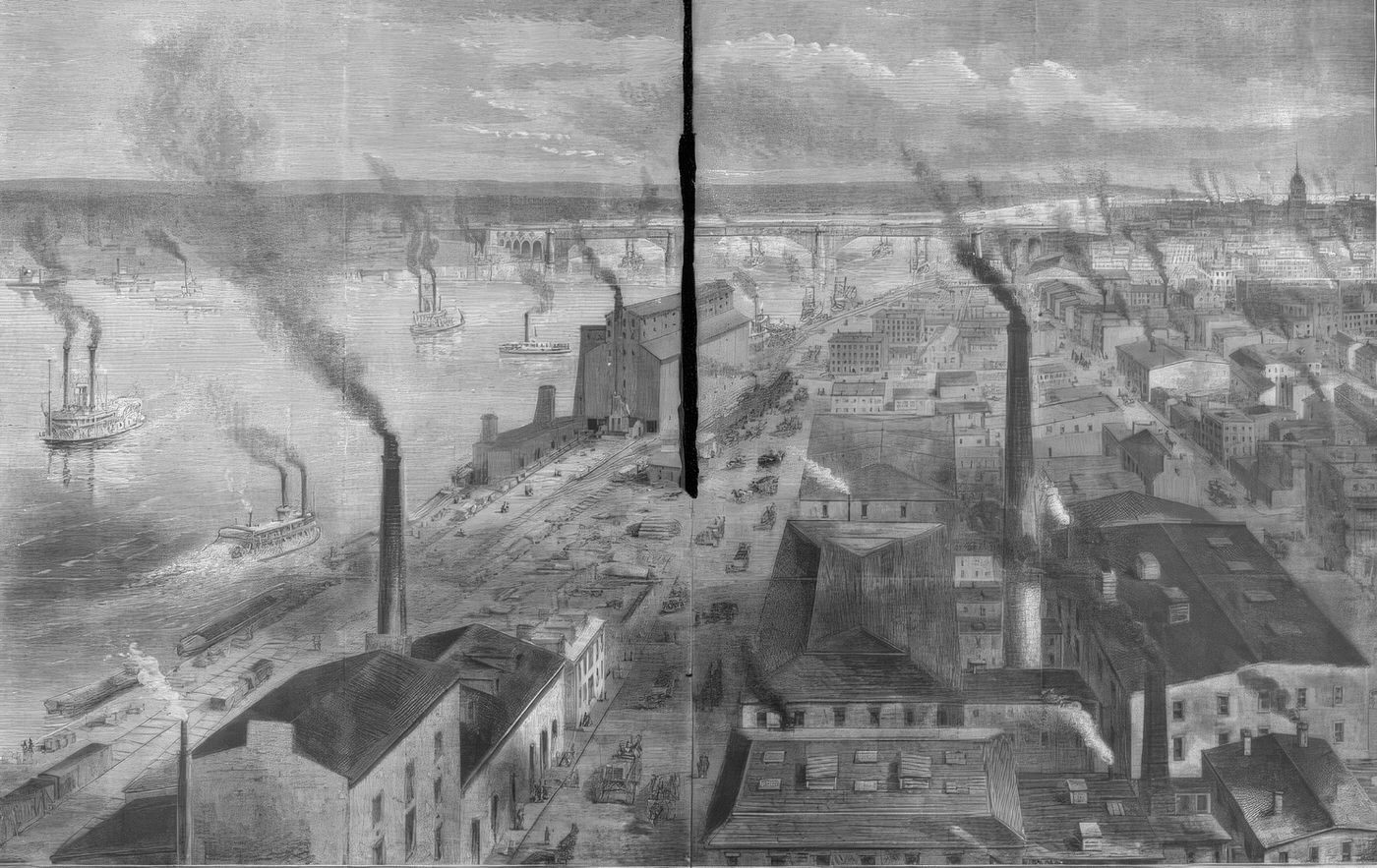

The 1870s were a period of dramatic change and development for St. Louis, Missouri. Fresh from the upheavals of the Civil War, the city was reshaping its physical landscape, its economy, and its social fabric. It stood as a significant urban center, grappling with rapid growth, pioneering new technologies, and navigating complex social issues.

Post-War Growth and a Shifting Urban Profile

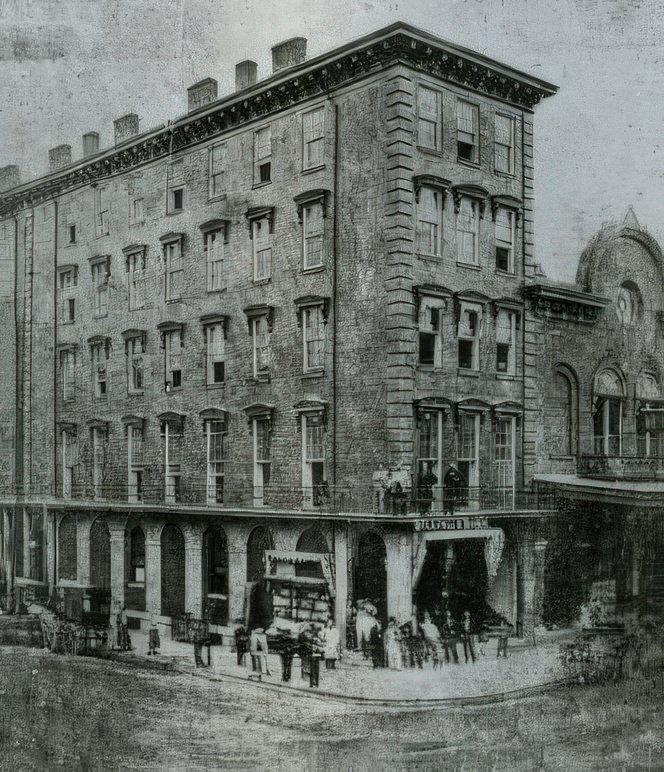

The decade following the Civil War saw St. Louis continue its trajectory as a major American city. Its population had surged impressively, growing from 160,773 residents in 1860 to 310,864 by 1870. This boom positioned St. Louis as the fourth-largest city in the United States at the dawn of the 1870s. This rapid influx of people brought with it vibrant energy and cultural richness. However, such quick expansion also placed considerable strain on the city’s resources and infrastructure, including housing, sanitation, and transportation systems.

As the decade progressed, the pace of this explosive growth began to moderate. By the 1880 census, the population reached 350,518, representing a 12.8% increase from 1870. While still substantial, this indicated a slowing trend compared to the previous decade’s 93% jump. This shift in growth rate might have reflected the strains of rapid urbanization, the economic tremors of events like the Panic of 1873, or evolving patterns of migration as other cities, particularly in the West, began to draw more settlers. The city’s national ranking also shifted, moving to sixth largest by 1880. There were contemporary suggestions that the 1870 census figures might have been somewhat inflated due to civic pride and the intense rivalry with other growing cities like Chicago, adding a layer of complexity to understanding St. Louis’s precise demographic standing. Regardless of exact numbers, St. Louis in the 1870s was undeniably a large and dynamic urban environment, setting the stage for many of the significant developments that would define the decade.

Immediate Economic Role and Challenges

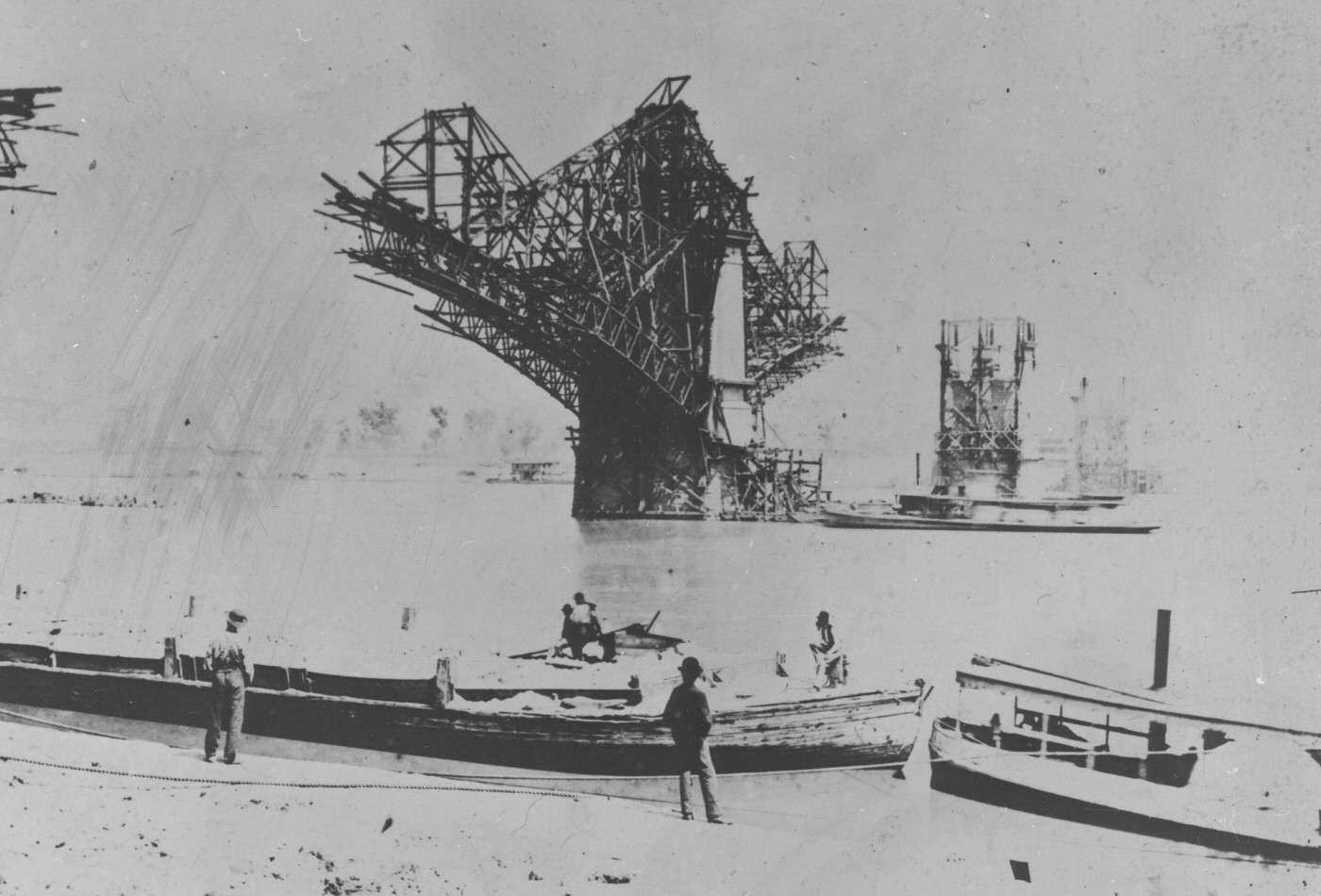

The Eads Bridge was conceived as a vital link for the nation’s expanding railroad network. Its primary purpose was to connect the railway lines terminating in East St. Louis, Illinois, with those extending westward from St. Louis, Missouri, thereby facilitating a more seamless flow of goods and passengers across the Mississippi River. The burgeoning cotton trade particularly underscored the necessity for such a railroad bridge, as shipping compressed cotton bales by rail to eastern markets was becoming more cost-effective than river transport.

