The Dallas of 1910 was a city straining against its own success. A decade of explosive growth had transformed it from a large town into a bustling regional center, but its infrastructure had failed to keep pace. The 1910s became a period of reckoning, where Dallas was forced by a series of crises—overcrowding, flooding, and drought—to fundamentally rethink its physical form. The solutions it pursued, from monumental engineering projects to the city’s first comprehensive master plan, were not acts of proactive vision but urgent reactions to the consequences of its own unchecked expansion. These responses laid the groundwork for the modern metropolis, establishing a pattern of confronting existential threats with ambitious, large-scale construction.

City Hall and Its Leaders

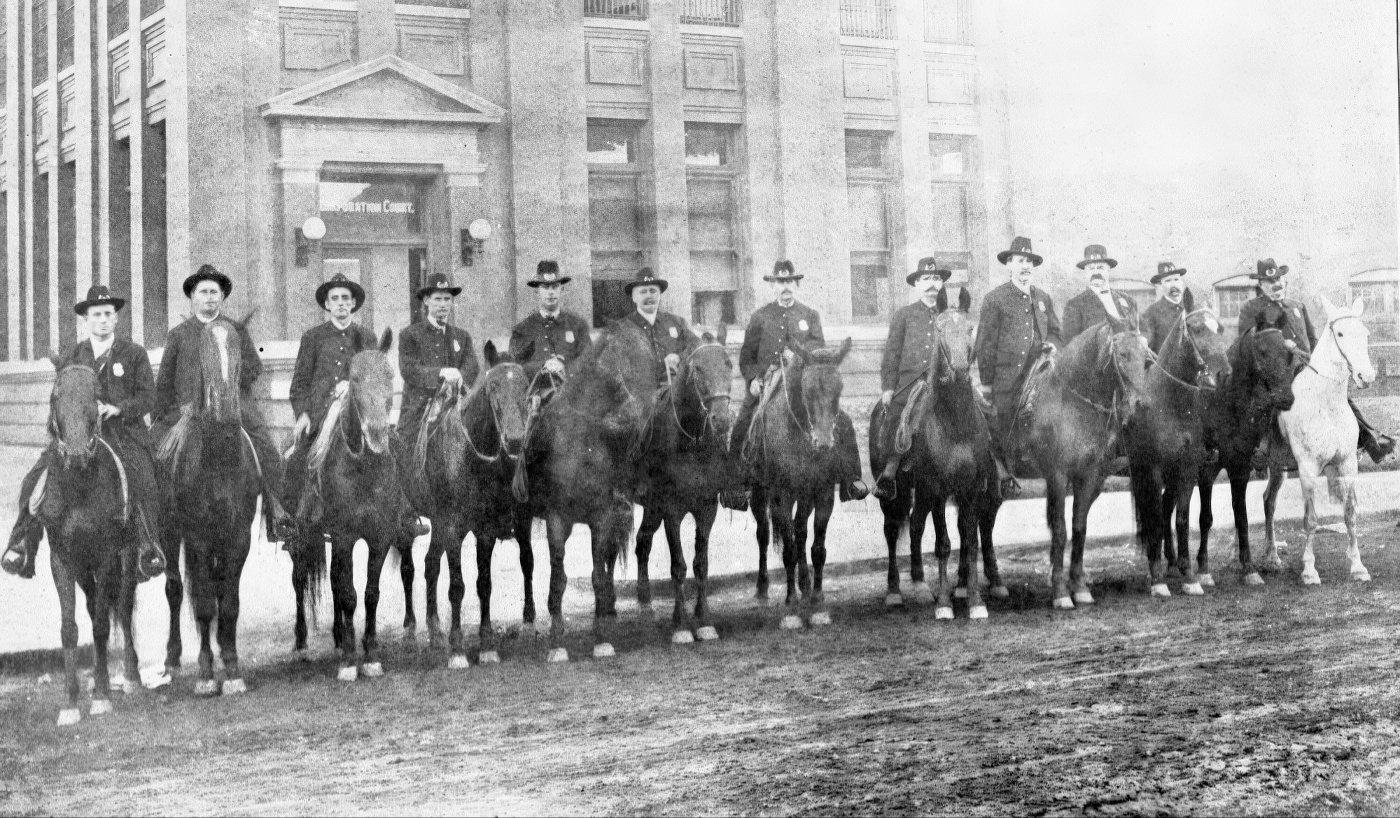

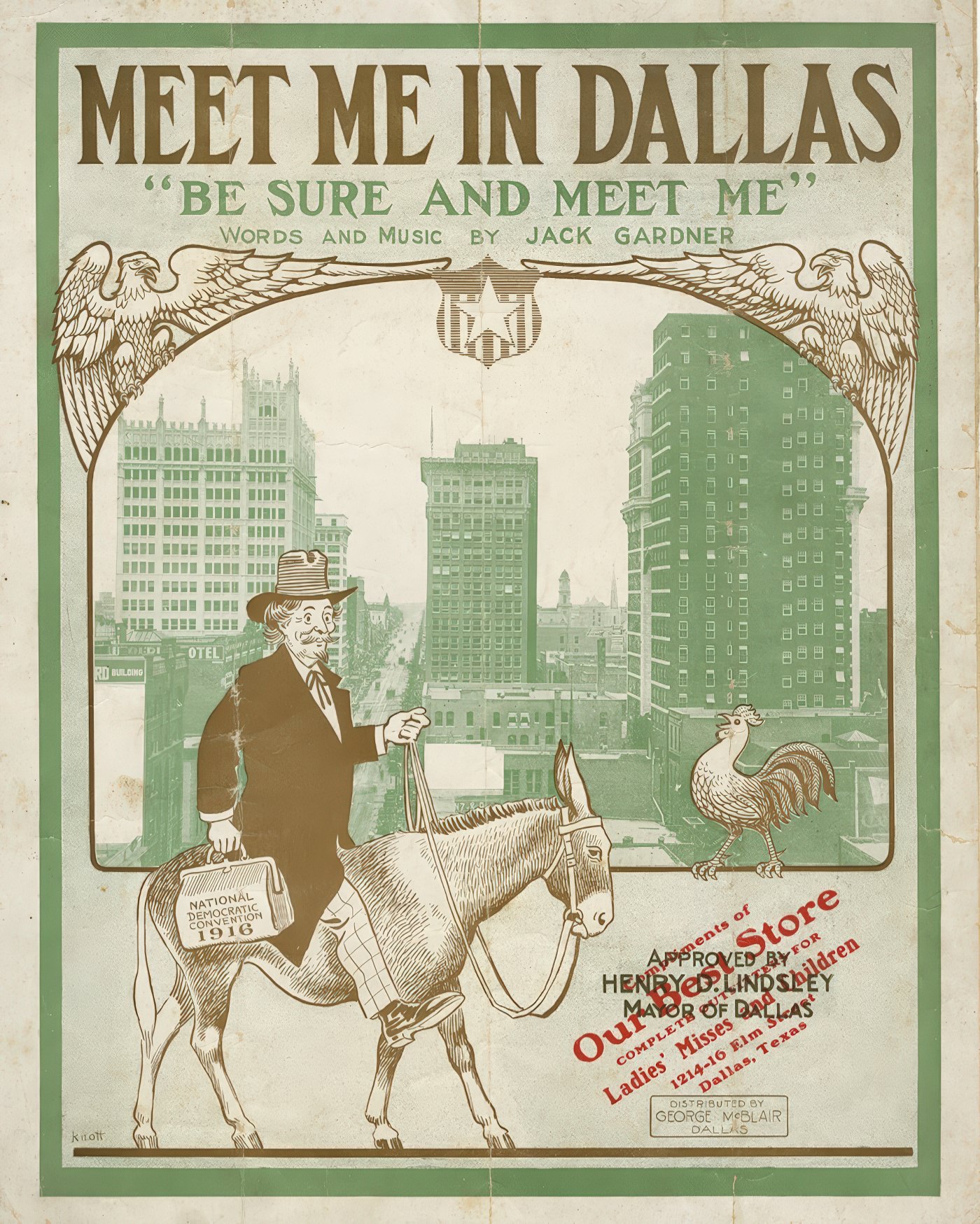

Throughout the 1910s, Dallas was governed under a commission form of government, which had been adopted in 1907 to replace the older alderman system. This structure consisted of a mayor and four commissioners who oversaw the city’s various departments. The decade was led by a series of mayors who presided over this period of rapid change.

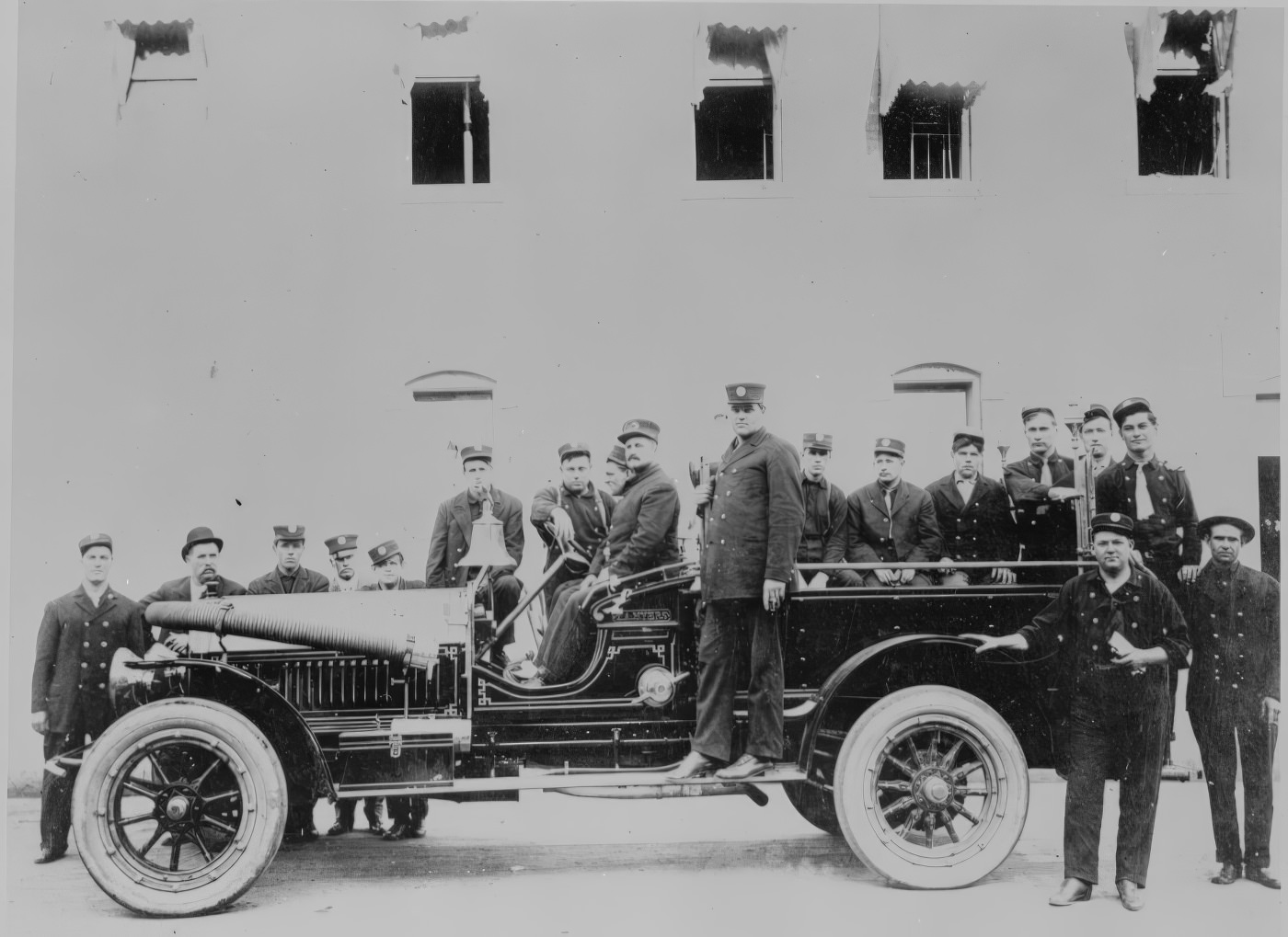

The city’s political life was dominated by the conservative, business-aligned Citizens’ Association, but it was not without opposition. A strong socialist and labor movement provided a consistent challenge. In the 1913 mayoral election, Socialist candidate George Clifton Edwards came in second to the Citizens’ Association candidate, William Meredith Holland, winning 7 of the city’s 33 precincts. Labor Day was a major civic event, with a parade in 1913 drawing over 6,000 marchers and thousands more spectators. As a symbol of its growing administrative needs, the city constructed a new, five-story Municipal Building on Harwood Street, which opened in 1914 to serve as the new City Hall.

