The 1930s were a period of immense difficulty across the United States, and the city of St. Louis, Missouri, was not spared. The decade was defined by the Great Depression, a severe economic downturn that affected every aspect of life, from employment and housing to public health and daily routines.

The Economic Landscape: Factories, Farms, and Finances

The Great Depression cast a long shadow over the nation’s economy. Factories closed their doors, farms were lost, and many people struggled with hunger. This economic slowdown created a cycle where lower incomes meant people could not spend or save, further worsening the crisis. Reduced prices and output led to decreased wages, rents, dividends, and profits throughout the economy.

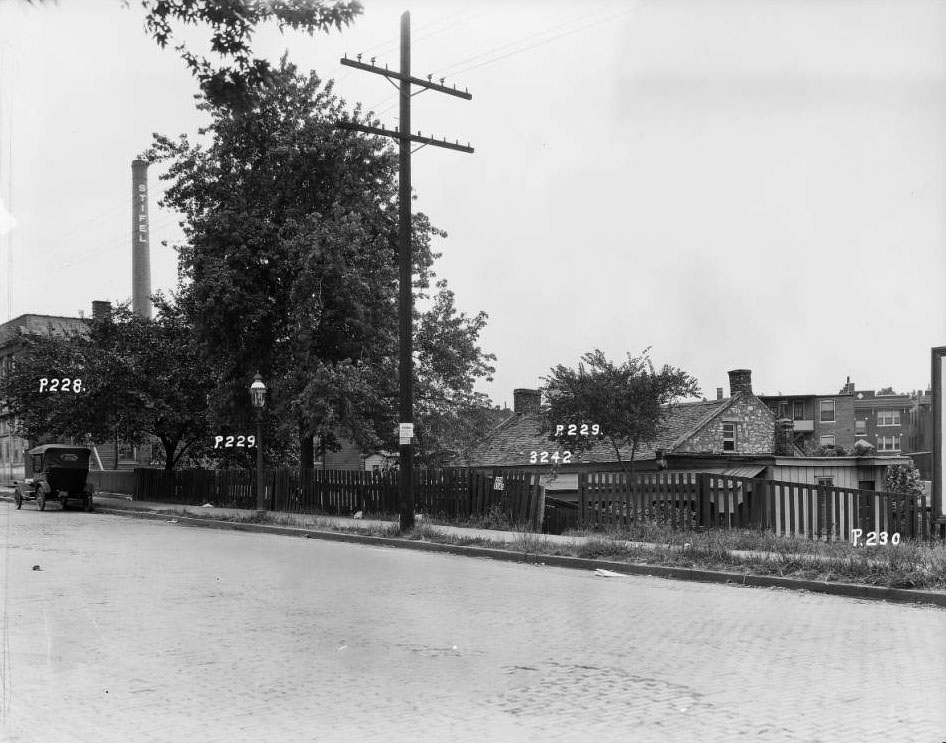

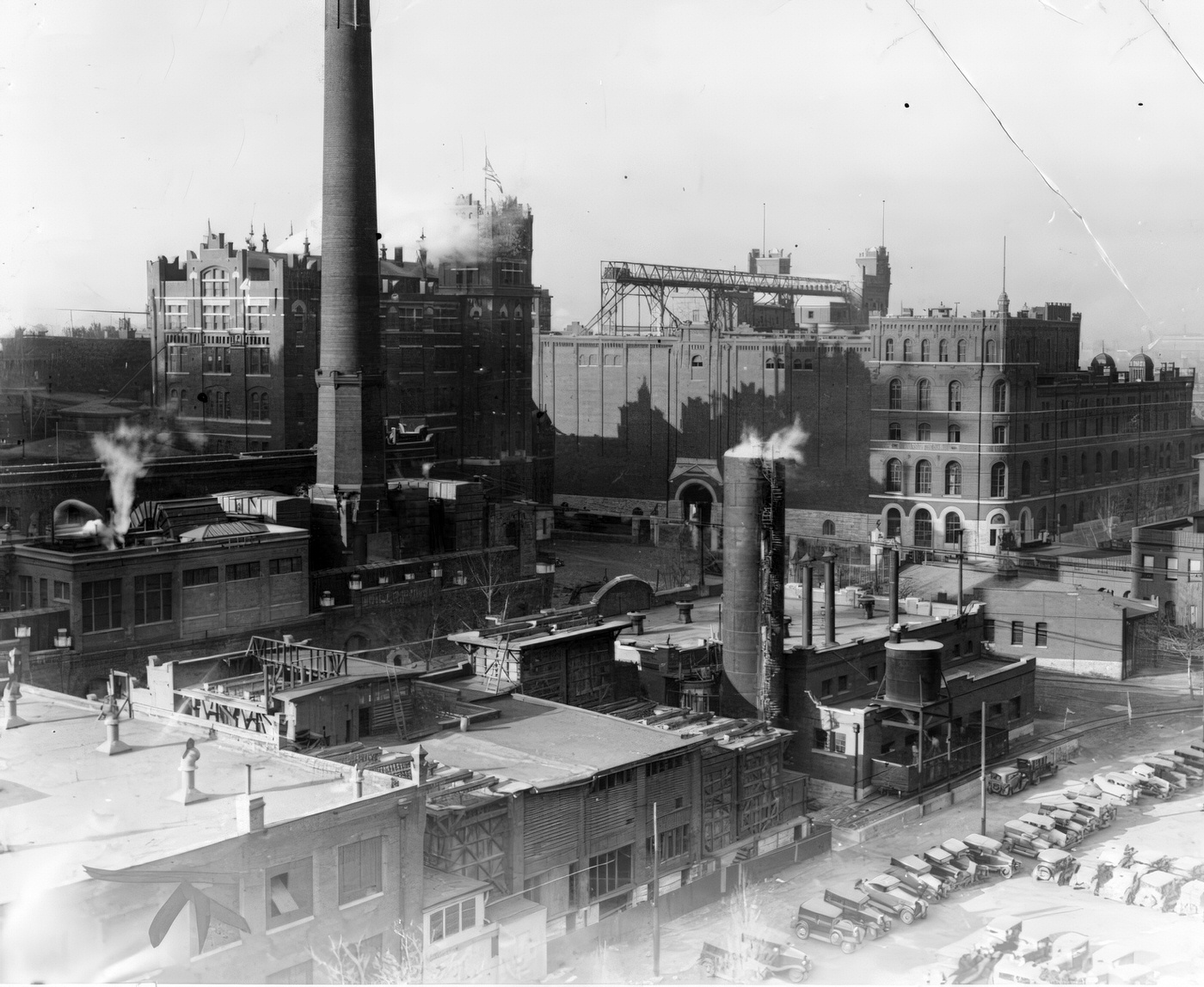

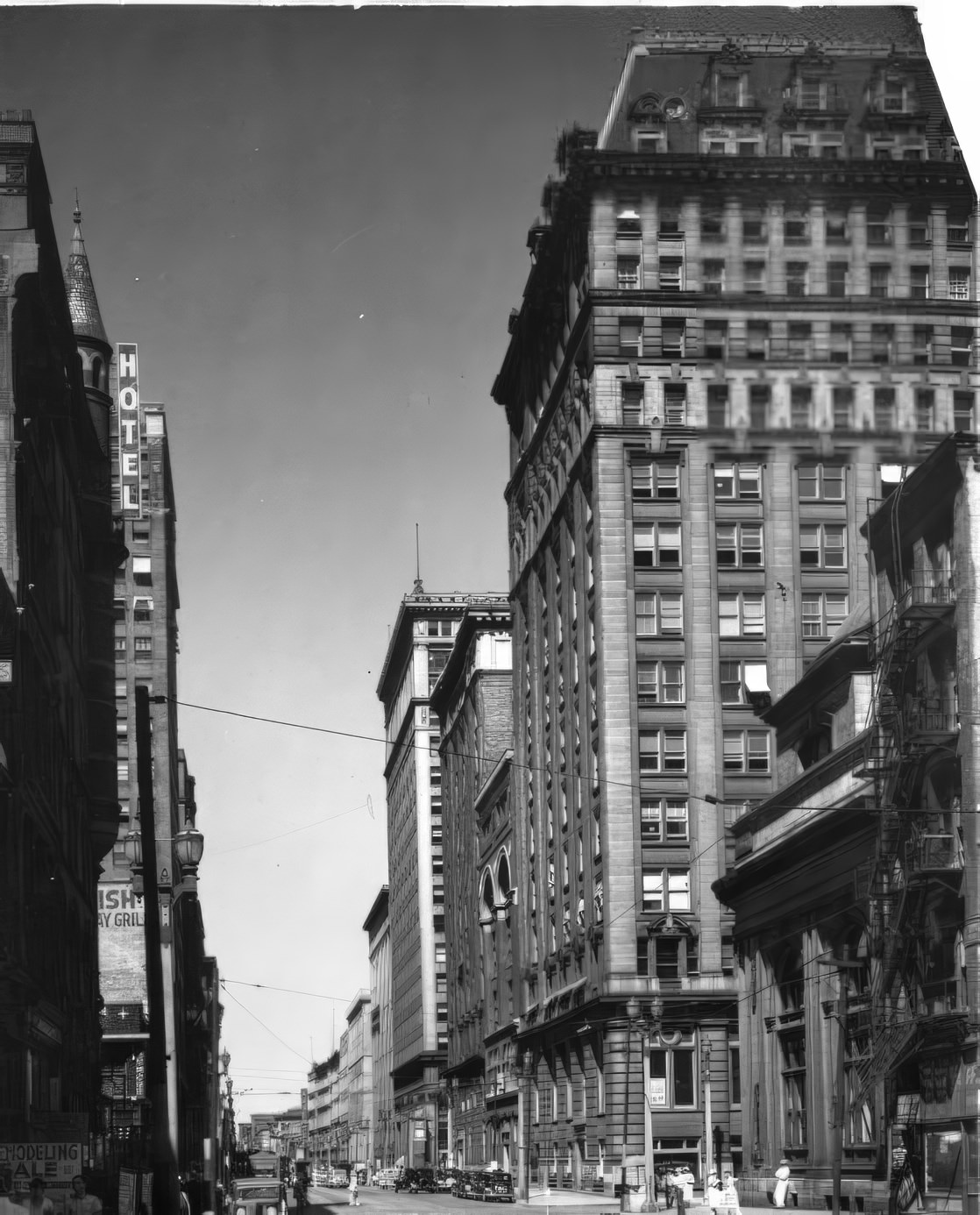

St. Louis, despite having a diverse economy, felt the sting of the Depression deeply, in some ways more than other similar cities during the initial years. The city’s manufacturing output experienced a significant decline, falling by 57 percent between 1929 and 1933. This drop was slightly more severe than the national average decrease of 55 percent. By 1939, St. Louis’s industrial production had only recovered to 70 percent of its 1929 levels, lagging behind the national recovery which reached 84 percent.

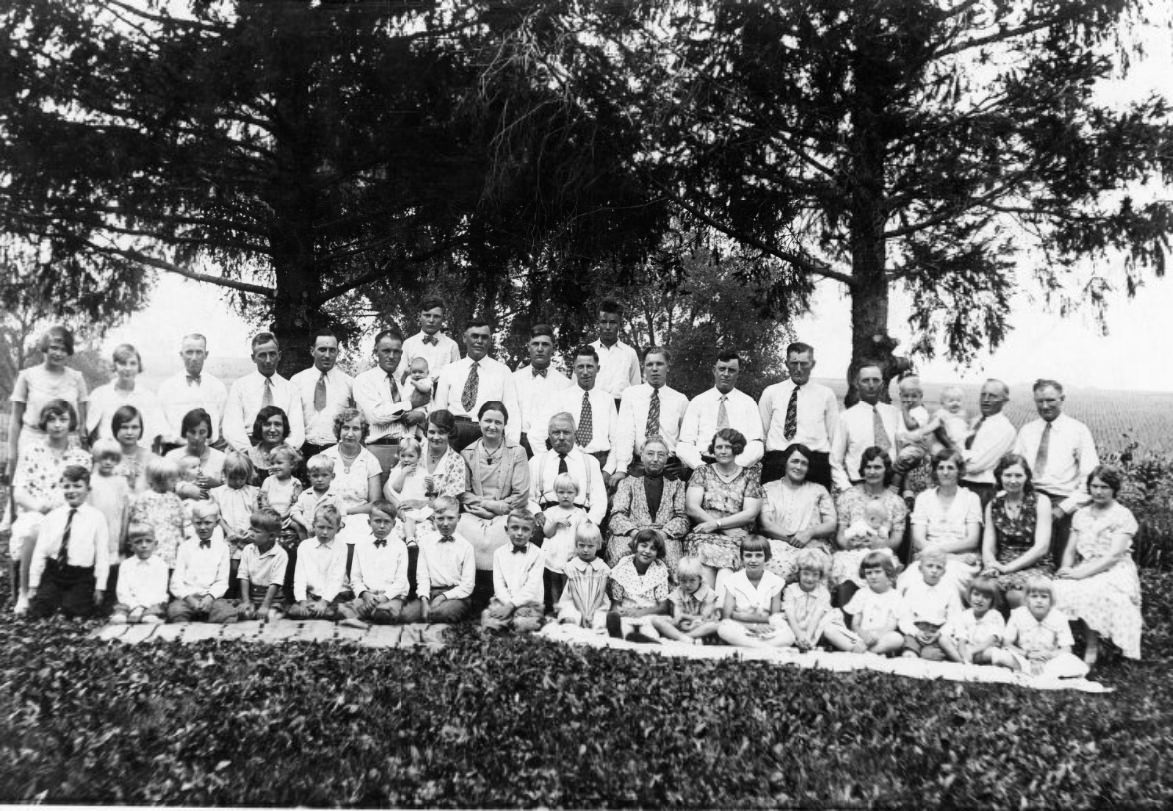

The state of Missouri, largely rural at the time, saw its farmers suffer greatly. Many families had little money and had to rely on what they could grow themselves. A severe drought in the early 1930s hit farmers in western Missouri particularly hard, forcing some to migrate west in search of work, mirroring the experiences described in John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath”.

Unemployment and Its Consequences

The declining value of farms, the slump in agriculture, and the lack of production resulted in record numbers of unemployed workers across Missouri. In St. Louis, the situation was dire. Unemployment climbed dramatically, reaching over 30 percent by 1933. This figure was higher than the national average, which stood at 24.9% in the same year.

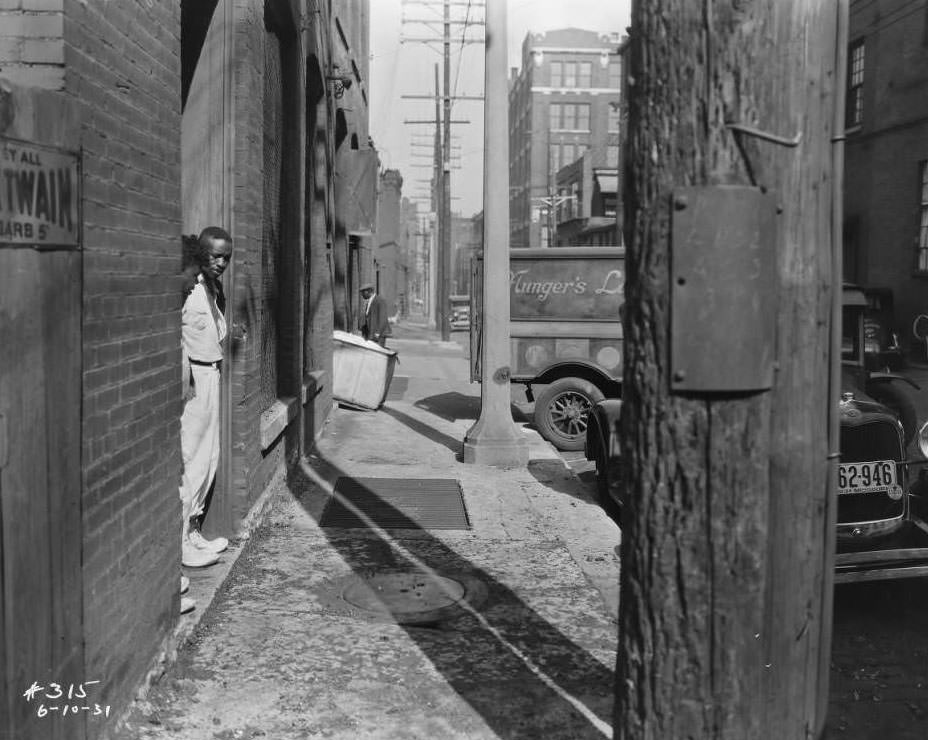

Black workers in St. Louis faced exceptionally high unemployment rates, reaching a staggering 80% in 1933. This disparity was due in part to discriminatory practices. Black workers were often the first to be fired and were sometimes replaced by white workers, particularly after mandatory minimum wage laws were introduced in the mid-1930s. In industries like meatpacking and steel mills, Black employees were laid off first. Many Black individuals working in domestic service received only room and board as compensation. Skilled Black craftsmen found themselves excluded from union membership and construction jobs. There were also instances where Black workers were underpaid and pressured into signing documents stating they had received proper wages.

The loss of jobs quickly led to the loss of homes for many St. Louisans. The widespread unemployment and economic hardship created a fertile ground for social unrest and a reevaluation of economic systems. The Federal Reserve’s initial response to the crisis was seen by some as inadequate. Many banks that failed in the 1930s were small, rural institutions not part of the Federal Reserve System, and thus could not borrow directly from the Fed. Even member banks were hesitant to borrow, fearing it would signal weakness and trigger bank runs. The Fed viewed the near-zero nominal interest rates as a sign they had done all they could, misinterpreting the economic situation. While nominal interest rates were low, real interest rates were actually rising due to deflation – falling prices and incomes. This made the real cost of borrowing very high, discouraging investment and spending. Firms stopped investing, consumers stopped borrowing for large purchases like cars, and businesses stopped hiring. This led to increased bankruptcies as borrowers could not repay loans, causing banks to fail because their borrowers defaulted.

