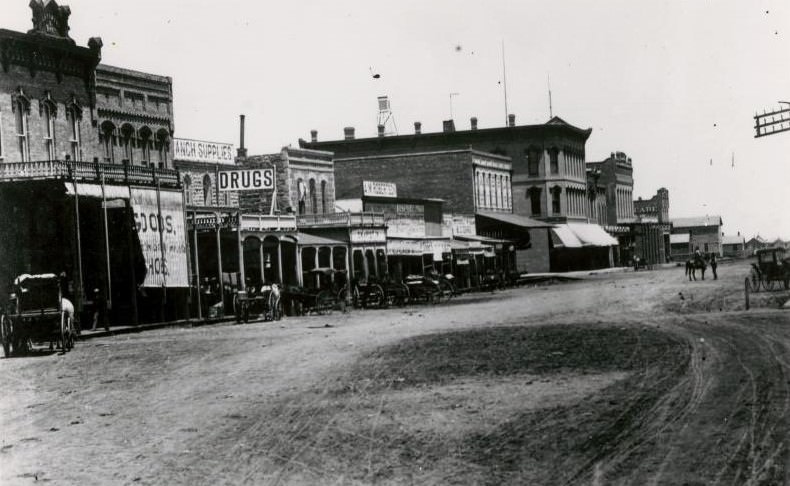

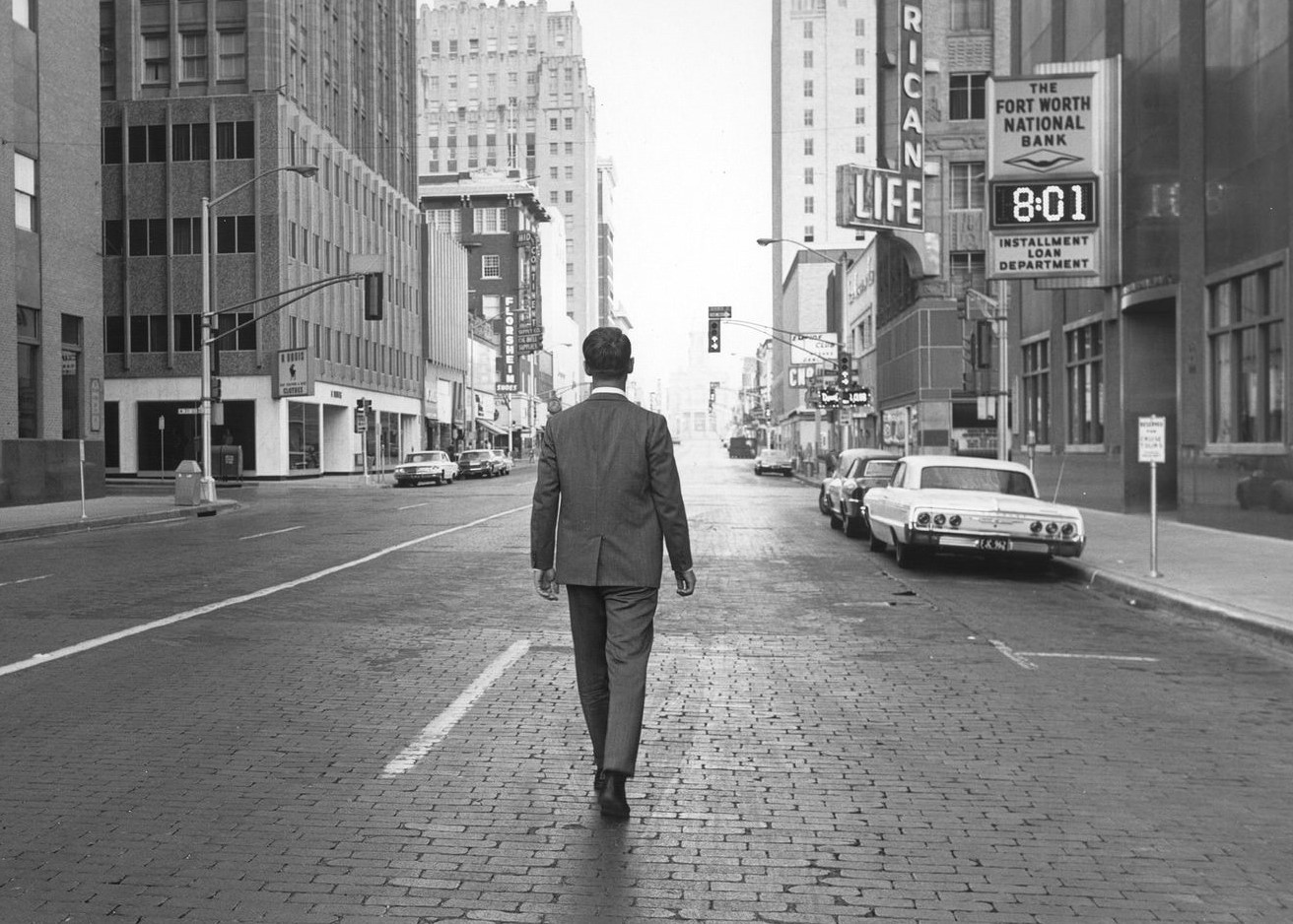

Fort Worth entered the 1960s carrying the legacy of its past – a city built on cattle trails, railroads, and the industrial might forged during World War II. The official count from the 1960 census showed 356,268 people called the city home, a significant jump from previous decades. Known widely as “Cowtown,” Fort Worth was on the cusp of major changes. The memory of the devastating 1949 Trinity River flood lingered, driving ongoing efforts to tame the river and protect the growing population. While post-war economic energy continued, the decade ahead would witness profound shifts in industry, the city’s physical layout, and the social landscape, particularly concerning civil rights.

Engines of Change: Economy Takes Flight

The 1960s marked a crucial economic transformation for Fort Worth. While the echoes of its cattle-driven past remained, the roar of jet engines increasingly defined the city’s financial pulse. The aerospace and defense sectors, already significant after World War II, solidified their dominance.

At the heart of this shift was Carswell Air Force Base. Established during the war years , Carswell was a cornerstone of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) throughout the Cold War, including the 1960s. The base was home to powerful long-range bomber wings. Having transitioned fully to the B-52 Stratofortress in the late 1950s, Carswell’s 7th Bombardment Wing was a constant presence in the skies. These B-52s weren’t just parked; starting in April 1965, many deployed to Guam to support combat operations in Southeast Asia, flying missions over Vietnam before returning later that year, with deployments continuing rotationally.

Sharing the spotlight was the futuristic B-58 Hustler, the world’s first operational supersonic bomber, built right next door at Air Force Plant 4. The 43rd Bombardment Wing, the first unit equipped with the B-58, called Carswell home from March 1960 until mid-1964. These sleek, delta-winged jets captured headlines, setting speed records. However, the B-58 proved challenging and expensive to operate and required frequent refueling, leading to its retirement by the end of the decade.

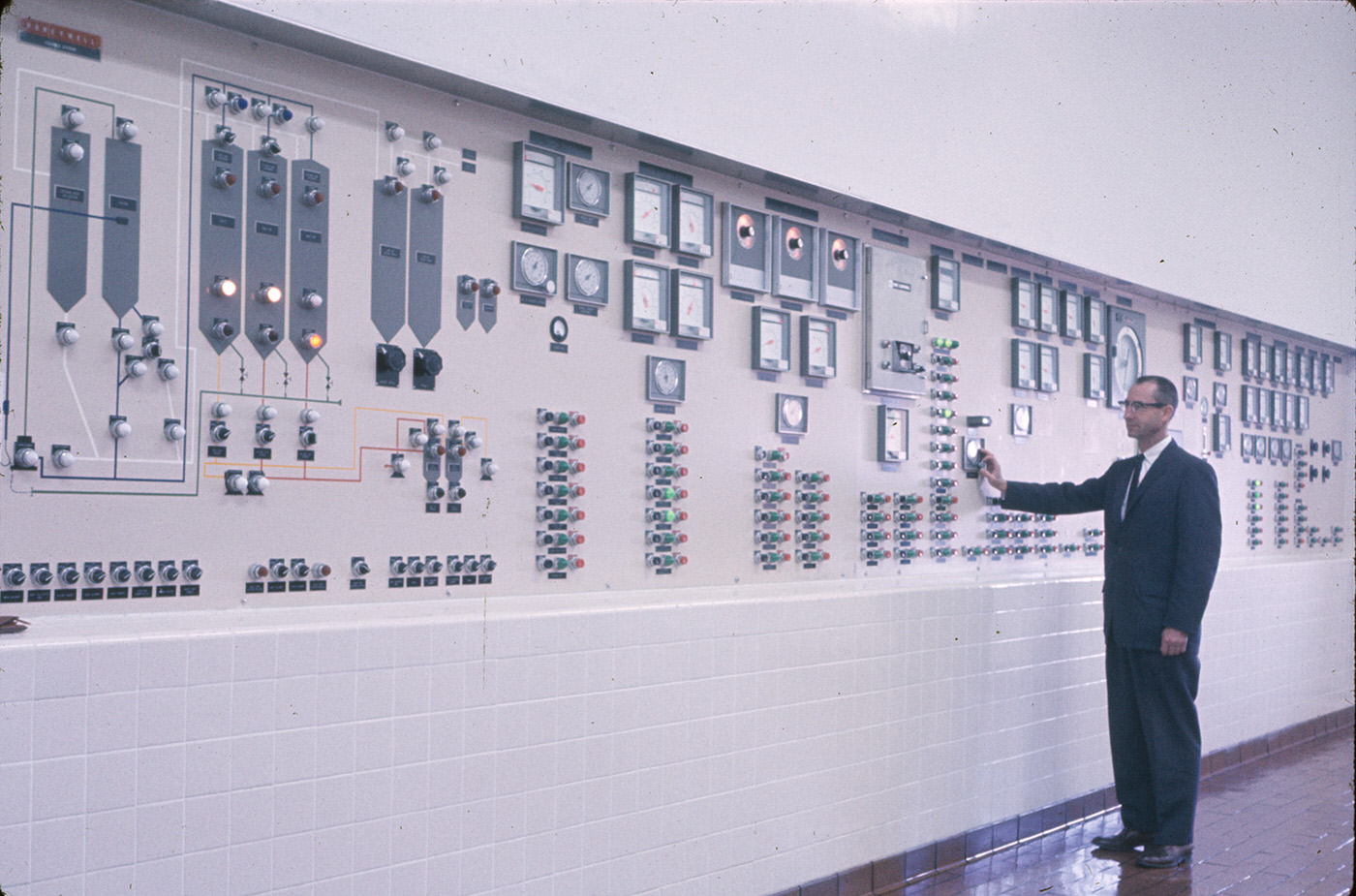

Air Force Plant 4, the sprawling industrial complex adjacent to the base, was the engine driving much of this activity. Operated first by Consolidated Vultee (Convair) and later by General Dynamics after their merger , this plant had a storied history, having churned out thousands of B-24 Liberators during World War II and the massive B-36 Peacemakers in the 1950s. The 1960s brought a new, groundbreaking project: the F-111 Aardvark. General Dynamics secured the massive federal contract for this Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX) program, a move that guaranteed the Fort Worth plant’s continued vitality. The F-111, featuring revolutionary variable-sweep wings that could change shape in flight, afterburning turbofan engines, and automated terrain-following radar for high-speed, low-level flight, represented the cutting edge of aviation technology. Its first flight took place in December 1964, with production models delivered to the Air Force starting in July 1967. The F-111 program cemented Fort Worth’s position as a critical hub for national defense manufacturing. This reliance on massive federal defense contracts created a powerful economic engine for the city, but it also meant Fort Worth’s prosperity was closely linked to government spending decisions and the ongoing tensions of the Cold War and the escalating conflict in Vietnam.

