Fort Worth, Texas entered the 1970s as a city undergoing significant transformation. The decade saw major shifts in its economy, the makeup of its population, its physical landscape, and its social fabric. Changes touched nearly every aspect of life, from the jobs people held to the way they navigated their city and interacted with each other. This period was defined by the end of some long-standing industries, the rise of new technological forces, ongoing struggles for equality, and the reshaping of the urban environment.

Building and Reshaping the City

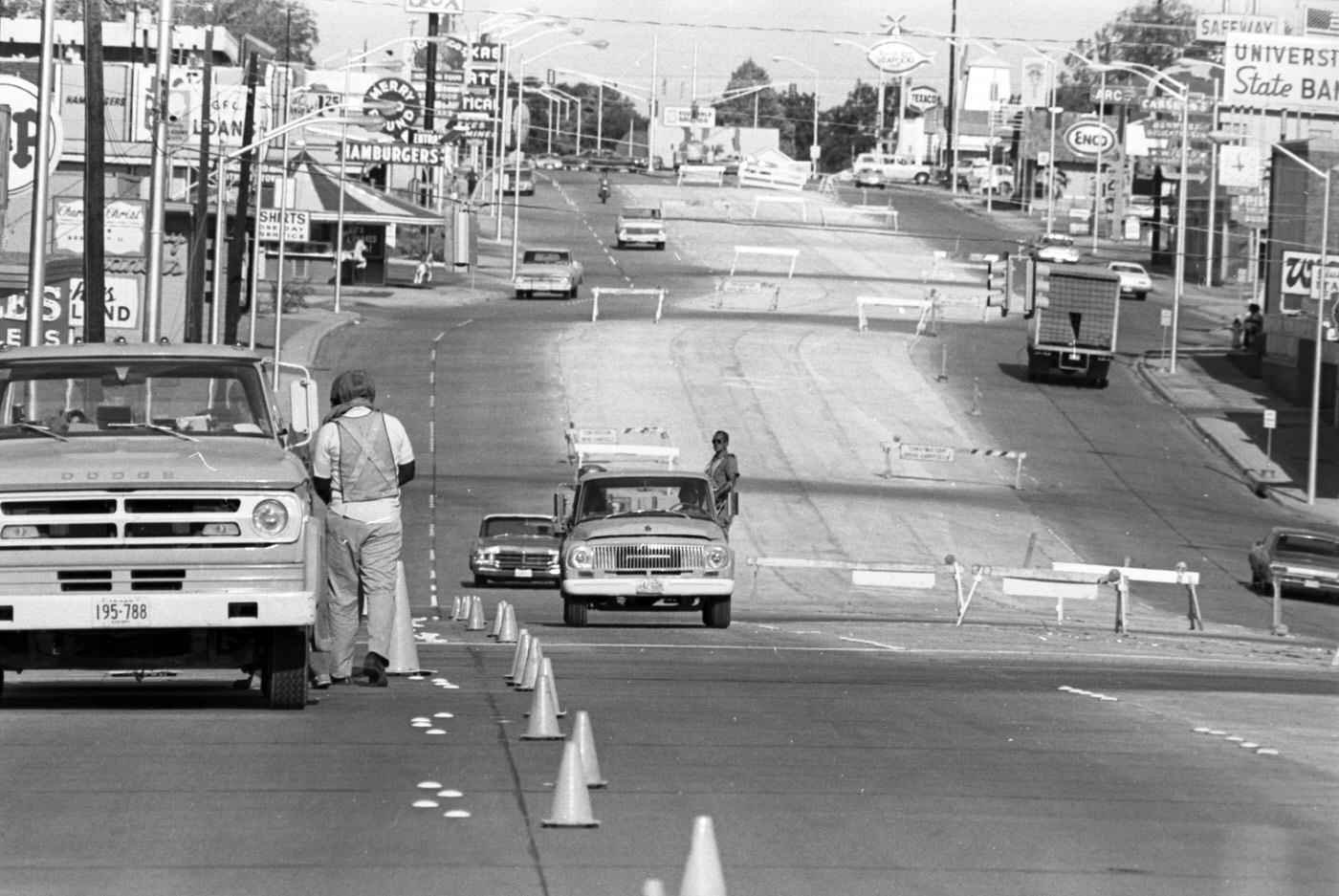

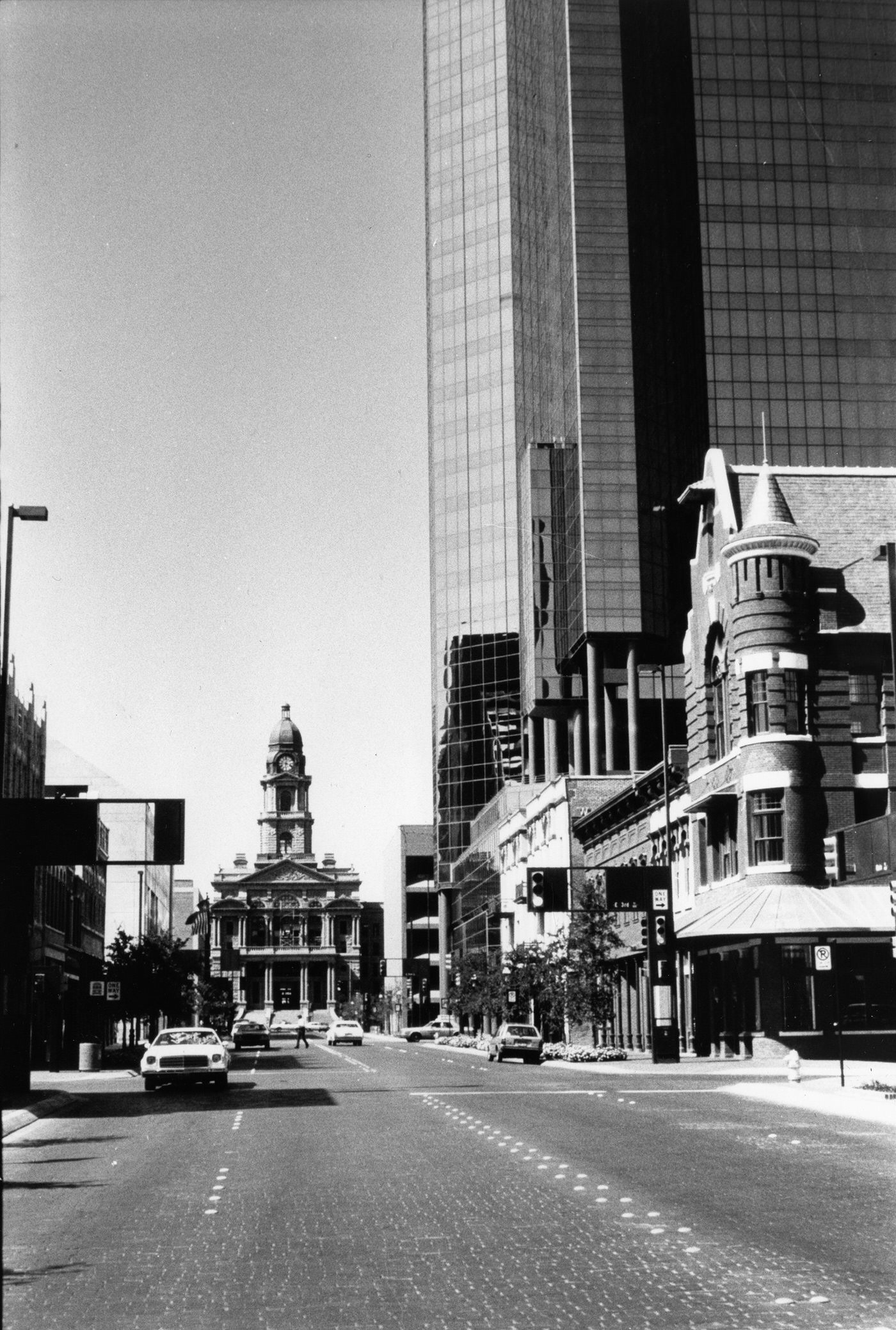

The physical form of Fort Worth continued to evolve in the 1970s, driven by ongoing highway construction, major downtown redevelopment projects, new civic buildings, and the management of the crucial Trinity River flood control system.

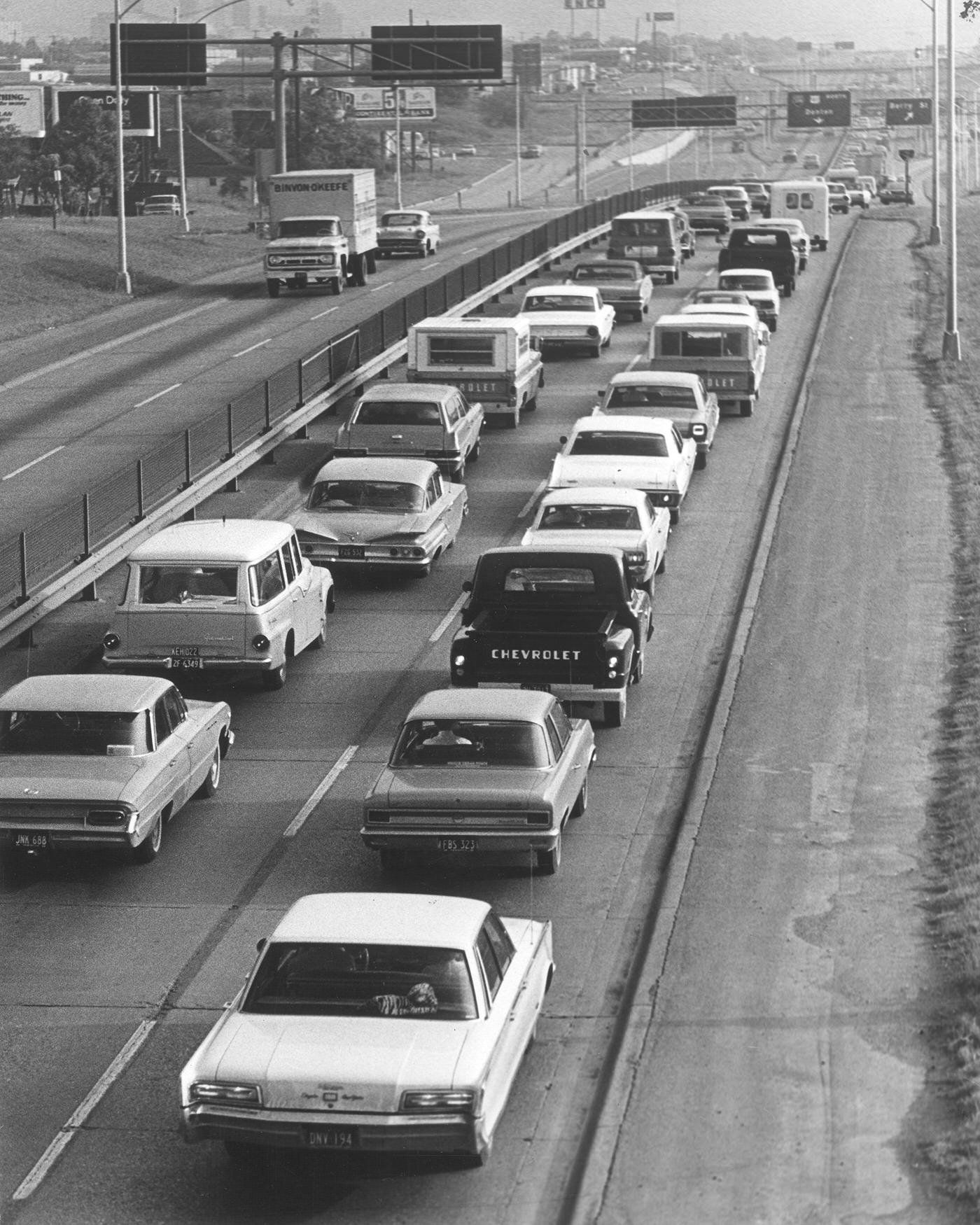

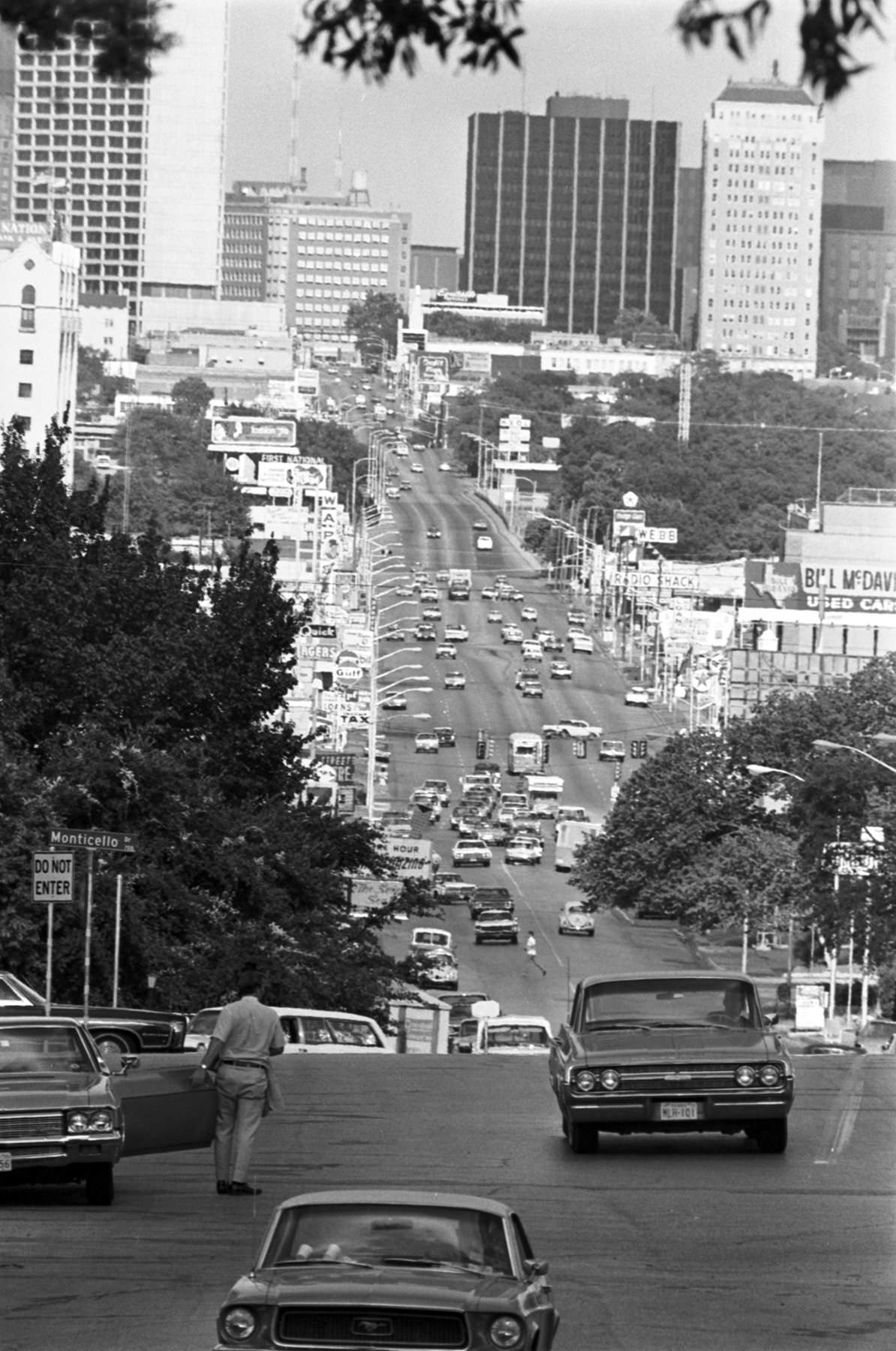

The extensive freeway system planned in the post-war years reached a greater degree of completion in the 1970s, profoundly shaping the city’s growth patterns. Construction on Loop 820, the circumferential highway around the city, continued; various segments had opened in the 1960s, and the northwest portion received its Interstate designation in 1968.

Interstate 20, the major east-west route across the southern part of the region, was formally established. The freeway sections on the south and west sides of Fort Worth, previously designated as Loop 217 or part of Loop 820, officially became I-20 in 1971. The completion of I-20 eastward through the suburbs of Arlington and Grand Prairie occurred in the late 1970s, paving the way for rapid development in those areas in subsequent decades.

Interstate 30, the main artery connecting downtown Fort Worth to downtown Dallas, had existed as the Dallas-Fort Worth Turnpike since 1957. Originally designated as part of I-20, it was later renumbered as I-30. The tolls on this route were removed on January 1, 1978, following some dispute between Dallas and Fort Worth interests over whether tolling should continue.

