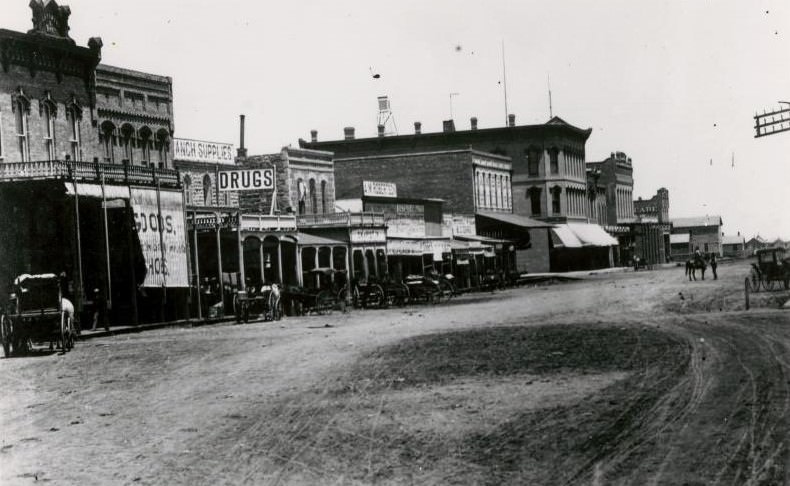

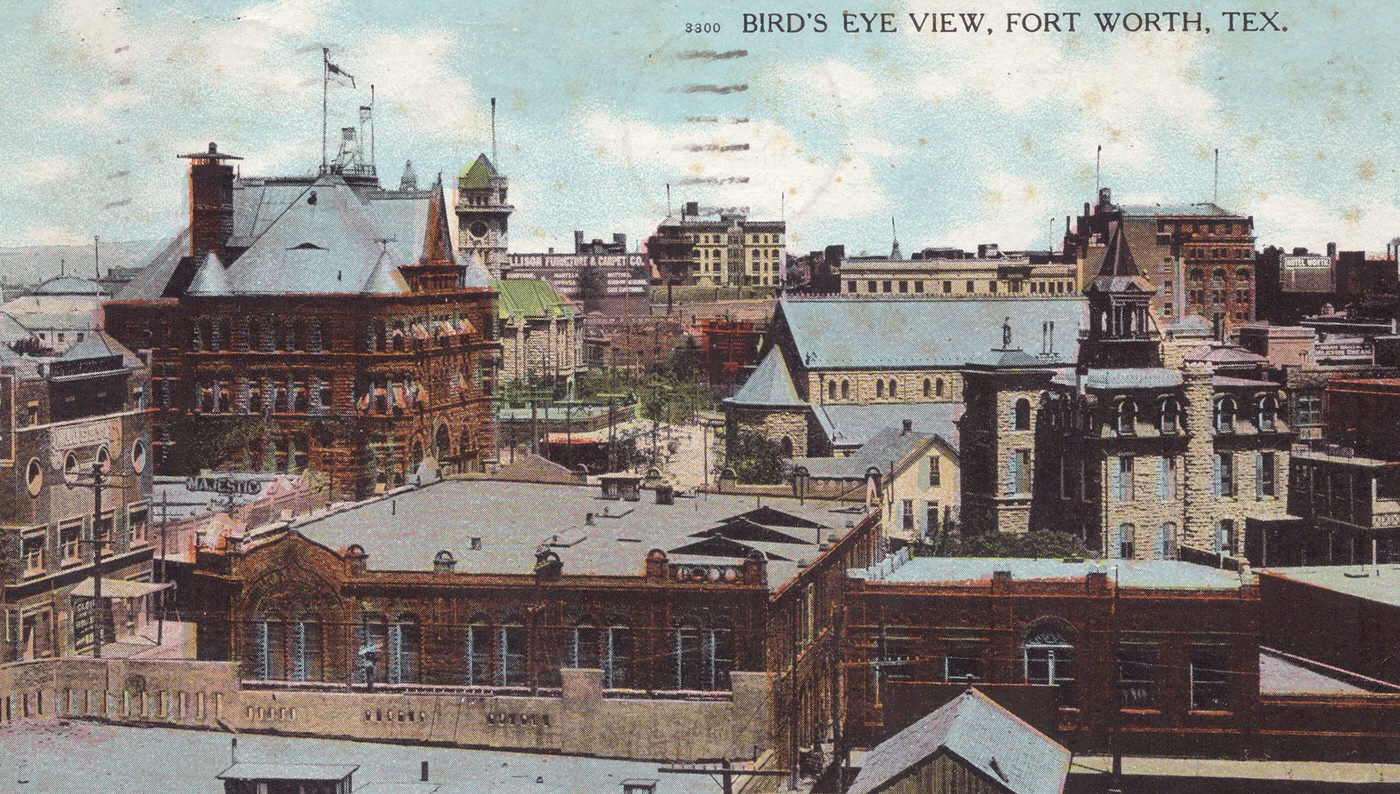

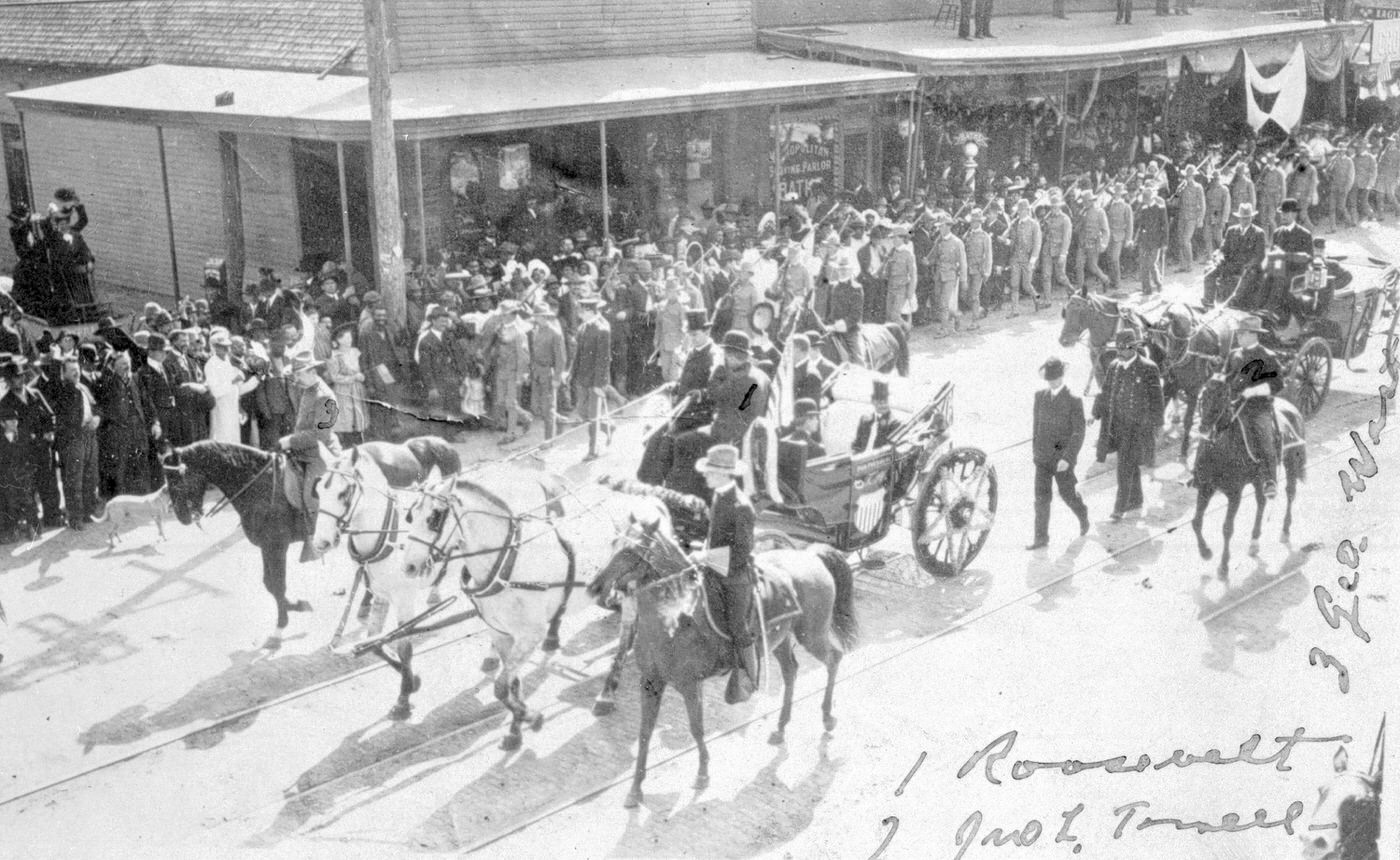

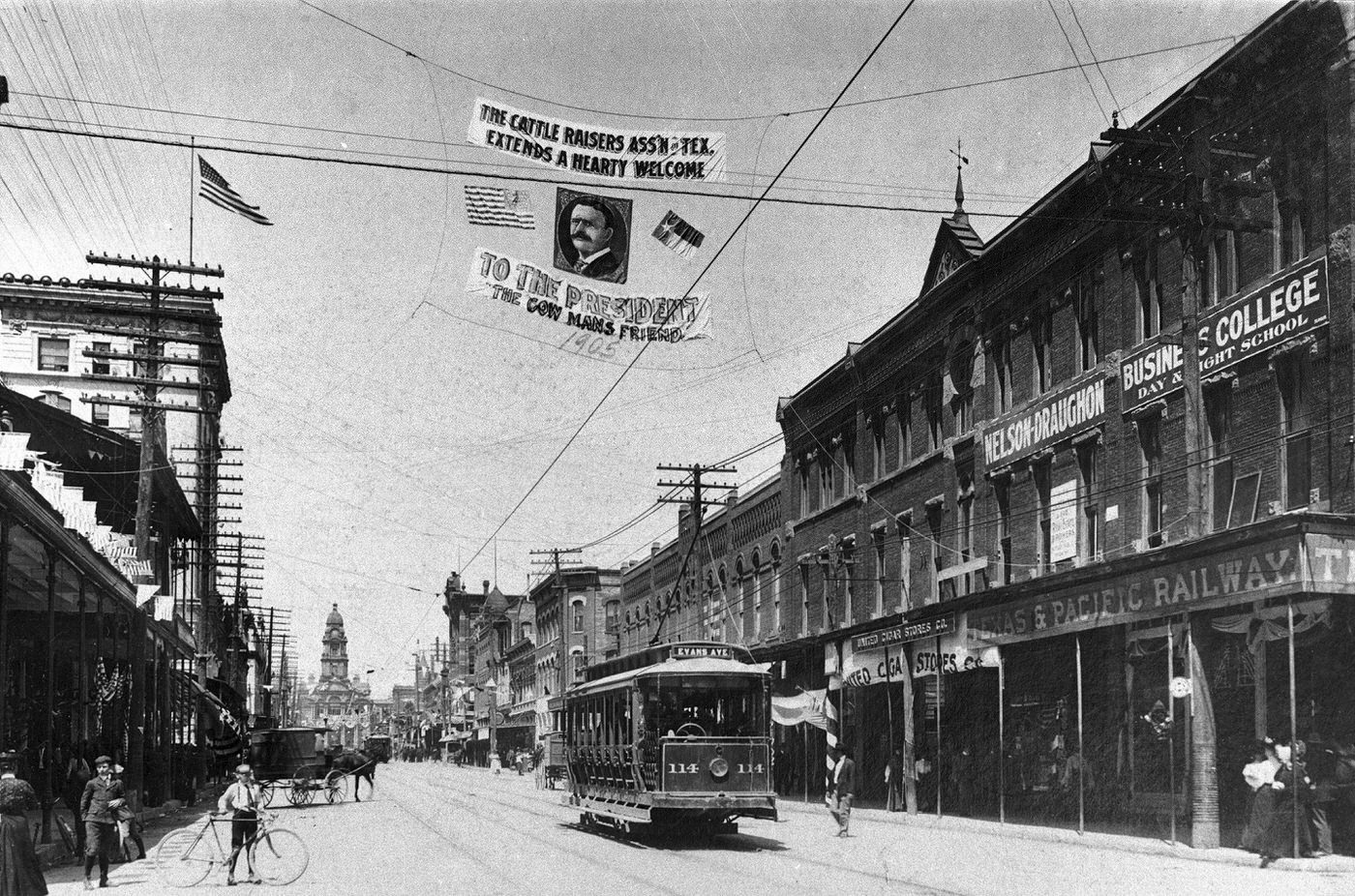

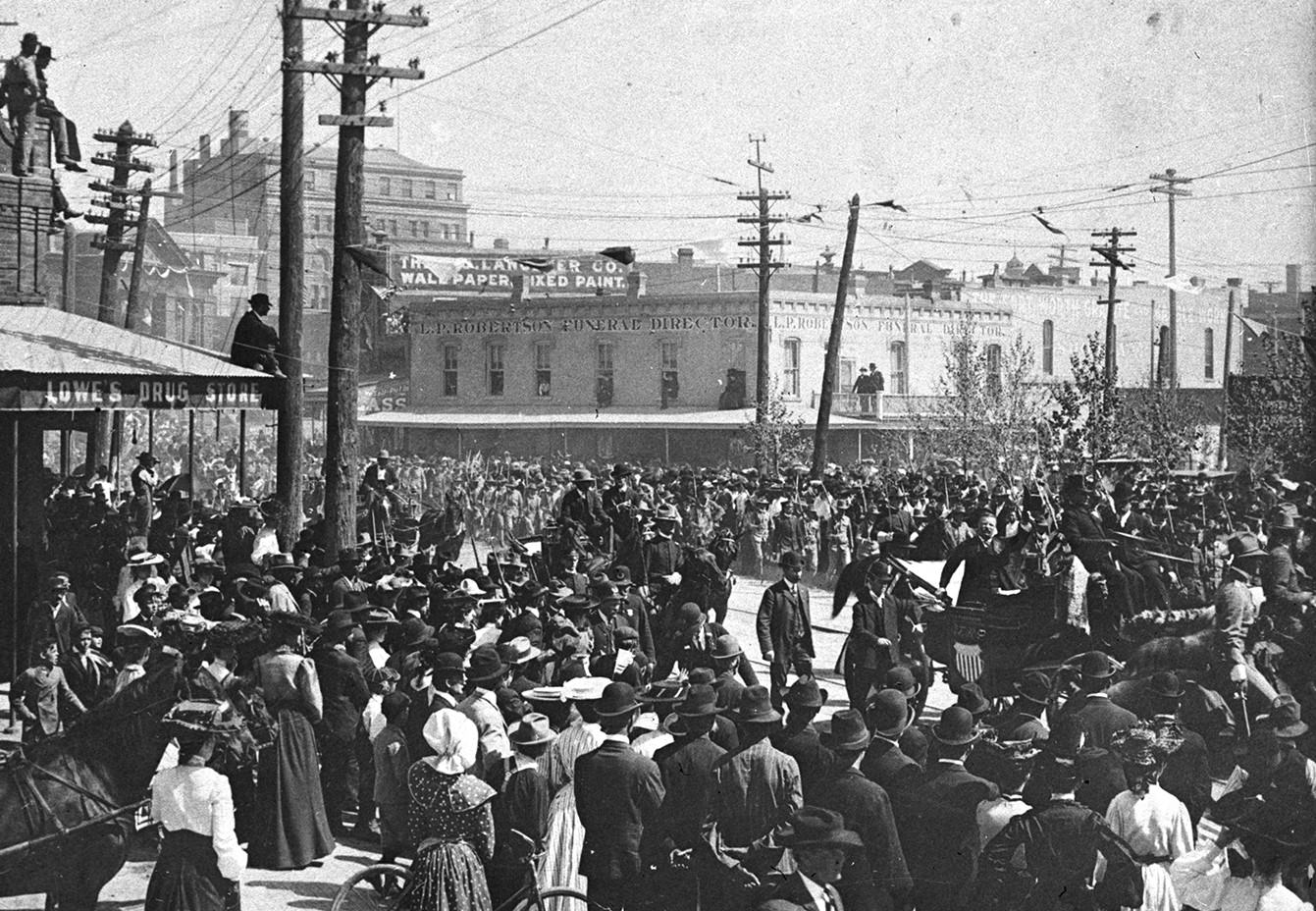

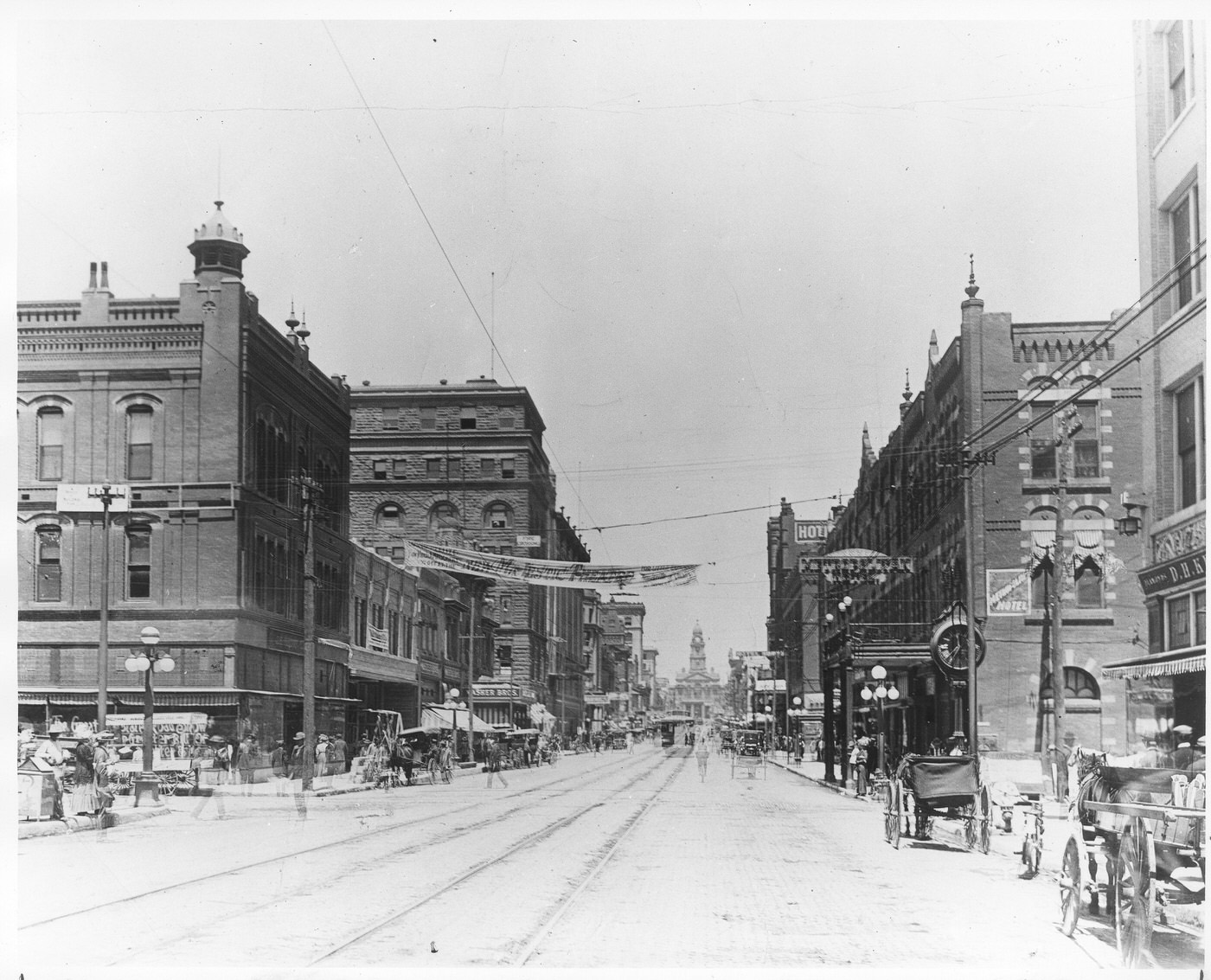

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, Fort Worth, Texas, stood at a crossroads. With a population of 26,688 in 1900, it ranked as the fifth-largest city in Texas. Its identity was deeply rooted in the cattle trade; the great herds driven north along the Chisholm Trail had earned it the enduring nickname “Cowtown”. The city had also weathered economic downturns, like the one in the mid-1870s that led a Dallas newspaper to sarcastically suggest a panther could sleep undisturbed on Fort Worth’s quiet streets, inadvertently bestowing the moniker “Panther City”.

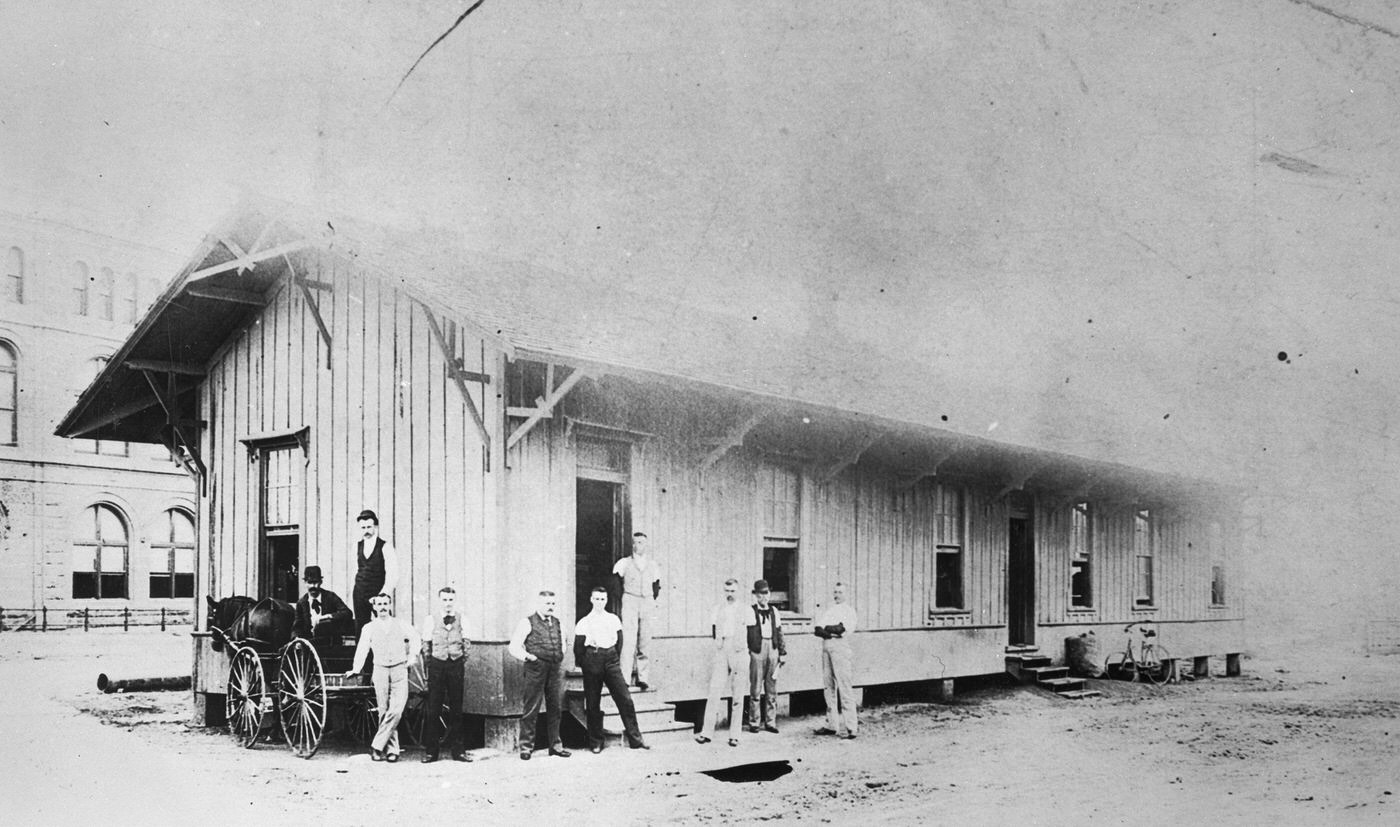

Crucially, by 1900, Fort Worth was no longer just a stop on the trail. It had become a significant railroad hub, a vital junction where multiple lines converged. The arrival of the Texas and Pacific Railway (T&P) in 1876, secured through heroic citizen effort, had been the catalyst, transforming the city’s economic prospects. In the following decades, other major lines arrived: the Missouri, Kansas and Texas (MKT or “Katy”) in 1880: the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe (GC&SF) in 1881: the Fort Worth and Denver City (FW&DC) beginning construction in 1881/82: and others followed. This robust rail network, established through late 19th-century enterprise and determination, provided the essential arteries for commerce and transportation. It was this very infrastructure that positioned Fort Worth for the dramatic, foundational transformation it would undergo in the first decade of the new century – a period of unprecedented growth fueled by industrial expansion that would reshape its economy, population, physical landscape, and civic identity forever.

The Meatpacking Magnet: Armour and Swift Arrive (1902-1903/04)

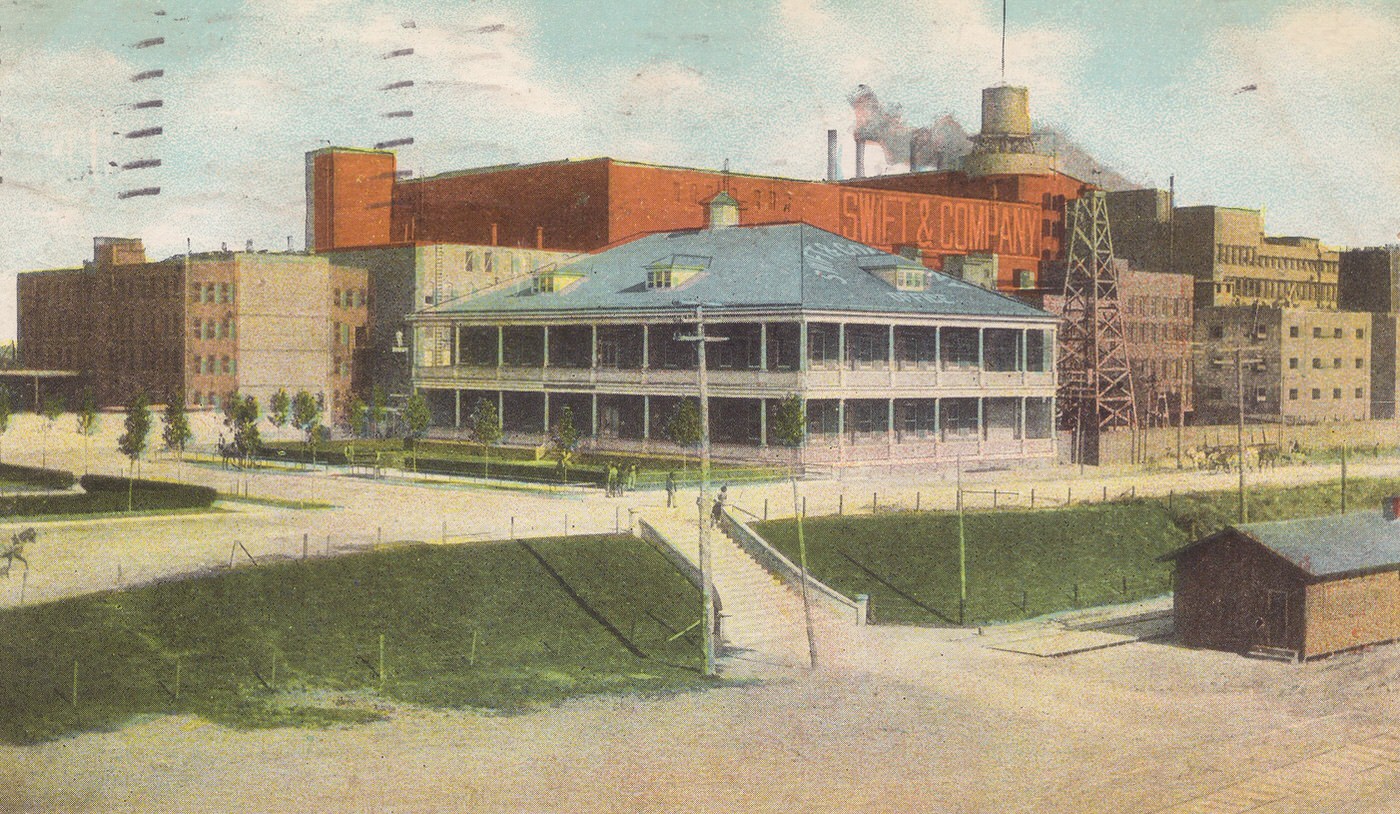

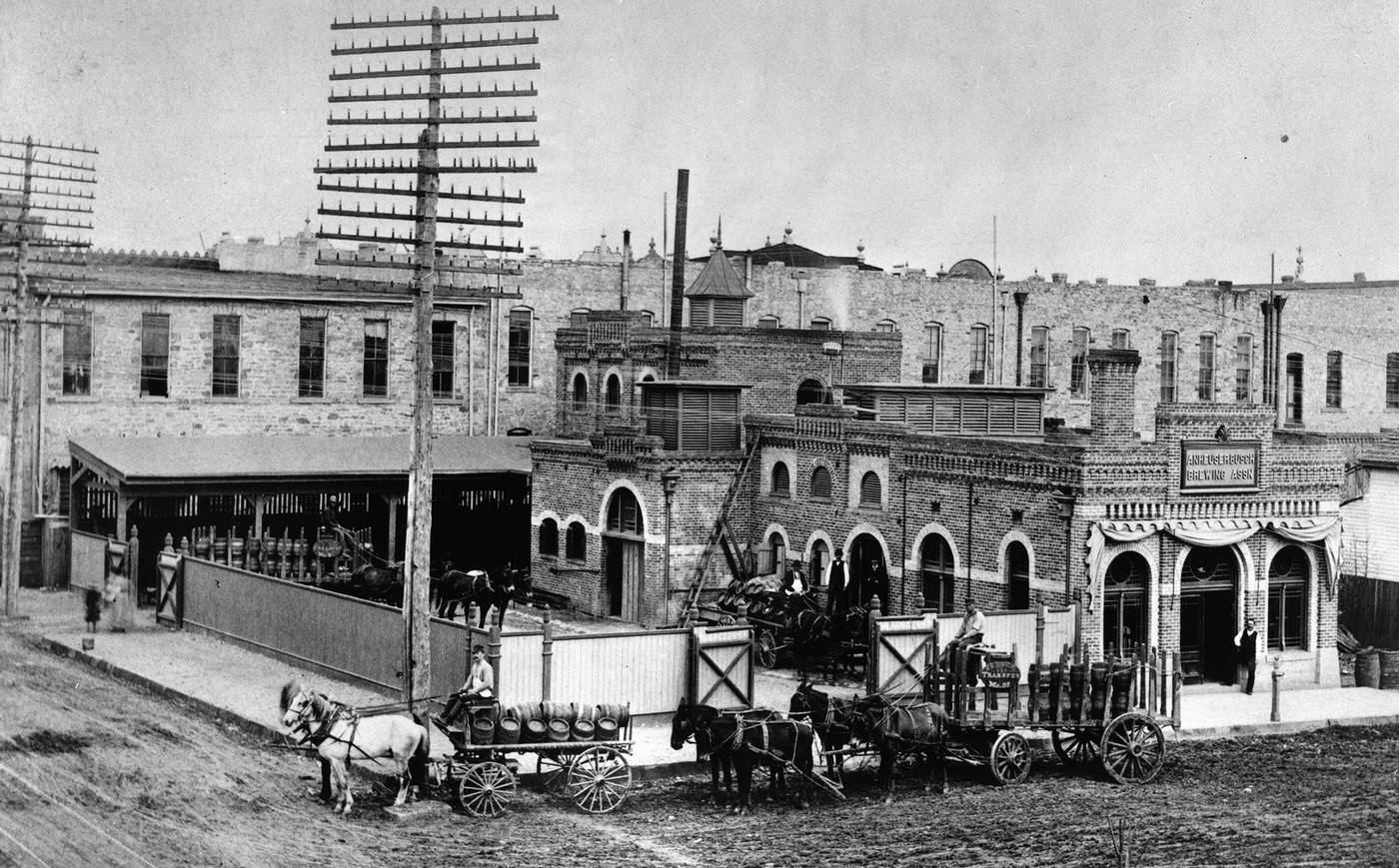

The single most transformative event for Fort Worth in the 1900s decade was the arrival of two giants of the American meatpacking industry: Armour & Company and Swift & Company. Their decision to establish massive operations in the city was not accidental but the result of deliberate efforts by local boosters and the leaders of the Fort Worth Stock Yards Company, notably Boston capitalists Greenleif W. Simpson and Louville V. Niles. Recognizing the potential of Fort Worth’s strategic location in the heart of cattle country and its excellent rail connections, these promoters actively recruited the packing giants.

