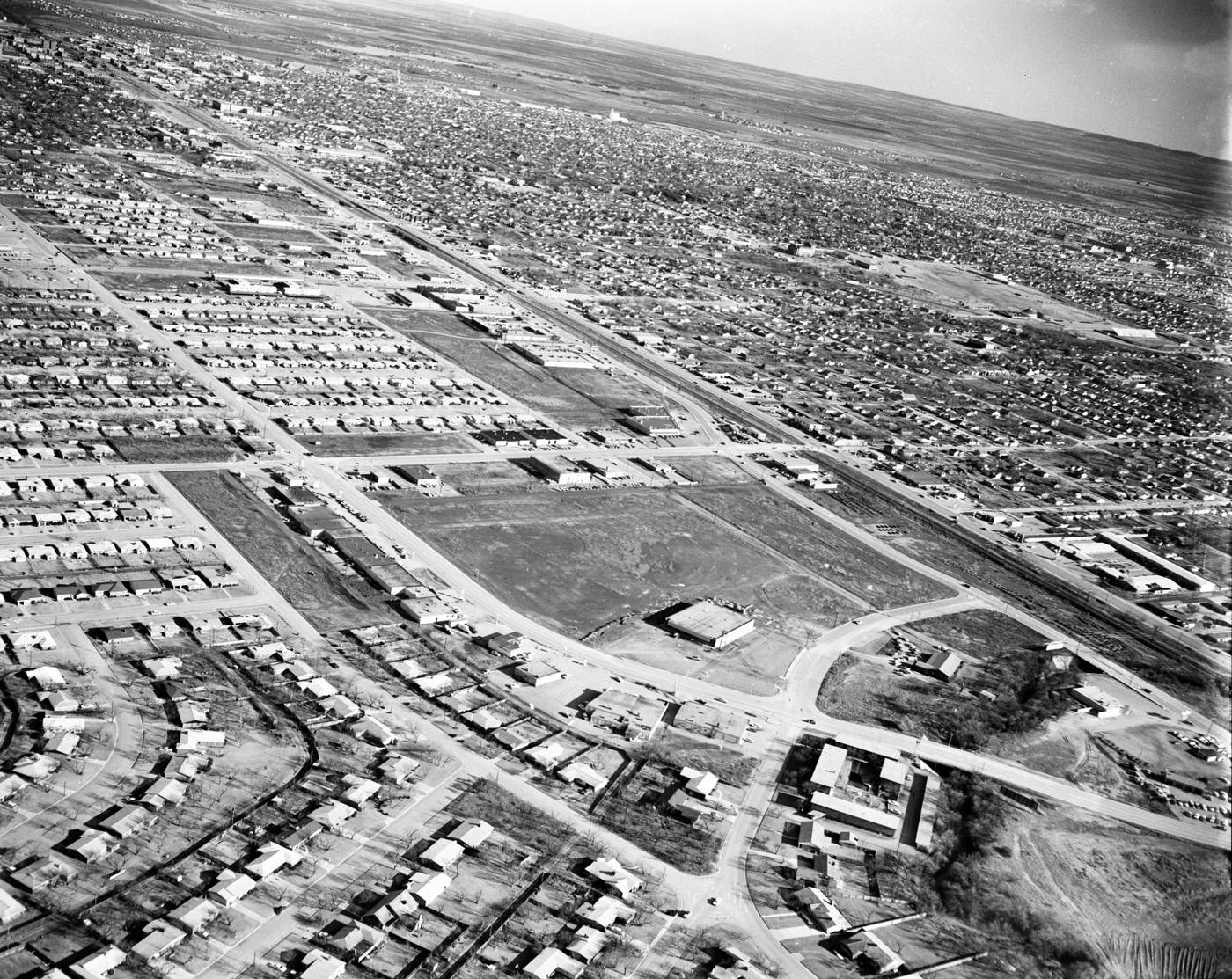

By the start of the 1960s, Abilene was experiencing a period of rapid growth. The previous decade had seen the city’s population nearly double, surging from 45,570 residents in 1950 to 90,368 by 1960. This expansion was driven by the general economic prosperity following World War II, the continued importance of the regional oil industry, and, most critically, the establishment and development of Dyess Air Force Base, which had been officially dedicated in 1956. Abilene was solidifying its position as a key commercial, retail, medical, and transportation center for the expansive West Texas region known as the “Big Country”. This backdrop of growth and change set the stage for the 1960s, a decade that would be profoundly shaped by the direct presence of the Cold War, the local struggles and advancements of the Civil Rights Movement, and ongoing urban transformation.

