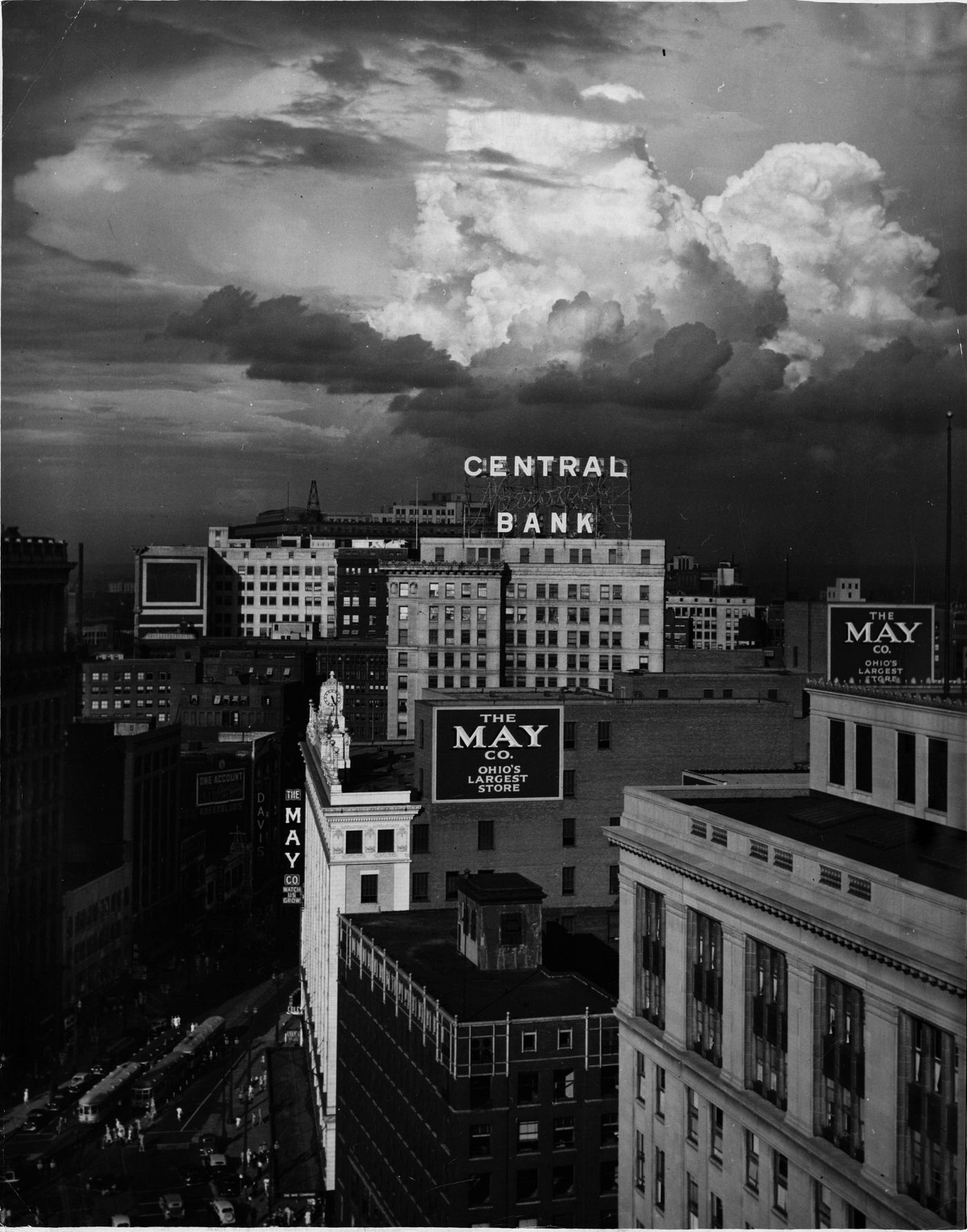

The 1930s began for Cleveland with the city standing as a significant American urban center. In 1920, it was the nation’s fifth-largest city, home to 796,841 people, a number that grew to 900,429 by the 1930 census. This growth, fueled by robust industry and waves of immigration, offered a stark contrast to the severe economic trials that would soon define the decade.

The Great Depression Takes Hold in Cleveland

The optimism of the 1920s shattered with the stock market crash of October 1929. The ensuing Great Depression struck Cleveland’s industrial heart with devastating force. As a city heavily reliant on manufacturing, particularly steel and automobiles, Cleveland saw its economic foundations crumble. The human cost mounted rapidly. A special federal census in January 1931 found that 99,233 Clevelanders were jobless. Another 25,400, while technically employed, were either laid off without pay or working drastically reduced hours. The Depression’s grip had directly tightened around half of the city’s population.

Unemployment rates continued to climb. By 1933, Cleveland, like many other industrial cities along the Great Lakes, faced unemployment levels hovering between thirty and seventy percent. Throughout the 1930s, the number of jobless individuals in Cuyahoga County each month ranged from 46,000 to a staggering 219,000. For many families, the prosperity of the previous decade became a cruel and distant memory.

The city government itself teetered on the brink of financial collapse. As businesses closed and incomes vanished, the tax base that funded public services dwindled. This led to severe cuts in funding for essential institutions. Public parks and libraries, vital community resources, were forced to operate with minimal funds. The plight of the Brookside Zoo, which struggled to feed and care for its animals, became a poignant symbol of the city’s widespread distress. The economic hardship was not just a matter of statistics; it was a daily reality that exposed the city’s dependence on a few core manufacturing sectors. When these sectors faltered, the entire edifice of urban life felt the strain.

One of the most visible and desperate manifestations of the Depression was the rise of “Hoovervilles.” These were shantytowns, named with bitter irony after President Herbert Hoover, constructed by homeless families using whatever materials they could find—cardboard, tar paper, scrap metal, and packing boxes. These makeshift communities sprang up in various parts of Cleveland, including the Kingsbury Run valley, on Whiskey Island, along the lakefront, and in a gully at the end of E. 114th Street. Life in these Hoovervilles was a testament to human resilience in the face of dire poverty, but also a stark indicator of the failure of existing systems to provide basic shelter. The very existence of these settlements signaled a breakdown in the traditional social contract, forcing a broader re-evaluation of societal responsibility.

Private charities, long the first line of defense for the needy, were quickly overwhelmed. Associated Charities (AC), Cleveland’s oldest and largest private relief agency, saw its expenditures for direct relief double by 1929. The number of families turning to AC for help skyrocketed from 712 in October 1929 to 26,000 by 1932. Wayfarers’ Lodge, an AC-run shelter for homeless men, provided refuge for more than 26,000 individuals in 1930 alone.

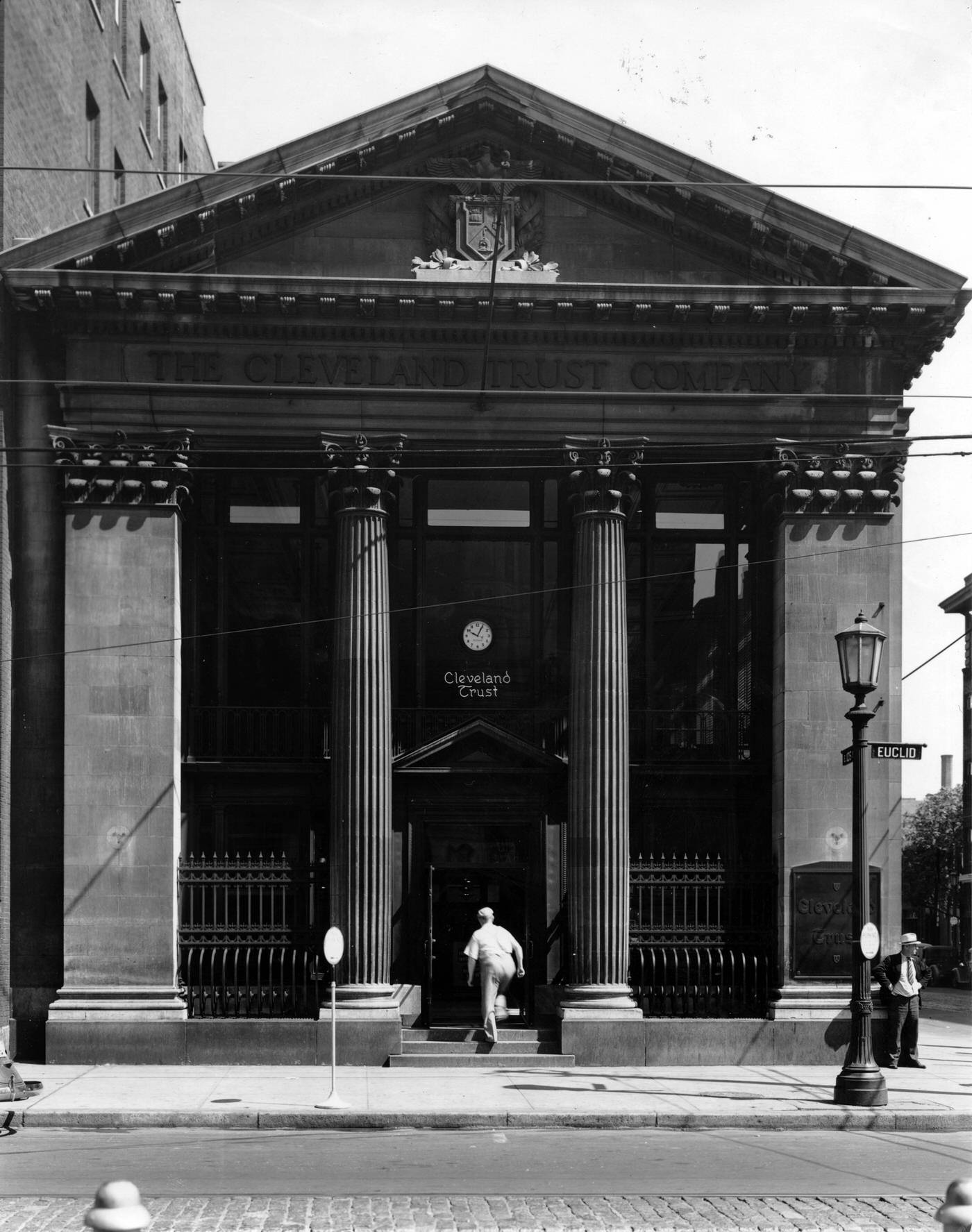

The banking crisis of early 1933 delivered yet another severe blow to Cleveland’s beleaguered economy. Following a bank holiday declared in Michigan, nervous depositors rushed to withdraw their money from Cleveland banks. Union Trust and Guardian Trust lost half their deposits and were eventually forced to remain closed after President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered a national bank holiday. While Cleveland Trust managed to survive, the closures wiped out the savings of countless small depositors and crippled organizations like the Community Fund, which supported many local charities.

The societal mood reflected the pervasive economic despair. A “growing feeling of insecurity in life and property” settled over the city. Faced with an uncertain future, many Clevelanders postponed significant life decisions, such as marriage and starting families. This widespread anxiety was more than just a reaction to lost jobs; it was a response to a lost sense of stability and predictability, the psychological scars of which would linger for a generation.

A New Deal for Cleveland

As the Depression deepened, it became clear that local government and private charities alone could not cope with the scale of the crisis. The federal government, under the leadership of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, responded with a series of programs collectively known as the New Deal. In May 1933, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) began providing direct financial aid to states for relief efforts. In Cleveland, these funds were distributed through the newly established Cuyahoga County Relief Administration (CCRA), which took over much of the staff and caseload from the overwhelmed Associated Charities. By July 1935, the CCRA was assisting 76,610 families and single men.

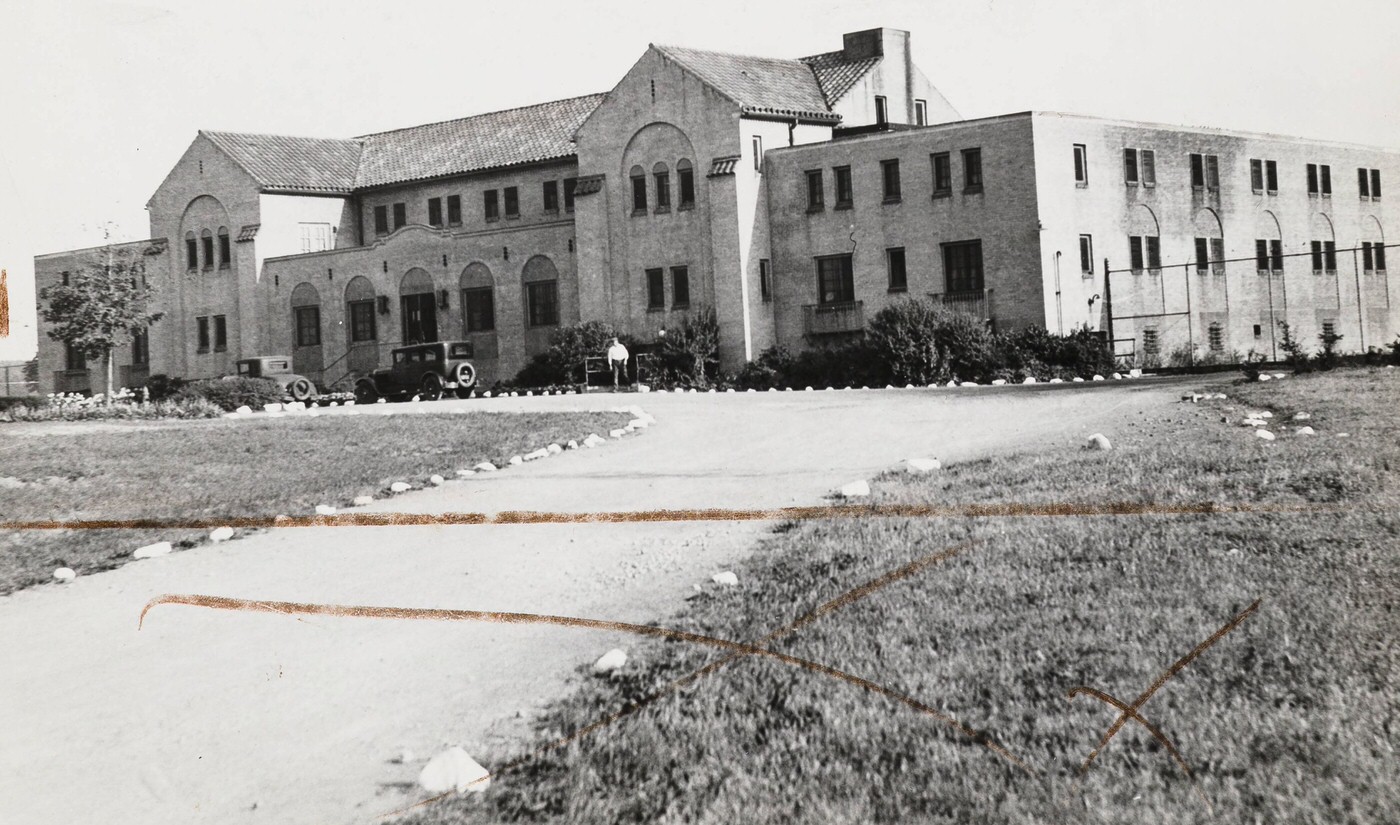

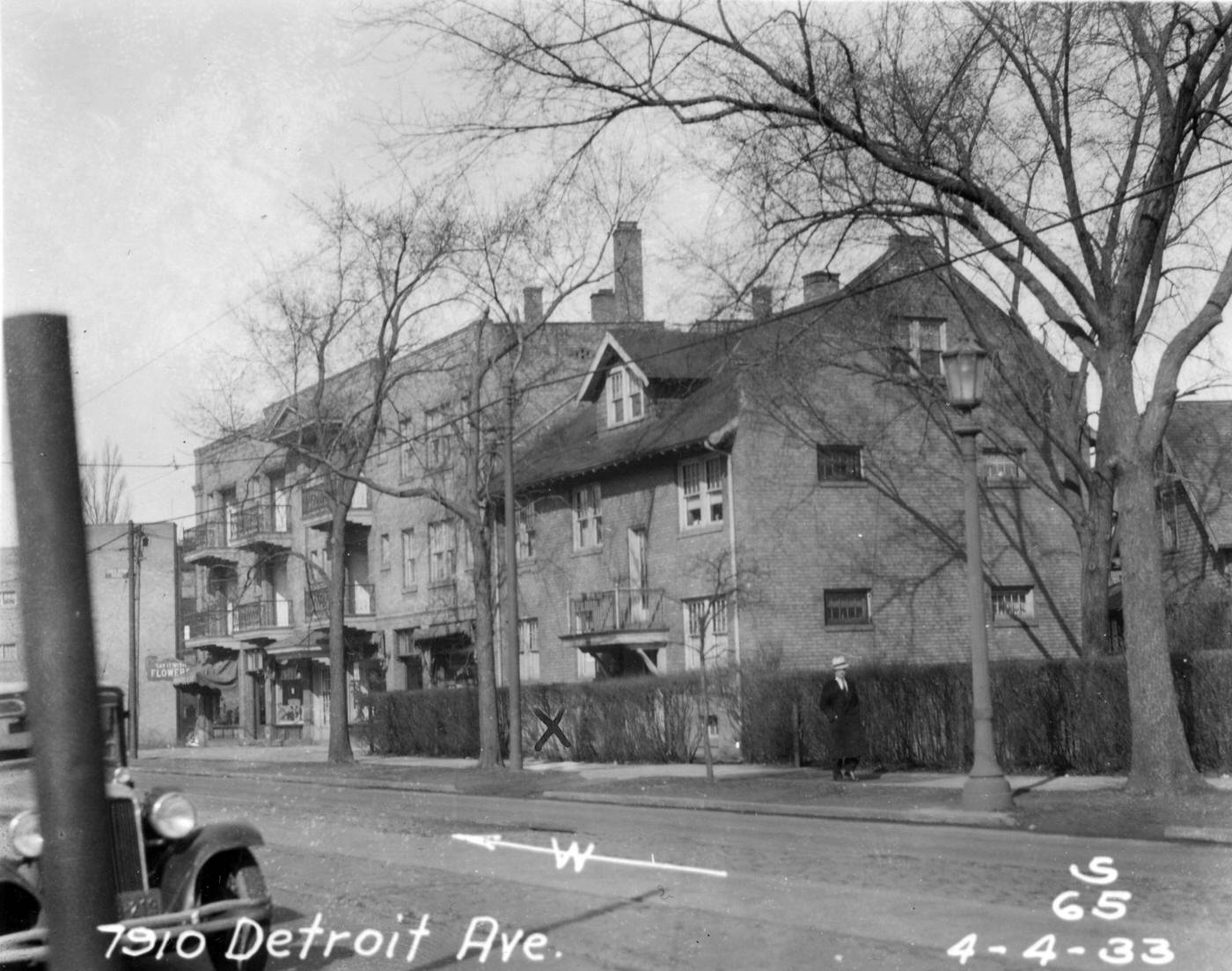

A central pillar of the New Deal was the creation of jobs through large-scale public works projects. The Public Works Administration (PWA), established in 1933, financed significant infrastructure development. In Cleveland, the PWA’s most visible legacy was the construction of the city’s first three federally funded public housing projects: Lakeview Terrace, Cedar-Central, and Outhwaite Homes. Built between 1935 and 1937, these projects were designed to clear slum areas and provide employment. While offering improved living conditions for some low-income families, these housing projects were developed with racial segregation, a practice criticized by the local NAACP. PWA funds also supported crucial upgrades to Cleveland’s wastewater treatment plants.

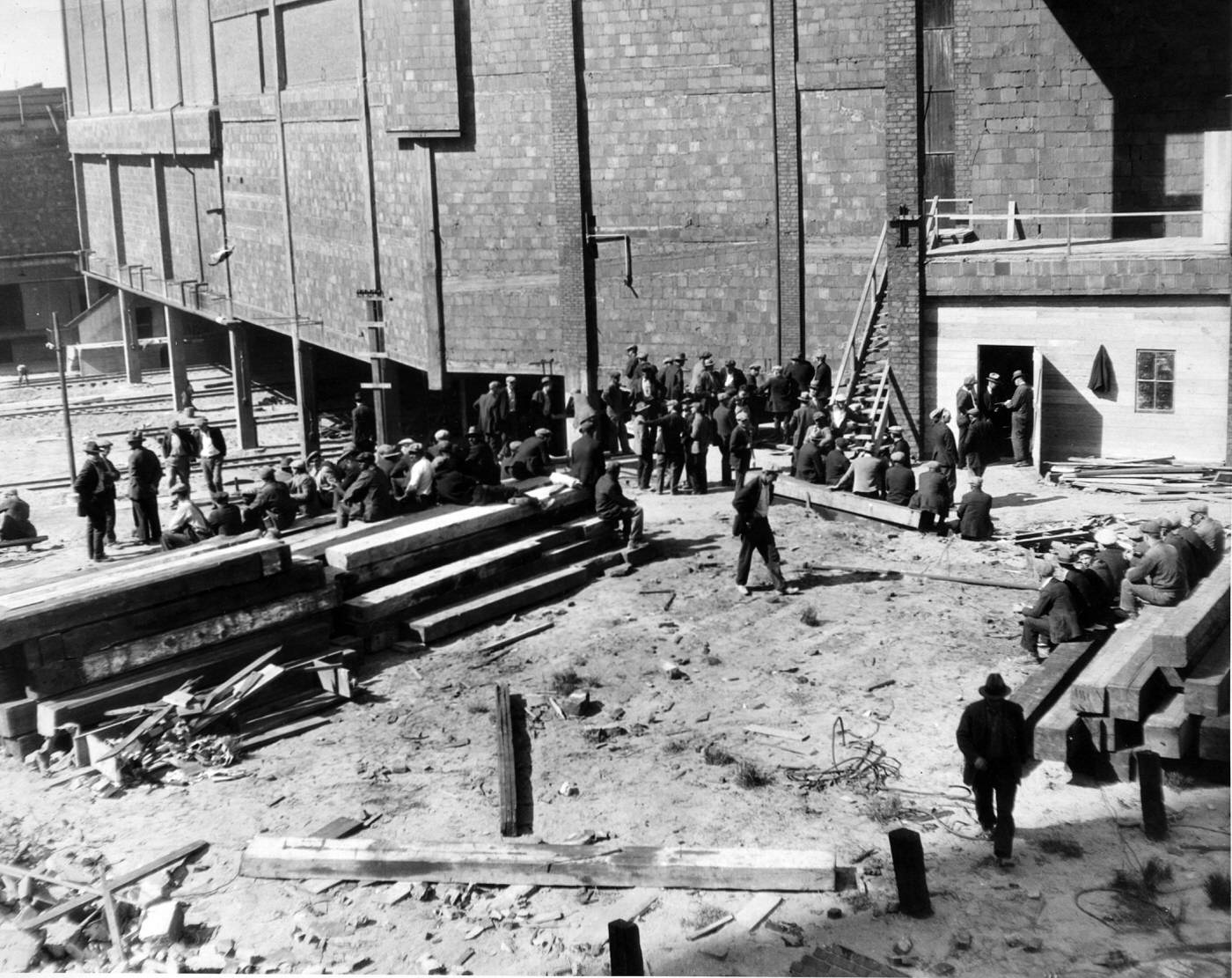

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), launched in 1935 and later renamed the Work Projects Administration, became the New Deal’s largest and most ambitious employment program. It aimed to provide jobs, primarily for unskilled workers, on a vast range of public projects, transforming not only the lives of those employed but also the physical landscape of the city.

Some of the WPA’s transformative infrastructure projects in Cleveland included:

