At the beginning of the 1880s, Cleveland was experiencing a remarkable surge in its population and physical size. In 1880, the city was home to 160,146 people. By the decade’s close in 1890, this number had swelled to 261,353. This dramatic increase of over 63% in just ten years showed a city that was a powerful magnet, drawing individuals and families seeking new opportunities. This rapid urbanization placed considerable pressure on the city’s housing, infrastructure, and social services. While specific land annexations for the exact years 1880-1889 are not clearly detailed, the process of incorporating surrounding areas was ongoing. For instance, the village of Brooklyn was formed in 1889 and officially became part of Cleveland in 1890. Earlier annexations, such as that of Newburgh in 1873 and parts of other townships, had already set the stage for Cleveland’s outward expansion.

Cleveland in the 1880s was truly a city of immigrants. The decade fell within what is known as the “East European era” of Jewish immigration, which lasted from 1870 to 1924. The Jewish population grew from 3,500 in 1880, with distinct communities of earlier German Jewish settlers and more recent arrivals from Eastern Europe often establishing their own institutions. Polish immigrants continued to arrive, forming noticeable neighborhoods such as Warszawa, centered around St. Stanislaus Church which was constructed in 1881. Other Polish settlements included Poznan, near East 79th Street and Superior Avenue, established by the late 1880s, and Kantowo in the Tremont area, which also grew in the late 1880s.

Czech immigrants, often referred to as Bohemians, established their own vibrant communities. “Little Bohemia,” located along Broadway, had been forming since the late 1870s and continued to thrive throughout the 1880s. These immigrants often worked as skilled laborers, such as tailors and masons, or found employment in the city’s burgeoning factories. Hungarian settlers also made their mark, creating communities on both the East Side, notably along Buckeye Road which began developing in the 1870s and expanded in the 1880s, and on the West Side, near the Kundtz Manufacturing company during the 1880s. Italian immigration was on the rise as well. Early Italian neighborhoods included “Big Italy,” around Woodland and Orange Avenues, and the beginnings of what would become the well-known “Little Italy” neighborhood near Mayfield and Murray Hill Roads. The formation of these distinct ethnic enclaves was a characteristic of Cleveland during this period, as newcomers sought the support of shared language and culture while contributing their labor to the city’s growth. These neighborhoods often grew around churches or specific industries, reflecting both the cultural needs of the immigrants and the economic realities that dictated where they could find work and housing.

Shaping the City: Urban Growth and New Technologies

Cleveland’s industrial might in the 1880s was supported and enabled by significant advancements in its transportation infrastructure and the adoption of new technologies that reshaped the urban landscape. The decade saw new railroad lines established, the first steps toward streetcar electrification, and continued development of its vital port.

The railroad network expanded considerably. A landmark development was the establishment of the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railway, more commonly known as the Nickel Plate Road, in 1881. This ambitious project connected Buffalo to Chicago, with Cleveland serving as a key point and the company’s headquarters. The Valley Railroad, which had begun construction before the Panic of 1873, finally completed its line from Cleveland to Canton via Akron in 1880, becoming an important route for coal transport. Another coal-hauling line, the Cleveland, Canton & Southern (which had its origins as the Connotton Northern), reached Cleveland in 1882. These rail lines were crucial for bringing raw materials like coal to Cleveland’s industries and for shipping finished products to national markets.

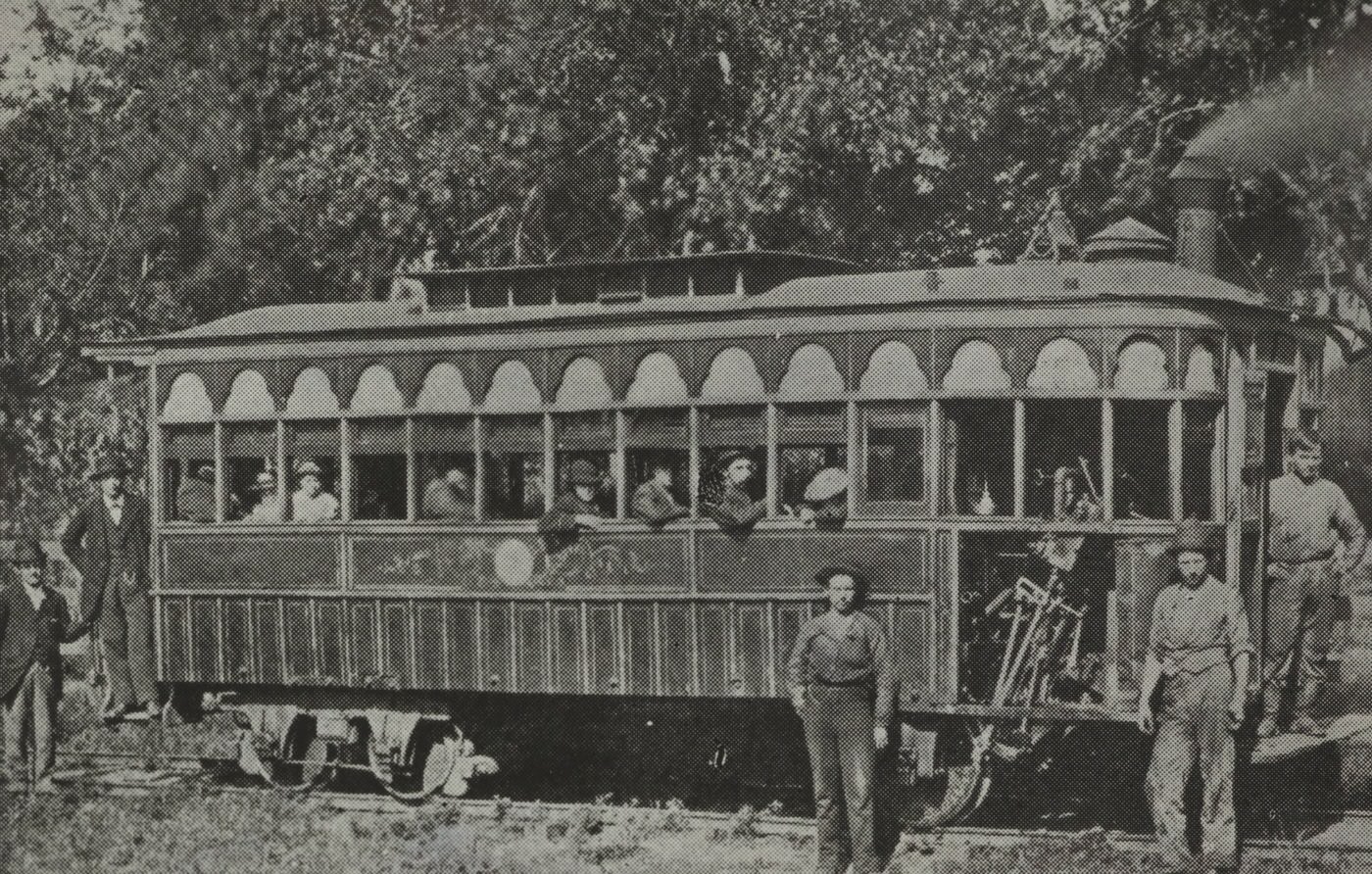

Within the city, public transportation was undergoing a transformation. The 1880s witnessed the initial experiments with electric streetcars. In 1884, Cleveland saw the opening of the first commercial electric streetcar line in the United States, running from Kennard Street to Lincoln Avenue. This early system faced safety and operational issues, such as power disruptions due to weather, and temporarily reverted to horse-drawn cars. However, these pioneering efforts laid the groundwork for the widespread adoption of electric streetcars that would occur in the following years, allowing the city’s workforce and residential areas to expand further from the downtown core. The Nickel Plate Railroad also contributed to local transit by upgrading former “dummy lines” (steam-powered street railways) for limited commuter service during the decade.

