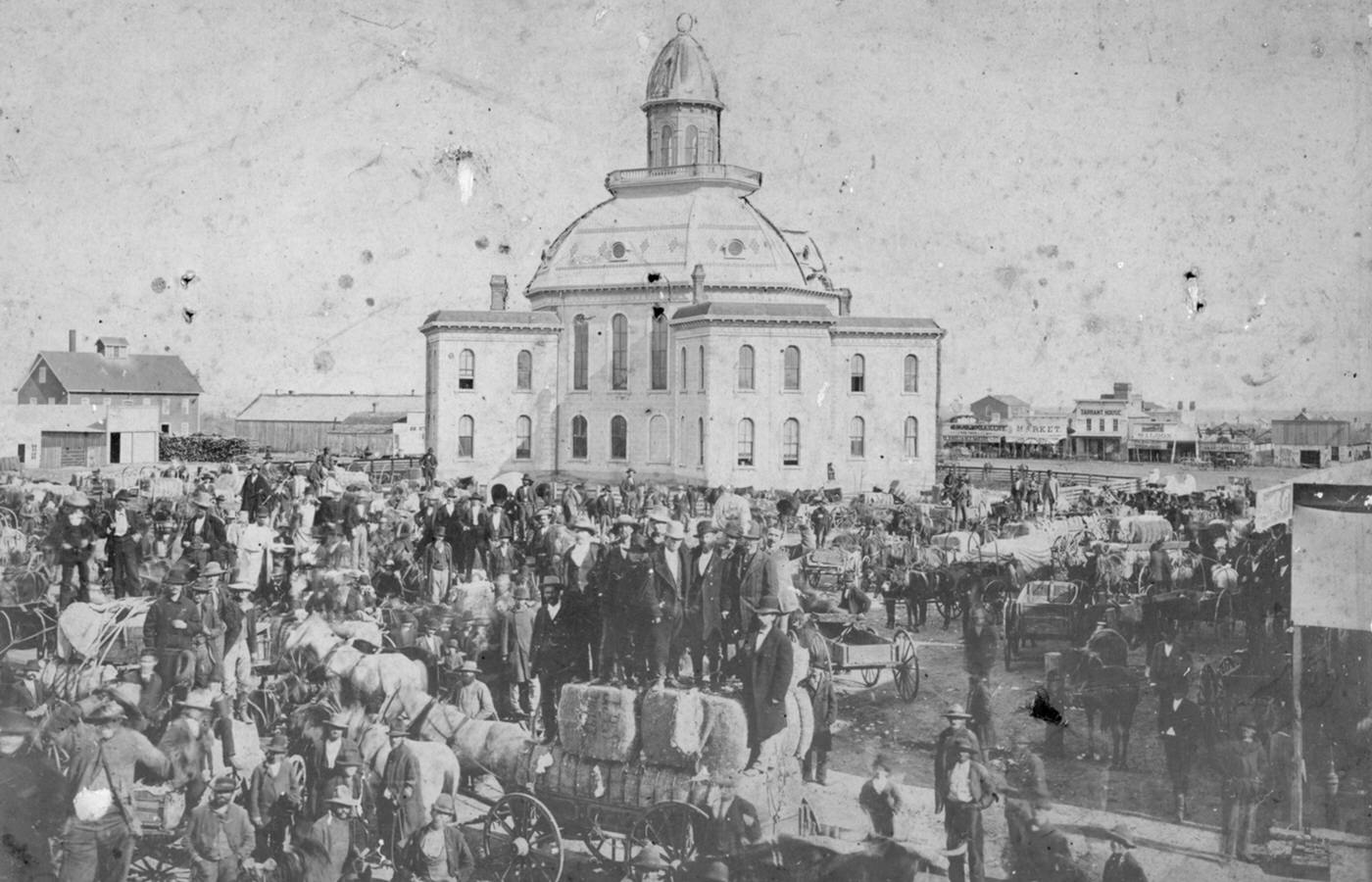

The year 1880 found Fort Worth, Texas, perched precariously between its wild past and an uncertain future. Just a few years prior, a Dallas newspaper had mockingly suggested the town was so dormant a panther could nap undisturbed on Main Street, earning Fort Worth the unlikely nickname “Panther City”. While the town had clawed its way back from post-Civil War lows, thanks largely to the thunder of cattle hooves on the Chisholm Trail and the determined, citizen-led effort to bring the Texas and Pacific (T&P) Railway to town in 1876, its footing was far from secure. The 1880 census counted 6,663 souls in this prairie town, a respectable number, but one dwarfed by the explosive growth about to ignite. The T&P line, initially terminating in Fort Worth, provided a vital link, but the city’s destiny as a major Southwestern hub hinged on what happened next. The 1870s had seen the decline of the great cattle drives beginning, leaving the local economy somewhat vulnerable, lacking commercial diversity in its landlocked geography. Fort Worth stood at a crossroads, the lone whistle of the T&P a hopeful sound, but not yet the chorus that would signal a true boom.

Cowtown’s Crossroads: From Trail Dust to Stockyard Pens

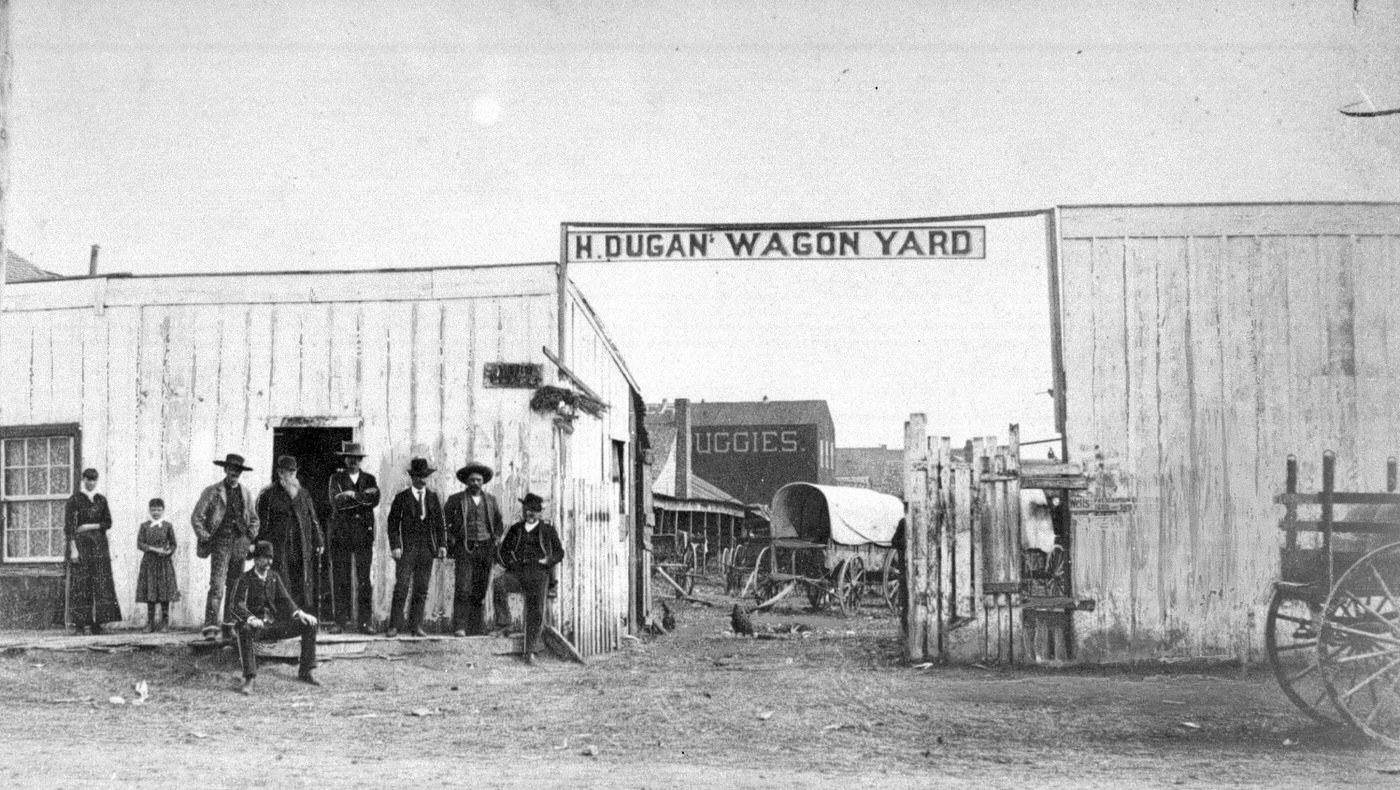

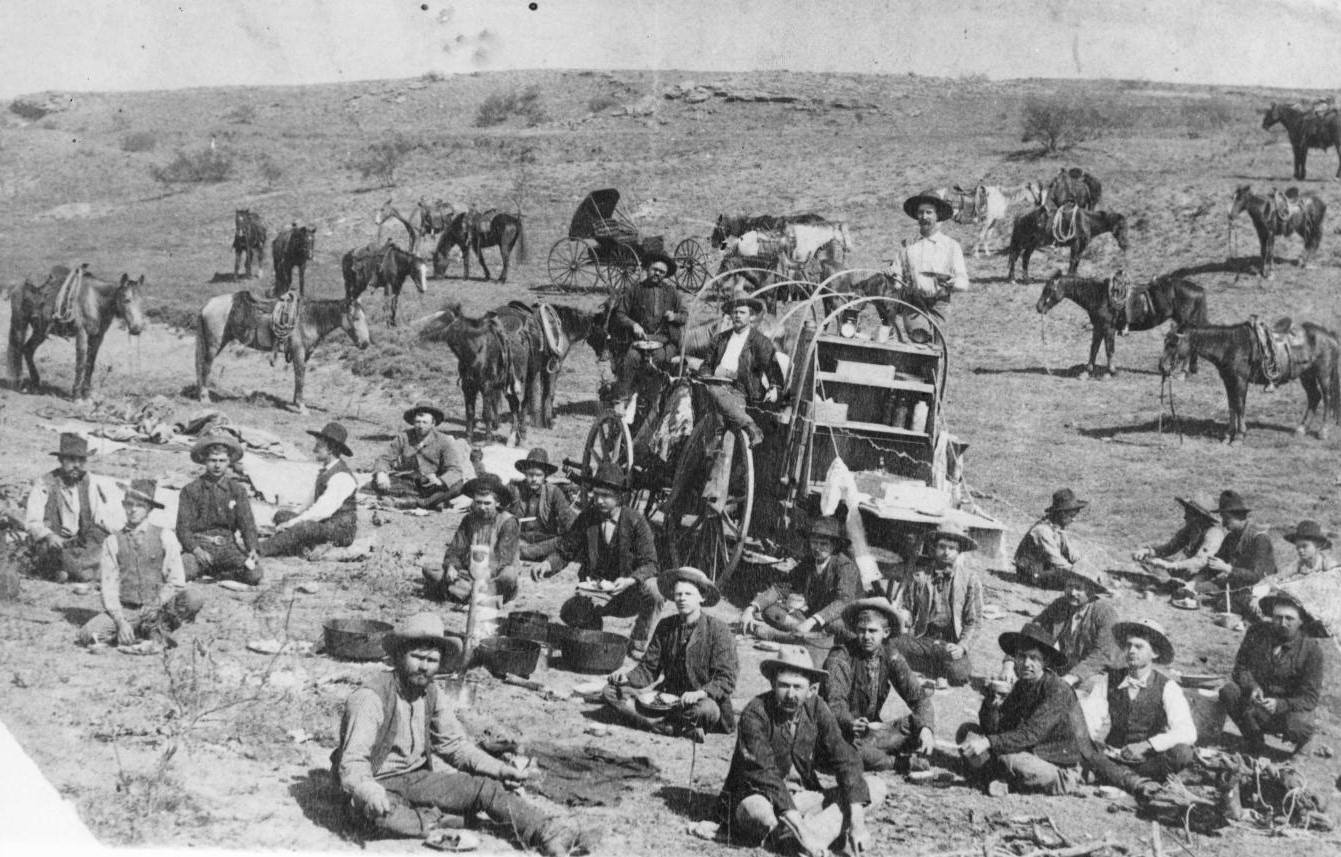

The 1880s witnessed a fundamental shift in the industry that gave Fort Worth its “Cowtown” moniker. The era of the great long-distance cattle drives, particularly along the Chisholm Trail which ran directly through the city, was drawing to a close. For roughly two decades, from the late 1860s, millions of longhorns had been pushed north from South Texas through Fort Worth, the last major stop for supplies and revelry before the push across the Red River to Kansas railheads. This seasonal flood of cowboys and cattle fueled the city’s early economy and its wild reputation.