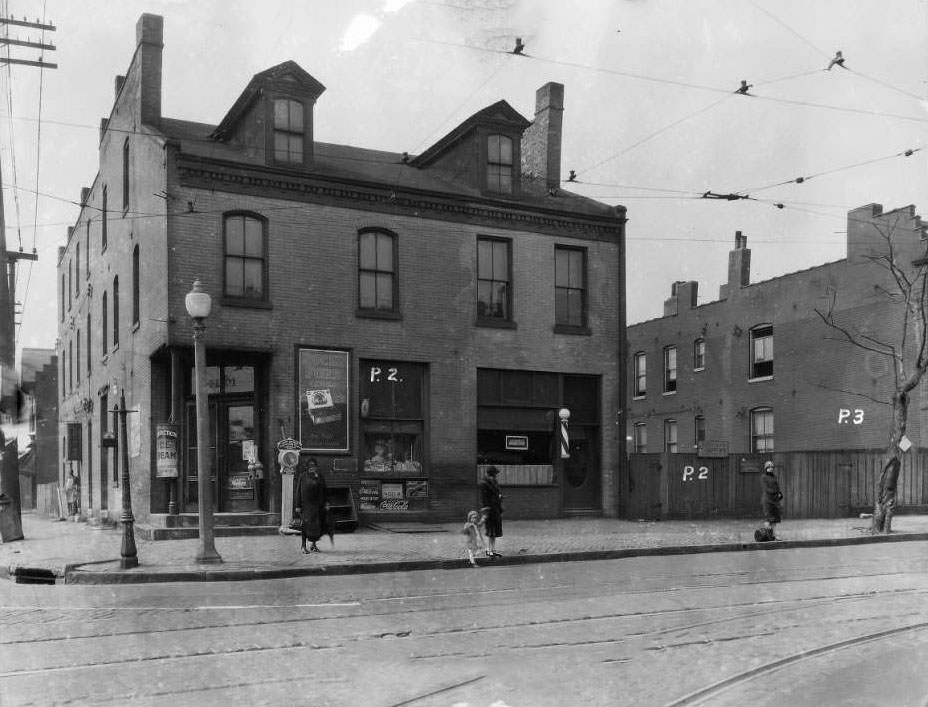

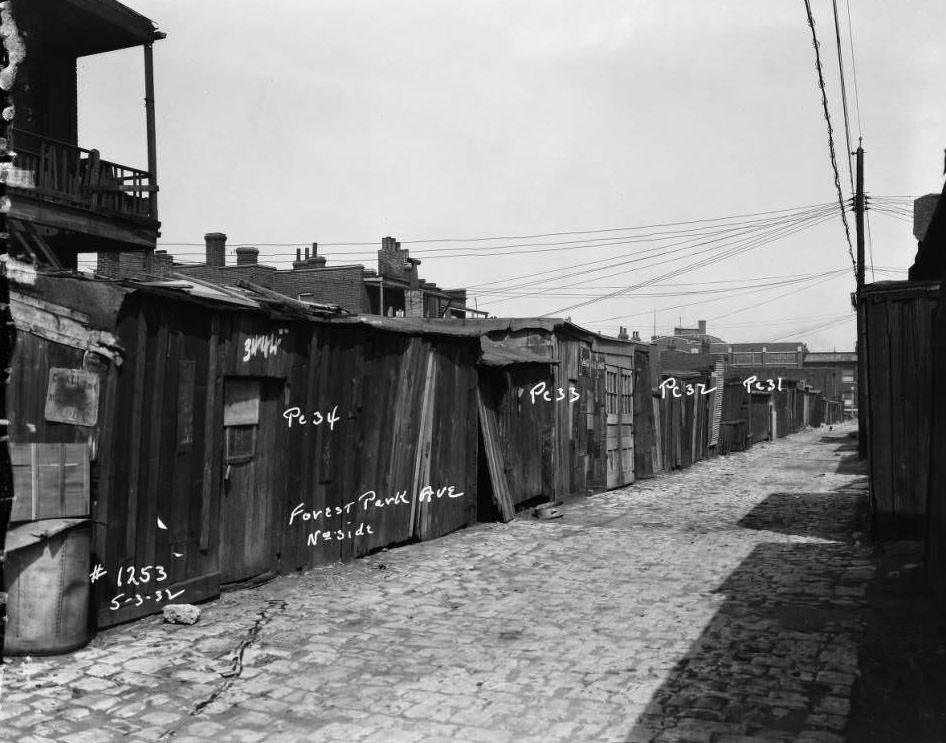

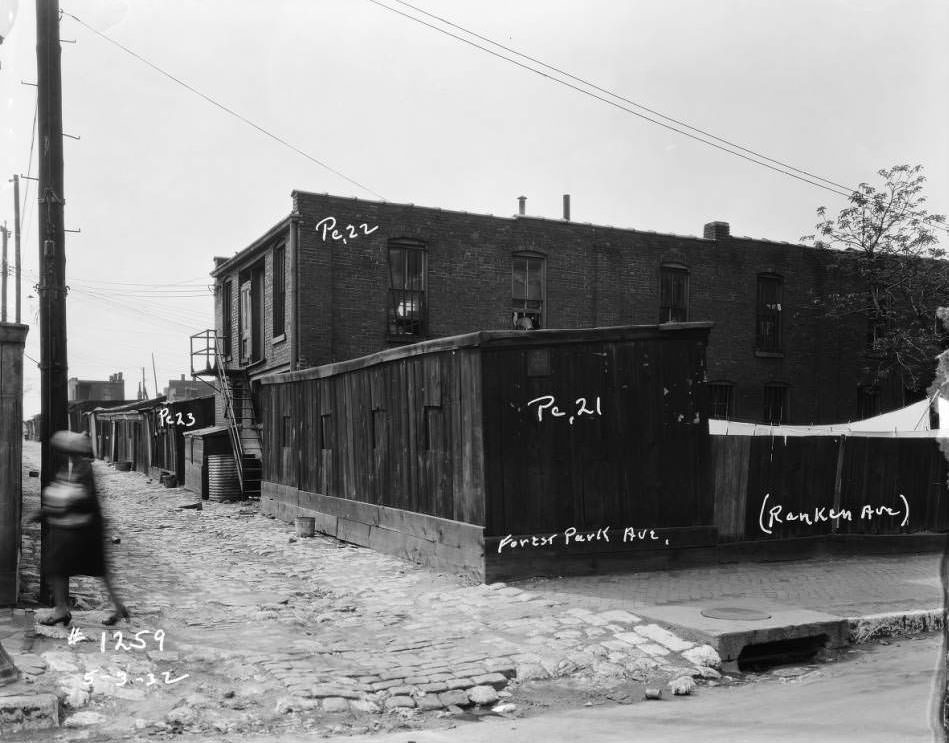

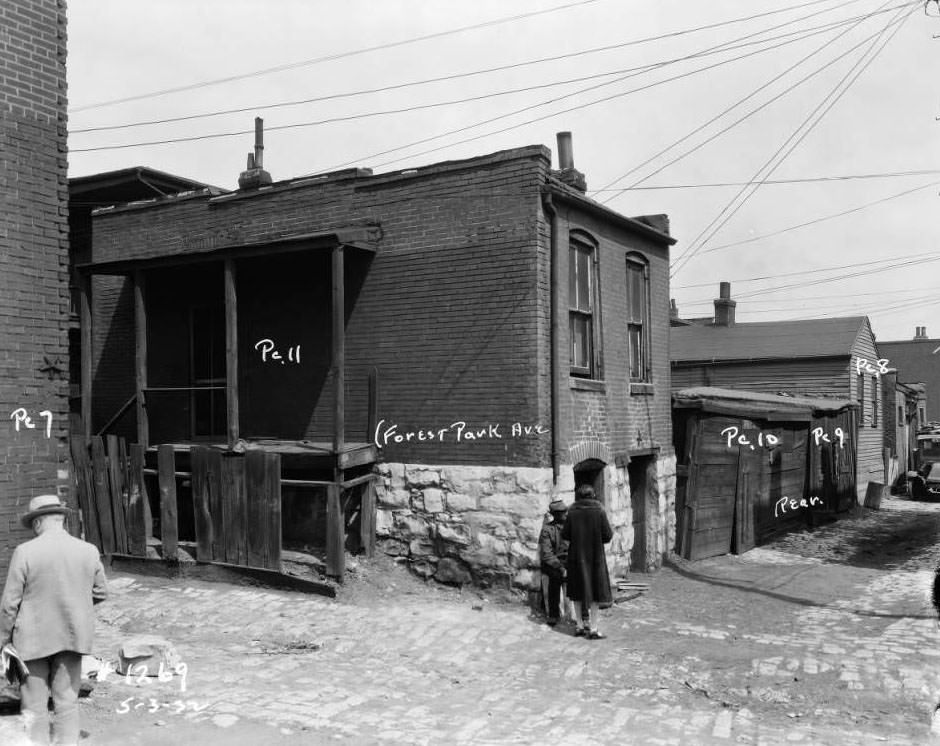

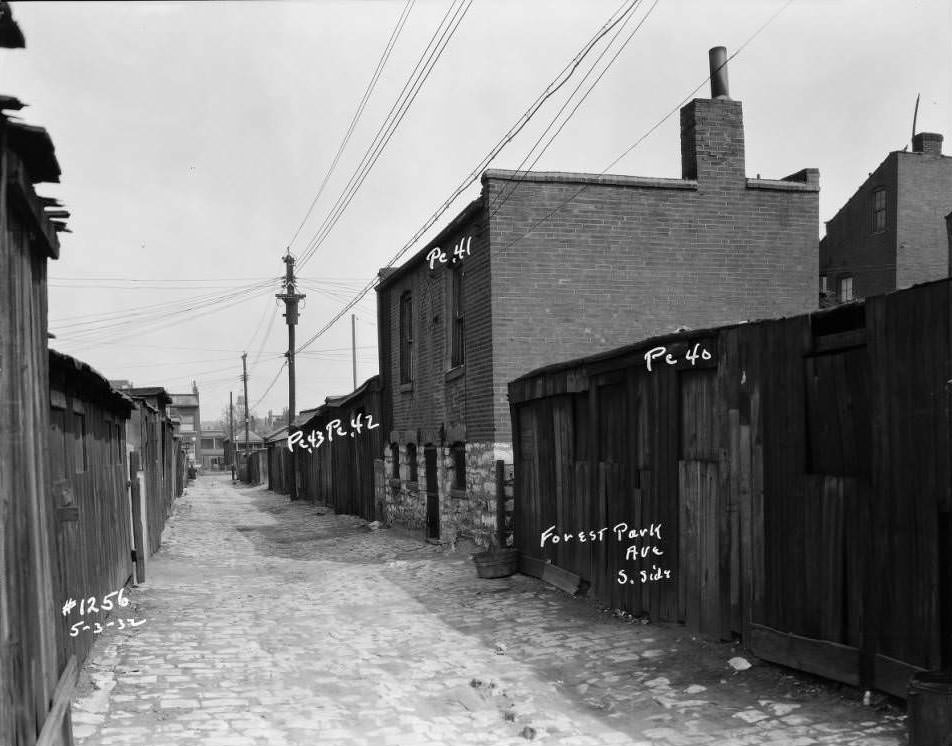

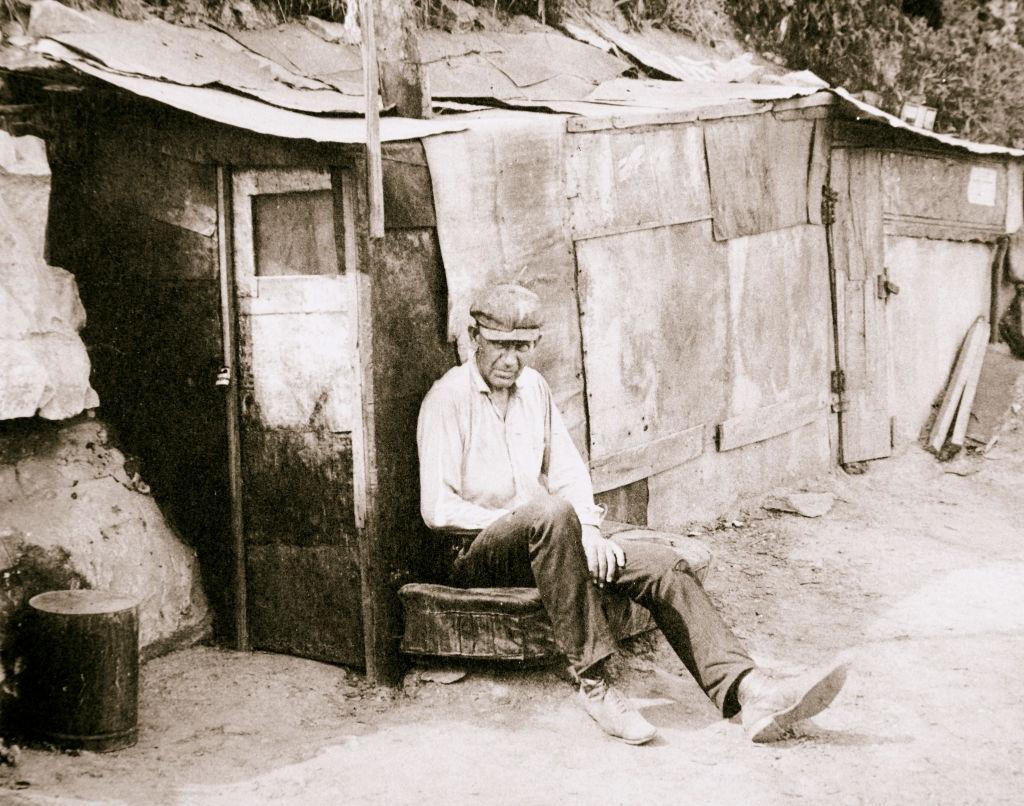

Hoovervilles: A Stark Reality

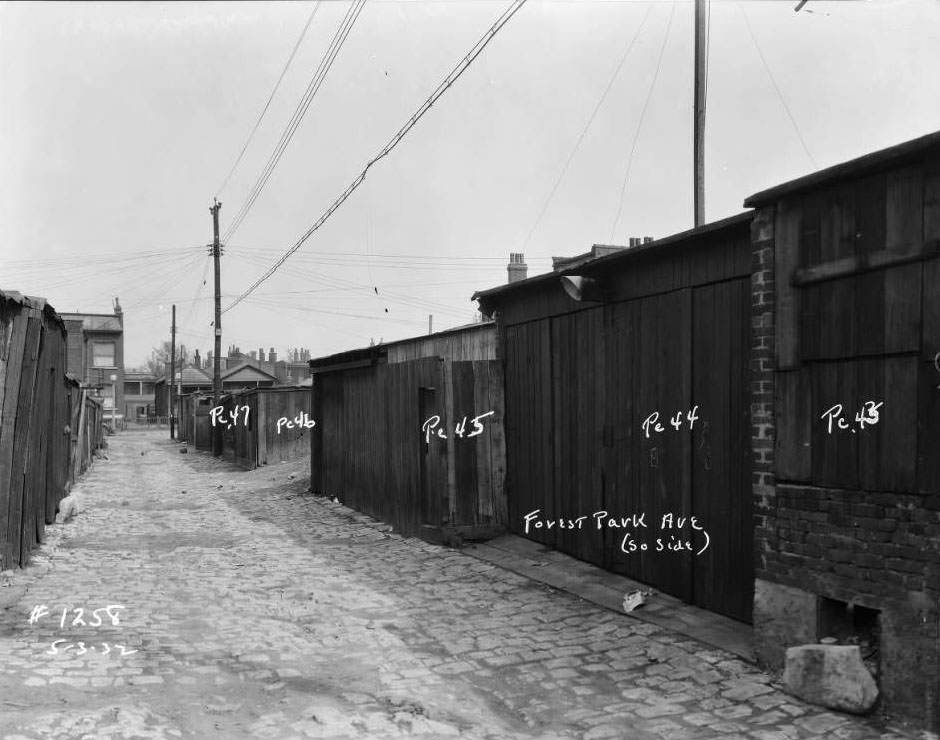

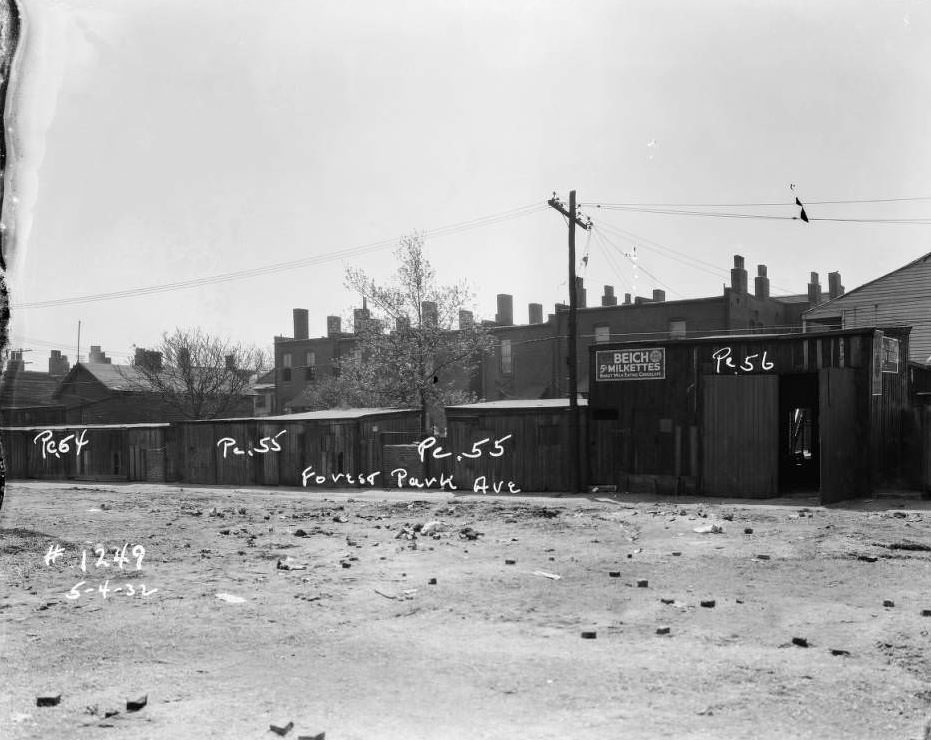

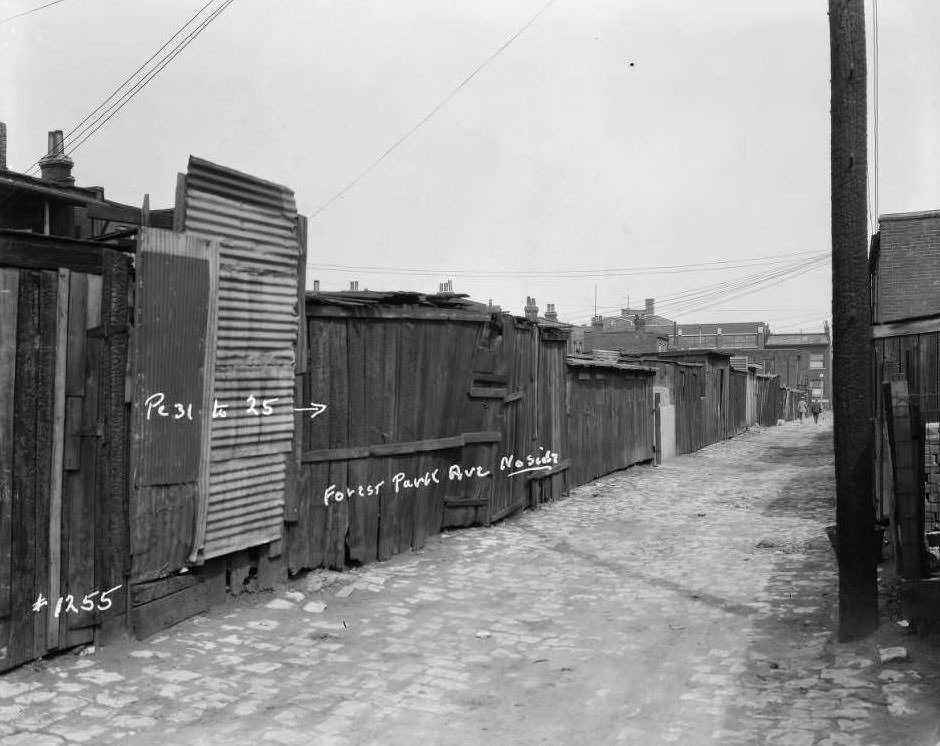

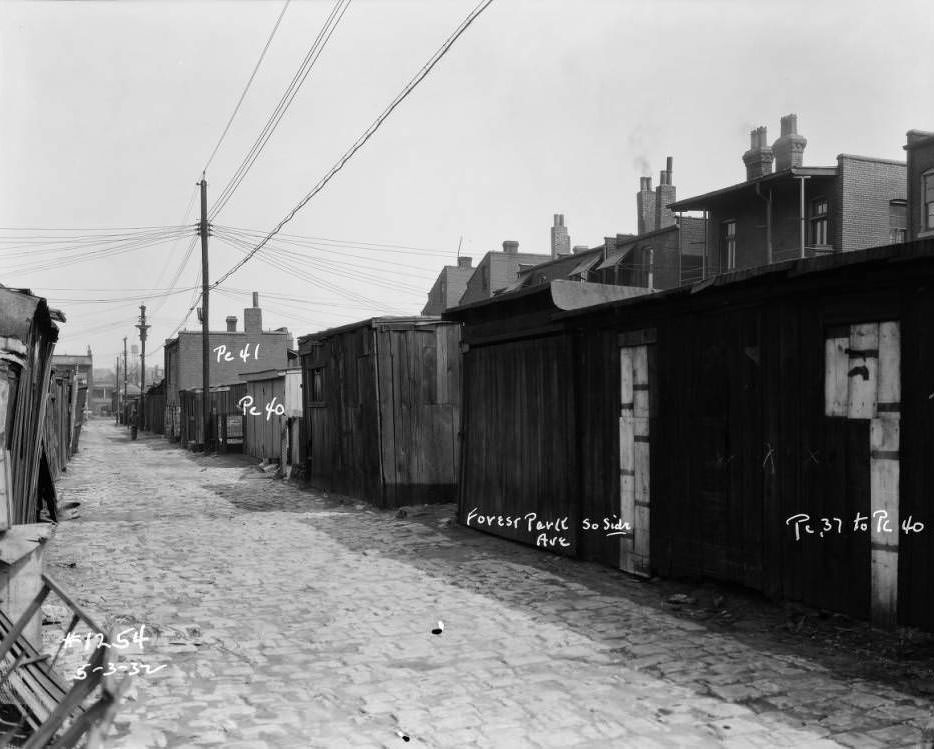

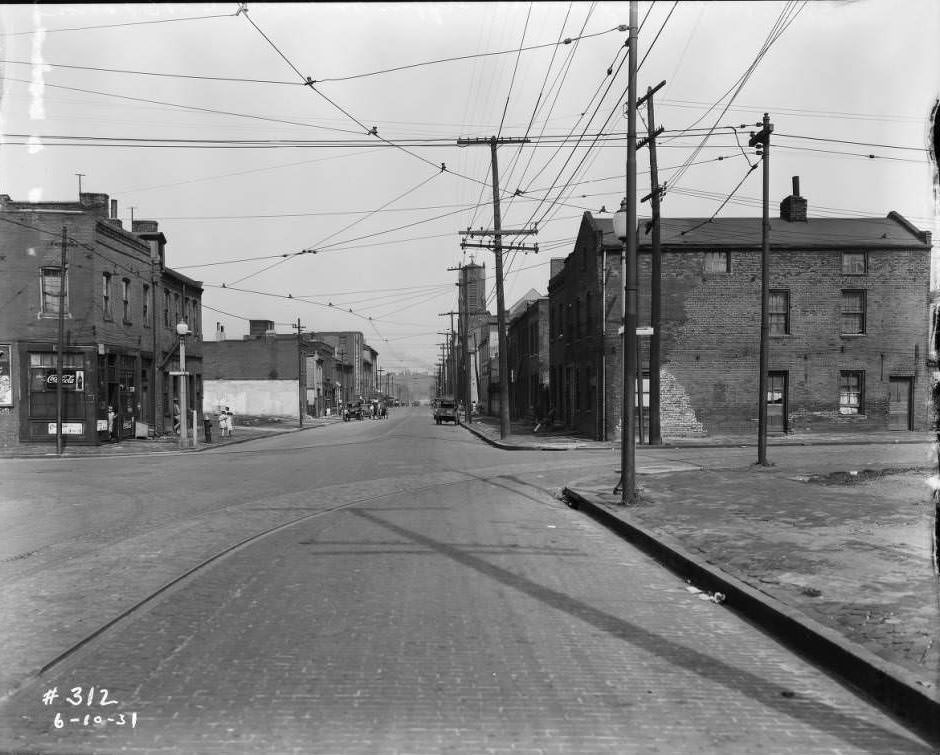

As people lost their jobs and homes, settlements of shacks, derisively named “Hoovervilles” after President Herbert Hoover whose administration was seen as failing to combat the Depression, appeared in cities across the United States. These makeshift dwellings were constructed from cardboard, scrap metal, and packing boxes.

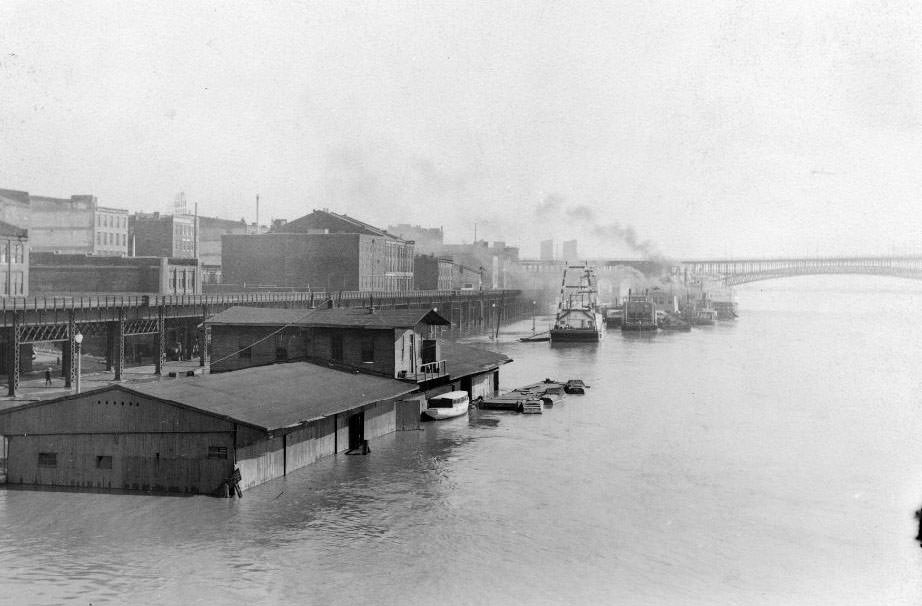

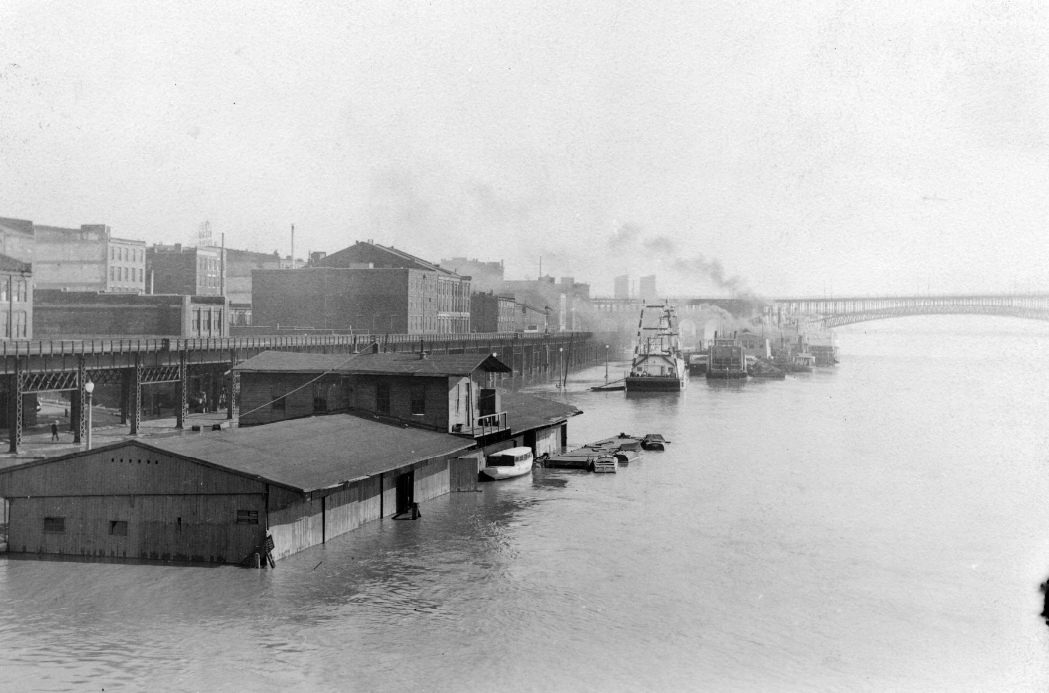

St. Louis was home to the nation’s largest Hooverville, situated just west of the Mississippi River. At its peak, this sprawling settlement housed between 1,000 to 5,000 people. Residents migrated to the riverbanks and built their homes from whatever materials they could find, such as orange crates and scavenged wood. These were primarily blue-collar workers who had recently lost their jobs.

Life in the St. Louis Hooverville was a daily struggle. Sanitation was a constant concern, with no running water or electricity. Police officer William Leahy recalled seeing children collecting the day’s water supply from the nearest fire hydrant using a wrench and jugs. The Mississippi River flooded the settlement three times, washing away shacks and worsening conditions. Despite the hardships, residents attempted to create a community. They gave their “neighborhoods” names like “Happyland” and “Merryland,” elected a mayor (Gus Smith, a former fruit vendor and pastor), and even established four churches, one famously made of orange crates. Children attended public schools, and charitable groups provided toys and clothing. The Hooverville was also notably one of the few racially integrated areas in St. Louis at the time.

