Cleveland stepped into the 1980s carrying the heavy weight of recent financial troubles and an economy undergoing painful changes. The city was working to find its footing after a period of significant difficulty.

The decade began with Cleveland still dealing with the fallout from its financial default on December 15, 1978. On that date, the city found itself unable to repay $14 million in loans owed to six local banks. This failure meant that for almost two years, Cleveland could not sell municipal bonds, which are loans investors make to cities to fund public projects like road repairs or new buildings. Without access to this crucial funding, improving the city became much harder. Because of the default, the State of Ohio stepped in to oversee Cleveland’s finances.

The Economic Climate: Industrial Tremors

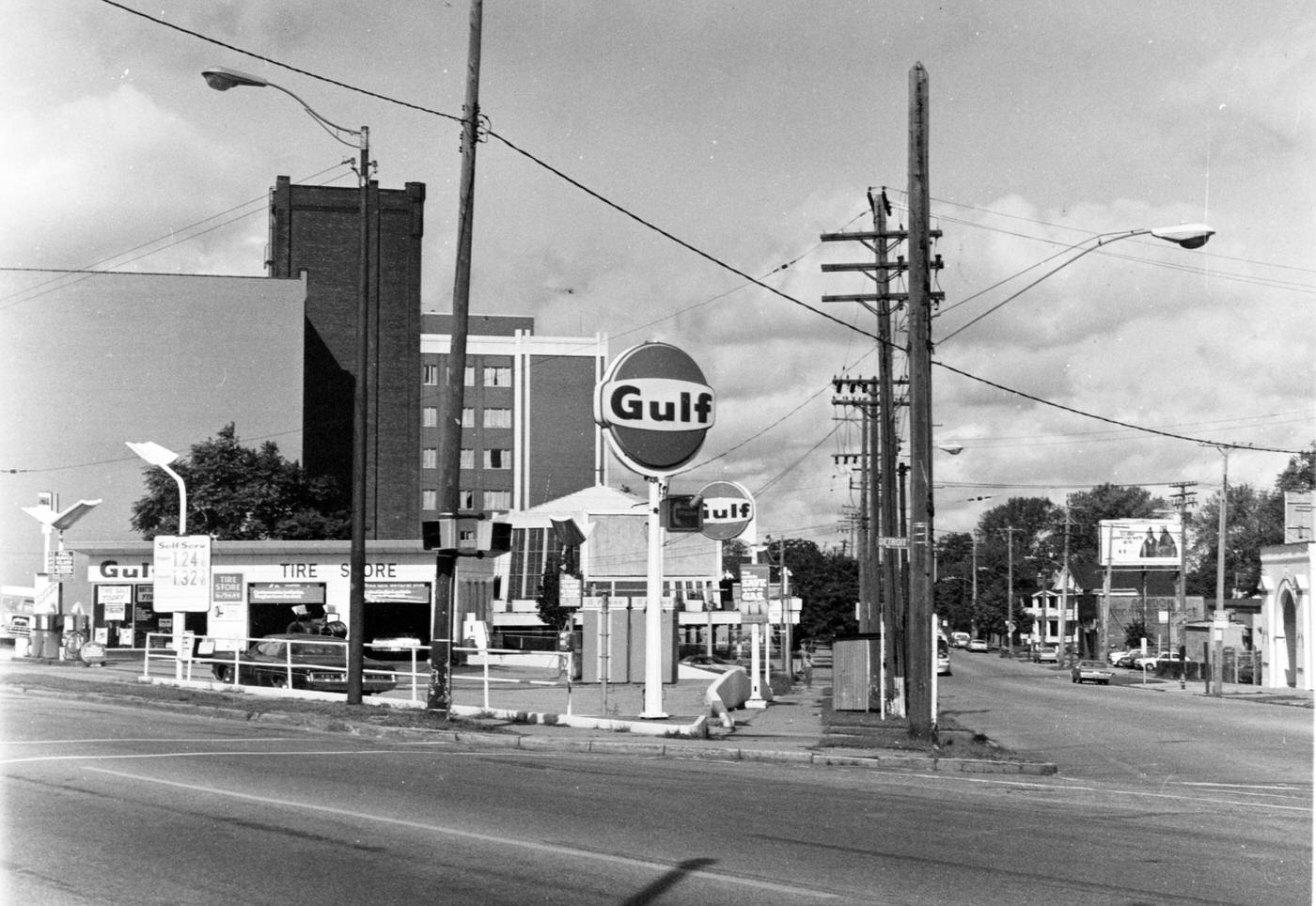

The early 1980s brought a national recession, an economic slowdown that hit Cleveland particularly hard because many of its jobs were in manufacturing. As factories struggled or closed, many people lost their jobs. Cleveland’s unemployment rate climbed, at one point reaching 13.8 percent higher than the national average, largely because several steel production plants shut down.

The steel and iron industry had long been a cornerstone of Cleveland’s economy. However, in the 1980s, it faced a storm of challenges: rising prices for goods (inflation), competition from steel made in other countries, new rules to protect the environment, slower production, and demands for higher wages from workers. These pressures led to major setbacks. For example, U.S. Steel closed its Cuyahoga Works, a significant local employer.

Other industries also suffered. The machine tool industry, which made machines used in other factories, declined. This was partly because companies were slow to adopt new technologies and faced more competition from around the world. Warner & Swasey, a large and well-known Cleveland company in this sector, was sold, and several of its local plants closed. The Cleveland Twist Drill Company, another important manufacturer, had to restructure and reduce its workforce in 1982. The garment industry, which makes clothing and was once a leading source of jobs, also continued a decline that had started after World War II. Many clothing factories moved away, were sold, or simply closed their doors. These events showed a broad shift away from the traditional industries that had once made Cleveland a powerhouse. The city’s financial instability was directly linked to this industrial decline; fewer jobs meant fewer people paying taxes, which reduced the city’s income and made it harder to pay its debts or invest in new solutions. This lag in adapting to a changing global economy, such as the machine tool industry’s slow uptake of new technology, suggested that some of Cleveland’s economic wounds were due to an inability to change with the times, a common story in many older industrial cities.

Socio-Economic Indicators: A City in Distress

The economic troubles had a clear impact on the people of Cleveland. The city’s population, which had been shrinking for some time, continued to fall. In 1980, Cleveland had 573,822 residents and was no longer one of the ten largest cities in the United States. By the end of the decade, in 1990, the population would drop to 505,616, a decrease of nearly 12%.

