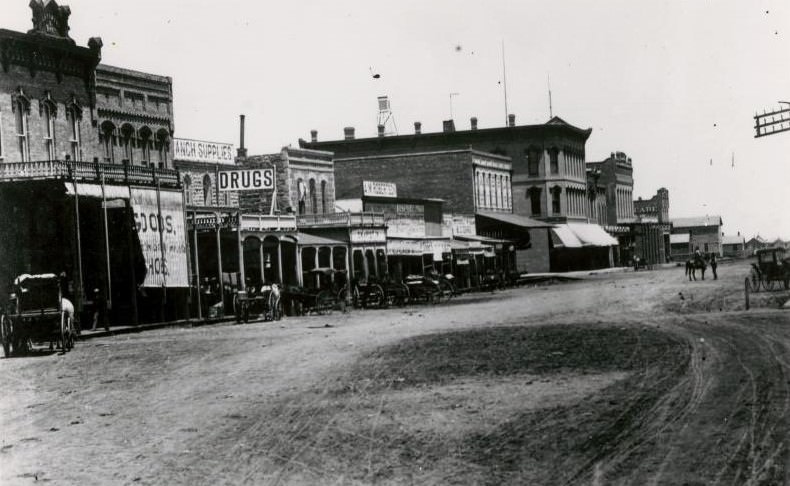

The story of Dallas in the 1920s is one of explosive growth. The decade began with the city already established as a significant urban center, but the ten years that followed would transform it at a pace few could have predicted. This rapid expansion created the foundation for the modern city, driving demand for new buildings, new infrastructure, and new workers, while also straining the social fabric and deepening existing divisions.

The numbers tell a clear story of this transformation. In 1920, Dallas had a population of 158,976, which ranked it as the 42nd largest city in the United States. By the end of the decade, that number had surged by over 64% to 260,475. This intense period of urbanization saw the city’s population grow much faster than the surrounding county, pulling people from rural areas into its expanding economic orbit.

This wave of new residents was not uniform. A significant portion of the growth came from Mexican immigrants fleeing the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution. The U.S. Census in 1920 recorded 3,378 Mexicans living in Dallas, a community that would become essential to the city’s labor force but would also face severe segregation and difficult living conditions. The city’s workforce also saw other shifts. As Dallas grew into a major commercial hub, more opportunities opened for women. By 1927, local business organizations estimated that 15,000 women were employed across 125 different occupations and professions within the city, a sign of changing economic roles.

The Economic Engine: Finance, Oil, and Industry

The decade’s rapid growth was fueled by a powerful and increasingly diverse economic engine. While cotton remained a vital part of the economy, Dallas solidified its position as a major center for finance, manufacturing, and retail, and strategically positioned itself to capitalize on the region’s next great boom: oil.

