The year 1890 found Cleveland, Ohio, as a city experiencing dramatic transformation. Its population had swelled to 261,353 people, a testament to its burgeoning industries and the opportunities, real or perceived, that drew newcomers. This figure represented a significant jump from previous decades and was a prelude to further expansion, as by 1900, the city would house 381,768 residents.

This rapid demographic growth was mirrored by an expansion of Cleveland’s physical boundaries. In the years leading up to the 1890s, the city’s land area had more than doubled, largely due to the annexation of communities such as East Cleveland and Newburgh. This pattern of absorption continued throughout the decade. The village of Brooklyn officially became part of Cleveland in 1890, followed by West Cleveland in 1894, and both Glenville and South Brooklyn in 1895. These annexations were not merely passive occurrences; Cleveland was an “expansion-minded” entity actively seeking these mergers. Smaller, independent villages often struggled to provide essential urban amenities like paved and lighted streets, robust fire and police protection, and quality educational facilities that a larger, more resourceful city like Cleveland could offer. For Cleveland, these consolidations meant an increased tax base, more land for development, and greater control over the rapidly urbanizing region. This strategic approach to growth was essential for a city aspiring to, and achieving, the status of an industrial giant. The ability to offer superior services created a compelling case for amalgamation, strengthening Cleveland’s position as the dominant urban center on Ohio’s north coast.

The “Forest City” Takes Its Place Among America’s Industrial Giants

By the dawn of the 1890s, Cleveland had firmly established itself as a significant urban center, ranking as the 10th largest city in the United States. This position underscored its growing importance in the national landscape, driven largely by its industrial might.

The city was widely known as “The Forest City,” a nickname that evoked images of natural beauty and tree-lined streets, a legacy from its earlier days. Other affectionate monikers included “C-Town” and “The North Coast,” the latter a nod to its strategic location on the southern shore of Lake Erie. This lakeside position, coupled with its role as a convergence point for numerous railroad lines, provided Cleveland with a distinct advantage for industrial development. It became an ideal meeting place for the essential ingredients of 19th-century industry: iron ore, shipped down from the upper Great Lakes, and coal, transported by rail from the Appalachian fields.

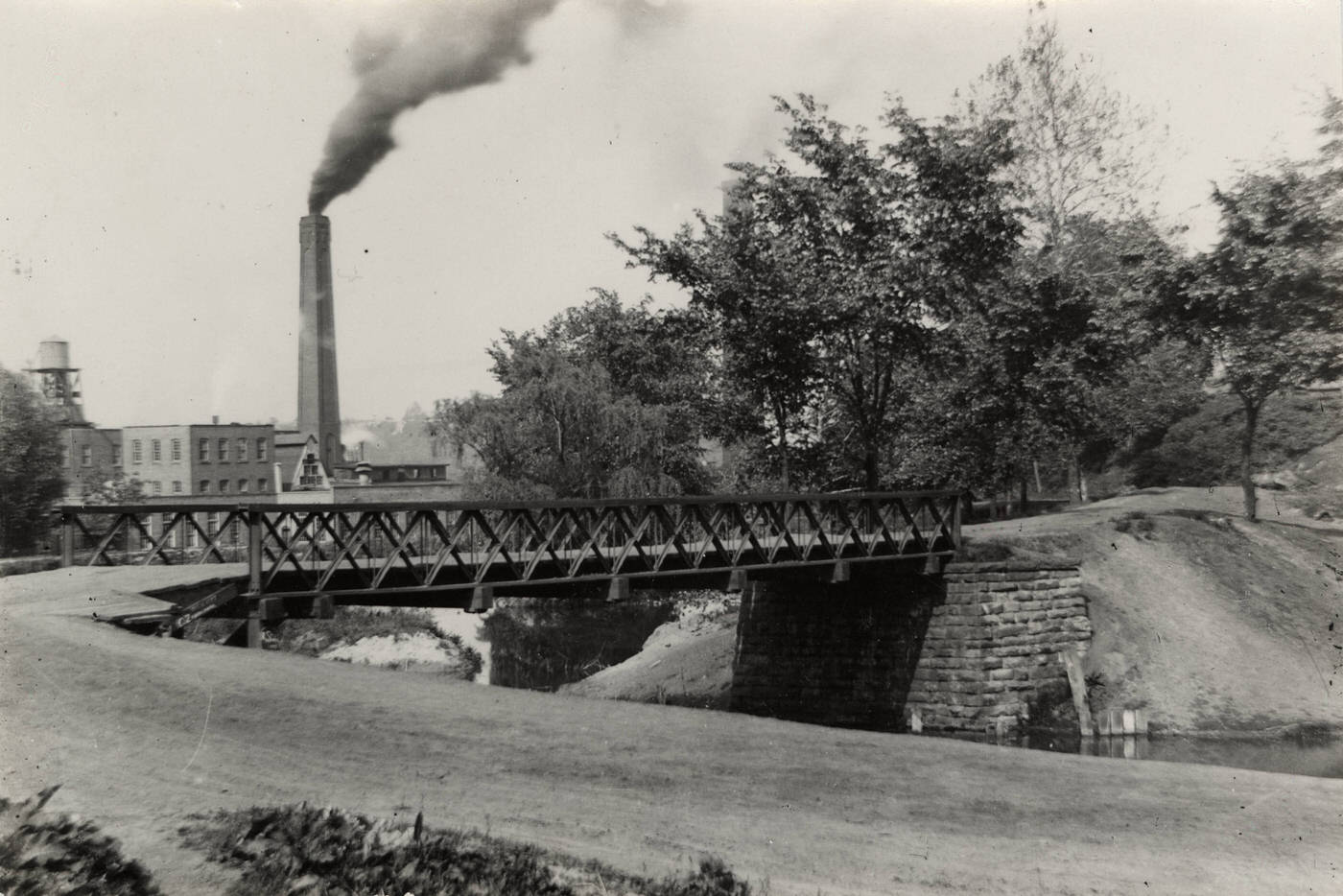

The persistence of the “Forest City” nickname presented an interesting contrast to the city’s increasingly industrial reality. The 1890s were characterized by the smoke and clamor of iron and steel mills, the sprawling complexes of oil refineries, and the ceaseless activity of numerous factories. This industrial activity inevitably brought pollution, with factory chimneys casting a pall over parts of the city. The duality of its nickname and its industrial character suggests a city in profound transition. Cleveland was perhaps clinging to an older, more pastoral identity while simultaneously and vigorously embracing a future defined by heavy industry. The development of significant parklands during this era, such as Wade Park and Gordon Park, also shows an effort to maintain green spaces even as the industrial footprint expanded, reflecting a complex, evolving urban identity.

Iron, Steel, and Oil: The Titans of Cleveland’s Economy

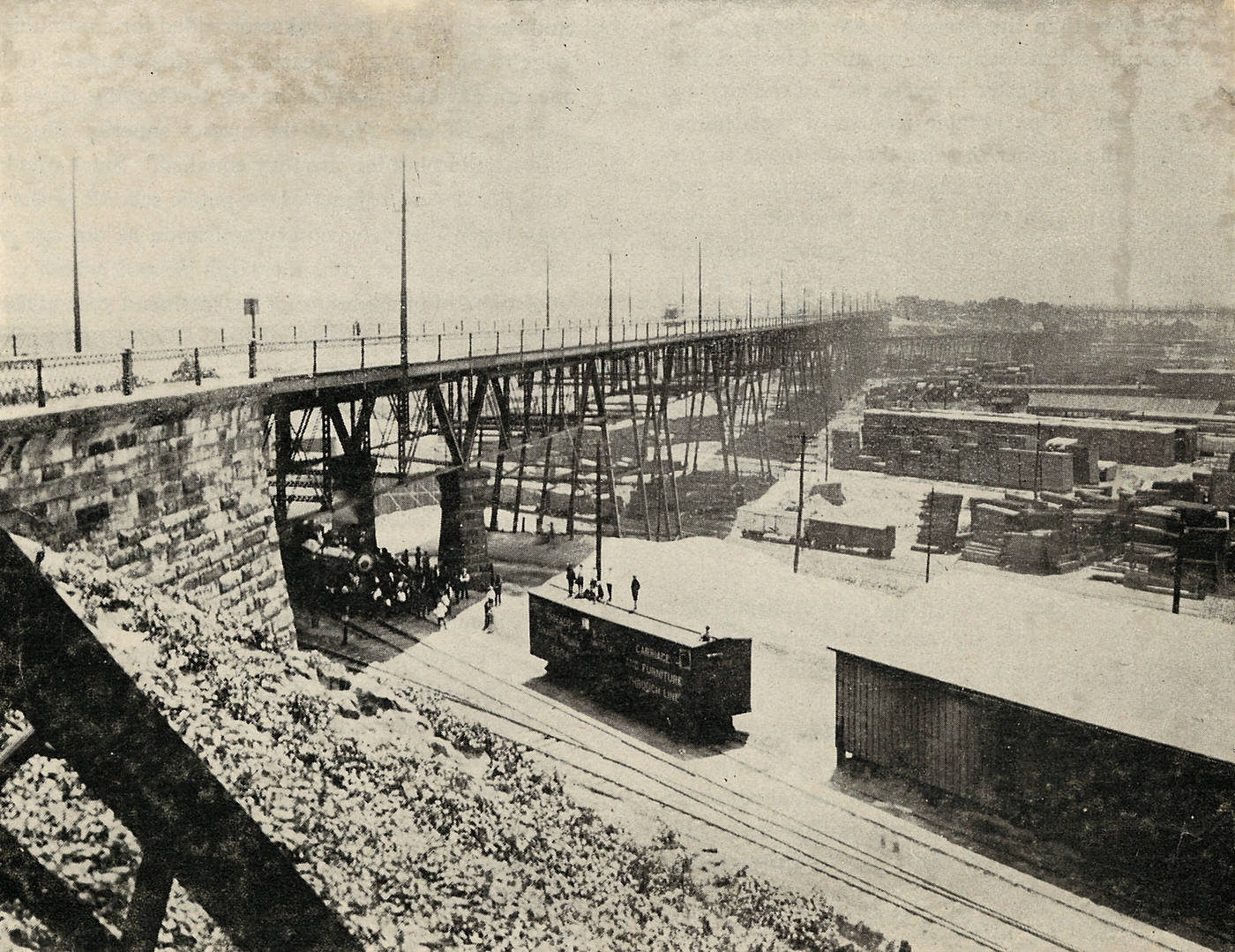

Throughout the 1890s and beyond, iron and steel production formed the backbone of Cleveland’s manufacturing economy, a dominance that would last until the 1930s. The city’s geographical position on Lake Erie, at a nexus of water and rail transport, made it a prime location for metallurgical industries, efficiently bringing together iron ore from the Lake Superior region and coal from Pennsylvania and southern Ohio.

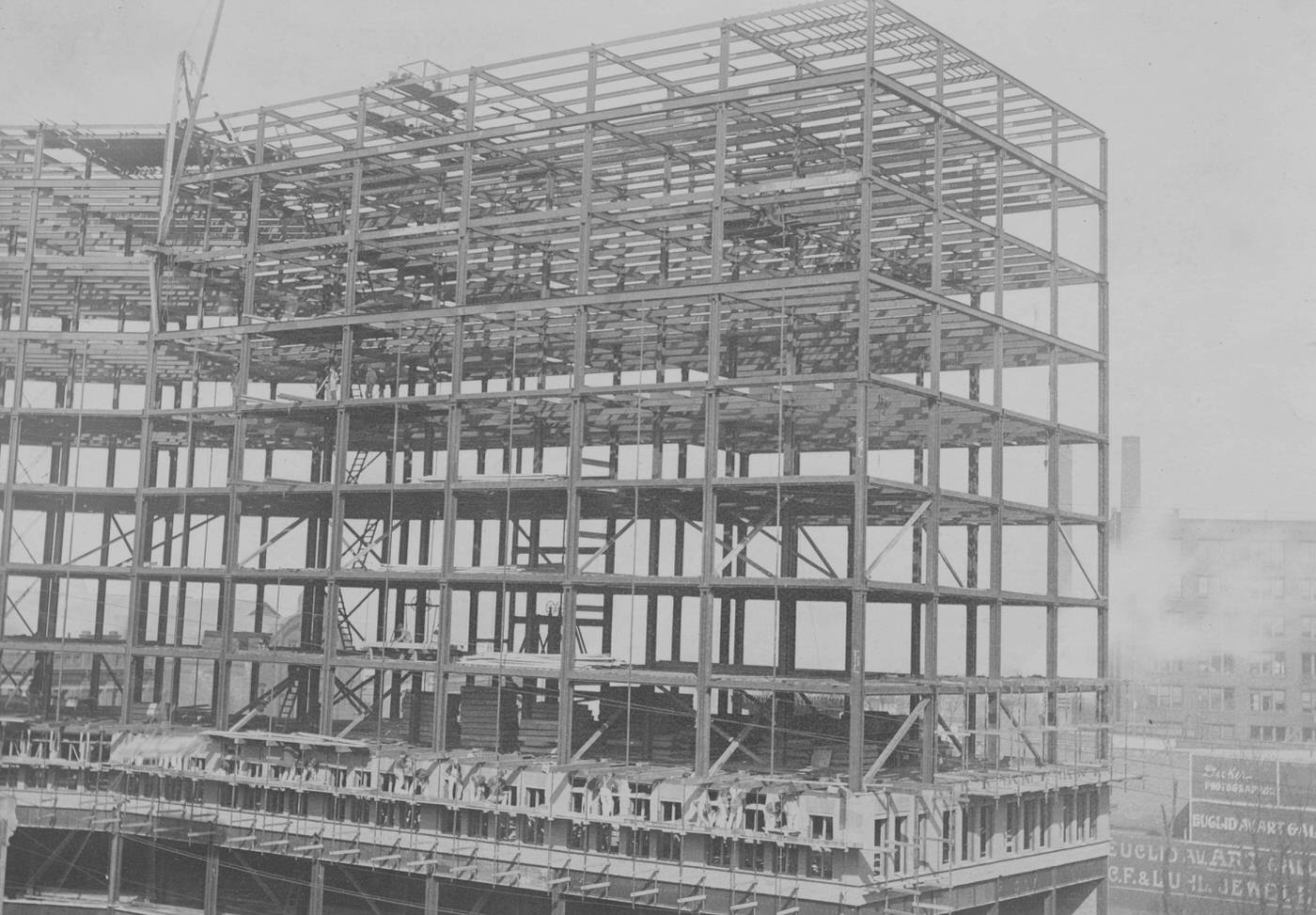

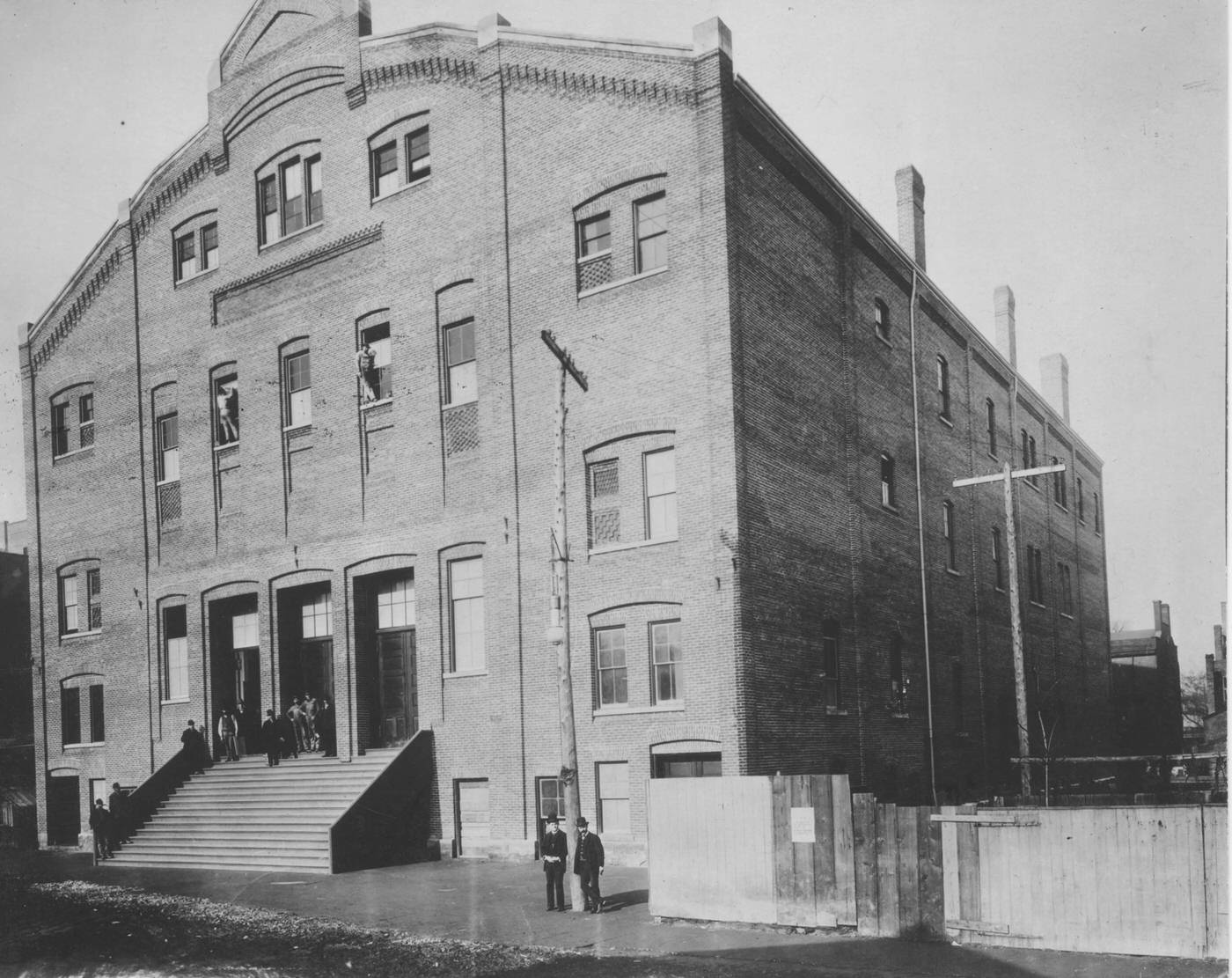

Several key companies and figures shaped this industrial landscape. The Cleveland Rolling Mill Co. stood as a giant, an integrated producer of pig iron, Bessemer steel, and a variety of steel products. In its late 1890s peak, it employed over 8,000 workers. Henry Chisholm, a pioneering ironmaster, was instrumental in its growth, notably installing the first Bessemer converters west of the Allegheny Mountains in 1868. However, the era of large-scale consolidation was dawning; in 1899, the Cleveland Rolling Mill Co. was absorbed into the American Steel and Wire Co. of New Jersey, which itself would soon become part of J. P. Morgan’s massive U.S. Steel Corporation. Another significant player was the Otis Iron & Steel Co., organized by Charles Augustus Otis in 1873. This firm became a particularly dynamic producer after 1886, when Samuel T. Wellman installed the first commercially successful basic open-hearth furnace in the United States at their facility, a technology that would eventually surpass the Bessemer process. The foundation for much of this industry rested on access to raw materials, and Clevelander Samuel Livingston Mather was a pivotal figure in opening up the rich iron ore resources of the Lake Superior region. He was a leading force behind the Cleveland Iron Mining Co., which was a parent company of the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Co., incorporated in 1891 and a dominant force in the Marquette Range. By 1884, the scale of this sector was evident, with 147 establishments in Cleveland dedicated to manufacturing iron and steel or their derivative products.