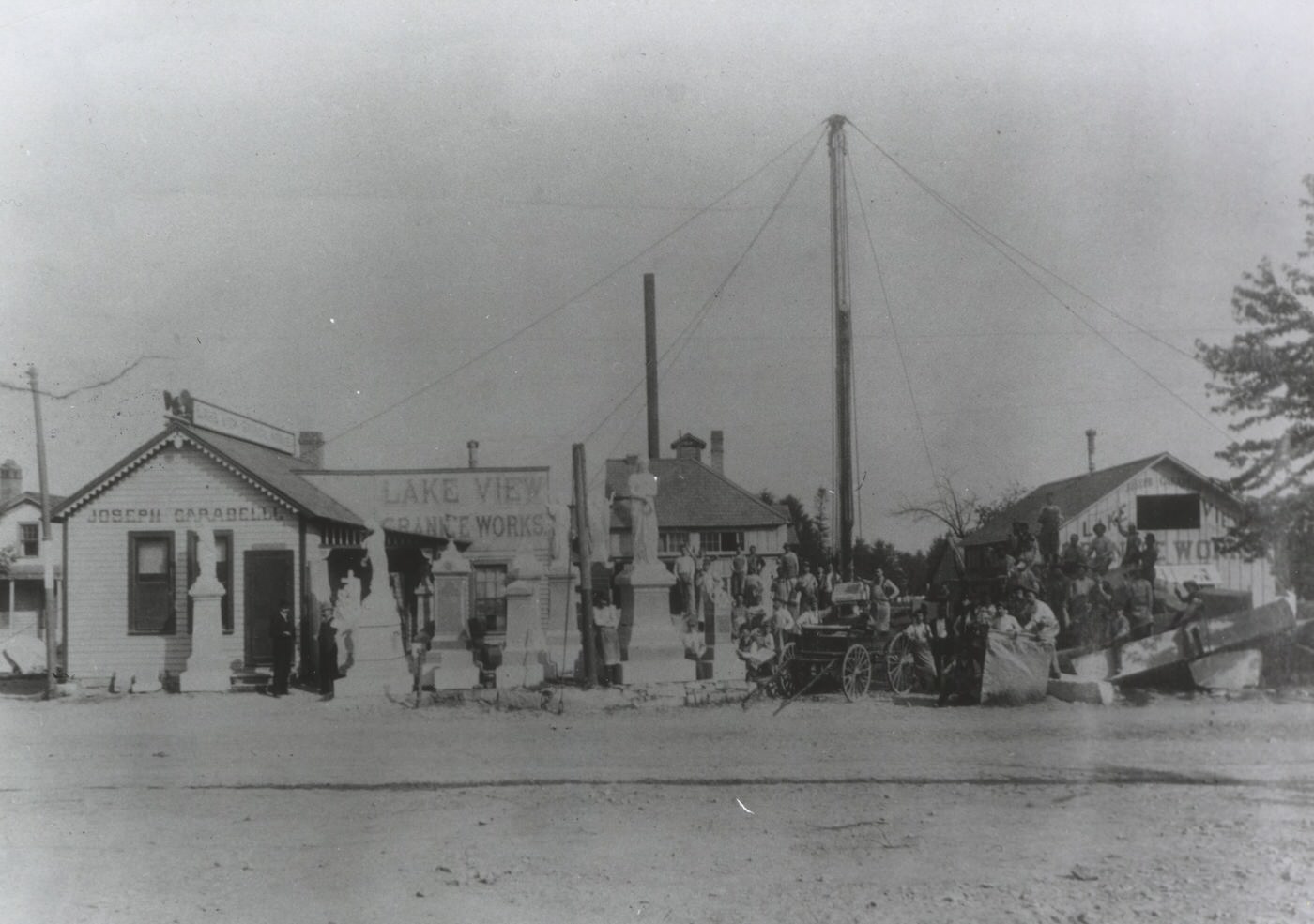

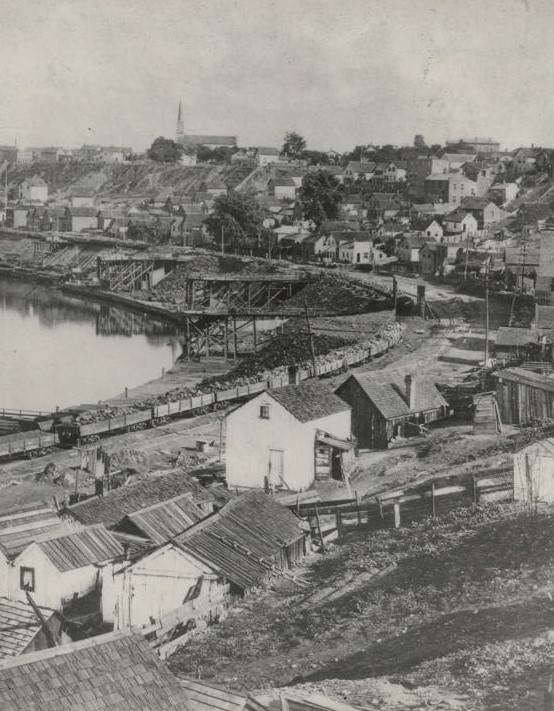

The Port of Cleveland remained a critical artery for the city’s economy. It was a primary receiving point for iron ore from the Upper Great Lakes and a shipping point for coal. In 1880, Cleveland’s docks handled over 750,000 tons of iron ore, a figure that impressively rose to over 1 million tons by 1886. The shipbuilding industry also thrived. The Globe Iron Works, through its Globe Shipbuilding arm formed in 1880, launched the iron-hulled freighter Onoko in 1882. This vessel is considered a prototype for the Great Lakes ore carriers. In 1886, the same company built the Spokane, the first steel-hulled bulk carrier on the lakes. To support this bustling maritime activity, the Cleveland Vessel Owners Association was formed in 1880 to represent the interests of shipping companies.

Connecting the rapidly growing east and west sides of Cleveland, divided by the Cuyahoga River, was a major engineering focus. The Superior Viaduct, which had opened in December 1878, was a vital link. However, its design included a pivoting center drawspan that had to open frequently for river traffic. This resulted in significant delays for street traffic – estimates suggest around 300 times per month, with each stop averaging five minutes. These interruptions were not only an annoyance but also put a strain on the bridge’s structure. To address the growing need for cross-river transit, construction of the Central Viaduct began in May 1887. This massive structure, which opened on December 2, 1888, connected Jennings Avenue (now West 14th Street) with Central Avenue (now Carnegie Avenue) and also featured a swing section to accommodate taller ships. Tragedy struck during its construction in January 1888 when a portion of the viaduct collapsed, resulting in the deaths of several workers. These large-scale bridge projects demonstrated the city’s commitment to overcoming geographical barriers to facilitate growth and commerce.

The urban environment itself was being transformed by new technologies. Charles F. Brush’s arc lighting system, first publicly demonstrated with great success on Cleveland’s Public Square in 1879, rapidly gained adoption. The Brush Electric Company, formed in 1880, became a major supplier of arc lighting systems across the country. Although gas lighting was still in use, electric street lighting offered brighter illumination at a lower cost. Cleveland’s City Council, after a brief reconsideration in 1883, committed to electric lighting, making the city an early adopter of this transformative technology which extended the hours of activity and enhanced public safety.

Another communication revolution was underway with the telephone. Following the first exchange opening in late 1879, the Cleveland Telephone Company was incorporated in January 1880. The number of subscribers grew steadily, from 76 in September 1879 to nearly 300 by 1880, and reaching 2,979 by 1890. Initially, due to the expense—$72 per year for a business line and $60 for a residential line in 1885—most subscribers were businesses. The first long-distance telephone line connected Cleveland to Youngstown in 1883, established by the Midland Telephone Company. While the telegraph remained dominant for long-distance communication, the telephone began to integrate into the city’s commercial life.

