The 1960s were a period of profound transformation for Cleveland, Ohio. The city experienced shifts in its population, economy, and social fabric, navigating a landscape of industrial change, suburban growth, cultural dynamism, and intense struggles for civil rights.

Cleveland’s demographic landscape underwent significant reshaping during the 1960s. These changes were evident in the overall city population, the growth of its African American community, the expansion of suburbs, and the evolving nature of its diverse ethnic neighborhoods.

Cleveland’s Changing Demographics

The decade marked a turning point for Cleveland’s population numbers. After reaching a peak of 914,000 in 1950, the city’s population saw a 4% drop by the 1960 census, which recorded 876,050 residents. This trend of decline accelerated through the 1960s. By 1970, Cleveland’s population had fallen to 750,903, a decrease of 14.3% over the decade. This was a stark contrast to previous decades of growth and signaled a new era for the city, mirroring a pattern seen in many large U.S. cities as residents began moving to suburban areas.

While the city’s total population was shrinking, its African American population had been growing significantly. Between 1950 and 1960, the number of African American residents increased by almost 70%, reaching over 251,000 and constituting nearly one-third of the city’s residents by 1960. This growth was a continuation of the Second Great Migration. By 1970, in Cleveland’s low-income areas alone—which housed 28% of the city’s total population—African Americans made up 75% of the residents. The simultaneous decrease in the overall city population and the substantial increase in the African American population indicated a significant outflow of white residents, contributing to a “hollowing out” of the traditional white urban core. This demographic restructuring had far-reaching consequences for the city’s tax base, political landscape, social services, and relationships between different groups throughout the 1960s.

The Growth of Suburbia and “White Flight”

The 1960s saw an acceleration of suburban growth around Cleveland. While the city’s population decreased by 127,457 residents during the decade, Cuyahoga County’s suburbs grew by a remarkable 631,042 people. The suburban share of the county’s total population rose dramatically, from 28% in 1940 to 62% by 1970. This trend was a continuation of patterns from the 1950s, where federal housing programs like the FHA and VA often subsidized white, middle-class families moving out of the city. These programs, at times, reinforced existing segregation through practices like restrictive covenants, which limited housing options for African Americans in many new suburban developments.

The phenomenon of “white flight” was not confined to movement from the central city to distant suburbs. Inner-ring suburbs also experienced rapid racial transitions. East Cleveland, for example, was the most densely populated suburb in 1950. Its African American population grew from just 2% in 1960 to 67% by 1970. This dramatic shift was often fueled by practices like blockbusting, where real estate agents would encourage white homeowners to sell quickly, often at lower prices, by stoking fears of declining property values due to incoming Black residents, and then sell those same homes to Black families at inflated prices. Between 1960 and 1970 alone, 23,000 African American Clevelanders moved to East Cleveland. This pattern indicated that suburbanization was not merely a quest for more space but also a mechanism that actively maintained and, in some cases, intensified racial segregation on a metropolitan scale. As one area began to integrate, white residents often moved further out, perpetuating segregation across a wider geographic area and creating a metropolitan region deeply divided by race, with significant disparities in resources and opportunities.

African American Communities: Growth, Concentration, and Conditions

By 1960, nearly all of Cleveland’s African American population resided in neighborhoods on the city’s East Side. This concentration was the result of decades of discriminatory housing practices that limited where Black families could live. Neighborhoods like Hough, Glenville, Mount Pleasant, and Kinsman became predominantly Black during this period. The Central neighborhood, historically a primary African American enclave, saw its population decline sharply from 52,675 in 1960 to 27,280 in 1970. This decrease occurred as some measure of desegregation on the East Side provided more residential options for African Americans, though these options often came with their own challenges.

