The story of Fort Worth in the 1870s begins not with a bang, but with the quiet struggles of a town nearly erased. Founded in 1849 by the U.S. Army, Fort Worth started as a military post on a bluff overlooking the Clear and West Forks of the Trinity River. It was the northernmost in a chain of forts designed to mark the frontier. Major Ripley A. Arnold established the post, naming it Fort Worth, though it was never officially called “Camp Worth”. The “fort” itself offered little real defense; it lacked a stockade and consisted of rough timber buildings constructed jacal-style, with logs stood upright and mud filling the gaps. Built hastily with green lumber, these structures were never intended to be permanent.

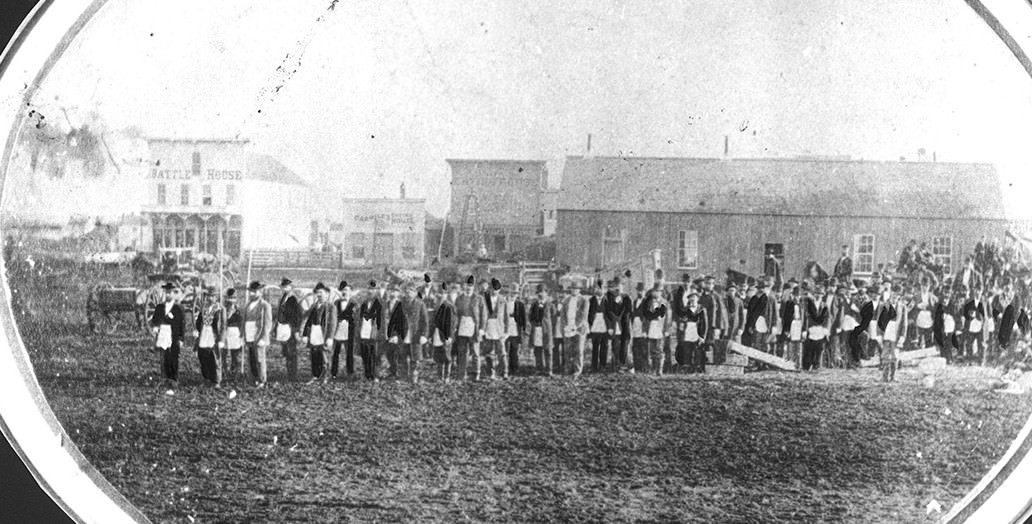

When the army departed in 1853, leaving behind about twenty-four buildings in various states of disrepair, local settlers moved in. Fewer than 100 people initially formed the civilian community of “Fort Town”. Early pioneers like Ephraim Daggett, who gave land for the town, John Peter Smith, who started the first school in 1854, merchants Archibald Leonard and Henry Daggett, and Julian Feild, who built a flour mill and became the first postmaster, laid the groundwork for a community. Stage lines connected the small village to the outside world starting in 1856.

However, the Civil War (1861-1865) and the difficult Reconstruction period that followed dealt a devastating blow. Tarrant County, which included Fort Worth and had 850 enslaved people in 1860, voted to secede from the Union along with the rest of Texas in 1861. The war brought widespread economic hardship, shortages, and damaged transportation across the state. Fort Worth suffered immensely; its population dropped from about 350 before the war to a low point of only 175 residents. Food, supplies, and money were desperately scarce. The Reconstruction era, bringing federal occupation and forced changes like the abolition of slavery (formalized in Texas with the Juneteenth proclamation on June 19, 1865 ), created further turmoil, resentment, and widespread violence, particularly targeting newly freed African Americans. This instability hampered recovery even after Texas was readmitted to the Union in March 1870. The town’s near collapse demonstrated the vulnerability of frontier settlements reliant on specific economic conditions or external support like a military garrison.

