The 1970s were a period of profound transformation for Cleveland, Ohio. The city experienced significant shifts in its population, economy, political landscape, and social fabric. These changes brought both difficulties and new beginnings, shaping Cleveland into the city it would become in later decades.

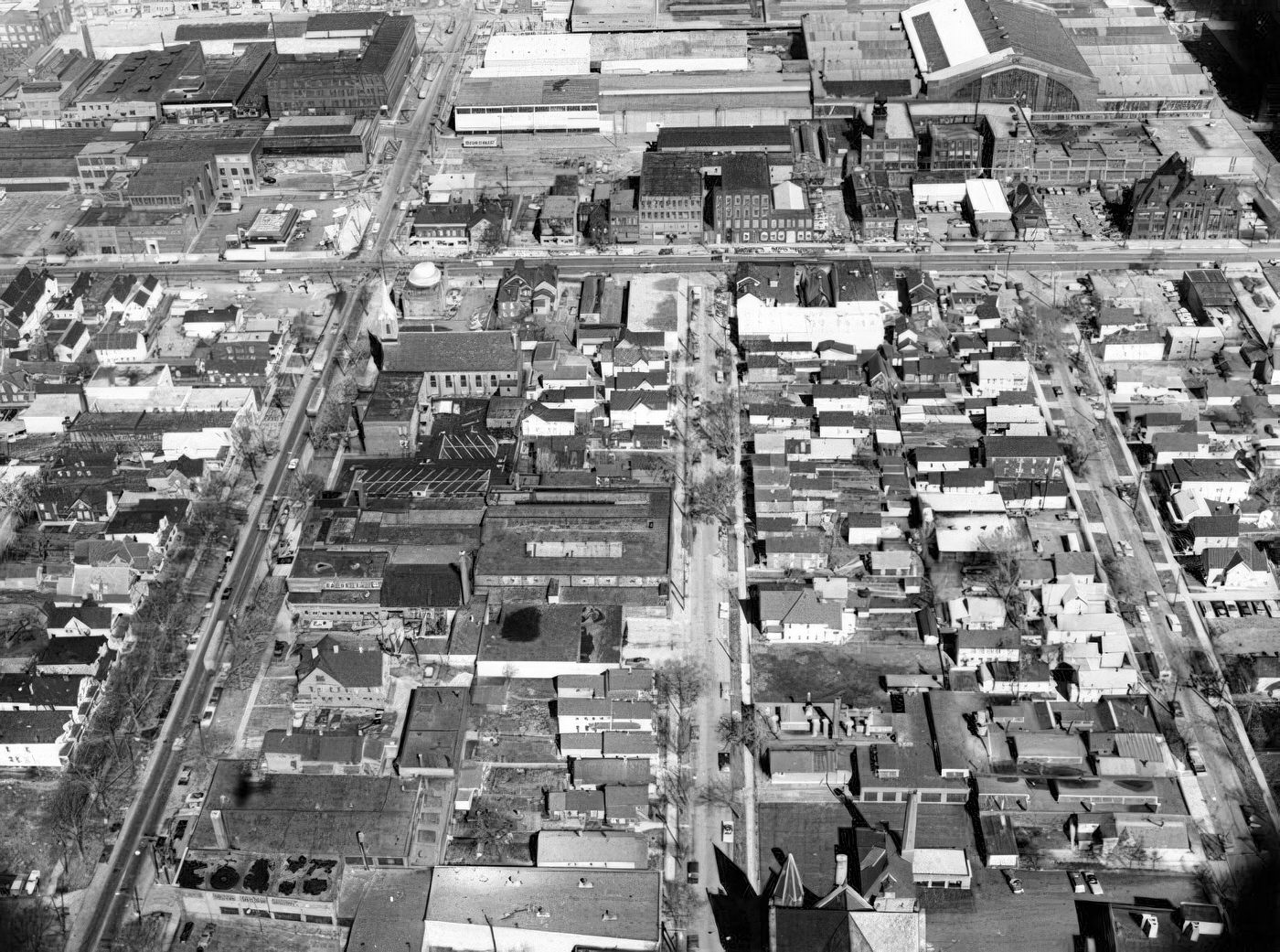

Cleveland’s population landscape underwent dramatic alterations during the 1970s. The number of people living in the city decreased noticeably. In 1970, Cleveland had 750,903 residents. By 1980, that number had fallen to 573,822, a drop of 23.6% in ten years. This continued a trend that had started in the 1960s; the city’s population was 876,050 in 1960, down from its peak of 914,808 in 1950. This overall decline was part of a larger pattern seen in many American cities at the time, as industries changed and people moved to suburban areas.

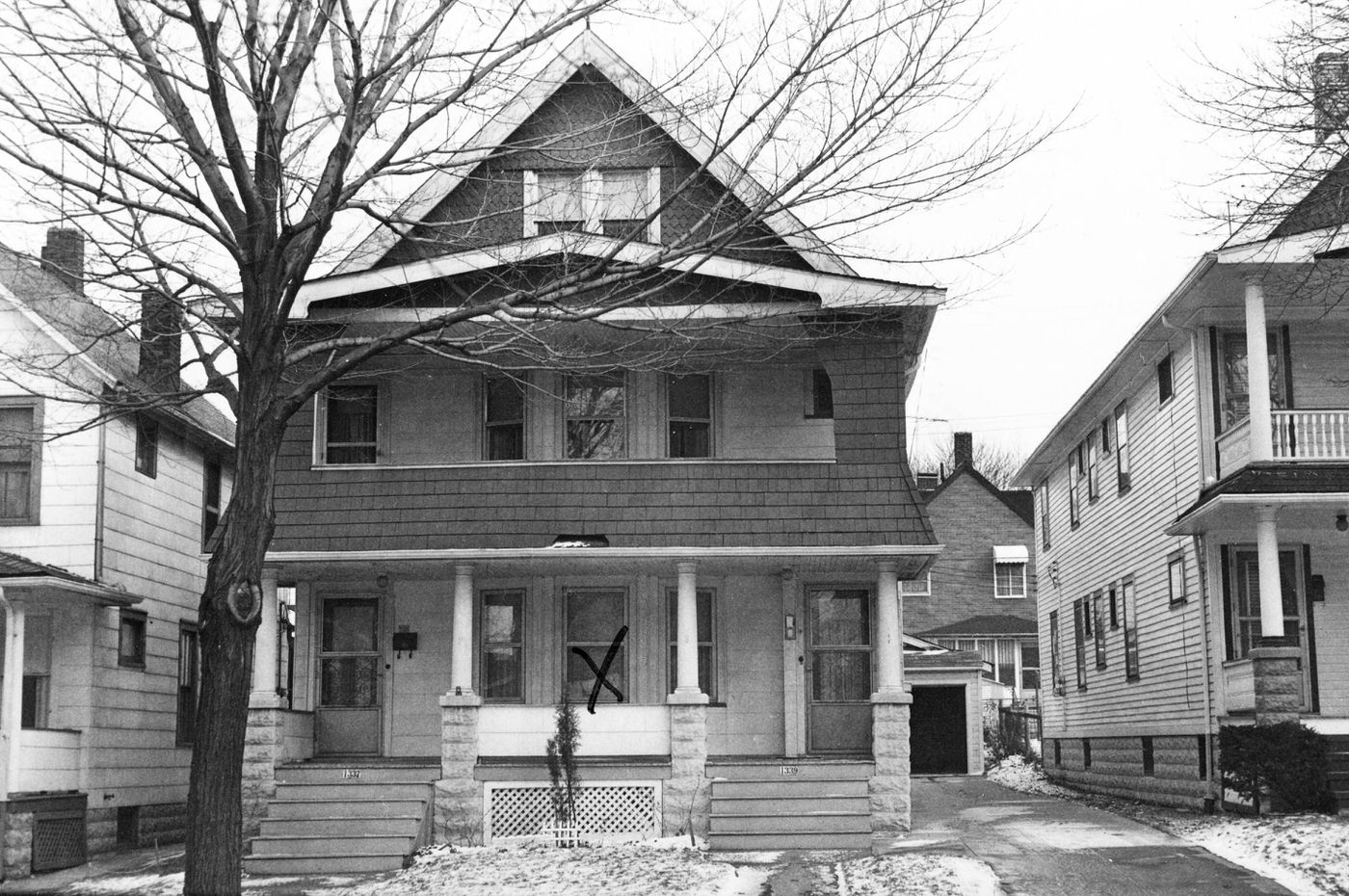

While Cleveland’s city population shrank, its suburbs grew substantially. Between 1940 and 1970, Cuyahoga County’s suburbs gained 631,042 residents, and by 1970, 62% of the county’s population lived in these suburban areas. This movement was driven by desires for newer housing and schools and was also facilitated by government home loan programs that were more accessible to white families than to African American families. The departure of many residents, particularly middle-class taxpayers, had a direct impact on the city’s finances. With fewer people paying taxes in the city, Cleveland had less money to fund public services and meet its financial obligations. This shrinking tax base was a key reason the city faced a severe financial crisis in 1978.

The Economic Beat: Industry, Work, and Commerce in the 1970s

Cleveland’s economy, long powered by manufacturing, faced serious challenges during the 1970s. The decline in its traditional industries, which had started in earlier decades, picked up speed.

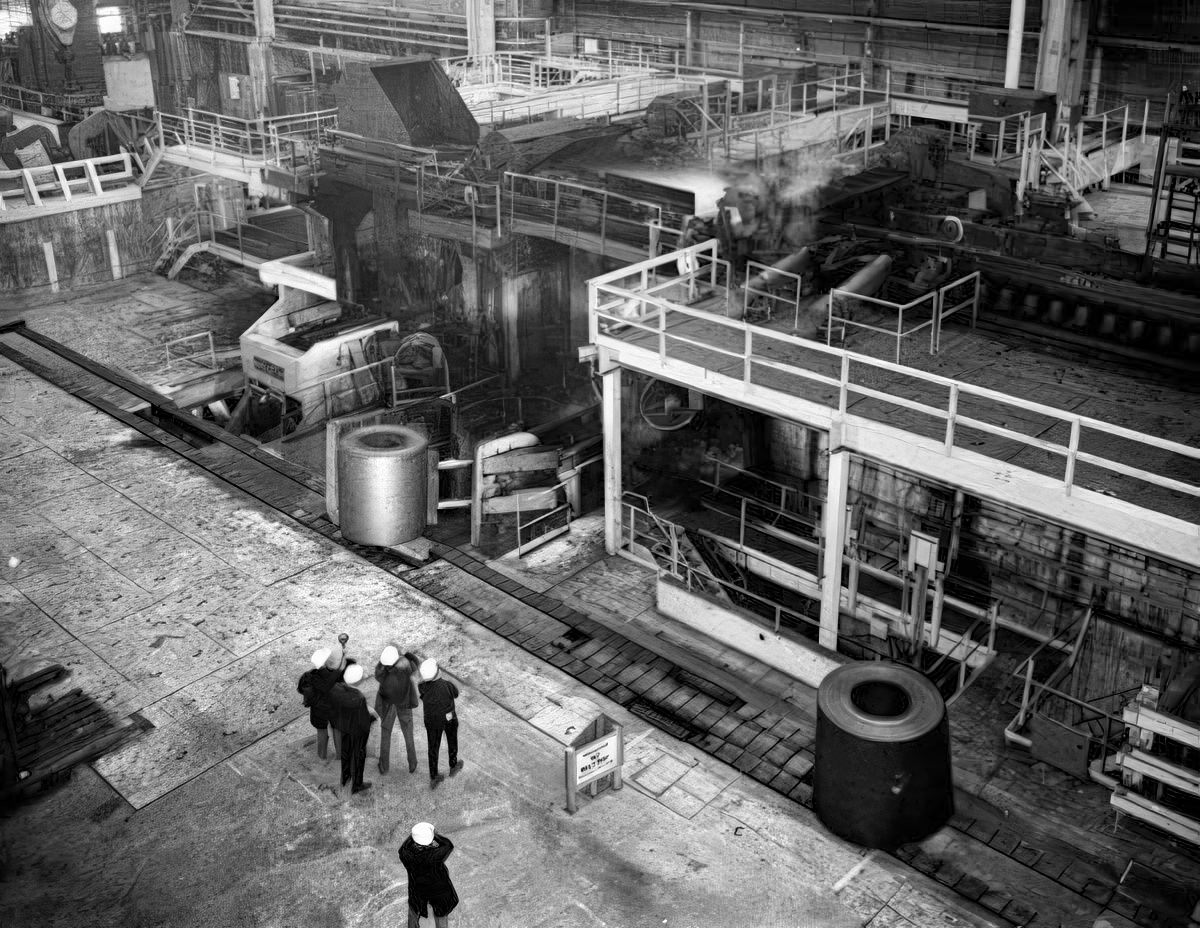

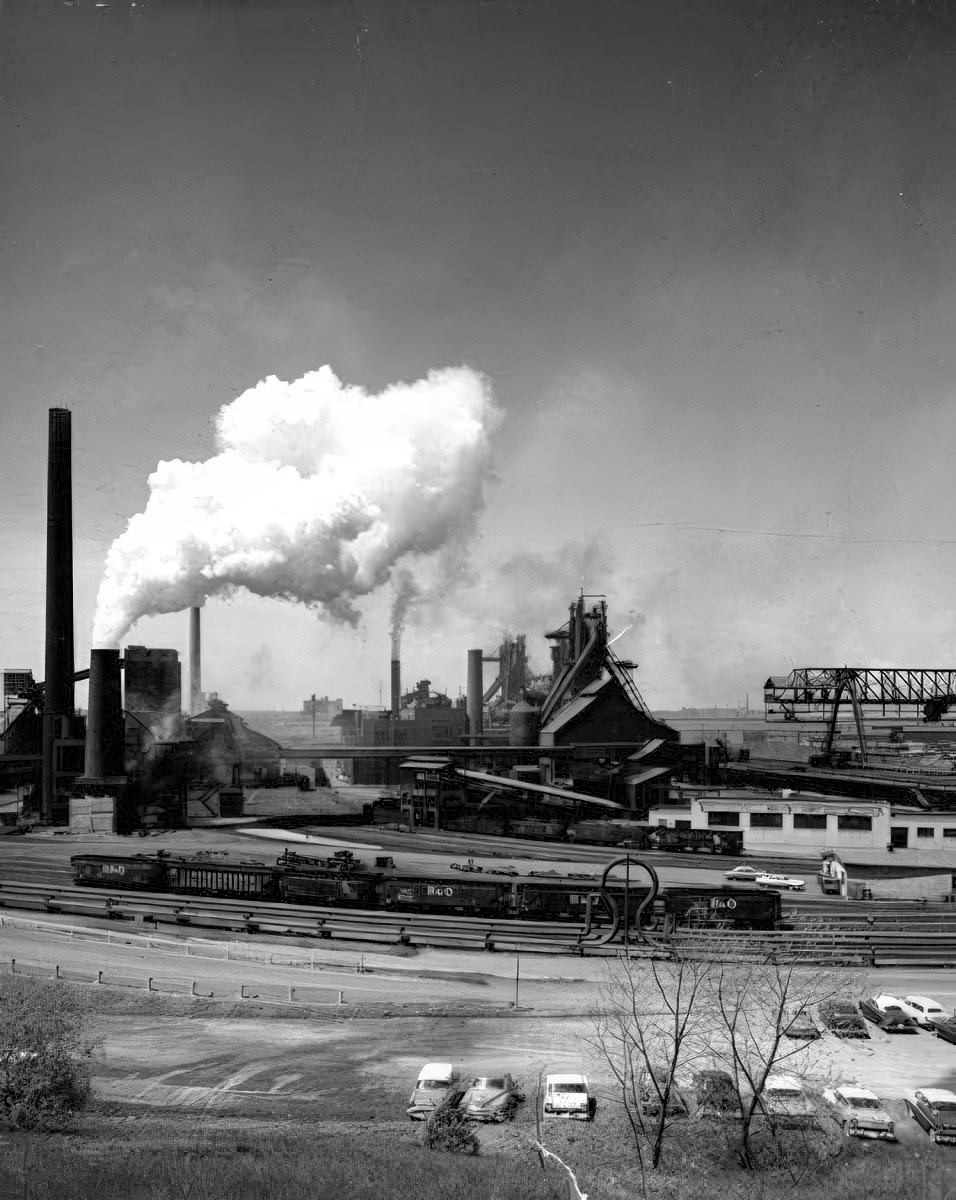

The city’s main industries, such as steel, automotive, and machine tools, all struggled.

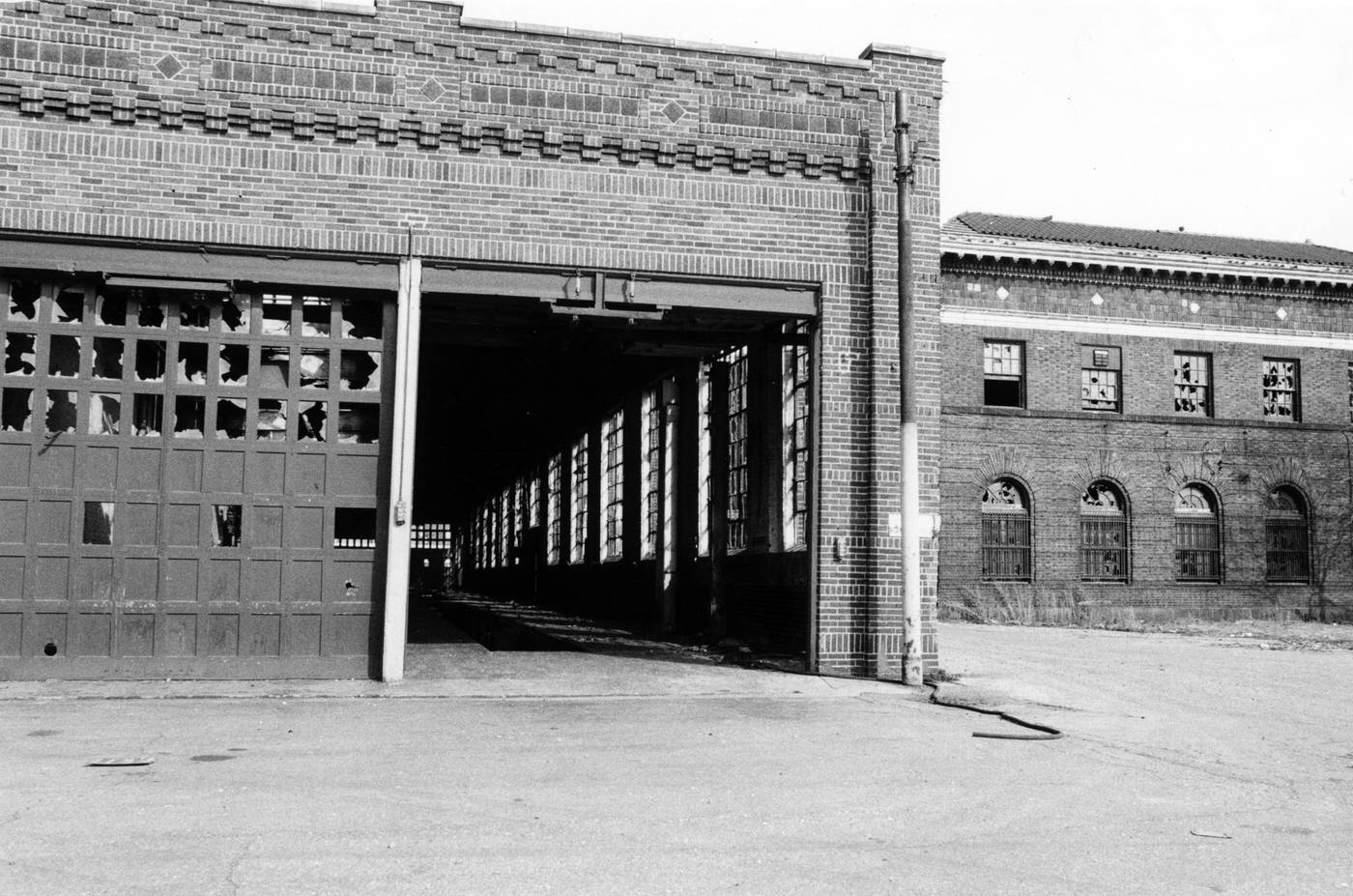

Steel Industry: This once-mighty industry was hit hard by several problems at once: rising prices (inflation), more competition from steel made in other countries, new and expensive environmental rules, lower productivity, and higher labor costs. These issues forced big changes. U.S. Steel closed its historic Central Furnaces plant in 1979. Five years later, its Cuyahoga Works also shut down. Republic Steel, which had spent money to modernize its plants in the 1960s , and Jones & Laughlin (J&L) also faced tough times. The 1960s and 1970s were described as “difficult times” for Republic Steel because of these pressures.

Automotive Industry: Cleveland had been a major center for making cars and car parts, but its best years were in the 1950s and early 1960s. In the 1970s, American car companies faced strong competition from automakers in Japan and Europe. Higher gas prices also made people want different kinds of cars, forcing local plants to close or spend a lot of money to change their equipment.

Machine Tool Industry: This industry, which made machines used in factories, had also seen its peak pass by the 1950s and continued to struggle against competition. For example, the Cleveland Twist Drill Company, a large local manufacturer, merged with another company in 1968 and had to restructure in 1982 because of competition.

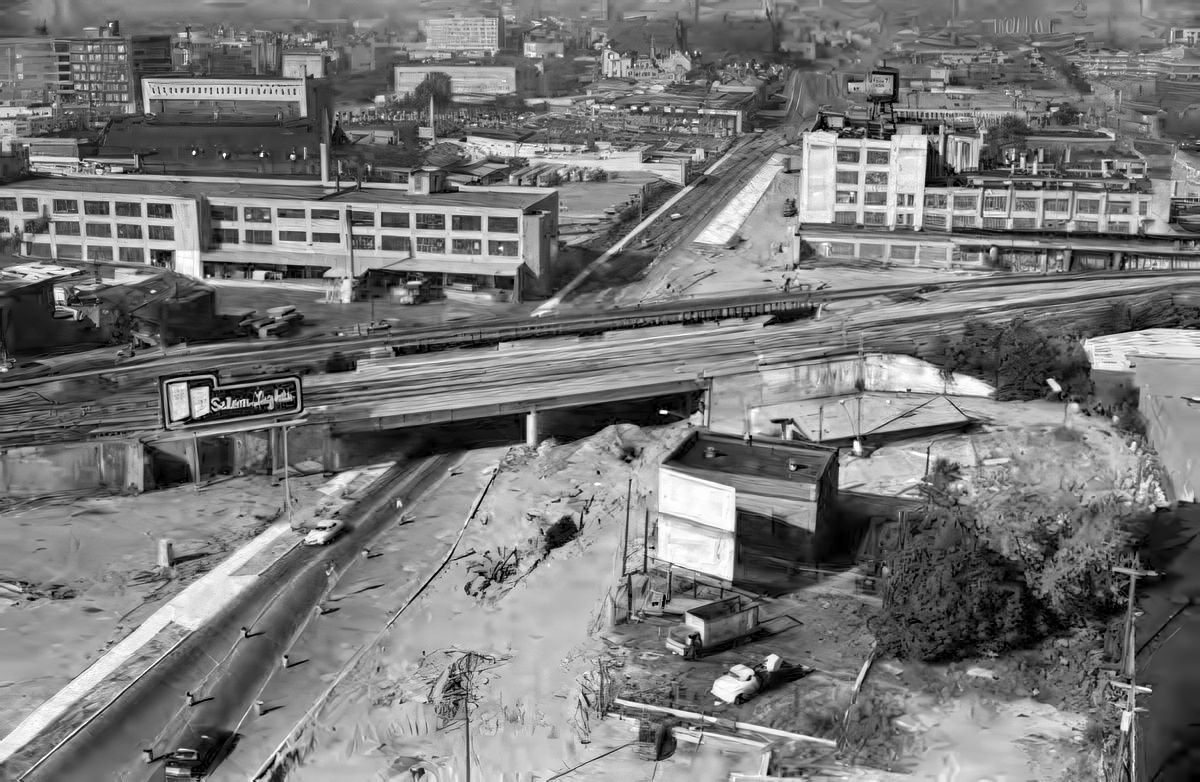

The decline of these core manufacturing industries was more than just an economic problem for Cleveland. It changed the city’s identity and caused widespread hardship. The loss of many well-paying, unionized factory jobs had a deep impact on families and neighborhoods. This economic shift was a major reason for many of the city’s other problems, including people moving away, neighborhoods decaying, and the city’s financial crisis.

Employment and Labor

With factories closing or cutting back, unemployment became a growing worry. Manufacturing jobs in the Cleveland metropolitan area dropped from 307,000 in 1967 to 245,200 in 1981. Nationally, the number of jobs in the steel industry fell sharply between 1974 and 1980. In early 1970, the unemployment rate in the broader economic district that included Cleveland rose, partly due to strikes.

The 1970s were also a time of significant labor activity.

The Great Postal Strike of 1970: This was a national strike that included Cleveland’s postal workers. It was a major event that led to the Postal Reorganization Act, which gave postal workers the right to bargain collectively for their wages, benefits, and working conditions. Bill Burris, a Cleveland postal worker who took part in the strike, later became the national president of the American Postal Workers Union (APWU).

Lordstown Strike (1972): Though not in Cleveland, the strike at the General Motors plant in nearby Lordstown received national attention. Workers protested the fast pace of the assembly line and difficult working conditions. The strike lasted 22 days and cost GM around $150 million. It showed growing unhappiness among auto workers.

Other Local Strikes: Cleveland saw other labor disputes during the decade. In January 1973, a strike by 2,500 non-teaching school employees closed most Cleveland schools. In 1975, budget problems led Cleveland City Council to lay off 119 firefighters, after 169 police officers had already been laid off. Cleveland police officers themselves went on a wildcat strike (an unofficial strike) in July 1978, during which Mayor Kucinich asked for the National Guard to help keep order. The garment industry, once strong in Cleveland, continued its decline, leading to more job losses. A Teamsters strike in Ohio in April 1970 became violent enough that the National Guard was called in to escort freight trucks.

These labor actions were often a response to economic uncertainty, including rising prices and fears about job security, as well as demands for better pay and conditions. The strikes by city workers also showed that public employee unions were becoming more assertive. The city’s severe financial problems made these labor disputes even more intense. With less money available, the city found it harder to meet union demands. This sometimes led to longer and more bitter strikes, which disrupted city services and further shook public confidence.

