The 1920s marked a pivotal decade for Arlington, Virginia. This period saw the area transform from a largely rural landscape into a distinct and growing community, laying the groundwork for the modern Arlington known today. Major shifts in its identity, population, and physical structure defined these ten years, alongside significant social and cultural developments.

Arlington’s New Beginning: The Roaring Twenties

The 1920s brought a crucial change for Arlington, as it officially became a separate county in 1920, no longer simply a part of larger areas like Alexandria or Fairfax. This marked a significant step in establishing its own unique identity. The name “Arlington” was chosen that same year, taking its name from the historic Custis-Lee estate, a decision made to avoid confusion with the nearby City of Alexandria.

A Virginia Supreme Court ruling in 1922 further solidified Arlington’s unique status. The court declared Arlington a “continuous, contiguous and homogeneous community,” meaning it could not be divided or taken over by neighboring areas. This legal decision was foundational, shaping Arlington’s future development by ensuring all growth and planning occurred within a single county framework. This approach likely led to more centralized planning efforts, such as the land-use and zoning ordinances adopted later in the decade , and a unified approach to public services. This made Arlington distinct from many other counties that contain separate towns or cities, cementing its position as the smallest self-governing county in the U.S. without any incorporated towns or cities within its borders.

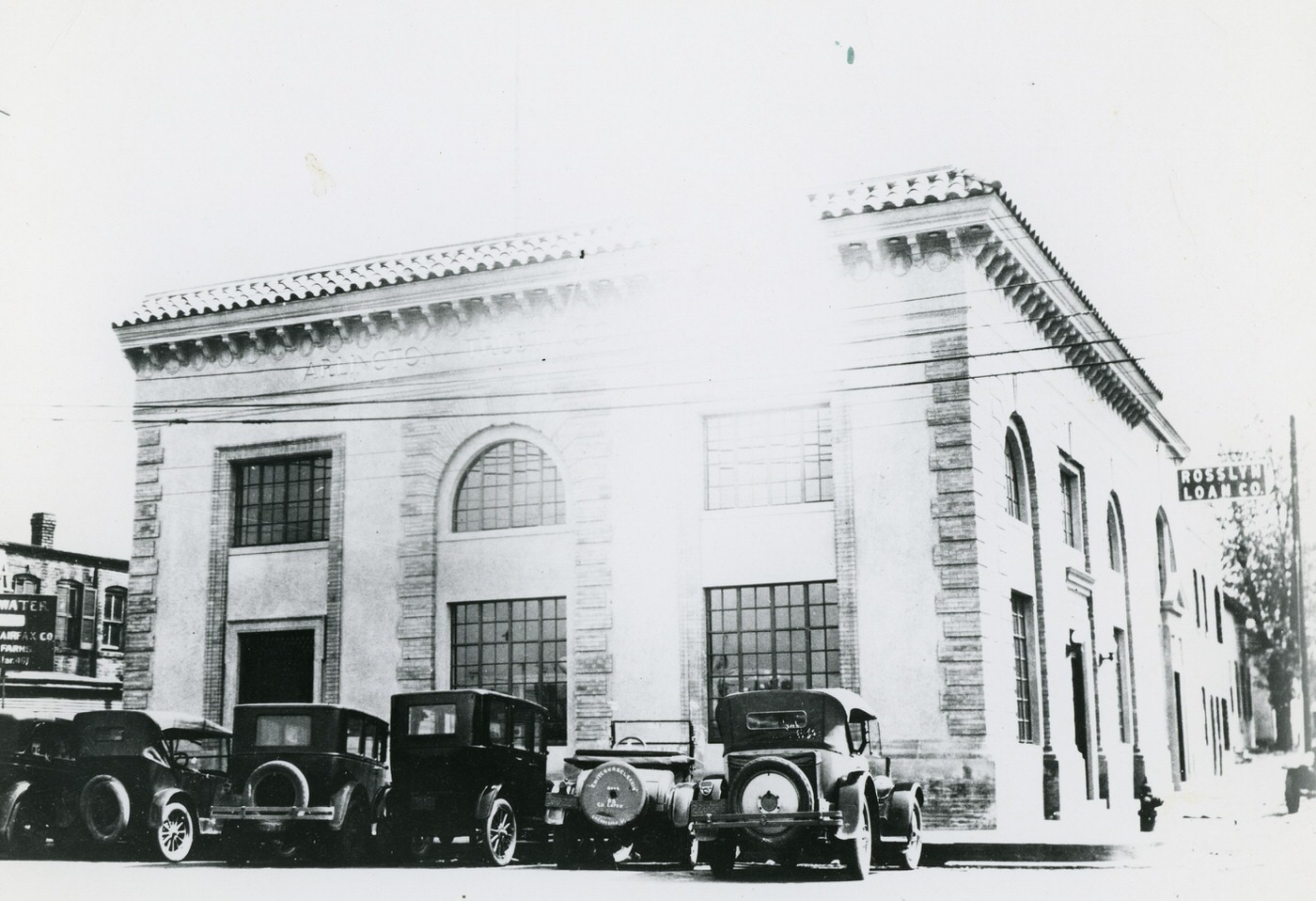

At the start of the 1920s, Arlington was primarily rural, characterized by farmlands and dairies. However, important centers for transportation and business began to emerge in areas like Clarendon and Rosslyn. Arlington’s population experienced rapid growth during this time, increasing by 40% between 1920 and 1930. This followed an earlier surge of 60% between 1910 and 1920. This expansion was largely driven by the federal government’s workforce, which tripled during World War I, leading to a housing shortage in Washington D.C.. As a result, many people looked to nearby suburbs like Arlington for places to live. The expansion of the federal government directly caused housing shortages in D.C., which in turn prompted people to move to Arlington, resulting in its rapid population increase. This established a long-term pattern where Arlington’s future became deeply connected to the federal government’s presence, explaining its swift transformation from a rural area to a residential one, and why government employment became a dominant occupation.