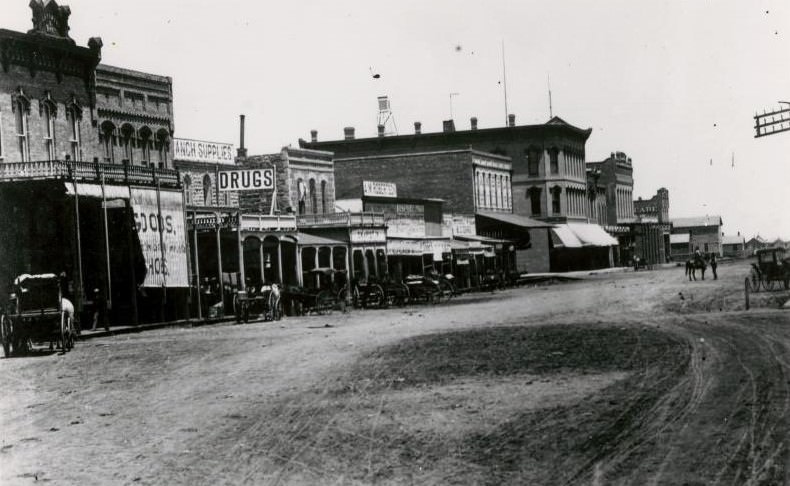

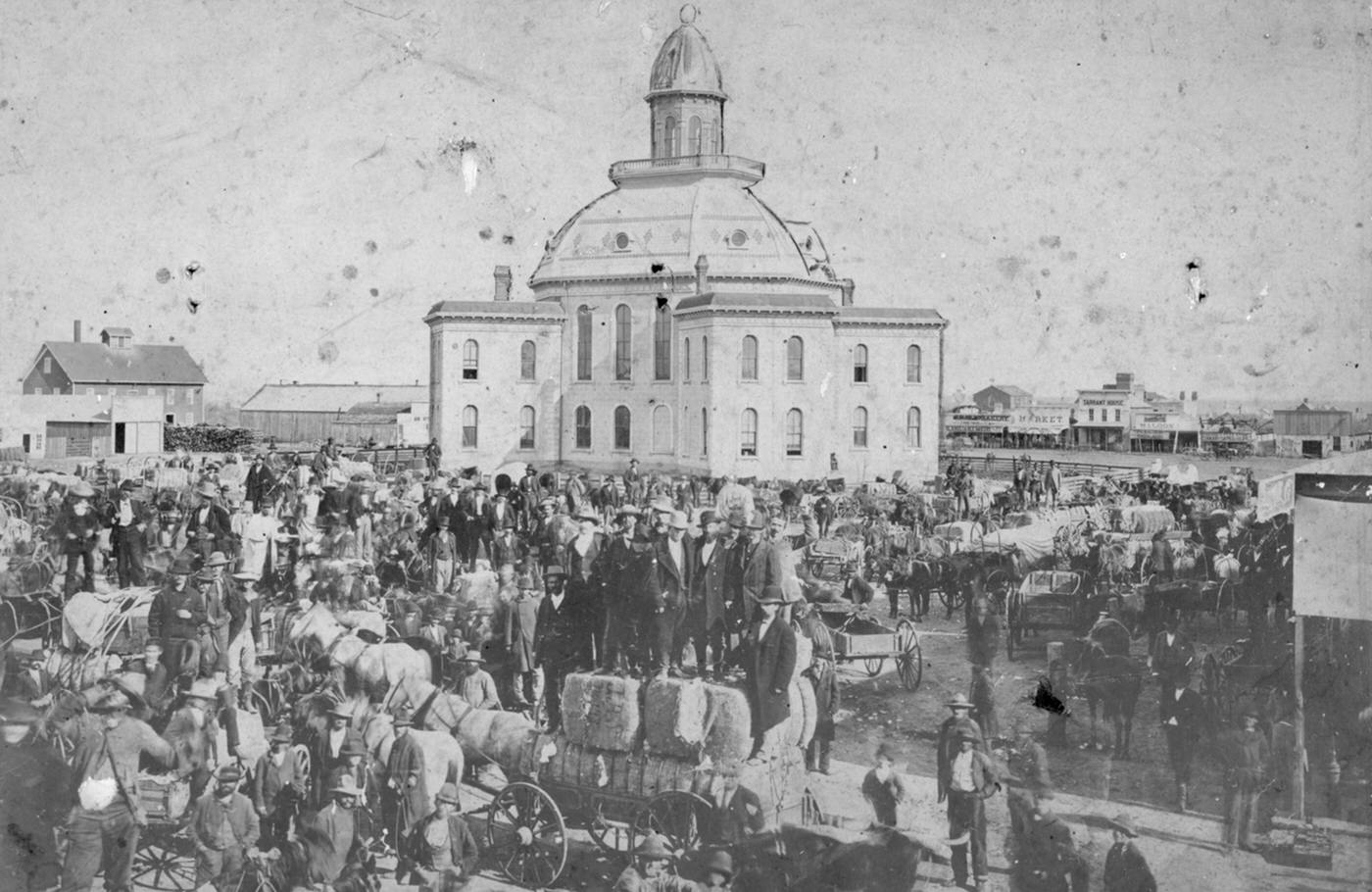

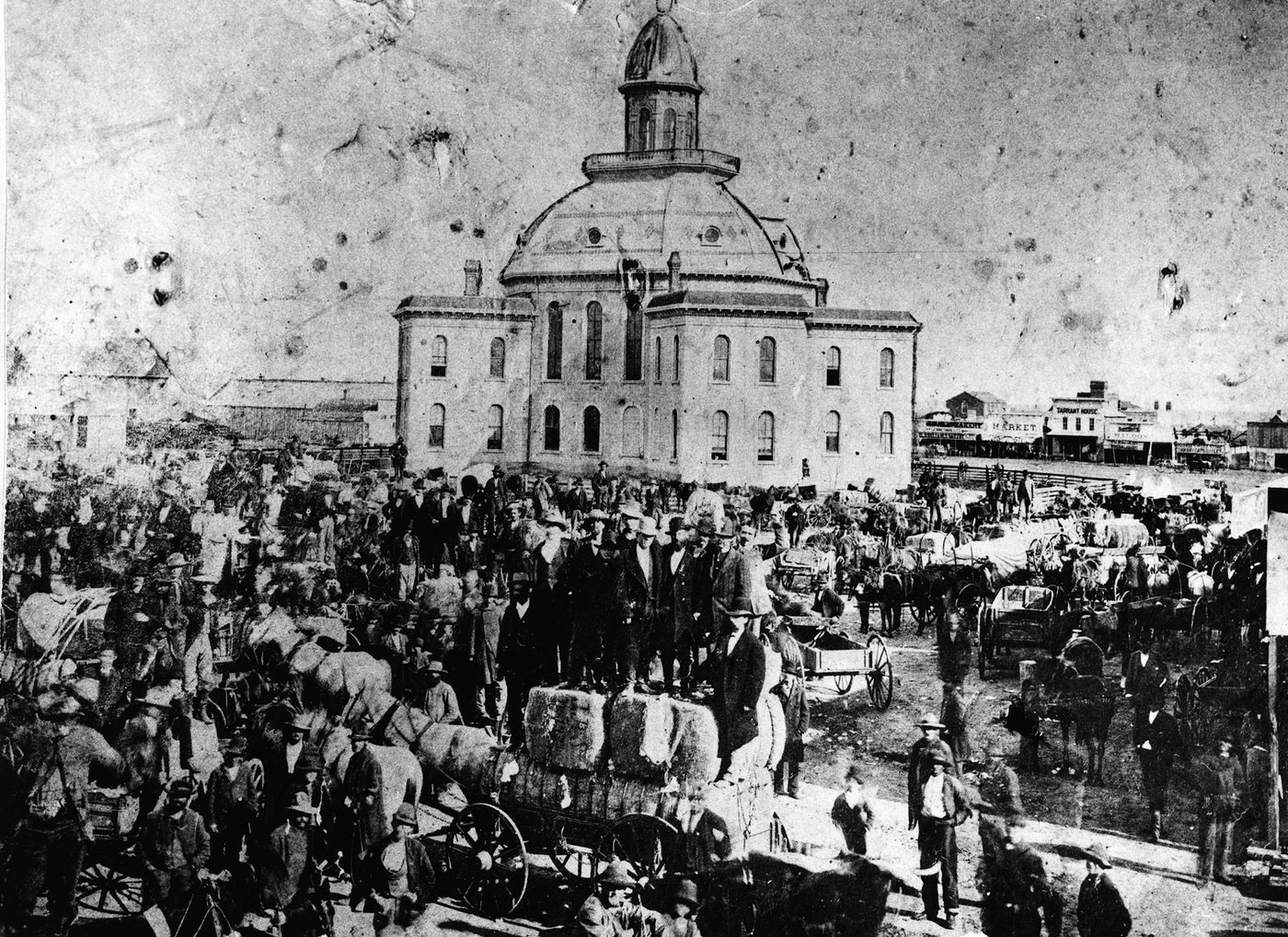

By the early 1870s, faint signs of life returned. In 1872, new general stores opened, run by men like William C. Boaz, William Henry Davis, and Jacob Samuels. Saloons such as Tom Prindle’s and Steele’s Tavern catered to travelers. Schools gradually reopened. A two-story stone courthouse, begun in 1860 but halted by the war, was finally completed in 1869, providing a symbol of civic presence, though it would tragically burn down in 1876. The town’s population slowly climbed back, reaching perhaps 2,500 people just before it officially became a city. Fort Worth was stirring, but its future remained uncertain, heavily dependent on finding a new reason to exist.

The Chisholm Trail Boom: Cowtown Emerges

That reason arrived on the hoof. After the Civil War, Texas overflowed with millions of longhorn cattle, worth only about $4 a head locally but fetching $40 or more up north where beef was in high demand. Starting around 1866-1867, massive cattle drives began pushing these herds north to railroad towns in Kansas, like Abilene. Fort Worth found itself perfectly positioned on the main route – the Chisholm Trail. Used heavily from 1867 until the early 1880s, this trail saw herds gather near the Rio Grande or San Antonio, travel north through Austin and Waco, and then pass directly through Fort Worth before crossing the Red River into Indian Territory. For cowboys making the arduous journey north, Fort Worth became the last significant stop for supplies and rest before the long, isolated stretch ahead.