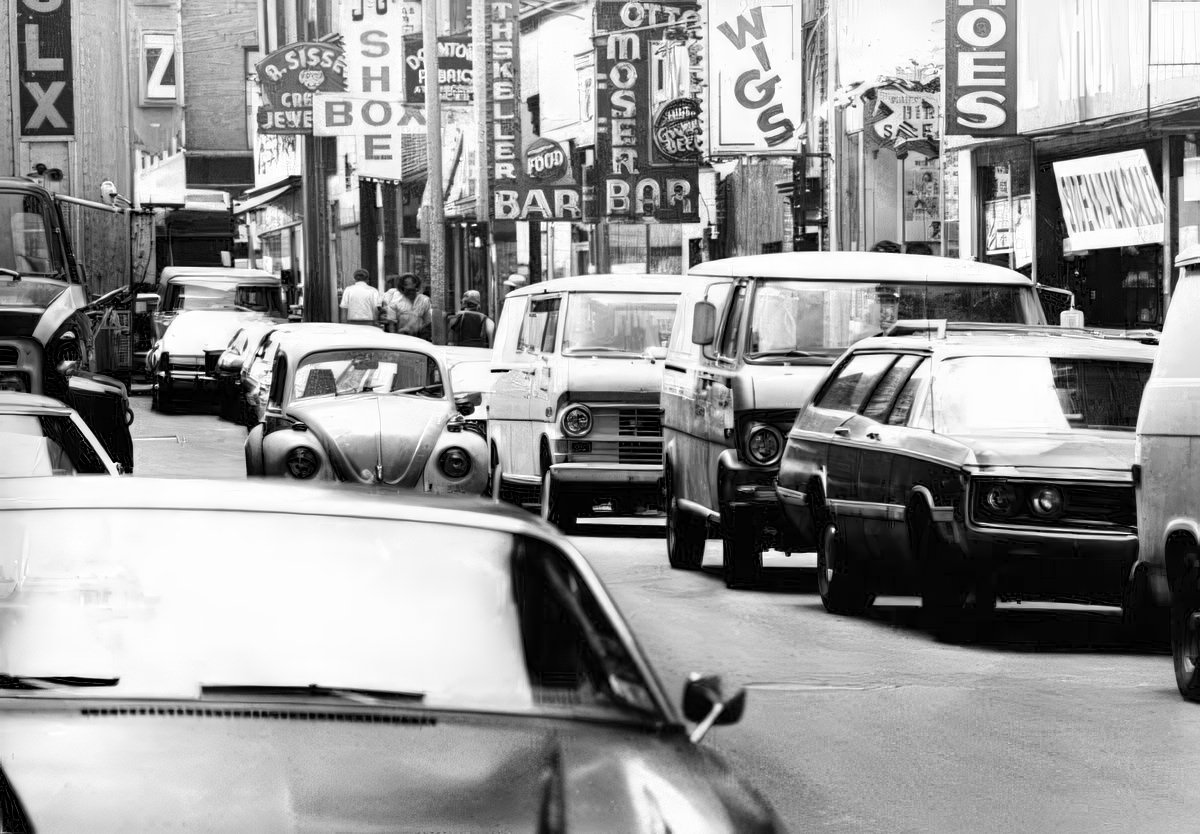

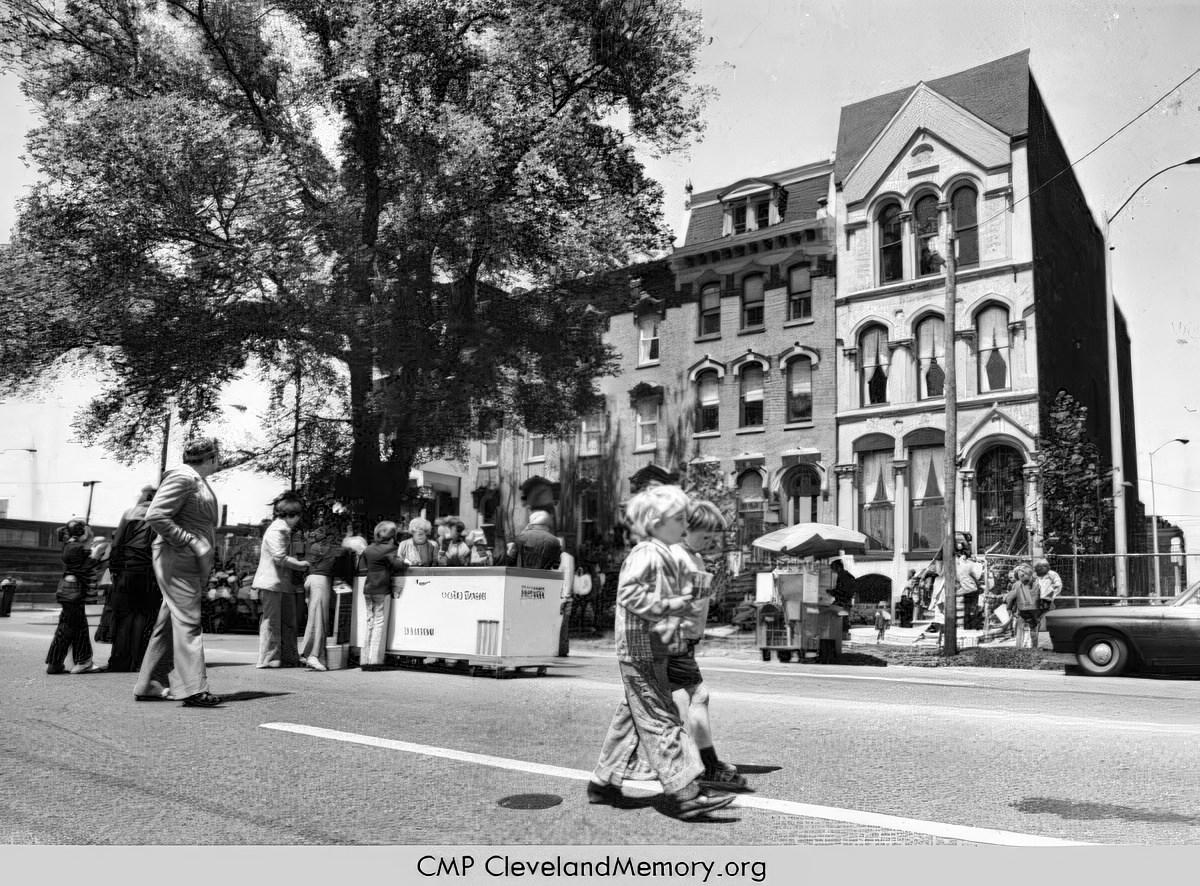

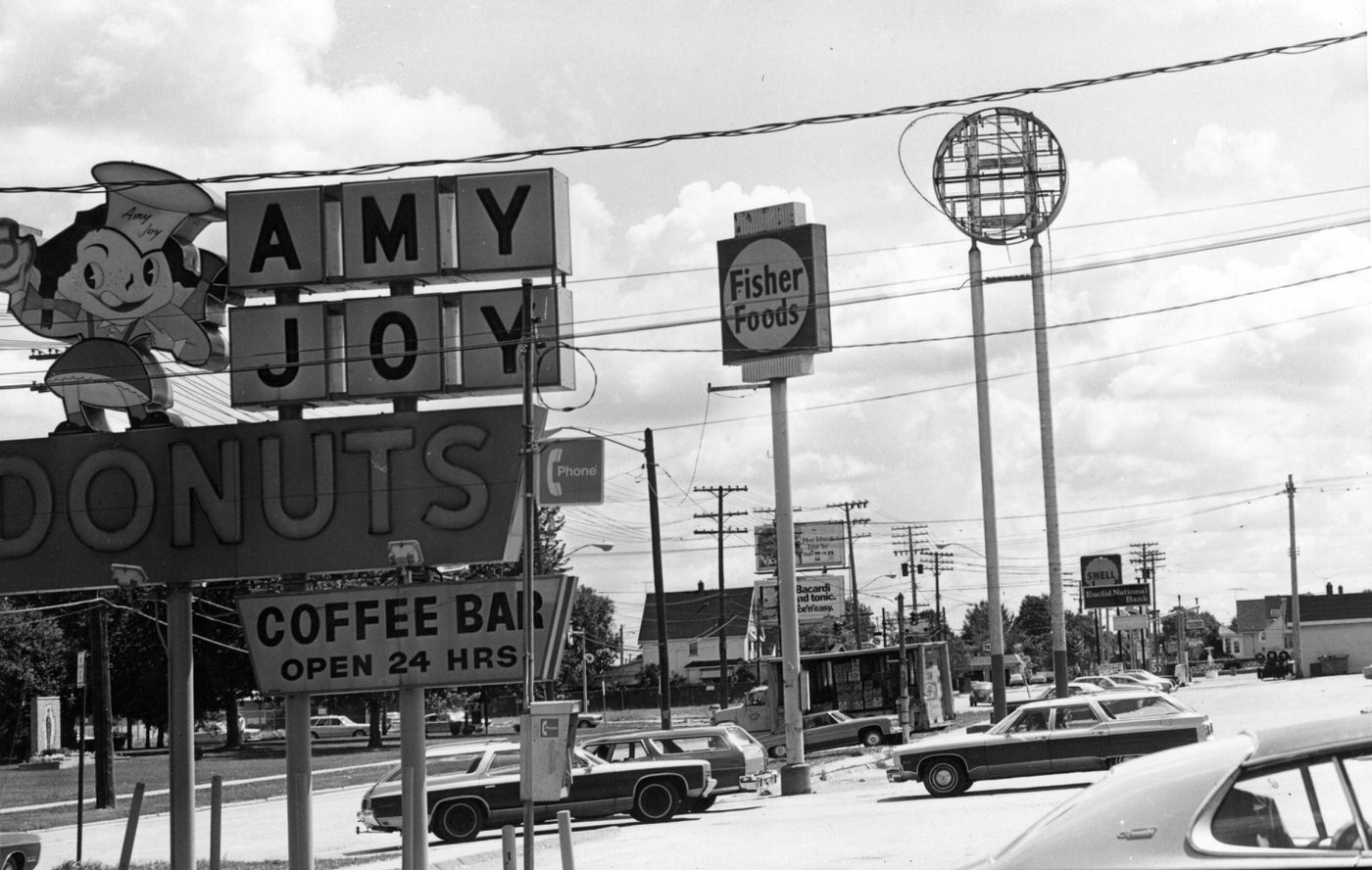

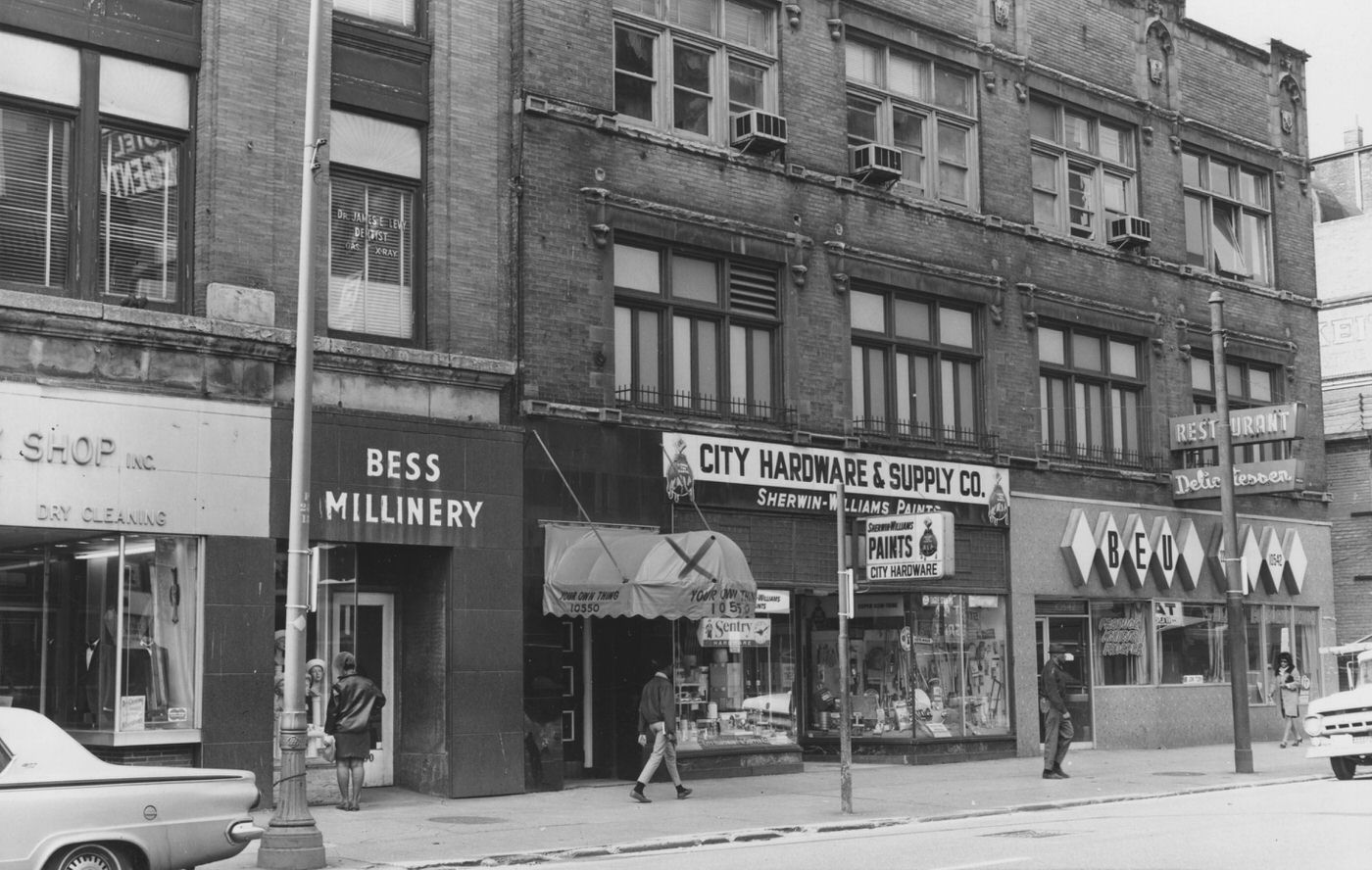

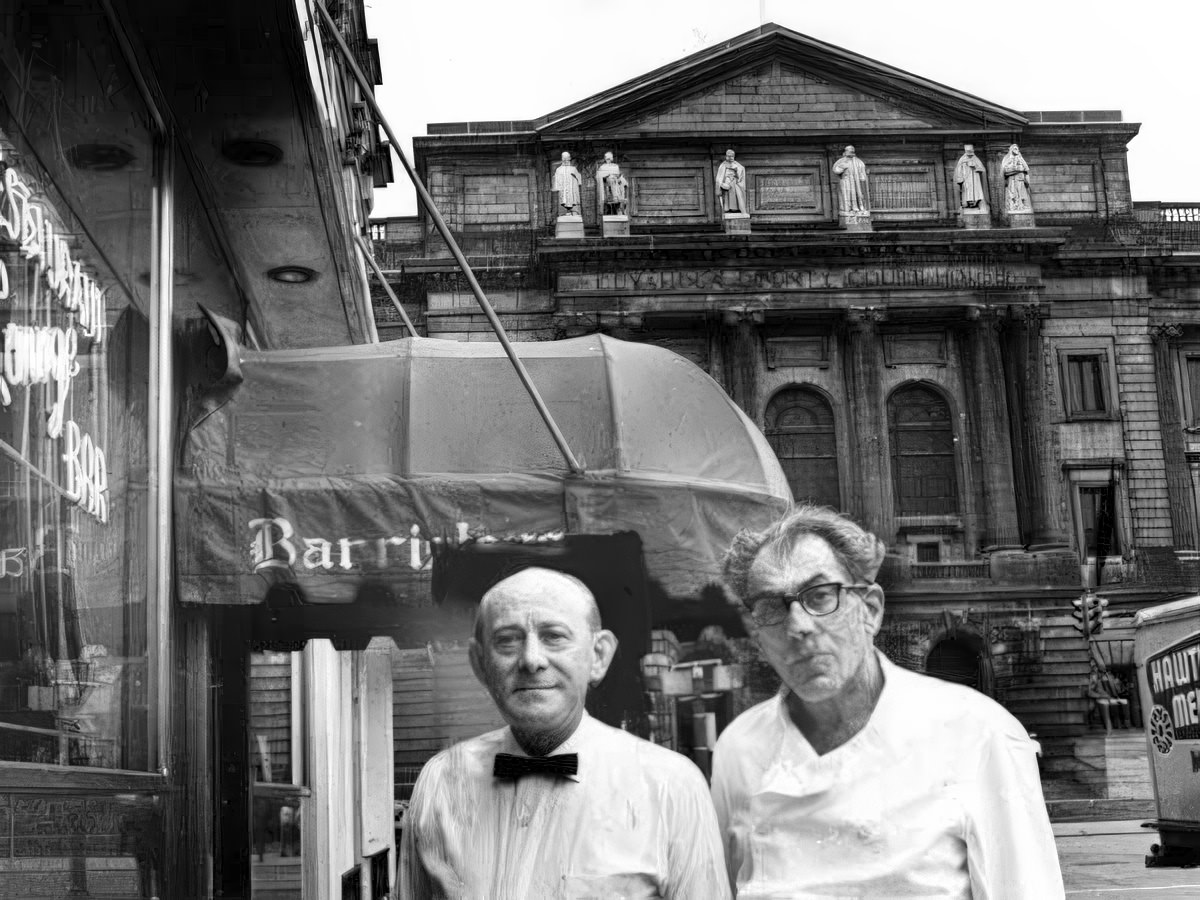

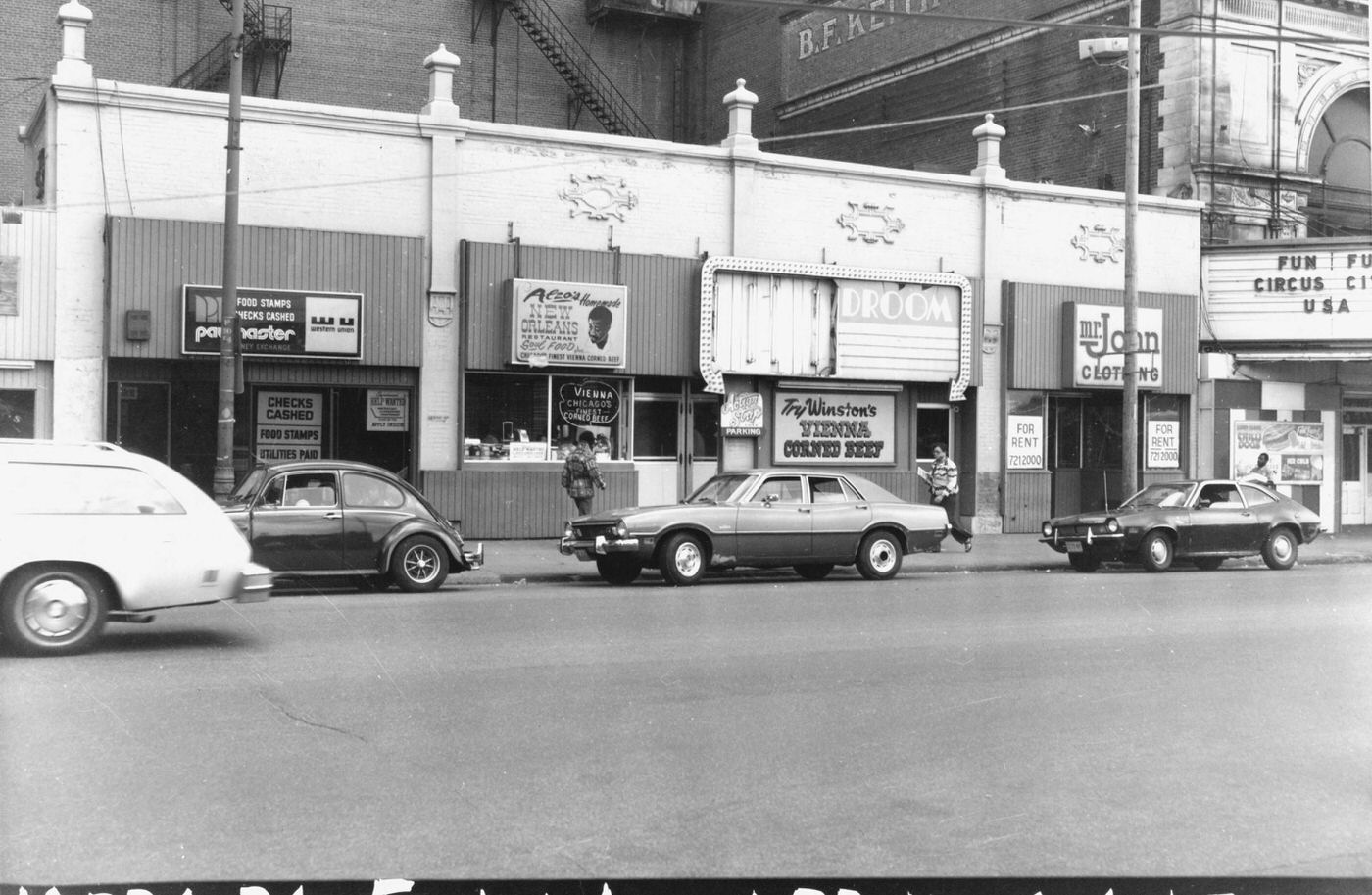

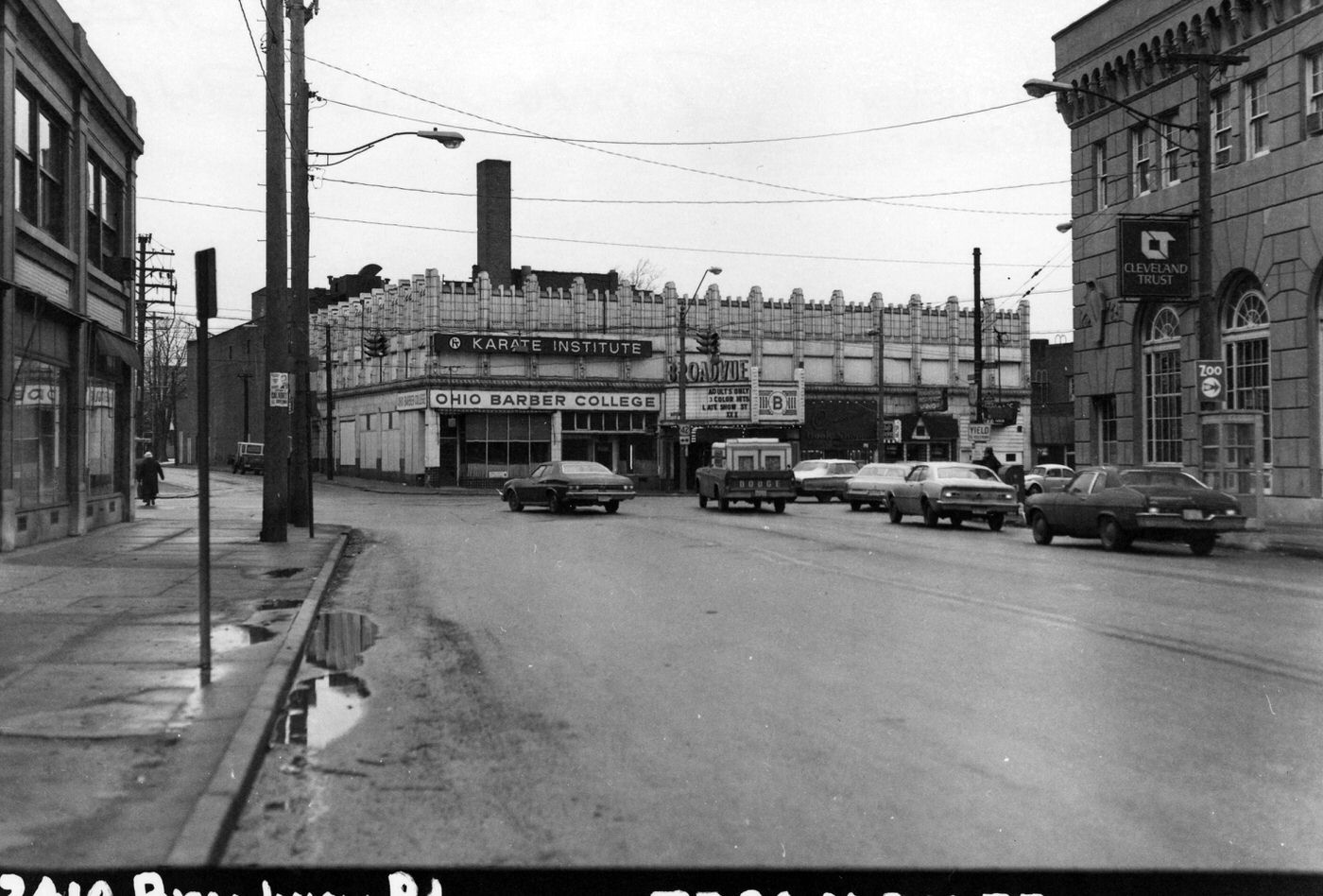

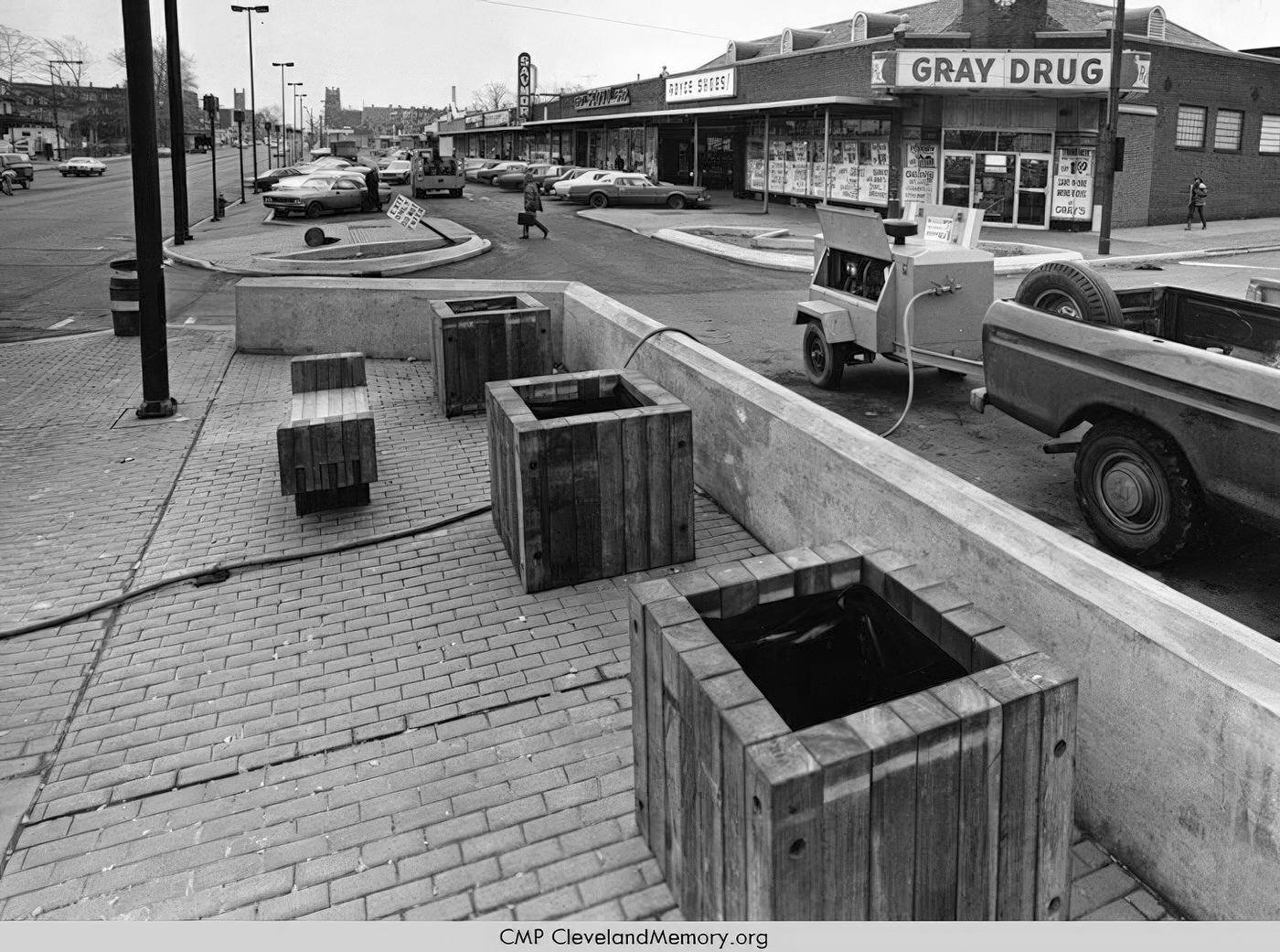

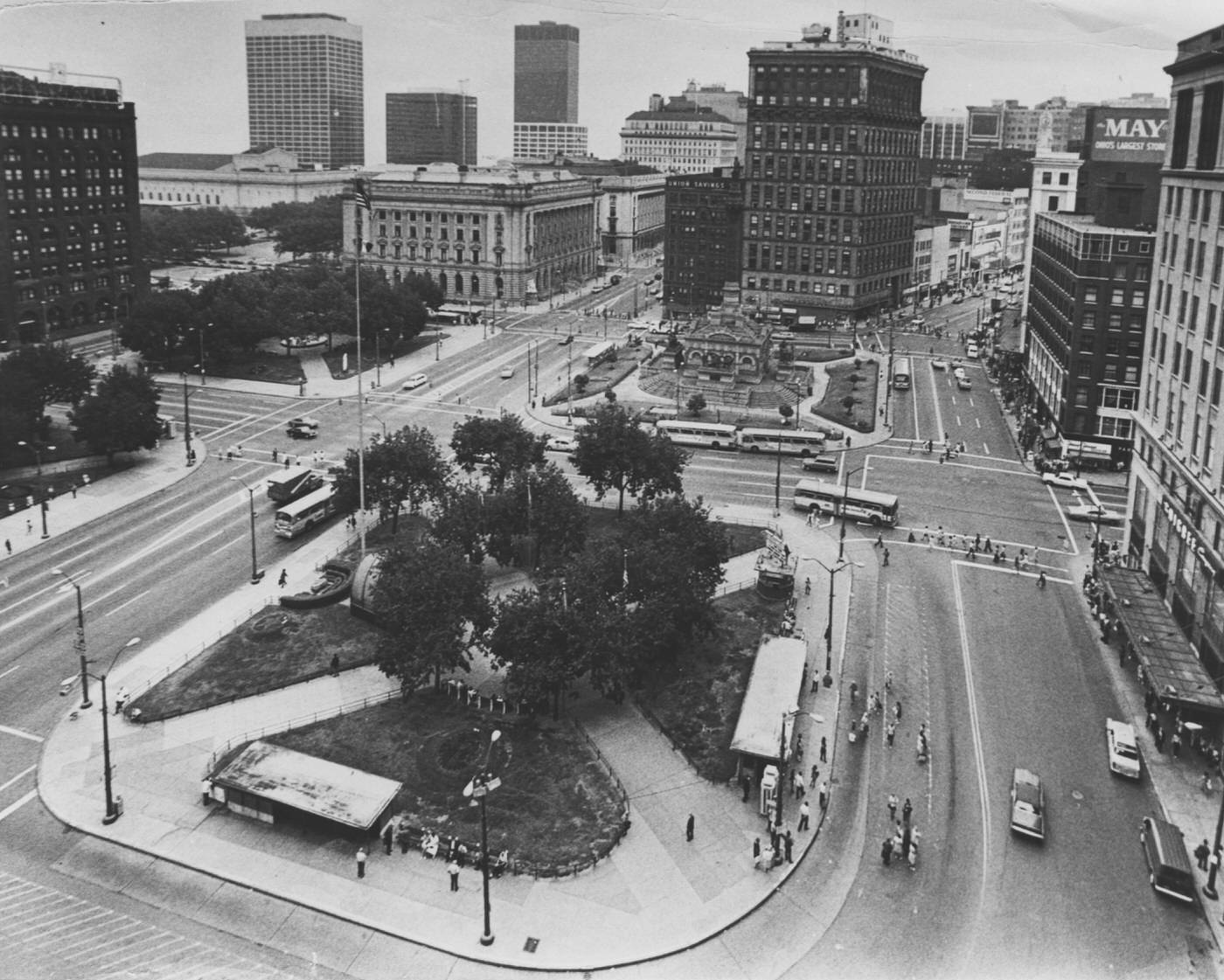

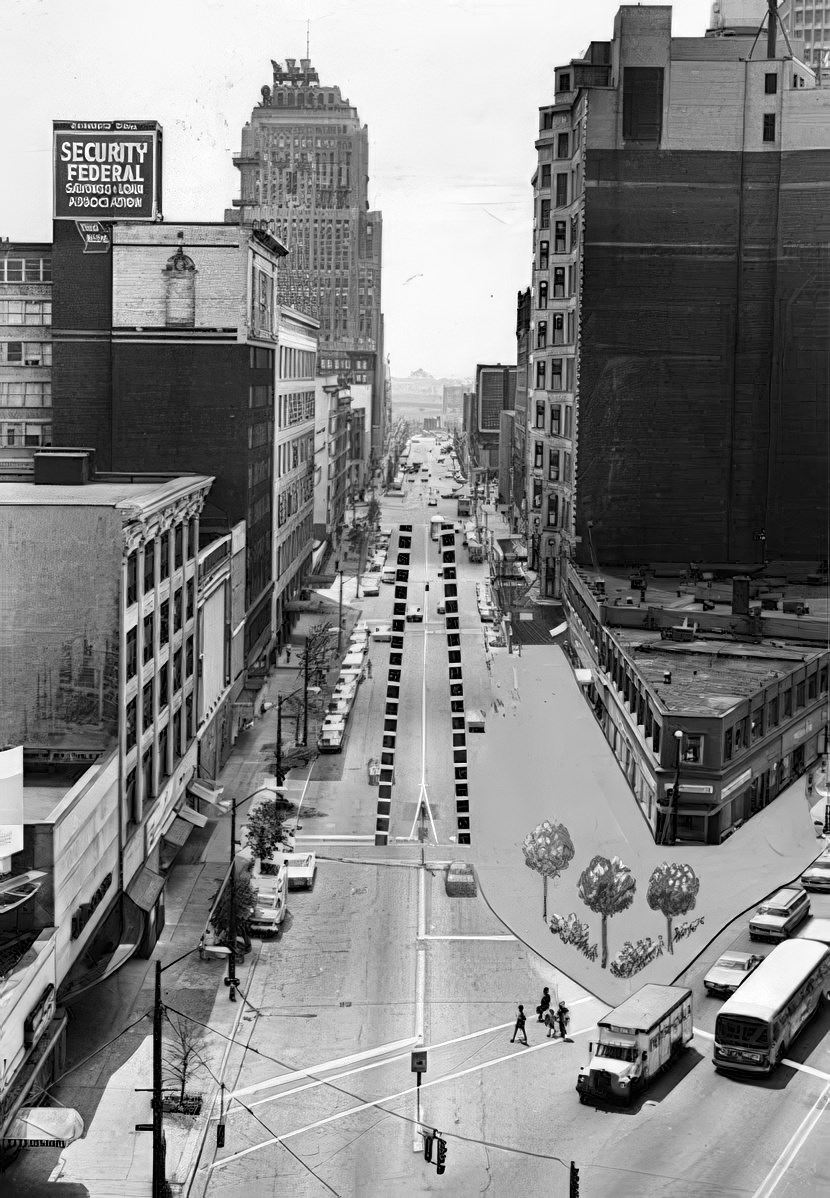

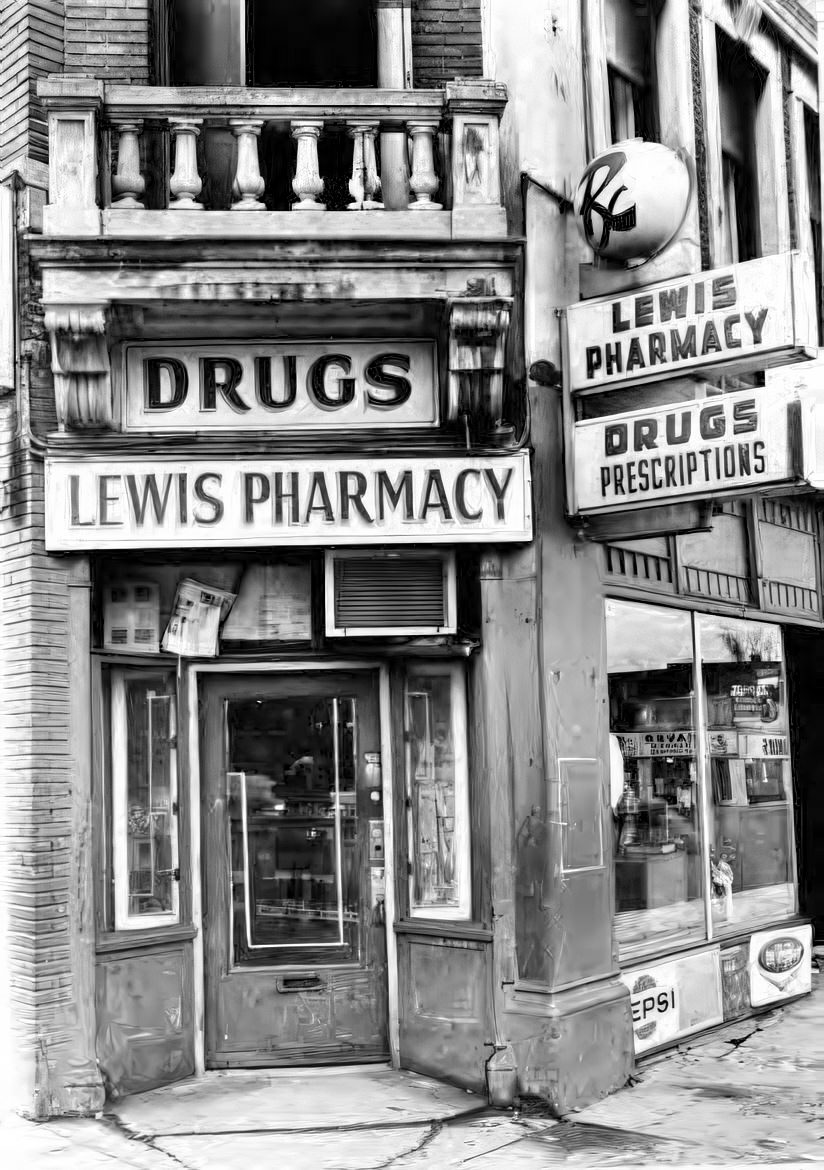

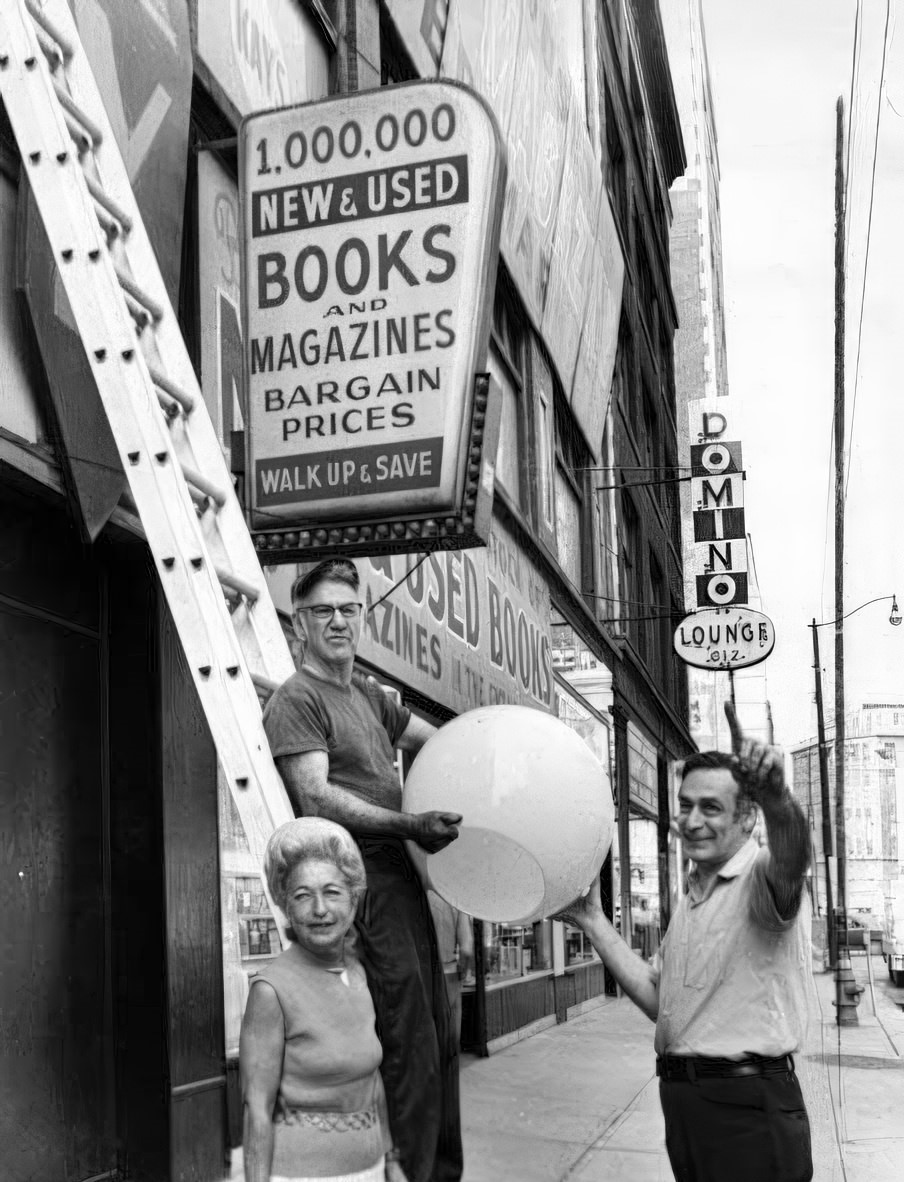

Downtown’s Changing Face and Retail Shifts

Downtown Cleveland, once the main place for shopping and entertainment, continued to lose ground to the suburbs in the 1970s. Many of the large department stores that had been famous landmarks on Euclid Avenue had closed or were struggling. After 1960, several well-known department stores shut down, and others were bought by discount chains. Halle’s, a beloved Cleveland store, was sold in 1970, and its business declined afterward.

The growth of suburban shopping malls, which started in the 1950s and boomed in the 1960s, kept pulling shoppers away from downtown. Severance Center in Cleveland Heights, which opened in 1963, was Ohio’s first indoor mall. The Arcade, a historic indoor shopping gallery downtown, also felt the effects. In 1978, a new owner bought The Arcade and tried to update it by adding a food court, similar to what was found in suburban malls. But The Arcade still struggled to keep tenants as downtown jobs decreased and stores followed people to the suburbs. The shift of retail activity from downtown to suburban malls was a clear sign of how people’s lifestyles and the city’s economy were changing.

The 1970s brought significant political and developmental challenges to Cleveland, a decade largely defined by fiscal struggles and efforts to reshape the city’s urban core.