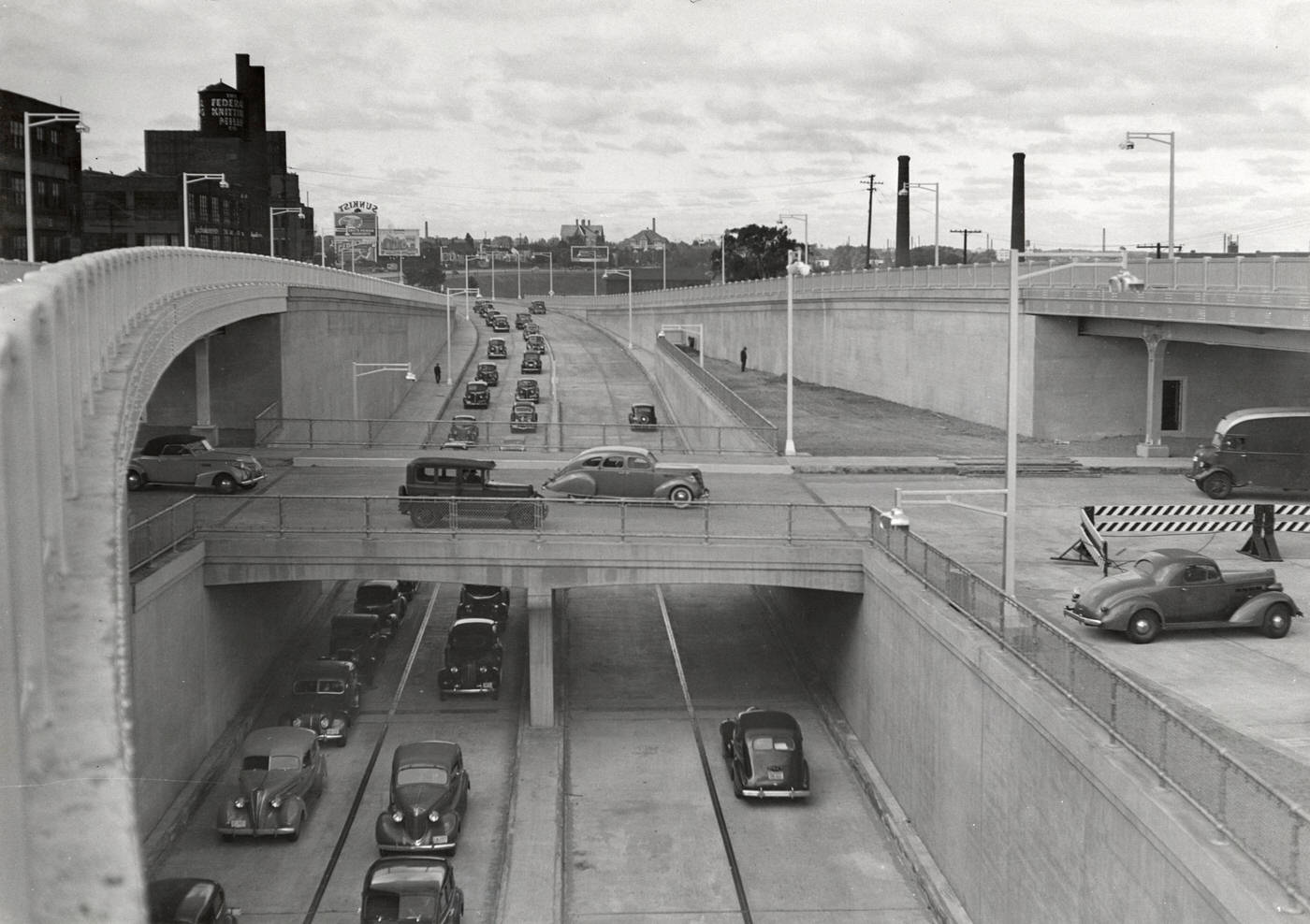

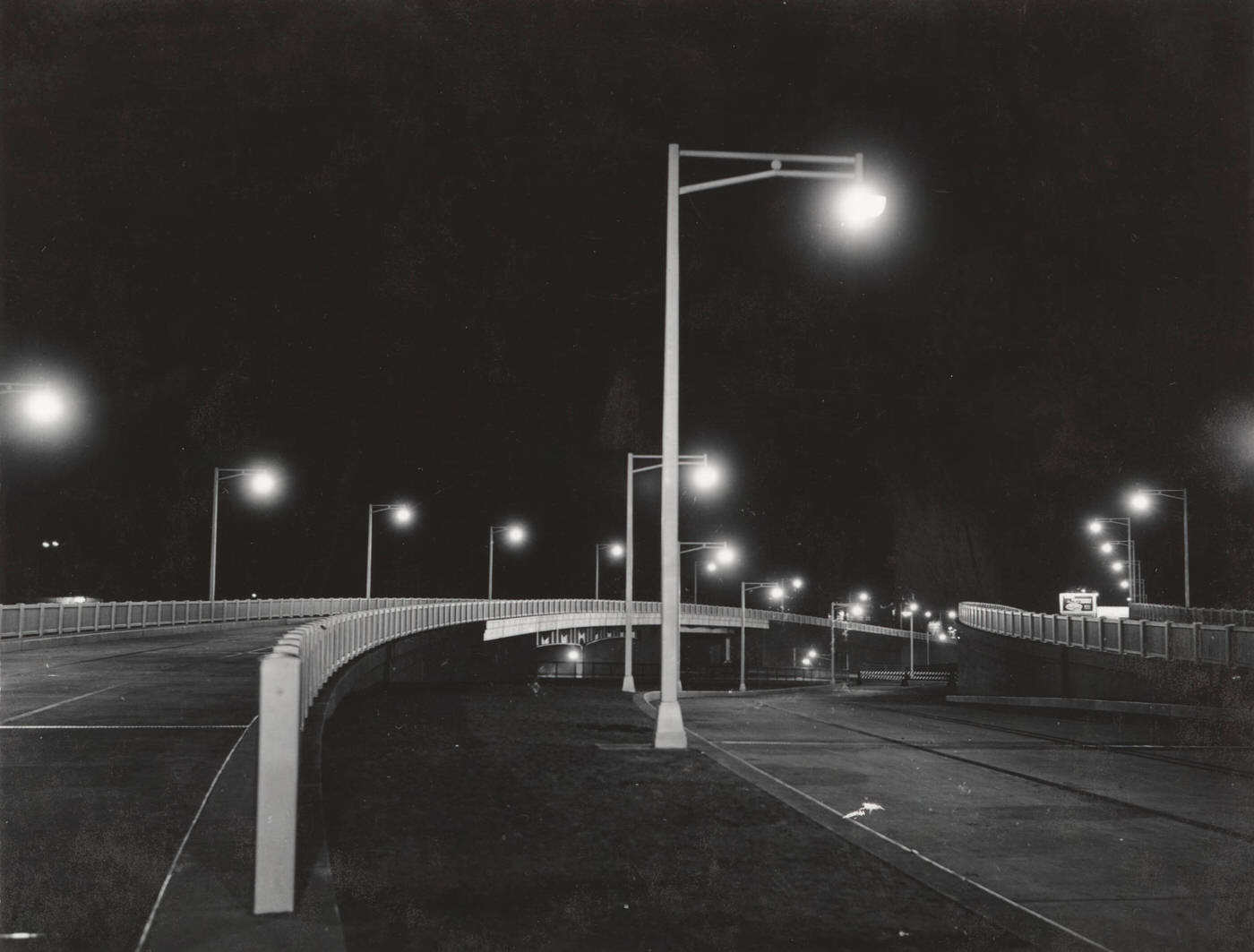

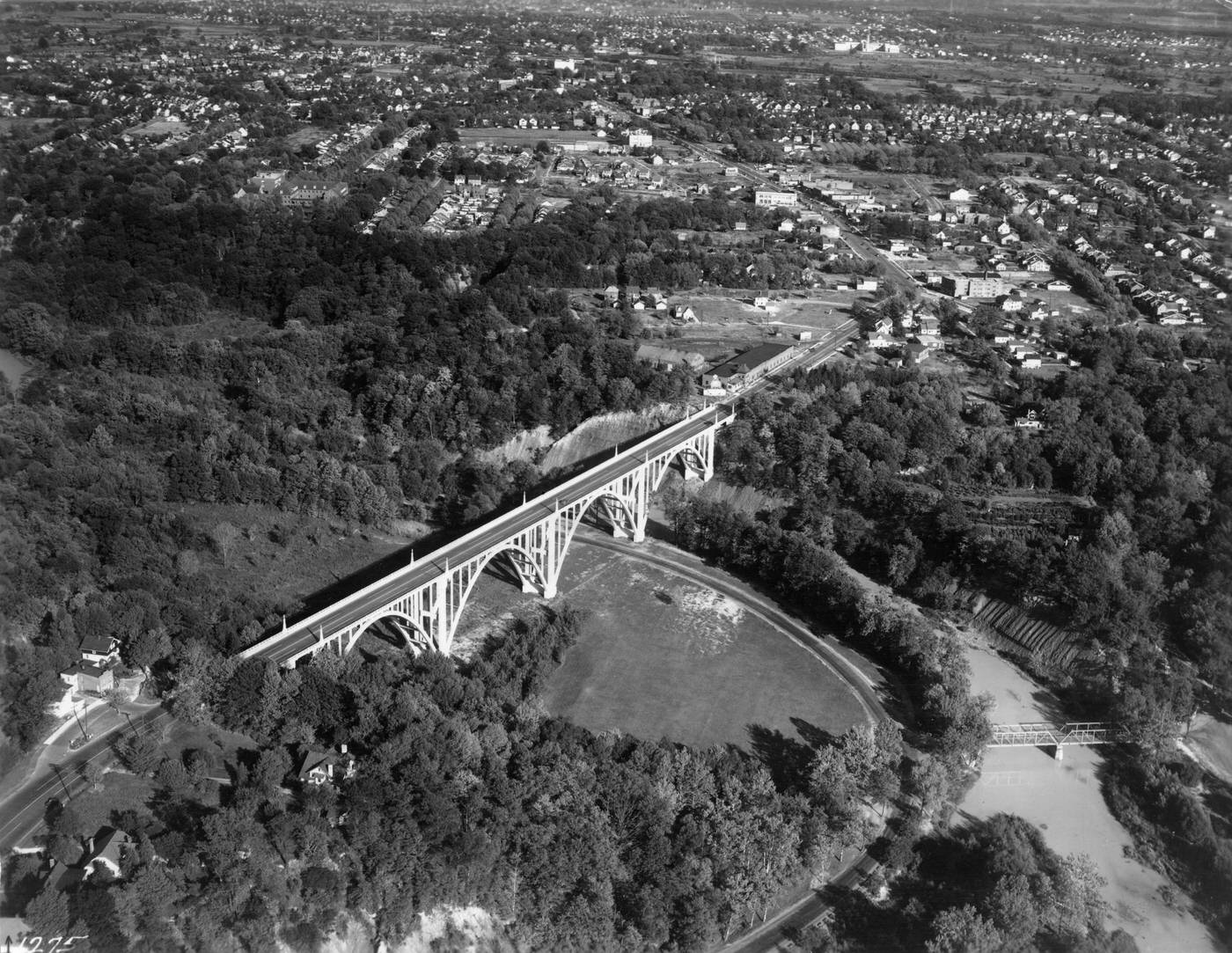

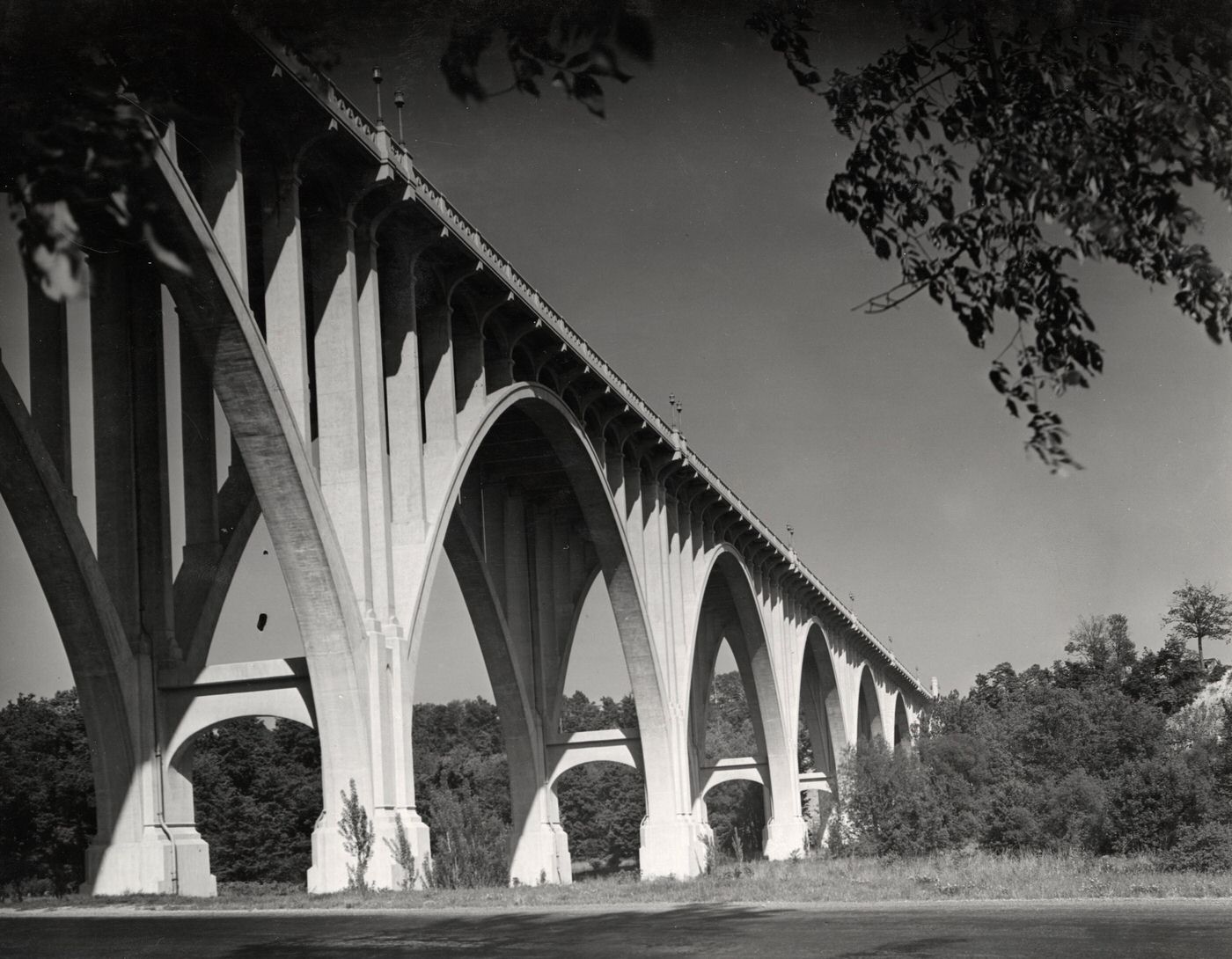

- The Memorial Shoreway (now part of Interstate 90), a massive undertaking involving building demolition, lakefront expansion using landfill, and roadway paving. Completed in 1938, it was hailed as “the largest WPA job in the nation”.

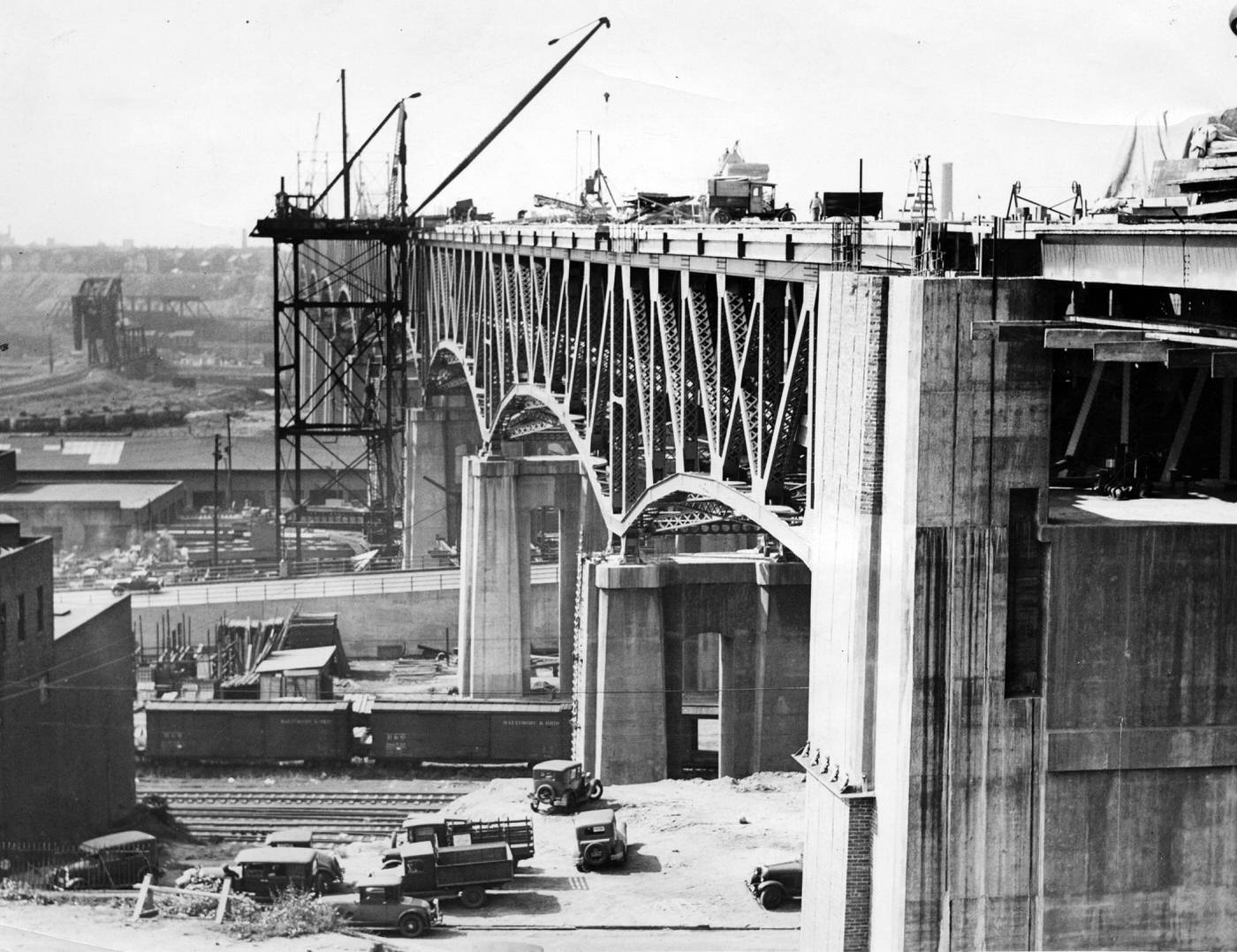

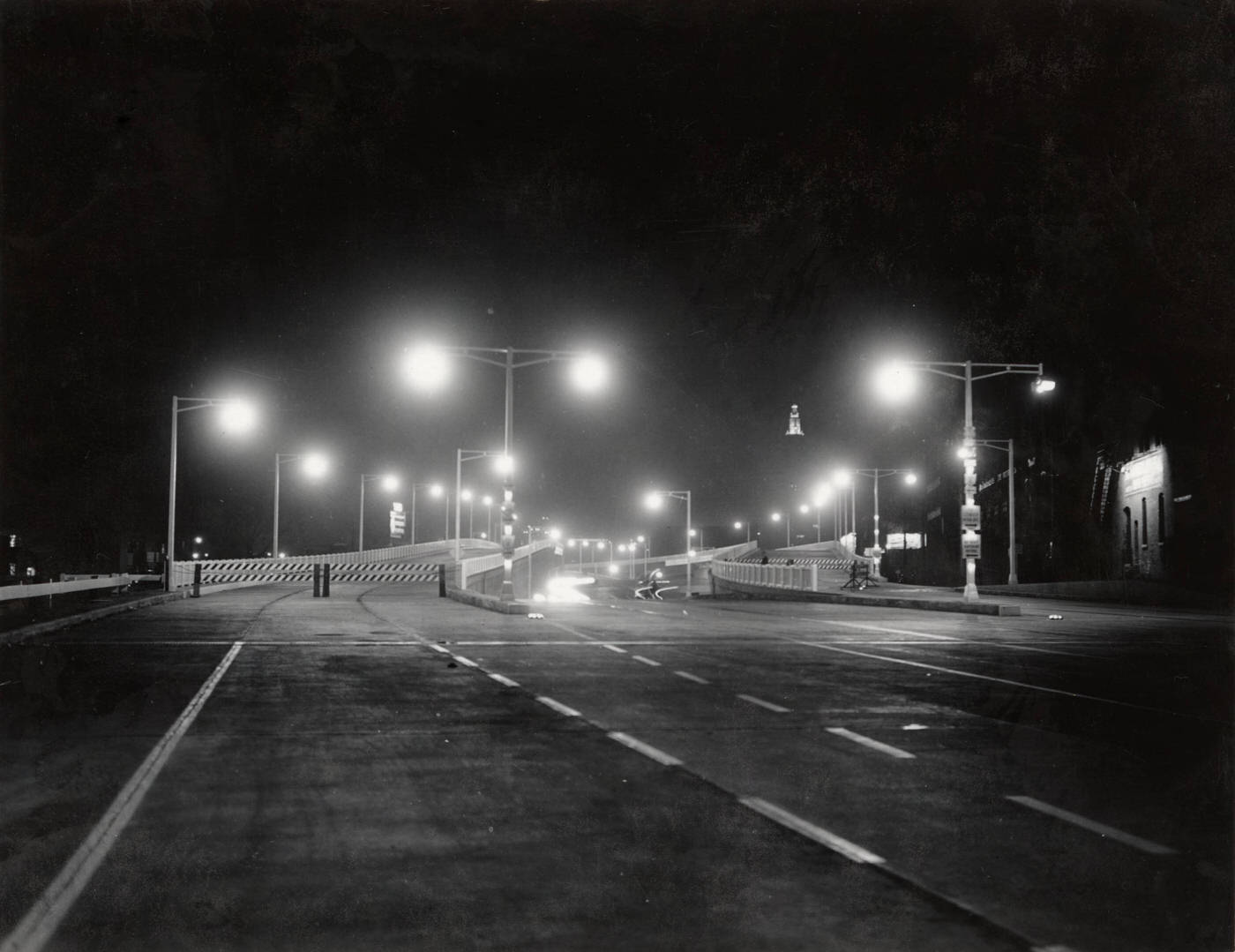

- The Main Avenue Bridge, finished in 1939, which connected the Memorial Shoreway to Cleveland’s west side, significantly improving cross-city transportation.

- Extensive repairs and modernizations to Cleveland public schools, valued at $4.8 million.

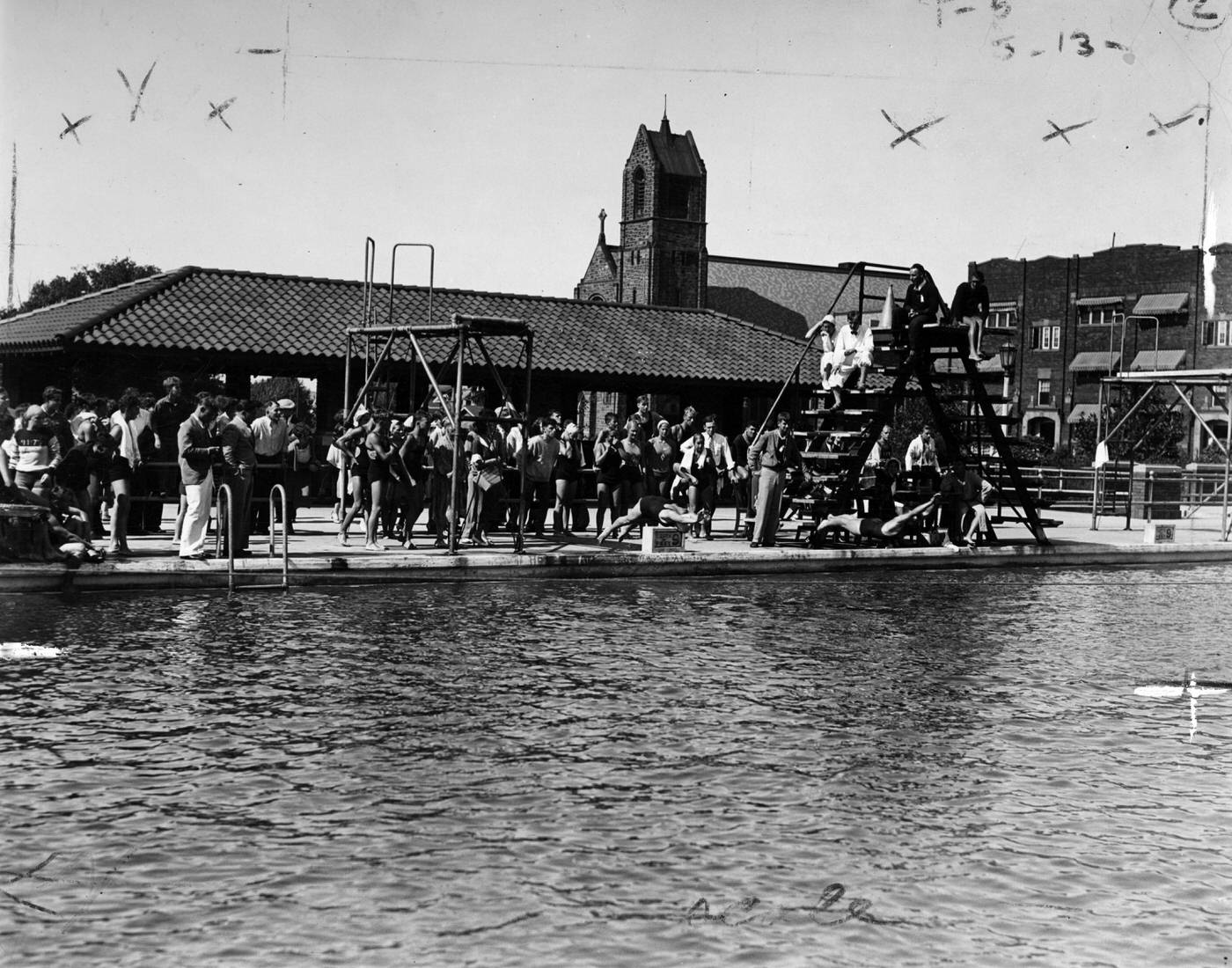

- Widespread improvements to parks and recreational facilities. WPA crews planted tens of thousands of trees in city parks and along parkways. They constructed baseball diamonds, tennis courts (including at Brookside Zoo), picnic shelters, bridges, and retaining walls throughout the Cleveland MetroParks system, including projects in the Berea Reservation where abandoned quarries were transformed into lakes. Cain Park and Forest Hill Park also benefited from WPA labor. By 1936, federal work relief programs employed 5,000 men in the Cleveland MetroParks alone.

- The WPA also contributed to the development and beautification of some of Cleveland’s internationally recognized Cultural Gardens.

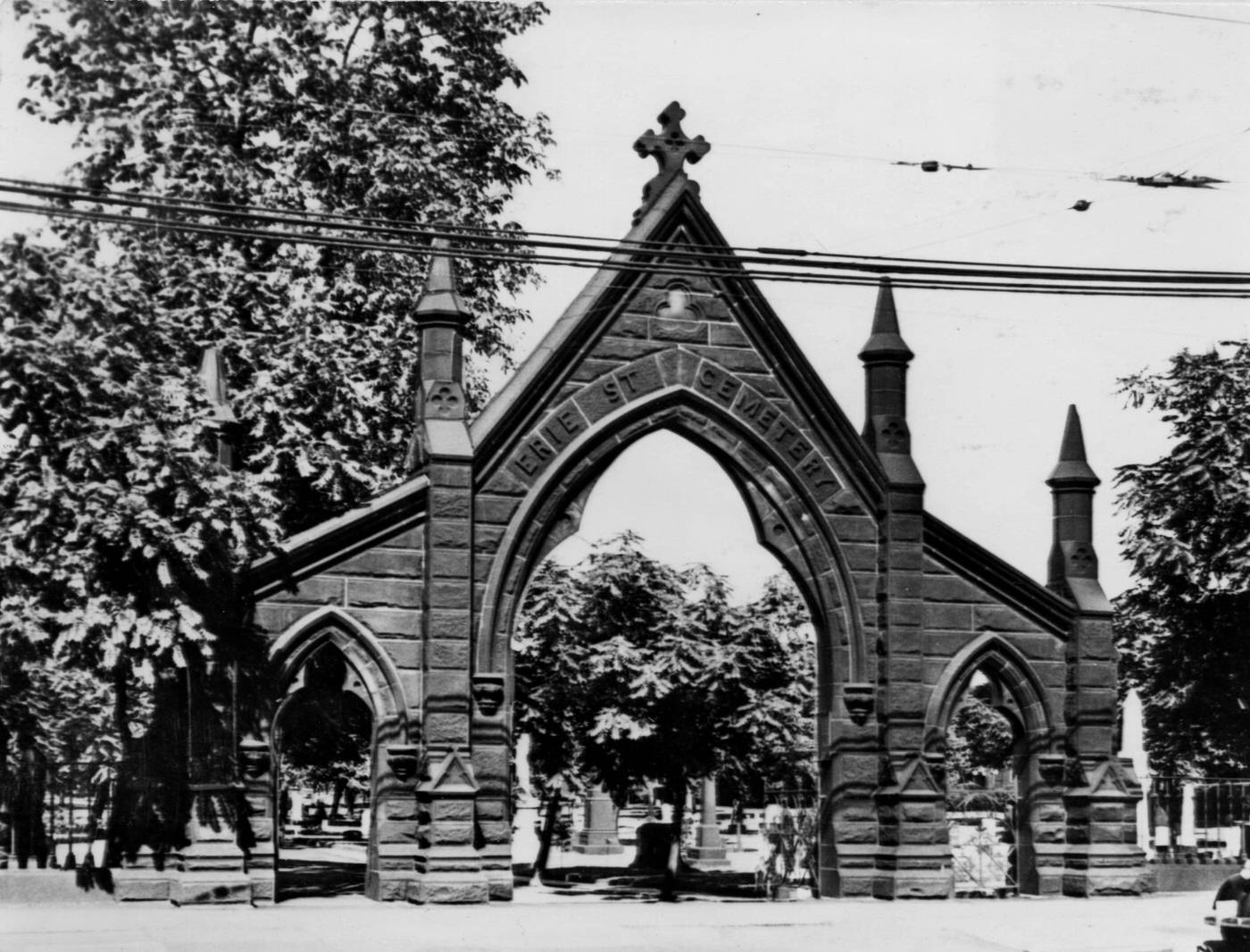

- Other civic enhancements included building a new sandstone wall for the historic Erie Street Cemetery and relandscaping Lincoln Park and Washington Park.

At its peak in October 1938, the WPA employed 78,000 people in Cuyahoga County. It is estimated that approximately 27% of Cleveland’s total population, including workers and their families, directly benefited from WPA employment.

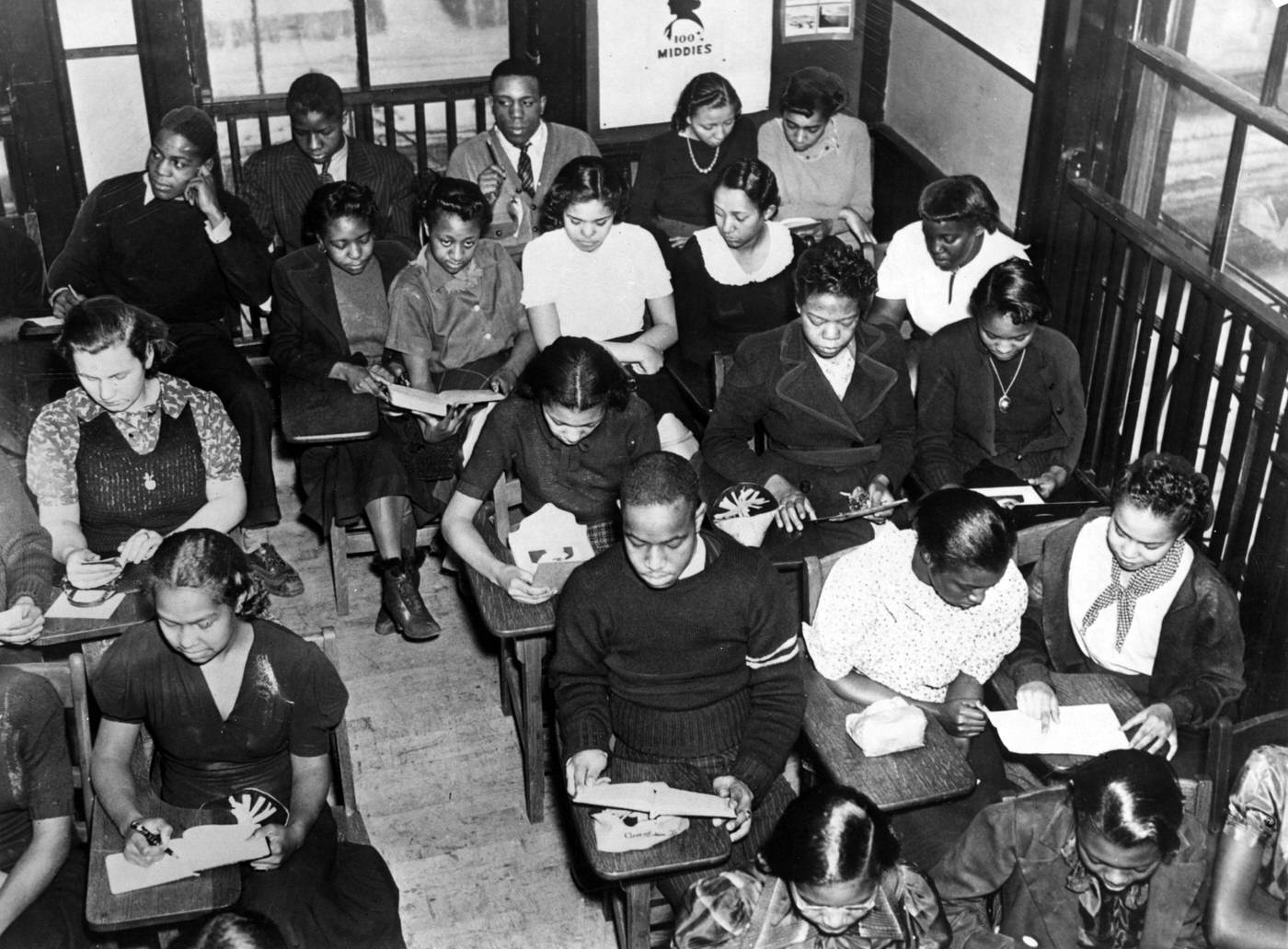

The New Deal also targeted specific demographic groups. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) offered young men aged 18-28 employment in forestry, park development, and soil erosion projects. CCC camps were established in local reservations such as Euclid Creek, North Chagrin, and Brecksville. Enrollees planted trees and constructed trails and shelters, earning $30 a month, a significant portion of which was sent home to their families. Around 2,000 young men from Cuyahoga County participated in the CCC annually. The National Youth Administration (NYA) provided part-time jobs and vocational training for young men and women aged 15-25, enabling them to continue their education. Participants often worked in public recreation facilities, city playgrounds, parks, and in clerical roles.

Recognizing that the Depression had idled talent across all sectors, the New Deal included Federal Arts Projects under the WPA, providing employment for artists, writers, musicians, and theater professionals.

The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), part of the earlier Civil Works Administration, was led in the Midwest by William M. Milliken, director of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Beginning in late 1933, it employed 72 artists who created significant public art, including murals for the Cleveland Public Auditorium and the Cleveland Public Library.

The Federal Art Project (FAP) succeeded PWAP and over seven years employed 350 artists. They were commissioned to create murals and sculptures for 19 Cleveland-area post offices, public schools, the Cleveland Botanical Garden, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and public housing projects. Thousands of posters and ceramic figures were also produced.