However, the very forces transforming the West began to choke off the trails. The relentless march of settlement brought farmers who fenced their lands, often with the newly invented and increasingly ubiquitous barbed wire. This invention, patented in the 1870s, rapidly enclosed the open range, obstructing the wide paths needed for massive herds. Simultaneously, concerns about “Texas Fever,” a tick-borne disease carried by longhorns (though they were immune), led states like Kansas to enact strict quarantine laws, barring or heavily restricting the entry of Texas cattle. By 1884, the Chisholm Trail was effectively closed north of southern Kansas, and the era of the long drive was over.

All Aboard! The Railroad Revolution Reaches Fort Worth

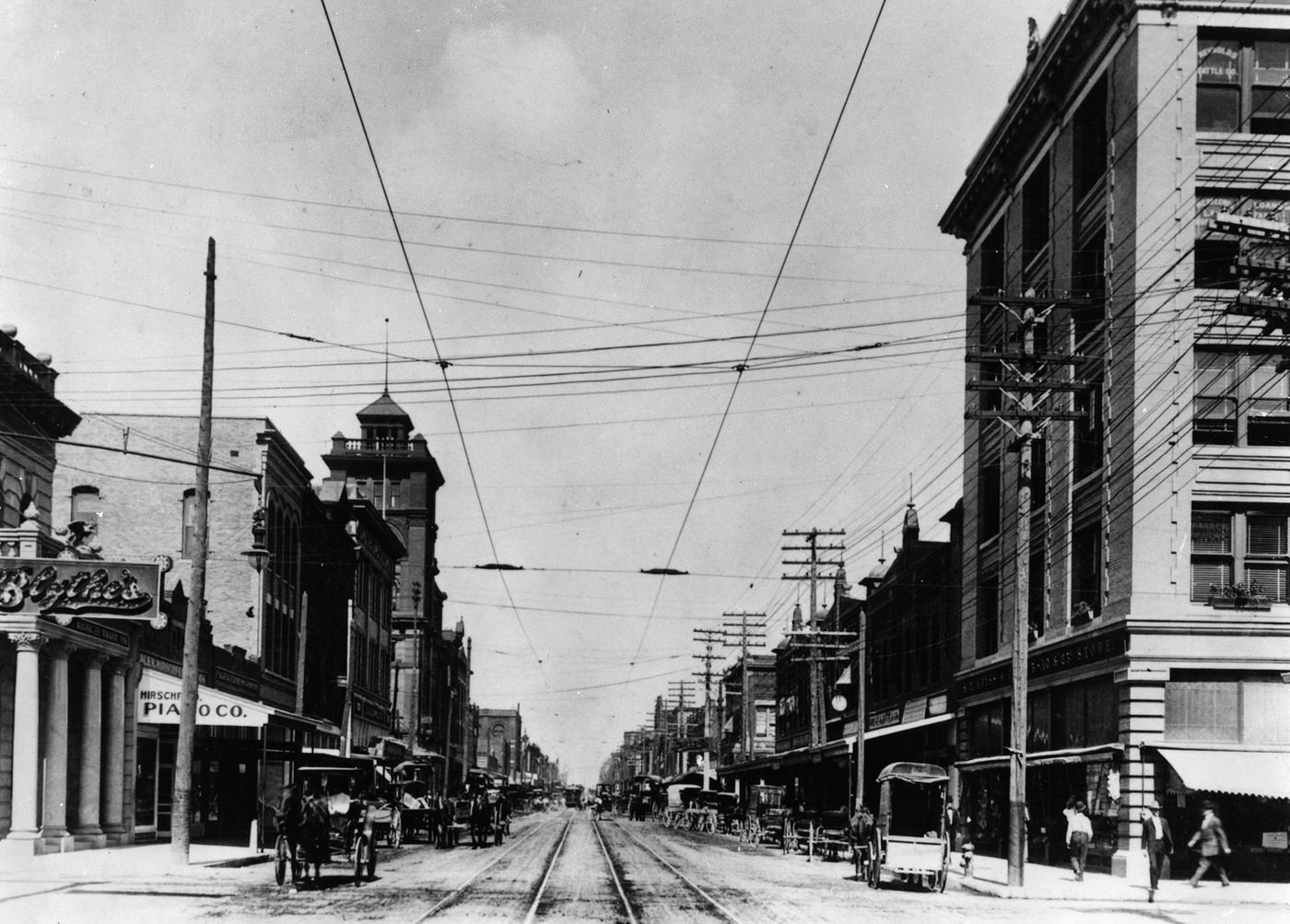

The single T&P line, hard-won by determined citizens who literally laid track themselves to meet a legislative deadline, was merely the overture. The 1880s symphony of progress arrived on multiple iron horses, transforming Fort Worth from a terminus town into a critical railway intersection. The arrival of these additional lines wasn’t just about connecting points on a map; it was the very engine driving Fort Worth’s explosive transformation throughout the decade.

First came the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway (MKT), affectionately known as the “Katy,” steaming into town in 1880. Having reached Denison from the north in 1872 and connected Texas to St. Louis, the Katy’s arrival in Fort Worth, utilizing shared tracks with the T&P from Whitesboro, opened up vital northern and eastern connections. Jay Gould, the railroad magnate who had gained control of the T&P in 1879, also controlled the Katy at this time, leasing it to his Missouri Pacific system, further integrating Fort Worth into his expanding network.

Close on the Katy’s heels was the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway (GC&SF). Chartered initially by Galveston businessmen seeking to bypass Houston, the GC&SF pushed north aggressively after being reorganized under George Sealy in 1879. Reaching Temple from the south, the line arrived in Fort Worth by the end of 1881, establishing another crucial north-south artery and connecting the city directly to the Gulf Coast. The AT&SF system acquired the GC&SF in 1887, further solidifying its importance.

Completing the quartet of major lines arriving in the early 1880s was the Fort Worth and Denver City Railway (FW&DC). Championed by local boosters since the 1870s and spearheaded by famed railroad engineer Grenville M. Dodge (who also oversaw the T&P’s westward expansion from Fort Worth starting in 1880), construction began north of Fort Worth in late 1881. Reaching Wichita Falls by 1882 and completing its connection to Denver via the New Mexico Territory line in March 1888, the FW&DC opened up the vast Texas Panhandle and the markets of Colorado. Other lines, like the Fort Worth and New Orleans (1885-86, later part of Southern Pacific) and the Fort Worth and Rio Grande (began construction 1886), further added to the network.

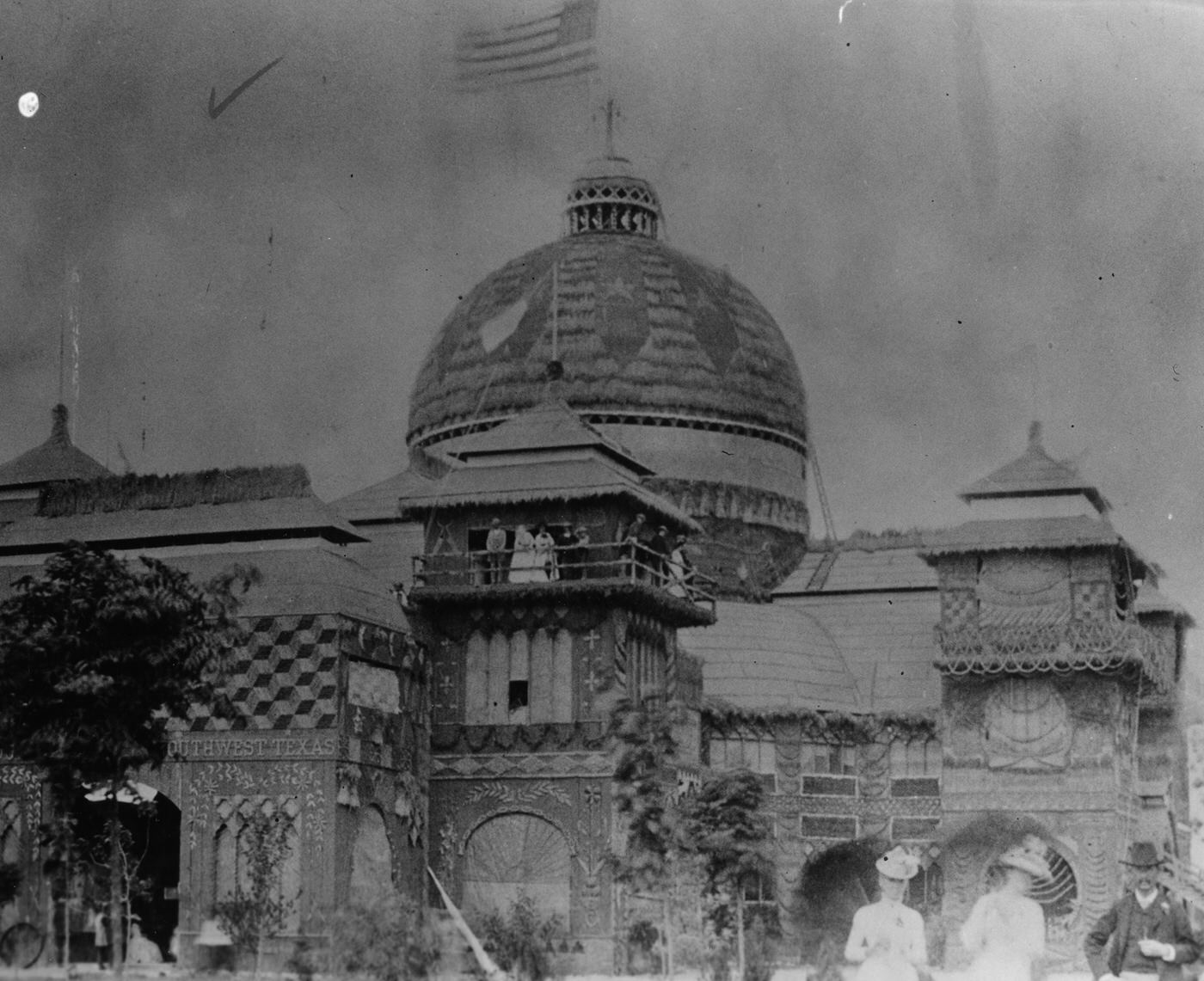

By the mid-1880s, Fort Worth was no longer just a stop; it was a junction, a hub, a place where cattle, cotton, grain, goods, and people converged from all directions. The “Tarantula Map” envisioned by booster B.B. Paddock in 1873, showing rail lines radiating from the city long before most existed, had become a reality. This convergence of steel rails cemented Fort Worth’s status as a major transportation and distribution center for the entire Southwest, setting the stage for unprecedented growth.

