In the 1910s, St. Louis stood as a prominent and rapidly growing American city. Its population reached 687,029, a notable increase from 575,238 just a decade earlier in 1900, and a precursor to the 772,897 residents it would count by 1920. This steady growth signaled a dynamic period for the city. The racial makeup of St. Louis in 1910 was predominantly white, accounting for approximately 93.5% of the populace. The African American community represented about 6.4% of the total, with other racial groups comprising a very small segment, around 0.1%.

A significant characteristic of St. Louis at this time was its large immigrant population. In 1910, 126,287 residents, or 13.3% of the city’s total, were foreign-born. This figure was estimated to have risen to 143,723 by 1915, indicating a continued influx of people from around the world. This blend of native-born citizens, established immigrant communities, new arrivals from overseas, and a growing African American population created a vibrant, though at times complex, urban environment. The city was a crucible of cultures and ambitions, drawing people who sought new opportunities and a different way of life. This demographic dynamism was a fundamental force that would shape nearly every aspect of St. Louis throughout the 1910s, from its industrial workforce and housing needs to its cultural expressions and social interactions.

A City of Many Faces: People and Neighborhoods

The 1910s were a period of significant demographic shifts for St. Louis, as waves of newcomers arrived, adding to the city’s diverse character. European immigrants continued to seek opportunities, joining established communities and forming new ones. Nationalities represented in St. Louis around this time included Armenians, Belgians, Bohemians (Czechs), Slovaks, French, Greeks, Hungarians, Italians, Mexicans, Poles, Romanians, South Slavs, and Ukrainians. These groups added to the already substantial German and Irish populations that had settled in earlier decades. The foreign-born population was a considerable segment of the city, numbering 126,287 in 1910 and growing to an estimated 143,723 by 1915.

Simultaneously, the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South was reshaping urban centers across the North and Midwest, and St. Louis was a key destination. Drawn by the prospect of factory jobs and an escape from the harsh realities of Jim Crow in the South, African Americans moved to the city in increasing numbers. This migration accelerated during World War I, as the conflict drastically reduced European immigration, creating labor shortages in St. Louis’s burgeoning industries. Consequently, the city’s Black population grew from 6.4% of the total in 1910 to 9.0% by 1920. This influx of diverse populations created a dynamic, multifaceted city but also laid the groundwork for competition over resources and heightened social tensions.

These diverse groups often settled in distinct neighborhoods, creating a patchwork of ethnic and cultural enclaves across St. Louis. “The Hill,” for instance, was solidifying its identity as a predominantly Italian-American neighborhood. Many early Italian immigrants were drawn to the area by employment in the numerous clay mines and foundries that exploited the rich clay deposits nearby; by 1910, six foundries were operational. The Hill developed into a self-sufficient community with its own shops, the prominent St. Ambrose Catholic Church (a wooden structure founded in 1903, replaced by brick in 1926 after a fire), and a vibrant social life centered around family and local businesses.

Soulard, one of St. Louis’s oldest residential areas, had a rich history of French and later German settlement. By the early 20th century, it had also become home to a significant number of Eastern European immigrants, leading to the nickname “Bohemian Hill”. The neighborhood was characterized by its distinctive brick four-family flats, alley houses, and the historic Soulard Market, a central point for commerce and community gathering.

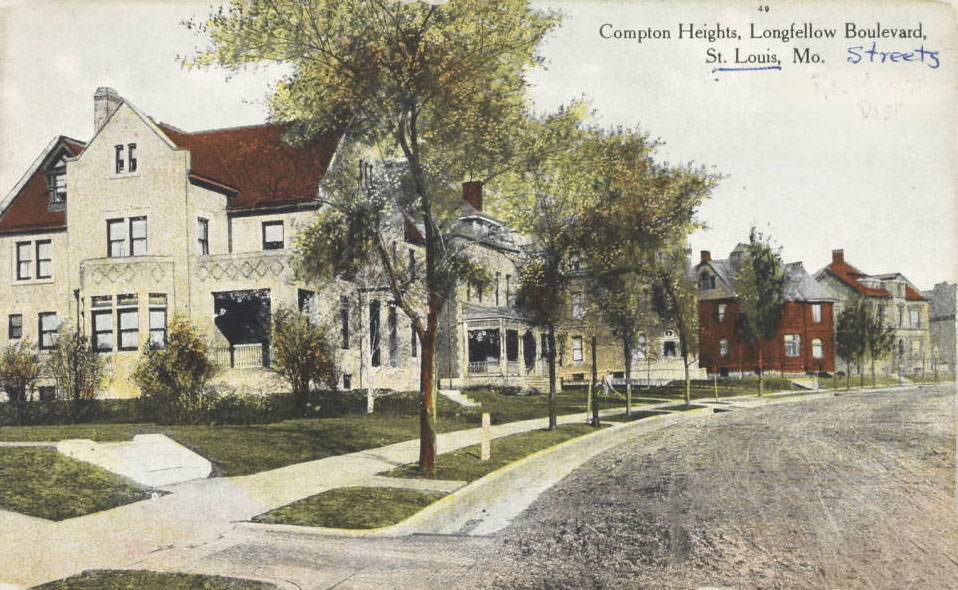

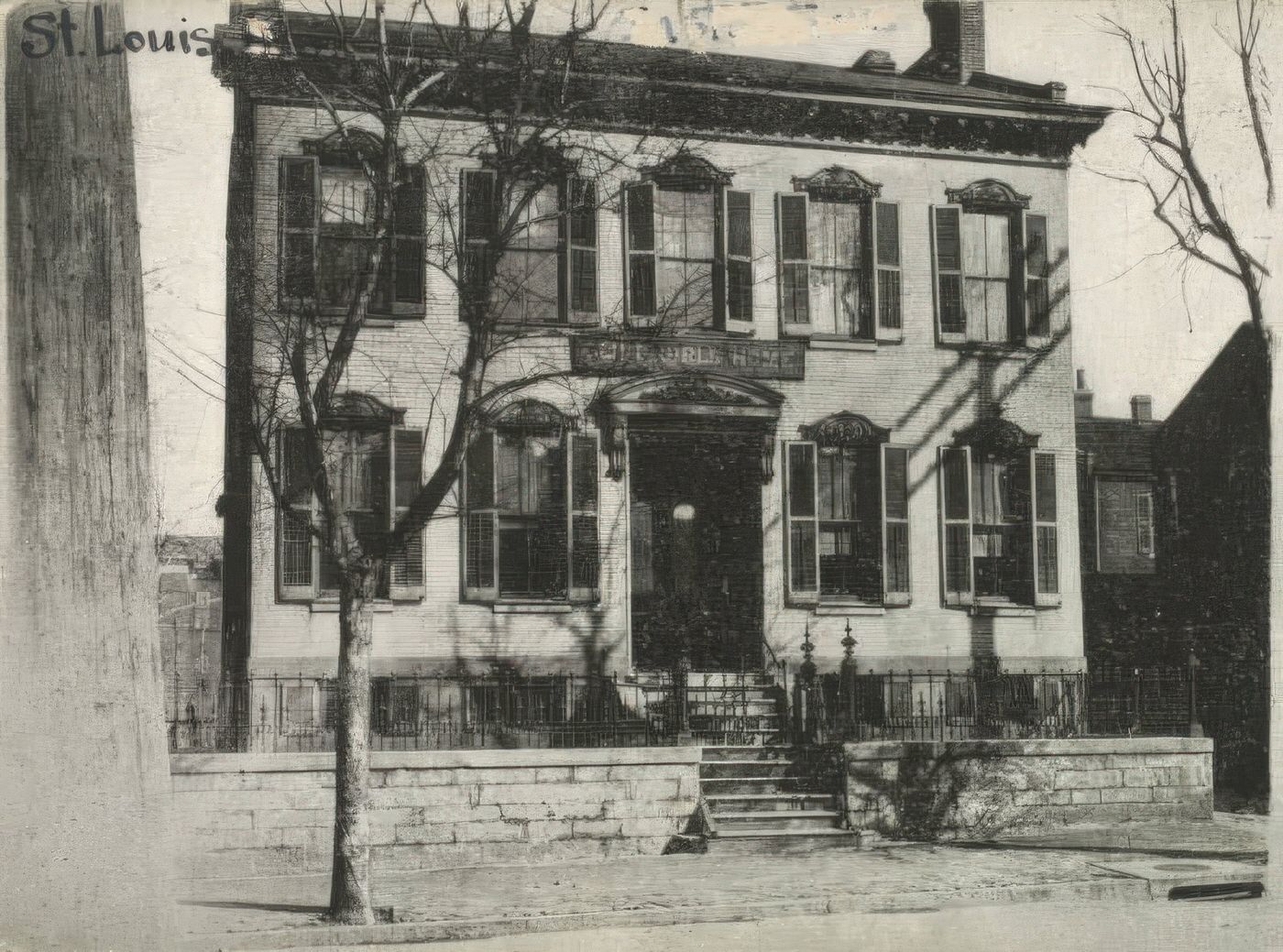

Kerry Patch, though less detailed in the provided materials for the 1910s, was known as a historically Irish neighborhood. Meanwhile, African American communities were concentrated in areas like Mill Creek Valley and The Ville. Mill Creek Valley, with its origins in 18th-century European settlement and 19th-century industrial and railroad development, had become a vital residential and commercial hub for Black St. Louisans by the 1910s. The Ville also grew in prominence as a center of African American life and culture. Dogtown, officially known as Clayton-Tamm, developed as a working-class neighborhood with a strong Irish immigrant presence, its growth spurred by nearby coal mining operations and the 1904 World’s Fair. The housing stock in Dogtown largely consisted of small frame or brick bungalows, many of which were constructed in the subsequent decades but whose community roots were forming in this period. These neighborhoods, each with its unique character shaped by the origins and occupations of its residents, formed the intricate social fabric of St. Louis.

Housing conditions in St. Louis during the 1910s varied dramatically across different social classes and neighborhoods. For many working-class families, immigrants, and African Americans, living conditions were often harsh and unsanitary. At the turn of the century, St. Louis, like many large American cities, contended with overcrowded ethnic tenement slums. A 1908 survey revealed dire sanitation realities: in the city’s poorest districts, there was only one bathtub for every 200 residents. In the densely packed tenements, this ratio was an alarming one bathtub for every 2,479 people. These tenements often lacked basic amenities such as running water, proper ventilation, and private toilets, creating environments where diseases could spread rapidly. Mill Creek Valley, for example, while a vibrant African American community, suffered from deteriorating housing stock, with many homes lacking indoor plumbing.

Public health was a critical issue, directly linked to these living conditions. Streets were often poorly paved and muddy, garbage collection was inadequate, and street lighting could be sparse, contributing to safety concerns. A major health hazard was the pervasive air pollution caused by the widespread burning of cheap, soft coal from nearby Illinois coalfields. This pollution frequently blanketed the city in thick smoke, leading to respiratory problems and even damaging buildings and vegetation. The city’s water supply, drawn from the Mississippi River, was also notoriously polluted with sand and sewage.

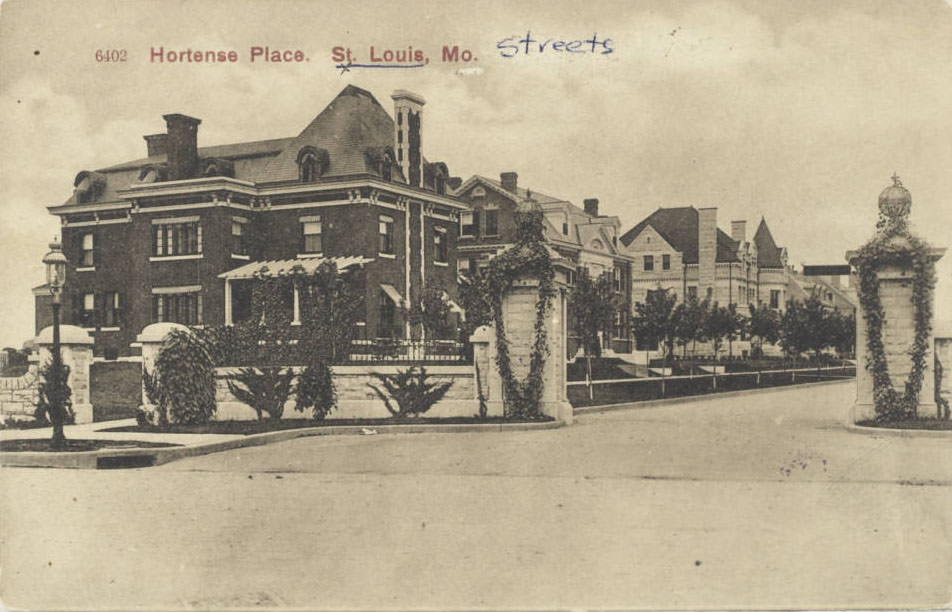

In contrast to these grim realities, new housing developments and architectural styles were emerging, particularly in areas further from the industrial core. Working-class housing included various multi-family structures like row houses, two-family and four-family flats, “triple-deckers,” duplexes, and walk-up apartment buildings, often found in neighborhoods developing along streetcar lines. Distinctive local housing types like shotgun houses and flounder houses were common in older, dense working-class areas such as Soulard. The single-family bungalow was also beginning to appear, particularly in newer neighborhoods like Dogtown. The Progressive Era brought a focus on improving these conditions. City planning efforts aimed to enhance housing quality, and public health initiatives included the establishment of public bathhouses to improve hygiene; Public Bath House No. 3, for example, opened in 1910.

The desire to control neighborhood demographics and maintain property values led to overt efforts to enforce residential segregation. In the early 1910s, white residents in areas bordering African American communities formed the United Welfare Association (UWA) to advocate for a formal segregation ordinance. This culminated in the passage of a city ordinance by a two-thirds majority in a referendum on February 29, 1916. The ordinance stipulated that no individual could move onto a residential block where 75% of the inhabitants were of a different race. This measure made St. Louis the first city in the United States to impose racial segregation in housing through a direct initiative vote.

The passage occurred despite opposition from some civic leaders, Mayor Henry Kiel, and the city’s major daily newspapers. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in St. Louis actively campaigned against the ordinance, distributing pamphlets and filing a lawsuit, though their initial legal challenge within the city was unsuccessful. However, the ordinance’s lifespan was short. A court injunction invalidated it in April 1916, and this was made permanent following the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Buchanan v. Warley in 1917, which declared such municipal segregation ordinances unconstitutional. Despite this legal victory against de jure segregation, the drive to separate housing along racial lines persisted. In the aftermath of the ordinance’s failure, racially restrictive covenants written into property deeds became a common tool to prevent African Americans from purchasing or occupying homes in white neighborhoods. This practice would continue to shape St. Louis’s residential patterns for decades.