The End of an Era: Stockyards and Meatpacking Decline

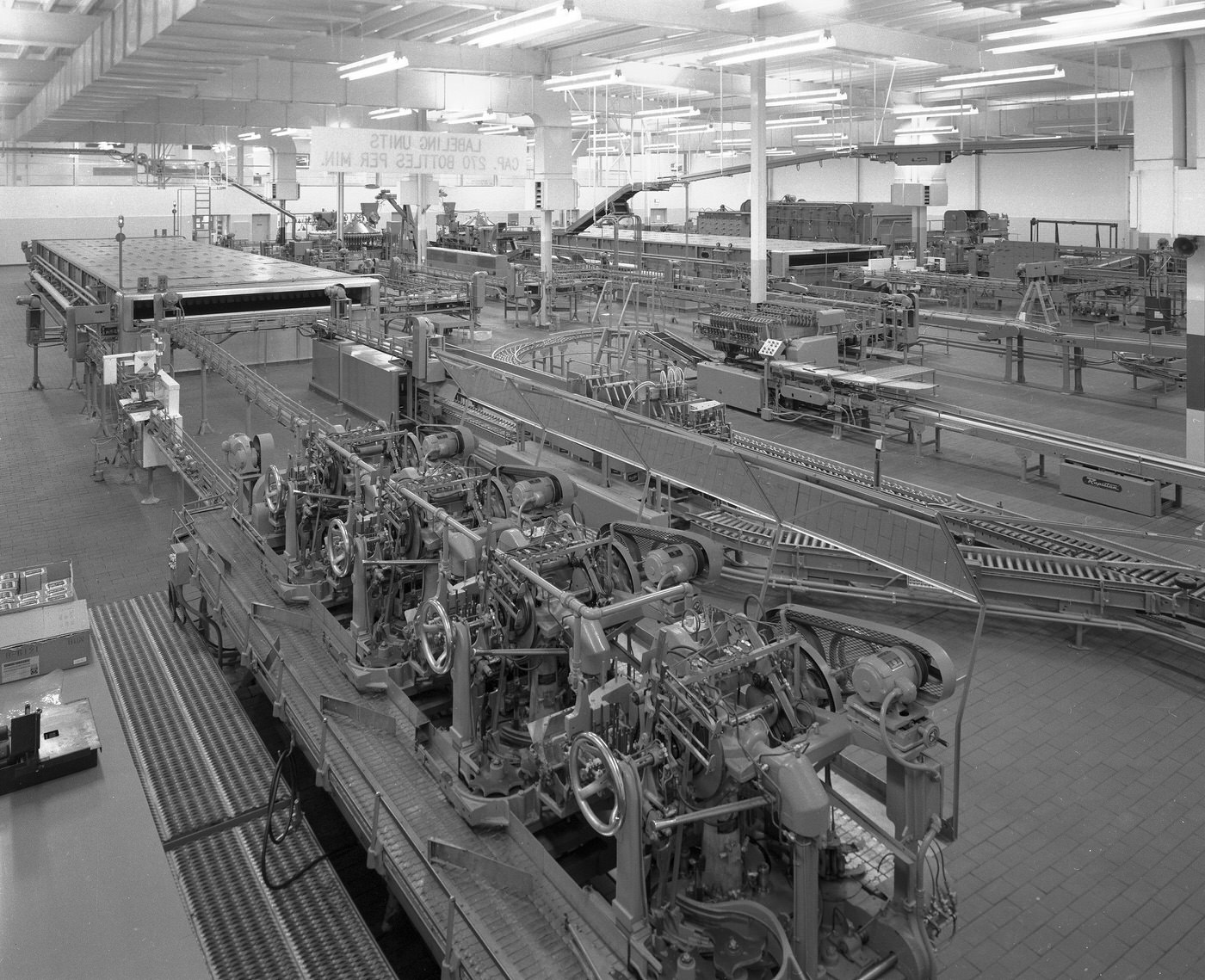

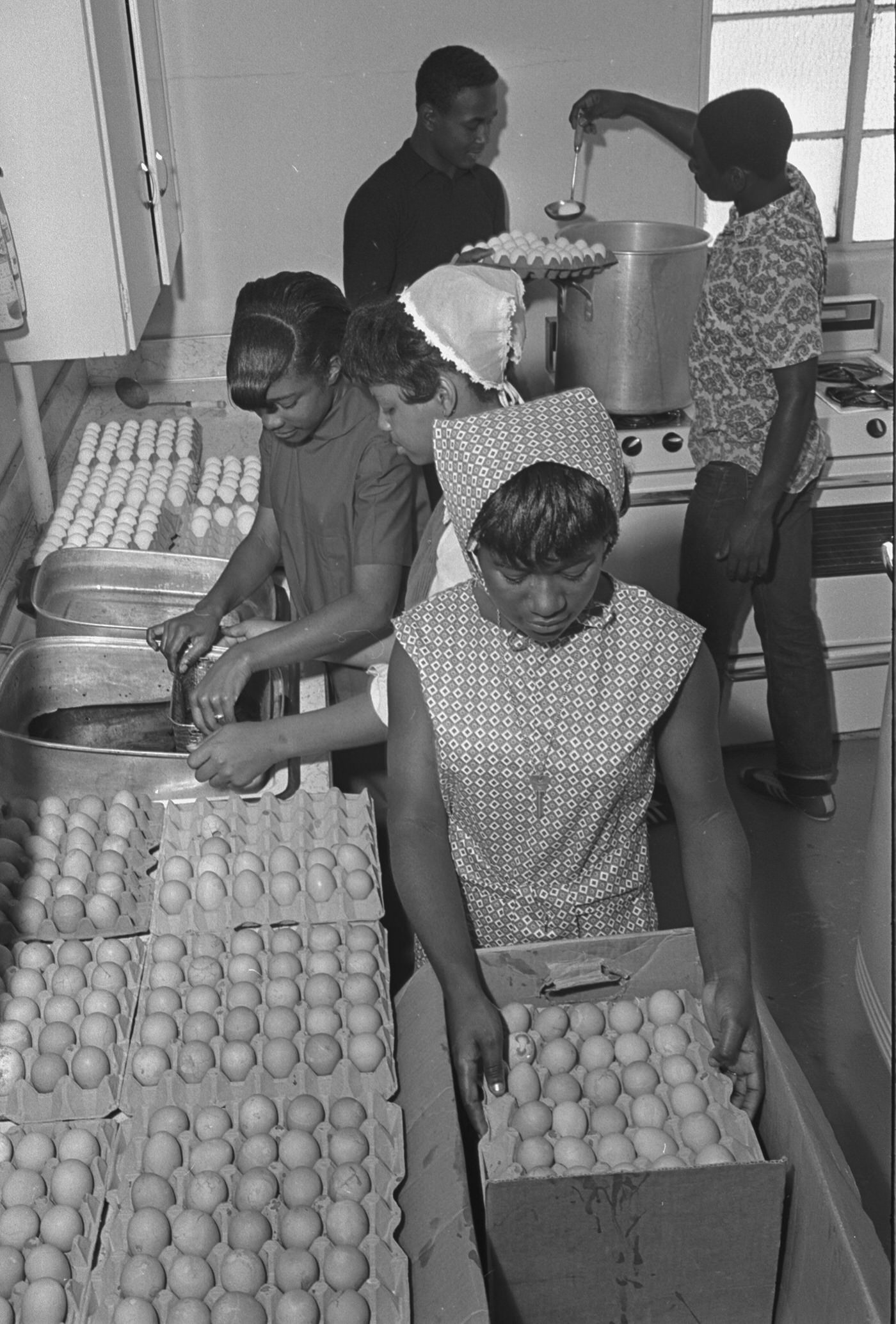

While the aerospace industry soared, Fort Worth’s traditional economic pillar, the livestock and meatpacking industry, faced a steady decline. The Fort Worth Stockyards, once a dominant force nationally, ranking among the top markets for decades , saw a dramatic drop in activity. The peak year of 1944, when over 5.25 million cattle, sheep, and hogs passed through the pens, became a fading memory. Annual receipts fell significantly through the 1950s and continued to decrease in the 1960s.

Several factors contributed to this downturn. The rise of the trucking industry offered greater flexibility and lower costs than the railroads, which had been essential to the Stockyards’ success. Smaller, local livestock auctions closer to ranches became more common, drawing business away from the large, centralized Fort Worth market. Furthermore, the development of large-scale feedlots, especially in the Texas Panhandle, changed how cattle were raised and marketed.

A major blow came in 1962 with the closure of the massive Armour & Co. meatpacking plant. Although parts of the facility were used by other companies for a time, the closure signaled the end of an era for Fort Worth’s identity as a primary meatpacking center. The adjacent Swift & Co. plant held on longer but would eventually close in 1971. The decline was visible not just in numbers but in the physical state of the Stockyards district itself, which began to show signs of neglect as activity dwindled.

In sharp contrast to the fading fortunes of the Stockyards, another Fort Worth company was rapidly ascending. Tandy Corporation, headquartered downtown, embarked on a path of significant growth and transformation. Originally the Hinckley-Tandy Leather Company, it officially became Tandy Corporation in 1961 under the leadership of the ambitious Charles Tandy.

Spreading Out: A Growing City

The economic shifts of the 1960s occurred alongside significant physical growth and changes to Fort Worth’s landscape. The city’s population continued its upward trend, increasing from 278,778 in 1950 to 356,268 by the 1960 census. The wider Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area also experienced steady growth throughout the decade. This expanding population created pressing needs for more housing, roads, and public services.

