At the dawn of the 1860s, St. Louis, Missouri, stood as a bustling and rapidly expanding city, a key player on the American frontier. Its population had swelled to 160,773 by 1860, ranking it as the eighth-largest city in the United States. This remarkable growth continued even through the turbulent decade, with the population reaching 310,864 by 1870, elevating St. Louis to the nation’s fourth-largest urban center. The city’s strategic position at the confluence of the Missouri, Illinois, and Mississippi Rivers was a primary driver of its prominence, making it a natural crossroads for people and goods.

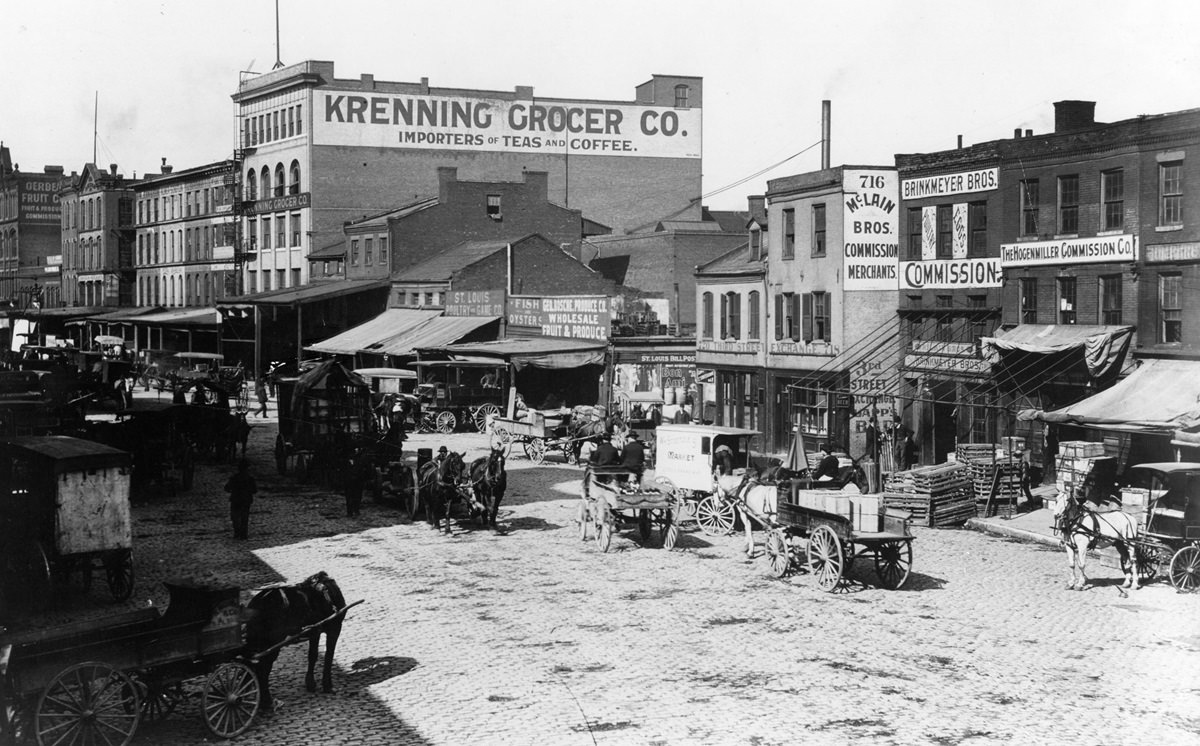

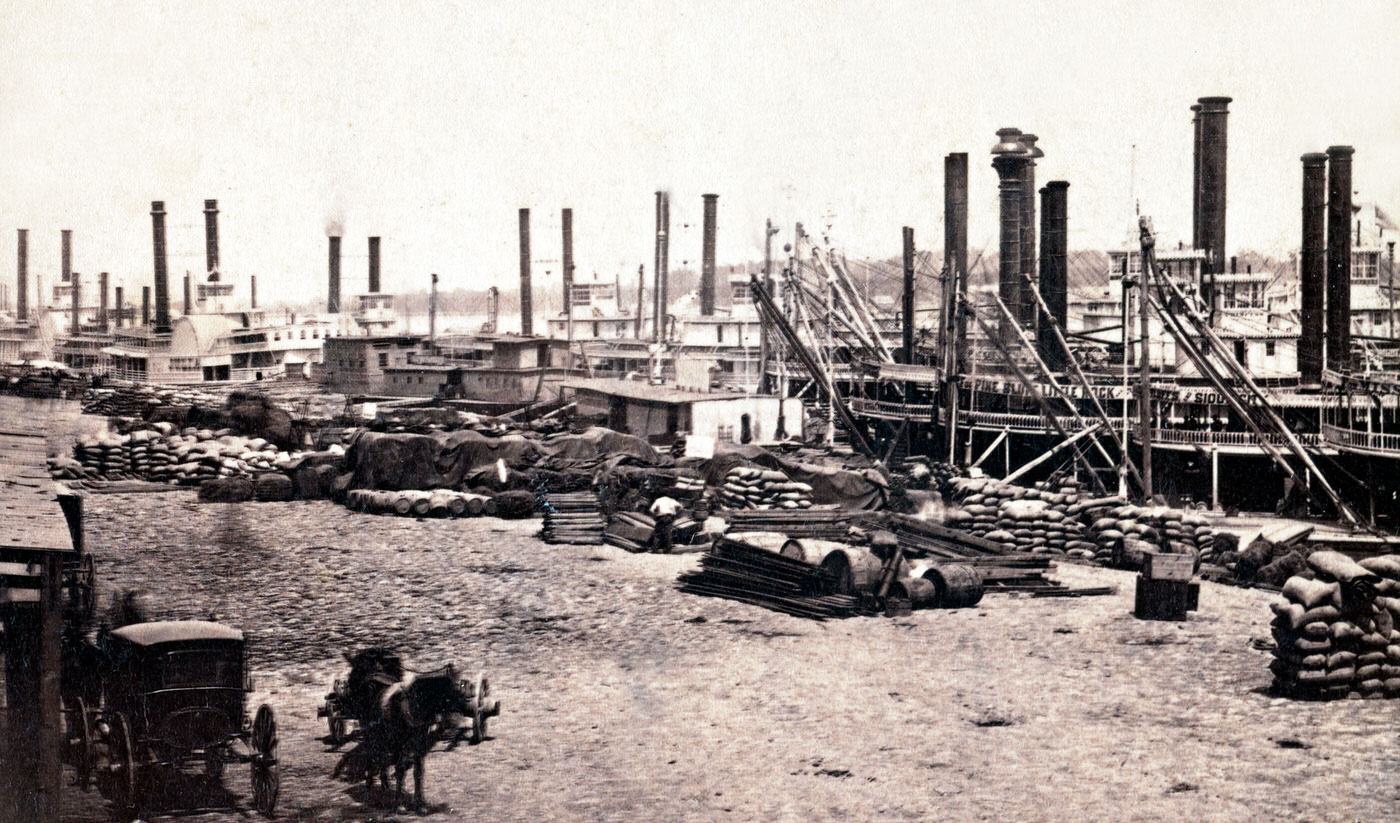

This geographical advantage cemented St. Louis’s role as the most important economic hub on the upper Mississippi River. Before the outbreak of the Civil War, its riverfront was a scene of constant activity, making it the third busiest port in the country. Steamboats, the lifeblood of river commerce, often lined the levee for a mile, sometimes docked three deep, waiting to load or unload their cargo. For decades, St. Louis had been celebrated as the “Gateway to the West.” It was famously the launching point for the Lewis and Clark Expedition years earlier and continued to serve as a vital departure point for those venturing into the western territories.

