The decade of the 1870s was a period of profound change for Cleveland, Ohio. The city grew at a remarkable pace, its industries boomed, and its streets filled with people from many parts of the world. This era laid much of the groundwork for the major American city Cleveland would become.

Cleveland’s landscape, both physically and demographically, was reshaped during the 1870s. The city experienced a significant increase in its population, expanded its official boundaries through the annexation of neighboring areas, and welcomed a diverse array of immigrants who contributed to its evolving character.

Cleveland’s Expanding Population

The 1870s began with Cleveland already in the midst of a population boom. By the start of the decade, the city proper housed 92,829 residents. This figure was more than double its 1860 population of 43,417, highlighting an astonishing rate of growth. This surge meant that Cleveland accounted for 70 percent of Cuyahoga County’s total population of 132,010 by 1870. Such rapid urbanization placed considerable strain on the city’s existing infrastructure, including housing, sanitation, and transportation, necessitating swift development to meet the needs of its swelling populace. The city was quickly becoming a major urban center in the post-Civil War United States, attracting people seeking opportunities in its burgeoning industries.

To manage its rapid growth and increase its resources, Cleveland actively expanded its geographical boundaries throughout the 1870s by annexing adjacent townships and villages. This expansion was not merely about finding space for more people; it was a strategic effort to incorporate valuable industrial assets and solidify the city’s economic and political dominance in the region.

Several key annexations took place during this decade:

- A part of Newburgh Township was brought into the city on March 9, 1870.

- The village of East Cleveland was annexed on October 24, 1872.

- Further portions of Brooklyn, Newburgh, and East Cleveland townships were added on February 8, 1873.

- Another segment of Newburgh Township became part of Cleveland on December 8, 1873.

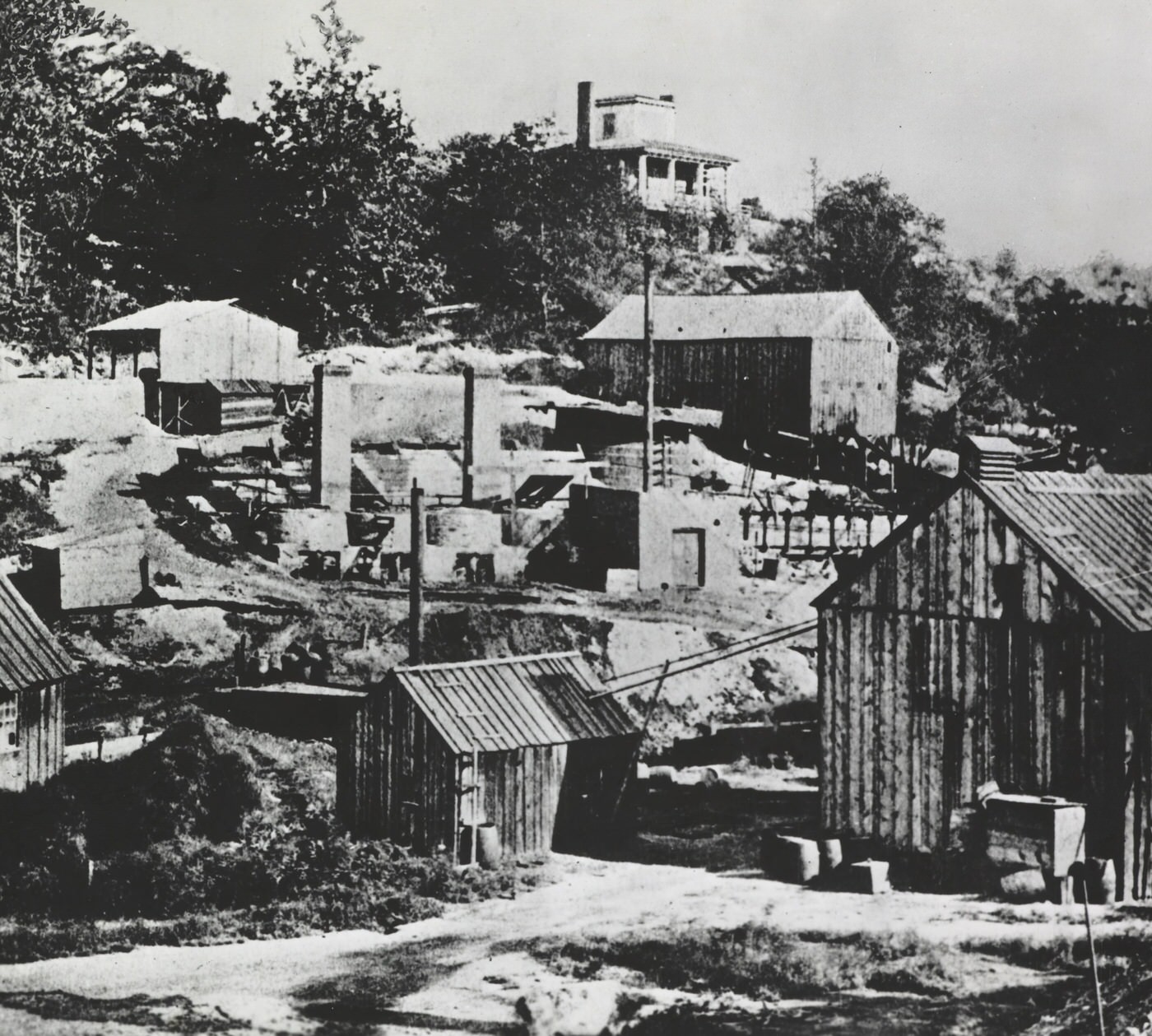

The annexation of the central part of Newburgh in 1873 was particularly noteworthy, as this area, later known as the “iron ward,” was rich in industrial facilities, especially iron and steel mills. By incorporating these industrial zones, Cleveland directly boosted its manufacturing capacity and its tax revenue, further fueling its economic engine.

A City of Immigrants: Diverse New Arrivals

The 1870s marked a significant phase in Cleveland’s demographic evolution, characterized by the arrival of the “new immigration” wave from Southern and Eastern Europe. These newcomers joined established communities of Germans and Irish, transforming Cleveland into a truly multiethnic metropolis.

German immigrants remained a substantial group. They had established communities prior to the 1870s, primarily along Lorain Street, Superior Avenue, and Central Avenue. Germans were well-represented among the city’s skilled craftsmen, including cabinetmakers, machinists, and brewers.

Irish immigrants, many hailing from County Mayo, numbered nearly 10,000 by 1870, making up about 10% of Cleveland’s population. They typically settled near the Cuyahoga River, in neighborhoods like “The Angle,” and found work as laborers on the docks and in the burgeoning steel mills.

Czech immigrants, also known as Bohemians, arrived in increasing numbers, often seeking to escape economic hardship and compulsory military service in the Austrian Empire. They formed distinct neighborhoods, such as “Little Bohemia” around Broadway Avenue, and were known for their small vegetable and flower gardens. Many Czechs were skilled artisans, working as tailors, shoemakers, and masons, while others found employment in the oil refineries.

Hungarian immigrants began to arrive in significant numbers during the 1870s. Initially, many were single men or men who had left their families behind, intending to earn money and return to Hungary. They settled in areas like Buckeye Road and on the near west side. Hungarians found employment in various manufacturing enterprises, including foundries. Theodor Kundtz’s cabinetmaking company became a major employer for Hungarians on the West Side.

Polish immigrants started to form their own neighborhoods in the late 1870s. Warszawa, which later became part of Slavic Village, developed near the Cleveland Rolling Mills. Another Polish settlement, Poznan, emerged around East 79th Street and Superior Avenue. A primary source of employment for Polish immigrants was the steel industry.

Italian immigrants began to establish a community in Cleveland during this period. The 1870 census recorded 35 native Italians in the city. Early Italian settlements were located in the Ontario Street market district and in the area that would become “Little Italy” on Mayfield Road. Many early Italian immigrants worked in marble works, and later, in the produce industry or on public works projects like street and sewer construction.

The Jewish community, initially established by German Jewish immigrants, began to see the arrival of Eastern European Jews in the 1870s. By 1880, the Jewish population in Cleveland was approximately 3,500. Members of the Jewish community were active in retail and wholesale businesses, and increasingly in manufacturing, particularly the garment industry.

Slovenes and Slovaks also contributed to Cleveland’s growing ethnic diversity, arriving in larger numbers during this decade.

The scale of immigration was so substantial that by 1874, the city recognized the need for a formal response. “Emigrant officers,” who were members of the police force, were stationed at Cleveland’s railroad stations. Their duties included counting the new arrivals and providing assistance, indicating an official acknowledgment of the profound demographic shifts underway. This wave of diverse immigration laid the foundation for the multicultural fabric that would characterize Cleveland in the 20th century, bringing new skills, traditions, and also the complexities of social integration and competition in a rapidly industrializing urban environment.

The Roar of Progress: Cleveland’s Industrial Might

The 1870s were a period of intense industrial expansion for Cleveland, solidifying its position as a manufacturing powerhouse. Key sectors like iron and steel, oil refining, chemicals, and the nascent electrical industry experienced significant growth, driven by technological innovation and ambitious entrepreneurs.

Iron and Steel: The Backbone of Industry

Cleveland’s iron and steel industry, already spurred by the demands of the Civil War, continued its ascent in the 1870s, forming the bedrock of the city’s economy. By 1880, the production of iron and steel would account for a remarkable 20% of the total value of all manufactured goods in Cleveland.

At the forefront of this industrial dominance were companies like the Cleveland Rolling Mill, led by the influential Henry Chisholm. This firm was an early adopter of advanced steelmaking technology, having installed Bessemer converters in 1868. By the close of 1872, the Newburgh plants of the Cleveland Rolling Mill were a significant operation, boasting two puddling mills, two blast furnaces, two Bessemer converters, and mills for producing various steel products, including rails and wire. Another key enterprise, the Otis Iron & Steel Co., further advanced the city’s technological edge by introducing open-hearth steel manufacturing in 1873, another recent and important European innovation.

The rapid expansion of this sector was heavily reliant on the abundant iron ore deposits of the Lake Superior region, which were efficiently transported to Cleveland’s port facilities. The willingness of Cleveland’s industrialists to invest in and implement cutting-edge technologies like the Bessemer and open-hearth processes was a critical factor. These innovations allowed for the mass production of higher quality steel, essential for the nation’s booming railroad construction and a wide array of other industrial applications. This technological foresight, combined with access to raw materials, cemented Cleveland’s status as a leading national industrial center.

The Standard Oil Empire Takes Shape

The 1870s witnessed the meteoric rise of John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company, an enterprise that would redefine industrial organization in America. Rockefeller, a figure of immense ambition and business acumen, formally established the Standard Oil Company of Ohio in Cleveland on January 10, 1870.

Throughout the decade, Rockefeller pursued a relentless strategy of consolidation. Focusing on efficiency and leveraging his company’s growing scale, he systematically acquired or drove out competitors. A notable episode in this campaign was the “Cleveland Massacre” in early 1872, during which Standard Oil took control of 22 of its 26 local refining competitors within a matter of weeks. This aggressive expansion was facilitated by practices such as negotiating preferential rebate agreements with railroads, which lowered transportation costs for Standard Oil and made it difficult for smaller refiners to compete. The company also invested in research and development, for instance, devising methods to refine “sour” oil that other refiners considered less desirable.

By the end of the 1870s, Standard Oil had achieved a dominant position in the American oil refining industry, making Cleveland its undisputed capital. The formation of the Standard Oil Trust in 1879 further centralized control over its vast and expanding operations. Rockefeller’s methods, though often criticized for their ruthlessness, were instrumental in creating one of the nation’s first and most powerful monopolies, pioneering corporate structures and business strategies that would be emulated and debated for generations. Cleveland, in the 1870s, was thus the crucible where a new model of industrial empire was forged.