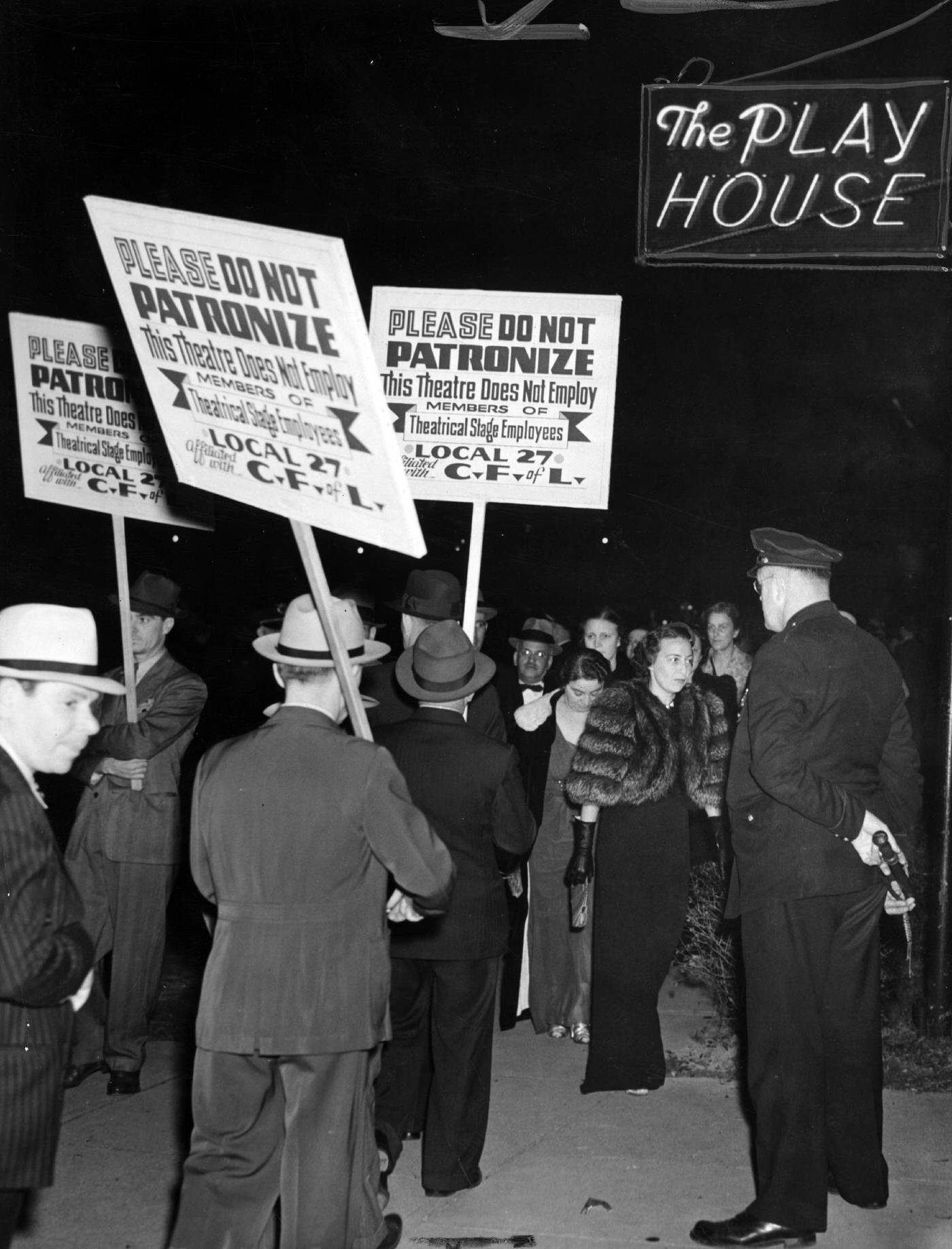

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP) provided work for actors, playwrights, and other theater professionals. In Cleveland, directors Frederic McConnell and K. Elmo Lowe of the Cleveland Play House oversaw productions ranging from an all-African American “Macbeth” to politically engaged “Living Newspapers.” The FTP was often controversial for its social commentary and was discontinued by Congress in 1939.

The Federal Music Project (FMP), under the direction of Nikolai Sokoloff, former conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, employed hundreds of local musicians. The project emphasized American compositions and research into traditional folk music. Cleveland’s FMP supported opera ensembles, a folksong group, military and gypsy bands, a dance orchestra, and the Cleveland Civic Orchestra. Many performances were free and held in accessible public venues, often featuring local ethnic musical traditions. By May 1936, FMP concerts had reached an audience of 60,000, and local opera companies attracted 100,000 attendees in 1936.

The Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) employed writers, researchers, editors, historians, and cartographers. Notable Cleveland productions included the Annals of Cleveland, an invaluable index and digest of early Cleveland newspapers, and a Foreign Language Newspaper Digest, which preserved important historical records of the city’s diverse communities.

Finally, the Social Security Act of 1935 laid the foundation for a national system of social welfare, establishing programs for old-age insurance, unemployment compensation, and aid to dependent children. While its full impact would unfold over subsequent decades, it marked a fundamental shift in the government’s role in providing a safety net for its citizens. The diverse array of New Deal programs demonstrated an understanding that unemployment affected all sectors of the workforce, requiring tailored approaches that went beyond simple manual labor to preserve skills and provide meaningful work.

These programs represented a multifaceted approach to the crisis, aiming not only for immediate economic relief but also for long-term community enrichment through infrastructure development, public health improvements, and cultural preservation. However, the implementation of these programs was not without its complexities. For example, the establishment of racially segregated public housing showed that federal initiatives sometimes operated within, and even reinforced, existing discriminatory frameworks. Similarly, the political controversies surrounding ventures like the Federal Theatre Project highlighted the challenges inherent in government-funded arts and the sensitive political climate of the era.

Overview of Key New Deal Programs and Projects in Cleveland (1930s)

| Program | Key Cleveland Projects/Activities | Primary Beneficiaries/Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Public Works Administration (PWA) | Lakeview Terrace, Cedar-Central, Outhwaite Homes (public housing); upgrades to wastewater treatment plants. | Job creation in construction, slum clearance, improved sanitation, low-income housing. |

| Works Progress Administration (WPA) | Memorial Shoreway, Main Avenue Bridge, school repairs, park and recreational facility development (MetroParks, Cultural Gardens), public building enhancements. | Mass employment for unskilled workers, significant infrastructure improvements, enhanced public spaces. |

| WPA – Federal Art Project (FAP) | Murals and sculptures in post offices, schools, public buildings; poster and ceramic production. | Employment for visual artists, public beautification, creation of accessible art. |

| WPA – Federal Theatre Project (FTP) | Productions by Cleveland Play House, including “Living Newspapers” and diverse theatrical performances. | Employment for theater professionals, providing affordable and socially relevant theater. |

| WPA – Federal Music Project (FMP) | Cleveland Civic Orchestra, opera ensembles, folk groups, bands; free public concerts. | Employment for musicians, promotion of American and ethnic music, accessible cultural experiences. |

| WPA – Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) | Annals of Cleveland (newspaper index), Foreign Language Newspaper Digest. | Employment for writers and researchers, preservation of historical records, documentation of local and ethnic history. |

| Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) | Reforestation, trail and shelter construction in Euclid Creek, North Chagrin, and Brecksville Reservations. | Employment and vocational training for young men, conservation of natural resources. |

| National Youth Administration (NYA) | Part-time jobs and training for youth in recreation facilities, parks, clerical work. | Enabling young people to continue education while gaining work experience. |

Cleveland’s Diverse Communities

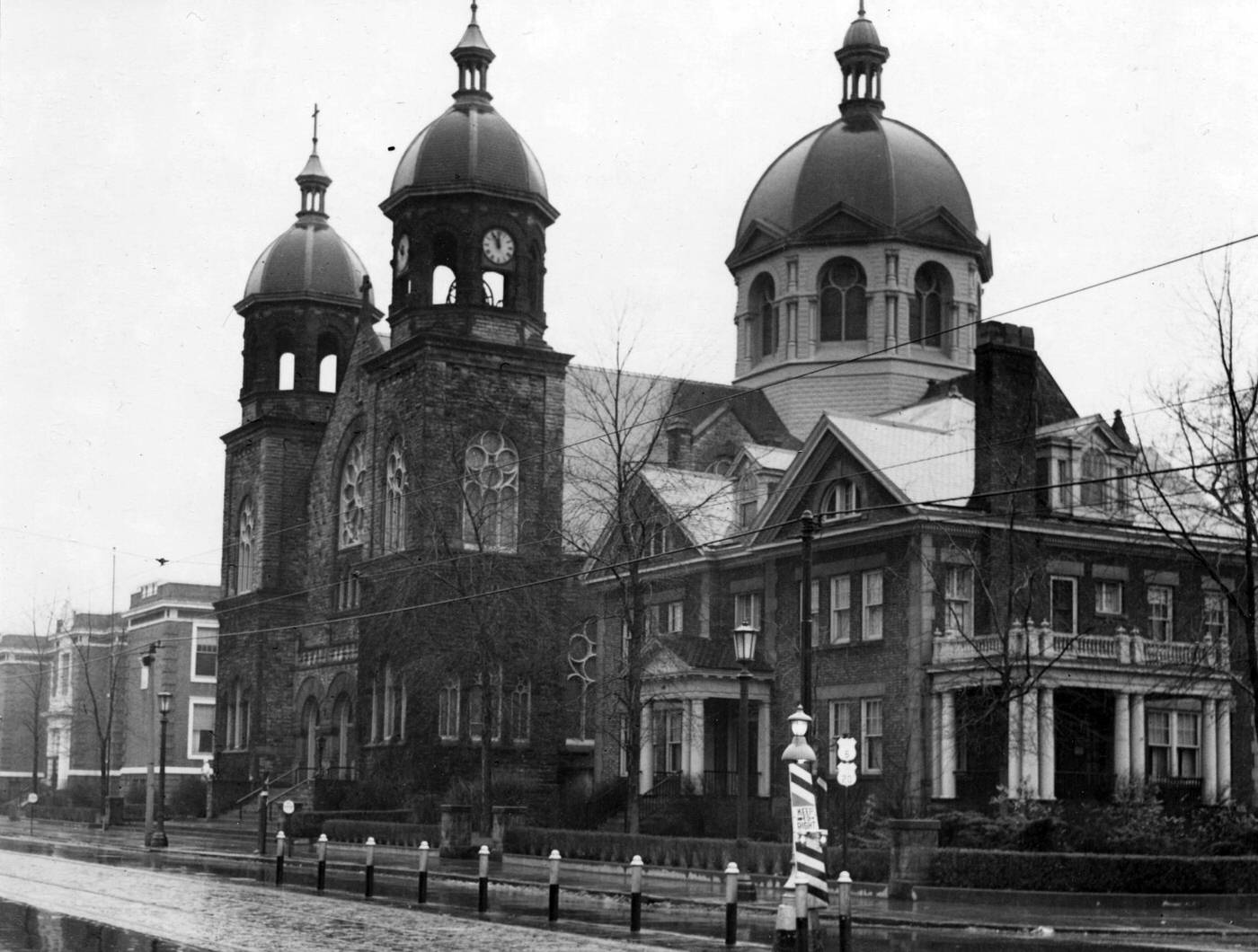

Cleveland in the 1930s was a mosaic of cultures, a “melting pot of nationalities”. Its numerous European immigrant groups and a growing African American community had largely established distinct neighborhoods, each with its own network of social, cultural, and religious institutions developed in the preceding decades. These communities faced the Great Depression with varying degrees of internal resources and external pressures.

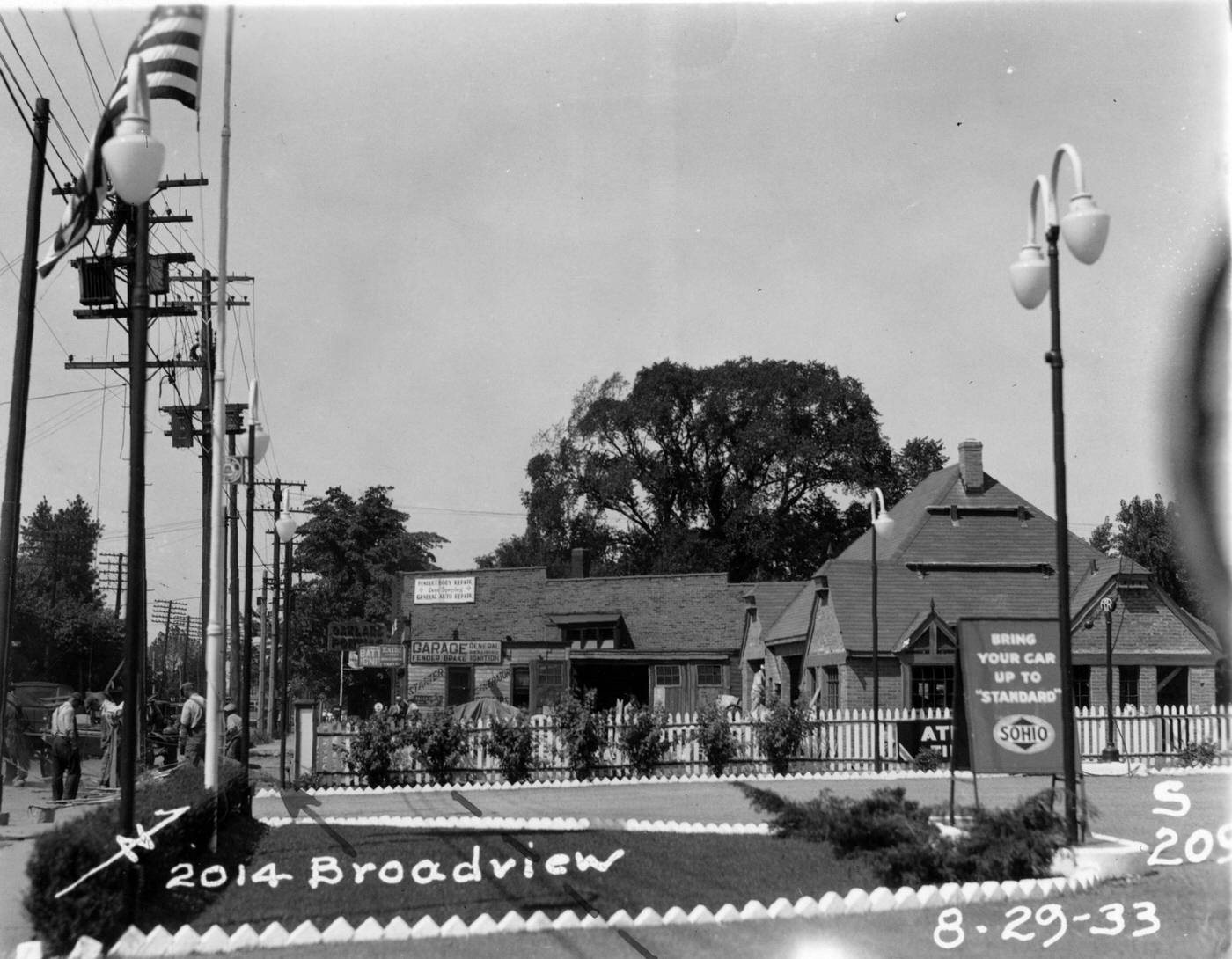

The Hungarian community, centered around Buckeye Road, was one of the largest Hungarian settlements outside Hungary. The 1930s marked a period of stability for this neighborhood. While acculturation was evident, especially among the American-born second generation who formed their own social and civic groups, many families retained their native language and customs. During the Depression, community organizations proved vital. The United Hungarian Societies coordinated charitable activities and welfare efforts, including establishing a job-placement service. The Women’s Hungarian Social Club formed charity committees, homeowners’ associations worked to prevent evictions, and Hungarian-language labor groups, including a section of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), offered support. Politically, the Hungarian community was a strong Democratic voting bloc, achieving significant representation on the city council and in municipal courts.

Cleveland’s Polish community reached its peak foreign-born population of 36,668 in 1930. The community sustained two Polish-language daily newspapers, Wiadomosci Codzienne and Monitor Clevelandski, and supported several Polish banks and savings and loan associations. Despite its size, the community experienced internal divisions, primarily over political developments in the newly independent Polish state. These differences, often reflecting support for rival Polish leaders like Pilsudski or Paderewski, were mirrored in their newspapers and sometimes hindered unified political action beyond the ward level. Joseph Sawicki was a prominent Polish political figure, serving as a municipal court judge during the 1930s. Due to restrictive U.S. immigration quotas enacted in the 1920s, the influx of new Polish immigrants had slowed, and the foreign-born segment of the community began a gradual decline.

The 1930s were a period of “transformation” for Cleveland’s Italian community. Political activism within the community increased significantly, largely in response to discrimination experienced during Prohibition and the economic hardships of the Depression. Italians organized to counter negative stereotypes and discriminatory practices, such as police targeting of the Little Italy neighborhood. Most politically active Italians aligned with the Democratic party. There was initially strong symbolic support for Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime in Italy, which was seen by some as restoring national pride. This was demonstrated by community donations to the Italian Red Cross during Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. However, this support largely evaporated after Italy declared war on France and England in 1940. World War II became a defining moment, leading to an identity crisis as Italian-Americans were classified as “enemy aliens.” The community then overwhelmingly redirected its loyalty and energies towards the American war effort. Many served in the U.S. military, and community organizations renamed lodges from Italian royalty to American historical figures, signifying a profound shift in identity.

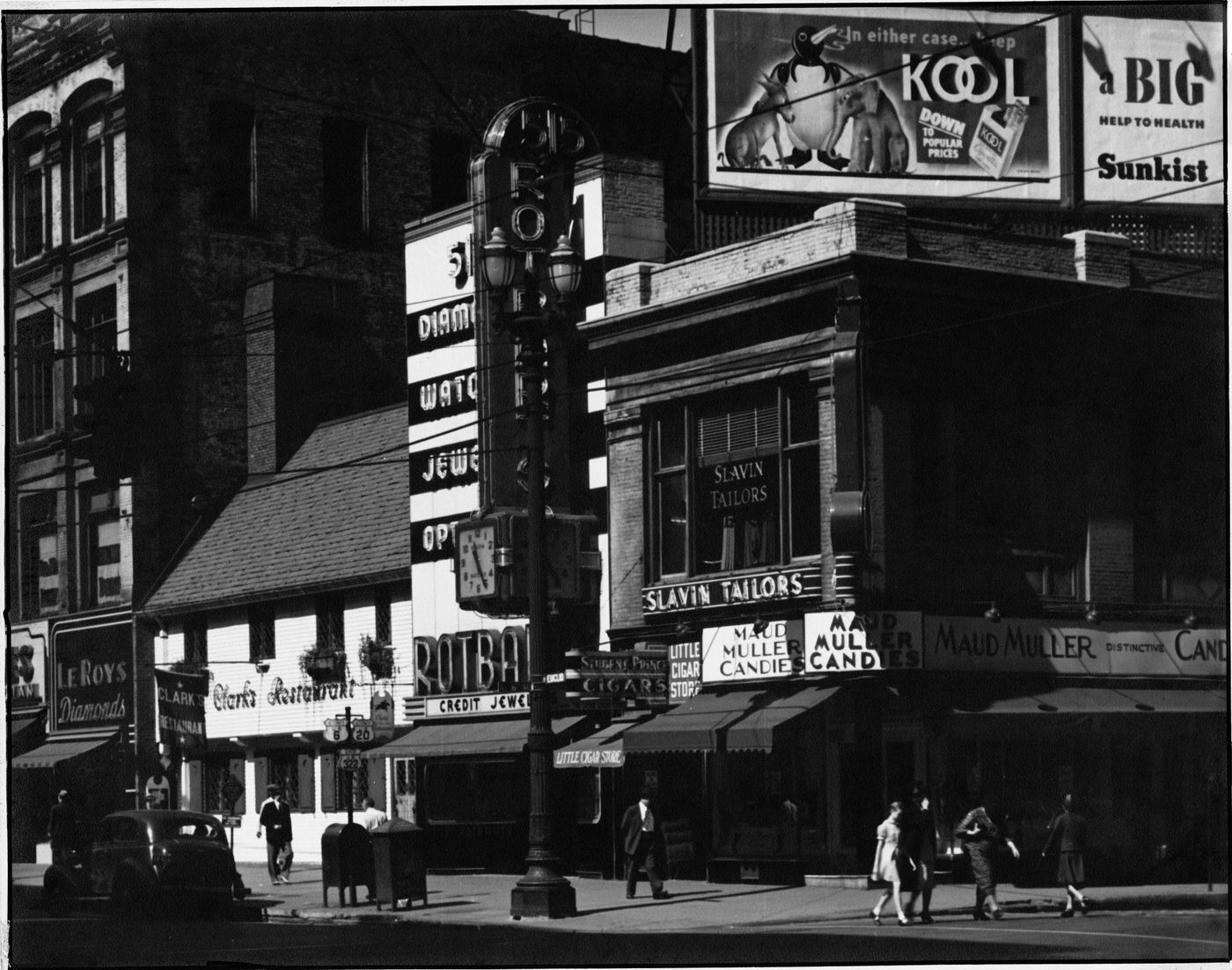

The Jewish community in Cleveland was substantial, with a population around 90,000 by 1920, concentrated in neighborhoods like Glenville, Kinsman, and Hough. East 105th Street was a vibrant commercial and cultural hub known as “Yiddishe Downtown”. The Kinsman Jewish Center, formally established in 1930 from an earlier congregation, became an important Orthodox institution. The Depression forced the abandonment of plans for a dedicated synagogue building, so the community center itself served this dual purpose. The congregation grew significantly, from fewer than 30 families to nearly 400 by 1940, and established a Hebrew school and a nursery. The personal story of Jerry Siegel, co-creator of Superman, offers a glimpse into the lives of Jewish families in Cleveland’s Glenville neighborhood during this era. His family faced financial hardship after his father’s death, and the cold, unheated apartments were a common reality for many.

Czech immigrants had earlier established “Little Bohemia” around Broadway and E. 55th Street, a thriving settlement leading into the 1920s. By the 1930s, the 1924 National Origins Act had significantly curtailed new immigration from Czechoslovakia. The community maintained institutions like St. Wenceslas Church and the Bohemian National Hall, which served as a center for various societies and Czech language classes. Protestant missions also catered to the Czech population.

Cleveland was also a major center for Slovaks, with an estimated 35,000 residing in the city by 1918. They had established neighborhoods and robust institutions. During the 1920s and 1930s, Cleveland Slovaks were actively involved in advocating for the fulfillment of the Pittsburgh Agreement, which concerned power-sharing in the newly formed nation of Czechoslovakia. Like other Eastern European groups, Slovak immigration significantly decreased during this period due to U.S. quota laws.

Ukrainian immigrants arriving between World War I and World War II settled primarily in Cleveland’s Tremont neighborhood. They established the Ukrainian National Home in the 1920s, which served as a vital center for ethnic pride and cultural events throughout the 1930s.

The African American community in Cleveland numbered 72,000 by 1930. The Central Avenue ghetto, the primary residential area for Black Clevelanders, consolidated and expanded eastward during this time. This expansion was often a result of white residents moving to outlying areas and increasing discrimination that limited housing options for African Americans, even those of middle-class status. Discrimination was pervasive in public accommodations, with restaurants, theaters, and amusement parks like Euclid Beach Park often excluding or segregating Black patrons. Public schools in predominantly Black neighborhoods also faced discriminatory practices, with curriculums sometimes altered from liberal arts to manual training. Despite these hardships, the growth of the Black population created new opportunities for businesses and professionals within the community. Institutions like the Phillis Wheatley Association, which expanded its building in 1928, and the NAACP played crucial roles in providing support and advocating for civil rights. The Future Outlook League (FOL), founded in 1935 by John O. Holly, effectively used boycotts with the slogan “Don’t Spend Your Money Where You Can’t Work” to pressure white-owned businesses in Black neighborhoods to hire African American workers. Politically, the Black community gained influence. Starting in 1927 and for eight years thereafter, Black councilmen held a balance of power on the city council, leading to key appointments of African Americans to positions like the Civil Service Commission and the Board of Education, and an end to segregation at City Hospital. While many Black Clevelanders remained Republican at the local level during the 1930s, there was a significant shift towards the Democratic party in national politics, largely influenced by New Deal relief policies. This political realignment would have lasting consequences for the city’s future.