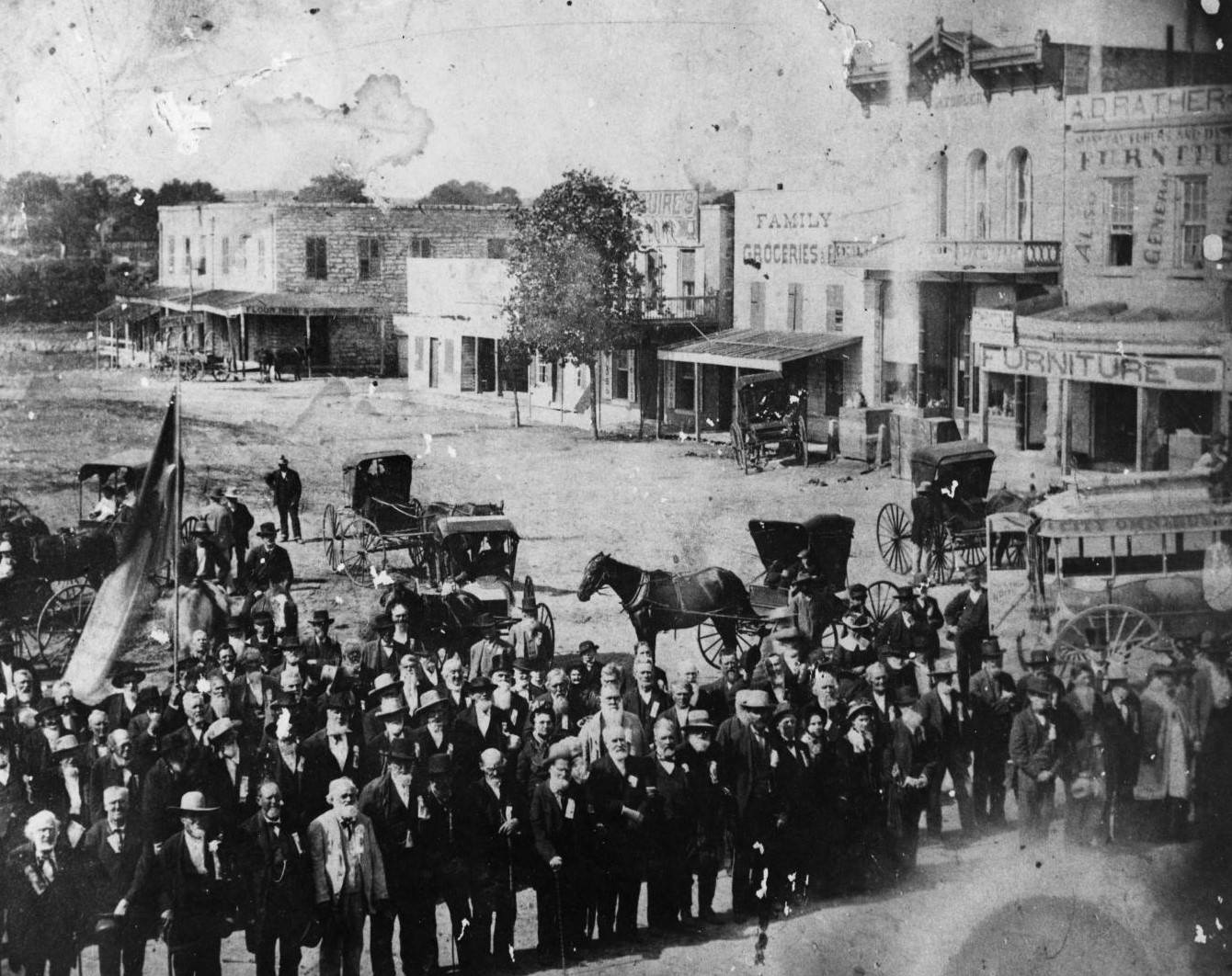

The Population Boom: Panther City Roars to Life

The convergence of railroads and the evolving cattle industry ignited a population explosion in Fort Worth during the 1880s unlike anything the city had ever seen. Starting the decade with 6,663 residents, Fort Worth’s population more than tripled in just ten years, reaching a staggering 23,076 by the 1890 census.

This dramatic increase propelled Fort Worth into the ranks of Texas’s major cities, making it the fifth largest in the state by 1890, trailing only Dallas, San Antonio, Galveston, and Houston. This wasn’t just gradual growth; it was a boom, fueled by the promise of opportunity that the railroads brought. Migrants poured in, many from other parts of the war-torn South seeking a fresh start, alongside immigrants and entrepreneurs drawn by the city’s burgeoning economy. The city that Dallas had recently mocked was now a formidable rival, rapidly transforming from a dusty outpost into a bustling urban center. This demographic surge was a direct consequence of the economic shifts catalyzed by the railroads and the stockyards, providing the labor force and the market necessary for the city’s physical and commercial expansion.

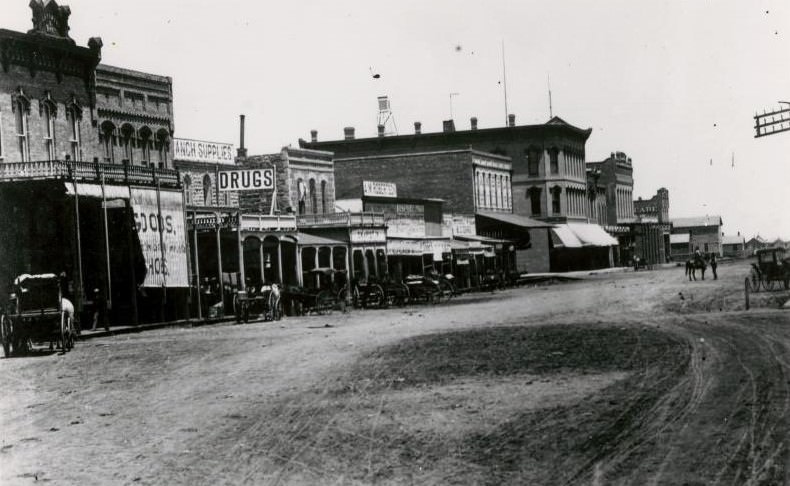

Building a City: Streets, Structures, and Sprawl

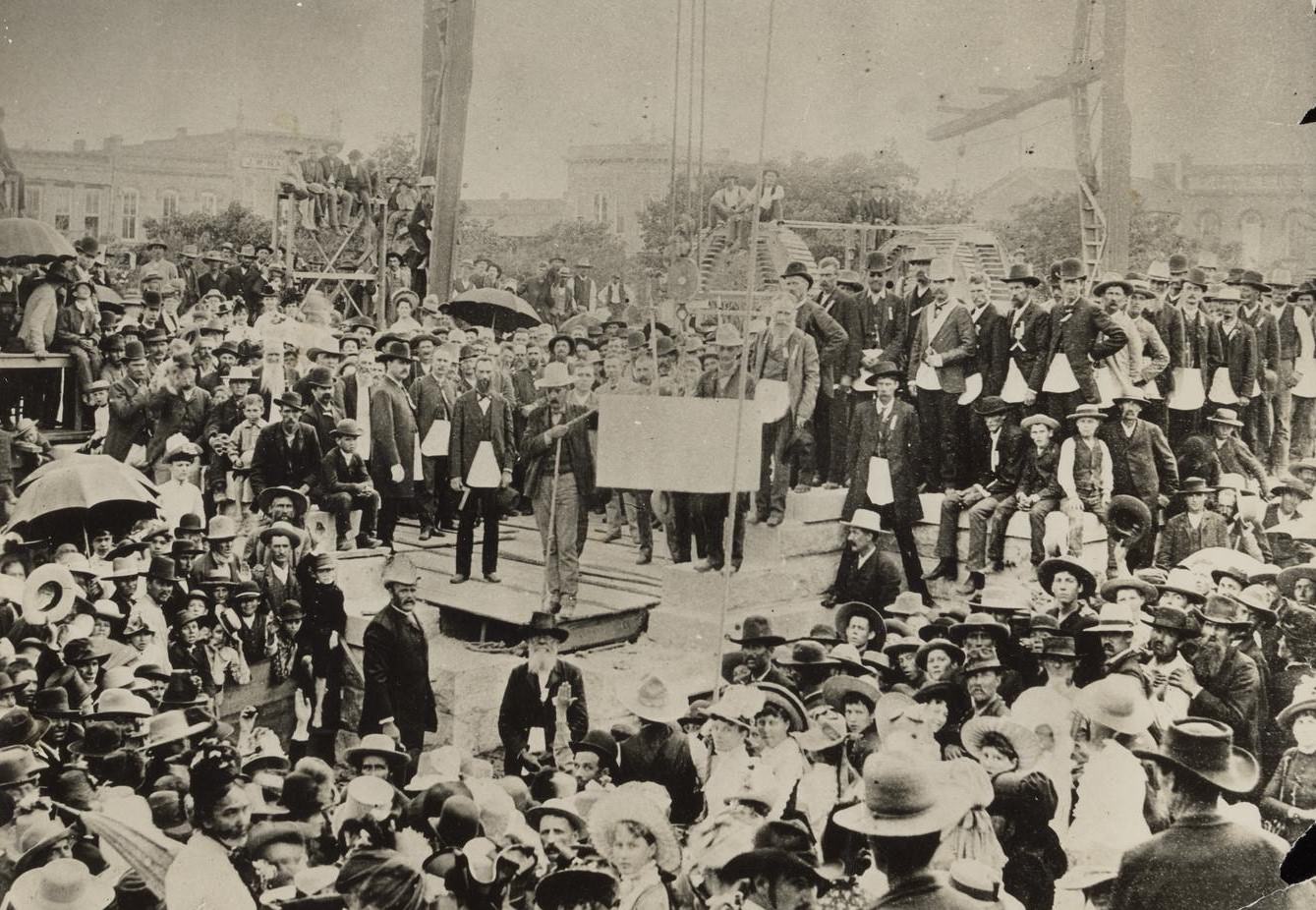

The tripling of Fort Worth’s population demanded a corresponding expansion of its physical form. The 1880s saw the city shed its frontier village skin and begin constructing the bones of a modern metropolis. Infrastructure, commercial buildings, and residential areas rapidly developed to accommodate the influx of people and commerce.

