In the final decade of the 19th century, the 25.8-square-mile tract of land across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., was known officially as Alexandria County. The name “Arlington,” so familiar today, would not be adopted until 1920. That change was made specifically to resolve the ongoing confusion with the adjacent, but entirely separate, City of Alexandria. For anyone living in or dealing with the county during the 1890s, this distinction was a fundamental fact of daily life and governance.

The political landscape of the 1890s was the direct result of a formal separation that had occurred two decades earlier. In 1870, Alexandria County and the City of Alexandria were officially divided, establishing the county as a distinct political jurisdiction with its own government. Before this split, the bustling town of Alexandria had served as the county seat, the center of its legal and administrative life. After 1870, the now-independent rural county had to forge its own path.

Local governance for this newly defined county rested with a Board of Supervisors. To manage its affairs, the county was organized into three magisterial districts, each representing a distinct geographical section: the Washington district covered the northern part, the Arlington district occupied the central area, and the Jefferson district comprised the south. This structure formed the basis of local government and service provision throughout the 1890s. The decade closed with a significant development that would shape the county’s future: in 1898, the county courthouse was relocated into the area now known as Arlington, a move that immediately began to spur development in nearby communities like Cherrydale.

The 1870 separation was not merely an administrative reshuffling; it was a strategic political maneuver rooted in the complex racial dynamics of the post-Civil War era. The new Virginia constitution of 1870 included a clause that allowed any urban area with a population over 10,000 to become an independent city, severing its ties to its surrounding county. The leadership of Alexandria City moved immediately to take advantage of this provision. The primary motivation for this decision was explicitly described at the time as “racial”. The core issue was the significant political power of the newly enfranchised African American men living in Freedman’s Village, a large settlement located squarely within the rural county’s boundaries. This community was substantial, making up at least 63 percent of the rural population. When allied with the Black population of the city, they formed a powerful county-wide voting bloc that threatened the established white political order. By separating, the City of Alexandria effectively drew new political lines that isolated this large Black population within the rural county, thereby diluting its influence within the city’s new, smaller jurisdiction. This act of political engineering fundamentally shaped the social and political environment of Alexandria County as it entered the 1890s.

The People of the County: A Demographic Snapshot

According to an 1890 population table for Virginia, the combined total for “ARLINGTON/ALEXAND” was 18,597 residents. It is difficult to precisely separate the rural county’s population from the city’s within this figure. For context, census data from 1870, immediately after the political separation, showed the rural county had a population of 3,185 people. A truly precise demographic breakdown for the 1890s is impossible to construct, as most of the 1890 U.S. Federal Census schedules were destroyed in a Commerce Department fire in 1921, a major loss for historians and genealogists.

