As the final decade of the nineteenth century dawned, Fort Worth, Texas, stood at a crossroads. No longer a mere military outpost on the edge of the frontier, it had blossomed into a significant urban center. The official U.S. Census recorded a population of 23,076 in 1890, a staggering increase from just 6,663 residents only ten years prior, making it the fifth-largest city in Texas. This explosive growth, fueled largely by the relentless westward push and the city’s strategic position, set the stage for a decade of profound transformation.

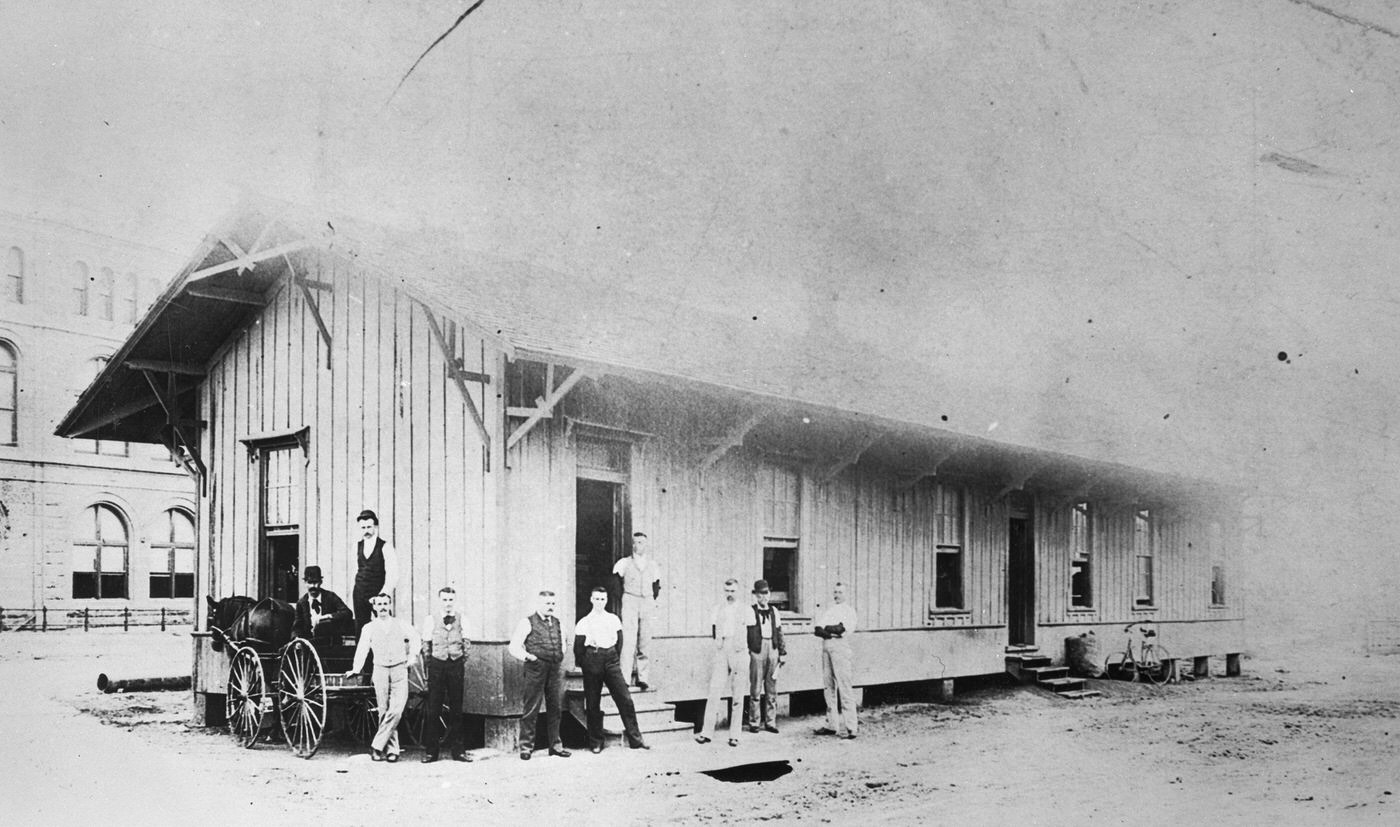

Central to Fort Worth’s identity and economy was its status as a burgeoning railroad metropolis. Since the celebrated arrival of the Texas and Pacific Railway (T&P) in 1876 – an event secured by the sheer will and collective effort of its citizens – the city had become a critical junction. By 1890, an impressive network of iron arteries converged here: the T&P (1876), the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MKT or “Katy,” 1880), the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF, 1881), the Fort Worth & Denver City (FW&DC, 1881/82), the Fort Worth & New Orleans (FW&NO, 1886), the Fort Worth & Rio Grande (FW&RG, 1887), and the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas (SLA&T / Cotton Belt, 1888). Fort Worth was rapidly fulfilling the vision of becoming the rail hub of the Southwest.

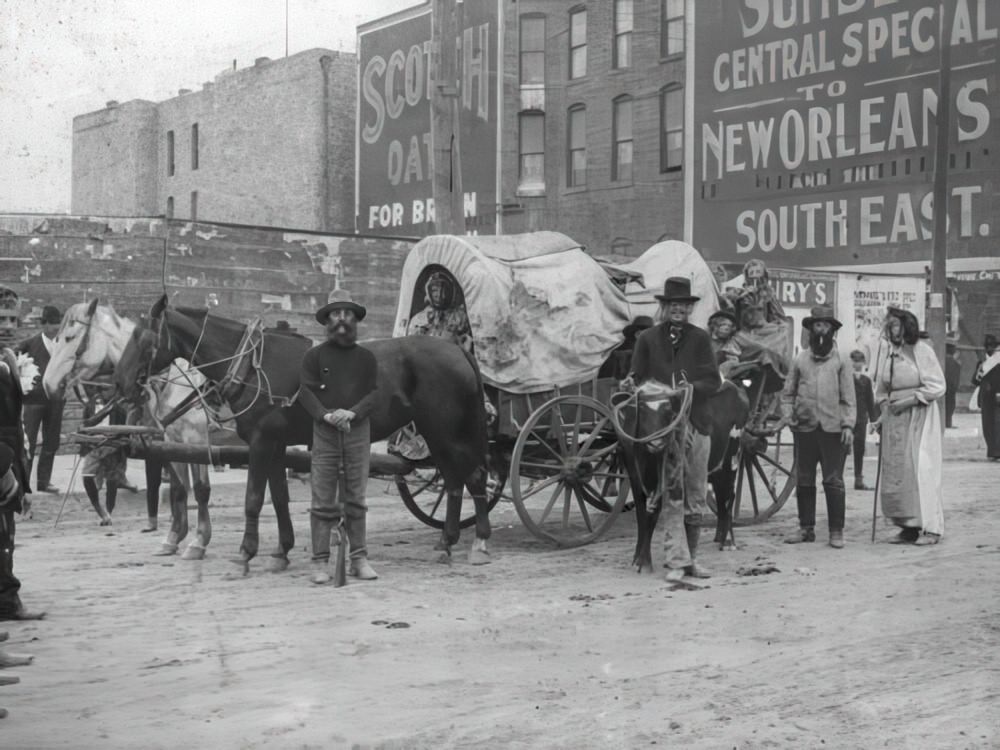

Yet, this decade also marked the definitive end of an era that had fundamentally shaped the city’s early character. The great open-range cattle drives, which had thundered up the Chisholm Trail, making Fort Worth the last supply stop before Indian Territory and earning it the enduring nickname “Cowtown,” were fading into legend by 1890. The relentless march of barbed wire across the plains, fencing off the vast ranges, coupled with increasingly strict quarantine laws enacted by states like Kansas to combat “Texas Fever” spread by ticks on Longhorns, had choked off the trails. Furthermore, the expanding railroad network within Texas itself made the arduous overland drives to distant railheads largely obsolete.

The Stockyards Take Shape: From Union Yards to Industrial Hub

The demise of the long cattle drives did not spell the end of Fort Worth’s connection to the livestock industry; rather, it catalyzed its transformation. With cattle now arriving by rail instead of hoof, the focus shifted from provisioning drovers to creating a centralized market for buying, selling, and processing. Building upon the initial efforts of local businessmen who established the Union Stockyards in 1887 and opened the facility north of the Trinity River in mid-summer 1889, the 1890s saw the formal organization and strategic development that would turn Fort Worth into a national livestock powerhouse.

A crucial turning point came with the infusion of substantial outside capital. Local interests, recognizing the need for greater investment, invited Boston capitalist Greenleif W. Simpson to Fort Worth. Intrigued by the potential, Simpson, along with several Boston and Chicago associates (including his Boston neighbor Louville V. Niles, a figure with significant meatpacking experience from his leadership at the Boston Packing and Provision Company), took a decisive step. On March 23, 1893, they officially incorporated the Fort Worth Stock Yards Company. This new entity promptly purchased the existing Union Stock Yards and the Fort Worth Packing Company in April and August 1893, respectively, consolidating the local livestock operations under a well-financed umbrella.

The timing, however, proved challenging. The ink was barely dry on the incorporation papers when the nation plunged into the severe financial Panic of 1893. This economic downturn undoubtedly strained the new venture, testing the resolve of its investors. Yet, Simpson and Niles remained committed to a larger vision: transforming Fort Worth from a mere shipping point for live cattle into a major meat processing center. They understood that attracting major national packers like Armour & Company and Swift & Company was key to long-term success and stability.

The remainder of the 1890s was dedicated to laying the groundwork for this ambitious goal. Despite the financial headwinds, the Fort Worth Stock Yards Company actively courted these industry giants. While the final agreements that brought Armour and Swift plants to Fort Worth were cemented just after the turn of the century (around 1901-1902, with plant openings following), the persistent negotiations, strategic planning, and promotional efforts occurred throughout the 1890s. A key element of this strategy was the inauguration of the Fort Worth Fat Stock Show in 1896. Initially a modest event held on Marine Creek, it served not only to showcase local livestock but also to demonstrate the region’s potential and attract the attention of the very packers the Stock Yards Company sought to recruit. The formalization of the Stockyards under experienced, well-capitalized leadership in 1893, and the subsequent strategic push to integrate large-scale packing operations, defined the 1890s as the critical foundational period for the industry that would dominate Fort Worth’s economy in the early twentieth century.

Economic Currents: Panic, Progress, and Diversification

The economic landscape of Fort Worth in the 1890s was marked by both national turbulence and local resilience. The decade began with momentum, but the severe nationwide Panic of 1893 cast a long shadow, testing the city’s foundations and ultimately reinforcing the need for economic diversity beyond the dominant cattle trade.

The Panic of 1893, triggered by factors including falling gold reserves and slowing economic activity, led to widespread financial distress across the United States. Hundreds of banks failed – over 500 nationally, including state, private, and savings institutions – alongside some 15,000 businesses. Major railroads, the lifelines of commerce, declared bankruptcy, credit markets froze, and unemployment soared, reaching devastating levels in some parts of the country.

While specific data on Fort Worth bank failures during the panic is scarce in the available records, the impact was undoubtedly felt. The newly established Fort Worth Stock Yards Company, launched right as the crisis hit, faced significant struggles. Neighboring Dallas saw five local banks collapse, indicating the regional severity of the downturn. Across Texas, the panic exacerbated existing agricultural problems, driving down already low farm prices (especially for cotton), increasing debt, and forcing many farmers into tenancy. It is almost certain that Fort Worth businesses faced similar pressures, with tightened credit, reduced investment, and a general economic slowdown hindering development plans. The experience likely served as a stark reminder of the vulnerabilities associated with an economy heavily reliant on the fluctuating fortunes of the cattle industry.

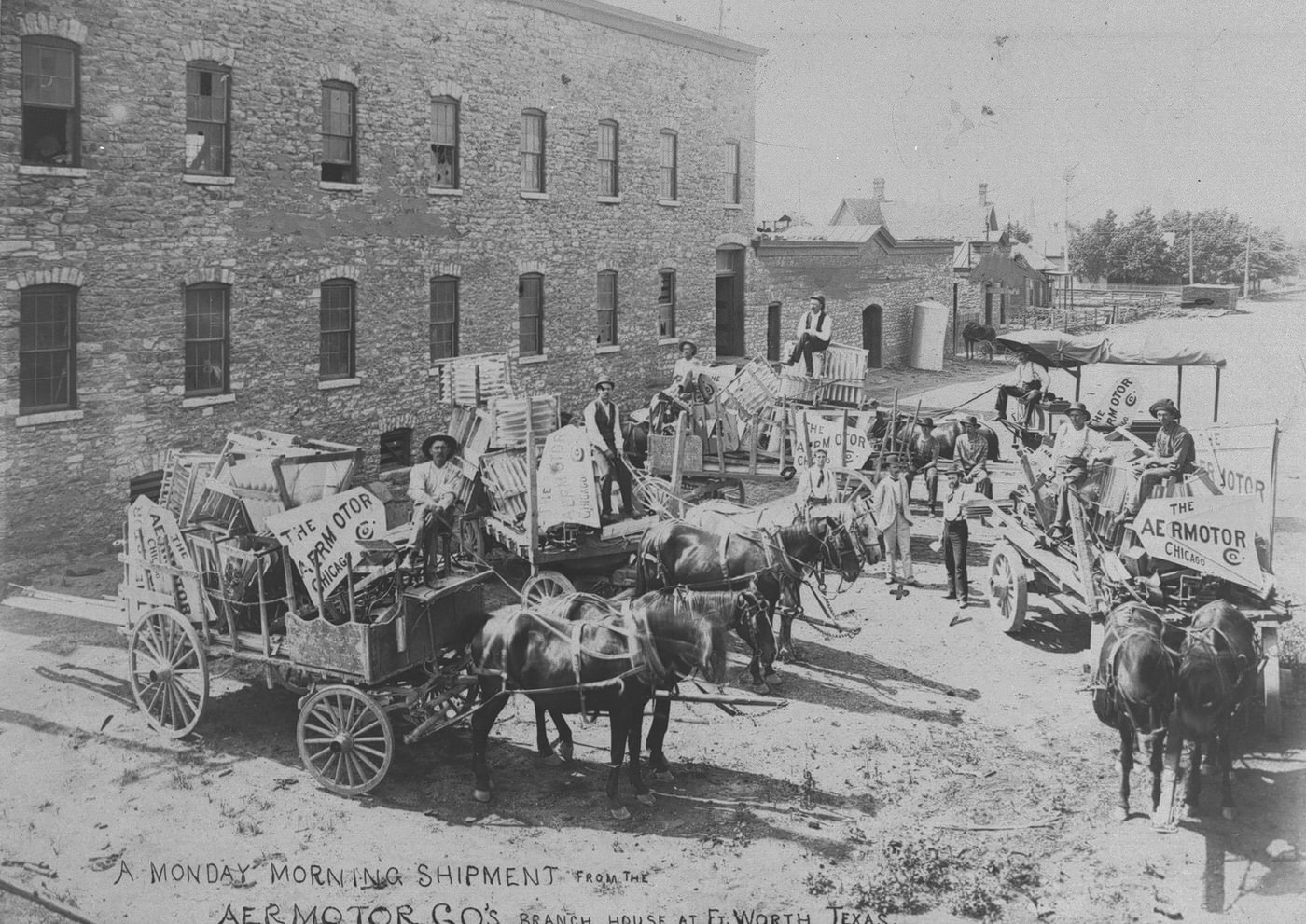

This period of economic uncertainty underscored the importance of diversification, a trend already underway. Fort Worth was strategically positioned not just for cattle, but also as a hub for the region’s agricultural output. Grain processing, in particular, was a growing sector. The city had established its first grain elevator in 1878, and by 1890, boasted five such facilities. Flour milling was also significant, with established operations like M.P. Begley’s Mill (founded 1882) and the Cameron Mill and Elevator (opened 1888) contributing to the city’s capacity. The extensive railroad network was pivotal, allowing grain to be efficiently transported from surrounding farms to Fort Worth for milling, storage, and shipment to wider markets, laying the groundwork for the city’s later claim as a major grain market. Beyond these core industries, other enterprises were taking root, signaling a broadening commercial base. Pendery’s, a name still associated with spices in Fort Worth, began operations in 1890. The O.B. Macaroni Company followed in 1899. While the cattle industry, embodied by the developing Stockyards, remained central to Fort Worth’s identity and future plans, the economic trials of the 1890s highlighted the crucial role of these diversifying industries in building a more resilient and multifaceted urban economy.

Building the Modern City: Bricks, Mortar, and Boundaries

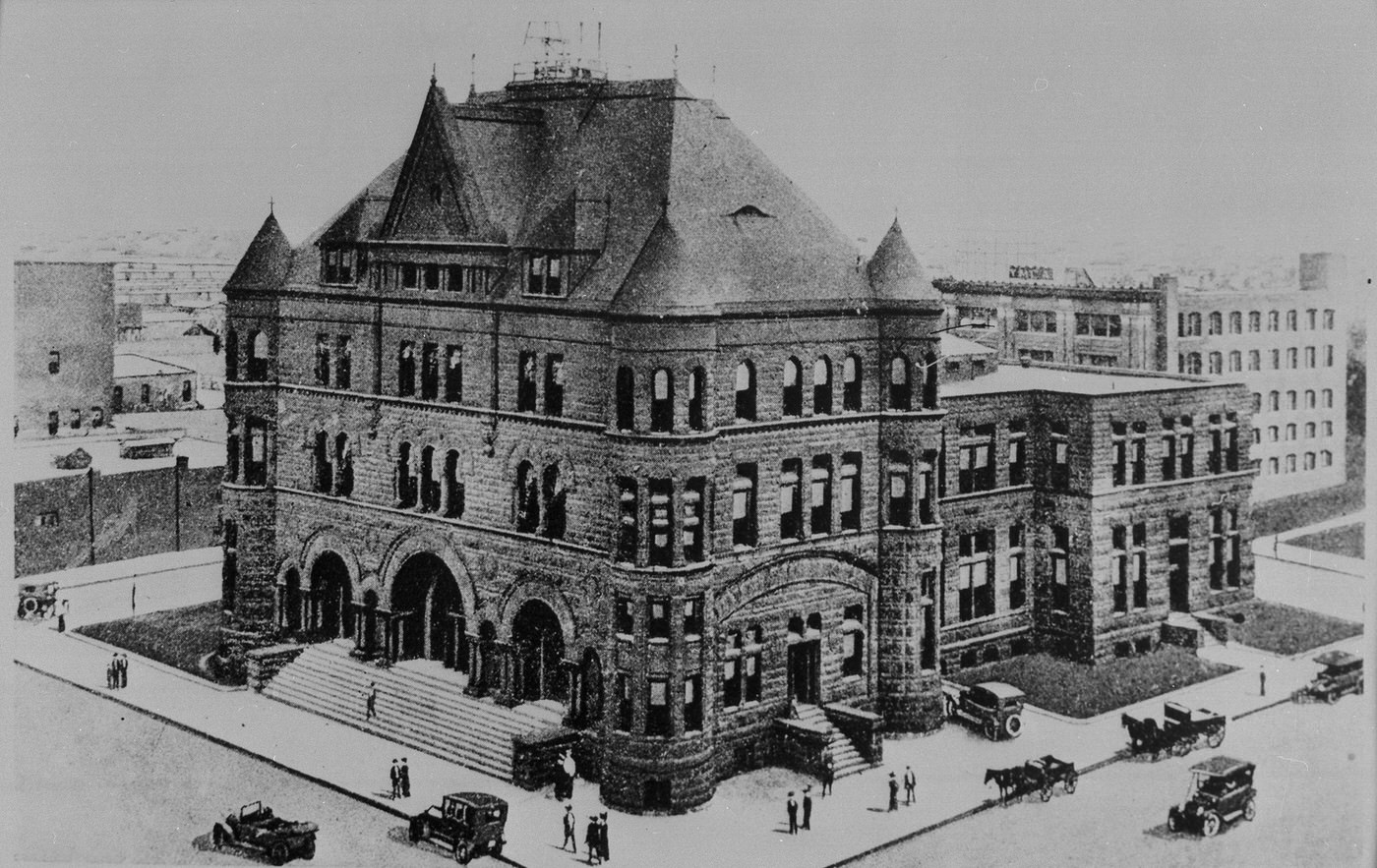

Reflecting its rapid population growth and burgeoning economic ambitions, Fort Worth underwent significant physical transformation during the 1890s. The city literally expanded its borders, erected monumental public buildings, and invested in the essential infrastructure required of a modern urban center.