Political Leadership and Its Challenges

Two mayors led Cleveland through much of this turbulent decade:

Ralph J. Perk (Republican, Mayor 1971-1977): Perk’s time in office was marked by growing financial difficulties for the city. Inflation and a national recession in 1973 caused city expenses to rise sharply. To cope, his administration relied on federal revenue sharing—money given by the federal government to states and cities—and federal grants. These funds were used to help cover daily operating costs, support crime-fighting efforts, and establish a citywide emergency medical service. Important regional projects during Perk’s tenure included the creation of a regional sewer district in 1972 and the formation of the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) in 1975. Perk was reelected in 1973 and 1975 but did not win the 1977 nonpartisan primary election. His leadership reflected attempts to manage Cleveland’s increasing financial woes through federal aid and regional cooperation.

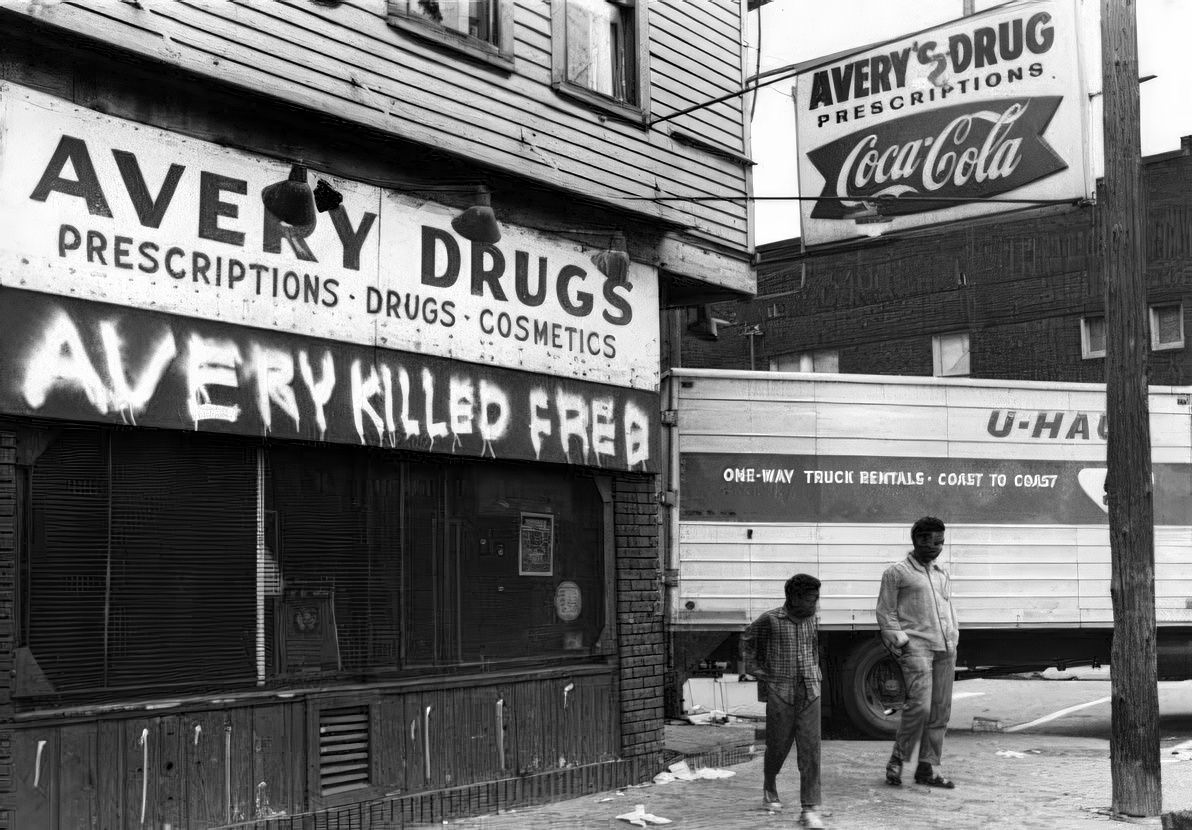

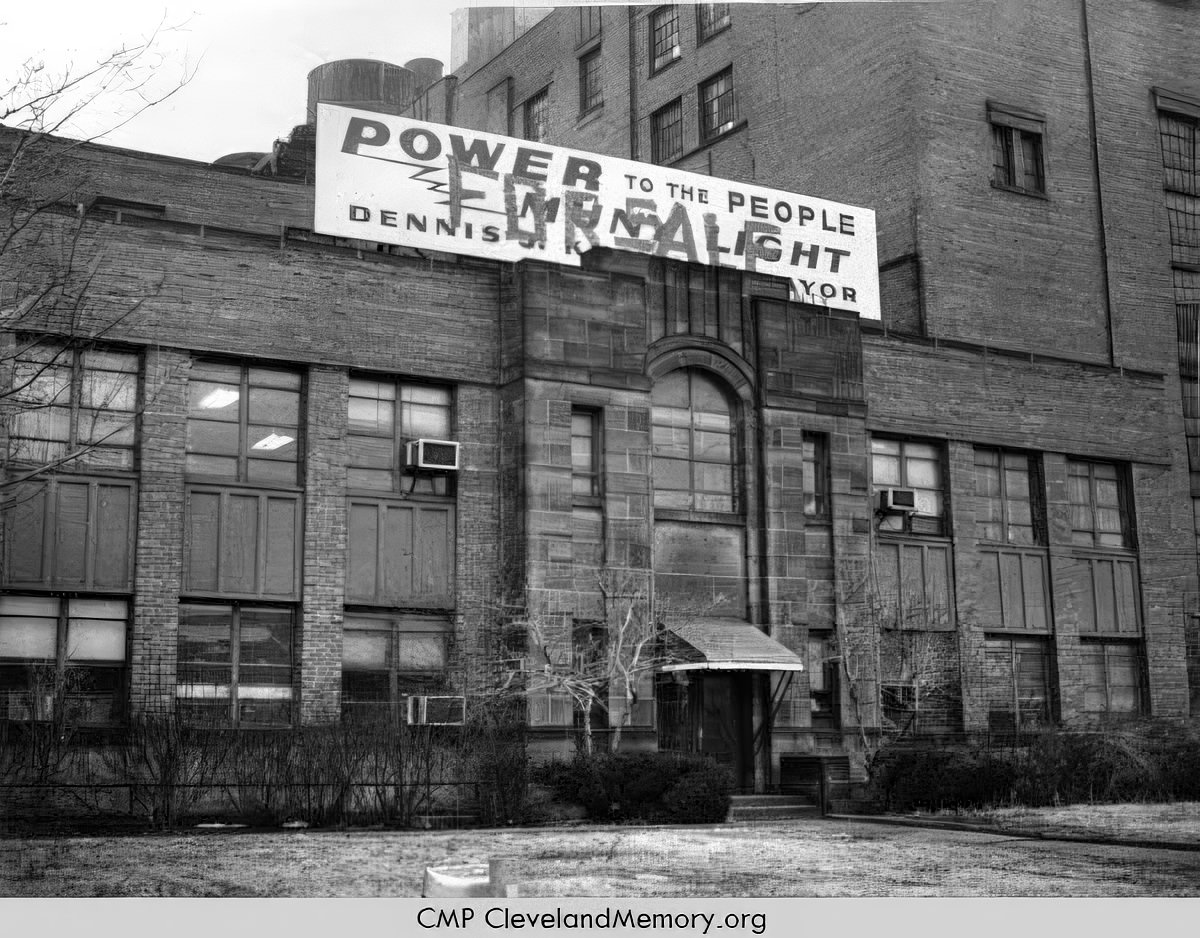

Dennis J. Kucinich (Democrat, Mayor 1977-1979): Kucinich’s brief term as mayor was exceptionally stormy, filled with intense political battles and culminating in the city’s financial default. Elected at the young age of 31, Kucinich was known as the “boy mayor.” He adopted a populist approach, strongly defending the interests of the working class. However, his confrontational style often led to clashes with the city council and Cleveland’s business leaders. Kucinich’s defiance of powerful interests during a time of severe crisis made his mayoralty a symbol of Cleveland’s struggles.