Cowtown’s New Look: The Stockyards Transform

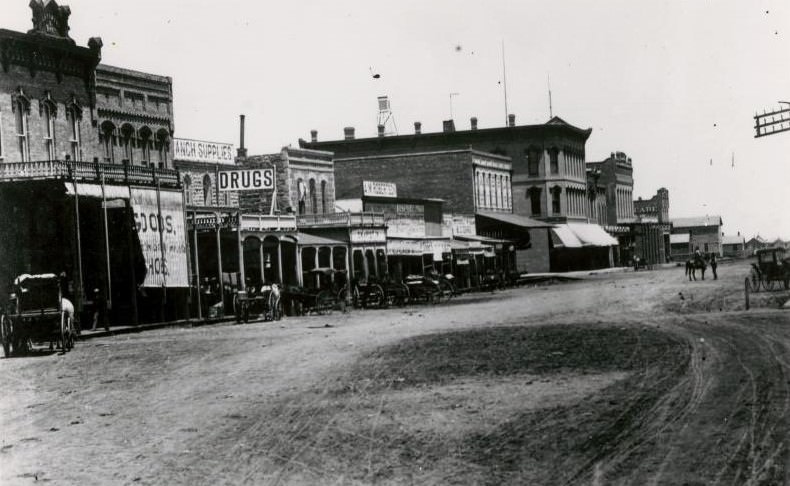

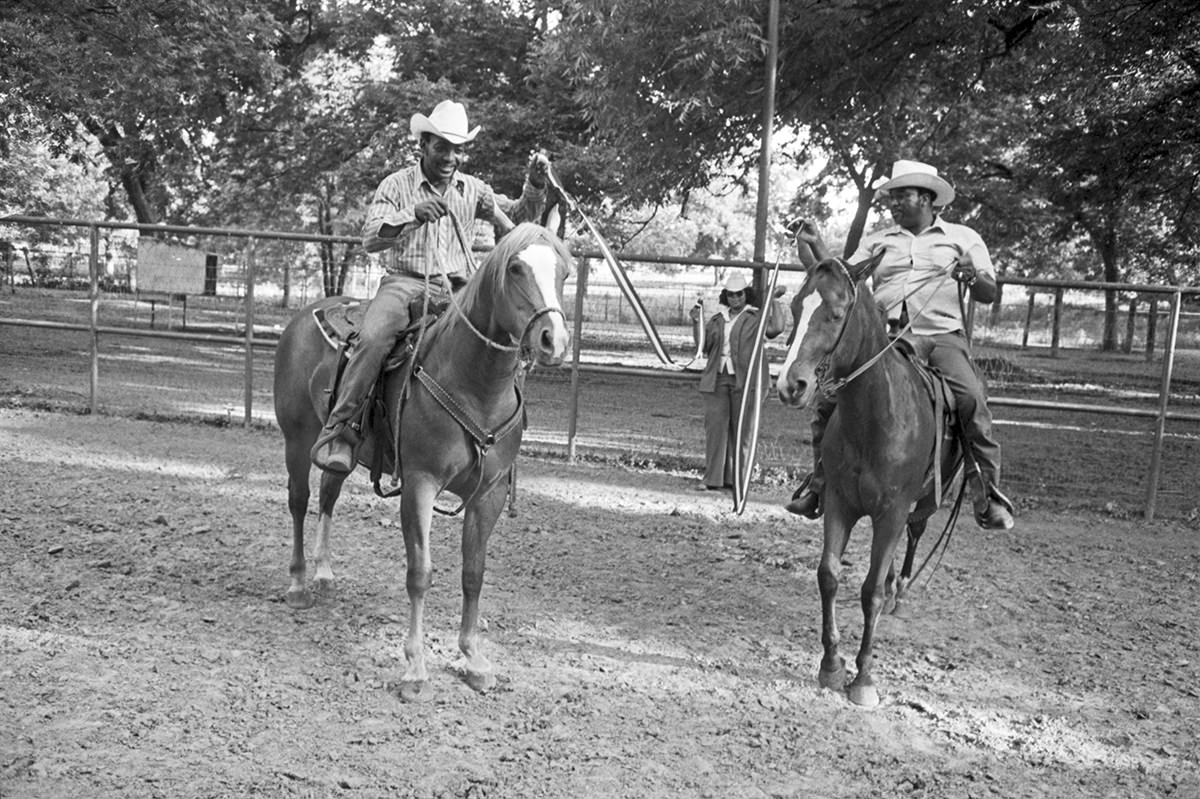

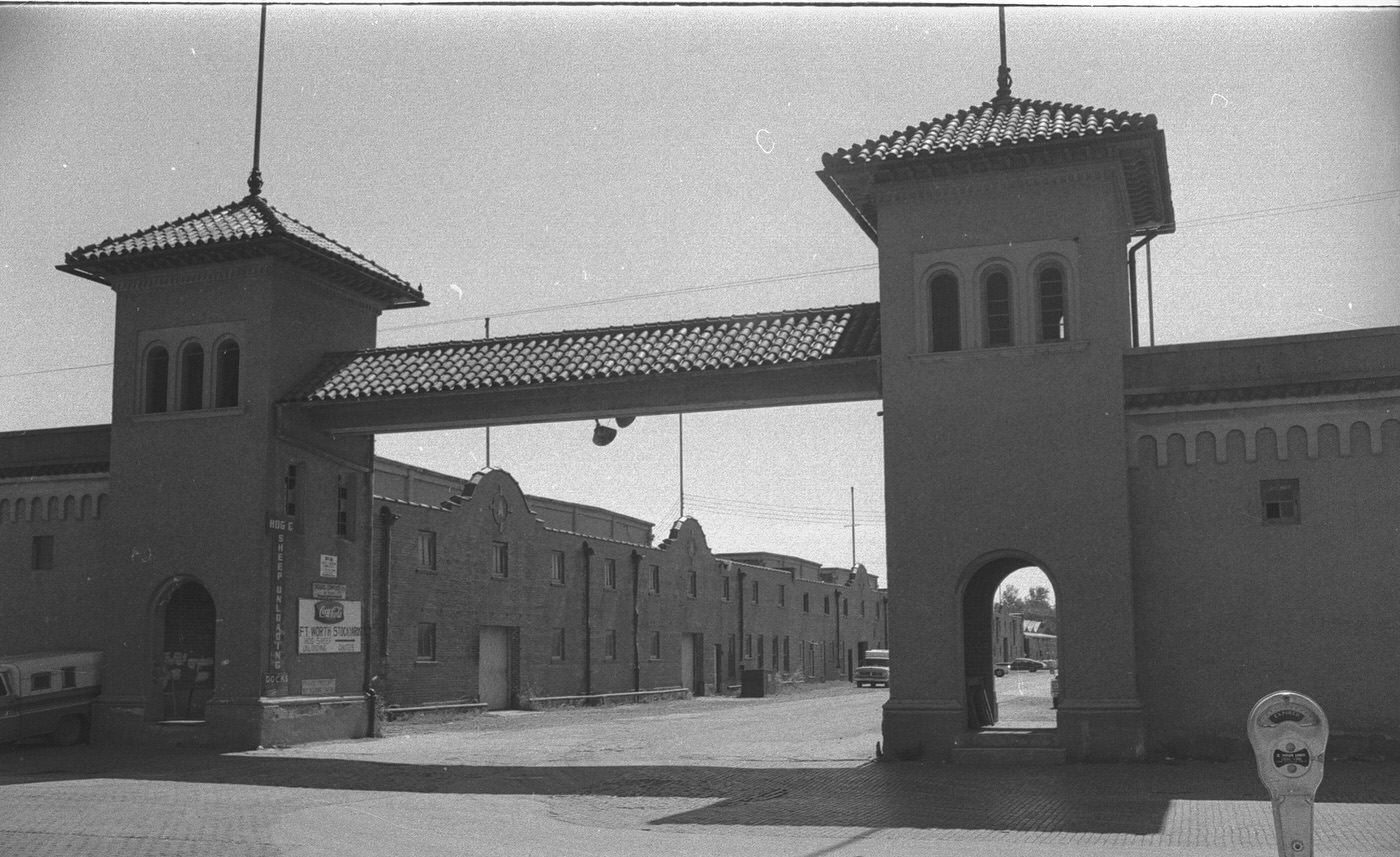

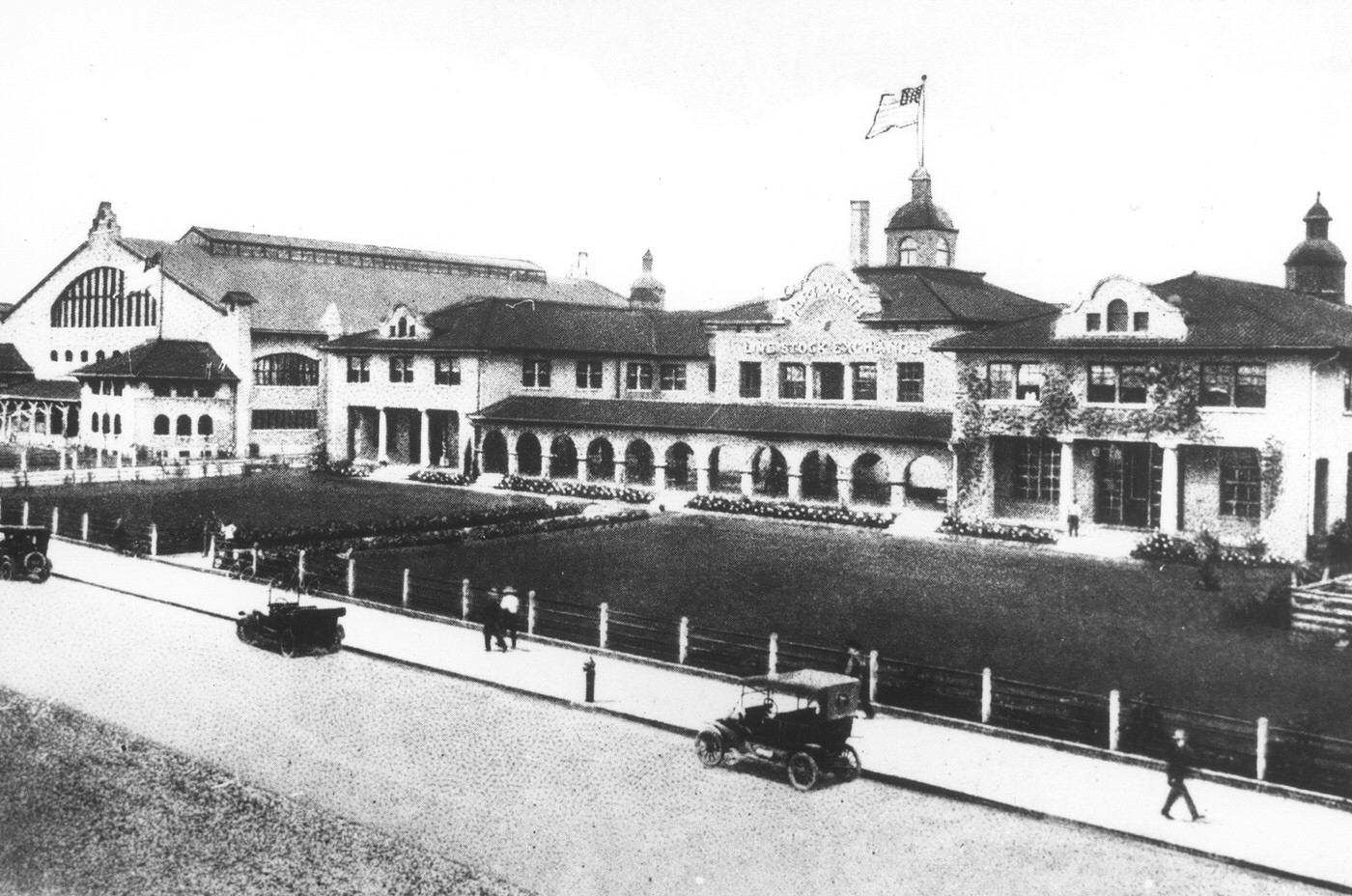

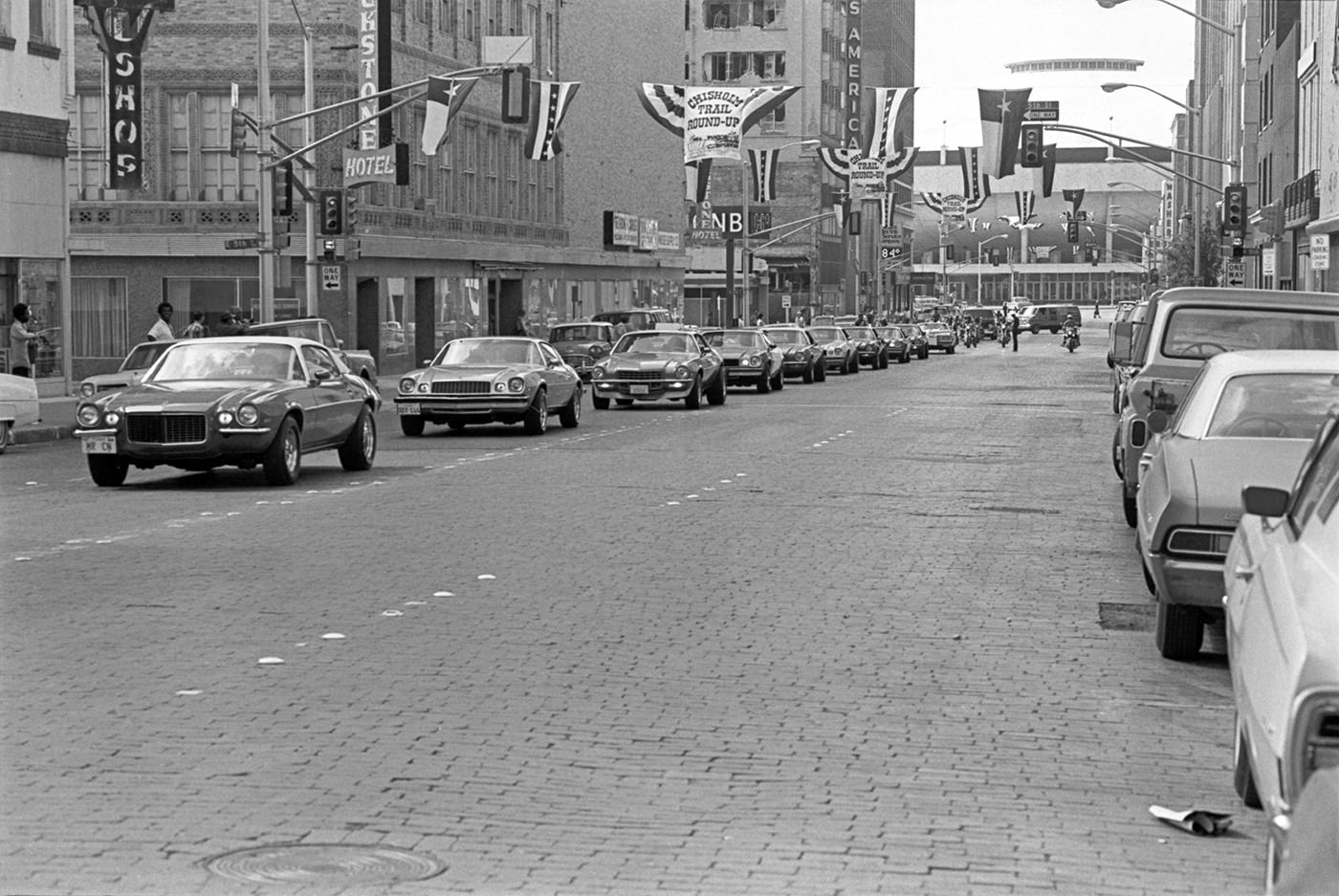

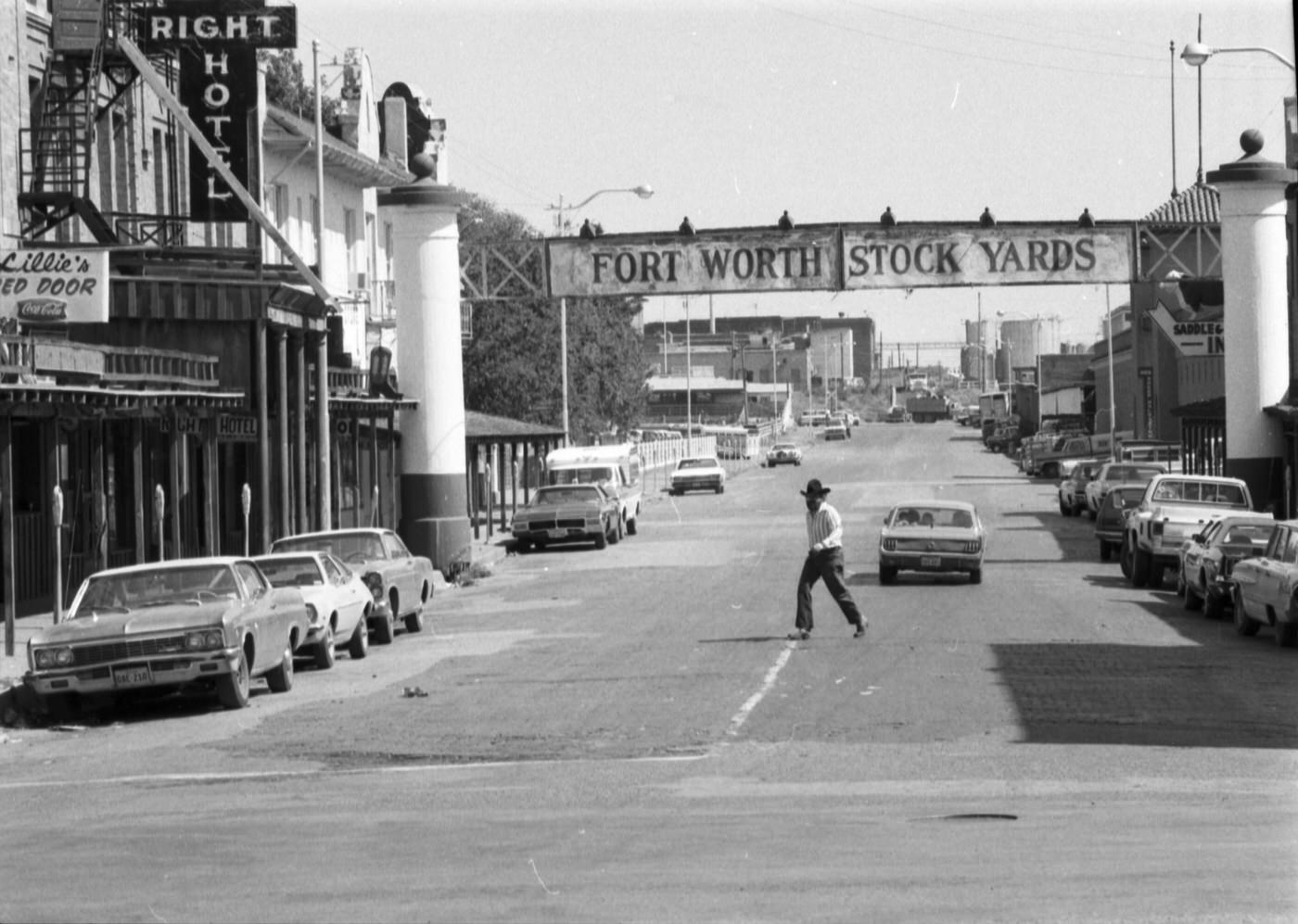

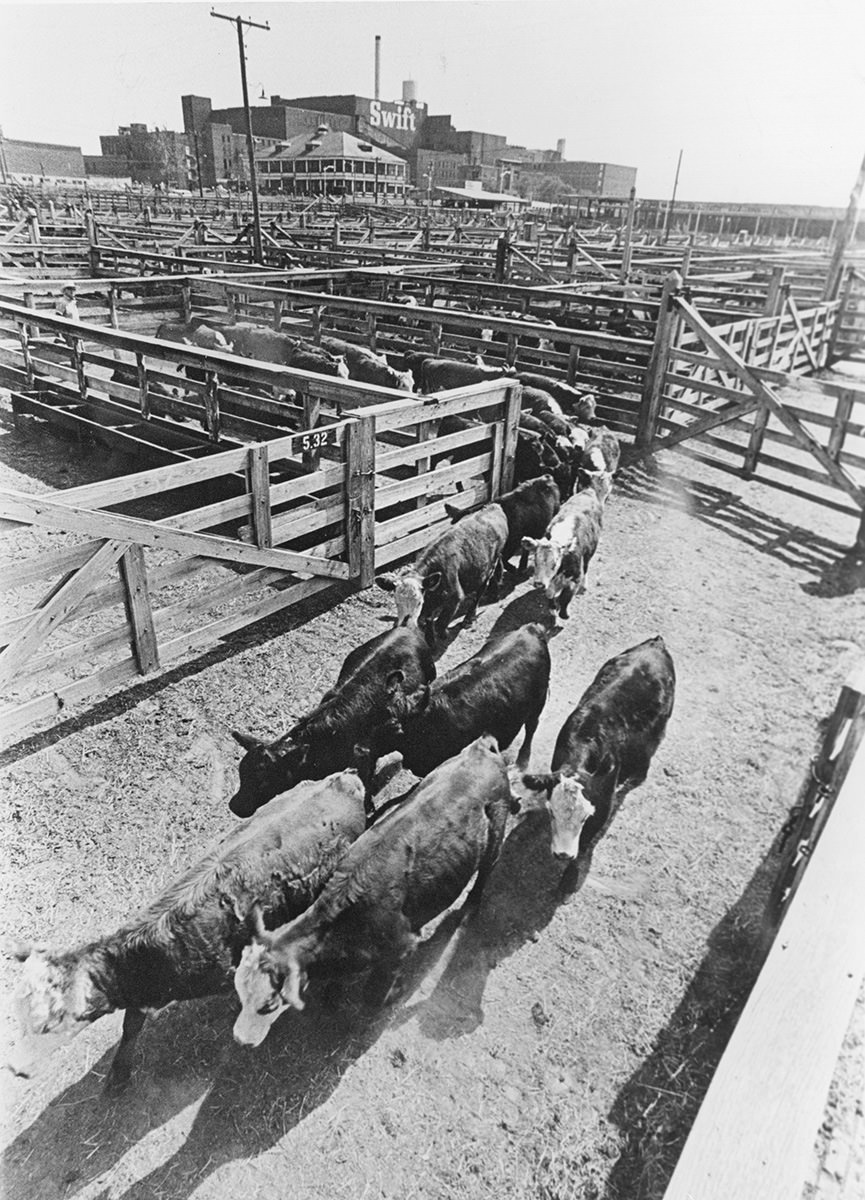

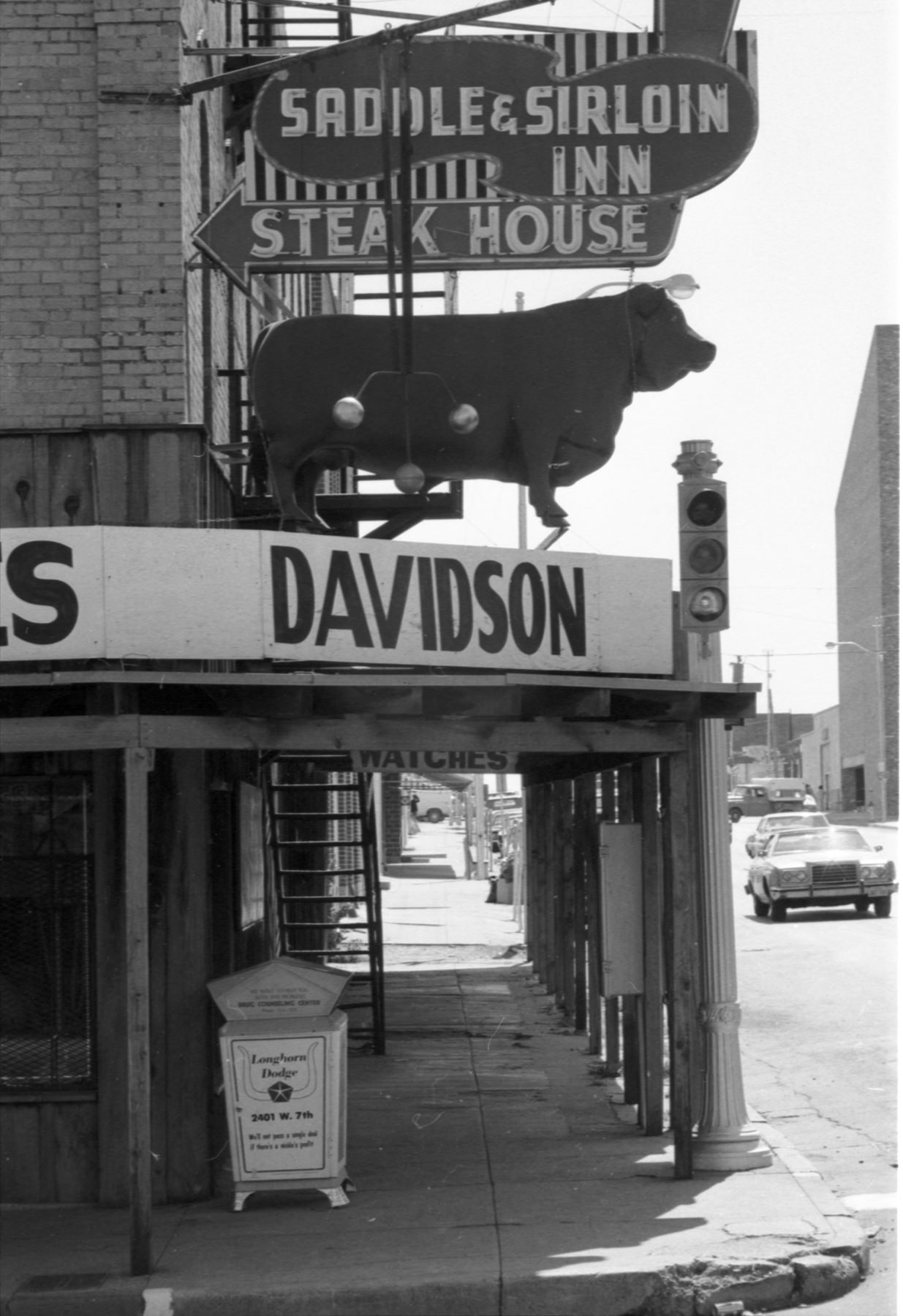

While the aviation sector adapted, another defining Fort Worth industry reached its end. The Fort Worth Stockyards, once the largest livestock market in the Southwest and a symbol of the city’s “Cowtown” identity, saw its long decline accelerate in the 1970s. The shift from rail transport to trucking, coupled with the growth of smaller, local livestock auctions and feedlots, had been drawing business away since the 1950s. Annual animal receipts had fallen dramatically from the peak of over 5.25 million head processed in 1944.

The final blow to the Stockyards’ industrial era came in 1971 with the closure of the Swift & Company meatpacking plant. Armour & Company, the other major packer, had already closed its adjacent plant in 1962. Efforts by Swift workers to keep the plant open, including accepting pay cuts, proved unsuccessful. The closure of Swift marked the definitive end of the large-scale meatpacking operations that had anchored the North Side economy for nearly 70 years.

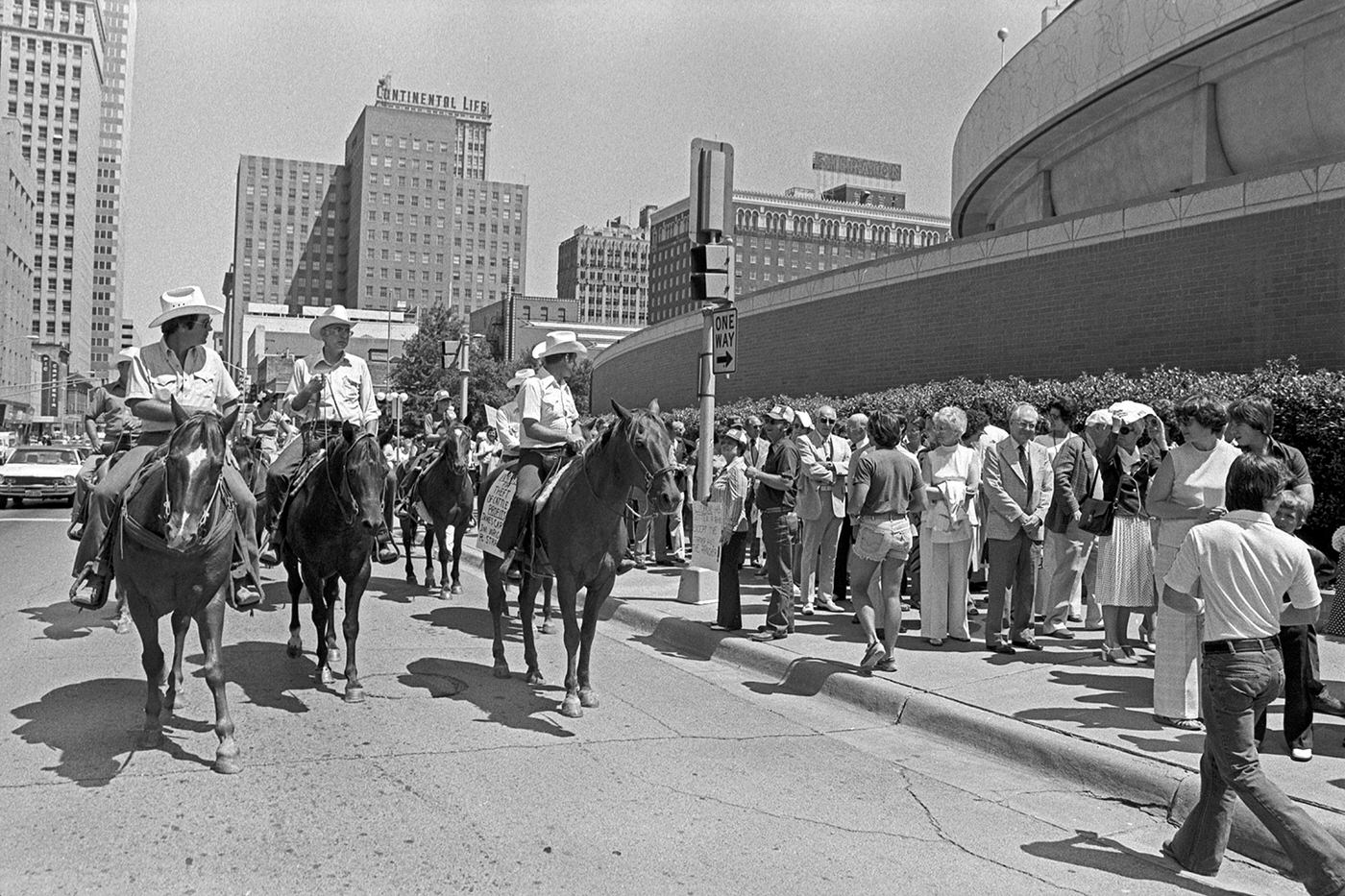