The deal, finalized around 1902, involved significant incentives. A Fort Worth citizens’ committee raised $100,000 (a substantial sum at the time) to be divided between the two companies. Furthermore, Armour and Swift each received about twenty-two acres of land adjacent to the Stockyards to build their plants and were granted a one-third interest each in the reorganized Fort Worth Stock Yards Company. In return, the packers agreed that all livestock they processed would pass through the Stockyards, ensuring a steady revenue stream for the yards via standard fees.

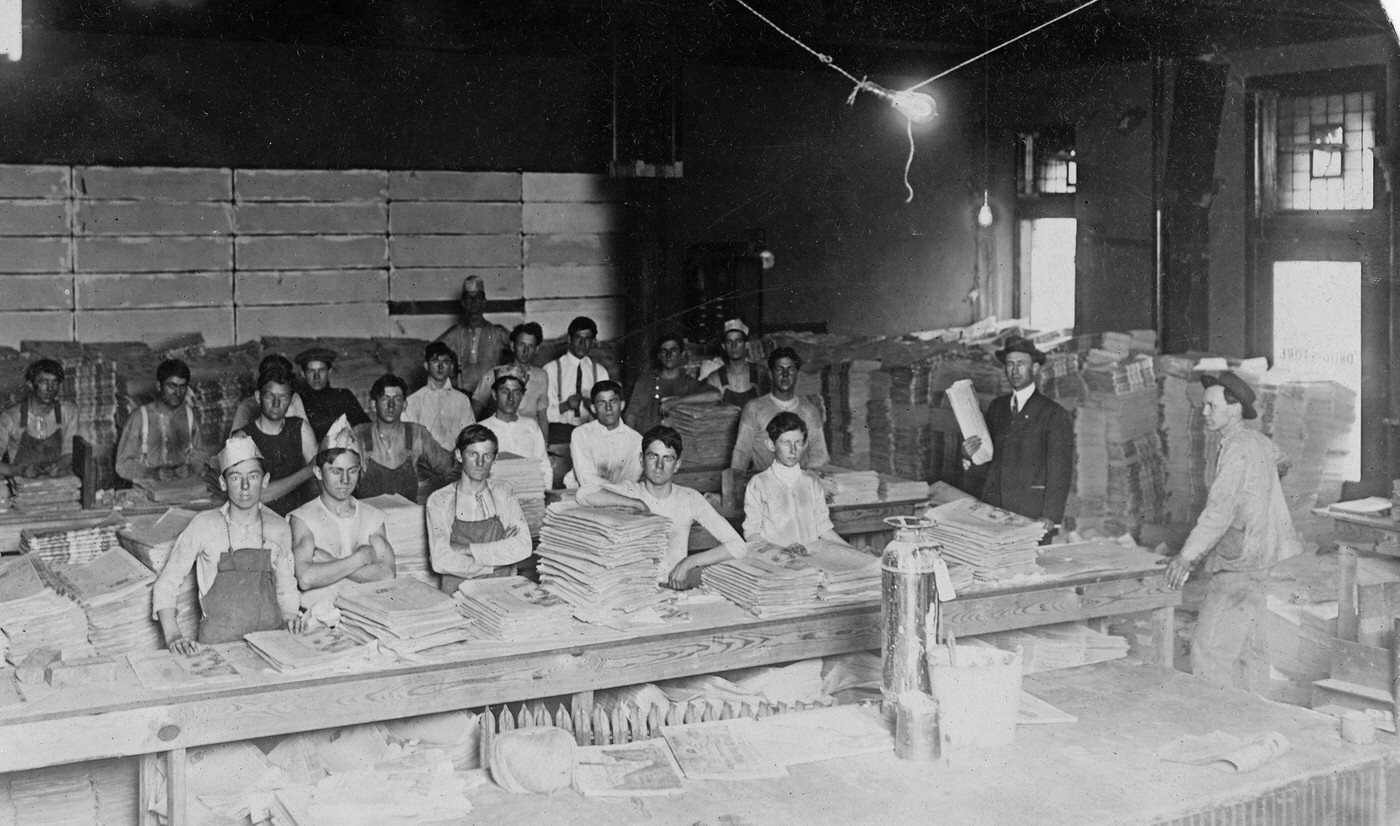

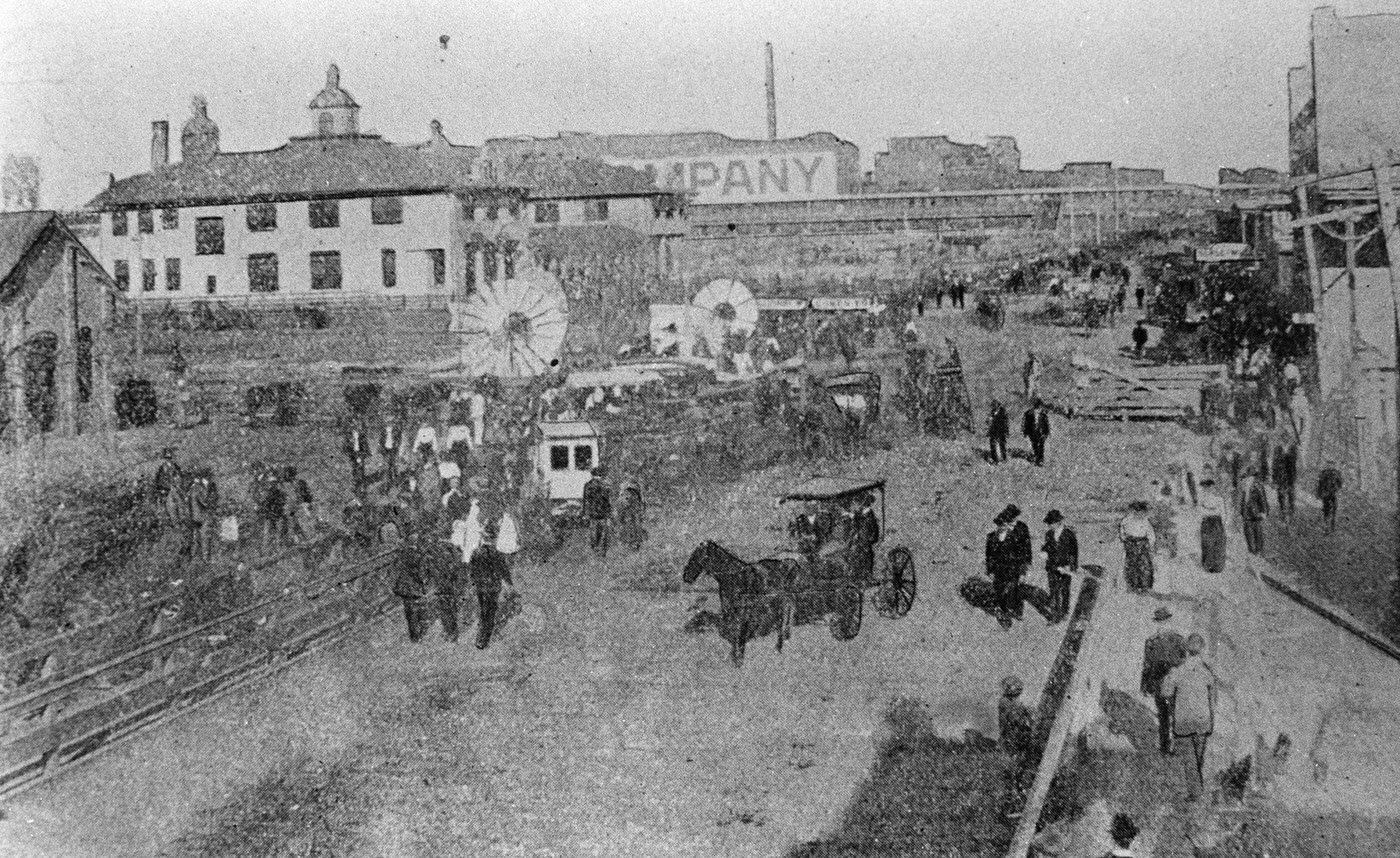

Construction commenced on a massive scale in 1902. A coin toss determined the location, with Armour choosing the site north of East Exchange Avenue and Swift taking the southern plot – which fortuitously contained a gravel pit used in construction. Both plants were built using brick from the Acme Brick plant in Bennett, Texas. Swift began operations in late 1902 or early 1903, with an official opening often cited as March 1904. Armour’s opening likely occurred in a similar timeframe. These were not mere slaughterhouses; they were vast industrial complexes featuring state-of-the-art facilities for the time, including power plants, cooling rooms, lard and oleo refineries, fertilizer plants, cooperages (for barrel making), and box factories. Swift quickly expanded, adding a canning factory in 1906 and nearly doubling its plant capacity in 1908, adding more coolers and processing areas. By 1909, the Swift plant alone could process 5,000 hogs daily, alongside large numbers of cattle and sheep.

The immediate economic impact was staggering. Thousands of new jobs were created, attracting workers to the city. In their first ten months of operation, the two plants collectively spent six million dollars purchasing livestock – over 265,000 cattle, nearly 129,000 hogs, and over 40,000 sheep. This influx of capital and employment fundamentally shifted Fort Worth’s economic trajectory. The city had long been a crucial transit point for cattle moving north, but the arrival of Armour and Swift transformed it into a major processing center. This industrialization, representing enormous fixed investment and providing year-round employment, was far more profound and lasting than the seasonal ebb and flow of the earlier cattle drives. It set the stage for Fort Worth’s explosive growth throughout the decade.

“Cowtown” Evolves: The Stockyards Boom and North Fort Worth’s Rise

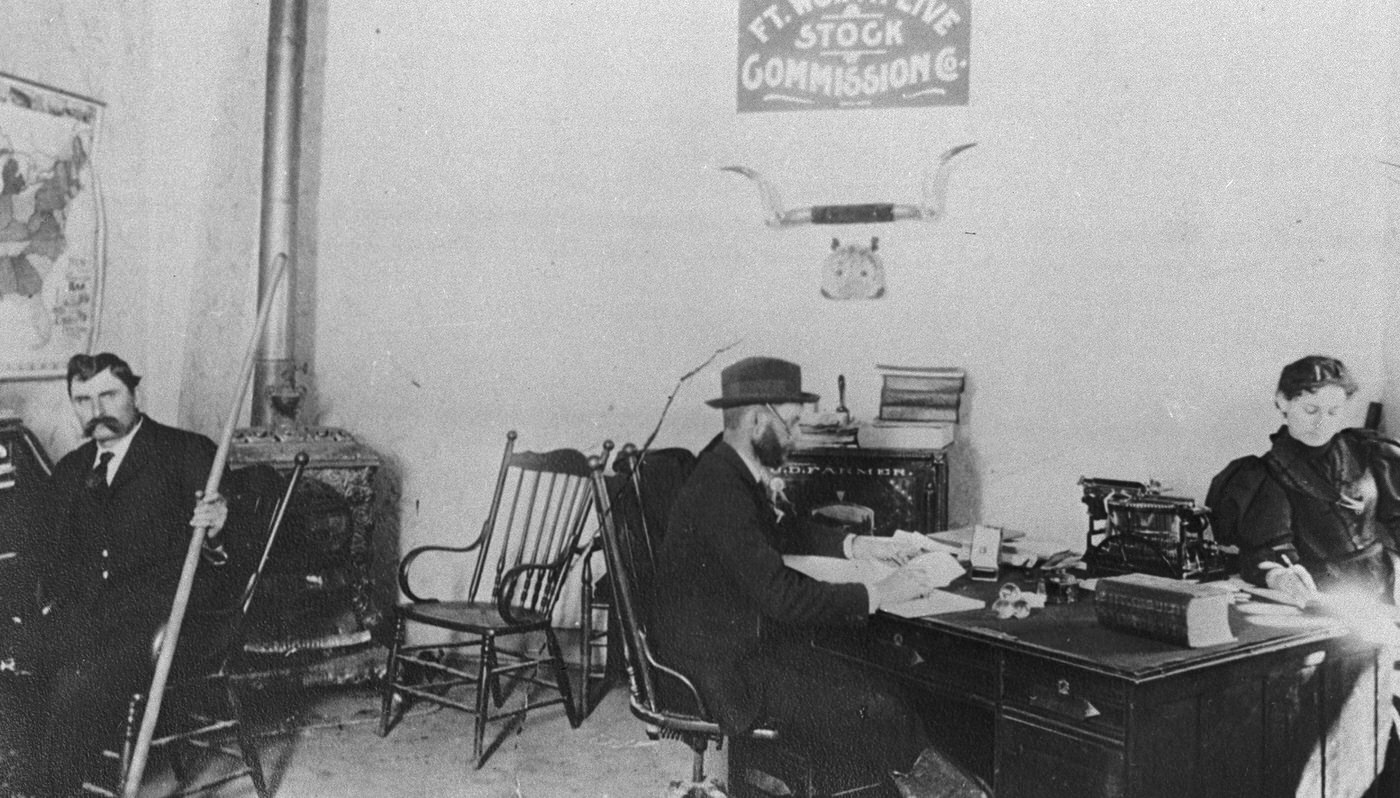

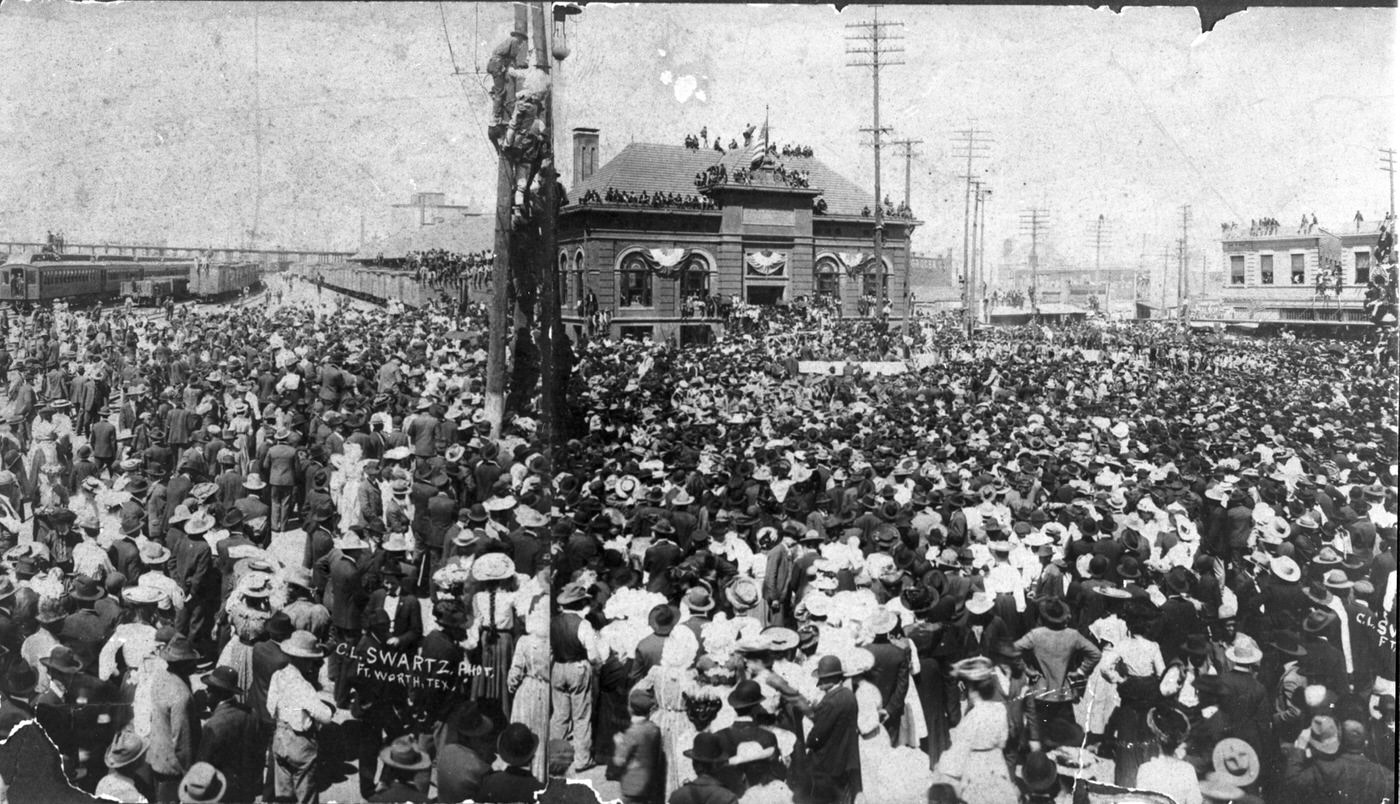

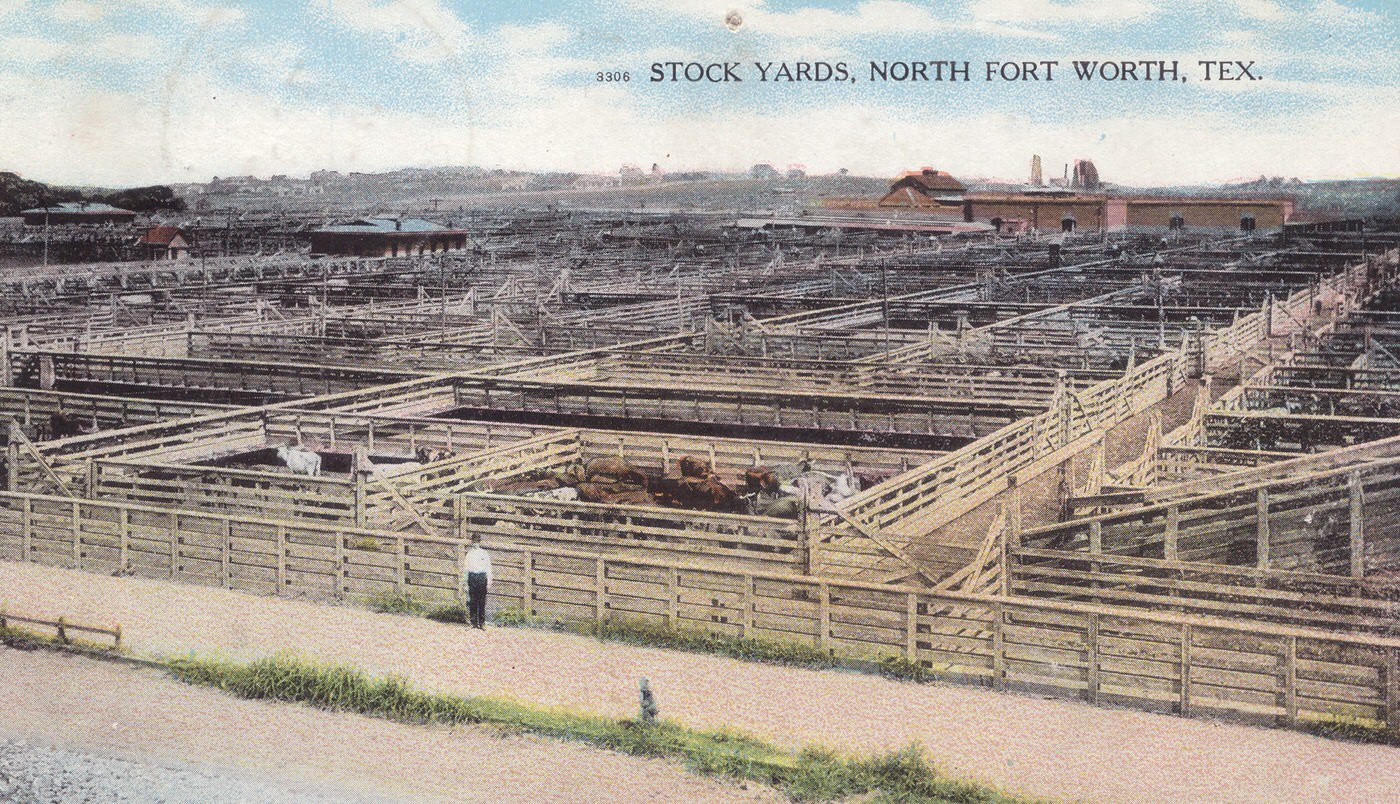

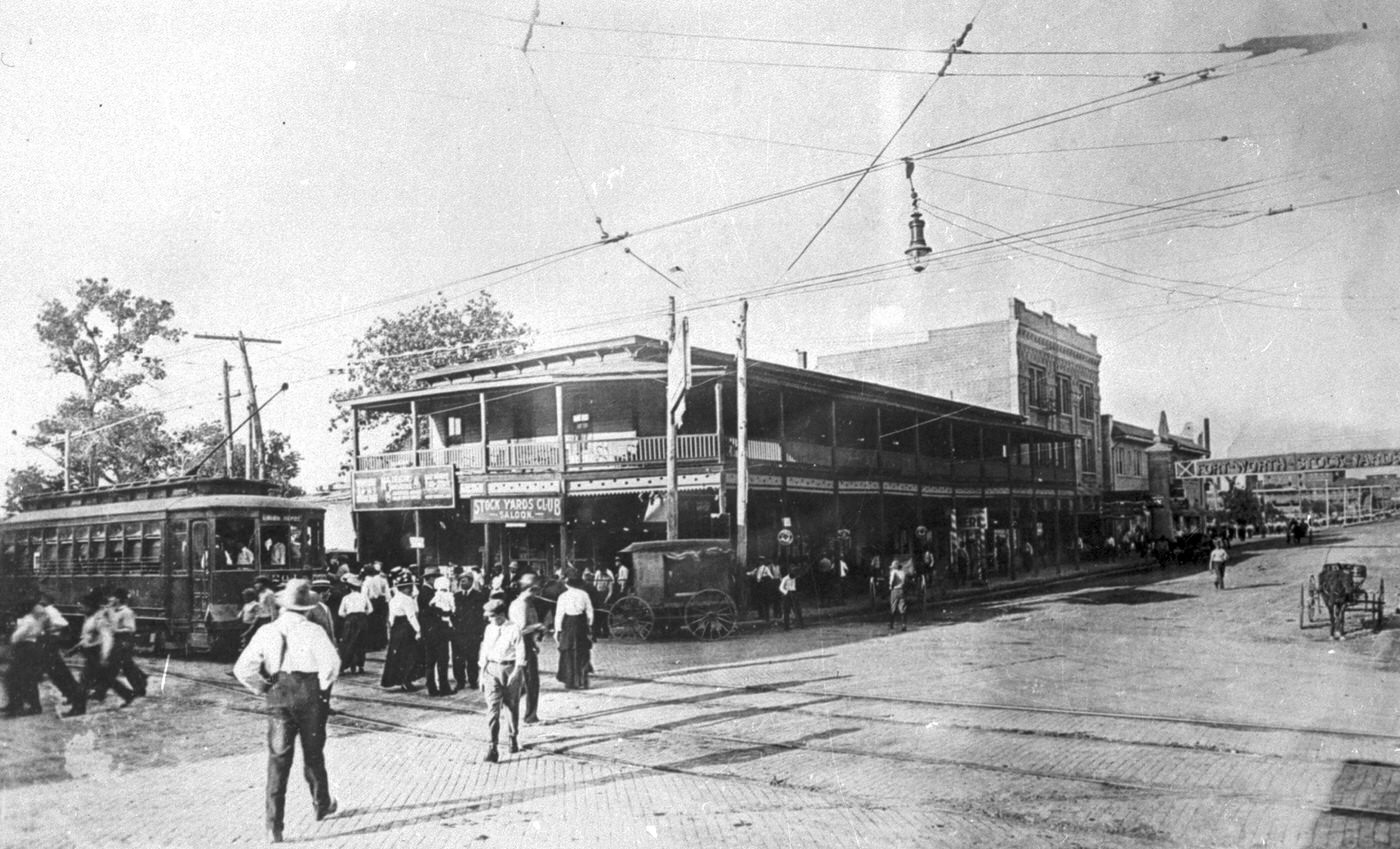

The establishment of the Armour and Swift plants breathed new life and immense scale into the Fort Worth Stockyards. While stockyards had existed near the railroads since the 1880s, with the Fort Worth Stock Yards Company formally incorporated in 1893, the arrival of the major packers catalyzed a period of dramatic expansion and modernization. The 1902 reorganization, which gave Armour and Swift controlling two-thirds ownership, ensured the yards would serve these industrial giants.