The city’s explosive population growth in the years leading up to 1860, with Greater St. Louis seeing an 81.5% increase between 1850 and 1860, created a dynamic and sometimes crowded urban environment. This rapid influx of diverse people occurred against a backdrop of increasing national division over issues like slavery, meaning the city was not just growing in size but also in potential for social and political friction. St. Louis’s very identity and economic prosperity were deeply intertwined with the Mississippi River. This Waterway was its main commercial artery, bringing wealth and connecting it to distant markets. However, this reliance also created a vulnerability. The city’s strong trade links, particularly southward along the river, meant its economic fortunes were closely tied to regions that would soon form the Confederacy. Any disruption to this river traffic, such as a wartime blockade, would inevitably strike at the heart of St. Louis’s economy.

A City of Many Faces: The People of St. Louis

The population of St. Louis in the 1860s was a diverse mix of native-born Americans and a large number of recent immigrants, each contributing to the city’s unique character.

German immigrants formed a particularly large and influential segment of the population. Many had arrived in the United States following the failed European revolutions of 1848, bringing with them strong democratic ideals, an opposition to slavery, and a firm belief in the Union. They established vibrant communities with their own German-language newspapers and cultural institutions, most notably the “Turnvereins.” These were gymnastics clubs that also served as centers for promoting German culture and political discussion. Neighborhoods such as Soulard, Benton Park, and Hyde Park (formerly known as Bremen) became distinctly German enclaves. The unwavering loyalty of this German population to the Union would prove to be a critical factor in keeping St. Louis, and indeed Missouri, aligned with the North during the Civil War.

Irish immigrants constituted another major group, with many having fled the Great Famine in their homeland. By the 1860s, St. Louis had a sizable Irish population, adding to the city’s multicultural fabric. Many Irish found work as laborers, contributing to the city’s growth. While often facing prejudice and economic hardship, the Irish community began to establish itself and gain political influence, frequently aligning with the Democratic Party. When the war came, many Irishmen from St. Louis and elsewhere would volunteer for military service, some driven by economic necessity as much as by allegiance.

The African American community in St. Louis was also a significant presence. By 1860, people of African descent made up ten percent of Missouri’s total population, a legacy of slavery introduced by earlier settlers from Southern states. In St. Louis itself, as of 1850, there were 2,656 enslaved individuals and 1,398 free persons of color. The city was home to a pre-existing free Black community, some of whose members achieved considerable economic success, forming what was sometimes referred to as the “Colored Aristocracy”. Free Black men and women worked in various trades, as barbers, blacksmiths, and carpenters, and some owned their own businesses or land. Life for enslaved people in an urban setting like St. Louis differed from that on rural plantations; it sometimes offered limited opportunities for self-hire or, in rare cases, the ability to purchase their freedom. However, this was still a system of bondage, and harsh “Black Codes” severely restricted the lives and movements of all African Americans, enslaved or free. The organized nature and pro-Union stance of the German community, in particular, provided a powerful counterbalance to pro-Confederate sentiments within the state, directly influencing the city’s ability to remain under Union control. For African Americans, St. Louis presented a complex reality: a place with a visible free Black population and some avenues for advancement, yet still deeply entrenched in a slave state where freedom was always conditional and racial control was a daily fact of life. The coming decade would dramatically reshape this landscape.

The City at a Crossroads: The Civil War Arrives

As the nation fractured in 1861, Missouri found itself in a precarious position. As a border state, its loyalties were deeply divided. Many Missourians, particularly those residing in agricultural regions like “Little Dixie” along the Missouri River where the economy relied heavily on enslaved labor, sympathized with the Southern cause. The state’s governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, was an ardent supporter of the Confederacy and worked to align Missouri with the seceding states.

Despite these strong pro-Southern elements within the state, the city of St. Louis remained firmly under Union control throughout the Civil War. This was in large part due to the city’s substantial German immigrant population. These residents, many of whom had fled political oppression in Europe, were fiercely loyal to the Union and actively opposed secession, forming a powerful bloc against Confederate sympathizers. Their commitment provided a crucial anchor for Unionism in a deeply divided state.