The city’s footprint grew substantially through annexations carried out in 1890 and 1891. These additions incorporated 2.1 square miles of territory, primarily extending the southern boundary to near present-day Jessamine Street. This expansion, increasing the city’s area significantly from its original 1873 incorporation size of roughly 4.2 square miles, was a direct response to the population boom of the 1880s and early 1890s. By 1891, the enlarged city was divided into nine distinct wards.

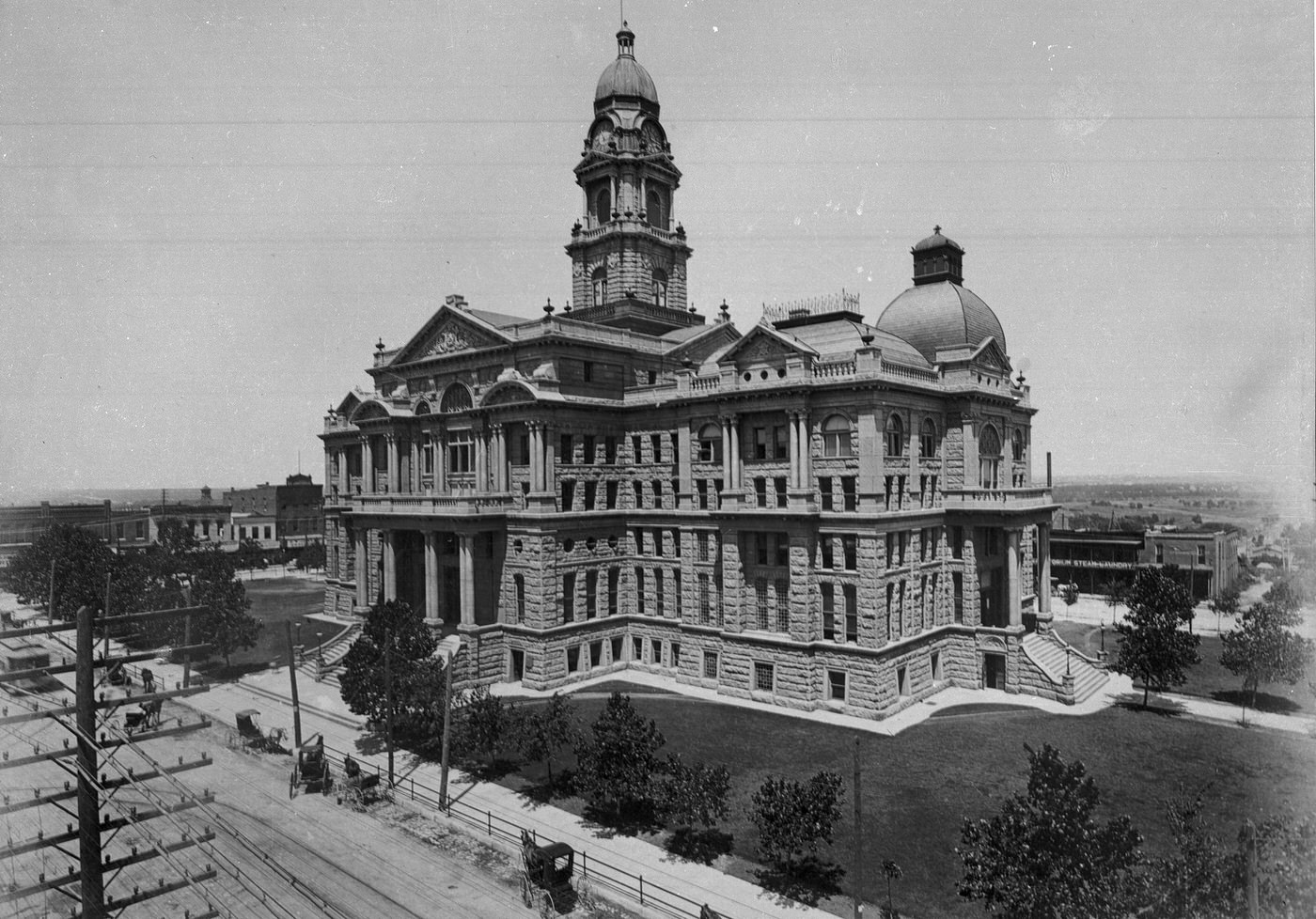

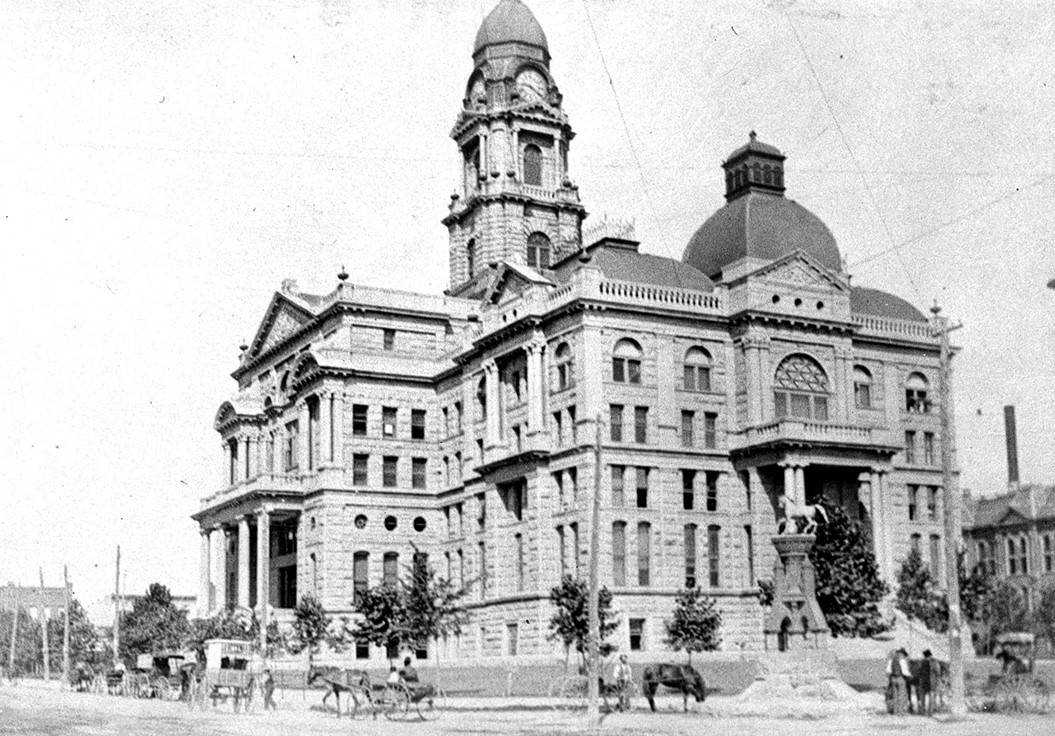

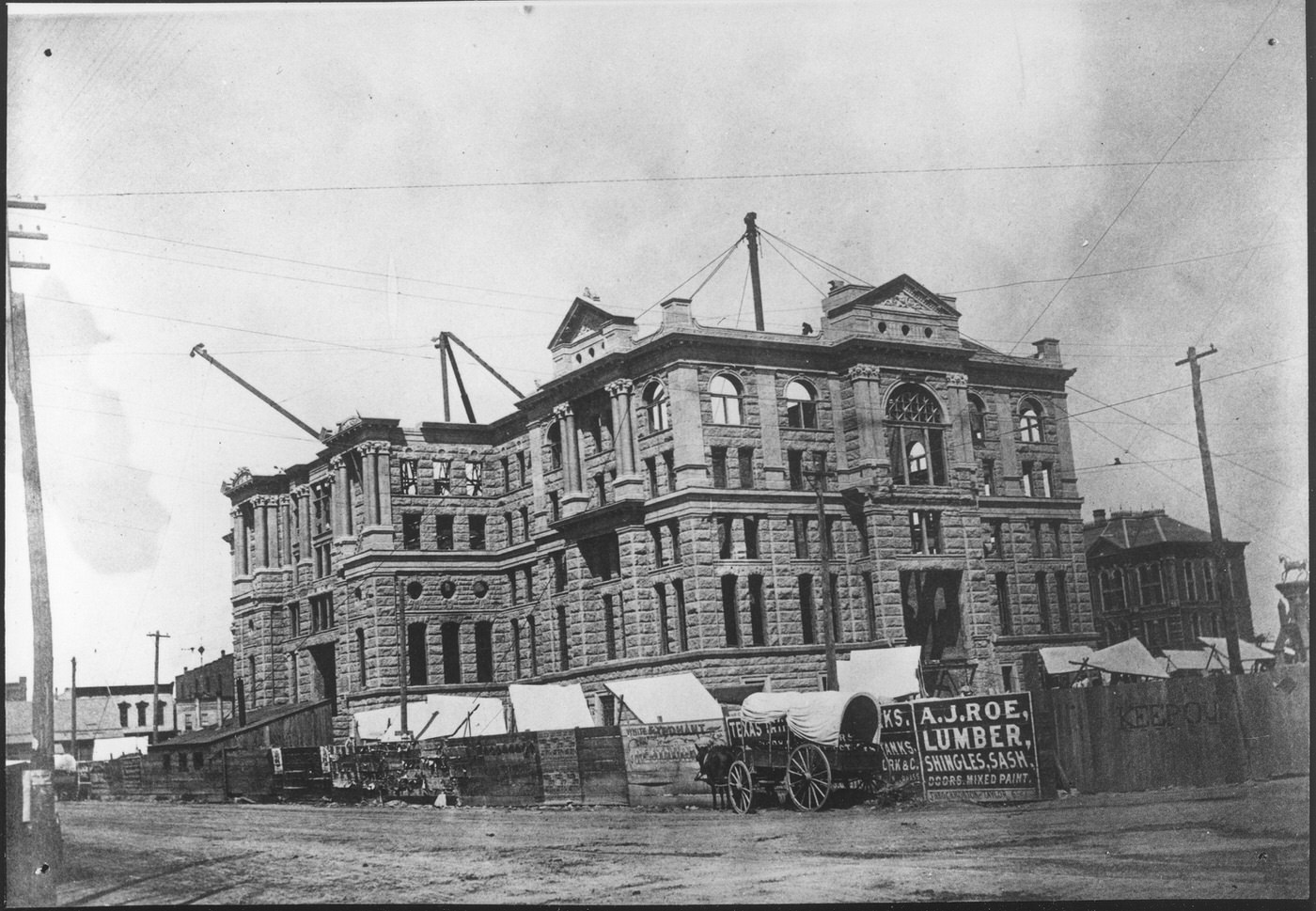

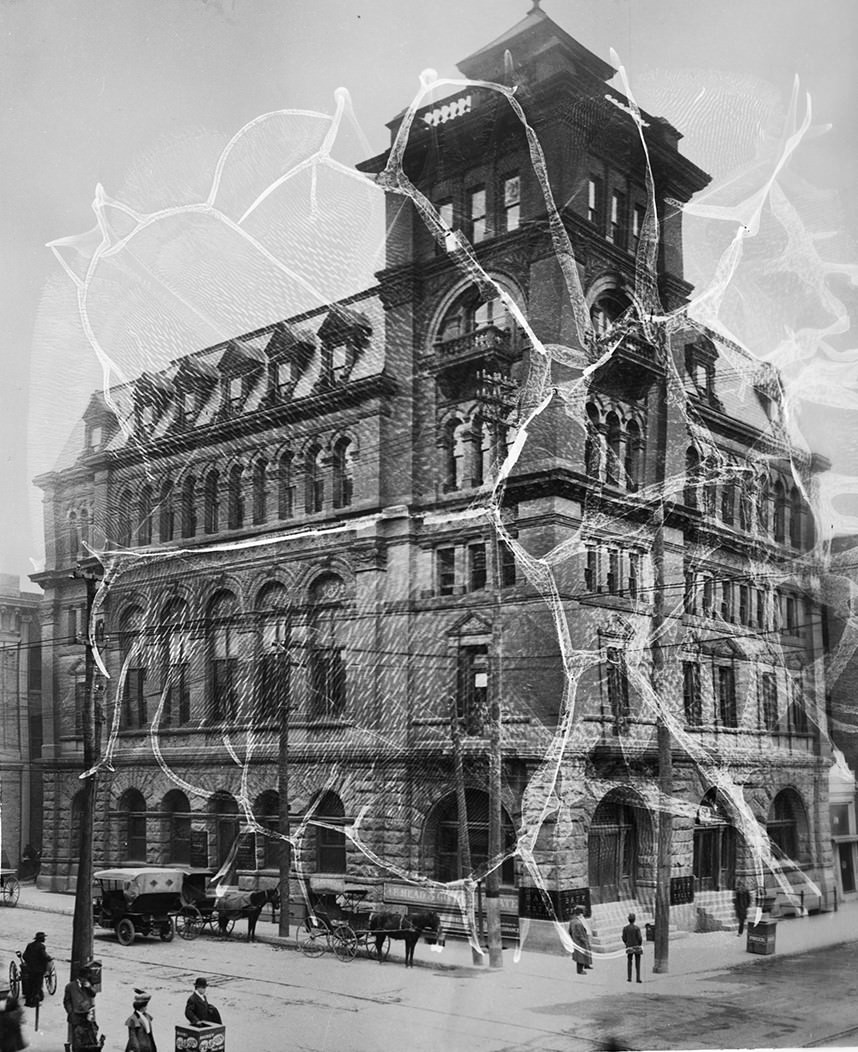

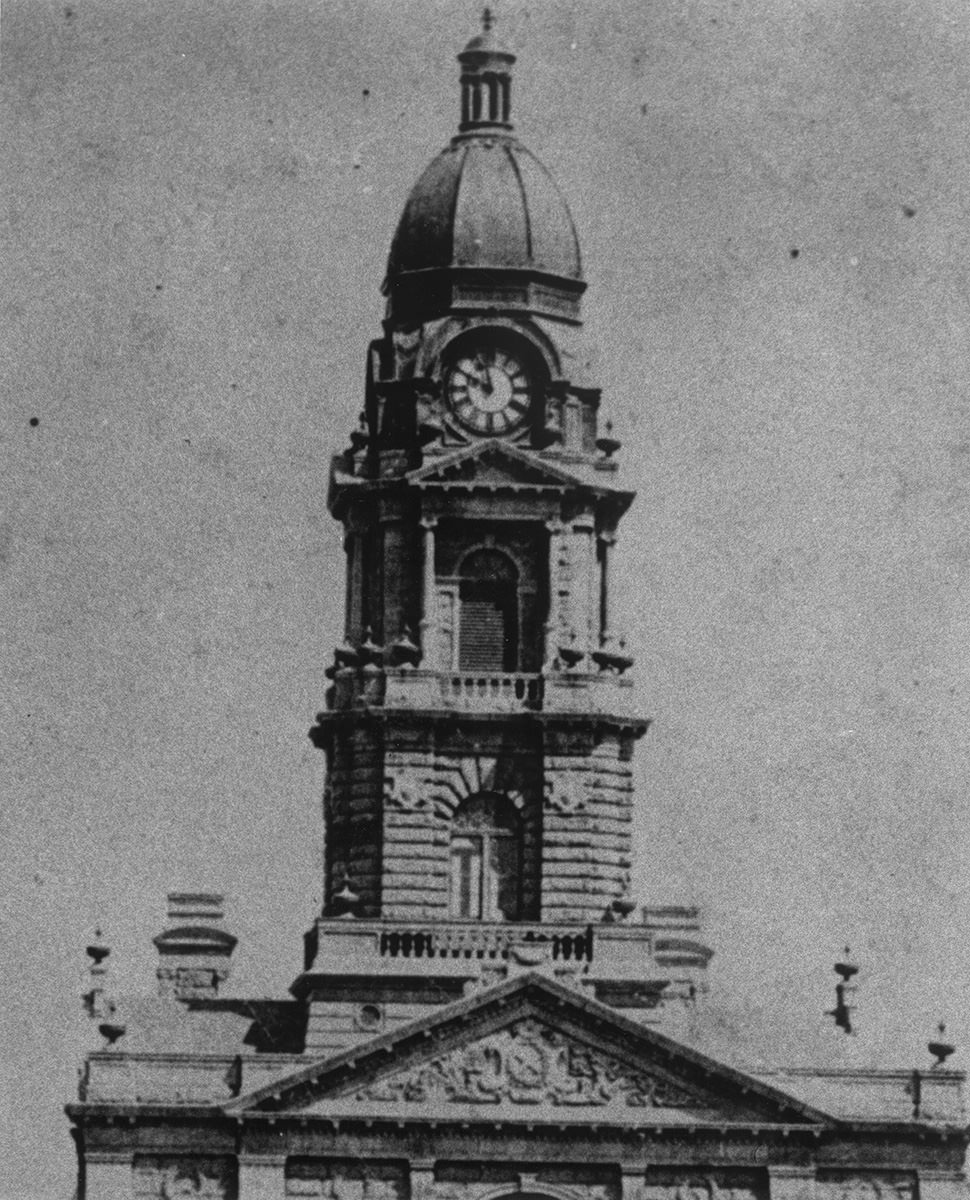

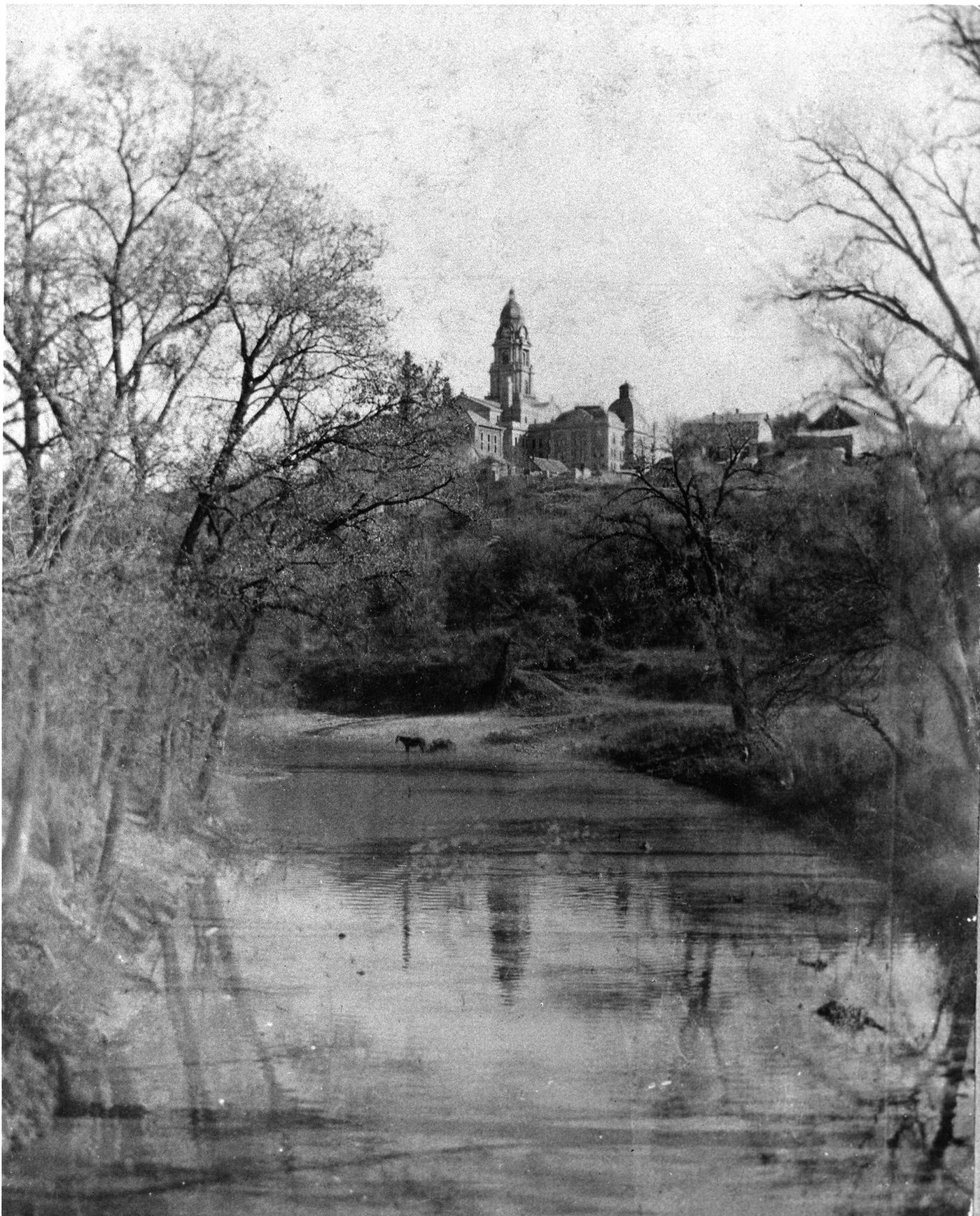

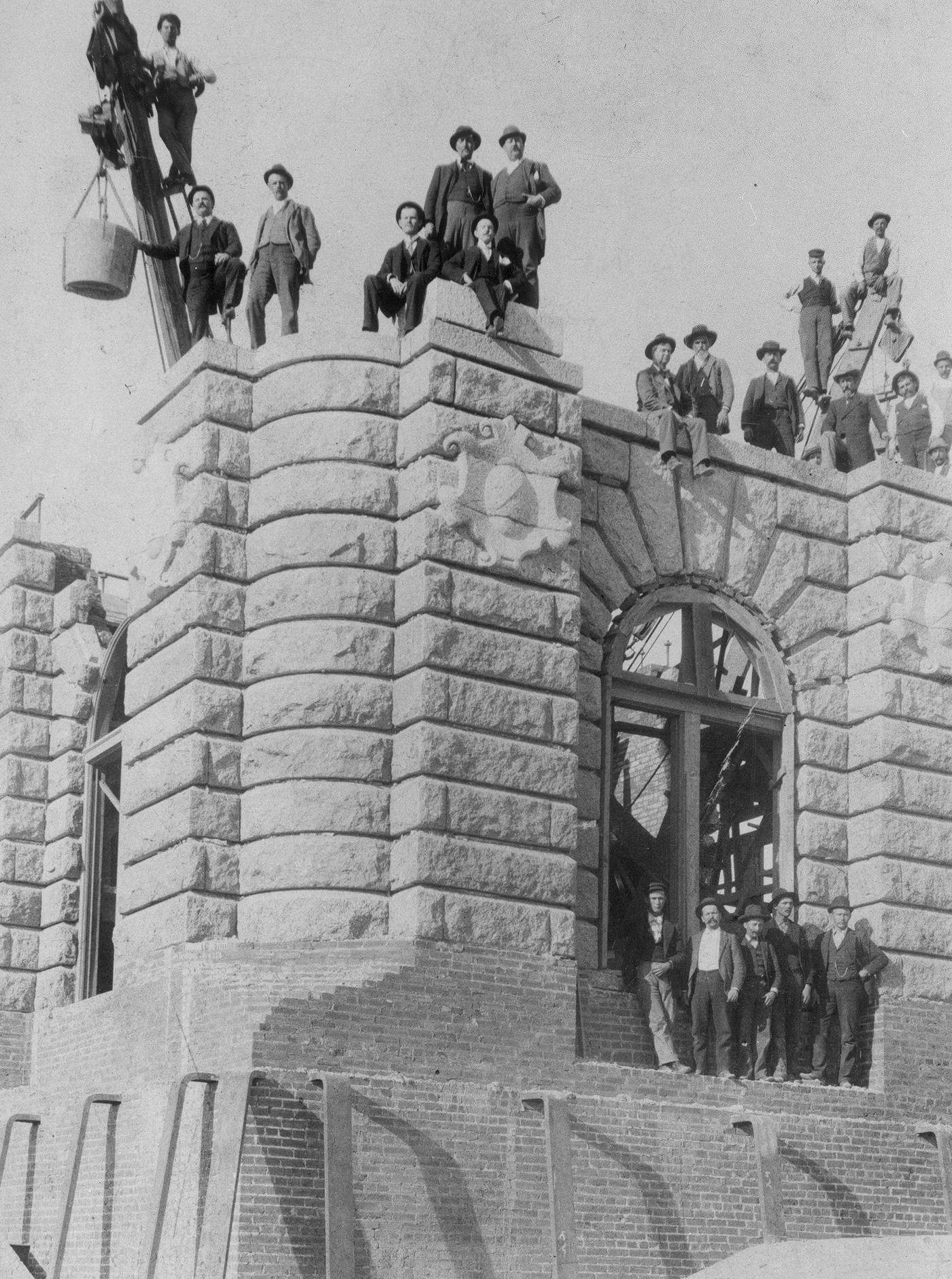

Perhaps the most visible symbol of Fort Worth’s progress and aspirations during this decade was the construction of the magnificent Tarrant County Courthouse. Replacing an earlier, smaller structure that had been enlarged in 1882, the county commissioners voted in 1893 to allocate a substantial $500,000 for a new building commensurate with the county’s growing stature. Designed by the Kansas City architectural firm of Gunn and Curtiss, the courthouse, built between 1893 and 1895, is a commanding example of American Beaux Arts Eclecticism, drawing heavily on Renaissance Revival influences. Constructed with a structural steel frame – an early adoption of this technology in the Southwest – and faced with striking pink granite from the same Central Texas quarry that supplied the State Capitol, the building was intended as a grand statement. Despite its final cost of $408,380 coming in under budget, the sheer expense scandalized many Tarrant County voters, who promptly voted the responsible commissioners out of office in the next election. Nonetheless, upon completion in 1895, the courthouse stood as the undeniable anchor and architectural jewel of the city.

