The decade of the 1950s opened with Cleveland, Ohio, standing as a significant American urban center. In 1950, the city’s official population count reached 914,808 residents. This figure marked a 4.2% increase from the census taken in 1940 and represented the highest population Cleveland had ever recorded, making it the seventh largest city in the United States at that time. This period of growth, captured in the 1950 census, was, however, the last era of population increase the city would experience. The vibrancy of this peak population was mirrored in the city’s bustling core.

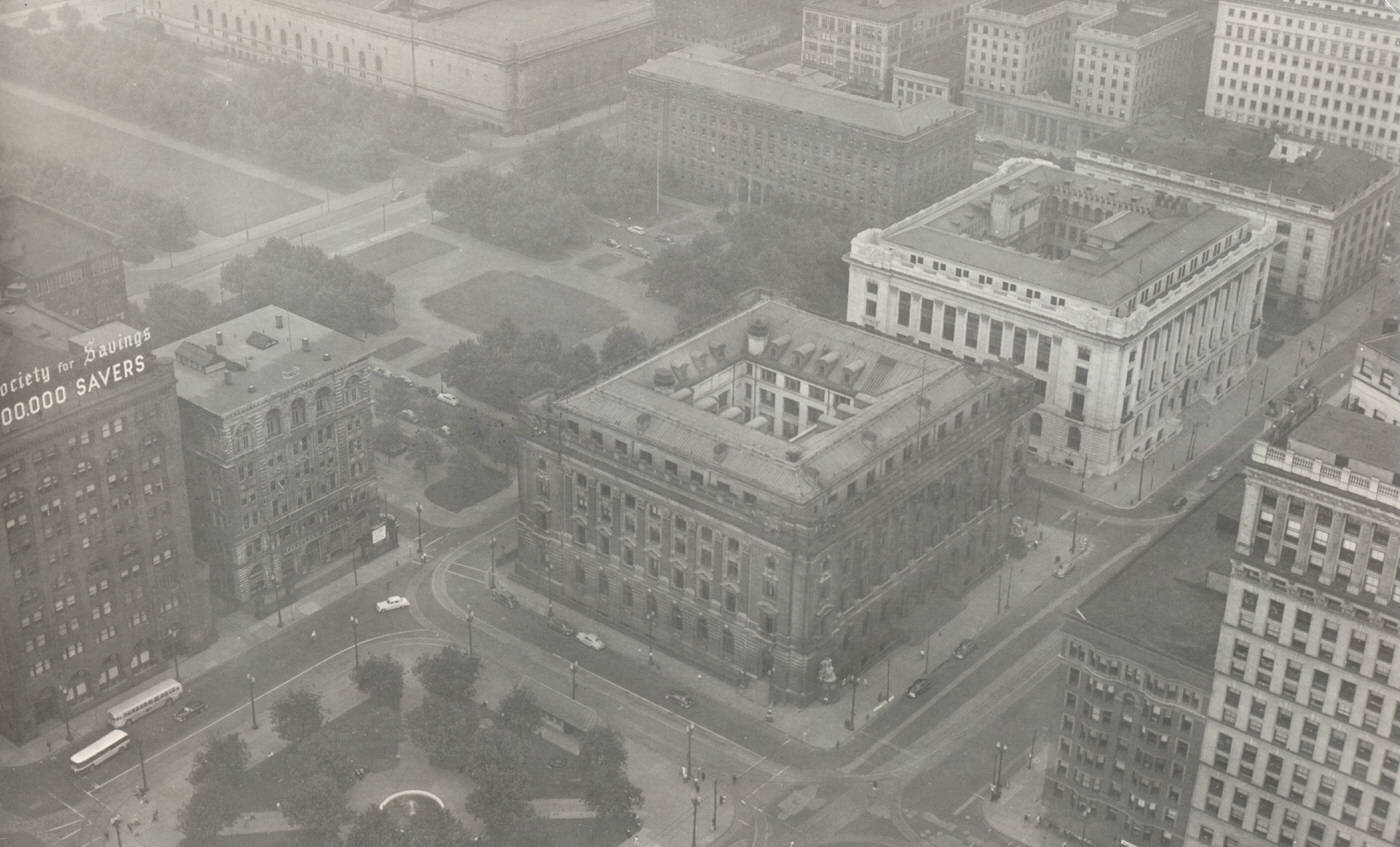

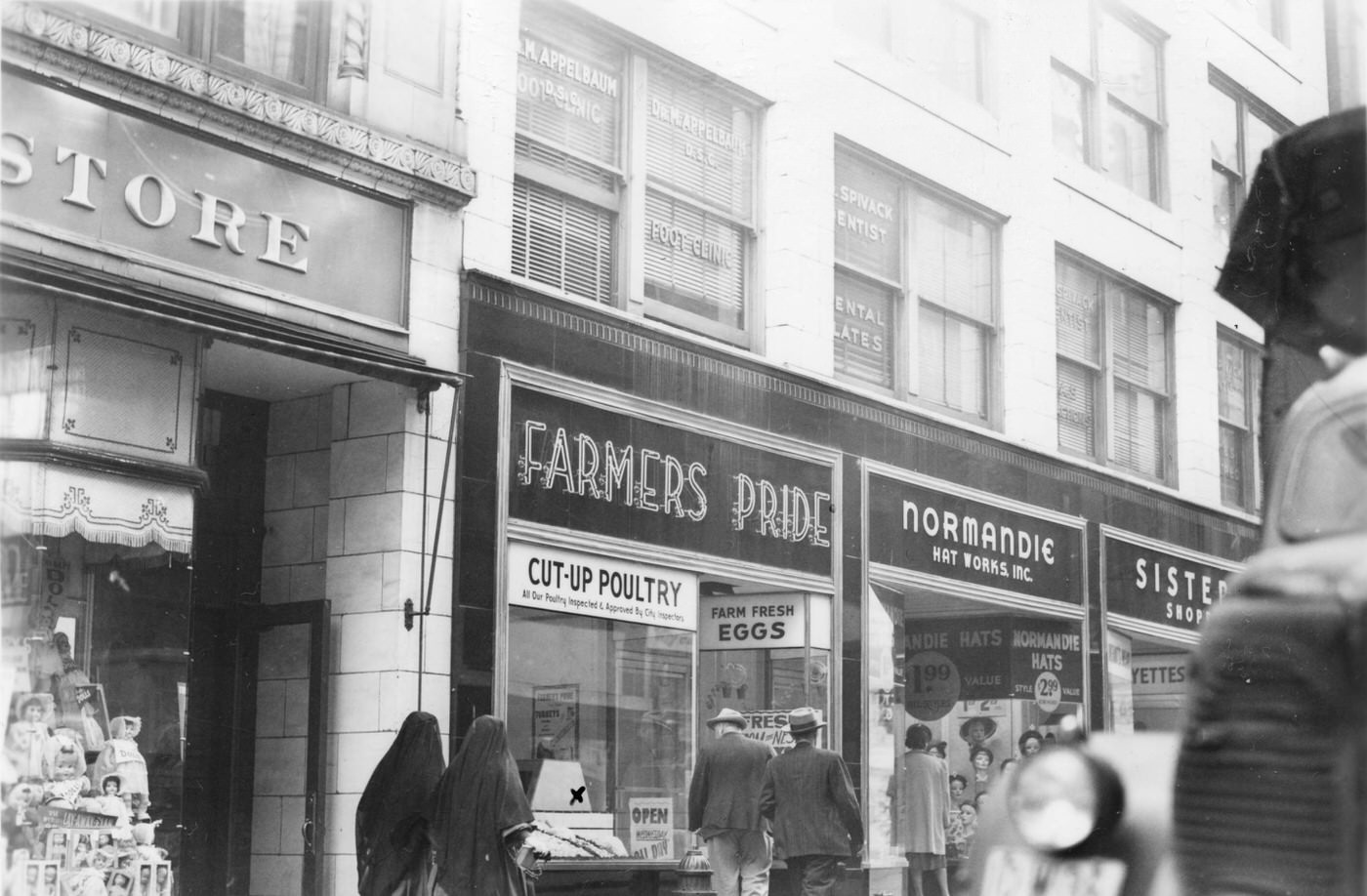

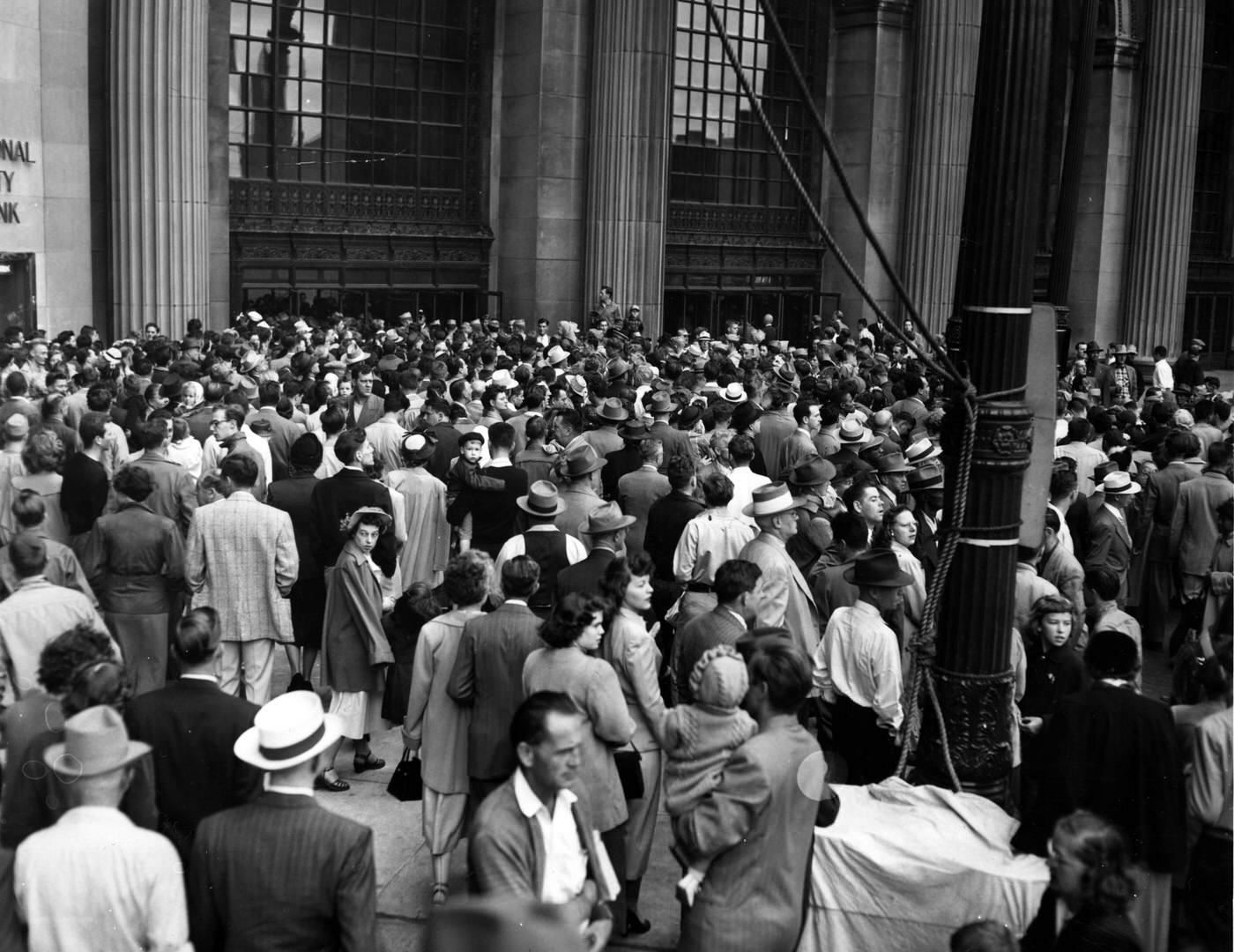

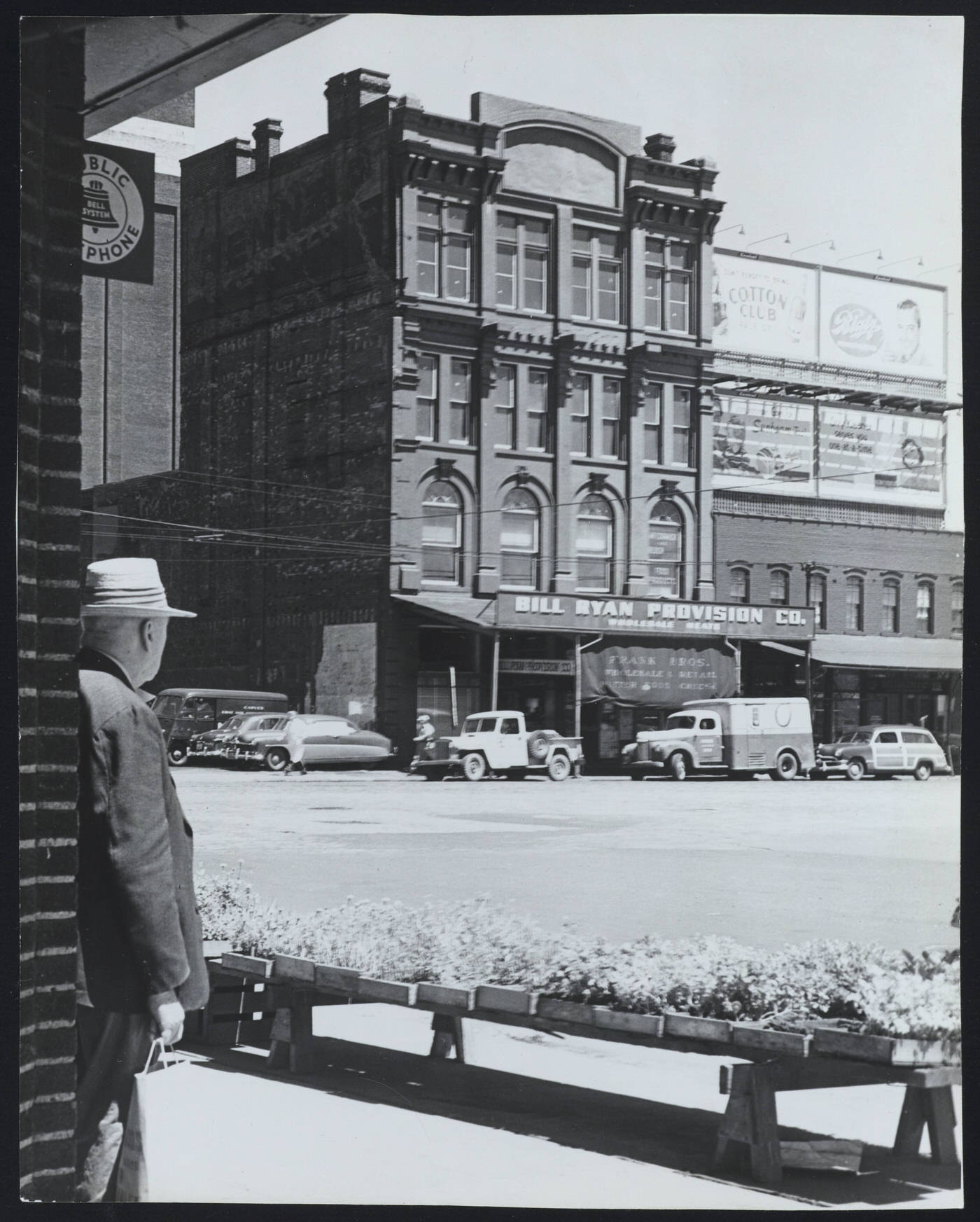

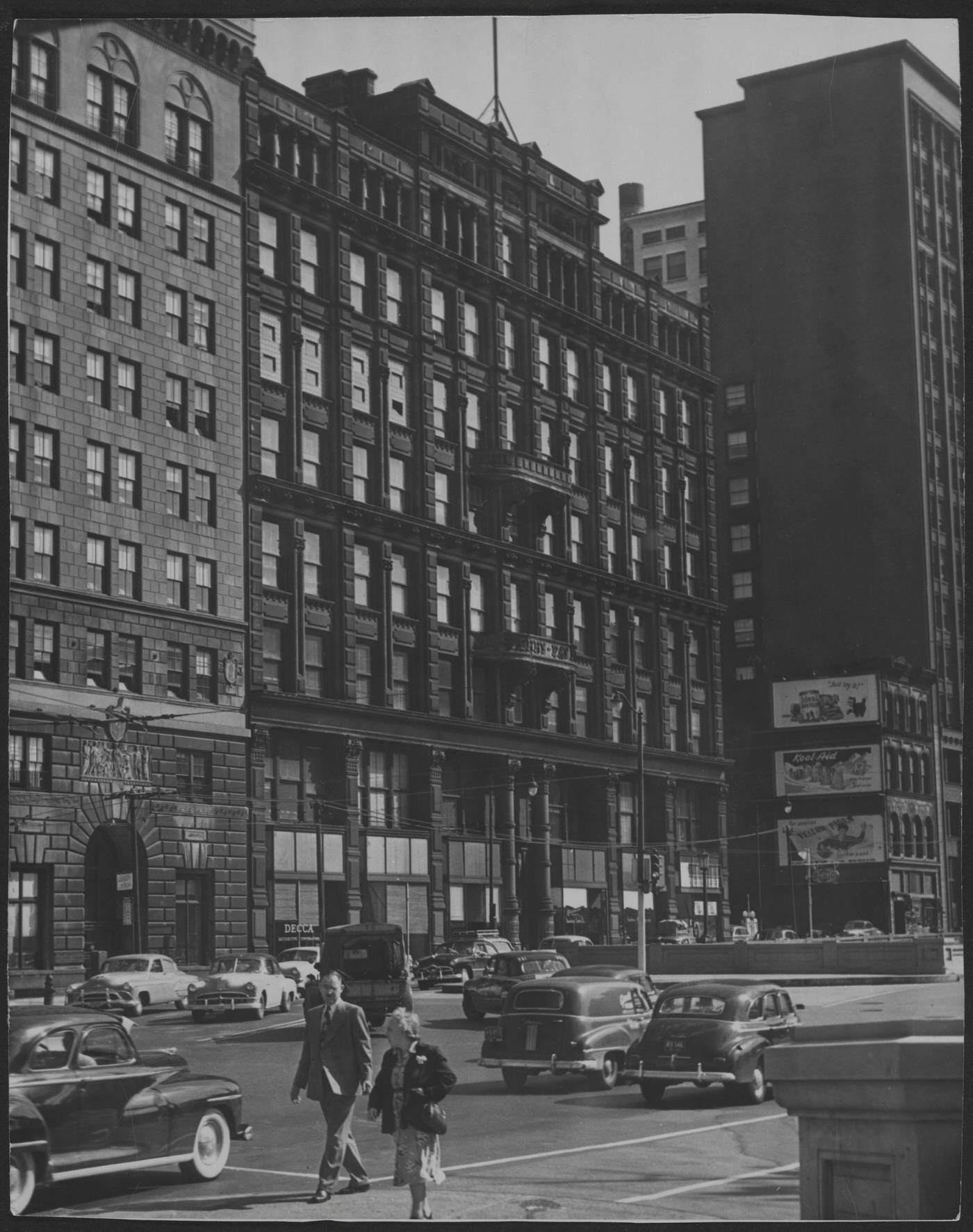

Throughout the 1950s, Downtown Cleveland was the undisputed retail, financial, and entertainment heart of the entire region. Its streets teemed with activity, drawing people from across Northeast Ohio and beyond. Central to this energetic atmosphere were its grand department stores, each a landmark in its own right. Halle Brothers Co., often referred to as Halle’s, was particularly renowned for its commitment to high-quality merchandise and exceptional customer service. Following World War II, Halle’s embarked on an ambitious expansion, establishing suburban branches starting in 1948 and completing a $10 million modernization program for its flagship downtown store in 1949. This downtown anchor then employed a workforce of over 3,000 people. Known affectionately as the “carriage store,” Halle’s offered a luxurious shopping experience, often compared to New York’s Saks Fifth Avenue, complete with uniformed doormen attending to customers. Despite its prestige and these significant investments in modernization, the very size of its over-expanded downtown store began to present challenges, and Halle’s started to see its annual sales figures fall behind those of its main competitors, the May Company and Higbee’s.

