At the dawn of the 1910s, the area known as Alexandria County was a place of rolling hillsides, dotted with small rural villages and working farms. Officially, it was Alexandria County, Virginia, a name it retained after being returned to the state from the District of Columbia in 1847. This name created persistent confusion with the adjacent, and entirely separate, City of Alexandria. This shared identity was not just a matter of semantics; it was the source of a political struggle that would define the county’s path throughout the decade. The county was a place caught between its agricultural past and an encroaching suburban future, its identity shaped by the powerful gravitational pulls of Washington, D.C., and its older Virginian namesake.

he City of Alexandria viewed the county’s growing suburban communities as its natural territory for expansion. New residential areas like Rosemont, though located on county land, were functionally dependent on the city for their survival. They relied on Alexandria for essential services, including fire and police protection, as well as for their supply of gas, water, and electricity. This dependency became the city’s primary justification for annexation. The control over this vital infrastructure was a powerful political tool, allowing the city to argue that these suburbanites were already its residents in all but name. The county’s inability to provide these modern services made its borders vulnerable, demonstrating that in this new era of development, the lines for water and power were becoming more significant than the lines on a map.

This tension came to a head in 1912 when a lawsuit was filed in the Circuit Court for Alexandria County to block the city’s formal plan to annex a large swath of county territory, including the prosperous suburb of Rosemont. The economic stakes were high; the land in question had an assessed value of nearly $1 million, but residents and county officials asserted its actual value was closer to $5 million. Despite the legal challenge, the city’s efforts ultimately succeeded. In 1915, the City of Alexandria officially annexed 866 acres from the county, incorporating the neighborhoods of Braddock and Rosemont into its domain.

The 1915 annexation was a significant loss of land and tax revenue, but it also served as a powerful catalyst. It forced the county to confront its ambiguous identity and assert its independence. No longer willing to be a passive resource for the city to consume, county leaders began to forge a distinct political path. By December 1915, they were formally considering a bold legal maneuver: incorporating the entire county as a new, independent city. This move was designed with the specific purpose of creating a legal barrier that would prevent the City of Alexandria from annexing any more of its territory. This reaction marked a conscious political break. The conflict over land and resources solidified the county’s trajectory away from Alexandria City and toward its future as a suburb of Washington, D.C. This process would culminate in 1920 with the official renaming of the county to Arlington, a final severing of the tie to its old identity.

The Growth of Streetcar Suburbs

The primary engine of change in Alexandria County during the 1910s was the electric railway system. The network of trolleys was the county’s lifeline, connecting its fields and fledgling neighborhoods to the federal jobs of Washington, D.C., and making the dream of suburban life a practical reality for thousands. This decade saw the transportation infrastructure mature, which in turn fueled a calculated and aggressive expansion of residential development.

In 1913, the two main trolley operators, the Washington, Arlington & Falls Church Railway and the Washington, Alexandria and Mount Vernon Railway, merged their operations to form the new Washington-Virginia Railway. This consolidation created a more powerful and unified network, streamlining travel and making the county an even more attractive option for commuters looking to escape the crowded capital. The relationship between the railway and real estate was symbiotic; the trolley lines created the commuter corridors, and the existence of these corridors created a booming market for developers. The success of one directly fueled the other, transforming the county’s landscape according to a private-sector blueprint for growth.

At the heart of this new suburban world was Clarendon. The convergence of trolley lines at this crossroads boosted its growth, quickly establishing it as the county’s commercial and social hub—its unofficial “downtown”. The community modernized at a rapid pace. In 1913, gas, water, and electricity were made available to all residents. Just a year later, in 1914, Clarendon became one of the first communities in the nation to adopt formal zoning regulations, a clear sign of its transition from a simple village to a planned suburban center. This rapid growth also fostered a new form of civic life. The Clarendon Citizens Association was formed in 1912, providing a political voice for residents and a mechanism to manage the needs of their growing community. One of its first acts was to organize a volunteer firefighting force in 1909, a direct response to the practical challenges of a denser, more urban environment. The creation of such organizations marked a pivotal shift from a collection of disconnected rural settlements to organized suburban communities demanding order and services.

