Arlington, Virginia, experienced a profound transformation during the 1940s. What was once a largely rural area began to quickly change into a bustling center of activity. This rapid growth was primarily driven by the United States’ entry into World War II. The federal government’s expansion brought a massive influx of people to Arlington, reshaping its landscape and the daily lives of its residents. This period saw an unprecedented population boom, large-scale building projects, and significant social changes, all shaped by the urgent demands of wartime.

Arlington’s Population Boom: A County Transformed

Arlington County was already growing steadily before the 1940s. Its population more than tripled from about 16,000 in 1920 to 57,000 by 1940. However, this growth dramatically accelerated with the onset of World War II, making Arlington the “fastest growing county in America” by 1942. The number of residents nearly doubled in just four years, soaring from 57,000 in 1940 to 120,000 by 1944.

The main reason for this population explosion was the rapid expansion of the federal government, especially due to the war effort. By 1940, more than half of Arlington’s employed adults worked for the federal government. This provided many jobs for people already living in the area and attracted tens of thousands of new workers from across the country. Many of these new residents worked at federal sites within Arlington or commuted to jobs in Washington D.C., which led to Arlington being seen as a “bedroom community”. This role as a place where federal employees lived was not just a simple demographic shift. It meant Arlington played a crucial part in supporting the national war effort. By providing homes for a huge number of essential government and military staff, Arlington directly helped the federal government and military operate smoothly during a time of national emergency. The county’s rapid development was therefore a direct result of its strategic location and its close connection to the federal government’s wartime needs.

This massive influx of people put immense pressure on Arlington’s existing infrastructure. Roads needed significant upgrades, and zoning rules were changed to allow for more apartment buildings to be constructed. Schools also had to be reorganized to handle the rapidly growing number of students. To meet the demands of its expanding population, Arlington County also established professional police and fire departments in 1940.

Building Homes for a Growing Nation: Solutions and Shortages

With thousands of new workers arriving in Arlington, the county faced a severe housing shortage. A survey in 1942 revealed the extreme demand, showing that 4,300 applicants sought only 650 available family housing units. In response, the federal government stepped in with many programs to build homes quickly.

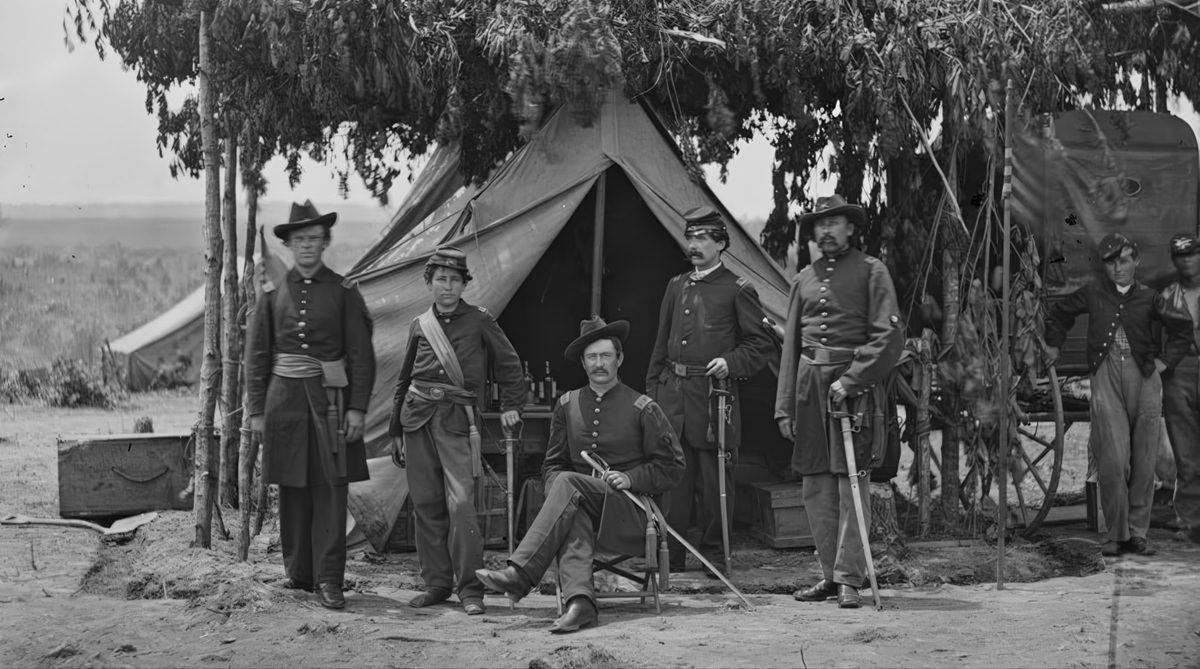

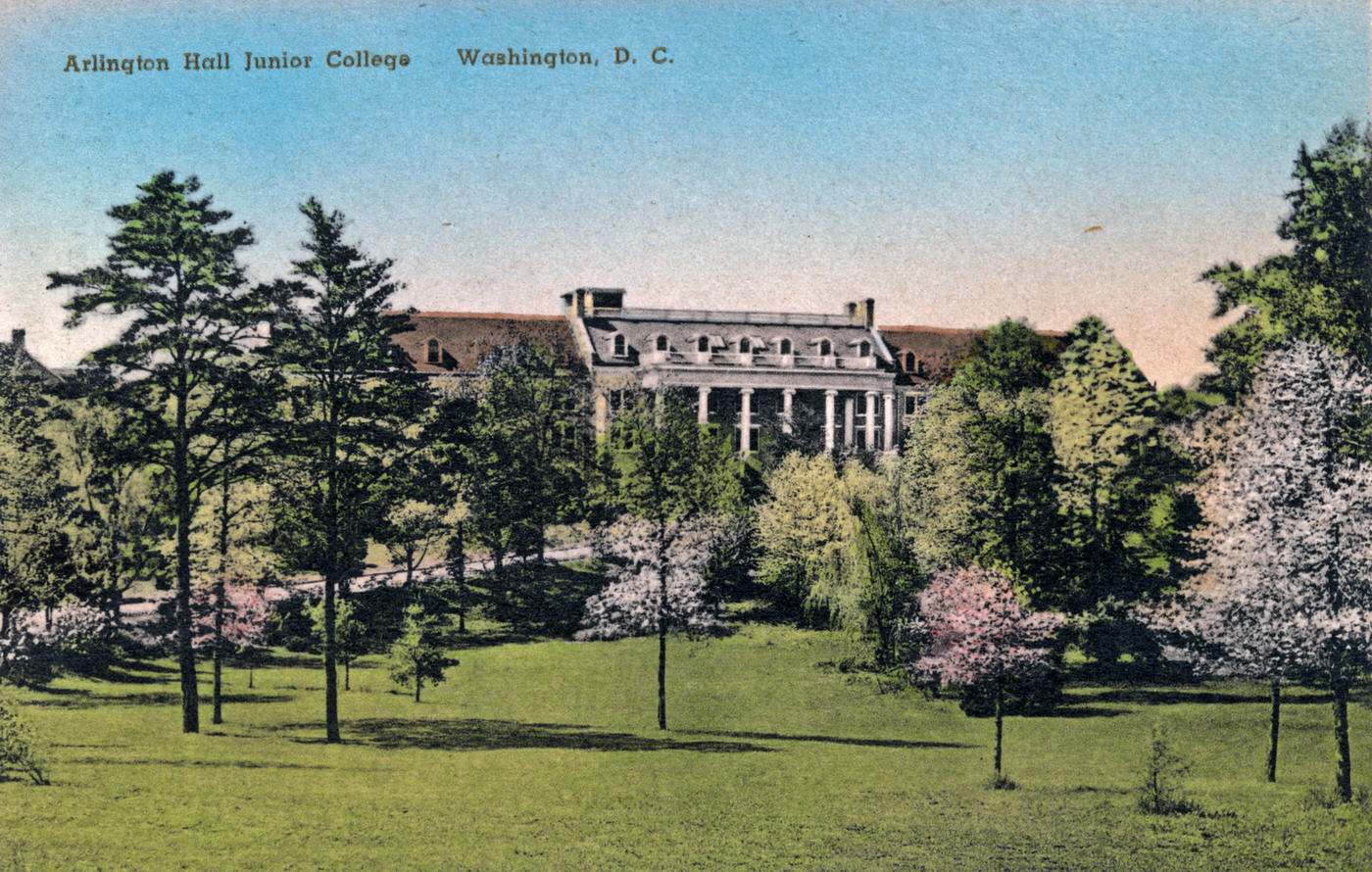

One major solution was Arlington Farms, a large temporary housing complex built between late 1942 and early 1943. It was designed to house up to 9,000 female civil servants and military members, primarily Naval Reserve WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services). The complex featured ten dormitories, each named after a U.S. state, along with an infirmary and a recreation hall. While the exteriors were described as “gray and extremely temporary” with walls made of cemesto, the interiors were “brightly painted” and “pleasantly furnished” with modern furniture, aiming to create a more cheerful living environment. Residents received fresh linen twice a week and had weekly maid service. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was even involved in its design and presided over its formal dedication in October 1943. Women living at Arlington Farms came from all over the country to work in government jobs at places like the Pentagon or Arlington Hall. The complex became widely known as the “28 Acres of Girls”. It continued to operate for five years after the war, though the number of residents began to decline.

