The 1950s marked a period of significant change for Arlington, Virginia. Building on the rapid growth from World War II, the county continued its transformation from a mostly rural area into a bustling suburban community. This decade saw a growing population, new types of homes, a changing economy, and important shifts in daily life and public services. Arlington’s close ties to the federal government and its role during the Cold War shaped many of these developments.

A Growing Population and New Homes

Arlington’s population continued to expand in the 1950s, though at a slightly slower pace than the peak wartime years. This ongoing growth fueled a demand for more housing and led to changes in how the county was built.

Arlington County experienced substantial population growth leading into the 1950s. The county’s population had more than doubled from 57,000 people in 1940 to 120,000 by 1944, a direct result of World War II and the influx of federal government operations. This rapid increase established Arlington as the fastest-growing county in the nation for that decade.

The expansion continued into the 1950s. In 1950, Arlington County had a total population of 135,449 people. By 1960, this number had grown to 163,401 residents. This represented a 20.6% increase over the decade. The consistent rise in residents showed that Arlington was firmly established as a desirable suburban area. The factors that drew people to the county, such as its closeness to Washington, D.C., and the availability of federal employment, remained strong. This sustained growth reinforced Arlington’s role as a “bedroom community,” where many residents commuted to jobs in the capital.

The Suburban Housing Boom

The demand for housing led to intense development. Between 1934 and 1954, 176 new apartment buildings or complexes were constructed. Notable projects included Fairlington, which was the nation’s largest defense housing complex, and Colonial Village, the first apartment complex backed by the Federal Housing Administration. Fairlington, built during the war, continued its evolution from temporary wartime rentals into a permanent community. Arlington Village, an early large-scale garden apartment community from 1939, also continued to provide housing and was sold in 1950, showing its ongoing importance.

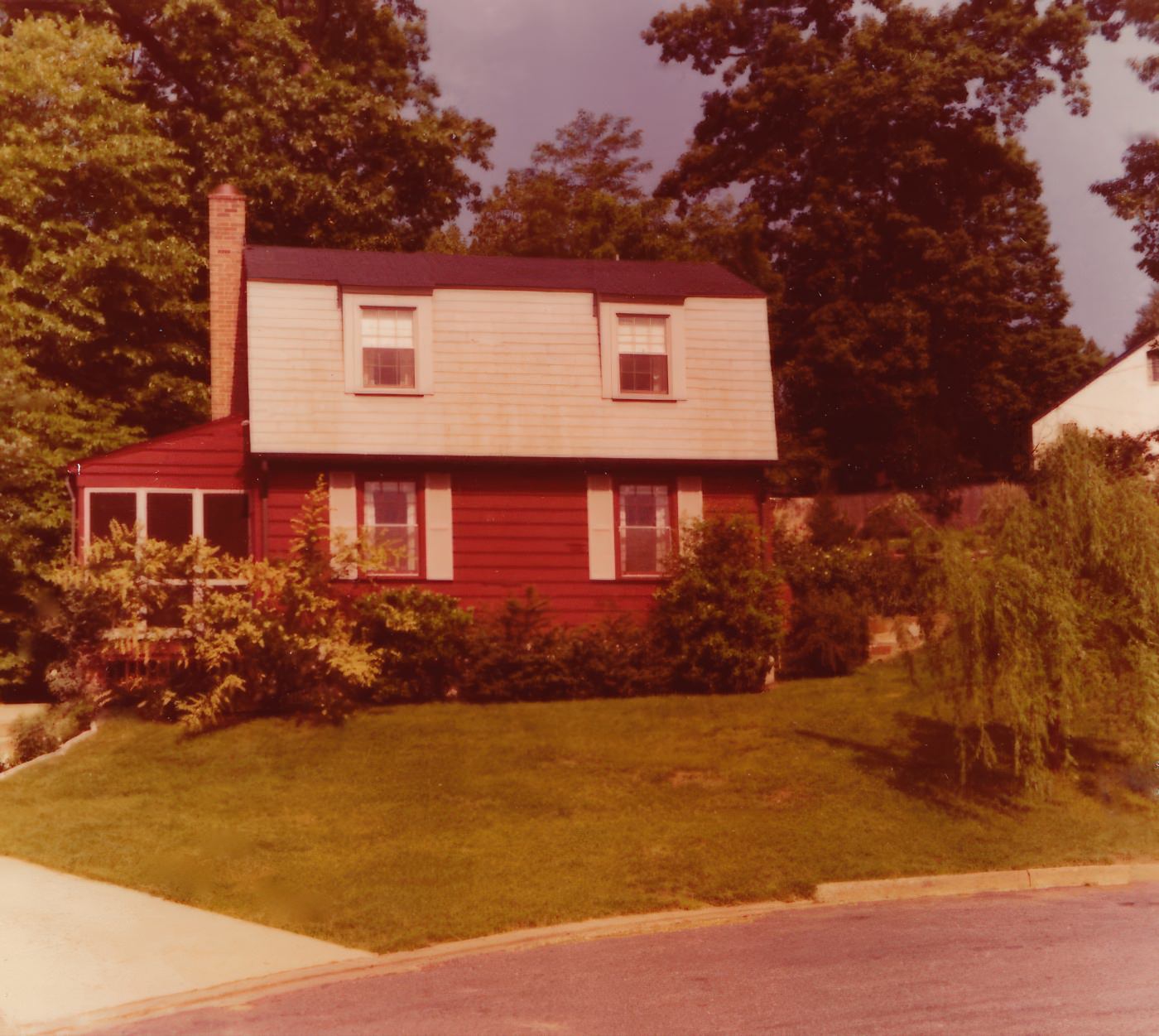

Newer, more contemporary housing styles also became popular in the 1950s. This included one-story brick homes built in Forest Park in 1950 and 1951, and brick ramblers constructed on 2nd Street North in 1956 and North Carlin Springs Road in 1958. Split-level homes also appeared in the late 1960s, bordering original subdivisions. Many single-family homes, especially ramblers, were built by companies like Marvin T. Broyhill and Sons. These homes often featured modern amenities, such as all-electric GE kitchens with the latest appliances, including dishwashers. These houses were well-regarded and sometimes purchased sight unseen. Older neighborhoods also saw new houses built on subdivided lots throughout the 1950s, adding to the housing stock.