That reason arrived on the hoof. After the Civil War, Texas overflowed with millions of longhorn cattle, worth only about $4 a head locally but fetching $40 or more up north where beef was in high demand. Starting around 1866-1867, massive cattle drives began pushing these herds north to railroad towns in Kansas, like Abilene. Fort Worth found itself perfectly positioned on the main route – the Chisholm Trail. Used heavily from 1867 until the early 1880s, this trail saw herds gather near the Rio Grande or San Antonio, travel north through Austin and Waco, and then pass directly through Fort Worth before crossing the Red River into Indian Territory. For cowboys making the arduous journey north, Fort Worth became the last significant stop for supplies and rest before the long, isolated stretch ahead.

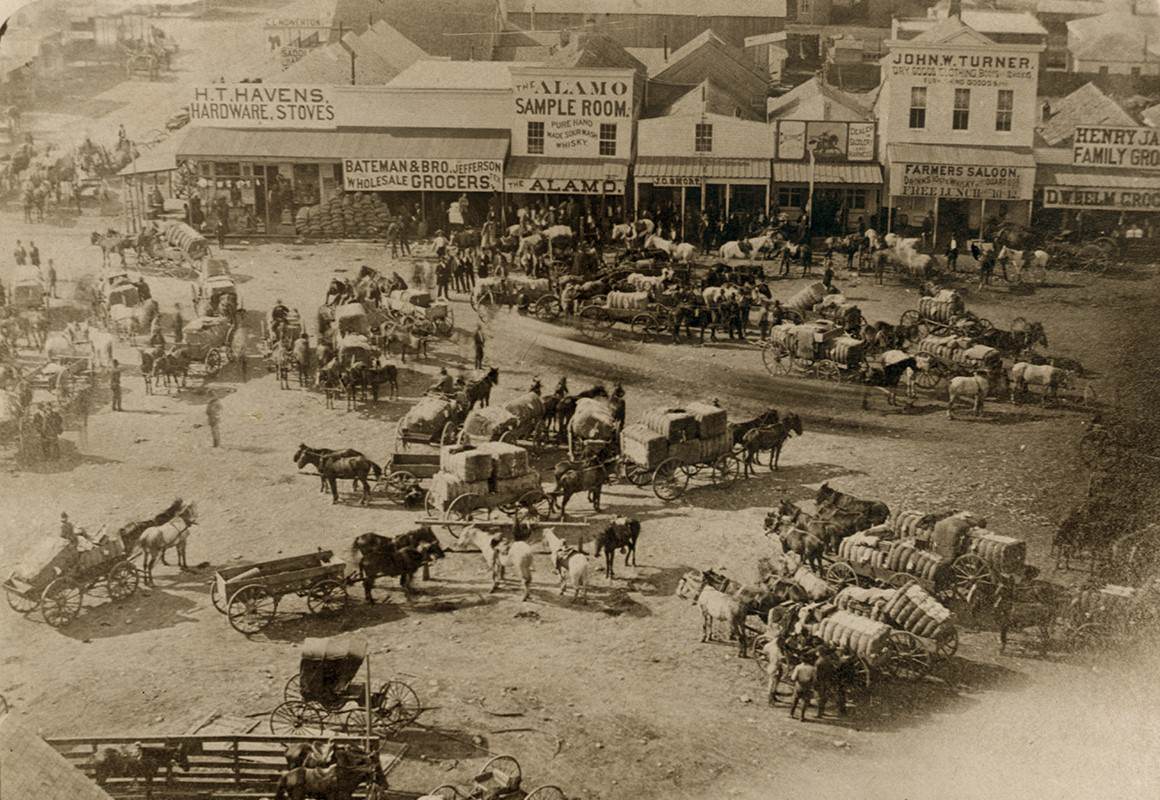

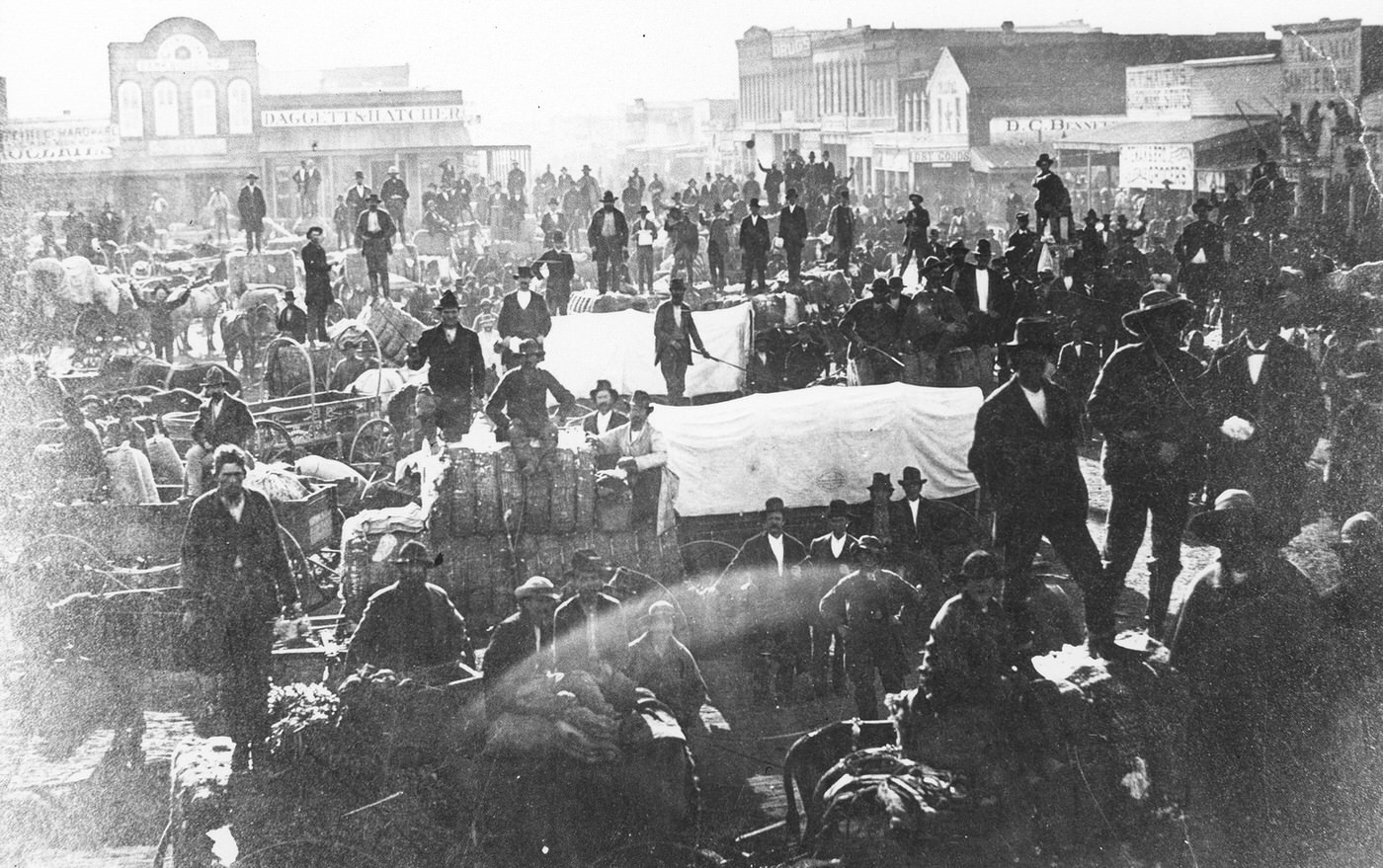

The arrival of these drives transformed Fort Worth almost overnight. Huge herds camped on the outskirts, and dusty cowboys surged into town. Eager for entertainment after weeks on the trail, they filled the streets, sometimes firing their pistols in the air or even riding their horses directly into saloons. This constant influx of transient men and money acted like an adrenaline shot to the town’s struggling economy.