As the decade closed, this model of transit-oriented development reached its apex with the birth of Lyon Park. In 1919, developer Frank Lyon’s firm, Lyon & Fitch, subdivided a massive 300-acre tract of land, launching what was, at the time, the largest real estate development in Virginia’s history. The marketing for this new neighborhood was aimed squarely at Washington commuters. A 1919 promotional pamphlet highlighted modern amenities like paved roads, sidewalks, and complete water and sewer infrastructure. It promised a life of suburban convenience, boasting that “the iceman, the laundry man, and the mailman call at each home”. Lots with 50-foot frontages were sold for between $350 and $500. The neighborhood’s proximity to the railway was a key selling point, as it made it easy for builders to receive and construct mail-order home kits from companies like Sears & Roebuck, further accelerating the transformation of farmland into residential streets.

A Segregated Community

Life in Alexandria County in the 1910s was governed by a rigid system of racial segregation. This was not a matter of custom alone; it was the law of the land. The 1902 Virginia Constitution had codified Jim Crow, creating a legal framework for a society of “separate but equal” that was, in practice, a system of deliberate and sustained inequality. This legal structure mandated separate schools, separate seats on trolleys and trains, and separate public spaces. It outlawed interracial marriage, classifying it as a felony. Crucially, it implemented poll taxes and literacy tests designed to disenfranchise the vast majority of Black voters, effectively silencing their political voice and leaving them with little power to challenge the discriminatory treatment they faced.

Despite these oppressive conditions, the county’s African American population built and sustained vibrant, self-sufficient communities. Neighborhoods like Nauck, also known as Green Valley, had roots stretching back to before the Civil War and saw their populations grow as families relocated from the recently closed Freedman’s Village. Hall’s Hill, the oldest enclave in Northern Virginia founded by newly freed slaves, was another tight-knit community with its own businesses, schools, and social structures. The systemic exclusion from the white economy and society forced these communities to develop powerful internal networks of support. This segregation was not just about separation; it was an active political strategy of resource deprivation that, in turn, fostered an intense, resilient, and necessarily isolated society-within-a-society.

At the heart of these communities were the Black churches. They served not only as places of worship but as the primary centers for social life, community organizing, and leadership. Mount Zion Baptist Church, the oldest African American church in the county, was a vital institution. Its leaders in the 1910s were men who embodied the community’s need for both spiritual and practical guidance. Rev. Frank W. Graham, who served as pastor from 1908 to 1914, was also a federal clerk at the U.S. Department of the Treasury. His successor, Rev. James E. Green (1914-1950), was a building contractor before he was called to the ministry. This bivocational leadership was a direct result of the segregated system. In a community denied access to mainstream power structures, its leaders had to be deeply embedded in its economic and social fabric, providing skills and stability that went far beyond the pulpit.

Nowhere was the injustice of the segregated system more apparent than in public education. While the county invested in new facilities for its white students, it practiced a policy of deliberate neglect toward its Black schools. By 1911, the two schools for African American children—the Snowden School for boys (also called Seaton) and the Hallowell School for girls—were in a state of dangerous disrepair. The county superintendent’s official report for the 1910-1911 school year noted the “very bad condition” of the classrooms, but his request for repairs was ignored.

The situation reached a crisis point on March 27, 1915, when the Seaton school was completely destroyed by a fire. Students were forced to attend classes in temporary spaces, including a local Sunday school building. In the fire’s aftermath, community leaders like principals John Parker and Henry White carefully approached the superintendent to advocate for a new school, taking pains to assure him they were not “agitators”. They received permission to raise funds for a new building, but with the strict condition that they solicit donations only from “their own people.” The Black community responded, raising $4,000. When the new, consolidated Parker-Gray School finally opened in 1920, the city failed to provide basic furnishings. The money raised by the community was used to buy everything from desks and chairs to books and a typewriter. This entire episode reveals how neglect was an active policy, designed to shift the burden of public education onto the Black community itself.

Daily Life, Work, and Recreation

Everyday life in Alexandria County during the 1910s reflected a community in transition. The landscape was a patchwork of competing land uses, where the fading agricultural world coexisted with the rising suburban one. While the economy was shifting decisively toward Washington, D.C., the rhythms of rural life had not yet disappeared.