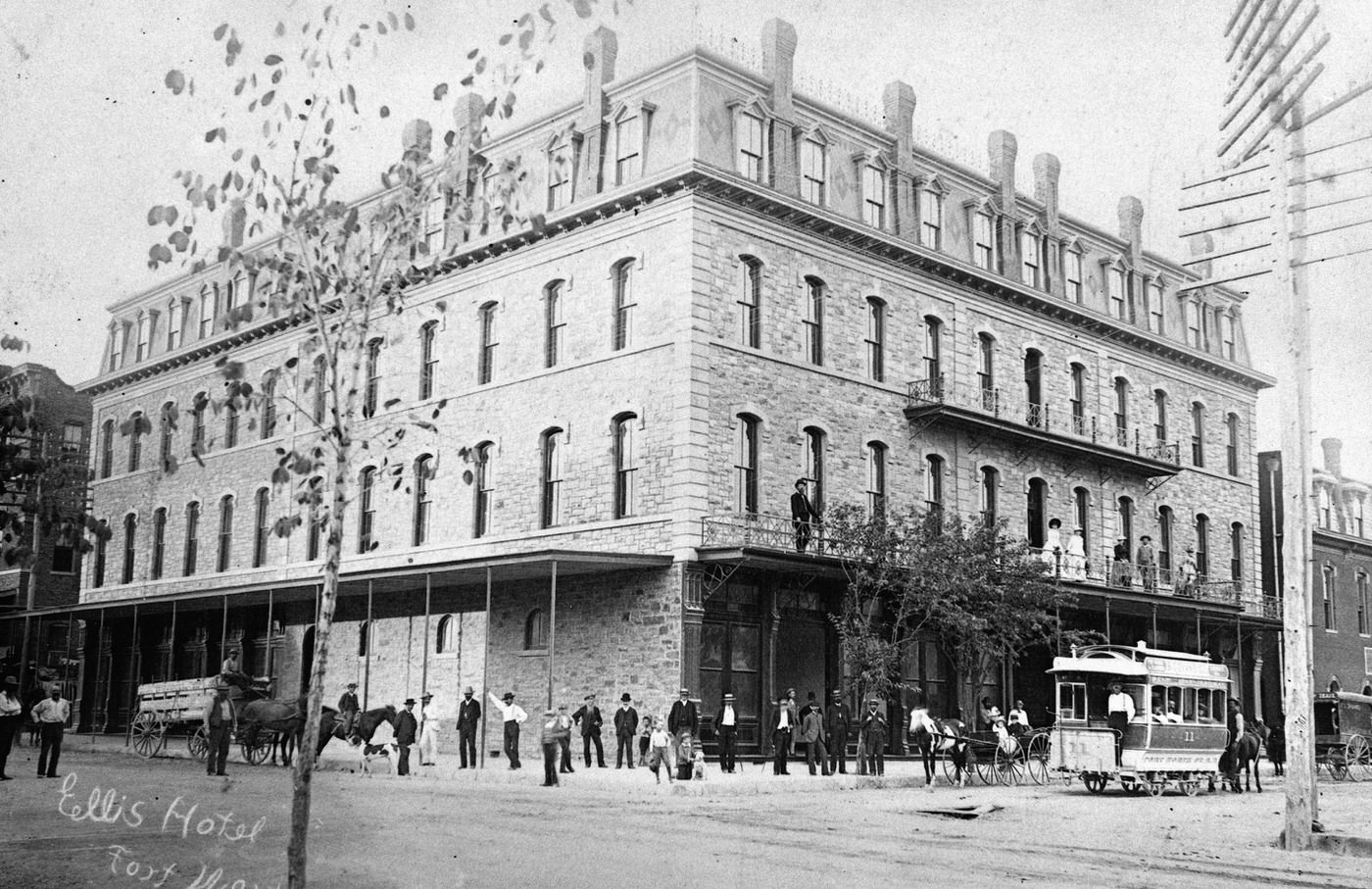

While dirt roads turning to mud were long the norm, the 1880s marked the beginning of serious efforts toward urban infrastructure. The city had established a gas works for artificial gas lighting back in 1876, the same year the first mule-drawn streetcar line connected the courthouse to the T&P station. In 1882, recognizing the inadequacy of relying solely on wells and the Trinity River, civic leaders like Mayor John Peter Smith (who also served as president of the Fort Worth Gas Light and Coal Company) initiated the city’s first water department. A private company, the Fort Worth Water Works Company, was organized in 1882 and completed a basic system in 1883; the city purchased this system in 1884-85, laying the groundwork for municipal water service. Though major street paving with materials like Thurber brick wouldn’t become widespread until the late 1890s (Main Street was first paved around 1897-99), the need for better roads was increasingly recognized as the city grew. Electric streetlights began replacing gas lamps in some areas by the end of the decade, signaling a move towards modernization.