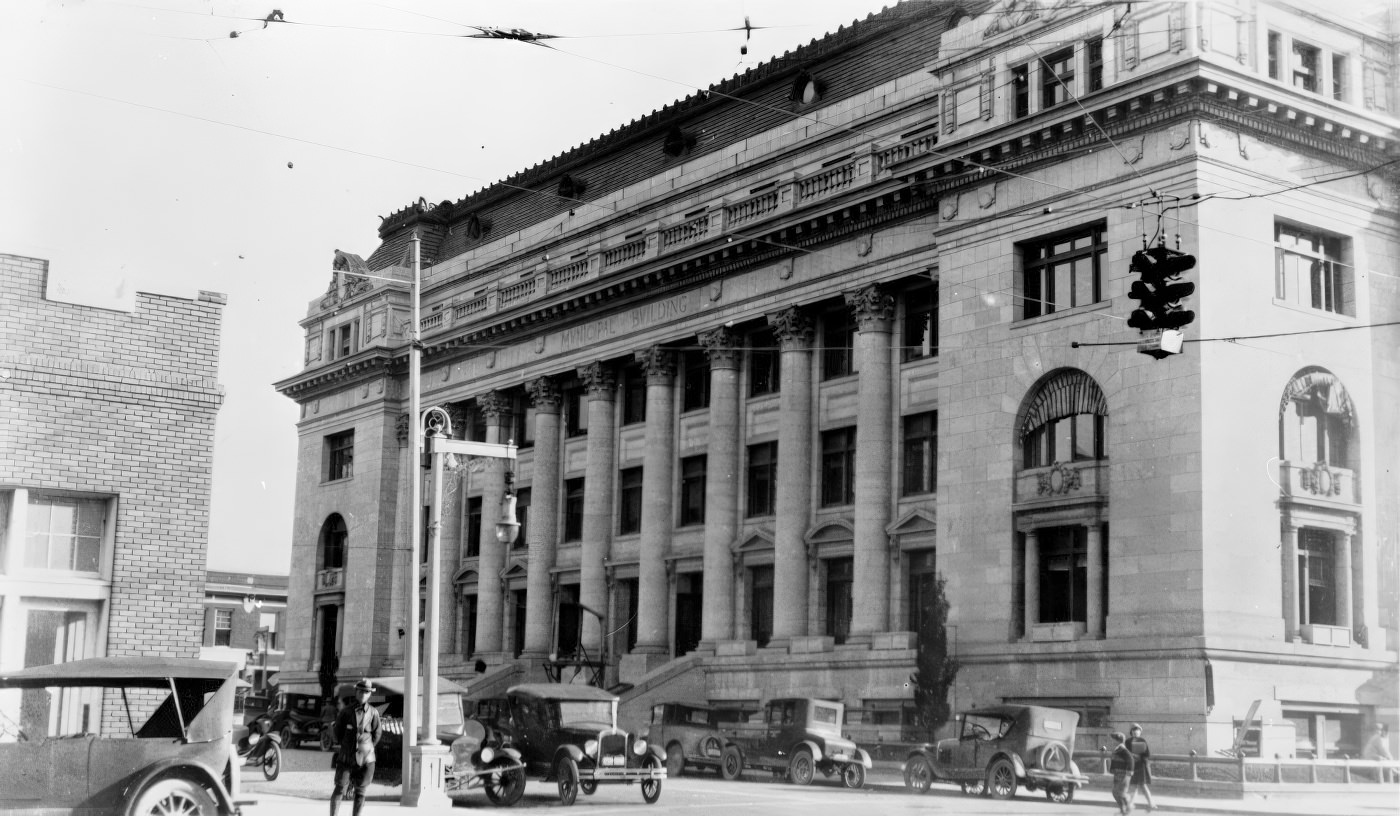

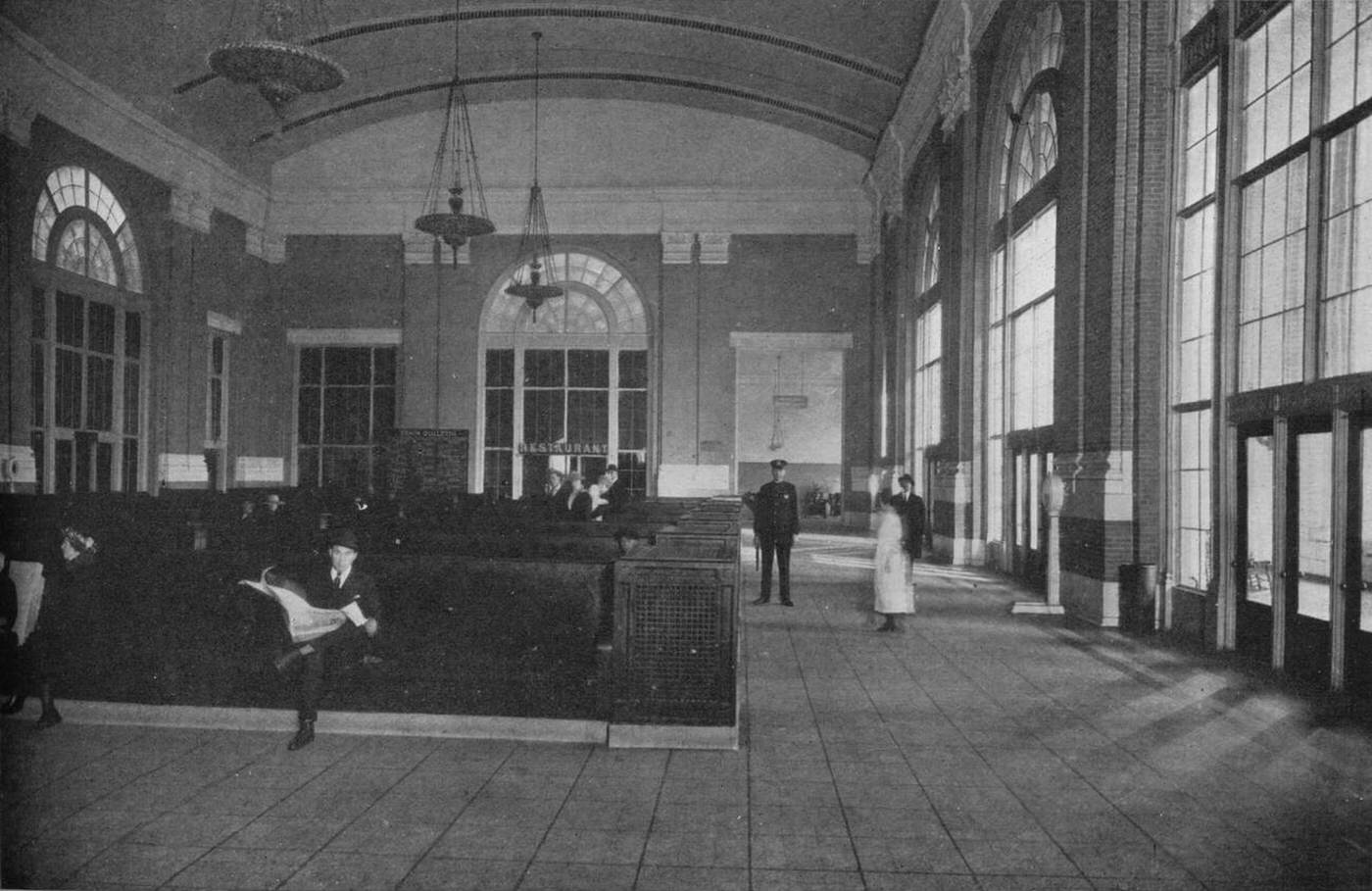

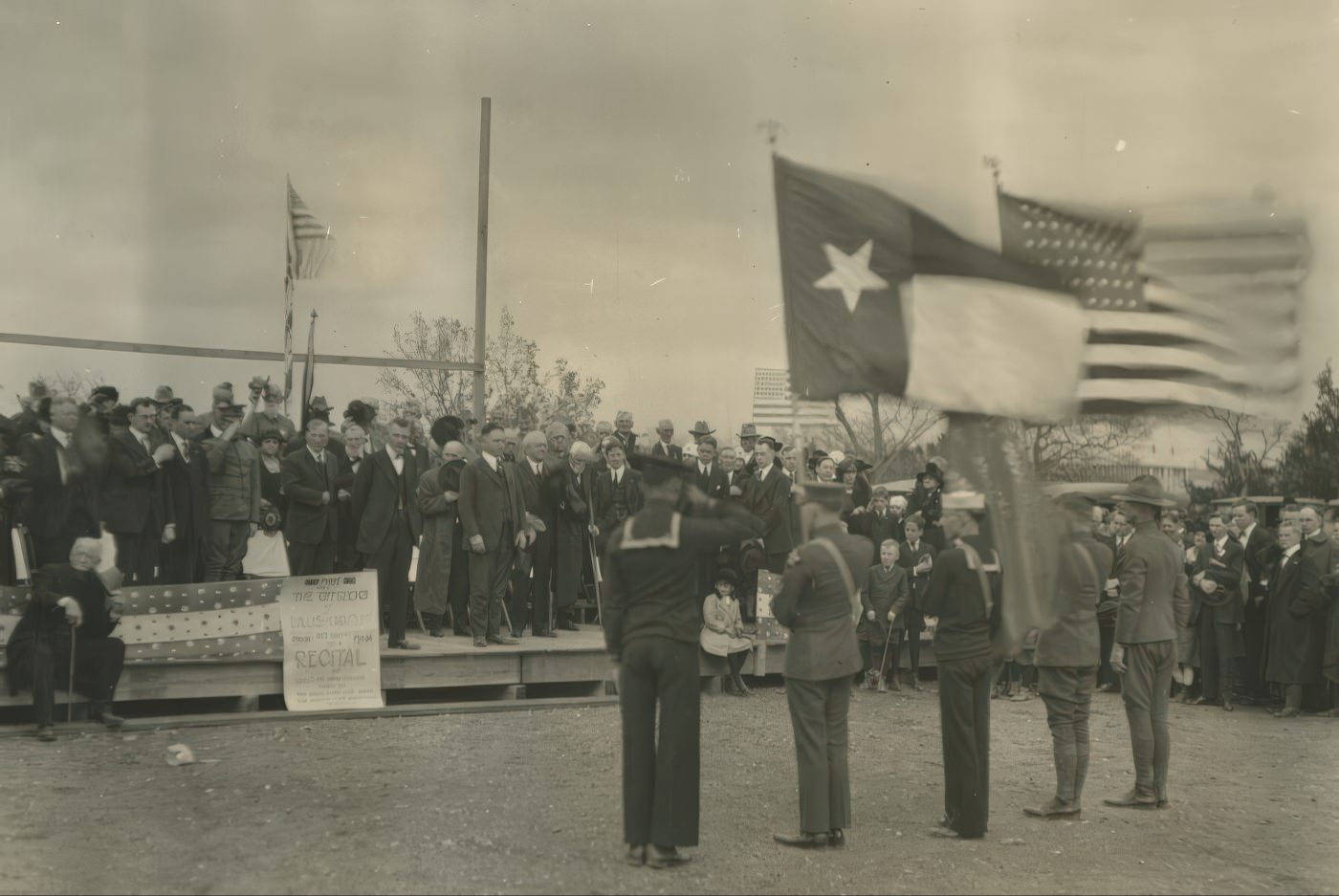

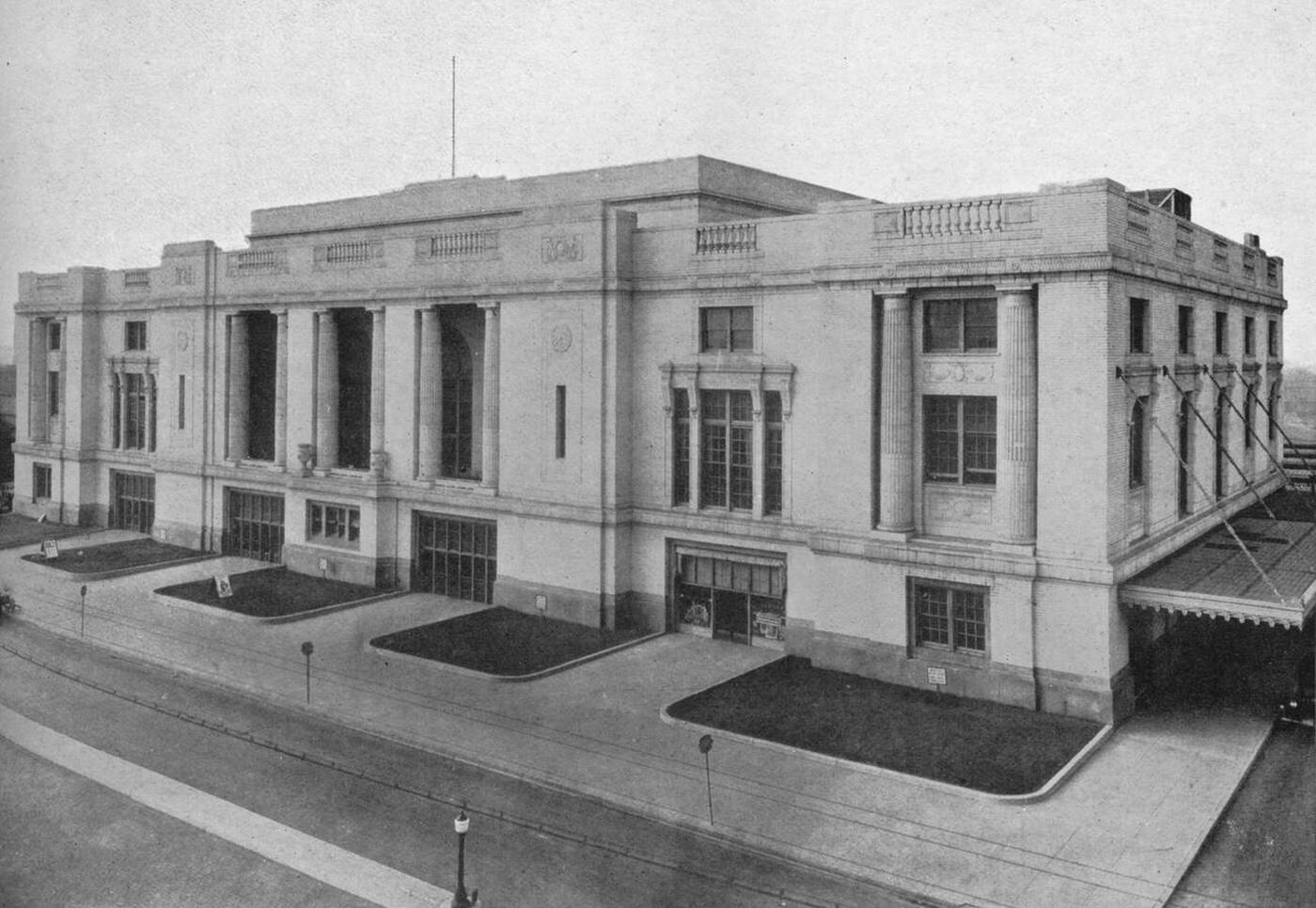

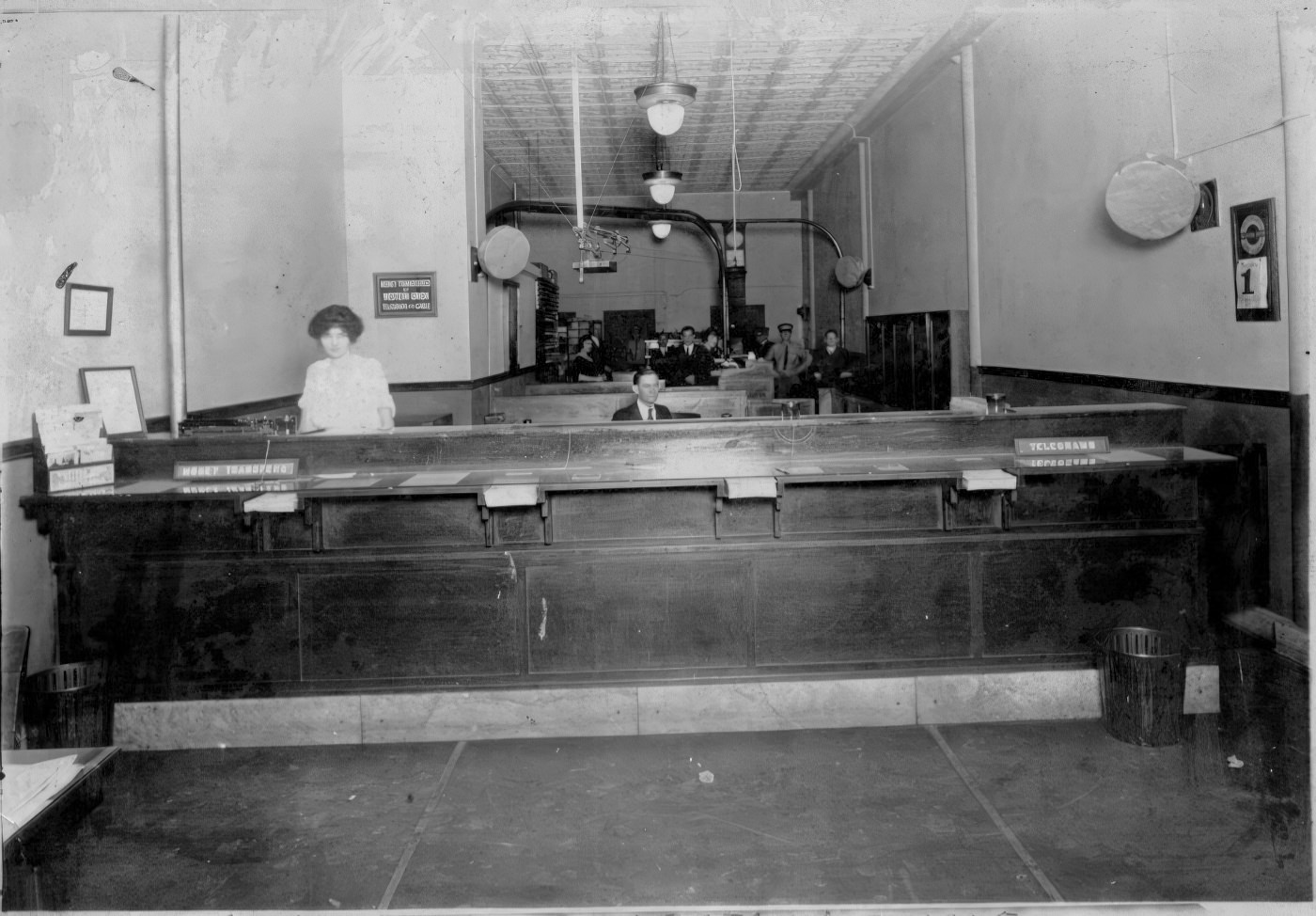

At the core of the city’s economic power was its status as a financial capital. The Federal Reserve Bank of the Eleventh District, which Dallas had secured in the previous decade, was a critical institution. Its presence anchored the city’s financial sector and facilitated the immense flow of capital through the region. The bank’s own growth was a testament to the area’s prosperity. In 1920, its gross earnings reached $4.9 million, a 60.1% increase from the year before. To reflect its importance, the bank constructed a monumental new headquarters at 400 Akard Street. The cornerstone for the imposing neo-classical building, designed by the Chicago firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst, and White, was laid on April 2, 1920, and the building was completed in 1921.

The broader banking sector in Texas operated within a unique regulatory environment. A state-run deposit insurance system, established in 1909, was mandatory for all state-chartered banks, creating a distinct set of risks and opportunities compared to nationally chartered banks. Alongside banking, Dallas also grew as a center for the insurance industry. This combination of a strong federal banking presence, a dynamic state banking system, and a growing insurance sector created a robust financial infrastructure. This infrastructure was not merely a response to the existing cotton and agricultural economy; it became a proactive force. Dallas bankers were among the first in the nation to pioneer the practice of using oil reserves as collateral for loans. This innovation meant that when the East Texas oil boom began, Dallas was not just a bystander but the primary financier, uniquely equipped to fund the exploration and development that would define the state’s economy for generations. This pre-existing financial strength, combined with its industrial base, allowed Dallas to weather the initial years of the Great Depression far better than cities dependent on a single industry.

King Cotton and Black Gold

Throughout the 1920s, Dallas maintained its title as one of the world’s largest inland cotton markets. The Dallas Cotton Exchange was a vital institution, and the industry supported a vast network of farmers, merchants, and laborers. However, the agricultural economy was prone to instability, and fluctuating cotton prices caused periods of economic difficulty during the decade.

The true economic game-changer arrived at the very end of the 1920s. In 1930, wildcatters struck oil in East Texas, discovering the largest petroleum field in the world at the time. The effect on Dallas was immediate and profound. Because of its established financial institutions and transportation links, Dallas became the undisputed financial and corporate headquarters for the boom. Oil companies established their offices in the city, and a new wave of wealth flowed into its banks, fueling another round of construction and development that would carry the city through the economic hardships of the 1930s.