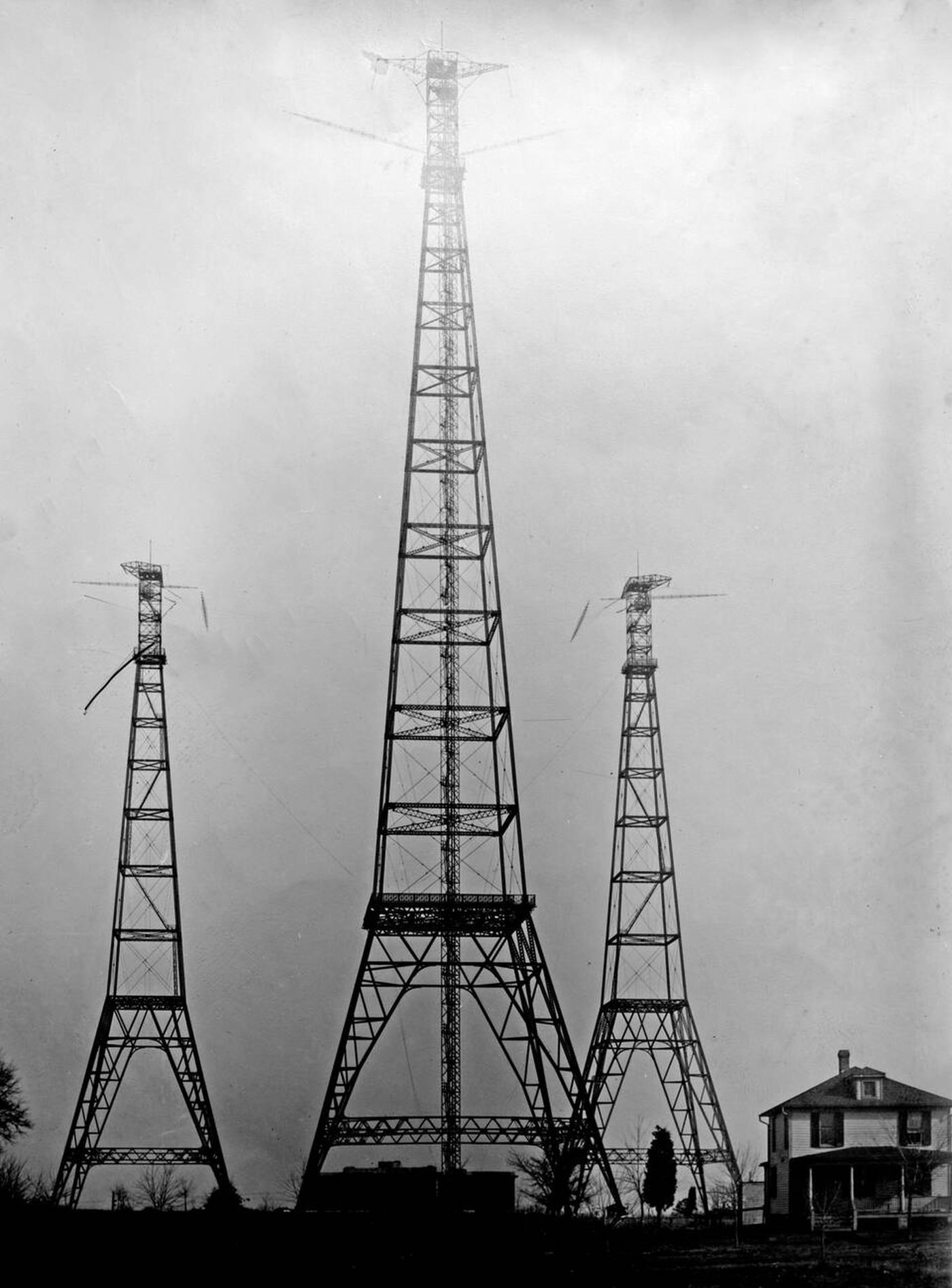

Dairy farming remained a visible and important part of the local economy. Well-established farms, such as the George Crossman farm in East Falls Church and the Reevesland farm operated by the Reeves family, were successful enterprises. They supplied fresh milk and butterfat both to their immediate neighbors and to larger regional distributors like the Maryland and Virginia Milk Producers Association. These farms represented the “old” economy, a remnant of the county’s rural past. At the same time, a unique federal agricultural presence existed at the Arlington Experimental Farm. Established by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1900, this 400-acre facility was a major center for plant science research. During the 1910s, its projects included extensive work on hemp cultivation. USDA researcher Lyster Dewey developed new, highly productive hemp cultivars at the farm, including varieties named “Chington” and “Kymington,” which grew up to 10 feet tall and were widely adopted by farmers in Kentucky.