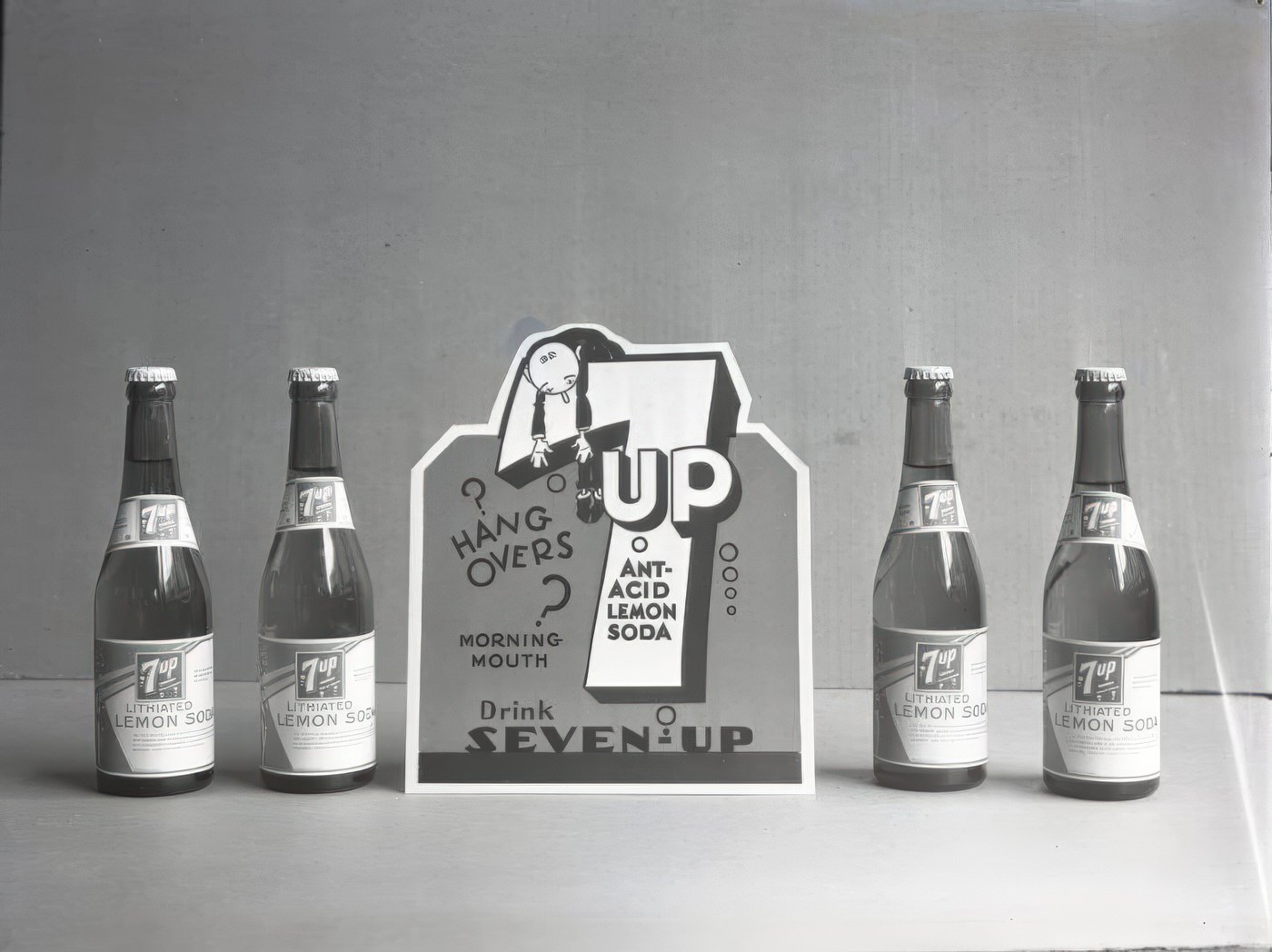

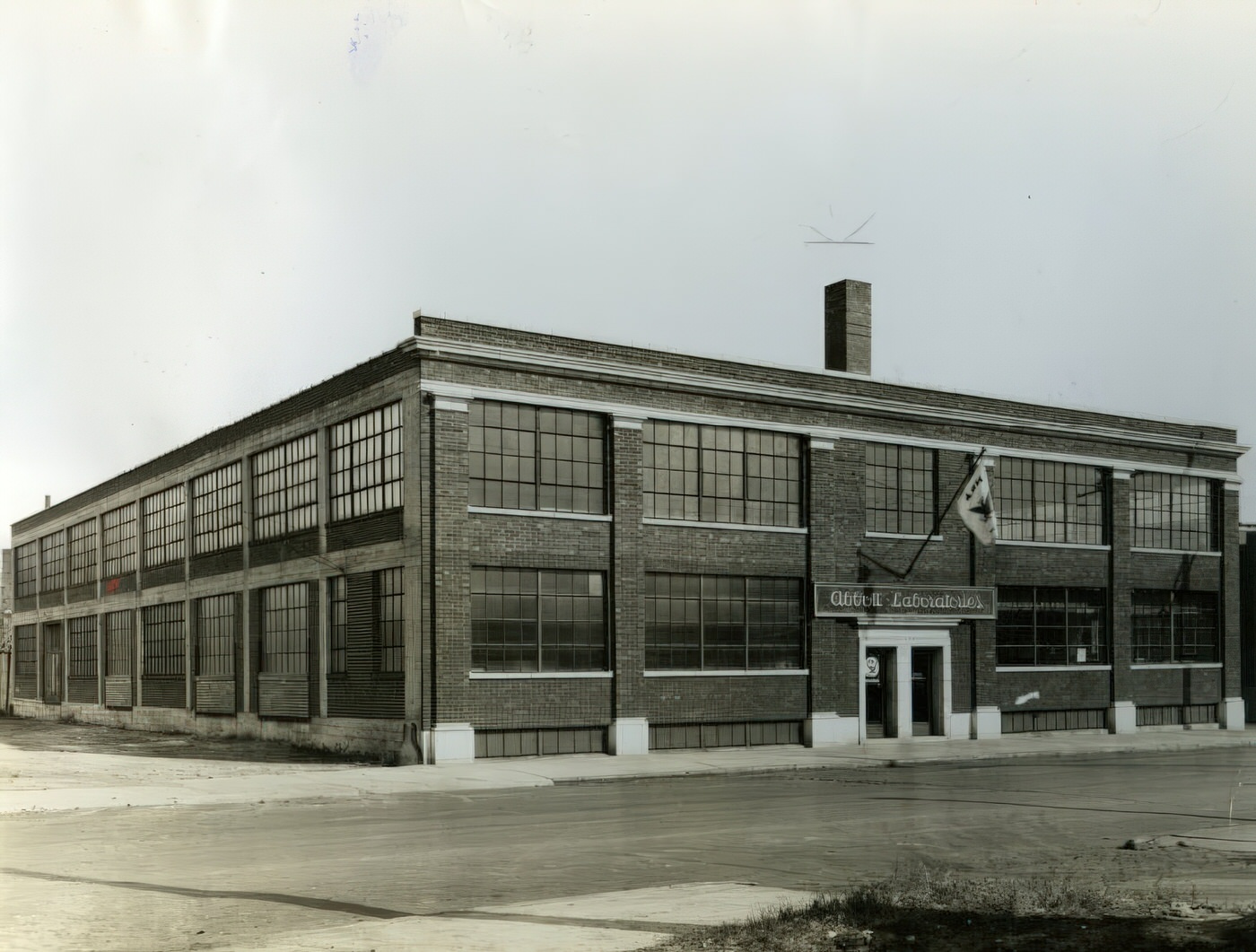

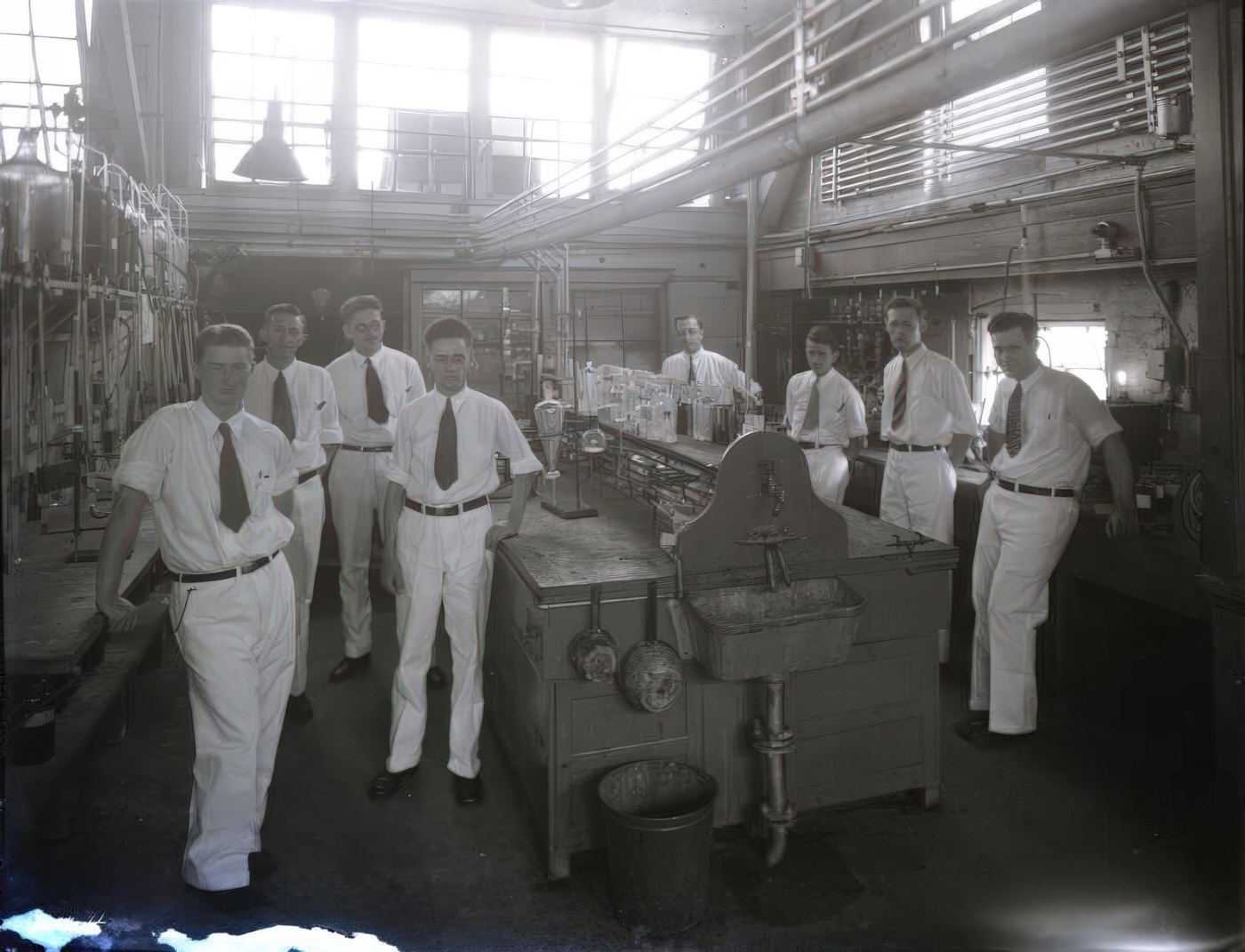

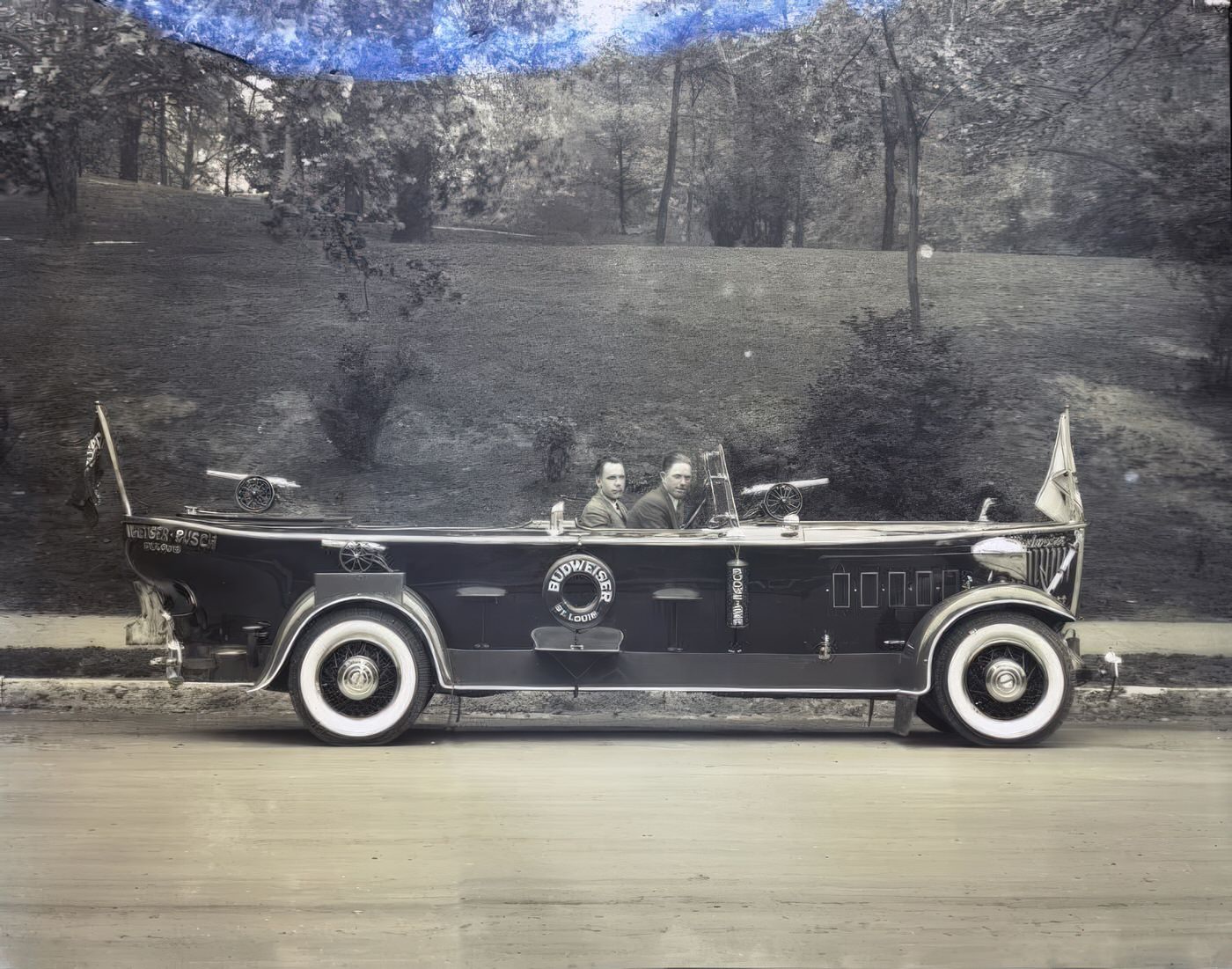

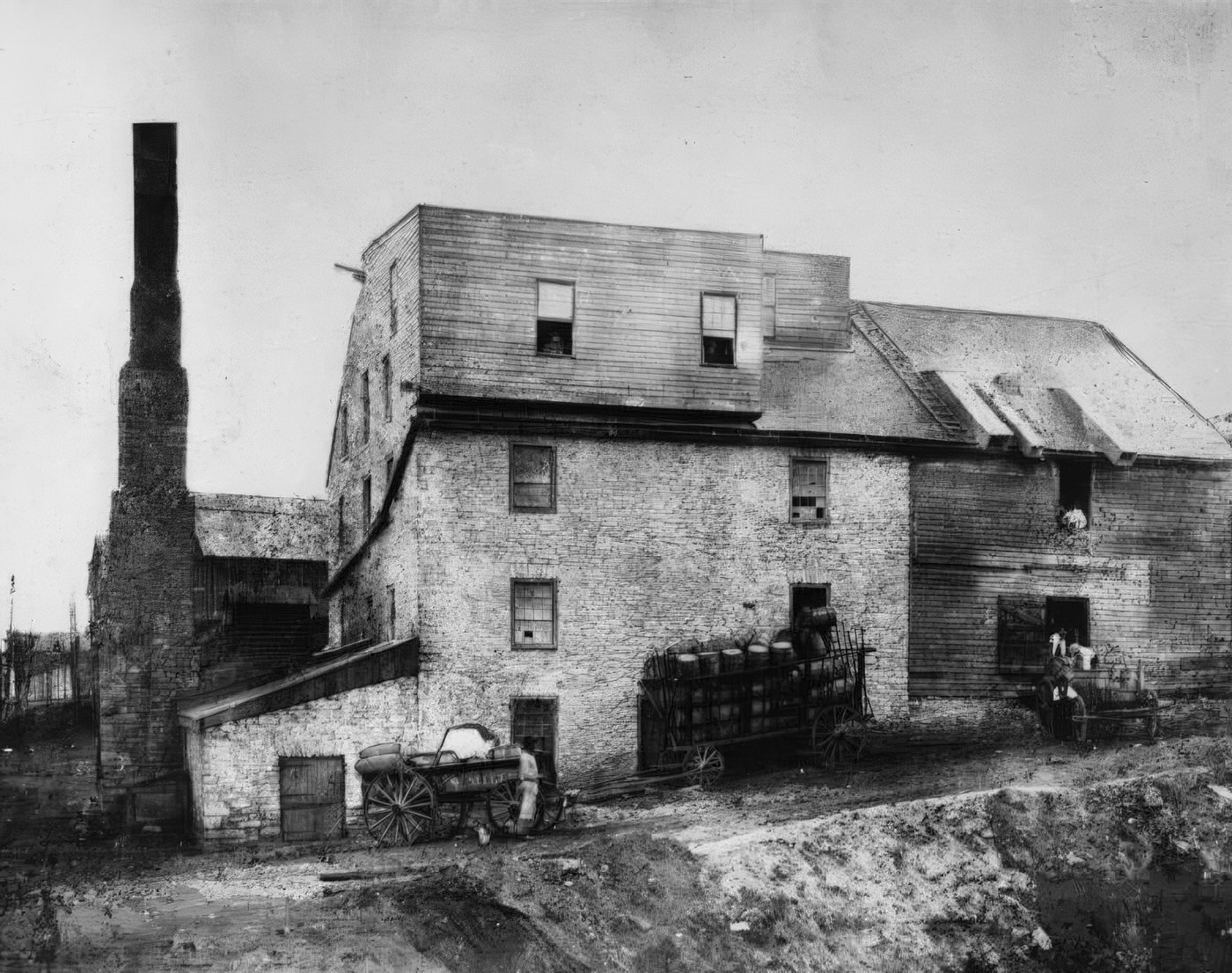

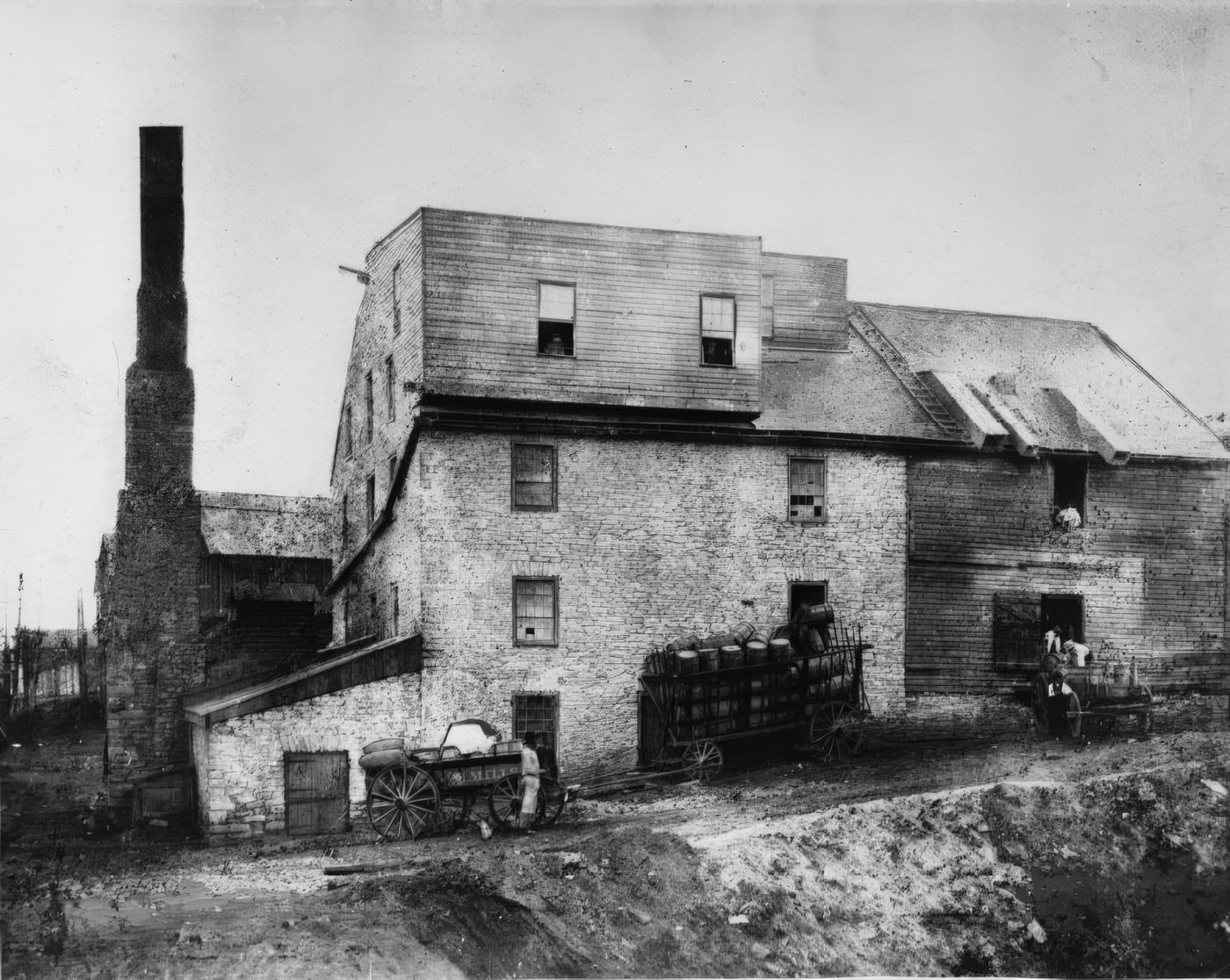

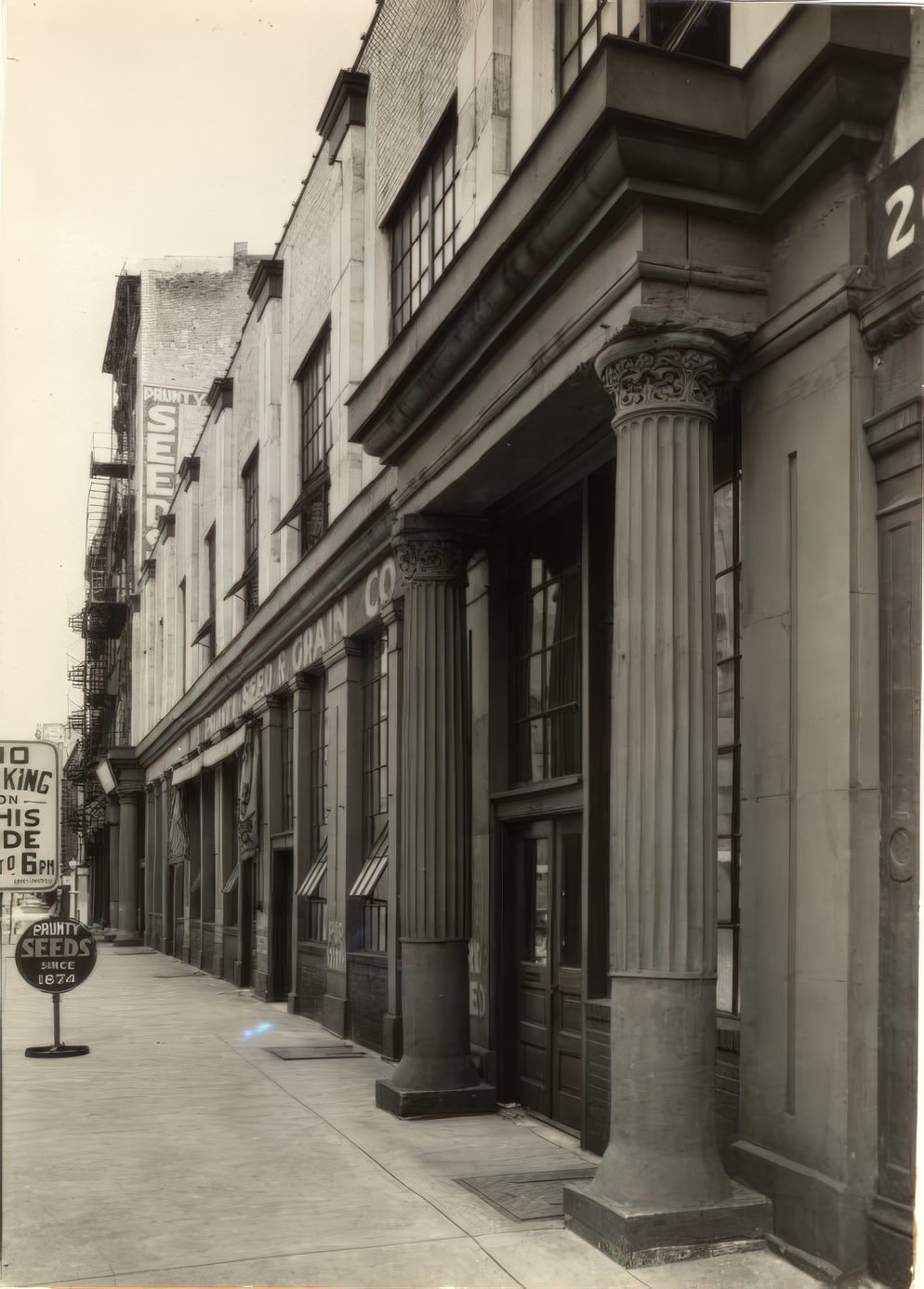

Business and Industry Struggles

The city’s diversified economy, which included food processing, chemical production, steelmaking, and clothing and shoe manufacturing, was hit hard. The International Shoe Company (ISC), headquartered in St. Louis and the world’s largest shoe manufacturer for many decades, was a major employer. During the Depression, ISC, like many other businesses, periodically laid off workers and cut wages and salaries when necessary to survive. The company also reduced the prices of its shoes and kept most of its factories operating, though at reduced levels. In 1932, ISC’s rate of return on investment dropped significantly from its 1929 high but remained positive. By 1935, the rate of return had improved. The company faced its most difficult period in the later years of the Depression, rescinding wage increases in 1938 due to another economic downturn. However, by 1939, ISC’s sales in dollars were the highest since 1930, and production surpassed any year since 1929. The Pennington-Gilbert Shoe Company in Rolla, Missouri, closed in 1932 due to financial strain, though its factory was later taken over by Johnson-Stephens and Shinkle Shoe Company in December 1933, employing up to 500 people at its peak.

Nationally, thousands of banks failed between 1930 and 1933, representing nearly a third of the banking system. Many of these were smaller, rural banks not members of the Federal Reserve System.

Poverty and Relief Efforts

The economic crisis placed immense strain on the social fabric of St. Louis. Families struggled to put food on the table, and the need for assistance grew rapidly. Across America, unemployed fathers sometimes stayed away from home during mealtimes so their children would have more to eat, often waiting in breadlines for a simple meal of soup, bread, and coffee. Many felt a personal responsibility for their family’s welfare and even blamed themselves for their situation. Breadlines and soup kitchens became common sights, operated by organizations like the Red Cross, Salvation Army, Catholic charities, and even individuals. In early 1931, New York City alone had 82 breadlines serving about 85,000 meals daily. A strong social stigma was attached to seeking such aid, as the prevailing belief was that neediness indicated a character flaw.

In St. Louis, the city government allocated $1.5 million for relief operations between 1930 and 1932, with the Salvation Army and the St. Vincent de Paul Society contributing an additional $2 million. In late 1932, voters approved a $4.6 million bond issue for more relief funds. The city balanced its budget in spring 1933 by cutting spending by 11 percent. Federal relief funds through New Deal programs began arriving in May 1933. St. Louis issued another bond for $3.6 million in February 1935. Of the total $68 million spent on relief in St. Louis from 1932 to 1936, the federal government provided the largest share ($50 million), followed by the city and local agencies ($12 million), and the state ($6 million). Direct relief aid provided by the city was distributed equitably to Black residents, despite workplace discrimination.