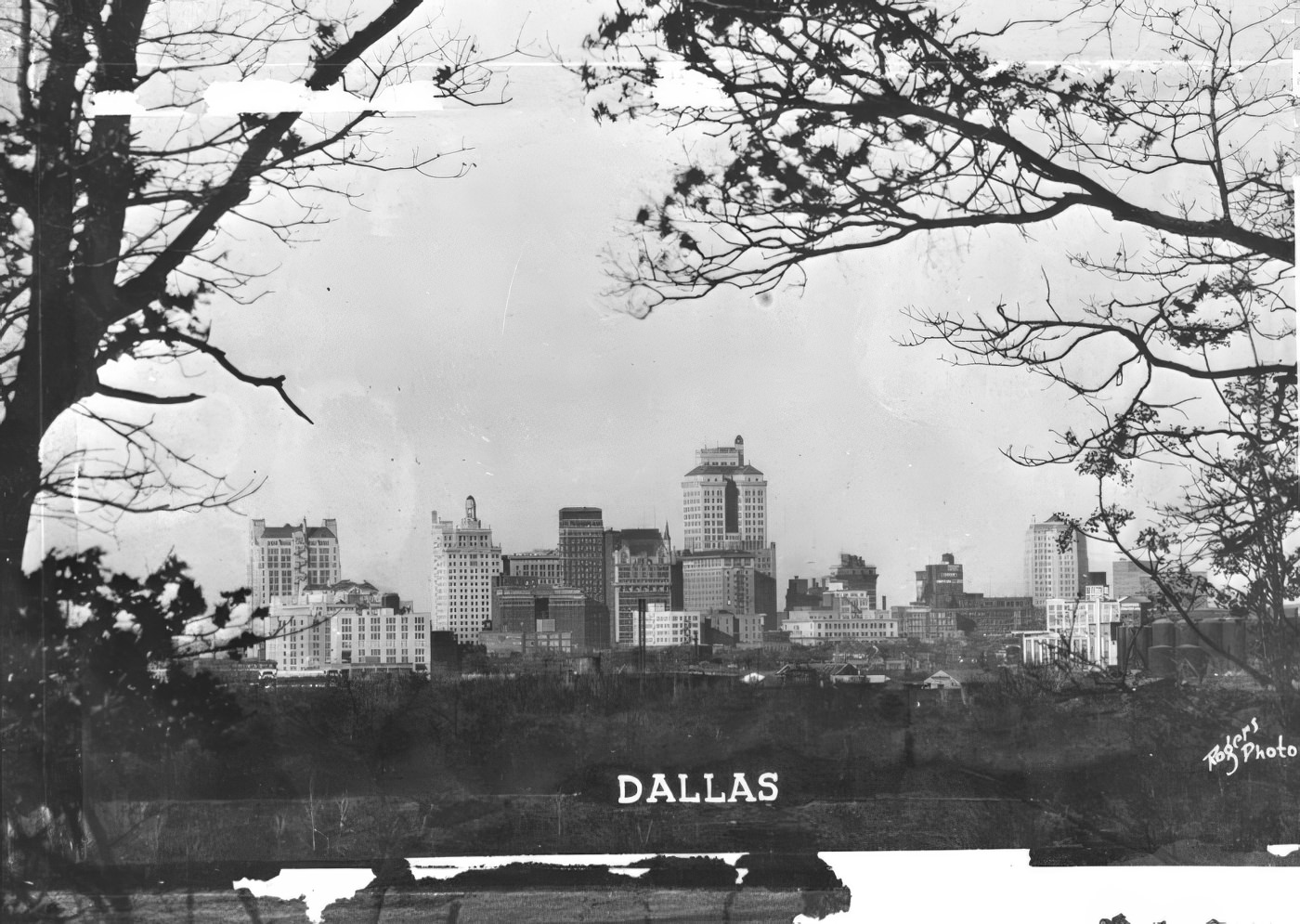

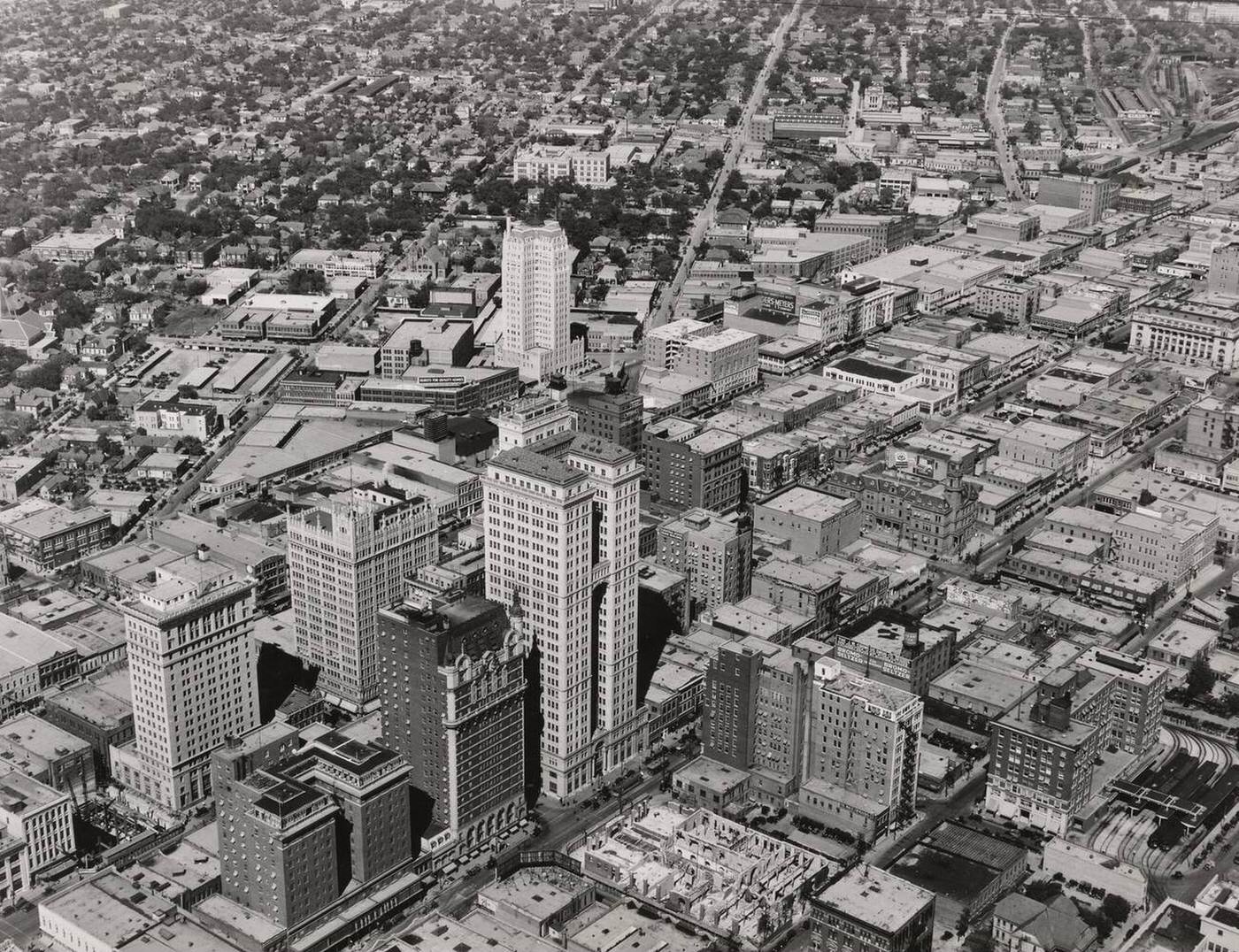

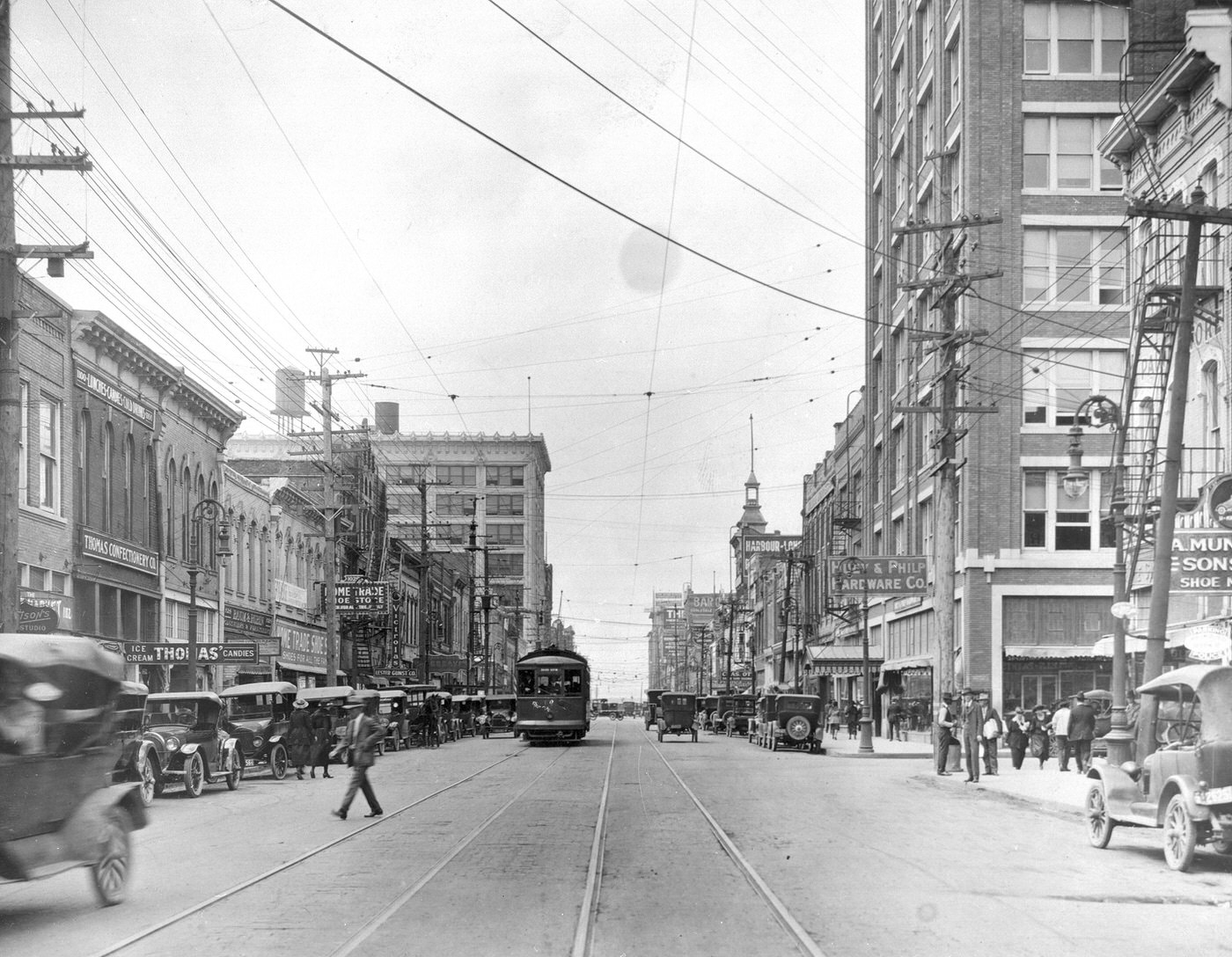

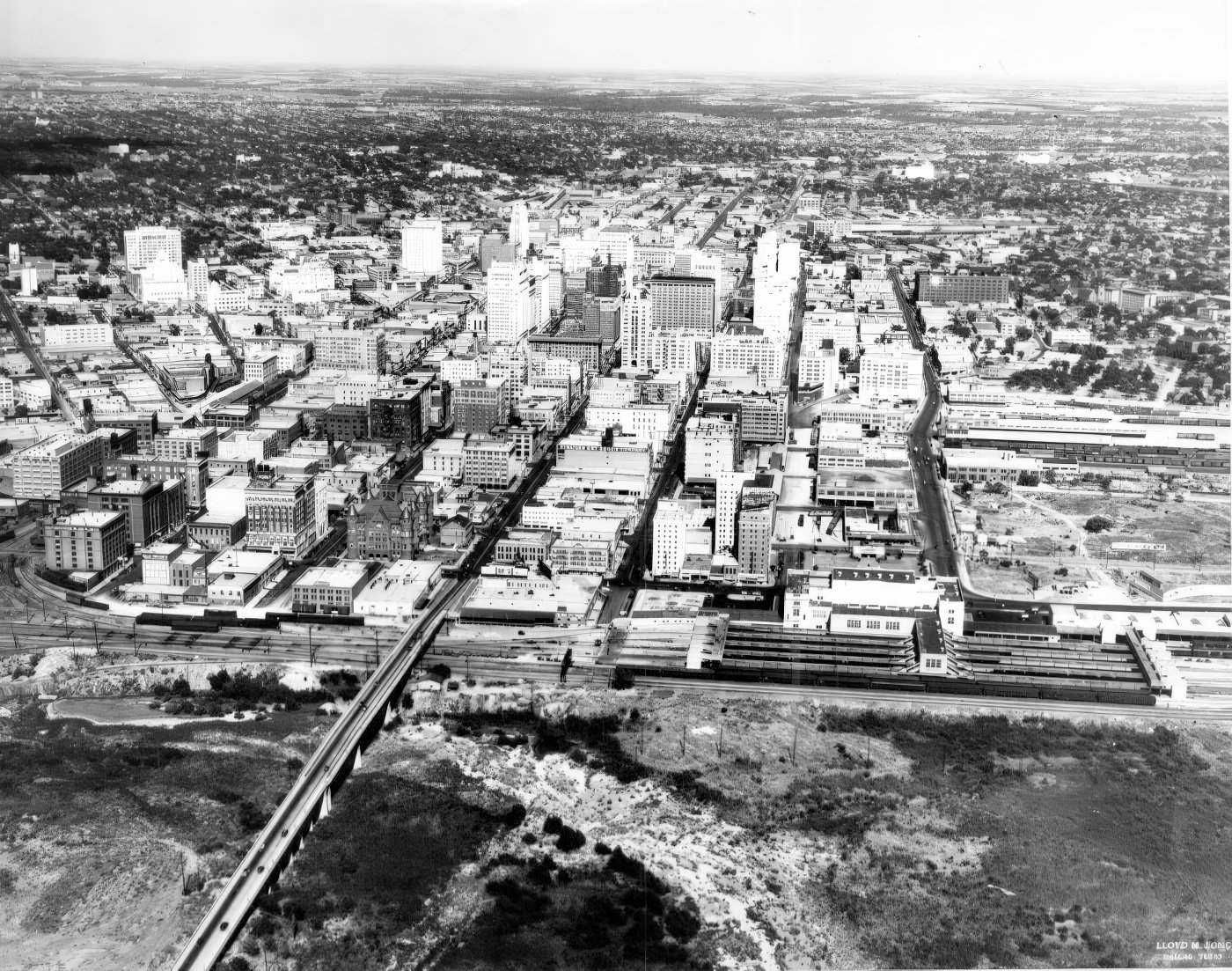

Forging a Modern City: Skylines and Infrastructure

The economic energy of the 1920s was made visible in the very fabric of the city. A construction boom reshaped the downtown skyline with towering new structures of steel and concrete, while a renewed focus on civic planning began to address the challenges of a rapidly growing metropolis.

The most dramatic symbol of the new Dallas was the Magnolia Building. Completed in 1922 for the Magnolia Petroleum Company, the 29-story skyscraper was the tallest building in the city for nearly two decades. Designed by the British architect Sir Alfred C. Bossom at a cost of $4 million, its Beaux-Arts-influenced design was a statement of the city’s rising economic power and ambition.

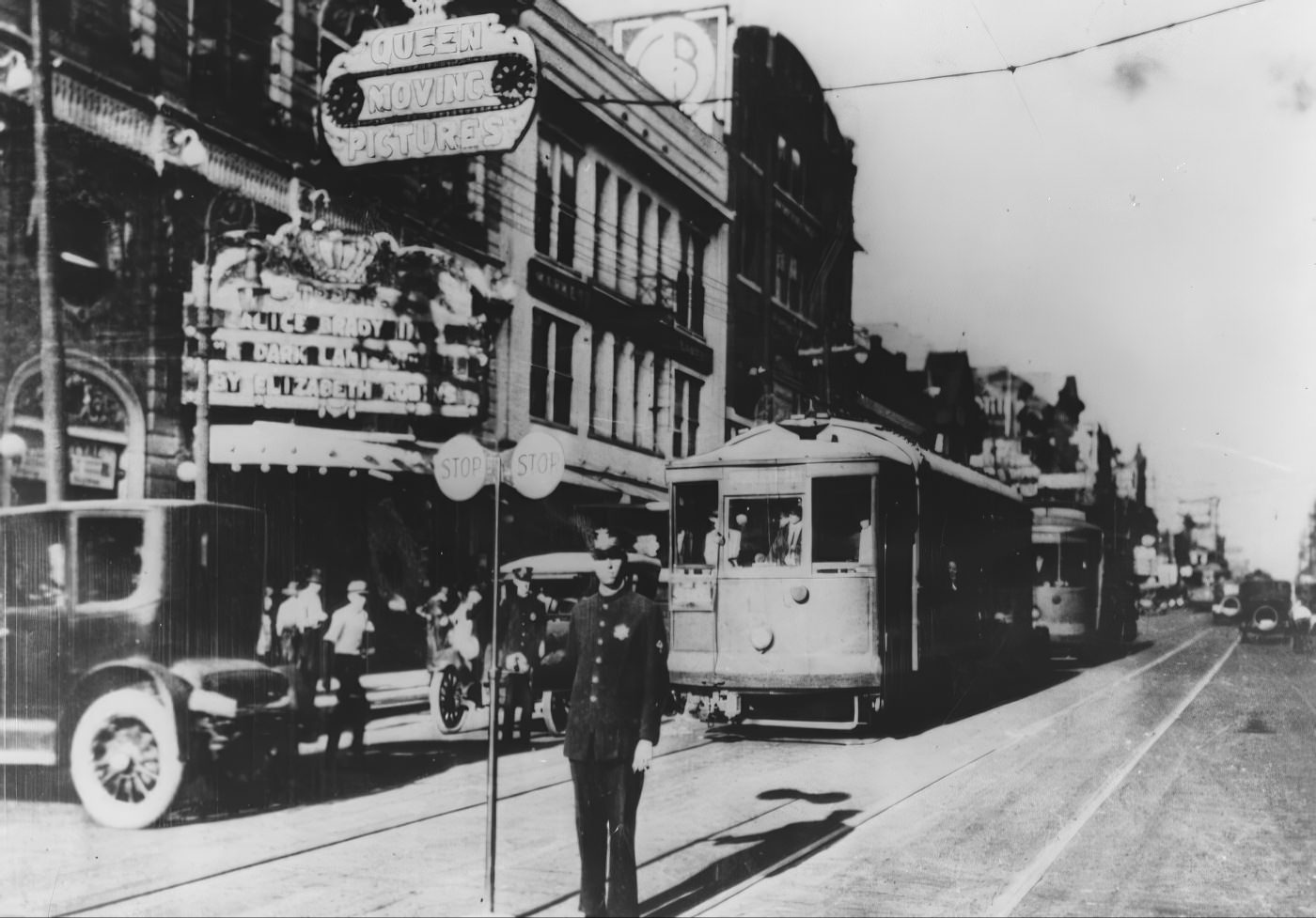

The Magnolia Building did not rise in isolation. It was the centerpiece of a building boom that defined the modern downtown. The Majestic Theatre, an ornate Renaissance-style movie palace, opened its doors on Elm Street in 1921, becoming the flagship of the Interstate Theatres chain. Other major projects, like the Baker Hotel and the Dallas Athletic Club building, also contributed to the new, more vertical skyline. This wave of construction saw the replacement of older, smaller timber buildings with modern, fireproof structures of steel and masonry, showcasing popular architectural styles of the era like Beaux-Arts, Neoclassical, and the first hints of Art Deco.

The Kessler Plan in Action

While private enterprise was building skyscrapers, city leaders turned their attention to public works. The guiding document for this effort was the Kessler Plan, a comprehensive master plan for Dallas’s development that had been drafted in 1911 but largely ignored for over a decade. Frustrated by the city’s haphazard growth, traffic congestion, and persistent threat of flooding from the Trinity River, a group of business leaders formed the Kessler Plan Association (KPA) in 1924. Their goal was to finally implement the plan’s vision of a more orderly, efficient, and beautiful city. The KPA launched a public education campaign, arguing that coordinated planning and civic improvements would benefit the entire city.