This population loss was one sign of what experts called urban “distress.” Cleveland was identified as one of the nation’s more distressed cities during this period. This meant it faced high levels of poverty and unemployment. The percentage of people living in poverty rose from 17.1% in 1980 to 22.1% in 1990. At the same time, the average real income per person, adjusted for inflation, actually went down by 4.3% between 1979 and 1989. Families were forced to leave Cleveland, and those who remained often faced significant financial stress, struggling to make ends meet as paychecks bought less and less.

Other social indicators also pointed to hardship. The percentage of families headed by women increased from 17.1% in 1980 to 20.5% in 1990. Such households often face greater economic challenges. While the overall population declined, the city’s demographic makeup was also changing. The proportion of Black residents increased from 31.6% in 1980 to 35.2% in 1990. The total minority population, including Black and Hispanic residents, grew from 35.0% to 39.9% over the decade. These figures paint a picture of a city experiencing not just economic transformation, but also significant social and human impact.

New Leadership and a Path to Recovery

As Cleveland navigated these turbulent waters, new leadership emerged with a focus on steering the city back to financial health.

In November 1979, George Voinovich, a Republican, became Cleveland’s mayor. He stepped into office facing an enormous challenge: the city was in default, owing $110 million on its financial obligations. Voinovich brought a background in state and county government, having served in the Ohio legislature and as Cuyahoga County Auditor and Commissioner, as well as Ohio’s Lieutenant Governor. This experience would be vital in tackling Cleveland’s deep-seated fiscal problems.

Mayor Voinovich’s top priority was clear: balance the city’s budget and lift Cleveland out of default. To achieve this, he took several decisive actions. One of his first major initiatives was creating an Operations Improvement Task Force. This group brought together executives from local private industries to lend their expertise to city government. This marked the beginning of public-private partnerships in Cleveland, a strategy where the city government and private businesses work together for common goals. This collaboration was instrumental, as it allowed the city to tap into a wider pool of knowledge and resources to find efficiencies.

Under this guidance, the city government itself underwent significant changes. Ten city departments were reorganized, and a new accounting system with internal auditing was put in place to better control spending and reduce administrative costs. These were practical steps toward making the city run more efficiently.

A critical breakthrough came in October 1980. Mayor Voinovich successfully negotiated a plan to repay the city’s debts. This agreement allowed Cleveland to officially escape default, a major symbolic and practical victory. However, the state of Ohio continued to supervise the city’s finances to ensure stability.

To further strengthen Cleveland’s financial position, Voinovich proposed an increase in the city income tax from 1.5% to 2%. In February 1981, voters approved this measure. Gaining public support for a tax increase, especially during a time of economic hardship and federal aid cutbacks , demonstrated a level of trust in the new administration’s plan for recovery and a shared understanding of the necessity of such measures.

The structure of city government also changed early in Voinovich’s tenure. In 1980, the term for mayor and city council members was extended from two years to four years. Voinovich was reelected twice under this new system, serving as mayor until 1989. This longer period of leadership provided stability and continuity crucial for implementing and seeing through the long-term recovery plan. While focused on the immediate financial crisis, Voinovich also looked to the city’s future, supporting the development of major civic projects like North Coast Harbor, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and the Great Lakes Science Center. This indicated a vision that extended beyond just balancing budgets, aiming to rebuild Cleveland’s image and diversify its economic attractions for the years to come.

The National Civic League honored Cleveland with its All-American City Award in 1982, 1984, and 1986. These awards were a national acknowledgment of the city’s hard work and progress in overcoming its significant challenges and beginning a new chapter.

The Changing Face of Cleveland’s Neighborhoods and Infrastructure

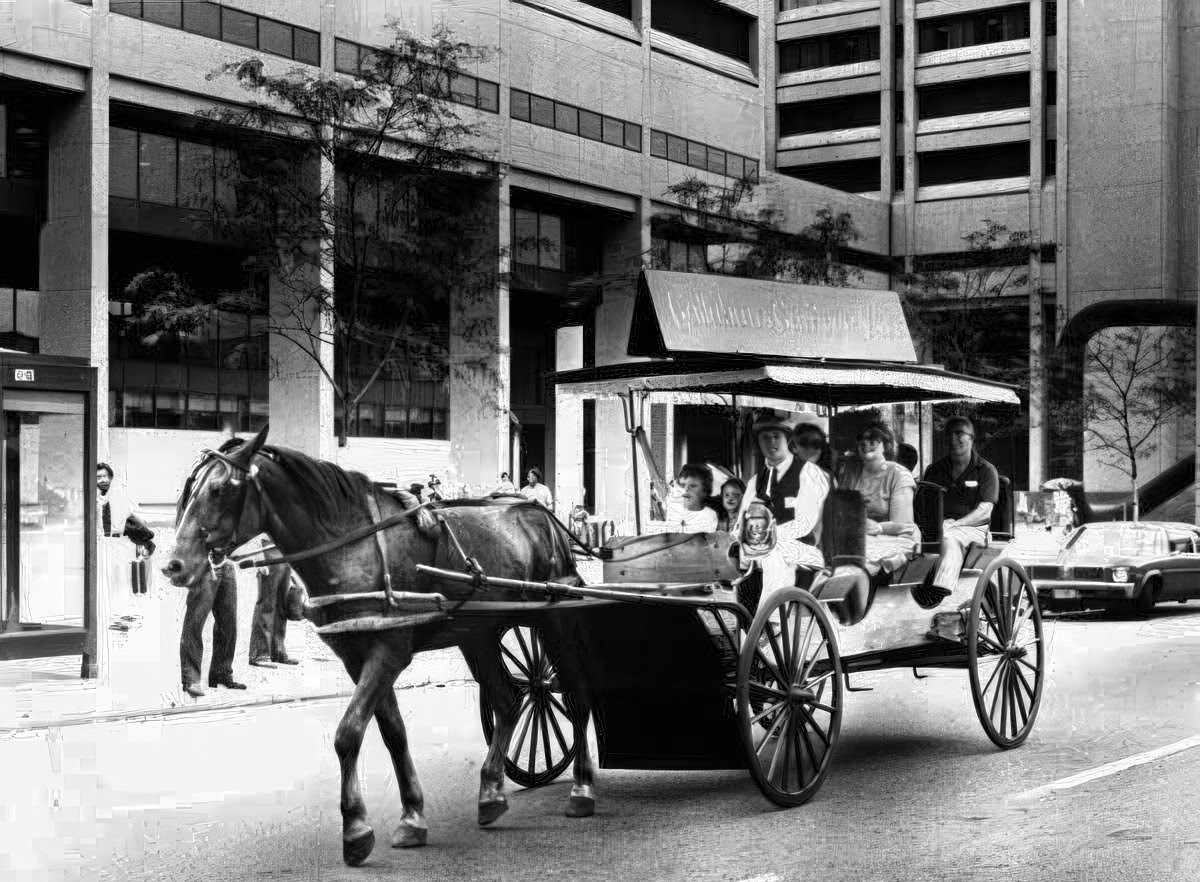

While city leaders tackled financial recovery, Cleveland’s physical landscape—from its downtown core to its many neighborhoods and transportation systems—was also undergoing significant transformation throughout the 1980s.

