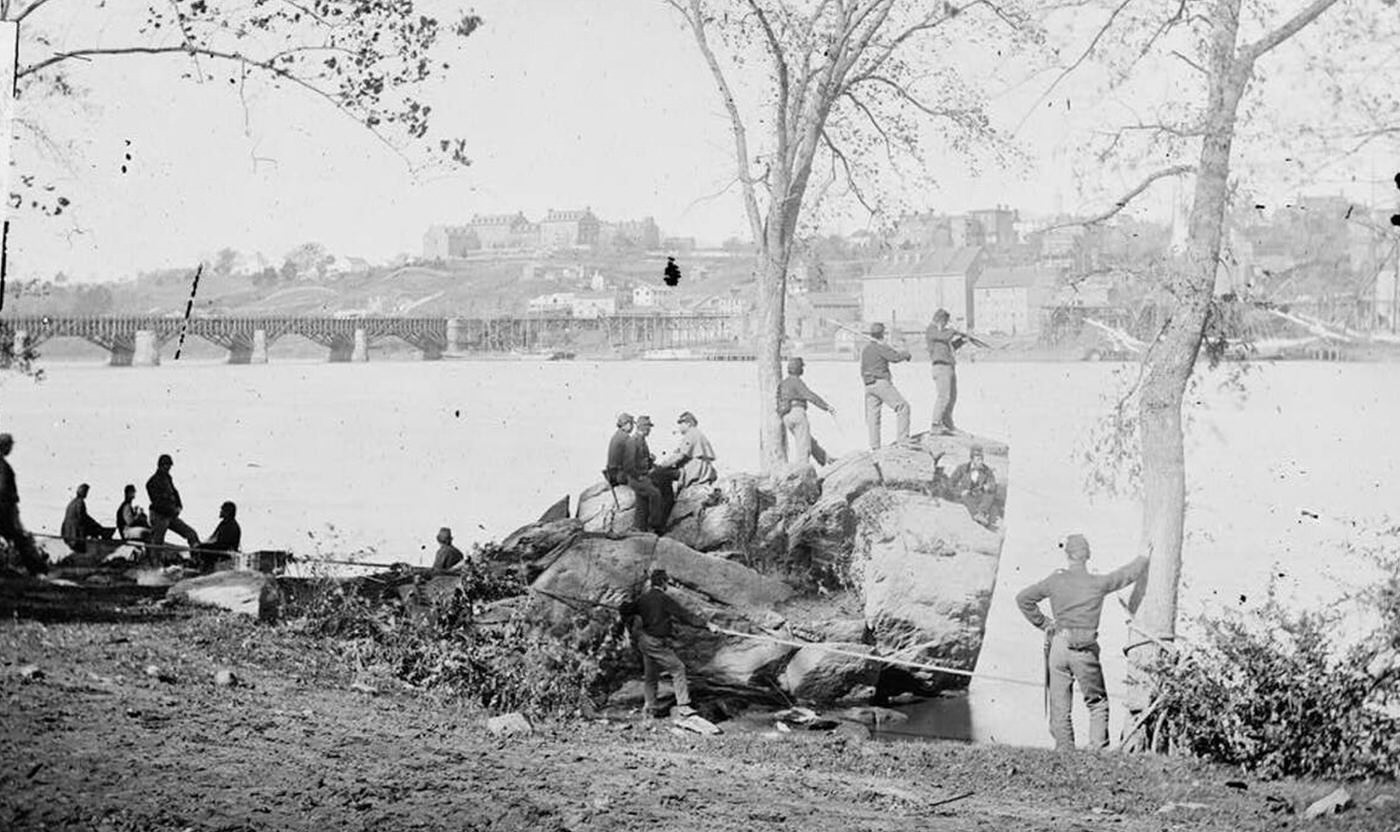

At the dawn of the 20th century, the area known today as Arlington was officially Alexandria County, Virginia. This 25.8-square-mile jurisdiction sat directly across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., but it was a world away from the nation’s capital in character and development. Though it had once been part of the ten-mile square surveyed for the District of Columbia, it was returned to Virginia in 1847 and, by 1870, was administratively separate from the neighboring City of Alexandria.