The 1950s marked a clear shift from the quickly built, temporary wartime housing to more permanent, planned suburban homes and apartment complexes. During the war, many homes were built on concrete slabs, lacked basements, and were heated by coal stoves, often described as “quickly/poorly built”. The move to well-constructed ramblers and architect-designed mid-century modern homes reflected a community settling down after the war. This investment in long-term residential infrastructure indicated a more stable and prosperous post-war outlook.

Building and Improving Infrastructure

The ongoing population growth in the 1950s continued to put pressure on Arlington’s public services, leading to significant investments and improvements in roads, utilities, and public buildings.

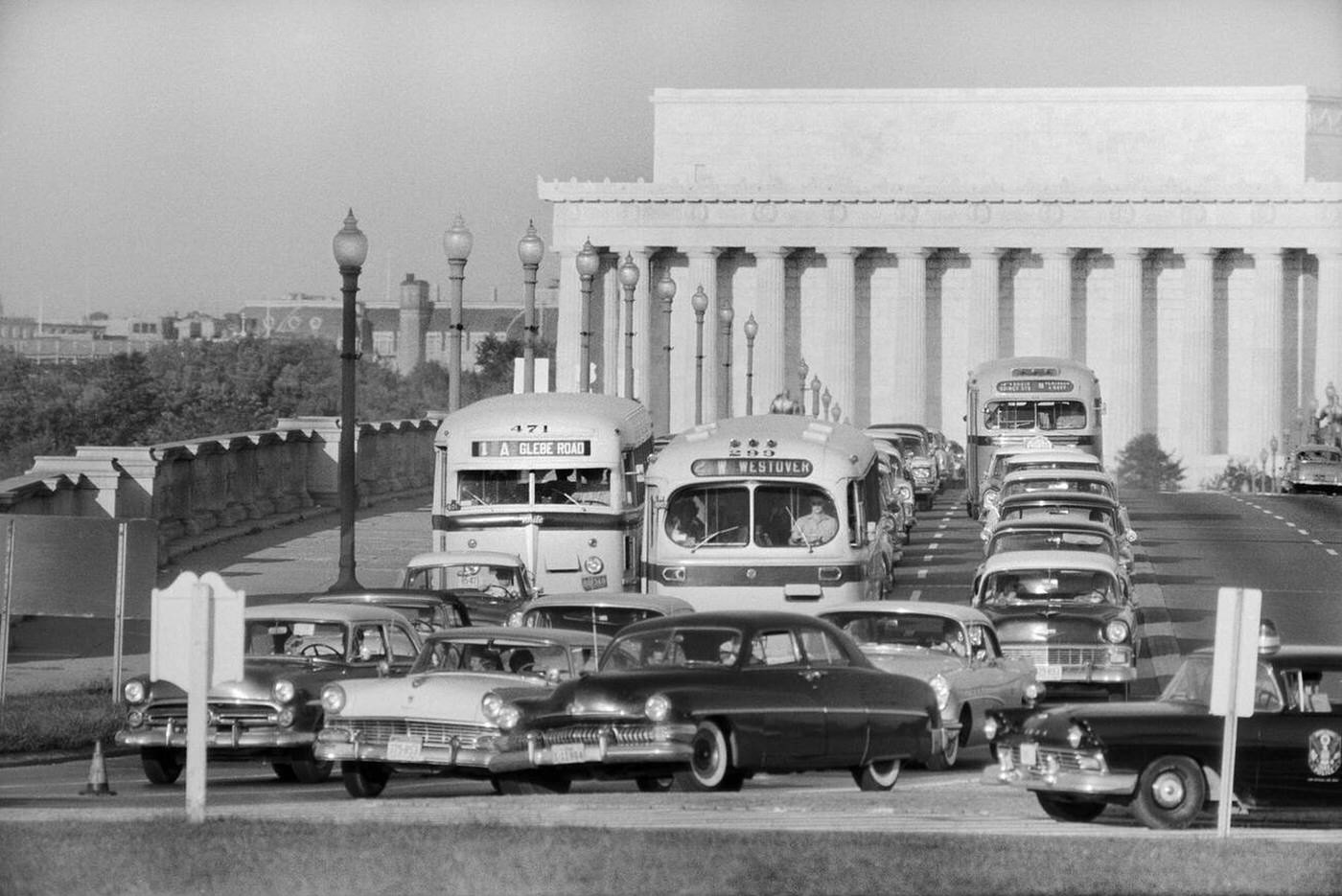

The increasing population led to a dramatic rise in traffic. Traffic volumes on U.S. Route 50 increased by 190% between 1945 and 1958, from 11,800 to 34,200 vehicles per day. Traffic on bridges over the Potomac River also surged by 93% during the same period. While the trolley system and the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad still provided transportation, the last passenger car on the railroad ran in May 1951. Bus companies also operated throughout the county, becoming a more preferred mode of public transportation.

Discussions began in the late 1950s for major transportation projects like Interstate Route 66 and the Metro subway system, though these were completed much later. Improvements were also made to existing infrastructure. For example, the Courthouse Road bridge on Arlington Boulevard, originally built in the early 1950s, was slated for replacement, and plans included adding dedicated acceleration/deceleration lanes to improve traffic flow and safety. The dramatic increase in traffic volume and the beginning of discussions about major highway projects like I-66 showed Arlington’s rapid adaptation to the automobile as the primary mode of transport. This shift shaped urban planning and the need for new road infrastructure.

Work and Economy

The federal government remained a dominant force in Arlington’s economy, but the 1950s also saw important growth in retail and the beginnings of a new technology sector.

The federal government was Arlington’s top employer. By 1940, over half of the county’s employed adults worked for the federal government, a pattern that continued through the 1950s. This expansion provided stable, well-paying jobs for many residents, including African Americans, who could rely on merit-based federal employment. Federal government operations and buildings occupied a large portion of the county’s land, nearly 18% by 1959.