Cleveland’s Industrial Might: Factories and Foundries

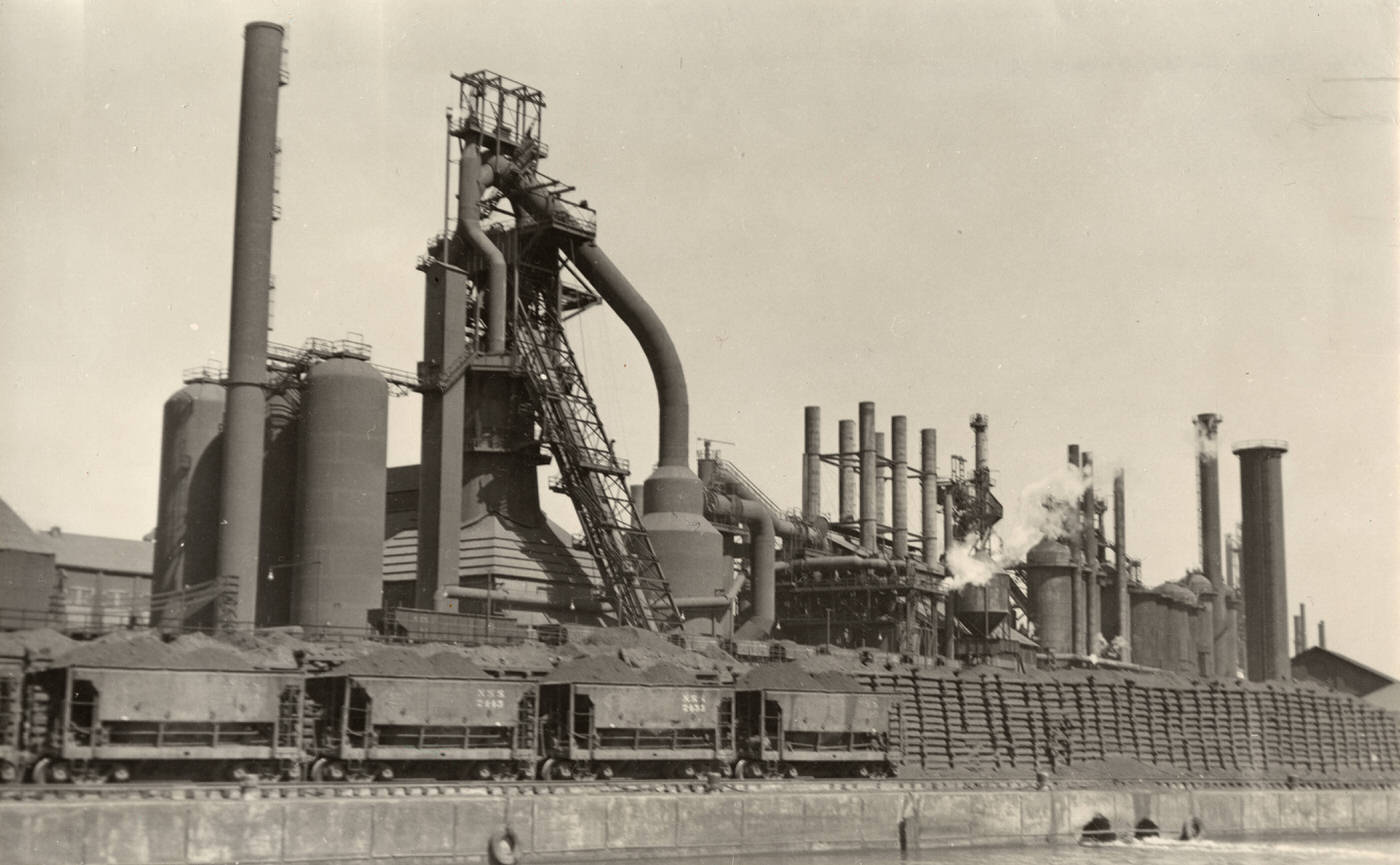

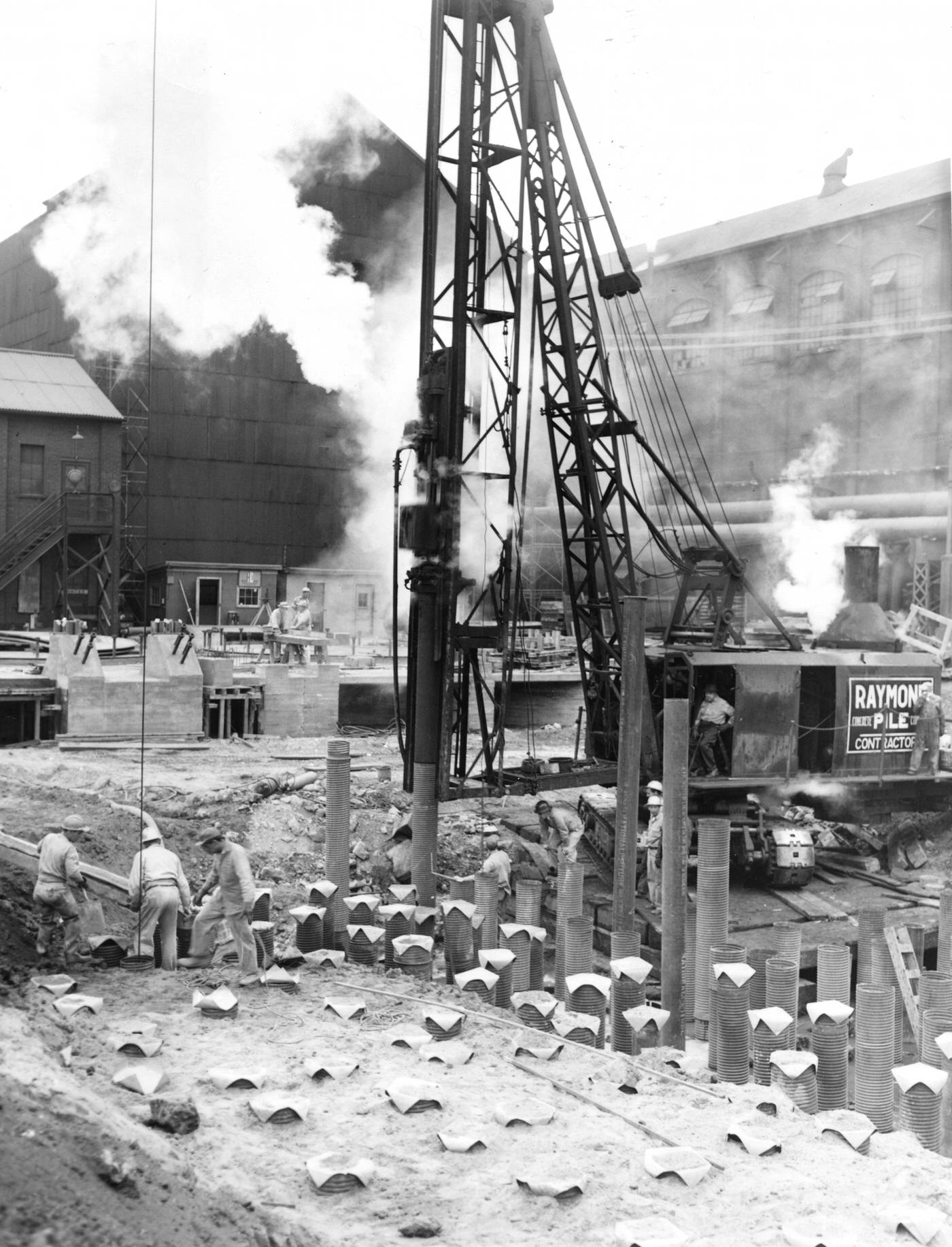

In the 1950s, Cleveland’s economy was powerfully propelled by its major industries, which served as pillars of its economic strength. Iron and steel production, the machine tool industry, and automotive manufacturing were fundamental to the city’s identity as an industrial powerhouse, providing substantial employment and driving regional prosperity.

The iron and steel industry, a long-standing cornerstone of Cleveland’s economy, experienced continued growth and significant expansion throughout the 1950s. This era saw the construction of taller blast furnaces and an overall increase in the output capacity of steel mills. Republic Steel Corporation was a dominant force in this sector, with its Cleveland plant ranking among the ten largest steelmaking facilities in the United States. The company thrived through the economic demands of the 1940s and maintained its robust operations well into the 1950s. Similarly, the Lakeside plant of Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, which had formerly been the Otis Iron & Steel Company, also underwent considerable expansion after World War II. Its original furnaces were replaced, and new mill buildings were constructed during the 1950s and 1960s, further boosting production capabilities. In the post-World War II era, the steel industry as a whole employed over 30,000 workers in Cleveland, underscoring its importance as a major employer. These large industrial centers, with their multiple refinery buildings, offices, and towering smokestacks, were often surrounded by dedicated worker housing, leading to the formation of distinct “pocket neighborhoods” such as Tremont and Slavic Village, whose character was intrinsically linked to the mills. The development of these neighborhoods, often featuring modest, similar houses, alongside community centers like the Merrick House in Tremont which served immigrant workers and their families, illustrates the direct link between heavy industry and community formation.

The machine tool industry also played a crucial role in Cleveland’s mid-century economy. While the absolute peak boom years for this sector were prior to 1950, the industry remained remarkably robust and healthy throughout the decade. The 1954 U.S. Census of Manufactures identified machinery production as the second leading industry in Cleveland, both in terms of the number of people employed and the total value of products manufactured. A notable trend within this sector during the 1950s was the consolidation of smaller companies through acquisition by larger manufacturers, such as Warner & Swasey and National Acme. The sustained health of the machine tool industry was a vital indicator of the overall vitality of Cleveland’s broader manufacturing ecosystem, as these tools were essential for the operations of the automotive, steel, and other metalworking industries.

The automotive industry was another giant in Cleveland’s industrial landscape. Historically, Cleveland held a significant position in the American automotive sector, second only to Detroit in the manufacture of automobiles, as well as parts and accessories. The 1950s and 1960s represented the peak period of activity and output for this industry in Cleveland. General Motors’ Chevrolet Division made a major commitment to the area by opening a substantial plant in Parma in 1949. This facility, which focused on producing transmissions, became one of the largest Chevrolet plants in the country and continued to be a major employer throughout the 1950s. Ford Motor Company also made significant investments in the Cleveland region during this decade, constructing two new major plants. A large foundry was built in Brook Park in 1953, which was responsible for producing most of Ford’s 6-cylinder engines and all of its V-8 Mercury engines at that time. Following this, in 1954, Ford opened a new stamping plant in Walton Hills. The automotive sector was a critical source of employment; by 1963, it was estimated that approximately 13% of Cleveland’s entire workforce was employed in this industry.

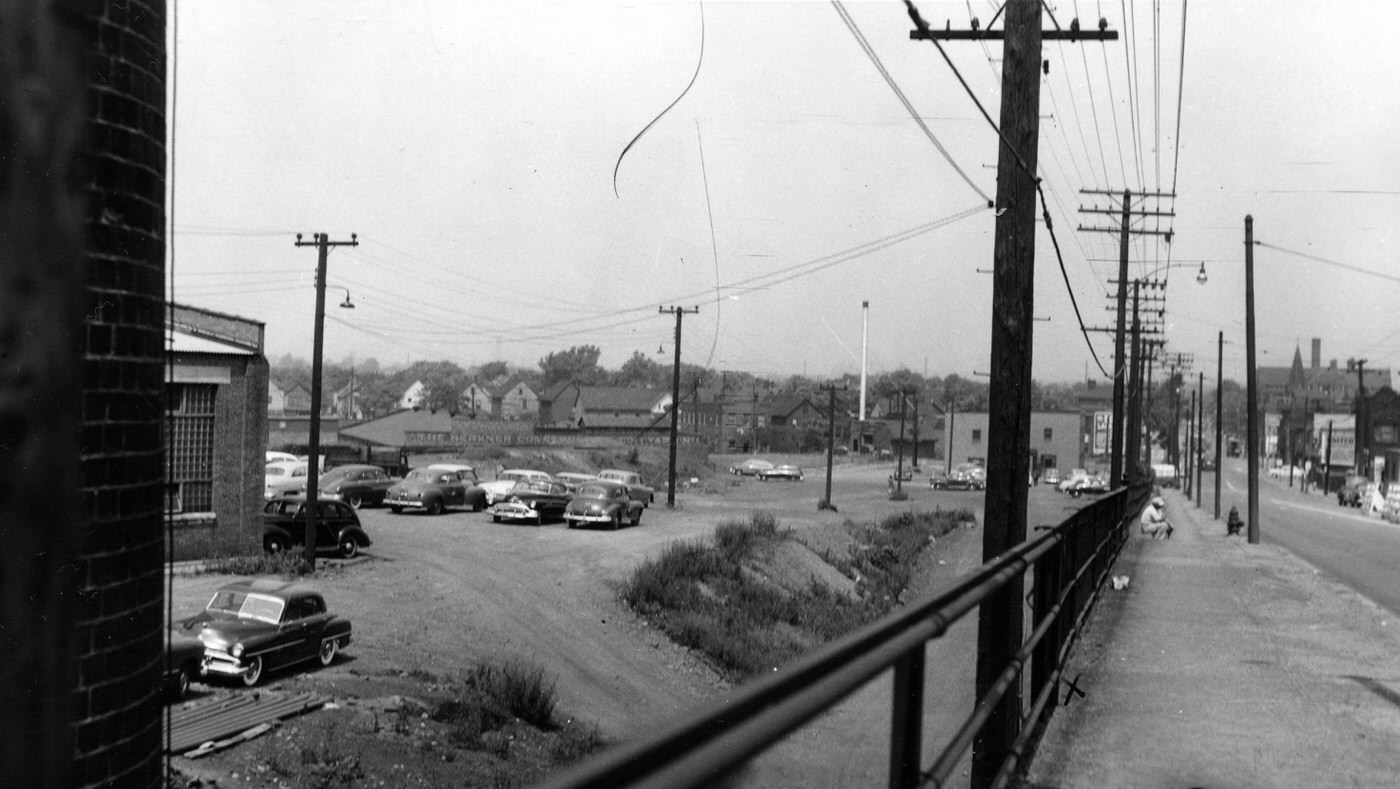

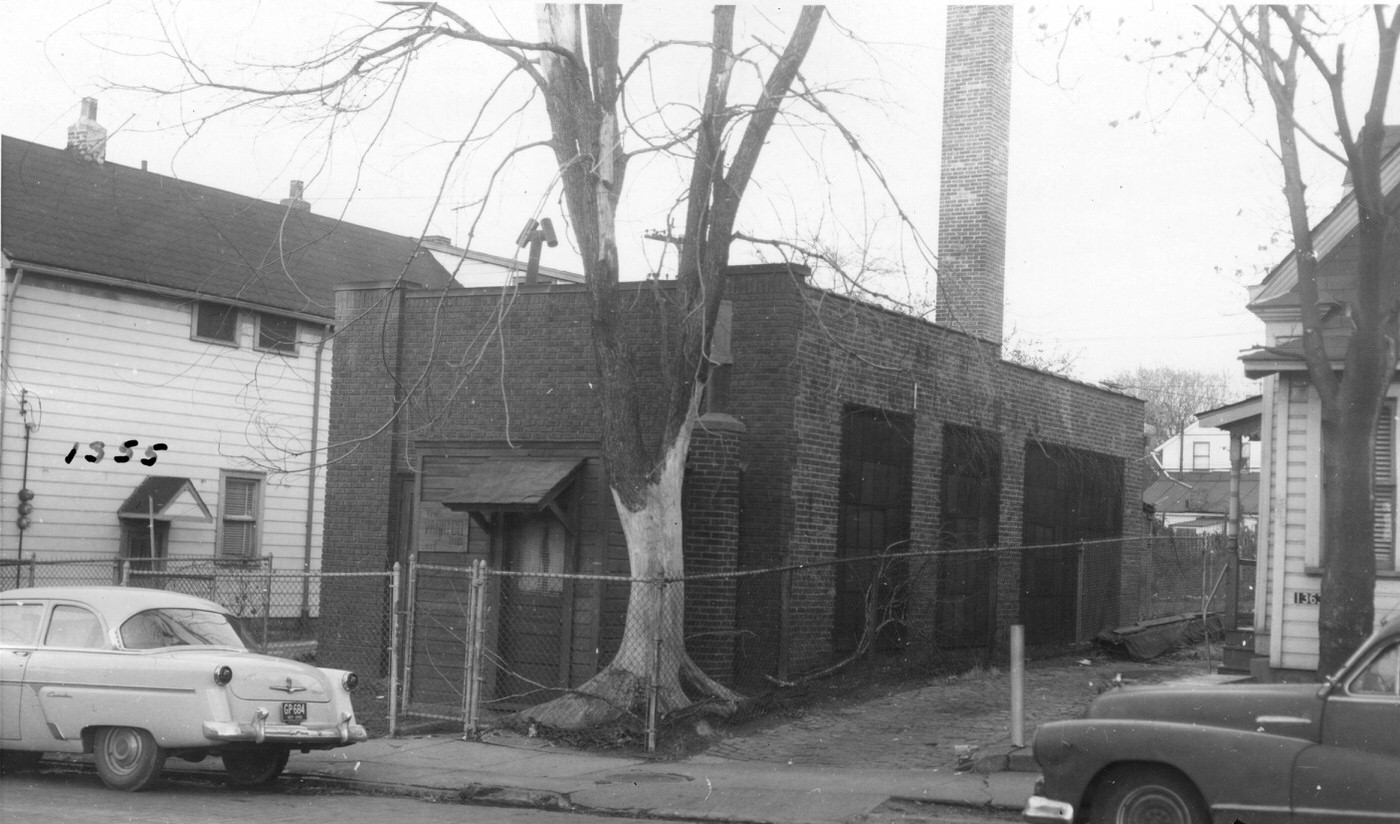

The 1950s also witnessed the physical expansion of Cleveland’s industrial footprint. Many existing industrial plants underwent significant enlargement, often characterized by the construction of taller smokestacks—a visual marker of industrial activity—and the development of larger, more complex industrial parks designed to accommodate increased production and logistical needs.