The county in 1900 was a sparsely populated, largely rural landscape of farms, fields, and woodlands. Its government was minimal, with services largely limited to basic law and order and tax collection. Roads were rudimentary, and essential utilities like drinking water and waste disposal were considered the responsibility of each household. The county was divided into three magisterial districts for administrative purposes: Washington in the north, Arlington in the center, and Jefferson in the south. Within these boundaries, there were no incorporated towns or cities. While Washington D.C. was lit by gas, residents in Alexandria County still relied on kerosene lamps for illumination.

The 1900 United States Federal Census recorded a total population of 6,430 people living in Alexandria County. This small community was defined by a significant racial dynamic; African American residents made up 38% of the total population, a demographic reality that shaped every aspect of life in the county.

This demographic and infrastructural profile reveals a community caught between two powerful, competing identities. On one hand, its small population and minimal government services reflected a traditional, rural Virginia county. On the other hand, its unique history and location placed it on a different trajectory. The substantial African American population was a direct legacy of the Civil War and the federal establishment of Freedman’s Village on the Arlington estate, making the county’s demography distinct from that of its rural peers. Furthermore, its immediate proximity to the expanding federal capital created an external pressure for growth and change. The county in 1900 was not simply a rural area; it was a hybrid entity, shaped by the social structures of the post-Reconstruction South but with a destiny being actively redefined by the economic and demographic engine of Washington, D.C. This tension between its past and its future would become the defining characteristic of the decade that followed.

The Alexandria County of the early 1900s was a place of stark contrasts, home to communities with vastly different characters, from a notorious vice district to newly planned, orderly suburbs.

Rosslyn: The Vice District

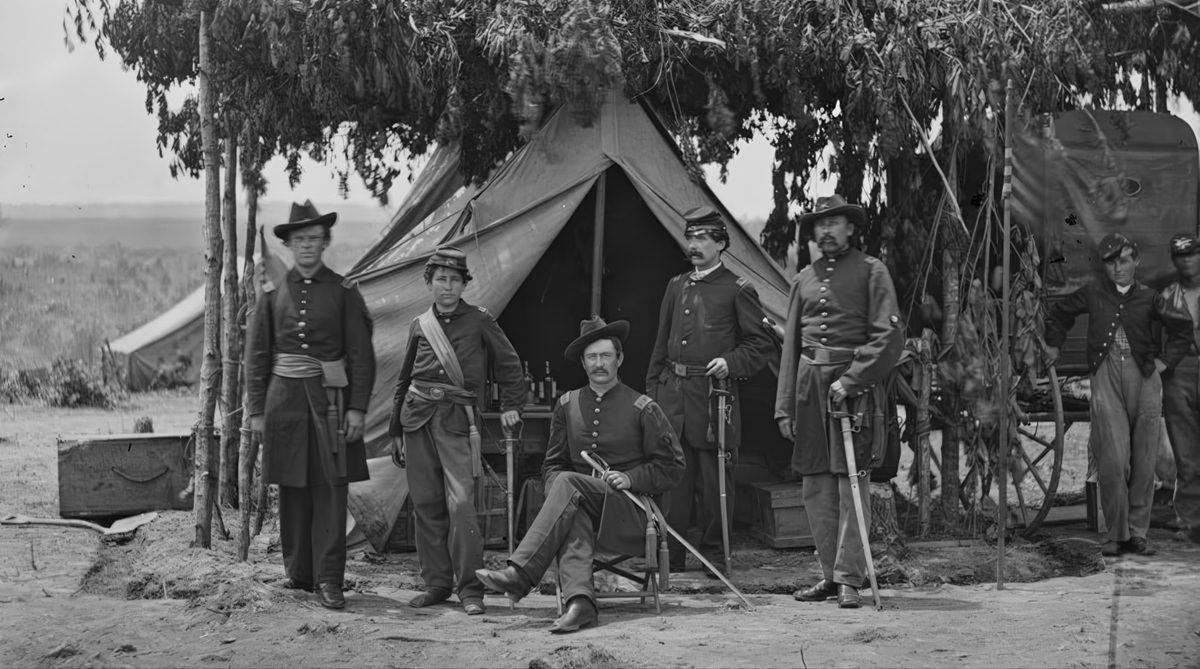

At the turn of the century, Rosslyn was infamous. It was widely known as a “den of gambling and prostitution awash in alcohol,” a rough-and-tumble area that served as the “adult playground” for nearby Washington, D.C.. Its reputation was a holdover from the post-Civil War era, when soldiers stationed at Fort Myer were regular patrons of its saloons, brothels, and 24-hour gambling halls. A nearby ravine, grimly known as “Dead Man’s Hollow,” was the scene of frequent robberies, assaults, and murders.