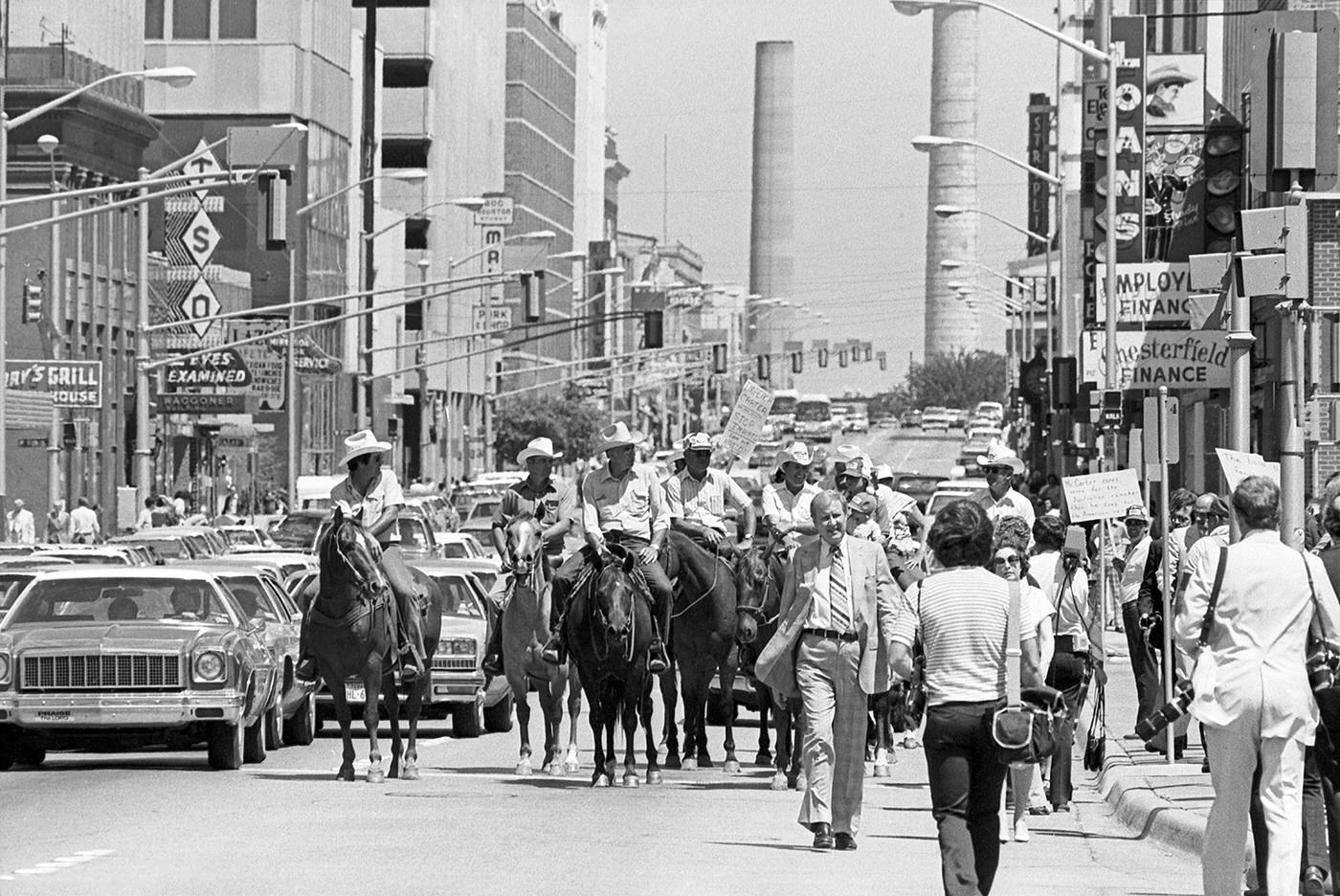

With the packing plants gone, the Stockyards area fell into significant disrepair in the early 1970s. Described as “dodgy and dangerous” and an “embarrassment,” many of the historic buildings and pens languished. City leaders discussed demolishing the structures. However, a movement towards preservation and revitalization began. In 1972, the City of Fort Worth established the Stockyards Area Restoration Committee to guide redevelopment efforts. Spurred by public funds, private investors began to see potential in the area’s history. Canal-Randolph, the parent company of the stockyards operation, invested in remodeling pens and renovating the historic Livestock Exchange Building for new uses, such as office space. Preservation-minded individuals and groups acquired properties to prevent demolition and start cleaning up the district.

A major turning point came in 1976 when the Fort Worth Stockyards was officially listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This designation recognized the area’s immense historical significance and provided a framework for its preservation. The closure of the packing plants and the subsequent decline forced a fundamental shift: the Stockyards began its transition from a defunct industrial center to a unique historic district focused on tourism, entertainment, and celebrating its Western heritage.