The Erieview urban renewal plan, a major initiative launched in 1960 to modernize the area northeast of downtown, continued to shape the city center into the 1980s. New structures rose as part of this long-term vision, including the Ohio Bell Building, One Cleveland Centre, Eaton Centre, and the Northpoint office complex. These projects added new commercial and public spaces to the city.

A particularly notable downtown development was the transformation of the Erieview Tower. In 1985, developers Jacobs, Visconsi & Jacobs acquired the tower, renaming it the Tower at Erieview. They then constructed an attached shopping mall, the Galleria, on the site of what had been the E. 9th Street plaza. The Galleria opened its doors on October 15, 1987, introducing a new type of retail and social space to downtown and significantly altering the original Erieview concept. These high-profile downtown projects were part of a broader push for revitalization, with Mayor Voinovich’s administration securing $149 million in Urban Development Action Grants that helped attract $770 million in private investment, contributing to an estimated $3 billion in overall construction activity during his tenure.

Beyond downtown, Cleveland’s many residential neighborhoods were also areas of focus, though they faced immense challenges. This loss of residents affected communities across Cleveland, often leaving behind vacant homes and a reduced tax base. Neighborhood revitalization was a stated priority for Mayor Voinovich, with one of the earliest projects being the Lexington Village housing development in the Hough neighborhood. Completed in 1987 after years of planning and complex partnerships involving public and private funding, Lexington Village aimed to bring new, quality housing to an area that had seen little positive investment for decades.

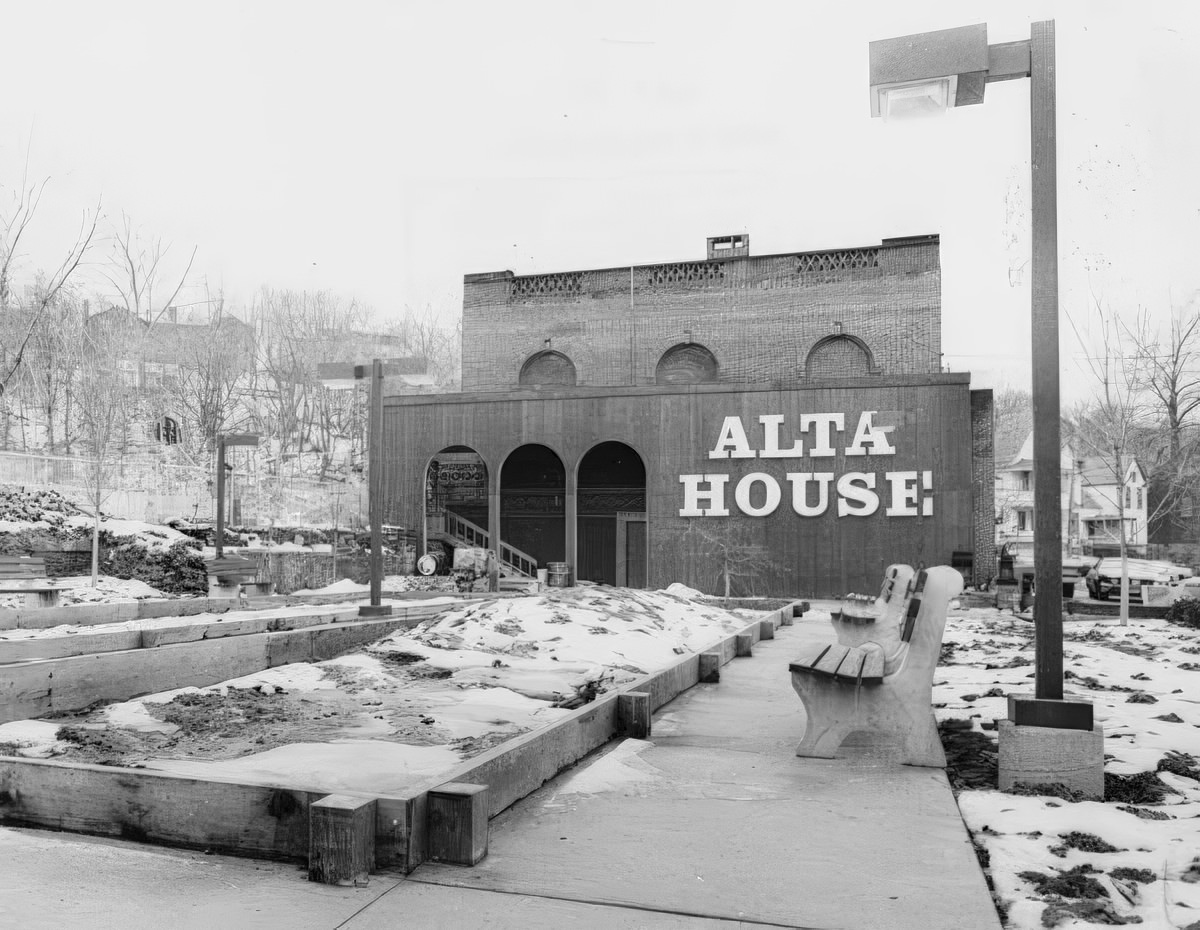

Community Development Corporations (CDCs) became increasingly important players in these neighborhood efforts. Groups like the Famicos Foundation in Hough, the Tremont West Development Corporation , and the Slavic Village Association (which later merged to become the Slavic Village Broadway Development Corporation) worked on a variety of local initiatives. These included rehabilitating aging houses, fostering local economic growth, and working to preserve the unique character of their communities. The Cleveland Housing Network, established in 1981 by Famicos and Tremont West, was a pioneer in developing a lease-purchase model, which helped low-income families eventually buy the renovated homes they lived in.