By 1903, a group of citizens, seeking to improve the county’s reputation for both moral and economic reasons, formed the Good Citizens’ League and backed a new candidate for Commonwealth’s Attorney: Crandal Mackey. Upon taking office in 1904, Mackey launched a series of dramatic raids on Rosslyn’s vice establishments. He gathered a dozen men armed with sledgehammers and axes and, in broad daylight, led them on a campaign of destruction, smashing bars, gambling equipment, and furniture. These raids sent a clear message and effectively dismantled the district’s illicit economy.

The New “Streetcar Suburbs”

While Rosslyn was being “cleaned up,” new communities were being carefully planned and built along the trolley lines. These “streetcar suburbs” were designed to attract middle-class white families seeking a tranquil life outside the city.

Clarendon was established as a village in 1900. Platted on 25 acres along the trolley line on what is now Wilson Boulevard, it was marketed as an attractive and convenient suburb for D.C. commuters. From its inception, Clarendon was designed as an exclusive community, with racially restrictive covenants in its property deeds to prevent African Americans from living there. As the community grew, residents formed the Clarendon Citizens Association, which organized a volunteer firefighting force in 1909.

Ballston also emerged as a well-defined village by 1900, with its growth centered around the Ballston Station on the WA&FC electric railroad. The community’s layout was dictated by the trolley tracks, which ran along the route of modern-day Fairfax Drive.

The communities of Del Ray and St. Elmo also experienced significant growth during this period. By 1900, Del Ray had a population of 130, and St. Elmo had 55. In 1908, these and other nearby tracts were officially incorporated together as the Town of Potomac, formalizing their status as a growing suburban center.

The simultaneous existence of Rosslyn’s vice district and the creation of racially exclusive suburbs reveals a deep social tension within the county. The “taming” of Rosslyn and the construction of segregated communities were two sides of the same effort by the county’s emerging white middle class to impose a specific vision of social order. The violent, public destruction of Rosslyn’s saloons was a symbolic purging of what were considered “undesirable” elements. The meticulous planning of segregated suburbs was a constructive act to build a “desirable” alternative. Both actions were driven by the same underlying goal: to transform Alexandria County from a rough, rural, and racially mixed area into a controlled, predictable, and respectable white suburb, thereby increasing property values and attracting the “right” kind of residents.

Black Life, Resilience, and Institution Building

For the 38% of Alexandria County’s population that was African American, the first decade of the 20th century was defined by the twin forces of displacement and proactive community creation. As one door was forcibly closed by the government, new ones were opened through the resilience and institutional strength of the Black community itself.

The decade began with a pivotal event: the permanent closure of Freedman’s Village in 1900. This community, established by the federal government on the former Arlington estate of Robert E. Lee after the Civil War, had grown from a temporary refugee camp into a self-sustaining town. It had its own duplex homes, schools, a hospital, churches, and a vibrant social life. However, as the land became increasingly valuable for development, the government moved to disband the village. Despite years of impassioned protests and political organizing by residents, the eviction was finalized in 1900. The federal government paid the residents a total of $75,000 for their homes and property, and the town was torn down, displacing hundreds of families who had known no other home since emancipation.

The response to this displacement was not despair, but action. Instead of seeking another government solution, the Black community turned inward, relying on its own institutions to build new foundations.