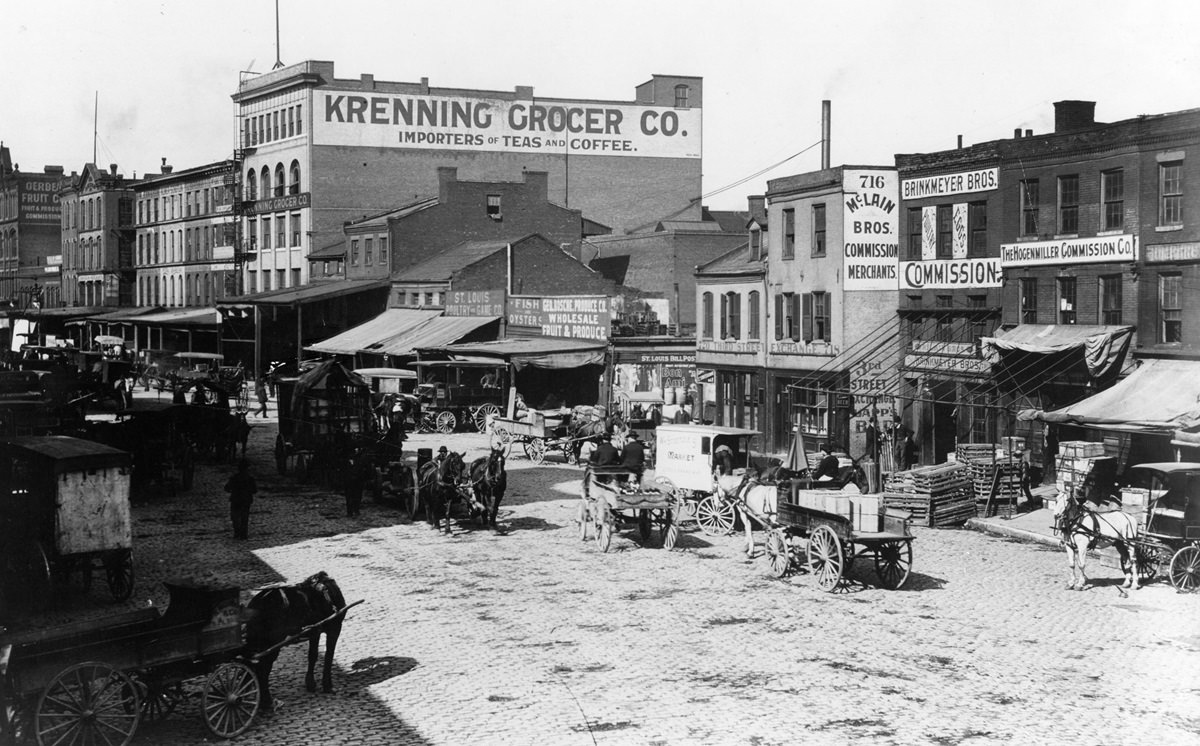

The Engine of St. Louis: Industry, Work, and Labor

St. Louis in the 1910s was an industrial powerhouse, its economy driven by a diverse range of manufacturing sectors. Brewing remained a cornerstone of the city’s identity and economy. Anheuser-Busch, which had its origins as the Bavarian Brewery in 1852, was a dominant force. Under the leadership of Adolphus Busch, who became president in 1880, the company had pioneered innovations like pasteurization and the use of refrigerated railroad cars, allowing for widespread distribution. The company continued its expansion in the new century, building a new stockhouse in 1905 and reaching a production of nearly 1.6 million barrels of beer by 1907. As the decade progressed and the shadow of Prohibition loomed, Anheuser-Busch began to diversify by producing non-alcoholic beverages, most notably “Bevo,” a malt beverage introduced in 1908. The Lemp Brewery was another major brewery contributing to the city’s reputation, built upon a strong German immigrant heritage and fondness for beer.

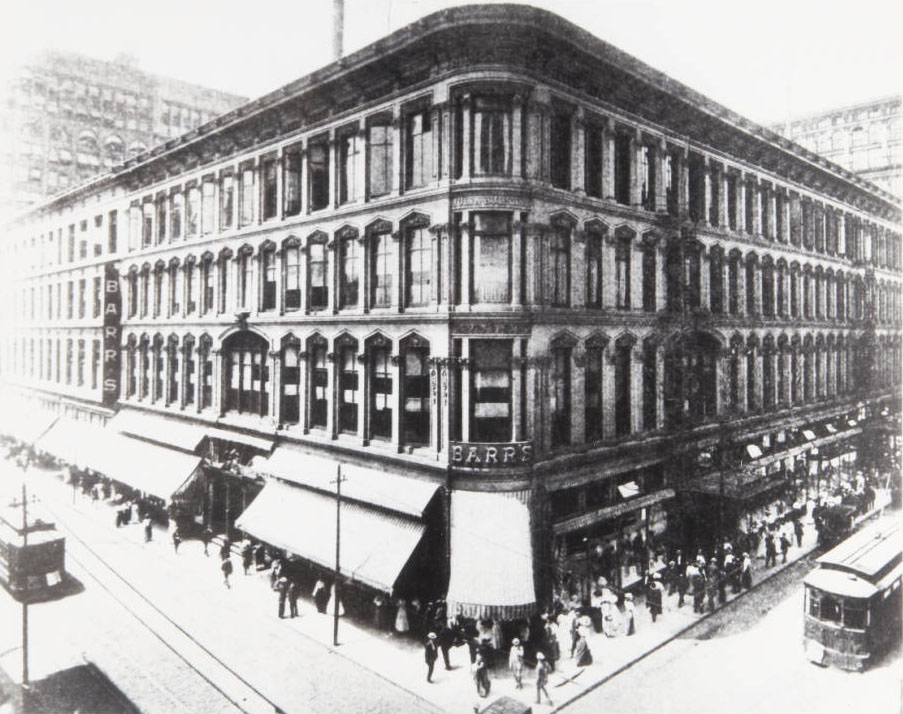

Shoe manufacturing was another leading industry, with St. Louis ranking as one of the nation’s largest production centers in the early 20th century. Giants like the International Shoe Company (ISC), headquartered in the city and for many decades the world’s largest shoe manufacturer, and the Brown Shoe Company, operated numerous factories and employed thousands. Many of these factories had been constructed around the turn of the century. The garment industry also thrived, with Washington Avenue serving as a major hub for clothing manufacturing.

The electrical goods industry was a significant and growing sector. Emerson Electric, founded in 1890, produced electric motors and fans, while Wagner Electric, established in 1891, manufactured a range of electrical equipment including engines, motors, automotive starters, and lighting. Century Electric Company, which began selling custom-built motors in 1900, quickly grew to become one of the “big three” electrical manufacturers in St. Louis, known for innovations like repulsion type motors that made early household appliances possible.

The historic fur trade continued to be a vital part of the St. Louis economy, experiencing a renaissance that positioned the city as a global fur center during the 1910s. Furs from across North America, including Alaska and Canada, were channeled through St. Louis. By the 1912-1913 harvesting season, the value of furs sold in the city reached approximately $12 million. Federal policies, such as the Fur Seal Act of 1910 and the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911, along with the influence of local fur magnates like Philip Fouke of Funsten Brothers, helped cement St. Louis’s dominance. Fouke successfully lobbied for government-regulated fur harvests to be sold through St. Louis instead of London, and the St. Louis Fur Exchange was established in 1916.

Beyond key industrial sectors, St. Louis had a diversified manufacturing base. Food processing was prominent, with companies like Ralston Purina (founded in 1894 by William H. Danforth) expanding from horse and mule feed into cereals and other animal feeds, gaining significant exposure at the 1904 World’s Fair. Switzer’s Licorice Company was a well-known local confectioner. The Pet Milk Company, though officially named in 1923, had its origins earlier and supplied evaporated milk during World War I. The chemical industry was also growing, with Monsanto Chemical Works, founded in 1901 by John Francis Queeny, initially producing food additives like saccharin, caffeine, and vanillin before expanding into industrial chemicals later in the decade and into the 1920s. Mallinckrodt Chemical Works was another key chemical producer, manufacturing pharmaceuticals like morphine and codeine, as well as chemicals for industry and photography, such as barium sulfate for X-ray diagnoses. Steelmaking and the production of automobile parts for companies like Ford and General Motors, alongside local brands such as the Dorris Motor Company, further contributed to the industrial landscape. Factories like the American Brake Company (with its office built in 1901 and a factory addition in 1919) and the Hall and Brown Woodworking Company (1910) exemplified the varied manufacturing activities taking place.

he daily lives of St. Louis workers in the 1910s were shaped by the demands of these industries. National employment data from 1910 to 1920 indicated a shift, with growth in professional, managerial, clerical, sales, and service occupations, while traditional laboring and farming jobs saw declines. In St. Louis, specific wage information from the era shows variation. A 1914 study documented wages for African American workers across different jobs, and city employee salaries for 1913 were also recorded. Data on hourly wages for certain skilled trades in St. Louis between 1913 and 1920 exists, as does information for the Missouri shoe industry (1913-1922). While detailed city-wide wage and hour statistics for all sectors in St. Louis during the 1910s are not fully available in the provided information, national figures for manufacturing sectors prominent in St. Louis, such as clothing (including boot and shoe manufacturing) and textiles, offer a general sense of pay scales. Working conditions were often challenging by modern standards. Long hours were typical, and nationally, child labor persisted, even in hazardous occupations, though this was more prevalent outside major urban centers like St. Louis city.

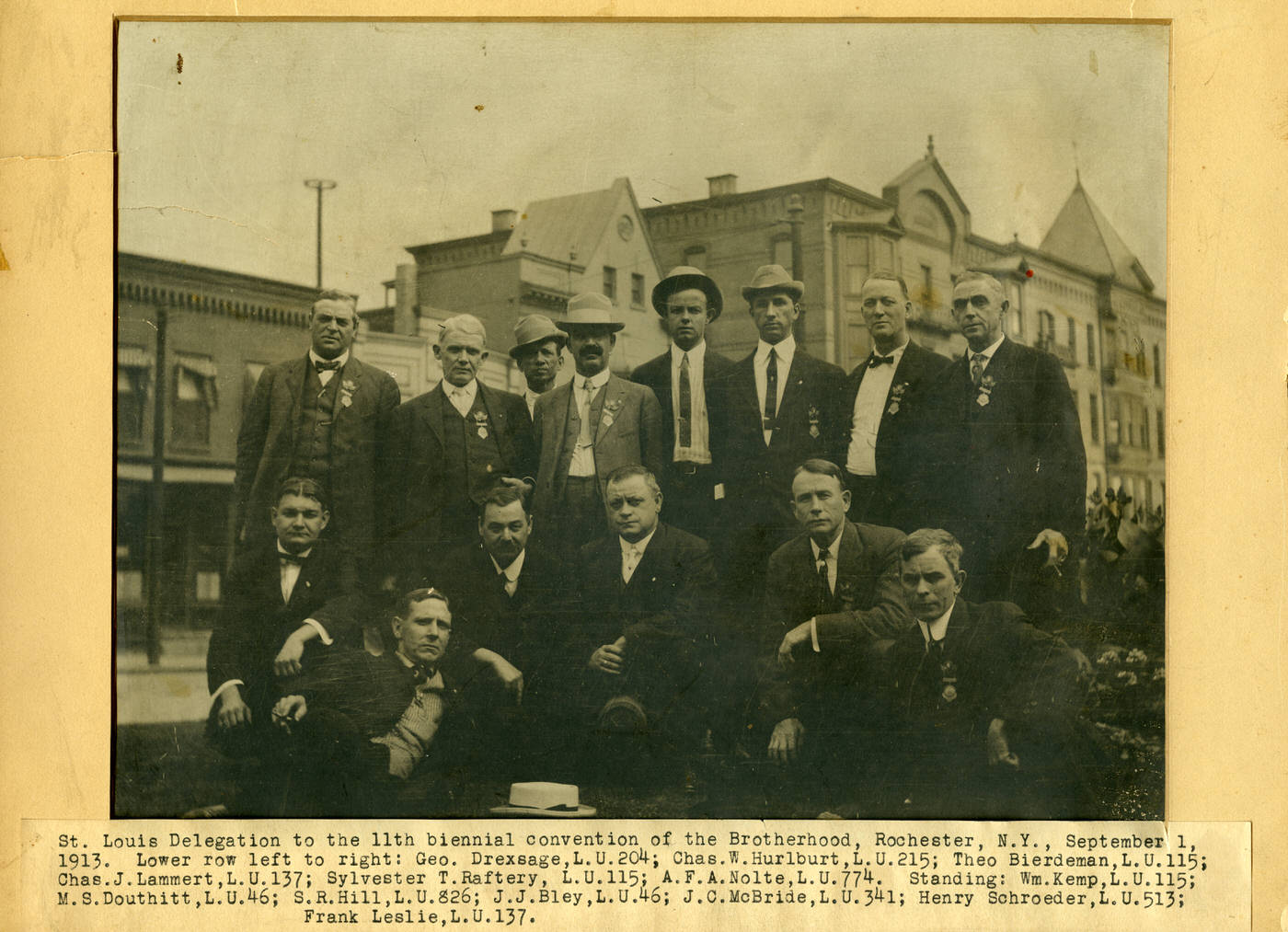

In response to these conditions, St. Louis had a well-established labor movement by the 1910s. Workers organized to advocate for better wages, shorter working hours, and improved safety on the job. The St. Louis Trades and Labor Assembly, formed in 1887 through the merger of earlier labor groups, was a significant force. By 1893, its membership had reached 35,000 and included diverse groups such as the Women’s Trade Union, the Ladies Garment Workers Union, and the Colored Waiters Union. This assembly had a history of supporting major industrial actions, including the notable Streetcar Men’s Union Railway Strike of 1900. Records from the St. Louis Labor Council, affiliated with the AFL-CIO, begin in 1913, indicating continued organized labor activity throughout the decade. The national “Eight Hour” movement, advocating for a shorter workday, also had a presence and support among St. Louis trade unions. Nationally, industries like coal mining, iron and steel, and textiles had strong unions. The increasing migration of African Americans to northern cities like St. Louis between 1910 and 1920, often to fill labor demands, also influenced the dynamics of the labor market and union organization. These labor activities were part of a broader Progressive Era push for social and economic reform.

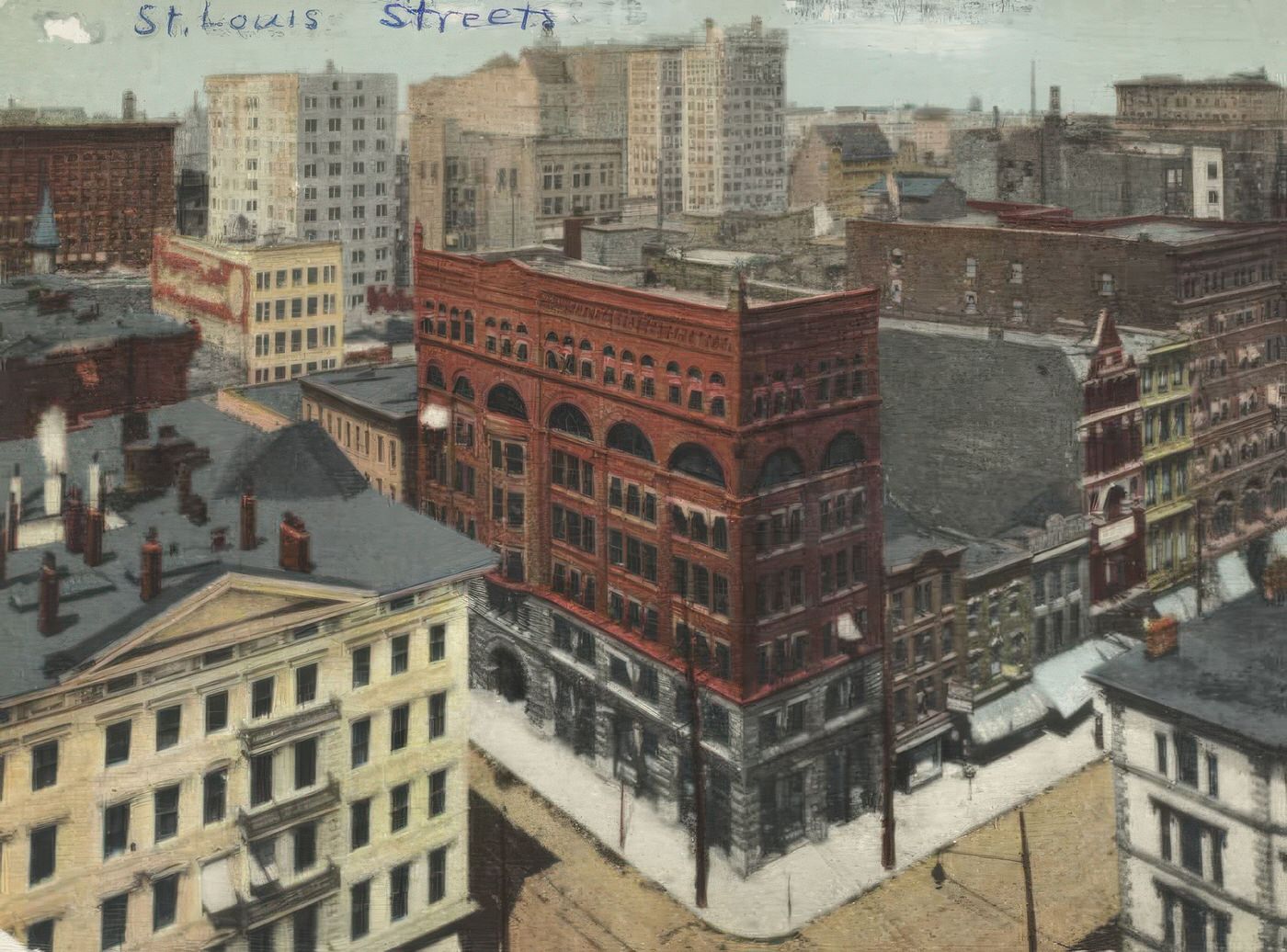

Shaping the City: Urban Growth and Modernization

The 1910s were a period of significant transition in St. Louis’s transportation landscape, as established modes of transit contended with the rise of new technologies. Streetcars remained the backbone of public transportation. United Railways operated the extensive system, which had been consolidated from various independent lines by 1903, with the St. Louis and Suburban line joining in 1907. The company continued to manage and adapt its services throughout the decade. The last physical extension of a streetcar line by United Railways occurred in 1916, adding two miles to an existing route. During the 1910s, United Railways also updated its rolling stock, replacing some older streetcars with new ones built in-house. These newer cars maintained the style of the popular World’s Fair-era cars but featured different exterior appearances. An example of streetcar infrastructure development was the Wellston Station, an Arts and Crafts style depot constructed around 1910 at 6111 Dr. Martin Luther King Drive. This station served the growing turn-of-the-century suburb of Wellston, located on the northwestern edge of the city.