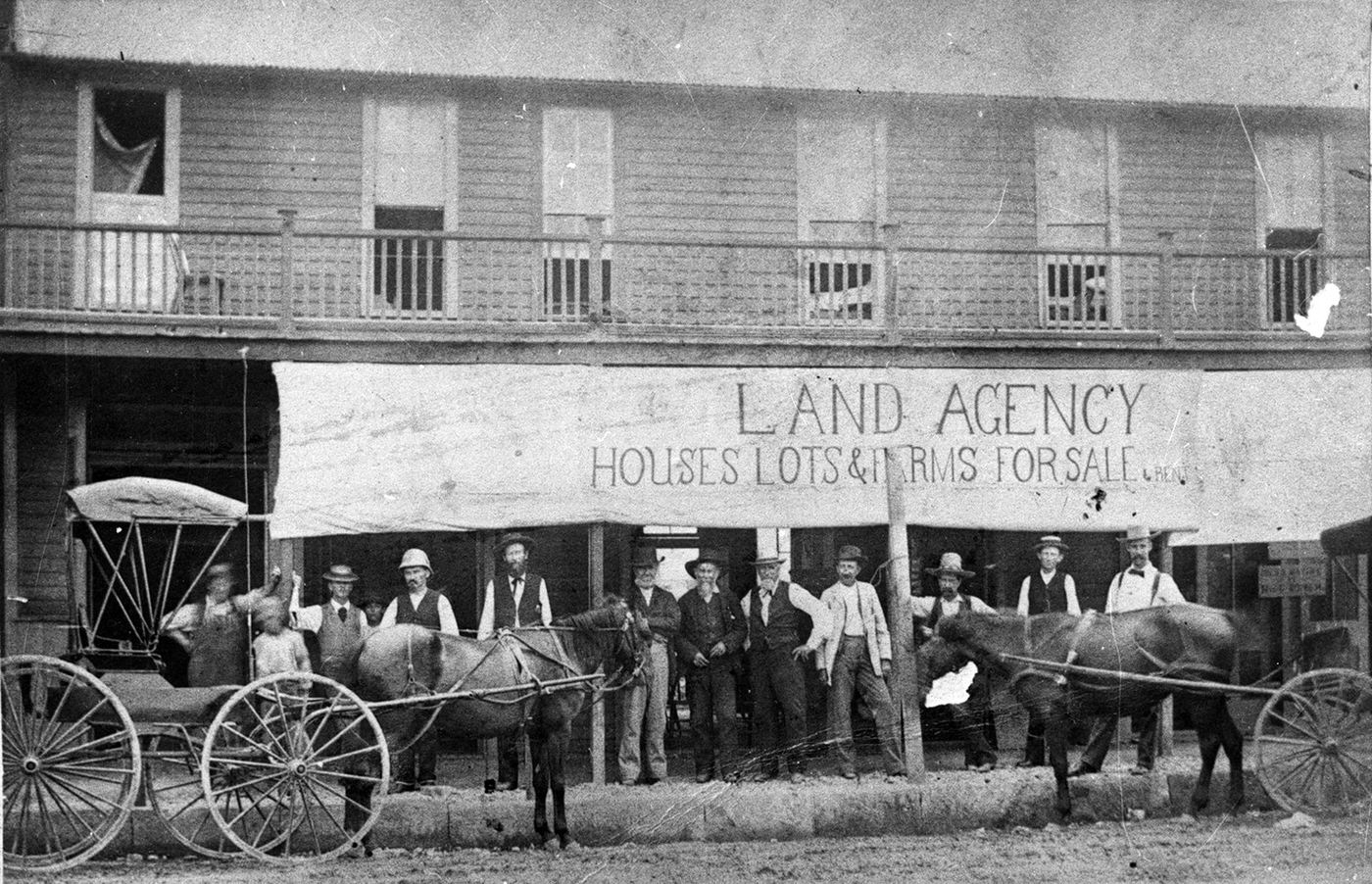

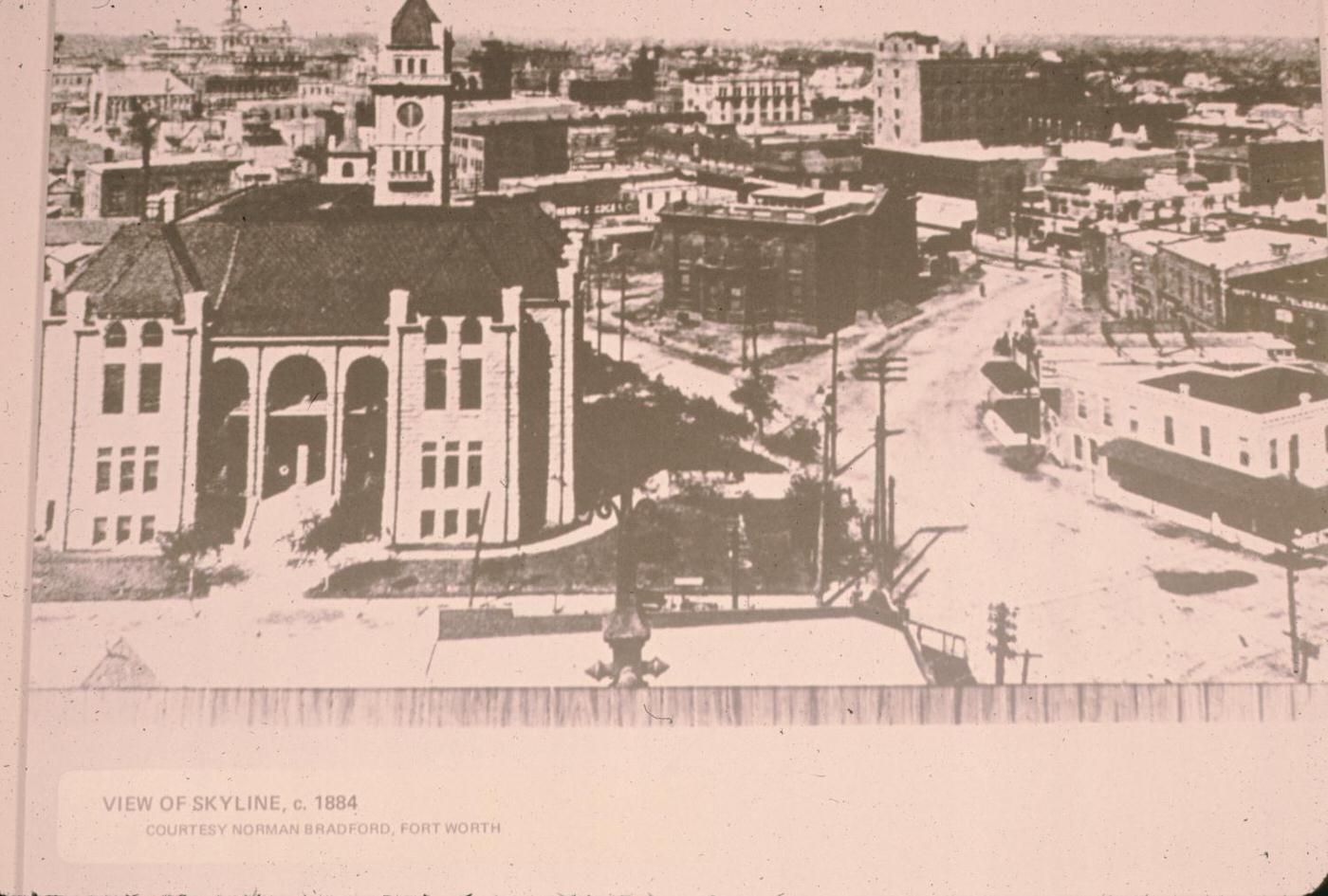

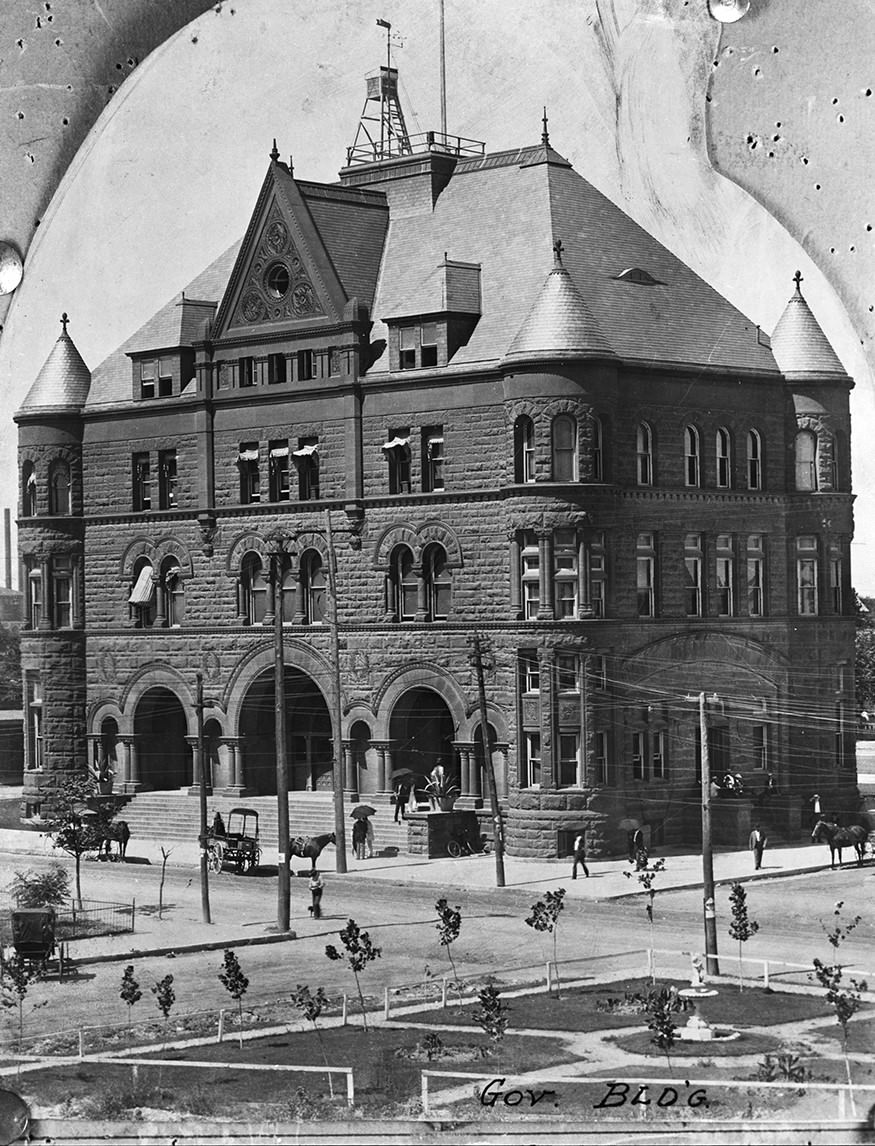

The city’s skyline, previously dominated by modest wood-frame structures, began to change. While the iconic pink granite Tarrant County Courthouse wasn’t completed until 1895, its predecessor, a stone courthouse finished in 1877, was significantly enlarged in 1882 with the addition of a third story. A larger county jail was constructed near the courthouse in 1884. Downtown saw the construction of more substantial commercial buildings, often two-to-three-story brick structures in Victorian styles. Examples from the 1880s that, in some form (often reconstructed facades), still hint at this era include structures within Sundance Square like the City National Bank Building (c. 1884-85), the Reata building (incorporating 1884 & 1887 facades), and the Jarvis Building (1884, now Jubilee Theatre). The Land Title Block (1889) also stands as a prominent example of late-decade commercial architecture.

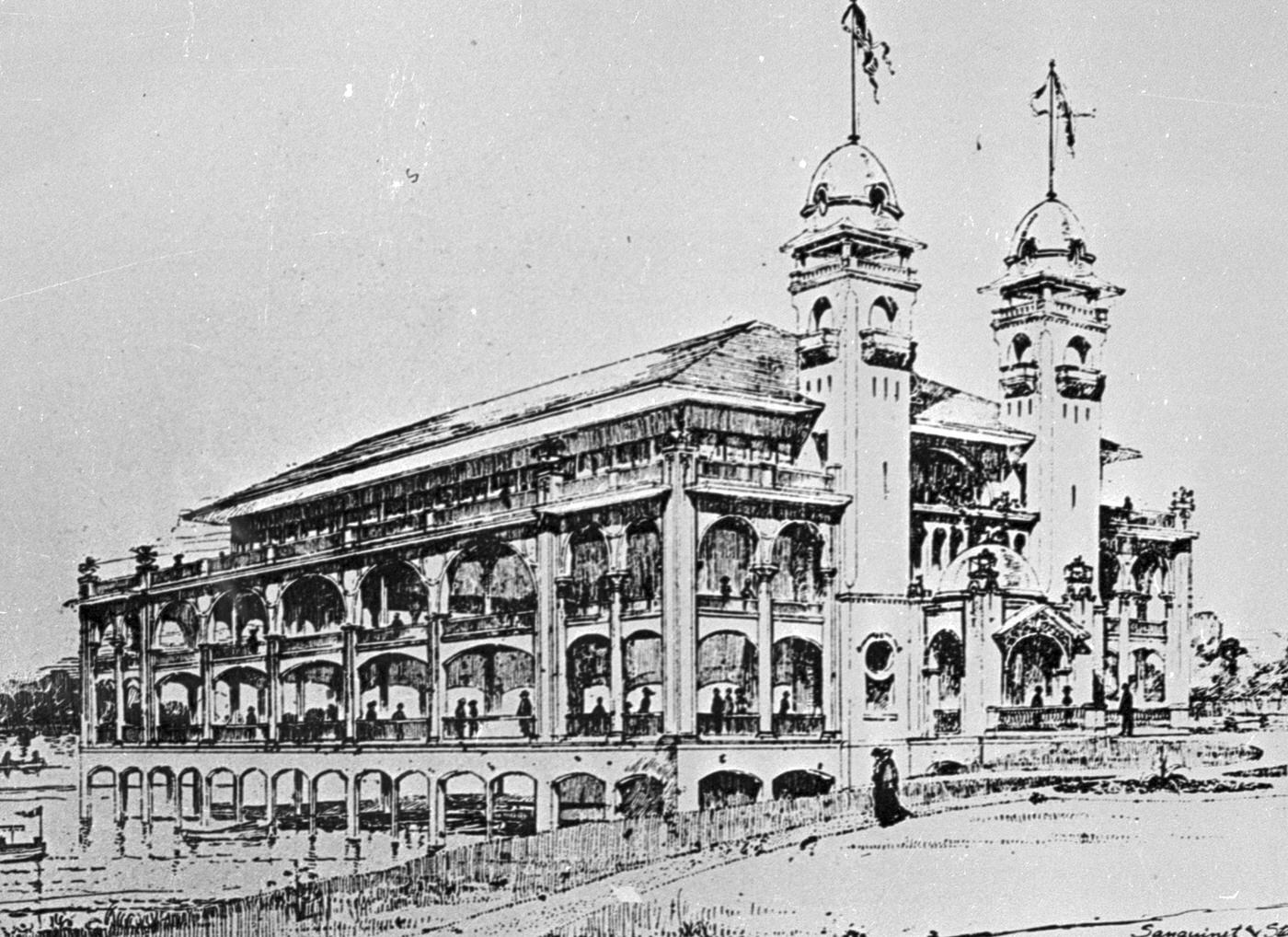

Residential areas expanded significantly beyond the original townsite. The city annexed over two square miles of land to the south in 1890-91, pushing the limits towards what is now Jessamine Street. Neighborhoods like the Southside began to fill in, initially north of Pennsylvania Avenue, appearing as a densely built-up area in illustrations from the era. While grander homes were built on the western bluffs (like the Eddleman-McFarland House, built just after the decade in 1899), much of the new housing likely consisted of smaller, closely spaced homes typical of developing urban neighborhoods. This physical expansion, driven by population growth and facilitated by early streetcar lines, marked the decade Fort Worth truly began to take on the appearance and scale of a city, moving decisively beyond its outpost origins.

Hell’s Half Acre: Vice, Violence, and the Stirrings of Reform

Even as Fort Worth strove towards respectability with new buildings and infrastructure, its notorious heart still beat loudly in Hell’s Half Acre. This infamous red-light district, born in the 1870s to cater to Chisholm Trail cowboys, remained a defining feature of the city throughout the 1880s. Sprawling across several blocks south of the courthouse, encompassing parts of Main, Rusk (Commerce), Calhoun, and Jones streets down towards the railroad depots, the Acre was a chaotic mix of saloons, dance halls, gambling parlors, and brothels (“cribs” and “female boarding houses”).

It was the wild side of Cowtown, a place where fortunes were won and lost, liquor flowed freely, and violence was a constant threat. The “bloody Third Ward,” as it was sometimes known, attracted not just cowboys but also railroad workers, travelers, and a rogues’ gallery of gamblers, gunmen, and outlaws. Legends like Bat Masterson, Doc Holliday, Wyatt Earp, and the Sundance Kid were known visitors during this era. The White Elephant Saloon, technically just outside the Acre but intrinsically linked to its milieu, was famous for both its elegance and its gunfights.