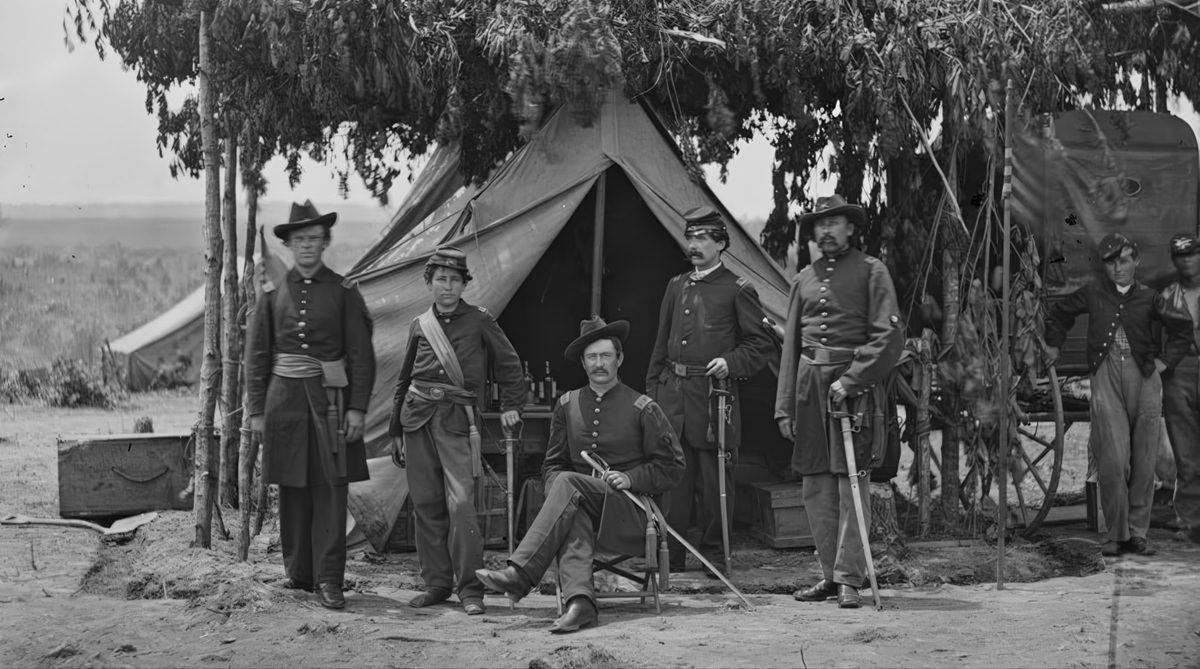

In the absence of the main census, a key demographic resource for the decade is the Special Schedule of Union Veterans and Widows of the Civil War. This special census, conducted in 1890, provides a window into the county’s population, confirming the continued presence of Civil War veterans—both Black and white—a full generation after the conflict’s end. The records list names and military details for residents across the county’s districts, including a number of men who served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Surnames such as Adams, Allen, Barrow, and Beckley appear in the Arlington and Jefferson districts, giving a name to some of the veterans who called the county home.

A significant African American community, Freedman’s Village, had been a major feature of the county since its establishment in 1863 on the Arlington estate, the former home of Robert E. Lee. What began as a temporary camp for formerly enslaved people grew into a thriving, semi-permanent settlement with a population that may have reached 3,000 at its peak. The village had its own schools, churches, a hospital, and homes, representing a powerful symbol of Black self-sufficiency. By the 1890s, however, this community was being systematically erased. The federal government, viewing the land as essential for military purposes and the expansion of Arlington National Cemetery, began closing the village in the late 1880s. By 1890, all residents had been forced to leave, though they received some compensation for the improvements they had made to their properties. The physical structures of the village were leveled during the 1890s, and in 1900 the land was officially transferred to the Department of Agriculture, its history as a Black community paved over to make way for the expansion of the national cemetery.

As Freedman’s Village was being dismantled, other African American enclaves were taking root elsewhere in the region. By the end of the century, Black families had established a neighborhood known as Cross Canal in Alexandria, likely situated to be close to work opportunities on the wharves and in nearby factories. This indicates a geographic shift of the Black population from the federally controlled Arlington estate to other developing areas.

The 1890s, therefore, represented a period of active and intentional reshaping of the county’s racial landscape. The closure of Freedman’s Village was not just an administrative decision but a pivotal event that removed a large, politically organized African American community from a strategic and highly symbolic location. The village was a powerful symbol of Black freedom, a thriving community built on the former plantation of the Confederacy’s most famous general. The federal government had considered closing it as early as 1868, with pressure mounting as the Arlington property became more desirable for military development. The final closure was justified by army regulations that prevented civilians from living on a military reservation—a rule strictly enforced once the government secured clear title to the land from the Lee family in 1883. The dismantling of the village in the 1890s was the final step in prioritizing the site’s identity as a national cemetery over its identity as a flourishing Black community, physically and symbolically erasing a legacy of Reconstruction-era progress from the heart of the county

Life on the Land: Farming, Dairies, and Rural Routines

Outside of its few developing settlements, Alexandria County in the 1890s remained a largely rural place, with an economy grounded in agriculture. In the decades after the Civil War, the old plantation system had given way to smaller farms. In many parts of Virginia, particularly where cash crops like tobacco were grown, a system of sharecropping emerged, where landowners provided tenants with land and supplies in exchange for a share of the crop. The county’s farms were becoming increasingly connected to a national market economy, with new railroad lines providing the means to transport agricultural products to Washington, D.C., and other urban centers.

A key feature of the county’s evolving economy was its growing dairy industry. This specialization was driven by several factors: the large and concentrated market for fresh milk in the nation’s capital, a post-war national interest in scientific farming and sanitation, and the expansion of the railroad, which was crucial for transporting perishable goods quickly and efficiently.