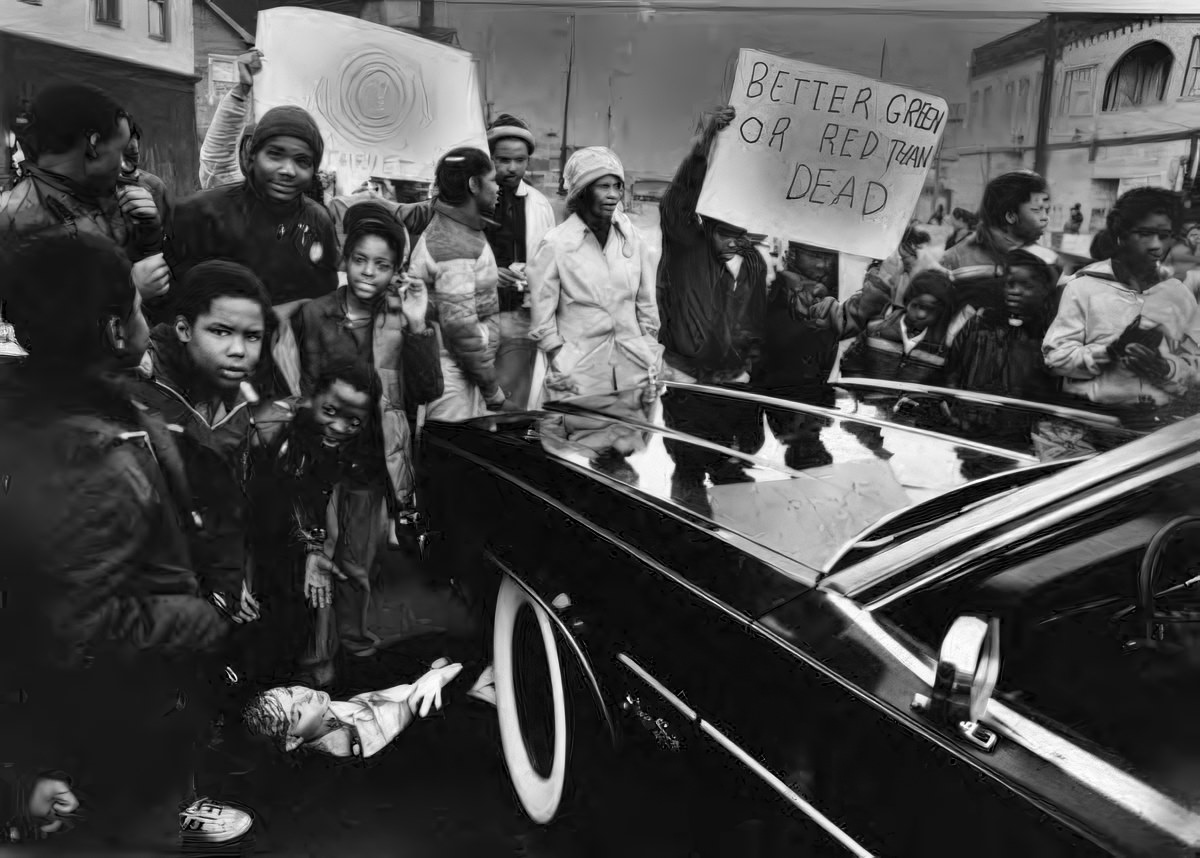

These CDCs often grew out of strong community activism. Residents and local leaders, concerned about deteriorating conditions, organized to demand change. For instance, in 1981, neighborhood activists picketed a corporate event for Standard Oil of Ohio (Sohio), an action that contributed to increased corporate willingness to support community

development projects. Advocacy from community groups also played a part in the creation of the Cleveland Housing Court, designed to address housing issues and tenant rights. By 1989, the City of Cleveland had begun to formalize its support for CDCs, dedicating nearly $9 million in Community Development Block Grant funds to housing-focused non-profits. This signaled a growing recognition of the vital role these grassroots organizations played in tackling neighborhood problems.

Despite these efforts, many neighborhoods continued to struggle. Tremont, for example, was described in the 1980s as still being run-down and somewhat cut off from the rest of the city, with many old homes and a significantly smaller population than it once had. The contrast between the visible progress downtown and the persistent challenges in many residential areas highlighted the complexity of urban renewal; the benefits of downtown development did not always quickly or evenly reach all parts of the city.

The Music Scene: Rock, New Wave, and Local Heroes

Cleveland’s reputation as a rock and roll city was further solidified in the 1980s. A key development was the establishment of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Foundation in Cleveland in 1983 , a crucial step that would eventually lead to the physical museum opening in the city. Radio station WMMS continued its reign as an influential force in rock radio, winning Rolling Stone magazine’s “Radio Station of the Year” award multiple times into the 1980s.

Live music venues were central to the scene. The Phantasy Entertainment Complex in nearby Lakewood was a haven for alternative, goth, and industrial rock music. It played a role in launching the careers of nationally recognized bands like Devo and Exotic Birds, and notably, it was the debut location for Nine Inch Nails. The Phantasy also drew major touring acts such as Iggy Pop, The Ramones, and The Psychedelic Furs. Another legendary venue, The Agora, continued to host a wide array of musical talent. Although it suffered a fire in October 1984 and closed temporarily, it reopened three years later at the Metropolitan Theater. The Agora was so well-regarded that Billboard magazine named it the “Best Club in the Country” in 1980.

Local bands enjoyed strong followings. The Michael Stanley Band was particularly popular, setting attendance records at the Blossom Music Center in 1982. Other notable Cleveland-linked acts making waves included The Pretenders, fronted by Akron native Chrissie Hynde, whose debut album in 1980 was a critical and commercial success. Bands like Pere Ubu and The Waitresses also contributed to the diverse soundscape. Beyond rock, R&B group LeVert also rose to prominence during this period. The launch of MTV in 1981 also changed how music was consumed, making music videos an important promotional tool. The vibrancy of the music scene, from local heroes to emerging national acts, was a powerful part of Cleveland’s cultural identity.

A Day to Remember (or Forget): Balloonfest ’86

On September 27, 1986, Cleveland’s Public Square became the scene of a unique and ultimately infamous event: Balloonfest ’86. Organized by the United Way, the goal was twofold: to raise funds for the charity and to set a spectacular world record by simultaneously releasing nearly 1.5 million helium-filled balloons.