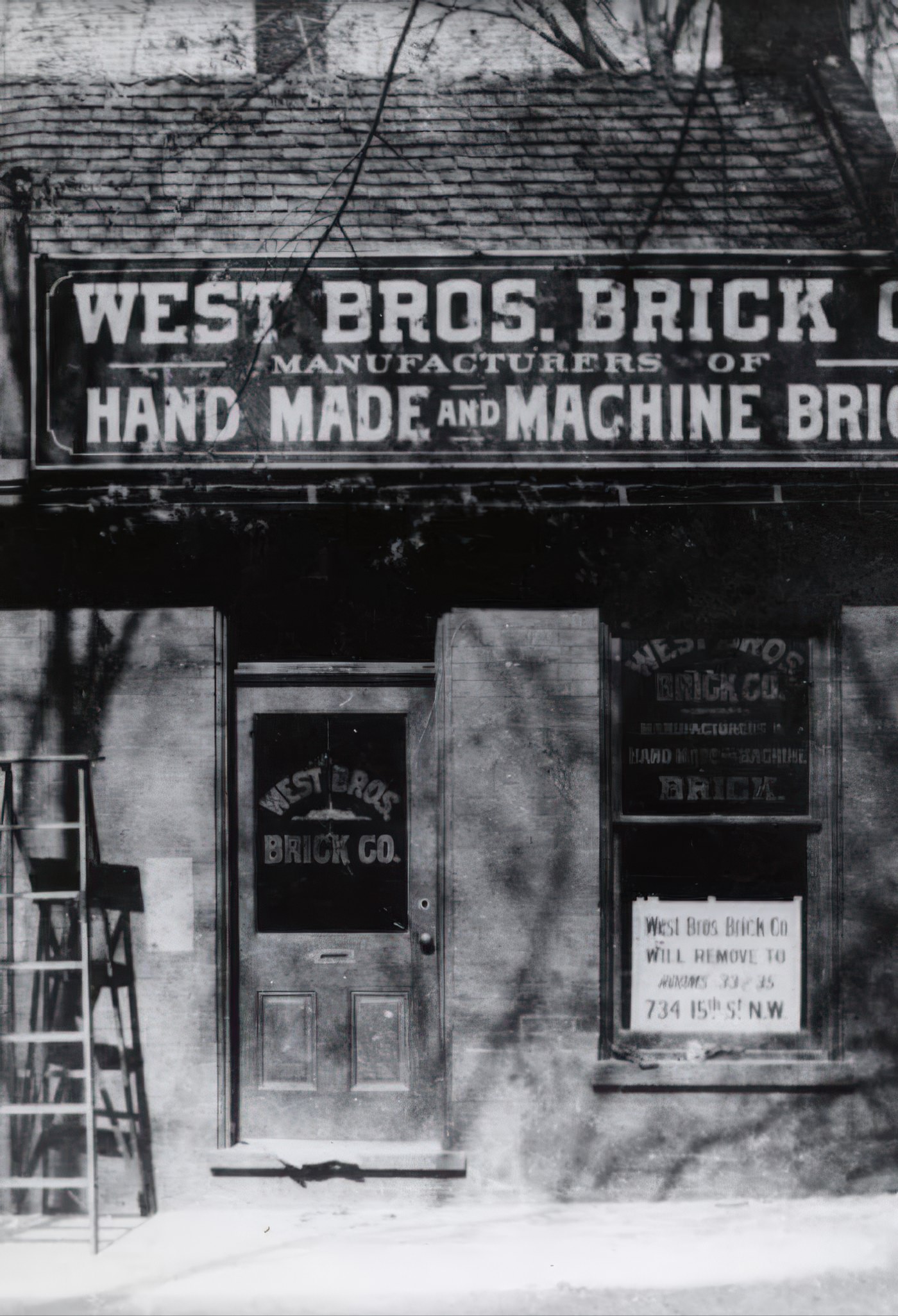

Queen City was born directly from the ashes of Freedman’s Village. The Mount Olive Baptist Church purchased two acres of land in East Arlington, creating a new, thriving community for displaced residents and other African American families. Queen City became a close-knit neighborhood of homeowners. Men often found work at the nearby brickyards, using the Queen City trolley stop for their commute, while women contributed to household incomes with work such as sewing.

Hall’s Hill, also known as High View Park, was another center of Black life. As one of the oldest Black enclaves in Northern Virginia, it had been founded by formerly enslaved people on land they purchased from a local landowner, Brazil Hall. During the Jim Crow era, Hall’s Hill grew into a remarkably self-sufficient community. It had its own stores, schools, and professional services, including doctors and lawyers. It even established its own volunteer fire department, a necessity because white fire services refused to respond to calls in the neighborhood.

The cornerstones of these communities were their churches and fraternal organizations. Mount Zion Baptist Church, founded in 1866, was the oldest Black church in the county and a vital center for the community after its own forced relocation from Freedman’s Village. In Hall’s Hill,

Mount Salvation Baptist Church provided a fundamental intersection of faith, social life, and leadership. These churches, along with groups like the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, did more than hold services; they hosted social events, provided burial services, and organized mutual aid funds to support their members.