While the cowboys’ rowdiness fueled a wild reputation, it also spurred legitimate business. Fort Worth quickly became a vital trading point for the entire region. Cattle buyers set up headquarters. Businesses catering directly to the drives flourished: Pendery and Wilson’s liquor wholesale, B. C. Evans’ dry goods store, and Martin B. Loyd’s Exchange Office provided needed services. Joseph H. Brown’s wholesale grocery became so successful it was, for a time, the largest south of St. Louis, handling enormous quantities of supplies. This period, defined by the thunder of hooves and the jingle of spurs, firmly established Fort Worth’s identity and enduring nickname: “Cowtown”. The trail wasn’t just a path; it was a moving economic force that pulled Fort Worth back from the brink, though it also brought significant challenges.

Cowtown Life: Building a Community Amidst the Boom

While cowboys came and went, permanent residents worked to build a lasting community amidst the energy and chaos of the cattle boom. Daily life in 1870s Fort Worth was a blend of frontier simplicity and burgeoning commerce. Early housing often consisted of the repurposed, leaky military buildings or basic log cabins built from the abundant oaks of the surrounding Cross Timbers. These log homes were typically single rooms, hand-hewn with notched corners, chinked with clay or mud, and assembled with wooden pegs instead of nails. They featured simple wood shutters, perhaps a few gun ports for defense, and a sleeping loft for children above the main room, which held basic furniture like tables, chairs, and rope beds with shuck mattresses. As the town grew, more frame houses appeared, often built closely together on small lots, especially in developing residential areas.

