In 1860, the area known today as Arlington was a quiet, rural jurisdiction officially named Alexandria County. It was a land of farms and orchards, with a small population that stood in stark contrast to the bustling, adjacent City of Alexandria. The 1860 census recorded the rural county’s population at fewer than 1,500 people, a tiny fraction of the more than 11,000 residents living in the city. Life revolved around agriculture, with the massive 1,100-acre Arlington estate, home of Robert E. Lee and his wife Mary Anna Custis Lee, being the dominant feature of the landscape.

This tranquil surface, however, masked deep divisions. The county was home to a significant population of enslaved African Americans. While the Arlington estate held nearly 200 enslaved individuals, hundreds more labored on smaller farms throughout the county. In 1860, the enslaved population of Alexandria City was 1,386, and the rural county had roughly 265 enslaved people. These individuals built the grand homes, including Arlington House itself, and cultivated the crops of corn and wheat that sustained the local economy.

As the nation hurtled toward conflict, the political sentiments within Alexandria County were sharply divided. The urban center, the City of Alexandria, was a major slave-trading hub and its residents were strongly pro-Confederate. In the crucial statewide referendum on secession held on May 23, 1861, the voters of Alexandria County as a whole voted 958 to 48 in favor of leaving the Union. This overwhelming result, however, was driven by the city’s population. The farmers and residents of the rural county were largely pro-Union, a loyalty that would soon place them directly in the path of the war. The strategic importance of the county was undeniable. Its hills, known as Arlington Heights, offered a commanding view of Washington, D.C., and were within cannon range of the White House and the Capitol. President Abraham Lincoln and his cabinet were acutely aware that if Confederate forces placed artillery on those heights, the capital itself would be indefensible.

The Union Arrives: Occupation and Transformation

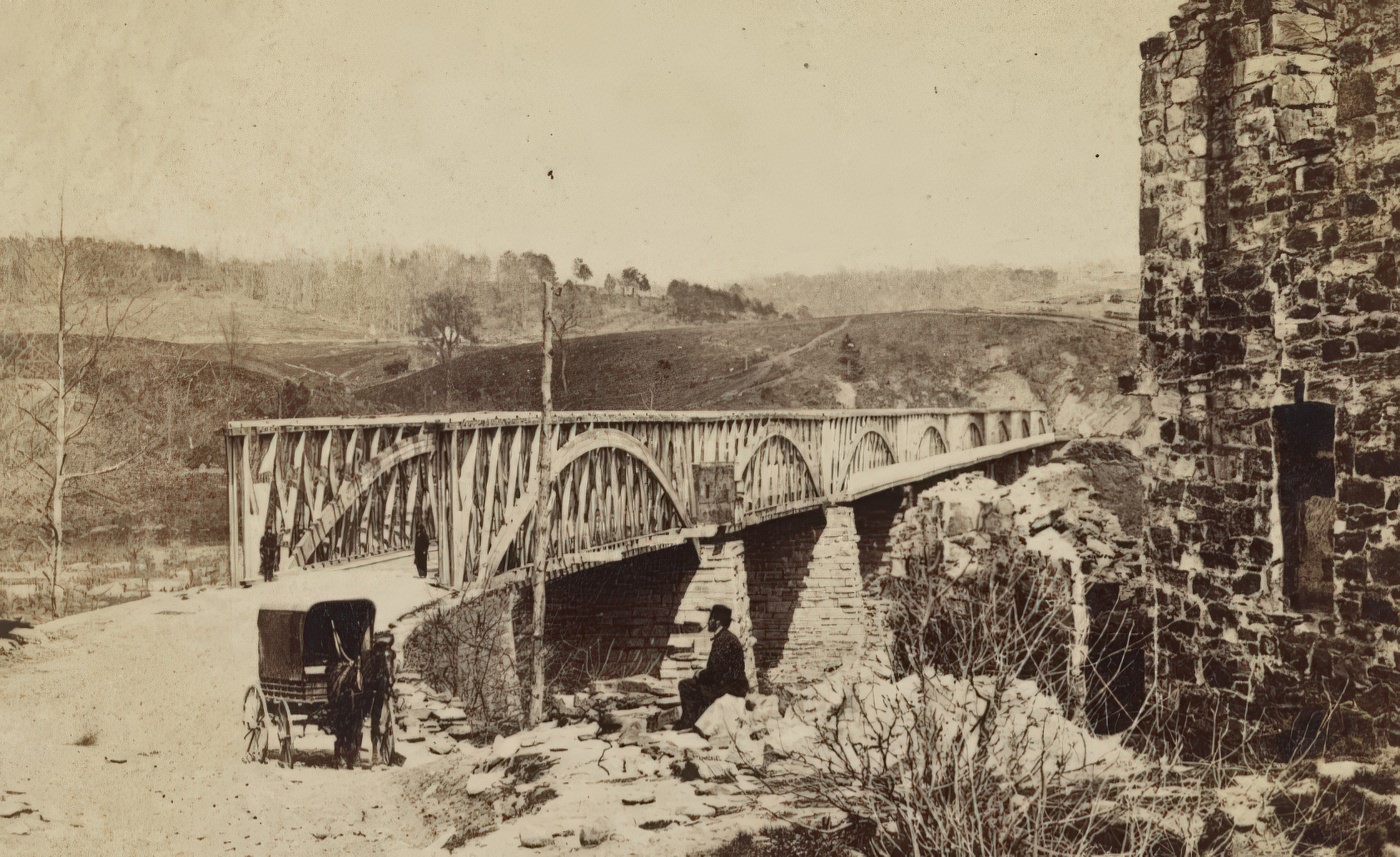

The day after Virginia’s voters ratified secession, the Union Army moved. In the pre-dawn hours of May 24, 1861, Federal troops crossed the Potomac River and entered Alexandria County. The occupation was swift and largely unopposed in the rural areas. While local militia units in the city of Alexandria boarded trains and fled south, Union soldiers marched in from multiple directions, securing key transportation and communication hubs like the railroad depot and telegraph office.