The very streets Clevelanders walked and drove on were also evolving. By 1880, the city maintained 975 streets, 183 avenues, and numerous lanes and alleys. The 1880s saw a shift in paving materials. Earlier wooden pavements, such as Nicholson or wood-block paving, were being replaced by more durable Medina sandstone, although this material was known for providing a rough ride. By 1875, sections of prominent thoroughfares like Euclid Avenue had already been paved with Medina sandstone. Newer materials like asphalt also began to appear; by 1880, Cleveland had 2.2 miles of asphalted streets and another 1.2 miles of streets paved with a combination of asphalt and stone. This decade also saw increased efforts to develop and enforce street ordinances, a response to earlier, often haphazard, street development that had resulted in poor grading and foundations.

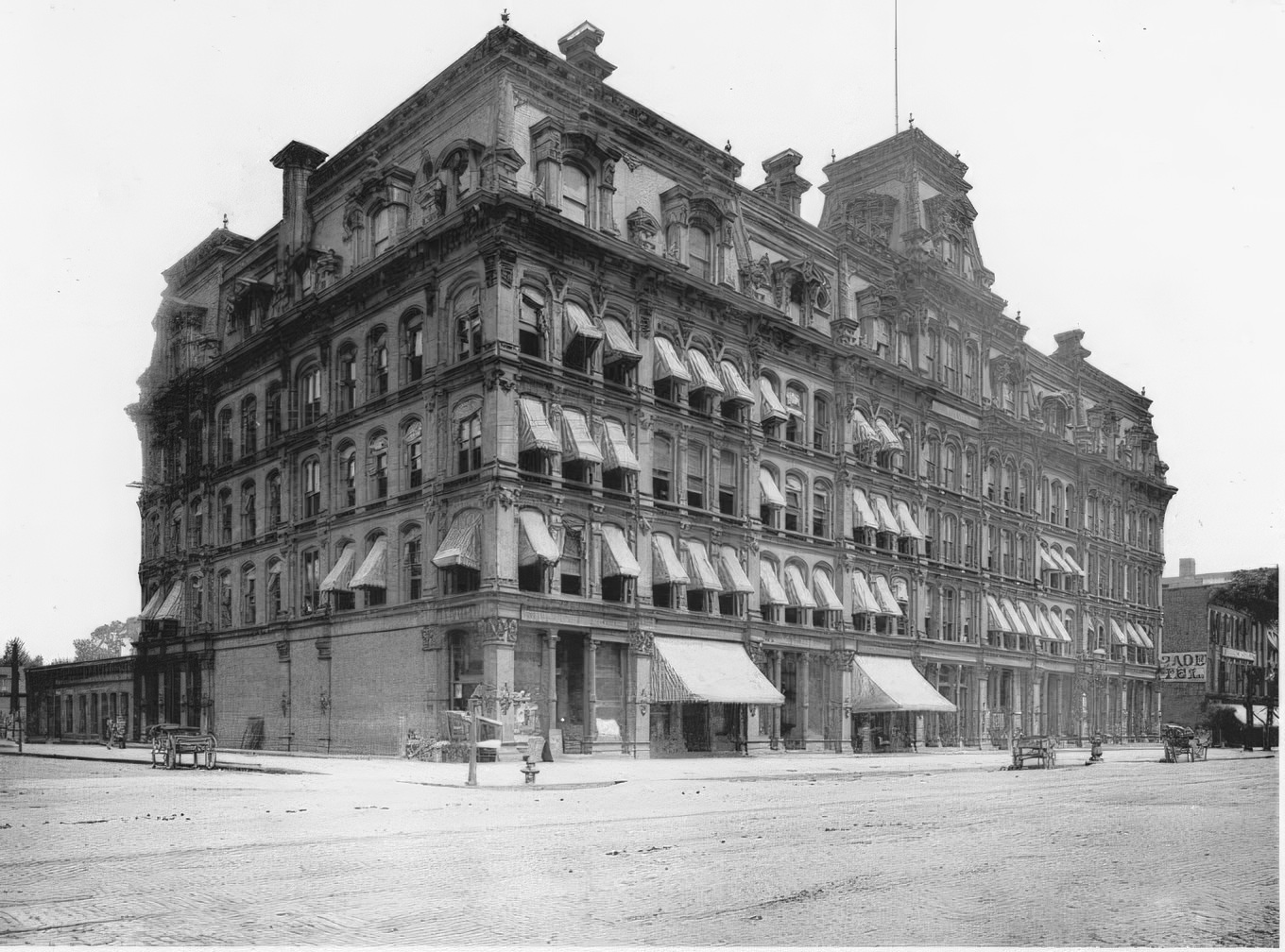

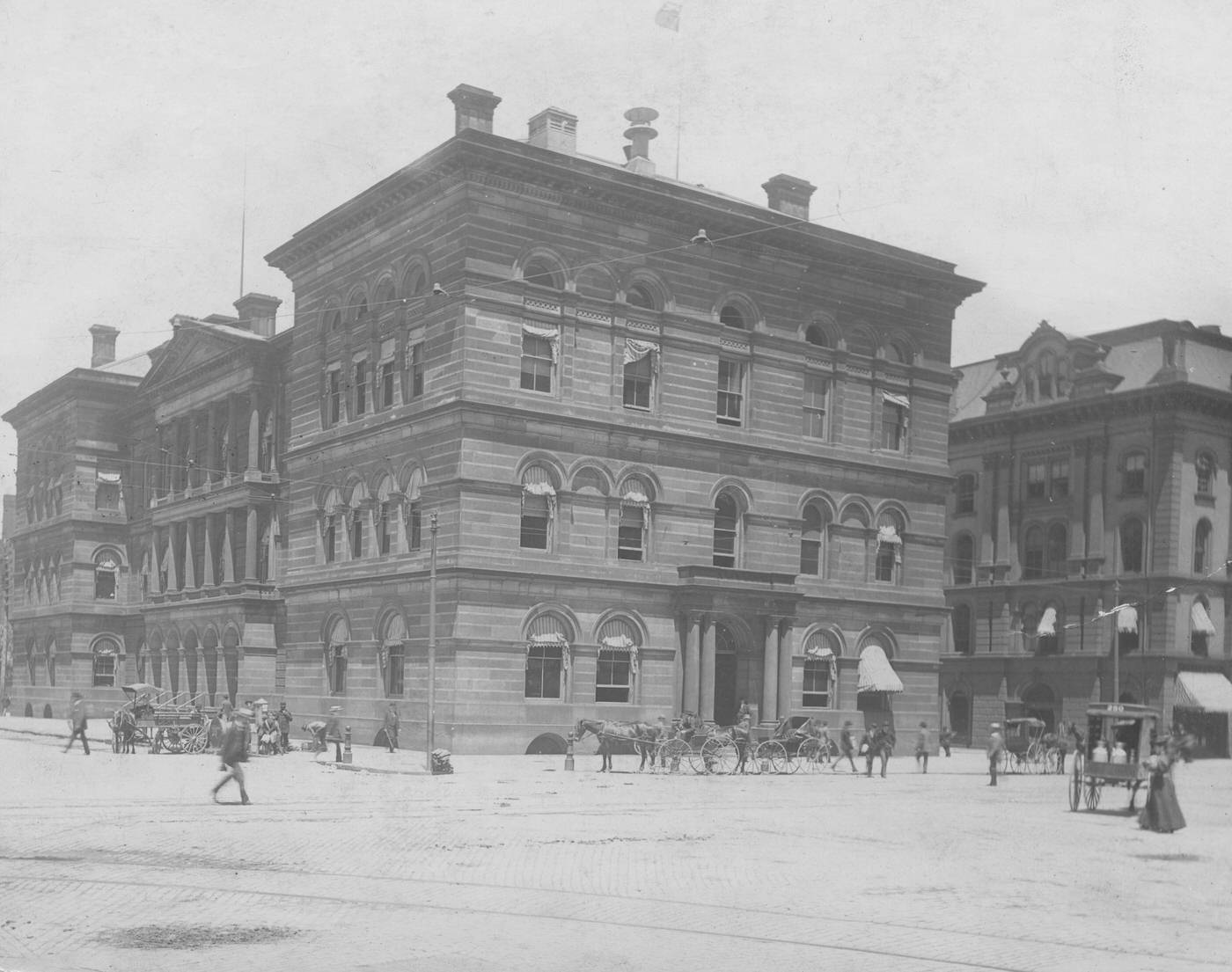

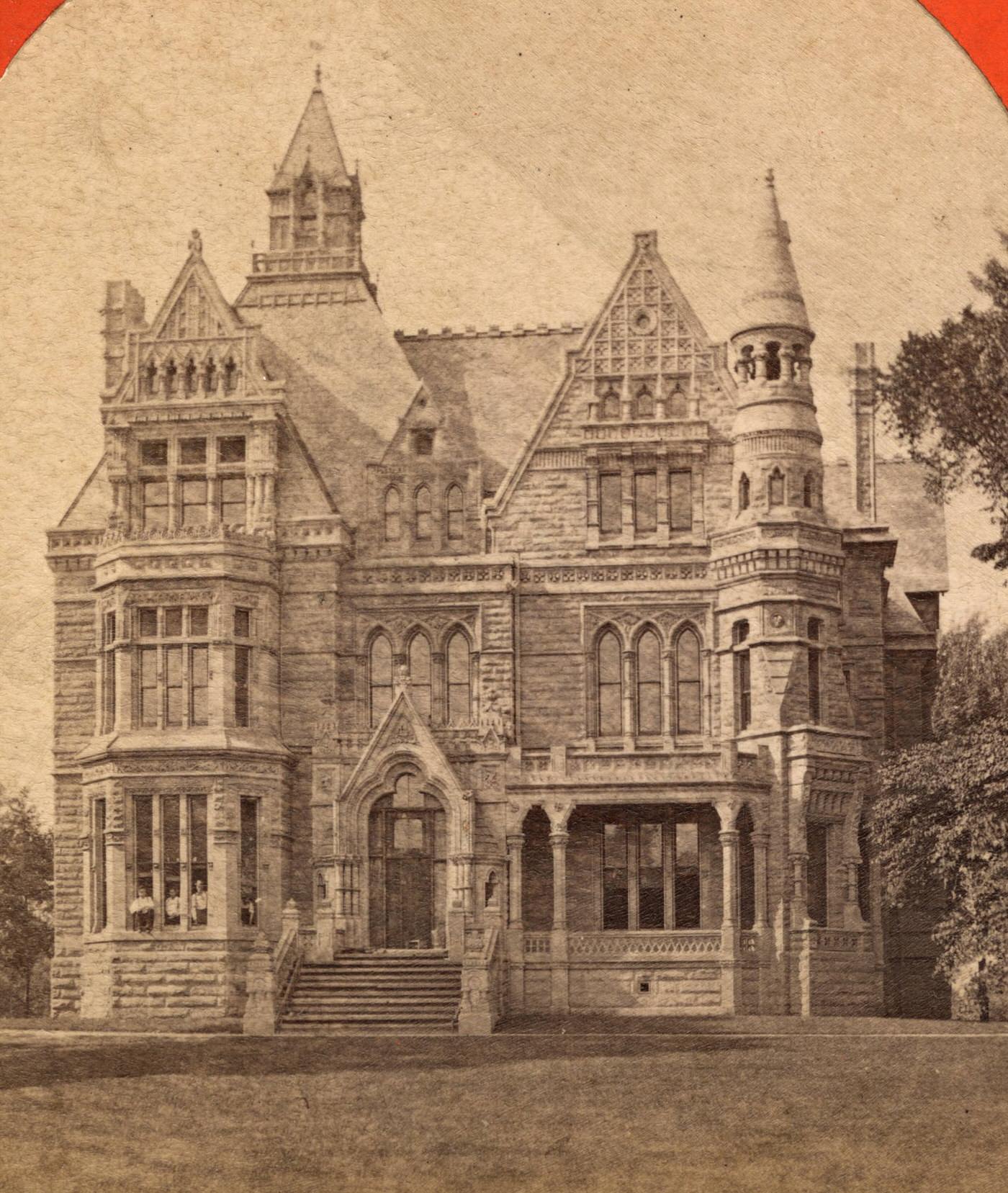

The city’s physical structures reflected its prosperity and growth. In the 1880s, the U.S. Post Office, Custom House, and Courthouse building on Public Square saw the addition of large symmetrical wings, maintaining its Italian Renaissance style. The City of Cleveland itself still did not have a dedicated City Hall building, continuing to lease office space in commercial structures like the five-story Case Block. Commercial architecture was undergoing a revolution, with a focus on fireproof construction and the use of iron and steel for lighter, more open designs. Architects Frank E. Cudell and John N. Richardson were prominent in this movement, designing buildings like the Geo. Worthington