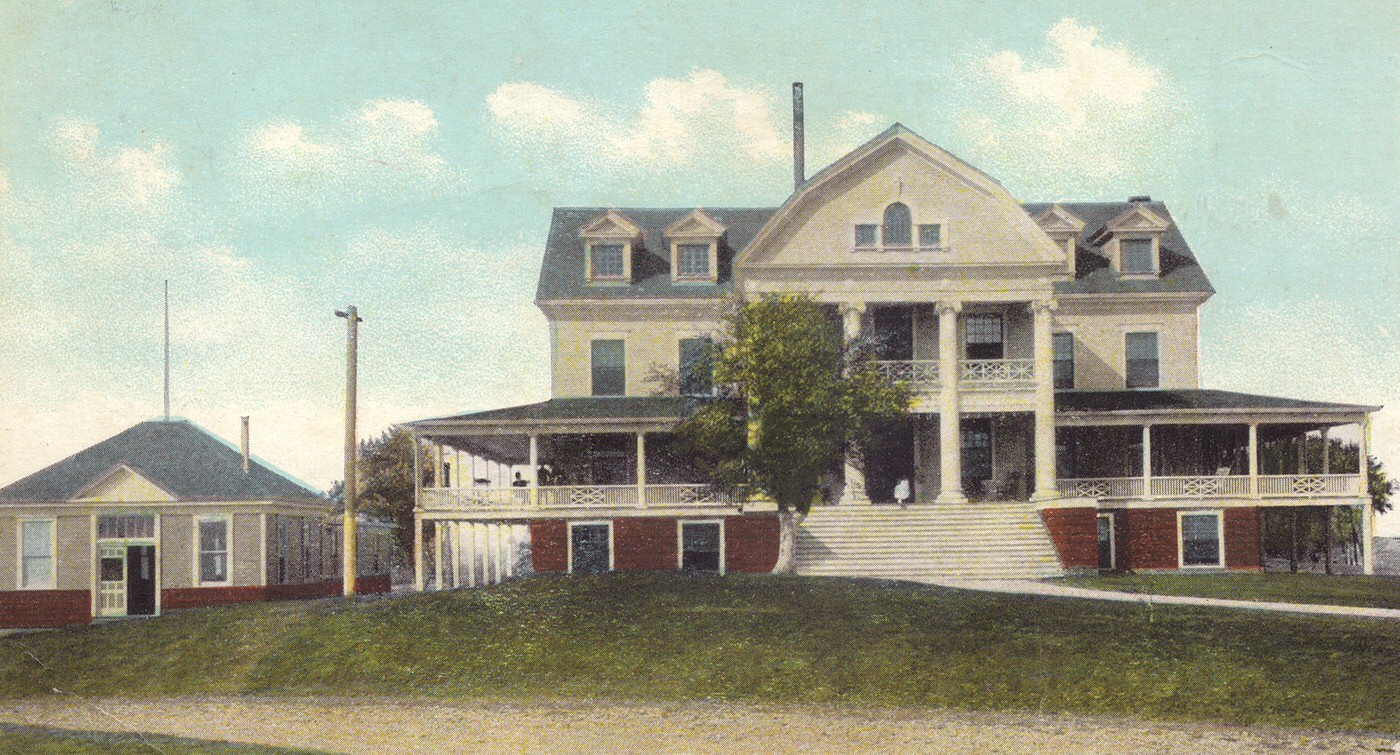

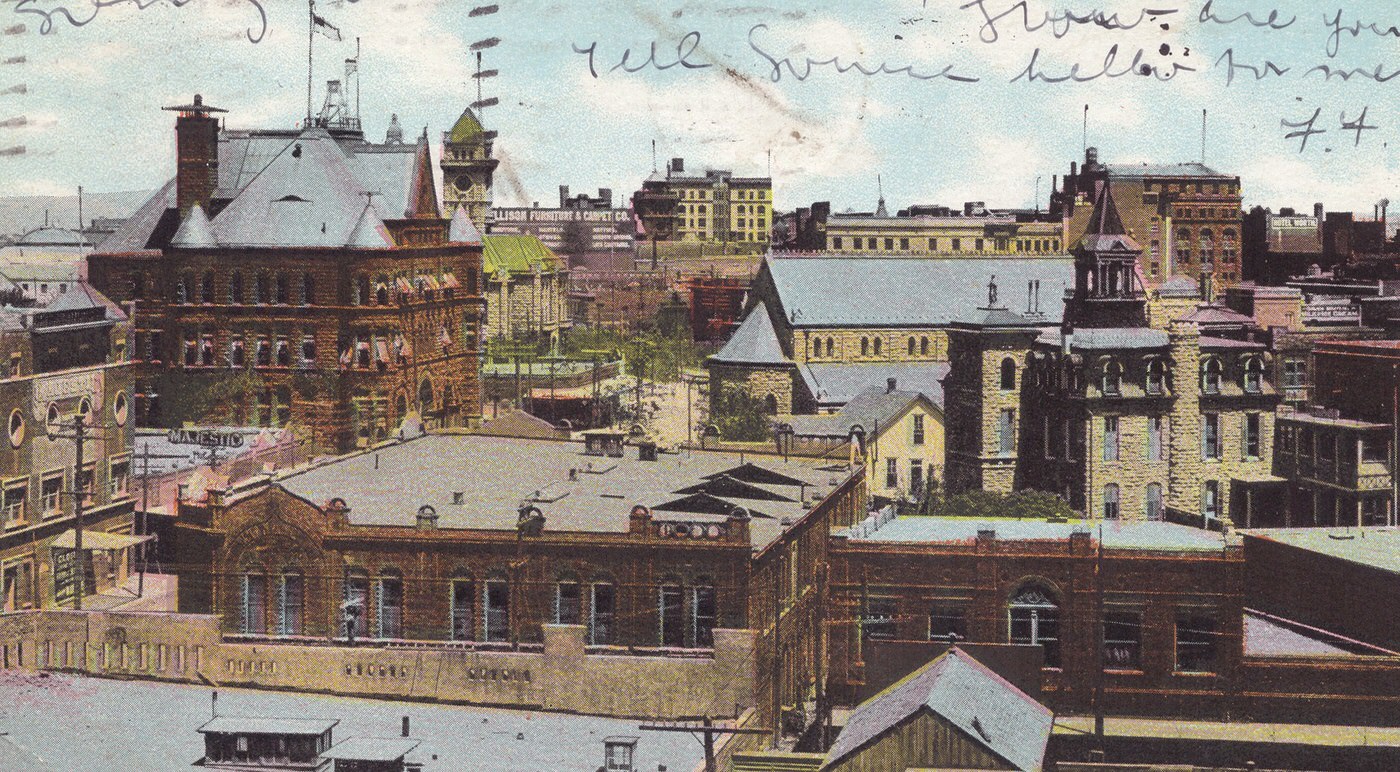

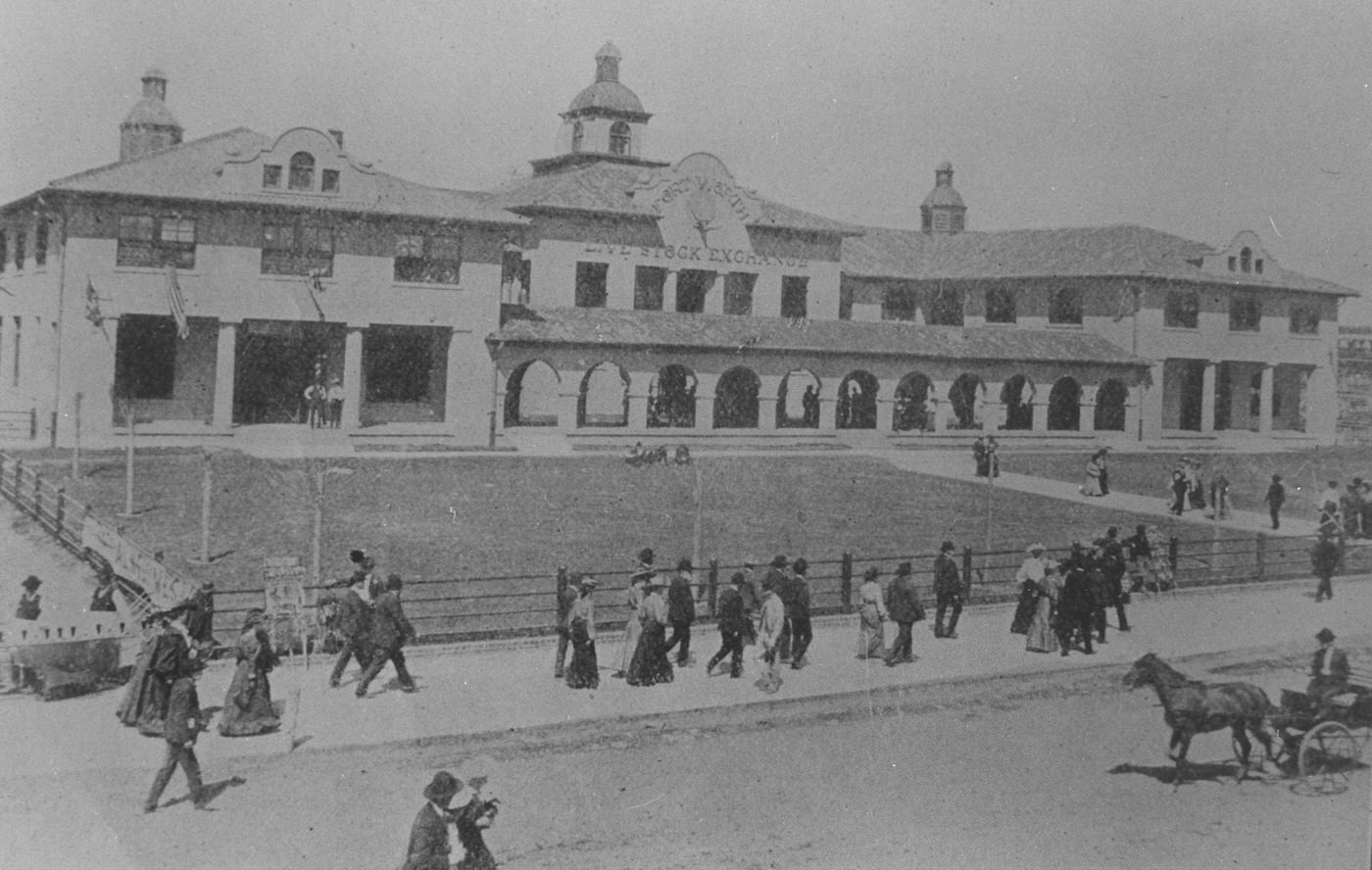

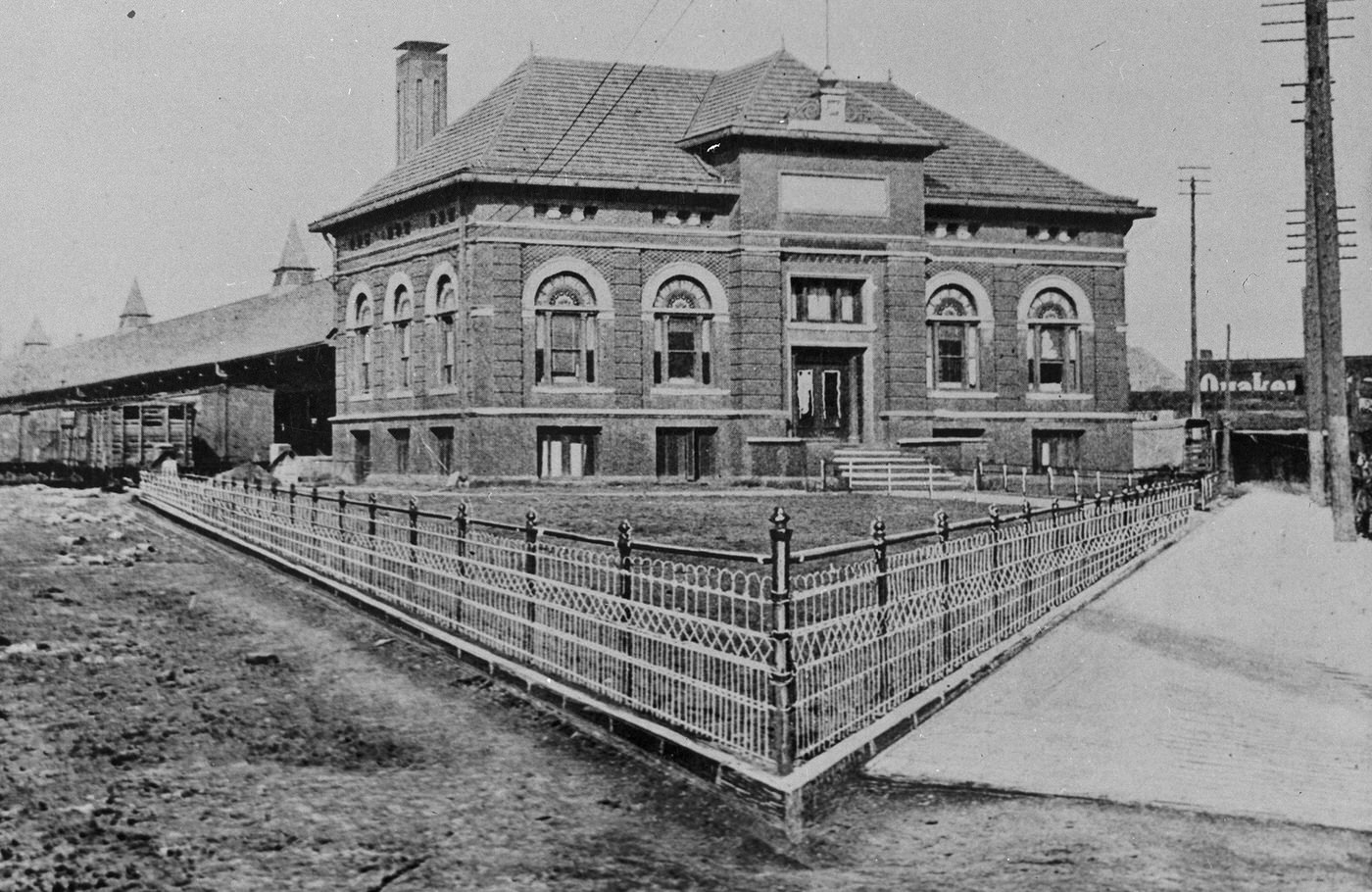

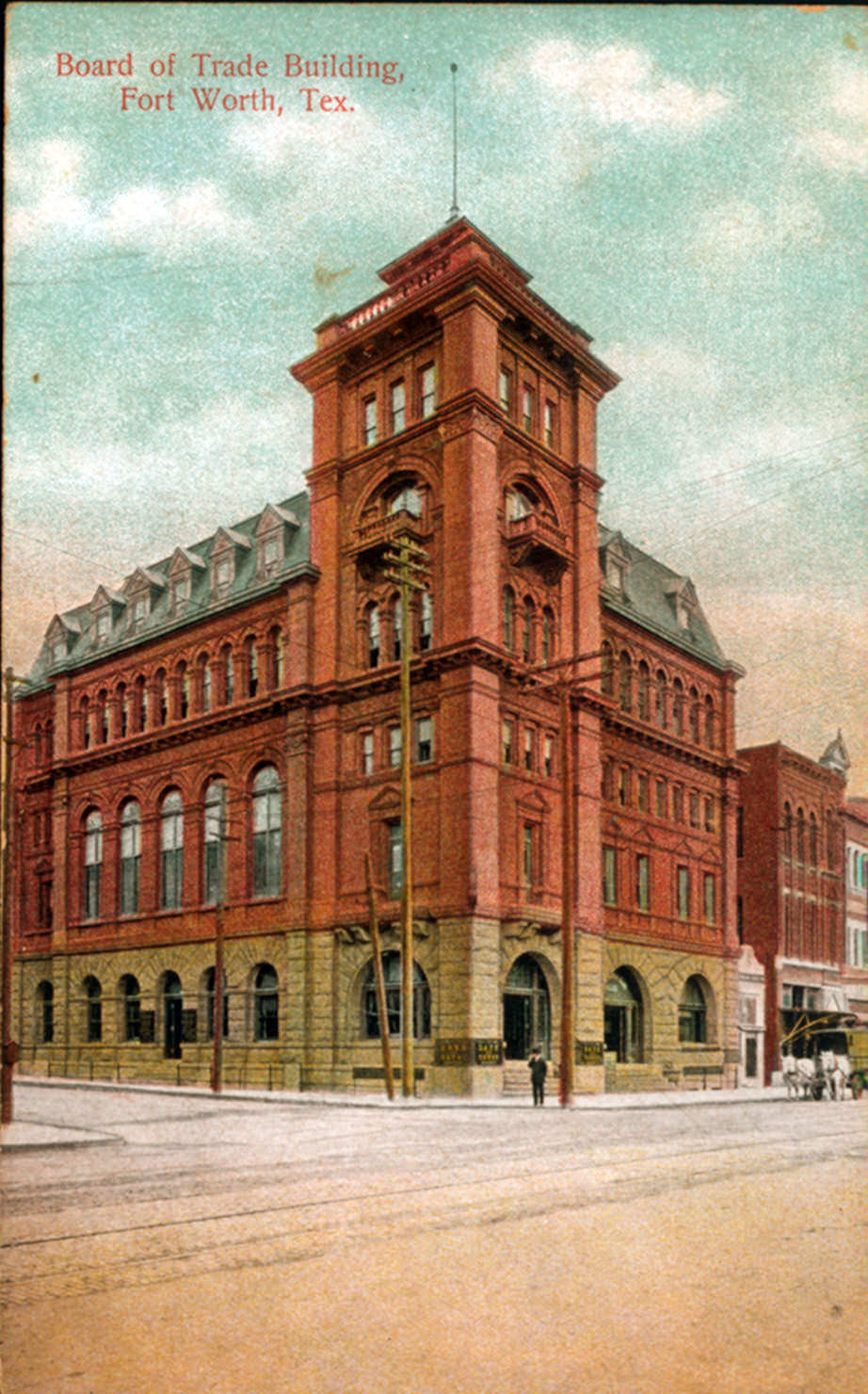

The company invested heavily, spending $125,000 on a grand, two-story Spanish-style Livestock Exchange Building, completed in 1902-03. This building quickly became the nerve center of the booming trade, housing commission companies, telegraph offices, railroad offices, and other support businesses, earning it the moniker “The Wall Street of the West”. The pens themselves were significantly upgraded and expanded, paved with brick and enlarged to hold a capacity of 24,500 animals.

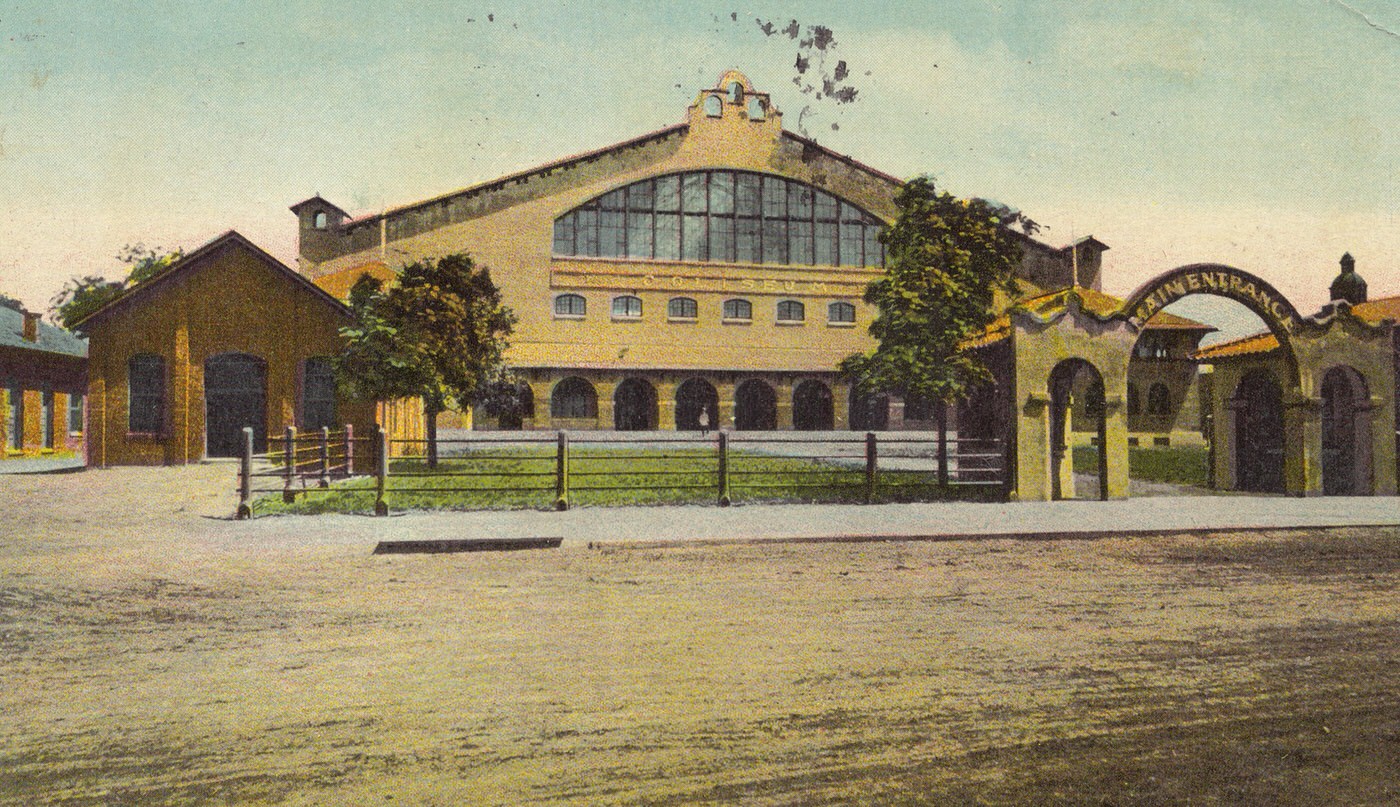

The success was immediate and remarkable. By 1905, the Fort Worth market ranked fifth nationally, and by 1906, its calf market was second only to Chicago. This rapid growth necessitated further infrastructure. To accommodate the increasingly popular Fat Stock Show (established 1896) and provide a venue for other events, the impressive Cowtown Coliseum was constructed in 1907-08 at a cost of $175,000. Completed in just 88 working days, it hosted the first indoor rodeo and cutting-horse contest under electric lights, solidifying the Stockyards’ role as an entertainment hub as well as a commercial one.

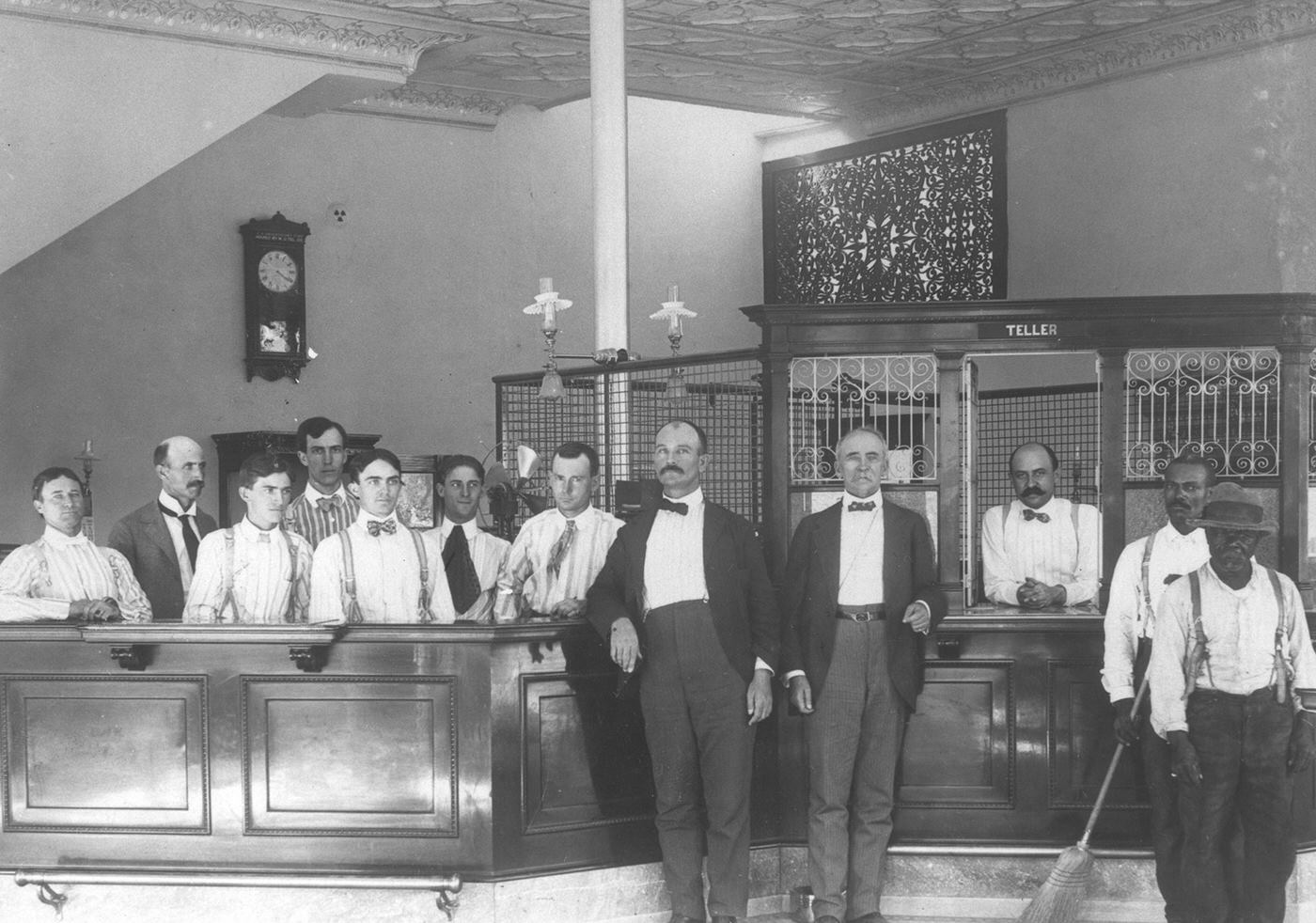

This intense concentration of industry and commerce north of the Trinity River created a powerful economic ecosystem. A distinct community, often referred to as North Fort Worth, rapidly developed around the Stockyards and packing plants. It included not only the industrial facilities but also vital support businesses like the Stockyards National Bank, the Fort Worth Cattle Loan Company, and the Weekly Livestock Reporter newspaper. The Fort Worth Belt Railway Company provided crucial rail connections within the district. This area became so economically powerful and self-contained that it was known as “the richest little city in the world”. Initially, this industrial zone was deliberately kept outside Fort Worth’s city limits, likely operating as a tax-free district. This geographic separation and immense concentration of wealth fostered a unique identity, laying the groundwork for its eventual, though brief, incorporation as the separate municipality of Niles City in 1911. While incorporation occurred just after this decade, the economic and social forces that birthed Niles City were firmly established between 1900 and 1909.

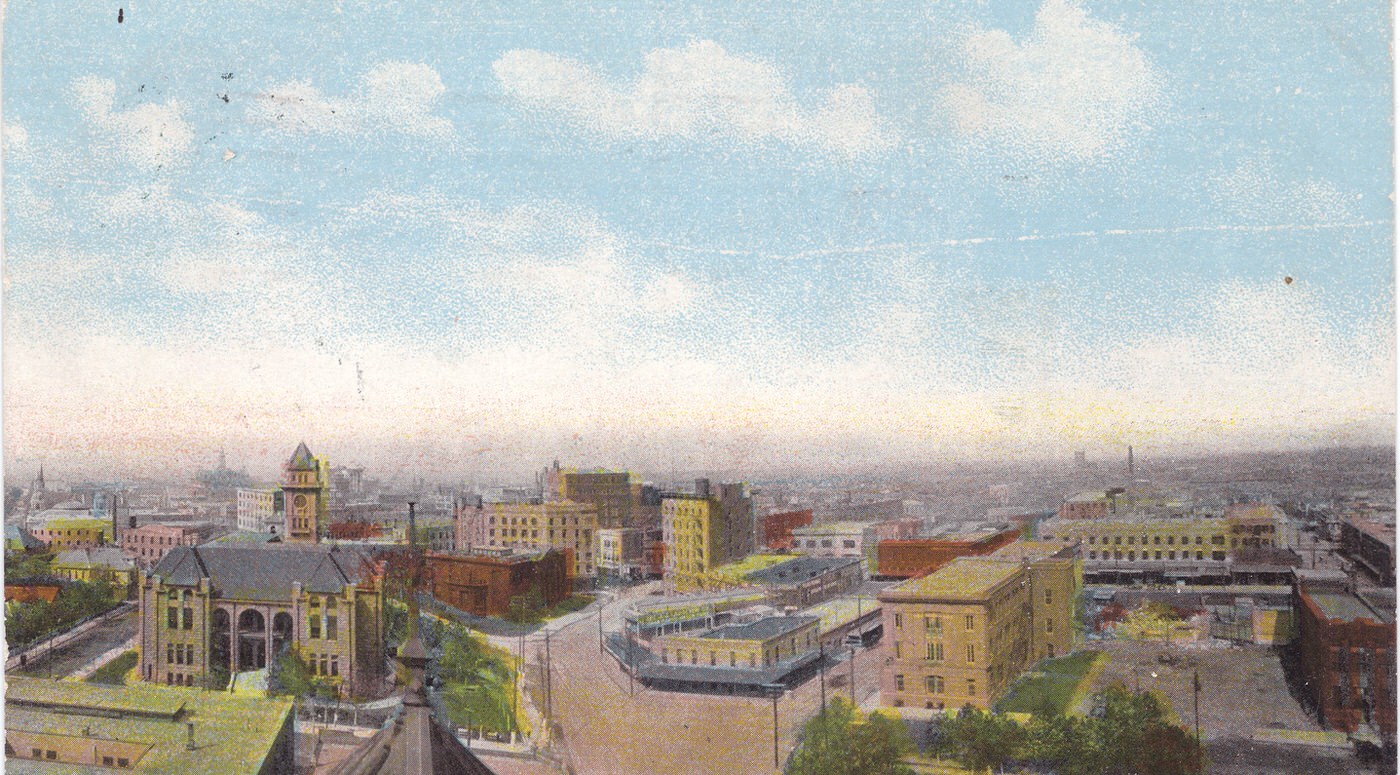

A City Exploding: The Population Surge and Migration

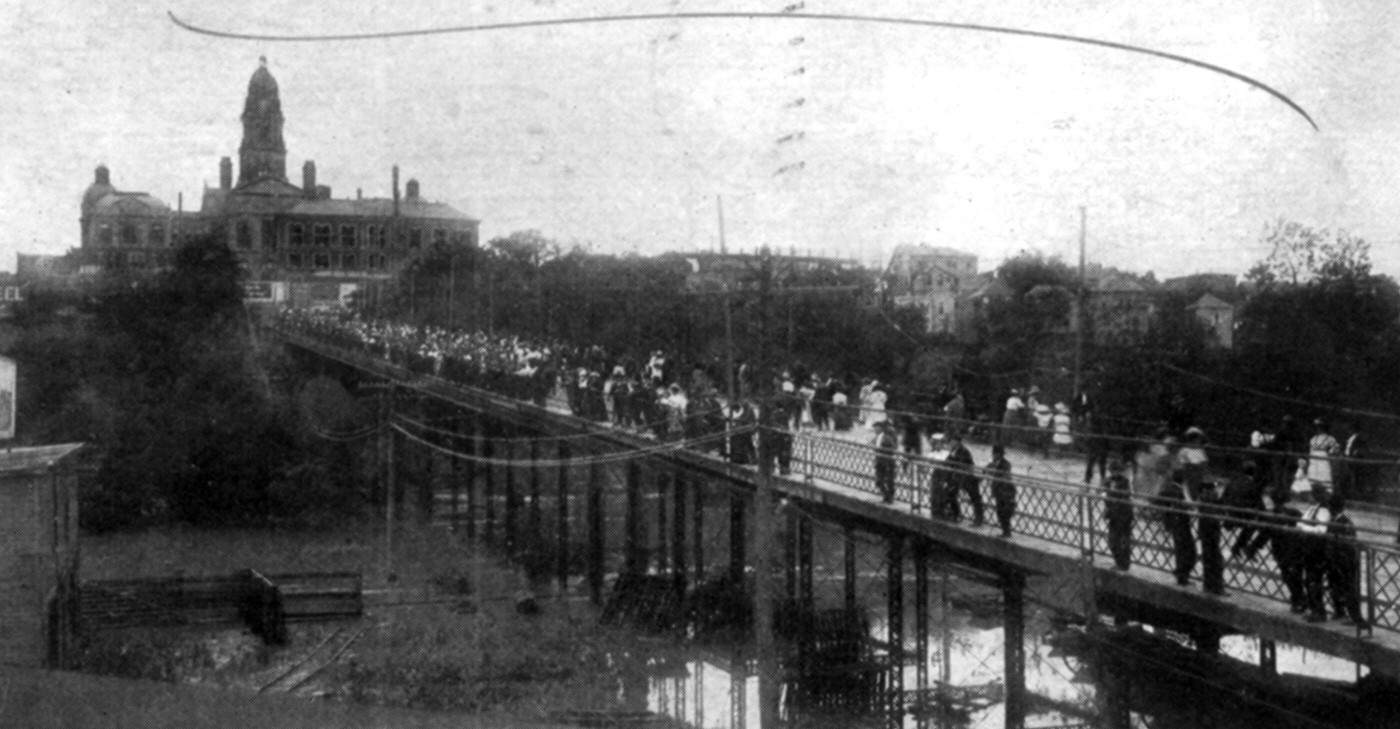

The economic boom ignited by the meatpacking industry fueled a population explosion unparalleled in Fort Worth’s history. In 1900, the city counted 26,688 residents. By the 1910 census, that number had skyrocketed to 73,312. This represented a staggering 175% increase in just ten years – the city’s population nearly tripled.