Dyess AFB: Cold War Sentinel and Economic Anchor

Throughout the 1960s, Dyess Air Force Base operated as a crucial installation under the U.S. Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC). Its core mission during this tense period was nuclear deterrence against the Soviet Union. The base, like other SAC installations, maintained a constant state of readiness, prepared for the possibility of nuclear war at any moment.

The primary instruments of this deterrence at Dyess were the long-range B-52 Stratofortress bombers of the Ninety-sixth Bomb Wing (96th BW), which had been stationed there since 1957. These aircraft formed the airborne backbone of America’s nuclear triad. Supporting the B-52s were KC-135 Stratotanker aerial refueling aircraft, also based at Dyess, ensuring the bombers could reach targets deep within potential enemy territory. Photographic evidence from the era documents the constant maintenance, refueling operations, and daily life surrounding these vital aircraft and their crews.

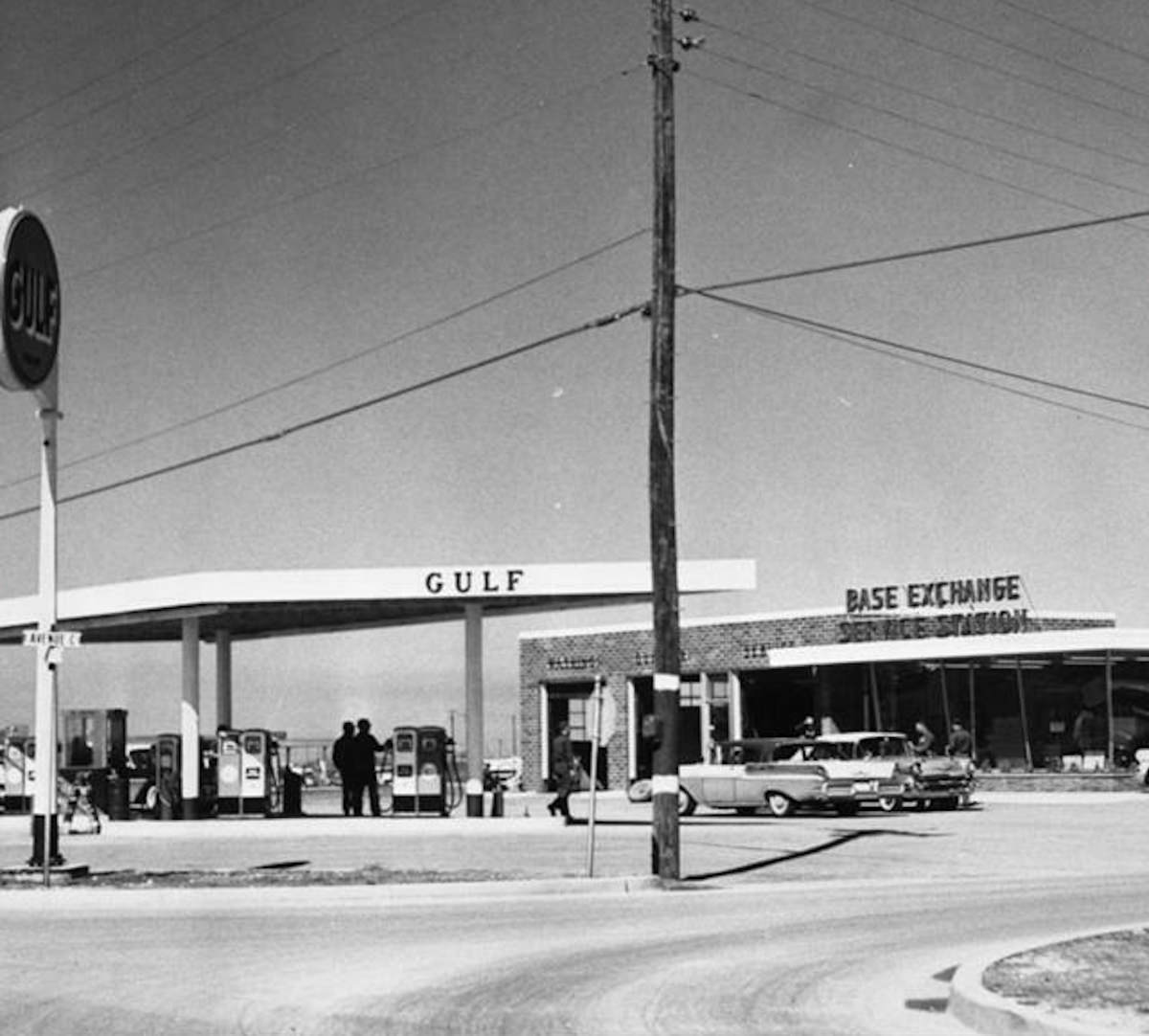

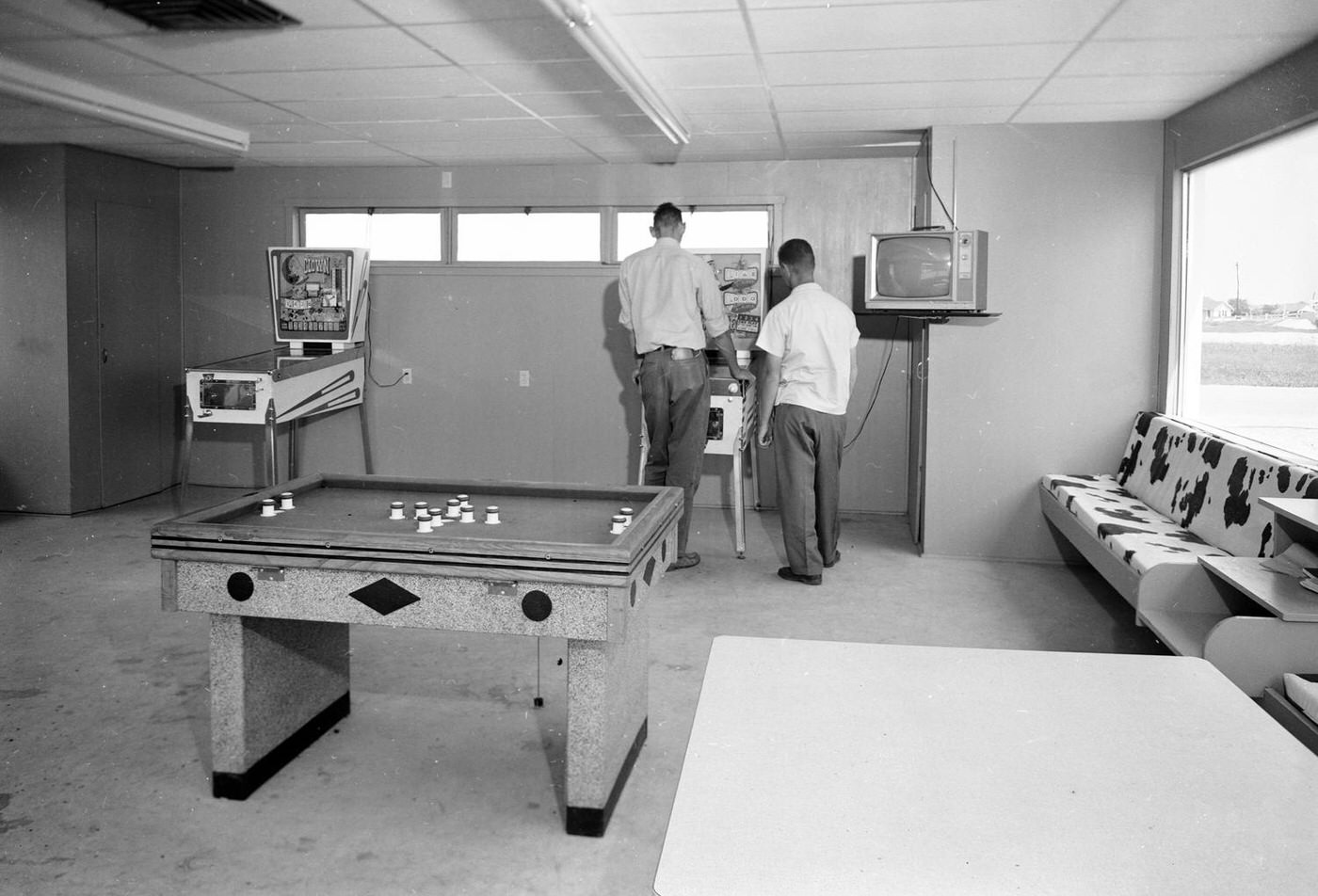

Beyond its military mission, Dyess AFB was deeply integrated into the life of Abilene. It served as the city’s largest employer throughout the decade, providing thousands of jobs and a stable economic foundation. The constant influx and presence of military personnel and their families shaped the city’s social character and boosted local businesses. The base itself functioned as a community, with its distinctive red brick, ranch-style architecture housing dining halls, gymnasiums, swimming pools, and family housing units. The relationship between the base and the city was actively nurtured, notably by the Military Affairs Committee (MAC) of the Abilene Chamber of Commerce, which worked to foster positive ties. Dyess personnel were visible participants in local life, attending events like the Chamber’s “World’s Largest Barbecue”. This integration demonstrates that Dyess was more than just a workplace; it was a fundamental part of Abilene’s economic engine and social identity in the 1960s.