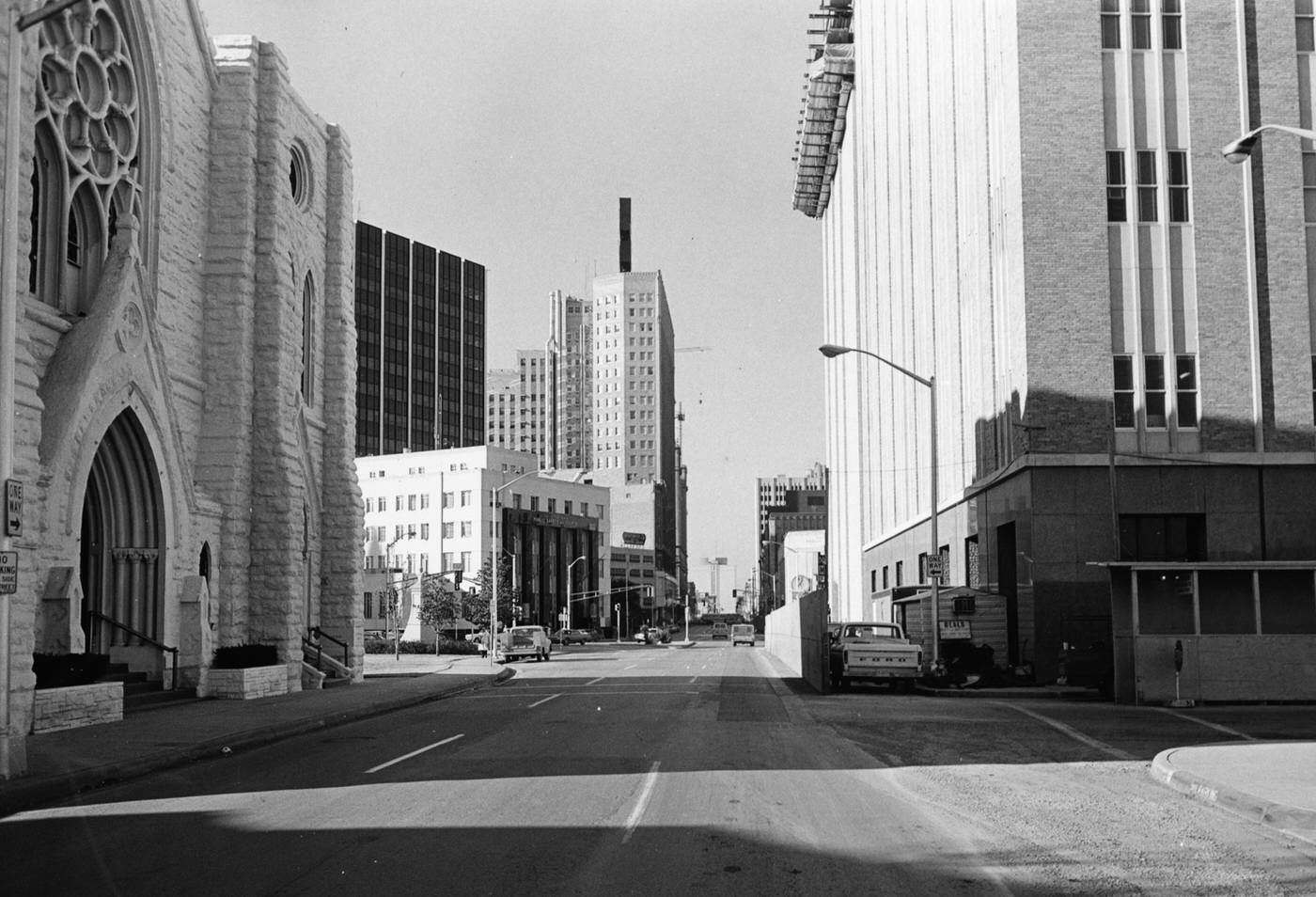

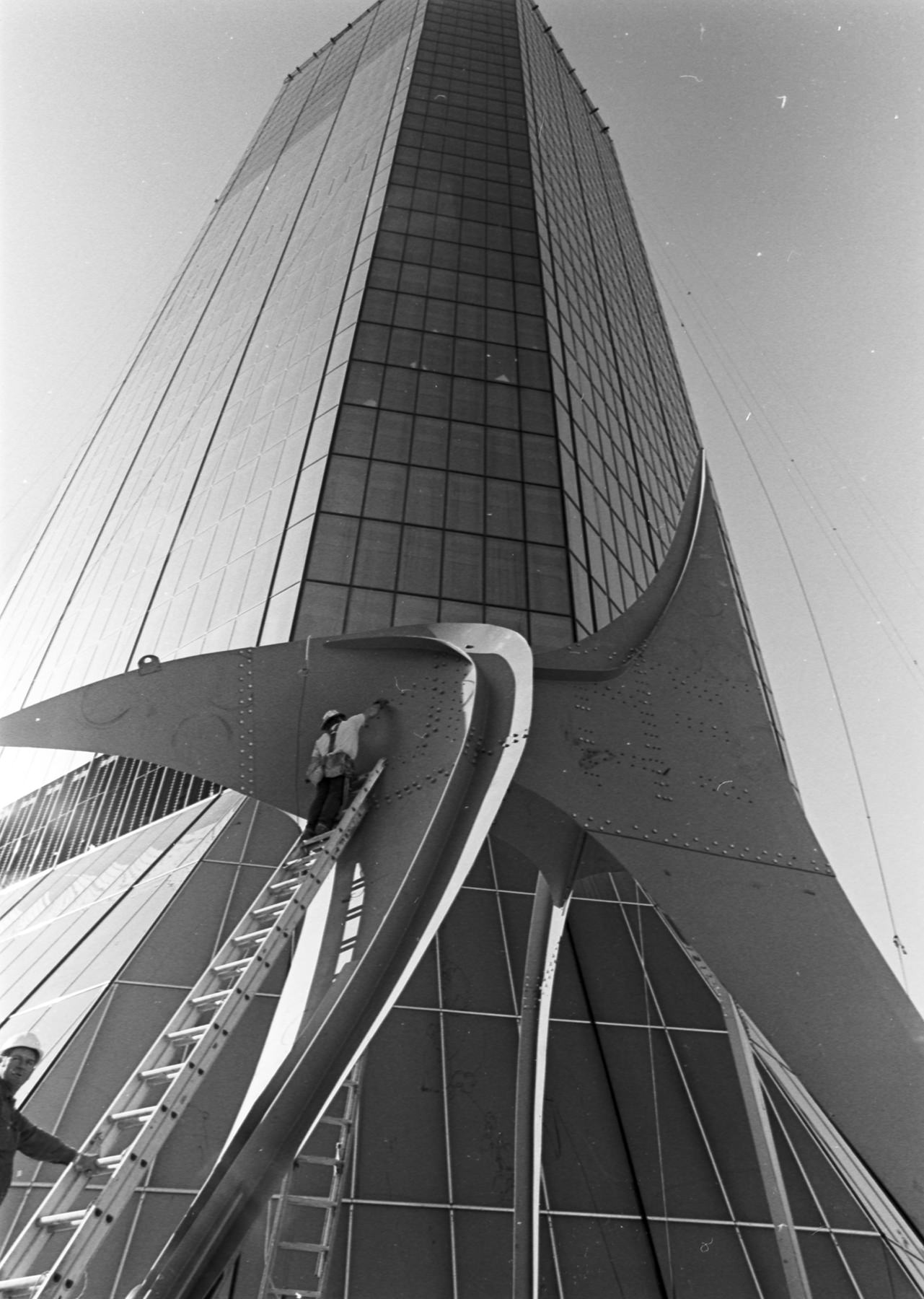

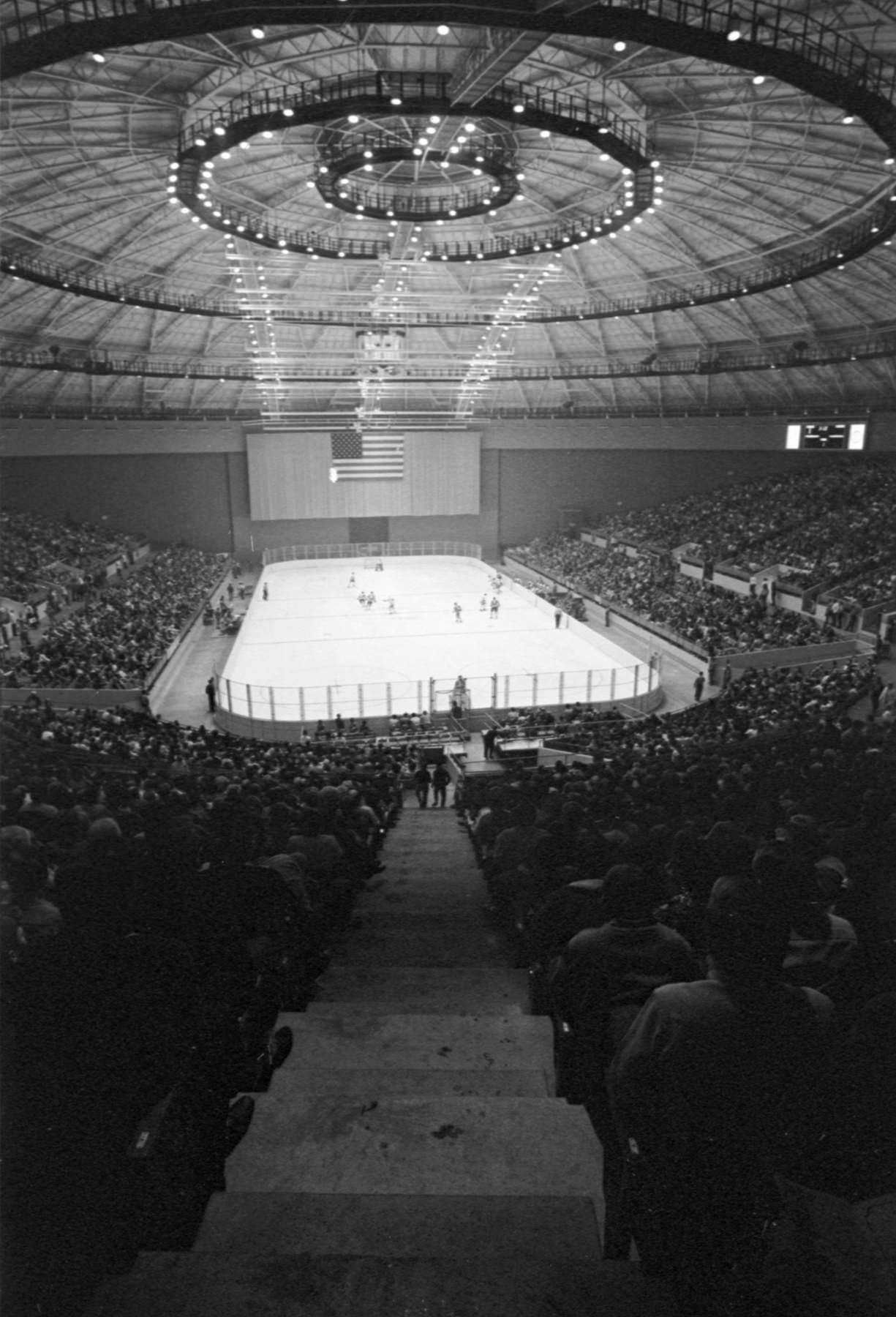

Downtown Fort Worth underwent significant physical changes during the 1970s, driven by large-scale urban renewal concepts and major development projects. The most prominent project was the Tandy Center. Spearheaded by Tandy Corporation, construction began in 1975 on this multi-block complex designed to house the company’s headquarters and revitalize a section of downtown. Completed in phases between 1976 and 1978, it featured two 20-story office towers, a large indoor shopping mall with an ice skating rink, and utilized the existing M&O Subway line that had previously served Leonard’s Department Store. The project was built on the site of the former Leonard’s Home Store and adjacent blocks, requiring the creation of superblocks that interrupted the traditional downtown street grid. Older buildings, including the main Leonard’s store complex, were demolished in 1979 to clear the site for the connected Worthington Hotel (then called the Americana), which opened in 1981.

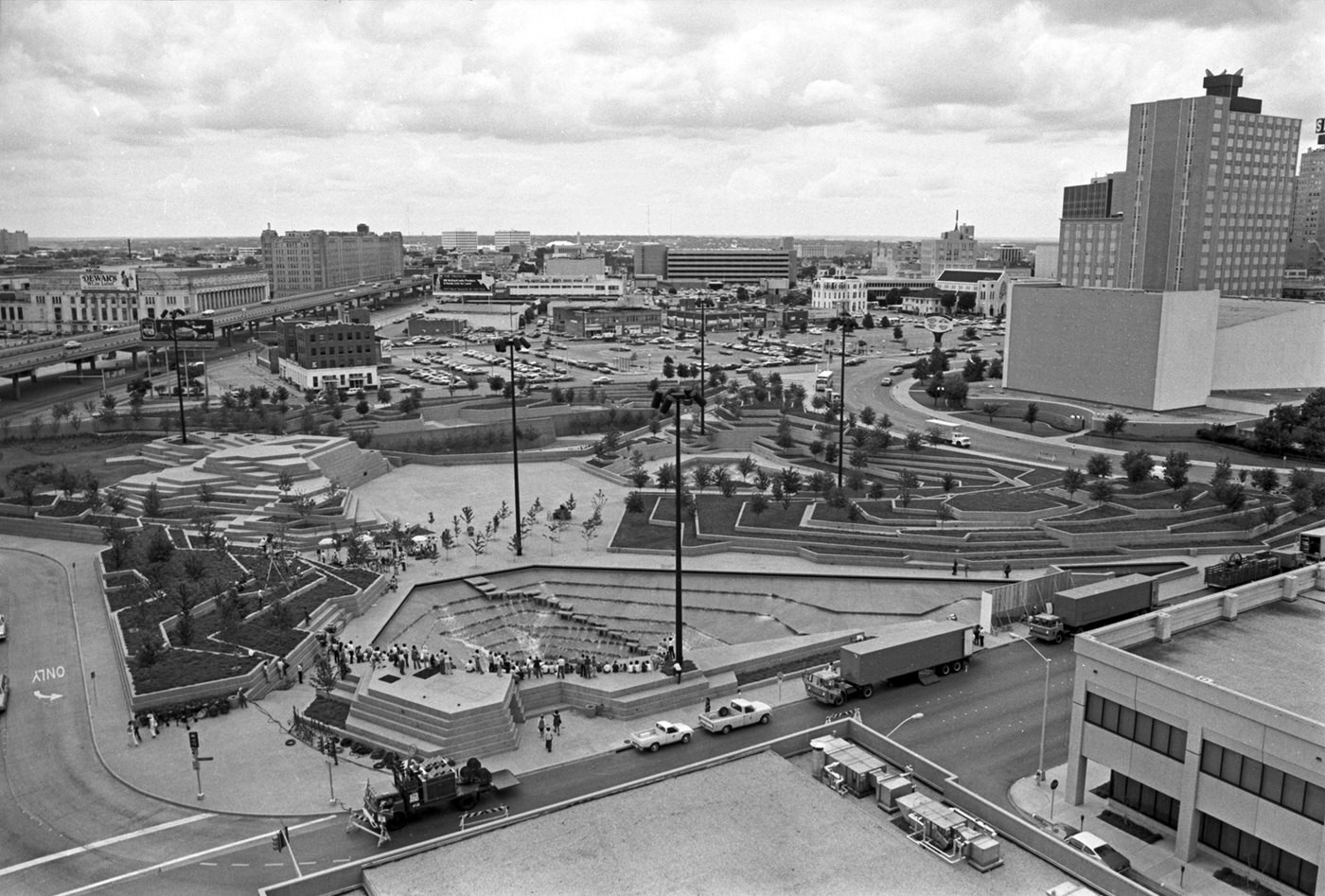

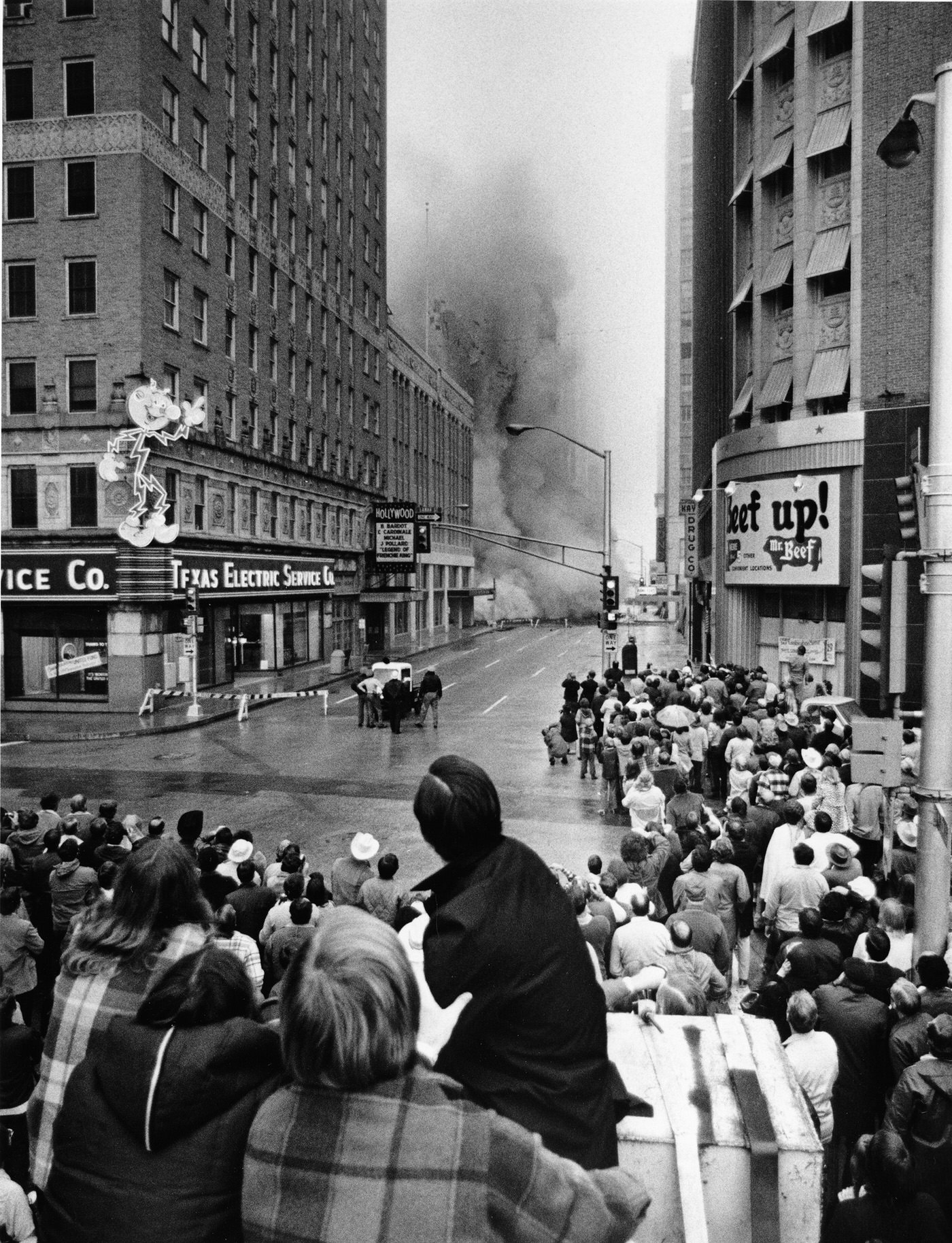

Another area targeted for renewal was the southern end of downtown, the site of the historic, and notorious, “Hell’s Half Acre.” The Tarrant County Convention Center had opened there in 1968, built on 14 blocks of cleared land. Efforts to improve this area continued into the 1970s. The Fort Worth Water Gardens, a significant public park featuring dramatic water structures designed by architect Philip Johnson, opened in 1974 adjacent to the convention center. Funded by the Amon G. Carter Foundation as a gift to the city, the Water Gardens aimed to bring beauty and public activity to the redeveloping area. These projects reflected the era’s urban renewal philosophy, which often favored large-scale demolition and new construction, sometimes replacing fine-grained urban fabric with monumental modern structures and public spaces. The Tandy Center exemplified private corporate-led redevelopment, while the Convention Center and Water Gardens represented public and foundation-driven initiatives to reshape the urban core.