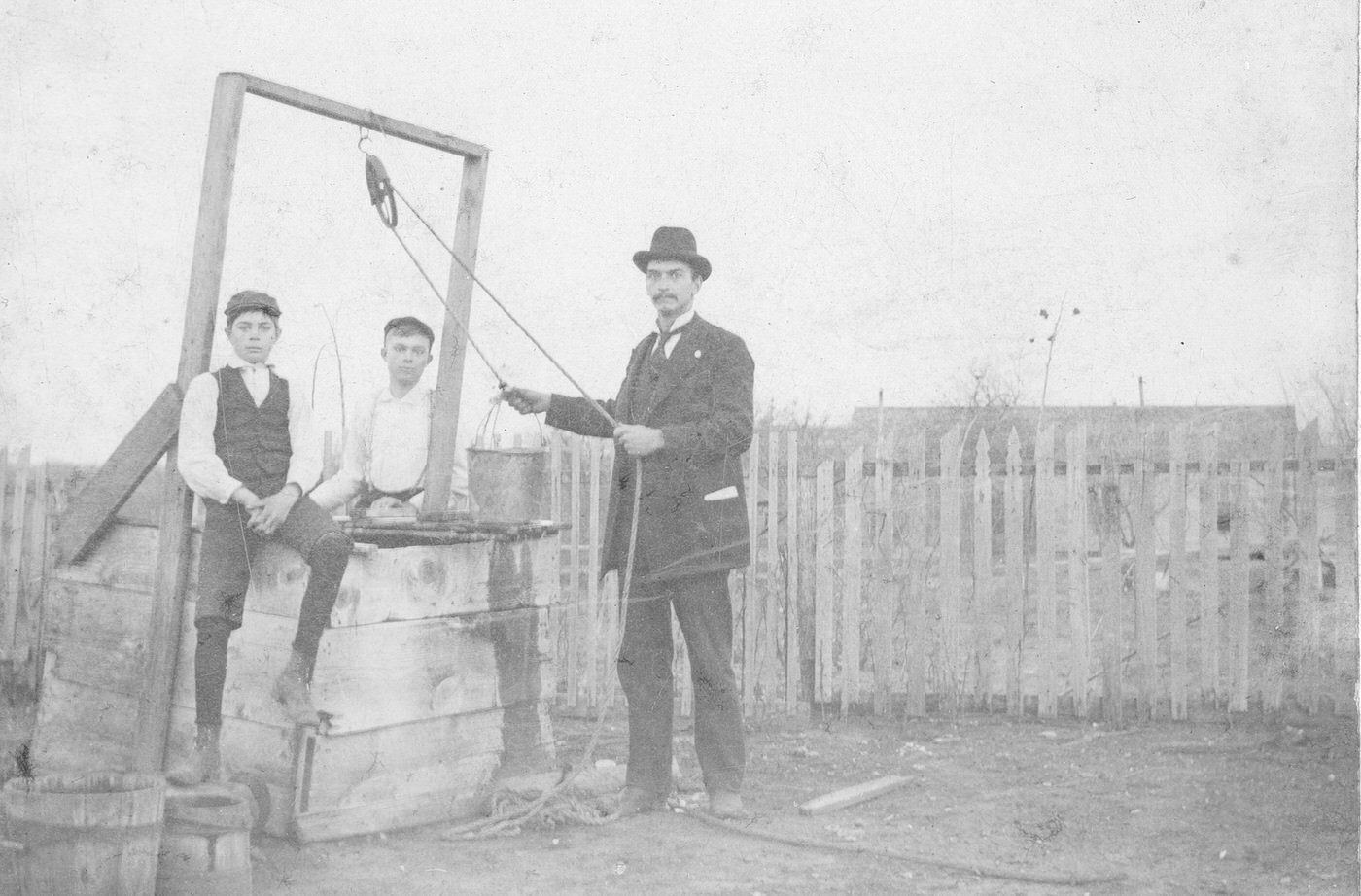

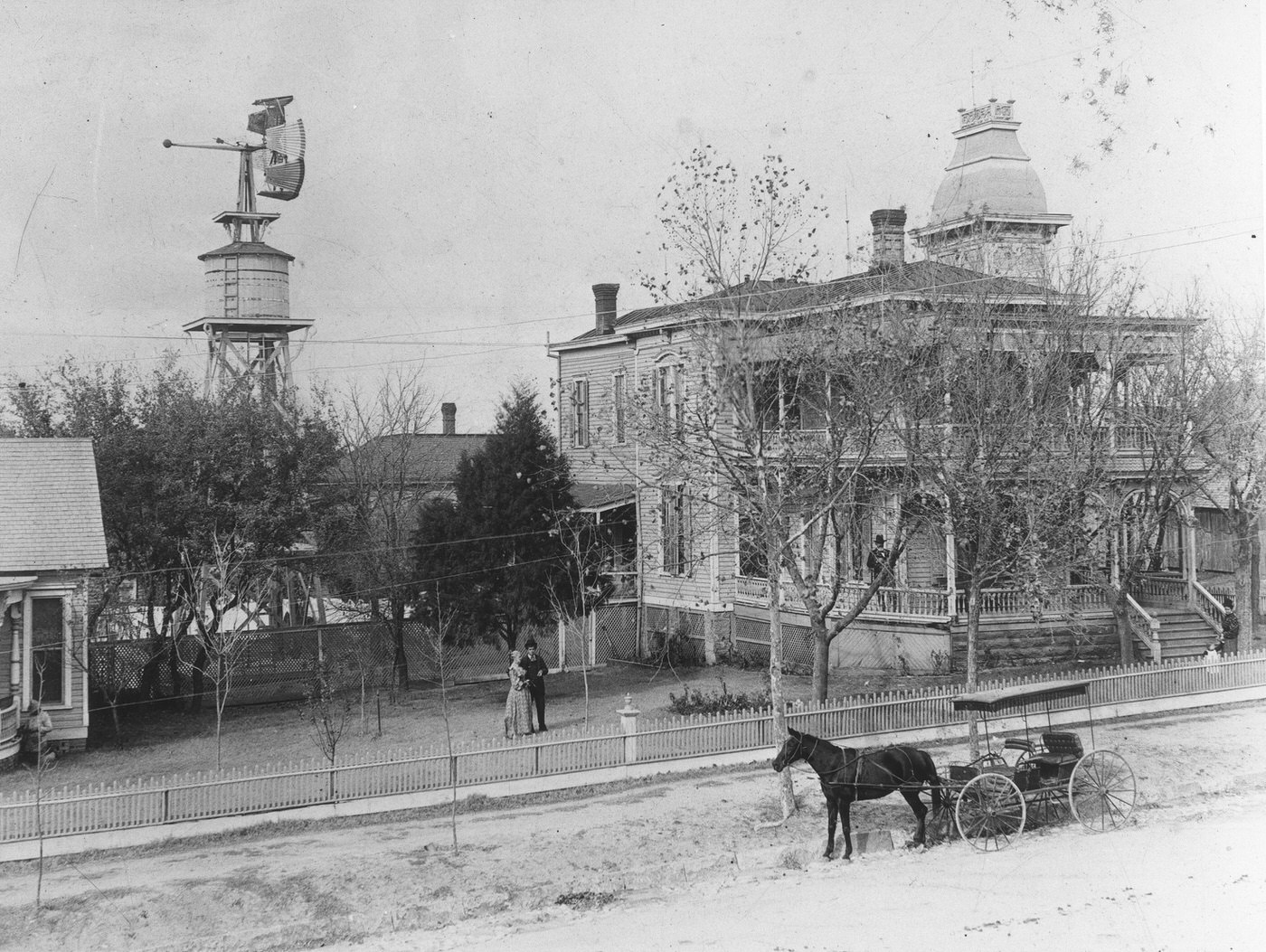

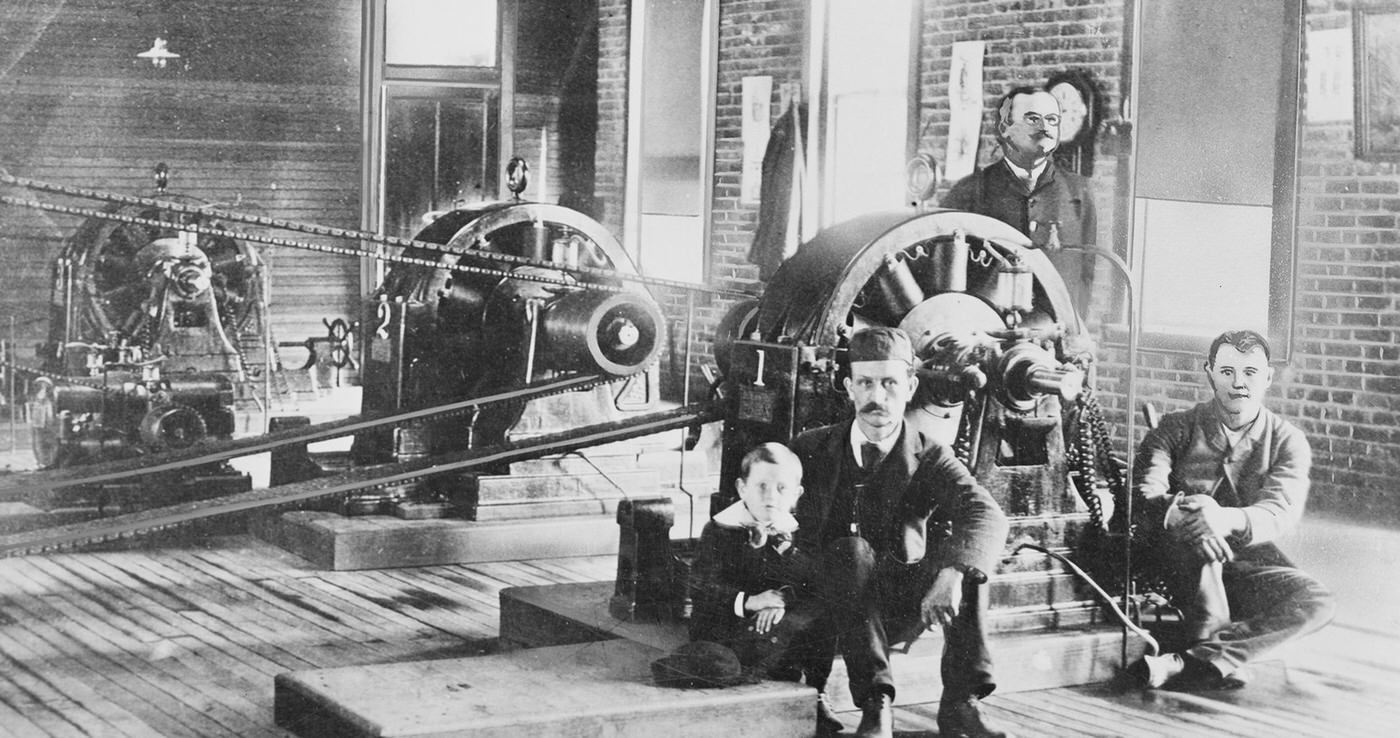

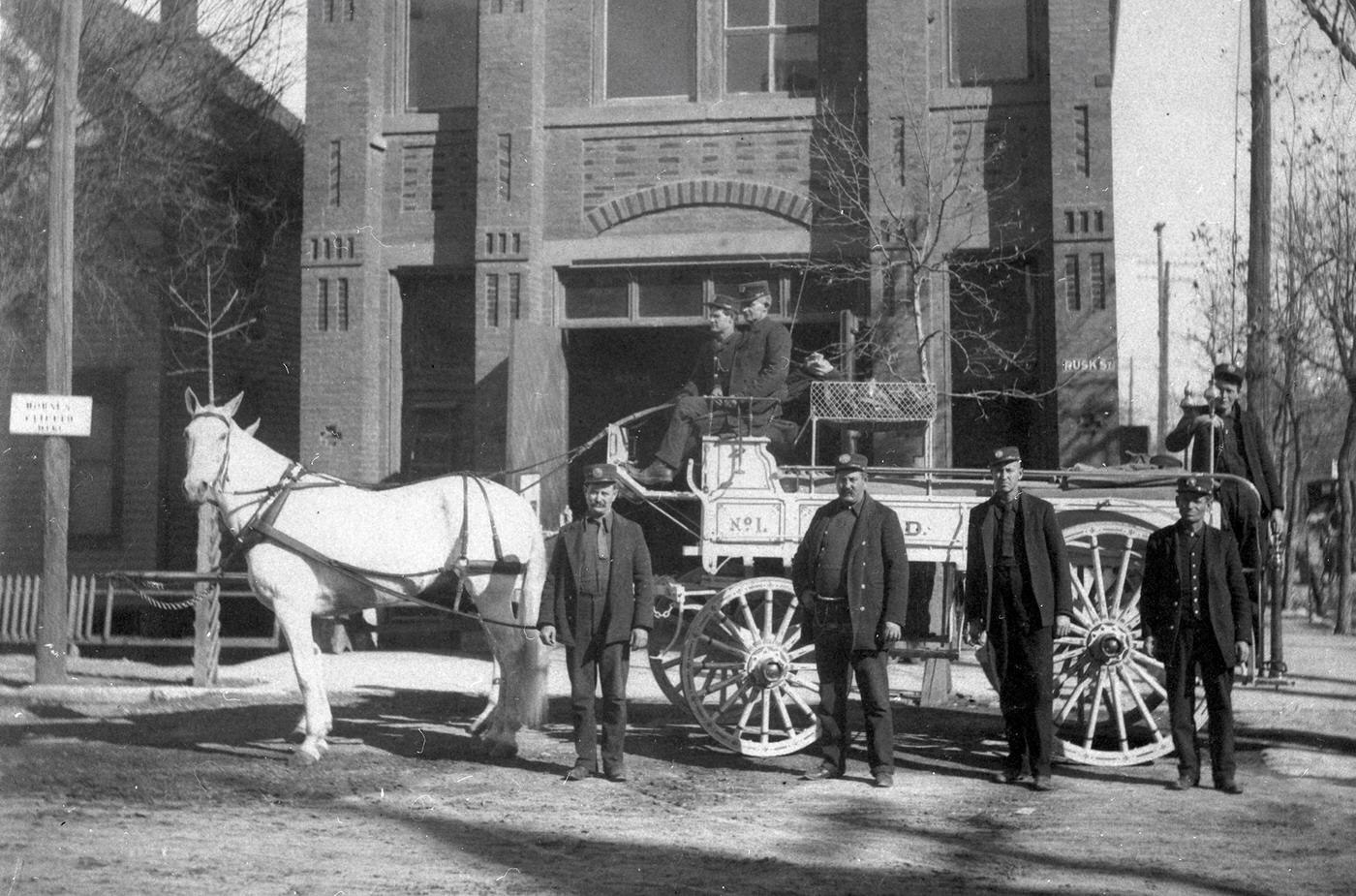

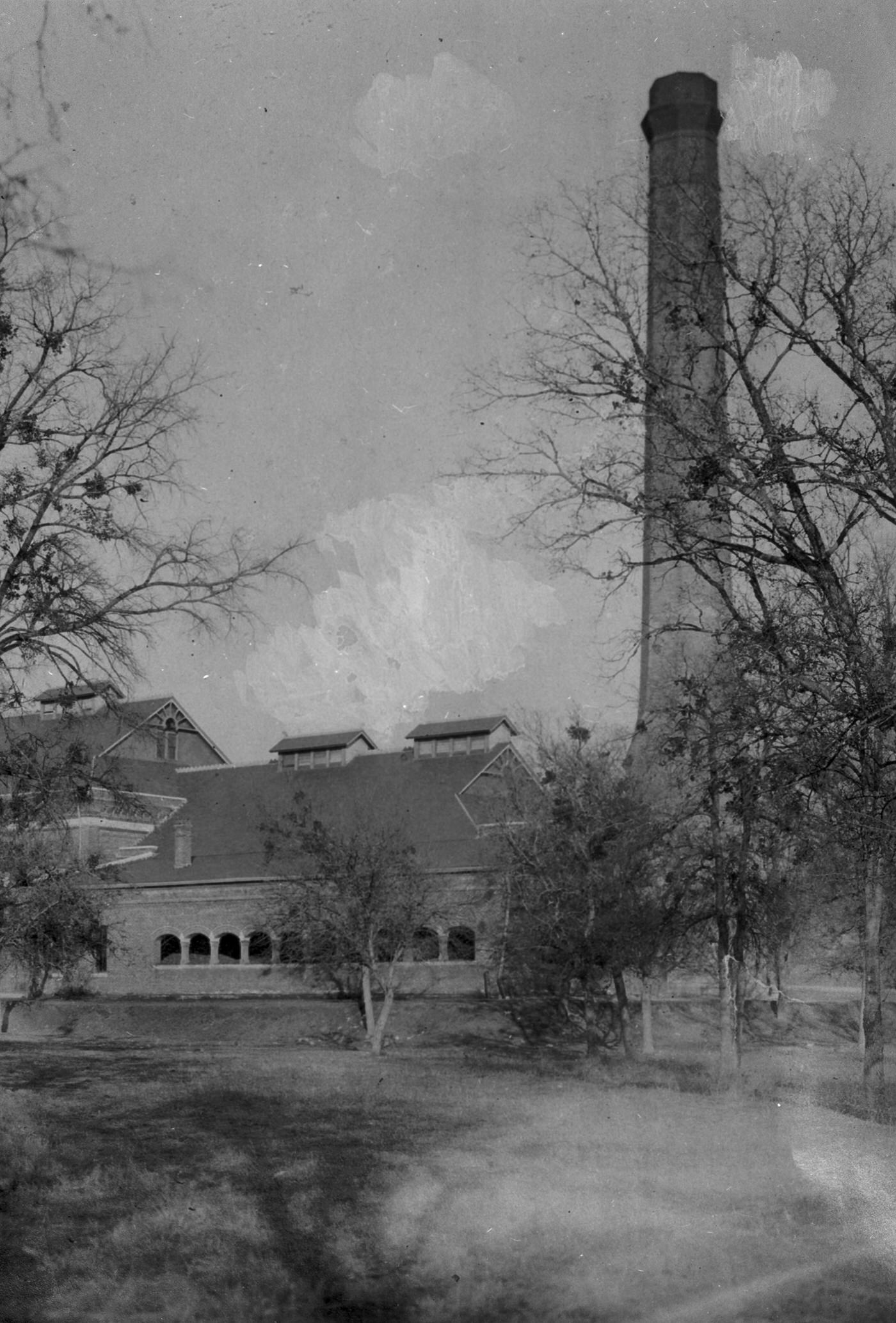

Essential utilities and infrastructure also saw critical upgrades. The city’s water supply, initially reliant on wells, springs, and the Trinity River, had been formalized when the city purchased the private Fort Worth Water Works Company (originally founded by B.B. Paddock in 1882) in 1884. To cope with the demands of the rapidly growing population, the Holly Pump Station was constructed in 1892 near the Clear Fork of the Trinity. Named after the Holly Manufacturing Company of Lockport, New York, which supplied the original pumps purchased in 1891, this station represented a major investment in public health and urban capacity and, remarkably, remains a part of the city’s water system today after numerous upgrades.