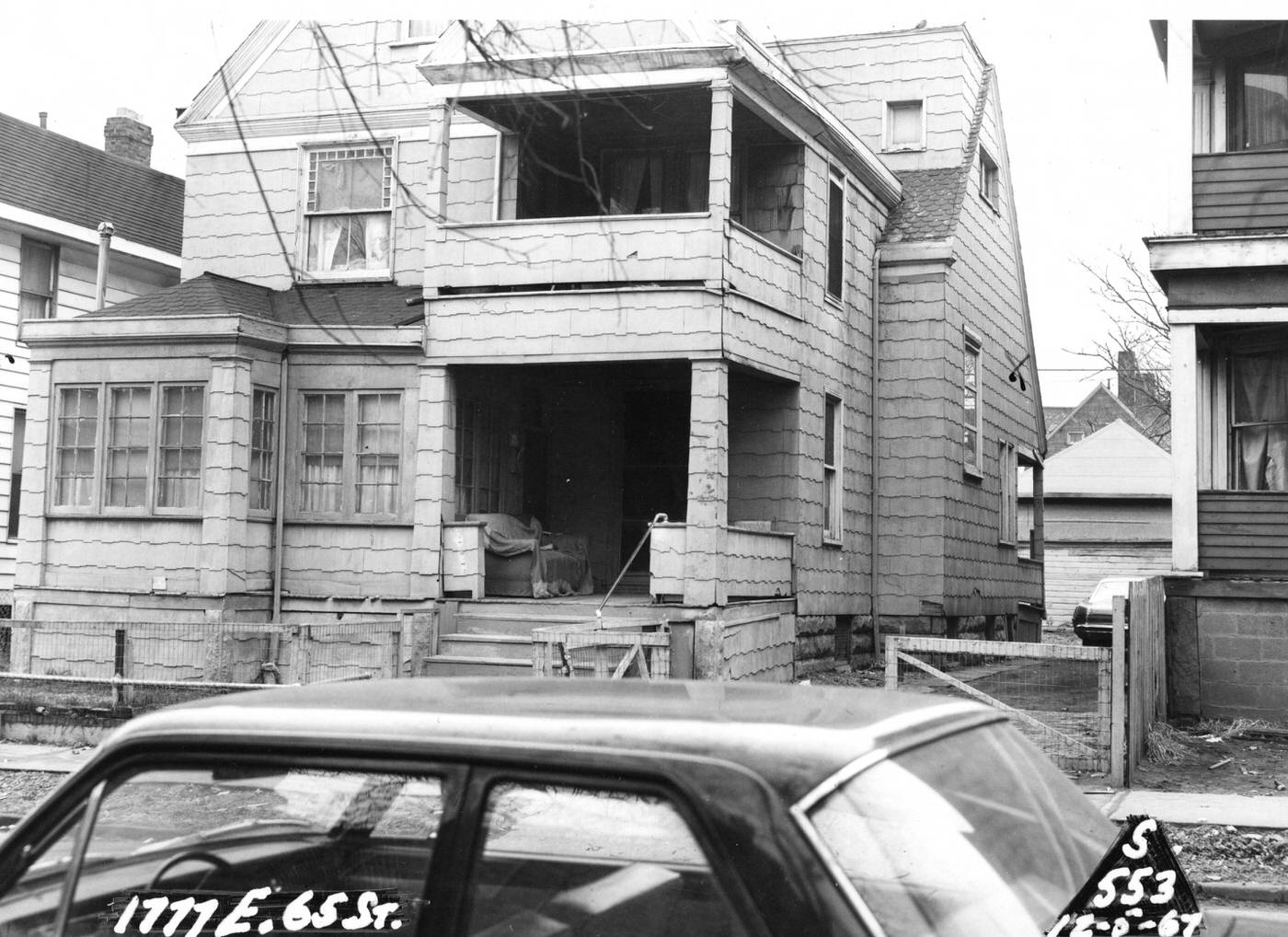

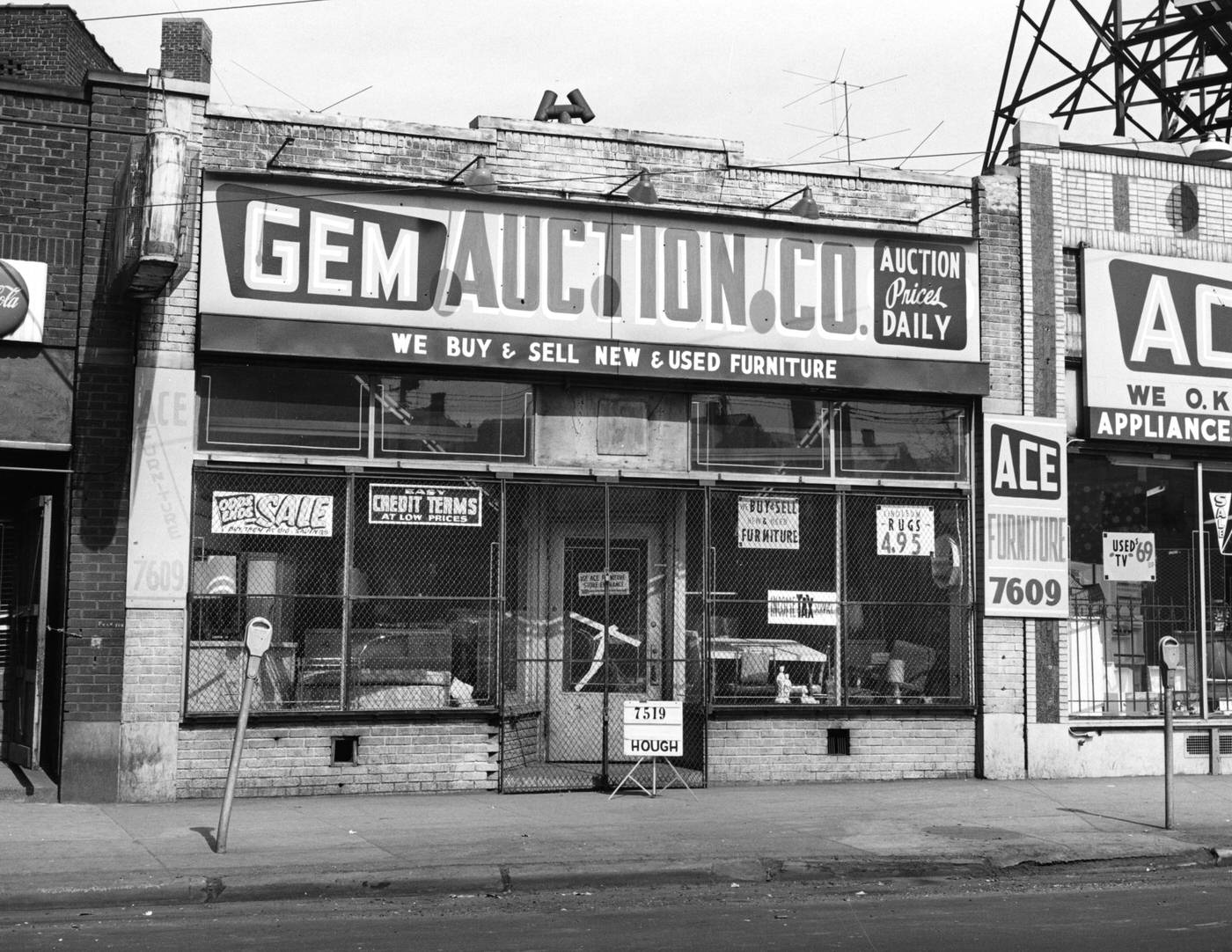

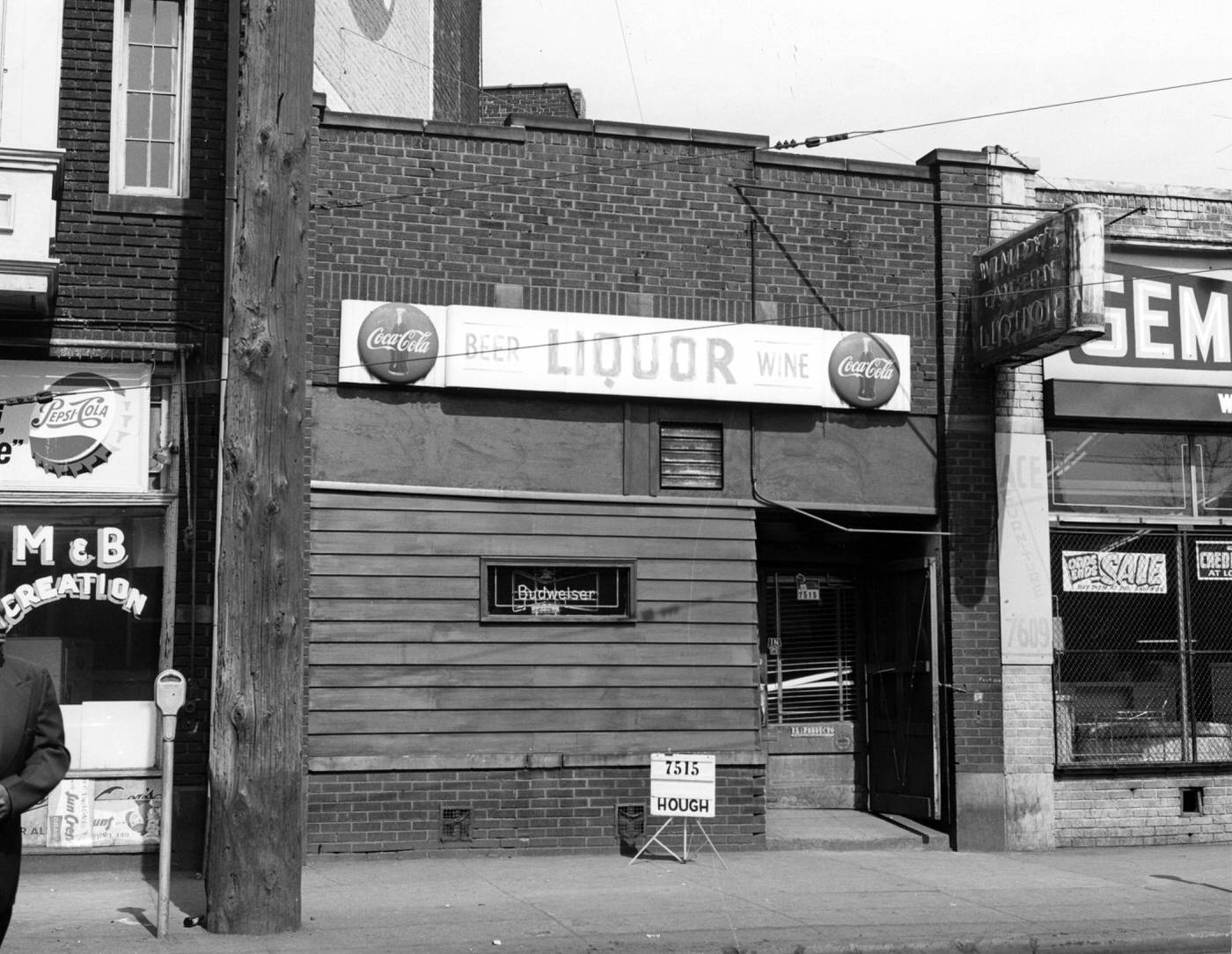

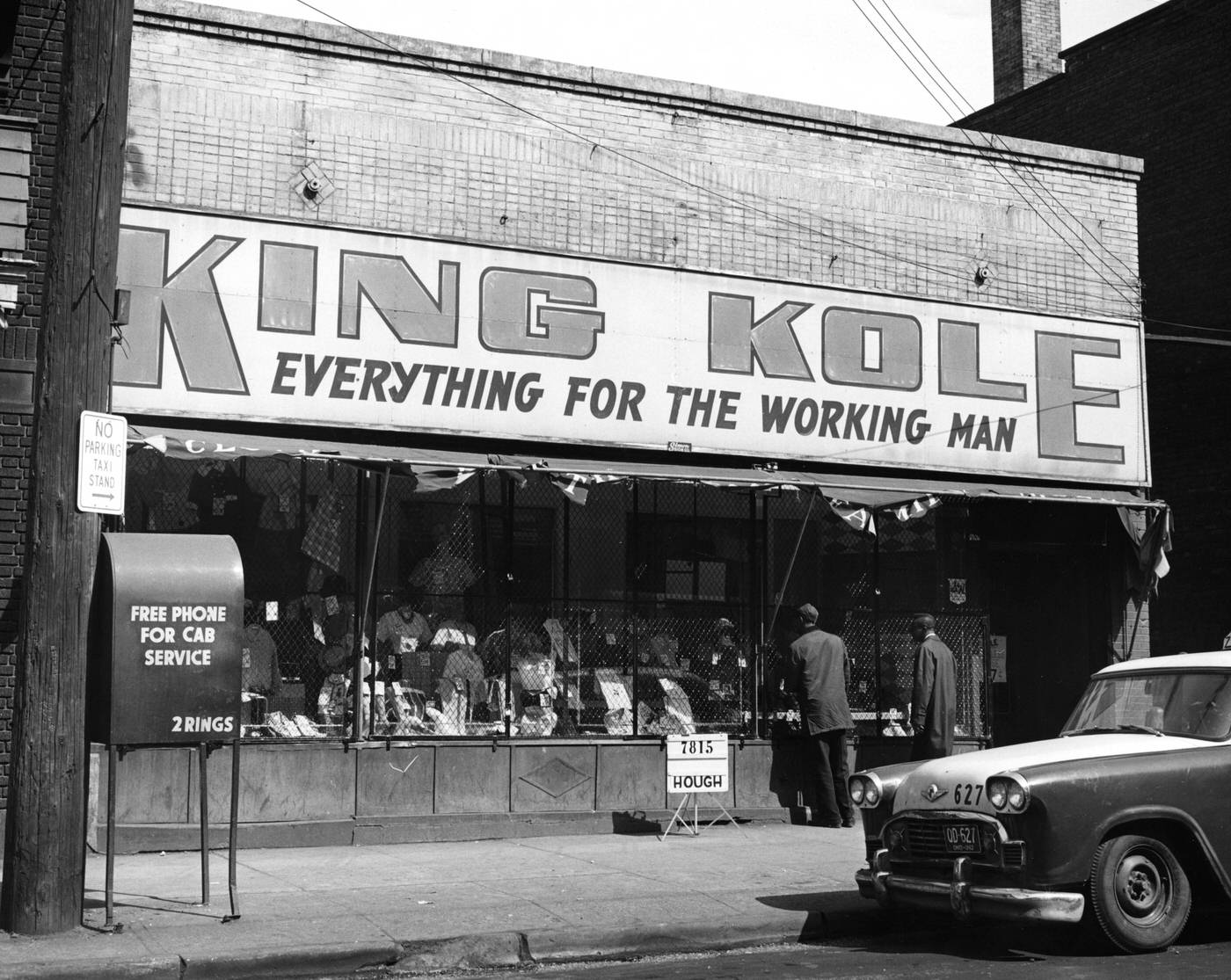

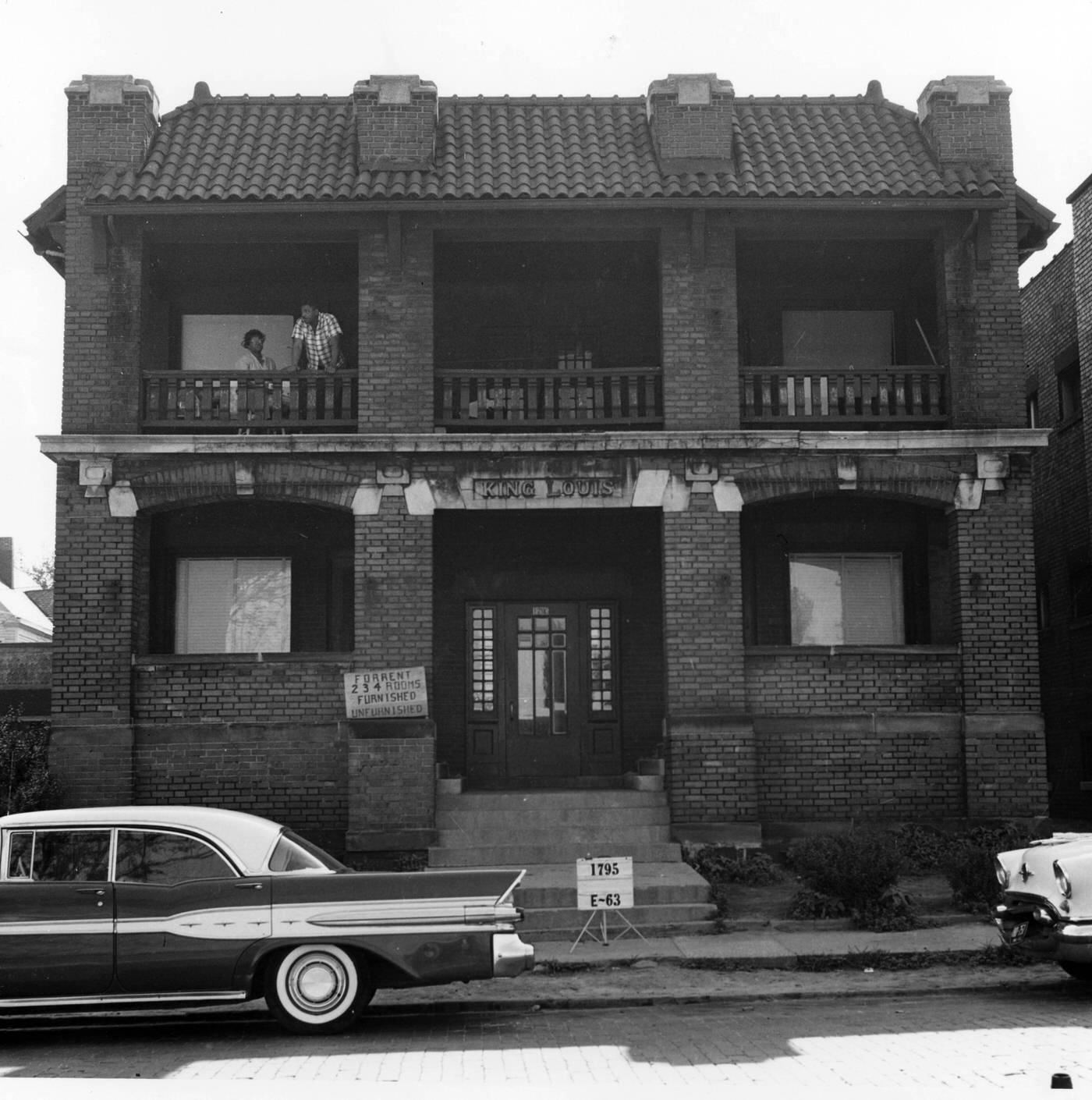

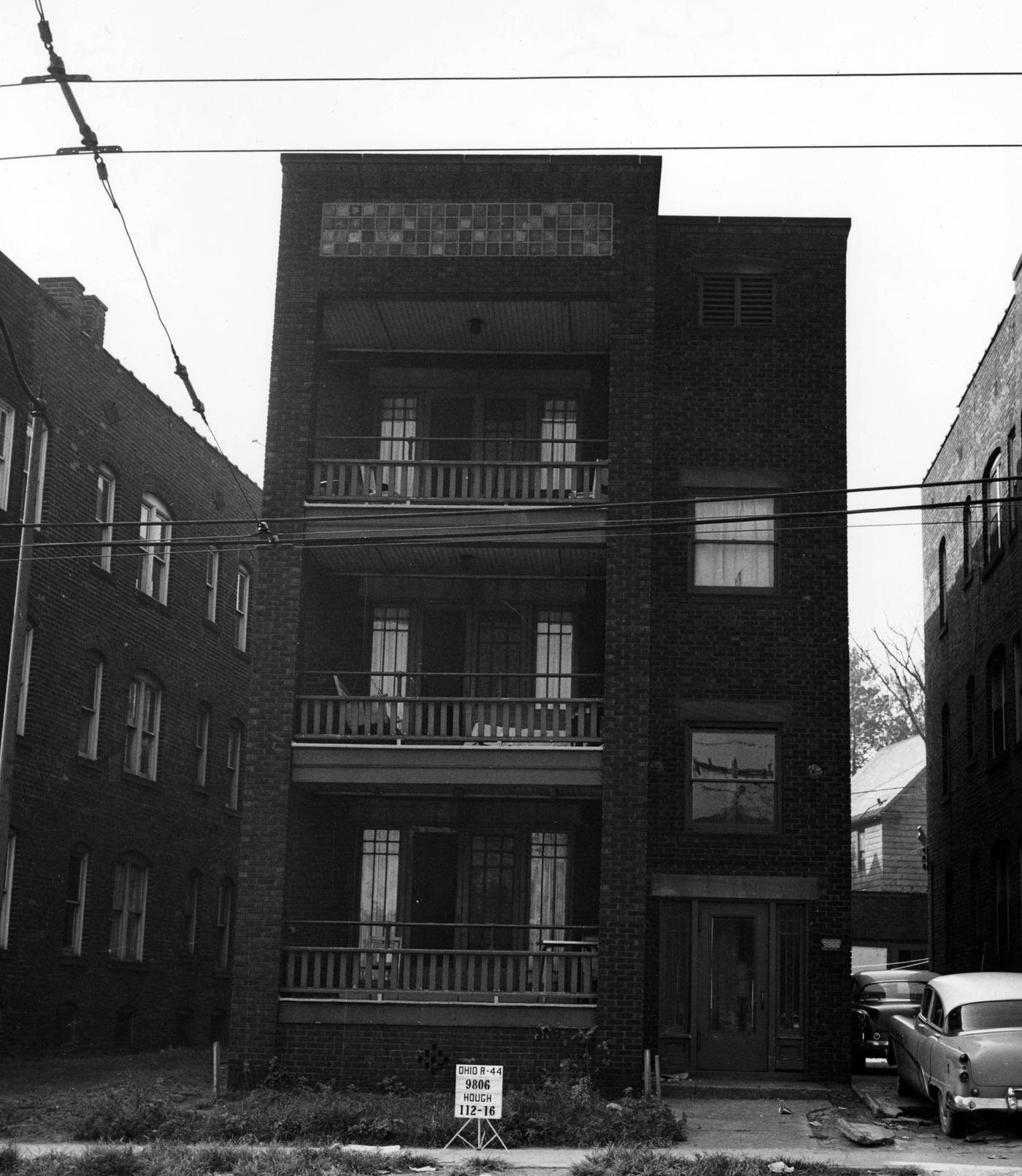

The Hough neighborhood, for instance, transitioned from a largely white area to a predominantly Black community by 1960. By 1966, nearly 90% of Hough’s over 66,000 residents were African American. The neighborhood faced severe issues, including overcrowded and substandard housing. A fifth of all housing units were considered dilapidated, and absentee landlords were common. Urban renewal projects in other parts of the city often displaced Black residents, many of whom then moved into Hough, further straining its resources.

Glenville, another East Side neighborhood, also became predominantly Black by the 1960s as its Jewish population moved to eastern suburbs. Before the 1968 shootout, Glenville residents contended with urban decay, harassment from police, and neglect from city government. The experience of these neighborhoods revealed a paradox: while new areas “opened up” to African American residents, this often occurred because of white flight. The subsequent concentration of Black residents was frequently followed by a decline in city services, disinvestment, and deteriorating housing quality, leading to new forms of de facto segregation and concentrated poverty. Thus, the expansion of Black residential areas did not always translate to improved living conditions or true integration.

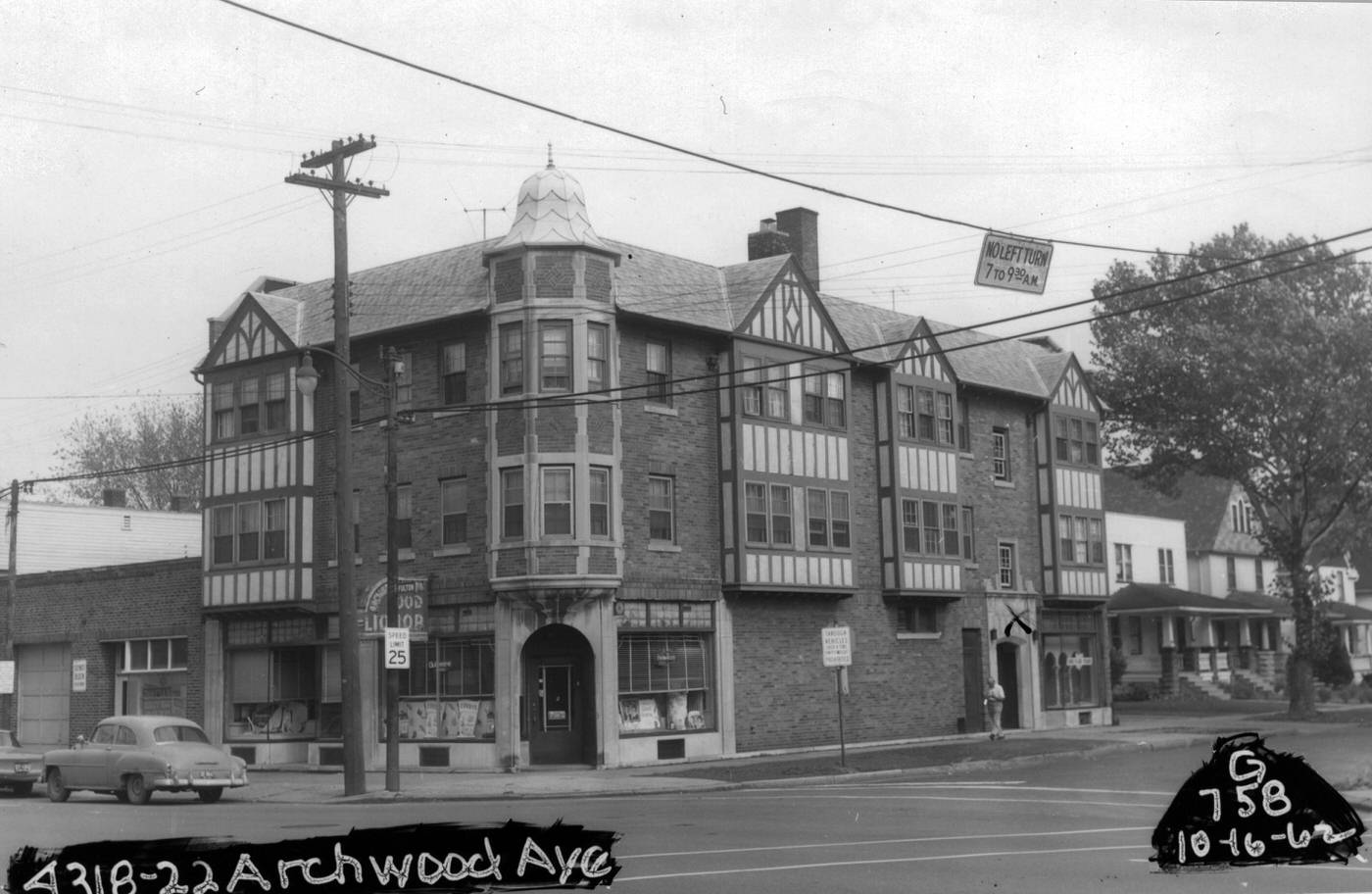

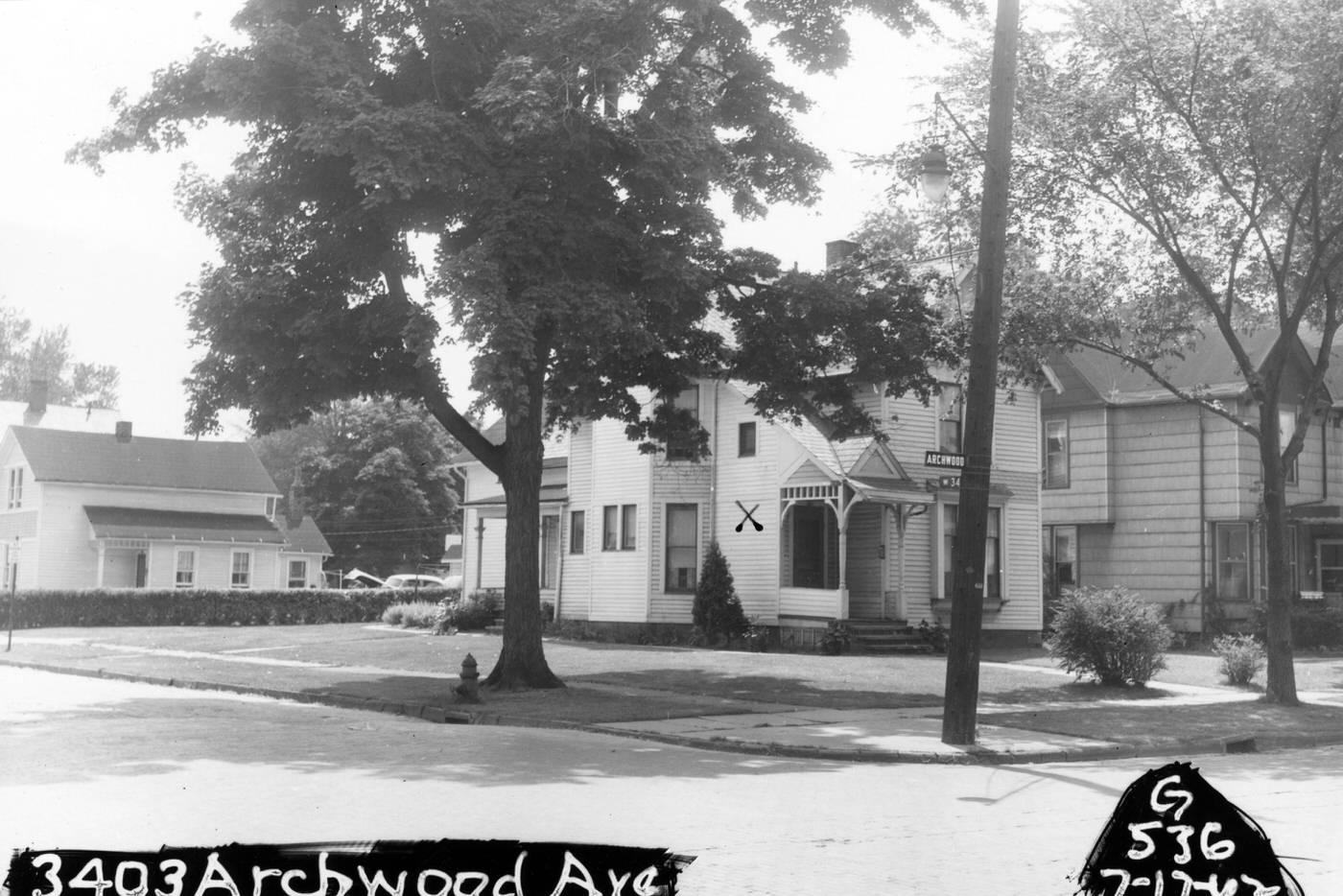

Shifting Ethnic Enclaves

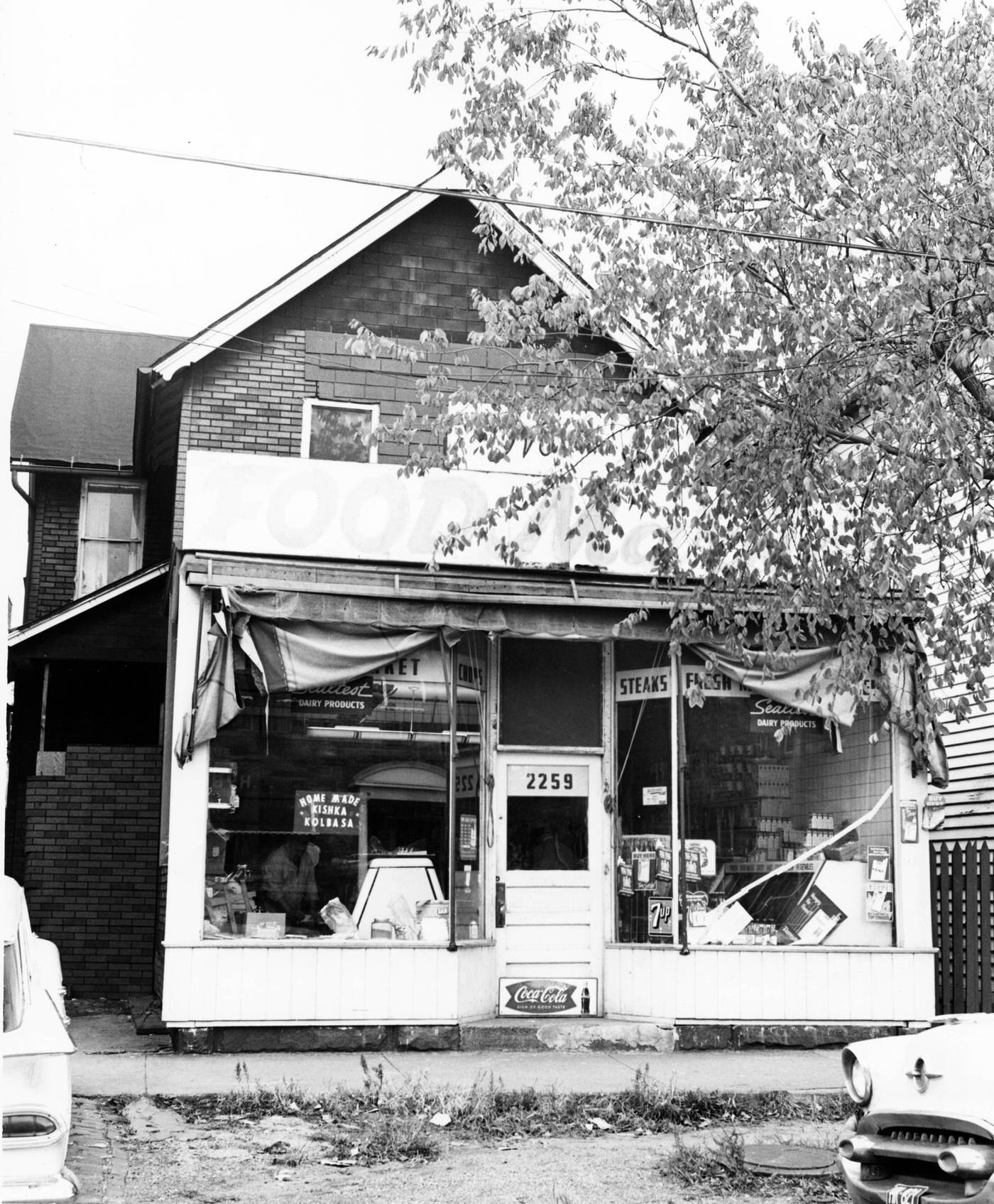

Cleveland’s various ethnic communities also experienced significant changes during the 1960s. Many older European ethnic groups saw their traditional neighborhoods transform due to suburbanization and demographic shifts. The original Polish neighborhoods, with the exception of the Warszawa area (later known as Slavic Village) around Fleet Avenue, had greatly diminished by the 1990s. This process was well underway in the 1960s, as the children and grandchildren of original immigrants moved to suburbs like Garfield Heights and Parma. This suburban migration had begun as early as 1910 and resumed with vigor in the 1950s. The decline of these old neighborhoods was often linked to the closure of the basic industries that had once provided employment for their residents; many factories around Fleet Avenue, for example, closed by the end of the 1960s.

Slovenian communities were invigorated by a wave of post-World War II immigrants (1949-1960), many of whom were educated political refugees. They contributed to Cleveland’s Slovenian cultural scene, despite some ideological divisions within the community. Ukrainians also saw a new wave of immigration in the 1960s, with many choosing to settle in Parma rather than older neighborhoods like Tremont, which had received displaced Ukrainians in the 1950s. By 1965, approximately 18,000 people of Ukrainian descent lived in the Cleveland Metropolitan area. Andrew Fedynsky, who grew up in Tremont, recalled how various immigrant groups, including Ukrainians, eventually left the neighborhood for the suburbs. Similarly, by 1970, an estimated 48,000 Slovaks lived in Greater Cleveland, and by 1980, most had relocated to the suburbs, with Parma being a popular destination.

In contrast, Cleveland’s Little Italy neighborhood, bordered by Lake View Cemetery and the Case Western Reserve University campus, maintained a greater degree of stability as an ethnic enclave. Its distinct Italian character largely endured through the 1960s, with cultural traditions like the Feast of the Assumption, observed since 1950, continuing to be a significant annual event. However, Little Italy was not immune to racial tensions; some accounts suggest residents actively worked to limit incursions by African Americans, sometimes through violence, which, along with its unique geography, contributed to its demographic stability compared to surrounding areas that underwent significant racial change.