The automobile, however, was rapidly emerging as a transformative force. Nationally, car ownership began to climb after 1910 as mass production techniques, pioneered by figures like Ransom Olds and Henry Ford, made vehicles increasingly affordable for the average consumer. St. Louis was an early participant in this automotive revolution, developing into a center for automobile manufacturing, sales, and service. During the first three decades of the 20th century, the city was home to a remarkable 219 car manufacturing companies, although many of these were small-scale operations. One such local manufacturer was the Dorris Motor Car Company, organized by George Dorris in 1905. The proliferation of automobiles necessitated new types of urban structures, leading to the construction of dedicated automobile showrooms, filling stations, and parking garages.

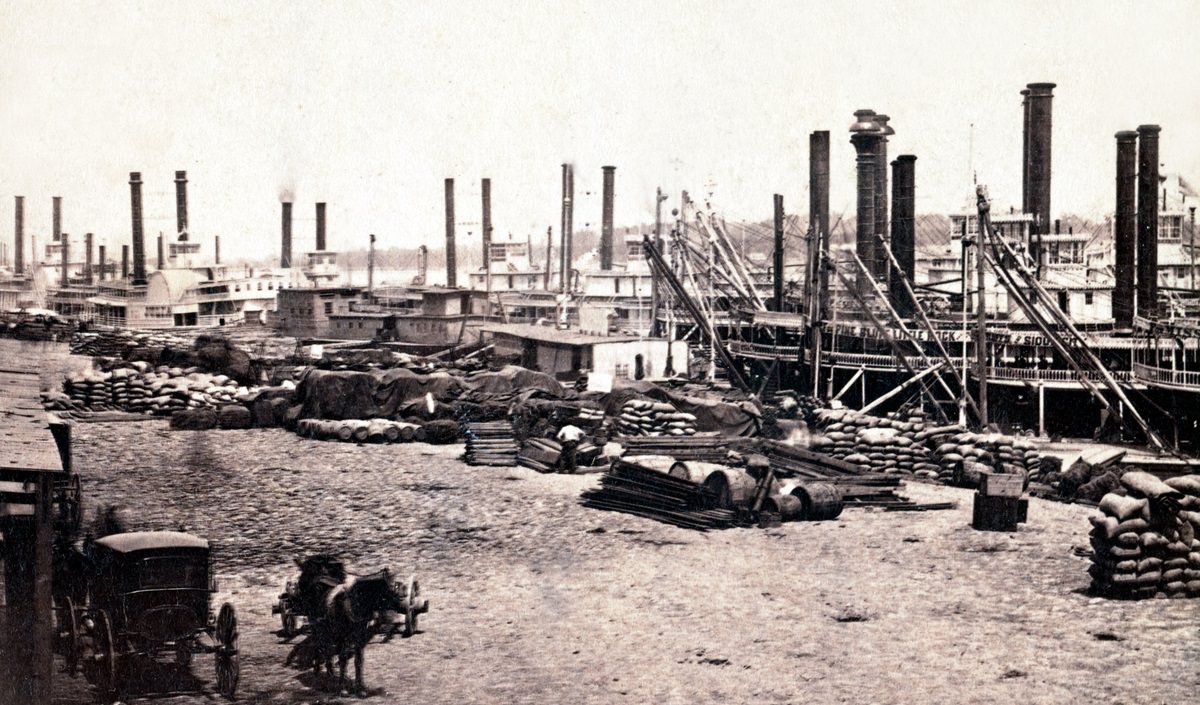

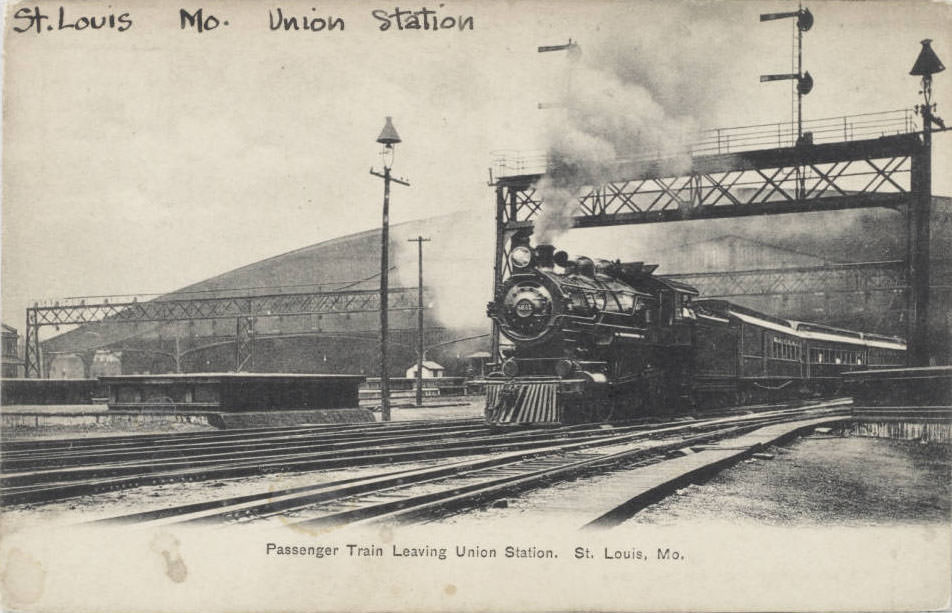

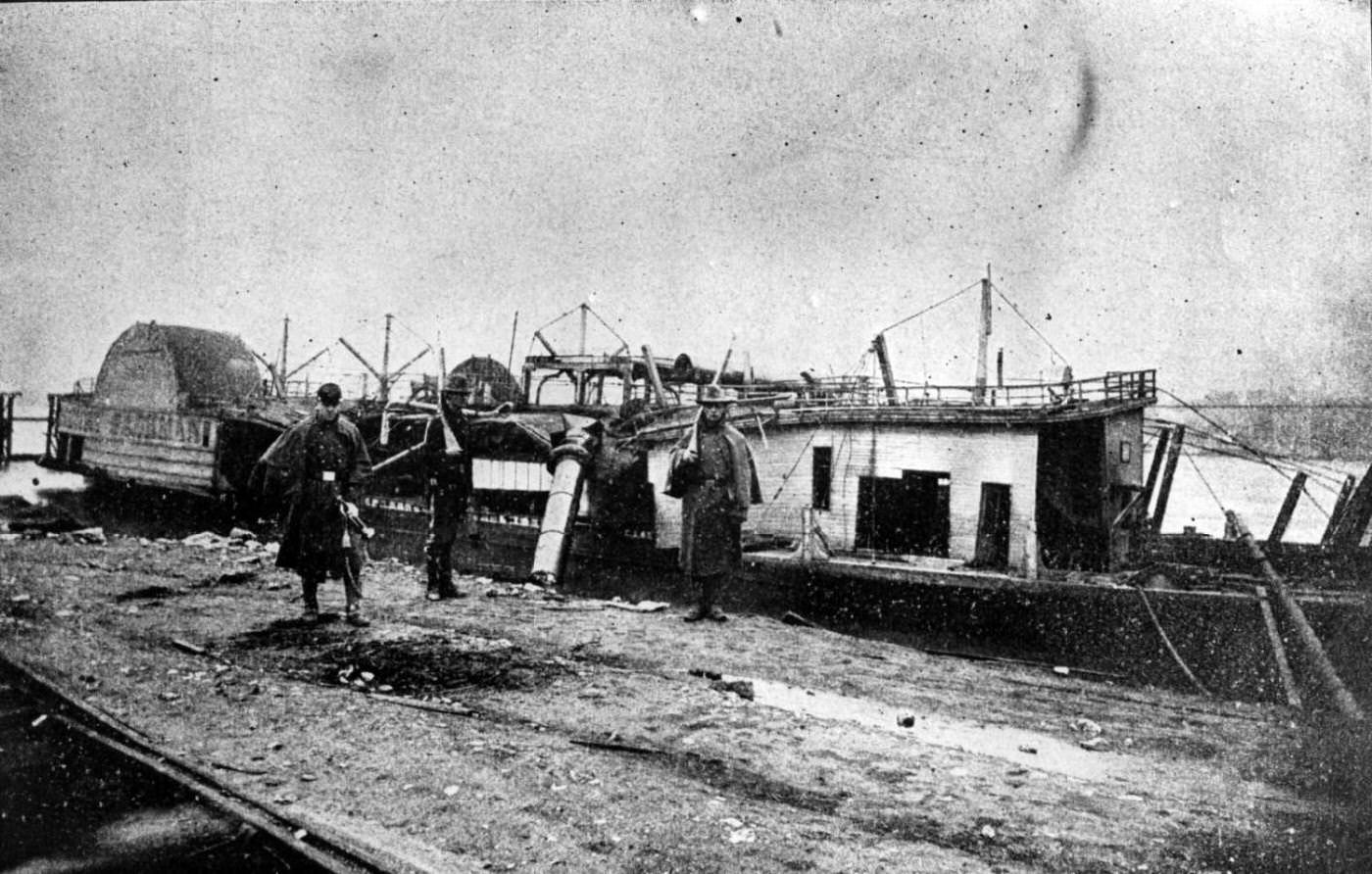

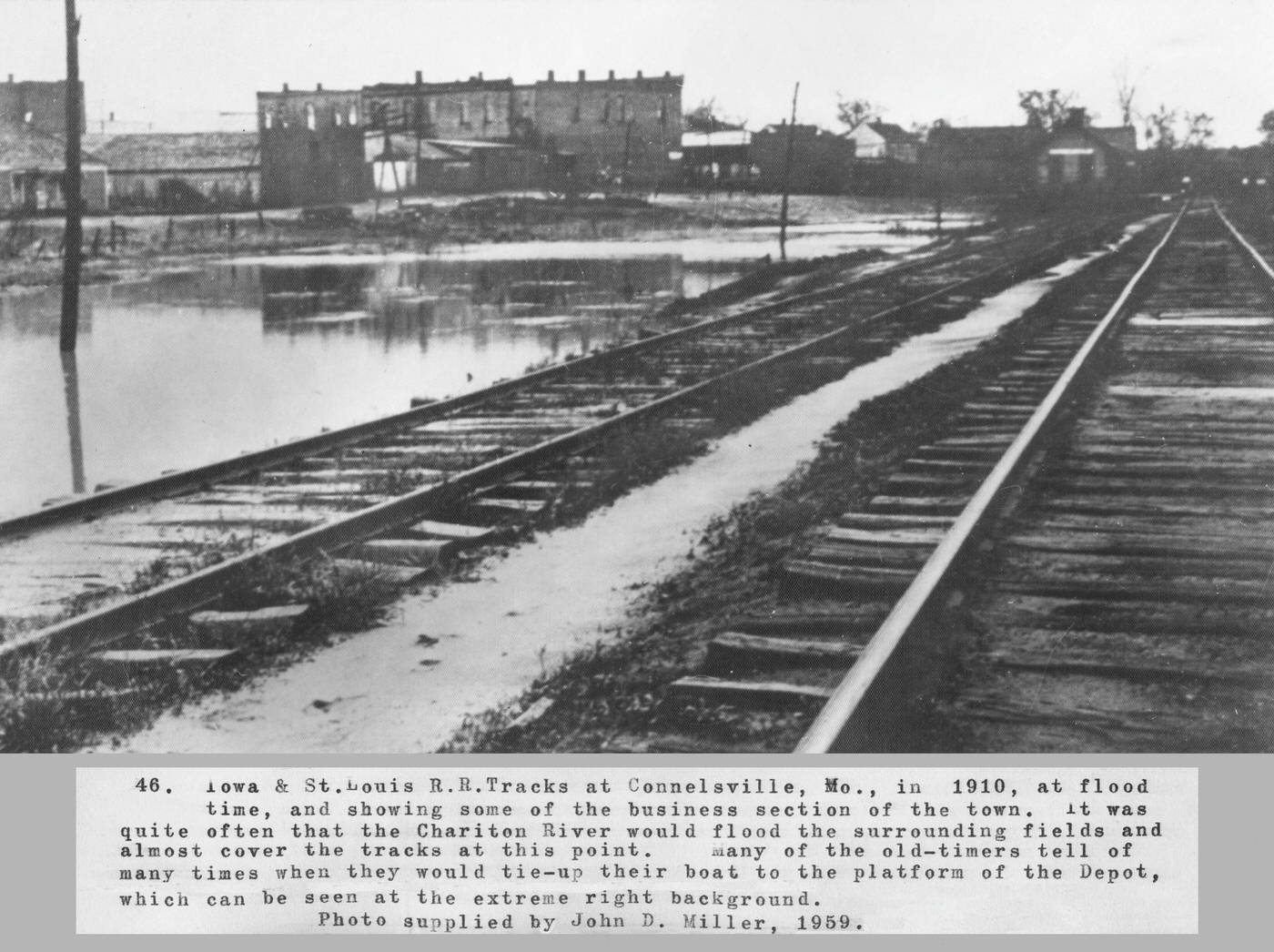

Railroads maintained their critical role in St. Louis for both passenger and freight transport. The city’s Union Station was a major national rail hub. A significant infrastructure project of the era was the Municipal Free Bridge. Construction began intermittently between 1907 and 1910, driven by a civic desire to break the perceived monopoly of the Terminal Railroad Association, which owned the existing Eads and Merchants Bridges. After facing financial and political delays, the highway deck of the Municipal Free Bridge finally opened to traffic on January 20, 1917. Its primary purpose was to offer railroads free use, thereby compelling a reduction in tolls on the other bridges, particularly for crucial commodities like coal. The Eads Bridge, a marvel of 19th-century engineering, continued to serve the city, carrying streetcars, carriages, and increasingly, automobiles on its upper deck, while its lower deck accommodated rail traffic. However, its relative importance for rail began to diminish as newer bridges were constructed. The convergence of these transportation modes – the mature streetcar system, the ascendant automobile, and the enduring railroads – defined St. Louis’s urban mobility in the 1910s, presenting both opportunities for growth and challenges for city planners.

The growth of St. Louis in the 1910s necessitated significant investment in urban infrastructure. The city actively worked to modernize its physical foundations to support its expanding population and industrial base. Street paving was a key area of development. While many St. Louis streets were unpaved and often muddy in the 19th century, by the 1910s, improvements were being made. Creosoted wood blocks, set in a Portland cement bed, represented an advancement in paving technology, offering a more durable surface than earlier materials. The increasing popularity of the automobile during this decade further underscored the need for all-weather, surfaced roads.

The city’s sewer system, much of which dated to the early 1900s, also underwent crucial development. A major undertaking was the transformation of the River Des Peres. This natural waterway had long been used as an open sewer, receiving wastewater and stormwater drainage, leading to unsanitary conditions. In 1910, Mayor Frederick Kreismann announced an ambitious $4 million plan to create a permanent enclosure for the river channel from the city limits down to Manchester Avenue. Although this comprehensive plan was initially deemed too costly for immediate full implementation, progress was made in sections. A significant $1 million project to separate sewage from stormwater along the stretch of the River Des Peres from Lansdowne Avenue to the Mississippi River was completed by 1913. This section, an open channel, was the first part of the larger River Des Peres engineering project that remains in place today. These efforts marked the beginning of a multi-decade civil engineering endeavor to manage the city’s wastewater and mitigate flooding.