Arlington Hall, which started as a private women’s college, became the headquarters for the U.S. Army’s Signal Intelligence Service during World War II. After the war, its “Russian Section” expanded, and the facility came under the National Security Agency (NSA) in 1952. Arlington Hall was a key site for cryptography operations, including efforts to break Soviet messages. In the late 1950s, it also housed the Armed Services Technical Information Agency (ASTIA), which shared classified research with defense contractors. The continued expansion of federal agencies and the establishment of intelligence and defense-related operations like the NSA at Arlington Hall solidified Arlington’s role as a critical hub for national security during the early Cold War. This concentration of strategic operations meant ongoing federal investment and a unique identity tied to national defense.

Growth in Retail and Shopping Centers

Commercial development continued to expand, with Clarendon establishing itself as the county’s main commercial center. Major department stores opened there, including J.C. Penney in 1940, Sears in 1942, G.C. Murphy’s in 1949, and Kann’s in 1951.

A significant development was the Parkington shopping center at Ballston, which opened in 1951. It was hailed as “the area’s most dramatic venture in retail merchandising” and became one of the first major shopping malls in the Washington, D.C. area, notably featuring a four-tiered parking garage. An economic survey in 1952 even suggested that Arlington could become the principal shopping center for Northern Virginia. The opening of large department stores and the innovative Parkington shopping center in the 1950s demonstrated the rise of suburban consumer culture in Arlington. This reflected a shift from smaller, local shops to larger, more centralized retail experiences designed for an increasingly car-dependent population.

Emerging Industries Beyond Government and Retail

While federal employment was a cornerstone, other industries also began to emerge. A Western Electric telephone manufacturing facility opened in Pentagon City during the 1950s, providing non-government jobs. Technology companies like Melpar, founded in 1945, expanded significantly in Northern Virginia during the decade. Melpar built an expensive, modern plant near Seven Corners in 1952. It focused on government research and development, including electronics for missiles and aircraft, and even early artificial intelligence research. Melpar also opened positions for minorities and females at unprecedented levels.

Raytheon, a multinational aerospace and defense company, also has roots in this period. It developed the first guidance system for a missile that could intercept a flying target after World War II and began manufacturing guided missiles in 1948. In Rosslyn, a former industrial area with lumber yards and fuel storage, a major transformation began. The county changed its zoning from industrial to commercial office, removing height limits and allowing for 12-story buildings. The first high-rise office building in Arlington was completed in Rosslyn in 1956, with RCA (Radio Corporation of America) as its first tenant. This building was designed with special facilities for a computing center, marking the beginning of a “new high-tech age” for Arlington. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) also established its headquarters in a new high-rise office building in Rosslyn. The clear emergence of a defense and technology sector in Arlington, beyond just government offices, showed the beginnings of a diversified economy. This development foreshadowed Arlington’s future as a hub for innovation and defense contractors, moving beyond its “bedroom community” identity.

Suburban Lifestyle and Social Trends

Life in Arlington in the 1950s reflected the national trend of suburban growth, with new amenities and activities, but also the continued presence of racial segregation.

As Arlington became more suburban, daily life began to reflect national trends. While some residents still found local grocery stores, drug stores, and other businesses within walking distance , car ownership became more important for shopping at larger, newer centers. Home services like milk delivery in glass bottles and laundry pickup were still common. The summer heat was managed with fans and wet washcloths, as residential air conditioning was not yet widespread.

Children enjoyed playing outside until dark , and informal activities like roller skating were popular. The decade saw the rise of new American lifestyle elements, including TV dinners, drive-in movies, and clearly defined gender roles within families, where the father was often the breadwinner and the mother managed the home. The blend of walkable local services and the rise of car-dependent shopping centers and new housing styles illustrates the developing suburban ideal in Arlington. This reflected a national shift towards a more family-centric, car-oriented lifestyle, but with local variations still present.

Community Centers and Recreational Programs

Arlington County actively developed recreational facilities during the decade. The Department of Parks and Playgrounds was established in 1944. In 1951, the Henderson House was converted into the Arlington Recreation Center, the county’s first recreation center. The first senior adult program in Virginia, the Silver Age Club No. 1, was established in Arlington in 1954. Another key facility, the Lubber Run Community Center, welcomed its first guests in 1956. By 1959, the Parks and Recreation Department sponsored its first free outdoor performance series at Lubber Run Park and started summer day camps for children.