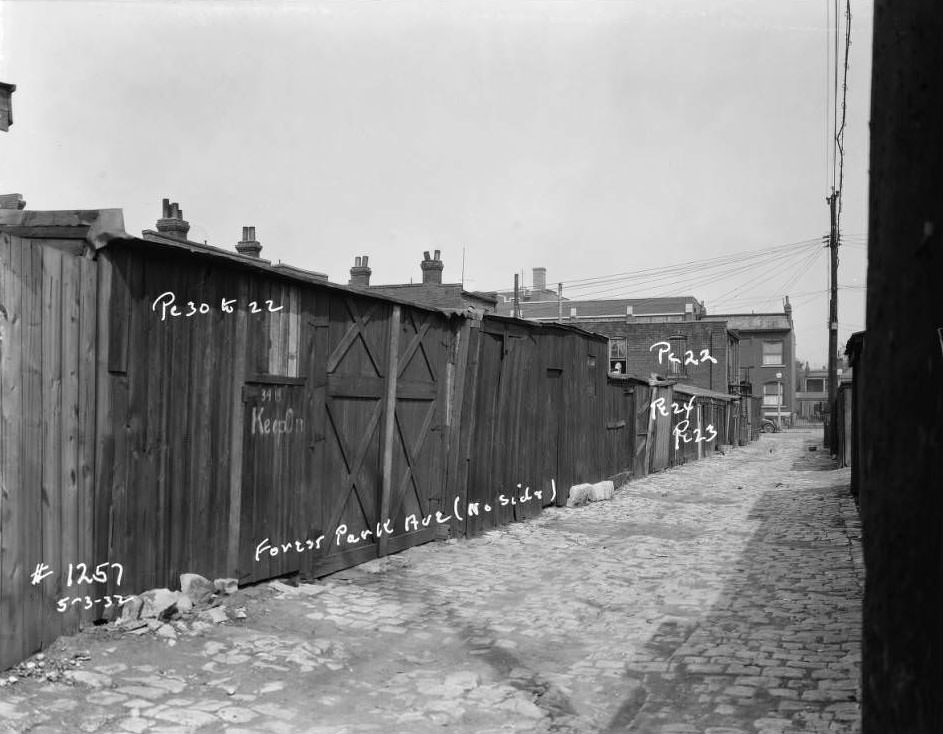

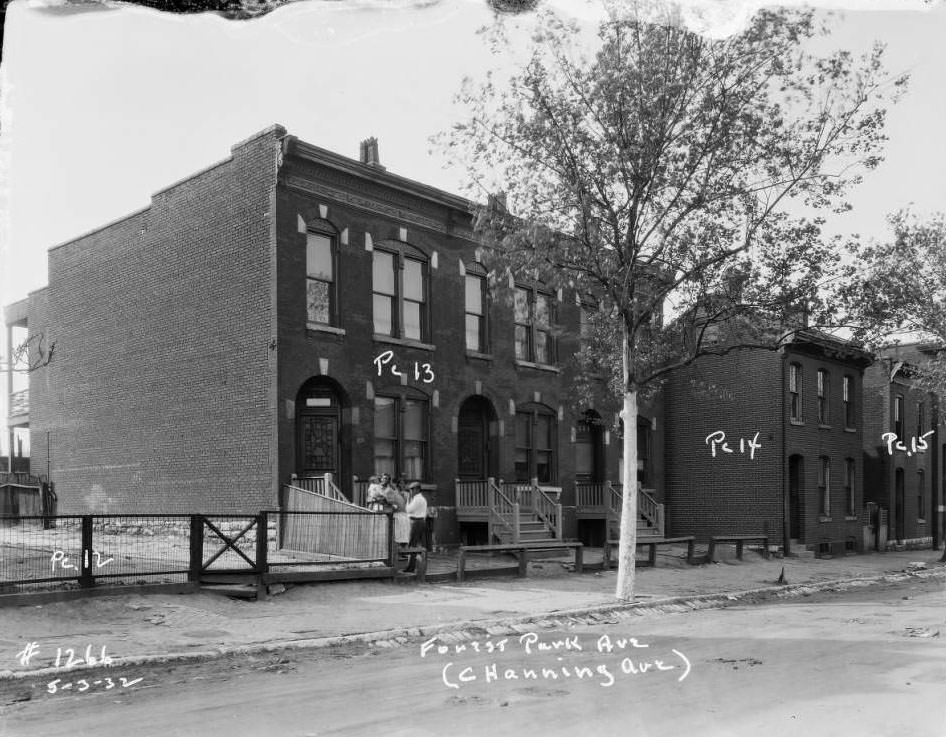

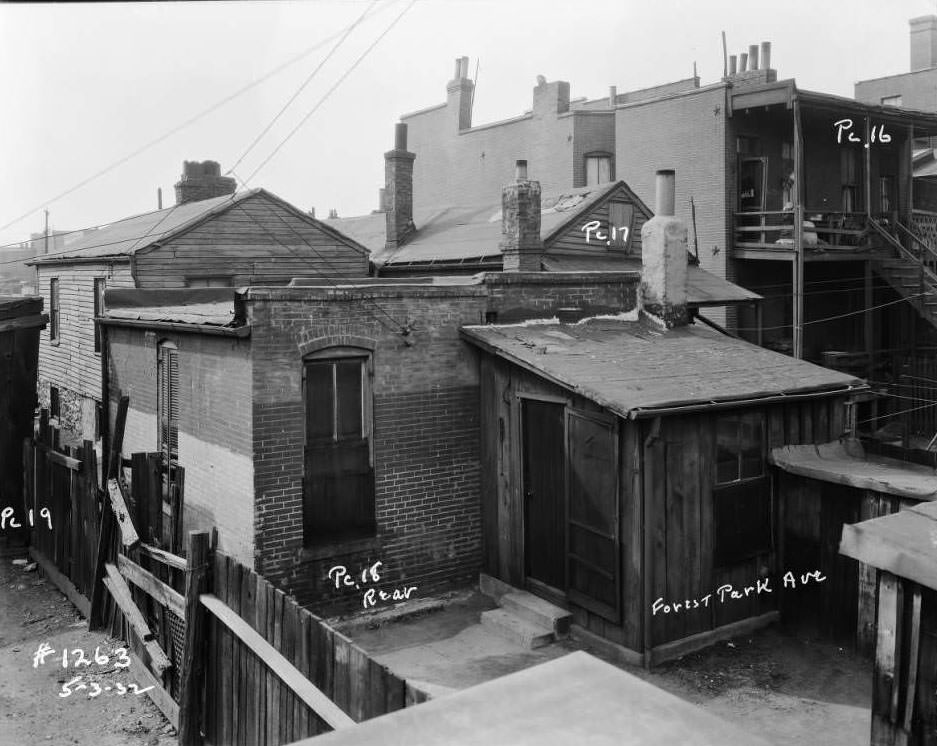

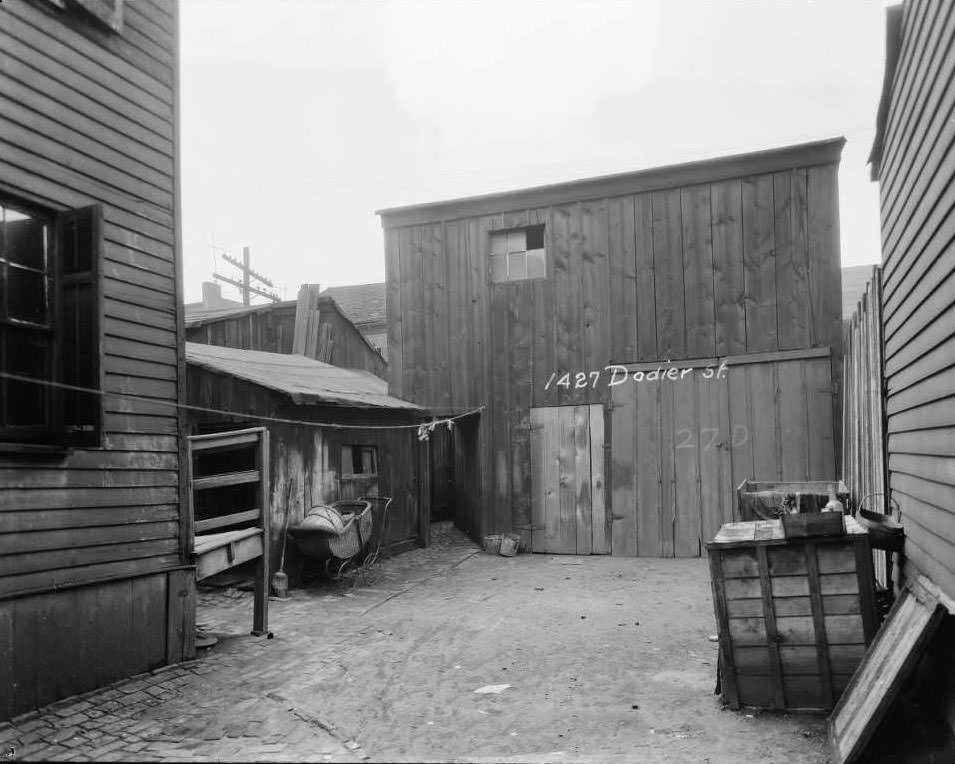

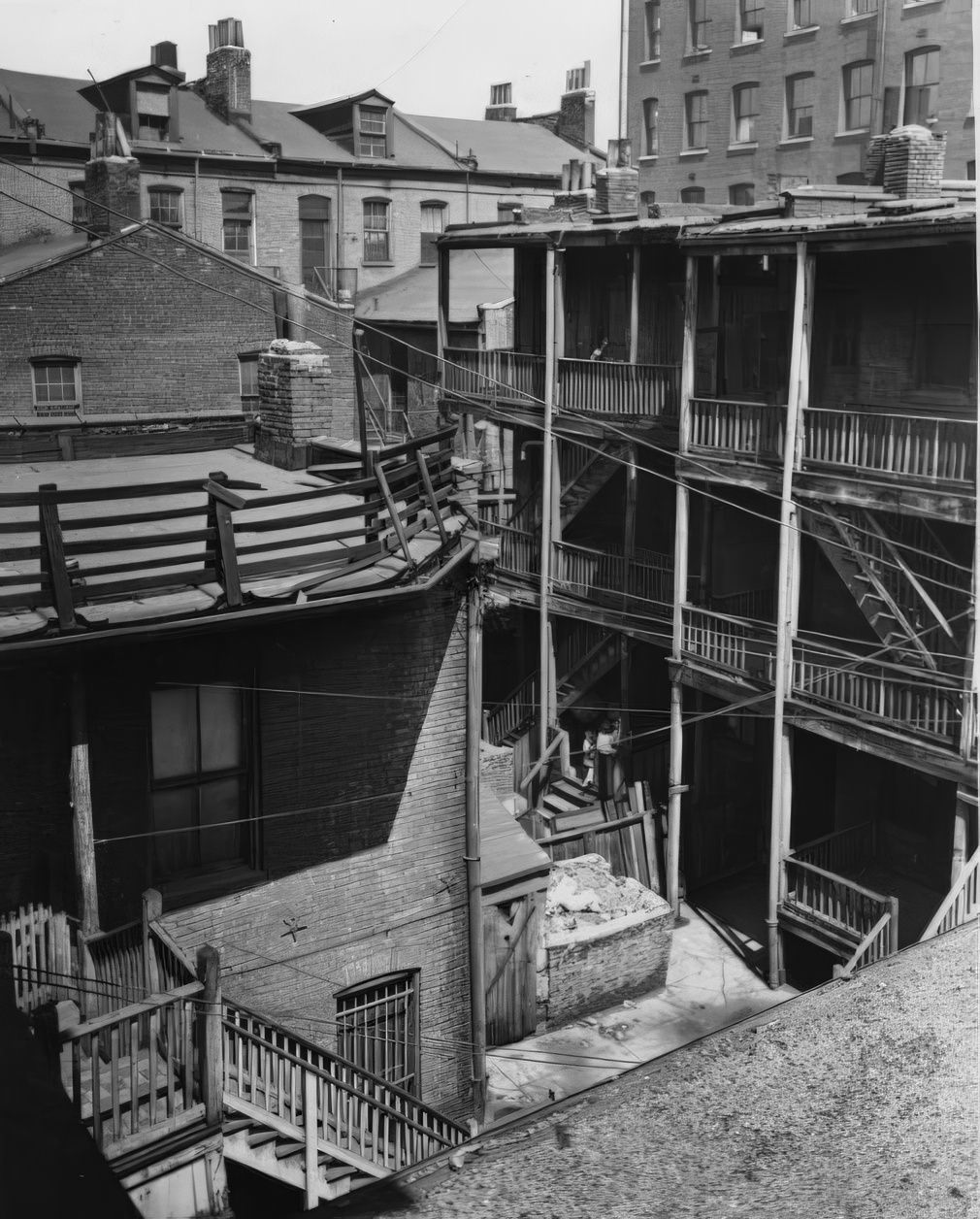

Charitable efforts within the St. Louis Hooverville included The Welcome Inn, which served up to 4,000 meals a day and acted as a community center and post office. Ruth Hornby, a local high school student, started “Ruth’s Haven,” offering a kindergarten, entertainment, and other services, supported by donations from local businesses. Much of St. Louis’s housing stock had been neglected during the Great Depression. Many residents lived in “cold water flats,” where heating required dirty Southern Illinois coal, leading to significant air pollution. Air conditioning and widespread refrigeration were uncommon outside of commercial operations like breweries. Overcrowding was an issue, with some older residents recalling nine children sleeping in a single bedroom. Sanitation in older tenements was poor, with shared latrines that were often several stories tall and reached by rickety bridges, becoming sources of disease. The filth from coal dust was a pervasive problem, affecting residents’ health.

Public Health Challenges

The 1930s brought significant public health challenges. Malnutrition became more common as diets deteriorated. Overcrowded city slums and rural shanties often had poor sanitary conditions.

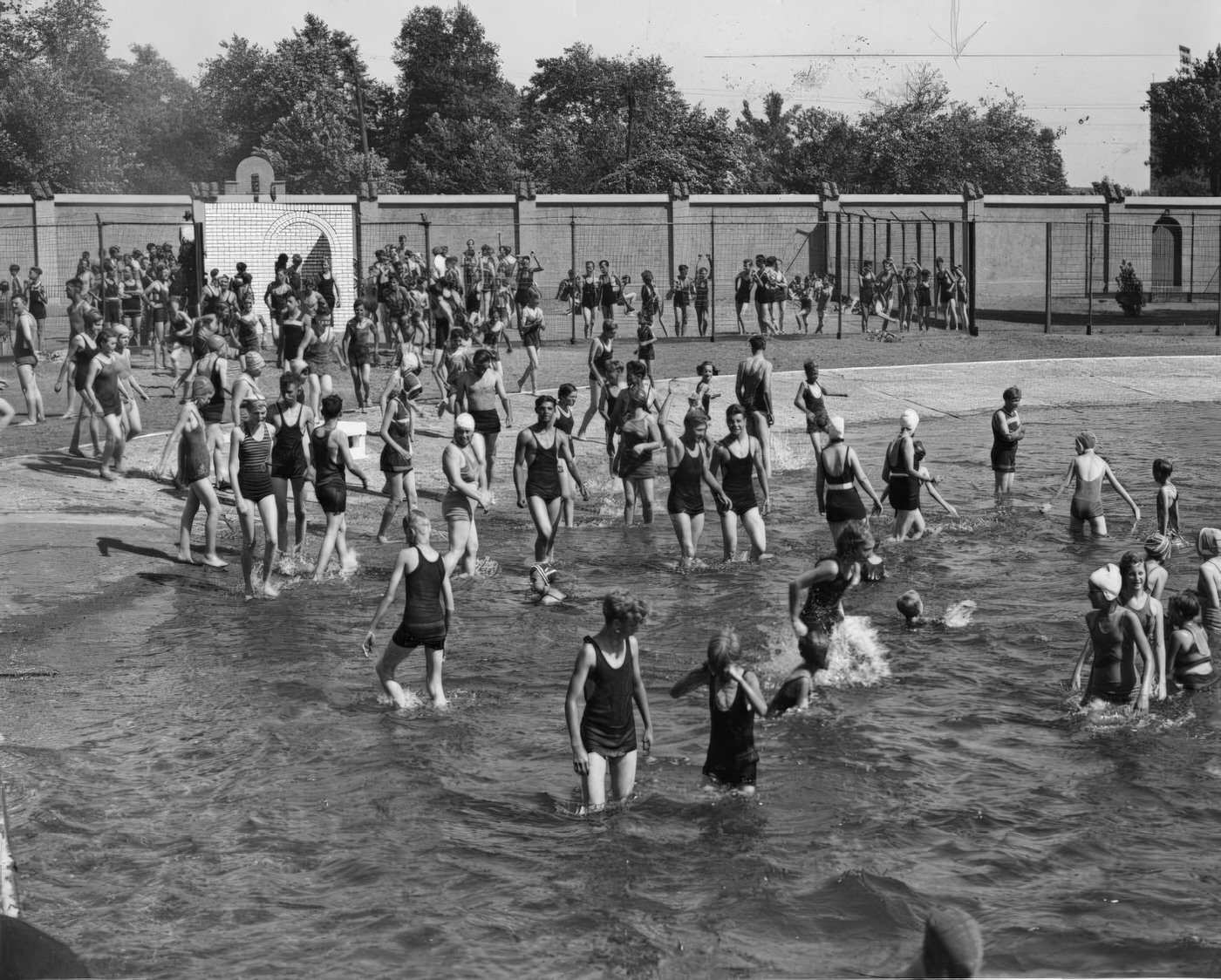

St. Louis experienced a major epidemic of St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV) in the summer of 1933. This mosquito-borne virus resulted in 1,095 clinical human cases and 201 deaths. Retrospective analysis estimated that the actual number of infections, including subclinical cases, might have affected nearly 40% of the city’s population of 821,960 (based on 1930 census data). Another SLEV epidemic occurred in St. Louis in 1937, though specific case numbers for that year are not detailed in the provided information. Urban SLE epidemics were often linked to Culex pipiens mosquitoes, which breed in aquatic habitats like storm drains and sewage treatment facilities. Missouri also saw outbreaks of other diseases historically, such as diphtheria, smallpox, and typhoid fever, with crowded conditions and poor sanitation in places like the Missouri State Penitentiary leading to chronic outbreaks.

Labor Movements and Workers’ Rights

The Great Depression initially saw a decline in labor union influence, but the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) in 1933, particularly section 7a granting workers the right to organize, sparked a resurgence in labor activism. In 1933 alone, 1.2 million people went on strike nationally, a sixfold increase from 1930.