The KPA’s advocacy was successful. In 1927, Dallas voters approved the Ulrickson Program, a massive $23.9 million bond package designed to fund the projects outlined in the Kessler Plan. This program represented a major commitment to reshaping the city’s infrastructure. Funds were allocated for a variety of projects, including the widening and extension of major streets to ease traffic, large-scale improvements to the sewer system, and the beginning of the ambitious Trinity River reclamation project, which involved building a system of levees to protect the city from the river’s devastating floods.

The Kessler Plan also emphasized the importance of public green spaces. Under its guidance, the Dallas park system expanded rapidly. By 1923, the city had 32 parks covering 3,773 acres. This commitment to parks and recreation was so extensive that the U.S. Department of Labor named Dallas’s park system the best in the nation for a city of its size.

This push for civic improvement, however, carried a hidden cost. The implementation of the Kessler Plan was a top-down effort driven by the city’s business elite to solve problems that directly affected the commercial core, such as flooding and traffic. While these projects brought undeniable benefits to downtown and affluent residential areas, they often had severe consequences for the city’s minority communities. The process of “slum clearance” required for projects like street widening and levee construction led directly to the displacement of residents in neighborhoods like Little Mexico. These families, with few resources and limited housing options due to segregation, were often pushed into even more crowded conditions or into undeveloped areas like West Dallas, which lacked basic city services such as paved roads, running water, or electricity. The progress that built a modern downtown was achieved, in part, by dismantling the homes of the city’s most vulnerable residents.

