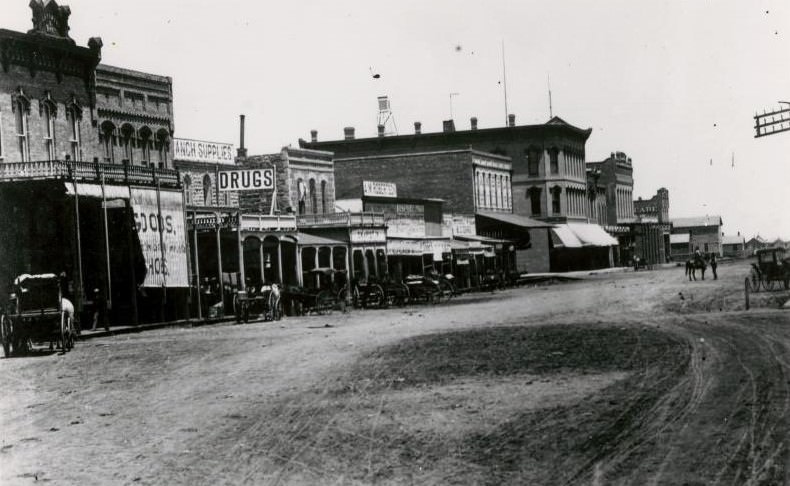

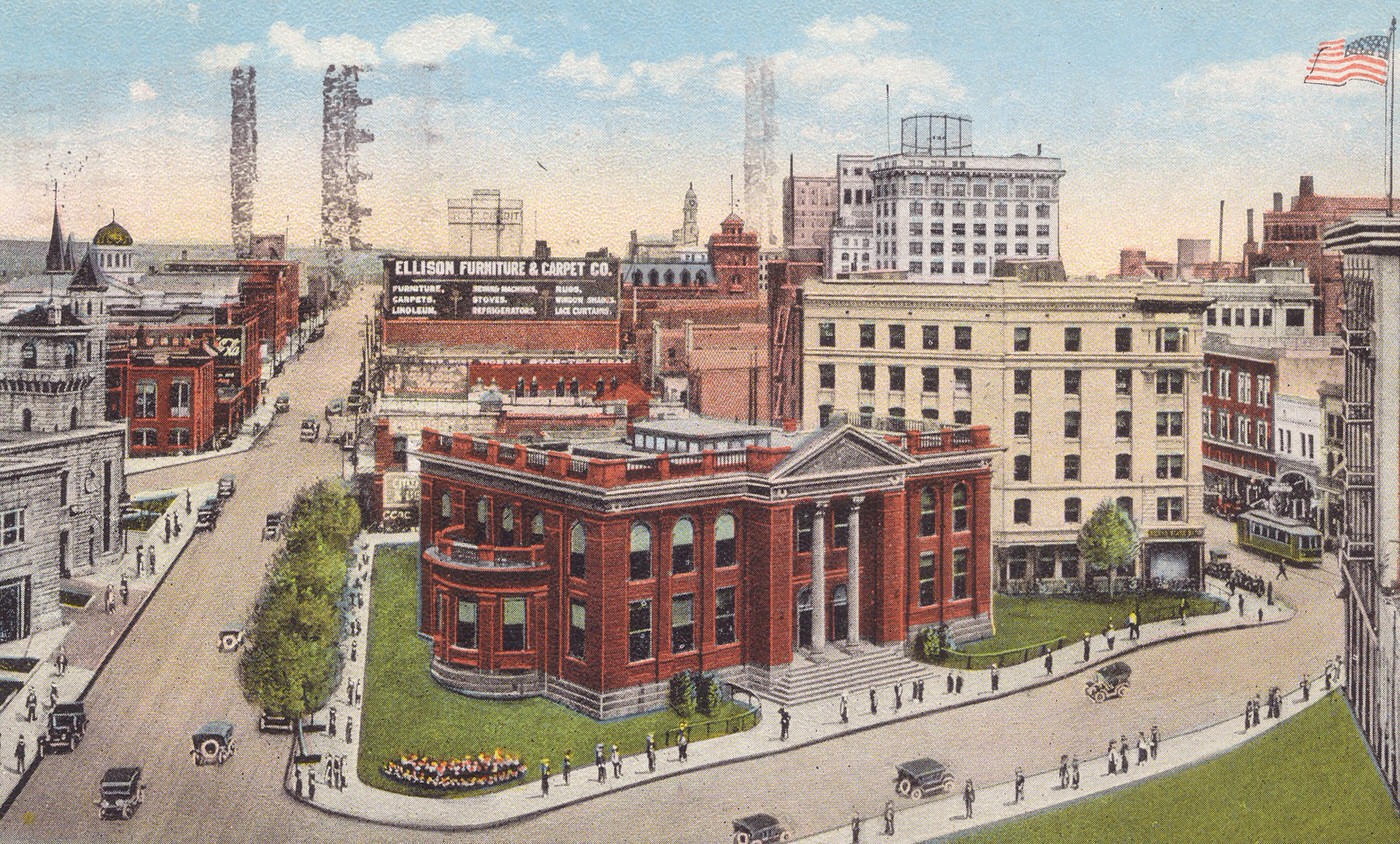

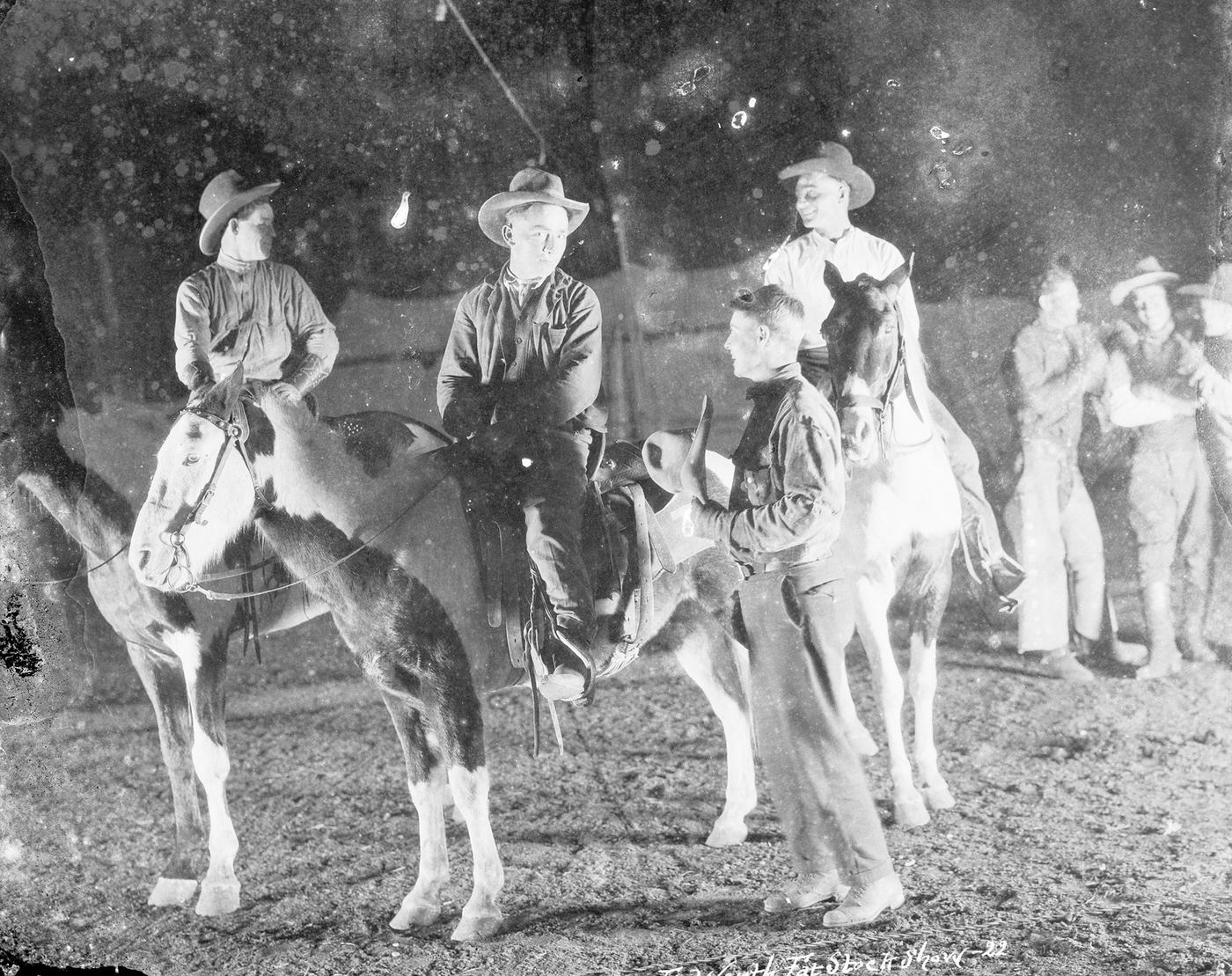

When the 1920s began, Fort Worth, Texas, was a city with one foot in the old West and the other stepping into the future. It still proudly wore the name “Cowtown,” a reminder of its deep roots in the cattle trade. Years earlier, the Chisholm Trail had run close by, turning Fort Worth into a key stop for cowboys moving herds north after the Civil War. By 1920, those long cattle drives were mostly finished, but you could still feel their importance in the city’s way of life and how people did business.

Fort Worth’s population had swelled to 106,482, a significant jump from 73,312 just ten years prior in 1910, largely thanks to the packing plants. Yet, even as the city solidified its “Cowtown” identity, another economic force was emerging just over the horizon. The discovery of oil in West Texas towns like Ranger (1917) and Desdemona (1918) was beginning to send ripples eastward. Fort Worth, with its established rail lines and growing financial sector, was perfectly positioned to become the command center for this nascent “black gold” rush, already hosting a few small refineries. The stage was set for a decade of unprecedented transformation, where the thrum of oil derricks would compete with the lowing of cattle, forever changing the face and future of Fort Worth.

Black Gold Rush: Oil Transforms Fort Worth

The tentative whispers of oil discovered before 1920 erupted into a full-throated roar throughout the decade, permanently altering Fort Worth’s trajectory. The massive oil fields unearthed in West Texas—particularly the “Roaring Ranger” field discovered in 1917, followed by significant strikes in Desdemona, Breckenridge, and Burkburnett—unleashed a frenzy unlike anything the region had seen. These discoveries created classic boomtowns almost overnight; Ranger’s population, for instance, exploded from under 1,000 to over 30,000 as fortune-seekers flooded the area.

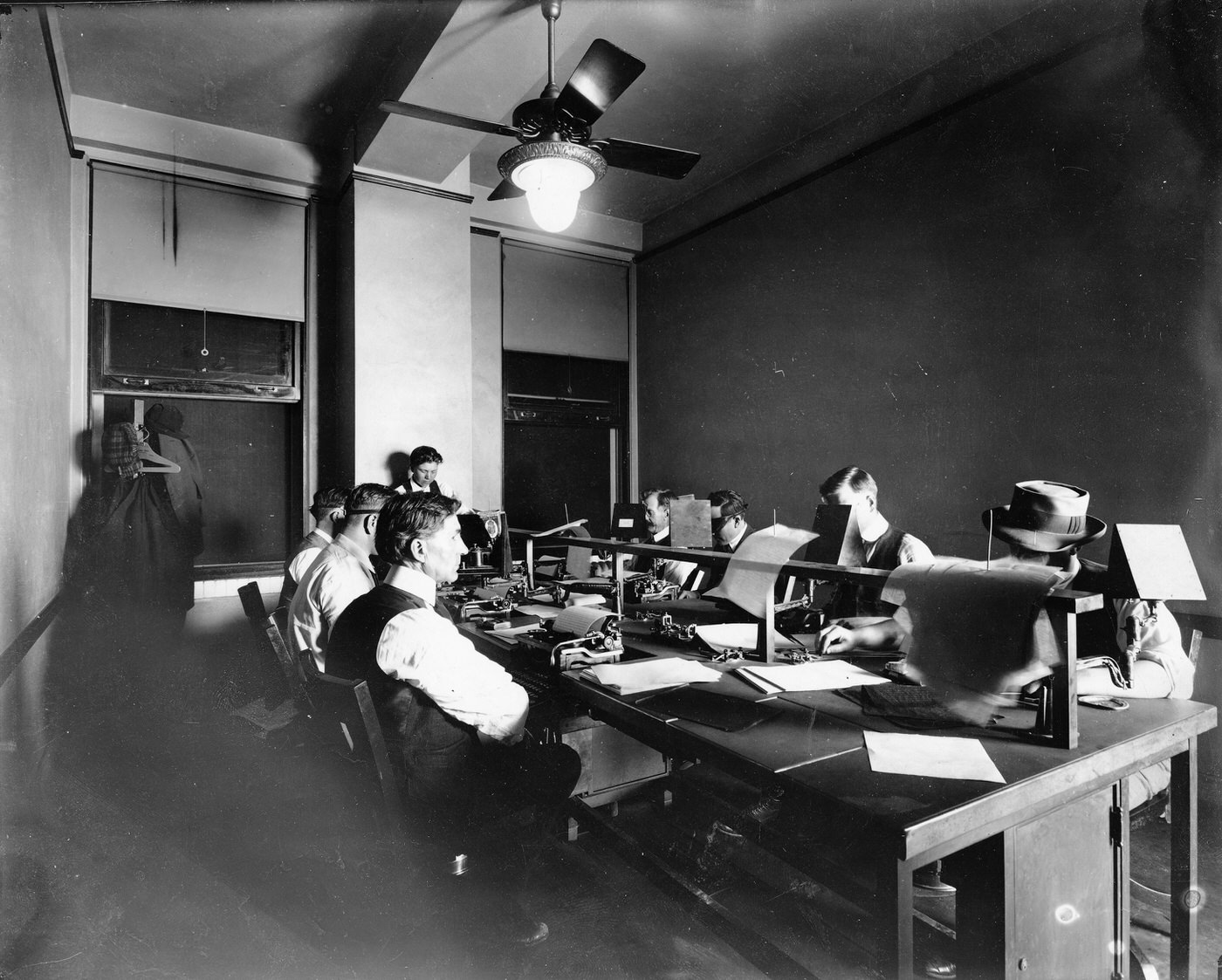

Though geographically removed from the drilling activity, Fort Worth rapidly became the undisputed nerve center of the West Texas oil boom. Its strategic advantages were undeniable. The city’s well-established railroad network, a legacy of its cattle-trading past, became the essential conduit for transporting drilling equipment, supplies, and workers to the remote oilfields, and for shipping crude oil out. Fort Worth businesses thrived by supplying the needs of the burgeoning boomtowns.