Occupations reflected the town’s dual nature. Beyond the drovers, saloon keepers, and gamblers associated with the trail, Fort Worth had merchants running general stores and groceries, bankers like Khleber M. Van Zandt whose firm Tidball, Van Zandt, and Company (founded 1873) became the Fort Worth National Bank, millers like Julian Feild, the town’s first physician Dr. Carroll Peak, and teachers like John Peter Smith and the Clark siblings. Newspaper editors, such as B.B. Paddock of the Fort Worth Democrat, played a vital role in promoting the town. Laborers, including a small but growing number of Mexican-born men often employed seasonally or in manual tasks like kitchen work, filled essential roles. Women managed households and often contributed economically, particularly in the aftermath of the war.

Commerce centered around the needs of both residents and the cattle trade. Besides the stores, saloons, and early hotels established by figures like Ephraim Daggett, the town had Feild’s flour and corn mill and weekly newspapers like the Chief and the Democrat. The physical infrastructure, however, struggled to keep pace. The first stone courthouse, finished in 1869, burned in March 1876, destroying many county records; a new one was designed and completed by 1877. Before the railroad, transportation relied on stagecoaches for mail and passengers, including an ambitious line connecting Fort Worth to Yuma, Arizona – a 1,500-mile, seventeen-day journey started in 1877 or 1878. Streets remained mostly unpaved dirt, turning into impassable mud during rains, making the movement of goods slow and expensive. This transportation bottleneck underscored the desperate need for a railroad.

Even as the town pulsed with the energy of the cattle drives, residents took steps to create civic structure. Fort Worth was officially incorporated as a city by the state legislature in 1873, adopting a mayor-council form of government. W. P. Burts served as the first mayor, with aldermen elected to represent different city wards. This move towards formal governance occurred right in the middle of the Chisholm Trail’s peak years, highlighting a conscious effort to establish permanence and order. The population reflected this growth, swelling from perhaps 2,500 before incorporation to over 4,000 by the fall of 1873. Key figures emerged who would shape the city’s future, including the banker K.M. Van Zandt, who would be instrumental in bringing the railroad, and the boosterish editor B.B. Paddock. The town’s diversity also grew, encompassing not only Anglo settlers but also African Americans navigating the difficult post-Reconstruction era, European immigrants, and a developing Jewish community that established the city’s first B’nai B’rith Lodge in 1874 with merchant Jacob Samuels among the founders.

Hell’s Half Acre: The City’s Wild Side

The most famous, or infamous, manifestation of Fort Worth’s wild side was Hell’s Half Acre. This notorious red-light district emerged in the early 1870s, specifically to cater to the desires of the thousands of cowboys passing through on the Chisholm Trail. Located on the south side of the downtown business area – the first part of town drovers reached – it quickly gained a reputation for lawlessness. The name “Hell’s Half Acre” was used for similar districts in other frontier towns, but Fort Worth’s became legendary. First appearing in the local newspaper in 1874, the district was already well established. It was sometimes referred to as the “Bloody Third Ward” after Fort Worth created political wards in 1876.

Though initially perhaps only half an acre, the district rapidly expanded as Fort Worth boomed. It eventually sprawled across several blocks, roughly from Seventh Street south to Fifteenth (or Front) Street, encompassing parts of Main, Rusk (now Commerce), Calhoun, and Jones streets. Today, this area includes the Fort Worth Convention Center and the Water Gardens. Within its ill-defined boundaries was a dense concentration of one- and two-story buildings housing saloons (like the Waco Tap and the Blue Light), dance halls, gambling parlors, cheap brothels known as cribs, and more elaborate bawdy houses. A few legitimate businesses were scattered amongst the vice dens.

The atmosphere was one of raw, often violent, energy. Brawling, gambling, drinking, prostitution, cockfighting, and even horse racing were common activities, frequently spilling out from the buildings onto the streets and alleys. It was a place people went looking for “trouble or excitement,” where cowboys could gamble away their earnings, party, and find companionship. Its reputation attracted thieves, violent criminals, and legendary figures of the Old West, including Bat Masterson, Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp, and possibly Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. This concentration of vice gave Fort Worth a “less-than-angelic reputation” and formed the basis for many popular images of the Wild West.

Policing this chaotic district presented enormous challenges. Illegal activities like gambling and prostitution operated openly, often tolerated by city authorities who recognized the Acre’s significant contribution to the local economy. Fines levied against these establishments often went towards paying the salaries of the lawmen themselves, creating a complex and often compromised system. For many civic leaders and reformers, the priority was less about eliminating vice entirely and more about controlling the violence – to “stop the flow of blood, but not that of liquor”.