Civil Rights in Abilene: A Slow March Forward

Abilene entered the 1960s operating under the system of racial segregation common throughout Texas and the South. Public schools were strictly separated by race. Carter G. Woodson Junior and Senior High School, opened in 1953, served the city’s Black students. Woodson Elementary and Sam Houston Elementary also operated as segregated schools, with Sam Houston primarily serving Hispanic students until 1970. Public accommodations like restaurants, theaters, and other facilities were also largely segregated, reflecting statewide Jim Crow practices.

The opening of Cooper High School in 1960 initially occurred within this segregated framework, serving only white students. Its establishment created a second major high school in the city, sparking a crosstown rivalry with the established Abilene High School.

The first significant steps toward desegregation began in 1963. Following a Texas Attorney General ruling against a state law designed to block integration, the Abilene School Board approved new attendance zones in January 1963. A key provision allowed Black military families stationed at Dyess Air Force Base the choice to send their children to the base’s elementary school (Dyess Elementary) instead of the segregated Woodson schools. In April 1963, thirty-eight Black students made that transfer, marking the first instance of Black students attending a previously all-white public school in Abilene. For the following school year (1963-1964), the district officially desegregated all elementary schools and the seventh grade, implementing a “freedom of choice” plan that allowed Black students to attend the formerly white school in their zone or remain at Woodson.

