Arlington, Virginia, held a unique position near Washington D.C. in the 1930s. While the rest of the nation struggled through the Great Depression, Arlington experienced rapid changes and significant growth. This period was crucial in shaping the county into the place it is today, largely due to the expansion of the federal government and the New Deal programs. It was a time when Arlington’s future began to truly take shape.

A Growing Population and New Homes

In the 1930s, Arlington saw a remarkable increase in its population. The number of residents nearly doubled, growing from 26,615 in 1930 to 57,040 by 1940. This significant growth was mainly driven by federal workers moving into the area. The federal government expanded greatly during the New Deal era, creating many new jobs, and also in preparation for World War II. People working for the government looked for homes outside of Washington D.C., and Arlington became a popular choice.

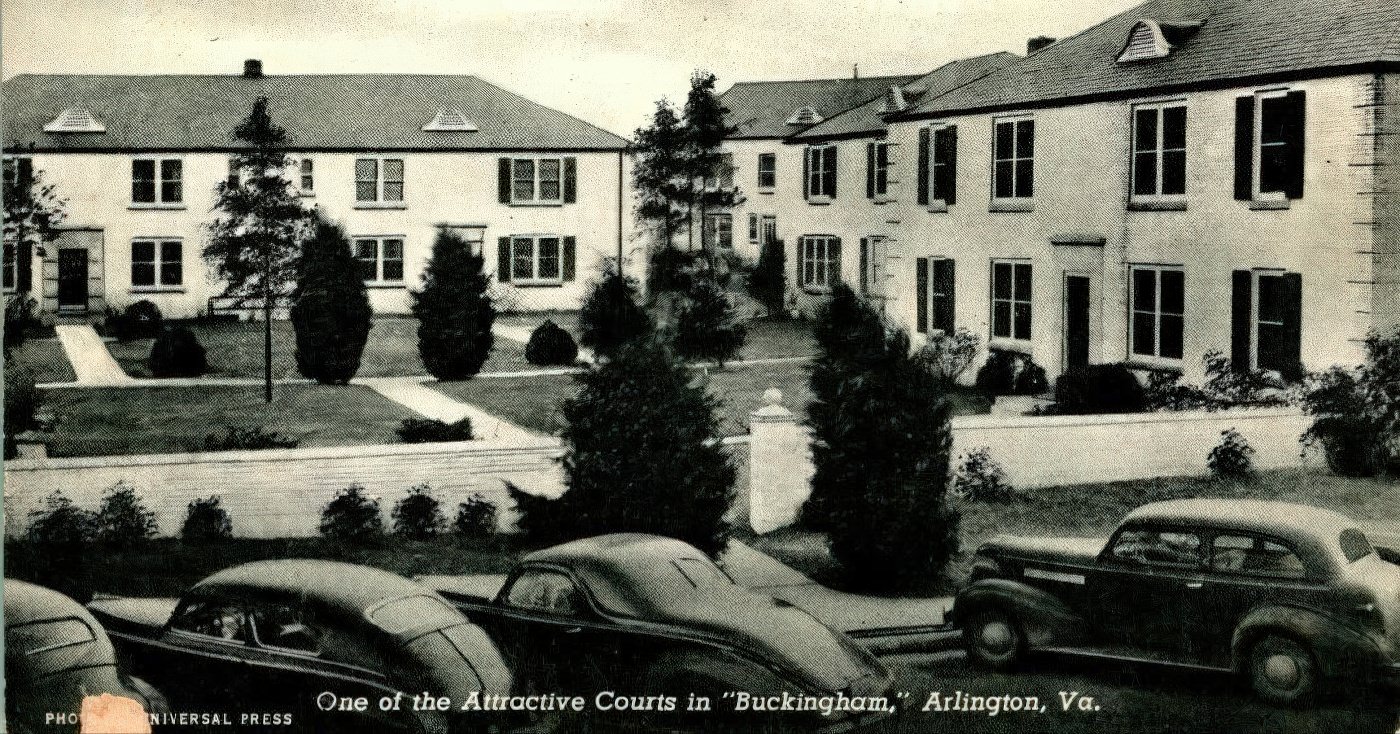

The Great Depression generally slowed down new home construction across the country. However, Arlington was different. While the nation faced widespread economic hardship and stalled residential development, Arlington experienced a population boom. This growth was not typical for the time but was a direct result of the federal government expanding its workforce, especially through New Deal programs designed to combat the Depression. This unique situation set Arlington apart from most other places in the country and laid the groundwork for its future as a key federal suburb. The large number of incoming government employees created a strong demand for housing, which pushed for new building projects. Public housing projects, like Colonial Village, were built with financial support from the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to help house this expanding population.

Building Modern Infrastructure

New Deal programs, especially the Public Works Administration (PWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA), played a crucial role in improving Arlington’s infrastructure during the 1930s. These programs provided much-needed jobs and funding for major public projects across the county. These federal programs did more than just create temporary jobs; they brought fundamental upgrades to Arlington’s basic services and physical layout.