Mirroring national trends, Fort Worth experienced a wave of suburbanization. New housing developments sprang up on what had recently been farmland on the city’s edges. Areas like Ridglea Hills, where development began in the late 1940s around a new country club , continued to grow. The development of Overton Park, on former ranch land in southwest Fort Worth, began during the 1960s, featuring deed restrictions that mandated brick or stone homes and attached garages, reflecting the styles of the era. Established pre-war suburbs like Oakhurst, known for its winding streets designed by landscape architects Hare and Hare, provided a template for the character of some newer developments, though many post-war suburbs featured the popular ranch-style homes. This outward migration was made possible by rising car ownership and, crucially, a massive investment in new highways.

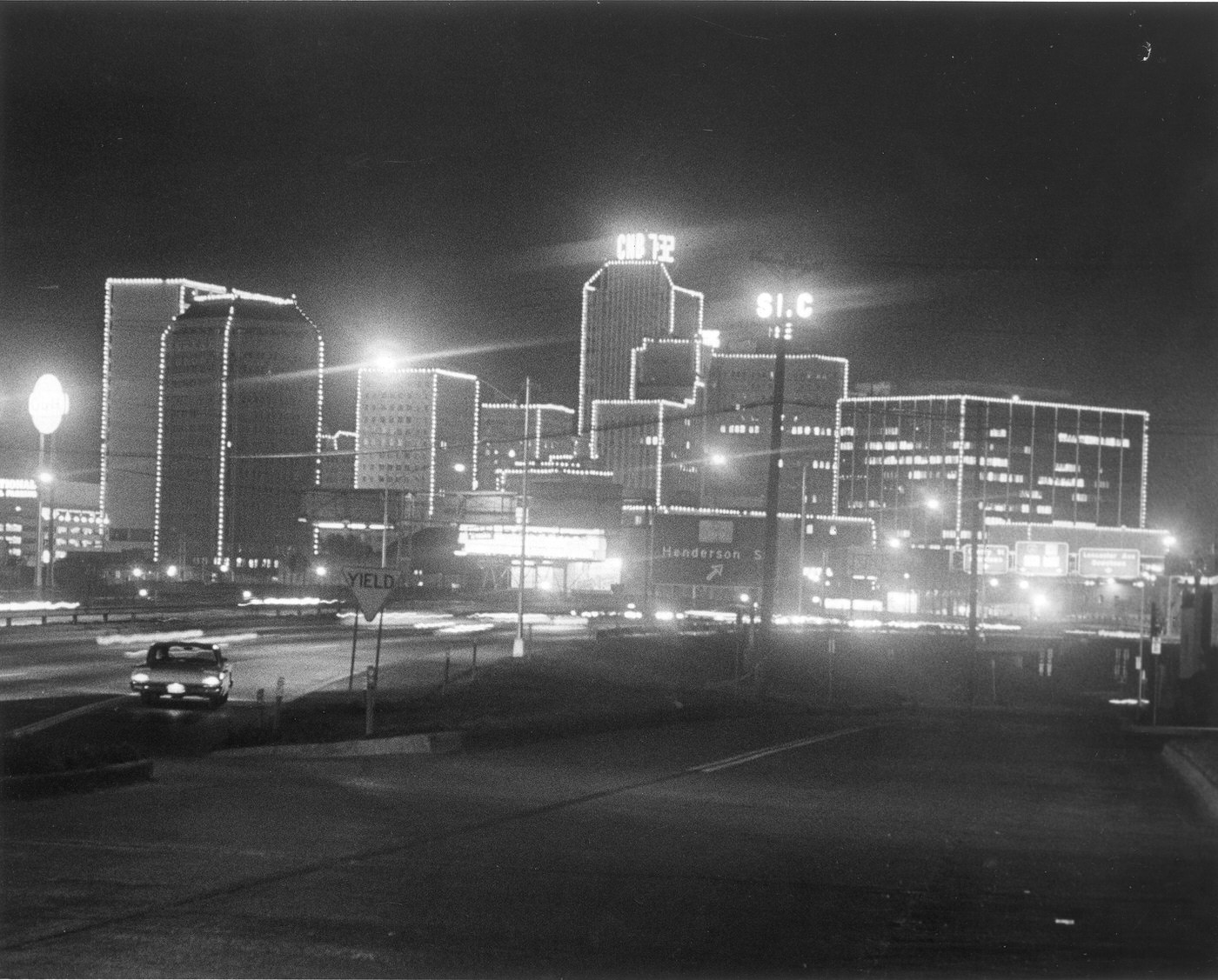

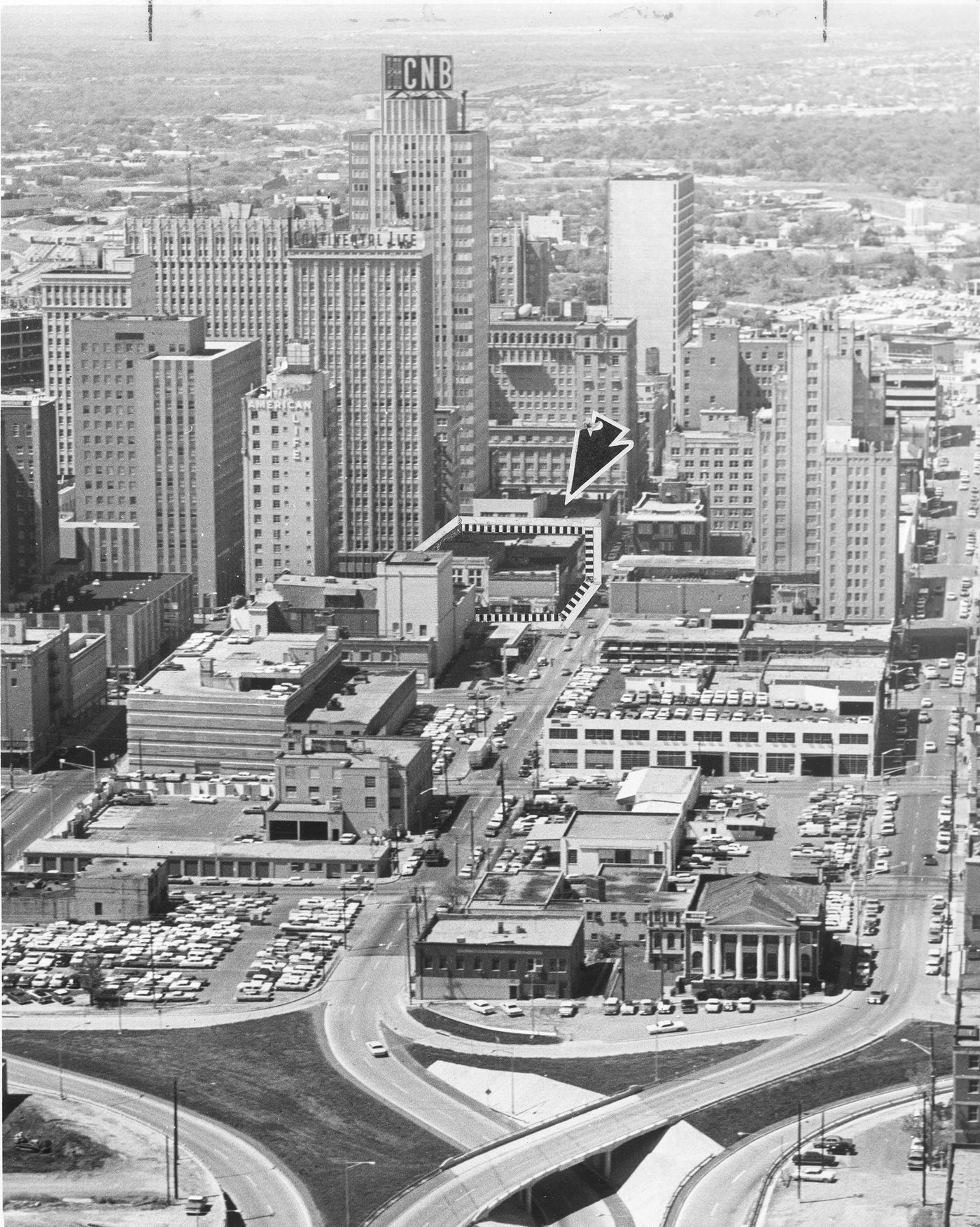

The 1960s were the golden age of freeway construction in Fort Worth, dramatically reshaping how people moved around the city and accelerating the pace of suburban development. Building upon projects initiated in the 1950s, the Interstate Highway System carved new paths across the landscape.

Interstate 35W: This vital north-south artery saw major progress. The segment from downtown (near the I-30 interchange) northward to Belknap Street was completed in 1960. The next stretch, from Belknap north to the Loop 820 interchange, opened in 1966. Finally, in 1967, I-35W was finished from Loop 820 all the way to the Denton County line, creating a modern highway link to the north. The complex interchange connecting I-35W and I-30 downtown, quickly nicknamed the “Mixmaster” for its tangle of ramps, had been largely completed in 1958 and fully finished by 1960.

Interstate 30: The Dallas-Fort Worth Turnpike, a toll road opened in 1957 connecting the two cities’ downtowns, was incorporated into the I-30 route. West of downtown, the I-30 freeway (West Freeway) was extended and completed out to the Parker County line by 1966.

Interstate 20 & Loop 820: The routes for the southern and western loops around Fort Worth evolved during the decade. Sections initially built as Loop 217 were incorporated into what became I-20 and Loop 820. Construction on various segments of Loop 820 progressed steadily, with openings recorded in July 1961, September 1963, 1965, and July 1966. The northwest portion of Loop 820 received its official Interstate designation in 1968.

This expanding network of high-speed roads made previously distant areas accessible, directly fueling the construction of new homes and shopping centers farther from the traditional city core and fundamentally altering Fort Worth’s geography.

Less visible but equally critical to the city’s growth was the ongoing work on the Trinity River Flood Control Project. The devastating flood of May 1949, which killed ten people and left thousands homeless, spurred a major federal and local effort. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers designed and constructed an extensive system of levees along the Clear and West Forks of the Trinity River. Much of this 27-mile Fort Worth Floodway system was built during the 1950s and completed in the 1960s. Maintained by the Tarrant Regional Water District (TRWD), these levees were designed to protect the city’s population as it stood in the 1960s. This crucial infrastructure provided a sense of security against future floods, making development safer in areas near the river and underpinning the confidence needed for the city’s continued expansion.