The district’s desegregation plan proceeded gradually after 1963, integrating one additional grade level each year. However, this process was slow, and challenges remained. Racially identifiable schools persisted, and the primary burden of integration often fell upon Black students, teachers, and administrators.

Simultaneously, the fight for desegregation extended to public accommodations. While the provided sources don’t detail specific sit-ins in Abilene, the city existed within the context of a statewide and national movement. Starting in March 1960, student-led sit-ins occurred across Texas, targeting segregated lunch counters, theaters, and other public facilities. These protests, often organized by NAACP youth councils and college students, were part of the broader nonviolent direct action campaign challenging Jim Crow laws throughout the South.

Shaping the City: Infrastructure and Growth

The 1960s saw significant investments in Abilene’s public infrastructure, alongside a continuing shift in the city’s physical layout. Recognizing the need for larger, modern venues for events and gatherings, community leaders initiated plans for major civic construction projects. A citizens’ bond study group, known as the “Committee of 100,” put forth proposals in early 1967. Later that year, voters approved a substantial bond package that allocated funds for building both the Abilene Civic Center and the Taylor County Coliseum. Construction commenced soon after. The Taylor County Coliseum was completed in 1969 , followed shortly by the opening of the Abilene Civic Center (now the Abilene Convention Center) in November 1970.

Road development, a focus in the post-war era across Texas , likely continued in and around Abilene to support the growing population and economic activity, including improvements related to Interstate 20, which passes along the city’s northern edge.