The Push for Reform

The political landscape of the 1920s was overseen by a series of mayors, including Frank W. Wozencraft (1919-1921), Sawnie R. Aldredge (1921-1923), Louis Blaylock (1923-1927), and Robert E. Burt (1927-1929). Throughout their tenures, a growing movement for political reform was taking shape.

Many progressive reformers and business leaders grew dissatisfied with the city’s commission form of government. They argued that it was inefficient and led officials to focus on the narrow interests of their own districts rather than the well-being of the city as a whole. This movement advocated for a more centralized and professional council-manager system of government. The successful passage of the Ulrickson bond program in 1927 gave momentum to the reformers, and their efforts culminated in 1930, when Dallas voters approved a new city charter that established the council-manager form of government that continues to this day.

Power, Politics, and Prohibition

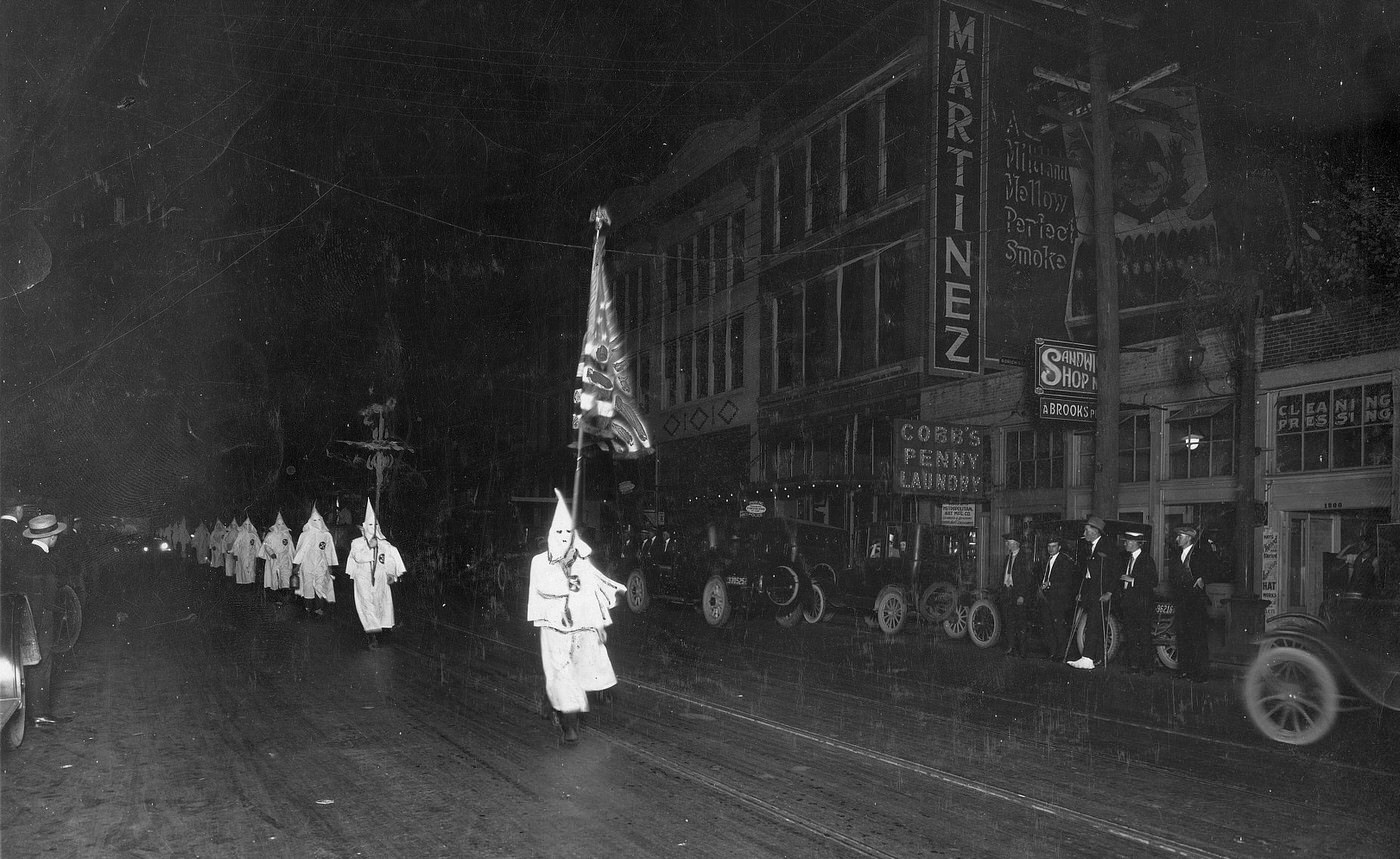

Beneath the surface of Dallas’s economic boom and civic progress, the 1920s were a decade of deep social and political turmoil. The city was a battleground for competing visions of morality and power, dominated by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the divisive issue of Prohibition.

n the early 1920s, Dallas was a national stronghold for the revived Ku Klux Klan. The local chapter, Dallas Klan No. 66, was not a fringe group but a dominant force in the city’s political and social life. Some historical accounts suggest that Dallas had the largest per capita KKK membership in the United States. Their power was made explicit in the 1922 elections, when Klan-backed candidates won nearly every contested office in Dallas County, effectively giving the organization control over the city and county governments.

The Klan’s presence was public and intimidating. They held massive parades through the streets of downtown, marching in full regalia of hoods and robes. In May 1921, a silent march of 789 Klansmen brought the city to a standstill. They used these displays, along with cross burnings and acts of violence, to terrorize African Americans, Catholics, Jews, and any other groups that did not fit their narrow definition of “100% Americanism” and “traditional morality”. This created a pervasive climate of fear that reinforced the city’s rigid system of racial segregation.

The Klan’s absolute control, however, was short-lived. By the latter half of the decade, their power began to crumble. A combination of internal power struggles, growing opposition from civic and religious groups, and widespread public disgust at their violent methods led to a rapid decline. Statewide, the Klan’s membership fell from a peak of around 150,000 to just 2,500 by the late 1920s.

A City Divided by Prohibition

The 1920s were the era of national Prohibition, and Texas had one of the strictest prohibition laws in the country. The Dean Act of 1919, which went into effect before the federal Volstead Act, made violations a felony rather than a misdemeanor. North Texas, including Dallas, was a center of the “dry” movement, with strong support for Prohibition from religious and temperance groups.