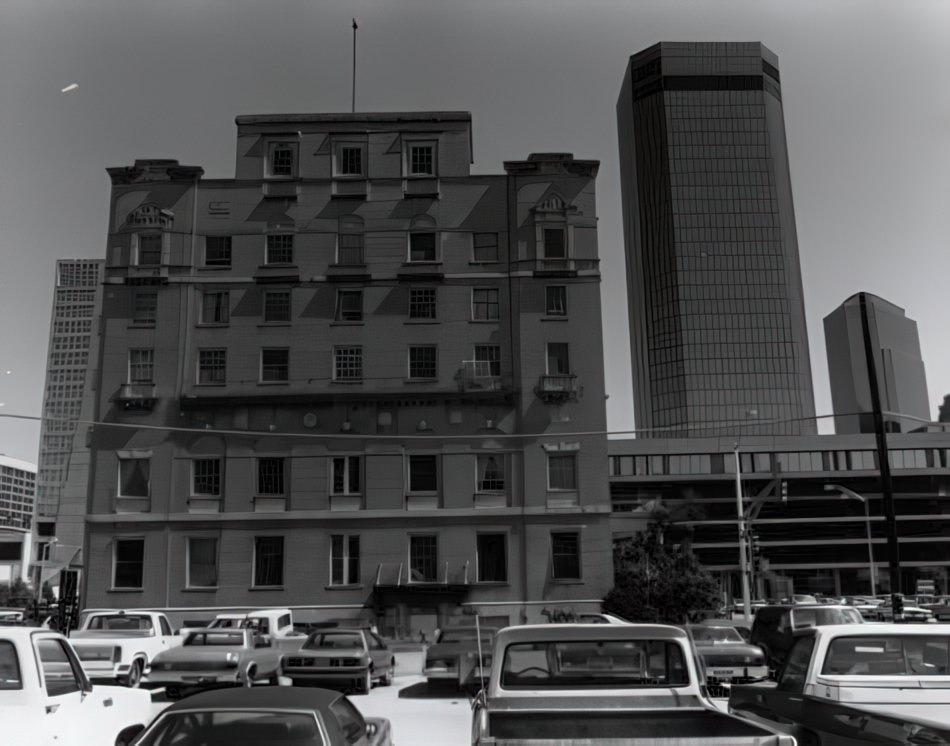

Older Neighborhood Conditions

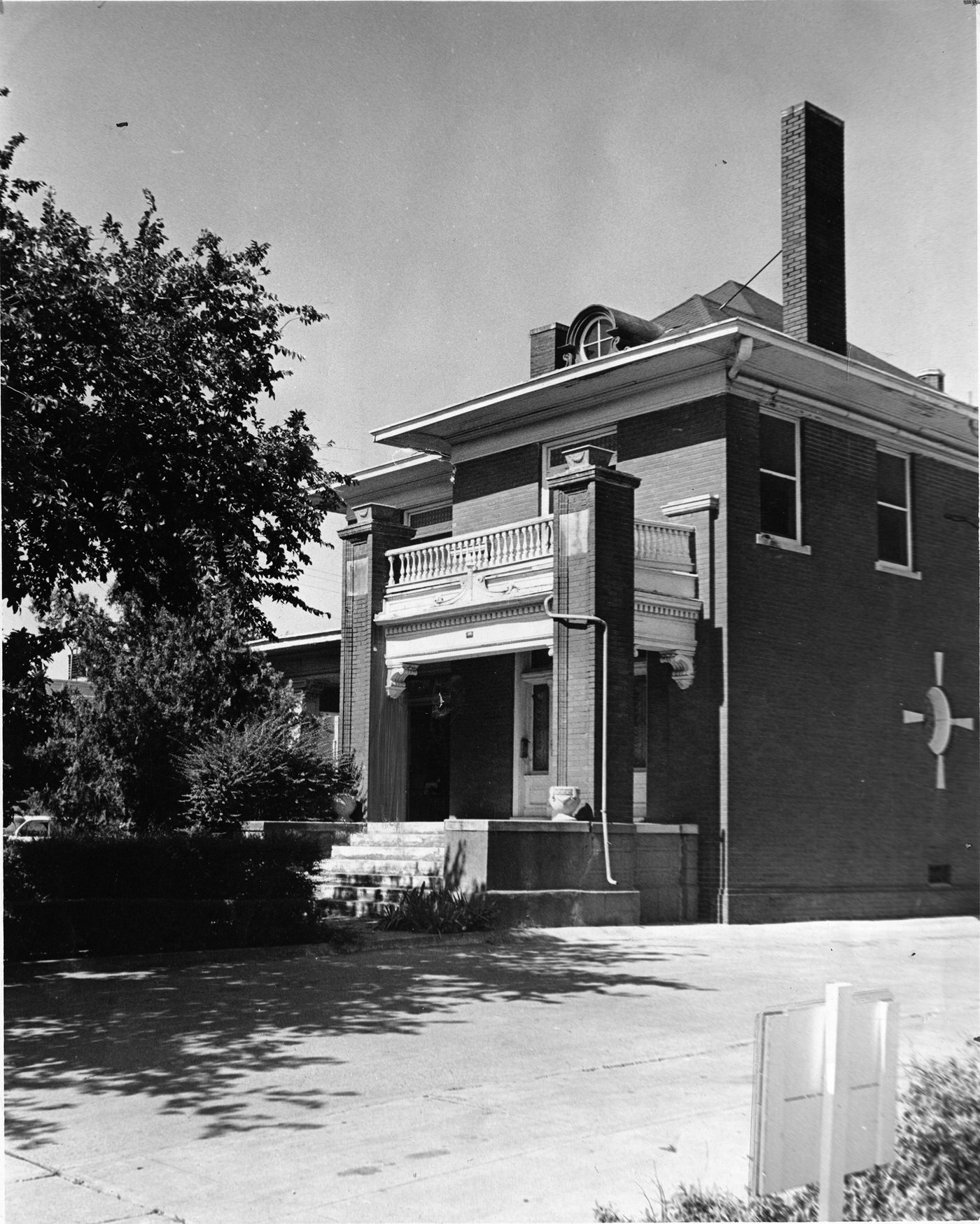

The rapid growth of new suburbs often came at the expense of older, established neighborhoods closer to downtown. Ryan Place, known for its stately mansions built in the early 20th century, had already suffered during the Great Depression. By the early 1960s, the neighborhood experienced significant neglect as residents moved to newer areas. Many of its grand homes fell into disrepair. This decline prompted residents to organize; the Ryan Place Improvement Association was formed in 1969 specifically to fight a city plan to widen streets, marking the beginning of a long revitalization effort. Similarly, the Fairmount neighborhood, largely built between 1905 and 1920 with many bungalows and Four Square homes, faced the pressures of aging housing stock and the lure of the suburbs, though its historic character would later fuel its own revival. The contrast between the brand-new subdivisions rising on the outskirts and the struggles of these historic inner-city neighborhoods highlighted the uneven pattern of development and investment during the 1960s.