Other federally funded, low-cost housing projects were built quickly with minimal amenities to meet the urgent demand. These homes, such as the Shirley Homes, were often described as “very small and had been quickly/poorly built”. They were typically constructed on concrete slabs, lacked basements, were heated by coal stoves, and had only a shower in the tiny bathroom.

Planned Communities

Beyond temporary housing, some larger, more permanent communities were also developed. Fairlington was the largest and most ambitious of these projects, built from 1942 to 1944. It included 3,449 Colonial Revival apartment and townhouse units. Unlike many wartime projects, Fairlington was designed to be a lasting community, featuring careful architecture, landscaping, parks, a community center, and a school.

Arlington Forest was another significant community, planned and built by Meadowbrook Construction Company starting in 1939, with much of its construction continuing through and after World War II. It featured Colonial Revival homes with various designs and floor plans. Due to wartime material shortages, some homes in the Greenbrier section of Arlington Forest had slightly smaller floor plans. Meadowbrook installed essential services like sewers, water, electricity, gas, and paved streets. Arlington Forest was designed for young families, many of whom experienced fathers going to war and mothers beginning to work. It aimed for a “country-like atmosphere” and included its own shopping center for daily needs like groceries, a drug store, and a bakery.

The Columbia Forest neighborhood, built in 1941, was intended for “young married officers and ranking government officials”. It had simpler designs compared to Fairlington and faced significant problems. Its internal roads, for example, did not connect well to the county’s road networks, and some families lived for months without sewer services.

The urgent demand for housing and the material shortages caused by the war meant that some housing was built hastily, leading to quality issues. Residents in Columbia Forest, for example, faced dire conditions where streets were “pitted with yawning holes filled six feet or more deep with water”. After the war, some of the lower-quality wartime homes deteriorated as residents moved out. Arlington County chose not to take over these properties for low-income housing, partly because establishing a local Housing Authority was a controversial idea at the time.

The wide variety of housing projects, from temporary dorms and trailer camps to carefully planned permanent communities, shows a complex and often reactive approach to an unprecedented housing crisis. There was no single, unified strategy. This indicates the immense pressure and the lack of a clear plan for such rapid urbanization. Both the government and private developers were largely improvising and responding to immediate, overwhelming needs. This resulted in a mix of housing solutions with very different standards of quality, intentions (temporary versus permanent), and outcomes for the residents. The urgency of wartime and the limits on building materials meant that while some projects like Fairlington were well-designed for the long term, others were rushed and problematic, creating uneven living experiences across the county. This reactive approach, rather than a centrally planned one, is a key feature of Arlington’s development during this period.

The table below highlights some of the key housing projects in Arlington during the 1940s:

| Project Name | Type of Housing | Purpose/Target Residents | Key Features/Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arlington Farms | Temporary Dormitories | Female civil servants & military members | 10 dorms, “gray and temporary” exteriors, “pleasantly furnished” interiors, segregated, weekly maid service |

| Fairlington | Planned Community (Apartments/Townhouses) | Defense workers and their families | 3,449 Colonial Revival units, permanent, detailed architecture, landscaping, parks, community center, school |

| Arlington Forest | Planned Community (Colonial Revival Homes) | Young families | Privately built, FHA loans, various floor plans, own shopping center, “country-like atmosphere” |

| Columbia Forest | Planned Community (Brick Homes) | Young married officers & government officials | Simple brick homes, less planning, internal roads not linked, some areas lacked sewer services |

| J.E.B. Stuart, George Pickett, Shirley, Jubal Early Homes | Federally Funded Low-Cost Housing | White residents (wartime workers) | Built quickly on concrete slabs, no basements, coal stoves, minimal amenities, deteriorated post-war |

| George Washington Carver, Paul Dunbar Homes | Federally Funded Low-Cost Housing | Black residents (wartime workers) | Built quickly on concrete slabs, no basements, coal stoves, minimal amenities, deteriorated post-war |

| Green Valley Trailer Camp | Emergency Temporary Housing | Displaced Queen City residents (African American) | Cramped trailers, no running water, prone to flooding, rats, unhealthy conditions |