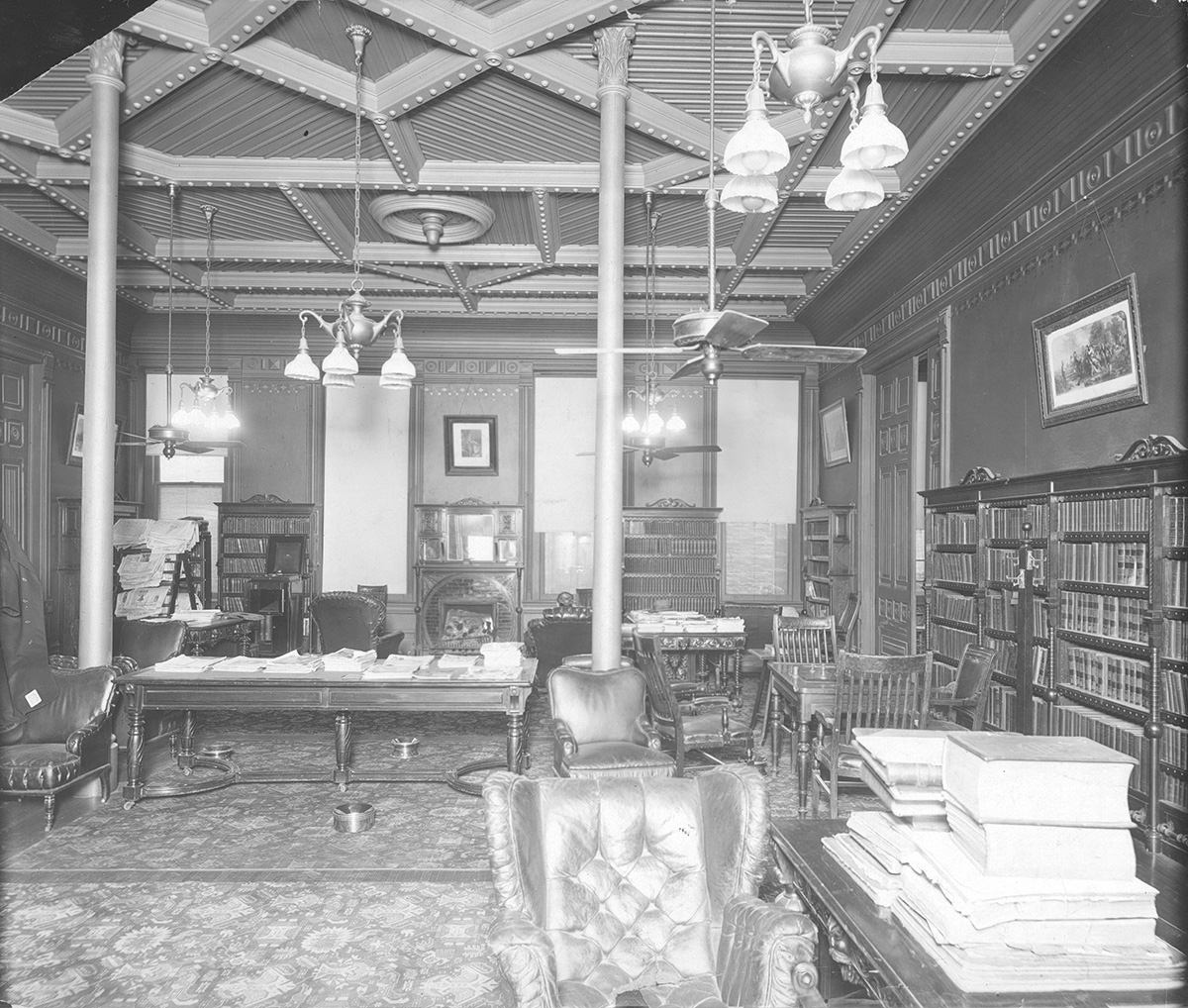

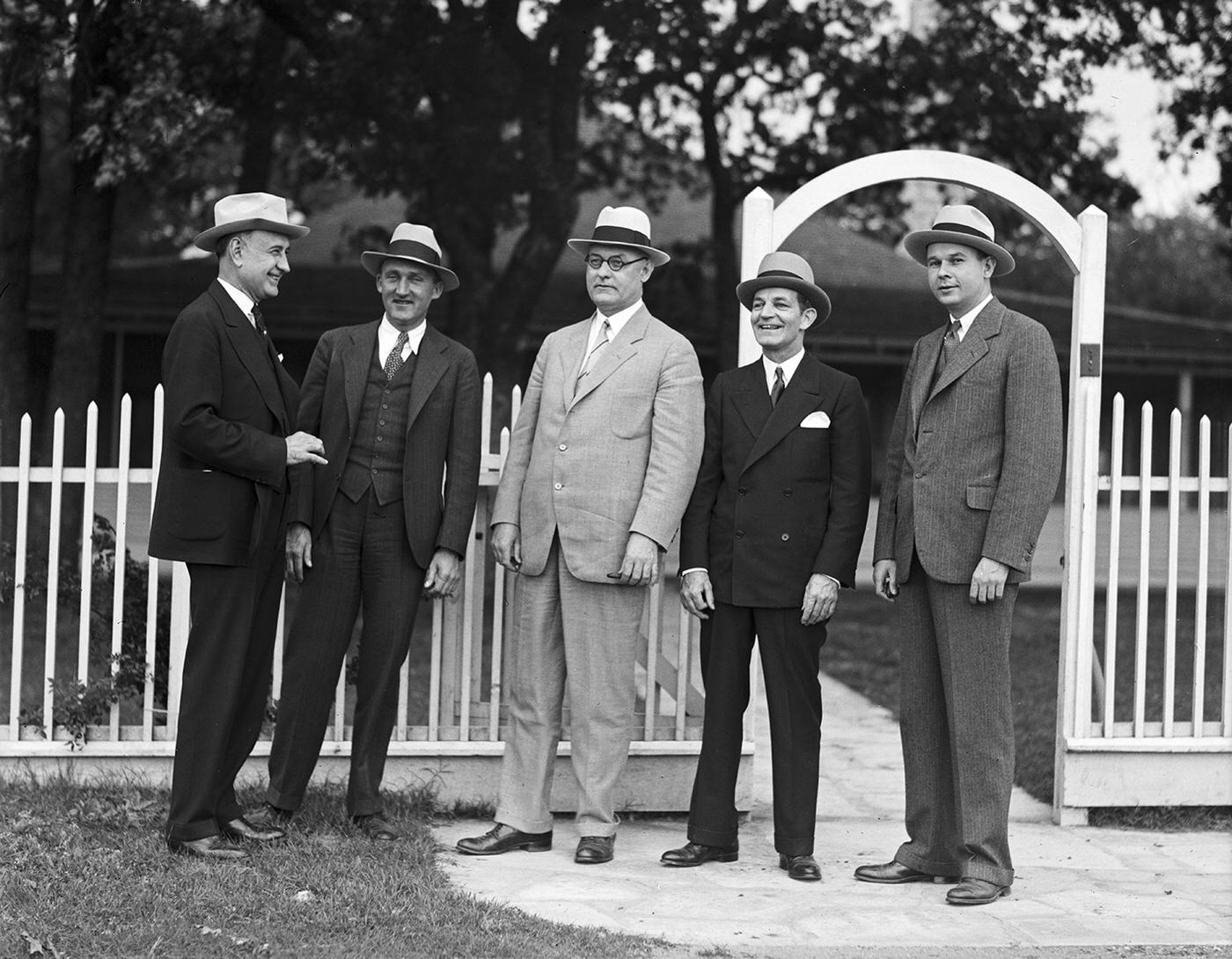

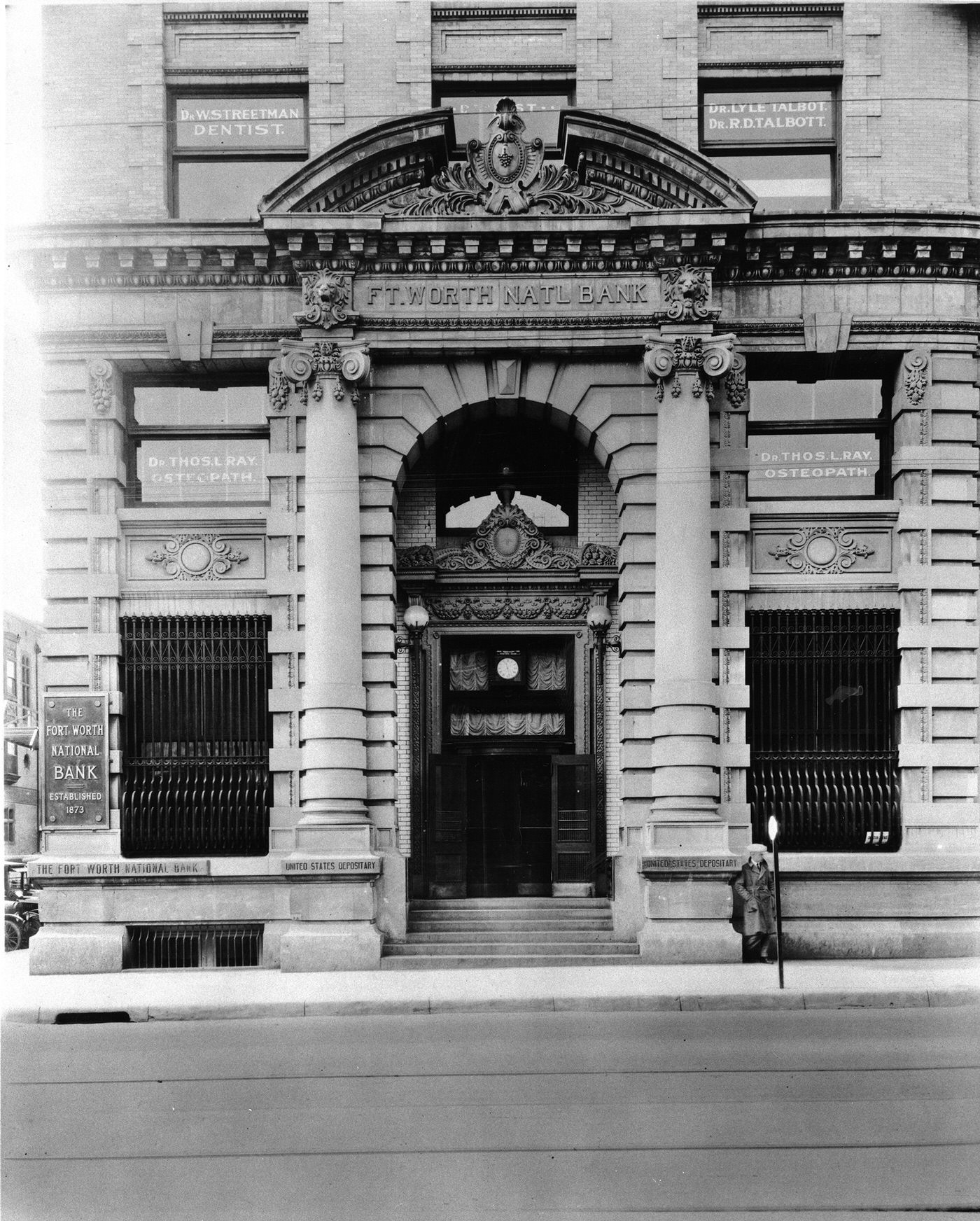

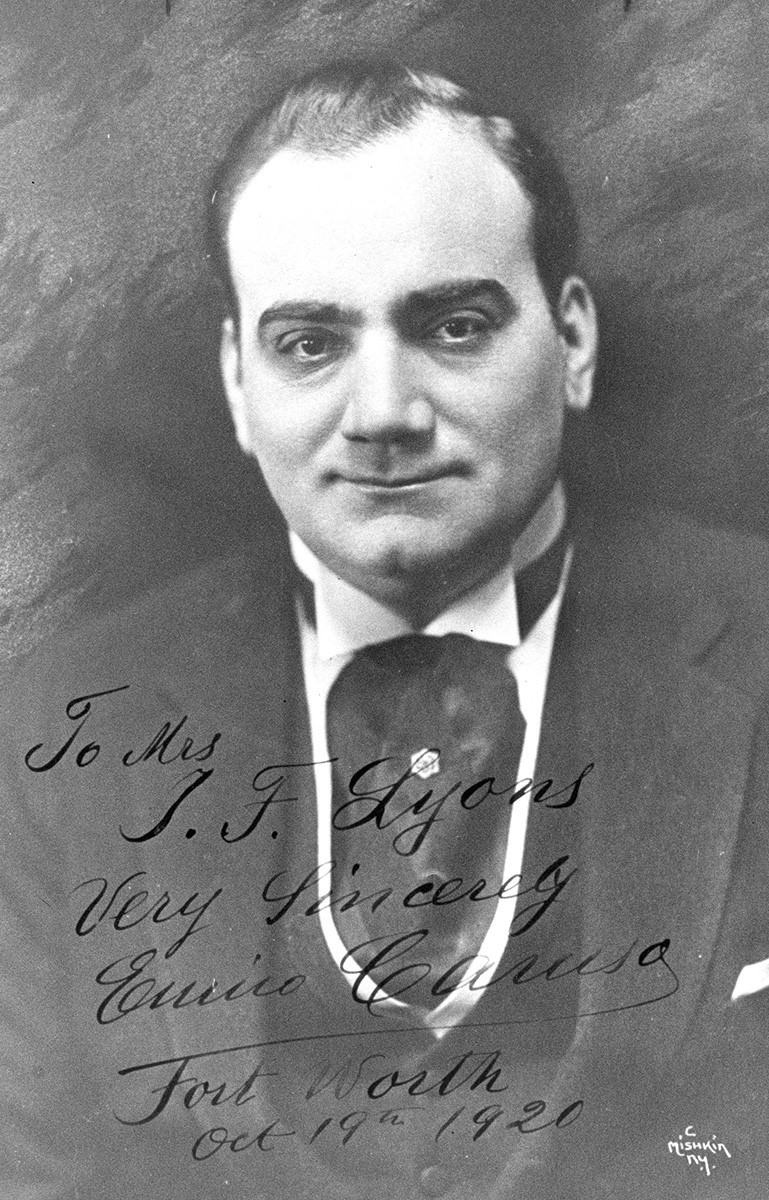

Beyond logistics, Fort Worth emerged as the financial and operational headquarters for the burgeoning industry. Deals worth millions were struck in the lobbies of downtown hotels like the Westbrook and, later in the decade, the Blackstone, and over drinks in the city’s bars. Local banks, such as the Fort Worth National Bank, played a crucial role in financing exploration and development. The city became a magnet for oil company headquarters and regional offices; virtually every major player, including Gulf Oil, Magnolia Petroleum (later Mobil), Humble Oil (later Exxon), Sinclair, and Texaco, established a significant presence. The Petroleum Producers Association even organized in Fort Worth in 1922.

The influx of corporate activity demanded infrastructure. Fort Worth’s refining capacity exploded. Already home to three refineries before the major boom, the city saw five more constructed by the summer of 1920, with another four underway. Companies like Transcontinental Oil Company invested heavily, building a $1.5 million facility capable of refining 15,000 barrels per day by 1924. This concentration of refining power added another layer to Fort Worth’s strategic importance in the oil economy.

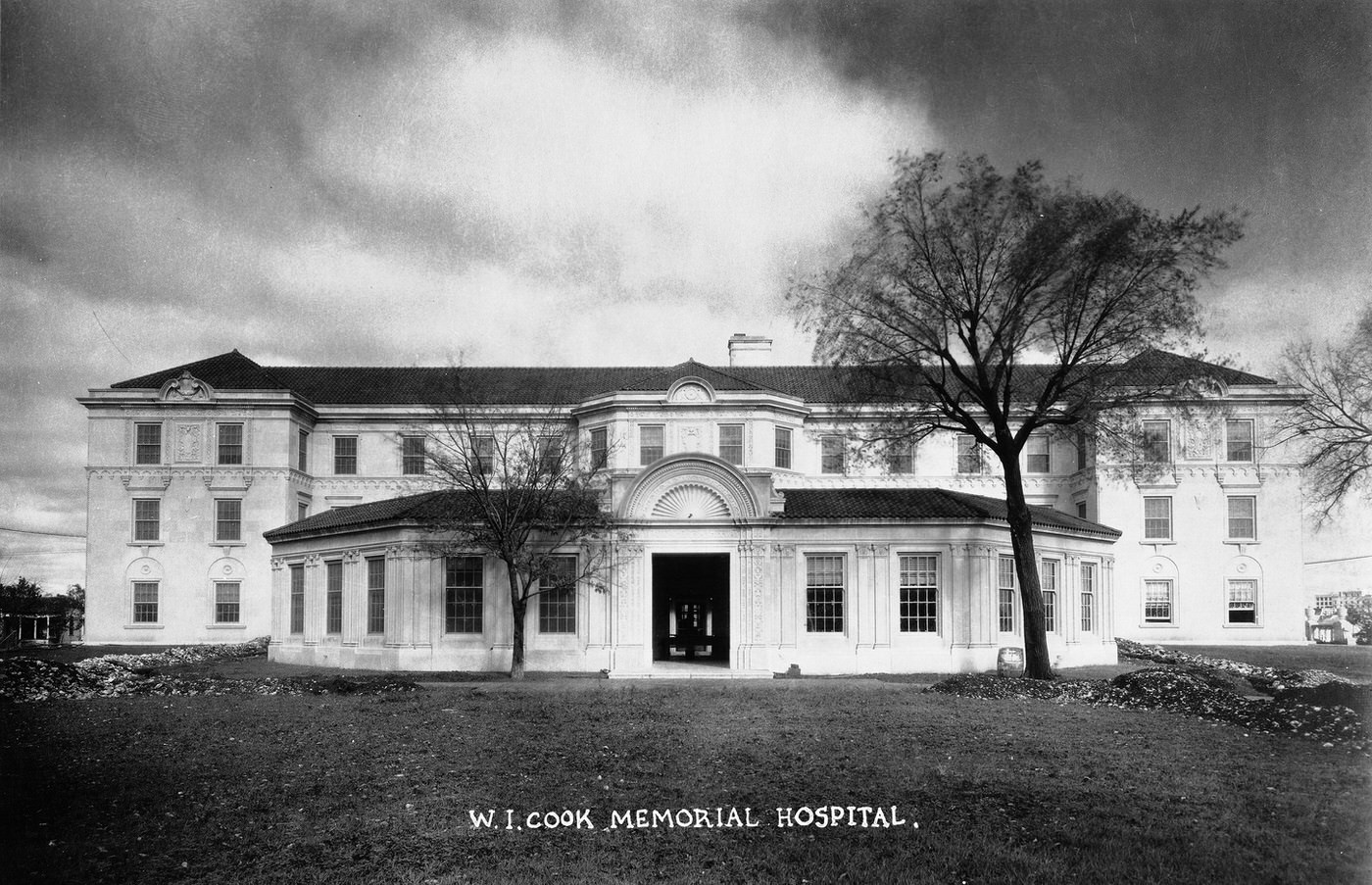

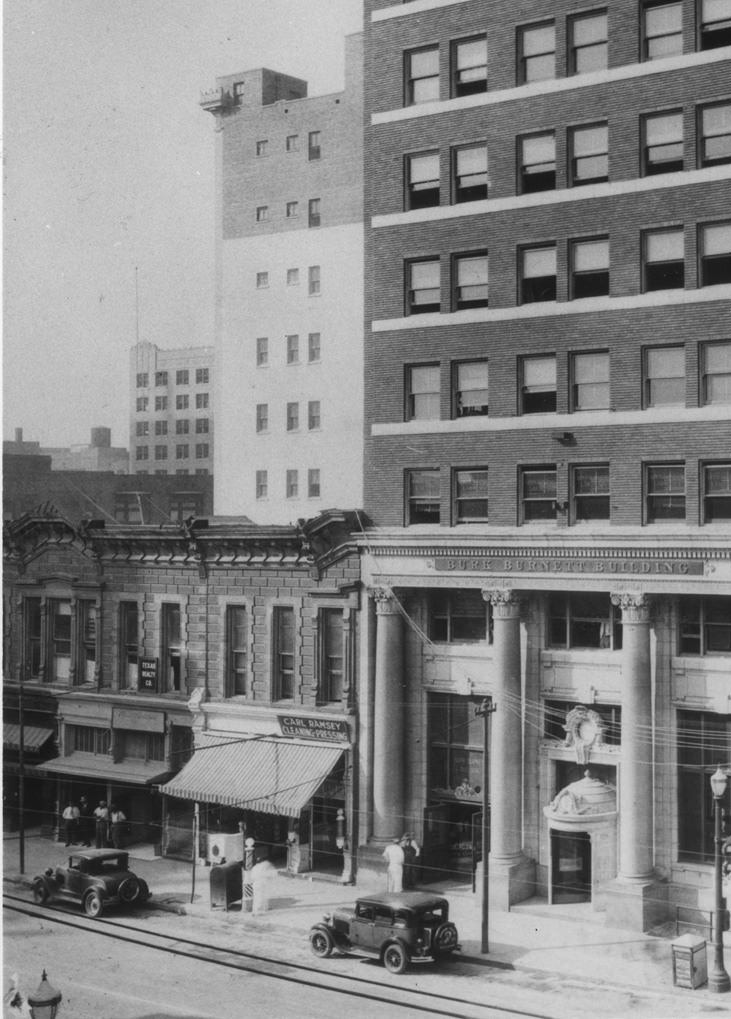

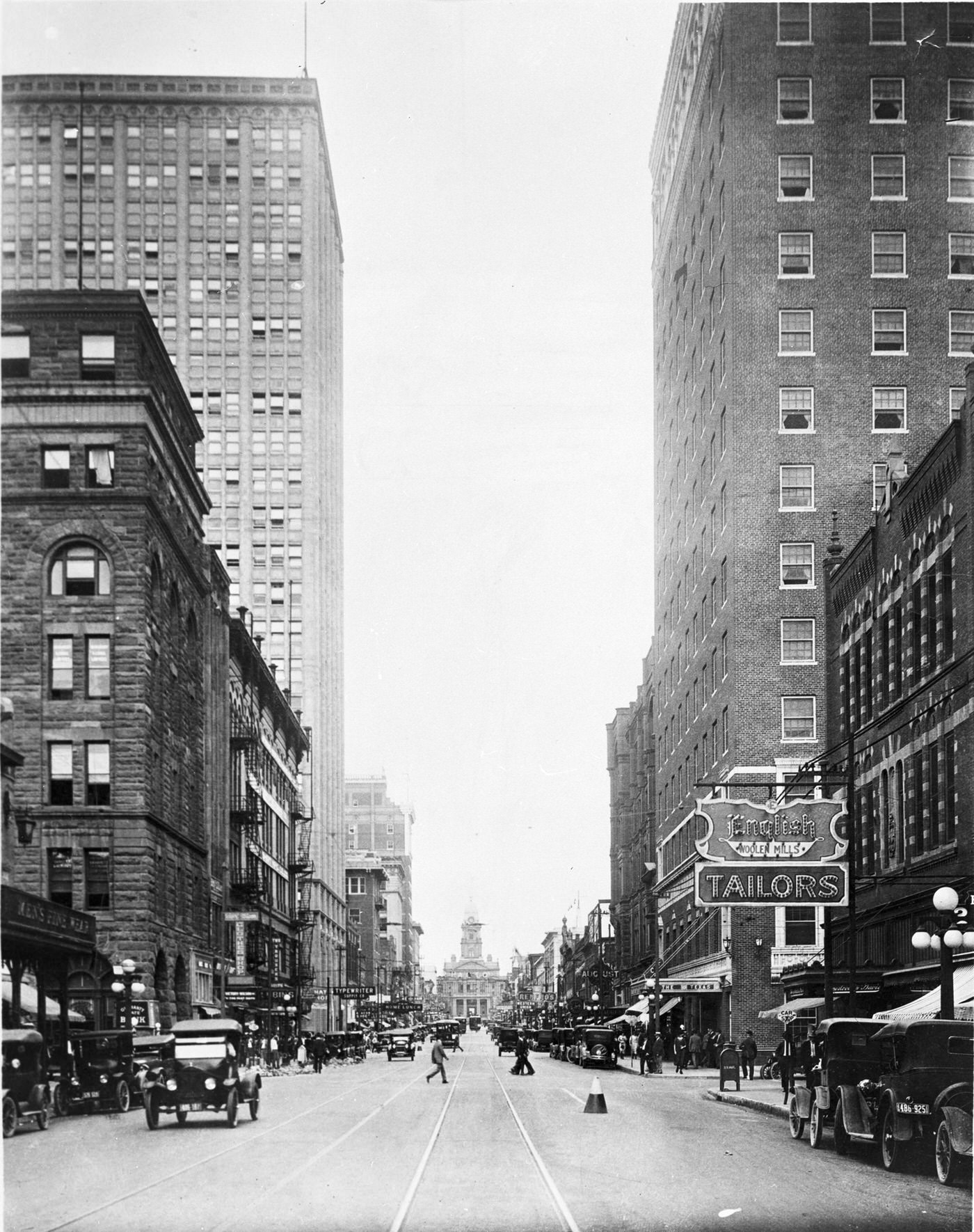

The most transformative impact, perhaps, was the creation of immense wealth. The oil boom minted new millionaires, with families like the Waggoners (whose patriarch, W.T. Waggoner, had ironically struck oil years earlier while drilling for water) and the Moncriefs rising to prominence. This newfound oil wealth would have lasting effects, funding philanthropic endeavors and fueling further business growth in the decades to come. The physical manifestation of this boom was immediate and striking: the demand for office space for oil companies and the associated legal, financial, and service industries directly led to the construction of Fort Worth’s first generation of skyscrapers, forever altering the city’s skyline and symbolizing its arrival as a modern economic center.

Fort Worth began its push for annexation in earnest around 1921. The Texas legislature became the arena for this fight. An initial state law passed in January 1921 allowed cities over 50,000 (like Fort Worth) to annex adjacent territories with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants, enabling Fort Worth’s move. Niles City countered by quickly extending its own city limits to surpass the 2,000-resident threshold. Undeterred, Fort Worth lobbied the legislature again, and a second bill passed in July 1921 raised the population needed to block annexation to 5,000, a number Niles City couldn’t meet. Following meetings to build support and a special election in June/July 1922 approving charter amendments for annexation, Niles City officially became part of Fort Worth on August 1, 1923, despite legal challenges. This annexation was a major victory for Fort Worth, bringing the economic engine of the Stockyards and packing plants firmly within its tax jurisdiction, providing crucial revenue to support the city’s own explosive growth fueled by both cattle and oil.

The Dawn of Aviation

While Fort Worth’s identity remained tied to the earth – to cattle trails and railroad tracks – the 1920s saw the city decisively turn its eyes to the sky, embracing the nascent technology of aviation and laying the foundation for its future role as an aerospace center.

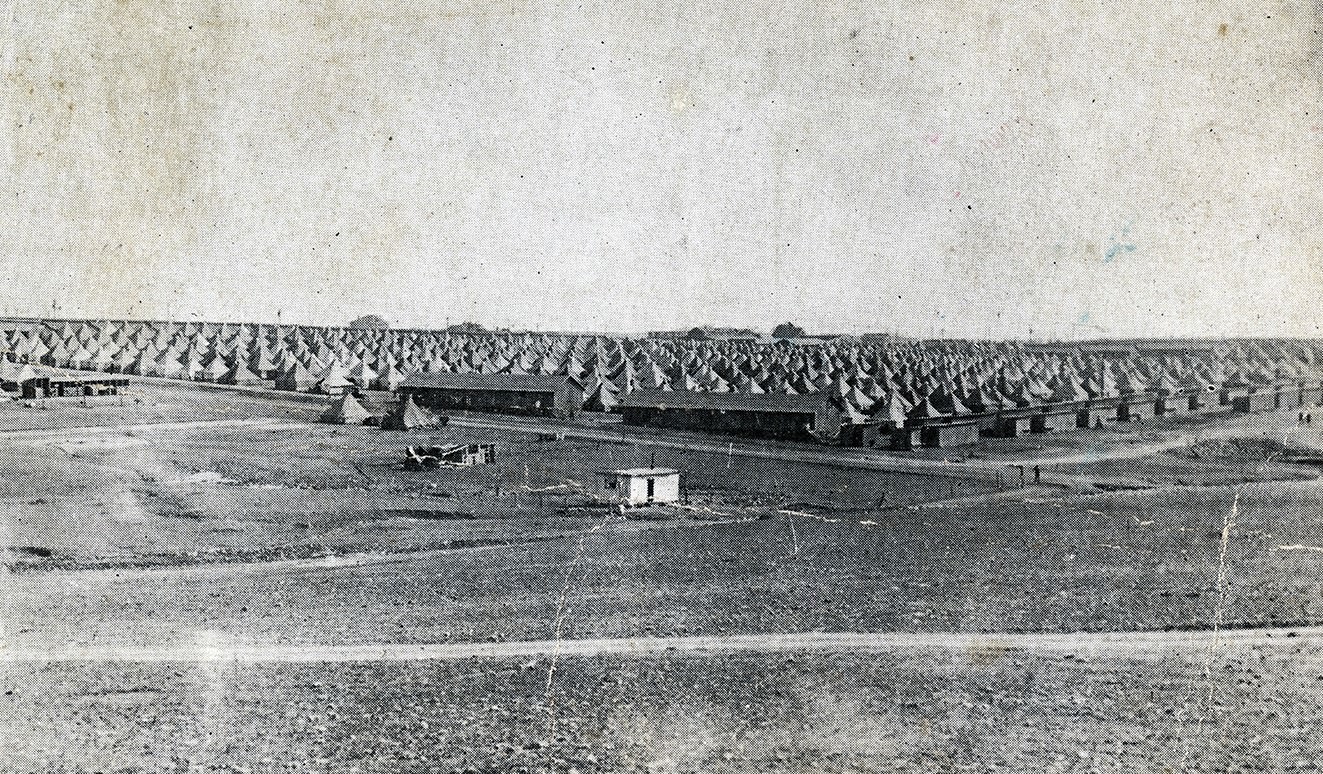

The groundwork had been laid during World War I. Due to Fort Worth’s favorable climate allowing for year-round training, the Canadian Royal Flying Corps (RFC) established three training fields nearby in 1917: Taliaferro Fields 1, 2, and 3. When the U.S. entered the war, the American military took over these facilities, renaming two of them Carruthers Field (in Benbrook) and Barron Field (in Everman). Simultaneously, the massive Camp Bowie was constructed west of town, serving as the training ground for the 36th Infantry Division and further cementing the region’s connection to military activity. Though Camp Bowie closed in 1919, the presence of these airfields and the trained personnel associated with them created a pool of expertise and interest in aviation.