Who Lived in Arlington?

In 1920, Arlington was home to approximately 13,812 residents. When combined with the Alexandria area, the overall population reached 16,040. The average age of Arlington residents was relatively young, at 26.9 years. Most people living in Arlington were born in the United States. Those who were born in other countries primarily came from England, Germany, Russia, Canada, and Ireland.

The average household in Arlington had 4.24 people, which was more than double the average household size seen today. Most homes were family households, meaning everyone living there was related. World War I, which had recently concluded, had a clear impact on families. In 9.5% of households led by a woman, no male was present, and 67% of these female heads of household were widows. This statistic reveals the personal toll of World War I on Arlington’s families, as a significant portion of households were directly affected by the loss of male family members. This led to a higher number of female-headed households, suggesting a societal adaptation where women took on new roles as primary household providers or heads of families. This detail provides a human element to the census data, showing how major global events filtered down to individual homes in Arlington and reshaped daily life.

Population distribution varied across the county. District 10, located in the central-eastern part of Arlington, held over a third (38% or 5,250) of the county’s population. In this district, 90% of residents were white, and the remaining 10% were Black or Mulatto. District 12 had the highest number (232) and percentage (10.8%) of residents identified as Mulatto. This district also had the highest percentage of family households, at 87%.

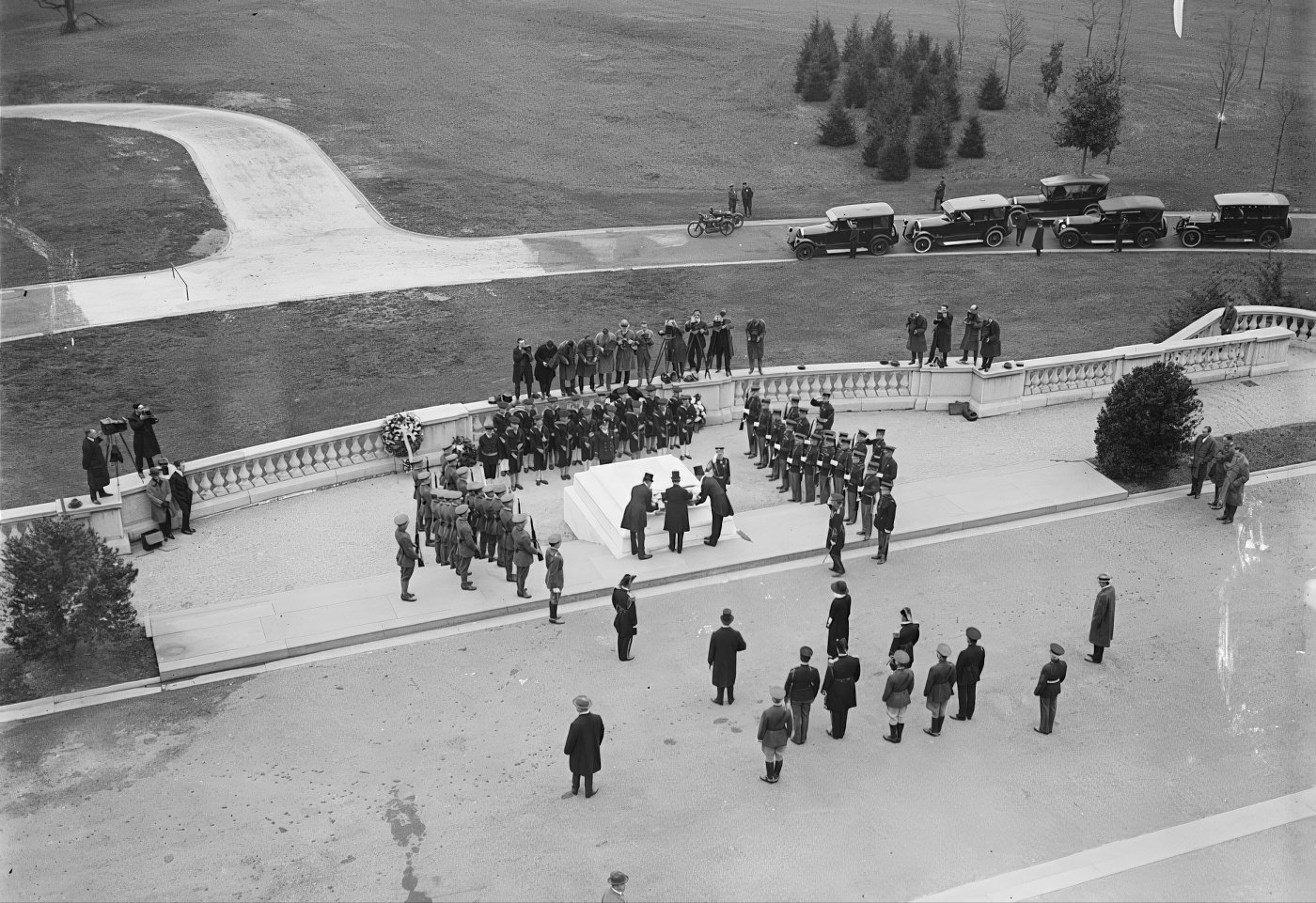

Notable people living in Arlington during this period included General Peyton C. March, who served as the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army and resided at Fort Myer. Sergeant Frank Witchey, another resident, famously played Taps at the burial of the Unknown Soldier on November 11, 1921.