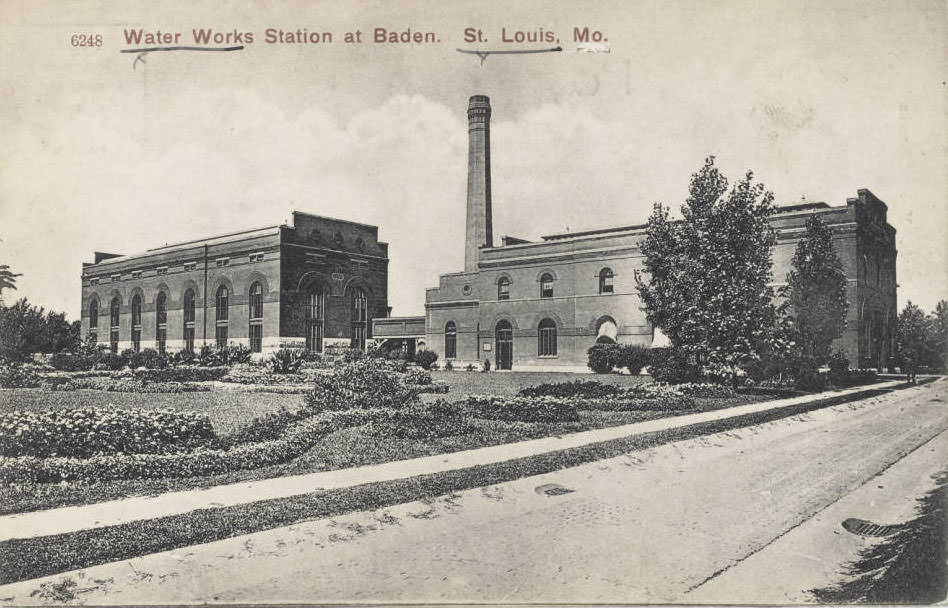

Essential utilities also saw expansion and modernization. The St. Louis Water Works enhanced its facility at Chain of Rocks Park with the construction of Water Intake Tower No. 2 in the Mississippi River in 1913. This impressive structure, designed by Roth and Study in the Renaissance Revival style, was built of white limestone and played a vital role in securing the city’s water supply. Electric power generation was critical for the city’s industries and growing residential areas. The Union Electric Light and Power Company, a major provider, had established ornate facilities like its Renaissance Revival building from 1902, and smaller generating plants, such as the one at 1711 Locust Street (1903), were built to power the streetcar system. The Laclede Gas Light Company was the primary supplier of gas for lighting and heating, and Southwestern Bell was expanding telephone service, though specific 1910s activities for the latter two are less detailed in the information provided. These infrastructure projects were fundamental to St. Louis’s ability to function and grow as a modern industrial city.

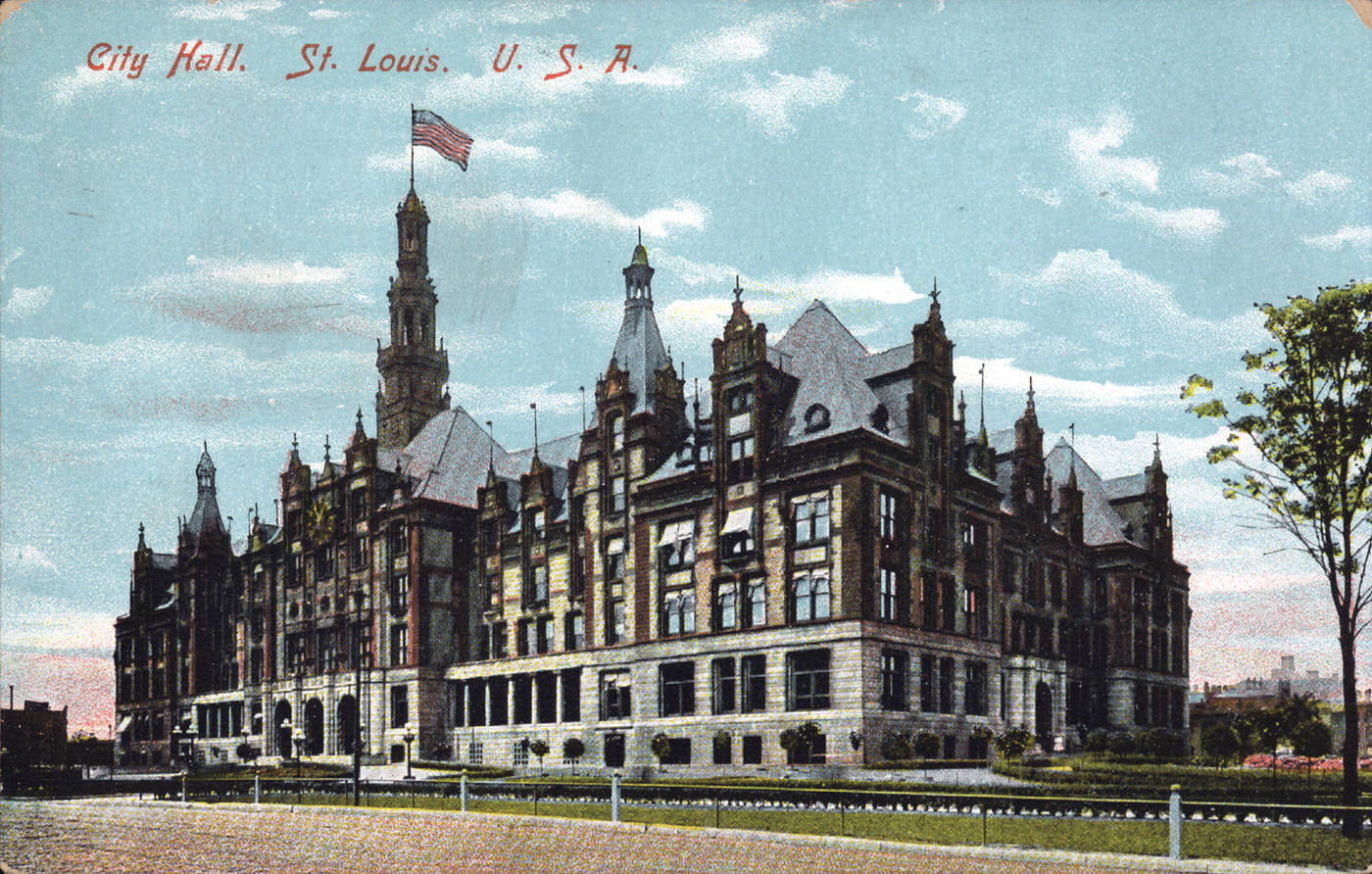

The 1910s were a period of significant intellectual and civic ferment regarding the future shape of St. Louis, deeply influenced by the national Progressive Era movement. This movement aimed to improve the quality of American life, particularly in rapidly industrializing and diversifying urban centers. In St. Louis, these ideals translated into a burgeoning city planning effort. The St. Louis Civic Improvement League, founded in 1901, laid the groundwork for these endeavors. This was followed by the formal establishment of the St. Louis City Plan Commission by city ordinance in 1911, which grew out of the Civic League’s initiatives.

One of the earliest comprehensive visions for the city was “A City Plan for St. Louis,” published by the Civic League in 1907. This plan was ambitious, proposing the creation of a public buildings group, the development of neighborhood civic centers, a system of interconnected parks and parkways, and substantial improvements to the major street grid, the riverfront, and railway infrastructure. Many of these proposals became guiding principles for the City Plan Commission’s work in the subsequent decade. In 1916, the city brought in Harland Bartholomew, who would become one of the nation’s most influential city planners, to direct the Commission and spearhead its efforts.

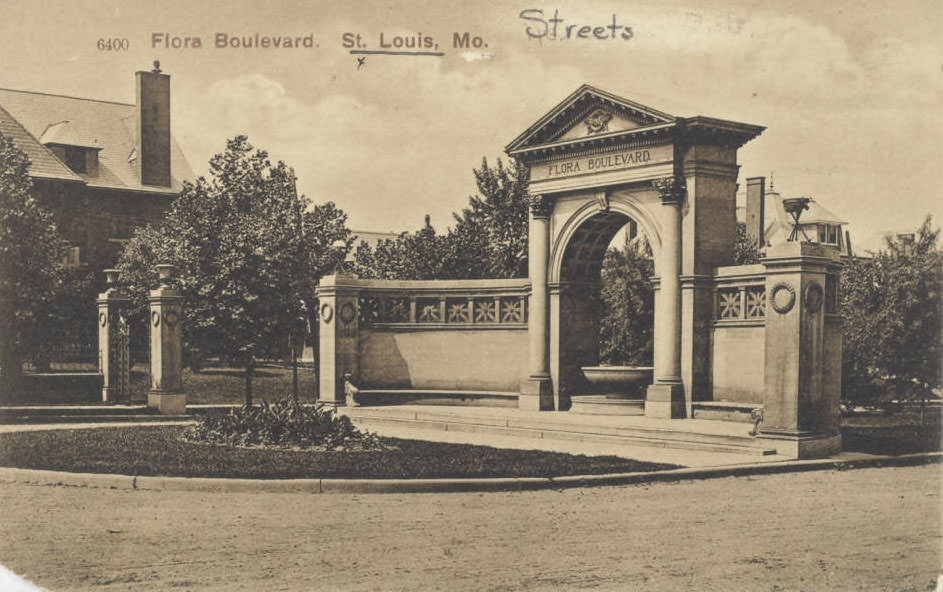

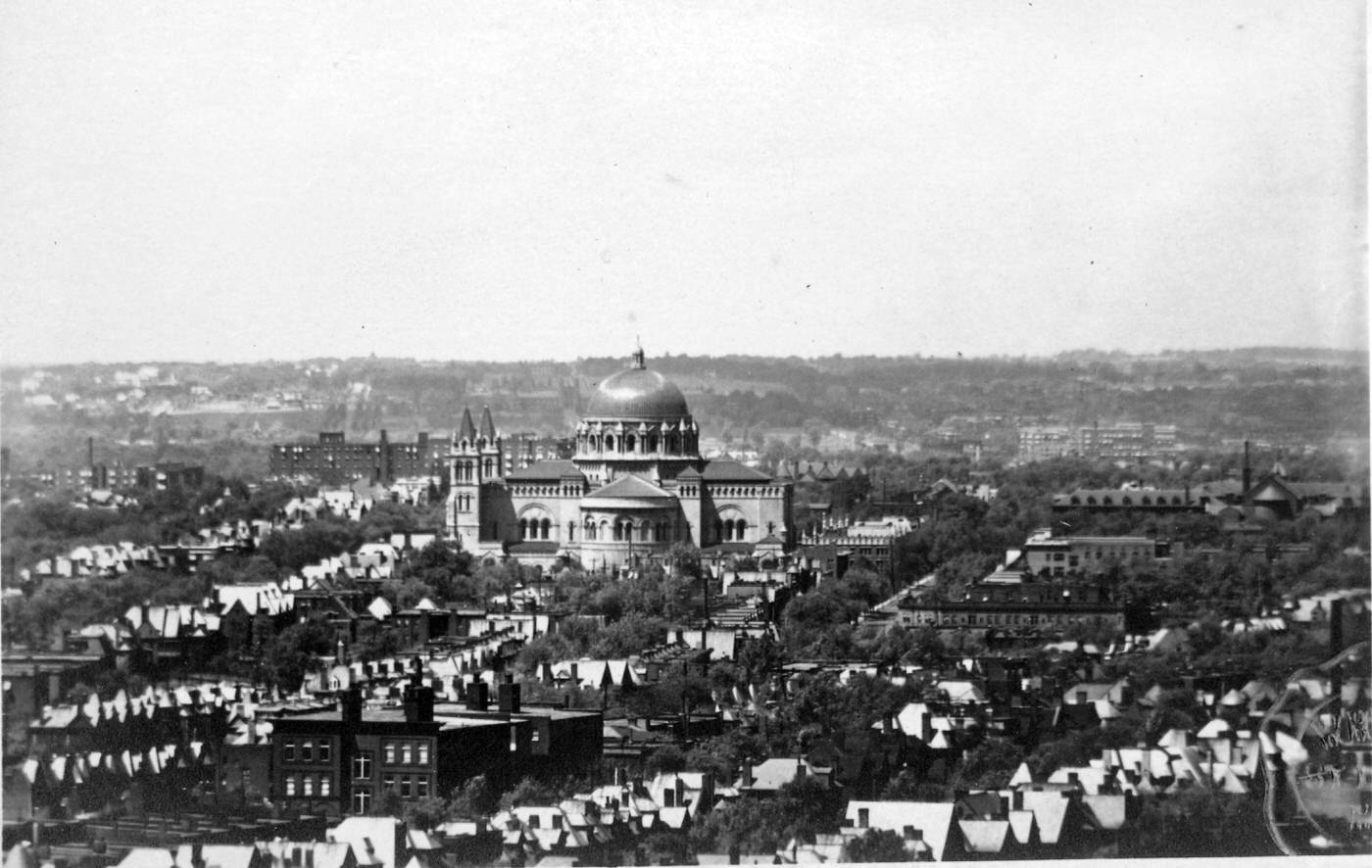

The City Beautiful movement, which gained prominence after the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and was further reinforced by St. Louis’s own 1904 World’s Fair, heavily influenced the aesthetic direction of these planning efforts. This movement advocated for grand, orderly, and aesthetically pleasing urban environments, often drawing on Beaux-Arts Classicism for the design of public buildings and finer residential areas. In St. Louis, this architectural style found expression in the elegant private streets of the Central West End.

The overarching goals of city planning in the 1910s were multifaceted: to enhance the quality of housing, to beautify downtown areas and city parks, and to improve public transportation, recreational facilities, and cultural life. A landmark achievement of these efforts was the 1918 zoning plan. This plan was a pioneering attempt to segregate industrial land uses from residential areas, aiming to create more livable neighborhoods. In adopting such comprehensive industrial and residential zoning, St. Louis was second only to New York City among major American urban centers. These planning initiatives of the 1910s laid a critical foundation for the city’s 20th-century development, seeking to manage growth, address social issues, and create a more functional and visually appealing urban landscape.

Life and Leisure in the Gateway City

The 1910s saw St. Louisans enjoying a growing array of leisure and recreational opportunities, with significant developments in public parks and entertainment venues. Forest Park, already a vast green space, became a focal point for these activities. Under the leadership of Parks Commissioner Dwight F. Davis, who took office in 1911, the park’s recreational facilities were notably expanded. In 1912, St. Louis’s first official public golf course opened in Forest Park, a facility that was soon enlarged to 18 holes, with an additional nine-hole course added later to meet demand. Davis, an avid proponent of athletics, also oversaw the construction of 32 public tennis courts within the park. Even before the formal establishment of some of its iconic institutions, Forest Park was a place where families gathered for picnics and to enjoy outdoor musical events.

A major addition to Forest Park was the St. Louis Zoo. The effort to establish a permanent zoo gained momentum with the formation of the St. Louis Zoological Society in 1910. This group raised funds and lobbied the city for the zoo’s creation. Their efforts were bolstered by the support of Mayor Henry Kiel, elected in 1913. The city allocated 77 acres within Forest Park for the zoo, and in October 1916, a dedicated zoo tax was passed, ensuring ongoing funding for its maintenance and development. One of the early significant animal exhibits, the bear pits, was completed in 1919 with design assistance from the renowned animal enclosure designer Carl Hagenbeck.