The Fiscal Crisis and Default of 1978

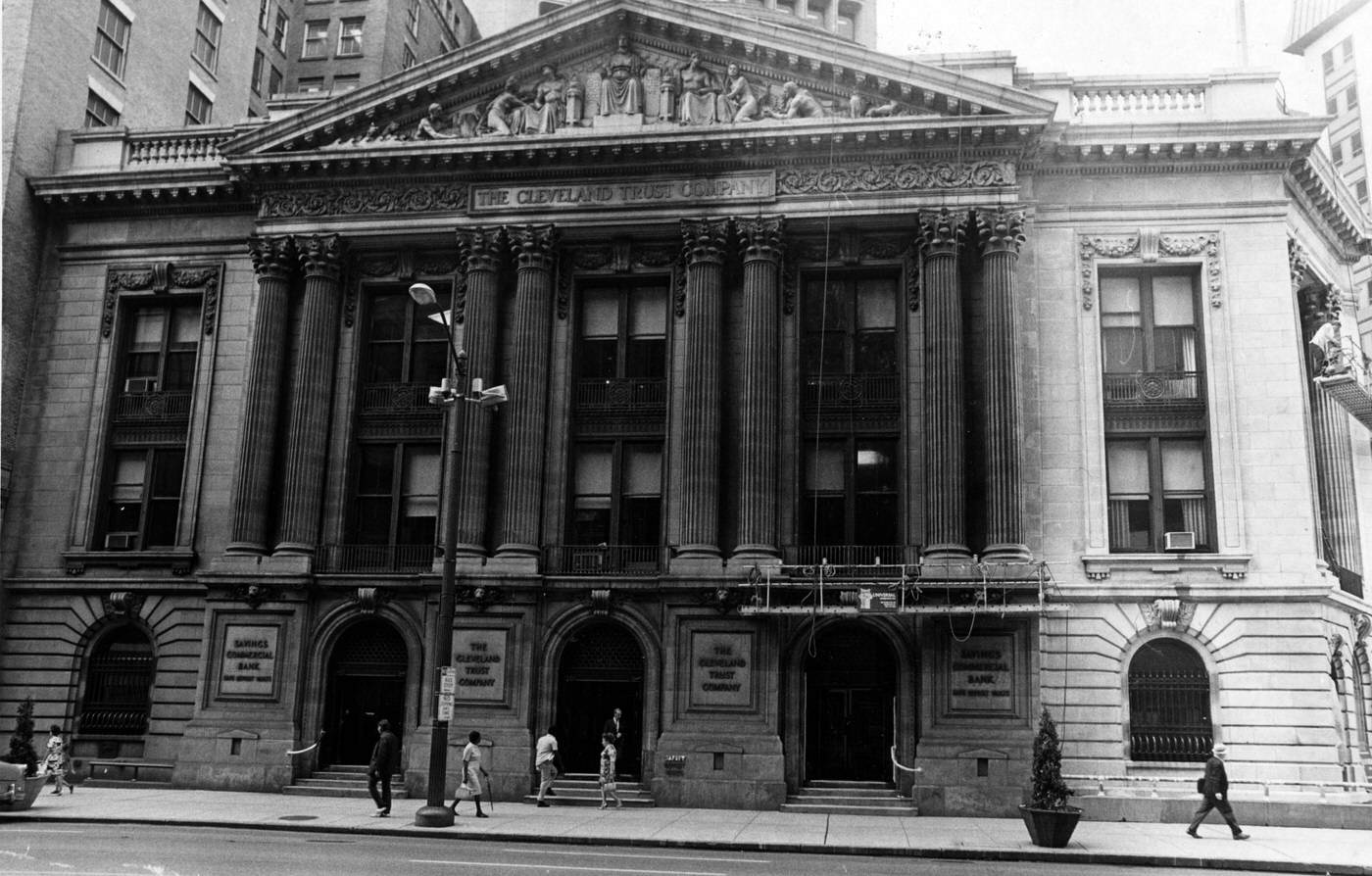

A defining event of the decade was Cleveland’s financial default. On December 15, 1978, Cleveland became the first major American city to fail to meet its debt obligations since the Great Depression. The city could not repay $14 million in short-term loans owed to six local banks.

The reasons for the default were complex and had been building for years. A long-term decline in the city’s manufacturing base, a significant loss of jobs and residents (which reduced the city’s tax income), and questionable city financial practices, such as using money meant for long-term projects (bond funds) to pay for daily operating costs, all contributed. The city’s budget had not been truly balanced since 1971. Earlier in 1978, Moody’s Investor Service, a company that rates the financial health of governments and businesses, had lowered Cleveland’s credit rating twice before the default occurred.

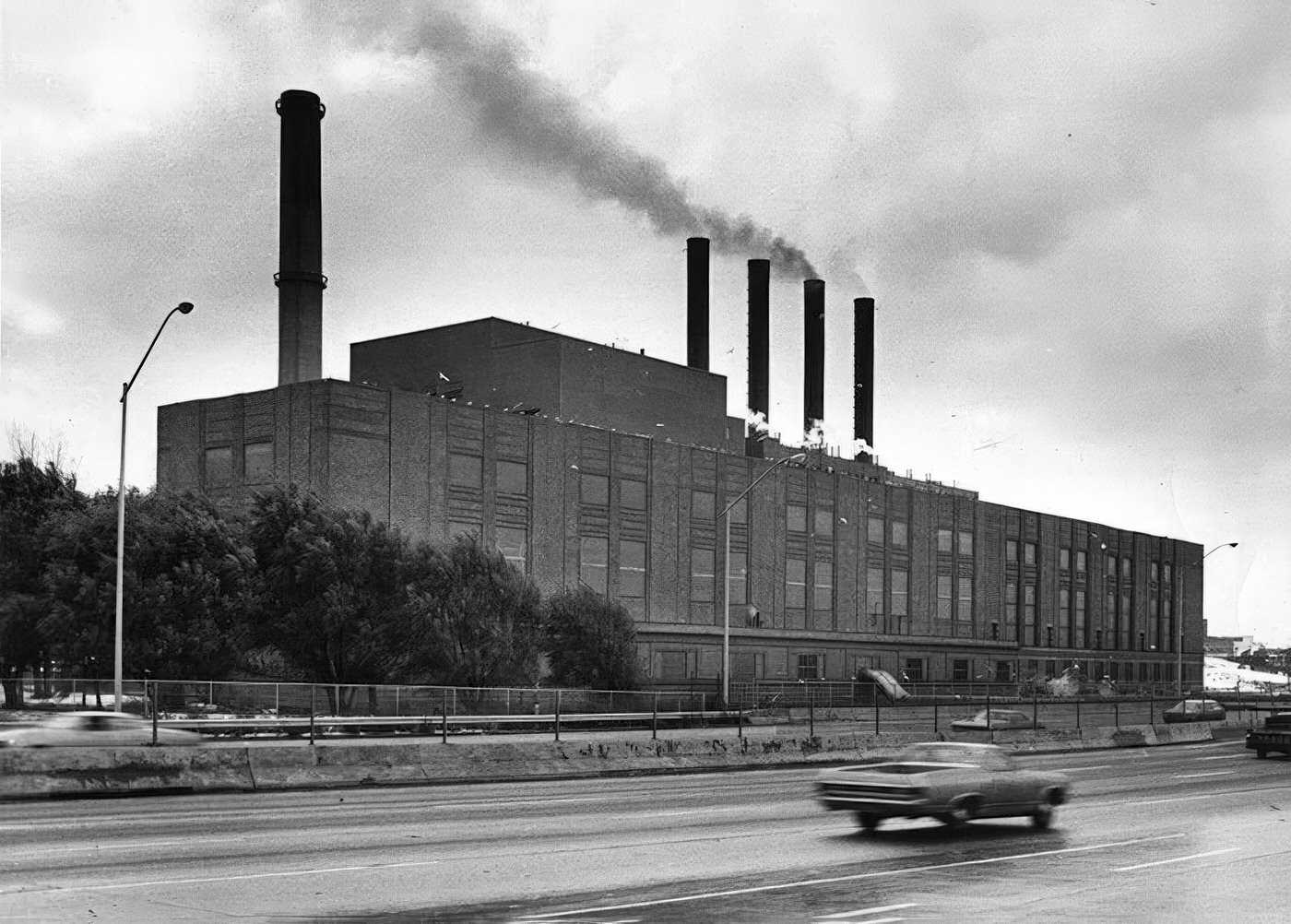

The Muny Light Controversy: A central battle during this crisis was over the city-owned Municipal Light Plant, often called Muny Light. Mayor Kucinich strongly opposed selling Muny Light to the private Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. (CEI). He argued that public ownership of the utility provided competition to CEI and helped keep electricity rates more affordable for residents. However, local banks, especially Cleveland Trust, and the city’s business community pressured Kucinich to sell Muny Light. They made the sale a condition for extending new loans or refinancing the city’s existing debt. When Kucinich refused to sell, the banks refused to refinance the city’s loans, directly causing the default.

Recall Attempt Against Kucinich: Earlier in 1978, Kucinich had faced a recall election, which he survived by a very small number of votes. The effort to remove him from office was driven by opposition to his leadership and policies and was financially supported by some business leaders and banks.

Resolution Efforts: The city’s financial problems continued after the default. In February 1979, voters approved an increase in the city income tax from 1% to 1.5%. However, they once again voted against selling Muny Light. George Voinovich was elected mayor in November 1979, defeating Kucinich. The following year, Voinovich’s administration put together a plan to refinance the defaulted loans. The state of Ohio also stepped in, passing the Municipal Fiscal Emergencies Act in November 1979. In January 1980, the state declared a fiscal emergency in Cleveland and created a Financial Planning and Supervision Commission to oversee the city’s finances. This commission remained in place until 1987, when the city was deemed to have recovered financially.

The 1978 default was not simply a matter of the city running out of money. It was also a very public and intense political struggle. On one side was a populist mayor, Dennis Kucinich, determined to protect a public asset (Muny Light) and resist what he saw as harmful corporate influence. On the other side was a powerful group of business and banking leaders who believed the sale of Muny Light was necessary for the city’s financial health and who sought to impose their vision for Cleveland’s economic future. The Muny Light issue became the main point of conflict, showing the deep disagreements within the city about its direction during a time of severe economic hardship.

Urban Development Projects and Infrastructure

Despite the economic troubles, some urban development projects moved forward, while public services faced significant strain.

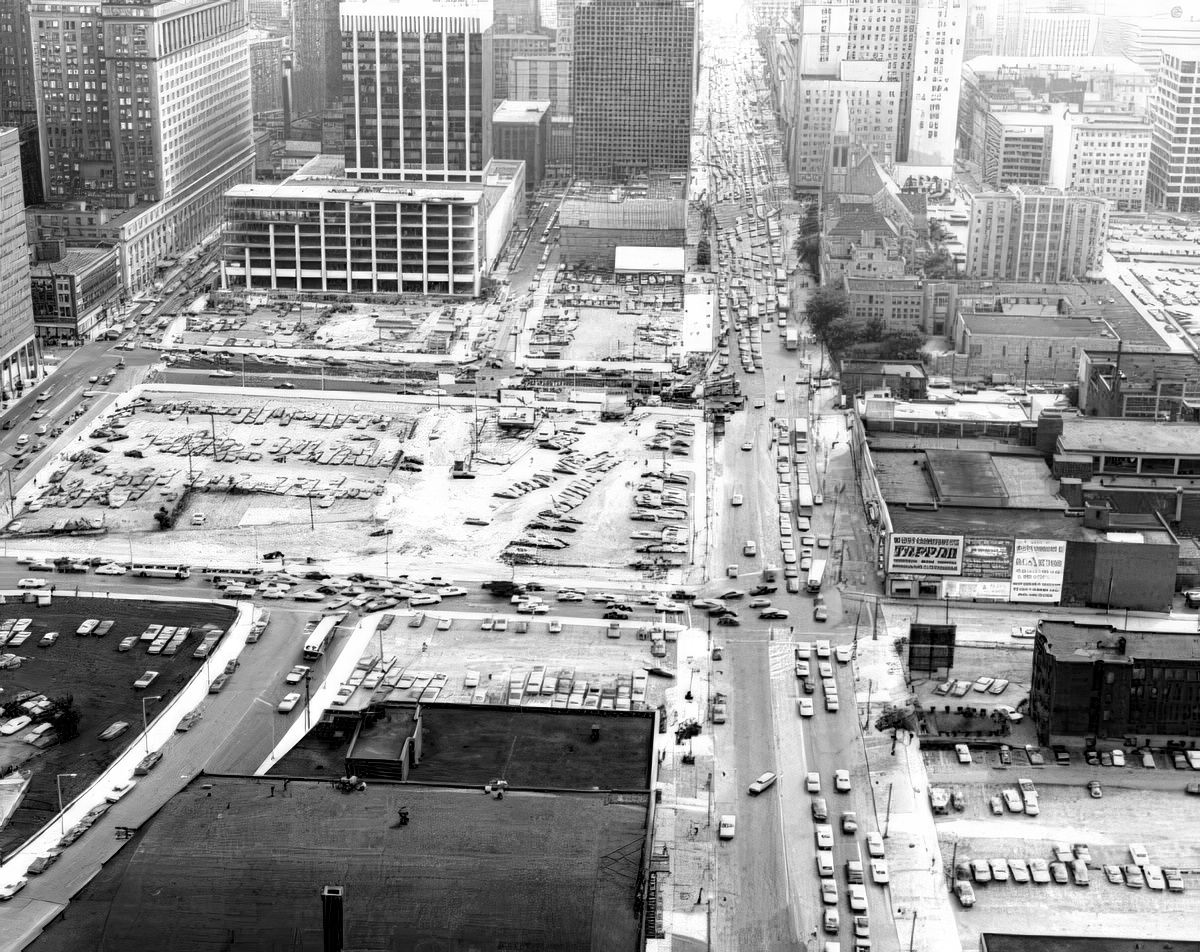

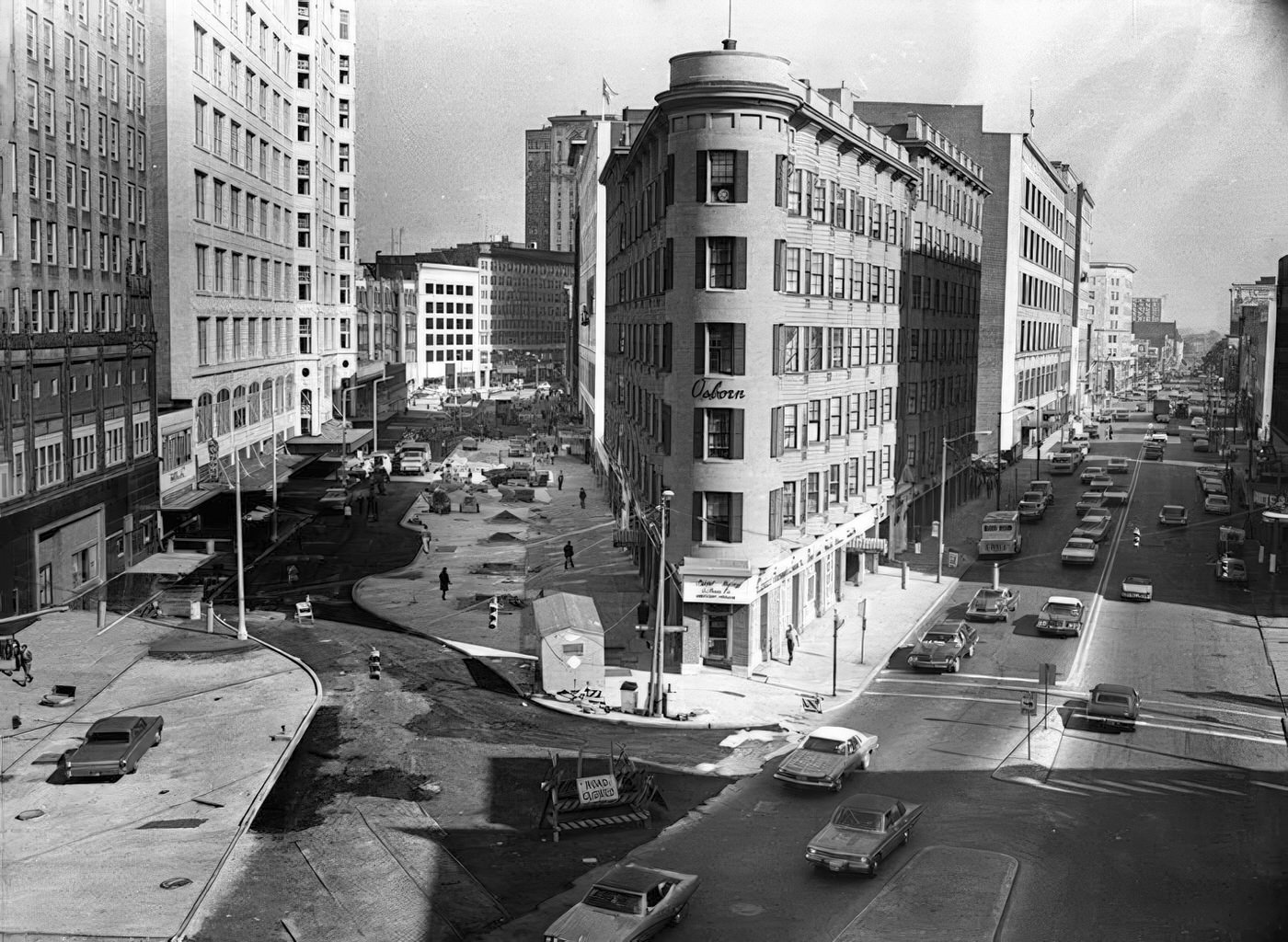

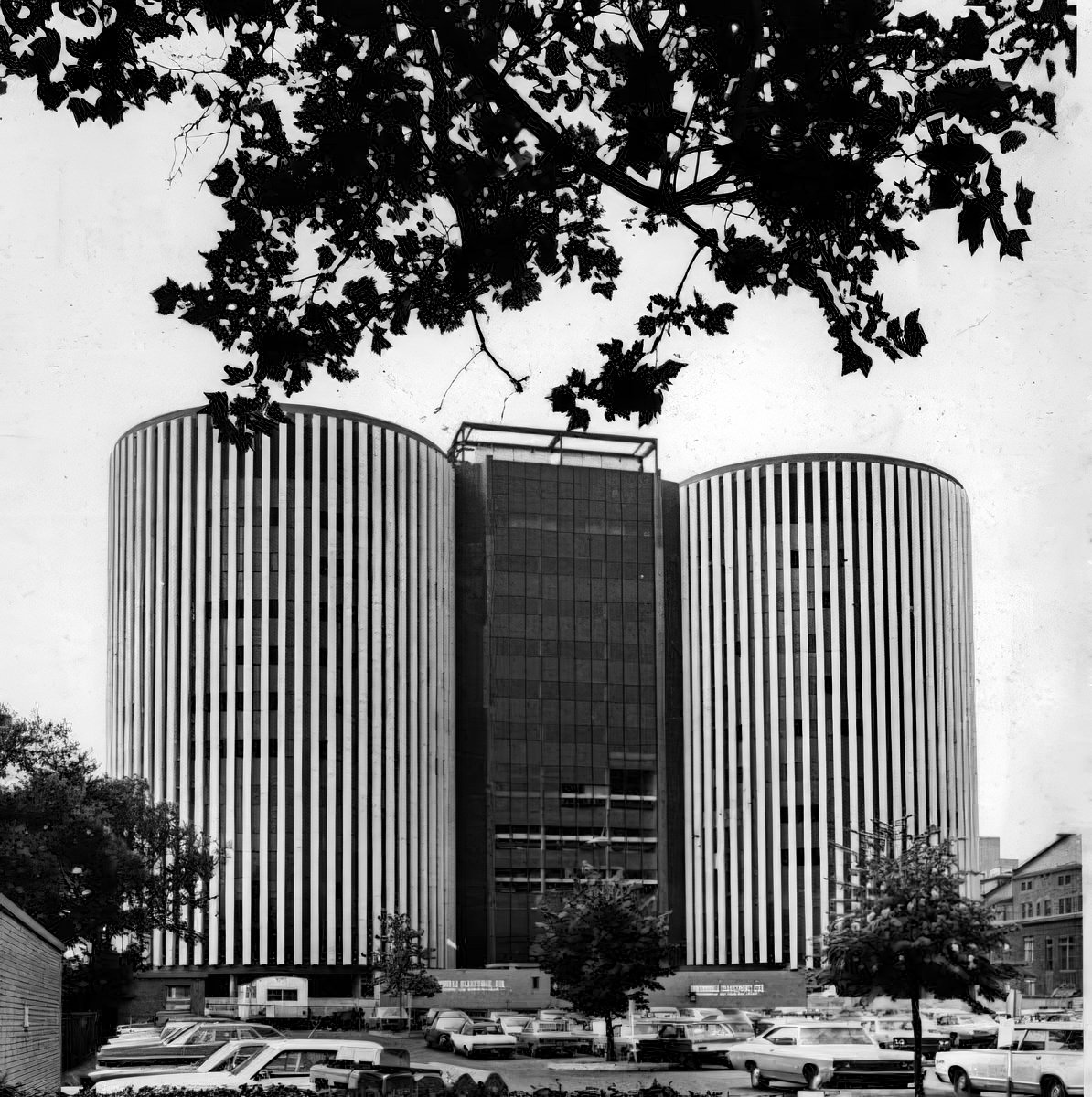

Erieview Project: This large downtown urban renewal project, started in the 1960s , saw some of its later buildings completed in the early 1970s. These included the Bond Court office building (1971), the Public Utilities Building (1971), and Park Centre (which included Reserve Square apartments and a mall, 1973). However, Erieview was often criticized for displacing existing businesses and residents and for its large, underused plaza.

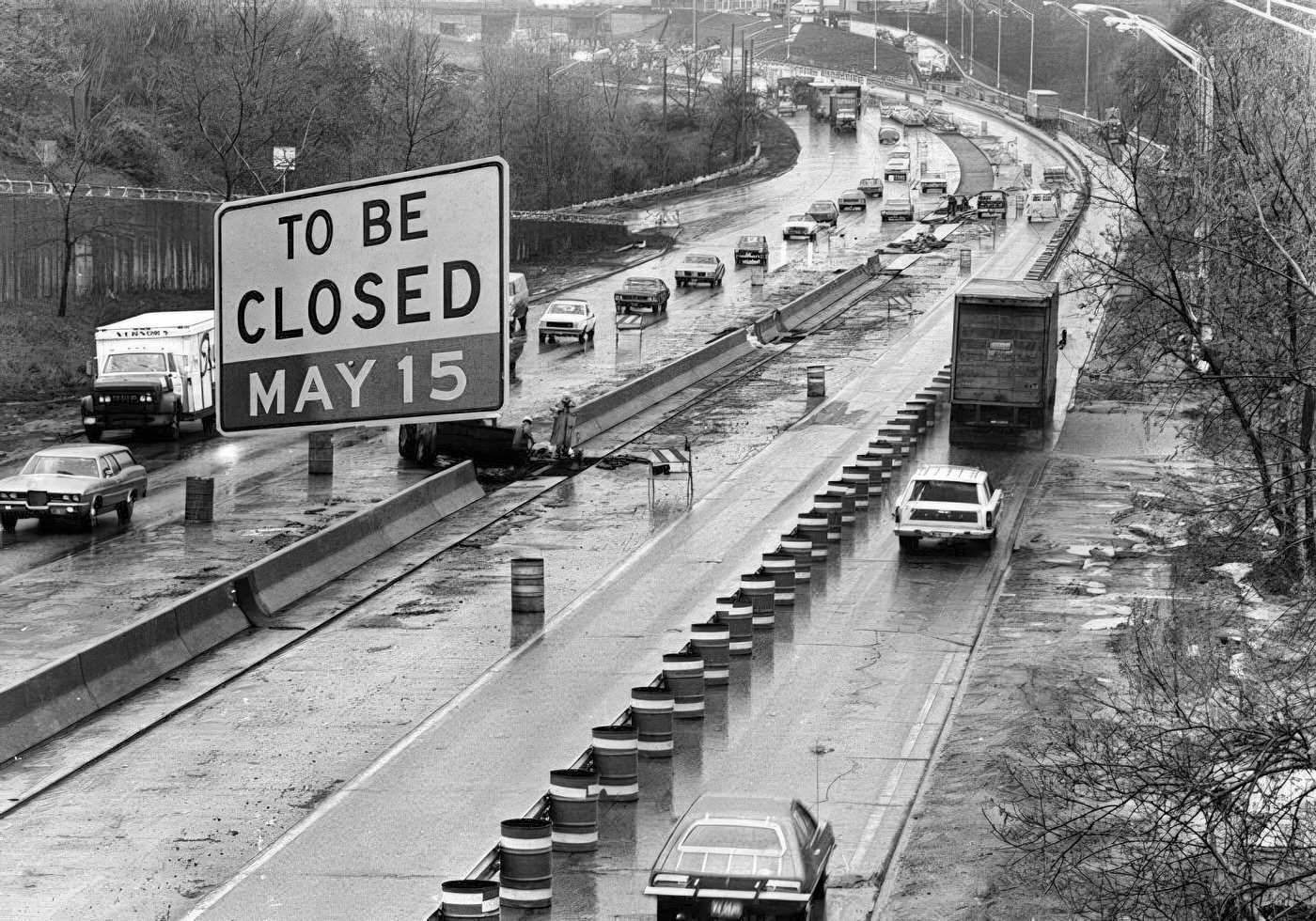

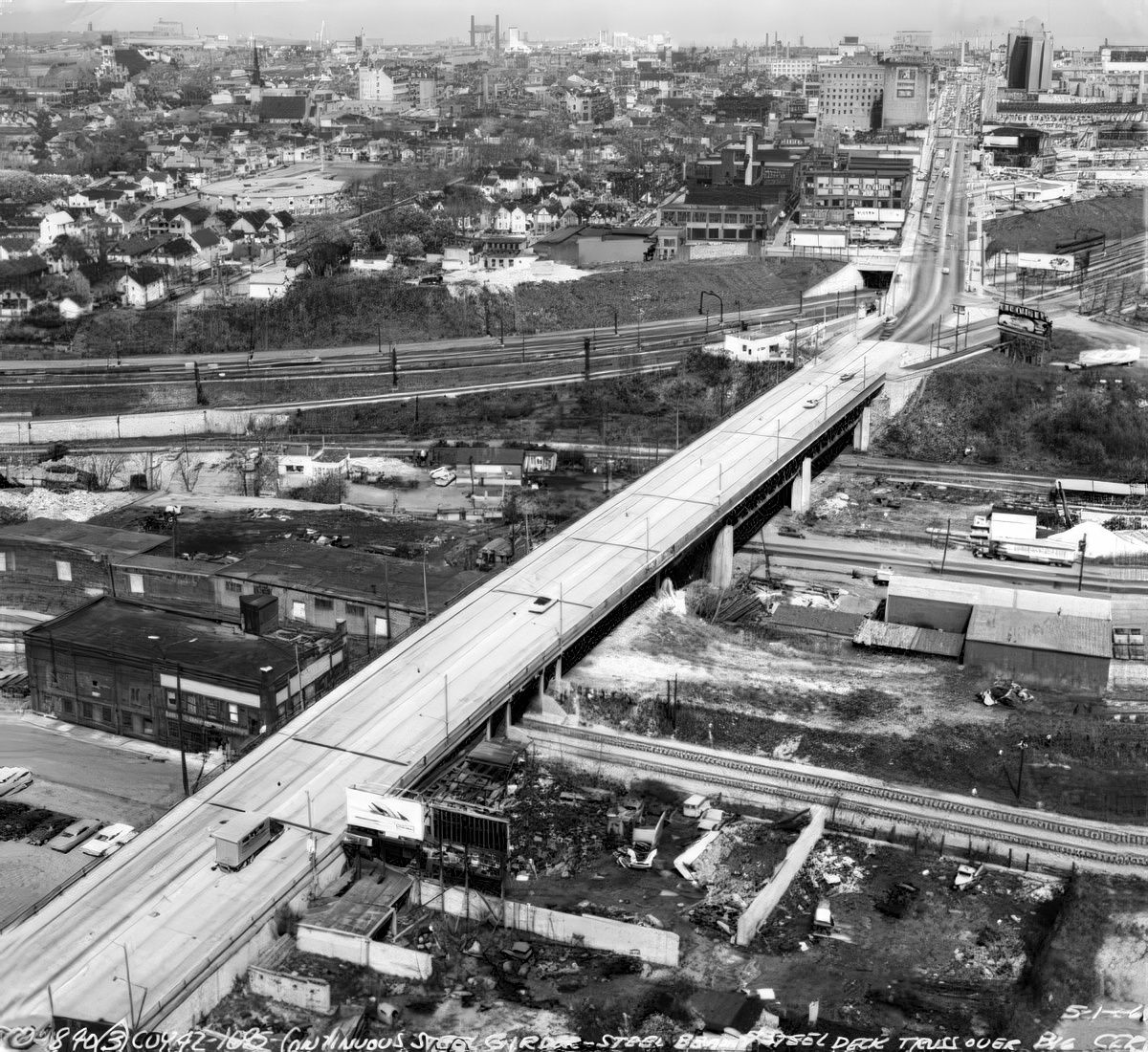

Innerbelt Freeway: This highway system, mostly finished in the 1960s , continued to shape how people moved around the city, notably by directing traffic around the downtown area.