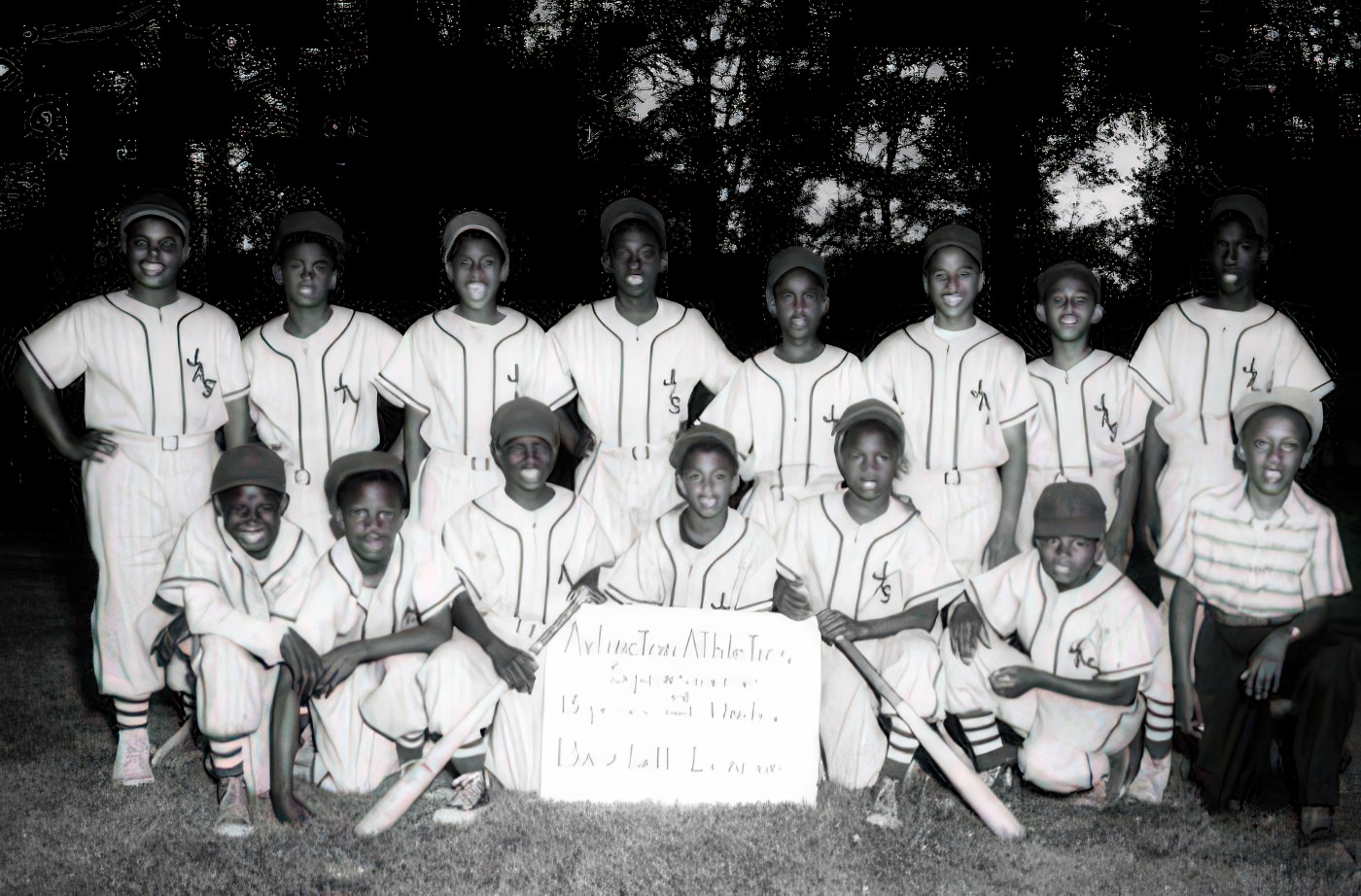

For African Americans, recreational facilities were limited due to segregation. Jennie Dean Park offered outdoor play fields and tennis courts, and the Green Valley Ball Park hosted amateur baseball games. The Veterans Memorial YMCA, dedicated in 1949, provided a 25-meter swimming pool and other facilities. This offered one of the few swimming opportunities for Black children, as they were not allowed at neighboring pools. The establishment of dedicated recreation centers and programs in the 1950s showed a deliberate effort by Arlington County to support the social and leisure needs of its growing suburban population. This indicated a maturing community structure, moving beyond informal gatherings to organized public services for recreation.

Public Buildings: Schools, Hospitals, and Libraries

Providing education for the growing number of school-aged children remained a major challenge in the 1940s and 1950s, with schools constantly needing to stretch to accommodate larger student populations. New schools, like Taylor Elementary, opened in 1954.

Arlington Hospital, which opened as a 100-bed facility in 1944, embarked on a major expansion plan in the 1950s. The first phase, a three-story South Wing, opened in 1953, adding 77 beds and expanded laboratory facilities. The second phase, a three-story North Wing, opened in July 1957, adding 70 more beds and new, larger emergency, X-ray, and outpatient facilities, bringing the hospital’s total capacity to 250 beds.

