At the dawn of the 20th century, Dallas, Texas was thriving and progressing rapidly. Its population in 1900 stood at 42,638, a number that, while modest, represented a significant increase from just 10,358 residents two decades earlier. This upward trend was not left to chance; the city’s expansion was the result of deliberate and ambitious civic engineering. In 1905, a group of influential businessmen formed the “150,000 Club,” a booster organization with the single, aggressive goal of pushing the city’s population to 150,000 by 1910. While this specific target was not met within the decade, the campaign signaled a coordinated effort to transform Dallas into a major urban center. The results of these efforts were dramatic. By 1910, the city’s population had more than doubled, reaching 92,104 people.

A primary tool for achieving this rapid growth was geographic expansion. On April 10, 1903, Mayor Ben E. Cabell approved an ordinance for Dallas to annex its neighboring city, Oak Cliff. This move, which followed years of debate, instantly added nearly 4,000 new citizens and doubled the city’s total area to 18.31 square miles. The annexation had been a contentious issue; an initial vote in Oak Cliff in 1900 had rejected the merger, partly due to a Dallas ordinance that banned cows from city streets—a rule that contrasted with Oak Cliff’s more lenient law allowing them to roam during the day. The final, successful vote in 1903 marked a pivotal moment in Dallas’s physical consolidation of the region.

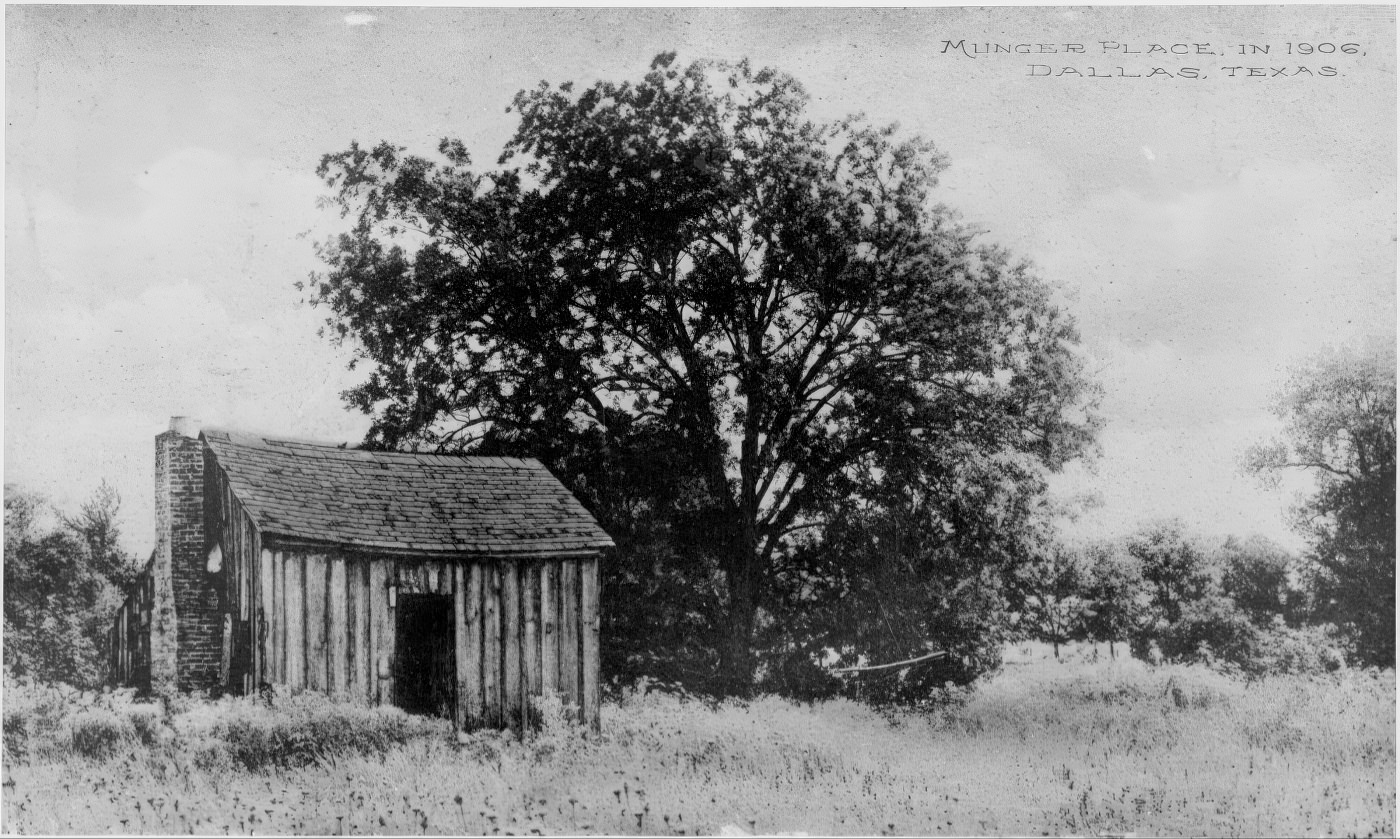

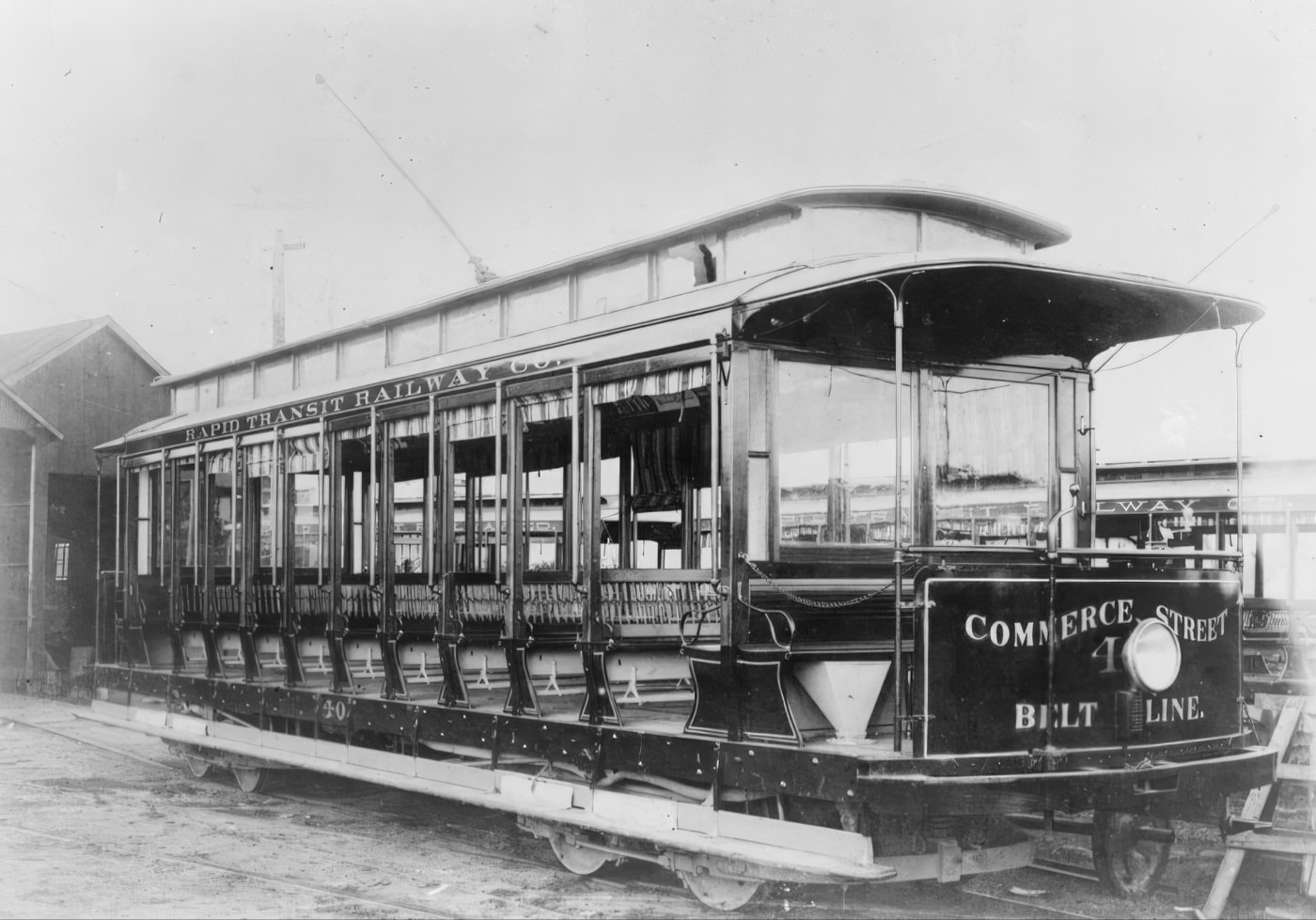

This expansion fueled a boom in residential development, which simultaneously created exclusive enclaves for the wealthy and reinforced the boundaries of segregated communities. In East Dallas, developers established planned, upscale suburbs designed to attract affluent families. Munger Place, founded in 1905 by cotton gin manufacturer Robert S. Munger, was one of Dallas’s first elite suburbs. Nearby, Swiss Avenue was developed with deed restrictions requiring homes to be at least two stories and cost a minimum of $10,000 to build, ensuring a uniform appearance of prestige. These neighborhoods showcased a rich variety of early 20th-century architectural styles, including Prairie School, Tudor Revival, and Neoclassical designs. The creation of Junius Heights in 1906 as a “streetcar suburb” highlighted the direct connection between new transportation lines and the outward spread of residential life.