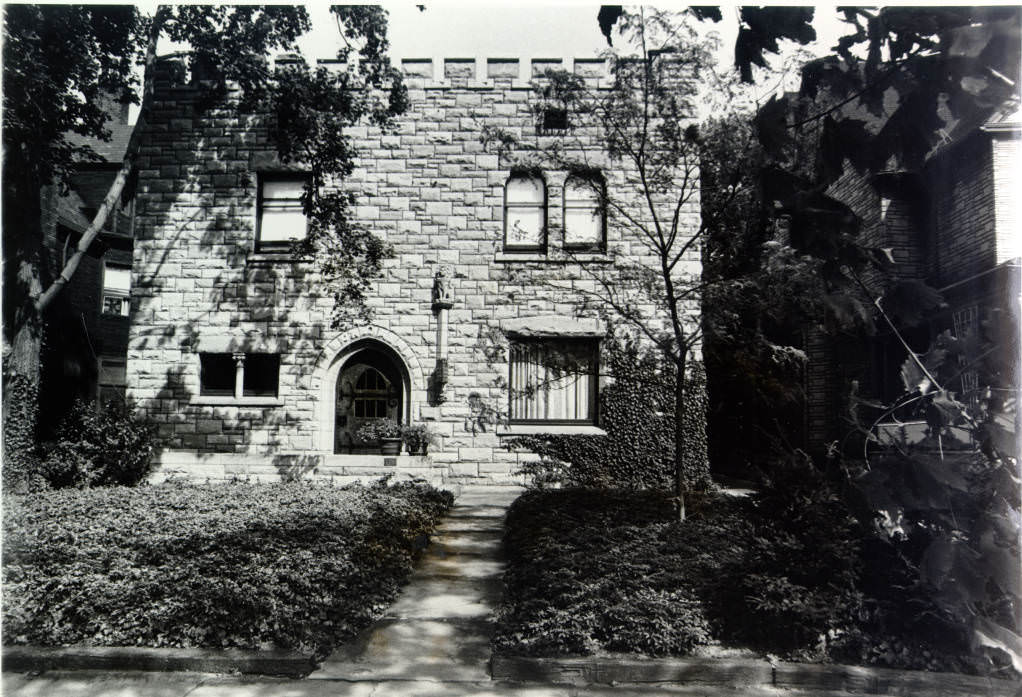

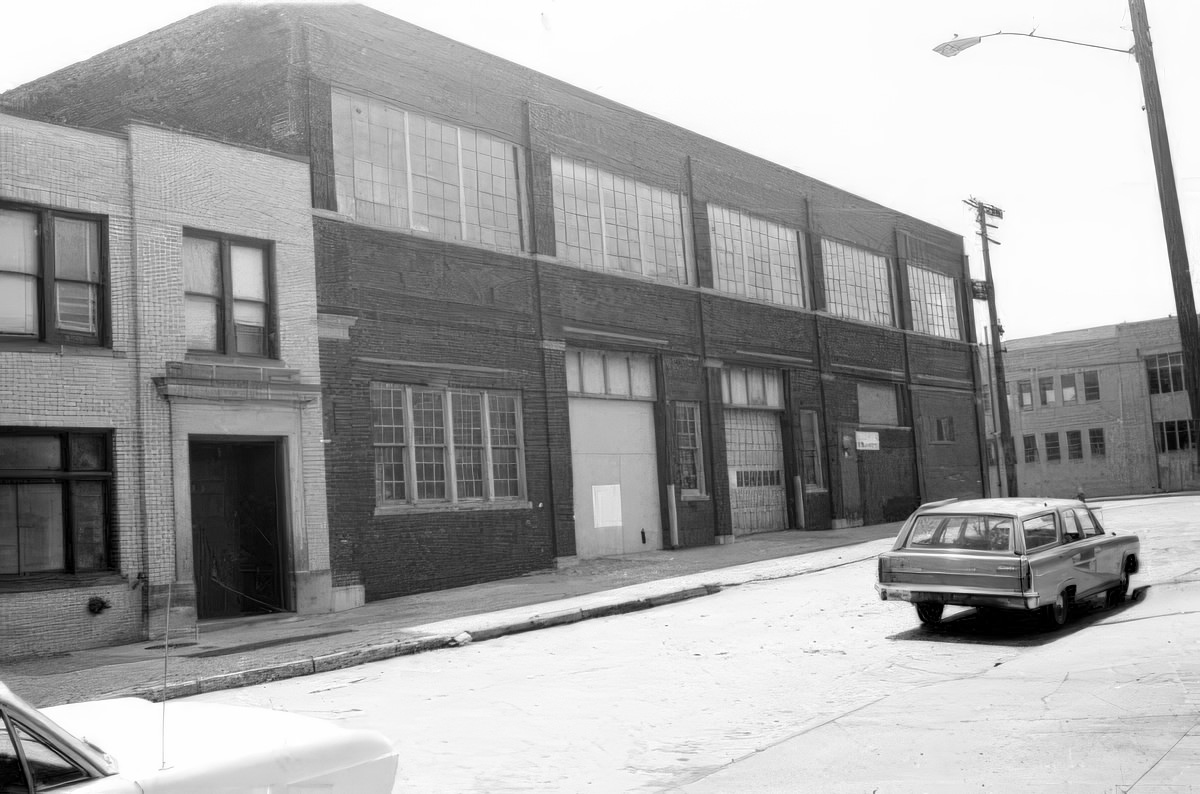

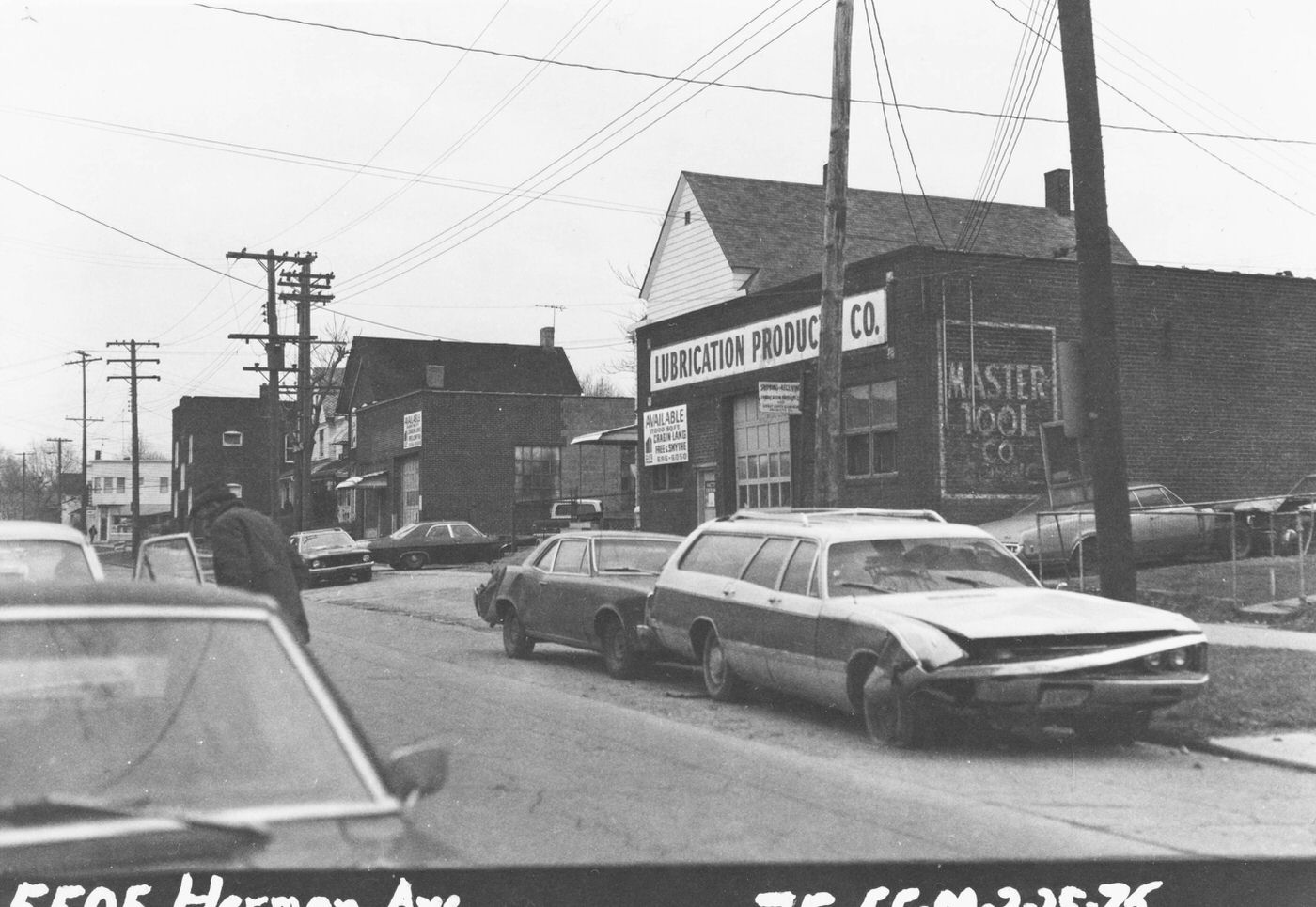

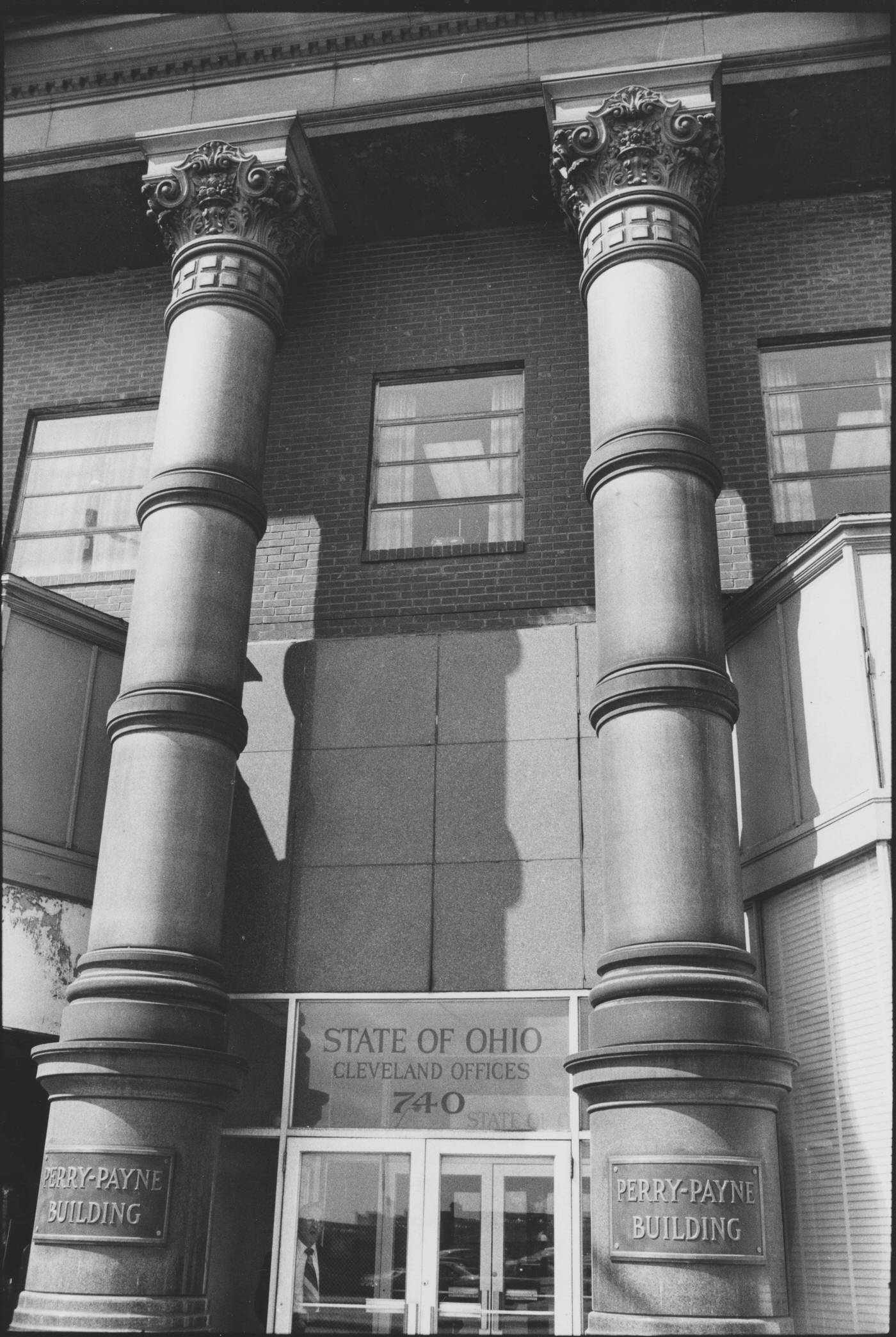

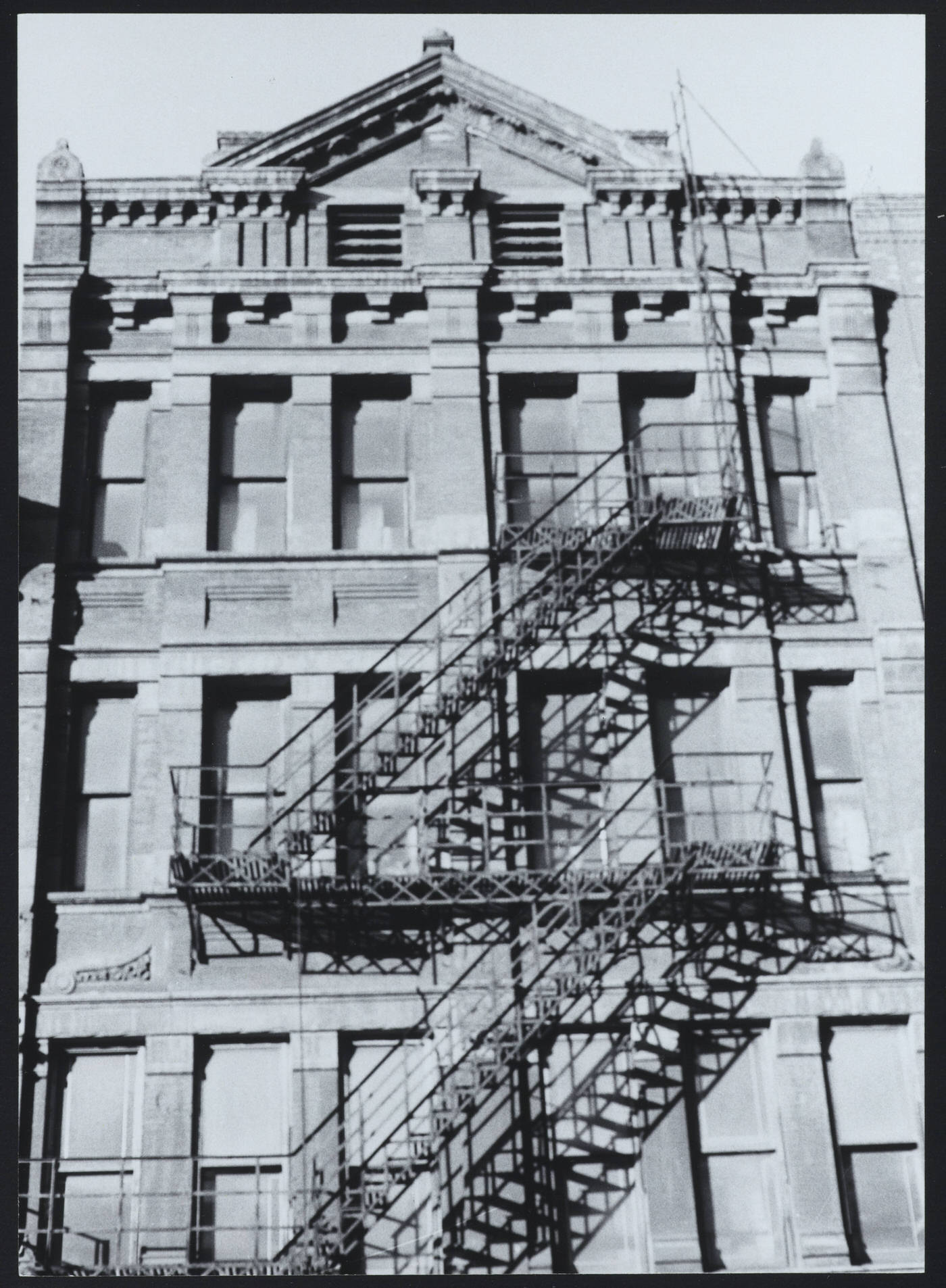

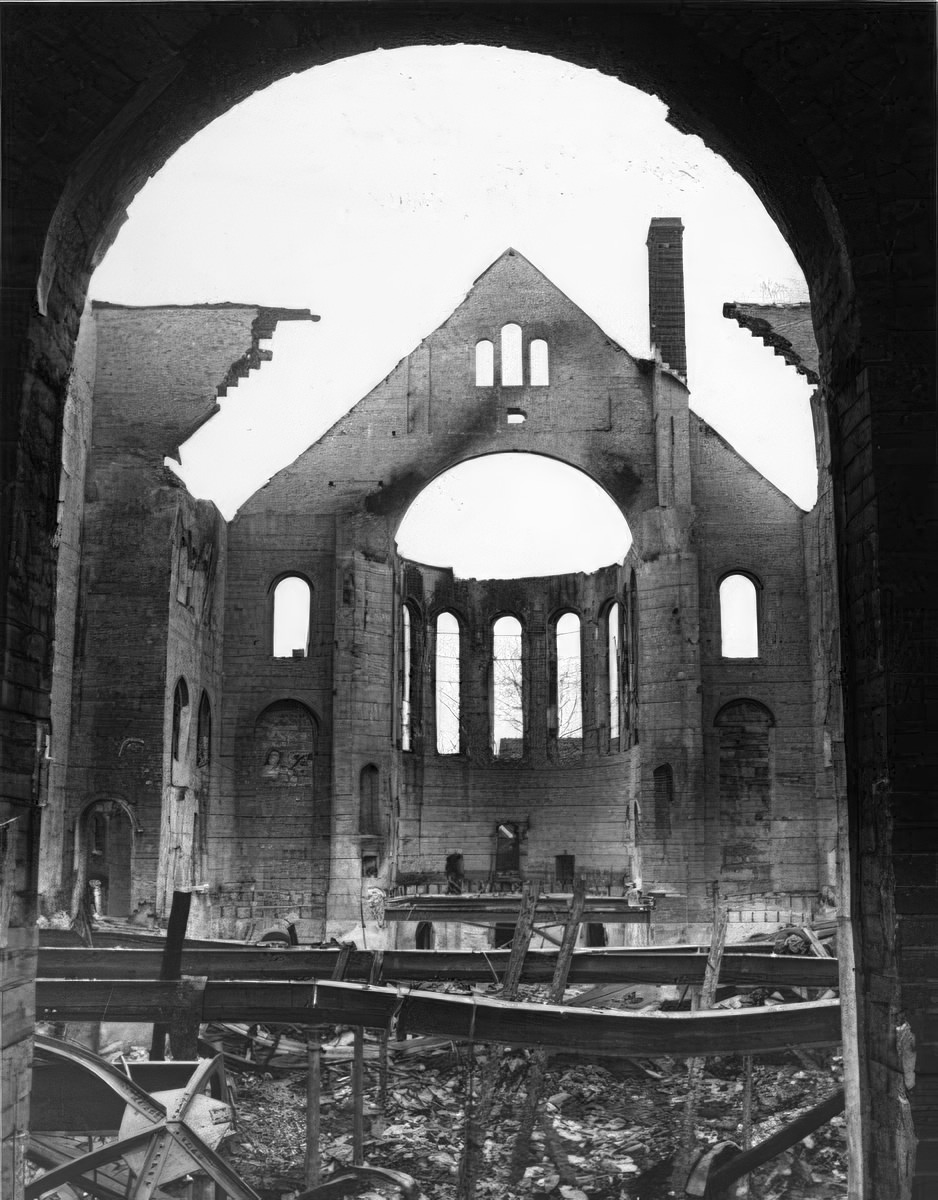

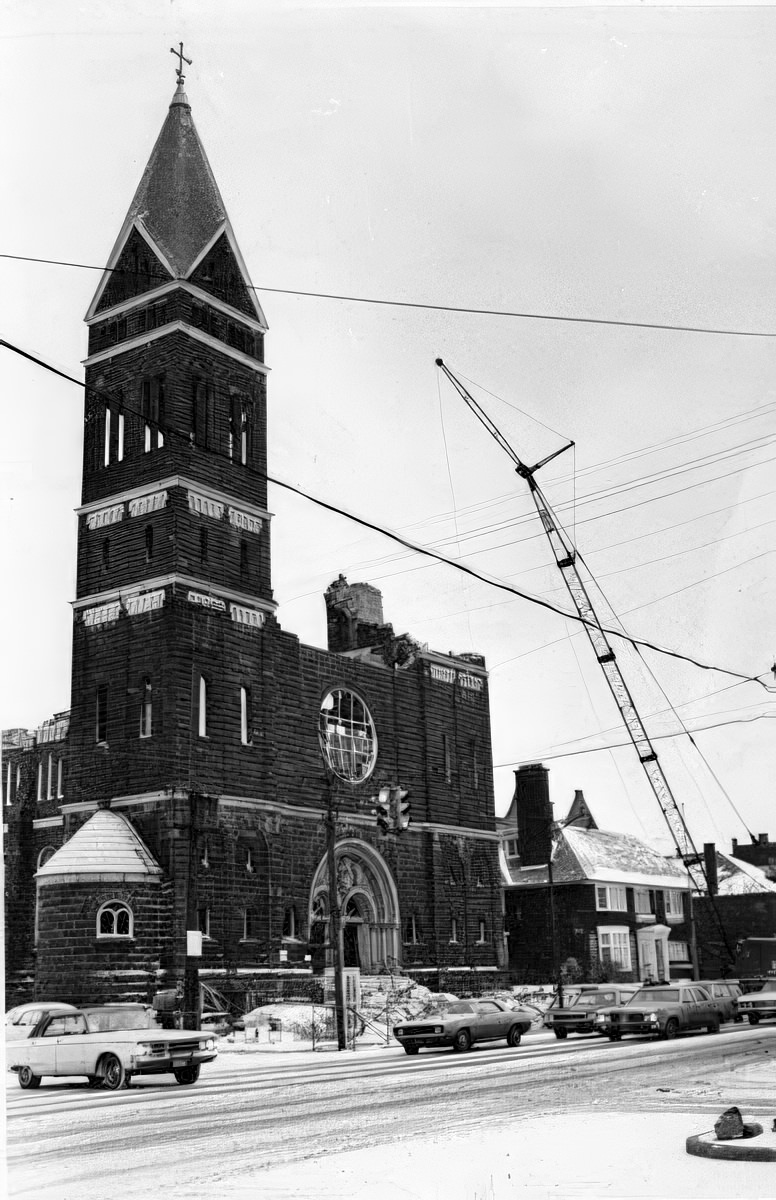

Warehouse District Revitalization: As the decade progressed, there was a growing interest in preserving and reusing historic areas. The Cleveland Landmarks Commission began planning for the future of the Warehouse District in the late 1970s. A study in 1977 looked at the buildings in the district and their potential for being turned into housing, offices, or shops. The first building renovations in the Warehouse District started around 1975. This shift showed a move away from large-scale demolition projects towards valuing and adapting older structures.