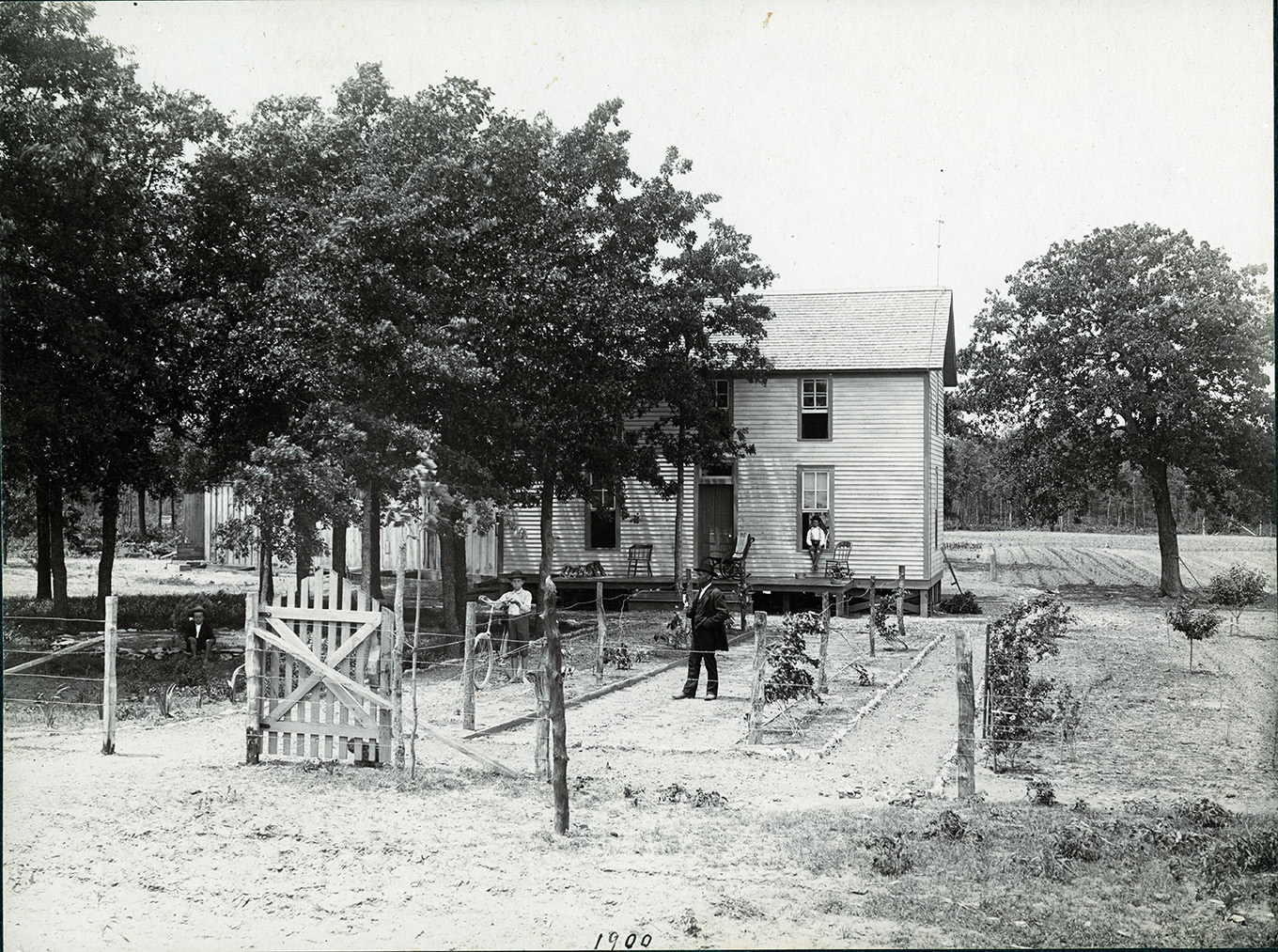

Who were these newcomers flocking to Fort Worth? The available information suggests the majority were native-born white Americans, migrating primarily from other parts of Texas and the American South. This internal migration was supplemented by a smaller but growing Hispanic population. In the late 19th century, only a handful of individuals of Mexican descent resided in the city, often working transiently as railroad laborers or vaqueros. By 1900, census schedules listed 94 individuals of Mexican birth or descent in Tarrant County, with 74 in Fort Worth proper. These residents typically worked as day laborers, small craftspeople (barbers, tailors), or food vendors (chili, tamales), often living in rented rooms or houses near the downtown area and rail yards. The established African American community, numbering nearly 2,000 in Tarrant County in 1887, also grew, although systemic segregation often excluded Black workers from the higher-paying jobs emerging in the new meatpacking plants.

The primary engine driving this massive influx was undeniably the abundance of jobs created by the Armour and Swift plants and the numerous supporting businesses in the Stockyards district. Fort Worth’s extensive railroad network served as the conduit, making it relatively easy for migrants seeking opportunity to reach the rapidly growing city. This wave of migration signified more than just numerical growth; it marked a fundamental shift in the city’s workforce composition. While the image of the cowboy remained central to Fort Worth’s “Cowtown” identity, the reality was that the city was increasingly populated by industrial workers – employees of the packing plants, railroads, and construction trades, along with the service workers needed to support a burgeoning urban-industrial center. This demographic transformation laid the social foundation for the modern city.