The Pentagon’s Construction and Community Changes: A Defining Landmark

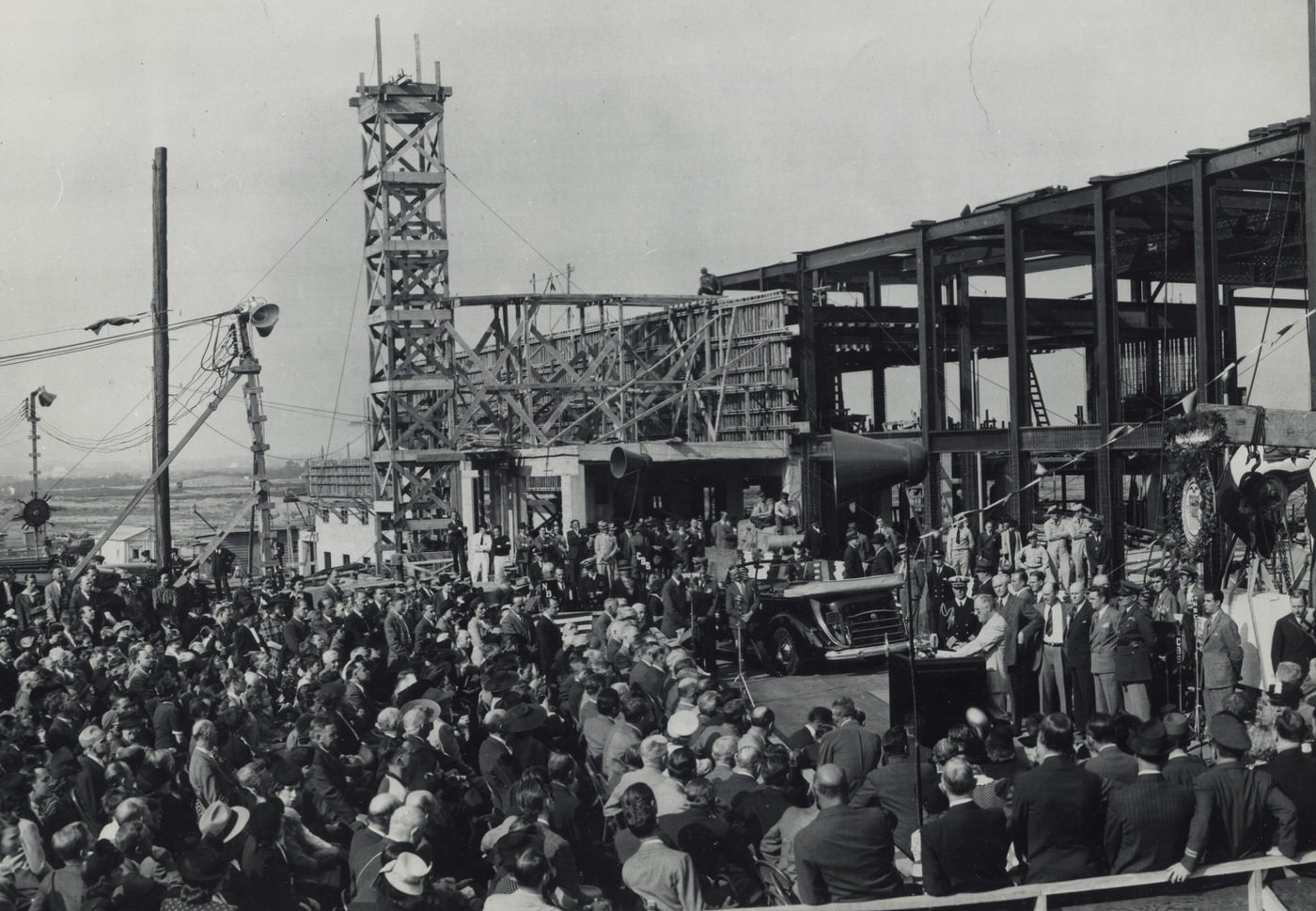

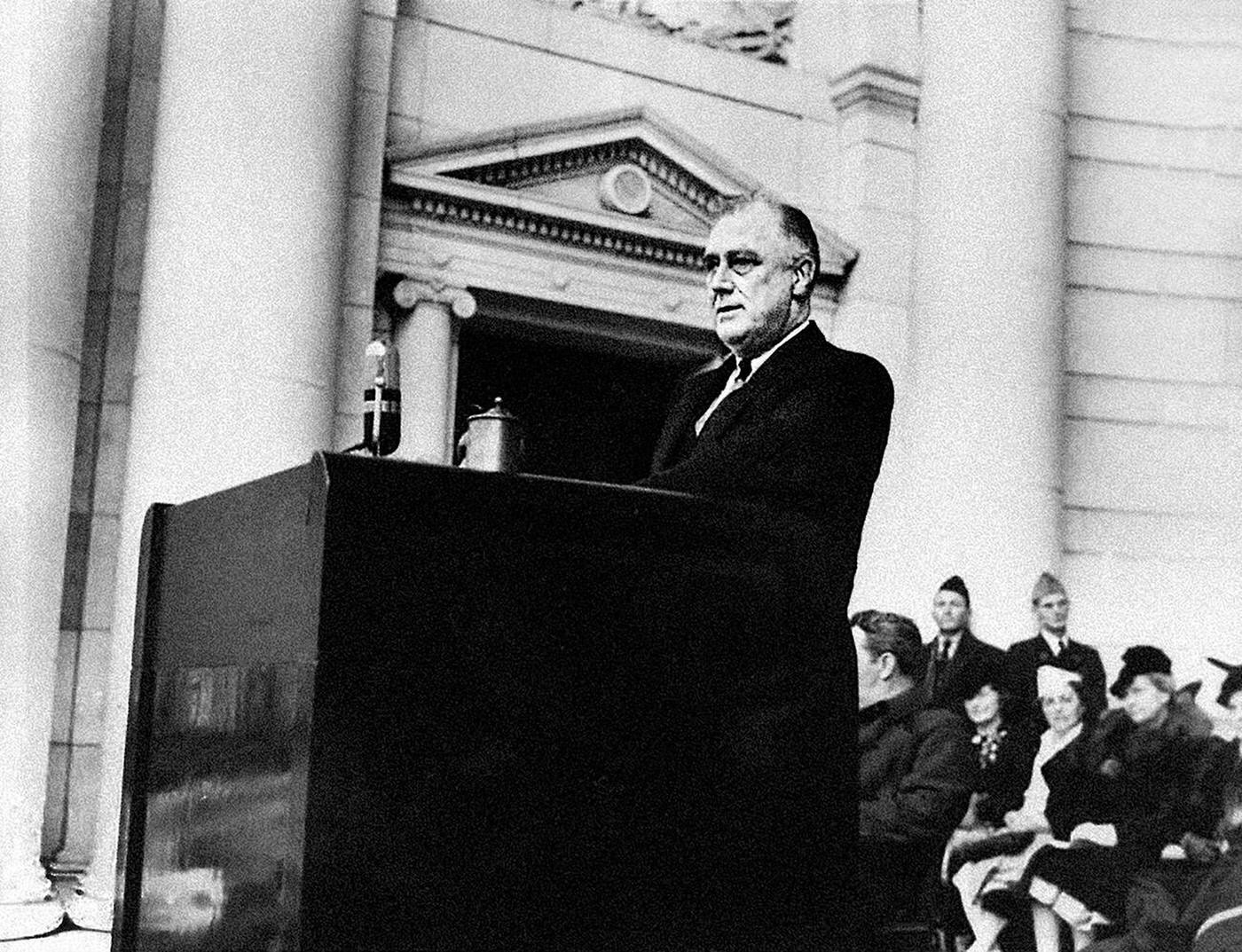

The Pentagon, which serves as the headquarters for the U.S. War Department, was a massive construction project that began on September 11, 1941. It was initially planned as a temporary solution to the War Department’s urgent need for more space. The building’s unique five-sided shape came about because the original plot of land chosen for its construction was bordered by five roadways.

The building was completed at an astonishing speed, taking only 16 months to finish and officially opening in January 1943. This huge undertaking required 1,000 architects and 14,000 tradesmen who worked around the clock in three shifts. The first tenants began moving into the building even before it was fully completed, starting in April 1942.

However, the construction of the Pentagon and its surrounding road networks had a devastating effect on local communities. It led to the demolition of Queen City and East Arlington, which were neighborhoods primarily inhabited by African Americans. In January 1942, work began on the road networks that ran directly through Queen City, but the residents were not informed of these plans. They received notice in February 1942 that they had to leave their homes by March 1. Their property was taken through eminent domain laws, and homeowners received only “modest payments”. In total, 225 families were evicted from 70 acres of land.

After their displacement, these families, almost all of whom were African American, faced a severe housing shortage in Arlington. Many were forced into emergency trailer camps located on “mud flats” at the edge of Green Valley. These trailers were cramped, lacked running water, and were often unhealthy environments, prone to flooding and attracting rats. Despite these extremely difficult living conditions, the displaced families relied on strong social, religious, and community networks to support each other. As one resident remembered, “the love and association of people is what kept people together” during that trying time. After the war, the trailers were removed, and many residents found new homes with family or in other existing Black communities like Green Valley or Hall’s Hill.

The building of the Pentagon, while representing a national effort and efficiency, also shows how the urgency of wartime could overlook social justice and worsen existing racial inequalities. The federal authorities described Queen City as an “industrial slum,” a view that helped justify its demolition. This indicates that decisions were made that prioritized military infrastructure over the well-being of a marginalized community. The fact that the Pentagon was initially considered “temporary” while the loss of Queen City was permanent highlights the unequal distribution of burdens and benefits. This act of displacement fundamentally changed Arlington’s racial geography, concentrating Black residents into specific, often neglected, areas, thereby increasing existing inequalities under the banner of national necessity.

Daily Life and Community Spirit: Adapting to Wartime Realities

For many Arlington residents in the 1940s, daily life was more “city-oriented rather than suburb-oriented”. Many families did not own cars and did not need them, as grocery stores, drug stores, barber shops, banks, bakeries, and florists were all within easy walking distance. Downtown Washington D.C. was also easily reached by streetcar.