Public Services and Infrastructure Challenges

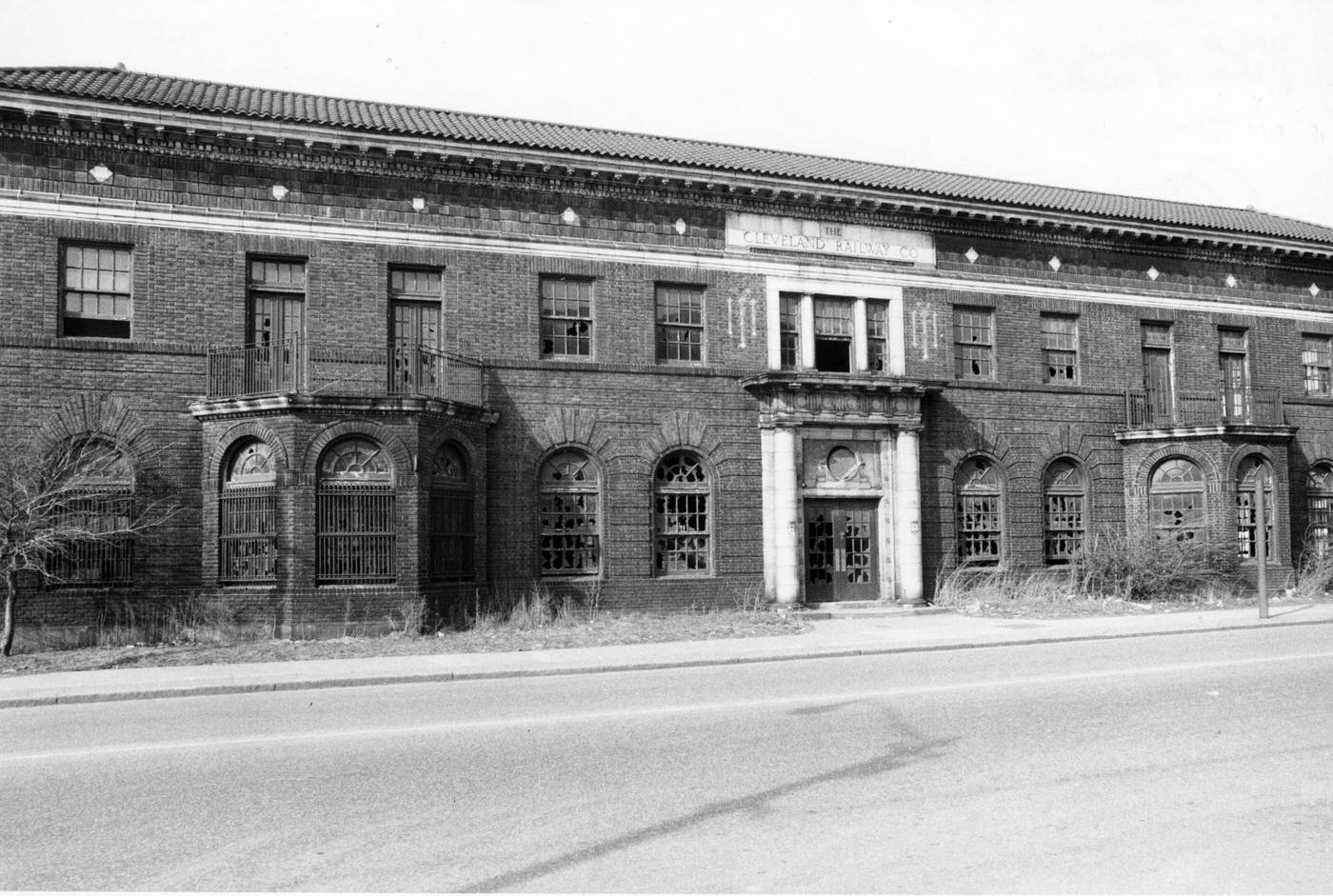

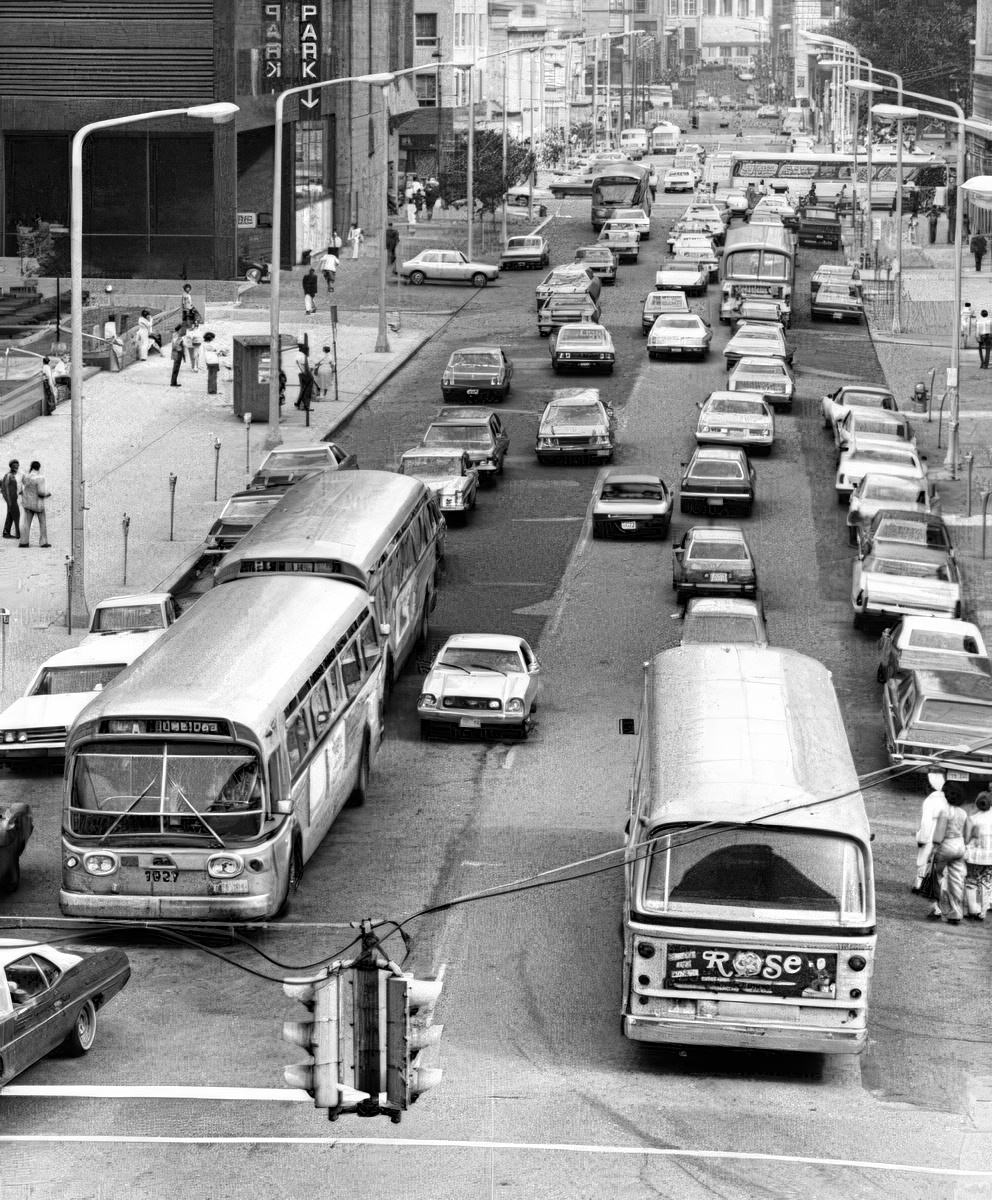

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA): The RTA was created in December 1974 and began operating in September 1975. It combined the Cleveland Transit System (CTS) and the Shaker Heights Rapid Transit into one regional system. Funding came from a 1% sales tax across Cuyahoga County, which voters approved in July 1975. They were promised lower fares (25 cents for local rides) and better service. At first, many more people started riding the buses and trains (ridership was up 71% by 1978 compared to before RTA). RTA bought new buses and introduced a color-coded system for its rapid transit lines. However, by the late 1970s, less money from the federal government and lower-than-expected sales tax income forced RTA to raise fares. In 1979, RTA started a major project to rebuild its light-rail lines.

Cleveland Hopkins International Airport: The airport underwent a large $60 million renovation from 1974 to 1982 to modernize its terminal and concourses. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 also began to change how airlines operated, which would affect Cleveland’s role as an airline hub in the future. The North Concourse at Hopkins opened in August 1978.

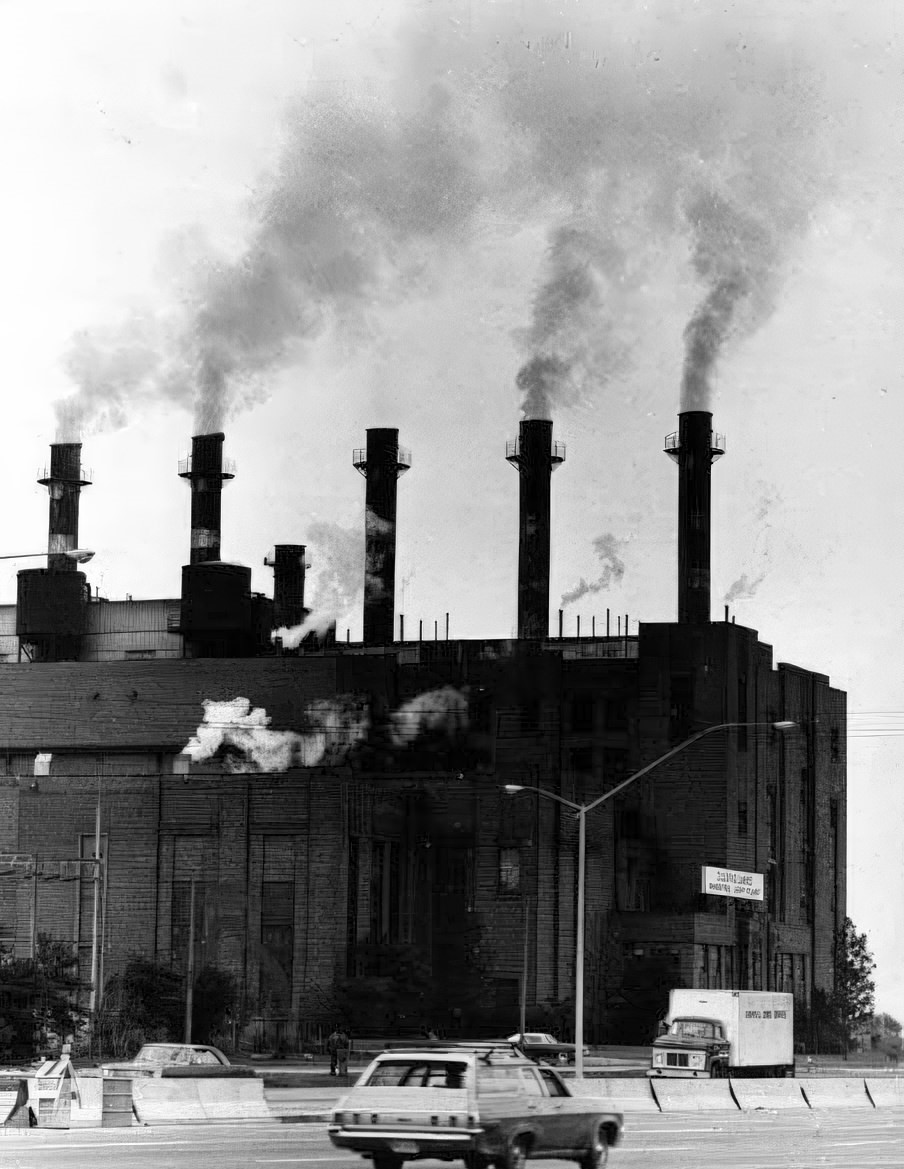

Sanitation and Public Works: The city’s incinerators, which burned solid waste, were closed in the 1970s because they could not meet new federal air pollution standards. Cleveland then started taking its trash to sanitary landfills outside the city. The city’s financial crisis in the late 1970s certainly made it difficult to fund services like road maintenance and park upkeep.

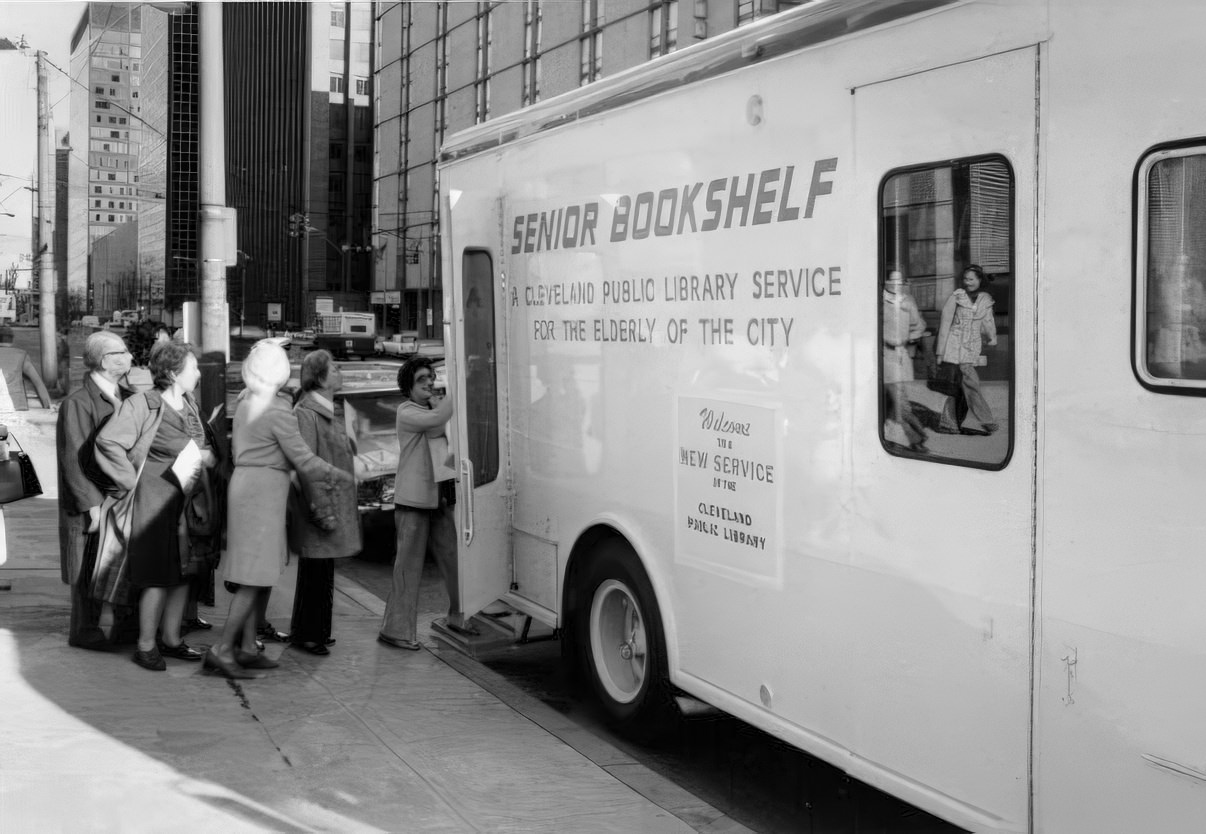

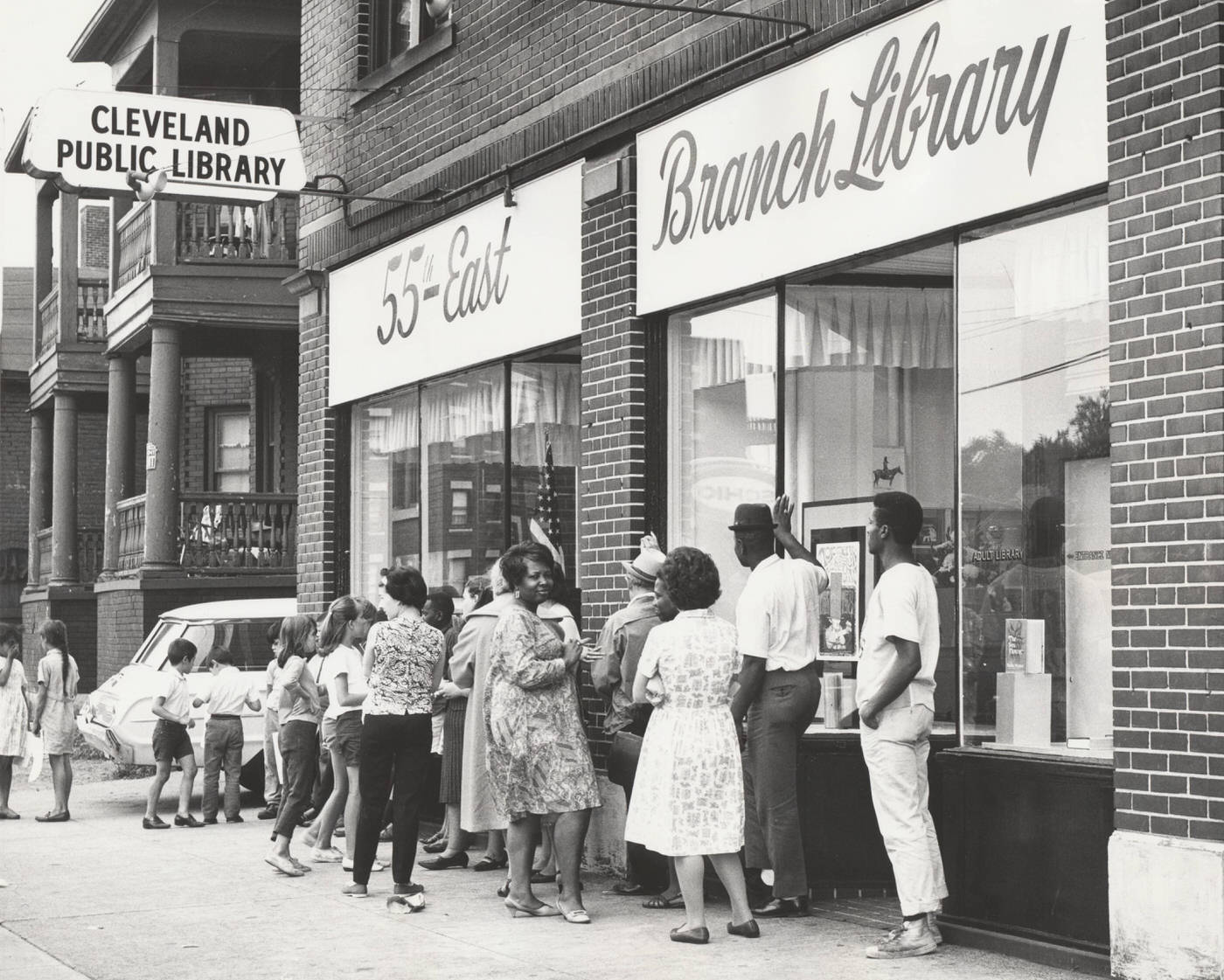

Cleveland Public Library: After voters turned down a property tax levy in November 1974, the library managed to get funding through a city tax levy in 1975. This money supported a $20 million program to improve library branches. In 1975, the library also began the major task of computerizing its card catalog and switched to the Library of Congress classification system for its books.

Cleveland Metroparks: Responding to the energy crisis of the 1970s, the Metroparks opened an innovative solar-powered nature center in the North Chagrin Reservation in 1976. This project was partly funded by a grant from the Cleveland Foundation.

The 1970s were a critical time for Cleveland’s public services. New regional systems like the RTA were created, and modernization efforts were made at the airport and library. However, these efforts happened against a backdrop of shrinking city income, aging infrastructure, and new, expensive federal rules for things like environmental protection and school desegregation. This created a difficult situation where the need for better services was high, but the city’s ability to pay for them was decreasing.

The 1970s in Cleveland were not just about economic struggles and political battles; the decade also saw significant shifts in education, vibrant social movements, and a dynamic cultural scene.

Education in Transformation

Cleveland’s educational institutions underwent profound changes during the 1970s.

Cleveland Public Schools – Reed v. Rhodes and Busing: A major legal battle over school segregation dominated much of the decade. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sued the Cleveland Public Schools and the State of Ohio in 1973, arguing that they had intentionally created and maintained a segregated school system. In 1976, U.S. District Judge Frank J. Battisti ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, finding that the schools were indeed unconstitutionally segregated.

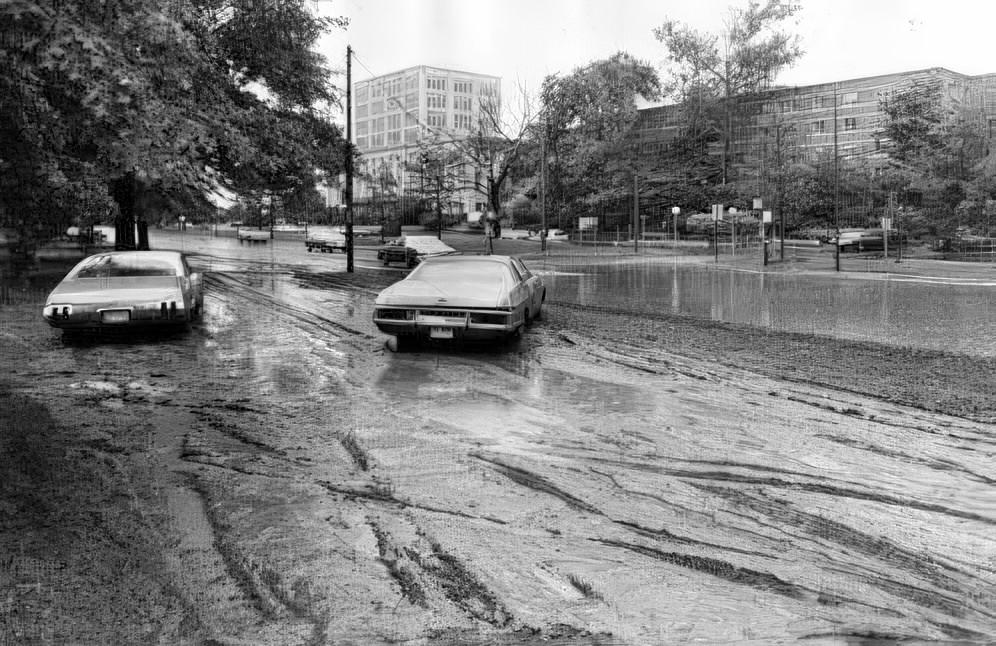

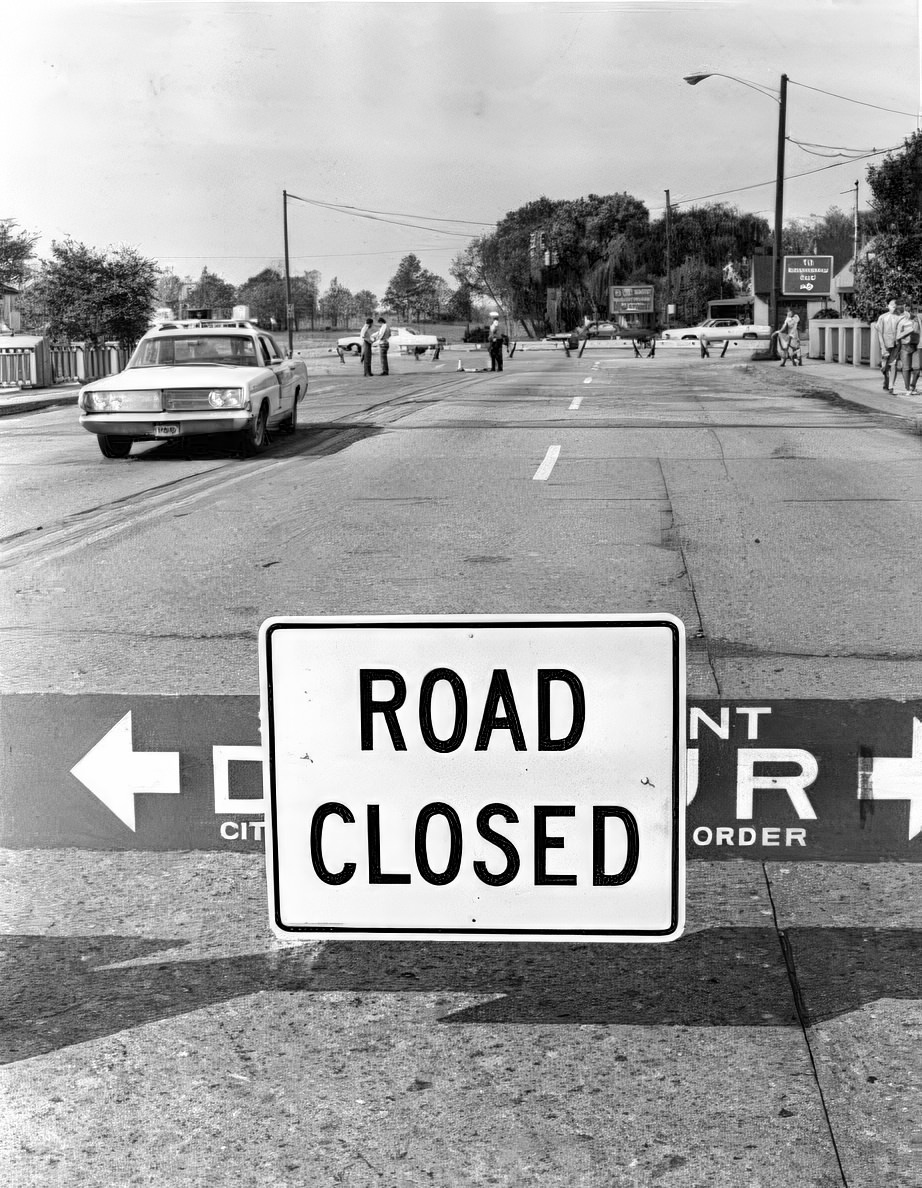

This ruling led to a comprehensive desegregation plan that included the highly controversial practice of cross-town busing. The plan aimed to achieve racial balance in schools by transporting students to schools outside their neighborhoods. Implementation began with some junior high students in the 1978-79 school year, and full system-wide busing started in September 1979 and continued into 1980.

Community reactions to busing were mixed and often intense. Groups like CORK (Citizens Opposed to Rearranging Kids) protested against the plan, while organizations such as WELCOME (West-East Siders Let’s Come Together) worked to promote a peaceful implementation. Despite the anxieties and some protests, Cleveland’s busing program was generally more peaceful than in some other major cities like Boston. The desegregation efforts represented a massive social and logistical undertaking, profoundly affecting families and communities as the city grappled with how to provide equal educational opportunities.