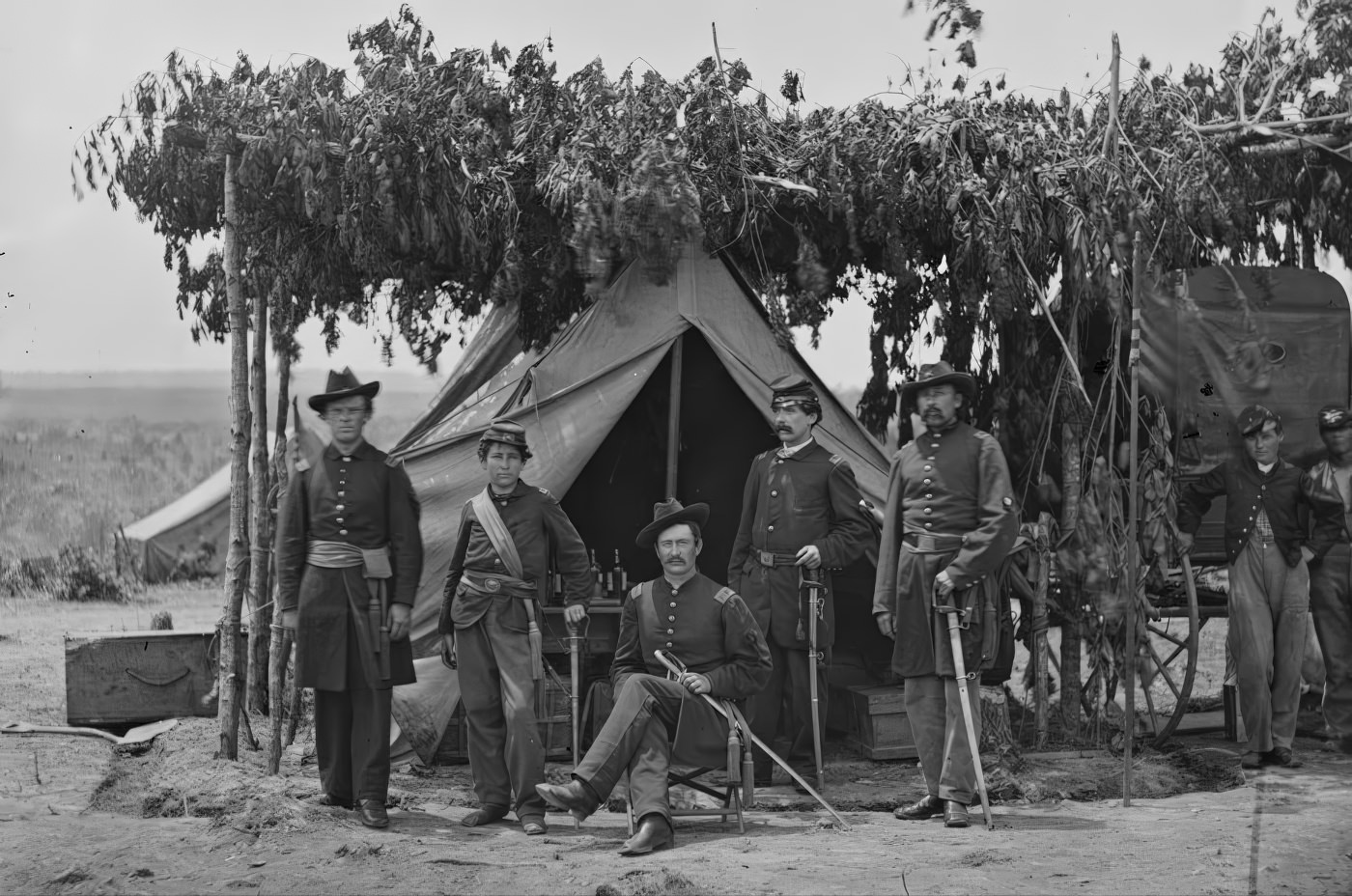

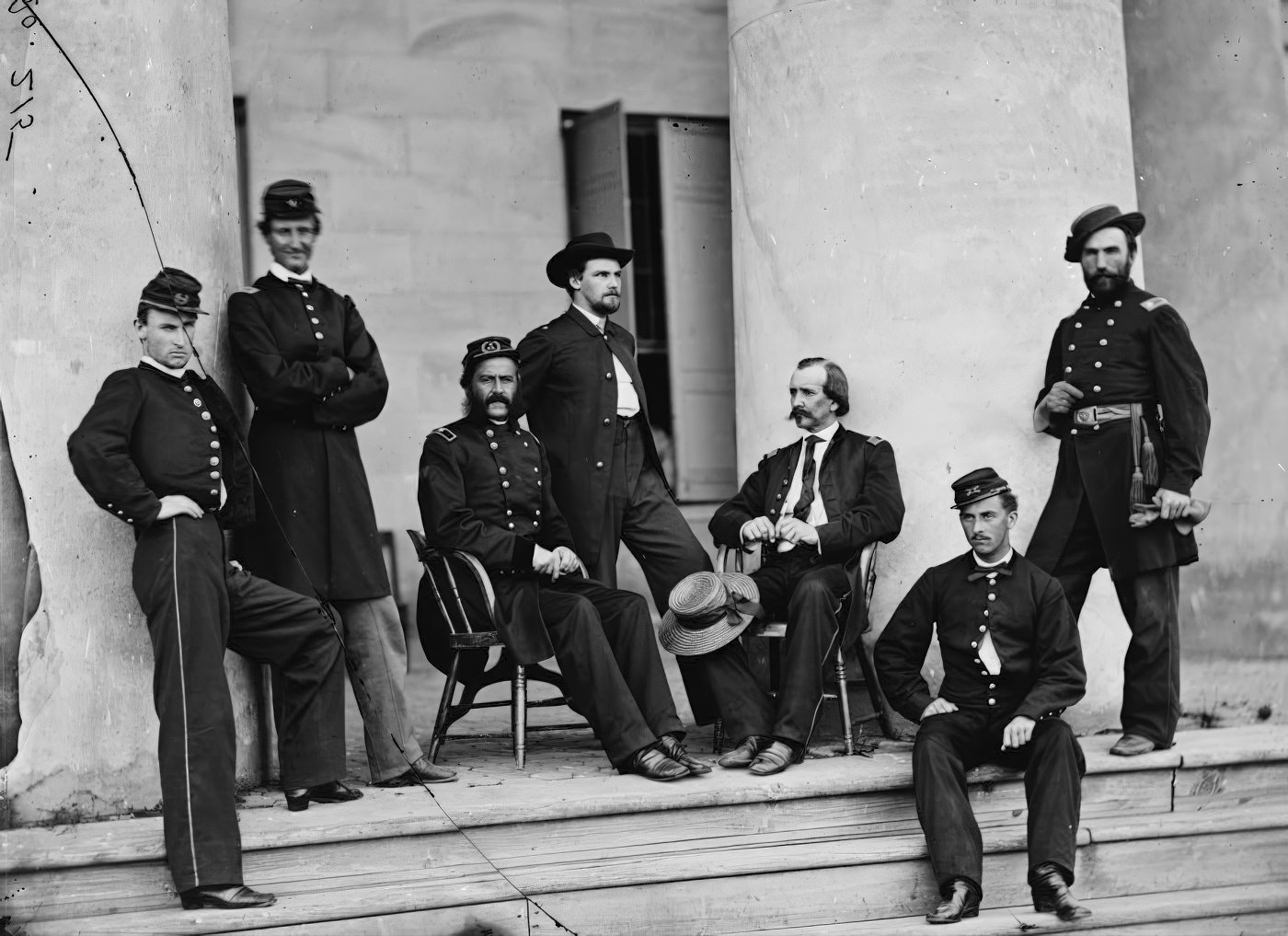

The immediate impact on the civilian population was profound. The county was placed under martial law, with a 9 p.m. curfew and a ban on public gatherings. Many pro-Confederate residents fled, leaving their homes and properties behind. For those who remained, daily life was upended by military regulations, supply shortages, and the constant presence of thousands of soldiers. The Union Army quickly began to transform the landscape, taking over private homes, public buildings, and churches for use as offices, headquarters, and hospitals.