Building and the Perry-Payne Building (constructed between 1882-1889). The Perry-Payne Building was notable as the first in Cleveland to utilize iron columns throughout all eight of its stories. This trend culminated in the planning and early construction phases of The Arcade, which would open in 1890, a magnificent iron-and-glass structure designed by John Eisenmann and George H. Smith. Residential architecture showcased the city’s wealth, particularly along Euclid Avenue’s “Millionaires’ Row,” where grand mansions in styles like Romanesque Revival, Victorian Gothic, Queen Anne, and Renaissance were built by prominent architects such as Charles F. Schweinfurth, Levi T. Scofield, and George H. Smith. A notable example was Samuel Andrews’s enormous mansion, dubbed “Andrews’s Folly,” constructed between 1882 and 1885. In contrast, housing for the working class typically consisted of wood frame buildings, often built closely together, two to a city lot, with their gabled ends facing the street.

Geographically, Cleveland continued its outward expansion. While specific annexations for each year of the 1880s are not exhaustively listed in the available information, the pattern of growth involved the formation of new villages on the city’s periphery, which were then often incorporated into Cleveland. For example, the village of Brooklyn was officially formed in 1889 and was annexed by Cleveland in 1890. The village of Collinwood was formed in 1883, indicating active suburban development that would later lead to its annexation. This process of absorbing surrounding communities was a key driver of Cleveland’s increasing size and population during the decade.