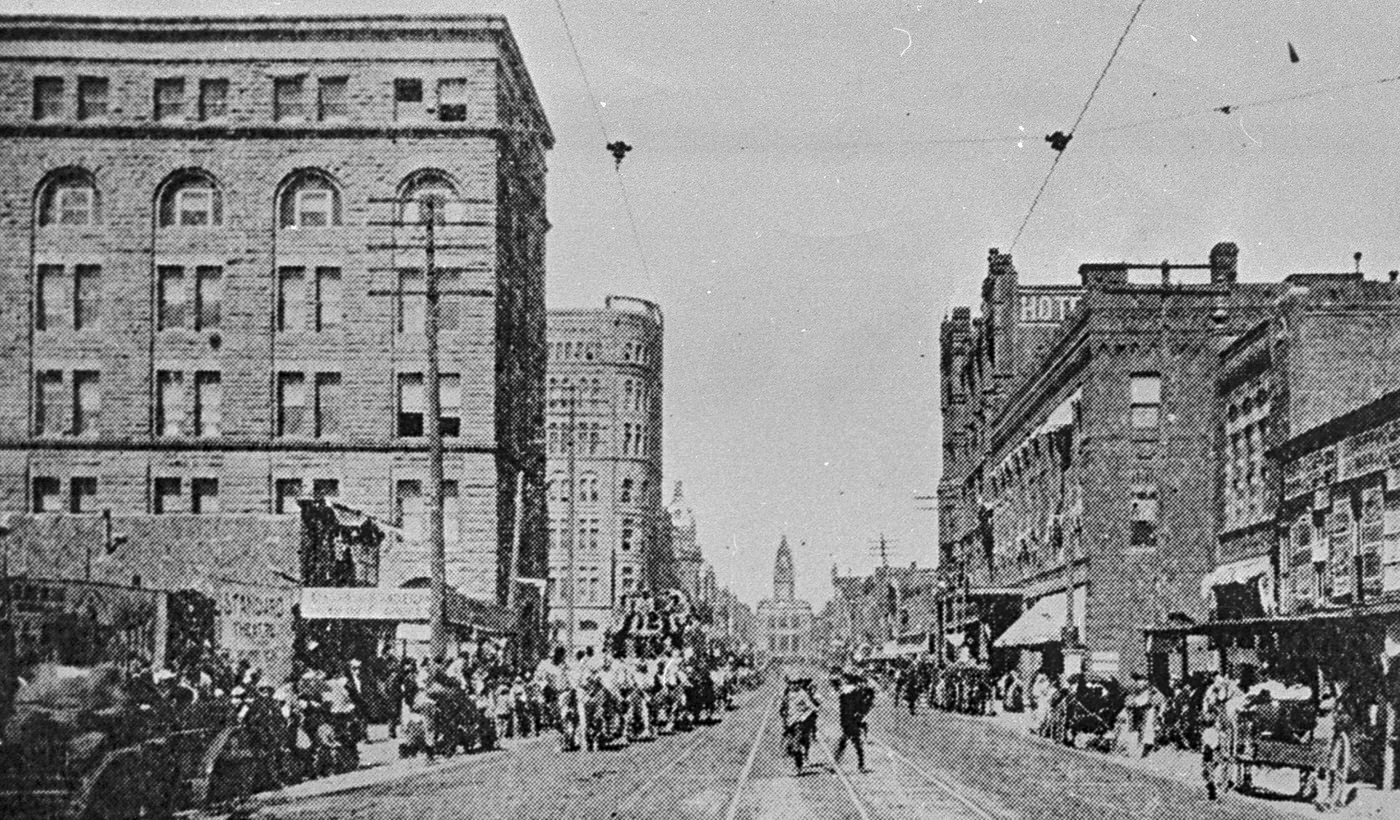

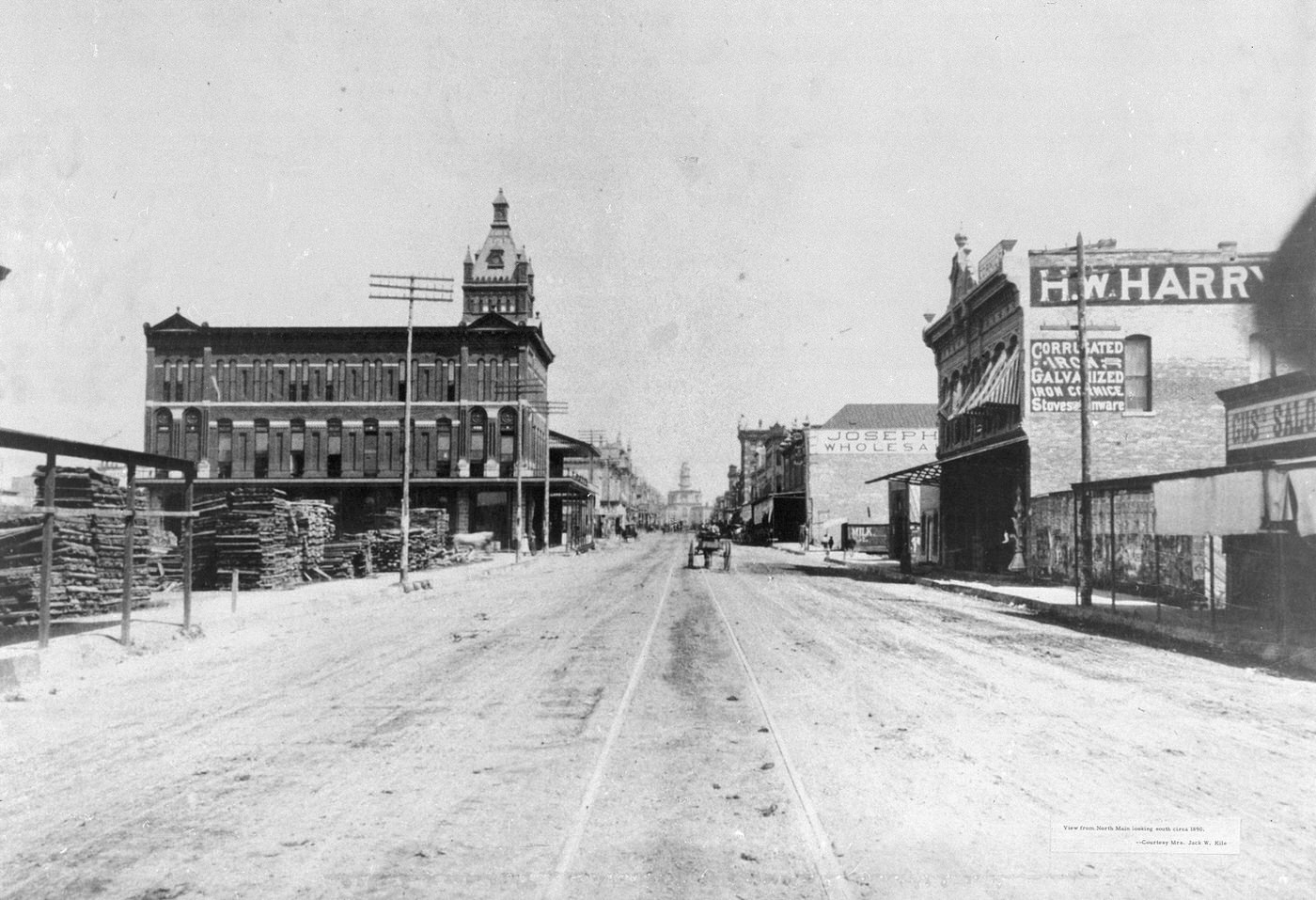

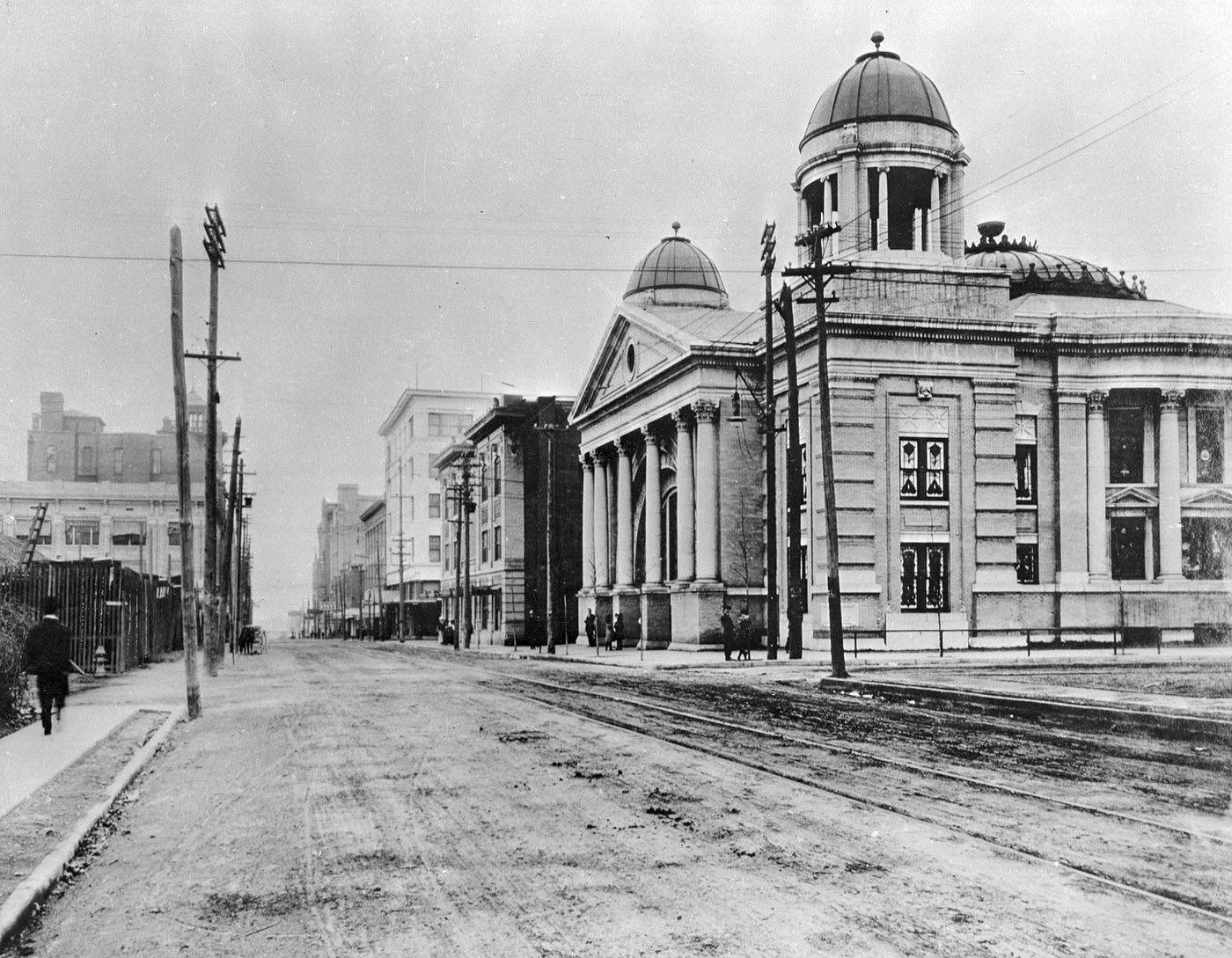

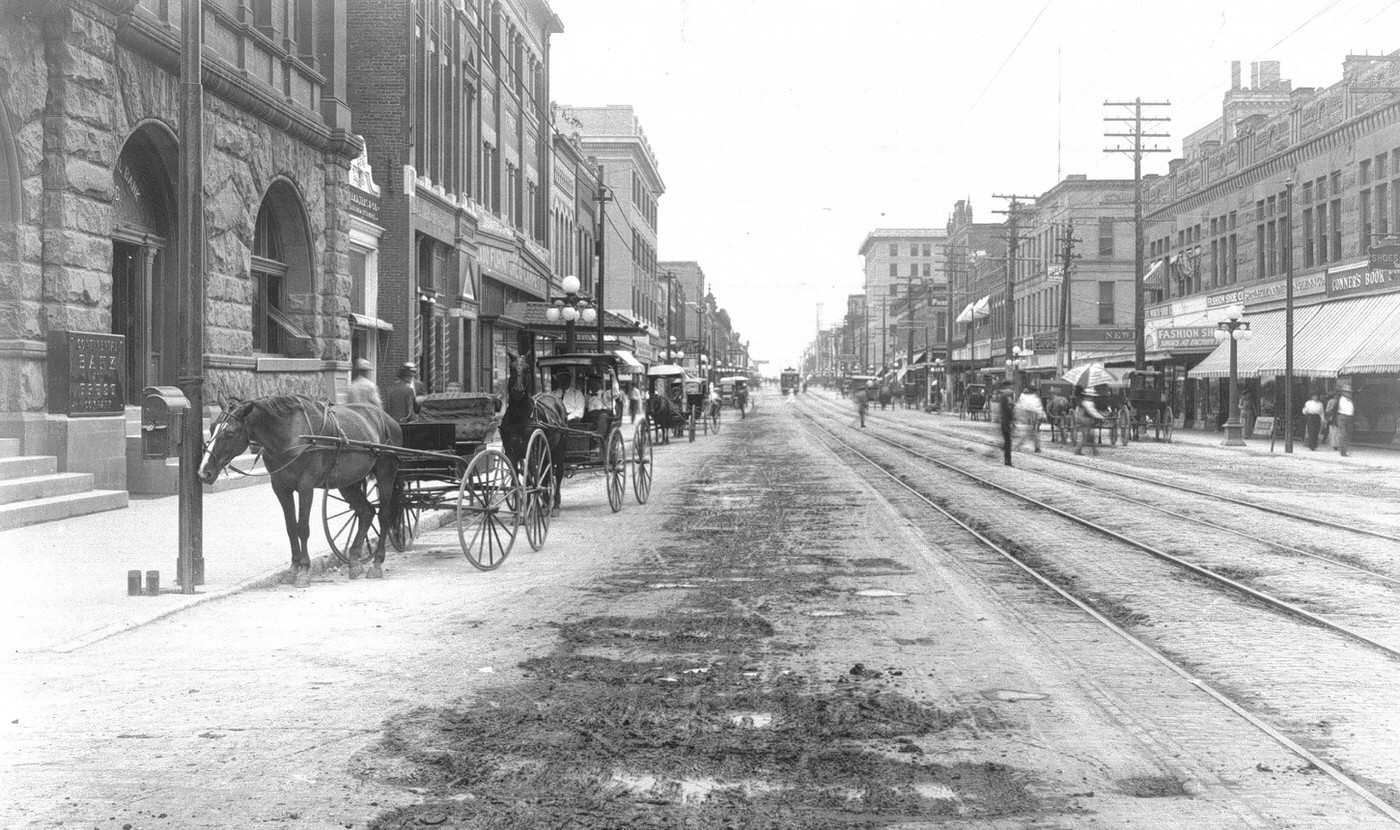

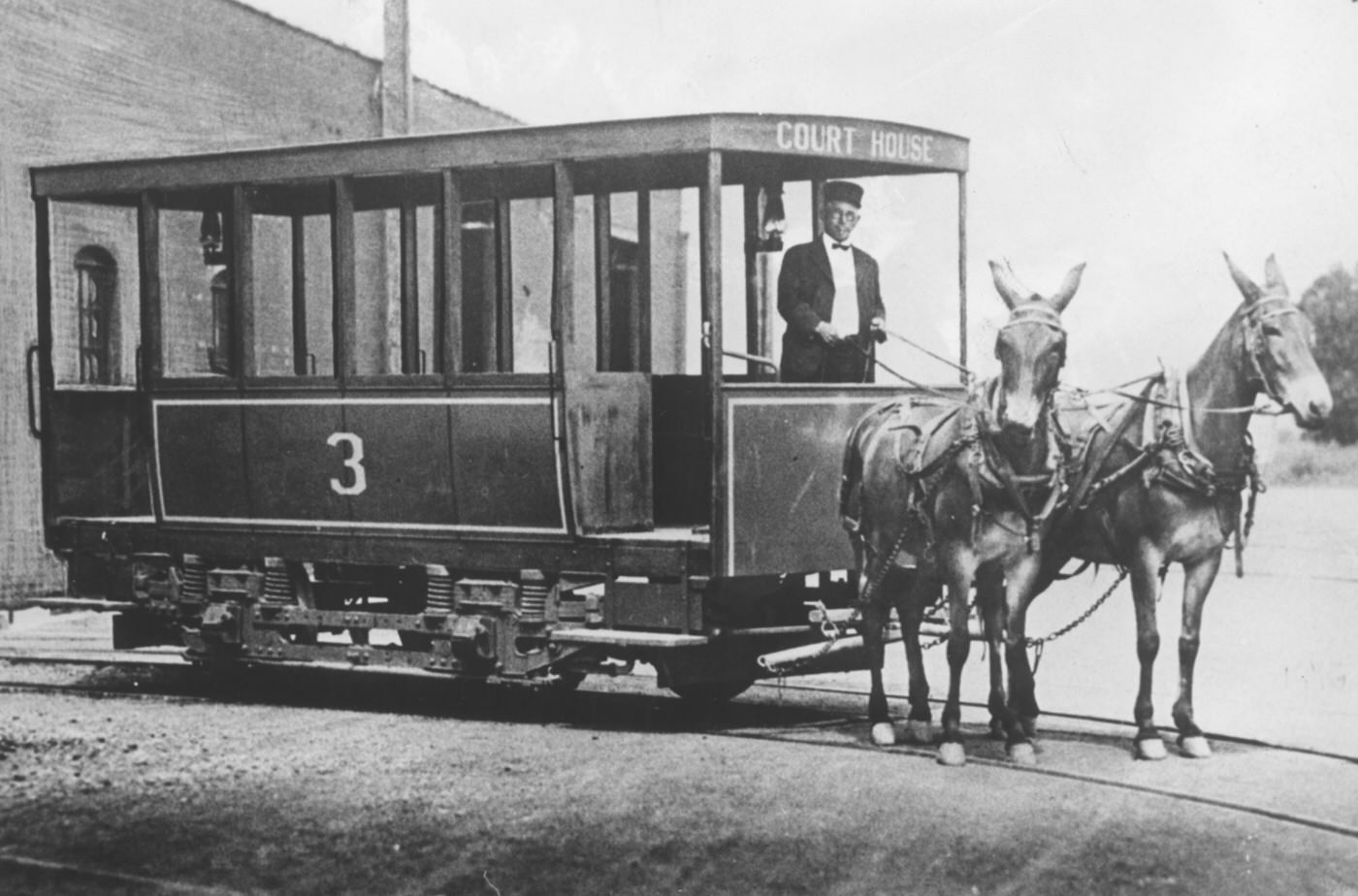

The city also began to tackle its muddy thoroughfares. Moving beyond the dirt roads that characterized its earlier years, Fort Worth saw its first brick-paved street in the late 1890s. Main Street was paved with durable Thurber brick around 1897-99, marking a significant step towards a cleaner, more modern urban streetscape. While artificial gas lighting had existed since 1876, electric lighting was also emerging as a feature of the modernizing city. Public transportation, too, saw technological advancement. The mule-drawn streetcars that had served the city since 1876 were joined, and soon surpassed, by the city’s first electric streetcar line, the North Side Street Railway Company, which became operational in 1889 or 1890. These infrastructure projects – annexation, a grand courthouse, improved waterworks, paved streets, and electric transit – were not merely functional upgrades; they were deliberate investments solidifying Fort Worth’s transition from a frontier settlement into a permanent, aspiring modern city.

A Community’s Fabric: Schools, Faith, and Festivities

Beyond the economic engines and physical infrastructure, the 1890s were a formative period for Fort Worth’s social and cultural landscape. As the city grew and diversified, residents established institutions that catered to educational needs, spiritual life, and civic celebration, weaving a richer community fabric.

Public education, officially established in 1882 after overcoming initial resistance , took significant strides. A top priority for the early school board was constructing permanent facilities. The decade saw the erection of the city’s first dedicated Fort Worth High School building. Constructed in 1890 (though some sources cite 1891), this impressive three-story structure, designed by the notable local firm Haggert & Sanguinet, stood at the corner of Hemphill and West Daggett streets. Praised for its blend of Richardsonian Romanesque and Renaissance Revival styles and built at a cost of $75,000, it was a testament to the city’s commitment to secondary education. Just after, in 1892, Stephen F. Austin Elementary School opened its doors. Originally known as the Sixth Ward School or Broadway School, this Romanesque-influenced building, designed by Messer, Sanguinet & Messer, holds the distinction of being the oldest extant public school building constructed by the Fort Worth school system. Higher education also gained a foothold with the founding of the Methodist-affiliated Polytechnic College in 1890 (which eventually became Texas Wesleyan University).

The city’s religious life also diversified and solidified. While various Protestant denominations were already established, the 1890s saw the formal organization of the Jewish community and the completion of a major Catholic landmark. Congregation Ahavath Sholom, Fort Worth’s first Jewish congregation, was established in 1892 by a group of 31 founders, predominantly immigrants from Russia and Poland. Meeting initially in homes and rented spaces, this Orthodox congregation quickly raised funds and constructed its first modest, wood-frame synagogue in 1895, having already acquired land for the Emanuel Hebrew Rest cemetery in 1879. Also in 1892, the Catholic community celebrated the dedication of the new St. Patrick Cathedral on July 10th. Designed by architect J.J. Kane in the Gothic Revival style and built of native limestone, it replaced the earlier St. Stanislaus Church and became the seat of the diocese. By the end of the decade, Fort Worth hosted a wide array of denominations, reflecting its growing populace.