Recognizing the potential of this new form of transport, the City of Fort Worth took a significant step on July 3, 1925, by establishing its first municipal airport on a 100-acre site north of the city. Initially just featuring dirt and sod runways, this facility replaced the former military site at Barron Field as the city’s primary airfield. In 1927, the airport was officially named Meacham Field in honor of former Mayor Henry C. Meacham, a key proponent who had personally contributed funds for its early development.

The Exploding Metropolis: Population and People

The Roaring Twenties saw Fort Worth’s population continue its dramatic upward trajectory. The official U.S. Census recorded 106,482 residents in 1920; by 1930, that number had surged to 163,447. This represented an increase of over 56,965 people, or approximately 53.5%, in just ten years – a clear indicator of the powerful economic forces reshaping the city.

This explosive growth was fed by multiple streams of migration. The most significant driver was undoubtedly the West Texas oil boom. Fort Worth, as the industry’s hub, attracted a diverse influx of people connected to oil: experienced wildcatters seeking new fortunes, roughnecks to work the rigs and refineries, engineers and geologists, financiers and lawyers to manage the deals, and countless others providing services to the booming sector.

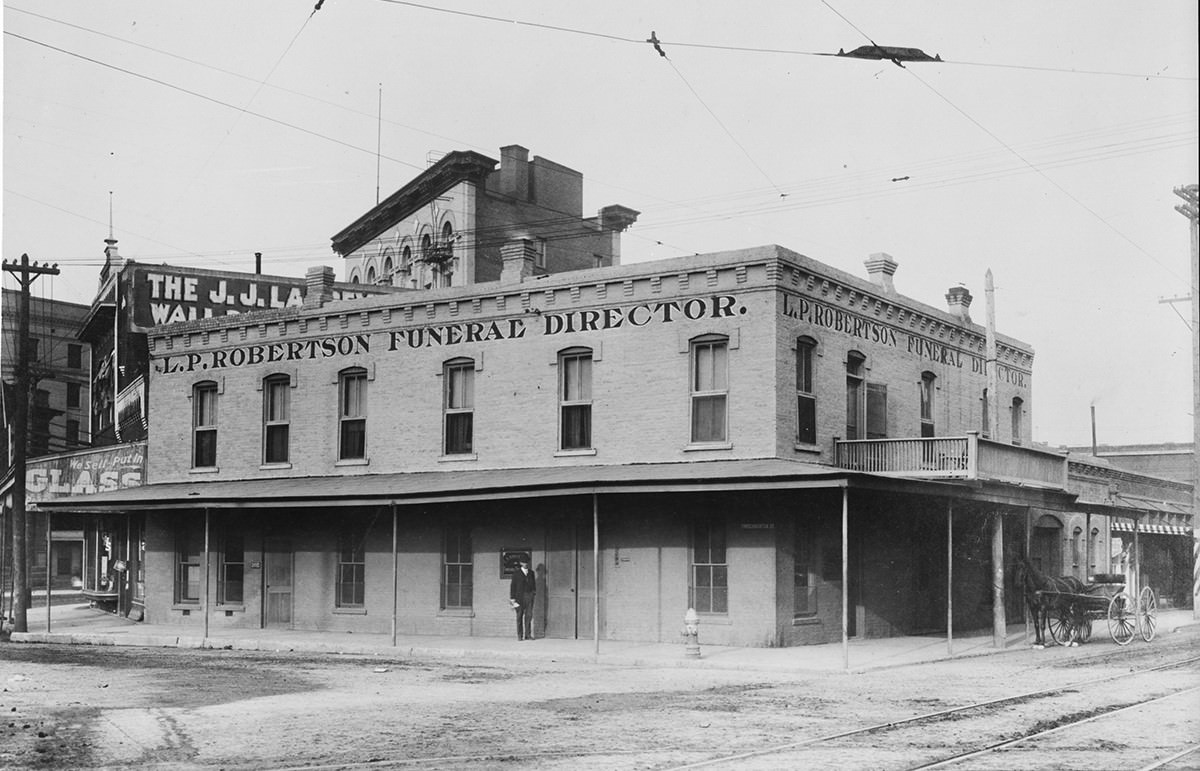

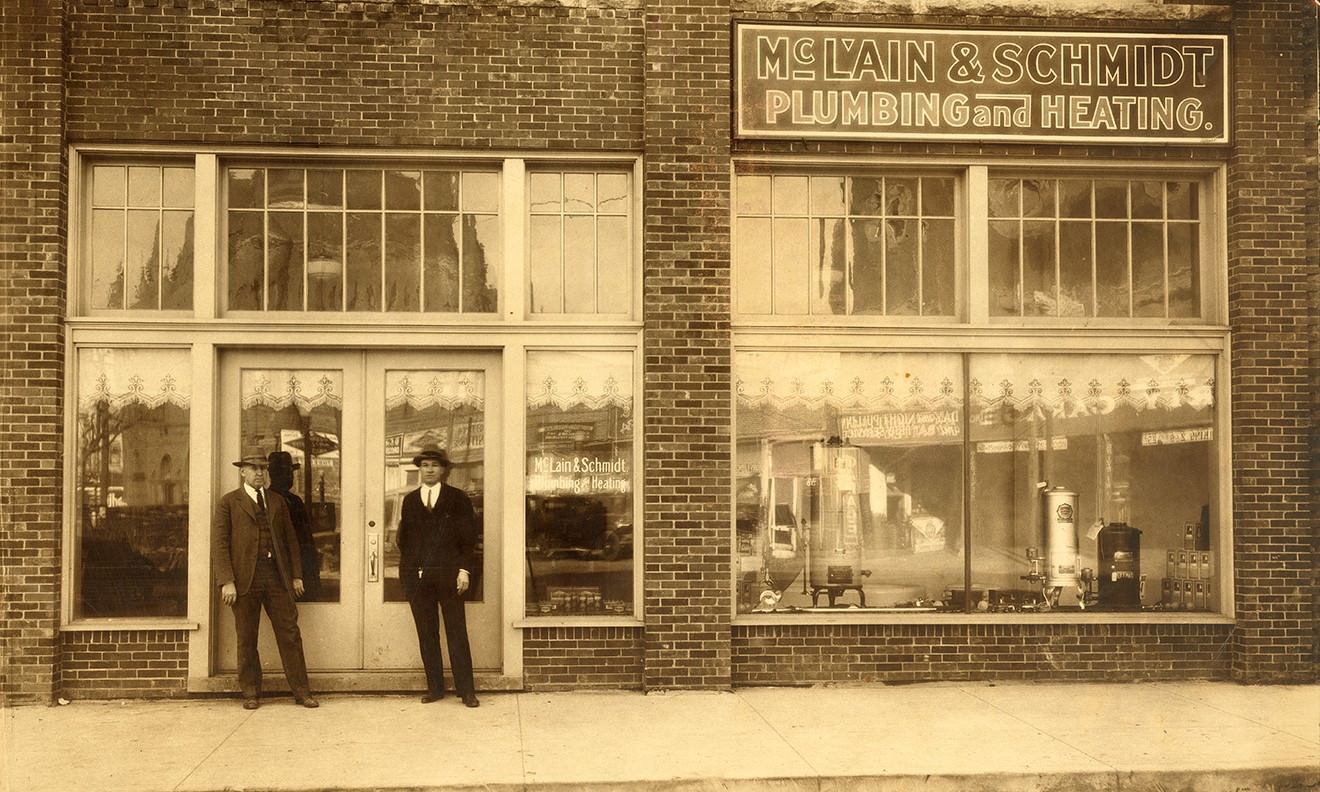

Simultaneously, Fort Worth’s established industries continued to draw workers. The massive Armour and Swift meatpacking plants remained major employers, pulling laborers into the Stockyards district. The city’s role as a critical railroad hub also provided steady employment. Furthermore, other industries were expanding, such as garment manufacturing, which saw factories like Williamson-Dickie (established 1918/1922) grow on the Southside. Beyond specific industries, Fort Worth benefited from broader migration trends, attracting people from other parts of Texas and the American South seeking opportunity in the growing urban center, a pattern continuing from the post-World War I era. Simultaneously, Fort Worth’s established industries continued to draw workers. The massive Armour and Swift meatpacking plants remained major employers, pulling laborers into the Stockyards district. The city’s role as a critical railroad hub also provided steady employment. Furthermore, other industries were expanding, such as garment manufacturing, which saw factories like Williamson-Dickie (established 1918/1922) grow on the Southside. Beyond specific industries, Fort Worth benefited from broader migration trends, attracting people from other parts of Texas and the American South seeking opportunity in the growing urban center, a pattern continuing from the post-World War I era.

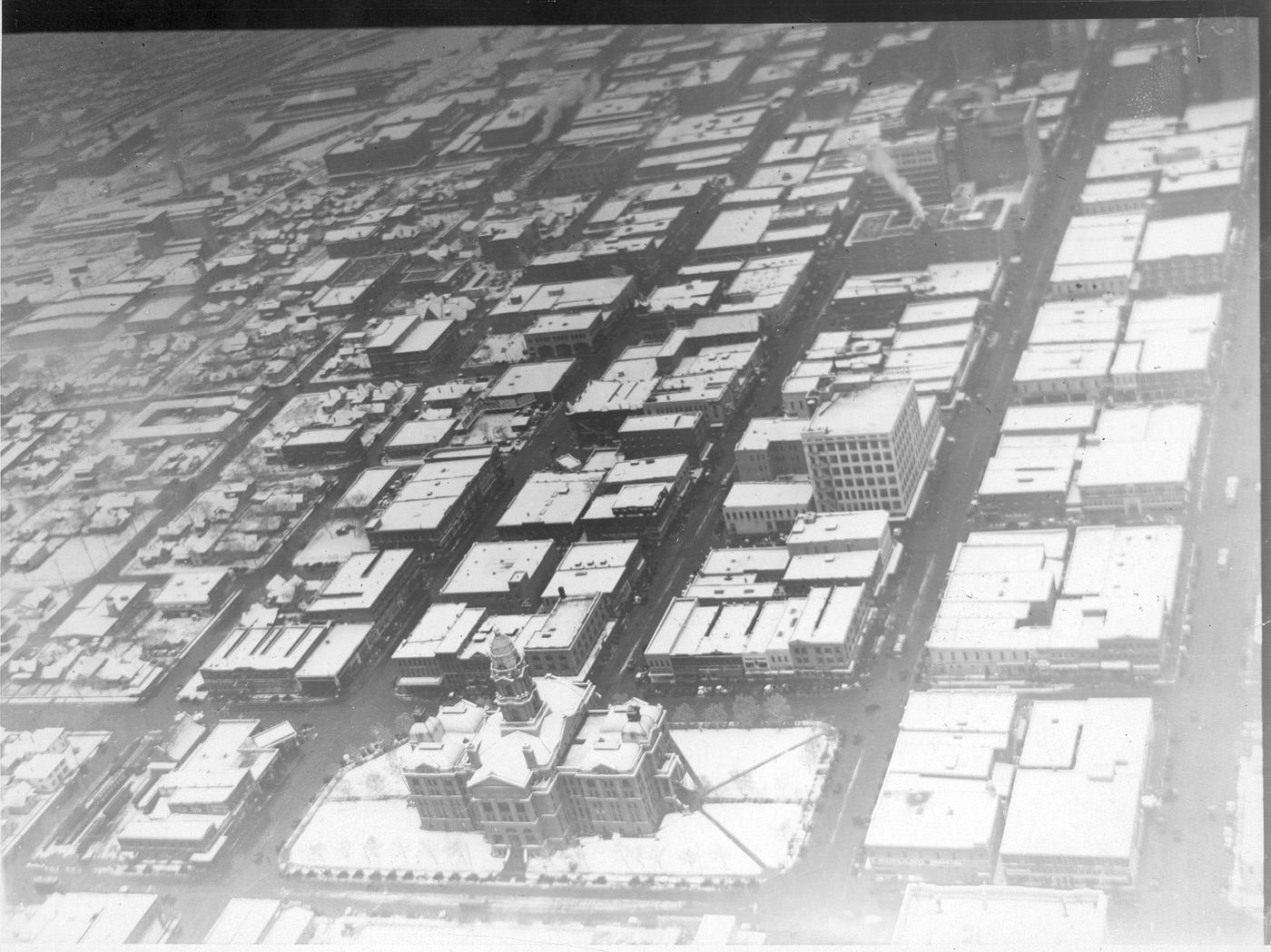

Building the Modern City: Skyscrapers, Suburbs, and Streets

The immense energy and wealth generated primarily by the oil boom, layered upon the solid foundation of the cattle and railroad industries, physically reshaped Fort Worth during the 1920s. The decade witnessed the rise of the city’s first true skyline, the outward sprawl of new residential neighborhoods, and crucial investments in the infrastructure needed to support a modernizing metropolis.