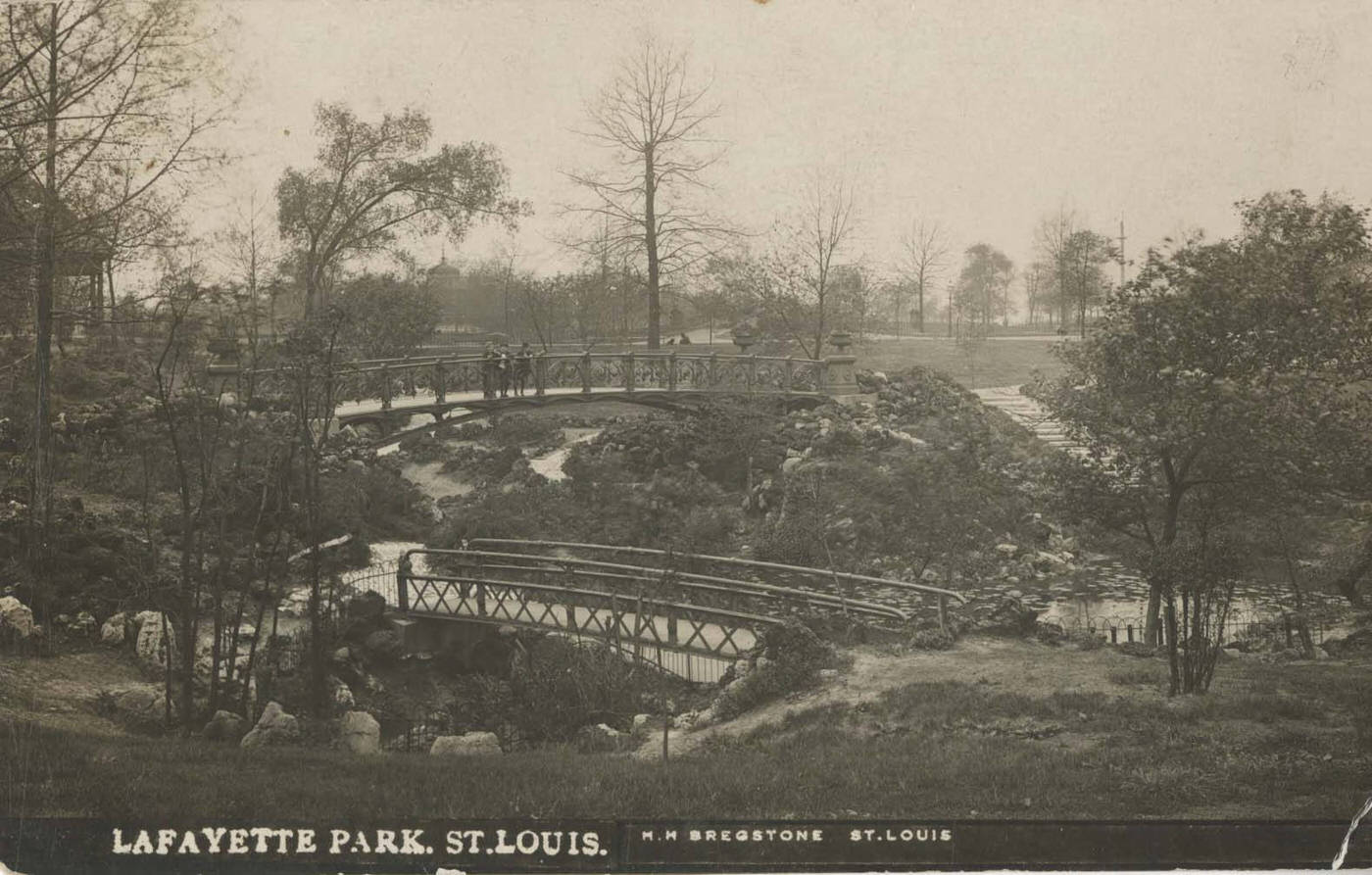

Another cultural cornerstone of Forest Park, the Municipal Theatre, or “The Muny,” was founded in 1917. A coalition of civic leaders and arts supporters raised the funds and public interest to construct the impressive 10,000-seat outdoor amphitheater. The vision for such an outdoor venue had roots tracing back to the 1904 World’s Fair. The Muny staged its first productions, the operas “Aida” and “I Pagliacci,” in 1917, and its official summer season commenced in 1919, establishing a tradition of offering free seats to the public alongside ticketed ones. Beyond Forest Park, Tower Grove Park, which had officially opened in 1872, continued to serve as a significant and well-preserved 19th-century Gardenesque style city park for residents.

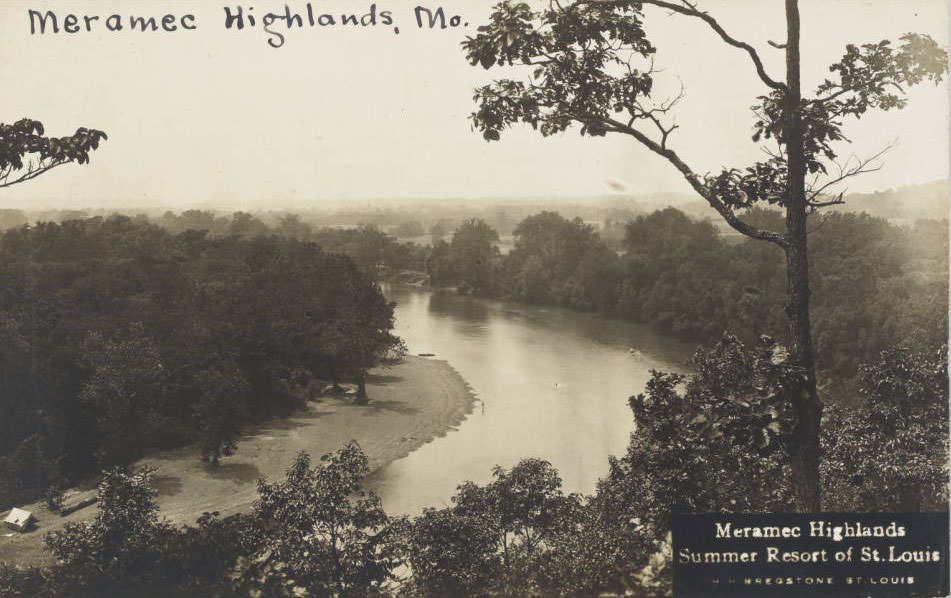

Entertainment options in St. Louis during the 1910s were diverse and evolving. Amusement parks offered popular family entertainment. Delmar Garden Amusement Park, situated at the end of the Delmar streetcar line, had opened around the turn of the century and remained a favored destination through the late teens. It featured a variety of rides, entertainment venues, and places to eat and drink. Forest Park Highlands, which began as a beer garden in 1896, also flourished as an amusement park, boasting attractions like a pagoda from the 1904 World’s Fair, a Ferris wheel, a miniature railway, and various rides and games. It was a common destination for school picnics and family outings.

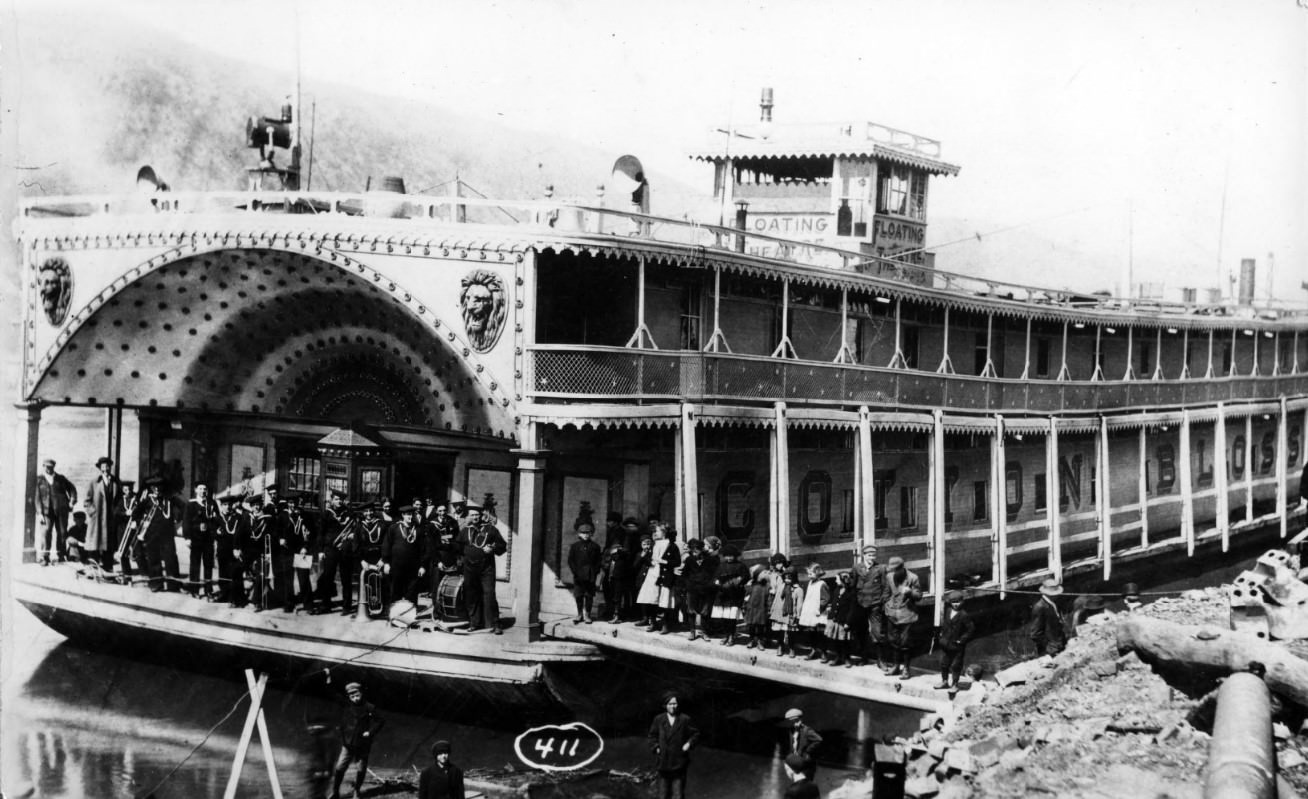

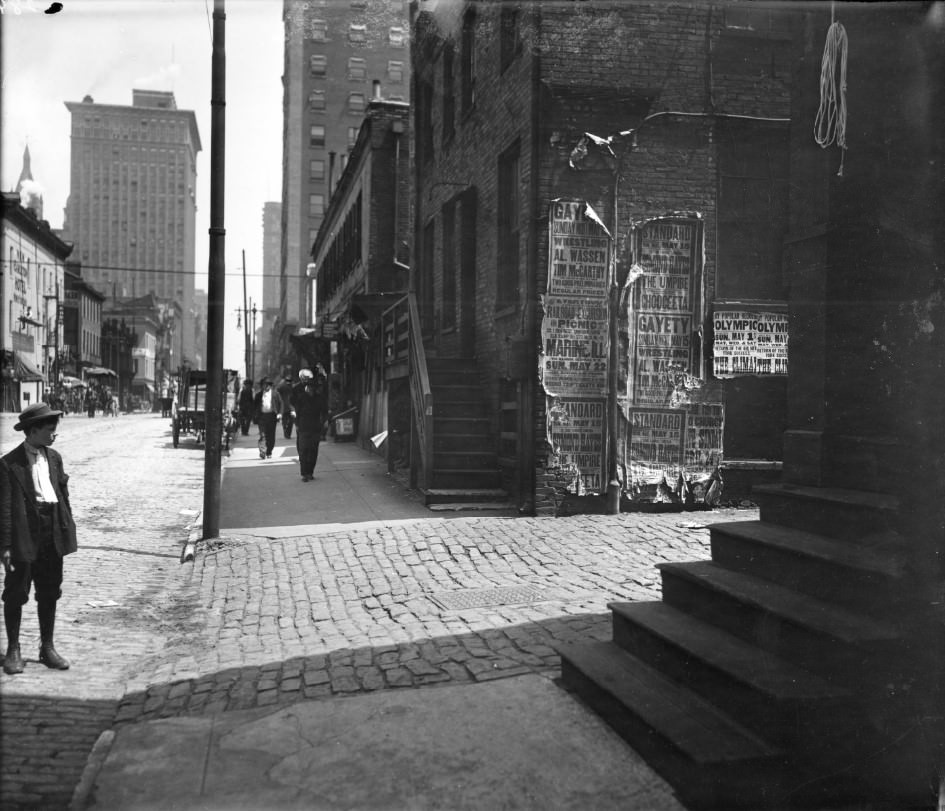

Vaudeville was a dominant form of live entertainment, with shows that appealed across economic and ethnic lines. St. Louis had a vibrant theater scene catering to this popularity. The Garrick Theater, which opened in 1904, presented high-class vaudeville and drama throughout the 1910s. The American Theater, opened in 1908, initially as a vaudeville house, transitioned to presenting dramas by 1917. The Shubert Theater, inaugurated in 1910, specialized in musical theater. The Grand Opera House was reconstructed and reopened in 1913, featuring vaudeville acts. Adding to the city’s vaudeville offerings, the Orpheum Theater opened its doors in 1917. Other venues like the Princess Theater (1910) and the Empress Theater (1913) also contributed to the lively vaudeville circuit.

The 1910s also marked the ascent of a new form of entertainment: motion pictures. Initially viewed as novelties or as acts within vaudeville shows, movies quickly gained popularity and dedicated venues. By 1913, the St. Louis City Directory listed over one hundred establishments where films could be seen, the majority being neighborhood movie houses. This decade witnessed the beginning of the “movie palace” era nationally, with larger and more ornate theaters being constructed specifically for film exhibition. The burgeoning film industry was rapidly transforming how St. Louisans, and Americans generally, spent their leisure time.