The Roar of Industry: Factories, Forges, and Fortunes

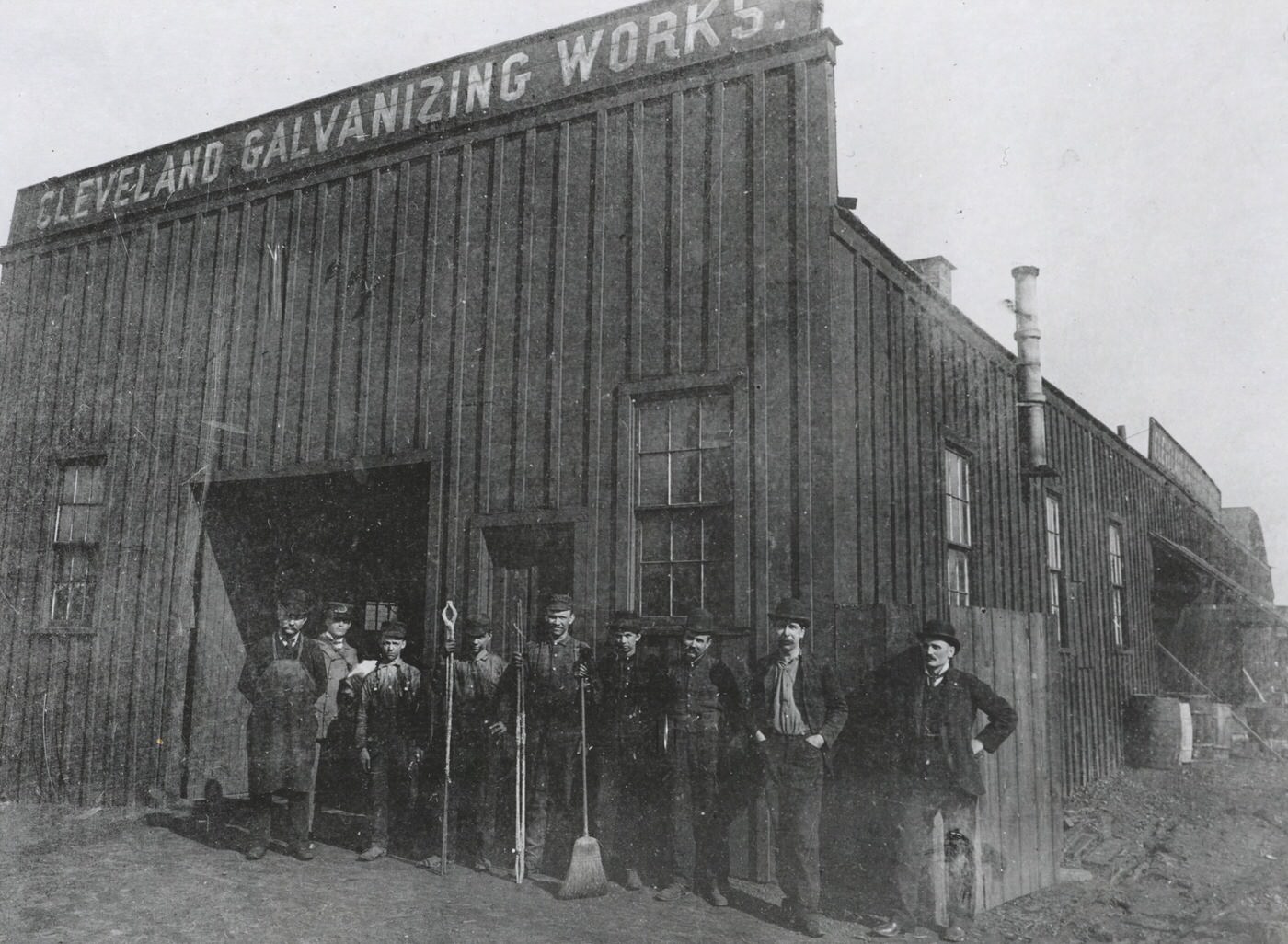

Cleveland’s identity in the 1880s was inextricably linked to its powerful industrial base. The making of iron and steel was a dominant force. By the year 1880, this sector accounted for a significant 20% of the total value of all manufactured goods produced in the city. The scale of this industry was impressive; in 1880, the primary iron and steel operations employed nearly 3,000 individuals across 10 main establishments. Just four years later, in 1884, the number of businesses involved in iron and steel production and the manufacturing of their products had grown to 147. These companies employed a workforce of 14,000 and generated products valued at $25.2 million.

Two companies stood out as leaders in this sector. The Cleveland Rolling Mill Company, which had pioneered the use of the Bessemer steel process west of the Allegheny Mountains back in 1868, was a major employer, with over 8,000 workers at its peak. The Otis Iron & Steel Company also made significant strides, installing the first commercially successful basic open-hearth furnace in the United States in 1886. This was a pivotal technological advancement for steel production. Efficiency at the port, crucial for an industry reliant on raw materials, was improved by innovations like Alexander E. Brown’s mechanical hoist, introduced in 1880 for unloading iron ore. The sheer volume of production and the adoption of new technologies solidified Cleveland’s position as a national industrial heavyweight, attracting a continuous stream of labor and fueling economic expansion.

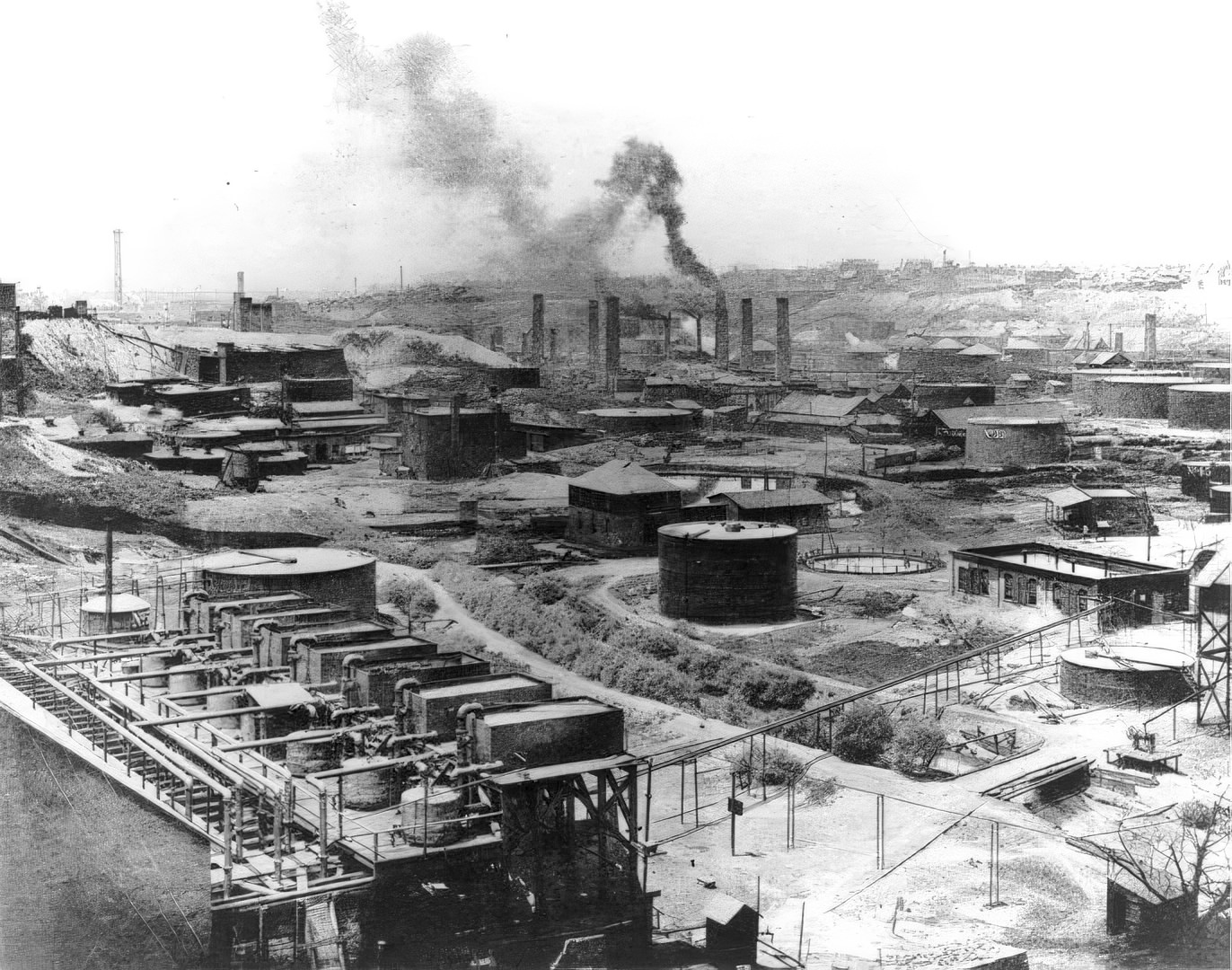

The 1880s also witnessed the consolidation of another Cleveland-born giant: Standard Oil. John D. Rockefeller had already brought much of Cleveland’s oil refining capacity under his control during the 1870s. A pivotal moment came in January 1882 with the formation of the Standard Oil Trust. This new corporate structure, which placed the stock of 40 constituent companies (including Standard Oil of Ohio) under the control of nine trustees, was designed to allow the enterprise to operate on a national scale, bypassing limitations imposed by individual state charters. By that year, Standard Oil controlled an estimated 90% of the oil refining capacity in the United States. Cleveland was not just a production site but also a center of innovation for the company; Standard Oil established a permanent research department in 1889, formalizing work that chemist Herman Frasch had been doing in the city since 1877. This is often regarded as the first dedicated research department in the petroleum industry. The creation of the Standard Oil Trust, with its significant Cleveland operations, marked a new era in business organization and market control, positioning Cleveland at the heart of a powerful and often controversial economic entity.