Building a Modern Community

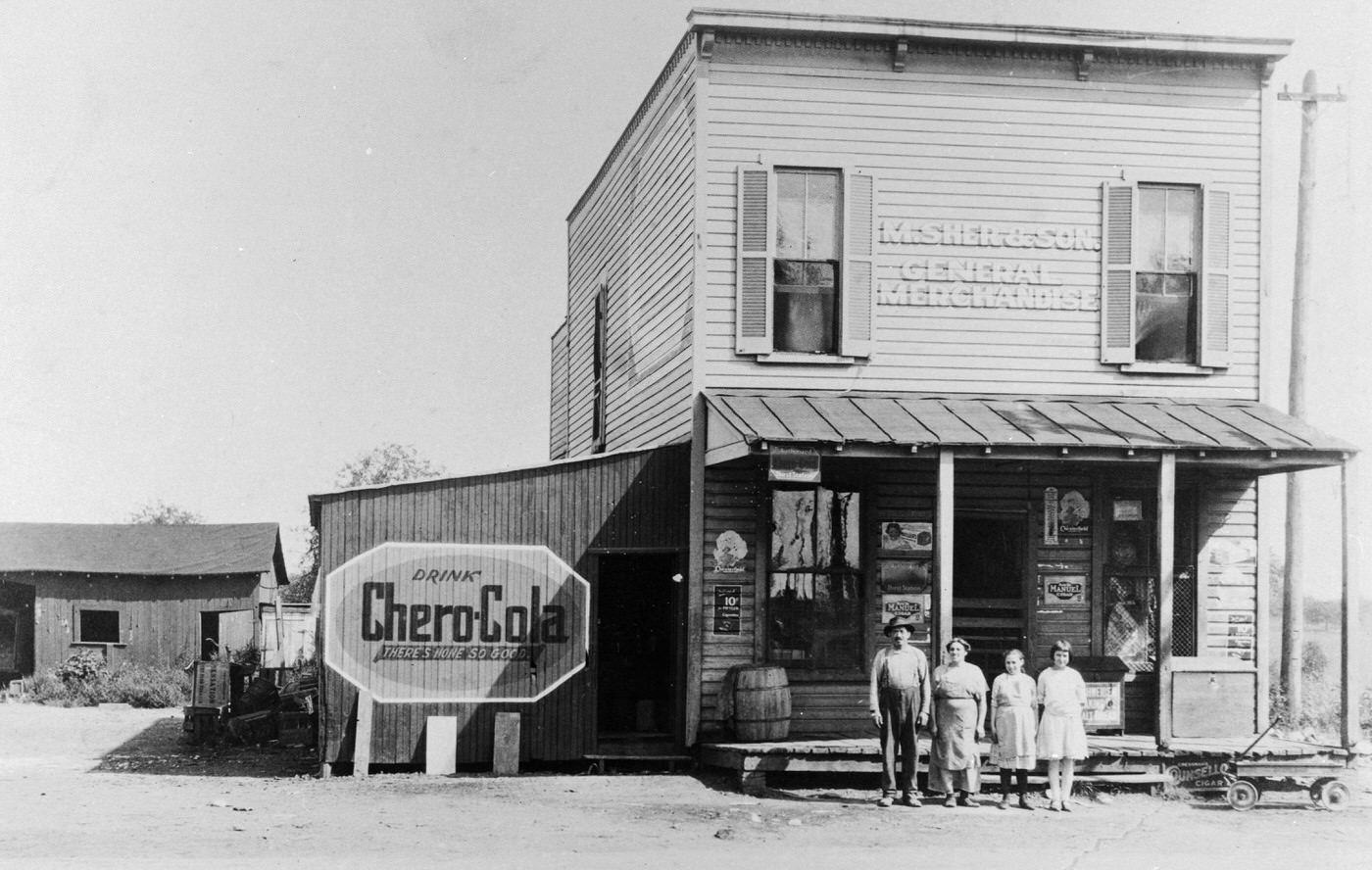

Before World War I, Arlington was characterized by rolling hillsides dotted with small, rural villages. Local leaders and real estate investors actively sought to transform Arlington from a rural area into a residential community. They emphasized factors like crime reduction and the improvement of roads, railways, and public water and sewer systems as key selling points to attract new residents. The number of families moving to Arlington grew as new subdivisions were built to house them. Early examples of these developments included Lyon Park, Lyon Village, Ashton Heights, and Livingstone Heights.

The Barcroft community had already established a business center by 1905, which included a general store and a blacksmith shop. However, the Barcroft Mill, which was once the largest mill on the eastern seaboard, was destroyed by fire in the 1920s. The emphasis on “crime reduction” and “moral order” alongside infrastructure development reveals a deliberate strategy by civic leaders to attract a specific type of resident, likely middle-class families seeking a “respectable” suburban life. This was not just about building houses; it was about shaping the county’s social character and reputation. The transformation from its earlier nickname, “Monte Carlo of the East,” to a desirable suburb was a conscious effort, with real estate development acting as a tool for social engineering and rebranding. This shows a deeper societal aspiration intertwined with economic development.

Laying the Groundwork: Roads and Planning

Arlington’s first formal planning efforts began in 1927 with the adoption of a land-use ordinance, a set of rules for how land could be used. This was followed by a zoning ordinance in 1930, designed to guide development and prevent different types of land uses from clashing. The county’s population growth relied heavily on better transportation routes, allowing commuters to easily cross the Potomac River into Washington D.C.. Building good roads, electric railroads, and trolleys helped attract families to live in Arlington, with new neighborhoods often built along these transportation lines.