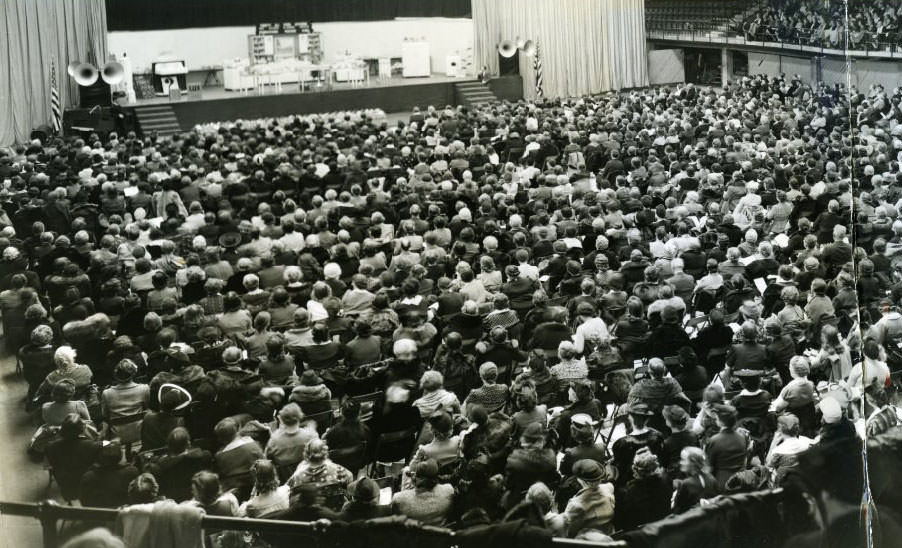

In St. Louis, Black women domestic workers faced severe exploitation. While white women often held clerical or manufacturing jobs, 79 percent of Black women in the city worked in domestic and personal service. Many employers paid no cash wages, offering only room and board, often in poor conditions like a cot in the kitchen. These workers organized with the St. Louis Urban League (UL) to fight for better conditions, as labor unions often ignored the needs of Black people and women. The UL acted as a hiring hall and helped workers organize. Following the NIRA, the St. Louis UL held a mass meeting in September 1933, attended by 500 to 1,000 people, where domestic workers demanded a living wage. In response, the UL established a minimum wage for employers using its bureau: $1.50 plus carfare for a day, or $5 plus carfare for a week. While less than requested, it was the city’s first minimum wage for domestic workers and became a standard.

A notable labor action was the 1933 Funsten Nut Strike. For eight days, about two thousand predominantly Black female industrial workers picketed five Funsten Nut Company factories. The strike was a response to racial wage disparities (Black women earned 3-4 cents per pound of shelled nuts, while white women earned 4-6 cents), unequal work assignments, longer hours with less break time for Black workers, poor and unsanitary working conditions, and repeated wage cuts. Led by radical Black working-class women like Carrie Smith, the strikers, who carried Bibles and bricks, demanded “ten and four” (ten cents per pound for halves and four cents for pieces). White women coworkers joined the picket lines by the second day, showing multiracial solidarity. The St. Louis Communist Party aided the organizers. After nine days, the company conceded, offering to nearly double their wages, a proposal unanimously approved by the strikers. This strike was a significant victory, highlighting the leadership of Black women in the labor movement and bringing attention to racial and economic injustice.

City Under New Leadership and New Deals

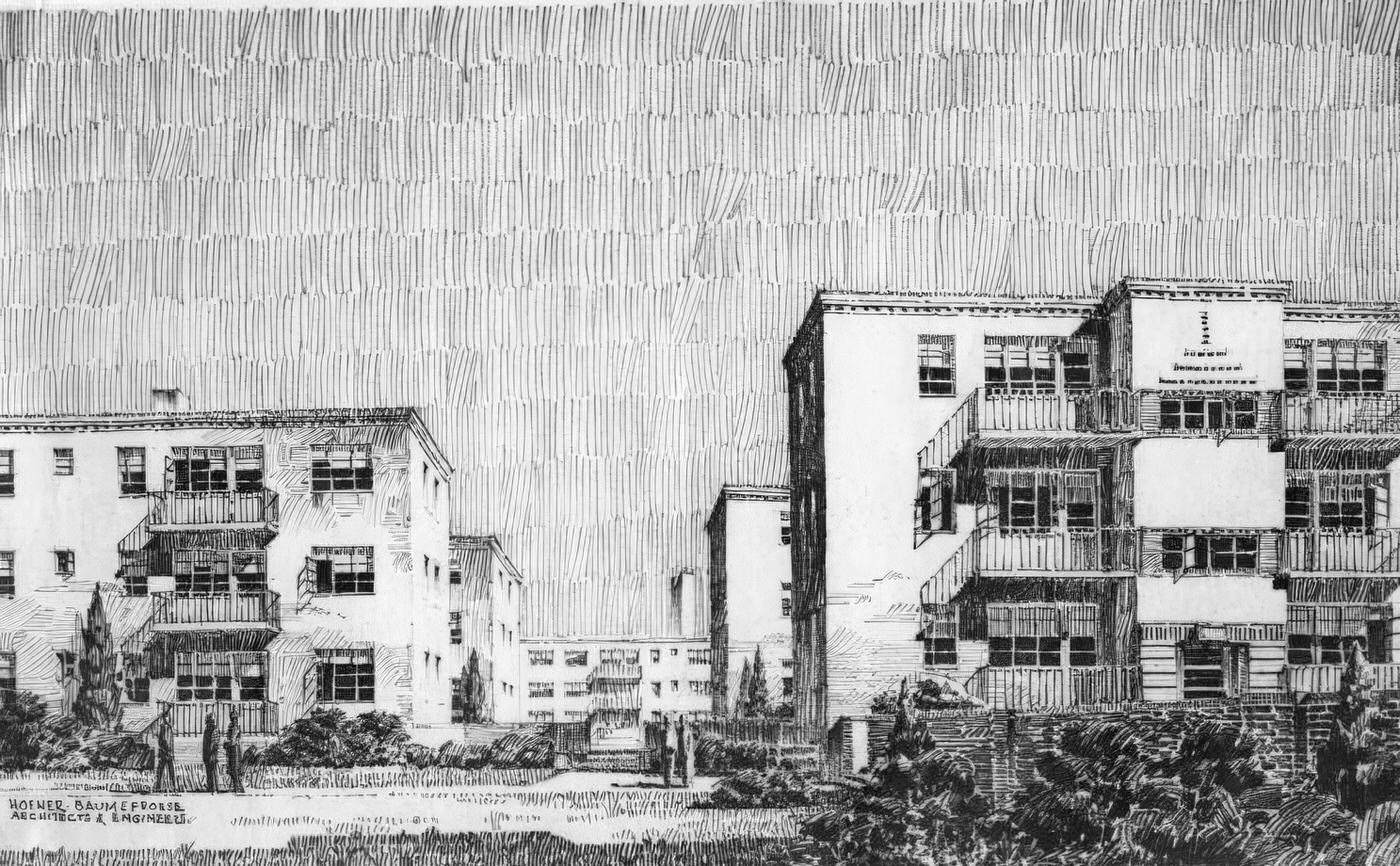

The 1930s saw changes in city leadership and the arrival of federal New Deal programs aimed at combating the Depression.

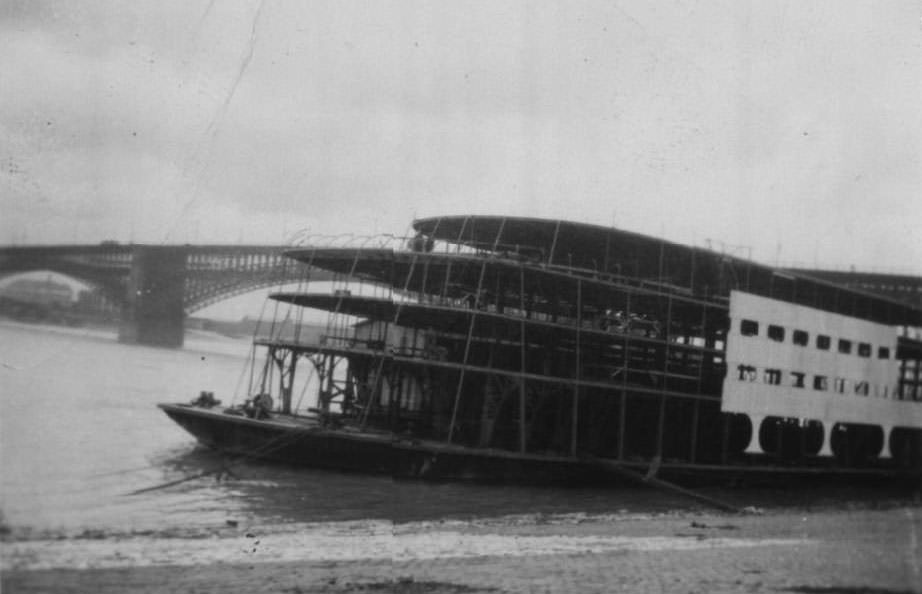

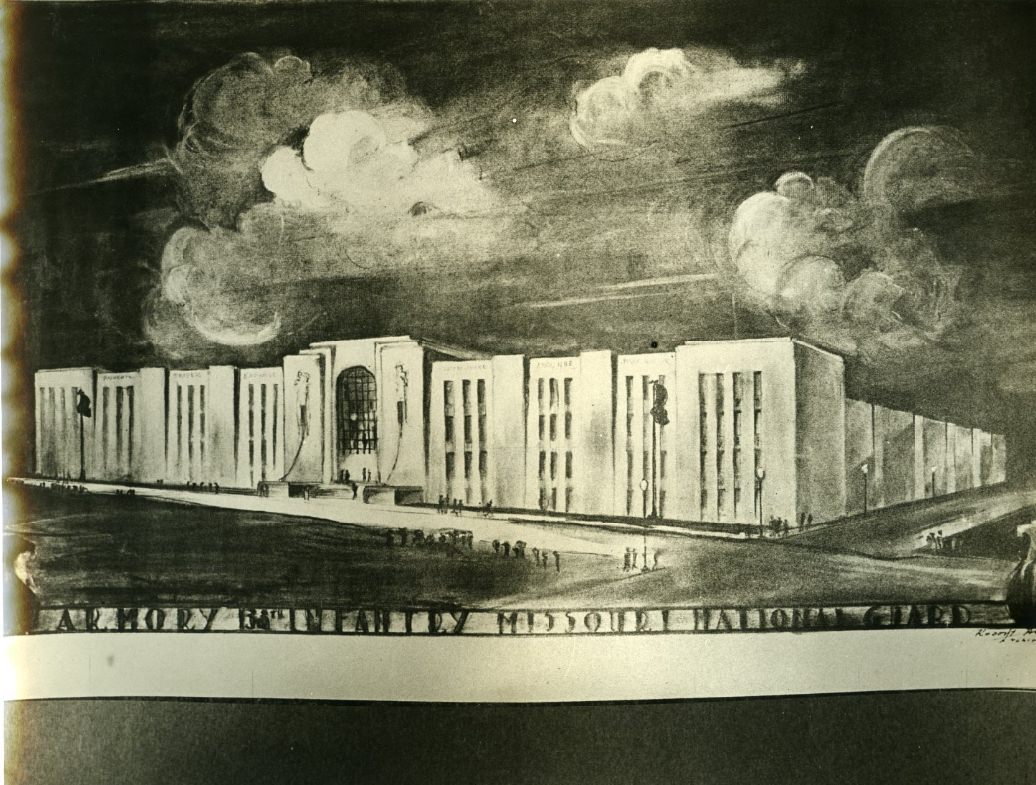

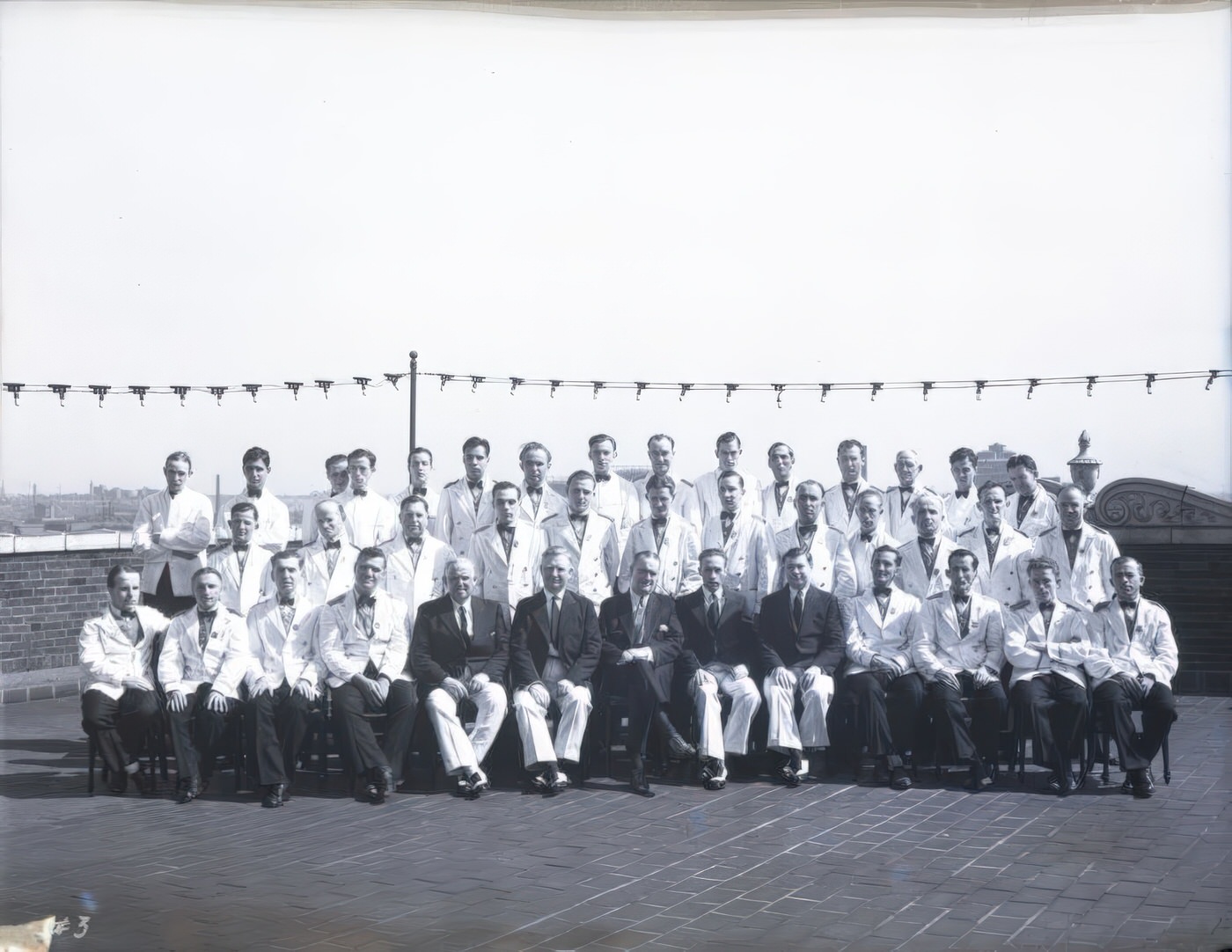

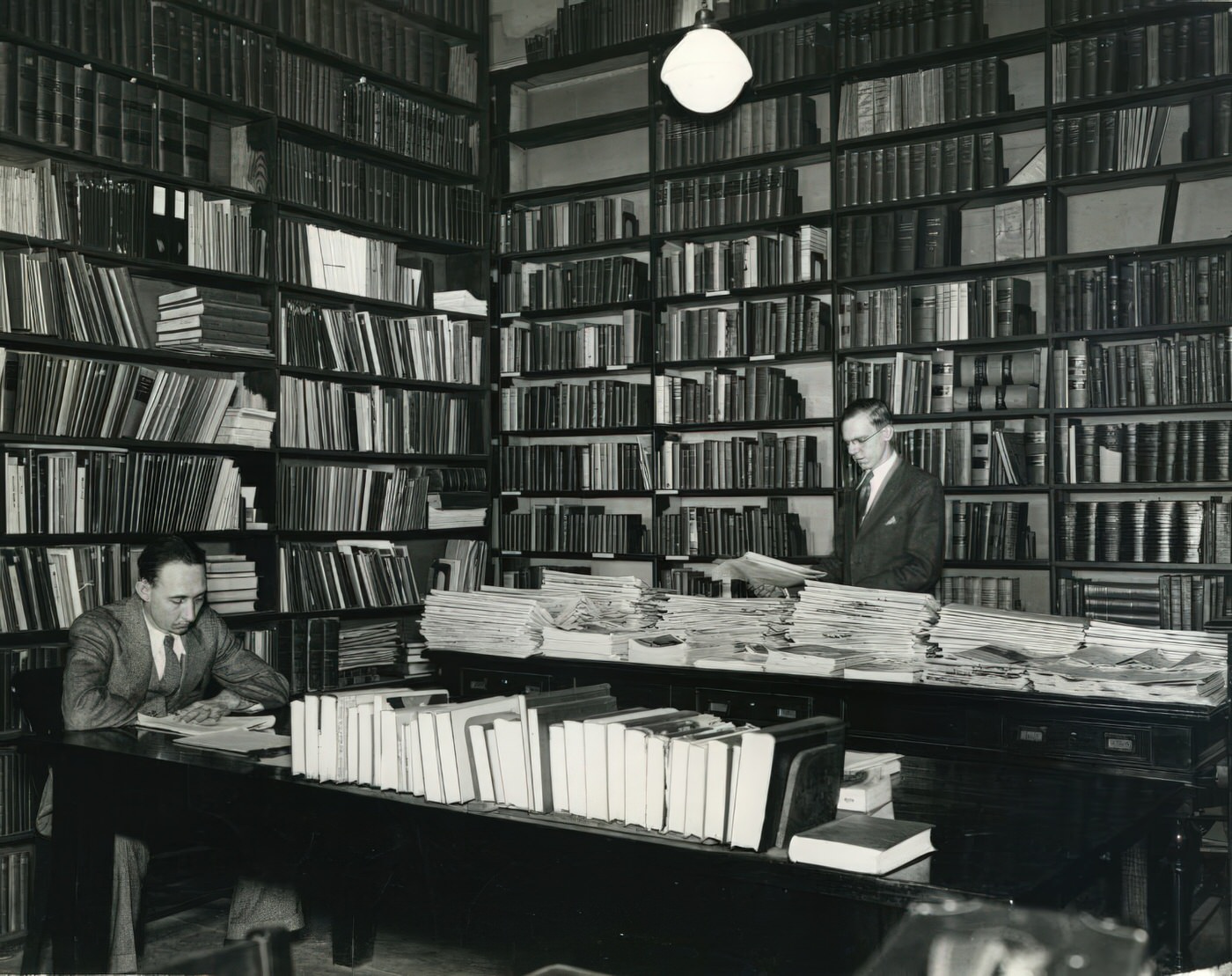

Bernard F. Dickmann became the first Democratic mayor of St. Louis in 24 years, serving two terms from 1933 to 1941. His administration faced the enormous task of guiding the city through the Depression. Key accomplishments included the completion of the Municipal Auditorium (later Kiel Auditorium) and the Civil Court building, and the installation of electric streetlights throughout the city. The initial steps for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, which would later feature the Gateway Arch, were taken during his tenure. His administration also passed a standard milk ordinance and an anti-smoke ordinance. In 1941, a civil service amendment to the city charter placed municipal employees under civil service, aiming for a more merit-based system. Dickmann initiated the first comprehensive survey of the city’s government, services, and finances to improve efficiency.