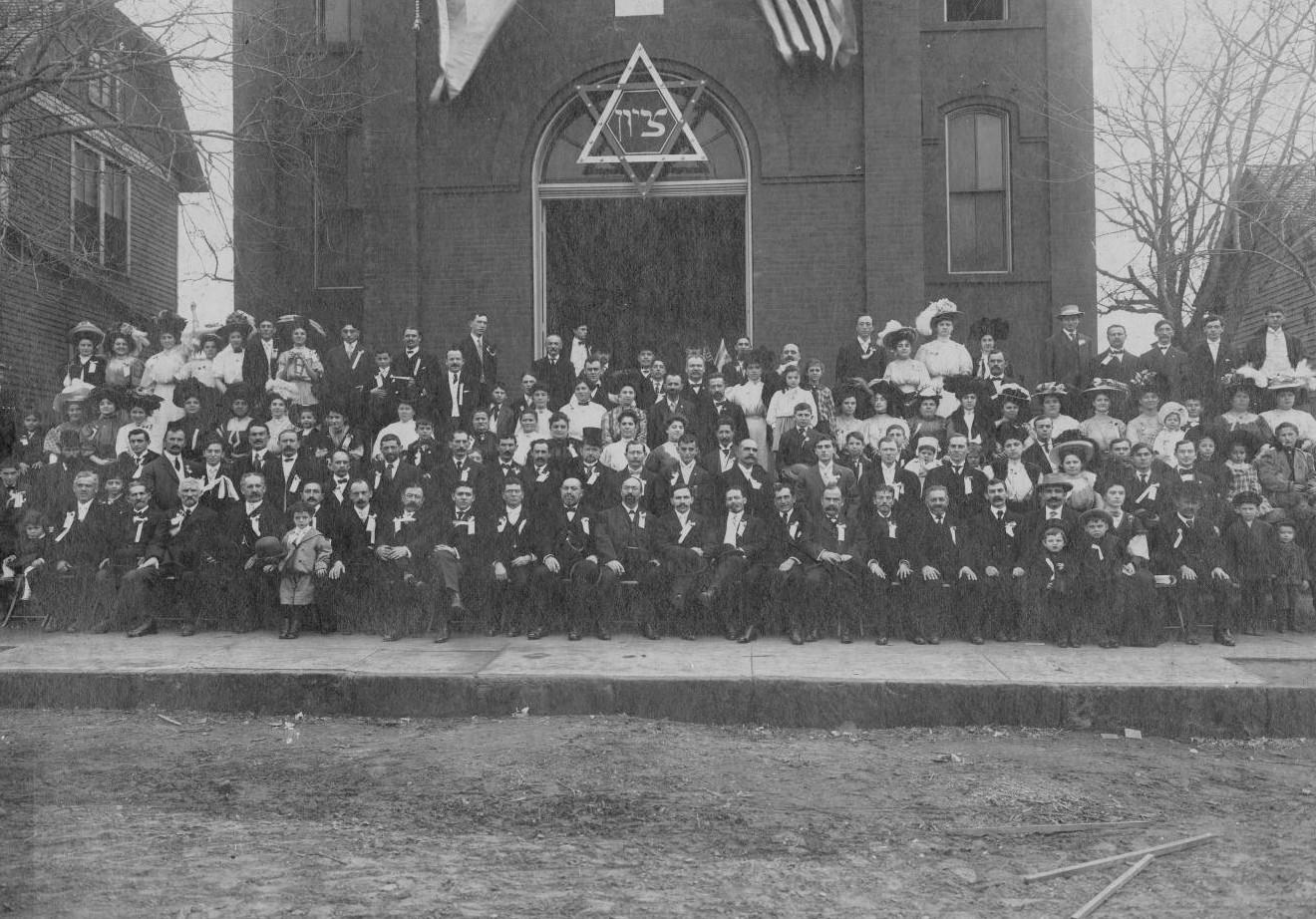

This carefully planned growth for the city’s white elite occurred alongside the continued development of established communities for minority residents. African American life was centered in neighborhoods like Freedman’s Town and Deep Ellum, which had been settled after the Civil War. In Oak Cliff, the Tenth Street district emerged as a vibrant, self-sufficient African American community, complete with its own school, churches, and a commercial district that included banks, pharmacies, and funeral homes. The city’s social and geographic landscape was further defined by the settlement of Jewish families in The Cedars neighborhood, European immigrants in East Dallas, and a growing population of Mexican immigrants in an area northwest of downtown that would become known as Little Mexico. The city was being built outward and sorted inward at the same time, with a vision of progress for some defined by the exclusion and containment of others.

The Engine of Commerce: Economy and Industry

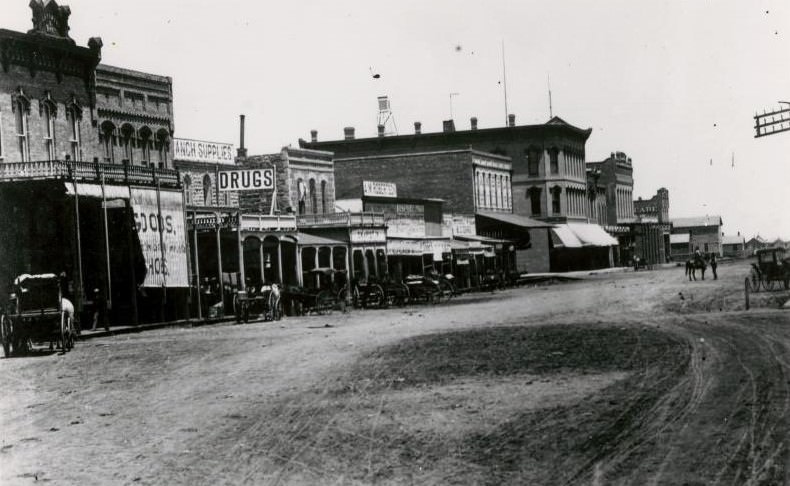

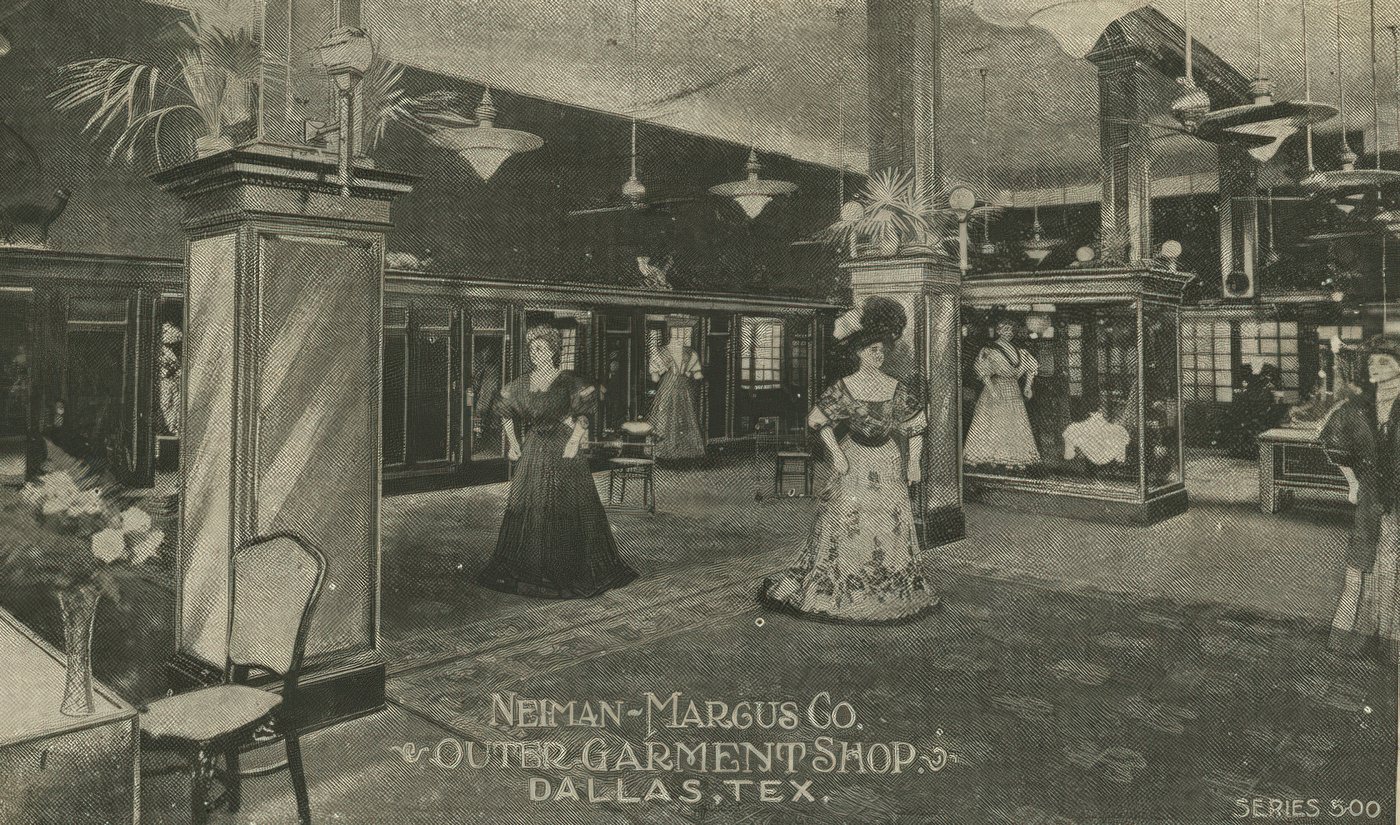

The economic identity of Dallas in the 1900s was built on a powerful, self-reinforcing system of trade, manufacturing, and finance. Its strategic location at a major railroad crossroads, a substitute for a seaport, allowed it to become the undisputed commercial hub of the Southwest. This position enabled its dominance in the region’s most valuable cash crop: cotton. By the turn of the century, Dallas was the world’s leading inland cotton market, a title that formed the bedrock of its prosperity. To formalize this status, the Dallas Cotton Exchange was organized in 1907, creating a central institution for the global trade of the commodity.