The event was intended to bring positive attention to Cleveland. However, it quickly turned into an environmental and public relations problem. Unfavorable weather conditions, including strong winds and rain, caused the massive cloud of balloons to descend rapidly over the city and Lake Erie instead of drifting away as planned. The fallen balloons created widespread litter, clogged waterways, and forced a temporary shutdown of a runway at Burke Lakefront Airport. Most tragically, the blanket of balloons on Lake Erie severely hampered a U.S. Coast Guard search and rescue operation for two fishermen who had gone missing. The Coast Guard was unable to locate the men in time. The incident also led to lawsuits, including one from the owner of a prized horse in Medina County that was reportedly spooked by the falling balloons. Balloonfest ’86 ended up costing United Way money and became a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of large-scale public spectacles, particularly concerning environmental impact and safety, issues that perhaps received less foresight than they might today.

Ethnic Communities: Traditions and Transitions

Cleveland’s rich tapestry of ethnic communities continued to be a defining feature of the city in the 1980s, with groups actively working to maintain their cultural heritage amidst the decade’s changes. This cultural activity provided a source of stability and pride for many.

The Italian community, centered in Little Italy, remained a strong presence. A highlight was the annual Feast of the Assumption, sponsored by Holy Rosary Church. By the 1980s, this had become one of the few surviving traditional Italian religious feasts and had grown into a very large and popular event. Further institutionalizing their heritage, the Mayfield-Murray Hill District Council officially established the Little Italy Historical Museum in 1983.

For the Polish community, the Slavic Village neighborhood (also known as Warszawa) was the primary area where traditions were actively maintained. The Slavic Village Association, formed in 1978, organized the annual Slavic Village Harvest Festival, which became a major attraction, drawing large crowds each year. Polka music, central to many Eastern European cultures in Cleveland, did face some decline in the 1980s as popular radio stations changed their music formats. However, the popularity of button-box accordion clubs, especially among Slovenians, persisted.

Cleveland’s Hispanic community was experiencing growth and increased organization. By 1983, there were approximately 25,000 people of Puerto Rican descent, around 4,000 of Mexican descent, and about 650 Cubans (as of 1980) living in the Greater Cleveland area. Reflecting this growing presence, the Hispanic Community Forum sponsored Cleveland’s first annual Hispanic convention in 1984. Social service organizations like the Spanish American Committee were also active in supporting the community.

The Irish community, while its distinct neighborhoods had largely dispersed by earlier decades , also saw efforts to celebrate its heritage. The Cleveland Irish Cultural Festival was founded in 1982 and quickly gained popularity, expanding from a two-day to a three-day event by 1985. Events like the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike, though occurring in Ireland, resonated deeply within the local Irish American community and were subjects of discussion and remembrance. These varied activities across different ethnic groups demonstrated a collective desire to preserve cultural identities and provide a sense of community, offering a source of strength and continuity during a period of widespread economic and social flux.

Theater: Premieres, Expansions, and Experimental Stages

The Cleveland Play House (CPH), one of the nation’s oldest regional theaters, underwent significant physical changes in the 1980s. Its older 77th Street Theatre was closed as CPH consolidated its operations. The company purchased the adjacent Sears building, and renowned architect Philip Johnson designed major additions, including the new Bolton Theatre. This expansion transformed CPH into the largest regional theatre complex in the United States at the time.

Artistically, CPH presented notable productions. In 1984, it staged the world premiere of Arthur Miller’s play The Archbishop’s Ceiling. A 1988 revival of Born Yesterday, starring Ed Asner and Madeline Kahn and directed by new Artistic Director Josephine R. Abady, was successful enough to move to Broadway. In 1989, CPH was the first theater to produce Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie with an all-African-American cast.

Other theaters also contributed to the scene. Cain Park Theater, an outdoor venue in Cleveland Heights, continued to offer productions in its amphitheater and the smaller Alma Theater. A new canopy was added over the amphitheater in 1989 to protect against weather, and the theater received the Governor’s Award for the Arts in 1987. A newer force, Cleveland Public Theatre (CPT), was founded in 1982 by James Levin. CPT quickly became a vital space for experimental and original theater works by contemporary artists, moving into its permanent home on Detroit Avenue in 1984.

Visual Arts: Museums and Galleries

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) maintained its status as a leading cultural institution. Under the directorship of Evan H. Turner (1983-1993), the museum hosted major exhibitions with themes focusing on Japanese art, the works of Picasso, and ancient Egypt. A significant acquisition in 1980 was Jackson Pollock’s abstract expressionist painting “Number 5, 1950 (Elegant Lady)”. The museum also organized thematic exhibitions like “Creativity in Art and Science, 1860-1960” in 1987.

For local artists, the annual May Show at the CMA continued its long run (until 1993), providing a prestigious juried exhibition opportunity that highlighted talent from Cleveland and the surrounding Western Reserve region. Beyond the CMA, the gallery scene was also evolving. SPACES, founded in 1978 to support emerging and alternative artists, moved twice in the 1980s due to rising rents in gentrifying neighborhoods. It relocated to the Bradley Building in the Warehouse District in 1983, and then, with the help of major grants, purchased its own building on the Superior Viaduct in 1990. This provided a stable home for artists working outside the mainstream. The ARTneo Museum, dedicated to preserving and showcasing the work of Cleveland-area artists, also traces its origins to the 1980s.

Public Education: Navigating Desegregation and New Models

Cleveland Public Schools underwent profound changes during the 1980s, largely shaped by the full implementation of court-ordered desegregation by 1980. This followed the Reed v. Rhodes judicial decision, which found the school system had engaged in segregation. The primary method used to achieve desegregation was widespread cross-city busing of students, a practice that had begun in 1978 and continued throughout the decade.

Busing was a deeply divisive issue. While community groups like WELCOME (West-East Siders Let’s Come Together) organized rallies to promote a peaceful transition , there was also significant community unrest and opposition. A major consequence was that many white families opted to send their children to private schools or moved out of Cleveland to suburban districts. As a result, Cleveland’s public schools became predominantly non-white during the 1980s. This demographic shift within the school system, while individual schools became more racially balanced according to court mandates (aiming for a racial composition within plus or minus 15% of the district average ), may have contributed to a different kind of segregation between the city’s schools and those in surrounding suburbs.