The Growing Chemical and Paint Industries

The expansion of Cleveland’s oil refining industry created a ripple effect, stimulating growth in related chemical and paint manufacturing. The Grasselli Chemical Company, which had established a facility in Cleveland in 1866 to supply sulfuric acid to the refiners, broadened its production in the 1870s to include a diverse range of industrial chemicals. This demonstrates a clear industrial symbiosis, where the needs of one major sector directly fostered the development of another.

Similarly, the paint and varnish industries flourished, benefiting in part from the availability of petroleum byproducts as raw materials. In 1870, Henry Sherwin and Edward Williams formed the Sherwin-Williams Co., a paint-manufacturing enterprise that would become a household name. A decade later, in 1880, they successfully introduced a ready-mixed paint, a significant innovation for consumers. Another key player, Francis H. Glidden, established his paint and varnish company in 1875, focusing on varnishes and enamels. The development of these industries showcased Cleveland’s diversifying economic base, moving beyond primary resource processing to more complex manufacturing.

Pioneering Electrical Technology

Cleveland also emerged as a significant center for innovation in the nascent field of electrical technology during the 1870s. Local inventor Charles F. Brush was a pivotal figure in this development. During the decade, he engineered an effective dynamo (an electrical generator) and a practical outdoor arc-lighting system.

This technology was not confined to laboratories. Brush’s arc lights had their first continuous public demonstration on Cleveland’s Public Square in April 1879. This event was groundbreaking, showcasing the potential of electricity to illuminate urban spaces. The success of this demonstration quickly led to the adoption of Brush’s system in major cities across the United States and internationally. Cleveland was thus not merely a consumer of new electrical technologies but an active hub for their invention and initial dissemination, contributing significantly to a technology that would revolutionize urban life and industry worldwide.

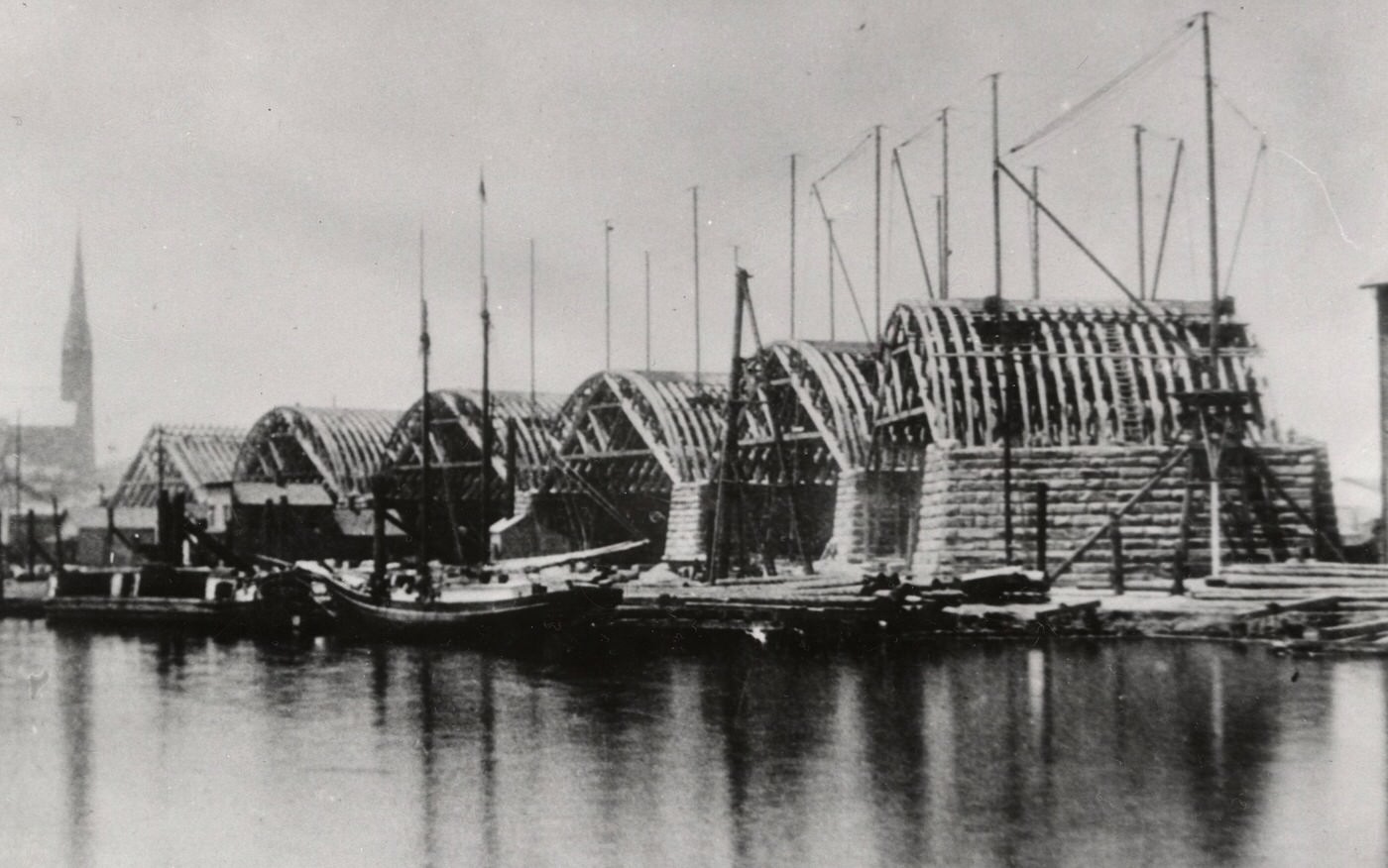

Shipbuilding and Lake Trade

Cleveland’s strategic location on the southern shore of Lake Erie, coupled with its direct access to iron ore from the upper Great Lakes and coal from regional mines, fostered a thriving shipbuilding industry. The 1870s saw important innovations in this sector that were directly tied to the needs of the city’s dominant industries.

In 1869, the Cleveland firm of Peck & Masters launched the R.J. Hackett. This vessel is recognized as the first ship specifically designed for the burgeoning iron ore trade. The ability to transport bulk raw materials more efficiently was crucial. Complementing this, Clevelander Robert Wallace introduced a steam-powered engine for unloading iron ore from ships along the docks of the Old River Bed around the same period, a significant improvement over the horse-powered methods previously used, drastically reducing unloading times. By 1870, the city’s importance as a shipping hub was further evidenced by the presence of local offices for four different lake steamer lines. These advancements in shipbuilding and cargo handling were not isolated developments; they were critical for efficiently supplying the massive quantities of iron ore demanded by Cleveland’s rapidly expanding steel mills. This demonstrates a vital synergy where maritime strength directly supported and enabled industrial prowess.

Other Important Manufacturing Sectors

Beyond the dominant industries of iron, steel, and oil, Cleveland’s manufacturing economy in the 1870s was diversifying.

Machinery and Machine Tools: The production of machinery and machine tools was becoming increasingly important. Companies like Warner & Swasey and the Cleveland Twist Drill Co. (founded in 1876) were laying the groundwork for Cleveland’s future prominence in this sector, producing lathes, drill presses, and other essential equipment for various manufacturing processes. The White Sewing Machine Co. was a significant local manufacturer that not only produced sewing machines but also developed and consumed machine tools for its own production needs.

Textiles and Clothing: The garment industry, which was already Cleveland’s third-largest manufacturing sector by value in 1860, continued its growth trajectory in the 1870s. It was a major employer and a significant consumer of locally produced sewing machines.

Food Processing: Flour and grist milling, serving the productive agricultural regions connected to Cleveland by canal and rail, remained a vital part of the city’s economy. The brewing industry also had a strong presence. By 1870, there were 17 breweries operating in Cleveland, a number that grew to 23 by 1880. The introduction of pasteurization techniques in the 1870s allowed brewers to bottle their products and reach wider markets.

The Cleveland Board of Trade continued to play a role in fostering the city’s commercial and industrial environment. While specific annual reports from the 1870s are not extensively detailed in the available information, the organization was active. For instance, in 1870, a member of the Board of Trade proposed improvements to Cleveland’s harbor, which eventually led to the construction of the city’s first breakwater in 1885. This indicates the Board’s involvement in advocating for infrastructure developments crucial for trade and industry.

The following table summarizes some of the key industries and entrepreneurs active in Cleveland during the 1870s:

| Industry | Key Companies/Entrepreneurs | Major Developments in the 1870s |

|---|---|---|

| Iron & Steel | Cleveland Rolling Mill (Henry Chisholm), Otis Iron & Steel Co. | Adoption of Bessemer and open-hearth processes, significant output growth |

| Oil Refining | Standard Oil Co. (John D. Rockefeller) | Consolidation of Cleveland refineries (“Cleveland Massacre”), became center of U.S. refining |

| Chemicals | Grasselli Chemical Co. | Expansion to supply various industrial chemicals, linked to oil refining needs |

| Paints & Varnishes | Sherwin-Williams Co., Glidden Co. | Founding of major companies, development of ready-mixed paint |

| Electrical Technology | Brush Electric Co. (Charles F. Brush) | Development of dynamo and arc-lighting system, first public street lighting (1879) |

| Shipbuilding | Peck & Masters | Construction of specialized ore carriers (e.g., R.J. Hackett), innovations in cargo handling |

| Machinery & Machine Tools | Cleveland Twist Drill Co., White Sewing Machine Co. | Growth of firms producing essential industrial equipment |

| Brewing | Various local breweries | Growth in number of breweries, adoption of pasteurization enabling wider distribution |

The 1870s in Cleveland were characterized by economic volatility, the growing assertiveness of labor, and the often-challenging conditions faced by the city’s working population. The decade began with industrial expansion but was soon rocked by a major national financial crisis.

The Panic of 1873 and Its Reverberations

The nationwide financial crisis known as the Panic of 1873 cast a long shadow over Cleveland and the rest of the country. Triggered in September 1873 by the collapse of Jay Cooke and Company, a major banking firm heavily invested in railroad construction, the panic led to a severe and prolonged economic depression. Nationally, the crisis resulted in the failure of 89 railroads, the collapse of 18,000 businesses within two years, and a surge in unemployment, reaching 14% by 1876.

While specific data on Cleveland bank failures directly attributable to the 1873 panic is not detailed in the available records, Ohio banks were generally affected by the crisis. Cleveland’s financial institutions, which had helped fund the expansion of numerous local railroads, found these investments strained as the panic depleted funds available for such ventures. The economic downturn, often referred to as the “Long Depression,” lasted until 1879 and significantly impacted the city’s growth trajectory. One clear consequence in Cleveland was an increase in the number of homeless and vagrant individuals, placing immense pressure on the city’s charitable organizations and relief efforts. This period served as a stark illustration of the vulnerabilities inherent in the 19th-century industrial capitalist system, where national financial shocks could quickly translate into local hardship, particularly for the working class.

The Rise of Labor Movements and Industrial Strife

The economic pressures and social changes of the 1870s fueled a growing labor movement in Cleveland. Workers increasingly organized to protect their interests and challenge the power of large industrial employers. The Industrial Council of Cuyahoga County, established in 1873, represented a significant step in local labor consolidation, bringing together ten unions, including three locals of the Coopers’ Union, with Robert Schilling as its president. This council even hosted the National Industrial Congress in Cleveland in 1873, indicating the city’s emerging role in the national labor scene.