Building the Future: Homes, Suburbs, and Urban Renewal

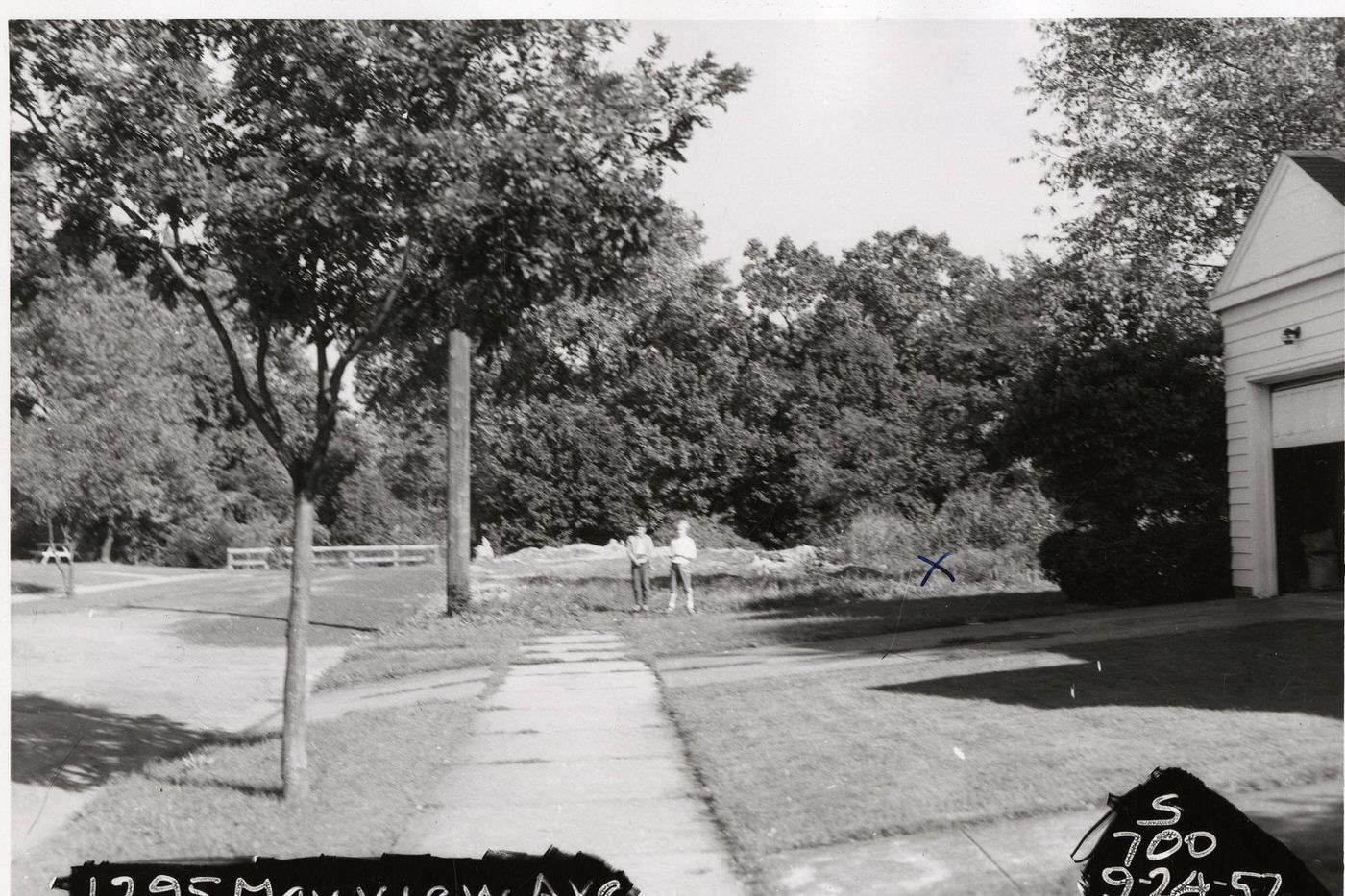

The 1950s marked a significant shift in how and where Clevelanders lived, characterized by the rapid expansion of suburbs and ambitious, often controversial, efforts to reshape the urban core. This period was defined as one of “automobile suburbs and suburban supremacy”. The movement of population outward from the central city was propelled by a confluence of factors, including a widespread aspiration for what was perceived as a “rural ideal,” a desire to escape perceived urban problems such as overcrowding and aging infrastructure, advancements in transportation technology—most notably the increasing affordability and ownership of automobiles—and various private and public policies at local, state, and federal levels that encouraged suburban development.

East Cleveland, for example, reached its peak population of 40,047 in 1950. Despite experiencing a slight 5% decline in its population over the course of the decade, it remained the most densely populated suburb in the Cleveland area. The growth in newly developing suburbs such as Parma, Warrensville, and Brook Park was particularly dramatic and swift. The flourishing automotive industry played a direct role in enabling this suburban boom, as reliable personal transportation made it feasible for workers to commute from greater distances to industrial jobs in and around the city. This outward migration fundamentally altered the metropolitan landscape, drawing population, commerce, and resources away from the central city and establishing new patterns of daily life and community.

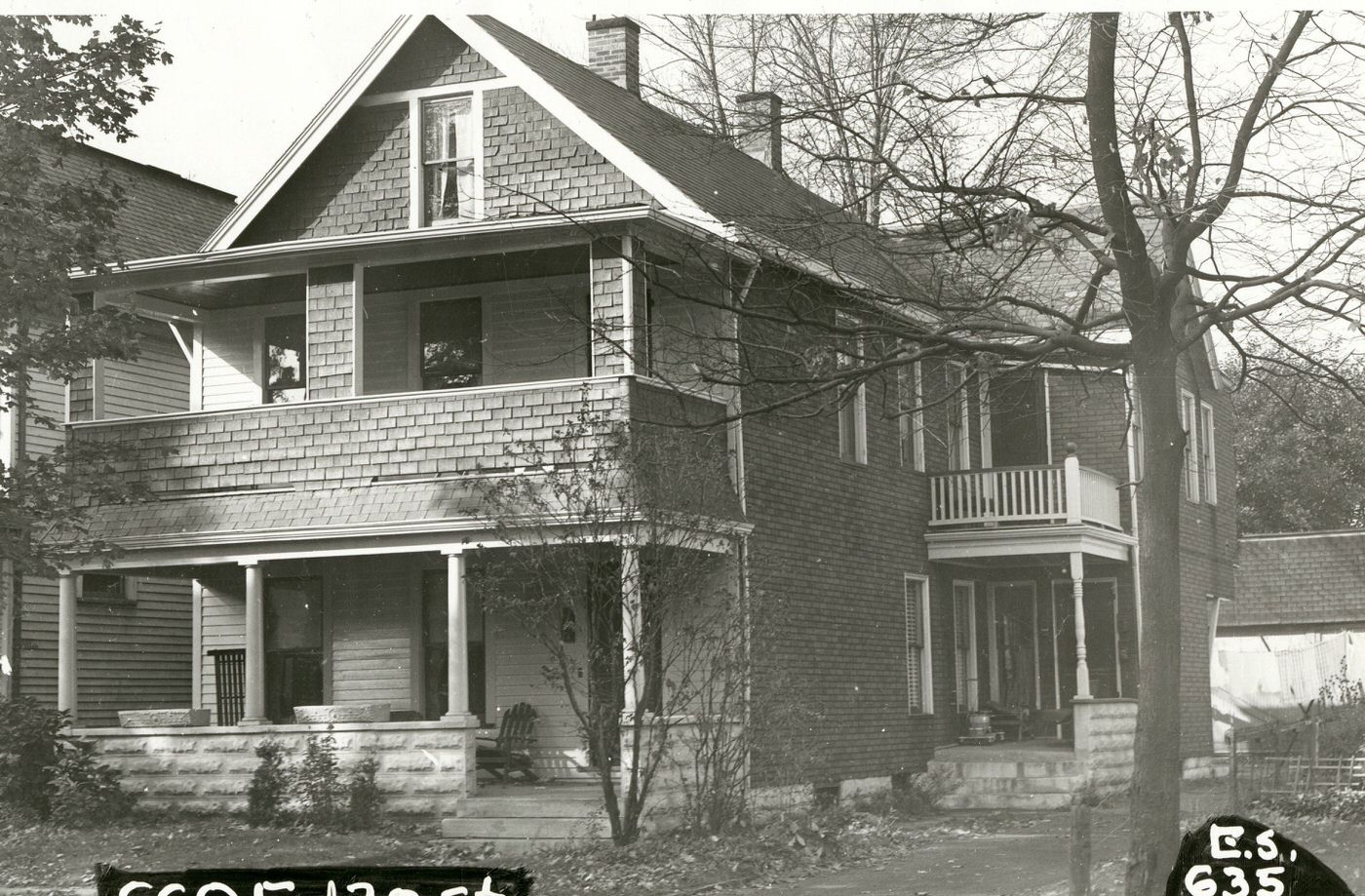

This era also saw a transformation in housing preferences and architectural styles. In the burgeoning suburbs, the California ranch-style home became a widely popular choice, particularly in new developments in communities like Pepper Pike, Beachwood, Solon, and Moreland Hills. These homes were typically single-story structures, often characterized by their asymmetrical layouts, rectangular footprints, and distinctive long, low rooflines. More broadly, suburban houses constructed in the 1950s were frequently “builders’ houses.” These were often based on standardized designs, such as Cape Cods, two-story Colonials, split-levels, and various iterations of the ranch style, with attached garages becoming a prominent and defining feature, reflecting the centrality of the automobile to suburban life.

While new forms were taking root in the suburbs, the city itself contained a significant stock of older housing types. “Cleveland Doubles,” two-family houses with identical stacked units, had seen their peak construction period earlier in the century, typically along streetcar lines. While these remained a common feature of Cleveland’s urban neighborhoods, the rise of automobile ownership and the preference for single-family homes in suburban settings meant that the Cleveland Double became a less desirable model for new construction as the 1950s progressed. Amidst the prevalence of these more conventional styles, a unique cluster of a dozen modern houses, designed by architect Robert A. Little, was completed in Pepper Pike during the 1950s. These homes, reflecting a functionalist architectural style, were built for a private cooperative community on a parcel of rural land that was not subject to the stringent design restrictions common in other affluent suburbs like Shaker Heights.