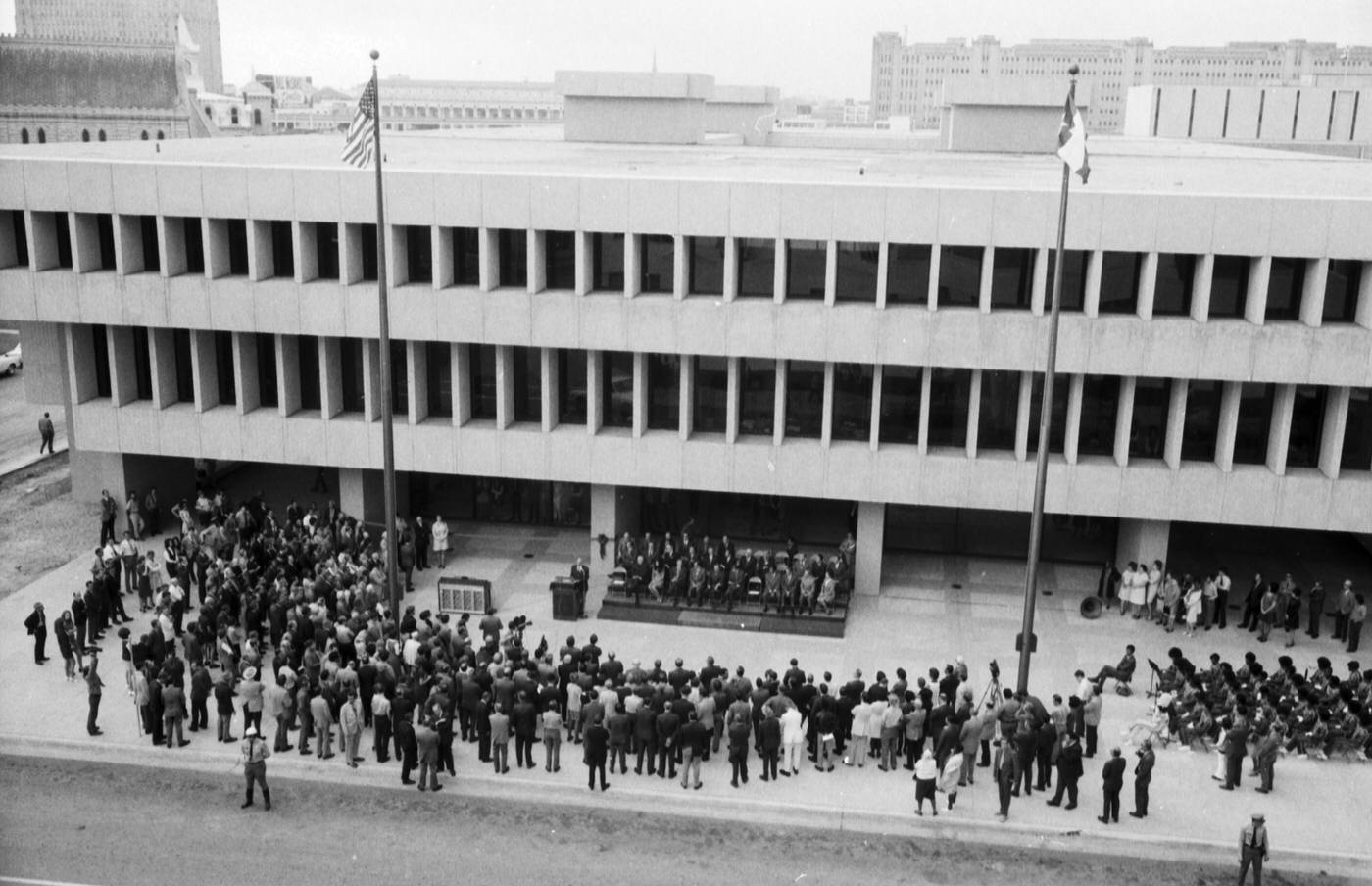

The modernization of downtown included the construction of a new primary facility for city government. The current Fort Worth City Hall, located at 1000 Throckmorton Street, opened in 1975. Designed by the prominent New York architect Edward Durell Stone, the building introduced the Brutalist architectural style, characterized by its heavy concrete forms, to the city center. It replaced the previous City Hall (built 1938), which remained standing but was repurposed and renamed the Public Safety and Courts Building. The site itself had a longer history, having previously held the city’s 1896 federal building and post office, which was demolished in 1970 to make way for the new municipal headquarters. The construction of this modern, architecturally distinct City Hall served as a symbol of the city government’s adaptation to growth and its embrace of contemporary design during the decade’s redevelopment push.

Shifting Economic Gears

The economic landscape of Fort Worth experienced considerable flux during the 1970s. While the established defense and aviation sector underwent a crucial transition, the historic meatpacking industry faded, and a new force in electronics emerged. The decade was also marked by the nationwide energy crises, which brought both opportunities and challenges to the region.

The aviation and defense industry remained a cornerstone of Fort Worth’s economy throughout the 1970s, primarily centered around the massive Air Force Plant 4 and the adjacent Carswell Air Force Base. These facilities had been vital economic engines for the city since their establishment during World War II.

A significant transition occurred at Plant 4, operated by General Dynamics. Production of the complex F-111 Aardvark tactical bomber, a mainstay since the mid-1960s, concluded in 1976. This aircraft, born from the TFX program, featured pioneering technologies like variable-sweep wings and automated terrain-following radar. Its phase-out marked the end of a major production run for the facility.

Simultaneously, Carswell Air Force Base saw the retirement of another notable aircraft. The Convair B-58 Hustler, the world’s first operational bomber capable of sustained Mach 2 flight, had been based at Carswell with the 43rd Bombardment Wing from 1960 to 1964. The B-58 program was officially retired from the Air Force inventory on January 31, 1970, closing a chapter on supersonic strategic bombing at the base.

The potential economic gap left by the conclusion of the F-111 program and the earlier retirement of the B-58 was filled by a new, highly successful project. General Dynamics had designed and built the YF-16 prototype in Fort Worth during the early 1970s. After winning the intense Lightweight Fighter competition against the Northrop YF-17, the F-16 Fighting Falcon was selected for production. The first YF-16 prototype rolled out of the Fort Worth plant on December 13, 1973, and the U.S. Air Force officially accepted the first production F-16 on August 17, 1978. The initiation of the F-16 program represented a crucial “economic rebirth” for Fort Worth, ensuring the continued viability of Plant 4 and solidifying the city’s role as a leading aerospace manufacturing center for decades to come. Over 3,600 F-16s would eventually be delivered from the Fort Worth facility.

Throughout this transition, Carswell Air Force Base remained a critical installation for the Strategic Air Command (SAC). The 7th Bombardment Wing continued to operate the B-52 Stratofortress, the long-range strategic bomber that formed the backbone of America’s nuclear deterrent force. B-52 crews based at Carswell had participated in combat operations during the Vietnam War, flying missions from bases in Guam and Thailand, with these rotational deployments continuing on a reduced scale until 1975.

Tandy Takes Off: Electronics Boom

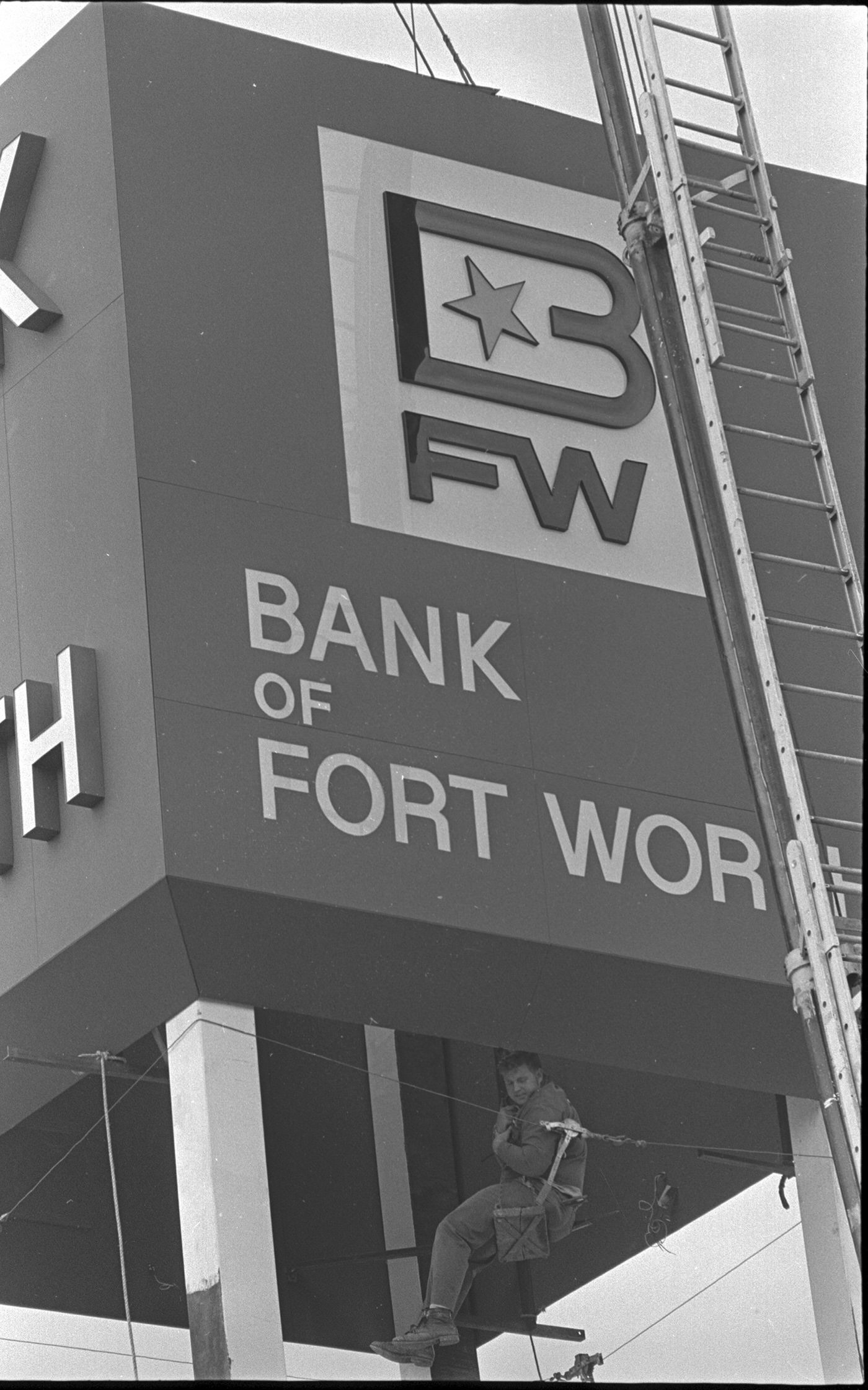

As traditional industries like meatpacking faded, a modern economic powerhouse was rapidly ascending in Fort Worth: Tandy Corporation. Headquartered downtown, Tandy, under the leadership of CEO John Roach, experienced remarkable growth throughout the 1970s. Having acquired the struggling Boston-based RadioShack electronics chain in 1963, Charles Tandy had engineered a dramatic turnaround.

In 1977, Tandy Corporation made a move that placed it at the forefront of a technological revolution. The company launched the TRS-80 Micro Computer System, one of the world’s first mass-produced, pre-assembled personal computers. Sold through its thousands of RadioShack retail stores, the TRS-80 made computing accessible to a broad audience beyond hobbyists who previously had to assemble kits.

The initial TRS-80 Model I came as a complete package including a keyboard with the Zilog Z80 processor inside, 4 kilobytes of RAM, a 12-inch video monitor, and a cassette recorder for loading programs and saving data, all for $599. It was an immediate success, selling over 100,000 units in its first year and, for a time, outselling the competing Apple II. Tandy aggressively supported its new computer line, offering upgrades, peripherals like disk drives, software, and establishing dedicated Radio Shack Computer Centers. By the early 1980s, computers had become the most crucial part of Tandy’s business.

This success was physically manifested in the downtown skyline with the Tandy Center. Groundbreaking for the complex occurred in 1975, and the development included twin 20-story office towers serving as the corporate headquarters, an upscale indoor shopping mall featuring an ice skating rink, and even its own privately operated subway line connecting to parking lots. Tandy’s phenomenal growth in the high-tech consumer electronics and personal computer sector provided a vital economic counterweight to the challenges faced by Fort Worth’s older industrial base, diversifying the city’s economy and positioning it within a major new growth industry.

People, Homes, and Daily Life

The social and demographic landscape of Fort Worth also underwent changes during the 1970s, influenced by population shifts, evolving neighborhoods, and the lingering effects of national events like the Vietnam War and the energy crisis.

The rapid population boom Fort Worth experienced after World War II slowed considerably in the 1970s. In fact, the city proper saw a slight decrease in population between the 1970 and 1980 U.S. Census counts.

Despite this small decline within the city limits, Fort Worth maintained its position as one of Texas’s five largest cities. The decrease in the central city stood in contrast to the continued robust growth of the surrounding region. The Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area population grew substantially, crossing the 2 million mark early in the decade and approaching 2.5 million by 1980. Tarrant County also saw significant gains, increasing from 716,317 residents in 1970 to 860,880 in 1980.

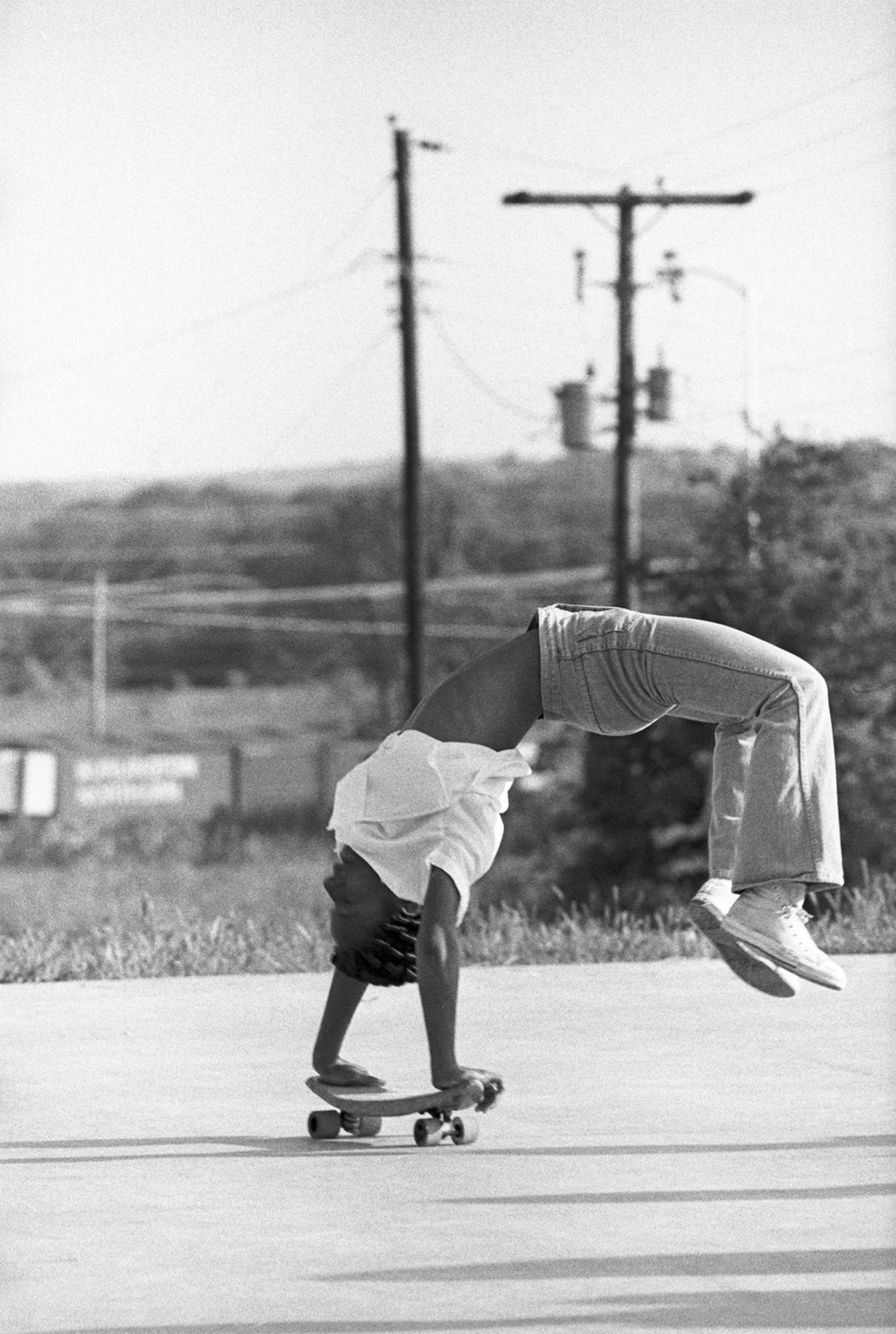

This pattern indicated that the trend of suburbanization, which had reshaped American cities since the 1950s, was ongoing. Growth was increasingly concentrated in the suburban communities surrounding Fort Worth and Dallas. New housing developments, featuring the popular ranch-style homes, continued to spread across former farmland. Suburbs within Tarrant County, such as North Richland Hills, experienced rapid population increases; North Richland Hills nearly doubled its population during the decade, growing from 16,514 in 1970 to 30,592 in 1980. This divergence—a slight decline in the central city coupled with strong growth in the surrounding county and metropolitan area—demonstrated a clear “doughnut effect,” where new growth largely bypassed the urban core in favor of the expanding suburbs.

Fort Worth’s neighborhoods presented a varied picture in the 1970s. While new suburbs expanded, older residential areas faced different circumstances and trajectories.

Established neighborhoods close to downtown, like Ryan Place, had seen better days. Developed in the early 20th century with grand homes, the area suffered during the Depression and experienced neglect as residents migrated to newer suburbs after World War II and into the 1960s, leaving many houses in disrepair. However, the 1970s marked the beginning of a turnaround for Ryan Place. In 1969, residents organized the Ryan Place Improvement Association, successfully opposing city plans to widen arterial streets through the neighborhood. This grassroots effort signaled a commitment to preserving the neighborhood’s character and initiated a slow process of revitalization. A significant milestone was achieved in 1979 when Elizabeth Boulevard was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, establishing Ryan Place as Fort Worth’s only residential historic district at that time. Fairmount, another large streetcar-era neighborhood known for its bungalows, likely faced similar pressures of aging housing stock and competition from the suburbs, though its specific condition in the 1970s requires further detail.

Meanwhile, newer suburban areas like North Richland Hills continued their expansion, offering modern housing options that drew residents from the central city. The decade thus saw different paths for Fort Worth’s neighborhoods: some older areas began resident-driven preservation efforts, others grappled with the legacy of overt segregation, while new suburbs continued to grow outwards.

The Times We Lived In

Daily life in Fort Worth during the 1970s was also colored by the conclusion of the Vietnam War and the ongoing energy crisis. The final withdrawal of U.S. combat troops from Vietnam occurred in March 1973. For veterans returning home, the reception was often difficult and unwelcoming, starkly different from the homecomings after previous wars. Protests and expressions of hostility were reported by some returning service members. Fort Worth, with Carswell AFB and a large defense workforce, had a substantial connection to the military and the war. Tarrant County lost at least 220 residents in the conflict. The need to properly recognize the sacrifices of these veterans led to later efforts to establish memorials.

The energy crises of 1973 and 1979, as previously discussed, brought the realities of global politics and resource scarcity directly into Fort Worth homes and onto its streets. The frustrating experience of waiting in long gas lines and the necessity of adopting conservation measures like lowering thermostats became shared experiences, creating a backdrop of adjustment and perhaps anxiety during parts of the decade. These overlapping national events—the end of a controversial war and the onset of energy uncertainty—shaped the local atmosphere of the early and mid-1970s.