Key transportation links were established or improved during this decade. The Key Bridge, which connected Arlington to D.C., was completed in 1923, replacing an older bridge. Other bridges like the 14th Street Bridge and the Chain Bridge also linked Arlington to the District. In 1922, the U.S. government decided to build the Arlington Memorial Bridge. This bridge was planned to connect the Lincoln Memorial to Arlington House and Arlington National Cemetery, serving as a physical and symbolic link between the North and South, representing national reunion after the Civil War. A federal parkway was also built during this time to connect Washington D.C. to Mount Vernon. The development of these bridges and transportation links directly facilitated daily commuting, making Arlington a viable and attractive residential area for federal workers. The planning of the Arlington Memorial Bridge, specifically designed to link the North (Lincoln Memorial) and South (Arlington House/Cemetery) as a symbol of reunion, demonstrates that infrastructure projects in Arlington were not just about practical commuting; they also carried significant national symbolic weight in the post-Civil War era. This elevates Arlington’s infrastructure development beyond local needs to a stage of national reconciliation and strategic urban planning.

Uneven Access to Modern Conveniences

Real estate developers assured potential residents that living in Arlington offered the same modern conveniences as city living, especially access to water and sewer lines. Initially, developers paid for and installed private water meters and sewer lines. Later, county taxes and government grants also helped fund these improvements.

However, while newer subdivisions included plans for modern amenities in their deeds, many older areas, particularly African American communities, continued to rely on well water and septic systems. This uneven development allowed real estate investors to buy “undeveloped” land in African American areas at lower prices. They could then use their connections to secure county services for these properties, significantly increasing their value. While civic leaders promoted “modern amenities” as a selling point for Arlington’s residential appeal, the information shows that this “modernity” was not equally distributed. The uneven access to water and sewer lines was not accidental; it was a consequence of discriminatory real estate practices. Investors exploited the lack of infrastructure in African American communities to acquire land at lower prices, then leveraged their social and political connections to secure county services, thereby increasing the value of their holdings, not necessarily benefiting the original residents equitably. This reveals a systemic issue where infrastructure development, instead of being a universal public good, became a mechanism for reinforcing racial segregation and generating wealth for a select few at the expense of marginalized communities.

Work and Innovation in Arlington

The 1920s saw a clear picture of employment in Arlington. Most working residents were employed by the U.S. Army or the U.S. Government. This confirms Arlington’s fundamental economic identity as a government suburb, not an industrial or agricultural hub. This reliance on federal employment meant its economic stability and growth were directly tied to the expansion or contraction of government agencies. This pattern, established in the 1920s, continued to define Arlington’s economy for decades, making it less susceptible to the industrial downturns seen elsewhere in Virginia and more resilient to broader economic shifts due to the consistent demand for federal workers.

In District 12, a specific area of Arlington, the top five jobs included Clerk, Laborer, Mechanic, Carpenter, and Electrician. Julia Rhinehart was a notable figure during this period, being one of the first women to enlist in the U.S. military during World War I.