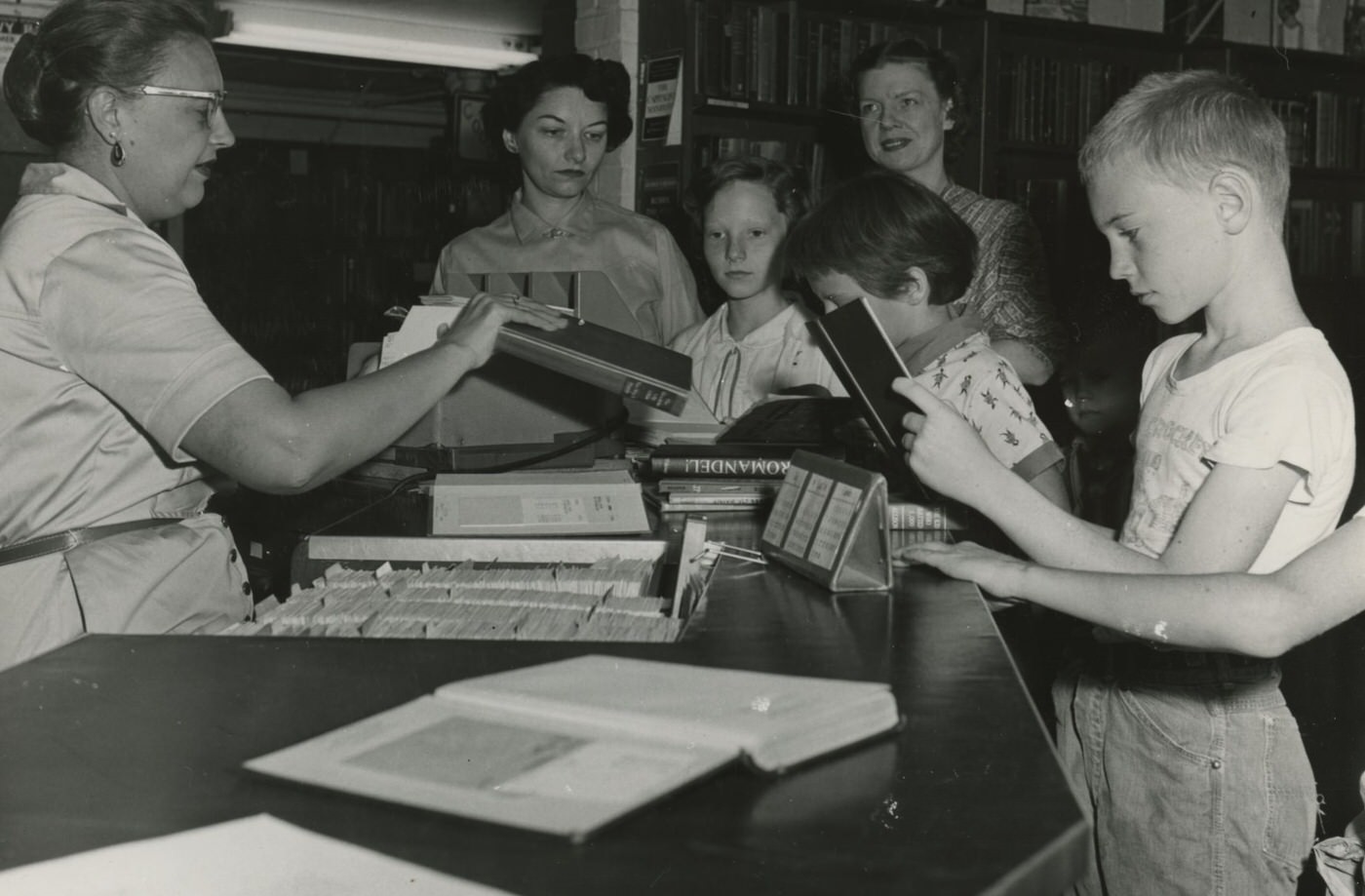

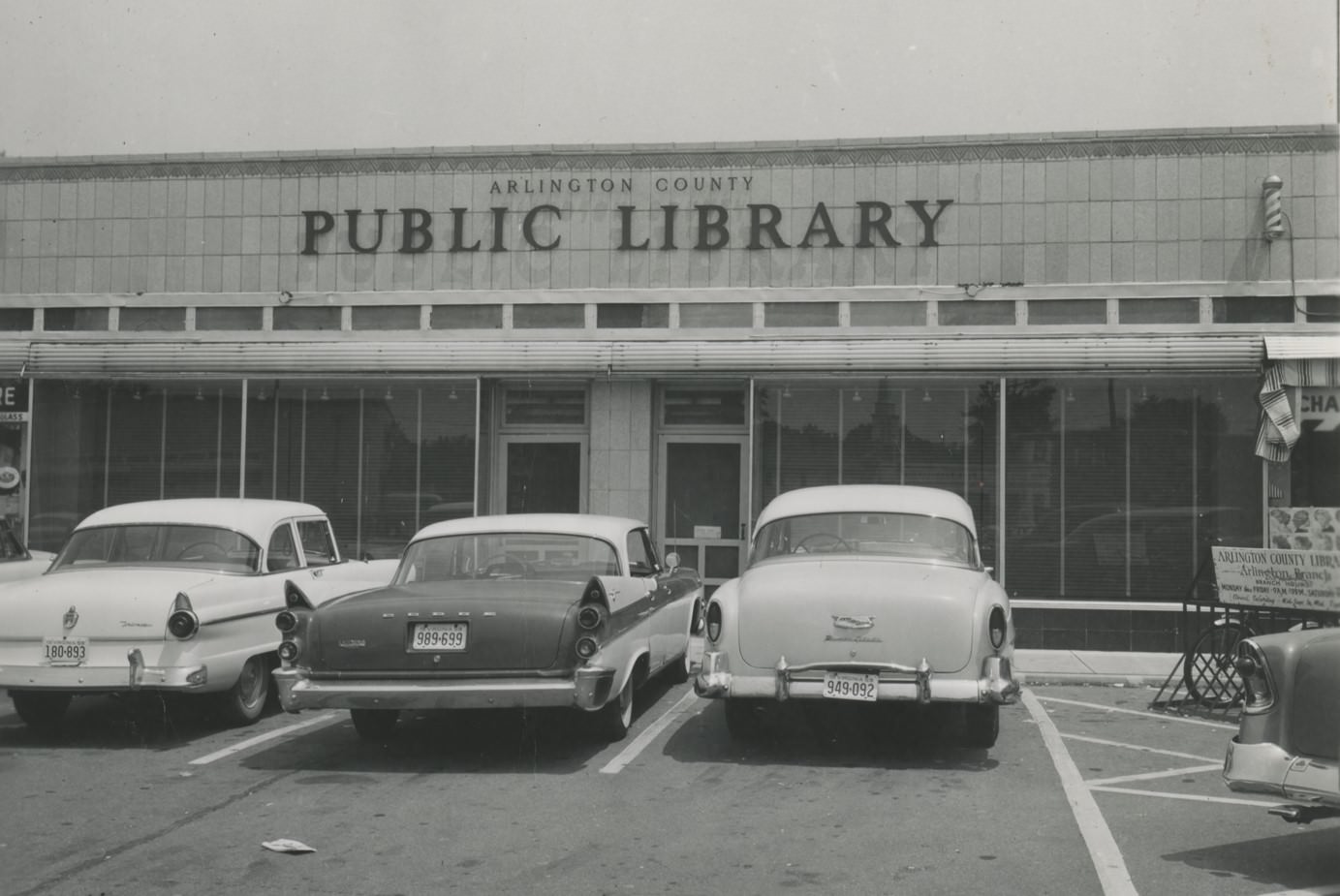

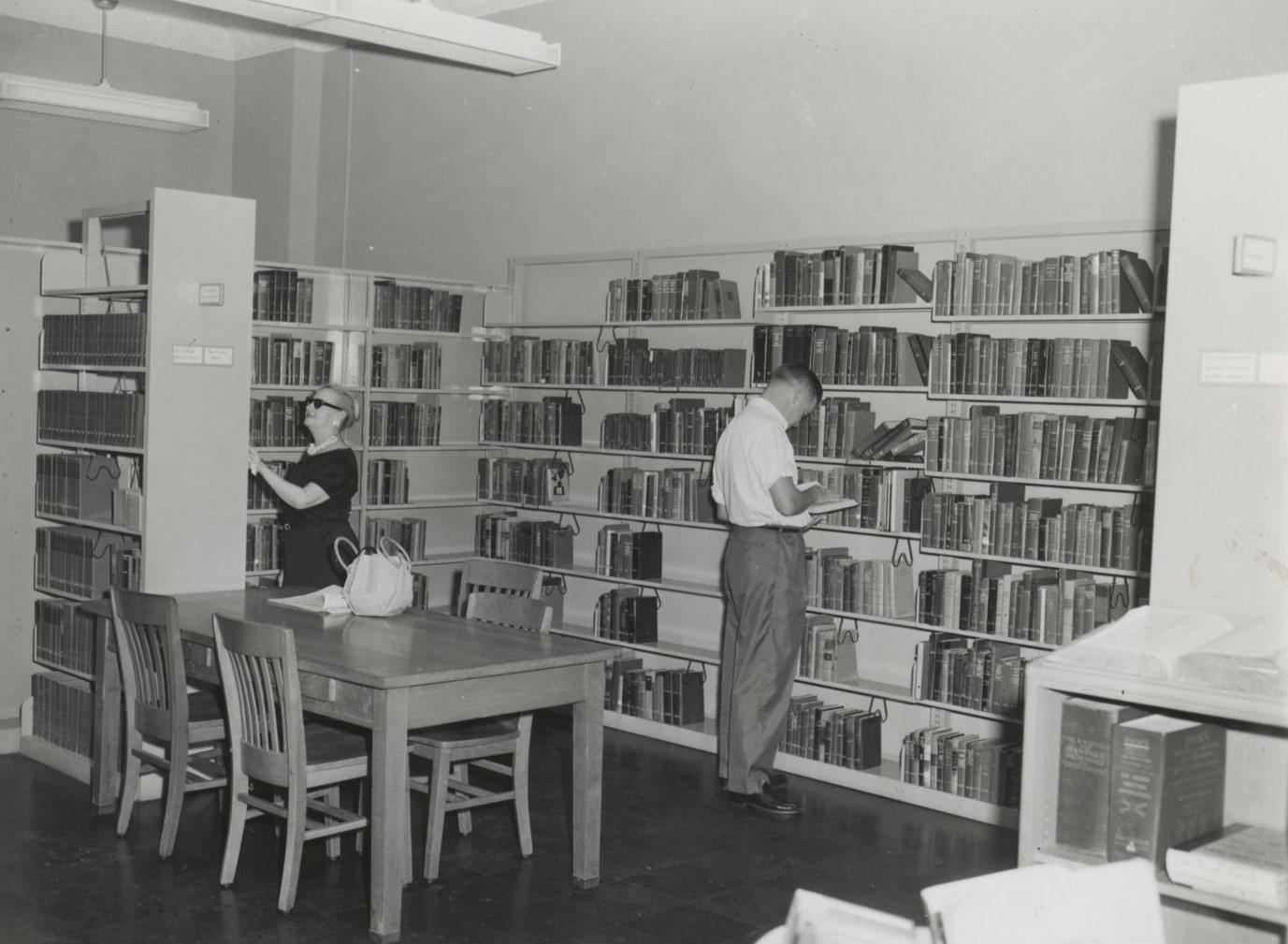

In the library system, the Henry L. Holmes library, which was the official “colored” branch, closed in 1950. Later in the decade, in 1958, the county approved the creation of the Central Library, with construction beginning in 1960 and its opening in 1961. The significant expansion of Arlington Hospital and the planning and construction of the Central Library in the 1950s demonstrated the county’s commitment to building robust social infrastructure to serve its growing and increasingly settled population. This indicated a shift from basic provision to a focus on quality and capacity in public services.

Segregation and the Fight for Equality

Racial segregation remained a stark reality in Arlington during the 1950s, affecting housing, public services, and especially schools. However, the decade also saw significant legal challenges and early steps toward desegregation.

Housing projects built during the war were segregated by race, reflecting the customs of the time. For instance, the George Pickett and Shirley homes were designated for whites, while the George Washington Carver and Paul Dunbar homes were for Black residents. The community of Arlington Forest, developed in phases from 1939, initially had restrictive covenants that prohibited non-Caucasians and non-Christians from living there.

The Hall’s Hill neighborhood, a Black enclave, was physically separated from adjacent white neighborhoods by a 7-foot cement wall, built by white residents between 1930 and 1940 to prevent contact. Roads within Hall’s Hill were often dead ends, and residents faced unequal access to basic public services for decades. This included relying on wells for water, outhouses for sanitation, and having unpaved, dark roads without sidewalks or drainage. Police presence was minimal, and the fire department often did not respond to calls in Black neighborhoods, leading Hall’s Hill to form its own volunteer fire department. Access to medical care was also segregated; Black mothers were barred from the maternity ward at Arlington Hospital and had to travel to hospitals in Washington, D.C., or Alexandria to give birth. The physical and systemic segregation in housing, infrastructure, and public facilities demonstrated that Arlington’s suburban growth was not equitable. It created deeply divided communities where access to modern amenities and quality of life varied drastically by race.