Beyond these two titans, Cleveland’s manufacturing landscape in the 1880s was diverse and interconnected. The chemical and paint industries flourished. Grasselli Chemical Co. continued its expansion. The Sherwin-Williams Co. officially adopted its name in 1884 and, along with the Glidden Varnish Co. (founded in the 1870s), supplied paints and coatings to the city’s growing construction, shipbuilding, and railroad car industries. Sherwin-Williams demonstrated a commitment to innovation by hiring its first full-time chemist in 1884.

The machinery sector was another area of strength. Warner & Swasey, founded in 1880 and relocated to Cleveland in 1881, became known for its turret lathes and astronomical telescopes. The Cleveland Twist Drill Co., which had started marketing its products in 1876, was a key manufacturer of machine tools and drills. The White Sewing Machine Co. not only produced sewing machines but also developed advanced multi-spindle automatic screw machines, eventually forming a subsidiary, the Cleveland Automatic Screw Machine Co., to manufacture these for a wider market.

The nascent electrical equipment industry also had strong Cleveland roots. The Brush Electric Co., established in 1880 following Charles F. Brush’s successful demonstration of his arc lighting system on Public Square in 1879, initially captured 80% of the U.S. arc lighting market. Although its dominance waned by the mid-1880s due to increased competition and a failure to invest sufficiently in research and expansion, its early success was a catalyst for the broader electrical industry.

Shipbuilding was also a vital part of Cleveland’s industrial fabric. The Globe Iron Works formed Globe Shipbuilding in 1880. This company made history by launching the iron-hulled Onoko in 1882, a vessel that served as a prototype for future Great Lakes ore carriers. In 1886, they built the Spokane, the first steel-hulled bulk carrier on the Great Lakes. The city’s port was bustling, with ore receipts exceeding 1 million tons in 1886. The clothing industry, which was already Cleveland’s third-largest by value in 1860, continued to be a significant employer and a major consumer of locally manufactured sewing machines. This web of interconnected industries, where machine shops supplied parts to sewing machine makers, which in turn supplied the garment trade, created a resilient and dynamic local economy.

The 1880s brought gradual improvements for Cleveland’s workforce. Real wages generally increased, and employment was relatively plentiful. Homeownership also rose, with 20% of Clevelanders owning their homes in 1880. However, working conditions in factories often remained harsh. A typical workday was long, commonly ten to twelve hours. Safety was a major concern, with industrial accidents being a frequent occurrence in an era with few regulations.

In response to these conditions, labor organizations grew in strength. The Knights of Labor was a significant presence, with nearly 50 local assemblies in Cleveland. The city’s carpenters’ union was formed in 1881 under the Knights’ banner. In 1887, the Cleveland Central Labor Union (CLU) was chartered by the rival American Federation of Labor, marking another step in the organization of the city’s workers. The period was also marked by significant labor disputes. Strikes at the Cleveland Rolling Mills in 1882 and 1885 were particularly notable. In 1882, skilled workers, members of the Amalgamated Association of Iron & Steel Workers, struck for a closed shop. The company responded by hiring Polish and Czech immigrants as strikebreakers, and the strike ultimately failed. Three years later, in 1885, these same Polish and Czech workers went on strike to protest wage cuts and successfully had their previous wages restored. Overall, between 1881 and 1886, a high percentage of strikes in Cleveland—around 70-80%—were successful for the workers. In response, employers increasingly turned to tactics like yellow-dog contracts (agreements not to join a union) and blacklists to counter union efforts. The 1880s, therefore, represented a complex period for labor, with tangible economic gains for some, alongside persistent harsh conditions and ongoing struggles for worker rights and representation.

Daily Life in a Bustling City

Life in Cleveland during the 1880s was characterized by stark contrasts and dynamic changes, reflecting its status as a rapidly growing industrial center. The city’s neighborhoods showcased a wide spectrum of living conditions. Euclid Avenue, famously known as “Millionaires’ Row,” was a testament to the immense wealth generated by industry. It was lined with what observers called a “continuous succession of charming residences and such uniformly beautiful grounds”. Prominent figures like John D. Rockefeller resided there until 1884. The opulent mansions, designed in styles such as Romanesque Revival, Victorian Gothic, and Queen Anne, were set on spacious lawns. Samuel Andrews’s enormous home, built between 1882 and 1885 and popularly known as “Andrews’s Folly,” exemplified the grandeur of the era on this prestigious avenue.

In sharp contrast, working-class families and newly arrived immigrants often lived in more modest and crowded conditions. Their housing typically consisted of wood-frame buildings, sometimes constructed two to a single lot, often with their gabled ends facing the street. These neighborhoods were frequently situated near the factories and mills, leading to a daily life lived in close proximity to industrial activity. The advent of mass transit, particularly the horsecar in the 1870s and the early electric streetcars in the 1880s, began to alter this geography, allowing some who could afford the fare to live further from the industrial core, leading to increasing social segregation based on income and ethnicity. Ethnic enclaves like “Little Bohemia” for Czechs, Warszawa for Poles, and the burgeoning Hungarian and Italian settlements had their own distinct character, with housing often clustered near specific industries or community institutions like churches.

Education underwent significant development in the 1880s. Public school enrollment was on the rise; Cleveland had 49,256 school-age children in 1880, a number that grew to 64,550 by 1887. Actual student enrollment increased from 24,262 in 1880 to 33,150 in 1887. The curriculum expanded to include more practical subjects, reflecting the needs of an industrial society. Manual training programs for high school students were introduced in 1884, and a cooking course, noted as a first in the country, was added in 1887. The German bilingual education program continued in some schools to serve the large German-speaking population. Efforts to ensure school attendance were strengthened with the appointment of the city’s first truant officer in 1889, tasked with enforcing a new compulsory attendance law that required children to attend school for at least 20 weeks a year. Teacher training was formalized through the Normal School, which had been established in 1874 and was reorganized in 1882 under Superintendent Burke A. Hinsdale.

Alongside the public school system, Catholic parochial schools saw substantial growth. Following the mandate from the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884, which required parishes to build schools, the number of Catholic schools and enrolled students increased significantly. By 1884, the diocese reported 123 parochial schools with 26,000 children enrolled. A diocesan school board was established in 1887 to oversee these schools.

Higher education also laid significant foundations in Cleveland during the 1880s. The Case School of Applied Science, founded in 1880, moved to its University Circle location in 1883. Western Reserve College relocated from Hudson to Cleveland in 1882, becoming Western Reserve University. It established Adelbert College for men and, in 1888, the College for Women, which would later be known as Flora Stone Mather College. The Jesuit order founded St. Ignatius College (the forerunner of John Carroll University) in 1886. For those seeking education outside of traditional degree paths, the YMCA offered evening classes throughout the 1880s in subjects like art, bookkeeping, and French.