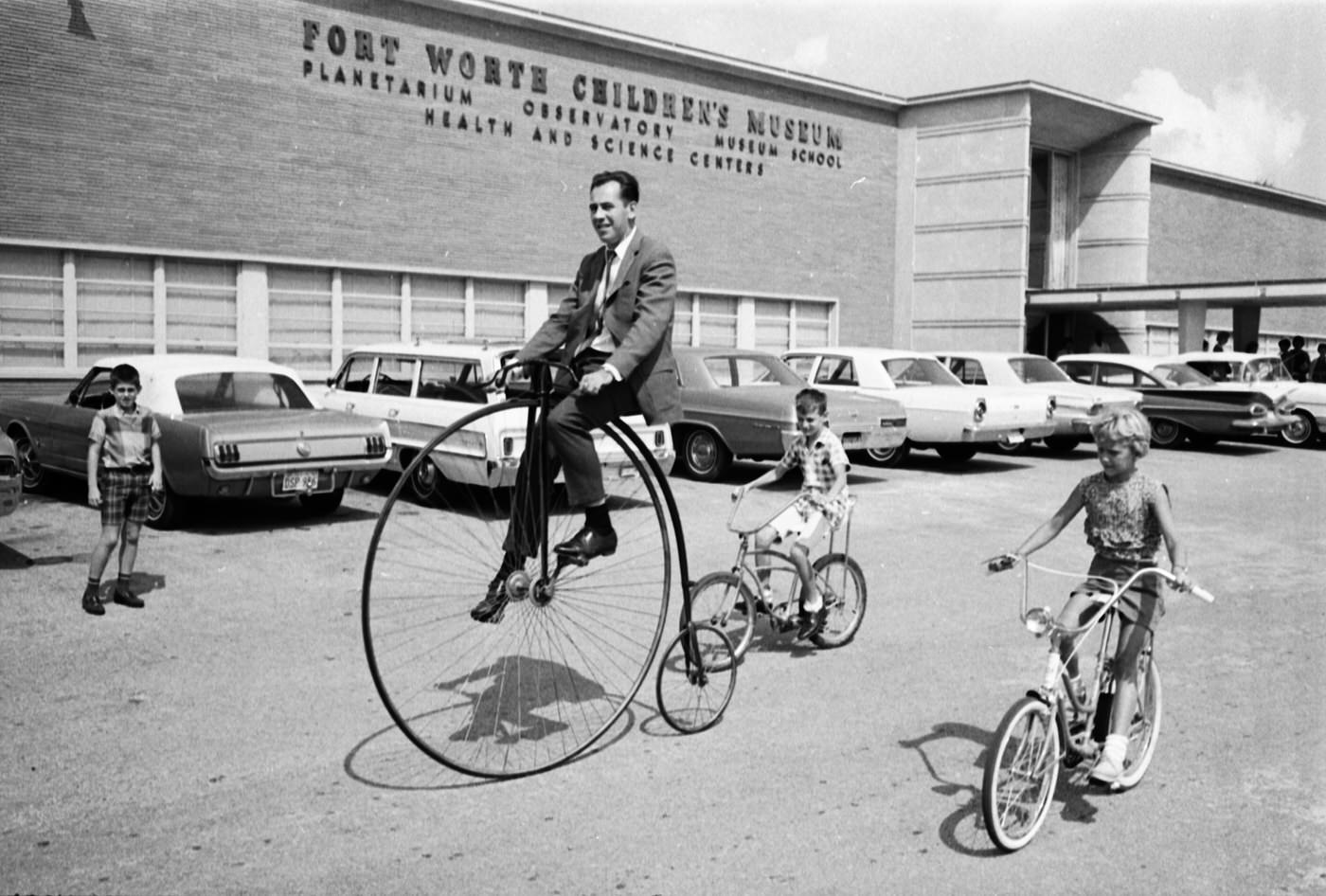

Culture & Entertainment

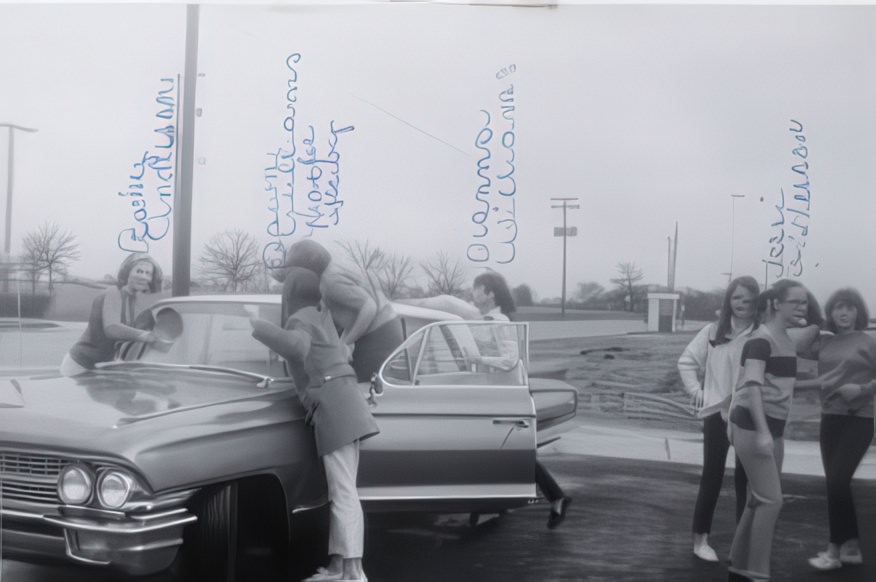

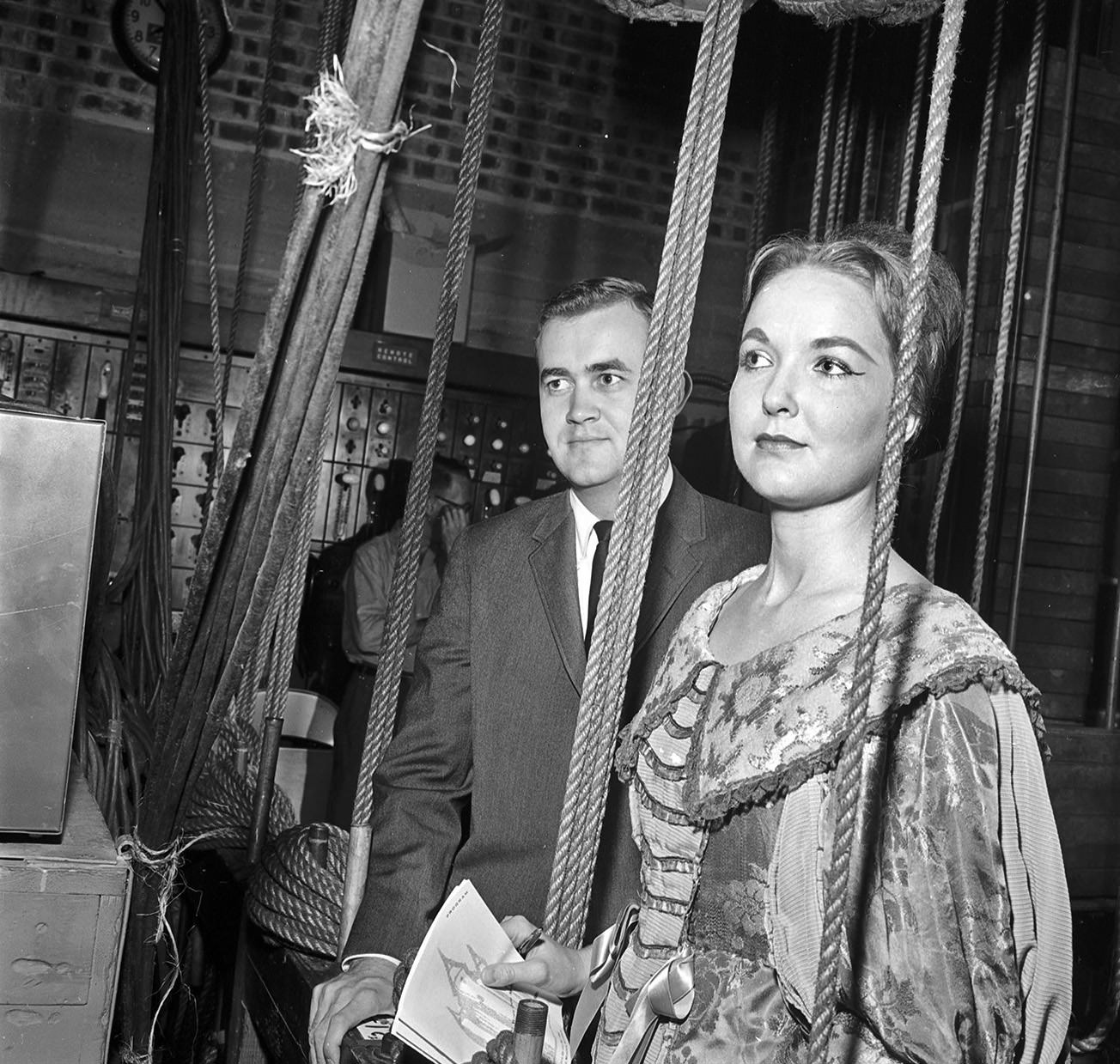

Life in 1960s Fort Worth wasn’t just about work and new highways; residents sought entertainment and cultural enrichment, creating a scene that blended local traditions with national trends.

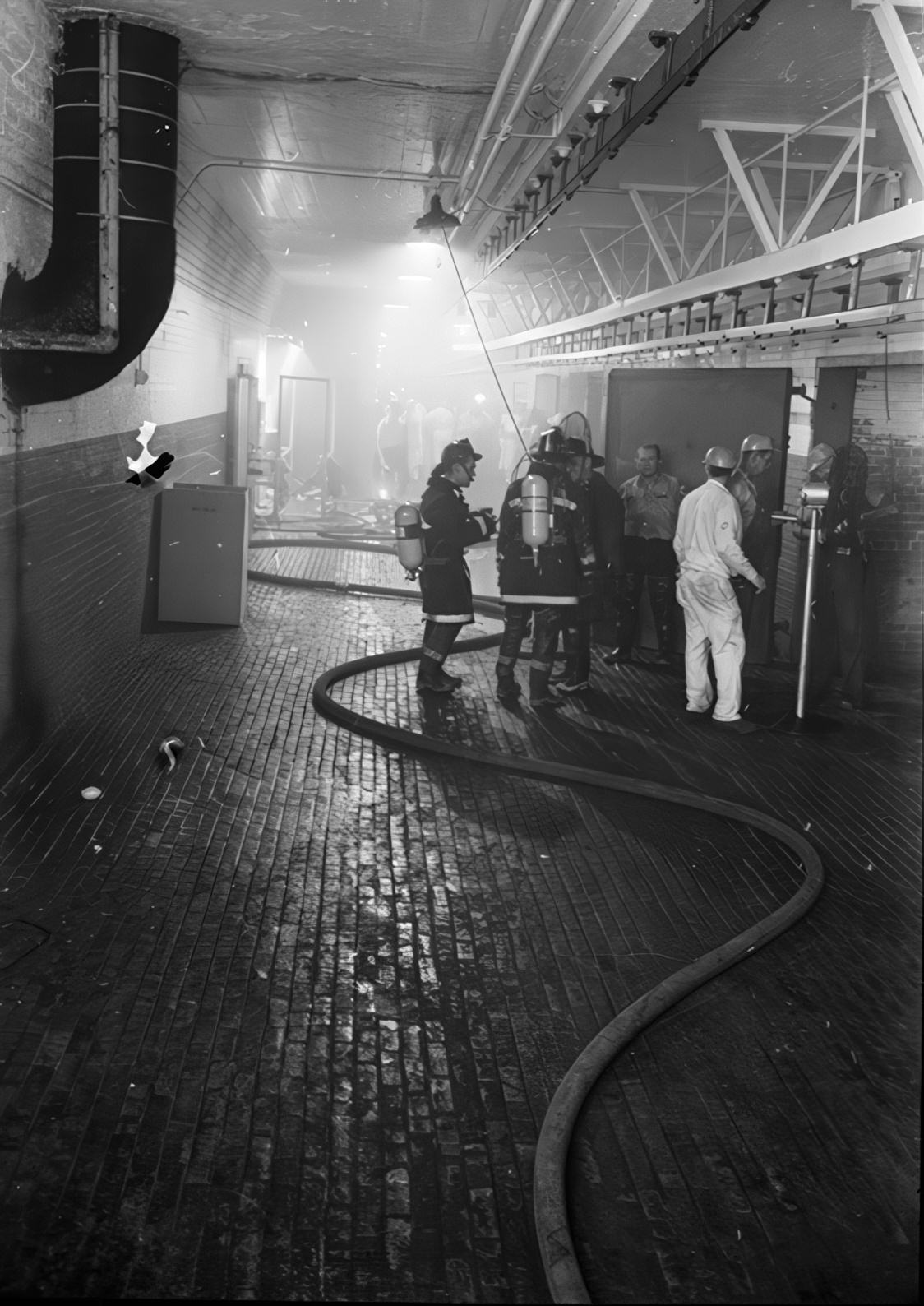

Fort Worth’s musical heritage, particularly Western Swing, still resonated. This unique blend of country fiddle, jazz, blues, and swing rhythms had found its footing in local venues like the Crystal Springs Dance Pavilion back in the 1930s, with pioneers like Bob Wills and Milton Brown. Crystal Springs, located on White Settlement Road, continued to operate as a popular country music dance hall into the early 1960s, hosting acts like Jimmy Capps and the Country Boys. However, the national peak of Western Swing’s popularity had passed. A definitive end to an era came in December 1966, when a fire completely destroyed the historic Crystal Springs Dance Pavilion, silencing a venue that had been central to Fort Worth’s music identity for half a century. Alongside country and western traditions, the sounds of rock and roll were increasingly part of the national and local soundtrack.