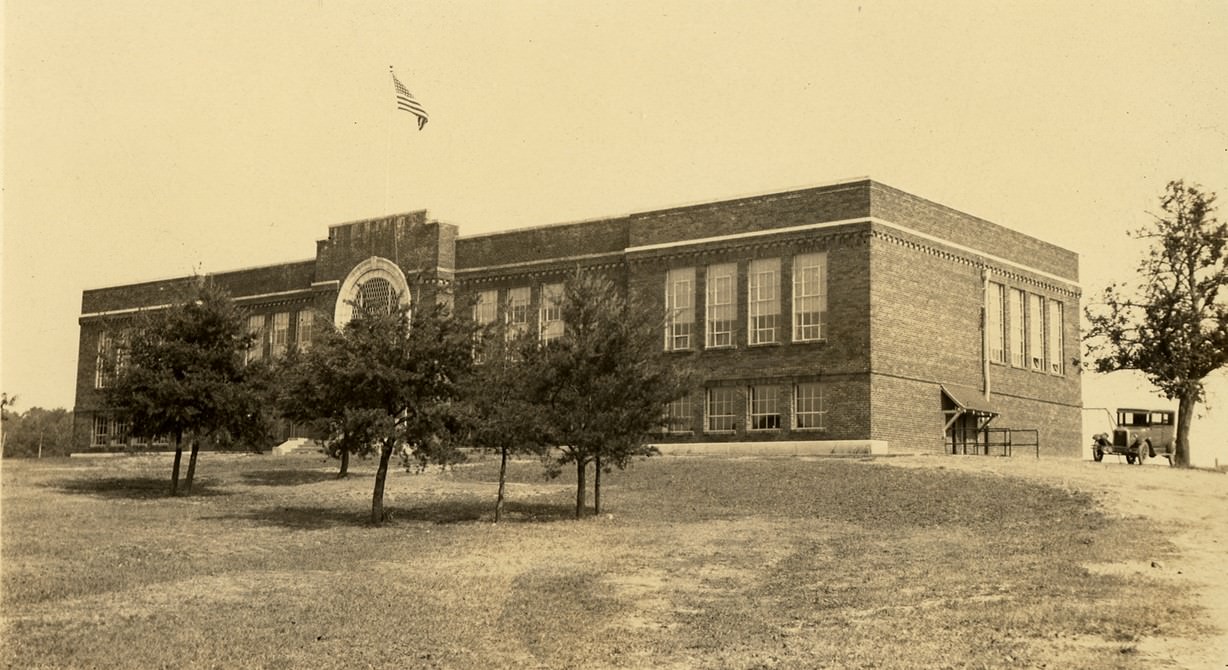

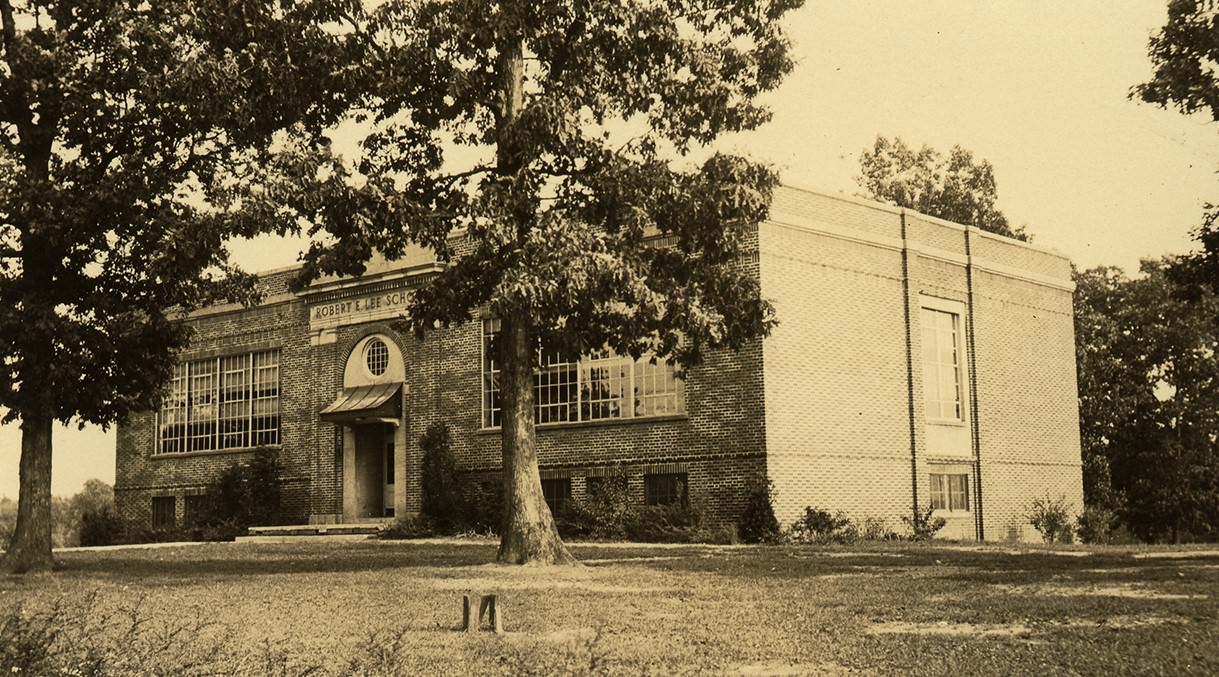

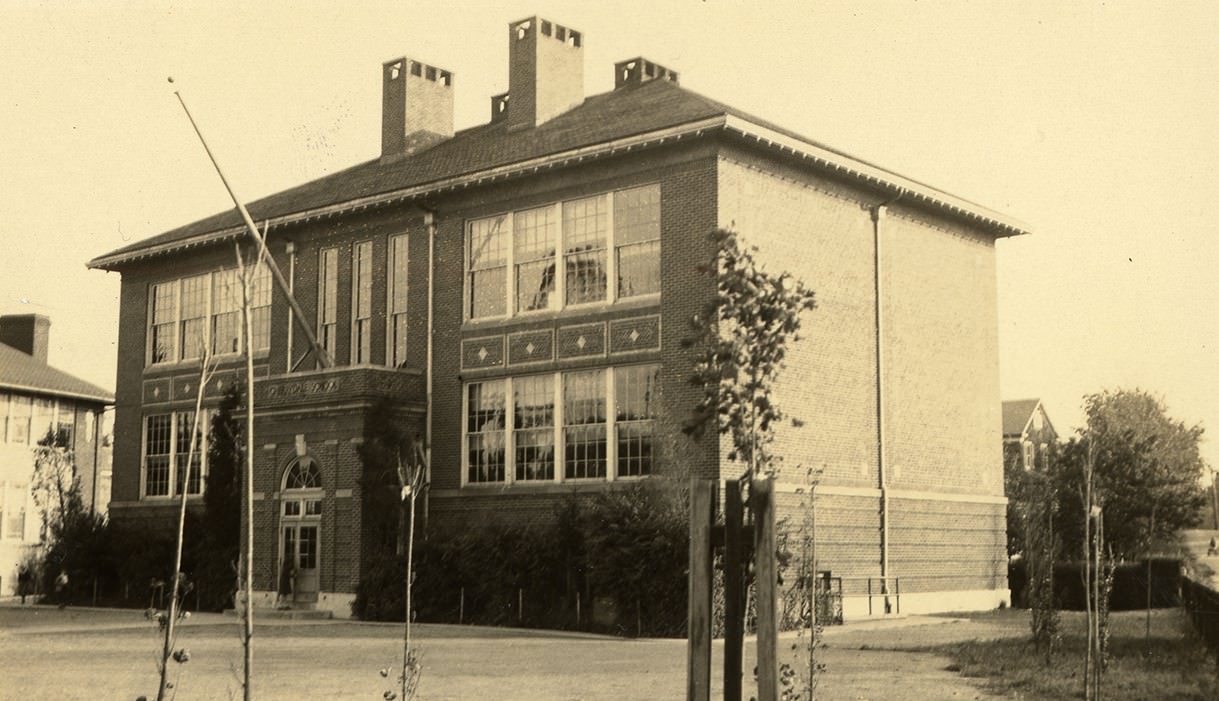

A significant achievement was the completion of an overhauled sewer system in 1937. This brought modern sanitation to more areas of the county, a vital improvement for public health. Local public schools also received important renovations, improving educational facilities for the growing number of children. The extensive sewer system and improved schools meant the county could support its rapidly growing population and transition from a rural area into a modern suburb. This level of development would have been difficult for the county to achieve on its own, showing how national efforts during the Depression significantly shaped Arlington’s physical landscape and public services.