White Rock Lake: A Solution to a Water Crisis

Just as the city was grappling with the problem of too much water from the Trinity, it was confronted with the problem of not enough drinking water. The same population boom that strained its streets and rail lines also taxed its water supply. A severe drought in 1910 brought the city to a crisis point, forcing an immediate and large-scale response.

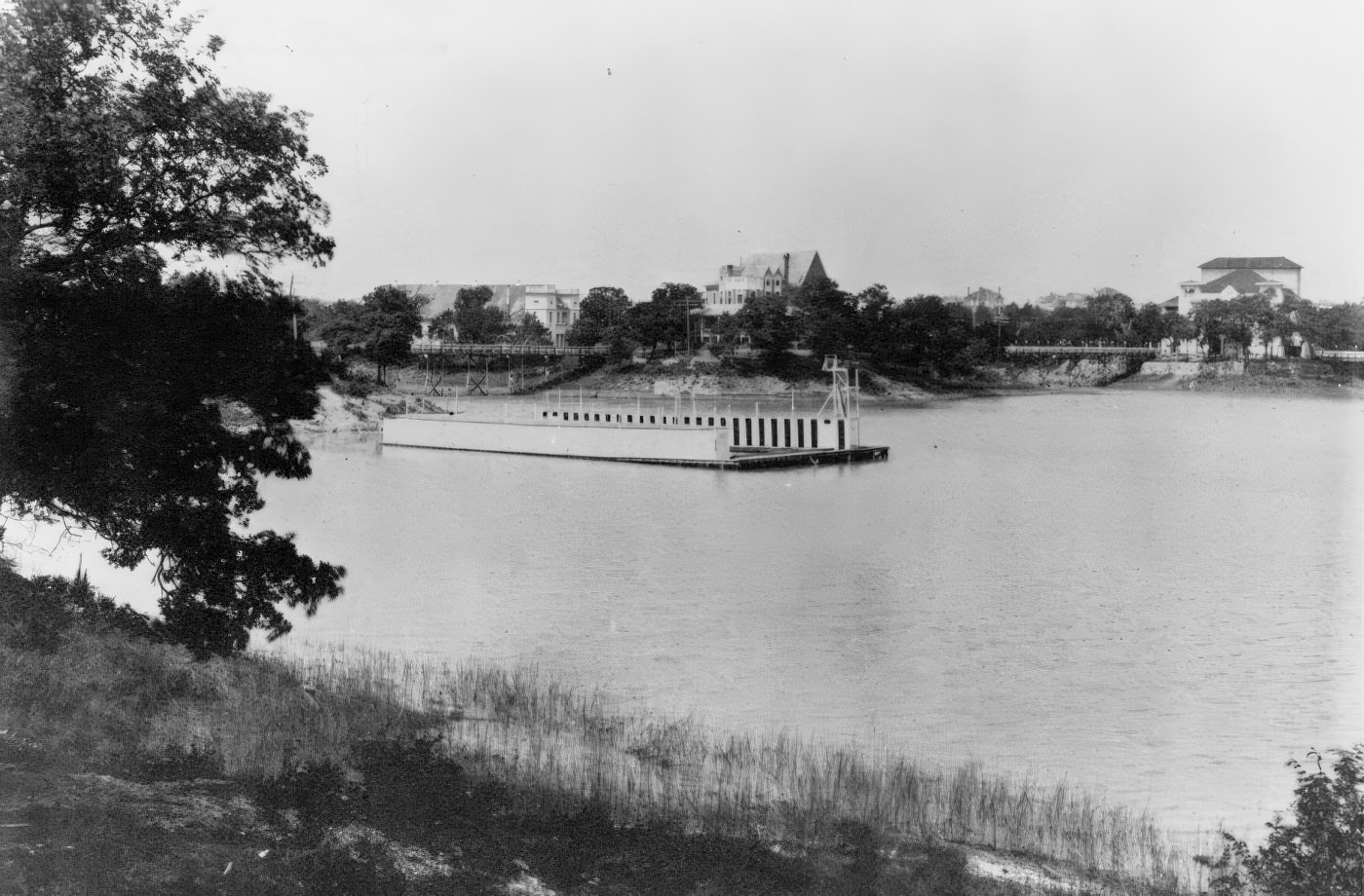

On January 11, 1910, city commissioners officially adopted a plan to create a new reservoir by damming White Rock Creek, then located in undeveloped countryside northeast of the city. Construction of the dam and spillway began that year and was completed with remarkable speed in 1911. The new lake filled quickly, and by April 1914, White Rock Lake reached its capacity for the first time. In his city plan, George Kessler recognized the new lake’s potential as a civic asset and recommended that all surrounding land “be retained in public hands and used for park purposes”.

Initially, the spring-fed water was so pure that it was pumped directly into the city’s water mains without treatment. However, the lake quickly became a popular recreational destination for swimming, fishing, and boating, and this human contact soon compromised the water quality. By 1913, Dallas dispensed its first chlorinated water from the White Rock pump station to ensure its safety for the growing population. The creation of White Rock Lake was a direct reaction to a crisis, demonstrating the city’s emerging capacity to undertake massive public works projects when its viability was threatened.

The Population Boom and Urban Sprawl

At the dawn of the decade, Dallas was experiencing a population surge of remarkable intensity. The 1910 U.S. Census recorded 92,104 residents, more than double the 42,638 counted just ten years earlier in 1900. This rate of growth far outpaced that of the United States as a whole and was part of a broader trend of urbanization across Texas. People flocked to the city from other parts of the South, particularly from Tennessee, Missouri, and Arkansas, drawn by the promise of opportunity in North Texas. This migration was supplemented by a significant wave of immigrants from Mexico, who began arriving in large numbers after 1910 to escape the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution.

This influx of people put immense pressure on the city’s physical boundaries. By 1910, Dallas had already doubled its land area to over 18 square miles, a size increase driven in part by the 1904 annexation of the neighboring city of Oak Cliff. As the population continued to swell throughout the decade, reaching 158,976 by 1920, the city sprawled outwards, creating new residential areas that demanded new services and infrastructure. This rapid, often haphazard expansion created a chaotic urban environment that would soon prove unsustainable.

The Kessler Plan: A Blueprint for Order

The very engine of Dallas’s prosperity—the railroad—had become one of its greatest liabilities. By the early 1900s, numerous rail lines crisscrossed the central business district, with passenger and freight stations scattered throughout the city’s core. This tangled web of tracks created daily conflict and confusion, effectively “suffocating Dallas” and stifling its commercial life.

In 1909, the Dallas Chamber of Commerce acknowledged the severity of the problem and hired George E. Kessler, a nationally recognized city planner, to draft a master plan for the city’s future. Unveiled in 1911, the Kessler Plan was a comprehensive blueprint designed to bring order to the city’s chaotic growth. It addressed Dallas’s most critical challenges: the dangerous railroad crossings, the narrow and crooked downtown streets, and the constant threat of flooding from the Trinity River.

A central component of the plan was a radical reorganization of the city’s rail system. Kessler proposed building a “belt” rail line to loop around the central business district, consolidating the scattered tracks of the various railroad companies. He also called for the construction of a single, grand passenger terminal to replace the multiple depots. This vision materialized with the opening of Union Station in 1916. Another key recommendation was the removal of the Texas and Pacific railroad tracks from Pacific Avenue, a project that was finally completed in 1919, freeing up a major downtown thoroughfare. While many of the plan’s ambitious proposals were initially dismissed by city leaders as impractical, the ongoing problems of congestion and flooding made it clear that change was necessary. The Kessler Plan was repeatedly revisited and became the guiding document for major civic improvements for the next two decades.

A Decade of Global and Local Crises

The final years of the 1910s saw Dallas drawn into global and national crises that tested the city’s resilience and exposed critical weaknesses in its social fabric. The entry of the United States into World War I transformed Dallas into a major military center, bringing with it a surge of patriotic activity. This same military mobilization, however, also made the city a vulnerable entry point for the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. The city’s response to this public health emergency revealed a dangerous tension between its well-honed machinery of civic boosterism and the quiet caution required to manage a deadly epidemic. The crisis demonstrated that the very tools Dallas used to promote its identity—large public gatherings and patriotic spectacle—could become the vectors of its own devastation.

Dallas and the Great War

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, Dallas quickly became a vital hub for the nation’s military mobilization effort. The city’s strategic location and extensive rail network made it an ideal site for training facilities. In October 1917, the U.S. Army Air Service established a major training base on the northern outskirts of the city. Named Love Field in honor of a fallen Army pilot, it became one of the country’s key aviation training centers.