Despite its groundbreaking engineering and strategic importance, the Eads Bridge encountered significant economic headwinds immediately after its opening. The Illinois and St. Louis Bridge Company, formed to finance and own the structure, found itself in financial distress less than a year after the bridge’s dedication. Several factors contributed to these woes. Established ferry companies, which held a monopoly on cross-river freight, and competing railroad interests initially boycotted the bridge. Furthermore, the bridge was initially connected to only one railroad line, limiting its immediate utility and revenue. The nationwide financial crisis known as the Panic of 1873 further exacerbated the bridge company’s financial instability, leading to its bankruptcy. In 1878, the magnificent Eads Bridge was sold at auction. This early failure highlighted that even the most technologically advanced infrastructure projects require careful integration with existing economic networks and can be vulnerable to broader financial downturns and competitive pressures. The bridge’s long-term value was undeniable, but its initial years were a stark reminder of the complex interplay between innovation, business, and economics.

The Eads Bridge: A Monumental Connection and Economic Catalyst

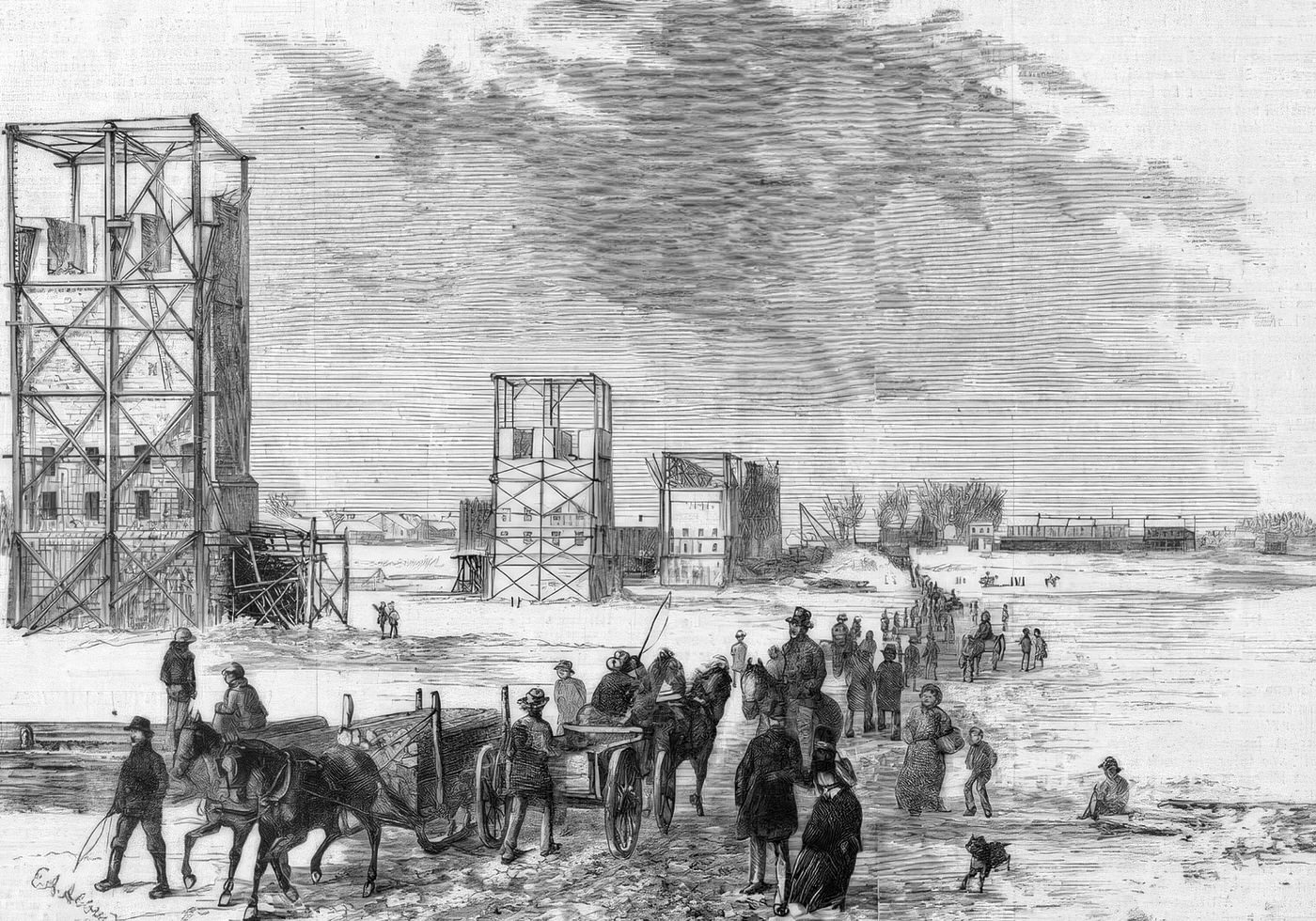

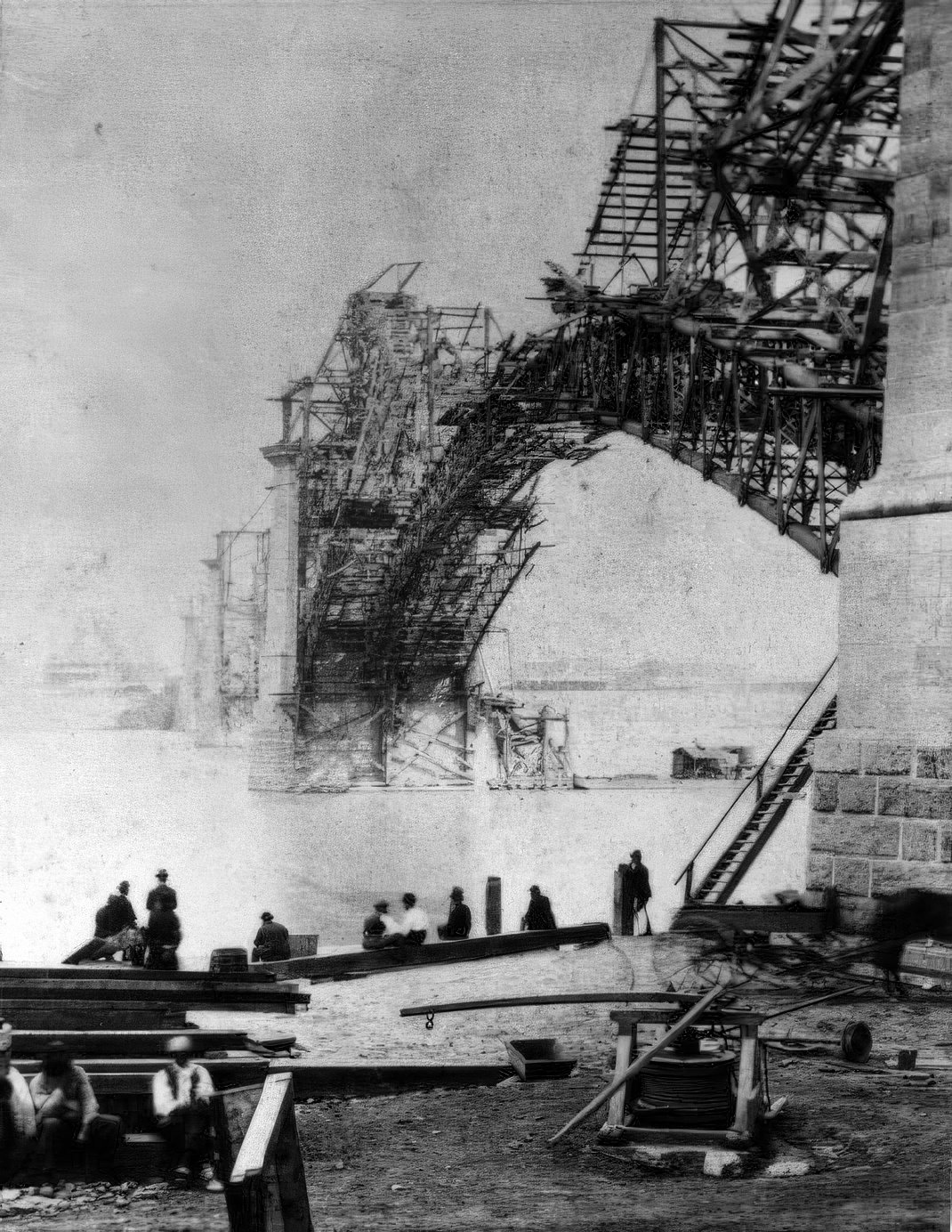

One of the most defining achievements in St. Louis during the 1870s was the completion of the Eads Bridge. This architectural and engineering marvel, the world’s first bridge to extensively use steel in its trusses, spanned the Mississippi River and was officially dedicated on July 4, 1874. The bridge was the vision of James B. Eads, a brilliant, self-taught engineer who, remarkably, had no prior experience in bridge construction but had gained fame for building ironclad gunboats for the Union during the Civil War.

Construction commenced in 1867 and was a monumental undertaking, pushing the boundaries of engineering knowledge. Eads employed pioneering techniques, most notably the use of pneumatic caissons to sink the bridge’s support piers to unprecedented depths of over 100 feet into the riverbed. This innovative method, however, came at a human cost. Workers laboring in the compressed air environment of the caissons often suffered from a mysterious ailment then known as “caisson disease”—now understood as decompression sickness or “the bends.” Tragically, 14 workers died as a result of this condition during the bridge’s construction. The bridge’s arches were built using a cantilever method, suspending them from temporary wooden towers, another innovative approach for such a large structure. Costing nearly $10 million, a colossal sum at the time, the Eads Bridge was a testament to American ingenuity and St. Louis’s ambition to remain a key national hub.