The escalating crisis came to a head when President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for troops following the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. Governor Jackson refused to comply with Lincoln’s request. Instead, he ordered the Missouri state militia to assemble near St. Louis, officially for training exercises. However, Union officials widely suspected that the true purpose of this mobilization was to prepare the militia to seize federal property, particularly the St. Louis Arsenal, for the Confederacy. The control of St. Louis, with its strategic river location, large population, and industrial capacity, was not merely a local concern; it was vital for the Union’s ability to maintain influence over Missouri and secure a critical portion of the Mississippi River and access to the western frontier. Had St. Louis fallen to Confederate sympathizers, it would have represented a severe setback for the Union war effort in the West. While some Missourians initially hoped the state could remain neutral in the conflict , the determined actions of Governor Jackson on one side, and staunch Unionists like Captain Nathaniel Lyon on the other, quickly polarized the situation. St. Louis, in particular, became a focal point where the abstract desire for neutrality collided with the reality of active, and increasingly armed, partisanship.

Under Union Banners: Military Life and Control

The simmering tensions in St. Louis boiled over in the spring of 1861. Captain Nathaniel Lyon, the assertive commander of the St. Louis Arsenal, grew increasingly concerned about the intentions of the pro-Confederate state militia encamped at “Camp Jackson,” located on the western outskirts of the city (on land that is now part of the St. Louis University campus). Suspecting a plot to seize the arsenal’s valuable cache of weapons, Lyon took decisive action. On May 10, 1861, leading a force of U.S. Regulars and newly formed Union volunteer regiments, many of them composed of German immigrants, Lyon surrounded Camp Jackson and compelled its surrender.

The “Camp Jackson Affair,” as it came to be known, did not end with the militia’s capitulation. As Lyon’s troops marched their prisoners through the streets of St. Louis, angry crowds gathered, taunting the soldiers and expressing pro-Confederate sentiments. The situation escalated rapidly, and Union troops opened fire on the civilians. The fusillade left 28 dead and at least 90 wounded. This tragic event had profound consequences, deeply embittering many Missourians and pushing citizens who had previously favored neutrality toward the Confederate cause. It solidified Union control over St. Louis but also ignited a fierce and brutal guerrilla war that would ravage much of Missouri for years to come.

With the city secured, St. Louis transformed into a major Union military base, a critical staging and supply point for operations in the Western Theater of the war. Benton Barracks, established at what is now Fairground Park, became a vast training facility for Union soldiers. As the war progressed and casualties mounted, Benton Barracks also became home to the Post and Convalescent Hospitals. Under the dedicated direction of nurse Emily Elizabeth Parsons, this facility grew into the largest Civil War hospital in the American West, caring for as many as 2,000 sick and wounded soldiers at a time, both Black and white.

St. Louis also served as an important center for military recruitment. A significant development was the organization of the First Regiment of Missouri Colored Infantry in June 1863, mustered at Schofield Barracks. This unit, later redesignated the 62nd Regiment, United States Colored Troops (USCT), was one of many Black regiments that played a vital role in the Union victory. Ultimately, over 8,000 African American men from Missouri served in the Union Army , their enlistment marking a profound step towards freedom and citizenship.

To maintain control in such a divided city and state, Union authorities implemented stringent measures. Martial law was declared across Missouri by General John C. Frémont in August 1861, granting the military sweeping powers to administer justice and suppress dissent. In St. Louis, this meant that anyone suspected of Confederate sympathies faced the threat of arrest, trial by military commission, and imprisonment. Provost marshals were tasked with enforcing these regulations, which included issuing passes, administering loyalty oaths, and levying assessments against suspected secessionists. While intended to maintain order, these measures sometimes led to abuses and corruption, further alienating some citizens. Despite the crackdown, secret pro-Confederate organizations, such as the Order of American Knights, continued to operate covertly in St. Louis, leading to arrests and banishments of their members. The extensive records kept by the Union Provost Marshal offer a detailed glimpse into the tightly controlled and often tense daily life under military rule. The Camp Jackson Affair demonstrated the Union’s unwavering resolve to hold Missouri, by force if necessary, effectively ending widespread hopes for state neutrality. While martial law aimed to secure the city, its sometimes harsh application risked turning passive sympathizers into active opponents, illustrating the complex challenges of governing a divided populace during wartime. Amidst this, the growth of Benton Barracks into a major hospital underscored the war’s human cost, while the recruitment of Black soldiers in the same city signaled a powerful movement towards emancipation and a redefinition of American citizenship.