The story of the George Crossman dairy farm in the East Falls Church area exemplifies this trend. The family farmhouse, a two-story vernacular building, was constructed in 1892 on a 60-acre property. This land had been deeded to George Crossman by his father, Isaac, who by 1890 was already considered one of the principal farmers in the area. The farm was a typical operation of its time, complete with two barns, a garage, a hog pen, and a windmill to pump water. By the turn of the century, the Crossman farm was well-established and gaining a reputation for its top-producing cows. Its dairy products were sold to local neighbors and to the larger Maryland and Virginia Milk Producers Association. The Crossman Farm would continue operating for decades, becoming one of the last working dairy farms in the county before it finally closed in 1949.

While agriculture was the dominant economic activity, other small industries existed. In the rough-and-tumble community of Rosslyn, the Arlington Brewery was in operation, though it would later be converted into a Cherry Smash soft drink bottling plant after Prohibition. The county’s proximity to the more industrialized City of Alexandria and to Washington, D.C., also provided residents with access to jobs in industries there, including brickworks, furniture and machinery factories, and other breweries.

The county’s economic identity in the 1890s was fundamentally shaped by its relationship with Washington, D.C. This proximity created both respectable and disreputable economic zones that were, in different ways, dependent on the federal capital. The dairy industry, for example, did not just benefit from the city’s demand; it was actively molded by it. Washington’s implementation of health regulations, such as an 1895 law requiring the inspection of dairies, pushed Northern Virginia farmers to improve their sanitation and quality control, ultimately making the region a leading milk producer for the metropolitan area. At the same time, the county’s most notorious economic hub, Rosslyn, thrived for a very different reason. Its economy of saloons, gambling halls, and brothels was sustained in large part by the patronage of soldiers stationed at Fort Myer, a major federal military installation located nearby. The overall growth of the federal government and its payroll brought prosperity to the entire region. In this way, the economic landscape of Alexandria County in the 1890s can be seen as a direct response to two very different demands emanating from the federal presence across the river: the domestic needs of a growing city for food and the vices sought by its soldiers

Settlements of Contrast: From Vice to Vision

Within Alexandria County, the 1890s saw stark contrasts between its developing communities. The county was home to both a notorious den of vice and the beginnings of quiet, modern suburbs, each with its own distinct character and trajectory.

At one extreme was Rosslyn. Located at the Virginia foot of the Aqueduct Bridge connecting it to Georgetown, Rosslyn in the 1890s had a widespread reputation for lawlessness. It was described in a newspaper of the era as a “notorious den of gambling and prostitution awash in alcohol”. The small community was packed with saloons, brothels, and gambling houses that catered heavily to soldiers from nearby Fort Myer. The atmosphere was one of vice and violence. The area was considered so dangerous that, according to one account, many people hesitated to travel there even in the daytime, while at night “only the bravest men” would dare pass through. A nearby ravine earned the grim nickname “Dead Man’s Hollow” because it was a frequent site of robberies, assaults, and even murders.

In sharp contrast to Rosslyn, the community of Clarendon was still mostly open farmland during the 1890s. It was a quiet agricultural area, but it was on the verge of a dramatic transformation driven by real estate speculation. A single land transaction from the period illustrates the rapidly escalating value of property. In 1897, a 25-acre parcel of land was sold for $25 per acre, for a total of $625. Just two years later, that same parcel was resold for $8,000—a more than twelve-fold increase in value. This speculative boom was a prelude to Clarendon’s future. By 1900, real estate firms would officially dedicate the “Town of Clarendon,” promoting it with incentives like free trolley rides to attract homebuyers from Washington, D.C..

Meanwhile, another community, Cherrydale, was already emerging as a residential suburb. Its growth was slow through the late 19th century but began to accelerate toward the end of the decade. Two key events spurred its development: the relocation of the Alexandria County Courthouse to Arlington in 1898 and the establishment of a commuter railroad that would make it easier for residents to work in Washington. The first residential subdivision, known as Schutt’s Subdivision, had been platted, and the earliest houses in the community were being constructed in the popular architectural styles of the day.

The Engines of Change: Trolleys, Bridges, and New Construction

The 1890s was a decade of profound physical transformation for Alexandria County, driven by new technologies that reshaped the landscape, connected its communities, and enabled new forms of suburban life. The arrival of the electric streetcar and the construction of modern homes began to knit the rural county into the growing metropolitan region of Washington, D.C.