Industry and Labor: The Changing World of Work

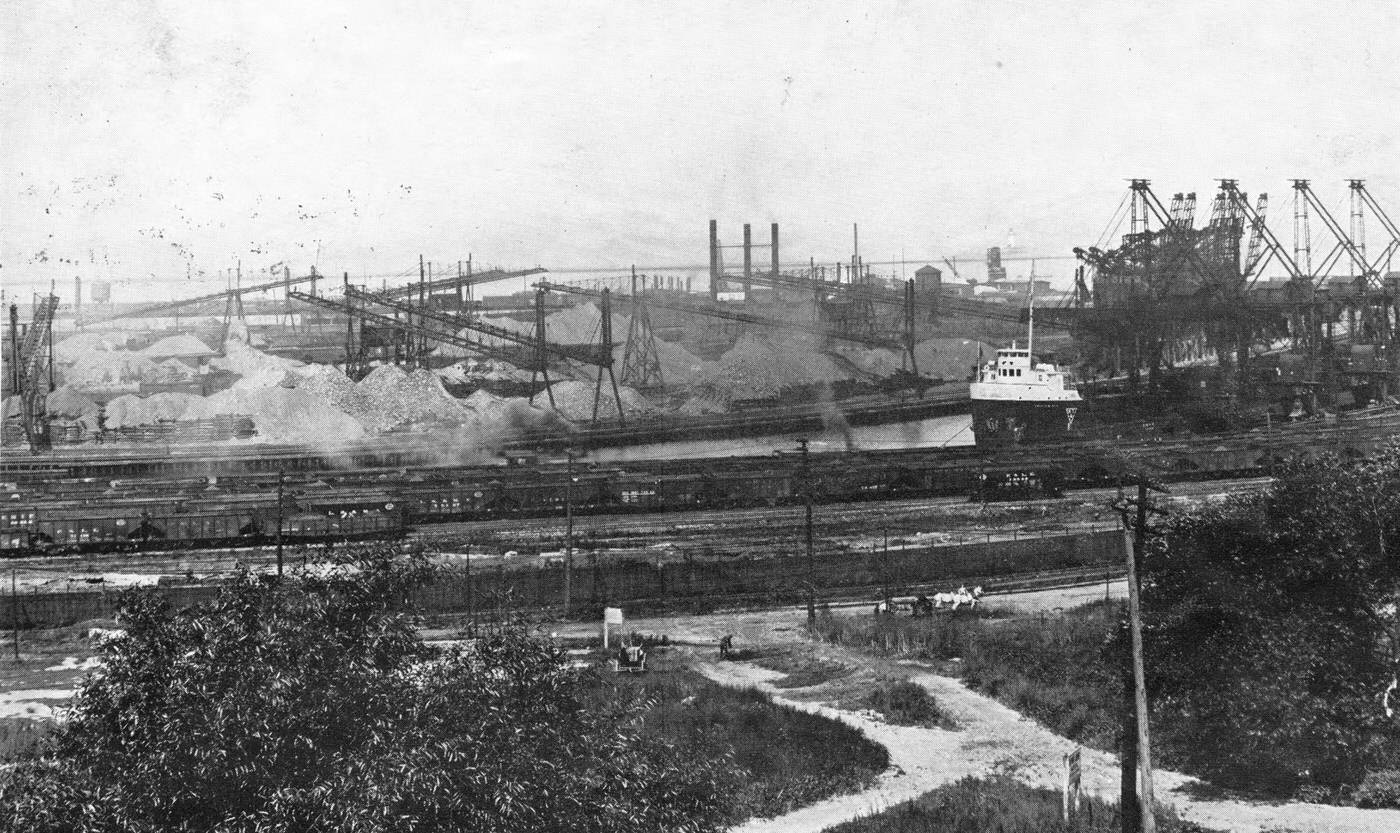

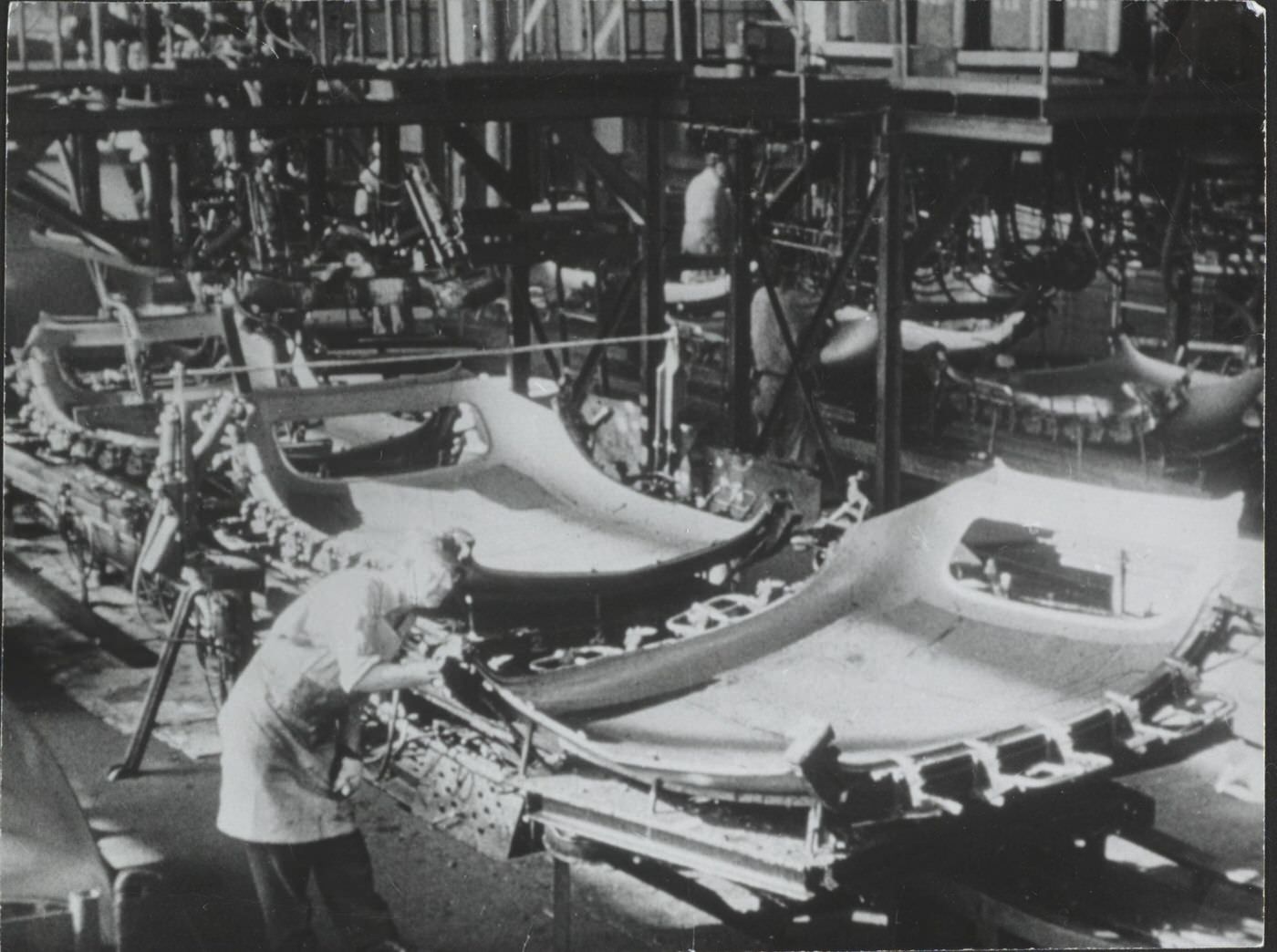

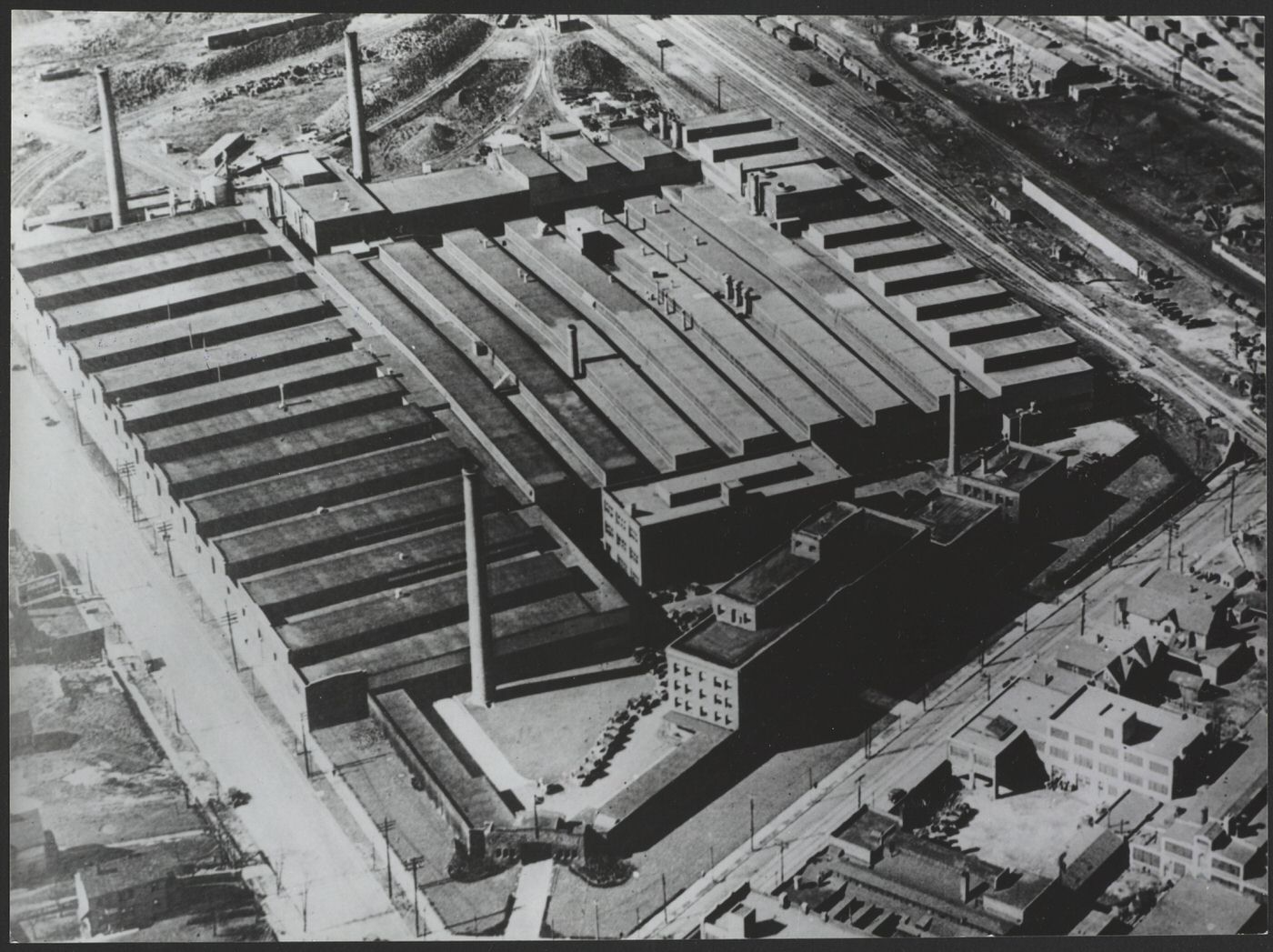

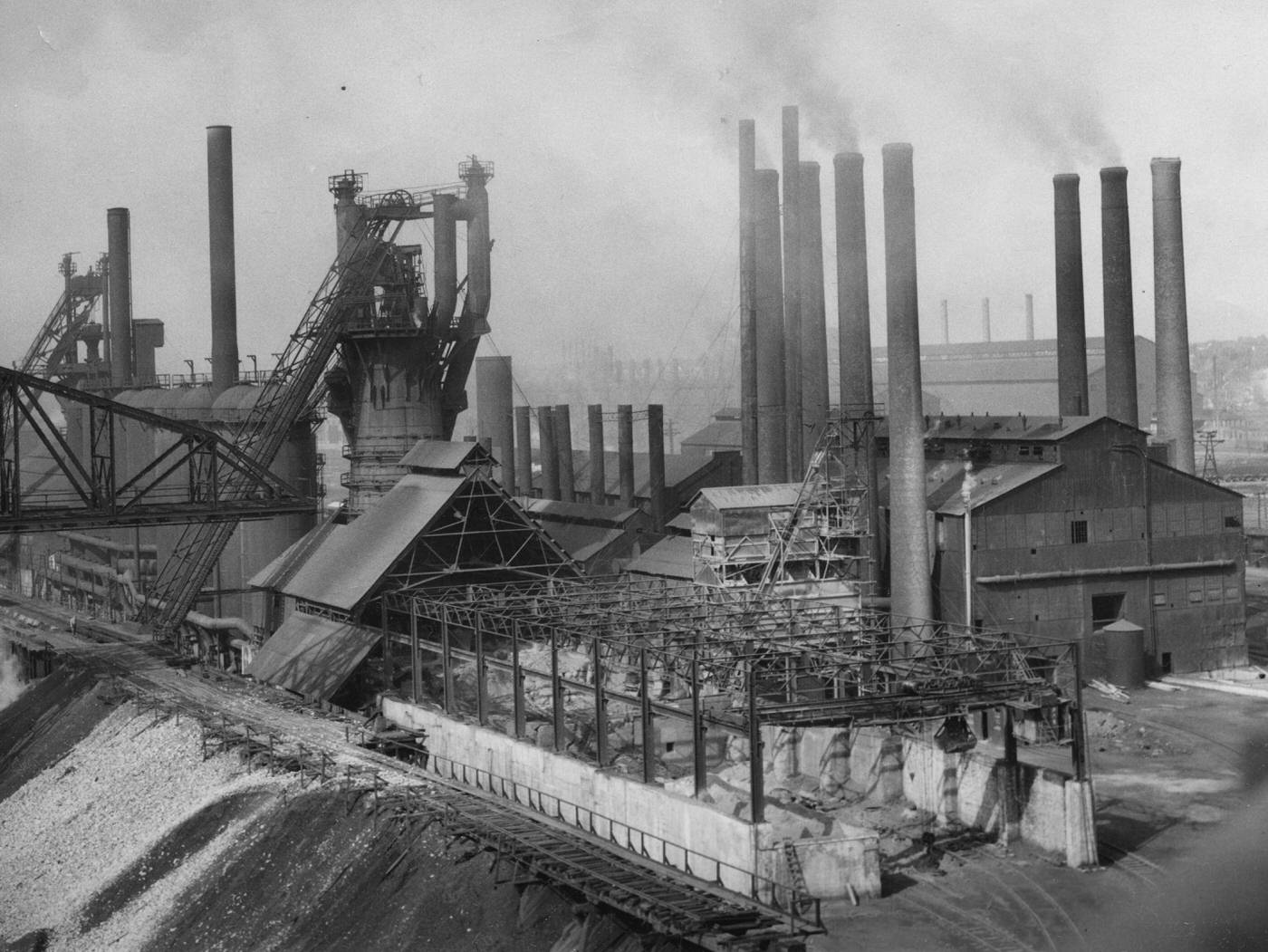

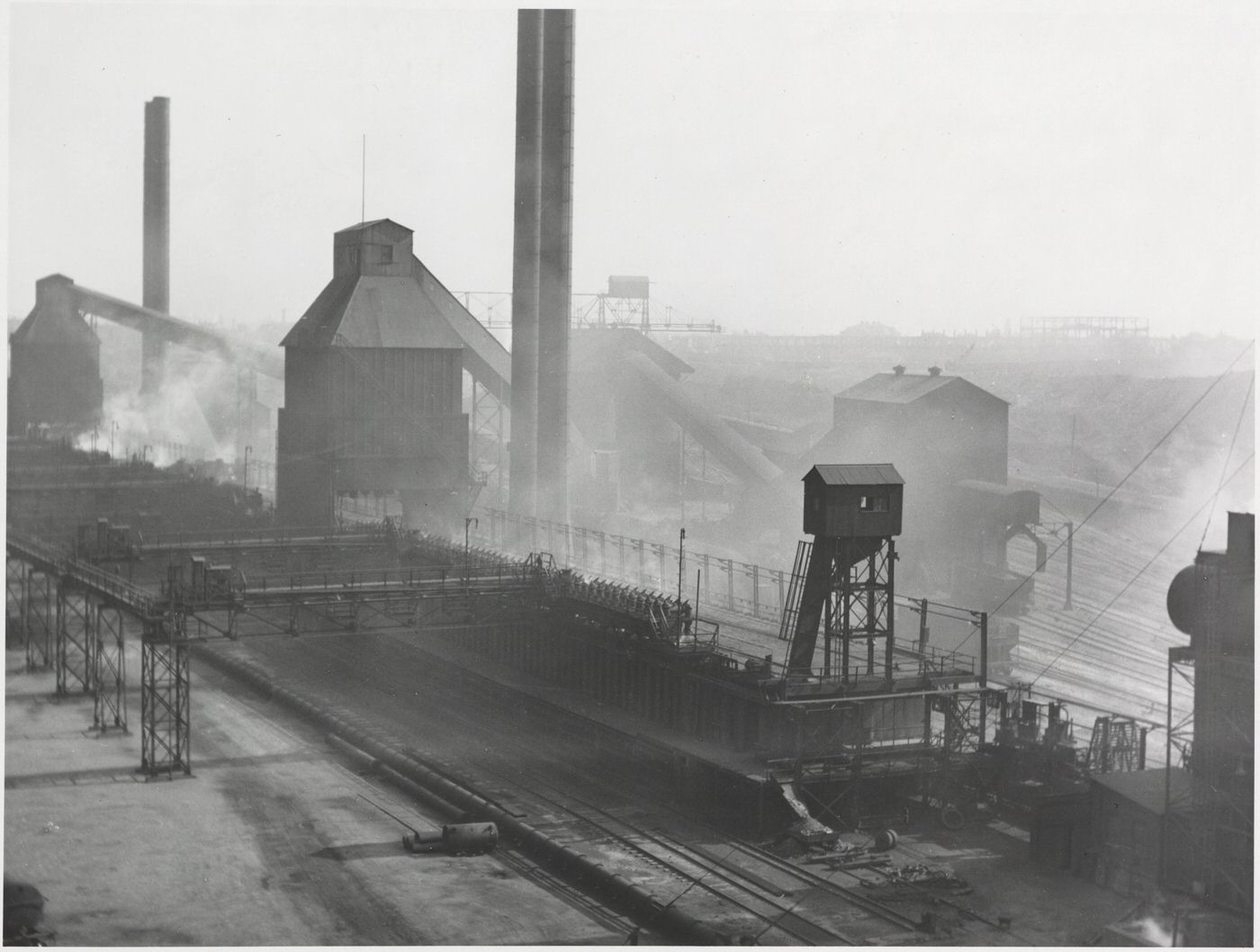

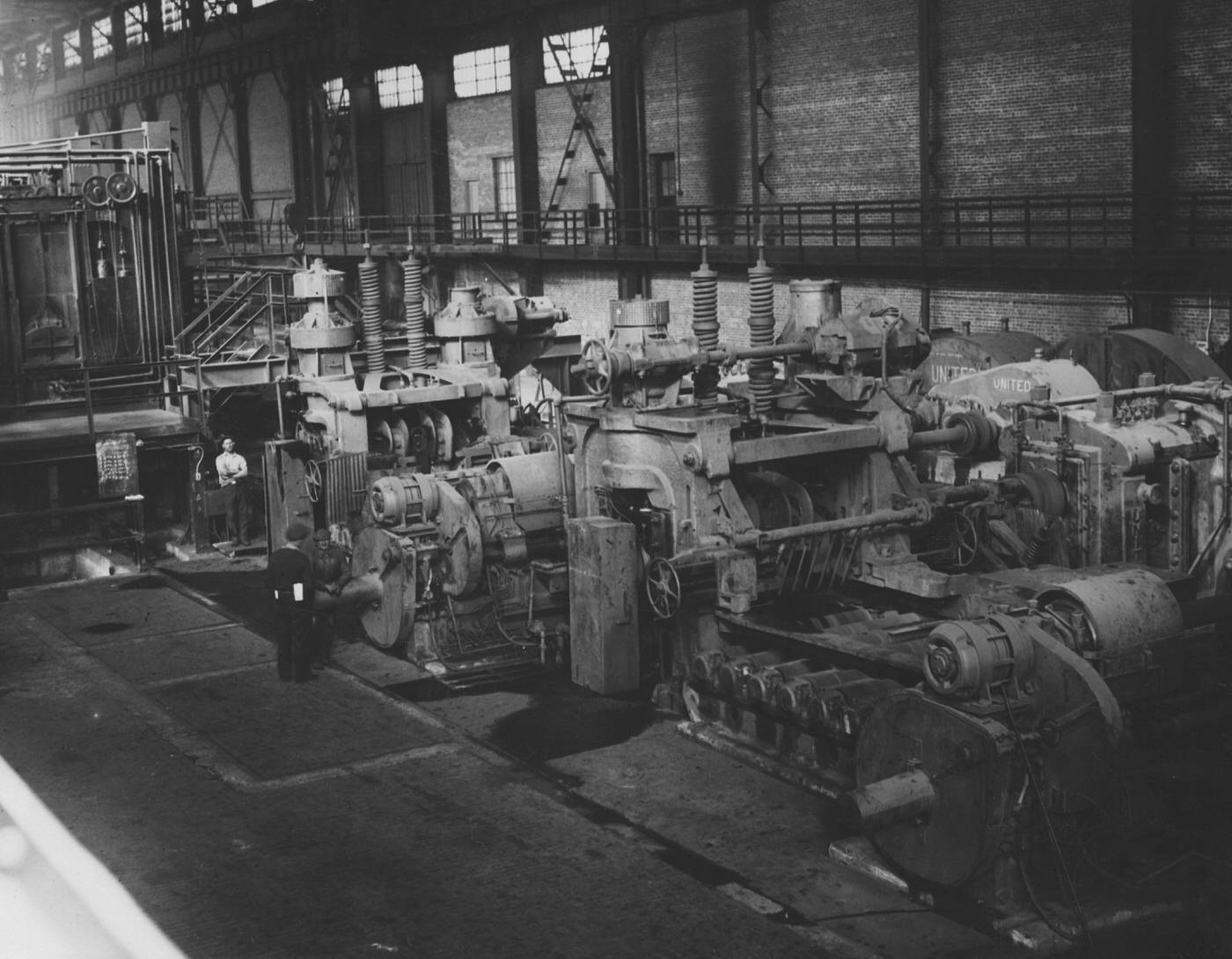

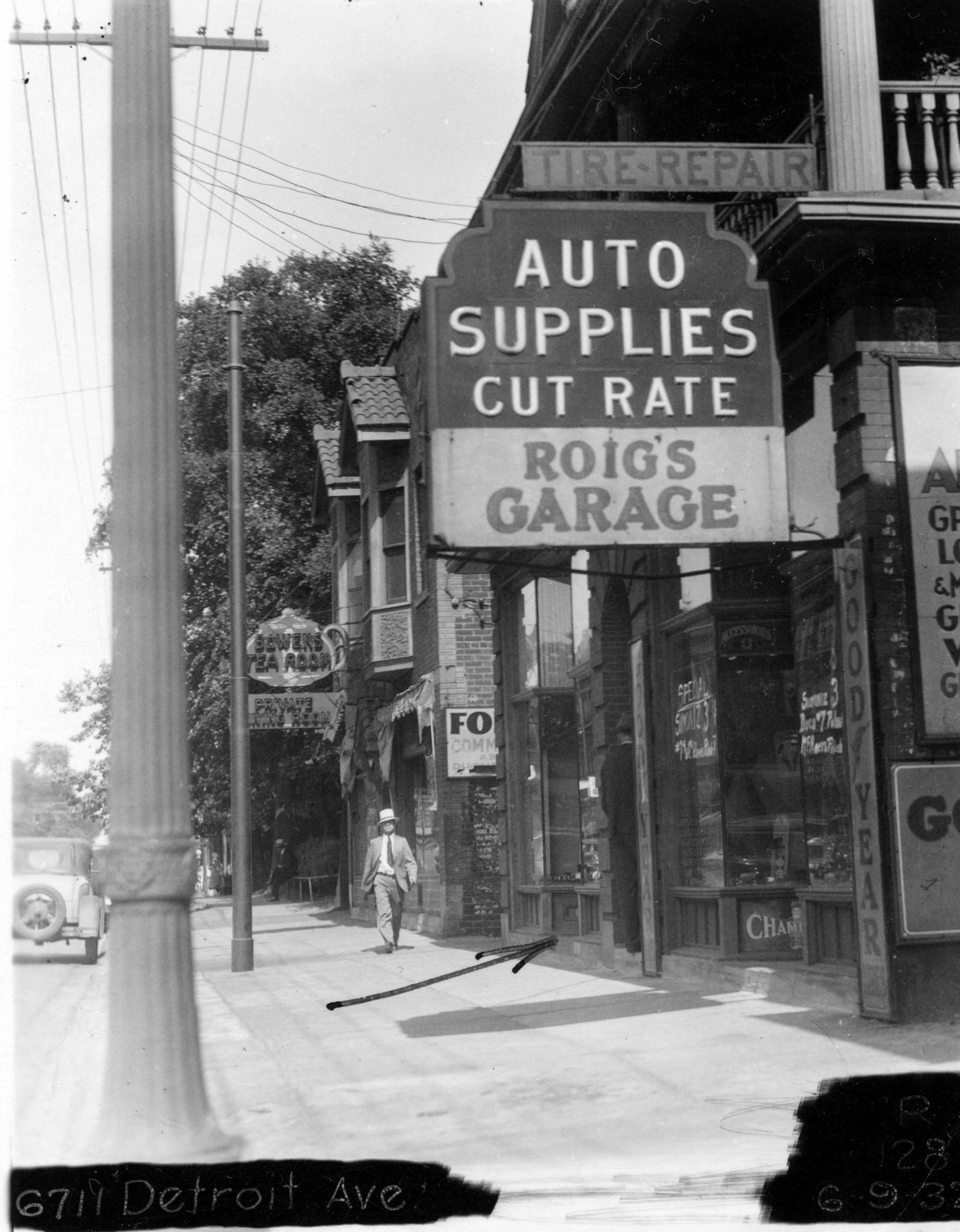

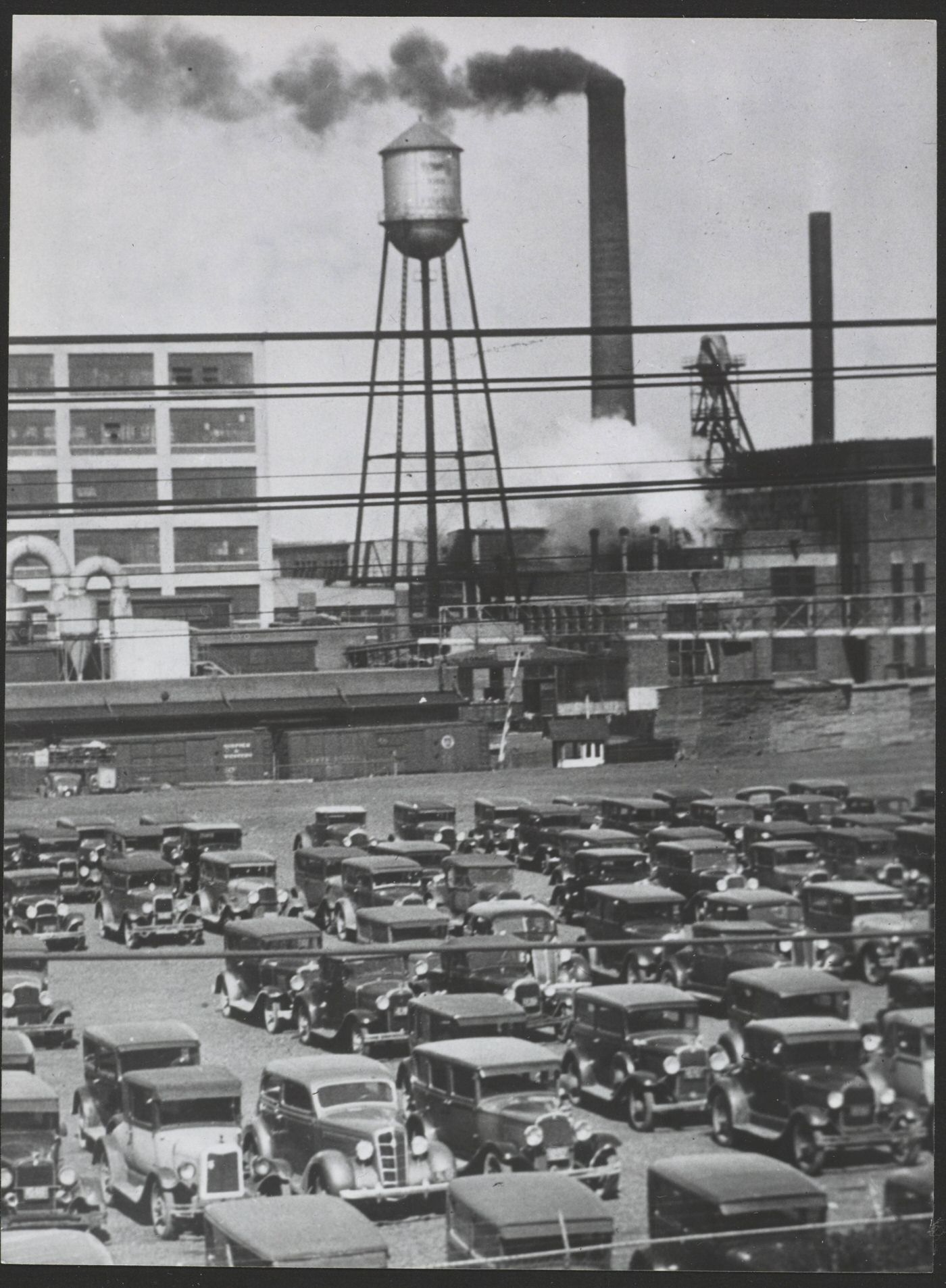

Cleveland’s economy in the 1930s, characterized by its diverse industrial base specializing in automotive manufacturing, machine tools, and industrial equipment, faced unprecedented challenges due to the Great Depression. The era of rapid industrial expansion that had defined the city in previous decades slowed considerably after 1920 and was severely disrupted by the economic collapse.

The automotive industry in Cleveland underwent significant transformation. While the 1930s saw the failure of most local automobile manufacturing companies, the city, particularly its East Side industrial corridor, maintained its importance as a major supplier of automotive parts. Midland Steel Products Company, formerly Parrish and Bingham Co., located on West 106th Street, emerged as a key national supplier of steel automotive frames and axle housings, becoming the country’s largest producer of automotive frames during this period. The national 1937-38 recession delivered another blow to the auto industry, with sales and production plummeting by over 40%. This downturn was attributed to labor strife-induced wage increases and rising raw material costs, which led manufacturers to raise car prices in late 1937, further depressing demand. This shift from complete vehicle assembly to a focus on component manufacturing signaled a long-term restructuring of Cleveland’s role in the automotive sector.

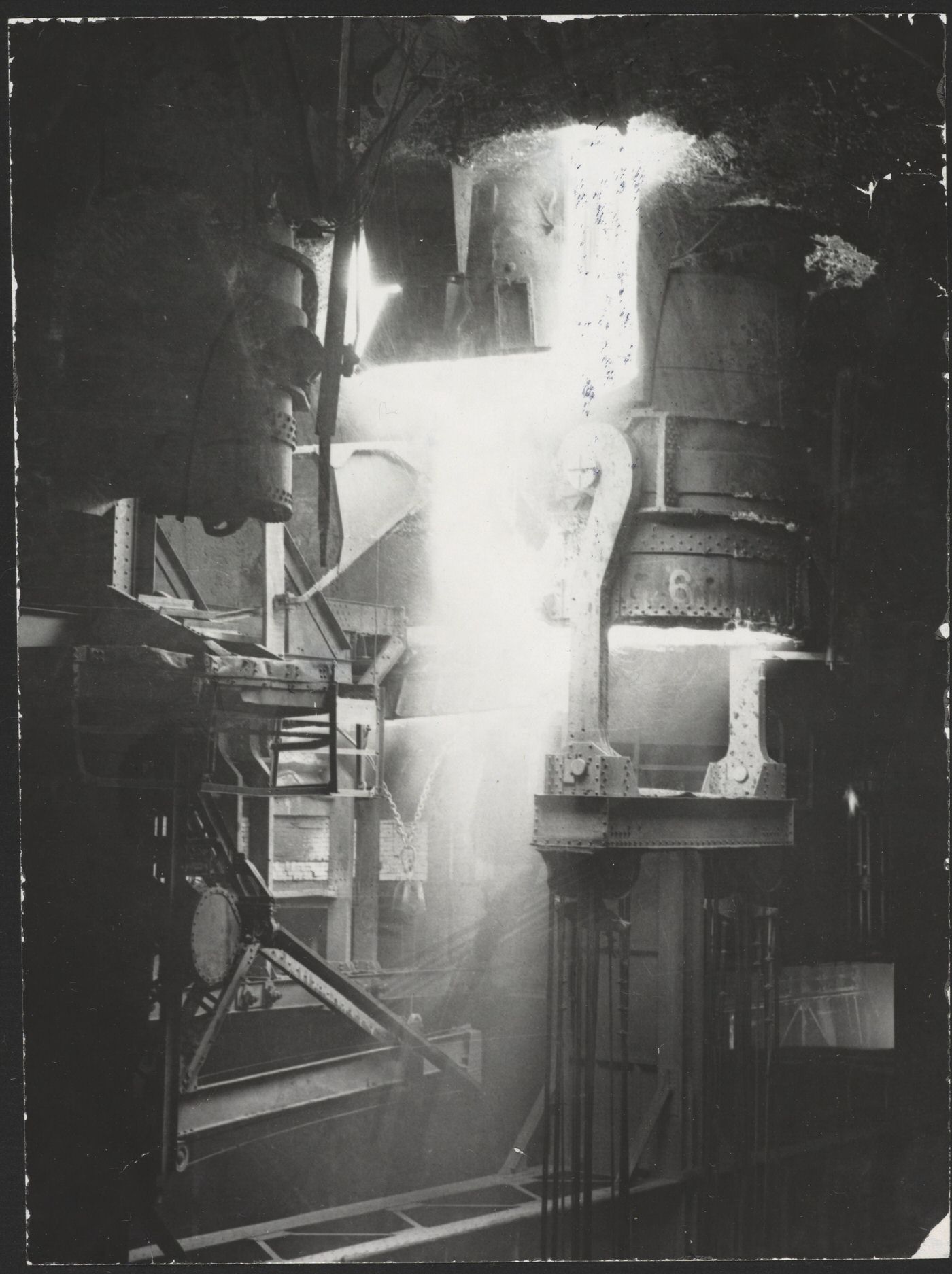

The steel industry, a traditional backbone of Cleveland’s economy, was also hit hard. Markets for steel products, especially heavy structural shapes, shrank dramatically. Companies that produced light-rolled sheets used in automobiles and home appliances fared comparatively better. Youngstown Sheet & Tube, for example, struggled due to delays in modernizing its facilities to produce these in-demand hot-strip mill products. Republic Steel, despite facing similar geographical disadvantages to Armco (neither being located directly on the Great Lakes or the Ohio River), managed its operations more effectively due to its existing capacity in light-steel production and a strategy of aggressive acquisitions after 1935. U.S. Steel utilized the Depression as an opportunity to modernize its plants and diversify into consumer goods markets, increasing its production of steel for cars and appliances. Despite the economic turmoil, Ohio, and Cleveland within it, remained a critical center for the American steel industry, with most major national steel corporations maintaining significant operations in the state.

Cleveland’s garment industry, which had been a leading national center in the 1920s, began a period of decline during the Depression. Manufacturers who managed to survive the initial economic shock found themselves facing a newly empowered and assertive labor movement. Working conditions in the industry, while sometimes better than in garment centers like New York, often involved low wages and long hours, particularly in the smaller workshops located in ethnic neighborhoods. Some larger firms, like Joseph & Feiss, had implemented progressive “welfare capitalism” policies in the 1910s and 1920s, offering better working environments and employee programs, which may have delayed unionization efforts there. Richard Feiss, the architect of these programs, was forced out of the company in 1925 because his initiatives were deemed too costly by other family members. It wasn’t until 1934, amidst the Depression and New Deal labor reforms, that the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America successfully organized the workers at Joseph & Feiss.

Regarding manufacturing employment, Cleveland in 1930 ranked second only to Detroit in the proportion of its workforce engaged in industry. This heavy reliance on manufacturing meant that Cleveland’s workers often experienced more severe hardship during economic downturns, though they also benefited more during periods of growth. Despite the Depression, there were signs of continued innovation; the number of Cleveland firms with industrial research laboratories increased from 23 in 1927 to 38 in 1931, and further to 53 by 1940. For about half a century after the 1890s, approximately 7% of Cleveland’s workforce was employed in its numerous garment factories.