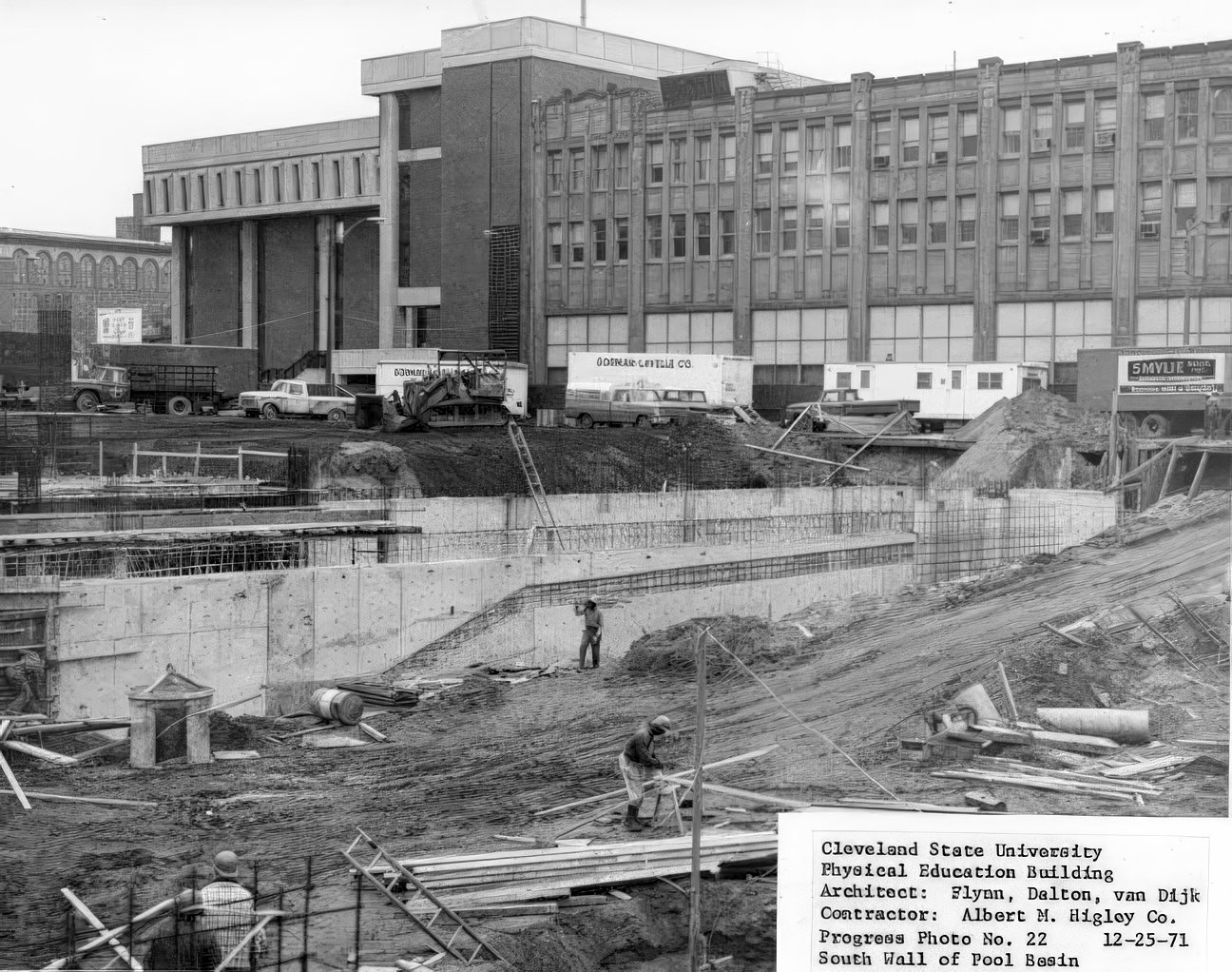

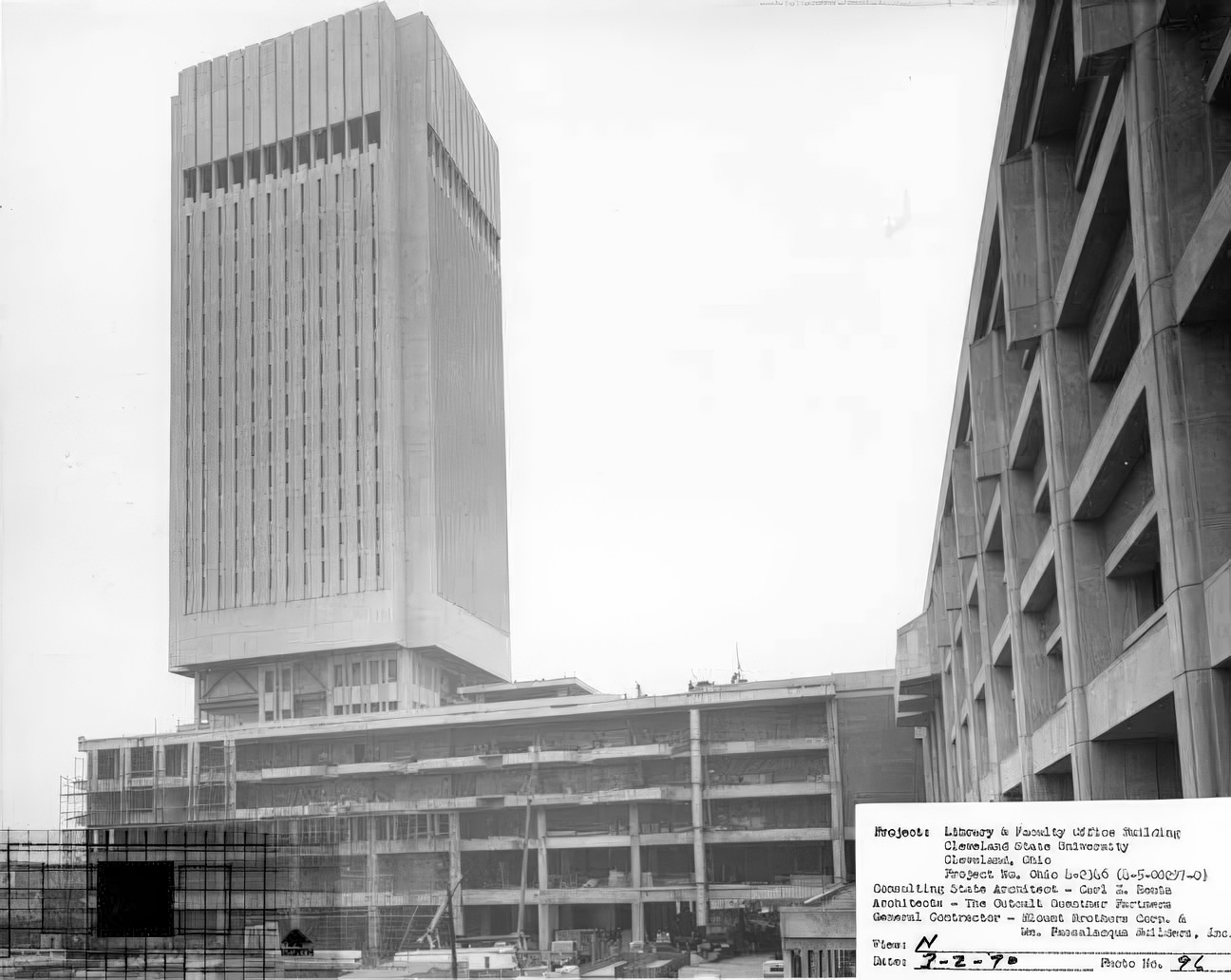

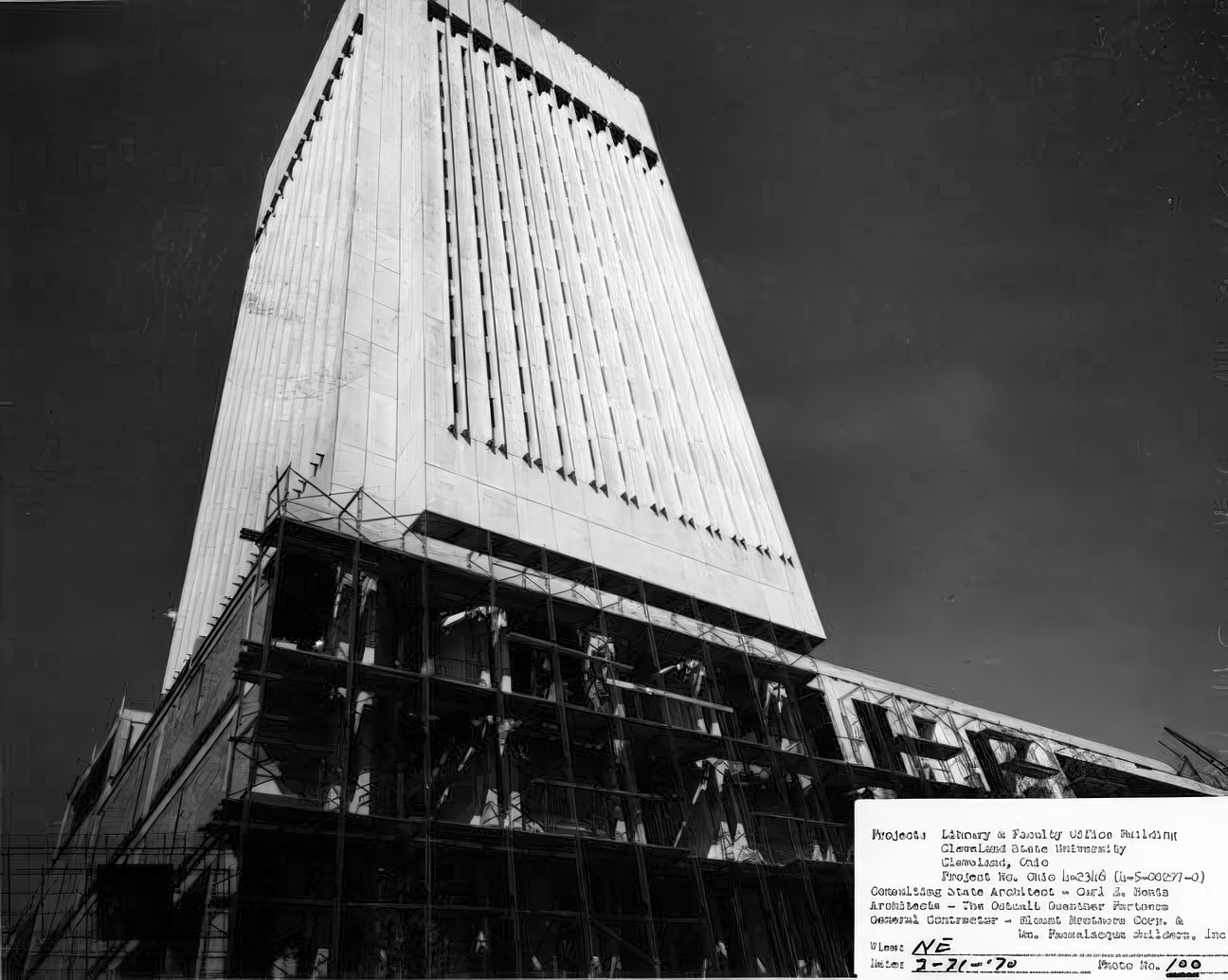

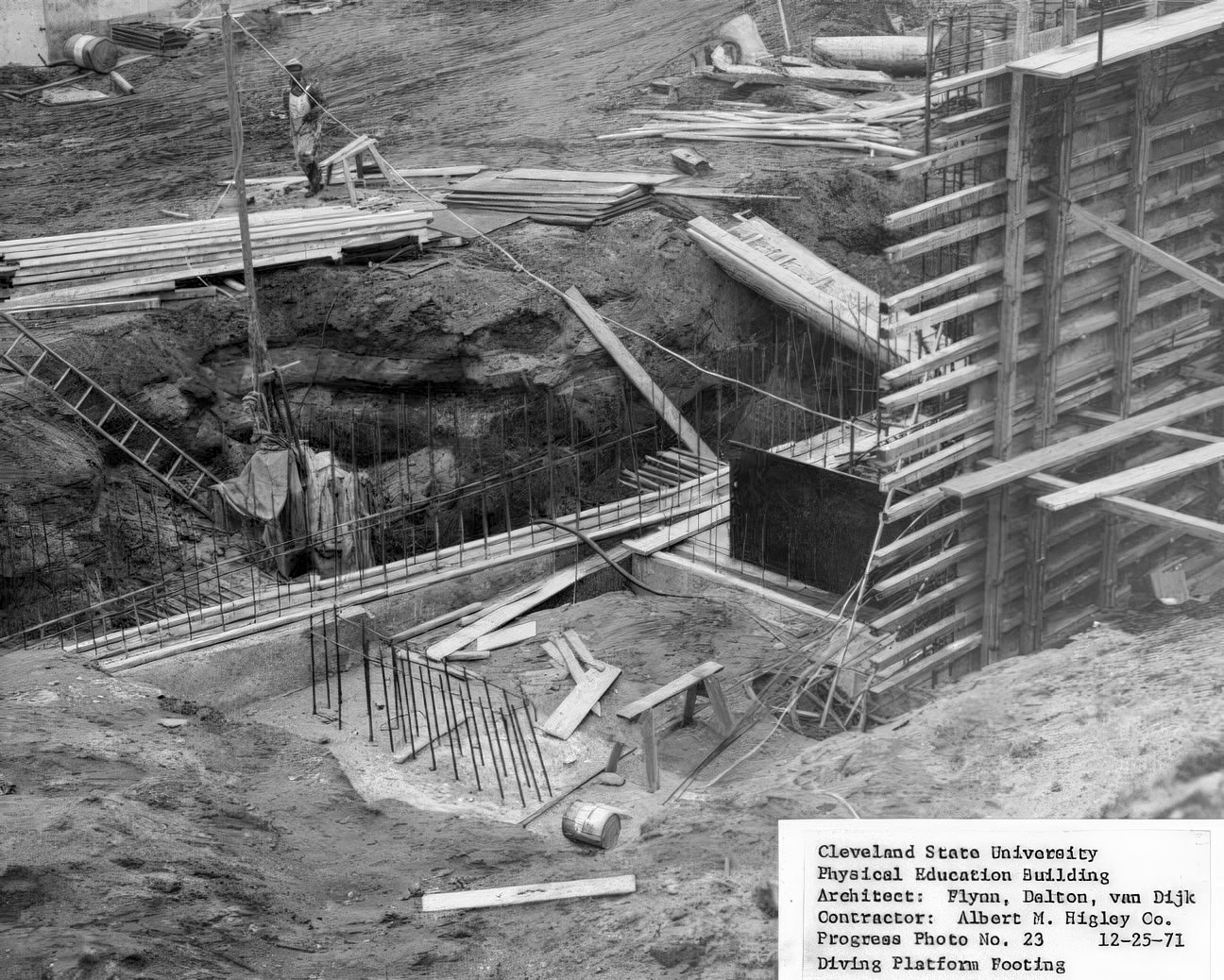

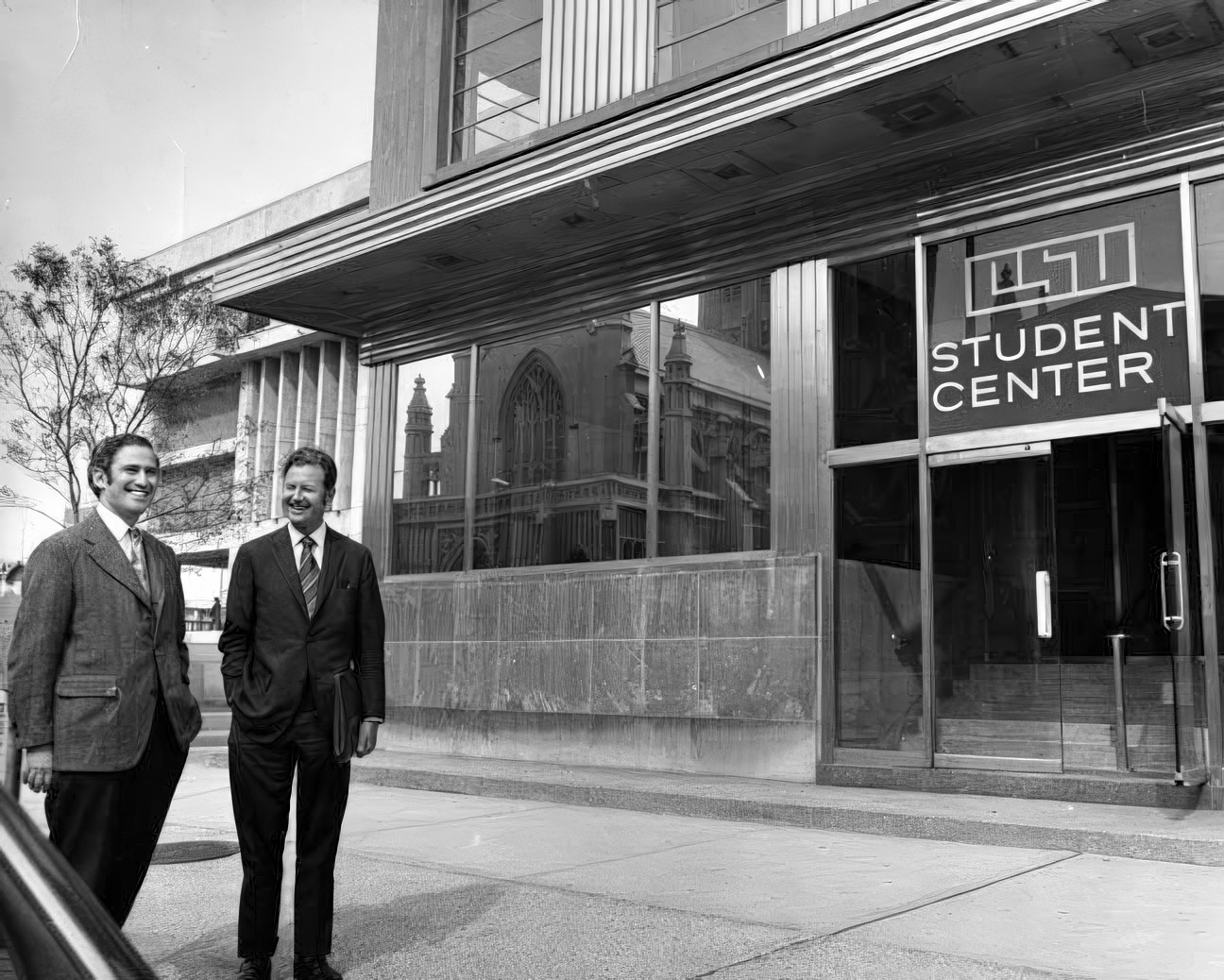

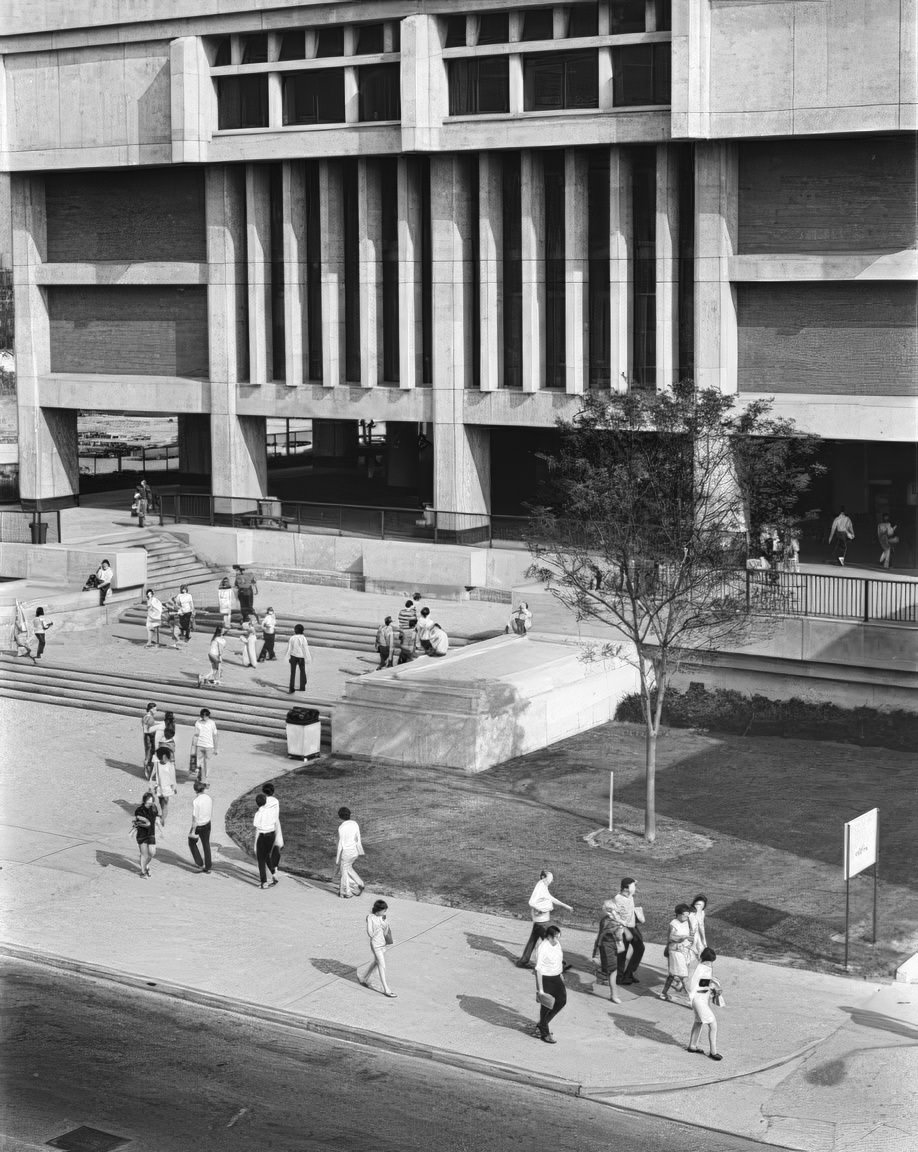

Cleveland State University (CSU): Established in 1964 by acquiring Fenn College, and merging with Cleveland-Marshall College of Law in 1969, CSU continued to grow and define its mission as an urban university in the 1970s. Under President Walter Waetjen (1973-1988), CSU expanded its academic programs and developed public service initiatives like the Legal Clinic and the Center for Neighborhood Development. The campus itself grew with new buildings, including the Physical Education Building (1973), University Center (1974), and the Law Building (1977). Enrollment was high in the late 1970s, sometimes requiring classes to be held in temporary spaces.

Case Western Reserve University (CWRU): Formed by the 1967 federation of Case Institute of Technology and Western Reserve University , CWRU saw continued campus development in the early part of the decade. An experimental January term called “Intersession,” offering unique courses, ran from 1973 to 1976. The university’s computer engineering program became the first accredited program of its kind in the nation in 1971, and various engineering departments were reorganized. Student activism, particularly against the Vietnam War, was prominent in the early 1970s, leading to protests and the eventual removal of the Air Force ROTC program from campus. The Women’s Liberation movement at CWRU also advocated for reproductive rights, increased opportunities for women in science and technology fields, and the Equal Rights Amendment.

Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C): Tri-C continued its expansion to serve the community. The permanent Western Campus in Parma was built in 1975, and the Eastern Campus in Warrensville Township (now Highland Hills) opened in 1981, with planning likely occurring in the late 1970s. Tri-C provided a range of programs, including courses for transfer to four-year colleges, developmental education, and career training.

The educational scene in 1970s Cleveland was thus one of major adjustments and significant social debate. Public schools were being reshaped by federal court orders aimed at racial equality, while universities were responding to student activism, new academic needs, and their evolving roles in a city facing many changes.

Social Movements and Civic Engagement

The 1970s were a time of active social movements in Cleveland, reflecting national trends.

Women’s Movement: The Cleveland chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW), re-established in 1970, actively campaigned for women’s rights. They supported the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), formed a political action committee to support candidates, pushed for non-sexist textbooks in schools, advocated for more athletic opportunities for girls, and challenged discriminatory hiring practices at local television and radio stations. The Cleveland Pro-Choice Action Committee (PCAC), formed in 1978, focused on reproductive rights, supporting legal abortion, opposing coercive sterilization, and defending health clinics. They often worked with NOW and other progressive groups. Student groups at CWRU also campaigned for reproductive rights and the ERA. This activism mirrored a national push for greater legal, economic, and social equality for women.

Environmental Movement: The infamous Cuyahoga River fire of June 1969 became a national symbol of industrial pollution and a powerful catalyst for the environmental movement. This event, along with growing national awareness, contributed to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 and the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972. Cleveland’s Mayor Carl Stokes and his brother, Congressman Louis Stokes, were important voices advocating for environmental laws, connecting environmental quality to the well-being of urban residents, especially those in poverty. The first Earth Day in 1970 saw widespread participation in Cleveland, with an estimated 500,000 students taking part in a “Crisis of the Environment Week”. Efforts to improve air quality also gained momentum with new federal regulations in the 1970s. Cleveland, spurred by its own visible pollution problems, played a significant role in the growing national concern for the environment.