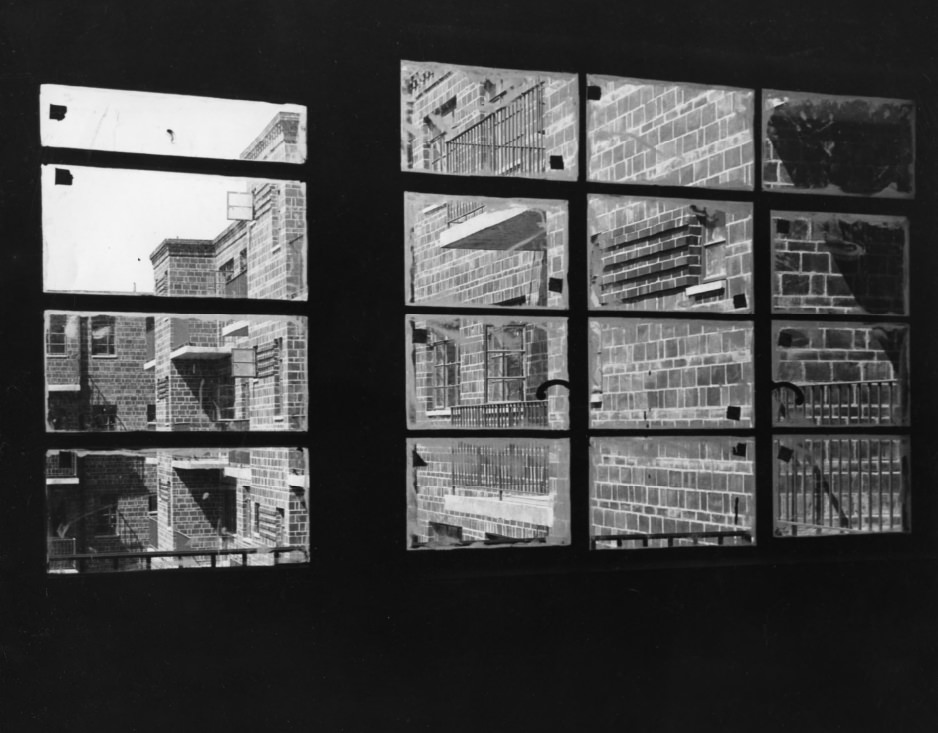

One of Mayor Dickmann’s most significant challenges was the city’s severe smoke pollution problem. For years, St. Louis had struggled with air quality due to the burning of soft, bituminous coal for heat and power. In February 1937, a Smoke Ordinance was passed, creating the Division of Smoke Regulation. Raymond R. Tucker was appointed City Smoke Commissioner. Tucker used newspapers and radio to educate the public on cleaner power and his inspectors examined furnaces and coal supplies. Despite these efforts, and a reduction in emissions from commercial smokestacks by 1938, the problem persisted, especially from smaller businesses and domestic users where 97% of homes still used coal. The city council was initially hesitant to pass stricter laws.

The infamous “Black Tuesday” smog event of November 28, 1939, when thick black smoke turned day into night, and nine subsequent days of intense smog, finally forced decisive action. The city secured cleaner, affordable semi-anthracite (hard) coal from Arkansas. This, along with a new smoke ordinance and furnace improvements, led to a significant and permanent improvement in air quality. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch played a crucial role with its campaign for cleaner air, for which it won a Pulitzer Prize in 1941.

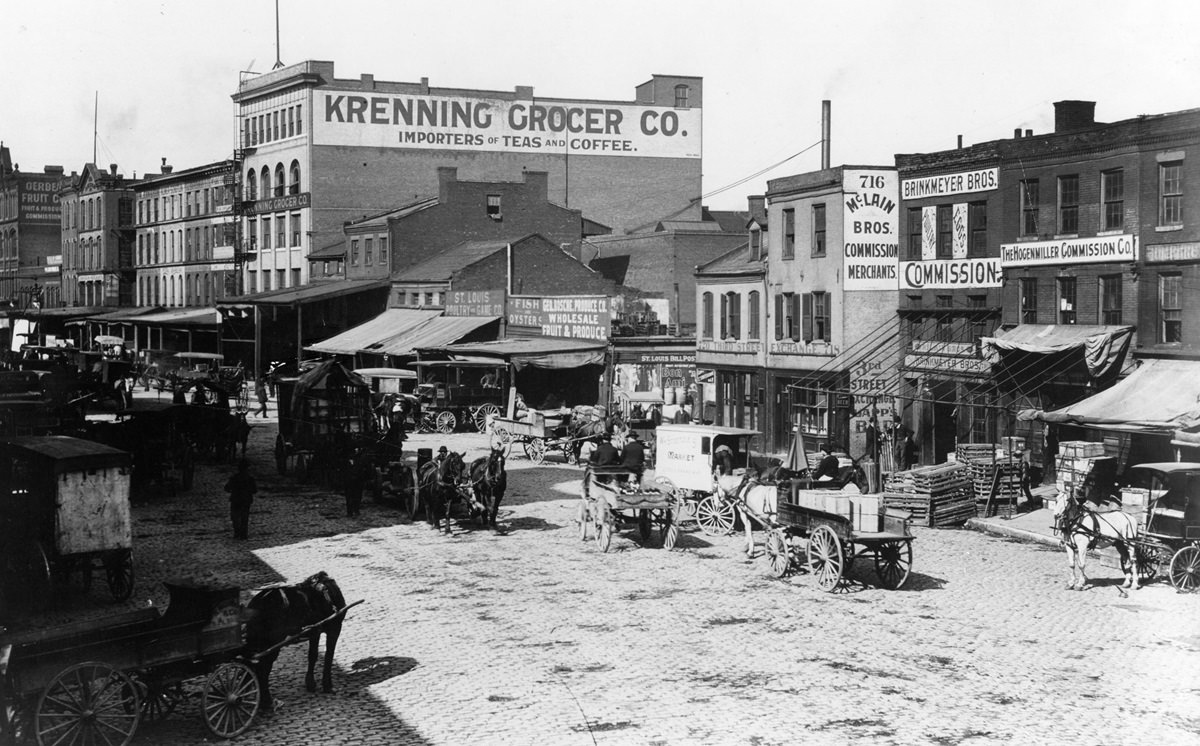

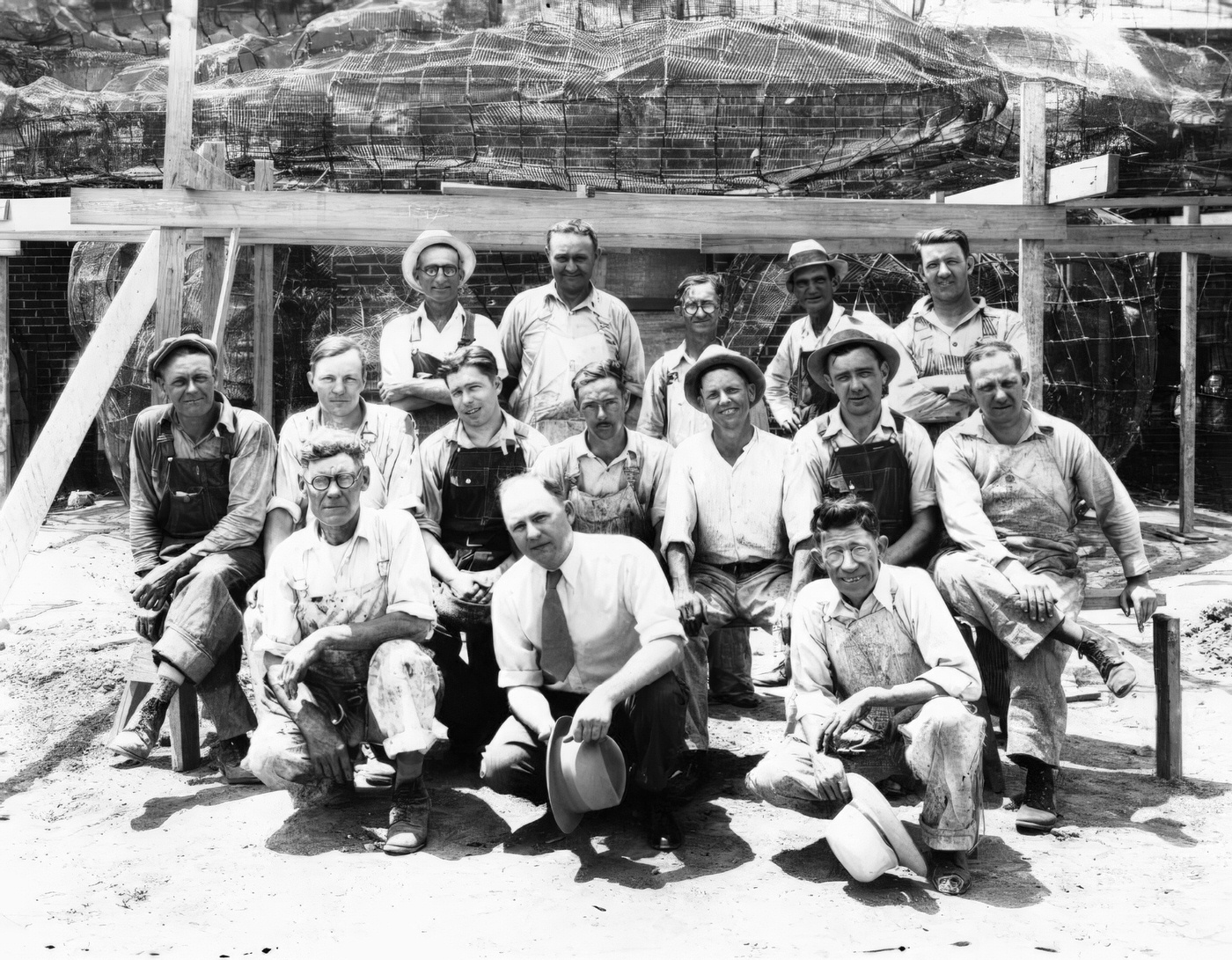

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs provided crucial relief and employment. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), established in 1935, created jobs for millions of unemployed Americans on useful public projects. In Missouri, the WPA helped further develop Forest Park, including the construction of the Jewel Box and the Municipal Opera buildings. The WPA’s Federal Art Project (FAP) employed artists, writers, and actors. In St. Louis, FAP murals were created in public buildings, such as “Louisiana Purchase Exposition” by Trew Hocker in the University City Post Office and “Old Levee and Market at St. Louis” by Lumen Martin Winter at the Wellston Public School. Edward Millman and Mitchell Siporin painted historical cycles at the St. Louis Post Office. FAP sculptures included “Courage, Vision, Sacrifice, Loyalty” by Walker Hancock in Memorial Plaza and “Law and Order” and “Equal Justice” by Benjamin Hawkins in the Customs House. The construction of the Jewel Box was, in part, a response to the high levels of smog and soot, as it was designed to protect plants. These projects provided livelihoods and also enriched the city’s cultural and physical landscape.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), established in 1933, provided national conservation work for young, unmarried men. They planted trees, built parks, and worked on flood control. CCC camps operated near St. Louis, undertaking projects in state parks. These included Meramec State Park (Companies #739, #2728), Washington State Park (Company #1743-C), Cuivre River State Park (Company #739), and Babler State Park (Companies #2729, #3763). New Deal programs like the Public Works Administration (PWA) also provided employment for thousands in St. Louis, and bond issues for airport construction and city beautification helped reduce unemployment. The number of people on direct relief in St. Louis fell from over 100,000 in 1933 to 35,000 in 1936 due to these combined efforts.