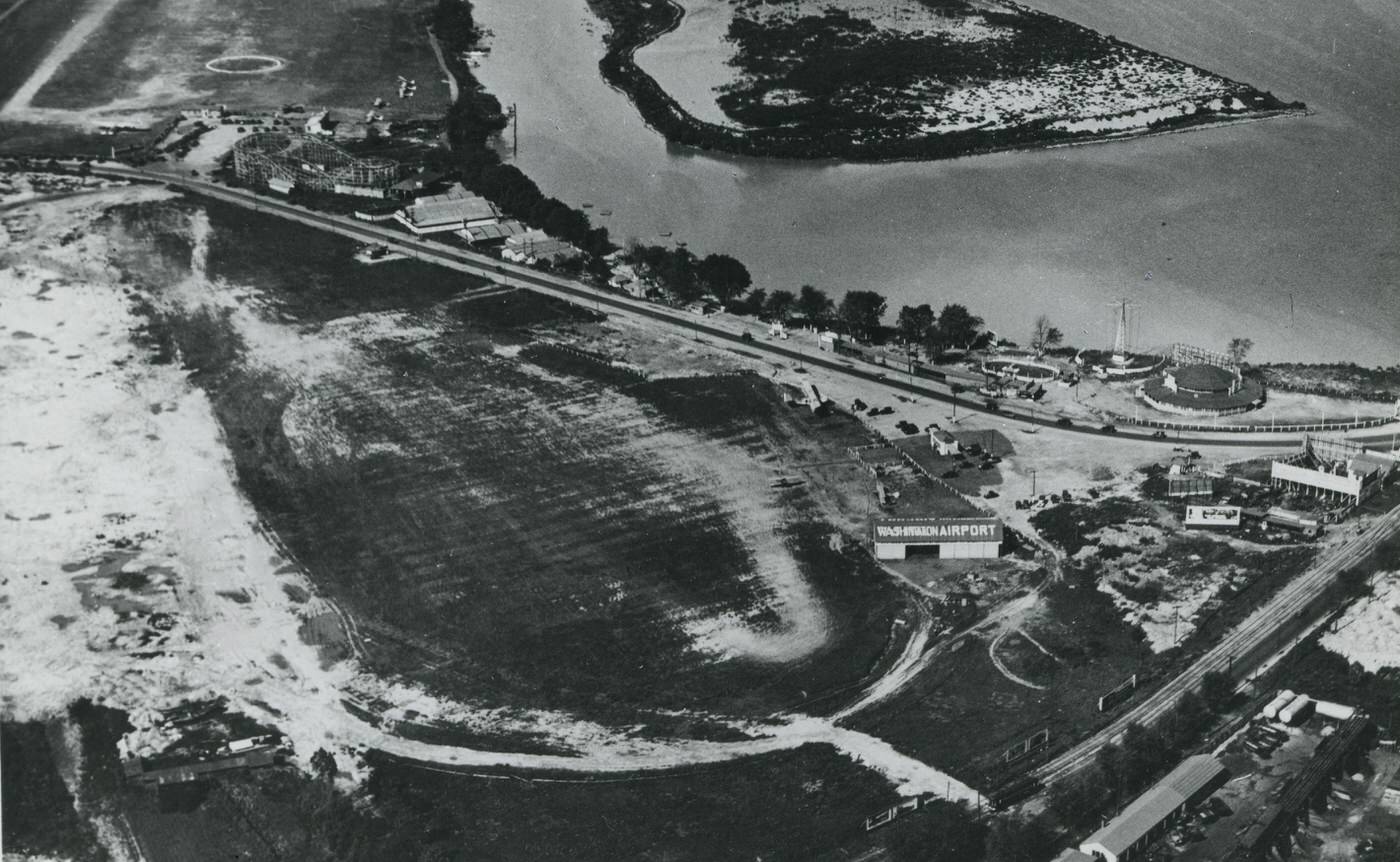

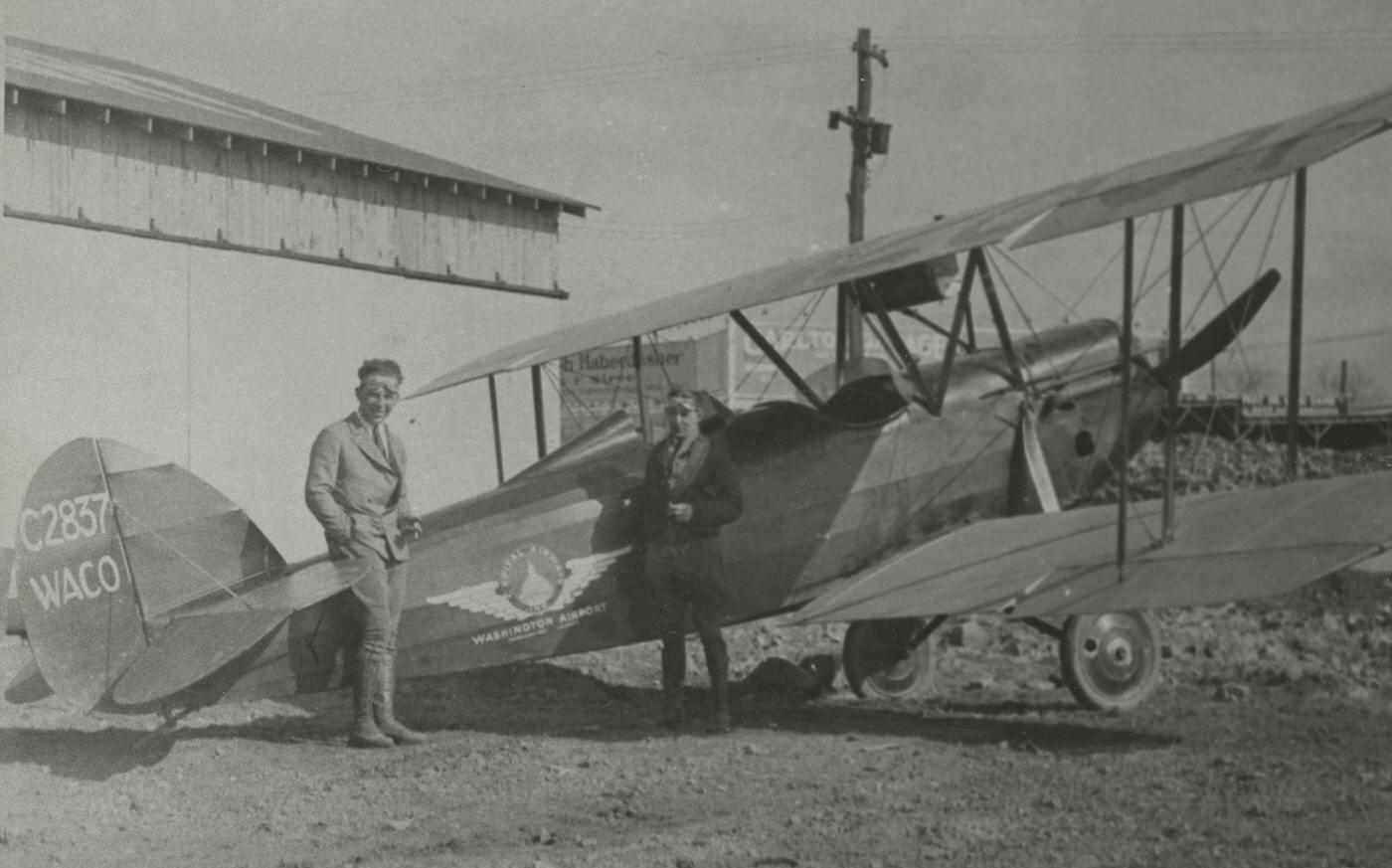

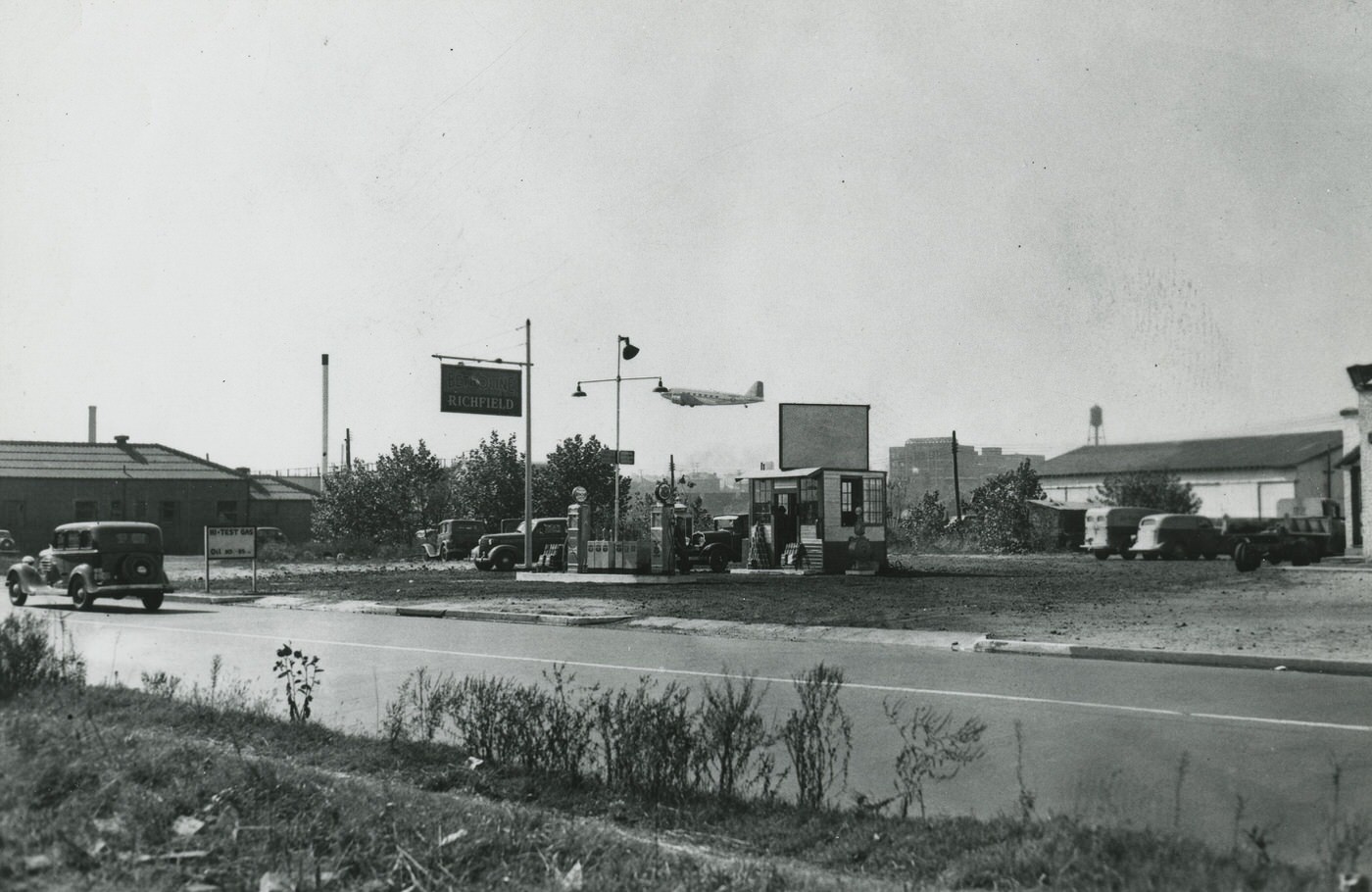

The decade also brought new and innovative businesses to Arlington, reflecting broader national trends. The Potomac Flying Service, for example, started in the spring of 1927. By the end of 1928, it had flown over 25,000 passengers on sightseeing trips over Washington D.C., becoming the largest flying business of its kind. This company offered various aviation services, including air taxi, sightseeing, aerial photography, and flying lessons. Passengers even received certificates confirming their flight.

Henry A. Berliner organized the Potomac Flying Service, with Lowell S. Harding as the general manager. Berliner and other investors bought Hoover Field, which was once a horse racing track with an amusement park, and built a hangar there. The flying service used clever advertising methods, such as sending representatives to hotels and tourist spots, distributing leaflets, encouraging tour guides to mention them, and placing small ads in 500 D.C. taxi cabs.

Beyond aviation, consumer goods also saw innovation. The West Electric Hair Curler Company, which patented a new metal curler in the 1920s, reported that over 50 million of their curlers were in use by 1923. These curlers were first sold to women with long hair and later included directions for bobbed hair. Another example of smart marketing aimed at women was the S&H Green Stamp Sewing Kits, from around 1926, offering a useful item that could make household chores easier. Green Stamps were an early form of retail loyalty program where shoppers collected stamps to exchange for household items and other goods, influencing where people chose to shop. The presence of these diverse businesses demonstrates that Arlington, despite its rural past and federal employment focus, was actively participating in the broader “Roaring Twenties” economic boom. The Potomac Flying Service represents the excitement and commercialization of new technologies like aviation, while the hair curlers and Green Stamps point to the rise of consumer culture, advertising innovation, and a focus on household efficiency and leisure, particularly for women. This shows Arlington was not just a government bedroom community but also a place where modern American consumerism and technological advancements were taking root, making it a dynamic economic environment beyond just federal jobs.

Life and Culture in a Changing County

Arlington households in the 1920s were largely focused on family, with an average of 4.24 people living together. Dr. Corbett, who was the only physician in the area for many years, played a vital role in public health. He helped create the county’s first health department and set strict rules for sanitation, leading efforts to treat contagious diseases. Religious life was also present, with James E. Green serving as a pastor for seven years at Mt. Zion Baptist Church. For African American travelers, Letitia, the second wife of a notable resident, transformed their home into the Fireside Inn, a restaurant and lodging specifically for them.