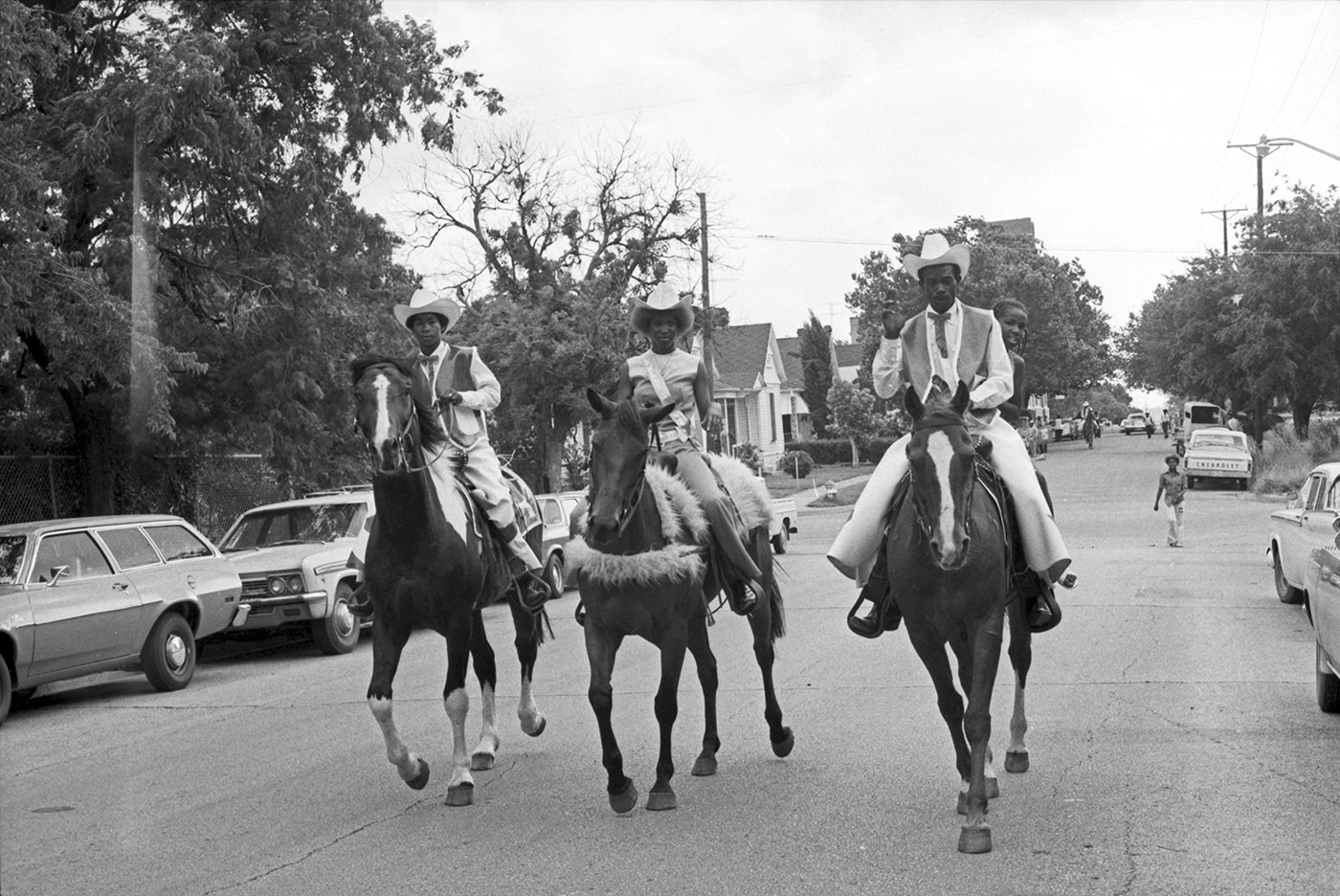

The Continuing Struggle for Civil Rights

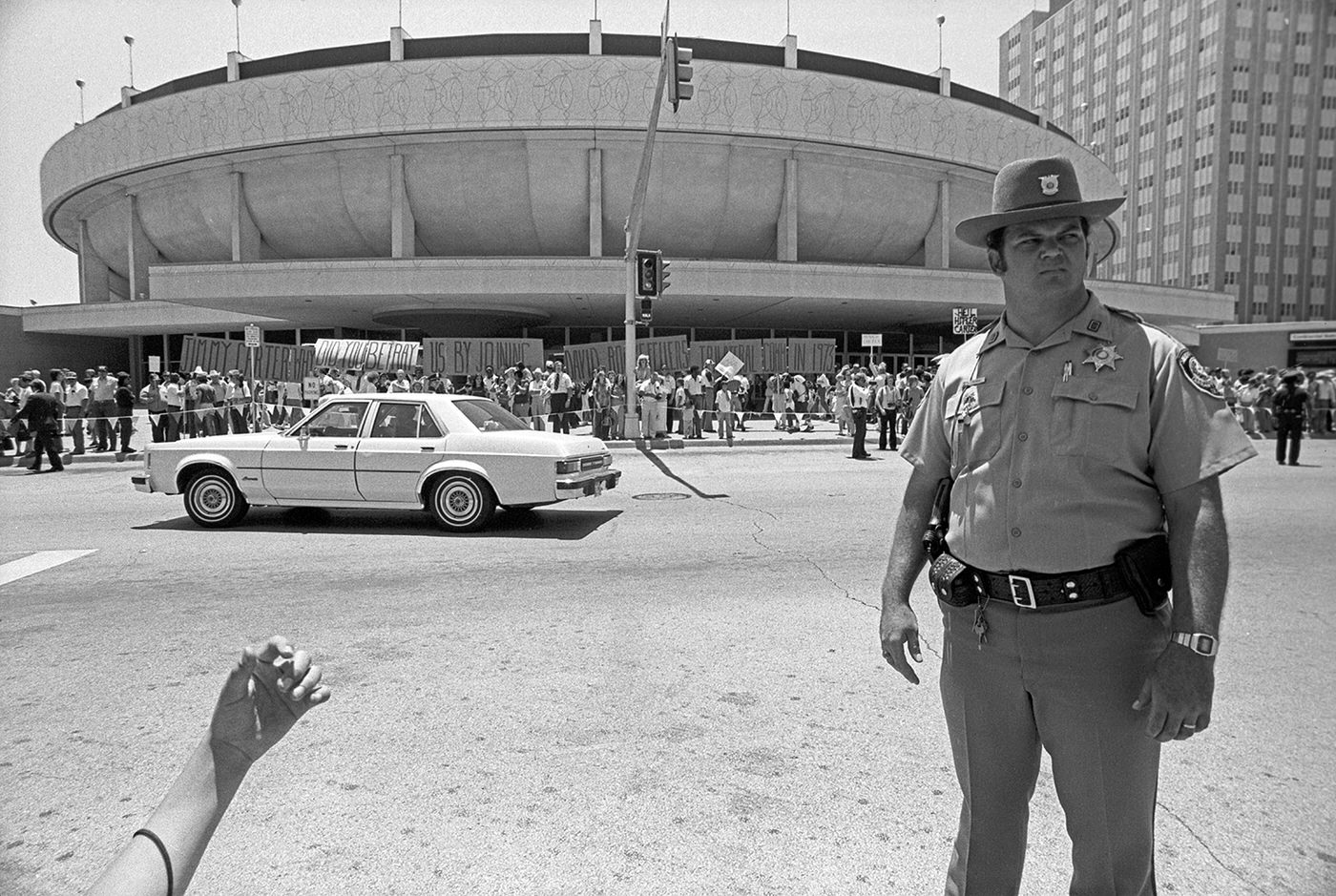

The 1970s were a critical period for the implementation of civil rights measures in Fort Worth, particularly concerning school desegregation, access to public facilities, and political representation.

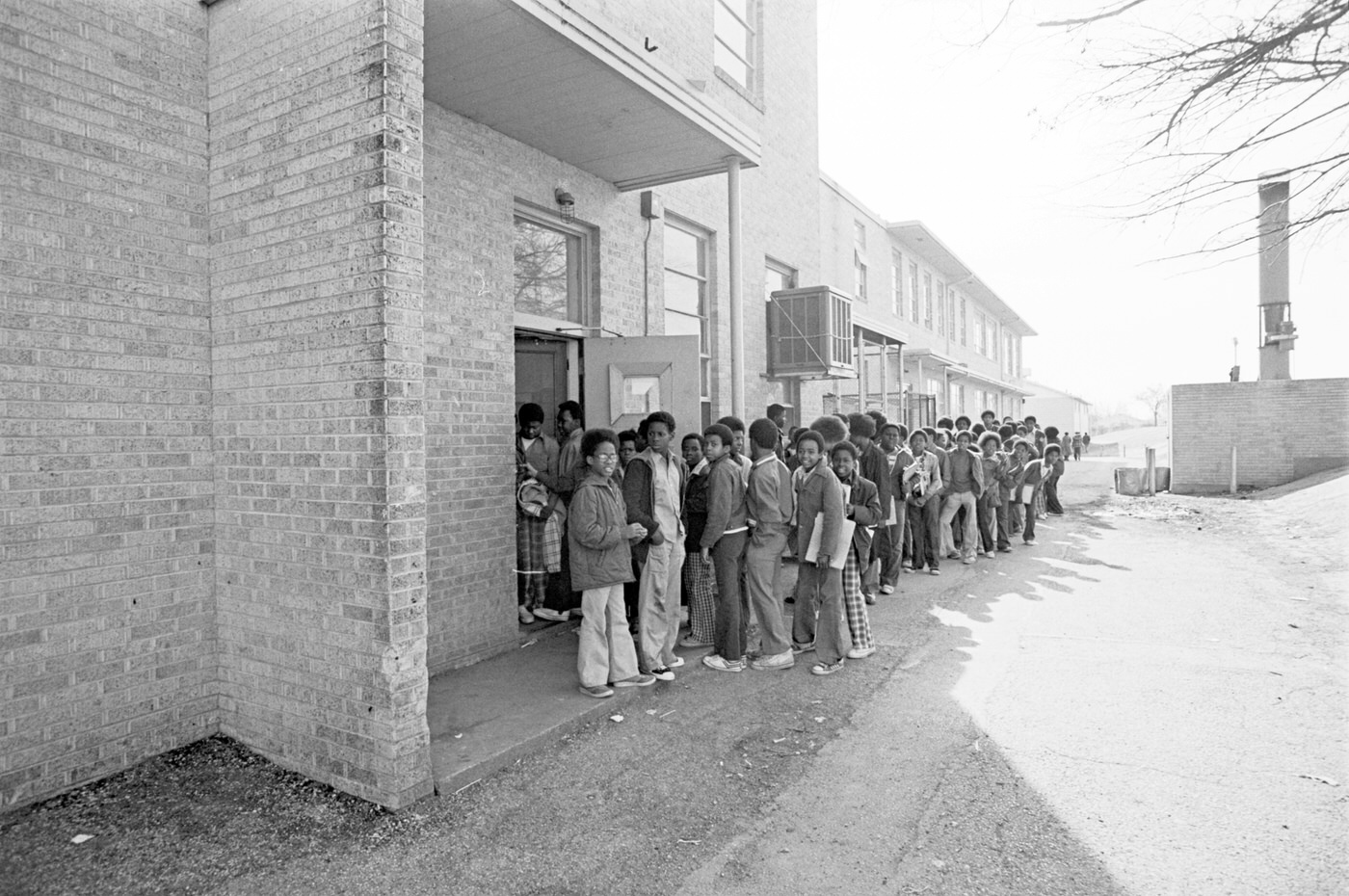

Efforts to desegregate Fort Worth’s public schools, mandated by the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision but long resisted locally, intensified significantly in the early 1970s. A 1961 federal court ruling had already declared the city’s dual (separate Black and White) school system unconstitutional.

In 1971, following the Supreme Court’s Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg decision which upheld busing as a tool to remedy segregation, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the Fort Worth Independent School District (FWISD) to take more direct action. The court rejected the school board’s argument that segregated housing patterns excused the existence of one-race schools, mandating student reassignments to overcome these patterns.

This led to the highly contentious introduction of mandatory busing. After initially approving a plan in July 1971 that integrated faculty but resisted mandatory student busing, the school board was given an ultimatum by federal District Judge Leo Brewster. Facing the prospect of having a plan imposed, the board narrowly approved a revised plan that included busing. This plan involved “clustering” elementary schools and transporting approximately 11,000 students (about 12% of the district’s total) to different schools to achieve better racial balance, with bus rides intended to be relatively short.

The initial 1971 busing plan proved insufficient. A year later, 56 schools in the district remained effectively segregated by race (16 predominantly Black, 40 predominantly White). The Fifth Circuit Court deemed the plan inadequate in 1972 because it failed to address the continued existence of numerous all-Black schools. Consequently, Judge Brewster ordered further modifications in August 1973. This revised plan expanded the school clustering and busing program to include the remaining segregated schools. It also mandated that faculty assignments reflect the district’s overall racial ratio within a specified tolerance (initially 12%, later tightened to 10%) and required the district to submit regular, detailed reports on the racial makeup of each school. Busing thus became a central, highly visible battleground, but it was only one component of a complex, court-supervised desegregation process that faced significant resistance and required multiple judicial interventions throughout the 1970s and beyond to achieve integration.