The Economic Pulse: Industry, and Trade

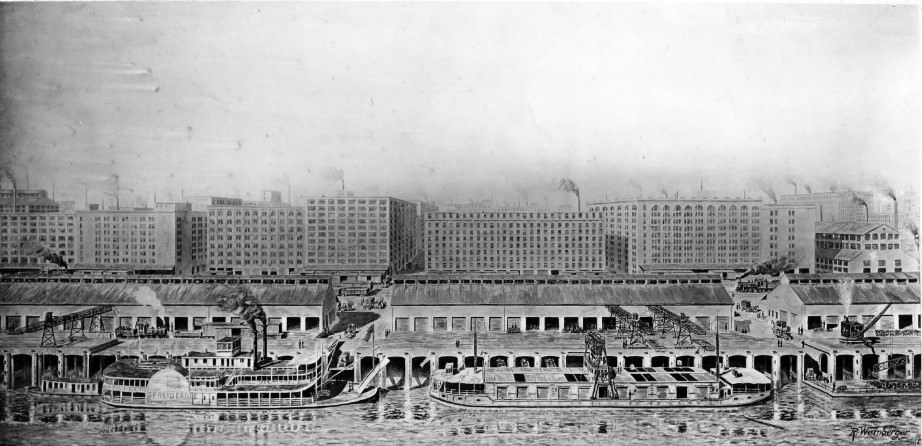

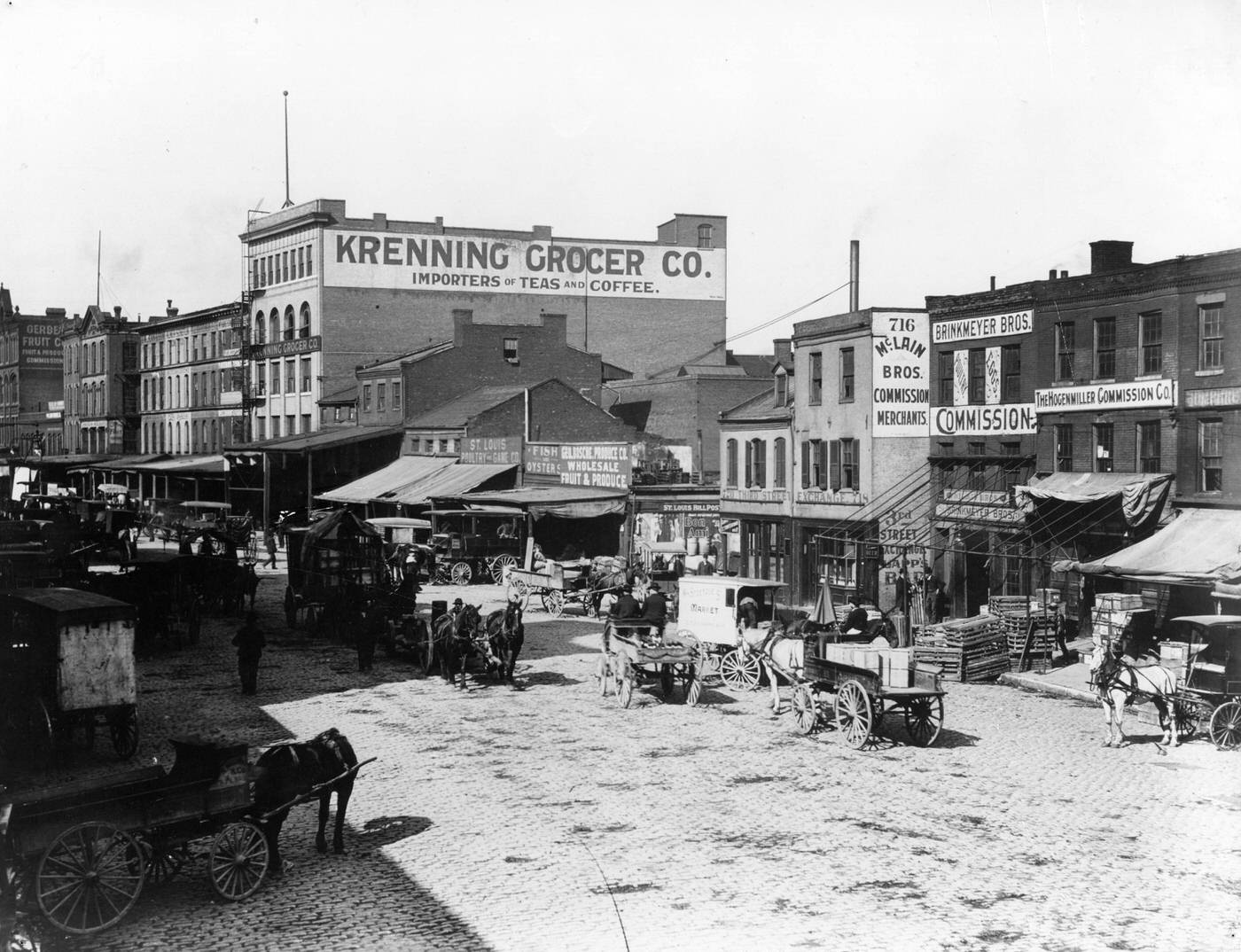

Throughout the 1870s, St. Louis solidified its position as a major manufacturing and trading center. The city’s diverse industrial base was a key driver of its economy. Iron production flourished, with factories and foundries turning out essential goods like pipes, plows, stoves, and tools. The brewing industry, significantly shaped by the expertise of its large German immigrant population, abundant water resources, and the natural limestone caves ideal for lagering beer, was another cornerstone of the local economy. By 1870, there were at least 50 breweries in the city. Flour milling and tobacco processing were also major industries, with St. Louis being a leading national producer of plug chewing tobacco. A newer industry, cotton compressing, gained prominence, and by the end of the decade, St. Louis had become the third-largest raw cotton market in the United States, with the vast majority of this cotton arriving via the expanding railroad network. The overall value of goods manufactured in St. Louis reflected this industrial might, estimated at $58 million in 1870 and growing to $104 million by 1880.