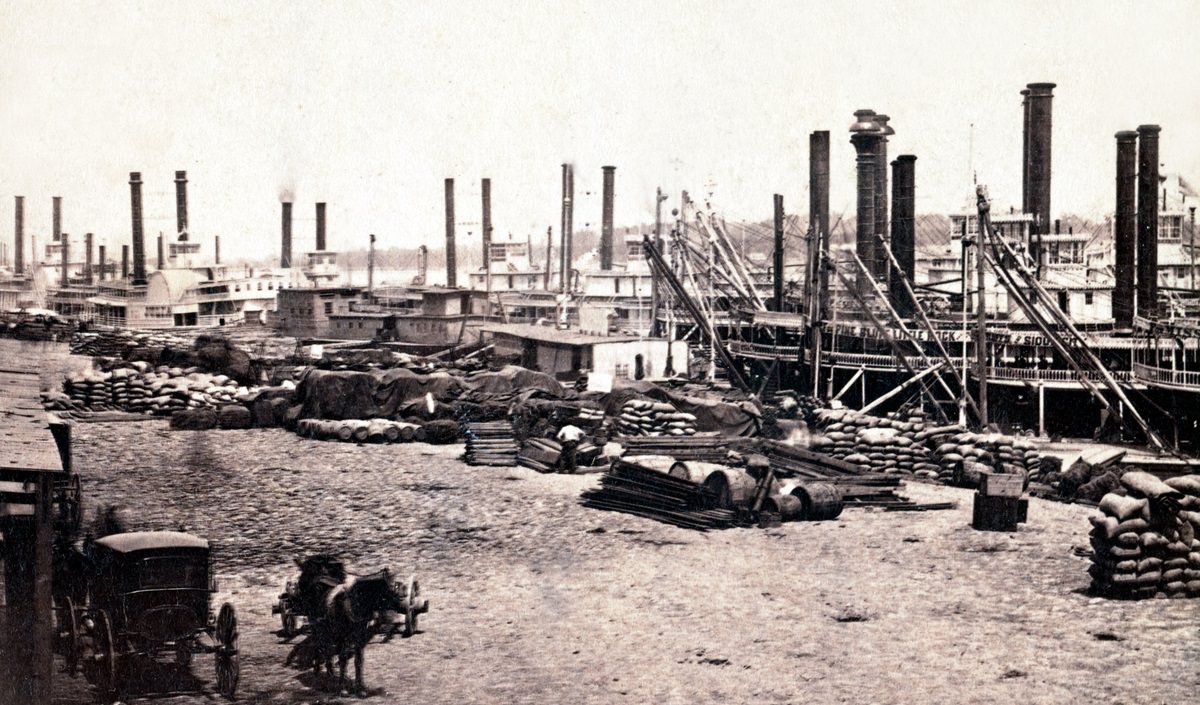

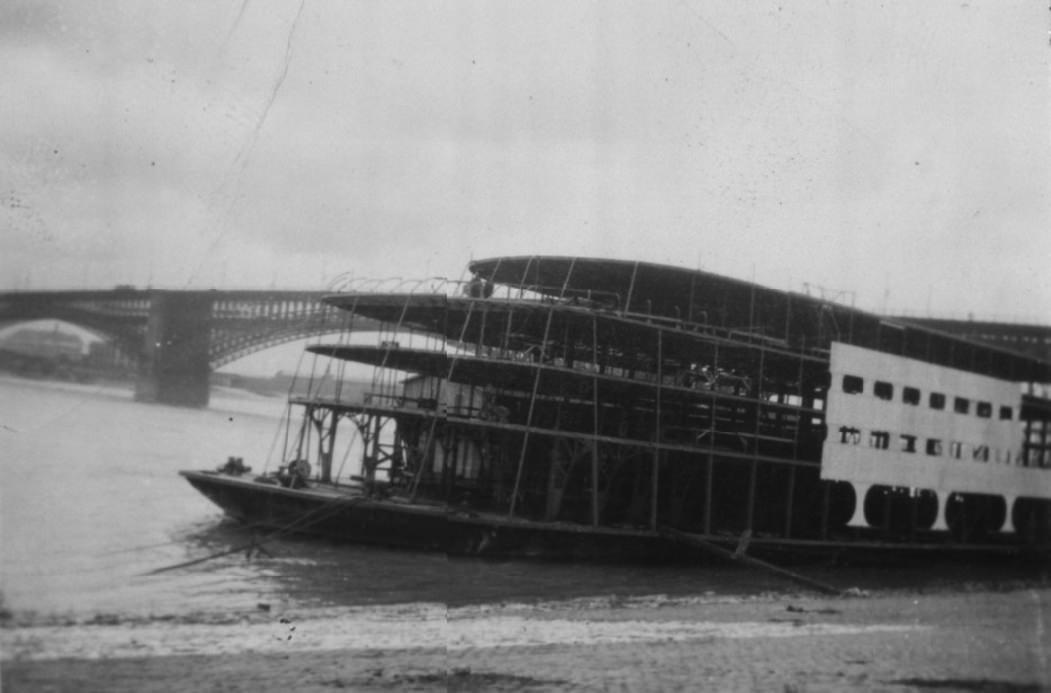

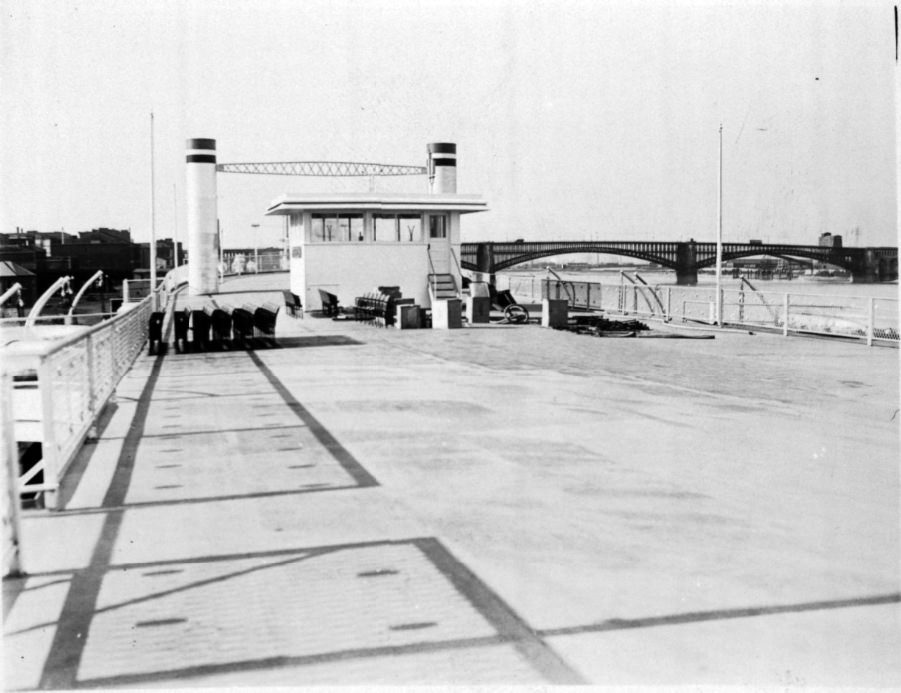

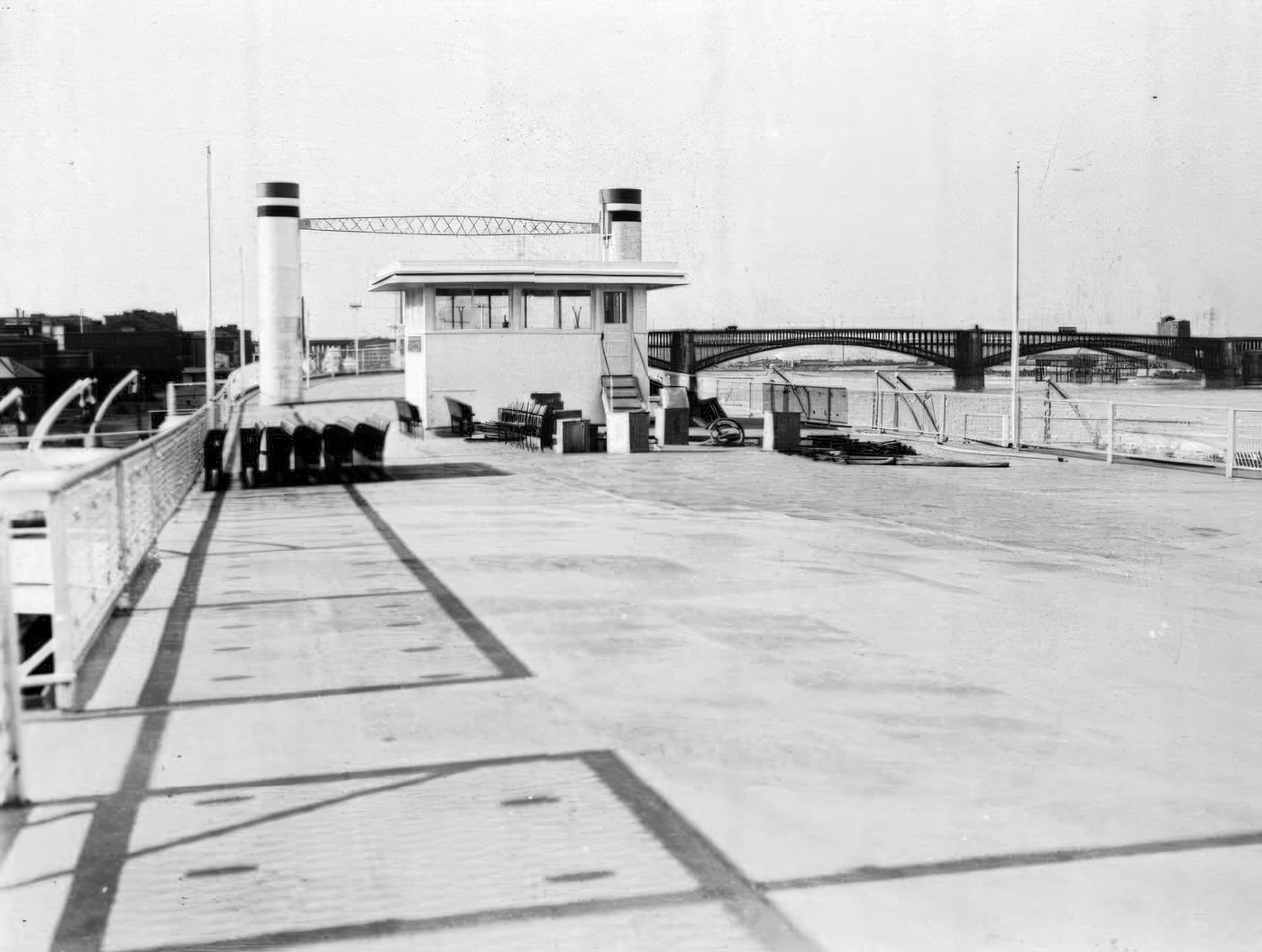

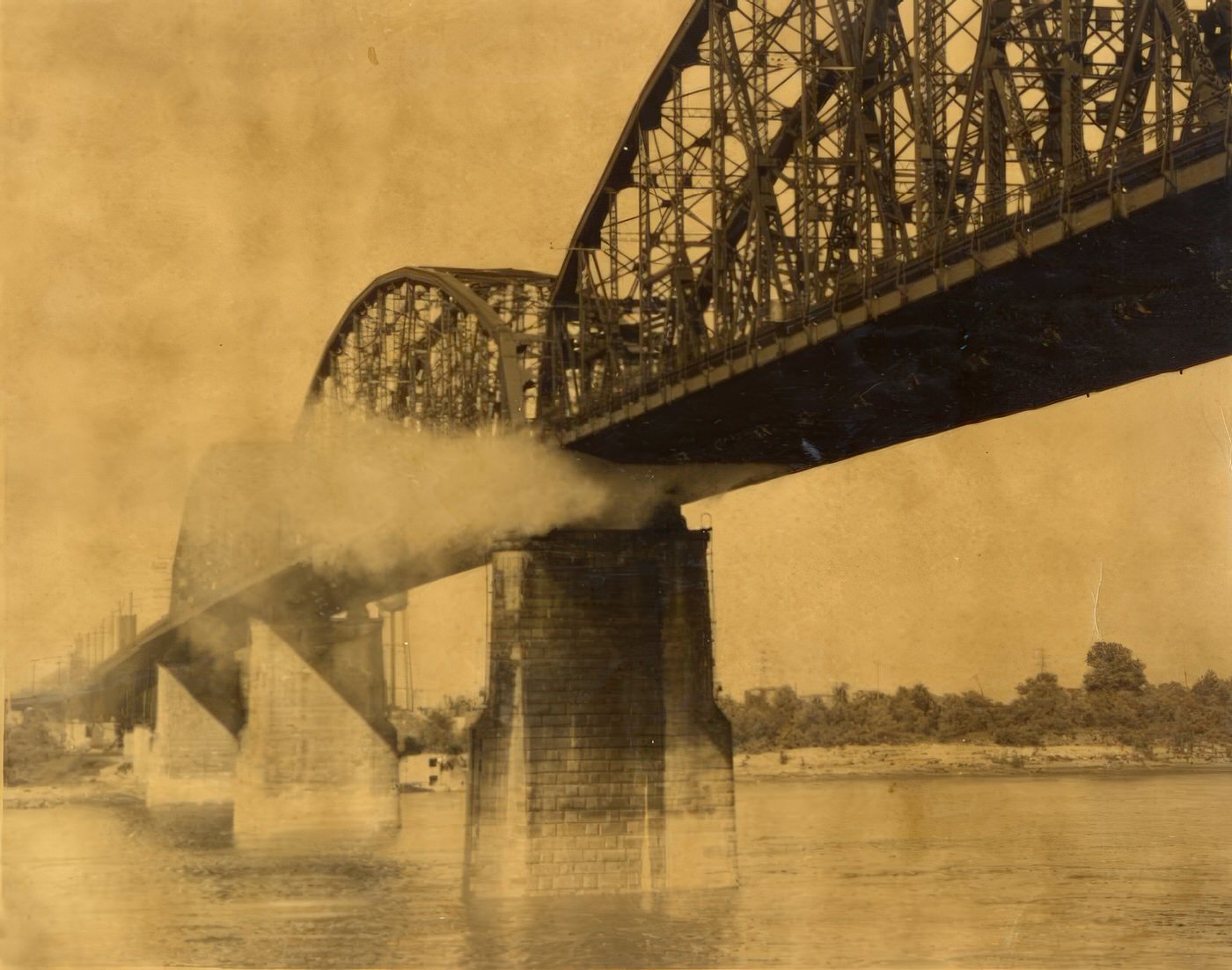

St. Louis’s history is intrinsically linked to the Mississippi River as a vital trade route. Plans to deepen the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers for improved navigation were approved in the 1920s, but President Hoover blocked funding. Work finally began in 1933 under President Roosevelt as a Great Depression initiative. By 1940, twenty-nine locks and dams were completed. This massive infrastructure project allowed heavier commercial barges to transport goods like oil, coal, chemicals, fertilizers, raw materials, and agricultural products, laying the groundwork for future economic activity. While the immediate impact on St. Louis trade volume during the Depression years is not clearly quantified in the available information, the federal investment demonstrated a long-term strategy for economic recovery and development by enhancing this critical waterway.

Life Goes On: Culture, Crime, and Commute

Despite the economic despair, daily life continued, with St. Louisans finding ways to cope, entertain themselves, and navigate their city.

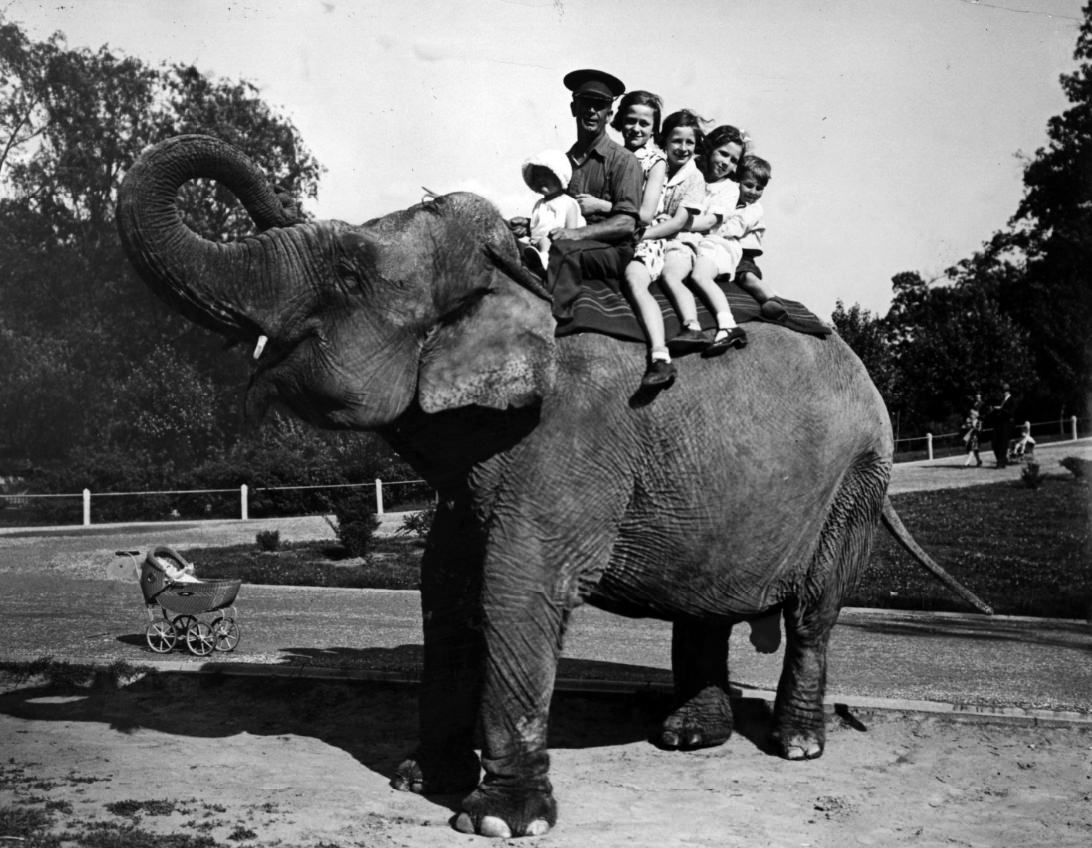

Escapism and Entertainment

Nationally, movie attendance surged during the Depression, with approximately 65% of the U.S. population going to the cinema weekly in 1930. Movies offered an affordable escape. St. Louis boasted grand movie palaces. The Fox Theatre, an opulent venue with “Siamese Byzantine” architecture, opened in 1929 with 5,060 seats and featured a large Wurlitzer organ. It was a premier spot for films and stage shows. The Art Deco-style Beverly Theater in University City was built in 1937. These venues provided a temporary reprieve from the harsh realities of the era.

The Sounds of the City

St. Louis maintained a vibrant music scene, particularly for jazz and blues, with influences from New Orleans and the wider region. East St. Louis, Illinois, was a blues hotbed. Pianist Peetie Wheatstraw, known as “The Devil’s Son in Law,” gained popularity in the 1930s with his songs reflecting working-class struggles. Musicians from Mississippi riverboats often played improvised jazz in city clubs after their official duties. Notable jazz clubs of the era in St. Louis included Club Riviera, Peacock Alley, and Club Plantation. Prominent musicians like trumpeter Clark Terry began their careers in St. Louis bands during this time. Miles Davis, who grew up in East St. Louis, also started his musical journey in the area, playing at Club Riviera in the early 1940s. This active music scene provided both entertainment and a cultural identity for the city.

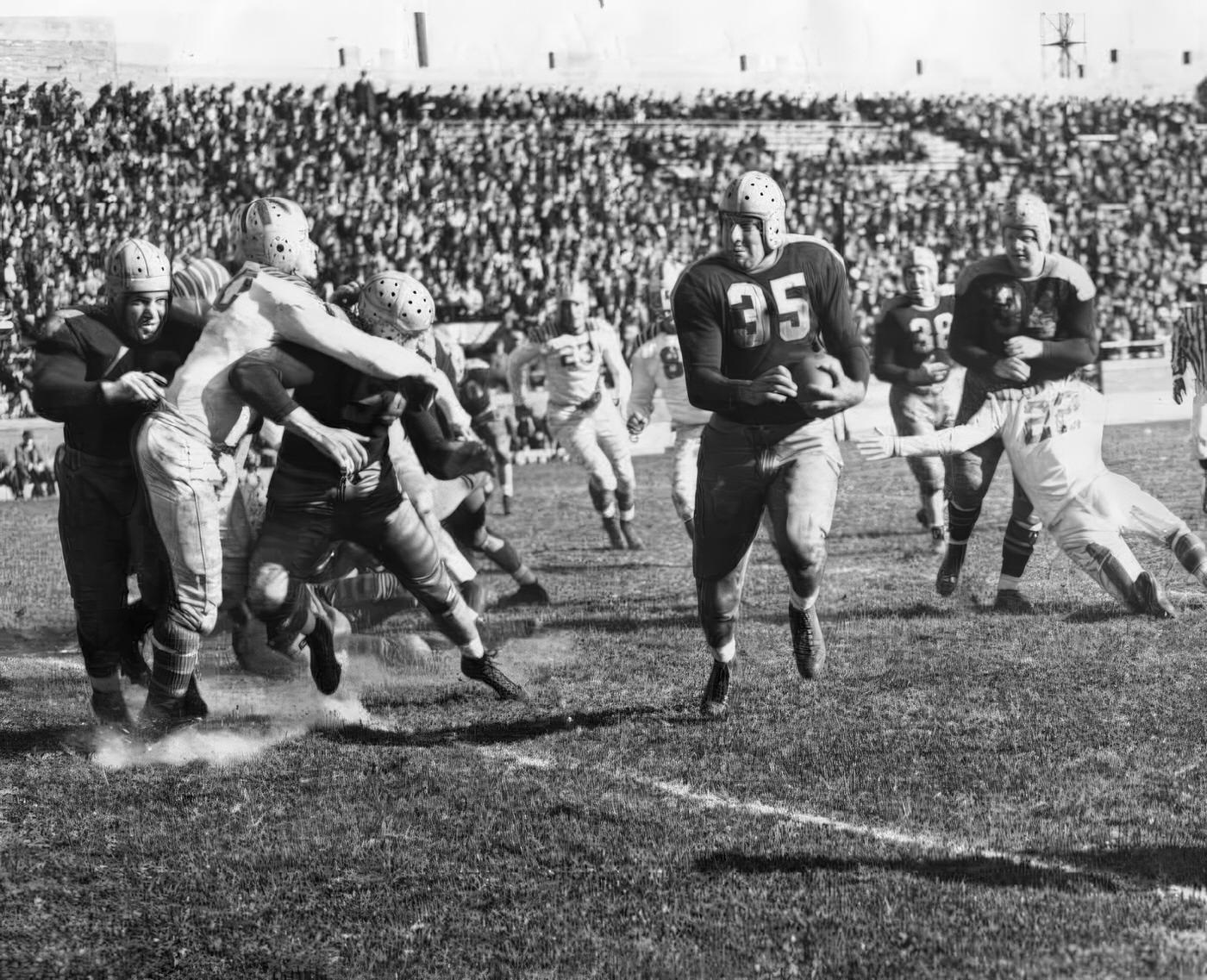

Sporting Life

St. Louis was home to two Major League Baseball teams: the St. Louis Cardinals (National League) and the St. Louis Browns (American League). In 1930, the Cardinals won the National League pennant but were defeated by the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. The St. Louis Stars, a Negro National League baseball team, achieved success, winning championships in 1928, 1930, and 1931. For a brief period, St. Louis also had an NHL team, the St. Louis Eagles, which played the 1934-35 season after relocating from Ottawa. Sports provided a popular diversion and a source of civic pride.

Navigating the City

The extensive streetcar system was the primary mode of public transportation. A route numbering system was implemented in 1928. During the 1930s, some streetcar lines began to be converted to bus routes. For example, the widening of Vandeventer Avenue in 1930 led to the replacement of streetcars with buses on that line, as the city preferred the removal of overhead wires if streetcars were discontinued. Other conversions followed around 1940. The St. Louis Car Company was a local manufacturer of streetcars, including the modern PCC cars. Despite these changes, the core streetcar system remained largely intact and would handle increased ridership during World War II. The #1 Kirkwood-Ferguson line, for instance, operated until 1950 , indicating that urban development and transportation modernization continued even amidst economic hardship.

The Shadow of Crime

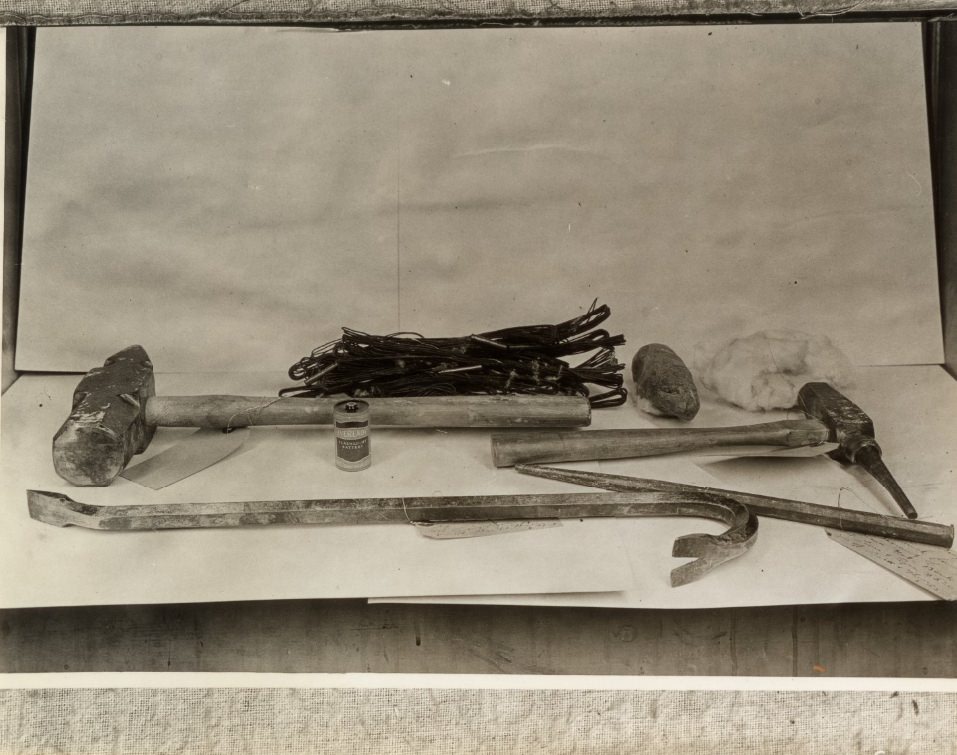

The Great Depression era saw a rise in organized crime nationally, with “gangsters” involved in activities like bootlegging (until Prohibition ended in 1933), kidnapping, and bank robbery. Missouri became a significant area for such criminal networks. The St. Louis Division of the FBI was actively involved in combating this crime wave. While violent crime rates, including homicide, initially increased in the early 1930s (the national homicide mortality rate reached 9.7 per 100,000 people in 1933), they began to decline by 20 percent between 1934 and 1937 and continued to fall for the remainder of the decade. This reduction was likely influenced by the economic improvements brought by New Deal programs and the end of Prohibition. This suggests that while desperation fueled some criminal activity, broader societal interventions and economic recovery played a role in mitigating it.

Image Credits: Library of Congress, St. Louis Public Library, University of Missouri Digital Libraries, wikimedia, Missouri Digital Heritage, The State Historical Society of Missouri

Found any mistakes? 🥺 Let us Know