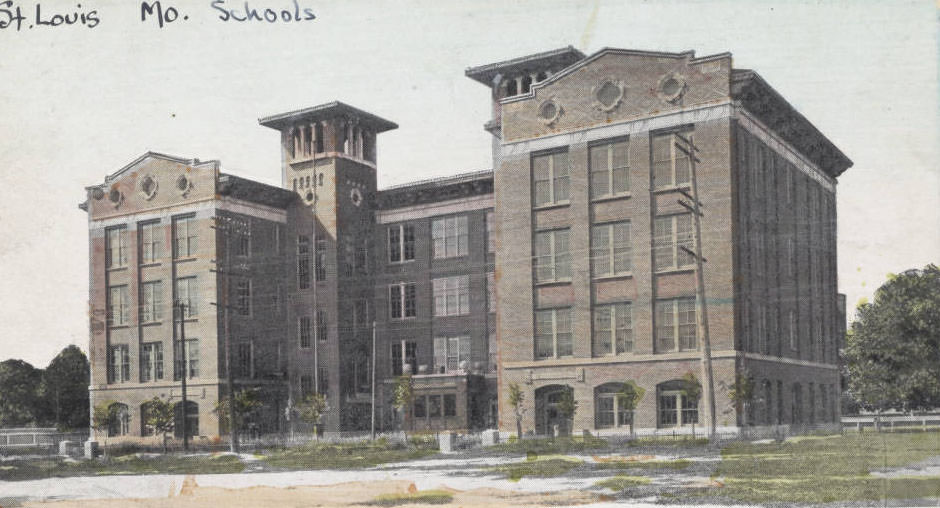

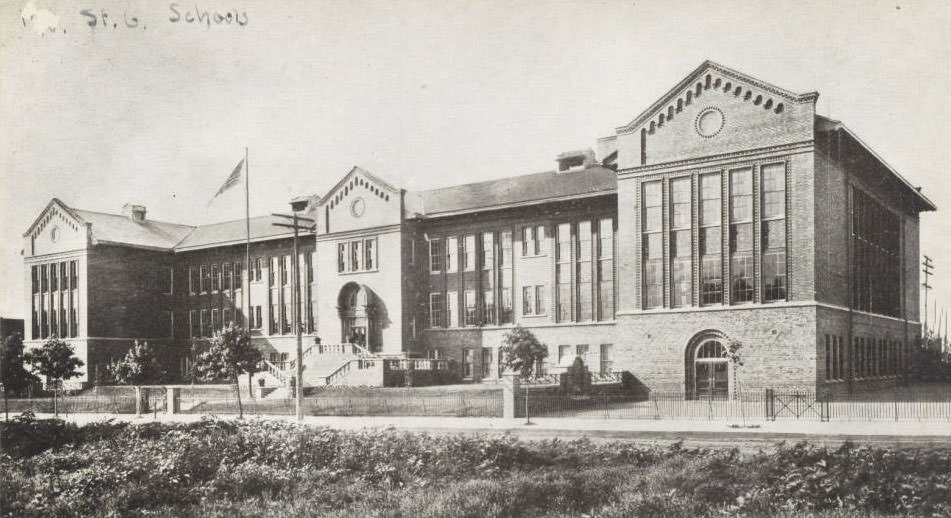

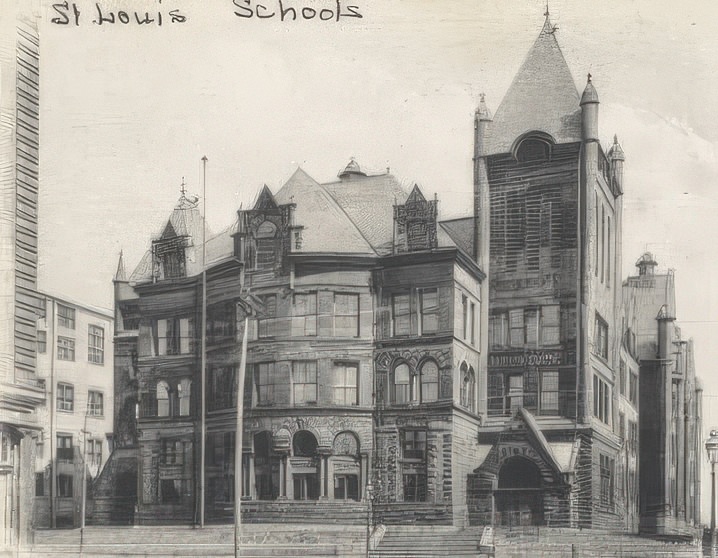

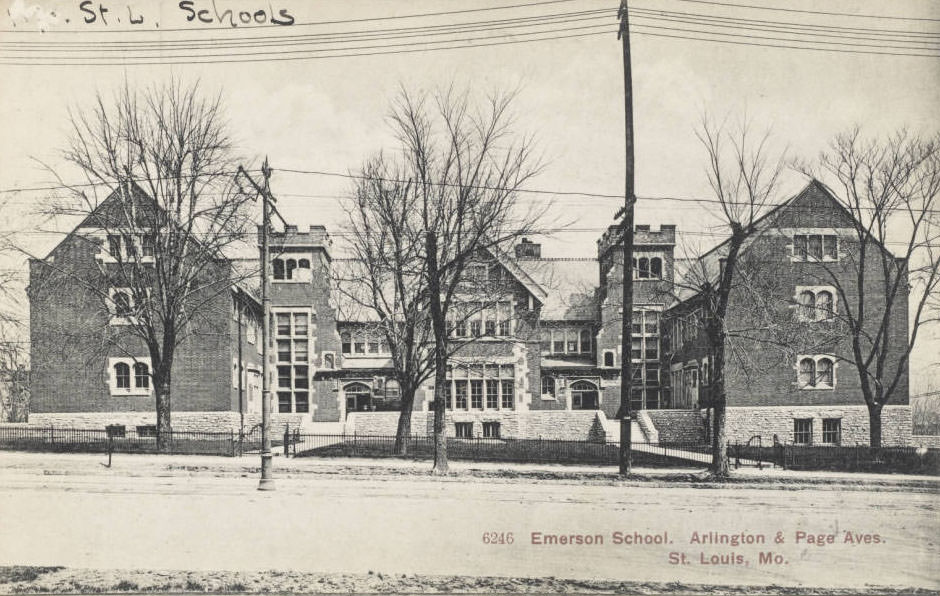

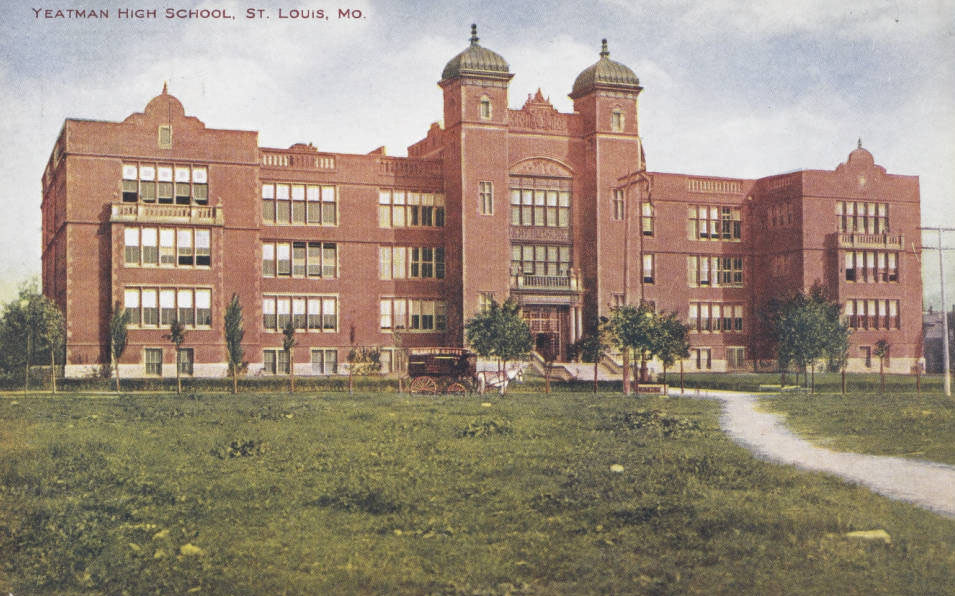

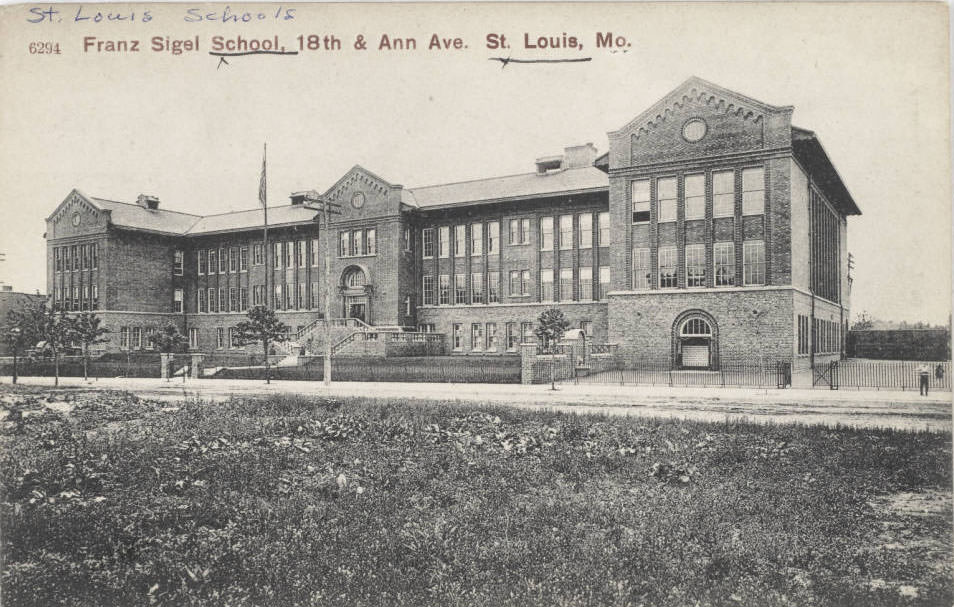

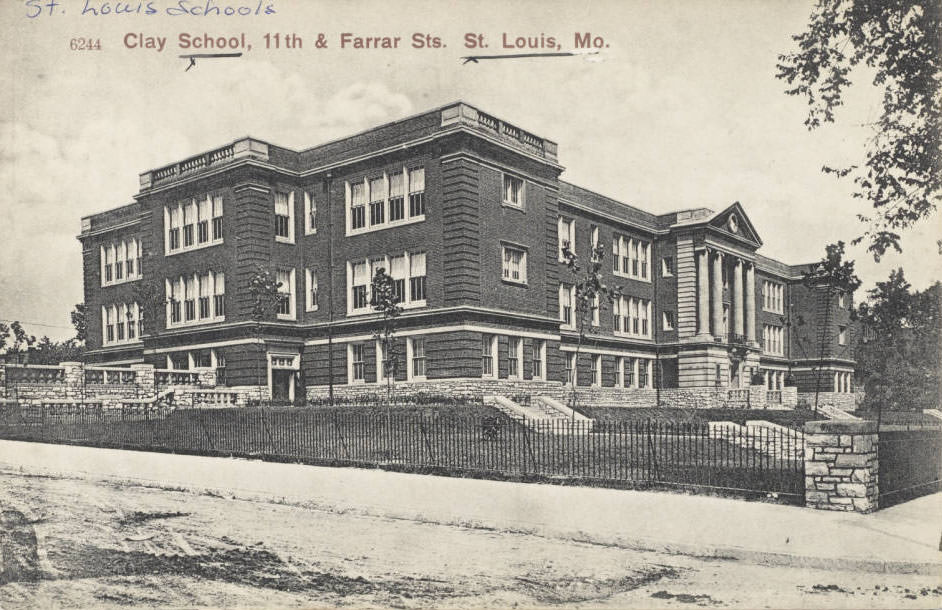

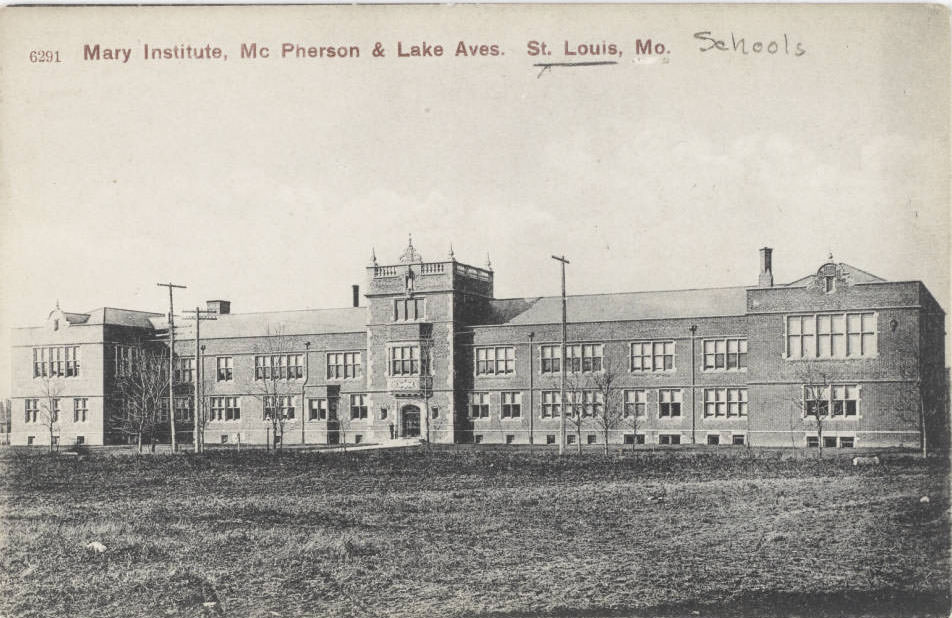

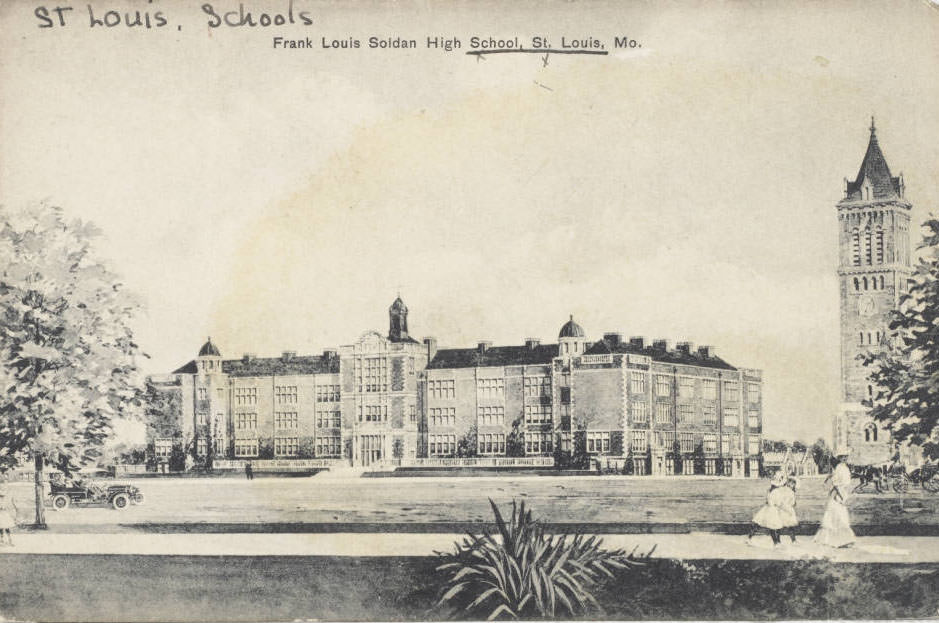

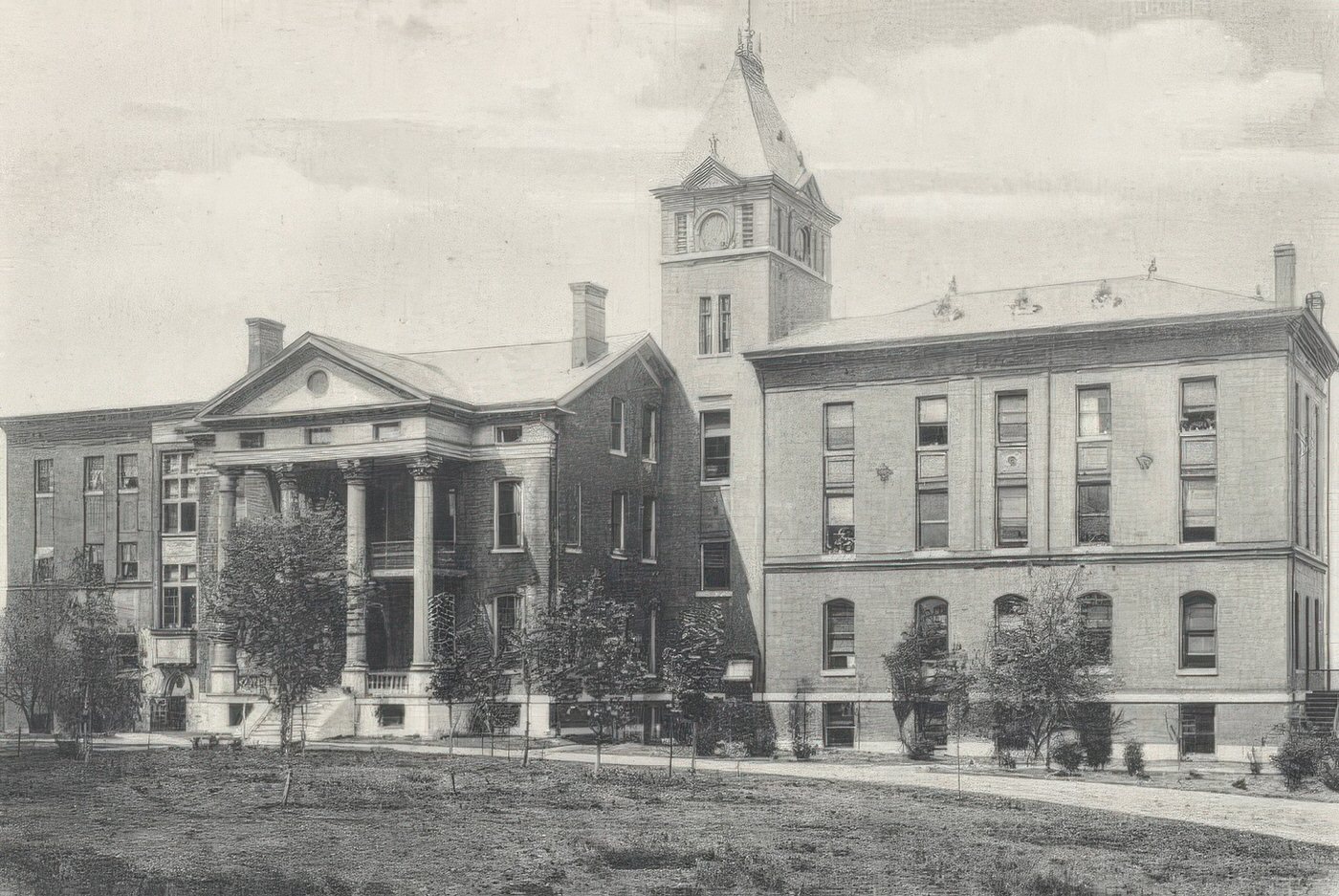

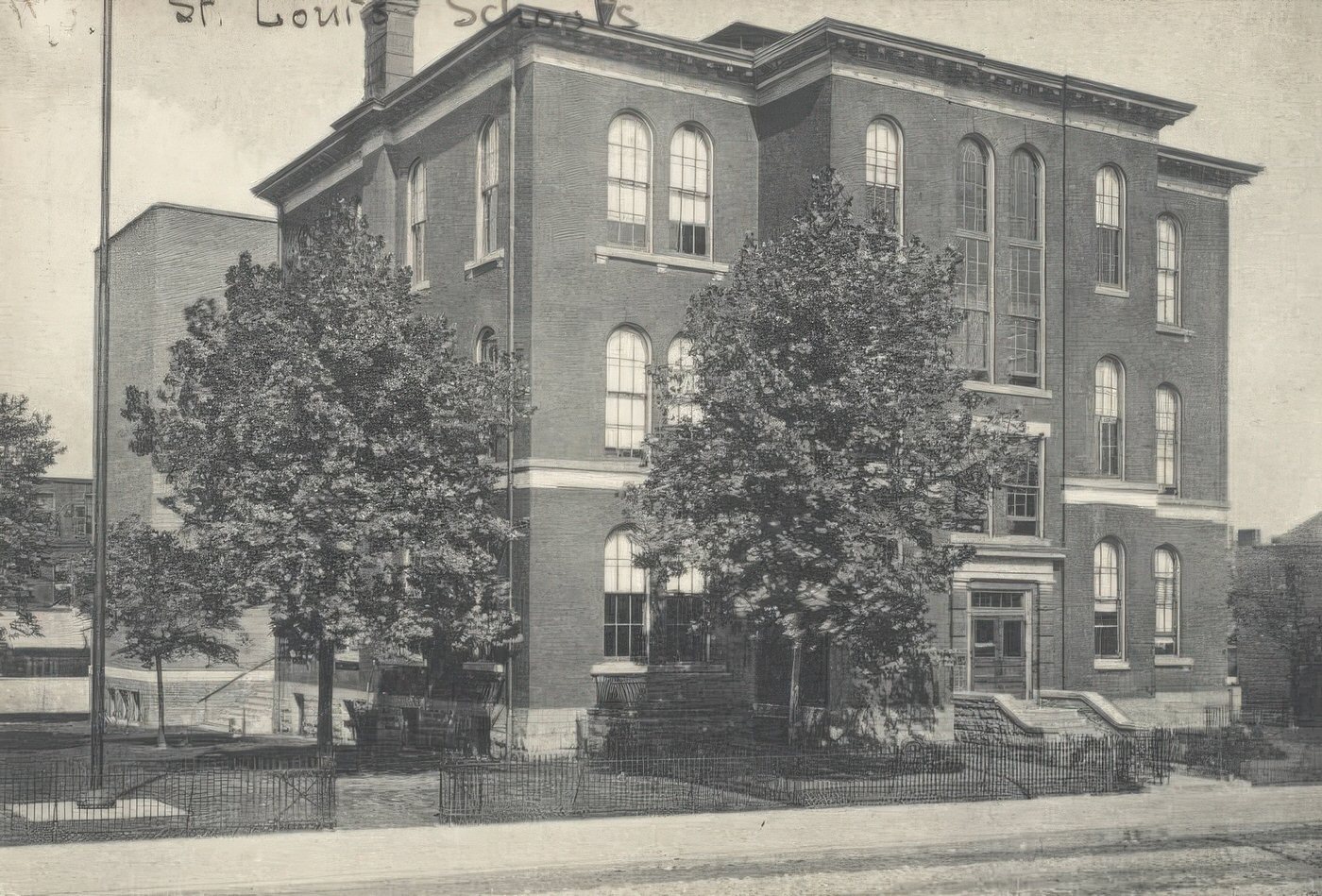

The 1910s were a period of significant growth and development for St. Louis’s cultural and educational institutions, alongside ongoing challenges related to equity and access. In public education, the work of architect William B. Ittner, who served as Commissioner of School Buildings from 1897 to 1914, had a profound impact. He designed fifty schools in St. Louis, introducing his innovative “open plan” concept. This design emphasized natural lighting, improved ventilation, and enhanced safety features, moving away from the dark, box-like schools of the past. Several Ittner-designed schools were constructed or planned in the 1910s, including Sumner High School (a new building in 1910/1911), Madison School (1910), Bryan Hill School (1911), Dunbar School (1912), Cleveland High School (1912-13), Laclede School (1913), Mark Twain School (1912), and Mullanphy School (1915). Sumner High School, historically the first high school for African Americans west of the Mississippi, received its new, modern Ittner-designed facility in 1911, a testament to community advocacy for better educational facilities.

However, the educational landscape was deeply marked by racial segregation. Missouri law mandated separate schools for Black and white children, a practice upheld by the state supreme court in Lehew v. Brummell (1890). While some accounts suggest that St. Louis City provided comparable funding for its segregated schools prior to the Brown v. Board