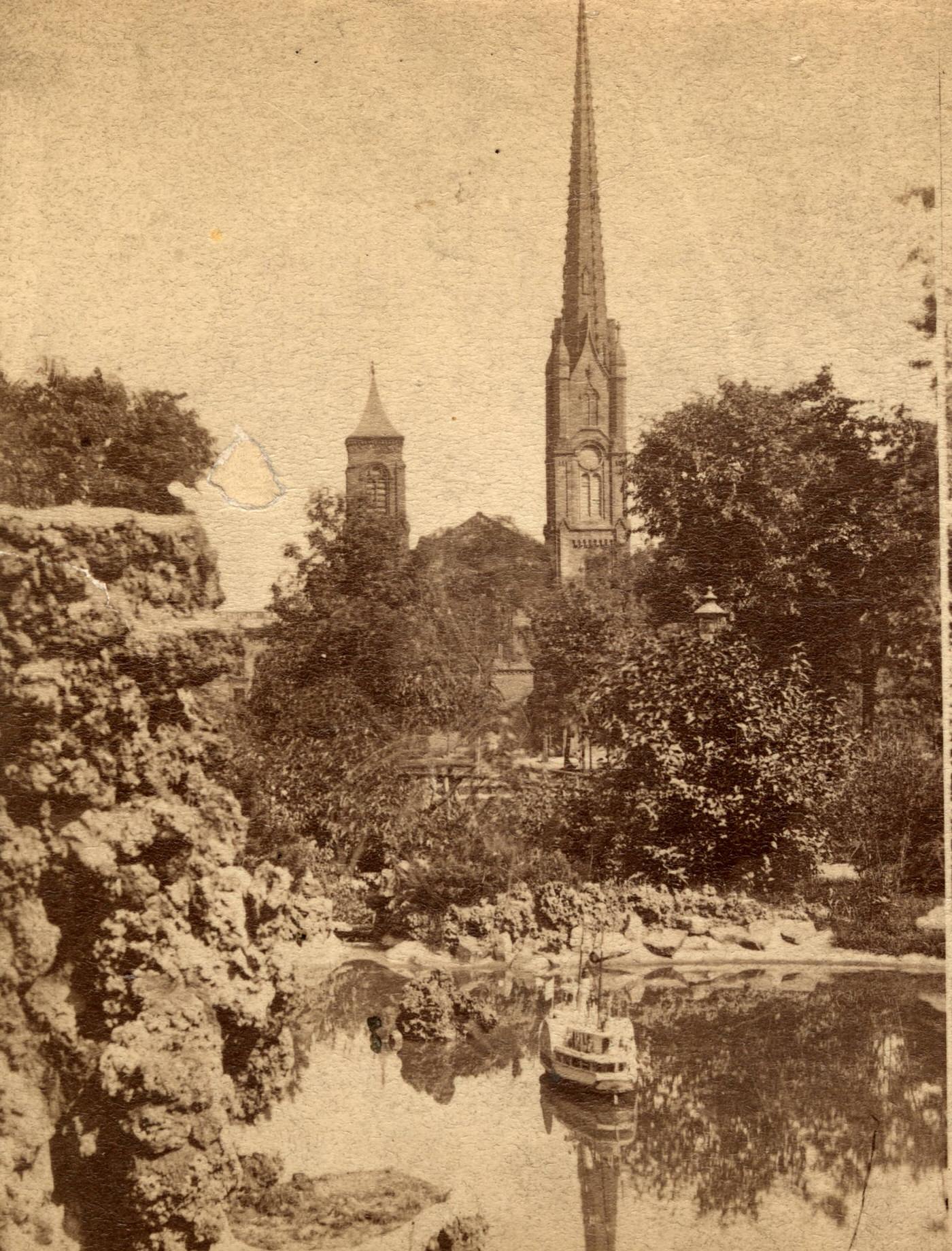

Religious life was a cornerstone of many communities within Cleveland. Jewish congregations were active and evolving. Anshe Chesed continued its adoption of Reform practices under Rabbi Michaelis Machol. In 1880, the congregation hired James H. Rogers as its organist, and in 1887, it dedicated a new synagogue at East 25th and Scovill, selling its former building on Eagle Street to B’nai Jeshurun. B’nai Jeshurun, in its newly acquired building, moved towards a more liberalized form of Orthodoxy under the leadership of Rabbi Sigmund Drechsler, who was hired in 1886. Tifereth Israel, led by Rabbi Aaron Hahn, also continued to develop its Reform practices. Protestant denominations also saw growth, with new church buildings reflecting various architectural styles. The North Presbyterian Church, an eclectic mix of Gothic Revival and Romanesque Revival styles, was constructed between 1886 and 1887. Calvary Presbyterian Church, which began as a mission of the Old Stone Church, started construction of its Romanesque stone building in 1888, dedicating it in 1890. Catholic parishes expanded to serve the growing immigrant populations, with Holy Trinity Parish established in 1880 for German Catholics (church dedicated 1881) and St. Colman Catholic Church founded in 1880 for the Irish community. These religious institutions were often the social and cultural centers of their respective communities.