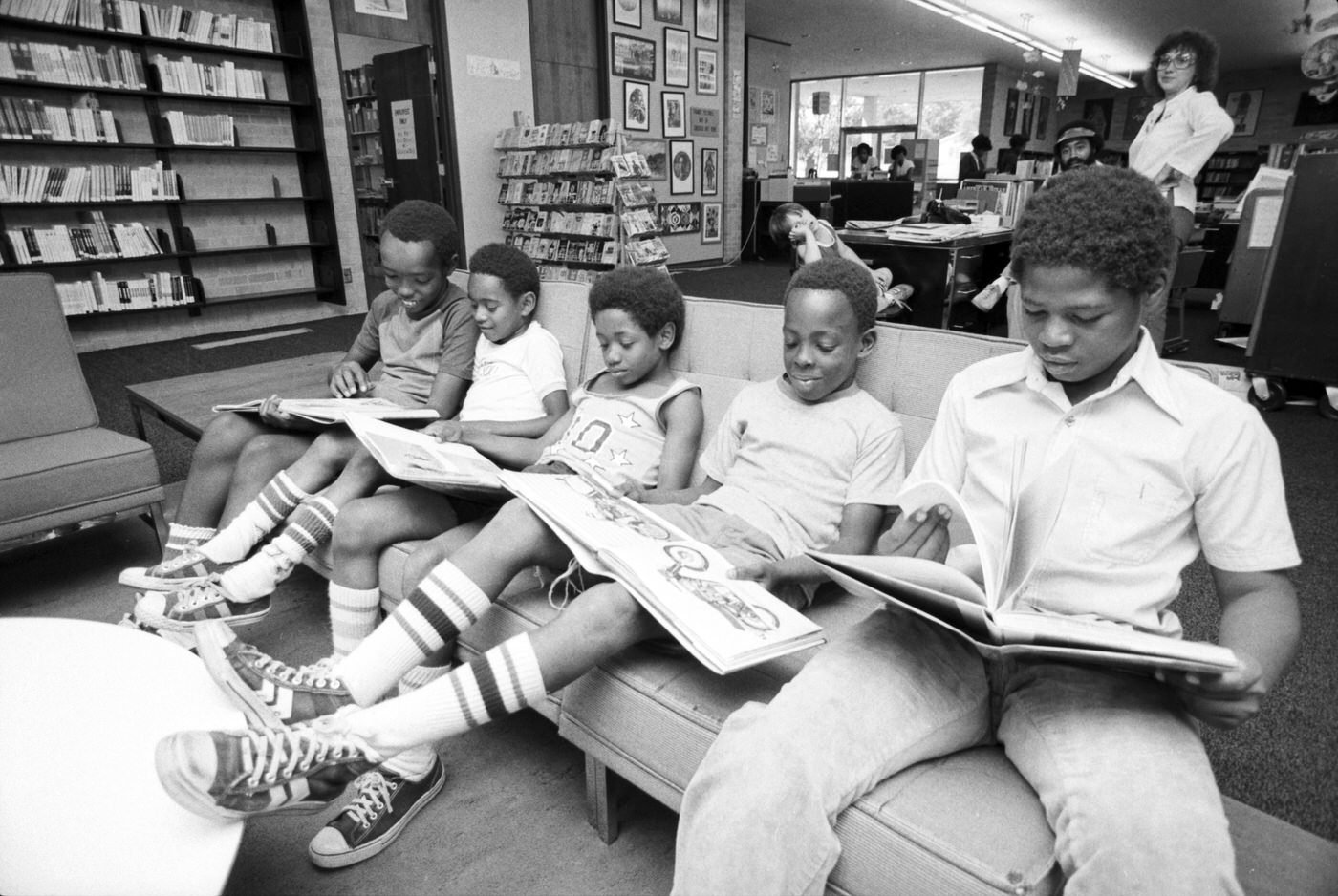

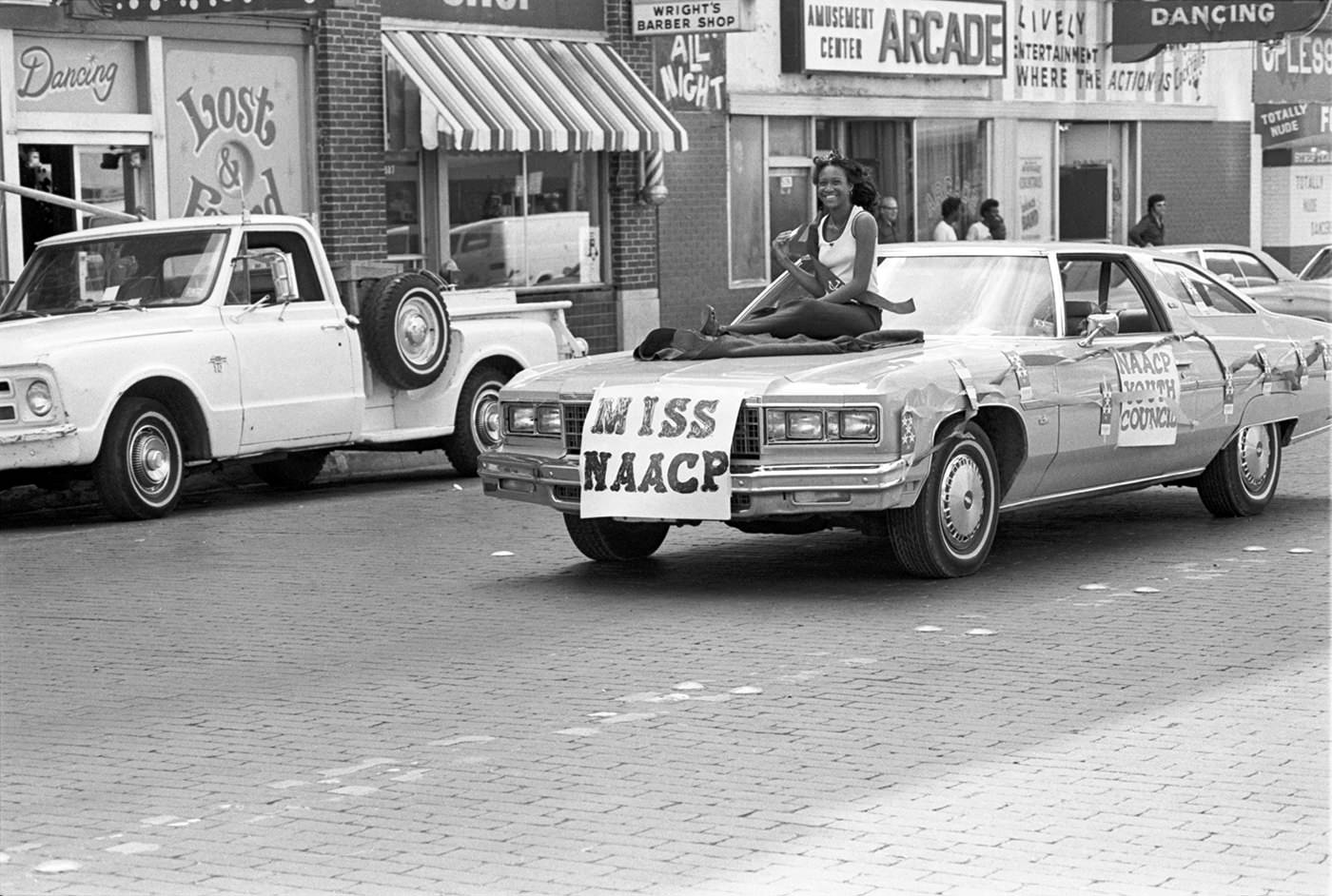

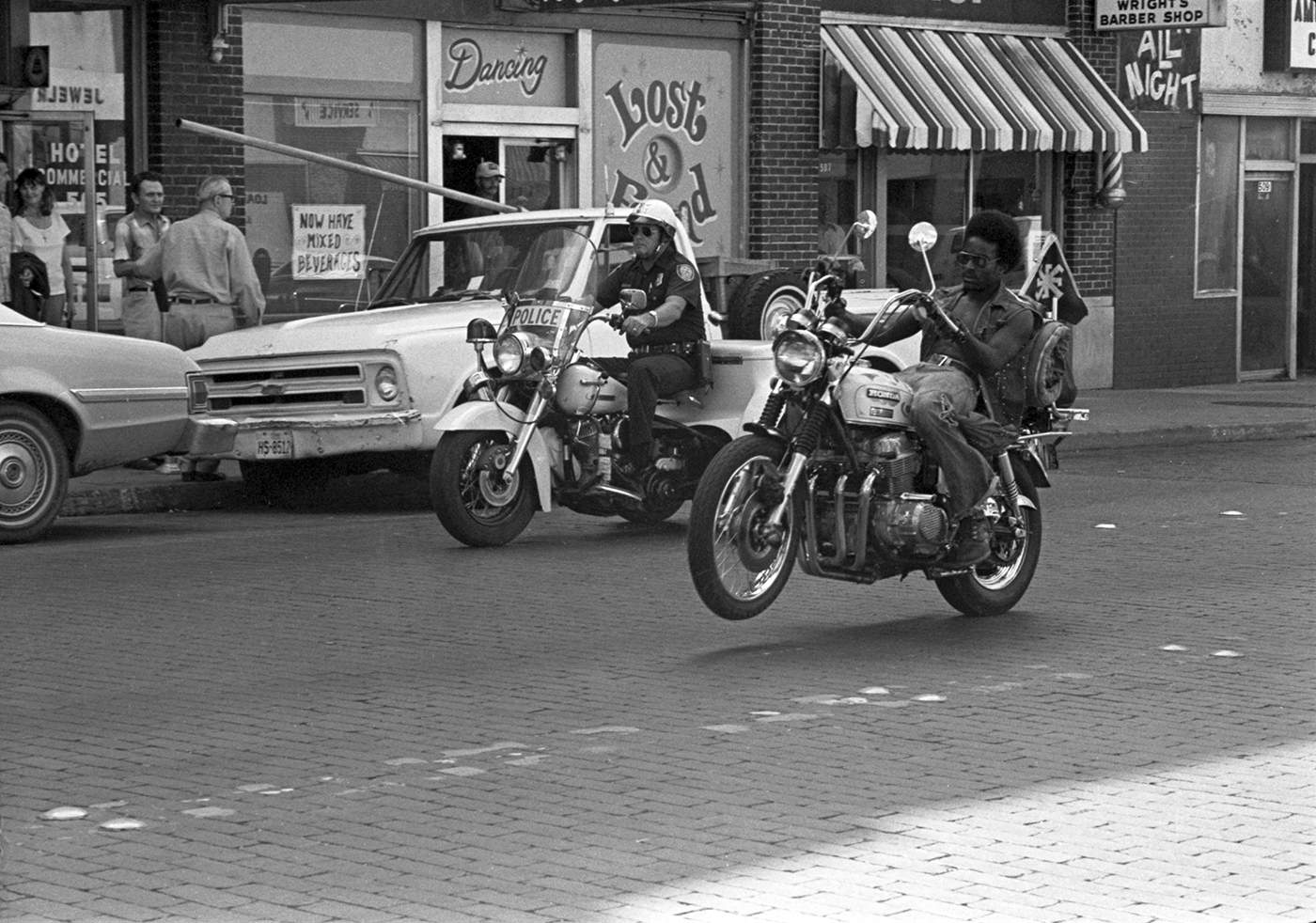

Progress continued in integrating public facilities and employment, building on earlier gains like the desegregation of city golf courses and buses in the 1950s. Public swimming pools, which had remained largely segregated even into the mid-1960s despite NAACP petitions , were finally integrated during the 1970s.

By the early part of the decade, the city had enacted an ordinance prohibiting racial discrimination in a wide range of public accommodations, including hotels, restaurants, bars, theaters, bowling alleys, laundromats (“washaterias”), and skating rinks. This ordinance, hailed as a significant step by Dr. Edward Guinn, Fort Worth’s first African American City Council member, provided a local legal basis for equal access.

Federal and state laws, notably Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Texas Labor Code, alongside the city’s Human Relations Ordinance, provided the framework for combating employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, and disability. Fort Worth’s city ordinance also included protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression. The City of Fort Worth was designated as a Fair Employment Practice Agency by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), authorizing it to investigate local employment discrimination complaints. While these legal and policy changes were crucial, the ongoing struggles in areas like school desegregation suggest that achieving de facto integration in all public spheres and workplaces was a continuing process throughout the 1970s.

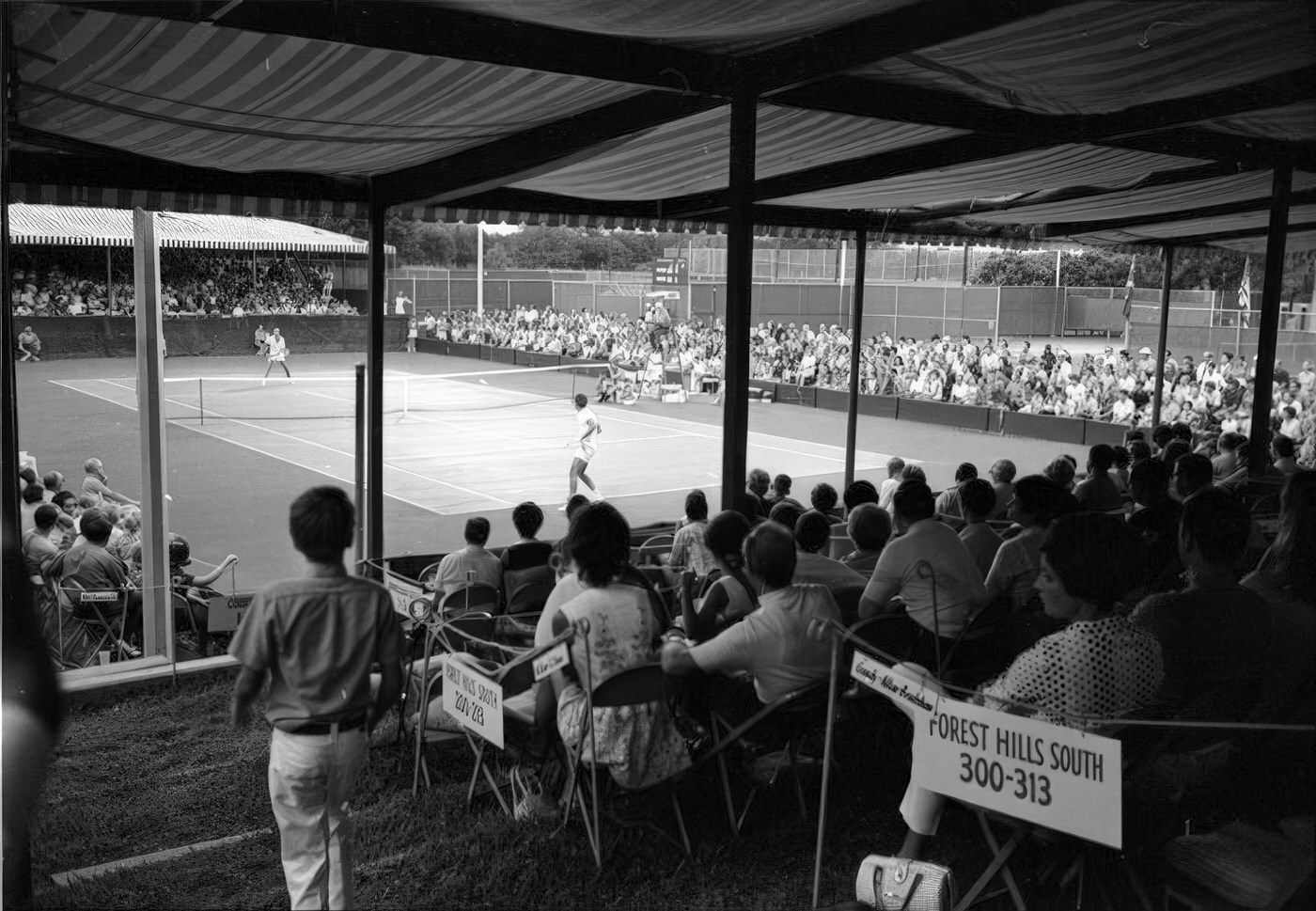

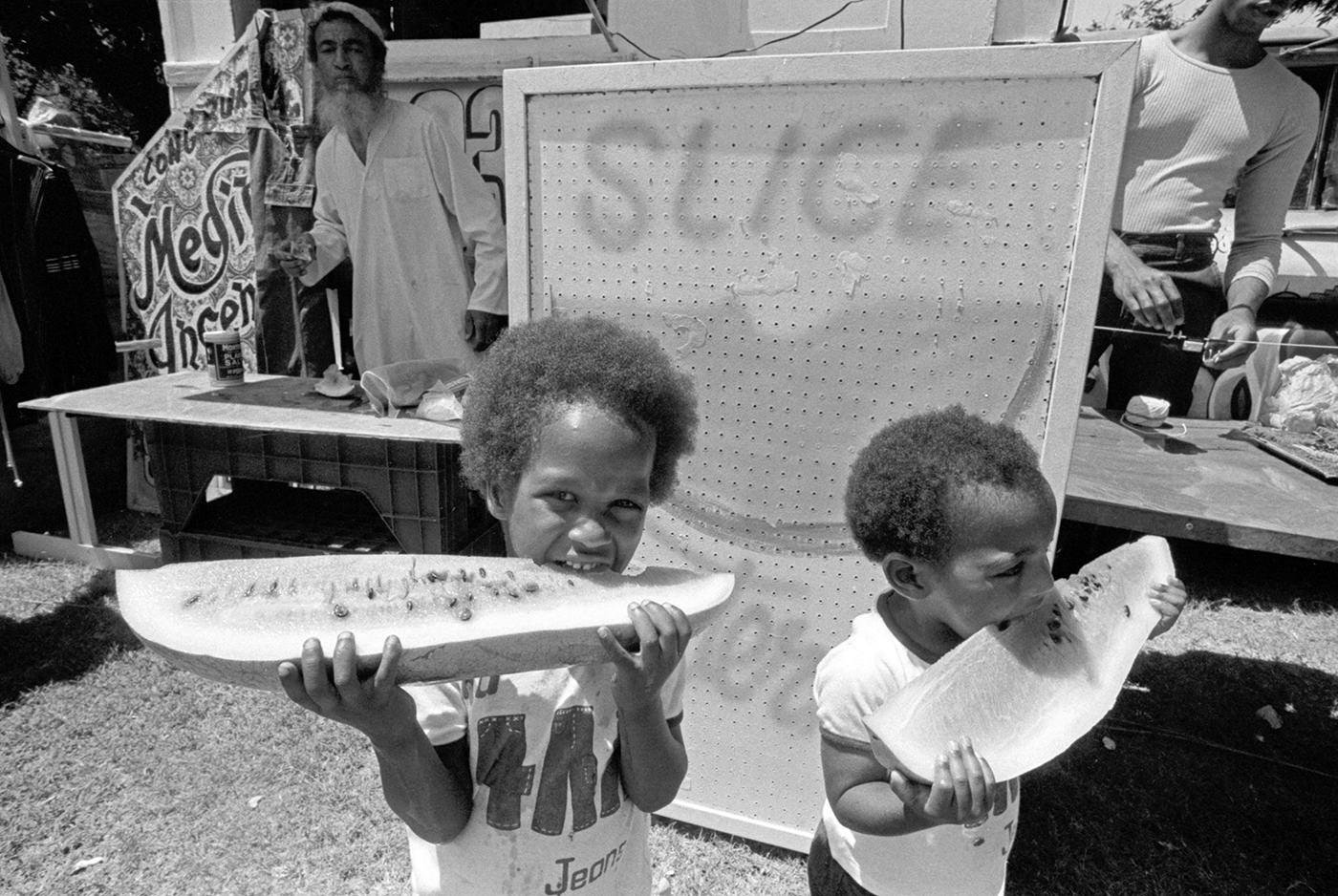

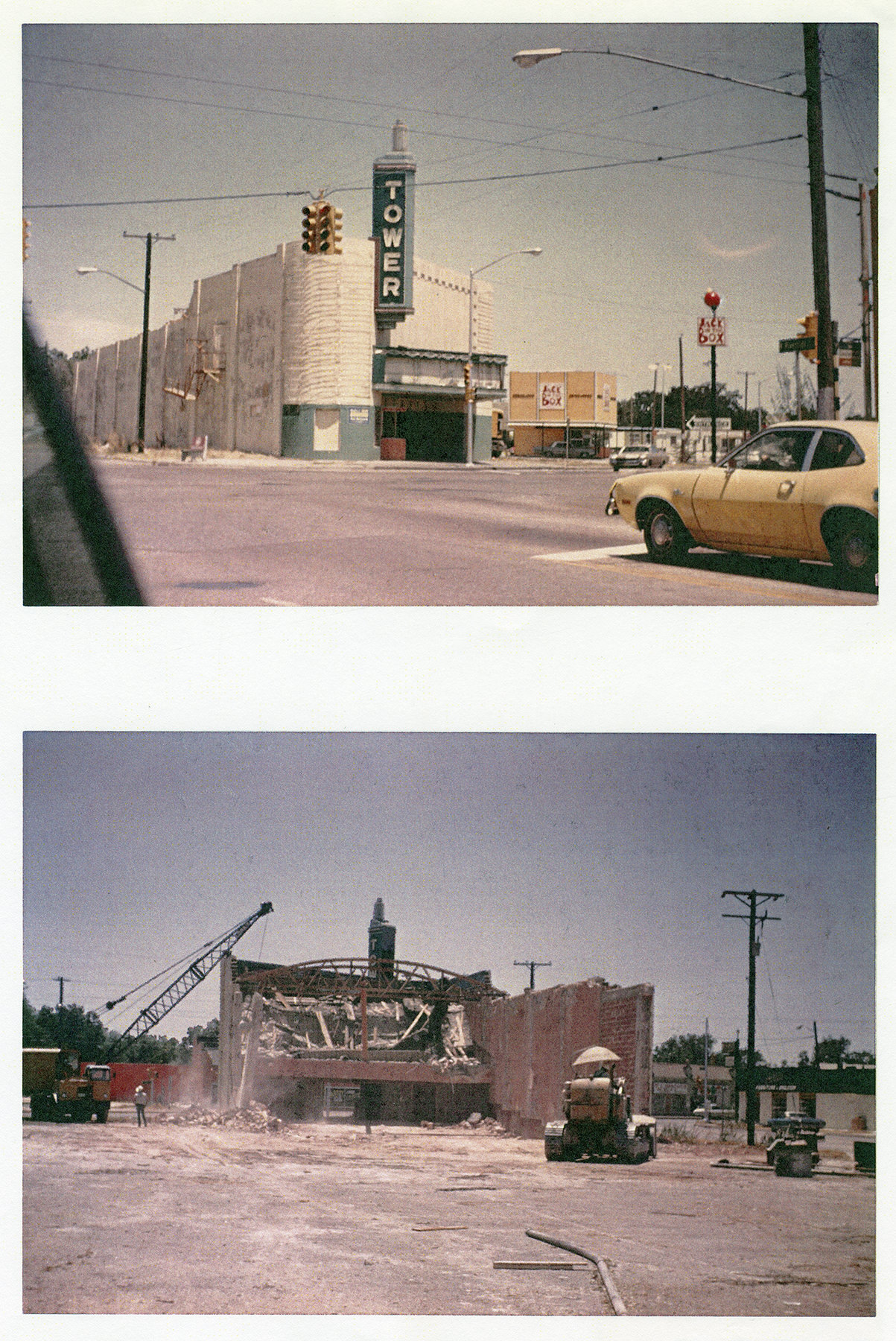

Culture, Arts, and Entertainment

The 1970s brought shifts and new developments to Fort Worth’s cultural and entertainment scene, reflecting both local traditions and national trends in music, movies, dining, sports, and the arts.