Paving the Future: Urban Development and Infrastructure

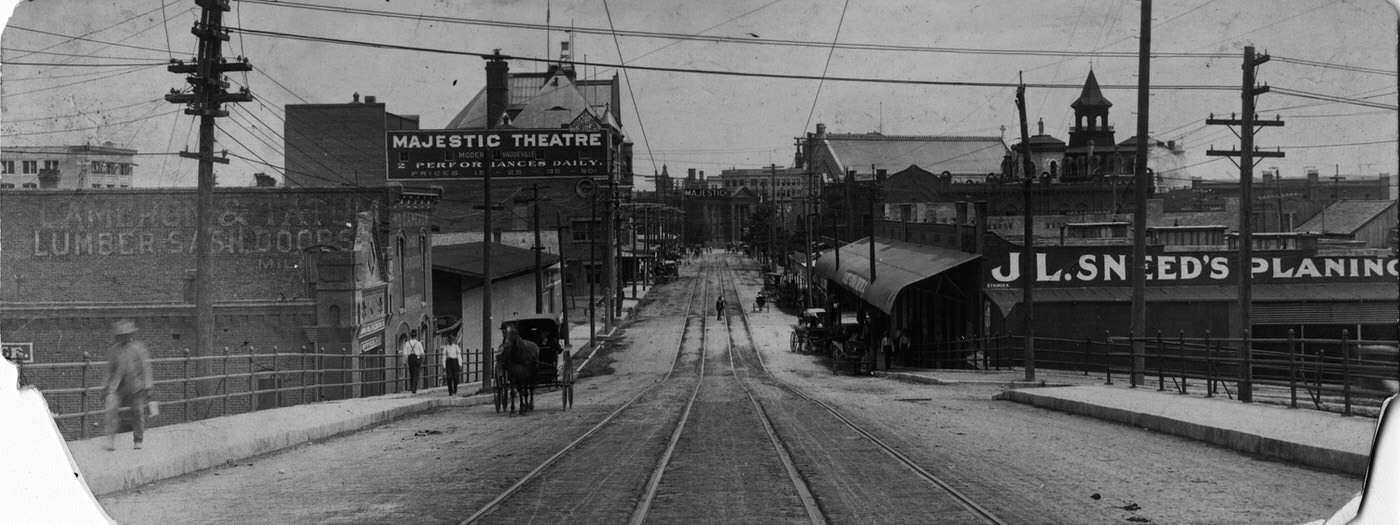

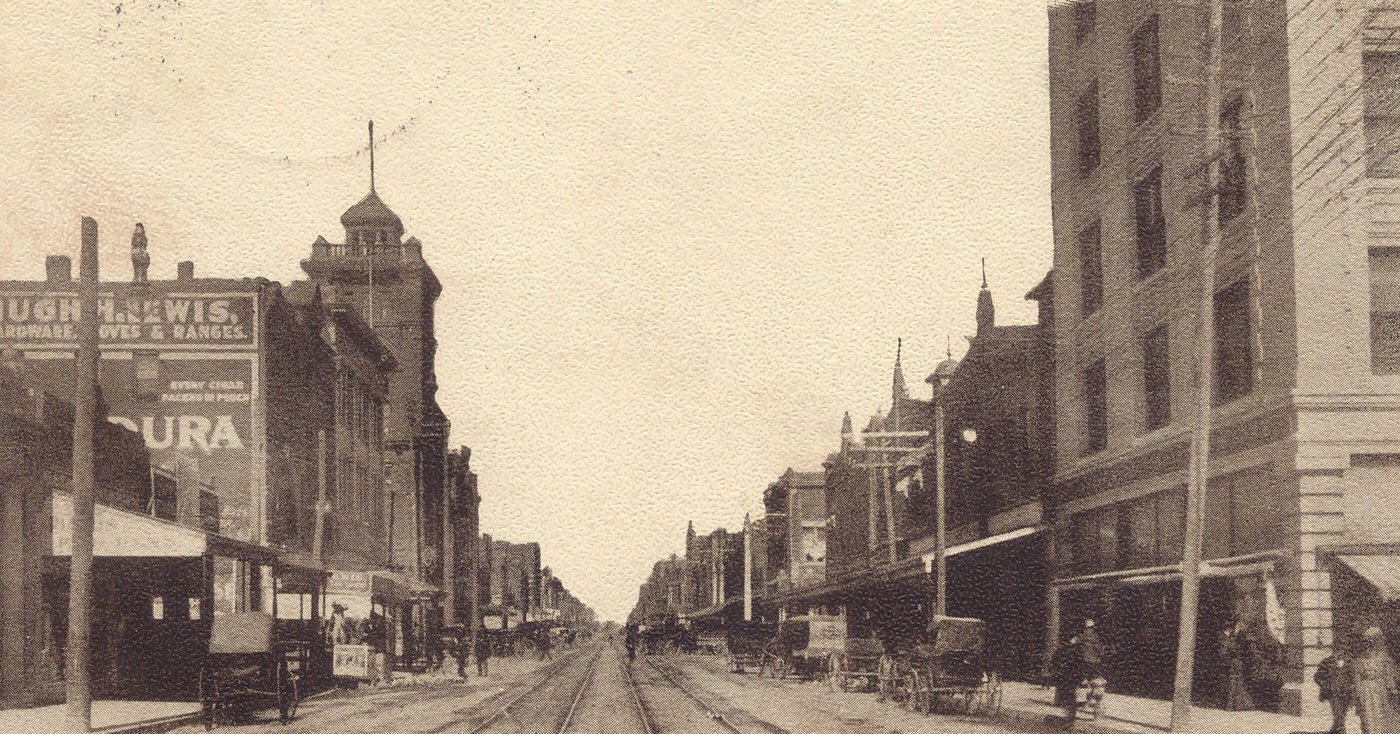

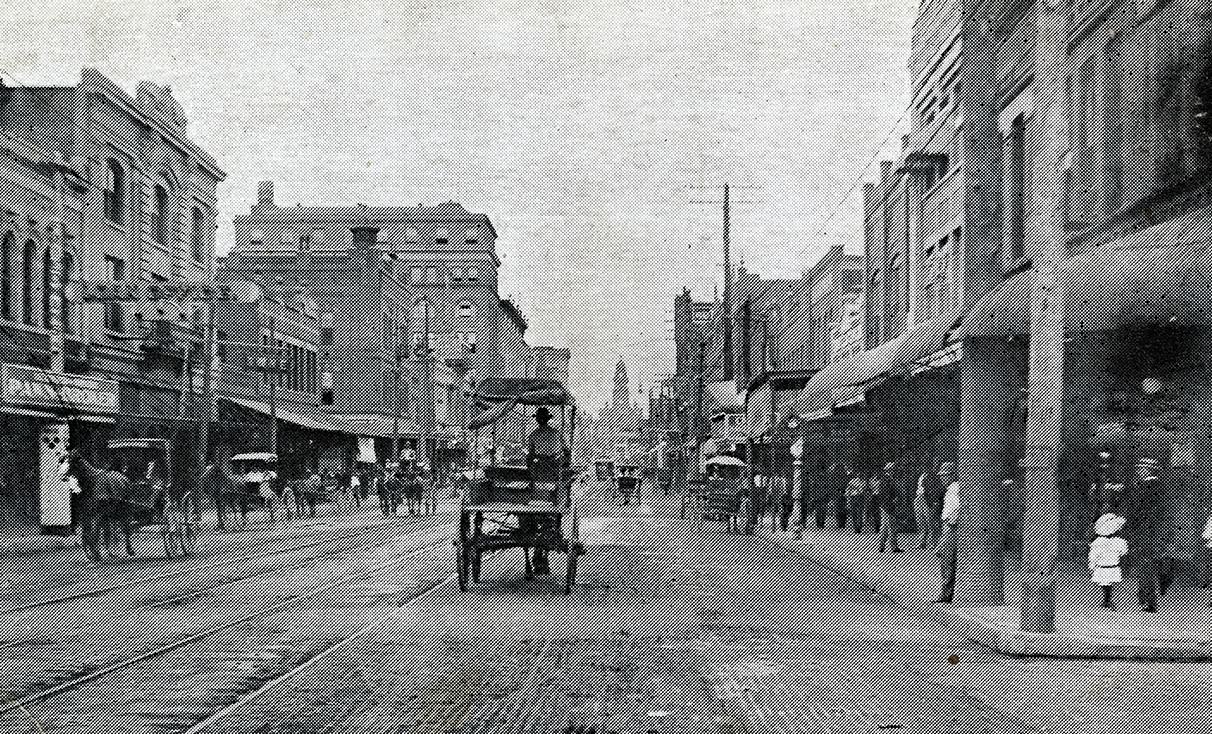

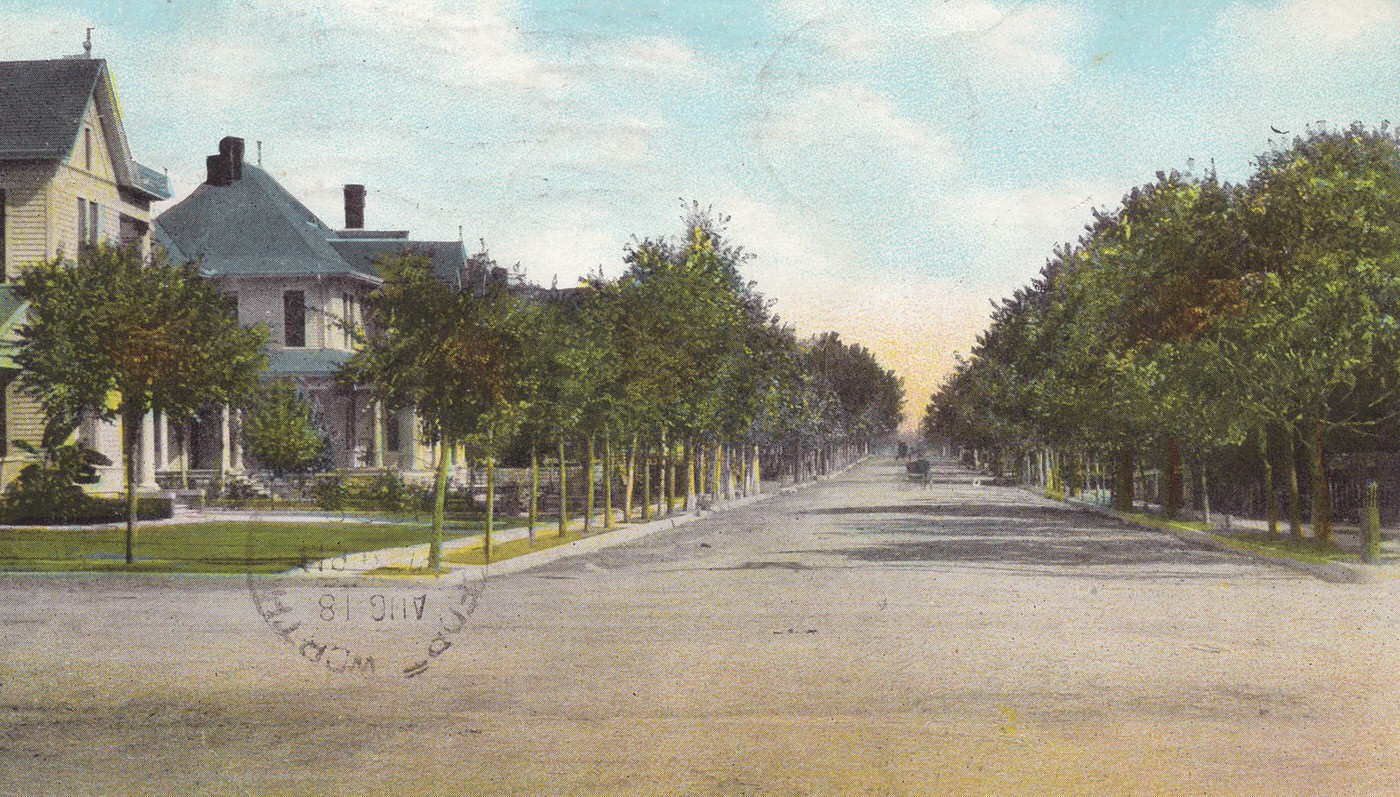

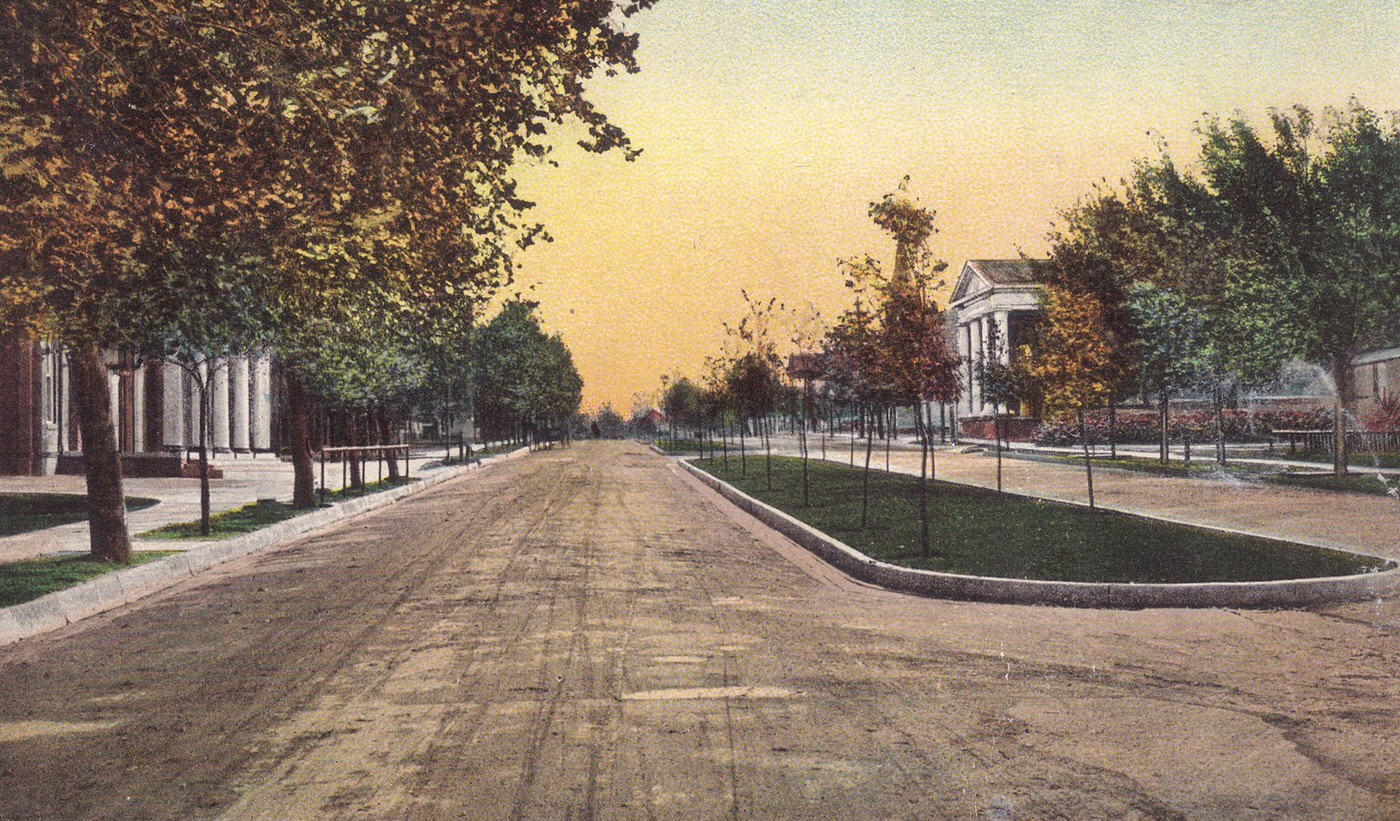

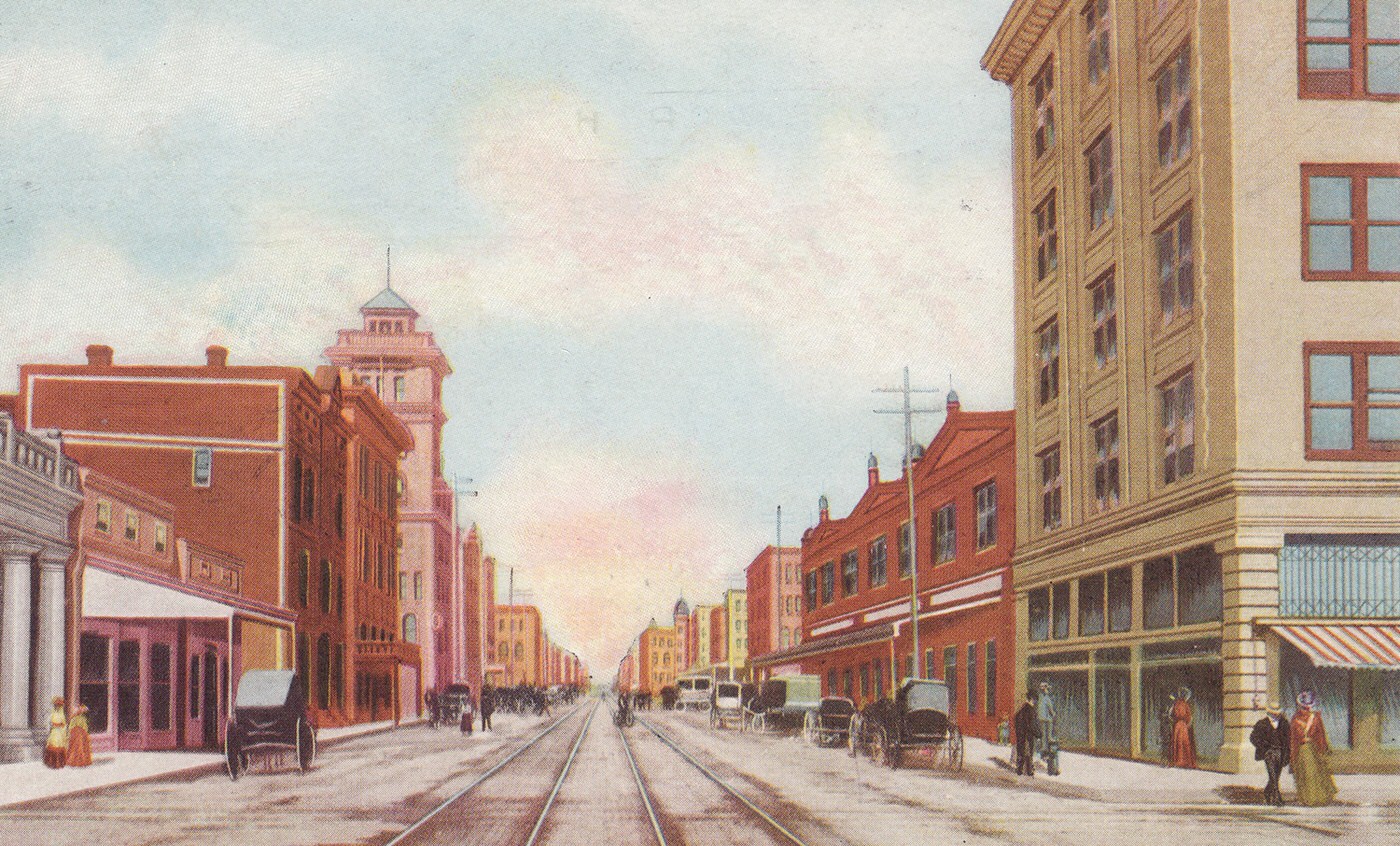

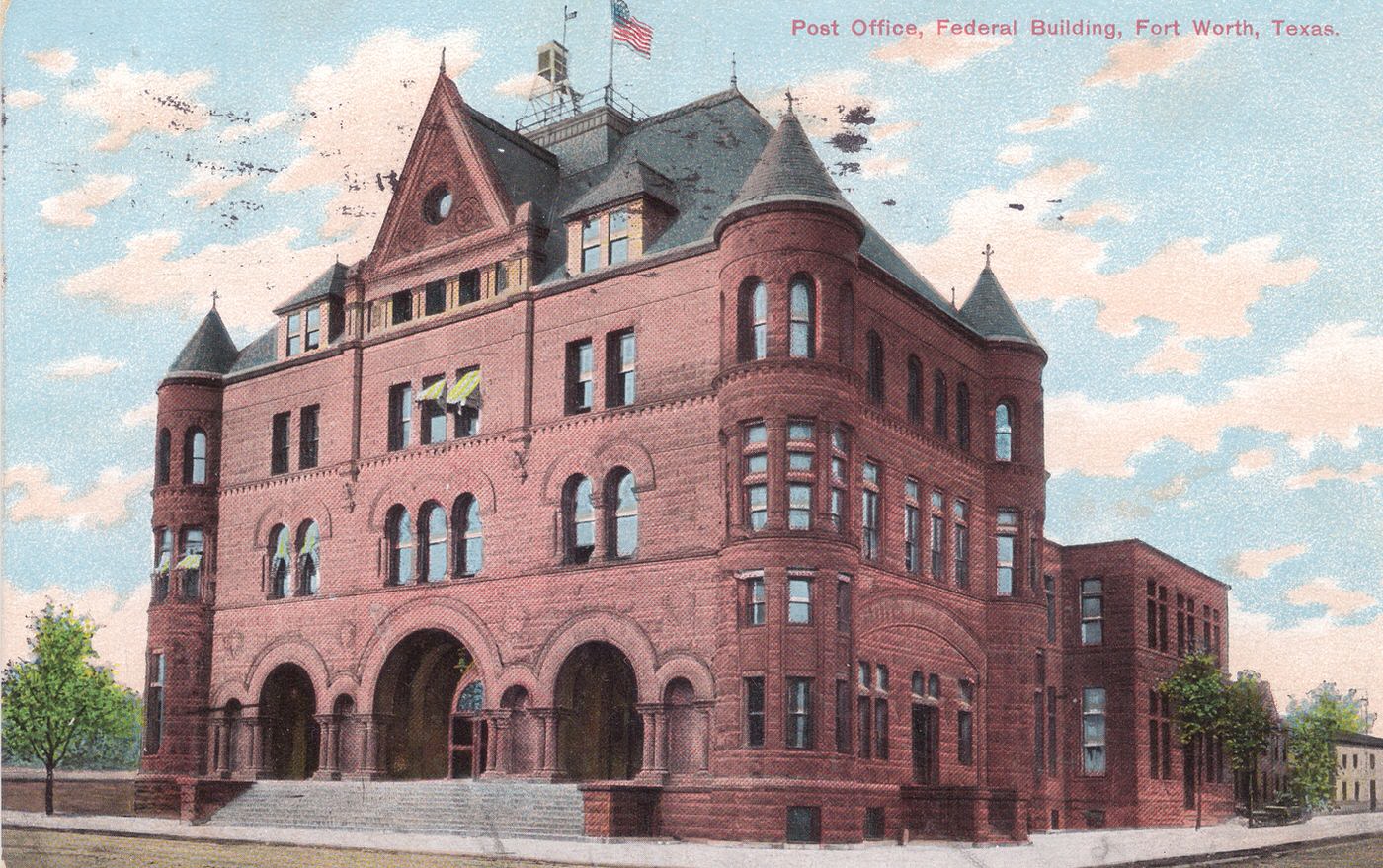

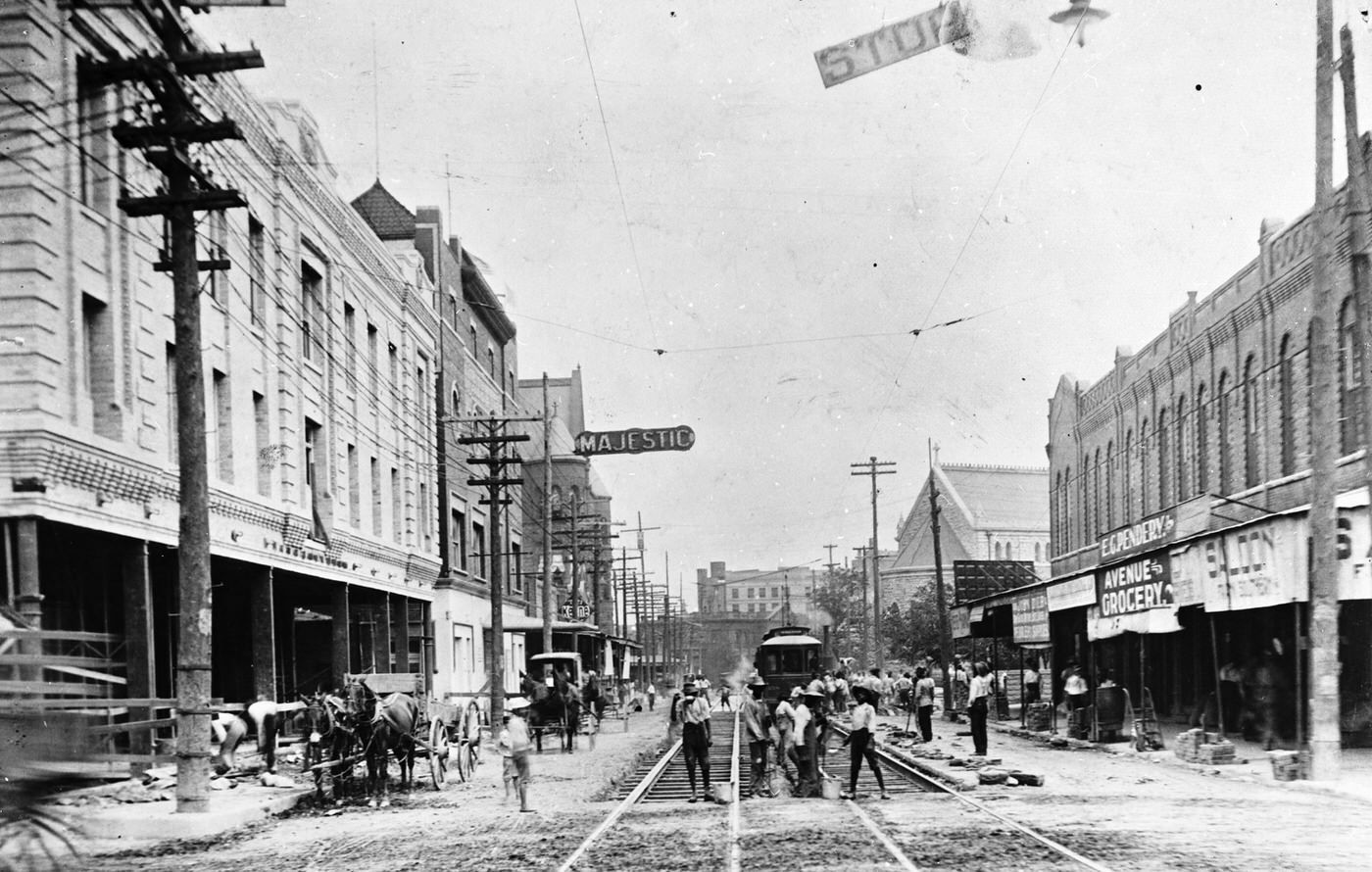

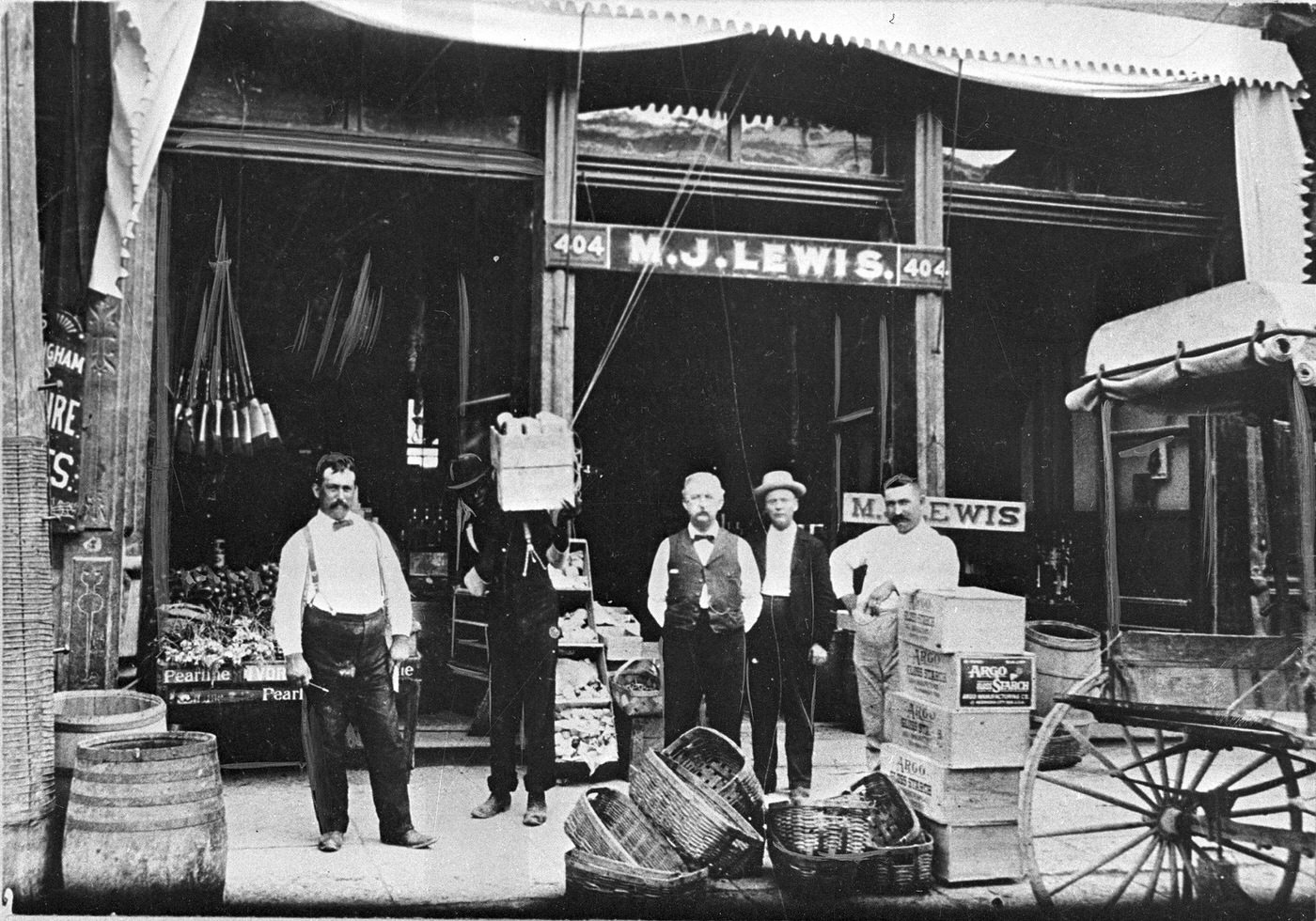

The dramatic surge in population and industry during the 1900s demanded significant upgrades to Fort Worth’s urban infrastructure. The city, which still bore hallmarks of its frontier past with unpaved streets susceptible to mud, began embracing modernization. The turn of the century saw a growing movement across Texas and the nation to improve roads, spurred by the advent of the automobile and bicycle. Brick paving became a common solution, particularly in downtown areas. Fort Worth had already taken a step in this direction by paving Main Street with Thurber brick in the late 1890s. While specific records for 1900-1909 are limited in the provided materials, it is highly probable that other key downtown thoroughfares saw brick paving during this decade to handle increased traffic and project a more modern image. Tarrant County was a leader in Texas road improvement efforts, allocating significant funds starting around 1912, indicating the growing importance placed on paved surfaces in the preceding years.

Utility systems also strained under the growth. The city had owned its waterworks since 1884, supplied by the Trinity River via the Holly Pump Station built in 1892. However, the existing system faced challenges; repairs to dams were needed as early as 1900 to prevent erosion and ensure supply. The immense population growth necessitated a more substantial solution. Planning for a major new water source, Lake Worth, likely commenced during this period, although its construction and the associated Holly Filtration Plant were completed just after the decade ended, starting around 1912-1916. Gas lighting, initially from artificial gas works established in 1876, saw a major upgrade with the formation of the Fort Worth Gas Company in 1909. This new entity began supplying natural gas to nearly 4,000 customers through a 90-mile pipeline originating in Petrolia, Texas. Electrical power, already present for streetcar operations and likely some lighting, Utility systems also strained under the growth. The city had owned its waterworks since 1884, supplied by the Trinity River via the Holly Pump Station built in 1892. However, the existing system faced challenges; repairs to dams were needed as early as 1900 to prevent erosion and ensure supply. The immense population growth necessitated a more substantial solution. Planning for a major new water source, Lake Worth, likely commenced during this period, although its construction and the associated Holly Filtration Plant were completed just after the decade ended, starting around 1912-1916. Gas lighting, initially from artificial gas works established in 1876, saw a major upgrade with the formation of the Fort Worth Gas Company in 1909. This new entity began supplying natural gas to nearly 4,000 customers through a 90-mile pipeline originating in Petrolia, Texas. Electrical power, already present for streetcar operations and likely some lighting, undoubtedly expanded to meet the demands of new industries and residences, following statewide trends of increasing electrical generation and the construction of transmission lines, though specifics for Fort Worth plants in this decade are scarce.

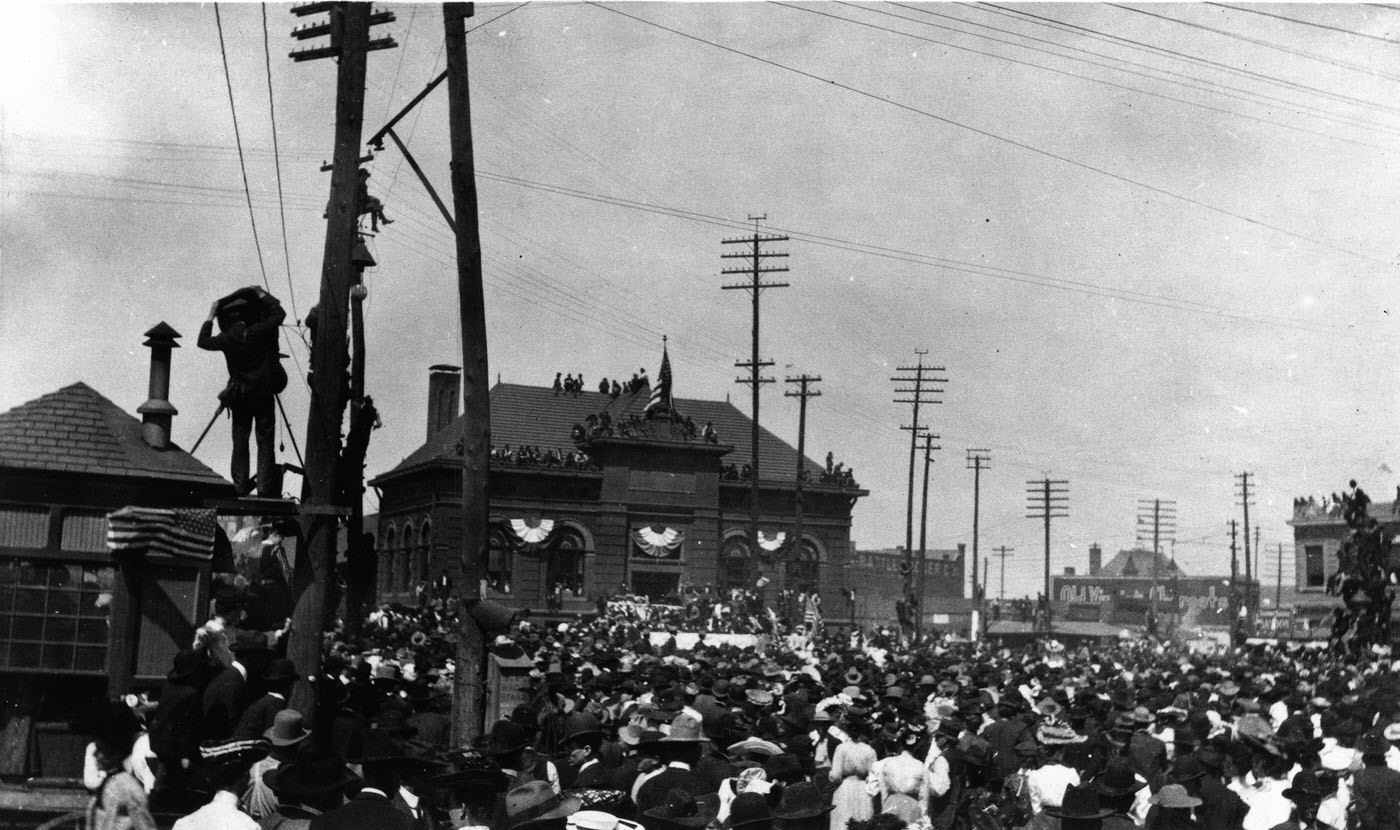

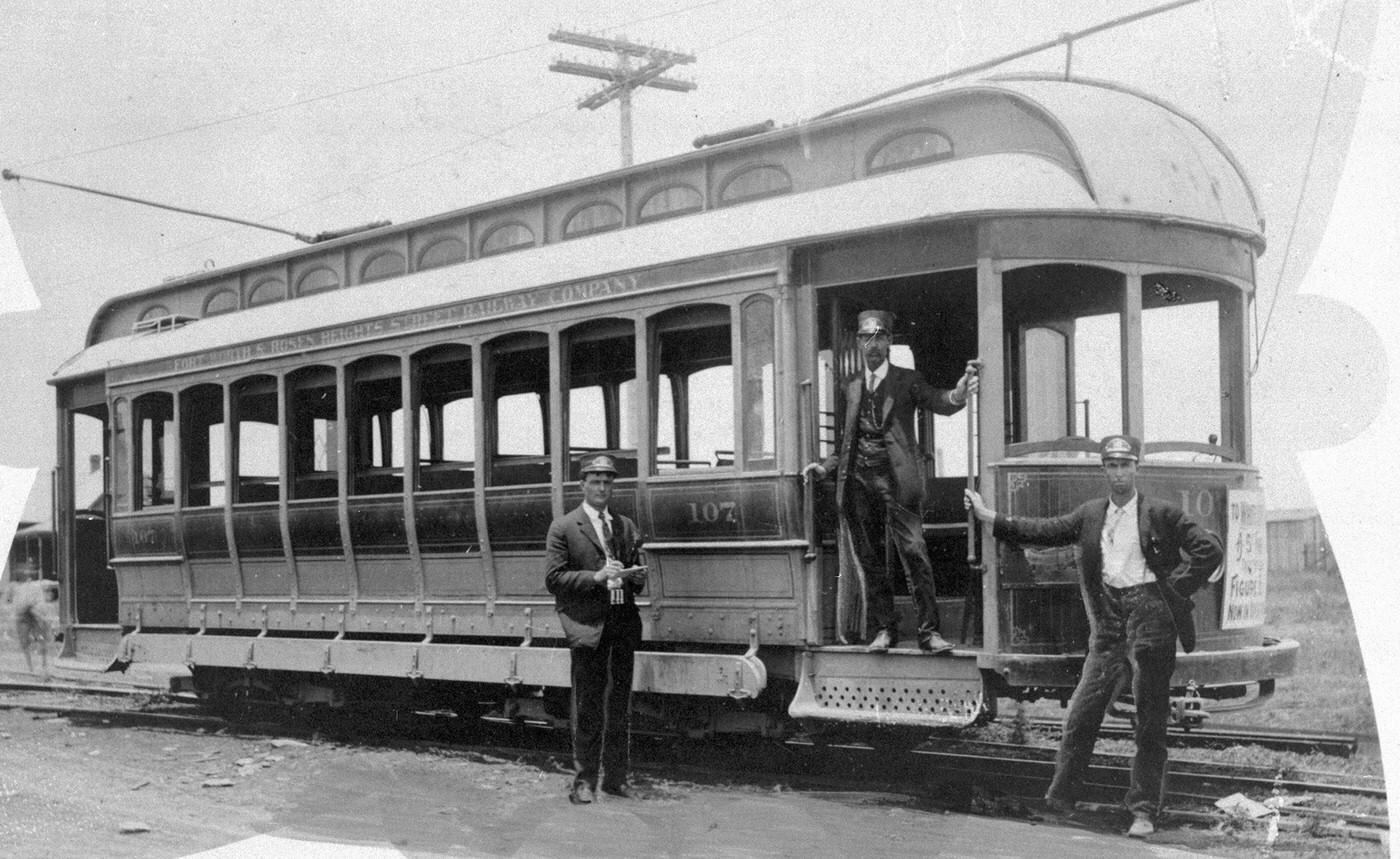

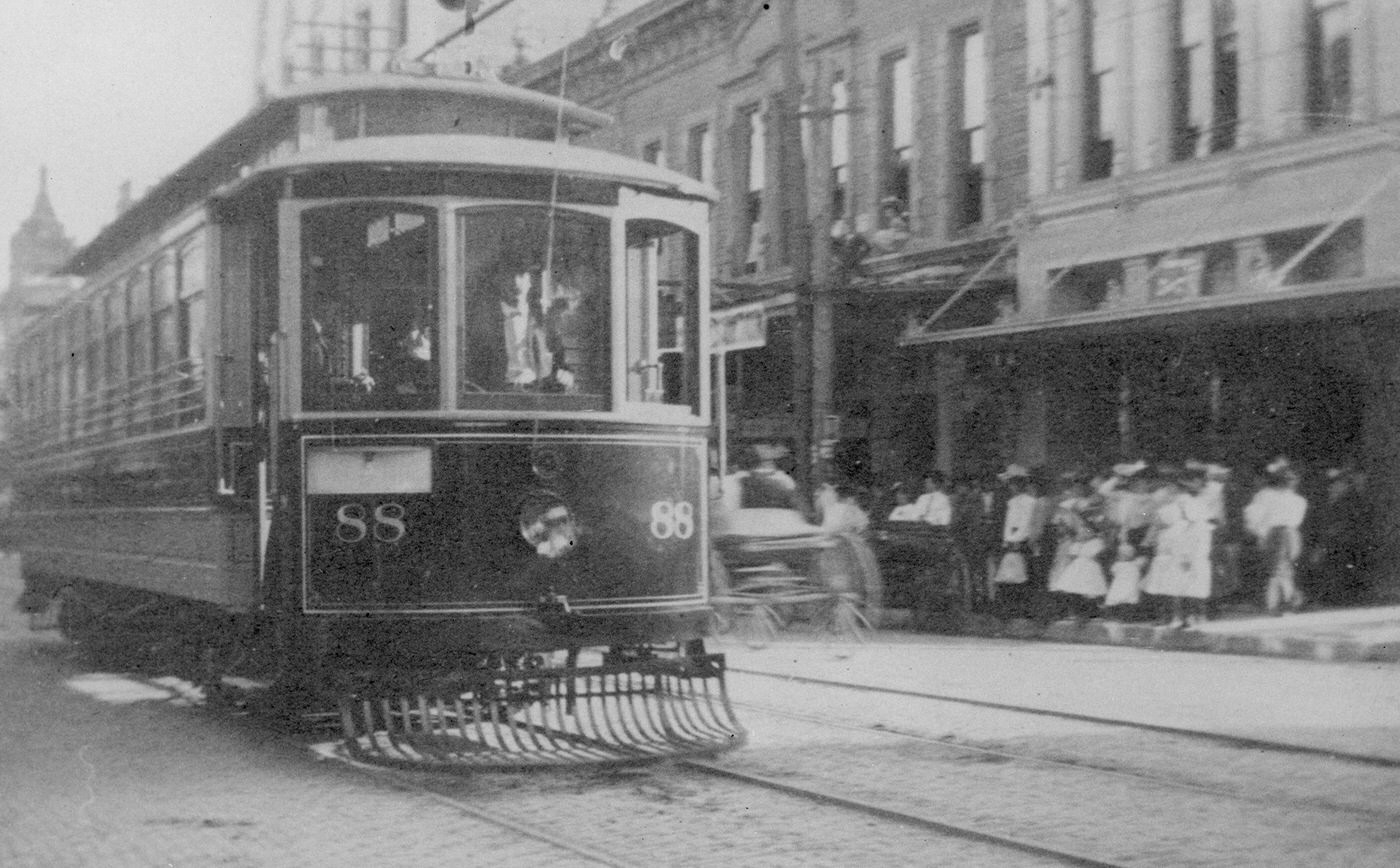

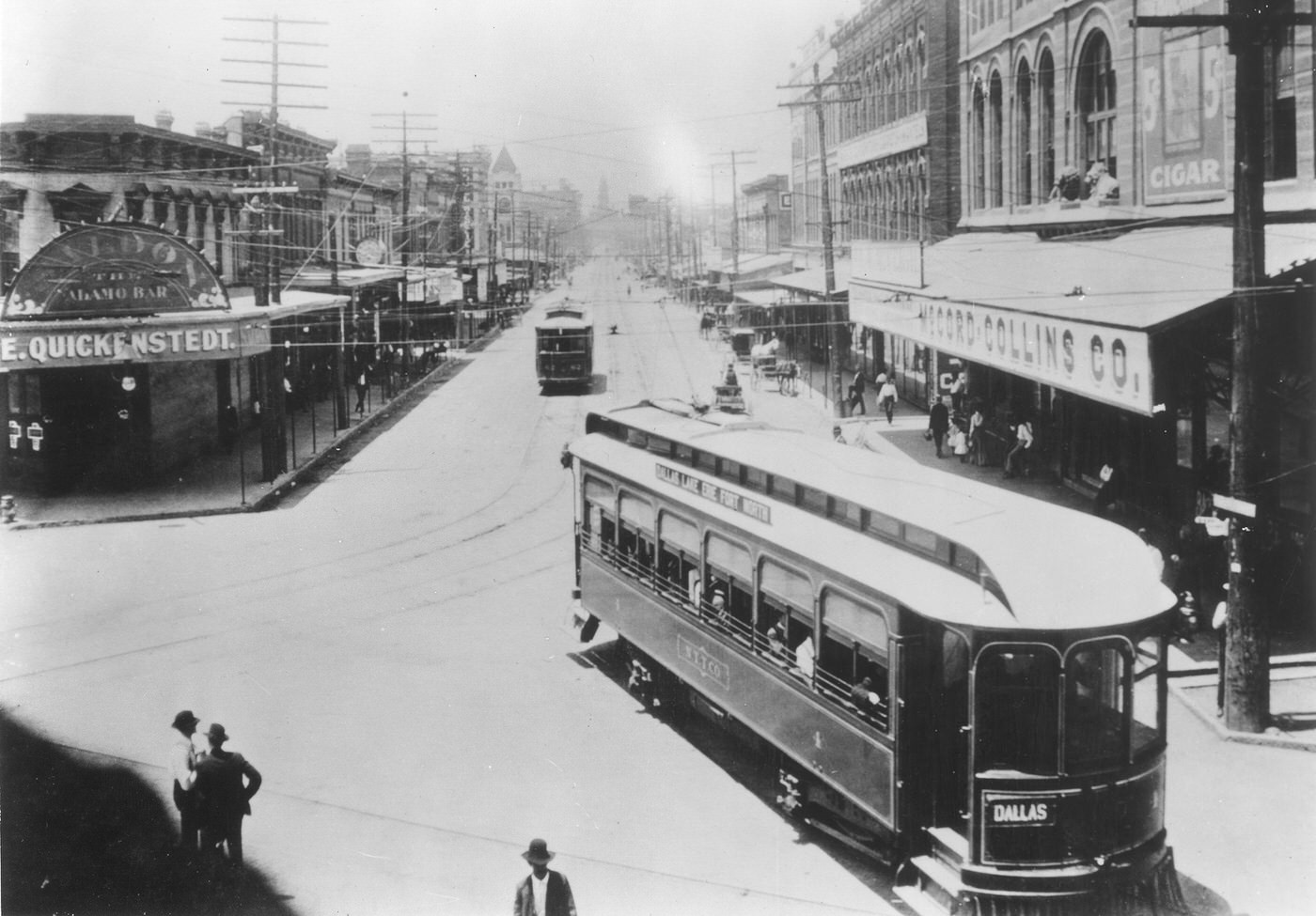

Public transportation was crucial for the expanding city. The Northern Texas Traction Company operated the local streetcar network and, significantly, launched the electric interurban line connecting Fort Worth and Dallas on July 1, 1902. This vital link facilitated regional commerce and movement. The company, acquired by the engineering firm Stone & Webster in 1905, also extended streetcar lines to serve the burgeoning industrial areas, notably providing transportation for workers to the Stockyards and packing plants. Streetcars played a key role in enabling the development of new residential areas further from the city center.