of Education decision , other evidence from later periods, such as the late 1940s, indicated disparities in resources like libraries and per-pupil expenditures, which likely reflected conditions in the 1910s as well. Detailed reports on the conditions specifically within African American schools during the 1910s are somewhat limited, with more comprehensive data emerging in the 1920s.

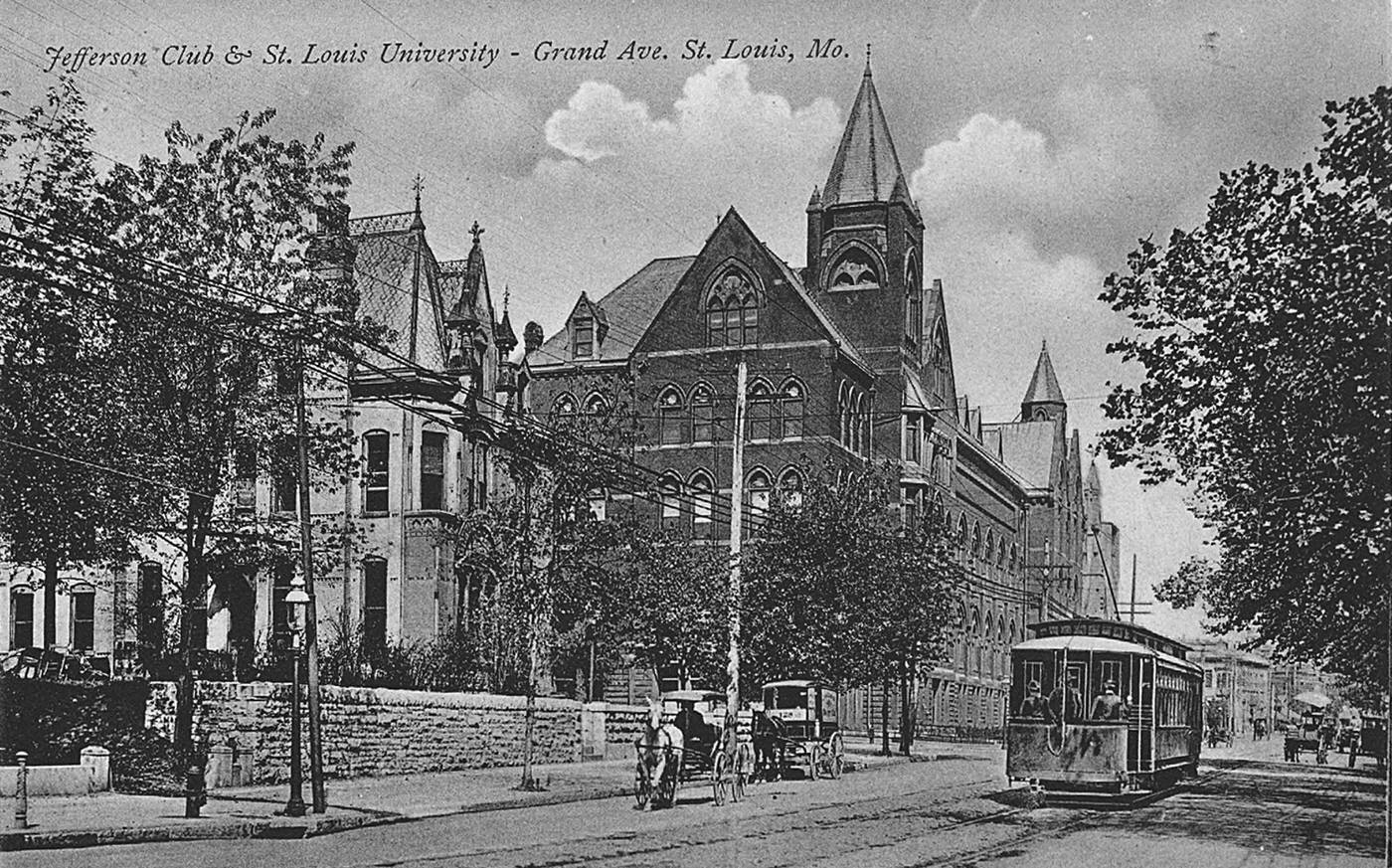

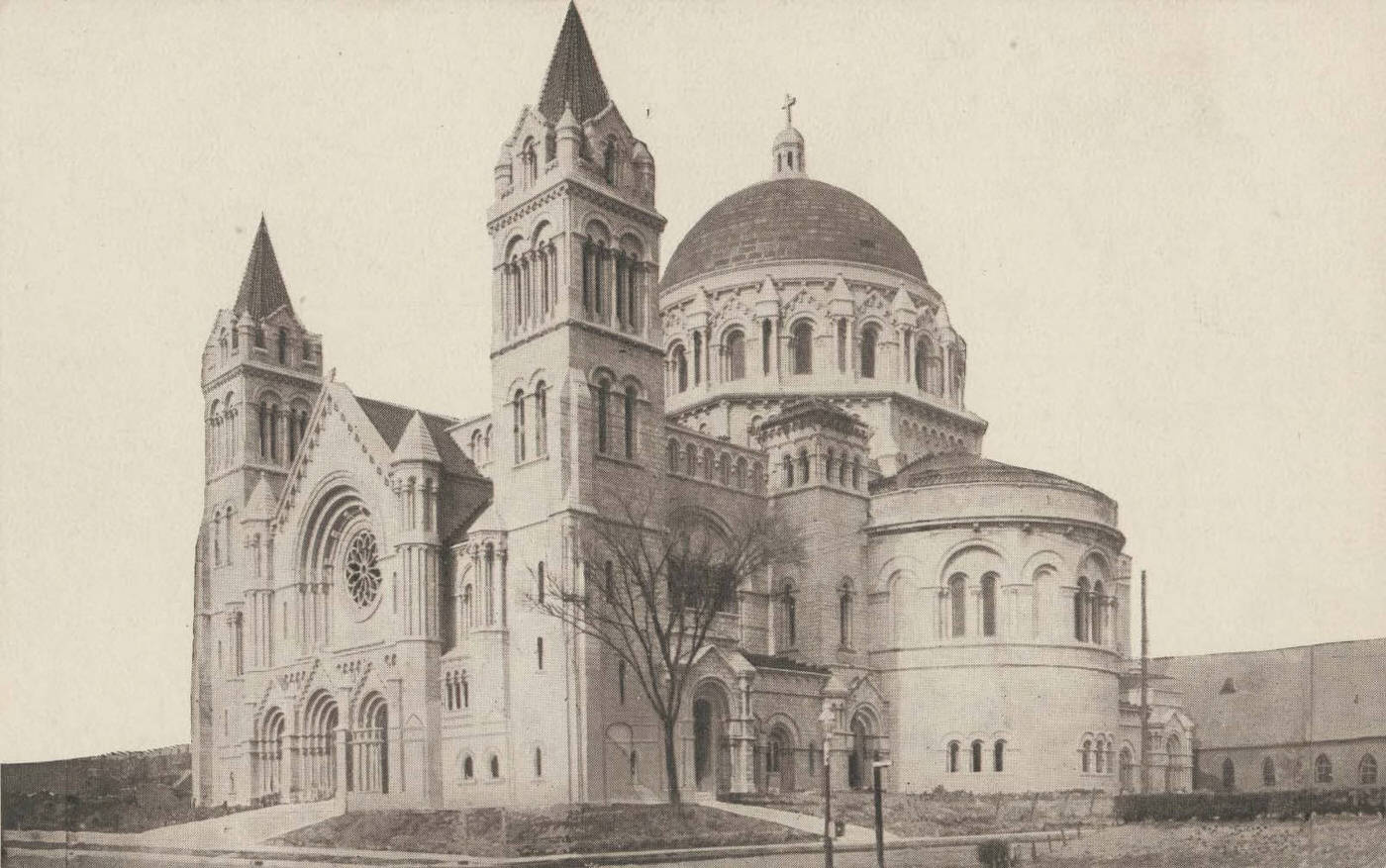

Higher education institutions in St. Louis also experienced growth. Washington University established its School of Architecture in 1910. Its Medical School underwent a significant reorganization during this decade, largely driven by the efforts of Robert Brookings and influenced by the critical Flexner Report. This overhaul included recruiting new faculty, establishing affiliations with Barnes Hospital (which opened in 1914) and St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and developing a new medical campus that was formally dedicated in 1915. Saint Louis University also expanded its academic offerings, founding its School of Business & Administration in 1910. The Principia, established in 1898 for Christian Scientist students, had grown into a six-year junior college program by 1910.

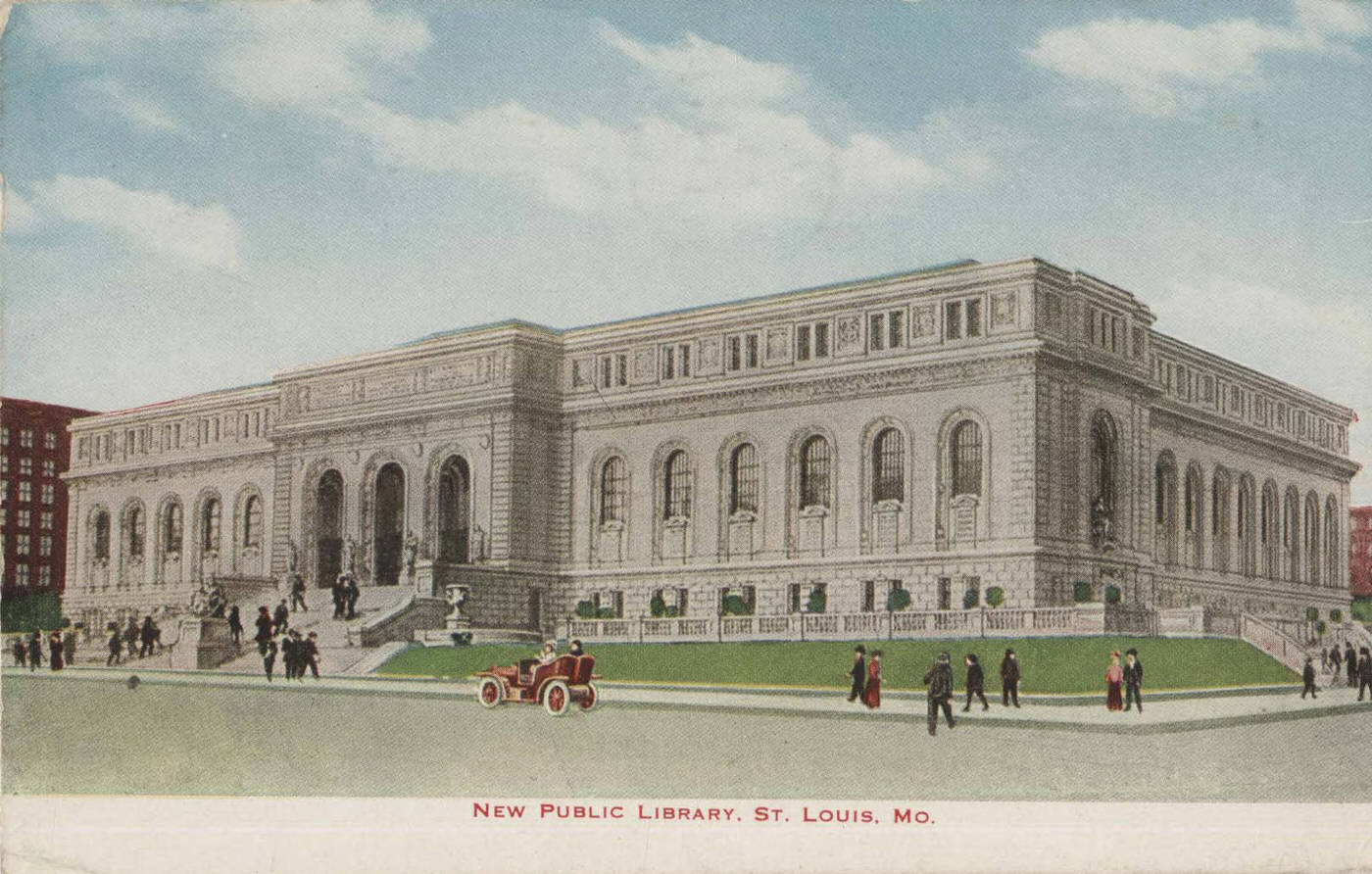

Public access to knowledge was enhanced by the St. Louis Public Library system. The magnificent Central Library building, designed by renowned architect Cass Gilbert, opened its doors in 1912. Its construction was partly funded by a significant donation from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie in 1901, which also supported the establishment of several branch libraries, including the Soulard and Divoll branches that opened in 1910. Frederick Crunden, the chief librarian, was a leading figure in the national library movement and instrumental in the library’s development.