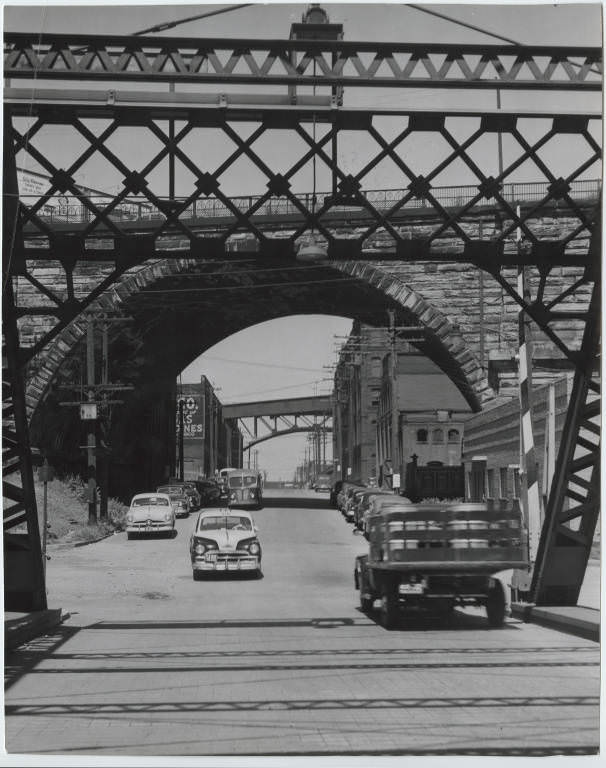

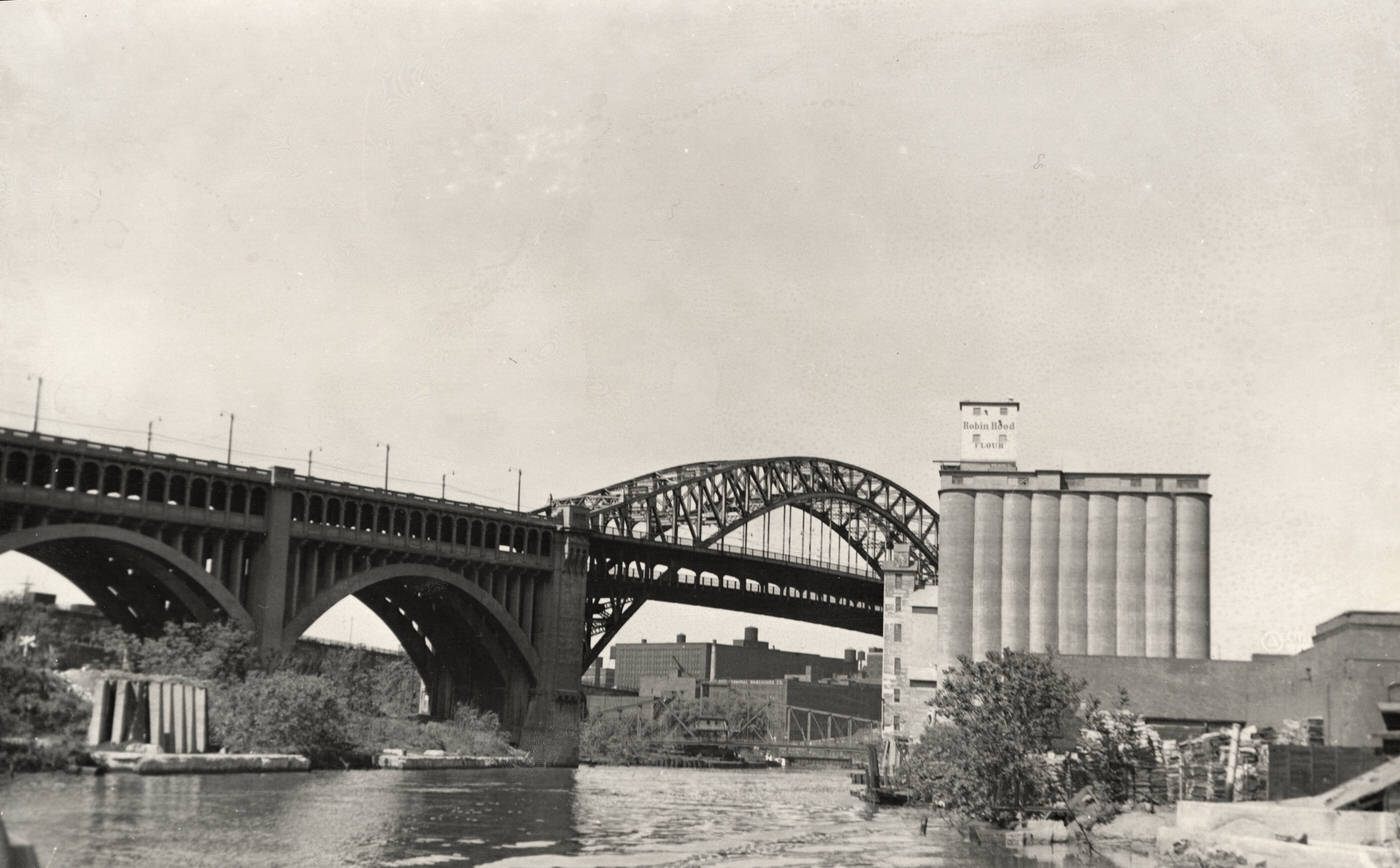

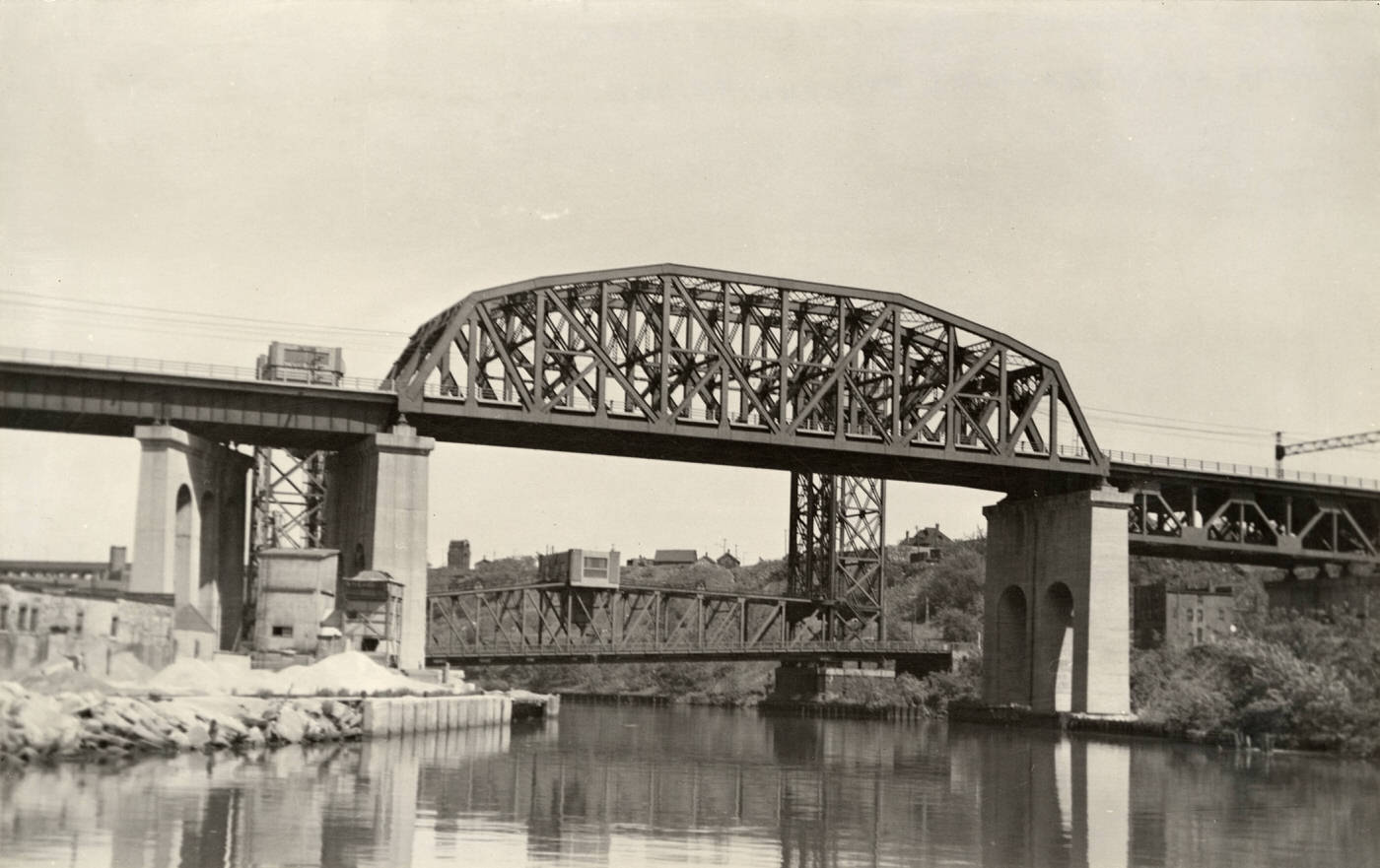

On the Move: Transportation Transformation

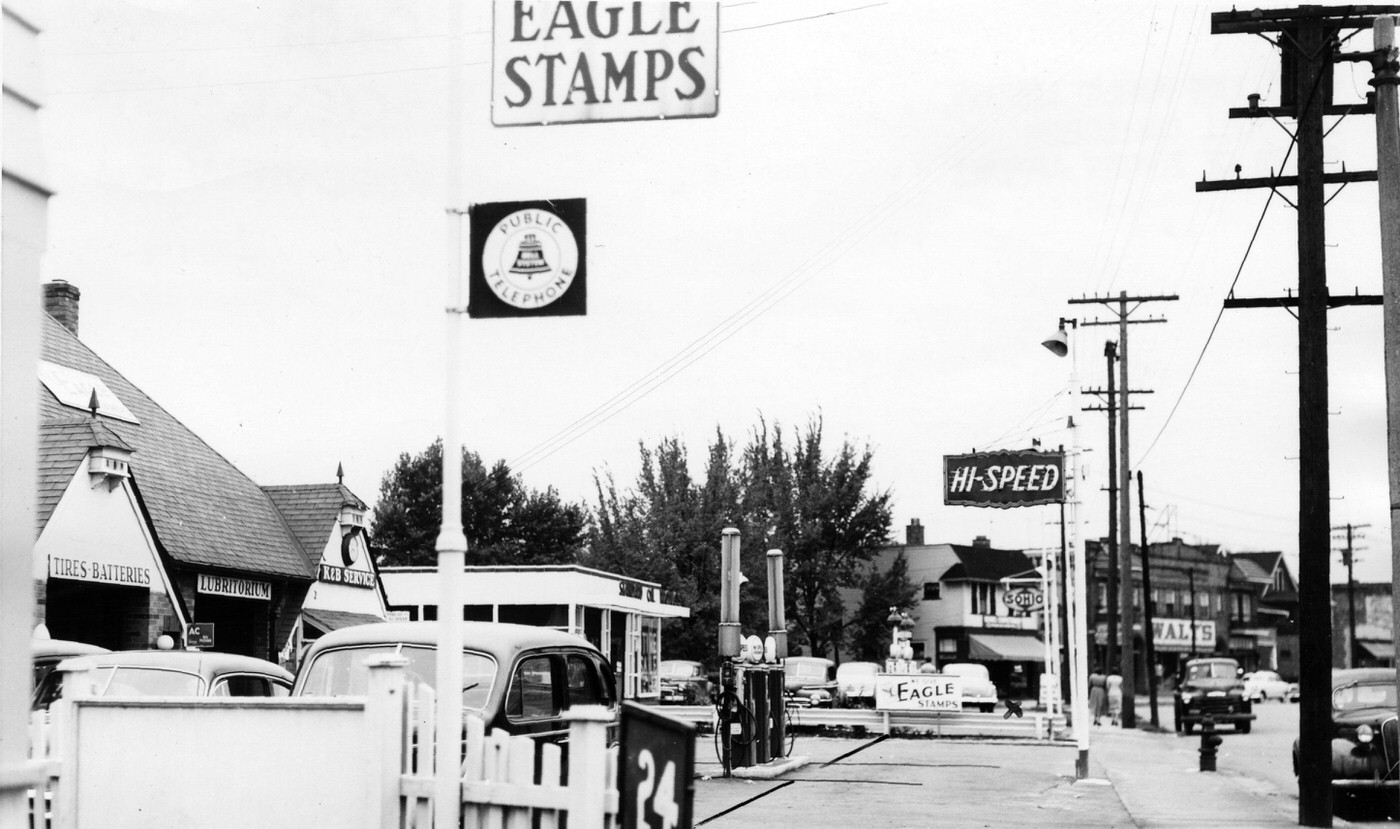

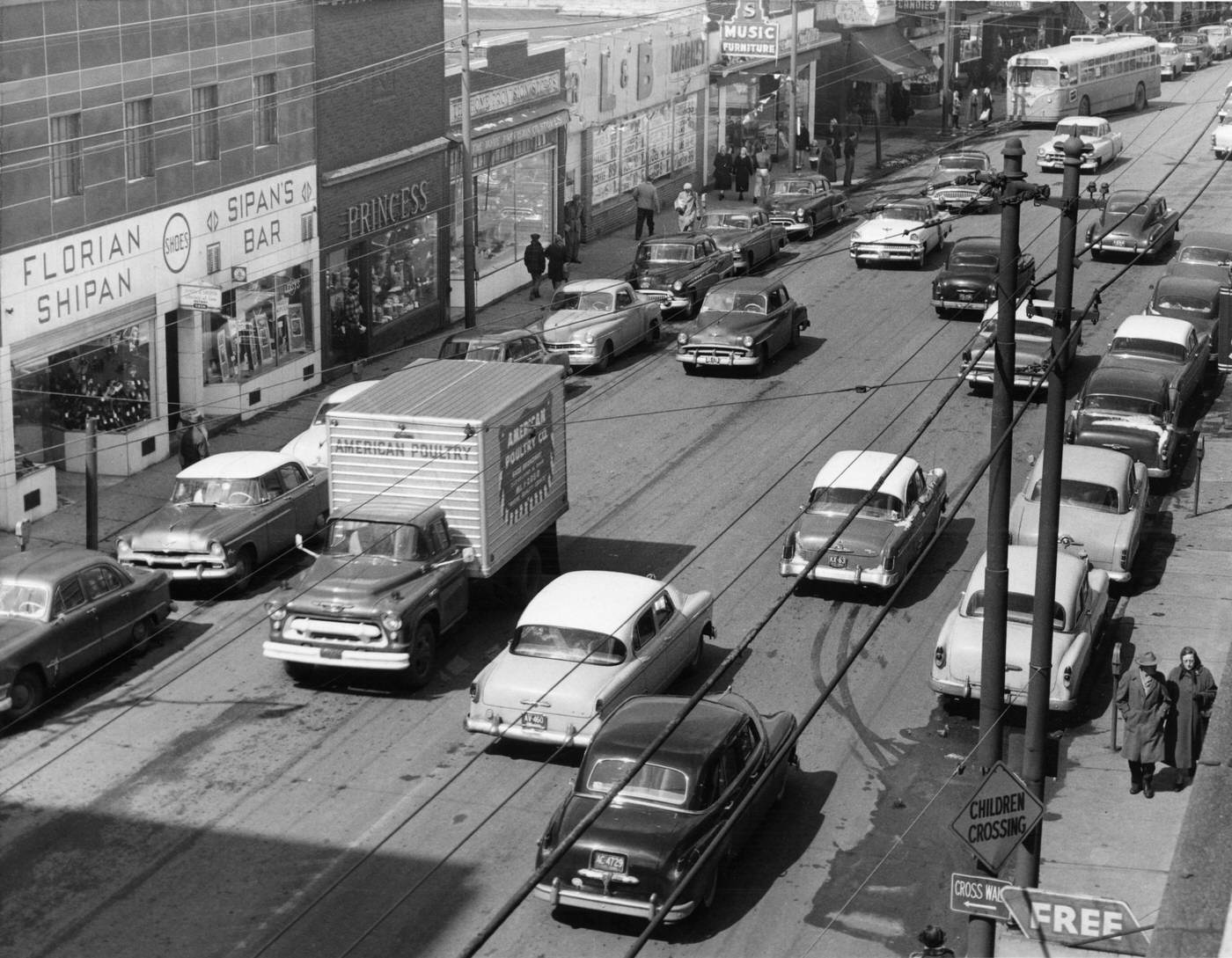

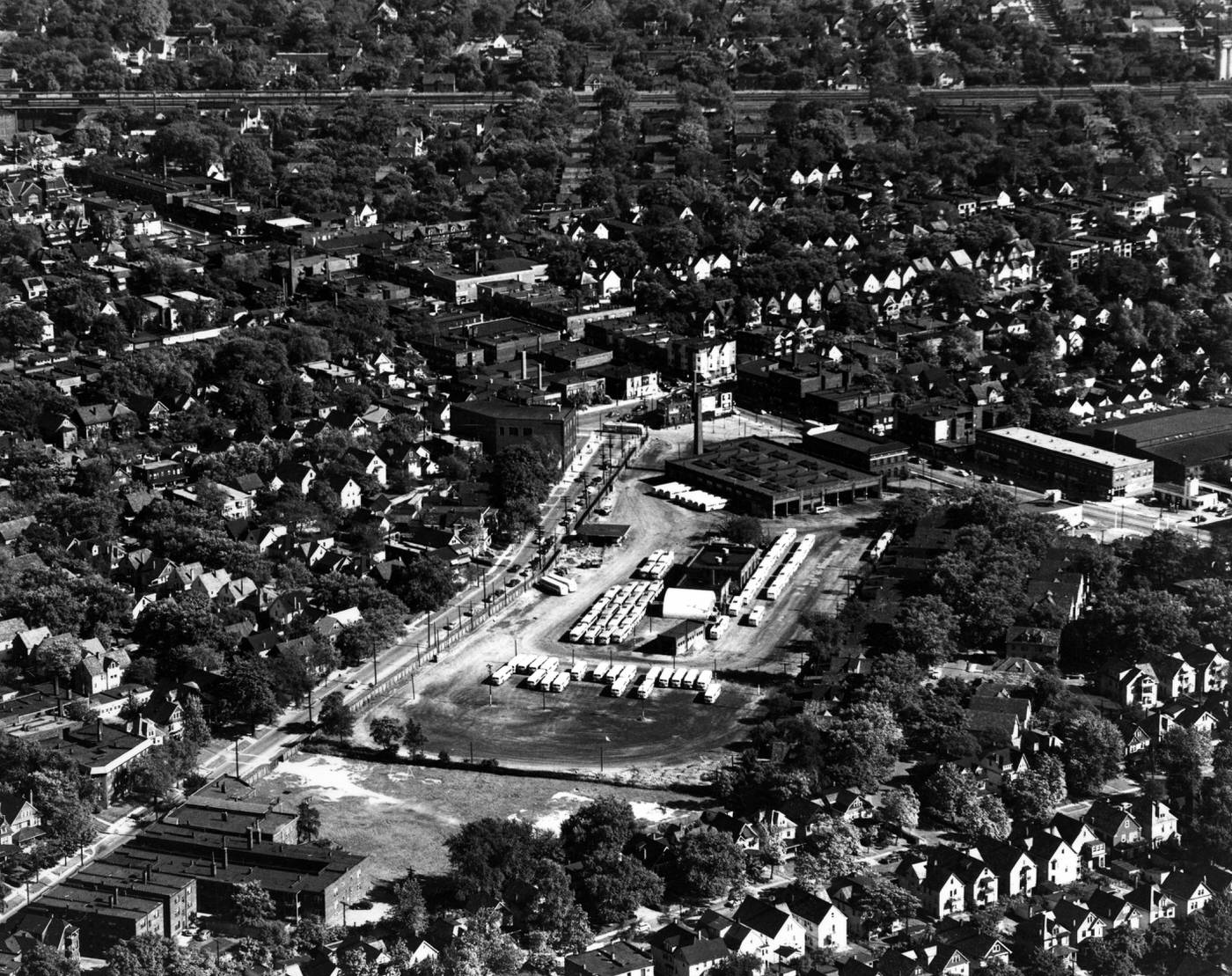

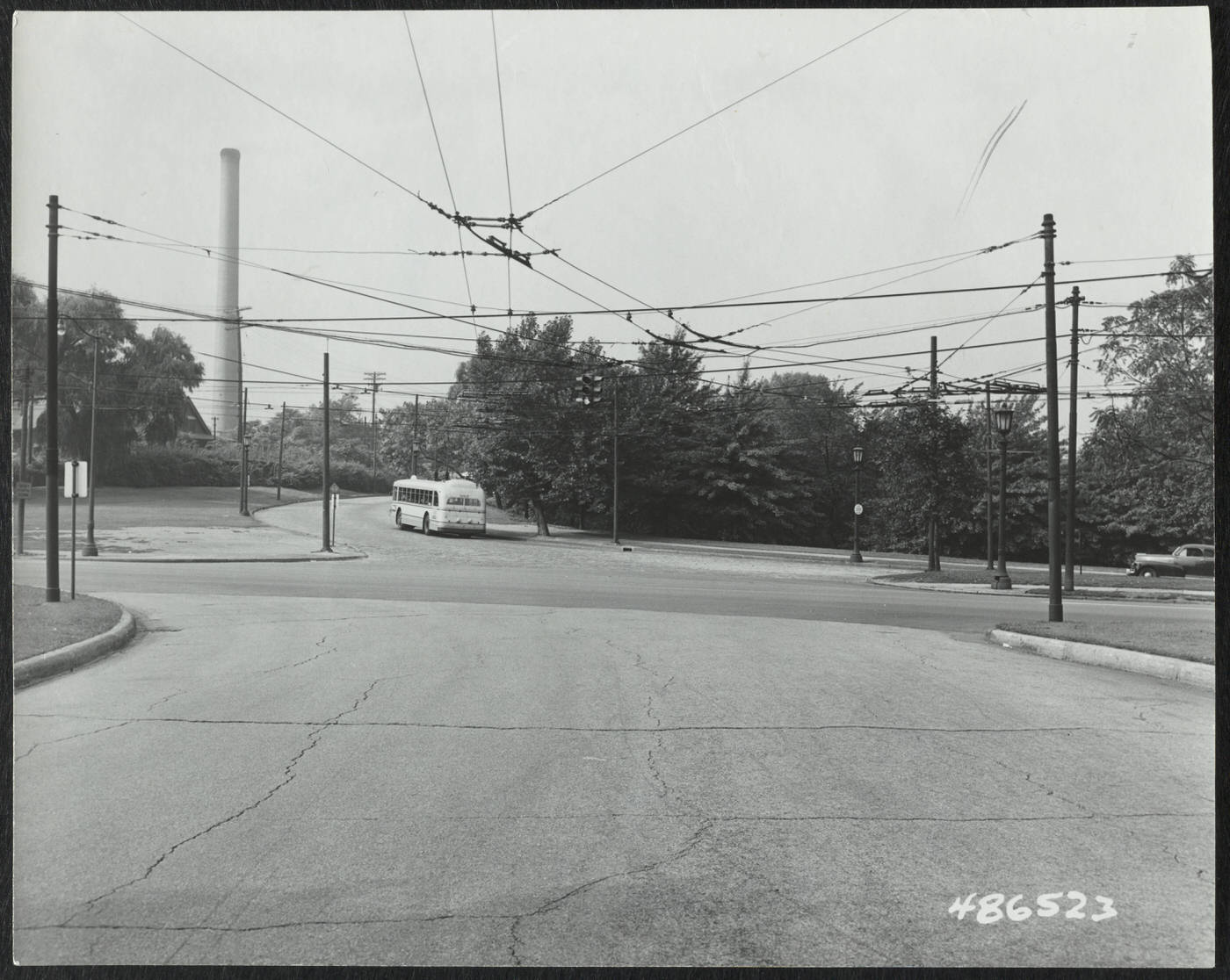

The 1950s witnessed a profound transformation in how Clevelanders moved around their city and region, marked by the definitive decline of the streetcar, the rise of bus and automobile use, and the exciting debut of a new rapid transit system.

The once-extensive streetcar system, a hallmark of Cleveland for decades, entered its waning era in the 1950s. At the beginning of the decade, the Cleveland Transit System (CTS) still operated a considerable fleet, boasting 1,039 streetcars running across 25 distinct lines. However, a confluence of factors was contributing to their steady demise. The most significant of these was the rapidly increasing dominance of the private automobile as the preferred mode of transportation for many. Additionally, the streetcar system itself faced challenges, including issues stemming from the overexpansion of lines in earlier years, growing congestion on shared roadways, consistently falling ridership numbers, and persistent financial difficulties that made modernization and upkeep problematic. Even in areas with excellent public transit, like Shaker Heights with its pioneering off-grade rapid transit, automobile use was high; nearly 75% of principal income earners there commuted by car.