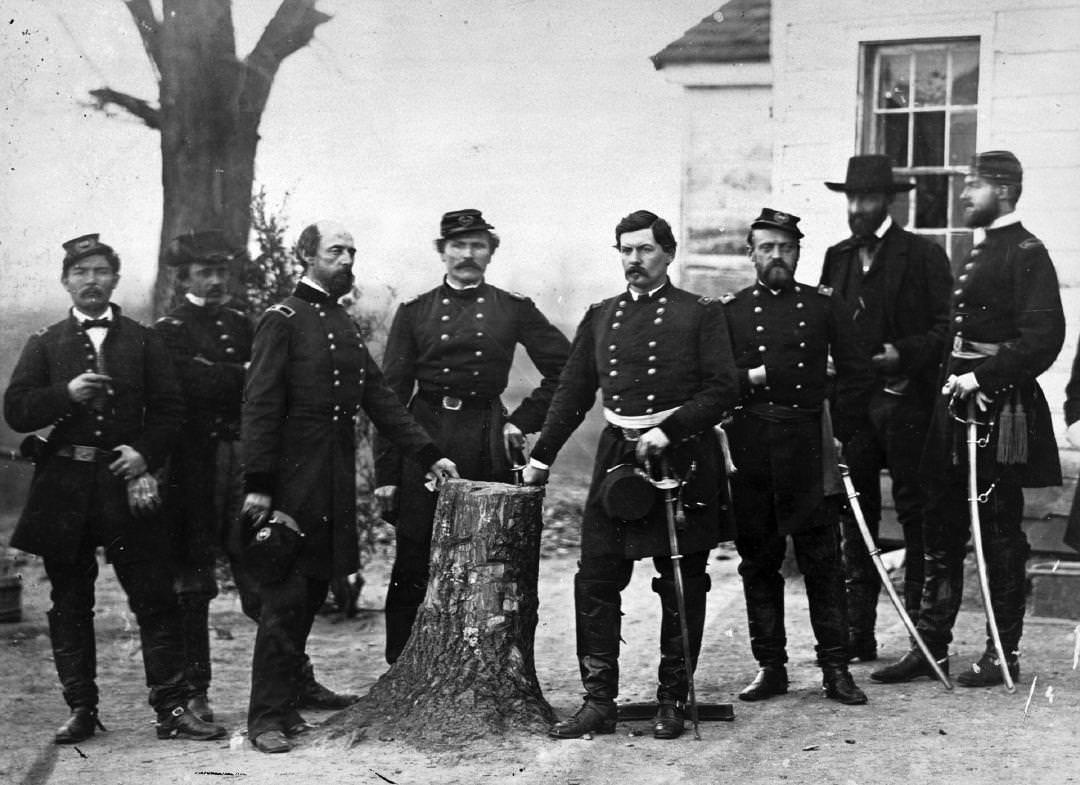

The most symbolic seizure was that of Arlington House. Robert E. Lee had departed for Richmond in April to accept command of Virginia’s forces, and his wife, Mary, left the estate in May. She entrusted the keys to the mansion and its priceless heirlooms—mementos from George Washington—to Selina Gray, the head housekeeper and an enslaved woman. On May 24, Union troops occupied the estate, converting the grand home into a military headquarters and the surrounding grounds into a massive camp. The occupation of the Lee family home was a clear and powerful statement. The Union Army now controlled the strategic high ground, and the former plantation of the Confederacy’s most famous general had become a stronghold for the Federal war effort.