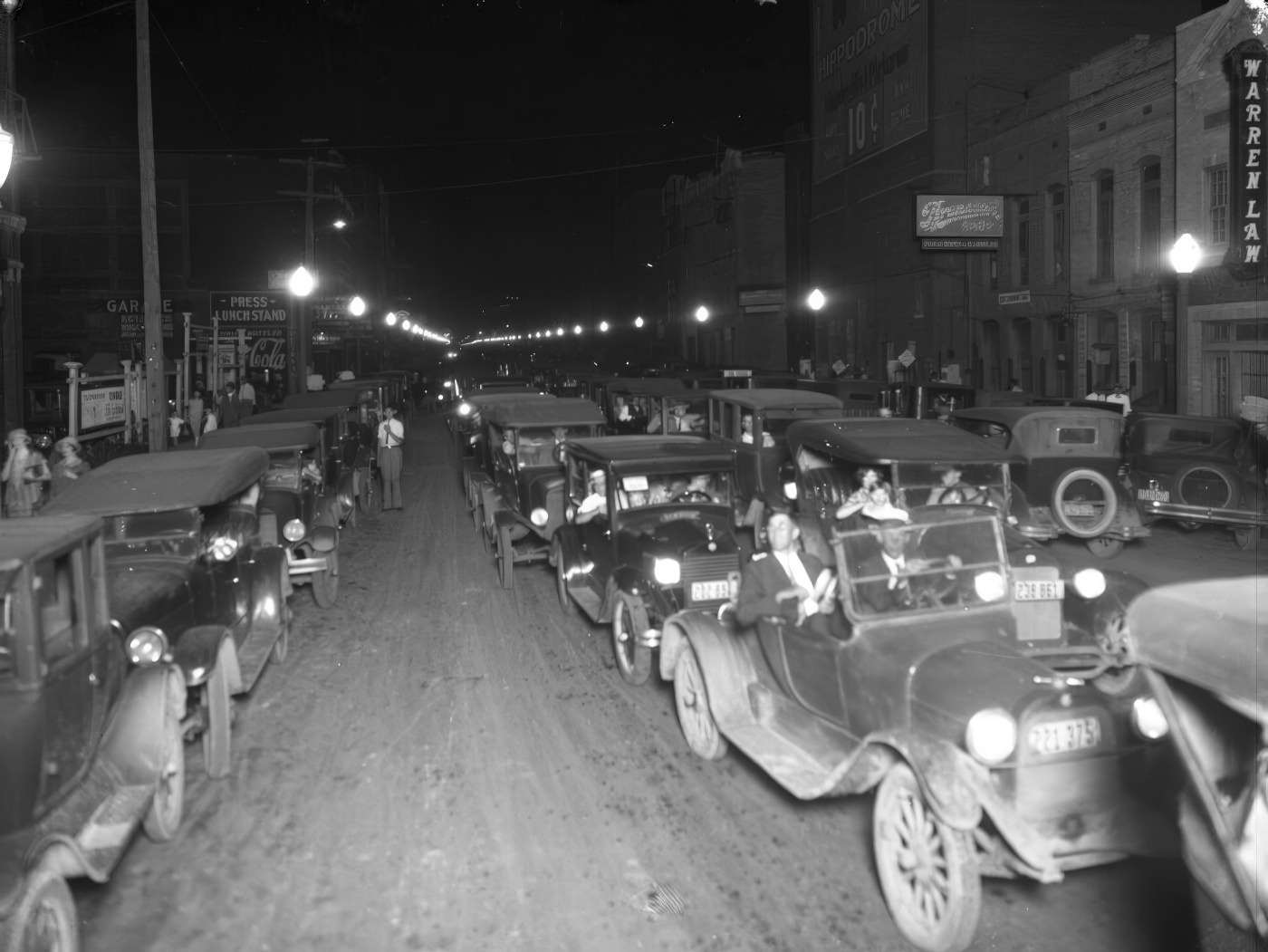

The law, however, was one thing; reality was another. Enforcement of Prohibition was notoriously difficult and often half-hearted. A thriving underground economy of moonshining, smuggling, and illegal bars known as speakeasies emerged in Dallas and other Texas cities. Corruption was rampant. Law enforcement officers, including some Texas Rangers, were known to take bribes to look the other way, and juries were often sympathetic to defendants, making convictions difficult to secure. The

Dallas Morning News, which took a courageous stand in condemning the Ku Klux Klan, had a more complex position on Prohibition, reporting on the activities of temperance societies but also reflecting a city where the law was widely flouted.

This situation created a stark hypocrisy at the heart of Dallas’s power structure. The same Ku Klux Klan that controlled city politics and preached a violent form of moral purity was either unable or unwilling to stop the widespread violation of Prohibition laws. This disconnect between the public pronouncements of political leaders and the daily reality of city life eroded public trust in government and law enforcement. It created an environment where organized crime could flourish and where a culture of civic corruption operated just beneath the veneer of progress and prosperity.

Daily life in 1920s Dallas was a study in contrasts. While the mainstream, white population enjoyed new forms of entertainment in grand downtown theaters, the city’s segregated minority communities built vibrant, self-sufficient cultural worlds of their own, creating spaces for expression and community in the face of widespread discrimination.

The Bright Lights of Deep Ellum

For the African American community of Dallas, Deep Ellum was the center of the universe. Located just east of the white downtown, it was a “city within a city,” a bustling commercial and cultural district born out of the necessity of segregation. Barred from white-owned businesses, Black residents created their own economic and social hub.

By the 1920s, Deep Ellum had become a nationally recognized hotbed for blues and jazz music. Its streets, dance halls, and vaudeville houses echoed with the sounds of legendary artists like Blind Lemon Jefferson, who was discovered singing on its street corners, and Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter. The neighborhood’s “theatre row” was a major attraction, featuring movie palaces that screened films with all-Black casts, offering a rare source of entertainment and cultural affirmation that was denied in segregated white theaters.

Deep Ellum was also home to vital community institutions. The Grand Temple of the Black Knights of Pythias, a handsome brick building opened in 1916, served as a professional center, housing the offices of Black doctors, dentists, and lawyers. The community’s voice was the

Dallas Express, a Black-owned weekly newspaper that reported on news ignored by the mainstream press, including lynchings and mob violence, while also denouncing segregation and promoting Black-owned businesses. In 1925, community leaders organized the Dallas Negro Chamber of Commerce to further advocate for their economic interests.