Students were reassigned and bused annually to meet these court-ordered racial balance requirements, and some students faced long bus rides, sometimes exceeding 80 minutes each way, to schools across town. Despite the difficulties and tensions, the implementation of busing in Cleveland was generally more peaceful than in some other major U.S. cities.

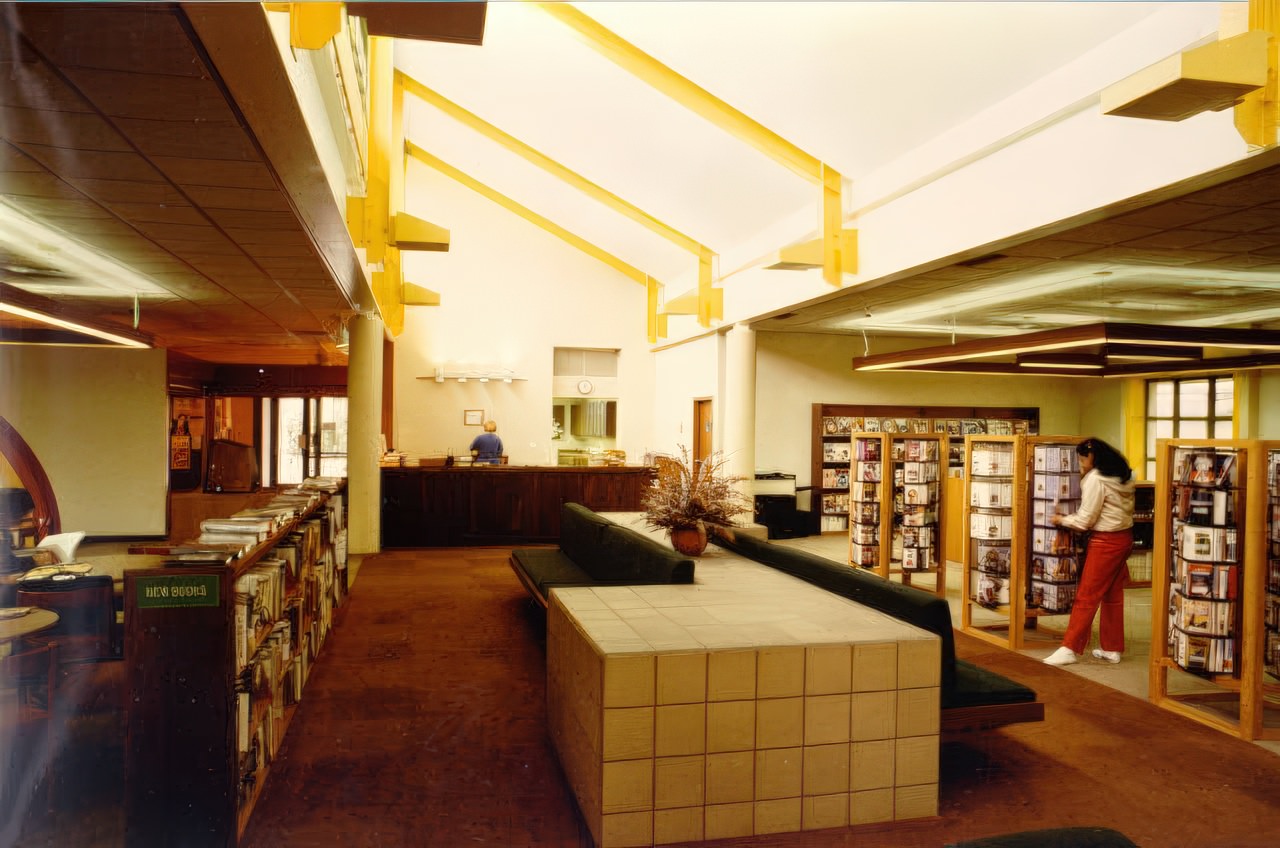

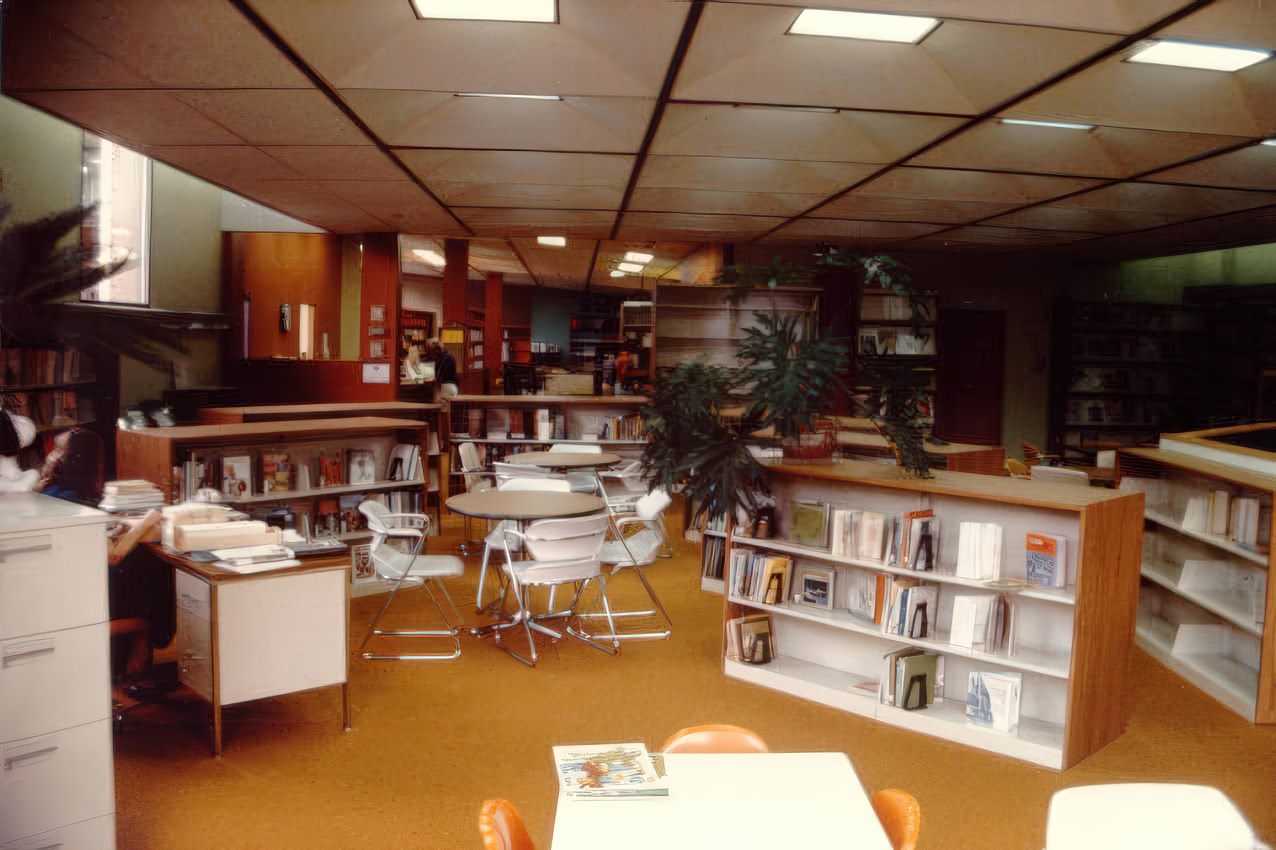

In an effort to enhance educational offerings and encourage voluntary integration, the district also introduced magnet schools. The Cleveland School of the Arts opened in February 1981, becoming the district’s first magnet school. It was designed to attract students of all races from across the city through specialized arts programming and required applications and auditions for entry. Pilot programs for three other magnet schools, including a Montessori school, were also launched around this time.

Throughout this period, Cleveland’s public schools continued to face underlying challenges common to many urban school systems, including a declining tax base due to population loss and economic shifts, and the ongoing need to address the educational impacts of poverty and racial discrimination. Extracurricular activities were considered important for student development, and court orders related to desegregation included provisions for such programs.

Public Transportation (RTA) Upgrades and Changes

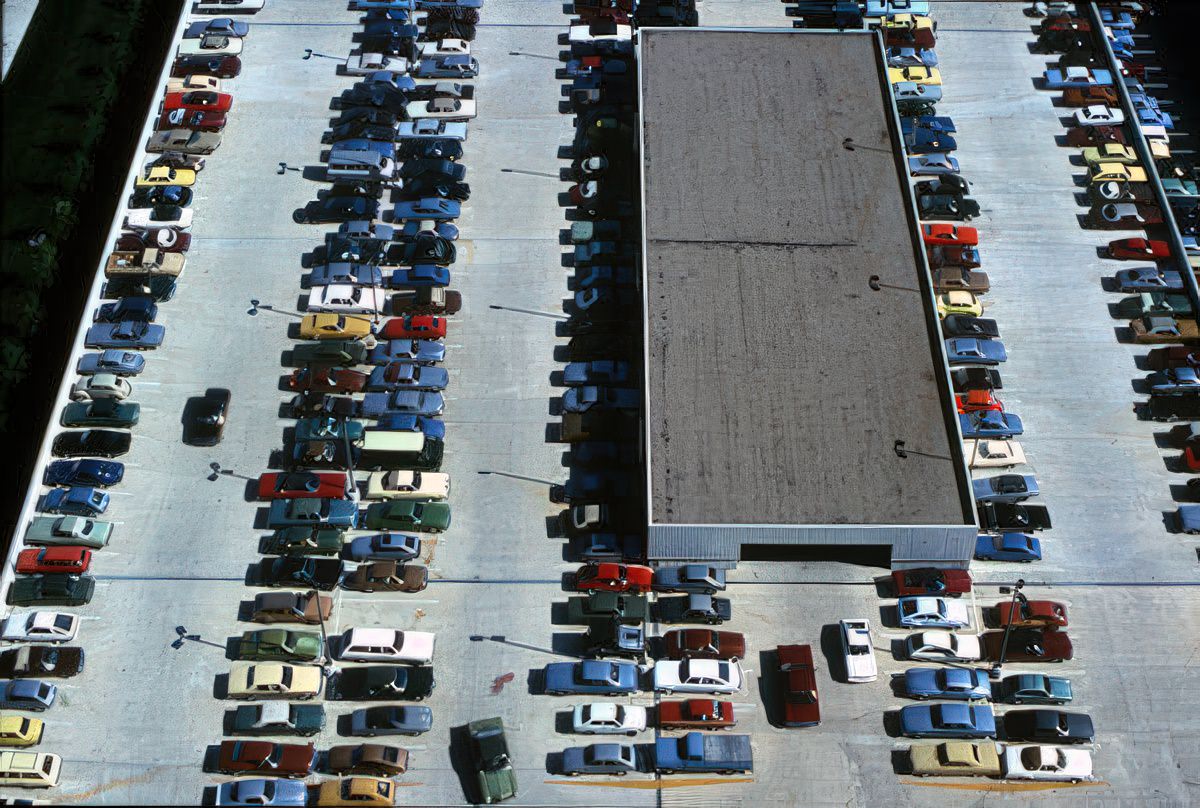

The Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) was also busy in the 1980s, investing significantly in its infrastructure and services. This commitment to public transit, even as the city faced financial recovery and population decline, suggested a long-term strategic view of its importance. In 1980, the Garfield Heights Transit system became part of RTA, expanding its reach, and fares were increased to help cover costs.