| Industry | Value of Products (1875) |

| Flour and Meal | $13,557,690 |

| Pork Products | $9,730,000 |

| Tobacco | $6,217,675 |

| Beer and Ale | $4,576,920 |

| Iron (Foundries, Rolling Mills, Machine Shops) | $4,500,000 (approx.) |

| Boots and Shoes | $2,850,000 |

| Bread and Crackers | $2,515,000 |

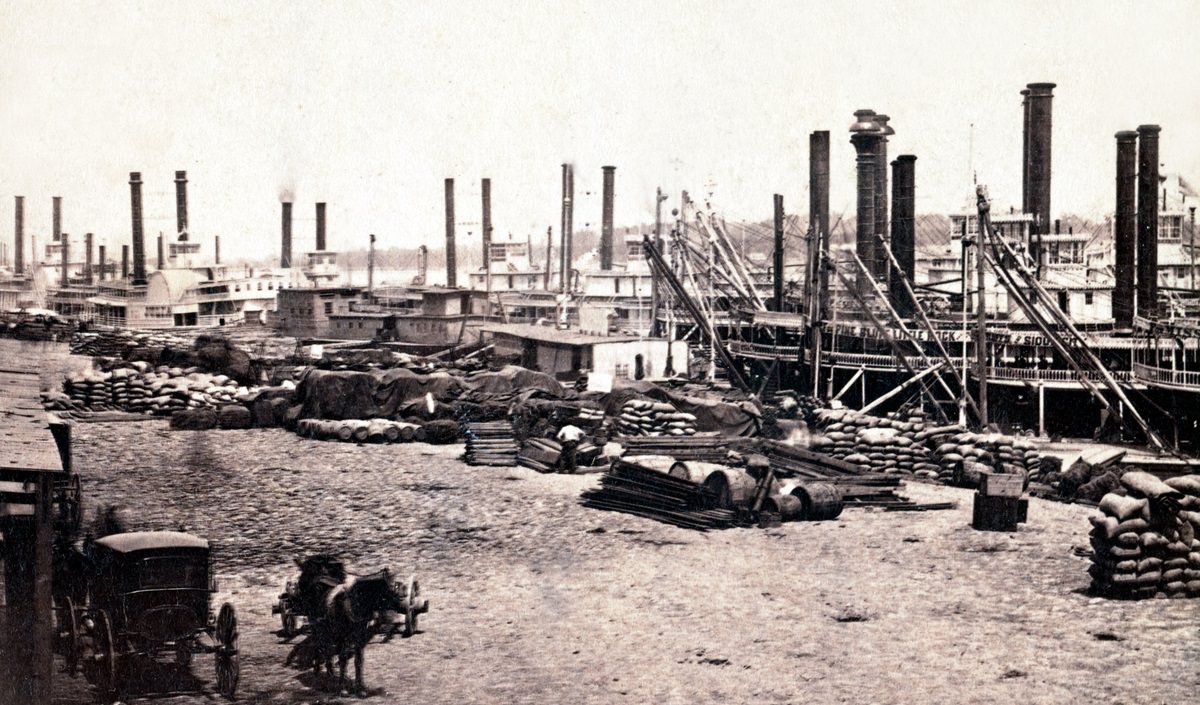

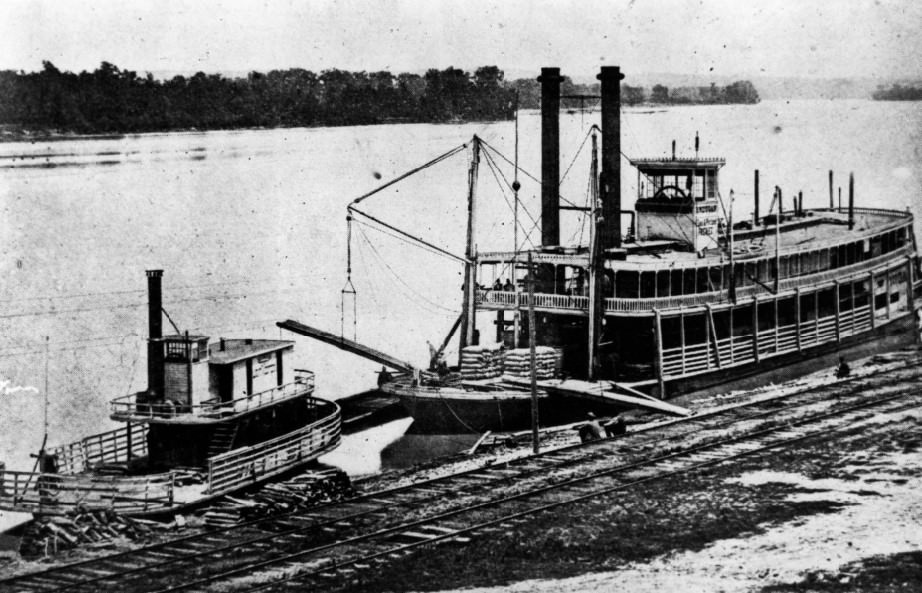

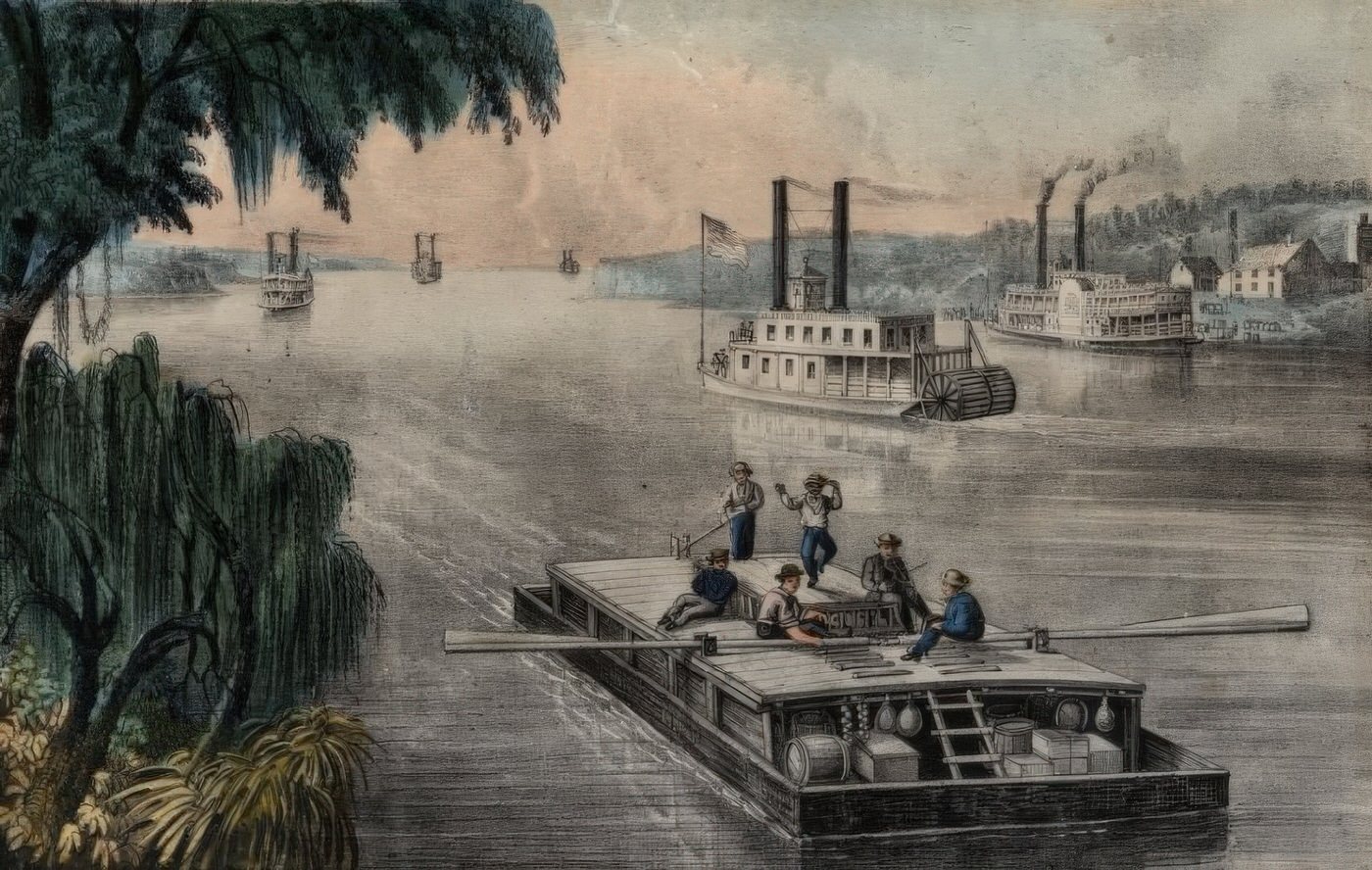

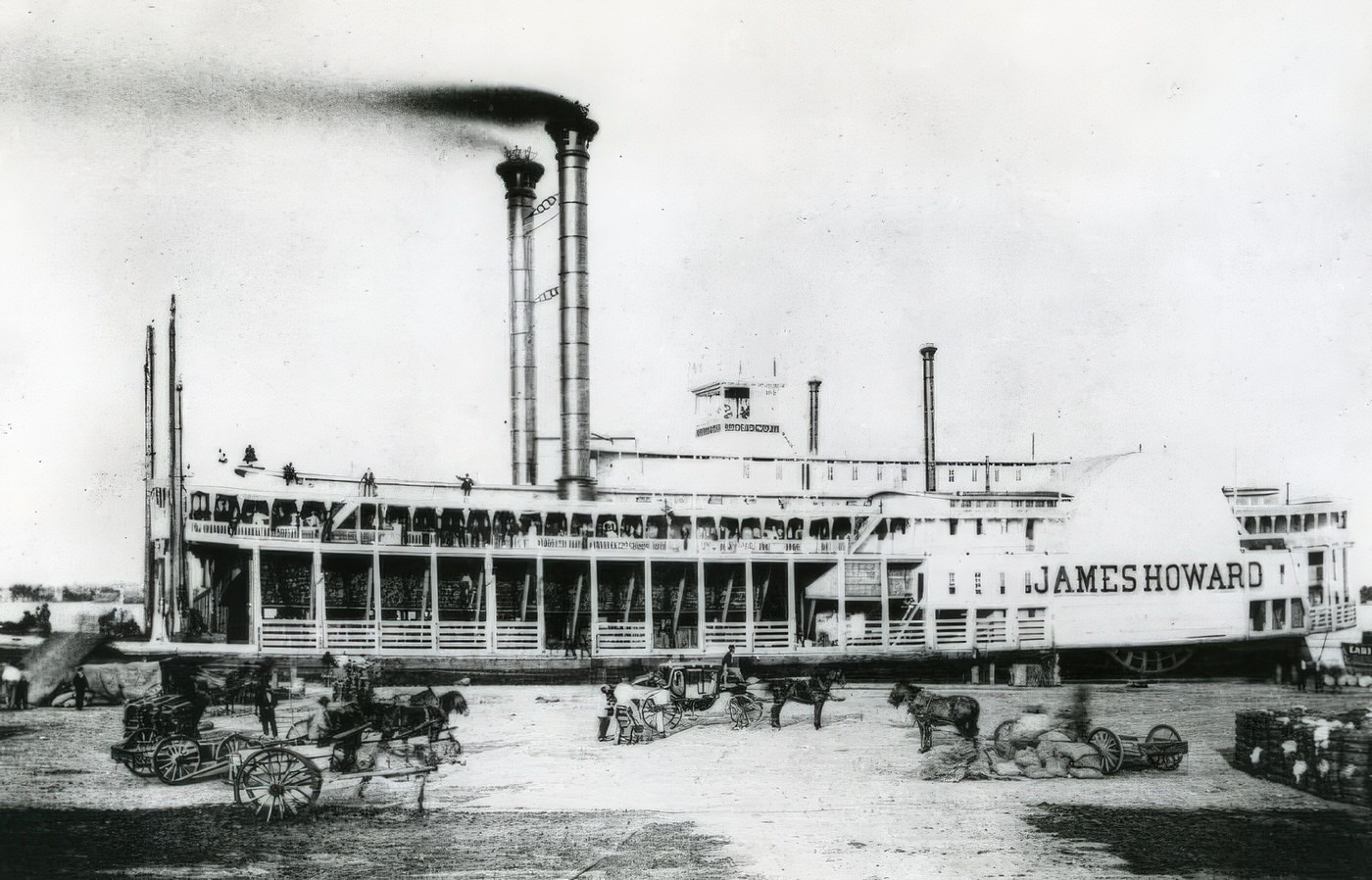

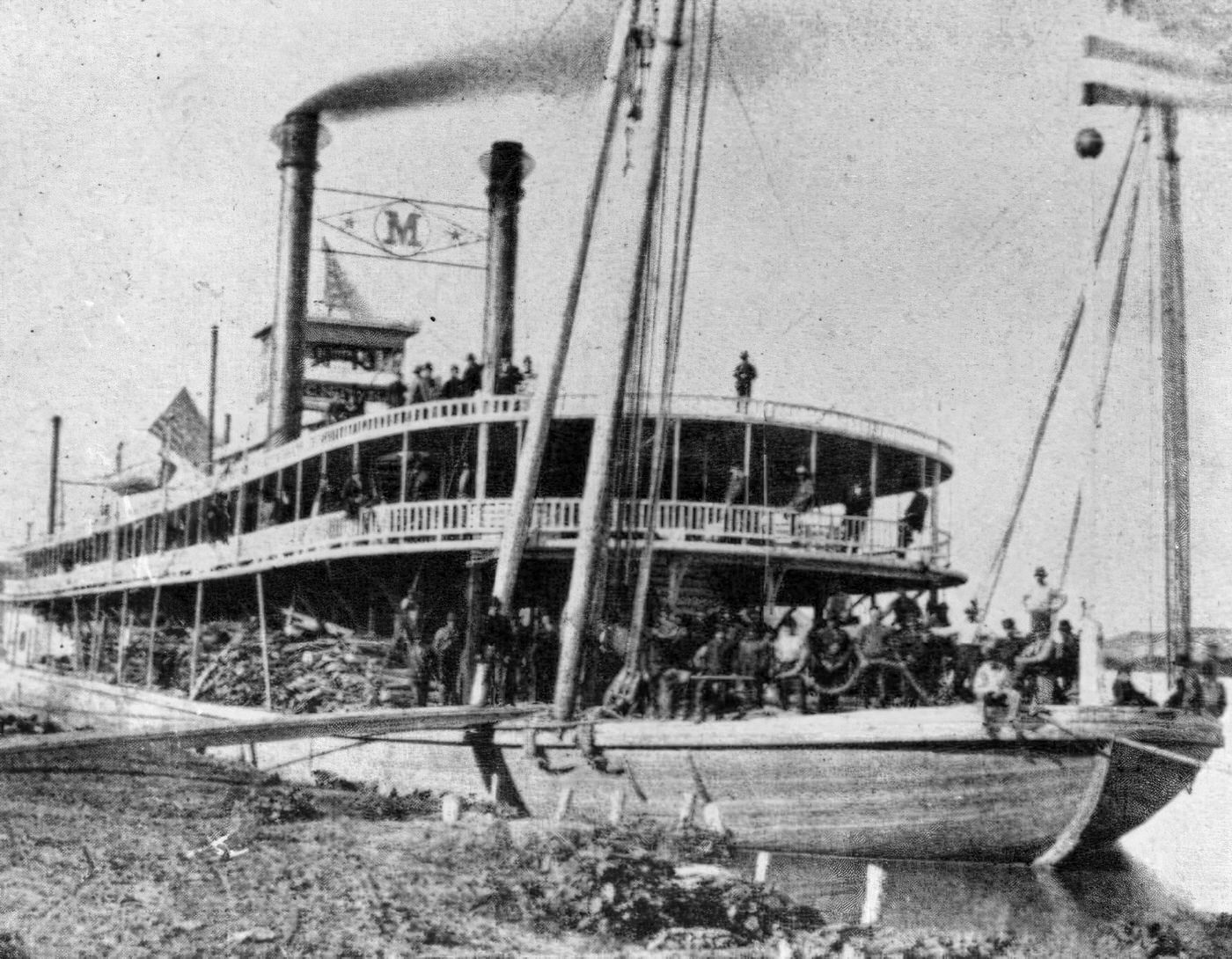

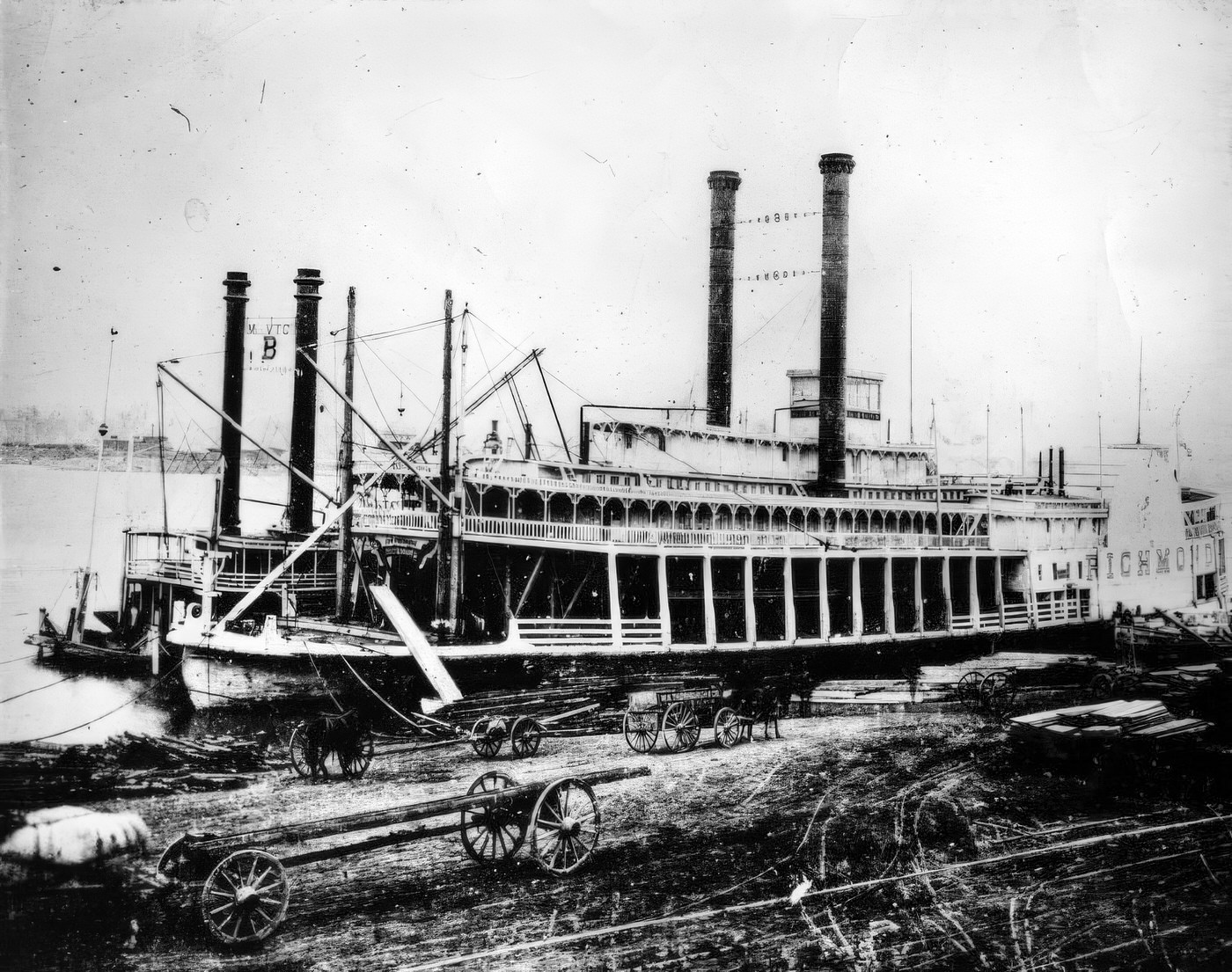

This diverse manufacturing output fueled a dynamic trade network. While steamboats had long been the lifeblood of St. Louis commerce, dominating river transport until the Civil War and into the early 1870s , the 1870s marked a clear shift. Railroads became increasingly crucial for east-west trade, a trend accelerated by the opening of the Eads Bridge. St. Louis traded a wide array of goods, including agricultural products, animals, hardware, and tools, with the developing West and the recovering South. Recognizing the changing economic landscape, city business leaders had formed the Union Merchants’ Exchange in 1866. Throughout the 1870s, the Exchange actively worked to bolster the city’s commercial standing, focusing particularly on expanding trade routes into the Southwest. The types of cargo moving through the city also evolved, with traditional items like furs diminishing in importance relative to agricultural products and manufactured goods.

The Panic of 1873 and Its Local Tremors

The national economy experienced a severe shock with the Panic of 1873. This financial crisis, largely precipitated by overspeculation in the rapidly expanding railroad sector and the failure of the prominent banking firm Jay Cooke & Company in Philadelphia, had far-reaching consequences across the United States. The Panic led to a cascade of bank failures, business bankruptcies, and a prolonged period of economic depression, often referred to as the “Long Depression,” characterized by falling prices, wage cuts, and high unemployment nationally.

St. Louis was not immune to these national tremors. The financial strain was evident in the bankruptcies of several key local enterprises. The company that owned the newly completed Eads Bridge, the St. Louis Tunnel Company (responsible for the railway tunnel connecting to the bridge), and the Union Depot railroad terminal (constructed in 1875) all succumbed to financial failure in the wake of the Panic. The St. Louis branch of the National Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company, an institution vital to the African American community, also closed its doors in 1873. Records from March 1875 show the insolvency of Harris, Rice & Co., a St. Louis business corporation that was forced to make a general assignment for the benefit of its creditors.

Despite these significant failures, some contemporary accounts suggested that St. Louis’s established banking houses exhibited a degree of “unusual stability” during the bank runs of 1873, particularly when compared to previous financial crises. This might indicate that while specific, perhaps over-leveraged or narrowly focused ventures collapsed, the city’s core financial institutions were somewhat more resilient. The annual reports of the St. Louis Merchants’ Exchange from 1873 through 1875 provide detailed contemporary accounts of business conditions and would offer deeper insights into this mixed economic picture.