The Hungarian community, historically concentrated around Buckeye Road, experienced decline in its original enclave during the 1960s due to suburbanization. As younger Hungarian-Americans moved out, African Americans began moving into the Buckeye-Woodhill area. This transition led to ethnic tensions and the formation of groups like the Buckeye Neighborhood Nationalities Community Association (BNNCA), which aimed to maintain Hungarian ethnic predominance in the Upper Buckeye (now Buckeye-Shaker) area.

Newer immigrant groups were also shaping the city’s fabric. The largest influx of Puerto Ricans to northern Ohio occurred between 1945 and 1965. By 1960, Puerto Ricans comprised about 82% of Cleveland’s Spanish-speaking residents. Starting in 1958 and continuing through the 1960s, many Puerto Ricans moved from the East Side to the Near West Side, particularly the area from West 5th to West 65th streets, between Detroit and Clark avenues. This shift was driven by deteriorating conditions in inner-city east side neighborhoods and the desire to be closer to jobs in the Flats. The Clark-Fulton neighborhood became a prominent Puerto Rican area. Community organizations like the Spanish American Committee, established in 1966, provided support, and cultural events like “Puerto Rican Friendly Day” began in 1969. Migration from Cuba also occurred following the 1959 revolution.

Large-scale migration of people from Appalachia to Cleveland, which began after World War II, continued into the 1960s. The 1960s also marked the expansion of Cleveland’s Asian Indian population, particularly after the Immigration Act of 1965 removed previous national quotas. The India Association of Cleveland was formed in October 1963, and the community’s monthly newspaper, The Lotus, was founded in 1967, reflecting the growth and organization of this new community. These varied experiences show that there was no single “ethnic experience” in 1960s Cleveland. Instead, it was a complex tapestry of neighborhood decline, stability, new community formation, and inter-group relations, all shaped by the timing of arrival, socioeconomic factors, geographic location, and responses to the city’s broader transformations.

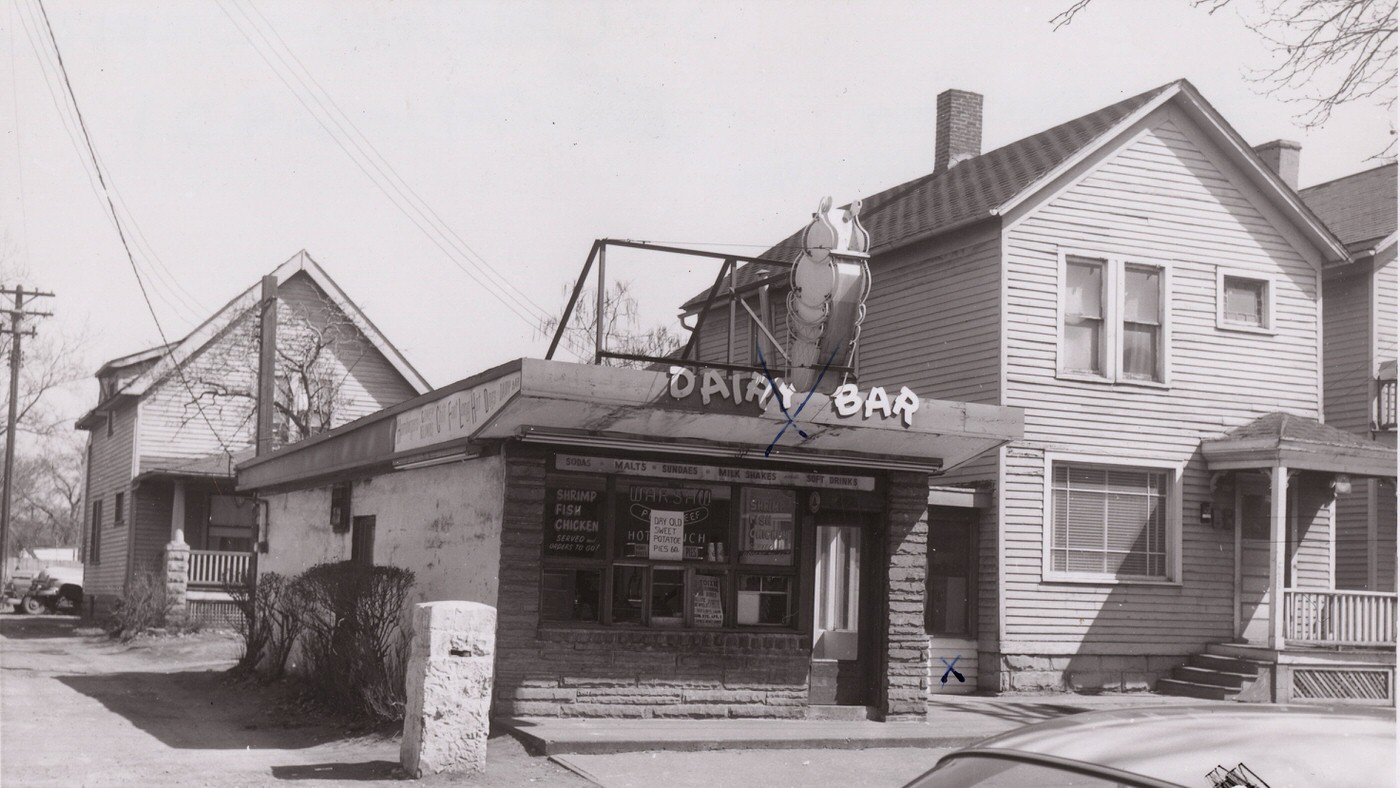

Dining out offered various experiences. Otto Moser’s restaurant, a Cleveland institution known for its walls adorned with autographed portraits of stage personalities, continued to be a popular spot in the 1960s, owned by Max A. Joseph and Max B. Joseph. For a more casual experience, especially for teenagers, drive-in restaurants like Kenny King’s and Manner’s Big Boy were popular hangouts, reflecting the car culture of the era.

The landscape for live theater and movies was changing. In downtown’s Playhouse Square, only the Hanna Theatre consistently featured live entertainment and touring Broadway shows during the 1950s and 1960s, as first-run movies increasingly opened in new suburban shopping malls. Some downtown theaters attempted to adapt; the Palace Theatre was renovated in 1960, and the Allen Theatre followed suit in 1961. The State Theatre had introduced the wide-screen Cinerama format in 1957. Despite these efforts, the decline of downtown as the primary entertainment district continued. The Allen Theatre closed in 1968, and the State, Ohio, and Palace theaters all ceased operations in 1969, marking the end of an era for these grand venues. The shift in leisure patterns—the decline of the traditional amusement park and downtown theater district alongside the rise of suburban entertainment and new youth-oriented gathering places—reflected broader societal changes, including suburbanization and evolving entertainment technologies, as well as the impact of social tensions on public spaces.

Housing Conditions and Urban Development’s Human Cost

The massive demographic and social changes of the 1950s and 1960s were intertwined with issues of housing and urban development. Urban renewal projects and highway construction, while aimed at modernizing the city, displaced over 11,000 people by 1966. Many of those displaced were African Americans, who then faced limited housing options due to discrimination.

Public housing estates existed, but racial segregation within them persisted. Despite city ordinances passed in 1949 banning racial discrimination in public housing, African American tenants remained concentrated in a few East Side estates well into the late 1960s.

In neighborhoods like Hough, community organizations like the Bell Neighborhood Center, established in the late 1950s, worked to address the pressing social needs. In the early 1960s, the Center was involved in voter registration, cleanup campaigns, youth employment programs, and interracial workshops.

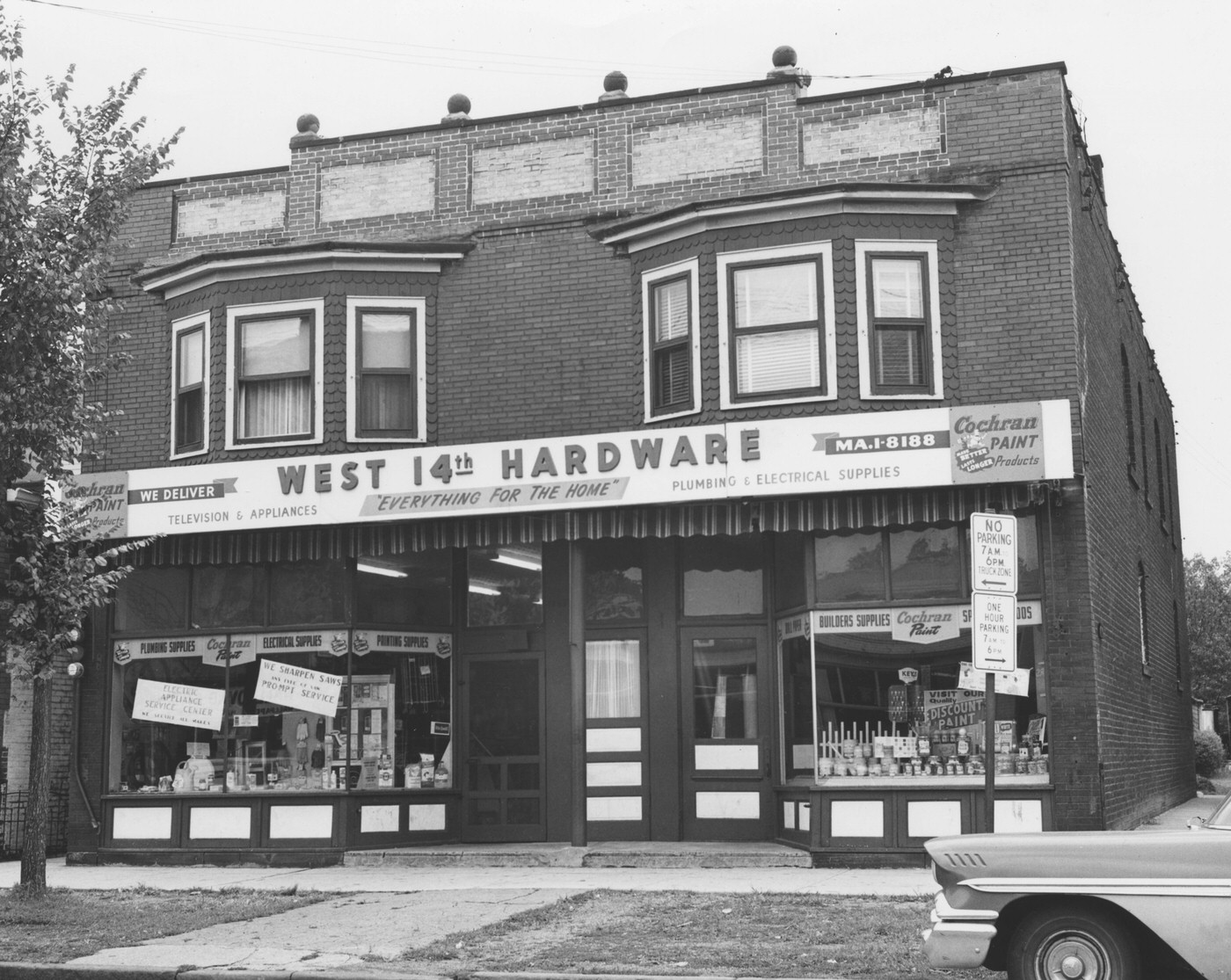

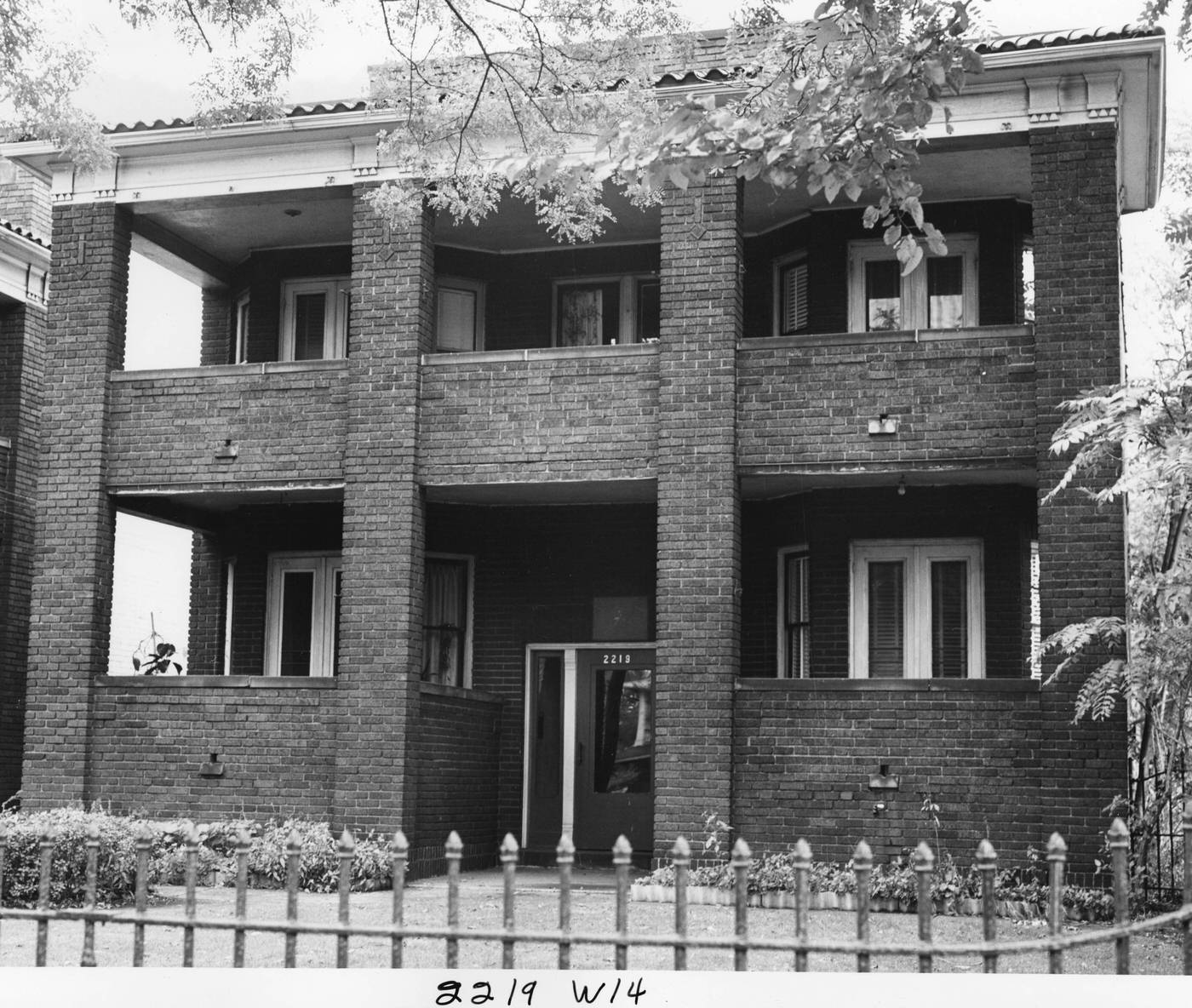

The city’s housing stock itself was varied. The “Cleveland Double,” a two-family dwelling with identical units on the first and second floors and often a two-story front porch, was a common sight in many city neighborhoods. These were built in large numbers in the early 1900s along streetcar lines. As automobile ownership became more widespread and suburbs expanded, the desirability of Cleveland Doubles waned for some. In contrast, post-World War II suburban developments increasingly featured “builders’ houses”—typically single-family homes in styles like Cape Cod, ranch, or split-level, often with attached garages, reflecting a more car-dependent lifestyle. These urban renewal and development efforts, while intended to “improve” the city, often came at a significant human cost, particularly for minority communities who were displaced and then faced limited and segregated housing choices, contributing to the overcrowding and neighborhood deterioration that these projects ostensibly sought to solve elsewhere.