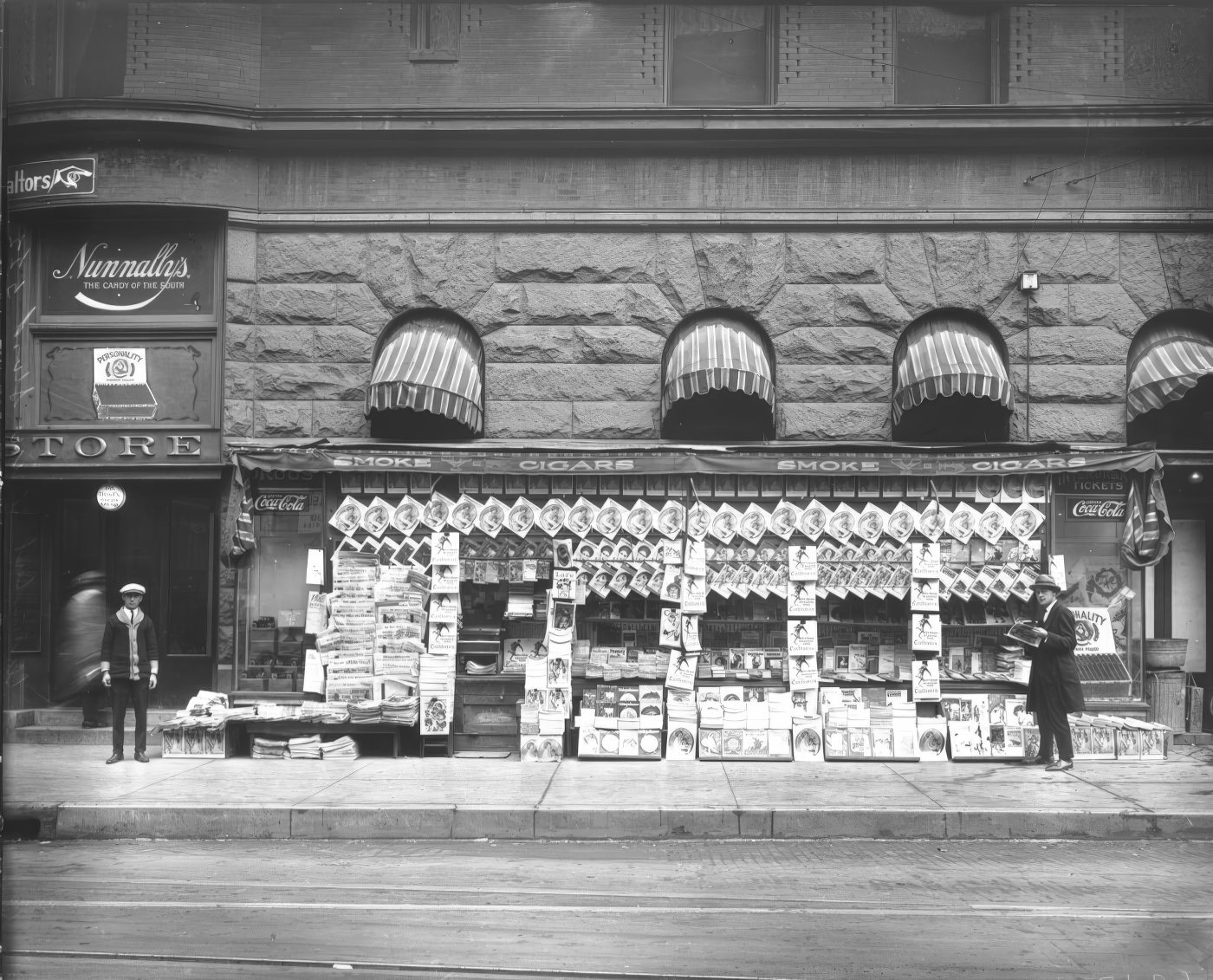

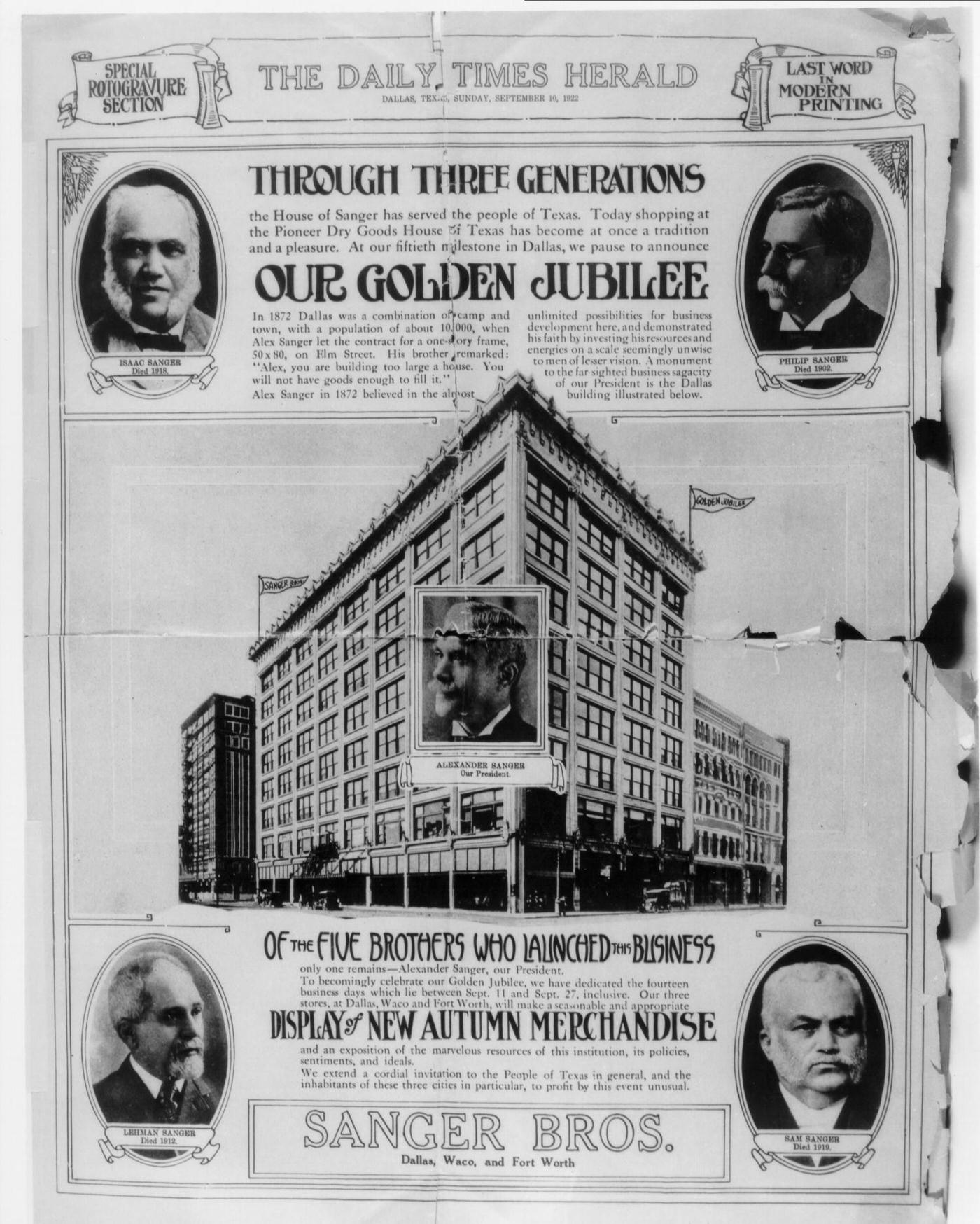

The Rise of Manufacturing and Retail

Dallas was more than just a center of finance and trade; it was also an industrial city. It was the world’s leading manufacturer of cotton gin machinery, a natural extension of its role in the cotton market. The 1920s also saw a significant expansion of the city’s garment and textile industries. Several new cotton mills were built across Texas during this period, and Dallas emerged as a key center for clothing manufacturing.

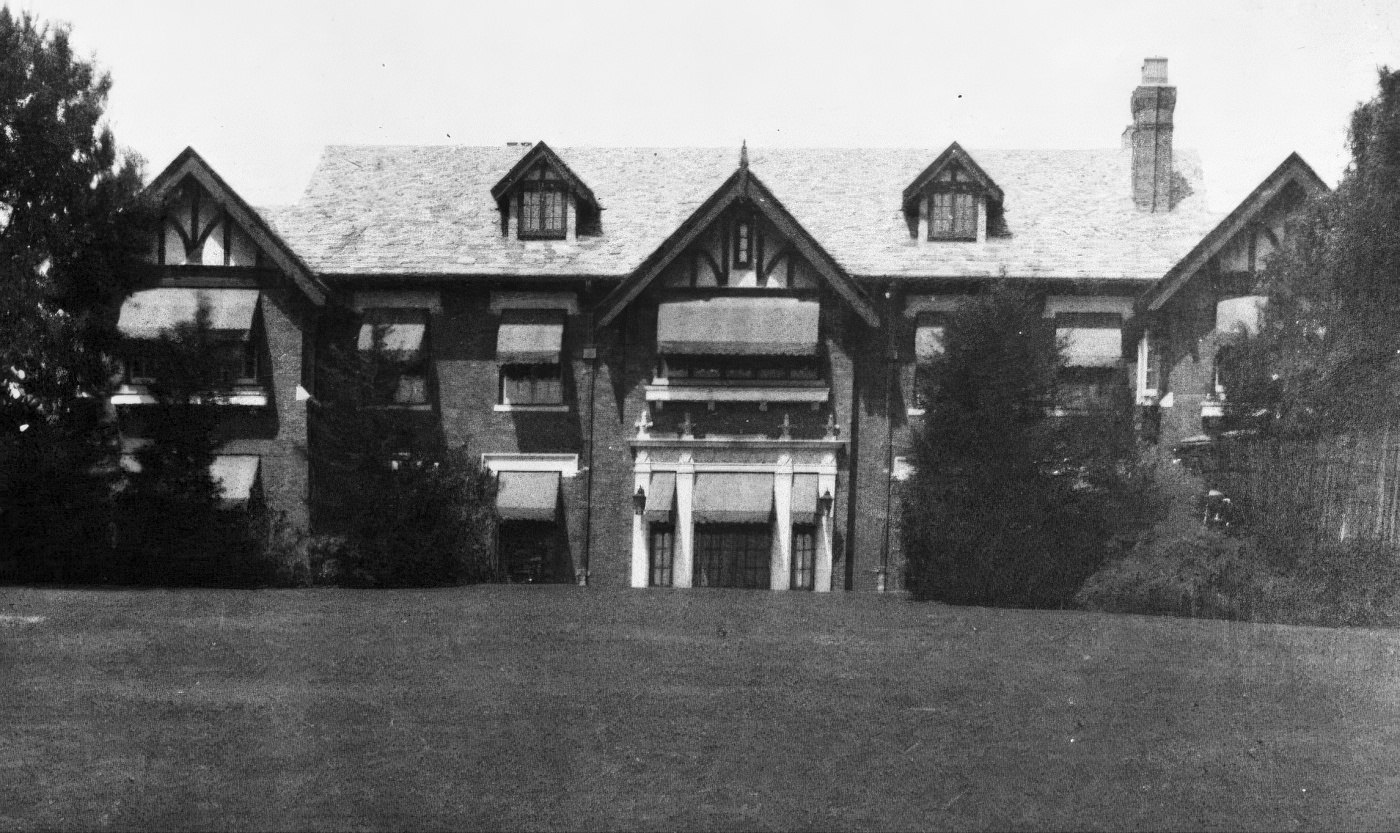

The city’s prosperity was vividly displayed in its bustling retail district. Downtown Dallas was home to numerous shops, but none symbolized its identity as a center of fashion and luxury more than Neiman Marcus. The store, which catered to the wealthy elite whose fortunes were built on Texas oil, cattle, and cotton, underwent a major expansion in the mid-1920s. In 1926, the company leased adjacent property, and by 1927, it had opened a grand four-story addition designed by the noted architect George Dahl. The project doubled the store’s size and gave it a new, elegant facade of white terra cotta, replacing the original brick. Alongside this temple of high fashion, other retailers thrived, including men’s clothing stores like Hurst Bros. that catered to the city’s growing class of businessmen and professionals.

The Heart of the Barrio: Little Mexico

North of downtown, another distinct community thrived. The neighborhood known as “Little Mexico” was formed by a wave of immigrants who had fled the violence of the Mexican Revolution. In the face of poverty and discrimination, they created a strong, self-reliant community built around a shared language, culture, and faith.

Life in the barrio was marked by hardship. Housing was scarce and of poor quality, with many families living in crowded shacks made of scrap wood and tar paper, or even in abandoned railroad boxcars. These homes often lacked indoor plumbing, and the streets were left unpaved by the city. A 1920 report described the living conditions as “atrocious”. Access to medical care was limited, which contributed to a high mortality rate, particularly among children.

Despite these challenges, the community built its own institutions. Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, which moved into a new building in 1925, was the spiritual and social heart of the neighborhood. Pike Park, a public park located within the barrio, became a central gathering place for community celebrations, especially the patriotic festivals of

Diez y Seis de Septiembre and Cinco de Mayo. The park, however, was also a painful symbol of segregation. For years, Mexican children were barred from using its playground equipment and were subjected to humiliating rituals at the swimming pool, where they were only allowed to swim at certain times and were then forced to clean the pool for the white children who would use it next.

The residents of Little Mexico primarily worked in low-wage, unskilled labor jobs, with the railroads and local cement plants being major employers. Yet, a local economy also emerged from within the community. Small grocery stores, barbershops, and restaurants opened to serve the neighborhood. Some of these businesses would grow to become Dallas institutions. The first El Fenix restaurant, which helped pioneer Tex-Mex cuisine, was founded in 1918. In 1924, a widow named María Luna started a small business making and selling tortillas from her home. Her business, Luna’s Tortilla Factory, grew quickly and became a beloved local enterprise.

A Night on the Town

For the white population of Dallas, entertainment options were expanding. The grandest venue was the Majestic Theatre, which opened on Elm Street in 1921. It began as a lavish vaudeville house, hosting traveling acts on its stage. As the decade wore on and the popularity of vaudeville began to fade, the Majestic, like other theaters in the powerful Interstate Theatres chain, transitioned to showing motion pictures, becoming one of the city’s premier movie palaces.

For those with more literary tastes, the “little theatre” movement provided an alternative. The Little Theatre of Dallas was founded in 1920, offering a stage for non-professional actors from the community to perform quality dramatic works. The city also invested in large civic venues. In 1925, the Music Hall at Fair Park was built. Designed by the architectural firm Lang & Witchell, it was the largest enclosed performing arts venue in Dallas, capable of hosting large-scale concerts and productions.

Image Credits: Dallas Public Library, Texas History Portal, Library of Congress, Wikimedia, UTA Libraries

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know