The Panic of 1873 undoubtedly contributed to a challenging economic environment in St. Louis for several years. Nationally, unemployment soared, reaching 14% by 1876. While precise unemployment figures for St. Louis during the mid-1870s are scarce in available records, it is reasonable to assume that an industrial city like St. Louis experienced significant job losses and hardship for its working population. This period of economic distress, characterized by business failures and precarious employment, created a fertile ground for worker dissatisfaction and was a significant contributing factor to the labor unrest that would erupt later in the decade, most notably the St. Louis General Strike of 1877. Information on specific organized relief efforts by the city or charitable organizations in St. Louis during this period is not extensively detailed in the available records, though such efforts were discussed and implemented in various forms nationally. Local newspapers of the time, such as the Missouri Republican and the St. Louis Globe-Democrat (which began publication in 1875), would have chronicled the local manifestations of the Panic, reflecting the anxieties and realities faced by St. Louisans.

The People of St. Louis: Diverse Communities and Daily Life

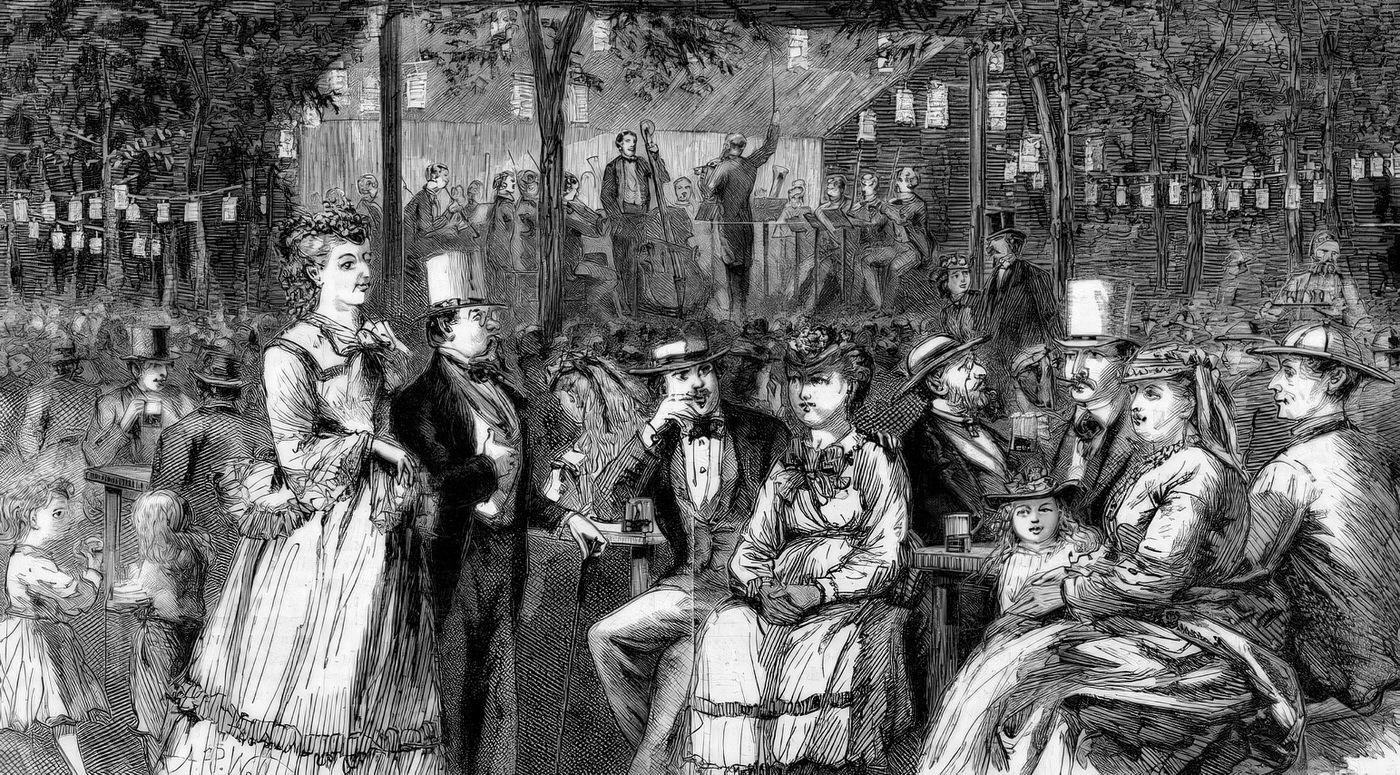

German immigrants were a foundational element of St. Louis’s population and cultural identity in the 1870s. Having arrived in substantial numbers since the 1830s, by mid-century they constituted a significant portion of the city’s residents. During the 1870s, their presence was so pronounced that it was said one could walk the streets of South St. Louis and hear little English spoken. They established vibrant, close-knit communities in neighborhoods such as Soulard, Benton Park, Hyde Park (formerly known as Bremen), and Dutchtown, shaping the character of these areas with their distinctive architecture and social life.

The German community made profound contributions to the city’s economy. Their expertise was particularly evident in the flourishing brewing industry, but they were also integral to various skilled trades and businesses. Beyond commerce, German immigrants were instrumental in shaping the city’s intellectual and political discourse. They founded influential German-language newspapers, most notably the Westliche Post, which was edited by prominent figures Emil Preetorius and Carl Schurz, and Amerika, established in 1872. These publications served not only as sources of news but also as vital forums for community discussion, cultural preservation, and political mobilization.

By the 1870s, the Irish community was also a well-established and integral part of St. Louis’s diverse population. Many Irish immigrants had arrived in the city during the 1850s, driven from their homeland by the Great Famine. Often arriving with few resources and facing literacy challenges, they contributed significantly to the city’s labor force. Despite initial hardships, members of the Irish community found opportunities for advancement. An example of Irish entrepreneurial spirit is Joseph Murphy, who, after learning the wagon-building trade, established a successful business producing durable “Murphy Wagons” used by traders on the Santa Fe Trail and “prairie schooners” for westward pioneers. While the German community was perhaps more visibly dominant in terms of large-scale industries like brewing and influential press, the Irish were a vital component of the city’s working class and contributed to its growth and character in numerous ways.

The 1870s represented a critical period of community building and striving for African Americans in St. Louis, following the abolition of slavery and the promises of Reconstruction. The Ville neighborhood began to emerge as a distinct and important African American residential area during this decade. Known earlier as Elleardsville, it started attracting African American families in the early 1870s, laying the foundation for what would become a cultural center.

