber of Commerce’s War Committee transitioned into the Military Affairs Committee (MAC), specifically tasked with securing a new, permanent military base. They understood the value the bases brought and launched an aggressive campaign, lobbying legislators in Washington, Pentagon officials, and the Strategic Air Command.

Demonstrating extraordinary commitment, the citizens of Abilene raised nearly $1 million—a significant sum at the time—to purchase over 5,000 acres of land near the former Tye Field site. This land was then offered as a gift to the Air Force. This proactive community investment, coupled with the city’s positive track record in supporting Camp Barkeley and the political support of figures like Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, proved decisive. In July 1952, Congress approved funding for what would become Dyess Air Force Base.

In the interim, the physical remnants of Camp Barkeley continued to benefit the area. Buildings were dismantled, and materials were auctioned off and repurposed throughout Abilene and the surrounding region. Former Army vehicles found new life, sometimes converted for civilian use like grocery delivery. Materials from the camp were incorporated into new constructions, including downtown buildings. Abilene’s response to the post-war transition showed foresight and a powerful community drive to secure its economic future, successfully leveraging its wartime experience to ensure continued prosperity.

From Bust to Boom: The Wartime Economy

The arrival of Camp Barkeley and Tye Army Air Field acted as a powerful antidote to the economic stagnation that had marked Abilene and much of Texas during the 1930s. The preceding decade had seen cripplingly low farm prices, the lingering effects of the Dust Bowl, bank failures, and widespread unemployment, forcing some Abilene residents to leave in search of work.

The construction and operation of the military bases injected millions of dollars into the local economy. Camp Barkeley alone represented an investment of around $25-27 million. The constant flow of soldiers—estimated at 1.5 million passing through the area during the war—created immense demand for goods and services. Military payrolls provided a steady stream of income. This surge in activity created numerous jobs, both in constructing the bases and in supporting the needs of tens of thousands of soldiers. Texas saw nearly full employment during the war years.

Local businesses thrived. Restaurants like the Dixie Pig, El Fenix Cafe, and Farolito Restaurant saw soldiers filling their booths and counter stools. Shops, banks, and entertainment venues benefited from the increased population and spending power. The economic revitalization extended to infrastructure as well. A WPA project completed in 1936, a concrete overpass near the T&P Depot, helped manage the increased traffic spurred by the growing city and anticipated military activity. This sudden shift from Depression-era hardship to wartime prosperity transformed Abilene’s economic landscape, creating widespread opportunity and ending the struggles of the previous decade.

A City Transformed: Social Shifts of the Decade

The 1940s brought profound social changes to Abilene, driven largely by the military presence. The most dramatic shift was in population size.

This remarkable 71.2% increase in just ten years was fueled by the soldiers at Camp Barkeley and Tye Field, their families, and workers drawn to defense-related jobs. This influx brought people from diverse regions and backgrounds, accelerating the urbanization trend seen across Texas during the war.

The war created new roles and opportunities, particularly for women. With millions of men serving overseas, women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers, taking jobs in factories and other fields previously considered male domains. The image of “Rosie the Riveter” symbolized this shift. Nearby Sweetwater hosted the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) training program, bringing female pilots to the region. However, these opportunities often came with challenges, including lower pay compared to men and societal expectations that they would return home after the war.

Minority groups also experienced shifts. African Americans found some new employment in defense industries, although segregation and discrimination persisted. Camp Barkeley housed Black trainees, including officer candidates, within its medical center, but Abilene maintained separate schools for Black children long after the war. Similarly, Hispanic residents faced discrimination but also contributed to the war effort. The shared wartime experience, despite inequalities, laid groundwork for future civil rights activism.

The decade also saw the formal organization of Abilene’s Jewish community. Before the war, the small community met informally. The arrival of Jewish servicemen and merchants with Camp Barkeley provided the catalyst for establishing Congregation Mizpah on July 23, 1941. Responding to the needs of the servicemen, particularly after Pearl Harbor, the congregation rapidly constructed a modest synagogue in just one month during the summer of 1942. Temple Mizpah became a busy center during the war, hosting packed services, numerous weddings, and large holiday gatherings for hundreds of soldiers. This rapid community development underscores how the military influx reshaped Abilene’s social and religious landscape.

Beyond the War Effort

While the war and its aftermath dominated the decade, other developments shaped Abilene. The city’s governance structure evolved, adopting the city-manager form in 1947, a system discussed as early as 1940. Local political leadership saw figures like Mayor Will Hair and Commissioner W.E. Beasley serve through the war years.