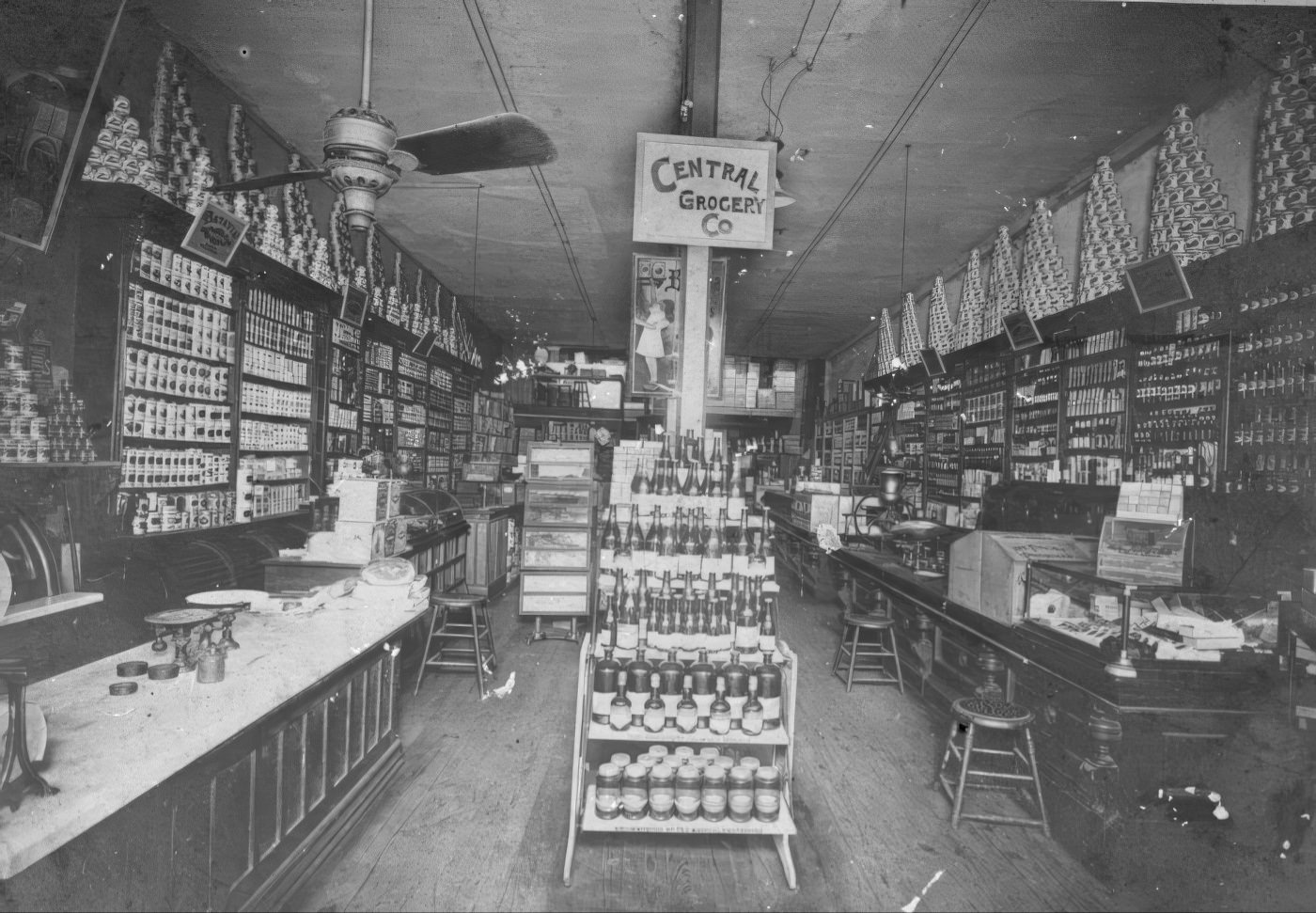

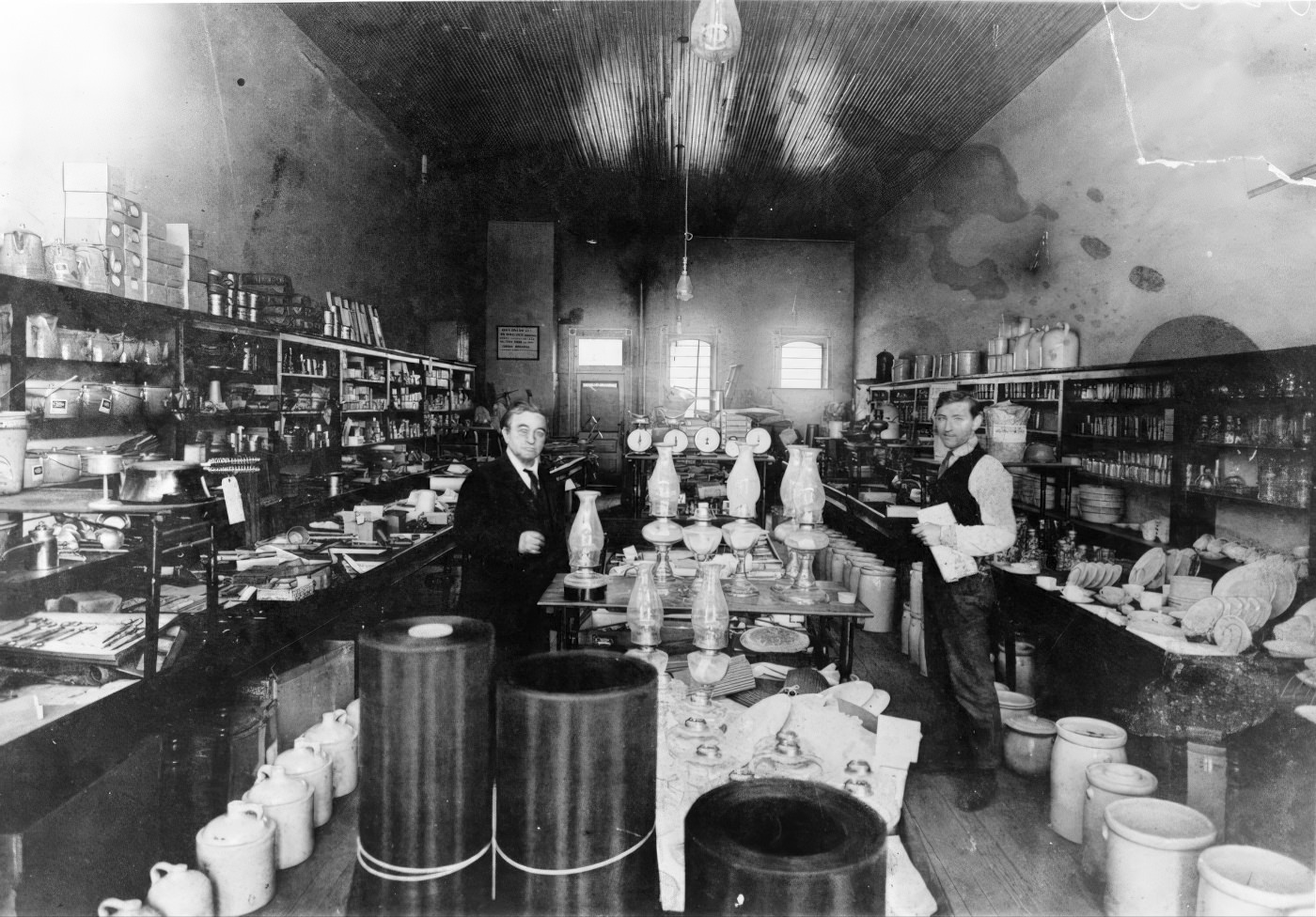

Dallas was more than just a marketplace; it was a center of production. The city led the world in the manufacturing of two key products essential to the cotton economy: cotton-gin machinery and saddlery. This industrial capacity was complemented by its role as the primary wholesale and distribution center for the entire Southwestern United States. Goods of all kinds—from books and drugs to jewelry and liquor—flowed through Dallas warehouses before reaching smaller markets across the region. Other manufacturing sectors also took root, including food processing and textiles. The Paulding County Cotton Manufacturing Company opened a factory in 1900, and the Dallas Hosiery Mill began operations five years later.