A major flashpoint was the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. This nationwide action reached Cleveland on July 23, 1877, when brakemen and firemen employed by the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad at the Collinwood yards walked off the job to protest a 20% wage cut. Workers on other Cleveland rail lines soon joined the strike. While the strike in Cleveland was notably less violent than in some other American cities, it caused significant disruption. Freight service was halted, and passenger and mail services were delayed, leading to business closures due to lack of supplies and shipping capabilities. In response to the unrest, Mayor William G. Rose mobilized local militia and armed patrolmen. However, the striking railroad workers in Cleveland generally maintained a peaceful demeanor and even pressured local saloons to close to prevent alcohol-fueled disorder, earning them a degree of community respect. The strike ended locally on August 3, 1877, with a settlement that included the restoration of wage cuts and better compensation for layovers. However, the line’s head, William Henry Vanderbilt, initially refused to honor these terms, though a threatened second strike did not materialize.

The Coopers’ Union was also particularly active and militant during this period. In 1877, its members, communicating in Czech, German, and English, organized a strike at the Standard Oil Company. The strike leaders, some of whom were Czech socialists, issued a call for a citywide general strike of all workers earning less than $1 per day. This call was heeded by sewer masons, bricklayers, cigarmakers, and others, marking an early instance of broad-based labor solidarity in the city. The strike, however, took a violent turn when strikers’ wives confronted police, leading to a riot. The strike ended three days later, but the call for a general strike alarmed conservative elements in Cleveland.

The growing strength of labor was also reflected in the decision of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers (BLE), one of the oldest labor organizations in the U.S. (founded in 1863 as the Brotherhood of the Footboard), to establish its national headquarters in Cleveland in 1870, chosen for its central geographic location.

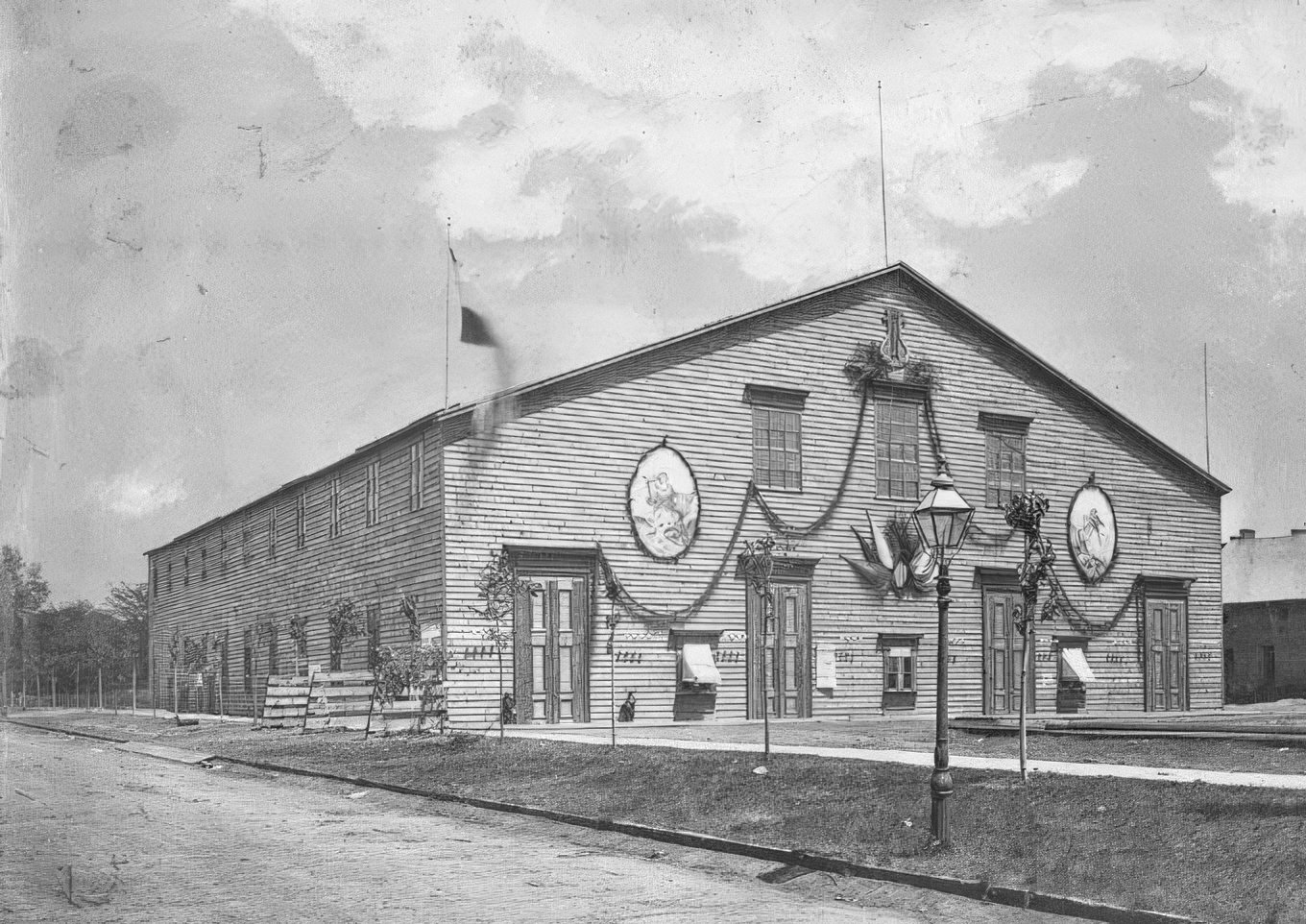

The city’s elite and employers did not remain passive in the face of this rising labor activism. Concerned by the potential for disorder, wealthy Clevelanders organized the First City Troop of Light Cavalry in 1877 and the Cleveland Gatling Gun Battery in 1878. An armory, designed with loopholes for defense, was constructed in 1879, though it was never used in a conflict and, ironically, later hosted a meeting of the Federation of Organized Trades & Labor Unions, a precursor to the American Federation of Labor. These actions underscore the deep divisions and growing tensions between capital and labor in industrializing Cleveland.

Wages, Hours, and Factory Conditions

For the average worker in Cleveland’s burgeoning factories, daily life in the 1870s often involved long hours and challenging conditions. Nationally, factory work typically meant ten to twelve hour days, often in environments where safety was a secondary concern, leading to frequent and sometimes deadly accidents. The increasing mechanization of industry often translated into repetitive and monotonous tasks for employees.

Specific, comprehensive wage data for Cleveland workers in the 1870s is somewhat scarce in the available records. However, a report titled “Industrial wages in Ohio, 1878,” found in the Fifth Annual Report of the State Mine Inspector (pages 63-66), provides tables showing weekly wages and earnings for skilled and unskilled men, as well as boys, across various industrial and manufacturing jobs throughout Ohio. This report would offer a more detailed picture of earnings for different occupations during that year. An earlier benchmark from 1871 indicates that a wage reduction for coopers from $15 to $13.50 per week was a point of contention, especially when monthly rents for working-class housing ranged from $15 to $20. This suggests that even for skilled workers, wages could be tight relative to the cost of living.

Factory safety was a significant concern nationally, and Cleveland was unlikely an exception. While specific Cleveland factory inspection reports from the 1870s are not detailed, events like the 1874 Granite Mill fire in Fall River, Massachusetts, which resulted in the deaths of many young female workers, brought the dangers of industrial workplaces to national attention. General accounts suggest that safety standards in major industries like mining and steel manufacturing were minimal around the turn of the century, implying that conditions in the 1870s were also likely poor, with workers bearing the primary risk of industrial accidents. The lack of robust safety regulations and systematic factory inspections during this period meant that the workforce often faced hazardous environments with little recourse beyond collective action.

Cleveland’s rapid industrial and population growth in the 1870s necessitated significant developments in its urban infrastructure. Major projects were undertaken to connect the city, improve its streets, expand essential services like water and sanitation, and accommodate its diverse and growing populace. These changes visibly reshaped the city’s physical form.

Bridging the Cuyahoga: The Superior Viaduct

A landmark achievement in Cleveland’s 1870s infrastructure development was the construction of the Superior Viaduct. Proposed to enhance connectivity between the city’s east and west sides—particularly important after the 1854 annexation of Ohio City—the project addressed the inefficiencies of earlier “low-level” bridges that frequently had to open for river traffic. City voters approved the viaduct’s construction in April 1872.

Work on this ambitious project commenced in March 1875. The viaduct, a significant engineering undertaking for its era, was completed at a cost of $2.17 million and officially opened to traffic on December 28, 1878. Its design was impressive: the structure stretched 3,211 feet in total, featuring a 64-foot wide roadway. The western approach was distinguished by ten Berea sandstone arches, built upon piles driven 20 feet into the soft subsoil, rising 72 feet above their foundations and covering a length of 1,382 feet. Connecting this masonry section to the eastern part of the bridge was a 332-foot pivoting center span, designed to swing open to allow taller vessels to pass along the Cuyahoga River. The eastern end of the viaduct utilized a girder design and extended 936 feet. Councilman John Huntington was a notable supporter of this vital project.

The Superior Viaduct was more than just a bridge; it was a symbol of Cleveland’s growing ambition and its commitment to unifying its expanding urban core. However, the inclusion of the center draw span, while a nod to the continuing importance of river commerce, meant that traffic on the viaduct still faced interruptions—halting approximately 300 times each month for an average of five minutes per opening. This highlighted the ongoing challenge of balancing the needs of land-based transportation with those of a busy industrial waterway.

Paving the Streets and Laying the Groundwork

The 1870s saw concerted efforts to improve the quality of Cleveland’s streets, moving beyond rudimentary surfaces to more durable and reliable paving materials. This was essential for facilitating commerce, improving public health by reducing mud and dust, and enhancing the overall modern appearance of the rapidly growing city.

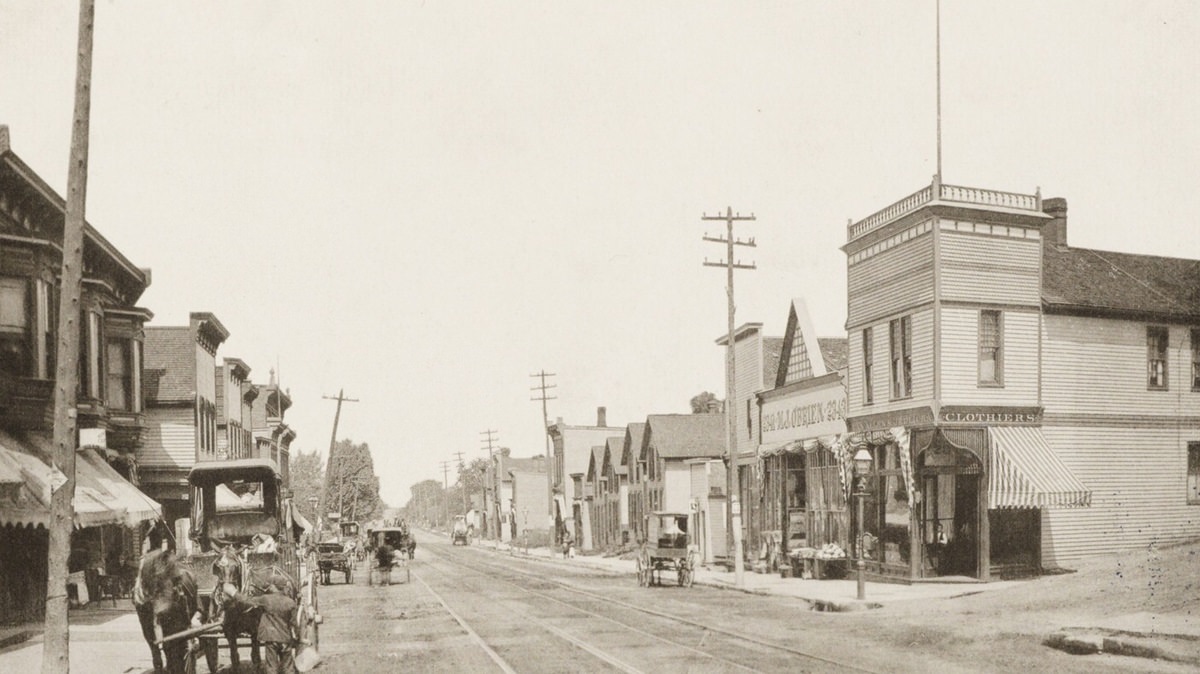

By 1870, Cleveland already had more than ten miles of stone pavement and nearly nine miles of Nicholson pavement, a type of wood-block paving. The city continued to experiment with and implement better road surfaces throughout the decade. In 1871, an experiment with McAdam pavement (macadam) was initiated near Public Square, and the city demonstrated its commitment to improved road construction by purchasing a steamroller in 1872.