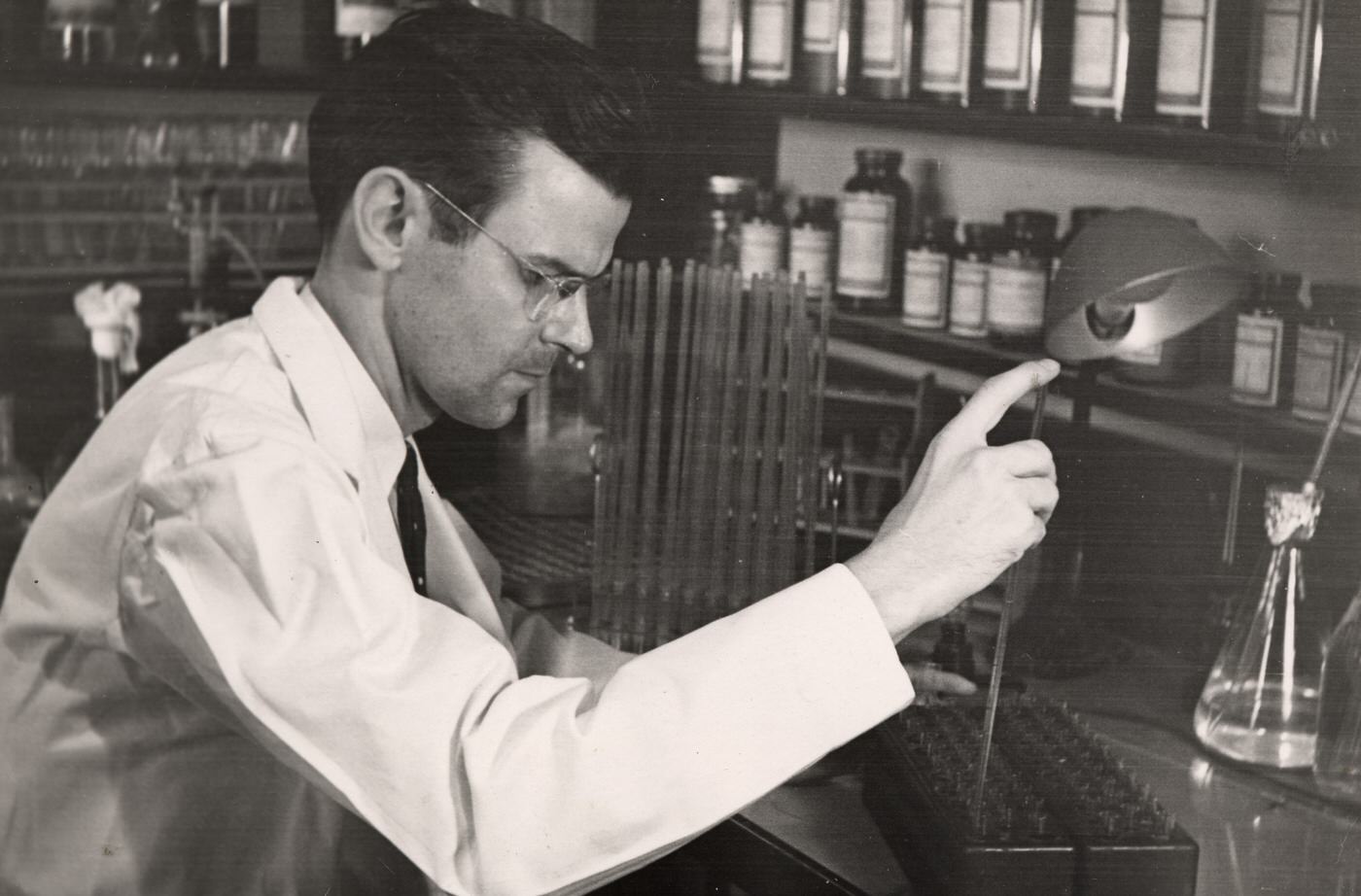

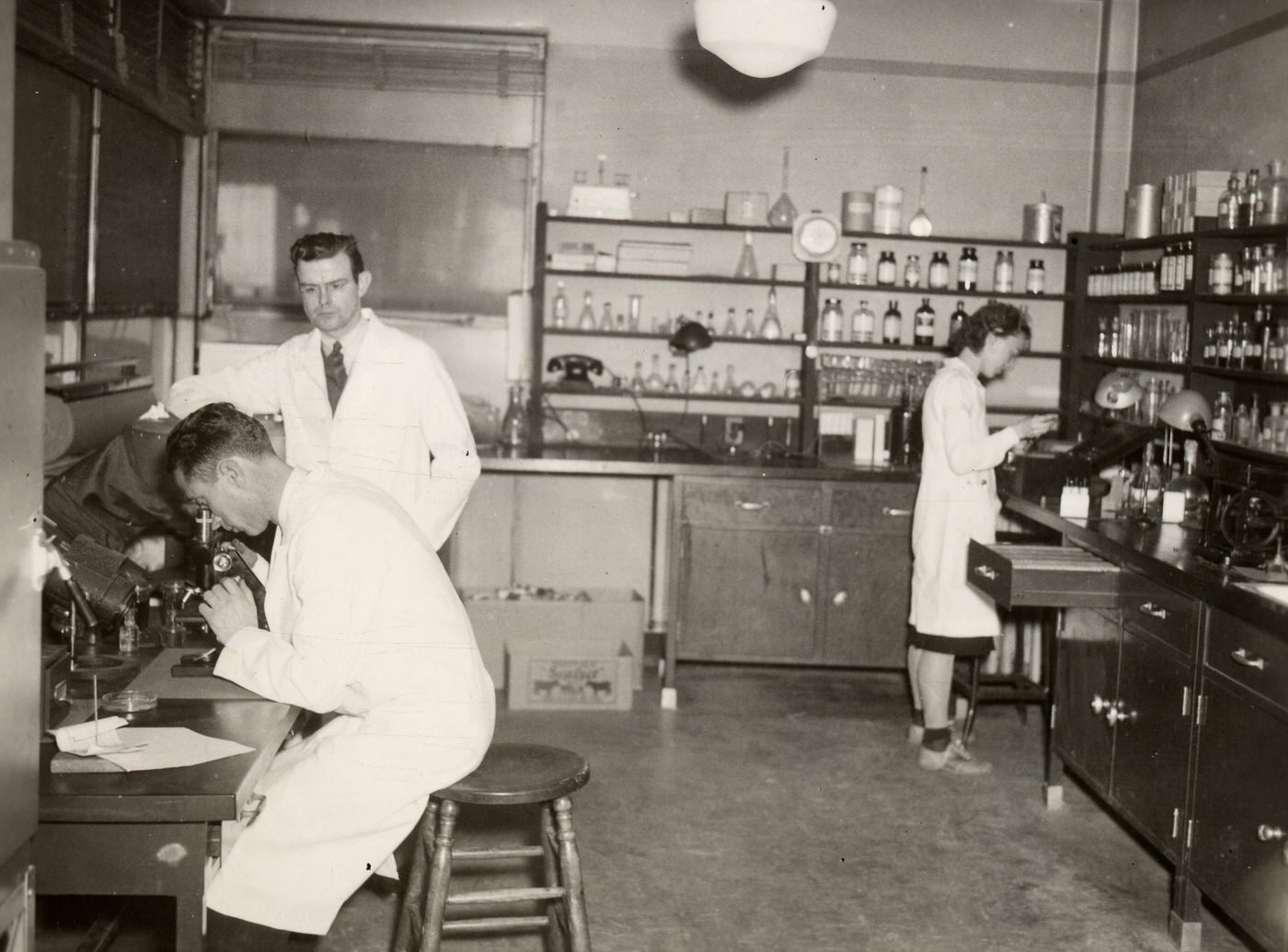

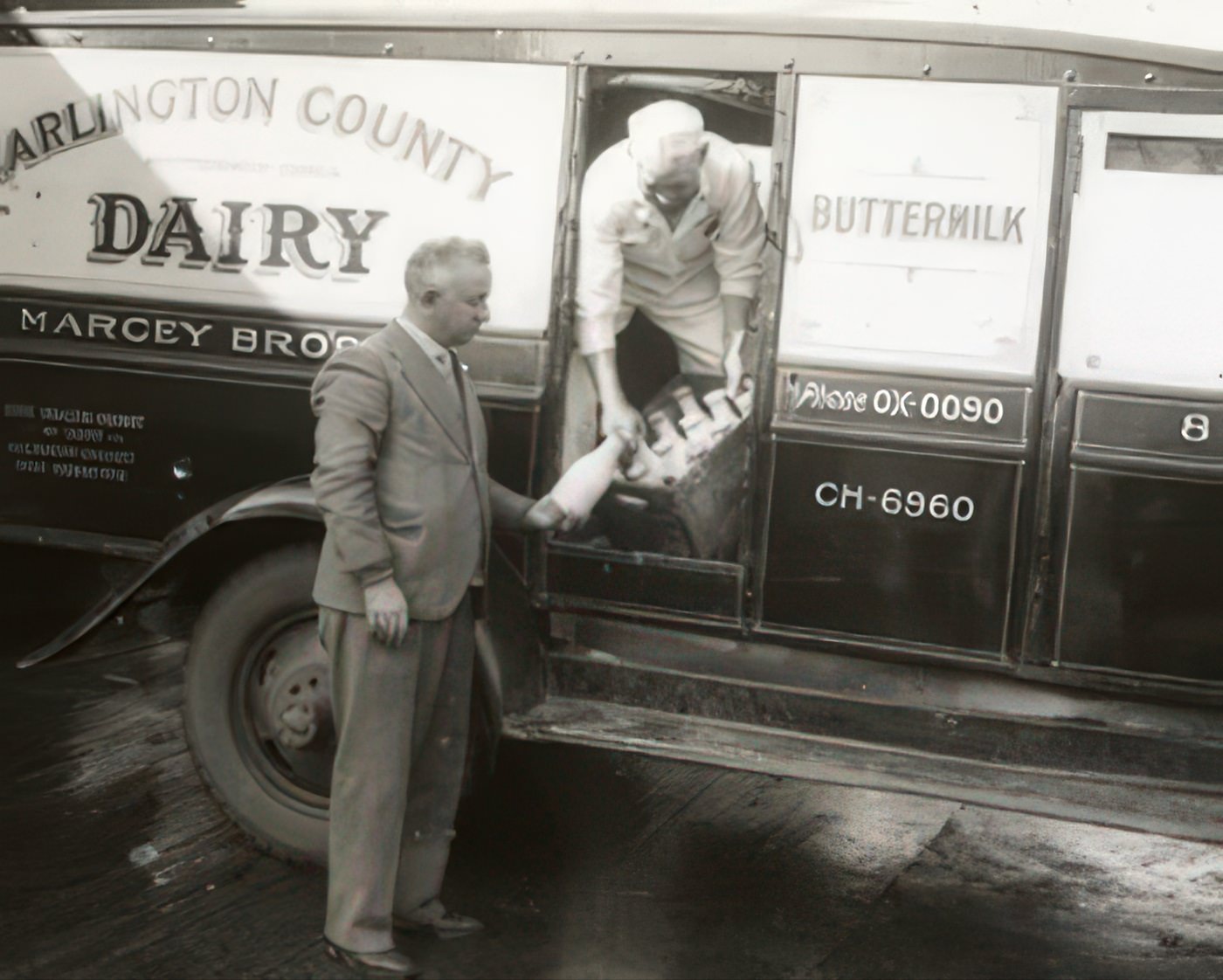

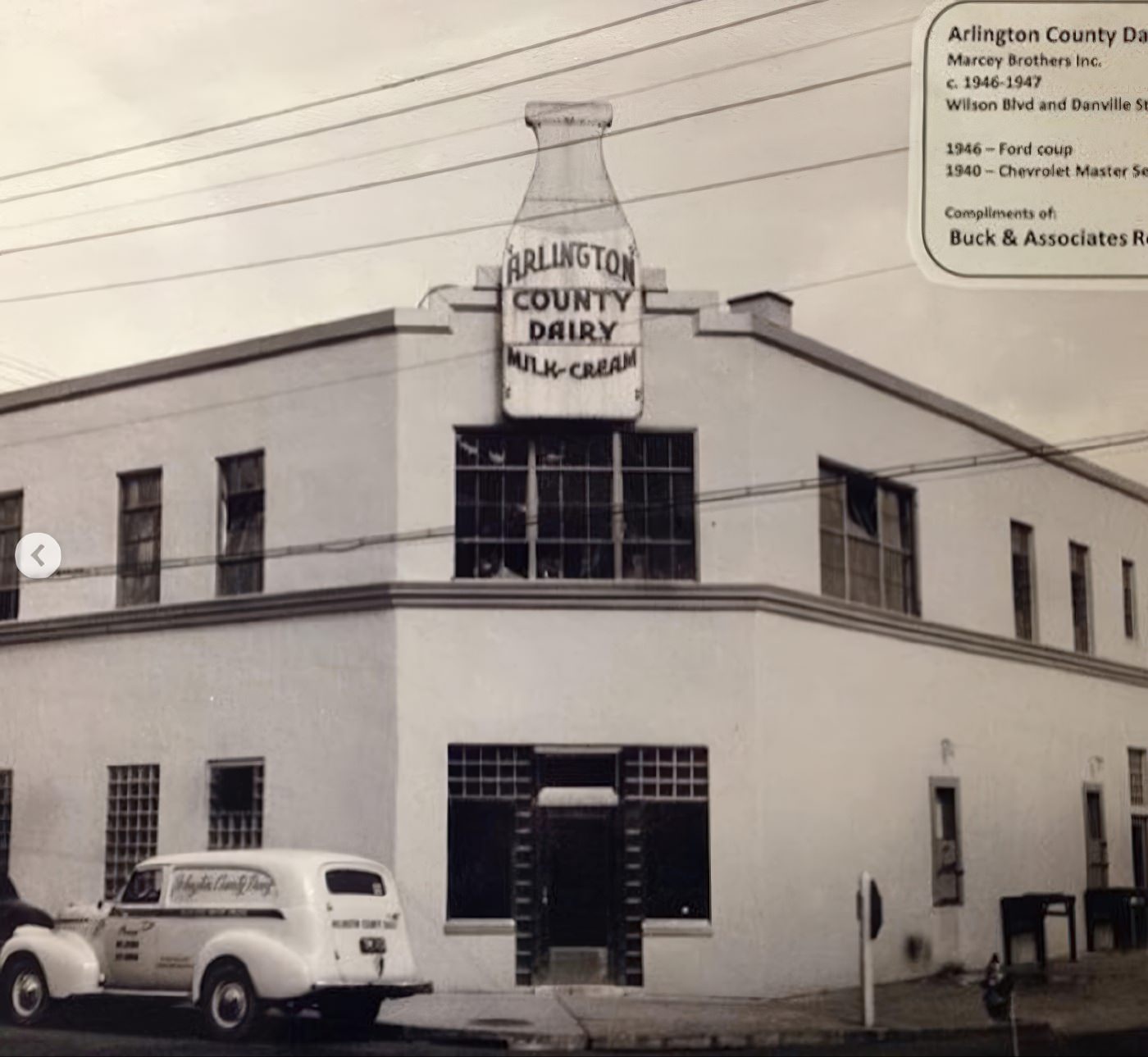

Some services even came directly to people’s homes. Milkmen delivered milk in glass bottles, and bread was also delivered. Local laundries offered home pick-up and delivery services. Doctors made house calls, even bringing the newly available penicillin shots. During the hot Washington summers, with no residential air conditioning, people relied on fans and wet washcloths, or rode streetcars for a cooling breeze. Ice cream trucks, like Good Humor and Jack and Jill, were a favorite sight for children.

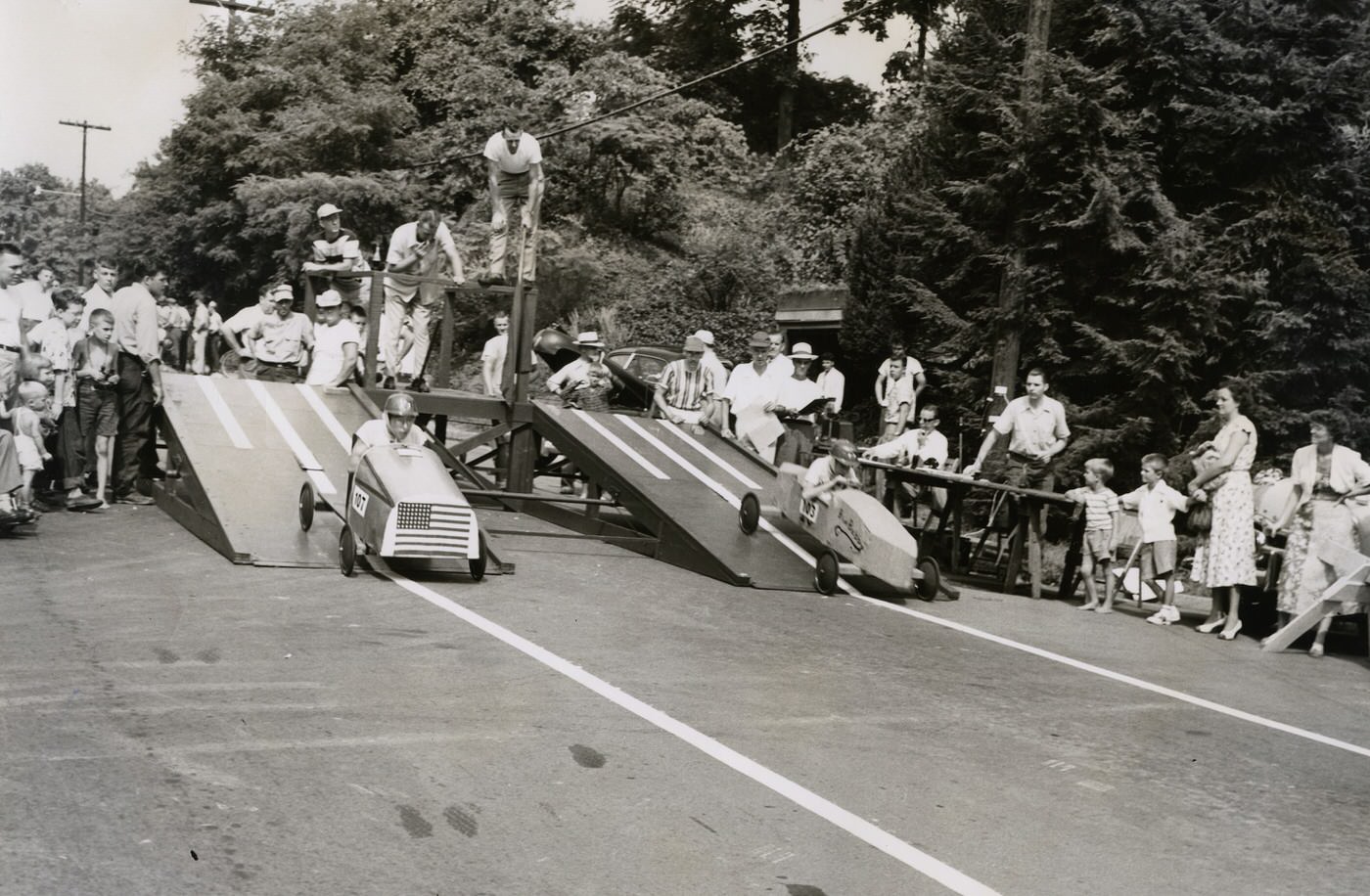

Entertainment and recreation options were available in the county. The Arlington Cinema ‘N’ Drafthouse, originally known as the “Arlington Theater & Bowling Alleys,” opened in 1940, showing movies for 25 cents and selling popcorn for 10 cents. It also featured a large bowling alley. The Westover Shopping Center, built in 1940, provided a Safeway grocery store, a “five and dime” store, and a pharmacy, serving as a convenient, pedestrian-friendly hub for the community. Swimming pools were limited, mostly found at private country clubs, with only a few public options available.

The presence of military families was common, with many officers and their children living in the area. Air raid drills became a regular part of school life, and organized air raid wardens helped prepare the community for potential attacks.