The control over these raw materials was as crucial as the manufacturing capacity itself. Industrialists like Mather, and companies such as M.A. Hanna Co. and Pickands Mather & Co., did not just use iron ore; they dominated the ore trade, controlling vast tracts of ore-rich land and the fleets of vessels that transported the ore across the Great Lakes. This command over the supply chain was a critical factor in Cleveland’s rise as an iron and steel powerhouse.

Parallel to the growth of iron and steel was the ascent of the oil refining industry, largely under the direction of John D. Rockefeller. He, along with partners like Henry M. Flagler and Samuel Andrews, founded the Standard Oil Co. (Ohio) in 1870. The company’s rise was swift and decisive. By 1872, Standard Oil controlled 21 of Cleveland’s 26 oil refineries, and by 1890, the broader Standard Oil trust, encompassing 40 companies, commanded nearly 90% of the oil refining capacity in the United States. This dominance was achieved through aggressive business tactics, including buying out competitors or driving them out of business. However, this concentration of power faced legal challenges. In 1892, the Ohio Supreme Court ordered the dissolution of the Standard Oil trust within the state. This led to Standard Oil of Ohio becoming an independent entity, while the larger national enterprise eventually reorganized in 1899 under the umbrella of Standard Oil (New Jersey). Rockefeller’s strategy of controlling the processing and distribution of oil mirrored the control exerted by iron magnates over their raw materials, showcasing a key Gilded Age business model where command over resources and production was central to achieving industrial supremacy.

Building the Future: Ships, Garments, and More

While iron, steel, and oil were dominant, Cleveland’s industrial prowess in the 1890s extended to other vital sectors, including shipbuilding and garment manufacturing, creating a diverse economic base.

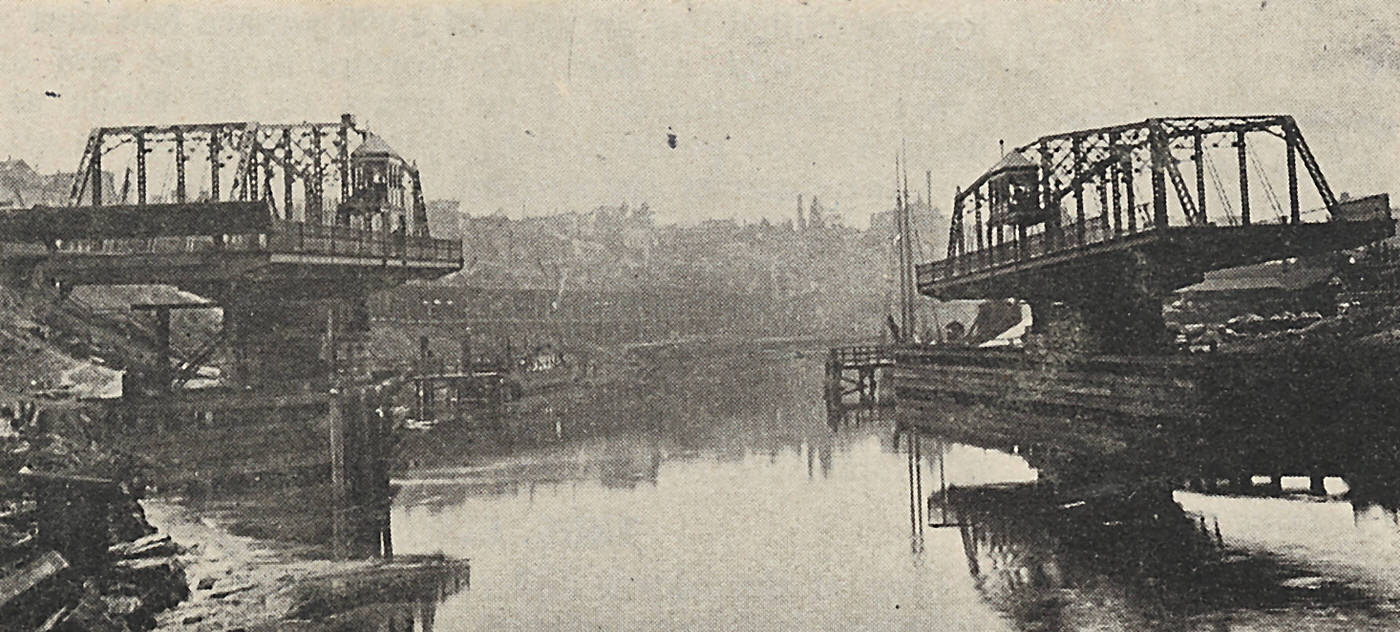

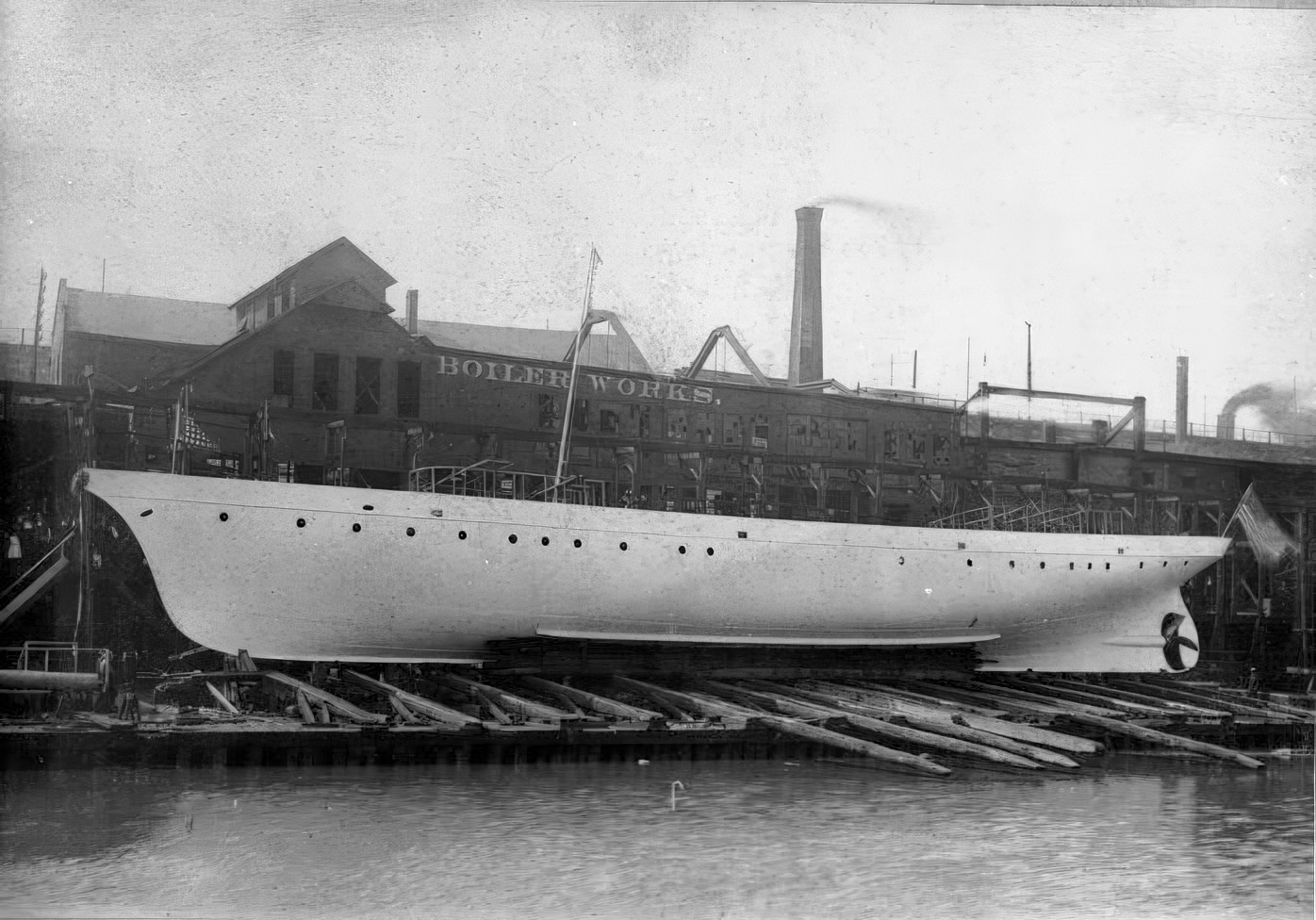

By 1890, Cleveland had earned the distinction of being the foremost shipbuilding center in the United States. This achievement was significantly driven by innovators like Henry Darling Coffinberry. His Globe Iron Works, through its Globe Ship Building Company arm, launched pivotal vessels: the Onoko in 1882, the first large commercial freighter built of iron to sail the Great Lakes, and the Spokane in 1886, the first steel freighter on the lakes. These ships were prototypes for modern Great Lakes freighters. After a dispute, Coffinberry and partner Robert Wallace left Globe to form the Cleveland Shipbuilding Co. in 1886, which quickly became a successful competitor. The strength of these and other local shipbuilders was such that, by the end of the decade, a consolidation formed the American Shipbuilding Company in 1899, a major industrial enterprise.

The garment industry also experienced a significant boom in Cleveland during the late 19th century, propelled by the same forces of urbanization and mass immigration that were reshaping other American cities. Cleveland became a major center for ready-to-wear clothing, ranking second only to New York City in the production of men’s and women’s coats and suits. Key companies included H. Black & Co., known for women’s suits and cloaks; the Joseph & Feiss Co., a long-standing manufacturer of men’s clothing; the Richman Bros. Co., which specialized in men’s suits and coats and moved to Cleveland in the late 1890s; and the Printz-Biederman Co., founded in 1893 by Moritz Printz, a former designer for H. Black & Co., focusing on women’s suits and coats. Supplying these manufacturers with fabric was the Cleveland Worsted Mills, under the control of Kaufman Hays after 1893, which operated numerous mills and served a national market. The garment trade provided employment for a substantial portion of the city’s workforce; after the 1890s, about 7% of Cleveland’s workers toiled in its garment factories.

Other manufacturing activities contributed to the city’s economy. The meatpacking industry, centered around the Cleveland Union Stockyards, was the city’s third largest. The wagon and carriage industry was also well-established by the 1890s, with numerous firms specializing in various types of vehicles and Cleveland serving as a significant producer of wagon and carriage parts.

These varied industries did not exist in isolation. The iron and steel mills provided the essential steel plates and components for the shipyards. The expanding railroad network, itself a major consumer of steel, was vital for transporting raw materials to all factories and distributing finished goods to markets across the country. The burgeoning oil industry supplied lubricants necessary for the machinery in every manufacturing sector. Furthermore, industries like garment making, meatpacking, and carriage production created a substantial demand for labor, attracting the diverse immigrant populations who also found work in the heavier industries. This interconnectedness created a dynamic industrial ecosystem where advancements or growth in one area often spurred development in others, contributing significantly to Cleveland’s overall economic vitality during the decade.

New Technologies Transforming the City

The 1890s were a period of remarkable technological advancement, and Cleveland was both a contributor to and a beneficiary of these innovations, which reshaped its industries, infrastructure, and daily life.

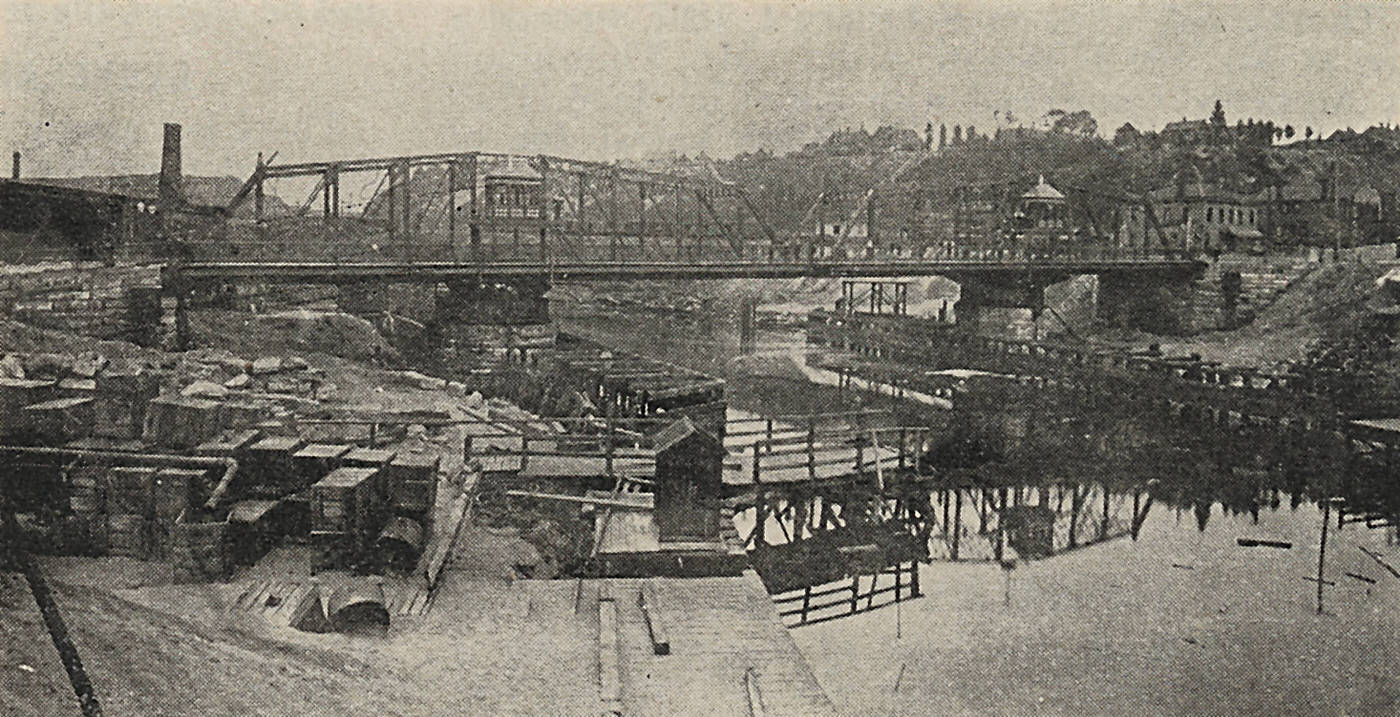

One of the most impactful local inventions occurred on the city’s busy docks. The efficient unloading of massive quantities of iron ore from Great Lakes freighters was a critical bottleneck. While Alexander E. Brown had developed an improved mechanical hoist in 1880, it was George H. Hulett’s invention in 1899 that truly revolutionized the process. The Hulett unloader, a colossal machine featuring a large-capacity grab bucket suspended from a walking beam, could scoop tons of ore from a ship’s hold at a time, completely eliminating the need for manual shoveling. This innovation drastically reduced labor costs and unloading times, enabling ships to make quicker turnarounds and influencing the design of even larger, specialized ore boats.

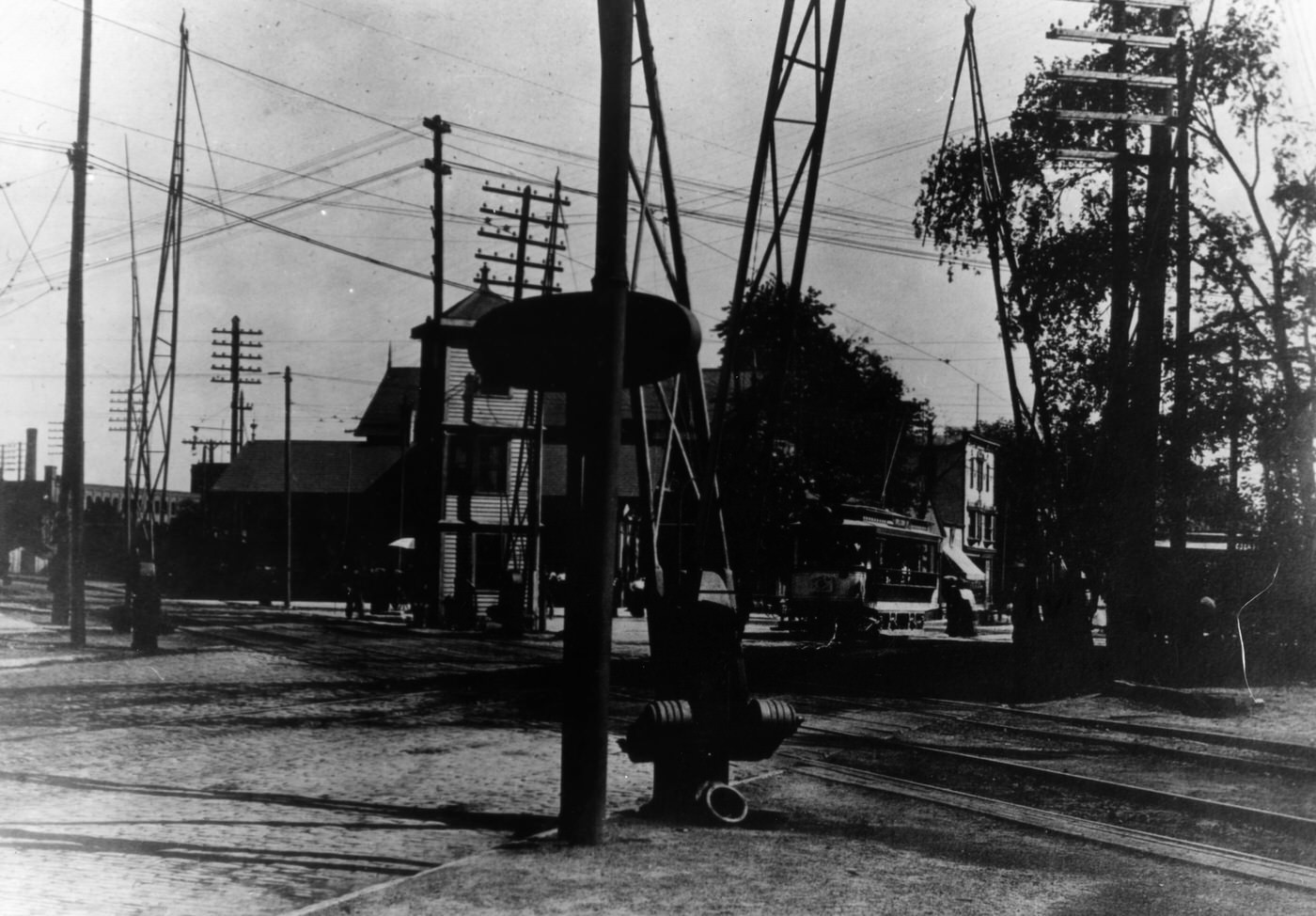

The transformative power of electricity was also becoming increasingly evident. Euclid Avenue famously boasted the world’s first electric streetlight, and electric streetcars, which first appeared in Cleveland in 1884, had largely replaced horse-drawn lines by 1894. By 1890, commercial applications of electricity were energizing new construction and manufacturing projects throughout the city. The call for municipal ownership of utilities began to surface, with a social activist group petitioning the city council in 1890 for a city-run electric lighting plant. Meanwhile, private enterprise was also active; the Cleveland General Electric Co., a forerunner of the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company (CEI), was formed in 1892 by the electrical pioneer Charles F. Brush, with CEI establishing its formal offices in 1894.