A Landscape Remade by War: Forts and Freedpeople

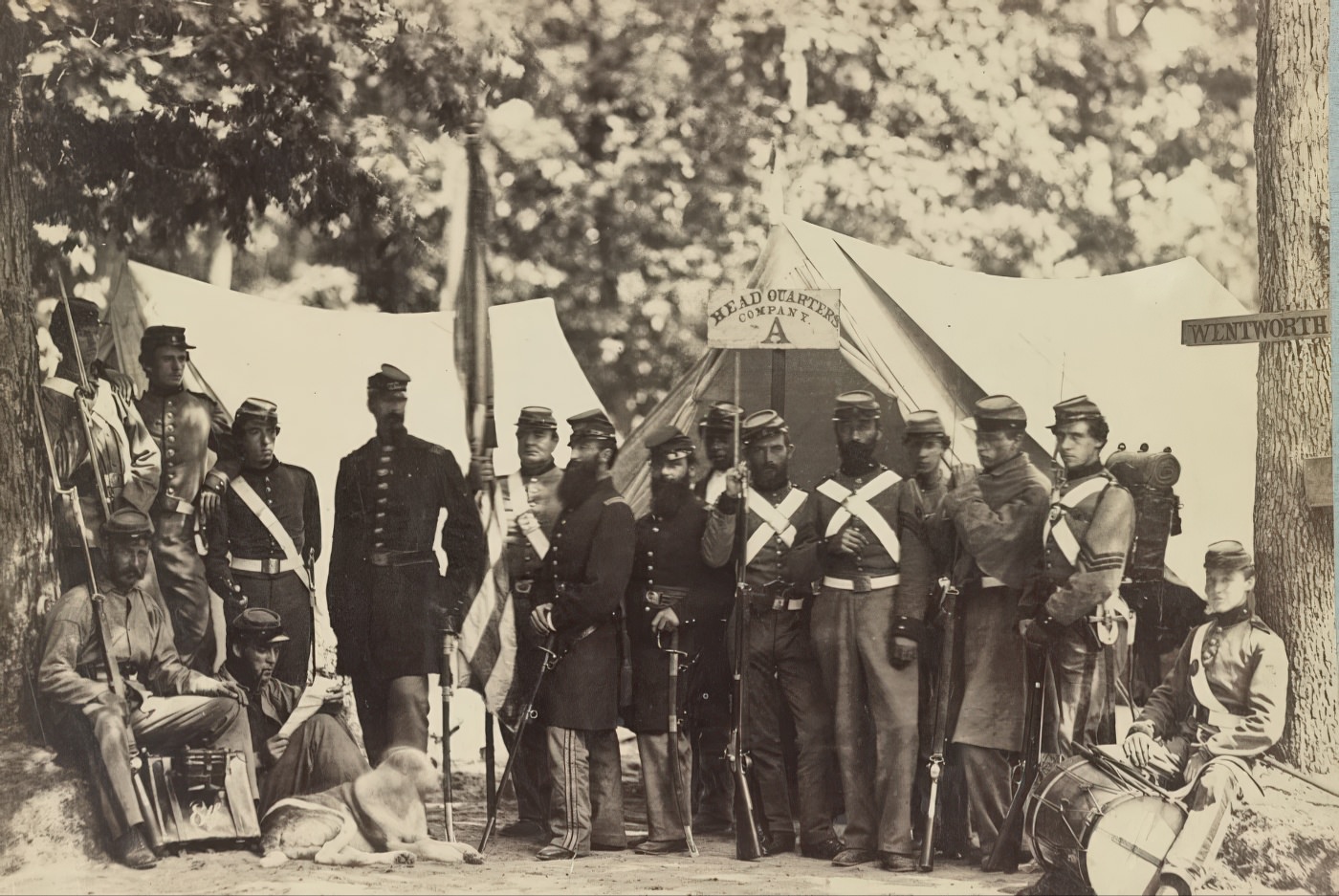

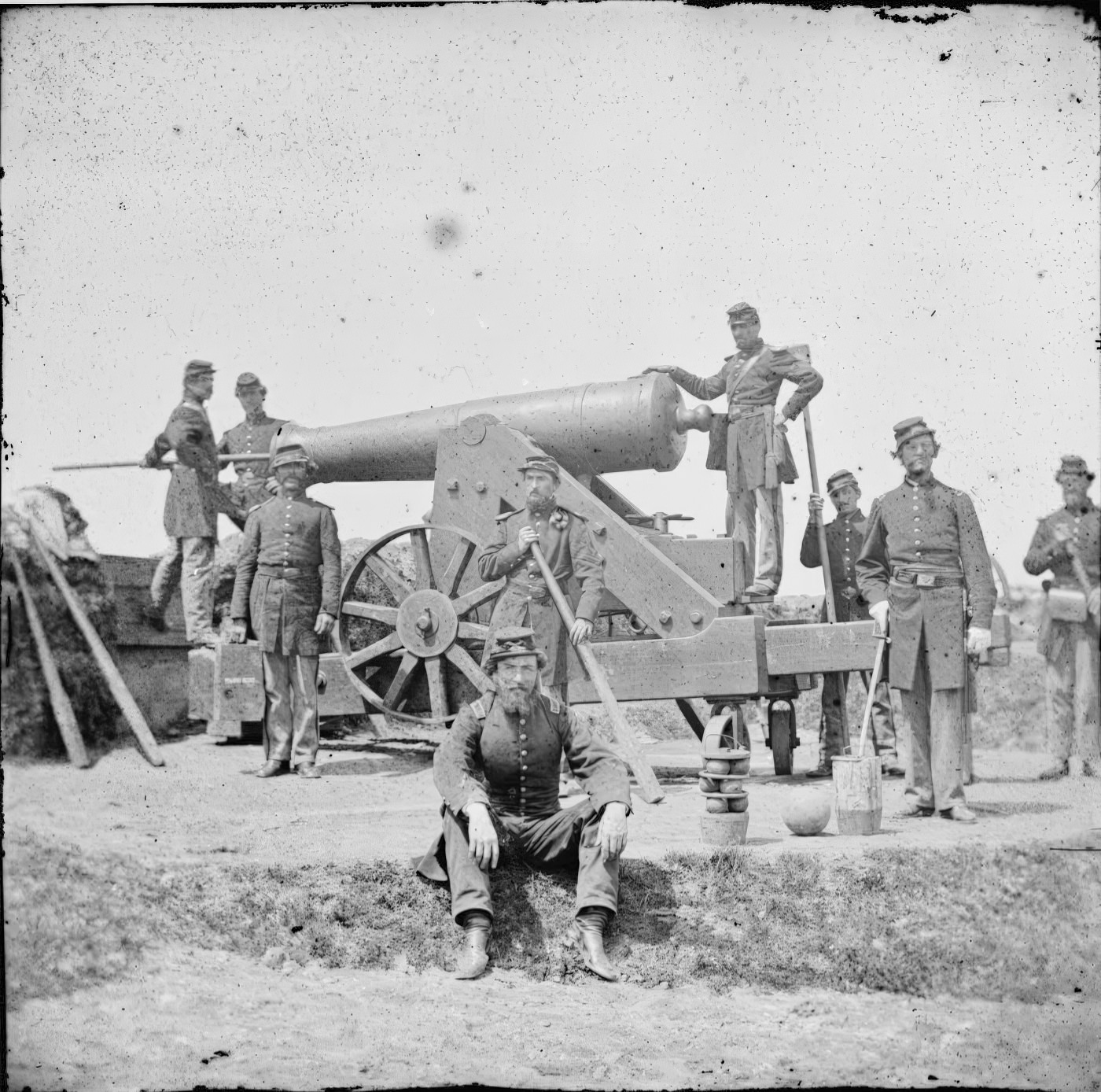

The Union occupation turned the quiet farms of Alexandria County into a massive, fortified military zone. To protect Washington, D.C., from a Confederate attack, the Union Army began constructing a formidable ring of defenses. This network, known as the Arlington Line, eventually consisted of some 30 earthwork forts and 93 artillery batteries that stretched across the county’s hills.