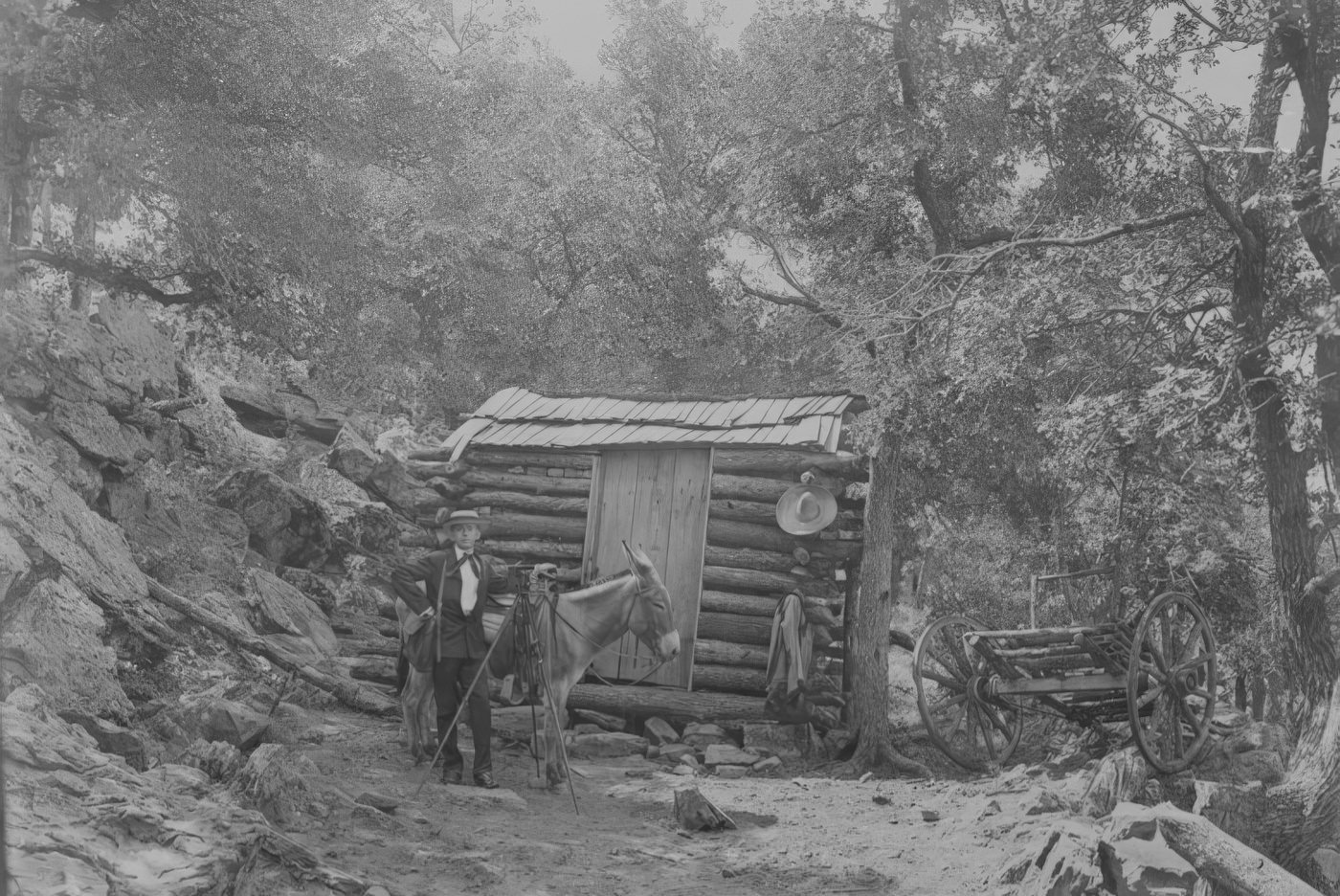

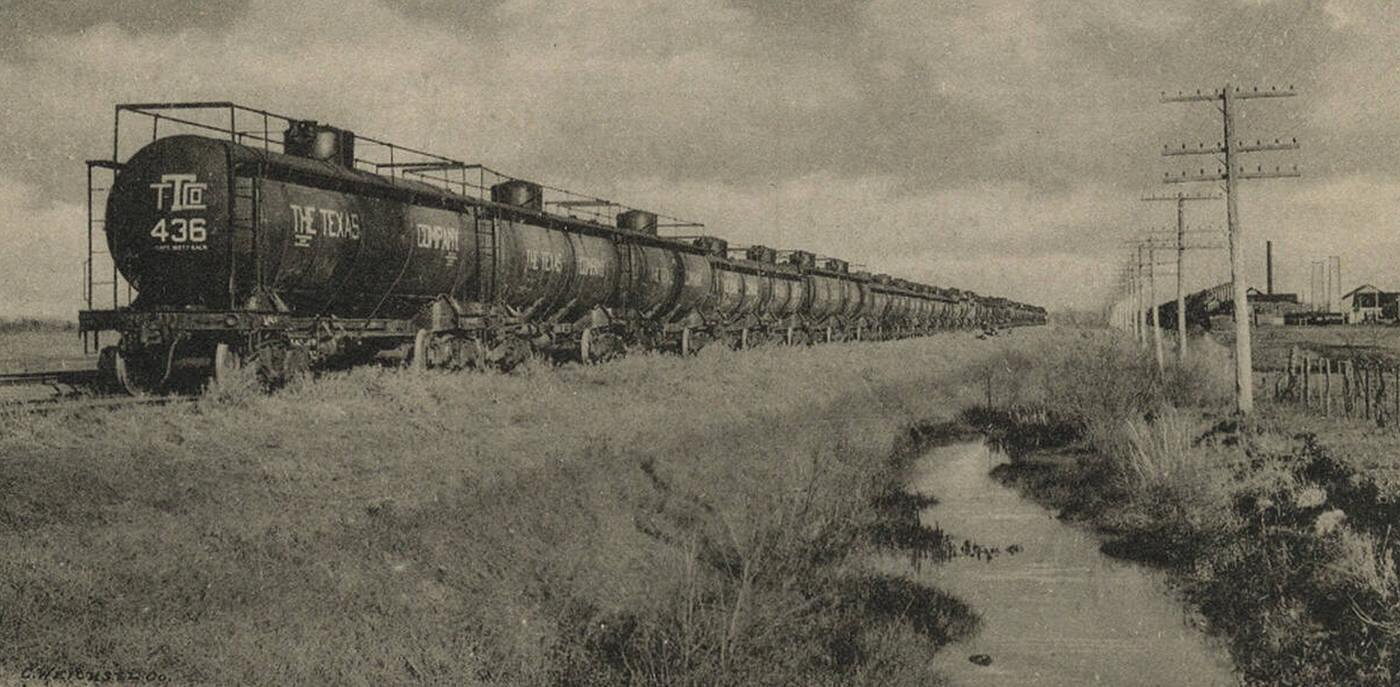

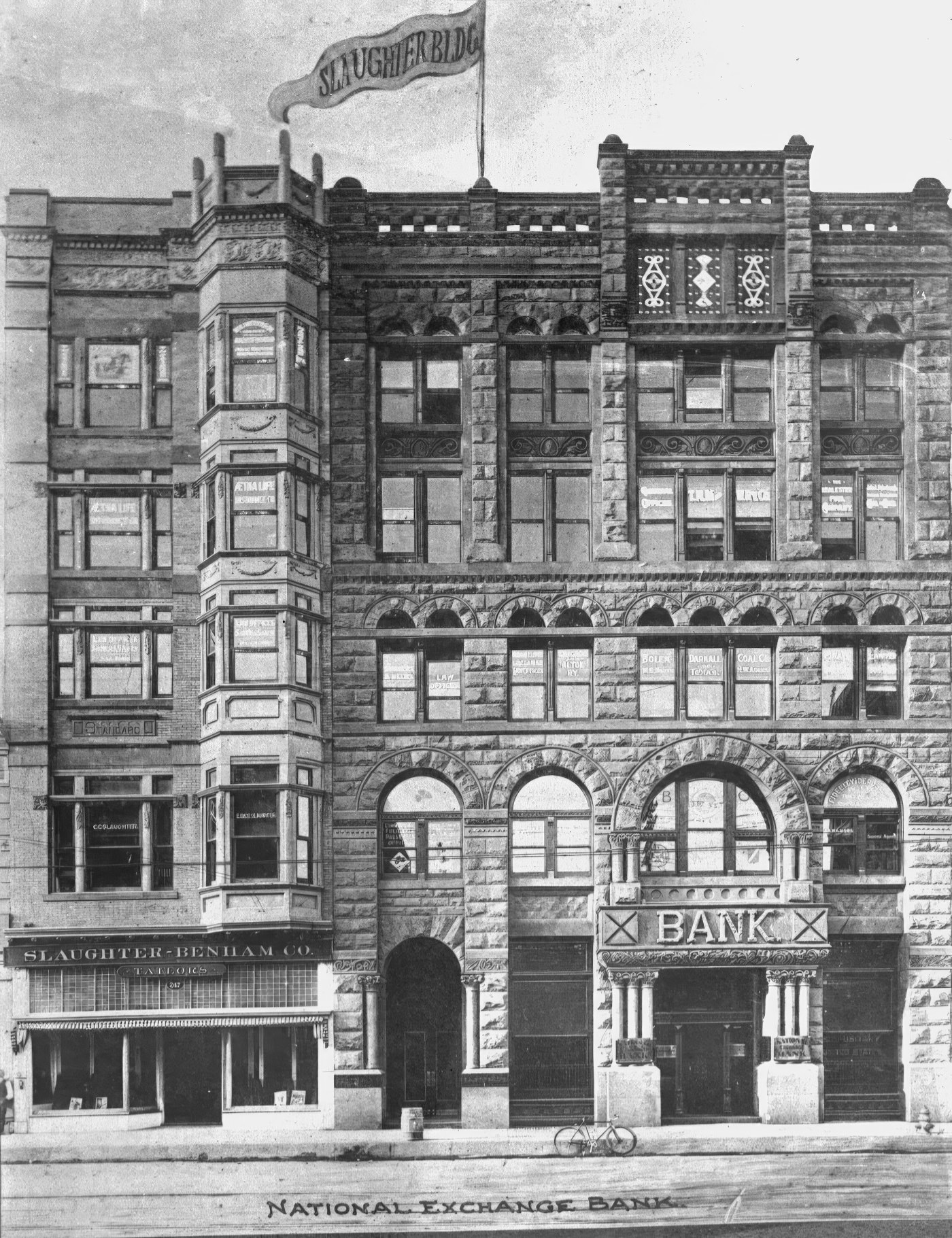

The immense capital generated by these commercial and industrial activities fueled the city’s rapid transformation into a major financial center. By 1900, Dallas was home to more than a dozen significant banking institutions. The legal framework for banking in Texas evolved during this time, when a constitutional ban on state-chartered banks was lifted in 1904. A new state banking system was established the following year, leading to a surge in the number of local banks. Dallas bankers demonstrated notable foresight, becoming pioneers in a field that would later define the Texas economy. They were among the first in the nation to finance oil exploration by lending money against oil reserves as collateral. This innovative practice was established even before the discovery of major oil fields in North Texas, positioning the city’s financial institutions to capitalize on the petroleum boom that followed the 1901 Spindletop gusher near Beaumont. The initial advantage of the railroads led to dominance in cotton, which in turn created the capital and infrastructure needed to expand into new sectors like wholesale trade and oil finance, creating an economic flywheel that accelerated the city’s growth.