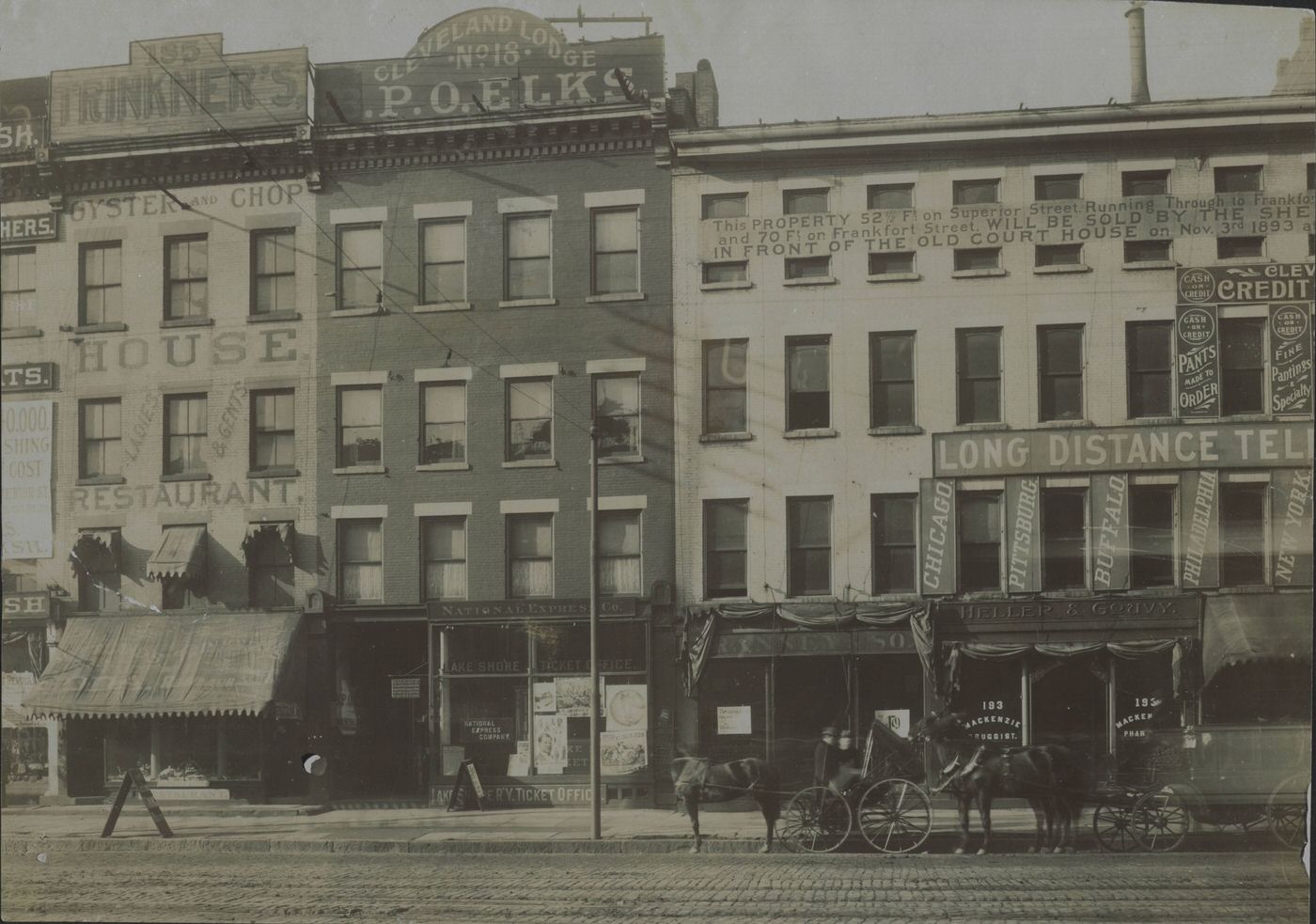

Communication technologies were also advancing. The telephone, though still a luxury for many, was growing in use. Cleveland had 2,979 telephone subscribers by 1890, up from just 76 a decade earlier, though most were businesses due to the high annual cost. The expiration of Bell’s patents in 1893 and 1894 spurred competition, leading to the organization of the Cuyahoga Telephone Co. in 1898 (which began as the Home Telephone Co. in 1895). Long-distance telephone service also became more reliable towards the end of the decade with the introduction of metallic two-wire circuits.

The very end of the decade saw the dawn of a new transportation era. Cleveland was, for a time, considered the automobile capital of America. In 1897, Scottish immigrant and bicycle company owner Alexander Winton established the Winton Motor Carriage Company, which began building its first automobiles by hand.

These technological strides, while crucial for Cleveland’s industrial expansion and modernization, had complex effects on the workforce. Innovations like the Hulett unloader and mechanized charging in steel mills significantly boosted productivity but also displaced manual laborers or fundamentally changed the skills required for certain jobs. This could lead to job insecurity for some, even as new industries like electrical work created fresh opportunities. Workers in these emerging electrical trades also faced their own struggles for fair wages and safe working conditions, leading to early unionization efforts, such as the formation of the National Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (NBEW), which chartered a local in Cleveland. Thus, while technology fueled Cleveland’s industrial engine, its impact on the labor force was multifaceted, creating new avenues for employment while simultaneously posing challenges to existing labor arrangements.

The People of a Bustling City

Cleveland in the 1890s was profoundly an immigrant city. The 1890 census revealed that of its 261,353 inhabitants, 164,258 were native-born; however, only about a quarter of these native-born residents had parents who were also born in America. The foreign-born population itself numbered 97,095. This demographic reality meant that the city’s character, its neighborhoods, workplaces, and cultural life were being continuously shaped by people from across the globe. Nationality influences, it was noted, had almost obliterated the mark of the original New England pioneers.

Germans remained one of the most numerous immigrant groups, with 4,735 individuals from Germany itself, part of a larger “Germanic peoples” contingent of 5,770. They established homes in various parts of the city, sometimes alongside other groups, such as the Irish in the East Madison and Superior Avenue neighborhood. Irish immigration, while past its peak, still contributed to the city’s fabric, with 2,831 arrivals from Great Britain and Ireland combined in 1890. Historic Irish enclaves were located north of Superior Avenue near the lake, around the St. Bridget parish (spanning East 22nd to East 55th Streets, south of Prospect Avenue), and on the West Side in areas like “Irishtown Bend” and the St. Colman parish vicinity. By the 1890s, many Irish families were moving eastward from these older downtown settlements.

A significant development during the decade was the noticeable increase in immigrants from Slavic countries. This included a growing Polish community, which founded a church in the East Madison and Superior Avenue area in the early 1890s. Bohemians (Czechs) also formed a substantial community, with many finding work in the garment industry. The 1890s also marked the period when Syrian-Lebanese immigrants began to put down firm roots in Cleveland. Their numbers escalated from about 1890, with many arriving from agricultural villages around Beirut and Damascus, especially the fertile Bekaa Valley of Lebanon. These newcomers often started as peddlers of religious artifacts and other small goods before moving into factory work, various trades, and eventually establishing their own businesses, from grocery stores to contracting firms. They primarily settled in the Haymarket District (an area encompassing Woodland, Orange, Carnegie, and Webster Avenues, between East 9th and East 22nd Streets) and on the near West Side in Ohio City and along West 14th Street. Hungarians and Italians were also vital parts of the immigrant workforce, contributing to industries like garment manufacturing and often residing in distinct neighborhoods or boarding houses.

Living conditions in many immigrant and working-class neighborhoods were challenging. Overcrowding was common, with families often squeezed into modest wood-frame houses, sometimes two to a city lot. By 1890, the population density in such housing reached an average of 5.96 persons per dwelling. For single male immigrants, particularly from Hungary, large boarding houses were a typical arrangement, where beds might even be shared in shifts by men working different timetables. These boarding houses, often run by immigrant women from the same ethnic group, provided not just shelter but also familiar, home-cooked meals, which was a significant comfort.

These ethnic enclaves played a complex role. On one hand, they were essential support systems. Within these neighborhoods, newcomers could find familiar languages, foods, customs, and religious institutions (like churches and synagogues) that helped preserve their cultural heritage and provided a sense of community in a new and often bewildering land. They offered mutual aid and a buffer against the hardships of assimilation. On the other hand, this clustering, while providing crucial support, also reflected and sometimes deepened the lines of segregation within the rapidly diversifying city. While fostering strong internal bonds, these neighborhoods could also limit interaction with the broader native-born population and other ethnic groups, sometimes perpetuating language barriers for those who remained primarily within their communities. Cleveland in the 1890s was thus a city of distinct ethnic islands, each contributing to the overall urban mosaic while navigating the complexities of life in a new industrial society.

Education and Community Institutions

The 1890s witnessed significant developments in Cleveland’s educational landscape and the strengthening of its community institutions, as the city grappled with the needs of its diverse and growing population.

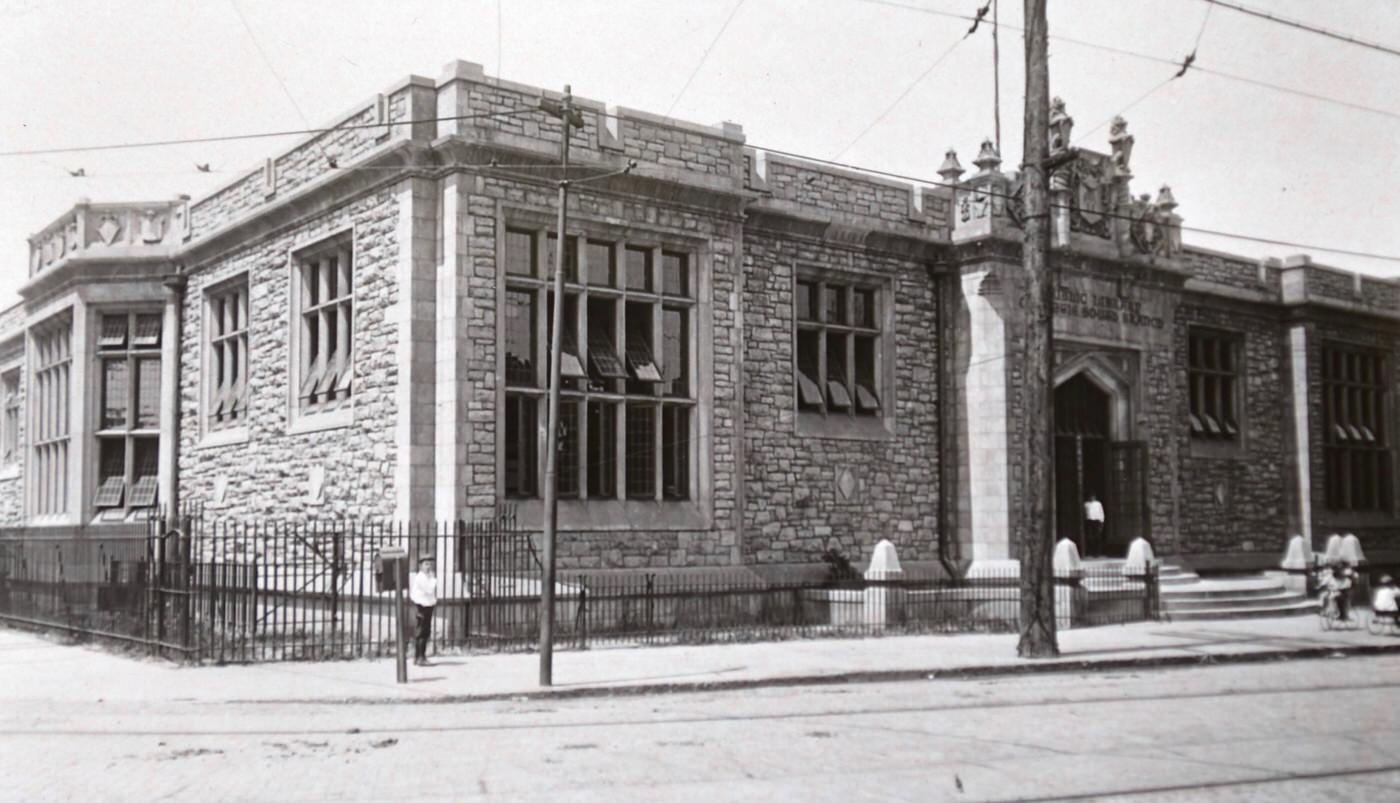

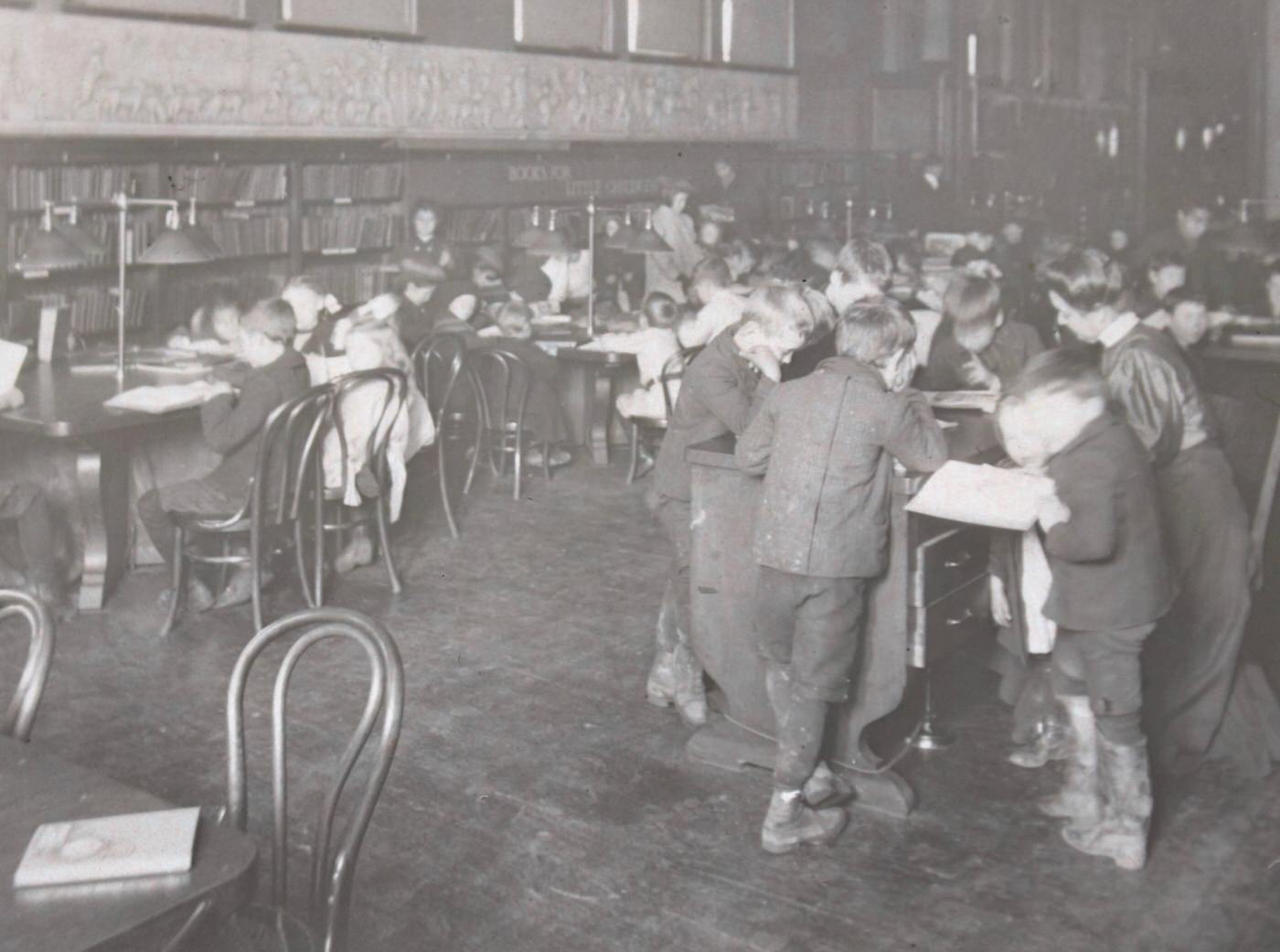

The Cleveland Public Schools (CPS) system underwent several important changes. To address issues of absenteeism, the first truant officer was hired in 1889 to enforce a new compulsory attendance law, which required school-age children to attend classes for 20 weeks a year. In 1891, a new governance structure known as the “Federal Plan” was adopted for the school system. This plan allowed for the public election of a seven-member school board, which acted as a legislative branch, and a school director, who served as an executive. Andrew Draper, appointed superintendent in 1891, focused on improving the quality of the teaching staff. During his tenure, a manual training room was opened in Central High School, providing practical skills education, and a school for deaf children was established. His successor, Louis H. Jones, continued these progressive efforts by opening the city’s first public kindergartens in 1896 and initiating a medical inspection program for students. Recognizing the needs of the large immigrant population, evening schools increasingly focused on teaching English and civics to help newcomers prepare for naturalization exams. Despite these efforts and the public schools being touted as a “melting pot” and a “poor man’s college,” many children from impoverished and immigrant families, unfortunately, did not typically attend school beyond the elementary grades, often due to economic pressures requiring them to work.

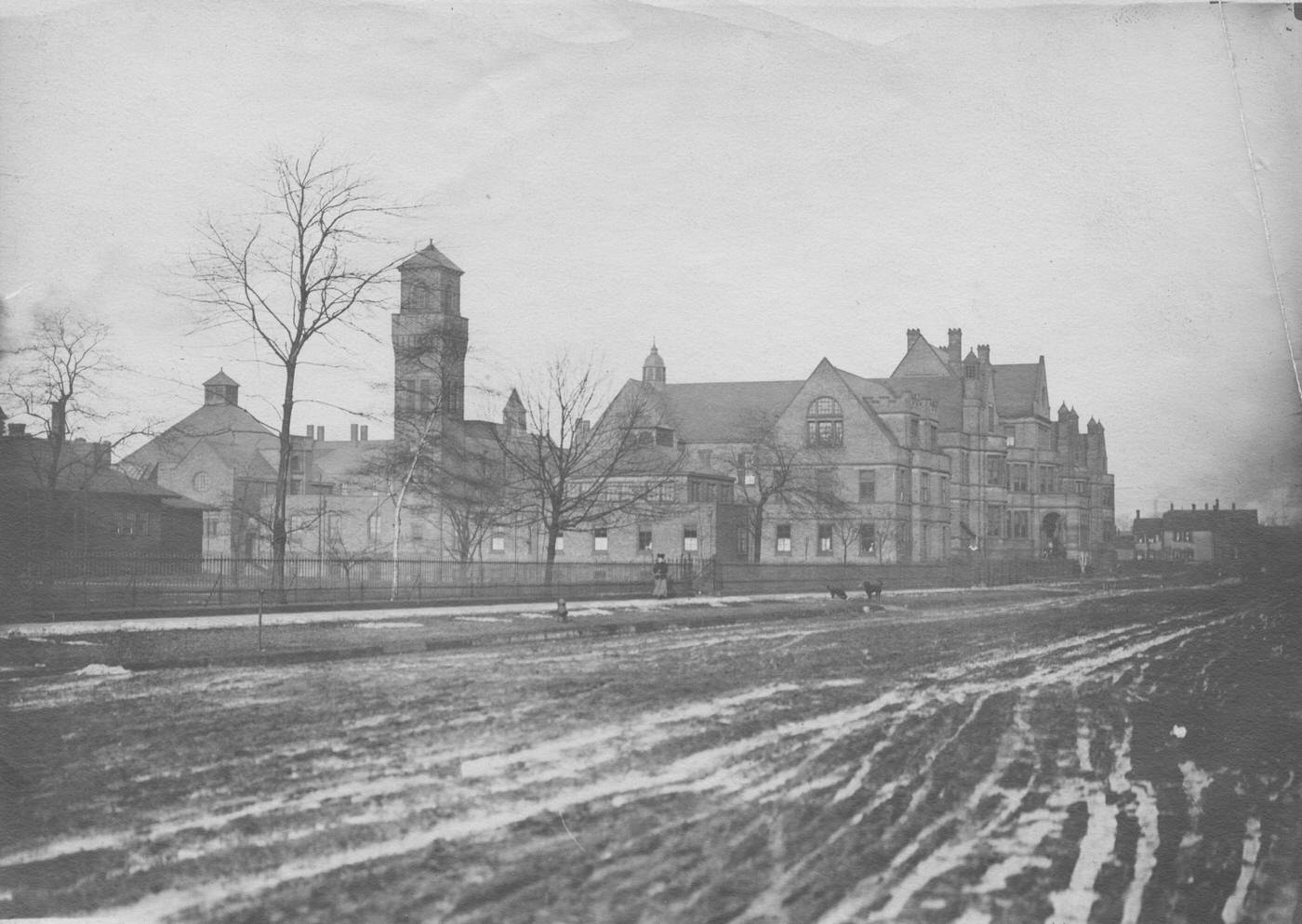

Higher education in Cleveland also expanded during this period. Western Reserve University (WRU) and the Case School of Applied Science, though separate institutions, were located adjacently, fostering some collaboration. In 1890, WRU comprised two undergraduate colleges and a medical school. Under the leadership of President Charles F. Thwing, who served from 1890 to 1921, WRU significantly broadened its offerings by establishing several new professional schools. A law school, a dental school, and a graduate school were all founded in 1892. Notably, the WRU School of Law enrolled its first African American student in its inaugural class of 1892.