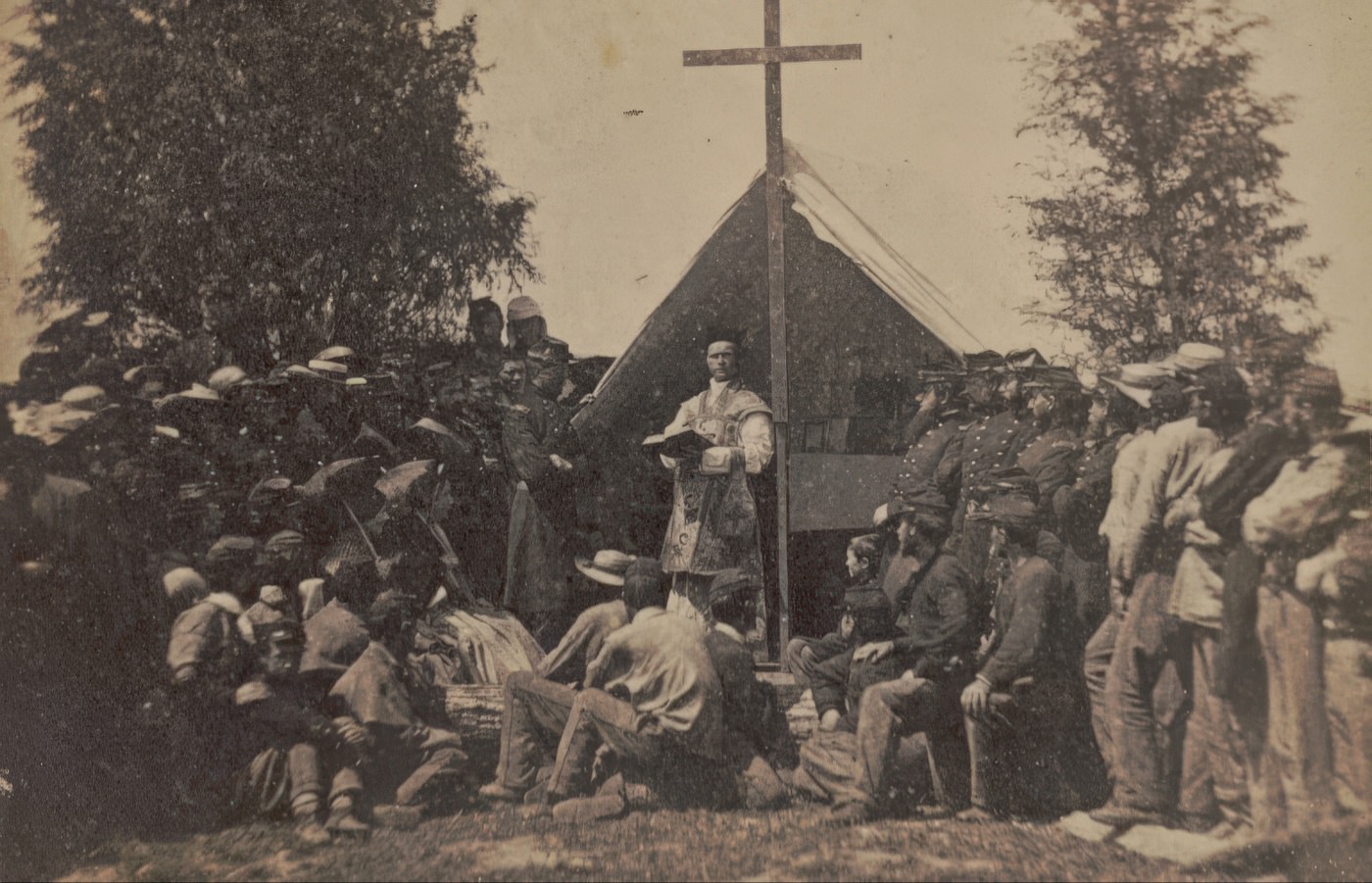

Construction began immediately after the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. Forts with names like C.F. Smith, Whipple, and Ward rose from the farmland. Fort Ward, one of the largest and strongest in the system, had a perimeter of over 800 yards and emplacements for 36 guns. These were not small outposts; they were major engineering projects. To build them and to clear lines of fire, soldiers cut down vast tracts of forest, fundamentally altering the county’s landscape. At various times during the war, as many as 150,000 Union troops were encamped in the area, overrunning farms and disrupting what was left of civilian life.