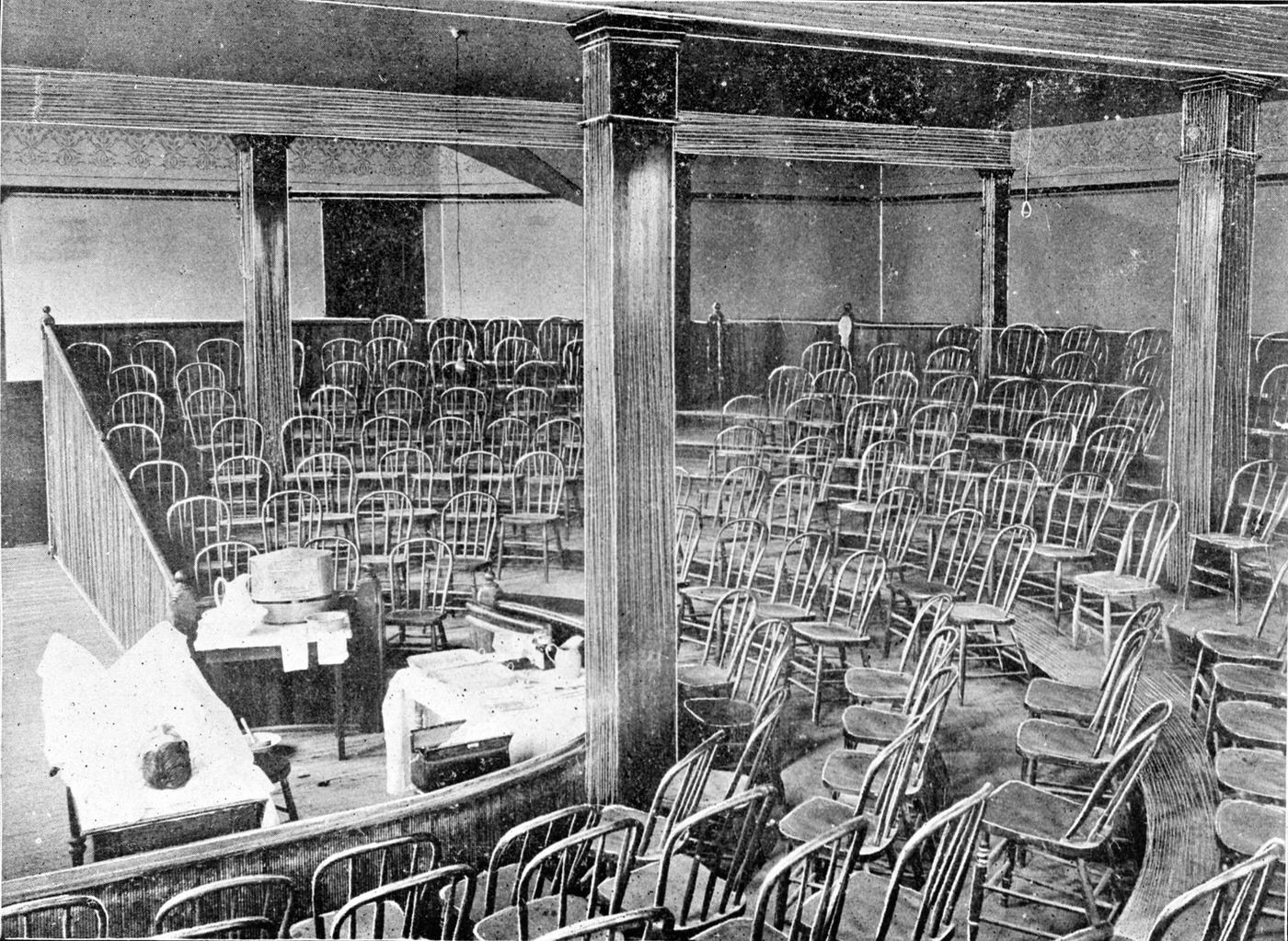

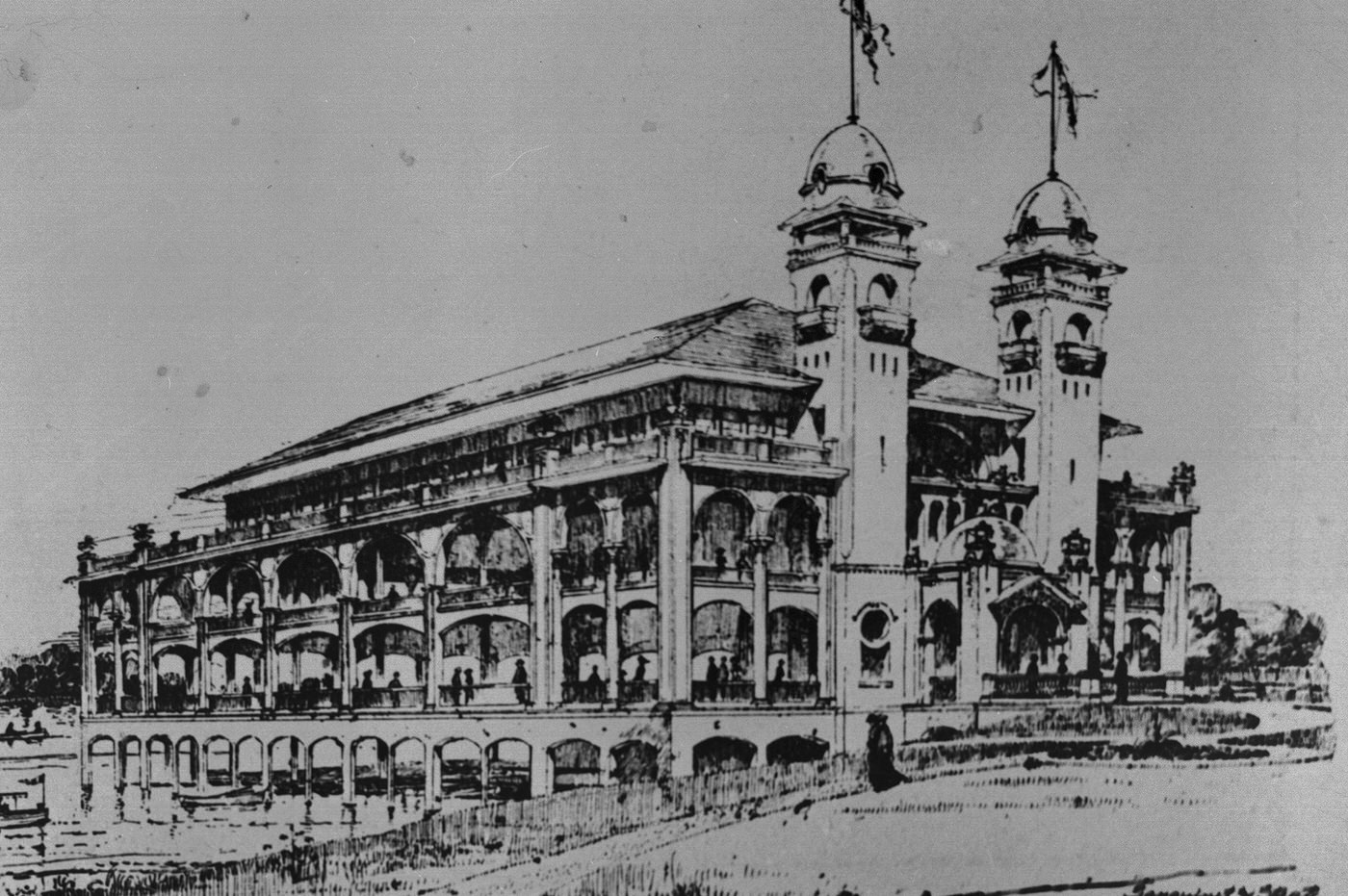

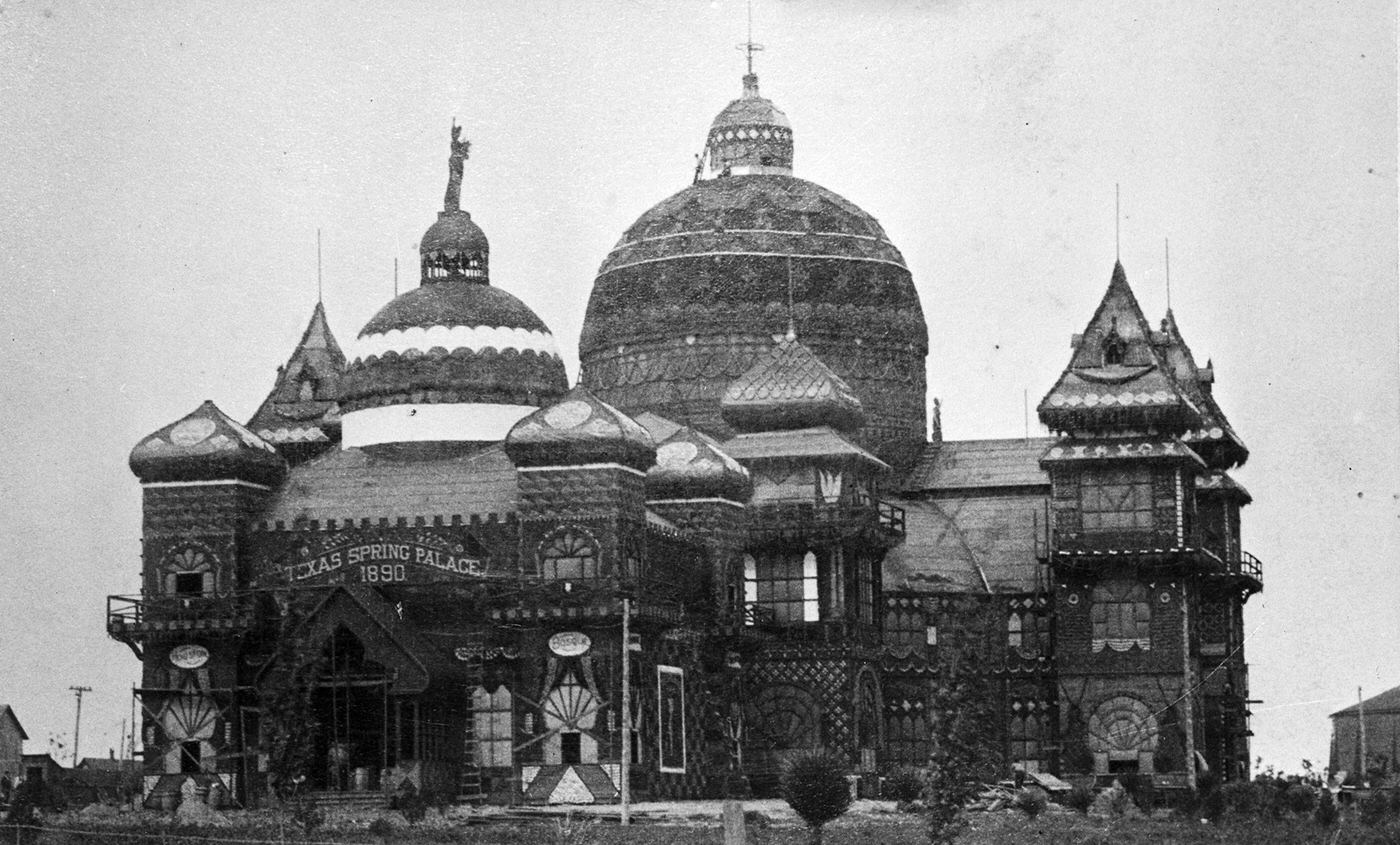

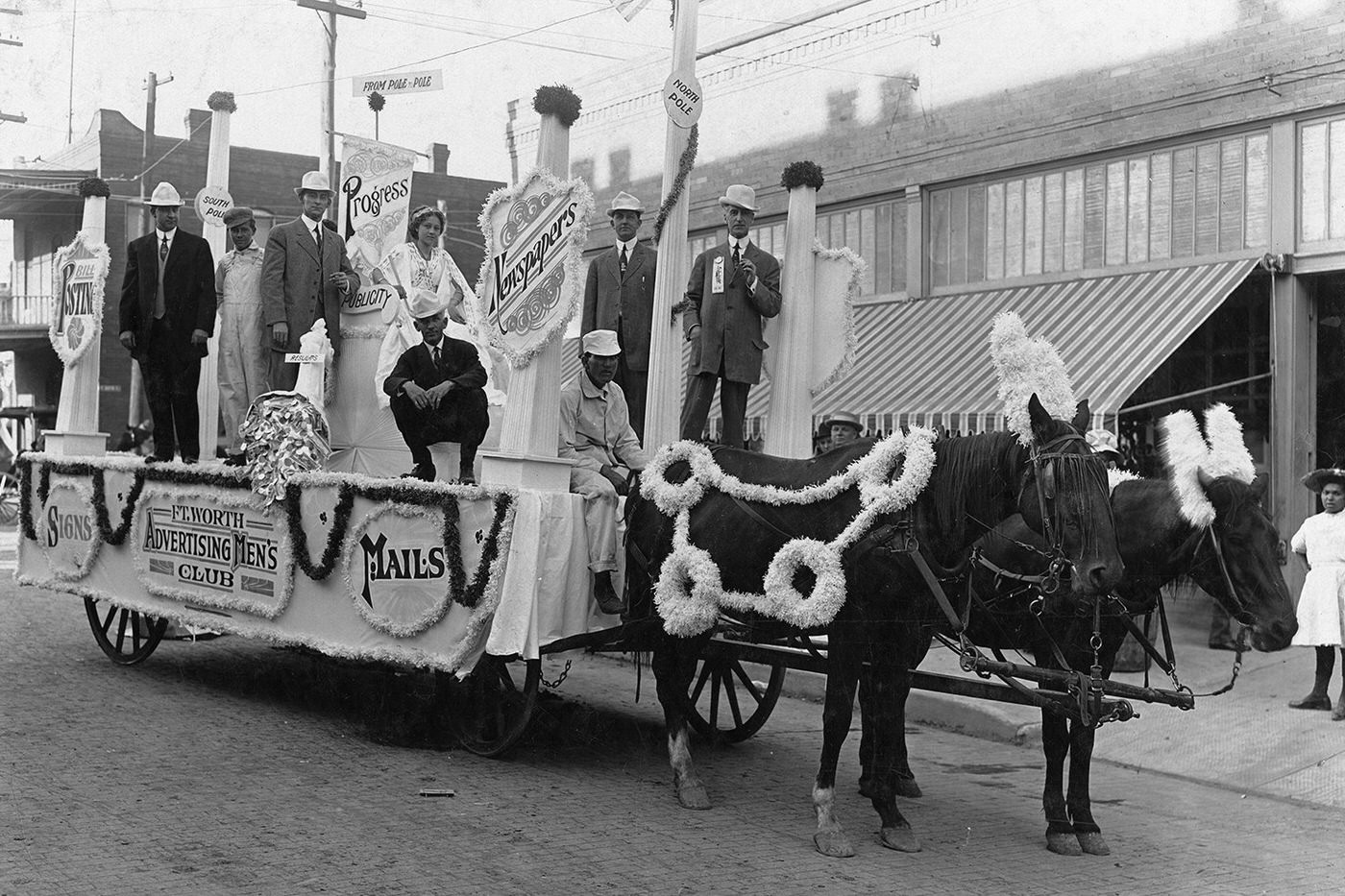

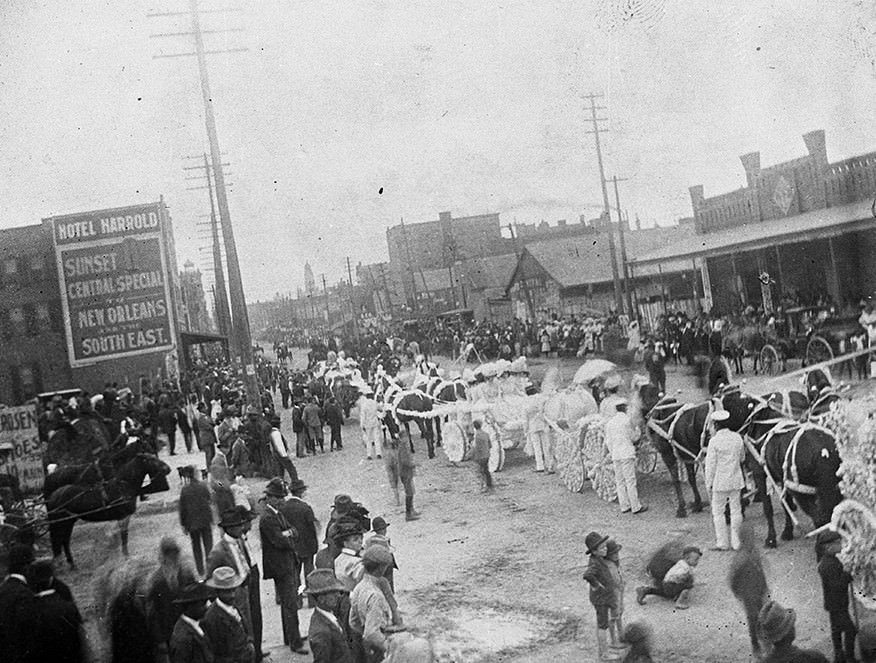

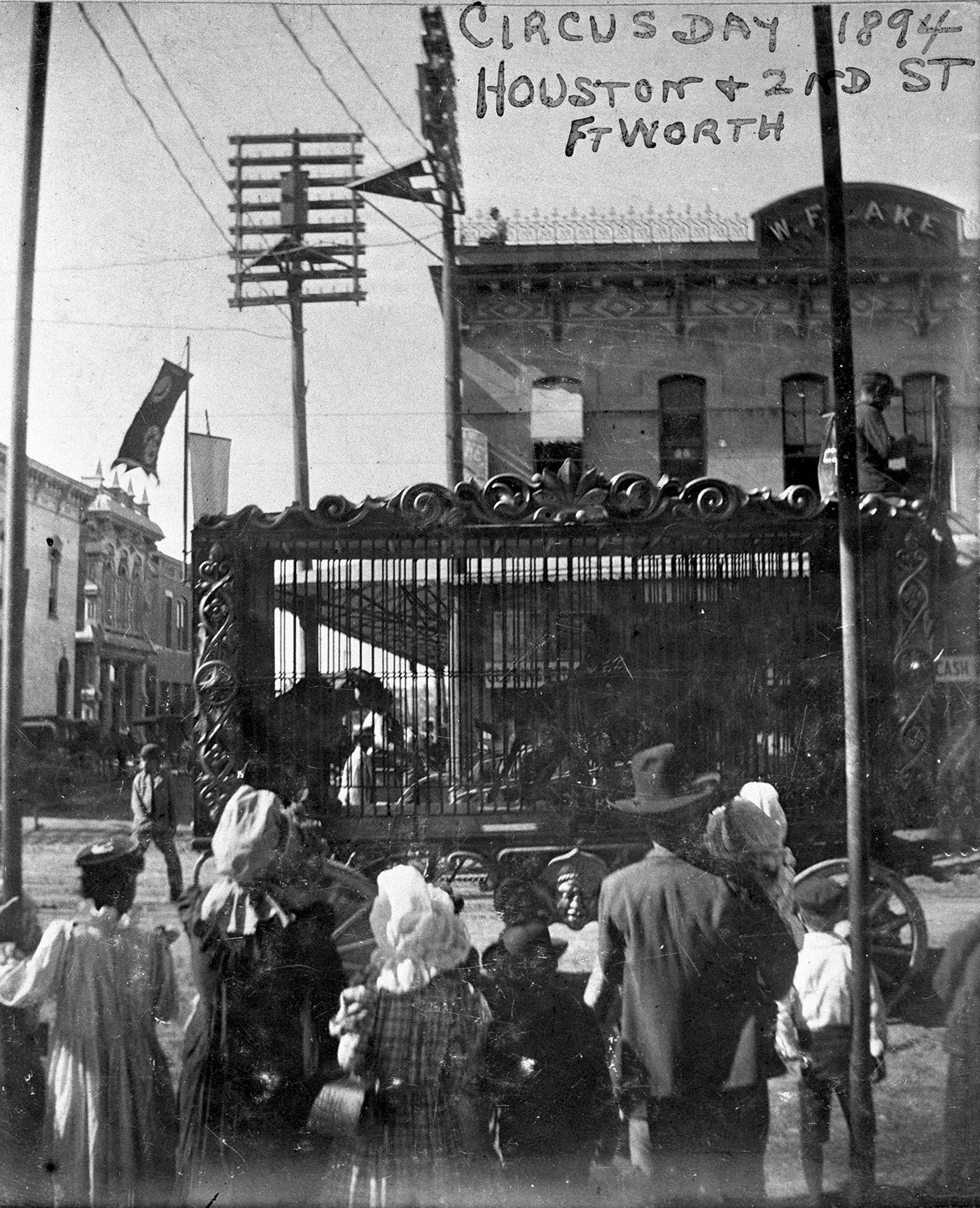

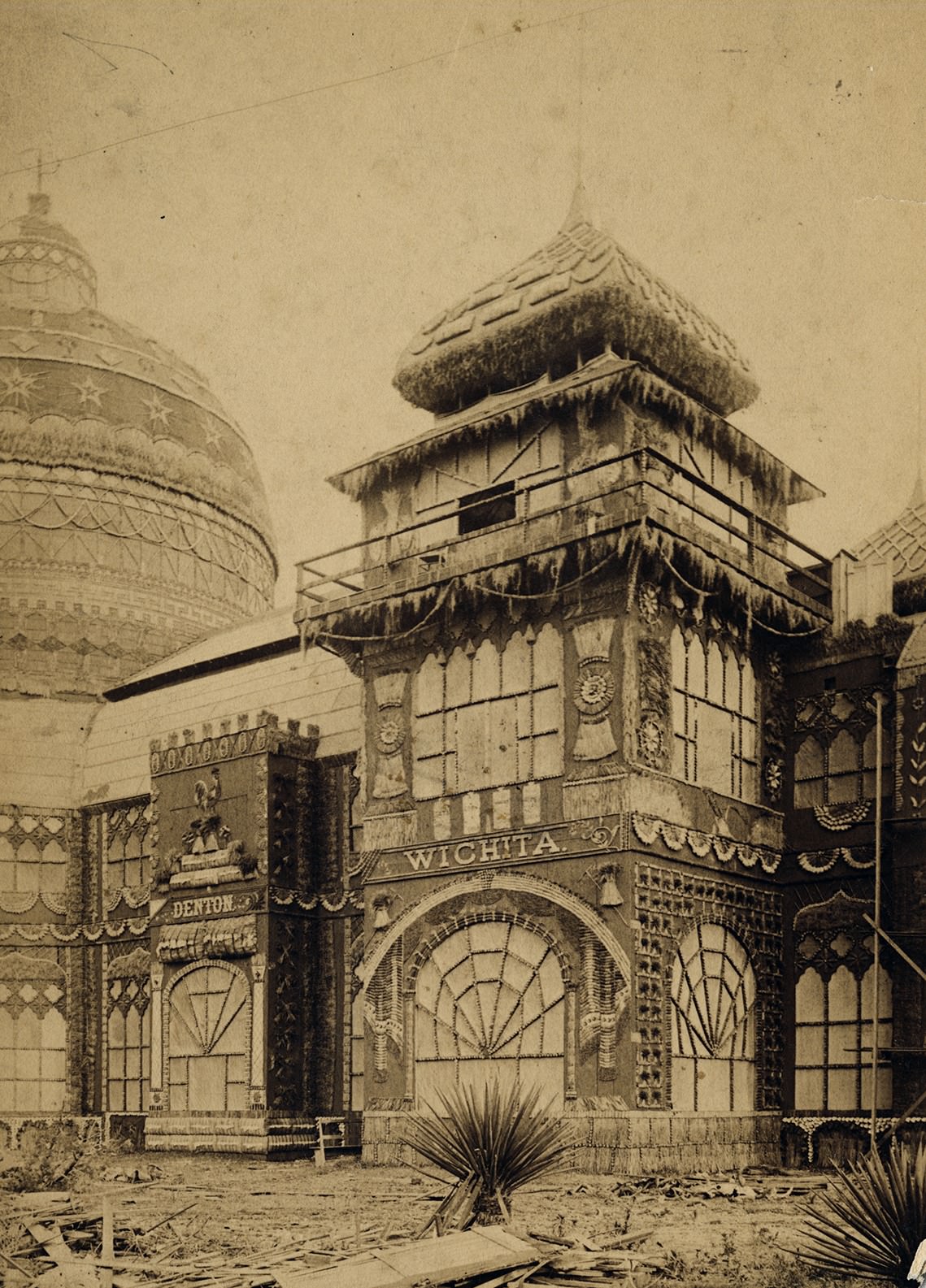

Civic life found expression in large public gatherings, though not without setbacks. The ambitious Texas Spring Palace, an exposition designed by Armstrong & Messer to showcase Texas’s agricultural bounty and attract settlers, opened in 1889 near the T&P tracks. Covered inside and out with the state’s natural products, the massive, domed wooden structure was a source of immense local pride and drew national attention. Its second season in 1890, however, ended in disaster. On the night of May 30th, during a grand ball attended by thousands, fire engulfed the building, destroying it within minutes. Tragically, one man, Al Hayne, an English civil engineer, perished while heroically rescuing others from the flames. Despite its short, fiery existence, the Spring Palace succeeded in attracting investment and settlers. A more enduring tradition began in 1896 with the first Fort Worth Fat Stock Show. Held initially along Marine Creek, this event, rooted in the city’s cattle heritage, evolved into the Southwestern Exposition and Livestock Show, a major annual fixture in Fort Worth life. The establishment of these varied institutions – schools, diverse houses of worship, and civic events – demonstrates a community actively shaping its identity and building the social underpinnings necessary for a stable, growing city.