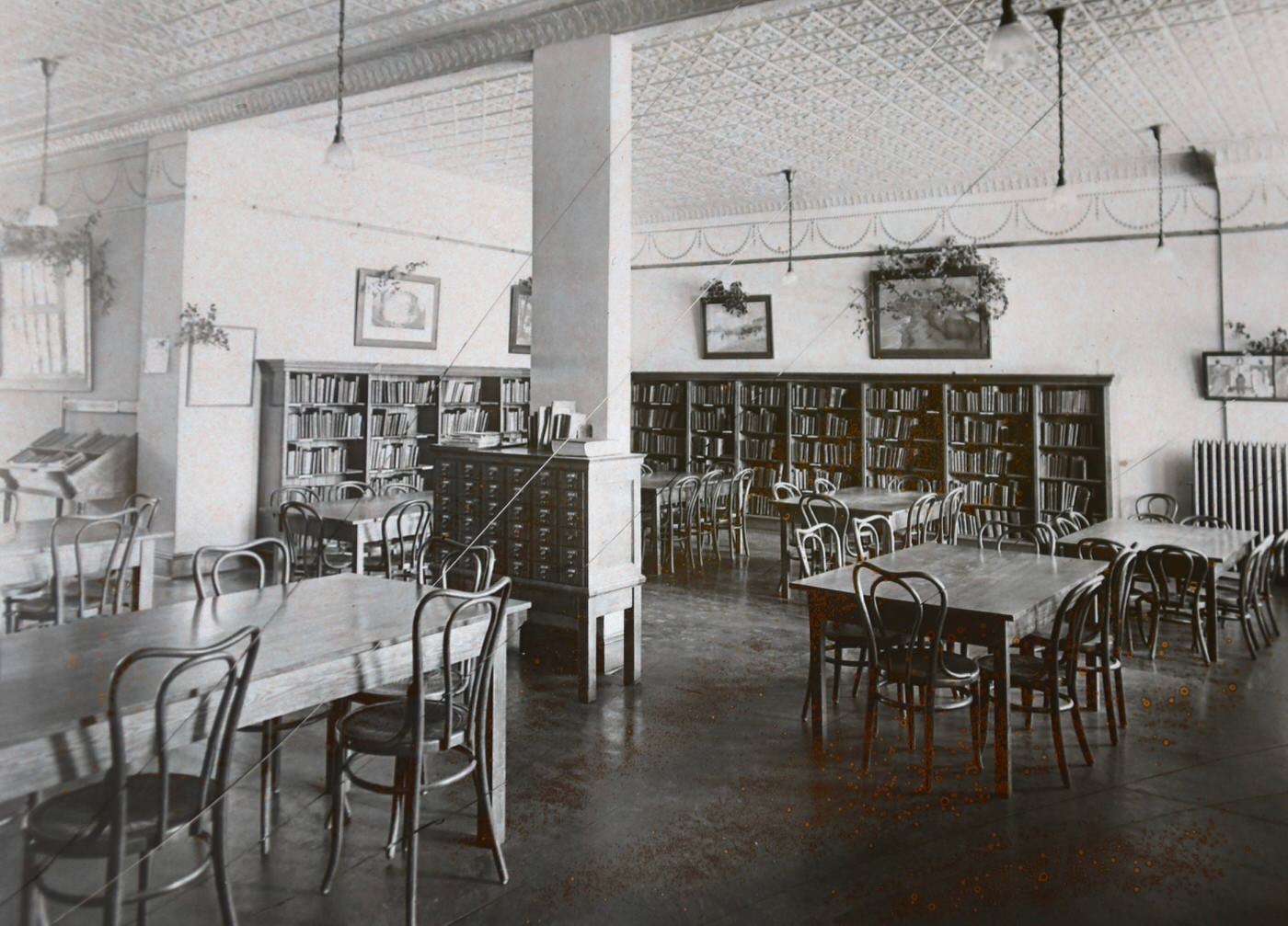

Access to information and news was also evolving. While the formal establishment of a grand public library as part of a civic center was an idea that began to emerge in the 1890s, existing libraries and a vibrant newspaper scene served the city. The Cleveland World, founded in 1889, was known for its “yellow journalism” tactics, especially during the Spanish-American War in 1898 when its sensational headlines helped boost circulation significantly. The Cleveland Plain Dealer continued its role as one of the city’s major daily newspapers. Catering to the growing labor movement, the Cleveland Citizen newspaper was founded in 1891 by Max S. Hayes and Henry C. Long, with support from the Central Labor Union, providing news and advocacy for working-class issues.

Philanthropic and religious institutions played a crucial role in the city’s social fabric, often stepping in to provide services and support where municipal efforts were insufficient. Philanthropy in Cleveland had strong historical ties to religious organizations. Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish groups were all active in establishing schools, charities, and cultural organizations that served their respective communities and the city at large. For instance, the Salvation Army opened a Rescue Home in 1892 to provide shelter for young women in need. By 1890, the YWCA operated a Home for Aged Women and a Working Women’s Home, in addition to providing lodging for transients. The National Council of Jewish Women, Cleveland Section, established the Council Educational Alliance in 1899, a settlement house aimed at assisting newer Jewish immigrants. The African American community also developed its own support structures, with the Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People being established in 1896.

This expansion of educational facilities, the growth of higher learning, the diversification of the press, and the vital work of philanthropic and religious organizations all point to a city actively building the civic infrastructure necessary to manage a large, complex, and rapidly changing urban society. These institutions were responding to both the opportunities and the significant challenges presented by Cleveland’s Gilded Age transformation.

Voices of Unrest: Strikes and Labor Disputes

The rapid industrialization and the often-difficult conditions faced by the working class in Cleveland during the 1890s created a fertile ground for labor unrest. The decade was punctuated by significant labor disputes, reflecting the deep tensions between a growing workforce seeking better terms and powerful industrial interests.

The preceding decade had already witnessed serious labor conflicts. Notably, the Cleveland Rolling Mill Co. experienced major strikes in 1882 and 1885, primarily over wage cuts. The company’s response, which included recruiting immigrant laborers to replace striking workers, established a pattern of contentious labor-management relations in the city.

In 1894, the Pullman Strike, a massive national railroad strike, sent ripples across the country, including Ohio. Originating in Pullman, Illinois, over wage reductions and high rents during a severe economic depression, the strike saw the American Railway Union (ARU) lead a boycott of all trains carrying Pullman sleeping cars. This action significantly disrupted national freight and passenger traffic, particularly west of Detroit, impacting Cleveland as a major rail hub. While specific strike actions within Cleveland itself are not extensively detailed in available records, the broad effect on rail lines operating through Ohio means the city’s extensive rail network would have faced service interruptions and delays. The federal government ultimately intervened with a court injunction and the deployment of the U.S. Army to break the strike, a move that had profound implications for the labor movement nationwide. Senator John Sherman of Ohio publicly commented on the strike, drawing attention to the low wages of workers like Pullman porters.

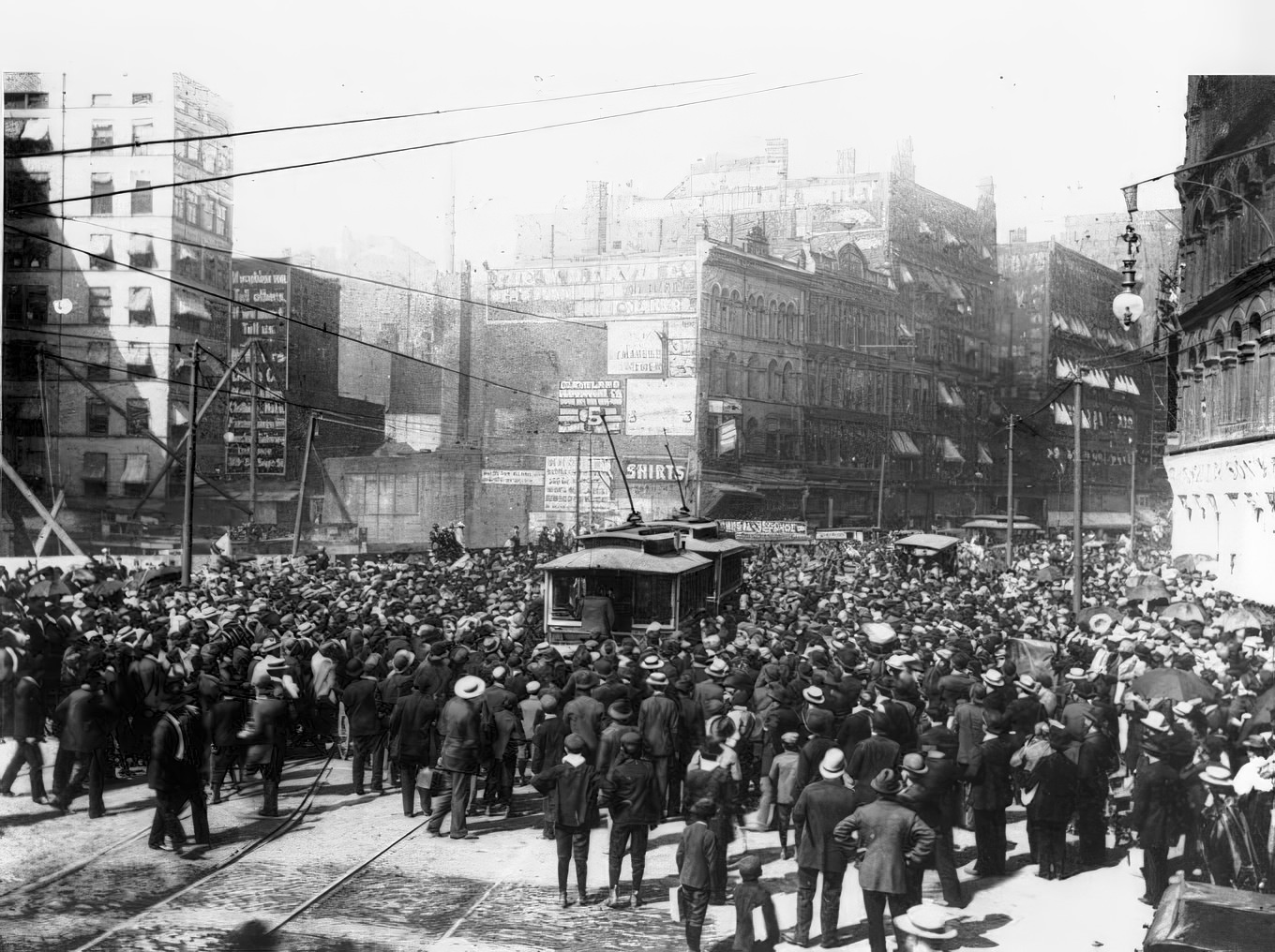

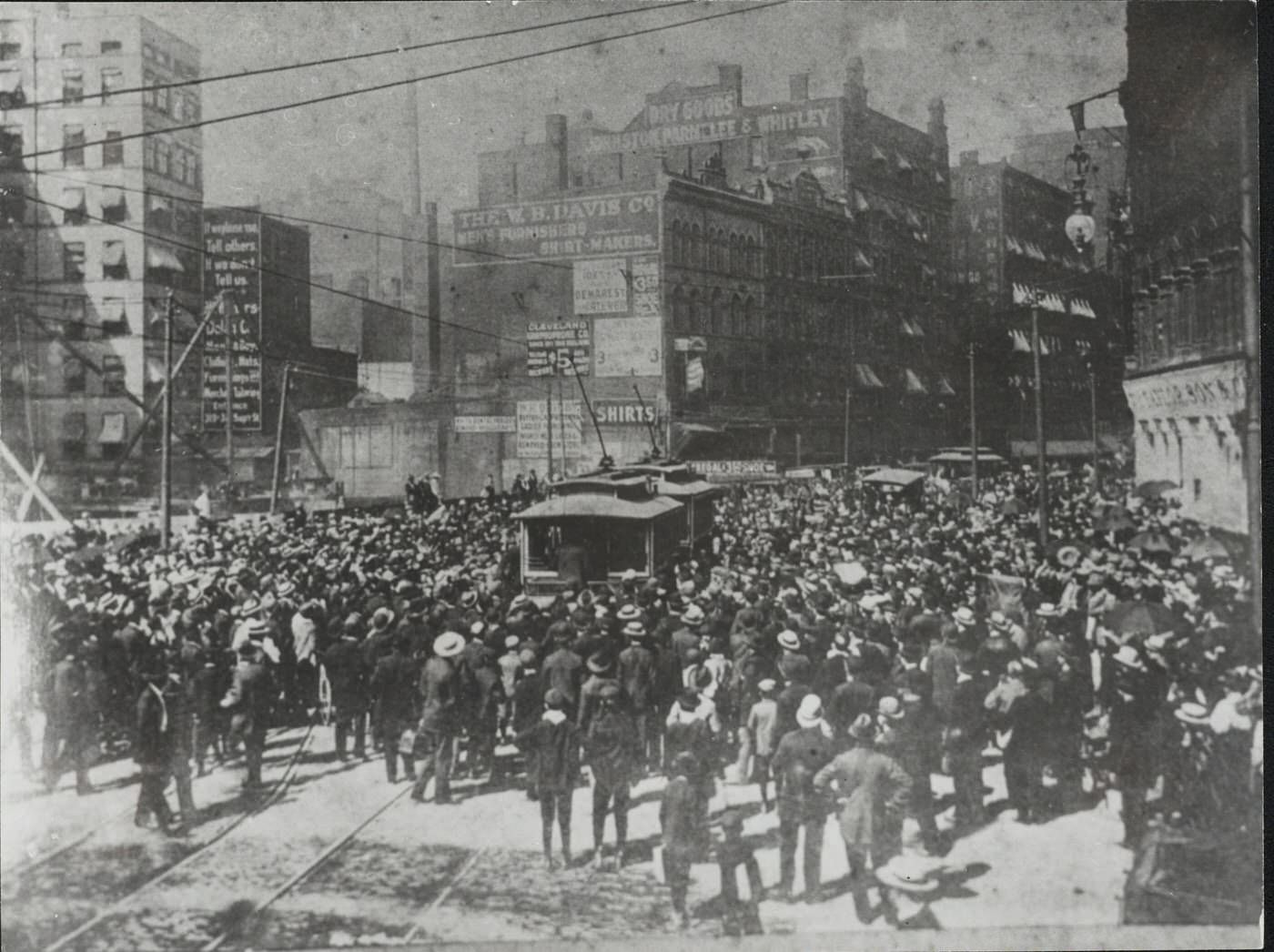

The most direct and intense labor conflict to grip Cleveland during the 1890s was the Great Streetcar Strike of 1899. This bitter dispute began on June 10, when over 850 conductors and motormen of the Cleveland Electric Railway Co., commonly known as the “Big Consolidated” or “Big Con,” walked off the job. Their demands were for better wages, improved working conditions, and, crucially, recognition of their union. The company, under the leadership of Henry Everett, staunchly refused these demands and immediately began hiring strikebreakers to keep the streetcars running.

The city quickly descended into turmoil. Widespread rioting broke out as large crowds, sympathetic to the strikers, attempted to prevent the operation of streetcars by nonunion crews. Cars were damaged, and strikebreakers were attacked. On June 20, a crowd estimated at 8,000 people besieged the company’s Holmden Street car barns on the city’s south side, threatening nonunion workers and wrecking cars before police managed to disperse them. A brief truce was reached on June 24, with the company agreeing to rehire most strikers and restore old work schedules. However, this peace was short-lived. Intermittent rioting continued, particularly on the south side where nonunion men still operated some lines. On July 17, the employees struck again, asserting that the company had reneged on its promises regarding work schedules. Everett responded by once again hiring strikebreakers, which precipitated even more destructive violence. Streetcar tracks were dynamited, and cars were bombed. The situation became so volatile that Mayor John H. Farley summoned state troops on July 21 to restore order. Everett announced he would only rehire men as individuals, refusing to recognize the union. Throughout August, as state troops, including Cleveland’s own Troop A, controlled the worst of the rioting, more men sought reinstatement. The union, in turn, attempted to organize a boycott of businesses and individuals who patronized the Big Consolidated lines. Although sporadic outbreaks of violence continued into the fall of 1899, the company gradually increased its level of service, and the strike eventually faded, a significant defeat for the unionized workers. The events of that summer were described as Cleveland’s most terrible episode of outright class warfare, a period of intense civic upheaval that deeply divided the city.

These labor disputes were not isolated incidents but rather symptoms of the broader societal shifts occurring during an era of rapid and often unchecked industrialization. The immense growth of industries created vast fortunes for some but often left workers facing low pay, long hours, and perilous conditions. The influx of a large immigrant labor pool sometimes provided companies with leverage to keep wages down or to replace striking workers, as seen in earlier conflicts. The power imbalance between large corporations—behemoths like Standard Oil, the major steel companies, or the railway conglomerates—and the individual worker was immense. Strikes, therefore, represented desperate attempts by workers to gain some measure of control over their working lives and to secure a fairer share of the wealth they helped create. The often violent nature of these confrontations, and the forceful responses from both companies (using strikebreakers and private security) and the government (through police action, militia deployment, and court injunctions), underscored the deep social and economic cleavages of the Gilded Age.

Work and Wages: Life for the Laboring Class

For the thousands who toiled in Cleveland’s factories, mills, and workshops, life in the 1890s was often a strenuous existence defined by long hours and modest pay. Working conditions, particularly in heavy industries like steel mills or in the rapidly expanding garment factories, were frequently harsh. A typical workday for unskilled laborers could stretch to 10 or 12 hours. Beyond the long days, safety was a major concern. Standards in workplaces like mines and steel mills were minimal by later measures, and accidents resulting in injury or death were not uncommon.

Wages varied considerably based on skill level, industry, and sometimes ethnicity or gender. While specific, comprehensive wage data for Cleveland in the 1890s is somewhat fragmented in available records, broader patterns and some specific examples offer a glimpse. Unskilled workers in the mid-19th century might have earned around $4 to $5 per week for working 60 or more hours. By the 1890s, some accounts of Hungarian unskilled laborers in Cleveland indicate earnings of $8 to $12 per week, or $10 to $11 for grueling 11 to 13-hour days. Across various U.S. cities between 1890 and 1898, machinists, a skilled trade, typically made $2 to $3 per day. A U.S. Bureau of Labor report from 1908 indicated that average hourly wages in manufacturing industries in 1907 were about 28.8% higher than the average for the 1890-1899 period, with average weekly hours being 5.0% lower. This suggests some gradual improvement in earning power and working hours over the decade, although these gains were partly offset by rising retail prices for essentials like food. More localized data exists in Ohio state reports, such as one detailing women’s pay by occupation in 1892 and another covering coal miners’ wages from 1894-1901, though these provide regional rather than purely Cleveland-specific figures.