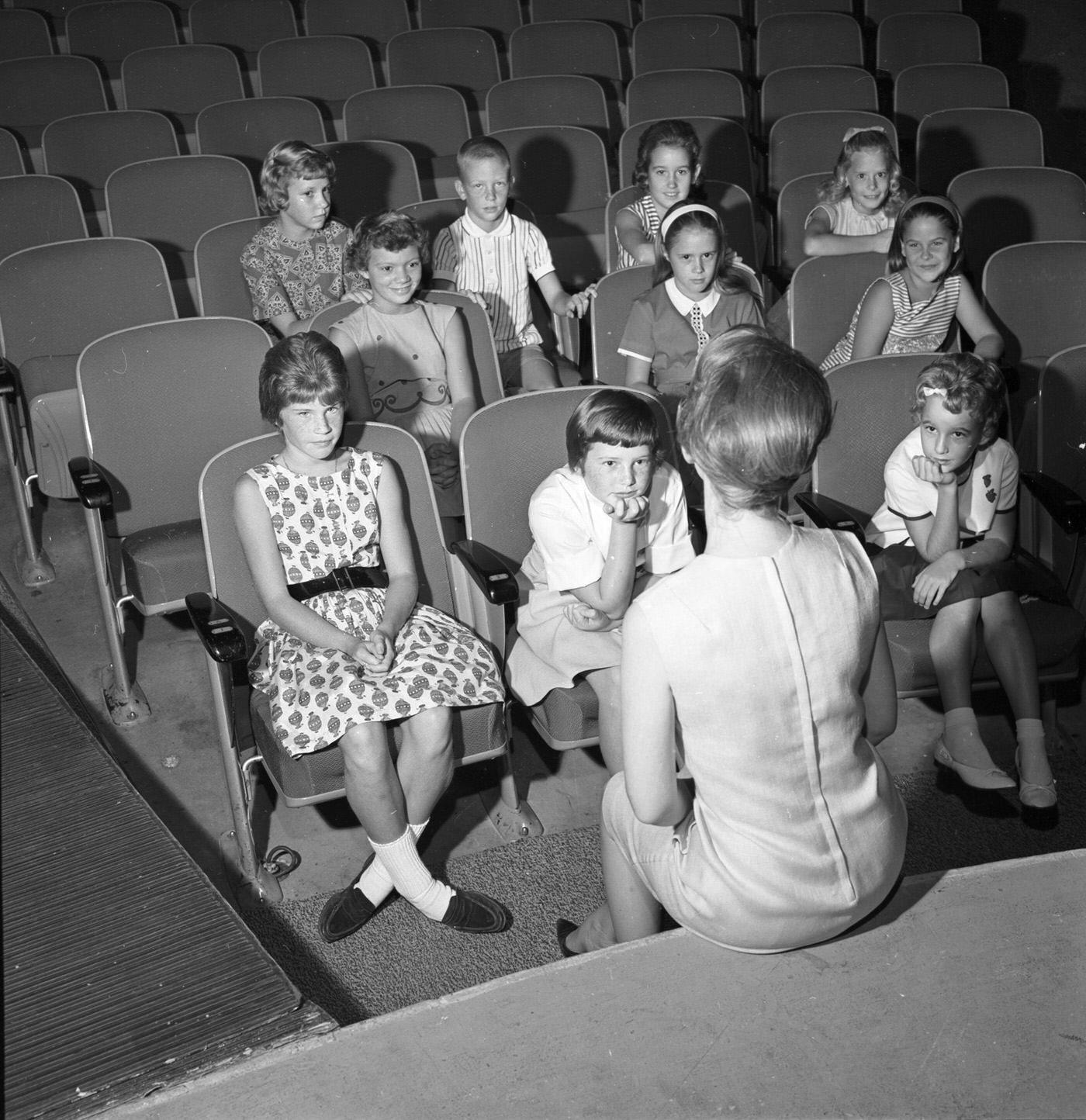

The way Fort Worth watched movies was also changing. The era of grand, single-screen “movie cathedrals” downtown was fading. Theaters like the Hollywood (opened 1930 inside the Electric Building), the Worth, and the Palace, which had been prime entertainment destinations in earlier decades, faced growing competition. The Hollywood Theater, for instance, remained closed for many years during this period.

Instead, drive-in theaters thrived, catering to the city’s car culture. Fort Worth and its surrounding areas boasted numerous drive-ins, offering a casual, family-friendly atmosphere. Some operating in or around the 1960s included the Fort Worth Twin (opened 1953 on East Lancaster) , the Meadowbrook , the Cherry Lane Twin , the Bowie Blvd Drive-in (possibly the city’s first) , the Jacksboro Drive-in (later the Corral) , the South Side Drive-in , the Southside Twin , the Belknap , the Pike , the Parkaire (near University) , the Downtown Drive-in (on Henderson) , the Cowtown , and the Westerner (in River Oaks). While many of these landmarks were eventually demolished to make way for other developments , they were a significant part of the 1960s entertainment landscape.

Eating out in the 1960s often meant visiting cafeterias, a format particularly popular with the generation that grew up during and after World War II. Wyatt’s Cafeteria had a location in the new Seminary South mall , and Finley’s Cafeteria operated for decades on Camp Bowie Boulevard in a building that originally housed Steve’s Cafe. Colonial Cafeteria was another well-known local chain. Diners and cafes serving classic American fare remained staples. Kincaid’s Hamburgers, founded in 1946 on Camp Bowie, was already establishing its reputation. Barbecue remained a Fort Worth favorite, with places like The Big Apple in the Stockyards area drawing crowds. The growth of suburban shopping centers also brought new dining options, like the El Chico Mexican restaurant located within Seminary South.

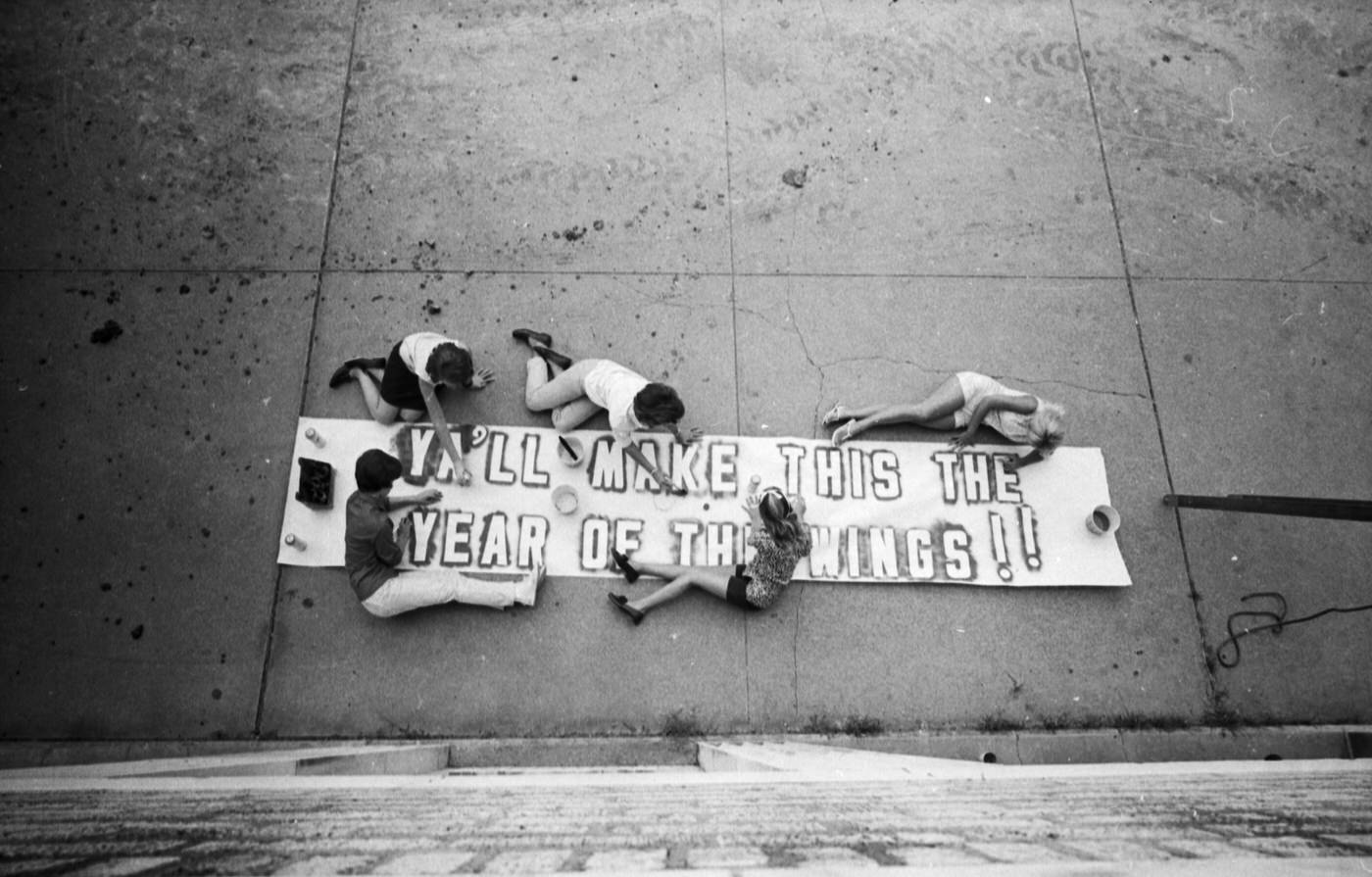

Fort Worth’s long relationship with minor league baseball saw a major interruption in the 1960s. The Fort Worth Cats, a fixture in the Texas League for decades, played their home games at LaGrave Field. After the 1958 season, the team left the Texas League, played one year in the American Association (1959), and then merged with the Dallas team to form the Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers. The Cats briefly re-emerged as a separate Texas League team for just one season in 1964, finishing in last place before merging again with Dallas the following year. This marked the end of the original Cats franchise. LaGrave Field itself had been rebuilt and rededicated for the 1950 season after suffering damage from both fire and flood in May 1949.