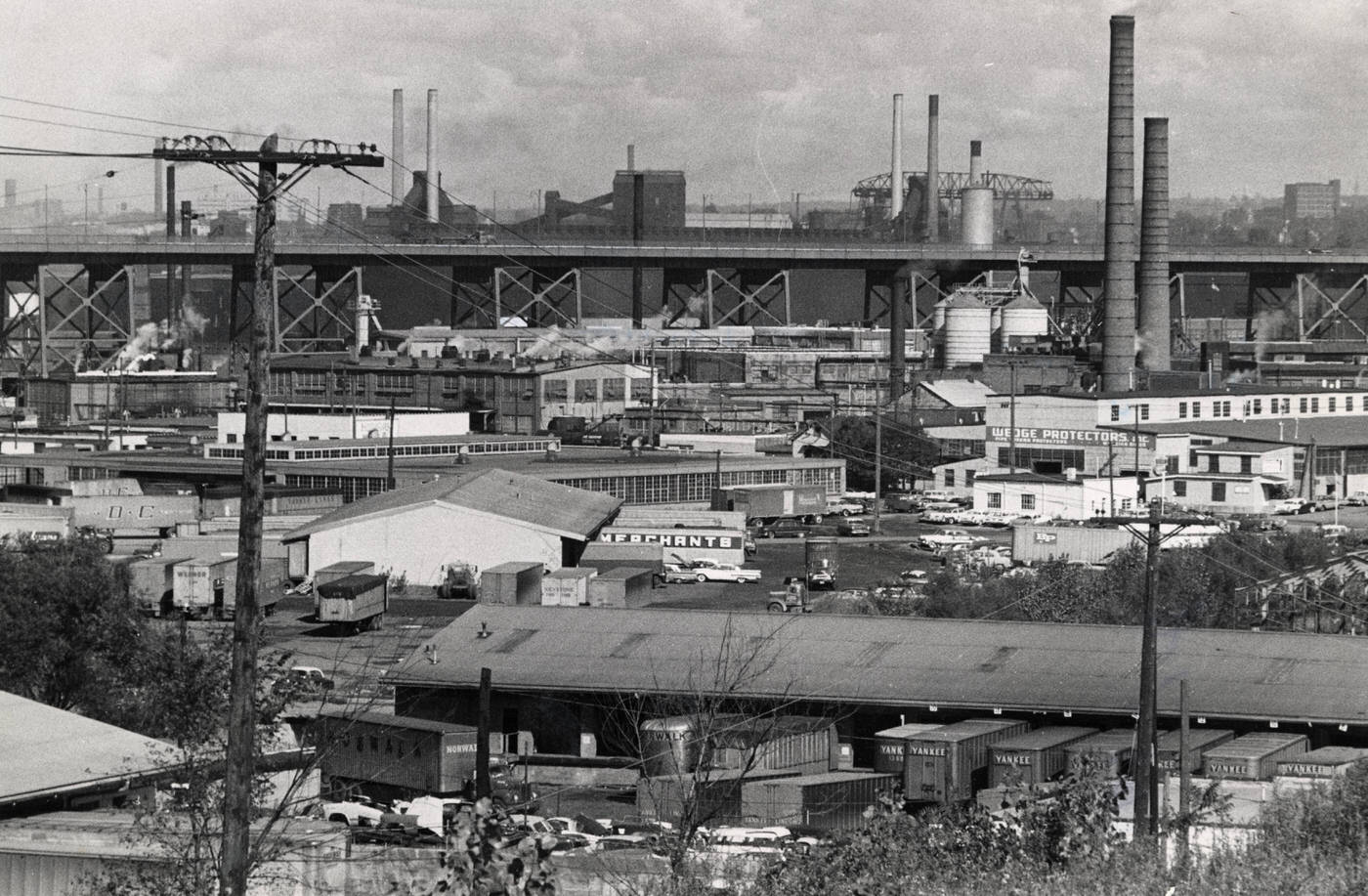

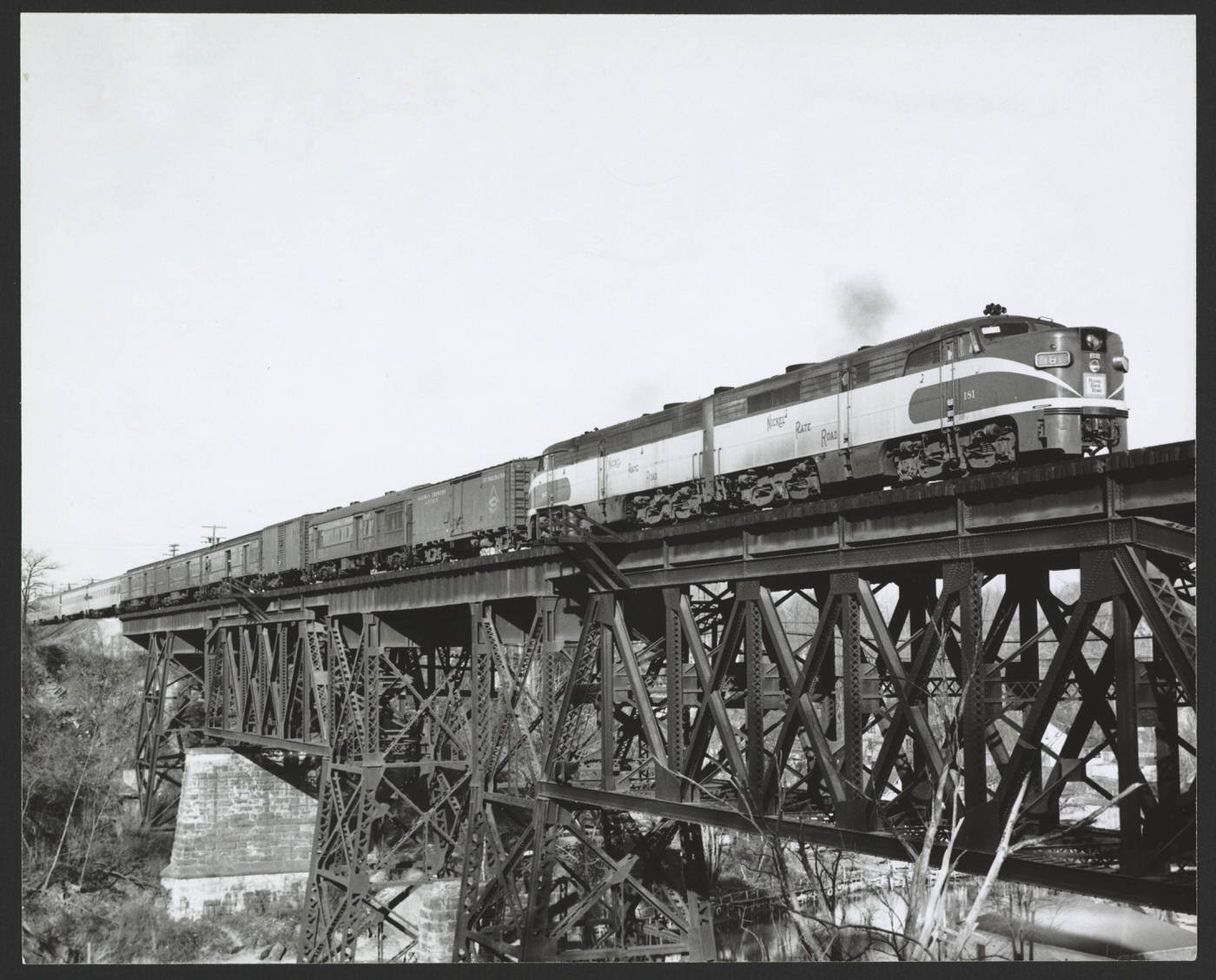

Shifting Tides in Manufacturing: Steel and Automotive Sectors

By the 1960s, the robust expansion that had characterized Cleveland’s economy for decades began to slow, particularly as its manufacturing sector encountered new pressures. This was part of a broader trend of deindustrialization affecting many “Rust Belt” cities. Republic Steel Corporation, a cornerstone of Cleveland’s industrial might, undertook significant modernization efforts during the 1960s, spending $1.2 billion. By 1965, its Cleveland works was the company’s largest steel plant. These investments were made against a backdrop of emerging global competition in the steel industry, a challenge that would become more acute in the following decades. The American steel industry as a whole had seen employment peak in 1953, and the 1960s marked a period of growing unease.

Manufacturing employment in the Cleveland Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) reflected these shifting tides. After years of growth, it began to decline in the mid-1960s. Figures show a drop from 307,000 manufacturing jobs in 1967 to 245,200 by 1981, indicating the latter half of the 1960s as the starting point of this contraction.

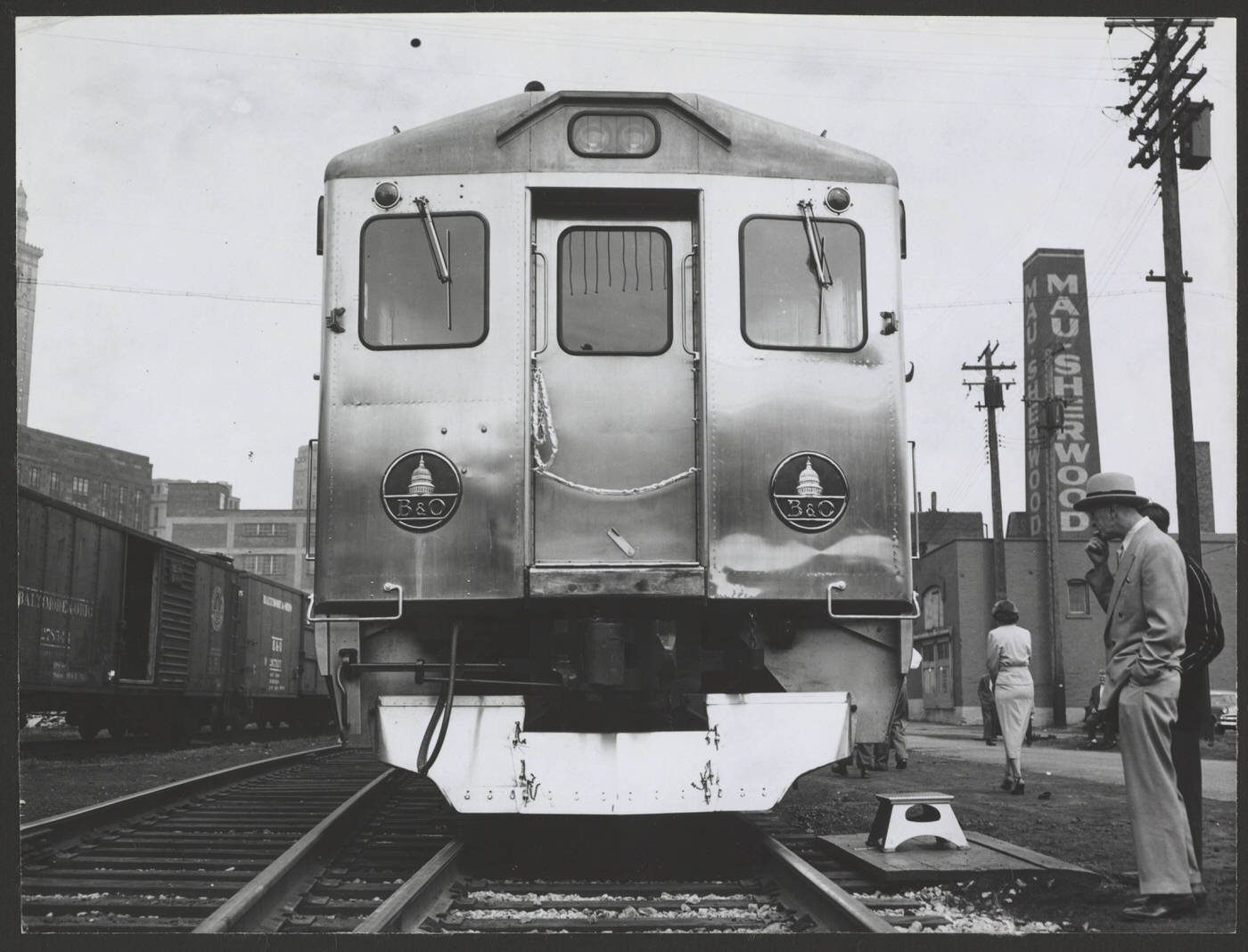

The automotive industry, another pillar of Cleveland’s economy, also experienced changes. Ford’s Brook Park complex, with its engine plants and foundry established in the 1950s, and General Motors’ Parma transmission plant, remained significant employers. These facilities were vital, with the Brook Park foundry, for instance, producing most of Ford’s 6-cylinder engines and all V-8 Mercury engines in 1953. While specific major plant closures or mass layoffs in the automotive sector are not prominently documented for the 1960s in the provided materials, the groundwork for future difficulties was being laid. National shifts in the auto industry, including rising foreign competition and changing consumer preferences, would lead to plant shutdowns and retooling in Cleveland in the late 1970s and beyond. For many African American workers, jobs in the auto industry, often unionized, had provided a pathway to the middle class since the post-WWII era, making any decline in this sector particularly impactful. The 1960s, therefore, represented a period where the initial signs of erosion in Cleveland’s manufacturing dominance became apparent, setting the stage for more pronounced economic challenges in the years to come.

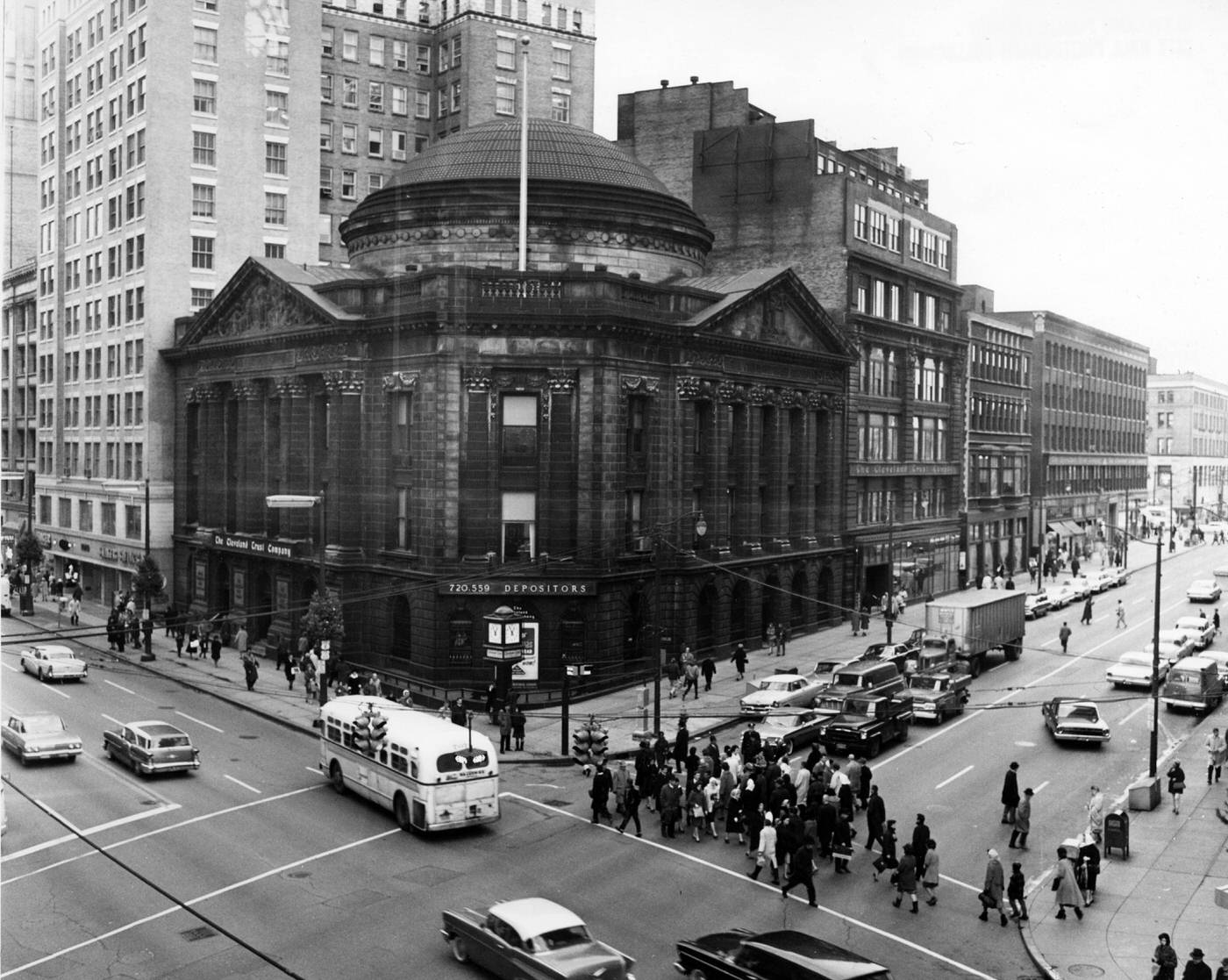

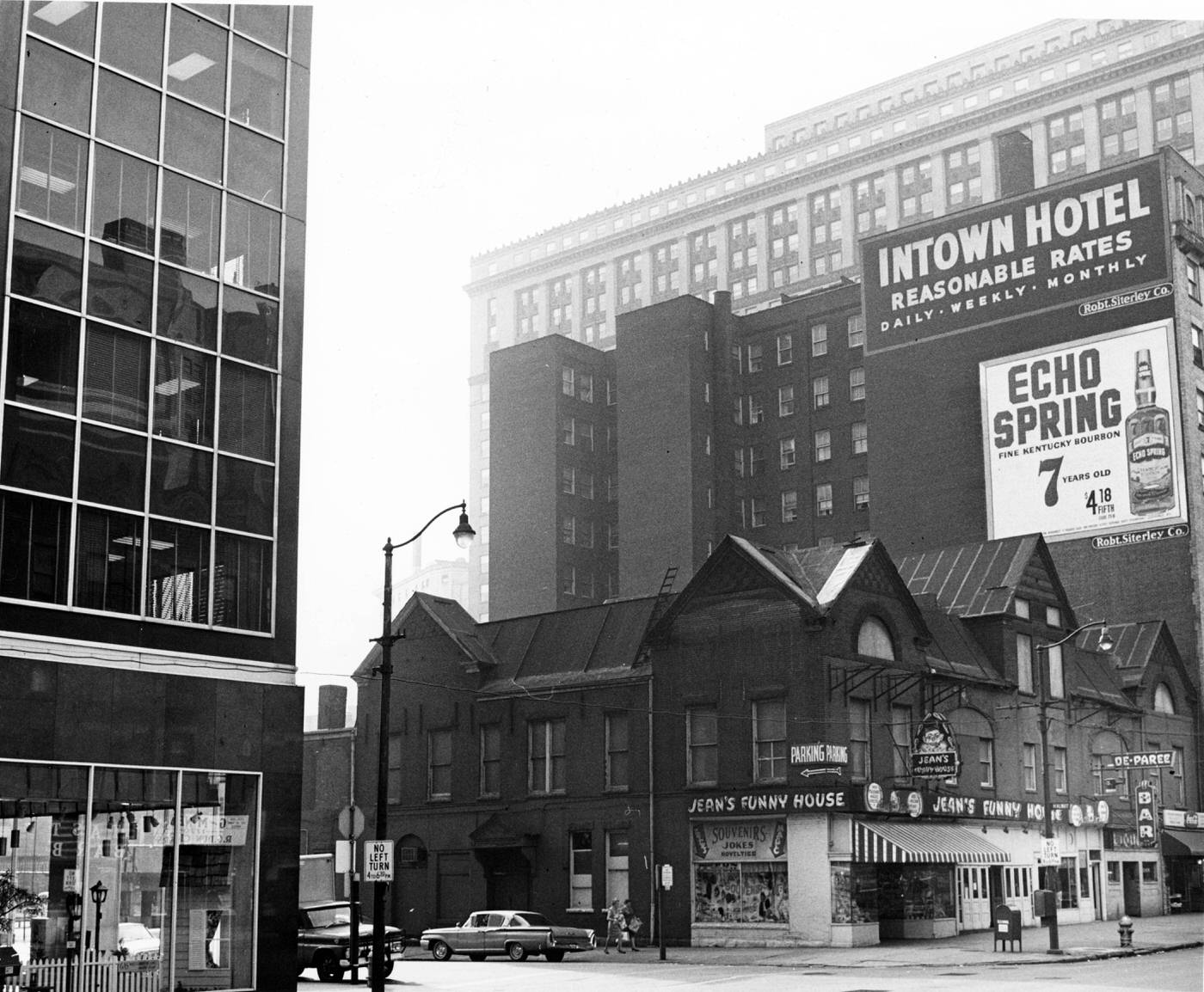

Downtown Cleveland: Retail Hub and Redevelopment Visions

In the early 1960s, Downtown Cleveland still held its position as the region’s primary retail, financial, and entertainment hub, a status solidified in the 1950s. Euclid Avenue was lined with prominent department stores. Halle Brothers Co. (Halle’s) was known as the city’s high-end “carriage store,” offering exclusive merchandise and personal service. Higbee’s occupied a position just below Halle’s, aiming for an upscale market, while the May Company catered to a broader, mid-range clientele, comparable to Macy’s or Gimbels. These stores were central to the downtown shopping experience.

However, by the late 1950s, concerns began to surface that the rapid growth of suburbs and new suburban shopping options posed a threat to downtown’s supremacy. In response, city planners and business leaders began to envision ways to strengthen the urban core. The “Downtown Cleveland 1975” plan, adopted in 1959, proposed significant redevelopment, including new office and residential spaces in the Playhouse Square area and enhancements to Euclid Avenue to create more of a mall-like atmosphere.

The massive Erieview urban renewal project, initiated in the early 1960s, also had an impact on downtown retail. Although some criticized Erieview for potentially drawing activity away from the traditional retail heart on Euclid Avenue, its ambitious scale prompted existing department stores to invest in their own facilities. Between 1963 and 1965, Higbee’s, May Company, Sterling-Lindner Co., and Halle Brothers Co. all undertook major renovations of their downtown stores. These actions can be seen as defensive maneuvers, attempts by the established retail giants to adapt and maintain their relevance in a changing commercial landscape. Halle’s, for example, also modernized its branding around this time, changing its logo in 1969. These investments showed a commitment to downtown, but they were made against the strong current of decentralization.