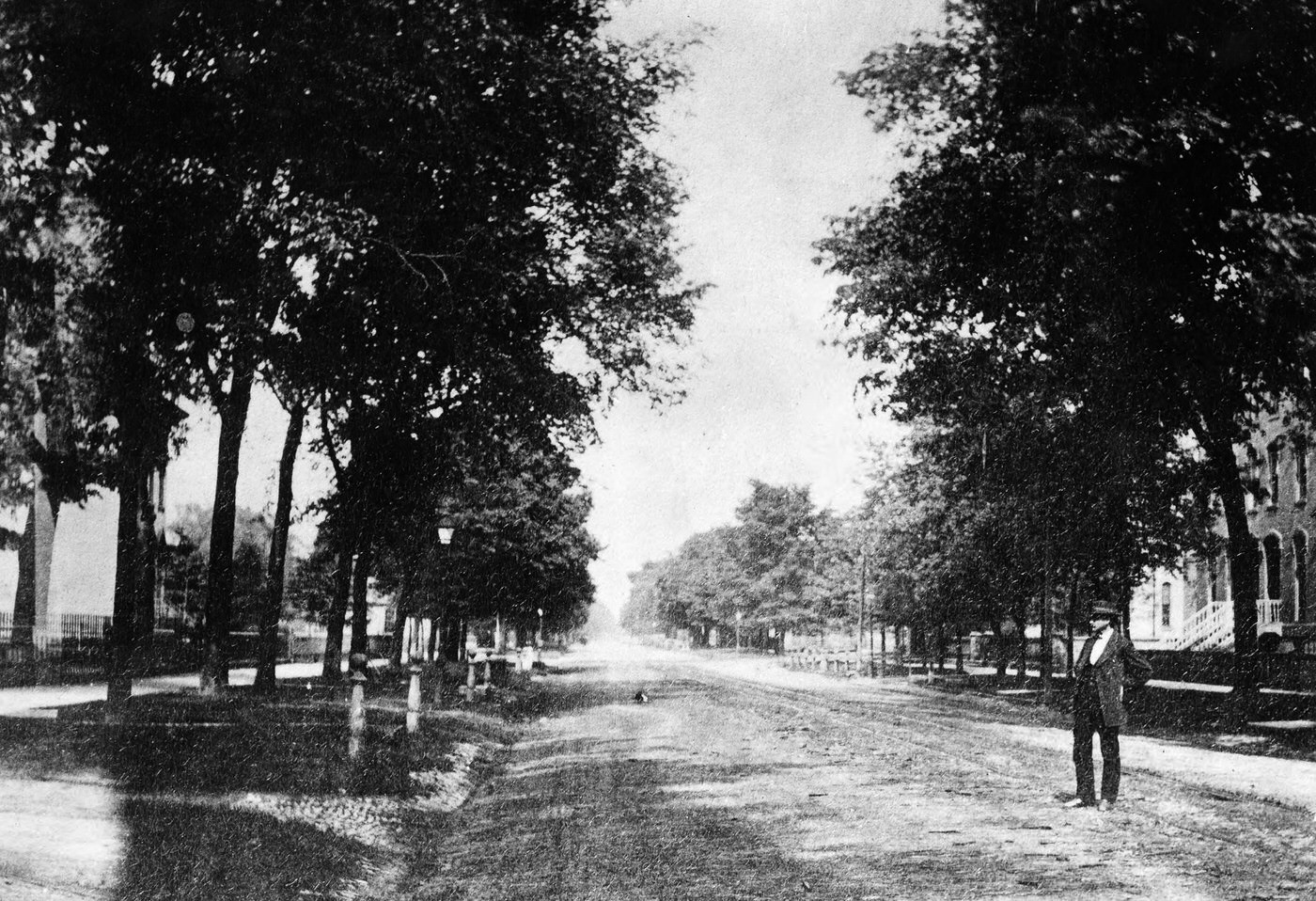

A preferred material for street surfacing during this period was Medina sandstone. By 1875, prominent thoroughfares like Euclid Avenue were paved with this durable stone as far east as Willson Avenue (now East 55th Street). These investments in street paving were a fundamental component of Cleveland’s urbanization, directly supporting its burgeoning economic activity and contributing to a higher quality of urban life for its residents.

Expanding Essential Utilities

The demands of a rapidly growing population and industrial base placed immense pressure on Cleveland’s essential utilities in the 1870s. The city undertook significant projects to expand and improve its water supply, sewer systems, lighting, and communication networks, though these efforts often struggled to keep pace with the relentless growth.

Sewer System: The development of an adequate sewer system was a pressing concern. While a basic system of open drains conveying wastewater towards the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie had begun in the 1850s, it was insufficient for the growing city. By the early 1870s, pollution in waterways like Walworth Run, which residents complained was being used as an open sewer by slaughterhouses and other industries, led to public outcry and petitions for the construction of enclosed underground sewers. Councilman John Huntington was a proponent of developing a comprehensive municipal sewer system. Despite these efforts, the problem of sewage polluting the city’s water sources remained acute throughout the decade.

Water Works: Securing a clean and reliable water supply was paramount. Due to increasing pollution near the Lake Erie shoreline, a major project was undertaken between 1869 and 1874 to construct a new 6,600-foot-long water intake tunnel, extending further into the lake to access purer water. In a move towards better management and billing, the first water meters were installed in the Cleveland Water system in 1870. By 1881, just after the close of the decade, the city had completed 125 miles of water mains, significantly expanding the reach of the public water system.

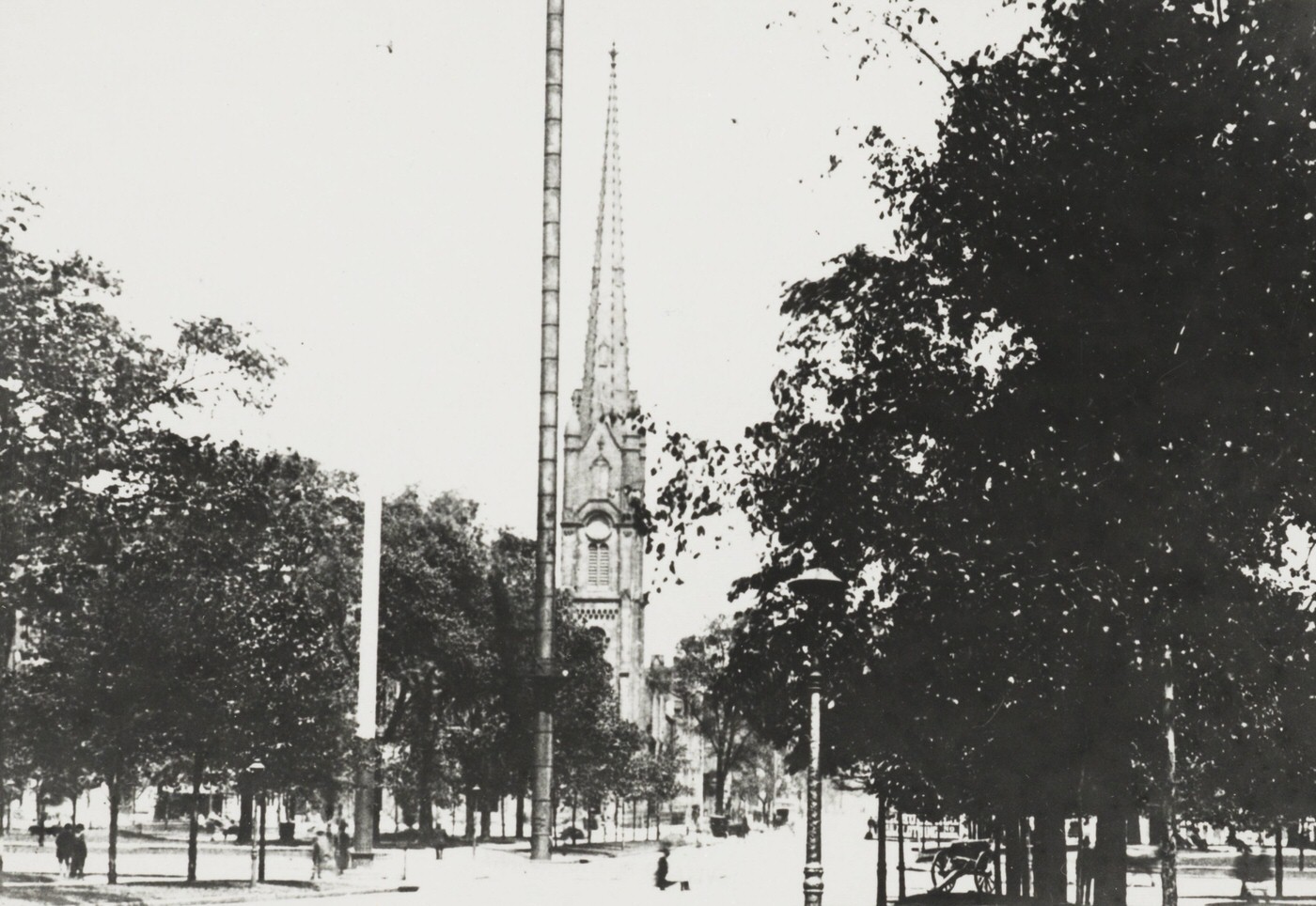

Gas Lighting: Gas lighting continued to illuminate Cleveland’s streets and buildings. The Cleveland Gas Light & Coke Company, founded in 1849, served the downtown area and the east side. Recognizing the needs of the growing west side, the People’s Gas Company was established in 1868 to provide gas lighting to that section of the city. Gas lamps remained the predominant form of street lighting until the very end of the decade, when Charles Brush’s revolutionary electric arc lights made their debut on Public Square in April 1879, heralding a new era in urban illumination.

Telegraph and Early Telephone: Communication technologies also advanced. District telegraph companies were organized during the 1870s to facilitate local messaging within the Cleveland metropolitan area. The city’s first fire-alarm telegraph system, a crucial tool for public safety, was already operational by 1869. The decade also saw the arrival of a transformative new technology: the telephone. Cleveland’s first telephone line was installed in June 1877, connecting the yard and office of Rhodes & Co., a local coal dealer. The city’s first telephone exchange opened on September 15, 1879, initially serving 76 subscribers.

These utility developments, though often reactive to pressing needs, were essential for supporting Cleveland’s growth, improving public health and safety, and facilitating commerce in an increasingly complex urban environment.