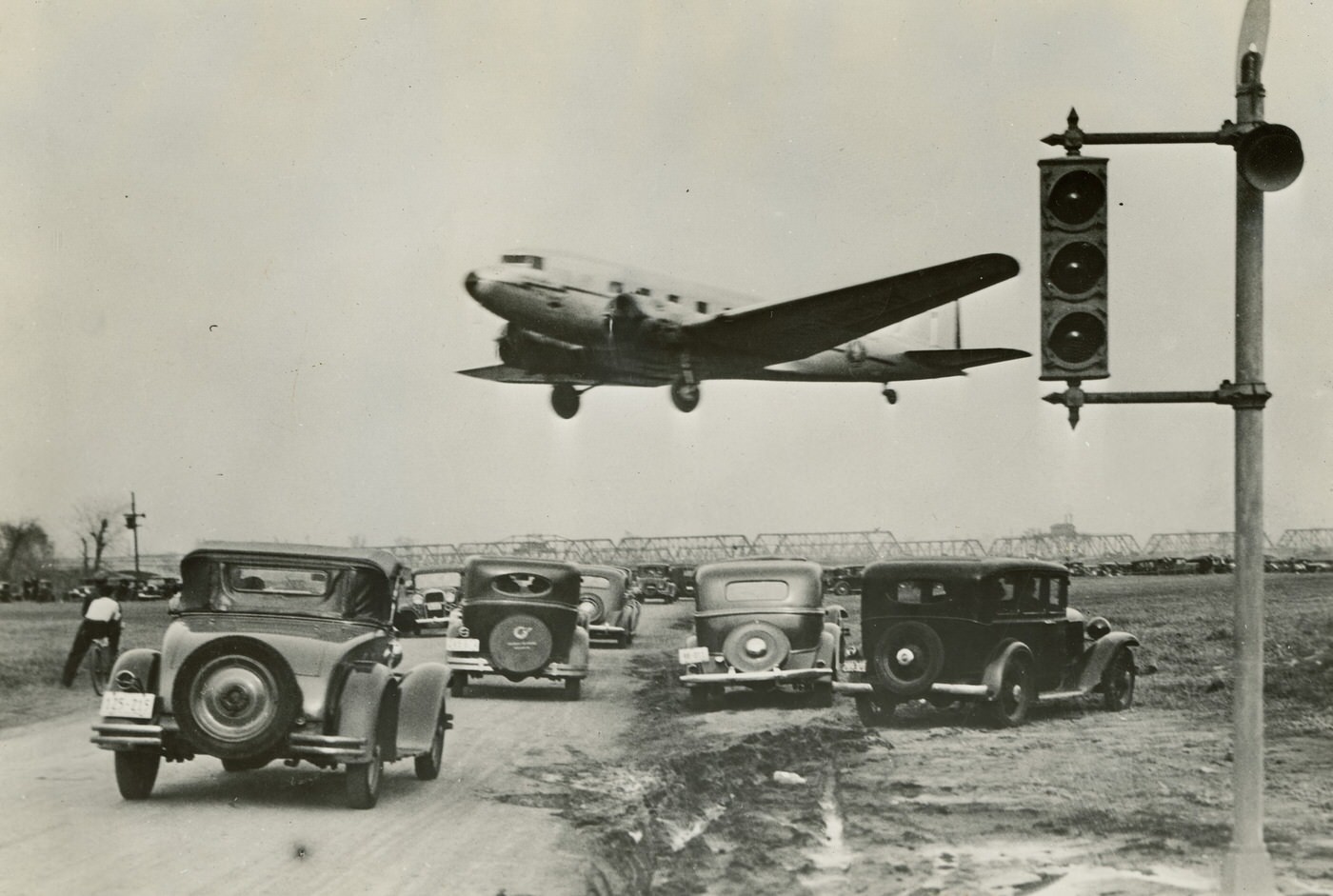

The 1930s also brought big changes to how people traveled in Arlington. As more people bought cars, the older trolley lines that had served the county began to close down. A public bus system replaced them, marking a move towards more modern and flexible transportation options. The move from fixed trolley lines to more flexible bus routes, combined with the completion of major roads like the Arlington Memorial Bridge approaches, clearly showed Arlington becoming more urban. This made it easier for people to commute by car, further connecting Arlington with Washington D.C. This adaptation of transportation infrastructure to the growing popularity of personal vehicles reinforced Arlington’s role as a commuter suburb of the nation’s capital.

Connecting Arlington to Washington D.C. was a major undertaking. The Arlington Memorial Bridge, a symbol of national unity, opened in 1932. However, building the roads leading to and from the bridge on the Virginia side was a complex project that lasted 16 years. This involved long debates between county and state officials, challenges in acquiring land, and discussions over different proposed routes like Lee Boulevard (which later became Arlington Boulevard, also known as Route 50). Federal funding from the New Deal helped push these projects forward, with the first main connection to the bridge opening in October 1938.