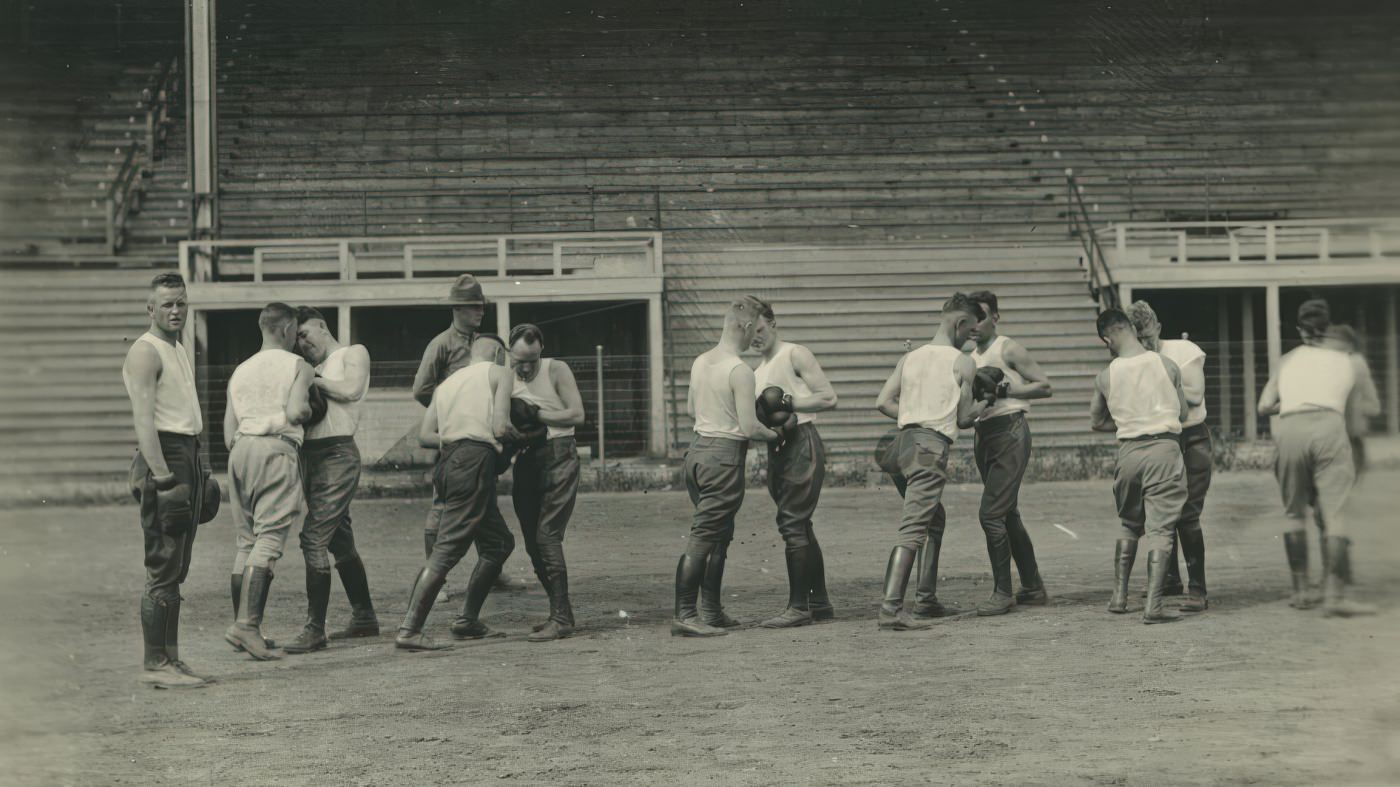

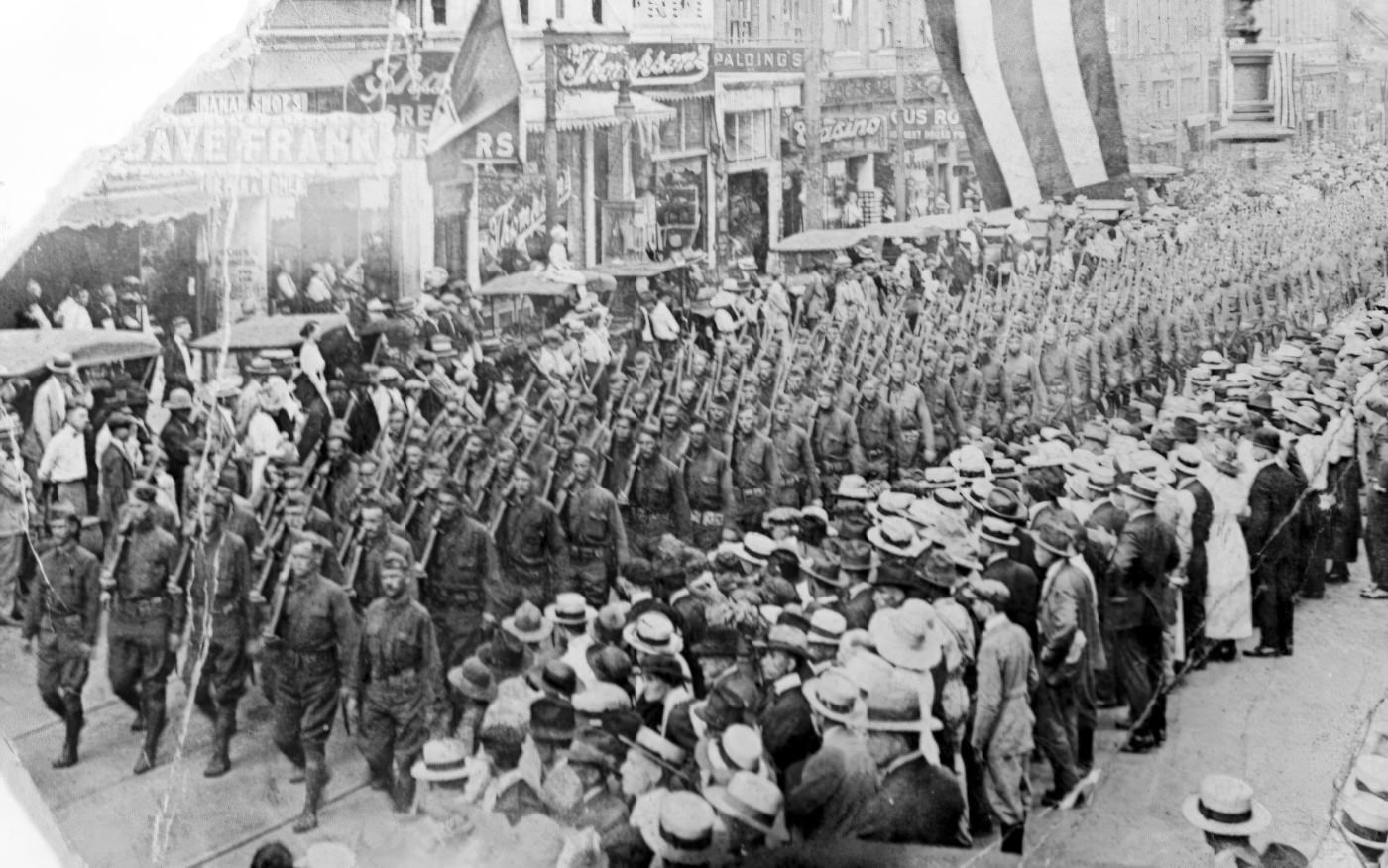

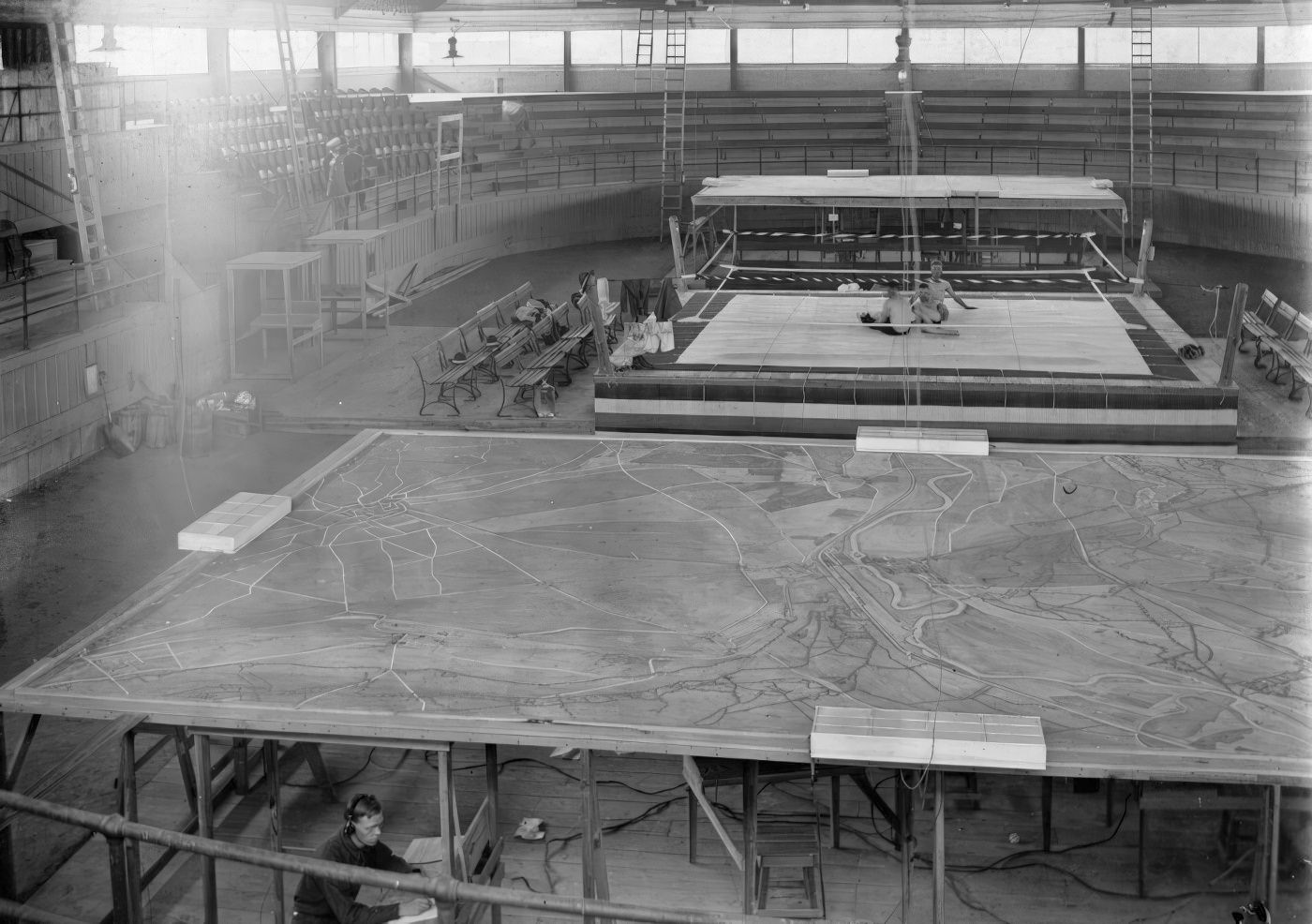

In January 1918, a second military installation was established directly within the city. The grounds of Fair Park were converted into Camp John Dick Aviation Concentration Camp, a facility for ground school graduates awaiting assignment to flight schools. To accommodate the camp, the State Fair of Texas was canceled for 1918, the first interruption in its history. On the home front, Dallas civilians threw themselves into the war effort. The primary method of fundraising was the sale of Liberty Loan bonds, which were promoted through a series of large and enthusiastic public parades held in the downtown streets.

The Economic Powerhouse of the Southwest

In the 1910s, Dallas solidified its position as the undisputed commercial and financial capital of the Southwest. This dominance was not accidental; it was the result of a deliberate strategy executed by the city’s business elite. They built upon Dallas’s existing strengths in agriculture and trade while aggressively pursuing the modern industries of finance and manufacturing. The city’s leaders understood that geographic advantage was no longer sufficient. To secure its future, Dallas had to actively create it, transforming itself from a regional marketplace into an institutional hub of capital and industry. The successful campaigns to land the Federal Reserve Bank and the state’s first Ford assembly plant were not just economic victories; they were calculated power plays that defined the city’s trajectory for the rest of the century.