For many immigrant families, economic survival depended on the collective income of all able-bodied members, often including children whose earnings supplemented the household budget. Single male immigrants frequently lived in boarding houses, which offered a bed and meals for around $3 per week, a significant portion of their earnings.

Many immigrants arrived in America, and by extension Cleveland, with hopes of economic betterment, often fleeing poverty or lack of opportunity in their homelands. While the city’s booming industries provided employment, the promise of prosperity—the “American Dream”—was often a deferred one for the laboring class. The wages, though sometimes appearing substantial compared to what could be earned in their native countries ($1 a day was a common benchmark that seemed high to some newcomers ), were often barely enough to cover the cost of living in an American industrial city. There was no social safety net in the form of unemployment benefits or widespread public assistance as understood in later eras, meaning that illness, injury, or economic downturns could quickly push families to the brink of destitution. While skilled workers, entrepreneurs, or those with fortunate circumstances could achieve upward mobility, for a large segment of the unskilled immigrant workforce, the path to a comfortable life was arduous and slow. The “gold-paved streets” that some might have envisioned were, for most, a far cry from the daily reality of industrial Cleveland.

A Decade of City Life: Streets, Homes, and Leisure

The residential landscape of Cleveland in the 1890s was one of sharp contrasts, reflecting the economic disparities of the Gilded Age. The city’s housing ranged from the modest dwellings of its working class and immigrant populations to the opulent mansions of its industrial magnates.

For many working-class families and newly arrived immigrants, housing typically consisted of wood-frame buildings, often one-and-a-half or two stories high, with gabled ends frequently facing the street. It was not uncommon for these structures to be built two to a city lot, leading to increased population density, which by 1890 had reached an average of 5.96 persons per dwelling. Earlier Irish immigrant neighborhoods downtown, for example, were characterized by tightly packed A-frame houses. Despite the crowding, Cleveland generally lacked the massive, densely packed tenement blocks found in some other large American cities of the era, possibly because its industries were somewhat more dispersed throughout the urban area. Living conditions in heavily industrialized areas, such as “The Triangle” on the near west side, were often poor, with residents contending with pervasive smoke, soot, and pollution from nearby factories and mills. In response, new suburban developments like the Village of West Cleveland were marketed as offering healthier environments for working-class families, away from the grime of the industrial core. The challenges of urban life for the less fortunate also spurred the rise of settlement houses. Institutions like Hiram House (established in 1896), Alta House (1900, primarily serving Italians in Little Italy), and Goodrich House (1897) began their work in immigrant neighborhoods, offering educational programs, healthcare assistance, and resources to help residents cope with difficult living conditions. Homelessness was also a visible problem, particularly exacerbated by economic downturns like the Panic of 1896. During the severe winter of 1893-94, an estimated 25,000 unemployed individuals in Cleveland sought relief from various charitable organizations.

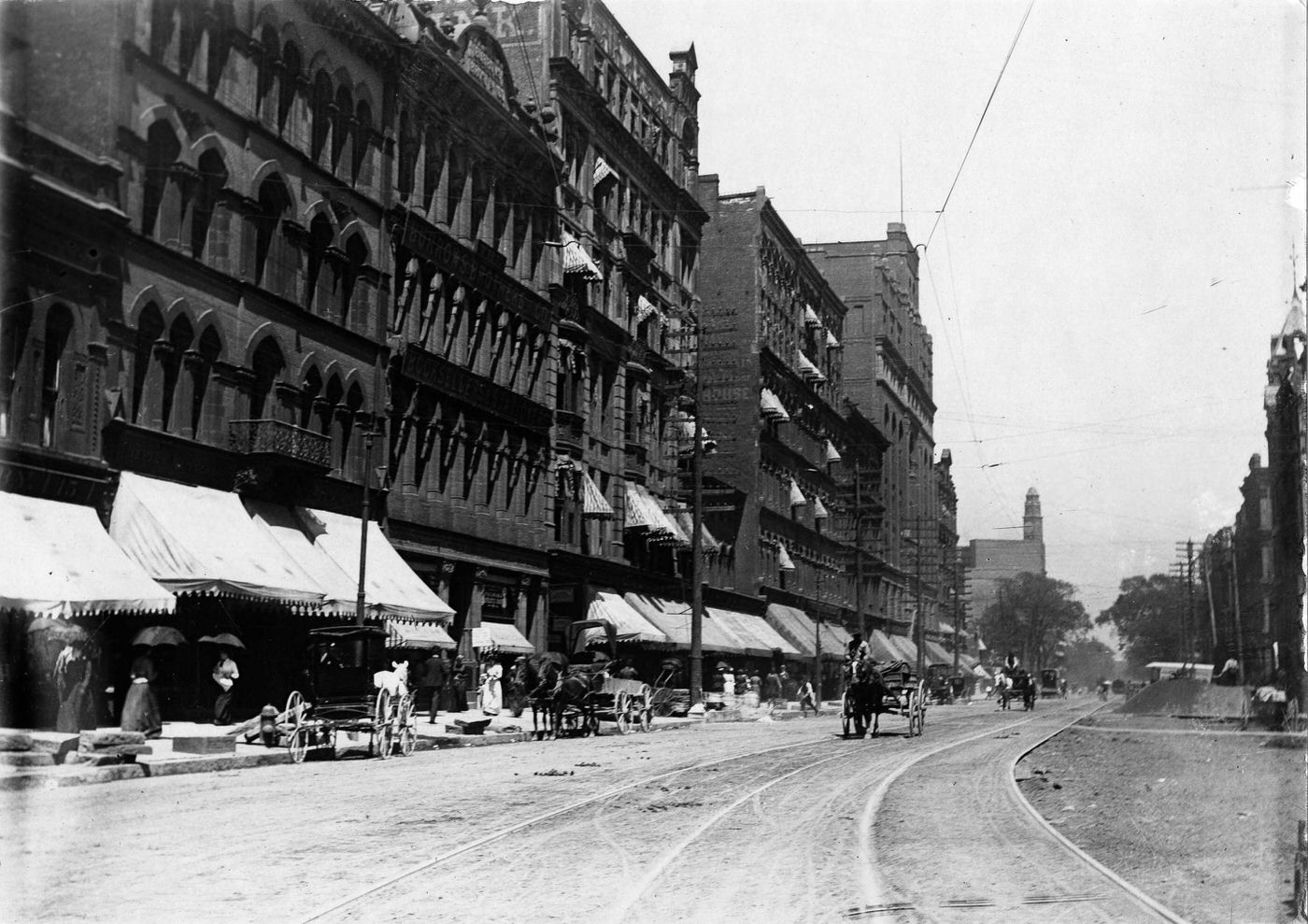

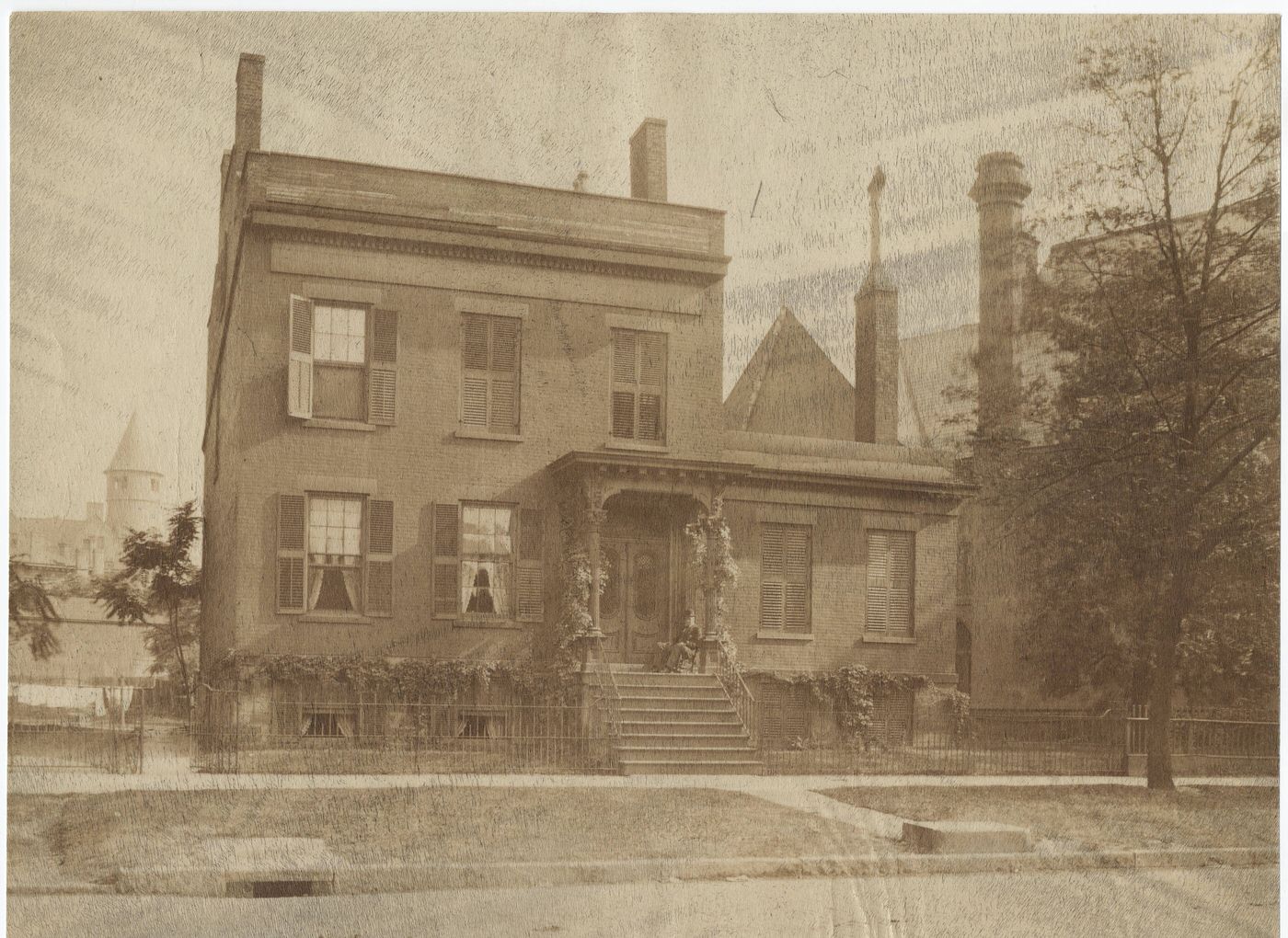

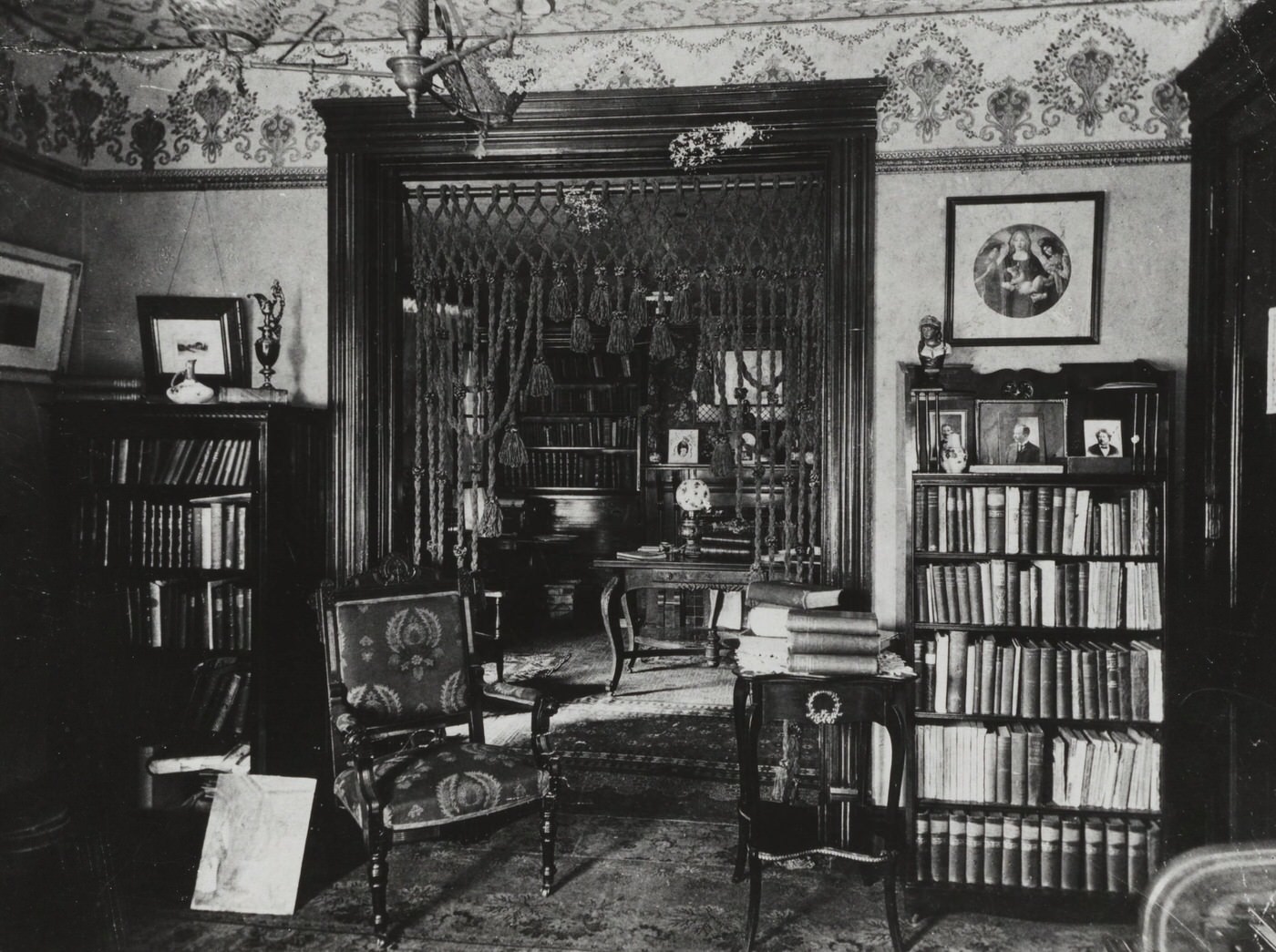

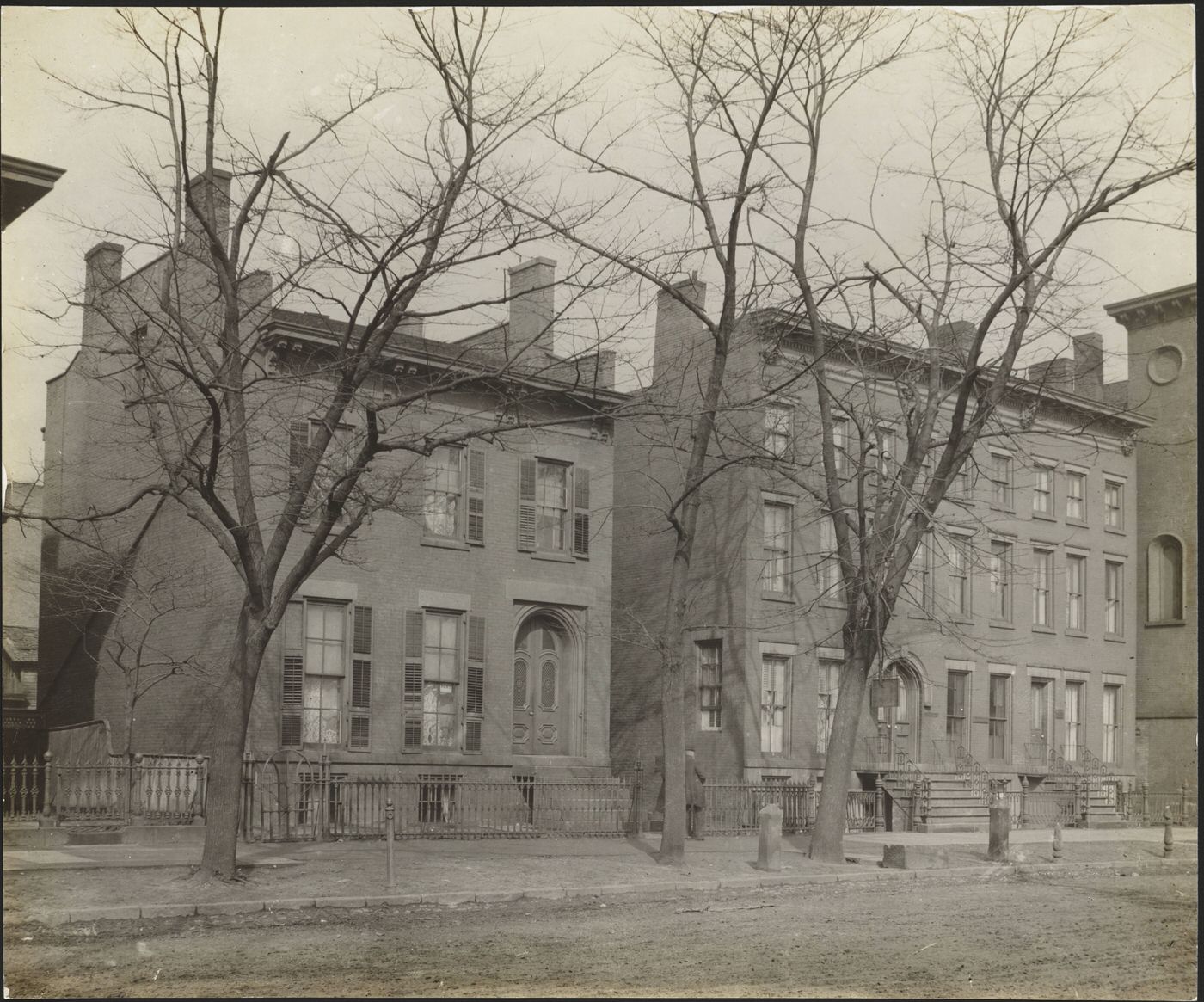

At the other end of the social spectrum was Euclid Avenue, famously known as “Millionaires’ Row”. By the 1890s, this thoroughfare was considered one of the grandest residential streets in America, drawing comparisons to Berlin’s Unter den Linden and Paris’s Champs-Élysées. Nearly 260 magnificent homes lined the avenue, some sprawling to 50,000 square feet. These mansions were architectural showcases, displaying a variety of popular late Victorian styles, including High Victorian Gothic, Queen Anne, and Richardsonian Romanesque, often set back on wide, spacious lawns. Euclid Avenue was home to some of the nation’s wealthiest industrialists, including John D. Rockefeller and Samuel Andrews, whose particularly extravagant mansion was dubbed ‘Andrews’s Folly’. The avenue was also a site of technological firsts, boasting the world’s first electric streetlight and electric streetcar line.

This stark juxtaposition of opulent mansions on Euclid Avenue and the often-crowded, less sanitary conditions in working-class and immigrant neighborhoods, sometimes located in close proximity, vividly illustrated the extreme economic disparities that characterized the Gilded Age. Cleveland in the 1890s was not just a city of booming industry; it was a city of profound social and economic contrasts, where the benefits of industrial success were distributed with striking unevenness.