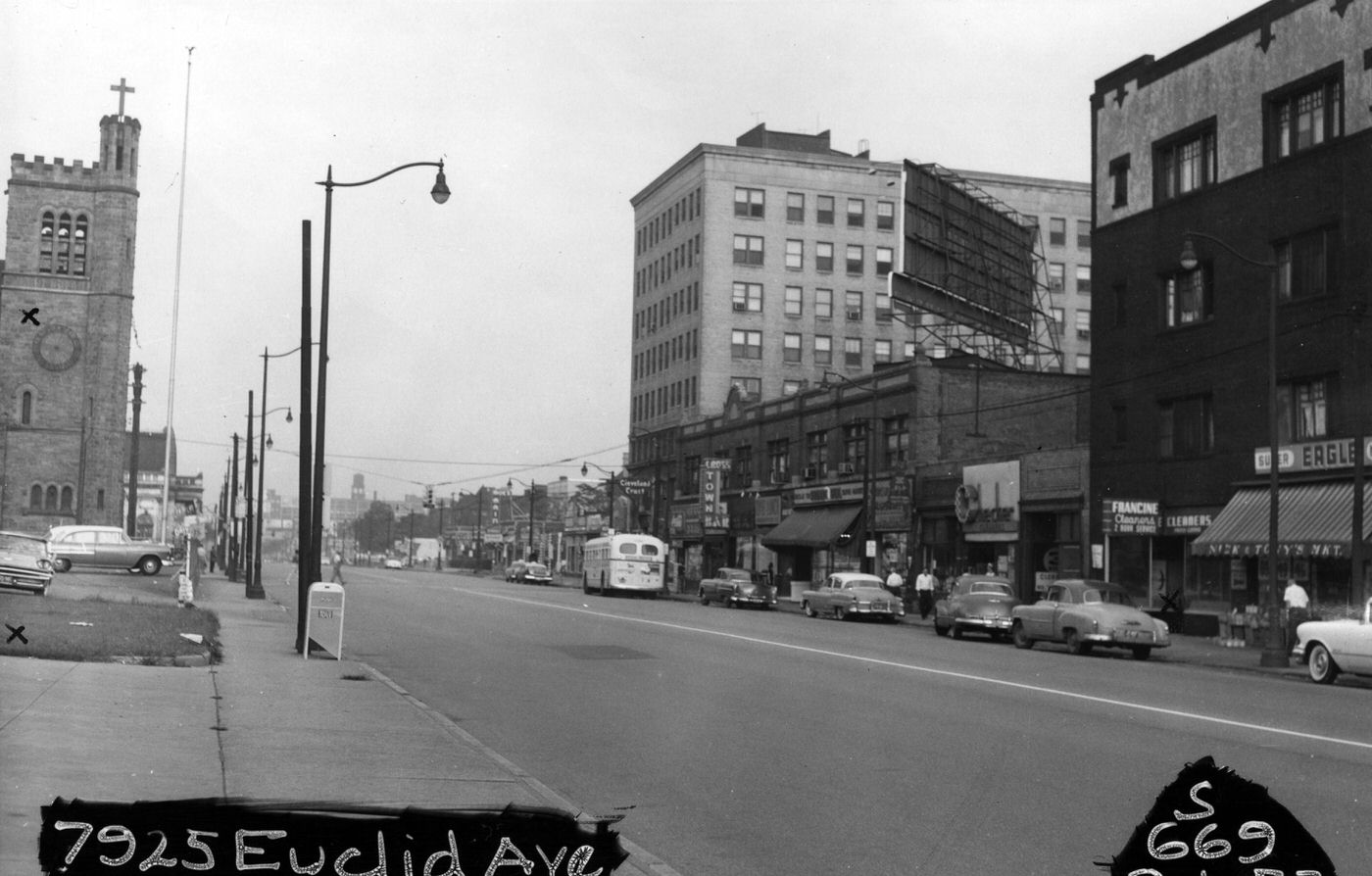

Throughout the early 1950s, numerous streetcar lines were systematically phased out and replaced by either buses or trackless trolleys, which offered more flexibility and lower operational costs on many routes. For example, the Kinsman line (No. 14) saw its streetcars replaced by trackless trolleys starting on March 25, 1950. Portions of the St. Clair line (No. 1) were converted to bus operation in April 1951, with other sections transitioning to trackless trolleys in November of the same year. The Euclid Avenue line (No. 6), one of the city’s busiest, was converted to bus operation on April 26, 1952. This pattern continued across the city, with lines like the Detroit (No. 26), Superior (No. 3), West 25th (No. 20), Clark (No. 23), East 55th (No. 16), and Madison (No. 25) all ceasing streetcar operations between 1951 and January 1954, replaced by buses or trackless trolleys. This transition was part of a broader strategy by CTS, following World War II, to fully integrate buses into their mass transit routes and completely phase out the aging streetcar infrastructure.

As streetcars faded, a new era of public transportation was dawning with the development of a modern rapid transit system. In 1951, the Cleveland Transit System embarked on plans for this alternative heavy-rail system, securing a nearly $30-million loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to fund the development of an eastern and a western route. The primary goals of this new rapid transit were to provide efficient transportation for suburban residents into the city center, help revive the downtown commercial district by making it more accessible, and offer convenient access to Cleveland Hopkins International Airport.

Service on the eastern line of the new rapid transit commenced in March 1955. This line stretched approximately 7.8 miles, connecting Terminal Tower at Public Square with the Windermere station in East Cleveland. For a portion of its route, from downtown to East 35th Street, it shared tracks with the existing Shaker Heights Rapid Transit system. Just a few months later, in August 1955, the 5.3-mile western line opened for service. It extended from Terminal Tower to West 117th Street and Berea Road in Lakewood. This western line saw a further extension to West 143rd Street in 1958. The opening of these rapid transit lines, particularly the two stations in East Cleveland in 1954 (likely referring to preparations or early phases before full line operation in 1955), marked a significant modernization of the city’s public transit infrastructure. This investment in a heavy-rail system was a deliberate effort to reshape the metropolitan landscape into a network capable of supporting multi-modal transportation needs in an increasingly decentralized region.

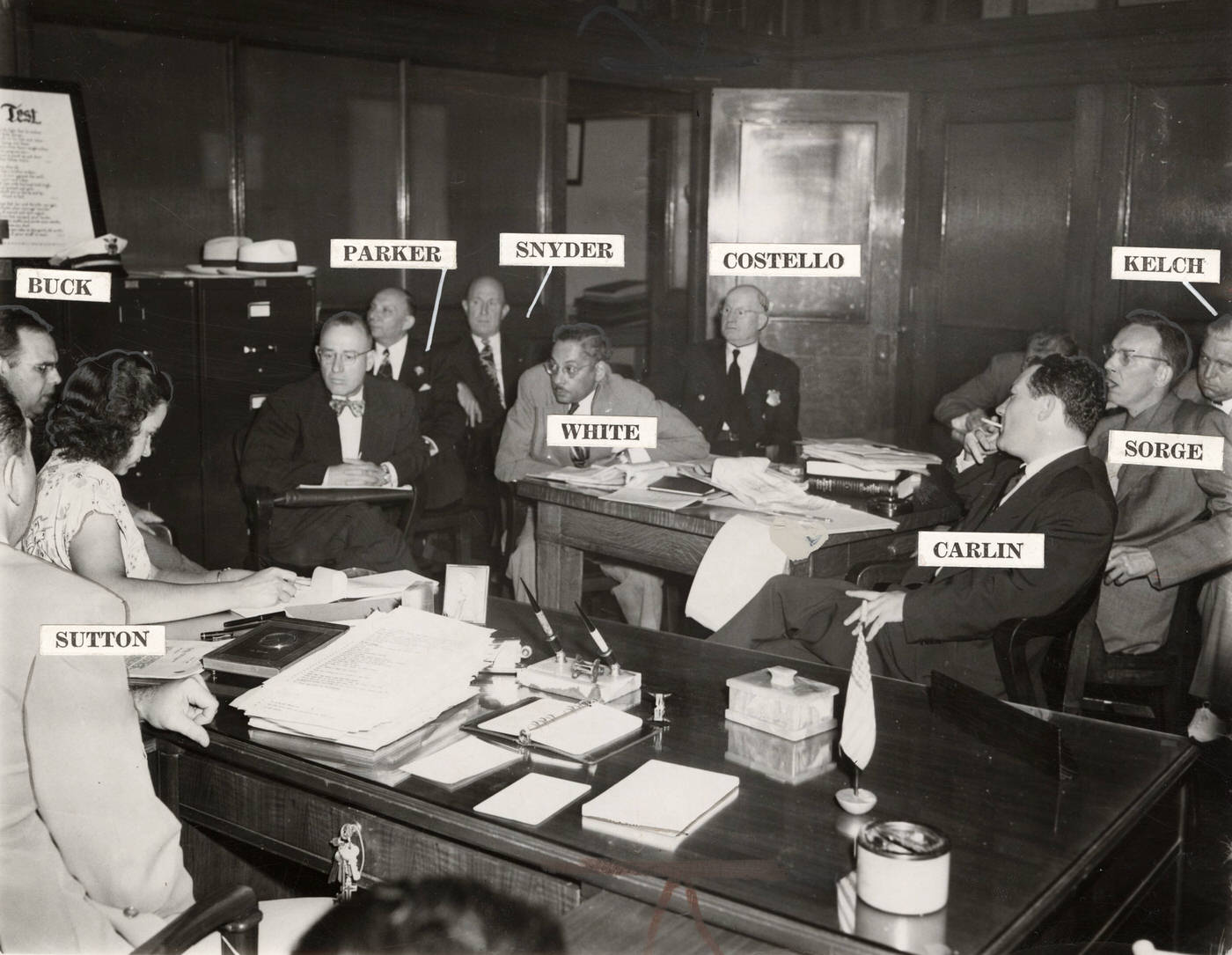

Concurrent with suburban expansion, Cleveland embarked on extensive urban renewal projects aimed at modernizing and revitalizing the city’s core. The Cleveland Development Foundation (CDF), established in 1954, was a pivotal organization in these endeavors. Founded by influential local business leaders including John C. Virden of the Federal Reserve Bank, Elmer Lindseth of the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company (CEI), and Thomas F. Patton of Republic Steel, the CDF drew inspiration from Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Conference on Community Development. Its primary mission was to offer financial backing and planning assistance for projects designed to eliminate what were termed “slum conditions” and to promote comprehensive urban redevelopment. To this end, the CDF successfully raised an initial $2 million revolving fund through membership subscriptions and the sale of development notes.

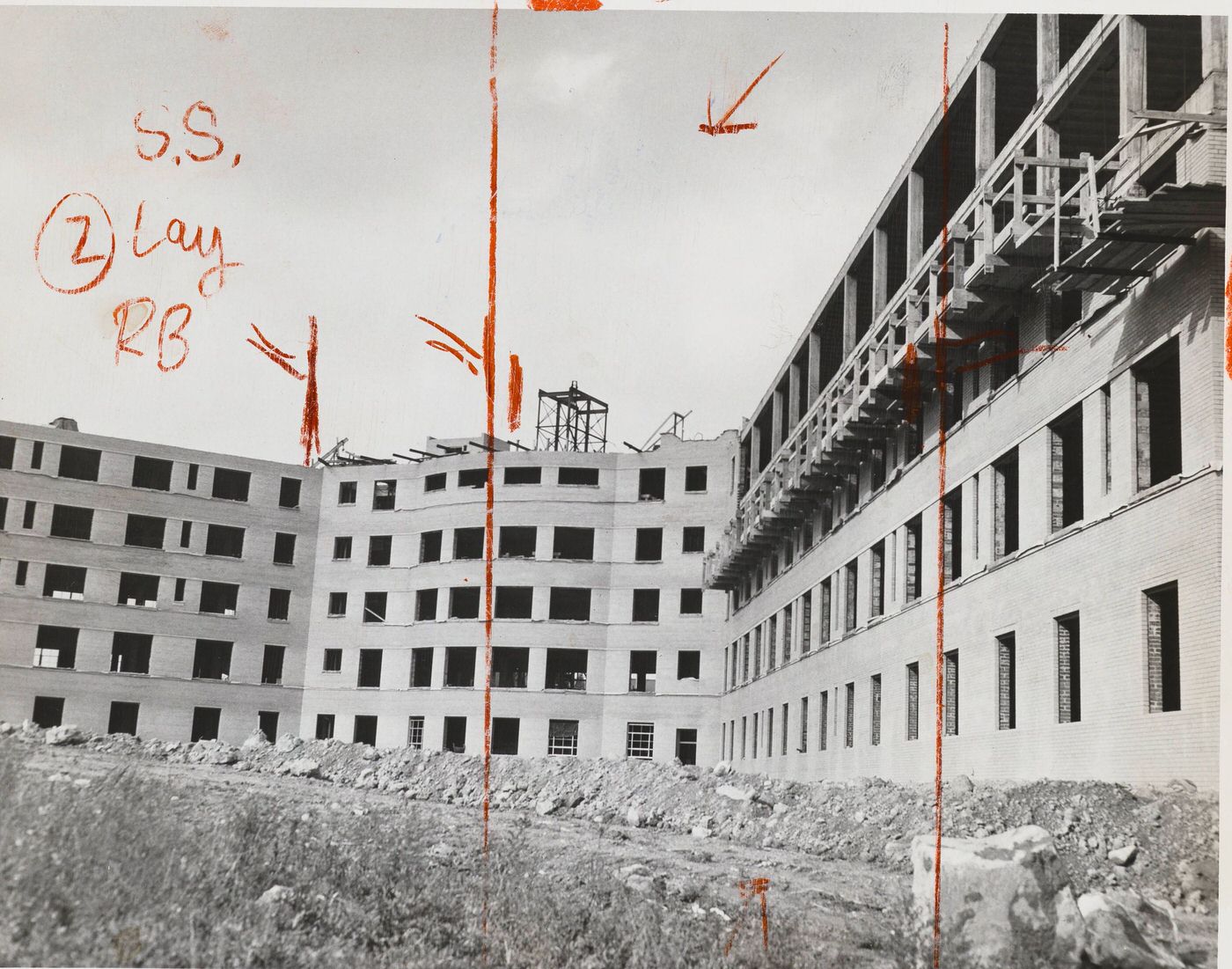

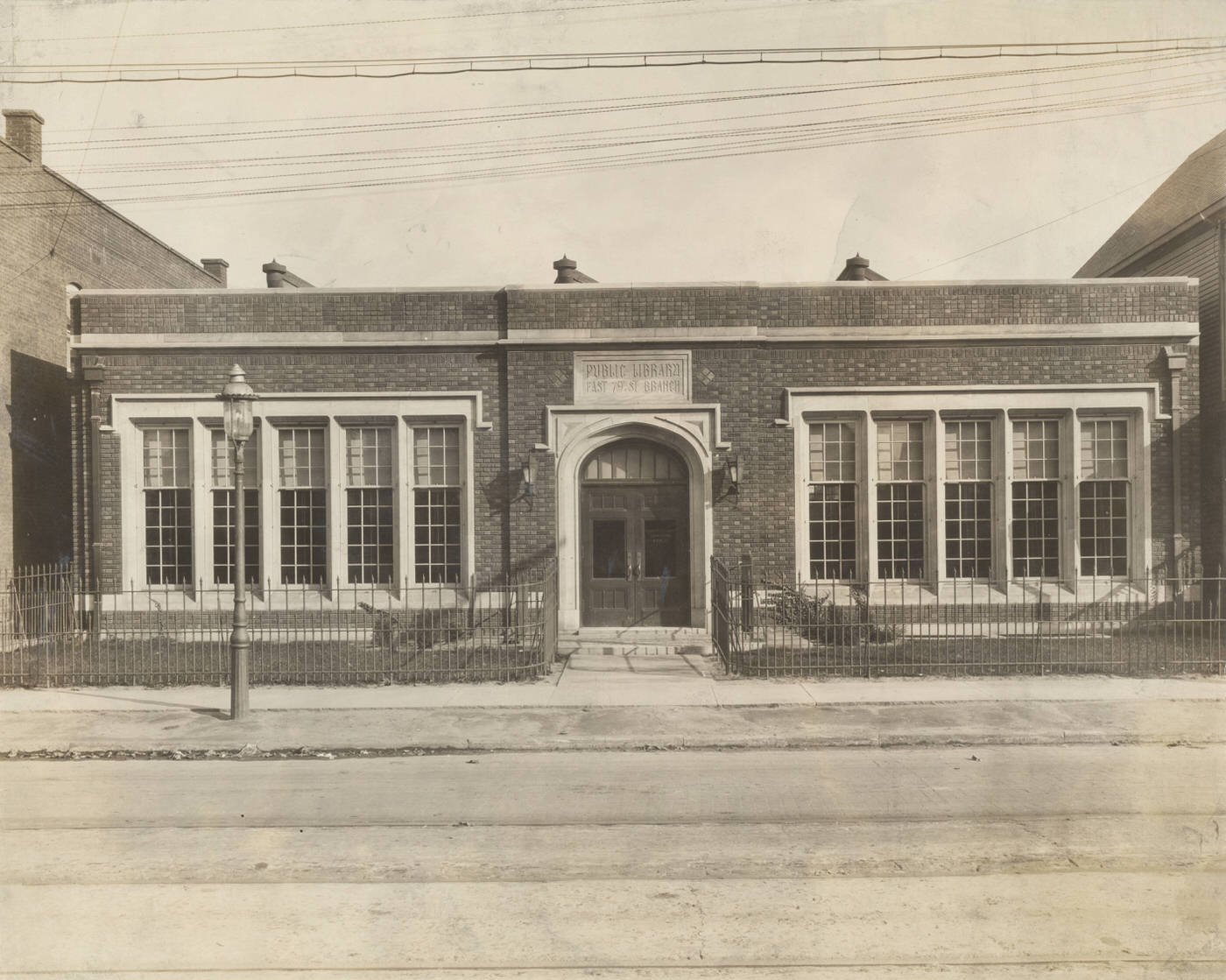

Several key urban renewal projects defined this era. The Garden Valley housing project, situated at East 79th Street and Kingsbury Run, was the CDF’s first major undertaking. It was conceived to provide new housing for individuals and families displaced by the clearance of other urban renewal districts. Planners initially envisioned Garden Valley as a “model neighborhood for all of Cleveland”—a modern, clean community featuring mixed land uses and, ambitiously, racial and economic integration. However, the chosen site, Kingsbury Run, presented formidable challenges. It was a notoriously polluted and dangerous gully with a grim history of heavy industrial use and Depression-era shantytowns. Despite the lofty goals and significant investment, the project struggled; within just two years of the first residential units being constructed, Garden Valley was already widely considered rundown and undesirable, failing to live up to its initial promise.