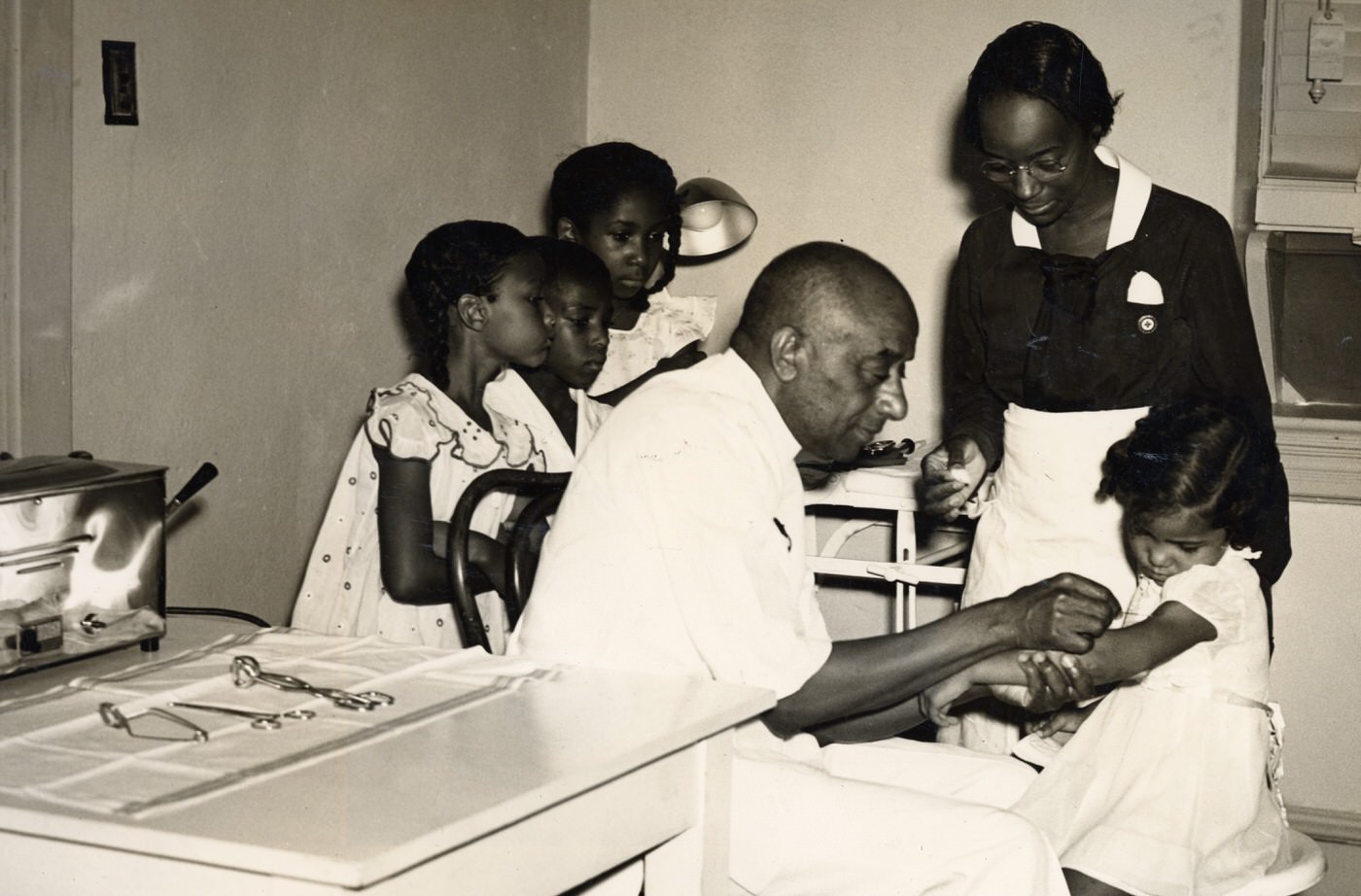

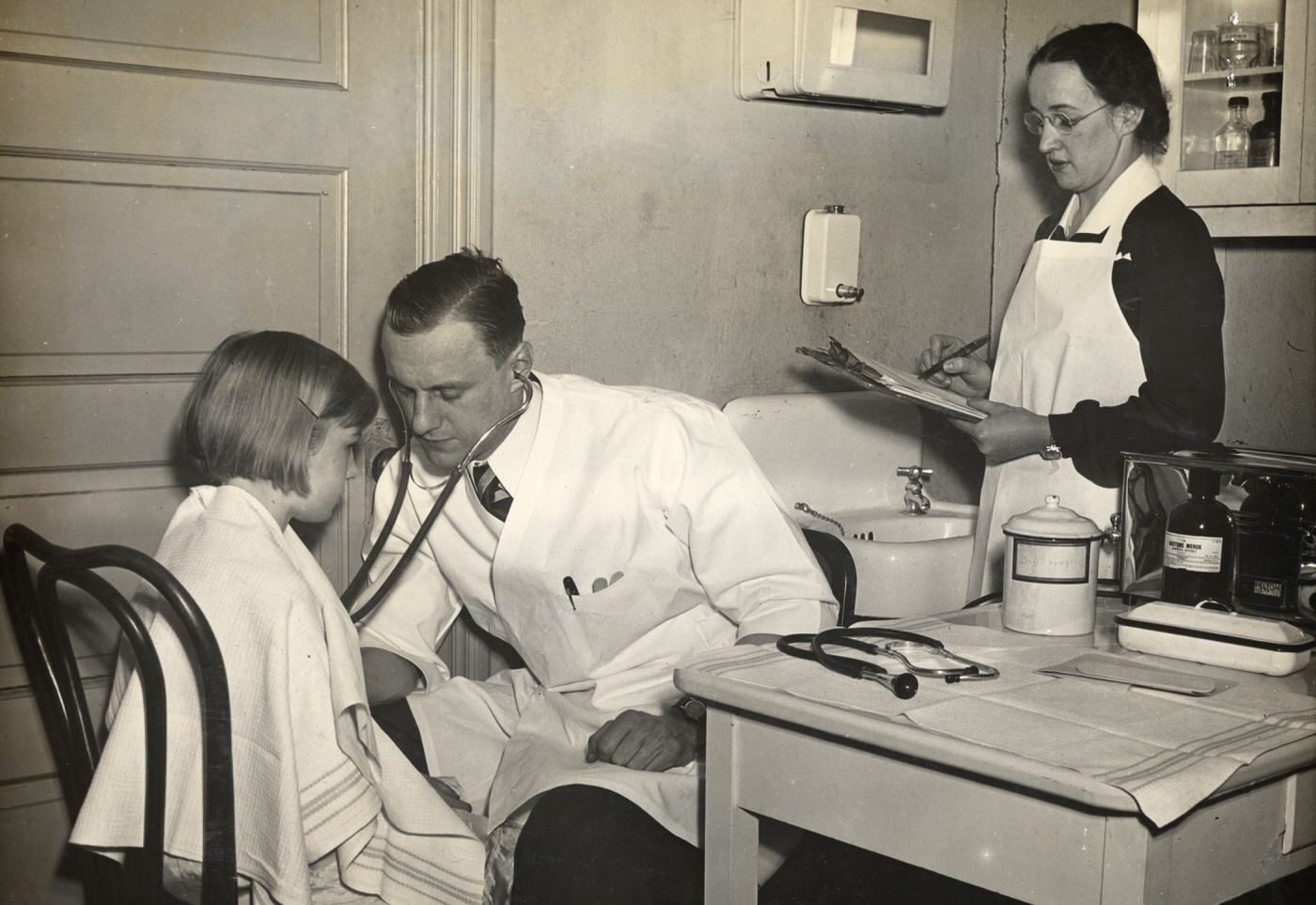

Segregation and Community Life

Despite its growth and modernization, Arlington in the 1930s was deeply affected by Jim Crow policies. These laws and customs enforced strict racial segregation in housing, recreation, and many aspects of daily life. The 1930s in Arlington presented a striking contrast: rapid modernization, population growth, and infrastructure development occurred alongside the strengthening of racial segregation. This segregation was often supported by both federal policies and local ordinances.

When new public housing projects, such as Colonial Village, were built with federal backing, they were specifically closed off to Black residents and other minority groups. This meant that while the white population gained new housing options, Black families faced severely limited choices and were often confined to older, underserved areas. The growth for some residents (white) meant increased restrictions and inequality for others (Black). This period created housing patterns and racial divides that continued for many years, showing how even programs meant for progress could be used to uphold social inequality.

A stark example of physical segregation was the 7-foot cinder block wall built in the late 1930s. Residents of white-only communities constructed this wall to separate themselves from the historically Black neighborhood of Hall’s Hill (also known as High View Park). It is important to note that developers often built these walls because the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) required them for obtaining financing for new housing developments, showing how federal policies reinforced local segregation.