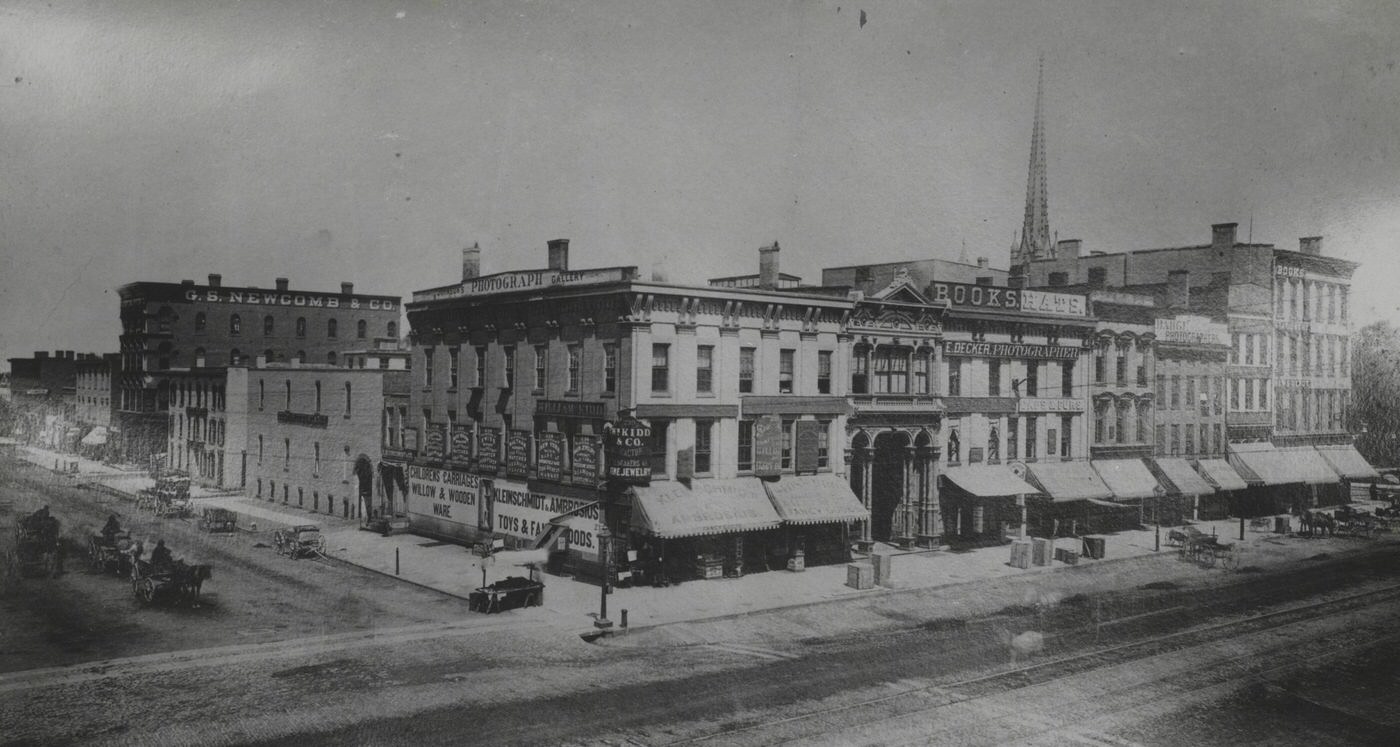

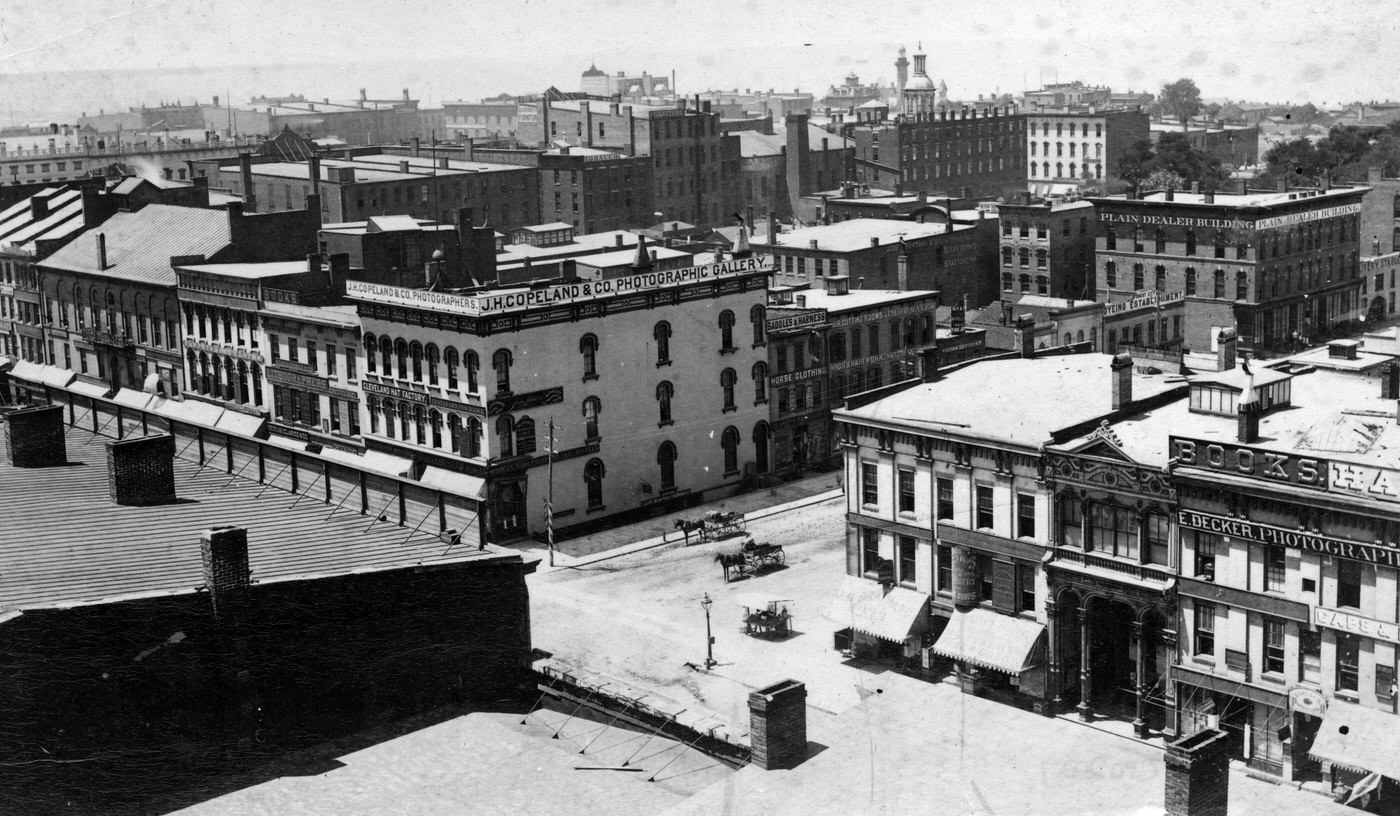

The Changing Face of Cleveland: Architecture and Neighborhoods

The rapid growth and industrialization of the 1870s brought about visible changes in Cleveland’s built environment, with new public and commercial buildings altering the downtown landscape, and distinct residential patterns emerging that reflected the city’s evolving social structure.