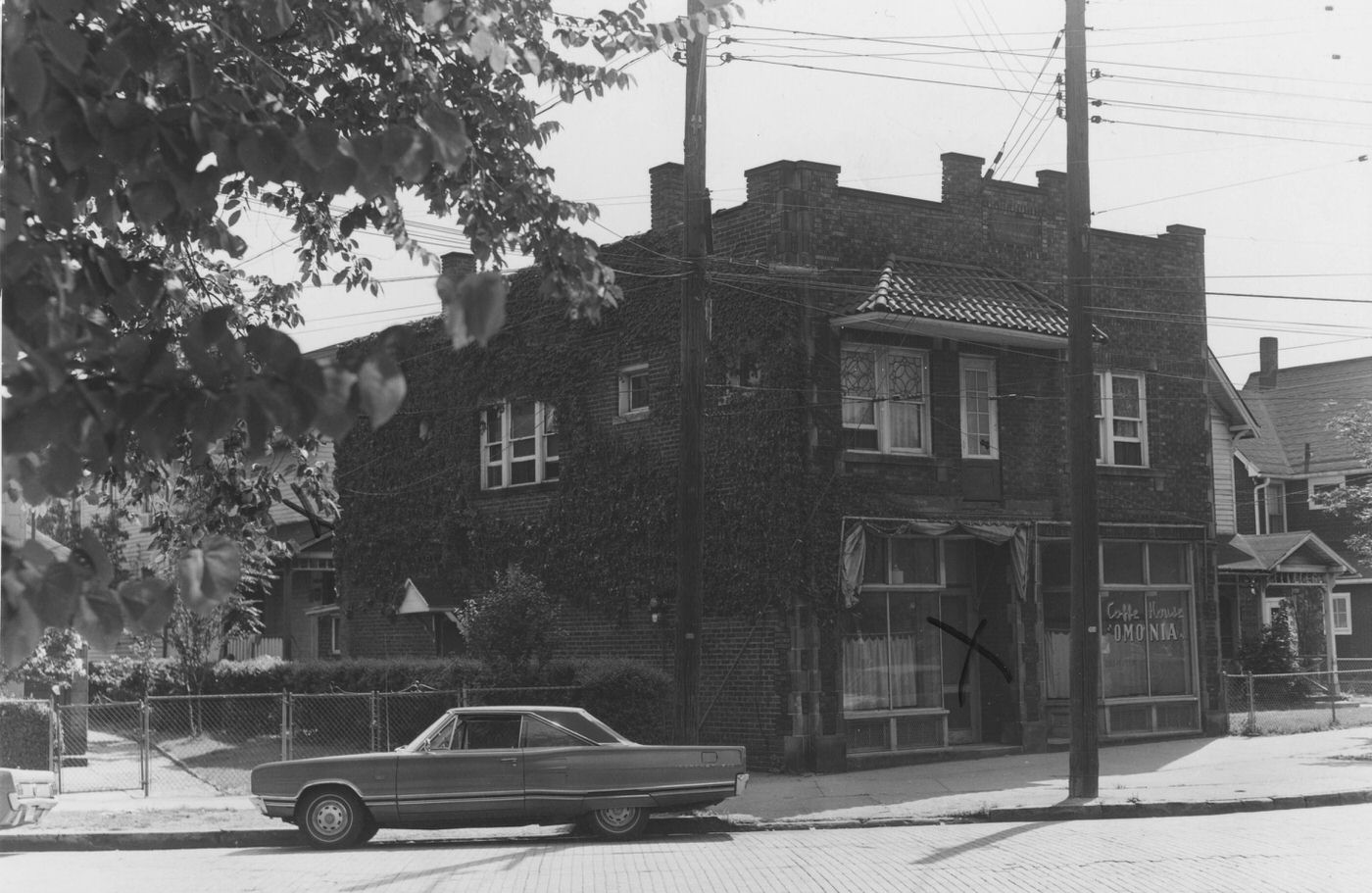

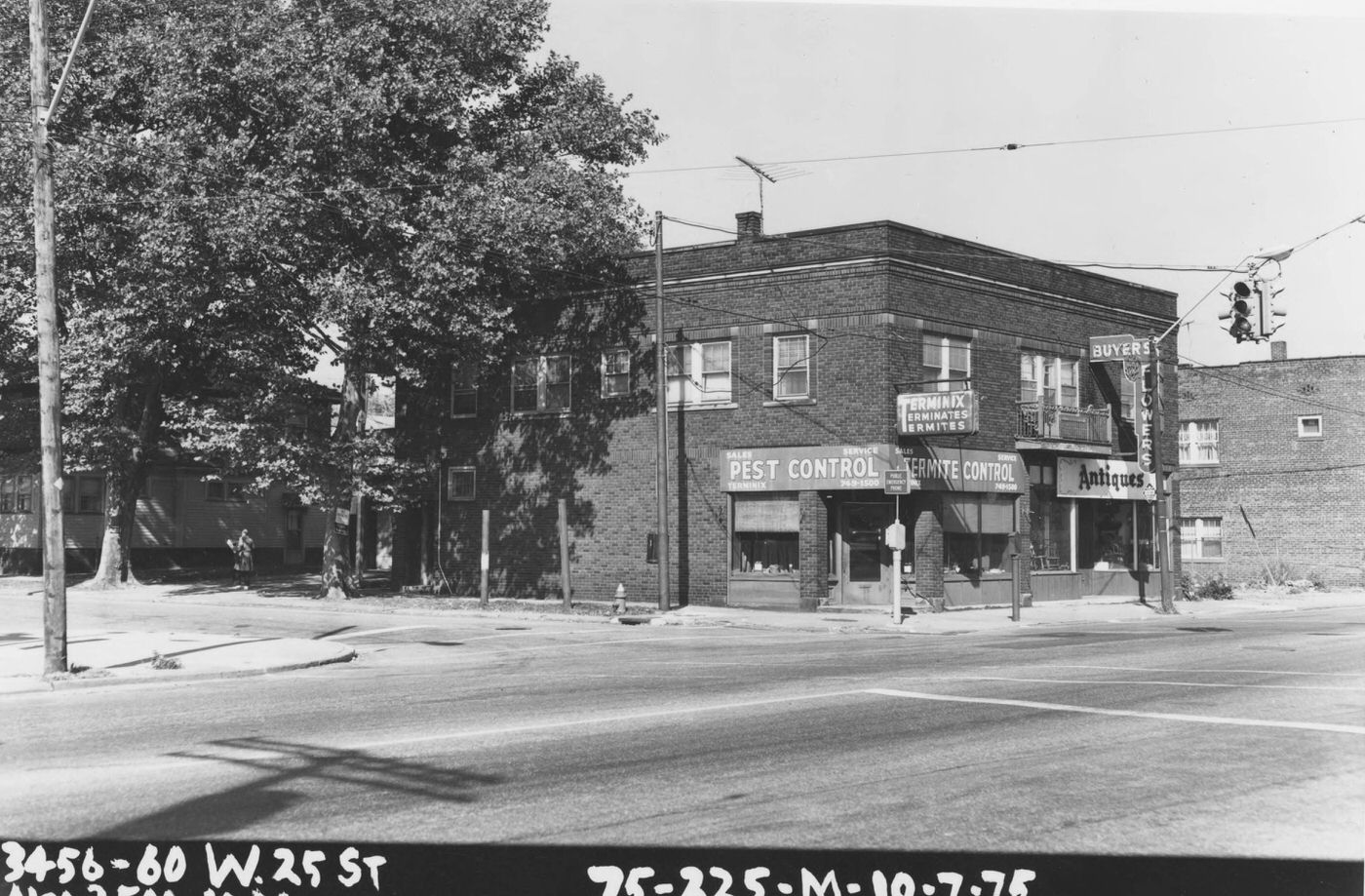

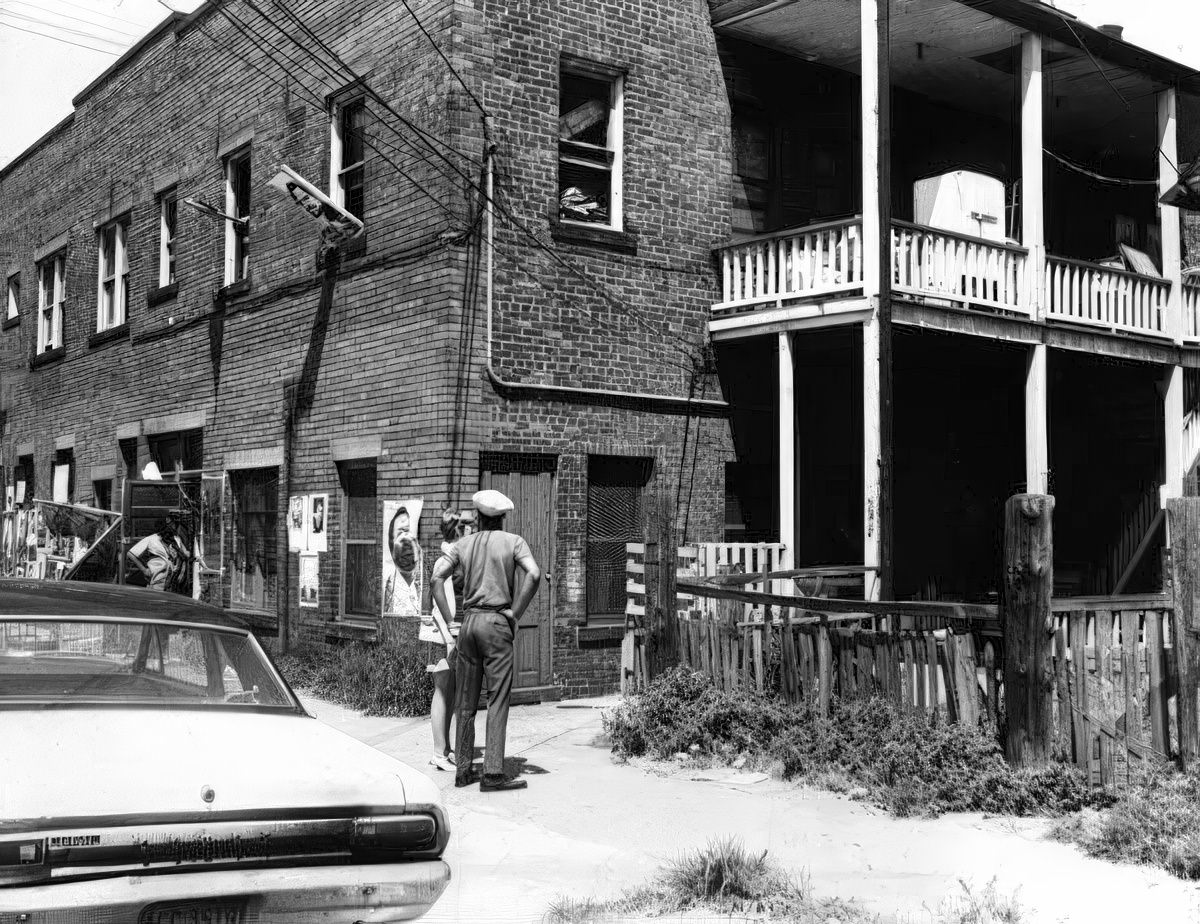

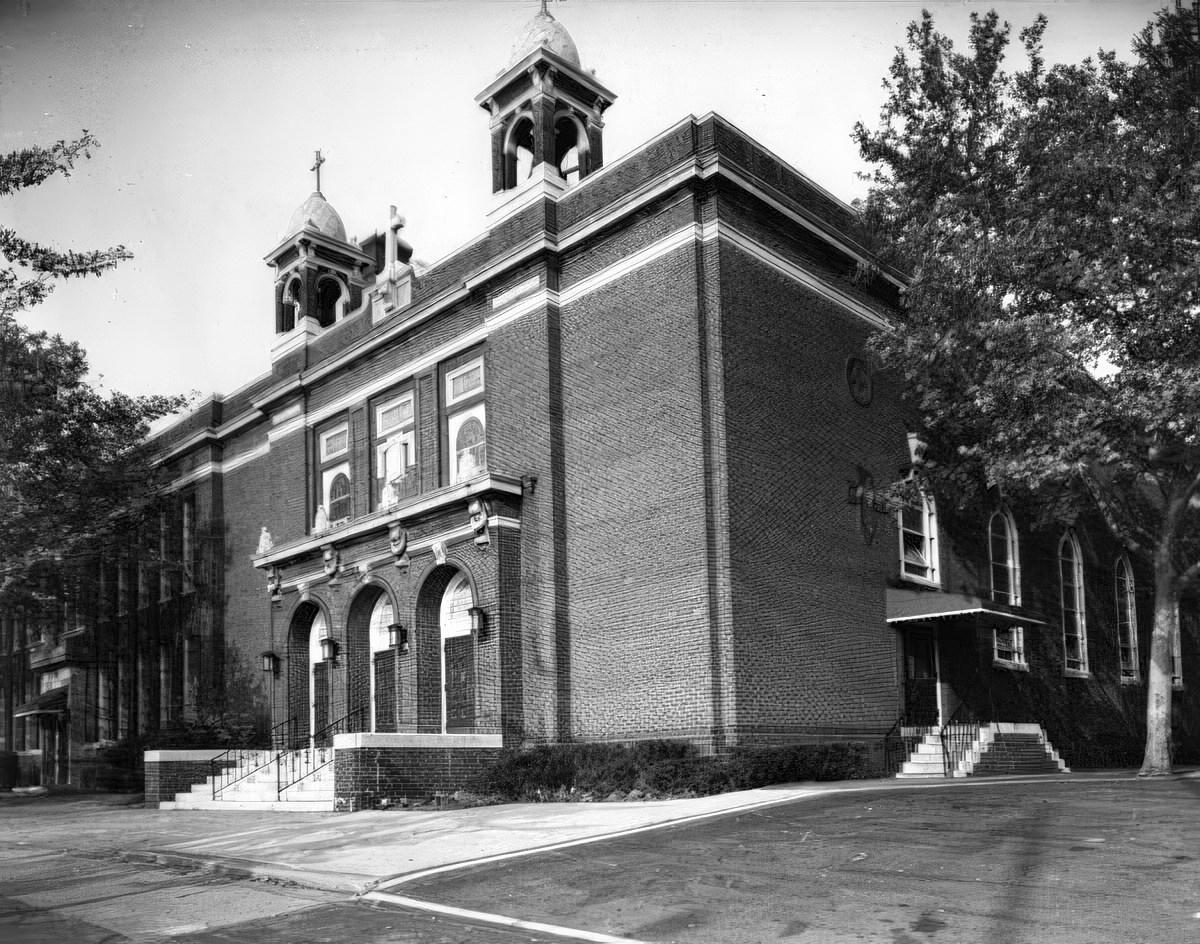

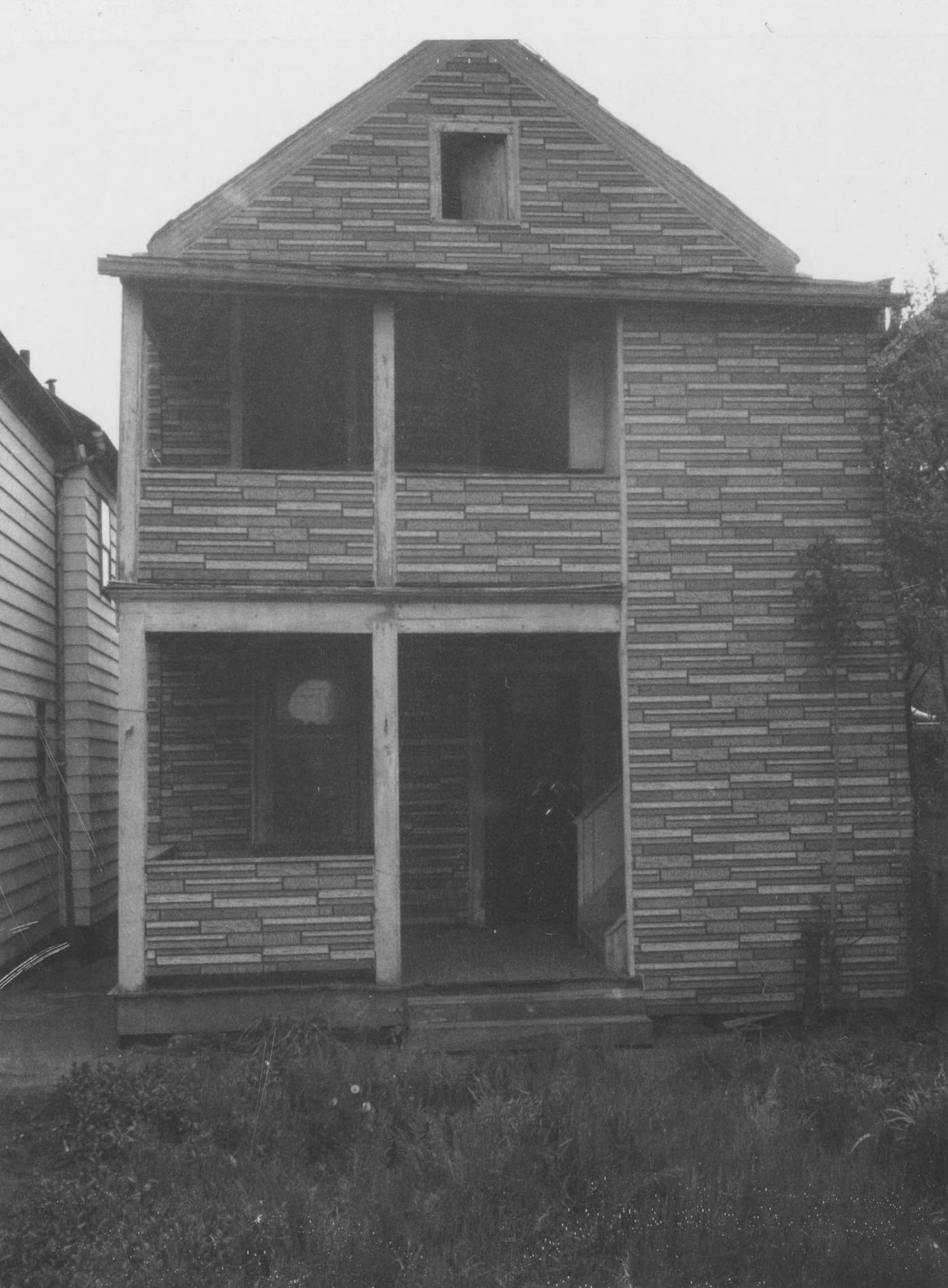

Neighborhood Activism: Throughout the 1970s, various community organizations were active in addressing issues like neighborhood decline, poor housing, and discrimination. Groups worked to stabilize communities and advocate for fair housing practices. The Cuyahoga Plan, formed in 1974, specifically focused on combating discriminatory practices in the real estate market. This grassroots activism was a key feature of the decade, as residents organized to tackle local problems and fight for their communities.

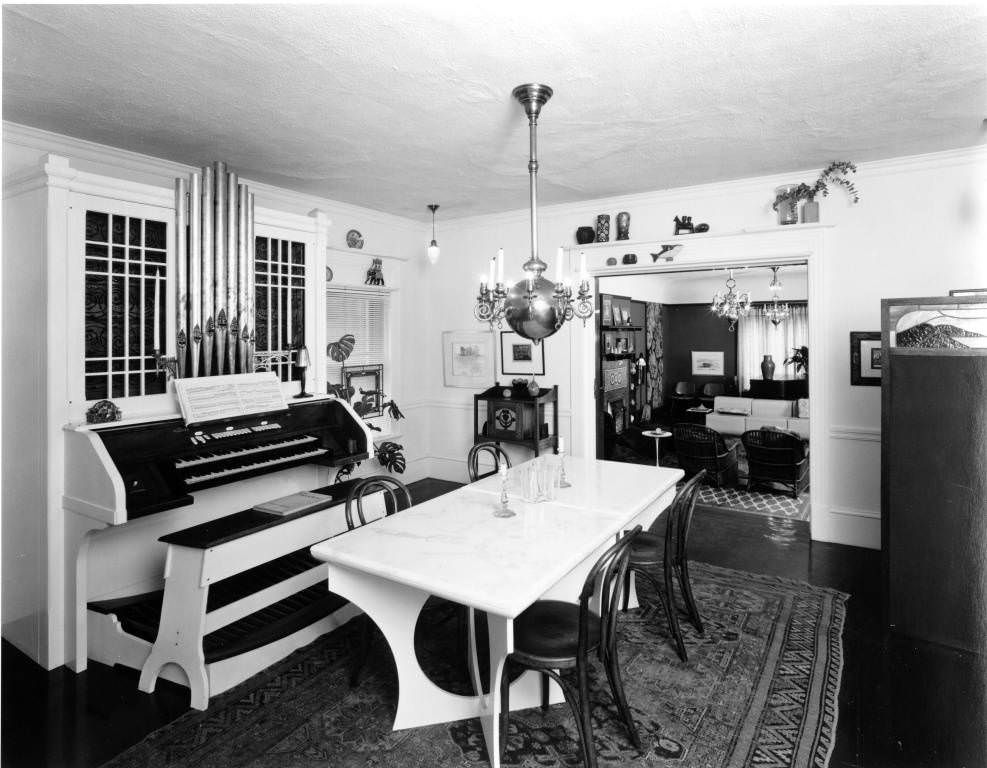

Cleveland’s cultural scene in the 1970s offered both entertainment and a reflection of the times. The city had a vibrant rock and roll scene.

Genres: A wide range of music was popular. Hard rock acts like Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin performed in the city. Glam rock, with its flamboyant style, was represented by artists like David Bowie, who played in Cleveland in 1972. Softer rock, folk-rock, and jazz-influenced rock also had a following. Disco music became very popular by the middle of the decade, with local clubs like the Mad Hatter, Nite Moves, and the Piccadilly becoming hotspots. In contrast to mainstream sounds, punk rock also emerged, with both national and local bands playing in smaller venues.

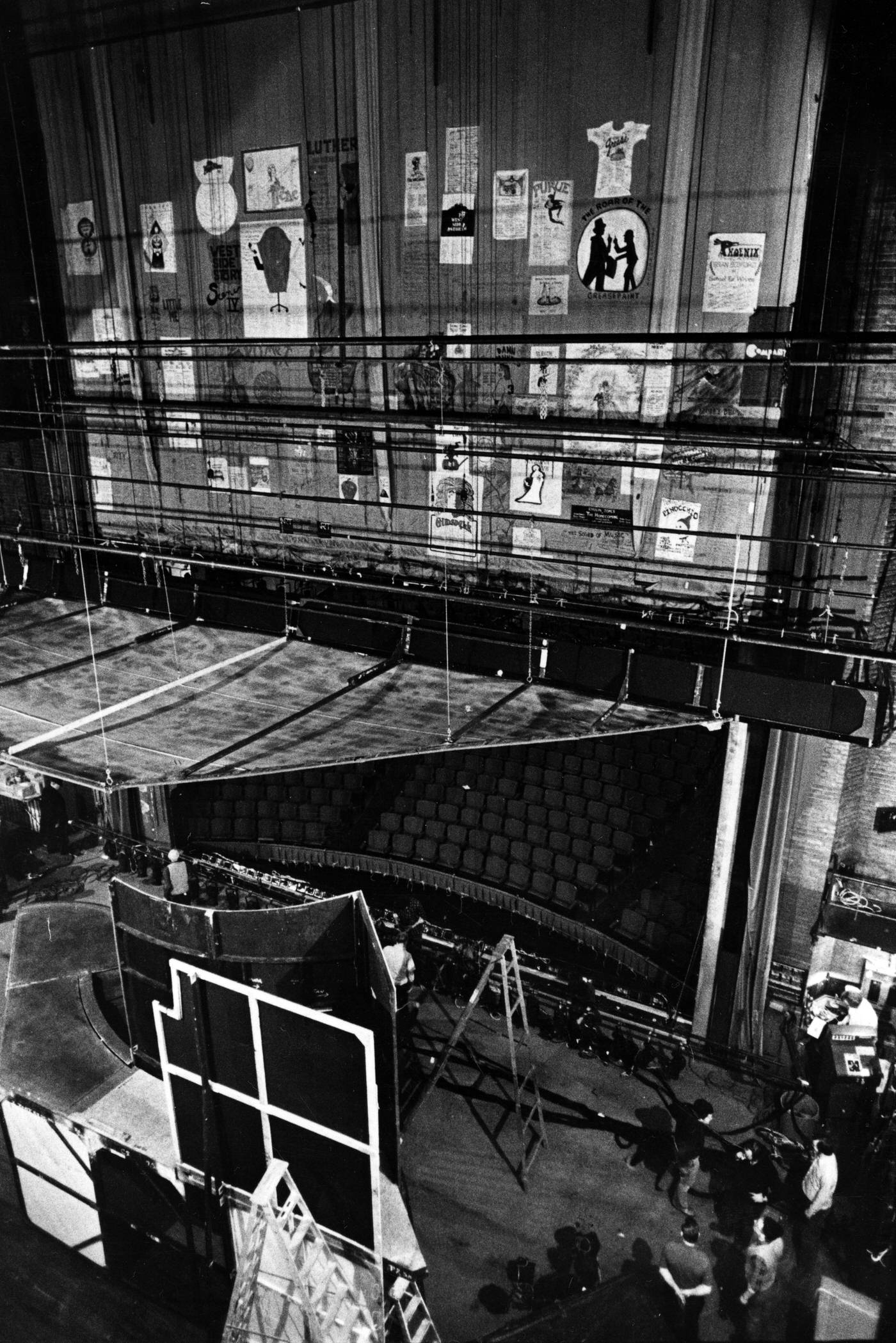

Venues: The Agora continued to be an important club, hosting famous acts like Paul Simon. Leo’s Casino, a major venue for soul music in the 1960s, had featured legendary performers like Otis Redding and Stevie Wonder, but it closed in 1972. Musicarnival, a summer tent theater, hosted many rock and pop concerts, including Led Zeppelin and The Doors, until it closed in 1975 due to rising rent and competition from newer venues like the Front Row Theater, Blossom Music Center, and the Richfield Coliseum. The Richfield Coliseum, which opened in 1974, became a major arena for large rock concerts. Starting in 1974, Cleveland Municipal Stadium hosted the World Series of Rock, which were large, day-long, multi-band summer concerts featuring major national acts.

Radio: Cleveland radio played a big role in the music scene. WNCR was a pioneering FM station with a “progressive rock” format, playing album tracks beyond the Top 40 hits. WMMS became one of the most influential rock stations in the country, known for its popular DJs and for helping to launch the careers of artists like Bruce Springsteen and David Bowie. The popular music show Soul Train began airing on Cleveland’s WKYC television station in 1971.

Local Sports Teams

Cleveland Browns (NFL): The Browns had a mixed record in the 1970s. They made the playoffs in 1971 and 1972 but did not advance far. Their season records during the decade included: 1970 (7-7), 1971 (9-5), 1972 (10-4), 1973 (7-5-2), 1974 (4-10), 1975 (3-11), 1976 (9-5), 1977 (6-8), 1978 (8-8), and 1979 (9-7).

Cleveland Indians (MLB): The Indians generally struggled throughout the 1970s. In 1970, for example, they finished fifth in the American League East with a 76-86 record. The team also experienced instability in its ownership during this period.

Cleveland Cavaliers (NBA): The Cavaliers basketball team began playing in 1970. A major highlight was the 1975-76 season, famously known as the “Miracle of Richfield.” That year, the Cavaliers won their first Central Division championship and reached the Eastern Conference Finals. Their coach, Bill Fitch, was named Coach of the Year. The team also made playoff appearances in 1977 and 1978.

Media Landscape

Television: Local television programming was a part of daily life. “Morning Exchange,” a daily show on Channel 5 featuring interviews, news, and weather, began in 1972 and became a long-running fixture. UHF stations like WUAB (Channel 43) offered viewers movies, reruns of network shows, and sports broadcasts. Cable television started to become available in Cleveland’s suburbs in 1974.

Newspapers: The Plain Dealer and the Cleveland Press were the city’s major daily newspapers. The Plain Press, a community newspaper focusing on issues on the near west side, started publishing in March 1971. The Cleveland Press faced financial difficulties and declining readership; it had lost its circulation lead to the Plain Dealer in 1968. The Press was sold in 1980 and eventually closed in 1982. The editorial positions of these newspapers on major issues of the day, such as school busing and the city’s fiscal crisis, were closely watched and often sparked public discussion and disagreement. For instance, reporting by Bob Holden of The Plain Dealer was credited with significantly informing the public during the Muny Light controversy, influencing a voter decision to save the public utility despite initial polls suggesting it would be sold and alleged pressure from CEI on the newspaper.

Cleveland’s cultural scene in the 1970s, especially its music, reflected national trends while also maintaining a strong local flavor. It provided an outlet for expression and a source of community pride during a time of economic and social difficulty. The city’s media, while also undergoing changes, played a vital role in shaping public understanding and debate about the critical issues Cleveland faced.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress, Cleveland State University Collection, Cleveland Press Collection, clevelandmemory.org

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know