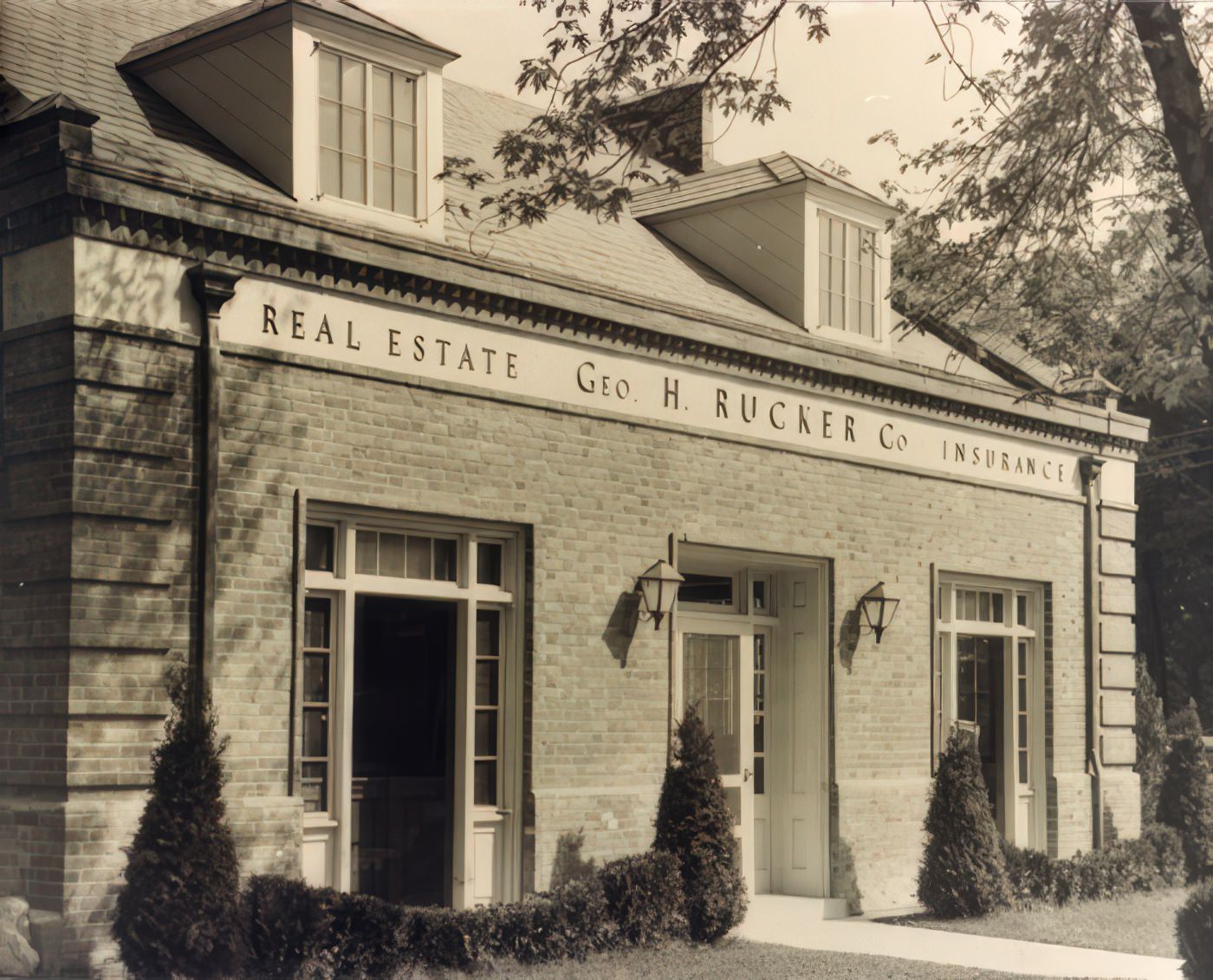

Further limiting housing options for Black families, Arlington banned row houses in 1938. These were a common and often more affordable type of housing for Black residents in nearby Alexandria and Washington D.C. The county deemed these homes “distasteful,” a policy that contributed to shaping the county’s housing patterns and restricting access for Black families.

Faced with systematic exclusion from public services and white-dominated spaces, Arlington’s organized Black communities showed great resilience. They created their own institutions and activities. For example, they sponsored sports at community parks like Peyton Field in Nauck (Green Valley) and formed their own semi-professional baseball team, the Black Sox. These communities also provided their own essential services, such as a volunteer fire department, homemade street lanterns, and a Black-owned bus line, because county services were often absent or inadequate in their neighborhoods. The systematic exclusion of African American residents from public services and opportunities in Arlington directly led to strong internal community organization and self-reliance. This demonstrates the strong community spirit and resourcefulness of these neighborhoods, even when faced with unfair treatment and neglect from the wider county government.

In terms of local governance, Arlington made a significant change in 1932. It became the first county in the United States to implement the County Manager Plan form of government. This new system centralized administrative responsibilities, aiming for more efficient operations. Under this plan, a five-member Board, elected by all county voters, governed Arlington and appointed the County Manager, who served as the chief administrative officer.