The River City’s Working Heart: Economy and Industry

The 1860s were a period of significant economic transformation for St. Louis, largely shaped by the Civil War. River commerce, long the backbone of the city’s prosperity, continued, though its patterns were dramatically altered. Before the war, St. Louis proudly stood as the nation’s third busiest port. However, the Union blockade of Southern ports severed crucial trade links with traditional partners down the Mississippi River. This disruption was severe; by the war’s end, the city’s overall trade volume had reportedly fallen to just one-third of its prewar levels. Despite this, the Mississippi remained a vital artery for the Union, facilitating the movement of troops and essential supplies. Even in 1865, the St. Louis levee was far from idle, with records showing 70 steamboats in port on a given day and over 3,800 arrivals of steamboats and barges throughout that year. Furthermore, new trade routes were developing, particularly with the burgeoning territories in Montana, accessed via the Missouri River.

While traditional trade faced challenges, St. Louis was also a growing industrial center, and the war spurred further development in manufacturing. Key industries already established before the war included iron production, with foundries and factories churning out pipes, plows, stoves, and tools from pig iron. The city’s brewing industry was also flourishing; German immigrant Adam Lemp had introduced lager beer, and by 1860, St. Louis boasted forty breweries producing around 200,000 barrels annually. Among these was the Bavarian Brewery, the precursor to the famed Anheuser-Busch company. Wagon making was another important trade, with craftsman Joseph Murphy producing sturdy wagons renowned for their use on the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails. Flour milling, clothing, and shoe manufacturing also contributed to the city’s industrial output.

The demands of the Civil War provided a significant boost to St. Louis’s manufacturing sector. Factories in the city retooled to produce arms, ammunition, uniforms, and a wide array of other supplies essential for the Union war effort. A standout example of this wartime industrial prowess was the work of James B. Eads. His boatyard, located at Carondelet just south of St. Louis, rapidly designed and constructed a fleet of formidable ironclad gunboats. These “City Class” ironclads were built in less than 100 days and played a crucial role in Union naval campaigns on the western rivers, helping to secure control of the Mississippi.

Railroad development in Missouri was still in its early stages compared to some eastern states, but it was expanding. By 1860, Missouri had approximately 800 miles of railroad track. St. Louis served as a hub for a nascent network of rail lines that radiated into the state’s rich agricultural and mineral-producing hinterlands. The war underscored the strategic importance of railroads for moving troops and supplies, and St. Louis found itself at a disadvantage compared to cities like Chicago, which had a more developed rail network connecting it to the East. The vision for greater rail connectivity was present, however, as evidenced by the planning of the Eads Bridge during this era, a structure that, upon its completion in 1874, would become a vital link for east-west railroad commerce.

The city’s financial infrastructure also evolved during the decade. Several banks had been established under an 1857 state law. The nature of currency changed in 1862 when the federal government instituted a national banking system, leading to the disappearance of state bank notes. The city’s economic activity, even amidst wartime disruptions, remained substantial. In 1865, the assessed value of real and personal property in St. Louis was $100,000,000. That same year, the sales reported by 612 St. Louis firms exceeded $1.1 billion, a figure reflecting the nominal values of the time but indicative of significant commercial transactions. The Civil War thus acted as a catalyst, forcing St. Louis to adapt its economy. The loss of Southern markets necessitated a pivot towards Northern trade, commerce with the Western territories, and, critically, an expansion of its manufacturing capabilities to meet wartime demands. This period of crisis fostered innovation and highlighted the city’s industrial potential, setting the stage for its continued growth as a manufacturing center in the post-war years. The rise of the brewing industry, driven by German immigrants who introduced new products like lager and adapted to local conditions by using caves for aging before the advent of artificial refrigeration , serves as a compelling example of how immigrant entrepreneurship and technological adoption contributed to the city’s economic vitality.