The Dawn of the Automobile Age

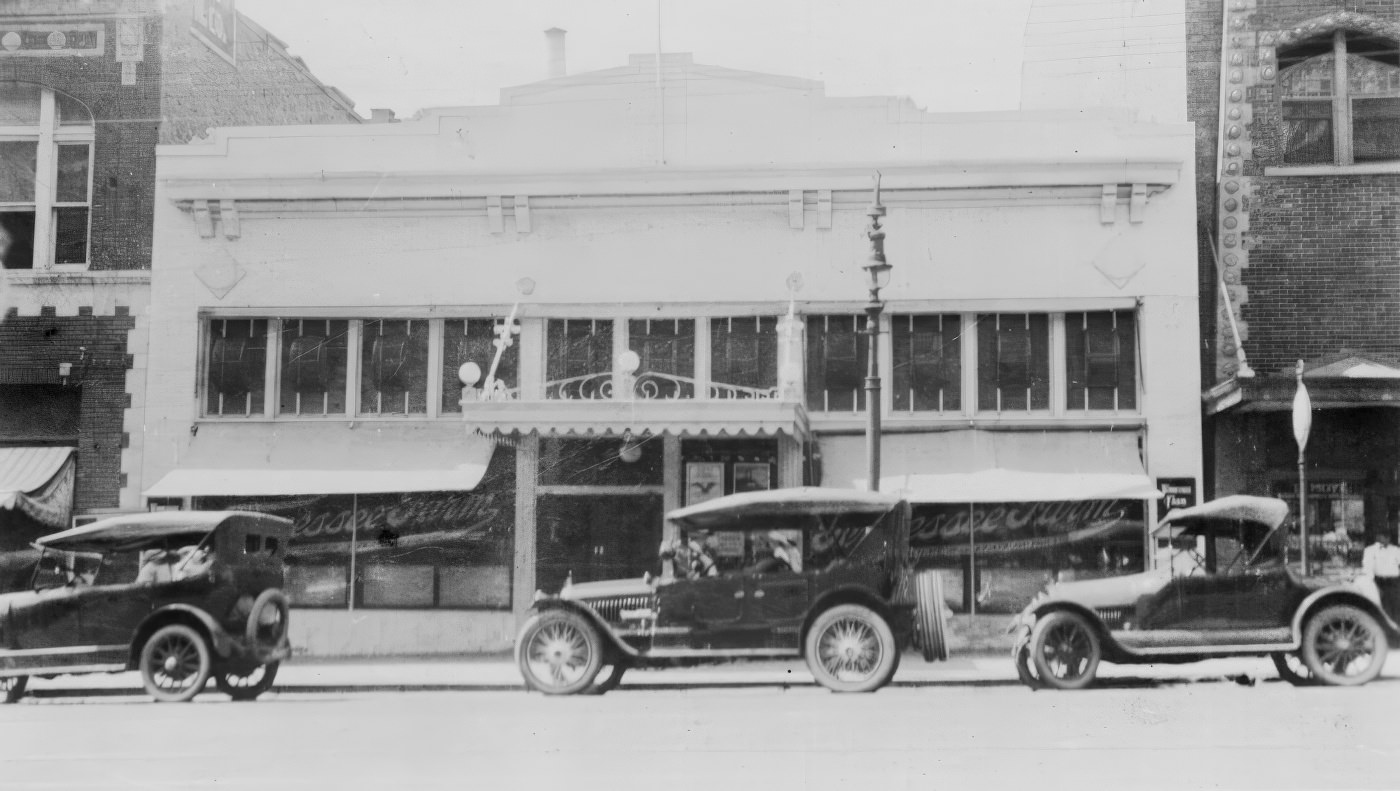

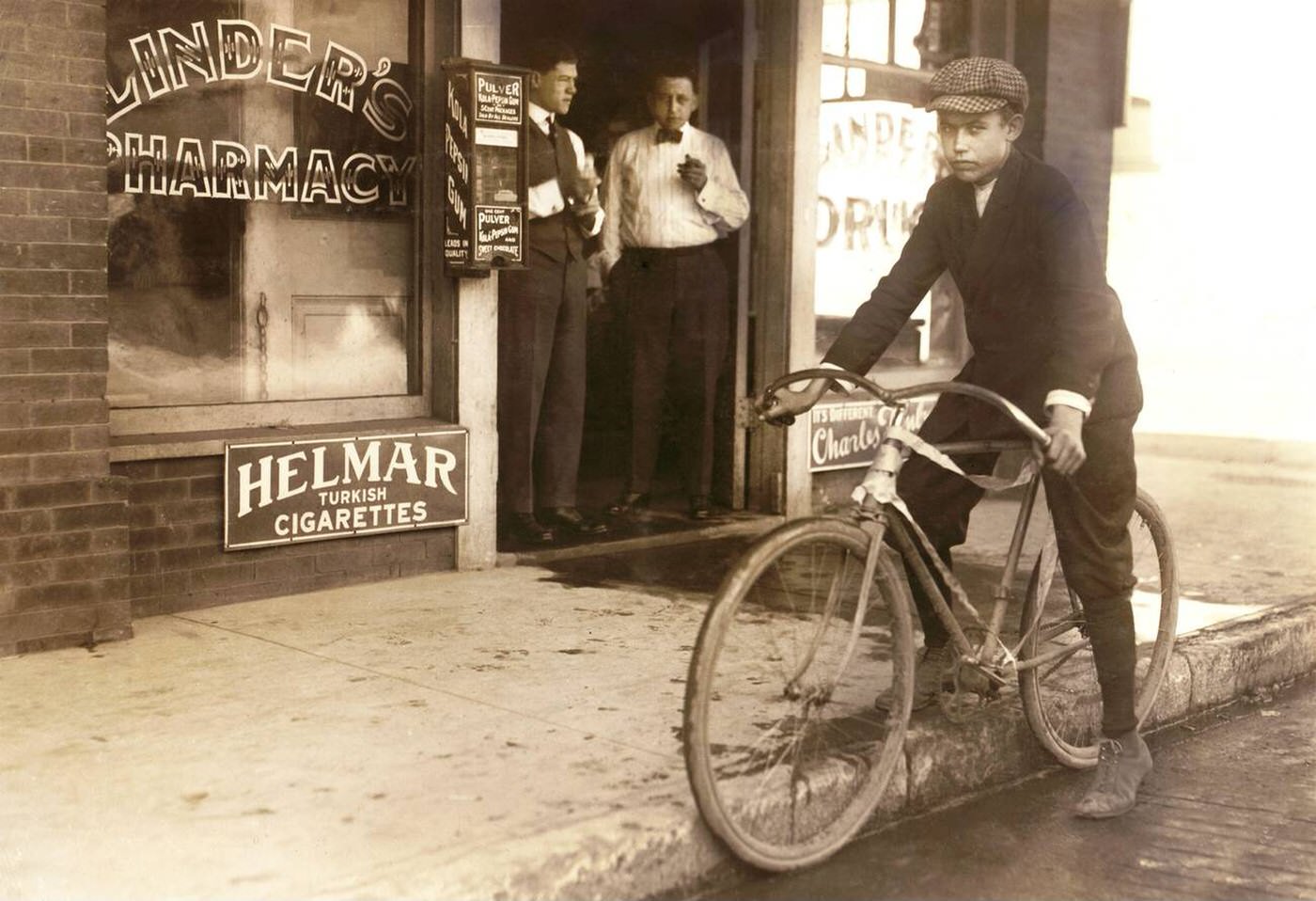

As Dallas secured its future in finance, it also embraced the defining technology of the new century: the automobile. In 1914, Henry Ford chose Dallas as the site for the Ford Motor Company’s first assembly plant in Texas. The four-story brick plant was constructed at 2700 Commerce Street in the Deep Ellum neighborhood. At the time, no other automobiles were being manufactured anywhere in the state, making the Dallas plant a unique industrial asset.

Ford had perfected his revolutionary assembly line process between 1910 and 1914, dramatically reducing the time it took to build a Model T from over 12 hours to just 93 minutes. The Dallas plant became an important regional production and service hub for the company, which dominated the American auto market. The vehicles produced there carried a sticker that read “Built in Texas by Texans,” a slogan that became a source of immense local pride and a symbol of the city’s growing industrial capabilities. The arrival of Ford signaled Dallas’s successful diversification beyond its agricultural and trade-based roots into modern, heavy manufacturing.

The Social Landscape: Division and Community

The story of 1910s Dallas is one of profound contradiction. While the city’s elite were building the physical and economic structures of a modern, progressive metropolis, they were also enforcing a rigid and often brutal social hierarchy. The decade saw the formation of vibrant new immigrant and minority communities, but their existence was defined by segregation, hardship, and the constant threat of violence. The city’s celebrated progress was built upon a foundation of cheap, segregated labor, and the social control mechanisms used to maintain this order—from segregated housing patterns to the ultimate terror of lynching—were as integral to the Dallas of the 1910s as its new skyscrapers and banks. The era’s public face of ambition and modernity was inseparable from the private realities of inequality and fear.

Building a Modern Skyline

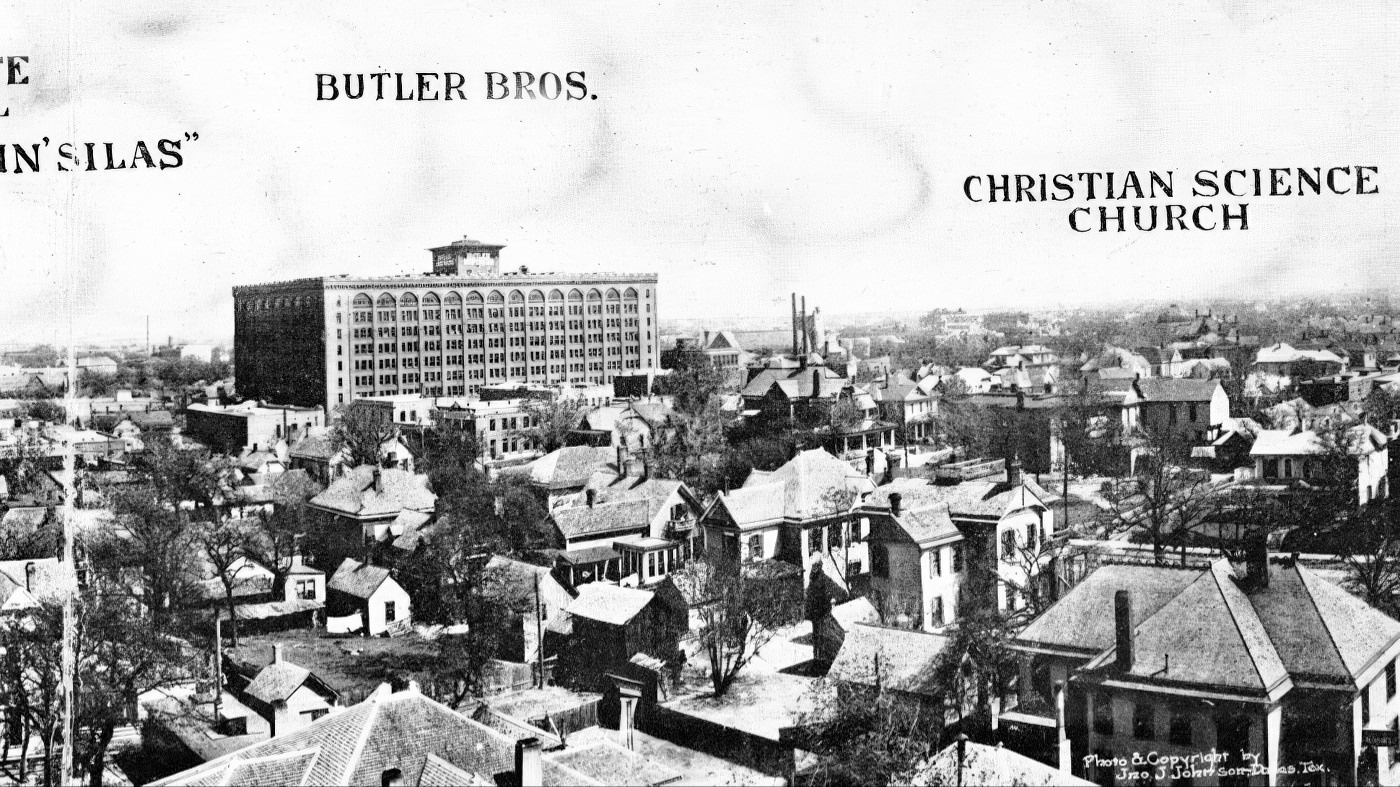

Nothing symbolized Dallas’s ambition more than the transformation of its skyline. The decade began with the completion of the city’s first true skyscraper. The 15-story Praetorian Building, which opened in 1909 at Main and Stone Streets, was the tallest building in Texas and the entire Southwestern United States. Designed as the headquarters for a fraternal insurance company, the steel-frame tower was a marvel of modernity, featuring three electric elevators and providing electricity, telephone connections, and hot and cold running water in every office.