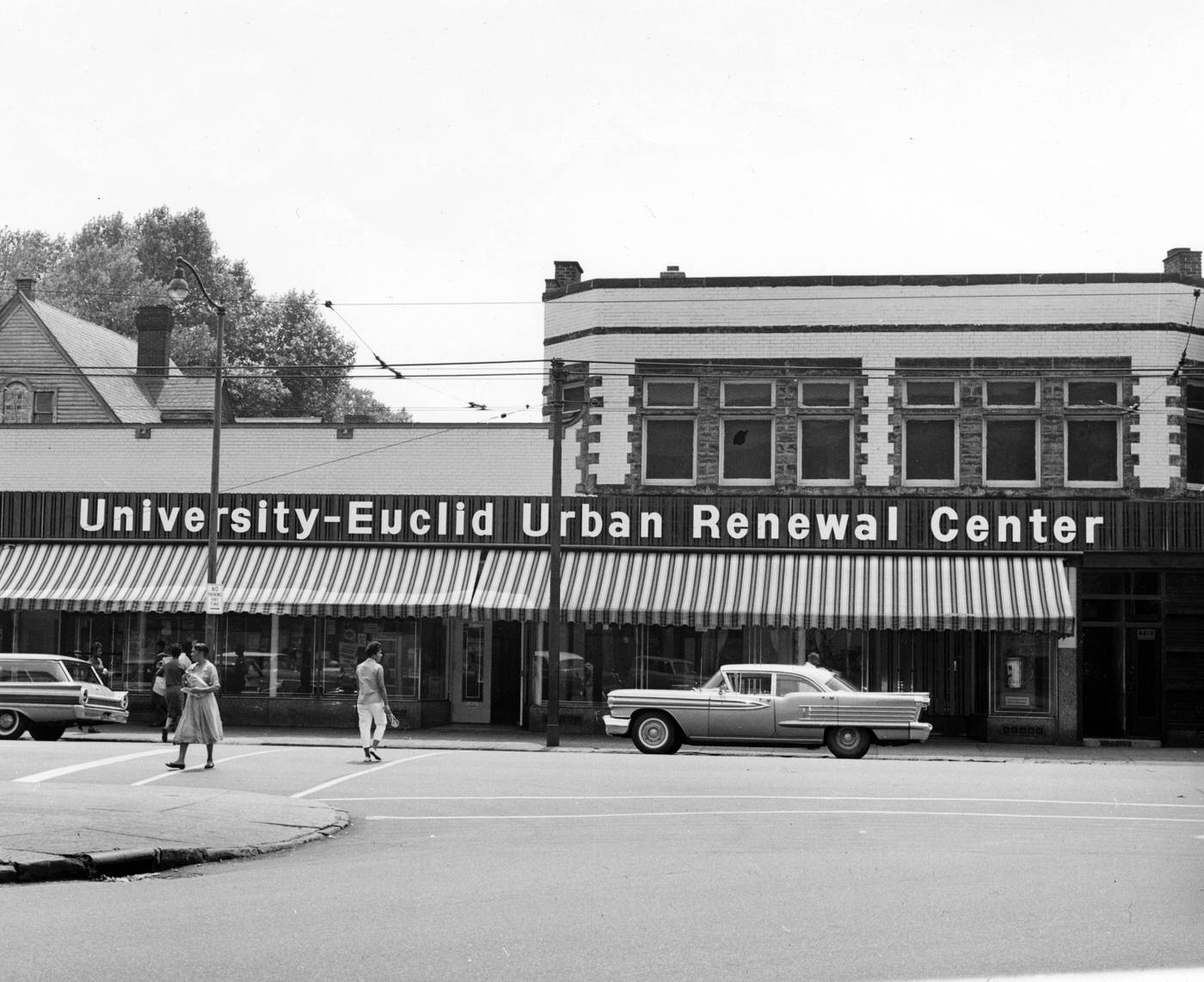

Urban Renewal: The Innerbelt Freeway and Erieview Project

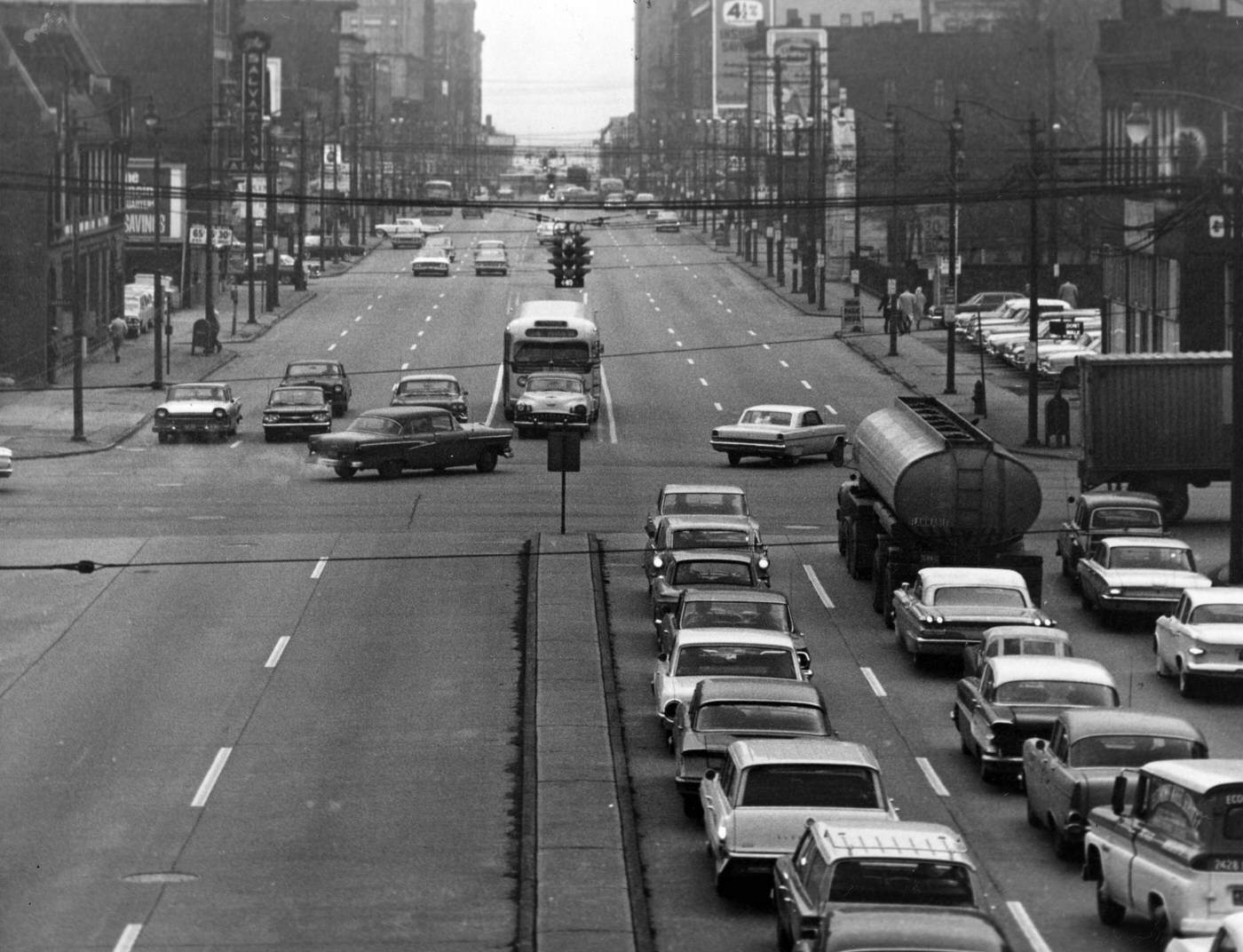

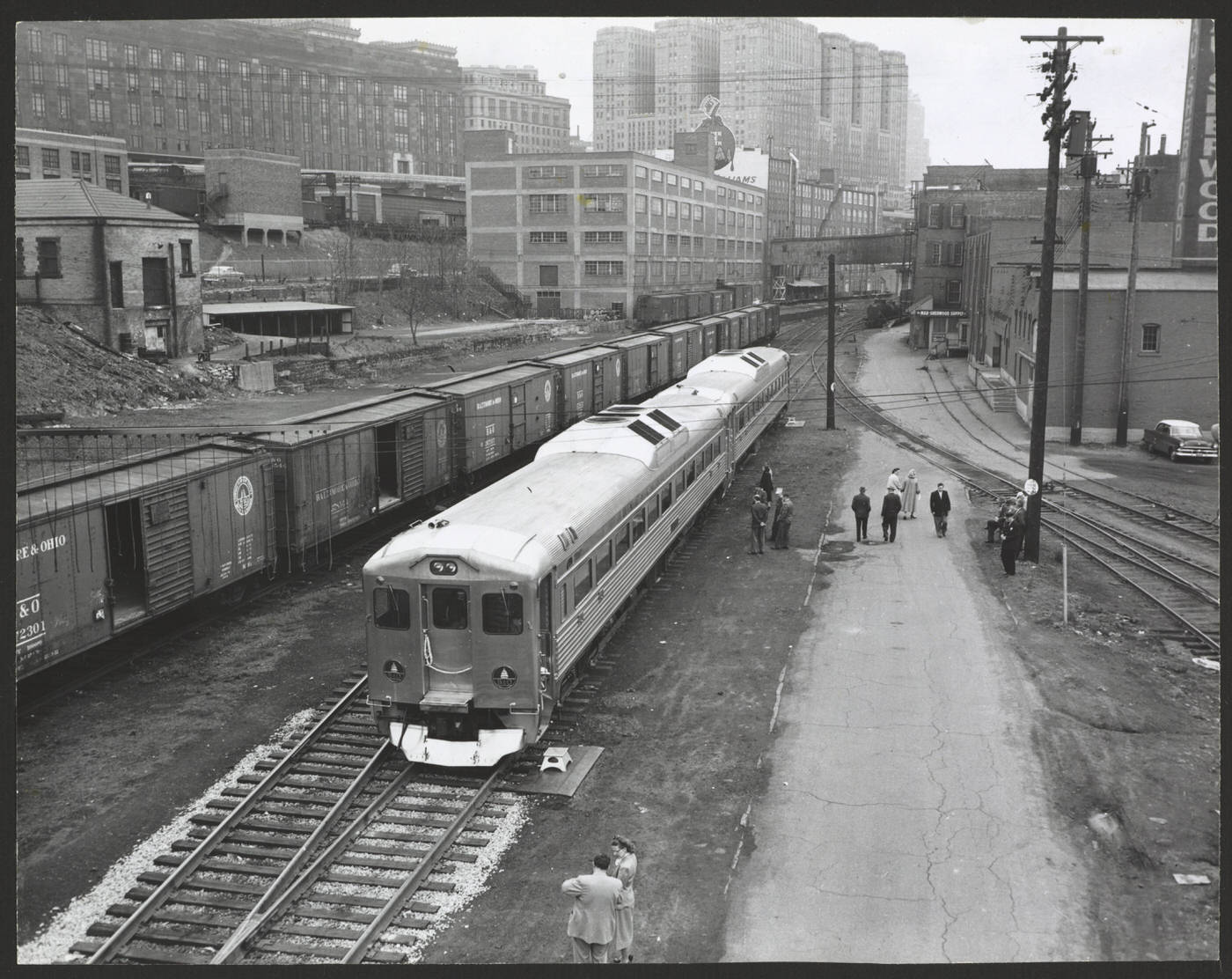

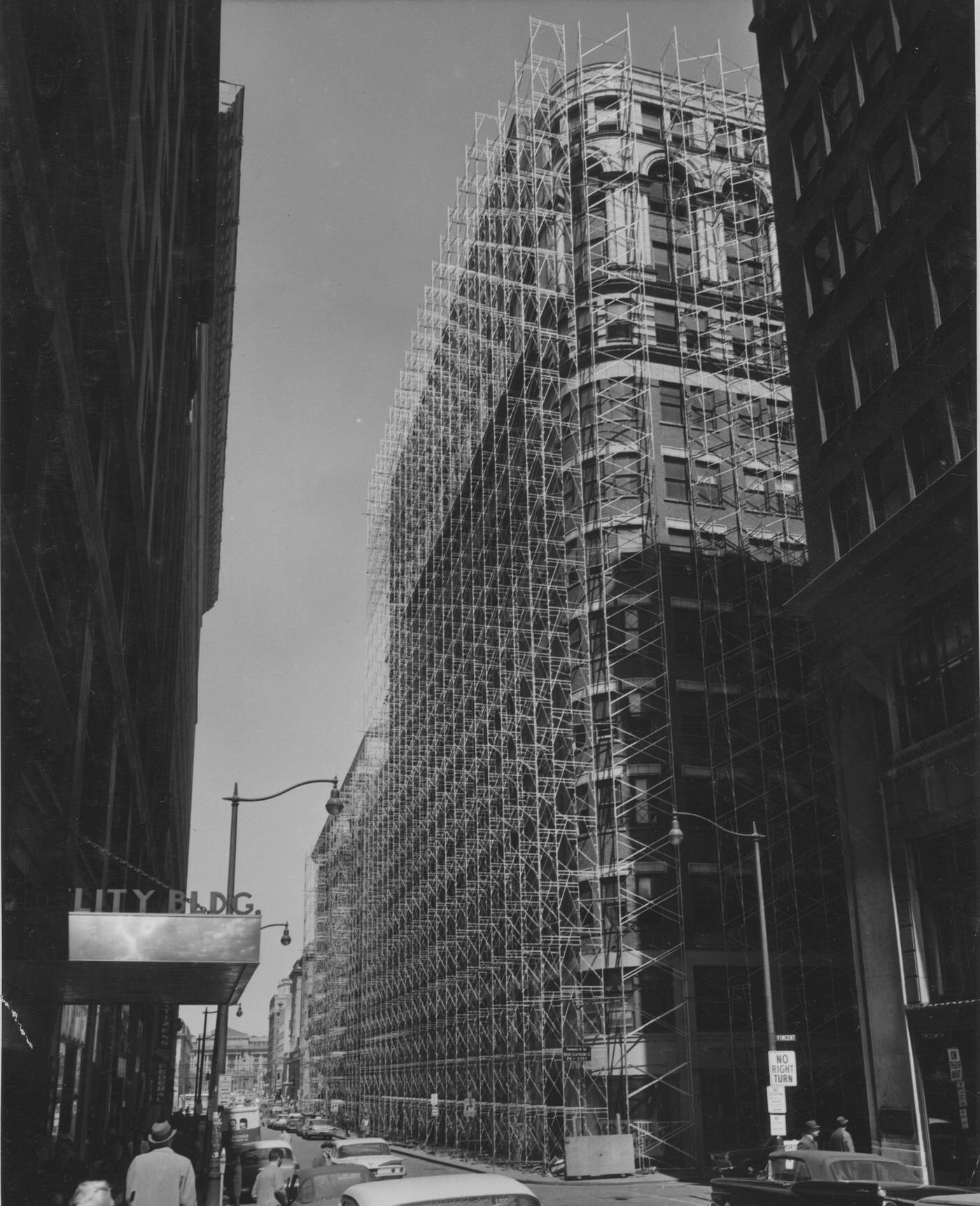

The 1960s were a period of large-scale urban renewal projects in Cleveland, most notably the completion of the Innerbelt Freeway and the progression of the Erieview project. The central portion of the Innerbelt Freeway, designed to divert traffic around downtown and connect with regional highways, opened in December 1961. The last of its 37 ramps became operational in August 1962. This freeway significantly altered traffic patterns, removing an estimated 50,000 vehicles daily from downtown streets and eventually becoming a crucial link to Interstates 77, 71, and 90. However, its construction was a massive undertaking, requiring the acquisition of 1,250 parcels of land and, like many highway projects of the era, it created new physical divisions within the city, in this case separating Downtown from the largely African American Central neighborhood.

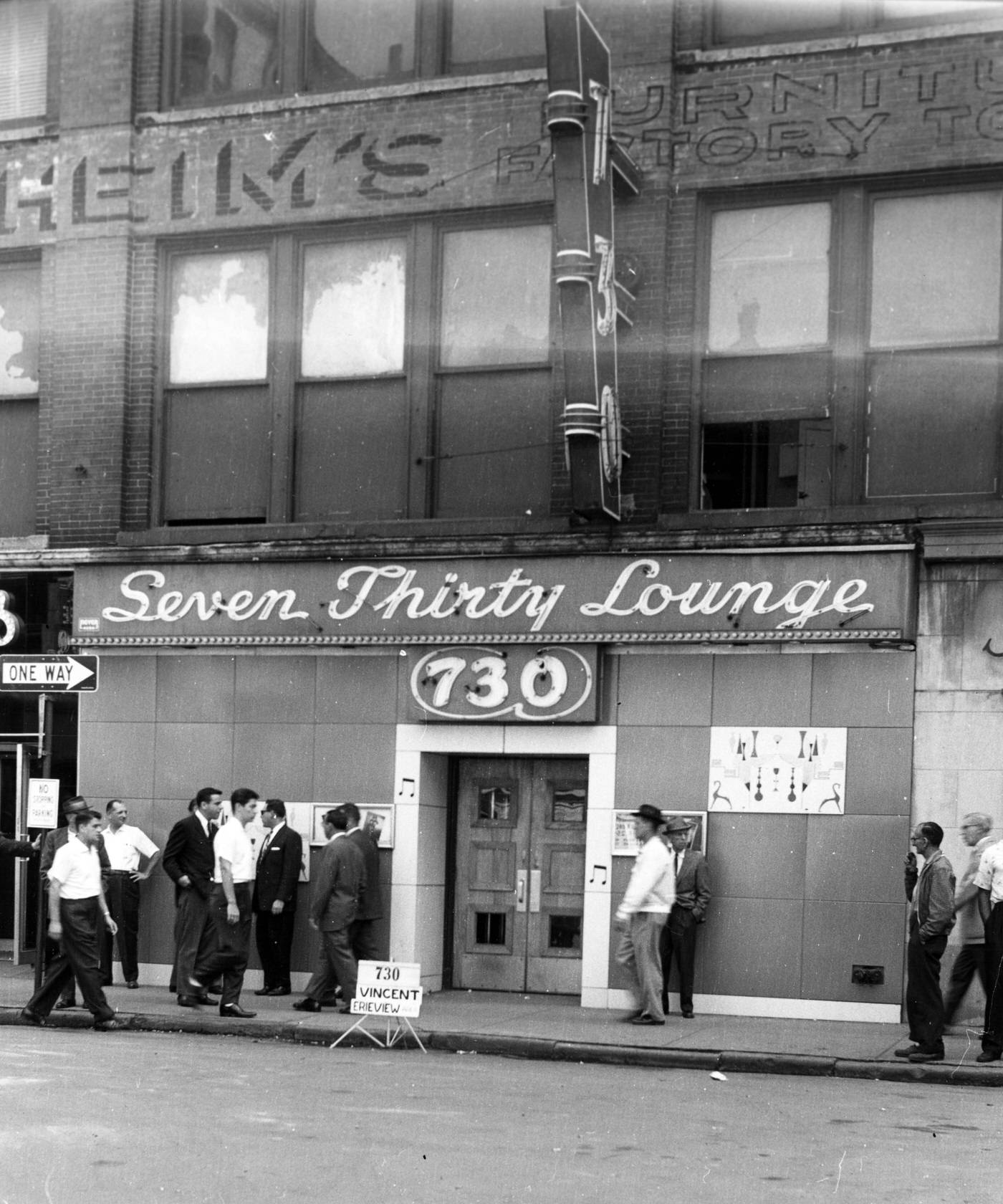

The Erieview urban renewal plan, adopted in 1960, was even more ambitious. Designed by the renowned architectural firm of I.M. Pei & Associates, it covered a 125-acre area northeast of downtown, stretching from East 6th to East 17th Streets and from Chester Avenue to the lakefront. Declared the nation’s largest downtown urban renewal project at the time, its goal was to eliminate perceived blight and create a modern complex of office towers, public plazas, and residential buildings. The 40-story Erieview Tower, the project’s centerpiece, was completed in 1964. Other significant structures followed, including the Federal Building (1967), One Erieview Plaza (1965), and several apartment towers like Park Center (originally Chesterfield Apartments and Reserve Square). The project involved the demolition of 224 buildings and displaced over 500 businesses.

Erieview, however, was met with considerable criticism. Some observers, like architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable, derided its main plaza as “huge, bleak, near empty” and the overall project as a “monument to everything that was wrong with urban renewal thinking in America in the 1960s”. Concerns were raised that Erieview siphoned vitality from the traditional downtown retail core along Euclid Avenue and that it created a sterile, isolated “surrogate downtown” that failed to integrate with the existing urban fabric. The grand visions of such large-scale projects often overlooked the nuanced needs of existing communities and the human cost of displacement, leading to mixed results and lasting debates about their true value to the city.