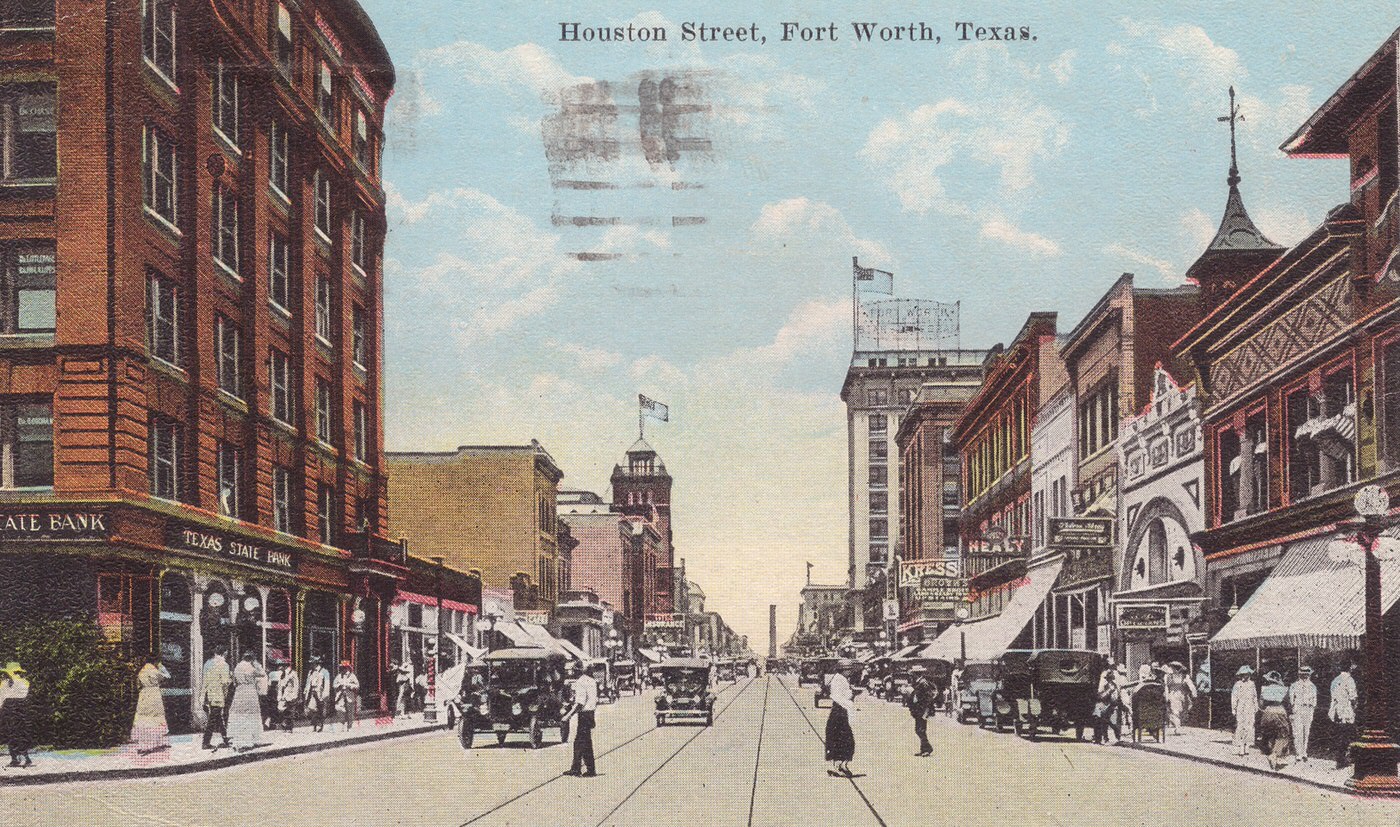

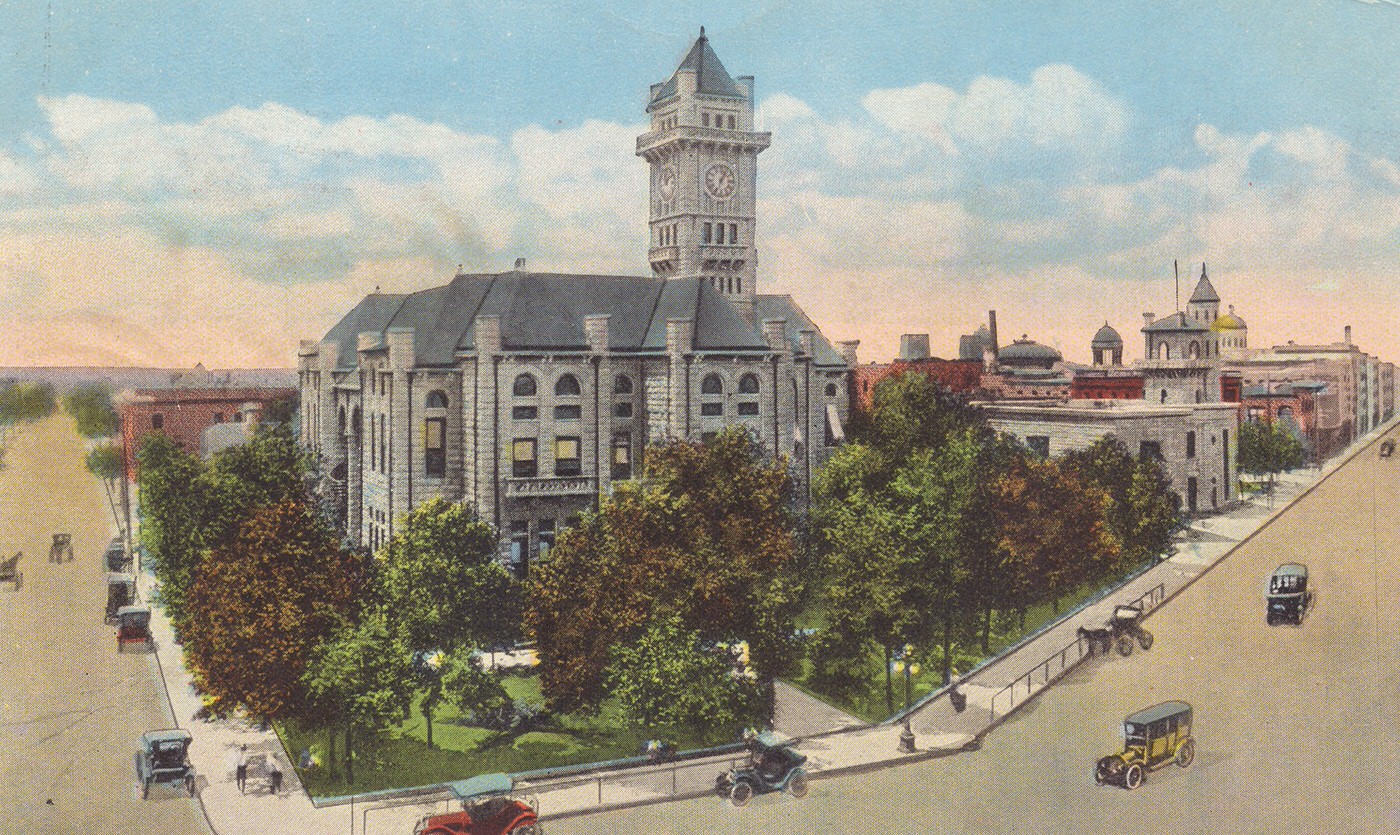

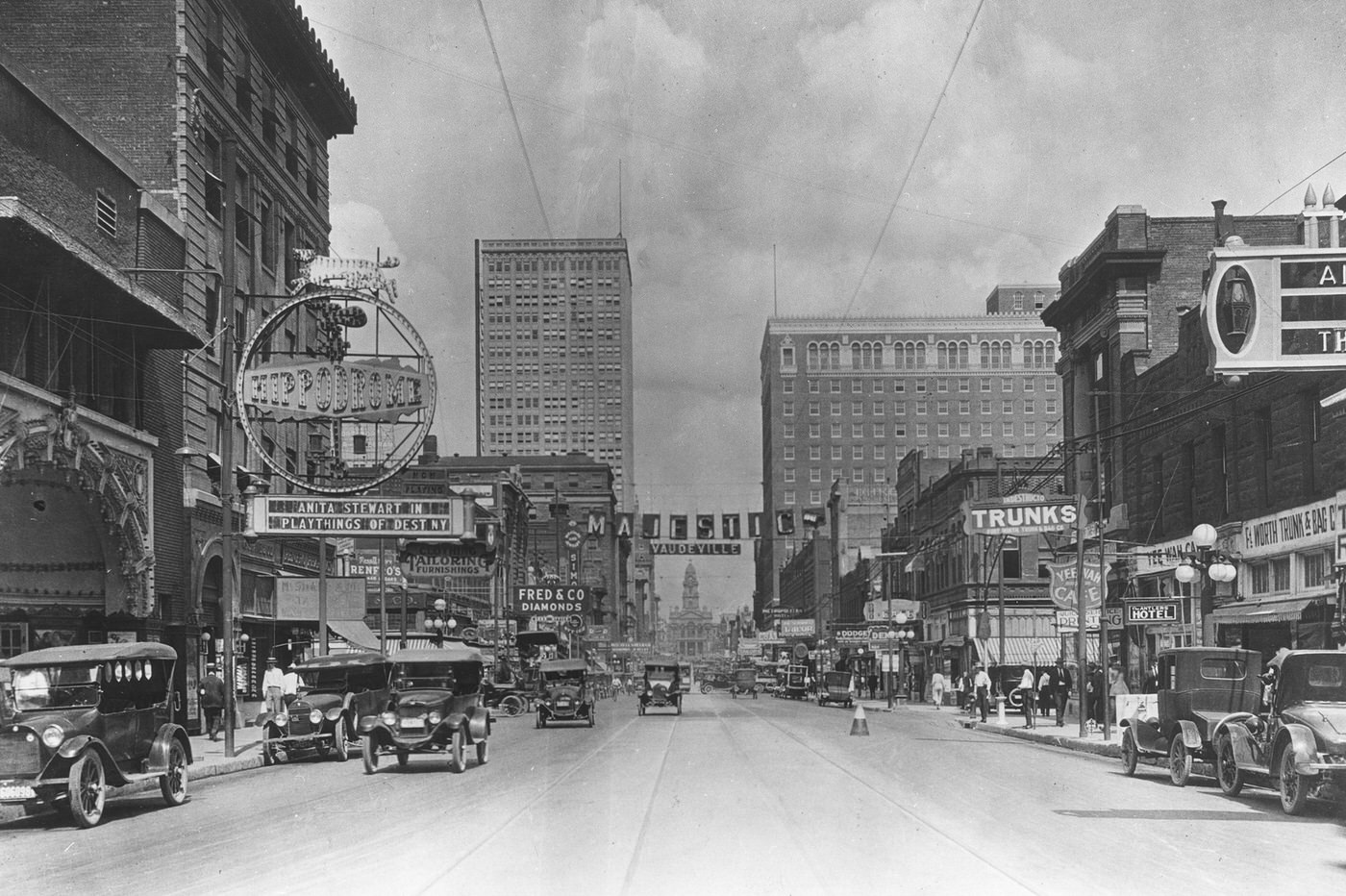

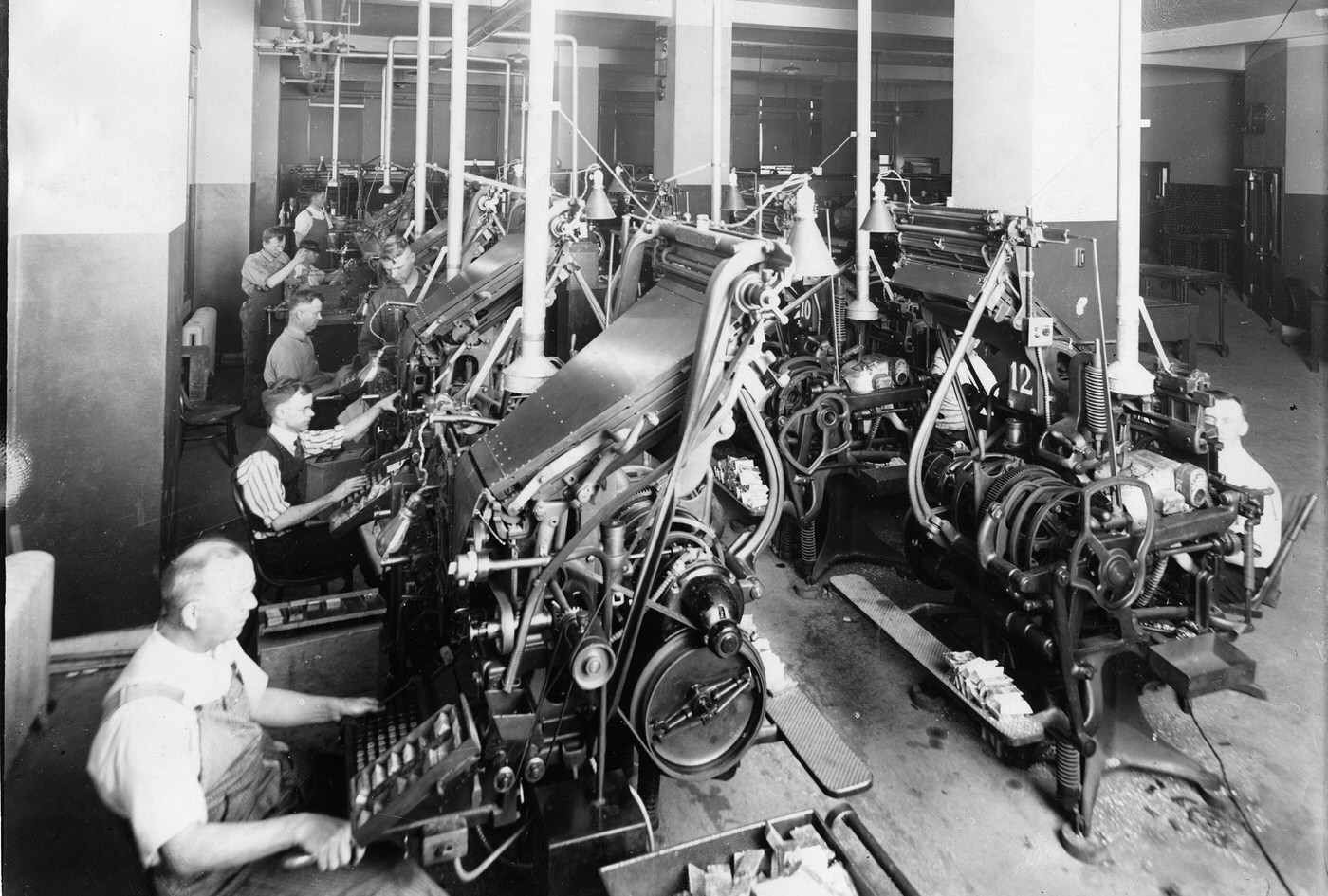

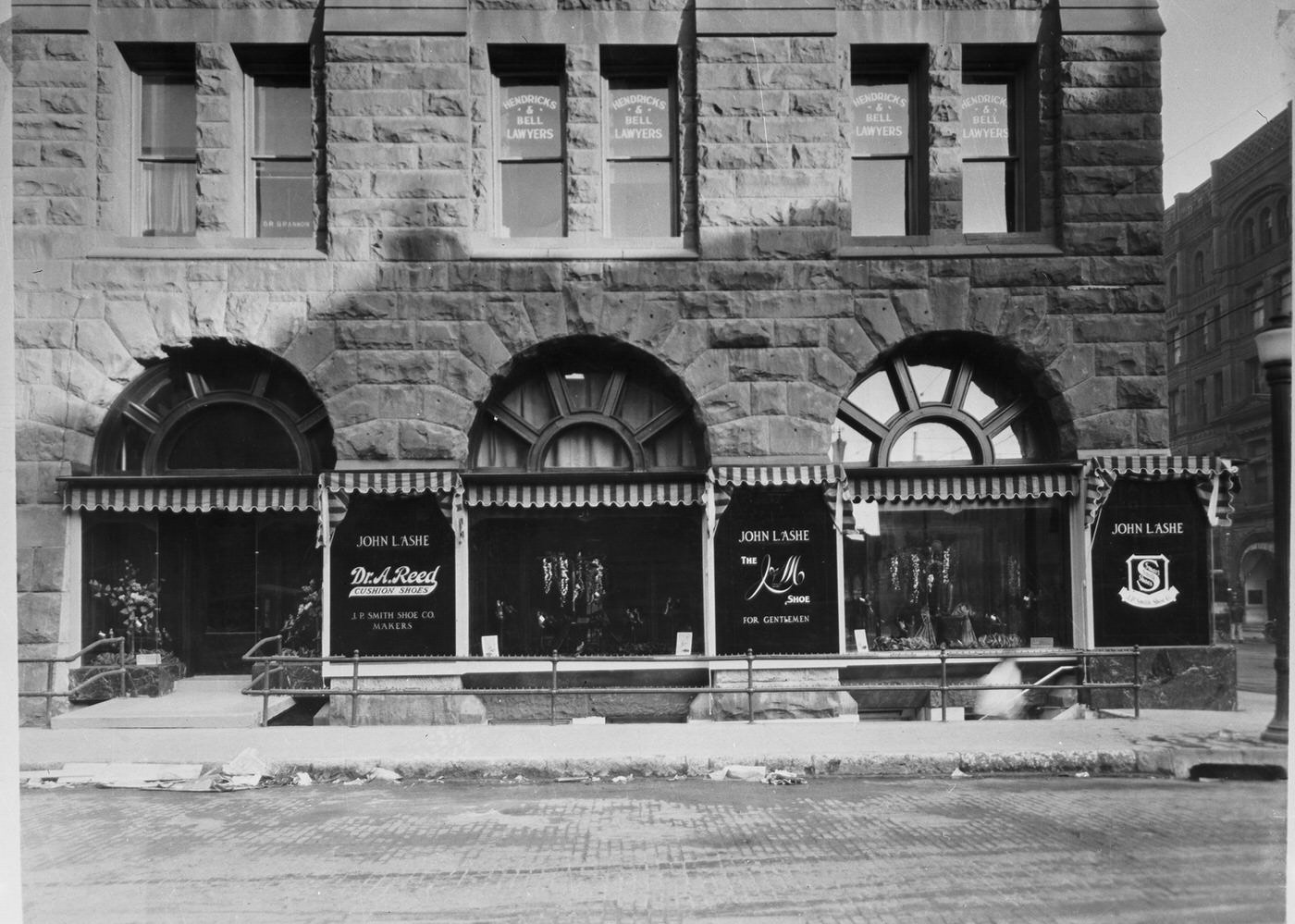

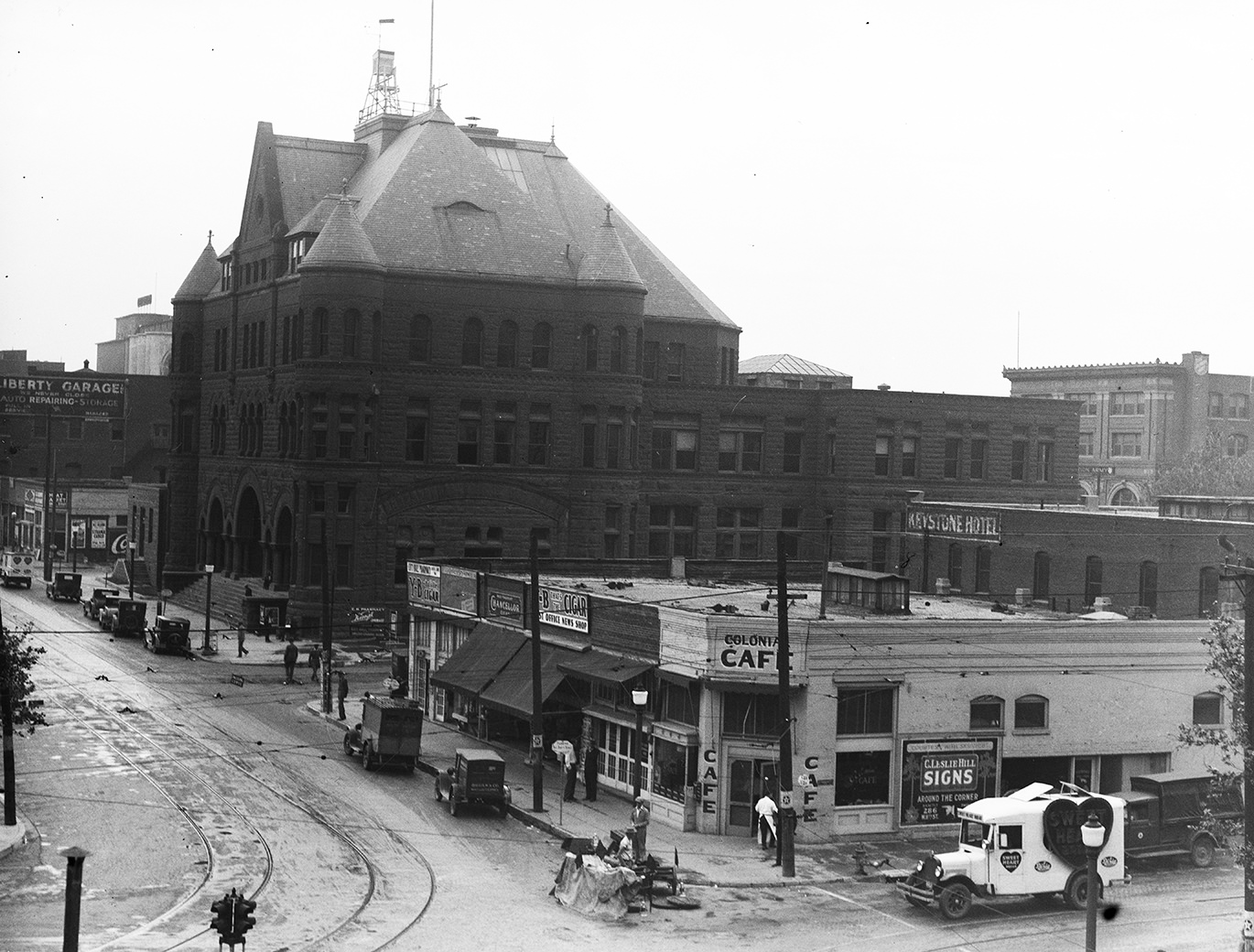

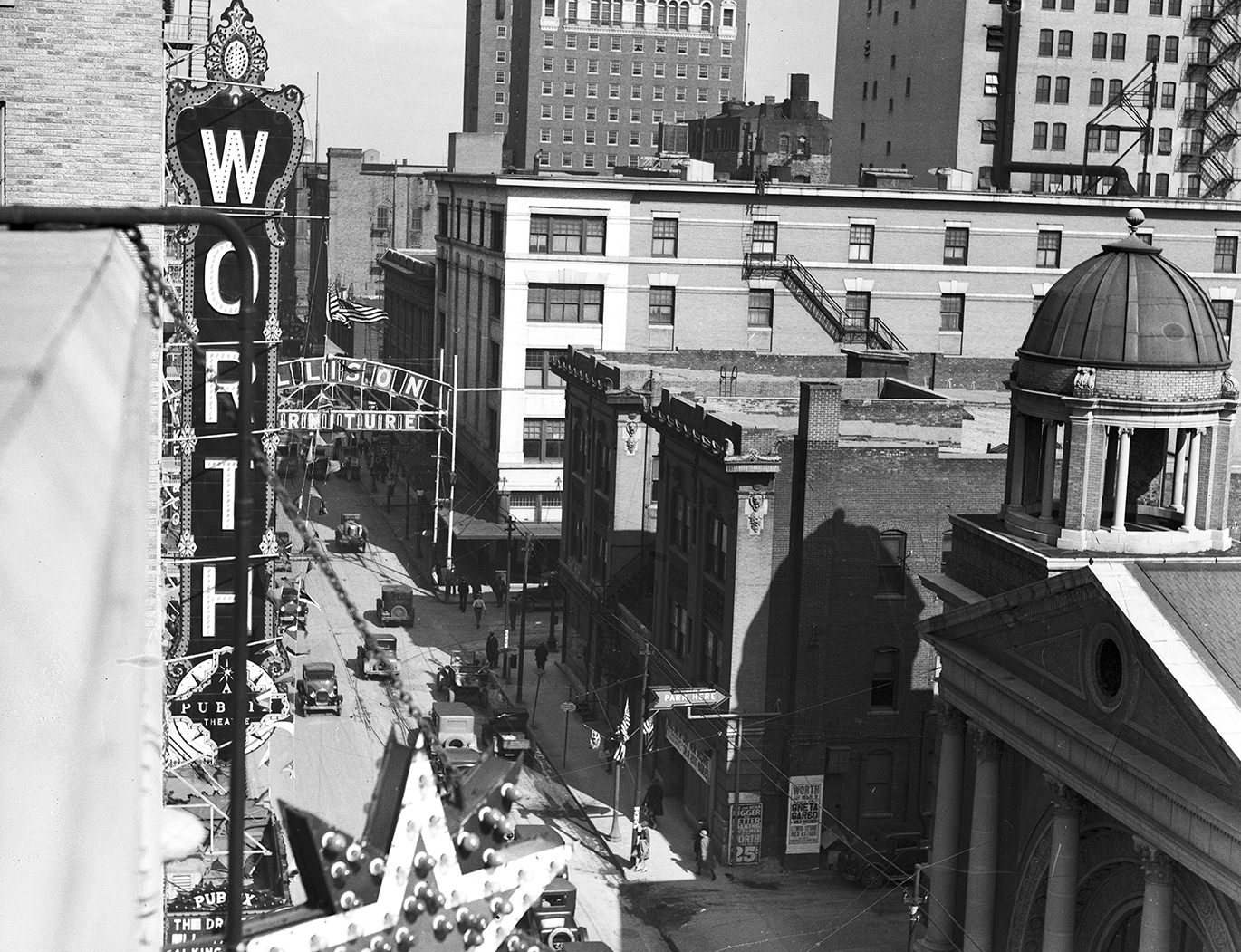

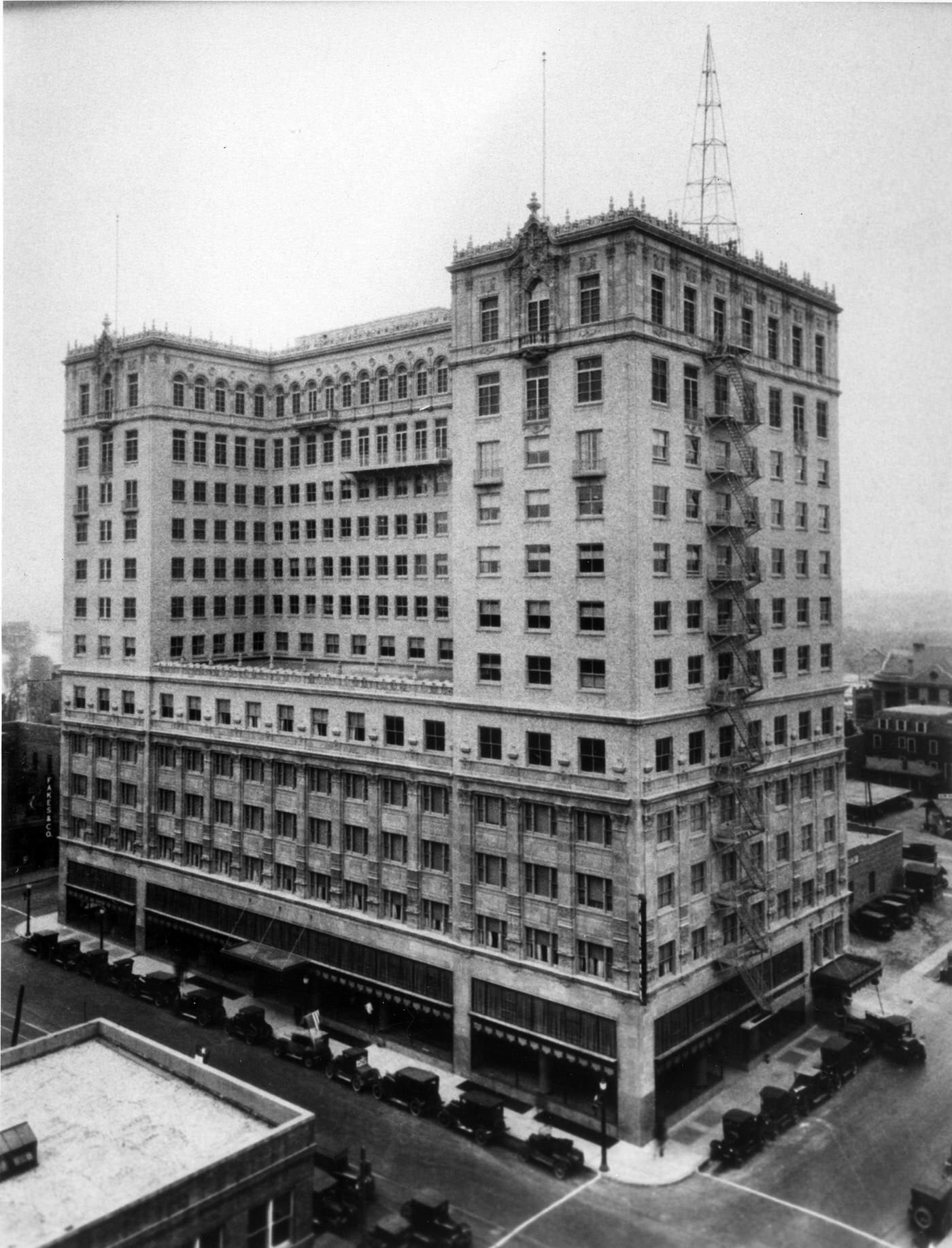

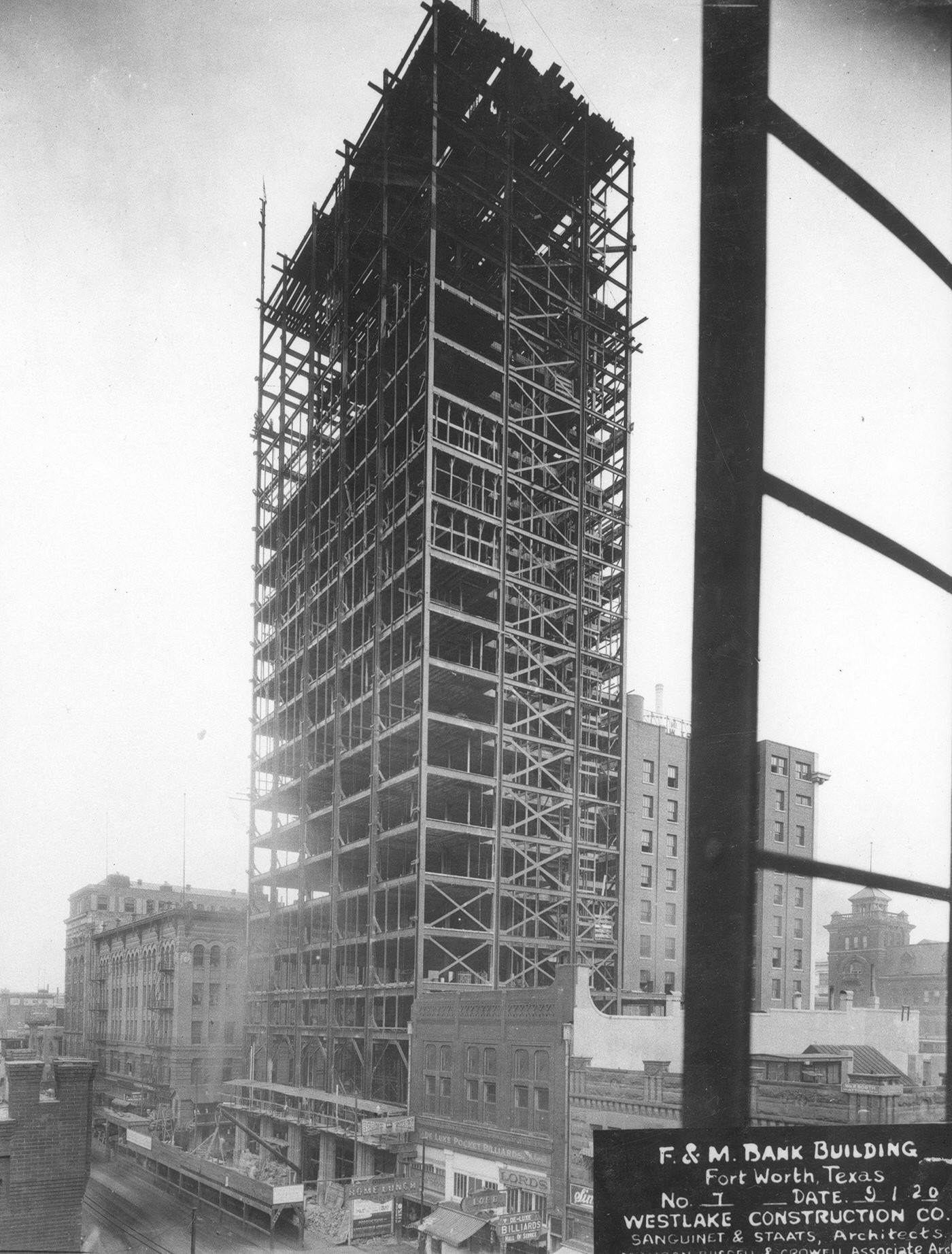

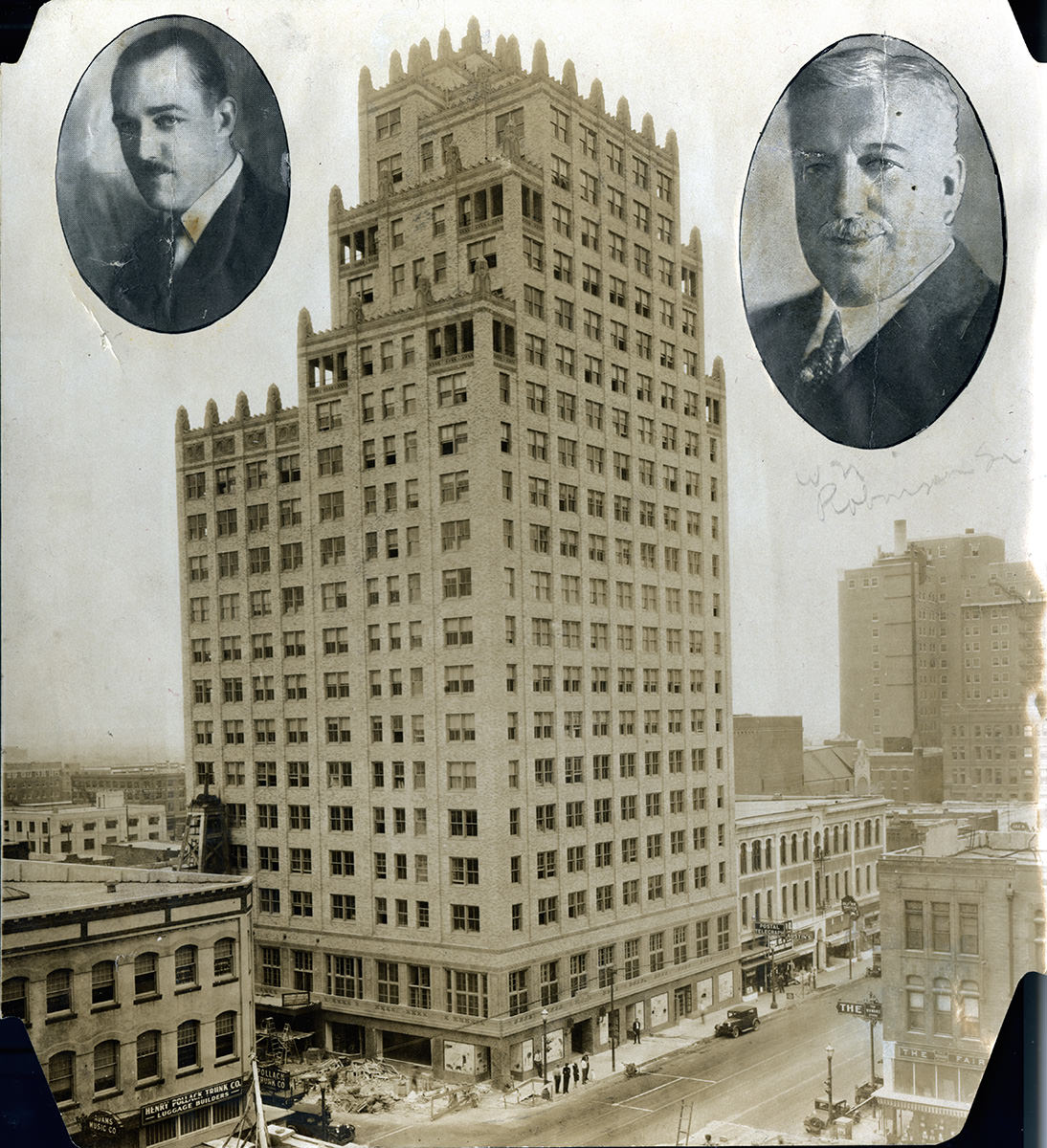

Perhaps the most visible symbols of Fort Worth’s transformation were its early skyscrapers, built to house the burgeoning oil companies, banks, and associated professional services that flocked to the city. The W.T. Waggoner Building, a 20-story tower reflecting Chicago School architectural influence, opened its doors at 810 Houston Street in 1920, a testament to the wealth of the ranching and oil magnate it was named after. Close on its heels came the Farmers and Mechanics National Bank Building at 714 Main Street in 1921. Designed by the prominent local firm Sanguinet & Staats, this 24-story structure reigned as Fort Worth’s tallest building until 1957, a powerful symbol of the city’s oil and cattle prosperity. The specialization of the modern city was reflected in the Medical Arts Building, a 19-story tower designed by Wyatt C. Hedrick and completed in 1926 at 911 Burnett Park (formerly 911 Calhoun St.), catering specifically to the growing medical community (though sadly demolished