Community hubs were important. Carlin Hall, built in 1892, served as a central place for the community, functioning as a social center, church, school, and public library. It became a popular community meeting place in the early 1920s. The Cherrydale Volunteer Fire House, built in 1919, was another important community institution. The establishment of institutions like the health department by Dr. Corbett, the multi-purpose use of Carlin Hall, and the creation of the Fireside Inn by Letitia, demonstrate a proactive effort by residents and leaders to create a functional and supportive community environment. This was crucial for integrating the influx of new residents and maintaining social cohesion during a period of significant transition from a rural to a more urbanized setting. It shows both bottom-up and top-down approaches to community development, addressing both basic needs like health and lodging, and fostering social cohesion.

Prohibition and Its Challenges

Before Prohibition, Arlington had earned the nickname “Monte Carlo of Virginia” due to its many gambling halls, brothels, and illegal saloons located along the Potomac River. Virginia’s “blue laws” required businesses to close on Sundays. However, areas like Jackson City and Rosslyn were known for their “Sunday saloons,” which kept their front doors closed but their back doors open for drinkers.

The Arlington Brewing Co. stopped making beer after 1918 when production was banned. It then switched to making a non-alcoholic soft drink called Cherry Smash. With alcohol now illegal, many residents began making their own, like moonshine and “bathtub gin,” at home. As demand for illegal alcohol grew, some started small bootlegging operations. Arlington’s pre-Prohibition reputation meant it already had an established network of illicit activities. When Prohibition was enacted, Arlington’s strategic location, with its bridges connecting directly to D.C., made it an ideal “rum running” corridor. This highlights how geographic proximity to the nation’s capital, combined with existing social patterns, turned Arlington into a key player in the illegal liquor trade.

Arlington became a major route for “rum runners” who smuggled an estimated 22,000 gallons of alcohol into D.C. every week. They used key bridges like the Key Bridge (completed in 1923), the 14th Street Bridge, and the Chain Bridge. To combat this, Sheriff Howard Fields created a special “vice squad” in 1924 to tackle liquor-related crimes, making arrests of both Black and white individuals involved in illegal alcohol activities. By the late 1920s, the public was growing tired of Prohibition, and Arlington’s jail became overcrowded with people arrested for liquor offenses. Some groups, like the Alexandria City–Arlington chapter of a women’s organization, even encouraged women to boycott voting if a party supported repealing Prohibition. The overcrowding of jails and public disenchantment demonstrate the law’s practical failure and the social strain it imposed, revealing a hidden economy and a challenge to law enforcement that defined a significant part of Arlington’s 1920s culture.

Segregation and Community Resilience

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, housing, recreation, and daily life became increasingly segregated by race across Arlington, Virginia, and the Southern states. White recreational facilities were often supported by public and private groups. In response, Arlington’s organized Black community created their own institutions and activities. For example, Arlington had a Bathing Beach along the Potomac River in the 1920s, but it was exclusively for white people. Because of this segregation, Black children had to find other places to swim, like a creek called “Blue Man Junction” near Route 50, which was less safe than the official Bathing Beach.

Black communities organized their own youth and family activities, including sports at parks like Peyton Field in Nauck (formerly Green Valley). This park was home to the semi-professional Black Sox African American baseball team, which toured the East Coast. African American land ownership rates in Arlington were relatively high, increasing from 59% in 1900 to 64% in 1920, which was above the national average. Despite this, African Americans were largely excluded from the new subdivisions being built. Instead, they bought and divided land to create their own communities, such as Green Valley/Nauck, Highview Park/Halls Hill, and Johnson’s Hill/Arlington View.

Real estate practices during this time actively worked to expand racially restricted communities. Black families often had to pay for their land in full before they could build a home, which significantly delayed homeownership for them. This reveals a stark reality: while Arlington was “building a modern community” and attracting new residents, it was simultaneously entrenching racial segregation. The high rate of Black land ownership is a testament to their agency and resilience, but their exclusion from new, developed subdivisions forced them to create their own communities. This was not just accidental segregation; it was a systemic practice driven by real estate policies and broader societal racism.

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) saw a large increase in membership in the early 1920s. This group was against Black people, Catholics, and Jews, and promoted white supremacy. In 1925, tens of thousands of KKK members marched through the streets of Washington D.C.. The creation of separate Black institutions, like Peyton Field, was a direct response to this exclusion, demonstrating self-determination and community-building in the face of discriminatory practices. This shows that the “growth” of Arlington in the 1920s was not a uniform experience for all residents.

Landmarks and Legacies of the Decade

The 1920s witnessed both the loss of old landmarks and the creation of new ones, reflecting Arlington’s ongoing transformation. Fort Myer remained an important military post, home to prominent figures like General Peyton C. March and Sergeant Frank Witchey. The Barcroft Mill, once the largest mill on the eastern seaboard, was destroyed by fire in the 1920s. The destruction of the Barcroft Mill, once the largest on the eastern seaboard, symbolizes the decline of Arlington’s rural-industrial past and its transition away from a mill-based economy.

New structures began to define the changing landscape. Notable local historic districts include the Joseph Fisher Post Office in Clarendon and the Green Valley Pharmacy in Nauck. Community buildings from this era include the Clarendon Citizens Hall (built in 1921) and the Cherrydale Volunteer Fire House (built in 1919). The Brennan House, built in 1920, is listed as a historic house. The Hume School, built in 1891, now serves as the Arlington Historical Museum. The Gulf Branch Nature Center, housed in a fieldstone-and-quartz bungalow from the 1920s, is located on a site that was once a Native American fish camp. The construction of new public buildings like the Clarendon Citizens Hall and Cherrydale Fire House reflects the growth of organized community services and civic life. The 1920s were a period where the physical environment of Arlington was actively being reshaped, with new structures replacing or coexisting with older ones, marking a tangible shift in its identity.