Taming the Frontier? Hell’s Half Acre and Civic Order

While Fort Worth diligently constructed the edifices of a modern city during the 1890s – its grand courthouse, new schools, and paved streets – a significant remnant of its wilder frontier past persisted: Hell’s Half Acre. This notorious red-light district, a sprawling concentration of saloons, dance halls, gambling parlors, and brothels, remained a fixture on the city’s south side, presenting a complex challenge to civic leaders and reformers.

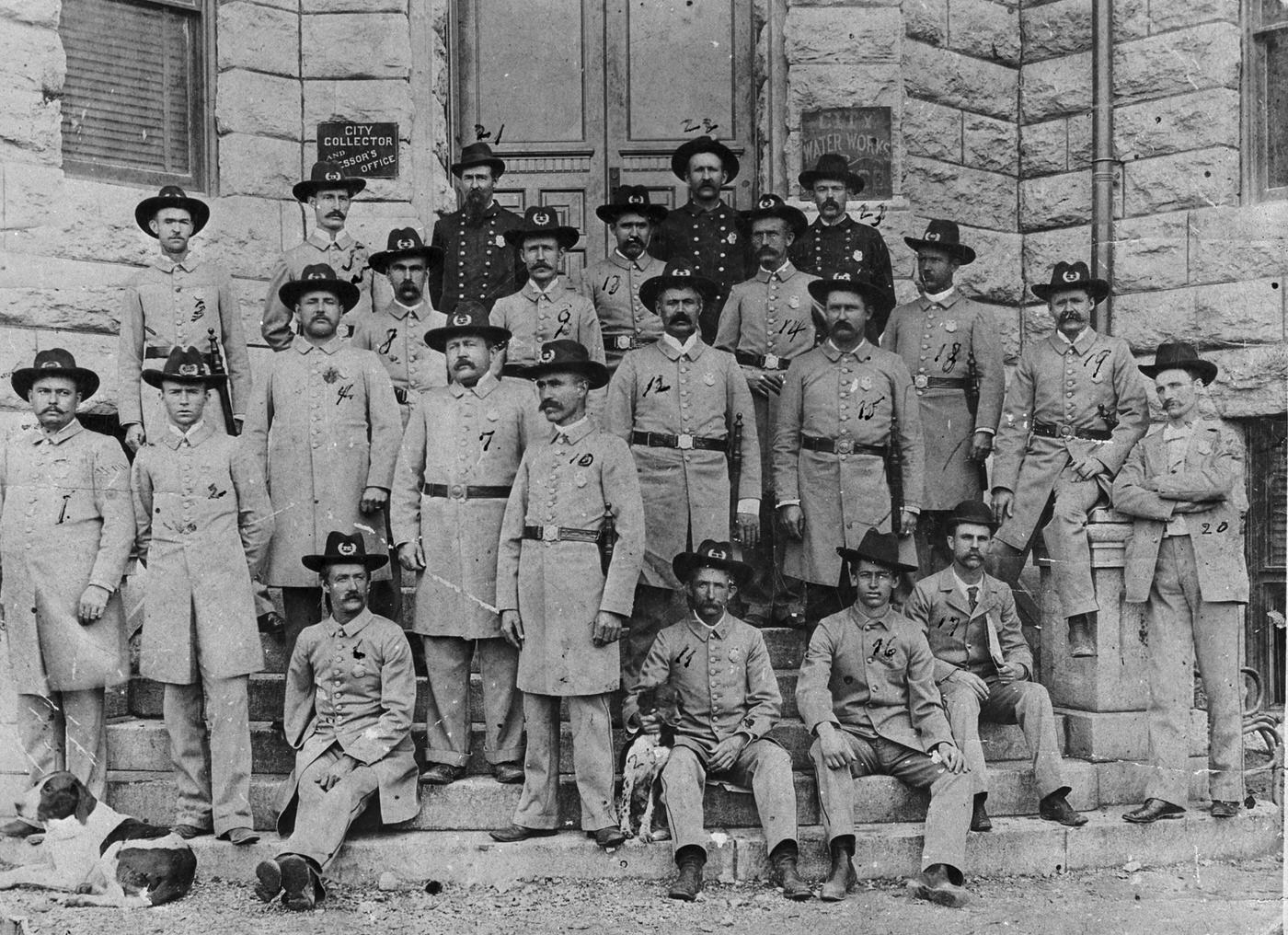

Born in the 1870s to cater to the legions of cowboys passing through on the Chisholm Trail, the Acre had expanded significantly by the 1890s, generally understood to encompass the area between 7th and 15th Streets, spilling across Main, Rusk (Commerce), Calhoun, and Jones streets. It was infamous for its boisterous atmosphere, where brawling, gambling, and vice were commonplace, often spilling out into the streets. Contemporary accounts painted a picture of frequent violence; one newspaper lamented that “it was a slow night which did not pan out a cutting or shooting scrape among its male denizens or a morphine experiment by some of its frisky females”. Despite its unsavory reputation, the Acre was a significant economic engine, attracting visitors and generating income (albeit illicit) for the city, making officials reluctant to completely eradicate it.

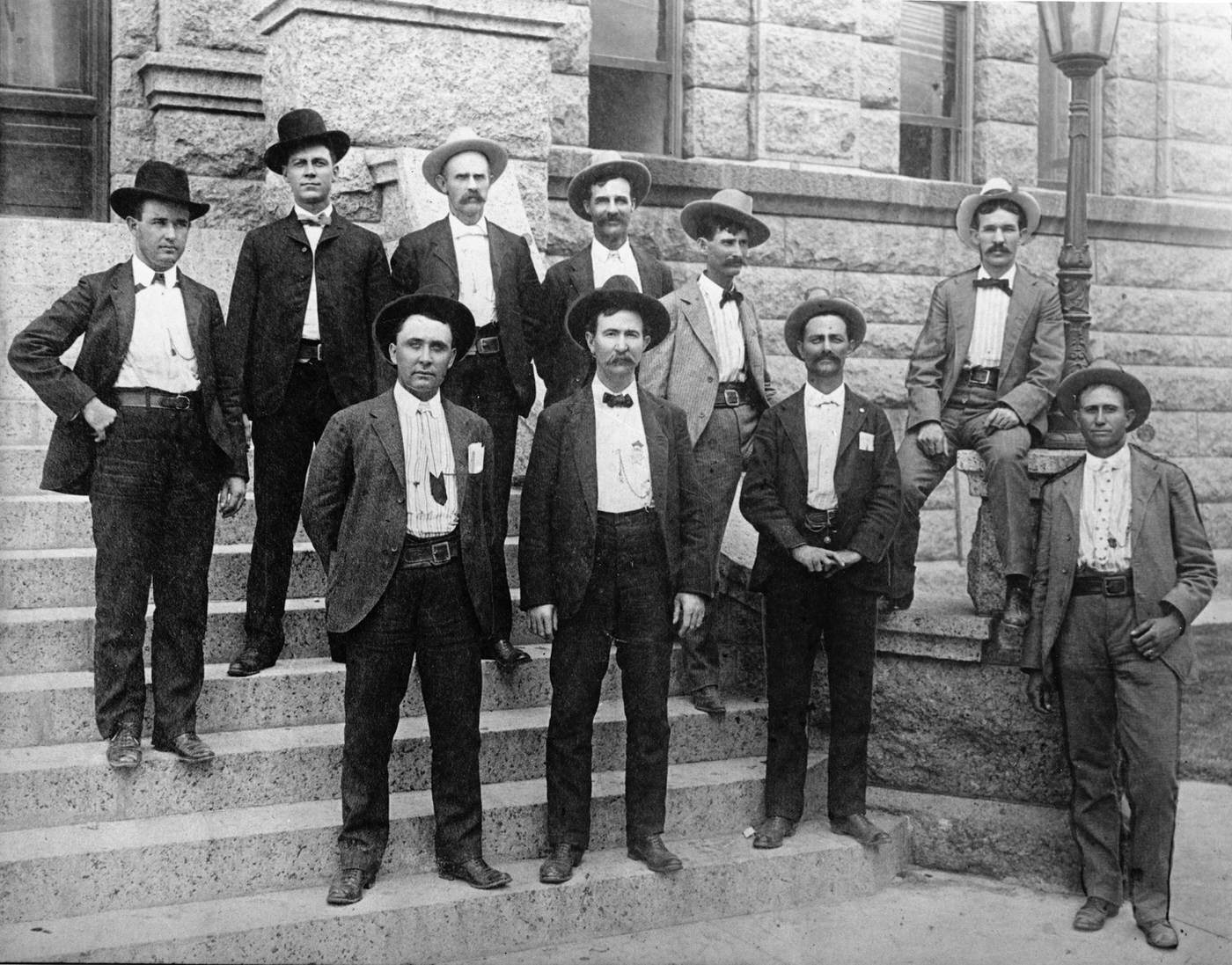

Reform efforts ebbed and flowed. A major crackdown occurred in 1889, likely spurred by high-profile violence like the 1887 shootout between former marshal Jim Courtright and gambler Luke Short. This led officials to shut down some of the activities deemed most problematic, particularly the dance halls where men and women mingled, which drew more ire from reformers than the predominantly male gambling parlors and saloons. However, these reforms proved temporary, and the Acre largely survived throughout the 1890s.

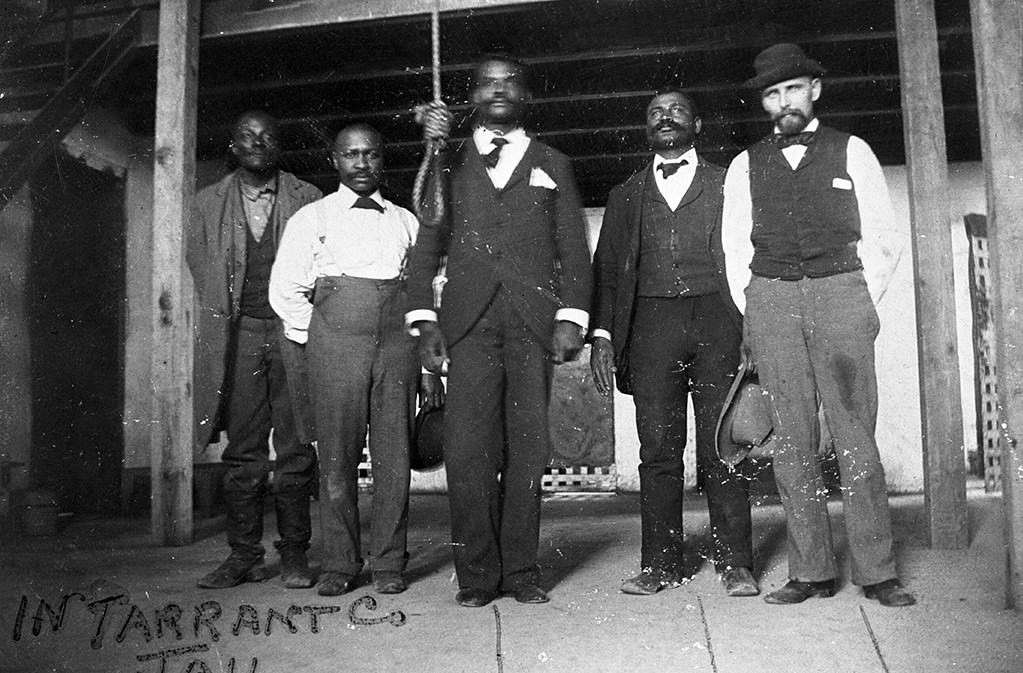

The decade did, however, witness subtle but significant shifts in the district’s character. With the end of the massive cattle drives, the traditional cowboy clientele dwindled. By the turn of the century, the Acre’s popularity as a destination for out-of-town visitors had noticeably diminished. The area saw an increase in homeless individuals and derelicts. Concurrently, Fort Worth’s growing African American population, largely excluded from other parts of the city by segregation, began settling and establishing businesses (both legitimate and illicit, like the Black Elephant Saloon) in the southern reaches of the Acre district.

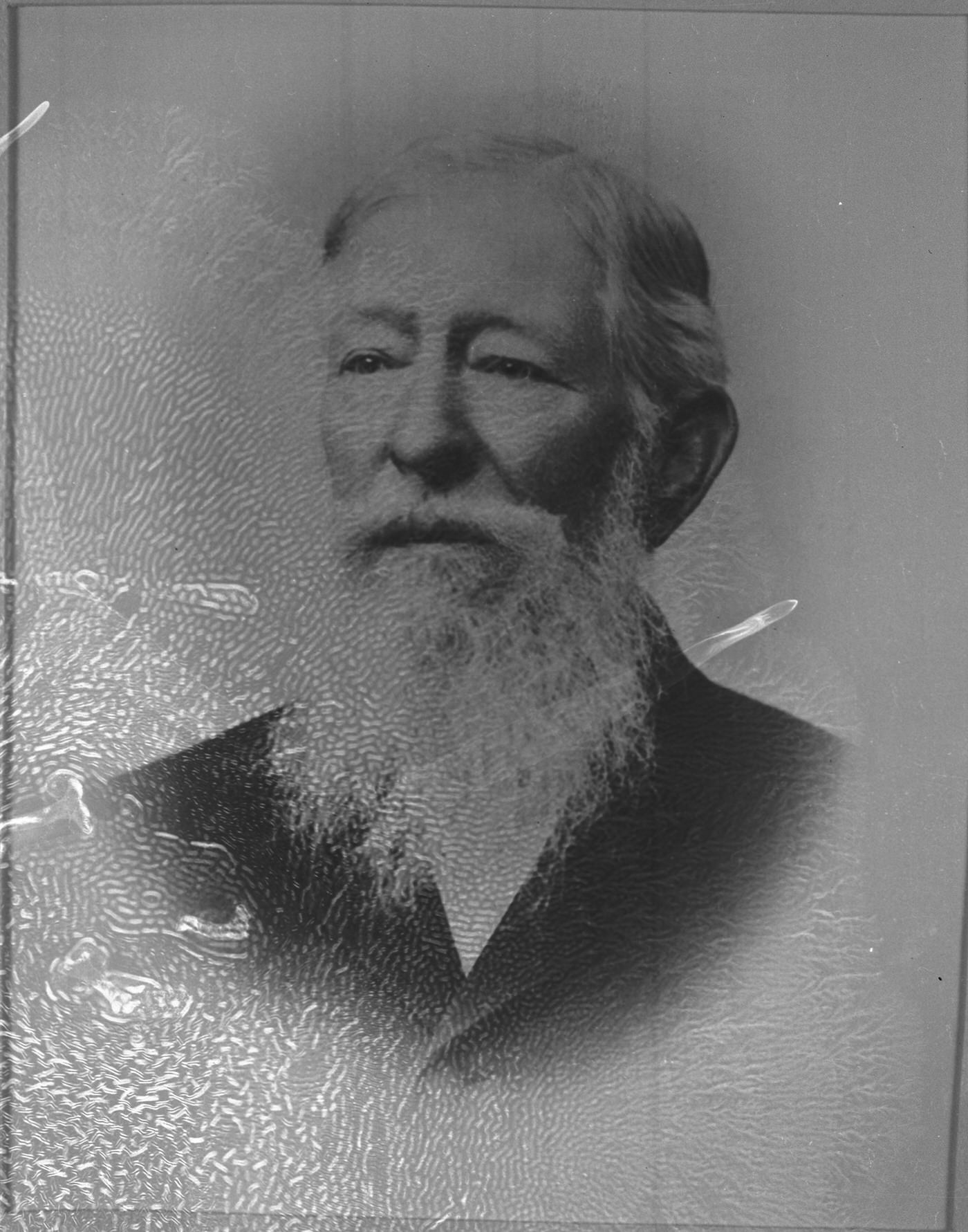

Overseeing the city during much of this period was Mayor Buckley Burton (B.B.) Paddock, who began his first of four consecutive terms in 1892. Paddock, a prominent civic booster and former newspaper editor known for his crusades against the Acre’s excesses , faced the political tightrope of managing the district’s persistent problems while fostering the city’s overall progress and image. The continued existence of the Acre throughout his 1890s mayoralty, despite his reformist background, highlights the complex interplay of economic interests, social mores, and political realities in a city grappling with its transition. The final curtain on Hell’s Half Acre wouldn’t fall until the Progressive Era reforms and the pressures associated with World War I in the following decades.