One of the most substantial projects was the $100-million rebuilding of the 15-mile Shaker Rapid lines (now known as the Green and Blue Lines). This overhaul, completed in October 1981, included new tracks, support structures, wiring, and the introduction of 48 new Breda light rail cars. Stations along these lines were also reconstructed.

RTA also focused on improving its operational capabilities. A new training facility opened at the West Park Rapid Station in 1983, followed by a new Central Bus Maintenance Facility in the same year, and a Central Rail Maintenance Facility in 1984. The fleet was updated with new “Metro” buses arriving in early 1984, and the last of 60 new heavy-rail cars, made by Tokyu, were put into service in September 1985.

By 1985, RTA celebrated its 10th anniversary, having spent over $400 million on capital improvements and purchased more than 550 new buses in its first decade. Improvements continued with new light-rail stations opening at Shaker Square and Woodhill in 1986. In 1987, RTA launched its RTAnswerline for customer information and, significantly, its annual report first mentioned plans for the Dual Hub Corridor project. This project would eventually evolve into the Euclid Corridor Transportation Project, later known as the HealthLine, a bus rapid transit system that would become a key feature of Cleveland’s public transit network.

Social Conditions and Challenges

Cleveland in the 1980s was a city grappling with serious social issues. It consistently identified as having high concentrations of poverty and unemployment. The poverty rate climbed from 17.1% at the start of the decade to 22.1% by 1990, reflecting the economic difficulties many residents faced.