The 1930s were a period of intense labor union activity and significant growth for industrial unions. The passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) in 1933, which affirmed workers’ right to organize, spurred the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) to intensify its efforts to unionize workers along industry-wide lines, rather than by specific crafts. This approach often brought the CIO into conflict with the established American Federation of Labor (AFL). In Cleveland, this dynamic led to the formation of the Cleveland Industrial Union Council (CIUC) by 1938. The CIUC became the local CIO representative after several industrial unions—including the United Auto Workers (UAW), Amalgamated Clothing Workers, Textile Workers, Steel Workers (Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel & Tin Workers), and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU)—were expelled from the AFL’s Cleveland Federation of Labor (CFL) in 1937.

A pivotal moment in local labor history was the sit-down strike at the General Motors Fisher Body plant on Coit Road in December 1936. This action was a significant catalyst in the broader effort to unionize the automobile industry. The CFL initially showed support for the strikers but later condemned the CIO-led work stoppage. The “Little Steel” Strike of 1937 was another major confrontation, involving the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC), a CIO affiliate, striking against independent steel producers like Republic Steel, Youngstown Sheet & Tube, and Inland Steel. In Cleveland, the strike led to tense situations. Mayor Harold Burton revoked Republic Steel’s permit to use a local airfield to transport non-striking workers. Ohio Governor Martin Davey deployed the National Guard to protect employees wishing to return to work, and the Cuyahoga County Sheriff briefly declared military rule. Violence erupted at Republic Steel’s Corrigan-McKinney plant between striking workers and those attempting to enter. The strike ultimately dissipated by late August 1937, with the companies resisting union recognition until the early 1940s, when decisions by the National Labor Relations Board compelled them to sign contracts. In the garment industry, the ILGWU and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, aided by New Deal labor legislation, successfully organized many workers. The internal dynamics of the labor movement were also complex, with ideological struggles playing out. The national CIO held its “Purge” Convention in Cleveland in 1949, expelling leftist elements, a move that eventually facilitated the merger with the AFL. This event, though occurring after the 1930s, had its roots in the ideological currents and power struggles that shaped the labor movement during the Depression. The decade fundamentally altered the balance of power between labor and capital in Cleveland, with industrial unionism emerging as a formidable force.

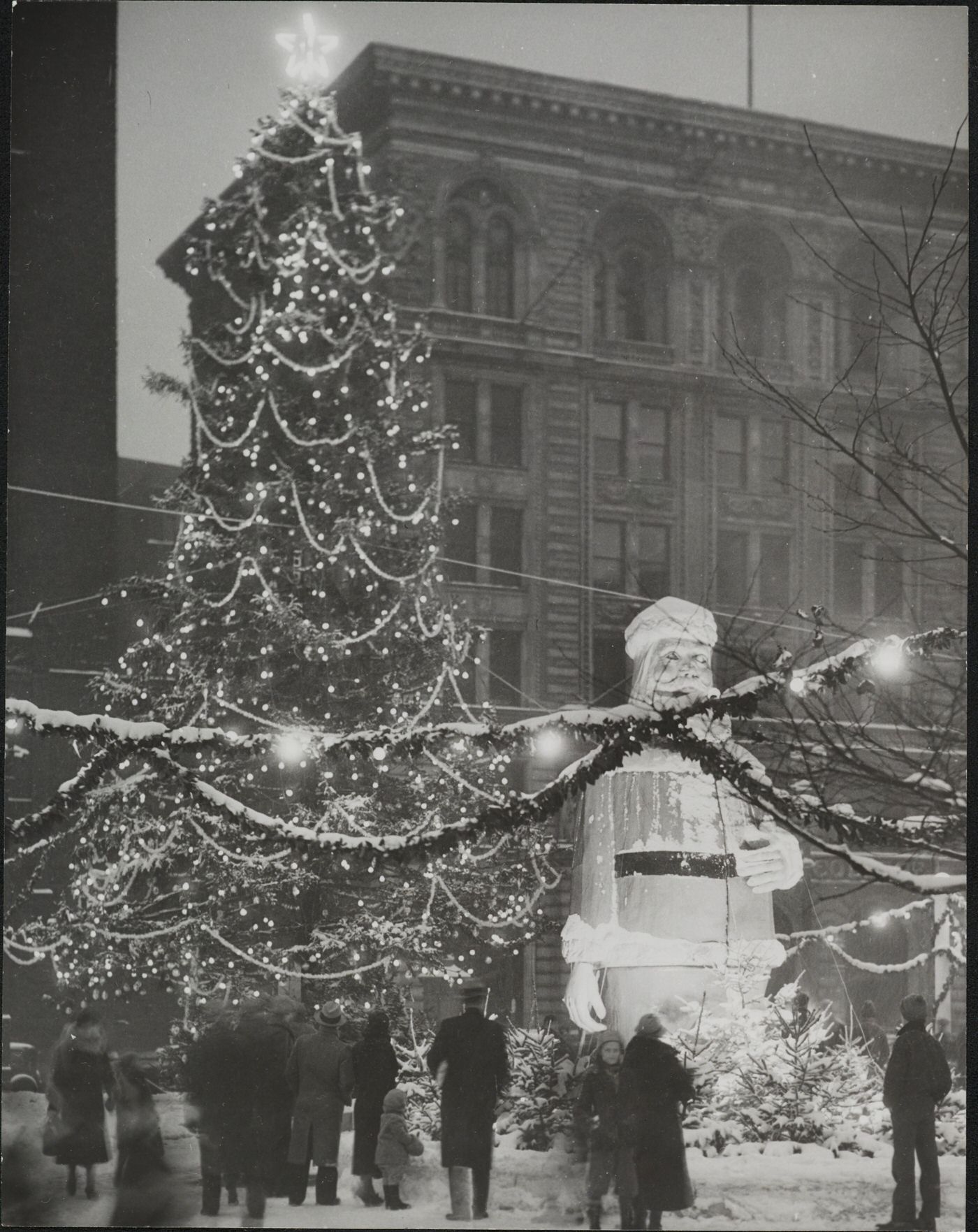

The 1930s in Cleveland were a decade of sharp contrasts. Deep economic hardship cast long shadows, yet the period also witnessed vibrant cultural expressions and determined efforts to maintain civic life and provide leisure for its citizens.

Crime and Insecurity

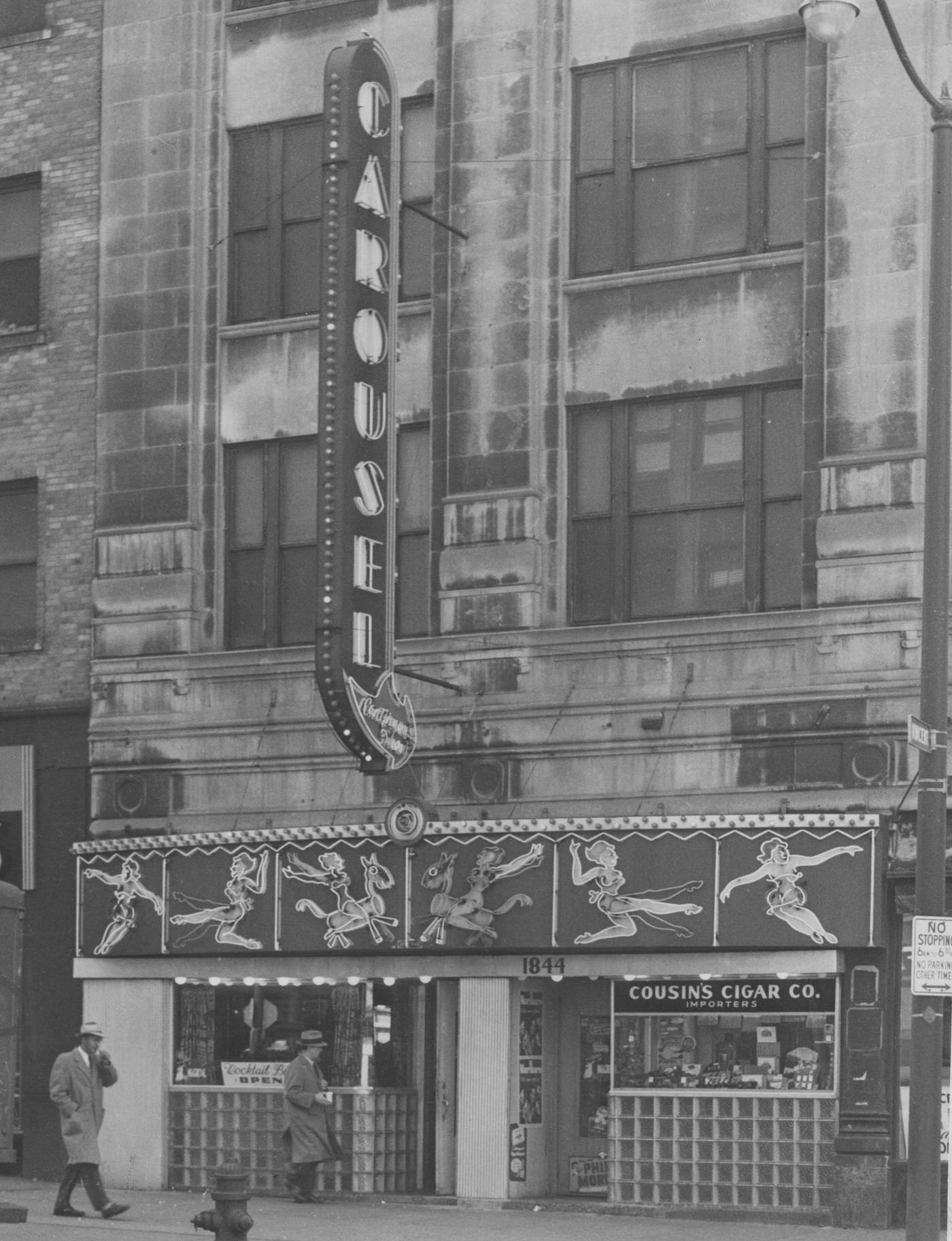

The economic desperation of the Great Depression contributed to a “growing feeling of insecurity in life and property” among Clevelanders, with high rates of murder and property crime reported. The era of Prohibition, which officially ended in Ohio in December 1933 , had already fostered a significant rise in organized crime, leaving a legacy of illicit networks and violence. Nationally, murder rates peaked during the 1930s , and studies later indicated that increased relief spending during this period was correlated with a reduction in property crime rates in large American cities, suggesting a link between economic aid and public safety.

The most horrifying manifestation of crime during this period was the reign of the Cleveland Torso Murderer, also known as the “Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.” Between 1935 and 1938 (some sources indicate the first murder may have been as early as 1934), this elusive serial killer terrorized the city. At least twelve, and possibly thirteen or more, victims, mostly transients and individuals living in the shantytowns of Kingsbury Run’s “Hobo Jungle,” were brutally murdered and dismembered with surgical precision. Despite the intense efforts of Safety Director Eliot Ness and the Cleveland Police, the killer was never caught. Ness, in a desperate measure, ordered the shantytowns in Kingsbury Run to be burned to the ground, hoping to disrupt the killer’s activities. The gruesome case captivated and horrified the public, generating a media frenzy as newspapers reported on the killings and the frustrating lack of suspects.

Entertainment and Leisure

Despite the grim realities, Clevelanders sought solace and diversion in various forms of entertainment.

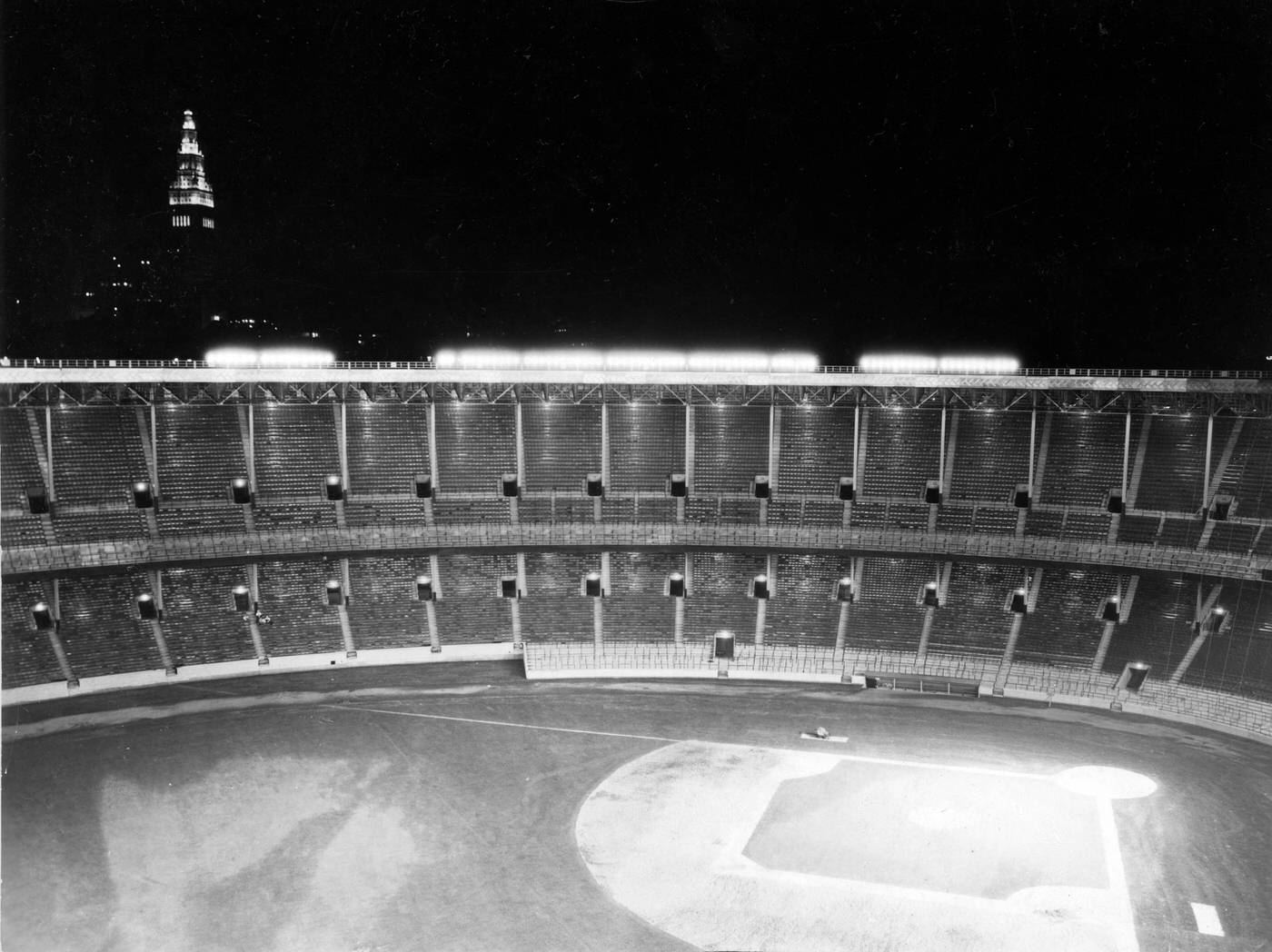

Radio became an increasingly central part of daily life. By the end of the 1930s, local stations offered diverse programming, including news, live remote broadcasts from hotel dining rooms, nightclubs, Severance Hall, and the Public Auditorium. Sports coverage was popular, with WTAM’s Tom Manning becoming a well-known voice for Cleveland Indians baseball games broadcast from League Park. Ethnic programming, often aired on Sunday mornings, catered to the city’s diverse immigrant communities. Stations also produced their own scripted shows and musical productions.

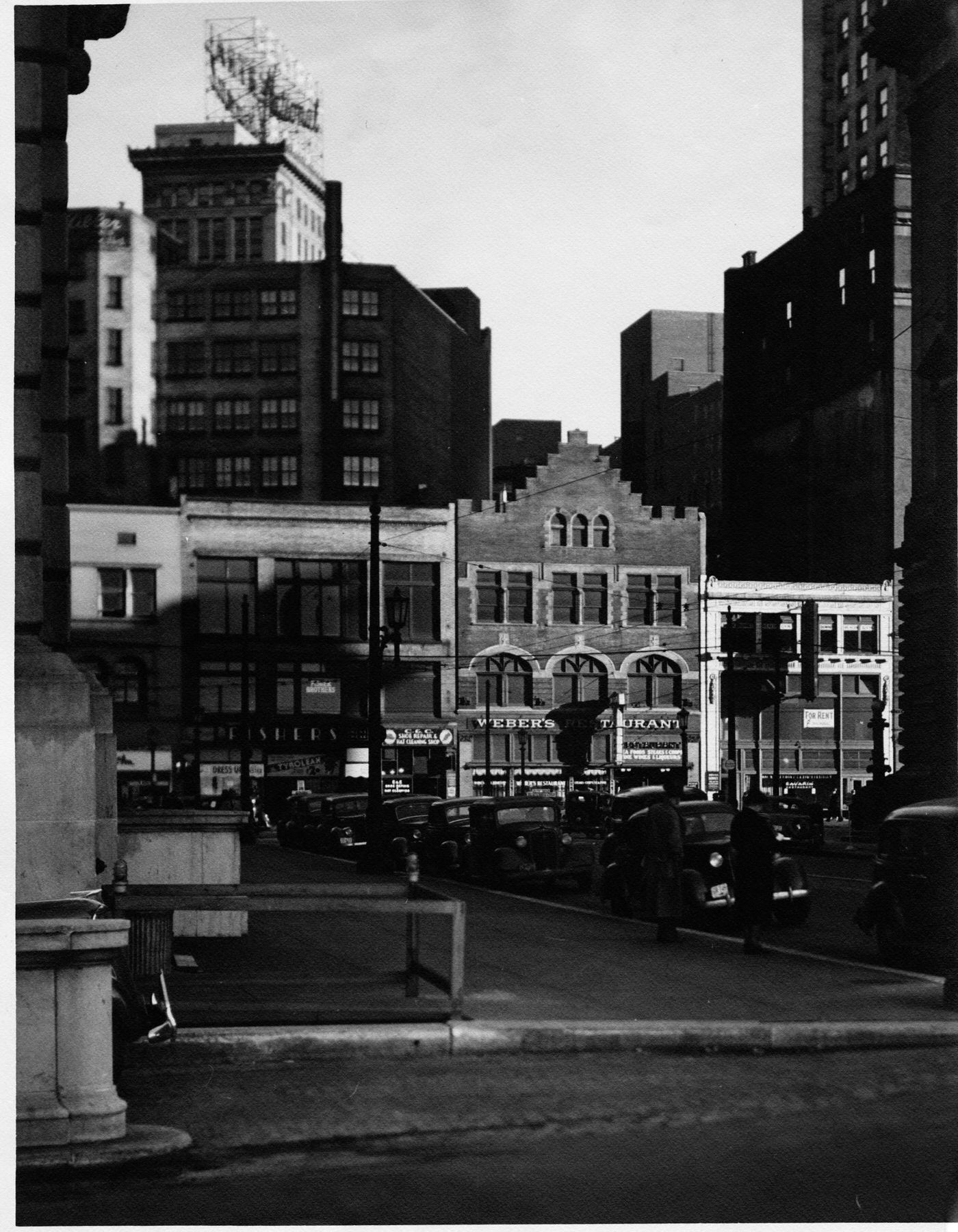

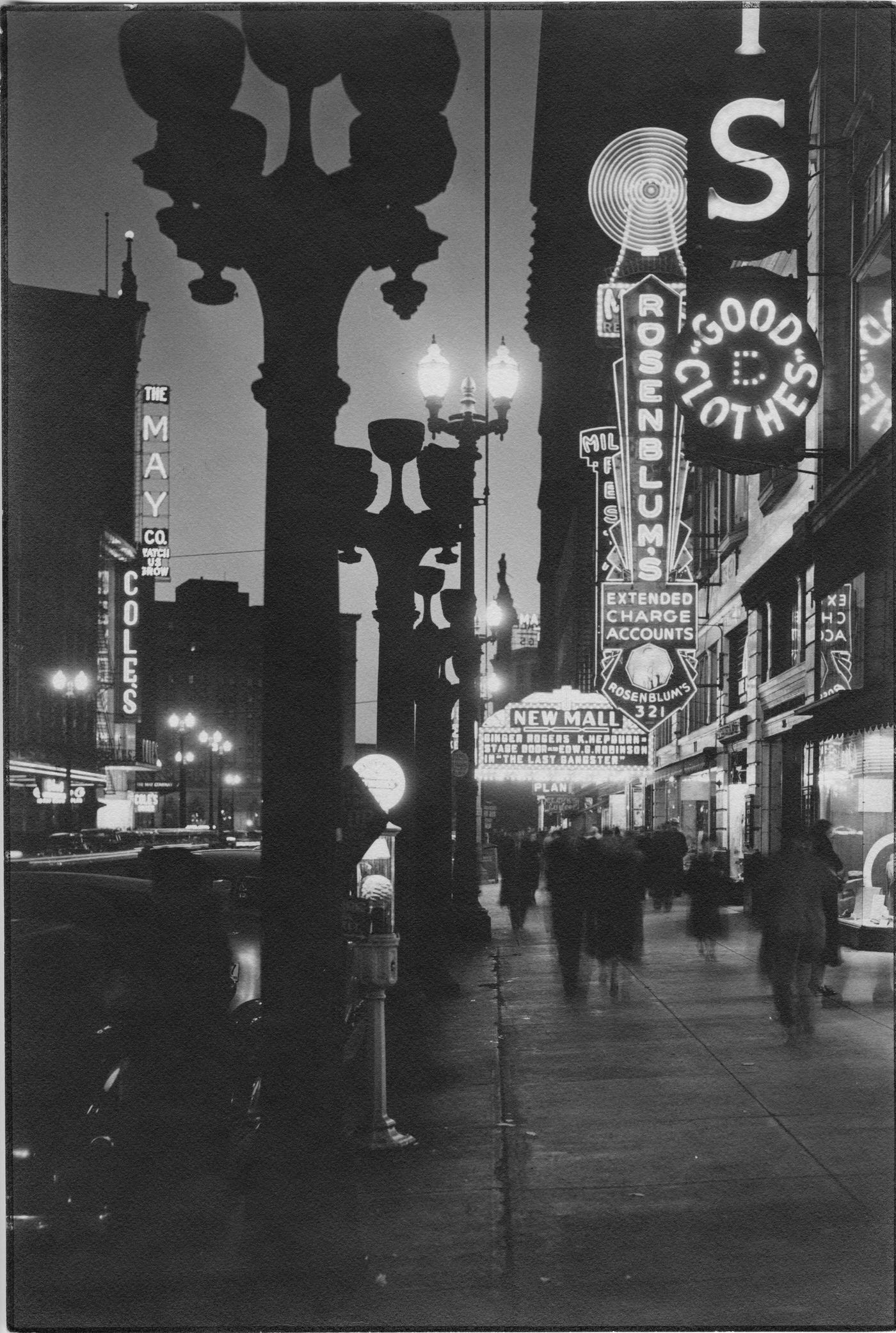

Movies remained a major form of entertainment. The grand movie palaces of Playhouse Square, constructed in the 1920s, continued to draw audiences. While live theater faced declining attendance due to the Depression and the rise of Hollywood films, movies offered an affordable escape. Some films were even set or shot in Cleveland, reflecting the city’s presence on the national stage.

The jazz scene in Cleveland, which had blossomed in the 1920s, continued to thrive. The 1930s saw increased racial integration in jazz concerts and club sessions. Val’s in the Alley, located at Cedar Avenue and East 86th Street, gained national fame due to the residency of the legendary pianist Art Tatum. His presence attracted other jazz greats like Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman for impromptu jam sessions. Several Cleveland musicians, including trumpeter Pee Wee Jackson, future bandleaders Artie Shaw, Guy Lombardo, and Woody Herman from the 1920s, and later figures like trumpeter George Thow (Dorsey Brothers Orchestra), drummer Morey Feld (Benny Goodman), and the influential Tadd Dameron (a key figure in the emerging be-bop style), achieved national prominence.