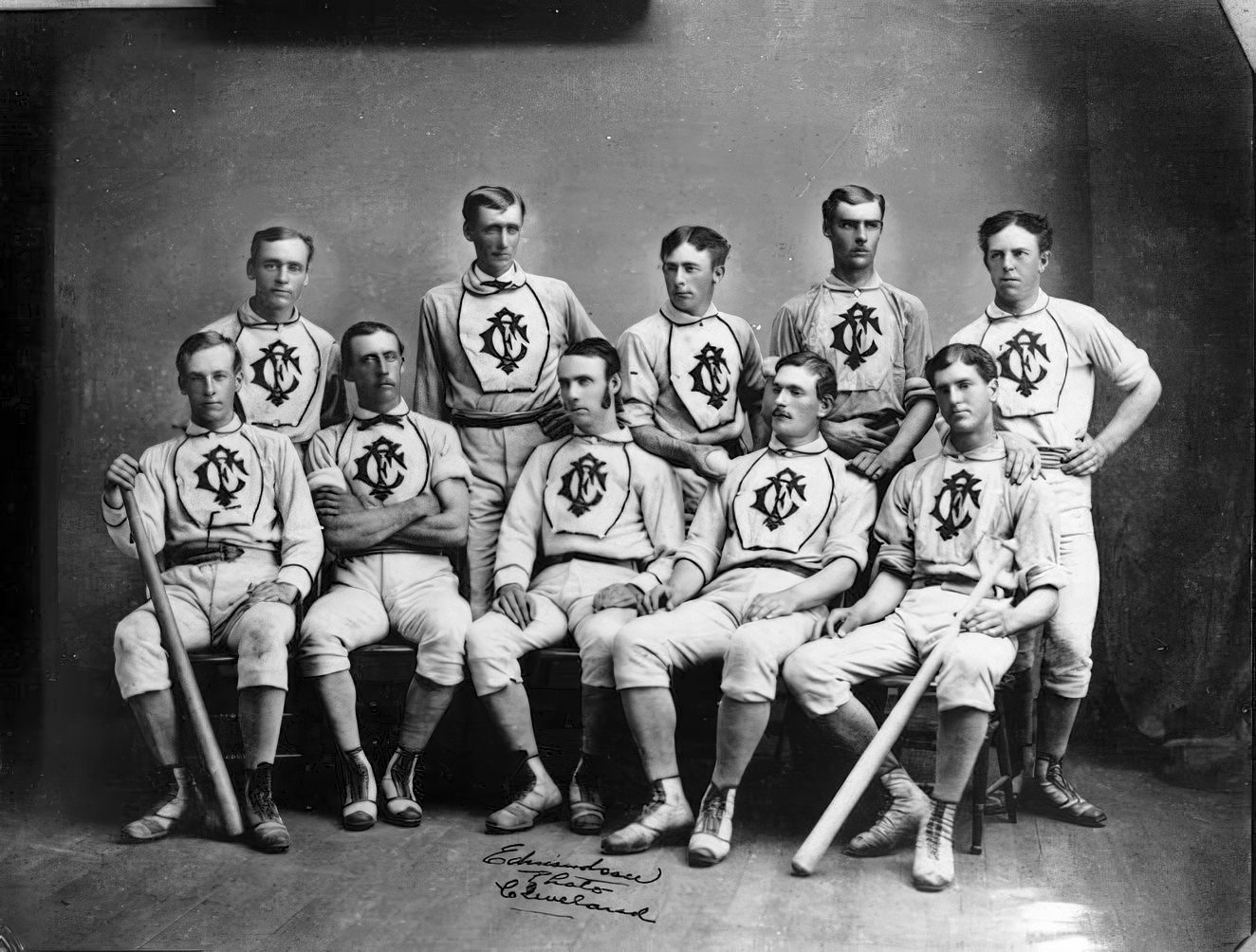

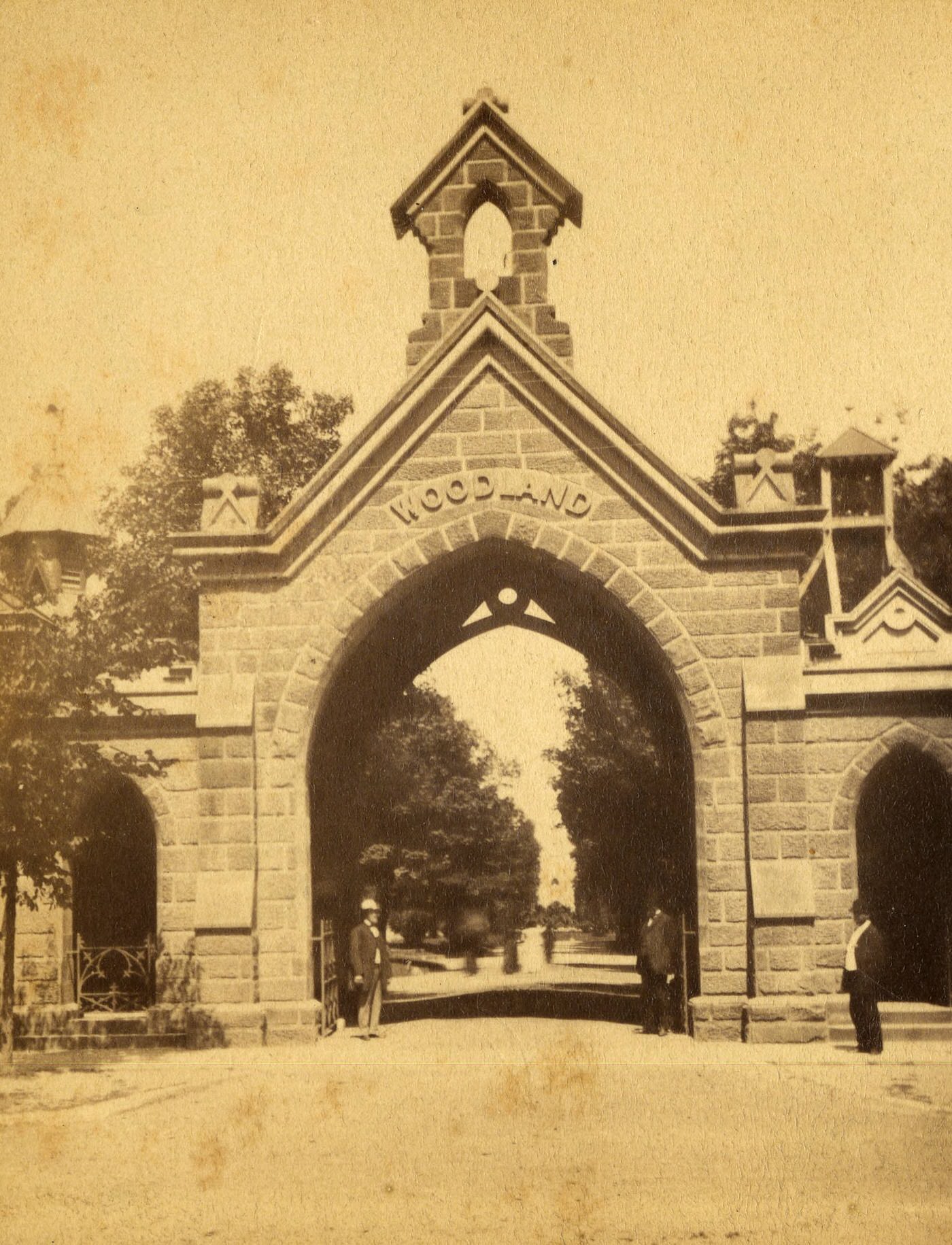

Leisure and entertainment options were expanding. The Euclid Avenue Opera House maintained its status as a premier venue for theatrical performances. Several new theaters opened their doors in the 1880s, including the Park Theater in 1883 (which became the Lyceum Theater in 1889), the Cleveland Theater in 1885, and the Columbia Theater in 1887, the latter offering vaudeville and melodrama. For outdoor entertainment, Haltnorth’s Gardens was a popular spot, likely featuring light opera and concerts in an alfresco setting. Professional baseball was a growing pastime. The Forest Citys team played in the National League from 1879 to 1884. Later in the decade, the team known as the Cleveland Spiders (initially also called the Forest Citys) played in the American Association from 1887 to 1888 before joining the National League in 1889. Social clubs also played a role in the city’s life. The Union Club, incorporated in 1872, served as an important meeting place for the city’s industrialists and professionals. In 1882, a significant development occurred when women—specifically, the wives and family members of club members—were granted full, though separate, privileges within the clubhouse. The Early Settlers Association of Cuyahoga County, formed in November 1879, began holding annual meetings and publishing its Annals in 1880, dedicated to preserving the region’s history.

The general atmosphere of Cleveland in the 1880s, as gleaned from newspaper accounts and descriptions of the era, was one of energetic and sometimes chaotic growth. The Cleveland Gazette, founded in 1883, offered glimpses into daily life through local event notices, news stories, and even poetry and fiction. While detailed first-hand travelogues specifically from the 1880s are not abundant in the provided materials, earlier accounts from the 1870s paint a picture of lively ethnic neighborhoods like the “Isle of Cuba” with its saloons and dance halls. The introduction of electric street lighting was beginning to change the character of the city after dark, extending hours of activity and visibility. The streets themselves were a mix of older paving materials and newer experiments, bustling with horse-drawn vehicles, early streetcars, and pedestrians navigating a city in constant flux.

Governing a Growing City: Public Health, Safety, and Politics

Managing Cleveland’s explosive growth in the 1880s presented considerable challenges for the city government, particularly in the realms of public health and safety. The Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie, vital for industry and water supply, were heavily polluted. As early as 1881, Mayor Rensselaer R. Herrick declared the riverfront an “open sewer,” a stark assessment of the contamination from industrial and household waste. This pollution was directly linked to high rates of diseases like typhoid fever and other enteric illnesses. Garbage disposal was another pressing issue, as much of the city’s waste ended up in waterways or on the streets. Health officer Dr. Frank Wells, in 1876, had already attributed Cleveland’s high death rate to poor sanitation, germs, and unfavorable socioeconomic conditions. While specific mortality statistics for the 1880s are not detailed in the provided information, these earlier reports indicate ongoing public health crises.

In response, the Cleveland Board of Health, which was restored as an independent body in 1882 after a period under police department control, intensified its efforts. Health officers were appointed for each city ward, and the Board focused on improving the milk supply, tackling sewage and garbage problems, and exposing unqualified medical practitioners. A significant step was taken in 1886 when the state legislature authorized the Board to appoint sanitary police officers, at a ratio of one for every 15,000 residents, to help enforce health regulations. Air quality also became a concern, leading to the passage of the Smoke Ordinance in April 1882 (amended July 1883). This ordinance aimed to reduce the dense smoke from coal burning that plagued the city. However, enforcement proved difficult, facing resistance and legal challenges, with any early improvements in air quality likely due more to public sentiment or voluntary industrial changes than to strict legal enforcement.

The city’s leadership during this transformative decade included several mayors. Rensselaer R. Herrick served from 1879 to 1882, followed by John H. Farley (1883-1884), George W. Gardner (1885-1886 and again 1889-1890), and Brenton D. Babcock (1887-1888). These administrations, through the City Council, were responsible for enacting and enforcing municipal ordinances related to public works, sanitation, and safety. An 1882 publication, for example, compiled the general and special ordinances of public interest then in force, indicating an ongoing effort to codify and manage the city’s legal framework. The governance of Cleveland in the 1880s was a continuous effort to adapt to and manage the pressures of rapid industrialization and population growth, laying the groundwork for the city’s future development.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know