Forging Connections: Transportation and Infrastructure

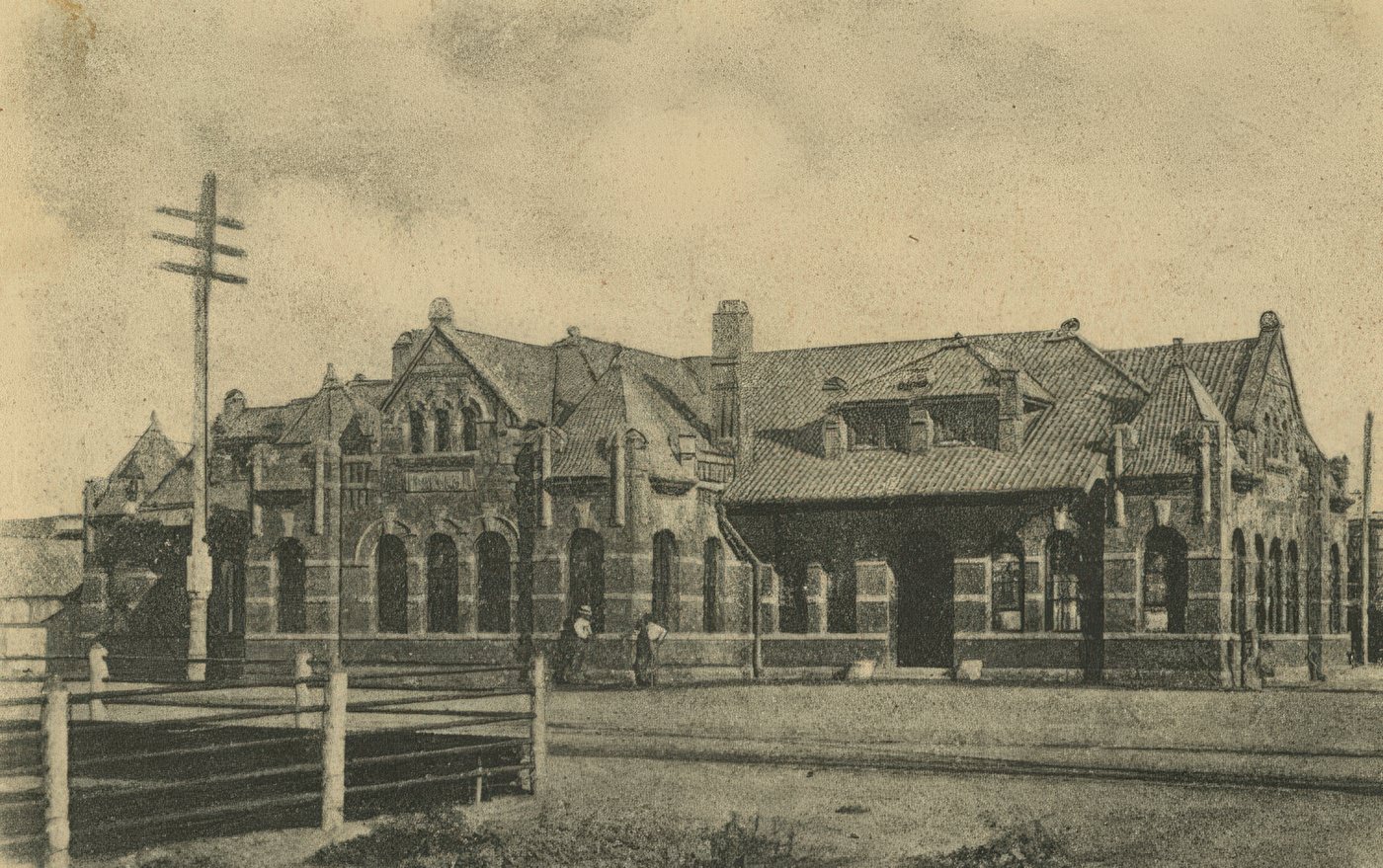

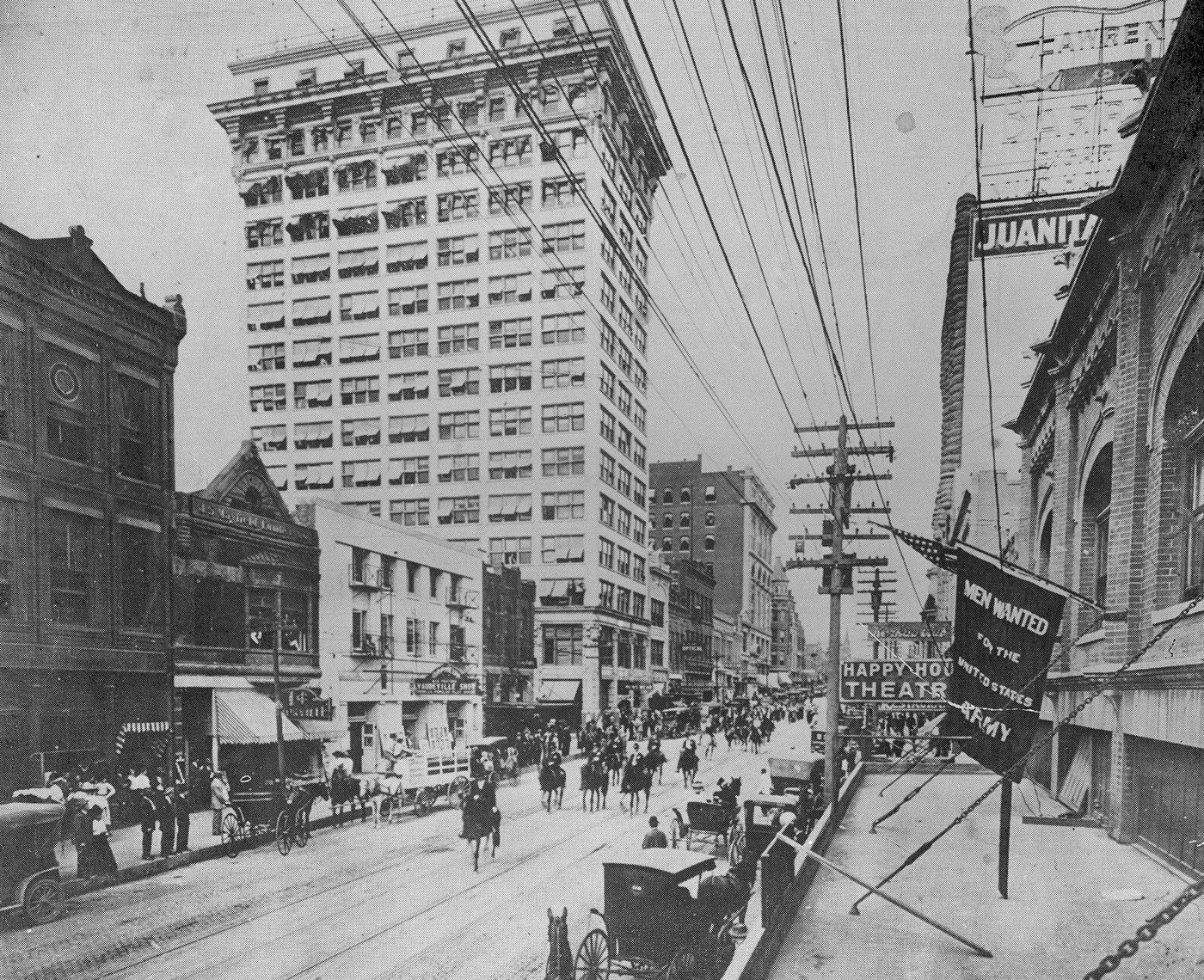

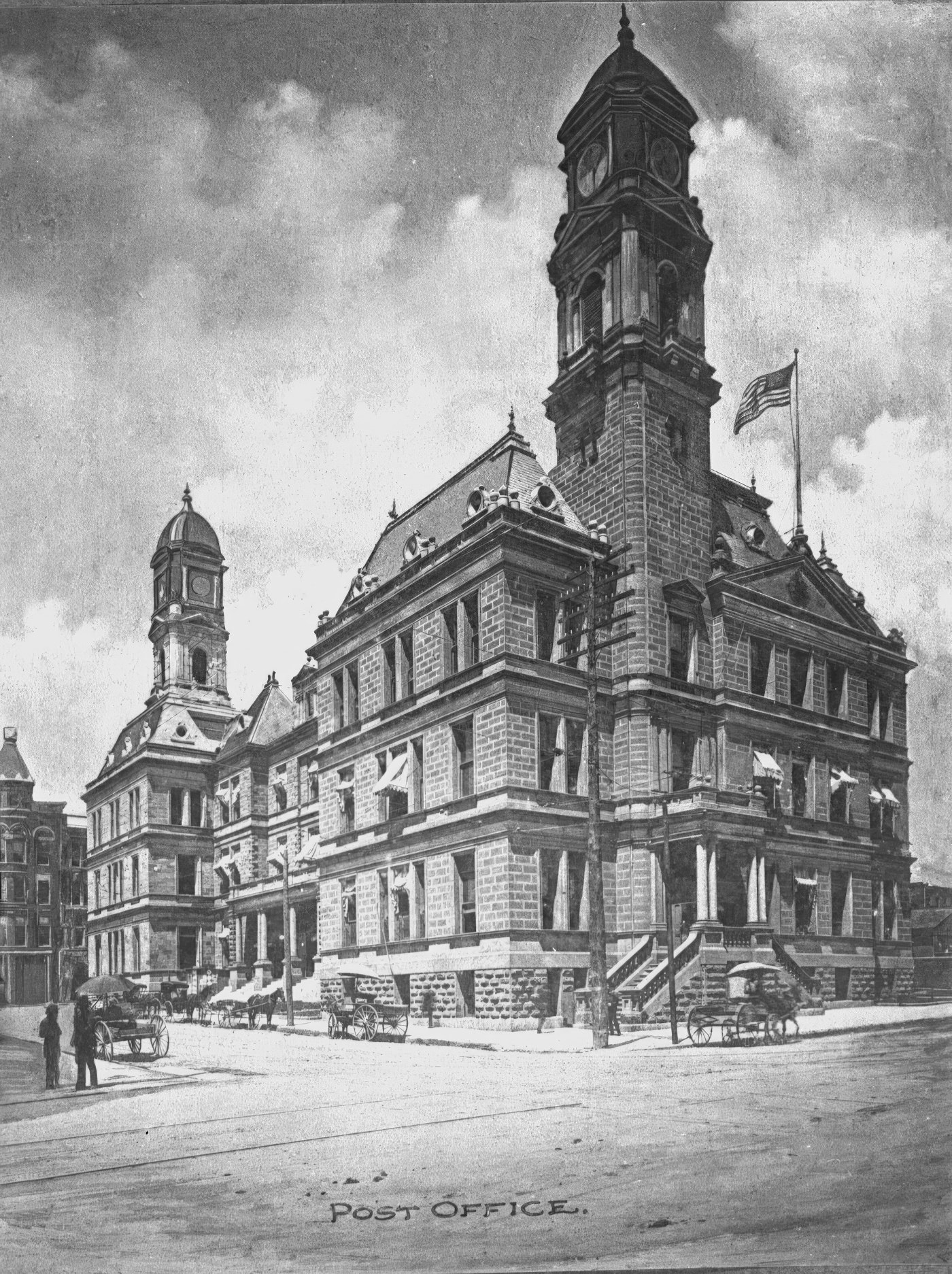

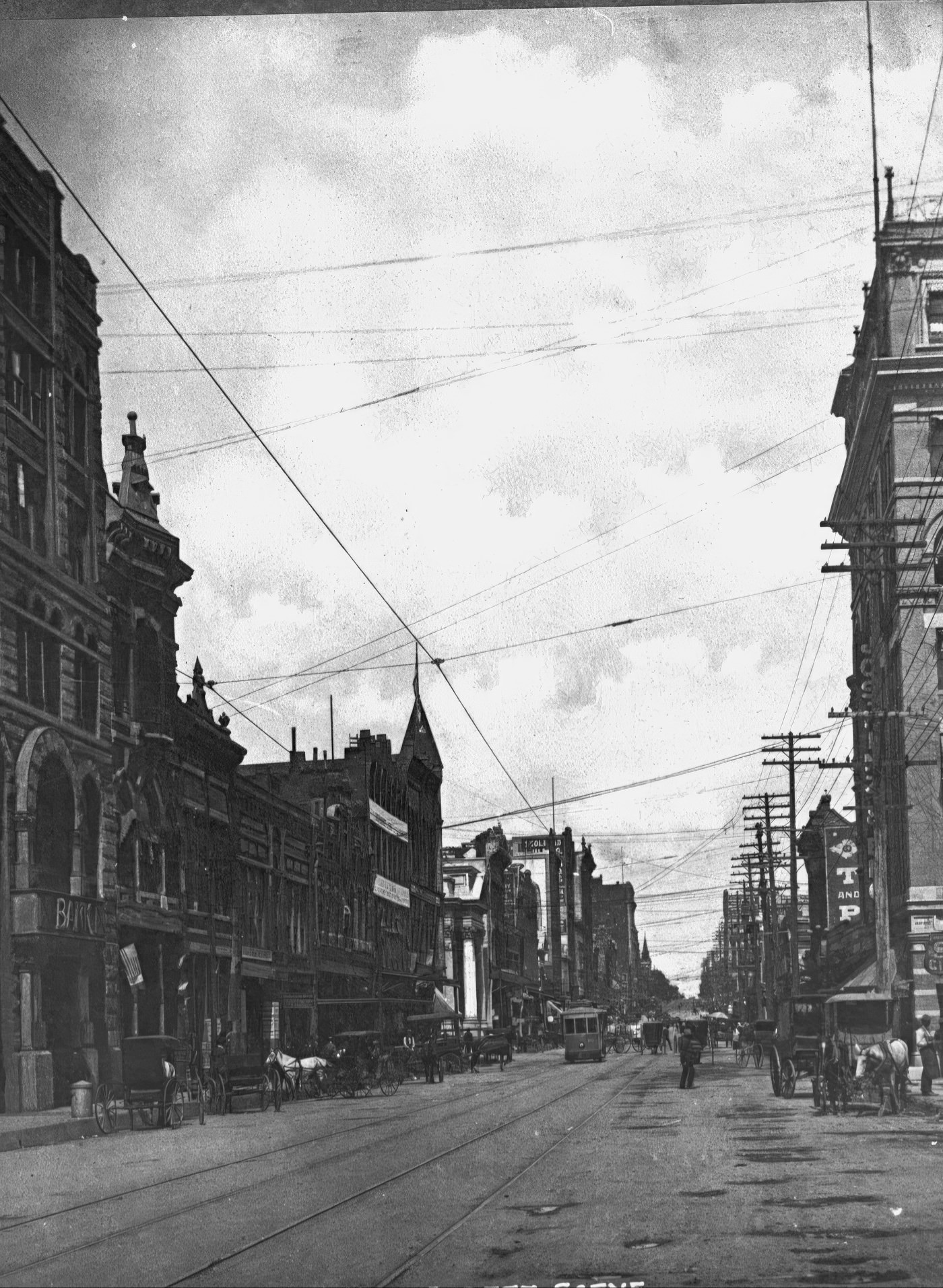

The physical networks and structures built during the 1900s were not merely functional; they were deliberate statements of Dallas’s ambition to become the preeminent city of the Southwest. Its economic engine was powered by a transportation system that was the envy of the region, and its skyline began to reflect its rising status. The foundation of this success was the railroad. Through skillful political maneuvering in the 1870s, city leaders had ensured that two major railways—the Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) and the Texas & Pacific (T&P)—intersected in Dallas, giving it a critical advantage over competing towns like McKinney and Ennis.

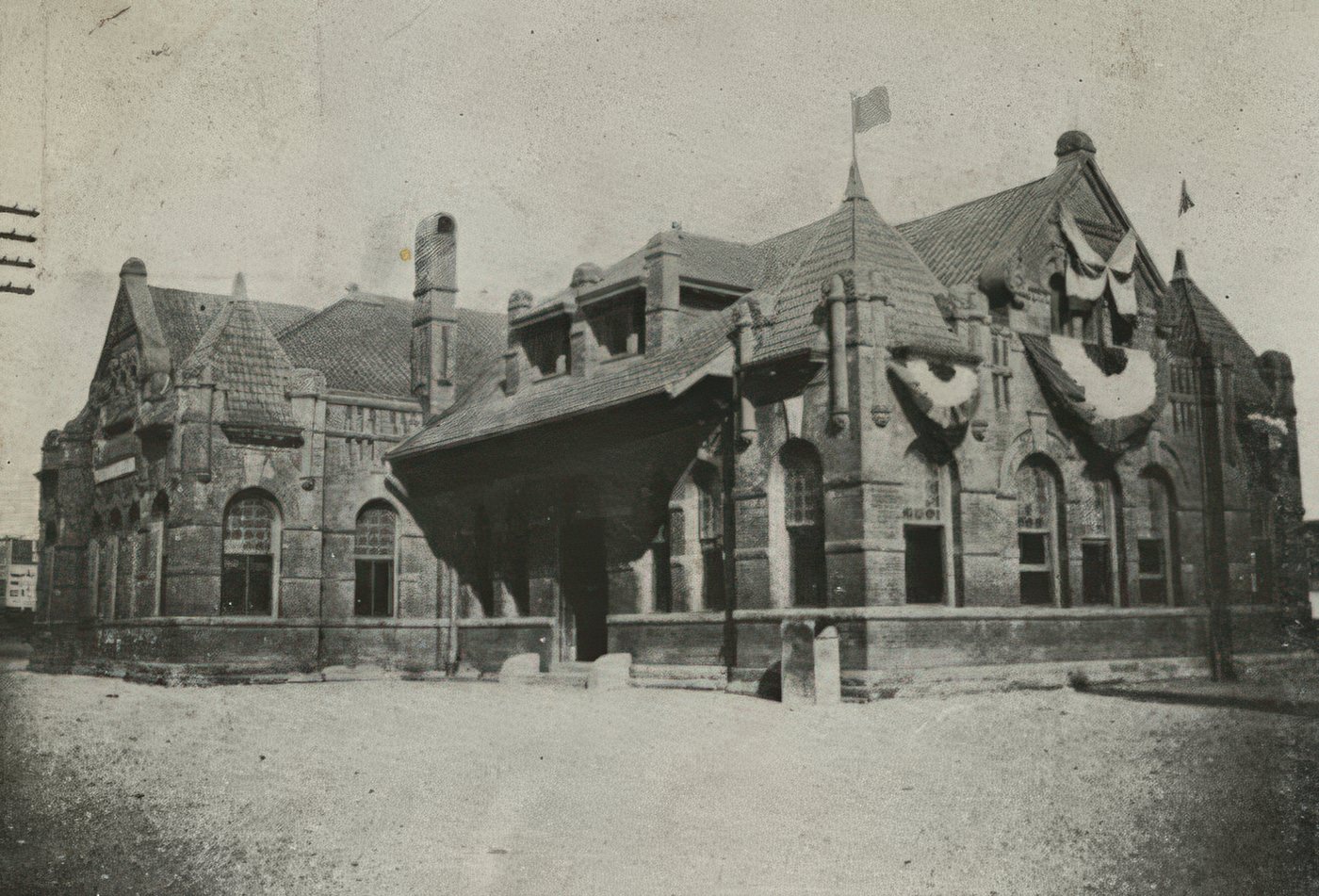

By 1900, the city contained forty-eight miles of railroad tracks, a figure that would more than double in the following decades. The volume of rail traffic was substantial. At the crossing of the T&P and Santa Fe lines east of downtown, an interlocking control tower known as Tower 22 was commissioned in 1903 to manage the flow of trains. By 1906, it was directing an average of 23 trains per day. The city’s depots, such as the East Dallas Depot built in 1897, were bustling hubs of commerce and travel, connecting Dallas to industries in the Northeast and Midwest.