Navigating the City: Streets, Streetcars, and the First Automobiles

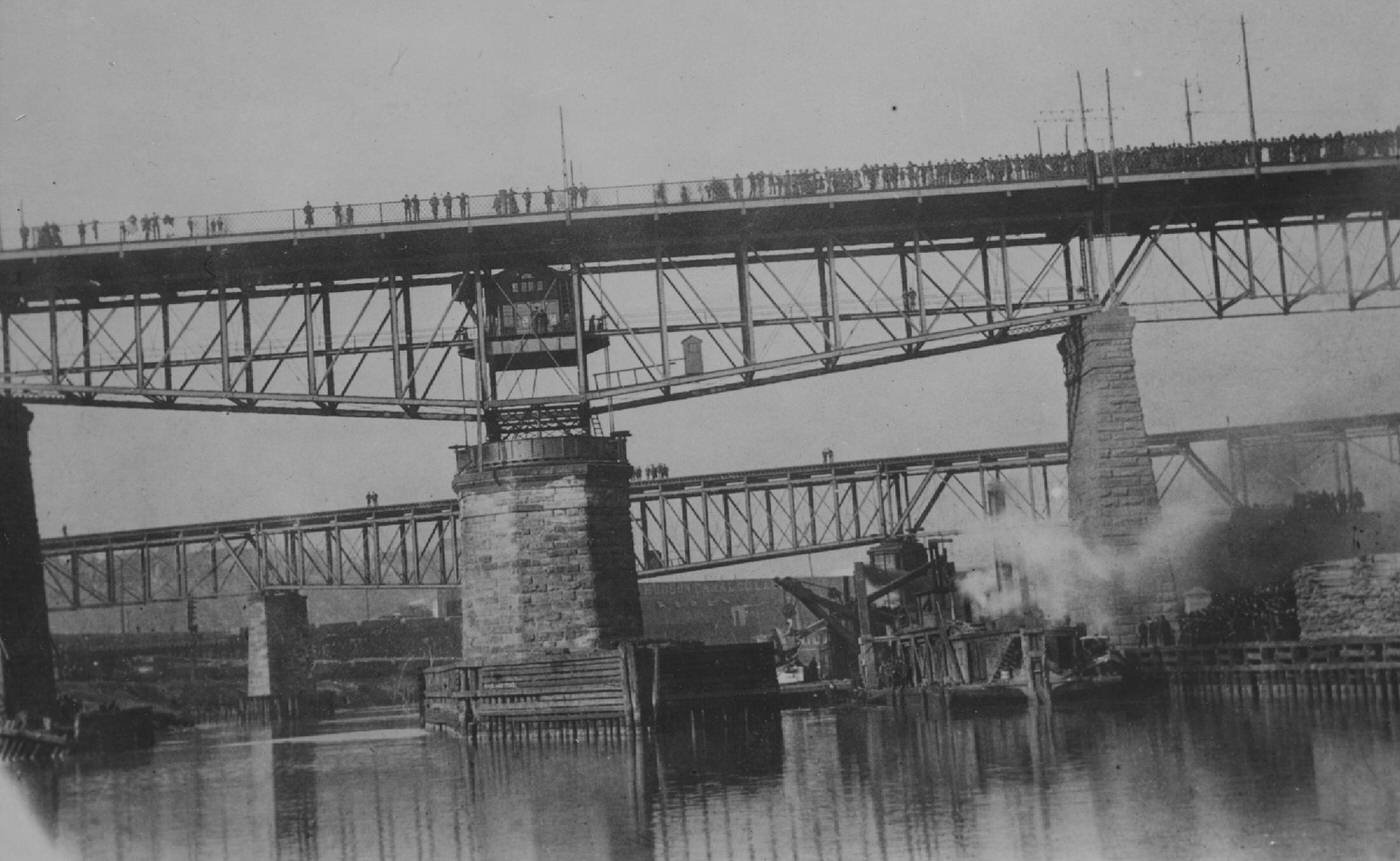

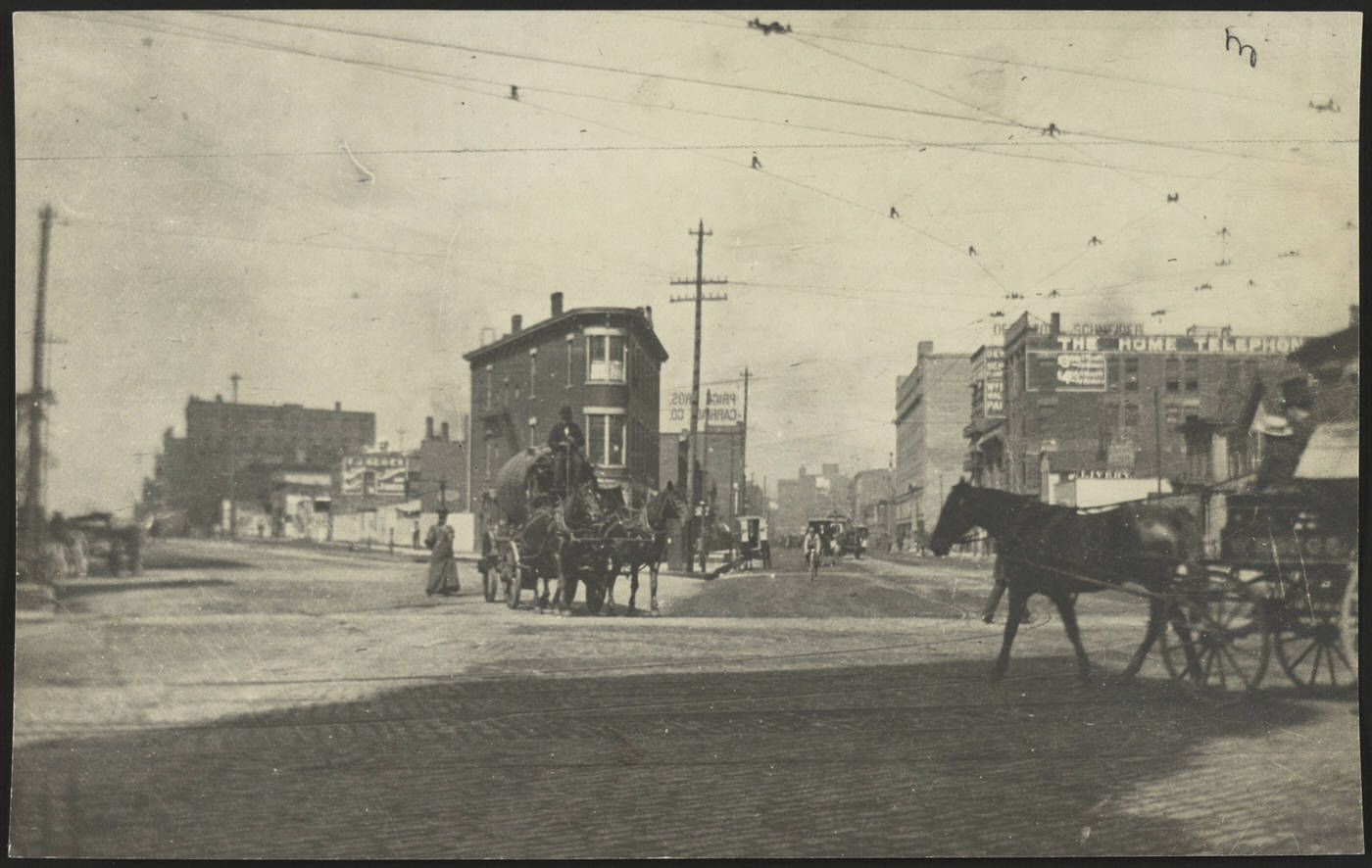

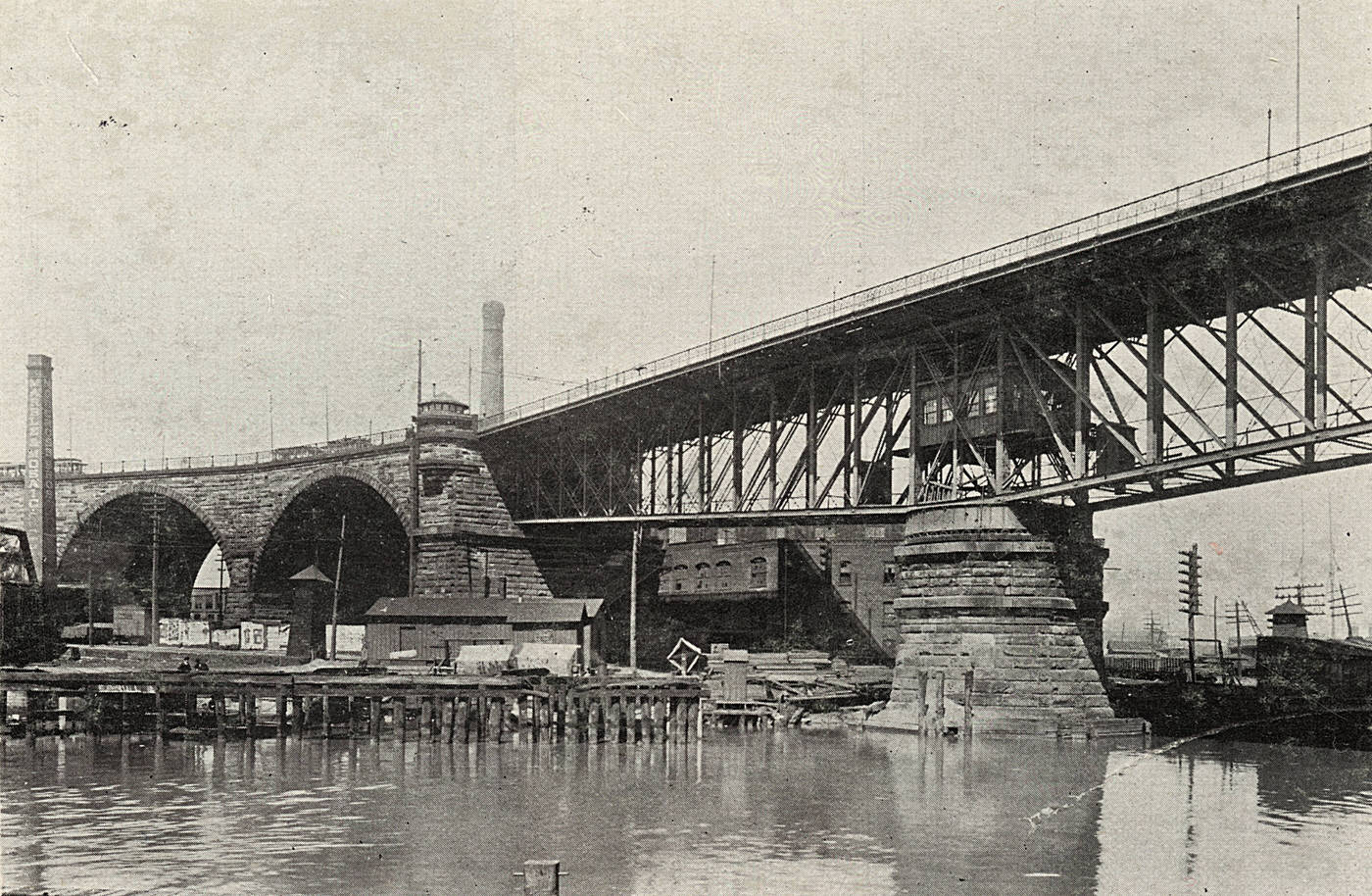

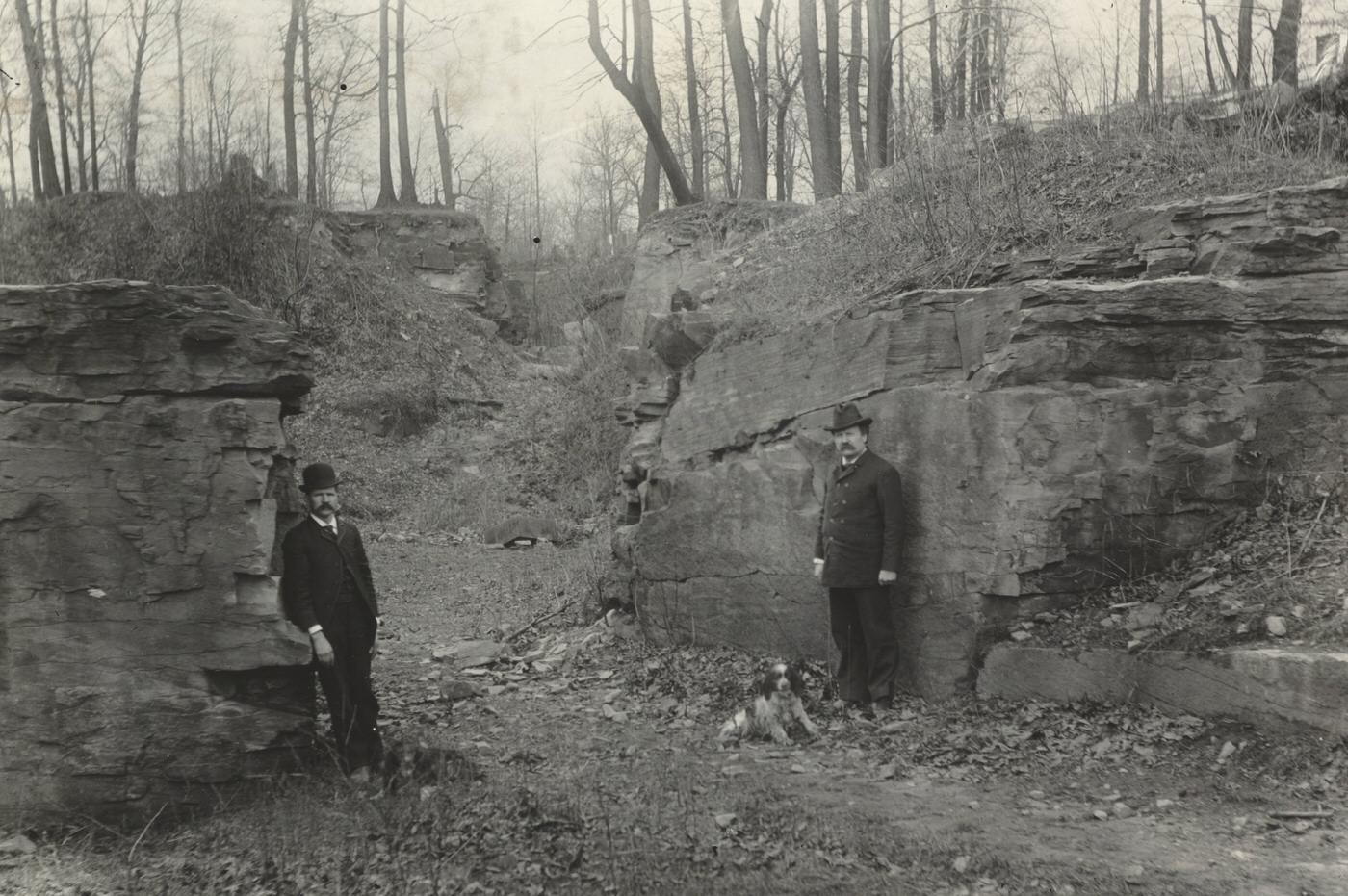

Getting around Cleveland in the 1890s involved a mix of established and emerging modes of transportation, on streets that were themselves undergoing significant changes. By 1889, the city encompassed 440 miles of streets and alleys, but the process of paving these thoroughfares was slow, with less than two miles being improved each year. Before this period, common paving materials included tar concrete, Nicholson wood blocks, and Medina sandstone. Medina stone, while durable, was known for providing a jarring ride for passengers in wheeled vehicles. The 1890s saw the increased adoption of brick for paving, a material that gained popularity due to its relative affordability and durability. The first brick pavements had been laid in 1888 or 1889, and throughout the 1890s, many new brick streets used tar as a filler for the joints. Asphalt also began to be used more frequently, challenging the dominance of Medina stone. Interestingly, the soil in some parts of Cleveland, being a fine sand with some loam, was permeable enough that the usual concrete foundations for pavements were sometimes deemed unnecessary, at least initially. A new voice in the demand for better roads came from the rapidly growing number of bicyclists; by the mid-1890s, an estimated 50,000 Clevelanders were cycling, and they actively campaigned for smoother street surfaces.

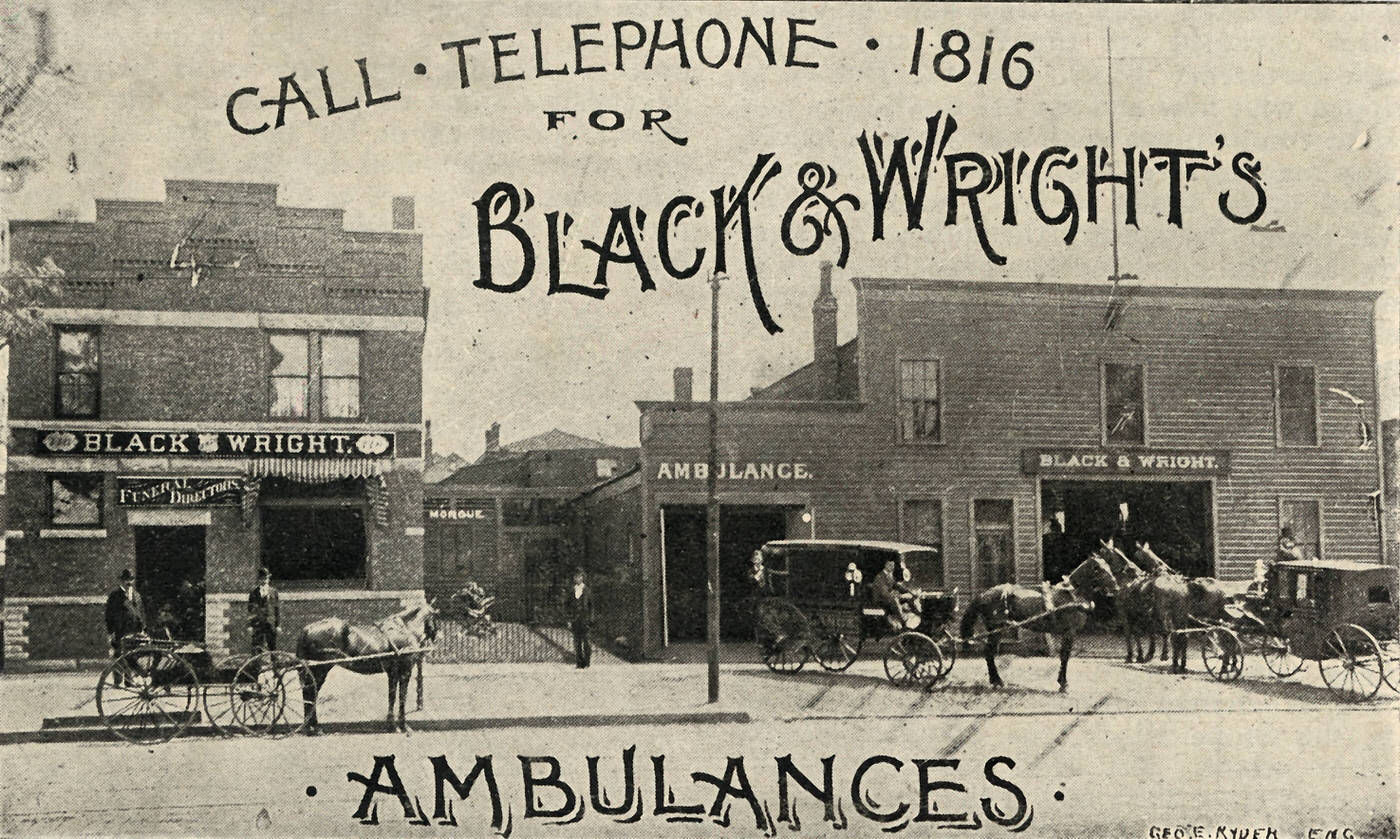

Public transportation was dominated by the electric streetcar. The first electric streetcar line in Cleveland had begun operation in 1884, and by 1894, nearly all of the city’s streetcar lines had been electrified, replacing the older horse-drawn cars. The Cleveland Electric Railway Co., known as the “Big Consolidated” or “Big Con,” was a major operator of these lines and became a central figure in the significant streetcar strike of 1899. Despite the rise of streetcars, horse-drawn carriages and wagons remained essential for personal transportation and the delivery of goods. Cleveland had a mature carriage-making industry, with firms like Rauch & Lang producing expensive luxury carriages for the city’s elite.