The closure of Freedman’s Village in 1900 thus marks a critical turning point. It represented a transition for Black Arlingtonians from a quasi-dependent status within a government-administered settlement to a model of self-determined, institution-led community building. The leadership to found Queen City came not from federal administrators, but from a local Black church. This shift in agency, from residents in a government village to landowners and town-builders, was a necessary adaptation for survival in the increasingly hostile environment of Jim Crow Virginia.

A Divided Society: Life Under a New Constitution

The decade of 1900-1909 was the period when racial segregation in Alexandria County transformed from a set of social customs into a rigid, legally mandated system. This change was cemented by a new state constitution and manifested in every aspect of daily life, from education to recreation.

In 1902, the Commonwealth of Virginia adopted a new state constitution. This document, drafted by an all-white convention, took the existing practices of racial separation and codified them into law, a system that came to be known as Jim Crow. The new laws explicitly mandated segregation in all public spaces. Black and white residents could not attend the same schools, sit together on trains or steamboats, or share public halls and theaters. The constitution also outlawed interracial marriage, making it a felony.

With this legal framework in place, inequality was woven into the fabric of the county. The public school system was strictly segregated and profoundly unequal. In 1900, Alexandria County opened the Mount Vernon School to educate white children up to the eighth grade. For the 1909-1910 school year, it had a principal and four teachers. In contrast, the schools for Black children, such as the Snowden and Hallowell schools, were chronically underfunded by the white-run school board and allowed to fall into disrepair.