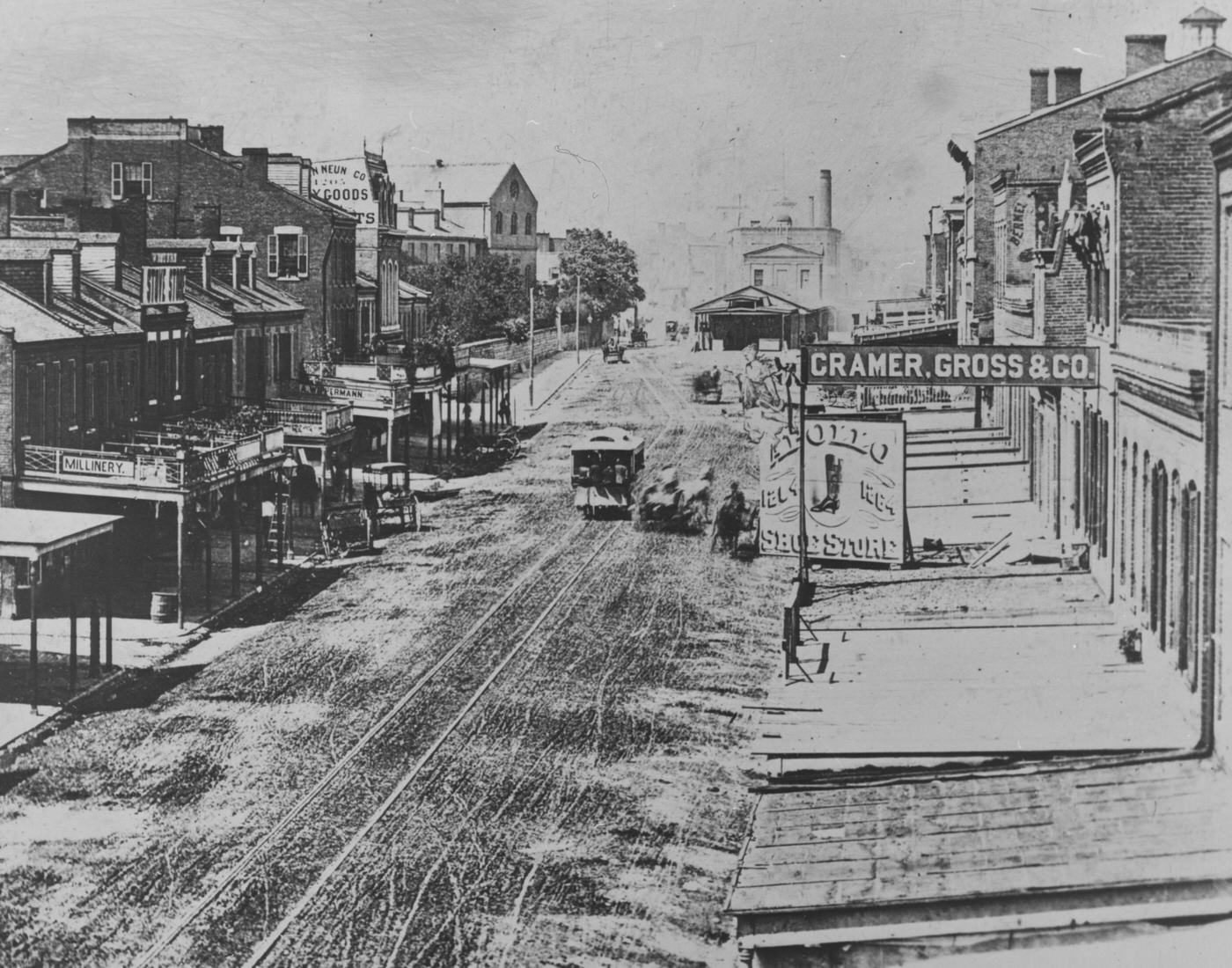

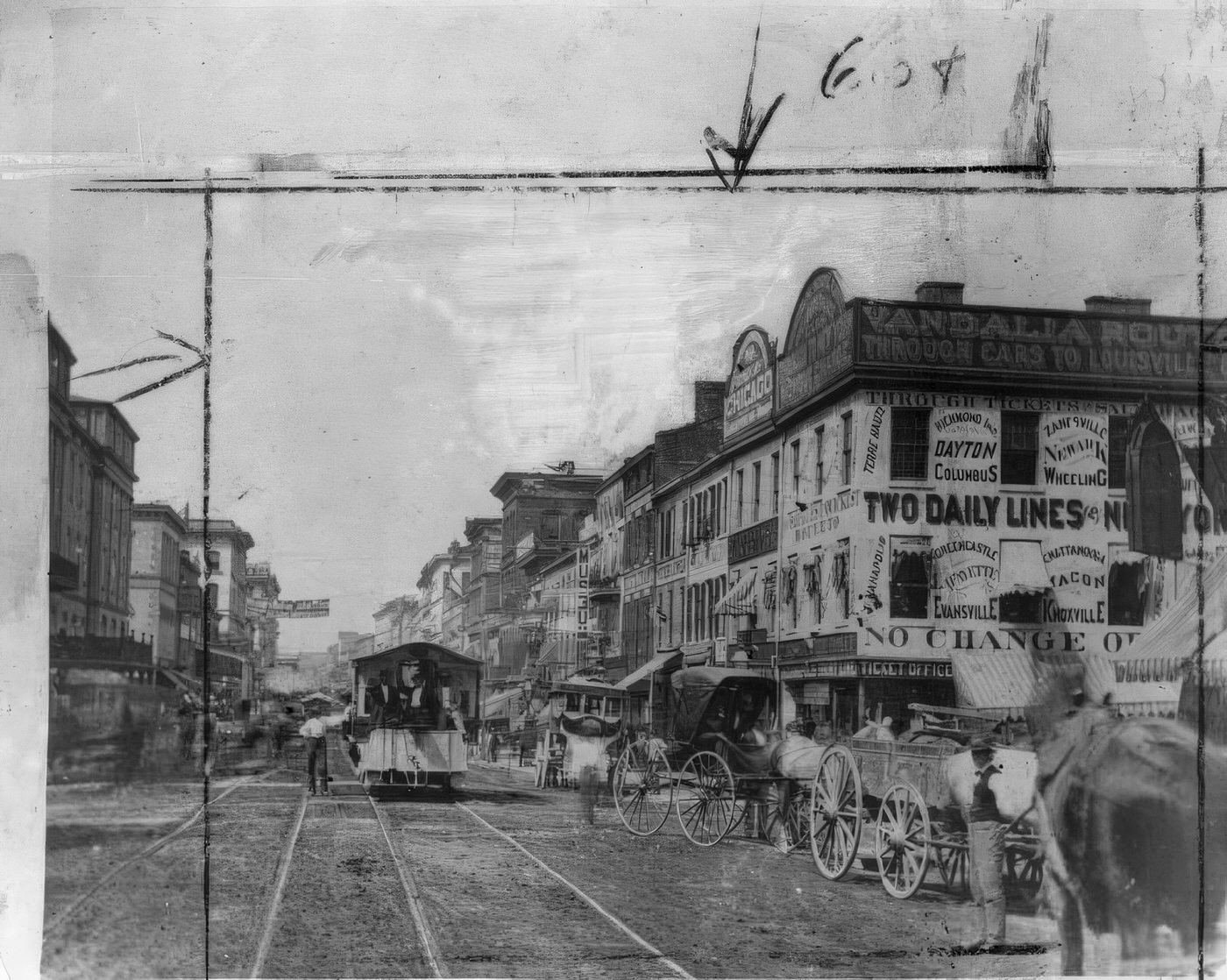

Expanding Streetcar Network

Public transportation was vital for a city spreading outwards. In the 1870s, St. Louis’s streetcar network, primarily composed of horse-drawn lines, continued to expand, connecting the downtown core with developing residential areas further west. A significant milestone in 1874 was the establishment of a new streetcar line that crossed the Mississippi River via the newly completed Eads Bridge, linking St. Louis with East St. Louis, Illinois. While horsepower remained the dominant mode of propulsion for streetcars, experiments with mechanical traction continued. A steam-powered line, operating as an extension of the Olive Street route, had become fully operational in 1868. This line, however, was not integrated with the broader horse-drawn network and utilized a different track gauge, indicating that the transition to mechanized urban transit was still in its early and somewhat fragmented stages.

Education was a paramount concern. A significant step was the establishment of Elleardsville Colored School No. 8 in 1873. While initially staffed by white teachers, by 1877, African American educators and administrators had assumed leadership of the school, a testament to the community’s drive for self-determination in education. The creation of Sumner High School in 1875, the first high school for African Americans west of the Mississippi, was another landmark achievement, mandated by the new Missouri Constitution of that year which, while providing for education, also institutionalized segregated schooling.

Churches were the bedrock of the African American community, serving as spiritual centers, social hubs, and platforms for organization and activism. In 1872, St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church erected a new building at 11th and Lucas, notable as the first church edifice in St. Louis constructed entirely by and for an African American congregation. St. Paul’s AME became a vital center for community organization, relief efforts, and advocacy. Around 1873, St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Church opened as the first Catholic parish for Black St. Louisans, located in the former Vinegar Hill Hall at 14th and Gay. The Oblate Sisters of the Poor, an order of Black nuns associated with St. Elizabeth’s, further contributed to the community by establishing a parish school in 1880, demonstrating the church’s commitment to education. Alongside these Christian institutions, traditional African American spiritual practices, often referred to as Hoodoo, which blended West and Central African religious elements with Christian influences, continued to be a part of the community’s spiritual life.

The political sphere also saw increased African American participation. The ratification of the 15th Amendment by Missouri in 1870 granted Black men the right to vote. Leaders like James Milton Turner, who had been instrumental in the Missouri Equal Rights League (formed in 1865 to advocate for education and suffrage), played a significant role in mobilizing the Black electorate. Turner was credited with helping to deliver a substantial number of Black votes to the Republican Party in the 1870 election. These efforts to build institutions, pursue education, establish businesses, and engage in the political process demonstrate the resilience, agency, and aspirations of the African American community in St. Louis during a transformative and often challenging decade.

Social Challenges and Civic Responses: The “Social Evil” Ordinance

In July 1870, the St. Louis city government embarked on a controversial experiment in public health and social regulation with the enactment of the “Social Evil” Ordinance. This law effectively legalized prostitution, provided it occurred within licensed brothels and involved prostitutes who were registered and underwent mandatory weekly medical examinations for venereal diseases. To support this system, the Social Evil Hospital was constructed in 1872-73, dedicated to the treatment of infected women and funded by taxes on brothels and prostitutes. A House of Industry was also planned to teach “fallen women” alternative vocational skills.

The ordinance was a product of its time, reflecting a pragmatic, if contentious, approach to a persistent social issue. Proponents, including St. Louis Police Chief James McDonough, argued that regulation was a more effective means of controlling illicit behavior and, crucially, curbing the spread of venereal diseases than outright prohibition. However, the “Social Evil” Ordinance quickly drew significant opposition. Prominent civic leaders, such as Reverend William Greenleaf Eliot, the founder of Washington University, spearheaded campaigns against the law, arguing on moral and religious grounds. Women’s groups also criticized the ordinance, pointing out its discriminatory nature: it targeted female prostitutes for registration and medical examination while imposing no such requirements on their male clients or male sex workers. These reformers argued that the focus should be on addressing the root causes of prostitution, such as lack of economic opportunities and education for women.