Despite the challenges of rapid growth and sometimes difficult living conditions, a strong sense of community developed among residents. Those who lived in wartime housing projects often remembered positive aspects, such as neighbors looking out for each other, children playing freely, and a general feeling of safety. In Arlington Forest, young families formed strong friendships due to their shared experiences, especially during wartime when many fathers were away and mothers began working. For displaced Black communities like Queen City, strong social, religious, and fraternal networks were essential for survival and emotional support.

Daily life in 1940s Arlington was a mix of traditional, small-town conveniences and the emerging pressures and adaptations of a rapidly urbanizing, wartime environment. This combination fostered a unique form of community resilience. The continued presence of traditional services and walkable neighborhoods suggests that Arlington, despite its rapid growth, kept some characteristics of its more rural or small-town past. This created a distinct transitional urban experience, different from the later, more car-dependent suburban model. The widespread community spirit and strong social bonds, especially in the face of poor housing conditions and forced displacement, show that shared difficulties and a sense of belonging became powerful forces that brought people together. These bonds helped residents cope with problems in infrastructure and unfair systems, proving that even under restrictive and challenging circumstances, people found ways to create meaningful lives and supportive environments. The regular air raid drills highlight the constant, underlying anxiety of wartime, which affected even the most ordinary parts of daily life, yet did not diminish the community’s vitality.