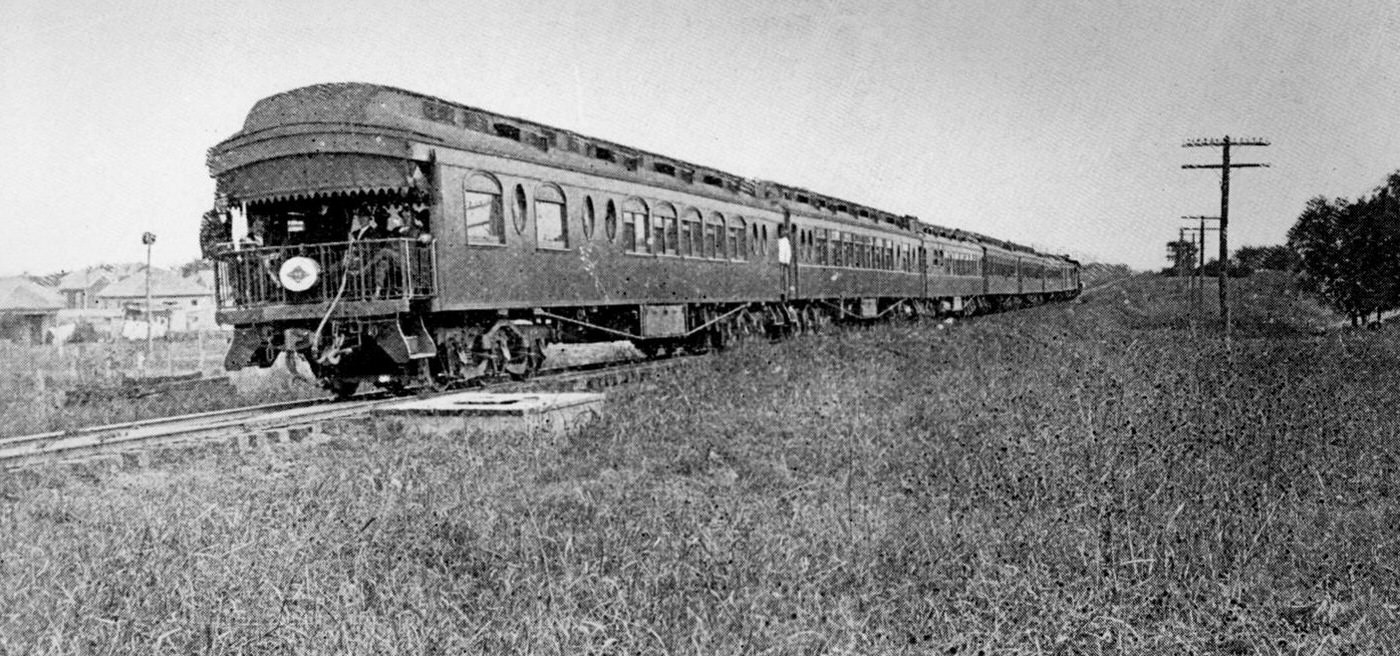

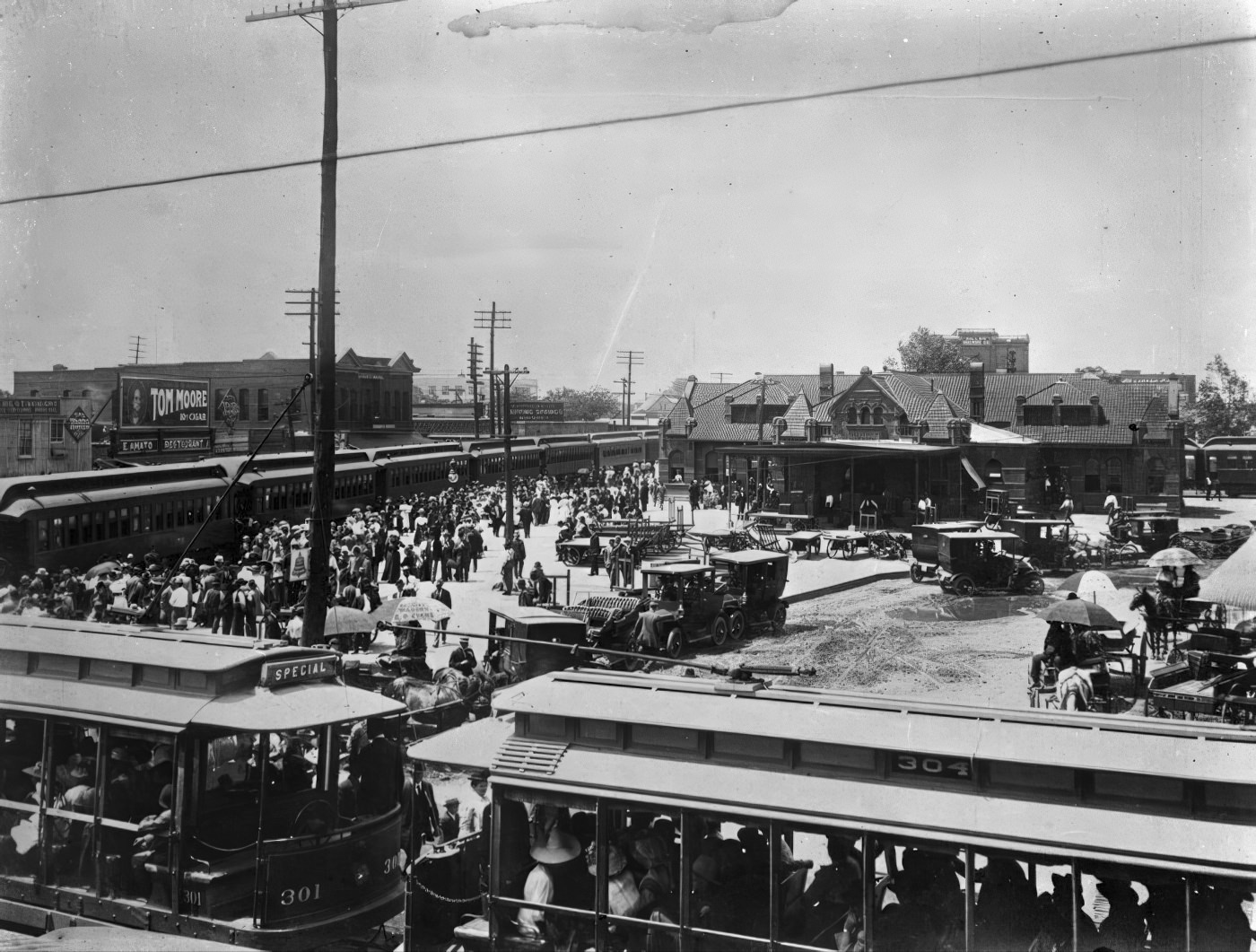

Within the city, an expanding network of electric streetcars provided modern public transportation. First introduced in 1889, the electric streetcar system grew significantly after 1900. The first interurban electric lines began operating in 1902, connecting Dallas with surrounding cities and integrating the entire region with Dallas at its center. By the end of the decade, the Dallas area was the hub of a 350-mile interurban system reaching communities like Denison, Terrell, and Waco. The Dallas Consolidated Electric Street Railway, formed in 1898, was the primary operator of the city’s local lines.

The decade also marked the dawn of the automobile age in Dallas. The first car appeared in the area in 1899, when Col. E. H. R. Green had a vehicle shipped by train to Terrell and then driven 30 miles to Dallas—a journey that took five hours. For most of the decade, automobiles remained a curiosity for the wealthy. It was not until 1909 that the Ford Motor Company established its first presence in the city, a small two-man dealership that signaled the beginning of a new era in personal transportation.

The ultimate symbol of Dallas’s modernization and ambition rose into the sky in 1909 with the completion of the Praetorian Building. Located at Main and Stone Streets, the 15-story, 190-foot-tall structure was the first skyscraper in Texas and the entire Southwestern United States. It was a physical declaration that Dallas was no longer a flat frontier town but a vertical, modern American metropolis. Built with a steel frame, the building featured a neoclassical exterior of gray granite and terra cotta columns. It was a marvel of modern engineering, equipped with three elevators, steam heating, and two artesian wells. Each office came with electricity, telephone and telegraph connections, and hot and cold running water. From its rooftop observatory, visitors could look out over a city that was rapidly and intentionally building itself into a regional powerhouse.

Daily Life and Civic Structure

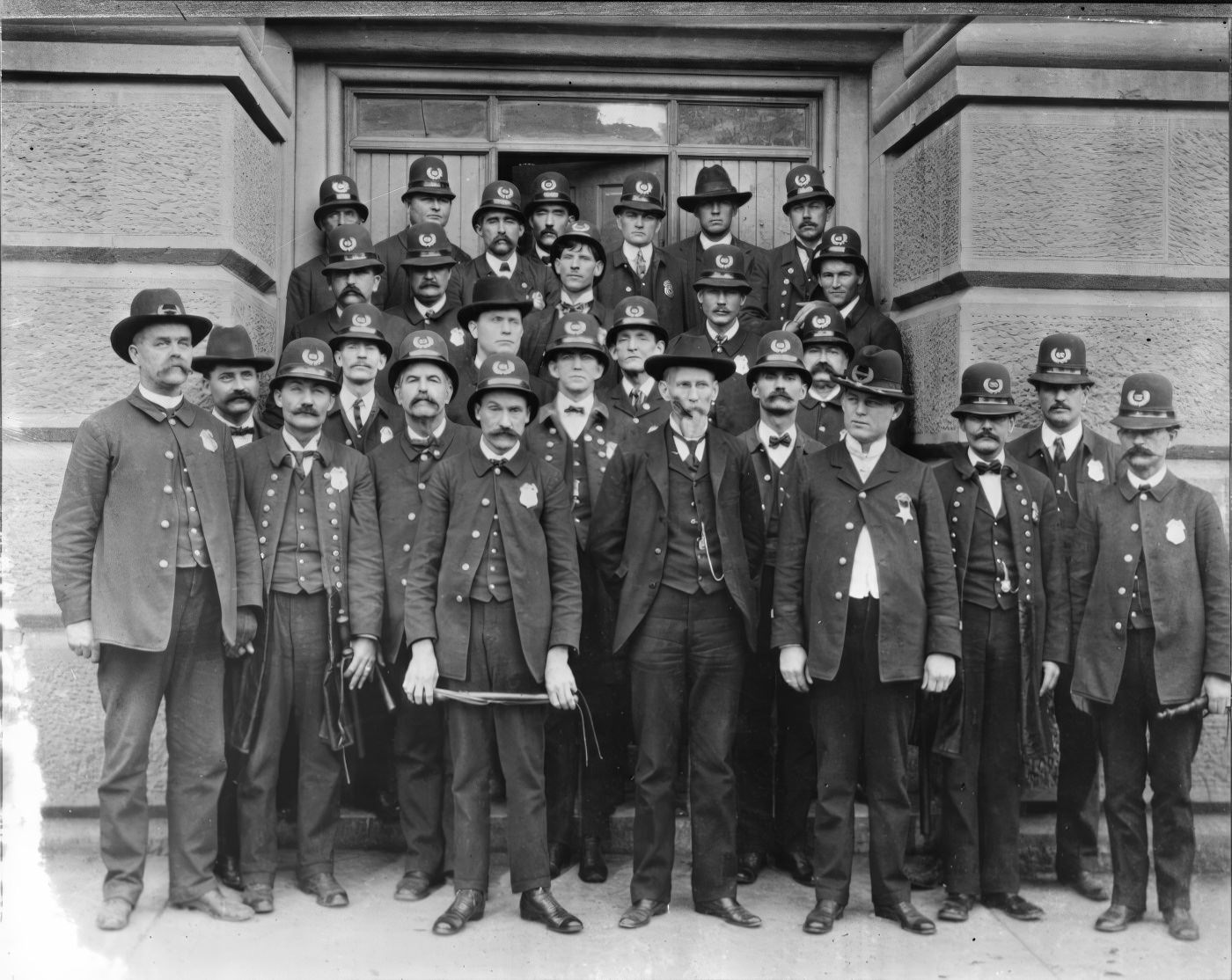

The governance and public services of Dallas underwent significant changes during the first decade of the 20th century, reflecting a Progressive Era push for civic improvement and efficiency. This modernization, however, was implemented within a rigid framework of racial segregation, creating a deep contradiction in the city’s public life.