The Acre presented a paradox for city leaders. While reformers and respectable citizens decried its immorality, violence, and the exploitation inherent in its trades (particularly prostitution), the district was a significant economic engine, pouring money (legal and illicit) into local coffers. Law enforcement often walked a fine line, maintaining a semblance of order while allowing the lucrative vices to continue largely unchecked, sometimes enforcing laws primarily to collect fines.

However, the character of the Acre began to face increasing pressure in the late 1880s. A pivotal event occurred on February 8, 1887: the fatal shootout between former marshal Jim Courtright and gambler Luke Short. Courtright, operating a “detective agency” widely seen as a protection racket, confronted Short outside the White Elephant, allegedly over protection money. In the ensuing quick-draw, Short, despite Courtright drawing first, fired multiple shots, killing the former marshal. Short was arrested but later acquitted on grounds of self-defense. The death of the popular, albeit controversial, Courtright, followed weeks later by the murder of a prostitute, galvanized reform sentiment. Reform-minded mayors like H.S. Broiles, backed by figures like newspaper editor B.B. Paddock and spurred by events like the 1887 shootout and the first statewide prohibition campaign in 1889, began to crack down more seriously on the Acre’s “worst excesses”. While the Acre would persist into the 20th century, the late 1880s marked a turning point, as the city began a long, slow process of attempting to tame its wild heart, reflecting the growing tension between its frontier past and its urbanizing future.

Policing the Panther City: Marshals, Mayhem, and Maintaining Order

Keeping the peace in a city experiencing explosive growth, fueled by railroads and cattle money, and hosting a notorious vice district like Hell’s Half Acre, was a formidable challenge throughout the 1880s. Fort Worth’s law enforcement, evolving from a lone City Marshal in the early 1870s, struggled to impose order on the often-chaotic streets.

The decade began shortly after the tenure of perhaps the most famous (and infamous) Fort Worth lawman, Timothy “Longhair Jim” Courtright. Elected City Marshal in 1876, Courtright, known for his skill with his twin Colt revolvers worn butts-forward, brought a measure of control through sheer intimidation and reputation. He significantly reduced the murder rate but was also widely believed to run protection rackets and rule with a heavy, sometimes brutal, hand. His approach embodied the era’s conflict: stop the bloodshed, but don’t stop the flow of money from the Acre. Courtright was defeated for reelection in 1879 by S.M. Farmer. (Note: While S.M. Farmer is mentioned as Courtright’s successor, specific term dates for Farmer and subsequent 1880s marshals like John Stocker (preceded Courtright ), T.M. Ewing (elected 1874 ), Ben H. Shipp (Sheriff 1886-88, involved post-Courtright/Short shootout ), or J.C. Richardson (Sheriff 1888-92 ) are difficult to pin down precisely from the provided snippets, reflecting the sometimes turbulent nature of city politics). Walter T. Maddox served as Tarrant County Sheriff from 1880-1886.

The police force itself remained small relative to the city’s size and volatility. Under Courtright, the marshal was authorized only two assistants. The first detective was appointed in 1883. By 1887, after years of political disputes over control of the force, the department reportedly consisted of only a chief, two mounted officers, two patrolmen, a jailer, and two sanitary officers – a remarkably small contingent for a city nearing 20,000 people with a district like the Acre.

Policing faced inherent challenges: the constant influx of transient populations (cowboys, railroad workers), the economic importance of the vice district which discouraged strict enforcement, and the general lawlessness often associated with frontier boomtowns. Events like the 1886 railroad strike, during which a deputy was killed, and the ever-present potential for violence spilling out of the Acre, kept law enforcement constantly tested. The struggle to balance economic interests with public safety and morality, particularly concerning Hell’s Half Acre, was a defining characteristic of law enforcement in 1880s Fort Worth. The city was growing up, but the process was often turbulent and contested on its streets and in its saloons.

Daily Bread and Civic Spirit: Life in 1880s Fort Worth

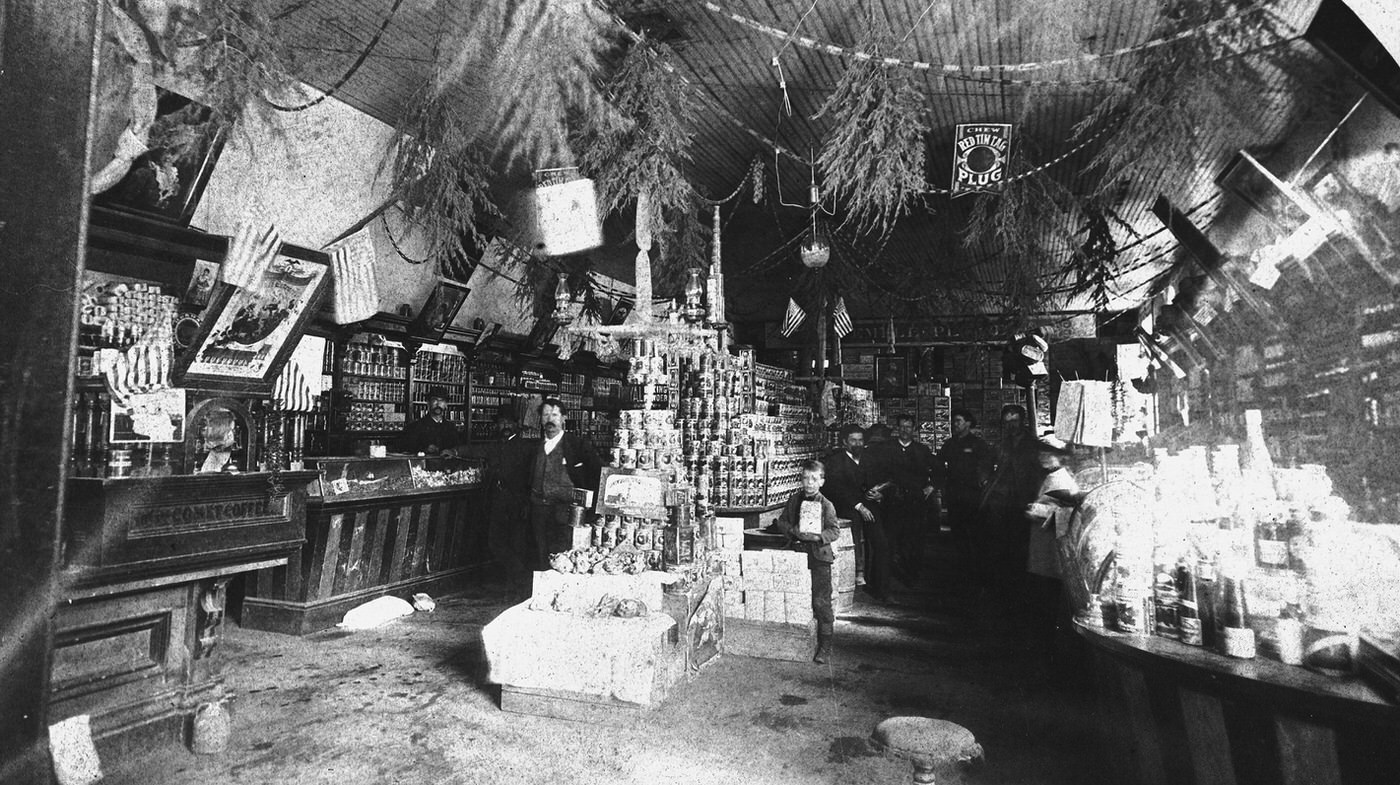

Beyond the dramatic headlines of railroad arrivals and saloon shootouts, the 1880s saw the steady development of everyday life and the establishment of institutions that knitted the rapidly growing population into a community. Fort Worth was transitioning from a raw frontier settlement into a more structured urban society.