Civil Rights and National Events

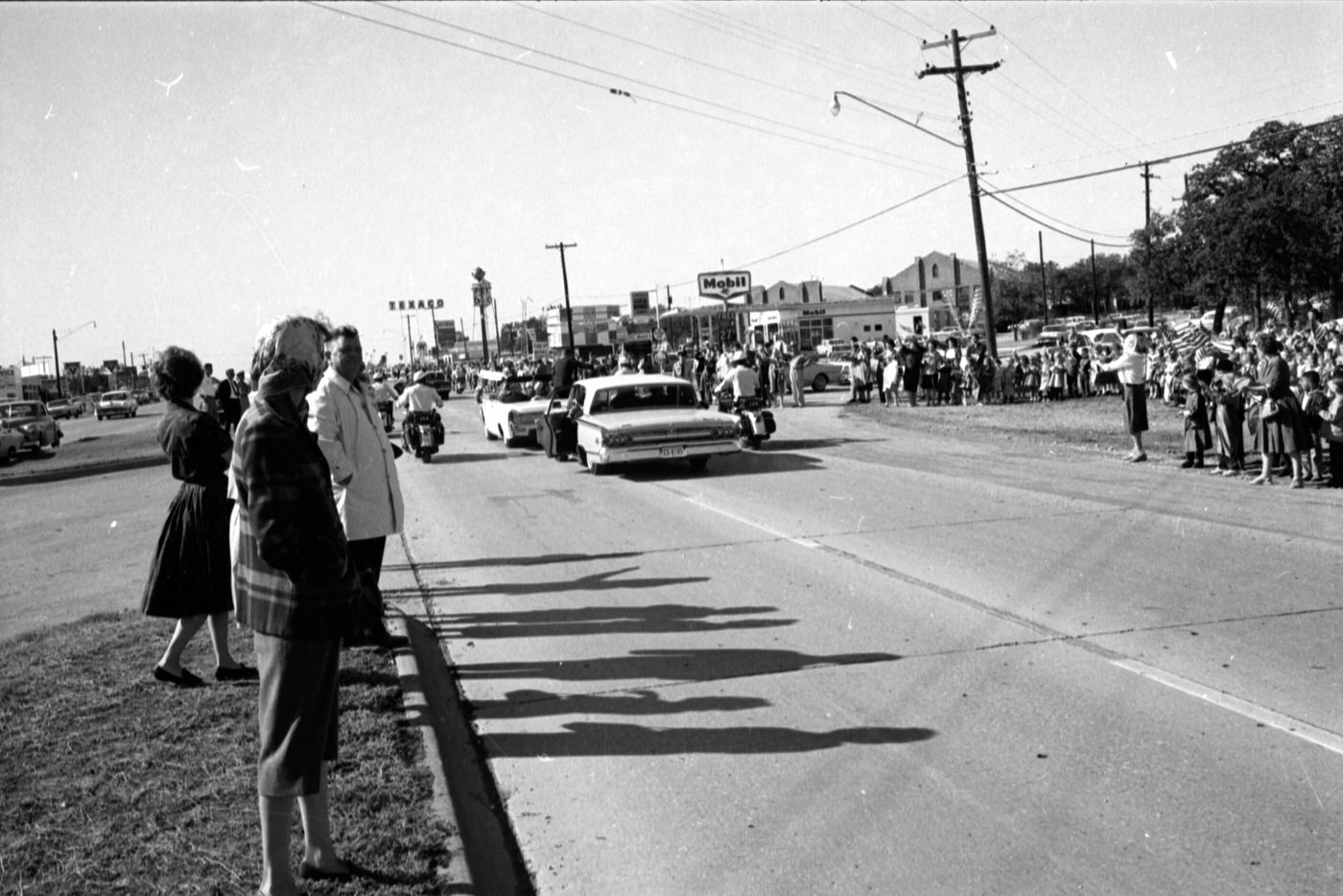

The 1960s were a time of national upheaval, and Fort Worth was deeply affected by the struggle for civil rights and the profound impact of national political events.

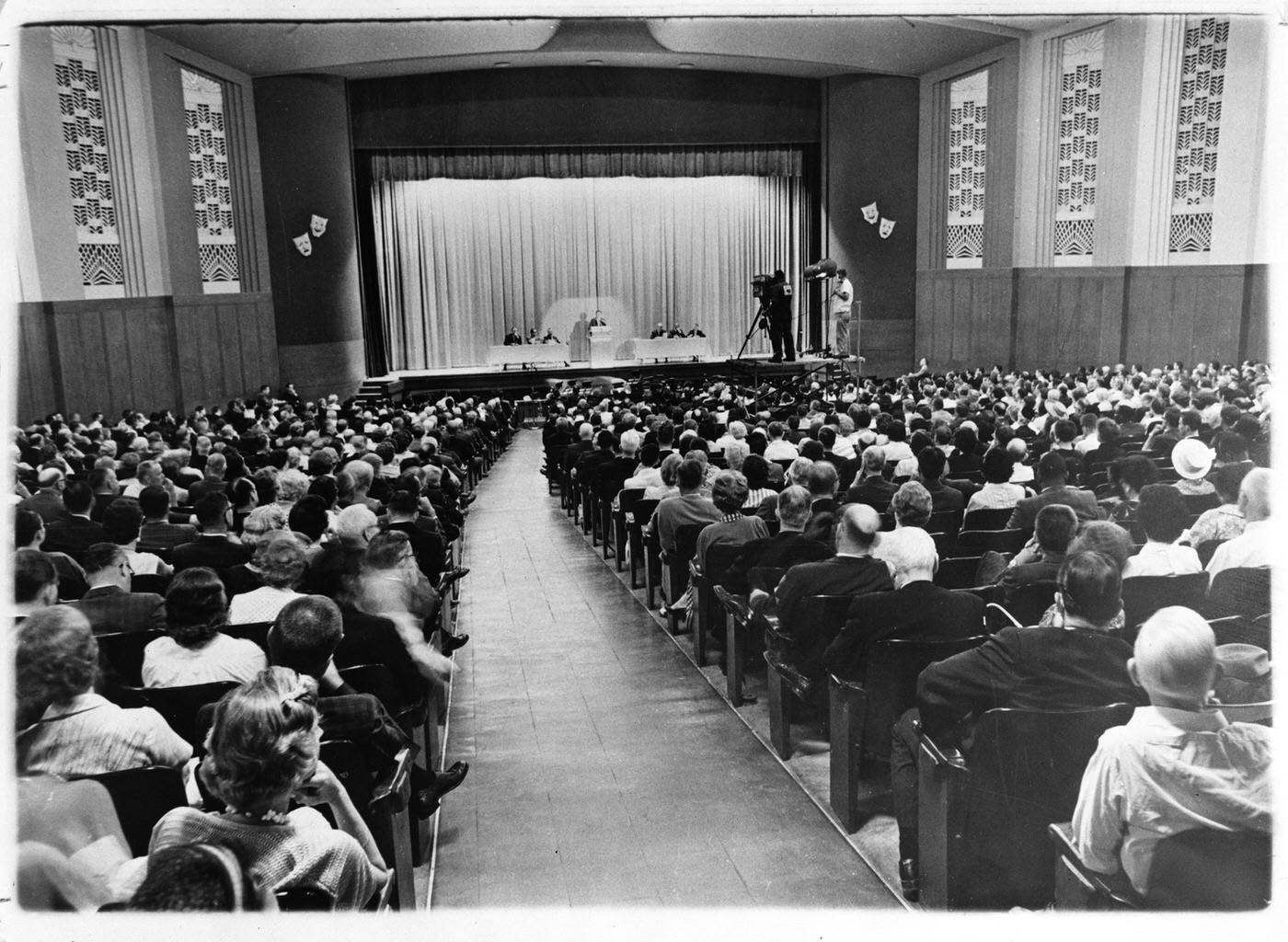

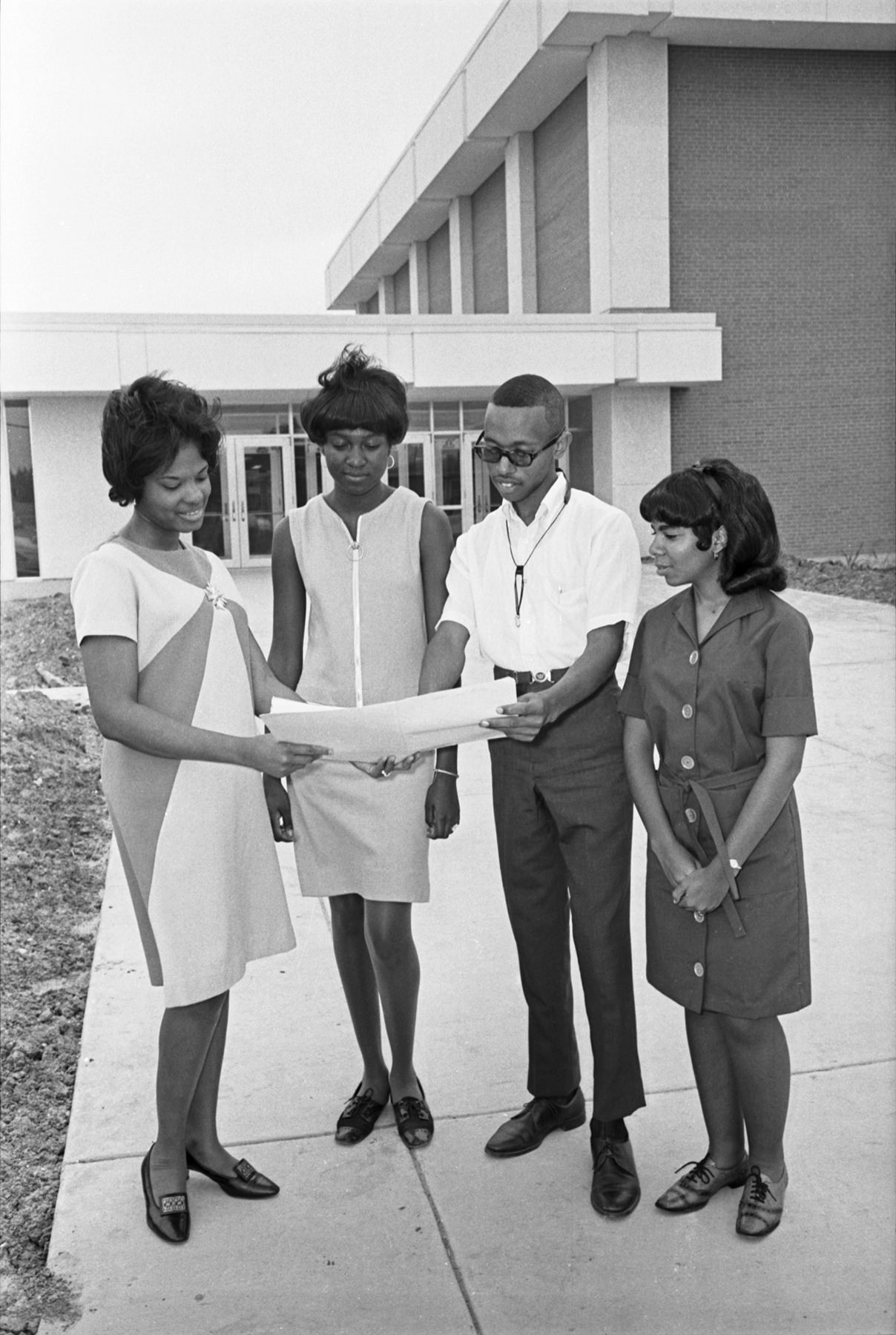

he landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision mandated school desegregation, but Fort Worth schools remained segregated. Local Black parents filed a lawsuit in 1959. In a key ruling on December 14, 1961, U.S. District Judge Leo Brewster declared the Fort Worth Independent School District’s dual system unconstitutional and ordered the district to submit a desegregation plan. The first court-approved plan was adopted in May 1963. Despite these legal victories, actual integration proceeded slowly, and Fort Worth lagged behind other major Texas cities in fully desegregating its schools. More comprehensive measures like busing and school clustering would come later, often under further court orders in the 1970s.