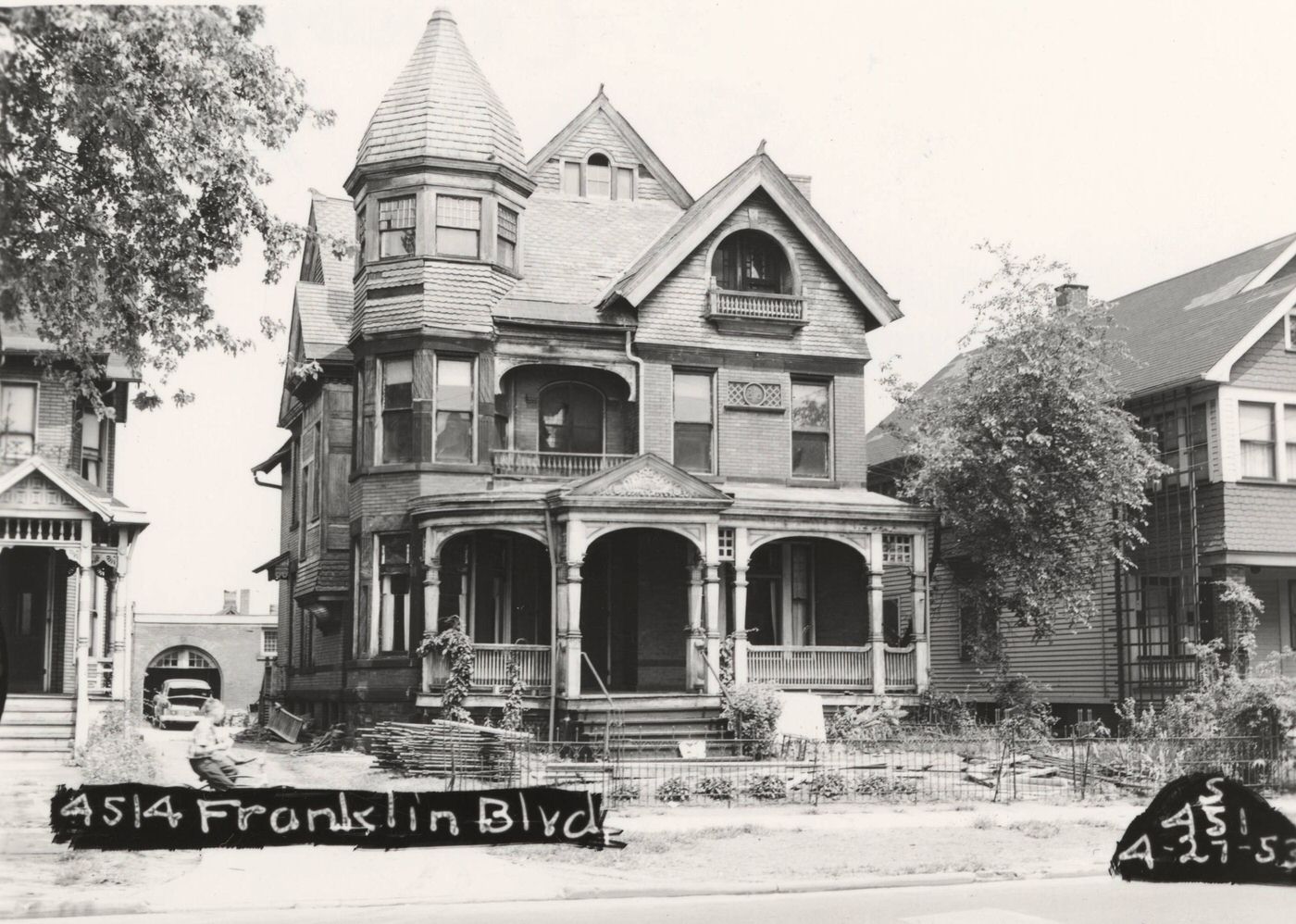

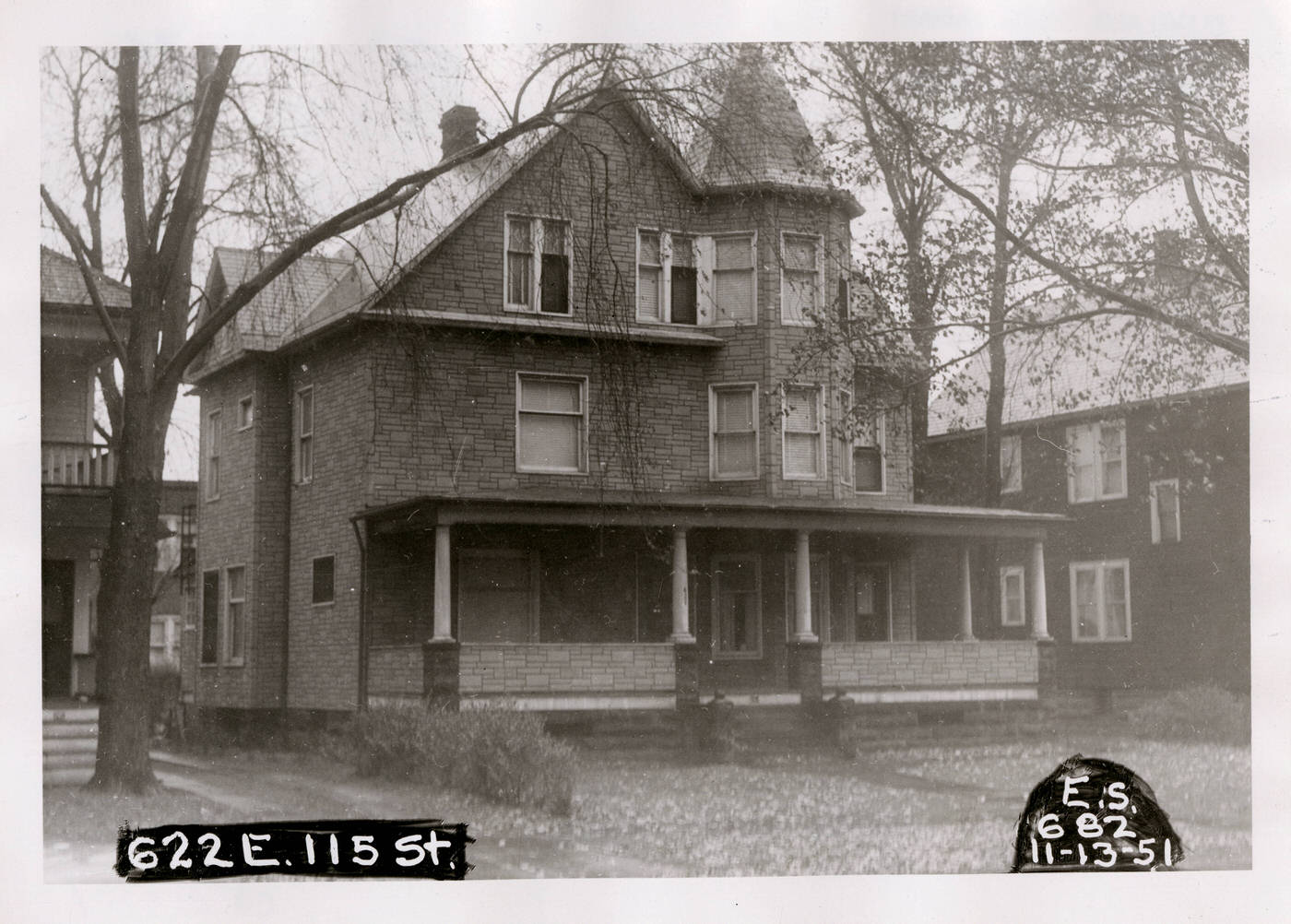

Another significant initiative was the Longwood Project, which originated from the city’s 1949 General Plan and was Cleveland’s first official urban renewal plan. This project involved the large-scale demolition of entire streets of older housing to make way for the construction of new, modern housing units. The CDF also participated in the Longwood housing project located at East 40th Street. The Longwood Apartments, built in the late 1950s as part of these efforts, eventually fell into disrepair over subsequent decades. Later in the decade and into the early 1960s, the Erieview project, heavily promoted by the CDF and designated as a federal urban renewal area in 1960, aimed to redevelop a substantial portion of downtown Cleveland.

The aims of these urban renewal programs were multifaceted, but some plans explicitly sought to remove existing lower-income populations and attract more affluent, middle-class residents by constructing new, more appealing housing. However, the consequences of these large-scale interventions were often severe for existing communities. Urban renewal projects, including Erieview and the St. Vincent renewal area near downtown, frequently resulted in the destruction of significant amounts of affordable housing located on the periphery of the central business district. This demolition, in turn, exacerbated problems of homelessness and housing insecurity for displaced residents.

These redevelopment efforts also had profound racial dimensions. Federal home ownership loan programs available in the mid-20th century disproportionately benefited white homebuyers, often facilitating their move to new suburban developments. Simultaneously, these same programs often supported the clearance of many lower-income urban areas, which were predominantly inhabited by Black residents. These areas were razed to make way for new middle-class homes, commercial developments, or infrastructure projects like highways. Specifically, urban renewal initiatives undertaken in Cleveland during the 1950s led to the wholesale demolition of large sections of the city’s near east side. This forced tens of thousands of African Americans to seek housing elsewhere, primarily channeling them into the Hough and Glenville neighborhoods to the north and east. This process demonstrates a critical interconnection: the growth of largely white suburbs, facilitated by new housing types and the automobile, occurred in tandem with urban renewal projects that often targeted and demolished African American neighborhoods. This displacement, compounded by discriminatory federal loan and public housing policies that limited options for Black families, fundamentally reshaped Cleveland’s demographics and deepened patterns of racial segregation.

The public housing landscape of the 1950s also reflected these complex dynamics. Efforts to provide public housing continued, but these initiatives were often marked by de facto racial segregation. Despite a city ordinance passed in 1949 that officially prohibited racial discrimination in public housing, and sustained activism by civil rights groups like the NAACP in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Black and white tenants were generally housed in separate public housing estates or projects. The decade witnessed a substantial increase in Cleveland’s African American population, largely due to ongoing migration from the Southern states. This occurred at the same time as a large-scale exodus of white residents from the city to the suburbs. This profound demographic shift, coupled with discriminatory housing practices and the limited availability of adequate housing, led to increasingly crowded conditions and the physical deterioration of housing stock in many city neighborhoods predominantly occupied by African Americans. The very mechanisms designed to improve housing often fell short of creating equitable or integrated communities, highlighting a significant gap between the stated ideals of urban planning and the lived realities of many Cleveland residents.

Daily Life and Leisure: From Shopping to Sports

Daily life in 1950s Cleveland was characterized by a blend of traditional community activities and the burgeoning influence of new technologies and leisure pursuits. For families, the Cleveland Zoological Park, which had been renamed from the Brookside Zoo in the 1940s, was reinvented as a prime destination for children and families. Throughout the 1950s, the zoo continued to expand its attractions and educational programming. It converted the basement of its main building into a classroom, introduced a miniature train, and even operated a traveling zoo that visited city parks. School visits and art classes became common sights, and a teacher from the Cleveland Board of Education was stationed onsite starting in 1951. Feeding times for animals like sea lions and penguins were daily highlights. In 1956, to promote the new Pachyderm Building and spark interest among schoolchildren, thousands were sworn in as “Zoo Rangers”. The YMCA also played a significant role in youth activities, with its River Road Camp in the Cleveland Metroparks offering summer programs focused on fitness, nature study, and crafts. The YMCA’s emphasis on health and sports aligned with a national focus on fitness during the Cold War era. Nearly 1,500 boys could annually participate in 10-day excursions at the North Chagrin Reservation camp.