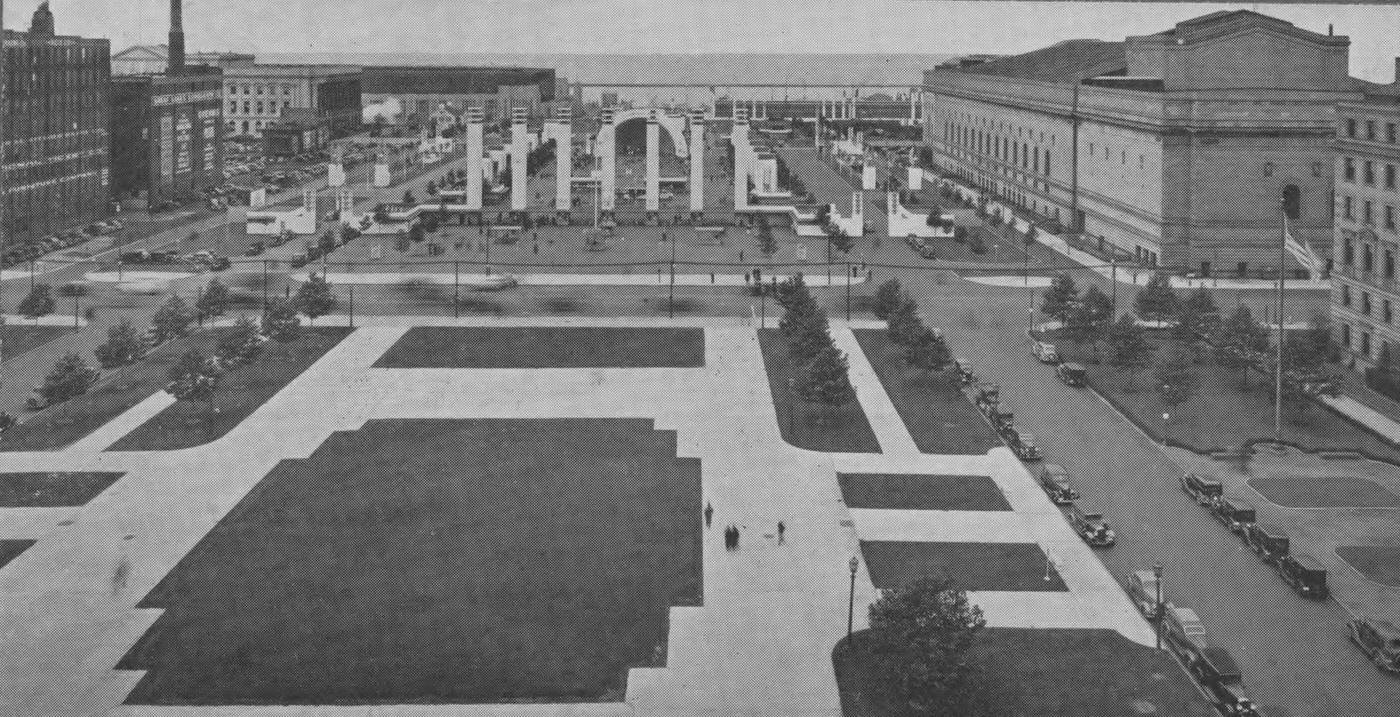

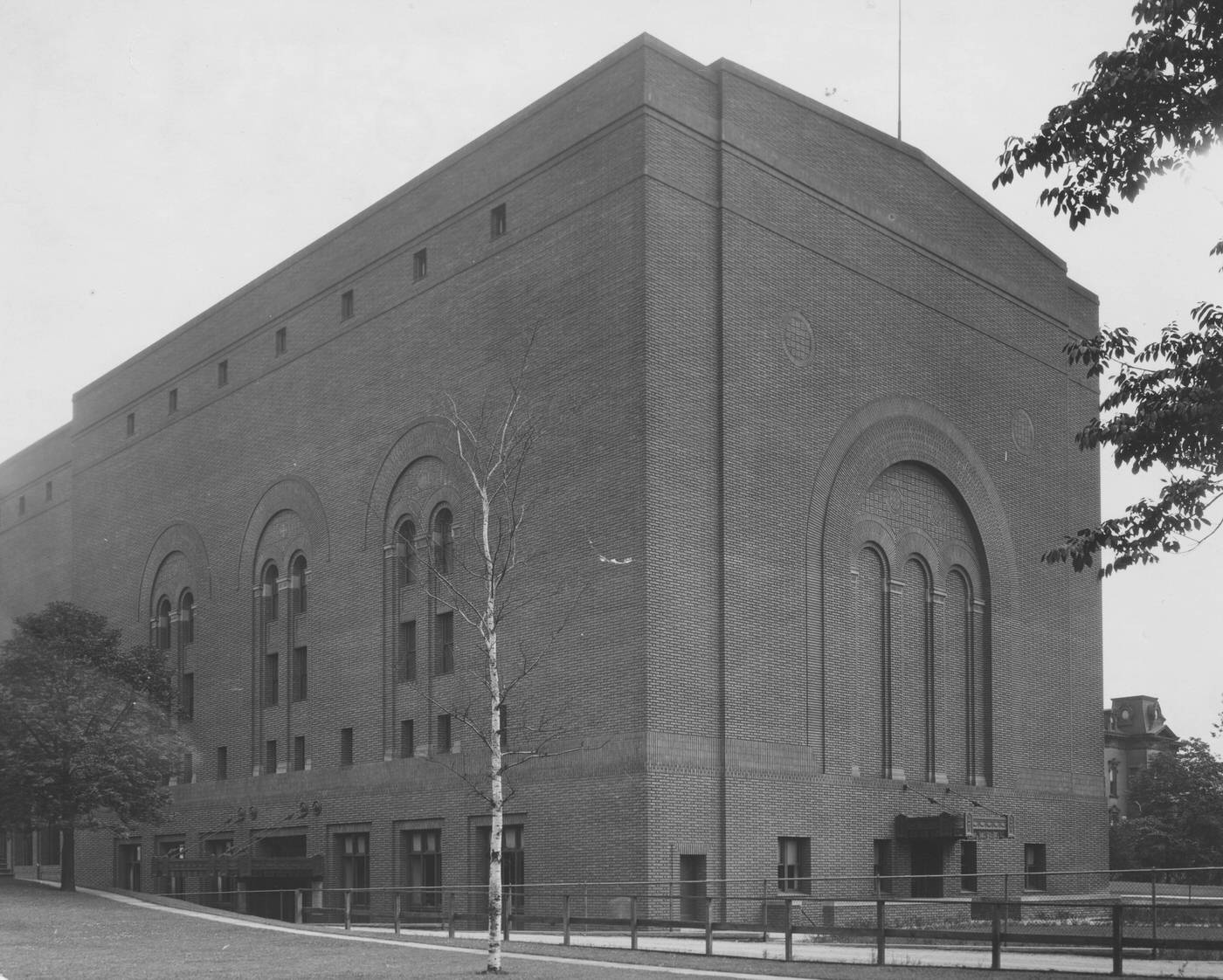

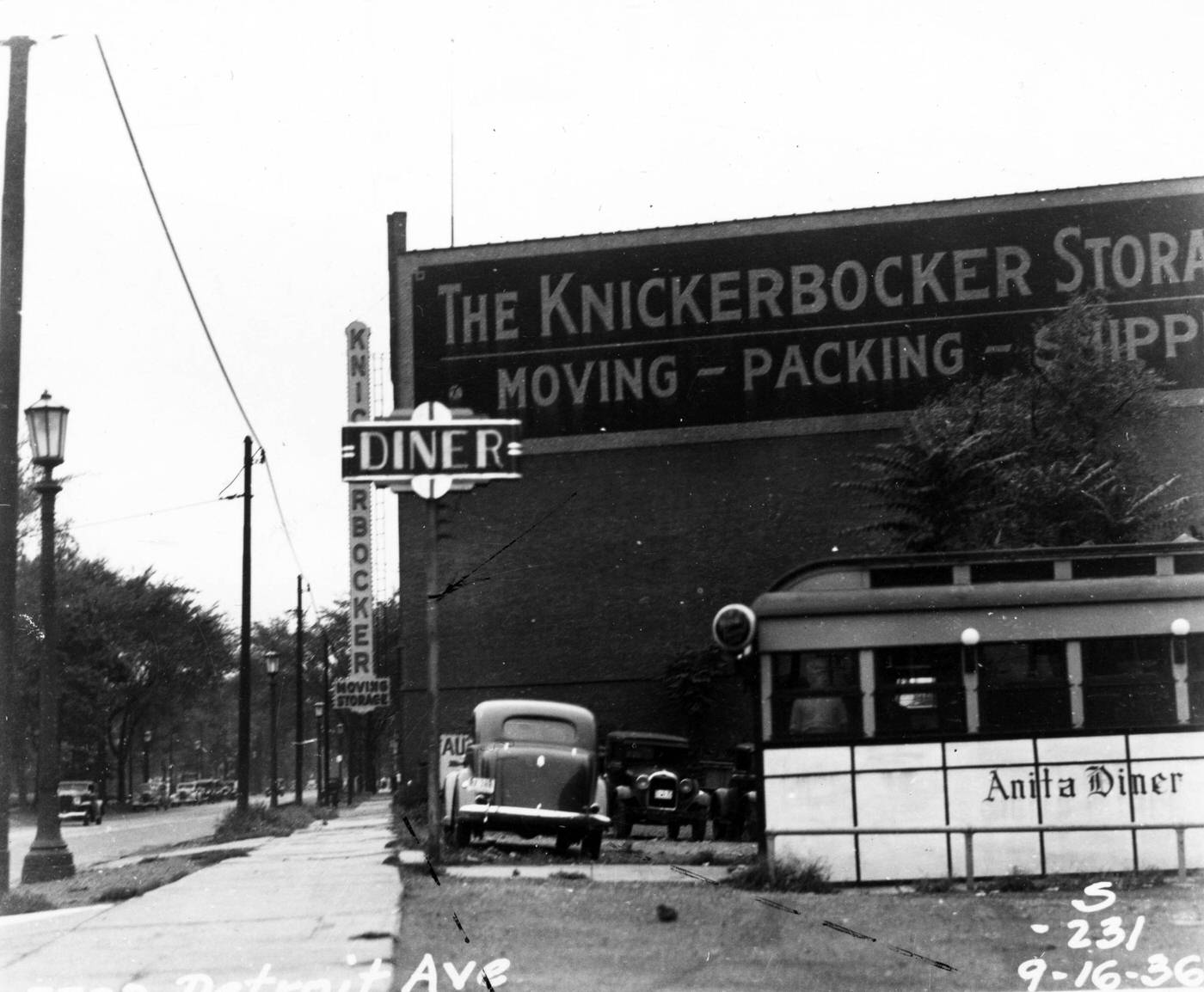

The Public Auditorium remained a key venue for large events. It hosted the Republican National Convention for the second time in 1936 (the first being in 1924) and was a regular site for numerous industrial shows and expositions, solidifying Cleveland’s reputation as a leading national convention city. The addition of the Music Hall in 1929 and an underground exhibition hall in 1932 further expanded its capabilities. Smaller venues, like the Irish American Hall on Detroit Avenue, served as popular spots for community dances, social club meetings, and ethnic gatherings.

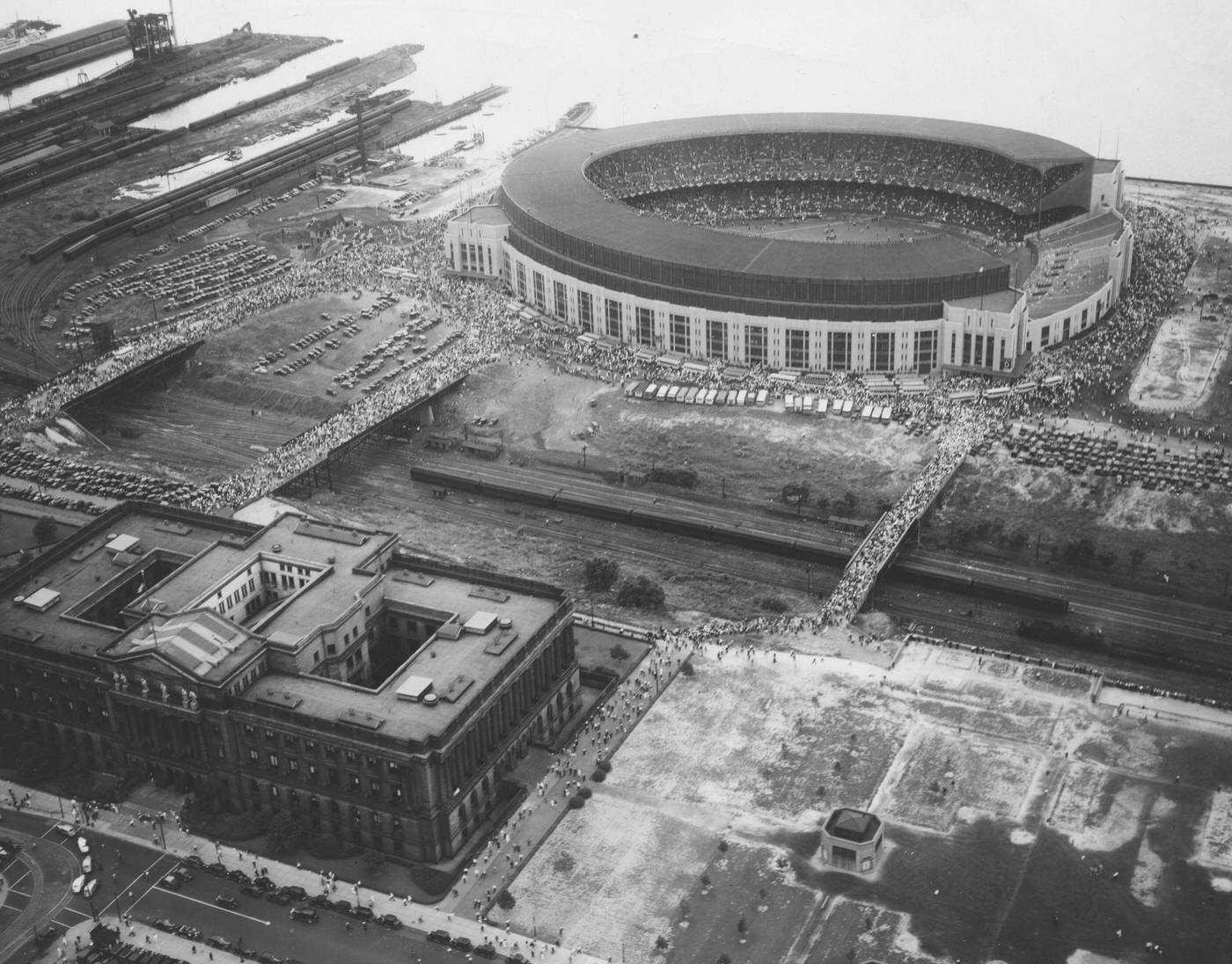

A major highlight of the decade was the Great Lakes Exposition, held in 1936 and 1937. Conceived to celebrate Cleveland’s centennial and to provide an economic and psychological boost during the Depression, the Expo was a resounding success.

- It attracted 7 million visitors over its two seasons and was estimated to have pumped between $60 million and $70 million into the local economy.

- The Exposition grounds, sprawling across the lakefront, featured impressive exhibits such as “The Romance of Iron and Steel,” extensive automotive displays (including a futuristic bus designed by the White Motor Company), model homes showcasing the latest building techniques, and Radioland in the Public Auditorium, which hosted live broadcasts of popular national radio shows.

- Entertainment was abundant, with performances by the Great Lakes Symphony Orchestra, appearances by celebrities like Jesse Owens and Jimmy Durante, and the spectacular Billy Rose’s Aquacade, a water ballet show starring Eleanor Holm and Johnny Weissmuller.

- The “Streets of the World” section offered immersive cultural experiences from over 30 countries, while a midway provided amusement rides and various sideshows.

- The Expo was particularly renowned for its dazzling nighttime illumination, a “gorgeous fantasy” that showcased Cleveland’s prominence in the lighting industry. This grand fair offered a temporary escape from hardship and a vision of progress and resilience

City Leadership and Law Enforcement in a Turbulent Decade

The 1930s ushered in significant political and administrative adjustments in Cleveland, as the city grappled with the dual challenges of economic depression and rising crime. A notable shift occurred at the very start of the decade when, in November 1931, Cleveland voters chose to repeal the City Manager Plan, which had been in place since 1924. This decision marked a return to the more traditional Mayor/Council form of government. The repeal was driven by several factors: a public perception that the appointed city manager had accumulated too much power, lingering concerns about political corruption, the perceived complexity of the proportional representation voting system used for council elections, and a general dissatisfaction with governmental efficacy amidst the deepening economic crisis. This move suggested a public desire for more direct political accountability through an elected mayor during a period of profound uncertainty.

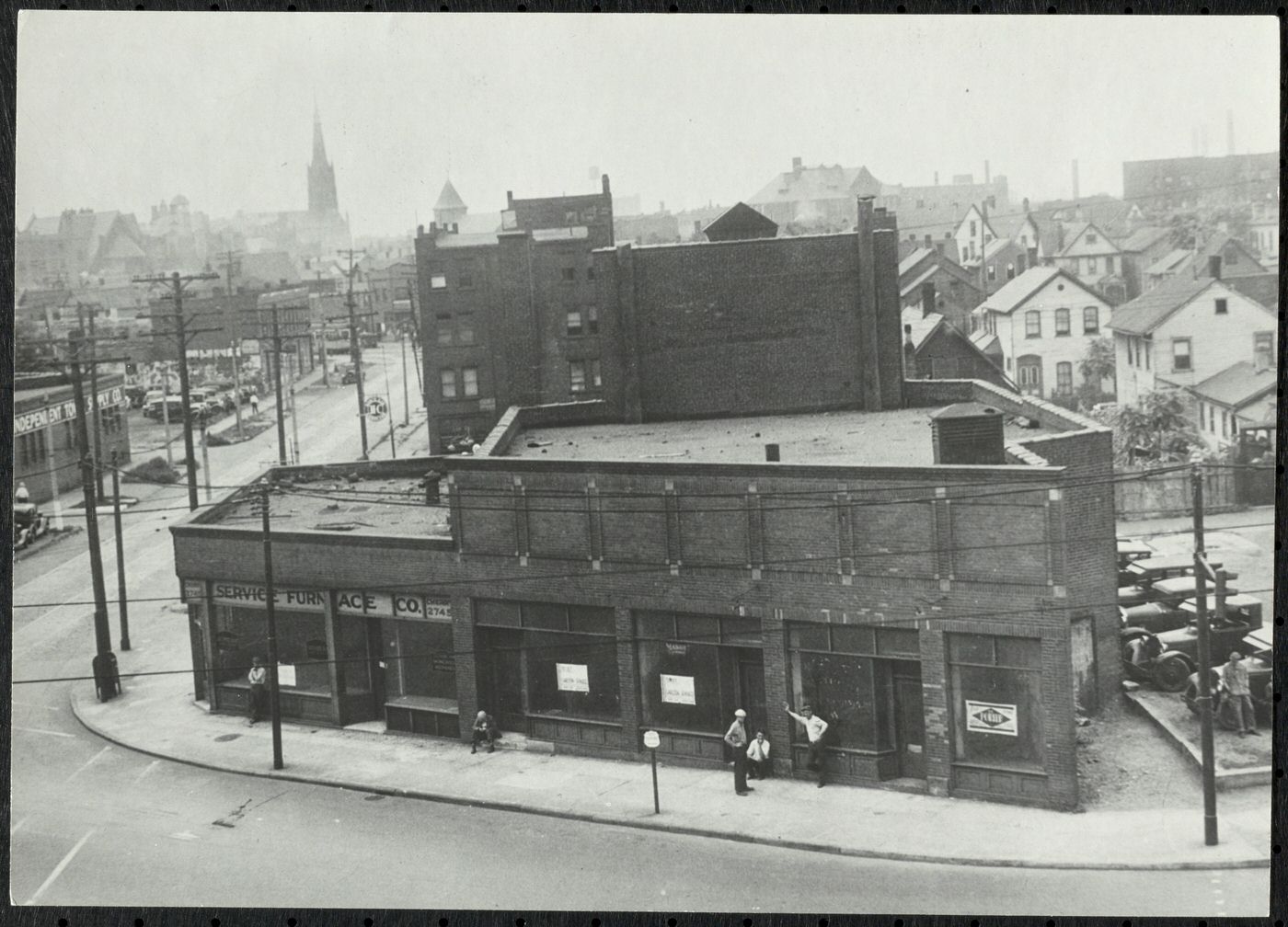

Ray T. Miller, a Democrat, became the first mayor under the restored system, serving from 1932 to 1933. His administration was immediately confronted by the worst years of the Depression. Miller’s primary focus was on fiscal austerity, implementing drastic cuts in city expenditures to maintain essential services such as garbage collection and police and fire protection. These measures included unpopular steps like mandatory unpaid leave for city employees, salary reductions, and administrative streamlining. Simultaneously, Miller actively sought federal aid through the Public Works Administration (PWA) for a range of infrastructure projects, including plans for straightening the Cuyahoga River, harbor dredging, eliminating railroad grade crossings, street paving, constructing sewage plants, and completing the Huron Road Hospital. His tenure was also marked by significant social unrest, including the need to manage welfare programs, address Communist political activity and protests, handle a railway strike in 1933, and navigate the public fallout from a police shooting of two unemployed men at a relief station.

In 1935, Harold H. Burton, a Republican, was elected mayor, defeating former mayor Ray T. Miller. Burton served until 1940. Known for his integrity, he earned the nickname the “Boy Scout Mayor”. Burton was a strong advocate for New Deal programs, particularly the WPA, recognizing their vital role in providing relief and employment to Clevelanders. His administration prioritized combating organized crime and improving employment opportunities. A key move in this direction was his appointment of Eliot Ness as the city’s Director of Public Safety.

Eliot Ness took office as Cleveland’s Safety Director in December 1935 and served until April 1942. Arriving with a formidable reputation from his efforts against Al Capone in Chicago, Ness found Cleveland to be, by some accounts, the most dangerous city in the United States. He launched a comprehensive campaign against corruption within the police department. His investigations led to the indictment and conviction of several high-ranking police officials for bribery and graft, which in turn prompted numerous resignations. Ness seized the opportunity to reshape the force, filling vacancies with new recruits, many of whom were college-educated and subjected to rigorous character checks and improved training methods.

Ness was instrumental in modernizing both the police and fire departments. He established a scientific “rookie” training school for police officers, drawing inspiration from J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI academy. He also improved traffic control by creating a dedicated department and introducing new equipment like motorcycles, an initiative credited with halving auto accident deaths. The mounted police force was enhanced, and police communications were centralized and upgraded with two-way radio, radio-telegraph, and teletype systems. Ness personally led raids against organized crime figures, gamblers, and vice operations, aiming to dismantle racketeering in Cleveland. His efforts were credited with a 25% drop in total crimes and an 80% reduction in juvenile crime within his first 18 months, alongside an increase in arrests and convictions. Furthermore, Ness established Cleveland’s Emergency Medical Services (EMS) unit and introduced accident prevention patrol cars, which contributed to Cleveland receiving the American Legion’s National Safety Award in 1939. To address juvenile delinquency, he supported the city-wide formation of Boy Scout troops, often with police officers serving as troop leaders, and founded Cleveland Boys Town. He also created a Welfare Department within the police force to support officers’ families in need.

A dark chapter during Ness’s tenure was the hunt for the Cleveland Torso Murderer, also known as the “Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.” Between 1935 and 1938, this elusive serial killer murdered and dismembered at least twelve individuals. Despite intensive investigation, the killer was never apprehended. In a controversial move, Ness ordered the shantytowns in Kingsbury Run, where many of the victims were discovered, to be burned to the ground, hoping to disrupt the killer’s activities and remove potential targets from the area. While Ness’s reforms were significant, the intractability of organized crime and the mystery of the Torso Murders underscored the profound challenges facing law enforcement in a city grappling with economic despair and its social consequences.

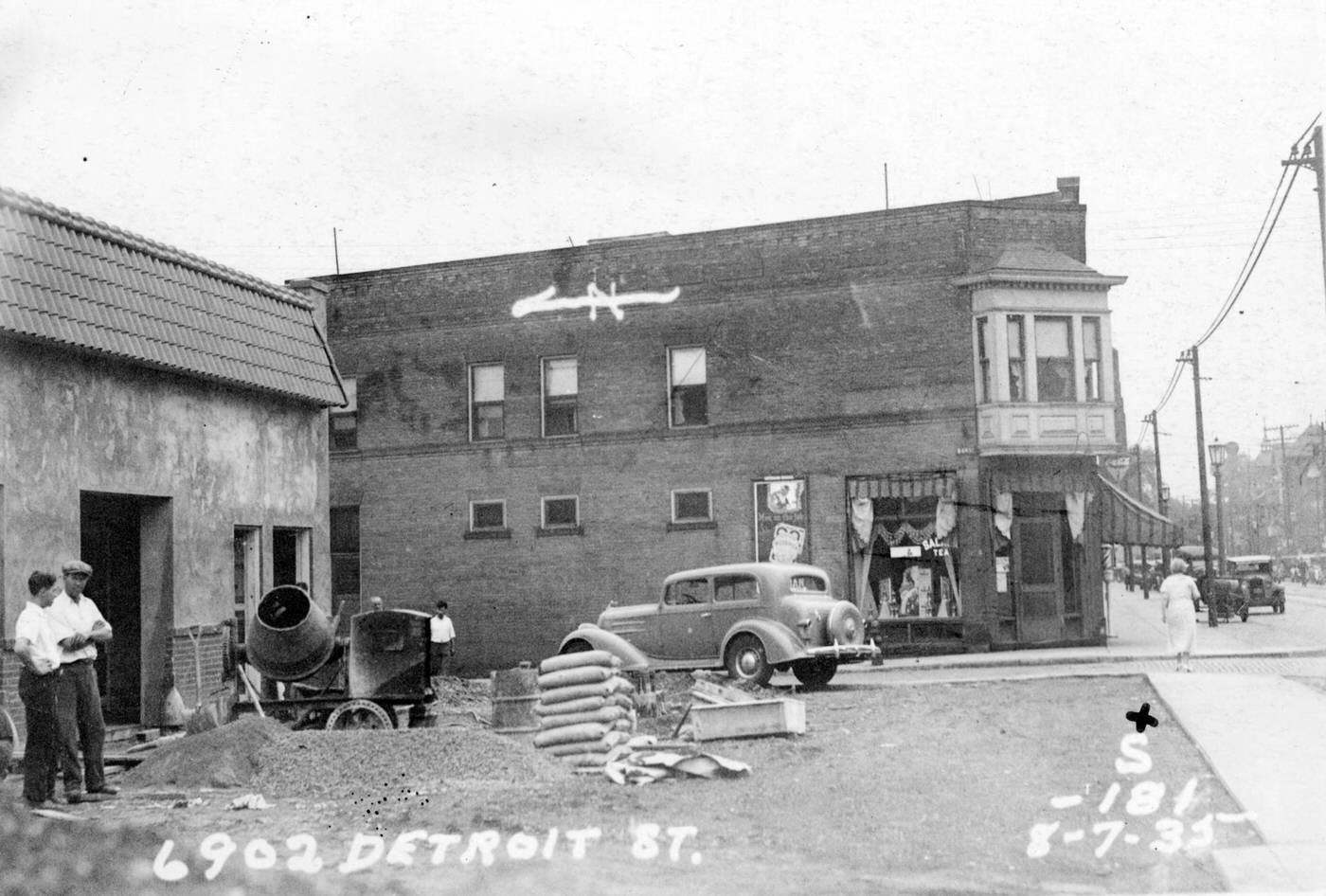

The broader political and social climate of 1930s Cleveland was turbulent. Partisan politics continued, with the city generally led by Republicans, though Democratic support was growing, especially within immigrant communities. Ethnic and religious power dynamics played a role in city politics. The rise of labor unions often led to confrontations with police and city authorities. The city’s police force, numbering around 1,300 officers, was under immense pressure due to escalating crime rates linked to the legacy of Prohibition and the desperation born of the Depression. This era highlighted an increasing tension between the need for robust police intervention to address crime and public fear, and concerns over civil liberties, particularly in a society already strained by economic hardship and social unrest.

Social Life

Amidst the difficulties, community life found ways to endure. Ethnic communities, as detailed earlier, maintained their social and cultural activities, providing a sense of continuity and mutual support. Free recreational opportunities became increasingly important. The Brookside Zoo, despite its own financial struggles, saw increased attendance as cash-strapped residents sought affordable leisure. WPA projects played a significant role in developing and improving city parks and recreational facilities, with an explicit aim to combat juvenile delinquency and provide wholesome outlets for leisure time. The stark contrast between the grim realities of crime and poverty and the vibrant efforts to maintain cultural life and community spirit defined much of Cleveland’s social landscape in the 1930s.

Building Through the Hardship: City Development Continues

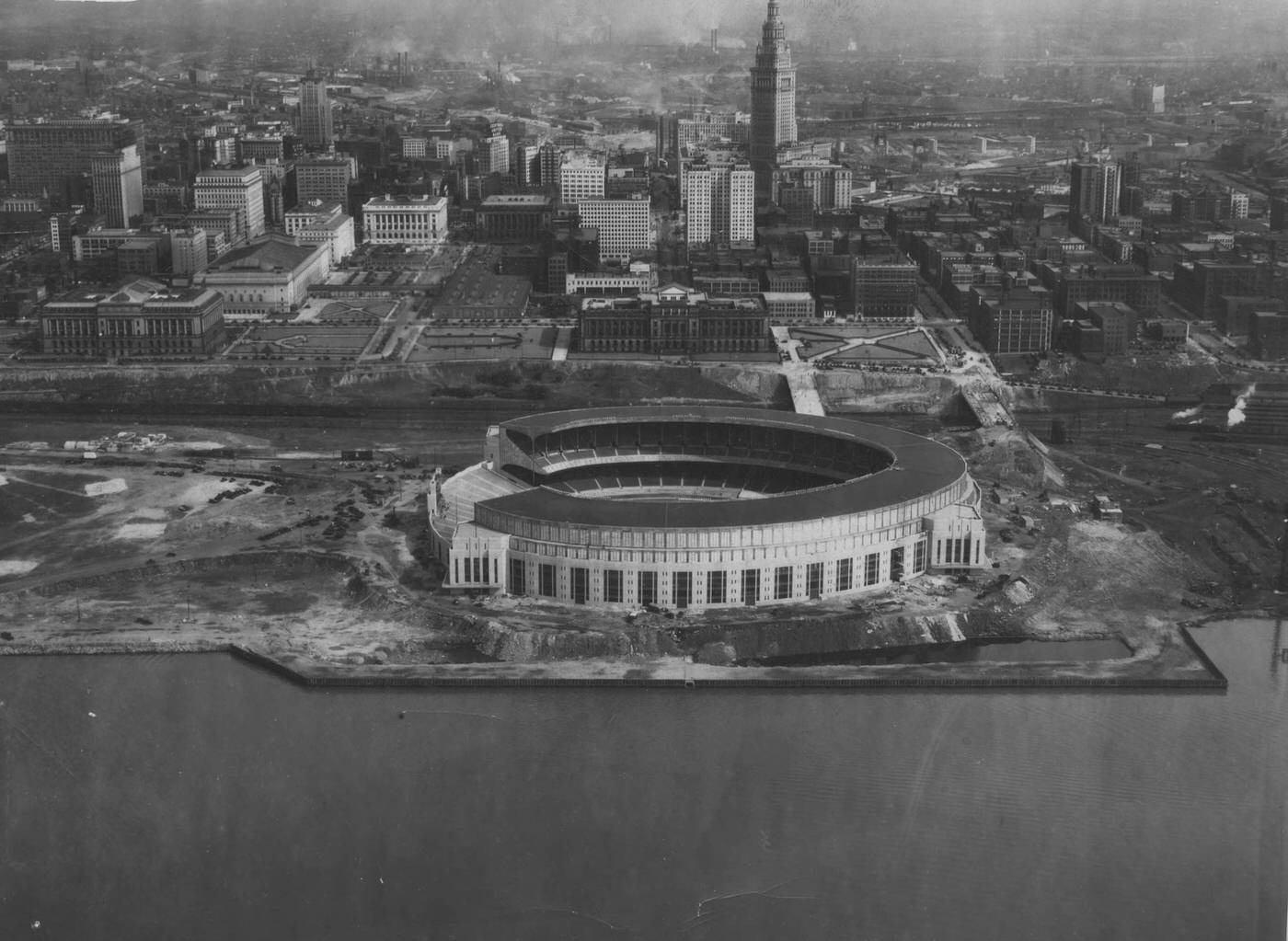

Despite the severe economic constraints of the Great Depression, several monumental civic and infrastructure projects, largely conceived and financed during the more prosperous 1920s, reached completion in the 1930s. These developments significantly altered Cleveland’s urban fabric and stood as symbols of enduring civic ambition.