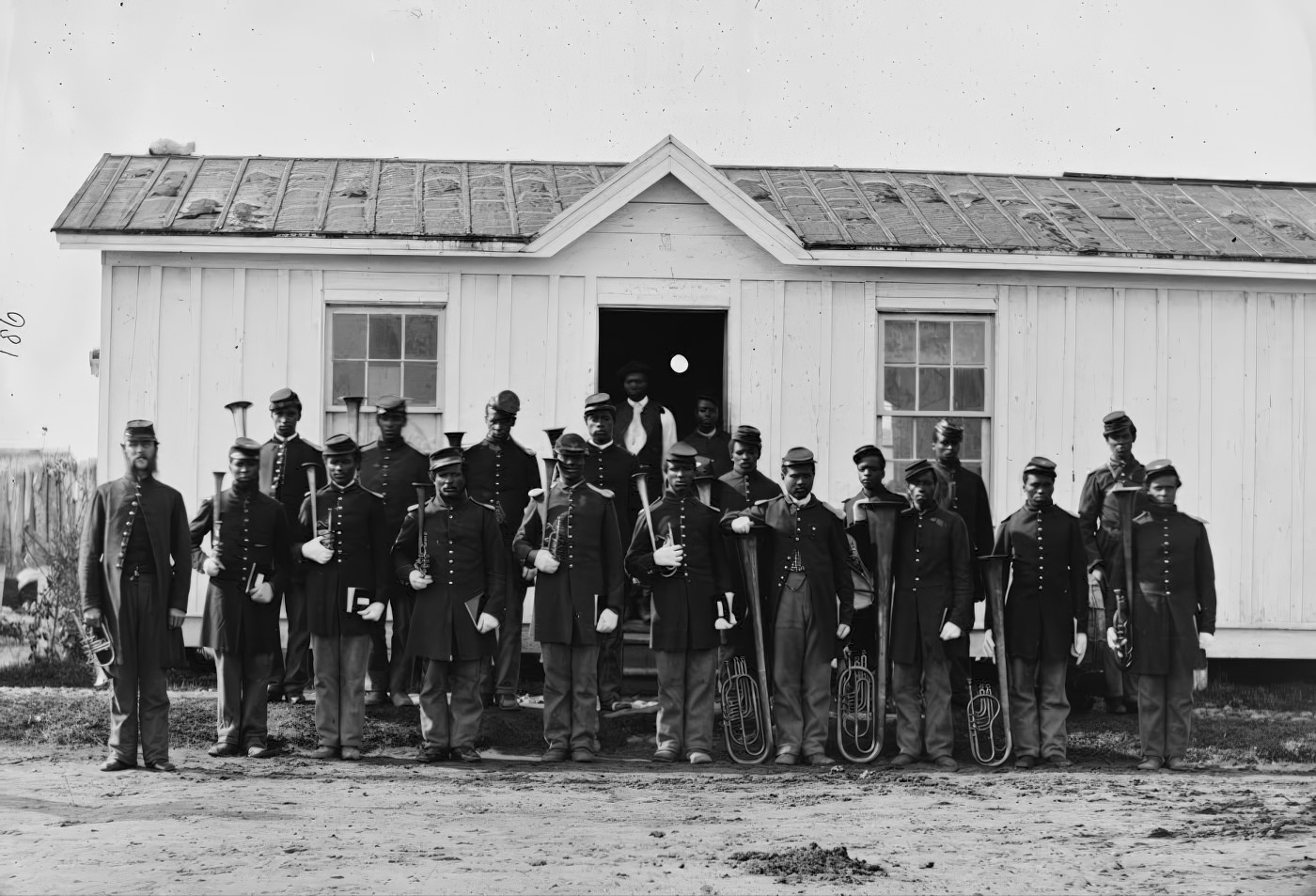

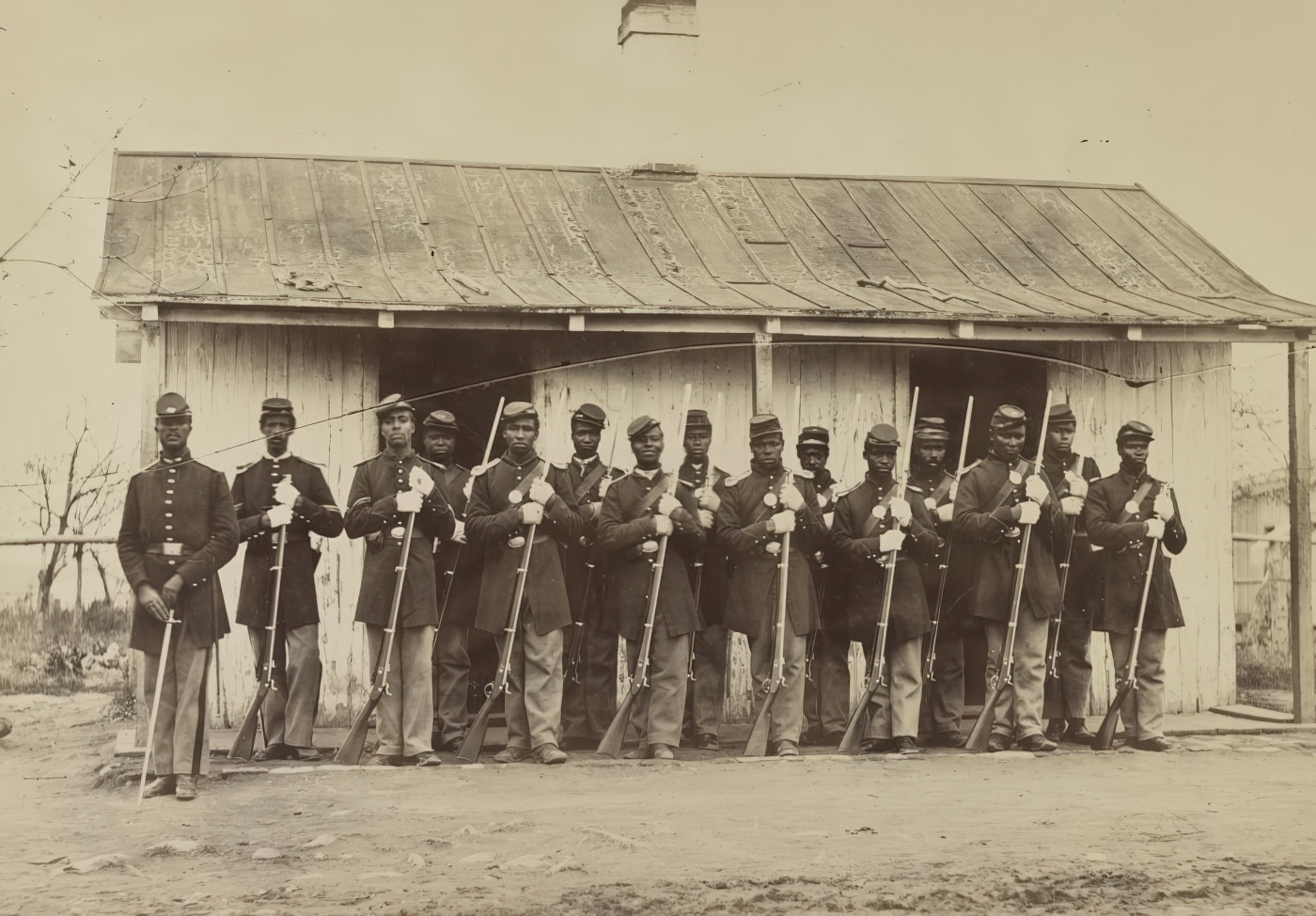

As the Union Army solidified its control, another profound transformation was taking place. The war was a catalyst for emancipation. Thousands of enslaved African Americans from across Virginia and the South fled their plantations and sought refuge behind Union lines. Washington, D.C., and Alexandria County became primary destinations for these “contrabands,” as they were then called. The influx of people, many arriving in poor health and with few possessions, created a refugee crisis.