In 1912, an even more imposing structure joined the skyline: the Adolphus Hotel. Financed by beer baron Adolphus Busch, the 20-story, Beaux Arts-style hotel was built on the prominent downtown site of the former City Hall. As the tallest hotel in the South, the opulent Adolphus immediately became the center of Dallas society and a landmark of civic pride. These two buildings were soon joined by other high-rises, including the 16-story Busch Building (1912) and the 17-story Southwestern Life Building (1913). This building boom extended to institutions as well. Southern Methodist University opened its doors in 1915, its location secured after Dallas citizens pledged $300,000 to the Methodist church. The university’s first building, the iconic Dallas Hall, was named in gratitude for this civic support.

Taming the Trinity River

The need to control the Trinity River was not an abstract planning goal but a matter of survival. The city was founded on its banks, but the river was a notoriously volatile neighbor. This danger became terrifyingly clear during the great flood of May 1908, when the Trinity swelled to a depth of 52.6 feet and a width of 1.5 miles. The floodwaters killed five people, left 4,000 homeless, and caused property damage estimated at $2.5 million.

The 1908 disaster created an undeniable mandate for action. Kessler’s 1911 plan provided a detailed strategy for taming the river, which included straightening its channel and constructing a massive levee system to protect the floodplain where much of the city’s industrial and residential property lay. The city took a major step in connecting its two halves in 1912 with the opening of the Houston Street Viaduct, a monumental concrete bridge that spanned the Trinity floodplain to link Dallas with Oak Cliff. At the time of its completion, it was the longest concrete bridge in the world. In 1914, a boat captained by Commodore Duncan successfully navigated the Trinity from the Gulf of Mexico all the way to Dallas, a journey intended to prove the river’s potential for commercial navigation. While the full levee system envisioned by Kessler would not be completed until the 1930s, the planning and initial steps taken in the 1910s marked the beginning of Dallas’s long and costly effort to bring its defining natural feature under control.

The Federal Reserve Bank: A Financial Coup

The most significant economic victory for Dallas in the decade came in 1914. When Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in late 1913, it authorized the creation of eight to twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks. A fierce competition immediately erupted among cities across the nation to host one of these powerful new financial institutions. In the Southwest, Dallas faced a strong challenge from New Orleans, a much larger city with a long-established financial community.

Dallas, however, mounted a sophisticated and aggressive campaign led by George Dealey, the influential publisher of the Dallas Morning News. The city’s leaders did not simply apply; they launched a multi-pronged lobbying effort that combined public promotion with shrewd political maneuvering. They compiled a document for the Reserve Bank Organization Committee that showcased Dallas as the dynamic heart of the most progressive section of the United States. This presentation was a masterclass in “Texas bravado and the art of promotion”. It highlighted the city’s explosive population growth of 116% between 1900 and 1910, dwarfing that of New Orleans. It boasted that Dallas had “the largest telephone development per capita of any city in the United States” and led the world in key manufacturing sectors.

Behind the scenes, Dealey leveraged his political connections, ensuring that Dallas’s case was made directly to key members of the Wilson administration. The strategy worked. In 1914, Dallas was officially chosen as the headquarters for the Eleventh Federal Reserve District. The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas opened for business on November 16, 1914, in a rented space at 1309 Main Street with a staff of just 27 people. Its arrival was a transformative moment. It assured Dallas’s place as a major financial center, attracting insurance companies, investment capital, and banking talent that would fuel its growth for decades to come.

King Cotton and the Wholesale Trade

At the heart of the city’s economy was cotton. By the early 20th century, Dallas was the world’s leading inland cotton market, a title it held with pride. The Dallas Cotton Exchange, organized in 1907, became one of the largest and most important cotton markets on the globe. The industry’s influence extended beyond trade; Dallas also led the world in the manufacturing of cotton-gin machinery and was a major producer of saddlery and harnesses.

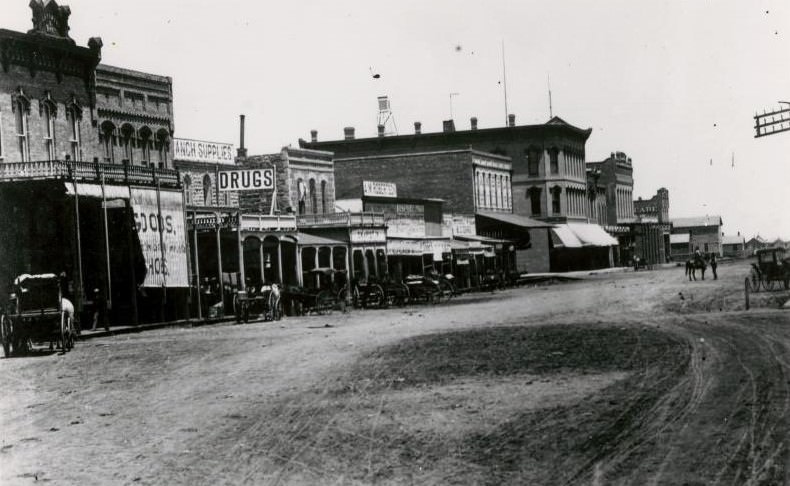

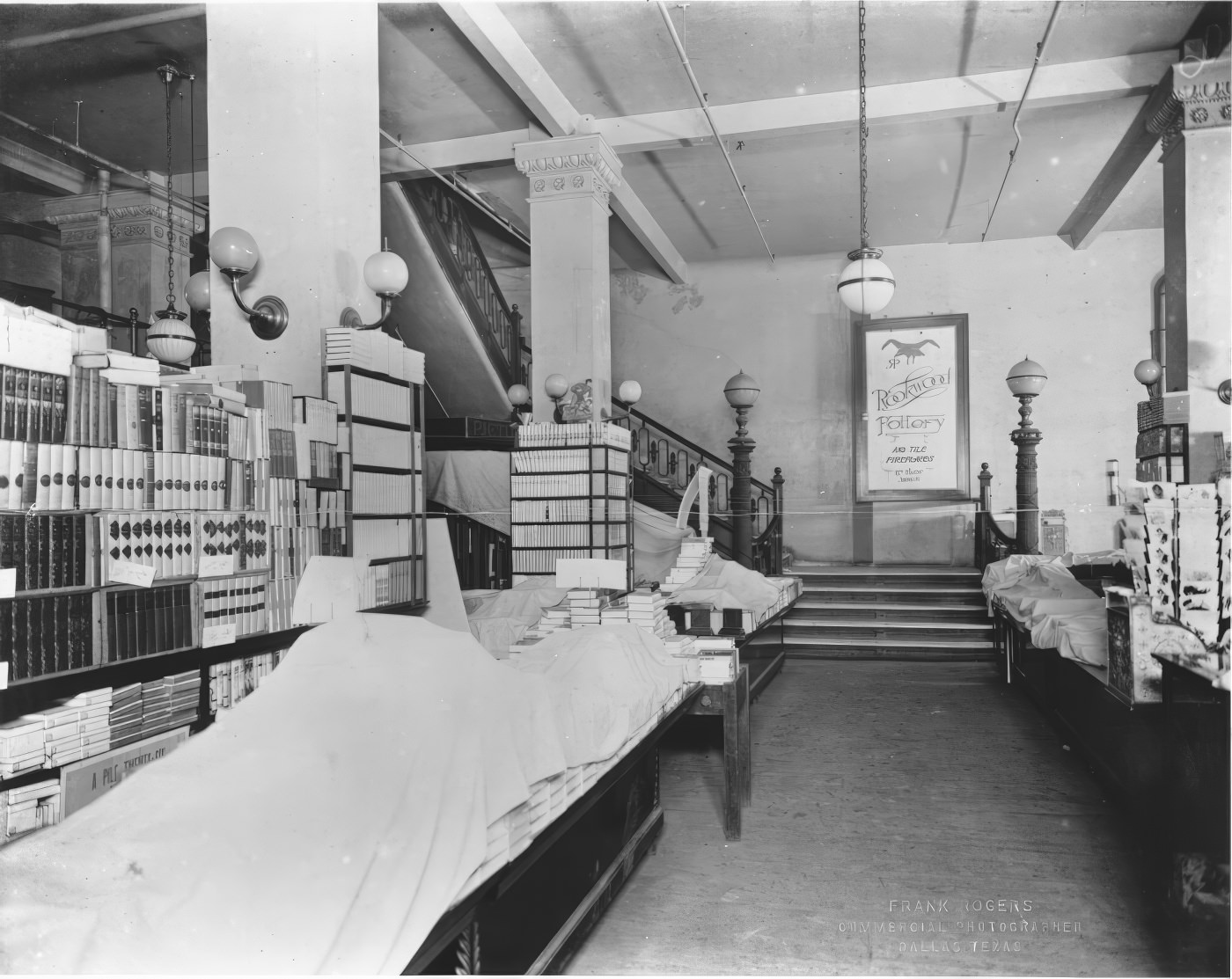

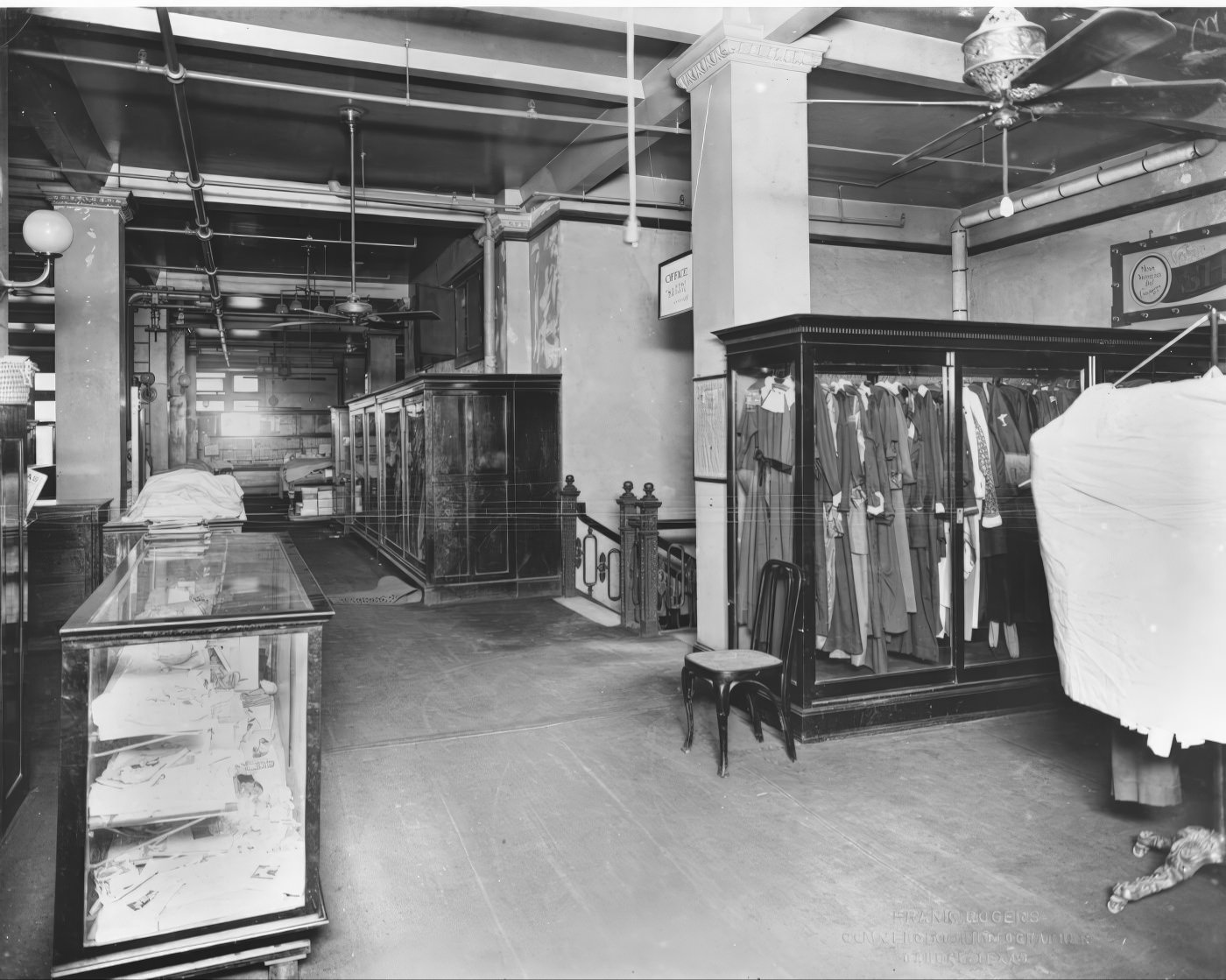

The city’s role as a cotton hub attracted international attention. In 1910, the Japan Cotton Trading Company (Nippon Menka) established its American headquarters in the region, anticipating that the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 would make Texas cotton more competitive with supplies from India. By 1912, the company was responsible for shipping the majority of Texas cotton bound for Japan, solidifying Dallas’s connection to the global economy. Beyond the cotton trade, Dallas was the premier wholesale market in the entire Southwestern United States for a wide range of goods, including drugs, books, jewelry, and liquor. Its extensive railroad network made it the natural distribution point for a vast and rapidly developing region.