The city’s arts and literary scene was active. The City Art Museum, located in the former Palace of Fine Arts from the 1904 World’s Fair, hosted notable exhibitions, such as a highly successful showing of works by Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla in 1911. St. Louis was home to respected literary figures. Poet Sara Teasdale was publishing significant works during this period, including “Helen of Troy and Other Poems” (1911) and “Rivers to the Sea” (1915); her “Love Songs” would win the Pulitzer Prize in 1918. William Marion Reedy’s literary magazine, “Reedy’s Mirror,” was an influential publication based in the city. The legacy of Scott Joplin, the “King of Ragtime,” who had resided in St. Louis from 1901 to 1907, continued to resonate, with his compositions like the “St. Louis Rag” (composed in 1903, published 1904) remaining popular. The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of Max Zach from 1907 to 1921, contributed to the city’s musical life. These developments illustrate a city investing in its intellectual and cultural future, even as it grappled with deep-seated social inequalities.

Civic life in St. Louis during the 1910s was characterized by active reform movements, the growth of new institutions, and notable political developments. Public health remained a significant concern. Initiatives like the Holy Cross Dispensary, which merged with Grace Church Mission and relocated in 1910, expanded its services to include a baby-feeding clinic and a milk program by 1914, addressing critical needs in the community. The city also operated public bathhouses, such as Bath House No. 3 which opened in 1910, to improve sanitation among its poorer residents. Organizations like the St. Louis Society for the Relief and Prevention of Tuberculosis and the St. Louis Pure Milk Commission were also active, though specific details of their work in the 1910s are limited in the provided materials.

The women’s suffrage movement gained considerable momentum. The Equal Suffrage League of St. Louis, established in 1910 with leaders such as Florence Wyman Richardson, was at the forefront of local efforts. They organized meetings, brought in speakers, and staged visible demonstrations, most notably the “Golden Lane” protest during the 1916 National Democratic Convention held in St. Louis, where thousands of women lined the streets to silently advocate for the right to vote.

The city’s political landscape was evolving. The era of dominant political figures like “Boss” Edward Butler, who passed away in 1911, was giving way to new leadership and the influences of the Progressive Era. Mayors serving St. Louis during the 1910s included Frederick H. Kreismann (1909-1913) and Henry W. Kiel (1913-1925). A significant milestone in local politics occurred in 1910 with the election of Charles Turpin as constable of the Fourth District, making him the first African American to be elected to public office in Missouri. Progressive ideals spurred reforms aimed at improving city governance, efficiency, and the overall quality of urban life. The St. Louis Bar Association played a role in these reforms by helping to establish the Legal Aid Society around 1909-1910, aiming to provide legal services to those who could not afford them.

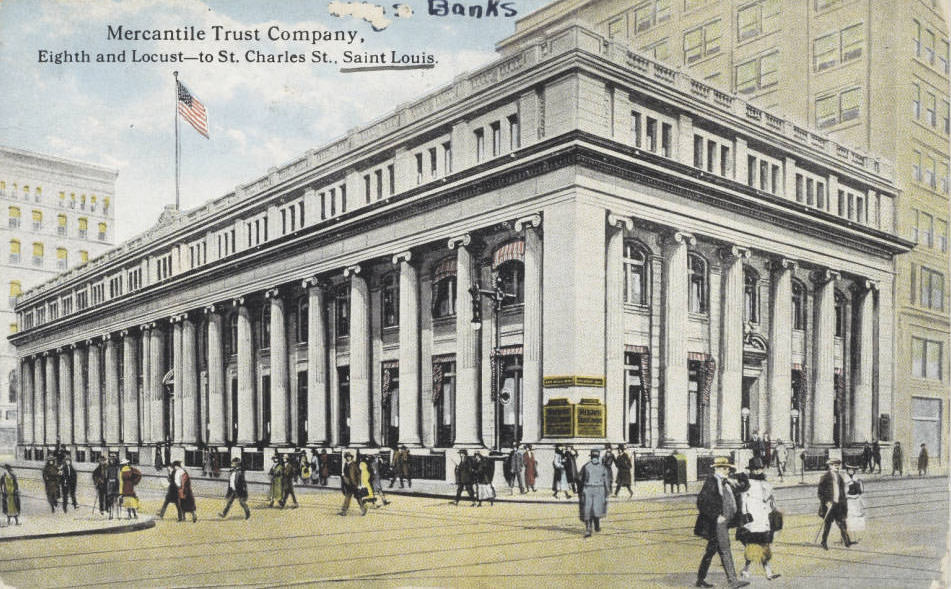

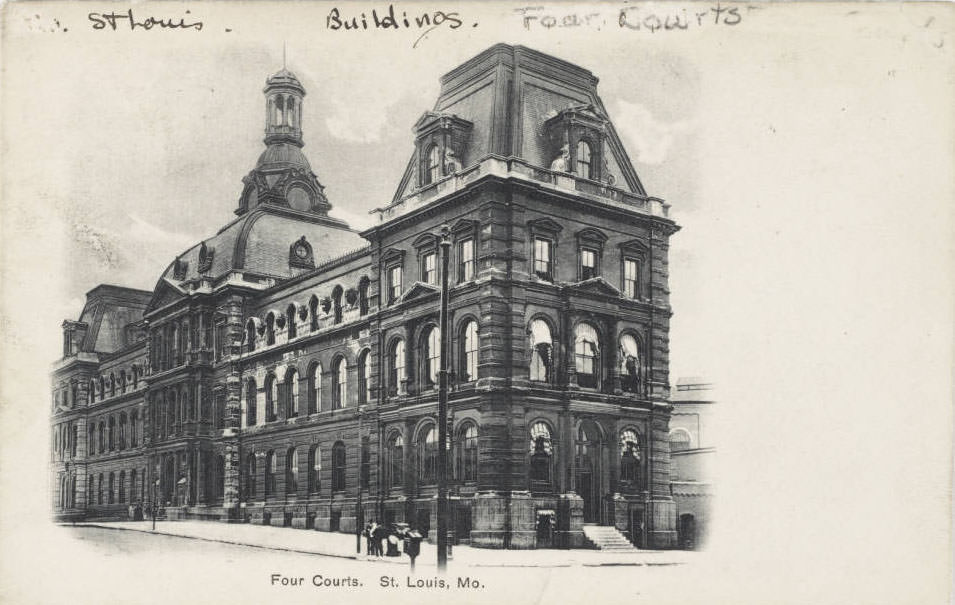

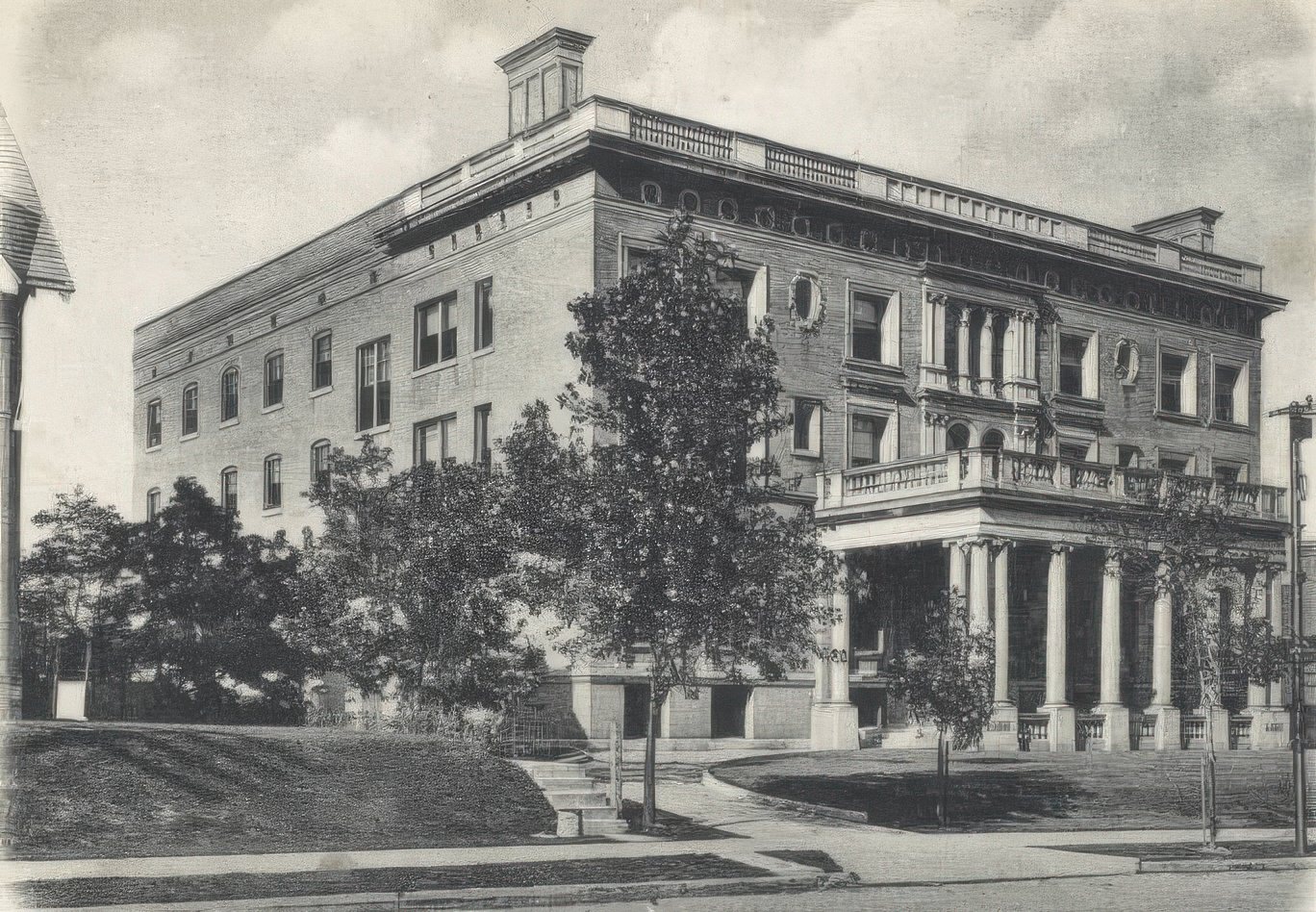

St. Louis’s importance as a financial center was underscored by the establishment of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis on May 18, 1914. The bank officially opened its doors on November 16, 1914, initially operating from the Marquette Building at Broadway and Olive streets. It served as the headquarters for the Eighth Federal Reserve District. Local financial institutions like the Mercantile Trust Company, which had played a role in financing the 1904 World’s Fair, and the long-established Boatmen’s Bank, continued to be significant players in the city’s economy. The First National Bank in St. Louis was also an active entity, formed through various consolidations. These developments in public health, civic engagement, political reform, and financial infrastructure were all part of St. Louis’s journey as a modernizing American city in the 1910s.

St. Louis and the Great War (World War I)

The outbreak of World War I in Europe in 1914, and the eventual entry of the United States in 1917, profoundly affected St. Louis. On the home front, the city mobilized its industries and citizens to support the war effort. The St. Louis Aircraft Corporation, founded in September 1917, quickly became a key contributor, selected as one of six companies nationwide to manufacture the Curtiss JN-4D “Jenny” training aircraft. By October 1918, the company was delivering 30 of these vital airplanes per month. While specific details for other St. Louis companies’ WWI production are limited in the provided information, it is known that industries like Wagner Electric and the Laclede Gas Light Company’s coke byproduct plant were operational and likely contributed to war-related needs, similar to how U.S. Cartridge became a major ammunition producer during World War II.

Women in St. Louis played a crucial role on the home front. Nationally, as men left for military service, women stepped into manufacturing and agricultural jobs. In St. Louis, women were actively involved in war-related activities through organizations like the Missouri Division of the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, which focused on initiatives such as food conservation and promoting Liberty Loan drives. The Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in St. Louis also undertook important work, with its efforts to support foreign-born women and girls being funded by the War Work Council, an organization established during WWI. Liberty Loan campaigns were a significant feature of civilian life, and St. Louisans actively participated in these drives to raise funds for the war. The National Women’s Liberty Loan Committee, formed in May 1917, highlighted the prominent role women played in these patriotic fundraising efforts.

The war also had a substantial impact on the city’s labor market. With European immigration slowing to a trickle due to the conflict and men enlisting in the military, St. Louis faced labor shortages. These shortages created new employment opportunities for African Americans, accelerating the Great Migration from the South to industrial centers like St. Louis. Nationally, the wartime demand for labor and products also increased the negotiating power of unions.

The war, however, also brought deep social divisions to St. Louis, particularly in the form of anti-German sentiment. St. Louis had a large and historically influential German-American population, and as the United States entered the war against Germany, this community faced suspicion and hostility. Public opinion, which had initially favored neutrality, shifted towards the Allies, and St. Louis newspapers began publishing anti-German editorials. One newspaper even campaigned to “wipe out everything German in this city”. This atmosphere led to tangible acts of cultural suppression. Streets with German names were changed; for example, Berlin Avenue was renamed Pershing Avenue, Bismark Street became Fourth Street, and Kaiser Street was changed to Gresham Street. The teaching of the German language in public schools was discontinued, German-language newspapers faced closure, and some Lutheran churches ceased offering services in German. The most tragic manifestation of this anti-German hysteria occurred in April 1918 with the lynching of Robert Paul Prager, a German immigrant who had previously lived in St. Louis, in the nearby town of Collinsville, Illinois. Prager was accused of making “disloyal utterances” and was killed by a mob. This event underscored the dangerous climate of fear and xenophobia that the war engendered.

St. Louisans also contributed directly to the military effort through service in the armed forces. Across Missouri, over 156,000 individuals served during World War I, with more than 10,000 either wounded or killed. A notable St. Louis unit was Base Hospital 21. Staffed by doctors and nurses from Washington University Medical Center, along with civilian volunteers from the St. Louis area, it was one of the first six American military hospital units deployed to France. Organized in July 1916 and mobilized in April 1917, Base Hospital 21 arrived in Rouen, France, in June 1917, where it took over operations of British General Hospital No. 12. During its service, the unit treated an immense number of patients – 61,543 in total, comprising 29,706 surgical cases and 31,837 medical cases. While the majority of these patients were British and other Allied forces, 2,833 were American soldiers. The expertise of its staff was recognized through promotions; for example, chief neurologist Sydney Schwab was reassigned to command the first American hospital for shell shock cases, orthopedic surgeon Nathaniel Allison became co-director of orthopedic surgery in the combat zone, and head nurse Julia Stimson was appointed head of Red Cross nursing. Base Hospital 21 served overseas for 23 months, being demobilized in January 1919 and returning to the United States in the spring of that year. Tragically, three members of the unit died while serving in France.

The region was also profoundly affected by the East St. Louis Race Riot of July 1917. Occurring just across the Mississippi River in East St. Louis, Illinois, this brutal outbreak of racial violence saw white mobs attack African American residents, resulting in hundreds of deaths and extensive property destruction. The riot was largely fueled by racial tensions exacerbated by the Great Migration, as between 10,000 and 12,000 African Americans had moved to East St. Louis for jobs in wartime industries, leading to competition for employment and housing. Animosity had particularly surged when African American workers replaced striking white workers at a local aluminum plant. As a result of the terror, an estimated 6,000 Black citizens fled East St. Louis, with many seeking refuge in St. Louis, Missouri. This influx of displaced and traumatized individuals undoubtedly strained resources in St. Louis and brought the stark realities of racial violence to the city’s immediate attention, likely intensifying existing racial tensions and civil rights concerns.

As the 1910s drew to a close, St. Louis, like much of the world, faced the devastating impact of the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. While specific local details for St. Louis’s public health response during the 1910s are not extensively covered in the provided information, the global scale of this pandemic means it would have inevitably affected the city profoundly. The experience of Base Hospital 21, which treated 1,700 influenza cases among soldiers in the final months of 1918, gives a glimpse into the pandemic’s reach. This public health crisis would have strained medical resources, led to school closures and restrictions on public gatherings, and caused significant illness and mortality, casting a somber shadow as the decade ended.

Image Credits: St. Louis Mercantile Library, Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library, Library of Congress, St. Louis Public Library, The State Historical Society of Missouri, Library of Congress, Wikimedia,

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know