in 1973). Other notable towers contributing to the changing skyline in the late 1920s and very early 1930s included the Petroleum Building (1927), the Electric Building (housing the Hollywood Theater, 1929), the Blackstone Hotel (1929), and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram Building (1930).

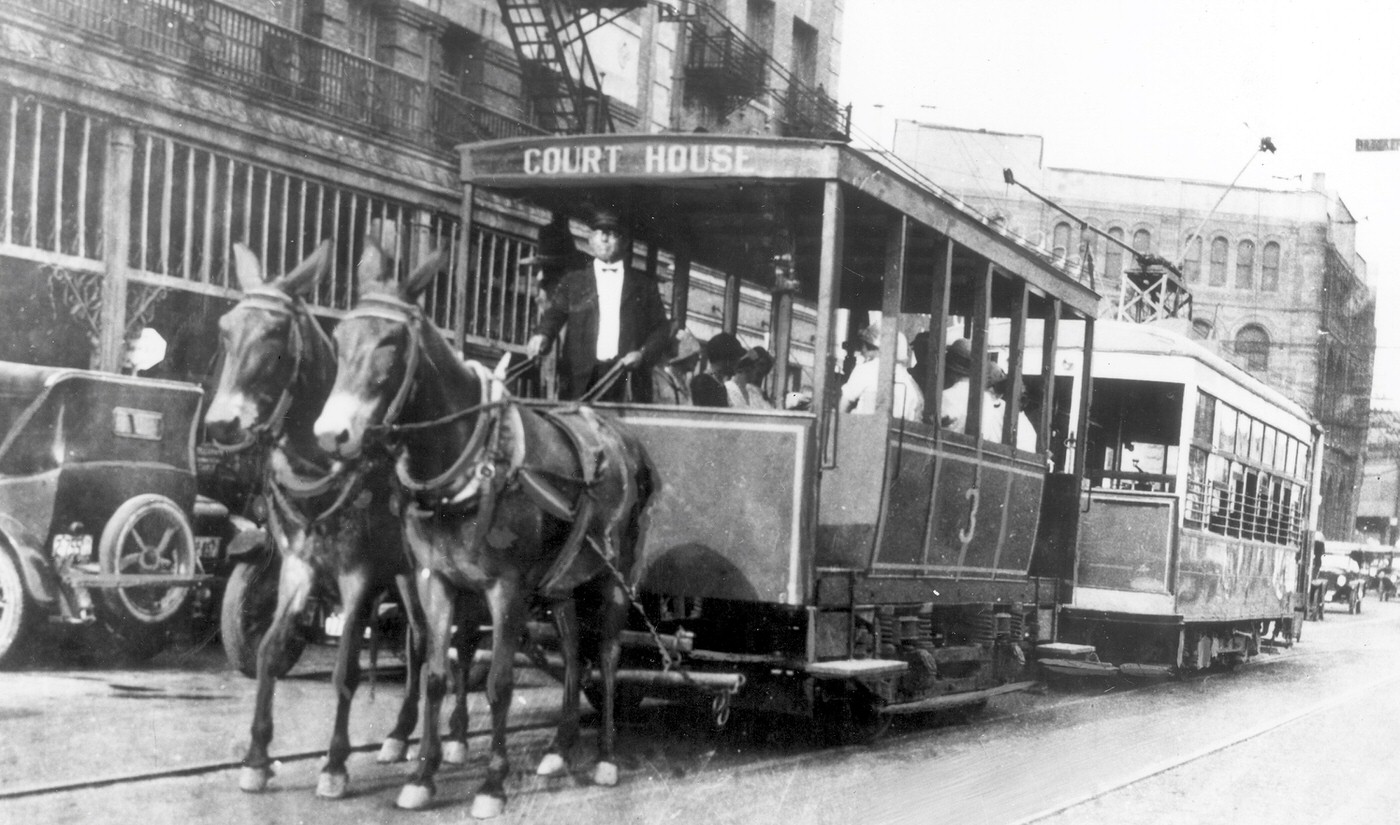

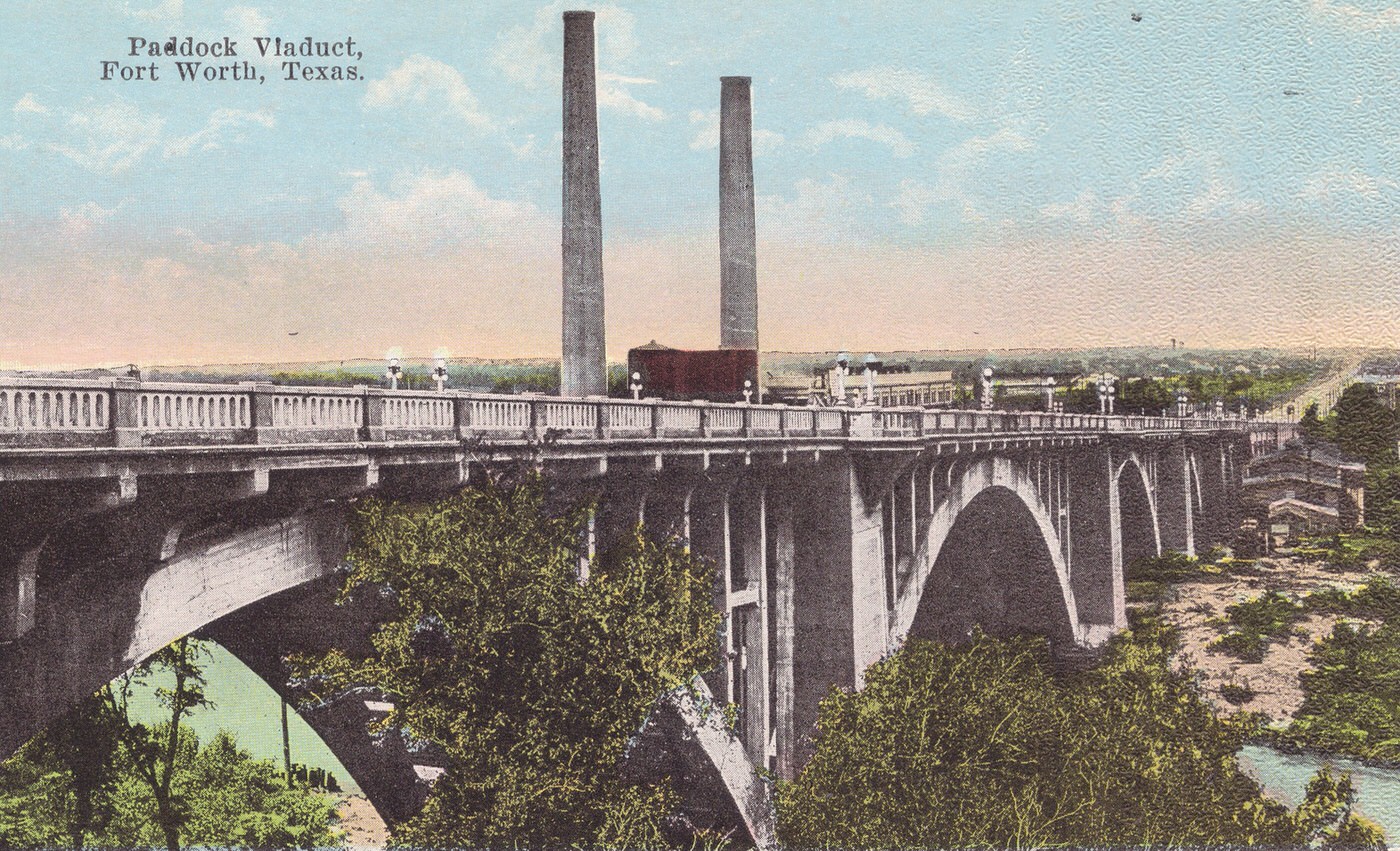

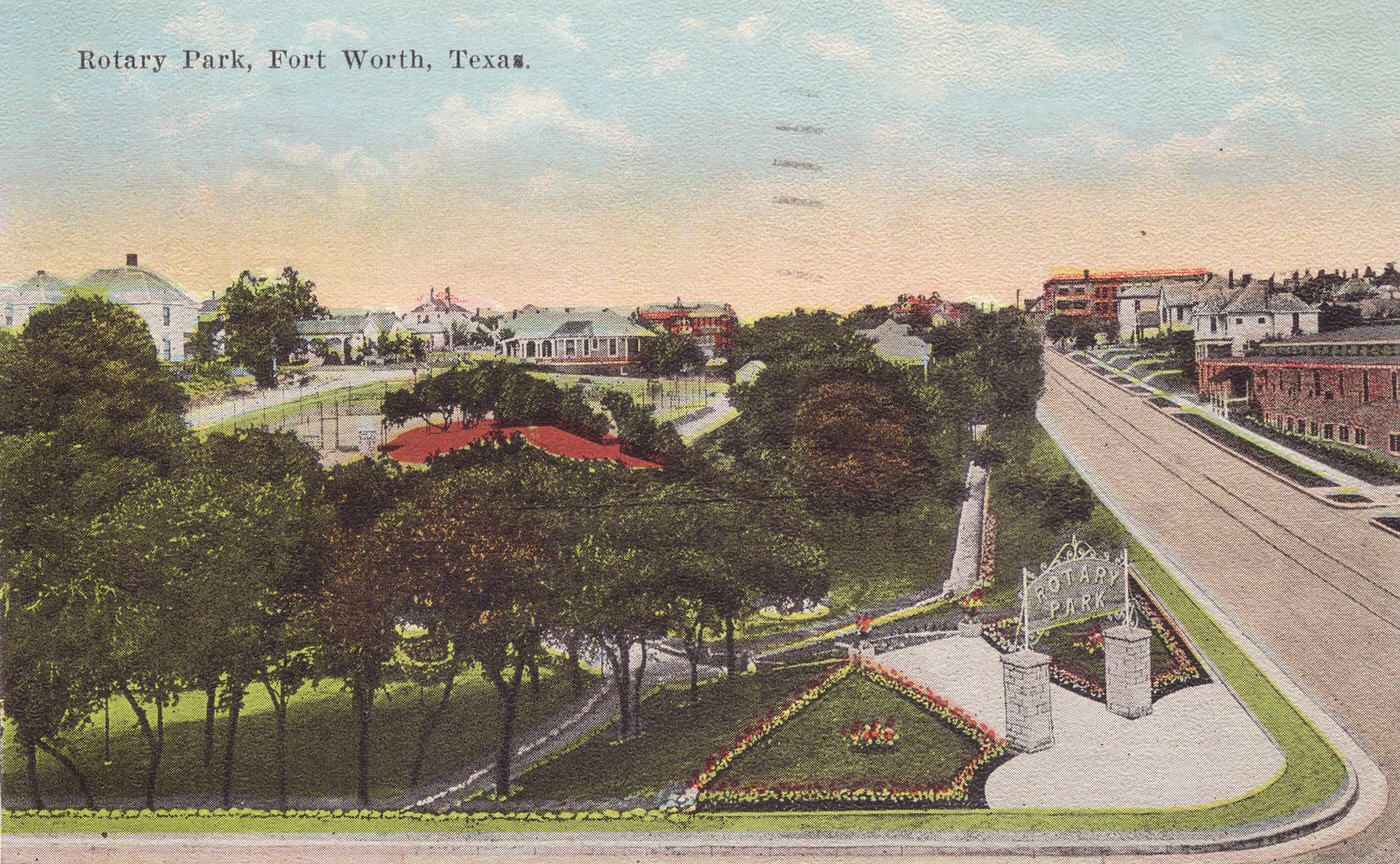

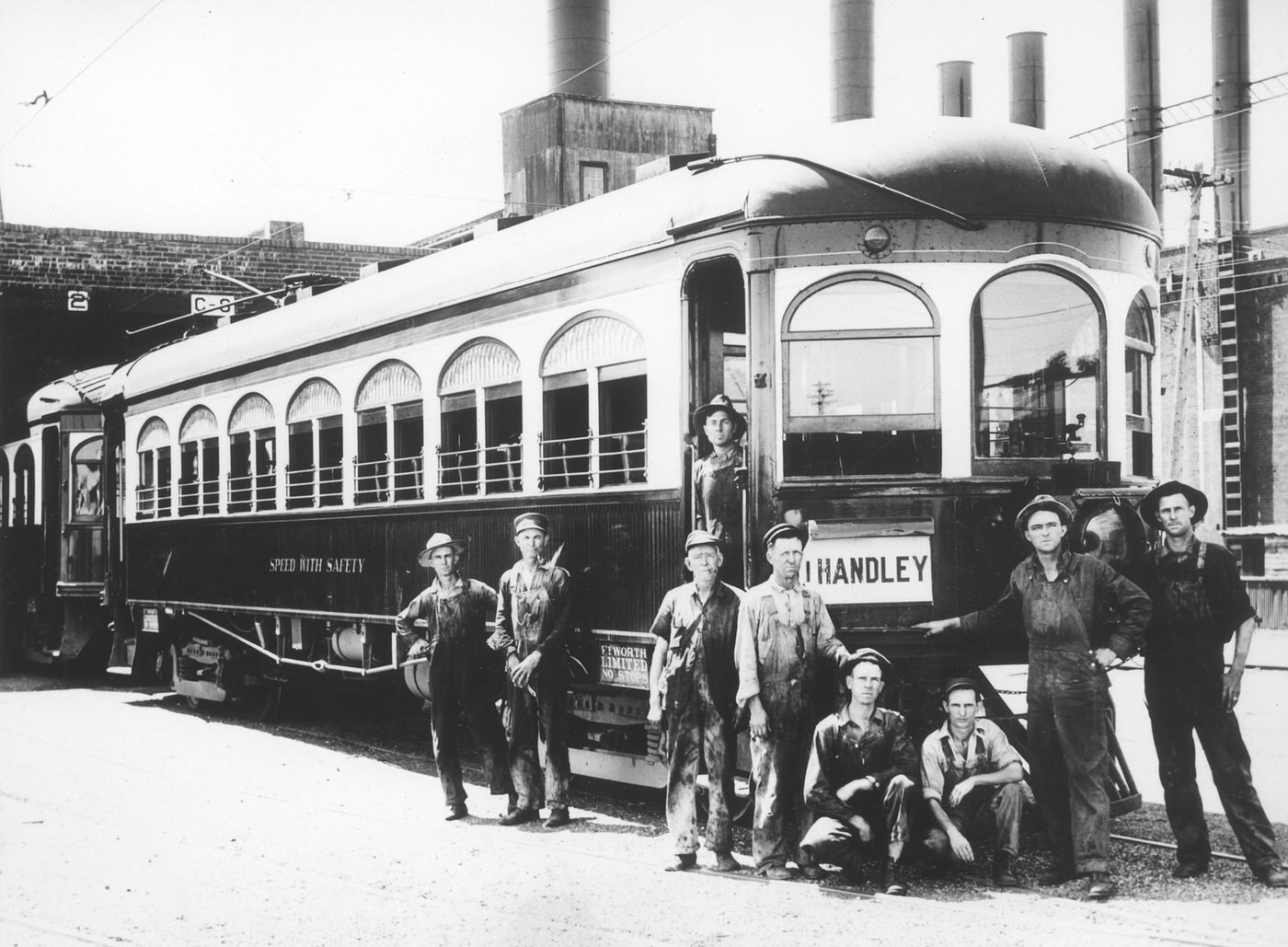

As the downtown core densified with these new towers, the city’s population spilled outwards into new residential areas. This suburban expansion was initially driven by the city’s streetcar network, operated by the Northern Texas Traction Company (NTTC), and increasingly by the proliferation of the automobile. Several distinct neighborhoods took shape or significantly expanded during this era:

Arlington Heights: Located west of downtown, its development accelerated rapidly in the 1920s, benefiting significantly from the utility infrastructure (water, sewer, electricity) installed for Camp Bowie during World War I. It was reportedly the city’s fastest-growing section between 1920 and 1926. The area became characterized by charming English Cottage and Arts and Crafts bungalow style homes. Camp Bowie Boulevard, the main artery renamed in 1919, was paved with distinctive red Thurber bricks in 1927-28, further enhancing access.