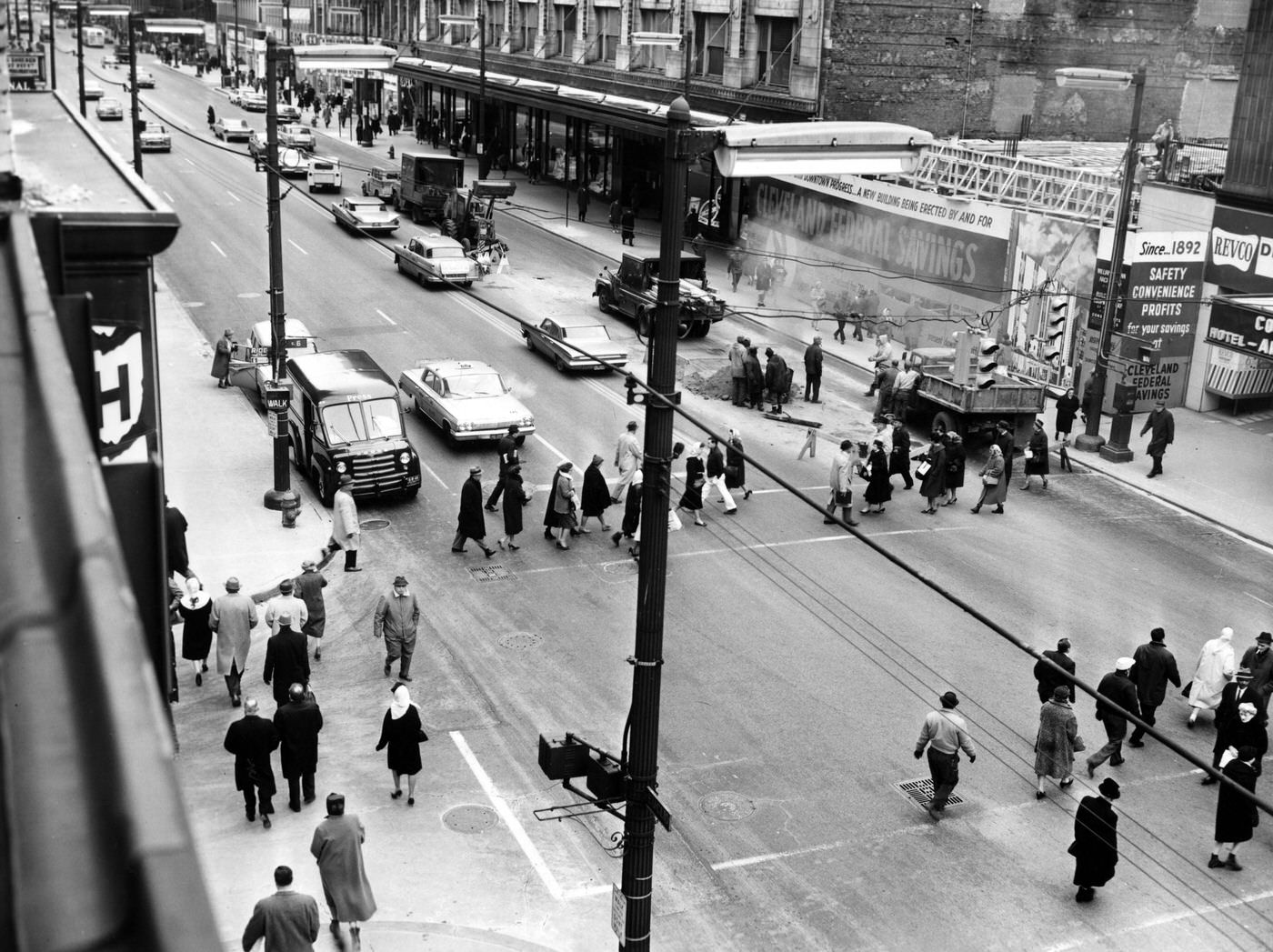

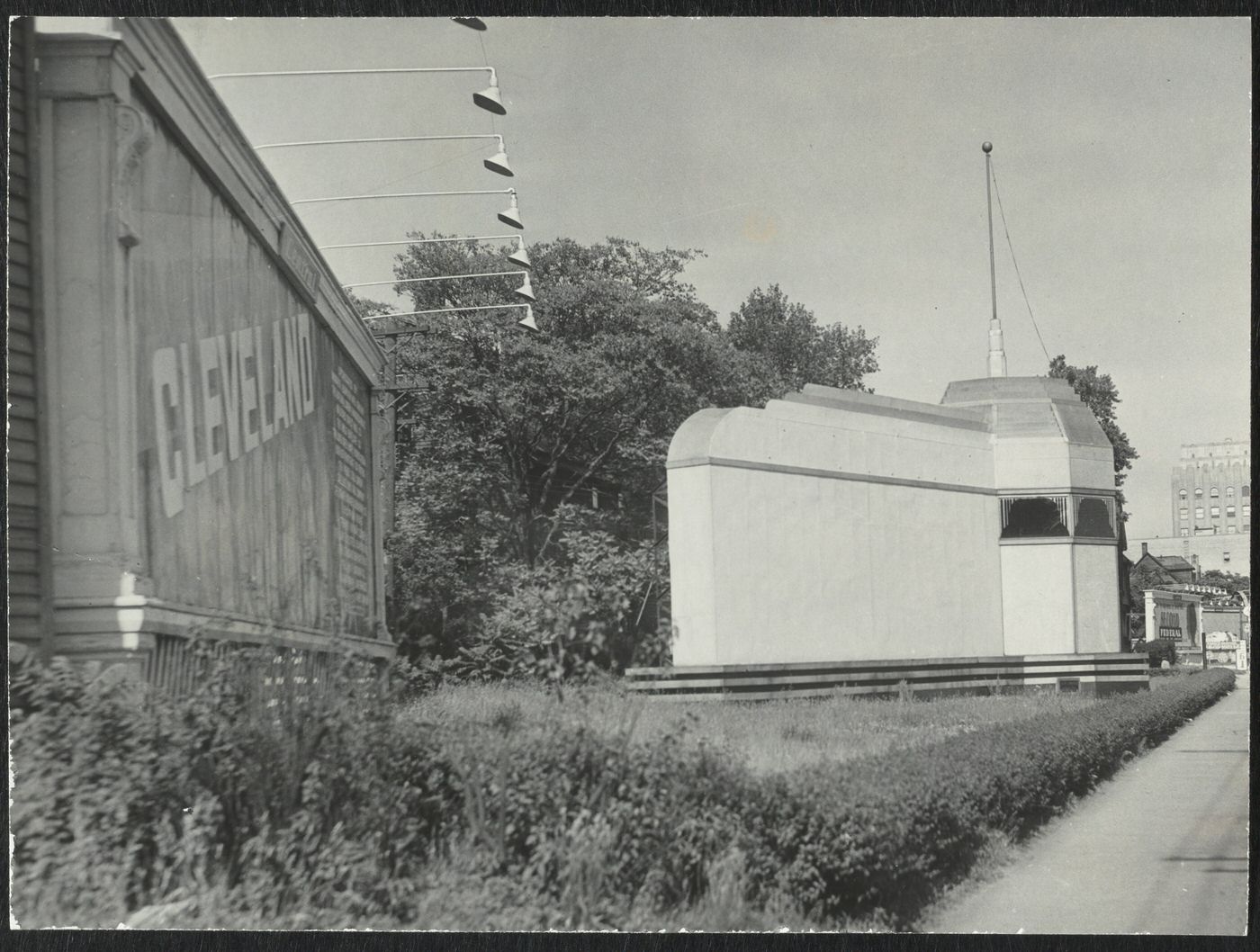

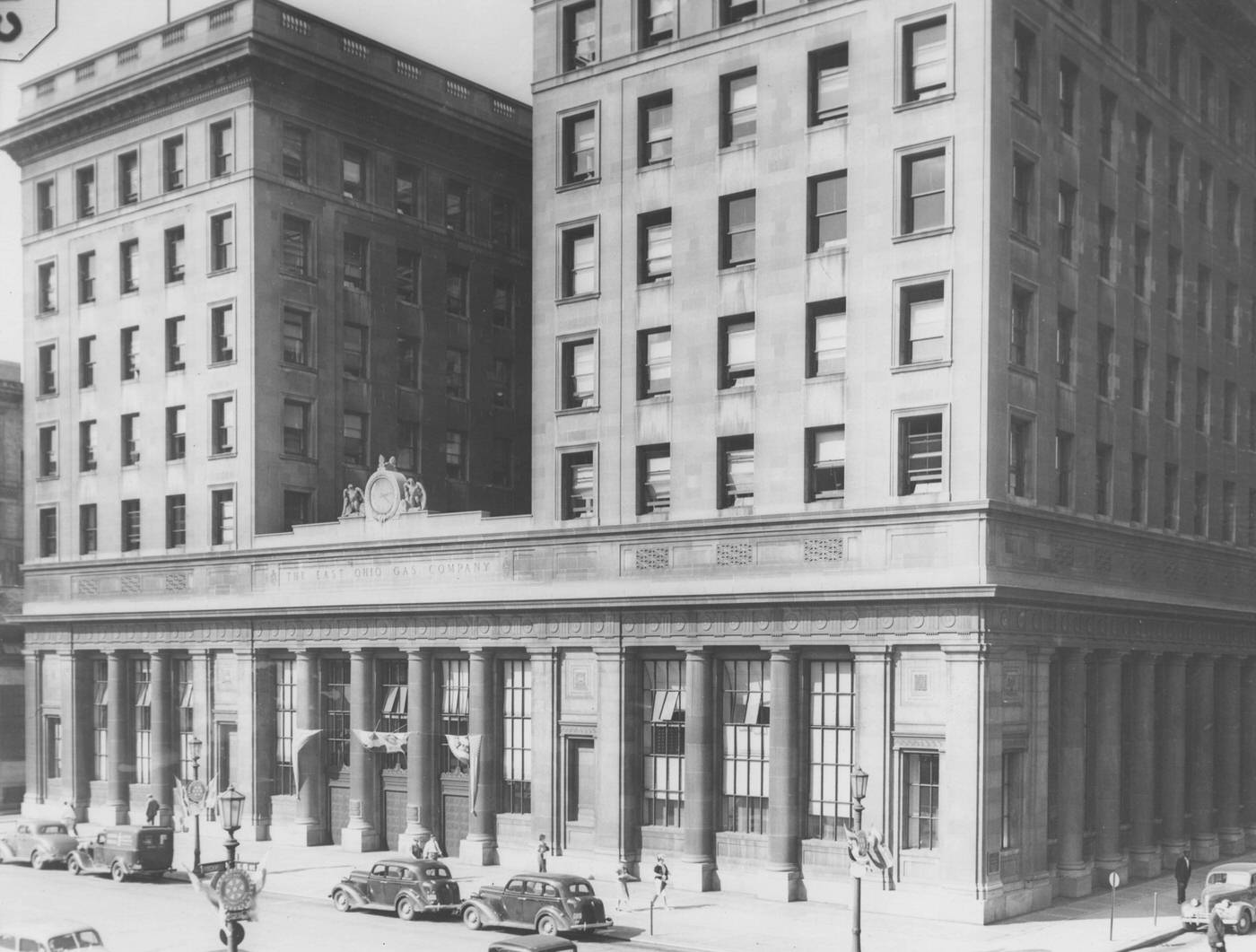

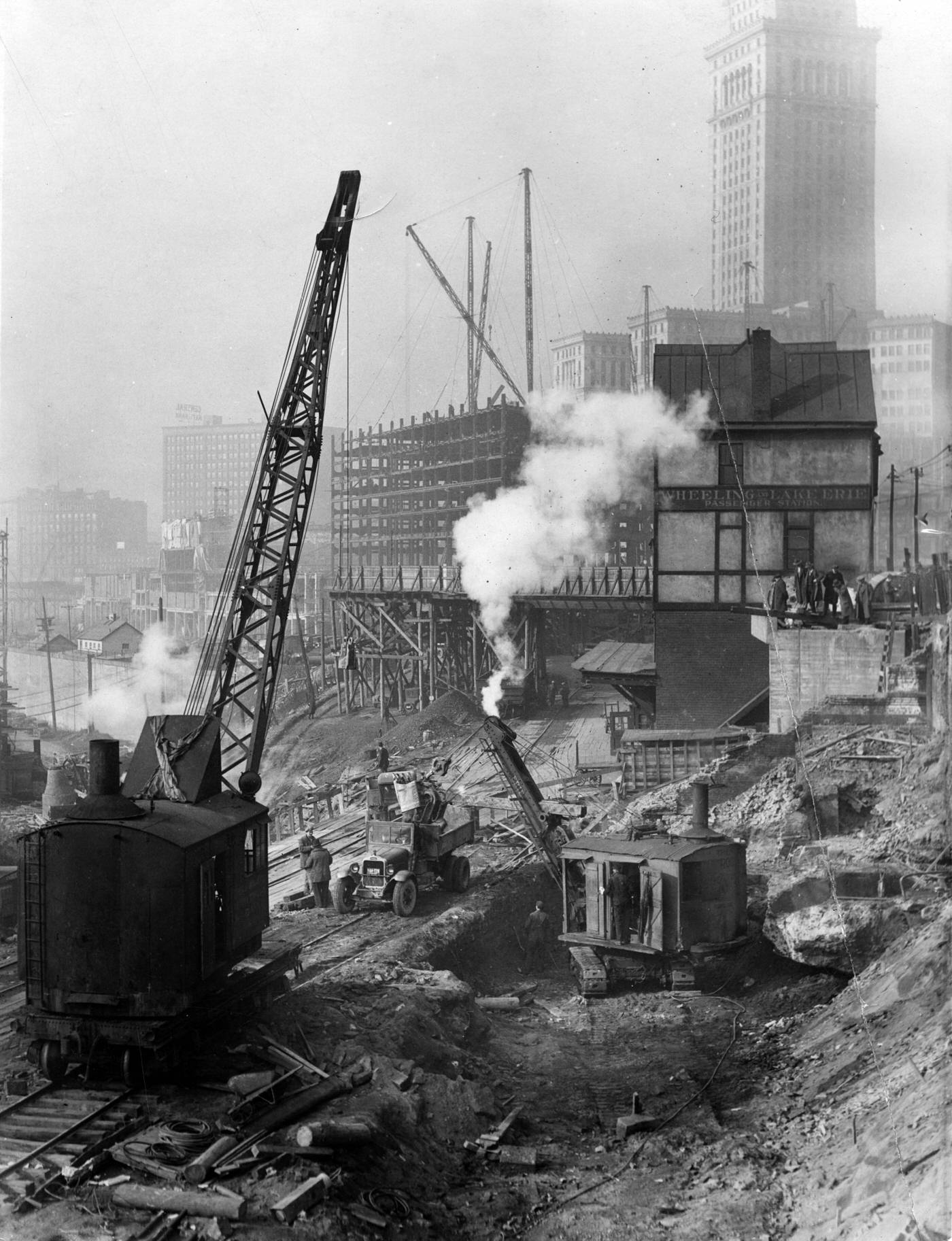

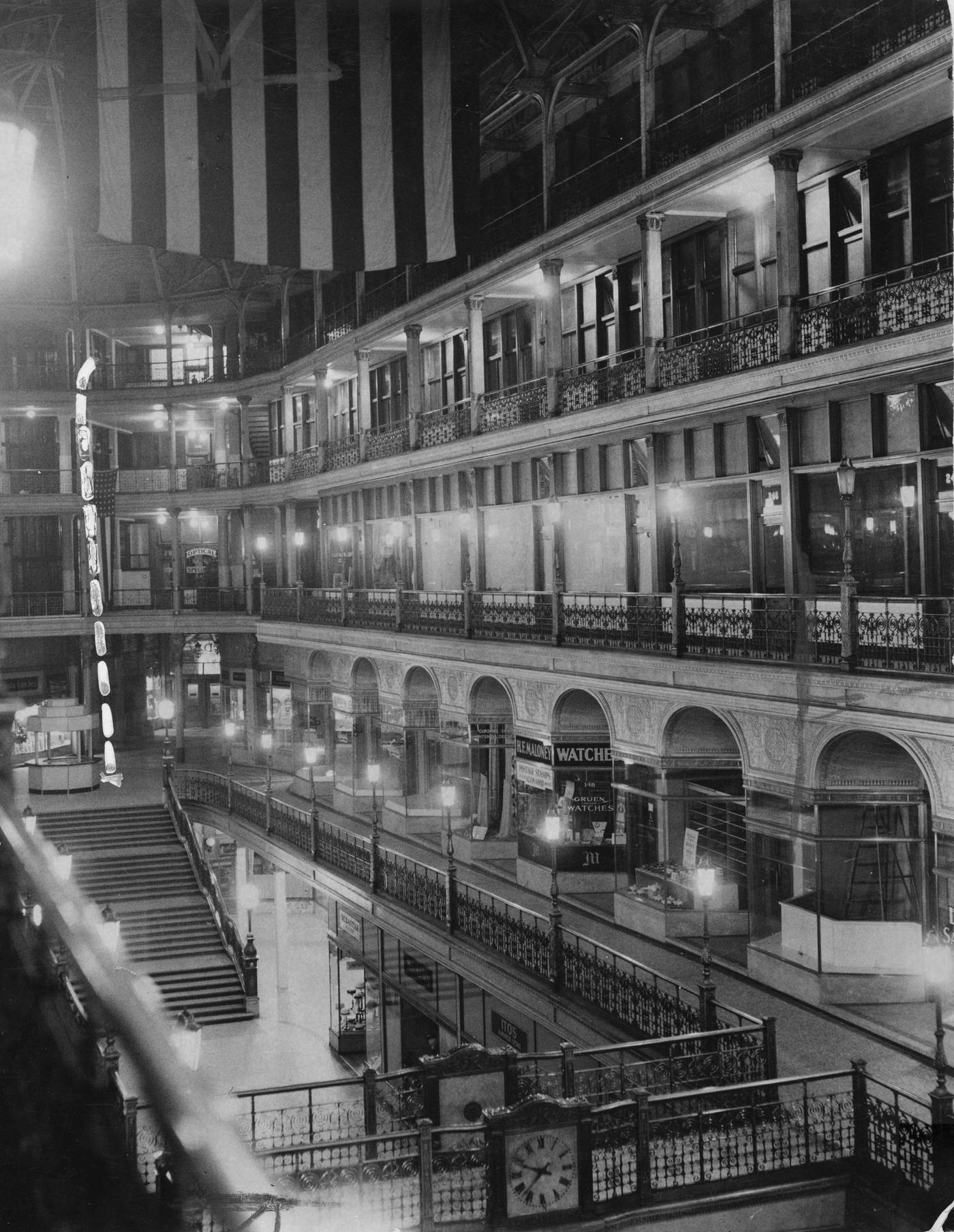

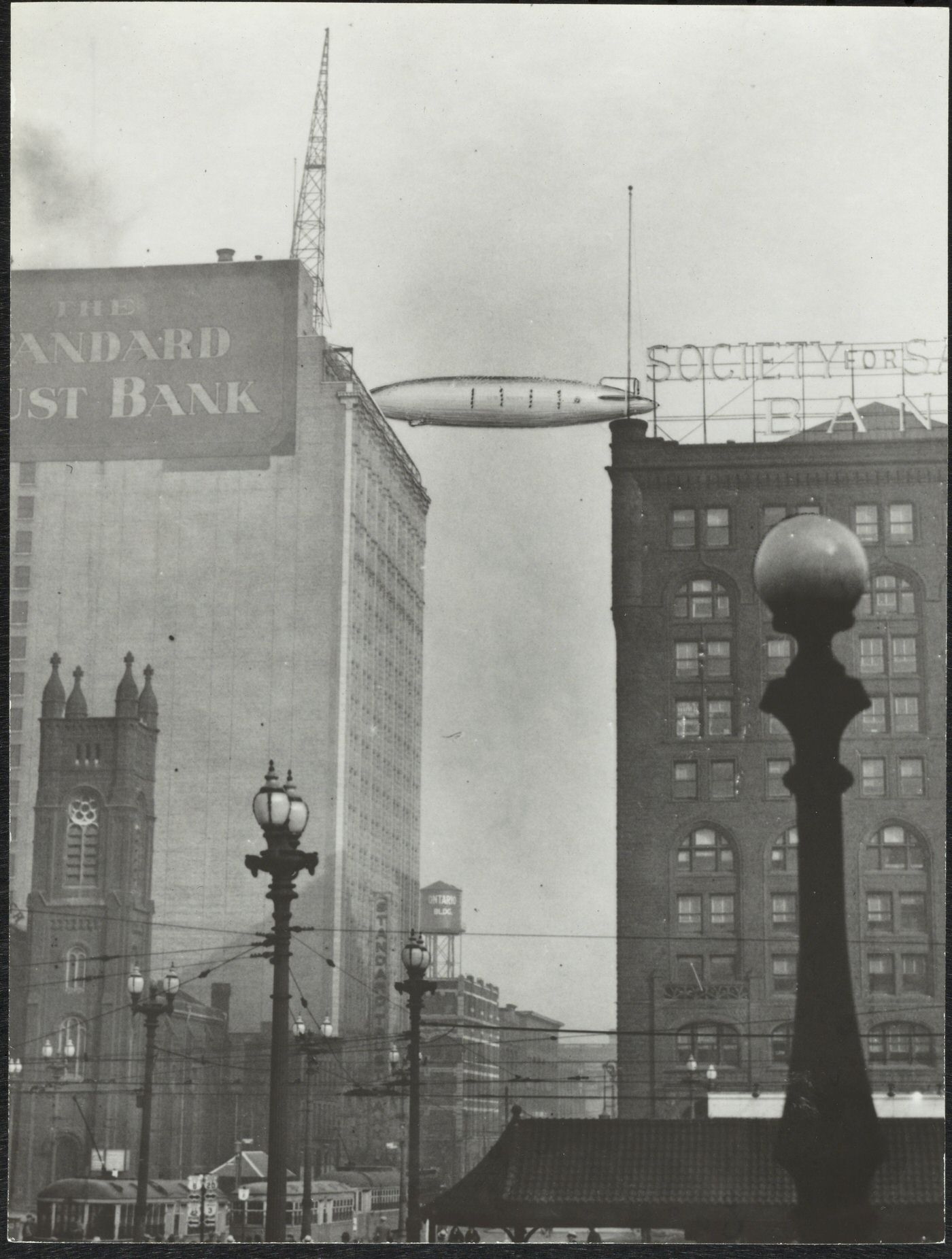

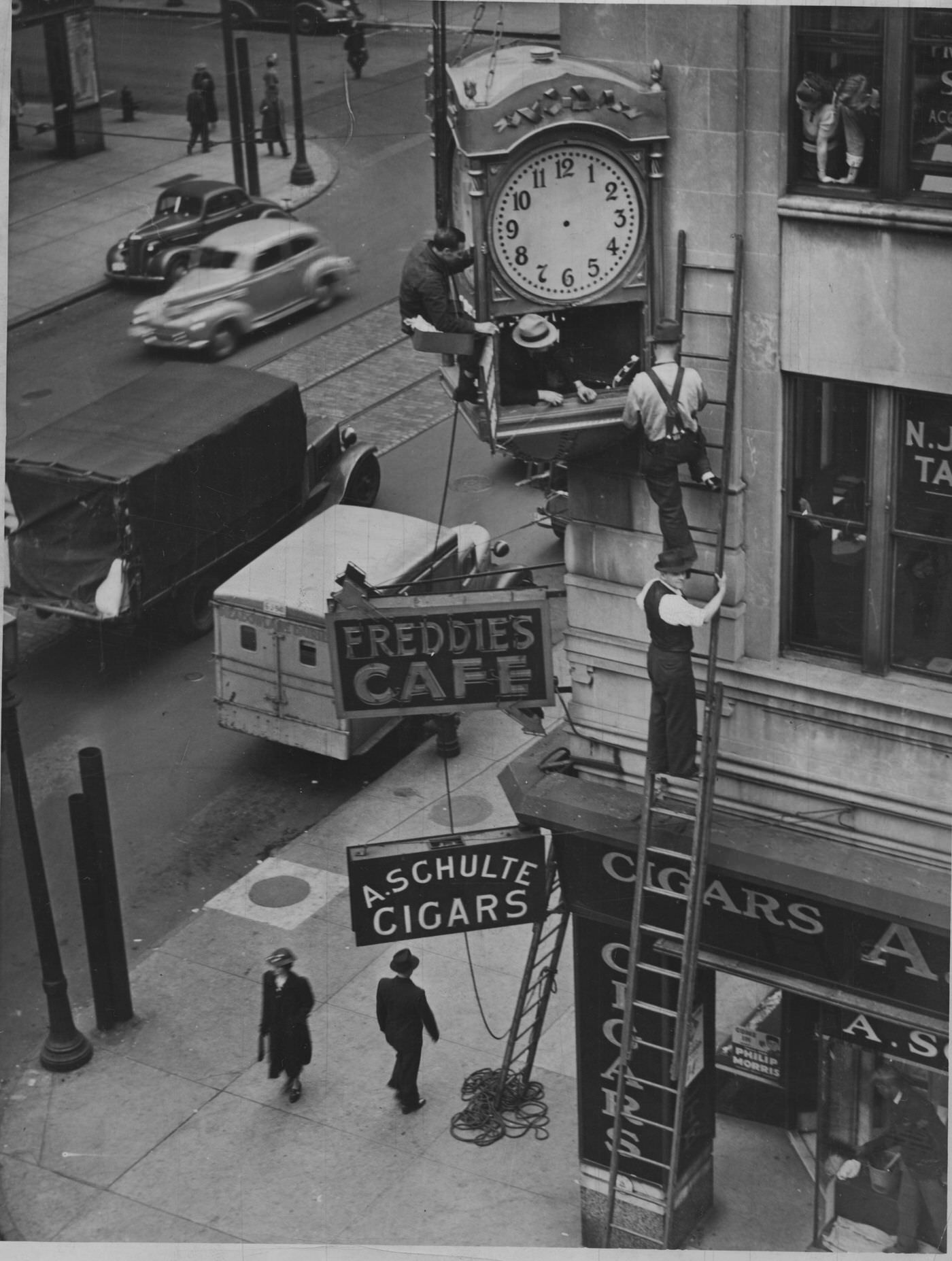

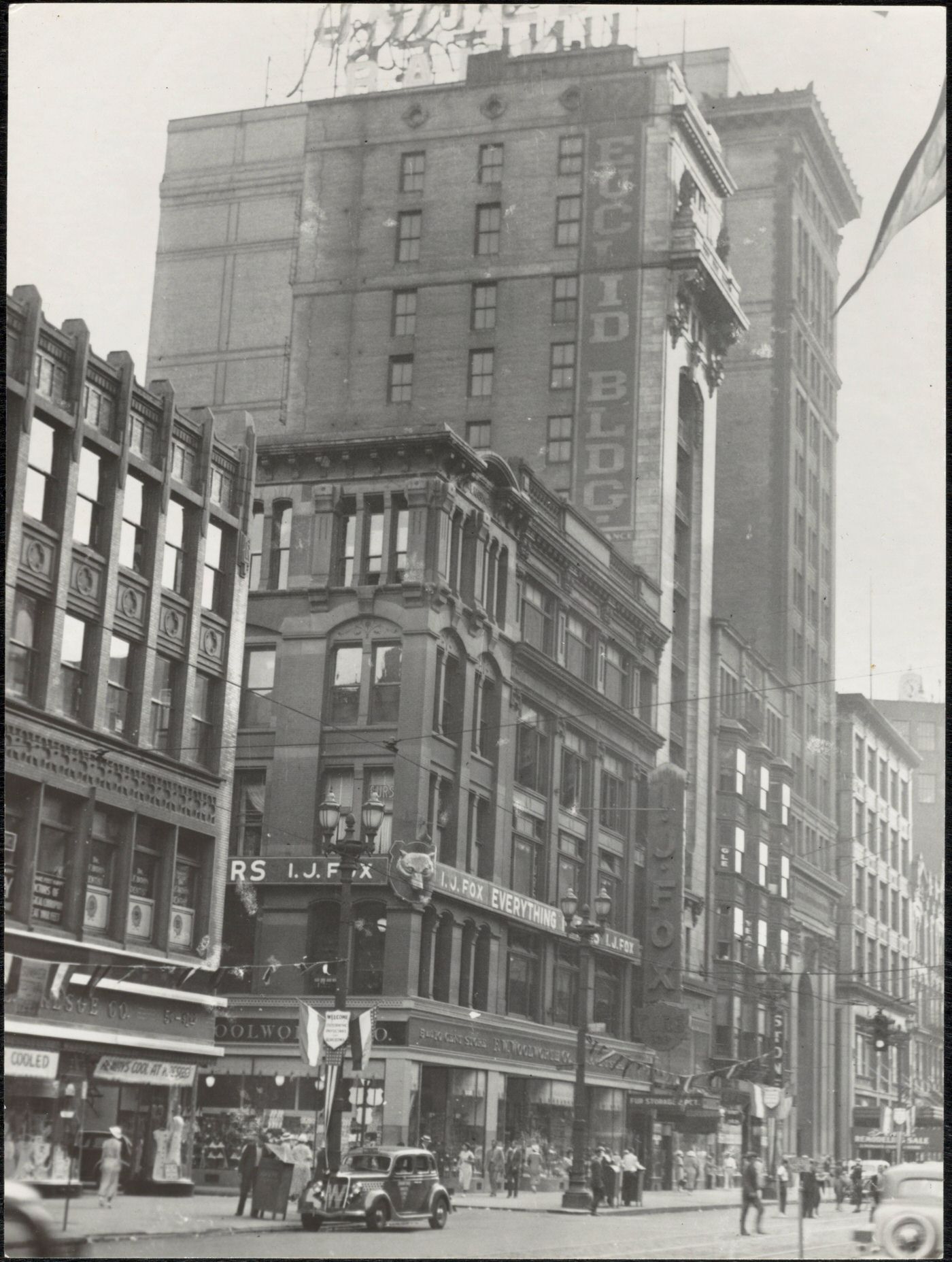

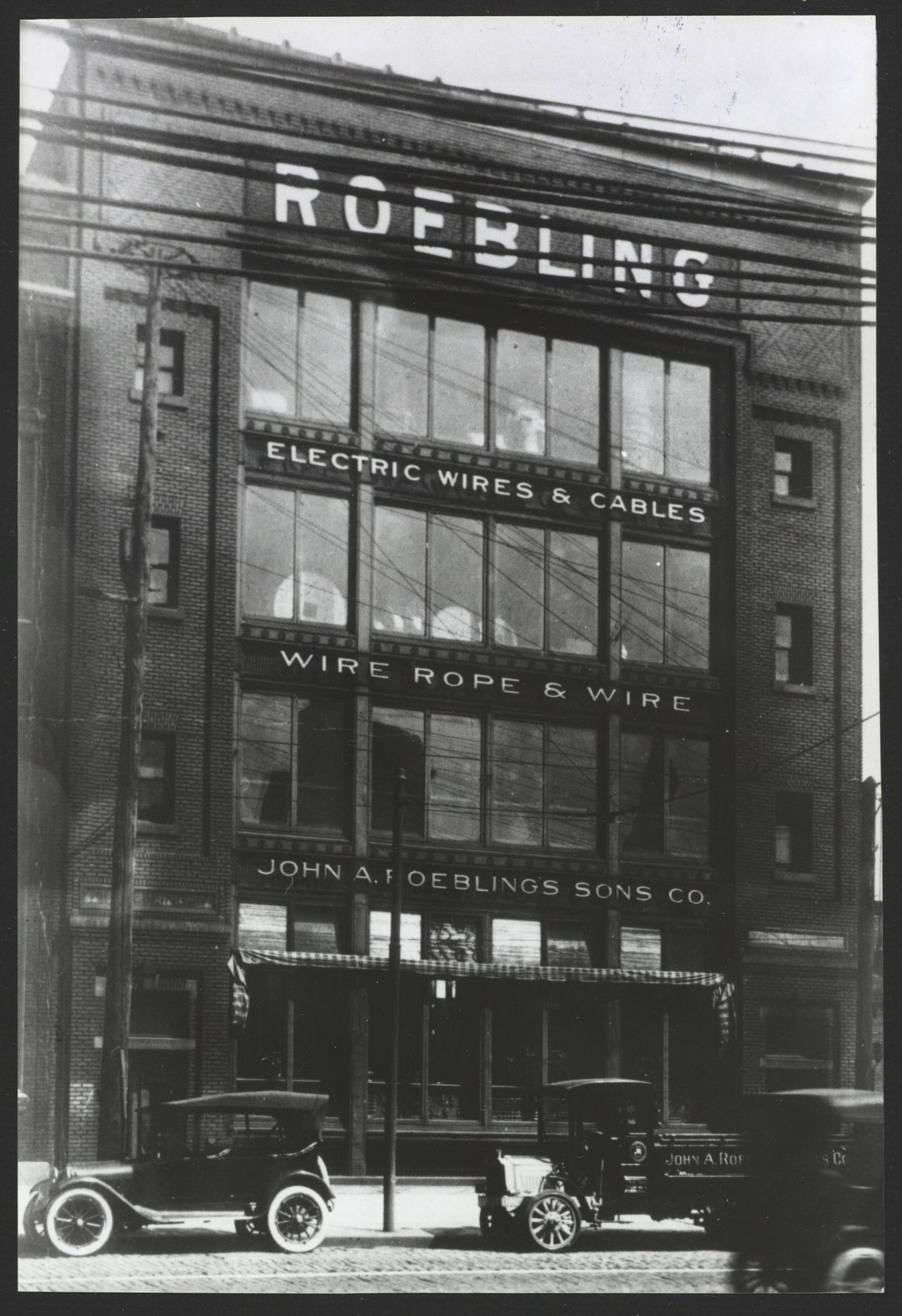

The most prominent of these was the Cleveland Union Terminal Complex. Excavation for this massive project began in 1924, and the iconic 708-foot Terminal Tower, its centerpiece, was completed in 1927, briefly holding the title of the world’s tallest building outside New York City. The formal opening of the entire terminal group, which included the Guildhall, Republic, and Midland office buildings (now Landmark Office Towers), took place on June 29, 1930. Designed by the Chicago architectural firm Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, the complex was an engineering marvel, requiring foundations sunk 250 feet to bedrock for the tower, the demolition of over 1,000 existing buildings, and the construction of numerous bridges and viaducts to accommodate the railroad approaches. The complex also integrated the existing Hotel Cleveland (built in 1918) and later incorporated Higbee’s Department Store, which opened its doors there in 1931, and a new U.S. Post Office, completed in 1934. The terminal served as a vital transportation hub for multiple railroads, including the New York Central and Baltimore & Ohio, as well as for the local Shaker Heights Rapid Transit line. The completion of such a grand project in the early Depression years offered a striking contrast to the widespread economic distress, symbolizing both past prosperity and hopes for future recovery.