Life in ‘Little Mexico’

The outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 triggered a wave of migration, as people from all walks of life fled the violence and instability in their home country. Many found their way to Dallas, seeking work in the city’s factories, cotton fields, and, most notably, on its expanding railroad network. These newcomers settled primarily in an area bordered by Maple Avenue and McKinney Avenue, a neighborhood that had previously been home to Polish Jewish immigrants. Through a process of ethnic succession, the area transformed, and by 1919 it was widely known as “Little Mexico”.

Life for the residents of Little Mexico was marked by severe hardship. As the population grew, housing became scarce, and many families lived in crowded conditions. Homes were often hastily constructed from scrap wood and tar paper, and the city left the streets unpaved. A later survey revealed that in the following decades, the vast majority of residents lived without indoor plumbing or gas for heating, relying on wood and kerosene instead. Access to medical care was extremely limited, contributing to a high mortality rate, particularly among children.

Despite these difficult conditions, the residents of Little Mexico forged a strong, self-reliant community. They established their own businesses, including grocery stores, bakeries, and barbershops. In 1911, Miguel Martinez Sr., an immigrant who arrived that year, founded a small restaurant that would eventually become the Dallas institution El Fenix. The heart of the neighborhood was Pike Park, which opened in 1912 and provided a vital public space for recreation and social gatherings.

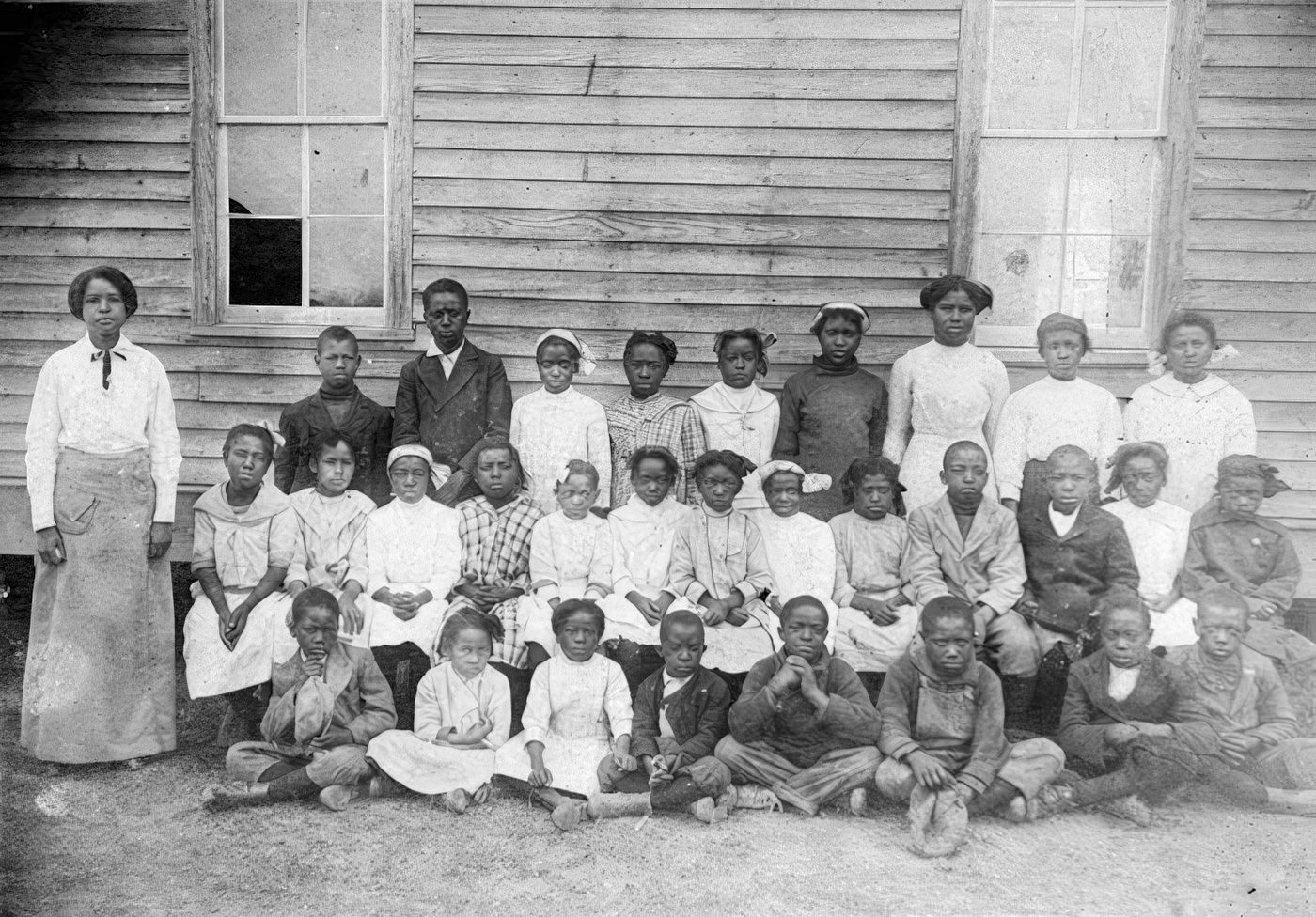

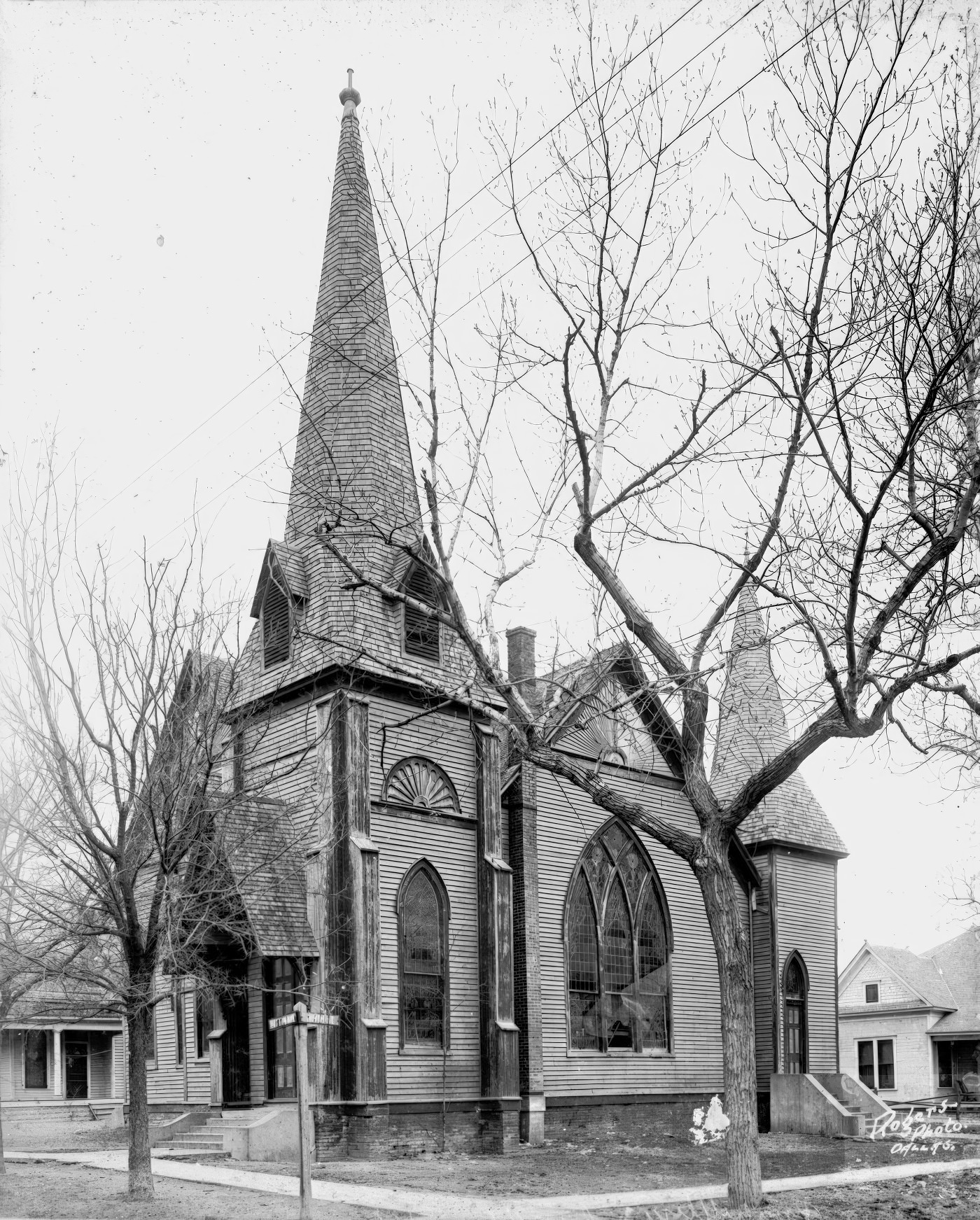

The African American Experience and the Lynching of Allen Brooks

Dallas’s African American residents lived within a system of strict racial segregation. They built thriving, self-contained communities, such as the historic Freedman’s Town (also known as State-Thomas) just north of downtown and the Tenth Street district in Oak Cliff. These neighborhoods contained a diverse population, from railroad laborers to a settled professional class, and supported their own schools, churches, businesses, and social organizations.

This self-sufficiency existed within a larger context of systemic discrimination and the ever-present threat of racial violence. On March 3, 1910, that threat became a horrifying public spectacle. A mob of several thousand white citizens lynched Allen Brooks, a 58-year-old Black handyman who had been accused of assaulting a three-year-old white girl.

The events unfolded in the heart of the city. The mob broke into the Dallas County Courthouse where Brooks was being held for trial, seized him from the custody of law enforcement, and threw him from a second-story window to the crowd below. They then tied a rope around his neck and dragged his body down Main Street to the intersection of Main and Akard. There, they hanged him from a telephone pole attached to the Elks Arch, a large decorative structure that had been erected to welcome visitors to the city. The lynching was treated as a public event; thousands of men, women, and children came to watch, and souvenir postcards depicting the scene were printed and sold. Despite the public nature of the murder and the presence of numerous witnesses, no one was ever charged with a crime. The event stood as a brutal affirmation of mob rule and the powerlessness of the Black community before the city’s white establishment.