The dominant economic force of the decade, however, was the “new” economy, driven by the expansion of the federal government. The primary source of employment for the county’s growing population was work in the federal civil service or military in Washington, D.C.. This trend turned Alexandria County into a quintessential commuter suburb. The eventual fate of the county’s agricultural lands—subdivided to make way for housing, schools, and highways—shows which economic model would ultimately triumph. The 1910s were the critical decade where this contest for the future of the land was visibly playing out.

To serve the families of this new federal workforce, the county expanded its public school system for white children. In September 1910, the Clarendon School opened its doors. It was a modern, two-story brick building that stood in stark contrast to the facilities provided for Black students. With seven teachers and an initial enrollment of 298 students in grades one through six, it replaced the previous makeshift school, which consisted of two rooms rented in a local teacher’s home.

For leisure and entertainment, the county’s premier destination was Luna Park. Opened in 1906, it was a 34-acre amusement park located along Four Mile Run, near the present-day intersection of South Glebe Road and South Eads Street. As a “trolley park,” it was a thoroughly modern invention, designed to be accessed via the electric streetcar lines that fed the suburbs. The railway even offered a special discounted round-trip fare of fifteen cents to entice visitors from Washington and Alexandria. The park’s brochures described it as an “architectural fashion plate” and a “Fairyland of Amusement,” offering a host of attractions. These included a figure-eight roller coaster, a “shoot the chutes” water slide, a grand ballroom, a circus arena, a moving picture theater, and picnic grounds large enough for 3,000 people. This new, commercialized form of public recreation, however, was built upon the era’s social hierarchy. Luna Park was a formally segregated space, and African American residents were barred from entry. This shows that as the county modernized, so too did its methods of racial exclusion; new technologies and forms of commerce were adapted to reinforce the Jim Crow social order. The park’s reign as the county’s top attraction was brief. On April 15, 1915, sparks from a fire in the adjacent woods drifted over and ignited the park’s signature wooden roller coaster. With its main ride destroyed, the park was dismantled later that year, bringing an end to a unique chapter in the county’s social history.

The Decade of Upheaval

The latter half of the 1910s was defined by two global crises that profoundly reshaped Alexandria County. World War I and the 1918 influenza pandemic were not distant events; they were powerful forces that accelerated the county’s transformation, altered its demographic makeup, and tested the resilience of its new suburban communities.

World War I acted as the great accelerator of the county’s development. While the shift from a rural to a suburban economy was already underway, the war supercharged this process, making it sudden and irreversible. The region became a critical hub for the nation’s war effort. Fort Myer was transformed into a major staging and training ground for a large number of Army units, including engineering, artillery, and chemical regiments. To prepare American soldiers for the realities of the Western Front, French officers were brought to the fort to conduct training in a specially constructed system of trenches. The war also triggered a massive expansion of the government. Between 1916 and 1918, the federal workforce in the Washington, D.C., area tripled in size. This created an unprecedented and immediate demand for housing that the capital could not meet. The result was a demographic explosion in the Virginia suburbs. From 1910 to 1920, the population of Alexandria County surged by 60 percent, a rate of growth that permanently sealed its economic destiny as a community inextricably linked to the federal government.

Close on the heels of the war came a second, more insidious crisis. In the autumn of 1918, the influenza pandemic, often called the “Spanish Flu,” swept across Virginia. The virus spread to the civilian population directly from the crowded military camps that were driving the county’s growth; the very engine of prosperity had become a vector for disease. This strain of influenza was unusually lethal, striking hardest not at the very young or old, but at healthy adults between the ages of 20 and 40—the exact demographic of the soldiers and new federal workers flooding the region. The toll was immense. More American military personnel died from influenza and other diseases during the war than were killed by enemy weapons. At Camp A. A. Humphreys (now Fort Belvoir), just south of the county, the death rate at the epidemic’s peak reached an average of 56 soldiers per day.

The public health response was drastic and disruptive. As reported in the Alexandria Gazette, local authorities ordered the closure of all public gathering places in an effort to slow the contagion. Schools, churches, stores, and movie theaters were all shut down. This response was a direct assault on the new civic and social structures that were just beginning to define the suburban communities. The pandemic acted as a stress test, revealing the fragility of this new way of life. The increased population density and reliance on commuter transit had created public health vulnerabilities that did not exist in the more isolated rural era. By the time the pandemic subsided in 1919, it had claimed the lives of at least 16,000 Virginians, leaving a deep scar on the communities it had ravaged.

Image Credits: Image Credits: Library of Congress, wikimedia, Arlignton Public Library, Flickr

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know