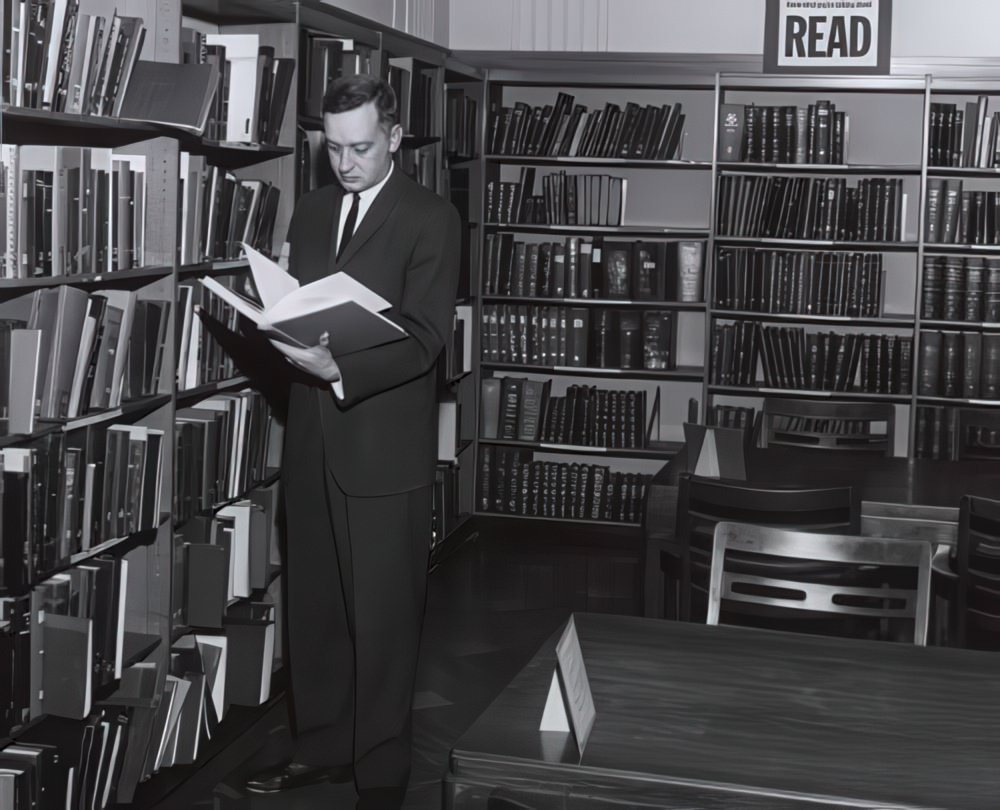

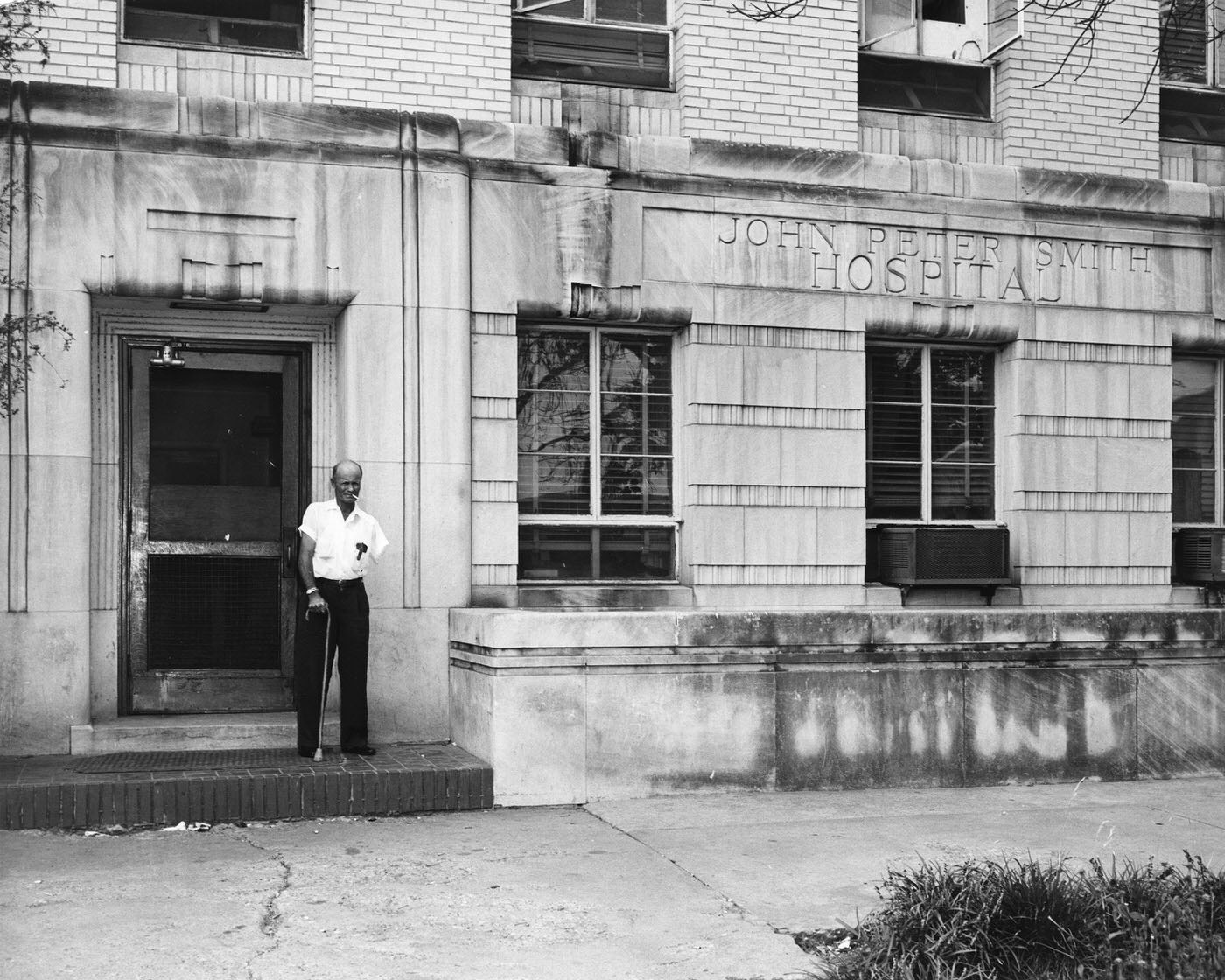

Desegregation of public facilities was uneven. City-owned swimming pools remained largely segregated until the mid-1960s or even into the 1970s, years after the NAACP and Black residents first petitioned for integration in the mid-1950s. Activists like Dr. Marion J. Brooks fought for Black doctors to have admitting privileges at all city hospitals, a right finally secured around the mid-1960s. Public libraries also faced integration efforts.

The national sit-in movement, which began dramatically in Greensboro, North Carolina, in February 1960, spread across the South, including Texas. While specific details of large-scale, coordinated sit-ins at Fort Worth lunch counters like Leonard’s, Cox’s, or Stripling’s are not prominent in the available records, local activism targeted discriminatory business practices. Dr. Brooks organized successful protests against biased employment at Safeway grocery stores and segregated shopping policies at Leonard’s Department Store. By 1963, a Mayor’s Commission on Human Relations reported that many downtown restaurants, hotels, and stores had voluntarily integrated. Progress culminated late in the decade with a city ordinance formally prohibiting racial discrimination in various public accommodations, including hotels, restaurants, and theaters.

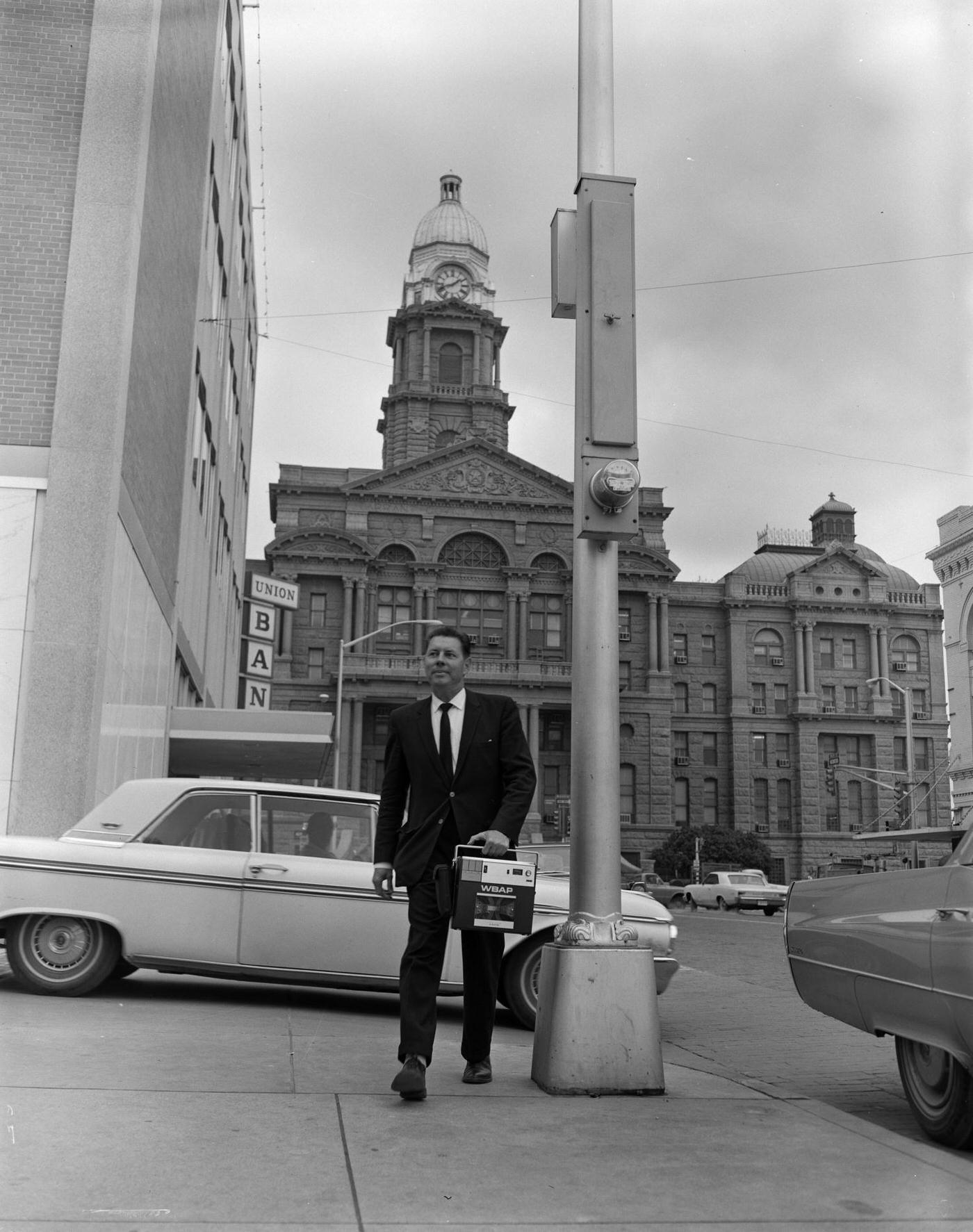

Image Credits: Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Basil Clemons Photograph Collection, Jan Jones Papers, UTA Libraries, Texas History Portal, Jack White Photograph Collection

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know