The very end of the decade witnessed the arrival of a technology that would eventually revolutionize urban transport: the automobile. Alexander Winton, a Scottish immigrant and bicycle manufacturer, established the Winton Motor Carriage Company in Cleveland in 1897, and his firm began producing some of the city’s first automobiles, built by hand. For a brief period, Cleveland was considered a leading center of early automobile manufacturing in America.

The city’s rapid expansion in population and geographic area, coupled with intense industrial and commercial activity, placed enormous strain on its transportation infrastructure. The slow pace of street paving meant that many thoroughfares remained unpaved, turning into muddy quagmires in wet weather and dusty tracks in dry conditions. While the electric streetcar network was extensive, the overall development of infrastructure, including well-paved roads and comprehensive sanitation systems, struggled to keep pace with the city’s explosive growth. These were common challenges for rapidly industrializing cities of the era, creating daily difficulties for residents and businesses alike.

Public Spaces and Architectural Marvels

Amidst the industrial clamor and rapid growth, Cleveland in the 1890s also saw the creation of significant public spaces and architectural landmarks that began to shape its civic identity and offer new experiences to its citizens.

One of the most celebrated architectural achievements of the decade was The Arcade. Opened to the public on Memorial Day in 1890, it was a pioneering structure, considered the first indoor shopping center in the United States. Located at 401 Euclid Avenue and financed by prominent figures including John D. Rockefeller, The Arcade was quickly dubbed “Cleveland’s Crystal Palace”. Its design was inspired by the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan, Italy, featuring two nine-story towers connected by a spectacular 300-foot-long, five-story-high skylight made of 1,600 glass panels set in an ornate iron frame. This Victorian-era marvel became a bustling hub of commerce and social life.

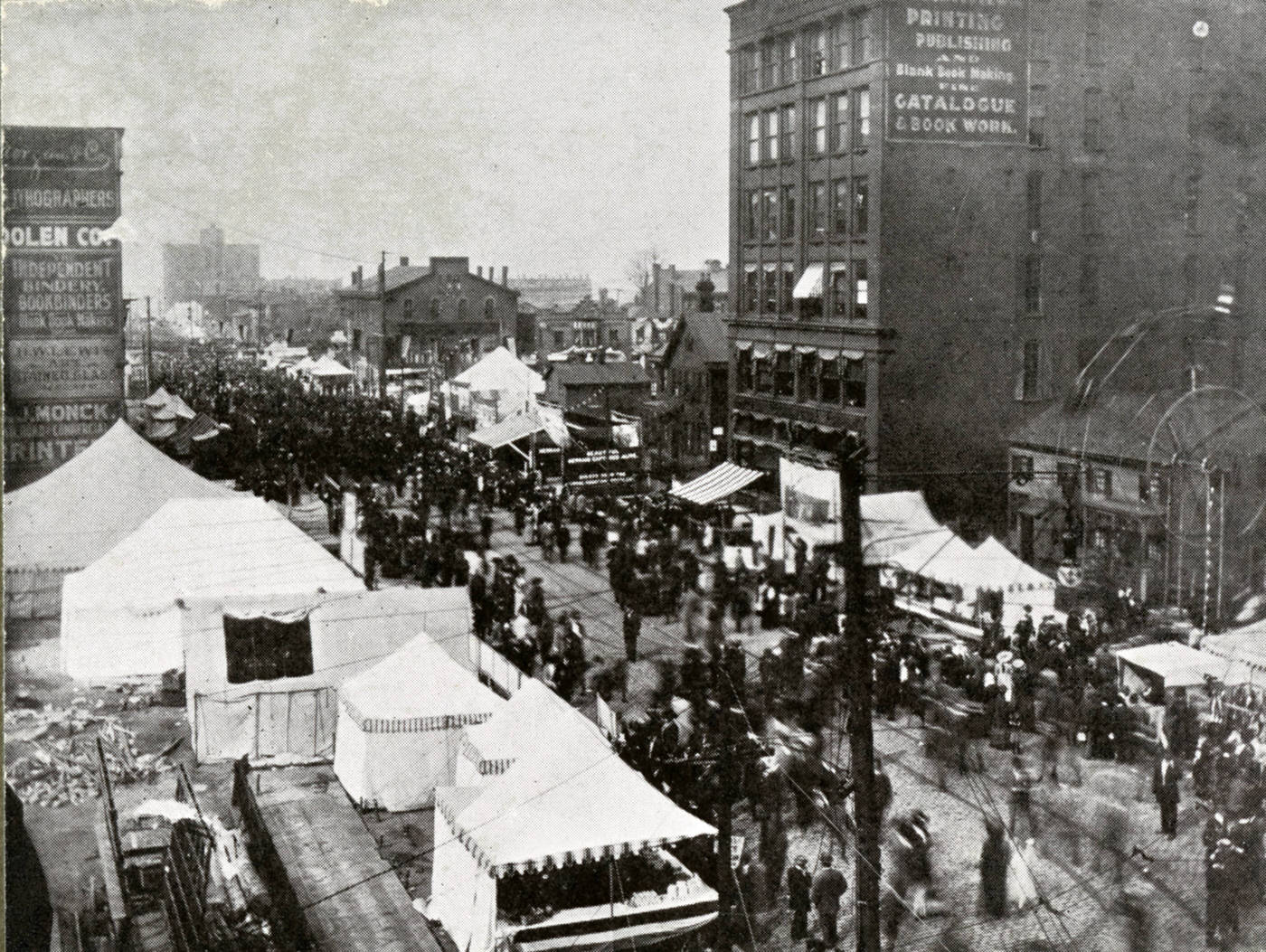

The development of public parks also gained momentum during the 1890s. Earlier in its history, the city had lagged in this area; in 1890, park commissioners themselves reported that Cleveland was “at the foot of the list” among major U.S. cities in terms of park development. However, significant gifts had laid some groundwork. Jeptha H. Wade’s donation of 64 wooded acres in 1882 had formed Wade Park, the city’s first large park area. Upon his death in 1892, William J. Gordon bequeathed approximately 129 acres of already improved land, which became Gordon Park, providing much-needed recreational space on the east side. Recognizing the growing need, the state legislature passed a park act in 1893, granting park boards expanded authority to acquire land and issue bonds. A new board of commissioners was appointed in Cleveland with the charge “to provide for the Forest City a system of parks commensurate with her size and importance.” They adopted the city’s first general plan for park development, envisioning a series of large parks on the city’s outskirts, connected by broad, paved boulevards. The renowned Boston landscape architect Ernest W. Bowditch was hired to help implement this vision. By 1896, substantial progress had been made, with some 1,200 acres of parkland assembled and improved.

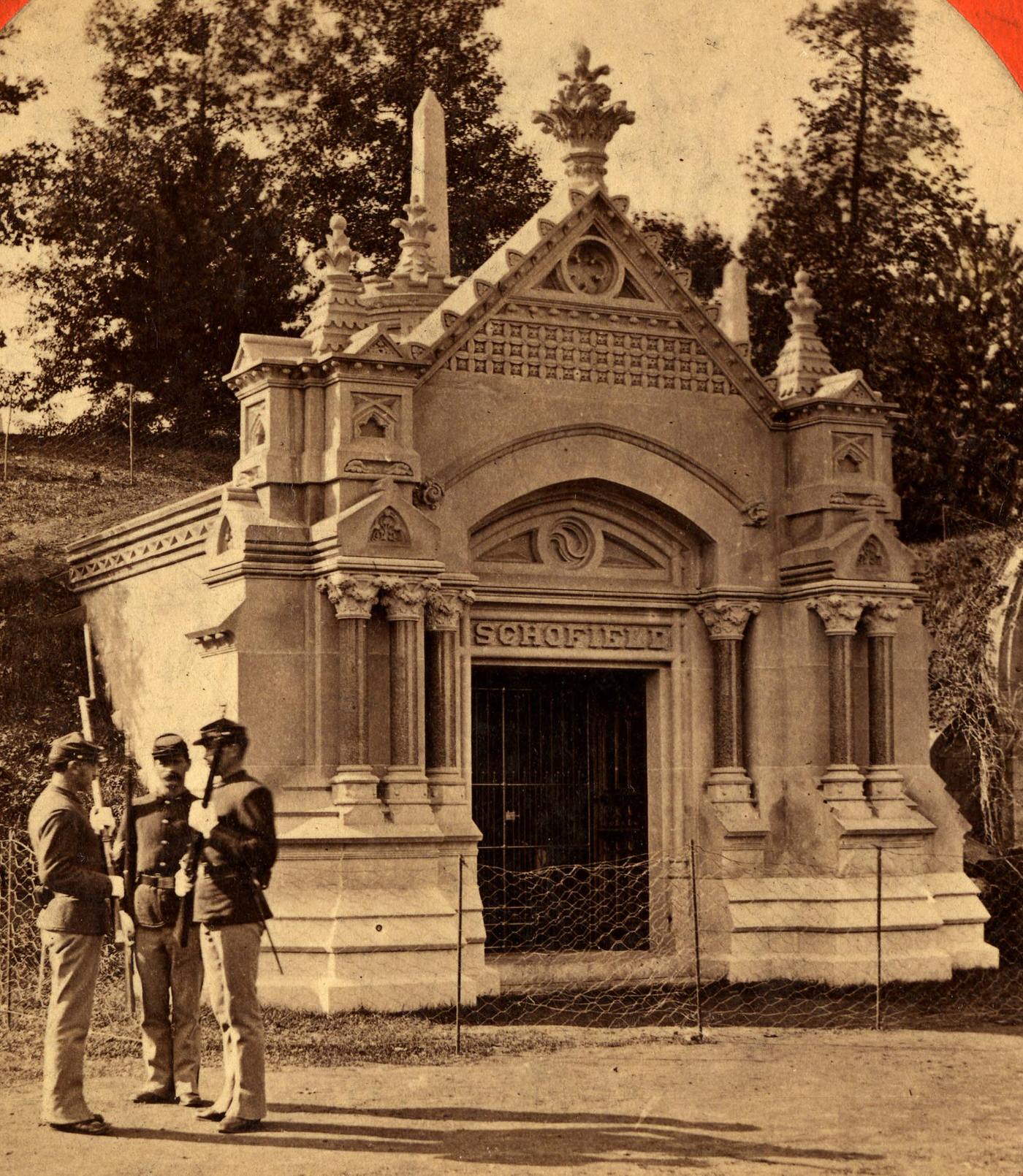

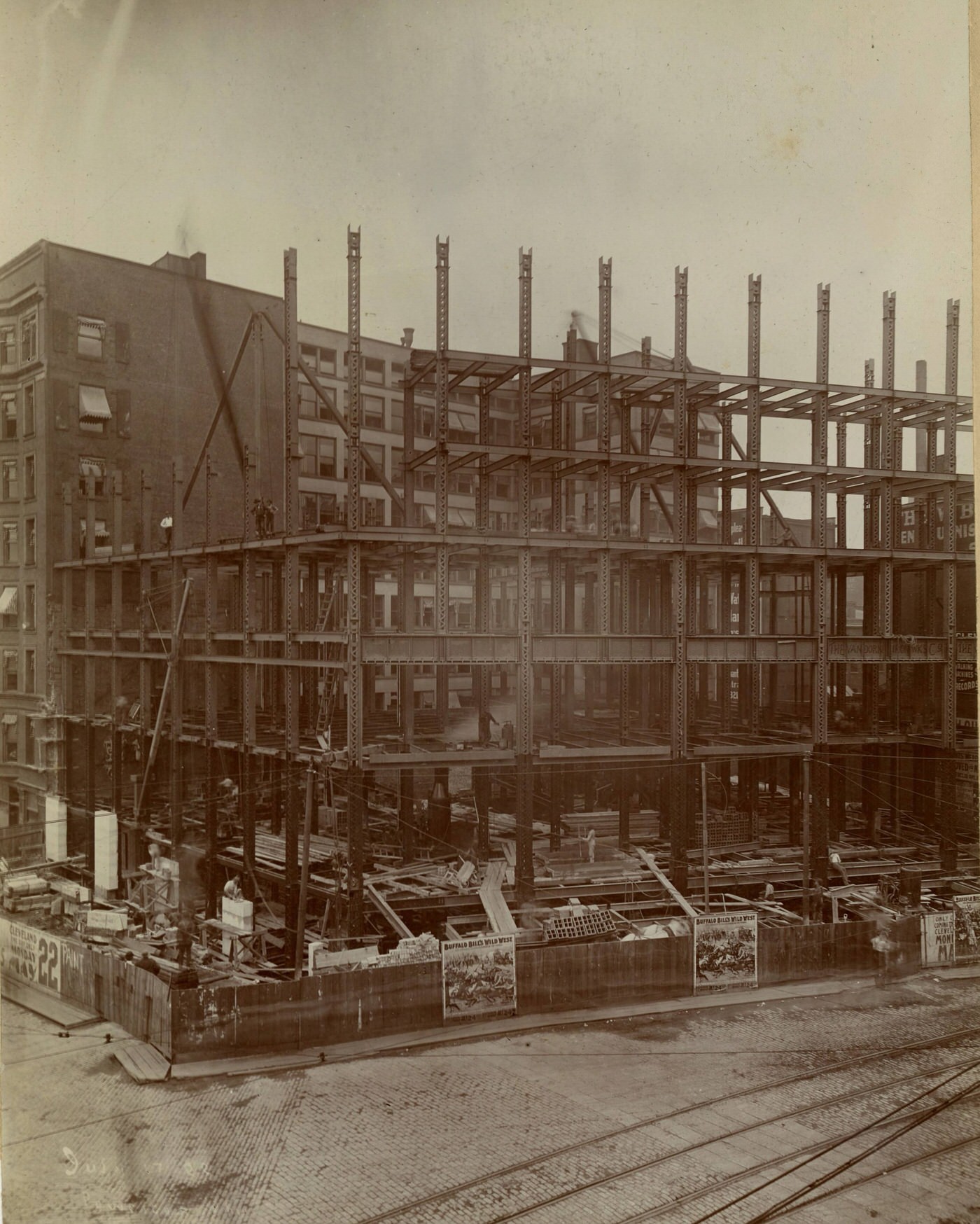

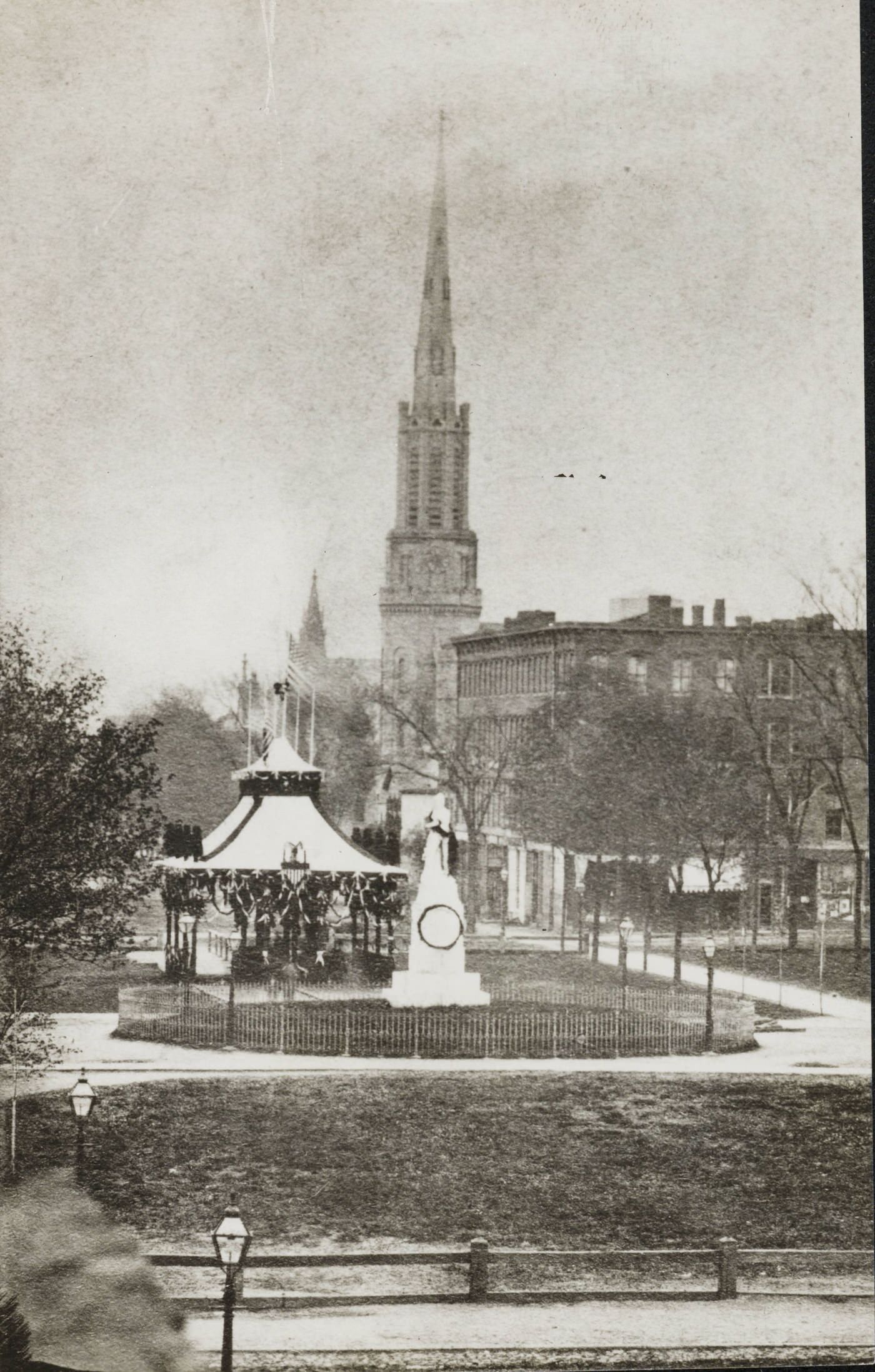

In terms of civic architecture, the 1890s marked a conceptual shift. While existing public buildings like the Cuyahoga County Courthouse and the City Hall (which was originally designed as a commercial block) were predominantly in classical or Renaissance styles and scattered around Public Square, the idea of grouping monumental public buildings into a unified ensemble began to take hold during this decade. New federal, county, and city buildings were being contemplated, and the logic of creating a grand civic center started to emerge, laying the groundwork for what would later become Cleveland’s famed Group Plan and the Mall. The decade also saw the dedication of two major public monuments: the James A. Garfield Monument in Lake View Cemetery in 1890, and the Cuyahoga County Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument on Public Square in 1894.