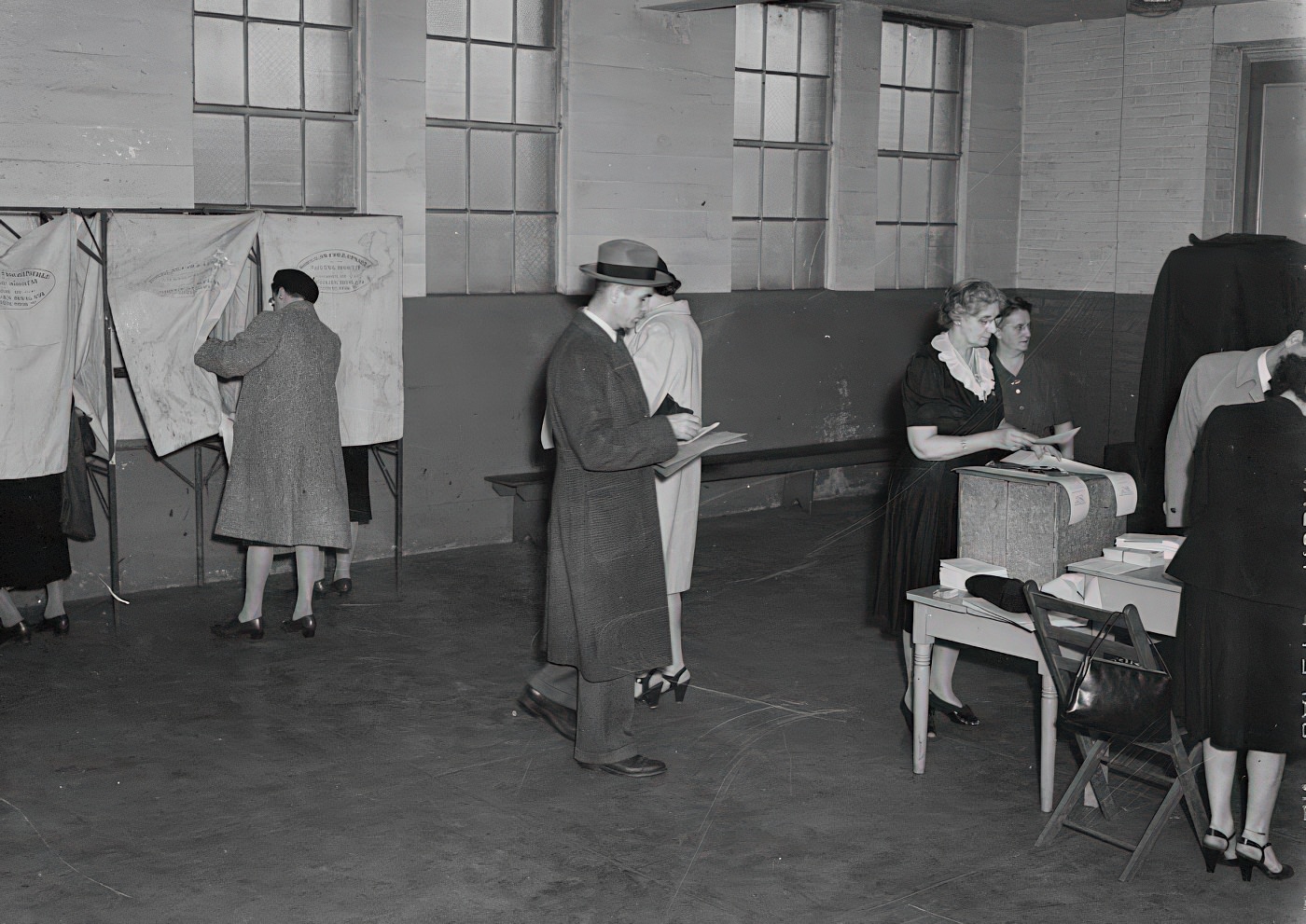

Social Shifts and Public Services: Navigating Inequality and Growth

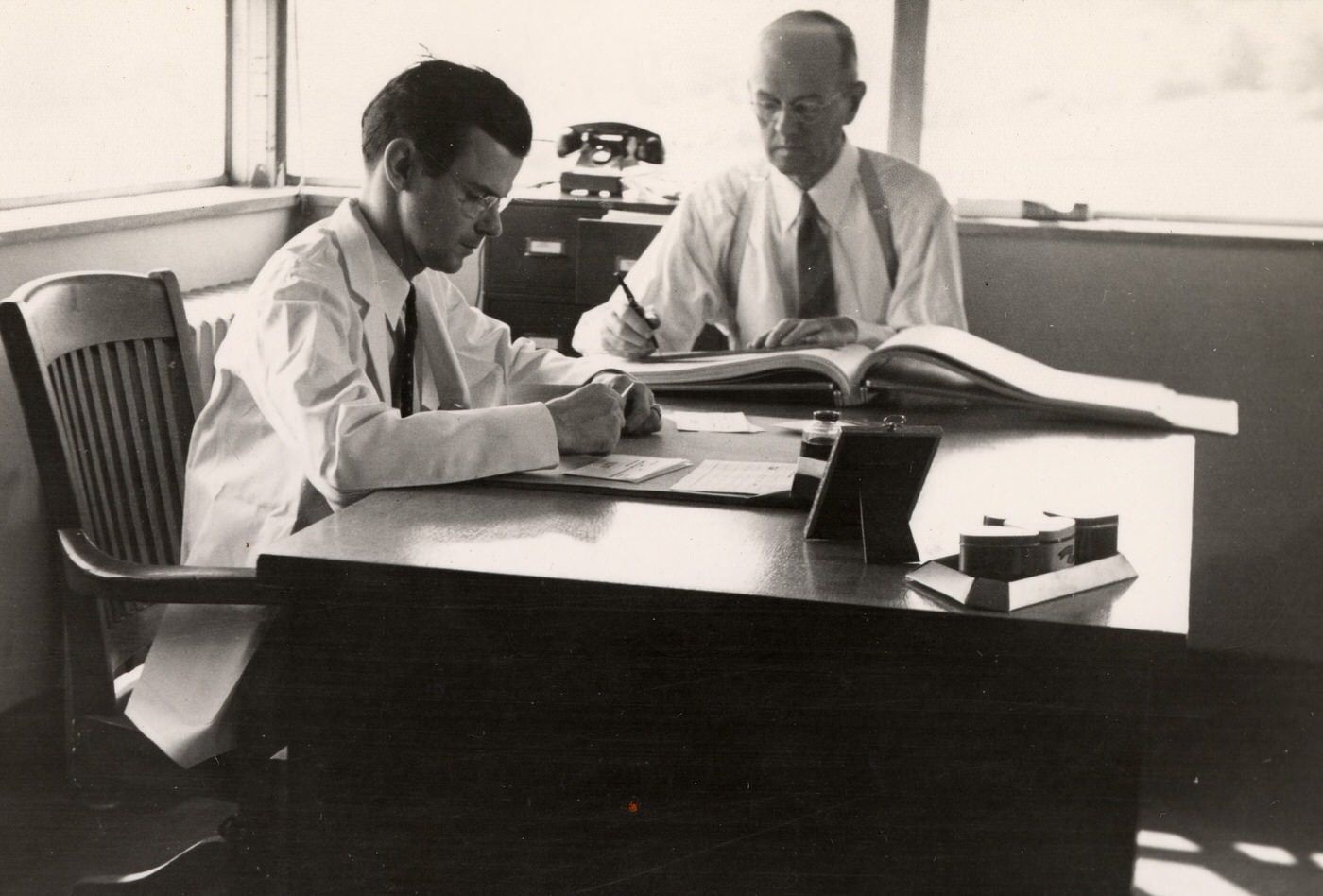

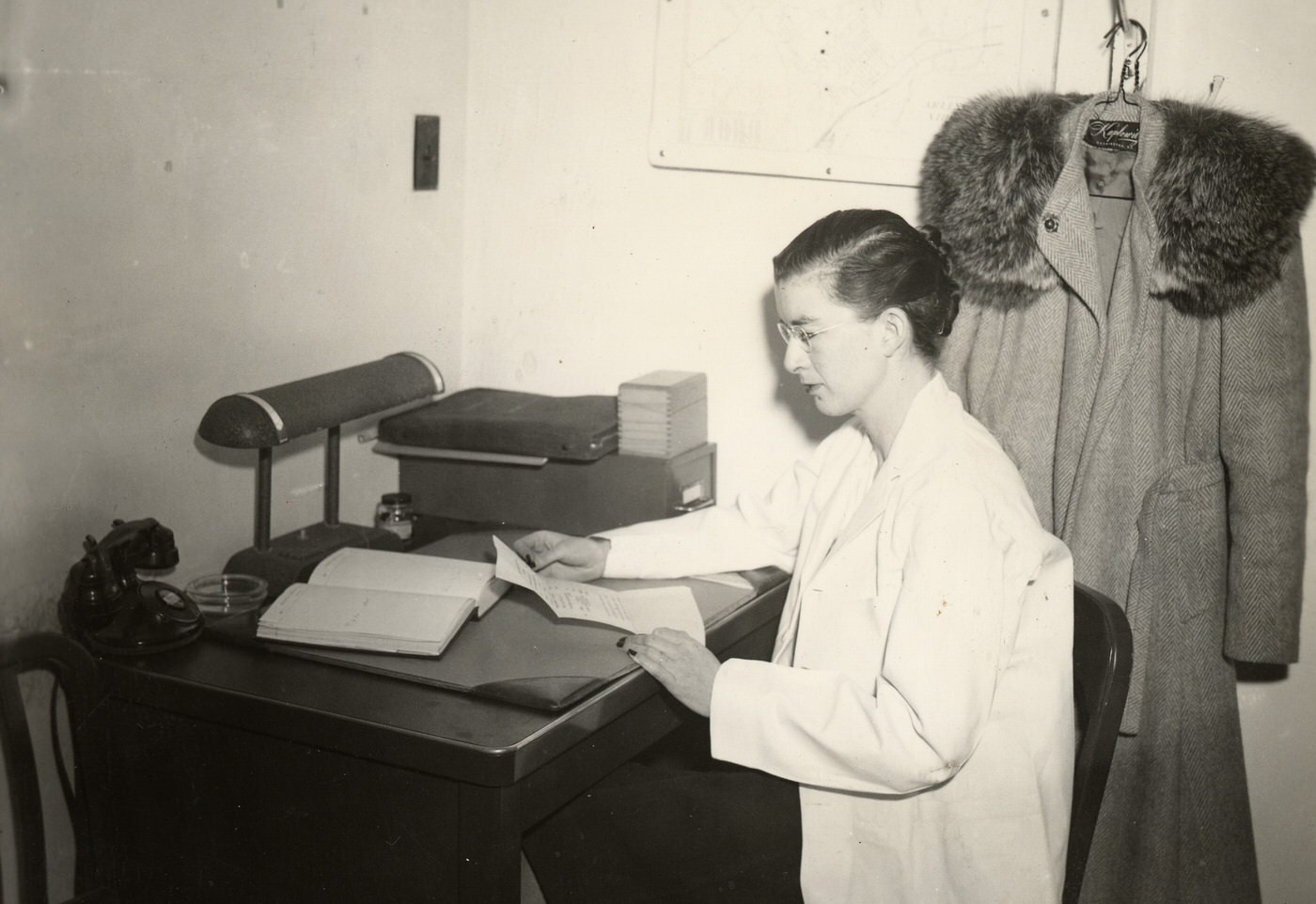

World War II brought significant changes for women. Across the nation, over 250,000 women joined military auxiliary units like the WAVES, often receiving equal pay and taking on non-combat roles. On the home front, 6.3 million women entered the workforce, and for the first time in history, married working women outnumbered single working women. “Rosie the Riveter” became a popular symbol of women taking on jobs in defense industries. In Arlington, many women worked in federal government jobs, and thousands lived in complexes like Arlington Farms. This shift challenged traditional ideas about women’s behavior, though some social critics blamed working mothers for issues like juvenile delinquency.