The nationwide “war on drugs” had a noticeable impact on Cleveland, and crime rates were a growing concern. While crime would peak in the early 1990s, the trend was building throughout the 1980s, with homicides also reaching their highest point in 1991. In response to some of these pressures, there were official efforts to address community-police relations. For instance, the Mayor’s Committee on Police-Community Relations issued its final report in 1983. Despite such initiatives, issues like complaints of police brutality continued to be a challenge for the city.

Literary Scene: A Pulitzer and Local Voices

Cleveland’s literary connections were highlighted in 1988 when Toni Morrison received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for her powerful novel Beloved, published in 1987. Morrison, who grew up in nearby Lorain, often drew upon her Ohio experiences in her work, and this prestigious award helped affirm the region’s place in the national literary landscape. Her novel Tar Baby was also published earlier in the decade, in 1981.

A significant event in the local media and literary world was the closure of The Cleveland Press newspaper on June 17, 1982. This left The Plain Dealer as the city’s sole major daily newspaper, a change that impacted how Clevelanders received their news and how local stories were told. The reduction from two major daily papers to one represented a notable shift in the city’s information ecosystem during a period of critical self-examination and change. Towards the end of the decade, Cleveland’s distinctive industrial character and ethnic diversity began to attract writers in the mystery genre, with authors like Les Roberts using the city as a backdrop for their stories.

Cleveland Browns: The “Kardiac Kids” and Playoff Pain

The decade kicked off with an unforgettable football season. The 1980 Cleveland Browns were dubbed the “Kardiac Kids” because so many of their games were decided in the dramatic final moments. Coached by Sam Rutigliano, who was named NFL Coach of the Year, and led by quarterback Brian Sipe, the league’s Most Valuable Player, the Browns finished with an 11-5 record and captured their first AFC Central division title since 1971. Key players on this exciting team included Sipe, tight end Ozzie Newsome, running back Mike Pruitt, center Tom DeLeone, and tackle Doug Dieken.

However, the dream season ended in heartbreak. In the AFC Divisional Playoff game against the Oakland Raiders on January 4, 1981, played in brutally cold conditions at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, the Browns trailed 14-12 in the final minute. Positioned deep in Raiders territory, instead of attempting a game-winning field goal, the Browns opted for a pass play known as “Red Right 88.” Sipe’s pass intended for Newsome in the end zone was intercepted by Raiders safety Mike Davis, sealing the Browns’ fate.

The latter half of the 1980s saw the Browns, then coached by Marty Schottenheimer and featuring quarterback Bernie Kosar, make several more playoff runs. Unfortunately, these too ended in legendary disappointment, often at the hands of the Denver Broncos in AFC Championship Games. On January 11, 1987, in the title game for the 1986 season, Broncos quarterback John Elway led his team on a 98-yard game-tying drive late in the fourth quarter, a sequence forever known as “The Drive.” Denver went on to win in overtime. Almost exactly a year later, on January 17, 1988, in the AFC Championship for the 1987 season, Browns running back Earnest Byner, on his way to a potential game-tying touchdown, fumbled the ball near the Broncos’ goal line. This play became known as “The Fumble,” and Denver again emerged victorious, 38-33. The Browns would lose to the Broncos once more in the AFC Championship game for the 1989 season. Despite never reaching the Super Bowl, the Browns’ consistent contention and the dramatic nature of their games kept football fans intensely engaged. The repeated close calls, however, cemented a narrative of resilience mixed with profound frustration.

Cleveland Cavaliers: Turbulent Times and a Rebuild

The Cleveland Cavaliers experienced a tumultuous early 1980s. Ted Stepien bought the team in 1980, and his three-year ownership was chaotic. It was characterized by frequent coaching changes (six coaches in three years, including four in the 1981-82 season alone), controversial player trades that depleted future draft picks (leading the NBA to institute the “Stepien Rule” to prevent teams from trading away first-round picks in consecutive years), dwindling attendance, and substantial financial losses totaling around $15 million. On the court, the team struggled mightily, compiling a record of 66 wins and 180 losses during Stepien’s tenure. This included a disastrous 15-67 finish in the 1981-82 season and a 24-game losing streak that stretched across the 1981-82 and 1982-83 seasons.

A turning point came in 1983 when George and Gordon Gund purchased the franchise. The new ownership brought stability and a commitment to rebuilding. Under coach Lenny Wilkens, the Cavaliers transformed into a consistent playoff contender in the latter half of the decade. This resurgence was built around a core of talented young players acquired primarily through the 1986 NBA draft: center Brad Daugherty and guard Mark Price. They were soon joined by guard Ron Harper (though he was later traded in 1989) and forward Larry Nance, who was acquired via trade in 1988.

The 1988-89 season was a particular high point, as the Cavaliers finished with an impressive 57-25 regular-season record. That season, however, also ended in a memorable playoff defeat when Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls hit his famous game-winning jump shot over Craig Ehlo, known simply as “The Shot,” to eliminate the Cavaliers. The stark contrast between the Stepien years and the success under the Gunds and Wilkens demonstrated how critical stable and competent leadership was to the team’s fortunes.

Cleveland Indians: Ownership Changes and Seeds of Revival

The Cleveland Indians baseball team continued to struggle for wins and consistent fan interest through much of the 1980s. The 1980 team, for instance, finished with a losing record of 79 wins and 81 losses. Ownership changes were a significant storyline for the franchise during this period. Francis “Steve” O’Neill had become the principal owner in 1978, but by the mid-1980s, his family was looking to sell the team.

In 1986, brothers Richard E. and David H. Jacobs purchased the Indians. The period before their acquisition, particularly from 1960 to 1986, was often described as a low point for the franchise, marked by frequent managerial changes (15 in that span) and a lack of on-field success or financial strength. Under the new Jacobs ownership and with Peter Bavasi as team president, the Indians showed some signs of improvement, managing a couple of winning seasons in the mid-1980s. Crucially, the Jacobs brothers began to invest in and revitalize the team’s farm system—the network of minor league teams that develop young players. This long-term strategy, focusing on player development, laid the essential groundwork for the Indians’ resurgence and sustained success in the 1990s.

Image Credits: Cleveland Public Library, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Library of Congress, Cleveland State University Collection, Cleveland Press Collection, clevelandmemory.org

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know