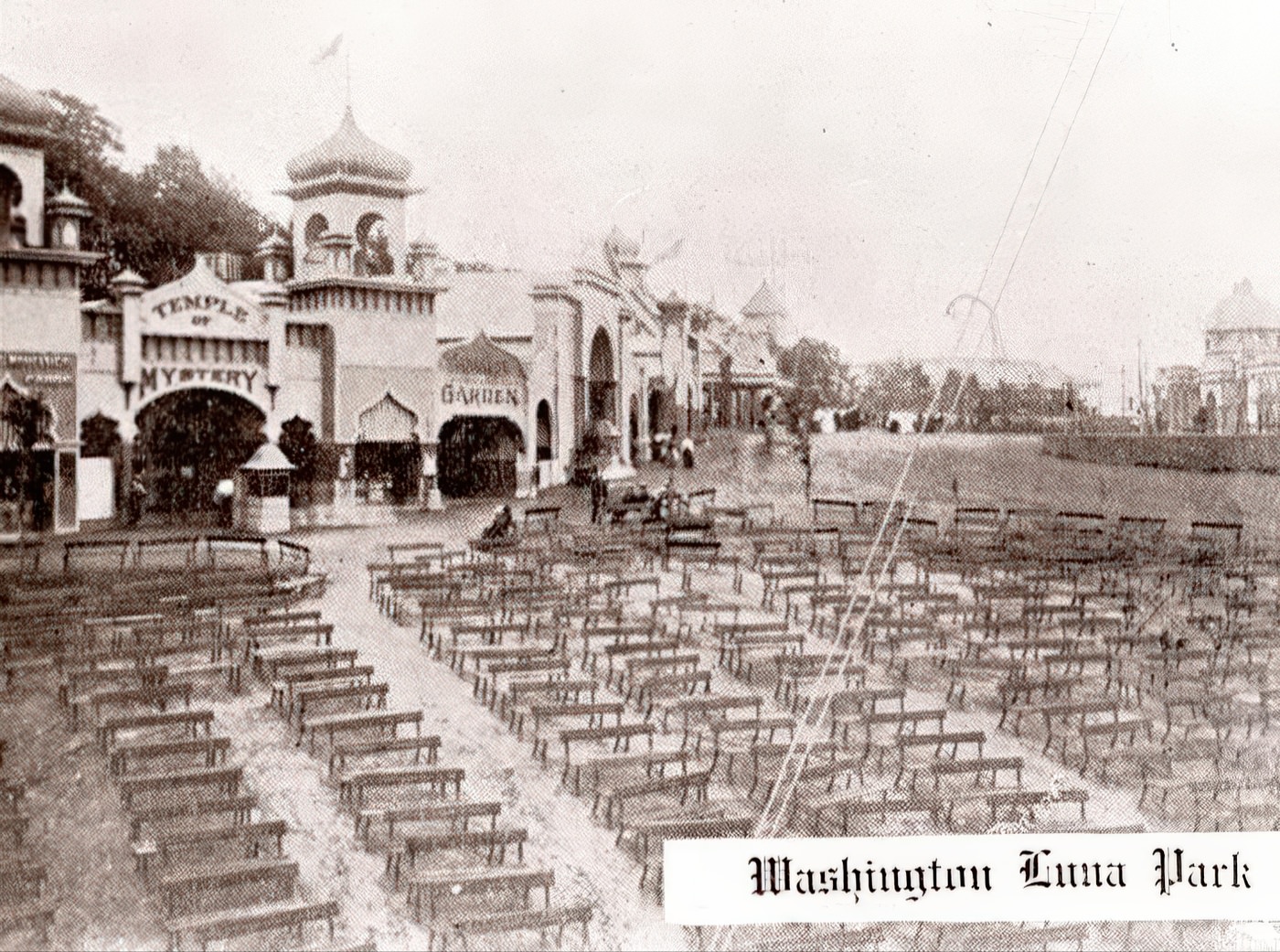

Leisure and recreation were also divided by race. In 1906, Luna Park, a modern amusement park, opened along Four Mile Run. It was a popular “trolley park,” easily accessible from Washington and Alexandria, and featured a roller coaster, a ballroom, a “shoot the chutes” water ride, and a moving picture theater. It was also a formally segregated facility, open only to white patrons. In response to being excluded from such venues, Black communities created their own recreational opportunities. Community-based sports were central to social life. Baseball was especially popular, and the Nauck neighborhood was home to the

Black Sox, a semi-professional African American baseball team that toured and played throughout the East Coast.

This period was not just one of social separation; it was the period of the systematization of that separation. The 1902 Constitution provided the legal justification, and the disenfranchisement of Black voters removed the political means of resistance. With this framework established, other forms of segregation became entrenched. New infrastructure like Luna Park could be built with the legal certainty that it could exclude 38% of the county’s population. New schools for white children could be funded while Black schools were neglected, with no political recourse for the affected families. The decade represents the codification of a racial hierarchy, where the informal barriers of the late 19th century were replaced with the legal, political, and economic walls of the 20th-century Jim Crow era.

The Business of the County: Farms, Government, and Innovation

The economy of Alexandria County in the 1900s was a blend of traditional agriculture and the growing, modernizing influence of the federal government. This dual economy shaped the county’s landscape and created new social dynamics that fueled its suburban transformation.

At its heart, the county was still an agricultural community. Dairy farming was a primary local industry, with several prominent operations supplying milk and butter to the region. The George Crossman farm, located in what is now East Falls Church, was well-established by 1901 and was recognized for its herd of top-producing cows. Another key dairy was Reevesland, operated by the Reeves family, which would eventually become the last working dairy farm in Arlington. Alongside the dairies, market gardens were common. Families like the Birches cultivated large tracts of land, growing crops like wheat, corn, and potatoes for local sale.

While farming defined the local landscape, the most powerful economic force was the federal government in Washington, D.C. A growing number of county residents were commuters, holding stable, merit-based jobs in the federal civil service. This trend provided economic opportunity for both white and Black residents and was the primary driver of population growth.

The federal government also established a direct physical and scientific presence in the county. In 1900, the U.S. Department of Agriculture opened the Arlington Experimental Farm on a 400-acre tract of the old Arlington estate near the Potomac River. This was not a typical farm but a state-of-the-art research facility. Scientists there conducted experiments on fertilization, irrigation, and crop development. The farm had its own laboratories, greenhouses, and a central heating plant. One of its notable research programs involved the cultivation of hemp, where botanists like Lyster Dewey developed new, improved varieties such as the “Kymington” and “Chington” cultivars. The facility also experimented with growing roses and maintained a garden of medicinal plants.

The county thus operated under a dual economy: a traditional, land-based agricultural economy and a modern, salary-based commuter economy. This economic divide fueled the very development that was reshaping the county. The influx of federal workers created a powerful demand for new housing, which was met by developers building subdivisions along the new trolley lines. This new suburban growth, driven by the commuter economy, began to encroach upon the land of the agricultural economy, as farms were sold and subdivided into housing lots. The economic story of the decade is one of a fundamental transition, where the wealth and social status derived from the new commuter economy began to eclipse that of the old agricultural economy, physically and socially remaking the county in the process.