The electric trolley era dawned in Northern Virginia in 1892, and its impact was immediate. That year, two key companies were founded: the Washington, Arlington and Falls Church Railway Company and the Washington, Alexandria, and Mount Vernon Railway. These new electric railways became the engines of suburban growth. Real estate developers quickly began subdividing land along the new routes, creating communities designed for commuters. Small developments like Fostoria, founded in 1890, and the growing suburb of Cherrydale sprang up along the trolley lines. By 1896, the network was expanding rapidly. One line ran from Rosslyn through Clarendon and on to Falls Church, while another extended south from Alexandria to the Mount Vernon estate and then north to Rosslyn. Crucially, this network included a connection across the Long Bridge, allowing passengers to travel directly from the Virginia suburbs into downtown Washington, D.C..

The county’s connection to the capital depended on a handful of critical bridges over the Potomac River. The most important of these was the Long Bridge, the primary artery for both railroad and carriage traffic. The version of the bridge in use during the 1890s was a timber and iron structure that had been built in 1872. It was notoriously problematic, frequently damaged by ice floes and floods, and was considered too narrow to handle the increasing traffic. By the 1890s, plans were already being made for its replacement. Despite its flaws, it was a vital link. In 1895, the Washington, Alexandria, and Mount Vernon Electric Railway began running its streetcars across the bridge, creating the first direct public transit line into the city. Other important crossings included the Aqueduct Bridge, which connected the vice-ridden town of Rosslyn to Georgetown, and the Chain Bridge at Little Falls, a wrought iron truss bridge built in 1874 that was the oldest crossing in the area.

This new infrastructure supported a boom in residential construction. In emerging suburbs like Cherrydale, new homes were built in the architectural styles popular in the late Victorian era. These included the Queen Anne style, with its distinctive corner towers, wrap-around porches, and patterned shingles, and the Italianate style, marked by decorative bracketed cornices and elongated windows. The Colonial Revival style also began to appear, with one early example built on Quebec Street in 1897. A new and influential trend also emerged in this decade: the mail-order kit house. Large companies like Sears, Roebuck and Company began selling entire house kits through their catalogs in the mid-1890s. The new railway lines made it easy to deliver these kits directly to communities like Cherrydale, allowing for rapid and affordable construction.

These new technologies acted as a double-edged sword, simultaneously creating the modern suburb while exacerbating the county’s existing social and moral divisions. The electric trolley, a clear symbol of progress, was the direct catalyst for the development of “respectable” suburban communities like Cherrydale and Fostoria, allowing for the separation of home and workplace that is a hallmark of suburban life. Yet, this same technology also made the county’s more disreputable areas more accessible. The trolley lines converged in Rosslyn, reinforcing its status as a regional hub for vice, while the streetcars running across the Long Bridge brought a steady stream of patrons to its saloons and gambling halls. Similarly, mail-order homes democratized homeownership and allowed for rapid construction, but this developer-driven growth often occurred without comprehensive planning, leading to distinct pockets of development with very different characters. Technology in the 1890s was not a uniform force for good; it was an accelerant, speeding up both the creation of idyllic new communities and the entrenchment of old vices, deepening the contrasts that defined Alexandria County.

A Divided Society: Race, Law, and Violence in the Jim Crow Era

The 1890s unfolded during the nadir of American race relations, a period when racial segregation was being systematically and brutally encoded into law and custom across the South. In Alexandria County and throughout Virginia, this was the era of Jim Crow, and its oppressive reality shaped every aspect of life for African American residents.

The legal framework for segregation was already well-established. Following the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s, white Virginians had moved swiftly to re-establish a system of racial oppression through state law. By the 1890s, statutes already mandated separate schools for Black and white children (passed in 1870 and 1882) and strictly outlawed interracial marriage, with severe penalties for violators (passed in 1873 and 1878). While laws requiring segregation on public transportation like railroads and steamboats would be formally passed in 1900, the social and legal precedents for such separation were firmly in place throughout the 1890s.