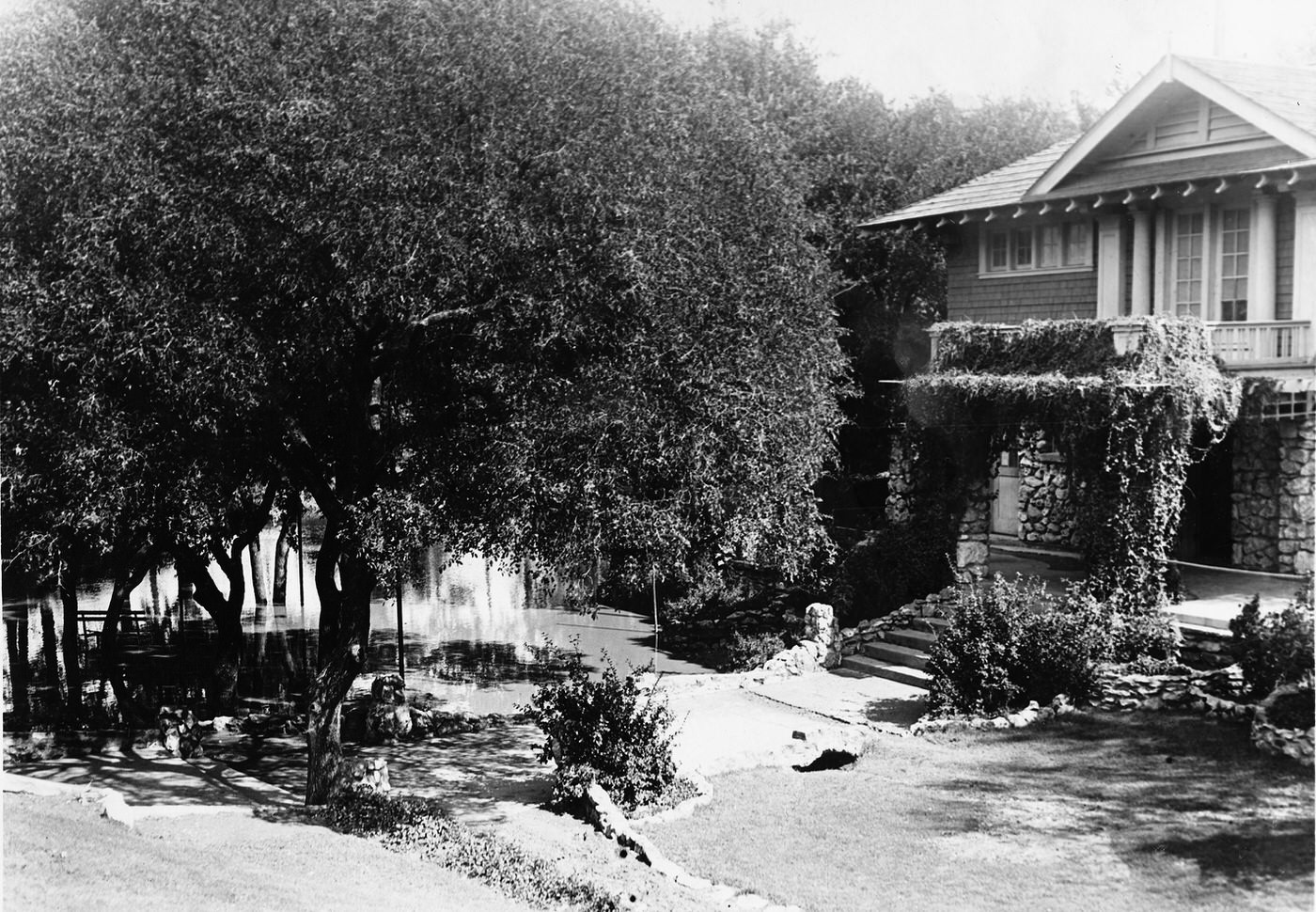

Ryan Place: Conceived in 1911 by developer John C. Ryan and situated south of downtown, this neighborhood became Fort Worth’s most prestigious address by the 1920s. It featured large, elegant mansions in styles like Mediterranean and Georgian, boasting luxurious amenities and landscaping designed by the renowned George E. Kessler.

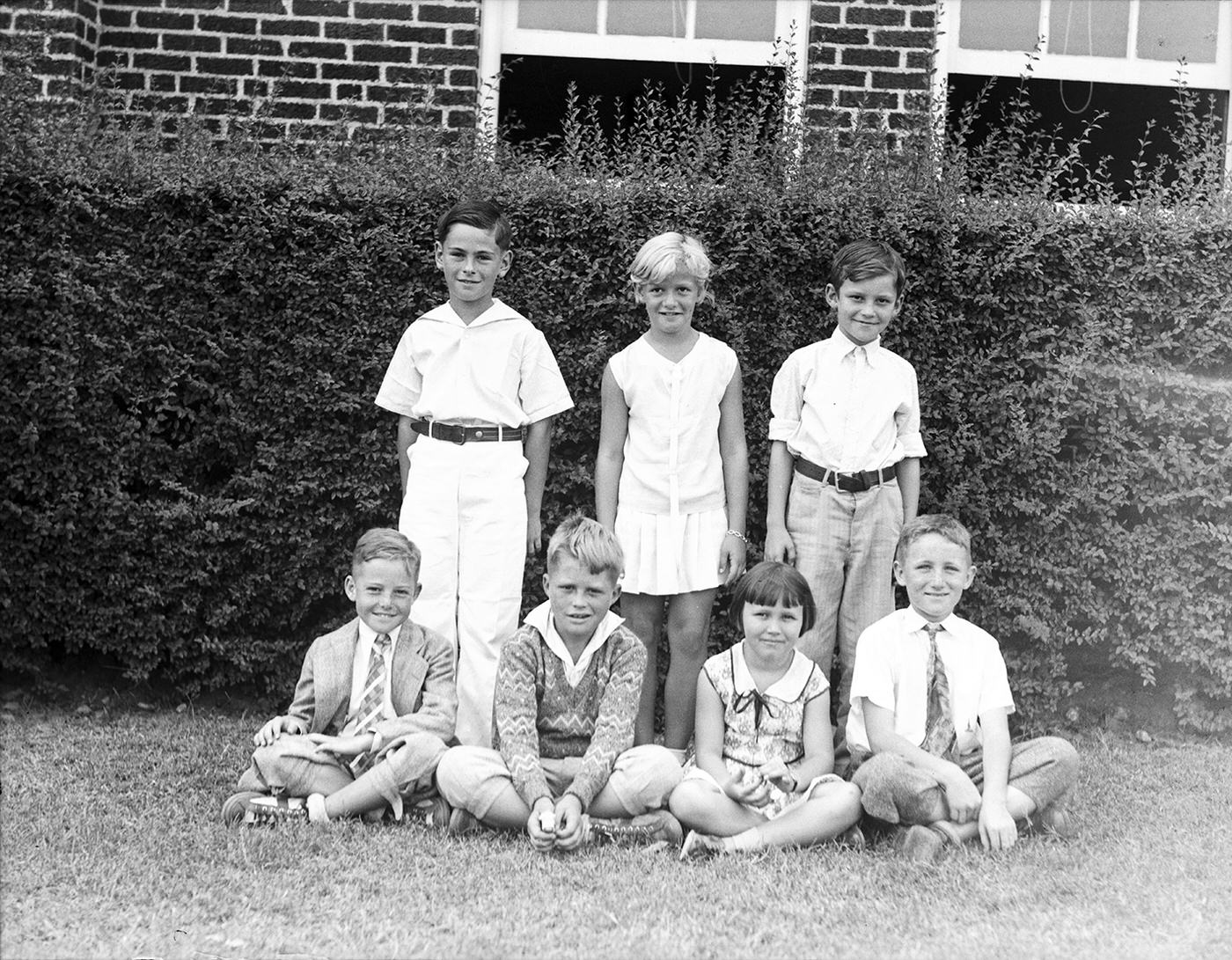

Mistletoe Heights: Southwest of downtown near the newly relocated Texas Christian University (TCU), this area saw significant development after its annexation in 1909 and 1922. The arrival of TCU (1911) and the extension of a streetcar line spurred growth, making lots increasingly valuable. The neighborhood school, Lily B. Clayton Elementary, was constructed in 1922 to serve the growing families.

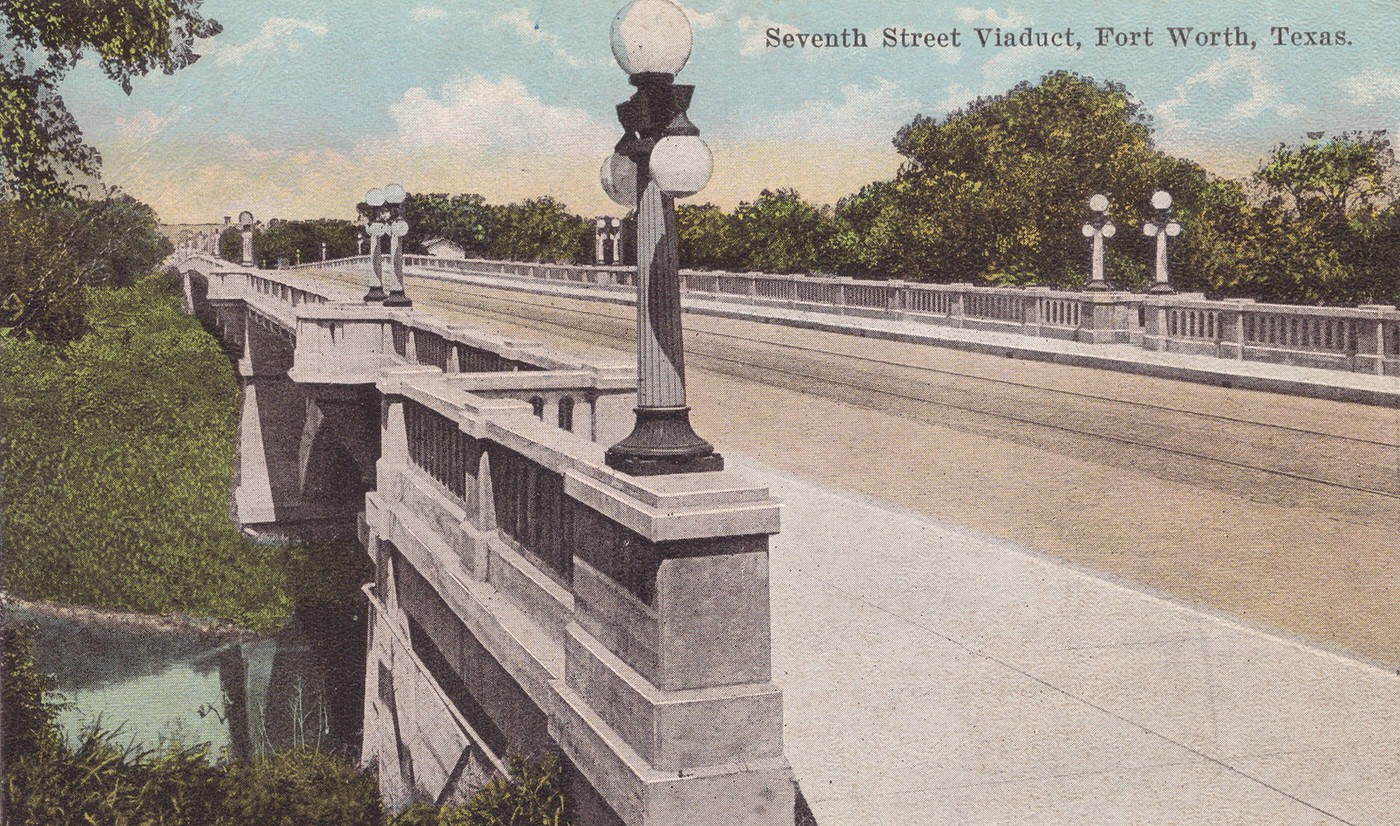

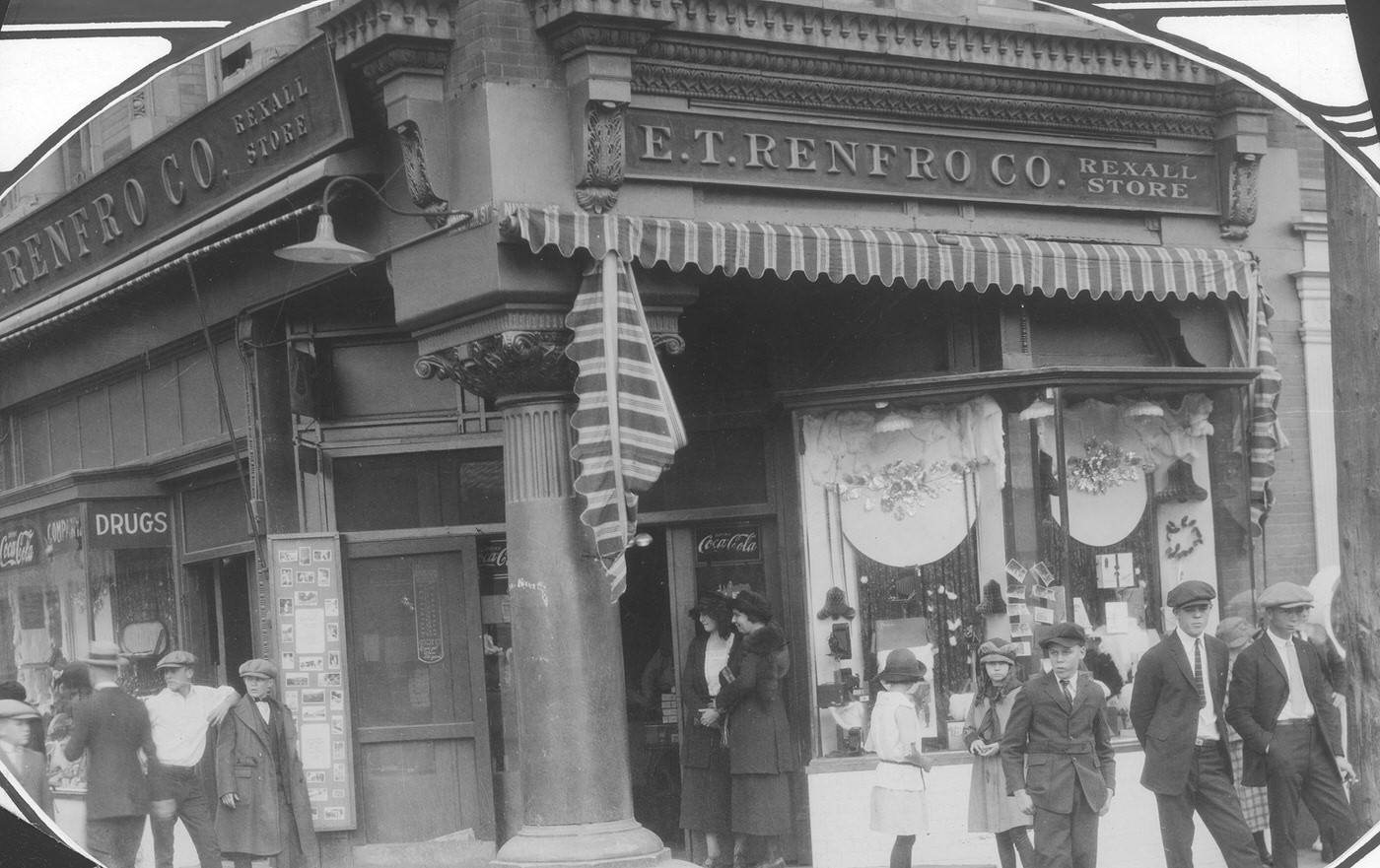

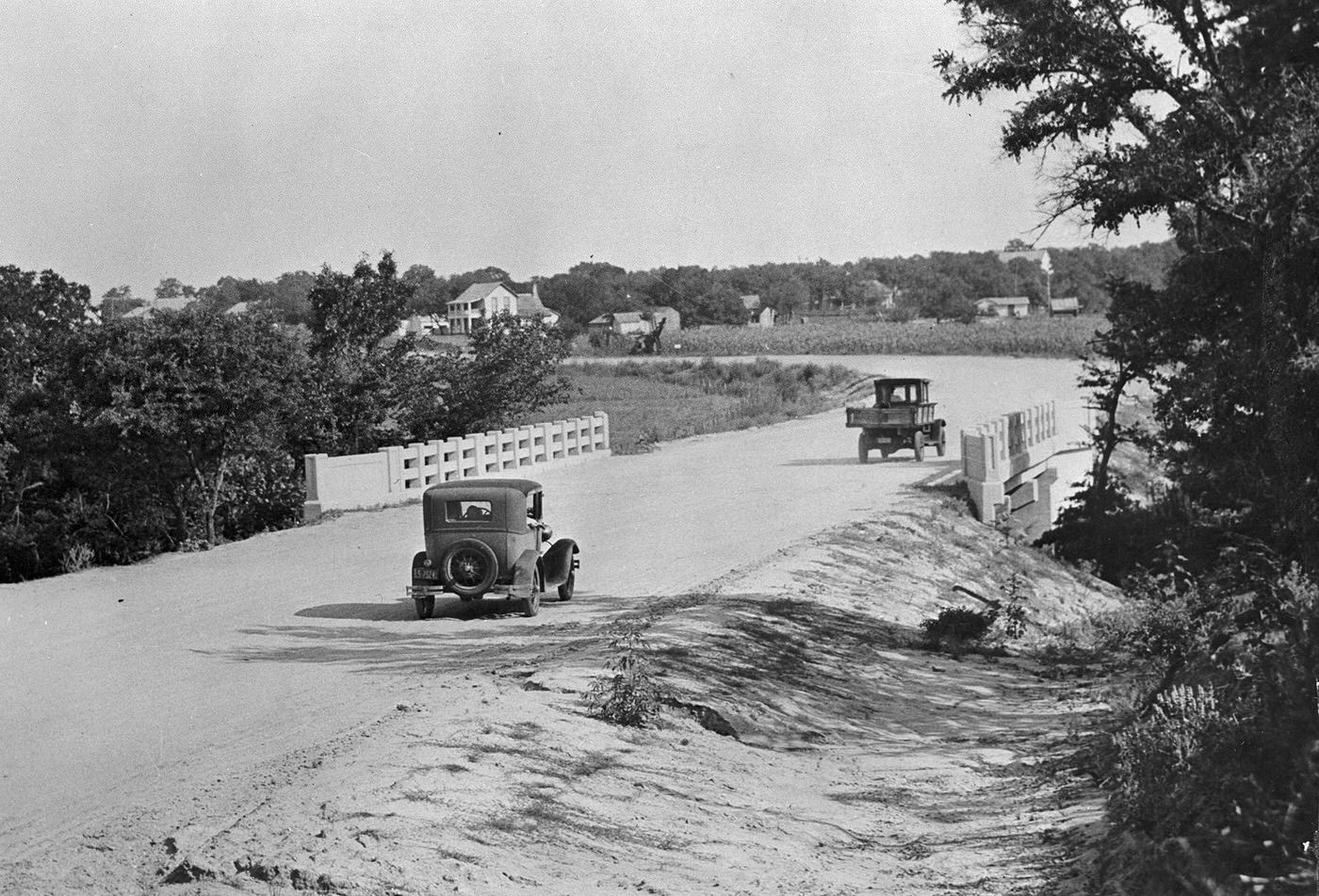

Supporting this urban and suburban growth required massive infrastructure investment. The transition from the muddy, unpaved streets of the 19th century accelerated. While Main Street had seen early brick paving in the late 1890s , the 1920s saw more extensive efforts, notably the paving of Camp Bowie Boulevard. Tarrant County also invested heavily in improving roadways connecting Fort Worth to surrounding areas. The city’s utility systems strained to keep pace. The water supply, critically dependent on Lake Worth (completed 1914) and the Holly Water Treatment Plant (operational 1912, fully operational 1918), had to serve a rapidly growing population and thirsty industries. The artificial gas works established in 1876 had been supplemented by the Fort Worth Gas Company in 1909, bringing natural gas via pipeline, and the electrical grid continued its expansion. The streetcar system, run by the NTTC, remained vital for commuting, connecting downtown to burgeoning neighborhoods like Arlington Heights and Mistletoe Heights, and the interurban line to Dallas continued to operate. The NTTC actively competed with the automobile, even winning a prestigious industry award in 1927 for its efforts to maintain ridership. While essential, the expansion of this infrastructure often lagged behind the breakneck pace of population growth, creating challenges common to boomtowns across America.