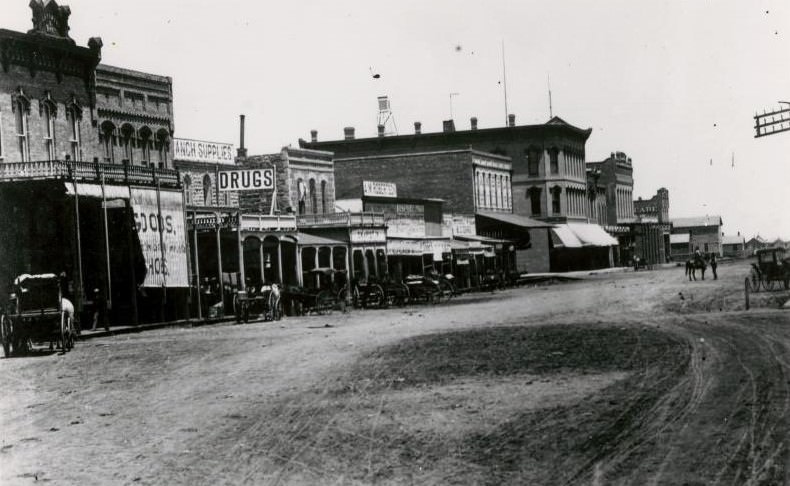

A distinct pattern of urban growth emerged during the decade: residential and commercial development increasingly shifted southward. This trend was influenced partly by the location of the new Cooper High School (opened 1960) south of the traditional downtown. This southward migration contrasted with a noticeable decline in activity within the historic downtown core, situated north of the Texas & Pacific railroad tracks.