Into this environment stepped Timothy Isaiah “Longhair Jim” Courtright, elected City Marshal in 1876. Known for his long hair and skill with his two forward-facing pistols, Courtright had a formidable reputation as a gunman. Tasked with keeping the peace in Hell’s Half Acre, he reportedly succeeded in drastically reducing the murder rate through intimidation and force. His presence alone was often enough to deter trouble. However, Courtright also operated in the gray areas of the law, allegedly running protection rackets and demanding payments from businesses. His tenure represented the pragmatic, often brutal, approach to law enforcement in the Acre, focused on managing chaos rather than strict adherence to statutes. He served until 1879 when he was defeated for re-election. The casual violence of the era is illustrated by an 1877 incident where a gambler named Ben Tutt shot up the Blue Light Saloon, was briefly detained, and later accidentally shot himself in the hand at another venue. The threat of mob justice also loomed; in 1879, a man named Rush Loyd, accused of rape, was nearly lynched before lawmen managed to hold off the mob. While Fort Worth itself faced little threat from Native American raids , events like the Salt Creek Massacre near Graham in 1871, where Kiowa warriors attacked a wagon train, contributed to the overall sense of frontier danger. Hell’s Half Acre was not separate from Fort Worth; its growth and notoriety mirrored the city’s own explosive, uncontrolled expansion during the cattle boom years.

The Iron Horse and the Panther: Salvation by Rail

Just as the cattle trade began showing signs of decline in the mid-1870s, Fort Worth faced another crisis that threatened its very existence. The Texas and Pacific (T&P) Railway had been steadily building its tracks westward, reaching Dallas in 1873. Fort Worth eagerly anticipated its arrival, seeing the railroad as essential for future prosperity. But construction ground to a halt somewhere between 6 and 30 miles east of Fort Worth. The cause was twofold: the nationwide financial Panic of 1873 and the subsequent bankruptcy of T&P’s primary investment bank.

The impact on Fort Worth was immediate and catastrophic. Having banked its future on the railroad, the town saw its economy collapse. Investors who had moved to Fort Worth in anticipation of the T&P quickly packed up and relocated, many heading to the now rail-connected Dallas. The city’s population plummeted once again, dropping from over 4,000 to perhaps as low as 600 residents in less than a year. Businesses shuttered, and despair settled over the town.

It was during this bleak period, in 1875, that Fort Worth gained another famous nickname. Robert E. Cowart, a Dallas lawyer formerly of Fort Worth, wrote a scathing article in the Dallas Herald mocking his former home’s demise. He claimed the town was so deserted and lifeless that he had seen a panther peacefully sleeping undisturbed on a downtown street near the courthouse. Intended as a deep insult, the story caught the attention of B.B. Paddock, the fiery editor of the Fort Worth Democrat. Rather than shrink from the mockery, Paddock defiantly embraced it, dubbing the town “Pantherville” and later “Panther City”. This act of turning an insult into a badge of honor came to symbolize Fort Worth’s resilience.

As the deadline loomed in the summer of 1876, the task seemed impossible. But the people of Fort Worth rallied in an extraordinary display of collective action. Citizens from all walks of life began leaving their jobs early each day to volunteer their labor. They worked tirelessly alongside the hired crews, grading the land, hauling materials, laying track, and providing food and support. In the final frantic days, the last miles of track were laid with desperate haste, sometimes on minimal wooden ties or even directly on the dirt, just stable enough to support an engine. Inside the state capitol, Tarrant County’s representative, Nicholas Henry Darnell, though ill, was carried into the House chamber daily to vote against adjournment, keeping the legislative session open just long enough.

Their monumental effort paid off. On July 19, 1876, the first T&P steam locomotive triumphantly chugged into Fort Worth, meeting the deadline. The town erupted in jubilation and relief. The arrival of the Iron Horse instantly reversed Fort Worth’s fortunes. The railroad secured the city’s future, transforming it from a remote outpost into a vital transportation hub. It revolutionized the cattle industry, allowing livestock to be shipped directly from the Fort Worth Stockyards, which became a premier trading center, diminishing the need for the long, perilous drives north. Other railroads soon followed, solidifying Fort Worth’s position. New businesses, like grain elevators (the first appearing in 1878), sprang up, and the city became connected to regional and national markets. The population rebounded dramatically, as shown below.