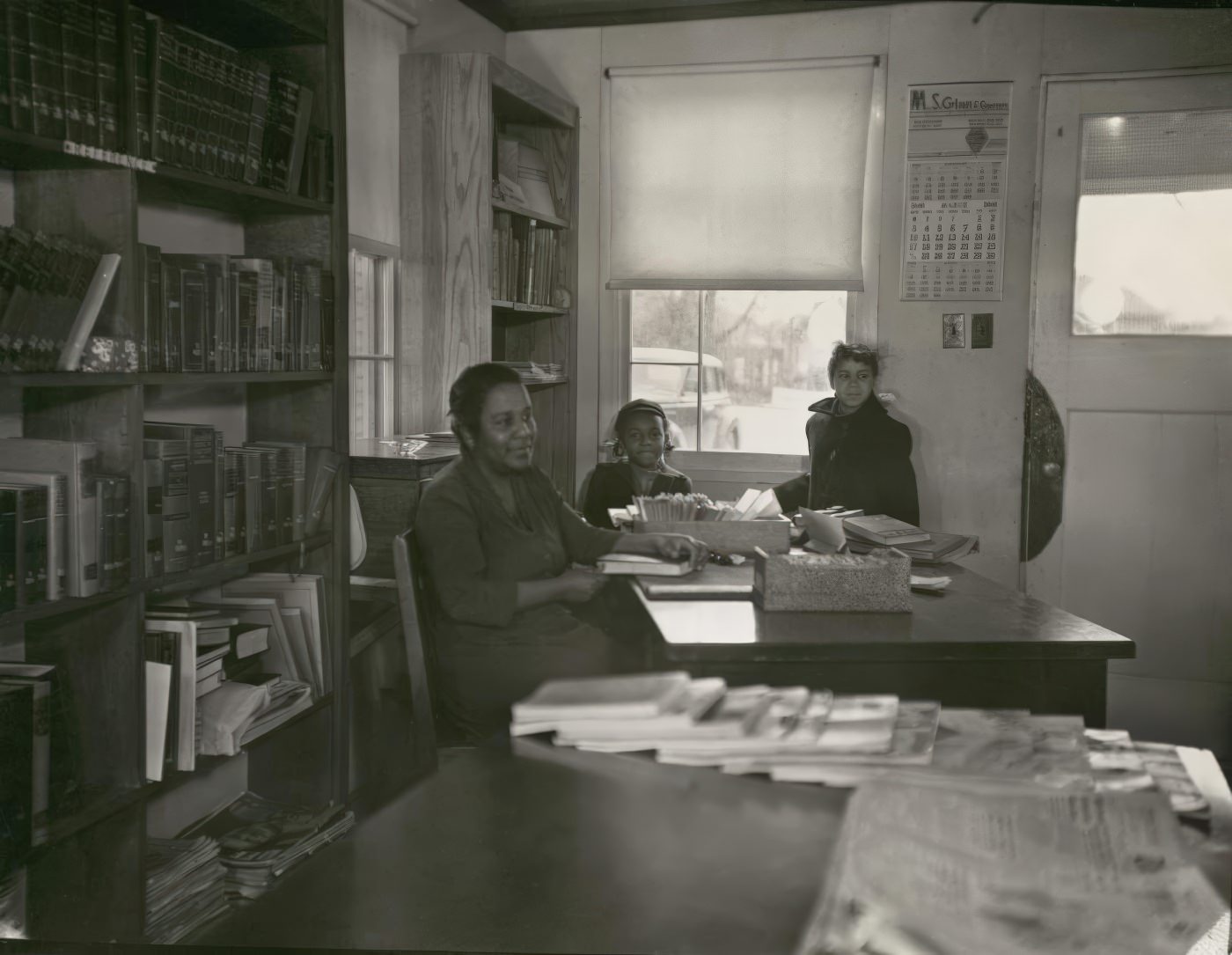

Despite the opportunities for federal employment for African Americans, racial segregation, known as Jim Crow, was deeply ingrained in Arlington society during the 1940s. Federally funded wartime housing projects were segregated by race. For instance, the J.E.B. Stuart Homes were for white residents, while the George Washington Carver Homes were for Black residents. Restrictive covenants in planned communities like Arlington Forest also prevented non-Caucasians from living there, with the exception of domestic servants.

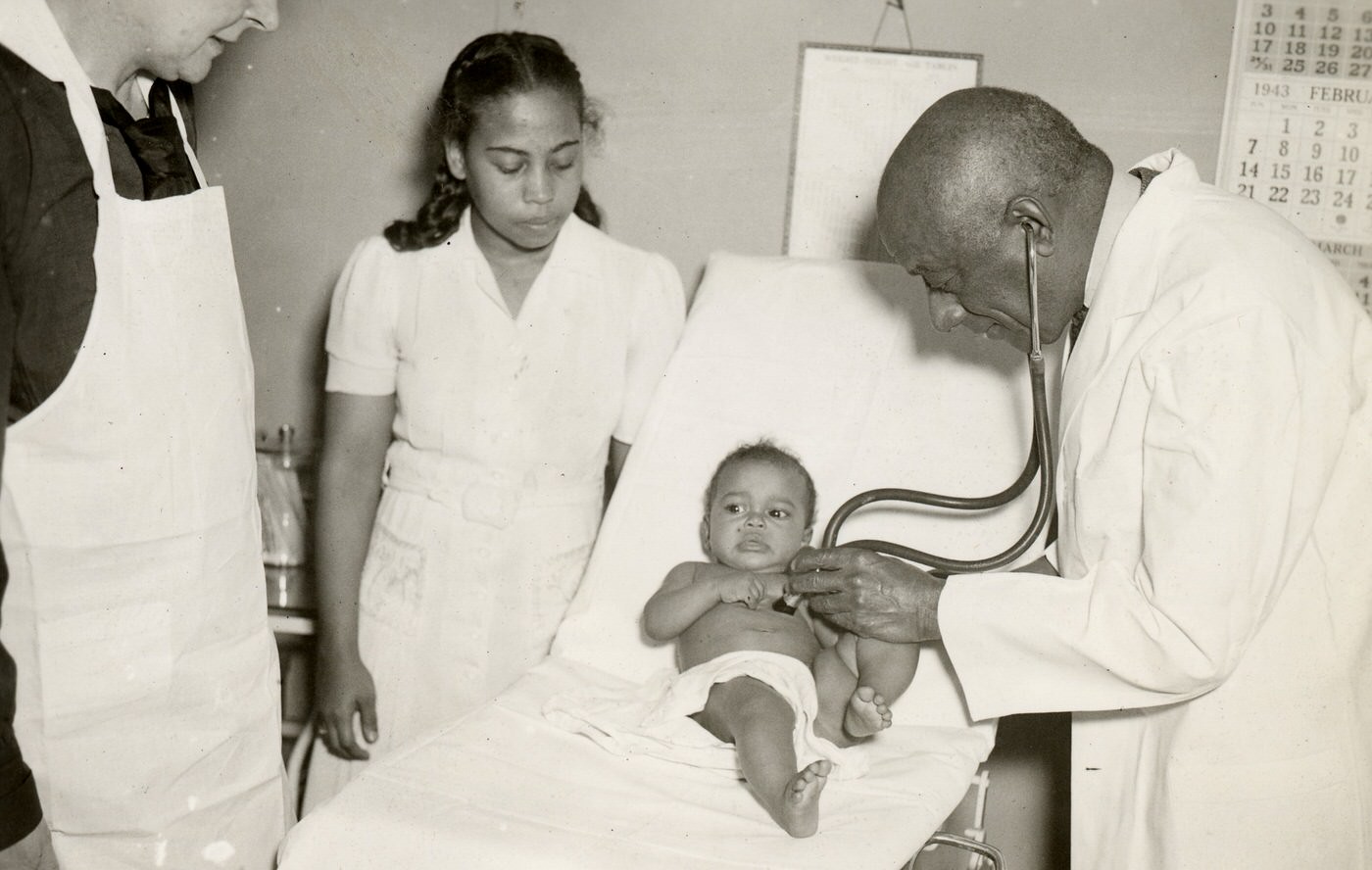

African Americans faced discrimination in eating establishments, businesses, and recreation facilities. Access to medical care was also divided; Black mothers were not allowed in the maternity ward at Arlington Hospital and had to travel to hospitals in Washington D.C. or Alexandria to give birth. In some stores, Black children were closely watched to prevent theft. Black residents were often not welcome in white establishments like barber shops or theaters.