The Growth of Segregated Suburbs

The expansion of Dallas’s streetcar system in the 1910s was the primary engine of suburban development. By 1910, over 20 streetcar lines radiated out from the central business district, making previously remote land accessible for residential construction. This growth, however, was not uniform; it was explicitly structured along lines of class and race.

Wealthy and middle-class white families began moving to newly platted, “premier neighborhoods” like the Belmont Addition in East Dallas. Developers advertised these areas as exclusive enclaves with “attractive home sites,” shaded lots, and homes built in the fashionable architectural styles of the day, such as Craftsman bungalows and Prairie School four-squares. The creation of these neighborhoods was part of a larger trend of the well-to-do abandoning older residential areas closer to the industrializing city center.

At the same time, housing for the city’s working class and minority populations was developed in less desirable areas. Poorly constructed frame dwellings and shotgun houses were built for renters, many of whom were African American, along the noisy and polluted railroad rights-of-way, close to the factories where they provided cheap labor. City directories from the period reveal a clear, if proximate, geography of class: factory owners and managers often lived on streets directly adjacent to the much smaller, more crowded homes of their workers. This deliberate residential segregation physically encoded the city’s social hierarchy into its very landscape.

Civic Life, Politics, and Public Spectacle

The 1910s were a decade in which Dallas’s leaders consciously crafted a public identity for the city. This identity was built on tangible symbols of modernity, ambition, and civic spectacle. Through the construction of a new skyline, the acquisition of prestigious institutions, and the hosting of technologically advanced entertainment, they projected an image of Dallas as a dynamic, forward-looking metropolis. This public branding, however, was a highly curated performance, one that often stood in stark contrast to the segregated and conflicted realities of life for many of its citizens. The city’s new buildings, universities, and public events were not just amenities; they were tools used to build a powerful narrative of progress.

Entertainment for the Masses

Dallas in the 1910s developed a vibrant and diverse entertainment scene that catered to the public’s fascination with new technologies and national celebrities. Elm Street became the city’s “Theater Row,” and by 1913, Dallas had 28 motion picture theaters—24 designated for white patrons and 4 for African Americans.

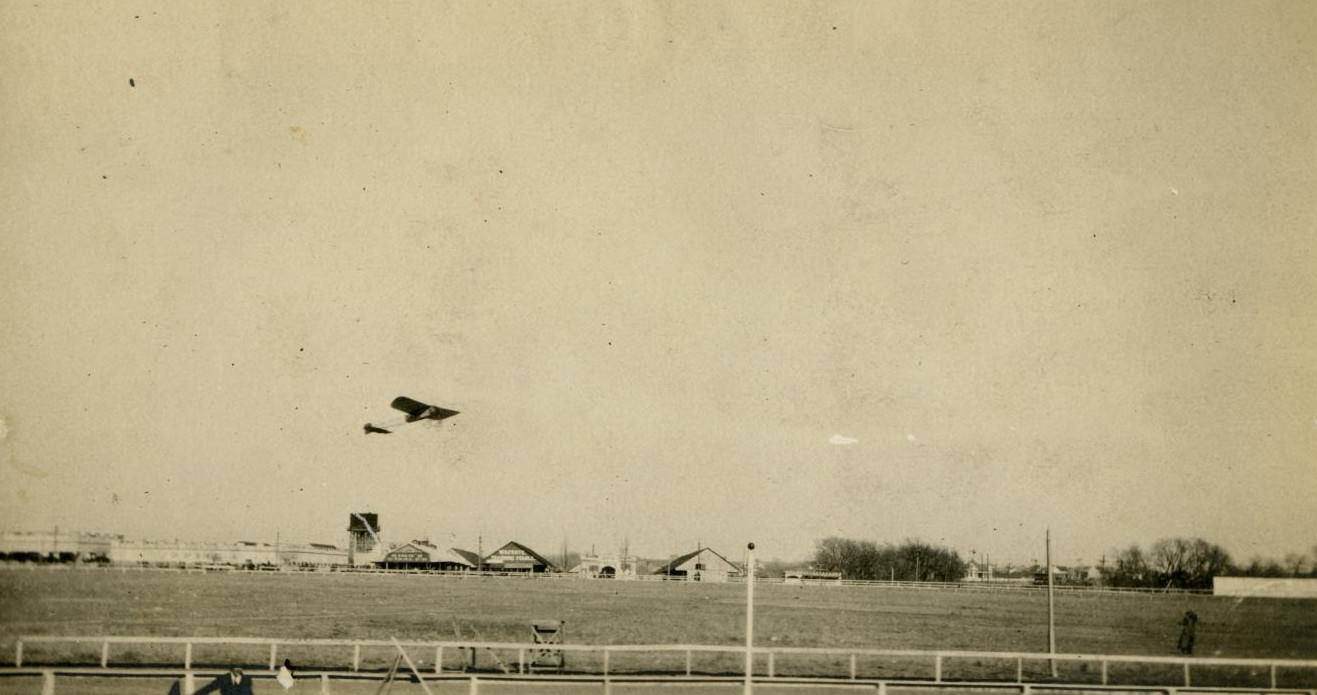

Aviation, the most thrilling new technology of the era, was a particularly popular form of public spectacle. The city hosted a series of aviation meets at Fair Park throughout the decade. These events drew large crowds to see celebrated pioneer aviators like Roland Garros, Cal Rodgers, and Lincoln Beachey, as well as famed female pilots like Mathilde Moisant and Katherine Stinson, perform daring aerial exhibitions.