The Roaring Twenties: Society, Culture, and Conflict

The nationwide ban on alcohol production and sale, enacted by the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act (1920-1933), cast a long shadow over Fort Worth’s social life. Like other cities, Fort Worth saw the rise of an illicit alcohol economy. Speakeasies – hidden, unlicensed bars often requiring a password for entry – proliferated, catering to thirsty citizens. Bootlegging, the illegal manufacture and transport of liquor, became a major criminal enterprise, often linked to organized crime. Enforcement proved a significant challenge for both local police and federal Prohibition agents. While raids occurred, sometimes netting large quantities of contraband (one 1927 raid reportedly destroyed 16,000 bottles of beer), bribery and corruption often hampered efforts. The infamous Hell’s Half Acre district, though officially suppressed by this time, likely remained a hub for illegal alcohol activity.

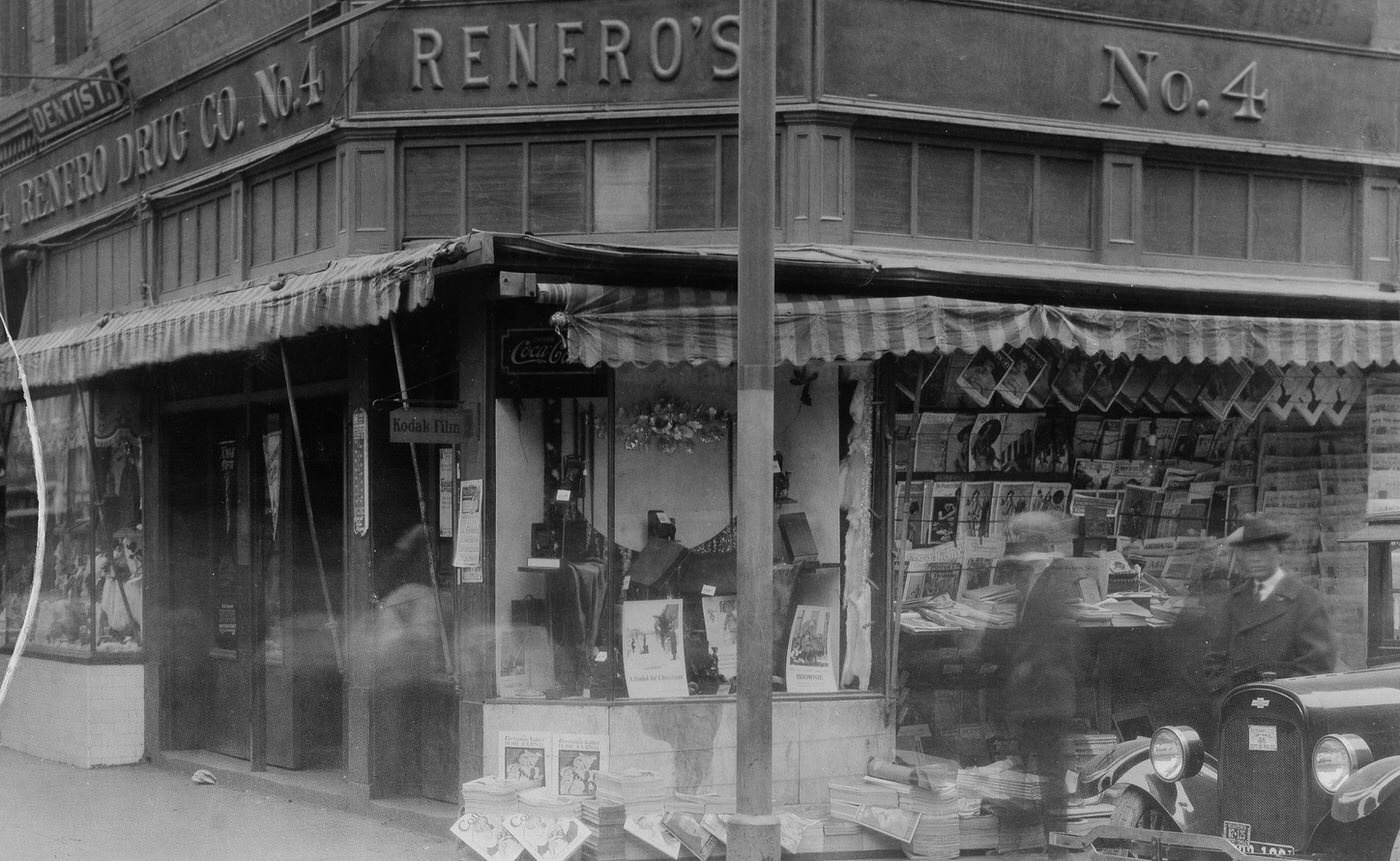

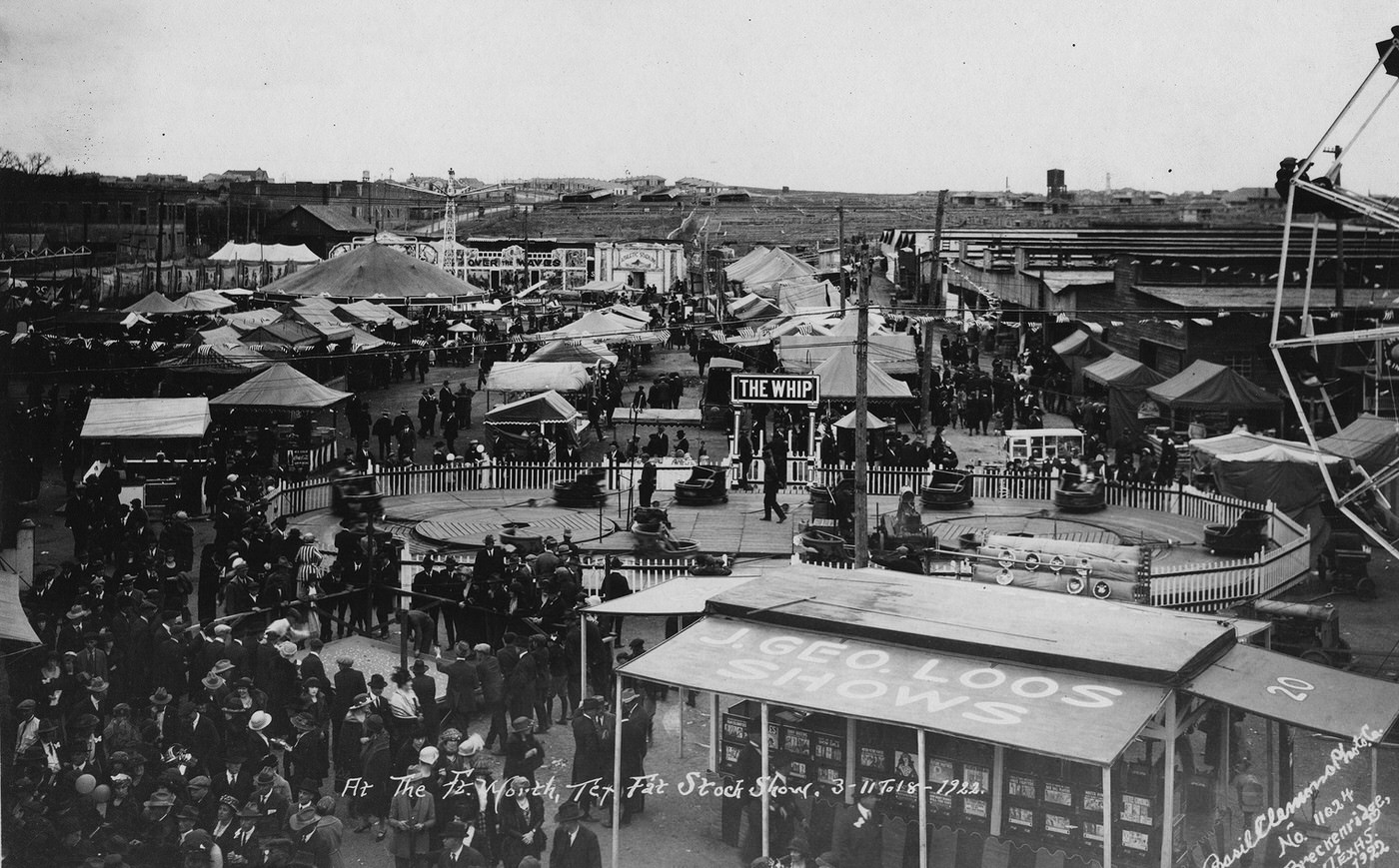

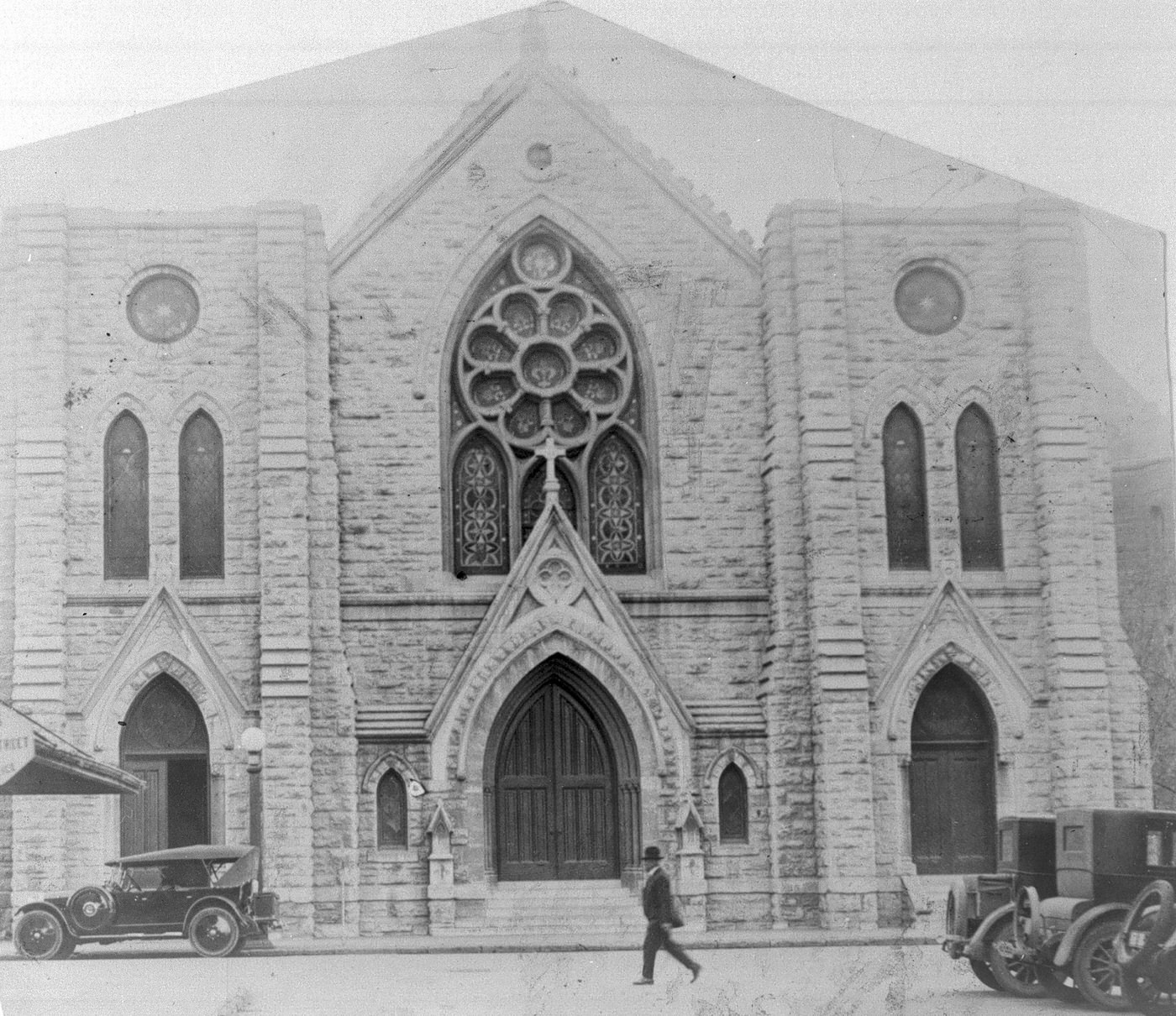

Despite Prohibition, or perhaps partly because of its rebellious spirit, Fort Worth’s entertainment scene flourished. The era saw the rise of the “movie palace,” large, ornately decorated theaters offering escapism to growing audiences. Fort Worth boasted several such venues, often transitioning from earlier vaudeville houses. The Majestic (opened 1911), the Palace (formerly the Byers/Greenwall Opera House), and the Worth (built 1928) were prominent downtown destinations. The Hollywood Theater, an Art Deco gem designed by Wyatt C. Hedrick, opened in 1930 within the 1929 Electric Building, specifically designed for the new “talking pictures”. Dance halls and ballrooms pulsed with the energy of jazz and the emerging sounds of Western Swing. Crystal Springs Dance Pavilion, opened in 1916 and rebuilt in 1925, became a legendary venue, later known as a birthplace of Western Swing under Milton Brown. The Casino Ballroom, built on the shores of Lake Worth in 1927 (and rebuilt after a fire in 1928), hosted major national acts. Amusement parks like the short-lived White City in Rosen Heights (c. 1906-1911/12) and the Casino Park complex at Lake Worth, featuring a boardwalk, rides, and the ballroom, provided popular recreational outlets.

Higher education also expanded its footprint. Texas Christian University (TCU), having relocated to Fort Worth in 1910-11, experienced significant growth, gaining accreditation, joining the Southwest Athletic Conference, opening its library, and establishing its Graduate School and Journalism Department during the 1920s. Texas Woman’s College (later TWU) in nearby Denton, focused on liberal arts and practical training for women, also gained accreditation in 1923, offering crucial opportunities for female students in the region. The city’s public school system continued to expand to accommodate the booming population.