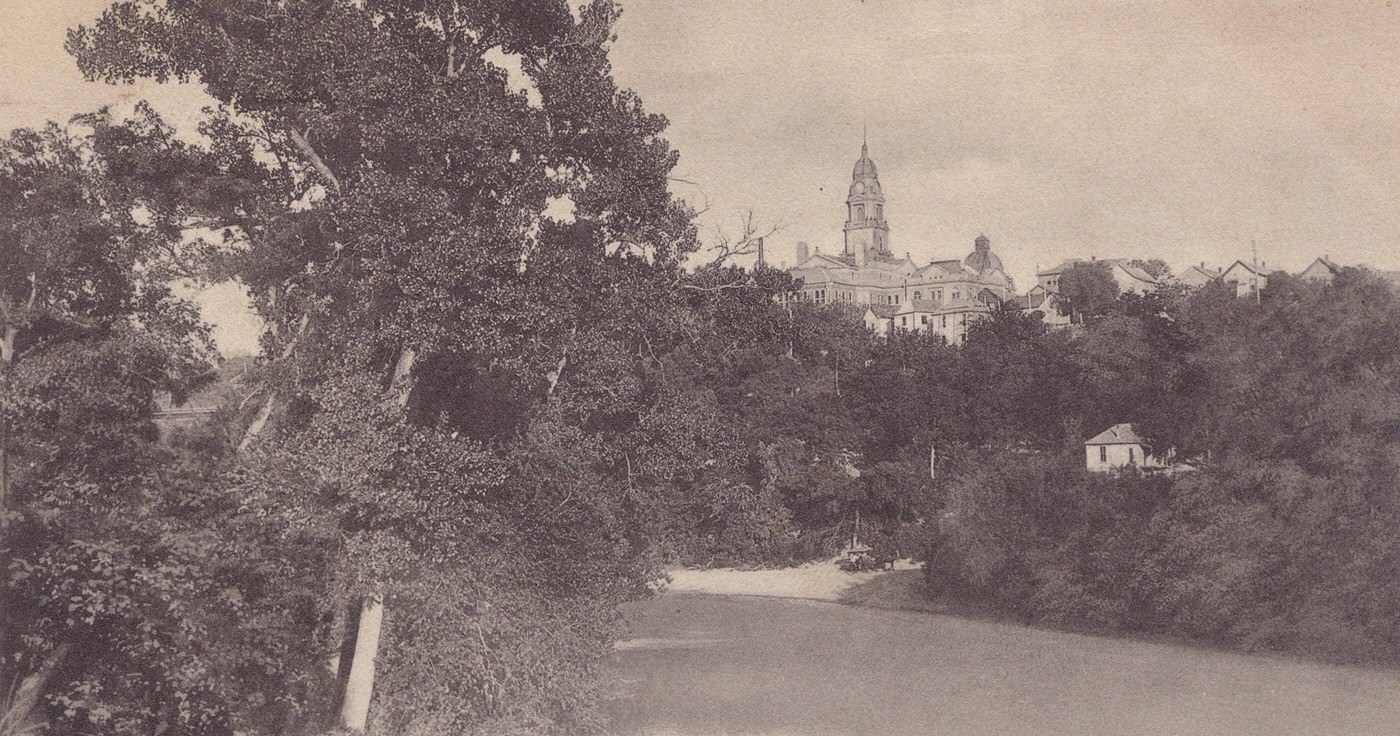

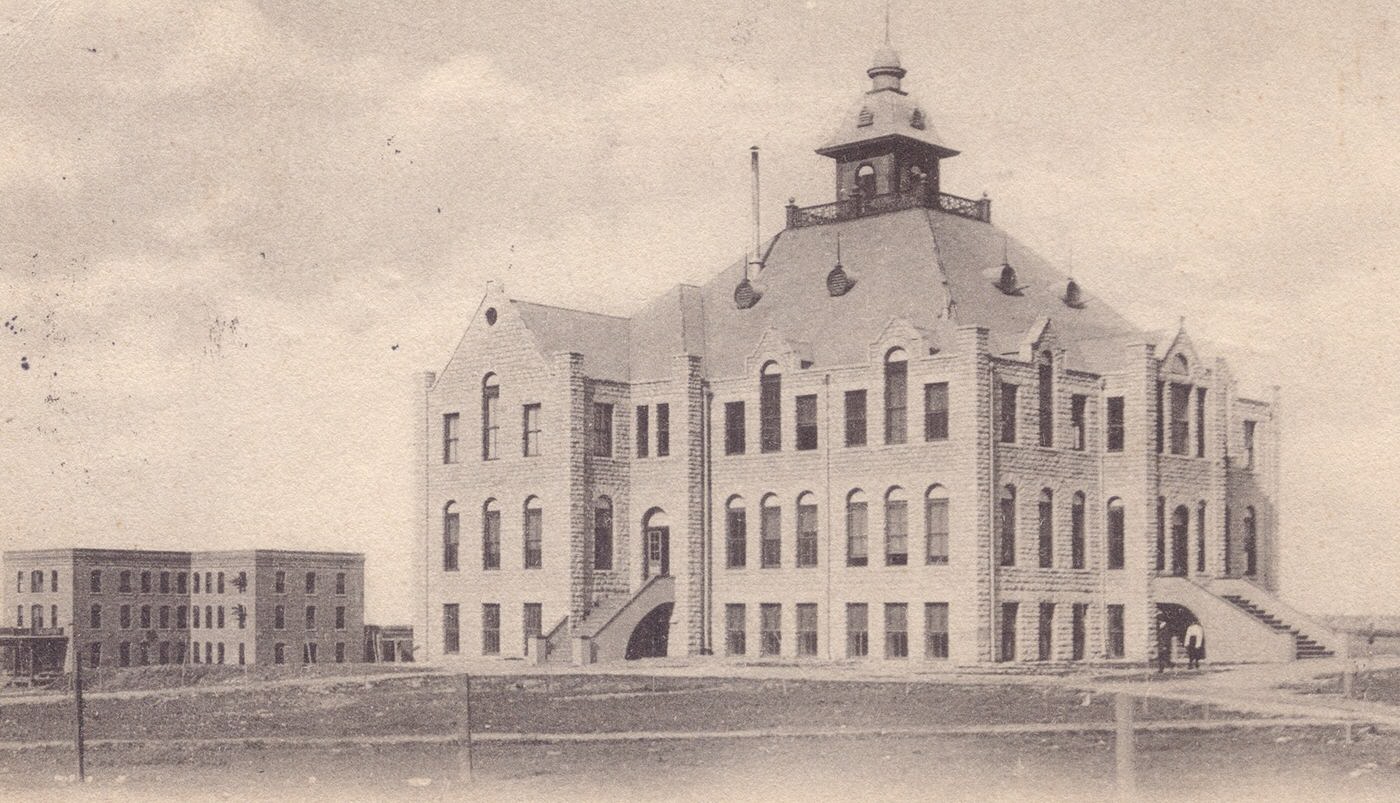

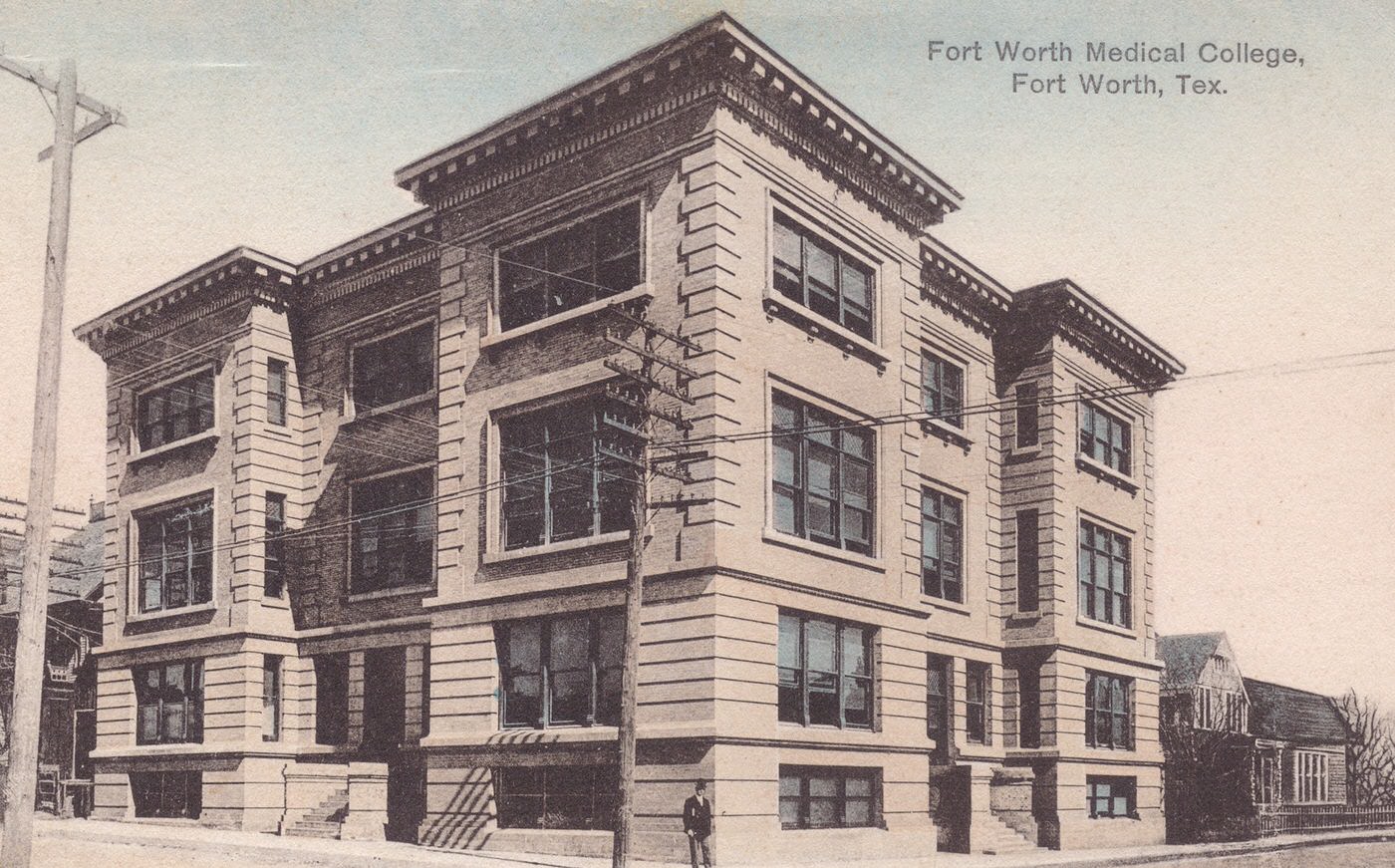

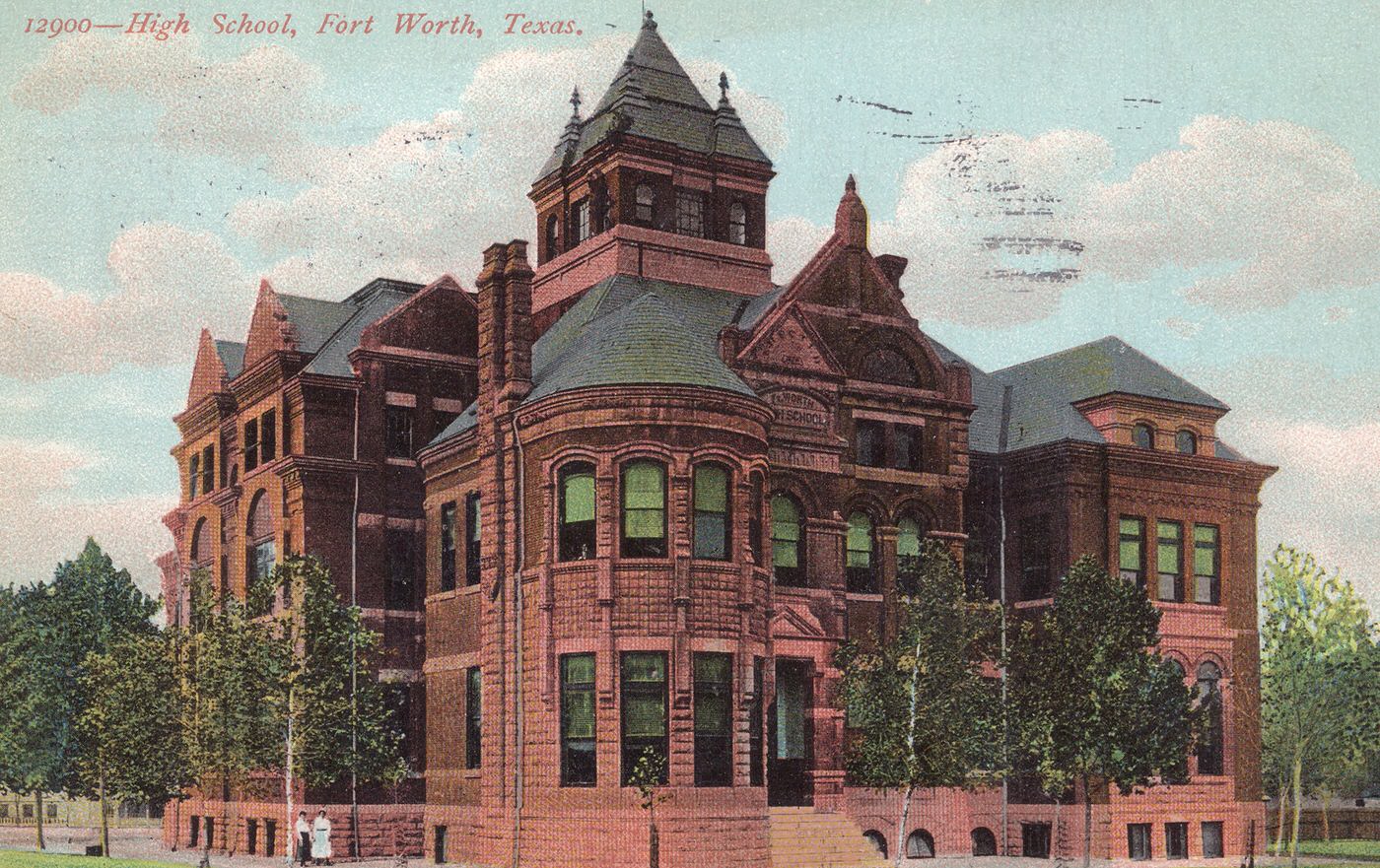

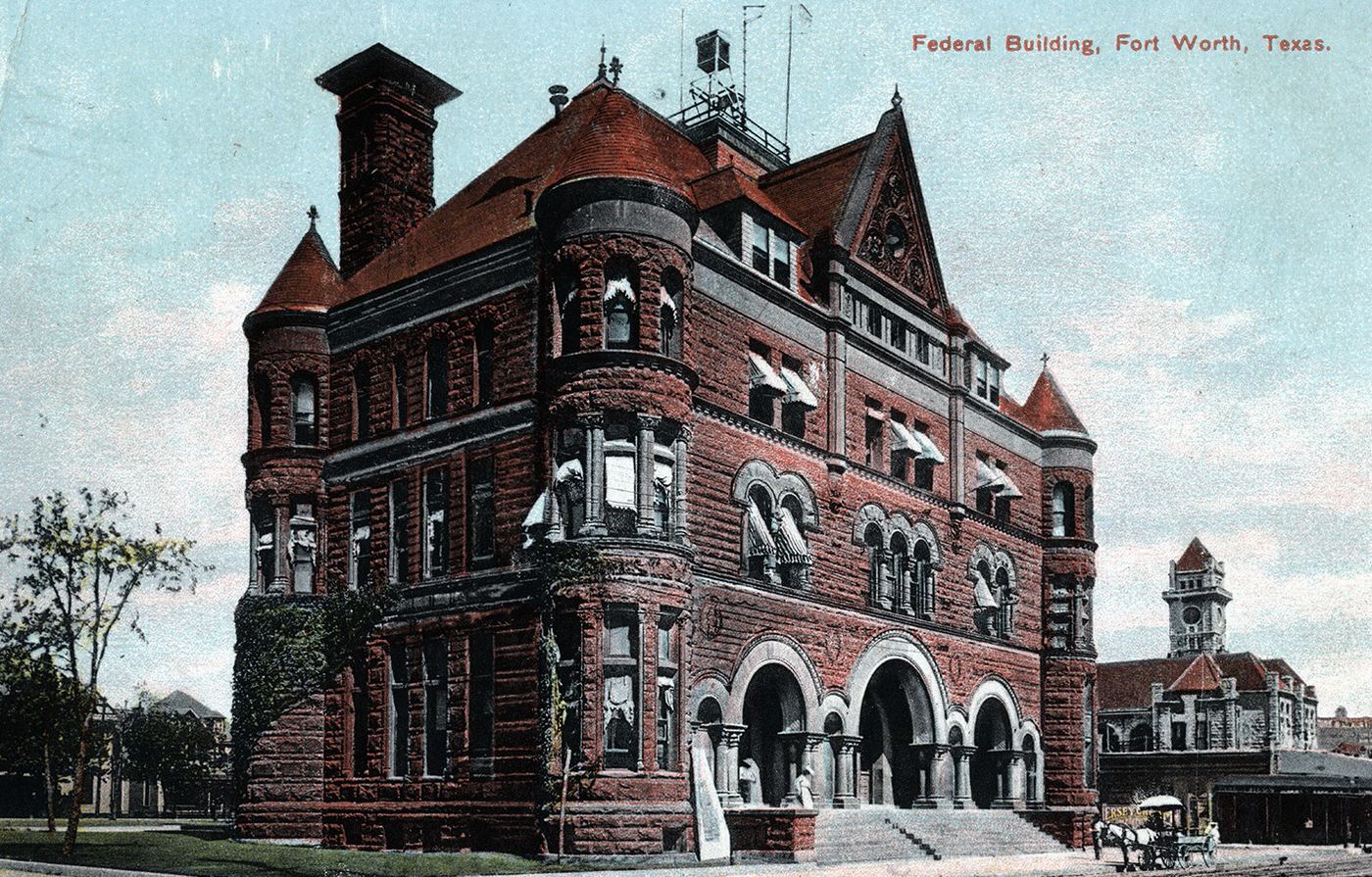

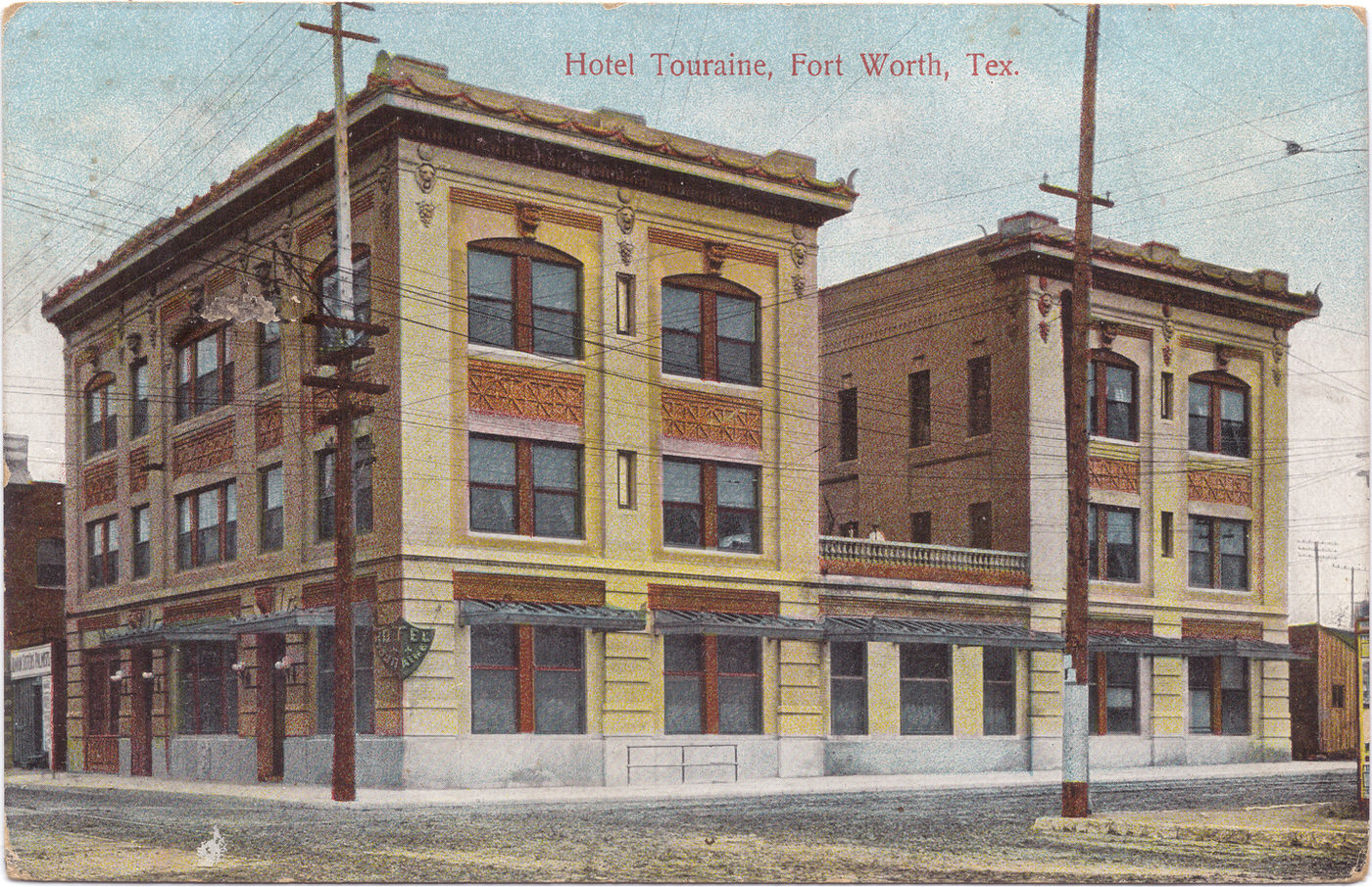

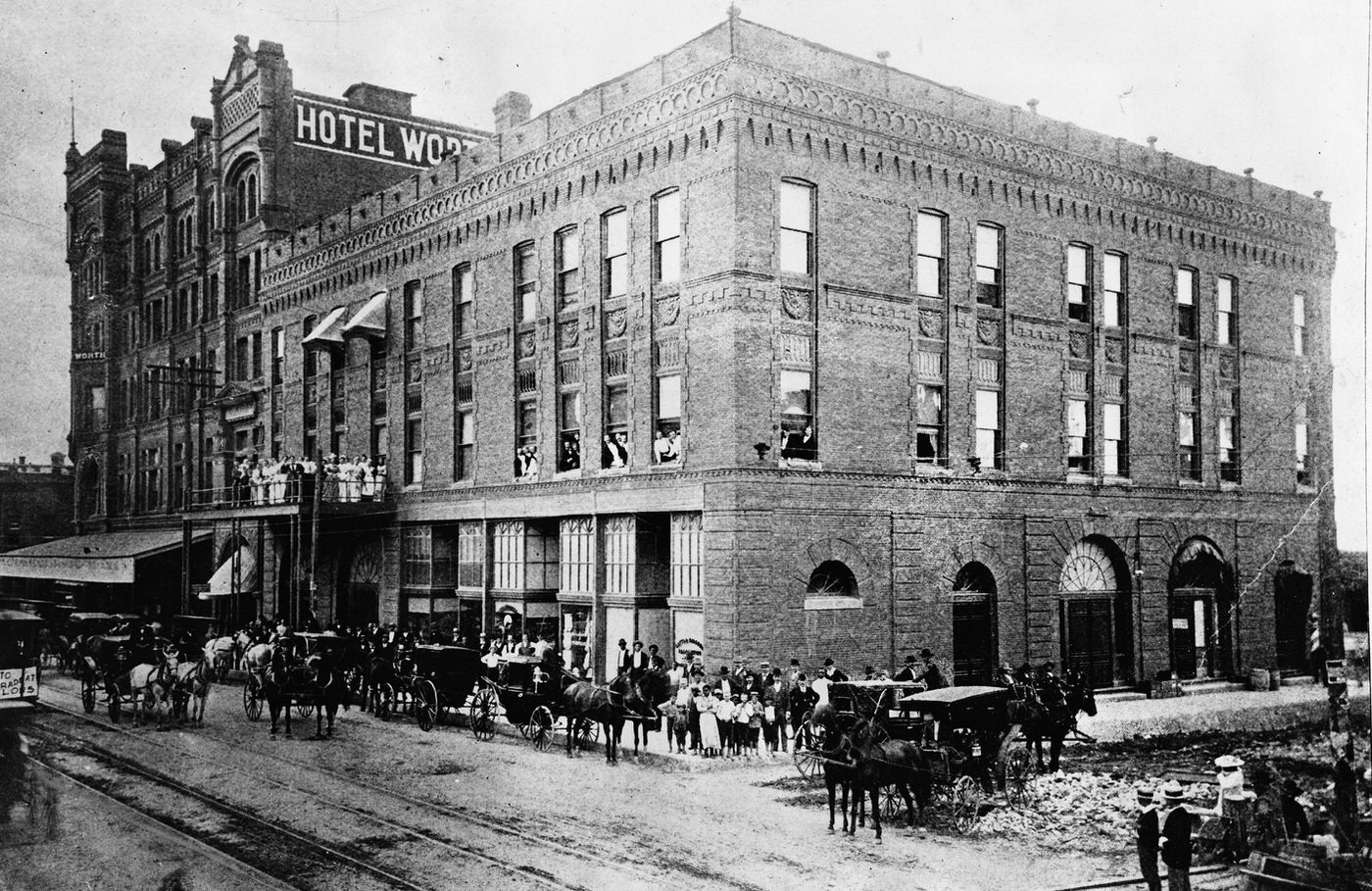

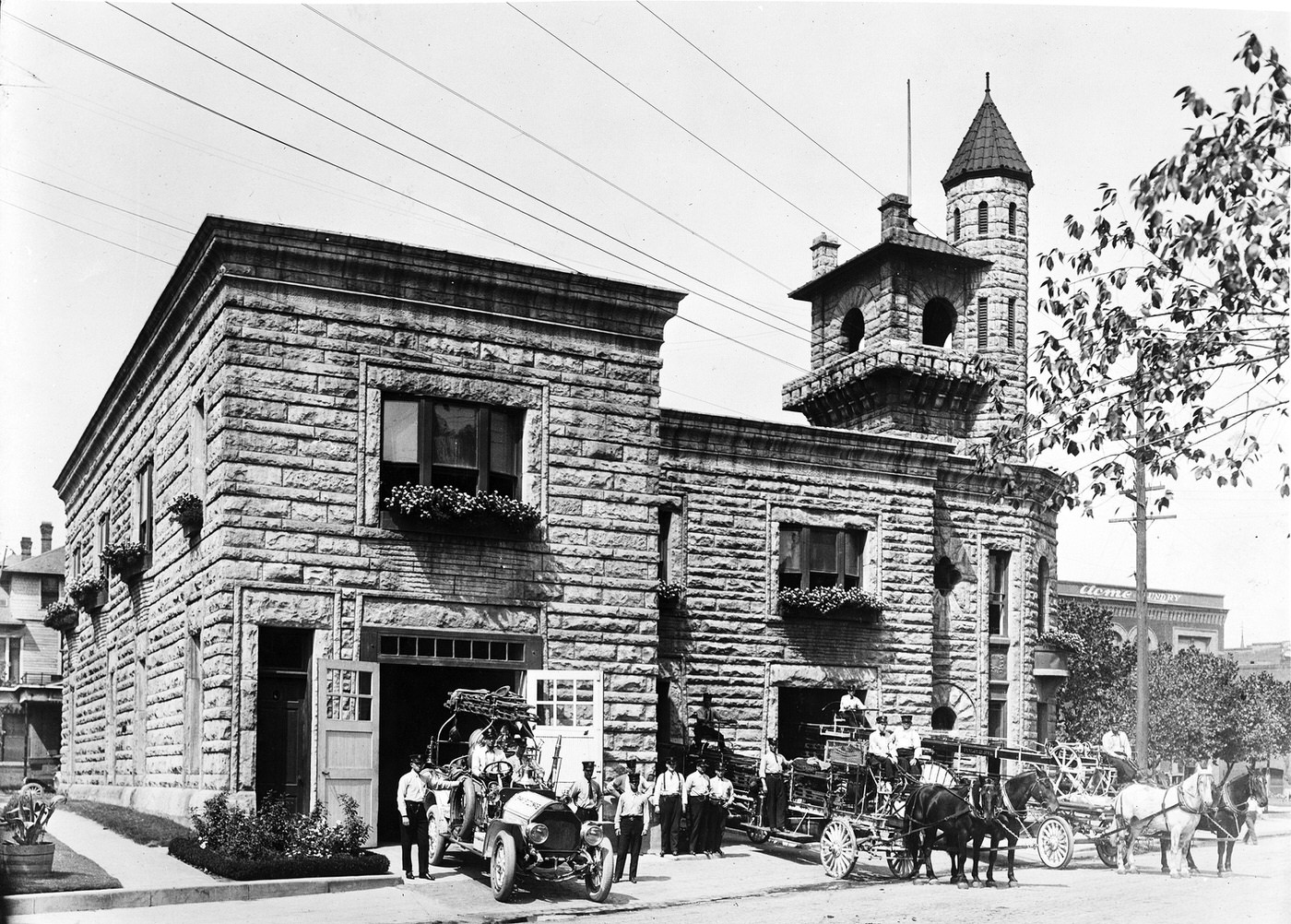

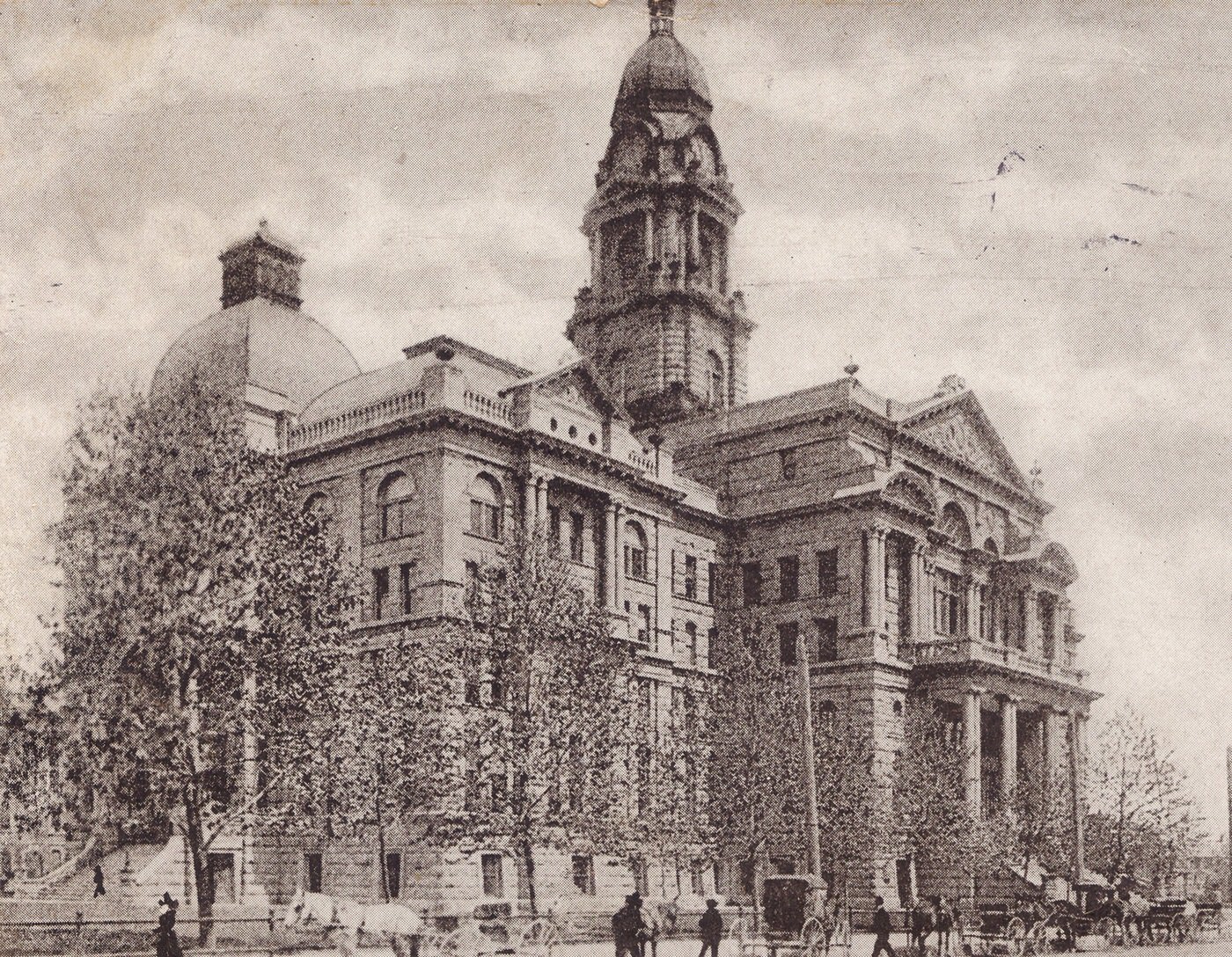

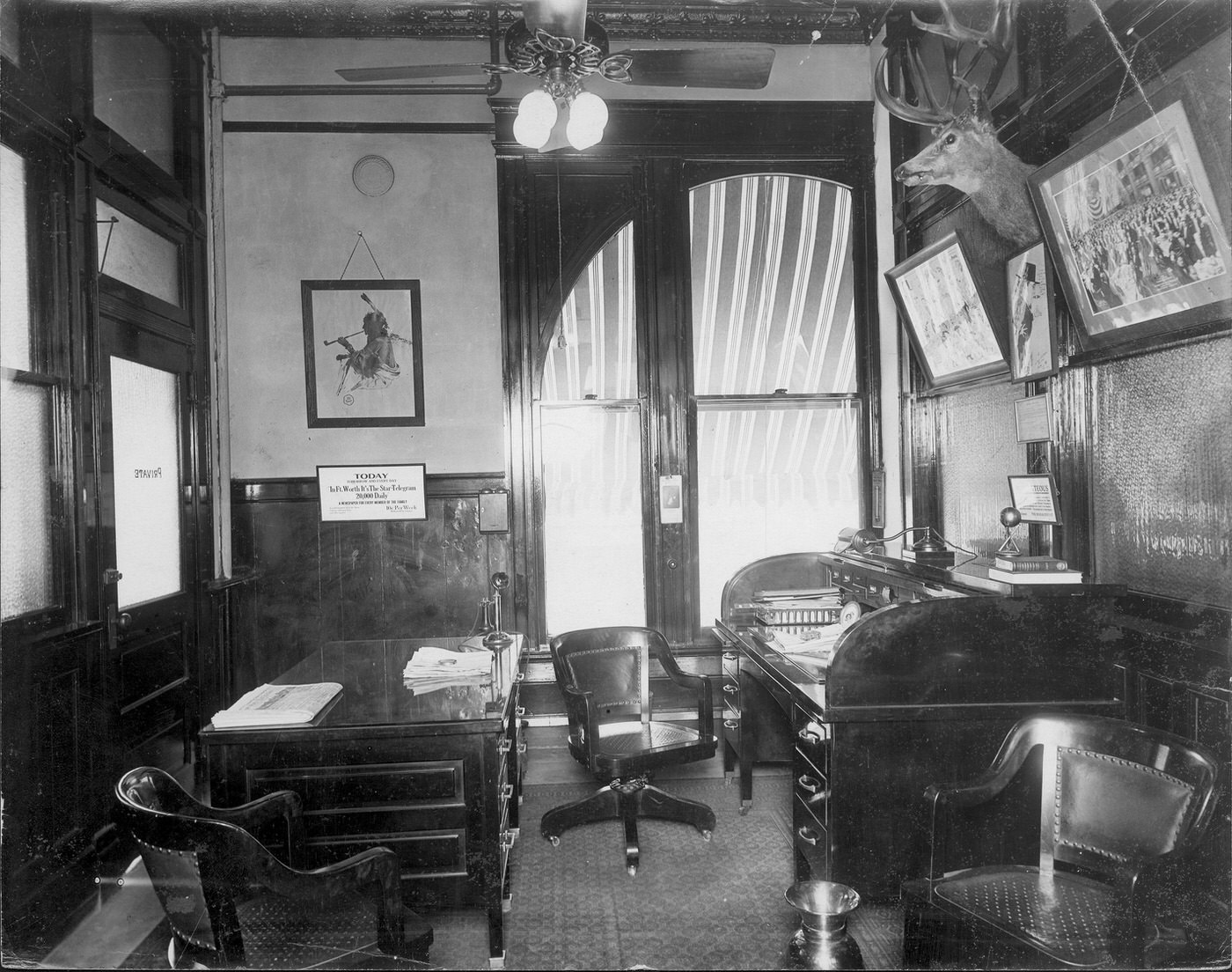

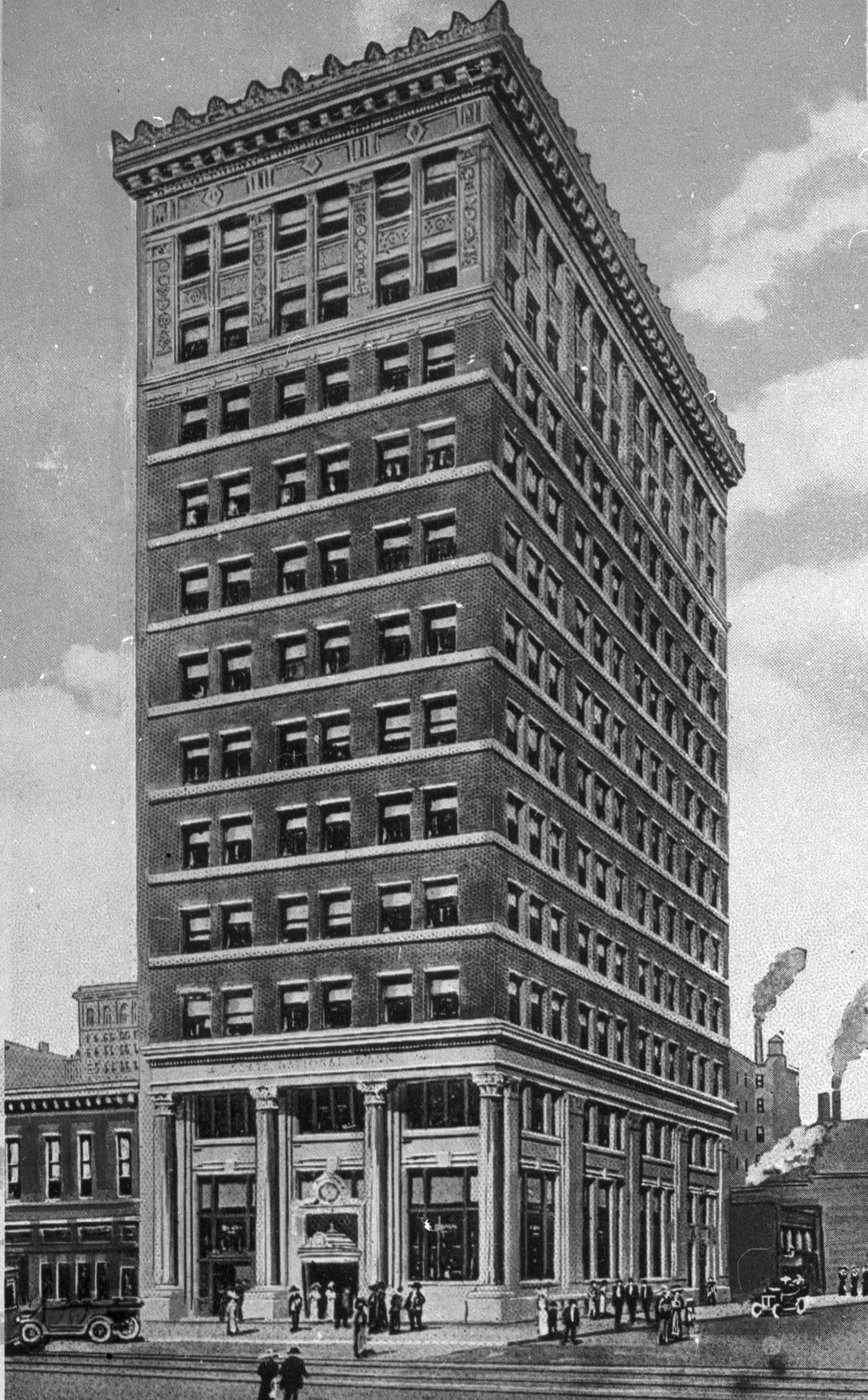

Major construction projects reshaped the city’s skyline and public spaces. While the iconic pink granite Tarrant County Courthouse was completed in 1895, it remained a dominant landmark throughout the decade. The Stockyards saw the construction of its impressive Exchange Building (1902-03) and the Cowtown Coliseum (1907-08). Recognizing the need for modern educational facilities, the city initiated a major school building program in 1909, leading immediately to the construction of the new Fort Worth High School (later Parker Middle School) starting that year. The Southwest Bell Telephone Exchange building also rose in 1909. This period of intense building and infrastructure development reflected Fort Worth’s transition from a frontier outpost relying on basic services to a rapidly modernizing city striving to meet the needs of its industrial economy and exploding population.