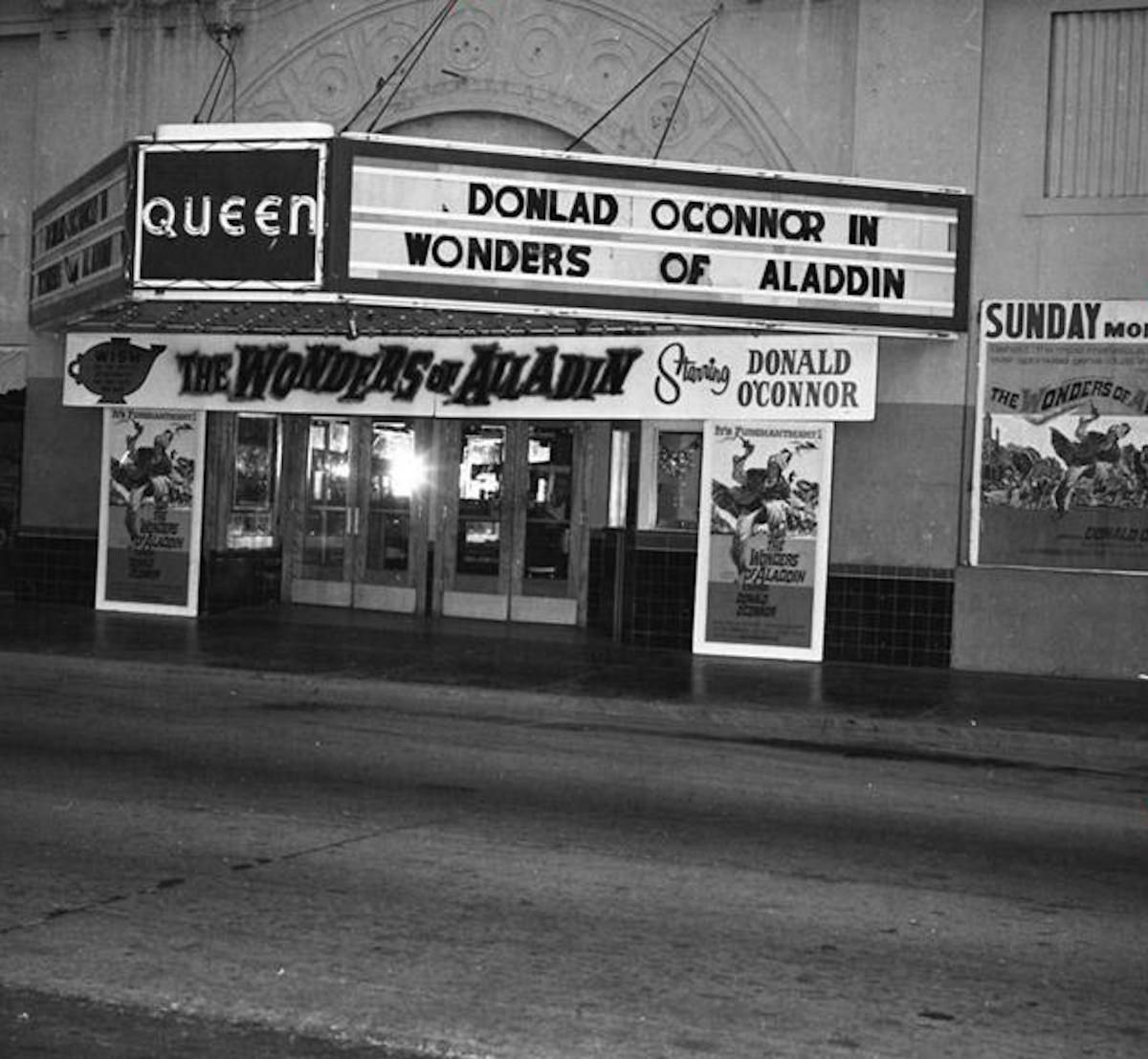

Downtown Abilene experienced visible changes reflecting this shift. Passenger train service, a vital part of Abilene’s founding and early growth, ceased in March 1967, diminishing the role of the T&P Depot. Some landmark buildings, like the elegant Drake Hotel (formerly The Grace), began to decline as downtown traffic thinned. The Queen Theater, a fixture since 1915, was torn down. Even as the historic center faced challenges, the approval and initiation of construction for the new Civic Center and Coliseum signaled a significant public investment aimed at anchoring civic life, albeit on the periphery of the oldest commercial district. This combination of major new public construction and the simultaneous southward drift of private development illustrates a city physically reorienting itself in response to post-war growth patterns.

After the dramatic population boom of the 1950s, where Abilene’s numbers nearly doubled, the 1960s brought a period of relative stagnation and even a slight decrease.

This leveling off, marking a -0.8% change over the decade, stands in sharp contrast to the nearly 100% growth seen between 1950 and 1960. Several factors likely contributed to this shift. The peak of the post-war oil boom had passed, with Taylor County’s production declining after 1960. Agriculture continued its trend of consolidation, potentially reducing rural employment opportunities. Additionally, the phase-out of the Atlas missile system in 1965 and the Nike missile system in 1966 at Dyess might have led to a reduction in associated military personnel and civilian contractor jobs. The ongoing Vietnam War also influenced population movements nationwide. This population data strongly suggests that the rapid expansion phase driven by the specific conditions of the 1950s had concluded, and Abilene was entering a period of economic adjustment during the 1960s.

The Pulse of the Economy

The oil industry, a major engine of Abilene’s explosive growth in the 1950s , saw production in Taylor County peak around 1960 at just over 5 million barrels. Production levels began to decline thereafter, falling to under 2.5 million barrels by the mid-1970s. This tapering off of the oil boom likely contributed to a slowdown in the rapid economic expansion experienced in the previous decade and may have been a factor in the slight population decrease observed between 1960 and 1970.

Agriculture remained a cornerstone of the regional economy. The post-World War II trend of diversification continued, with cattle ranchers expanding into raising pigs and sheep, and poultry farming gaining traction. However, the agricultural landscape was also changing due to ongoing farm consolidation and increased mechanization, which resulted in fewer, albeit larger, farming operations over time.

Recognizing the potential vulnerability of an economy heavily reliant on fluctuating oil prices and consolidating agriculture, Taylor County and Abilene leaders took steps during the 1960s and 1970s to encourage industrialization and further diversify the economic base. Abilene also maintained its role as a regional center for commerce, retail trade, banking, and healthcare services. The combination of a stable military presence, a declining (though still significant) oil sector, a consolidating agricultural base, and initial efforts toward industrial diversification suggests the 1960s were a period of economic transition for Abilene, moving beyond the primary drivers of the 1950s boom.

Daily Life and Culture in 1960s Abilene

Life in 1960s Abilene offered a mix of traditional West Texas pursuits and emerging modern entertainment. Drive-in movie theaters, such as the Town & Country which opened in 1956, were popular destinations, especially for dates. Downtown, the historic Paramount Theatre, an atmospheric movie palace opened in 1930, continued to screen first-run films , while the Queen Theater was also operational early in the decade before being torn down later. Radio broadcasts remained a common source of news and entertainment, and television ownership was expanding, although Abilene’s third major local station, KTAB-TV, wouldn’t begin broadcasting until late 1979. A popular pastime, particularly for young people, was “cruise night,” driving cars around town.

High school life saw a new dynamic with the opening of Cooper High School in 1960, creating an immediate crosstown rivalry with the established Abilene High School. Football remained a central part of the community’s identity, building on the legacy of Abilene High’s dominant teams of the 1950s.