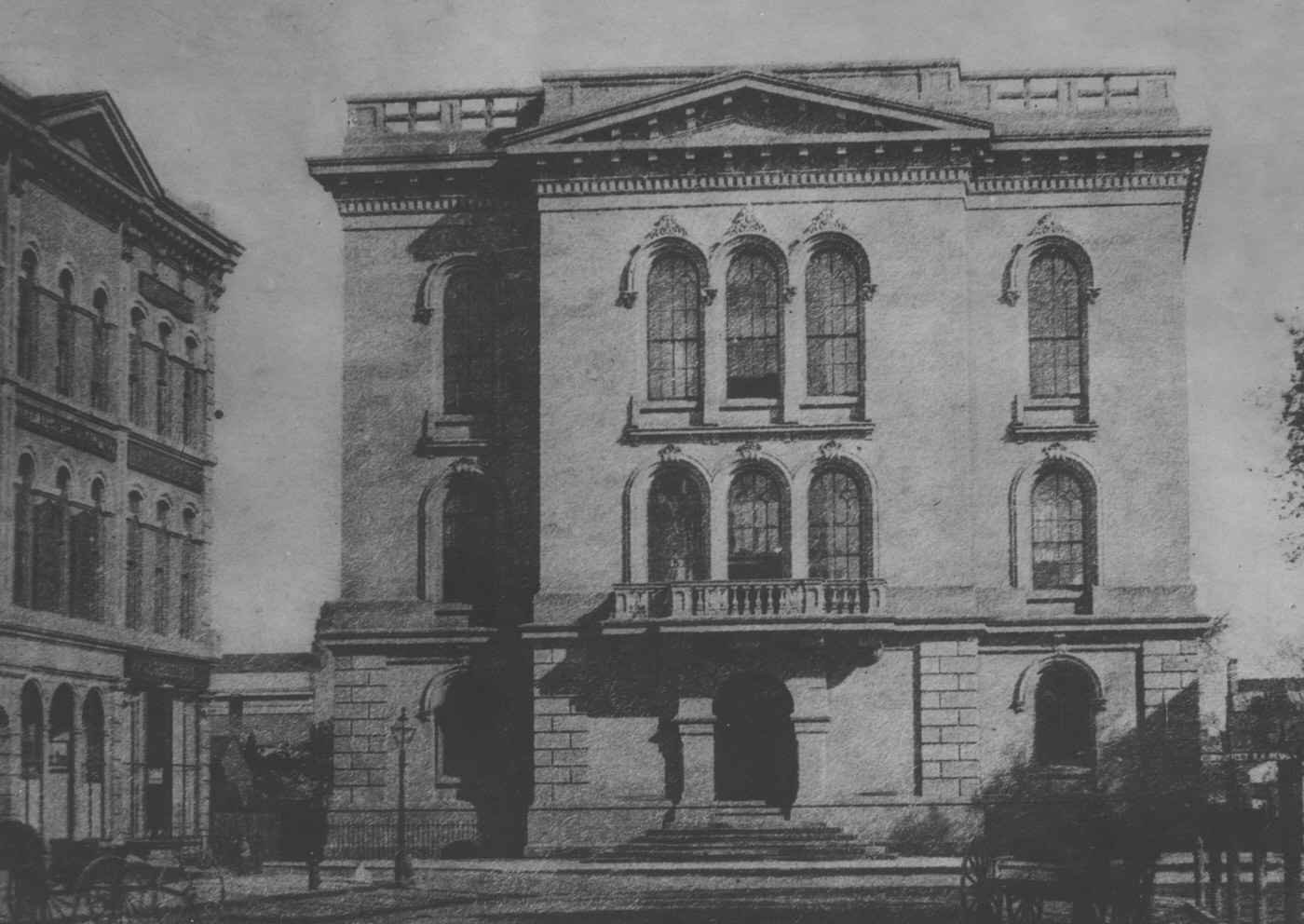

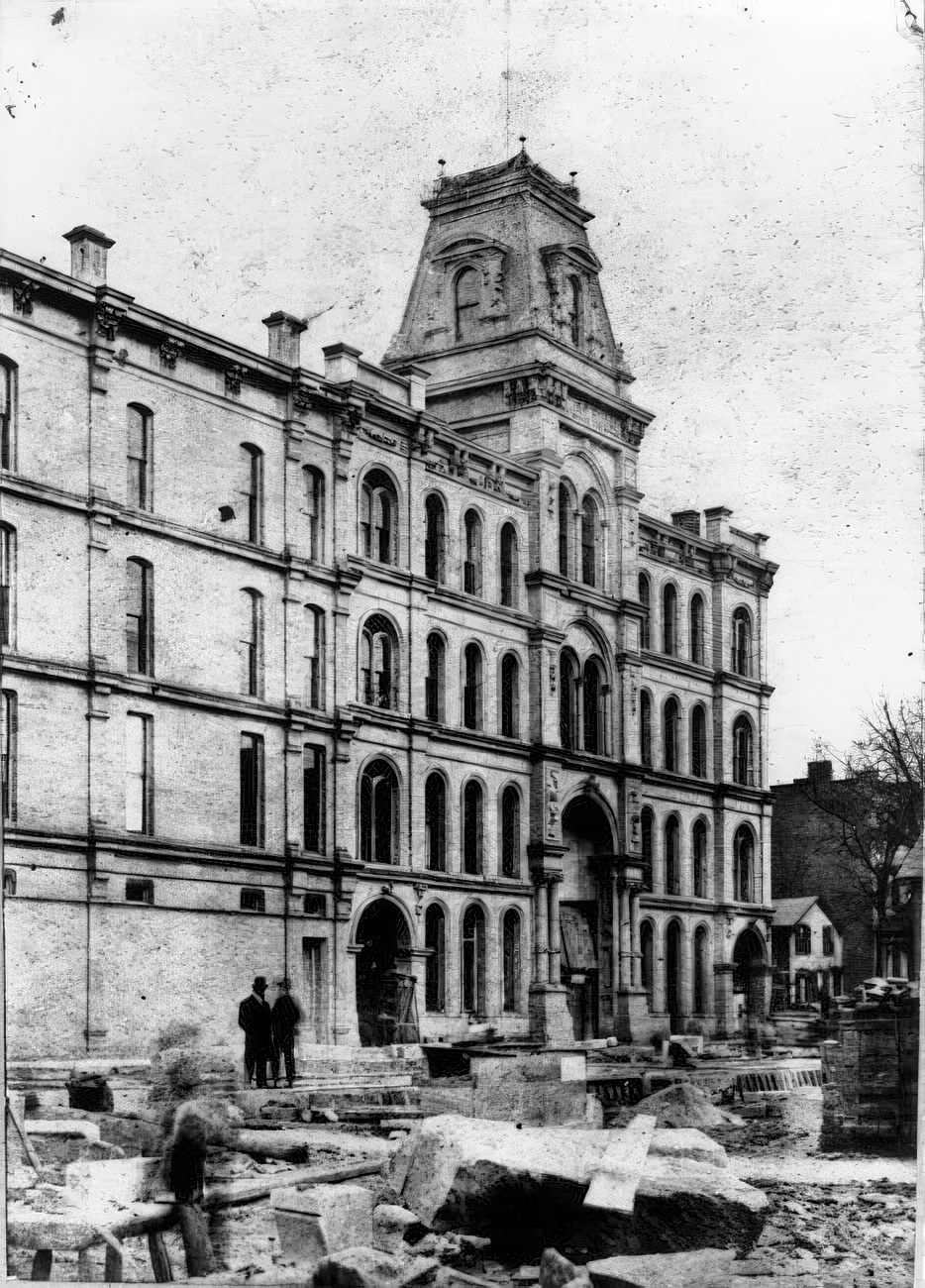

Public and Commercial Buildings: Several significant public buildings were constructed or occupied during this period. A new, more impressive Cuyahoga County Courthouse, the city’s fourth, was erected in 1875. This four-story Renaissance-style structure, faced with cut stone, was located on Seneca Street (now West 3rd Street). While a dedicated City Hall was not yet built (a competition for one in 1869, featuring a lavish French Second Empire design, did not result in construction), the city government leased offices in the five-story Case Block on Superior Street in 1875. This commercial building, also designed in the Second Empire style by Charles W. Heard, effectively served as Cleveland’s City Hall for many years.

Euclid Avenue – “Millionaires’ Row”: Euclid Avenue solidified its reputation as one of the grandest residential streets in America during the 1870s. Officially designated an avenue in 1870, it was lauded for its “continuous succession of charming residences and such uniformly beautiful grounds”. The city’s wealthiest industrialists and financiers, including John D. Rockefeller who had purchased his home there in 1868, built opulent mansions set on deep, spacious lawns. The architectural styles were varied and impressive, with many new residences filling the open spaces east of Willson Avenue (East 55th Street). Prominent Cleveland architect Charles F. Schweinfurth designed numerous mansions along the avenue, often employing the imposing Romanesque Revival style, which seemed to embody the ambition and power of their owners.

Working-Class Housing: In stark contrast to the grandeur of Euclid Avenue, the housing available to Cleveland’s growing working class and immigrant populations was often basic and, in many areas, overcrowded. Modest wood-frame houses, typically one-and-a-half or two stories high with gabled ends facing the street, were common. These were sometimes built two to a single city lot, reflecting the pressure for housing. In industrial areas like the Flats, rudimentary housing, frequently lacking modern amenities such as running water, sprang up to accommodate factory workers. For some, particularly Irish dock workers, shantytowns developed on the hillsides sloping down to the Cuyahoga River, with some dwellings ingeniously constructed on stilts. Overcrowding was a persistent issue, with an average of nearly six persons per dwelling reported by 1890, a trend that was well underway in the 1870s.

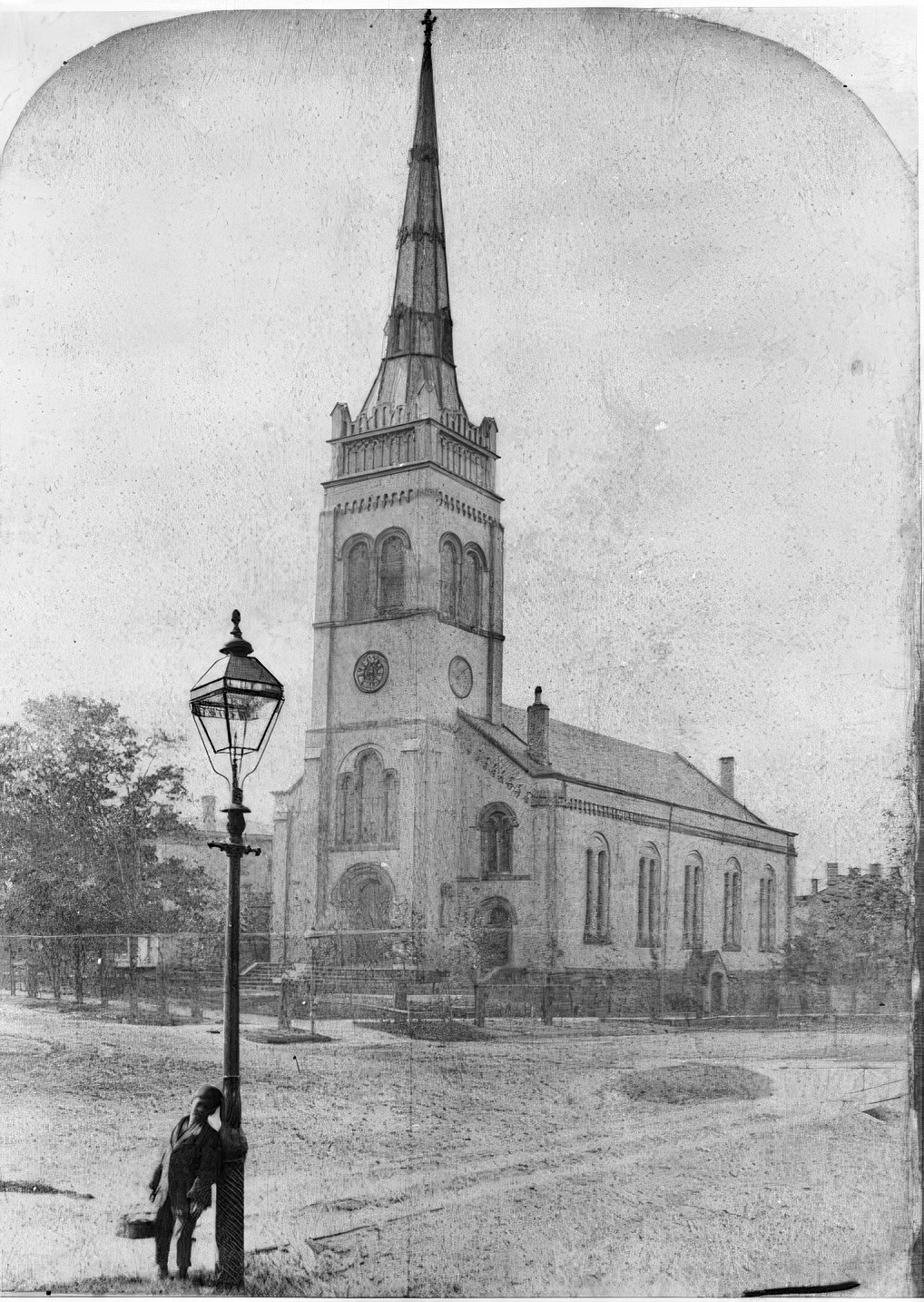

Architectural Styles: Beyond the Romanesque Revival popular for mansions and the Second Empire style seen in some commercial and public buildings, Cleveland’s churches built in the 1870s also reflected prevailing architectural trends. Architects like Franz Cudell designed churches such as St. Joseph’s (cornerstone laid 1871, dedicated 1873) and St. Stephen’s (cornerstone laid 1873, dedicated 1881) in Victorian Gothic styles, often incorporating German and French architectural influences.

Education for a Growing City

Amidst the industrial clamor and urban expansion, Clevelanders in the 1870s developed a complex social fabric, with evolving educational systems, public safety services, charitable institutions, and a growing array of leisure and cultural activities. The city’s public and parochial school systems worked to educate an increasingly numerous and diverse student population.

Public Schools: Cleveland’s public school enrollment grew substantially during the decade. By the end of the 1870 school year, 12,275 students were enrolled; this number rose to 17,512 by the end of the 1873 school year. This growth was within a total school-aged population (youths) in the city of 32,157 in 1870. Recognizing the need for broader educational participation, a state law passed in 1877 made school attendance compulsory for children aged 8 to 14 for a minimum of 12 weeks per year. To address specific student needs, the school board established a separate school for “disruptive students” in 1877. The physical infrastructure of the school system also expanded, with new school buildings constructed, including Garden Street School and Detroit Street School (both in 1870), Tremont School (1873), Outhwaite School (1874), and Case Avenue School (1876). A significant development for teacher education was the establishment of the Normal School (for teacher training) in 1874, initially housed in the Eagle Street School building before later moving. In an effort to integrate the large German immigrant population, bilingual education, with some classes taught in German, was introduced into the public elementary schools in 1870.

Catholic Schools: The Catholic parochial school system also saw continued growth, as immigrant communities viewed these schools as vital for preserving their faith and cultural heritage. St. Columbkille parish, along with its school, was founded in 1871. St. Peter’s Church, a German Catholic parish, constructed a new school building during the 1870s and recruited teaching staff from the Sisters of Notre Dame (for girls) and the Brothers of Mary (for boys).

These educational efforts, encompassing infrastructure expansion, curriculum considerations, specialized schooling, and attempts to address the needs of a diverse student body, reflect Cleveland’s adaptation to its role as a growing urban and industrial center.

Maintaining Order and Public Safety

As Cleveland grew, so did the challenges of maintaining public order and safety. Both the police and fire departments underwent developments to meet these increasing demands.

Police Force: The Cleveland Police Department, established in 1866, was under the leadership of Superintendent Jacob W. Schmitt for a significant portion of the 1870s (he served from 1871 to 1893). By 1872, the city was divided into seven police districts, but the force numbered fewer than 60 officers to protect a rapidly expanding population. The governance of the police force saw changes during this decade; in 1872, the state legislature transferred control of the department to a local Board of Police Commissioners, which included the mayor and four locally elected members. Recognizing the large influx of newcomers, by 1874 the city stationed “emigrant officers” (police members) at railroad depots to provide assistance and protection to immigrants. The police also played a role in managing public order during labor disputes, such as the Railroad Strike of 1877, when Mayor William G. Rose armed local patrolmen. The first Cleveland police officer killed in the line of duty was Michael Kick in 1875, while confronting burglars.