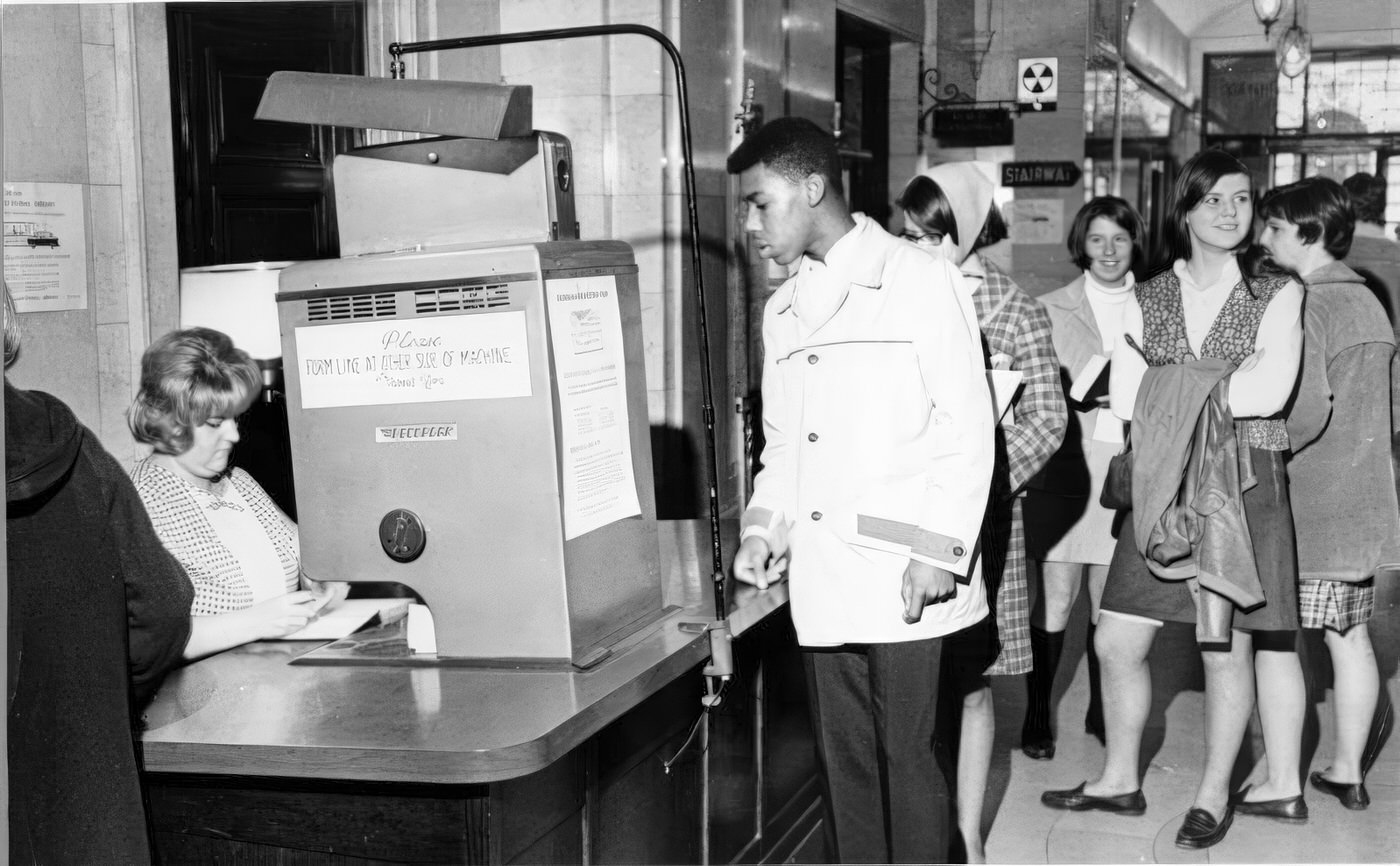

The Civil Rights Movement in Cleveland: Voices and Actions

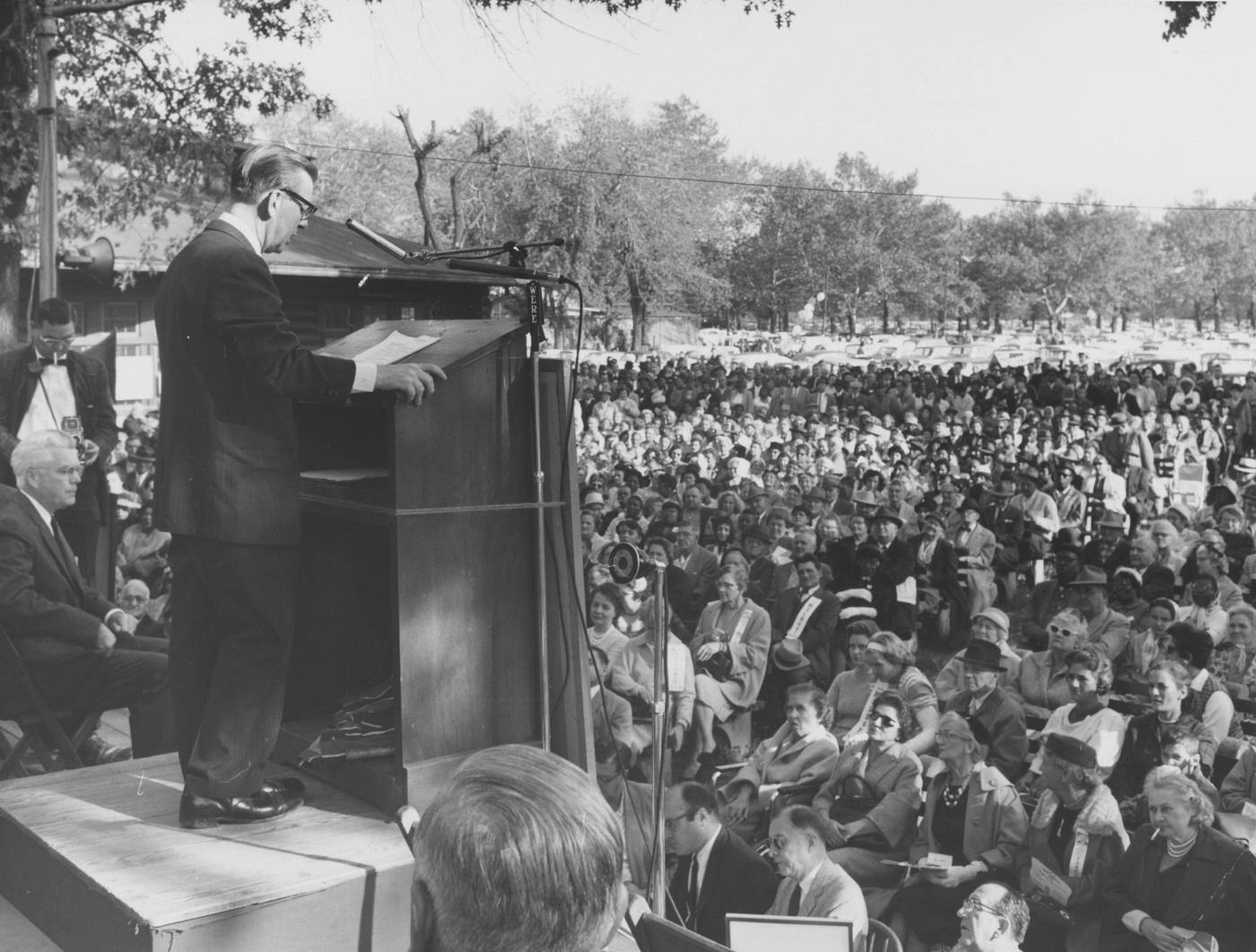

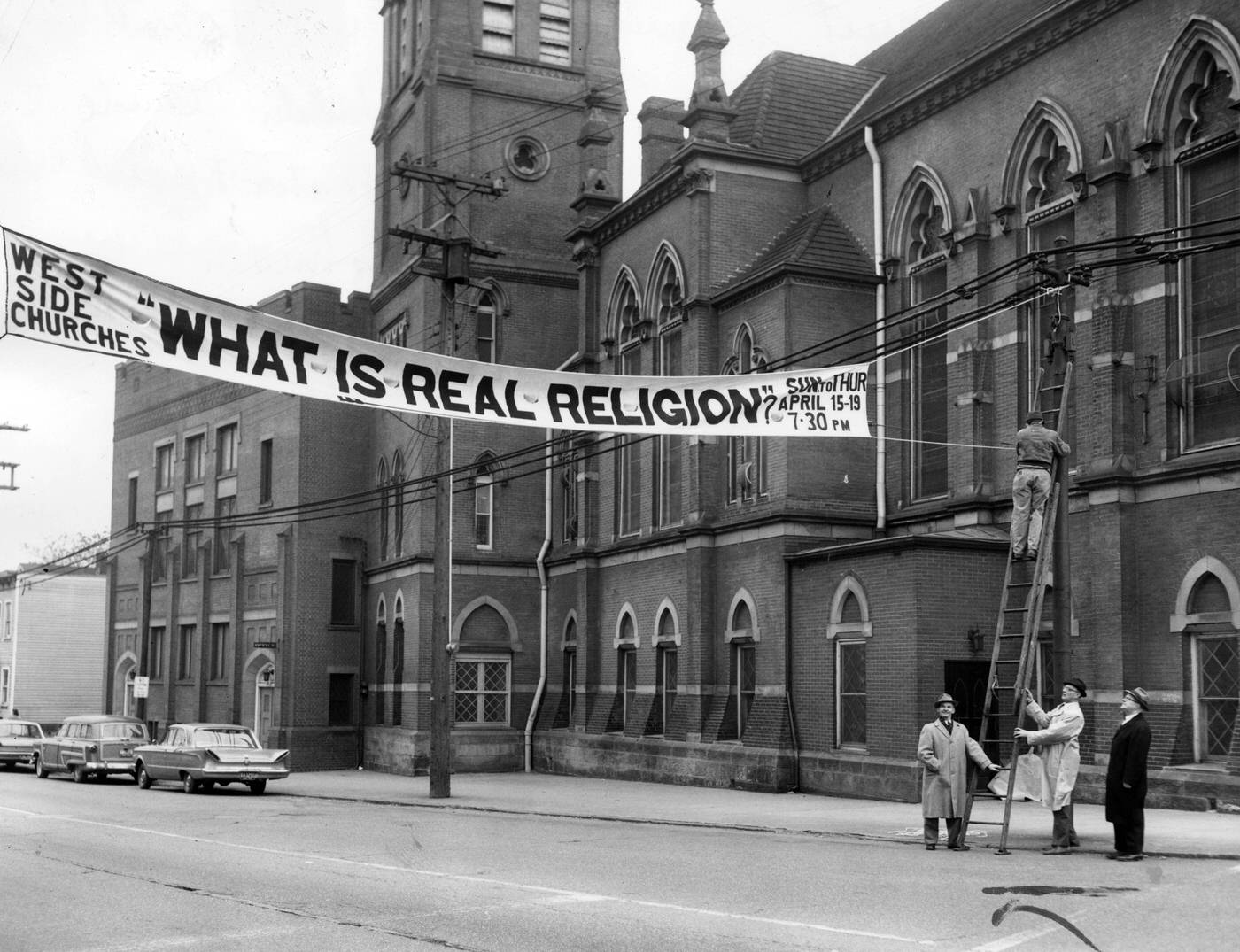

School segregation was a central focus of Cleveland’s Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s. The United Freedom Movement (UFM), established in June 1963, became a powerful coalition of over 50 civic, religious, and civil rights organizations, including the NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). The UFM spearheaded efforts to combat segregation and discrimination in the city.

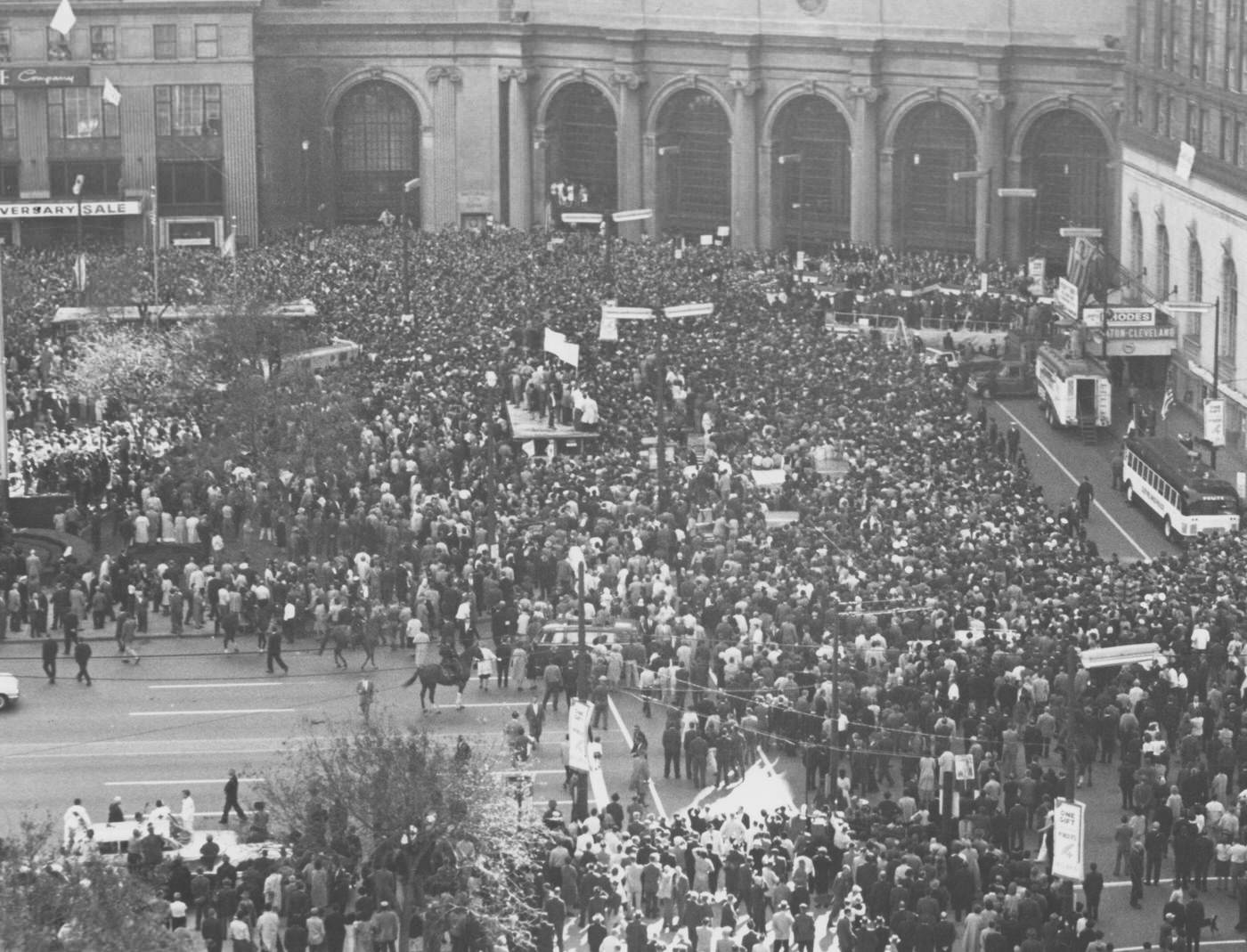

Protests against the Cleveland Public Schools’ policies were frequent and intense. Activists challenged practices like “intact busing,” where Black students were bused to predominantly white schools but kept segregated within them, and opposed school construction plans that were perceived as reinforcing existing segregation patterns. Demonstrations included picketing the school administration building and “receiving” white schools. A tragic moment in this struggle occurred on April 7, 1964, when Reverend Bruce Klunder, a white Presbyterian minister and CORE leader, was accidentally killed by a bulldozer while protesting at a school construction site. His death galvanized the movement, leading to a massive school boycott on April 20, 1964, during which 85-95% of Black students stayed home from school, many attending “freedom schools” set up by activists.

Beyond school desegregation, the UFM also tackled other forms of discrimination. In 1963, the coalition challenged discriminatory hiring practices at the downtown Convention Center construction site, which resulted in a negotiated non-discrimination agreement considered a national model at the time. That same July, the UFM organized a Freedom March and Rally that drew between 15,000 and 25,000 participants to Cleveland Municipal Stadium, where local and national civil rights leaders spoke about racial discrimination in northern cities. These actions were part of a broader movement addressing systemic issues of employment discrimination, police brutality, poor housing conditions, and ongoing school segregation that affected Cleveland’s African American community. Earlier efforts, like the Ludlow Community Association founded in 1957, had already been working to create integrated neighborhoods. The grassroots mobilization and multifaceted struggle of the Civil Rights Movement in 1960s Cleveland fundamentally challenged the city’s existing power structures and social norms.

Suburban Expansion: New Malls and Housing Styles

The 1960s solidified the shift towards a suburban-oriented lifestyle in Greater Cleveland, marked by the development of new shopping malls and distinct residential architecture. Severance Center in Cleveland Heights, which opened in October 1963, was a landmark development as Ohio’s first fully enclosed regional shopping mall. Anchored by downtown department store giants Halle’s and Higbee’s, it offered a new, climate-controlled alternative to traditional Main Street shopping. Westgate Center in Fairview Park, which had opened as an open-air shopping center in 1954 (Ohio’s first suburban mall), enclosed its plaza in the late 1960s to compete with newer malls like Severance and Parmatown Mall, which opened a May Company branch in 1960. These malls were designed around automobile access, featuring large expanses of parking, and they drew significant retail activity away from the central city.

Housing styles in the rapidly growing suburbs also reflected this autocentric trend. The post-World War II era saw the rise of “builders’ houses”—often basic, standardized designs like Cape Cods, two-story Colonials, split-levels, and especially the California ranch-style home. Ranch homes, characterized by their single-story, sprawling layouts and often featuring attached garages, became particularly popular in suburbs such as Pepper Pike, Beachwood, Solon, and Moreland Hills. This contrasted sharply with older city housing like the “Cleveland Double,” which was typically built along streetcar lines for pedestrian accessibility. The new suburban developments of the 1960s underscored a lifestyle increasingly reliant on the automobile, fundamentally altering retail patterns, residential design, and the overall spatial organization of the Cleveland metropolitan area.

The 1960s in Cleveland were a time of vibrant cultural activity and evolving daily life, reflected in its media, music, leisure pursuits, community organizations, and educational and artistic institutions.

On the Air: Radio and Television in Cleveland Homes

Cleveland’s television landscape saw significant changes in the 1960s. A major station trade between 1956 and 1965 resulted in NBC moving its Cleveland television (and radio) operations to Philadelphia, while Westinghouse brought its KYW radio and TV to Channel 3 in Cleveland. KYW-TV Channel 3 became known for live, innovative local programming and an expanded news operation. Its daily variety show, hosted by Mike Douglas, gained national syndication and was a major success. In 1965, NBC returned to Cleveland, and Channel 3’s call letters changed from KYW-TV to WKYC-TV, becoming the city’s first all-color television station. Popular local children’s shows, like Linn Sheldon’s “Barnaby” on Channel 3/WKYC and Gene Carroll’s “Uncle Jake” and Ronald Penfound’s “Captain Penny” on Channel 5/WEWS, were beloved by young Clevelanders.

The decade also saw the launch of new television stations. WVIZ Channel 25 began broadcasting in February 1965 as an educational station, supported by public subscription. It aired classroom-type programs and, as part of the Public Broadcasting Network, popular shows like “Sesame Street” and “The Electric Company”. In August 1968, Kaiser Broadcasting put WKBF Channel 61 on the air, a UHF station with a limited schedule of local programs, an innovative 10 P.M. newscast, and a heavy rotation of old movies.

Radio remained a powerful medium. While network radio continued, independent local stations had introduced the “disc jockey” in the 1950s, a trend that flourished in the 60s. WIXY 1260 AM, launching its Top 40 format in December 1965, became a dominant force in Cleveland radio. It featured popular personalities such as Al Gates, Howie Lund, Johnny Canton, and later Larry “the Duker” Morrow and Lou “King” Kirby. WIXY was deeply connected to youth culture, sponsoring concerts, including an appearance by The Beatles in 1966. Ethnic programming also continued to have a presence on Cleveland’s airwaves, with stations like WXEN and WZAK broadcasting such content in the early 1960s. This diversification of the media landscape, with popular local TV shows, influential Top 40 radio, and the emergence of educational and UHF television, played a role in shaping local culture and providing shared experiences for Clevelanders.

Cleveland’s passion for sports remained a constant in the 1960s, with the city’s professional football and baseball teams experiencing contrasting fortunes during the decade.