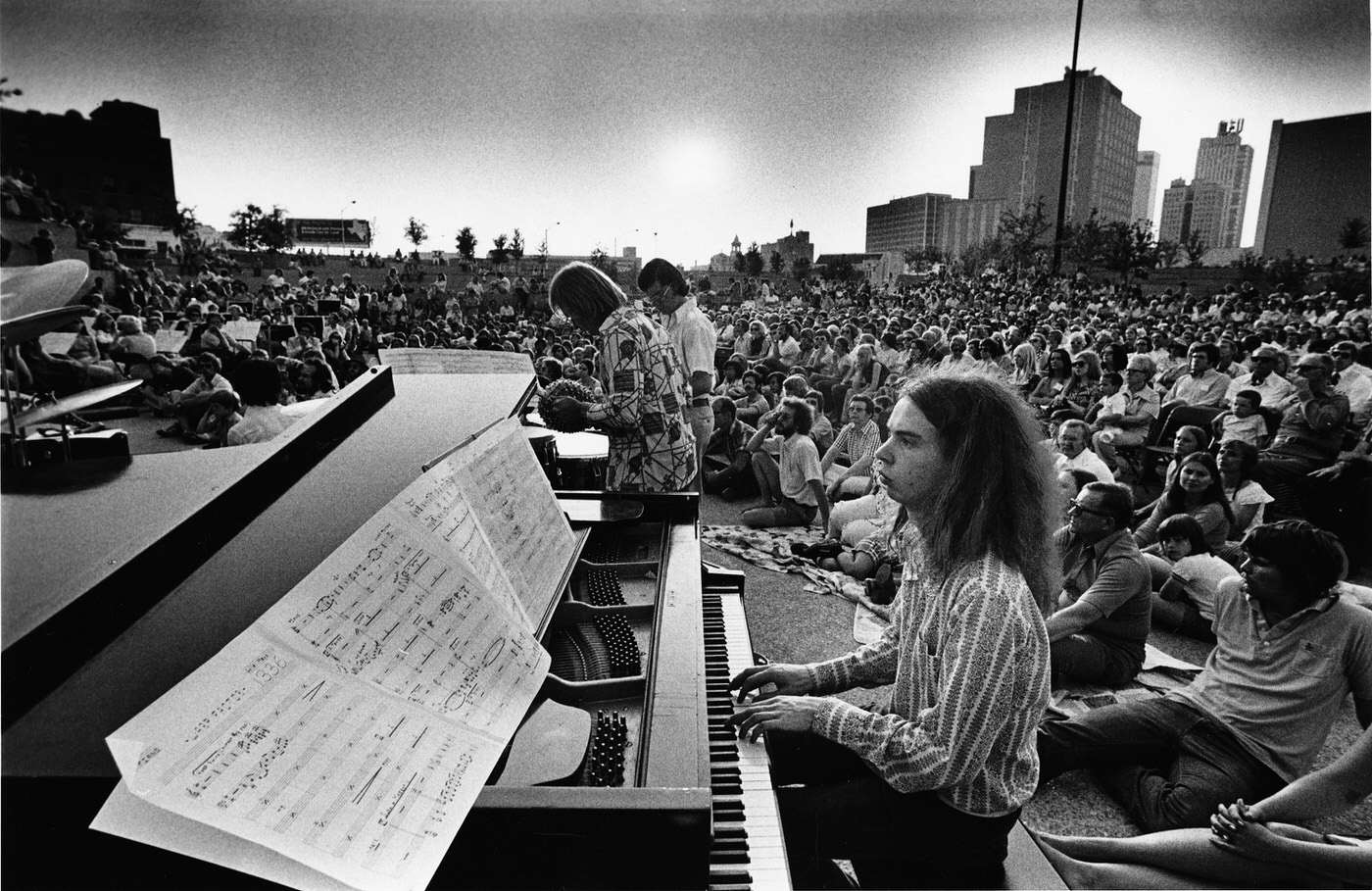

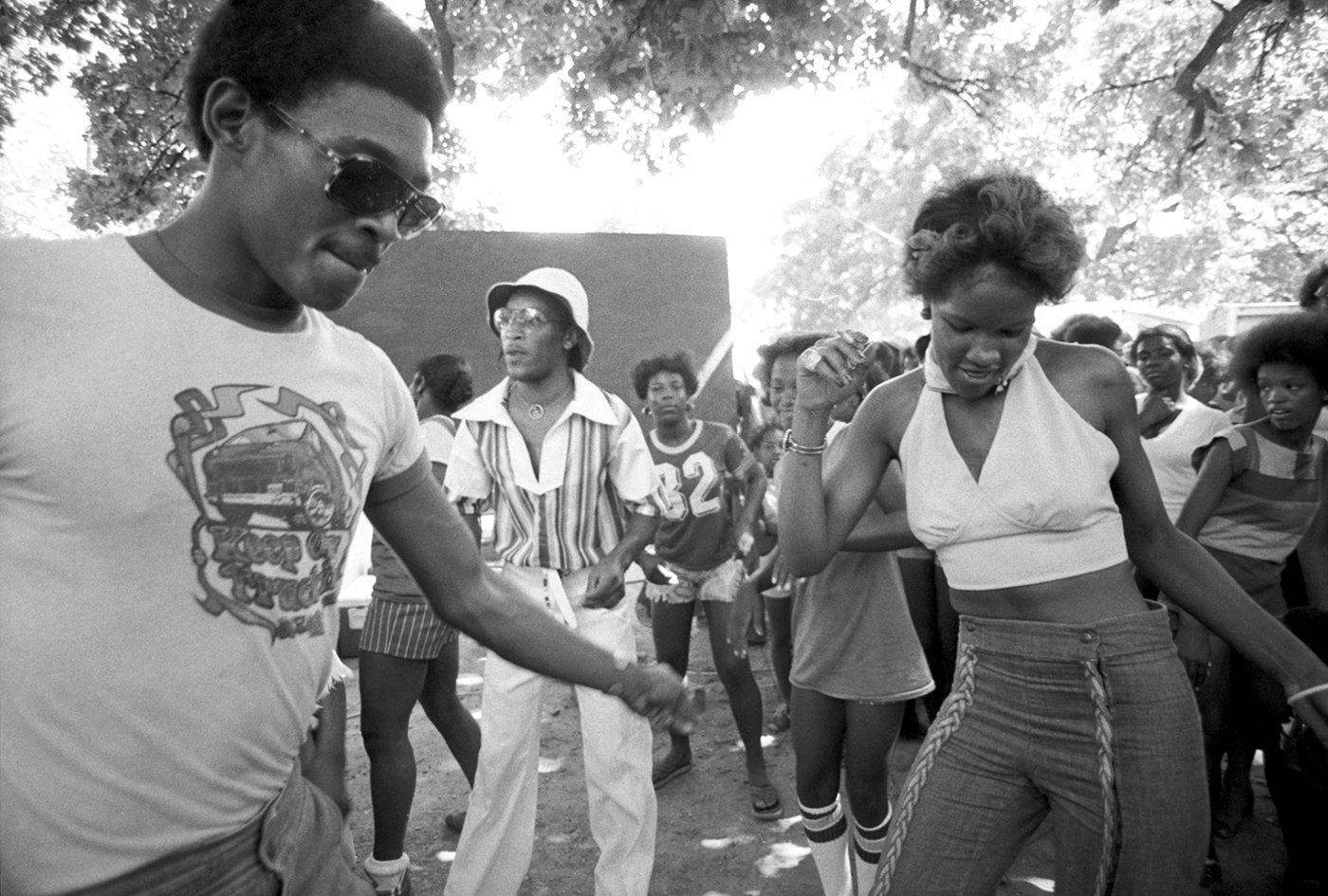

Fort Worth’s musical landscape in the 1970s was diverse. Country music maintained a strong presence, continuing the legacy of Western Swing that had thrived in earlier decades at venues like the Crystal Springs Dance Pavilion (which burned down in 1966). Rock and roll remained popular, and the nationwide phenomenon of disco music found a vibrant home in the city as well.

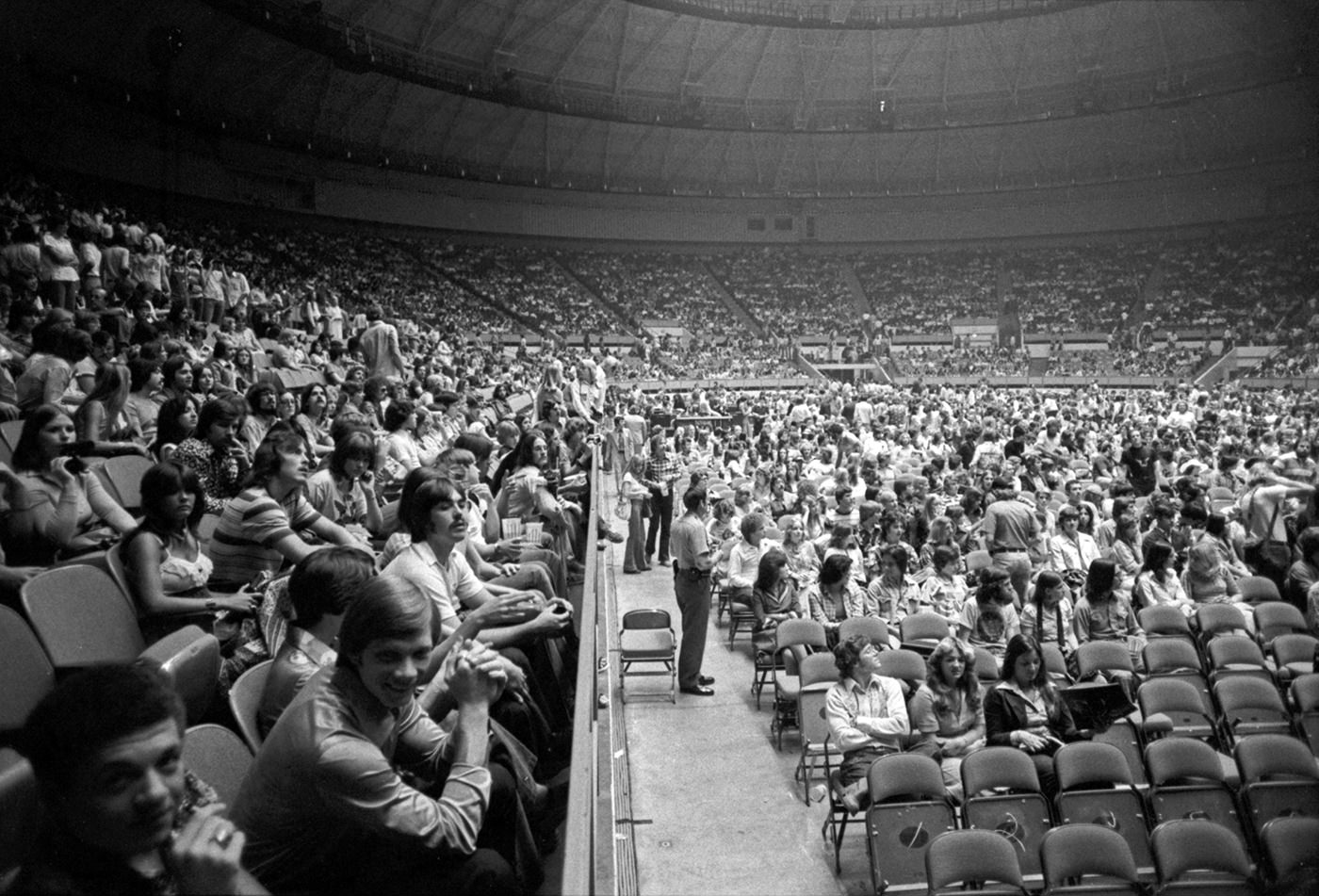

Several venues played key roles during the decade. Panther Hall, a large venue that opened in 1963, was a major center for country music until its closure in 1978. It hosted performances by country music royalty, including Willie Nelson, Loretta Lynn, George Jones, Johnny Cash, and Tanya Tucker. The hall also featured the Cowtown Jamboree, broadcast locally on KTVT television.

For rock music fans, The Cellar offered a unique, if unconventional, experience. Known for having patrons lounge on cushions instead of dancing and for its late hours (open until 5 AM), it hosted a mix of rock, blues, and other genres, featuring artists like Doug Sahm, Joe Ely, and future members of ZZ Top in their early band, American Blues. Due to Texas liquor laws at the time, it sold setups for patrons who brought their own alcohol. The Cellar closed by the mid-1970s as liquor laws changed and different club styles emerged. Other rock venues included The HOP (House of Pizza) near TCU.

The disco craze was evident at clubs like Spencer’s Palace and the smaller Spencer’s Corner, both owned by Spencer Taylor. These clubs were known for drink specials, large crowds, and events like wet T-shirt contests, capturing the spirit of the disco era. The White Elephant Saloon in the Stockyards also reopened its doors in 1970, adding to the city’s nightlife options. This mix of major country venues, rock clubs, and popular discos shows that Fort Worth’s music scene catered to a variety of tastes, embracing national trends while maintaining its “Cowtown” musical roots.

Dining Developments

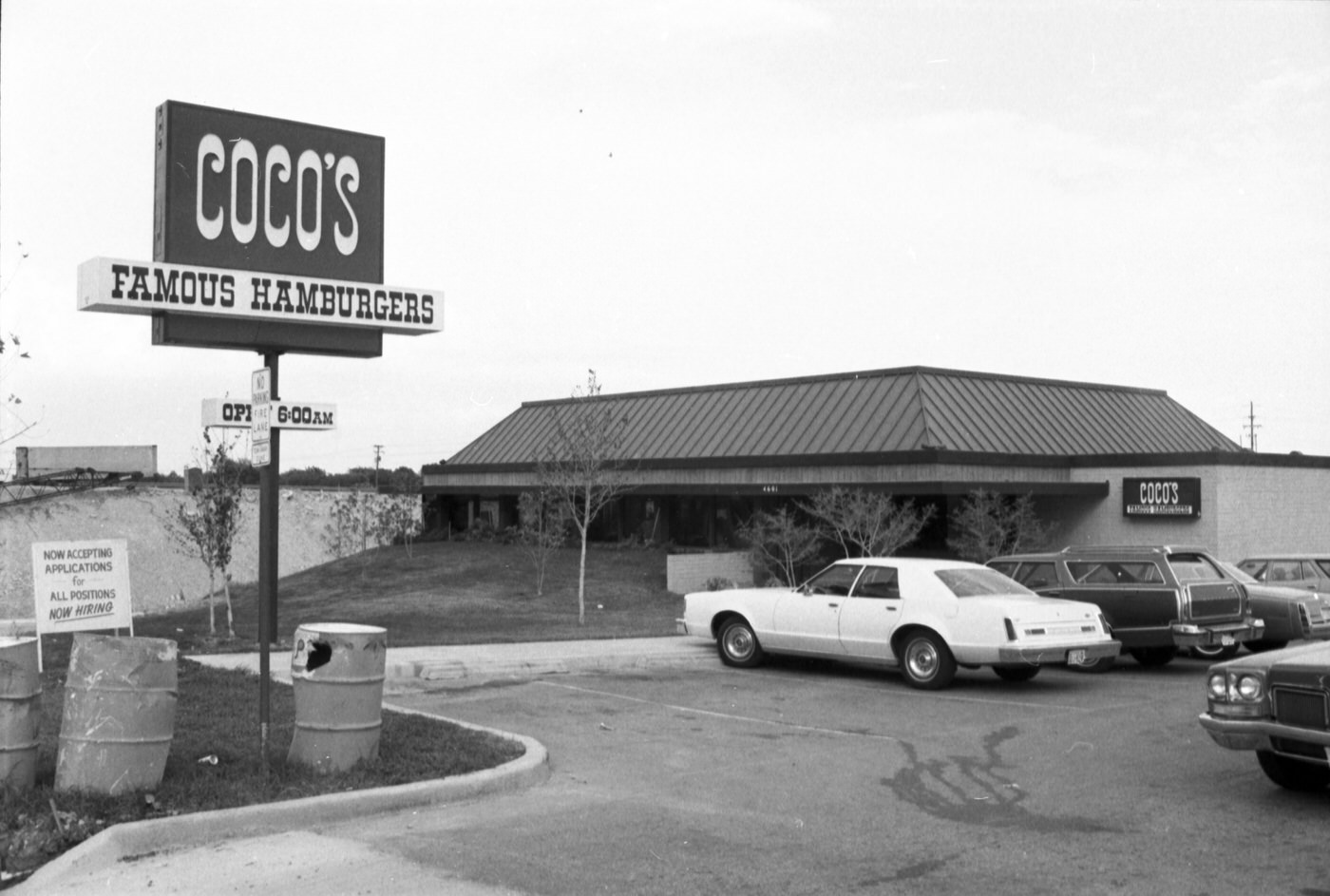

Dining trends in the 1970s saw the national growth of casual dining chains, offering sit-down meals in a relaxed atmosphere, appealing to families with more working mothers. There was also an emerging national interest in health foods and vegetarianism , while French nouvelle cuisine, emphasizing fresh ingredients and lighter preparations, influenced fine dining.

Fort Worth’s dining scene likely reflected a combination of these trends and long-standing local traditions. Established local favorites serving BBQ, Tex-Mex, and American diner fare remained popular, such as Angelo’s BBQ, Joe T. Garcia’s, Kincaid’s Hamburgers (operating since 1946), the Paris Coffee Shop (which moved to its Magnolia Avenue location in 1974), and Riscky’s Barbeque. The Ol’ South Pancake House, open since 1962, was a well-known spot for late-night or early-morning meals. Cafeterias, though perhaps declining in popularity nationally among younger generations compared to the WWII generation , were still present. Newer establishments reflecting the times included restaurants and bars associated with the disco scene and casual spots near new developments like the Tandy Center. Places like Terry’s Grill downtown carried on local culinary traditions, in this case, the sauce recipe from the earlier Big Apple BBQ. The Bluebonnet Cafe evoked a 1960s diner feel. This suggests a diverse restaurant landscape catering to both traditional tastes and the evolving social scene.

Cultural Cornerstones

Fort Worth’s reputation as a significant center for arts and culture solidified during the 1970s, largely due to the growth and prominence of its museums in the Cultural District.

The highly anticipated Kimbell Art Museum opened its doors on October 4, 1972. Designed by the internationally acclaimed architect Louis I. Kahn, the building itself was hailed as a masterpiece of modern architecture, renowned for its use of natural light filtered through distinctive cycloid vaults. Kahn had been commissioned in 1966 by the Kimbell Art Foundation. Guided by the Kimbell family’s vision and the museum’s 1966 policy statement, the museum focused on acquiring works of “definitive excellence” and “highest possible aesthetic quality” from across global art history, rather than aiming for comprehensive historical surveys. Even before opening, the foundation acquired over 100 significant pieces, and the museum quickly established an ambitious program of loan exhibitions, starting with a major show of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings from the Soviet Union in 1973.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art, established in 1961 based on Amon G. Carter Sr.’s collection of Western art by Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, also continued its development. The museum underwent a physical expansion with an addition completed in 1977. Its collection grew significantly during the decade, acquiring important works of 19th-century landscape painting and, notably, strengthening its holdings in American modernism with works by artists like Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and Georgia O’Keeffe. The Carter also solidified its position as a major center for American photography, acquiring important groups of work by photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz and Robert Adams, and archiving materials like the records of the Roman Bronze Works foundry.

Image Credits: Image Credits: Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, W.D. Smith Commercial Photography, Inc. Collection, Basil Clemons Photograph Collection, Jan Jones Papers, UTA Libraries, Texas History Portal, Jack White Photograph Collection,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know