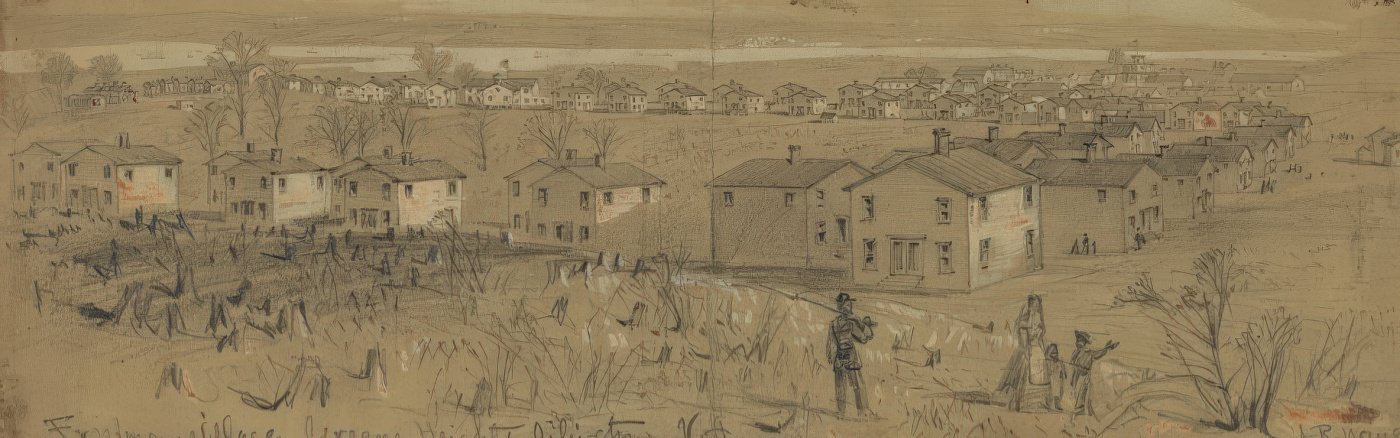

To address the overcrowding and unsanitary conditions in the contraband camps in Washington, the federal government established Freedman’s Village in 1863 on the southern portion of the Arlington estate. This was not just a temporary camp; it was envisioned as a model, planned community where formerly enslaved people could transition to a life of freedom. The village grew into a thriving settlement with over 50 duplex houses, a hospital, schools, churches, and a home for the elderly. At its peak, the population of Freedman’s Village may have reached 3,000 residents.

Life in the village was structured and, at times, difficult. Residents were under the jurisdiction of the military and later the Freedmen’s Bureau. Able-bodied adults were required to work, either on surrounding government farms or in workshops where they learned trades like blacksmithing and carpentry. They were paid for their labor, but a portion of their wages was deducted for rent and to support the village’s upkeep, a policy that caused resentment among some residents. Despite these challenges, Freedman’s Village represented a powerful symbol of Black self-sufficiency and progress, a community built on the former plantation of a Confederate general. It became a place where residents organized politically, established social organizations, and educated their children. The famed abolitionist Sojourner Truth lived in the village for a year, working as a counselor and teacher.

Hallowed Ground: The Birth of a National Cemetery

By 1864, the Civil War’s staggering death toll had created a grim necessity. The military cemeteries in and around Washington, D.C., were rapidly filling up with the bodies of Union soldiers who died in battle or from disease in the area’s crowded hospitals. A new, large burial ground was needed.

The Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army, Montgomery C. Meigs, was tasked with finding a suitable location. Meigs, who had served with Robert E. Lee in the pre-war army and now considered him a traitor, selected the Arlington estate. The choice was both practical and punitive. The high ground was beautiful and serene, but establishing a cemetery there would also make it impossible for the Lee family to ever return and live in their home.

The first military burial at Arlington took place on May 13, 1864, when Private William Henry Christman of Pennsylvania was laid to rest in what is now Section 27. On June 15, 1864, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton officially designated 200 acres of the estate as a national cemetery.

The burials reflected the segregated society of the era. Section 27 became the primary burial ground for African Americans, including approximately 1,500 soldiers from the United States Colored Troops and nearly 3,800 “contrabands” who had died in the refugee camps. Their headstones were marked simply with “Citizen” or “Civilian.”

To permanently seal the estate’s fate, Meigs took a further step. In August 1864, he ordered that burials be made right next to Arlington House, in Mary Lee’s beloved rose garden. Two years later, he had the remains of 2,111 unknown Civil War soldiers exhumed from various battlefields and reburied in a single mass grave in the middle of the garden. The Tomb of the Civil War Unknowns was a final, deliberate act to transform the private home into a public, national shrine to the Union’s sacrifice. By the end of the 1860s, the Arlington estate was no longer a plantation; it was a vast and growing city of the dead, a permanent monument to the war that had reshaped the county and the nation.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, Wikimedia, Arlington Public Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know