These developments—the innovative Arcade, the dedication of significant public monuments, the ambitious new plans for a comprehensive park system, and the nascent ideas for a grand civic center—collectively signaled a maturing city. Cleveland was becoming increasingly conscious of its growing status and was actively investing in public spaces and structures that reflected not only its industrial might but also a burgeoning civic pride and a vision for a more organized, aesthetically pleasing, and impressive urban environment. This was a move beyond purely utilitarian development towards creating a city with a distinct and distinguished character.

Keeping the City Running: Water, Sanitation, and Light

The rapid growth of Cleveland’s population and industry in the 1890s placed immense strain on its essential services, particularly water supply, sanitation, and public lighting. Addressing these challenges required significant investment and engineering efforts.

The city’s water supply was a pressing concern. The Cuyahoga River and the nearshore waters of Lake Erie, the primary sources for drinking water, were heavily polluted by industrial discharge, raw sewage from the city’s rudimentary sewer systems, and waste from oil refineries. This contamination posed a serious public health risk. To access cleaner water, the city embarked on ambitious engineering projects to extend its water intakes further into Lake Erie. A new seven-foot diameter water inlet tunnel, stretching 9,117 feet offshore, was completed in 1890. As pollution concerns continued, an even larger project was undertaken: a nine-foot diameter intake tunnel, extending an unprecedented 26,000 feet (nearly five miles) into the lake, was begun in 1896. This tunnel, one of the longest of its kind in the world at that time, was completed in 1904, but its construction was fraught with danger and resulted in considerable loss of life, remembered through the Waterworks Tunnel Disasters.

Sanitation systems were still relatively basic. Wastewater was largely conveyed through open drains and rudimentary sewers directly into the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie, contributing to the pollution of the water supply. The Board of Health’s role was often focused on what was termed “sanitary policing,” dealing with nuisances and attempting to control the spread of disease primarily by addressing filth, although the scientific understanding of germ theory was beginning to emerge and influence public health approaches. For a period, from 1892 to 1902, the authority for Board of Health activities was even vested in the Board of Police Commissioners.

Public lighting was another area of development. Electrical lighting was beginning to transform the urban environment, allowing Cleveland to become more of a “day and night” society. In 1890, a group of social activists petitioned the city council to establish a municipal electric lighting plant, advocating for underground wiring to serve residents. While municipal ownership would take longer to realize, private enterprise was active. Charles F. Brush, a pioneer in electric lighting, was instrumental in the formation of the Cleveland General Electric Co. in 1892, which was the predecessor to the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company (CEI).

These efforts to improve water supply, sanitation, and lighting were not merely for convenience or aesthetic improvement; they were critical responses to the severe public health challenges created by Cleveland’s own industrial success and dense urban living conditions. The scale and cost of projects like the extended water intake tunnels underscored the gravity of the problems the city faced in maintaining a livable environment for its rapidly growing population. These infrastructure investments were essential for the city’s continued viability as a major urban center.

Entertainment and Pastimes: From Vaudeville to Baseball

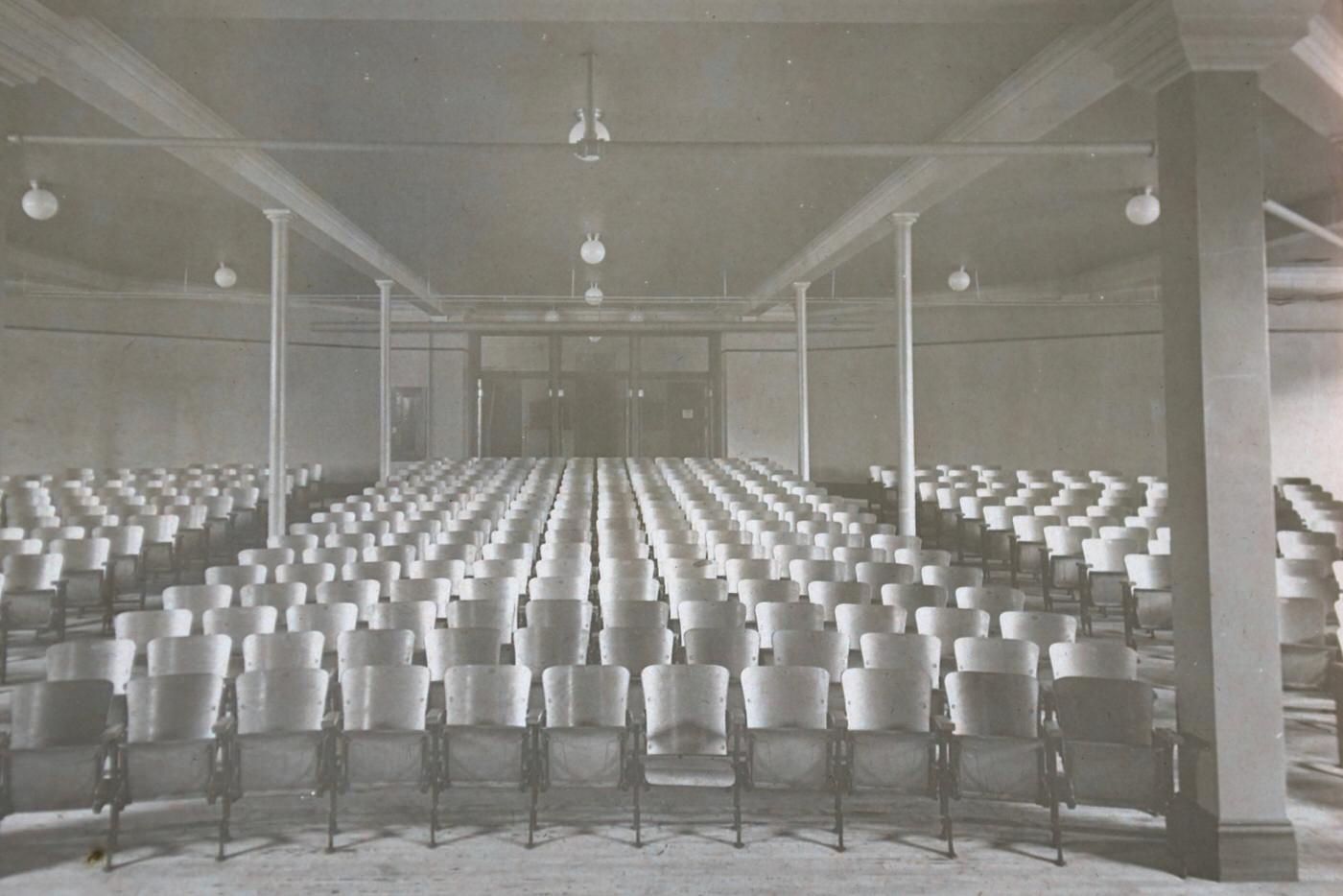

Clevelanders in the 1890s had an expanding array of options for leisure and entertainment, reflecting both national trends and local developments. Vaudeville was a dominant form of popular entertainment, and Cleveland was a significant stop on the national circuit. Between 1885 and 1930, the city boasted over 60 theaters that featured vaudeville shows. These performances were variety shows, a “potpourri” of 8 to 10 disparate acts, including animal performances, acrobats, comedians, singers, dancers, instrumental bands, and magicians. Prominent venues like the Euclid Avenue Opera House and the Columbia Theatre hosted famous performers of the day, such as the comedy team Weber & Fields, and monologists Will Rogers and Fanny Brice.

Professional baseball also captured the public’s imagination. The Cleveland Spiders competed in the National League from 1889 to 1899. Under manager Patsy Tebeau, the team enjoyed a period of success, with seven consecutive winning seasons and three second-place finishes in the National League (1892, 1895, 1896). The pinnacle of their achievement came in 1895 when the Spiders, featuring future Hall of Fame pitcher Cy Young and outfielder Jesse Burkett, won the Temple Cup, a championship series that predated the modern World Series, by defeating the formidable Baltimore Orioles. However, the decade ended disastrously for the team. In 1899, the team’s owners, Frank and Stanley Robison, who had acquired the St. Louis National League franchise, transferred all of the Spiders’ top talent to their St. Louis club. The depleted Cleveland Spiders finished the 1899 season with a record of 20 wins and 134 losses, which remains the worst single-season record in major league history. Attendance at League Park plummeted, and the Spiders were one of four teams contracted by the National League at the end of that season. During the team’s final three seasons (1897-1899), outfielder Louis Sockalexis, a member of the Penobscot Nation, played for the Spiders and is often credited as the first Native American to play major league baseball.

Amusement parks were also emerging as popular destinations. Euclid Beach Park opened on the shore of Lake Erie in 1895, established by a group of five Cleveland businessmen. In its initial years, the park featured attractions such as a beer garden, games of chance, and a few mechanical amusement rides. The Humphrey family, who would later transform the park into a more strictly family-oriented venue, operated a popcorn concession there in 1899 but reportedly left due to the “unsavory atmosphere” of gambling and alcohol sales at that time.

Beyond these organized entertainments, Clevelanders embraced other recreational fads. Bicycling became immensely popular, with an estimated 50,000 cyclists in the city by the mid-1890s. Roller skating rinks also drew crowds. Professional boxing was gaining a following, with champion prizefighters like John L. Sullivan making appearances in the city, and well-attended, no-decision bouts held at the newly constructed Cleveland Athletic Club. Cleveland hosted its first championship boxing match on March 17, 1898, at the Central Armory.

The growth and variety of these leisure activities point to a significant shift in how Clevelanders spent their free time. Leisure was becoming increasingly commercialized, with dedicated venues, professional performers and athletes, and a public willing to pay for entertainment. This diversification of recreational options, from attending a vaudeville show or a baseball game to visiting an amusement park or engaging in individual pursuits like bicycling, reflected a society with more defined periods of leisure and, for some, more disposable income.

Governing a Growing Metropolis: City Hall and Politics

Governing Cleveland in the 1890s was a complex task, marked by attempts at structural reform, the enduring influence of powerful interests, and the rise of new political figures. In 1891, the city adopted a new form of government known as the “Federal Plan.” This system was modeled directly after the national government, intending to create a clearer separation of powers by having authority shared between a legislature (the City Council) and an executive (the Mayor). Under this plan, the Mayor received an annual salary of $6,000 and, along with six department heads whom the mayor appointed with council approval, formed a Board of Control. The City Council consisted of 20 members, two from each of the city’s ten districts, which represented the 40 wards. This structural change was a response to widespread dissatisfaction with previous governance models, which had often distributed power among numerous boards and commissions, leading to inefficiency and a lack of clear accountability.

Despite the intentions behind the Federal Plan, it did not eradicate long-standing issues. The system of granting franchises for public utilities, such as street railways, continued, and this remained a significant source of political maneuvering and potential corruption. Party machines, often reflecting the city’s deep divisions along class, religious, and ethnic lines, continued to wield considerable influence, frequently being the real engines driving formal municipal government. The 1890 census had shown that a large majority of Cleveland’s population was either foreign-born or of foreign parentage, and these demographic realities played a significant role in shaping the city’s political dynamics.

Several mayors led the city during the 1890s. Robert Blee served from 1893 to 1895. He was succeeded by Robert E. “Curly-headed Bob” McKisson, who took office in April 1895 and served until 1899. McKisson initially gained popularity for his opposition to the “street railway ring,” a term used to describe the close and often criticized alliance between city administration and traction magnates. However, McKisson’s second term became mired in scandal, with charges of misusing public patronage to build a personal political machine and exacting political contributions, which ultimately ended his political career. Following McKisson, John H. Farley, who had previously served as mayor from 1883 to 1885, returned to office in the spring of 1899 and served into the new century. Farley campaigned on a platform of economy and clean government, initially positioning himself against the street railway “franchise grabbers.” However, he too, according to critics, later appeared to align himself with these powerful traction interests.

An emerging figure who would later dominate Cleveland politics, Tom L. Johnson, was active in business and national politics during the 1890s, though he did not become mayor until 1901. Johnson was a highly successful and wealthy street railway magnate, with significant holdings in Cleveland as well as in other cities like Detroit and Brooklyn. He also had substantial interests in the steel industry, having established the Cambria Co. steel company in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and the Lorain Steel Co. in Lorain, Ohio, in 1889. In 1890, Johnson was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives from Cleveland’s 21st district, and he was reelected in 1892, serving until 1894. During his time in Congress, he became a vocal advocate for free trade. A pivotal moment in his ideological development came after reading the works of Henry George, which led him to become a fervent supporter of the single land tax and free trade principles—economic philosophies that were, ironically, in direct opposition to the monopolistic practices that had helped him accumulate his considerable fortune. His early business dealings in Cleveland, particularly concerning streetcar franchises, brought him into conflict with another powerful local figure, Mark Hanna, setting the stage for future political battles. In 1899, just before the turn of the century, Johnson was involved in a campaign in Detroit advocating for public ownership of streetcar systems and reduced fares, foreshadowing the reformist agenda he would later bring to Cleveland’s mayoralty.

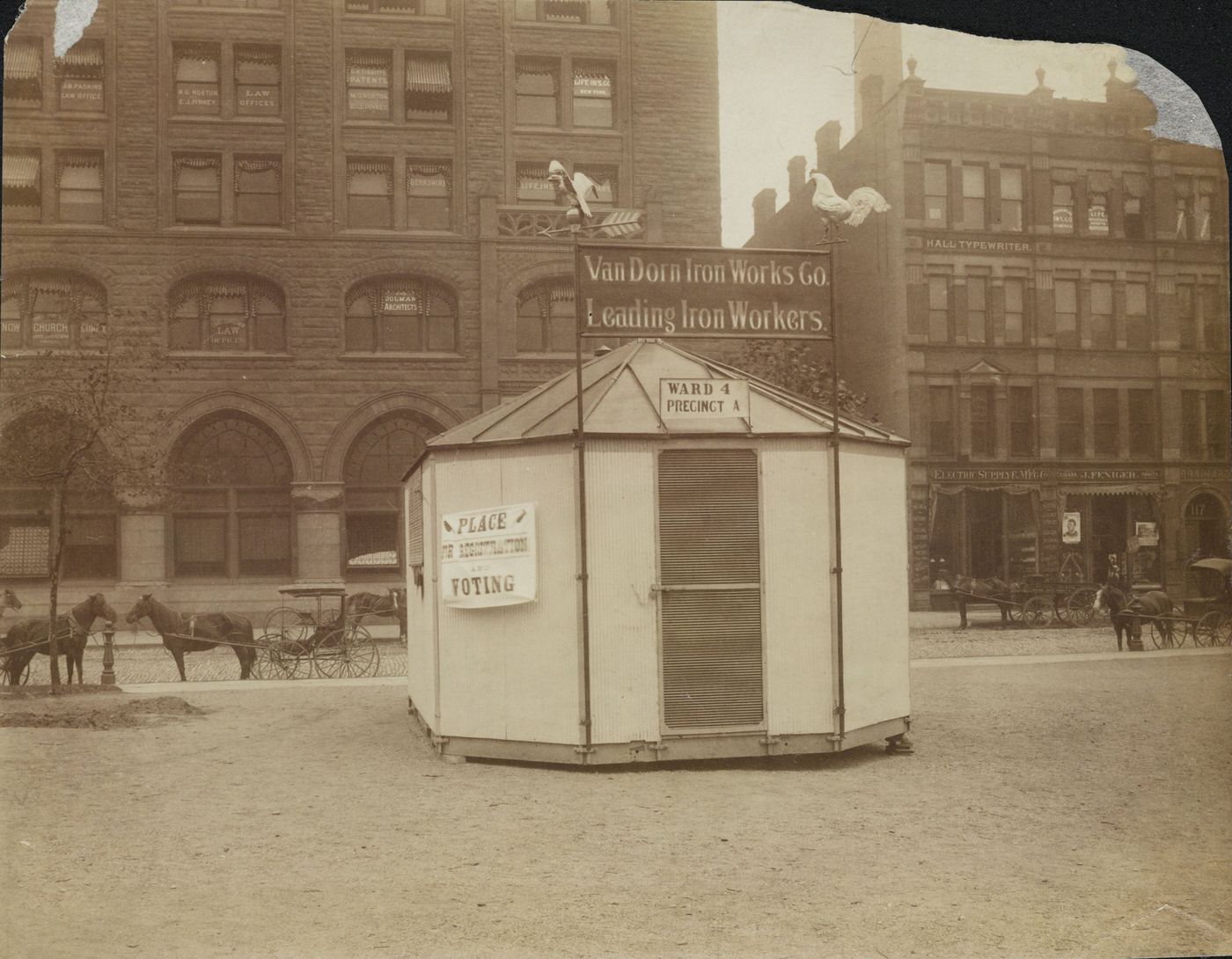

Broader civic issues also occupied the political landscape of the 1890s. Concerns about patronage and the “spoils system” led to ongoing civil service reform efforts; for example, competitive examinations for positions in the police department had been required since 1886. In 1891, the Australian (secret) ballot was adopted for elections, aiming to reduce voter intimidation and fraud. The continuous growth of the city and the increasing needs of its diverse population, particularly immigrants, led to an expansion of municipal services, which, in turn, often necessitated increased city borrowing and higher municipal debt. Throughout the decade, the granting of franchises, especially for the lucrative street railway lines, remained a contentious issue, frequently at the center of political debate and accusations of corruption. The political environment of Cleveland in the 1890s thus reflected a fundamental tension of the Gilded Age: a public desire for more efficient and honest governance coexisting with, and often being undermined by, the immense influence of private capital and well-entrenched political interests.

Reading the News: Cleveland’s Daily Papers

The citizens of Cleveland in the 1890s had access to a lively and varied press, with daily newspapers playing an increasingly important role in disseminating information, shaping public opinion, and reflecting the city’s diverse voices.

The Cleveland World, which began publication in 1889, quickly gained a reputation for engaging in “yellow journalism,” a style characterized by sensational headlines and often dramatic storytelling to attract readers. This approach was particularly evident during the heightened public interest surrounding the Spanish-American War in 1898. The World’s circulation saw a significant jump during this period, rising from 21,695 in February 1898 to 33,892 by May of the same year. The paper was sold for the affordable price of one cent, making it accessible to a broad readership. Under the ownership of Robert P. Porter, who acquired it in April 1895, the World also became known for its outspokenly Republican stance.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer was another of the city’s prominent daily newspapers, with a long history and a significant presence in the community. While specific articles from the 1890s are not detailed in the provided research, its archives confirm its continuous operation and importance during this decade. Newspapers like the Plain Dealer provided comprehensive coverage of local, national, and international news, as well as advertisements and community information that offer a window into the daily life of the period.

Catering to the specific interests and concerns of the city’s substantial working-class population was the Cleveland Citizen. This labor-focused newspaper was founded in 1891 by Max S. Hayes and Henry C. Long and received support from the Central Labor Union. It provided a platform for labor news, advocated for workers’ rights, and often promoted a moderate socialist viewpoint.

Beyond these English-language dailies, Cleveland’s diverse immigrant communities were also served by ethnic newspapers published in their native languages. These papers were vital for helping newcomers stay connected to their cultural heritage, receive news relevant to their communities, and navigate life in a new country.

Newspapers in the 1890s were more than just sources of information; they were active participants in the city’s civic life. They played a crucial role in shaping public discourse on major issues of the day, such as the frequent labor strikes, political campaigns, and controversies surrounding municipal governance. The intense battle during the 1899 streetcar strike, for example, was fought not only in the streets but also in the columns of the city’s newspapers, each side attempting to sway public sentiment. In an era of increasing literacy, a rapidly growing and diversifying urban population, and complex social and political challenges, the mass media, primarily through its daily newspapers, became an indispensable and powerful force in Cleveland’s evolving urban democracy.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know