Daily Activities and Leisure

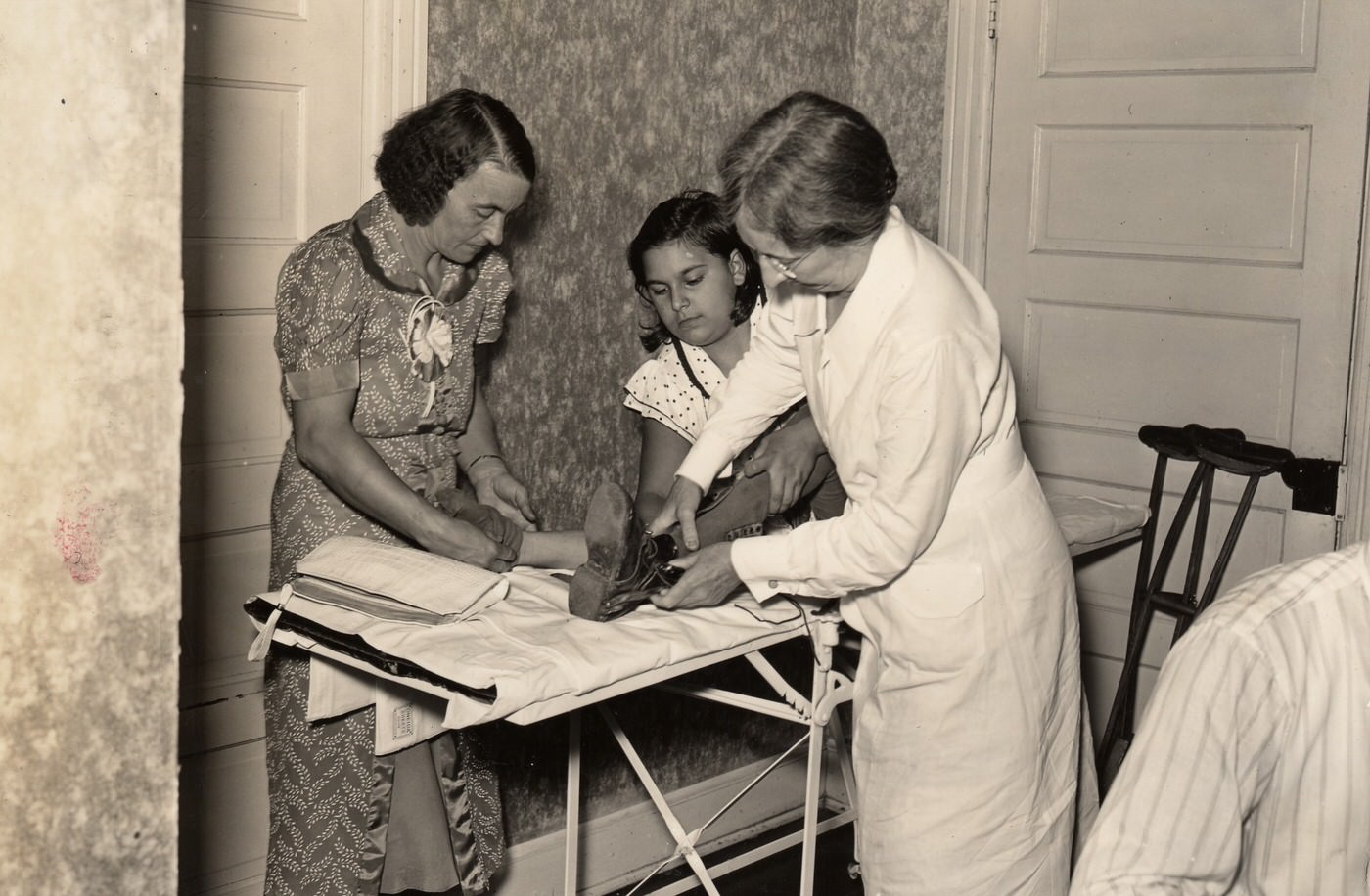

Formal public recreation programs began in Arlington County in 1933, when the County Board set aside money for the development of parks and playgrounds. By 1935, specific funds were budgeted for staffing summer playground programs, marking a new era for organized leisure activities.

Even as new recreation opportunities emerged, segregation remained a harsh reality. White residents had access to facilities like the Bathing Beach along the Potomac River, which featured swimming, concessions, and a ferris wheel. However, Black children had to find their own places to swim, such as the “Blue Man Junction” creek. This natural swimming spot was less safe than the formal, guarded white beaches, highlighting the unequal access to public amenities. The development of public recreation programs and new entertainment venues, while indicating modernization, simultaneously highlighted and reinforced the county’s deep racial divisions through strictly segregated facilities. This shows that even as Arlington modernized, racial inequality was deeply woven into its daily life and public spaces.

Towards the end of the decade, new entertainment options appeared. The Arlington Cinema ‘N’ Drafthouse, originally known as the “Arlington Theater & Bowling Alleys,” was commissioned in 1939 and officially opened in August 1940. This Art Deco style building on Columbia Pike was part of a larger recreational center. It included a large 24-lane bowling alley, department stores, and “The Arlington Pharmacy”. The theater was equipped with modern features like a Carrier air conditioning system, ensuring a “cool and refreshing” experience for its patrons.

For many residents, daily life during the Great Depression involved careful economizing. Families often did their own laundry, garaged cars to save on expenses, and cut back on luxuries like magazine subscriptions and vacations. Some people continued illegal bootlegging from the Prohibition era, which had been a significant activity in Arlington due to its proximity to Washington D.C., even after the national repeal of Prohibition in 1933. Even after Prohibition ended in 1933, Arlington’s past as a center for illegal alcohol continued to shape its culture. The established networks for bootlegging, which earned Arlington the nickname “Monte Carlo of Virginia” in the 1920s, likely persisted into the early 1930s. This suggests a more complex social reality where illegal activities continued to play a role, even as the county grew and changed.

Image Credits: Image Credits: Library of Congress, wikimedia, Arlignton Public Library, Flickr

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know