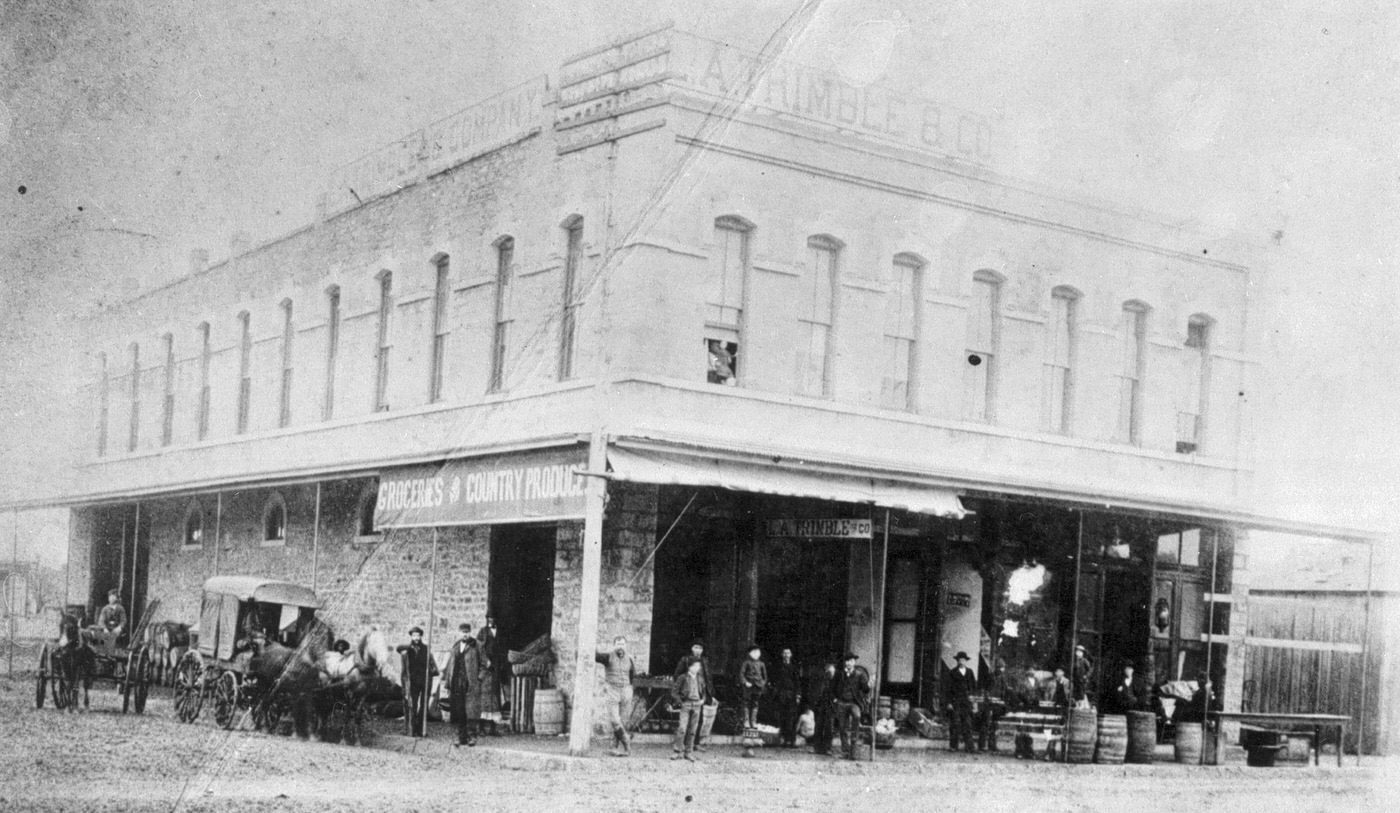

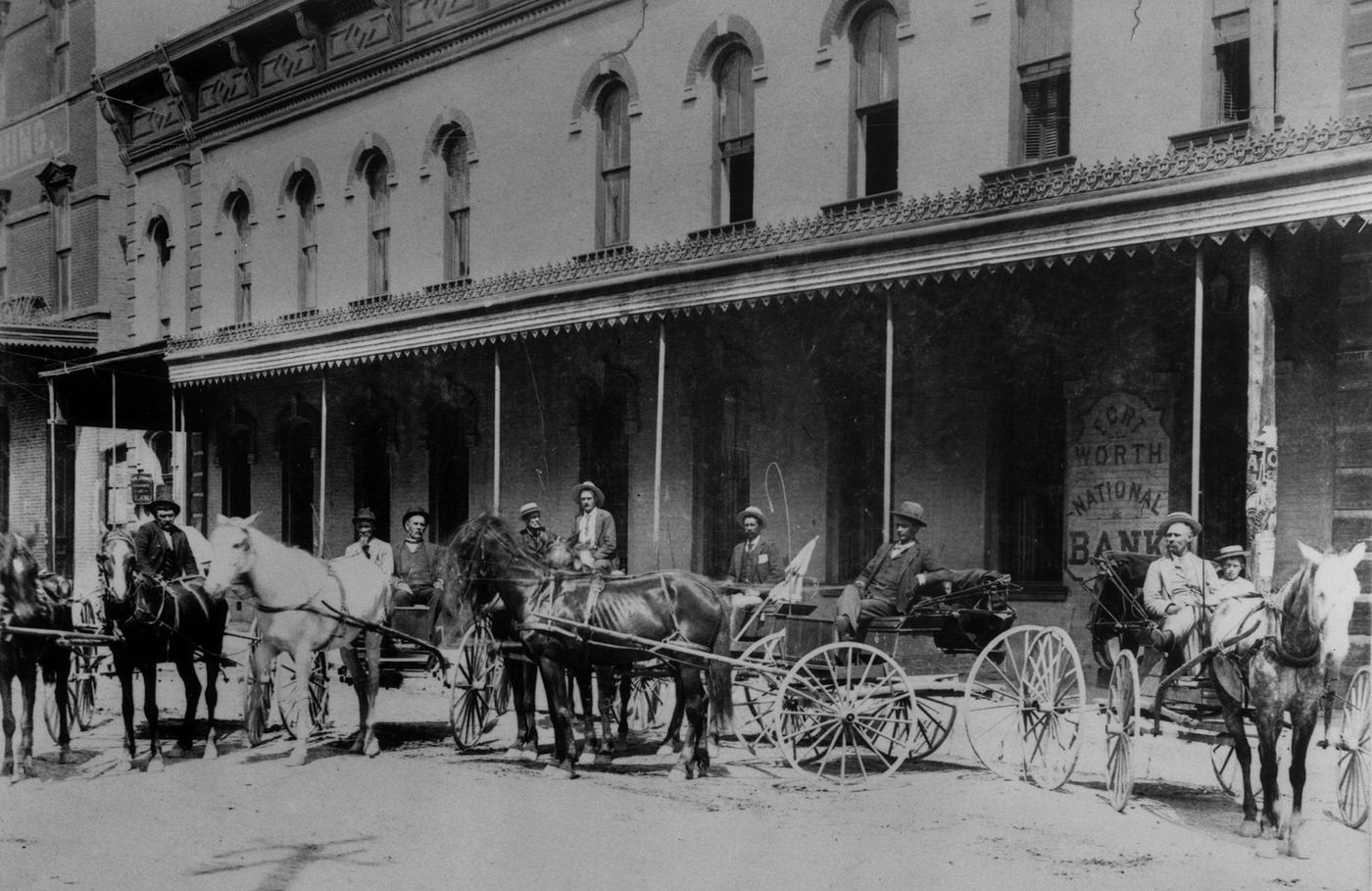

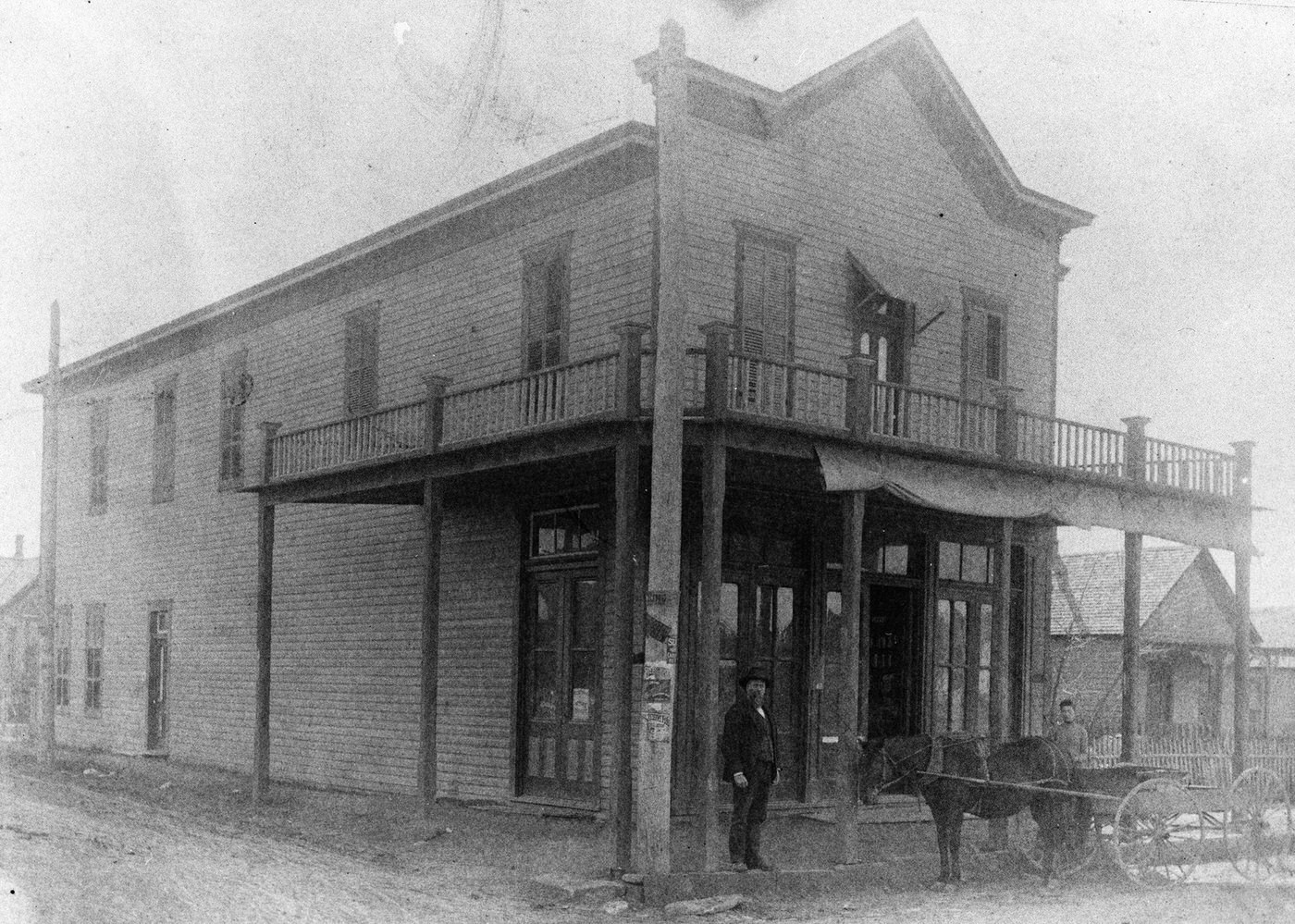

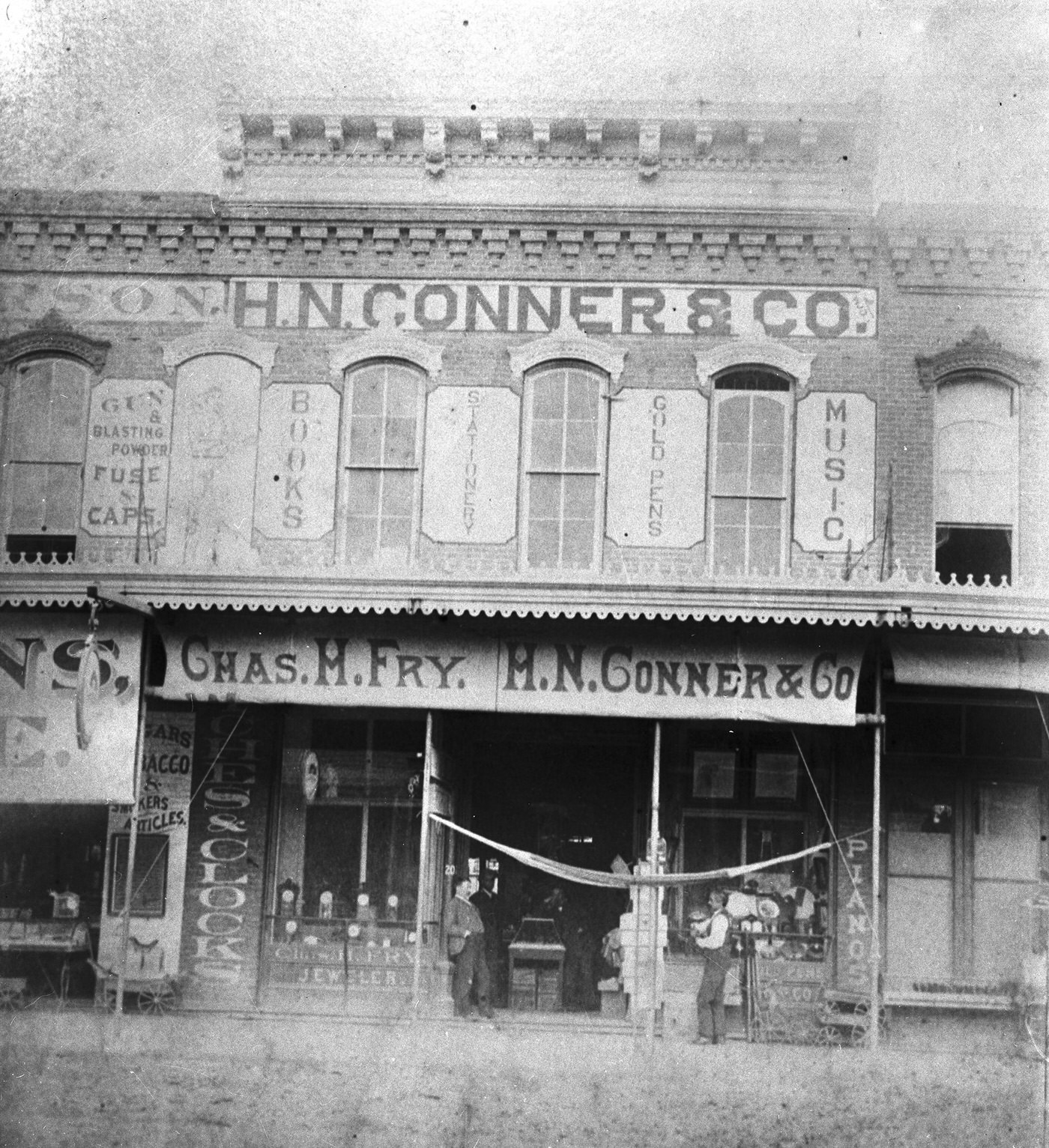

Commerce thrived beyond the cattle trade and vice. General stores like those opened in the 1870s continued to serve residents. Banks played a crucial role; Tidball, Van Zandt, and Company, established in 1873 by K.M. Van Zandt (a key figure in bringing the T&P railroad ), became the Fort Worth National Bank in 1884. Wholesale grocers like Joseph H. Brown did significant business supplying the region. New industries began to emerge alongside the dominant cattle and railroad sectors. Flour milling gained importance, with M.A. Begley establishing a significant mill in 1882, followed by others like the Cameron Mill in 1888. Grain elevators appeared as early as 1878. Businesses catering to diverse needs, from furniture dealers and clothiers like Washer Brothers (est. 1882) to spice merchants like Pendery’s (est. 1890), multiplied, reflecting a diversifying economy.