Daily Existence in a Decade of Change

Life in St. Louis during the 1860s varied greatly depending on one’s background and circumstances, especially as the Civil War reshaped society.

For the large German immigrant population, the decade was marked by a strong sense of community and an unwavering commitment to the Union. They maintained their cultural cohesion through institutions like the “Turnvereins,” which were centers for gymnastics, cultural activities, and political discussion, and through a vibrant German-language press. Viewing the Civil War as a fundamental struggle for democracy and against the institution of slavery, many German men readily enlisted in Union regiments. Their distinct neighborhoods, such as Soulard and Hyde Park, were hubs of German life, complete with traditional festivals and popular beer gardens.

Irish immigrants, another significant group, often faced more challenging circumstances. Many had arrived in America seeking refuge from famine and poverty, and they frequently encountered discrimination in their new homeland. In St. Louis, as elsewhere, Irish immigrants often found work in demanding, low-paying labor jobs. Despite these hardships, a sizable Irish community had developed in St. Louis by the time of the Civil War. For many Irish men, joining the Union Army offered the promise of steady pay and a degree of stability for their families.

For African Americans in St. Louis, the 1860s brought profound and revolutionary changes. The outbreak of war and the subsequent imposition of martial law created new avenues for enslaved people to assert their claims to freedom. Some courageously reported disloyal enslavers to Union military authorities, thereby demonstrating their support for the Union and seeking protection. Although President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 did not directly apply to Missouri, as it was a Union state not in rebellion, its issuance sent a powerful message and emboldened many enslaved individuals to leave their bondage. The institution of slavery was officially abolished in Missouri by a state ordinance on January 11, 1865, eleven months before the Thirteenth Amendment abolished it nationwide.

A pivotal development was the recruitment of Black soldiers into the United States Colored Troops, beginning in St. Louis in 1863. This provided African American men with a direct opportunity to fight for their own freedom and for the preservation of the Union, a deeply significant step towards citizenship and self-determination. The war also spurred vital educational initiatives. Thousands of Black refugees, including many children, sought safety and opportunity in St. Louis. In response, organizations such as the Freedmen’s Relief Society, the Ladies Union Aid Society, the Western Sanitary Commission, and the American Missionary Association established schools to provide education for these newcomers. These efforts were often supported by leaders within St. Louis’s established free Black community, who had a history of promoting education, exemplified by the pre-war schools operated by figures like Mary and John Berry Meachum. A lasting legacy of this period was the founding of the Lincoln Institute (later Lincoln University) in 1866 by Black Civil War soldiers, dedicated to the higher education of African Americans in Missouri.

The African American community also began to organize politically. In October 1865, the Missouri Equal Rights League was formed in St. Louis. Considered Missouri’s first Black political activist organization, the League championed the cause of legal equality, with a particular focus on securing educational opportunities and voting rights. However, the transition from slavery to freedom was fraught with challenges. In the post-emancipation period, many African Americans struggled to find stable employment and faced an environment of increasing intolerance and discrimination. While many continued to work as farm laborers, significant progress was made in education, as evidenced by declining illiteracy rates. The war served as a powerful catalyst, accelerating the end of slavery and fostering the growth of crucial Black institutions that would underpin the long struggle for civil rights in the decades to come.