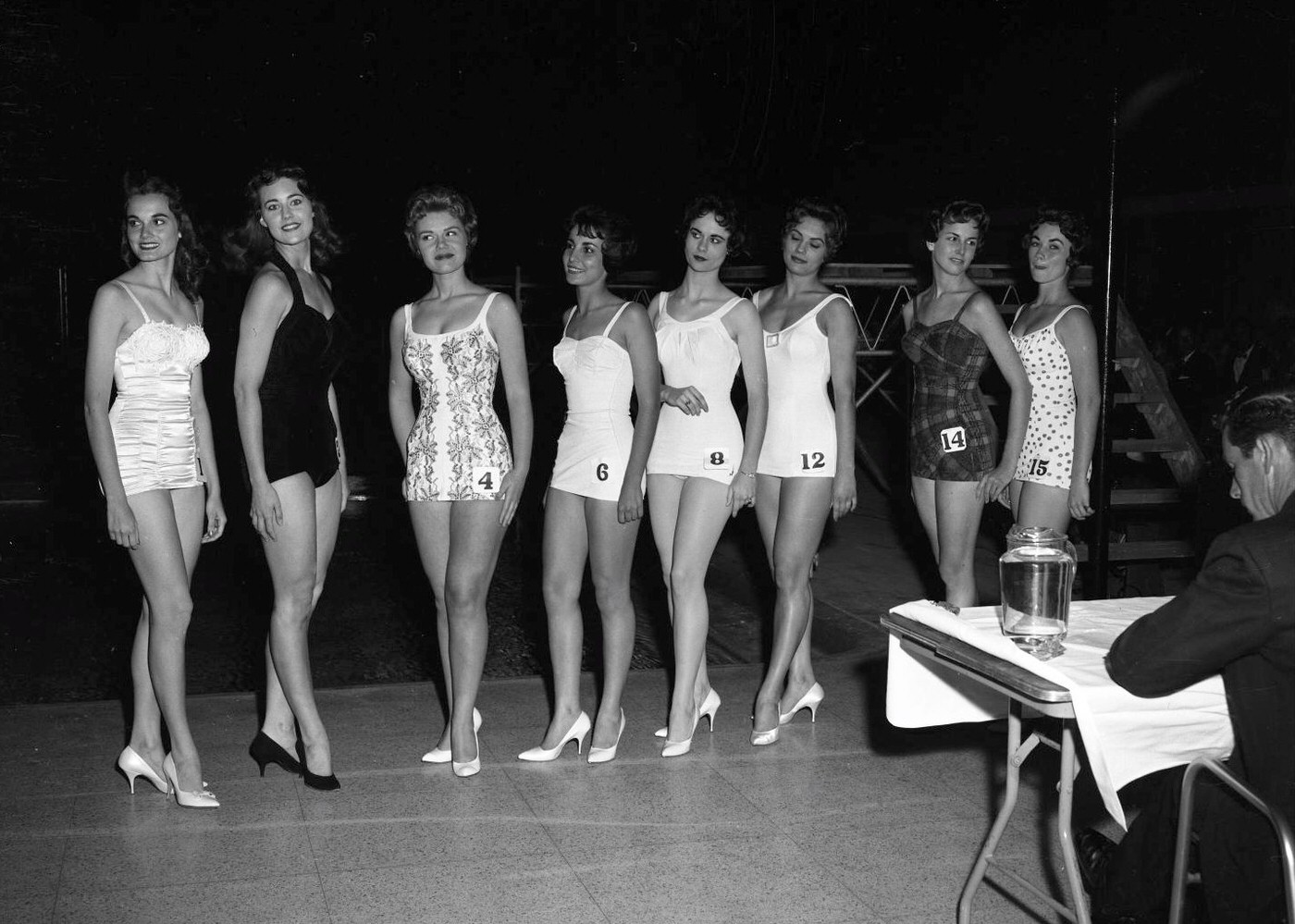

Community events brought residents together. The West Texas Fair and Rodeo, held annually at the Taylor County Expo Center grounds, was a major highlight. Large community gatherings, like the “World’s Largest Barbecue,” saw participation from both civilian residents and personnel from Dyess AFB, showcasing the connection between the city and the base.

Image Credits: Image Credits: Hardin-Simmons University Library, The Grace Museum, Abilene Christian University Library. Abilene Library Consortium, wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know