Even established Black communities like Halls Hill, despite paying taxes, often lacked basic services that white neighborhoods received. Water came from wells, bathrooms were outhouses, and roads remained unpaved until well after World War II. The police rarely came unless they were looking for someone, and the fire department would not respond to calls. In response to this neglect, Halls Hill residents formed their own volunteer fire department. Similarly, in 1947, a Black-owned “Friendly Cab Company” was created to help Black Arlingtonians get to D.C., especially for medical emergencies, as many could not afford their own cars.

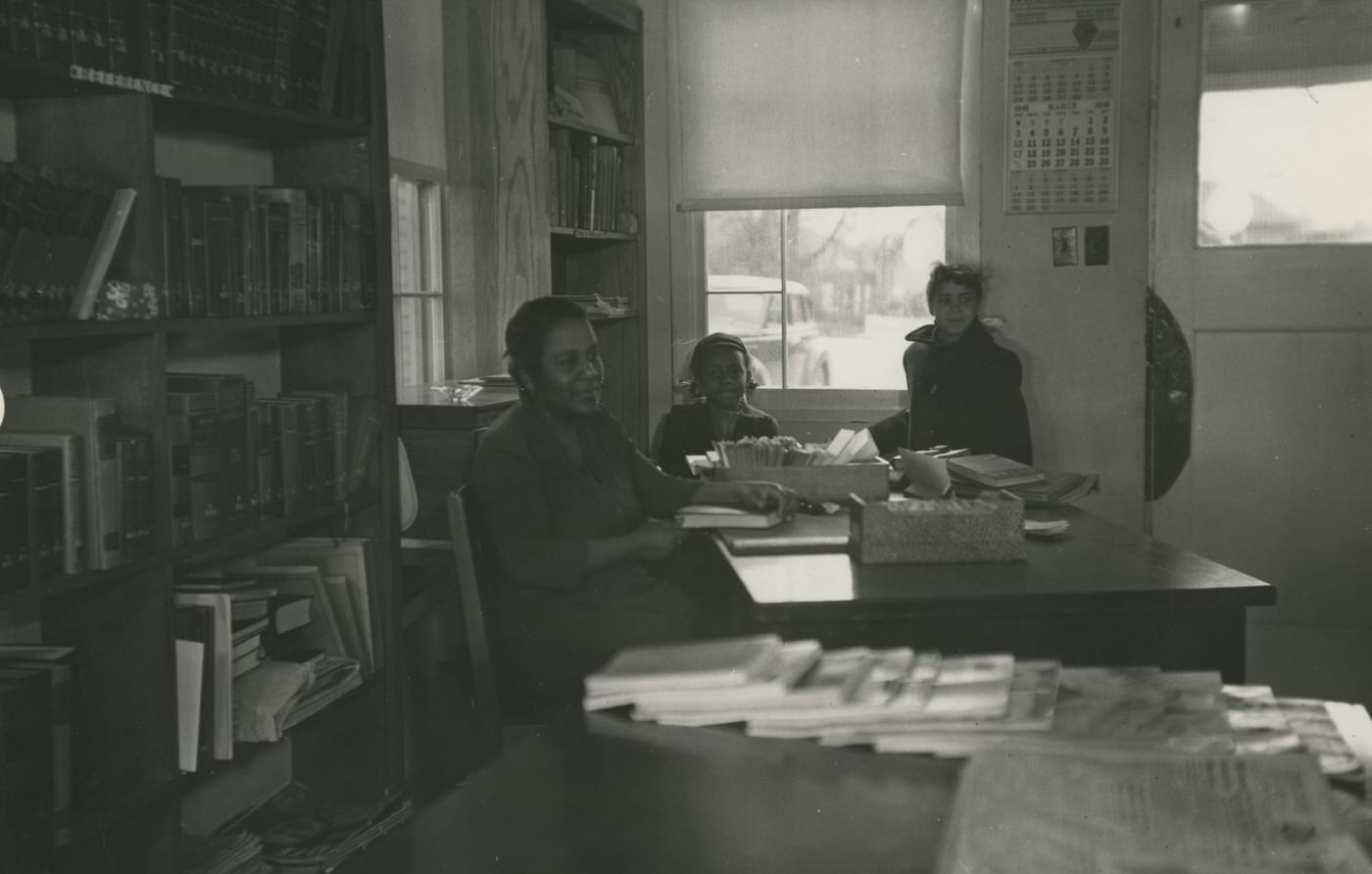

Arlington’s schools had to reorganize to handle the rapidly growing student population. However, the school system maintained separate schools for Black and white students, and these schools were far from equal. African American schools often had fewer class choices, fewer after-school activities, and were forced to use secondhand books and supplies. As a result, many African American families chose to send their children to schools in Washington D.C., which were seen as better options.

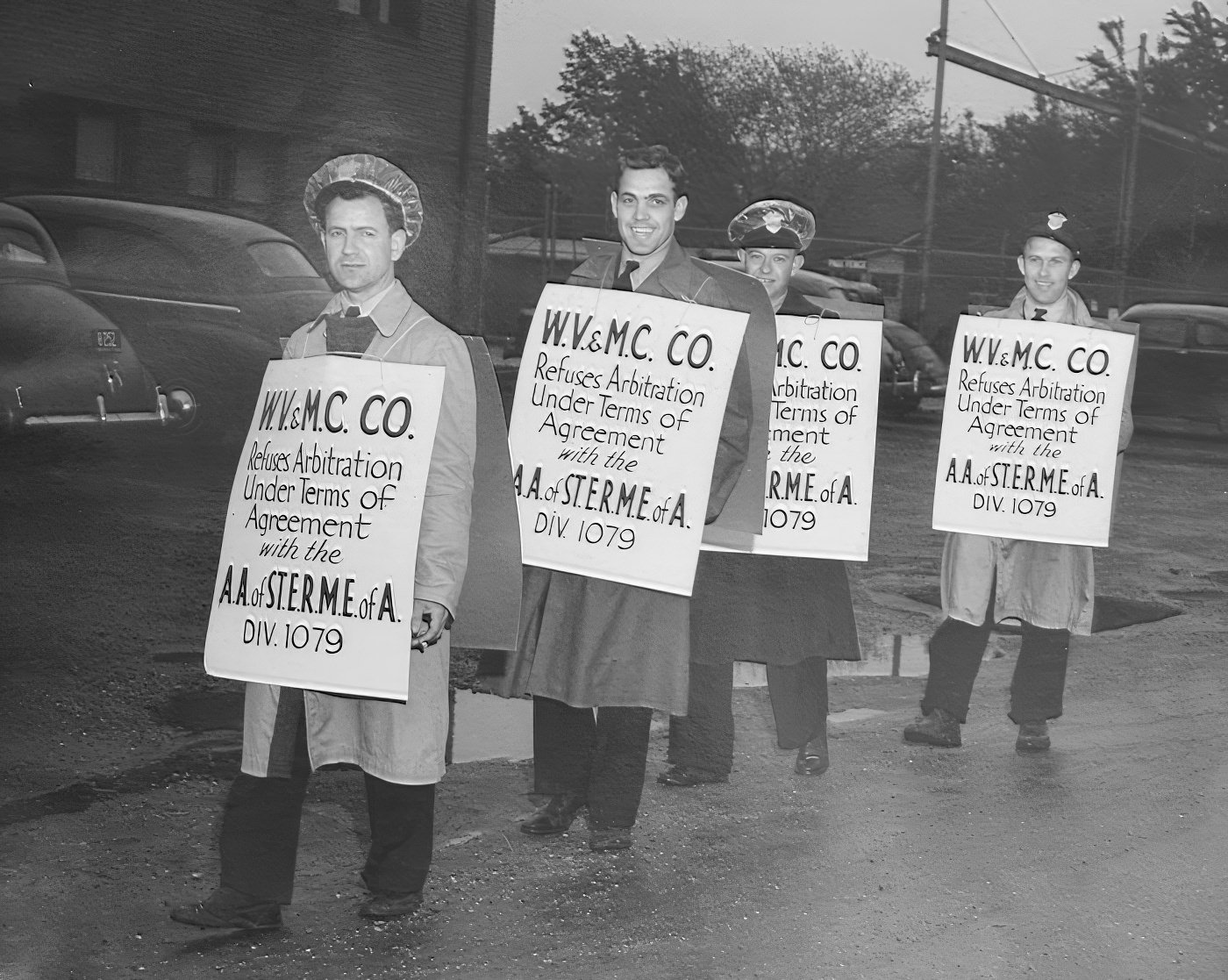

Transportation also saw changes. The war increased the popularity of rail transportation for moving troops and materials. After 1945, when government priorities on automobile parts were lifted, the use and demand for cars grew. The construction of major roads, like Route 50 in 1931, created physical barriers that further separated communities. The shift from streetcars to buses also changed how people moved around the county.

While World War II created new opportunities for women and brought federal jobs for African Americans, it also highlighted and, in some cases, deepened the racial inequalities in Arlington. The federal government, while providing economic advancement for some African Americans, simultaneously either directly supported segregated housing policies or failed to ensure fair public services for its Black citizens. This systemic neglect and discrimination forced Black communities, such as Halls Hill, to develop their own self-reliant institutions to fill critical gaps in services that were denied to them. This demonstrates a powerful act of determination and strength in the face of unfair systems. It shows that progress during wartime was not evenly distributed and often came with significant social costs and ongoing struggles for groups facing discrimination, creating a dual reality within the county.

Image Credits: Image Credits: Library of Congress, wikimedia, Arlignton Public Library, Flickr

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know