Challenges and Transformations in Urban Life

The 1860s presented St. Louis with a host of urban challenges, many of which were intensified by the strains of the Civil War. Public health was a significant concern. The city’s infrastructure, including sanitation systems, suffered from neglect during the war years. Diseases like typhoid fever were prevalent. A devastating cholera epidemic swept through the city in 1866, claiming the lives of more than 3,500 people. This public health crisis spurred civic action, leading to the establishment of the St. Louis Board of Health, which was tasked with creating and enforcing sanitary regulations. The city’s early waterworks, dating back to 1831, drew water directly from the Mississippi River. Treatment was minimal, primarily consisting of allowing sediment to settle in basins, a system that was increasingly inadequate for the rapidly growing population and the murky quality of the river water.

The war also brought a massive influx of refugees to St. Louis. Thousands of people, including many children and a large number of African Americans seeking freedom from enslavement, arrived in the city, placing considerable strain on its resources. This humanitarian crisis, however, also prompted remarkable community responses. Women’s volunteer organizations, such as the Ladies Union Aid Society, played an indispensable role in providing medical care, food, shelter, and other forms of assistance to soldiers and refugees alike. The tireless work of individuals like Emily Elizabeth Parsons, who managed the nursing staff at the enormous Benton Barracks Hospital, exemplified this spirit of service.

Notable Figures Shaping St. Louis

Several key individuals played pivotal roles in shaping the destiny of St. Louis during the tumultuous 1860s. Their actions, whether in military command, political maneuvering, medical service, or engineering innovation, left an indelible mark on the city and its contribution to the Civil War.

Nathaniel Lyon, a captain in the U.S. Army who was later promoted to brigadier general, was a central figure in the early days of the conflict in Missouri. A fervent Unionist, Lyon took decisive and often controversial actions to secure the strategically vital St. Louis Arsenal and prevent Missouri from seceding. His leadership during the Camp Jackson Affair in May 1861 was crucial in asserting Union control over St. Louis, though the ensuing violence alienated many Missourians. Lyon’s aggressive campaigning continued until he was killed in action at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in August 1861.

Frank P. Blair Jr. was a prominent Republican congressman from St. Louis and later a Union general. A skilled political operator, Blair was instrumental in organizing pro-Union support in Missouri, particularly among the German-American community. He played a key role in the political maneuvers that helped keep Missouri in the Union, including strongly backing Nathaniel Lyon’s appointment to command the St. Louis Arsenal. His efforts were vital in countering the influence of pro-Confederate factions within the state.

Emily Elizabeth Parsons exemplified dedication and compassion in her service as a Civil War nurse. Despite facing her own physical disabilities, she trained as a nurse and committed herself to caring for sick and wounded soldiers. In St. Louis, she served as head of nursing at the Lawson Hospital and later took on the immense responsibility of supervising the nursing staff at the Benton Barracks Hospital, the largest military hospital in the Western Theater. Parsons also tended to the wounded aboard the hospital steamship City of Alton during the Vicksburg campaign, enduring difficult and dangerous conditions.

James B. Eads was a brilliant, self-taught engineer whose intimate knowledge of the Mississippi River proved invaluable to the Union war effort. At the request of the federal government, Eads undertook the formidable task of designing and constructing a fleet of armor-plated gunboats. In a remarkable feat of rapid production, his St. Louis boatyard delivered seven “City Class” ironclads in less than 100 days. These powerful vessels were instrumental in the Union’s campaigns to control the Mississippi River and its tributaries. After the war, Eads would go on to design and build the iconic Eads Bridge across the Mississippi at St. Louis, with construction beginning in 1867 and the bridge opening in 1874.

Claiborne Fox Jackson, who served as Missouri’s governor in 1860 and 1861, stood in stark opposition to these Union figures. A strong Southern sympathizer, Jackson actively sought to lead Missouri out of the Union and into the Confederacy. His refusal to provide troops for the Union army and his mobilization of the state militia were key factors that precipitated the Camp Jackson Affair and plunged Missouri into civil conflict.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, The State Historical Society of Missouri-Columbia, wikimedia

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know