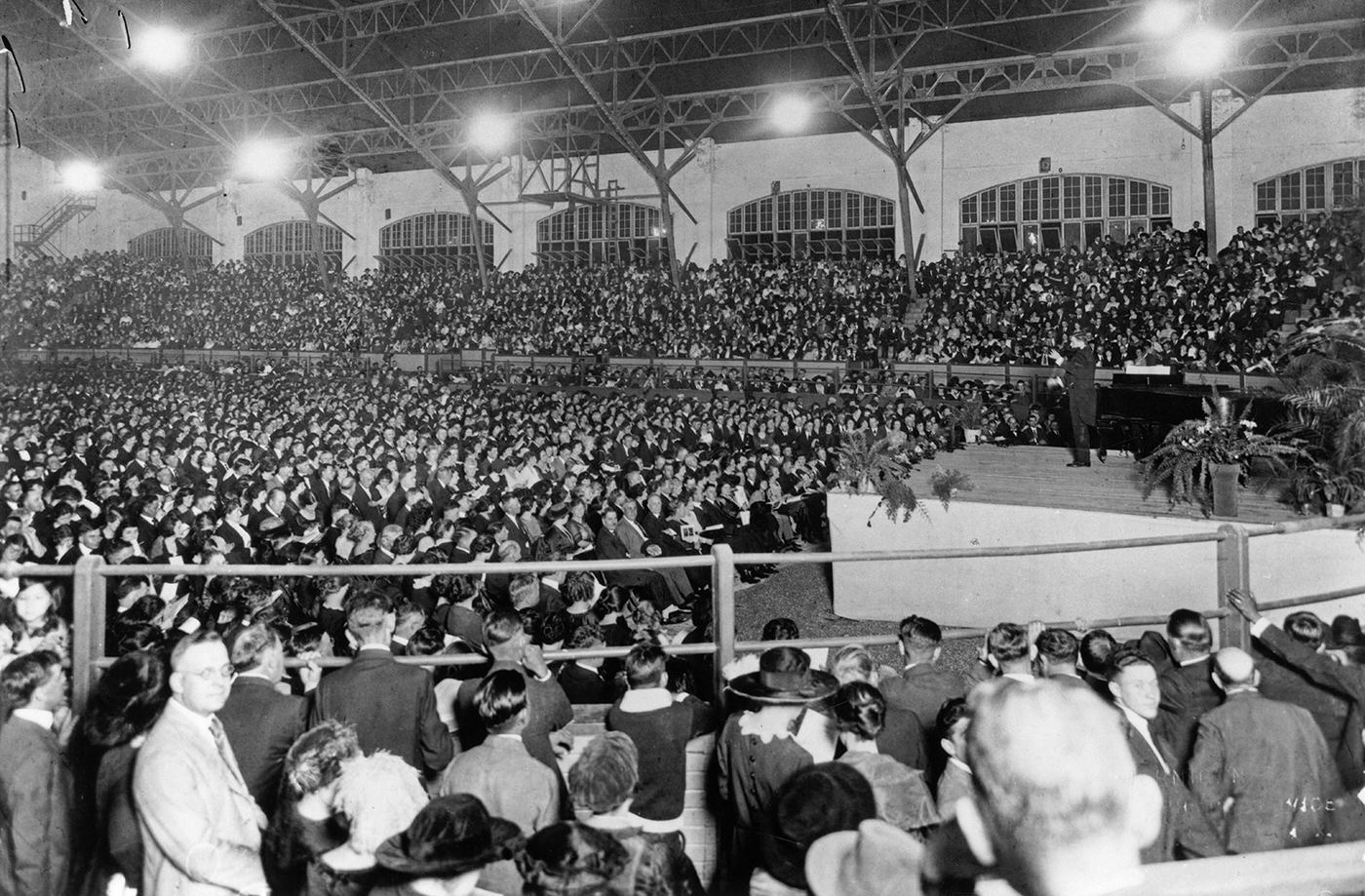

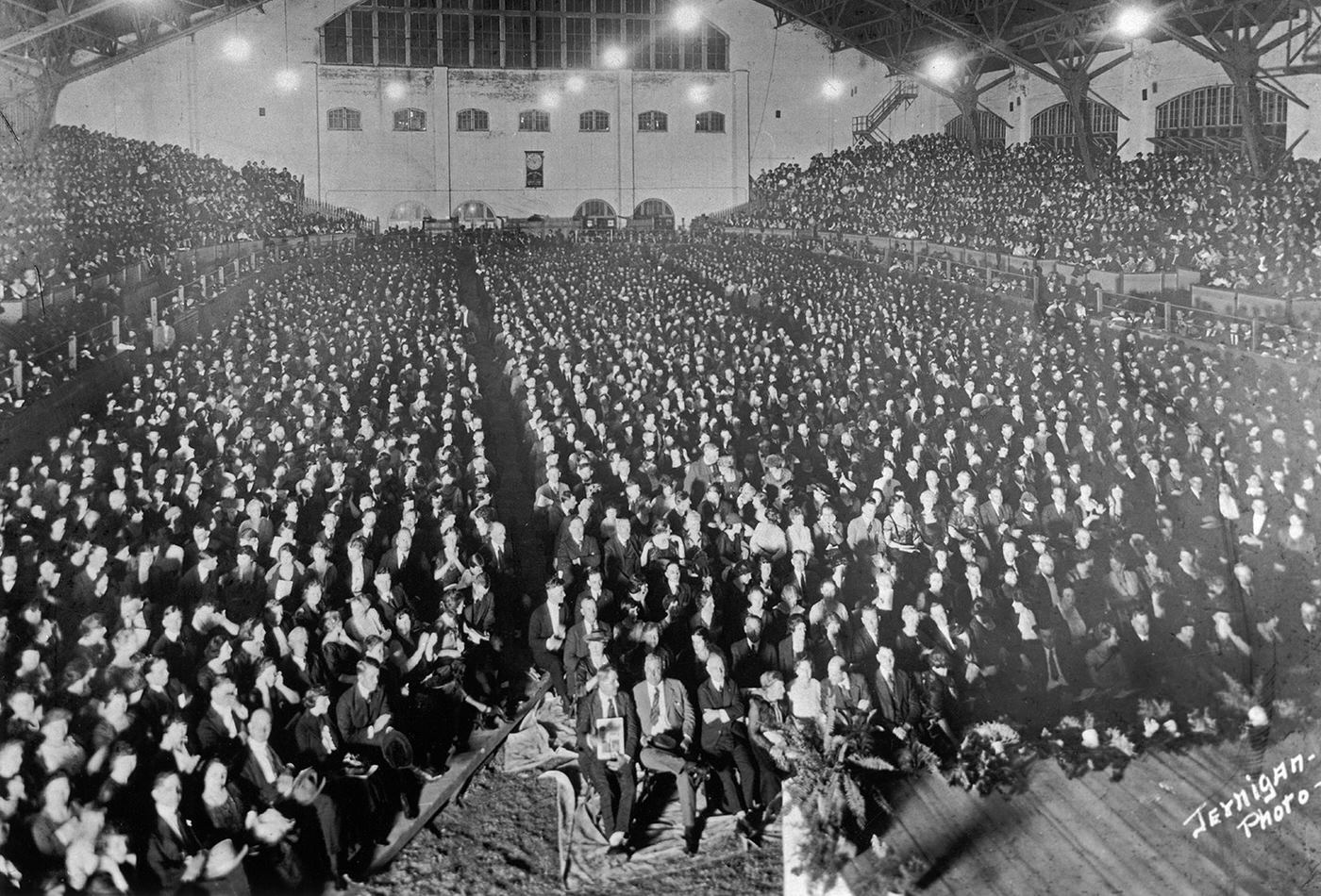

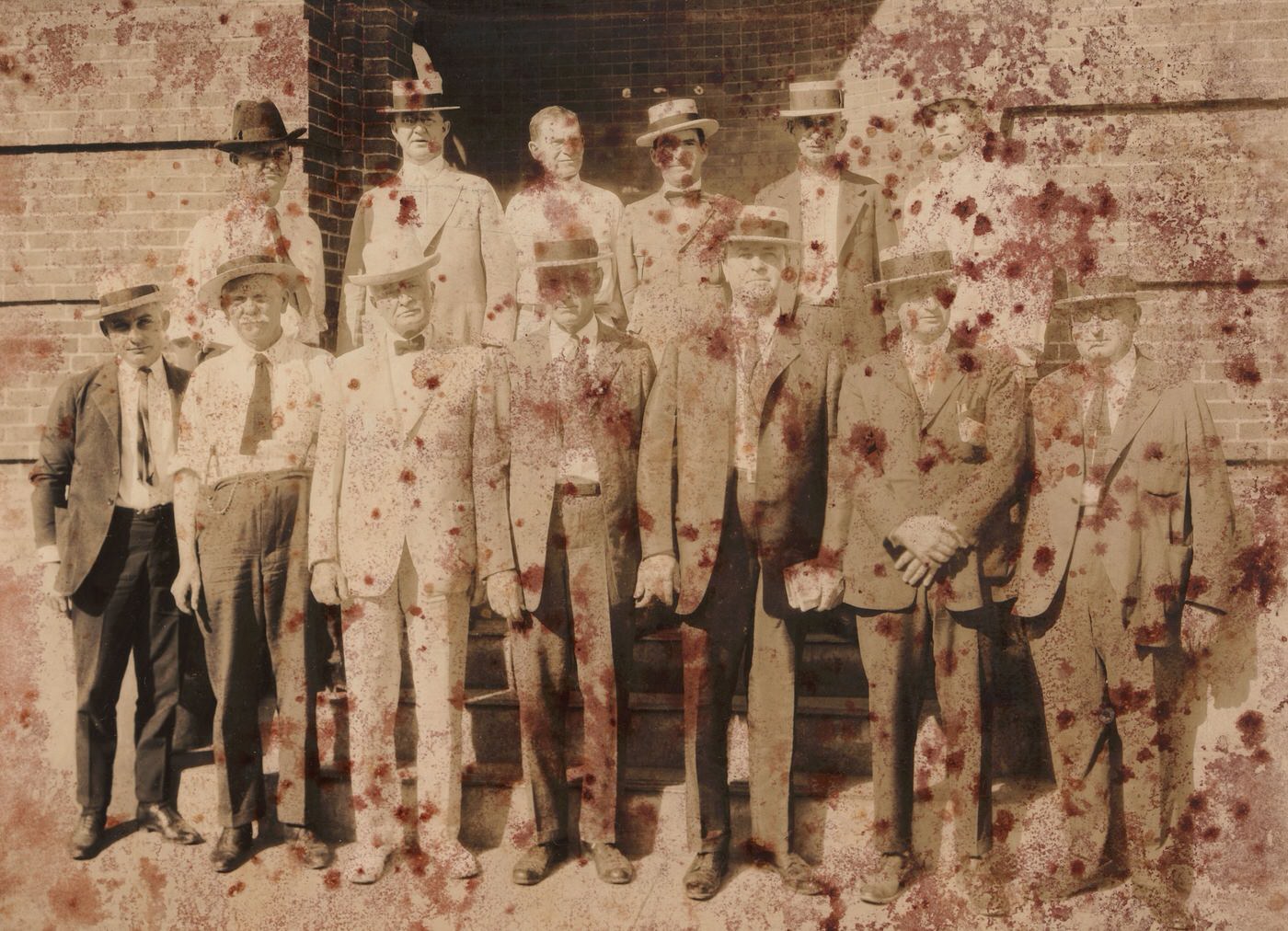

Beneath the surface of this cultural dynamism and economic growth, however, lay deep social tensions, most starkly represented by the powerful resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan. The second Klan, founded in 1915, exploited post-war anxieties, nativism, and religious prejudice, adding anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic hatred to its core white supremacist ideology. Fort Worth’s Klavern 101 became one of the largest and most visible Klan chapters in the nation, boasting a membership of around 6,000 by 1922 in a city of just over 100,000. Unlike the Reconstruction-era Klan, the 1920s version operated openly, participating in parades, donating to charities, and wielding significant political influence. Their power was symbolized by the construction of a massive, 2,000-seat auditorium and headquarters building at 1012 N. Main Street in 1924-25, a prominent structure intended to intimidate the nearby Black, Hispanic, and immigrant communities. This public face masked a darker reality of vigilante violence, including intimidation, beatings, and lynchings, targeting not only African Americans like Fred Rouse (lynched in 1921) but also whites deemed morally transgressive, like Tom Vickery (lynched 1920).

Fort Worth’s music scene reflected the era’s cultural blend. The city played a role in the development of Texas blues and jazz, which drew heavily on African American folk traditions. While specific jazz or blues clubs from the 1920s are hard to pinpoint from available sources, the foundations were being laid for future giants. Fort Worth native Euday L. Bowman penned “Twelfth Street Rag,” a tune that became a standard and influenced jazz pioneers like Louis Armstrong. The dance halls like Crystal Springs fostered the development of Western Swing, a unique Texas genre blending country, blues, and jazz. Later, Fort Worth would be instrumental in the careers of jazz innovators Charlie Christian and Ornette Coleman, who cut their teeth in the city’s rhythm-and-blues bands. The coexistence of the KKK’s public power with the vibrant, often Black-led, cultural expressions of blues and jazz underscores the profound contradictions of Fort Worth in the Roaring Twenties – a city simultaneously embracing modernity and grappling with deep-seated prejudice and social conflict.

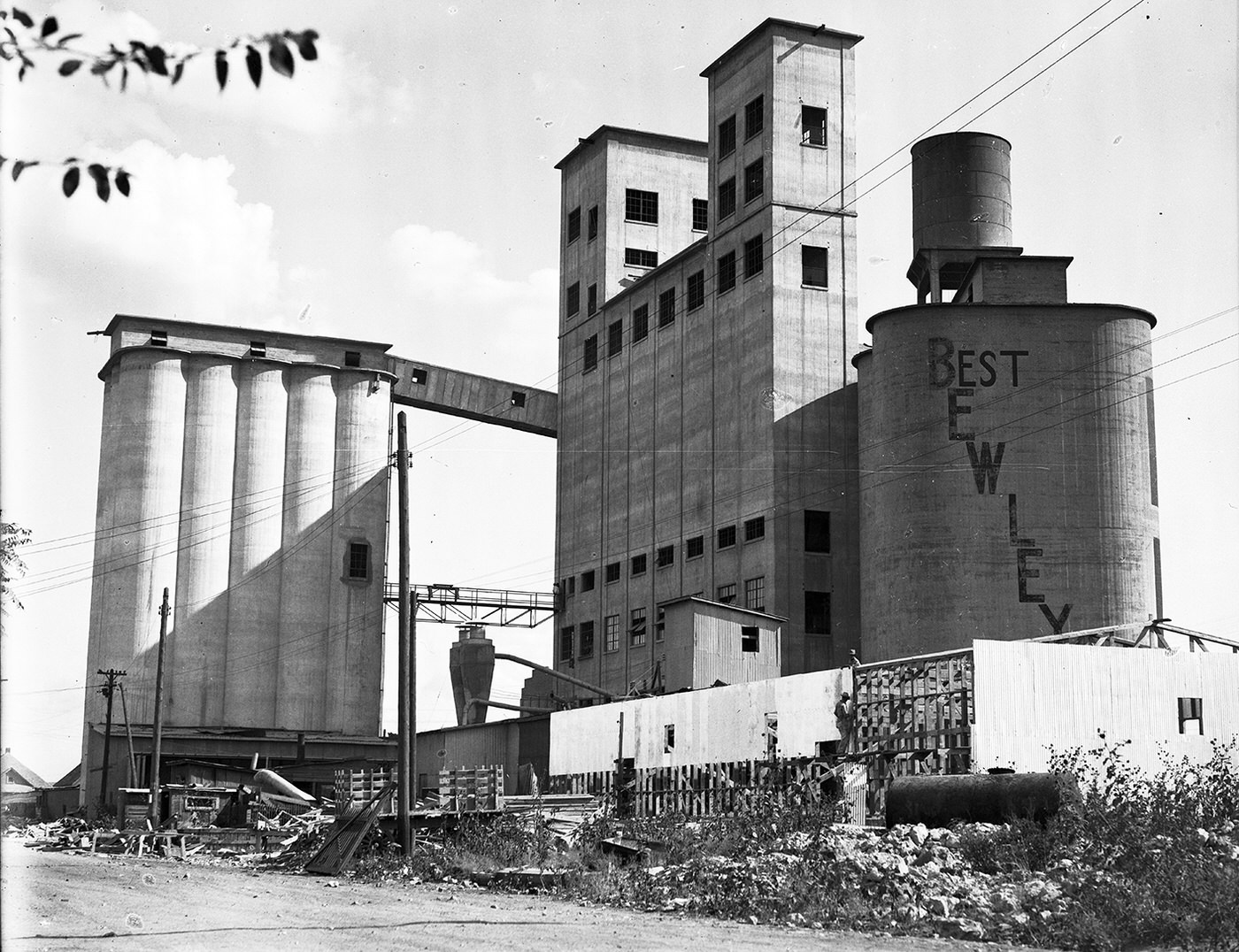

The Enduring Kingdom of Cattle: Stockyards and Packers

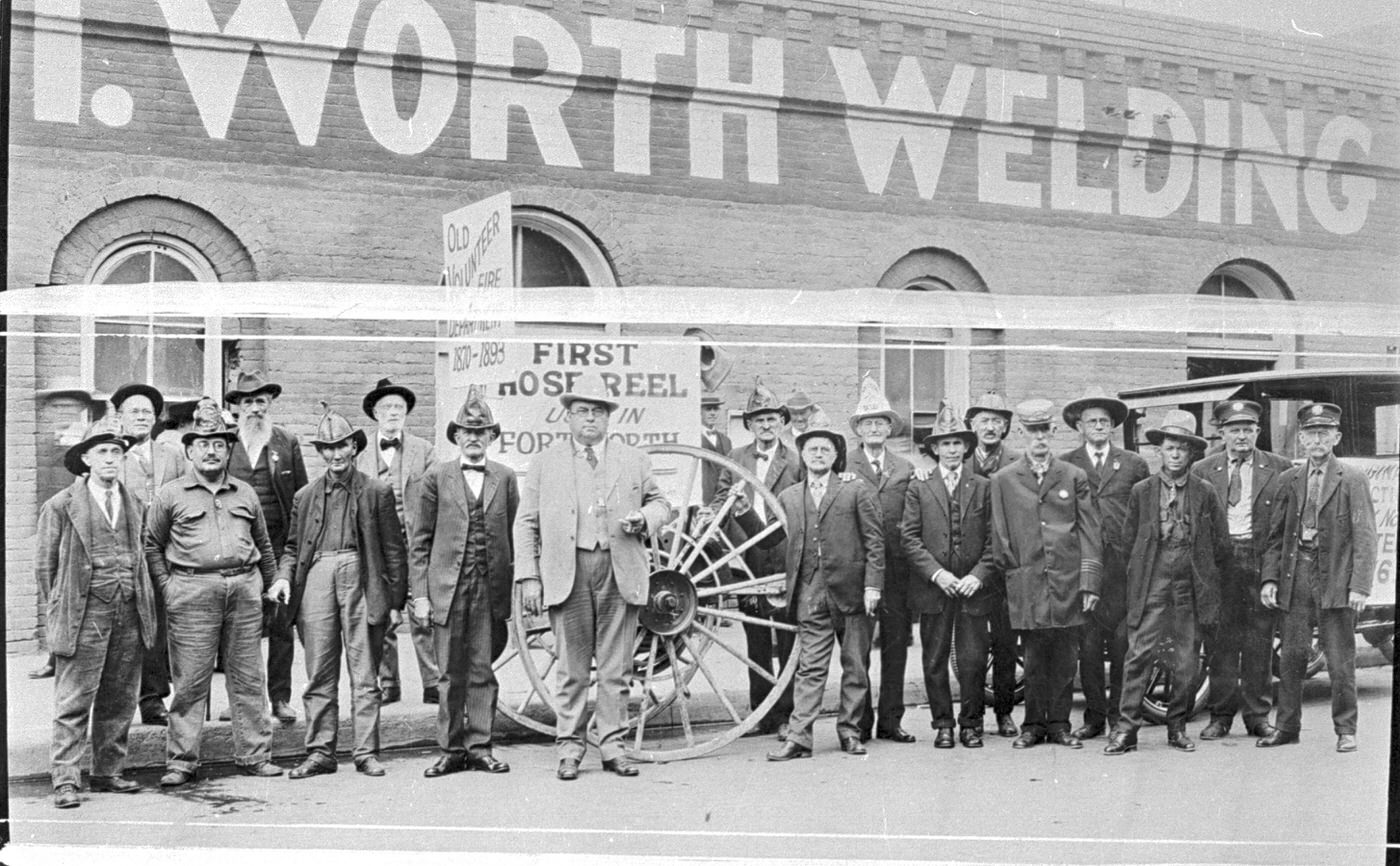

While the explosive growth of the oil industry dominated headlines and reshaped Fort Worth’s economy in the 1920s, the city’s foundational identity as “Cowtown” remained firmly entrenched. The Fort Worth Stockyards, established north of the Trinity River in the late 1880s and incorporated in 1893, along with the colossal Armour and Swift meatpacking plants that opened nearby around 1903-1904, continued to be pillars of the local economy and major employers throughout the decade.

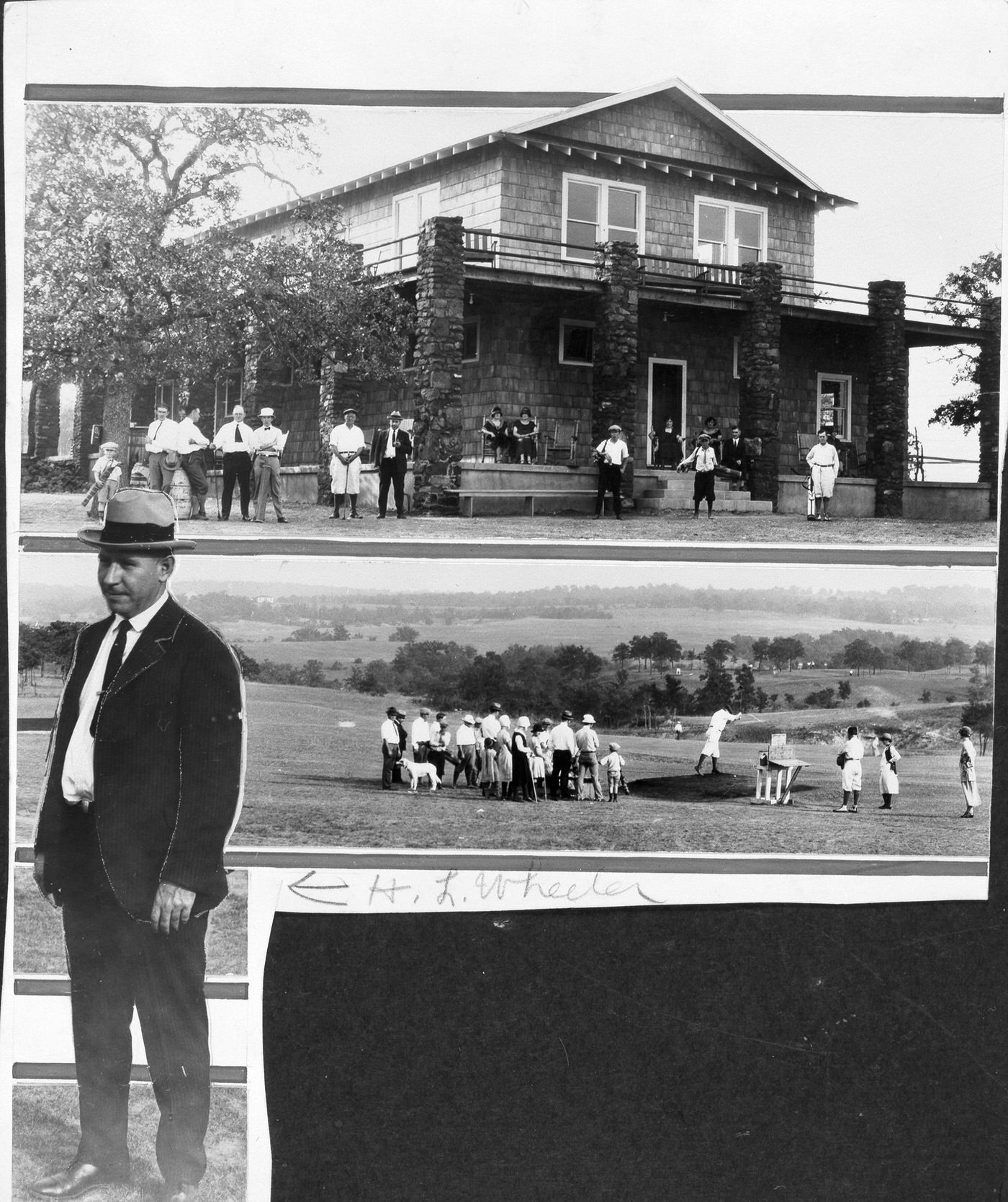

The scale of operations remained immense. Armour and Swift were not just processing meat; they were deeply integrated into the local financial and logistical infrastructure. They held joint ownership in critical support businesses, including the Fort Worth Belt Railway Company, the Stockyards National Bank of North Fort Worth, the Fort Worth Cattle Loan Company, and the Reporter Publishing Company, which produced the influential Live Stock Report. This integration, however, faced challenges. The federal Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 aimed to curb the market power of the big packers by requiring them to divest their interests in related enterprises like stockyards and banks. Although Armour and Swift resisted through litigation, this act set in motion a gradual restructuring of their holdings in Fort Worth over the following years.

A significant political and economic battleground related to the Stockyards complex played out in the early 1920s: the annexation of Niles City. This small municipality, encompassing the valuable Stockyards and packing plants, had been incorporated in February 1911 specifically to function as a tax haven, shielding the lucrative industries (valued between $12 million and $30 million by the early 1920s) from Fort Worth’s city taxes. Named after Louville V. Niles, a key Boston investor who helped bring Armour and Swift to the area, Niles City represented a substantial source of potential revenue that booming Fort Worth desperately wanted.

Governing the Boom: Civic Life and Politics

The sheer scale and pace of change in Fort Worth during the 1920s presented significant challenges for city governance. Managing the explosive population growth, burgeoning industries, and the demand for expanded infrastructure required evolving political structures and active civic engagement.

Throughout most of the decade, Fort Worth operated under the Commission form of government, which it had adopted in 1907. This system, a popular Progressive Era reform also implemented in Galveston, Houston, and Dallas around the same time, replaced the traditional mayor-alderman structure (where council members represented specific wards) with a small commission (typically 3-9 members) elected city-wide. Each commissioner was responsible for overseeing a specific municipal department (like streets, public safety, or finance), combining both legislative and executive functions within the commission itself. Proponents argued this model promoted efficiency, accountability, and a more “business-like” approach to city management, reducing the influence of localized ward politics. However, critics noted potential drawbacks, including the risk of commissioners becoming overly focused on their own departments (“departmental parochialism”) and the potential for political deadlock among a small group holding combined powers.

As Fort Worth continued its rapid expansion in the early 1920s, the perceived limitations of the commission form may have become more apparent. In 1924, the city underwent another significant governmental restructuring, adopting the council-manager form through a charter change. This model, also gaining traction nationally, aimed for further professionalization by separating administrative functions from political oversight. A professional city manager, appointed by the elected council, would handle the day-to-day operations of the city, while the mayor and council focused on policy-making and representing the citizenry. The mayor’s role shifted towards being the public face and ceremonial head of the city government. These shifts in governance reflect the ongoing effort to find effective ways to manage the complexities of a rapidly growing and industrializing urban center during a period of significant national experimentation with municipal structures.

Image Credits: W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, Tarrant County Agricultural Inspection Tour Photo Album, Barclay Family Photographs, Harry B. Friedman Building Construction Photographs, Charles M. Davis Photograph Collection, Jack White Photograph Collection, UTA Libraries, Texas History Portal

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know