School Desegregation Efforts

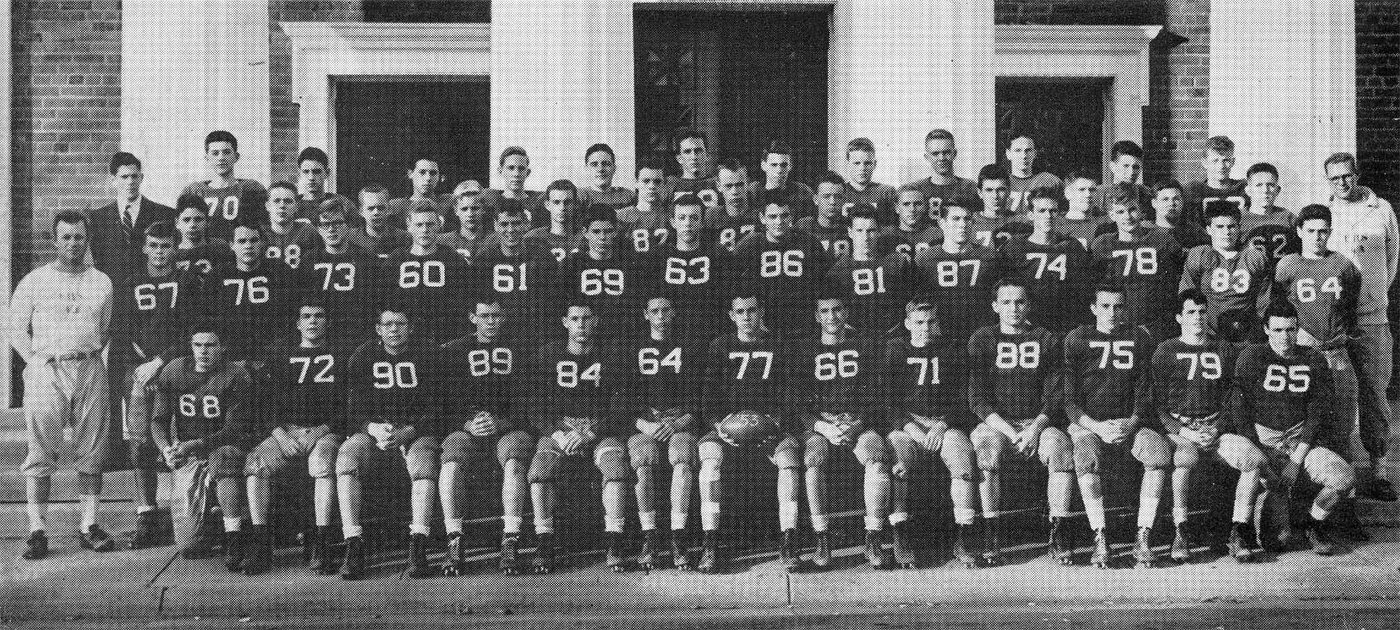

Arlington’s schools were separate for Black and white students, and Black schools like Hoffman-Boston Elementary and High School often had fewer class choices, after-school activities, and were forced to use secondhand books and supplies. Many African American families chose to send their children to D.C. schools for better educational opportunities. In 1950, a lawsuit by Constance Carter against the Arlington School Board regarding unequal facilities was initially unsuccessful. However, the landmark

Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 declared segregated schools unconstitutional.

Following the Brown ruling, Virginia adopted a policy of “Massive Resistance” to desegregation, which included threatening to close any schools that integrated. In January 1956, the Arlington School Board proposed a plan for gradual desegregation. However, the Virginia General Assembly quickly removed the democratically elected board and replaced it with officials more sympathetic to segregation, overturning the plan. Legal battles continued, and in January 1959, both the Virginia Supreme Court and a federal court declared “Massive Resistance” measures unconstitutional.

On February 2, 1959, four Black students—Ronald Deskins, Michael Jones, Gloria Thompson, and Lance Newman—entered Stratford Junior High School, making it the first public school in Virginia to desegregate. This event was widely noted for passing “without incident”. Despite this breakthrough, Arlington’s public schools continued to integrate slowly. The County School Board even ended school dances and athletic events after integration began in 1959. Arlington’s experience with school desegregation showcased its unique position as a Northern Virginia county caught between state-level “Massive Resistance” and local pressures. This ultimately made Arlington a pioneer in Virginia’s desegregation efforts, highlighting the complex legal and social battles fought at the local level.

Popular Entertainment

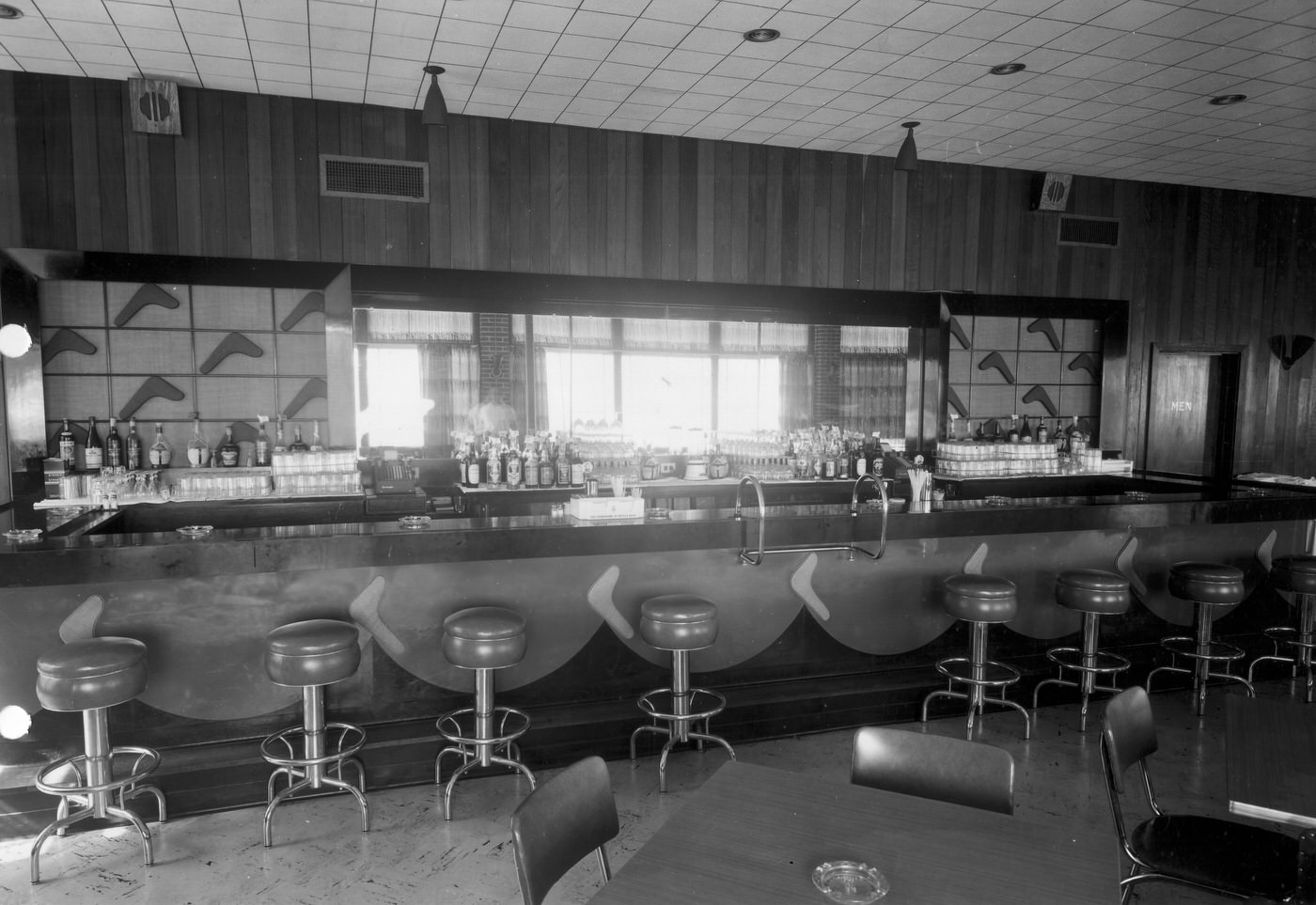

The Arlington Cinema ‘N’ Drafthouse, originally the “Arlington Theater & Bowling Alleys,” opened in 1940 and continued to operate as a movie theater in the 1950s. It showed films like “My Favorite Wife” for 25 cents a ticket. The Arlington Music Hall, which opened as the Arlington Theater in 1950, featured luxurious seating, a balcony, and air conditioning, becoming a popular spot for movies.