Social structures were evolving. While predominantly Anglo-American, the city included a growing African American population (nearly 2,000 in Tarrant County by 1887) and a small but present Hispanic community, mostly laborers, often living near the downtown edges. European immigrants, particularly Germans, also contributed to the mix. Housing ranged from simple wood-frame structures, sometimes built from rough-hewn local timber with basic amenities, to the beginnings of more substantial homes in developing residential areas.

Crucially, the 1880s saw the founding of key civic institutions. After several contested elections and legal challenges, the Fort Worth public school system was finally and firmly established in 1882. Led by Superintendent Alexander Hogg and an initial staff of 17 teachers (13 white, 4 black), schools opened in rented buildings, including churches for the segregated black students. Construction of permanent school buildings, like the first Fort Worth High School (precursor to Paschal High), began soon after.

Religious life also solidified. While circuit preachers served early settlers, the 1880s saw numerous denominations establish permanent roots and construct dedicated church buildings, moving beyond shared spaces or rented halls. By the end of the decade, Fort Worth boasted churches representing Baptists, Catholics (St. Patrick’s cornerstone laid 1888, replacing 1876 St. Stanislaus), Methodists (including the Fourth Street Methodist, built 1887), Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Christian churches, German Evangelicals, and the beginnings of an organized Jewish community (which established its first cemetery in 1879 and Congregation Ahavath Sholom in 1892).

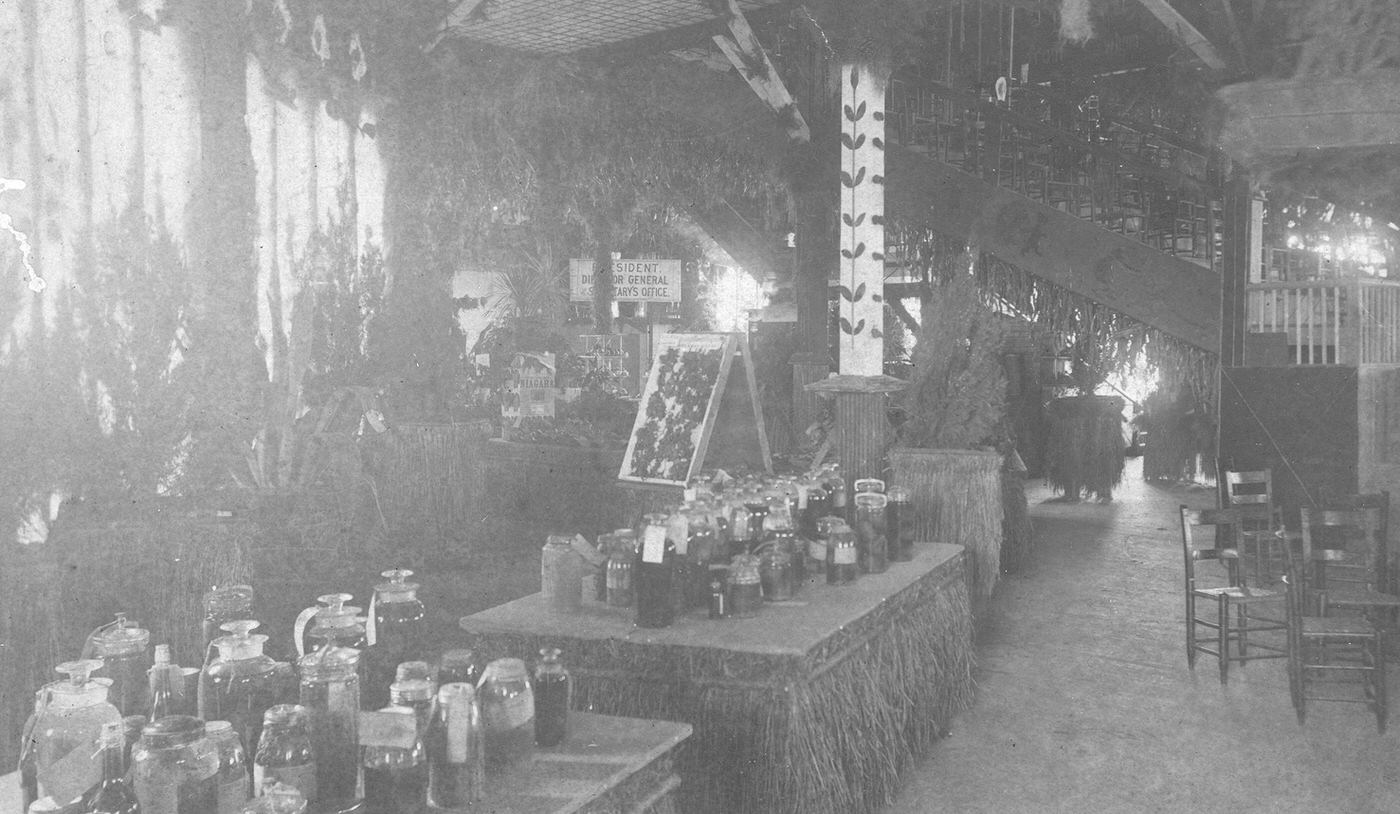

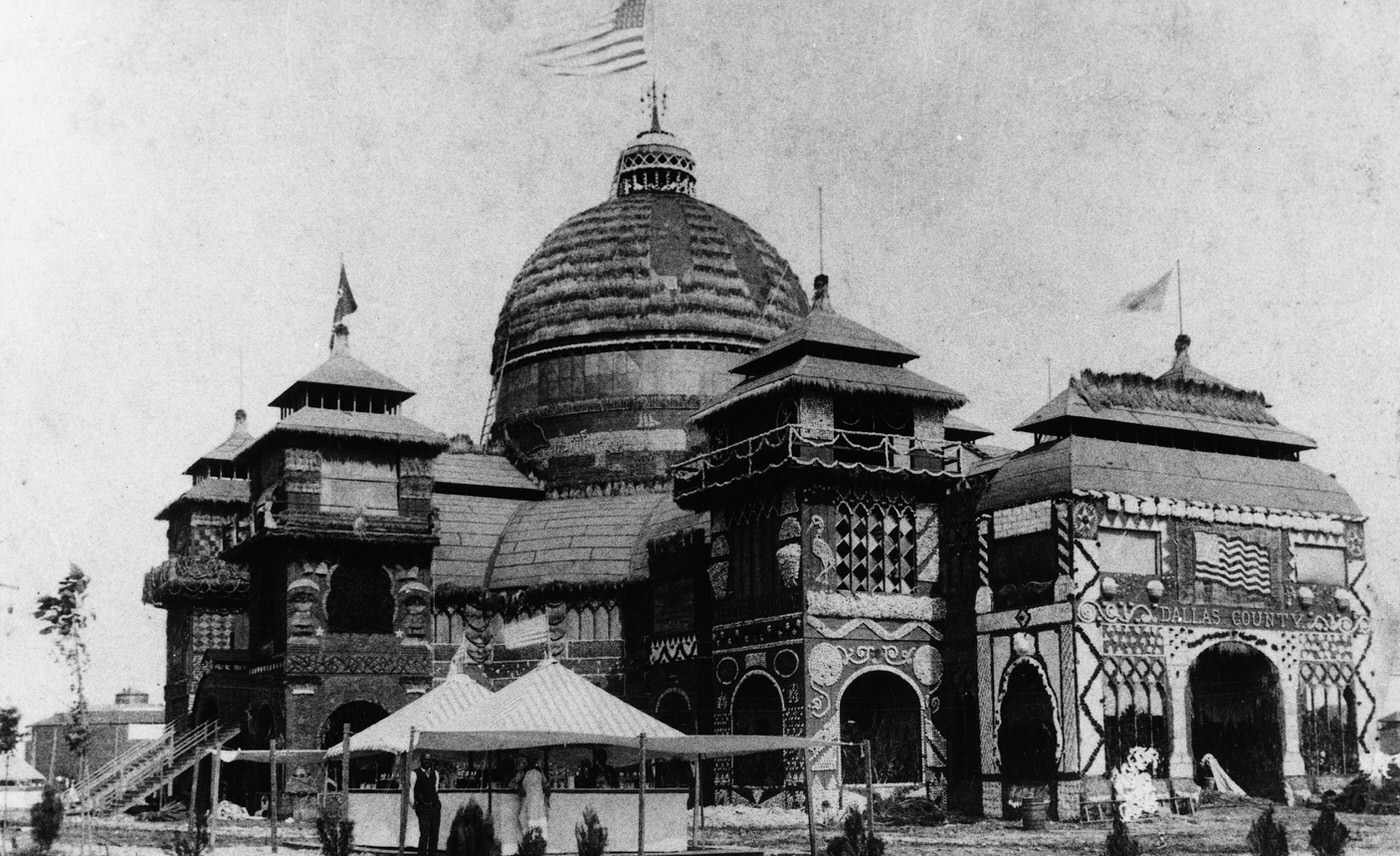

Community organizations flourished, fostering social connection and promoting civic interests. The Commercial Club, forerunner of the Fort Worth Club, was chartered in 1885 by businessmen aiming to advance the city’s interests. Agricultural groups like the Farmers’ Alliance gained prominence, and cattlemen organized through the Northwest Texas Cattle Raisers’ Association. Early women’s clubs were also forming, laying the groundwork for later federations. This deliberate creation of schools, diverse churches, and civic organizations marked Fort Worth’s maturation from a transient boomtown into a more permanent, structured community with deepening social and cultural roots.

Image Credits: Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, UTA Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, Wikimedia, Jack White Photograph Collection,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know