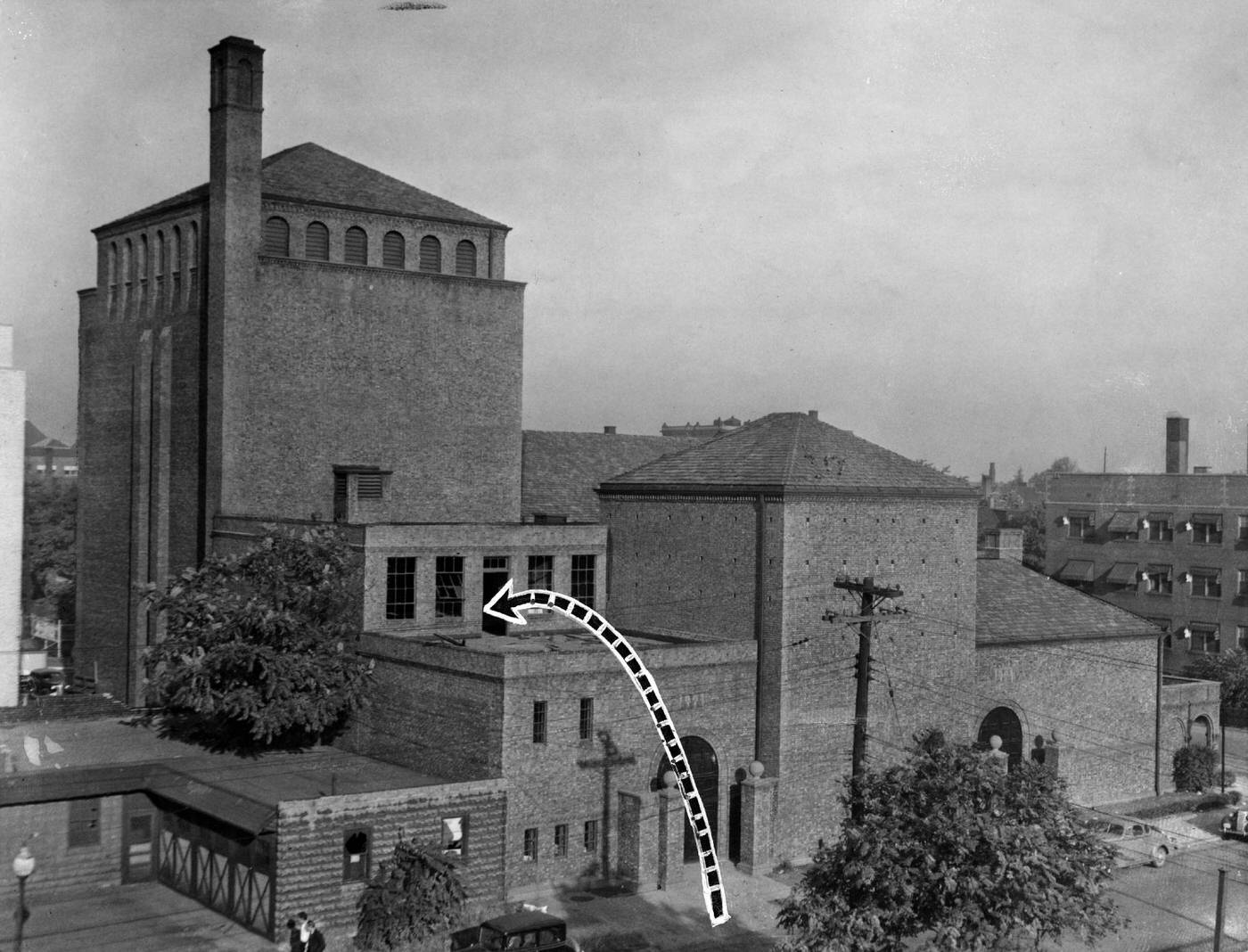

Another significant architectural and cultural achievement was the completion of Severance Hall, the permanent home of the Cleveland Orchestra. Constructed between 1929 and 1931, the hall was dedicated in 1931 to Elizabeth “Bessie” Dewitt Severance, the late wife of John L. Severance, the project’s primary benefactor. The construction, costing over $7 million, was funded through public donations, philanthropic gifts (including from John D. Rockefeller and Dudley Blossom), and a land grant from Western Reserve University. Severance Hall provided the orchestra with a world-class venue, featuring a concert hall seating nearly 2,000, a chamber music hall, a renowned Skinner pipe organ, and a recording studio, all of which greatly enhanced the orchestra’s national and international reputation. Like the Union Terminal, its opening provided a cultural bright spot amidst economic gloom.

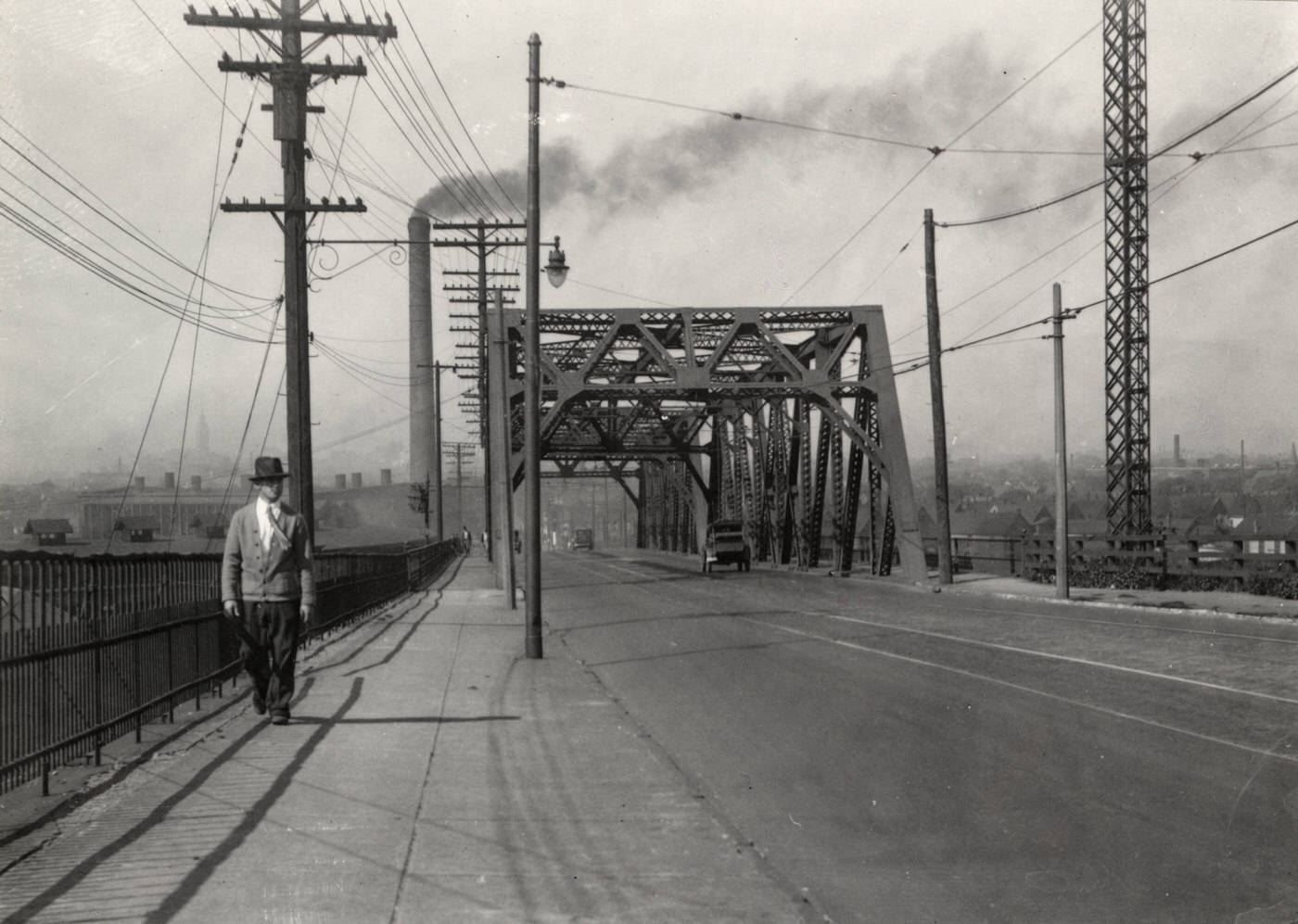

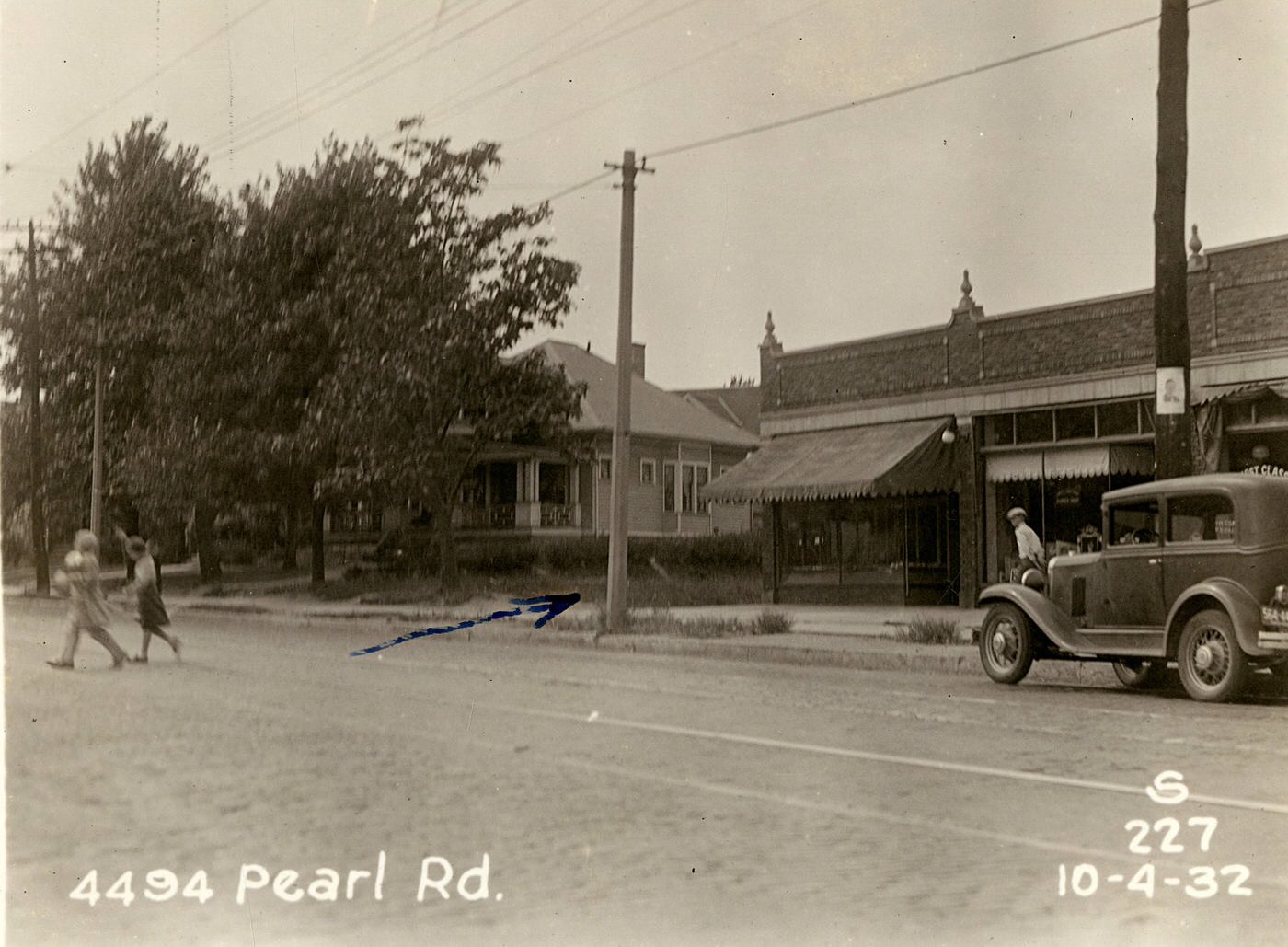

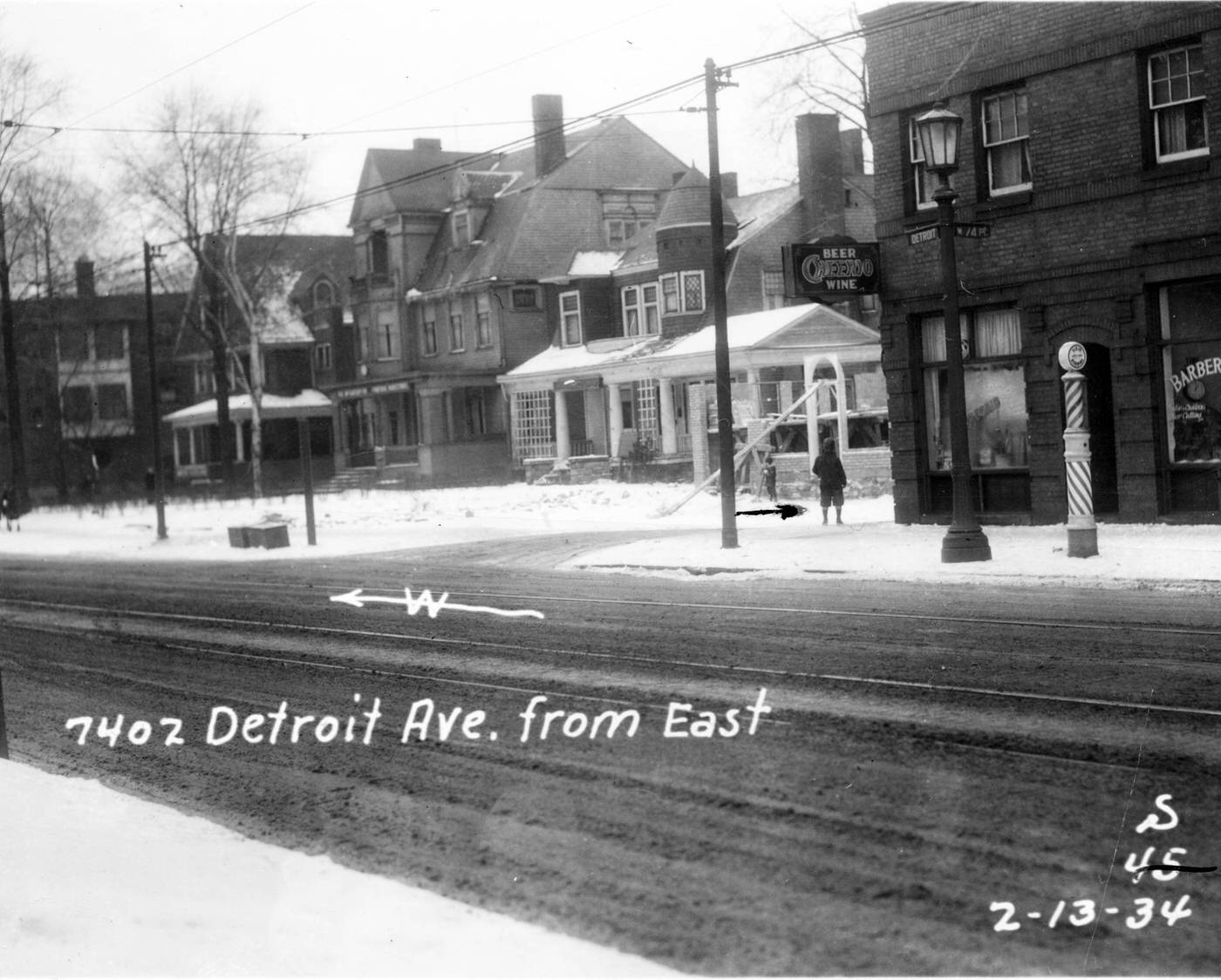

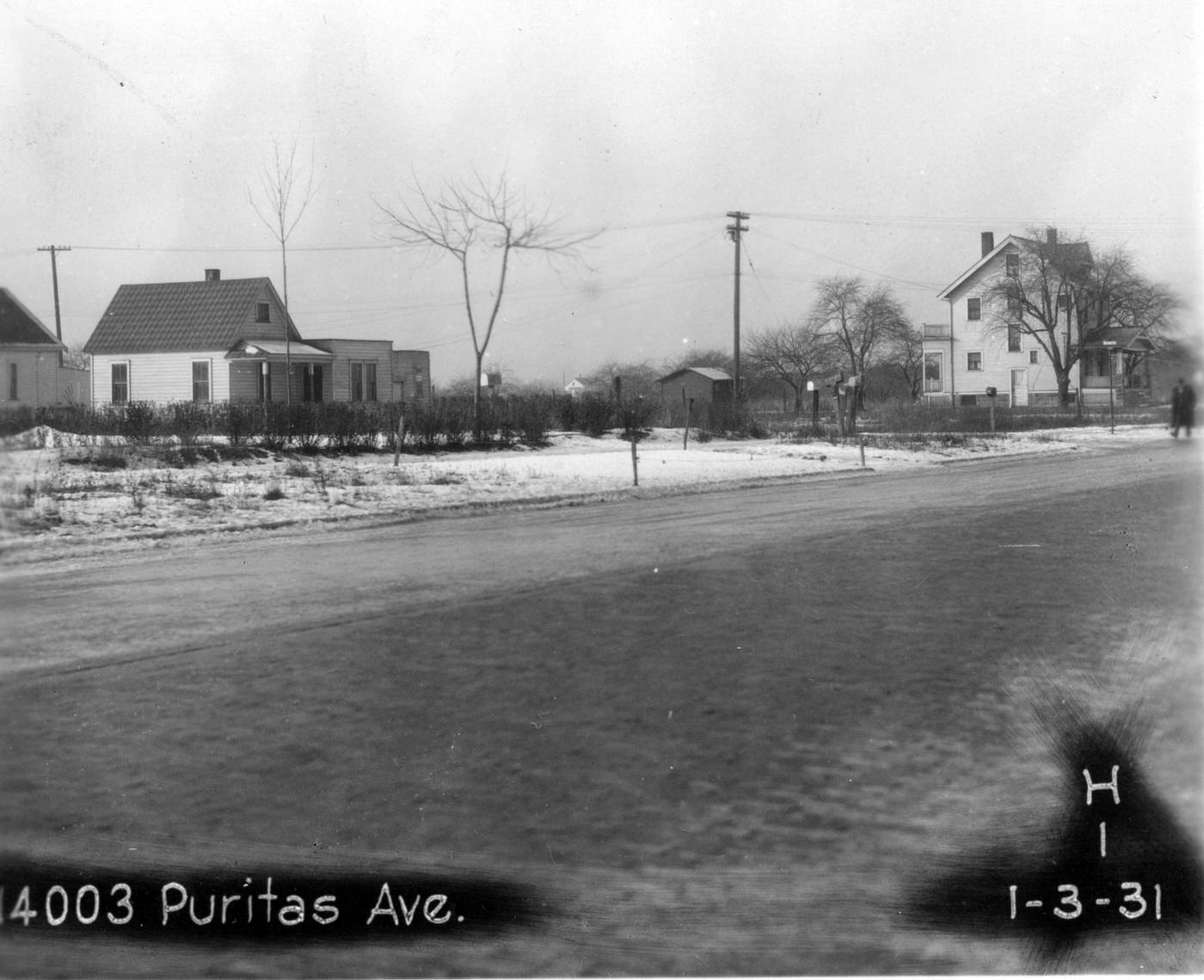

Cleveland’s public transportation system continued to evolve during the 1930s. The interurban electric railways, which had connected Cleveland to surrounding towns and cities, saw a significant decline due to increasing competition from automobiles and buses. In their place, intercity bus services grew and consolidated, with Cleveland-based companies like the Buckeye Stage System and Central Greyhound expanding their routes and becoming major regional carriers. The Shaker Heights Rapid Transit system, an electric rail line developed by the Van Sweringen brothers in the 1920s to serve their innovative suburban development of Shaker Heights , continued to operate, providing a crucial link for suburban commuters to the new Union Terminal in downtown Cleveland.

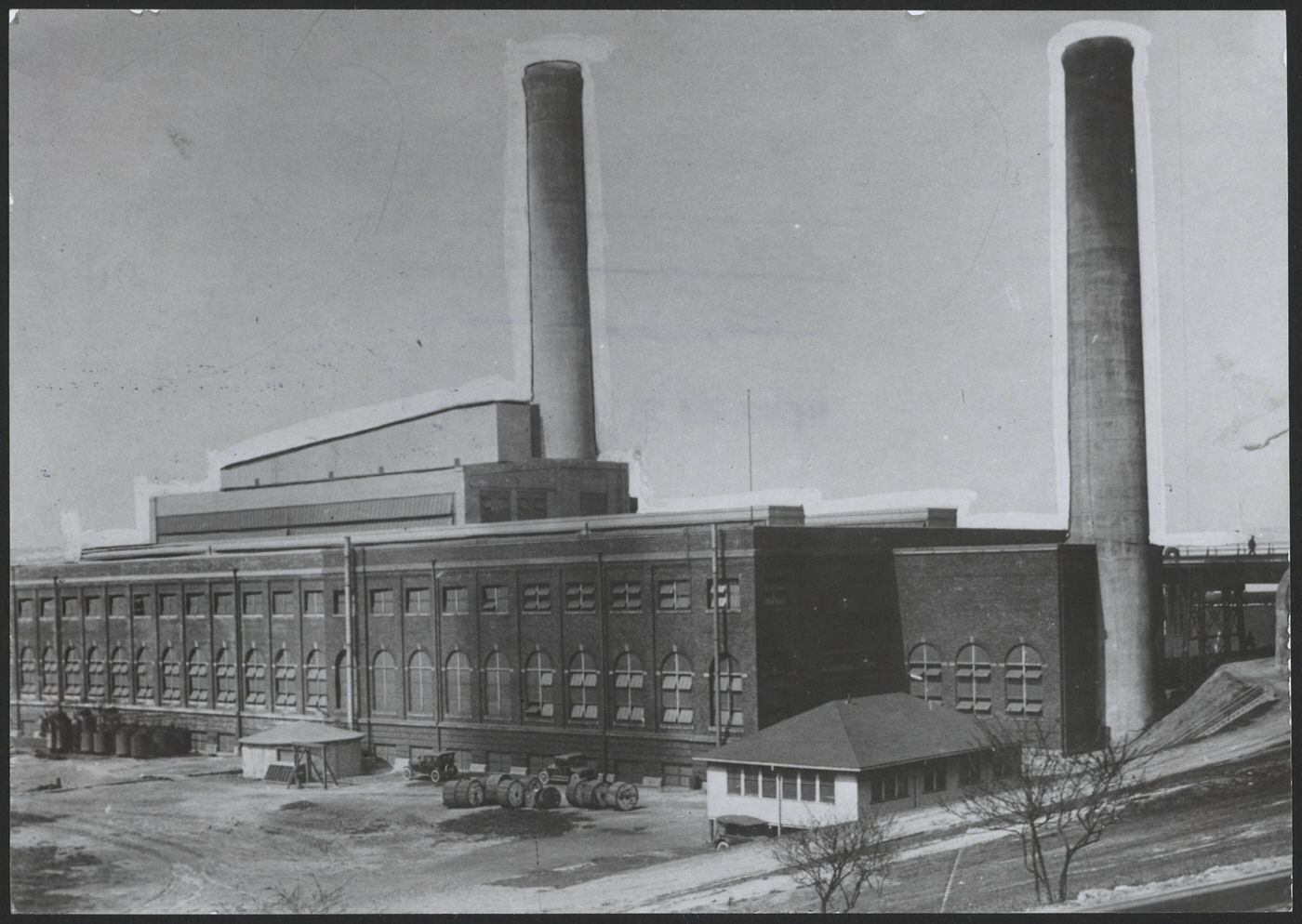

Investment in public utilities and sanitation also persisted, building on efforts from the previous decade. Cleveland’s water system had seen major upgrades with the completion of the Baldwin Filtration Plant in 1925 and the expansion of the Kirtland pumping station by 1927. These projects ensured a supply of wholly filtered and chlorinated water, which had virtually eliminated widespread water-borne diseases like typhoid fever by the late 1920s, a benefit that continued through the 1930s. The city’s wastewater treatment infrastructure also saw significant improvements. The Westerly (1922), Easterly (1925), and Southerly (1927/1928) treatment plants were upgraded during the 1930s, partly with federal PWA funds. A major advancement was the Easterly plant becoming Cleveland’s first activated-sludge facility in 1938, representing a more advanced method of sewage treatment. Additionally, the city’s first incineration plant for solid waste disposal became operational in 1935, replacing older, less sanitary methods. These ongoing investments in public health infrastructure were vital for supporting the city’s large population and its industrial base, even as that base faced economic struggles.

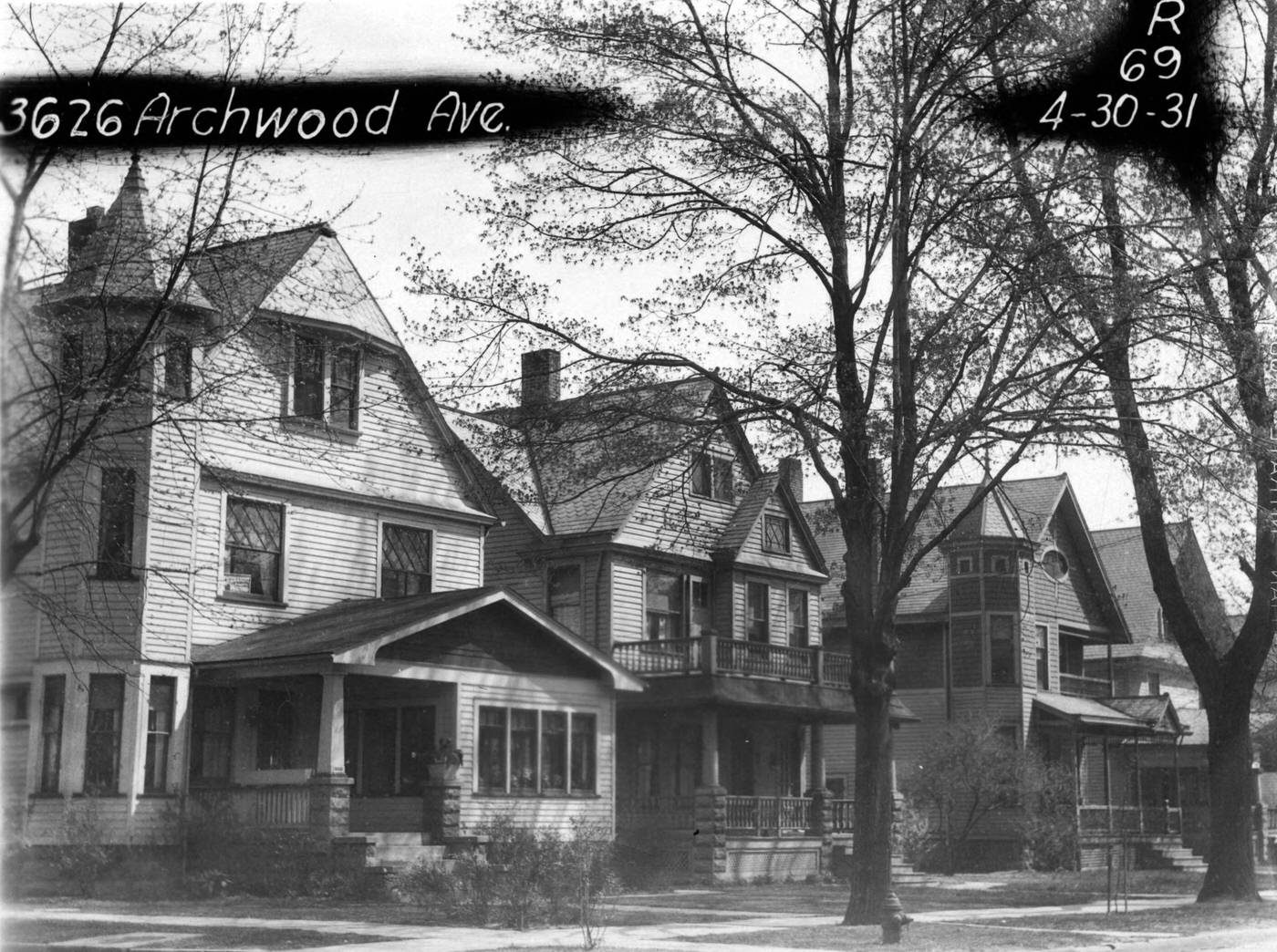

In terms of city planning, the ambitious Group Plan of 1903, which envisioned a monumental civic center around a grand mall, continued to influence downtown development. Key buildings of this plan, such as the Public Auditorium (1922), the Cleveland Public Library (1925/1926), and the Board of Education Building (1930), had been completed in the years leading up to or at the very beginning of the 1930s. However, the original vision of the Mall as the city’s new focal point was somewhat superseded by the development of the Union Terminal complex on Public Square, which became a new commercial and transportation nexus. Cleveland had also adopted its first comprehensive zoning ordinance in 1929, a measure intended to bring order to the city’s rapid and often haphazard growth. These developments, many initiated in an era of optimism, came to define much of Cleveland’s physical character during the challenging decade that followed.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know