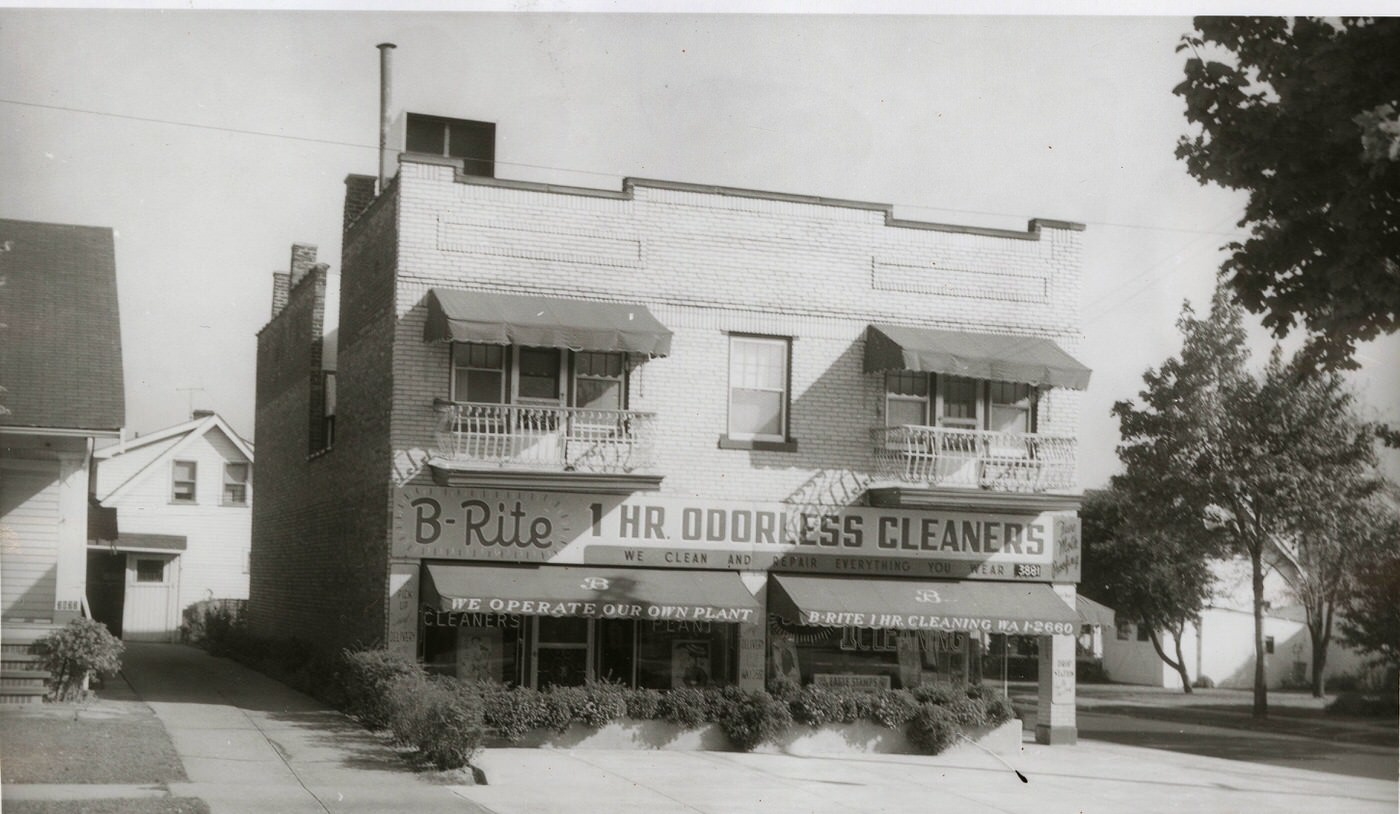

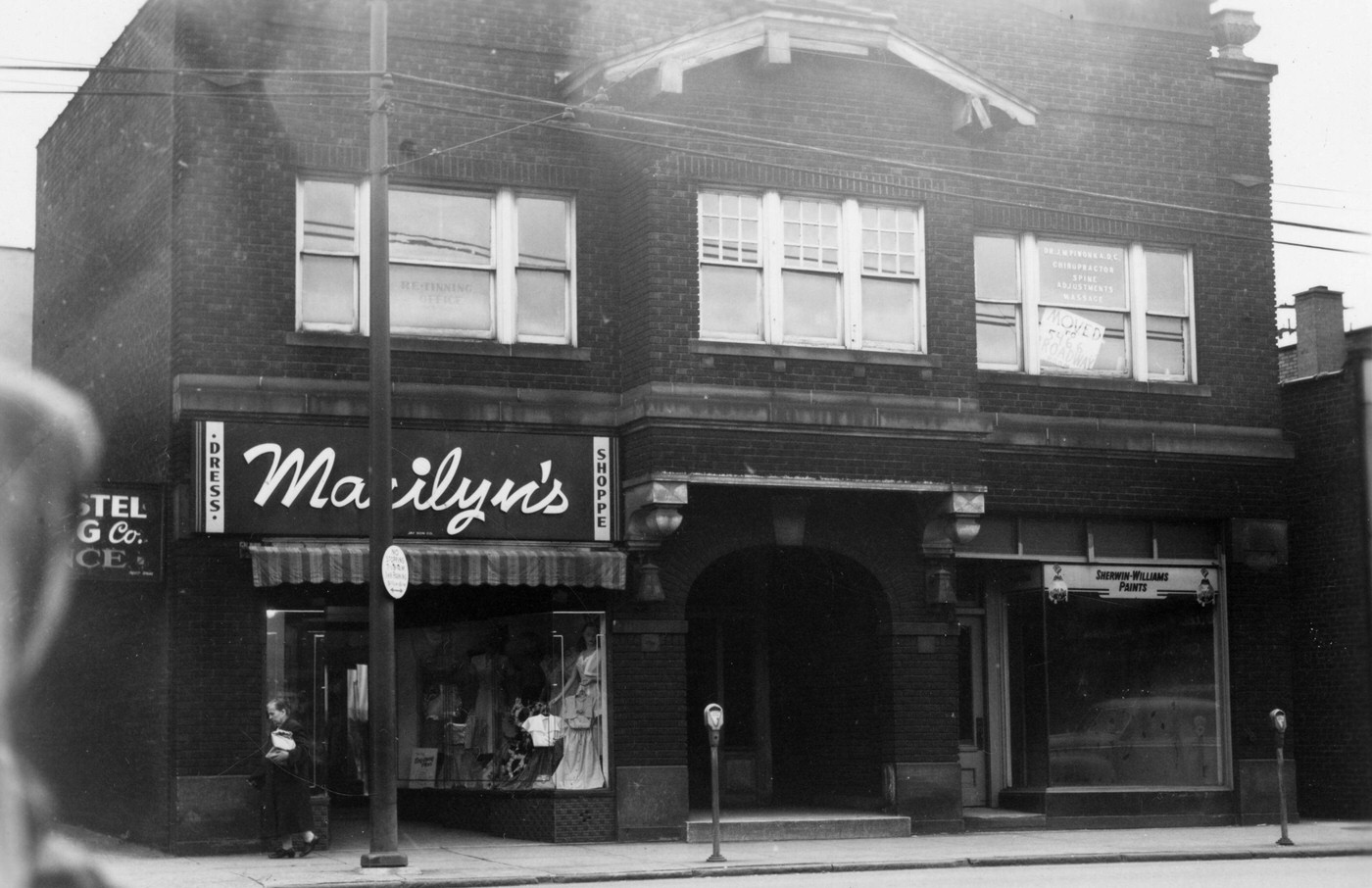

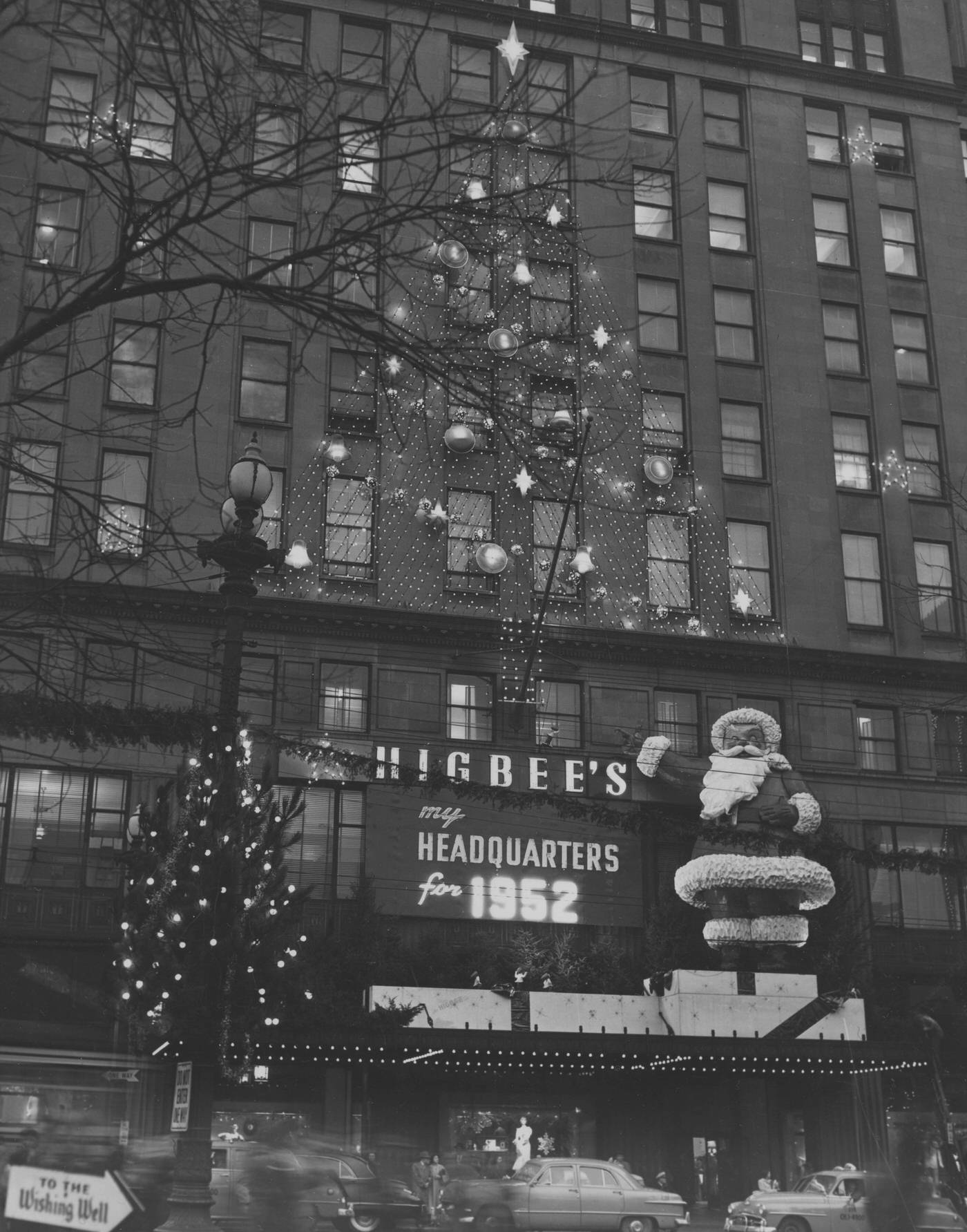

Shopping remained a central activity, with downtown department stores like Halle’s, Higbee’s, and May Company serving as major retail hubs. These stores were not just places to buy goods but also social centers, known for their elaborate holiday window displays and distinct atmospheres. Newspaper shopping columns, such as “Wise Buys” which ran in the Cleveland News and the Plain Dealer around 1950, guided consumers in their purchasing decisions. Advertisements from this era, like a 1950 Higbee’s holiday ad featuring Santa Claus, give a glimpse into the marketing of the time. The rise of consumer culture was also evident in the increasing prevalence of electrical appliances in homes. In affluent suburbs like Shaker Heights, by the early 1960s (reflecting trends from the 50s), ownership of washing machines (over 99%), televisions (98%), and cars (97%) was nearly universal, with these items becoming symbols of social status. The Tappan Model RL-1, the first microwave oven designed for home use, was introduced in 1955, though its high price limited initial sales; Raytheon’s first commercial microwave, the Radarange, had been purchased by a Cleveland restaurant back in 1947.

Entertainment options were diverse. Movie theaters, though facing increasing competition from television, still dotted the city. Playhouse Square, with its grand theaters like the State, Ohio, Allen, and Palace, had been a cinematic hub since the 1920s. While many downtown theaters eventually closed or converted to other uses by the late 1960s, and some neighborhood theaters also shut down due to the rise of television and suburban migration, cinema remained a popular pastime. During the 1950s and into 1960, only the Hanna Theatre consistently featured live entertainment and Broadway shows, as first-run movies began to open in new suburban shopping malls. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “Me and Juliet” had its world premiere at the Palace Theatre on April 20, 1953, and the State Theatre introduced Cinerama in 1957.

The arrival of television dramatically altered daily routines and the media landscape. By 1950, Cleveland had three operational television stations: WEWS (Channel 5), WNBK (Channel 4, later Channel 3), and WXEL (Channel 9, later Channel 8). Early television programming was often limited, with stations sometimes signing off in the early evening and resuming later. Children’s programs featuring personalities like Gene Carroll (Uncle Jake), Linn Sheldon (Barnaby), and Ronald Penfound (Captain Penny) were popular, as were shows aimed at housewives, such as Paige Palmer’s morning exercise program. News coverage initially consisted of established radio newscasters reading wire reports, but figures like Dr. Warren Guthrie on WXEL (later WJW-TV) became local television news pioneers. The coaxial cable network’s expansion in 1949 allowed live broadcasts from the East Coast, bringing national events like President Truman’s inauguration directly into Cleveland homes. Radio, in turn, had to adapt to television’s rise. While network radio remained, independent local stations increasingly featured disc jockeys, and FM broadcasting began its ascent. Ethnic programming, which had a strong presence on stations like WJAY, continued on new stations like WDOK, founded in 1950.

For leisure and amusement, Euclid Beach Park remained a beloved destination throughout the 1950s. Located on 90 acres of lakefront property, the park, managed by the Humphrey family since 1901, offered a wide array of attractions under the motto “One Fare – Free Gate – No Beer”. It featured a park railway, a dancehall (though its public use was curtailed after racial protests in 1946), a theater, a roller-skating rink, a Ferris wheel, merry-go-rounds, a funhouse, and thrilling rides like rocket cars, flying scooters, “dodgem” cars, and several roller coasters. Notable roller coasters operating during or into the 1950s included the Racing Coaster (built 1913), the Thriller (1924), and the innovative Flying Turns (1930), a toboggan-style coaster. The park was a popular spot for company picnics, concerts, and even political rallies; John F. Kennedy made a campaign stop there in 1960. However, the park’s history also included discriminatory racial policies that restricted African American visitors from using all facilities, leading to significant protests in 1946. Despite these issues, Euclid Beach Park continued to draw large crowds in the post-war years before its eventual closure in 1969.

Restaurants like Otto Moser’s, located on East 4th Street, were well-known establishments. In the 1950s, Otto Moser’s was owned by Max A. Joseph and Max B. Joseph and maintained its historic relationship with show business celebrities, often closing to the public to host performers from the Metropolitan Opera. Drive-in restaurants like Kenny King’s and Manner’s Big Boy were popular hangouts, especially for teenagers with cars.

The city’s sports teams also captured public attention. The Cleveland Browns were a dominant force in professional football. Having won all four AAFC championships before joining the NFL in 1950, they continued their success by winning the NFL Championship in their first year in the new league. Led by legendary players like quarterback Otto Graham, fullback Marion Motley, and kicker Lou Groza, the Browns reached the NFL championship game for six consecutive years (1950-1955), winning titles again in 1954 and 1955. In 1957, the team drafted future Hall of Fame running back Jim Brown. The Cleveland Indians baseball team also had a memorable decade, particularly the 1954 season. That year, the Indians, powered by a stellar pitching staff including Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, Mike Garcia, and Bob Feller, and an offense featuring Larry Doby, Al Rosen, and Bobby Avila, won an American League record 111 games. Fan favorite Rocky Colavito tied an MLB record in 1959 by hitting four home runs in a single game.

The Sound of the City: Cleveland’s Musical Landscape

Cleveland in the 1950s pulsed with a vibrant and evolving musical soundtrack, playing a pivotal role in the birth and popularization of rock and roll while also nurturing genres like R&B and doo-wop. The decade began with a strong R&B influence, famously marked by the Moondog Coronation Ball in 1952, an event widely recognized as one of the first major rock and roll concerts. Organized by legendary Cleveland radio DJ Alan Freed, who popularized the term “rock and roll” on his WJW radio show, the Moondog Coronation Ball at the Cleveland Arena aimed to feature R&B headliners like Paul Williams and his Hucklebuckers and Tiny Grimes and the Rocking Highlanders. Overwhelming demand and counterfeit tickets led to an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 fans attempting to enter the 10,000-capacity arena, forcing police to shut down the event shortly after it began.

This R&B foundation quickly absorbed the newer blues and country-influenced sounds of rockabilly. Numerous rockabilly greats performed in Cleveland. Elvis Presley made his first headlined concert appearance above the Mason-Dixon Line at Cleveland’s Brooklyn High School in October 1955; he had performed in the city months earlier at The Circle Theater as part of The Bill Black Trio. Other stars like Buddy Holly (Public Auditorium, April 1958) and Bo Diddley (Cleveland Arena) also brought their electrifying performances to the city.

The 1950s also saw the flourishing of doo-wop, a style characterized by smooth, multi-part harmonies often anchored by deep bass voices, influenced by earlier groups like The Ink Spots and The Mills Brothers. Cleveland’s own Moonglows were a notable local doo-wop group, and national acts like The Drifters, The Platters, and The Coasters frequently graced Cleveland stages. This music found a strong platform on WJMO-1490 AM, the first Cleveland radio station to adopt a Black-oriented format.

A variety of venues hosted these burgeoning musical forms. The Cleveland Arena, Palace Theater, and Keith’s East 105th St. Theatre were prominent spots for larger acts and doo-wop groups. Smaller rock and roll nightspots also gained prominence. Gleason’s Music Bar, located at 5219 Woodland Avenue, is considered Cleveland’s first dedicated rock and roll venue. Nearby, the Chatterbox Musical Bar & Grille at 5123 Woodland Avenue featured a diverse lineup of popular music. Otto’s Grotto, in the basement of the Statler Hotel on Euclid Avenue, also hosted local and national rock acts. The rise of “teen idols” in the latter part of the decade—singers like Ricky Nelson and Frankie Avalon—brought songs about high school life, sock hops, and teenage romance to the forefront, further shaping the popular music landscape enjoyed by Cleveland’s youth.

A City of Neighborhoods: Diverse Communities and Experiences

Cleveland in the 1950s was a mosaic of distinct neighborhoods, many defined by the ethnic and racial groups that inhabited them, each with its own unique community life, institutions, and experiences.

African American communities, largely concentrated on the city’s East Side due to discriminatory housing practices, faced significant challenges alongside vibrant cultural development. The Cedar-Central neighborhood had long been a primary area for Black residents, developing a lively cultural scene with jazz and blues clubs. However, as the African American population grew, particularly with the post-war Great Migration from the South which saw the Black population increase from 85,000 in 1940 to 148,000 by 1950, and further to 251,000 by 1960, overcrowding became a severe issue. Urban renewal projects in the 1950s, which often involved wholesale demolition in areas like Cedar-Central, displaced tens of thousands of African Americans. Many of these residents then moved into the Hough and Glenville neighborhoods to the north and east.

Hough, which transitioned from a predominantly white working-class neighborhood to a largely Black community during the 1950s, experienced severe strain on its resources. Schools became overcrowded, housing stock deteriorated as homes were subdivided, and infrastructure like sanitation services struggled to keep up [ (specifically referencing S45, S46 from its internal browsing)]. Despite these conditions, residents often faced high rents due to limited housing options elsewhere in the segregated city [ (S46)]. The Bell Neighborhood Center, established in Hough in the late 1950s as a branch of the Goodrich Settlement House, provided social services, youth programs, and became a locus for community activism. Glenville also saw a rapid influx of Black residents. Until the mid-1950s, African Americans rarely found housing outside the city limits or west of the Cuyahoga River. Glenville, Wade Park, and Mt. Pleasant offered some of the best available housing for Black families during these years. Karamu House, located at East 89th and Quincy after being rebuilt in 1949, was a nationally renowned center for interracial theater and African American arts, providing classes, performances, and nurturing Black talent. In the 1950s, under leaders like Benno Frank and Reuben Silver, Karamu gained a reputation as one of the country’s best amateur theater groups.

Eastern European communities also had a strong presence. Polish immigrants formed one of Cleveland’s largest nationality groups, with established neighborhoods like Warszawa (later Slavic Village) around Fleet Avenue and Tod (East 65th) Street, Poznan near East 79th and Superior, and Kantowo in the Tremont area. These neighborhoods were often anchored by Roman Catholic parishes like St. Stanislaus, St. John Cantius, and St. Casimir, which served as cultural and social centers. While the major wave of Polish immigration occurred before World War I, the communities and their institutions remained vital. However, by the 1950s, a gradual movement to the suburbs was underway, although many of the original neighborhood churches remained active.

Slovenian immigration saw a significant period between 1949 and 1960, with many post-World War II immigrants being political refugees who were often professionals and well-educated. This differed from earlier waves of Slovenian immigrants who were primarily from rural backgrounds. Cleveland, which already had the largest Slovene settlement in the U.S., became attractive to these newcomers and second-generation Slovenians due to its expanding industrial sector. This post-war immigration reinvigorated Cleveland’s Slovenian cultural scene, despite some ideological divisions within the community stemming from political situations in Yugoslavia.

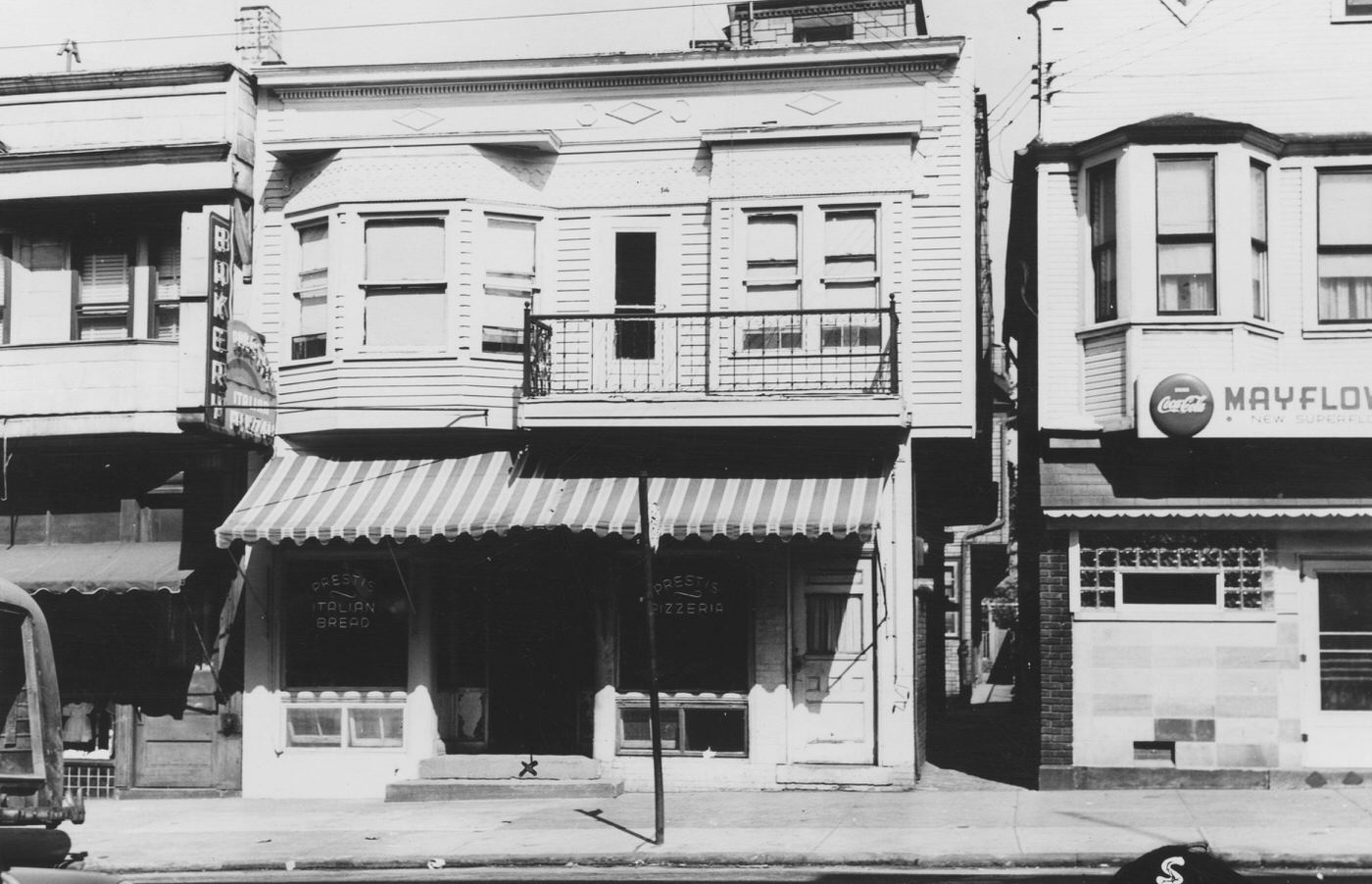

Little Italy, another enduring ethnic enclave, continued its traditions. The Feast of the Assumption, a major religious and cultural celebration featuring street fairs, food vendors, and entertainment along Mayfield Road, has been observed in Little Italy since 1950, drawing thousands of visitors annually. Neighborhood life historically revolved around Holy Rosary Church and the Alta House settlement.