Fire Department: Cleveland’s Fire Department continued to modernize its equipment and organization. The city acquired its first piston pump fire engine in 1875, a significant technological upgrade. Three years later, in 1878, the department obtained its first aerial ladder truck. The fire alarm telegraph system, which had been installed in 1864, remained a crucial component of the city’s fire response infrastructure. Leadership of the department changed during the decade: James Hill served as chief from 1864 until 1874, when he was succeeded by John A. Bennett, who held the position until James W. Dickinson took over in 1880. In 1873, the management of the fire department was transferred to a Board of Fire Commissioners.

These developments indicate that while Cleveland’s public safety services were professionalizing and adopting new technologies, they were continually challenged by the city’s rapid expansion and the complex issues arising from an industrial urban environment.

Health, Sanitation, and Welfare

Public health and social welfare were major concerns in 1870s Cleveland, a city grappling with the consequences of rapid industrialization and population density.

Public Health and Sanitation: The Cleveland Board of Health was active throughout the 1870s, focusing on critical issues such as ensuring the purity of the milk supply (appointing a full-time milk inspector), disseminating information about infectious diseases like cholera and diphtheria, and attempting to address the pervasive problems of inadequate sewage and garbage collection. In its 1876 annual report, City Health Officer Dr. Frank Wells explicitly linked Cleveland’s high death rate to poor sanitation, the prevalence of germs, and adverse socioeconomic conditions, emphasizing that the accumulation of filth was a leading cause of disease. The city’s waterways were severely polluted; the Cuyahoga River was notoriously described as “an open sewer,” and the contamination of Lake Erie posed a direct threat to the municipal drinking water supply.

Institutions of Care: Several institutions provided care and shelter for vulnerable populations. The Jewish Orphan Asylum (JOA), founded in 1868 on Woodland Avenue, was a significant charitable institution. It initially cared for Jewish children orphaned by the Civil War and other circumstances, growing from about 80 residents at its inception to house 400 children by 1900. The Cleveland Workhouse, also known as the House of Correction, was formally established as a separate city institution in January 1871, moving to a new building on Woodland Avenue at East 79th Street. Its purpose was to house individuals convicted of petty offenses. As part of the Workhouse, the House of Refuge and Correction was established in July 1871 for offenders under the age of sixteen. Inmates at the Workhouse engaged in various forms of labor, including chair making and brush making. The Friendly Inn Social Settlement, organized in 1874, was another important benevolent society, providing lodging and other forms of assistance to those in need.

These efforts, while crucial, often struggled to keep pace with the scale of the challenges. The combination of rapid population growth, industrial pollution, and economic downturns like the Panic of 1873 frequently overwhelmed the existing systems, contributing to high mortality rates and difficult living conditions for a significant portion of Cleveland’s population.

Leisure, Culture, and Civic Life

Despite the focus on industry and the challenges of urban life, Cleveland in the 1870s offered its residents a growing variety of leisure activities, cultural pursuits, and civic engagement opportunities.

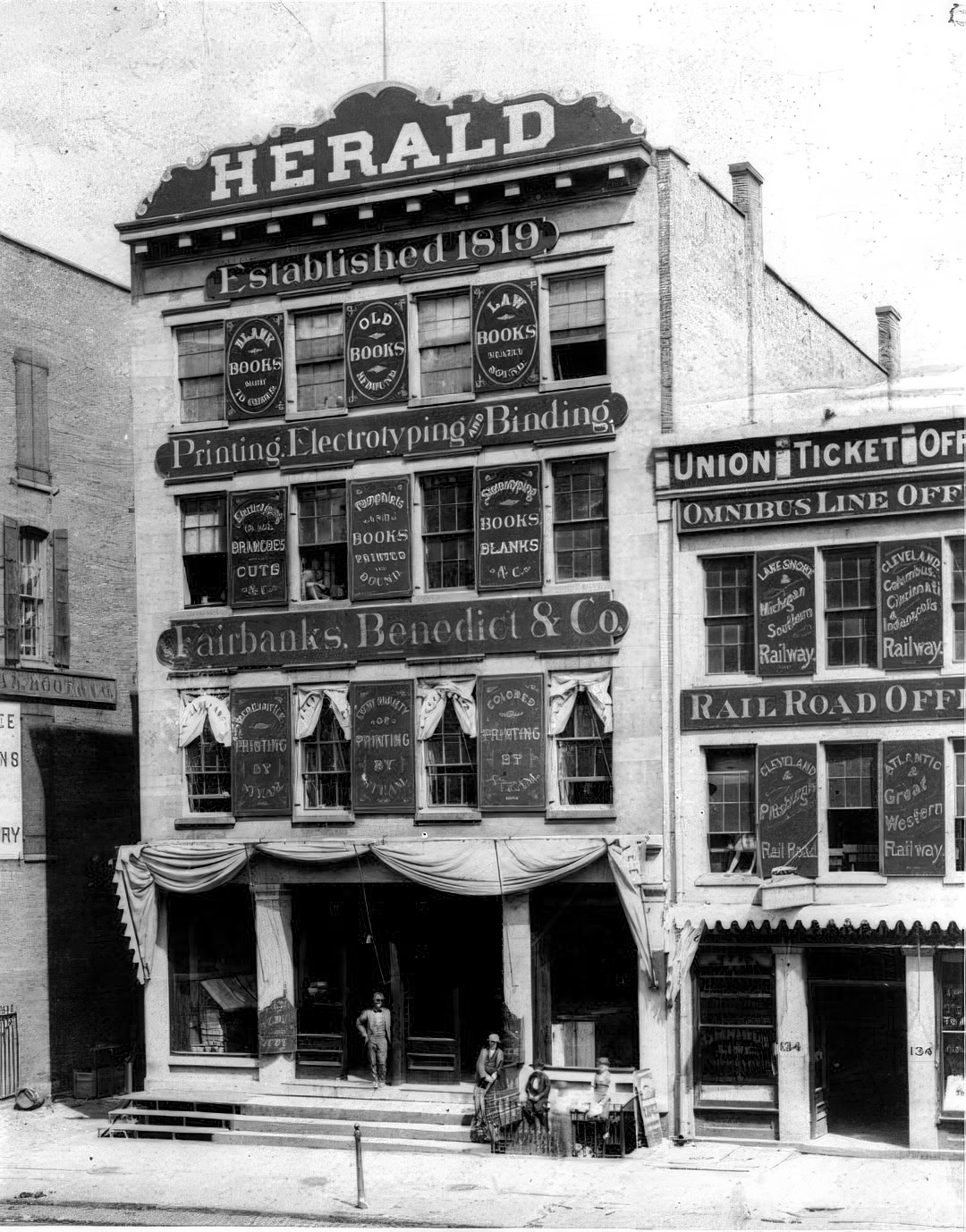

Newspapers: The city’s newspapers were vital sources of information and opinion. The Cleveland Leader, a staunch Republican paper edited by Edwin Cowles, boasted a circulation of 13,000 by 1875 and was known for its early adoption of new printing technologies like the perfecting press in 1877. The Plain Dealer served as the city’s primary Democratic voice. The Cleveland Herald, another Republican-leaning paper, saw its influence wane in comparison to the Leader and was eventually acquired by its rivals in 1885. These publications not only reported news but also shaped public discourse on local and national issues.

Theaters: Cleveland’s theatrical scene was vibrant. The Academy of Music on Bank Street (West 6th) had long been the city’s premier venue for legitimate theater. However, in 1875, the luxurious Euclid Avenue Opera House opened, providing a grander stage for performances and quickly becoming a major cultural landmark. This new venue hosted a variety of productions, including opera. Case Hall, which had opened in 1867, continued to be an important center for lectures by nationally renowned figures such as Mark Twain and Horace Greeley. It also hosted concerts and significant civic gatherings, including the first convention of the National Association of Woman Suffrage. For more informal entertainment, Haltnorth’s Gardens, a German beer garden located just outside the city limits on Woodland Avenue, offered patrons picnics, beer, and light opera performances in a wooded setting. Its earlier location on Kinsman Street had a more boisterous reputation, but by the 1870s, the Woodland Avenue venue was considered a relatively safe and welcoming destination.