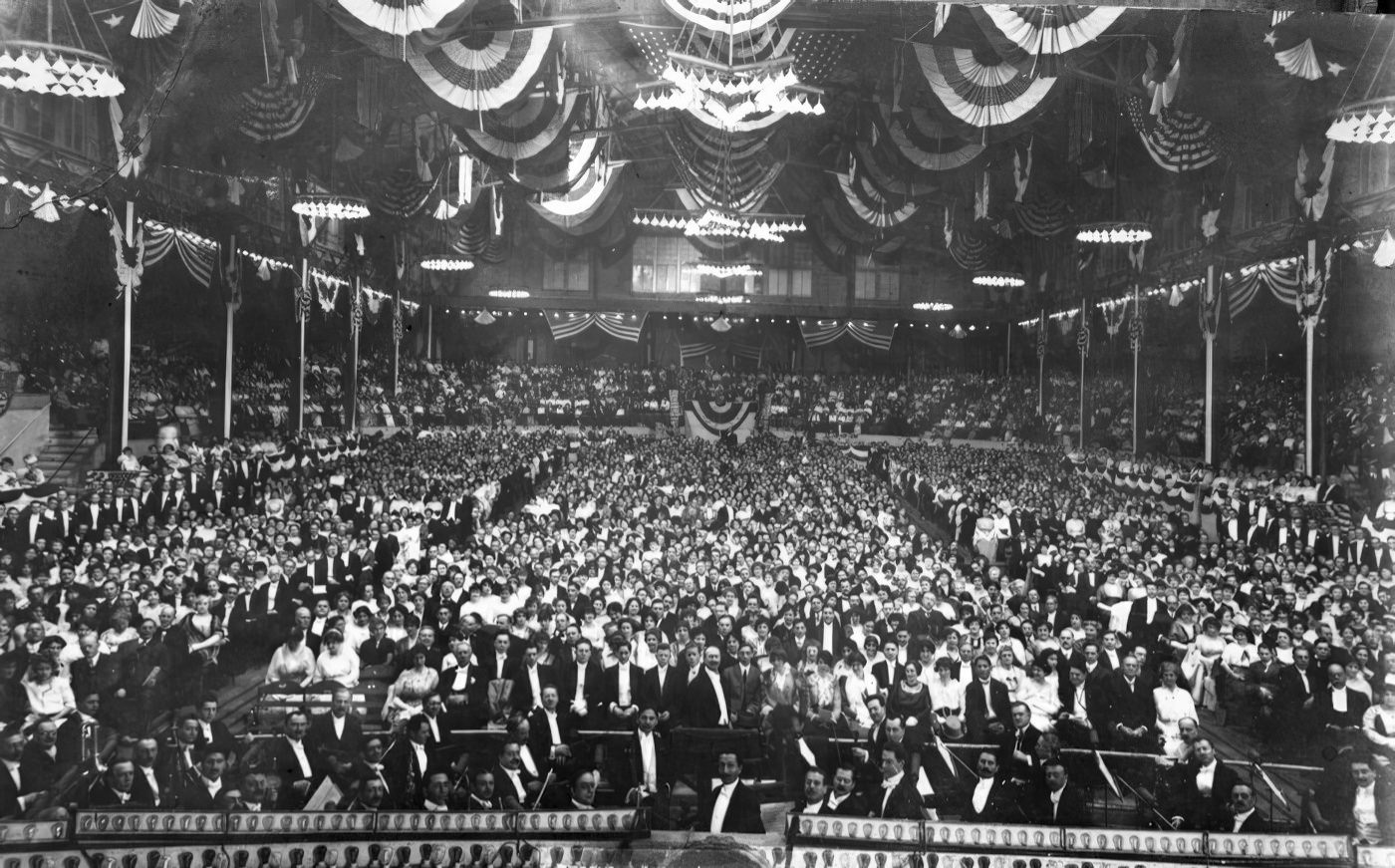

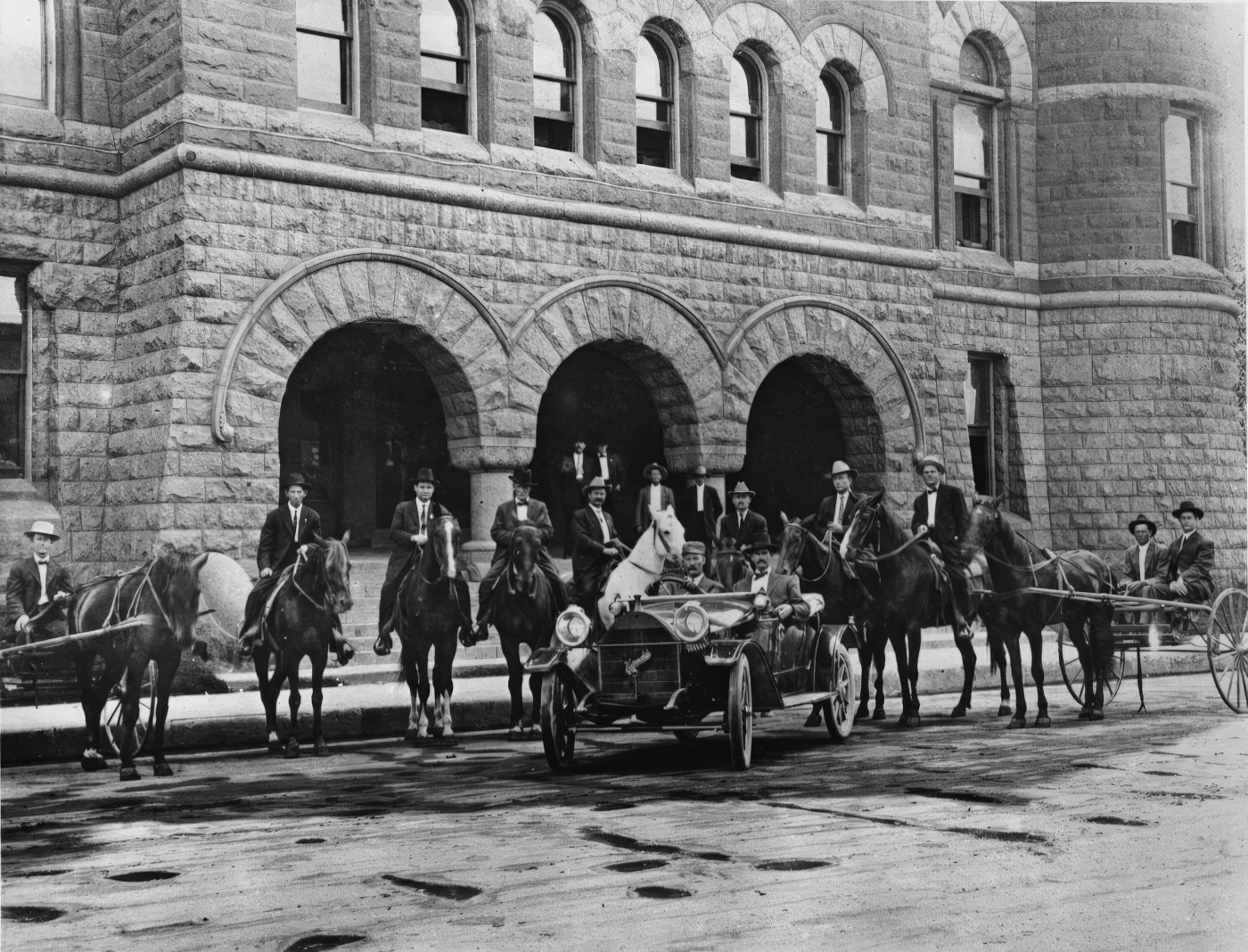

The State Fair of Texas was the city’s premier annual event, a showcase of agriculture, industry, and entertainment. The fair introduced its first automobile show in 1913 and hosted the first-ever football game between the University of Texas and the University of Oklahoma in 1914. It also served as a stage for national political figures, with former President Theodore Roosevelt (1911), future President Woodrow Wilson (1911), and Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs (1914) all delivering speeches at the Fair Park Coliseum. The fair, however, reflected the city’s racial divisions. The practice of holding a designated “Colored People’s Day” was discontinued in 1910, effectively excluding Black Texans from participating in the city’s main civic celebration for years. The fair was not held at all in 1918, as the grounds were converted for military use during World War I.

New Ways to Get Around

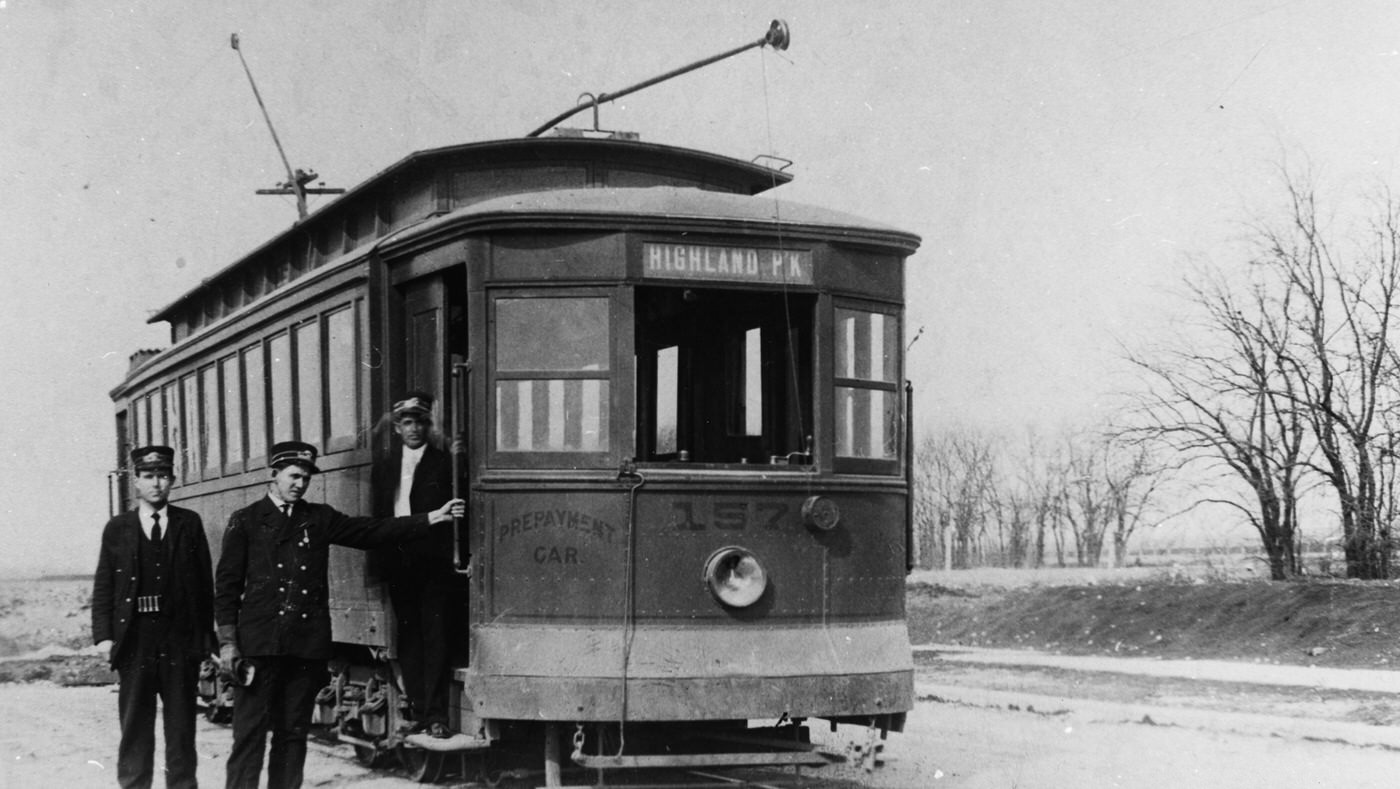

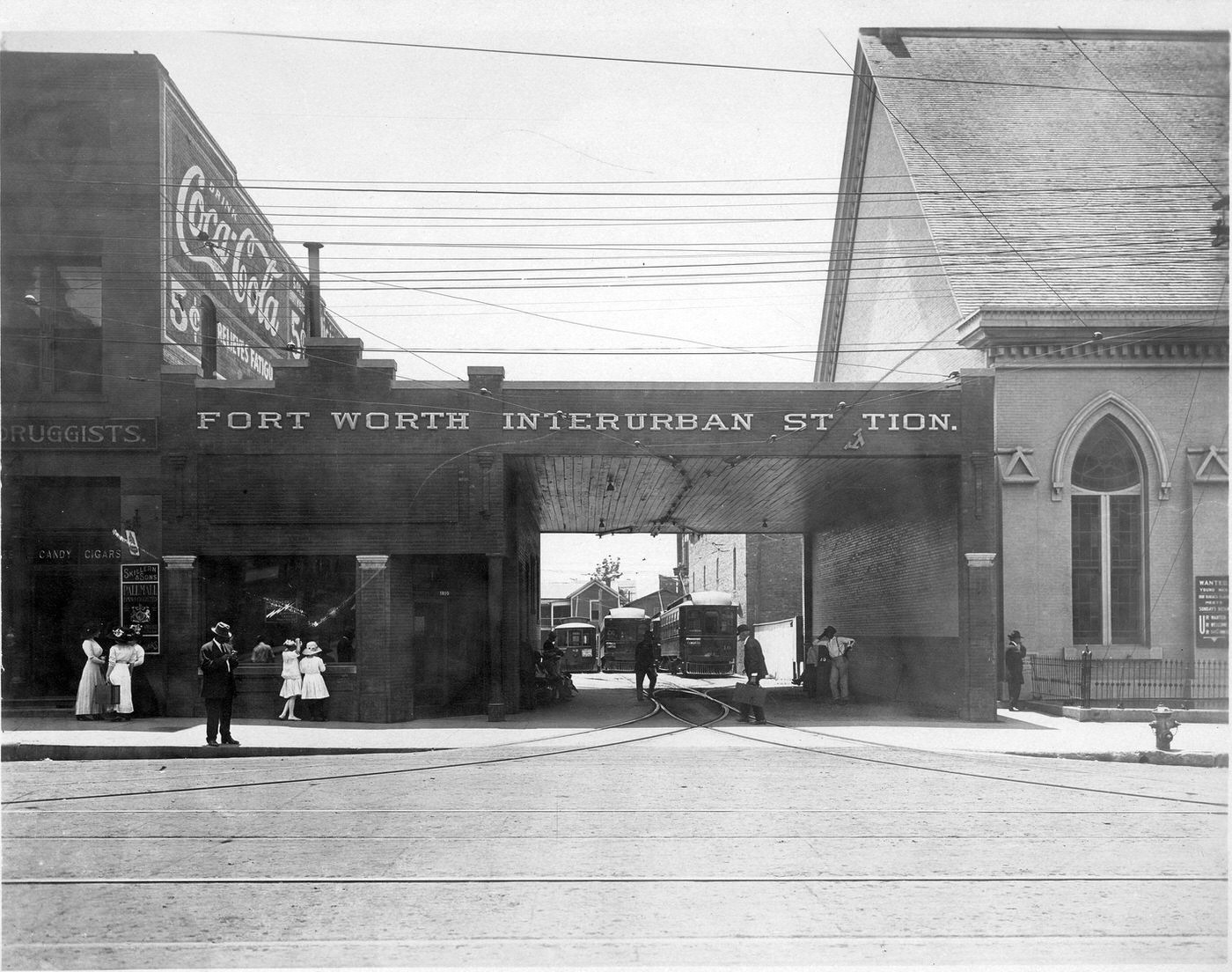

The backbone of daily life and urban expansion was the electric streetcar and interurban rail system. By the 1910s, the Dallas area was the hub of the largest electric railway network in Texas, boasting approximately 350 miles of track. The local streetcar system, with over 20 distinct lines, connected downtown to the growing residential neighborhoods of Oak Cliff, East Dallas, and the Cedars.

The interurban lines extended the city’s reach across North and Central Texas. The Texas Electric Railway, formed from the merger of two earlier companies, operated lines running north to Denison and south to Hillsboro, Waco, and Corsicana. The first interurban service connecting Dallas to Waco began on September 30, 1913, facilitating regional commerce and travel. This critical transportation network was also a site of labor conflict; in May 1911, Dallas streetcar workers went on strike, highlighting the tensions within one of the city’s most vital industries.

The 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic

The same military camps that symbolized Dallas’s contribution to the war effort became the entry point for the deadliest pandemic in modern history. During the summer of 1918, officials at Camp Dick began reporting a growing number of cases of a particularly virulent strain of influenza among the soldiers. The situation became so serious that 45 emergency tents were erected at St. Paul’s Hospital to care for the sick soldiers, and the Army imposed a quarantine on new arrivals at the camp.

Despite these clear warning signs from the military, city officials were slow to react and hesitated to alarm the public. On September 28, 1918, with the war effort at its peak, the city went forward with its massive Fourth Liberty Loan parade. Thousands of people crowded the streets of downtown Dallas to show their patriotic support and watch the procession, which included soldiers who had traveled from other cities. The parade was a catastrophic success. Within days, the Spanish Flu exploded across the civilian population. The virus spread like wildfire, striking down entire families and overwhelming the city’s limited medical resources as doctors and nurses fell ill themselves.

For two weeks, as cases and deaths mounted exponentially, city leaders delayed taking decisive action. Finally, on October 12, with the crisis undeniable, Mayor Joe E. Lawther ordered a complete shutdown of public life, closing all schools, colleges, churches, theaters, and other places of public gathering. The ban remained in effect until October 31, when the first wave of the virus began to subside. A second, less severe outbreak occurred in December, following the end of the war and the return of soldiers to their homes. The city’s public health infrastructure, still in its infancy with a state Bureau of Sanitary Engineering established only in 1917 and an inconsistent system for tracking vital statistics, was ill-equipped to handle a crisis of this magnitude. The pandemic laid bare the deadly consequences of prioritizing civic spectacle over public health.

Image Credits: Dallas Public Library, Texas History Portal, Library of Congress, Wikimedia, UTA Libraries

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know