Daily Life in a City in Flux

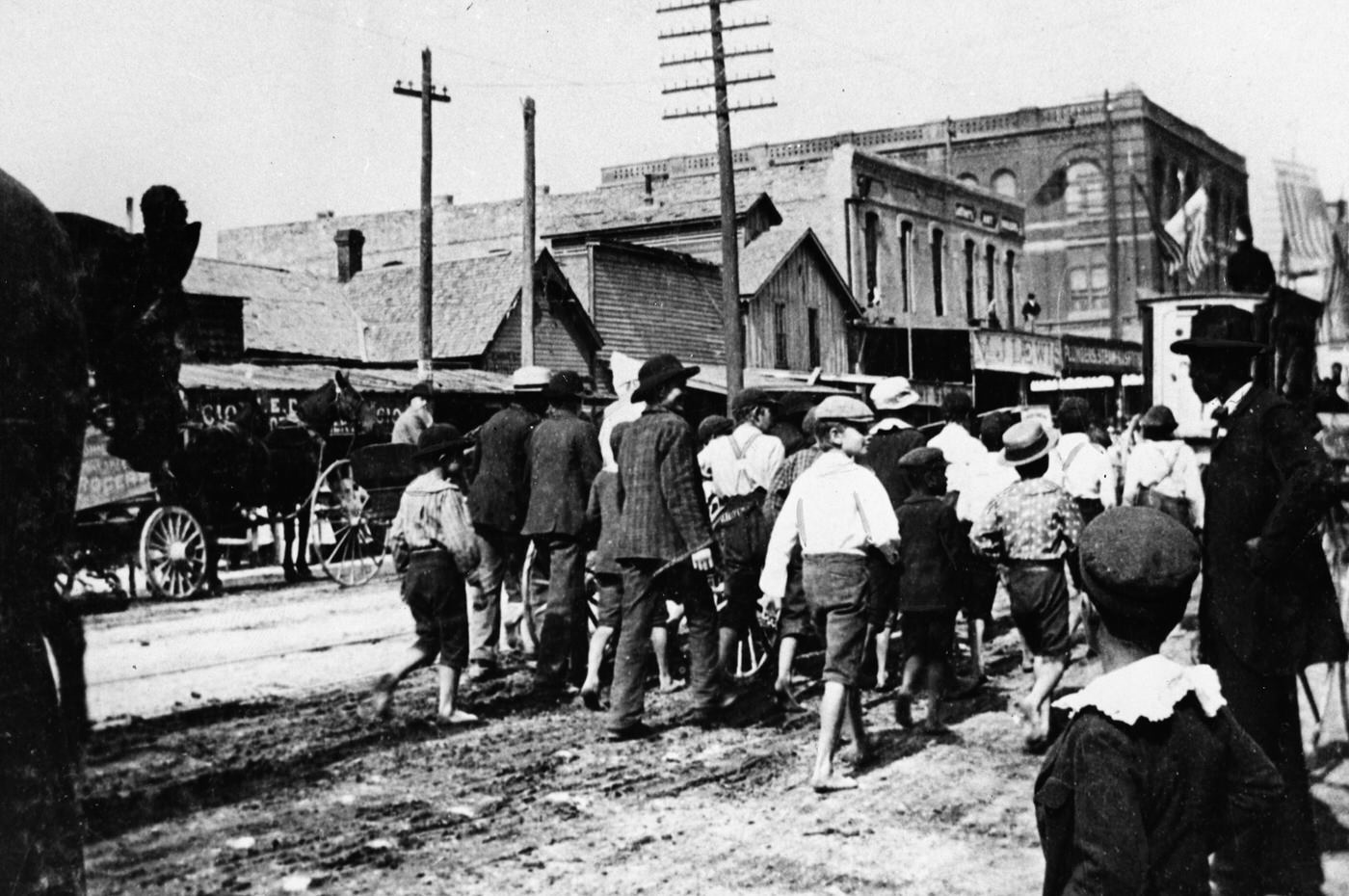

Life in Fort Worth during the 1890s was a mix of the old West and a growing modern city. Residents navigated a landscape of rapid change, where the symbols and routines of the past coexisted with the innovations and institutions of the future.

The dust from the old Chisholm Trail had settled, but people still called it “Cowtown.” Hell’s Half Acre, a rowdy part of town filled with saloons and dance halls, was still loud and lively on the south side. At the same time, the city was growing up. Workers laid stone for the towering Tarrant County Courthouse. Kids filled classrooms at new public schools like Fort Worth High and Stephen F. Austin Elementary. On Sundays, families attended services at St. Patrick Cathedral. The city’s Jewish community gathered at the newly formed Congregation Ahavath Sholom.

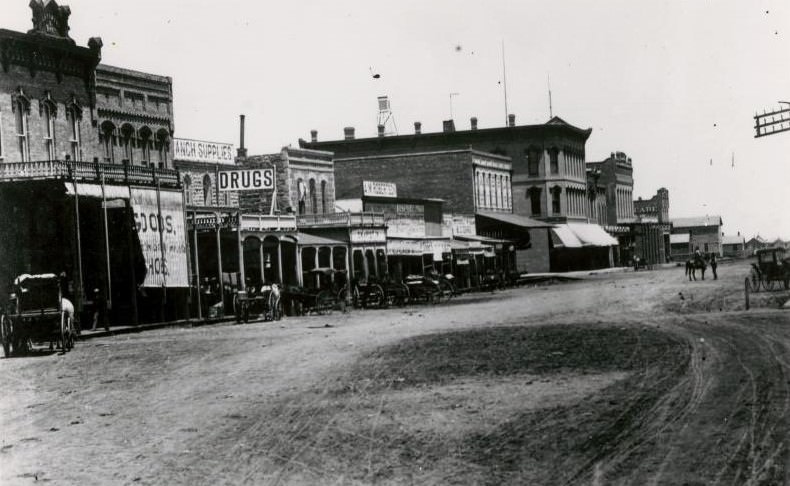

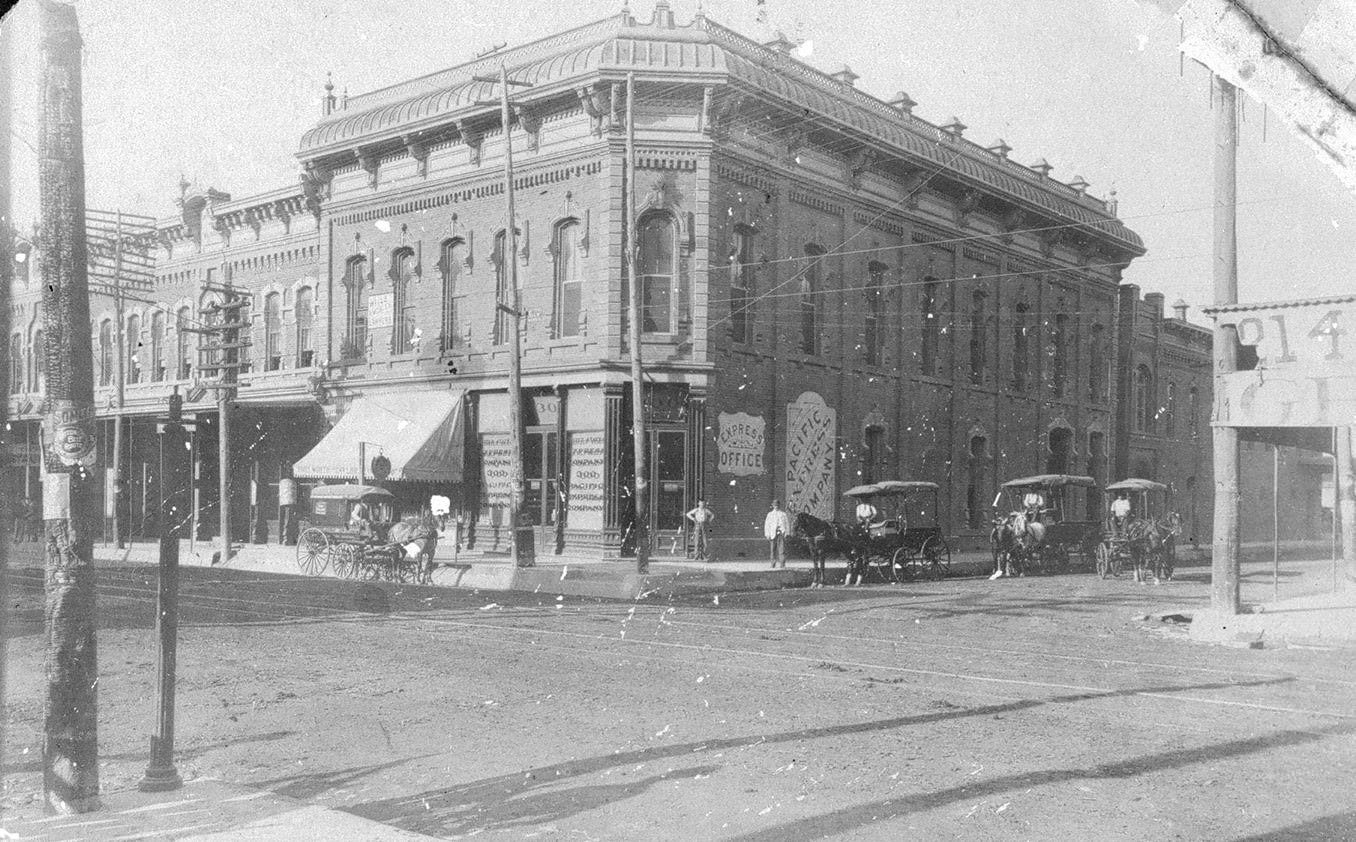

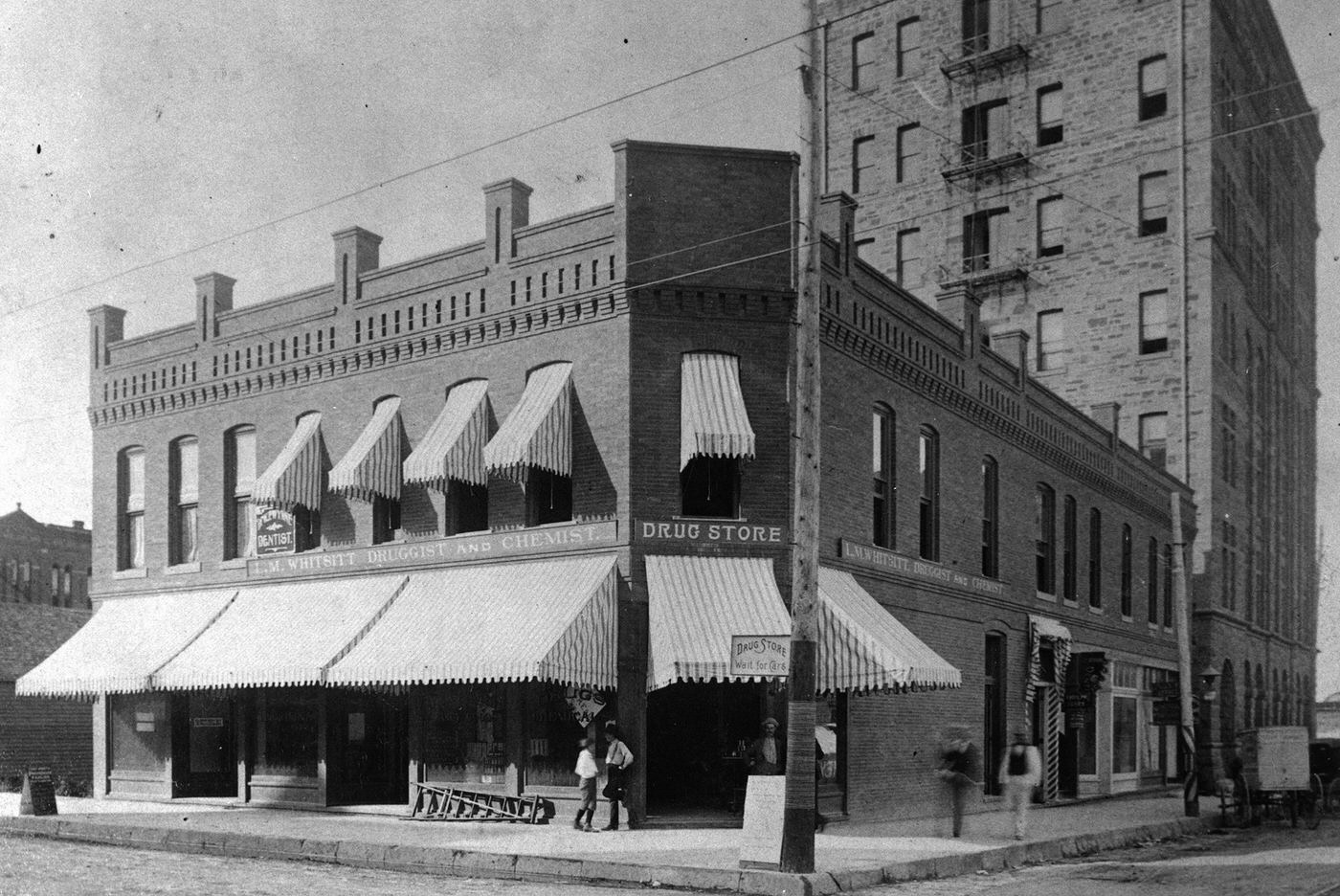

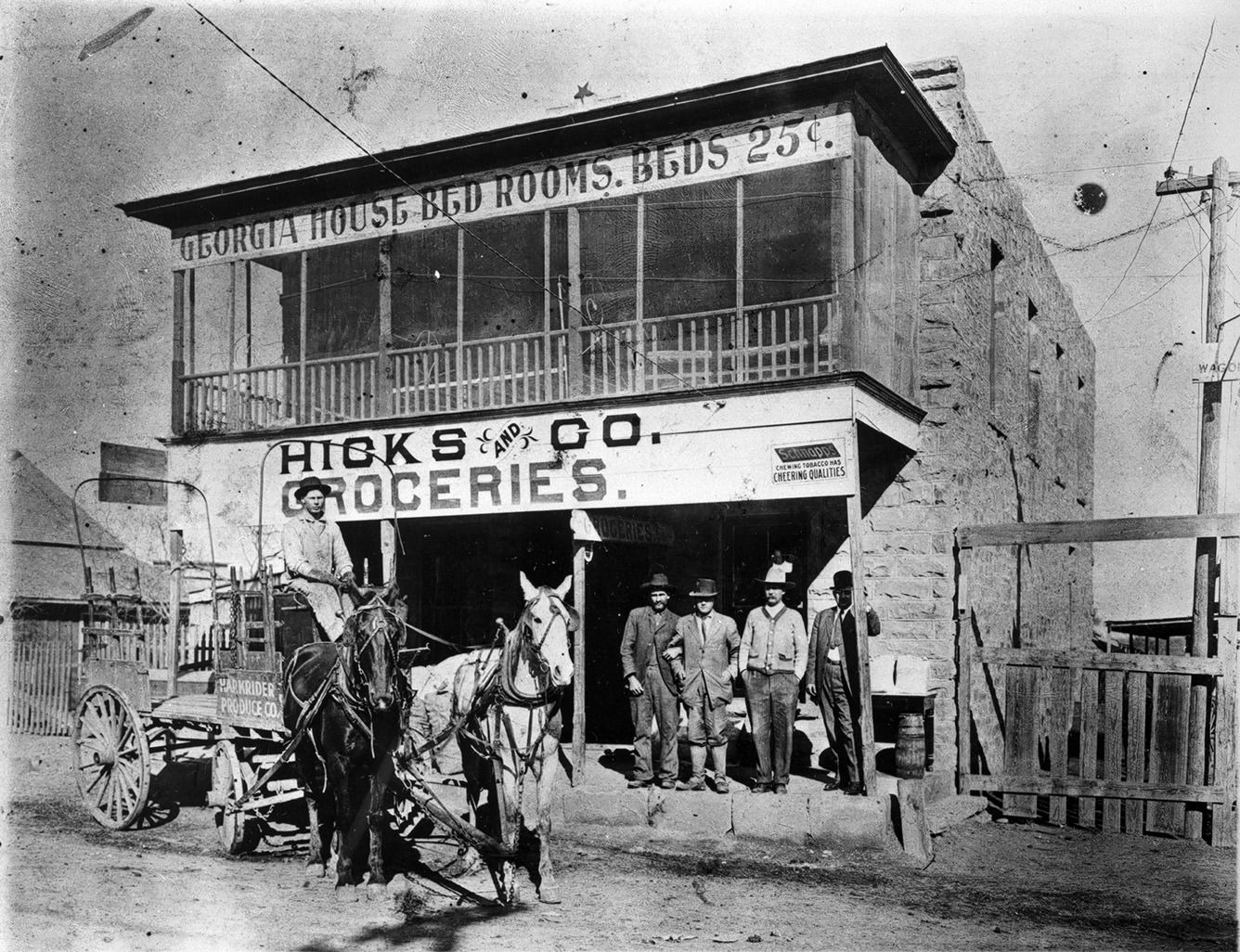

Daily commerce reflected this blend. While saloons and gambling parlors still catered to certain appetites , a growing array of legitimate businesses served the needs of the expanding population. General stores , wholesale grocers like Joseph H. Brown’s large establishment , meat markets , clothiers such as Washer Brothers (opened 1882) , hotels , banks like the Fort Worth National Bank , and specialized shops like Pendery’s Spices (1890) formed the backbone of the city’s retail and service economy. The hum of industry grew louder with flour mills and grain elevators processing the region’s harvest.

Community life was taking shape through various channels. Newspapers like the Fort Worth Daily Gazette provided news and fostered civic discourse, covering everything from commerce and politics to social events and the latest incidents in the Acre. Social and cultural organizations emerged, such as the influential Woman’s Wednesday Club (founded 1889), which played a key role in developing the city’s cultural sphere and establishing the public library association. Civic events, like the ill-fated but ambitious Texas Spring Palace and the nascent Fat Stock Show , brought citizens together for entertainment and promotion.

Getting around town was also evolving. While horses and wagons remained common, the transition from mule-drawn streetcars to the electric trolley system, beginning in 1889-90, offered a glimpse of modern urban transit. The first paving bricks laid on Main Street towards the end of the decade promised smoother passage than the dusty or muddy streets of the past. Housing likely reflected the city’s growth, with established residential areas expanding and new neighborhoods possibly beginning to form beyond the central core, replacing earlier, simpler frontier structures. Daily existence in 1890s Fort Worth was thus characterized by this dynamic interplay between the vestiges of its frontier origins and the accelerating pulse of urban modernity.

Image Credits: The Portal to Texas History, UTA Libraries, Wikimedia, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, Barclay Family Photographs, W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Jack White Photograph Collection,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know