The Engine of Change: Trolleys and Transportation

The primary catalyst for the transformation of Alexandria County during the 1900s was the expansion of the electric streetcar system. This network of interurban trolleys was the engine that began to turn the rural county into a collection of modern suburbs, physically and economically linking its scattered settlements to each other and to the job center of Washington, D.C..

The dominant operator at the turn of the century was the Washington, Arlington, and Falls Church Railway (WA&FC), whose lines, like the Fairfax line established in 1896, provided reliable commuter access into the capital. This new accessibility directly fueled a suburban boom. Between 1900 and 1910 alone, developers filed plats for seventy new subdivisions in the county’s deed books, all seeking to capitalize on the convenience offered by the trolley lines. The transportation network continued to grow throughout the decade. In 1908, the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad was formed, adding another passenger rail option. The opening of the grand Union Station in Washington in 1907 further spurred regional rail growth, making the Virginia suburbs more attractive than ever.

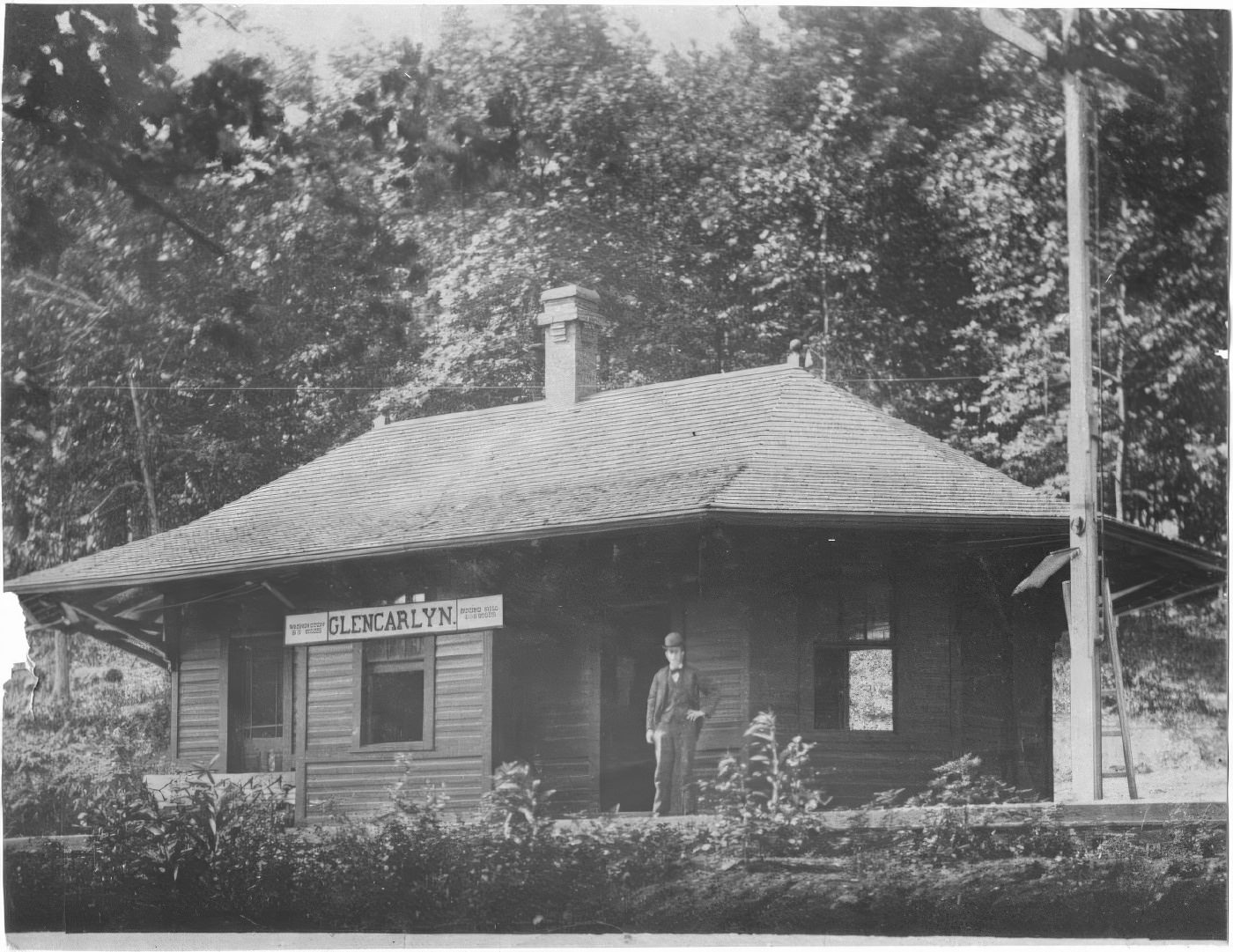

Key trolley stations became the nuclei around which new community life grew. The Rosslyn Terminal was a major commuter core connecting lines from Virginia and the District. Lacey Station served the growing community of Ballston, while Hunter Station provided a vital connection for the African American community of Butler-Holmes, later called Penrose.

This new infrastructure, however, was not a neutral force of progress. The trolley system became an active agent of social and economic segregation, physically laying the tracks for the county’s emerging racial divisions. The routes were strategically planned to serve new, exclusively white subdivisions, which were often founded with racially restrictive covenants written into their deeds to prohibit African Americans from buying property. The primary purpose of this massive infrastructure investment was to facilitate the growth of a white commuter class traveling to federal jobs in Washington. While a few stops existed near Black neighborhoods, the overall pattern of development shows that county amenities like paved roads, water lines, and sewer systems followed the trolleys into these new white communities, while established Black enclaves were systematically neglected. The trolley lines, therefore, did more than just move people; they created economic value along corridors where developers built segregated housing, embedding a pattern of racial and economic inequality into the very landscape of the county.

The first decade of the 20th century was a period of rapid and foundational change for Alexandria County. A series of key events, from the creation of new communities and institutions to the arrival of new technologies, set the course for the county’s future.

| 1900 | Freedman’s Village is permanently closed by the federal government. |