The public outcry and organized petitioning campaigns eventually proved effective. Despite initial legal challenges to the repeal efforts being unsuccessful, the St. Louis City Council nullified the “Social Evil” Ordinance in April 1874. The experiment in regulated prostitution ended, and in June 1875, a new ordinance aimed at suppressing prostitution was passed. The House of Industry, which had seen little success, closed quickly, while the Social Evil Hospital was repurposed, eventually becoming the Female Hospital. This episode illustrates the complex interplay of public health concerns, social mores, gender politics, and the power of civic activism in shaping urban policy in 19th-century St. Louis.

Building the Victorian City: Infrastructure and Green Spaces

The rapid urbanization of St. Louis in the 1870s necessitated significant upgrades to its basic infrastructure to support the growing population and ensure public health. A major focus was the city’s water supply. Following a bond issue, the St. Louis Water Works project moved forward, leading to the construction of settling basins at Bissell’s Point, north of the city, which began operations in 1871. Complementing this was the Compton Hill Reservoir and the impressive Grand Avenue Water Tower, a 175-foot Corinthian column built in 1870-1871 to provide necessary water pressure to the city’s mains.

Sanitation remained a pressing concern, as St. Louis, like many 19th-century cities, had previously suffered from devastating cholera epidemics. Efforts to expand and improve the sewer system, which had begun in the 1850s, continued throughout the 1870s. A revised city charter in 1870 formally established a public sewer system, with main lines constructed along principal drainage courses. The St. Louis Board of Health, created in the aftermath of the 1866 cholera outbreak, was tasked with creating and enforcing sanitary regulations and monitoring polluting industries. Reports from the Health Commissioner, such as one detailing patients at the Quarantine Hospital during an 1879 epidemic, provide glimpses into the ongoing public health challenges. These infrastructural projects, while sometimes reactive to crises, were also proactive measures to ensure the city’s long-term viability and the well-being of its inhabitants, though challenges such as waste dumping upriver from the new waterworks intake persisted.

The illumination of the city also saw advancements. The Laclede Gaslight Company, formed in the 1870s, extended gas lighting services to the south side of St. Louis. Gas lamps were the primary means of street illumination. However, the decade also witnessed the dawn of a new technology: in 1878, Faust’s Restaurant became the first commercial establishment in St. Louis to be illuminated by electric lighting, a harbinger of the transformative changes electric power would bring in the coming decades.

The Rise of Grand City Parks

The 1870s was a landmark decade for the development of public green spaces in St. Louis, reflecting a growing understanding of their importance for recreation, public health, and civic identity in rapidly industrializing urban centers. Building on earlier initiatives like the creation of Lafayette Park from common fields and philanthropist Henry Shaw’s 1868 donation of land for Tower Grove Park, the city embarked on its most ambitious park project to date.

Forest Park: The vision for a large western park took shape in 1870, proposed by real estate developer Hiram Leffingwell and legislator Nicholas Bell, among others. In 1872, the Missouri state legislature authorized the city to purchase over 1,000 acres of largely rural land on its western fringe for this purpose. The acquisition, costing $1.5 million, was not without controversy. Many citizens felt the park would be inaccessible to the general populace due to the lack of paved roads or horsecar lines connecting it to the city, arguing it would primarily benefit the wealthy. After overcoming legal challenges, the land purchase was completed in 1874, and Forest Park was officially dedicated and opened to the public in 1876. The chosen site was among the last in the St. Louis area to contain Native American burial mounds, remnants of the region’s earlier inhabitants. Although Forest Park opened as an integrated space, its accessibility to African Americans would later be restricted by Jim Crow laws. The creation of Forest Park was a monumental civic undertaking, shaping the city’s future development and providing a vast recreational area, even if its initial benefits and accessibility were subjects of debate.

Tower Grove Park: Founded in 1872, Tower Grove Park was the gift of Henry Shaw, who had donated the 289 acres of land in 1867-1868. Shaw personally oversaw its development, envisioning a grand Victorian pleasure ground. The park’s design, entrusted to English-born garden designer James Gurney, reflected an English gardenesque style suited to its prairie setting. By its formal opening in 1872, most of its distinctive Victorian pavilions, designed by St. Louis architects Eugene Greenleaf, Henry Thiele, and Francis Tunica, were completed. These fanciful structures, such as the Turkish Pavilion and the Chinese Shelter, along with ornamental sculptures and a diverse collection of trees imported from around the world, created a unique and picturesque landscape. Tower Grove Park remains one of the best-preserved examples of an 1870s Victorian park in the United States.

Governance and the “Great Divorce” of 1876

The most significant political event for St. Louis in the 1870s was the “Great Divorce” of 1876, a complex and contentious process that resulted in the City of St. Louis formally separating from St. Louis County to become an independent city. This movement was largely driven by influential city residents who had grown increasingly frustrated with the existing governance structure. They argued that city tax revenues were being disproportionately used to fund development and services in the less populated county areas. Furthermore, the county court was perceived by many city dwellers as being remote, inefficient, prone to corruption and patronage, and allowing undue interference from the state legislature in municipal affairs.

The legal framework for this separation was established in the new Missouri Constitution of 1875, which included provisions for St. Louis City to separate from the County and establish its own charter. Following this, a board of thirteen “freeholders” (property owners) was elected by voters across the city and county to draft the new city charter and the “Scheme of Separation.” Notable figures involved in this process included Joseph Pulitzer, who advocated for separation, and George Shields, who chaired the board of freeholders. The election of these freeholders saw a slate of “citizens” endorsed by the Merchants’ Exchange and the Taxpayers’ League triumph over candidates backed by established political party committees, indicating a public desire for reform.

The vote on the Scheme of Separation and the new City Charter took place on August 22, 1876. The initial tally indicated that the separation measure had failed by a narrow margin. However, supporters of separation quickly brought charges of voting fraud, leading to a recount. After four months, the recount determined that the vote for separation had indeed passed. The Missouri Supreme Court officially affirmed this outcome on April 26, 1877, finalizing the “Great Divorce”.

As a result of this separation, St. Louis became a unique entity in American governance: an independent city, not part of any county. A crucial and long-lasting consequence was the fixing of the city’s boundaries. While the city’s land area was more than tripled, expanding from roughly 18 to 61 square miles to encompass important developing areas and newly established parks like Forest Park, O’Fallon Park, and Tower Grove Park, these new limits were declared permanent. In exchange for this expanded territory, the City of St. Louis assumed the entirety of St. Louis County’s existing debt and pledged to maintain roads and bridges in the region. While this move was seen at the time as a way for the city to control its own destiny and resources, the permanent freezing of its boundaries would, in later decades, be viewed as a significant constraint on its ability to grow and adapt to changing urban patterns, particularly in comparison to cities that could annex surrounding suburban areas.

Education’s Expanding Reach: Kindergartens and High Schools

The 1870s were a transformative period for public education in St. Louis, largely due to the efforts of William Torrey Harris, who served as the city’s Superintendent of Schools from 1868 to 1880. Harris was a philosopher and a highly influential educator who believed that education was crucial for individual development and for equipping citizens to meet the demands of a rapidly industrializing society.

Under his leadership, the public school curriculum was significantly expanded. Harris championed the establishment and integration of high schools as a vital part of public education. The curriculum he advocated was rigorous, emphasizing core subjects like grammar, philosophy, and mathematics, but it also embraced innovation by incorporating art, music, and scientific and manual studies. This broader approach aimed to provide a more well-rounded education. Furthermore, Harris was a strong proponent of school libraries and encouraged all public schools in St. Louis to develop their own collections. His reforms and the dedication of St. Louis educators, many of whom were German immigrants with a strong belief in the value of education, led to the city’s school system being regarded as one of the best in the nation during this era.

A landmark achievement in American education occurred in St. Louis in September 1873 with the establishment of the nation’s first permanent public kindergarten. This pioneering initiative was led by Susan Blow, an ardent advocate of early childhood education, with the crucial support of Superintendent William Torrey Harris. The kindergarten was opened at the Des Peres School in Carondelet, a neighborhood that had been annexed by St. Louis.

Blow was deeply influenced by the educational philosophy of the German educator Friedrich Froebel, which emphasized “learning-through-play”. The curriculum at the Des Peres kindergarten reflected these principles, incorporating games, songs (many of which Blow translated from Froebel’s original German), activities with specially designed blocks and other manipulatives like paper and clay, weaving, modeling, and even gardening. The classroom environment was designed to be cheerful and engaging, a contrast to the more formal settings of the upper grades.

The experimental kindergarten proved to be an immediate success and grew rapidly. Within just three years, the St. Louis kindergarten system under Blow’s unofficial supervision expanded to include fifty teachers and over one thousand students. The demand for trained kindergarten teachers was so high that in 1874, Blow established a training school where aspiring educators would volunteer in kindergarten classes in the mornings and study Froebelian theory in the afternoons and on weekends. The impact of this St. Louis-born movement was recognized nationally; in 1876, the United States Centennial Commission in Philadelphia presented St. Louis and Susan Blow with an award for excellence in public school kindergarten education. This innovation in early childhood education, originating in St. Louis, would go on to influence educational practices across the country.

Stirrings of Labor: Seeds of the 1877 General Strike

The 1870s in St. Louis, as in much of industrial America, were characterized by significant growth in manufacturing and industry. This expansion, however, often came with challenging working conditions for the laboring classes. The decade was also marked by economic volatility, most notably the Panic of 1873, which led to widespread business failures, wage cuts, and significant unemployment nationally, creating a climate of hardship and discontent among workers.

Groups of workers in key St. Louis industries, such as railroad employees, machinists, coopers (barrel makers), and brewery workers, were forming the backbone of the city’s industrial workforce. The Workingmen’s Party of the United States, a political organization with Marxist leanings, was active in St. Louis during this time and was gaining traction among disillusioned workers. This party, along with the Knights of Labor, would soon play a pivotal role in one of the most dramatic labor confrontations in American history. The combination of economic hardship stemming from the depression and the availability of an ideological framework and organizational structure provided by groups like the Workingmen’s Party set the stage for widespread labor actions that were to erupt.

The simmering discontent among workers, exacerbated by the prolonged economic depression following the Panic of 1873, boiled over in the summer of 1877. As part of the Great Railroad Strike that swept the nation, St. Louis experienced a general strike that was remarkable for its scale and the degree of worker control achieved, however briefly.

The strike began on July 22, 1877, when railroad workers in East St. Louis, Illinois, walked off the job to protest wage cuts. The action quickly spread across the river to St. Louis, largely organized and directed by the Workingmen’s Party and the Knights of Labor. Strikers effectively shut down rail operations, initially allowing only passenger and mail trains to pass but soon halting all freight traffic. The movement rapidly expanded beyond the railroads. Strikers marched through the city, compelling workers at numerous factories, flour mills, sugar refineries, and other industrial establishments to cease operations. Steamboat workers were also forced to demand and receive higher wages.

For a short period, the executive committee of the Workingmen’s Party, operating from Turner Hall, effectively directed many city functions, issuing orders and coordinating the actions of thousands of striking workers. This level of worker control over a major American city was unprecedented and caused considerable alarm among business leaders and municipal authorities, who drew comparisons to the Paris Commune of 1871.