However, movie theaters in Arlington remained segregated. This was unlike those in Washington, D.C., which had desegregated in the early 1950s after extended boycotts, activism, and legal maneuvering by Black Washingtonians. Local radio stations, such as WARL radio, became platforms for country music celebrities like Jimmy Dean, who lived in Arlington and started his broadcasting career there in the 1950s. His show “Country Style” became the first nationally televised non-news show to originate from D.C.. While new entertainment venues offered modern leisure options, the continued segregation in places like movie theaters highlighted that social progress lagged behind economic and infrastructural development. This showed the dual reality of suburban growth alongside persistent racial discrimination.

Water and Sewer Systems

Arlington’s water system, which draws from the Potomac River via the Dalecarlia Plant in D.C., saw improvements initiated in 1953. The distribution system significantly expanded and updated from its original 1927 setup. By 1950, over 90% of Virginia farms had electricity, indicating widespread access in more developed areas like Arlington.

The county’s sanitary sewer system expanded rapidly through the 1930s and 1940s, with about 65% of its pipes built before 1950. Most wastewater treatment facilities in Virginia were built after World War II. For example, Alexandria’s wastewater treatment plant, which served some Virginia communities, began operation in 1956, treating raw sewage that was previously discharged into Four Mile Run. The 1950s saw critical upgrades and expansions to Arlington’s water and sewer systems. This moved beyond basic provision to more robust, modern infrastructure capable of supporting a large, dense suburban population. These improvements were essential for public health and continued residential development.

Arlington in the Cold War Era

The Cold War profoundly influenced Arlington, solidifying its strategic importance and shaping aspects of daily life.

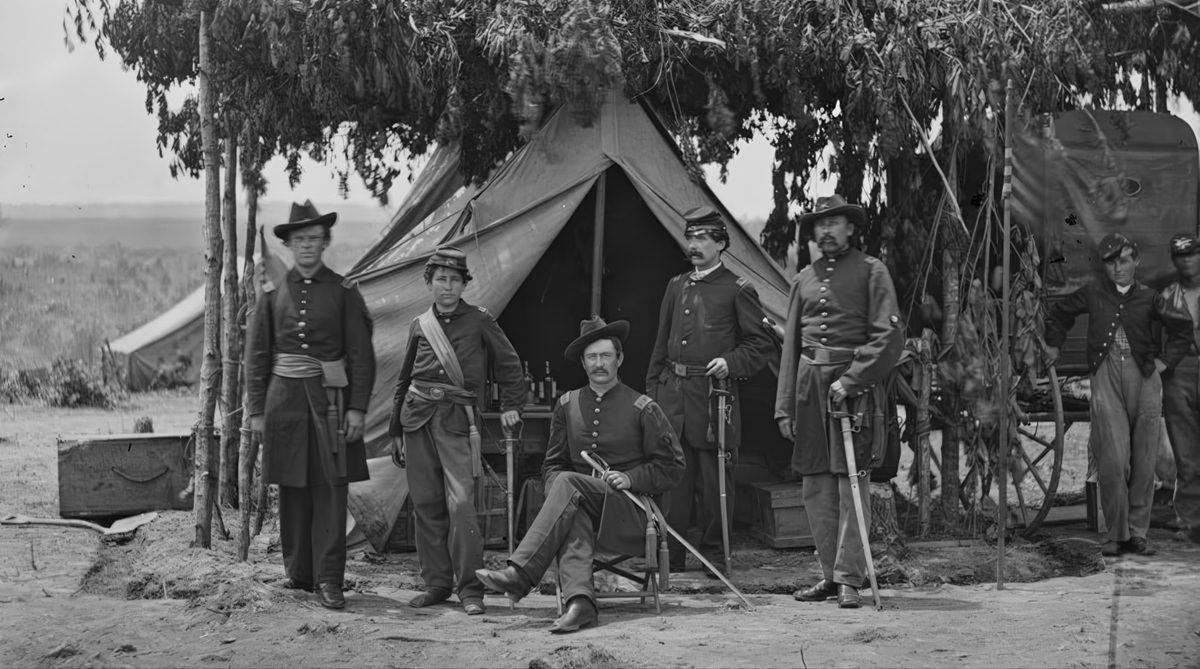

The Pentagon, completed in 1943, continued to be the headquarters of the U.S. Department of Defense and played a central role during the Cold War. Arlington Hall became the headquarters of the U.S. Army Security Agency from 1945 to 1977, and came under the National Security Agency (NSA) after its creation in 1952. It was a key site for cryptography operations, including extensive work on Soviet messages. New federal campuses were located in suburban Maryland and Virginia, a trend consistent with new highway systems and Cold War concerns about nuclear attack, which promoted the dispersal of federal facilities for security. Arlington’s concentration of critical defense and intelligence facilities, like the Pentagon and Arlington Hall (NSA), made it a vital nerve center for the Cold War. This strategic importance meant continued federal investment and a unique identity tied to national security.

The threat of nuclear war and the broader Cold War culture of the 1950s meant terms like “air raid drills,” “Conelrad” (a system for broadcasting emergency information), “bomb shelters,” and “duck and cover” became familiar to Americans. Virginia’s military bases and its proximity to Washington, D.C., made it a primary target for potential attacks. Northern Virginia had a special evacuation plan, though its population density and rural routes would have made a mass evacuation difficult. The Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) distributed survival literature, including evacuation maps, and encouraged families to build bomb shelters. The pervasive civil defense measures and public awareness campaigns demonstrated how the Cold War directly influenced the daily routines and anxieties of Arlington residents. This showed a community adapting to a new era of global tension and preparing for potential threats.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, wikimedia, Arlington Public Library, Pinterest, Flickr,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know