The city’s Jewish population, which had grown significantly in the early 20th century, continued its eastward movement from earlier settlements in Glenville and Mount Pleasant-Kinsman to suburban areas like Cleveland Heights, Shaker Heights, and University Heights. By the 1950s, several congregations and Jewish institutions were already establishing themselves further east, particularly in Beachwood. Cleveland Heights became a major center for Jewish life in the 1950s, with Taylor Road hosting the Jewish Community Center, Park Synagogue, Montefiore Home, and other key institutions. This migration pattern reflected both communal desires and the broader suburbanization trend.

Social clubs and community centers catered to various groups. Golden Age Clubs, providing social and educational activities for senior citizens, numbered at least 35 by 1952 and operated in locations like Karamu House and the Friendly Inn. Early clubs often mirrored existing racial and ethnic divisions, with separate groups for Jewish and African American seniors, for example. In 1954, the Golden Age Centers of Greater Cleveland, Inc. was formed to coordinate these activities. For the African American community, recreational spaces outside the city included establishments like Lake Glen Country Club, a “black-and-tan club” that catered to an integrated clientele from the 1950s to the 1970s, offering music, food, comedy, and dance.

Education and Institutions of Higher Learning

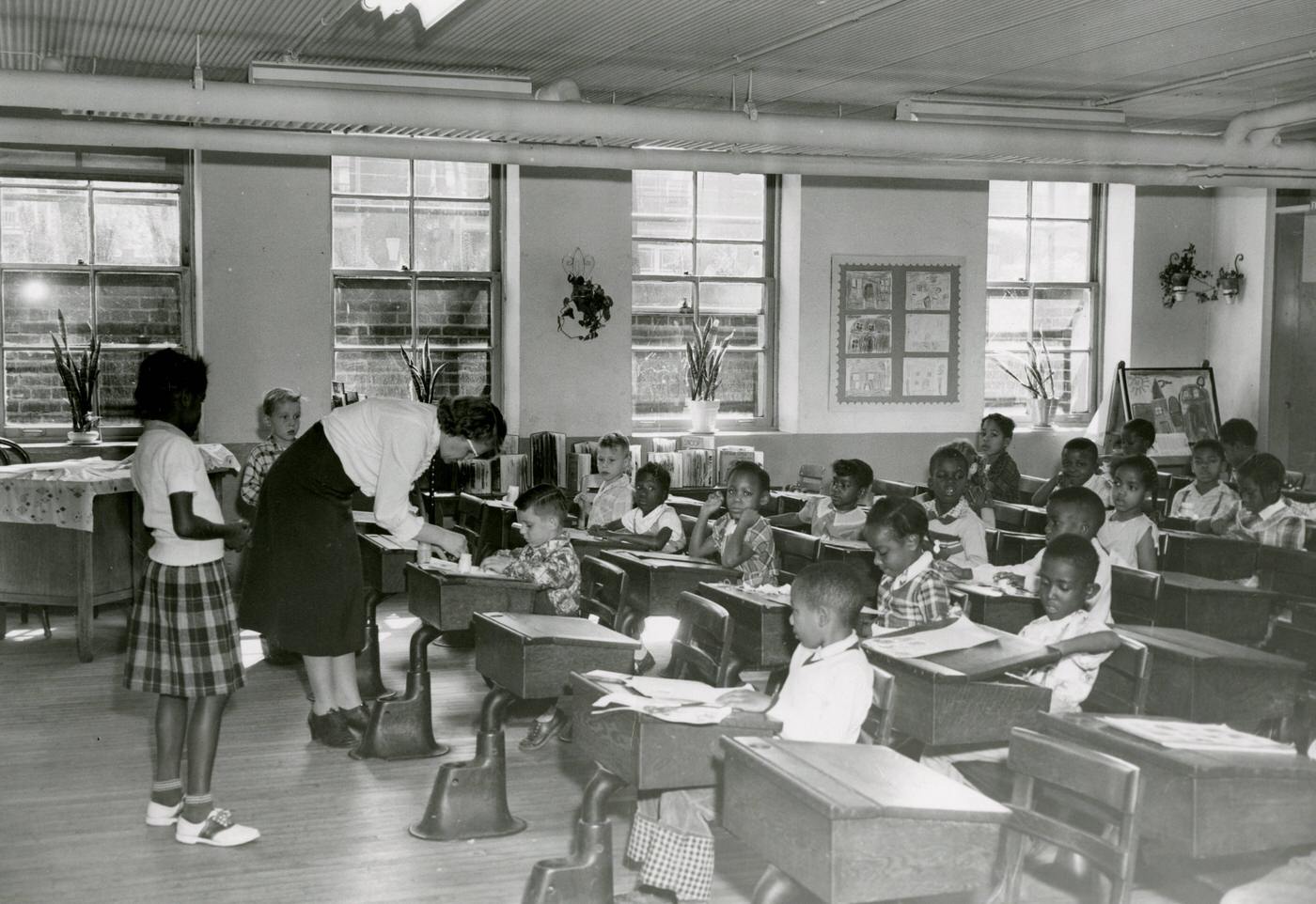

Cleveland’s educational landscape in the 1950s was marked by rapidly increasing student populations, significant overcrowding in public schools, and growing tensions over racial segregation. At the higher education level, the city’s major institutions continued their development.

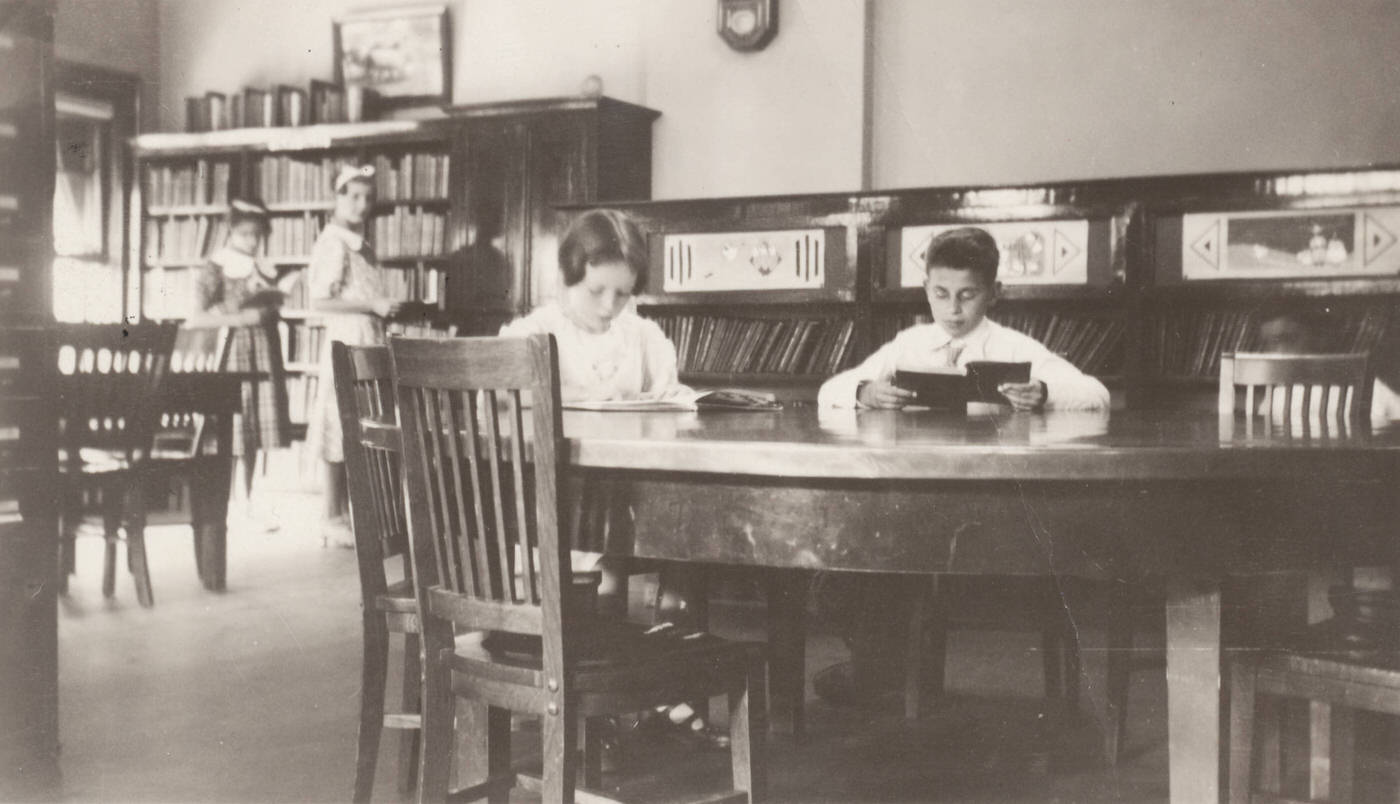

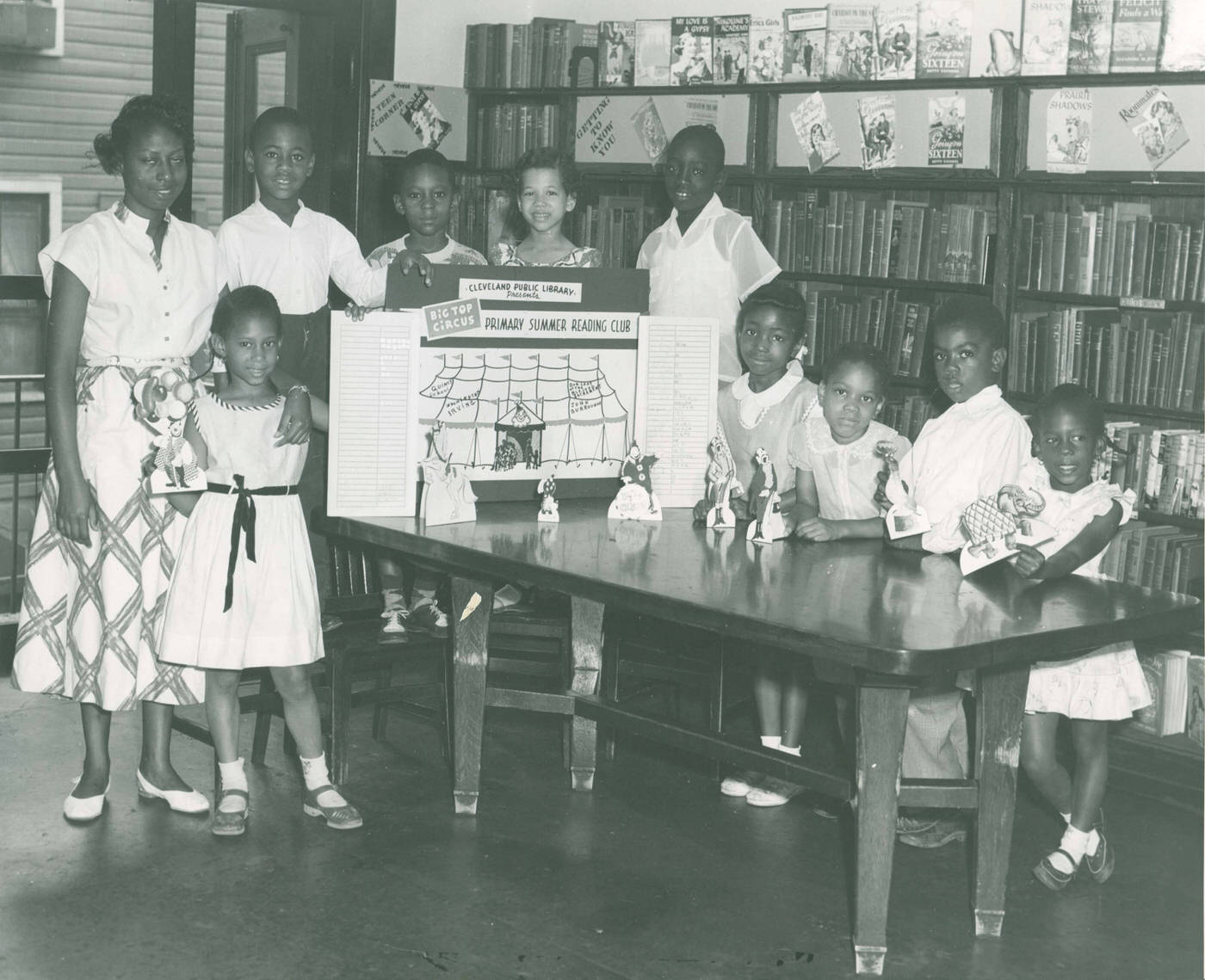

Cleveland Public Schools experienced a dramatic surge in enrollment during this period. Between 1950 and 1960, enrollment jumped from 99,686 to 134,765 students, and it reached 148,793 by 1963. This growth was largely fueled by the post-World War II “Baby Boom” and the continued migration of African American families from the South into the city. Elementary school enrollment in Cuyahoga County alone increased by nearly 40 percent between 1952 and 1963, from 66,798 to 92,395 students.

This rapid influx of students overwhelmed the existing school facilities, many of which had been built before this population boom. Schools lacked adequate classroom space, materials, and a sufficient number of teachers. To cope with the overcrowding, students were often taught in auxiliary spaces such as community buildings, libraries, churches, and even the former stadium of a local Negro League Baseball team. The situation became so acute that waiting lists were implemented for kindergarten enrollment; in 1956, 1,465 children were on such a list, a number that grew to approximately 1,700 by 1961. In an attempt to alleviate the crisis, school officials and the Ohio State Board of Education implemented “double sessions” in 1957, meaning half the students attended classes in the morning and the other half in the afternoon.

Compounding the issue of overcrowding was racial segregation. As most Black residents lived on the city’s East Side due to discriminatory housing patterns, and students were assigned to neighborhood schools, de facto segregation was prevalent. Urban schools, particularly those serving African American students, experienced the most severe overcrowding and consequently had poor student-to-teacher ratios, leading to a lower quality of education. By 1965, African American students constituted just over half of the entire student population in Cleveland public schools.

In higher education, Western Reserve University and the Case Institute of Technology continued to be prominent Cleveland institutions. John S. Millis served as the president of Western Reserve University from 1949 to 1967. During his tenure in the 1950s, Western Reserve University established a School of Business in 1952. T. Keith Glennan was the president of the Case Institute of Technology from 1947 to 1966, with Kent H. Smith serving as acting president from 1958 to 1961. Both institutions were located on adjoining campuses in the University Circle area and would eventually federate in 1967 to form Case Western Reserve University.

The city also saw the development of other post-secondary options. Cuyahoga Community College was established later, with land provided for its new campus through the St. Vincent urban renewal project in the early 1960s. Cleveland State University was also established around this time, with the city seeking urban renewal funds in 1965 to help construct its downtown campus. These developments indicated a growing recognition of the need for expanded higher education opportunities in the region.

The Higbee Company, or Higbee’s, positioned itself as another high-quality department store, perhaps a slight step below Halle’s in terms of sheer luxury, but aiming for an atmosphere comparable to a store like Bloomingdale’s. Higbee’s was known for distinctive features such as its notably fast escalators, which added a sense of verve to the shopping experience, and its popular “Frosty” malted drink bar, a treat for many shoppers. Elaborate holiday window displays were a major attraction, drawing Clevelanders downtown, with 1950s displays famously featuring electric trains. A Higbee’s holiday advertisement from 1950, for example, depicted Santa Claus with a sleigh brimming with toys, capturing the festive spirit of the era.

The May Company, another key player in downtown retail, offered a range of mid to higher-end fashion and home furnishings, with prices generally at or below those of Halle’s and Higbee’s. The May Company was an early adopter of suburban expansion, opening a store in Lorain’s Sheffield Shopping Center in 1953 and another in University Heights’ Cedar-Center Plaza in late 1956. Its market position was often likened to that of stores such as Macy’s or Gimbels. These department stores were more than just places to buy goods; they were significant employers, social destinations, and defining institutions of downtown Cleveland’s character. Their individual strategies, successes, and challenges reflected the evolving consumer landscape and economic currents of the 1950s. The fact that a prestigious store like Halle’s began to lose ground even after substantial modernization, while May Company was already venturing into suburban markets, indicates that the retail environment was dynamic and responding to subtle but powerful shifts in where and how people chose to shop.

Even as Downtown Cleveland thrived at its apparent zenith, discerning observers noted the growing movement of people and businesses towards the developing suburbs. Concerns began to surface that this outward trend could eventually lead to a decline in Downtown’s prominence. In response to these early warnings, city leaders initiated several ambitious projects aimed at strengthening the downtown area and ensuring its continued vitality. However, some of these significant efforts did not come to fruition as planned. For instance, a proposal for an underground expansion of the Public Auditorium was defeated by voters in 1957, although it was approved six years later. Ambitious plans for a subway system designed to distribute rapid transit riders throughout the Downtown area were turned down by county commissioners on two separate occasions, in 1957 and again in 1959. Furthermore, a proposed Hilton convention hotel, envisioned for the south end of the Mall, was also defeated by voters in 1959. This juxtaposition of peak success with underlying anxieties and these early, sometimes faltering, attempts at adaptation shows that Cleveland’s “golden age” was not one of untroubled prosperity. Instead, it was a complex period of transition where the city was already beginning to grapple, not always successfully, with emerging challenges to its established urban model.

Adding to the unique atmosphere of the decade, an unusual environmental event briefly captured the city’s attention. In late September 1950, smoke from distant forest fires raging in western Canada drifted over Cleveland and much of eastern North America, creating what became known as the “Great Smoke Pall”. The skies over Cleveland darkened so significantly during the day that artificial lights had to be turned on at Cleveland Municipal Stadium to allow an afternoon Indians-Tigers baseball game to proceed. This eerie, premature twilight alarmed many residents, who flooded police and newspaper telephone exchanges with calls seeking explanations. Some, reflecting the anxieties of the era, feared that an atomic explosion had occurred. This reaction, linking a natural phenomenon to the new and terrifying possibility of nuclear war (the first Soviet atomic bomb test had taken place in August 1949), demonstrates how deeply the tensions of the Cold War had permeated public consciousness, capable of coloring the interpretation of even unrelated events and underscoring a layer of unease beneath the surface of post-war prosperity.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress, Wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know