Under Mayor Ben E. Cabell, the city annexed Oak Cliff and constructed the Bachman Lake dam to improve the municipal water system. Bryan T. Barry’s administration was notable for the city’s purchase of Fair Park and the appointment of the first Dallas Park Board. Curtis P. Smith initiated the first modern street paving projects. A major structural change in governance occurred in 1907, when Dallas voters replaced the old alderman system with a commission form of government. Stephen J. Hay became the first mayor elected under this new system, which was designed to run the city more like a business. His administration launched the ambitious White Rock Reservoir plan to secure the city’s long-term water supply.

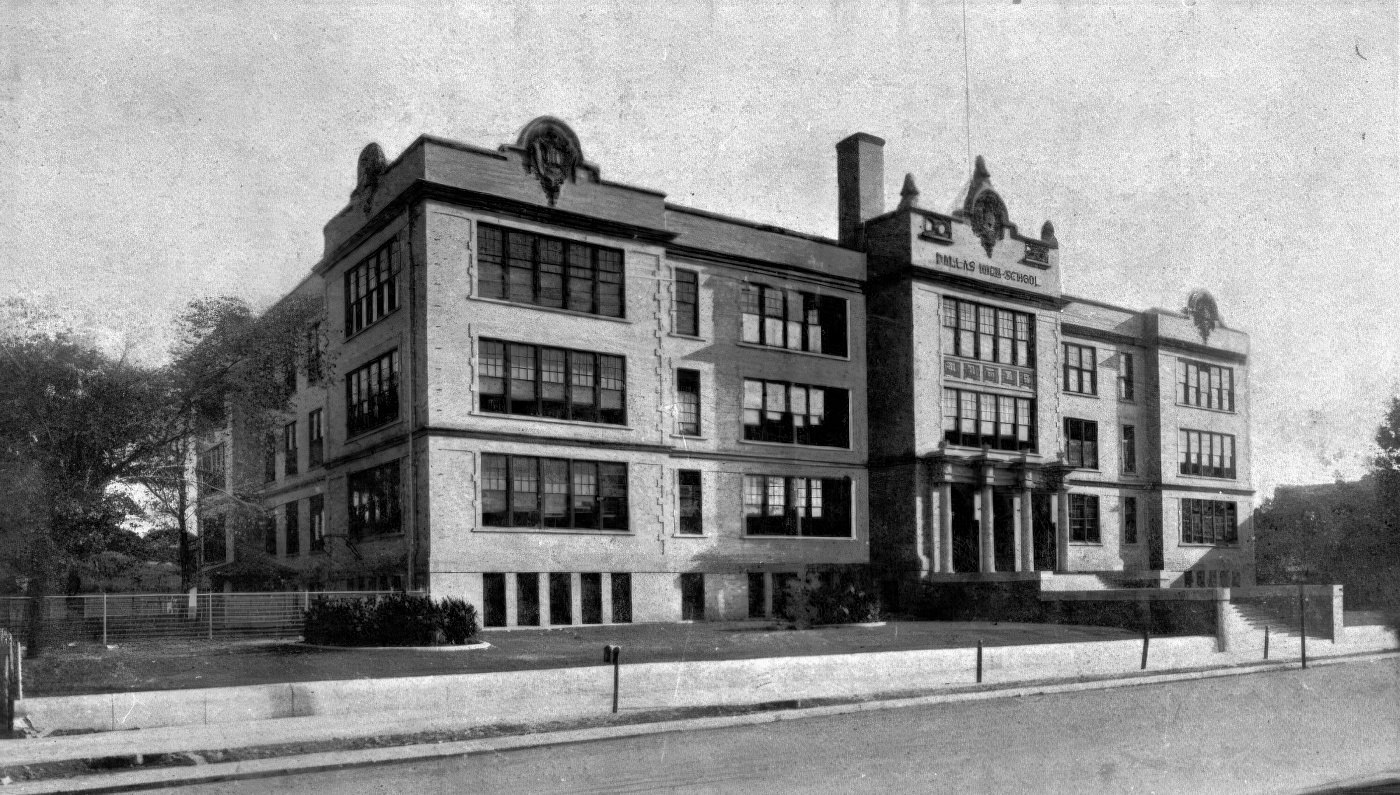

This era saw the founding of several key public institutions. The Dallas Public Library system was officially established on May 4, 1900, a project driven by the Dallas Federation of Women’s Clubs and made possible by a $50,000 grant from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. The first library building opened in 1901 with a collection of 9,852 volumes. Its second floor housed the city’s first public art gallery, the forerunner of the Dallas Museum of Art. The public school system also expanded. By 1907, the new Dallas High School offered a curriculum that included not only standard academic subjects but also vocational training in areas like manual arts, wood shop, and stenography.

These civic improvements, however, were not extended equally to all residents. The city’s park system, formally managed by a new Board of Park Commissioners created in 1905, operated under a system of de facto segregation. While no official laws barred African Americans from parks, convention and intimidation enforced a “White only” use of most facilities, which led Black citizens to petition for their own designated park spaces.

This policy of “separate and unequal” was most starkly evident in public health. The city was served by the public Parkland Hospital and several private institutions, but healthcare was strictly segregated. The Texas Baptist Memorial Sanatorium, which opened in 1909 after five years of construction, was built with a separate ward for African American patients. Black physicians were barred from practicing at the hospital and were required to refer their patients to a white doctor for admission. Because they were excluded from the city’s mainstream medical institutions, Black physicians were forced to create their own. In 1905, Dr. Benjamin Bluitt opened the Bluitt Sanatorium on Commerce Street, the first hospital in Dallas established to serve the African American community. The modernization of Dallas was, in effect, the modernization of its segregation policies, embedding them within its new public and private institutions.

Culture, Calamity, and Community

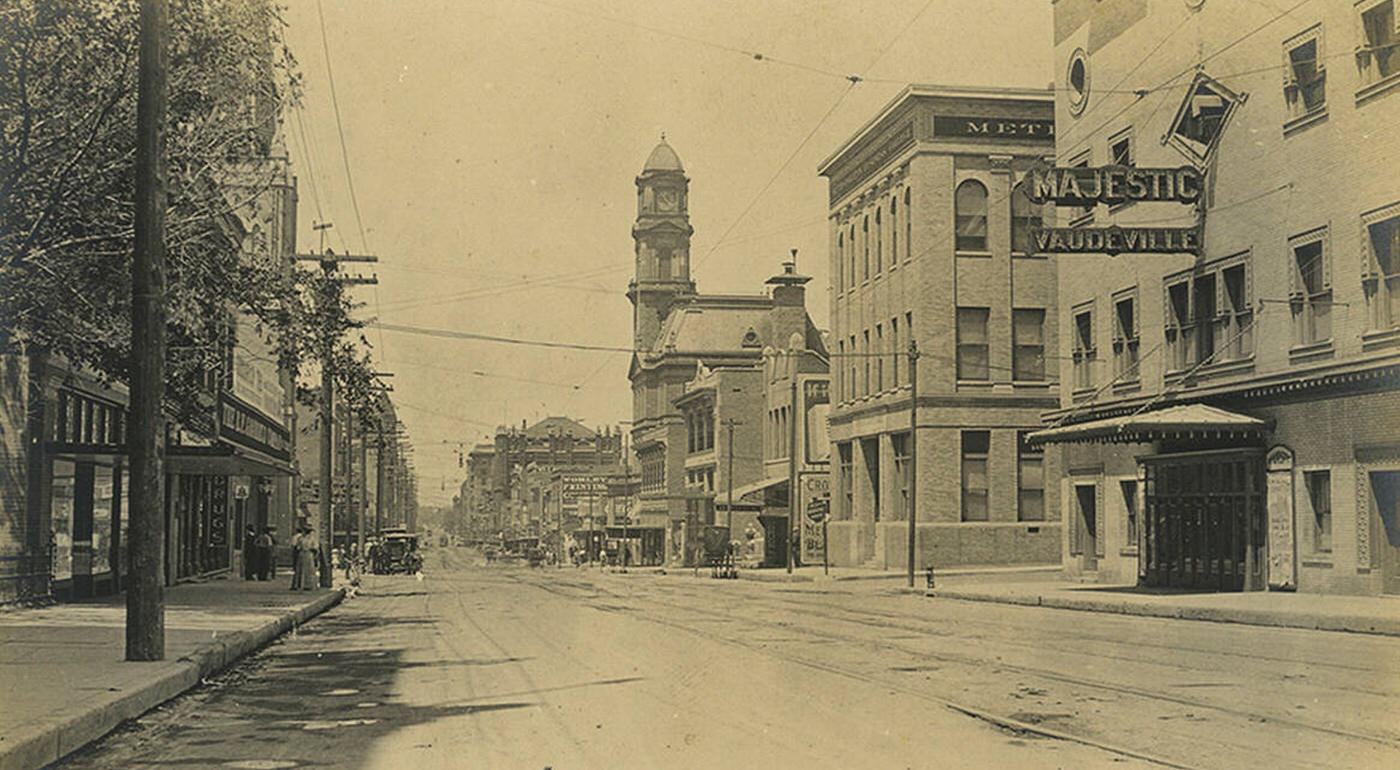

The social and cultural life of Dallas in the 1900s was a mixture of new forms of entertainment, long-standing community traditions, and the shared trauma of a natural disaster that would permanently alter the city’s future. As Dallas grew, so did its options for leisure. Vaudeville was the most popular form of live entertainment, and in 1905, promoter Karl Hoblitzelle opened the first Majestic Theatre at the corner of Commerce and St. Paul Streets. The 1,200-seat venue was specifically designed for vaudeville shows and quickly became a cultural centerpiece.

The decade also marked the birth of cinema in Dallas. The city’s first permanent movie theater, The Theatorium, opened in a converted Elm Street storefront in July 1905. With 350 seats, it showed “photoplays” to audiences eager for this new form of entertainment. Its immediate success led to the conversion of other storefronts along Elm Street into small movie houses, while T.P. Finnegan’s open-air theater in Oak Cliff brought motion pictures to the city’s residential districts.