Taming the Wild West? Hell’s Half Acre’s Changing Face

Fort Worth’s notorious red-light district, Hell’s Half Acre, remained a fixture in the city’s landscape during the first decade of the 20th century. Around 1900, it still sprawled across a significant portion of the southern downtown area, encompassing roughly four major north-south streets (Main, Rusk/Commerce, Calhoun, Jones) from about Seventh Street down to Fifteenth Street near the Union Station depot. It continued to be known as a haven for saloons, dance halls, gambling parlors, and prostitution, an area where vice operated openly, often with the tacit acceptance of authorities more concerned with revenue than reform.

However, the Acre’s heyday as the dominant force in Fort Worth’s social and economic life was likely waning during the 1900s. Its origins were deeply tied to the Chisholm Trail cattle drives of the 1870s and 1880s, serving the thousands of cowboys passing through. With the end of the major trail drives by the mid-1880s and the rise of the Stockyards and packing plants far to the north as the city’s new economic engine, the Acre’s primary clientele and central importance diminished. Its popularity as a destination, particularly for out-of-town visitors, began to decline.

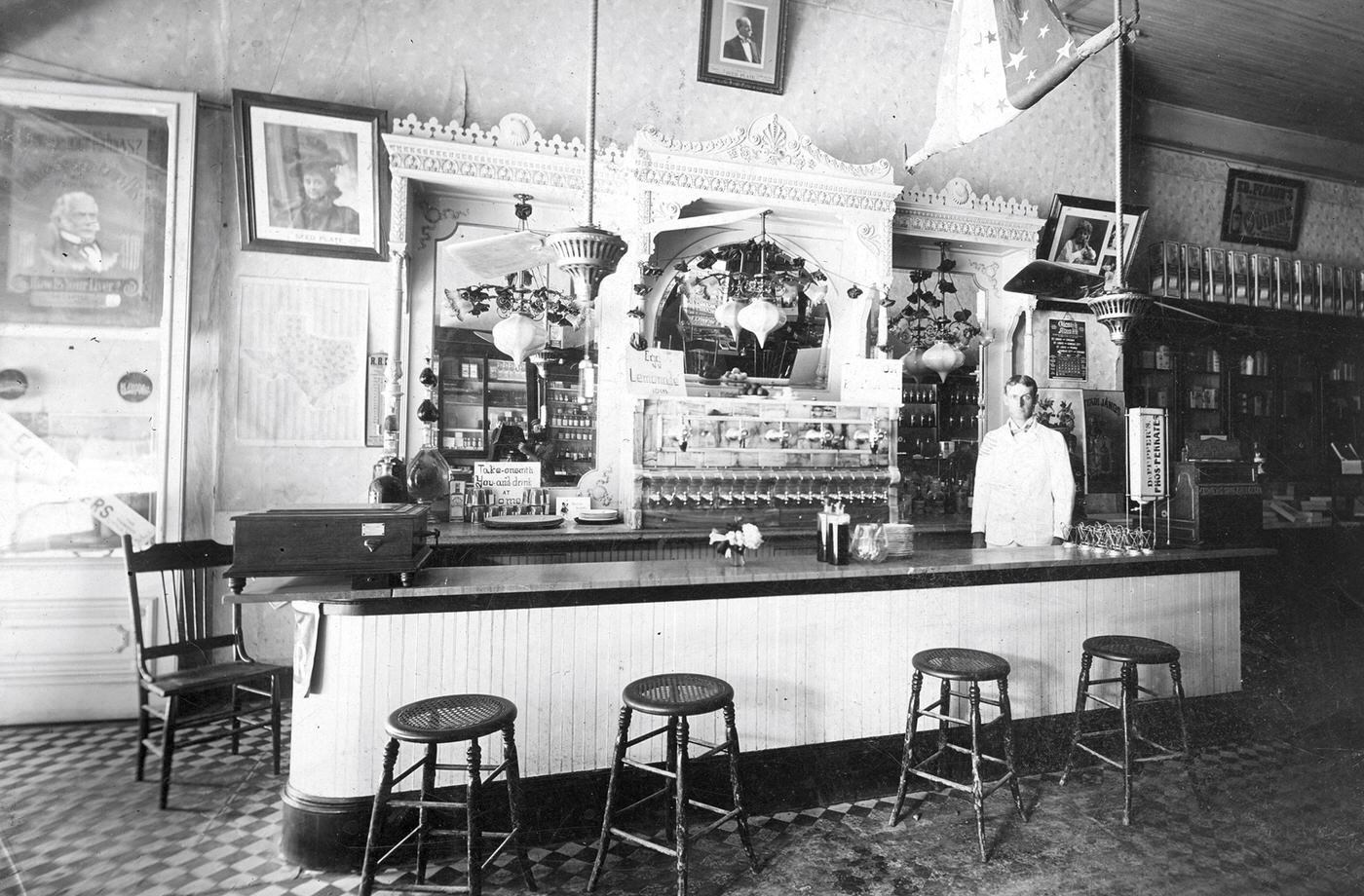

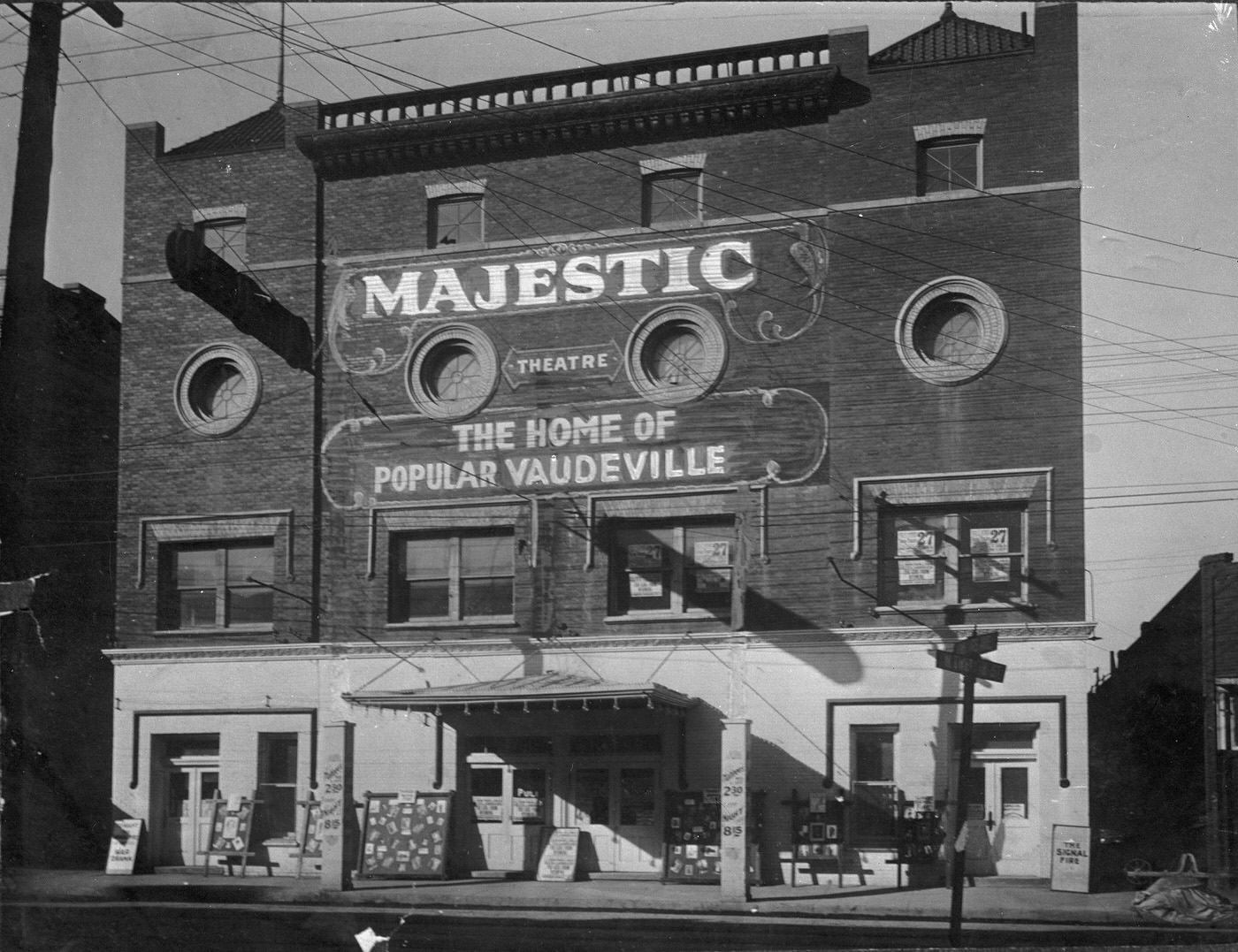

The character of the district likely shifted as well. While still a center for vice, the focus may have moved from the boisterous cowboy carousing of earlier decades towards cheaper variety shows and more entrenched, perhaps grimmer, forms of prostitution and gambling. Though famous figures of the Old West like Bat Masterson, Doc Holliday, and Wyatt Earp had frequented the Acre in the 1880s, its connection to that frontier era was fading. The famous White Elephant Saloon, technically located just outside the traditional boundaries, remained a noted establishment.

Reform efforts, which had gained momentum in the late 1880s following violent incidents like the 1887 shootout between former marshal Jim Courtright and gambler Luke Short, continued to exert pressure. An 1889 prohibition campaign had already targeted the district’s worst excesses. The rise of the Progressive Era in the early 20th century brought a renewed focus on civic morality and order nationwide, and Fort Worth was no exception. While the final closure of the Acre wouldn’t occur until the World War I era, driven by a combination of local reformers and federal pressure related to nearby military training camps, the decade from 1900 to 1909 was a period of continued scrutiny and likely gradual transformation. Hell’s Half Acre in these years embodied the tension between Fort Worth’s lingering, often romanticized, frontier past and its accelerating drive towards becoming a modern, industrialized city. Its slow decline reflected broader economic shifts, the cumulative impact of past reforms, and the growing influence of Progressive social values.

New Rules for a New Era: Adopting Commission Government (1907)

As Fort Worth grappled with the complexities of rapid growth, industrialization, and modernization, its system of municipal governance underwent a fundamental change. In 1907, the city abandoned the traditional Mayor-Council form of government, which had been in place since its incorporation in 1873. Under the old system, aldermen were elected to represent specific geographic wards within the city. This structure was replaced by the Commission form of government.

The Commission model, a hallmark of the Progressive Era municipal reform movement, involved electing a small number of commissioners (typically 3 to 9) on a city-wide, at-large basis. Each elected commissioner was assigned responsibility for overseeing a specific municipal department, such as streets, public safety, or finance. Crucially, these commissioners collectively held both legislative power (passing ordinances) and executive authority (running their departments), effectively merging these functions and eliminating the traditional separation of powers seen in the Mayor-Council system.

Fort Worth’s adoption of this system was part of a broader trend, particularly in Texas. The movement gained significant traction after Galveston implemented a commission government in 1901 as an emergency measure to rebuild following the devastating hurricane of 1900. Its perceived success in efficiently managing the crisis inspired other cities. Houston adopted the plan in 1905, and in 1907, Fort Worth joined Dallas, El Paso, and others in embracing what became known as the “Texas Idea”. Proponents, often including business groups and civic reformers, championed the commission form as a more efficient, expert-driven, and business-like approach to city management, intending to overcome the perceived inefficiency, parochialism, and potential corruption of ward-based politics.

The timing of Fort Worth’s switch in 1907 strongly suggests it was a direct response to the immense pressures generated by the preceding years of explosive growth. The tripling of the population between 1900 and 1910, the arrival of massive industries like the packing plants, and the corresponding need for large-scale infrastructure development (water, paving, utilities) likely overwhelmed the capacities of the older Mayor-Council structure. The Commission form, with its promise of specialized departmental oversight by elected officials and potentially faster decision-making, appeared better suited to the challenges of managing a rapidly expanding and industrializing urban center. It represented a deliberate attempt to modernize the city’s political machinery to match its transformed economic and demographic reality.

Daily Life in a Decade of Change

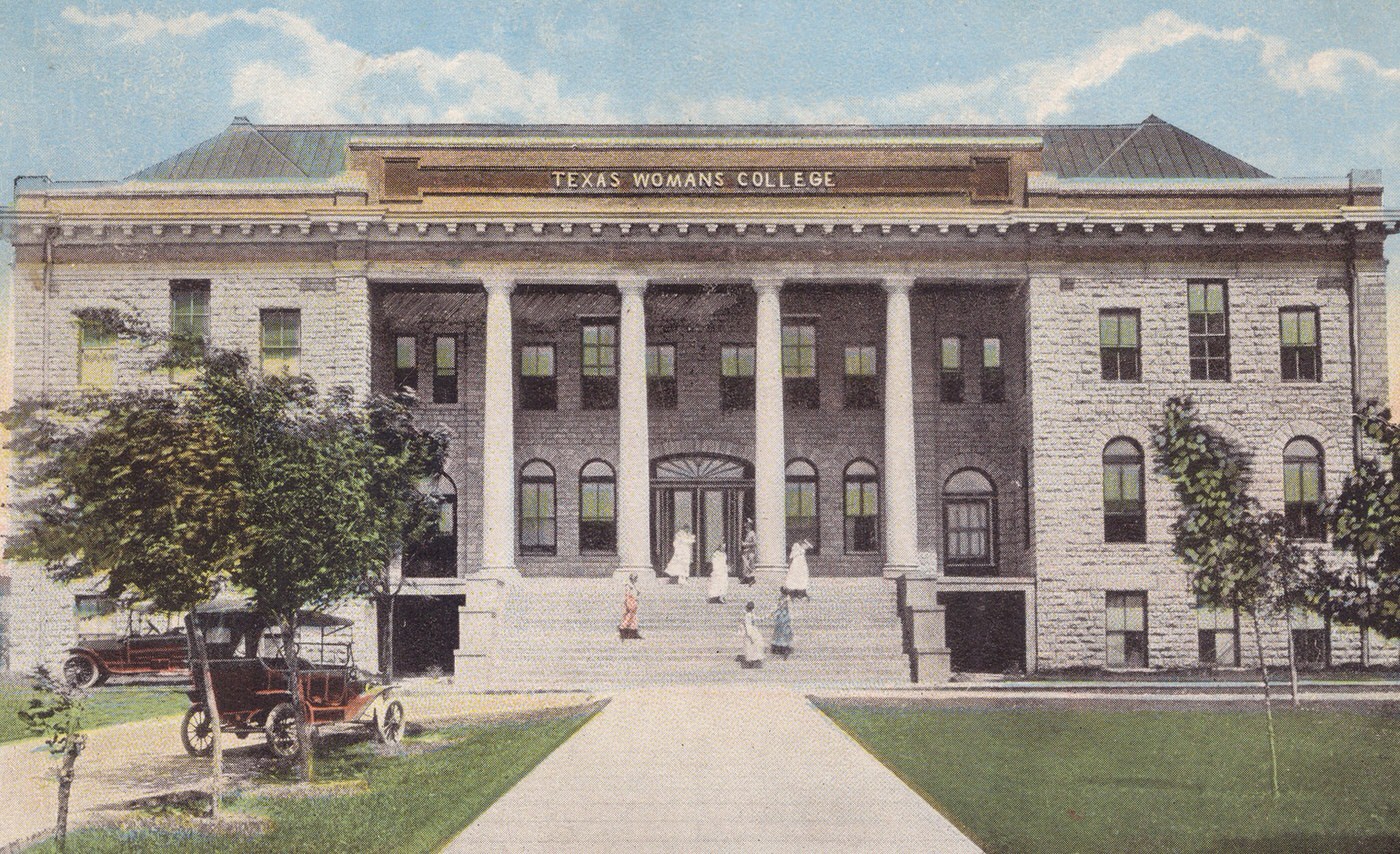

Beyond the dramatic economic and political shifts, the first decade of the 20th century reshaped the everyday lives and social fabric of Fort Worth. The sheer influx of people necessitated a rapid expansion of public services, particularly education. The Fort Worth Independent School District, officially established in 1882 after considerable struggle, faced immense pressure to accommodate the growing student population. By 1909, the city recognized the need for modern, fireproof school buildings and initiated a major construction program funded by a $450,000 bond issue. This program immediately led to the planning and construction of a new, grand Fort Worth High School (later Parker Middle School) on Jennings Avenue, designed in the Classical Revival style, beginning in 1909-1910. This investment reflected a growing commitment to public education and likely incorporated modern pedagogical approaches, possibly including vocational training like manual arts and domestic science, which had been part of the curriculum earlier. As was standard across Texas at the time, schools remained segregated by race.