The Cleveland Browns: A Decade of Football

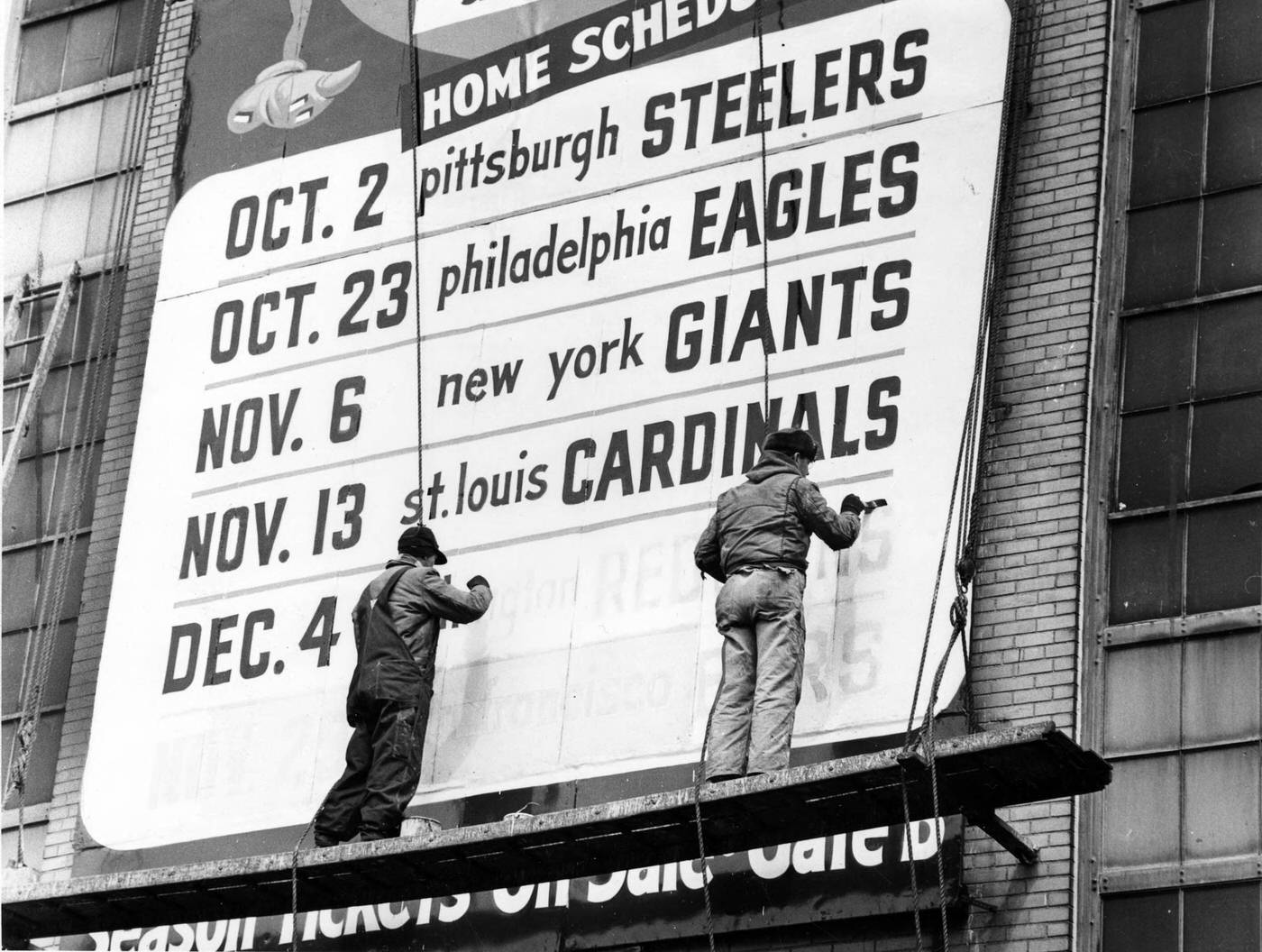

The 1960s were a significant and largely successful period for the Cleveland Browns. The decade began under the leadership of legendary coach Paul Brown, but his era came to an end after the 1962 season when new owner Art Modell controversially fired him in January 1963. Blanton Collier, Brown’s former assistant, took over as head coach.

Under Collier, and featuring the continued brilliance of iconic running back Jim Brown, who played for the team until his retirement after the 1965 season, the Browns achieved a major triumph. In 1964, they won the NFL Championship, decisively defeating the Baltimore Colts 27-0 in the title game. This victory remains the city’s most recent NFL championship and was a significant moment of civic pride.

The Browns remained a competitive force throughout much of the 1960s. They returned to the NFL Championship game in 1965, though they lost that contest. The team also made strong playoff runs, reaching the conference championship or league championship games in 1967, 1968, and 1969. Their overall regular season record for the decade (1960-1969) was an impressive 92 wins, 41 losses, and 5 ties. This consistent performance, highlighted by the 1964 championship, provided Cleveland sports fans with many memorable moments during a period of broader urban challenges.

The Cleveland Indians: On the Diamond in the Sixties

In contrast to the Browns’ successes, the Cleveland Indians baseball team entered a more challenging period in the 1960s. The decade began on a sour note for many fans with the infamous trade of popular slugger Rocky Colavito before the 1960 season. That year, the Indians finished in fourth place in the American League with a record of 76 wins and 78 losses.

Throughout the 1960s, the team struggled to maintain consistency and achieve the competitive respectability they had enjoyed in the 1950s, particularly during their record-setting 1954 season. The franchise faced issues such as declining attendance, frequent managerial changes, and a weakening of their farm system and scouting operations. These problems were compounded by instability in team ownership; William Daley owned the team in the early 1960s, and Vernon Stouffer took over in 1966. The struggles of the Indians during this decade offered fewer moments of civic triumph compared to the Browns, reflecting a fading of their earlier baseball power.

The Sound of the Sixties: Music Scenes and Venues

Cleveland’s music scene in the 1960s was exceptionally vibrant, reflecting national trends while fostering its own unique contributions. The early part of the decade saw the continuation of doo-wop’s popularity, though rockabilly’s influence waned. Mid-decade, the “British Invasion,” spearheaded by The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, swept through Cleveland, with both bands playing memorable concerts in the city.

Simultaneously, Soul music, in its various forms including the Motown sound, Deep Soul, and Memphis Soul, captured the spotlight. National stars like Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, and The Four Tops frequently performed in Cleveland, alongside homegrown talents such as the O’Jays and Bobby Womack. Later in the 1960s, rock music took harder-edged and more experimental turns, with psychedelic rock and folk/country rock also finding audiences.

Several Cleveland venues became legendary during this era. Leo’s Casino, which opened in 1963 at 7500 Euclid Avenue, was a premier showcase for R&B and Motown artists. It hosted iconic acts like The Supremes, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder (who gave some of his first performances there), and Otis Redding (who made his last stage appearance there). Leo’s was known for its racially mixed audiences and remarkably remained a haven of entertainment even during the 1966 Hough Riots, which occurred just blocks away.

The Agora, founded by Hank LoConti, opened its first location in 1966 near Case Western Reserve University. A second, larger venue, “Agora Beta,” opened in 1967 near Cleveland State University and quickly grew into one of the nation’s most influential concert clubs. The Agora became a proving ground for countless local, national, and international acts, including Grand Funk Railroad, ZZ Top, Peter Frampton, Bob Seger, Kiss, and Boston, as well as local bands that achieved national fame like The James Gang and The Raspberries.

Other important venues included Public Auditorium and Cleveland Arena, which hosted major British Invasion bands and other rock acts. Musicarnival, a unique theater-in-the-round, presented artists like Led Zeppelin and The Doors, while the subterranean La Cave in University Circle was a spot for acts like Jimi Hendrix and the Velvet Underground. The thriving music scene, supported by these iconic venues and passionate local radio, established Cleveland as a significant national music hub, offering a powerful cultural outlet during a decade of profound change.

Clevelanders in the 1960s had a variety of leisure and entertainment options, though some long-standing institutions saw decline while new trends emerged. Euclid Beach Park, a beloved amusement park on Lake Erie, remained a popular destination throughout much of the decade, finally closing its gates on September 28, 1969. Its famous roller coasters, such as the Thriller, the innovative Flying Turns, and the Racing Coaster, continued to thrill visitors. The park’s large dance pavilion, an original attraction from 1895, had witnessed evolving dance styles, from the big band swing of earlier decades to the twist and other rock and roll dances popular in the 1950s and into the 60s. However, Euclid Beach Park also had a history of discriminatory racial policies. “Strict regulation of African American visitors” had led to protests in 1946, after which the dance hall remained closed to the public. Racial incidents reportedly contributed to a decline in attendance during the 1960s, foreshadowing its eventual closure.

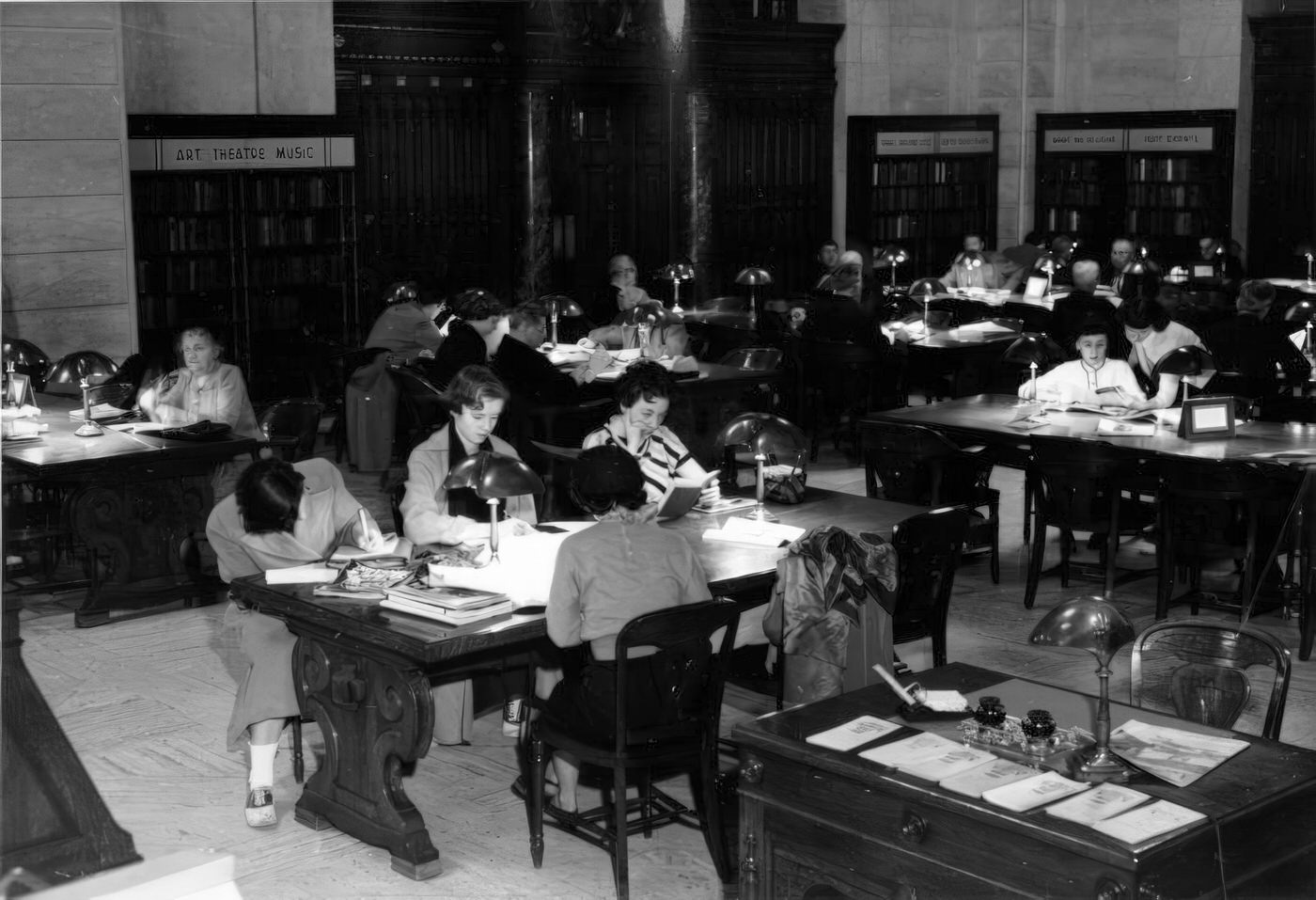

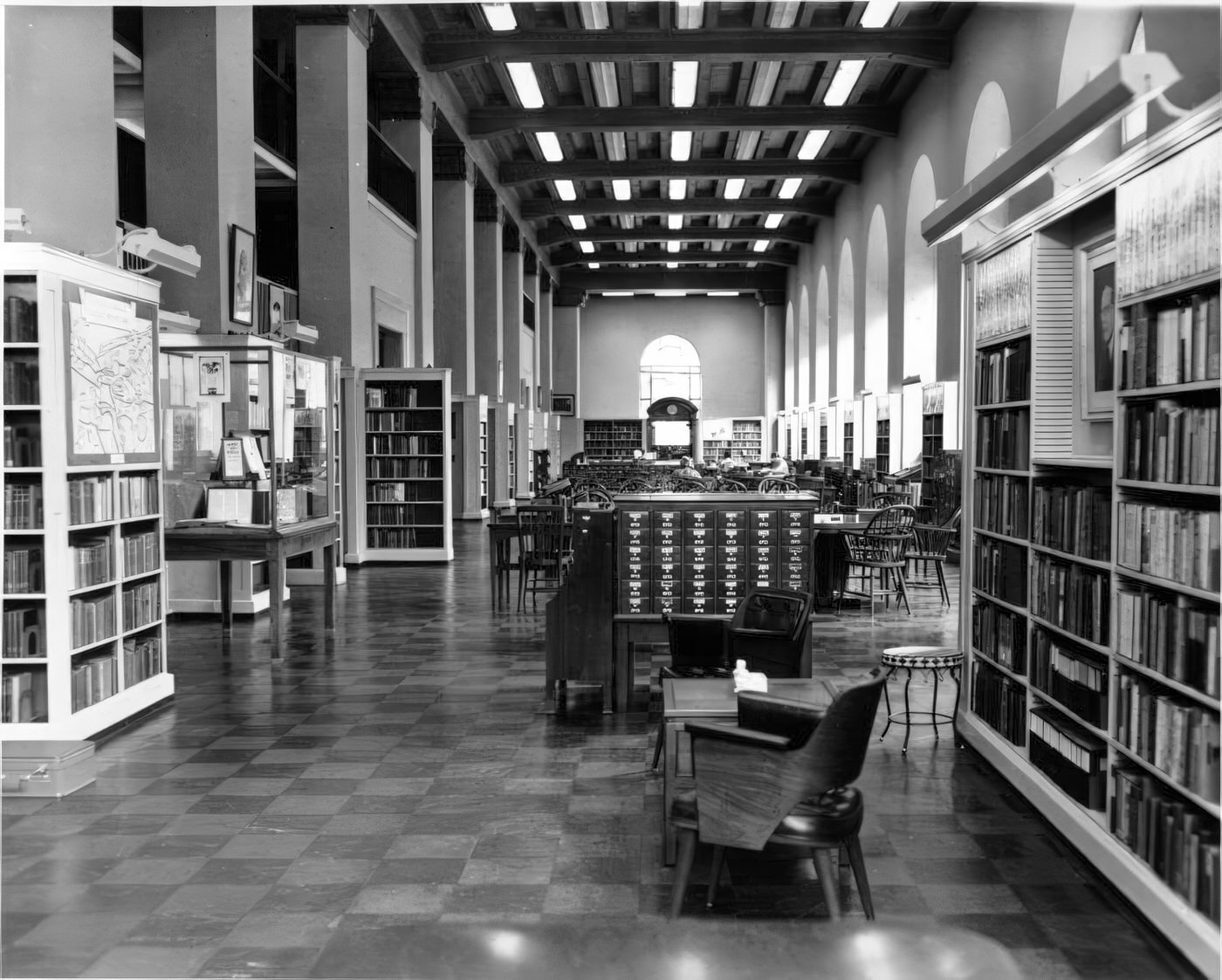

The Arts Scene: Karamu House and Cleveland Play House

Cleveland’s established arts institutions continued to contribute to the city’s cultural life during the 1960s, providing spaces for artistic expression and community engagement. Karamu House, located on the city’s East Side, had gained a national reputation as one of the country’s best amateur theatrical groups by the 1950s, a status it maintained into the 1960s under professional leadership that included Benno Frank and Reuben Silver. Karamu remained dedicated to interracial theater and the arts, presenting a regular yearly schedule of six plays that ranged from serious dramas to musicals. It also offered noteworthy programs and classes in dance and the visual arts, playing a vital role in nurturing African American actors and artists.

The Cleveland Play House (CPH), one ofr the oldest regional theaters in the country, also continued its work. In 1949, CPH had opened its 77th Street Theatre in a converted church, notable for featuring America’s first open stage, a design concept that prefigured the thrust stages popularized in the 1950s and 1960s. Frederic McConnell served as CPH’s artistic director until 1958, and was succeeded by K. Elmo Lowe, who led the institution from 1959 to 1970. While CPH had its own facilities, the Hanna Theatre in Playhouse Square was the primary downtown venue for live Broadway shows during the 1950s and 1960s. These institutions, Karamu House with its unique focus on interracial arts and African American talent, and the Cleveland Play House with its long tradition and innovative spirit, served as important cultural anchors, offering continuity and creative vitality during a decade of widespread urban change.

Community Gathering: Social Clubs and Family Activities

Amidst the changes of the 1960s, various organizations and institutions provided Clevelanders with opportunities for social connection, recreation, and community support. The Golden Age Clubs, established in 1941, continued to offer social and educational activities for senior citizens throughout the 1960s. With at least 35 local clubs active by 1952 at sites like Karamu House and the Friendly Inn, the Golden Age Centers of Greater Cleveland, Inc., formed in 1954, coordinated these efforts, providing a vital network for older residents.

A unique social space was the Lake Glen Country Club, which operated from the 1950s into the 1970s. Catering to a Black, white, and mixed-race clientele, it offered music, food, comedy, and dance, serving as a refuge and an “interzone” where patrons could discuss contemporary issues like Black consciousness and feminism. Despite facing police raids, particularly in 1957, which were often perceived by patrons as racially motivated, Lake Glen provided an important outlet for entertainment and social interaction.

Family activities were supported by institutions like the YMCA and the Cleveland Zoological Park. The YMCA continued its River Road Camp after World War II, emphasizing fitness, nature study, and crafts. The 1950s had seen a national focus on physical fitness, aligning with the YMCA’s mission, and its sports-themed camping experiences remained popular into the 1960s. The Cleveland Zoological Park, having established itself as a key civic institution by the end of the 1950s with a focus on children’s attractions and educational programming, continued this emphasis throughout the 1960s.