The St. Louis General Strike, however, was relatively short-lived. By July 27th, city authorities, backed by prominent citizens and business leaders, began to reassert control. A substantial force of armed men, including police, a newly organized “Citizens Guard,” and National Guard companies, was mobilized. Federal troops were also deployed, initially to protect federal property, but their presence signaled a decisive shift in power. The Union Depot was retaken, and train operations began to resume under protection. Crowds were dispersed, and strike leaders were arrested. By July 30th, the strike in St. Louis had effectively ended, and by early August, the related actions in East St. Louis were also suppressed with the arrival of Illinois National Guard troops. The St. Louis General Strike of 1877 stands as a pivotal moment in American labor history, demonstrating the growing strength and radical potential of the labor movement in an era of industrial capitalism and economic crisis.

Culture, Leisure, and Voices for Change

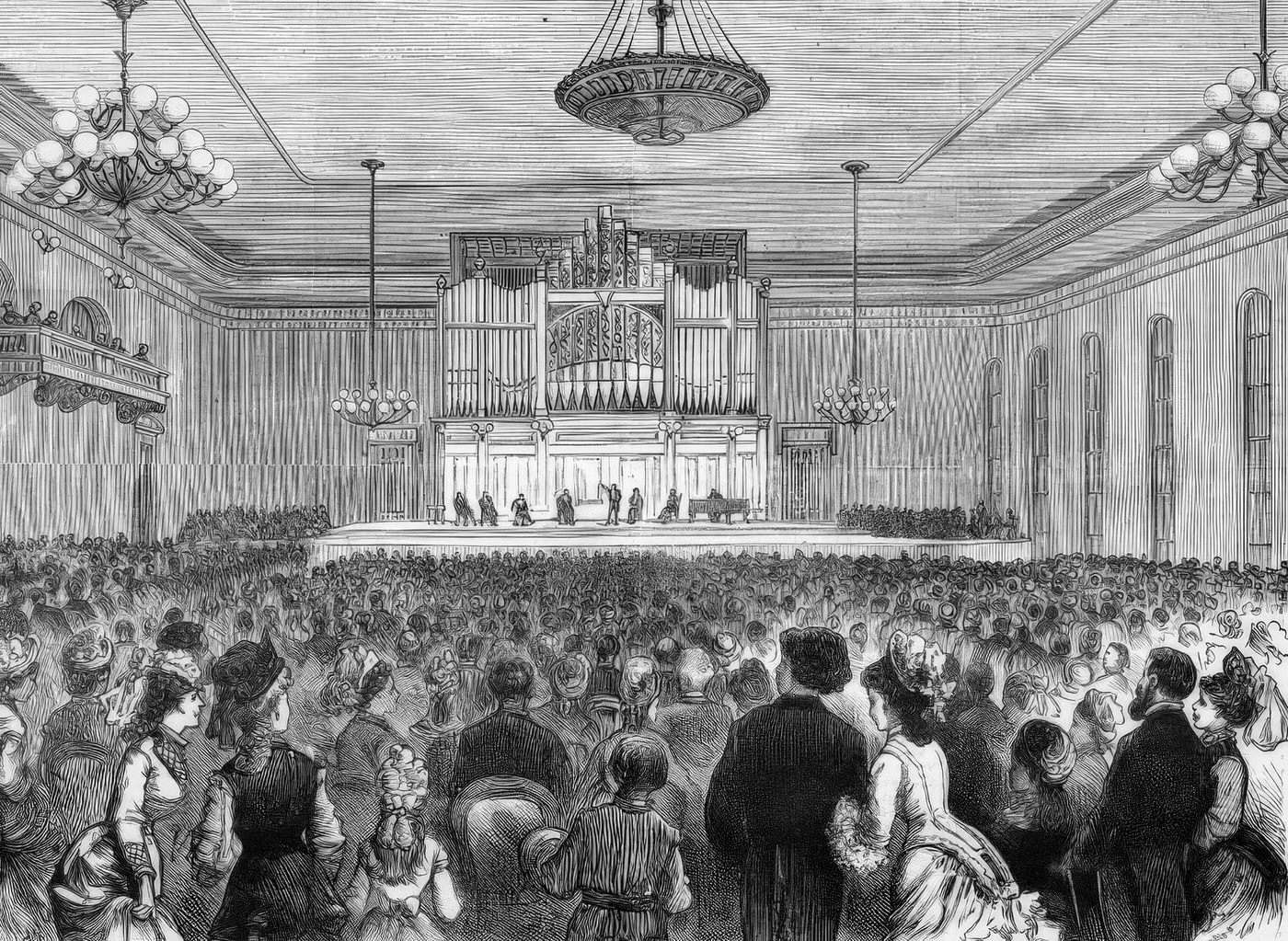

St. Louis in the 1870s offered its citizens a diverse array of entertainment and leisure options, reflecting the city’s growing prosperity and varied population. Theaters were a popular form of amusement. Prominent venues included the Grand Opera House (which had previously operated as the Varieties Theatre and DeBar’s Opera House), the Olympic Theatre, and Pope’s Theater. These establishments presented a wide repertoire, ranging from Shakespearean plays and contemporary dramas to operas, popular musical comedies (like Le Petit Faust and The Twelve Temptations at the Grand Opera House in 1870), minstrel shows, and vaudeville acts. The Southern Hotel, known for its luxury, served as a fashionable gathering place for the city’s elite and hosted distinguished guests such as author Mark Twain and former President Ulysses S. Grant.

Music also played a vital role in the city’s cultural life. While the famed St. Louis Symphony Orchestra officially traces its roots to the St. Louis Choral Society founded in 1880, this built upon a longer tradition of musical societies in the city, such as the St. Louis Sacred Music Society established in the 1830s.

The 1870s also saw the rise of professional baseball in St. Louis. The St. Louis Brown Stockings were formed in 1874 by prominent local businessmen, becoming the city’s first professional baseball team. The team competed in the National Association and later joined the National League, enjoying initial success both on the field and in establishing St. Louis as a baseball town. However, the team’s fortunes were complicated by a gambling scandal that emerged in 1877, casting a shadow over the early days of professional baseball in the city.

Social clubs were central to the community life of many St. Louisans. For the large German-American population, Turnvereins were particularly important. These gymnastic societies, such as the St. Louis Turnverein, emphasized physical fitness but also served as broader cultural centers, hosting choirs, theatricals, libraries, debates, and fostering fellowship. Other forms of social gathering included various baseball clubs active since before the war, and saloons like the 1860 Saloon in the Soulard neighborhood, which provided spaces for drink, food, and live music. This variety of leisure pursuits, from high-brow theater to community-based ethnic clubs and emerging professional sports, reflected the multifaceted social fabric of St. Louis.

Social Reform Movements

The 1870s were a period of active social reform movements in St. Louis, with residents engaging in efforts to bring about significant political and social change.

Woman Suffrage: St. Louis was a notable center for the burgeoning woman suffrage movement. Virginia Minor, a St. Louis resident, was a prominent national figure in this cause and an officer in the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). As early as 1867, she co-founded the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri in St. Louis, considered the first organization in the United States dedicated solely to achieving the vote for women. Minor and her husband, Francis, were architects of the “New Departure” strategy, which argued that the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, by granting citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, implicitly granted women the right to vote.

In a direct challenge to existing voting restrictions, Virginia Minor attempted to register to vote in St. Louis on October 15, 1872, but was refused by the registrar, Reese Happersett, solely because she was a woman. This act of civil disobedience led to the landmark legal case Minor v. Happersett. The case was argued through the Missouri courts and eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1874 (though some sources state the decision was in 1875), the Supreme Court ruled unanimously against Minor, asserting that while women were citizens, citizenship did not automatically confer the right to vote, and that states retained the power to define voter qualifications. Although a legal defeat, the Minor v. Happersett case generated considerable national publicity for the woman suffrage cause and clarified the legal battles ahead. Despite this setback, Virginia Minor remained a dedicated activist. In 1879, when the NWSA organized a Missouri branch, she was elected its president, continuing her leadership in the fight for women’s voting rights into the following decades.

Temperance: The temperance movement, aimed at curbing or prohibiting the consumption of alcohol, also gained momentum during the 1870s. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was founded nationally in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1874 and quickly grew into a powerful force for social reform. The WCTU often allied itself with the suffrage movement, with leaders like Frances Willard advocating for the “Home Protection” ballot, arguing that women needed the vote to protect their families and communities from the perceived evils of alcohol. While specific activities of a St. Louis WCTU chapter during the 1870s are not extensively detailed in the provided materials, the national organization encouraged activities such as prayer meetings, educating children about the dangers of alcohol, circulating temperance pledges, and lobbying for legal restrictions on alcohol sales. The presence of a large German-American population in St. Louis, with its strong brewing traditions and cultural acceptance of beer gardens, likely presented a complex local context for the temperance movement. The WCTU’s efforts and their alliance with suffragists sometimes faced opposition from groups connected to the liquor industry, including some German-American organizations.

Prominent Voices and Personalities

Several individuals played particularly influential roles in shaping St. Louis during the 1870s through their work in journalism, politics, and civic life.

Joseph Pulitzer: This future media magnate was honing his journalistic and political skills in St. Louis during this decade. Having arrived in the city after the Civil War, Pulitzer worked for the German-language newspaper Westliche Post in the late 1860s and early 1870s. His energy and ambition led him to politics; in 1869, he was nominated and won a seat in the Missouri House of Representatives, taking office in January 1870. As a young legislator, he was known for his efforts to combat corruption. Pulitzer’s most lasting contribution in the 1870s began in 1878 when he purchased the St. Louis Dispatch at auction and merged it with John A. Dillon’s Post to create the St. Louis Post and Dispatch (soon shortened to Post-Dispatch). From its inception, Pulitzer envisioned the paper as a vehicle for truth and a crusader against public evils, a style that would define his career. He also participated in the “Great Divorce” as one of the 13 freeholders elected to draft the new city charter.

Carl Schurz: A highly respected German-American statesman, journalist, and former Union general, Carl Schurz was a towering figure in St. Louis and national politics. He co-owned and edited the influential Westliche Post with Emil Preetorius. Elected as a U.S. Senator representing Missouri in 1868, Schurz served until 1875. During the early 1870s, his liberal views and opposition to the Grant administration’s policies led him to become a key leader in the formation of the Liberal Republican Party in 1870. Though this party was short-lived, its reform efforts had a notable impact on the national political scene. Schurz advocated for a moderate approach to Reconstruction and was a proponent of political equality for African Americans. In 1877, he was appointed U.S. Secretary of the Interior under President Rutherford B. Hayes.

Emil Preetorius: Another leading figure in the St. Louis German-American community, Emil Preetorius was the long-time editor and publisher of the Westliche Post, often working in close association with Carl Schurz. Arriving in St. Louis in the 1850s, Preetorius became editor-in-chief of the Westliche Post in 1864. Throughout the 1870s, the newspaper under his and Schurz’s guidance was a principal voice for German Republicans in the region. The Westliche Post supported the Liberal Republican movement in 1872. During the St. Louis General Strike of 1877, however, the paper took a stance against the demands of radical organized labor. Preetorius was deeply involved in civic life, advocating for immigrant rights and government reform, and was regarded as a leader of the German progressive community. The powerful platform provided by newspapers like the Westliche Post and the emerging Post-Dispatch allowed these individuals to shape public discourse and influence the political and social trajectory of St. Louis in a period of profound transformation.

Image Credits: John J. Buse, Jr. Collection, The State Historical Society of Missouri, St. Louis Mercantile Library, Library of Congress

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know