A City Taking Shape

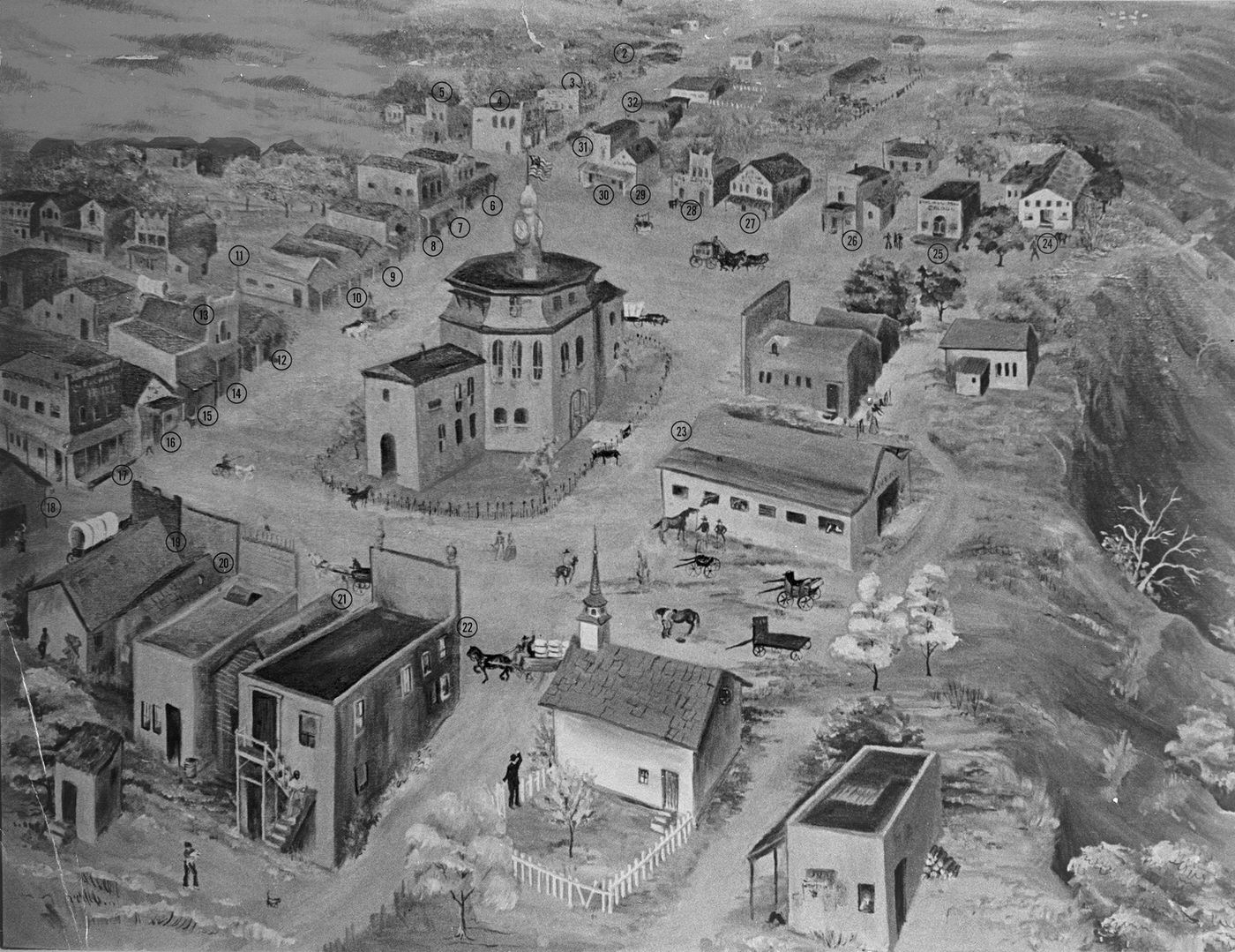

By the close of the 1870s, Fort Worth was a city transformed, yet still bearing the marks of its turbulent past. Its physical appearance was a mixture reflecting its history. Remnants of the early frontier – simple log cabins and perhaps some of the original fort’s timber structures – likely still stood alongside newer frame buildings. More substantial construction used stone, notably for the new courthouse completed in 1877 after the 1876 fire. The downtown area, centered on the courthouse square, featured one- and two-story commercial buildings housing stores, banks, hotels, and the numerous saloons, particularly concentrated in the still-thriving Hell’s Half Acre. Residential areas expanded, characterized by modest houses often situated close together.

The city’s layout followed a basic grid, with key north-south streets like Main, Rusk (Commerce), Calhoun, and Jones intersecting east-west thoroughfares. However, infrastructure remained basic. Streets were predominantly dirt, dusty in dry weather and muddy quagmires when wet, making wagon traffic difficult. Sidewalks were likely wooden planks where they existed at all. While the railroad brought multiple lines and the need for depots and supporting facilities, other services were rudimentary. Water came from wells or the Trinity River, and sanitation systems were minimal. A formal city fire department was just beginning to be organized towards the end of the decade.

Image Credits: fortworthtexasarchives.org, UTA Libraries, wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know