Events of National Significance

Arlington also played a central role in events of national significance during the 1920s. The Lincoln Memorial, a major national monument, was dedicated in 1922, located directly across the Potomac River from Arlington House. In the same year, the U.S. government decided to build the Arlington Memorial Bridge. This bridge was designed to connect the Lincoln Memorial to Arlington House and Arlington National Cemetery, serving as a powerful physical and symbolic link between the North and South, representing national reunion after the Civil War.

In 1925, Congress took action to restore Arlington House to honor Robert E. Lee. However, the U.S. government maintained control, ensuring the focus was on Lee’s efforts to promote peace and reunion after the war, rather than glorifying the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy. The 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcohol (Prohibition), was passed in 1920. On November 11, 1921, the interment of the Unknown Soldier took place at Arlington National Cemetery, a solemn event where Sergeant Frank Witchey played Taps. The clustering of these events and decisions in the 1920s positions Arlington not just as a growing suburb, but as a central stage for national memory and reconciliation after the Civil War. The dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, the deliberate symbolic design of the Arlington Memorial Bridge, and the controlled restoration of Arlington House to emphasize Robert E. Lee’s role in “peace and reunion” all point to a conscious effort by the federal government to use Arlington’s landscape and historical sites to foster national unity. The interment of the Unknown Soldier further cemented Arlington National Cemetery’s role as a sacred national space. This shows Arlington’s identity was dual: a local community growing rapidly, and a national site imbued with profound historical meaning.

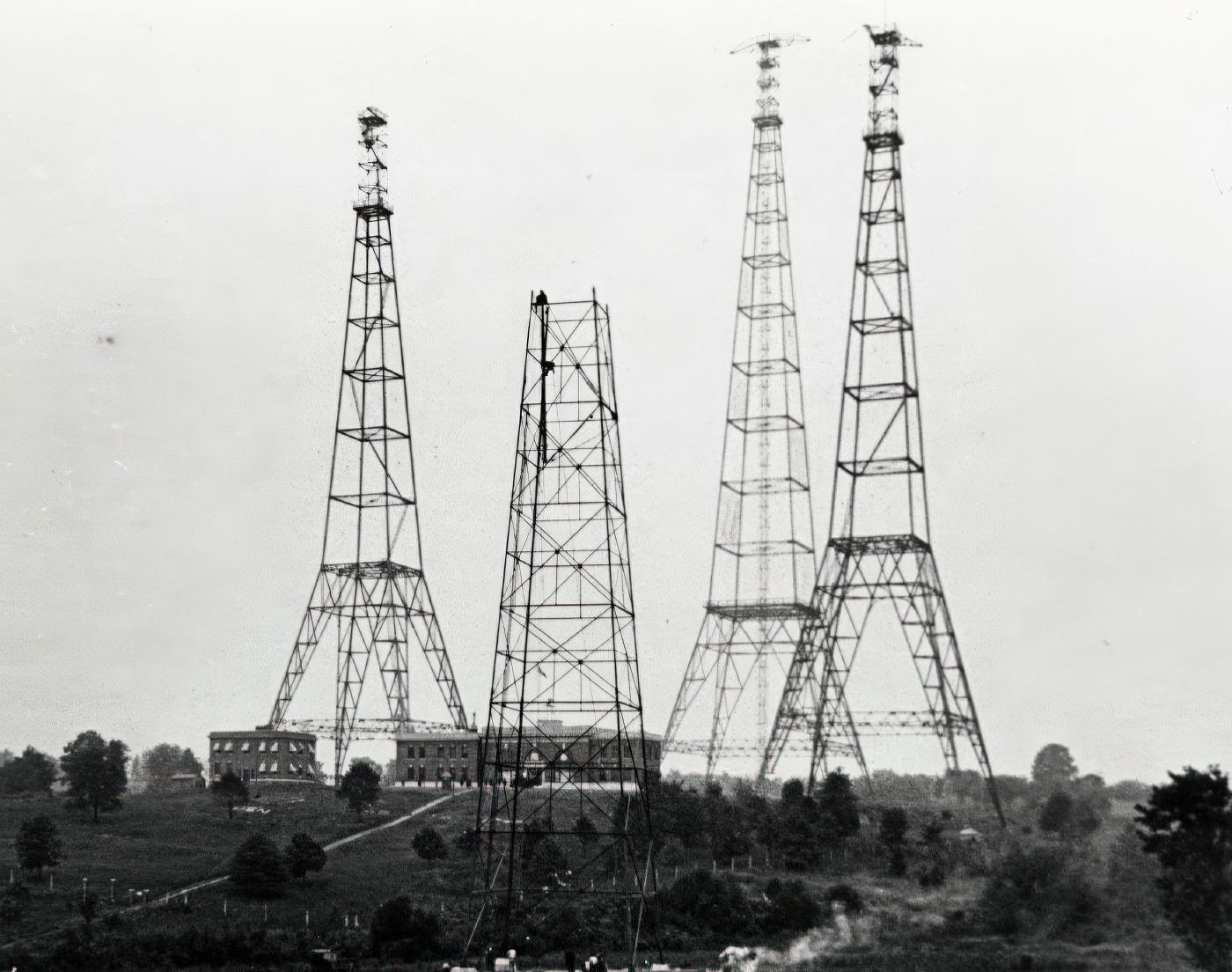

Image Credits: Library of Congress, wikimedia, Arlignton Public Library, Flickr,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know