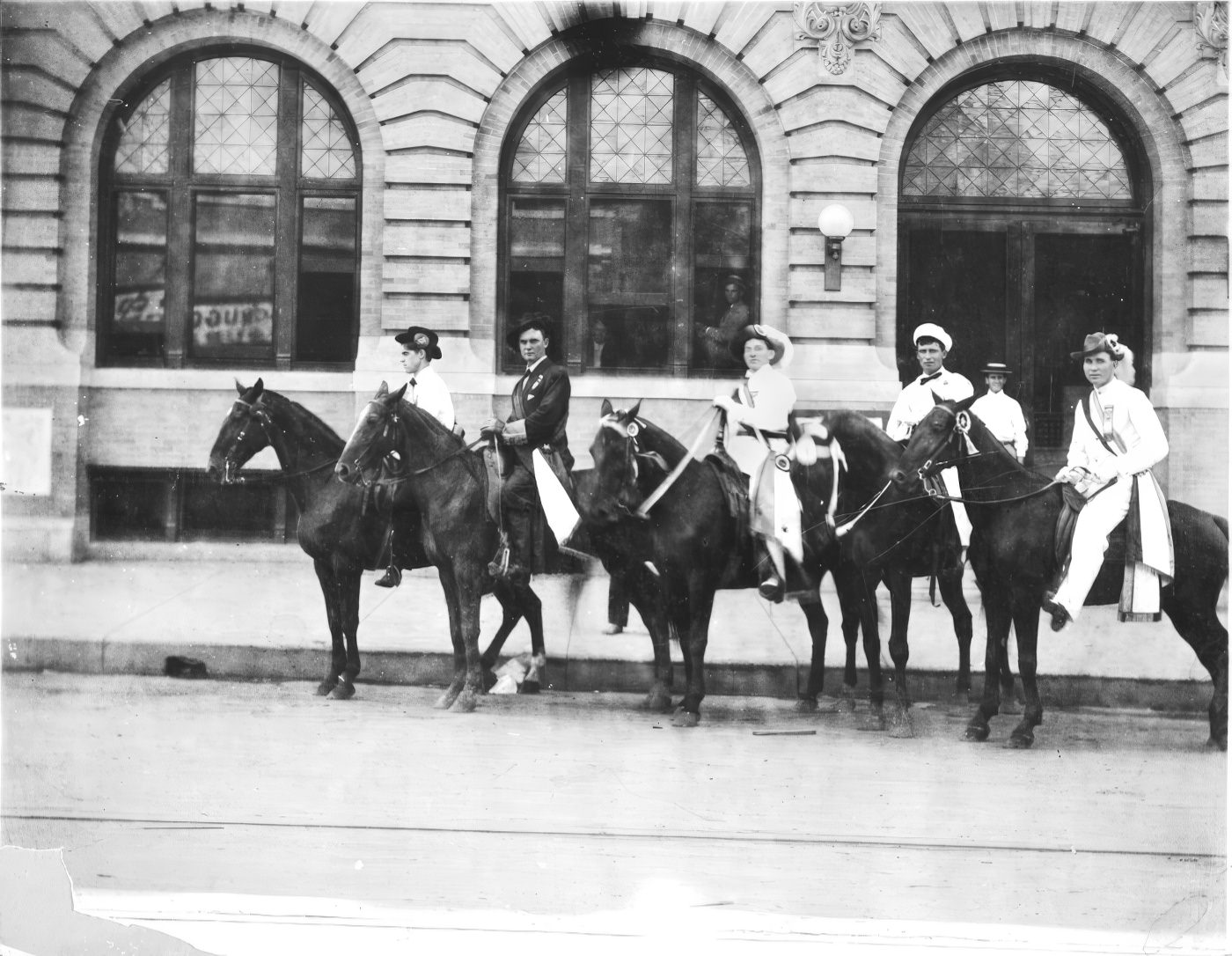

The largest annual gathering for the community was the State Fair of Texas. The decade was a tumultuous one for the fair. In 1900, a grandstand collapsed during a fireworks show, and in 1902, the main exhibit building burned to the ground. A statewide ban on horse race gambling in 1903 eliminated the fair’s primary source of income, pushing the association into a financial crisis. To save the institution, the fair association sold its property to the City of Dallas in 1904, ensuring its survival as a public asset. The reorganized fair thrived, drawing 300,000 visitors in 1905 and hosting a visit from President William Howard Taft in 1909. The fair was also a reflection of the era’s social order. African Americans were permitted to attend on only one day of the event, designated as “Colored People’s Day,” a practice that continued until it was discontinued in 1910.

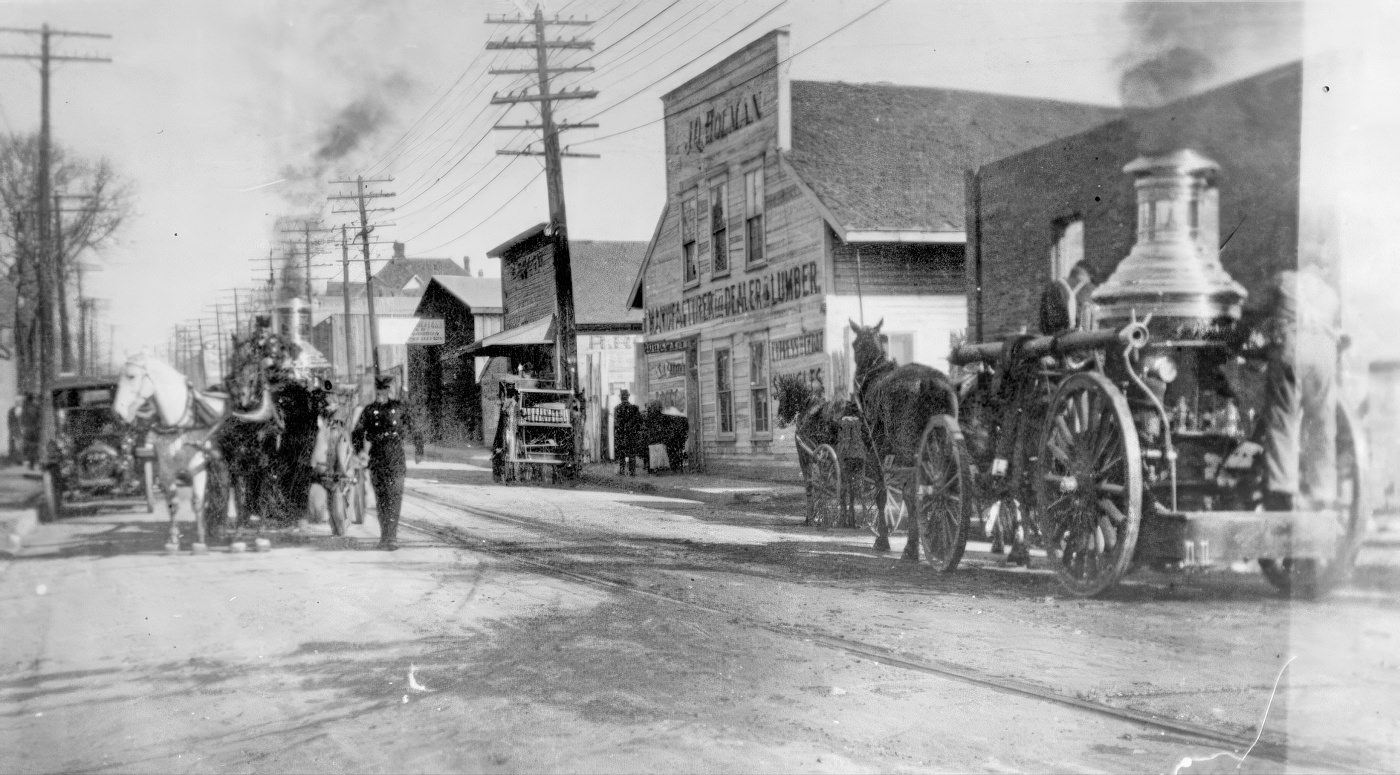

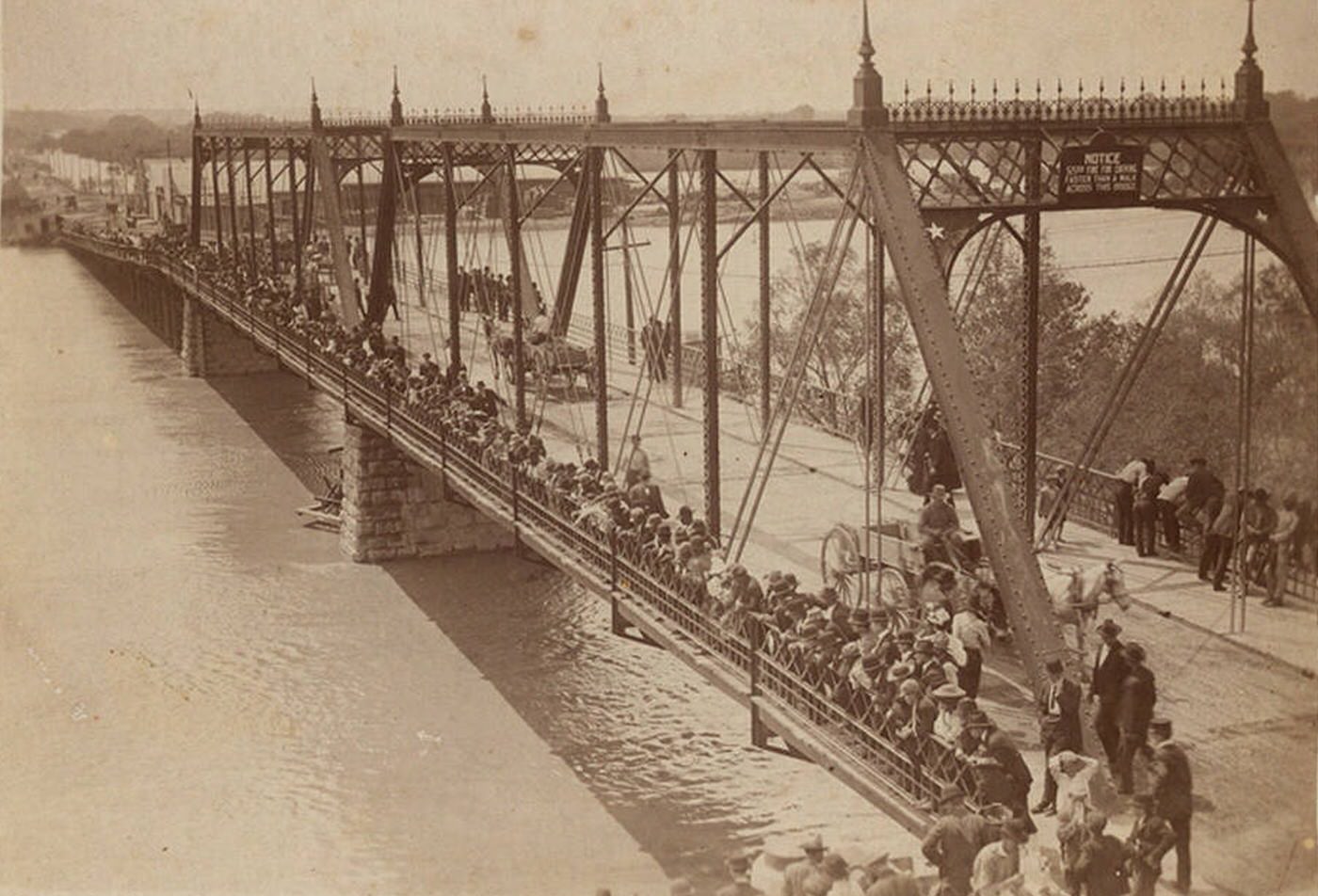

The most significant event of the decade was the Great Trinity River Flood of May 1908. After weeks of heavy rain across the region, the river overflowed its banks with devastating force, cresting at a record 52.6 feet and widening to 1.5 miles. The flood killed five people and left between 4,000 and 5,000 of the city’s 90,000 residents homeless. Property damage was estimated at $2.5 million, an astronomical sum at the time. The destruction paralyzed the city. The West Dallas neighborhood was completely submerged, downtown bridges were washed away, and Oak Cliff was cut off from the rest of the city. Power, water, and communication lines failed, and overflowing sewers created a public health emergency.

The flood was a traumatic, city-altering disaster that served as a powerful and undeniable catalyst for change. It exposed the severe inadequacy of the city’s infrastructure and laid bare the consequences of its “haphazard growth”. The crisis created the political will to end years of debate and embrace comprehensive urban planning. In response, city leaders hired the nationally recognized city planner George Kessler. In 1909, Kessler presented his master plan for Dallas, a visionary document that called for the construction of levees to tame the Trinity River, the consolidation of railroad lines, the widening of city streets, and the development of a connected park system. The 1908 flood marked the pivotal moment when Dallas was forced to shift from a rapidly growing but disorganized town into a city committed to large-scale, long-term, and systematic urban design.

Image Credits: Texas History Portal, Dallas Public Library, Library of Congress, UTA Libraries,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know