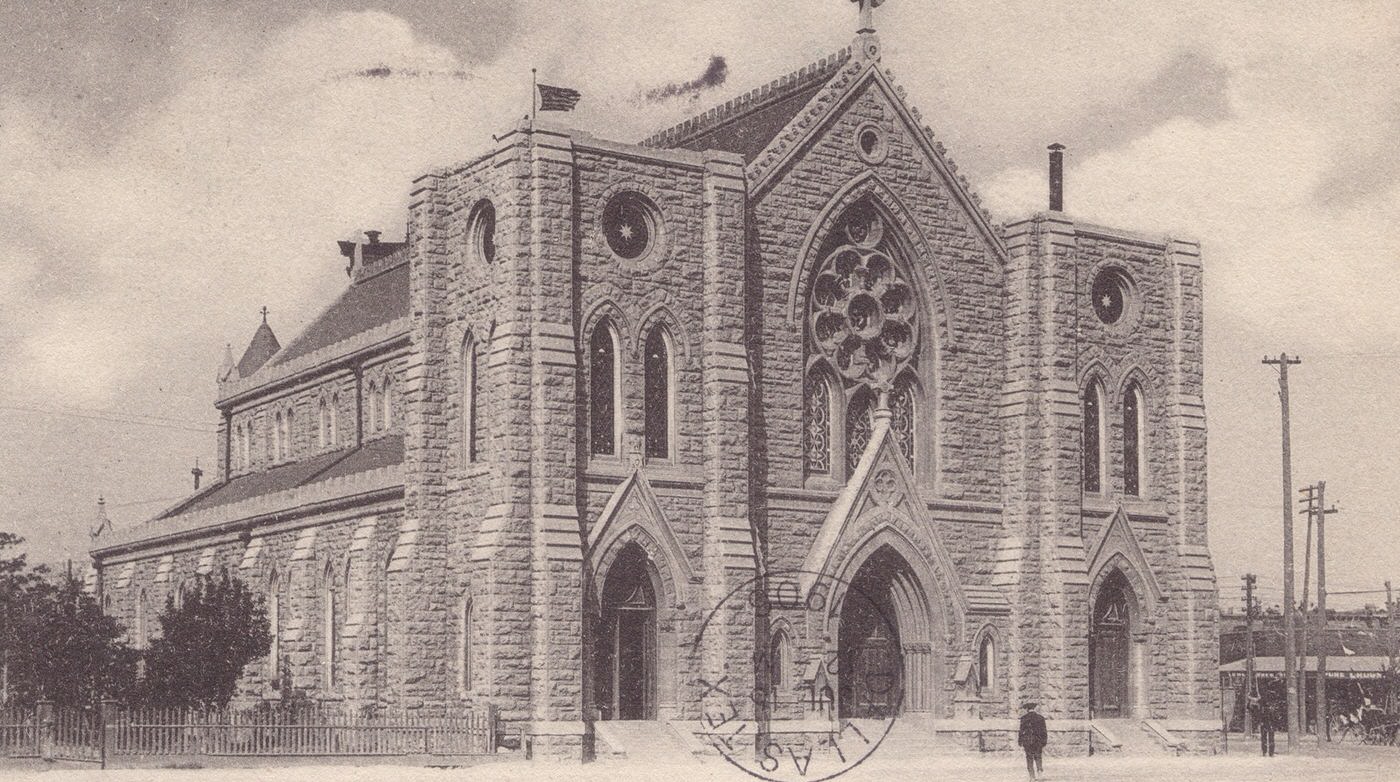

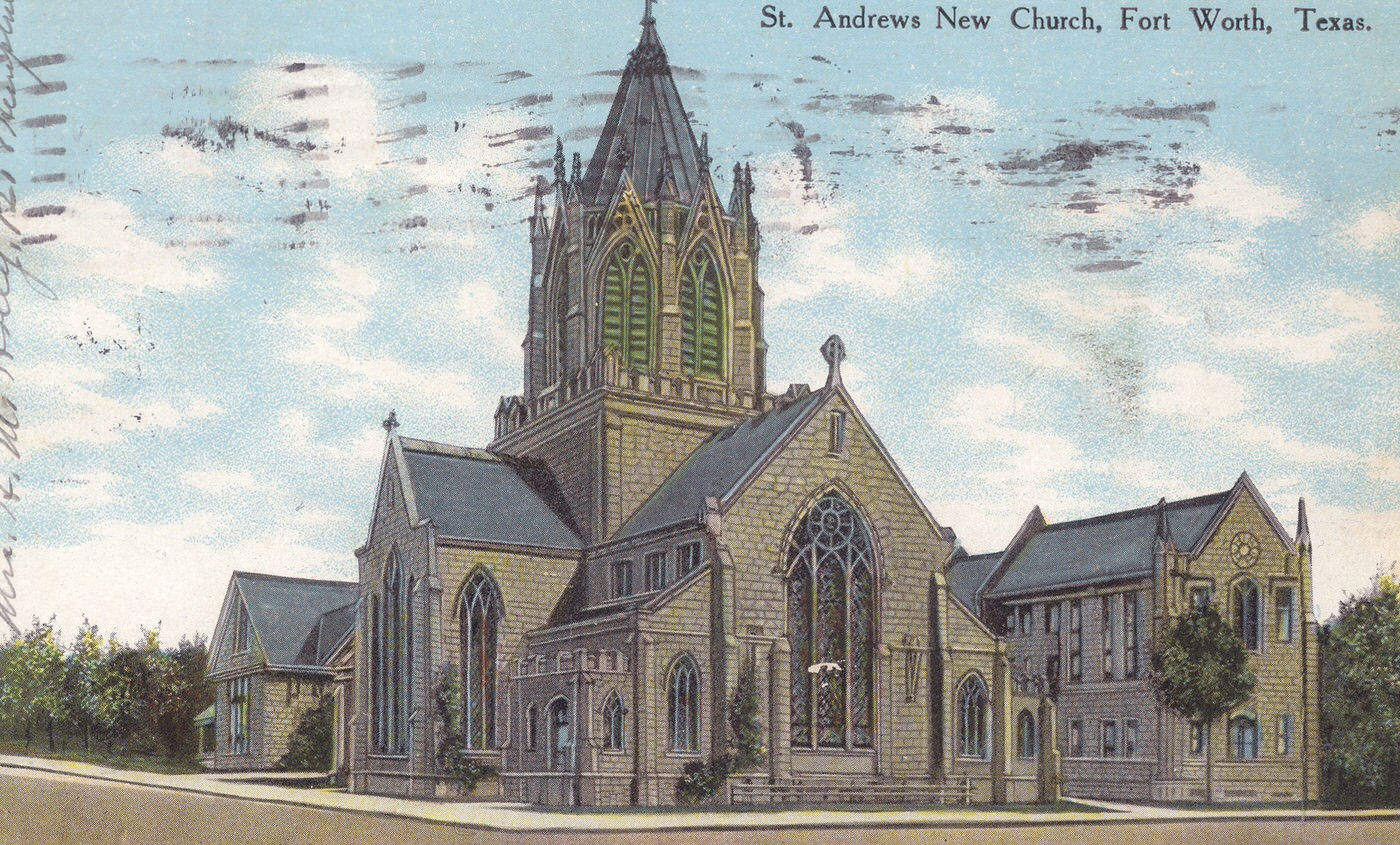

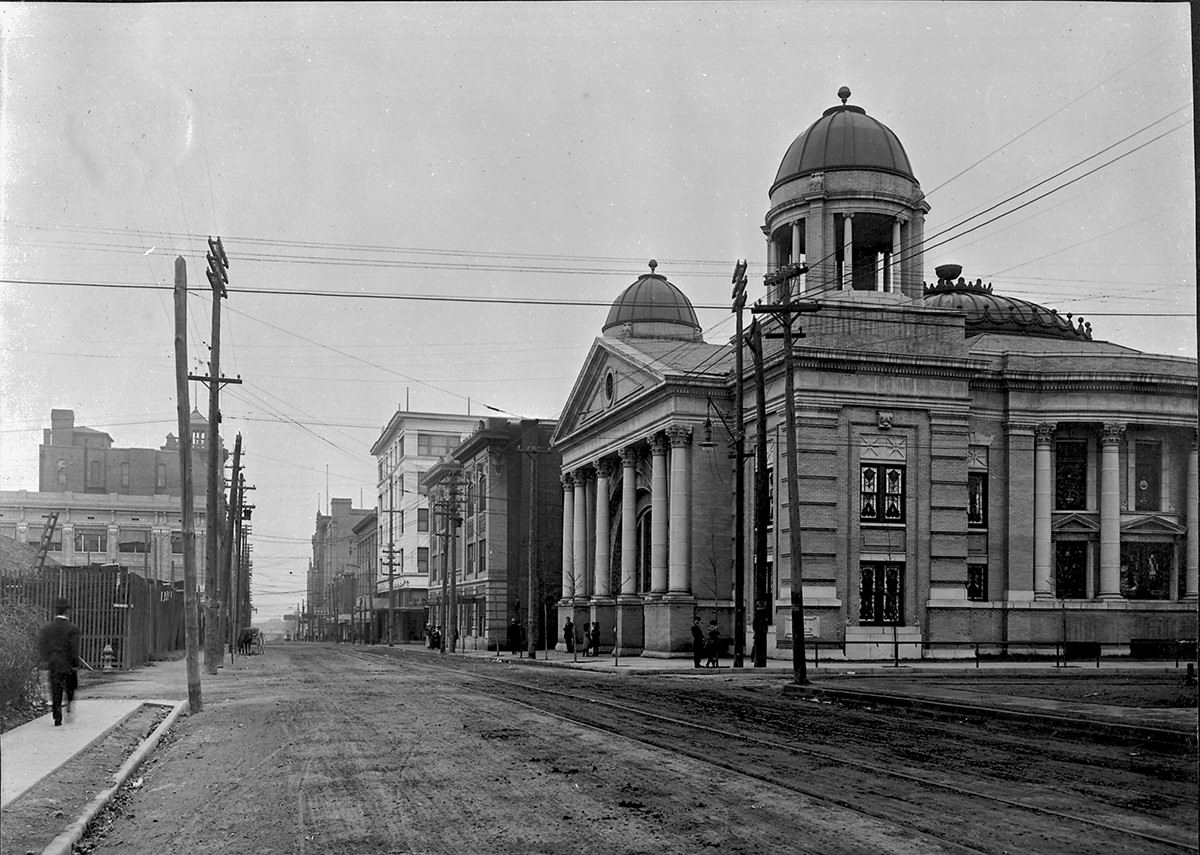

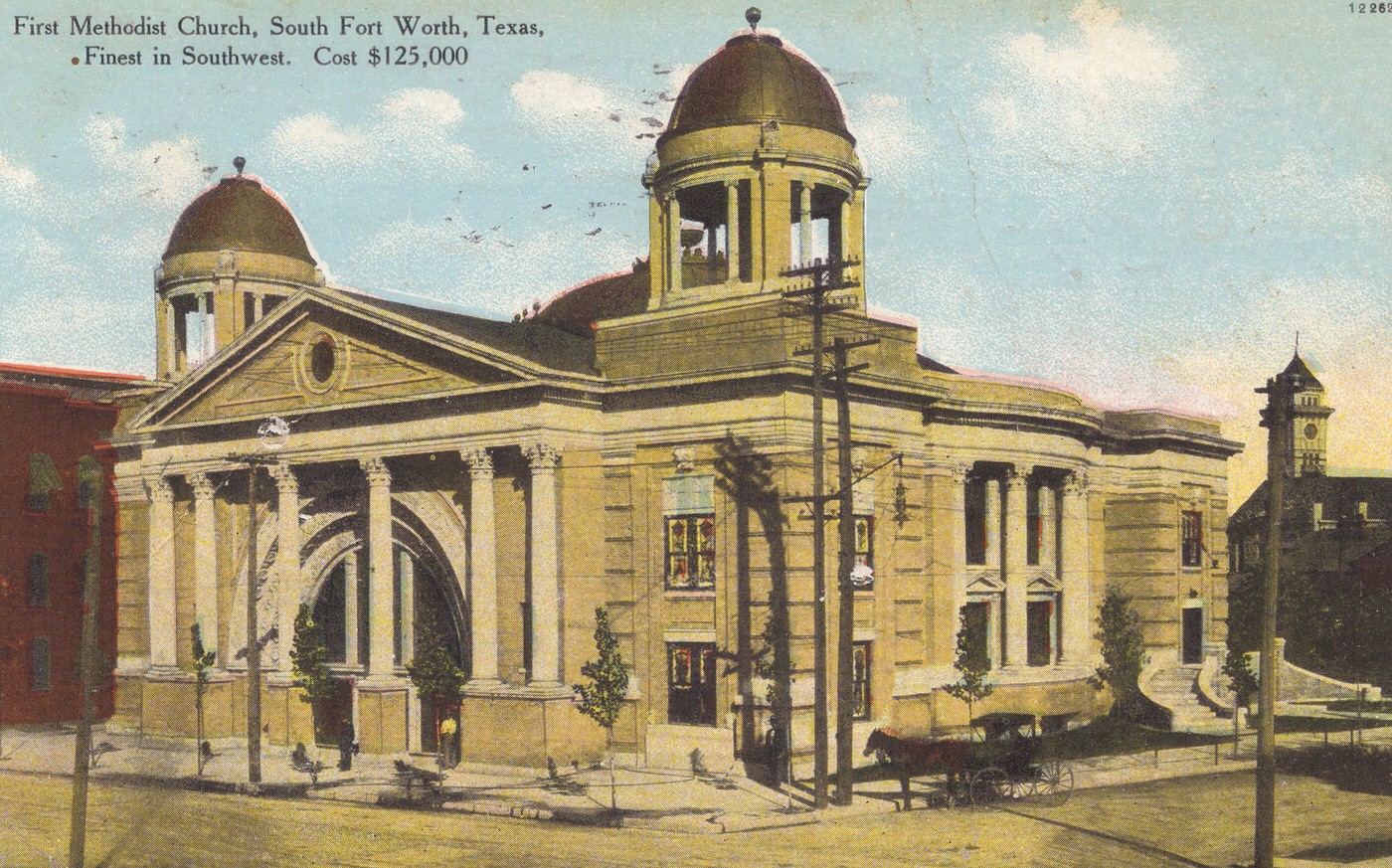

Religious institutions, long established as social and cultural anchors, continued to play a vital role. The city hosted a diverse range of denominations by 1900, including Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, Catholic, Episcopal, German Evangelical, and Jewish congregations. With the tripling of the population, these existing congregations undoubtedly experienced significant growth, likely leading to the construction of new or expanded houses of worship during the decade, although specific examples from 1900-1909 are limited in the source material. The imposing St. Patrick Catholic Cathedral, completed in 1892, served its growing parish.

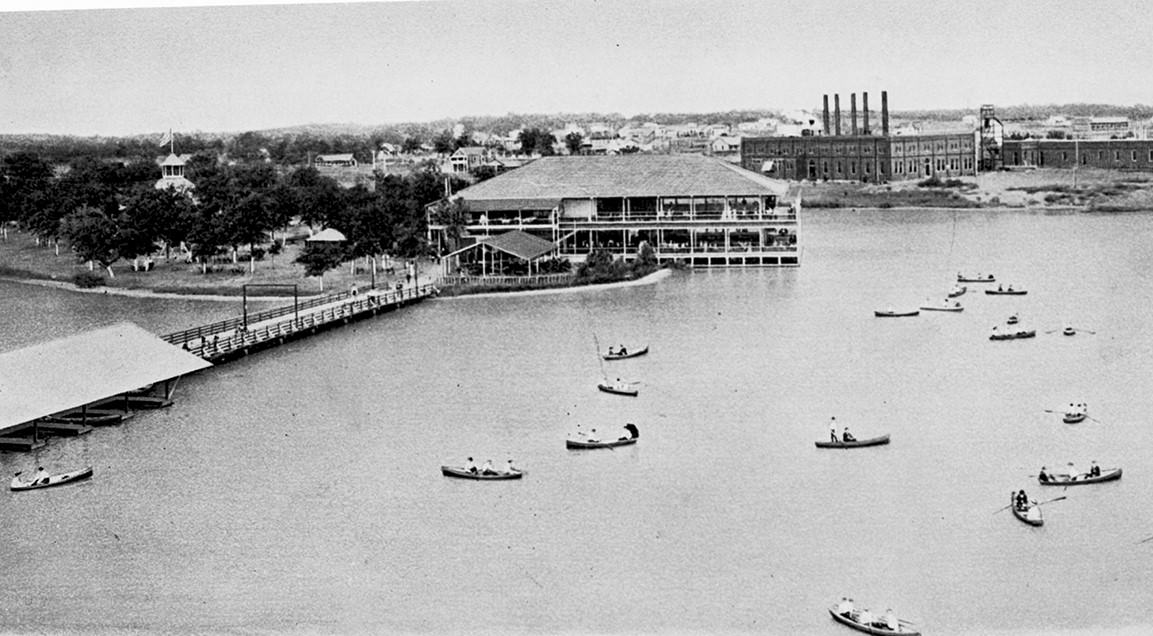

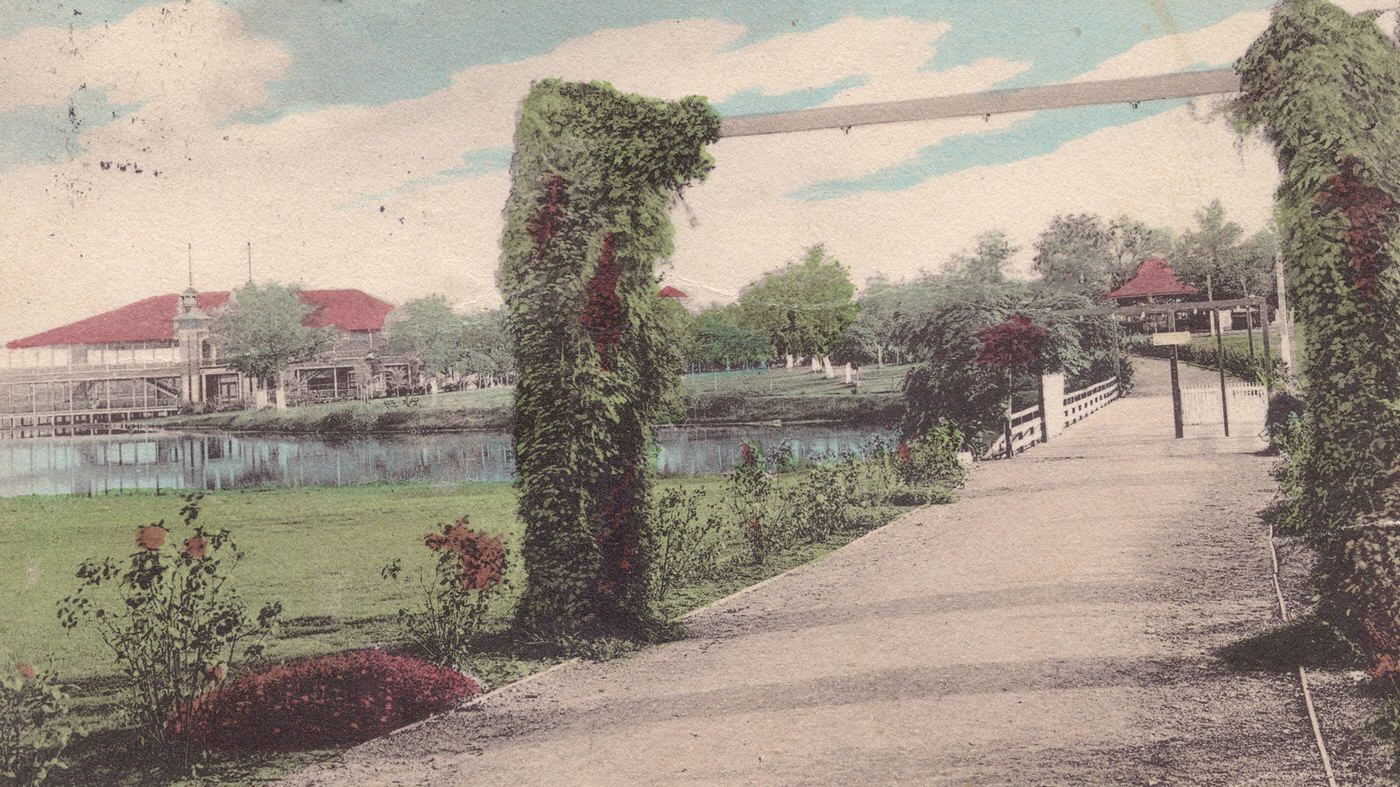

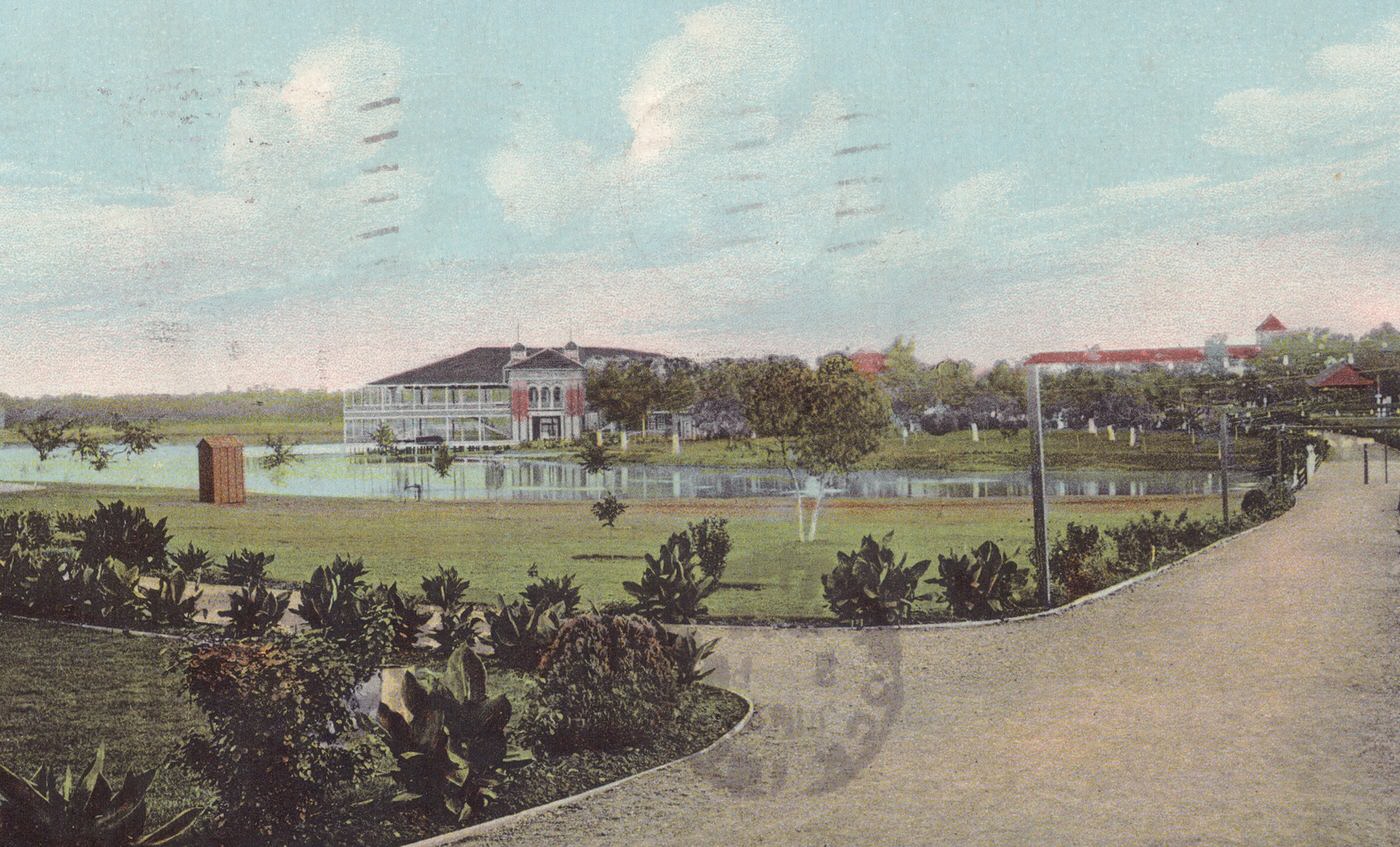

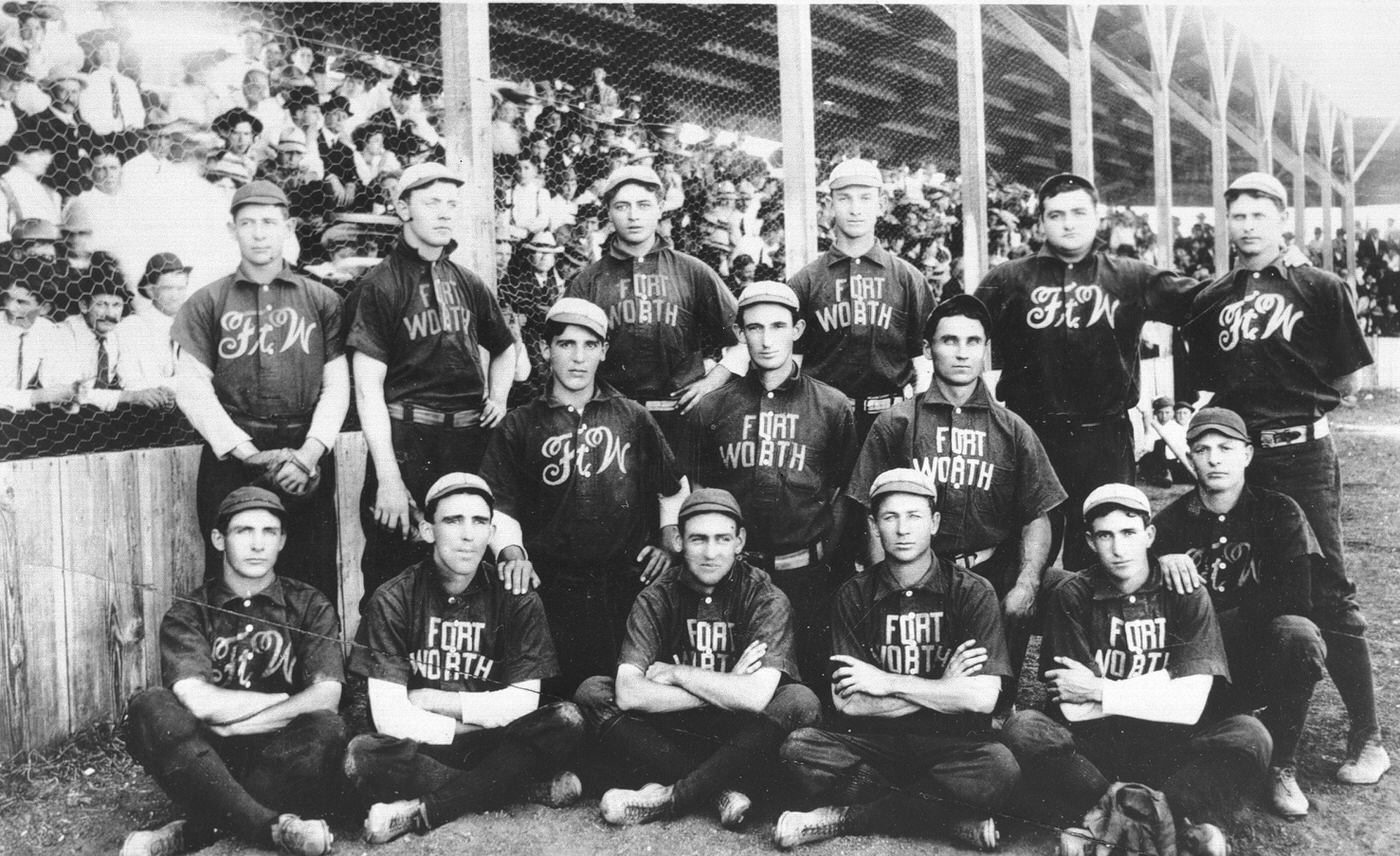

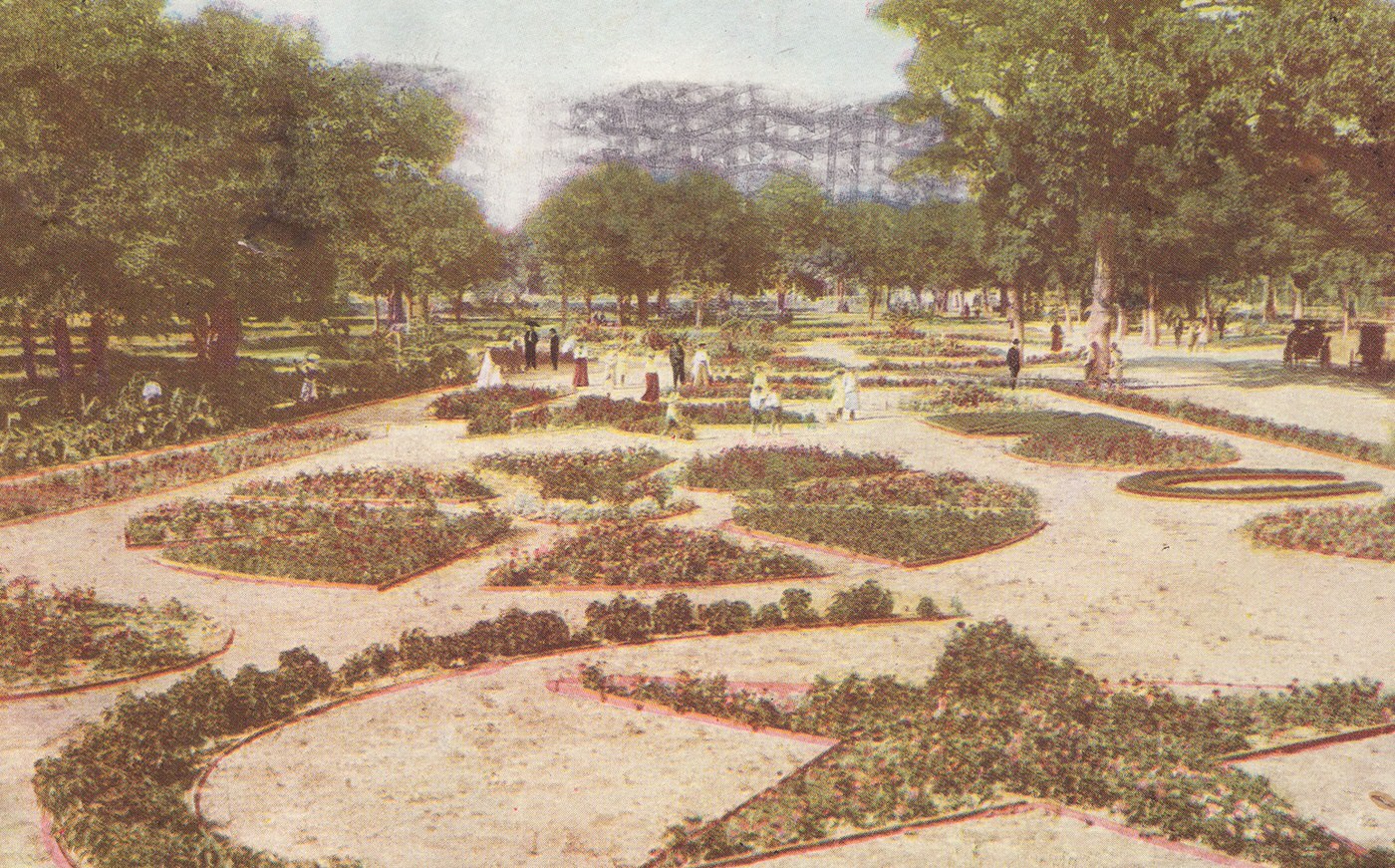

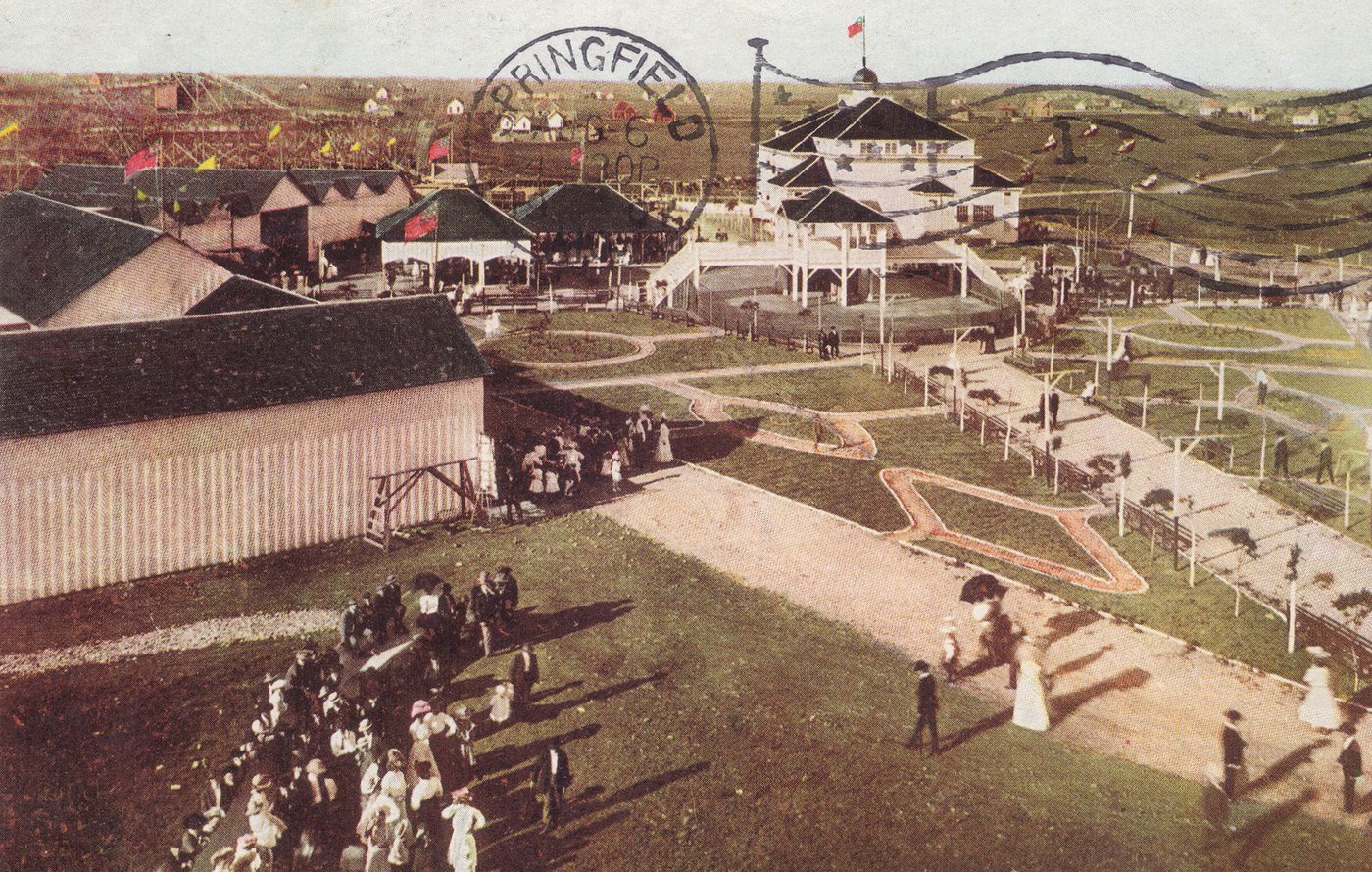

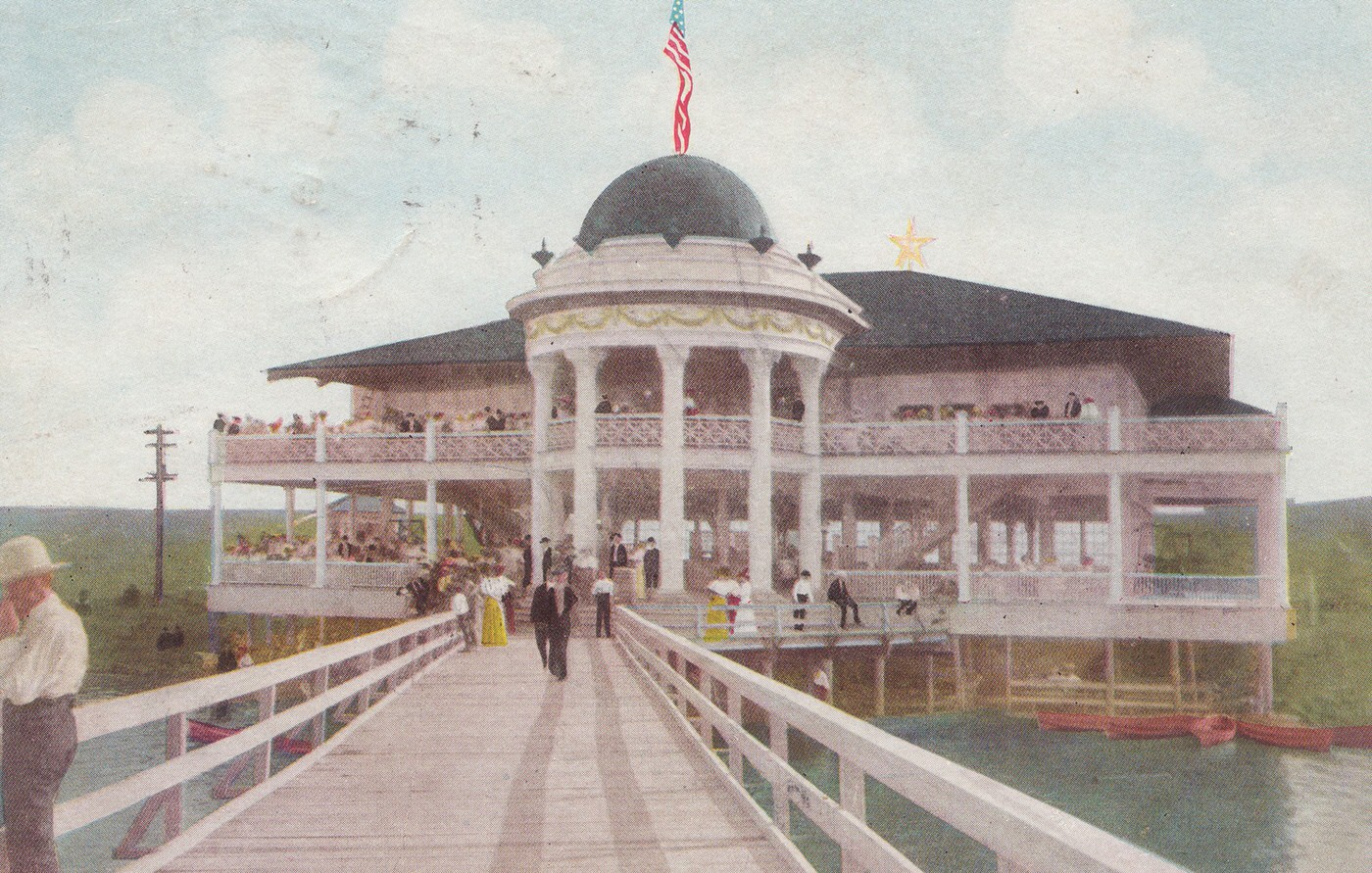

Entertainment options were also evolving. The Fort Worth Fat Stock Show, first held in 1896, grew in prominence, gaining its dedicated venue, the Cowtown Coliseum, in 1907-08. This era also saw the rise of amusement parks. Fort Worth’s own White City Amusement Park (also known as Rosen Heights Amusement Park, named after developer Sam Rosen) opened around 1905 or 1906. Located north of the river, likely near NW 24th Street and accessible by trolley, it featured attractions typical of the popular “White City” parks of the era, including a Figure Eight wooden roller coaster and likely lagoons, pavilions, and games. While its existence was relatively brief (closing around 1911-12), its presence signifies the city’s growing demand for organized leisure activities beyond the confines of Hell’s Half Acre. Saloons and theaters, of course, continued to operate.

Image Credits: UTA Libraries, Portal to Texas History, Jack White Photograph Collection, Jenkins Garrett Texas Postcard Collection, W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, Haynes-Stegall Photograph Collection, Texas Postcard Collection

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know