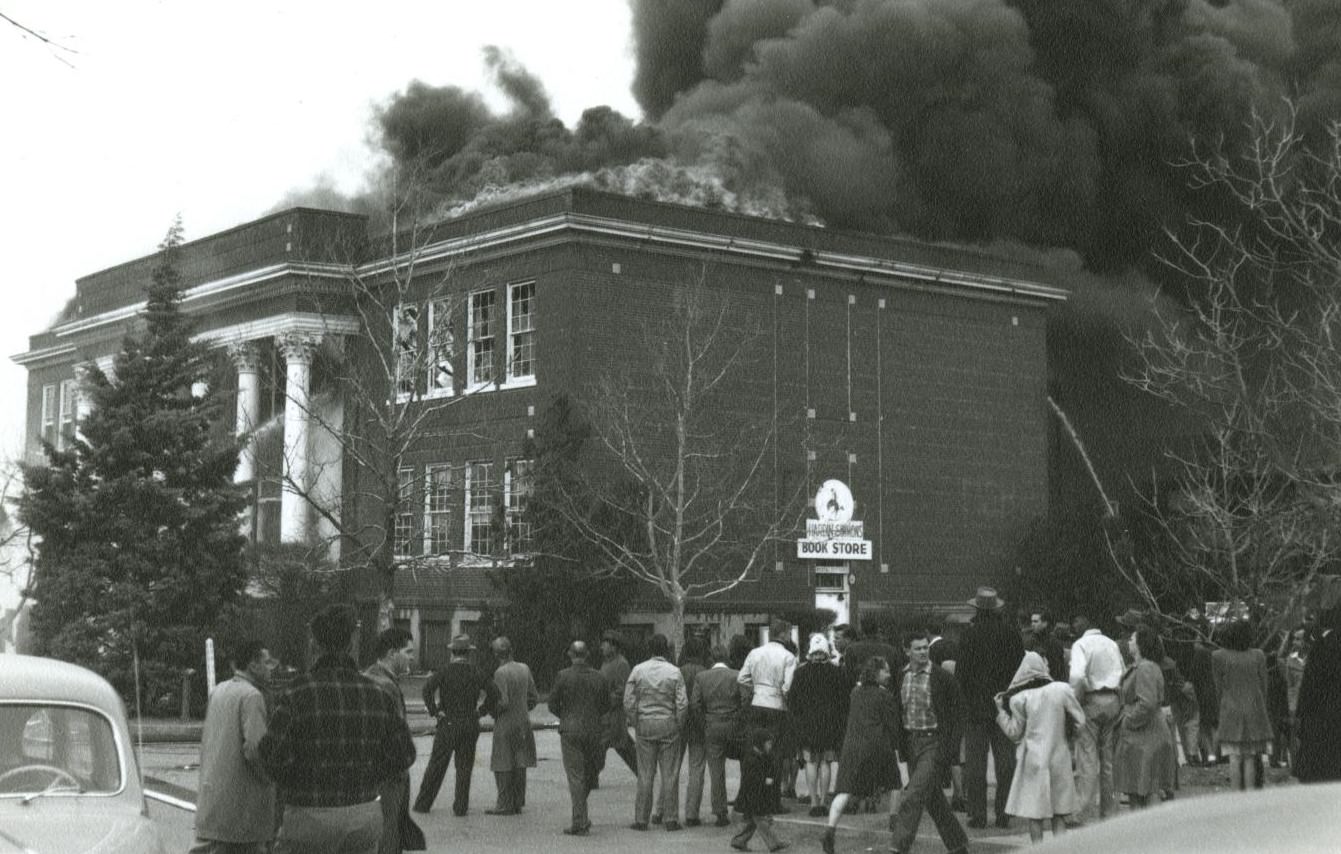

Local businesses continued to operate and adapt. Long-standing restaurants like the Dixie Pig (which expanded its building post-war), El Fenix Cafe, and Farolito Restaurant remained fixtures, serving both the military and local populations. Higher education also saw activity; Hardin-Simmons University participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program early in the decade, and Abilene Christian College began a period of post-war expansion. The presence of motels along the Bankhead Highway (South 1st Street) indicated the continuing importance of automobile travel.

Culturally, the city looked towards normalcy and recreation after the war. A professional baseball team, the Abilene Blue Sox, affiliated with the Brooklyn Dodgers, was established in 1946, offering entertainment to the community. The West Texas Chamber of Commerce continued to operate from Abilene. The immediate post-war economy saw returning veterans starting new businesses, contributing to a national boom. Abilene’s economy diversified further after the war, with growth in the oil industry, manufacturing, banking, and retail sectors, leading to a significant rise in per capita income by 1950. These non-military developments show a city adapting, growing, and laying the groundwork for its future beyond the immediate impact of the war bases.

Image Credits: The 12th Armored Division Memorial Museum, Hardin-Simmons University Library, Abilene Library Consortium, The Grace Museum, Abilene Christian University Library, wikimedia, Abilene Christian University Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know