The public school system, established in Virginia in 1870, was segregated from its very inception. In Alexandria County, local officials were tasked with drawing school district boundaries. Surviving records show that they drew these lines specifically to separate students by race, creating gerrymandered districts even in areas where Black and white families lived in close proximity. The schools for African American children were consistently and deliberately underfunded and neglected by the white authorities, leaving the Black community to find its own ways to support its institutions and champion the achievements of its students and teachers.

This system of legal segregation was reinforced by brutal, extra-legal violence. While no lynchings are documented within the rural county itself during the 1890s, the neighboring City of Alexandria was the site of two horrific acts of racial terror that reflected the violent climate of the entire region. On the evening of April 22, 1897, a 19-year-old Black man named Joseph McCoy was arrested, dragged from his jail cell by a mob, and lynched at a downtown intersection. Two years later, on August 8, 1899, a 16-year-old Black teenager, Benjamin Thomas, was taken from the city jail by what was described as a “white terror mob” and lynched near the public Market Square. These were not secret acts of vigilante justice; they were public spectacles of torture and murder, designed to control and intimidate the entire African American community and enforce the rigid racial hierarchy of the Jim Crow era.

The juxtaposition of these legal and extra-legal measures reveals the two-pronged strategy of white supremacy during this period. State-sanctioned segregation laws created a society of inequality, while the constant threat of mob violence ensured that any challenge to that order would be met with deadly force. This combination of discriminatory laws and racial terror created the deeply oppressive environment faced by Alexandria County’s African American residents in the 1890s.

Hallowed Ground: Arlington House and the National Cemetery

By the 1890s, Alexandria County’s most nationally significant landmarks—Arlington House and Arlington National Cemetery—were undergoing a final transformation that would cement their modern identities. The decade was pivotal in defining these spaces as sites of national memory, a process that involved both preservation and erasure.

Arlington House, the grand Greek Revival mansion built between 1802 and 1818, was no longer a private residence. After a legal battle over its confiscation during the Civil War, the U.S. government purchased the property from the Lee family in 1883 for $150,000, sealing its fate as public land. Throughout the 1890s, the house sat on its prominent hilltop overlooking Washington, D.C., but it was increasingly isolated. The grounds of the former 1,100-acre plantation were now almost entirely occupied by the ever-expanding rows of white headstones of Arlington National Cemetery. The final closure and leveling of Freedman’s Village during the decade removed the last vestiges of a living community from the estate, leaving the historic mansion, as one source described it, “a small island amid thousands of white headstones”.

The cemetery itself, officially established on June 15, 1864, experienced significant growth and evolution at the end of the 1890s. A major catalyst for this expansion was the Spanish-American War. In 1899, the U.S. government began a program to repatriate, at its own expense, the remains of service members who had died overseas. This led to the creation of new burial areas, with the cemetery expanding to include what are now Sections 21, 22, and 24.

Burial practices within the cemetery reflected the segregated society outside its walls. Like all national cemeteries at the time, Arlington was segregated by race and rank, a policy that would remain in effect until President Harry S. Truman desegregated the military in 1948. Section 27 was the primary burial ground for the more than 3,800 formerly enslaved people and freedpeople associated with the Arlington estate, including many from Freedman’s Village. Their headstones were marked not with military rank but with the words “Civilian” or “Citizen”. In a move toward national reconciliation after the Civil War, Congress authorized a designated section for Confederate soldiers in 1900, just after the decade’s close. This area, Section 16, would become the final resting place for 482 Confederate veterans and their spouses.

The 1890s thus finalized the Arlington estate’s transformation from a place of complex, lived history into a carefully curated landscape of national memory. The estate had held many identities over the century: it was a private plantation and a memorial to George Washington under the stewardship of G.W.P. Custis; it was the cherished family home of Robert E. Lee; and during the Civil War, it was a Union Army headquarters and the site of Freedman’s Village, a vibrant community of newly freed African Americans. The events of the 1890s represented the culmination of a process that prioritized one of these identities over all others. The government’s decision to level Freedman’s Village and expand the cemetery for the nation’s war dead was a conscious choice to foreground a specific, sanitized, and militarized version of national history. By 1900, the land’s other histories had been physically erased or subsumed. The mansion was a historic relic, the Black community was gone, and the landscape was redefined by the silent, orderly rows of military graves. The 1890s was the decade this redefinition became permanent.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, Wikimedia, Arlington Public Library

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know