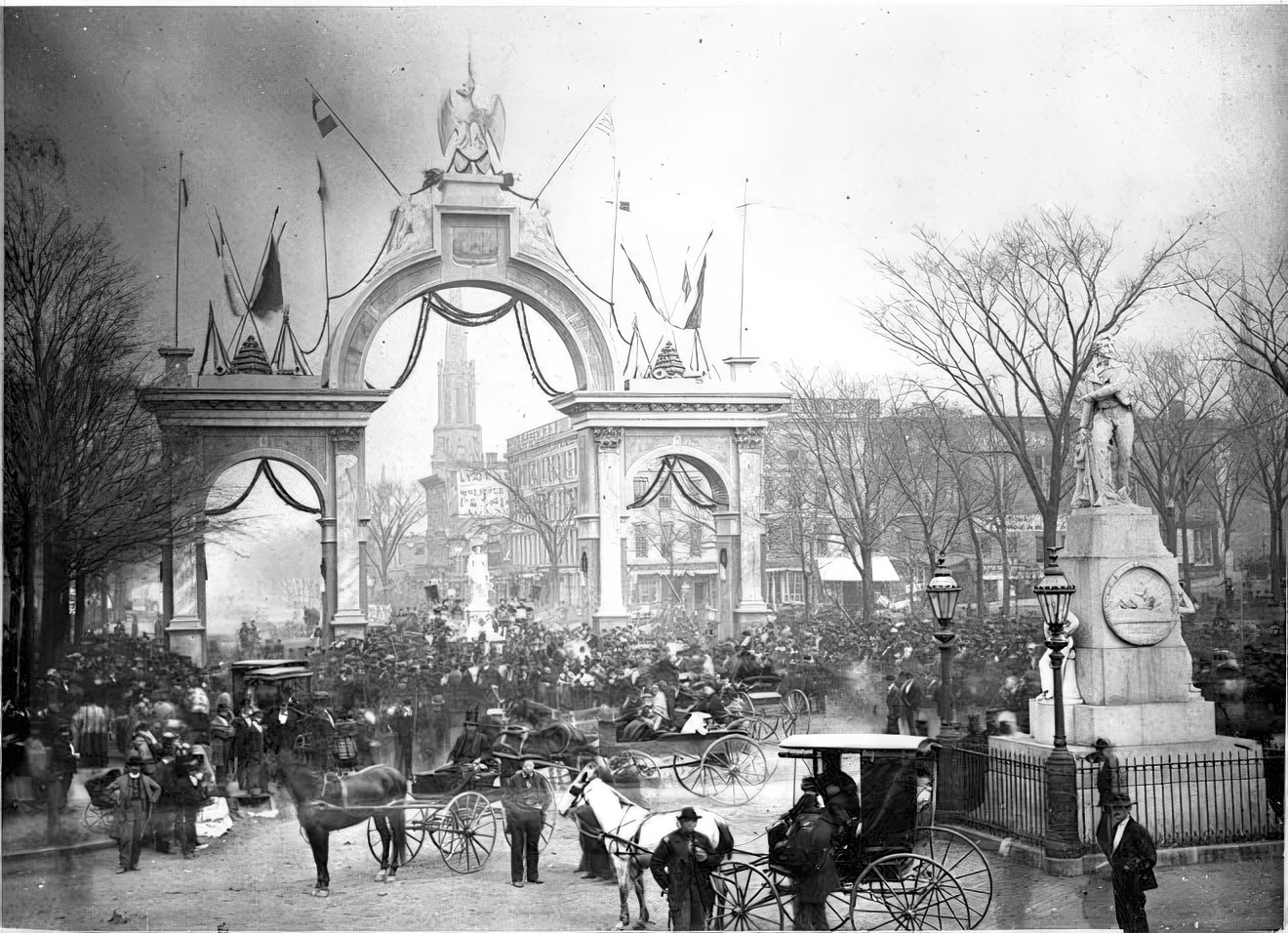

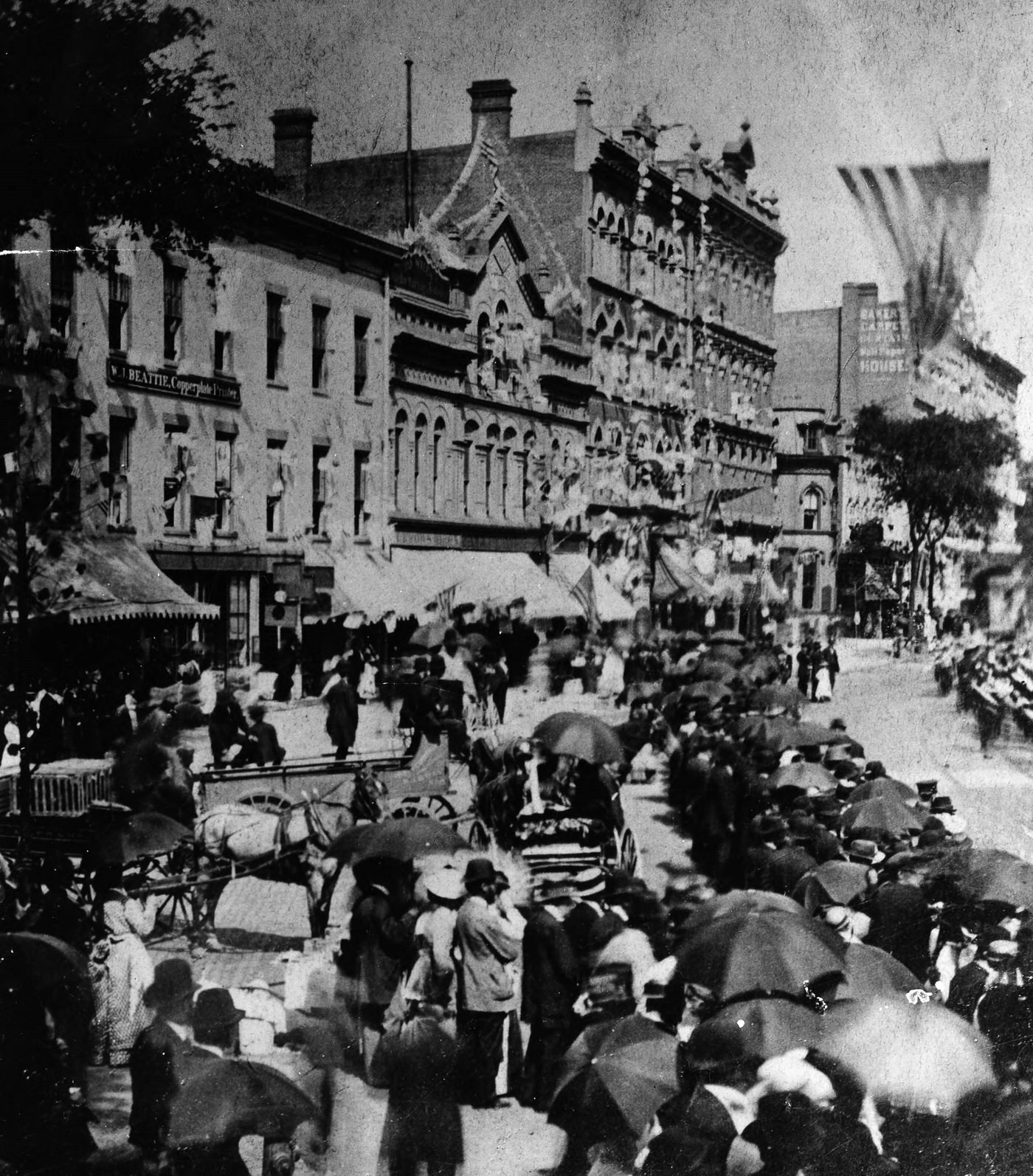

Fairs: A major public event was the Northern Ohio Fair. Organized by a group of prominent Cleveland businessmen, including Amasa Stone and Jeptha H. Wade, the Northern Ohio Fair Association held its inaugural fair in the Glenville area from October 4-7, 1870. The event was a tremendous success, attracting 85,000 visitors who viewed exhibits on agriculture, horticulture, and the mechanical arts, as well as enjoying trotting races.

Sports: Baseball was gaining popularity. The Forest Citys professional baseball team was a charter member of the National Association of Professional Baseball Players in 1871. Their home games were played at a field located at the intersection of Willson Avenue (East 55th Street) and Garden Street (Central Avenue). For the wealthier residents, sleighing races down Euclid Avenue during the winter months were a popular spectator sport.

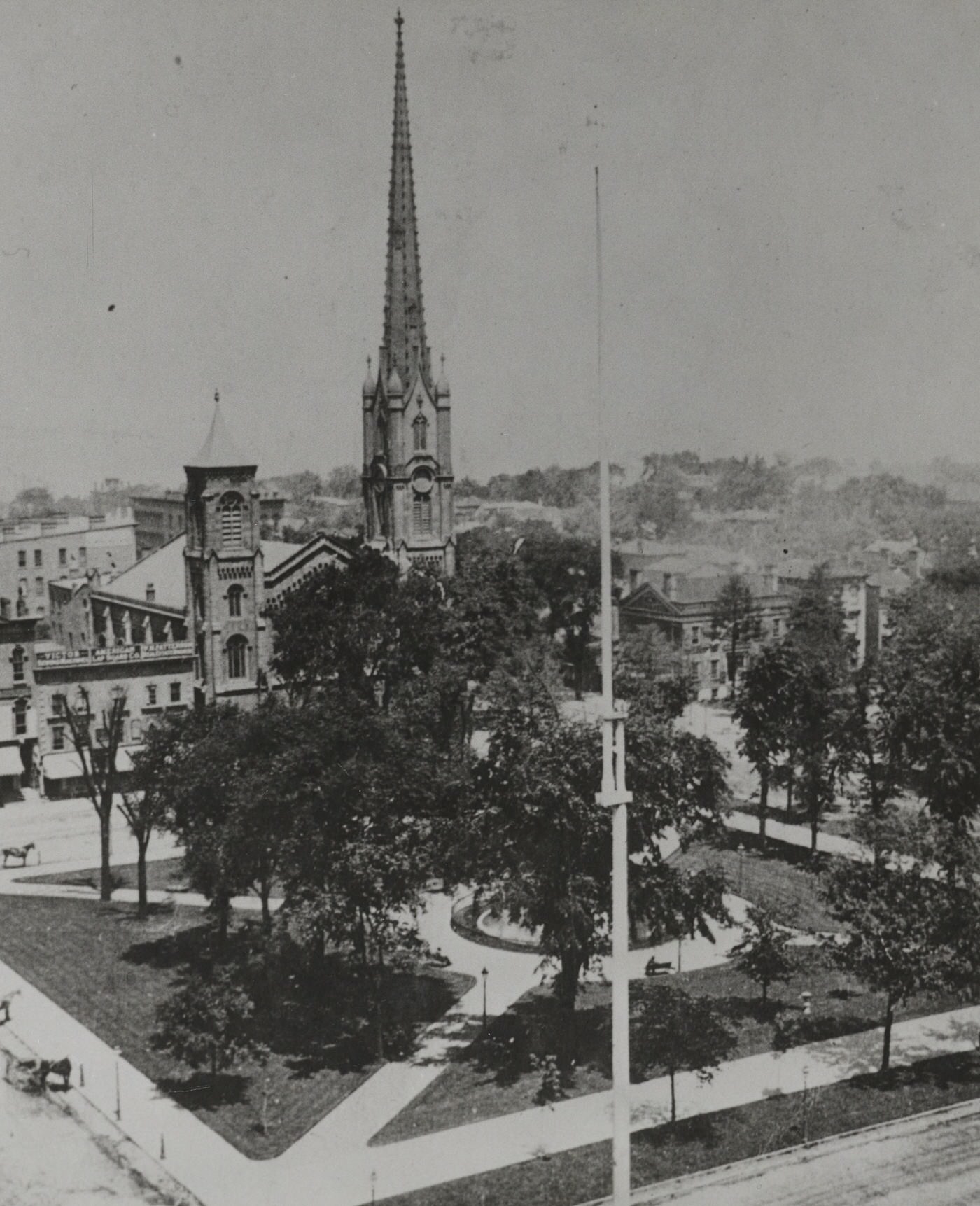

Public Spaces and Social Clubs: Efforts to create and improve public green spaces began in earnest. The city allocated public funds for parks for the first time in 1871, establishing a Board of Park Commissioners. Early work focused on enhancing Monumental Park (Public Square) and Franklin Circle. In 1874, bond issues were used to finance the purchase and improvement of Lake View Park. Beyond ethnic societies, more exclusive social clubs also emerged. The Union Club of Cleveland, one of the city’s oldest private social organizations, was incorporated on September 25, 1872. Founded by a group of the city’s leading industrialists, businessmen, and professionals, it provided a venue for reading, discussion, entertainment, and social networking. Literary societies were also common, such as the Cleveland Literary Society, organized at Shiloh Baptist Church in 1873.

Daily Life Accounts: Glimpses into the everyday atmosphere of the city can be found in contemporary accounts. Newspaper reports detailed the lively, and sometimes unruly, street life in immigrant neighborhoods. For example, the Czech area known as the “Isle of Cuba” was described as having numerous saloons and dance halls, with residents enjoying harmonica music, beer, and occasional altercations. Social reform movements were also visible; the Woman’s Temperance League, for instance, held public prayer demonstrations outside saloons on Public Square in 1874, aiming to curb alcohol consumption.

The diverse array of leisure and cultural activities available in 1870s Cleveland reflected a city that was not only an industrial engine but also a place where people from various backgrounds sought community, entertainment, and civic engagement.

City Leadership

The governance of Cleveland during the transformative decade of the 1870s was in the hands of several mayors, each navigating the challenges and opportunities of a rapidly growing industrial city. Their administrations oversaw significant infrastructure projects, responded to public health crises, and managed periods of labor unrest.

The following table lists the mayors who served Cleveland during the 1870s:

| Stephen Buhrer | 1867-1870 | Democratic |

| Frederick W. Pelton | 1871-1872 | Republican |

| Charles A. Otis | 1873-1874 | Democratic |

| Nathan P. Payne | 1875-1876 | Democratic |

| William G. Rose | 1877-1878 | Republican |

| Rensselaer R. Herrick | 1879-1882 | Republican |

Key political occurrences and decisions made by the city government during this decade included the approval for the construction of the Superior Viaduct in 1872, ongoing efforts to pave city streets, the expansion of the water works and sewer systems, and responses to public health concerns voiced by the Board of Health. The city leadership also had to contend with significant labor actions, most notably the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which required intervention to maintain public order. The structure of municipal governance itself saw changes, such as the legislature ceding control of the police department to a local board in 1872. These leaders and their councils were instrumental in shaping the physical and social landscape of Cleveland as it transitioned into a major American city.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress, Wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know