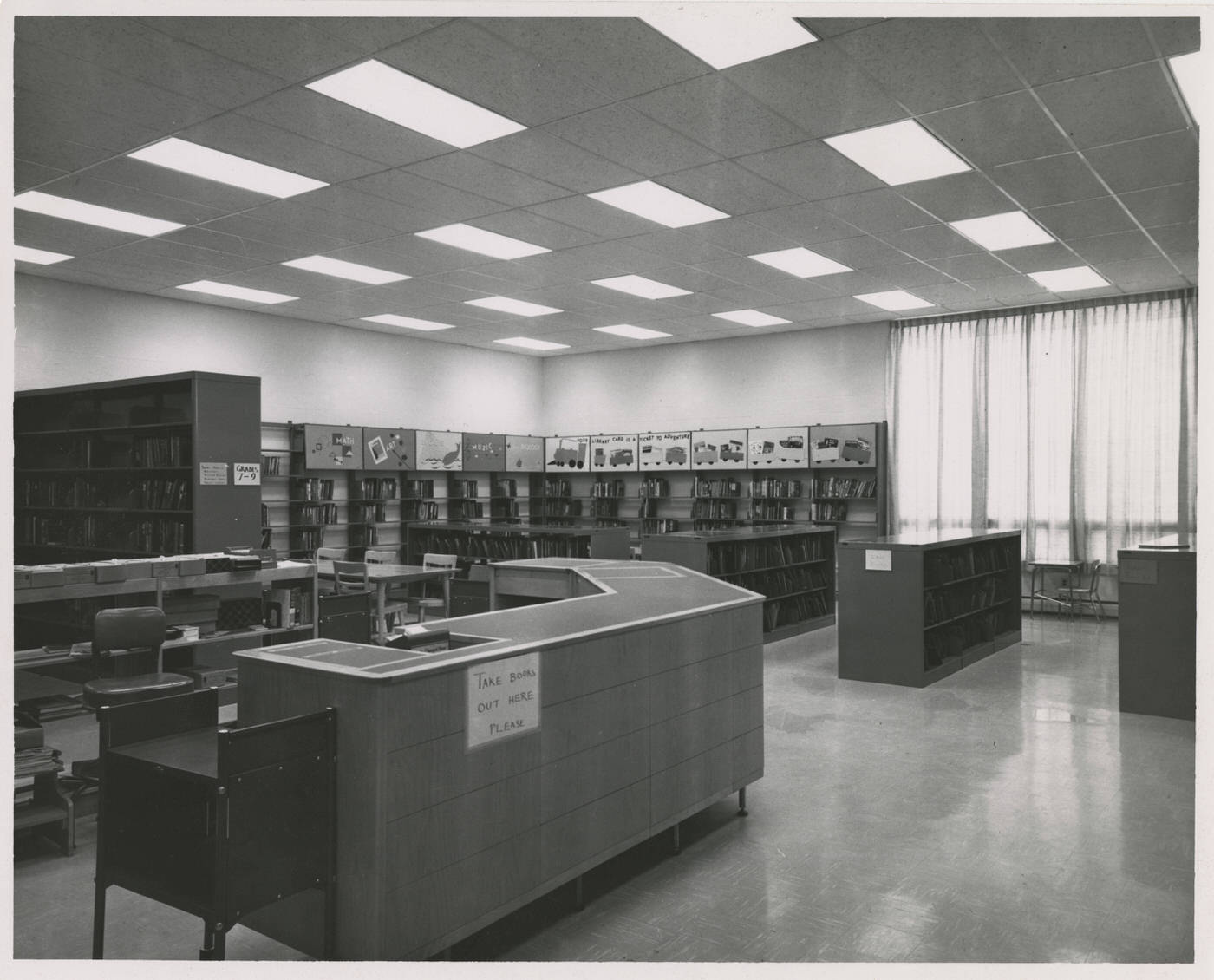

In neighborhoods facing significant challenges, community centers played a crucial role. The Bell Neighborhood Center in Hough, established in the late 1950s, became a hub for community activism in the 1960s. It offered interracial workshops, established a nursery school and library, ran Head Start programs, and formed a committee to improve citizen-police relations, directly addressing the pressing social issues of the era. These diverse examples demonstrate the resilience of community life in Cleveland, as residents sought connection, support, and recreation through various organizations and gathering places, adapting to the changing needs of different populations during a decade of intense transformation.

Times of Turmoil: The Hough Riots (1966) and Glenville Shootout (1968)

The deep-seated frustrations within Cleveland’s African American community erupted into major civil disturbances twice in the mid-1960s. The Hough Riots took place from July 18-24, 1966. The immediate spark was an incident where the white owner of the Seventy-Niners Cafe in the Hough neighborhood refused a Black customer a glass of water. However, the underlying causes were rooted in years of substandard and overcrowded housing, economic exploitation by area merchants, and persistent police harassment in the predominantly Black Hough neighborhood. The ensuing disorder involved angry protests, vandalism, looting, and arson. During the week of unrest, four African Americans were killed, about 30 people were injured, and nearly 300 were arrested. Approximately 240 fires were set, causing an estimated $1-2 million in property damage. Mayor Ralph Locher called in the National Guard to restore order.

Two years later, on July 23, 1968, the Glenville Shootout occurred. This was a gun battle between Cleveland Police and a Black militant group called the Black Nationalists of New Libya, led by Fred “Ahmed” Evans. The confrontation stemmed from FBI COINTELPRO surveillance of Evans’ group and Evans’ resulting paranoia of an imminent police assault. The shootout was a chaotic and violent event with conflicting accounts of who fired first. It resulted in seven confirmed deaths (three policemen, three nationalists, and one bystander) and many injuries. The violence precipitated four days of rioting in the surrounding Glenville neighborhood, causing an estimated $2.6 million in property damage. Mayor Carl Stokes, who was then in office, called in the National Guard. He also made the controversial decision to initially use only Black police officers and community leaders to patrol the area in an attempt to de-escalate tensions. These two major disturbances starkly exposed the profound racial and social fissures within Cleveland and were part of a national pattern of urban uprisings reflecting Black frustration over systemic inequality.

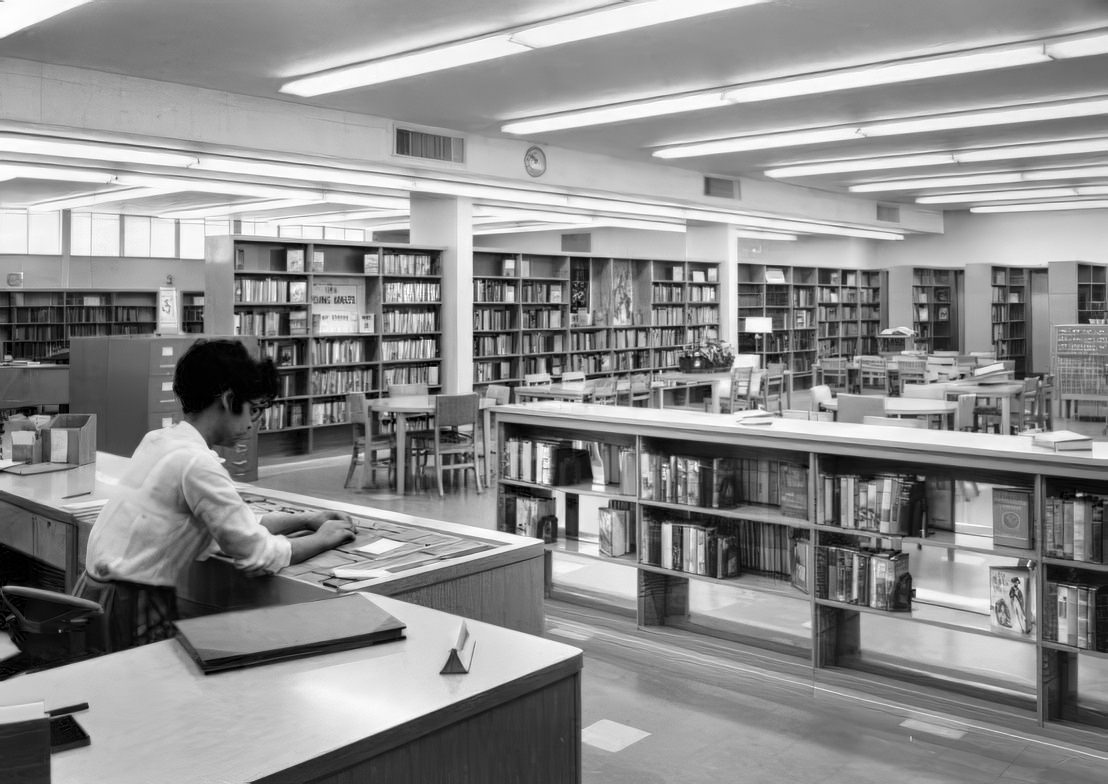

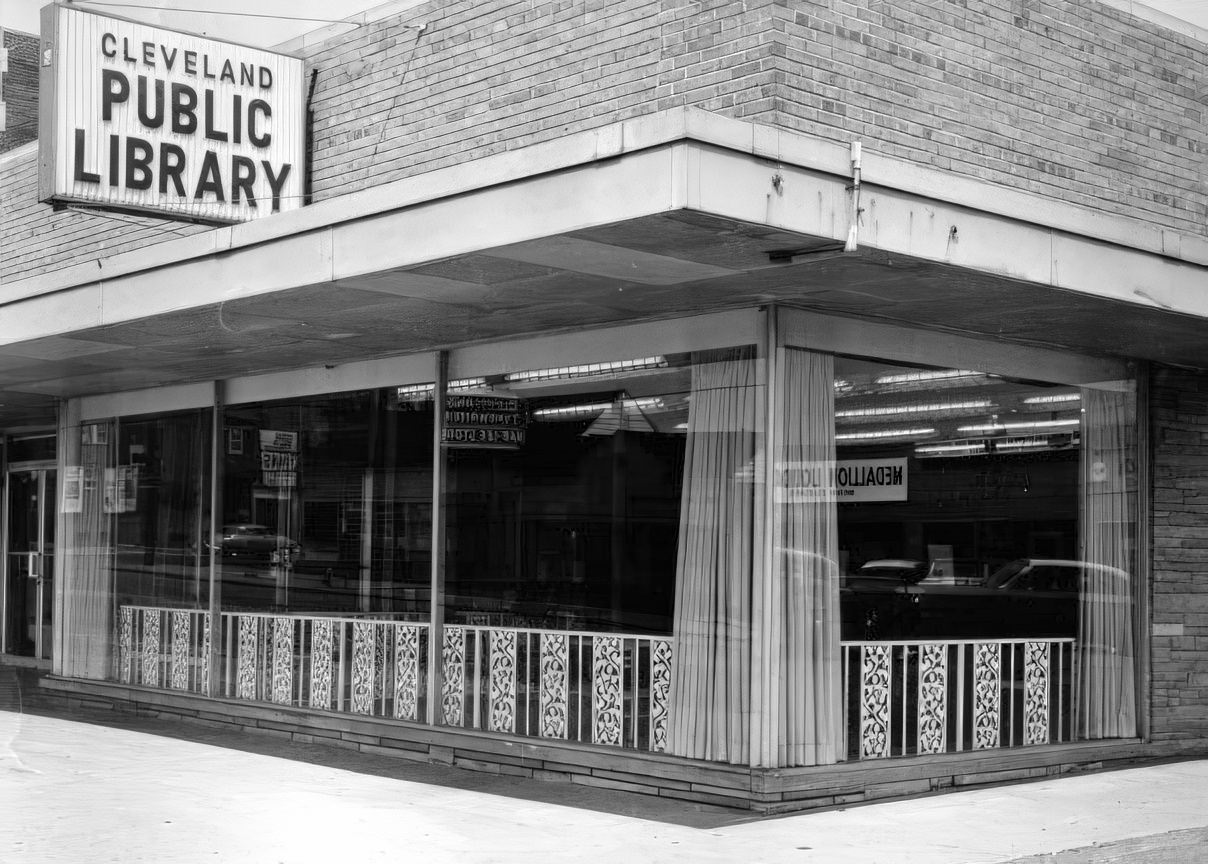

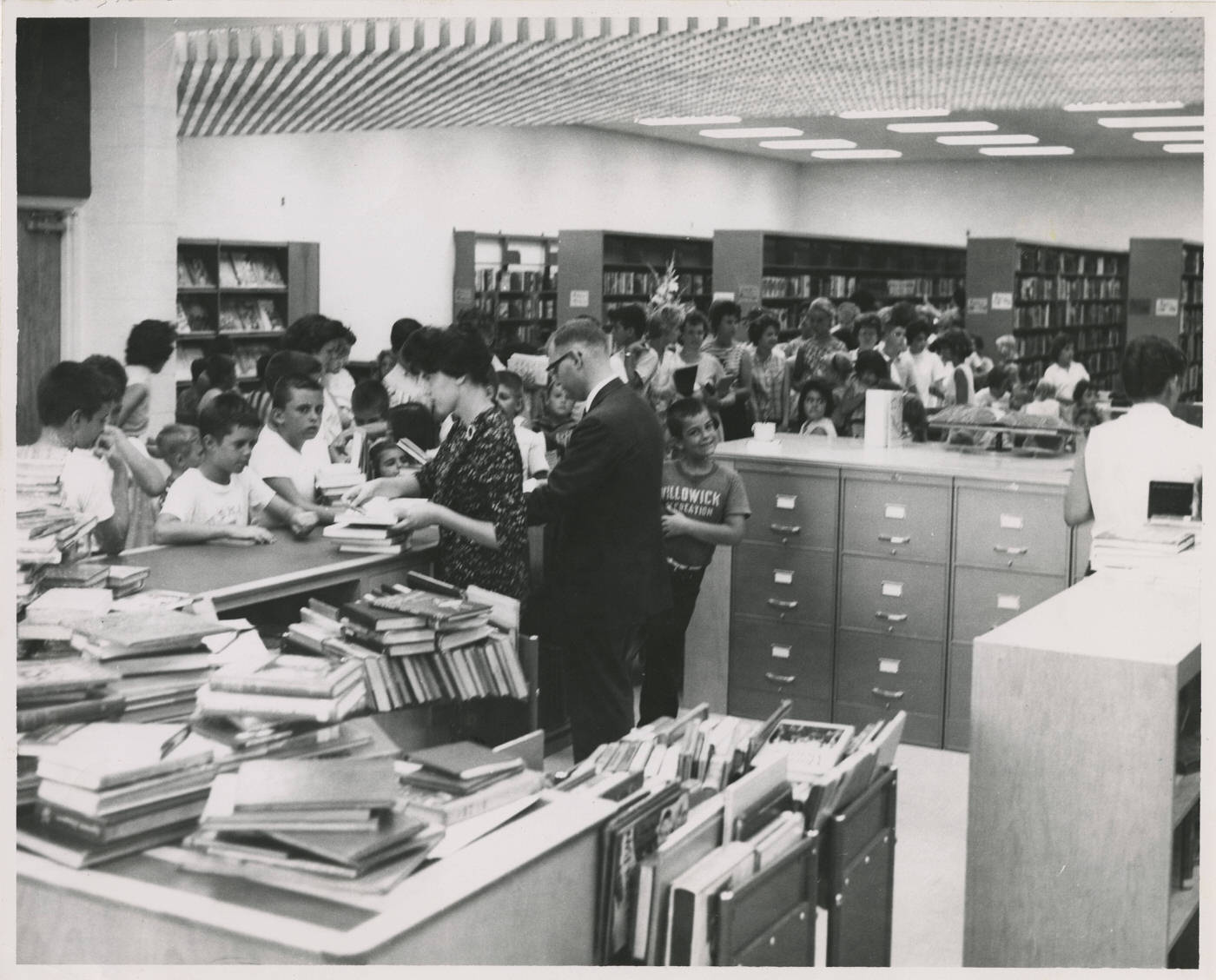

Education in Transition: Schools and Universities

Cleveland’s educational institutions experienced both turmoil and significant growth during the 1960s. The Cleveland Public Schools faced a crisis rooted in rapidly changing demographics and entrenched segregation. Student enrollment increased from 134,765 in 1960 to 148,793 by 1963. By 1965, African American students constituted 54% of the total student population of 149,655. This growth led to severe overcrowding in predominantly Black schools on the city’s East Side, resulting in measures like “relay classes” (half-day sessions) and long waiting lists for kindergarten.

These conditions, coupled with de facto segregation, made the school system a central battleground for the Civil Rights Movement. The practice of “intact busing,” initiated in 1962-63 to send Black students to underutilized white schools but keeping them segregated within those schools, sparked outrage and protests. The United Freedom Movement (UFM), a coalition of civil rights groups, led demonstrations against these policies and against school construction plans they believed would perpetuate segregation. Tensions reached a tragic peak on April 7, 1964, when Reverend Bruce Klunder, a white minister active in the movement, was accidentally killed by a bulldozer during a protest at the construction site of Stephen E. Howe Elementary School. This event spurred further activism, including a massive school boycott on April 20, 1964, where an estimated 85-95% of Black students stayed home from school.

Concurrently, higher education in Cleveland was undergoing significant expansion and restructuring. Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C), the area’s first public community college, opened in September 1963, initially in the old Brownell School building, and its downtown Metropolitan Campus opened in 1966. Cleveland State University (CSU) was established in 1964, with the existing Fenn College forming its institutional nucleus in 1965. A major development occurred in 1967 when Case Institute of Technology and Western Reserve University federated to form Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), creating a major research university in the University Circle area. John S. Millis served as president of Western Reserve University until the 1967 federation, while T. Keith Glennan was president of Case Institute of Technology until 1966. This period of struggle and growth in education highlighted Cleveland’s deep social divisions alongside its aspirations for future development.

A New Era in City Hall: The Mayoral Administration of Carl B. Stokes

In November 1967, Carl B. Stokes made history when he was elected Mayor of Cleveland, becoming the first African American mayor of a major American city. Running as a Democrat, he defeated Republican Seth Taft, securing nearly all of the Black community’s vote along with a significant 20% of the white vote. Stokes was reelected for a second term in 1969.

His administration brought several progressive policies and achievements. Stokes successfully persuaded the Department of Housing & Urban Development to release urban renewal funds that had been frozen under the previous administration. He also convinced the city council to increase the city income tax from 0.5% to 1% to bolster city finances. A key legislative achievement was the passage of the Equal Employment Opportunity Ordinance, requiring firms doing business with the city to actively increase their minority employment. Spending was increased for schools, welfare programs, and public safety, and voters approved a $100 million bond issue for improving sewage treatment facilities. One of his most notable initiatives was the “Cleveland: NOW!” program, launched to rehabilitate the city through a combination of public and private funding.

However, Stokes’ mayoralty was fraught with challenges. His relationship with the Cleveland Police Department deteriorated significantly after the Glenville Shootout, and his attempts to reform the department were largely unsuccessful. He also faced ongoing conflict with the city council and opposition to some of his policies, such as a plan to build public housing in the Lee-Seville area, which was resisted by both some city council members and some Black middle-class residents of that area. The voters’ failure to approve a further, needed increase in the city income tax ultimately persuaded him not to seek a third term in 1971. Stokes’ tenure was a pioneering effort in Black political leadership in a major American city, demonstrating both the potential for progressive change and the formidable obstacles posed by entrenched racial divisions and urban problems during a turbulent era.

Cleveland: NOW! – A Program for Change

The “Cleveland: NOW!” program was a bold, collaborative funding initiative launched by Mayor Carl Stokes on May 1, 1968. Its creation was spurred by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. earlier that year, which moved local business leaders to cooperate with the city in a major fundraising effort to address problems in Cleveland’s inner city and promote racial harmony.

The program had ambitious goals, aiming to raise $1.5 billion over a decade, with an initial target of $177 million for the first two years. These funds were intended for a wide range of projects, including youth activities, employment programs, the establishment of community centers, the development of health clinic facilities, the construction of housing units, and broader economic renewal initiatives designed to revitalize distressed areas of the city.

Fundraising was led by prominent business figures like George Steinbrenner III and the Group ’66 organization, which solicited contributions from businesses, institutions, and individuals. It was also anticipated that local funds from a recently passed 0.5% city income tax increase, along with state and federal funds, would supplement these private donations.

“Cleveland: NOW!” initially met its fundraising targets for the first few months. However, the program’s operations and public perception were severely damaged by the aftermath of the Glenville Shootout in July 1968. When it became known that some “Cleveland: NOW!” funds had indirectly been used by Fred Ahmed Evans’ militant group, reportedly for purchasing arms, public trust eroded, and donations declined sharply. Despite this setback, “Cleveland: NOW!” continued to operate actively until 1970. At that point, Mayor Stokes announced that its final major commitment would be the funding of four new community centers. The organization was not formally dissolved until October 1980, when its remaining $220,000 was transferred to the Cleveland Foundation to be used for youth employment and low-income housing initiatives. The program’s trajectory highlights the difficulty of implementing large-scale urban initiatives during times of intense social unrest and mistrust.

Labor Unions and Their Role

Organized labor, particularly the Teamsters Union, continued to be a significant force in Cleveland during the 1960s, though not without controversy. Following the death of Edward Murphy in 1950, leadership of the Cleveland Teamsters was assumed by William Presser and N. Louis “Babe” Triscaro. Their tenure was marked by accusations of violence and intimidation.

These issues came to a head in 1957 when allegations of corruption and ties to organized crime led to a federal investigation into the union and the finances of 20 Teamster leaders. Subsequently, the Teamsters, with its 40,000 members in Cleveland, were expelled from the newly formed AFL-CIO. Despite these challenges, Cleveland Teamster leaders William Presser and his son, Jackie Presser, wielded considerable influence, holding international office within the Teamster union. They used Joint Council 41 and the Central States Conference of Teamsters, which had been organized in 1953, as their power base.

A major achievement for the union during this period was the negotiation of the Master Freight Agreement (MFA) in 1964. This agreement, reached with 2,000 trucking companies, established standardized wages and working conditions for general freight haulers, who formed the bulk of the union’s membership. The activities of the Teamsters in the 1960s illustrate the complex nature of powerful labor organizations of the era, which could secure significant benefits for their members while simultaneously facing serious questions about their leadership and practices.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress, wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know