| 1900 | The streetcar suburb of Clarendon is established. |

| 1900 | The U.S. Department of Agriculture opens the Arlington Experimental Farm. |

| 1900 | Mount Vernon School opens for white students. |

| 1902 | Virginia passes a new state constitution, legalizing racial segregation. |

| 1904 | Commonwealth’s Attorney Crandal Mackey begins his raids on Rosslyn’s vice district. |

| 1906 | The segregated amusement park, Luna Park, opens. |

| 1907 | Washington’s Union Station opens, boosting regional rail travel. |

| 1908 | The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad is formed. |

| 1908 | The Town of Potomac (Del Ray and St. Elmo) is incorporated. |

| 1909 | Orville Wright conducts a demonstration flight for the U.S. Army from Fort Myer. |

The decade opened in 1900 with a cluster of foundational events that encapsulated the county’s conflicting forces. The federal government’s closure of Freedman’s Village displaced a large and historic Black community, forcing its residents to seek new homes and build new institutions. In the same year, the village of Clarendon was established, becoming the prototype for the new, planned, and segregated white streetcar suburb. The federal government further solidified its presence by opening the Arlington Experimental Farm, bringing agricultural science and federal resources to the rural county. The segregated school system also expanded with the opening of the Mount Vernon School for white children.

The legal landscape of Virginia was permanently altered in 1902 with the passage of a new state constitution. This document formally mandated racial segregation in all public spheres and implemented measures like poll taxes that effectively disenfranchised most Black voters, cementing a system of white political control.

A dramatic push for social reform began in 1904 when the newly elected Commonwealth’s Attorney, Crandal Mackey, launched his famous raids on the saloons and gambling dens of Rosslyn. His actions aimed to replace the neighborhood’s lawless reputation with one of civic order and respectability.

New forms of transportation and leisure arrived mid-decade. In 1906, the whites-only Luna Park opened, offering modern amusements like a roller coaster and a moving picture theater to a growing suburban population. The suburbanization trend was formalized in

1908 with the incorporation of the Town of Potomac, which consolidated the communities of Del Ray and St. Elmo. That same year, the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad was formed, adding to the expanding transit network that was making the county an increasingly popular place to live.

The decade ended with a remarkable glimpse of the technological future. On a flight that began and ended in Alexandria County, Orville Wright demonstrated his “flying machine” to the U.S. Army in 1909. He flew from the parade ground at Fort Myer to Shuter’s Hill in Alexandria and back, a feat that signaled the dawn of military aviation and marked another historic first for the rapidly changing county.